User login

Lead Has Not Gone Away — What Should Pediatric Clinicians Do?

following a 2023 outbreak of elevated levels of lead in children associated with consumption of contaminated applesauce.

Federal legislation in the 1970s eliminated lead from gasoline, paints, and other consumer products, and resulted in significantly reduced blood lead levels (BLLs) in children throughout the United States.

But recently published studies highlight persistent issues with lead in drinking water and consumer products, suggesting that the fight is not over.

It’s in the Water

In 2014 the city of Flint, Michigan, changed its water supply and high levels of lead were later found in the municipal water supply.

Effects of that crisis still plague the city today. An initial study found that elevated BLLs had doubled among children between 2013 and 2015.

Lead exposure in young children is associated with several negative outcomes, including decreased cognitive ability, brain volume, and social mobility, and increased anxiety/depression and impulsivity, and higher rates of criminal offenses later in life.

Many other water systems still contain lead pipes, despite a 1986 ban by the US Environmental Protection Agency on using them for installing or repairing public water systems. The mayor of Chicago announced a plan to start replacing lead service lines in 2020; however, 400,000 households are still served by these pipes, the most in the nation.

Benjamin Huynh, a native of Chicago, was curious about the impact of all those lead service lines. Now an assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Health and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, he and his colleagues researched how many children under the age of 6 years were exposed to contaminated water.

The results showed that lead contamination of water is widespread.

“We’re estimating that 68% of kids under the age of 6 in Chicago were exposed to lead-contaminated drinking water,” Mr. Huynh said.

He added that residents in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods had the highest risk for lead contamination in their water, but children living on these blocks were less likely to get tested, suggesting a need for more outreach to raise awareness.

Meanwhile, a little over one third of Chicago residents reported drinking bottled water as their main source of drinking water.

But even bottled water could contain lead. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has set a limit for lead in bottled water to five parts per billion. The FDA threshold for taking action in public drinking water systems is 15 parts per billion. But the American Academy of Pediatrics states that no amount of lead in drinking water is considered safe for drinking.

Mr. Huynh also pointed out that not all home water filters remove lead. Only devices that meet National Sanitation Foundation 53 standards are certified for lead removal. Consumers should verify that the filter package specifically lists the device as certified for removing contaminant lead.

Lead-tainted Cinnamon

Last fall, the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services identified several children with elevated levels of lead who had consumed WanaBana Apple Cinnamon Fruit Puree pouches.

An investigation by the FDA identified additional brands containing lead and issued a recall of applesauce pouches sold by retailers like Dollar Tree and Amazon.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 500 children were affected by the tainted applesauce. The FDA traced the source of the lead to cinnamon from a supplier in Ecuador.

An FDA spokesperson told this news organization the episode appears to have resulted from “economically motivated adulteration,” which occurs when a manufacturer leaves out or substitutes a valuable ingredient or part of a food. In the case of spices, lead may be added as a coloring agent or to increase the product weight.

“When we look at domestically made products from large, reputable companies, in general, they do a pretty good job of following safe product guidelines and regulations,” said Kevin Osterhoudt, MD, professor of pediatrics at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “But when we use third-party sellers and we import things from other countries that aren’t regulated as closely, we certainly take a lot more risk in the products that we receive.”

While the Food Safety Modernization Act of 2011 aimed to improve agency’s capacity to manage the ever-rising volume of food produced domestically and imported from overseas, the funding has stayed flat while the volume of inspections has increased. In the early 1990s, the number of shipments screened by the agency numbered in the thousands annually. Last year the FDA screened 15 million shipments from more than 200 countries, according to the agency.

Prompted by the finding of lead in applesauce, the FDA began a wider investigation into ground cinnamon by sampling the product from discount retail stores. It recalled an additional six brands of cinnamon sold in the United States containing lead.

Dr. Osterhoudt’s message to families who think their child might have been exposed to a contaminated product is to dispose of it as directed by FDA and CDC guidelines.

In Philadelphia, where Dr. Osterhoudt practices as an emergency room physician, baseline rates of childhood lead poisoning are already high, so he advises families to “do a larger inventory of all the source potential sources of lead in their life and to reduce all the exposures as low as possible.”

He also advises parents that a nutritious diet high in calcium and iron can protect their children from the deleterious effects of lead.

Current Standards for Lead Screening and Testing

Lead is ubiquitous. The common routes of exposure to humans include use of fossil fuels such as leaded gasoline, some types of industrial facilities, and past use of lead-based paint in homes. In addition to spices, lead has been found in a wide variety of products such as toys, jewelry, antiques, cosmetics, and dietary supplements imported from other countries.

Noah Buncher, DO, is a primary care pediatrician in South Philadelphia at Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania and the former director of a lead clinic in Boston that provides care for children with lead poisoning. He follows guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics that define an elevated BLL as ≥ 3.5 µg/dL. The guidelines recommend screening children for lead exposures during well child visits starting at age 6 months up to 6 years and obtaining a BLL if risks for lead exposure are present.

Dr. Buncher starts with a basic environmental history that covers items like the age, condition, zip code of home, parental occupations, or hobbies that might result in exposing family members to lead, and if another child in the home has a history of elevated BLLs.

But a careful history for potential lead exposures can be time-consuming.

“There’s a lot to cover in a routine well child visit,” Dr. Buncher said. “We have maybe 15-20 minutes to cover a lot.”

Clinics also vary on whether lead screening questions are put into workflows in the electronic medical record. Although parents can complete a written questionnaire about possible lead exposures, they may have difficulty answering questions about the age of their home or not know whether their occupation is high risk.

Transportation to a clinic is often a barrier for families, and sometimes patients must travel to a separate lab to be tested for lead.

Dr. Buncher also pointed to the patchwork of local and state requirements that can lead to confusion among providers. Massachusetts, where he formerly practiced, has a universal requirement to test all children at ages 1, 2, and 3 years. But in Pennsylvania, screening laws vary from county to county.

“Pennsylvania should implement universal screening recommendations for all kids under 6 regardless of what county you live in,” Dr. Buncher said.

Protective Measures

Alan Woolf, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, and director of the Pediatric Environmental Health Center at Boston Children’s Hospital, has a few ideas about how providers can step up their lead game, including partnering with their local health department.

The CDC funds Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Programs based in state and local health departments to work with clinicians to improve rates of blood lead testing, monitor the prevalence of lead in their jurisdictions, and ensure that a system of referral is available for treatment and lead remediation services in the home.

Dr. Woolf also suggested that clinicians refer patients under age 3 years with high BLLs to their local Early Intervention Program.

“They’ll assess their child’s development, their speech, their motor skills, their social skills, and if they qualify, it’s free,” Dr. Woolf said.

He cited research showing children with elevated lead levels who received early intervention services performed better in grade school than equally exposed children who did not access similar services.

Another key strategy for pediatric clinicians is to learn local or state regulations for testing children for lead and how to access lead surveillance data in their practice area. Children who reside in high-risk areas are automatic candidates for screening.

Dr. Woolf pointed out that big cities are not the only localities with lead in the drinking water. If families are drawing water from their own well, they should collect that water annually to have it tested for lead and microbes.

At the clinic-wide level, Dr. Woolf recommends the use of blood lead testing as a quality improvement measure. For example, Akron Children’s Hospital developed a quality improvement initiative using a clinical decision support tool to raise screening rates in their network of 30 clinics. One year after beginning the project, lead screenings during 12-month well visits increased from 71% to 96%.

“What we’re interested in as pediatric health professionals is eliminating all background sources of lead in a child’s environment,” Dr. Woolf said. “Whether that’s applesauce pouches, whether that’s lead-containing paint, lead in water, lead in spices, or lead in imported pottery or cookware — there are just a tremendous number of sources of lead that we can do something about.”

None of the subjects reported financial conflicts of interest.

A former pediatrician, Dr. Thomas is a freelance science writer living in Portland, Oregon.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

following a 2023 outbreak of elevated levels of lead in children associated with consumption of contaminated applesauce.

Federal legislation in the 1970s eliminated lead from gasoline, paints, and other consumer products, and resulted in significantly reduced blood lead levels (BLLs) in children throughout the United States.

But recently published studies highlight persistent issues with lead in drinking water and consumer products, suggesting that the fight is not over.

It’s in the Water

In 2014 the city of Flint, Michigan, changed its water supply and high levels of lead were later found in the municipal water supply.

Effects of that crisis still plague the city today. An initial study found that elevated BLLs had doubled among children between 2013 and 2015.

Lead exposure in young children is associated with several negative outcomes, including decreased cognitive ability, brain volume, and social mobility, and increased anxiety/depression and impulsivity, and higher rates of criminal offenses later in life.

Many other water systems still contain lead pipes, despite a 1986 ban by the US Environmental Protection Agency on using them for installing or repairing public water systems. The mayor of Chicago announced a plan to start replacing lead service lines in 2020; however, 400,000 households are still served by these pipes, the most in the nation.

Benjamin Huynh, a native of Chicago, was curious about the impact of all those lead service lines. Now an assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Health and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, he and his colleagues researched how many children under the age of 6 years were exposed to contaminated water.

The results showed that lead contamination of water is widespread.

“We’re estimating that 68% of kids under the age of 6 in Chicago were exposed to lead-contaminated drinking water,” Mr. Huynh said.

He added that residents in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods had the highest risk for lead contamination in their water, but children living on these blocks were less likely to get tested, suggesting a need for more outreach to raise awareness.

Meanwhile, a little over one third of Chicago residents reported drinking bottled water as their main source of drinking water.

But even bottled water could contain lead. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has set a limit for lead in bottled water to five parts per billion. The FDA threshold for taking action in public drinking water systems is 15 parts per billion. But the American Academy of Pediatrics states that no amount of lead in drinking water is considered safe for drinking.

Mr. Huynh also pointed out that not all home water filters remove lead. Only devices that meet National Sanitation Foundation 53 standards are certified for lead removal. Consumers should verify that the filter package specifically lists the device as certified for removing contaminant lead.

Lead-tainted Cinnamon

Last fall, the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services identified several children with elevated levels of lead who had consumed WanaBana Apple Cinnamon Fruit Puree pouches.

An investigation by the FDA identified additional brands containing lead and issued a recall of applesauce pouches sold by retailers like Dollar Tree and Amazon.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 500 children were affected by the tainted applesauce. The FDA traced the source of the lead to cinnamon from a supplier in Ecuador.

An FDA spokesperson told this news organization the episode appears to have resulted from “economically motivated adulteration,” which occurs when a manufacturer leaves out or substitutes a valuable ingredient or part of a food. In the case of spices, lead may be added as a coloring agent or to increase the product weight.

“When we look at domestically made products from large, reputable companies, in general, they do a pretty good job of following safe product guidelines and regulations,” said Kevin Osterhoudt, MD, professor of pediatrics at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “But when we use third-party sellers and we import things from other countries that aren’t regulated as closely, we certainly take a lot more risk in the products that we receive.”

While the Food Safety Modernization Act of 2011 aimed to improve agency’s capacity to manage the ever-rising volume of food produced domestically and imported from overseas, the funding has stayed flat while the volume of inspections has increased. In the early 1990s, the number of shipments screened by the agency numbered in the thousands annually. Last year the FDA screened 15 million shipments from more than 200 countries, according to the agency.

Prompted by the finding of lead in applesauce, the FDA began a wider investigation into ground cinnamon by sampling the product from discount retail stores. It recalled an additional six brands of cinnamon sold in the United States containing lead.

Dr. Osterhoudt’s message to families who think their child might have been exposed to a contaminated product is to dispose of it as directed by FDA and CDC guidelines.

In Philadelphia, where Dr. Osterhoudt practices as an emergency room physician, baseline rates of childhood lead poisoning are already high, so he advises families to “do a larger inventory of all the source potential sources of lead in their life and to reduce all the exposures as low as possible.”

He also advises parents that a nutritious diet high in calcium and iron can protect their children from the deleterious effects of lead.

Current Standards for Lead Screening and Testing

Lead is ubiquitous. The common routes of exposure to humans include use of fossil fuels such as leaded gasoline, some types of industrial facilities, and past use of lead-based paint in homes. In addition to spices, lead has been found in a wide variety of products such as toys, jewelry, antiques, cosmetics, and dietary supplements imported from other countries.

Noah Buncher, DO, is a primary care pediatrician in South Philadelphia at Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania and the former director of a lead clinic in Boston that provides care for children with lead poisoning. He follows guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics that define an elevated BLL as ≥ 3.5 µg/dL. The guidelines recommend screening children for lead exposures during well child visits starting at age 6 months up to 6 years and obtaining a BLL if risks for lead exposure are present.

Dr. Buncher starts with a basic environmental history that covers items like the age, condition, zip code of home, parental occupations, or hobbies that might result in exposing family members to lead, and if another child in the home has a history of elevated BLLs.

But a careful history for potential lead exposures can be time-consuming.

“There’s a lot to cover in a routine well child visit,” Dr. Buncher said. “We have maybe 15-20 minutes to cover a lot.”

Clinics also vary on whether lead screening questions are put into workflows in the electronic medical record. Although parents can complete a written questionnaire about possible lead exposures, they may have difficulty answering questions about the age of their home or not know whether their occupation is high risk.

Transportation to a clinic is often a barrier for families, and sometimes patients must travel to a separate lab to be tested for lead.

Dr. Buncher also pointed to the patchwork of local and state requirements that can lead to confusion among providers. Massachusetts, where he formerly practiced, has a universal requirement to test all children at ages 1, 2, and 3 years. But in Pennsylvania, screening laws vary from county to county.

“Pennsylvania should implement universal screening recommendations for all kids under 6 regardless of what county you live in,” Dr. Buncher said.

Protective Measures

Alan Woolf, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, and director of the Pediatric Environmental Health Center at Boston Children’s Hospital, has a few ideas about how providers can step up their lead game, including partnering with their local health department.

The CDC funds Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Programs based in state and local health departments to work with clinicians to improve rates of blood lead testing, monitor the prevalence of lead in their jurisdictions, and ensure that a system of referral is available for treatment and lead remediation services in the home.

Dr. Woolf also suggested that clinicians refer patients under age 3 years with high BLLs to their local Early Intervention Program.

“They’ll assess their child’s development, their speech, their motor skills, their social skills, and if they qualify, it’s free,” Dr. Woolf said.

He cited research showing children with elevated lead levels who received early intervention services performed better in grade school than equally exposed children who did not access similar services.

Another key strategy for pediatric clinicians is to learn local or state regulations for testing children for lead and how to access lead surveillance data in their practice area. Children who reside in high-risk areas are automatic candidates for screening.

Dr. Woolf pointed out that big cities are not the only localities with lead in the drinking water. If families are drawing water from their own well, they should collect that water annually to have it tested for lead and microbes.

At the clinic-wide level, Dr. Woolf recommends the use of blood lead testing as a quality improvement measure. For example, Akron Children’s Hospital developed a quality improvement initiative using a clinical decision support tool to raise screening rates in their network of 30 clinics. One year after beginning the project, lead screenings during 12-month well visits increased from 71% to 96%.

“What we’re interested in as pediatric health professionals is eliminating all background sources of lead in a child’s environment,” Dr. Woolf said. “Whether that’s applesauce pouches, whether that’s lead-containing paint, lead in water, lead in spices, or lead in imported pottery or cookware — there are just a tremendous number of sources of lead that we can do something about.”

None of the subjects reported financial conflicts of interest.

A former pediatrician, Dr. Thomas is a freelance science writer living in Portland, Oregon.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

following a 2023 outbreak of elevated levels of lead in children associated with consumption of contaminated applesauce.

Federal legislation in the 1970s eliminated lead from gasoline, paints, and other consumer products, and resulted in significantly reduced blood lead levels (BLLs) in children throughout the United States.

But recently published studies highlight persistent issues with lead in drinking water and consumer products, suggesting that the fight is not over.

It’s in the Water

In 2014 the city of Flint, Michigan, changed its water supply and high levels of lead were later found in the municipal water supply.

Effects of that crisis still plague the city today. An initial study found that elevated BLLs had doubled among children between 2013 and 2015.

Lead exposure in young children is associated with several negative outcomes, including decreased cognitive ability, brain volume, and social mobility, and increased anxiety/depression and impulsivity, and higher rates of criminal offenses later in life.

Many other water systems still contain lead pipes, despite a 1986 ban by the US Environmental Protection Agency on using them for installing or repairing public water systems. The mayor of Chicago announced a plan to start replacing lead service lines in 2020; however, 400,000 households are still served by these pipes, the most in the nation.

Benjamin Huynh, a native of Chicago, was curious about the impact of all those lead service lines. Now an assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Health and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, he and his colleagues researched how many children under the age of 6 years were exposed to contaminated water.

The results showed that lead contamination of water is widespread.

“We’re estimating that 68% of kids under the age of 6 in Chicago were exposed to lead-contaminated drinking water,” Mr. Huynh said.

He added that residents in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods had the highest risk for lead contamination in their water, but children living on these blocks were less likely to get tested, suggesting a need for more outreach to raise awareness.

Meanwhile, a little over one third of Chicago residents reported drinking bottled water as their main source of drinking water.

But even bottled water could contain lead. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has set a limit for lead in bottled water to five parts per billion. The FDA threshold for taking action in public drinking water systems is 15 parts per billion. But the American Academy of Pediatrics states that no amount of lead in drinking water is considered safe for drinking.

Mr. Huynh also pointed out that not all home water filters remove lead. Only devices that meet National Sanitation Foundation 53 standards are certified for lead removal. Consumers should verify that the filter package specifically lists the device as certified for removing contaminant lead.

Lead-tainted Cinnamon

Last fall, the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services identified several children with elevated levels of lead who had consumed WanaBana Apple Cinnamon Fruit Puree pouches.

An investigation by the FDA identified additional brands containing lead and issued a recall of applesauce pouches sold by retailers like Dollar Tree and Amazon.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 500 children were affected by the tainted applesauce. The FDA traced the source of the lead to cinnamon from a supplier in Ecuador.

An FDA spokesperson told this news organization the episode appears to have resulted from “economically motivated adulteration,” which occurs when a manufacturer leaves out or substitutes a valuable ingredient or part of a food. In the case of spices, lead may be added as a coloring agent or to increase the product weight.

“When we look at domestically made products from large, reputable companies, in general, they do a pretty good job of following safe product guidelines and regulations,” said Kevin Osterhoudt, MD, professor of pediatrics at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “But when we use third-party sellers and we import things from other countries that aren’t regulated as closely, we certainly take a lot more risk in the products that we receive.”

While the Food Safety Modernization Act of 2011 aimed to improve agency’s capacity to manage the ever-rising volume of food produced domestically and imported from overseas, the funding has stayed flat while the volume of inspections has increased. In the early 1990s, the number of shipments screened by the agency numbered in the thousands annually. Last year the FDA screened 15 million shipments from more than 200 countries, according to the agency.

Prompted by the finding of lead in applesauce, the FDA began a wider investigation into ground cinnamon by sampling the product from discount retail stores. It recalled an additional six brands of cinnamon sold in the United States containing lead.

Dr. Osterhoudt’s message to families who think their child might have been exposed to a contaminated product is to dispose of it as directed by FDA and CDC guidelines.

In Philadelphia, where Dr. Osterhoudt practices as an emergency room physician, baseline rates of childhood lead poisoning are already high, so he advises families to “do a larger inventory of all the source potential sources of lead in their life and to reduce all the exposures as low as possible.”

He also advises parents that a nutritious diet high in calcium and iron can protect their children from the deleterious effects of lead.

Current Standards for Lead Screening and Testing

Lead is ubiquitous. The common routes of exposure to humans include use of fossil fuels such as leaded gasoline, some types of industrial facilities, and past use of lead-based paint in homes. In addition to spices, lead has been found in a wide variety of products such as toys, jewelry, antiques, cosmetics, and dietary supplements imported from other countries.

Noah Buncher, DO, is a primary care pediatrician in South Philadelphia at Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania and the former director of a lead clinic in Boston that provides care for children with lead poisoning. He follows guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics that define an elevated BLL as ≥ 3.5 µg/dL. The guidelines recommend screening children for lead exposures during well child visits starting at age 6 months up to 6 years and obtaining a BLL if risks for lead exposure are present.

Dr. Buncher starts with a basic environmental history that covers items like the age, condition, zip code of home, parental occupations, or hobbies that might result in exposing family members to lead, and if another child in the home has a history of elevated BLLs.

But a careful history for potential lead exposures can be time-consuming.

“There’s a lot to cover in a routine well child visit,” Dr. Buncher said. “We have maybe 15-20 minutes to cover a lot.”

Clinics also vary on whether lead screening questions are put into workflows in the electronic medical record. Although parents can complete a written questionnaire about possible lead exposures, they may have difficulty answering questions about the age of their home or not know whether their occupation is high risk.

Transportation to a clinic is often a barrier for families, and sometimes patients must travel to a separate lab to be tested for lead.

Dr. Buncher also pointed to the patchwork of local and state requirements that can lead to confusion among providers. Massachusetts, where he formerly practiced, has a universal requirement to test all children at ages 1, 2, and 3 years. But in Pennsylvania, screening laws vary from county to county.

“Pennsylvania should implement universal screening recommendations for all kids under 6 regardless of what county you live in,” Dr. Buncher said.

Protective Measures

Alan Woolf, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, and director of the Pediatric Environmental Health Center at Boston Children’s Hospital, has a few ideas about how providers can step up their lead game, including partnering with their local health department.

The CDC funds Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Programs based in state and local health departments to work with clinicians to improve rates of blood lead testing, monitor the prevalence of lead in their jurisdictions, and ensure that a system of referral is available for treatment and lead remediation services in the home.

Dr. Woolf also suggested that clinicians refer patients under age 3 years with high BLLs to their local Early Intervention Program.

“They’ll assess their child’s development, their speech, their motor skills, their social skills, and if they qualify, it’s free,” Dr. Woolf said.

He cited research showing children with elevated lead levels who received early intervention services performed better in grade school than equally exposed children who did not access similar services.

Another key strategy for pediatric clinicians is to learn local or state regulations for testing children for lead and how to access lead surveillance data in their practice area. Children who reside in high-risk areas are automatic candidates for screening.

Dr. Woolf pointed out that big cities are not the only localities with lead in the drinking water. If families are drawing water from their own well, they should collect that water annually to have it tested for lead and microbes.

At the clinic-wide level, Dr. Woolf recommends the use of blood lead testing as a quality improvement measure. For example, Akron Children’s Hospital developed a quality improvement initiative using a clinical decision support tool to raise screening rates in their network of 30 clinics. One year after beginning the project, lead screenings during 12-month well visits increased from 71% to 96%.

“What we’re interested in as pediatric health professionals is eliminating all background sources of lead in a child’s environment,” Dr. Woolf said. “Whether that’s applesauce pouches, whether that’s lead-containing paint, lead in water, lead in spices, or lead in imported pottery or cookware — there are just a tremendous number of sources of lead that we can do something about.”

None of the subjects reported financial conflicts of interest.

A former pediatrician, Dr. Thomas is a freelance science writer living in Portland, Oregon.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Oncology Practice and Lab to Pay $4 Million in Kickback Case

The US Department of Justice (DOJ) announced on April 2 that Oncology San Antonio, PA, and its physicians have agreed to pay $1.3 million, and CorePath Laboratories, PA, has agreed to pay nearly $2.75 million plus accrued interest in civil settlements with the United States and Texas for alleged violations of the False Claims Act.

According to the DOJ, the diagnostic reference laboratory, CorePath Laboratories, conducted in-office bone marrow biopsies at Oncology San Antonio practice locations and performed diagnostic testing on the samples. CorePath Laboratories agreed to pay $115 for each biopsy referred by Oncology San Antonio physicians, and these biopsy payments were allegedly paid to the private practices of three physicians at Oncology San Antonio. This arrangement allegedly began in August 2016.

The DOJ claimed that the payments for referring biopsies constituted illegal kickbacks under the Anti-Kickback Statute, which prohibits offering or receiving payments to encourage referrals of services covered by federal healthcare programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

“Violations of the Anti-Kickback Statute involving oncology services can waste scarce federal healthcare program funds and corrupt the medical decision-making process,” Special Agent in Charge Jason E. Meadows with the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General said in a statement.

Oncology San Antonio told this news organization that the cost and distraction of prolonged litigation were the primary factors in its decision to settle. “The decision to settle was an extremely difficult one because Oncology San Antonio was confident that it would have prevailed in any action,” the practice said via email.

This civil settlement with Oncology San Antonio also resolved allegations that a physician affiliated with the practice, Jayasree Rao, MD, provided unnecessary tests, services, and treatments to patients covered by Medicare, TRICARE, and Texas Medicaid in the San Antonio Metro Area and billed these federal healthcare programs for the unnecessary services.

The DOJ identified Slavisa Gasic, MD, a physician formerly employed by Dr. Rao, as a whistleblower in the investigation. When asked for comment, Oncology San Antonio alleged Dr. Gasic was “disgruntled for not being promoted.”

According to Oncology San Antonio, the contract for bone marrow biopsies was negotiated and signed by a former nonphysician officer of the company without the input of Oncology San Antonio physicians. The contract permitted bone marrow biopsies at Oncology San Antonio clinics instead of requiring older adult and sick patients to go to a different facility for these services.

“Oncology San Antonio and Rao vehemently denied Gasic’s allegations as wholly unfounded,” the company told this news organization.

Dr. Rao retired in March and is no longer practicing. CorePath Laboratories, PA, did not respond to this news organization’s request for comment.

According to the DOJ press release, the “investigation and resolution of this matter illustrate the government’s emphasis on combating healthcare fraud.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Department of Justice (DOJ) announced on April 2 that Oncology San Antonio, PA, and its physicians have agreed to pay $1.3 million, and CorePath Laboratories, PA, has agreed to pay nearly $2.75 million plus accrued interest in civil settlements with the United States and Texas for alleged violations of the False Claims Act.

According to the DOJ, the diagnostic reference laboratory, CorePath Laboratories, conducted in-office bone marrow biopsies at Oncology San Antonio practice locations and performed diagnostic testing on the samples. CorePath Laboratories agreed to pay $115 for each biopsy referred by Oncology San Antonio physicians, and these biopsy payments were allegedly paid to the private practices of three physicians at Oncology San Antonio. This arrangement allegedly began in August 2016.

The DOJ claimed that the payments for referring biopsies constituted illegal kickbacks under the Anti-Kickback Statute, which prohibits offering or receiving payments to encourage referrals of services covered by federal healthcare programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

“Violations of the Anti-Kickback Statute involving oncology services can waste scarce federal healthcare program funds and corrupt the medical decision-making process,” Special Agent in Charge Jason E. Meadows with the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General said in a statement.

Oncology San Antonio told this news organization that the cost and distraction of prolonged litigation were the primary factors in its decision to settle. “The decision to settle was an extremely difficult one because Oncology San Antonio was confident that it would have prevailed in any action,” the practice said via email.

This civil settlement with Oncology San Antonio also resolved allegations that a physician affiliated with the practice, Jayasree Rao, MD, provided unnecessary tests, services, and treatments to patients covered by Medicare, TRICARE, and Texas Medicaid in the San Antonio Metro Area and billed these federal healthcare programs for the unnecessary services.

The DOJ identified Slavisa Gasic, MD, a physician formerly employed by Dr. Rao, as a whistleblower in the investigation. When asked for comment, Oncology San Antonio alleged Dr. Gasic was “disgruntled for not being promoted.”

According to Oncology San Antonio, the contract for bone marrow biopsies was negotiated and signed by a former nonphysician officer of the company without the input of Oncology San Antonio physicians. The contract permitted bone marrow biopsies at Oncology San Antonio clinics instead of requiring older adult and sick patients to go to a different facility for these services.

“Oncology San Antonio and Rao vehemently denied Gasic’s allegations as wholly unfounded,” the company told this news organization.

Dr. Rao retired in March and is no longer practicing. CorePath Laboratories, PA, did not respond to this news organization’s request for comment.

According to the DOJ press release, the “investigation and resolution of this matter illustrate the government’s emphasis on combating healthcare fraud.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Department of Justice (DOJ) announced on April 2 that Oncology San Antonio, PA, and its physicians have agreed to pay $1.3 million, and CorePath Laboratories, PA, has agreed to pay nearly $2.75 million plus accrued interest in civil settlements with the United States and Texas for alleged violations of the False Claims Act.

According to the DOJ, the diagnostic reference laboratory, CorePath Laboratories, conducted in-office bone marrow biopsies at Oncology San Antonio practice locations and performed diagnostic testing on the samples. CorePath Laboratories agreed to pay $115 for each biopsy referred by Oncology San Antonio physicians, and these biopsy payments were allegedly paid to the private practices of three physicians at Oncology San Antonio. This arrangement allegedly began in August 2016.

The DOJ claimed that the payments for referring biopsies constituted illegal kickbacks under the Anti-Kickback Statute, which prohibits offering or receiving payments to encourage referrals of services covered by federal healthcare programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

“Violations of the Anti-Kickback Statute involving oncology services can waste scarce federal healthcare program funds and corrupt the medical decision-making process,” Special Agent in Charge Jason E. Meadows with the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General said in a statement.

Oncology San Antonio told this news organization that the cost and distraction of prolonged litigation were the primary factors in its decision to settle. “The decision to settle was an extremely difficult one because Oncology San Antonio was confident that it would have prevailed in any action,” the practice said via email.

This civil settlement with Oncology San Antonio also resolved allegations that a physician affiliated with the practice, Jayasree Rao, MD, provided unnecessary tests, services, and treatments to patients covered by Medicare, TRICARE, and Texas Medicaid in the San Antonio Metro Area and billed these federal healthcare programs for the unnecessary services.

The DOJ identified Slavisa Gasic, MD, a physician formerly employed by Dr. Rao, as a whistleblower in the investigation. When asked for comment, Oncology San Antonio alleged Dr. Gasic was “disgruntled for not being promoted.”

According to Oncology San Antonio, the contract for bone marrow biopsies was negotiated and signed by a former nonphysician officer of the company without the input of Oncology San Antonio physicians. The contract permitted bone marrow biopsies at Oncology San Antonio clinics instead of requiring older adult and sick patients to go to a different facility for these services.

“Oncology San Antonio and Rao vehemently denied Gasic’s allegations as wholly unfounded,” the company told this news organization.

Dr. Rao retired in March and is no longer practicing. CorePath Laboratories, PA, did not respond to this news organization’s request for comment.

According to the DOJ press release, the “investigation and resolution of this matter illustrate the government’s emphasis on combating healthcare fraud.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Botanical Briefs: Fig Phytophotodermatitis (Ficus carica)

Plant Parts and Nomenclature

Ficus carica (common fig) is a deciduous shrub or small tree with smooth gray bark that can grow up to 10 m in height (Figure 1). It is characterized by many spreading branches, but the trunk rarely grows beyond a diameter of 7 in. Its hairy leaves are coarse on the upper side and soft underneath with 3 to 7 deep lobes that can extend up to 25 cm in length or width; the leaves grow individually, alternating along the sides of the branches. Fig trees often can be seen adorning yards, gardens, and parks, especially in tropical and subtropical climates. Ficus carica should not be confused with Ficus benjamina (weeping fig), a common ornamental tree that also is used to provide shade in hot climates, though both can cause phototoxic skin eruptions.

The common fig tree originated in the Mediterranean and western Asia1 and has been cultivated by humans since the second and third millennia

Ficus carica is a member of the Moraceae family (derived from the Latin name for the mulberry tree), which includes 53 genera and approximately 1400 species, of which about 850 belong to the genus Ficus (the Latin name for a fig tree). The term carica likely comes from the Latin word carricare (to load) to describe a tree loaded with figs. Family members include trees, shrubs, lianas, and herbs that usually contain laticifers with a milky latex.

Traditional Uses

For centuries, components of the fig tree have been used in herbal teas and pastes to treat ailments ranging from sore throats to diarrhea, though there is no evidence to support their efficacy.4 Ancient Indians and Egyptians used plants such as the common fig tree containing furocoumarins to induce hyperpigmentation in vitiligo.5

Phototoxic Components

The leaves and sap of the common fig tree contain psoralens, which are members of the furocoumarin group of chemical compounds and are the source of its phototoxicity. The fruit does not contain psoralens.6-9 The tree also produces proteolytic enzymes such as protease, amylase, ficin, triterpenoids, and lipodiastase that enhance its phototoxic effects.8 Exposure to UV light between 320 and 400 nm following contact with these phototoxic components triggers a reaction in the skin over the course of 1 to 3 days.5 The psoralens bind in epidermal cells, cross-link the DNA, and cause cell-membrane destruction, leading to edema and necrosis.10 The delay in symptoms may be attributed to the time needed to synthesize acute-phase reaction proteins such as tumor necrosis factor α and IL-1.11 In spring and summer months, an increased concentration of psoralens in the leaves and sap contribute to an increased incidence of phytophotodermatitis.9 Humidity and sweat also increase the percutaneous absorption of psoralens.12,13

Allergens

Fig trees produce a latex protein that can cause cross-reactive hypersensitivity reactions in those allergic to F benjamina latex and rubber latex.6 The latex proteins in fig trees can act as airborne respiratory allergens. Ingestion of figs can produce anaphylactic reactions in those sensitized to rubber latex and F benjamina latex.7 Other plant families associated with phototoxic reactions include Rutaceae (lemon, lime, bitter orange), Apiaceae (formerly Umbelliferae)(carrot, parsnip, parsley, dill, celery, hogweed), and Fabaceae (prairie turnip).

Cutaneous Manifestations

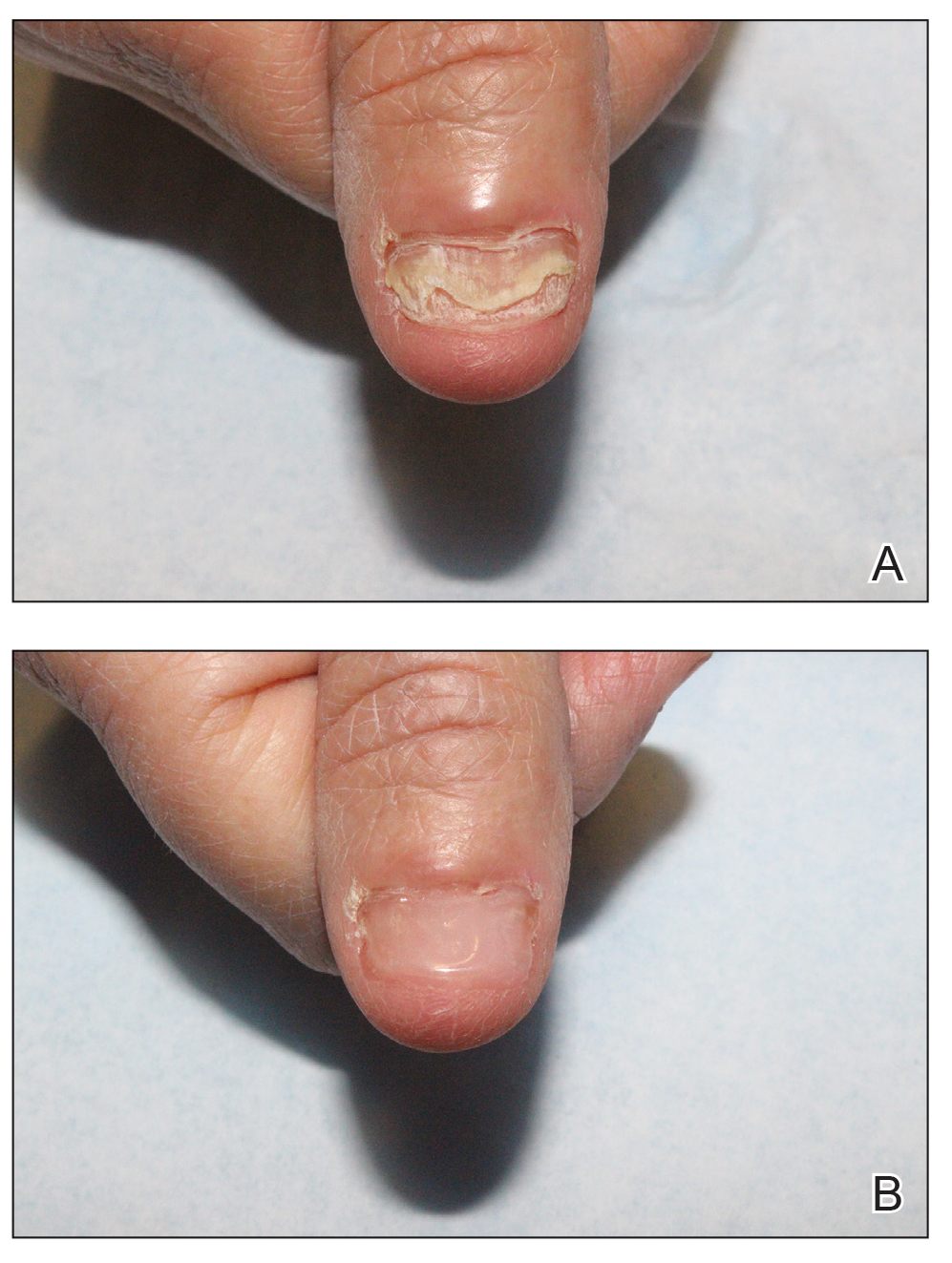

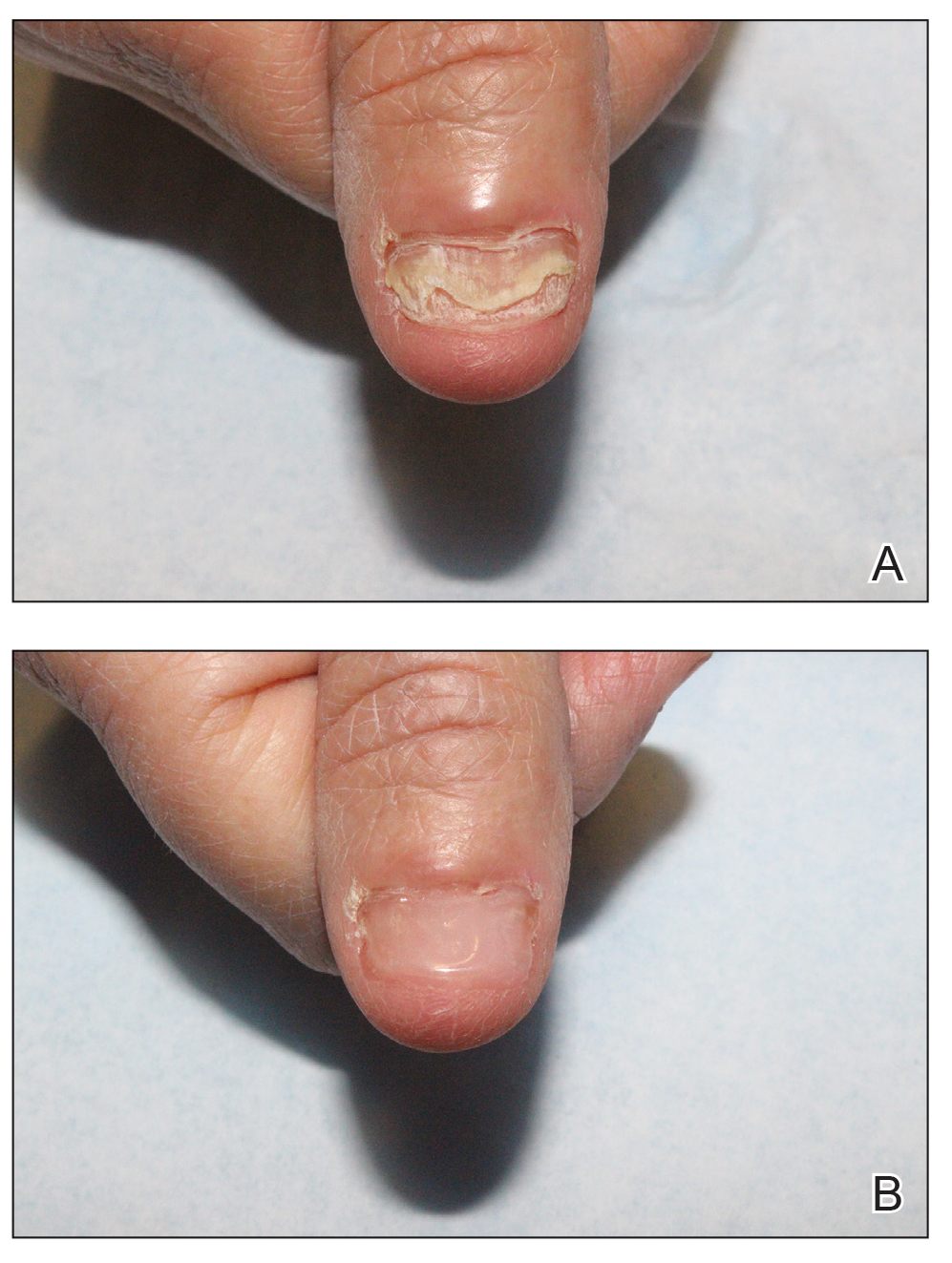

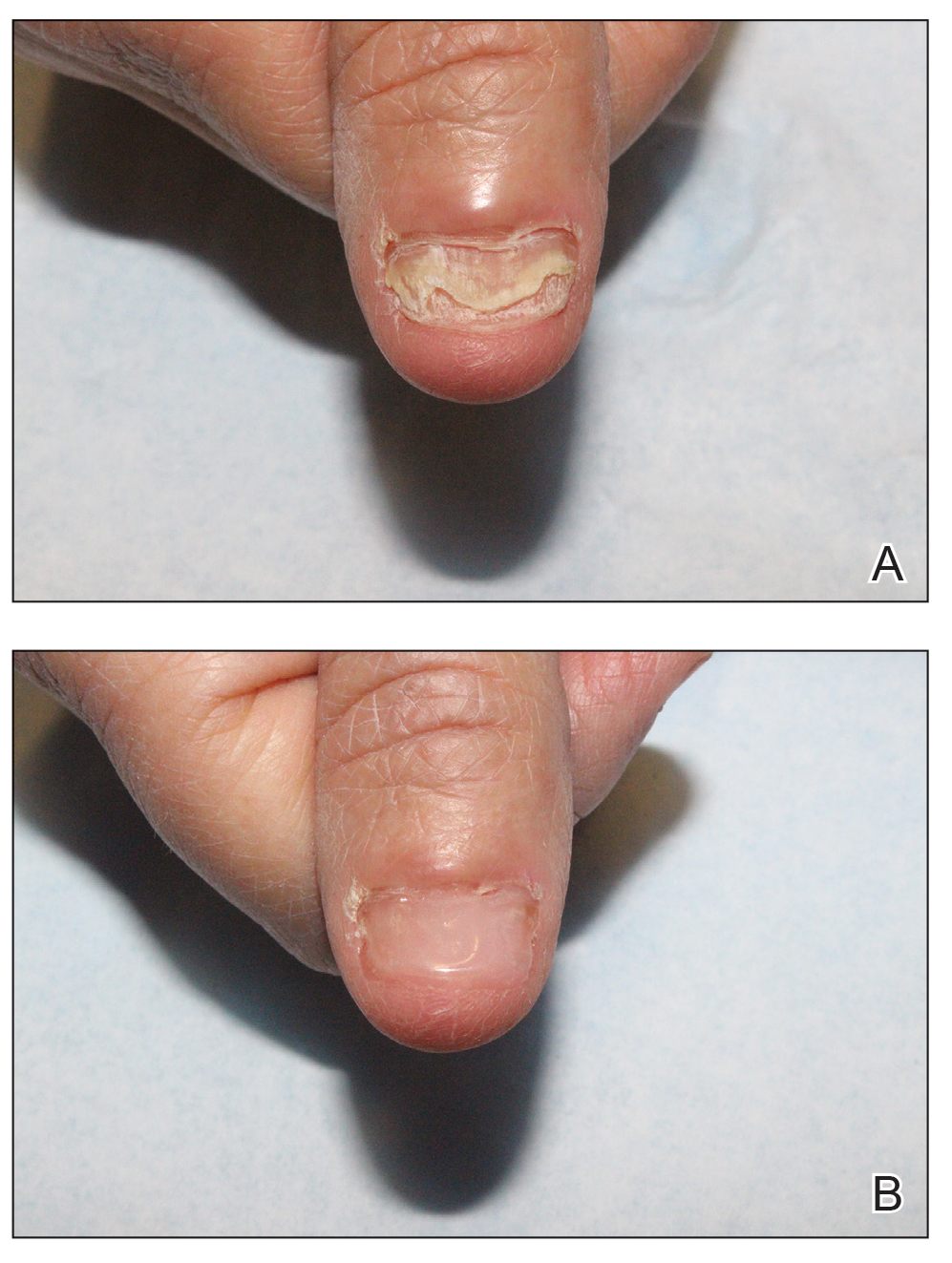

Most cases of fig phytophotodermatitis begin with burning, pain, and/or itching within hours of sunlight exposure in areas of the skin that encountered components of the fig tree, often in a linear pattern. The affected areas become erythematous and edematous with formation of bullae and unilocular vesicles over the course of 1 to 3 days.12,14,15 Lesions may extend beyond the region of contact with the fig tree as they spread across the skin due to sweat or friction, and pain may linger even after the lesions resolve.12,13,16 Adults who handle fig trees (eg, pruning) are susceptible to phototoxic reactions, especially those using chain saws or other mechanisms that result in spray exposure, as the photosensitizing sap permeates the wood and bark of the entire tree.17 Similarly, children who handle fig leaves or sap during outdoor play can develop bullous eruptions. Severe cases have resulted in hospital admission after prolonged exposure.16 Additionally, irritant dermatitis may arise from contact with the trichomes or “hairs” on various parts of the plant.

Patients who use natural remedies containing components of the fig tree without the supervision of a medical provider put themselves at risk for unsafe or unwanted adverse effects, such as phytophotodermatitis.12,15,16,18 An entire family presented with burns after they applied fig leaf extract to the skin prior to tanning outside in the sun.19 A 42-year-old woman acquired a severe burn covering 81% of the body surface after topically applying fig leaf tea to the skin as a tanning agent.20 A subset of patients ingesting or applying fig tree components for conditions such as vitiligo, dermatitis, onychomycosis, and motor retardation developed similar cutaneous reactions.13,14,21,22 Lesions resembling finger marks can raise concerns for potential abuse or neglect in children.22

The differential diagnosis for fig phytophotodermatitis includes sunburn, chemical burns, drug-related photosensitivity, infectious lesions (eg, herpes simplex, bullous impetigo, Lyme disease, superficial lymphangitis), connective tissue disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), contact dermatitis, and nonaccidental trauma.12,15,18 Compared to sunburn, phytophotodermatitis tends to increase in severity over days following exposure and heals with dramatic hyperpigmentation, which also prompts visits to dermatology.12

Treatment

Treatment of fig phytophotodermatitis chiefly is symptomatic, including analgesia, appropriate wound care, and infection prophylaxis. Topical and systemic corticosteroids may aid in the resolution of moderate to severe reactions.15,23,24 Even severe injuries over small areas or mild injuries to a high percentage of the total body surface area may require treatment in a burn unit. Patients should be encouraged to use mineral-based sunscreens on the affected areas to reduce the risk for hyperpigmentation. Individuals who regularly handle fig trees should use contact barriers including gloves and protective clothing (eg, long-sleeved shirts, long pants).

- Ikegami H, Nogata H, Hirashima K, et al. Analysis of genetic diversity among European and Asian fig varieties (Ficus carica L.) using ISSR, RAPD, and SSR markers. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2009;56:201-209.

- Zohary D, Spiegel-Roy P. Beginnings of fruit growing in the Old World. Science. 1975;187:319-327.

- Young R. Young’s Analytical Concordance. Thomas Nelson; 1982.

- Duke JA. Handbook of Medicinal Herbs. CRC Press; 2002.

- Pathak MA, Fitzpatrick TB. Bioassay of natural and synthetic furocoumarins (psoralens). J Invest Dermatol. 1959;32:509-518.

- Focke M, Hemmer W, Wöhrl S, et al. Cross-reactivity between Ficus benjamina latex and fig fruit in patients with clinical fig allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:971-977.

- Hemmer W, Focke M, Götz M, et al. Sensitization to Ficus benjamina: relationship to natural rubber latex allergy and identification of foods implicated in the Ficus-fruit syndrome. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1251-1258.

- Bonamonte D, Foti C, Lionetti N, et al. Photoallergic contact dermatitis to 8-methoxypsoralen in Ficus carica. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:343-348.

- Zaynoun ST, Aftimos BG, Abi Ali L, et al. Ficus carica; isolation and quantification of the photoactive components. Contact Dermatitis. 1984;11:21-25.

- Tessman JW, Isaacs ST, Hearst JE. Photochemistry of the furan-side 8-methoxypsoralen-thymidine monoadduct inside the DNA helix. conversion to diadduct and to pyrone-side monoadduct. Biochemistry. 1985;24:1669-1676.

- Geary P. Burns related to the use of psoralens as a tanning agent. Burns. 1996;22:636-637.

- Redgrave N, Solomon J. Severe phytophotodermatitis from fig sap: a little known phenomenon. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:E238745.

- Ozdamar E, Ozbek S, Akin S. An unusual cause of burn injury: fig leaf decoction used as a remedy for a dermatitis of unknown etiology. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2003;24:229-233; discussion 228.

- Berakha GJ, Lefkovits G. Psoralen phototherapy and phototoxicity. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:458-461.

- Papazoglou A, Mantadakis E. Fig tree leaves phytophotodermatitis. J Pediatr. 2021;239:244-245.

- Imen MS, Ahmadabadi A, Tavousi SH, et al. The curious cases of burn by fig tree leaves. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:71-73.

- Rouaiguia-Bouakkaz S, Amira-Guebailia H, Rivière C, et al. Identification and quantification of furanocoumarins in stem bark and wood of eight Algerian varieties of Ficus carica by RP-HPLC-DAD and RP-HPLC-DAD-MS. Nat Prod Commun. 2013;8:485-486.

- Oliveira AA, Morais J, Pires O, et al. Fig tree induced phytophotodermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:E233392.

- Bassioukas K, Stergiopoulou C, Hatzis J. Erythrodermic phytophotodermatitis after application of aqueous fig-leaf extract as an artificial suntan promoter and sunbathing. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:94-95.

- Sforza M, Andjelkov K, Zaccheddu R. Severe burn on 81% of body surface after sun tanning. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2013;19:383-384.

- Son JH, Jin H, You HS, et al. Five cases of phytophotodermatitis caused by fig leaves and relevant literature review. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:86-90.

- Abali AE, Aka M, Aydogan C, et al. Burns or phytophotodermatitis, abuse or neglect: confusing aspects of skin lesions caused by the superstitious use of fig leaves. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:E309-E312.

- Picard C, Morice C, Moreau A, et al. Phytophotodermatitis in children: a difficult diagnosis mimicking other dermatitis. 2017;5:1-3.

- Enjolras O, Soupre V, Picard A. Uncommon benign infantile vascular tumors. Adv Dermatol. 2008;24:105-124.

Plant Parts and Nomenclature

Ficus carica (common fig) is a deciduous shrub or small tree with smooth gray bark that can grow up to 10 m in height (Figure 1). It is characterized by many spreading branches, but the trunk rarely grows beyond a diameter of 7 in. Its hairy leaves are coarse on the upper side and soft underneath with 3 to 7 deep lobes that can extend up to 25 cm in length or width; the leaves grow individually, alternating along the sides of the branches. Fig trees often can be seen adorning yards, gardens, and parks, especially in tropical and subtropical climates. Ficus carica should not be confused with Ficus benjamina (weeping fig), a common ornamental tree that also is used to provide shade in hot climates, though both can cause phototoxic skin eruptions.

The common fig tree originated in the Mediterranean and western Asia1 and has been cultivated by humans since the second and third millennia

Ficus carica is a member of the Moraceae family (derived from the Latin name for the mulberry tree), which includes 53 genera and approximately 1400 species, of which about 850 belong to the genus Ficus (the Latin name for a fig tree). The term carica likely comes from the Latin word carricare (to load) to describe a tree loaded with figs. Family members include trees, shrubs, lianas, and herbs that usually contain laticifers with a milky latex.

Traditional Uses

For centuries, components of the fig tree have been used in herbal teas and pastes to treat ailments ranging from sore throats to diarrhea, though there is no evidence to support their efficacy.4 Ancient Indians and Egyptians used plants such as the common fig tree containing furocoumarins to induce hyperpigmentation in vitiligo.5

Phototoxic Components

The leaves and sap of the common fig tree contain psoralens, which are members of the furocoumarin group of chemical compounds and are the source of its phototoxicity. The fruit does not contain psoralens.6-9 The tree also produces proteolytic enzymes such as protease, amylase, ficin, triterpenoids, and lipodiastase that enhance its phototoxic effects.8 Exposure to UV light between 320 and 400 nm following contact with these phototoxic components triggers a reaction in the skin over the course of 1 to 3 days.5 The psoralens bind in epidermal cells, cross-link the DNA, and cause cell-membrane destruction, leading to edema and necrosis.10 The delay in symptoms may be attributed to the time needed to synthesize acute-phase reaction proteins such as tumor necrosis factor α and IL-1.11 In spring and summer months, an increased concentration of psoralens in the leaves and sap contribute to an increased incidence of phytophotodermatitis.9 Humidity and sweat also increase the percutaneous absorption of psoralens.12,13

Allergens

Fig trees produce a latex protein that can cause cross-reactive hypersensitivity reactions in those allergic to F benjamina latex and rubber latex.6 The latex proteins in fig trees can act as airborne respiratory allergens. Ingestion of figs can produce anaphylactic reactions in those sensitized to rubber latex and F benjamina latex.7 Other plant families associated with phototoxic reactions include Rutaceae (lemon, lime, bitter orange), Apiaceae (formerly Umbelliferae)(carrot, parsnip, parsley, dill, celery, hogweed), and Fabaceae (prairie turnip).

Cutaneous Manifestations

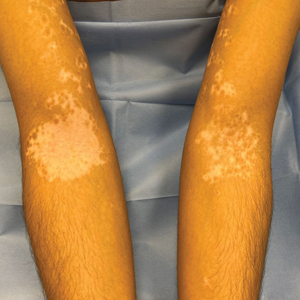

Most cases of fig phytophotodermatitis begin with burning, pain, and/or itching within hours of sunlight exposure in areas of the skin that encountered components of the fig tree, often in a linear pattern. The affected areas become erythematous and edematous with formation of bullae and unilocular vesicles over the course of 1 to 3 days.12,14,15 Lesions may extend beyond the region of contact with the fig tree as they spread across the skin due to sweat or friction, and pain may linger even after the lesions resolve.12,13,16 Adults who handle fig trees (eg, pruning) are susceptible to phototoxic reactions, especially those using chain saws or other mechanisms that result in spray exposure, as the photosensitizing sap permeates the wood and bark of the entire tree.17 Similarly, children who handle fig leaves or sap during outdoor play can develop bullous eruptions. Severe cases have resulted in hospital admission after prolonged exposure.16 Additionally, irritant dermatitis may arise from contact with the trichomes or “hairs” on various parts of the plant.

Patients who use natural remedies containing components of the fig tree without the supervision of a medical provider put themselves at risk for unsafe or unwanted adverse effects, such as phytophotodermatitis.12,15,16,18 An entire family presented with burns after they applied fig leaf extract to the skin prior to tanning outside in the sun.19 A 42-year-old woman acquired a severe burn covering 81% of the body surface after topically applying fig leaf tea to the skin as a tanning agent.20 A subset of patients ingesting or applying fig tree components for conditions such as vitiligo, dermatitis, onychomycosis, and motor retardation developed similar cutaneous reactions.13,14,21,22 Lesions resembling finger marks can raise concerns for potential abuse or neglect in children.22

The differential diagnosis for fig phytophotodermatitis includes sunburn, chemical burns, drug-related photosensitivity, infectious lesions (eg, herpes simplex, bullous impetigo, Lyme disease, superficial lymphangitis), connective tissue disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), contact dermatitis, and nonaccidental trauma.12,15,18 Compared to sunburn, phytophotodermatitis tends to increase in severity over days following exposure and heals with dramatic hyperpigmentation, which also prompts visits to dermatology.12

Treatment

Treatment of fig phytophotodermatitis chiefly is symptomatic, including analgesia, appropriate wound care, and infection prophylaxis. Topical and systemic corticosteroids may aid in the resolution of moderate to severe reactions.15,23,24 Even severe injuries over small areas or mild injuries to a high percentage of the total body surface area may require treatment in a burn unit. Patients should be encouraged to use mineral-based sunscreens on the affected areas to reduce the risk for hyperpigmentation. Individuals who regularly handle fig trees should use contact barriers including gloves and protective clothing (eg, long-sleeved shirts, long pants).

Plant Parts and Nomenclature

Ficus carica (common fig) is a deciduous shrub or small tree with smooth gray bark that can grow up to 10 m in height (Figure 1). It is characterized by many spreading branches, but the trunk rarely grows beyond a diameter of 7 in. Its hairy leaves are coarse on the upper side and soft underneath with 3 to 7 deep lobes that can extend up to 25 cm in length or width; the leaves grow individually, alternating along the sides of the branches. Fig trees often can be seen adorning yards, gardens, and parks, especially in tropical and subtropical climates. Ficus carica should not be confused with Ficus benjamina (weeping fig), a common ornamental tree that also is used to provide shade in hot climates, though both can cause phototoxic skin eruptions.

The common fig tree originated in the Mediterranean and western Asia1 and has been cultivated by humans since the second and third millennia

Ficus carica is a member of the Moraceae family (derived from the Latin name for the mulberry tree), which includes 53 genera and approximately 1400 species, of which about 850 belong to the genus Ficus (the Latin name for a fig tree). The term carica likely comes from the Latin word carricare (to load) to describe a tree loaded with figs. Family members include trees, shrubs, lianas, and herbs that usually contain laticifers with a milky latex.

Traditional Uses

For centuries, components of the fig tree have been used in herbal teas and pastes to treat ailments ranging from sore throats to diarrhea, though there is no evidence to support their efficacy.4 Ancient Indians and Egyptians used plants such as the common fig tree containing furocoumarins to induce hyperpigmentation in vitiligo.5

Phototoxic Components

The leaves and sap of the common fig tree contain psoralens, which are members of the furocoumarin group of chemical compounds and are the source of its phototoxicity. The fruit does not contain psoralens.6-9 The tree also produces proteolytic enzymes such as protease, amylase, ficin, triterpenoids, and lipodiastase that enhance its phototoxic effects.8 Exposure to UV light between 320 and 400 nm following contact with these phototoxic components triggers a reaction in the skin over the course of 1 to 3 days.5 The psoralens bind in epidermal cells, cross-link the DNA, and cause cell-membrane destruction, leading to edema and necrosis.10 The delay in symptoms may be attributed to the time needed to synthesize acute-phase reaction proteins such as tumor necrosis factor α and IL-1.11 In spring and summer months, an increased concentration of psoralens in the leaves and sap contribute to an increased incidence of phytophotodermatitis.9 Humidity and sweat also increase the percutaneous absorption of psoralens.12,13

Allergens

Fig trees produce a latex protein that can cause cross-reactive hypersensitivity reactions in those allergic to F benjamina latex and rubber latex.6 The latex proteins in fig trees can act as airborne respiratory allergens. Ingestion of figs can produce anaphylactic reactions in those sensitized to rubber latex and F benjamina latex.7 Other plant families associated with phototoxic reactions include Rutaceae (lemon, lime, bitter orange), Apiaceae (formerly Umbelliferae)(carrot, parsnip, parsley, dill, celery, hogweed), and Fabaceae (prairie turnip).

Cutaneous Manifestations

Most cases of fig phytophotodermatitis begin with burning, pain, and/or itching within hours of sunlight exposure in areas of the skin that encountered components of the fig tree, often in a linear pattern. The affected areas become erythematous and edematous with formation of bullae and unilocular vesicles over the course of 1 to 3 days.12,14,15 Lesions may extend beyond the region of contact with the fig tree as they spread across the skin due to sweat or friction, and pain may linger even after the lesions resolve.12,13,16 Adults who handle fig trees (eg, pruning) are susceptible to phototoxic reactions, especially those using chain saws or other mechanisms that result in spray exposure, as the photosensitizing sap permeates the wood and bark of the entire tree.17 Similarly, children who handle fig leaves or sap during outdoor play can develop bullous eruptions. Severe cases have resulted in hospital admission after prolonged exposure.16 Additionally, irritant dermatitis may arise from contact with the trichomes or “hairs” on various parts of the plant.

Patients who use natural remedies containing components of the fig tree without the supervision of a medical provider put themselves at risk for unsafe or unwanted adverse effects, such as phytophotodermatitis.12,15,16,18 An entire family presented with burns after they applied fig leaf extract to the skin prior to tanning outside in the sun.19 A 42-year-old woman acquired a severe burn covering 81% of the body surface after topically applying fig leaf tea to the skin as a tanning agent.20 A subset of patients ingesting or applying fig tree components for conditions such as vitiligo, dermatitis, onychomycosis, and motor retardation developed similar cutaneous reactions.13,14,21,22 Lesions resembling finger marks can raise concerns for potential abuse or neglect in children.22

The differential diagnosis for fig phytophotodermatitis includes sunburn, chemical burns, drug-related photosensitivity, infectious lesions (eg, herpes simplex, bullous impetigo, Lyme disease, superficial lymphangitis), connective tissue disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), contact dermatitis, and nonaccidental trauma.12,15,18 Compared to sunburn, phytophotodermatitis tends to increase in severity over days following exposure and heals with dramatic hyperpigmentation, which also prompts visits to dermatology.12

Treatment

Treatment of fig phytophotodermatitis chiefly is symptomatic, including analgesia, appropriate wound care, and infection prophylaxis. Topical and systemic corticosteroids may aid in the resolution of moderate to severe reactions.15,23,24 Even severe injuries over small areas or mild injuries to a high percentage of the total body surface area may require treatment in a burn unit. Patients should be encouraged to use mineral-based sunscreens on the affected areas to reduce the risk for hyperpigmentation. Individuals who regularly handle fig trees should use contact barriers including gloves and protective clothing (eg, long-sleeved shirts, long pants).

- Ikegami H, Nogata H, Hirashima K, et al. Analysis of genetic diversity among European and Asian fig varieties (Ficus carica L.) using ISSR, RAPD, and SSR markers. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2009;56:201-209.

- Zohary D, Spiegel-Roy P. Beginnings of fruit growing in the Old World. Science. 1975;187:319-327.

- Young R. Young’s Analytical Concordance. Thomas Nelson; 1982.

- Duke JA. Handbook of Medicinal Herbs. CRC Press; 2002.

- Pathak MA, Fitzpatrick TB. Bioassay of natural and synthetic furocoumarins (psoralens). J Invest Dermatol. 1959;32:509-518.

- Focke M, Hemmer W, Wöhrl S, et al. Cross-reactivity between Ficus benjamina latex and fig fruit in patients with clinical fig allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:971-977.

- Hemmer W, Focke M, Götz M, et al. Sensitization to Ficus benjamina: relationship to natural rubber latex allergy and identification of foods implicated in the Ficus-fruit syndrome. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1251-1258.

- Bonamonte D, Foti C, Lionetti N, et al. Photoallergic contact dermatitis to 8-methoxypsoralen in Ficus carica. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:343-348.

- Zaynoun ST, Aftimos BG, Abi Ali L, et al. Ficus carica; isolation and quantification of the photoactive components. Contact Dermatitis. 1984;11:21-25.

- Tessman JW, Isaacs ST, Hearst JE. Photochemistry of the furan-side 8-methoxypsoralen-thymidine monoadduct inside the DNA helix. conversion to diadduct and to pyrone-side monoadduct. Biochemistry. 1985;24:1669-1676.

- Geary P. Burns related to the use of psoralens as a tanning agent. Burns. 1996;22:636-637.

- Redgrave N, Solomon J. Severe phytophotodermatitis from fig sap: a little known phenomenon. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:E238745.

- Ozdamar E, Ozbek S, Akin S. An unusual cause of burn injury: fig leaf decoction used as a remedy for a dermatitis of unknown etiology. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2003;24:229-233; discussion 228.

- Berakha GJ, Lefkovits G. Psoralen phototherapy and phototoxicity. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:458-461.

- Papazoglou A, Mantadakis E. Fig tree leaves phytophotodermatitis. J Pediatr. 2021;239:244-245.

- Imen MS, Ahmadabadi A, Tavousi SH, et al. The curious cases of burn by fig tree leaves. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:71-73.

- Rouaiguia-Bouakkaz S, Amira-Guebailia H, Rivière C, et al. Identification and quantification of furanocoumarins in stem bark and wood of eight Algerian varieties of Ficus carica by RP-HPLC-DAD and RP-HPLC-DAD-MS. Nat Prod Commun. 2013;8:485-486.

- Oliveira AA, Morais J, Pires O, et al. Fig tree induced phytophotodermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:E233392.

- Bassioukas K, Stergiopoulou C, Hatzis J. Erythrodermic phytophotodermatitis after application of aqueous fig-leaf extract as an artificial suntan promoter and sunbathing. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:94-95.

- Sforza M, Andjelkov K, Zaccheddu R. Severe burn on 81% of body surface after sun tanning. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2013;19:383-384.

- Son JH, Jin H, You HS, et al. Five cases of phytophotodermatitis caused by fig leaves and relevant literature review. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:86-90.

- Abali AE, Aka M, Aydogan C, et al. Burns or phytophotodermatitis, abuse or neglect: confusing aspects of skin lesions caused by the superstitious use of fig leaves. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:E309-E312.

- Picard C, Morice C, Moreau A, et al. Phytophotodermatitis in children: a difficult diagnosis mimicking other dermatitis. 2017;5:1-3.

- Enjolras O, Soupre V, Picard A. Uncommon benign infantile vascular tumors. Adv Dermatol. 2008;24:105-124.

- Ikegami H, Nogata H, Hirashima K, et al. Analysis of genetic diversity among European and Asian fig varieties (Ficus carica L.) using ISSR, RAPD, and SSR markers. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2009;56:201-209.

- Zohary D, Spiegel-Roy P. Beginnings of fruit growing in the Old World. Science. 1975;187:319-327.

- Young R. Young’s Analytical Concordance. Thomas Nelson; 1982.

- Duke JA. Handbook of Medicinal Herbs. CRC Press; 2002.

- Pathak MA, Fitzpatrick TB. Bioassay of natural and synthetic furocoumarins (psoralens). J Invest Dermatol. 1959;32:509-518.

- Focke M, Hemmer W, Wöhrl S, et al. Cross-reactivity between Ficus benjamina latex and fig fruit in patients with clinical fig allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:971-977.

- Hemmer W, Focke M, Götz M, et al. Sensitization to Ficus benjamina: relationship to natural rubber latex allergy and identification of foods implicated in the Ficus-fruit syndrome. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1251-1258.

- Bonamonte D, Foti C, Lionetti N, et al. Photoallergic contact dermatitis to 8-methoxypsoralen in Ficus carica. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:343-348.

- Zaynoun ST, Aftimos BG, Abi Ali L, et al. Ficus carica; isolation and quantification of the photoactive components. Contact Dermatitis. 1984;11:21-25.

- Tessman JW, Isaacs ST, Hearst JE. Photochemistry of the furan-side 8-methoxypsoralen-thymidine monoadduct inside the DNA helix. conversion to diadduct and to pyrone-side monoadduct. Biochemistry. 1985;24:1669-1676.

- Geary P. Burns related to the use of psoralens as a tanning agent. Burns. 1996;22:636-637.

- Redgrave N, Solomon J. Severe phytophotodermatitis from fig sap: a little known phenomenon. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:E238745.

- Ozdamar E, Ozbek S, Akin S. An unusual cause of burn injury: fig leaf decoction used as a remedy for a dermatitis of unknown etiology. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2003;24:229-233; discussion 228.

- Berakha GJ, Lefkovits G. Psoralen phototherapy and phototoxicity. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:458-461.

- Papazoglou A, Mantadakis E. Fig tree leaves phytophotodermatitis. J Pediatr. 2021;239:244-245.

- Imen MS, Ahmadabadi A, Tavousi SH, et al. The curious cases of burn by fig tree leaves. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:71-73.

- Rouaiguia-Bouakkaz S, Amira-Guebailia H, Rivière C, et al. Identification and quantification of furanocoumarins in stem bark and wood of eight Algerian varieties of Ficus carica by RP-HPLC-DAD and RP-HPLC-DAD-MS. Nat Prod Commun. 2013;8:485-486.

- Oliveira AA, Morais J, Pires O, et al. Fig tree induced phytophotodermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:E233392.

- Bassioukas K, Stergiopoulou C, Hatzis J. Erythrodermic phytophotodermatitis after application of aqueous fig-leaf extract as an artificial suntan promoter and sunbathing. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:94-95.

- Sforza M, Andjelkov K, Zaccheddu R. Severe burn on 81% of body surface after sun tanning. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2013;19:383-384.

- Son JH, Jin H, You HS, et al. Five cases of phytophotodermatitis caused by fig leaves and relevant literature review. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:86-90.

- Abali AE, Aka M, Aydogan C, et al. Burns or phytophotodermatitis, abuse or neglect: confusing aspects of skin lesions caused by the superstitious use of fig leaves. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:E309-E312.

- Picard C, Morice C, Moreau A, et al. Phytophotodermatitis in children: a difficult diagnosis mimicking other dermatitis. 2017;5:1-3.

- Enjolras O, Soupre V, Picard A. Uncommon benign infantile vascular tumors. Adv Dermatol. 2008;24:105-124.

Practice Points

- Exposure to the components of the common fig tree (Ficus carica) can induce phytophotodermatitis.

- Notable postinflammatory hyperpigmentation typically occurs in the healing stage of fig phytophotodermatitis.

Micronutrient Deficiencies in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease

In 2023, ESPEN (the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism) published consensus recommendations highlighting the importance of regular monitoring and treatment of nutrient deficiencies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) for improved prognosis, mortality, and quality of life.1 Suboptimal nutrition in patients with IBD predominantly results from inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract leading to malabsorption; however, medications commonly used to manage IBD also can contribute to malnutrition.2,3 Additionally, patients may develop nausea and food avoidance due to medication or the disease itself, leading to nutritional withdrawal and eventual deficiency.4 Even with the development of diets focused on balancing nutritional needs and decreasing inflammation,5 offsetting this aversion to food can be difficult to overcome.2

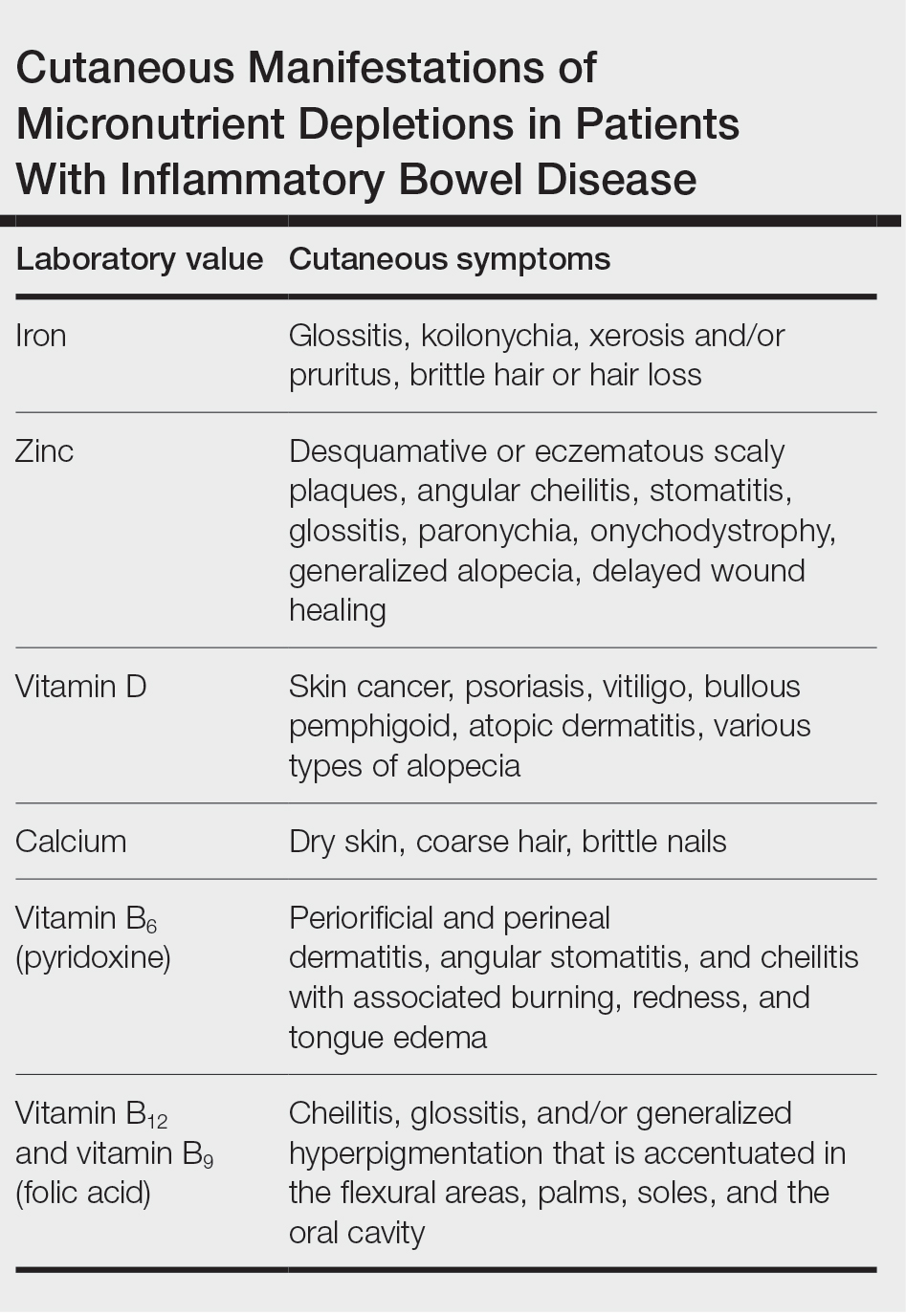

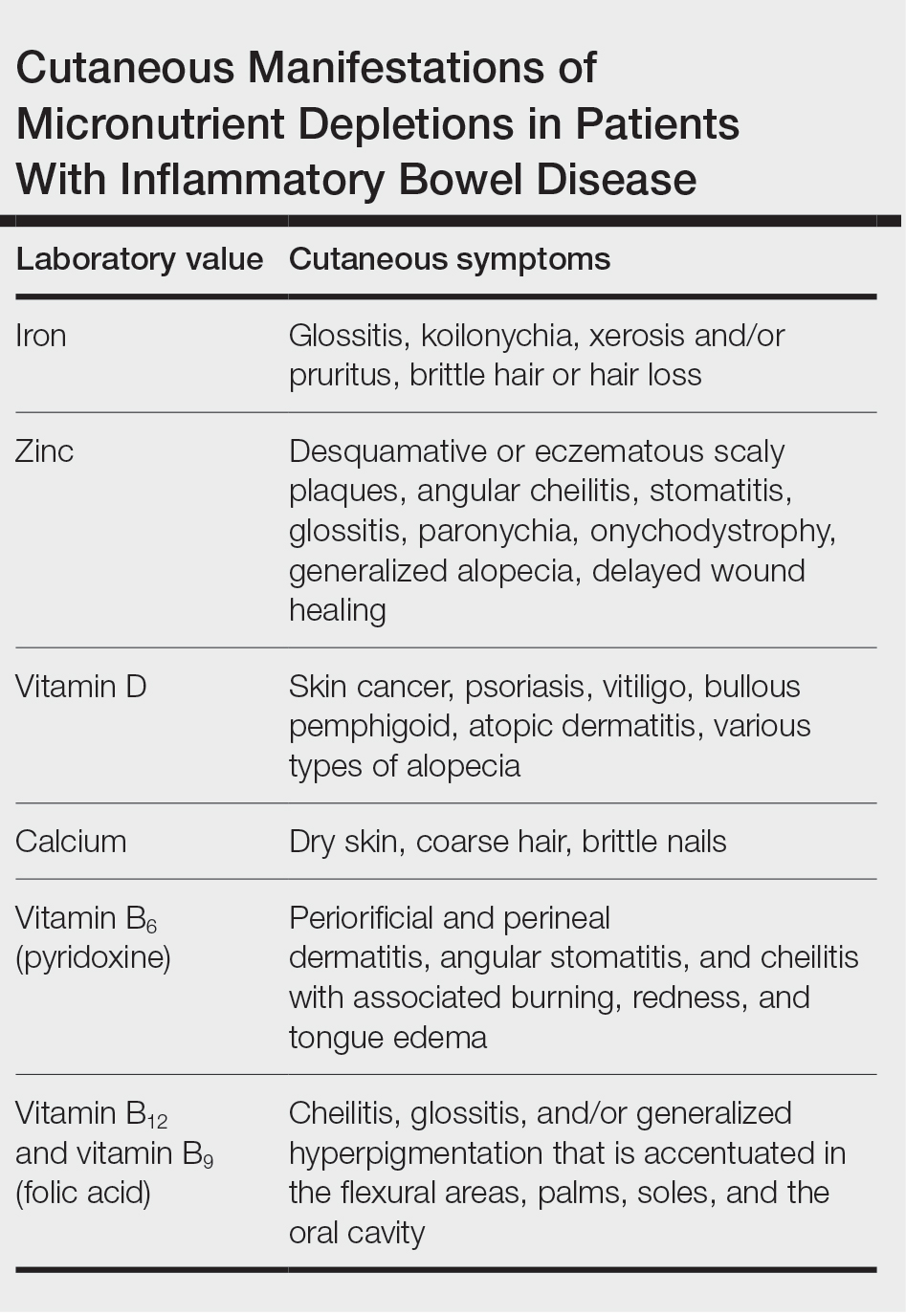

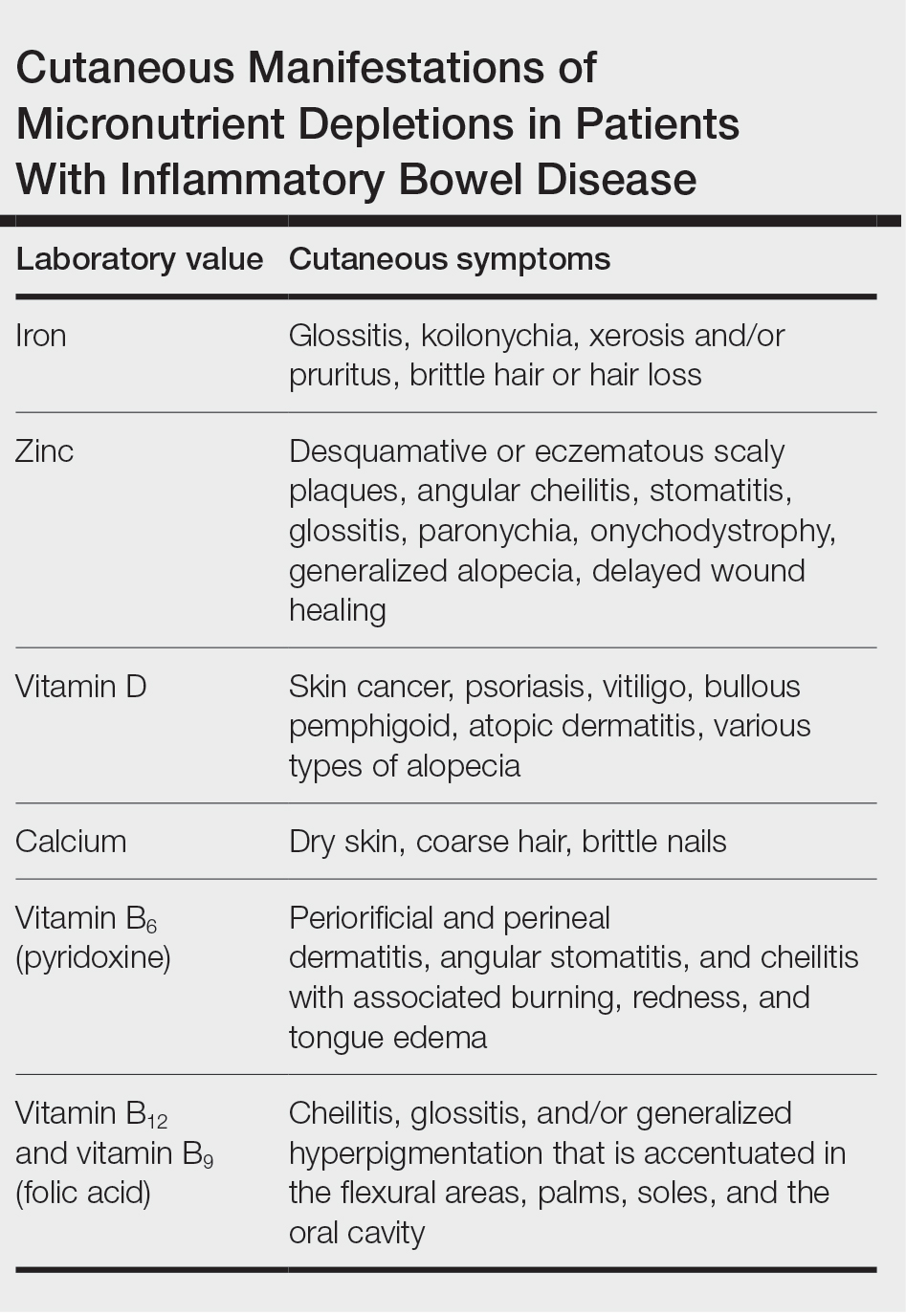

Cutaneous manifestations of IBD are multifaceted and can be secondary to the disease, reactive to or associated with IBD, or effects from nutritional deficiencies. The most common vitamin and nutrient deficiencies in patients with IBD include iron; zinc; calcium; vitamin D; and vitamins B6 (pyridoxine), B9 (folic acid), and B12.6 Malnutrition may manifest with cutaneous disease, and dermatologists can be the first to identify and assess for nutritional deficiencies. In this article, we review the mechanisms of these micronutrient depletions in the context of IBD, their subsequent dermatologic manifestations (Table), and treatment and monitoring guidelines for each deficiency.

Iron

A systematic review conducted from 2007 to 2012 in European patients with IBD (N=2192) found the overall prevalence of anemia in this population to be 24% (95% CI, 18%-31%), with 57% of patients with anemia experiencing iron deficiency.7 Anemia is observed more commonly in patients hospitalized with IBD and is common in patients with both Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis.8

Pathophysiology—Iron is critically important in oxygen transportation throughout the body as a major component of hemoglobin. Physiologically, the low pH of the duodenum and proximal jejunum allows divalent metal transporter 1 to transfer dietary Fe3+ into enterocytes, where it is reduced to the transportable Fe2+.9,10 Distribution of Fe2+ ions from enterocytes relies on ferroportin, an iron-transporting protein, which is heavily regulated by the protein hepcidin.11 Hepcidin, a known acute phase reactant, will increase in the setting of active IBD, causing a depletion of ferroportin and an inability of the body to utilize the stored iron in enterocytes.12 This poor utilization of iron stores combined with blood loss caused by inflammation in the GI tract is the proposed primary mechanism of iron-deficiency anemia observed in patients with IBD.13

Cutaneous Manifestations—From a dermatologic perspective, iron-deficiency anemia can manifest with a wide range of symptoms including glossitis, koilonychia, xerosis and/or pruritus, and brittle hair or hair loss.14,15 Although the underlying pathophysiology of these cutaneous manifestations is not fully understood, there are several theories assessing the mechanisms behind the skin findings of iron deficiency.

Atrophic glossitis has been observed in many patients with iron deficiency and is thought to manifest due to low iron concentrations in the blood, thereby decreasing oxygen delivery to the papillae of the dorsal tongue with resultant atrophy.16,17 Similarly, decreased oxygen delivery to the nail bed capillaries may cause deformities in the nail called koilonychia (or “spoon nails”).18 Iron is a key co-factor in collagen lysyl hydroxylase that promotes collagen binding; iron deficiency may lead to disruptions in the epidermal barrier that can cause pruritus and xerosis.19 An observational study of 200 healthy patients with a primary concern of pruritus found a correlation between low serum ferritin and a higher degree of pruritus (r=−0.768; P<.00001).20

Evidence for iron’s role in hair growth comes from a mouse model study with a mutation in the serine protease TMPRSS6—a protein that regulates hepcidin and iron absorption—which caused an increase in hepcidin production and subsequent systemic iron deficiency. Mice at 4 weeks of age were devoid of all body hair but had substantial regrowth after initiation of a 2-week iron-rich diet, which suggests a connection between iron repletion and hair growth in mice with iron deficiency.21 Additionally, a meta-analysis analyzing the comorbidities of patients with alopecia areata found them to have higher odds (odds ratio [OR]=2.78; 95% CI, 1.23-6.29) of iron-deficiency anemia but no association with IBD (OR=1.48; 95% CI, 0.32-6.82).22

Diagnosis and Monitoring—The American Gastroenterological Association recommends a complete blood cell count (CBC), serum ferritin, transferrin saturation (TfS), and C-reactive protein (CRP) as standard evaluations for iron deficiency in patients with IBD. Patients with active IBD should be screened every 3 months,and patients with inactive disease should be screened every 6 to 12 months.23

Although ferritin and TfS often are used as markers for iron status in healthy individuals, they are positive and negative acute phase reactants, respectively. Using them to assess iron status in patients with IBD may inaccurately represent iron status in the setting of inflammation from the disease.24 The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) produced guidelines to define iron deficiency as a TfS less than 20% or a ferritin level less than 30 µg/L in patients without evidence of active IBD and a ferritin level less than 100 µg/L for patients with active inflammation.25