User login

Intravascular lithotripsy hailed as ‘game changer’ for coronary calcification

aimed at gaining U.S. regulatory approval.

The technology is basically the same as in extracorporeal lithotripsy, used for the treatment of kidney stones for more than 30 years: namely, transmission of pulsed acoustic pressure waves in order to fracture calcium. For interventional cardiology purposes, however, the transmitter is located within a balloon angioplasty catheter, Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, explained in presenting the study results at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

In Disrupt CAD III, intravascular lithotripsy far exceeded the procedural success and 30-day freedom from major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) performance targets set in conjunction with the Food and Drug Administration. In so doing, the intravascular lithotripsy device developed by Shockwave Medical successfully addressed one of the banes of contemporary interventional cardiology: heavily calcified coronary lesions.

Currently available technologies targeting such lesions, including noncompliant high-pressure balloons, intravascular lasers, cutting balloons, and orbital and rotational atherectomy, often yield suboptimal results, noted Dr. Kereiakes, medical director of the Christ Hospital Heart and Cardiovascular Center in Cincinnati.

Severe vascular calcifications are becoming more common, due in part to an aging population and the growing prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and renal insufficiency. Severely calcified coronary lesions complicate percutaneous coronary intervention. They’re associated with increased risks of dissection, perforation, and periprocedural MI. Moreover, heavily calcified lesions impede stent delivery and expansion – and stent underexpansion is the leading predictor of restenosis and stent thrombosis, he observed at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. Disrupt CAD III was a prospective single-arm study of 384 patients at 47 sites in the United States and several European countries. All participants had de novo coronary calcifications graded as severe by core laboratory assessment, with a mean calcified length of 47.9 mm by quantitative coronary angiography and a mean calcium angle and thickness of 292.5 degrees and 0.96 mm by optical coherence tomography.

“It’s staggering, the level of calcification these patients had. It’s jaw dropping,” Dr. Kereiakes observed.

Intravascular lithotripsy was used to prepare these severely calcified lesions for stenting. The intervention entailed transmission of acoustic waves circumferentially and transmurally at 1 pulse per second through tissue at an effective pressure of about 50 atm. Patients received an average of 69 pulses.

This was not a randomized trial; there was no sham-treated control arm. Instead, the comparator group selected under regulatory guidance was comprised of patients who had received orbital atherectomy for severe coronary calcifications in the earlier, similarly designed ORBIT II trial, which led to FDA marketing approval of that technology.

Key outcomes

The procedural success rate, defined as successful stent delivery with less than a 50% residual stenosis and no in-hospital MACE, was 92.4% in Disrupt CAD III, compared to 83.4% for orbital atherectomy in ORBIT II. The primary safety endpoint of freedom from cardiac death, MI, or target vessel revascularization at 30 days was achieved in 92.2% of patients in the intravascular lithotripsy trial, versus 84.4% in ORBIT II.

The 30-day MACE rate of 7.8% in Disrupt CAD III was primarily driven by periprocedural MIs, which occurred in 6.8% of participants. Only one-third of the MIs were clinically relevant by the Society for Coronary Angiography and Intervention definition. There were two cardiac deaths and three cases of stent thrombosis, all of which were associated with known predictors of the complication. There was 1 case each of dissection, abrupt closure, and perforation, but no instances of slow flow or no reflow at the procedure’s end. Transient lithotripsy-induced left ventricular capture occurred in 41% of patients, but they were benign events with no lasting consequences.

The device was able to cross and deliver acoustic pressure wave therapy to 98.2% of lesions. The mean diameter stenosis preprocedure was 65.1%, dropping to 37.2% post lithotripsy, with a final in-stent residual stenosis diameter of 11.9%, with a 1.7-mm acute gain. The average stent expansion at the site of maximum calcification was 102%, with a minimum stent area of 6.5 mm2.

Optical coherence imaging revealed that 67% of treated lesions had circumferential and transmural fractures of both deep and superficial calcium post lithotripsy. Yet outcomes were the same regardless of whether fractures were evident on imaging.

At 30-day follow-up, 72.9% of patients had no angina, up from just 12.6% of participants pre-PCI. Follow-up will continue for 2 years.

Outcomes were similar for the first case done at each participating center and all cases thereafter.

“The ease of use was remarkable,” Dr. Kereiakes recalled. “The learning curve is virtually nonexistent.”

The reaction

At a press conference where Dr. Kereiakes presented the Disrupt CAD III results, discussant Allen Jeremias, MD, said he found the results compelling.

“The success rate is high, I think it’s relatively easy to use, as demonstrated, and I think the results are spectacular,” said Dr. Jeremias, director of interventional cardiology research and associate director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory at St. Francis Hospital in Roslyn, N.Y.

Cardiologists “really don’t do a good job most of the time” with severely calcified coronary lesions, added Dr. Jeremias, who wasn’t involved in the trial.

“A lot of times these patients have inadequate stent outcomes when we do intravascular imaging. So to do something to try to basically crack the calcium and expand the stent is, I think, critically important in these patients, and this is an amazing technology that accomplishes that,” the cardiologist said.

Juan F. Granada, MD, of Columbia University, New York, who moderated the press conference, said, “Some of the debulking techniques used for calcified stenoses actually require a lot of training, knowledge, experience, and hospital infrastructure.

I really think having a technology that is easy to use and familiar to all interventional cardiologists, such as a balloon, could potentially be a disruptive change in our field.”

“It’s an absolute game changer,” agreed Dr. Jeremias.

Dr. Kereiakes reported serving as a consultant to a handful of medical device companies, including Shockwave Medical, which sponsored Disrupt CAD III.

SOURCE: Kereiakes DJ. TCT 2020. Late Breaking Clinical Science session 2.

aimed at gaining U.S. regulatory approval.

The technology is basically the same as in extracorporeal lithotripsy, used for the treatment of kidney stones for more than 30 years: namely, transmission of pulsed acoustic pressure waves in order to fracture calcium. For interventional cardiology purposes, however, the transmitter is located within a balloon angioplasty catheter, Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, explained in presenting the study results at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

In Disrupt CAD III, intravascular lithotripsy far exceeded the procedural success and 30-day freedom from major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) performance targets set in conjunction with the Food and Drug Administration. In so doing, the intravascular lithotripsy device developed by Shockwave Medical successfully addressed one of the banes of contemporary interventional cardiology: heavily calcified coronary lesions.

Currently available technologies targeting such lesions, including noncompliant high-pressure balloons, intravascular lasers, cutting balloons, and orbital and rotational atherectomy, often yield suboptimal results, noted Dr. Kereiakes, medical director of the Christ Hospital Heart and Cardiovascular Center in Cincinnati.

Severe vascular calcifications are becoming more common, due in part to an aging population and the growing prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and renal insufficiency. Severely calcified coronary lesions complicate percutaneous coronary intervention. They’re associated with increased risks of dissection, perforation, and periprocedural MI. Moreover, heavily calcified lesions impede stent delivery and expansion – and stent underexpansion is the leading predictor of restenosis and stent thrombosis, he observed at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. Disrupt CAD III was a prospective single-arm study of 384 patients at 47 sites in the United States and several European countries. All participants had de novo coronary calcifications graded as severe by core laboratory assessment, with a mean calcified length of 47.9 mm by quantitative coronary angiography and a mean calcium angle and thickness of 292.5 degrees and 0.96 mm by optical coherence tomography.

“It’s staggering, the level of calcification these patients had. It’s jaw dropping,” Dr. Kereiakes observed.

Intravascular lithotripsy was used to prepare these severely calcified lesions for stenting. The intervention entailed transmission of acoustic waves circumferentially and transmurally at 1 pulse per second through tissue at an effective pressure of about 50 atm. Patients received an average of 69 pulses.

This was not a randomized trial; there was no sham-treated control arm. Instead, the comparator group selected under regulatory guidance was comprised of patients who had received orbital atherectomy for severe coronary calcifications in the earlier, similarly designed ORBIT II trial, which led to FDA marketing approval of that technology.

Key outcomes

The procedural success rate, defined as successful stent delivery with less than a 50% residual stenosis and no in-hospital MACE, was 92.4% in Disrupt CAD III, compared to 83.4% for orbital atherectomy in ORBIT II. The primary safety endpoint of freedom from cardiac death, MI, or target vessel revascularization at 30 days was achieved in 92.2% of patients in the intravascular lithotripsy trial, versus 84.4% in ORBIT II.

The 30-day MACE rate of 7.8% in Disrupt CAD III was primarily driven by periprocedural MIs, which occurred in 6.8% of participants. Only one-third of the MIs were clinically relevant by the Society for Coronary Angiography and Intervention definition. There were two cardiac deaths and three cases of stent thrombosis, all of which were associated with known predictors of the complication. There was 1 case each of dissection, abrupt closure, and perforation, but no instances of slow flow or no reflow at the procedure’s end. Transient lithotripsy-induced left ventricular capture occurred in 41% of patients, but they were benign events with no lasting consequences.

The device was able to cross and deliver acoustic pressure wave therapy to 98.2% of lesions. The mean diameter stenosis preprocedure was 65.1%, dropping to 37.2% post lithotripsy, with a final in-stent residual stenosis diameter of 11.9%, with a 1.7-mm acute gain. The average stent expansion at the site of maximum calcification was 102%, with a minimum stent area of 6.5 mm2.

Optical coherence imaging revealed that 67% of treated lesions had circumferential and transmural fractures of both deep and superficial calcium post lithotripsy. Yet outcomes were the same regardless of whether fractures were evident on imaging.

At 30-day follow-up, 72.9% of patients had no angina, up from just 12.6% of participants pre-PCI. Follow-up will continue for 2 years.

Outcomes were similar for the first case done at each participating center and all cases thereafter.

“The ease of use was remarkable,” Dr. Kereiakes recalled. “The learning curve is virtually nonexistent.”

The reaction

At a press conference where Dr. Kereiakes presented the Disrupt CAD III results, discussant Allen Jeremias, MD, said he found the results compelling.

“The success rate is high, I think it’s relatively easy to use, as demonstrated, and I think the results are spectacular,” said Dr. Jeremias, director of interventional cardiology research and associate director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory at St. Francis Hospital in Roslyn, N.Y.

Cardiologists “really don’t do a good job most of the time” with severely calcified coronary lesions, added Dr. Jeremias, who wasn’t involved in the trial.

“A lot of times these patients have inadequate stent outcomes when we do intravascular imaging. So to do something to try to basically crack the calcium and expand the stent is, I think, critically important in these patients, and this is an amazing technology that accomplishes that,” the cardiologist said.

Juan F. Granada, MD, of Columbia University, New York, who moderated the press conference, said, “Some of the debulking techniques used for calcified stenoses actually require a lot of training, knowledge, experience, and hospital infrastructure.

I really think having a technology that is easy to use and familiar to all interventional cardiologists, such as a balloon, could potentially be a disruptive change in our field.”

“It’s an absolute game changer,” agreed Dr. Jeremias.

Dr. Kereiakes reported serving as a consultant to a handful of medical device companies, including Shockwave Medical, which sponsored Disrupt CAD III.

SOURCE: Kereiakes DJ. TCT 2020. Late Breaking Clinical Science session 2.

aimed at gaining U.S. regulatory approval.

The technology is basically the same as in extracorporeal lithotripsy, used for the treatment of kidney stones for more than 30 years: namely, transmission of pulsed acoustic pressure waves in order to fracture calcium. For interventional cardiology purposes, however, the transmitter is located within a balloon angioplasty catheter, Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, explained in presenting the study results at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

In Disrupt CAD III, intravascular lithotripsy far exceeded the procedural success and 30-day freedom from major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) performance targets set in conjunction with the Food and Drug Administration. In so doing, the intravascular lithotripsy device developed by Shockwave Medical successfully addressed one of the banes of contemporary interventional cardiology: heavily calcified coronary lesions.

Currently available technologies targeting such lesions, including noncompliant high-pressure balloons, intravascular lasers, cutting balloons, and orbital and rotational atherectomy, often yield suboptimal results, noted Dr. Kereiakes, medical director of the Christ Hospital Heart and Cardiovascular Center in Cincinnati.

Severe vascular calcifications are becoming more common, due in part to an aging population and the growing prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and renal insufficiency. Severely calcified coronary lesions complicate percutaneous coronary intervention. They’re associated with increased risks of dissection, perforation, and periprocedural MI. Moreover, heavily calcified lesions impede stent delivery and expansion – and stent underexpansion is the leading predictor of restenosis and stent thrombosis, he observed at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. Disrupt CAD III was a prospective single-arm study of 384 patients at 47 sites in the United States and several European countries. All participants had de novo coronary calcifications graded as severe by core laboratory assessment, with a mean calcified length of 47.9 mm by quantitative coronary angiography and a mean calcium angle and thickness of 292.5 degrees and 0.96 mm by optical coherence tomography.

“It’s staggering, the level of calcification these patients had. It’s jaw dropping,” Dr. Kereiakes observed.

Intravascular lithotripsy was used to prepare these severely calcified lesions for stenting. The intervention entailed transmission of acoustic waves circumferentially and transmurally at 1 pulse per second through tissue at an effective pressure of about 50 atm. Patients received an average of 69 pulses.

This was not a randomized trial; there was no sham-treated control arm. Instead, the comparator group selected under regulatory guidance was comprised of patients who had received orbital atherectomy for severe coronary calcifications in the earlier, similarly designed ORBIT II trial, which led to FDA marketing approval of that technology.

Key outcomes

The procedural success rate, defined as successful stent delivery with less than a 50% residual stenosis and no in-hospital MACE, was 92.4% in Disrupt CAD III, compared to 83.4% for orbital atherectomy in ORBIT II. The primary safety endpoint of freedom from cardiac death, MI, or target vessel revascularization at 30 days was achieved in 92.2% of patients in the intravascular lithotripsy trial, versus 84.4% in ORBIT II.

The 30-day MACE rate of 7.8% in Disrupt CAD III was primarily driven by periprocedural MIs, which occurred in 6.8% of participants. Only one-third of the MIs were clinically relevant by the Society for Coronary Angiography and Intervention definition. There were two cardiac deaths and three cases of stent thrombosis, all of which were associated with known predictors of the complication. There was 1 case each of dissection, abrupt closure, and perforation, but no instances of slow flow or no reflow at the procedure’s end. Transient lithotripsy-induced left ventricular capture occurred in 41% of patients, but they were benign events with no lasting consequences.

The device was able to cross and deliver acoustic pressure wave therapy to 98.2% of lesions. The mean diameter stenosis preprocedure was 65.1%, dropping to 37.2% post lithotripsy, with a final in-stent residual stenosis diameter of 11.9%, with a 1.7-mm acute gain. The average stent expansion at the site of maximum calcification was 102%, with a minimum stent area of 6.5 mm2.

Optical coherence imaging revealed that 67% of treated lesions had circumferential and transmural fractures of both deep and superficial calcium post lithotripsy. Yet outcomes were the same regardless of whether fractures were evident on imaging.

At 30-day follow-up, 72.9% of patients had no angina, up from just 12.6% of participants pre-PCI. Follow-up will continue for 2 years.

Outcomes were similar for the first case done at each participating center and all cases thereafter.

“The ease of use was remarkable,” Dr. Kereiakes recalled. “The learning curve is virtually nonexistent.”

The reaction

At a press conference where Dr. Kereiakes presented the Disrupt CAD III results, discussant Allen Jeremias, MD, said he found the results compelling.

“The success rate is high, I think it’s relatively easy to use, as demonstrated, and I think the results are spectacular,” said Dr. Jeremias, director of interventional cardiology research and associate director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory at St. Francis Hospital in Roslyn, N.Y.

Cardiologists “really don’t do a good job most of the time” with severely calcified coronary lesions, added Dr. Jeremias, who wasn’t involved in the trial.

“A lot of times these patients have inadequate stent outcomes when we do intravascular imaging. So to do something to try to basically crack the calcium and expand the stent is, I think, critically important in these patients, and this is an amazing technology that accomplishes that,” the cardiologist said.

Juan F. Granada, MD, of Columbia University, New York, who moderated the press conference, said, “Some of the debulking techniques used for calcified stenoses actually require a lot of training, knowledge, experience, and hospital infrastructure.

I really think having a technology that is easy to use and familiar to all interventional cardiologists, such as a balloon, could potentially be a disruptive change in our field.”

“It’s an absolute game changer,” agreed Dr. Jeremias.

Dr. Kereiakes reported serving as a consultant to a handful of medical device companies, including Shockwave Medical, which sponsored Disrupt CAD III.

SOURCE: Kereiakes DJ. TCT 2020. Late Breaking Clinical Science session 2.

FROM TCT 2020

Key clinical point: Intravascular lithotripsy was safe and effective for treatment of severely calcified coronary stenoses in a pivotal trial.

Major finding: The 30-day rate of freedom from major adverse cardiovascular events was 92.2%, well above the prespecified performance goal of 84.4%.

Study details: Disrupt CAD III study is a multicenter, single-arm, prospective study of intravascular lithotripsy in 384 patients with severe coronary calcification.

Disclosures: The presenter reported serving as a consultant to Shockwave Medical Inc., the study sponsor, as well as several other medical device companies.

Source: Kereiakes DJ. TCT 2020. Late Breaking Clinical Science session 2.

Paraneoplastic Pemphigus With Cicatricial Nail Involvement

To the Editor:

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP), also known as paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome, is an autoimmune mucocutaneous blistering disease that typically occurs secondary to a lymphoproliferative disorder. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is characterized by severe erosive stomatitis, polymorphous skin lesions, and potential bronchiolitis obliterans that can mimic a wide array of conditions. The exact pathogenesis is unknown but is thought to be due to a combination of humoral and cell-mediated immunity. The condition usually confers a poor prognosis, with morbidity from 38% to upwards of 90%.1

A 47-year-old man developed prominent pink to dusky, ill-defined, targetoid, coalescing papules over the back; violaceous macules over the palms and soles; and numerous crusted oral erosions while hospitalized for an infection. He had a history of stage IVB follicular lymphoma (double-hit type immunoglobulin heavy chain/BCL2 fusion and rearrangement of BCL6) complicated by extensive erosive skin lesions and multiple lines of infections. The clinical differential diagnosis included Stevens-Johnson syndrome vs erythema multiforme (EM) major secondary to administration of oxacillin vs PNP. Herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction and Mycoplasma titers were negative. Skin biopsies from the back and right abdomen revealed severe lichenoid interface dermatitis (IFD) with numerous dyskeratotic cells mimicking EM and eosinophils; however, direct immunofluorescence of the abdomen biopsy revealed an apparent suprabasal acantholysis with intercellular C3 in the lower half of the epidermis. Histologically, PNP was favored, but indirect immunofluorescence with monkey esophagus IgG was negative.

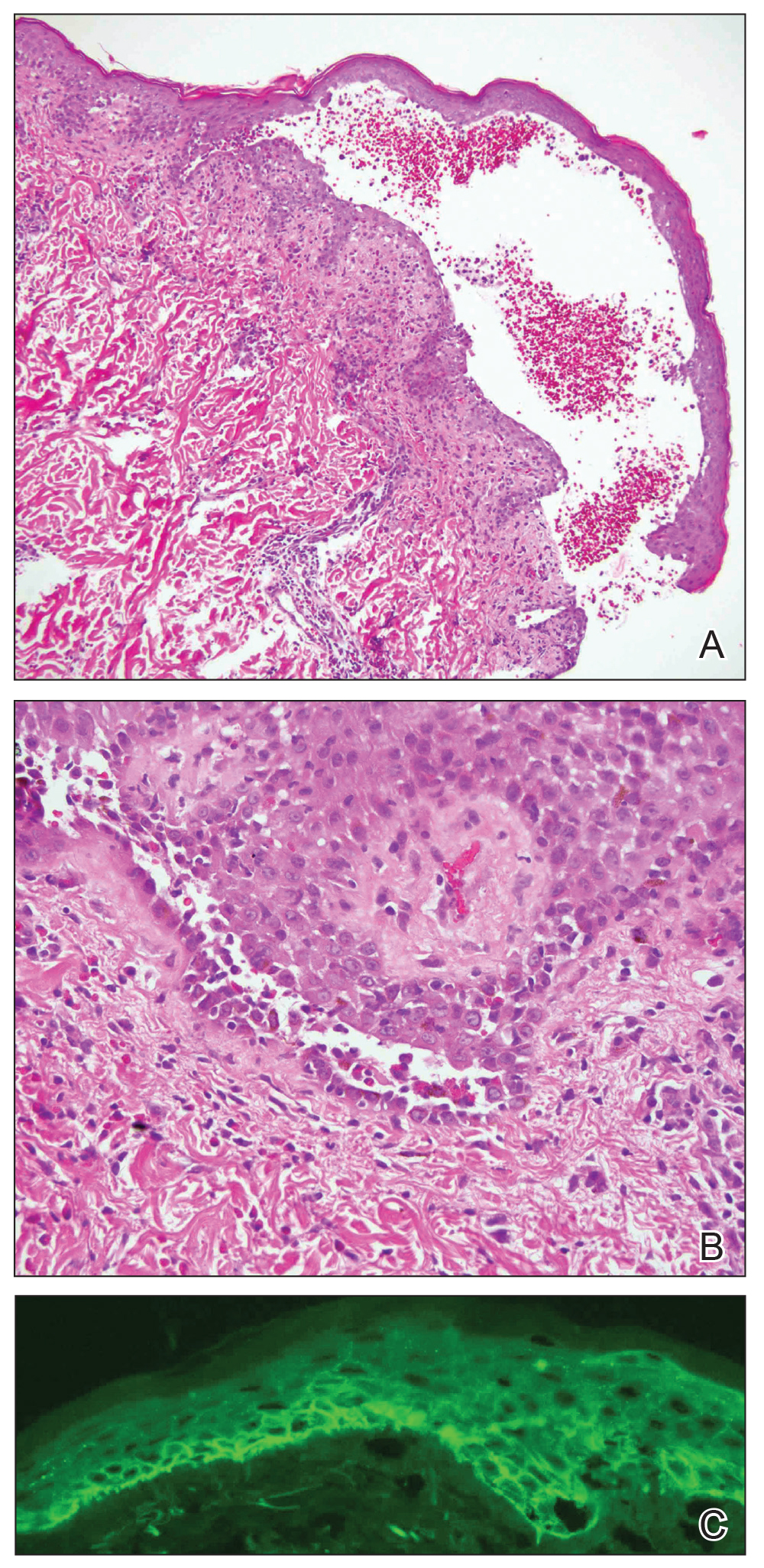

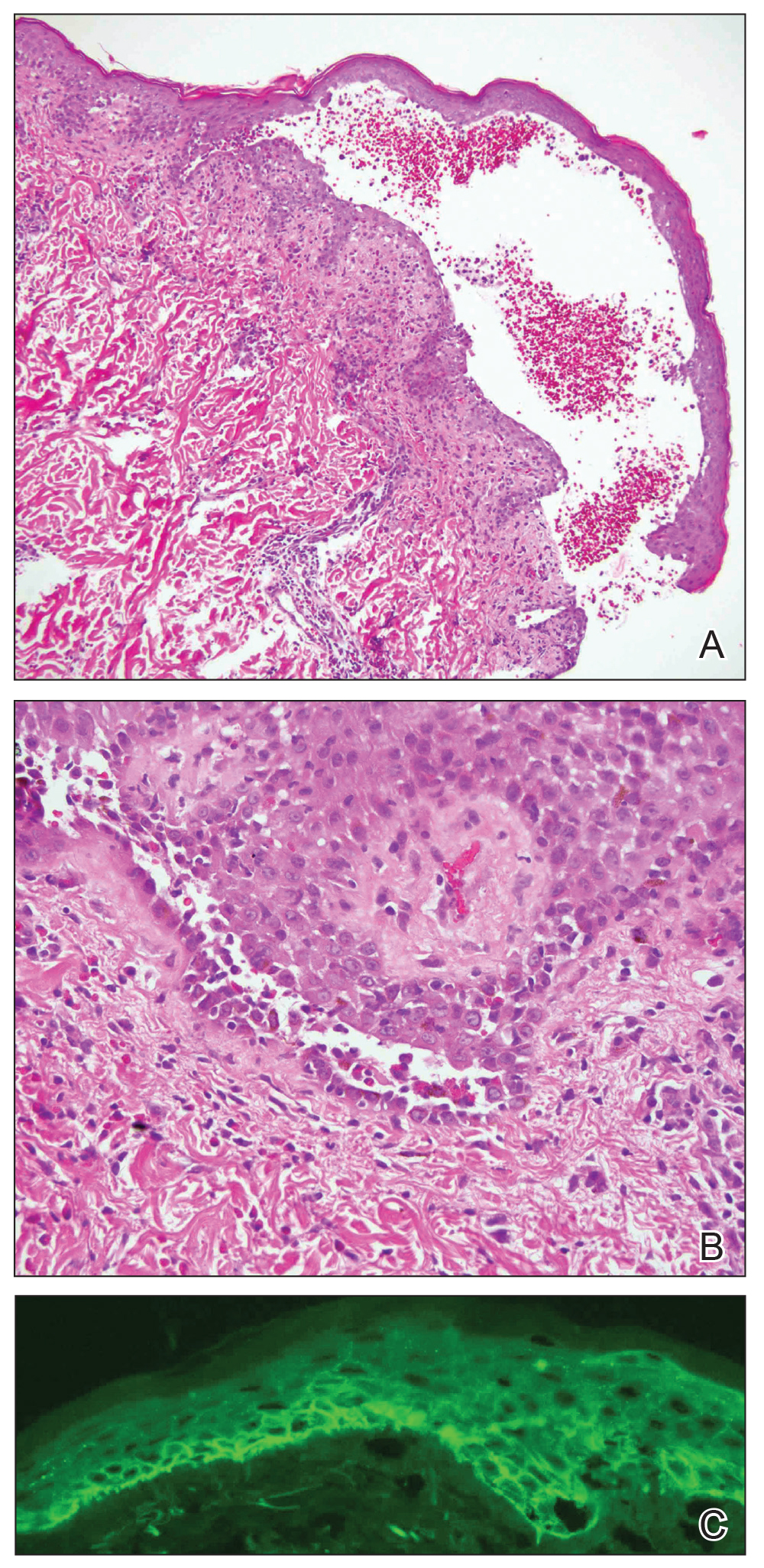

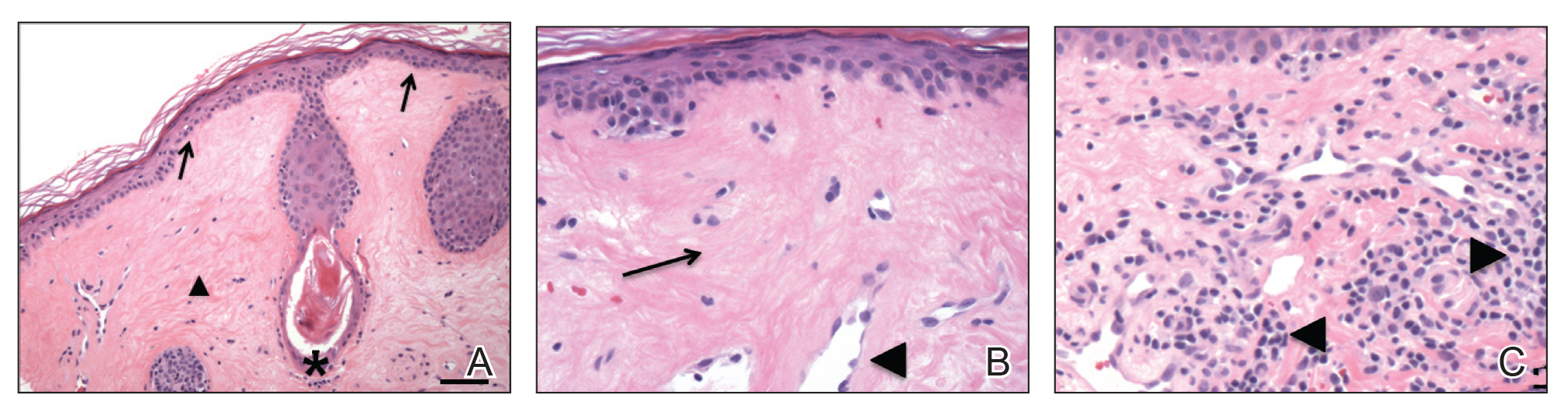

The skin lesions progressed, and an additional skin biopsy from the left arm performed 1 month later revealed similar histologic features with intercellular IgG and C3 in the lower half of the epidermis with weak basement membrane C3 (Figure 1). Serology also confirmed elevated serum antidesmoglein 1 and 3 antibodies. Thus, in the clinical setting of an erosive mucositis with EM-like and pemphigoidlike eruptions associated with B-cell lymphoma, the patient was diagnosed with PNP.

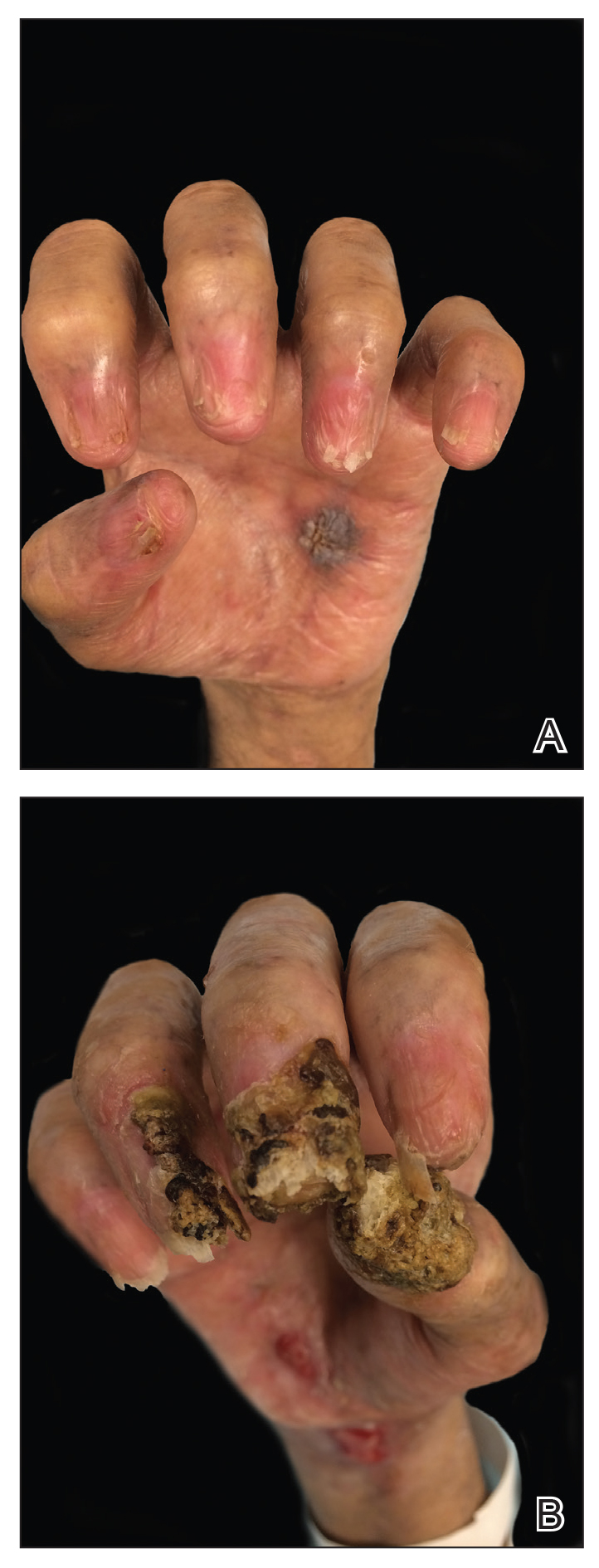

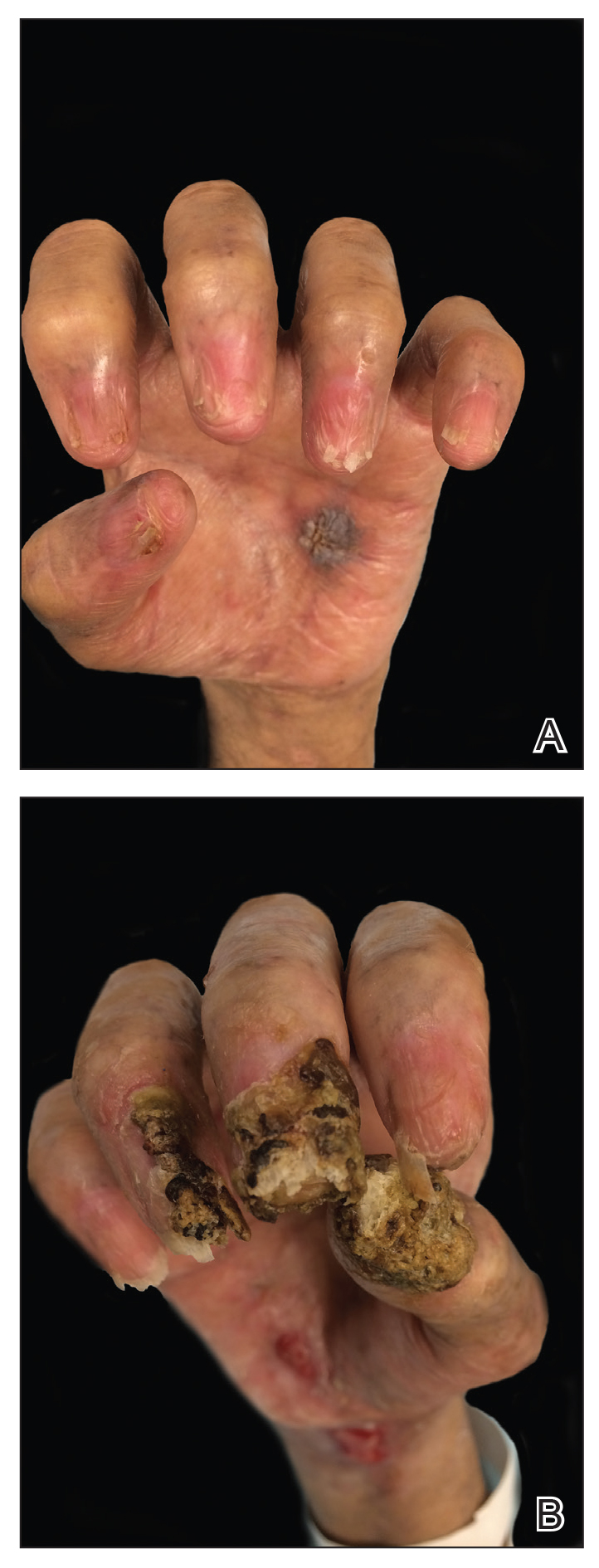

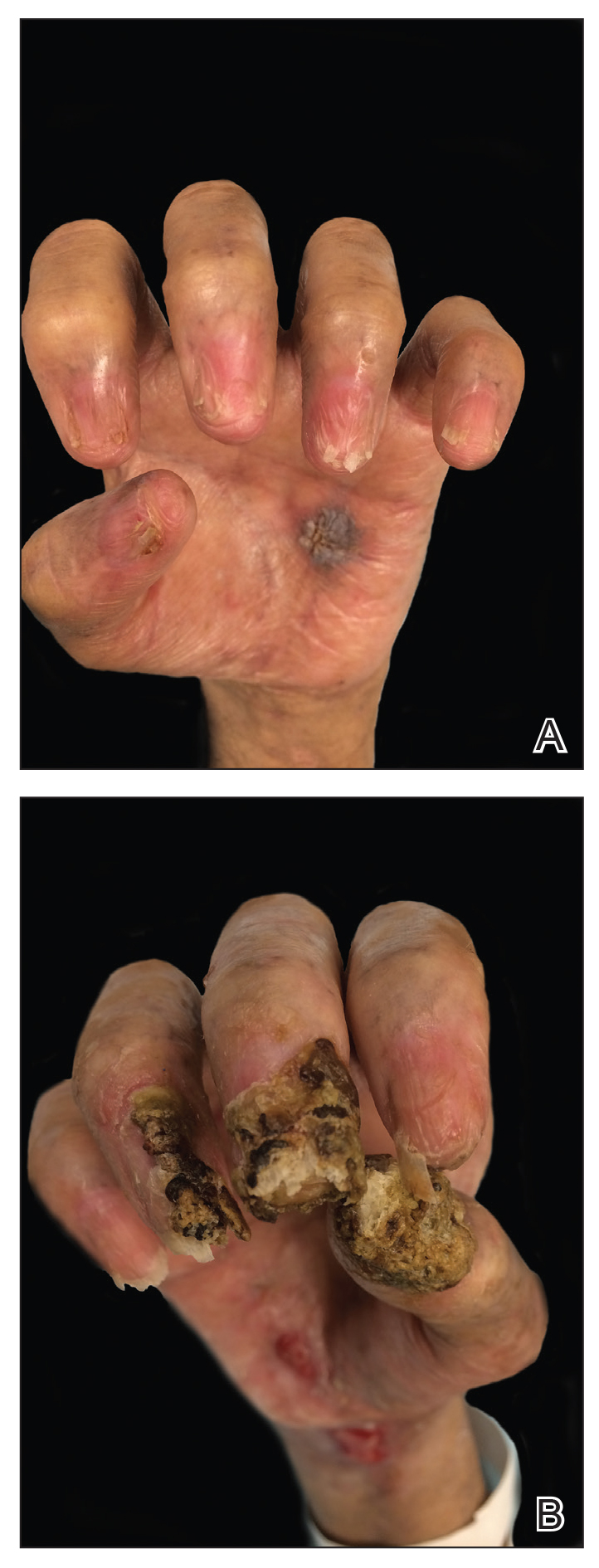

Despite multiple complications followed by intermittent treatments, the initial therapy with rituximab induction and subsequent cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone) for the B-cell lymphoma was done during his hospital stay. Toward the end of his 8-week hospitalization, the patient was noted to have new lesions involving the hands, digits, and nails. The left hand showed anonychia of several fingers with prominent scarring (Figure 2A). There were large, verrucous, crusted plaques on the distal phalanges of several fingers on the right hand (Figure 2B). At that time, he was taking 20 mg daily of prednisone (for 10 months) and had completed his 6th cycle of R-CHOP, which resulted in improvement of the skin lesions. Oral steroids were tapered, and he was maintained on rituximab infusions every 8 weeks but has since been lost to follow-up.

Paraneoplastic lymphoma is a rare condition that affects 0.012% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients.2 Reports of PNP involving the nails are even more rare, with 3 reports in the setting of underlying Castleman disease3-5 and 2 reports in patients with underlying non-Hodgkin6 and follicular1 lymphoma. These studies describe variable nail findings ranging from periungual erosions and edema, formation of dorsal pterygium, onycholysis with longitudinal furrowing, and destruction of the nail plate leading to onychomadesis and/or anonychia. These nail changes typically are seen in lichen planus or in bullous diseases affecting the basement membrane (eg, bullous pemphigoid, acquired epidermolysis bullosa) but not known in pemphigus, which is characterized by nonscarring nail changes.7

Although antidesmoglein 3 antibody was shown to be a pathologic driver in PNP, there is a weak correlation between antibody profiles and clinical presentation.8 In one case of PNP, antidesmoglein 3 antibody was negative, suggesting that lichenoid IFD may cause the phenotypic findings in PNP.9 Thus, the development of nail scarring in PNP may be explained by the presence of lichenoid IFD that is characteristic of PNP. However, the variation in antibody profile in PNP likely is a consequence of epitope spreading.

- Miest RY, Wetter DA, Drage LA, et al. A mucocutaneous eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1425-1427.

- Anhalt GJ, Mimouni D. Paraneoplastic pemphigus. In: LA G, Katz SI, Gilchrest, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine 8th Edition. Vol 1. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012:600.

- Chorzelski T, Hashimoto T, Maciejewska B, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman tumor, myasthenia gravis and bronchiolitis obliterans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:393-400.

- Lemon MA, Weston WL, Huff JC. Childhood paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman’s tumour. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:115-117.

- Tey HL, Tang MB. A case of paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman’s disease presenting as erosive lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e754-e756.

- Liang JJ, Cordes SF, Witzig TE. More than skin-deep. Cleve Clin J Med. 2013;80:632-633.

- Tosti A, Andre M, Murrell DF. Nail involvement in autoimmune bullous disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:511-513, xi.

- Ohyama M, Amagai M, Hashimoto T, et al. Clinical phenotype and anti-desmoglein autoantibody profile in paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:593-598.

- Kanwar AJ, Vinay K, Varma S, et al. Anti-desmoglein antibody-negative paraneoplastic pemphigus successfully treated with rituximab. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:576-579.

To the Editor:

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP), also known as paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome, is an autoimmune mucocutaneous blistering disease that typically occurs secondary to a lymphoproliferative disorder. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is characterized by severe erosive stomatitis, polymorphous skin lesions, and potential bronchiolitis obliterans that can mimic a wide array of conditions. The exact pathogenesis is unknown but is thought to be due to a combination of humoral and cell-mediated immunity. The condition usually confers a poor prognosis, with morbidity from 38% to upwards of 90%.1

A 47-year-old man developed prominent pink to dusky, ill-defined, targetoid, coalescing papules over the back; violaceous macules over the palms and soles; and numerous crusted oral erosions while hospitalized for an infection. He had a history of stage IVB follicular lymphoma (double-hit type immunoglobulin heavy chain/BCL2 fusion and rearrangement of BCL6) complicated by extensive erosive skin lesions and multiple lines of infections. The clinical differential diagnosis included Stevens-Johnson syndrome vs erythema multiforme (EM) major secondary to administration of oxacillin vs PNP. Herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction and Mycoplasma titers were negative. Skin biopsies from the back and right abdomen revealed severe lichenoid interface dermatitis (IFD) with numerous dyskeratotic cells mimicking EM and eosinophils; however, direct immunofluorescence of the abdomen biopsy revealed an apparent suprabasal acantholysis with intercellular C3 in the lower half of the epidermis. Histologically, PNP was favored, but indirect immunofluorescence with monkey esophagus IgG was negative.

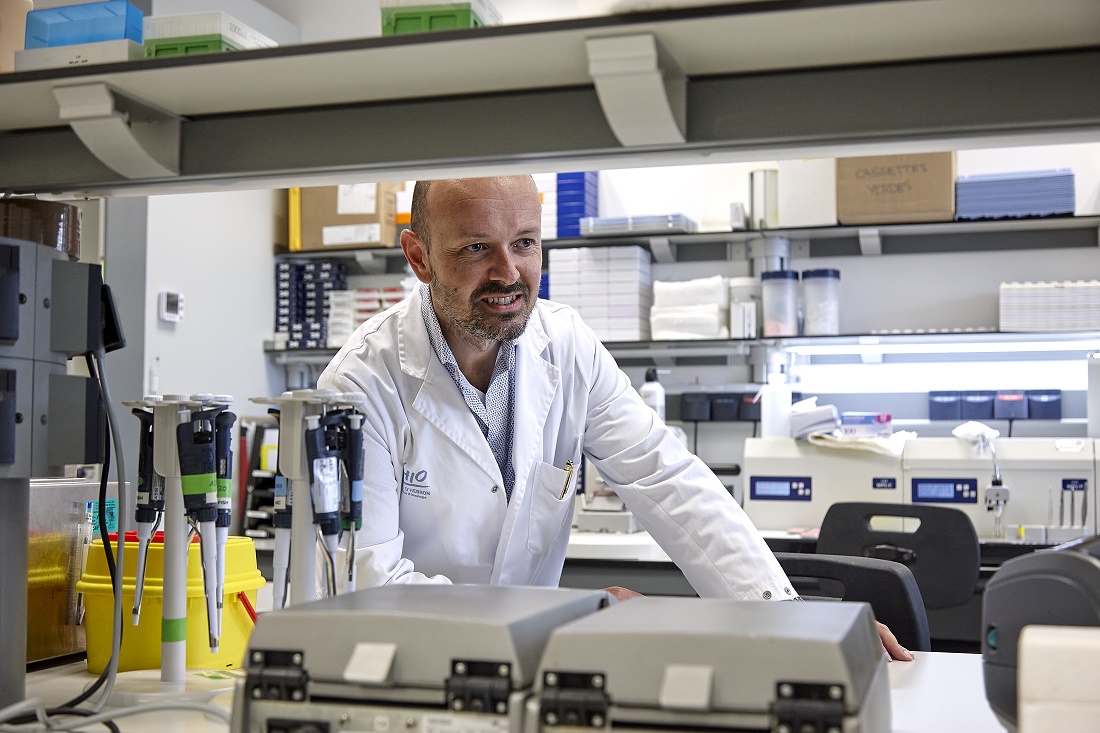

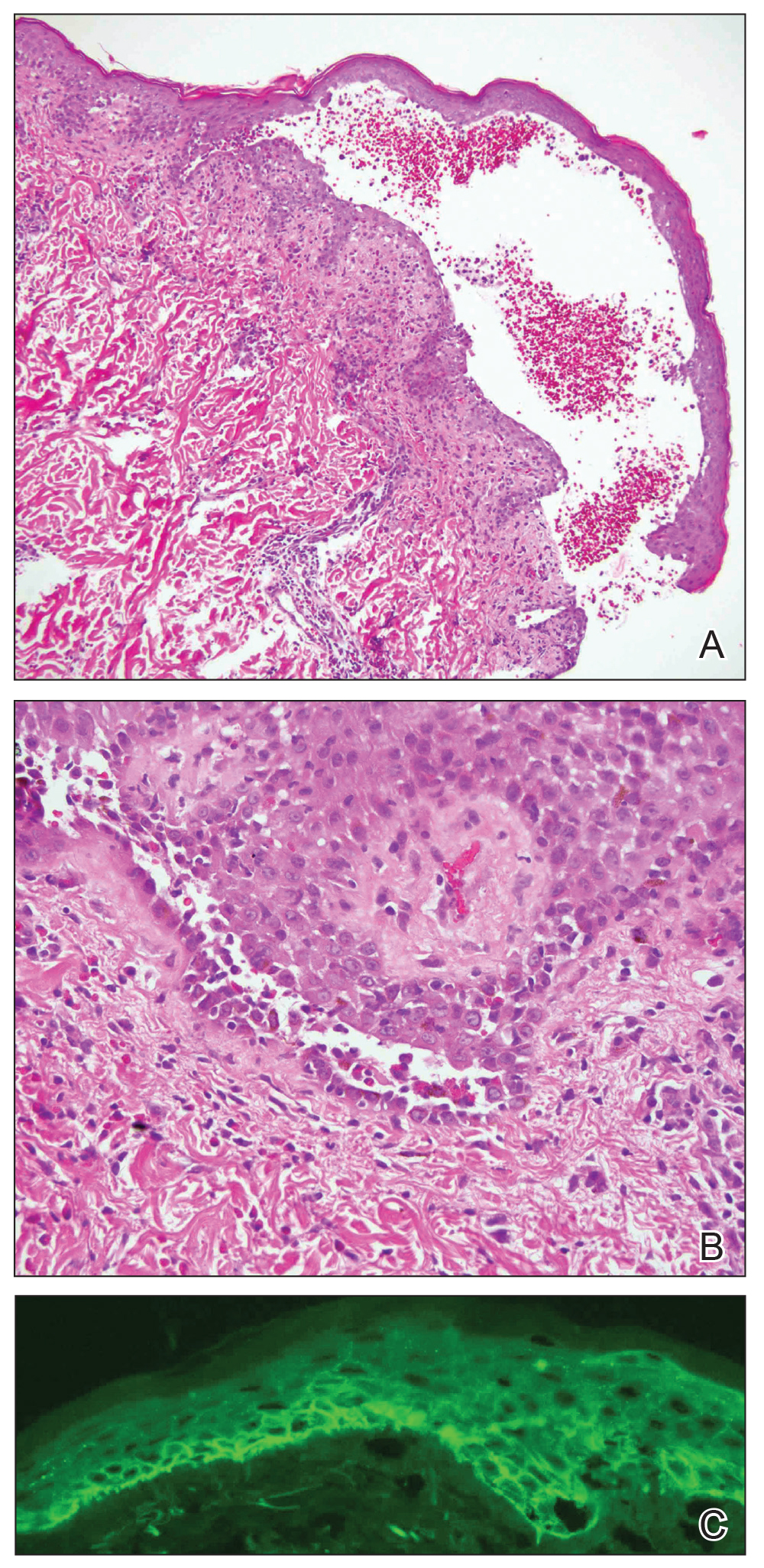

The skin lesions progressed, and an additional skin biopsy from the left arm performed 1 month later revealed similar histologic features with intercellular IgG and C3 in the lower half of the epidermis with weak basement membrane C3 (Figure 1). Serology also confirmed elevated serum antidesmoglein 1 and 3 antibodies. Thus, in the clinical setting of an erosive mucositis with EM-like and pemphigoidlike eruptions associated with B-cell lymphoma, the patient was diagnosed with PNP.

Despite multiple complications followed by intermittent treatments, the initial therapy with rituximab induction and subsequent cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone) for the B-cell lymphoma was done during his hospital stay. Toward the end of his 8-week hospitalization, the patient was noted to have new lesions involving the hands, digits, and nails. The left hand showed anonychia of several fingers with prominent scarring (Figure 2A). There were large, verrucous, crusted plaques on the distal phalanges of several fingers on the right hand (Figure 2B). At that time, he was taking 20 mg daily of prednisone (for 10 months) and had completed his 6th cycle of R-CHOP, which resulted in improvement of the skin lesions. Oral steroids were tapered, and he was maintained on rituximab infusions every 8 weeks but has since been lost to follow-up.

Paraneoplastic lymphoma is a rare condition that affects 0.012% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients.2 Reports of PNP involving the nails are even more rare, with 3 reports in the setting of underlying Castleman disease3-5 and 2 reports in patients with underlying non-Hodgkin6 and follicular1 lymphoma. These studies describe variable nail findings ranging from periungual erosions and edema, formation of dorsal pterygium, onycholysis with longitudinal furrowing, and destruction of the nail plate leading to onychomadesis and/or anonychia. These nail changes typically are seen in lichen planus or in bullous diseases affecting the basement membrane (eg, bullous pemphigoid, acquired epidermolysis bullosa) but not known in pemphigus, which is characterized by nonscarring nail changes.7

Although antidesmoglein 3 antibody was shown to be a pathologic driver in PNP, there is a weak correlation between antibody profiles and clinical presentation.8 In one case of PNP, antidesmoglein 3 antibody was negative, suggesting that lichenoid IFD may cause the phenotypic findings in PNP.9 Thus, the development of nail scarring in PNP may be explained by the presence of lichenoid IFD that is characteristic of PNP. However, the variation in antibody profile in PNP likely is a consequence of epitope spreading.

To the Editor:

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP), also known as paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome, is an autoimmune mucocutaneous blistering disease that typically occurs secondary to a lymphoproliferative disorder. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is characterized by severe erosive stomatitis, polymorphous skin lesions, and potential bronchiolitis obliterans that can mimic a wide array of conditions. The exact pathogenesis is unknown but is thought to be due to a combination of humoral and cell-mediated immunity. The condition usually confers a poor prognosis, with morbidity from 38% to upwards of 90%.1

A 47-year-old man developed prominent pink to dusky, ill-defined, targetoid, coalescing papules over the back; violaceous macules over the palms and soles; and numerous crusted oral erosions while hospitalized for an infection. He had a history of stage IVB follicular lymphoma (double-hit type immunoglobulin heavy chain/BCL2 fusion and rearrangement of BCL6) complicated by extensive erosive skin lesions and multiple lines of infections. The clinical differential diagnosis included Stevens-Johnson syndrome vs erythema multiforme (EM) major secondary to administration of oxacillin vs PNP. Herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction and Mycoplasma titers were negative. Skin biopsies from the back and right abdomen revealed severe lichenoid interface dermatitis (IFD) with numerous dyskeratotic cells mimicking EM and eosinophils; however, direct immunofluorescence of the abdomen biopsy revealed an apparent suprabasal acantholysis with intercellular C3 in the lower half of the epidermis. Histologically, PNP was favored, but indirect immunofluorescence with monkey esophagus IgG was negative.

The skin lesions progressed, and an additional skin biopsy from the left arm performed 1 month later revealed similar histologic features with intercellular IgG and C3 in the lower half of the epidermis with weak basement membrane C3 (Figure 1). Serology also confirmed elevated serum antidesmoglein 1 and 3 antibodies. Thus, in the clinical setting of an erosive mucositis with EM-like and pemphigoidlike eruptions associated with B-cell lymphoma, the patient was diagnosed with PNP.

Despite multiple complications followed by intermittent treatments, the initial therapy with rituximab induction and subsequent cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone) for the B-cell lymphoma was done during his hospital stay. Toward the end of his 8-week hospitalization, the patient was noted to have new lesions involving the hands, digits, and nails. The left hand showed anonychia of several fingers with prominent scarring (Figure 2A). There were large, verrucous, crusted plaques on the distal phalanges of several fingers on the right hand (Figure 2B). At that time, he was taking 20 mg daily of prednisone (for 10 months) and had completed his 6th cycle of R-CHOP, which resulted in improvement of the skin lesions. Oral steroids were tapered, and he was maintained on rituximab infusions every 8 weeks but has since been lost to follow-up.

Paraneoplastic lymphoma is a rare condition that affects 0.012% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients.2 Reports of PNP involving the nails are even more rare, with 3 reports in the setting of underlying Castleman disease3-5 and 2 reports in patients with underlying non-Hodgkin6 and follicular1 lymphoma. These studies describe variable nail findings ranging from periungual erosions and edema, formation of dorsal pterygium, onycholysis with longitudinal furrowing, and destruction of the nail plate leading to onychomadesis and/or anonychia. These nail changes typically are seen in lichen planus or in bullous diseases affecting the basement membrane (eg, bullous pemphigoid, acquired epidermolysis bullosa) but not known in pemphigus, which is characterized by nonscarring nail changes.7

Although antidesmoglein 3 antibody was shown to be a pathologic driver in PNP, there is a weak correlation between antibody profiles and clinical presentation.8 In one case of PNP, antidesmoglein 3 antibody was negative, suggesting that lichenoid IFD may cause the phenotypic findings in PNP.9 Thus, the development of nail scarring in PNP may be explained by the presence of lichenoid IFD that is characteristic of PNP. However, the variation in antibody profile in PNP likely is a consequence of epitope spreading.

- Miest RY, Wetter DA, Drage LA, et al. A mucocutaneous eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1425-1427.

- Anhalt GJ, Mimouni D. Paraneoplastic pemphigus. In: LA G, Katz SI, Gilchrest, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine 8th Edition. Vol 1. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012:600.

- Chorzelski T, Hashimoto T, Maciejewska B, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman tumor, myasthenia gravis and bronchiolitis obliterans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:393-400.

- Lemon MA, Weston WL, Huff JC. Childhood paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman’s tumour. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:115-117.

- Tey HL, Tang MB. A case of paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman’s disease presenting as erosive lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e754-e756.

- Liang JJ, Cordes SF, Witzig TE. More than skin-deep. Cleve Clin J Med. 2013;80:632-633.

- Tosti A, Andre M, Murrell DF. Nail involvement in autoimmune bullous disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:511-513, xi.

- Ohyama M, Amagai M, Hashimoto T, et al. Clinical phenotype and anti-desmoglein autoantibody profile in paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:593-598.

- Kanwar AJ, Vinay K, Varma S, et al. Anti-desmoglein antibody-negative paraneoplastic pemphigus successfully treated with rituximab. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:576-579.

- Miest RY, Wetter DA, Drage LA, et al. A mucocutaneous eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1425-1427.

- Anhalt GJ, Mimouni D. Paraneoplastic pemphigus. In: LA G, Katz SI, Gilchrest, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine 8th Edition. Vol 1. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012:600.

- Chorzelski T, Hashimoto T, Maciejewska B, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman tumor, myasthenia gravis and bronchiolitis obliterans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:393-400.

- Lemon MA, Weston WL, Huff JC. Childhood paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman’s tumour. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:115-117.

- Tey HL, Tang MB. A case of paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman’s disease presenting as erosive lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e754-e756.

- Liang JJ, Cordes SF, Witzig TE. More than skin-deep. Cleve Clin J Med. 2013;80:632-633.

- Tosti A, Andre M, Murrell DF. Nail involvement in autoimmune bullous disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:511-513, xi.

- Ohyama M, Amagai M, Hashimoto T, et al. Clinical phenotype and anti-desmoglein autoantibody profile in paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:593-598.

- Kanwar AJ, Vinay K, Varma S, et al. Anti-desmoglein antibody-negative paraneoplastic pemphigus successfully treated with rituximab. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:576-579.

Practice Points

- Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) is a rare blistering skin eruption commonly associated with an underlying malignancy.

- Paraneoplastic pemphigus generally presents with erosive stomatitis with involvement of the vermillion lip but also can involve the skin and nails.

- Nail involvement can lead to scarring of the nails and can mimic lichen planus, bullous pemphigoid, or epidermolysis bullosa of the nails. These nail changes likely are due to the pronounced lichenoid interphase dermatitis seen in PNP.

Lichen Sclerosus of the Eyelid

To the Editor:

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory skin disease of unknown cause that predominantly affects the anogenital region, but isolated extragenital lesions occur in 6% to 15% of patients. The buttocks, thighs, neck, shoulder, upper torso, and wrists most commonly are involved; the face rarely is affected.1,2 Although the etiology of lichen sclerosus remains undetermined, there is growing evidence that autoimmunity may play a role.1 Lichen sclerosus more commonly is seen in women, and the disease can present at any age, with a bimodal onset in prepubertal children and in postmenopausal women and men in the fourth decade of life.1-3 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms lichen and eyelid and manually screened revealed 6 cases of lichen sclerosus involving the eyelid.2-4 We describe a case of lichen sclerosus involving the eyelid and its histopathology.

A 45-year-old woman was referred to dermatology for evaluation of a right lower eyelid lesion of 3 months’ duration. She first noted a small white patch under the eyelid that had doubled in size and felt firm without bleeding or ulceration. Her medical history was unremarkable, and there was no history of ophthalmic conditions, autoimmune disease, trauma, or cancer. An ophthalmic examination was normal, except for a 20×8-mm, flat, depigmented, firm papule with scalloped borders involving the right lower eyelid margin and extending inferiorly without evidence of madarosis or ulceration (Figure 1). She underwent an incisional biopsy that revealed the diagnosis of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (Figure 2). A full dermatologic evaluation included a genital examination and did not reveal any additional lesions. Tacrolimus ointment was started to avoid the need for long-term use of periocular steroids and their complications.

Extragenital lichen sclerosus typically is asymptomatic and only rarely presents with pruritus, in contrast to genital lichen sclerosus, which characteristically involves pruritus and dyspareunia. Although eyelid involvement is rare, ophthalmic manifestations of lichen sclerosus have included lid notching, ectropion, acquired Brown syndrome, and associated keratoconjunctivitis sicca.3-5 It characteristically appears as a well-demarcated hypopigmented papule. The differential diagnosis for a hypopigmented papule also includes amelanotic melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, vitiligo, tinea versicolor, lichen simplex chronicus, lichen planus, morphea (localized scleroderma), and systemic scleroderma with eyelid involvement.1,5

Differentiating lichen sclerosus from these conditions is of importance, as some of them can have notable morbidity and/or mortality. Of all the autoimmune connective tissue disorders, systemic sclerosus has the highest disease-specific mortality.6 Morphea, on the other hand, can have considerable morbidity. Morphea involving the head and neck notably increases the risk for neurologic complications such as seizures or central nervous system vasculitis as well as ocular complications such as anterior uveitis.6 Of note, genital lichen sclerosus carries an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma and verrucous carcinoma; however, there have been no reported cases of malignant transformation with extragenital lesions.2

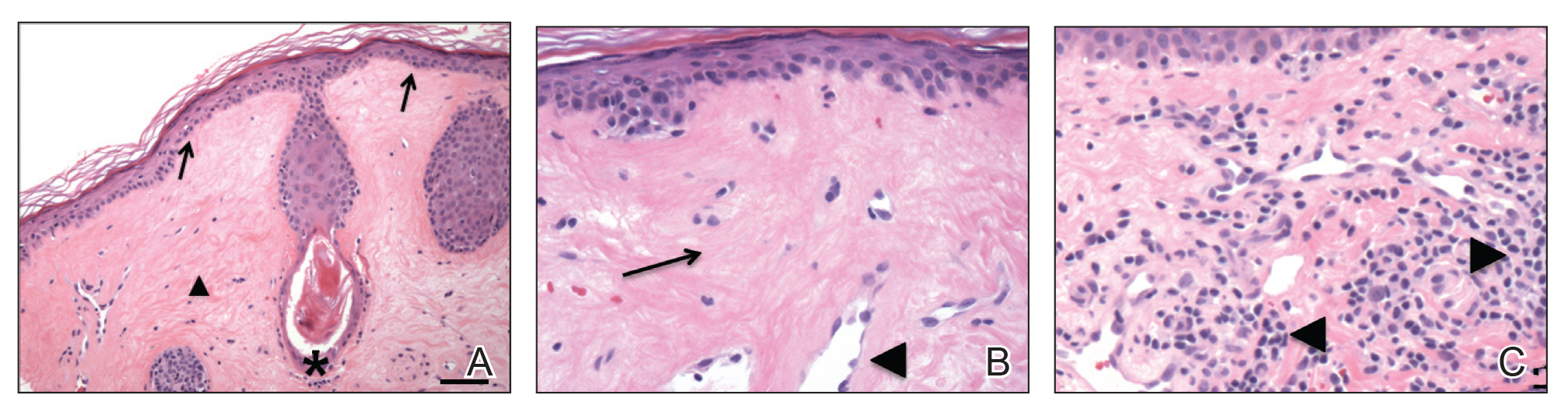

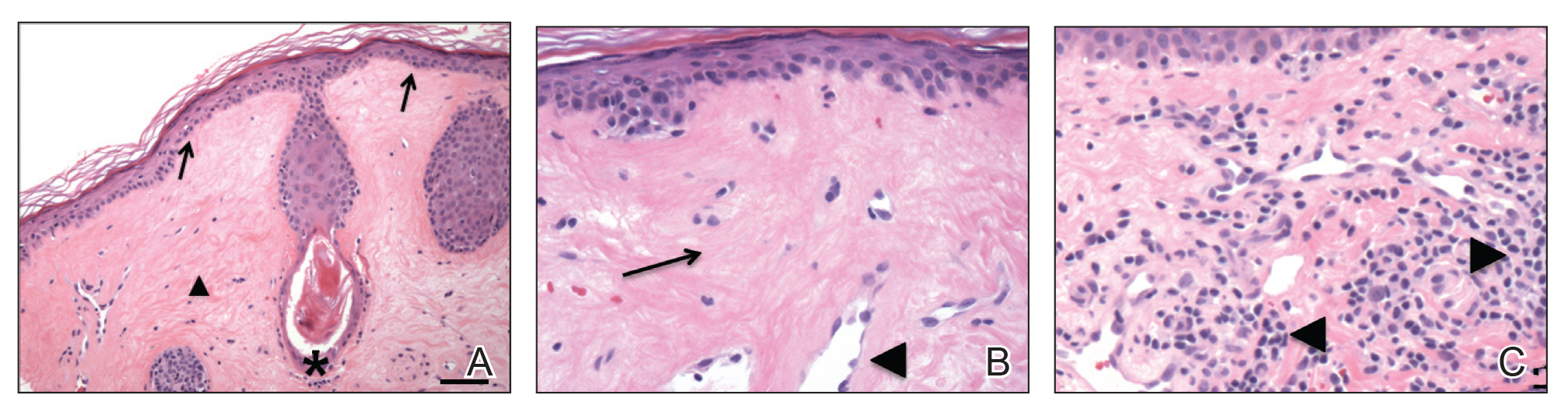

Histopathology is useful to distinguish among these entities. Although there are no specific features separating lichen sclerosus from a morphea overlap and both entities often are classified by clinical presentation, lichen sclerosus demonstrates epidermal atrophy, follicular plugging, homogenized collagen in the upper dermis with dermal edema, and lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2).1 Extragenital lesions in particular also have been noted to have more epidermal atrophy and decreased rete ridges.2

First-line treatment of lichen sclerosus includes topical corticosteroids with emollients for supportive therapy. A topical calcineurin inhibitor such as tacrolimus should be considered for patients who do not respond to corticosteroid therapy or in cases in which corticosteroid therapy is contraindicated to avoid steroid-induced glaucoma or undesirable skin atrophy and hypopigmentation.2 A collaborative approach including dermatology and internal medicine can help identify a systemic or multisystem process.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Rosenthal IM, Taube JM, Nelson DL, et al. A case of infraorbital lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20021.

- Rabinowitz R, Rosenthal G, Yerushalmy J, et al. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca associated with lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Eye. 2000;14:103-104.

- Olver J, Laidler P. Acquired Brown’s syndrome in a patient with combined lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and morphea. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:552-557.

- El-Baba F, Frangieh GT, Iliff WJ, et al. Morphea of the eyelids. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:125-128.

- Fett N. Scleroderma: nomenclatures, etiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatment: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:432-437.

To the Editor:

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory skin disease of unknown cause that predominantly affects the anogenital region, but isolated extragenital lesions occur in 6% to 15% of patients. The buttocks, thighs, neck, shoulder, upper torso, and wrists most commonly are involved; the face rarely is affected.1,2 Although the etiology of lichen sclerosus remains undetermined, there is growing evidence that autoimmunity may play a role.1 Lichen sclerosus more commonly is seen in women, and the disease can present at any age, with a bimodal onset in prepubertal children and in postmenopausal women and men in the fourth decade of life.1-3 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms lichen and eyelid and manually screened revealed 6 cases of lichen sclerosus involving the eyelid.2-4 We describe a case of lichen sclerosus involving the eyelid and its histopathology.

A 45-year-old woman was referred to dermatology for evaluation of a right lower eyelid lesion of 3 months’ duration. She first noted a small white patch under the eyelid that had doubled in size and felt firm without bleeding or ulceration. Her medical history was unremarkable, and there was no history of ophthalmic conditions, autoimmune disease, trauma, or cancer. An ophthalmic examination was normal, except for a 20×8-mm, flat, depigmented, firm papule with scalloped borders involving the right lower eyelid margin and extending inferiorly without evidence of madarosis or ulceration (Figure 1). She underwent an incisional biopsy that revealed the diagnosis of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (Figure 2). A full dermatologic evaluation included a genital examination and did not reveal any additional lesions. Tacrolimus ointment was started to avoid the need for long-term use of periocular steroids and their complications.

Extragenital lichen sclerosus typically is asymptomatic and only rarely presents with pruritus, in contrast to genital lichen sclerosus, which characteristically involves pruritus and dyspareunia. Although eyelid involvement is rare, ophthalmic manifestations of lichen sclerosus have included lid notching, ectropion, acquired Brown syndrome, and associated keratoconjunctivitis sicca.3-5 It characteristically appears as a well-demarcated hypopigmented papule. The differential diagnosis for a hypopigmented papule also includes amelanotic melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, vitiligo, tinea versicolor, lichen simplex chronicus, lichen planus, morphea (localized scleroderma), and systemic scleroderma with eyelid involvement.1,5

Differentiating lichen sclerosus from these conditions is of importance, as some of them can have notable morbidity and/or mortality. Of all the autoimmune connective tissue disorders, systemic sclerosus has the highest disease-specific mortality.6 Morphea, on the other hand, can have considerable morbidity. Morphea involving the head and neck notably increases the risk for neurologic complications such as seizures or central nervous system vasculitis as well as ocular complications such as anterior uveitis.6 Of note, genital lichen sclerosus carries an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma and verrucous carcinoma; however, there have been no reported cases of malignant transformation with extragenital lesions.2

Histopathology is useful to distinguish among these entities. Although there are no specific features separating lichen sclerosus from a morphea overlap and both entities often are classified by clinical presentation, lichen sclerosus demonstrates epidermal atrophy, follicular plugging, homogenized collagen in the upper dermis with dermal edema, and lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2).1 Extragenital lesions in particular also have been noted to have more epidermal atrophy and decreased rete ridges.2

First-line treatment of lichen sclerosus includes topical corticosteroids with emollients for supportive therapy. A topical calcineurin inhibitor such as tacrolimus should be considered for patients who do not respond to corticosteroid therapy or in cases in which corticosteroid therapy is contraindicated to avoid steroid-induced glaucoma or undesirable skin atrophy and hypopigmentation.2 A collaborative approach including dermatology and internal medicine can help identify a systemic or multisystem process.

To the Editor:

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory skin disease of unknown cause that predominantly affects the anogenital region, but isolated extragenital lesions occur in 6% to 15% of patients. The buttocks, thighs, neck, shoulder, upper torso, and wrists most commonly are involved; the face rarely is affected.1,2 Although the etiology of lichen sclerosus remains undetermined, there is growing evidence that autoimmunity may play a role.1 Lichen sclerosus more commonly is seen in women, and the disease can present at any age, with a bimodal onset in prepubertal children and in postmenopausal women and men in the fourth decade of life.1-3 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms lichen and eyelid and manually screened revealed 6 cases of lichen sclerosus involving the eyelid.2-4 We describe a case of lichen sclerosus involving the eyelid and its histopathology.

A 45-year-old woman was referred to dermatology for evaluation of a right lower eyelid lesion of 3 months’ duration. She first noted a small white patch under the eyelid that had doubled in size and felt firm without bleeding or ulceration. Her medical history was unremarkable, and there was no history of ophthalmic conditions, autoimmune disease, trauma, or cancer. An ophthalmic examination was normal, except for a 20×8-mm, flat, depigmented, firm papule with scalloped borders involving the right lower eyelid margin and extending inferiorly without evidence of madarosis or ulceration (Figure 1). She underwent an incisional biopsy that revealed the diagnosis of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (Figure 2). A full dermatologic evaluation included a genital examination and did not reveal any additional lesions. Tacrolimus ointment was started to avoid the need for long-term use of periocular steroids and their complications.

Extragenital lichen sclerosus typically is asymptomatic and only rarely presents with pruritus, in contrast to genital lichen sclerosus, which characteristically involves pruritus and dyspareunia. Although eyelid involvement is rare, ophthalmic manifestations of lichen sclerosus have included lid notching, ectropion, acquired Brown syndrome, and associated keratoconjunctivitis sicca.3-5 It characteristically appears as a well-demarcated hypopigmented papule. The differential diagnosis for a hypopigmented papule also includes amelanotic melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, vitiligo, tinea versicolor, lichen simplex chronicus, lichen planus, morphea (localized scleroderma), and systemic scleroderma with eyelid involvement.1,5

Differentiating lichen sclerosus from these conditions is of importance, as some of them can have notable morbidity and/or mortality. Of all the autoimmune connective tissue disorders, systemic sclerosus has the highest disease-specific mortality.6 Morphea, on the other hand, can have considerable morbidity. Morphea involving the head and neck notably increases the risk for neurologic complications such as seizures or central nervous system vasculitis as well as ocular complications such as anterior uveitis.6 Of note, genital lichen sclerosus carries an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma and verrucous carcinoma; however, there have been no reported cases of malignant transformation with extragenital lesions.2

Histopathology is useful to distinguish among these entities. Although there are no specific features separating lichen sclerosus from a morphea overlap and both entities often are classified by clinical presentation, lichen sclerosus demonstrates epidermal atrophy, follicular plugging, homogenized collagen in the upper dermis with dermal edema, and lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2).1 Extragenital lesions in particular also have been noted to have more epidermal atrophy and decreased rete ridges.2

First-line treatment of lichen sclerosus includes topical corticosteroids with emollients for supportive therapy. A topical calcineurin inhibitor such as tacrolimus should be considered for patients who do not respond to corticosteroid therapy or in cases in which corticosteroid therapy is contraindicated to avoid steroid-induced glaucoma or undesirable skin atrophy and hypopigmentation.2 A collaborative approach including dermatology and internal medicine can help identify a systemic or multisystem process.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Rosenthal IM, Taube JM, Nelson DL, et al. A case of infraorbital lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20021.

- Rabinowitz R, Rosenthal G, Yerushalmy J, et al. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca associated with lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Eye. 2000;14:103-104.

- Olver J, Laidler P. Acquired Brown’s syndrome in a patient with combined lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and morphea. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:552-557.

- El-Baba F, Frangieh GT, Iliff WJ, et al. Morphea of the eyelids. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:125-128.

- Fett N. Scleroderma: nomenclatures, etiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatment: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:432-437.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Rosenthal IM, Taube JM, Nelson DL, et al. A case of infraorbital lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20021.

- Rabinowitz R, Rosenthal G, Yerushalmy J, et al. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca associated with lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Eye. 2000;14:103-104.

- Olver J, Laidler P. Acquired Brown’s syndrome in a patient with combined lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and morphea. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:552-557.

- El-Baba F, Frangieh GT, Iliff WJ, et al. Morphea of the eyelids. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:125-128.

- Fett N. Scleroderma: nomenclatures, etiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatment: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:432-437.

Practice Points

- Lichen sclerosus is not confined to only the anogenital area and can affect the face in rare cases.

Dermatology Resident Education for Skin of Color

An article recently was published in The New York Times with a headline that read, “Dermatology Has a Problem With Skin Color.” 1 The article featured interviews with many well-known dermatologists who are experts in skin of color (SOC), and their points followed a similar pattern—skin disease often looks different in patients with darker skin, and diagnoses often are delayed or missed altogether as a consequence of clinical uncertainty. The article included an interview with Jenna Lester, MD, who leads the SOC clinic at the University of California, San Francisco. In the article, she discussed how dermatologists are trained to recognize findings through pattern recognition. However, if we are only trained to diagnose dermatologic diseases on white skin, we will be unable to recognize diseases in patients with darker skin, leading to suboptimal patient care. 1

Dermatology is a visual specialty, and residents go through thousands of photographs during residency training to distinguish different presentations and unique findings of a variety of skin diseases. Nevertheless, to Dr. Lester’s point, our learning is limited by the photographs and patients that we see.

Additionally, residents training in locations without diverse patient populations rely even more on images in educational resources to recognize clinical presentations in patients with darker skin. A study was published in Cutis earlier this year that surveyed dermatology residents about multiethnic training in residency.2 It showed that residents training in less ethnically diverse areas such as the Midwest and Northwest were more likely to agree that dedicated multiethnic clinics and rotations are important to gain competence compared to residents training in more ethnically diverse regions such as the Southeast, Northeast, and Southwest. Most residents believed 1 to 5 hours per month of lectures covering conditions affecting SOC and/or multiethnic skin are needed to become competent.2

Limitations of Educational Resources

The images in dermatology educational resources do not reflect the diversity of our country’s population. A research letter recently was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (JAAD) in which the authors assessed the number of images of dark skin—Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI—in dermatology educational resources.3 The authors analyzed images from 8 resources commonly used to study dermatology, including 6 printed texts and 2 online resources. Of the printed texts, Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin had the highest percentage of images of dark skin at 19.9%. Overall, VisualDx had the highest percentage of photographs of dark skin at 28.5%, while DermNet NZ had the lowest of all resources at only 2.8%.3

Similarly, a research letter published in the British Journal of Dermatology reviewed images in 2 standard dermatology textbooks.4 Although images of SOC made up 22% to 32% of the overall content, the number of images of sexually transmitted infections in SOC was disproportionate (47%–58%) compared to images of non–sexually transmitted infections (28%). The authors also stated that communities of color often have legacies of mistrust with the health care system, and diagnostic uncertainty can further impair the physician-patient relationship.4

The lack of diversity in clinical images and research was further exemplified by recent publications regarding the perniolike eruption associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), commonly referred to as COVID toes. A research letter was published in the British Journal of Dermatology earlier this year about the lack of images of SOC in publications about the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19.5 At that time, there were zero published images of cutaneous COVID-19 manifestations in Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI, yet COVID-19 disproportionately affects Black individuals and other people of color.5,6 A case series recently was published in JAAD Case Reports that included images of cutaneous COVID-19 findings in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III through V.7 The authors noted that the findings were more subtle on darker skin as the erythema was harder to discern. The inability to identify the perniolike eruption ultimately can delay diagnosis.7

Resident Education

Over the past few months, I have reflected on my role as a dermatology resident and my dedication to antiracism in my personal and professional life. It is not a valid response or excuse to say that certain diagnoses are harder to make because of darker skin tone. It is our responsibility to do better for all patients. To that end, our educational resources should reflect our entire patient population.

I have been working with my coresident Annika Weinhammer, MD, on a quality improvement project to strengthen our educational curriculum at the University of Wisconsin regarding SOC. This project aims to enhance our skills as dermatologists in diagnosing and treating diseases in SOC. Moving forward, we have set an expectation that all didactic lectures must include images of SOC. Below, I have listed some of our initiatives along with recommendations for educational resources. There are multiple dermatology textbooks focused on SOC, including the following:

- Clinical Cases in Skin of Color: Adnexal, Inflammation, Infections, and Pigmentary Disorders 8

- Clinical Cases in Skin of Color: Medical, Oncological and Hair Disorders, and Cosmetic Dermatology 9

- Dermatology Atlas for Skin of Color 10

- Fundamentals of Ethnic Hair: The Dermatologist’s Perspective 11

- Light-Based Therapies for Skin of Color 12

- Pediatric Skin of Color 13

- Skin of Color: A Practical Guide to Dermatologic Diagnosis and Treatment 14

- Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color 15

- Treatments for Skin of Color 16

Our program has provided residents with Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color15 and Treatments for Skin of Color.16 Residents and medical students should search their institution’s electronic library for e-books and other resources including VisualDx, which includes many photographs of SOC that can be used and cited in resident didactics.

There also are a variety of online resources. Mind the Gap is a handbook written by Malone Mukwende, a medical student in London.17,18 The handbook focuses on common clinical signs and how they present in black and brown skin. Another online resource with clinical images is Skin Deep (https://dftbskindeep.com/), a project aimed at improving the diversity of pediatric skin images. An additional online resource is Brown Skin Matters on Instagram (@brownskinmatters) that shows photographs of dermatologic conditions in SOC; however, these photographs are submitted by users and not independently verified.

I also encourage residents to join the Skin of Color Society, which promotes awareness and excellence within the special interest area of SOC. Some of the society's initiatives include educational series, networking events, diversity town halls, and a scientific symposium. Patient information for common dermatologic diagnoses exists on the society's website (https://skinofcolorsociety.org/). The society waives membership fees for resident applicants who provide a letter of good standing from their residency program. The society hosted the Skin of Color Update virtually this year (September 12–13, 2020). It costs $49 to attend, and the recorded lectures are available to stream through the end of 2020. Our department sponsored residents to attend virtually.

Finally, our department has been taking steps to implement antiracism measures in how we work, learn, conduct research, and treat patients. We are leading a resident book club discussing How to Be an Antiracist19 by Ibram X. Kendi. Residents are involved in the local chapter of White Coats for Black Lives (https://whitecoats4blacklives.org/). We also have compiled a list of antiracism resources that was shared with the department, including books, documentaries, podcasts, local and online Black-owned businesses to support, and local Black-led nonprofits.

Final Thoughts

Dermatology residents must be comfortable diagnosing and treating diseases in darker skin tones to provide the best possible care for patients with SOC. Although some common dermatology educational resources have a paucity of clinical images of SOC, there are a variety of additional educational resources through textbooks and websites.

- Rabin RC. Dermatology has a problem with skin color. New York Times. August 30, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/30/health/skin-diseases-black-hispanic.html. Accessed October 5, 2020.

- Cline A, Winter R, Kouroush S, et al. Multiethnic training in residency: a survey of dermatology residents. Cutis. 2020;105:310-313.

- Alvarado SM, Feng H. Representation of dark skin images of common dermatologic conditions in educational resources: a cross-sectional analysis [published online June 18, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.041.

- Lester JC, Taylor SC, Chren MM. Under-representation of skin of colour in dermatology images: not just an educational issue. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1521-1522.

- Lester JC, Jia JL, Zhang L, et al. Absence of images of skin of colour in publications of COVID-19 skin manifestations. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:593-595.

- Golden SH. Coronavirus in African Americans and other people of color. Johns Hopkins Medicine website. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus/covid19-racial-disparities. Published April 20, 2020. Accessed October 5, 2020.

- Daneshjou R, Rana J, Dickman M, et al. Pernio-like eruption associated with COVID-19 in skin of color. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:892-897.

- Love PB, Kundu RV, eds. Clinical Cases in Skin of Color: Adnexal, Inflammation, Infections, and Pigmentary Disorders. Switzerland: Springer; 2016.

- Love PB, Kundu RV, eds. Clinical Cases in Skin of Color: Medical, Oncological and Hair Disorders, and Cosmetic Dermatology. Switzerland: Springer; 2016.

- Jackson-Richards D, Pandya AG, eds. Dermatology Atlas for Skin of Color. New York, NY: Springer; 2014.

- Aguh C, Okoye GA, eds. Fundamentals of Ethnic Hair: The Dermatologist’s Perspective. Switzerland: Springer; 2017.

- Baron E, ed. Light-Based Therapies for Skin of Color. London: Springer; 2009.

- Silverberg NB, Durán-McKinster C, Tay Y-K, eds. Pediatric Skin of Color. New York, NY: Springer; 2015.

- Alexis AF, Barbosa VH, eds. Skin of Color: A Practical Guide to Dermatologic Diagnosis and Treatment. New York, NY: Springer; 2013.

- Taylor SC, Kelly AP, Lim H, et al. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Professional; 2016.

- Taylor SC, Badreshia-Bansal S, Calendar VD, et al. Treatments for Skin of Color. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2011.

- Page S. A medical student couldn’t find how symptoms look on darker skin. he decided to publish a book about it. Washington Post. July 22, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2020/07/22/malone-mukwende-medical-handbook/. Accessed October 5, 2020.

- Mukwende M, Tamony P, Turner M. Mind the Gap: A Handbook of Clinical Signs in Black and Brown Skin. London, England: St. George’s University of London; 2020. https://www.blackandbrownskin.co.uk/mindthegap. Accessed October 5, 2020.

- Kendi IX. How to Be an Antiracist. New York, NY: Random House; 2019.

An article recently was published in The New York Times with a headline that read, “Dermatology Has a Problem With Skin Color.” 1 The article featured interviews with many well-known dermatologists who are experts in skin of color (SOC), and their points followed a similar pattern—skin disease often looks different in patients with darker skin, and diagnoses often are delayed or missed altogether as a consequence of clinical uncertainty. The article included an interview with Jenna Lester, MD, who leads the SOC clinic at the University of California, San Francisco. In the article, she discussed how dermatologists are trained to recognize findings through pattern recognition. However, if we are only trained to diagnose dermatologic diseases on white skin, we will be unable to recognize diseases in patients with darker skin, leading to suboptimal patient care. 1

Dermatology is a visual specialty, and residents go through thousands of photographs during residency training to distinguish different presentations and unique findings of a variety of skin diseases. Nevertheless, to Dr. Lester’s point, our learning is limited by the photographs and patients that we see.

Additionally, residents training in locations without diverse patient populations rely even more on images in educational resources to recognize clinical presentations in patients with darker skin. A study was published in Cutis earlier this year that surveyed dermatology residents about multiethnic training in residency.2 It showed that residents training in less ethnically diverse areas such as the Midwest and Northwest were more likely to agree that dedicated multiethnic clinics and rotations are important to gain competence compared to residents training in more ethnically diverse regions such as the Southeast, Northeast, and Southwest. Most residents believed 1 to 5 hours per month of lectures covering conditions affecting SOC and/or multiethnic skin are needed to become competent.2

Limitations of Educational Resources

The images in dermatology educational resources do not reflect the diversity of our country’s population. A research letter recently was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (JAAD) in which the authors assessed the number of images of dark skin—Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI—in dermatology educational resources.3 The authors analyzed images from 8 resources commonly used to study dermatology, including 6 printed texts and 2 online resources. Of the printed texts, Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin had the highest percentage of images of dark skin at 19.9%. Overall, VisualDx had the highest percentage of photographs of dark skin at 28.5%, while DermNet NZ had the lowest of all resources at only 2.8%.3

Similarly, a research letter published in the British Journal of Dermatology reviewed images in 2 standard dermatology textbooks.4 Although images of SOC made up 22% to 32% of the overall content, the number of images of sexually transmitted infections in SOC was disproportionate (47%–58%) compared to images of non–sexually transmitted infections (28%). The authors also stated that communities of color often have legacies of mistrust with the health care system, and diagnostic uncertainty can further impair the physician-patient relationship.4

The lack of diversity in clinical images and research was further exemplified by recent publications regarding the perniolike eruption associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), commonly referred to as COVID toes. A research letter was published in the British Journal of Dermatology earlier this year about the lack of images of SOC in publications about the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19.5 At that time, there were zero published images of cutaneous COVID-19 manifestations in Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI, yet COVID-19 disproportionately affects Black individuals and other people of color.5,6 A case series recently was published in JAAD Case Reports that included images of cutaneous COVID-19 findings in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III through V.7 The authors noted that the findings were more subtle on darker skin as the erythema was harder to discern. The inability to identify the perniolike eruption ultimately can delay diagnosis.7

Resident Education

Over the past few months, I have reflected on my role as a dermatology resident and my dedication to antiracism in my personal and professional life. It is not a valid response or excuse to say that certain diagnoses are harder to make because of darker skin tone. It is our responsibility to do better for all patients. To that end, our educational resources should reflect our entire patient population.

I have been working with my coresident Annika Weinhammer, MD, on a quality improvement project to strengthen our educational curriculum at the University of Wisconsin regarding SOC. This project aims to enhance our skills as dermatologists in diagnosing and treating diseases in SOC. Moving forward, we have set an expectation that all didactic lectures must include images of SOC. Below, I have listed some of our initiatives along with recommendations for educational resources. There are multiple dermatology textbooks focused on SOC, including the following:

- Clinical Cases in Skin of Color: Adnexal, Inflammation, Infections, and Pigmentary Disorders 8

- Clinical Cases in Skin of Color: Medical, Oncological and Hair Disorders, and Cosmetic Dermatology 9

- Dermatology Atlas for Skin of Color 10

- Fundamentals of Ethnic Hair: The Dermatologist’s Perspective 11

- Light-Based Therapies for Skin of Color 12

- Pediatric Skin of Color 13

- Skin of Color: A Practical Guide to Dermatologic Diagnosis and Treatment 14

- Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color 15

- Treatments for Skin of Color 16

Our program has provided residents with Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color15 and Treatments for Skin of Color.16 Residents and medical students should search their institution’s electronic library for e-books and other resources including VisualDx, which includes many photographs of SOC that can be used and cited in resident didactics.

There also are a variety of online resources. Mind the Gap is a handbook written by Malone Mukwende, a medical student in London.17,18 The handbook focuses on common clinical signs and how they present in black and brown skin. Another online resource with clinical images is Skin Deep (https://dftbskindeep.com/), a project aimed at improving the diversity of pediatric skin images. An additional online resource is Brown Skin Matters on Instagram (@brownskinmatters) that shows photographs of dermatologic conditions in SOC; however, these photographs are submitted by users and not independently verified.

I also encourage residents to join the Skin of Color Society, which promotes awareness and excellence within the special interest area of SOC. Some of the society's initiatives include educational series, networking events, diversity town halls, and a scientific symposium. Patient information for common dermatologic diagnoses exists on the society's website (https://skinofcolorsociety.org/). The society waives membership fees for resident applicants who provide a letter of good standing from their residency program. The society hosted the Skin of Color Update virtually this year (September 12–13, 2020). It costs $49 to attend, and the recorded lectures are available to stream through the end of 2020. Our department sponsored residents to attend virtually.

Finally, our department has been taking steps to implement antiracism measures in how we work, learn, conduct research, and treat patients. We are leading a resident book club discussing How to Be an Antiracist19 by Ibram X. Kendi. Residents are involved in the local chapter of White Coats for Black Lives (https://whitecoats4blacklives.org/). We also have compiled a list of antiracism resources that was shared with the department, including books, documentaries, podcasts, local and online Black-owned businesses to support, and local Black-led nonprofits.

Final Thoughts

Dermatology residents must be comfortable diagnosing and treating diseases in darker skin tones to provide the best possible care for patients with SOC. Although some common dermatology educational resources have a paucity of clinical images of SOC, there are a variety of additional educational resources through textbooks and websites.

An article recently was published in The New York Times with a headline that read, “Dermatology Has a Problem With Skin Color.” 1 The article featured interviews with many well-known dermatologists who are experts in skin of color (SOC), and their points followed a similar pattern—skin disease often looks different in patients with darker skin, and diagnoses often are delayed or missed altogether as a consequence of clinical uncertainty. The article included an interview with Jenna Lester, MD, who leads the SOC clinic at the University of California, San Francisco. In the article, she discussed how dermatologists are trained to recognize findings through pattern recognition. However, if we are only trained to diagnose dermatologic diseases on white skin, we will be unable to recognize diseases in patients with darker skin, leading to suboptimal patient care. 1

Dermatology is a visual specialty, and residents go through thousands of photographs during residency training to distinguish different presentations and unique findings of a variety of skin diseases. Nevertheless, to Dr. Lester’s point, our learning is limited by the photographs and patients that we see.

Additionally, residents training in locations without diverse patient populations rely even more on images in educational resources to recognize clinical presentations in patients with darker skin. A study was published in Cutis earlier this year that surveyed dermatology residents about multiethnic training in residency.2 It showed that residents training in less ethnically diverse areas such as the Midwest and Northwest were more likely to agree that dedicated multiethnic clinics and rotations are important to gain competence compared to residents training in more ethnically diverse regions such as the Southeast, Northeast, and Southwest. Most residents believed 1 to 5 hours per month of lectures covering conditions affecting SOC and/or multiethnic skin are needed to become competent.2

Limitations of Educational Resources

The images in dermatology educational resources do not reflect the diversity of our country’s population. A research letter recently was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (JAAD) in which the authors assessed the number of images of dark skin—Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI—in dermatology educational resources.3 The authors analyzed images from 8 resources commonly used to study dermatology, including 6 printed texts and 2 online resources. Of the printed texts, Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin had the highest percentage of images of dark skin at 19.9%. Overall, VisualDx had the highest percentage of photographs of dark skin at 28.5%, while DermNet NZ had the lowest of all resources at only 2.8%.3

Similarly, a research letter published in the British Journal of Dermatology reviewed images in 2 standard dermatology textbooks.4 Although images of SOC made up 22% to 32% of the overall content, the number of images of sexually transmitted infections in SOC was disproportionate (47%–58%) compared to images of non–sexually transmitted infections (28%). The authors also stated that communities of color often have legacies of mistrust with the health care system, and diagnostic uncertainty can further impair the physician-patient relationship.4

The lack of diversity in clinical images and research was further exemplified by recent publications regarding the perniolike eruption associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), commonly referred to as COVID toes. A research letter was published in the British Journal of Dermatology earlier this year about the lack of images of SOC in publications about the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19.5 At that time, there were zero published images of cutaneous COVID-19 manifestations in Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI, yet COVID-19 disproportionately affects Black individuals and other people of color.5,6 A case series recently was published in JAAD Case Reports that included images of cutaneous COVID-19 findings in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III through V.7 The authors noted that the findings were more subtle on darker skin as the erythema was harder to discern. The inability to identify the perniolike eruption ultimately can delay diagnosis.7

Resident Education