User login

Bevacizumab/pembrolizumab deemed safe and active in mRCC

The combination of bevacizumab and pembrolizumab demonstrated acceptable safety and activity in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) in a phase 1b/2 study, according to researchers.

Grade 3-4 adverse events were seen in 45% of patients, which “compares favorably” with other combinations of immune checkpoint inhibitors and tyrosine kinase inhibitors, according to study author Arkadiusz Z. Dudek, MD, PhD, of HealthPartners Regions Cancer Care Center in St. Paul, Minn. and colleagues. Their report was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Phase 1b

The phase 1b portion of the study included 13 patients with clear cell mRCC that relapsed after or was refractory to multiple prior lines of therapy. The patients’ median age was 55 years (range, 33-68 years), and most were men (84.6%).

The patients received infusions of pembrolizumab at 200 mg plus bevacizumab at 10 mg/kg or 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks. The primary objective of the phase 1b component was to determine safety and identify the maximum tolerated dose of the combination.

The overall response rate was 41.7%. Five patients had partial responses, six had stable disease, one had progressive disease, and one was not evaluable.

The median progression-free survival was 9.9 months, and the median overall survival was 17.9 months. No dose-limiting toxicities were observed.

Phase 2

The phase 2 component included 48 patients with clear cell mRCC, all of whom were treatment naive. Their median age was 61 years (range, 42-84 years), and most were men (68.8%).

Based on the phase 1b data, the phase 2 dose of bevacizumab was 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks.

After a median time on treatment of 298 days, the overall response rate was 60.9%. One patient achieved a complete response, and two patients had complete responses in target lesions. Of the remaining patients, 25 achieved partial responses, 18 had stable disease, and 2 were unevaluable.

The median progression-free survival was 20.7 months, and the median overall survival was not reached at 28.3 months.

Safety

In the combined safety analysis, the most frequent treatment-related grade 3 adverse events were hypertension (25%), proteinuria (10%), adrenal insufficiency (6.7%), and pain/headaches (5.0%).

The most common grade 3 immune-related adverse events were adrenal insufficiency (6.7%), pneumonitis (3.3%), hepatitis (1.7%), skin rash (1.7%), gastritis (1.7%), hypothyroidism (1.7%), and oral mucositis (1.7%).

Two grade 4 adverse events (hyponatremia and duodenal ulcer) were reported. There were no treatment-related grade 5 events.

“The combination of 200 mg of pembrolizumab and a 15-mg/kg dose of bevacizumab given every 3 weeks is safe and active in metastatic RCC,” the authors wrote. “[The combination] could be further tested in patient populations where TKIs [tyrosine kinase inhibitors] are not well tolerated and can cause early treatment discontinuation.”

This study was funded by Merck. The authors disclosed financial affiliations with Merck and other companies.

SOURCE: Dudek AZ et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02394.

The combination of bevacizumab and pembrolizumab demonstrated acceptable safety and activity in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) in a phase 1b/2 study, according to researchers.

Grade 3-4 adverse events were seen in 45% of patients, which “compares favorably” with other combinations of immune checkpoint inhibitors and tyrosine kinase inhibitors, according to study author Arkadiusz Z. Dudek, MD, PhD, of HealthPartners Regions Cancer Care Center in St. Paul, Minn. and colleagues. Their report was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Phase 1b

The phase 1b portion of the study included 13 patients with clear cell mRCC that relapsed after or was refractory to multiple prior lines of therapy. The patients’ median age was 55 years (range, 33-68 years), and most were men (84.6%).

The patients received infusions of pembrolizumab at 200 mg plus bevacizumab at 10 mg/kg or 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks. The primary objective of the phase 1b component was to determine safety and identify the maximum tolerated dose of the combination.

The overall response rate was 41.7%. Five patients had partial responses, six had stable disease, one had progressive disease, and one was not evaluable.

The median progression-free survival was 9.9 months, and the median overall survival was 17.9 months. No dose-limiting toxicities were observed.

Phase 2

The phase 2 component included 48 patients with clear cell mRCC, all of whom were treatment naive. Their median age was 61 years (range, 42-84 years), and most were men (68.8%).

Based on the phase 1b data, the phase 2 dose of bevacizumab was 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks.

After a median time on treatment of 298 days, the overall response rate was 60.9%. One patient achieved a complete response, and two patients had complete responses in target lesions. Of the remaining patients, 25 achieved partial responses, 18 had stable disease, and 2 were unevaluable.

The median progression-free survival was 20.7 months, and the median overall survival was not reached at 28.3 months.

Safety

In the combined safety analysis, the most frequent treatment-related grade 3 adverse events were hypertension (25%), proteinuria (10%), adrenal insufficiency (6.7%), and pain/headaches (5.0%).

The most common grade 3 immune-related adverse events were adrenal insufficiency (6.7%), pneumonitis (3.3%), hepatitis (1.7%), skin rash (1.7%), gastritis (1.7%), hypothyroidism (1.7%), and oral mucositis (1.7%).

Two grade 4 adverse events (hyponatremia and duodenal ulcer) were reported. There were no treatment-related grade 5 events.

“The combination of 200 mg of pembrolizumab and a 15-mg/kg dose of bevacizumab given every 3 weeks is safe and active in metastatic RCC,” the authors wrote. “[The combination] could be further tested in patient populations where TKIs [tyrosine kinase inhibitors] are not well tolerated and can cause early treatment discontinuation.”

This study was funded by Merck. The authors disclosed financial affiliations with Merck and other companies.

SOURCE: Dudek AZ et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02394.

The combination of bevacizumab and pembrolizumab demonstrated acceptable safety and activity in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) in a phase 1b/2 study, according to researchers.

Grade 3-4 adverse events were seen in 45% of patients, which “compares favorably” with other combinations of immune checkpoint inhibitors and tyrosine kinase inhibitors, according to study author Arkadiusz Z. Dudek, MD, PhD, of HealthPartners Regions Cancer Care Center in St. Paul, Minn. and colleagues. Their report was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Phase 1b

The phase 1b portion of the study included 13 patients with clear cell mRCC that relapsed after or was refractory to multiple prior lines of therapy. The patients’ median age was 55 years (range, 33-68 years), and most were men (84.6%).

The patients received infusions of pembrolizumab at 200 mg plus bevacizumab at 10 mg/kg or 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks. The primary objective of the phase 1b component was to determine safety and identify the maximum tolerated dose of the combination.

The overall response rate was 41.7%. Five patients had partial responses, six had stable disease, one had progressive disease, and one was not evaluable.

The median progression-free survival was 9.9 months, and the median overall survival was 17.9 months. No dose-limiting toxicities were observed.

Phase 2

The phase 2 component included 48 patients with clear cell mRCC, all of whom were treatment naive. Their median age was 61 years (range, 42-84 years), and most were men (68.8%).

Based on the phase 1b data, the phase 2 dose of bevacizumab was 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks.

After a median time on treatment of 298 days, the overall response rate was 60.9%. One patient achieved a complete response, and two patients had complete responses in target lesions. Of the remaining patients, 25 achieved partial responses, 18 had stable disease, and 2 were unevaluable.

The median progression-free survival was 20.7 months, and the median overall survival was not reached at 28.3 months.

Safety

In the combined safety analysis, the most frequent treatment-related grade 3 adverse events were hypertension (25%), proteinuria (10%), adrenal insufficiency (6.7%), and pain/headaches (5.0%).

The most common grade 3 immune-related adverse events were adrenal insufficiency (6.7%), pneumonitis (3.3%), hepatitis (1.7%), skin rash (1.7%), gastritis (1.7%), hypothyroidism (1.7%), and oral mucositis (1.7%).

Two grade 4 adverse events (hyponatremia and duodenal ulcer) were reported. There were no treatment-related grade 5 events.

“The combination of 200 mg of pembrolizumab and a 15-mg/kg dose of bevacizumab given every 3 weeks is safe and active in metastatic RCC,” the authors wrote. “[The combination] could be further tested in patient populations where TKIs [tyrosine kinase inhibitors] are not well tolerated and can cause early treatment discontinuation.”

This study was funded by Merck. The authors disclosed financial affiliations with Merck and other companies.

SOURCE: Dudek AZ et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02394.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

First guidelines to address thyroid disease surgery

offering evidence-based recommendations on the wide-ranging aspects of thyroidectomy and the management of benign, as well as malignant, thyroid nodules and cancer.

Whereas various endocrine and thyroid societies issue guidelines on many aspects of the management of thyroid disease, the new AAES guidelines are the first specifically to address surgical management of thyroid disease in adults.

“These guidelines truly focus on the surgical decision-making and management of thyroid disease. However, there is something for all clinicians who take care of patients with thyroid disease,” lead author Kepal N. Patel, MD, of NYU Langone Health in New York City, said in an interview.

The guidelines, published in the Annals of Surgery, include a total of 66 recommendations from a multidisciplinary panel of 19 experts who reviewed medical literature spanning 1985-2018.

More than 100,000 thyroidectomies are performed each year in the United States alone, and as surgical indications and treatment paradigms evolve, the need for surgical guidance is more important than ever, Dr. Patel said.

“Such transformations have propagated differences in clinical interpretation and management, and as a result, clinical uncertainty, and even controversy, have emerged,” he said. “Recognizing the importance of these changes, the AAES determined that evidence-based clinical guidelines were necessary to enhance the safe and effective surgical treatment of benign and malignant thyroid disease.”

Key areas addressed in the guidelines include the addition of new cytologic and pathologic diagnostic criteria, molecular profiling tests, operative techniques, and adjuncts, as well as the nuances surrounding the sometimes challenging newer concept of “borderline” thyroid tumors, Dr. Patel noted.

In terms of imaging recommendations, for instance, the guidelines recommend the preoperative use of computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, as stated in Recommendation 6: “CT or MRI with intravenous contrast should be used preoperatively as an adjunct to ultrasound in selected patients with clinical suspicion for advanced locoregional thyroid cancer.” The recommendation is cited as being “strong,” with a “low quality of evidence.”

Further diagnostic recommendations cover issues that include voice assessment, the risk for vocal fold dysfunction related to thyroid disease and surgery, and the use of fine-needle aspiration biopsy in evaluating suspicious thyroid nodules and lymph nodes.

The guidelines also address the indications for thyroidectomy, with recommendations regarding the extent and outcomes of surgery spanning different categories of thyroid disease. A key recommendation along those lines, for instance, indicates that, when possible, thyroidectomy should be performed by surgeons who perform a high volume of such procedures.

Approaches for safe and effective perioperative management are also covered, and include measures to prevent complications and the use of thyroid tissue diagnosis during surgery, such as core-needle biopsy of the thyroid and cervical lymph nodes, and incisional biopsy of the thyroid, nodal dissection, and concurrent parathyroidectomy.

Other recommendations address the optimal management of thyroid cancer, with an emphasis on a personalized, evidence-based approach tailored to the patient’s situation and preferences.

The authors underscored that, as technology rapidly evolves, “in the future, this work will certainly and rightly need to be done again.” In the meantime, they wrote, recommendations should be relevant to “the target audience [of] the practicing surgeon in a community hospital, academic center, or training program.”

An AAES press release noted that “the members of the expert panel hope their efforts will meet the need for evidence-based recommendations to ‘define practice, personalize care, stratify risk, reduce health care costs, improve outcomes, and identify rational challenges for future efforts.’ ”

The authors of the guidelines reported no conflicts of interest in regard to the guidelines, although the article lists disclosures for six authors.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

offering evidence-based recommendations on the wide-ranging aspects of thyroidectomy and the management of benign, as well as malignant, thyroid nodules and cancer.

Whereas various endocrine and thyroid societies issue guidelines on many aspects of the management of thyroid disease, the new AAES guidelines are the first specifically to address surgical management of thyroid disease in adults.

“These guidelines truly focus on the surgical decision-making and management of thyroid disease. However, there is something for all clinicians who take care of patients with thyroid disease,” lead author Kepal N. Patel, MD, of NYU Langone Health in New York City, said in an interview.

The guidelines, published in the Annals of Surgery, include a total of 66 recommendations from a multidisciplinary panel of 19 experts who reviewed medical literature spanning 1985-2018.

More than 100,000 thyroidectomies are performed each year in the United States alone, and as surgical indications and treatment paradigms evolve, the need for surgical guidance is more important than ever, Dr. Patel said.

“Such transformations have propagated differences in clinical interpretation and management, and as a result, clinical uncertainty, and even controversy, have emerged,” he said. “Recognizing the importance of these changes, the AAES determined that evidence-based clinical guidelines were necessary to enhance the safe and effective surgical treatment of benign and malignant thyroid disease.”

Key areas addressed in the guidelines include the addition of new cytologic and pathologic diagnostic criteria, molecular profiling tests, operative techniques, and adjuncts, as well as the nuances surrounding the sometimes challenging newer concept of “borderline” thyroid tumors, Dr. Patel noted.

In terms of imaging recommendations, for instance, the guidelines recommend the preoperative use of computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, as stated in Recommendation 6: “CT or MRI with intravenous contrast should be used preoperatively as an adjunct to ultrasound in selected patients with clinical suspicion for advanced locoregional thyroid cancer.” The recommendation is cited as being “strong,” with a “low quality of evidence.”

Further diagnostic recommendations cover issues that include voice assessment, the risk for vocal fold dysfunction related to thyroid disease and surgery, and the use of fine-needle aspiration biopsy in evaluating suspicious thyroid nodules and lymph nodes.

The guidelines also address the indications for thyroidectomy, with recommendations regarding the extent and outcomes of surgery spanning different categories of thyroid disease. A key recommendation along those lines, for instance, indicates that, when possible, thyroidectomy should be performed by surgeons who perform a high volume of such procedures.

Approaches for safe and effective perioperative management are also covered, and include measures to prevent complications and the use of thyroid tissue diagnosis during surgery, such as core-needle biopsy of the thyroid and cervical lymph nodes, and incisional biopsy of the thyroid, nodal dissection, and concurrent parathyroidectomy.

Other recommendations address the optimal management of thyroid cancer, with an emphasis on a personalized, evidence-based approach tailored to the patient’s situation and preferences.

The authors underscored that, as technology rapidly evolves, “in the future, this work will certainly and rightly need to be done again.” In the meantime, they wrote, recommendations should be relevant to “the target audience [of] the practicing surgeon in a community hospital, academic center, or training program.”

An AAES press release noted that “the members of the expert panel hope their efforts will meet the need for evidence-based recommendations to ‘define practice, personalize care, stratify risk, reduce health care costs, improve outcomes, and identify rational challenges for future efforts.’ ”

The authors of the guidelines reported no conflicts of interest in regard to the guidelines, although the article lists disclosures for six authors.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

offering evidence-based recommendations on the wide-ranging aspects of thyroidectomy and the management of benign, as well as malignant, thyroid nodules and cancer.

Whereas various endocrine and thyroid societies issue guidelines on many aspects of the management of thyroid disease, the new AAES guidelines are the first specifically to address surgical management of thyroid disease in adults.

“These guidelines truly focus on the surgical decision-making and management of thyroid disease. However, there is something for all clinicians who take care of patients with thyroid disease,” lead author Kepal N. Patel, MD, of NYU Langone Health in New York City, said in an interview.

The guidelines, published in the Annals of Surgery, include a total of 66 recommendations from a multidisciplinary panel of 19 experts who reviewed medical literature spanning 1985-2018.

More than 100,000 thyroidectomies are performed each year in the United States alone, and as surgical indications and treatment paradigms evolve, the need for surgical guidance is more important than ever, Dr. Patel said.

“Such transformations have propagated differences in clinical interpretation and management, and as a result, clinical uncertainty, and even controversy, have emerged,” he said. “Recognizing the importance of these changes, the AAES determined that evidence-based clinical guidelines were necessary to enhance the safe and effective surgical treatment of benign and malignant thyroid disease.”

Key areas addressed in the guidelines include the addition of new cytologic and pathologic diagnostic criteria, molecular profiling tests, operative techniques, and adjuncts, as well as the nuances surrounding the sometimes challenging newer concept of “borderline” thyroid tumors, Dr. Patel noted.

In terms of imaging recommendations, for instance, the guidelines recommend the preoperative use of computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, as stated in Recommendation 6: “CT or MRI with intravenous contrast should be used preoperatively as an adjunct to ultrasound in selected patients with clinical suspicion for advanced locoregional thyroid cancer.” The recommendation is cited as being “strong,” with a “low quality of evidence.”

Further diagnostic recommendations cover issues that include voice assessment, the risk for vocal fold dysfunction related to thyroid disease and surgery, and the use of fine-needle aspiration biopsy in evaluating suspicious thyroid nodules and lymph nodes.

The guidelines also address the indications for thyroidectomy, with recommendations regarding the extent and outcomes of surgery spanning different categories of thyroid disease. A key recommendation along those lines, for instance, indicates that, when possible, thyroidectomy should be performed by surgeons who perform a high volume of such procedures.

Approaches for safe and effective perioperative management are also covered, and include measures to prevent complications and the use of thyroid tissue diagnosis during surgery, such as core-needle biopsy of the thyroid and cervical lymph nodes, and incisional biopsy of the thyroid, nodal dissection, and concurrent parathyroidectomy.

Other recommendations address the optimal management of thyroid cancer, with an emphasis on a personalized, evidence-based approach tailored to the patient’s situation and preferences.

The authors underscored that, as technology rapidly evolves, “in the future, this work will certainly and rightly need to be done again.” In the meantime, they wrote, recommendations should be relevant to “the target audience [of] the practicing surgeon in a community hospital, academic center, or training program.”

An AAES press release noted that “the members of the expert panel hope their efforts will meet the need for evidence-based recommendations to ‘define practice, personalize care, stratify risk, reduce health care costs, improve outcomes, and identify rational challenges for future efforts.’ ”

The authors of the guidelines reported no conflicts of interest in regard to the guidelines, although the article lists disclosures for six authors.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Putting diabetes tools ‘in the pocket’ improves HbA1c control

Patients with type 2 diabetes who were part of a health care plan and used a computer and/or app on a mobile device to access a portal (website) with tools for managing diabetes were more adherent with prescription refills and had improved hemoglobin A1c levels, according to findings from a 33-month study published online in JAMA Network Open.

The improvements were greater in patients without prior portal usage, who began accessing the portal via a mobile device (smartphone or tablet) app as well as computer, compared with those who used only a computer.

Moreover, the improvements were greatest in patients with poorly controlled diabetes (HbA1c greater than 8%) who began accessing the portal by both means.

“ lead author Ilana Graetz, PhD, an associate professor at the Rollins School of Health Policy and Management, Emory University, Atlanta, observed in a statement from Kaiser Permanente.

The results show that “patients can use technology to better manage their own care, their medications, and their diabetes,” added senior author Mary Reed, DrPH, a research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, California. “This is an example of how the health care system, by offering patients access to their own information and the ability to manage their health care online, can improve their health.”

“Offering this in a mobile-friendly way can give even more patients the ability to engage with their health care,” Dr. Reed noted. “It literally puts the access to these tools in the patient’s own pocket wherever they go.”

Checking refills and lab results

Dr. Graetz and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of data from 111,463 adults with type 2 diabetes who were not receiving insulin but were taking oral diabetes medications and were covered by a health care plan with Kaiser Permanente Northern California from April 1, 2015 to December 31, 2017. The patients were a mean age of 64 years, and 54% were men.

Patients could register online for free access to a portal that allowed them to get general health information and see their laboratory test results, as well as securely send and receive messages to and from their health care providers, make medical appointments, and request prescription refills.

Study outcomes were change in oral diabetes medication adherence and HbA1c levels at 33 months.

At baseline, 28% of patients had poor medication adherence (monthly days covered, less than 80%), and 20% had poor glycemic control.

After 33 months, the proportion of patients who never accessed the diabetes management portal dropped from 35% to 25%, and the proportion who accessed it from both a computer and an app increased from 34% to 62%.

Among patients with no prior portal access and who began accessing the portal by computer only, medication adherence increased by 1.16% and A1c dropped by 0.06%.

However, among patients with no prior portal access who began to access it using both a computer and an app, diabetes management improvement was greater: medication adherence increased by 1.67% and HbA1c levels dropped by 0.13%.

And among patients with no prior portal usage who had an initial HbA1c level of more than 8.0% and began to access the website by both means, medication adherence increased by 5.09%, equivalent to an added 1.5 medication-adherent days per month, and HbA1c levels fell by 0.19%.

There was also “a more modest, but still statistically significant increase,” of about 0.5 added medication-adherent days per month in patients with lower initial A1c levels who began accessing the portal both ways.

“Although medication adherence measured by medication dispensed cannot guarantee which medications were actually used by patients,” the authors wrote, “our findings of concurrent improvements in [HbA1c] levels confirm physiological improvements in diabetes control.”

“Convenient access to portal self-management tools through a mobile device could significantly improve diabetes management,” they conclude.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with type 2 diabetes who were part of a health care plan and used a computer and/or app on a mobile device to access a portal (website) with tools for managing diabetes were more adherent with prescription refills and had improved hemoglobin A1c levels, according to findings from a 33-month study published online in JAMA Network Open.

The improvements were greater in patients without prior portal usage, who began accessing the portal via a mobile device (smartphone or tablet) app as well as computer, compared with those who used only a computer.

Moreover, the improvements were greatest in patients with poorly controlled diabetes (HbA1c greater than 8%) who began accessing the portal by both means.

“ lead author Ilana Graetz, PhD, an associate professor at the Rollins School of Health Policy and Management, Emory University, Atlanta, observed in a statement from Kaiser Permanente.

The results show that “patients can use technology to better manage their own care, their medications, and their diabetes,” added senior author Mary Reed, DrPH, a research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, California. “This is an example of how the health care system, by offering patients access to their own information and the ability to manage their health care online, can improve their health.”

“Offering this in a mobile-friendly way can give even more patients the ability to engage with their health care,” Dr. Reed noted. “It literally puts the access to these tools in the patient’s own pocket wherever they go.”

Checking refills and lab results

Dr. Graetz and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of data from 111,463 adults with type 2 diabetes who were not receiving insulin but were taking oral diabetes medications and were covered by a health care plan with Kaiser Permanente Northern California from April 1, 2015 to December 31, 2017. The patients were a mean age of 64 years, and 54% were men.

Patients could register online for free access to a portal that allowed them to get general health information and see their laboratory test results, as well as securely send and receive messages to and from their health care providers, make medical appointments, and request prescription refills.

Study outcomes were change in oral diabetes medication adherence and HbA1c levels at 33 months.

At baseline, 28% of patients had poor medication adherence (monthly days covered, less than 80%), and 20% had poor glycemic control.

After 33 months, the proportion of patients who never accessed the diabetes management portal dropped from 35% to 25%, and the proportion who accessed it from both a computer and an app increased from 34% to 62%.

Among patients with no prior portal access and who began accessing the portal by computer only, medication adherence increased by 1.16% and A1c dropped by 0.06%.

However, among patients with no prior portal access who began to access it using both a computer and an app, diabetes management improvement was greater: medication adherence increased by 1.67% and HbA1c levels dropped by 0.13%.

And among patients with no prior portal usage who had an initial HbA1c level of more than 8.0% and began to access the website by both means, medication adherence increased by 5.09%, equivalent to an added 1.5 medication-adherent days per month, and HbA1c levels fell by 0.19%.

There was also “a more modest, but still statistically significant increase,” of about 0.5 added medication-adherent days per month in patients with lower initial A1c levels who began accessing the portal both ways.

“Although medication adherence measured by medication dispensed cannot guarantee which medications were actually used by patients,” the authors wrote, “our findings of concurrent improvements in [HbA1c] levels confirm physiological improvements in diabetes control.”

“Convenient access to portal self-management tools through a mobile device could significantly improve diabetes management,” they conclude.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with type 2 diabetes who were part of a health care plan and used a computer and/or app on a mobile device to access a portal (website) with tools for managing diabetes were more adherent with prescription refills and had improved hemoglobin A1c levels, according to findings from a 33-month study published online in JAMA Network Open.

The improvements were greater in patients without prior portal usage, who began accessing the portal via a mobile device (smartphone or tablet) app as well as computer, compared with those who used only a computer.

Moreover, the improvements were greatest in patients with poorly controlled diabetes (HbA1c greater than 8%) who began accessing the portal by both means.

“ lead author Ilana Graetz, PhD, an associate professor at the Rollins School of Health Policy and Management, Emory University, Atlanta, observed in a statement from Kaiser Permanente.

The results show that “patients can use technology to better manage their own care, their medications, and their diabetes,” added senior author Mary Reed, DrPH, a research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, California. “This is an example of how the health care system, by offering patients access to their own information and the ability to manage their health care online, can improve their health.”

“Offering this in a mobile-friendly way can give even more patients the ability to engage with their health care,” Dr. Reed noted. “It literally puts the access to these tools in the patient’s own pocket wherever they go.”

Checking refills and lab results

Dr. Graetz and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of data from 111,463 adults with type 2 diabetes who were not receiving insulin but were taking oral diabetes medications and were covered by a health care plan with Kaiser Permanente Northern California from April 1, 2015 to December 31, 2017. The patients were a mean age of 64 years, and 54% were men.

Patients could register online for free access to a portal that allowed them to get general health information and see their laboratory test results, as well as securely send and receive messages to and from their health care providers, make medical appointments, and request prescription refills.

Study outcomes were change in oral diabetes medication adherence and HbA1c levels at 33 months.

At baseline, 28% of patients had poor medication adherence (monthly days covered, less than 80%), and 20% had poor glycemic control.

After 33 months, the proportion of patients who never accessed the diabetes management portal dropped from 35% to 25%, and the proportion who accessed it from both a computer and an app increased from 34% to 62%.

Among patients with no prior portal access and who began accessing the portal by computer only, medication adherence increased by 1.16% and A1c dropped by 0.06%.

However, among patients with no prior portal access who began to access it using both a computer and an app, diabetes management improvement was greater: medication adherence increased by 1.67% and HbA1c levels dropped by 0.13%.

And among patients with no prior portal usage who had an initial HbA1c level of more than 8.0% and began to access the website by both means, medication adherence increased by 5.09%, equivalent to an added 1.5 medication-adherent days per month, and HbA1c levels fell by 0.19%.

There was also “a more modest, but still statistically significant increase,” of about 0.5 added medication-adherent days per month in patients with lower initial A1c levels who began accessing the portal both ways.

“Although medication adherence measured by medication dispensed cannot guarantee which medications were actually used by patients,” the authors wrote, “our findings of concurrent improvements in [HbA1c] levels confirm physiological improvements in diabetes control.”

“Convenient access to portal self-management tools through a mobile device could significantly improve diabetes management,” they conclude.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Osilodrostat gets FDA go-ahead for Cushing’s disease in adults

who either are not good candidates for pituitary gland surgery – the recommended first-line therapy – or in whom the disease persists after surgery.

Cushing’s disease is a rare condition caused when a pituitary tumor releases too much of the hormone adrenocorticotropin, which in turn, triggers the adrenal gland to overproduce cortisol. The condition is associated with serious health complications, including high blood pressure, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and compromised immunity.

Osilodrostat is the first therapy approved by the FDA to tackle the overproduction of cortisol, which it does by blocking the 11-beta-hydroxylase enzyme and thus preventing cortisol synthesis, the agency said in a press release.

In November 2019, the European Medicines Agency recommended the granting of a marketing authorization for osilodrostat, also for treating adults with Cushing’s disease.

The U.S. approval was based on outcomes from a study that evaluated the drug’s safety and efficacy in 137 adults with Cushing’s disease who had undergone pituitary surgery but were not cured, or who were not surgical candidates, according the release. About three-quarters of the patients were women, and the mean age was 41 years.

All of the patients started a 24-week, single-arm, open-label period at a dose of 2 mg of osilodrostat twice daily that could be increased every 2 weeks to 30 mg twice daily.

By week 24, cortisol levels in roughly half the patients were within the normal range, and 71 patients who did not need any more dose increases and who tolerated the drug were randomized to either osilodrostat or placebo for an 8-week withdrawal study. At the end of that time, 86% of the osilodrostat patients maintained their normal-range cortisol levels, compared with 30% of those taking placebo.

Osilodrostat is taken as an oral tablet twice a day, in the morning and evening. Among the common side effects reported in the study were adrenal insufficiency, headache, vomiting, nausea, fatigue, and edema, although hypocortisolism, QTc prolongation, and elevations in adrenal hormone precursors, and androgens may also occur, according to the release.

The drug had been given an Orphan Drug Designation in recognition of its intended use in the treatment of a rare disease. The approval was granted to Novartis.

who either are not good candidates for pituitary gland surgery – the recommended first-line therapy – or in whom the disease persists after surgery.

Cushing’s disease is a rare condition caused when a pituitary tumor releases too much of the hormone adrenocorticotropin, which in turn, triggers the adrenal gland to overproduce cortisol. The condition is associated with serious health complications, including high blood pressure, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and compromised immunity.

Osilodrostat is the first therapy approved by the FDA to tackle the overproduction of cortisol, which it does by blocking the 11-beta-hydroxylase enzyme and thus preventing cortisol synthesis, the agency said in a press release.

In November 2019, the European Medicines Agency recommended the granting of a marketing authorization for osilodrostat, also for treating adults with Cushing’s disease.

The U.S. approval was based on outcomes from a study that evaluated the drug’s safety and efficacy in 137 adults with Cushing’s disease who had undergone pituitary surgery but were not cured, or who were not surgical candidates, according the release. About three-quarters of the patients were women, and the mean age was 41 years.

All of the patients started a 24-week, single-arm, open-label period at a dose of 2 mg of osilodrostat twice daily that could be increased every 2 weeks to 30 mg twice daily.

By week 24, cortisol levels in roughly half the patients were within the normal range, and 71 patients who did not need any more dose increases and who tolerated the drug were randomized to either osilodrostat or placebo for an 8-week withdrawal study. At the end of that time, 86% of the osilodrostat patients maintained their normal-range cortisol levels, compared with 30% of those taking placebo.

Osilodrostat is taken as an oral tablet twice a day, in the morning and evening. Among the common side effects reported in the study were adrenal insufficiency, headache, vomiting, nausea, fatigue, and edema, although hypocortisolism, QTc prolongation, and elevations in adrenal hormone precursors, and androgens may also occur, according to the release.

The drug had been given an Orphan Drug Designation in recognition of its intended use in the treatment of a rare disease. The approval was granted to Novartis.

who either are not good candidates for pituitary gland surgery – the recommended first-line therapy – or in whom the disease persists after surgery.

Cushing’s disease is a rare condition caused when a pituitary tumor releases too much of the hormone adrenocorticotropin, which in turn, triggers the adrenal gland to overproduce cortisol. The condition is associated with serious health complications, including high blood pressure, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and compromised immunity.

Osilodrostat is the first therapy approved by the FDA to tackle the overproduction of cortisol, which it does by blocking the 11-beta-hydroxylase enzyme and thus preventing cortisol synthesis, the agency said in a press release.

In November 2019, the European Medicines Agency recommended the granting of a marketing authorization for osilodrostat, also for treating adults with Cushing’s disease.

The U.S. approval was based on outcomes from a study that evaluated the drug’s safety and efficacy in 137 adults with Cushing’s disease who had undergone pituitary surgery but were not cured, or who were not surgical candidates, according the release. About three-quarters of the patients were women, and the mean age was 41 years.

All of the patients started a 24-week, single-arm, open-label period at a dose of 2 mg of osilodrostat twice daily that could be increased every 2 weeks to 30 mg twice daily.

By week 24, cortisol levels in roughly half the patients were within the normal range, and 71 patients who did not need any more dose increases and who tolerated the drug were randomized to either osilodrostat or placebo for an 8-week withdrawal study. At the end of that time, 86% of the osilodrostat patients maintained their normal-range cortisol levels, compared with 30% of those taking placebo.

Osilodrostat is taken as an oral tablet twice a day, in the morning and evening. Among the common side effects reported in the study were adrenal insufficiency, headache, vomiting, nausea, fatigue, and edema, although hypocortisolism, QTc prolongation, and elevations in adrenal hormone precursors, and androgens may also occur, according to the release.

The drug had been given an Orphan Drug Designation in recognition of its intended use in the treatment of a rare disease. The approval was granted to Novartis.

Stillbirth linked to end-stage renal disease

and they were also at greater risk for chronic kidney disease (CKD), according to findings published in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Peter M Barrett, MB, of the University College Cork (Ireland), and colleagues conducted a population-based cohort study using data from the Swedish Medical Birth Register, National Patient Register, and the Swedish Renal Register to identify women who had live births and stillbirths. They then used anonymized unique personal identification numbers to cross-reference the registries.

From a full cohort of nearly 2 million women who gave birth during 1973-2012, and during a median follow-up of 20.7 years, 13,032 women experienced stillbirth, which, until 2008, was defined as fetal death after 28 weeks’ gestation, and after 2008, as occurring after 22 weeks. Women were excluded if they had any diagnosis of renal disease before their first pregnancy, as well as for a history of cardiovascular disease, chronic hypertension, diabetes, and certain other conditions at baseline.

Overall, 18,017 women developed CKD, and 1,283 developed ESRD. The fully adjusted model showed adjusted hazard ratios of 1.26 for CKD (95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.45) and 2.25 for ESRD (95% CI, 1.55-3.25) in women who had experienced stillbirth, compared with those who had not experienced stillbirth.

The researchers reported that associations between stillbirth and renal disease existed independently of underlying medical and obstetric comorbidities, such as congenital malformations, being small for gestational age, and preeclampsia, and that when those comorbidities were excluded, “the associations between stillbirth and maternal renal disease were strengthened (CKD: aHR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.13-1.57; and ESRD: aHR, 2.95; 95% CI, 1.86-4.68).”

In addition, they noted that there was no significant association between stillbirth and either CKD or ESRD in women who had prepregnancy medical comorbidities (CKD: aHR, 1.13; 95% CI 0.73-1.75; and ESRD: aHR 1.49; 95% CI, 0.78-2.85).

“Further research is required to better understand the underlying pathophysiology of this association and to determine whether affected women would benefit from closer surveillance and follow-up for future hypertension and renal disease,” the authors concluded.

The work was performed within the Irish Clinical Academic Training Programme and was funded by grants from several organizations. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Barret PM et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb 26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.031.

and they were also at greater risk for chronic kidney disease (CKD), according to findings published in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Peter M Barrett, MB, of the University College Cork (Ireland), and colleagues conducted a population-based cohort study using data from the Swedish Medical Birth Register, National Patient Register, and the Swedish Renal Register to identify women who had live births and stillbirths. They then used anonymized unique personal identification numbers to cross-reference the registries.

From a full cohort of nearly 2 million women who gave birth during 1973-2012, and during a median follow-up of 20.7 years, 13,032 women experienced stillbirth, which, until 2008, was defined as fetal death after 28 weeks’ gestation, and after 2008, as occurring after 22 weeks. Women were excluded if they had any diagnosis of renal disease before their first pregnancy, as well as for a history of cardiovascular disease, chronic hypertension, diabetes, and certain other conditions at baseline.

Overall, 18,017 women developed CKD, and 1,283 developed ESRD. The fully adjusted model showed adjusted hazard ratios of 1.26 for CKD (95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.45) and 2.25 for ESRD (95% CI, 1.55-3.25) in women who had experienced stillbirth, compared with those who had not experienced stillbirth.

The researchers reported that associations between stillbirth and renal disease existed independently of underlying medical and obstetric comorbidities, such as congenital malformations, being small for gestational age, and preeclampsia, and that when those comorbidities were excluded, “the associations between stillbirth and maternal renal disease were strengthened (CKD: aHR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.13-1.57; and ESRD: aHR, 2.95; 95% CI, 1.86-4.68).”

In addition, they noted that there was no significant association between stillbirth and either CKD or ESRD in women who had prepregnancy medical comorbidities (CKD: aHR, 1.13; 95% CI 0.73-1.75; and ESRD: aHR 1.49; 95% CI, 0.78-2.85).

“Further research is required to better understand the underlying pathophysiology of this association and to determine whether affected women would benefit from closer surveillance and follow-up for future hypertension and renal disease,” the authors concluded.

The work was performed within the Irish Clinical Academic Training Programme and was funded by grants from several organizations. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Barret PM et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb 26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.031.

and they were also at greater risk for chronic kidney disease (CKD), according to findings published in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Peter M Barrett, MB, of the University College Cork (Ireland), and colleagues conducted a population-based cohort study using data from the Swedish Medical Birth Register, National Patient Register, and the Swedish Renal Register to identify women who had live births and stillbirths. They then used anonymized unique personal identification numbers to cross-reference the registries.

From a full cohort of nearly 2 million women who gave birth during 1973-2012, and during a median follow-up of 20.7 years, 13,032 women experienced stillbirth, which, until 2008, was defined as fetal death after 28 weeks’ gestation, and after 2008, as occurring after 22 weeks. Women were excluded if they had any diagnosis of renal disease before their first pregnancy, as well as for a history of cardiovascular disease, chronic hypertension, diabetes, and certain other conditions at baseline.

Overall, 18,017 women developed CKD, and 1,283 developed ESRD. The fully adjusted model showed adjusted hazard ratios of 1.26 for CKD (95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.45) and 2.25 for ESRD (95% CI, 1.55-3.25) in women who had experienced stillbirth, compared with those who had not experienced stillbirth.

The researchers reported that associations between stillbirth and renal disease existed independently of underlying medical and obstetric comorbidities, such as congenital malformations, being small for gestational age, and preeclampsia, and that when those comorbidities were excluded, “the associations between stillbirth and maternal renal disease were strengthened (CKD: aHR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.13-1.57; and ESRD: aHR, 2.95; 95% CI, 1.86-4.68).”

In addition, they noted that there was no significant association between stillbirth and either CKD or ESRD in women who had prepregnancy medical comorbidities (CKD: aHR, 1.13; 95% CI 0.73-1.75; and ESRD: aHR 1.49; 95% CI, 0.78-2.85).

“Further research is required to better understand the underlying pathophysiology of this association and to determine whether affected women would benefit from closer surveillance and follow-up for future hypertension and renal disease,” the authors concluded.

The work was performed within the Irish Clinical Academic Training Programme and was funded by grants from several organizations. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Barret PM et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb 26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.031.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Frequent tooth brushing may reduce diabetes risk

Oral hygiene may be a key factor in diabetes risk, new data from a Korean national health database suggest.

“Frequent tooth brushing may be an attenuating factor for the risk of new-onset diabetes, and the presence of periodontal disease and increased number of missing teeth may be augmenting factors,” wrote Yoonkyung Chang, MD, of the Department of Neurology, Mokdong Hospital, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues.

they continued in an article published online in Diabetologia.

Periodontal disease involves inflammatory reactions that affect the surrounding tissues of the teeth. Inflammation, in turn, is an important cause of diabetes because it increases insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction, Dr. Chang and colleagues explained.

They analyzed data gathered during 2003-2006 from 188,013 individuals from the Korean National Health Insurance System – Health Screening Cohort who had complete data and did not have diabetes at baseline. Oral hygiene behaviors, including frequency of tooth brushing, and dental visits or cleanings, were collected by self-report.

Over a median follow-up of 10 years, there were 31,545 new cases of diabetes, with an estimated overall 10-year event rate of 16.1%. The rate was 17.2% for those with periodontal disease at baseline, compared with 15.8% for those without, which was a significant difference even after adjustments for multiple confounders (hazard ratio, 1.09; P less than .001).

Compared with patients who had no missing teeth, the event rate for new-onset diabetes rose from 15.4% for patients with 1 missing tooth (HR, 1.08; P less than .001) to 21.4% for those with 15 or more missing teeth (HR, 1.21; P less than .001).

Professional dental cleaning did not have a significant effect after multivariate analysis. However, the number of daily tooth brushings by the individual did. Compared with brushing 0-1 times/day, those who brushed 3 or more times/day had a significantly lower risk for new-onset diabetes (HR, 0.92; P less than .001).

In subgroup analyses, periodontal disease was more strongly associated with new-onset diabetes in adults aged 51 years and younger (HR, 1.14), compared with those who were 52 years or older (HR, 1.06).

The study was supported by a grant from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Oral hygiene may be a key factor in diabetes risk, new data from a Korean national health database suggest.

“Frequent tooth brushing may be an attenuating factor for the risk of new-onset diabetes, and the presence of periodontal disease and increased number of missing teeth may be augmenting factors,” wrote Yoonkyung Chang, MD, of the Department of Neurology, Mokdong Hospital, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues.

they continued in an article published online in Diabetologia.

Periodontal disease involves inflammatory reactions that affect the surrounding tissues of the teeth. Inflammation, in turn, is an important cause of diabetes because it increases insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction, Dr. Chang and colleagues explained.

They analyzed data gathered during 2003-2006 from 188,013 individuals from the Korean National Health Insurance System – Health Screening Cohort who had complete data and did not have diabetes at baseline. Oral hygiene behaviors, including frequency of tooth brushing, and dental visits or cleanings, were collected by self-report.

Over a median follow-up of 10 years, there were 31,545 new cases of diabetes, with an estimated overall 10-year event rate of 16.1%. The rate was 17.2% for those with periodontal disease at baseline, compared with 15.8% for those without, which was a significant difference even after adjustments for multiple confounders (hazard ratio, 1.09; P less than .001).

Compared with patients who had no missing teeth, the event rate for new-onset diabetes rose from 15.4% for patients with 1 missing tooth (HR, 1.08; P less than .001) to 21.4% for those with 15 or more missing teeth (HR, 1.21; P less than .001).

Professional dental cleaning did not have a significant effect after multivariate analysis. However, the number of daily tooth brushings by the individual did. Compared with brushing 0-1 times/day, those who brushed 3 or more times/day had a significantly lower risk for new-onset diabetes (HR, 0.92; P less than .001).

In subgroup analyses, periodontal disease was more strongly associated with new-onset diabetes in adults aged 51 years and younger (HR, 1.14), compared with those who were 52 years or older (HR, 1.06).

The study was supported by a grant from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Oral hygiene may be a key factor in diabetes risk, new data from a Korean national health database suggest.

“Frequent tooth brushing may be an attenuating factor for the risk of new-onset diabetes, and the presence of periodontal disease and increased number of missing teeth may be augmenting factors,” wrote Yoonkyung Chang, MD, of the Department of Neurology, Mokdong Hospital, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues.

they continued in an article published online in Diabetologia.

Periodontal disease involves inflammatory reactions that affect the surrounding tissues of the teeth. Inflammation, in turn, is an important cause of diabetes because it increases insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction, Dr. Chang and colleagues explained.

They analyzed data gathered during 2003-2006 from 188,013 individuals from the Korean National Health Insurance System – Health Screening Cohort who had complete data and did not have diabetes at baseline. Oral hygiene behaviors, including frequency of tooth brushing, and dental visits or cleanings, were collected by self-report.

Over a median follow-up of 10 years, there were 31,545 new cases of diabetes, with an estimated overall 10-year event rate of 16.1%. The rate was 17.2% for those with periodontal disease at baseline, compared with 15.8% for those without, which was a significant difference even after adjustments for multiple confounders (hazard ratio, 1.09; P less than .001).

Compared with patients who had no missing teeth, the event rate for new-onset diabetes rose from 15.4% for patients with 1 missing tooth (HR, 1.08; P less than .001) to 21.4% for those with 15 or more missing teeth (HR, 1.21; P less than .001).

Professional dental cleaning did not have a significant effect after multivariate analysis. However, the number of daily tooth brushings by the individual did. Compared with brushing 0-1 times/day, those who brushed 3 or more times/day had a significantly lower risk for new-onset diabetes (HR, 0.92; P less than .001).

In subgroup analyses, periodontal disease was more strongly associated with new-onset diabetes in adults aged 51 years and younger (HR, 1.14), compared with those who were 52 years or older (HR, 1.06).

The study was supported by a grant from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

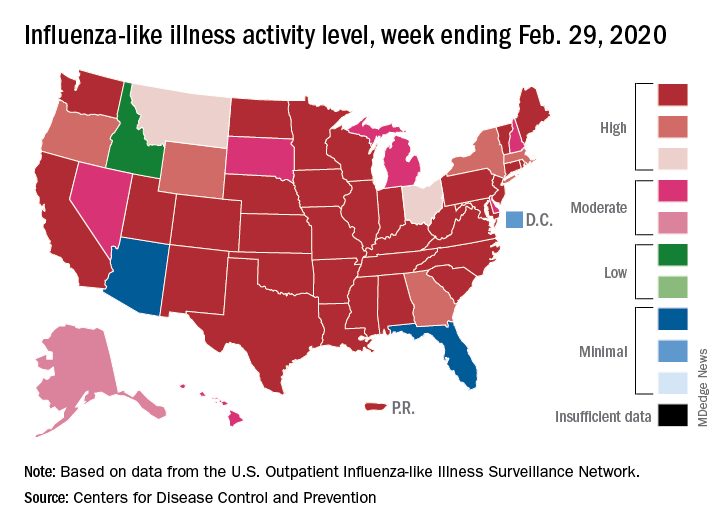

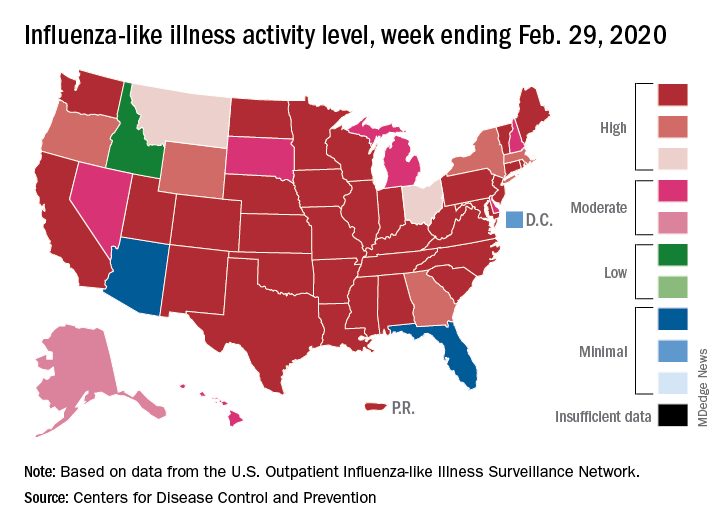

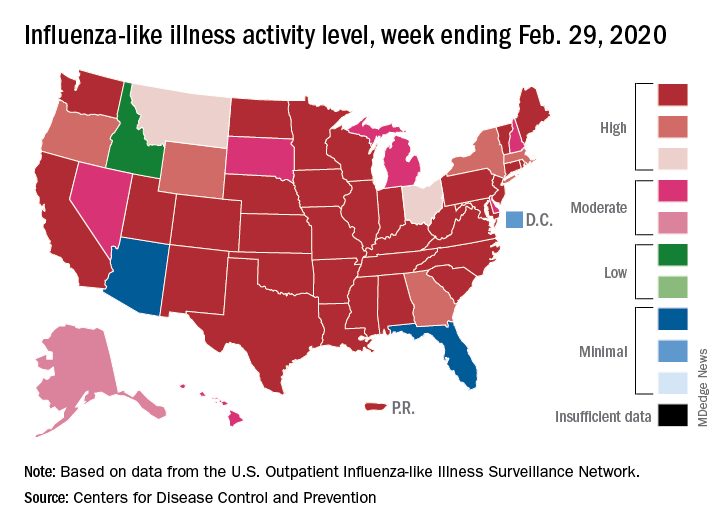

Flu activity declines again but remains high

Outpatient visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness dropped from 5.5% the previous week to 5.3% of all visits for the week ending Feb. 29, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said on March 6.

The national baseline rate of 2.4% was first reached during the week of Nov. 9, 2019 – marking the start of flu season – and has remained at or above that level for 17 consecutive weeks. Last year’s season, which also was the longest in a decade, lasted 21 consecutive weeks but started 2 weeks later than the current season and had a lower outpatient-visit rate (4.5%) for the last week of February, CDC data show.

This season’s earlier start could mean that even a somewhat steep decline in visits to below the baseline rate – marking the end of the season – might take 5 or 6 weeks and would make 2019-2020 even longer than 2018-2019.

The activity situation on the state level reflects the small national decline. For the week ending Feb. 29, there were 33 states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 activity scale, compared with 37 the week before, and a total of 40 in the “high” range of 8-10, compared with 43 the week before, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

The other main measure of influenza activity, percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive, also declined for the third week in a row and is now at 24.3% after reaching a high of 30.3% during the week of Feb. 2-8, the influenza division said.

The overall cumulative hospitalization rate continues to remain at a fairly typical 57.9 per 100,000 population, but rates for school-aged children (84.9 per 100,000) and young adults (31.2 per 100,000) are among the highest ever recorded at this point in the season. Mortality among children – now at 136 for 2019-2020 – is higher than for any season since reporting began in 2004, with the exception of the 2009 pandemic, the CDC said.

Outpatient visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness dropped from 5.5% the previous week to 5.3% of all visits for the week ending Feb. 29, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said on March 6.

The national baseline rate of 2.4% was first reached during the week of Nov. 9, 2019 – marking the start of flu season – and has remained at or above that level for 17 consecutive weeks. Last year’s season, which also was the longest in a decade, lasted 21 consecutive weeks but started 2 weeks later than the current season and had a lower outpatient-visit rate (4.5%) for the last week of February, CDC data show.

This season’s earlier start could mean that even a somewhat steep decline in visits to below the baseline rate – marking the end of the season – might take 5 or 6 weeks and would make 2019-2020 even longer than 2018-2019.

The activity situation on the state level reflects the small national decline. For the week ending Feb. 29, there were 33 states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 activity scale, compared with 37 the week before, and a total of 40 in the “high” range of 8-10, compared with 43 the week before, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

The other main measure of influenza activity, percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive, also declined for the third week in a row and is now at 24.3% after reaching a high of 30.3% during the week of Feb. 2-8, the influenza division said.

The overall cumulative hospitalization rate continues to remain at a fairly typical 57.9 per 100,000 population, but rates for school-aged children (84.9 per 100,000) and young adults (31.2 per 100,000) are among the highest ever recorded at this point in the season. Mortality among children – now at 136 for 2019-2020 – is higher than for any season since reporting began in 2004, with the exception of the 2009 pandemic, the CDC said.

Outpatient visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness dropped from 5.5% the previous week to 5.3% of all visits for the week ending Feb. 29, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said on March 6.

The national baseline rate of 2.4% was first reached during the week of Nov. 9, 2019 – marking the start of flu season – and has remained at or above that level for 17 consecutive weeks. Last year’s season, which also was the longest in a decade, lasted 21 consecutive weeks but started 2 weeks later than the current season and had a lower outpatient-visit rate (4.5%) for the last week of February, CDC data show.

This season’s earlier start could mean that even a somewhat steep decline in visits to below the baseline rate – marking the end of the season – might take 5 or 6 weeks and would make 2019-2020 even longer than 2018-2019.

The activity situation on the state level reflects the small national decline. For the week ending Feb. 29, there were 33 states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 activity scale, compared with 37 the week before, and a total of 40 in the “high” range of 8-10, compared with 43 the week before, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

The other main measure of influenza activity, percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive, also declined for the third week in a row and is now at 24.3% after reaching a high of 30.3% during the week of Feb. 2-8, the influenza division said.

The overall cumulative hospitalization rate continues to remain at a fairly typical 57.9 per 100,000 population, but rates for school-aged children (84.9 per 100,000) and young adults (31.2 per 100,000) are among the highest ever recorded at this point in the season. Mortality among children – now at 136 for 2019-2020 – is higher than for any season since reporting began in 2004, with the exception of the 2009 pandemic, the CDC said.

Arsenic levels in infant rice cereal are down

according to test results released by the Food and Drug Administration.

In April 2016, the FDA issued draft guidance calling for manufacturers of the product to reduce the level of arsenic in their cereals by establishing an action level of arsenic of 100 mcg/kg or 100 parts per billion.

Seventy-six percent of samples of infant rice cereal tested in 2018 had levels of arsenic at or below 100 parts per billion versus 47% of samples tested in 2014, according to a statement from the FDA. In 2011-2013, an even lower percentage of samples tested contained amounts of inorganic arsenic at or below the FDA’s current action level for this element, whose consumption has been associated with cancer, skin lesions, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes.

The 2018 data is based on the testing of 149 samples of infant white and brown rice cereal samples.

“Results from our tests show that manufacturers have made significant progress in ensuring lower levels of inorganic arsenic in infant rice cereal,” Susan Mayne, PhD, director of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, said in the FDA statement.

“Both white rice and brown rice cereals showed improvement in meeting the FDA’s 100 ppb proposed action level, but the improvement was greatest for white rice cereals, which tend to have lower levels of inorganic arsenic overall,” according to the statement.

according to test results released by the Food and Drug Administration.

In April 2016, the FDA issued draft guidance calling for manufacturers of the product to reduce the level of arsenic in their cereals by establishing an action level of arsenic of 100 mcg/kg or 100 parts per billion.

Seventy-six percent of samples of infant rice cereal tested in 2018 had levels of arsenic at or below 100 parts per billion versus 47% of samples tested in 2014, according to a statement from the FDA. In 2011-2013, an even lower percentage of samples tested contained amounts of inorganic arsenic at or below the FDA’s current action level for this element, whose consumption has been associated with cancer, skin lesions, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes.

The 2018 data is based on the testing of 149 samples of infant white and brown rice cereal samples.

“Results from our tests show that manufacturers have made significant progress in ensuring lower levels of inorganic arsenic in infant rice cereal,” Susan Mayne, PhD, director of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, said in the FDA statement.

“Both white rice and brown rice cereals showed improvement in meeting the FDA’s 100 ppb proposed action level, but the improvement was greatest for white rice cereals, which tend to have lower levels of inorganic arsenic overall,” according to the statement.

according to test results released by the Food and Drug Administration.

In April 2016, the FDA issued draft guidance calling for manufacturers of the product to reduce the level of arsenic in their cereals by establishing an action level of arsenic of 100 mcg/kg or 100 parts per billion.

Seventy-six percent of samples of infant rice cereal tested in 2018 had levels of arsenic at or below 100 parts per billion versus 47% of samples tested in 2014, according to a statement from the FDA. In 2011-2013, an even lower percentage of samples tested contained amounts of inorganic arsenic at or below the FDA’s current action level for this element, whose consumption has been associated with cancer, skin lesions, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes.

The 2018 data is based on the testing of 149 samples of infant white and brown rice cereal samples.

“Results from our tests show that manufacturers have made significant progress in ensuring lower levels of inorganic arsenic in infant rice cereal,” Susan Mayne, PhD, director of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, said in the FDA statement.

“Both white rice and brown rice cereals showed improvement in meeting the FDA’s 100 ppb proposed action level, but the improvement was greatest for white rice cereals, which tend to have lower levels of inorganic arsenic overall,” according to the statement.

2020 Update on gynecologic cancer

Over the past year, major strides have been made in the treatment of gynecologic malignancies. In this Update, we highlight 3 notable studies. The first is a phase 3, multicenter, international, randomized clinical trial that demonstrated a significant improvement in both overall and failure-free survival with the use of adjuvant chemoradiation versus radiotherapy alone in patients with stage III or high-risk uterine cancer. Additionally, we describe the results of 2 phase 3, multicenter, international, randomized clinical trials in ovarian cancer treatment: use of poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors in combination with platinum and taxane-based chemotherapy followed by the PARP inhibitor as maintenance therapy, and secondary cytoreductive surgery in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer.

We provide a brief overview of current treatment strategies, summarize the key findings of these trials, and establish how these findings have changed our management of these gynecologic malignancies.

Adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy improves survival in women with high-risk endometrial cancer

de Boer SM, Powell ME, Mileshkin L, et al; on behalf of the PORTEC Study Group. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in women with high-risk endometrial cancer (PORTEC-3): patterns of recurrence and post-hoc survival analysis of a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;1273-1285.

In the United States, it is estimated that more than 61,000 women were diagnosed with endometrial cancer in 2019.1 Women with endometrial cancer usually have a favorable prognosis; more than 65% are diagnosed with early-stage disease, which is associated with a 95% 5-year survival rate.1 However, 15% to 20% of patients have disease with high-risk features, including advanced stage (stage II-IV), high tumor grade, lymphovascular space invasion, deep myometrial invasion, or nonendometrioid histologic subtypes (serous or clear cell).2 The presence of these high-risk disease features is associated with an increased incidence of distant metastases and cancer-related death.

Adjuvant therapy in high-risk endometrial cancer

To date, the optimal adjuvant therapy for patients with high-risk endometrial cancer remains controversial. Prior data from Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) protocol 122 demonstrated that chemotherapy significantly improved progression-free survival and overall survival when compared with radiotherapy in patients with advanced-stage endometrial cancer.3 As such, chemotherapy now is frequently used in this population, often in combination with radiation, although data describing the benefit of chemoradiation are limited.4 For women with earlier-stage disease with high-risk features, the value of chemotherapy plus radiation is uncertain.5,6

Continue to: Benefit observed with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy...

Benefit observed with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy

In a multicenter, international, randomized phase 3 trial, known as the PORTEC-3 trial, de Boer and colleagues sought to determine if combined adjuvant chemoradiation improved overall survival (OS) and failure-free survival when compared with external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) alone in the treatment of women with high-risk endometrial cancer.7 Women were eligible for the study if they had histologically confirmed stage I, grade 3 endometrioid endometrial cancer with deep invasion and/or lymphovascular space invasion, stage II or III disease, or stage I-III disease with serous or clear cell histology.

Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio; 330 women received adjuvant EBRT alone (total dose of 48.6 Gy administered in 27 fractions), and 330 received adjuvant chemotherapy during and after radiation therapy (CTRT) (2 cycles of cisplatin 50 mg/m2 IV given on days 1 and 22 of EBRT followed by 4 cycles of carboplatin AUC 5 and paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 IV every 3 weeks).

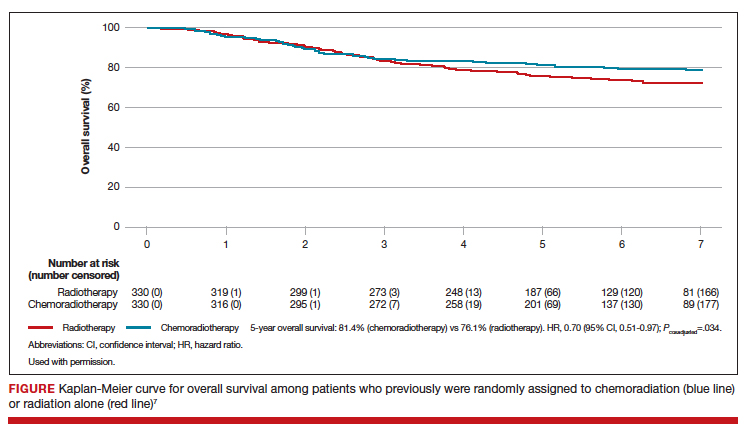

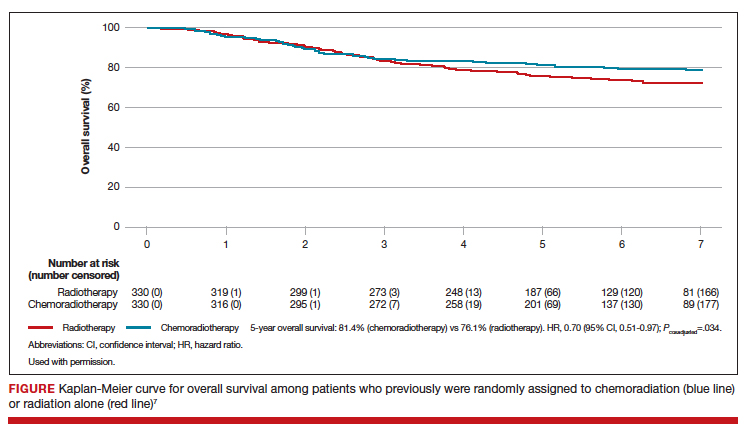

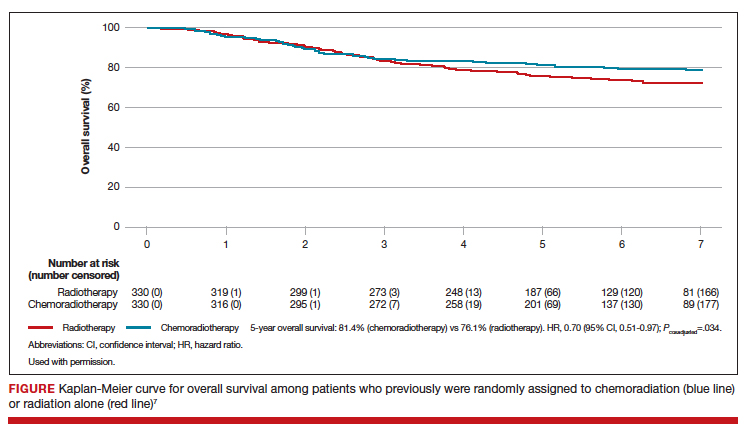

At a median follow-up of 73 months, treatment with adjuvant CTRT, compared with adjuvant EBRT alone, was associated with a significant improvement in both overall survival (5-year OS: 81.4% vs 76.1%, P = .034 [FIGURE]) and failure-free survival (5-year failure-free survival: 76.5% vs 69.1%, P = .016).

The greatest absolute benefit of adjuvant CTRT, compared with EBRT alone, in survival was among women with stage III endometrial cancer (5-year OS: 78.5% vs 68.5%, P = .043) or serous cancers (19% absolute improvement in 5-year OS), or both. Significant differences in 5-year OS and failure-free survival in women with stage I-II cancer were not observed with adjuvant CTRT when compared with adjuvant EBRT alone. At 5 years, significantly more adverse events of grade 2 or worse were reported in the adjuvant CTRT arm.

Results from similar trials

Since the publication of results from the updated analysis of PORTEC-3, results from 2 pertinent trials have been published.8,9 In the GOG 249 trial, women with stage I-II endometrial cancer with high-risk features were randomly assigned to receive 3 cycles of carboplatin-paclitaxel chemotherapy with vaginal brachytherapy or EBRT.8 There was no difference in survival, but a significant increase in both pelvic and para-aortic recurrences were seen after the combination of chemotherapy and vaginal brachytherapy.8

In GOG 258, women with stage III-IVA endometrial cancer were randomly assigned to receive chemotherapy alone (carboplatin-paclitaxel) or adjuvant chemotherapy after EBRT.9 No differences in recurrence-free or overall survival were noted, but there was a significant increase in the number of vaginal and pelvic or para-aortic recurrences in patients in the chemotherapy-only arm.9

The conflicting data regarding the ideal adjuvant therapy for endometrial cancer suggests that treatment decisions should be individualized. Pelvic EBRT with concurrent adjuvant chemotherapy should be considered in women with stage III endometrial cancer or serous cancers as combination therapy improves survival, although dual modality treatment is associated with increased toxicity. Chemoradiation appears to have less benefit for women with stage I–II cancers with other pathologic risk factors.

Role for PARP inhibitor plus first-line chemotherapy, and as maintenance therapy, in ovarian cancer treatment

Coleman RL, Fleming GF, Brady MF, et al. Veliparib with first-line chemotherapy and as maintenance therapy in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2403-2415.

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of gynecologic cancer-related deaths among women in the United States.10 Treatment consists of cytoreductive surgery combined with platinum and taxane-based chemotherapy.11 Despite favorable initial responses, more than 80% of patients experience a recurrence, with an 18-month median time to progression.12 As a result, recent efforts have focused on finding novel therapeutic approaches to improve treatment outcomes and mitigate the risk of disease recurrence.

Continue to: PARP inhibitors are changing the face of treatment...

PARP inhibitors are changing the face of treatment

Poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) are a family of enzymes that play a critical role in DNA damage repair. These enzymes promote DNA repair by recruiting proteins involved in repairing single-strand and double-strand DNA breaks and in protecting and restarting stalled DNA replication forks.13 The predominant mechanisms of action of PARP inhibitors in cells with homologous-recombination deficiency (HRD) include inhibiting repair of single-strand DNA breaks and trapping PARP-DNA complexes at stalled DNA replication forks.14

Germline or somatic BRCA1/2 mutations and genetic alterations resulting in HRD are present in about 20% and 30% of ovarian carcinomas, respectively, and increase the susceptibility of tumors to platinum-based agents and PARP inhibitors.15,16 Based on multiple clinical trials that demonstrated the efficacy of single-agent PARP in the treatment of recurrent ovarian carcinoma and as maintenance therapy after an initial response to platinum-based therapy, the US Food and Drug Administration approved olaparib, niraparib, and rucaparib for the treatment of high-grade epithelial ovarian cancer.17-19 Only olaparib is approved for maintenance therapy after initial adjuvant therapy in patients with BRCA mutations.20

Given the robust response to PARP inhibitors, there has been great interest in using these agents earlier in the disease course in combination with chemotherapy.

Efficacy of veliparib with chemotherapy and as maintenance monotherapy

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial, Coleman and colleagues sought to determine the efficacy of the PARP inhibitor veliparib when administered with first-line carboplatin and paclitaxel induction chemotherapy and subsequently continued as maintenance monotherapy.21

Women with stage III or IV high-grade epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal carcinoma were eligible for the study. Cytoreductive surgery could be performed prior to the initiation of trial treatment or after 3 cycles of chemotherapy.

Participants were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio: 371 women received carboplatin and paclitaxel plus placebo followed by placebo maintenance (control arm); 376 received chemotherapy plus veliparib followed by placebo maintenance (veliparib combination-only arm); and 377 received chemotherapy plus veliparib followed by veliparib maintenance therapy (veliparib-throughout arm). Combination chemotherapy consisted of 6 cycles, and maintenance therapy was an additional 30 cycles.

Progression-free survival extended

At a median follow-up of 28 months, investigators observed a significant improvement in progression-free survival in the veliparib-throughout (initial and maintenance therapy) arm compared with the control arm in 3 cohorts: the BRCA-mutation cohort, the HRD cohort, and the intention-to-treat population (all participants undergoing randomization).

In the BRCA-mutation cohort, the median progression-free survival was 12.7 months longer in the veliparib-throughout arm than in the control arm. Similarly, in the HRD cohort, the median progression-free survival was 11.4 months longer in the veliparib-throughout arm than in the control group. In the intention-to-treat population, the median progression-free survival increased from 17.3 to 23.5 months in the veliparib-throughout arm compared with the control arm.

Women who received veliparib experienced increased rates of nausea, anemia, and fatigue and were more likely to require dose reductions and treatment interruptions. Myelodysplastic syndrome was reported in 1 patient (BRCA1 positive) in the veliparib combination-only arm.

For women with newly diagnosed, previously untreated stage III or IV high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, carboplatin, paclitaxel, and veliparib induction therapy followed by single-agent veliparib maintenance therapy resulted in a significant improvement in median progression-free survival compared with induction chemotherapy alone. However, veliparib use was also associated with a higher incidence of adverse effects that required dose reduction and/or interruption during both the combination and maintenance phases of treatment.