User login

Scleromyxedema in a Patient With Thyroid Disease: An Atypical Case or a Case for Revised Criteria?

Scleromyxedema (SM) is a generalized papular and sclerodermoid form of lichen myxedematosus (LM), commonly referred to as papular mucinosis. It is a rare progressive disease of unknown etiology with systemic manifestations that cause serious morbidity and mortality. Diagnostic criteria were initially created by Montgomery and Underwood1 in 1953 and revised by Rongioletti and Rebora2 in 2001 as follows: (1) generalized papular and sclerodermoid eruption; (2) histologic triad of mucin deposition, fibroblast proliferation, and fibrosis; (3) monoclonal gammopathy; and (4) absence of thyroid disease. There are several reports of LM in association with hypothyroidism, most of which can be characterized as atypical.3-8 We present a case of SM in a patient with Hashimoto thyroiditis and propose that the presence of thyroid disease should not preclude the diagnosis of SM.

Case Report

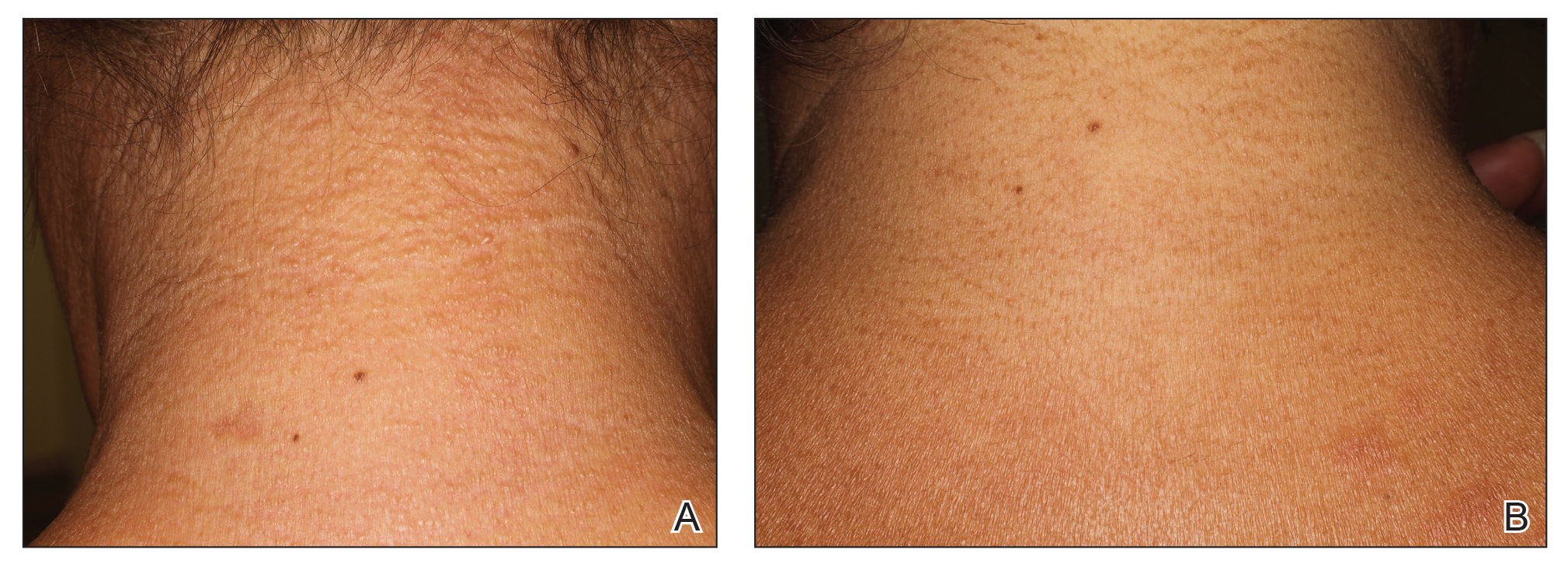

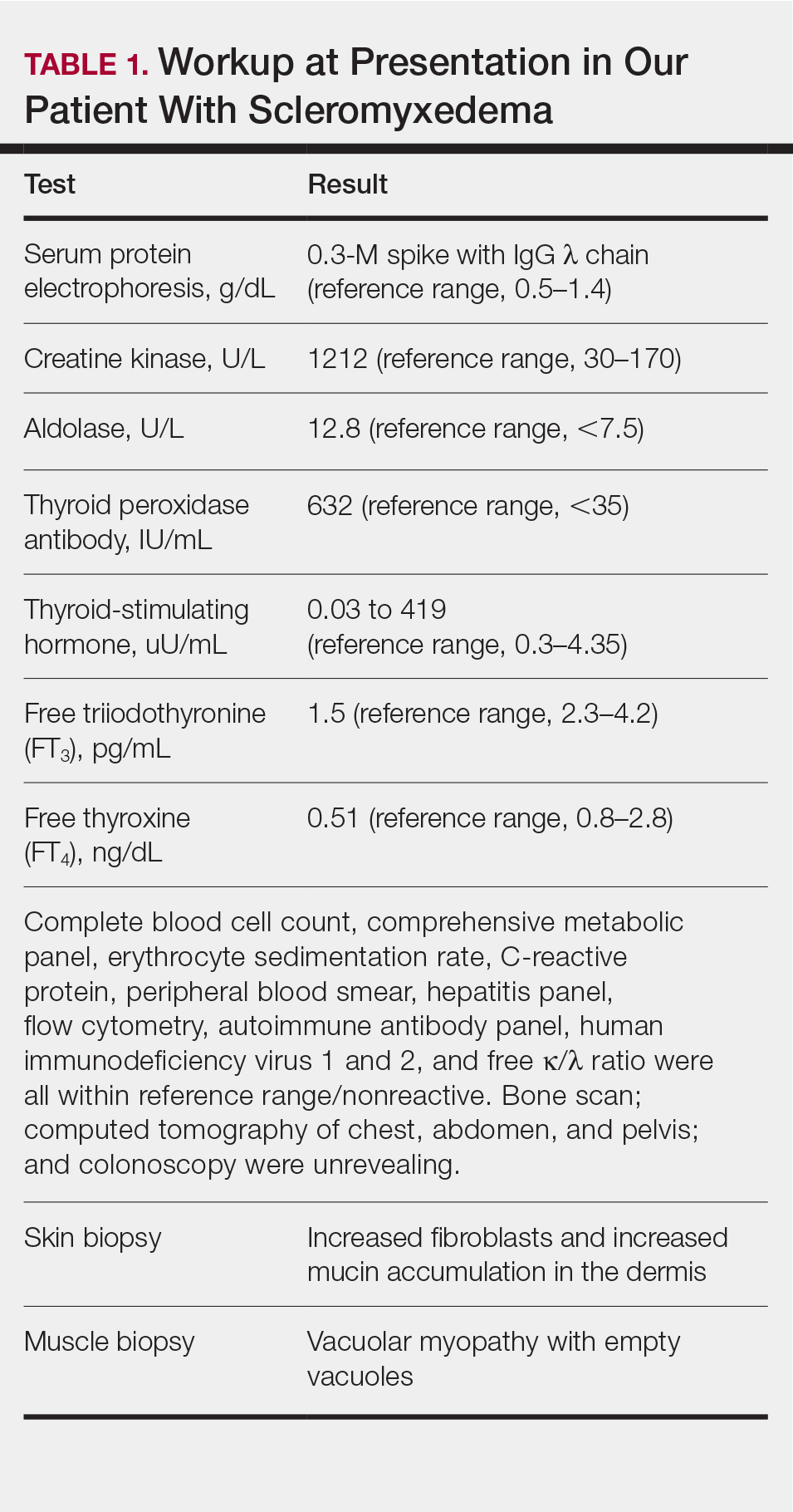

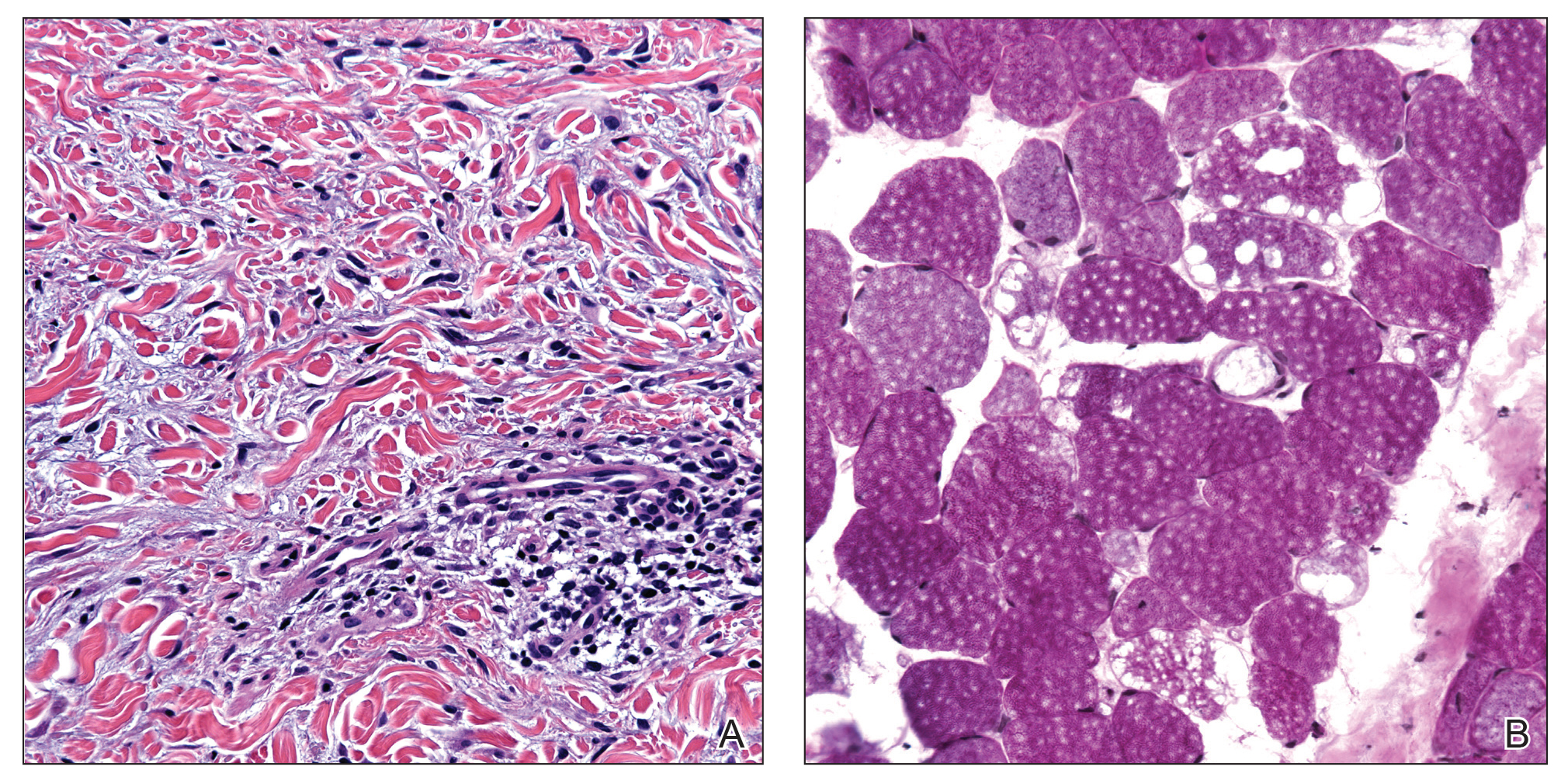

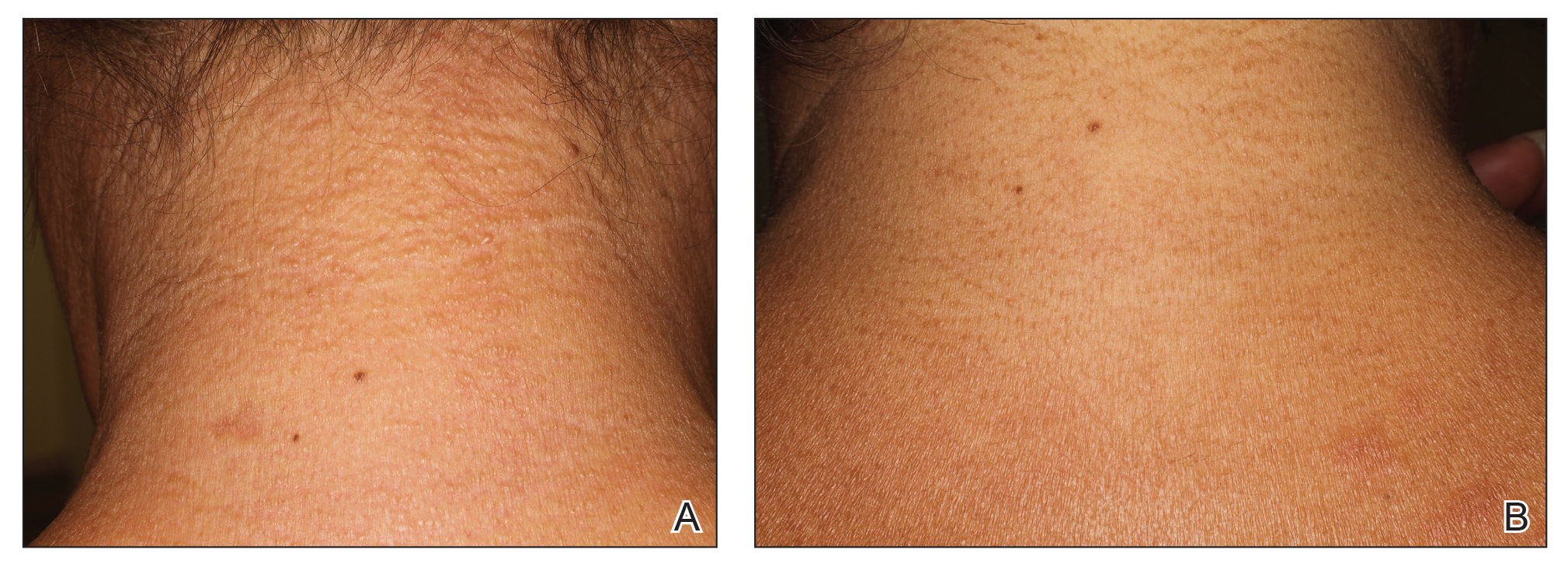

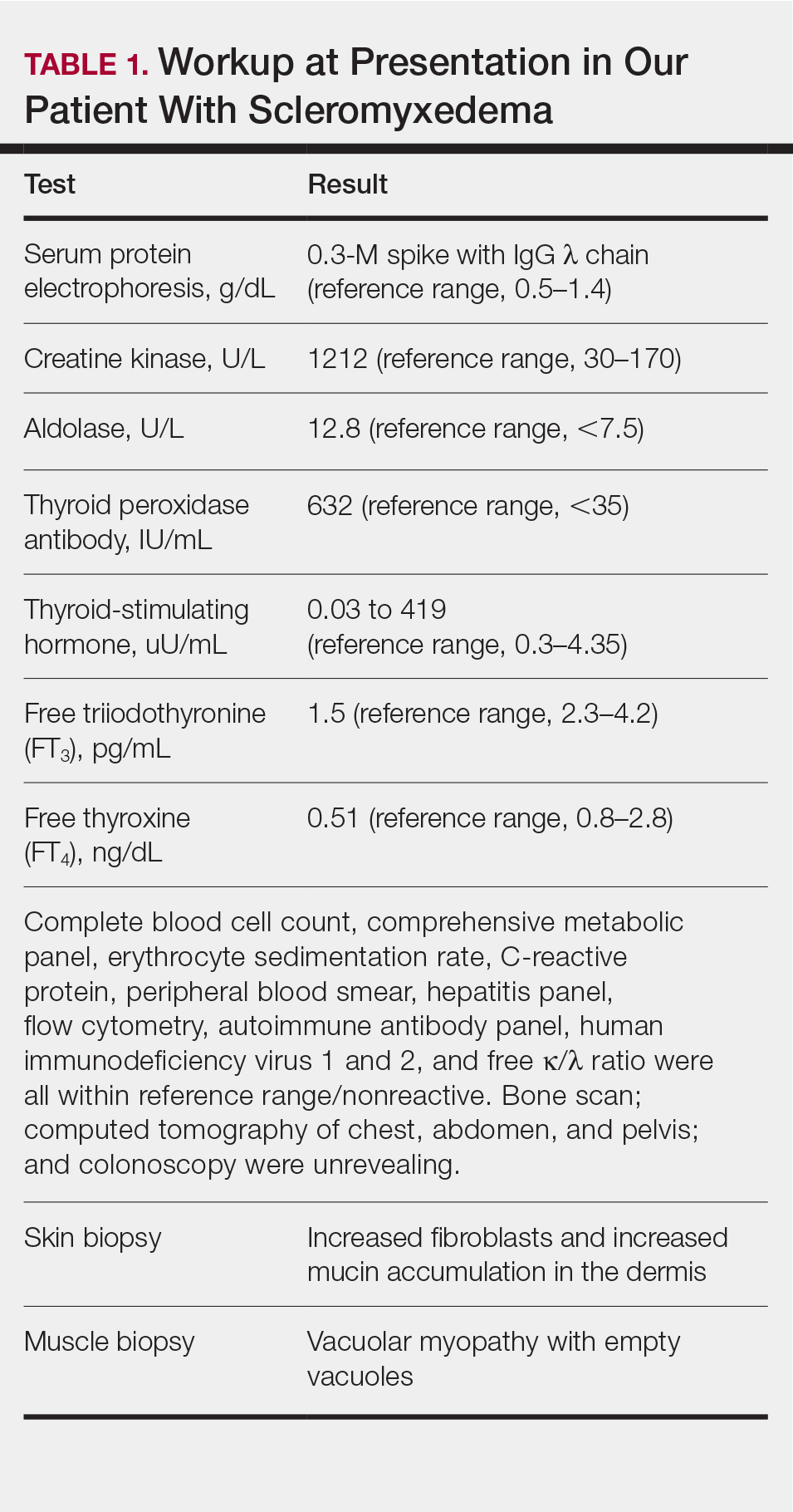

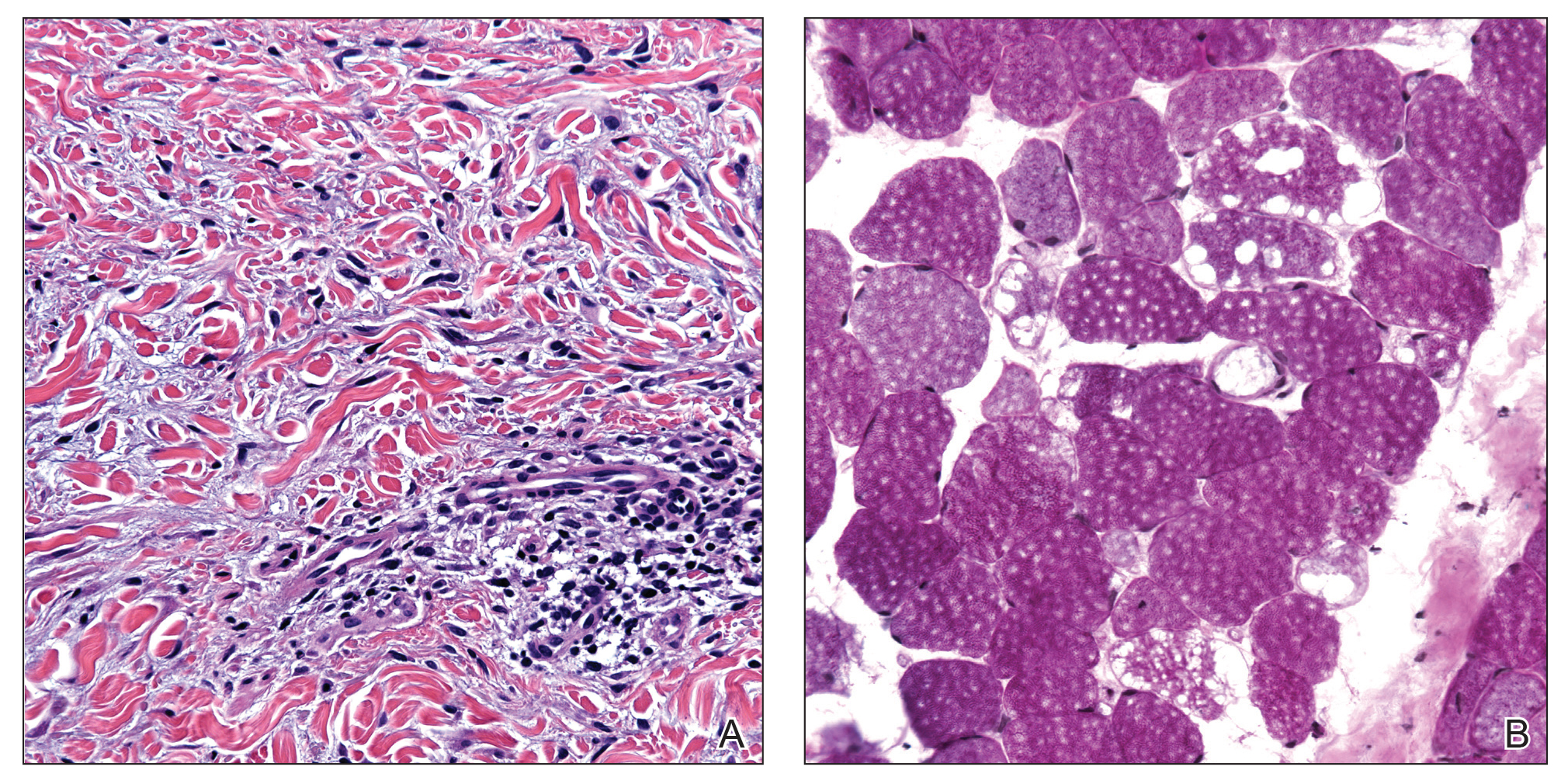

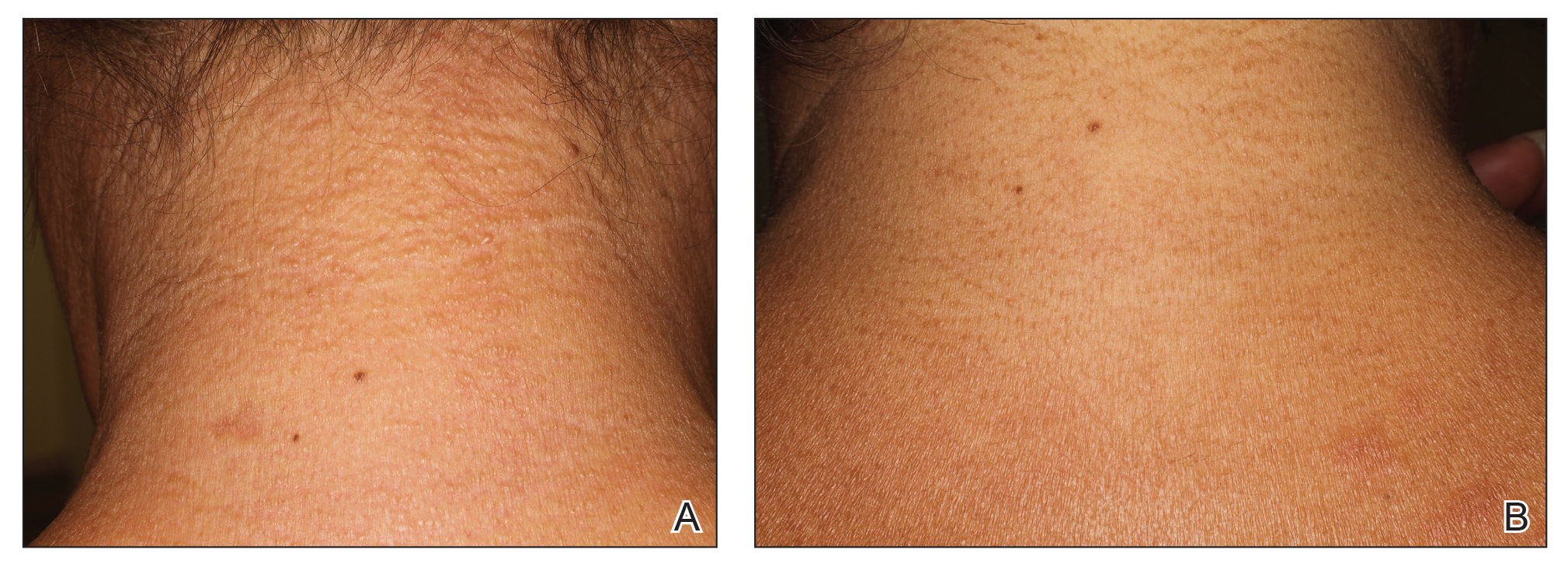

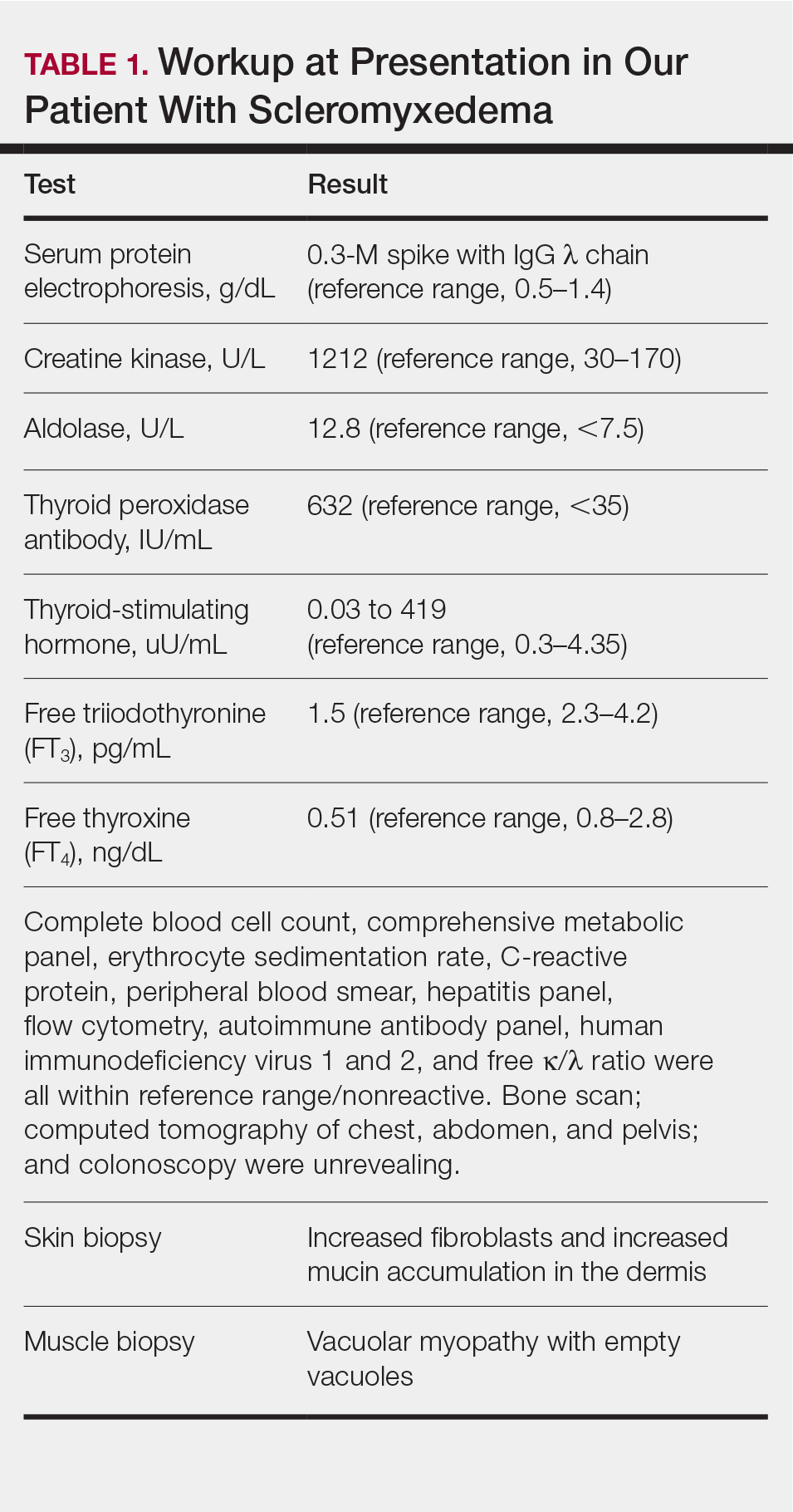

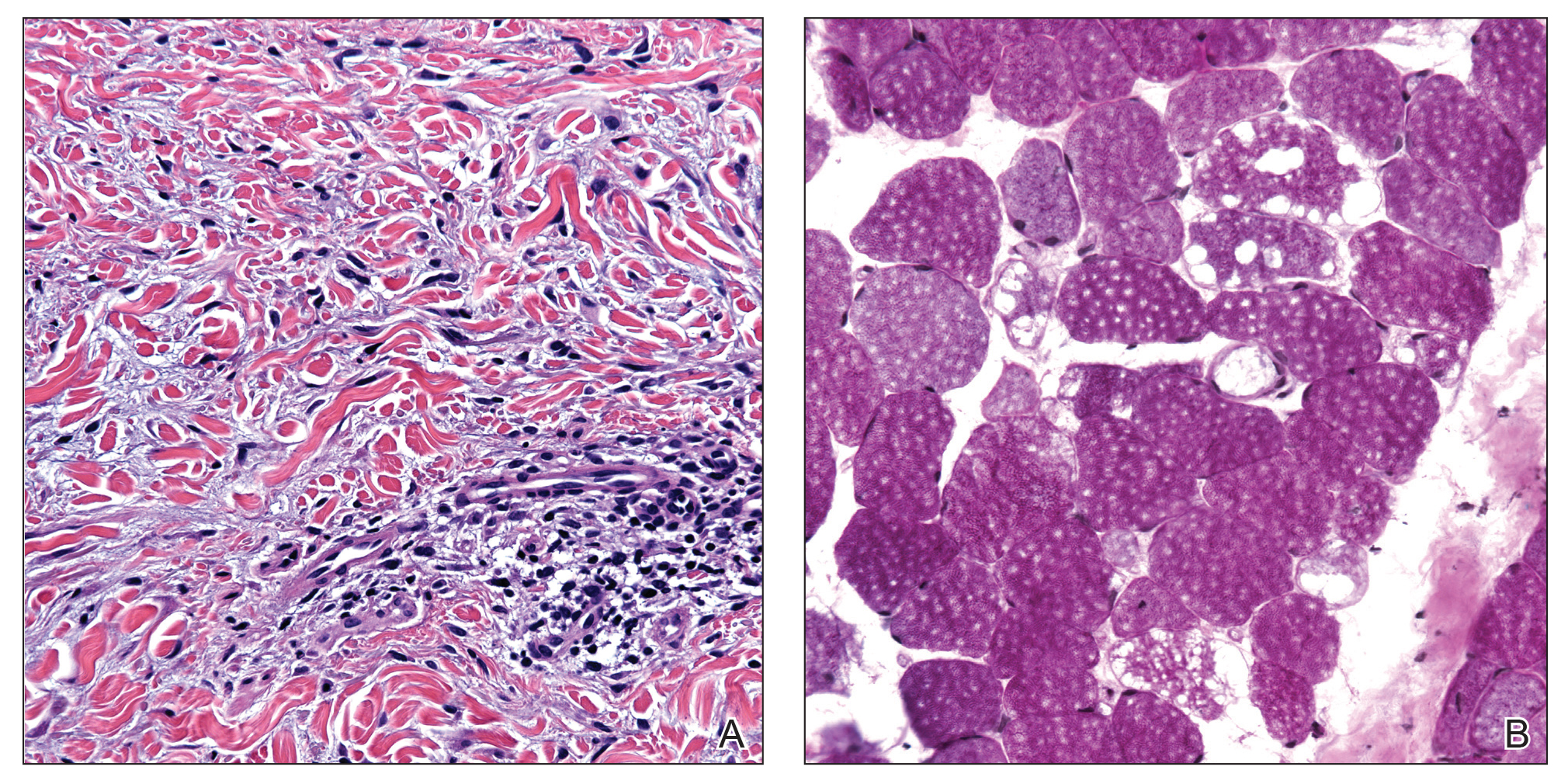

A 44-year-old woman presented with a progressive eruption of thickened skin and papules spanning many months. The papules ranged from flesh colored to erythematous and covered more than 80% of the body surface area, most notably involving the face, neck, ears, arms, chest, abdomen, and thighs (Figures 1A and 2A). Review of systems was notable for pruritus, muscle pain but no weakness, dysphagia, and constipation. Her medical history included childhood atopic dermatitis and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Hypothyroidism was diagnosed with support of a thyroid ultrasound and thyroid peroxidase antibodies. It was treated with oral levothyroxine for 2 years prior to the skin eruption. Thyroid biopsy was not performed. Her thyroid-stimulating hormone levels notably fluctuated in the year prior to presentation despite close clinical and laboratory monitoring by an endocrinologist. Laboratory results are summarized in Table 1. Both skin and muscle9 biopsies were consistent with SM (Figure 3) and are summarized in Table 1.

Shortly after presentation to our clinic the patient developed acute concerns of confusion and muscle weakness. She was admitted for further inpatient management due to concern for dermato-neuro syndrome, a rare but potentially fatal decline in neurological status that can progress to coma and death, rather than myxedema coma. On admission, a thyroid function test showed subclinical hypothyroidism with a thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 6.35 uU/mL (reference range, 0.3–4.35 uU/mL) and free thyroxine (FT4) level of 1.5 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8–2.8 ng/dL). While hospitalized she was started on intravenous levothyroxine, systemic steroids, and a course of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) treatment consisting of 2 g/kg divided over 5 days. On this regimen, her mental status quickly returned to baseline and other symptoms improved, including the skin eruption (Figures 1B and 2B). She has been maintained on lenalidomide 25 mg/d for the first 3 weeks of each month as well as monthly IVIg infusions. Her thyroid levels have persistently fluctuated despite intramuscular levothyroxine dosing, but her skin has remained clear with continued SM-directed therapy.

Comment

Classification

Lichen myxedematosus is differentiated into localized and generalized forms. The former is limited to the skin and lacks monoclonal gammopathy. The latter, also known as SM, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy and systemic symptoms. Atypical LM is an umbrella term for intermediate cases.

Clinical Presentation

Skin manifestations of SM are described as 1- to 3-mm, firm, waxy, dome-shaped papules that commonly affect the hands, forearms, face, neck, trunk, and thighs. The surrounding skin may be reddish brown and edematous with evidence of skin thickening. Extracutaneous manifestations in SM are numerous and unpredictable. Any organ system can be involved, but gastrointestinal, rheumatologic, pulmonary, and cardiovascular complications are most common.10 A comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation is necessary based on clinical symptoms and laboratory findings.

Management

Many treatments have been proposed for SM in case reports and case series. Prior treatments have had little success. Most recently, in one of the largest case series on SM, Rongioletti et al10 demonstrated IVIg to be a safe and effective treatment modality.

Differential Diagnosis

An important differential diagnosis is generalized myxedema, which is seen in long-standing hypothyroidism and may present with cutaneous mucinosis and systemic symptoms that resemble SM. Hypothyroid myxedema is associated with a widespread slowing of the body’s metabolic processes and deposition of mucin in various organs, including the skin, creating a generalized nonpitting edema. Classic clinical signs include macroglossia, periorbital puffiness, thick lips, and acral swelling. The skin tends to be cold, dry, and pale. Hair is characterized as being coarse, dry, and brittle with diffuse partial alopecia. Histologically, there is hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging and diffuse mucin and edema splaying between collagen fibers spanning the entire dermis.11 In contradistinction with SM, there is no fibroblast proliferation. The treatment is thyroid replacement therapy. Hyperthyroidism has distinct clinical and histologic changes. Clinically, there is moist and smooth skin with soft, fine, and sometimes alopecic hair. Graves disease, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, is further characterized by Graves ophthalmopathy and pretibial myxedema, or pink to brown, raised, firm, indurated, asymmetric plaques most commonly affecting the shins. Histologically there is increased mucin in the lower to mid dermis without fibroblast proliferation. The epidermis can be hyperkeratotic, which will clinically correlate with verrucous lesions.12

Hypothyroid encephalopathy is a rare disorder that can cause a change in mental status. It is a steroid-responsive autoimmune process characterized by encephalopathy that is associated with cognitive impairment and psychiatric features. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and should be suspected in women with a history of autoimmune disease, especially antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, a negative infectious workup, and encephalitis with behavioral changes. Although typically highly responsive to systemic steroids, IVIg also has shown efficacy.13

Presence of Thyroid Disease

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scleromyxedema and lichen myxedematosus, there are 7 cases in the literature that potentially describe LM associated with hypothyroidism (Table 2).3-8 The majority of these cases lack monoclonal gammopathy; improved with thyroid replacement therapy; or had severely atypical clinical presentations, rendering them cases of atypical LM or atypical thyroid dermopathy.3-6 Macnab and Kenny7 presented a case of subclinical hypothyroidism with a generalized papular eruption, monoclonal gammopathy, and consistent histologic changes that responded to IVIg therapy. These findings are suggestive of SM, but limited to the current diagnostic criteria, the patient was diagnosed with atypical LM.7 Shenoy et al8 described 2 cases of LM with hypothyroidism. One patient had biopsy-proven SM that was responsive to IVIg as well as Hashimoto thyroiditis with delayed onset of monoclonal gammopathy. The second patient had a medical history of hypothyroidism and Hodgkin lymphoma with active rheumatoid arthritis and biopsy-proven LM that was responsive to systemic steroids.8

Current literature states that thyroid disorder precludes the diagnosis of SM. However, historic literature would suggest otherwise. Because of inconsistent reports and theories regarding the pathogenesis of various sclerodermoid and mucin deposition diseases, in 1953 Montgomery and Underwood1 sought to differentiate LM from scleroderma and generalized myxedema. They stressed clinical appearance and proposed diagnostic criteria for LM as generalized papular mucinosis in which “[n]o relation to disturbance of the thyroid or other endocrine glands is apparent,” whereas generalized myxedema was defined as a “[t]rue cutaneous myxedema, with diffuse edema and the usual commonly recognized changes” in patients with endocrine abnormalities.1 With this classification, the authors made a clear distinction between mucinosis caused by thyroid abnormalities and LM, which is not caused by a thyroid disorder. Since this original description was published, associations with monoclonal gammopathy and fibroblast proliferation have been made, ultimately culminating into the current 2001 criteria that incorporate the absence of thyroid disease.2

Conclusion

We believe our case is consistent with the classification initially proposed by Montgomery and Underwood1 and is strengthened with the more recent associations with monoclonal gammopathy and specific histopathologic findings. Although there is no definitive way to rule out myxedema coma or Hashimoto encephalopathy to describe our patient’s transient neurologic decline, her clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, and biopsy results all supported the diagnosis of SM. Furthermore, her response to SM-directed therapy, despite fluctuating thyroid function test results, also supported the diagnosis. In the setting of cutaneous mucinosis with conflicting findings for hypothyroid myxedema, LM should be ruled out. Given the features presented in this report and others, diagnostic criteria should allow for SM and thyroid dysfunction to be concurrent diagnoses. Most importantly, we believe it is essential to identify and diagnose SM in a timely manner to facilitate SM-directed therapy, namely IVIg, to potentially minimize the disease’s notable morbidity and mortality.

- Montgomery H, Underwood LJ. Lichen myxedematosus; differentiation from cutaneous myxedemas or mucoid states. J Invest Dermatol. 1953;20:213-236.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Archibald GC, Calvert HT. Hypothyroidsm and lichen myxedematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:684.

- Schaeffer D, Bruce S, Rosen T. Cutaneous mucinosis associated with thyroid dysfunction. Cutis. 1983;11:449-456.

- Martin-Ezquerra G, Sanchez-Regaña M, Massana-Gil J, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with subclinical hypothyroidism: improvement with thyroxine therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1340-1341.

- Volpato MB, Jaime TJ, Proença MP, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with hypothyroidism. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:89-92.

- Macnab M, Kenny P. Successful intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of atypical lichen myxedematosus associated with hypothyroidism and central nervous system. involvement: case report and discussion of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:69-73.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Helfrich DJ, Walker ER, Martinez AJ, et al. Scleromyxedema myopathy: case report and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:1437-1441.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Jackson EM, English JC 3rd. Diffuse cutaneous mucinoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:493-501.

- Leonhardt JM, Heymann WR. Thyroid disease and the skin. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:473-481.

- Zhou JY, Xu B, Lopes J, et al. Hashimoto encephalopathy: literature review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;135:285-290.

Scleromyxedema (SM) is a generalized papular and sclerodermoid form of lichen myxedematosus (LM), commonly referred to as papular mucinosis. It is a rare progressive disease of unknown etiology with systemic manifestations that cause serious morbidity and mortality. Diagnostic criteria were initially created by Montgomery and Underwood1 in 1953 and revised by Rongioletti and Rebora2 in 2001 as follows: (1) generalized papular and sclerodermoid eruption; (2) histologic triad of mucin deposition, fibroblast proliferation, and fibrosis; (3) monoclonal gammopathy; and (4) absence of thyroid disease. There are several reports of LM in association with hypothyroidism, most of which can be characterized as atypical.3-8 We present a case of SM in a patient with Hashimoto thyroiditis and propose that the presence of thyroid disease should not preclude the diagnosis of SM.

Case Report

A 44-year-old woman presented with a progressive eruption of thickened skin and papules spanning many months. The papules ranged from flesh colored to erythematous and covered more than 80% of the body surface area, most notably involving the face, neck, ears, arms, chest, abdomen, and thighs (Figures 1A and 2A). Review of systems was notable for pruritus, muscle pain but no weakness, dysphagia, and constipation. Her medical history included childhood atopic dermatitis and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Hypothyroidism was diagnosed with support of a thyroid ultrasound and thyroid peroxidase antibodies. It was treated with oral levothyroxine for 2 years prior to the skin eruption. Thyroid biopsy was not performed. Her thyroid-stimulating hormone levels notably fluctuated in the year prior to presentation despite close clinical and laboratory monitoring by an endocrinologist. Laboratory results are summarized in Table 1. Both skin and muscle9 biopsies were consistent with SM (Figure 3) and are summarized in Table 1.

Shortly after presentation to our clinic the patient developed acute concerns of confusion and muscle weakness. She was admitted for further inpatient management due to concern for dermato-neuro syndrome, a rare but potentially fatal decline in neurological status that can progress to coma and death, rather than myxedema coma. On admission, a thyroid function test showed subclinical hypothyroidism with a thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 6.35 uU/mL (reference range, 0.3–4.35 uU/mL) and free thyroxine (FT4) level of 1.5 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8–2.8 ng/dL). While hospitalized she was started on intravenous levothyroxine, systemic steroids, and a course of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) treatment consisting of 2 g/kg divided over 5 days. On this regimen, her mental status quickly returned to baseline and other symptoms improved, including the skin eruption (Figures 1B and 2B). She has been maintained on lenalidomide 25 mg/d for the first 3 weeks of each month as well as monthly IVIg infusions. Her thyroid levels have persistently fluctuated despite intramuscular levothyroxine dosing, but her skin has remained clear with continued SM-directed therapy.

Comment

Classification

Lichen myxedematosus is differentiated into localized and generalized forms. The former is limited to the skin and lacks monoclonal gammopathy. The latter, also known as SM, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy and systemic symptoms. Atypical LM is an umbrella term for intermediate cases.

Clinical Presentation

Skin manifestations of SM are described as 1- to 3-mm, firm, waxy, dome-shaped papules that commonly affect the hands, forearms, face, neck, trunk, and thighs. The surrounding skin may be reddish brown and edematous with evidence of skin thickening. Extracutaneous manifestations in SM are numerous and unpredictable. Any organ system can be involved, but gastrointestinal, rheumatologic, pulmonary, and cardiovascular complications are most common.10 A comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation is necessary based on clinical symptoms and laboratory findings.

Management

Many treatments have been proposed for SM in case reports and case series. Prior treatments have had little success. Most recently, in one of the largest case series on SM, Rongioletti et al10 demonstrated IVIg to be a safe and effective treatment modality.

Differential Diagnosis

An important differential diagnosis is generalized myxedema, which is seen in long-standing hypothyroidism and may present with cutaneous mucinosis and systemic symptoms that resemble SM. Hypothyroid myxedema is associated with a widespread slowing of the body’s metabolic processes and deposition of mucin in various organs, including the skin, creating a generalized nonpitting edema. Classic clinical signs include macroglossia, periorbital puffiness, thick lips, and acral swelling. The skin tends to be cold, dry, and pale. Hair is characterized as being coarse, dry, and brittle with diffuse partial alopecia. Histologically, there is hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging and diffuse mucin and edema splaying between collagen fibers spanning the entire dermis.11 In contradistinction with SM, there is no fibroblast proliferation. The treatment is thyroid replacement therapy. Hyperthyroidism has distinct clinical and histologic changes. Clinically, there is moist and smooth skin with soft, fine, and sometimes alopecic hair. Graves disease, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, is further characterized by Graves ophthalmopathy and pretibial myxedema, or pink to brown, raised, firm, indurated, asymmetric plaques most commonly affecting the shins. Histologically there is increased mucin in the lower to mid dermis without fibroblast proliferation. The epidermis can be hyperkeratotic, which will clinically correlate with verrucous lesions.12

Hypothyroid encephalopathy is a rare disorder that can cause a change in mental status. It is a steroid-responsive autoimmune process characterized by encephalopathy that is associated with cognitive impairment and psychiatric features. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and should be suspected in women with a history of autoimmune disease, especially antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, a negative infectious workup, and encephalitis with behavioral changes. Although typically highly responsive to systemic steroids, IVIg also has shown efficacy.13

Presence of Thyroid Disease

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scleromyxedema and lichen myxedematosus, there are 7 cases in the literature that potentially describe LM associated with hypothyroidism (Table 2).3-8 The majority of these cases lack monoclonal gammopathy; improved with thyroid replacement therapy; or had severely atypical clinical presentations, rendering them cases of atypical LM or atypical thyroid dermopathy.3-6 Macnab and Kenny7 presented a case of subclinical hypothyroidism with a generalized papular eruption, monoclonal gammopathy, and consistent histologic changes that responded to IVIg therapy. These findings are suggestive of SM, but limited to the current diagnostic criteria, the patient was diagnosed with atypical LM.7 Shenoy et al8 described 2 cases of LM with hypothyroidism. One patient had biopsy-proven SM that was responsive to IVIg as well as Hashimoto thyroiditis with delayed onset of monoclonal gammopathy. The second patient had a medical history of hypothyroidism and Hodgkin lymphoma with active rheumatoid arthritis and biopsy-proven LM that was responsive to systemic steroids.8

Current literature states that thyroid disorder precludes the diagnosis of SM. However, historic literature would suggest otherwise. Because of inconsistent reports and theories regarding the pathogenesis of various sclerodermoid and mucin deposition diseases, in 1953 Montgomery and Underwood1 sought to differentiate LM from scleroderma and generalized myxedema. They stressed clinical appearance and proposed diagnostic criteria for LM as generalized papular mucinosis in which “[n]o relation to disturbance of the thyroid or other endocrine glands is apparent,” whereas generalized myxedema was defined as a “[t]rue cutaneous myxedema, with diffuse edema and the usual commonly recognized changes” in patients with endocrine abnormalities.1 With this classification, the authors made a clear distinction between mucinosis caused by thyroid abnormalities and LM, which is not caused by a thyroid disorder. Since this original description was published, associations with monoclonal gammopathy and fibroblast proliferation have been made, ultimately culminating into the current 2001 criteria that incorporate the absence of thyroid disease.2

Conclusion

We believe our case is consistent with the classification initially proposed by Montgomery and Underwood1 and is strengthened with the more recent associations with monoclonal gammopathy and specific histopathologic findings. Although there is no definitive way to rule out myxedema coma or Hashimoto encephalopathy to describe our patient’s transient neurologic decline, her clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, and biopsy results all supported the diagnosis of SM. Furthermore, her response to SM-directed therapy, despite fluctuating thyroid function test results, also supported the diagnosis. In the setting of cutaneous mucinosis with conflicting findings for hypothyroid myxedema, LM should be ruled out. Given the features presented in this report and others, diagnostic criteria should allow for SM and thyroid dysfunction to be concurrent diagnoses. Most importantly, we believe it is essential to identify and diagnose SM in a timely manner to facilitate SM-directed therapy, namely IVIg, to potentially minimize the disease’s notable morbidity and mortality.

Scleromyxedema (SM) is a generalized papular and sclerodermoid form of lichen myxedematosus (LM), commonly referred to as papular mucinosis. It is a rare progressive disease of unknown etiology with systemic manifestations that cause serious morbidity and mortality. Diagnostic criteria were initially created by Montgomery and Underwood1 in 1953 and revised by Rongioletti and Rebora2 in 2001 as follows: (1) generalized papular and sclerodermoid eruption; (2) histologic triad of mucin deposition, fibroblast proliferation, and fibrosis; (3) monoclonal gammopathy; and (4) absence of thyroid disease. There are several reports of LM in association with hypothyroidism, most of which can be characterized as atypical.3-8 We present a case of SM in a patient with Hashimoto thyroiditis and propose that the presence of thyroid disease should not preclude the diagnosis of SM.

Case Report

A 44-year-old woman presented with a progressive eruption of thickened skin and papules spanning many months. The papules ranged from flesh colored to erythematous and covered more than 80% of the body surface area, most notably involving the face, neck, ears, arms, chest, abdomen, and thighs (Figures 1A and 2A). Review of systems was notable for pruritus, muscle pain but no weakness, dysphagia, and constipation. Her medical history included childhood atopic dermatitis and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Hypothyroidism was diagnosed with support of a thyroid ultrasound and thyroid peroxidase antibodies. It was treated with oral levothyroxine for 2 years prior to the skin eruption. Thyroid biopsy was not performed. Her thyroid-stimulating hormone levels notably fluctuated in the year prior to presentation despite close clinical and laboratory monitoring by an endocrinologist. Laboratory results are summarized in Table 1. Both skin and muscle9 biopsies were consistent with SM (Figure 3) and are summarized in Table 1.

Shortly after presentation to our clinic the patient developed acute concerns of confusion and muscle weakness. She was admitted for further inpatient management due to concern for dermato-neuro syndrome, a rare but potentially fatal decline in neurological status that can progress to coma and death, rather than myxedema coma. On admission, a thyroid function test showed subclinical hypothyroidism with a thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 6.35 uU/mL (reference range, 0.3–4.35 uU/mL) and free thyroxine (FT4) level of 1.5 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8–2.8 ng/dL). While hospitalized she was started on intravenous levothyroxine, systemic steroids, and a course of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) treatment consisting of 2 g/kg divided over 5 days. On this regimen, her mental status quickly returned to baseline and other symptoms improved, including the skin eruption (Figures 1B and 2B). She has been maintained on lenalidomide 25 mg/d for the first 3 weeks of each month as well as monthly IVIg infusions. Her thyroid levels have persistently fluctuated despite intramuscular levothyroxine dosing, but her skin has remained clear with continued SM-directed therapy.

Comment

Classification

Lichen myxedematosus is differentiated into localized and generalized forms. The former is limited to the skin and lacks monoclonal gammopathy. The latter, also known as SM, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy and systemic symptoms. Atypical LM is an umbrella term for intermediate cases.

Clinical Presentation

Skin manifestations of SM are described as 1- to 3-mm, firm, waxy, dome-shaped papules that commonly affect the hands, forearms, face, neck, trunk, and thighs. The surrounding skin may be reddish brown and edematous with evidence of skin thickening. Extracutaneous manifestations in SM are numerous and unpredictable. Any organ system can be involved, but gastrointestinal, rheumatologic, pulmonary, and cardiovascular complications are most common.10 A comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation is necessary based on clinical symptoms and laboratory findings.

Management

Many treatments have been proposed for SM in case reports and case series. Prior treatments have had little success. Most recently, in one of the largest case series on SM, Rongioletti et al10 demonstrated IVIg to be a safe and effective treatment modality.

Differential Diagnosis

An important differential diagnosis is generalized myxedema, which is seen in long-standing hypothyroidism and may present with cutaneous mucinosis and systemic symptoms that resemble SM. Hypothyroid myxedema is associated with a widespread slowing of the body’s metabolic processes and deposition of mucin in various organs, including the skin, creating a generalized nonpitting edema. Classic clinical signs include macroglossia, periorbital puffiness, thick lips, and acral swelling. The skin tends to be cold, dry, and pale. Hair is characterized as being coarse, dry, and brittle with diffuse partial alopecia. Histologically, there is hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging and diffuse mucin and edema splaying between collagen fibers spanning the entire dermis.11 In contradistinction with SM, there is no fibroblast proliferation. The treatment is thyroid replacement therapy. Hyperthyroidism has distinct clinical and histologic changes. Clinically, there is moist and smooth skin with soft, fine, and sometimes alopecic hair. Graves disease, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, is further characterized by Graves ophthalmopathy and pretibial myxedema, or pink to brown, raised, firm, indurated, asymmetric plaques most commonly affecting the shins. Histologically there is increased mucin in the lower to mid dermis without fibroblast proliferation. The epidermis can be hyperkeratotic, which will clinically correlate with verrucous lesions.12

Hypothyroid encephalopathy is a rare disorder that can cause a change in mental status. It is a steroid-responsive autoimmune process characterized by encephalopathy that is associated with cognitive impairment and psychiatric features. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and should be suspected in women with a history of autoimmune disease, especially antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, a negative infectious workup, and encephalitis with behavioral changes. Although typically highly responsive to systemic steroids, IVIg also has shown efficacy.13

Presence of Thyroid Disease

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scleromyxedema and lichen myxedematosus, there are 7 cases in the literature that potentially describe LM associated with hypothyroidism (Table 2).3-8 The majority of these cases lack monoclonal gammopathy; improved with thyroid replacement therapy; or had severely atypical clinical presentations, rendering them cases of atypical LM or atypical thyroid dermopathy.3-6 Macnab and Kenny7 presented a case of subclinical hypothyroidism with a generalized papular eruption, monoclonal gammopathy, and consistent histologic changes that responded to IVIg therapy. These findings are suggestive of SM, but limited to the current diagnostic criteria, the patient was diagnosed with atypical LM.7 Shenoy et al8 described 2 cases of LM with hypothyroidism. One patient had biopsy-proven SM that was responsive to IVIg as well as Hashimoto thyroiditis with delayed onset of monoclonal gammopathy. The second patient had a medical history of hypothyroidism and Hodgkin lymphoma with active rheumatoid arthritis and biopsy-proven LM that was responsive to systemic steroids.8

Current literature states that thyroid disorder precludes the diagnosis of SM. However, historic literature would suggest otherwise. Because of inconsistent reports and theories regarding the pathogenesis of various sclerodermoid and mucin deposition diseases, in 1953 Montgomery and Underwood1 sought to differentiate LM from scleroderma and generalized myxedema. They stressed clinical appearance and proposed diagnostic criteria for LM as generalized papular mucinosis in which “[n]o relation to disturbance of the thyroid or other endocrine glands is apparent,” whereas generalized myxedema was defined as a “[t]rue cutaneous myxedema, with diffuse edema and the usual commonly recognized changes” in patients with endocrine abnormalities.1 With this classification, the authors made a clear distinction between mucinosis caused by thyroid abnormalities and LM, which is not caused by a thyroid disorder. Since this original description was published, associations with monoclonal gammopathy and fibroblast proliferation have been made, ultimately culminating into the current 2001 criteria that incorporate the absence of thyroid disease.2

Conclusion

We believe our case is consistent with the classification initially proposed by Montgomery and Underwood1 and is strengthened with the more recent associations with monoclonal gammopathy and specific histopathologic findings. Although there is no definitive way to rule out myxedema coma or Hashimoto encephalopathy to describe our patient’s transient neurologic decline, her clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, and biopsy results all supported the diagnosis of SM. Furthermore, her response to SM-directed therapy, despite fluctuating thyroid function test results, also supported the diagnosis. In the setting of cutaneous mucinosis with conflicting findings for hypothyroid myxedema, LM should be ruled out. Given the features presented in this report and others, diagnostic criteria should allow for SM and thyroid dysfunction to be concurrent diagnoses. Most importantly, we believe it is essential to identify and diagnose SM in a timely manner to facilitate SM-directed therapy, namely IVIg, to potentially minimize the disease’s notable morbidity and mortality.

- Montgomery H, Underwood LJ. Lichen myxedematosus; differentiation from cutaneous myxedemas or mucoid states. J Invest Dermatol. 1953;20:213-236.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Archibald GC, Calvert HT. Hypothyroidsm and lichen myxedematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:684.

- Schaeffer D, Bruce S, Rosen T. Cutaneous mucinosis associated with thyroid dysfunction. Cutis. 1983;11:449-456.

- Martin-Ezquerra G, Sanchez-Regaña M, Massana-Gil J, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with subclinical hypothyroidism: improvement with thyroxine therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1340-1341.

- Volpato MB, Jaime TJ, Proença MP, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with hypothyroidism. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:89-92.

- Macnab M, Kenny P. Successful intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of atypical lichen myxedematosus associated with hypothyroidism and central nervous system. involvement: case report and discussion of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:69-73.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Helfrich DJ, Walker ER, Martinez AJ, et al. Scleromyxedema myopathy: case report and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:1437-1441.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Jackson EM, English JC 3rd. Diffuse cutaneous mucinoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:493-501.

- Leonhardt JM, Heymann WR. Thyroid disease and the skin. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:473-481.

- Zhou JY, Xu B, Lopes J, et al. Hashimoto encephalopathy: literature review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;135:285-290.

- Montgomery H, Underwood LJ. Lichen myxedematosus; differentiation from cutaneous myxedemas or mucoid states. J Invest Dermatol. 1953;20:213-236.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Archibald GC, Calvert HT. Hypothyroidsm and lichen myxedematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:684.

- Schaeffer D, Bruce S, Rosen T. Cutaneous mucinosis associated with thyroid dysfunction. Cutis. 1983;11:449-456.

- Martin-Ezquerra G, Sanchez-Regaña M, Massana-Gil J, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with subclinical hypothyroidism: improvement with thyroxine therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1340-1341.

- Volpato MB, Jaime TJ, Proença MP, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with hypothyroidism. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:89-92.

- Macnab M, Kenny P. Successful intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of atypical lichen myxedematosus associated with hypothyroidism and central nervous system. involvement: case report and discussion of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:69-73.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Helfrich DJ, Walker ER, Martinez AJ, et al. Scleromyxedema myopathy: case report and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:1437-1441.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Jackson EM, English JC 3rd. Diffuse cutaneous mucinoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:493-501.

- Leonhardt JM, Heymann WR. Thyroid disease and the skin. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:473-481.

- Zhou JY, Xu B, Lopes J, et al. Hashimoto encephalopathy: literature review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;135:285-290.

Practice Points

- Scleromyxedema (SM) is progressive disease of unknown etiology with unpredictable behavior.

- Systemic manifestations associated with SM can cause serious morbidity and mortality.

- Intravenous immunoglobulin is the most effective treatment modality in SM.

- The presence of thyroid disease should not preclude the diagnosis of SM.

Cutaneous Pemphigus Vegetans Co-occurring With Oral Pemphigus Vulgaris

To the Editor:

A 74-year-old man with a history of colon cancer and no history of sexually transmitted diseases presented with tender, moist, vegetating, and verrucous plaques localized to the inguinal creases and behind the scrotum of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). The patient recently had taken lisinopril prescribed by his primary care physician for a couple of years for hypertension before switching to losartan prior to the current presentation. He later noticed the groin eruptions. He also noticed white tongue plaques temporally associated with the groin plaques and a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations. Prior to being seen in our clinic, outside physicians cultured methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus from the groin plaques and treated him with oral clindamycin, cephalexin, and topical mupirocin without a clinical response.

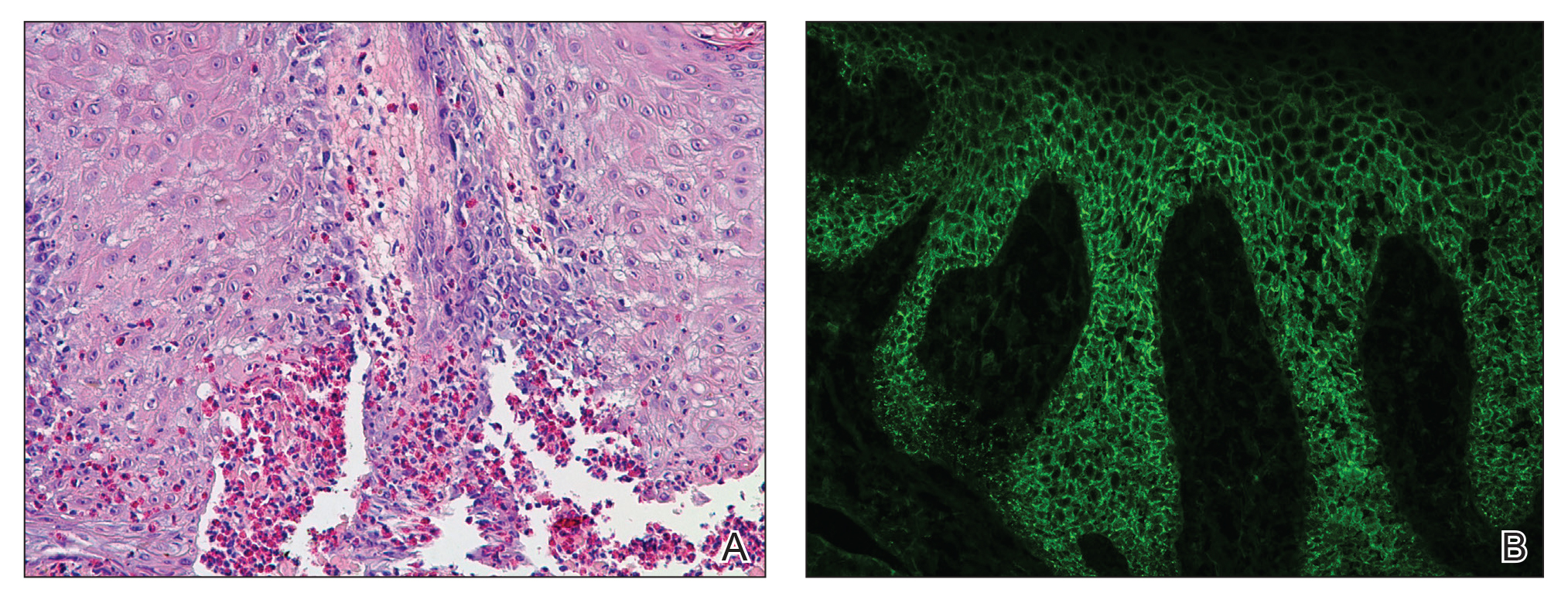

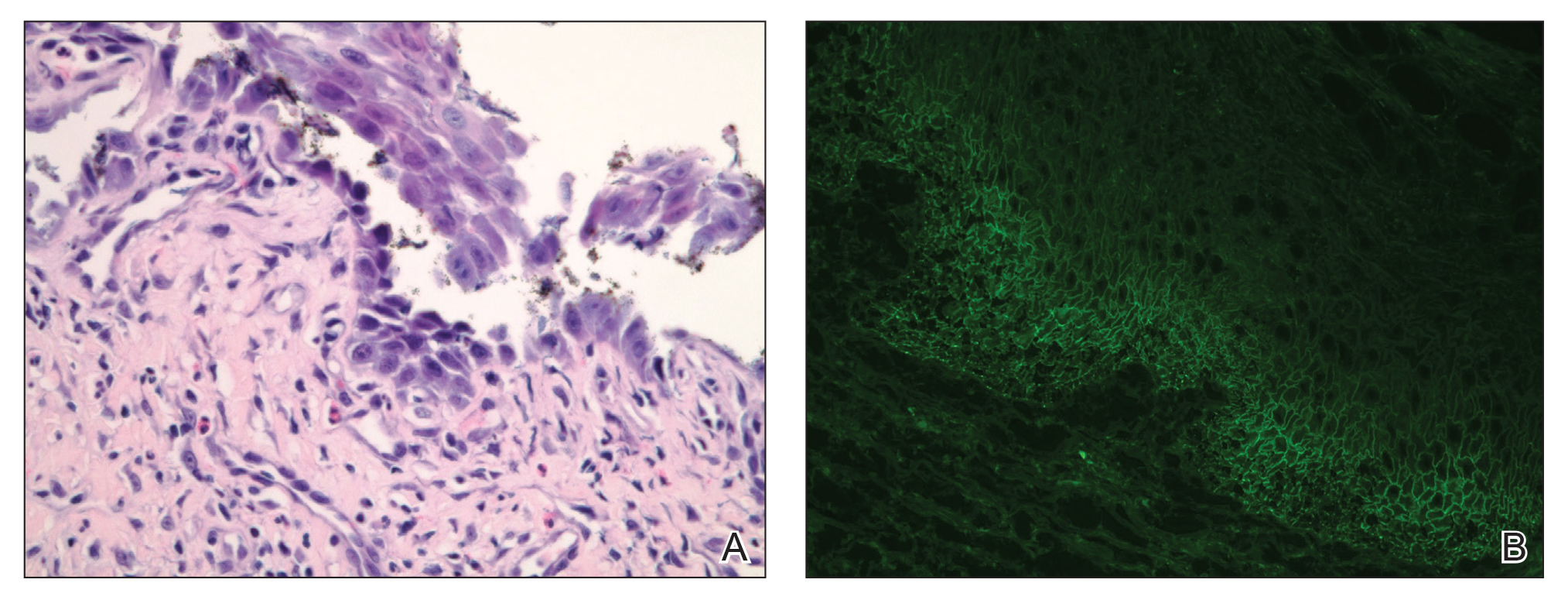

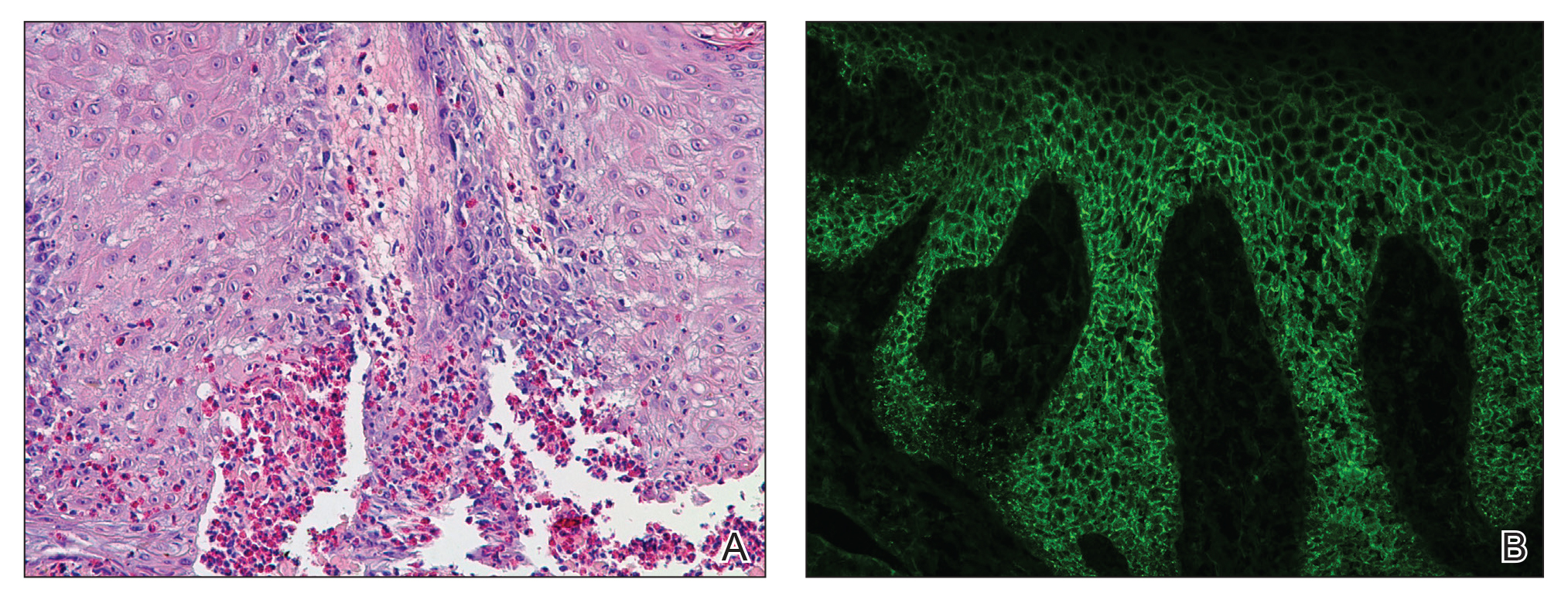

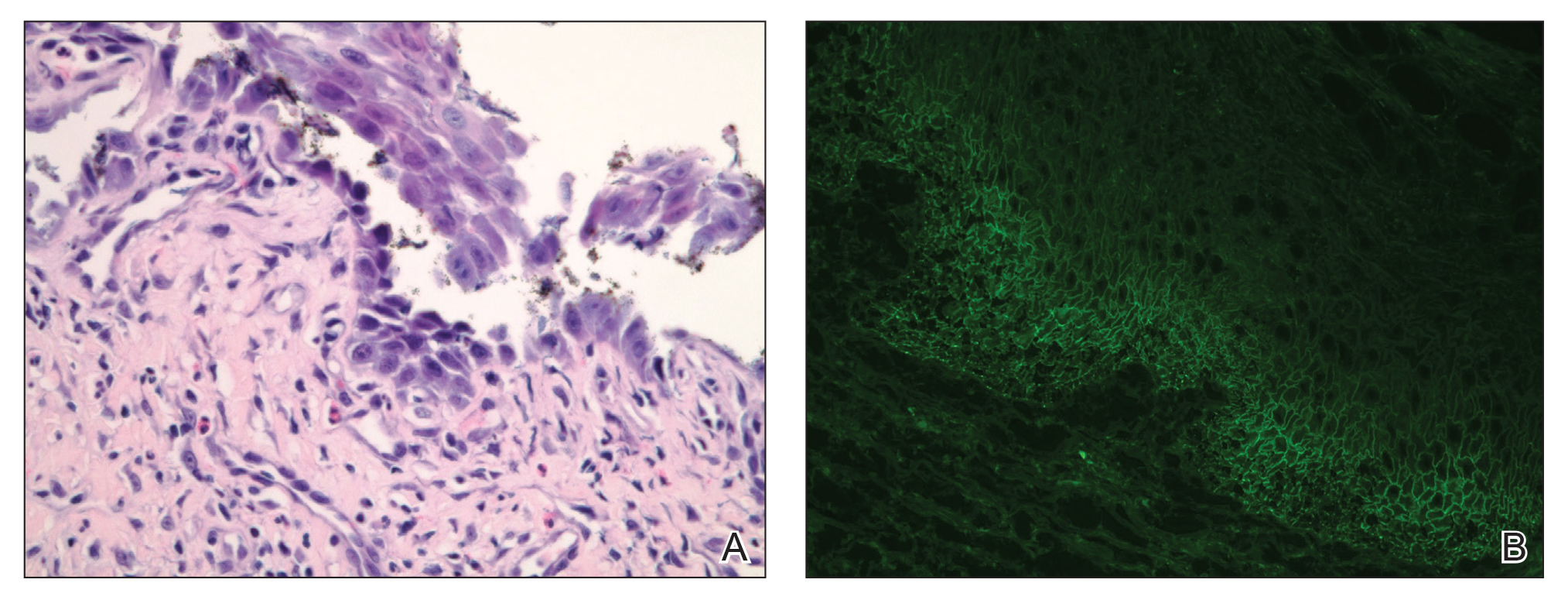

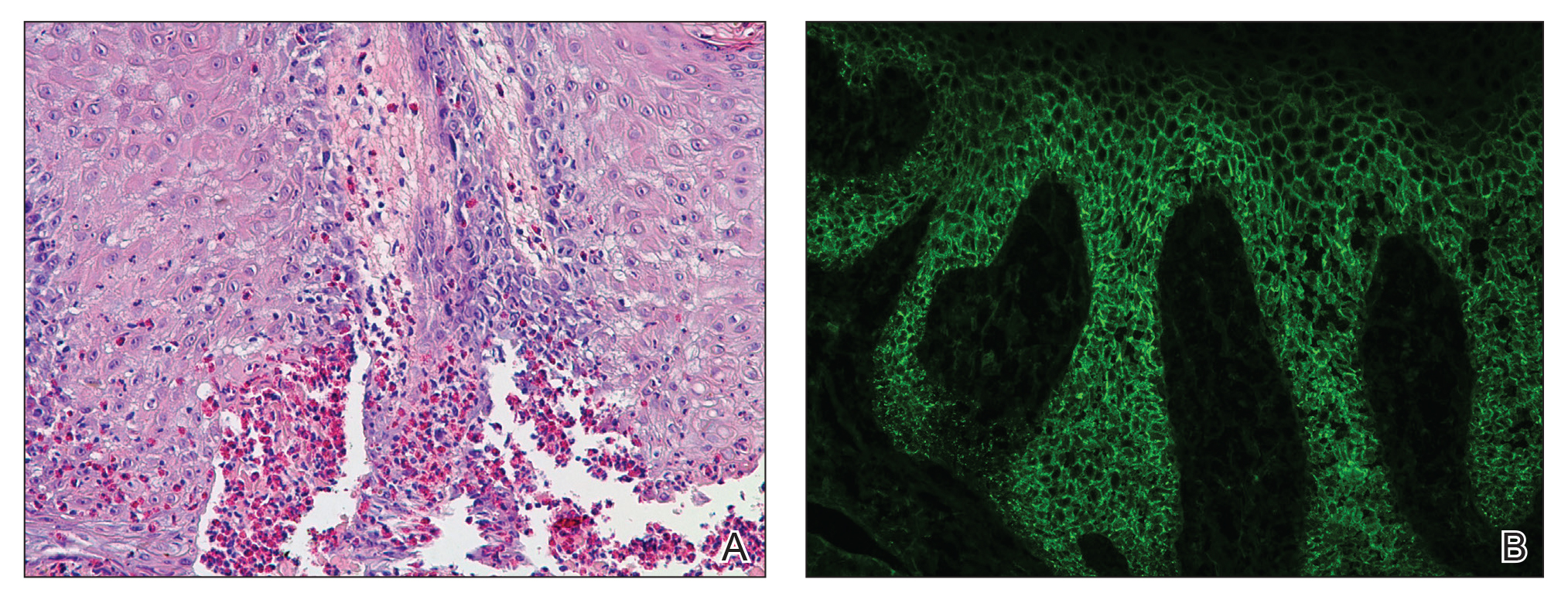

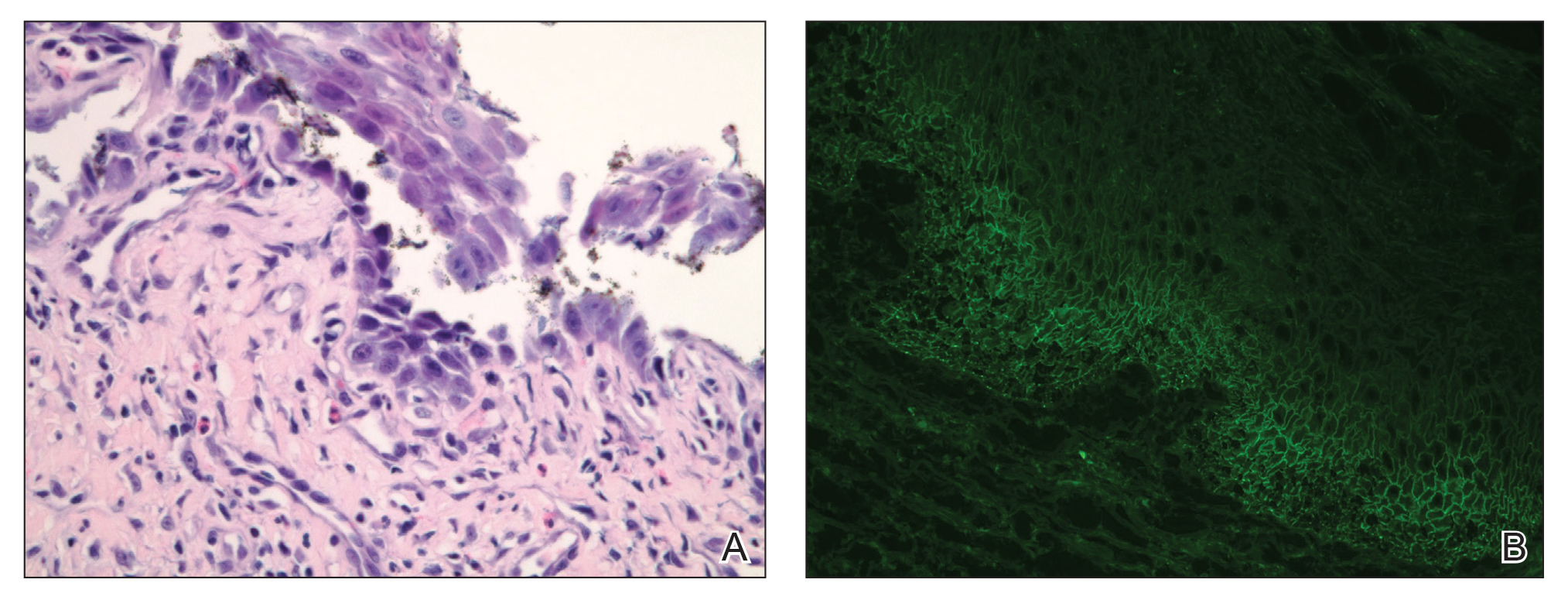

Our differential diagnosis included condyloma acuminata, condyloma lata, and cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Laboratory testing revealed a nonreactive rapid plasma reagin test and peripheral eosinophilia of 14.9% (reference range, 0%–6%). Biopsy of a left groin plaque revealed epidermal hyperplasia with spongiosis and an eosinophilic-rich infiltrate on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2A), and direct immunofluorescence revealed diffuse epidermal intercellular IgG deposits (Figure 2B). The patient’s clinical and histologic presentation was consistent with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Biopsy of an oral ulcer revealed denuded acantholytic mucositis with eosinophilic-rich submucosal infiltrate and fibrosis (Figure 3A). Direct immunofluorescence was positive for lacelike intercellular staining for IgG and C3 within the squamous epithelium (Figure 3B). Together the clinical and histologic findings were consistent with oral pemphigus vulgaris.

The patient initially was started on oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily and mometasone furoate cream 0.1% twice daily to affected groin areas. With these interventions, the groin plaques almost completely resolved after several months, leaving only residual hyperpigmentation (Figure 4). The oral pemphigus vulgaris initially was treated with dexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 mL solution 2 to 3 times daily, but the lesions were refractory to this approach and also did not improve after the losartan was discontinued for several months. As such, mycophenolate mofetil was started. He was titrated to the lowest effective dose and showed near-complete resolution with 500 mg 3 times daily.

Cutaneous pemphigus vegetans, a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris, is characterized by vegetating plaques commonly localized to the skin folds, scalp, face, and mucous membranes.1 Involvement of the oral mucosa occurs in a majority of cases. Although our patient had oral ulcerations, he did not have characteristic cerebriform changes of the dorsal tongue or associated verrucous hyperkeratotic lesions involving the buccal mucosa, hard and soft palate, or vermilion border of the lips that typically are seen in pemphigus vegetans.2-5 Subsequent biopsy of the oral mucosa confirmed oral pemphigus vulgaris in our patient.

This case presentation of co-occurring cutaneous pemphigus vegetans and oral pemphigus vulgaris is uncommonly reported in the literature. Although the etiology of this co-occurrence is not clear, it could represent a form of epitope spread, with the mechanism similar to that proposed for the progression of pemphigus vulgaris from the mucosal to the mucocutaneous stage by Chan et al,6 who suggested that an autoimmune reaction against specific desmoglein 3 epitopes (an important protein component for desmosomes and the autoantigen in pemphigus vulgaris) on mucosal membranes could induce local damage. These injuries could then expose the autoreactive immune cells to a secondary desmoglein 3 epitope present in the skin, leading to the development of cutaneous lesions.6 Salato et al7 also supported this idea of intramolecular epitope spread in pemphigus vulgaris, explaining that at various stages of the disease (mucosal and mucocutaneous), the antibodies have “different tissue-binding patterns and pathogenic activities, suggesting that they may recognize distinct epitopes.” This concept of epitope spread from the oral mucosal form to the cutaneous form of pemphigus vulgaris also could help explain our patient’s presentation, as he had a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations prior to developing the vegetating cutaneous plaques of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

We also appreciate that either the cutaneous pemphigus vegetans or oral pemphigus vulgaris could have been drug induced in our case. Captopril has been reported to cause pemphigus vulgaris,8 so it is conceivable that the related medication lisinopril was the culprit in our case. A prior case report described an elderly man who developed lisinopril-induced pemphigus foliaceus; however, there was no oral involvement in this case and no further blister formation within 48 hours of discontinuing lisinopril.9 An additional case report implicated lisinopril in the development of a bullous eruption on the oral mucosa in a female patient, though direct and indirect immunofluorescence did not reveal the autoantibodies that typically are seen in pemphigus vulgaris.10 Our patient’s blood eosinophilia also could support an adverse drug reaction. Our patient’s losartan was discontinued for several months without respite of the oral ulcerations and thus was restarted. The cutaneous pemphigus vegetans continues to be in remission and was unaffected by restarting the losartan, making it a less likely culprit for his presentation.

We identified another case in the literature in which an individual with a history of colon cancer was diagnosed with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.11 As such, we considered a possible link between the 2 diagnoses; however, the temporal disconnect between both conditions in our patient makes this less likely, unlike the other reported case in which the internal neoplasm and pemphigus vegetans appeared nearly simultaneously.11

Finally, our case supports a combination of topical steroids and minocycline for treatment of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

Our case demonstrates the importance of considering cutaneous pemphigus vegetans in the differential diagnosis, despite its rarity, when patients present with vegetating plaques. In addition, although oral involvement is common with this condition, if the patient’s oral lesions do not fit the characteristic oral findings seen in pemphigus vegetans, alternative diagnoses should be considered.

- de Almeida HL Jr, Neugebauer MG, Guarenti IM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans associated with verrucous lesions: expanding a phenotype. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2006;61:279-282.

- Danopoulou I, Stavropoulos P, Stratigos A, et al. Pemphigus vegetans confined to the scalp. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1008-1009.

- Markopoulos AK, Antoniades DZ, Zaraboukas T. Pemphigus vegetans of the oral cavity. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:425-428.

- Woo TY, Solomon AR, Fairley JA. Pemphigus vegetans limited to the lips and oral mucosa. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:271-272.

- Yuen KL, Yau KC. An old gentleman with vegetative plaques and erosions: a case of pemphigus vegetans. Hong Kong J Dermatol Venereol. 2012;20:179-182.

- Chan LS, Vanderlugt CJ, Hashimoto T, et al. Epitope spreading: lessons from autoimmune skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:103-109.

- Salato VK, Hacker-Foegen MK, Lazarova Z, et al. Role of intramolecular epitope spreading in pemphigus vulgaris. Clin Immunol. 2005;116:54-64.

- Dashore A, Choudhary SD. Captopril induced pemphigus vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1987;53:293-294.

- Patterson CR, Davies MG. Pemphigus foliaceus: an adverse reaction to lisinopril. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:60-62.

- Baričević M, Mravak Stipeti´c M, Situm M, et al. Oral bullous eruption after taking lisinopril—case report and literature review. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2013;125:408-411.

- Torres T, Ferreira M, Sanches M, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in a patient with colonic cancer. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:603-605.

To the Editor:

A 74-year-old man with a history of colon cancer and no history of sexually transmitted diseases presented with tender, moist, vegetating, and verrucous plaques localized to the inguinal creases and behind the scrotum of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). The patient recently had taken lisinopril prescribed by his primary care physician for a couple of years for hypertension before switching to losartan prior to the current presentation. He later noticed the groin eruptions. He also noticed white tongue plaques temporally associated with the groin plaques and a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations. Prior to being seen in our clinic, outside physicians cultured methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus from the groin plaques and treated him with oral clindamycin, cephalexin, and topical mupirocin without a clinical response.

Our differential diagnosis included condyloma acuminata, condyloma lata, and cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Laboratory testing revealed a nonreactive rapid plasma reagin test and peripheral eosinophilia of 14.9% (reference range, 0%–6%). Biopsy of a left groin plaque revealed epidermal hyperplasia with spongiosis and an eosinophilic-rich infiltrate on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2A), and direct immunofluorescence revealed diffuse epidermal intercellular IgG deposits (Figure 2B). The patient’s clinical and histologic presentation was consistent with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Biopsy of an oral ulcer revealed denuded acantholytic mucositis with eosinophilic-rich submucosal infiltrate and fibrosis (Figure 3A). Direct immunofluorescence was positive for lacelike intercellular staining for IgG and C3 within the squamous epithelium (Figure 3B). Together the clinical and histologic findings were consistent with oral pemphigus vulgaris.

The patient initially was started on oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily and mometasone furoate cream 0.1% twice daily to affected groin areas. With these interventions, the groin plaques almost completely resolved after several months, leaving only residual hyperpigmentation (Figure 4). The oral pemphigus vulgaris initially was treated with dexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 mL solution 2 to 3 times daily, but the lesions were refractory to this approach and also did not improve after the losartan was discontinued for several months. As such, mycophenolate mofetil was started. He was titrated to the lowest effective dose and showed near-complete resolution with 500 mg 3 times daily.

Cutaneous pemphigus vegetans, a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris, is characterized by vegetating plaques commonly localized to the skin folds, scalp, face, and mucous membranes.1 Involvement of the oral mucosa occurs in a majority of cases. Although our patient had oral ulcerations, he did not have characteristic cerebriform changes of the dorsal tongue or associated verrucous hyperkeratotic lesions involving the buccal mucosa, hard and soft palate, or vermilion border of the lips that typically are seen in pemphigus vegetans.2-5 Subsequent biopsy of the oral mucosa confirmed oral pemphigus vulgaris in our patient.

This case presentation of co-occurring cutaneous pemphigus vegetans and oral pemphigus vulgaris is uncommonly reported in the literature. Although the etiology of this co-occurrence is not clear, it could represent a form of epitope spread, with the mechanism similar to that proposed for the progression of pemphigus vulgaris from the mucosal to the mucocutaneous stage by Chan et al,6 who suggested that an autoimmune reaction against specific desmoglein 3 epitopes (an important protein component for desmosomes and the autoantigen in pemphigus vulgaris) on mucosal membranes could induce local damage. These injuries could then expose the autoreactive immune cells to a secondary desmoglein 3 epitope present in the skin, leading to the development of cutaneous lesions.6 Salato et al7 also supported this idea of intramolecular epitope spread in pemphigus vulgaris, explaining that at various stages of the disease (mucosal and mucocutaneous), the antibodies have “different tissue-binding patterns and pathogenic activities, suggesting that they may recognize distinct epitopes.” This concept of epitope spread from the oral mucosal form to the cutaneous form of pemphigus vulgaris also could help explain our patient’s presentation, as he had a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations prior to developing the vegetating cutaneous plaques of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

We also appreciate that either the cutaneous pemphigus vegetans or oral pemphigus vulgaris could have been drug induced in our case. Captopril has been reported to cause pemphigus vulgaris,8 so it is conceivable that the related medication lisinopril was the culprit in our case. A prior case report described an elderly man who developed lisinopril-induced pemphigus foliaceus; however, there was no oral involvement in this case and no further blister formation within 48 hours of discontinuing lisinopril.9 An additional case report implicated lisinopril in the development of a bullous eruption on the oral mucosa in a female patient, though direct and indirect immunofluorescence did not reveal the autoantibodies that typically are seen in pemphigus vulgaris.10 Our patient’s blood eosinophilia also could support an adverse drug reaction. Our patient’s losartan was discontinued for several months without respite of the oral ulcerations and thus was restarted. The cutaneous pemphigus vegetans continues to be in remission and was unaffected by restarting the losartan, making it a less likely culprit for his presentation.

We identified another case in the literature in which an individual with a history of colon cancer was diagnosed with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.11 As such, we considered a possible link between the 2 diagnoses; however, the temporal disconnect between both conditions in our patient makes this less likely, unlike the other reported case in which the internal neoplasm and pemphigus vegetans appeared nearly simultaneously.11

Finally, our case supports a combination of topical steroids and minocycline for treatment of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

Our case demonstrates the importance of considering cutaneous pemphigus vegetans in the differential diagnosis, despite its rarity, when patients present with vegetating plaques. In addition, although oral involvement is common with this condition, if the patient’s oral lesions do not fit the characteristic oral findings seen in pemphigus vegetans, alternative diagnoses should be considered.

To the Editor:

A 74-year-old man with a history of colon cancer and no history of sexually transmitted diseases presented with tender, moist, vegetating, and verrucous plaques localized to the inguinal creases and behind the scrotum of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). The patient recently had taken lisinopril prescribed by his primary care physician for a couple of years for hypertension before switching to losartan prior to the current presentation. He later noticed the groin eruptions. He also noticed white tongue plaques temporally associated with the groin plaques and a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations. Prior to being seen in our clinic, outside physicians cultured methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus from the groin plaques and treated him with oral clindamycin, cephalexin, and topical mupirocin without a clinical response.

Our differential diagnosis included condyloma acuminata, condyloma lata, and cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Laboratory testing revealed a nonreactive rapid plasma reagin test and peripheral eosinophilia of 14.9% (reference range, 0%–6%). Biopsy of a left groin plaque revealed epidermal hyperplasia with spongiosis and an eosinophilic-rich infiltrate on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2A), and direct immunofluorescence revealed diffuse epidermal intercellular IgG deposits (Figure 2B). The patient’s clinical and histologic presentation was consistent with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Biopsy of an oral ulcer revealed denuded acantholytic mucositis with eosinophilic-rich submucosal infiltrate and fibrosis (Figure 3A). Direct immunofluorescence was positive for lacelike intercellular staining for IgG and C3 within the squamous epithelium (Figure 3B). Together the clinical and histologic findings were consistent with oral pemphigus vulgaris.

The patient initially was started on oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily and mometasone furoate cream 0.1% twice daily to affected groin areas. With these interventions, the groin plaques almost completely resolved after several months, leaving only residual hyperpigmentation (Figure 4). The oral pemphigus vulgaris initially was treated with dexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 mL solution 2 to 3 times daily, but the lesions were refractory to this approach and also did not improve after the losartan was discontinued for several months. As such, mycophenolate mofetil was started. He was titrated to the lowest effective dose and showed near-complete resolution with 500 mg 3 times daily.

Cutaneous pemphigus vegetans, a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris, is characterized by vegetating plaques commonly localized to the skin folds, scalp, face, and mucous membranes.1 Involvement of the oral mucosa occurs in a majority of cases. Although our patient had oral ulcerations, he did not have characteristic cerebriform changes of the dorsal tongue or associated verrucous hyperkeratotic lesions involving the buccal mucosa, hard and soft palate, or vermilion border of the lips that typically are seen in pemphigus vegetans.2-5 Subsequent biopsy of the oral mucosa confirmed oral pemphigus vulgaris in our patient.

This case presentation of co-occurring cutaneous pemphigus vegetans and oral pemphigus vulgaris is uncommonly reported in the literature. Although the etiology of this co-occurrence is not clear, it could represent a form of epitope spread, with the mechanism similar to that proposed for the progression of pemphigus vulgaris from the mucosal to the mucocutaneous stage by Chan et al,6 who suggested that an autoimmune reaction against specific desmoglein 3 epitopes (an important protein component for desmosomes and the autoantigen in pemphigus vulgaris) on mucosal membranes could induce local damage. These injuries could then expose the autoreactive immune cells to a secondary desmoglein 3 epitope present in the skin, leading to the development of cutaneous lesions.6 Salato et al7 also supported this idea of intramolecular epitope spread in pemphigus vulgaris, explaining that at various stages of the disease (mucosal and mucocutaneous), the antibodies have “different tissue-binding patterns and pathogenic activities, suggesting that they may recognize distinct epitopes.” This concept of epitope spread from the oral mucosal form to the cutaneous form of pemphigus vulgaris also could help explain our patient’s presentation, as he had a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations prior to developing the vegetating cutaneous plaques of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

We also appreciate that either the cutaneous pemphigus vegetans or oral pemphigus vulgaris could have been drug induced in our case. Captopril has been reported to cause pemphigus vulgaris,8 so it is conceivable that the related medication lisinopril was the culprit in our case. A prior case report described an elderly man who developed lisinopril-induced pemphigus foliaceus; however, there was no oral involvement in this case and no further blister formation within 48 hours of discontinuing lisinopril.9 An additional case report implicated lisinopril in the development of a bullous eruption on the oral mucosa in a female patient, though direct and indirect immunofluorescence did not reveal the autoantibodies that typically are seen in pemphigus vulgaris.10 Our patient’s blood eosinophilia also could support an adverse drug reaction. Our patient’s losartan was discontinued for several months without respite of the oral ulcerations and thus was restarted. The cutaneous pemphigus vegetans continues to be in remission and was unaffected by restarting the losartan, making it a less likely culprit for his presentation.

We identified another case in the literature in which an individual with a history of colon cancer was diagnosed with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.11 As such, we considered a possible link between the 2 diagnoses; however, the temporal disconnect between both conditions in our patient makes this less likely, unlike the other reported case in which the internal neoplasm and pemphigus vegetans appeared nearly simultaneously.11

Finally, our case supports a combination of topical steroids and minocycline for treatment of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

Our case demonstrates the importance of considering cutaneous pemphigus vegetans in the differential diagnosis, despite its rarity, when patients present with vegetating plaques. In addition, although oral involvement is common with this condition, if the patient’s oral lesions do not fit the characteristic oral findings seen in pemphigus vegetans, alternative diagnoses should be considered.

- de Almeida HL Jr, Neugebauer MG, Guarenti IM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans associated with verrucous lesions: expanding a phenotype. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2006;61:279-282.

- Danopoulou I, Stavropoulos P, Stratigos A, et al. Pemphigus vegetans confined to the scalp. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1008-1009.

- Markopoulos AK, Antoniades DZ, Zaraboukas T. Pemphigus vegetans of the oral cavity. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:425-428.

- Woo TY, Solomon AR, Fairley JA. Pemphigus vegetans limited to the lips and oral mucosa. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:271-272.

- Yuen KL, Yau KC. An old gentleman with vegetative plaques and erosions: a case of pemphigus vegetans. Hong Kong J Dermatol Venereol. 2012;20:179-182.

- Chan LS, Vanderlugt CJ, Hashimoto T, et al. Epitope spreading: lessons from autoimmune skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:103-109.

- Salato VK, Hacker-Foegen MK, Lazarova Z, et al. Role of intramolecular epitope spreading in pemphigus vulgaris. Clin Immunol. 2005;116:54-64.

- Dashore A, Choudhary SD. Captopril induced pemphigus vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1987;53:293-294.

- Patterson CR, Davies MG. Pemphigus foliaceus: an adverse reaction to lisinopril. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:60-62.

- Baričević M, Mravak Stipeti´c M, Situm M, et al. Oral bullous eruption after taking lisinopril—case report and literature review. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2013;125:408-411.

- Torres T, Ferreira M, Sanches M, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in a patient with colonic cancer. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:603-605.

- de Almeida HL Jr, Neugebauer MG, Guarenti IM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans associated with verrucous lesions: expanding a phenotype. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2006;61:279-282.

- Danopoulou I, Stavropoulos P, Stratigos A, et al. Pemphigus vegetans confined to the scalp. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1008-1009.

- Markopoulos AK, Antoniades DZ, Zaraboukas T. Pemphigus vegetans of the oral cavity. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:425-428.

- Woo TY, Solomon AR, Fairley JA. Pemphigus vegetans limited to the lips and oral mucosa. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:271-272.

- Yuen KL, Yau KC. An old gentleman with vegetative plaques and erosions: a case of pemphigus vegetans. Hong Kong J Dermatol Venereol. 2012;20:179-182.

- Chan LS, Vanderlugt CJ, Hashimoto T, et al. Epitope spreading: lessons from autoimmune skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:103-109.

- Salato VK, Hacker-Foegen MK, Lazarova Z, et al. Role of intramolecular epitope spreading in pemphigus vulgaris. Clin Immunol. 2005;116:54-64.

- Dashore A, Choudhary SD. Captopril induced pemphigus vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1987;53:293-294.

- Patterson CR, Davies MG. Pemphigus foliaceus: an adverse reaction to lisinopril. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:60-62.

- Baričević M, Mravak Stipeti´c M, Situm M, et al. Oral bullous eruption after taking lisinopril—case report and literature review. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2013;125:408-411.

- Torres T, Ferreira M, Sanches M, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in a patient with colonic cancer. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:603-605.

Practice Points

- Recognize the clinical and histologic features of pemphigus vegetans, a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris.

- Consider mechanisms of co-occurring cutaneous pemphigus vegetans and oral pemphigus vulgaris.

Cardiovascular Medicine and Surgery NetWork

Evolution of point of care ultrasound (POCUS) education: cardiovascular, pulmonary, and beyond

A recent CHEST Physician article noted the ubiquity of POCUS employment but lamented inconsistencies and possible inadequacies of POCUS education amongst ACGME specialty fellowships (Satterwhite L. An update on the current standard for ultrasound education in fellowship. CHEST Physician. 2019 Dec. 9). POCUS education/training is no longer limited to physician fellowships but has percolated into the undergraduate medical education curricula of first-year medical students and physician assistant (PA) programs (Hoppmann RA, et al. Crit Ultrasound J. 2011;[3]:1; Rizzolo D, et al. J Physician Assist Educ. 2019;30[2]:103). Some PA residencies have long-incorporated POCUS training to varying degrees, providing emergency/critical care/cardiovascular ultrasound training comparable to that of physician residencies (Daymude ML, et al. J Physician Assist Educ. 2007;18[1]:29). A 12-month POCUS fellowship, which mirrors physician POCUS fellowship curricula, is also available for PAs at Madigan and Brooke Army Medical Centers and allows graduates the opportunity to earn RDMS/RDCS credentials (Monti J. J Physician Assist Educ. 2017;28[1]:27). POCUS employment is not limited to physicians and PAs, however. Respiratory therapists and other allied health professionals are also exploring the value of pulmonary, cardiovascular, and other critical care POCUS applications in their respective practices (Karthika M, et al. Respir Care. 2019;64[2]:217). Meanwhile, POCUS devices continue to evolve toward inexpensive handheld machines that incorporate machine learning/artificial intelligence, further mitigating barriers to integration of POCUS into routine clinical practice (Tsay D, et al. Circulation. 2018;138[22]:2569). With the expansion of POCUS across the full spectrum of health care, leadership from multiprofessional organizations, such as CHEST and the Society of Point-of-Care Ultrasound (SPOCUS), are well-positioned to leverage their diverse leadership to govern the training and safe employment of POCUS.

Robert Baeten II, DmSc, FCCP Steering Committee Member

Chest infections

New laboratory testing guidelines for diagnosing fungal infections

Secondary to a growing number of immunosuppressed individuals, the incidence of invasive fungal infections (IFI) is increasing. IFIs can be difficult to treat and are associated with a high mortality rate. Effective treatment is predicated on early recognition and accurate diagnosis (Limper AH, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183[1]:96). Therefore, the American Thoracic Society created a clinical practice guideline on laboratory diagnosis of the most common fungal infections (Hage CA, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200[5]:535). The most important diagnostic considerations for clinicians are summarized below:

1. Serum galactomannan and serum aspergillus PCR are recommended in severely immunocompromised patients suspected of having invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA).

2. Galactomannan and aspergillus PCR in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) are recommended for patients who are strongly suspected of having IPA, especially if serum is negative. In less severe immunocompromised patients, the BAL sensitivity of galactomannan is better compared with serum, without reducing specificity.

3. Due to low specificity/high false-positive rate, 1,3-B-D-glucan should not be used in isolation to diagnose invasive candidiasis.

4. No single best test exists for the diagnosis of blastomycosis or coccidioidomycosis; rather, more than one diagnostic test including fungal smear, culture, serum antibody, and antigen testing should be used for suspected blastomycosis or coccidioidomycosis.

5. Urine or serum antigen testing is recommended for patients with suspected disseminated or acute histoplasmosis. For immunocompetent patients suspected of pulmonary histoplasmosis, serologic testing is recommended; antigen testing may increase the diagnostic yield.

While these recommendations provide a basis for laboratory testing for the most common IFIs, they must be integrated into the clinical context to ensure accurate diagnosis.

Kelly Pennington, MD, Steering Committee MemberEva M. Carmona, MD, PhD, NetWork Member

Clinical pulmonary medicine

Definitive pleural interventions in malignant pleural effusions

Malignant pleural effusions (MPEs) contribute significantly to symptom burden, and an emphasis on patient-centered outcomes prioritizes palliation of symptoms and definitive management with pleurodesis. Clinical guidelines (Feller-Kopman DJ, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198[7]:839) for MPE recommend an indwelling pleural catheter (IPC) or chemical pleurodesis as first-line definitive pleural intervention. In a recent prospective study, Bhatnagar and colleagues (Bhatnagar R, et al. JAMA. 2019 Dec 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.19997) evaluated the effectiveness of thoracoscopy with talc poudrage compared with chest tube placement with talc slurry. The authors randomized 330 patients with MPE and expandable lung, and the primary outcome was pleurodesis failure at 90 days after randomization. There was no significant difference in primary outcome, and pleurodesis failure at 90 days was 22% with talc poudrage and 24% with talc slurry. Similar results for pleurodesis failure at 30 and 180 days were noted.

Secondary outcomes for all-cause mortality, quality of life measures, symptom (chest pain, dyspnea) scores, hospital days, and radiographic opacification also showed no difference. This supports an earlier study by Dresler and associates (Dresler CM, et al. Chest. 2005 Mar;127[3]:909) that reported similar efficacy of talc poudrage and talc slurry. Interestingly, Bhatnagar’s group (Bhatnagar R, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 5;378[14]:1313) previously demonstrated administration of talc slurry via IPC was safe and effective in the outpatient setting, but no direct comparison of IPC combined with talc poudrage or talc slurry is available.

These studies provide support for flexibility in MPE management, and selection of definitive pleural intervention can be tailored for each individual patient.

Saadia Faiz, MD, FCCP, Steering Committee Member

Mark Warner, MD, FCCP, NetWork Member

Interprofessional team

Interprofessional team and noninvasive ventilation in COPD exacerbation

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is a standard of care for treatment of COPD exacerbations, resulting in reduced need for mechanical ventilation, length of hospital stay, and mortality. Patient selection is as important to success as is choice of an appropriate interface, maintenance of synchrony, and a dedicated interprofessional team. Prior studies have identified that necessary factors for successful implementation of NIV in exacerbations of severe COPD include adequate equipment, sufficient numbers of qualified respiratory therapists, flexibility in staffing, provider buy-in, respiratory therapist autonomy, interdisciplinary teamwork, and staff education (Fisher et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14[11]:1674). These studies also suggest that efforts to increase the use of NIV in COPD need to account for the complex and interdisciplinary nature of NIV delivery and the need for team coordination. The authors further point out that although NIV is a cornerstone of treatment for patients with severe exacerbations of COPD with proven reduced need for intubation, hospital length of stay, and mortality and despite high-quality evidence and strong recommendations in clinical guidelines, use of NIV varies widely across hospitals.

Since interdisciplinary teamwork, respiratory therapy autonomy, and staff education have been identified as important factors in appropriate implementation of NIV, investigators are currently studying the effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility of interprofessional education for physicians, respiratory therapists, and nurses vs online education for increasing the delivery of NIV in patients hospitalized with COPD exacerbation (R01 HL 146615 – 01 Implementation of interprofessional training to improve uptake of noninvasive ventilation in patients hospitalized with severe COPD exacerbation).

More importantly, this work will further elucidate the interdisciplinary nature of NIV therapy and the benefit of an interprofessional approach to team education.

Mary Jo Farmer, MD, PhD, FCCP, Steering Committee Member Munish Luthra, MD, FCCP, Steering Committee Member

Evolution of point of care ultrasound (POCUS) education: cardiovascular, pulmonary, and beyond

A recent CHEST Physician article noted the ubiquity of POCUS employment but lamented inconsistencies and possible inadequacies of POCUS education amongst ACGME specialty fellowships (Satterwhite L. An update on the current standard for ultrasound education in fellowship. CHEST Physician. 2019 Dec. 9). POCUS education/training is no longer limited to physician fellowships but has percolated into the undergraduate medical education curricula of first-year medical students and physician assistant (PA) programs (Hoppmann RA, et al. Crit Ultrasound J. 2011;[3]:1; Rizzolo D, et al. J Physician Assist Educ. 2019;30[2]:103). Some PA residencies have long-incorporated POCUS training to varying degrees, providing emergency/critical care/cardiovascular ultrasound training comparable to that of physician residencies (Daymude ML, et al. J Physician Assist Educ. 2007;18[1]:29). A 12-month POCUS fellowship, which mirrors physician POCUS fellowship curricula, is also available for PAs at Madigan and Brooke Army Medical Centers and allows graduates the opportunity to earn RDMS/RDCS credentials (Monti J. J Physician Assist Educ. 2017;28[1]:27). POCUS employment is not limited to physicians and PAs, however. Respiratory therapists and other allied health professionals are also exploring the value of pulmonary, cardiovascular, and other critical care POCUS applications in their respective practices (Karthika M, et al. Respir Care. 2019;64[2]:217). Meanwhile, POCUS devices continue to evolve toward inexpensive handheld machines that incorporate machine learning/artificial intelligence, further mitigating barriers to integration of POCUS into routine clinical practice (Tsay D, et al. Circulation. 2018;138[22]:2569). With the expansion of POCUS across the full spectrum of health care, leadership from multiprofessional organizations, such as CHEST and the Society of Point-of-Care Ultrasound (SPOCUS), are well-positioned to leverage their diverse leadership to govern the training and safe employment of POCUS.

Robert Baeten II, DmSc, FCCP Steering Committee Member

Chest infections

New laboratory testing guidelines for diagnosing fungal infections

Secondary to a growing number of immunosuppressed individuals, the incidence of invasive fungal infections (IFI) is increasing. IFIs can be difficult to treat and are associated with a high mortality rate. Effective treatment is predicated on early recognition and accurate diagnosis (Limper AH, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183[1]:96). Therefore, the American Thoracic Society created a clinical practice guideline on laboratory diagnosis of the most common fungal infections (Hage CA, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200[5]:535). The most important diagnostic considerations for clinicians are summarized below:

1. Serum galactomannan and serum aspergillus PCR are recommended in severely immunocompromised patients suspected of having invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA).

2. Galactomannan and aspergillus PCR in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) are recommended for patients who are strongly suspected of having IPA, especially if serum is negative. In less severe immunocompromised patients, the BAL sensitivity of galactomannan is better compared with serum, without reducing specificity.

3. Due to low specificity/high false-positive rate, 1,3-B-D-glucan should not be used in isolation to diagnose invasive candidiasis.

4. No single best test exists for the diagnosis of blastomycosis or coccidioidomycosis; rather, more than one diagnostic test including fungal smear, culture, serum antibody, and antigen testing should be used for suspected blastomycosis or coccidioidomycosis.

5. Urine or serum antigen testing is recommended for patients with suspected disseminated or acute histoplasmosis. For immunocompetent patients suspected of pulmonary histoplasmosis, serologic testing is recommended; antigen testing may increase the diagnostic yield.

While these recommendations provide a basis for laboratory testing for the most common IFIs, they must be integrated into the clinical context to ensure accurate diagnosis.

Kelly Pennington, MD, Steering Committee MemberEva M. Carmona, MD, PhD, NetWork Member

Clinical pulmonary medicine

Definitive pleural interventions in malignant pleural effusions

Malignant pleural effusions (MPEs) contribute significantly to symptom burden, and an emphasis on patient-centered outcomes prioritizes palliation of symptoms and definitive management with pleurodesis. Clinical guidelines (Feller-Kopman DJ, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198[7]:839) for MPE recommend an indwelling pleural catheter (IPC) or chemical pleurodesis as first-line definitive pleural intervention. In a recent prospective study, Bhatnagar and colleagues (Bhatnagar R, et al. JAMA. 2019 Dec 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.19997) evaluated the effectiveness of thoracoscopy with talc poudrage compared with chest tube placement with talc slurry. The authors randomized 330 patients with MPE and expandable lung, and the primary outcome was pleurodesis failure at 90 days after randomization. There was no significant difference in primary outcome, and pleurodesis failure at 90 days was 22% with talc poudrage and 24% with talc slurry. Similar results for pleurodesis failure at 30 and 180 days were noted.

Secondary outcomes for all-cause mortality, quality of life measures, symptom (chest pain, dyspnea) scores, hospital days, and radiographic opacification also showed no difference. This supports an earlier study by Dresler and associates (Dresler CM, et al. Chest. 2005 Mar;127[3]:909) that reported similar efficacy of talc poudrage and talc slurry. Interestingly, Bhatnagar’s group (Bhatnagar R, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 5;378[14]:1313) previously demonstrated administration of talc slurry via IPC was safe and effective in the outpatient setting, but no direct comparison of IPC combined with talc poudrage or talc slurry is available.

These studies provide support for flexibility in MPE management, and selection of definitive pleural intervention can be tailored for each individual patient.

Saadia Faiz, MD, FCCP, Steering Committee Member

Mark Warner, MD, FCCP, NetWork Member

Interprofessional team

Interprofessional team and noninvasive ventilation in COPD exacerbation

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is a standard of care for treatment of COPD exacerbations, resulting in reduced need for mechanical ventilation, length of hospital stay, and mortality. Patient selection is as important to success as is choice of an appropriate interface, maintenance of synchrony, and a dedicated interprofessional team. Prior studies have identified that necessary factors for successful implementation of NIV in exacerbations of severe COPD include adequate equipment, sufficient numbers of qualified respiratory therapists, flexibility in staffing, provider buy-in, respiratory therapist autonomy, interdisciplinary teamwork, and staff education (Fisher et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14[11]:1674). These studies also suggest that efforts to increase the use of NIV in COPD need to account for the complex and interdisciplinary nature of NIV delivery and the need for team coordination. The authors further point out that although NIV is a cornerstone of treatment for patients with severe exacerbations of COPD with proven reduced need for intubation, hospital length of stay, and mortality and despite high-quality evidence and strong recommendations in clinical guidelines, use of NIV varies widely across hospitals.

Since interdisciplinary teamwork, respiratory therapy autonomy, and staff education have been identified as important factors in appropriate implementation of NIV, investigators are currently studying the effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility of interprofessional education for physicians, respiratory therapists, and nurses vs online education for increasing the delivery of NIV in patients hospitalized with COPD exacerbation (R01 HL 146615 – 01 Implementation of interprofessional training to improve uptake of noninvasive ventilation in patients hospitalized with severe COPD exacerbation).

More importantly, this work will further elucidate the interdisciplinary nature of NIV therapy and the benefit of an interprofessional approach to team education.

Mary Jo Farmer, MD, PhD, FCCP, Steering Committee Member Munish Luthra, MD, FCCP, Steering Committee Member

Evolution of point of care ultrasound (POCUS) education: cardiovascular, pulmonary, and beyond