User login

Neuro-politics: Will you vote with your cortex or limbic system?

It’s election season again. Every 4 years, October becomes the purgatory month of politics. But this year, it’s even more complicated, being juxtaposed against a chaotic mosaic of a viral pandemic, economic travails, social upheaval, and exceptionally toxic political hyperpartisanship.

The widespread expectation is that citizens will vote for their party’s candidates, but there is now a body of evidence suggesting that our brains may be pre-wired to be liberal or conservative.

Enter neuro-politics. This discipline is younger than neuro-economics, neuro-law, neuro-ethics, neuro-marketing, neuro-art, neuro-culture, or neuro-esthetics. Neuro-politics focuses on the intersection of politics with neuroscience.1 However, there are many antecedents to neuro-politics reflected in the writings of Plato, Aristotle, Niccolò Machiavelli, John Locke, Baruch Spinoza, Henri Bergson, William James, and others.

Neuro-politics attempts to generate data to answer a variety of questions about political behavior, such as:

- Is political orientation associated with differences in certain brain regions?

- Are there reliable neural biomarkers of political orientation?

- Is political orientation modifiable, and if so, why are some individuals ferociously entrenched to one political dogma while others are able to untether themselves and adopt another political doctrine?

- What are the brain characteristics of “swing voters” who may align themselves with different parties in different election cycles?

- Is there a “religification” of politics among the ardent fanatics who regard the tenets of their political beliefs as “articles of faith?”

- Is the brain modified by certain attributes (such as educational level, age, sex, marital status, race, ethnicity, and religious affiliation) that translate to political decision-making?

- Can neuro-politics explain the sprouting of psychiatric symptoms such as obsessions, anxiety, irritability, anger, hatred, and conspiracy theories?

- Is political extremism driven by cortical structures, limbic structures, or both?

Politics and the brain

Here is a brief review of some studies that examined the relationship of political orientation or voting behavior with brain structure and function:

1. Roger Sperry, the 1981 Nobel Laureate (for his studies on split-brain patients) reported that in patients who underwent callosotomy, both cerebral hemispheres gave the same ratings of politicians when their photos were shown to each hemisphere separately.2

2. A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study found that the faces of candidates activated participants’ ventromedial and anterior prefrontal cortices. Amygdala activation was associated with the intensity of the emotion.3

Continue to: A skin conductance...

3. A skin conductance study reported that politically liberal individuals had low reactivity to sudden noises and threatening stimuli, while conservative counterparts demonstrated high physiological reactions to noises and stimuli.4

4. Images of a losing candidate elicited greater activation on fMRI in the insula and ventral anterior cingulate compared to no activation by exposure to an image of the winning candidate.5

5. Another fMRI study found that “individualism” was associated with activation of the medial prefrontal cortex and temporo-parietal junction when participants listened to a set of political statements. On the other hand, “conservatism” activated the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, while “radicalism” activated the ventral striatum and posterior cingulate.6

6. An EEG activity study of healthy individuals revealed desynchronization in the alpha band related to the politicians who lost simulated elections and were judged as “less trustworthy” when the participant watched their faces.7

7. A structural MRI study of young adults reported that liberalism was associated with increased gray matter volume in the anterior cingulate, while conservatism was associated with increased volume of the right amygdala. The authors replicated their findings and concluded there is a possible link between brain structure and psychological mechanisms that mediate political attitudes.8

Continue to: To examine the effect of...

8. To examine the effect of a “first impression” based on the physical appearance of candidates, researchers compared individuals with damage to the lateral orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) with a group that had frontal damage that spared the lateral OFC and another group of matched healthy volunteers. They used a simulated elections paradigm in which participants voted based solely on photographs of the candidates’ faces. Only the group with OFC damage was influenced by attractiveness, while those with an intact frontal lobe or non-OFC frontal damage relied on other data, such as competence.9 These researchers concluded that an intact OFC is necessary for political decision-making.

9. A study using cognitive tasks reported that liberals are more adept at dealing with novel information than conservatives.10

What part of your brain will you use?

Regardless of the data generated by the neuro-politics studies, the bottom line is: What part of your brain do you use when you cast your vote for an issue, a representative, a senator, or a president? Is it a purely intellectual decision (ie, cortical), or is it driven by visceral emotions (ie, limbic)? Do you believe that every single item in your party’s platform is right and virtuous, while every item in the other party’s platform is wrong and evil? Can you think of any redeeming feature of the candidate you hate or the party you despise?

One attribute that we psychiatrists possess by virtue of our training and clinical work is that we are able to transcend dichotomies and to perceive nuances and shades of gray about controversial issues. So I hope we employ the circuits of our brain where wisdom putatively resides11 and which may develop further (via neuroplasticity) with the conduct of psychotherapy.12 Those brain circuits include:

- prefrontal cortex (for emotional regulation, decision-making, and value relativism)

- lateral prefrontal cortex (to facilitate calculated, reason-based decision-making)

- medial prefrontal cortex (for emotional valence and pro-social attitudes and behaviors).

However, being human, it is quite likely that our amygdala may “seep through” and color our judgment and decisions. But let us try to cast a vote that is not only good for the country but also good for our patients, many of whom may not even be able to vote. Election season is a time to make a positive difference in our patients’ lives, not just ours. Let’s hope our brains exploit this unique opportunity.

1. Schreiber D. Neuropolitics: twenty years later. Politics Life Sci. 2017;36(2):114-131.

2. Sperry RW, Zaidel E, Zaidel D. Self recognition and social awareness in the deconnected minor hemisphere. Neuropsychologia. 1979;17(2):153-166.

3. Knutson KM, Wood JN, Spampinato MV, et al. Politics on the brain: an FMRI investigation. Soc Neurosci. 2006;1(1):25-40.

4. Oxley DR, Smith KB, Alford JR, et al. Political attitudes vary with physiological traits. Science. 2008;321(5896):1667-1670.

5. Spezio ML, Rangel A, Alvarez RM, et al. A neural basis for the effect of candidate appearance on election outcomes. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2008;3(4):344-352.

6. Zamboni G, Gozzi M, Krueger F, et al. Individualism, conservatism, and radicalism as criteria for processing political beliefs: a parametric fMRI study. Soc Neurosci. 2009;4(5):367-383.

7. Vecchiato G, Toppi J, Cincotti F, et al. Neuropolitics: EEG spectral maps related to a political vote based on the first impression of the candidate’s face. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2010;2010:2902-2905.

8. Kanai R, Feilden T, Firth C, et al. Political orientations are correlated with brain structure in young adults. Curr Biol. 2011;21(8):677-680.

9. Xia C, Stolle D, Gidengil E, et al. Lateral orbitofrontal cortex links social impressions to political choices. J Neurosci. 2015;35(22):8507-8514.

10. Bernabel RT, Oliveira A. Conservatism and liberalism predict performance in two nonideological cognitive tasks. Politics Life Sci. 2017;36(2):49-59.

11. Meeks TW, Jeste DV. Neurobiology of wisdom: a literature overview. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(4):355-365.

12. Nasrallah HA. Does psychiatric practice make us wiser? Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(10):12,14.

It’s election season again. Every 4 years, October becomes the purgatory month of politics. But this year, it’s even more complicated, being juxtaposed against a chaotic mosaic of a viral pandemic, economic travails, social upheaval, and exceptionally toxic political hyperpartisanship.

The widespread expectation is that citizens will vote for their party’s candidates, but there is now a body of evidence suggesting that our brains may be pre-wired to be liberal or conservative.

Enter neuro-politics. This discipline is younger than neuro-economics, neuro-law, neuro-ethics, neuro-marketing, neuro-art, neuro-culture, or neuro-esthetics. Neuro-politics focuses on the intersection of politics with neuroscience.1 However, there are many antecedents to neuro-politics reflected in the writings of Plato, Aristotle, Niccolò Machiavelli, John Locke, Baruch Spinoza, Henri Bergson, William James, and others.

Neuro-politics attempts to generate data to answer a variety of questions about political behavior, such as:

- Is political orientation associated with differences in certain brain regions?

- Are there reliable neural biomarkers of political orientation?

- Is political orientation modifiable, and if so, why are some individuals ferociously entrenched to one political dogma while others are able to untether themselves and adopt another political doctrine?

- What are the brain characteristics of “swing voters” who may align themselves with different parties in different election cycles?

- Is there a “religification” of politics among the ardent fanatics who regard the tenets of their political beliefs as “articles of faith?”

- Is the brain modified by certain attributes (such as educational level, age, sex, marital status, race, ethnicity, and religious affiliation) that translate to political decision-making?

- Can neuro-politics explain the sprouting of psychiatric symptoms such as obsessions, anxiety, irritability, anger, hatred, and conspiracy theories?

- Is political extremism driven by cortical structures, limbic structures, or both?

Politics and the brain

Here is a brief review of some studies that examined the relationship of political orientation or voting behavior with brain structure and function:

1. Roger Sperry, the 1981 Nobel Laureate (for his studies on split-brain patients) reported that in patients who underwent callosotomy, both cerebral hemispheres gave the same ratings of politicians when their photos were shown to each hemisphere separately.2

2. A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study found that the faces of candidates activated participants’ ventromedial and anterior prefrontal cortices. Amygdala activation was associated with the intensity of the emotion.3

Continue to: A skin conductance...

3. A skin conductance study reported that politically liberal individuals had low reactivity to sudden noises and threatening stimuli, while conservative counterparts demonstrated high physiological reactions to noises and stimuli.4

4. Images of a losing candidate elicited greater activation on fMRI in the insula and ventral anterior cingulate compared to no activation by exposure to an image of the winning candidate.5

5. Another fMRI study found that “individualism” was associated with activation of the medial prefrontal cortex and temporo-parietal junction when participants listened to a set of political statements. On the other hand, “conservatism” activated the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, while “radicalism” activated the ventral striatum and posterior cingulate.6

6. An EEG activity study of healthy individuals revealed desynchronization in the alpha band related to the politicians who lost simulated elections and were judged as “less trustworthy” when the participant watched their faces.7

7. A structural MRI study of young adults reported that liberalism was associated with increased gray matter volume in the anterior cingulate, while conservatism was associated with increased volume of the right amygdala. The authors replicated their findings and concluded there is a possible link between brain structure and psychological mechanisms that mediate political attitudes.8

Continue to: To examine the effect of...

8. To examine the effect of a “first impression” based on the physical appearance of candidates, researchers compared individuals with damage to the lateral orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) with a group that had frontal damage that spared the lateral OFC and another group of matched healthy volunteers. They used a simulated elections paradigm in which participants voted based solely on photographs of the candidates’ faces. Only the group with OFC damage was influenced by attractiveness, while those with an intact frontal lobe or non-OFC frontal damage relied on other data, such as competence.9 These researchers concluded that an intact OFC is necessary for political decision-making.

9. A study using cognitive tasks reported that liberals are more adept at dealing with novel information than conservatives.10

What part of your brain will you use?

Regardless of the data generated by the neuro-politics studies, the bottom line is: What part of your brain do you use when you cast your vote for an issue, a representative, a senator, or a president? Is it a purely intellectual decision (ie, cortical), or is it driven by visceral emotions (ie, limbic)? Do you believe that every single item in your party’s platform is right and virtuous, while every item in the other party’s platform is wrong and evil? Can you think of any redeeming feature of the candidate you hate or the party you despise?

One attribute that we psychiatrists possess by virtue of our training and clinical work is that we are able to transcend dichotomies and to perceive nuances and shades of gray about controversial issues. So I hope we employ the circuits of our brain where wisdom putatively resides11 and which may develop further (via neuroplasticity) with the conduct of psychotherapy.12 Those brain circuits include:

- prefrontal cortex (for emotional regulation, decision-making, and value relativism)

- lateral prefrontal cortex (to facilitate calculated, reason-based decision-making)

- medial prefrontal cortex (for emotional valence and pro-social attitudes and behaviors).

However, being human, it is quite likely that our amygdala may “seep through” and color our judgment and decisions. But let us try to cast a vote that is not only good for the country but also good for our patients, many of whom may not even be able to vote. Election season is a time to make a positive difference in our patients’ lives, not just ours. Let’s hope our brains exploit this unique opportunity.

It’s election season again. Every 4 years, October becomes the purgatory month of politics. But this year, it’s even more complicated, being juxtaposed against a chaotic mosaic of a viral pandemic, economic travails, social upheaval, and exceptionally toxic political hyperpartisanship.

The widespread expectation is that citizens will vote for their party’s candidates, but there is now a body of evidence suggesting that our brains may be pre-wired to be liberal or conservative.

Enter neuro-politics. This discipline is younger than neuro-economics, neuro-law, neuro-ethics, neuro-marketing, neuro-art, neuro-culture, or neuro-esthetics. Neuro-politics focuses on the intersection of politics with neuroscience.1 However, there are many antecedents to neuro-politics reflected in the writings of Plato, Aristotle, Niccolò Machiavelli, John Locke, Baruch Spinoza, Henri Bergson, William James, and others.

Neuro-politics attempts to generate data to answer a variety of questions about political behavior, such as:

- Is political orientation associated with differences in certain brain regions?

- Are there reliable neural biomarkers of political orientation?

- Is political orientation modifiable, and if so, why are some individuals ferociously entrenched to one political dogma while others are able to untether themselves and adopt another political doctrine?

- What are the brain characteristics of “swing voters” who may align themselves with different parties in different election cycles?

- Is there a “religification” of politics among the ardent fanatics who regard the tenets of their political beliefs as “articles of faith?”

- Is the brain modified by certain attributes (such as educational level, age, sex, marital status, race, ethnicity, and religious affiliation) that translate to political decision-making?

- Can neuro-politics explain the sprouting of psychiatric symptoms such as obsessions, anxiety, irritability, anger, hatred, and conspiracy theories?

- Is political extremism driven by cortical structures, limbic structures, or both?

Politics and the brain

Here is a brief review of some studies that examined the relationship of political orientation or voting behavior with brain structure and function:

1. Roger Sperry, the 1981 Nobel Laureate (for his studies on split-brain patients) reported that in patients who underwent callosotomy, both cerebral hemispheres gave the same ratings of politicians when their photos were shown to each hemisphere separately.2

2. A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study found that the faces of candidates activated participants’ ventromedial and anterior prefrontal cortices. Amygdala activation was associated with the intensity of the emotion.3

Continue to: A skin conductance...

3. A skin conductance study reported that politically liberal individuals had low reactivity to sudden noises and threatening stimuli, while conservative counterparts demonstrated high physiological reactions to noises and stimuli.4

4. Images of a losing candidate elicited greater activation on fMRI in the insula and ventral anterior cingulate compared to no activation by exposure to an image of the winning candidate.5

5. Another fMRI study found that “individualism” was associated with activation of the medial prefrontal cortex and temporo-parietal junction when participants listened to a set of political statements. On the other hand, “conservatism” activated the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, while “radicalism” activated the ventral striatum and posterior cingulate.6

6. An EEG activity study of healthy individuals revealed desynchronization in the alpha band related to the politicians who lost simulated elections and were judged as “less trustworthy” when the participant watched their faces.7

7. A structural MRI study of young adults reported that liberalism was associated with increased gray matter volume in the anterior cingulate, while conservatism was associated with increased volume of the right amygdala. The authors replicated their findings and concluded there is a possible link between brain structure and psychological mechanisms that mediate political attitudes.8

Continue to: To examine the effect of...

8. To examine the effect of a “first impression” based on the physical appearance of candidates, researchers compared individuals with damage to the lateral orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) with a group that had frontal damage that spared the lateral OFC and another group of matched healthy volunteers. They used a simulated elections paradigm in which participants voted based solely on photographs of the candidates’ faces. Only the group with OFC damage was influenced by attractiveness, while those with an intact frontal lobe or non-OFC frontal damage relied on other data, such as competence.9 These researchers concluded that an intact OFC is necessary for political decision-making.

9. A study using cognitive tasks reported that liberals are more adept at dealing with novel information than conservatives.10

What part of your brain will you use?

Regardless of the data generated by the neuro-politics studies, the bottom line is: What part of your brain do you use when you cast your vote for an issue, a representative, a senator, or a president? Is it a purely intellectual decision (ie, cortical), or is it driven by visceral emotions (ie, limbic)? Do you believe that every single item in your party’s platform is right and virtuous, while every item in the other party’s platform is wrong and evil? Can you think of any redeeming feature of the candidate you hate or the party you despise?

One attribute that we psychiatrists possess by virtue of our training and clinical work is that we are able to transcend dichotomies and to perceive nuances and shades of gray about controversial issues. So I hope we employ the circuits of our brain where wisdom putatively resides11 and which may develop further (via neuroplasticity) with the conduct of psychotherapy.12 Those brain circuits include:

- prefrontal cortex (for emotional regulation, decision-making, and value relativism)

- lateral prefrontal cortex (to facilitate calculated, reason-based decision-making)

- medial prefrontal cortex (for emotional valence and pro-social attitudes and behaviors).

However, being human, it is quite likely that our amygdala may “seep through” and color our judgment and decisions. But let us try to cast a vote that is not only good for the country but also good for our patients, many of whom may not even be able to vote. Election season is a time to make a positive difference in our patients’ lives, not just ours. Let’s hope our brains exploit this unique opportunity.

1. Schreiber D. Neuropolitics: twenty years later. Politics Life Sci. 2017;36(2):114-131.

2. Sperry RW, Zaidel E, Zaidel D. Self recognition and social awareness in the deconnected minor hemisphere. Neuropsychologia. 1979;17(2):153-166.

3. Knutson KM, Wood JN, Spampinato MV, et al. Politics on the brain: an FMRI investigation. Soc Neurosci. 2006;1(1):25-40.

4. Oxley DR, Smith KB, Alford JR, et al. Political attitudes vary with physiological traits. Science. 2008;321(5896):1667-1670.

5. Spezio ML, Rangel A, Alvarez RM, et al. A neural basis for the effect of candidate appearance on election outcomes. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2008;3(4):344-352.

6. Zamboni G, Gozzi M, Krueger F, et al. Individualism, conservatism, and radicalism as criteria for processing political beliefs: a parametric fMRI study. Soc Neurosci. 2009;4(5):367-383.

7. Vecchiato G, Toppi J, Cincotti F, et al. Neuropolitics: EEG spectral maps related to a political vote based on the first impression of the candidate’s face. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2010;2010:2902-2905.

8. Kanai R, Feilden T, Firth C, et al. Political orientations are correlated with brain structure in young adults. Curr Biol. 2011;21(8):677-680.

9. Xia C, Stolle D, Gidengil E, et al. Lateral orbitofrontal cortex links social impressions to political choices. J Neurosci. 2015;35(22):8507-8514.

10. Bernabel RT, Oliveira A. Conservatism and liberalism predict performance in two nonideological cognitive tasks. Politics Life Sci. 2017;36(2):49-59.

11. Meeks TW, Jeste DV. Neurobiology of wisdom: a literature overview. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(4):355-365.

12. Nasrallah HA. Does psychiatric practice make us wiser? Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(10):12,14.

1. Schreiber D. Neuropolitics: twenty years later. Politics Life Sci. 2017;36(2):114-131.

2. Sperry RW, Zaidel E, Zaidel D. Self recognition and social awareness in the deconnected minor hemisphere. Neuropsychologia. 1979;17(2):153-166.

3. Knutson KM, Wood JN, Spampinato MV, et al. Politics on the brain: an FMRI investigation. Soc Neurosci. 2006;1(1):25-40.

4. Oxley DR, Smith KB, Alford JR, et al. Political attitudes vary with physiological traits. Science. 2008;321(5896):1667-1670.

5. Spezio ML, Rangel A, Alvarez RM, et al. A neural basis for the effect of candidate appearance on election outcomes. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2008;3(4):344-352.

6. Zamboni G, Gozzi M, Krueger F, et al. Individualism, conservatism, and radicalism as criteria for processing political beliefs: a parametric fMRI study. Soc Neurosci. 2009;4(5):367-383.

7. Vecchiato G, Toppi J, Cincotti F, et al. Neuropolitics: EEG spectral maps related to a political vote based on the first impression of the candidate’s face. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2010;2010:2902-2905.

8. Kanai R, Feilden T, Firth C, et al. Political orientations are correlated with brain structure in young adults. Curr Biol. 2011;21(8):677-680.

9. Xia C, Stolle D, Gidengil E, et al. Lateral orbitofrontal cortex links social impressions to political choices. J Neurosci. 2015;35(22):8507-8514.

10. Bernabel RT, Oliveira A. Conservatism and liberalism predict performance in two nonideological cognitive tasks. Politics Life Sci. 2017;36(2):49-59.

11. Meeks TW, Jeste DV. Neurobiology of wisdom: a literature overview. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(4):355-365.

12. Nasrallah HA. Does psychiatric practice make us wiser? Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(10):12,14.

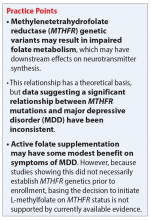

Impact of the MTHFR C677T genetic variant on depression

Ms. T, age 55, presents to her psychiatrist’s clinic with a chief complaint of ongoing symptoms of anhedonia and lethargy related to her diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD). She also has a history of peripheral arterial disease, hypothyroidism, and generalized anxiety disorder. Her current antidepressant regimen is duloxetine, 60 mg/d, and mirtazapine, 15 mg at night. She recently elected to undergo pharmacogenetic testing, which showed that she is heterozygous for the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T mutation (MTHFR C677T CT carrier). Her test report states that she may have impaired folate metabolism. Her psychiatrist adds L-methylfolate, 15 mg/d, to her current antidepressant regimen.

What is the relationship between folic acid and MTHFR?

Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase is an intracellular enzyme responsible for one of several steps involved in converting dietary folic acid to its physiologically active form, L-methylfolate.1 Once active, L-methylfolate can be transported into the CNS, where it participates in one-carbon transfer reactions.2,3 Mutations in the MTHFR gene have been associated with decreased activity of the enzyme, which has been shown to result in accumulation of homocysteine and may lead to decreased synthesis of neurotransmitters.2,4Commercial pharmacogenetic testing panels may offer MTHFR genetic testing to assist with prescribing decisions for patients with mental illness. The most well-characterized mutation currently is C677T (rsID1801133), which is a single amino acid base pair change (cytosine [C] to thymine [T]) that leads to increased thermolability and instability of the enzyme.5 Carrying 1 or 2 T alleles can lead to a 35% or 70% reduction in enzyme activity, respectively. The T variant allele is most frequent in Hispanics (20% to 25%), Asians (up to 63%), and Caucasians (8% to 20%); however, it is relatively uncommon in African Americans (<2%).5,6 Another variant, A1289C (rs1801131), has also been associated with decreased enzyme function, particularly when analyzed in combination with C677T. However, carrying the 1289C variant allele does not appear to result in as large of a reduction of enzyme function as the 677T variant.7

What is the relationship between MTHFR C677T and depression?

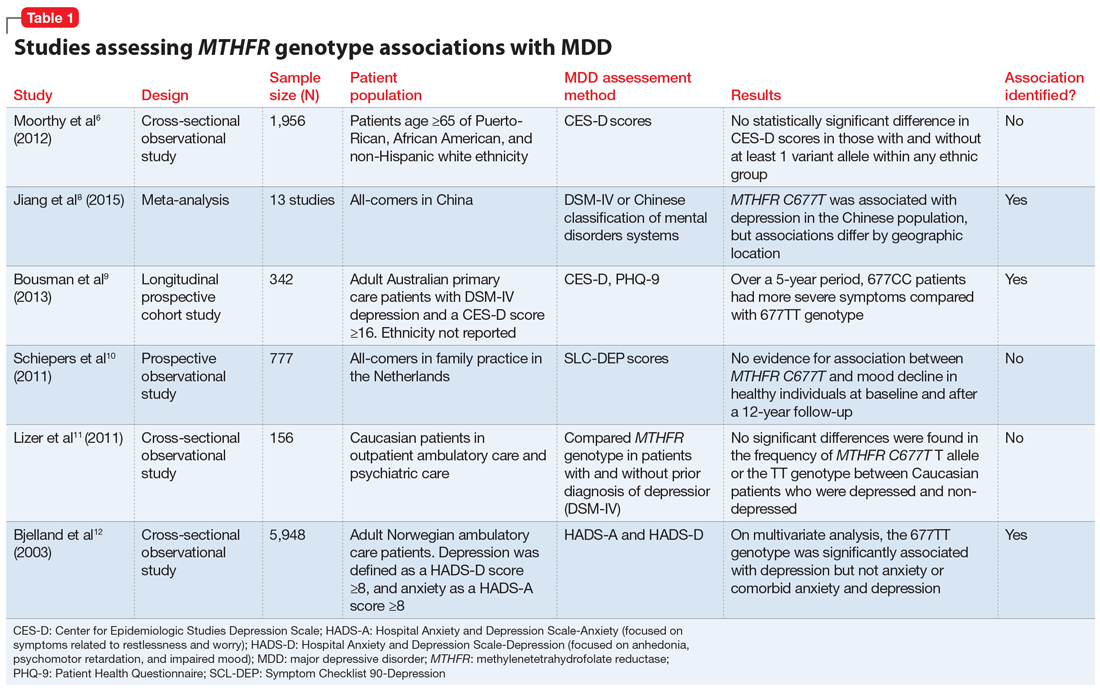

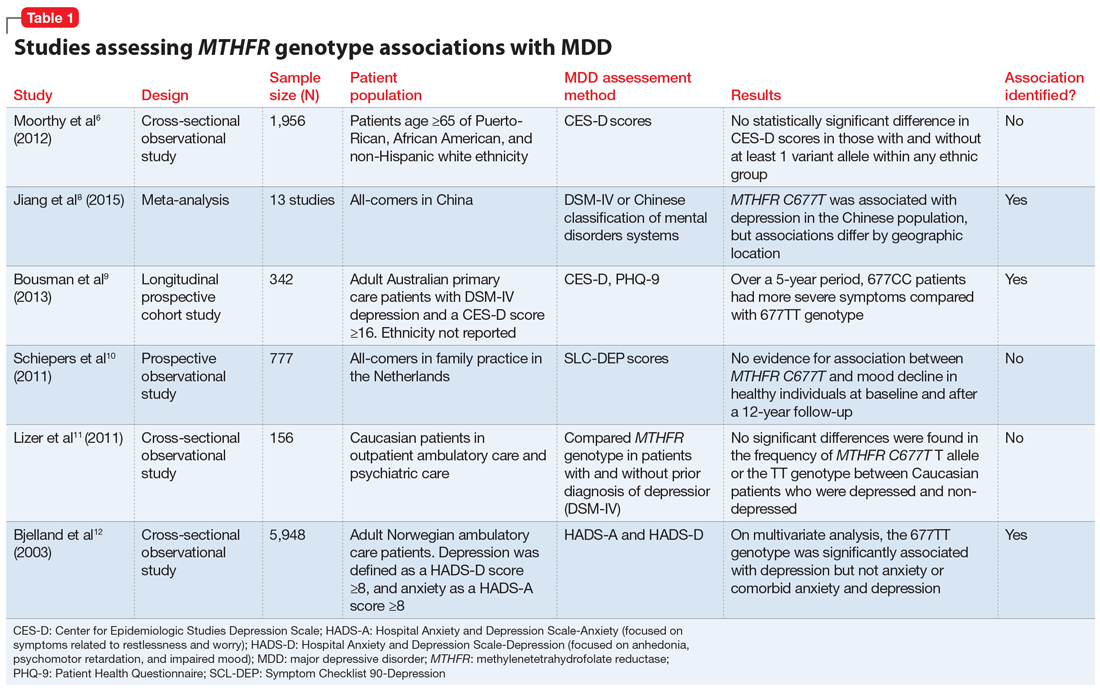

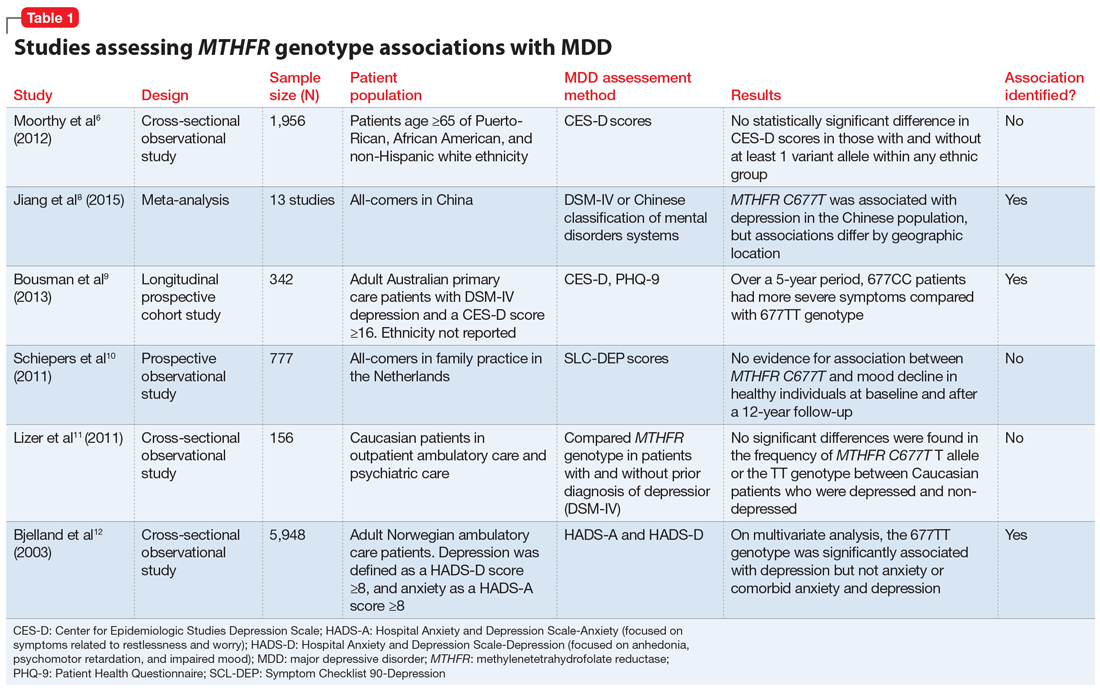

Some researchers have proposed that the C677T mutation in MTHFR may be associated with depression as a result of decreased neurotransmitter synthesis, but studies have not consistently supported this hypothesis. Several studies suggest an association between MTHFR mutations and MDD8-10:

Jiang et al8 performed a meta-analysis of 13 studies including 1,295 Chinese patients and found that having at least 1 C677T variant allele was significantly associated with an increased risk of depression (for T vs C odds ratio 1.52, 95% confidence interval 1.24 to 1.85). The authors noted a stronger association identified in the Northern Chinese population compared with the Southern Chinese population.8

Bousman et al9 found that American patients with MDD and the 677CC genotype had greater Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores at assessments at 24, 36, and 48 months post-baseline compared with those with the 677TT genotype (P = .024), which was unexpected based on previously reported associations.9

Schiepers et al10 also assessed the association between the MTHFR genotype in a Dutch ambulatory care population over 12 years. There was no association identified between scores on the depression subscale of the Symptom Checklist 90 and C677T diplotype.10

Table 16,8-12 provides summaries of these and other selected studies on MTHFR and MDD. Overall, although a pathophysiological basis for depression and decreased MTHFR function has been proposed, the current body of literature does not indicate a consistent link between MTHFR C677T genetic variants alone and depression.

Continue to: Medication changes based on MTHFR: What is the evidence?

Medication changes based on MTHFR: What is the evidence?

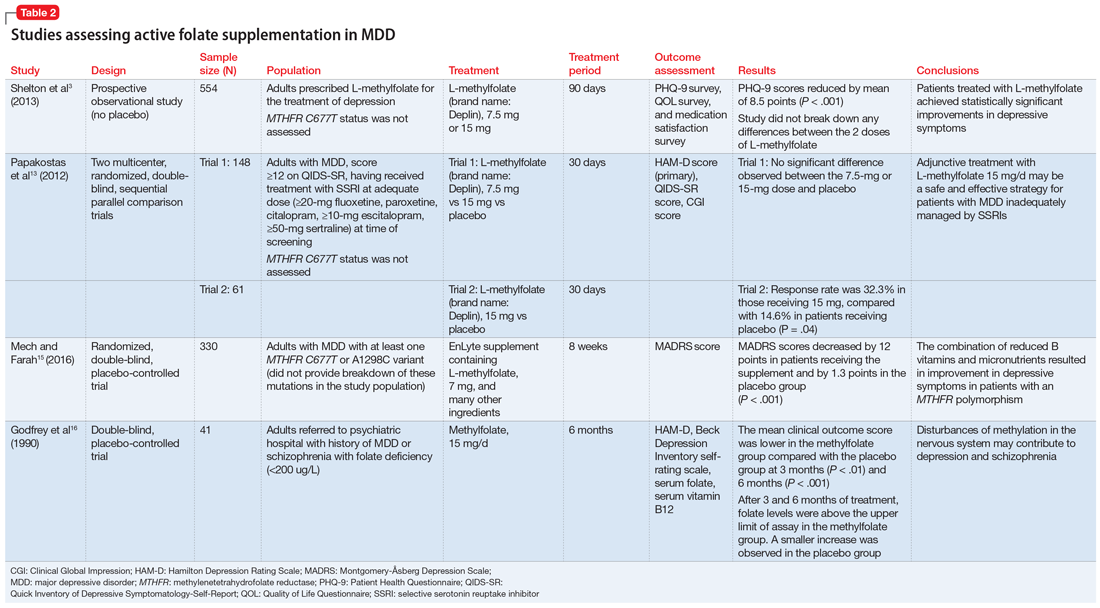

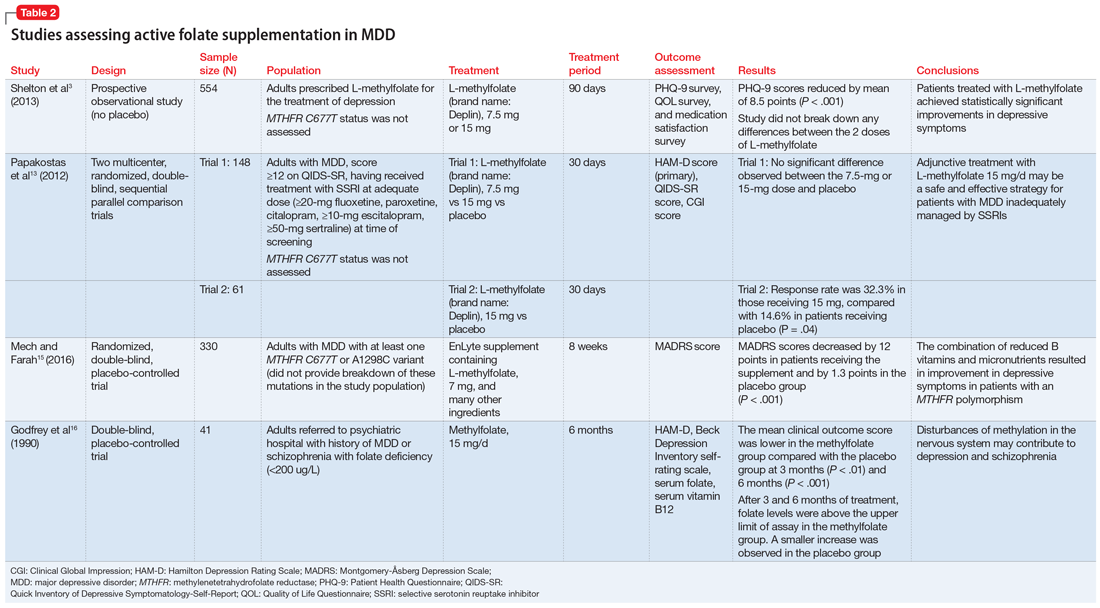

Some evidence supports the use of active folate supplementation to improve symptoms of MDD.

Shelton et al3 conducted an observational study that assessed the effects of adding L-methylfolate (brand name: Deplin), 7.5 or 15 mg, to existing antidepressant therapy in 502 patients with MDD who had baseline PHQ-9 scores of at least 5. After an average 95 days of therapy, PHQ-9 scores were reduced by a mean of 8.5 points, with 67.9% of patients achieving at least a 50% reduction in PHQ-9 scores. The study did not take into account patients’ MTHFR genotype or differentiate results between the 2 doses of L-methylfolate.3

Papakostas et al13 performed 2 randomized, double-blind, parallel-sequential, placebo-controlled trials of L-methylfolate for patients with MDD. The first compared L-methylfolate, 7.5 and 15 mg, to placebo, without regard to MTHFR genotype.13 There was no significant difference between the 7.5-mg dose and placebo, or the 15-mg dose and placebo. However, among the group receiving the 15-mg dose, the response rate was 24%, vs 9% in the placebo group, which approached significance (P = .1). Papakostas et al13 followed up with a smaller trial comparing the 15-mg dose alone to placebo, and found the response rate was 32.3% in patients treated with L-methylfolate compared with 14.6% in the placebo group (P = .04).13

Although the Shelton et al3 and Papakostas et al13 studies showed some improvement in depressive symptom scores among patients who received L-methylfolate supplementation, an important consideration is if MTHFR genotype may predict patient response to this therapy.

Papakostas et al14 performed a post hoc analysis of their earlier study to assess potential associations amongst multiple other biomarkers of inflammation and metabolic disturbances hypothesized by the authors to be associated with MDD, as well as body mass index (BMI), with treatment outcome.14 When change in the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-28 (HDRS-28) was analyzed by C677T and A1298C variant groups (677 CT vs TT and 1298 AC vs CC), no statistically significant improvements were identified (C677T mean change from baseline −3.8 points, P = .087; A1298C mean change from baseline −0.5 points, P = .807).14 However, statistically significant improvements in HDRS-28 scores were observed compared with baseline when the C677T genotype was pooled with other biomarkers, including methionine synthase (MTR 2756 AG/GG, −23.3 points vs baseline, P < .001) and a voltage-dependent calcium channel (CACNAIC AG/AA, −9 points vs baseline, P < .001), as well as with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (−9.9 points vs baseline, P = .001).14

Continue to: Mech and Farah...

Mech and Farah15 performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the use of EnLyte, a supplement containing 7-mg L-methylfolate, in patients with at least 1 variant of MTHFR (either C677T or A1298C) over an 8-week period. In addition to L-methylfolate, this supplement contains other active ingredients, including leucovorin (or folinic acid), magnesium ascorbate, and ferrous glycine cysteinate. Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Scale (MADRS) scores improved by 12 points in patients who received the supplement and by 1.3 points in patients who received placebo. However, because the supplement contained many ingredients, the response observed in this study cannot be attributed to L-methylfolate alone.15

Table 23,13,15,16 contains summaries of these and other selected studies assessing active folate supplementation in MDD.

CASE CONTINUED

Over the next several weeks, Ms. T experiences some modest improvement in mood while taking L-methylfolate and her antidepressant regimen, and she experiences no notable adverse effects. Unfortunately, after 3 months, Ms. T discontinues the supplement due to the cost.

The value of MTHFR testing

Ms. T’s case is an example of how clinicians may respond to MTHFR pharmacogenetic testing. Although L-methylfolate has shown some benefit in several randomized clinical trials, available data do not confirm the relevance of MTHFR functional status to symptom response. Additionally, there is likely interplay among multiple factors affecting patients’ response to L-methylfolate. Larger randomized trials prospectively assessing other pharmacogenetic and lifestyle factors may shed more light on which patients would benefit.

Based on available data, the decision to prescribe L-methylfolate should not necessarily hinge on MTHFR genetics alone. Both patients and clinicians must be aware of the potentially prohibitive cost if L-methylfolate is recommended, as prescription insurance may not provide coverage (eg, a recent search on GoodRx.com showed that generic L-methylfolate was approximately $40 for 30 tablets; prices may vary). Additionally, clinicians should be aware that L-methylfolate is regulated as a medical food product and is not subject to strict quality standards required for prescription medications. Future prospective studies assessing the use of L-methylfolate specifically in patients with a MTHFR variants while investigating other relevant covariates may help identify which specific patient populations would benefit from supplementation.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Gilbody S, Lewis S, Lightfoot T. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) genetic polymorphisms and psychiatric disorders: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(1):1-13.

- Trimmer E. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase: biochemical characterization and medical significance. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2013;19(4):2574-3595.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

L-methylfolate • Deplin

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Scaglione F, Panzavolta G. Folate, folic acid and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate are not the same thing. Xenobiotica. 2014;44(5):480-488.

2. Jadavji N, Wieske F, Dirnagl U, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency alters levels of glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid in brain tissue. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports. 2015;3(Issue C):1-4.

3. Shelton R, Manning J, Barrentine L, et al. Assessing effects of L-methylfolate in depression management: results of a real-world patient experience trial. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(4):pii:PCC.13m01520. doi: 10.4088/PCC.13m01520.

4. Brustolin S, Giugliani R, Felix T. Genetics of homocysteine metabolism and associated disorders. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2010;43(1):1-7.

5. Blom H, Smulders Y. Overview of homocysteine and folate metabolism. With special references to cardiovascular disease and neural tube defects. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34:75-81.

6. Moorthy D, Peter I, Scott T, et al. Status of vitamins B-12 and B-6 but not of folate, homocysteine, and the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism are associated with impaired cognition and depression in adults. J Nutr. 2012;142:1554-1560.

7. Lievers K, Boers G, Verhoef P, et al. A second common variant in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene and its relationship to MTHFR enzyme activity, homocysteine, and cardiovascular disease risk. J Mol Med (Berl). 2001;79(9):522-528.

8. Jiang W, Xu J, Lu X, et al. Association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and depression: a meta-analysis in the Chinese population. Psychol Health Med. 2015;21(6):675-685.

9. Bousman C, Potiriadis M, Everall I, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) genetic variation and major depressive disorder prognosis: a five-year prospective cohort study of primary care attendees. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2014;165B(1):68-76.

10. Schiepers O, Van Boxtel M, de Groot R, et al. Genetic variation in folate metabolism is not associated with cognitive functioning or mood in healthy adults. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(7):1682-1688.

11. Lizer M, Bogdan R, Kidd R. Comparison of the frequency of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T polymorphism in depressed versus nondepressed patients. J Psychiatr Pract. 2011;17(6):404-409.

12. Bjelland I, Tell G, Vollset S, et al. Folate, vitamin B12, homocysteine, and the MTHFR 677C->T polymorphism in anxiety and depression: the Hordaland Homocysteine Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(6):618-626.

13. Papakostas G, Shelton R, Zajecka J, et al. L-methylfolate as adjunctive therapy for SSRI-resistant major depression: results of two randomized, double-blind, parallel sequential trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(12):1267-1274.

14. Papakostas G, Shelton R, Zajecka J, et al. Effect of adjunctive L-methylfolate 15 mg among inadequate responders to SSRIs in depressed patients who were stratified by biomarker levels and genotype: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):855-863.

15. Mech A, Farah A. Correlation of clinical response with homocysteine reduction during therapy with reduced B vitamins in patients with MDD who are positive for MTHFR C677T or A1298C polymorphism: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):668-671.

16. Godfrey P, Toone B, Carney M, et al. Enhancement of recovery from psychiatric illness by methylfolate. Lancet. 1990;336(8712):392-395.

Ms. T, age 55, presents to her psychiatrist’s clinic with a chief complaint of ongoing symptoms of anhedonia and lethargy related to her diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD). She also has a history of peripheral arterial disease, hypothyroidism, and generalized anxiety disorder. Her current antidepressant regimen is duloxetine, 60 mg/d, and mirtazapine, 15 mg at night. She recently elected to undergo pharmacogenetic testing, which showed that she is heterozygous for the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T mutation (MTHFR C677T CT carrier). Her test report states that she may have impaired folate metabolism. Her psychiatrist adds L-methylfolate, 15 mg/d, to her current antidepressant regimen.

What is the relationship between folic acid and MTHFR?

Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase is an intracellular enzyme responsible for one of several steps involved in converting dietary folic acid to its physiologically active form, L-methylfolate.1 Once active, L-methylfolate can be transported into the CNS, where it participates in one-carbon transfer reactions.2,3 Mutations in the MTHFR gene have been associated with decreased activity of the enzyme, which has been shown to result in accumulation of homocysteine and may lead to decreased synthesis of neurotransmitters.2,4Commercial pharmacogenetic testing panels may offer MTHFR genetic testing to assist with prescribing decisions for patients with mental illness. The most well-characterized mutation currently is C677T (rsID1801133), which is a single amino acid base pair change (cytosine [C] to thymine [T]) that leads to increased thermolability and instability of the enzyme.5 Carrying 1 or 2 T alleles can lead to a 35% or 70% reduction in enzyme activity, respectively. The T variant allele is most frequent in Hispanics (20% to 25%), Asians (up to 63%), and Caucasians (8% to 20%); however, it is relatively uncommon in African Americans (<2%).5,6 Another variant, A1289C (rs1801131), has also been associated with decreased enzyme function, particularly when analyzed in combination with C677T. However, carrying the 1289C variant allele does not appear to result in as large of a reduction of enzyme function as the 677T variant.7

What is the relationship between MTHFR C677T and depression?

Some researchers have proposed that the C677T mutation in MTHFR may be associated with depression as a result of decreased neurotransmitter synthesis, but studies have not consistently supported this hypothesis. Several studies suggest an association between MTHFR mutations and MDD8-10:

Jiang et al8 performed a meta-analysis of 13 studies including 1,295 Chinese patients and found that having at least 1 C677T variant allele was significantly associated with an increased risk of depression (for T vs C odds ratio 1.52, 95% confidence interval 1.24 to 1.85). The authors noted a stronger association identified in the Northern Chinese population compared with the Southern Chinese population.8

Bousman et al9 found that American patients with MDD and the 677CC genotype had greater Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores at assessments at 24, 36, and 48 months post-baseline compared with those with the 677TT genotype (P = .024), which was unexpected based on previously reported associations.9

Schiepers et al10 also assessed the association between the MTHFR genotype in a Dutch ambulatory care population over 12 years. There was no association identified between scores on the depression subscale of the Symptom Checklist 90 and C677T diplotype.10

Table 16,8-12 provides summaries of these and other selected studies on MTHFR and MDD. Overall, although a pathophysiological basis for depression and decreased MTHFR function has been proposed, the current body of literature does not indicate a consistent link between MTHFR C677T genetic variants alone and depression.

Continue to: Medication changes based on MTHFR: What is the evidence?

Medication changes based on MTHFR: What is the evidence?

Some evidence supports the use of active folate supplementation to improve symptoms of MDD.

Shelton et al3 conducted an observational study that assessed the effects of adding L-methylfolate (brand name: Deplin), 7.5 or 15 mg, to existing antidepressant therapy in 502 patients with MDD who had baseline PHQ-9 scores of at least 5. After an average 95 days of therapy, PHQ-9 scores were reduced by a mean of 8.5 points, with 67.9% of patients achieving at least a 50% reduction in PHQ-9 scores. The study did not take into account patients’ MTHFR genotype or differentiate results between the 2 doses of L-methylfolate.3

Papakostas et al13 performed 2 randomized, double-blind, parallel-sequential, placebo-controlled trials of L-methylfolate for patients with MDD. The first compared L-methylfolate, 7.5 and 15 mg, to placebo, without regard to MTHFR genotype.13 There was no significant difference between the 7.5-mg dose and placebo, or the 15-mg dose and placebo. However, among the group receiving the 15-mg dose, the response rate was 24%, vs 9% in the placebo group, which approached significance (P = .1). Papakostas et al13 followed up with a smaller trial comparing the 15-mg dose alone to placebo, and found the response rate was 32.3% in patients treated with L-methylfolate compared with 14.6% in the placebo group (P = .04).13

Although the Shelton et al3 and Papakostas et al13 studies showed some improvement in depressive symptom scores among patients who received L-methylfolate supplementation, an important consideration is if MTHFR genotype may predict patient response to this therapy.

Papakostas et al14 performed a post hoc analysis of their earlier study to assess potential associations amongst multiple other biomarkers of inflammation and metabolic disturbances hypothesized by the authors to be associated with MDD, as well as body mass index (BMI), with treatment outcome.14 When change in the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-28 (HDRS-28) was analyzed by C677T and A1298C variant groups (677 CT vs TT and 1298 AC vs CC), no statistically significant improvements were identified (C677T mean change from baseline −3.8 points, P = .087; A1298C mean change from baseline −0.5 points, P = .807).14 However, statistically significant improvements in HDRS-28 scores were observed compared with baseline when the C677T genotype was pooled with other biomarkers, including methionine synthase (MTR 2756 AG/GG, −23.3 points vs baseline, P < .001) and a voltage-dependent calcium channel (CACNAIC AG/AA, −9 points vs baseline, P < .001), as well as with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (−9.9 points vs baseline, P = .001).14

Continue to: Mech and Farah...

Mech and Farah15 performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the use of EnLyte, a supplement containing 7-mg L-methylfolate, in patients with at least 1 variant of MTHFR (either C677T or A1298C) over an 8-week period. In addition to L-methylfolate, this supplement contains other active ingredients, including leucovorin (or folinic acid), magnesium ascorbate, and ferrous glycine cysteinate. Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Scale (MADRS) scores improved by 12 points in patients who received the supplement and by 1.3 points in patients who received placebo. However, because the supplement contained many ingredients, the response observed in this study cannot be attributed to L-methylfolate alone.15

Table 23,13,15,16 contains summaries of these and other selected studies assessing active folate supplementation in MDD.

CASE CONTINUED

Over the next several weeks, Ms. T experiences some modest improvement in mood while taking L-methylfolate and her antidepressant regimen, and she experiences no notable adverse effects. Unfortunately, after 3 months, Ms. T discontinues the supplement due to the cost.

The value of MTHFR testing

Ms. T’s case is an example of how clinicians may respond to MTHFR pharmacogenetic testing. Although L-methylfolate has shown some benefit in several randomized clinical trials, available data do not confirm the relevance of MTHFR functional status to symptom response. Additionally, there is likely interplay among multiple factors affecting patients’ response to L-methylfolate. Larger randomized trials prospectively assessing other pharmacogenetic and lifestyle factors may shed more light on which patients would benefit.

Based on available data, the decision to prescribe L-methylfolate should not necessarily hinge on MTHFR genetics alone. Both patients and clinicians must be aware of the potentially prohibitive cost if L-methylfolate is recommended, as prescription insurance may not provide coverage (eg, a recent search on GoodRx.com showed that generic L-methylfolate was approximately $40 for 30 tablets; prices may vary). Additionally, clinicians should be aware that L-methylfolate is regulated as a medical food product and is not subject to strict quality standards required for prescription medications. Future prospective studies assessing the use of L-methylfolate specifically in patients with a MTHFR variants while investigating other relevant covariates may help identify which specific patient populations would benefit from supplementation.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Gilbody S, Lewis S, Lightfoot T. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) genetic polymorphisms and psychiatric disorders: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(1):1-13.

- Trimmer E. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase: biochemical characterization and medical significance. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2013;19(4):2574-3595.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

L-methylfolate • Deplin

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Ms. T, age 55, presents to her psychiatrist’s clinic with a chief complaint of ongoing symptoms of anhedonia and lethargy related to her diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD). She also has a history of peripheral arterial disease, hypothyroidism, and generalized anxiety disorder. Her current antidepressant regimen is duloxetine, 60 mg/d, and mirtazapine, 15 mg at night. She recently elected to undergo pharmacogenetic testing, which showed that she is heterozygous for the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T mutation (MTHFR C677T CT carrier). Her test report states that she may have impaired folate metabolism. Her psychiatrist adds L-methylfolate, 15 mg/d, to her current antidepressant regimen.

What is the relationship between folic acid and MTHFR?

Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase is an intracellular enzyme responsible for one of several steps involved in converting dietary folic acid to its physiologically active form, L-methylfolate.1 Once active, L-methylfolate can be transported into the CNS, where it participates in one-carbon transfer reactions.2,3 Mutations in the MTHFR gene have been associated with decreased activity of the enzyme, which has been shown to result in accumulation of homocysteine and may lead to decreased synthesis of neurotransmitters.2,4Commercial pharmacogenetic testing panels may offer MTHFR genetic testing to assist with prescribing decisions for patients with mental illness. The most well-characterized mutation currently is C677T (rsID1801133), which is a single amino acid base pair change (cytosine [C] to thymine [T]) that leads to increased thermolability and instability of the enzyme.5 Carrying 1 or 2 T alleles can lead to a 35% or 70% reduction in enzyme activity, respectively. The T variant allele is most frequent in Hispanics (20% to 25%), Asians (up to 63%), and Caucasians (8% to 20%); however, it is relatively uncommon in African Americans (<2%).5,6 Another variant, A1289C (rs1801131), has also been associated with decreased enzyme function, particularly when analyzed in combination with C677T. However, carrying the 1289C variant allele does not appear to result in as large of a reduction of enzyme function as the 677T variant.7

What is the relationship between MTHFR C677T and depression?

Some researchers have proposed that the C677T mutation in MTHFR may be associated with depression as a result of decreased neurotransmitter synthesis, but studies have not consistently supported this hypothesis. Several studies suggest an association between MTHFR mutations and MDD8-10:

Jiang et al8 performed a meta-analysis of 13 studies including 1,295 Chinese patients and found that having at least 1 C677T variant allele was significantly associated with an increased risk of depression (for T vs C odds ratio 1.52, 95% confidence interval 1.24 to 1.85). The authors noted a stronger association identified in the Northern Chinese population compared with the Southern Chinese population.8

Bousman et al9 found that American patients with MDD and the 677CC genotype had greater Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores at assessments at 24, 36, and 48 months post-baseline compared with those with the 677TT genotype (P = .024), which was unexpected based on previously reported associations.9

Schiepers et al10 also assessed the association between the MTHFR genotype in a Dutch ambulatory care population over 12 years. There was no association identified between scores on the depression subscale of the Symptom Checklist 90 and C677T diplotype.10

Table 16,8-12 provides summaries of these and other selected studies on MTHFR and MDD. Overall, although a pathophysiological basis for depression and decreased MTHFR function has been proposed, the current body of literature does not indicate a consistent link between MTHFR C677T genetic variants alone and depression.

Continue to: Medication changes based on MTHFR: What is the evidence?

Medication changes based on MTHFR: What is the evidence?

Some evidence supports the use of active folate supplementation to improve symptoms of MDD.

Shelton et al3 conducted an observational study that assessed the effects of adding L-methylfolate (brand name: Deplin), 7.5 or 15 mg, to existing antidepressant therapy in 502 patients with MDD who had baseline PHQ-9 scores of at least 5. After an average 95 days of therapy, PHQ-9 scores were reduced by a mean of 8.5 points, with 67.9% of patients achieving at least a 50% reduction in PHQ-9 scores. The study did not take into account patients’ MTHFR genotype or differentiate results between the 2 doses of L-methylfolate.3

Papakostas et al13 performed 2 randomized, double-blind, parallel-sequential, placebo-controlled trials of L-methylfolate for patients with MDD. The first compared L-methylfolate, 7.5 and 15 mg, to placebo, without regard to MTHFR genotype.13 There was no significant difference between the 7.5-mg dose and placebo, or the 15-mg dose and placebo. However, among the group receiving the 15-mg dose, the response rate was 24%, vs 9% in the placebo group, which approached significance (P = .1). Papakostas et al13 followed up with a smaller trial comparing the 15-mg dose alone to placebo, and found the response rate was 32.3% in patients treated with L-methylfolate compared with 14.6% in the placebo group (P = .04).13

Although the Shelton et al3 and Papakostas et al13 studies showed some improvement in depressive symptom scores among patients who received L-methylfolate supplementation, an important consideration is if MTHFR genotype may predict patient response to this therapy.

Papakostas et al14 performed a post hoc analysis of their earlier study to assess potential associations amongst multiple other biomarkers of inflammation and metabolic disturbances hypothesized by the authors to be associated with MDD, as well as body mass index (BMI), with treatment outcome.14 When change in the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-28 (HDRS-28) was analyzed by C677T and A1298C variant groups (677 CT vs TT and 1298 AC vs CC), no statistically significant improvements were identified (C677T mean change from baseline −3.8 points, P = .087; A1298C mean change from baseline −0.5 points, P = .807).14 However, statistically significant improvements in HDRS-28 scores were observed compared with baseline when the C677T genotype was pooled with other biomarkers, including methionine synthase (MTR 2756 AG/GG, −23.3 points vs baseline, P < .001) and a voltage-dependent calcium channel (CACNAIC AG/AA, −9 points vs baseline, P < .001), as well as with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (−9.9 points vs baseline, P = .001).14

Continue to: Mech and Farah...

Mech and Farah15 performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the use of EnLyte, a supplement containing 7-mg L-methylfolate, in patients with at least 1 variant of MTHFR (either C677T or A1298C) over an 8-week period. In addition to L-methylfolate, this supplement contains other active ingredients, including leucovorin (or folinic acid), magnesium ascorbate, and ferrous glycine cysteinate. Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Scale (MADRS) scores improved by 12 points in patients who received the supplement and by 1.3 points in patients who received placebo. However, because the supplement contained many ingredients, the response observed in this study cannot be attributed to L-methylfolate alone.15

Table 23,13,15,16 contains summaries of these and other selected studies assessing active folate supplementation in MDD.

CASE CONTINUED

Over the next several weeks, Ms. T experiences some modest improvement in mood while taking L-methylfolate and her antidepressant regimen, and she experiences no notable adverse effects. Unfortunately, after 3 months, Ms. T discontinues the supplement due to the cost.

The value of MTHFR testing

Ms. T’s case is an example of how clinicians may respond to MTHFR pharmacogenetic testing. Although L-methylfolate has shown some benefit in several randomized clinical trials, available data do not confirm the relevance of MTHFR functional status to symptom response. Additionally, there is likely interplay among multiple factors affecting patients’ response to L-methylfolate. Larger randomized trials prospectively assessing other pharmacogenetic and lifestyle factors may shed more light on which patients would benefit.

Based on available data, the decision to prescribe L-methylfolate should not necessarily hinge on MTHFR genetics alone. Both patients and clinicians must be aware of the potentially prohibitive cost if L-methylfolate is recommended, as prescription insurance may not provide coverage (eg, a recent search on GoodRx.com showed that generic L-methylfolate was approximately $40 for 30 tablets; prices may vary). Additionally, clinicians should be aware that L-methylfolate is regulated as a medical food product and is not subject to strict quality standards required for prescription medications. Future prospective studies assessing the use of L-methylfolate specifically in patients with a MTHFR variants while investigating other relevant covariates may help identify which specific patient populations would benefit from supplementation.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Gilbody S, Lewis S, Lightfoot T. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) genetic polymorphisms and psychiatric disorders: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(1):1-13.

- Trimmer E. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase: biochemical characterization and medical significance. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2013;19(4):2574-3595.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

L-methylfolate • Deplin

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Scaglione F, Panzavolta G. Folate, folic acid and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate are not the same thing. Xenobiotica. 2014;44(5):480-488.

2. Jadavji N, Wieske F, Dirnagl U, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency alters levels of glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid in brain tissue. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports. 2015;3(Issue C):1-4.

3. Shelton R, Manning J, Barrentine L, et al. Assessing effects of L-methylfolate in depression management: results of a real-world patient experience trial. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(4):pii:PCC.13m01520. doi: 10.4088/PCC.13m01520.

4. Brustolin S, Giugliani R, Felix T. Genetics of homocysteine metabolism and associated disorders. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2010;43(1):1-7.

5. Blom H, Smulders Y. Overview of homocysteine and folate metabolism. With special references to cardiovascular disease and neural tube defects. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34:75-81.

6. Moorthy D, Peter I, Scott T, et al. Status of vitamins B-12 and B-6 but not of folate, homocysteine, and the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism are associated with impaired cognition and depression in adults. J Nutr. 2012;142:1554-1560.

7. Lievers K, Boers G, Verhoef P, et al. A second common variant in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene and its relationship to MTHFR enzyme activity, homocysteine, and cardiovascular disease risk. J Mol Med (Berl). 2001;79(9):522-528.

8. Jiang W, Xu J, Lu X, et al. Association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and depression: a meta-analysis in the Chinese population. Psychol Health Med. 2015;21(6):675-685.

9. Bousman C, Potiriadis M, Everall I, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) genetic variation and major depressive disorder prognosis: a five-year prospective cohort study of primary care attendees. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2014;165B(1):68-76.

10. Schiepers O, Van Boxtel M, de Groot R, et al. Genetic variation in folate metabolism is not associated with cognitive functioning or mood in healthy adults. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(7):1682-1688.

11. Lizer M, Bogdan R, Kidd R. Comparison of the frequency of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T polymorphism in depressed versus nondepressed patients. J Psychiatr Pract. 2011;17(6):404-409.

12. Bjelland I, Tell G, Vollset S, et al. Folate, vitamin B12, homocysteine, and the MTHFR 677C->T polymorphism in anxiety and depression: the Hordaland Homocysteine Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(6):618-626.

13. Papakostas G, Shelton R, Zajecka J, et al. L-methylfolate as adjunctive therapy for SSRI-resistant major depression: results of two randomized, double-blind, parallel sequential trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(12):1267-1274.

14. Papakostas G, Shelton R, Zajecka J, et al. Effect of adjunctive L-methylfolate 15 mg among inadequate responders to SSRIs in depressed patients who were stratified by biomarker levels and genotype: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):855-863.

15. Mech A, Farah A. Correlation of clinical response with homocysteine reduction during therapy with reduced B vitamins in patients with MDD who are positive for MTHFR C677T or A1298C polymorphism: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):668-671.

16. Godfrey P, Toone B, Carney M, et al. Enhancement of recovery from psychiatric illness by methylfolate. Lancet. 1990;336(8712):392-395.

1. Scaglione F, Panzavolta G. Folate, folic acid and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate are not the same thing. Xenobiotica. 2014;44(5):480-488.

2. Jadavji N, Wieske F, Dirnagl U, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency alters levels of glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid in brain tissue. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports. 2015;3(Issue C):1-4.

3. Shelton R, Manning J, Barrentine L, et al. Assessing effects of L-methylfolate in depression management: results of a real-world patient experience trial. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(4):pii:PCC.13m01520. doi: 10.4088/PCC.13m01520.

4. Brustolin S, Giugliani R, Felix T. Genetics of homocysteine metabolism and associated disorders. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2010;43(1):1-7.

5. Blom H, Smulders Y. Overview of homocysteine and folate metabolism. With special references to cardiovascular disease and neural tube defects. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34:75-81.

6. Moorthy D, Peter I, Scott T, et al. Status of vitamins B-12 and B-6 but not of folate, homocysteine, and the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism are associated with impaired cognition and depression in adults. J Nutr. 2012;142:1554-1560.

7. Lievers K, Boers G, Verhoef P, et al. A second common variant in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene and its relationship to MTHFR enzyme activity, homocysteine, and cardiovascular disease risk. J Mol Med (Berl). 2001;79(9):522-528.

8. Jiang W, Xu J, Lu X, et al. Association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and depression: a meta-analysis in the Chinese population. Psychol Health Med. 2015;21(6):675-685.

9. Bousman C, Potiriadis M, Everall I, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) genetic variation and major depressive disorder prognosis: a five-year prospective cohort study of primary care attendees. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2014;165B(1):68-76.

10. Schiepers O, Van Boxtel M, de Groot R, et al. Genetic variation in folate metabolism is not associated with cognitive functioning or mood in healthy adults. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(7):1682-1688.

11. Lizer M, Bogdan R, Kidd R. Comparison of the frequency of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T polymorphism in depressed versus nondepressed patients. J Psychiatr Pract. 2011;17(6):404-409.

12. Bjelland I, Tell G, Vollset S, et al. Folate, vitamin B12, homocysteine, and the MTHFR 677C->T polymorphism in anxiety and depression: the Hordaland Homocysteine Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(6):618-626.

13. Papakostas G, Shelton R, Zajecka J, et al. L-methylfolate as adjunctive therapy for SSRI-resistant major depression: results of two randomized, double-blind, parallel sequential trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(12):1267-1274.

14. Papakostas G, Shelton R, Zajecka J, et al. Effect of adjunctive L-methylfolate 15 mg among inadequate responders to SSRIs in depressed patients who were stratified by biomarker levels and genotype: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):855-863.

15. Mech A, Farah A. Correlation of clinical response with homocysteine reduction during therapy with reduced B vitamins in patients with MDD who are positive for MTHFR C677T or A1298C polymorphism: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):668-671.

16. Godfrey P, Toone B, Carney M, et al. Enhancement of recovery from psychiatric illness by methylfolate. Lancet. 1990;336(8712):392-395.

The boy whose arm wouldn’t work

CASE Drooling, unsteady, and not himself

B, age 10, who is left handed and has autism spectrum disorder, is brought to the emergency department (ED) with a 1-day history of drooling, unsteady gait, and left wrist in sustained flexion. His parents report that for the past week, B has had cold symptoms, including rhinorrhea, a low-grade fever (100.0°F), and cough. Earlier in the day, he was seen at his pediatrician’s office, where he was diagnosed with an acute respiratory infection and started on amoxicillin, 500 mg twice daily for 7 days.

At baseline, B is nonverbal. He requires some assistance with his activities of daily living. He usually is able to walk without assistance and dress himself, but he is not toilet trained. His parents report that in the past day, he has had significant difficulties with tasks involving his left hand. Normally, B is able to feed himself “finger foods” but has been unable to do so today. His parents say that he has been unsteady on his feet, and has been “falling forward” when he tries to walk.

Two years ago, B was started on risperidone, 0.5 mg nightly, for behavioral aggression and self-mutilation. Over the next 12 months, the dosage was steadily increased to 1 mg twice daily, with good response. He has been taking his current dosage, 1 mg twice daily, for the past 12 months without adjustment. His parents report there have been no other medication changes, other than starting amoxicillin earlier that day.

As part of his initial ED evaluation, B is found to be mildly dehydrated, with an elevated sedimentation rate on urinalysis. His complete blood count (CBC) with differential is within normal limits. A comprehensive metabolic panel shows a slight increase in his creatinine level, indicating dehydration. B is administered IV fluid replacement because he is having difficulty drinking due to excessive drooling.

The ED physician is concerned that B may be experiencing an acute dystonic reaction from risperidone, so the team holds this medication, and gives B a one-time dose of IV diphenhydramine, 25 mg, for presumptive acute dystonic reaction. After several minutes, there is no improvement in the sustained flexion of his left wrist.

[polldaddy:10615848]

The authors’ observations

B presented with new-onset neurologic findings after a recently diagnosed upper respiratory viral illness. His symptoms appeared to be confined to his left upper extremity, specifically demonstrating left arm extension at the elbow with flexion of the left wrist. He also had new-onset unsteady gait with a stooped forward posture and required assistance with walking. Interestingly, despite B’s history of antipsychotic use, administering an anticholinergic agent did not lessen the dystonic posturing at his wrist and elbow.

EVALUATION Laboratory results reveal new clues

While in the ED, B undergoes MRI of the brain and spinal cord to rule out any mass lesions that could be impinging upon the motor pathways. Both brain and spinal cord imaging appear to be essentially normal, without evidence of impingement of the spinal nerves or lesions involving the brainstem or cerebellum.

Continue to: Due to concerns...

Due to concerns of possible airway obstruction, a CT scan of the neck is obtained to rule out any acute pathology, such as epiglottitis compromising his airway. The scan shows some inflammation and edema in the soft tissues that is thought to be secondary to his acute viral illness. B is able to maintain his airway and oxygenation, so intubation is not necessary.

A CPK test is ordered because there are concerns of sustained muscle contraction of B’s left wrist and elbow. The CPK level is 884 U/L (reference range 26 to 192 U/L). The elevation in CPK is consistent with prior laboratory findings of dehydration and indicating skeletal muscle breakdown from sustained muscle contraction. All other laboratory results, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, urine drug screen, and thyroid screening panel, are within normal limits.

[polldaddy:10615850]

EVALUATION No variation in facial expression

B is admitted to the general pediatrics service. Maintenance IV fluids are started due to concerns of dehydration and possible rhabdomyolysis due to his elevated CPK level. Risperidone is held throughout the hospital course due to concerns for an acute dystonic reaction. B is monitored for several days without clinical improvement and eventually discharged home with a diagnosis of inflammatory mononeuropathy due to viral infection. The patient is told to discontinue risperidone as part of discharge instructions.

Five days later, B returns to the hospital because there was no improvement in his left extremity or walking. His left elbow remains extended with left wrist in flexion. Psychiatry is consulted for further diagnostic clarity and evaluation.

On physical examination, B’s left arm remains unchanged. Despite discontinuing risperidone, there is evidence of cogwheel rigidity of the left wrist joint. Reflexes in the upper and lower extremities are 2+ and symmetrical bilaterally, suggesting intact upper and lower motor pathways. Babinski sign is absent bilaterally, which is a normal finding in B’s age group. B continues to have difficulty with ambulating and appears to “fall forward” while trying to walk with assistance. His parents also say that B is not laughing, smiling, or showing any variation in facial expression.

Continue to: Additional family history...

Additional family history is gathered from B’s parents for possible hereditary movement disorders such as Wilson’s disease. They report that no family members have developed involuntary movements or other neurologic syndromes. Additional considerations on the differential diagnosis for B include juvenile ALS or mononeuropathy involving the C5 and C6 nerve roots. B’s parents deny any recent shoulder trauma, and radiographic studies did not demonstrate any involvement of the nerve roots.

TREATMENT A trial of bromocriptine

At this point, B’s neurologic workup is essentially normal, and he is given a provisional diagnosis of antipsychotic-induced tardive dystonia vs tardive parkinsonism. Risperidone continues to be held, and B is monitored for clinical improvement. B is administered a one-time dose of diphenhydramine, 25 mg, for dystonia with no improvement in symptoms. He is then started on bromocriptine, 1.25 mg twice daily with meals, for parkinsonian symptoms secondary to antipsychotic medication use. After 1 day of treatment, B shows less sustained flexion of his left wrist. He is able to relax his left arm, shows improvements in ambulation, and requires less assistance. B continues to be observed closely and continues to improve toward his baseline.

At Day 4, he is discharged. B is able to walk mostly without assistance and demonstrates improvement in left wrist flexion. He is scheduled to see a movement disorders specialist a week after discharge. The initial diagnosis given by the movement disorder specialist is tardive dystonia.

The authors’ observations

Tardive dyskinesia is a well-known iatrogenic effect of antipsychotic medications that are commonly used to manage conditions such as schizophrenia or behavioral agitation associated with autism spectrum disorder. Symptoms of tardive dyskinesia typically emerge after 1 to 2 years of continuous exposure to dopamine receptor blocking agents (DRBAs). Tardive dyskinesia symptoms include involuntary, repetitive, purposeless movements of the tongue, jaw, lips, face, trunk, and upper and lower extremities, with significant functional impairment.1

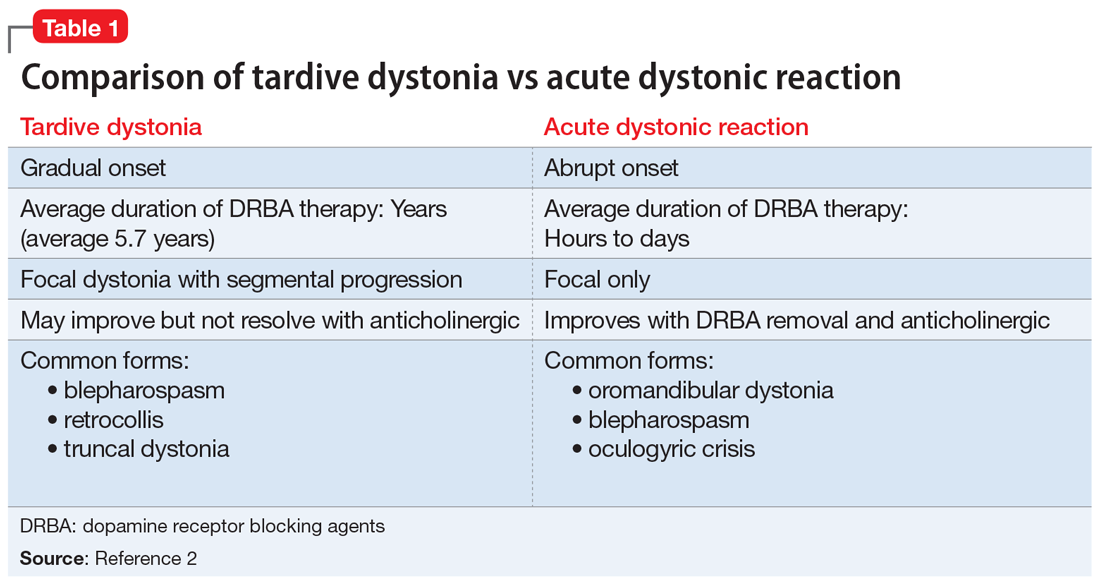

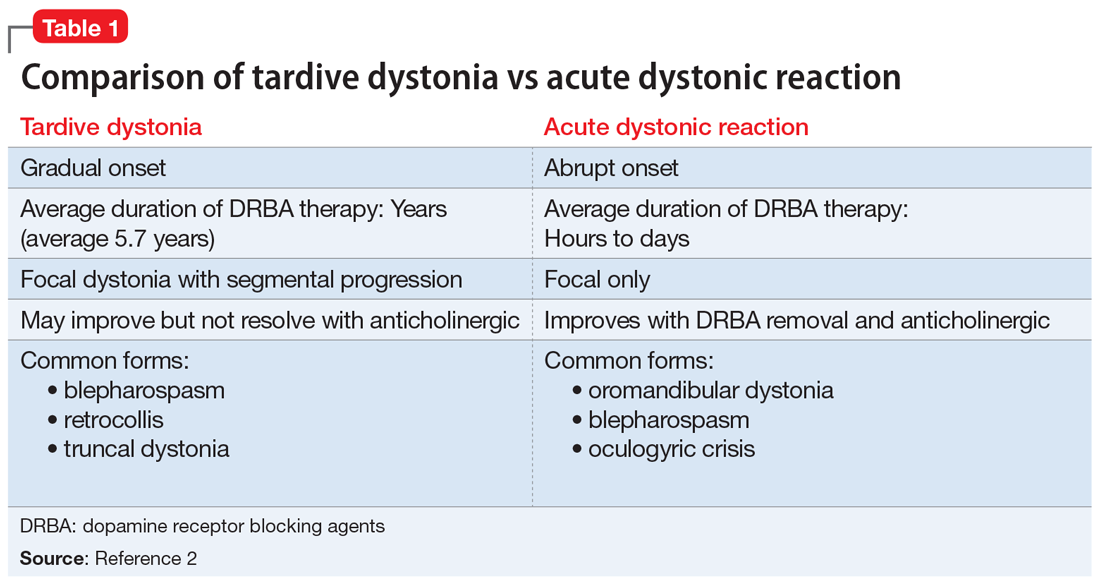

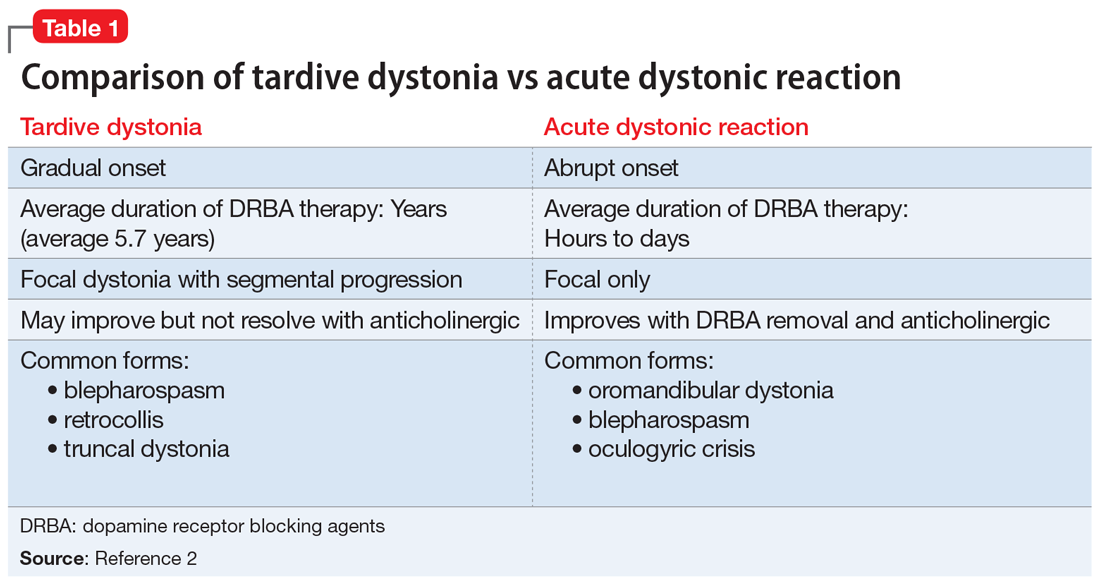

Tardive syndromes refer to a diverse array of hyperkinetic, hypokinetic, and sensory movement disorders resulting from at least 3 months of continuous DRBA therapy.2 Tardive dyskinesia is perhaps the most well-known of the tardive syndromes, but is not the only one to consider when assessing for antipsychotic-induced movement disorders. A key feature differentiating a tardive syndrome is the persistence of the movement disorder after the DRBA is discontinued. In this case, B had been receiving a stable dose of risperidone for >1 year. He developed dystonic posturing of his left wrist and elbow that was both unresponsive to anticholinergic medication and persisted after risperidone was discontinued. The term “tardive” emphasizes the delay in development of abnormal involuntary movement symptoms after initiating antipsychotic medications.3 Table 12 shows a comparison of tardive dystonia vs an acute dystonic reaction.

Continue to: Other tardive syndromes include...

Other tardive syndromes include:

- tardive tics

- tardive parkinsonism

- tardive pain

- tardive myoclonus

- tardive akathisia

- tardive tremors.

The incidence of tardive syndromes increases 5% annually for the first 5 years of treatment. At 10 years of treatment, the annual incidence is thought to be 49%, and at 25 years of treatment, 68%.4 The predominant theory of the pathophysiology of tardive syndromes is that the chronic use of DRBAs causes a gradual hypersensitization of dopamine receptors.4 The diagnosis of a tardive syndrome is based on history of exposure to a DRBA as well as clinical observation of symptoms.

Compared with classic tardive dyskinesia, tardive dystonia is more common among younger patients. The mean age of onset of tardive dystonia is 40, and it typically affects young males.5 Typical posturing observed in cases of tardive dystonia include extension of the arms and flexion at the wrists.6 In contrast to cases of primary dystonia, tardive dystonia is typically associated with stereotypies, akathisia, or other movement disorders. Anticholinergic agents, such as

The American Psychiatric Association has issued guidelines on screening for involuntary movement syndromes by using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS).7 The current recommendations include assessment every 6 months for patients receiving first-generation antipsychotics, and every 12 months for those receiving second-generation antipsychotics.7 Prescribers should also carefully assess for any pre-existing involuntary movements before prescribing a DRBA.7

[polldaddy:10615855]

The authors’ observations

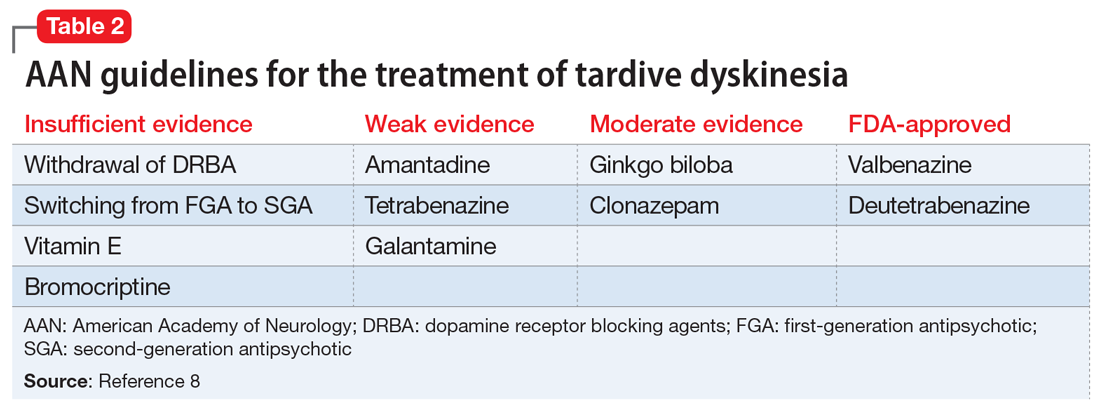

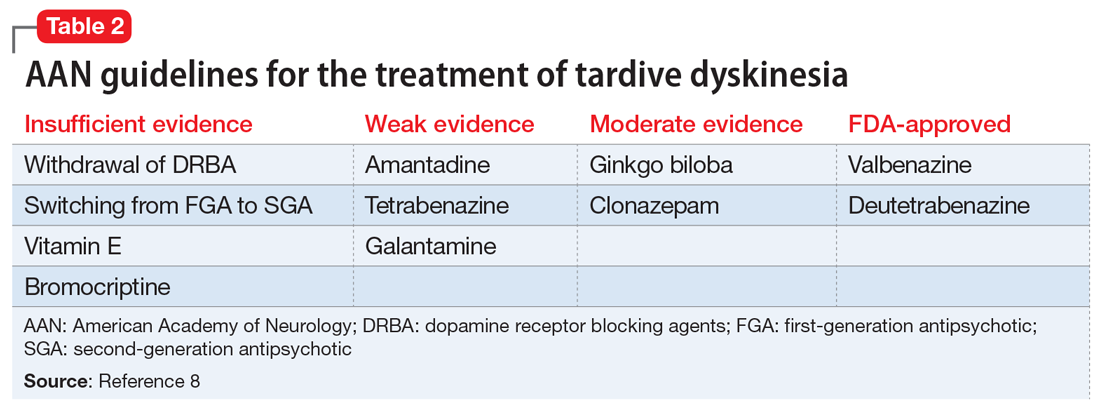

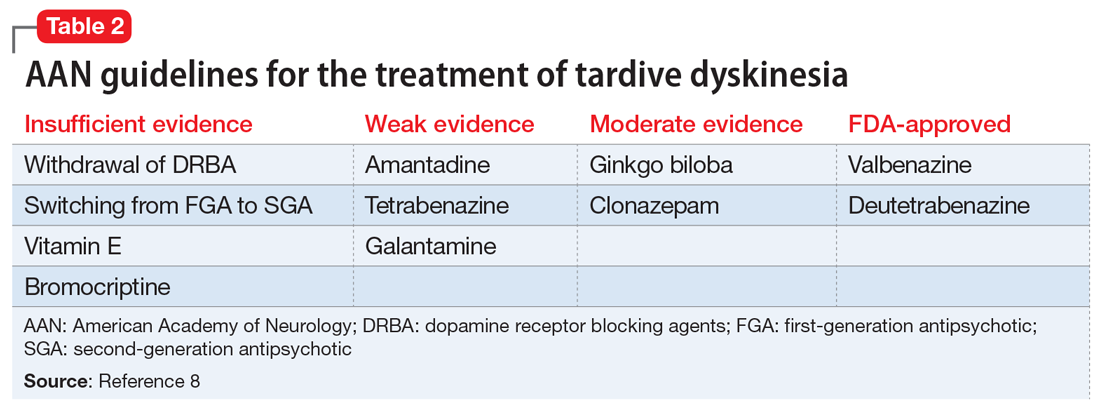

In 2013, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) published guidelines on the treatment of tardive dyskinesia. According to these guidelines, at that time, the treatments with the most evidence supporting their use were clonazepam, ginkgo biloba,

Continue to: In 2017, valbenazine and deutetrabenazine...

In 2017, valbenazine and deutetrabenazine became the first FDA-approved treatments for tardive dyskinesia in adults. Both medications block the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) system, which results in decreased synaptic dopamine and dopamine receptor stimulation. Both VMAT2 inhibitor medications have a category level A supporting their use for treating tardive dyskinesia.8-10

Currently, there are no published treatment guidelines on pharmacologic management of tardive dystonia. In B’s case, bromocriptine, a dopamine agonist, was used to counter the dopamine-blocking effects of risperidone on the nigrostriatal pathway and improve parkinsonian features of B’s presentation, including bradykinesia, stooped forward posture, and masked facies. Bromocriptine was found to be effective in alleviating parkinsonian features; however, to date there is no evidence demonstrating its effectiveness in countering delayed dystonic effects of DRBAs.

OUTCOME Improvement of dystonia symptoms

One week after discharge, B is seen for a follow-up visit. He continues taking bromocriptine, 1.25 mg twice daily, with meals after discharge. On examination, he has some evidence of tardive dystonia, including flexion of left wrist and posturing while ambulating. B’s parkinsonian features, including stooped forward posture, masked facies, and cogwheel rigidity of the left wrist muscle, have resolved. B is now able to walk on his own without unsteadiness. Bromocriptine is discontinued after 1 month, and his symptoms of dystonia continue to improve.

Two months after hospitalization, B is started on quetiapine, 25 mg twice daily, for behavioral aggression. Quetiapine is chosen because it has a lower dopamine receptor affinity compared with risperidone, and theoretically, quetiapine is associated with a lower risk of developing tardive symptoms. During the next 6 months, B is monitored closely for recurrence of tardive symptoms. Quetiapine is slowly titrated to 25 mg in the morning, and 50 mg at bedtime. His behavioral agitation improves significantly and he does not have a recurrence of tardive symptoms.

Bottom Line