User login

‘Hidden’ danger of type 2 diabetes diagnosis at early age

Those who are found to have type 2 diabetes at a younger age face “hidden” dangers. The issue is becoming more and more important, “since new diagnoses in this younger age group continue to rise,” said the authors of a new study, led by Natalie Nanayakkara, MD.

They believe clinical approaches should be based on age at diagnosis. The results of their new meta-analysis, published online in Diabetologia, reveal the extent of the problem.

Believed to be the first systematic review of its kind, the study showed that the younger the age at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, the greater the risks of dying and of having either microvascular or macrovascular complications each subsequent year (adjusted for current age).

“This difference in risk between younger and older people in terms of absolute versus lifetime risks of type 2 diabetes complications should perhaps be recognized in diabetes management guidelines,” wrote Dr. Nanayakkara, an endocrinologist at Monash University, Melbourne, and colleagues.

Those diagnosed at younger ages are more likely to develop complications that cause greater disability and lead to loss of productivity compared with people diagnosed at an older age, they stressed.

Hence, they suggested “a greater emphasis on preventive measures for younger people with type 2 diabetes,” with “early intensive multifactorial risk factor intervention ... sustained long term to minimize risks over time.”

Large dataset: Use age at diagnosis to risk stratify patients

Rates of type 2 diabetes have increased in all age groups and virtually all countries over the past 3 decades. Particularly worrying is a trend toward increased rates among adults aged 20-44 years. The increases are associated with higher rates of overweight and obesity, poor diet, and decreasing levels of physical activity, numerous studies have shown.

But few studies have examined the association between age at diagnosis and subsequent complications from type 2 diabetes, the authors noted.

Their review included 26 observational studies involving more than one million individuals from 30 countries in the Asia Pacific, Europe, and North America. The investigators found that each 1-year increase in age at diabetes diagnosis was significantly associated with a 4%, 3%, and 5% decreased risk for all-cause mortality, macrovascular disease, and microvascular disease, respectively, adjusted for current age (all P < .001).

Similar decreases in risk per 1-year increase in age at diabetes diagnosis were seen for coronary heart disease (2%), cerebrovascular disease (2%), peripheral vascular disease (3%), retinopathy (8%), nephropathy (6%), and neuropathy (5%); all associations were significant (P < .001).

Dr. Nanayakkara and colleagues noted that current treatment guidelines are limited in that they’re related to the management of patients with suboptimal blood glucose control, and there is no way to predict which people require intensified treatment.

Therefore, they said, “refined stratification using age at diagnosis may provide a method of identifying, at diagnosis, those at greatest risk of complications who would most benefit from targeted, individualized treatment regimens.”

Awareness of this “hidden” danger to younger adults with type 2 diabetes is becoming more and more important, because such cases continue to rise, they reiterated.

They also advised that “public health measures to delay and/or prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes until older age may yield benefits by reducing the duration of diabetes and the burden of complications.”

Dr. Nanayakkara disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Those who are found to have type 2 diabetes at a younger age face “hidden” dangers. The issue is becoming more and more important, “since new diagnoses in this younger age group continue to rise,” said the authors of a new study, led by Natalie Nanayakkara, MD.

They believe clinical approaches should be based on age at diagnosis. The results of their new meta-analysis, published online in Diabetologia, reveal the extent of the problem.

Believed to be the first systematic review of its kind, the study showed that the younger the age at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, the greater the risks of dying and of having either microvascular or macrovascular complications each subsequent year (adjusted for current age).

“This difference in risk between younger and older people in terms of absolute versus lifetime risks of type 2 diabetes complications should perhaps be recognized in diabetes management guidelines,” wrote Dr. Nanayakkara, an endocrinologist at Monash University, Melbourne, and colleagues.

Those diagnosed at younger ages are more likely to develop complications that cause greater disability and lead to loss of productivity compared with people diagnosed at an older age, they stressed.

Hence, they suggested “a greater emphasis on preventive measures for younger people with type 2 diabetes,” with “early intensive multifactorial risk factor intervention ... sustained long term to minimize risks over time.”

Large dataset: Use age at diagnosis to risk stratify patients

Rates of type 2 diabetes have increased in all age groups and virtually all countries over the past 3 decades. Particularly worrying is a trend toward increased rates among adults aged 20-44 years. The increases are associated with higher rates of overweight and obesity, poor diet, and decreasing levels of physical activity, numerous studies have shown.

But few studies have examined the association between age at diagnosis and subsequent complications from type 2 diabetes, the authors noted.

Their review included 26 observational studies involving more than one million individuals from 30 countries in the Asia Pacific, Europe, and North America. The investigators found that each 1-year increase in age at diabetes diagnosis was significantly associated with a 4%, 3%, and 5% decreased risk for all-cause mortality, macrovascular disease, and microvascular disease, respectively, adjusted for current age (all P < .001).

Similar decreases in risk per 1-year increase in age at diabetes diagnosis were seen for coronary heart disease (2%), cerebrovascular disease (2%), peripheral vascular disease (3%), retinopathy (8%), nephropathy (6%), and neuropathy (5%); all associations were significant (P < .001).

Dr. Nanayakkara and colleagues noted that current treatment guidelines are limited in that they’re related to the management of patients with suboptimal blood glucose control, and there is no way to predict which people require intensified treatment.

Therefore, they said, “refined stratification using age at diagnosis may provide a method of identifying, at diagnosis, those at greatest risk of complications who would most benefit from targeted, individualized treatment regimens.”

Awareness of this “hidden” danger to younger adults with type 2 diabetes is becoming more and more important, because such cases continue to rise, they reiterated.

They also advised that “public health measures to delay and/or prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes until older age may yield benefits by reducing the duration of diabetes and the burden of complications.”

Dr. Nanayakkara disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Those who are found to have type 2 diabetes at a younger age face “hidden” dangers. The issue is becoming more and more important, “since new diagnoses in this younger age group continue to rise,” said the authors of a new study, led by Natalie Nanayakkara, MD.

They believe clinical approaches should be based on age at diagnosis. The results of their new meta-analysis, published online in Diabetologia, reveal the extent of the problem.

Believed to be the first systematic review of its kind, the study showed that the younger the age at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, the greater the risks of dying and of having either microvascular or macrovascular complications each subsequent year (adjusted for current age).

“This difference in risk between younger and older people in terms of absolute versus lifetime risks of type 2 diabetes complications should perhaps be recognized in diabetes management guidelines,” wrote Dr. Nanayakkara, an endocrinologist at Monash University, Melbourne, and colleagues.

Those diagnosed at younger ages are more likely to develop complications that cause greater disability and lead to loss of productivity compared with people diagnosed at an older age, they stressed.

Hence, they suggested “a greater emphasis on preventive measures for younger people with type 2 diabetes,” with “early intensive multifactorial risk factor intervention ... sustained long term to minimize risks over time.”

Large dataset: Use age at diagnosis to risk stratify patients

Rates of type 2 diabetes have increased in all age groups and virtually all countries over the past 3 decades. Particularly worrying is a trend toward increased rates among adults aged 20-44 years. The increases are associated with higher rates of overweight and obesity, poor diet, and decreasing levels of physical activity, numerous studies have shown.

But few studies have examined the association between age at diagnosis and subsequent complications from type 2 diabetes, the authors noted.

Their review included 26 observational studies involving more than one million individuals from 30 countries in the Asia Pacific, Europe, and North America. The investigators found that each 1-year increase in age at diabetes diagnosis was significantly associated with a 4%, 3%, and 5% decreased risk for all-cause mortality, macrovascular disease, and microvascular disease, respectively, adjusted for current age (all P < .001).

Similar decreases in risk per 1-year increase in age at diabetes diagnosis were seen for coronary heart disease (2%), cerebrovascular disease (2%), peripheral vascular disease (3%), retinopathy (8%), nephropathy (6%), and neuropathy (5%); all associations were significant (P < .001).

Dr. Nanayakkara and colleagues noted that current treatment guidelines are limited in that they’re related to the management of patients with suboptimal blood glucose control, and there is no way to predict which people require intensified treatment.

Therefore, they said, “refined stratification using age at diagnosis may provide a method of identifying, at diagnosis, those at greatest risk of complications who would most benefit from targeted, individualized treatment regimens.”

Awareness of this “hidden” danger to younger adults with type 2 diabetes is becoming more and more important, because such cases continue to rise, they reiterated.

They also advised that “public health measures to delay and/or prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes until older age may yield benefits by reducing the duration of diabetes and the burden of complications.”

Dr. Nanayakkara disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Zoom Zoom Zoom: An end-of-year update from a virtual psychiatrist

In mid-April, a month into pandemic life with a stay-at-home order, I wrote about my experiences as a virtual outpatient psychiatrist in private practice. It’s been 10 months now and with this tragic year drawing to a close, it seems like a good time for an update.

In that April column, I describe how I created a makeshift home office. This entailed pushing my son’s baseball card collection and dusty sports trophies to the side of the room, bringing in a desk and a rug, a house plant, and a statue of a Buddha. I enjoyed watching out the window behind my computer screen as the neighbors and their dogs walked by, and I loved seeing the tree out the window blossom into gorgeous flowers.

With time, my physical space has changed. The remnants of my son’s childhood have all been moved to a closet, artwork has been added to the wall behind me, and the space is now clearly an office, though my laptop remains propped on a pile of books so that no one is looking up my nose. The room, with four large windows facing north and west, has issues with temperature control. In an old house, the heat works all too well in the adjacent bedroom (while the rest of the occupants in other rooms freeze), but the office itself has no heat: I have added both a fan and a space heater, and there are some very cold days where I’ve propped open one of the windows. And with the shortened days, large windows on two walls have presented a challenge as the sun changes positions throughout the day – there are times when the sun’s rays streak across my face in such a way that I look rather ethereal, and between sessions I have lowered, raised, and adjusted the blinds to avoid this. I finally pulled off the thin metal venetian blinds and took them to Lowe’s, where a partially masked young woman cut me new blinds with larger slats. An ergonomic office chair has replaced the wicker Ikea chair I was using, and between all these machinations, I am now physically comfortable most of the time. I believe I am still a bit too pixelated on the screen, but my patients are not complaining, and when the natural lighting fades at 4:30 p.m., the overhead lighting is all wrong again. These all are things I never considered – or long ago addressed – in my real-life practice of psychiatry in a office I have loved for years.

With time, I’ve grown more comfortable working from home on a screen and there are things about this life I’ve grown to like. My husband no longer travels, my daughter – my gift of the pandemic – returned home from New York City where she was in her final months of graduate school, and these unexpected months with her (and her cat) have been a pleasure. There is something nice about being trapped at home with people I love, even if we are all in our respective places, in front of our separate screens. There has been time for long walks, trips to the beach, and long bike rides. And as my daughter now prepares to move to Denver, I have been heartened by the hope of vaccines, and the knowledge that I will likely be able to see her again in the coming months. The people are not the only ones who have benefited from this time at home together – I have no idea how we would have managed with our elderly dog if we were not home to care for him.

My life has become more efficient. I used to find myself aggravated when patients forgot their appointments, a not-infrequent occurrence. People no longer get caught in traffic, they come on time, and they don’t complain about my crowded parking lot. When there is down time, I use it more efficiently at home – a load of laundry gets done, I get a chance to turn on the news or exercise, or make dinner early. And because I have two other family members working from home, I am not the only one mixing work with chores or exercise.

While my medical colleagues who work in settings where they must see patients in person have struggled or functioned in some state of denial, I have felt safe and protected, a bit cocooned with my family in a house big enough to give us all space, in a neighborhood with sidewalks and places to walk, and to protect my sanity, I am lucky to have a patio that has now been equipped with lights, patio heaters, a fire pit, and socially distanced tables so that I can still see friends outside.

Telemedicine has added a new dimension to treatment. I’ve had family sessions with multiple people joining a zoom link from different locations – so much easier than coordinating a time when everyone can travel to my office. I’ve had patients call in from cars and from closets in search of privacy, and from their gardens and poolsides. I’ve met spouses, children, many a dog and cat, plus the more unusual of pets and farm animals, including a goat, ferret, lizard, African grey parrot, and guinea pigs.

These are the good things, and while I wish I could say it was all good, so much of what remains is laden with anxiety. My son lives nearby, but he has shared a house with a hospital worker for much of the past year and there were COVID scares, months at a time without so much as a hug, and my husband has not seen his parents or brother for a year now. There are the awkward waves or salutes with friends I once gave carefree hugs, the constant thoughts of how far away is that person standing, and each person’s “beliefs” about what is safe when we still don’t fully understand how this virus spreads. I worry for myself, I worry for my family and friends, and I worry for my patients when they tell me about behaviors that clearly are not safe.

At first, I found my work as a telepsychiatrist to be exhausting, and I assumed it was because my patients were now just faces, inches from my own eyes, and no longer diffused by a visual field that included my whole office and the opportunity to break eye contact while I still listened with full attention. This has gotten much better – I’ve adjusted to my on-screen relationships, but what has not gotten better is both the acuity, and sometimes the boredom.

Patients are struggling; they are sad, lonely, and missing the richness of their former lives. They miss friends, meeting new people, cultural experiences, diversity in how they spend their time, and travel. They have all the same human experiences of loss, illness, and grief, but with the added burden of struggling alone or within the confines of pandemic life that has destroyed our ability to mark events with social and religious customs that guide healing. People who had done well for years are now needing more, and those who were not doing well are doing worse. It makes for long days.

I mentioned boredom: With less time spent with other people, so many sessions are about COVID – who has it, who might have it, what people are doing to avoid it, and still, how they get their groceries. The second most popular psychotherapy topic includes what they are watching on Netflix, and as human beings trudging through this together, I have appreciated my patients’ suggestions as much as they have appreciated mine.* Life for all of us has come to be more about survival, and less about self-discovery and striving. Many sessions have started to feel the same from 1 hour to the next, in ways they never did before.

There are other aspects to telepsychiatry that I have found difficult. The site I have used most – Doxy.me – works well with some patients, but with others there are technical problems. Sessions freeze, the sound goes in or out, and we end up switching to another platform, which may or may not work better. Sometimes patients have the camera at odd angles, or they bounce a laptop on their knees to the point that I get seasick. One of my family members has said that I can sometimes be overheard, so I now have a radio playing classical music outside my door, and I often use earbuds so that the patient can’t be overheard and I speak more softly with them – this has all been good in terms of improving privacy, but after a while I find that it’s stressful to have people talking to me inside my own ears! These are little kinks, but when you do it for hours a day, they add up to a sense of being stressed in ways that in-person psychiatry does not lend itself to.

Finally, three seasons into my work-at-home life, I still have not found a new rhythm for some of the logistical aspects of private practice that came so easily in my office. My mail still goes to the office, the plants there still need water, my files and computer are there, but tasks that were once a seamless part of my work day now spill into my time off and I go into the office each week to file, log medications, and attend to the business of my practice. My smartphone, with its ability to e-prescribe, invoice, and fax, has made it possible for me to manage and certainly, outpatient psychiatrists are very lucky that we have the option to continue our work with patients remotely during such difficult times.

I have sent people for virtual intensive substance treatment, and to virtual couples’ counseling, and these remote treatments have been useful. The one treatment that has been very difficult for patients to negotiate has been outpatient electroconvulsive therapy – this requires coordination with another person to drive the patient to treatments (and to wait outside in the parking lot), and also for separate weekly COVID testing. Transcranial magnetic stimulation, which also is still being done in person, has not been any different – patients can drive themselves and the one center I referred to has not required preprocedure COVID testing.

What does the future hold? Will we ever go back to practicing the way we did? While some of my patients miss real-life therapy, most do not; they too like the added efficiency, getting treatment from the comfort of their home without the stress of finding the time to travel. I’ve taken on new patients during this time, and while I anticipated that it would be difficult, it has gone surprisingly well – people I have never met in real life talk to me with ease, and both psychotherapy and medication management have gone well. The one area that I have found most difficult is assessing tremors and dyskinesias, and one patient mentioned she has gained nearly 50 pounds over the past year – something I certainly would have noticed and attended to sooner in real life. I have mixed feelings about returning to a completely live practice. I think I would like a combination where I see all my patients in person once in a while, but would like to be able to offer some times where I see people virtually from home at least one day a week.

Time will tell how that plays out with insurers. My best guess is that, with the lowered no-show rates that everyone is seeing and the higher levels of depression and anxiety that people are having, this may have been a costly time for mental health care. At the same time, inpatient psychiatric units have decreased their capacity, and perhaps more efficient delivery of outpatient care has lowered the overall cost. I suppose we will wait to hear, but for many, the transition to virtual care has allowed many people to get treatment who would have otherwise gone without care.

In my April article, I mentioned that I was having daily Facetime check-in visits with a distressed patient who was on a COVID unit with pneumonia. Since then, I have had several more patients contract COVID, and many of my patients have had family members who have tested positive or become symptomatic with COVID. It has been nice to have sessions with people during this time, and thankfully, I have not had any more patients who have required hospitalization for the virus.

I still catch myself thinking that, of all the things I have worried about over the years, “pandemic” was never on my list. It seems so strange that I left my office on a Friday with no idea that I would not be returning to work the following Monday, or that life would change in such a radical way. As we leave this awful year behind and greet the new one with the hope that vaccines and a new administration might offer solutions, I’d like to wish my readers the best for a healthy, safe, and gentle New Year.

*My top viewing picks for now are “The Queen’s Gambit” (Netflix), and “A Place to Call Home” (Acorn).

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

In mid-April, a month into pandemic life with a stay-at-home order, I wrote about my experiences as a virtual outpatient psychiatrist in private practice. It’s been 10 months now and with this tragic year drawing to a close, it seems like a good time for an update.

In that April column, I describe how I created a makeshift home office. This entailed pushing my son’s baseball card collection and dusty sports trophies to the side of the room, bringing in a desk and a rug, a house plant, and a statue of a Buddha. I enjoyed watching out the window behind my computer screen as the neighbors and their dogs walked by, and I loved seeing the tree out the window blossom into gorgeous flowers.

With time, my physical space has changed. The remnants of my son’s childhood have all been moved to a closet, artwork has been added to the wall behind me, and the space is now clearly an office, though my laptop remains propped on a pile of books so that no one is looking up my nose. The room, with four large windows facing north and west, has issues with temperature control. In an old house, the heat works all too well in the adjacent bedroom (while the rest of the occupants in other rooms freeze), but the office itself has no heat: I have added both a fan and a space heater, and there are some very cold days where I’ve propped open one of the windows. And with the shortened days, large windows on two walls have presented a challenge as the sun changes positions throughout the day – there are times when the sun’s rays streak across my face in such a way that I look rather ethereal, and between sessions I have lowered, raised, and adjusted the blinds to avoid this. I finally pulled off the thin metal venetian blinds and took them to Lowe’s, where a partially masked young woman cut me new blinds with larger slats. An ergonomic office chair has replaced the wicker Ikea chair I was using, and between all these machinations, I am now physically comfortable most of the time. I believe I am still a bit too pixelated on the screen, but my patients are not complaining, and when the natural lighting fades at 4:30 p.m., the overhead lighting is all wrong again. These all are things I never considered – or long ago addressed – in my real-life practice of psychiatry in a office I have loved for years.

With time, I’ve grown more comfortable working from home on a screen and there are things about this life I’ve grown to like. My husband no longer travels, my daughter – my gift of the pandemic – returned home from New York City where she was in her final months of graduate school, and these unexpected months with her (and her cat) have been a pleasure. There is something nice about being trapped at home with people I love, even if we are all in our respective places, in front of our separate screens. There has been time for long walks, trips to the beach, and long bike rides. And as my daughter now prepares to move to Denver, I have been heartened by the hope of vaccines, and the knowledge that I will likely be able to see her again in the coming months. The people are not the only ones who have benefited from this time at home together – I have no idea how we would have managed with our elderly dog if we were not home to care for him.

My life has become more efficient. I used to find myself aggravated when patients forgot their appointments, a not-infrequent occurrence. People no longer get caught in traffic, they come on time, and they don’t complain about my crowded parking lot. When there is down time, I use it more efficiently at home – a load of laundry gets done, I get a chance to turn on the news or exercise, or make dinner early. And because I have two other family members working from home, I am not the only one mixing work with chores or exercise.

While my medical colleagues who work in settings where they must see patients in person have struggled or functioned in some state of denial, I have felt safe and protected, a bit cocooned with my family in a house big enough to give us all space, in a neighborhood with sidewalks and places to walk, and to protect my sanity, I am lucky to have a patio that has now been equipped with lights, patio heaters, a fire pit, and socially distanced tables so that I can still see friends outside.

Telemedicine has added a new dimension to treatment. I’ve had family sessions with multiple people joining a zoom link from different locations – so much easier than coordinating a time when everyone can travel to my office. I’ve had patients call in from cars and from closets in search of privacy, and from their gardens and poolsides. I’ve met spouses, children, many a dog and cat, plus the more unusual of pets and farm animals, including a goat, ferret, lizard, African grey parrot, and guinea pigs.

These are the good things, and while I wish I could say it was all good, so much of what remains is laden with anxiety. My son lives nearby, but he has shared a house with a hospital worker for much of the past year and there were COVID scares, months at a time without so much as a hug, and my husband has not seen his parents or brother for a year now. There are the awkward waves or salutes with friends I once gave carefree hugs, the constant thoughts of how far away is that person standing, and each person’s “beliefs” about what is safe when we still don’t fully understand how this virus spreads. I worry for myself, I worry for my family and friends, and I worry for my patients when they tell me about behaviors that clearly are not safe.

At first, I found my work as a telepsychiatrist to be exhausting, and I assumed it was because my patients were now just faces, inches from my own eyes, and no longer diffused by a visual field that included my whole office and the opportunity to break eye contact while I still listened with full attention. This has gotten much better – I’ve adjusted to my on-screen relationships, but what has not gotten better is both the acuity, and sometimes the boredom.

Patients are struggling; they are sad, lonely, and missing the richness of their former lives. They miss friends, meeting new people, cultural experiences, diversity in how they spend their time, and travel. They have all the same human experiences of loss, illness, and grief, but with the added burden of struggling alone or within the confines of pandemic life that has destroyed our ability to mark events with social and religious customs that guide healing. People who had done well for years are now needing more, and those who were not doing well are doing worse. It makes for long days.

I mentioned boredom: With less time spent with other people, so many sessions are about COVID – who has it, who might have it, what people are doing to avoid it, and still, how they get their groceries. The second most popular psychotherapy topic includes what they are watching on Netflix, and as human beings trudging through this together, I have appreciated my patients’ suggestions as much as they have appreciated mine.* Life for all of us has come to be more about survival, and less about self-discovery and striving. Many sessions have started to feel the same from 1 hour to the next, in ways they never did before.

There are other aspects to telepsychiatry that I have found difficult. The site I have used most – Doxy.me – works well with some patients, but with others there are technical problems. Sessions freeze, the sound goes in or out, and we end up switching to another platform, which may or may not work better. Sometimes patients have the camera at odd angles, or they bounce a laptop on their knees to the point that I get seasick. One of my family members has said that I can sometimes be overheard, so I now have a radio playing classical music outside my door, and I often use earbuds so that the patient can’t be overheard and I speak more softly with them – this has all been good in terms of improving privacy, but after a while I find that it’s stressful to have people talking to me inside my own ears! These are little kinks, but when you do it for hours a day, they add up to a sense of being stressed in ways that in-person psychiatry does not lend itself to.

Finally, three seasons into my work-at-home life, I still have not found a new rhythm for some of the logistical aspects of private practice that came so easily in my office. My mail still goes to the office, the plants there still need water, my files and computer are there, but tasks that were once a seamless part of my work day now spill into my time off and I go into the office each week to file, log medications, and attend to the business of my practice. My smartphone, with its ability to e-prescribe, invoice, and fax, has made it possible for me to manage and certainly, outpatient psychiatrists are very lucky that we have the option to continue our work with patients remotely during such difficult times.

I have sent people for virtual intensive substance treatment, and to virtual couples’ counseling, and these remote treatments have been useful. The one treatment that has been very difficult for patients to negotiate has been outpatient electroconvulsive therapy – this requires coordination with another person to drive the patient to treatments (and to wait outside in the parking lot), and also for separate weekly COVID testing. Transcranial magnetic stimulation, which also is still being done in person, has not been any different – patients can drive themselves and the one center I referred to has not required preprocedure COVID testing.

What does the future hold? Will we ever go back to practicing the way we did? While some of my patients miss real-life therapy, most do not; they too like the added efficiency, getting treatment from the comfort of their home without the stress of finding the time to travel. I’ve taken on new patients during this time, and while I anticipated that it would be difficult, it has gone surprisingly well – people I have never met in real life talk to me with ease, and both psychotherapy and medication management have gone well. The one area that I have found most difficult is assessing tremors and dyskinesias, and one patient mentioned she has gained nearly 50 pounds over the past year – something I certainly would have noticed and attended to sooner in real life. I have mixed feelings about returning to a completely live practice. I think I would like a combination where I see all my patients in person once in a while, but would like to be able to offer some times where I see people virtually from home at least one day a week.

Time will tell how that plays out with insurers. My best guess is that, with the lowered no-show rates that everyone is seeing and the higher levels of depression and anxiety that people are having, this may have been a costly time for mental health care. At the same time, inpatient psychiatric units have decreased their capacity, and perhaps more efficient delivery of outpatient care has lowered the overall cost. I suppose we will wait to hear, but for many, the transition to virtual care has allowed many people to get treatment who would have otherwise gone without care.

In my April article, I mentioned that I was having daily Facetime check-in visits with a distressed patient who was on a COVID unit with pneumonia. Since then, I have had several more patients contract COVID, and many of my patients have had family members who have tested positive or become symptomatic with COVID. It has been nice to have sessions with people during this time, and thankfully, I have not had any more patients who have required hospitalization for the virus.

I still catch myself thinking that, of all the things I have worried about over the years, “pandemic” was never on my list. It seems so strange that I left my office on a Friday with no idea that I would not be returning to work the following Monday, or that life would change in such a radical way. As we leave this awful year behind and greet the new one with the hope that vaccines and a new administration might offer solutions, I’d like to wish my readers the best for a healthy, safe, and gentle New Year.

*My top viewing picks for now are “The Queen’s Gambit” (Netflix), and “A Place to Call Home” (Acorn).

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

In mid-April, a month into pandemic life with a stay-at-home order, I wrote about my experiences as a virtual outpatient psychiatrist in private practice. It’s been 10 months now and with this tragic year drawing to a close, it seems like a good time for an update.

In that April column, I describe how I created a makeshift home office. This entailed pushing my son’s baseball card collection and dusty sports trophies to the side of the room, bringing in a desk and a rug, a house plant, and a statue of a Buddha. I enjoyed watching out the window behind my computer screen as the neighbors and their dogs walked by, and I loved seeing the tree out the window blossom into gorgeous flowers.

With time, my physical space has changed. The remnants of my son’s childhood have all been moved to a closet, artwork has been added to the wall behind me, and the space is now clearly an office, though my laptop remains propped on a pile of books so that no one is looking up my nose. The room, with four large windows facing north and west, has issues with temperature control. In an old house, the heat works all too well in the adjacent bedroom (while the rest of the occupants in other rooms freeze), but the office itself has no heat: I have added both a fan and a space heater, and there are some very cold days where I’ve propped open one of the windows. And with the shortened days, large windows on two walls have presented a challenge as the sun changes positions throughout the day – there are times when the sun’s rays streak across my face in such a way that I look rather ethereal, and between sessions I have lowered, raised, and adjusted the blinds to avoid this. I finally pulled off the thin metal venetian blinds and took them to Lowe’s, where a partially masked young woman cut me new blinds with larger slats. An ergonomic office chair has replaced the wicker Ikea chair I was using, and between all these machinations, I am now physically comfortable most of the time. I believe I am still a bit too pixelated on the screen, but my patients are not complaining, and when the natural lighting fades at 4:30 p.m., the overhead lighting is all wrong again. These all are things I never considered – or long ago addressed – in my real-life practice of psychiatry in a office I have loved for years.

With time, I’ve grown more comfortable working from home on a screen and there are things about this life I’ve grown to like. My husband no longer travels, my daughter – my gift of the pandemic – returned home from New York City where she was in her final months of graduate school, and these unexpected months with her (and her cat) have been a pleasure. There is something nice about being trapped at home with people I love, even if we are all in our respective places, in front of our separate screens. There has been time for long walks, trips to the beach, and long bike rides. And as my daughter now prepares to move to Denver, I have been heartened by the hope of vaccines, and the knowledge that I will likely be able to see her again in the coming months. The people are not the only ones who have benefited from this time at home together – I have no idea how we would have managed with our elderly dog if we were not home to care for him.

My life has become more efficient. I used to find myself aggravated when patients forgot their appointments, a not-infrequent occurrence. People no longer get caught in traffic, they come on time, and they don’t complain about my crowded parking lot. When there is down time, I use it more efficiently at home – a load of laundry gets done, I get a chance to turn on the news or exercise, or make dinner early. And because I have two other family members working from home, I am not the only one mixing work with chores or exercise.

While my medical colleagues who work in settings where they must see patients in person have struggled or functioned in some state of denial, I have felt safe and protected, a bit cocooned with my family in a house big enough to give us all space, in a neighborhood with sidewalks and places to walk, and to protect my sanity, I am lucky to have a patio that has now been equipped with lights, patio heaters, a fire pit, and socially distanced tables so that I can still see friends outside.

Telemedicine has added a new dimension to treatment. I’ve had family sessions with multiple people joining a zoom link from different locations – so much easier than coordinating a time when everyone can travel to my office. I’ve had patients call in from cars and from closets in search of privacy, and from their gardens and poolsides. I’ve met spouses, children, many a dog and cat, plus the more unusual of pets and farm animals, including a goat, ferret, lizard, African grey parrot, and guinea pigs.

These are the good things, and while I wish I could say it was all good, so much of what remains is laden with anxiety. My son lives nearby, but he has shared a house with a hospital worker for much of the past year and there were COVID scares, months at a time without so much as a hug, and my husband has not seen his parents or brother for a year now. There are the awkward waves or salutes with friends I once gave carefree hugs, the constant thoughts of how far away is that person standing, and each person’s “beliefs” about what is safe when we still don’t fully understand how this virus spreads. I worry for myself, I worry for my family and friends, and I worry for my patients when they tell me about behaviors that clearly are not safe.

At first, I found my work as a telepsychiatrist to be exhausting, and I assumed it was because my patients were now just faces, inches from my own eyes, and no longer diffused by a visual field that included my whole office and the opportunity to break eye contact while I still listened with full attention. This has gotten much better – I’ve adjusted to my on-screen relationships, but what has not gotten better is both the acuity, and sometimes the boredom.

Patients are struggling; they are sad, lonely, and missing the richness of their former lives. They miss friends, meeting new people, cultural experiences, diversity in how they spend their time, and travel. They have all the same human experiences of loss, illness, and grief, but with the added burden of struggling alone or within the confines of pandemic life that has destroyed our ability to mark events with social and religious customs that guide healing. People who had done well for years are now needing more, and those who were not doing well are doing worse. It makes for long days.

I mentioned boredom: With less time spent with other people, so many sessions are about COVID – who has it, who might have it, what people are doing to avoid it, and still, how they get their groceries. The second most popular psychotherapy topic includes what they are watching on Netflix, and as human beings trudging through this together, I have appreciated my patients’ suggestions as much as they have appreciated mine.* Life for all of us has come to be more about survival, and less about self-discovery and striving. Many sessions have started to feel the same from 1 hour to the next, in ways they never did before.

There are other aspects to telepsychiatry that I have found difficult. The site I have used most – Doxy.me – works well with some patients, but with others there are technical problems. Sessions freeze, the sound goes in or out, and we end up switching to another platform, which may or may not work better. Sometimes patients have the camera at odd angles, or they bounce a laptop on their knees to the point that I get seasick. One of my family members has said that I can sometimes be overheard, so I now have a radio playing classical music outside my door, and I often use earbuds so that the patient can’t be overheard and I speak more softly with them – this has all been good in terms of improving privacy, but after a while I find that it’s stressful to have people talking to me inside my own ears! These are little kinks, but when you do it for hours a day, they add up to a sense of being stressed in ways that in-person psychiatry does not lend itself to.

Finally, three seasons into my work-at-home life, I still have not found a new rhythm for some of the logistical aspects of private practice that came so easily in my office. My mail still goes to the office, the plants there still need water, my files and computer are there, but tasks that were once a seamless part of my work day now spill into my time off and I go into the office each week to file, log medications, and attend to the business of my practice. My smartphone, with its ability to e-prescribe, invoice, and fax, has made it possible for me to manage and certainly, outpatient psychiatrists are very lucky that we have the option to continue our work with patients remotely during such difficult times.

I have sent people for virtual intensive substance treatment, and to virtual couples’ counseling, and these remote treatments have been useful. The one treatment that has been very difficult for patients to negotiate has been outpatient electroconvulsive therapy – this requires coordination with another person to drive the patient to treatments (and to wait outside in the parking lot), and also for separate weekly COVID testing. Transcranial magnetic stimulation, which also is still being done in person, has not been any different – patients can drive themselves and the one center I referred to has not required preprocedure COVID testing.

What does the future hold? Will we ever go back to practicing the way we did? While some of my patients miss real-life therapy, most do not; they too like the added efficiency, getting treatment from the comfort of their home without the stress of finding the time to travel. I’ve taken on new patients during this time, and while I anticipated that it would be difficult, it has gone surprisingly well – people I have never met in real life talk to me with ease, and both psychotherapy and medication management have gone well. The one area that I have found most difficult is assessing tremors and dyskinesias, and one patient mentioned she has gained nearly 50 pounds over the past year – something I certainly would have noticed and attended to sooner in real life. I have mixed feelings about returning to a completely live practice. I think I would like a combination where I see all my patients in person once in a while, but would like to be able to offer some times where I see people virtually from home at least one day a week.

Time will tell how that plays out with insurers. My best guess is that, with the lowered no-show rates that everyone is seeing and the higher levels of depression and anxiety that people are having, this may have been a costly time for mental health care. At the same time, inpatient psychiatric units have decreased their capacity, and perhaps more efficient delivery of outpatient care has lowered the overall cost. I suppose we will wait to hear, but for many, the transition to virtual care has allowed many people to get treatment who would have otherwise gone without care.

In my April article, I mentioned that I was having daily Facetime check-in visits with a distressed patient who was on a COVID unit with pneumonia. Since then, I have had several more patients contract COVID, and many of my patients have had family members who have tested positive or become symptomatic with COVID. It has been nice to have sessions with people during this time, and thankfully, I have not had any more patients who have required hospitalization for the virus.

I still catch myself thinking that, of all the things I have worried about over the years, “pandemic” was never on my list. It seems so strange that I left my office on a Friday with no idea that I would not be returning to work the following Monday, or that life would change in such a radical way. As we leave this awful year behind and greet the new one with the hope that vaccines and a new administration might offer solutions, I’d like to wish my readers the best for a healthy, safe, and gentle New Year.

*My top viewing picks for now are “The Queen’s Gambit” (Netflix), and “A Place to Call Home” (Acorn).

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

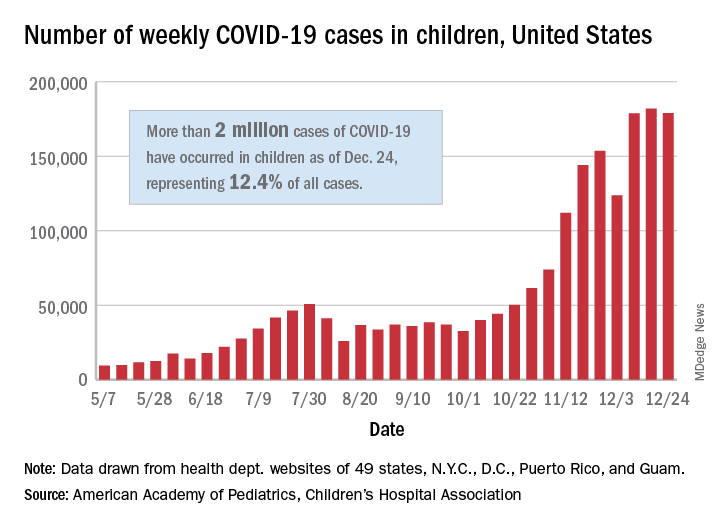

COVID-19 vaccine rollout faces delays

If the current pace of vaccination continues, “it’s going to take years, not months, to vaccinate the American people,” President-elect Joe Biden said during a briefing Dec. 29.

In fact, at the current rate, it would take nearly 10 years to vaccinate enough Americans to bring the pandemic under control, according to NBC News. To reach 80% of the country by late June, 3 million people would need to receive a COVID-19 vaccine each day.

“As I long feared and warned, the effort to distribute and administer the vaccine is not progressing as it should,” Mr. Biden said, reemphasizing his pledge to get 100 million doses to Americans during his first 100 days as president.

So far, 11.4 million doses have been distributed and 2.1 million people have received a vaccine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most states have administered a fraction of the doses they’ve received, according to data compiled by The New York Times.

Federal officials have said there’s an “expected lag” between delivery of doses, shots going into arms, and the data being reported to the CDC, according to CNN. The Food and Drug Administration must assess each shipment for quality control, which has slowed down distribution, and the CDC data are just now beginning to include the Moderna vaccine, which the FDA authorized for emergency use on Dec. 18.

The 2.1 million number is “an underestimate,” Brett Giroir, MD, the assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, told NBC News Dec. 29. At the same time, the U.S. won’t meet the goal of vaccinating 20 million people in the next few days, he said.

Another 30 million doses will go out in January, Dr. Giroir said, followed by 50 million in February.

Some vaccine experts have said they’re not surprised by the speed of vaccine distribution.

“It had to go this way,” Paul Offit, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told STAT. “We had to trip and fall and stumble and figure this out.”

To speed up distribution in 2021, the federal government will need to help states, Mr. Biden said Dec. 29. He plans to use the Defense Authorization Act to ramp up production of vaccine supplies. Even still, the process will take months, he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

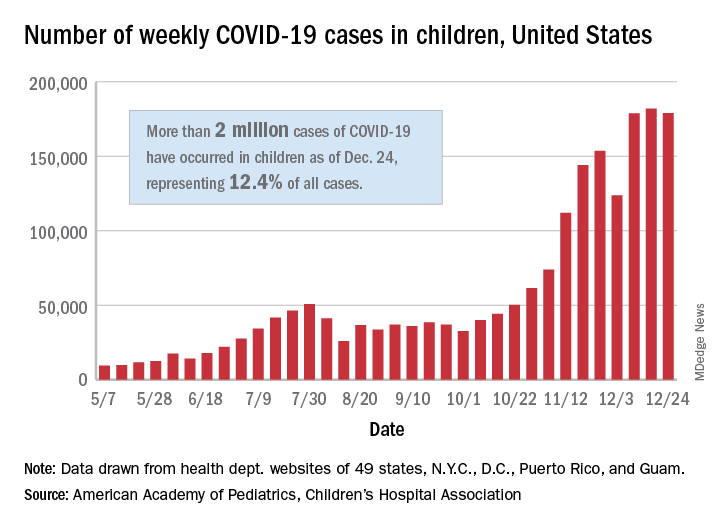

If the current pace of vaccination continues, “it’s going to take years, not months, to vaccinate the American people,” President-elect Joe Biden said during a briefing Dec. 29.

In fact, at the current rate, it would take nearly 10 years to vaccinate enough Americans to bring the pandemic under control, according to NBC News. To reach 80% of the country by late June, 3 million people would need to receive a COVID-19 vaccine each day.

“As I long feared and warned, the effort to distribute and administer the vaccine is not progressing as it should,” Mr. Biden said, reemphasizing his pledge to get 100 million doses to Americans during his first 100 days as president.

So far, 11.4 million doses have been distributed and 2.1 million people have received a vaccine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most states have administered a fraction of the doses they’ve received, according to data compiled by The New York Times.

Federal officials have said there’s an “expected lag” between delivery of doses, shots going into arms, and the data being reported to the CDC, according to CNN. The Food and Drug Administration must assess each shipment for quality control, which has slowed down distribution, and the CDC data are just now beginning to include the Moderna vaccine, which the FDA authorized for emergency use on Dec. 18.

The 2.1 million number is “an underestimate,” Brett Giroir, MD, the assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, told NBC News Dec. 29. At the same time, the U.S. won’t meet the goal of vaccinating 20 million people in the next few days, he said.

Another 30 million doses will go out in January, Dr. Giroir said, followed by 50 million in February.

Some vaccine experts have said they’re not surprised by the speed of vaccine distribution.

“It had to go this way,” Paul Offit, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told STAT. “We had to trip and fall and stumble and figure this out.”

To speed up distribution in 2021, the federal government will need to help states, Mr. Biden said Dec. 29. He plans to use the Defense Authorization Act to ramp up production of vaccine supplies. Even still, the process will take months, he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

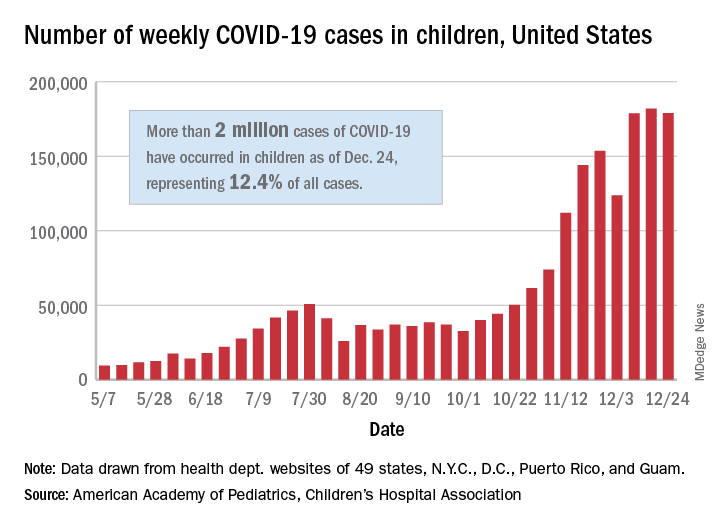

If the current pace of vaccination continues, “it’s going to take years, not months, to vaccinate the American people,” President-elect Joe Biden said during a briefing Dec. 29.

In fact, at the current rate, it would take nearly 10 years to vaccinate enough Americans to bring the pandemic under control, according to NBC News. To reach 80% of the country by late June, 3 million people would need to receive a COVID-19 vaccine each day.

“As I long feared and warned, the effort to distribute and administer the vaccine is not progressing as it should,” Mr. Biden said, reemphasizing his pledge to get 100 million doses to Americans during his first 100 days as president.

So far, 11.4 million doses have been distributed and 2.1 million people have received a vaccine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most states have administered a fraction of the doses they’ve received, according to data compiled by The New York Times.

Federal officials have said there’s an “expected lag” between delivery of doses, shots going into arms, and the data being reported to the CDC, according to CNN. The Food and Drug Administration must assess each shipment for quality control, which has slowed down distribution, and the CDC data are just now beginning to include the Moderna vaccine, which the FDA authorized for emergency use on Dec. 18.

The 2.1 million number is “an underestimate,” Brett Giroir, MD, the assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, told NBC News Dec. 29. At the same time, the U.S. won’t meet the goal of vaccinating 20 million people in the next few days, he said.

Another 30 million doses will go out in January, Dr. Giroir said, followed by 50 million in February.

Some vaccine experts have said they’re not surprised by the speed of vaccine distribution.

“It had to go this way,” Paul Offit, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told STAT. “We had to trip and fall and stumble and figure this out.”

To speed up distribution in 2021, the federal government will need to help states, Mr. Biden said Dec. 29. He plans to use the Defense Authorization Act to ramp up production of vaccine supplies. Even still, the process will take months, he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

Anorexia and diarrhea top list of GI symptoms in COVID-19 patients

Patients with severe COVID-19 were significantly more likely than those with milder cases to have GI symptoms of anorexia and diarrhea, as well as abnormal liver function, based on data from a meta-analysis of more than 4,500 patients.

Previous studies have shown that liver damage “was more likely to be observed in severe patients during the process of disease,” and other studies have shown varying degrees of liver insufficiency in COVID-19 patients, but gastrointestinal symptoms have not been well studied, wrote Zi-yuan Dong, MD, of China Medical University, Shenyang City, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, the researchers identified 31 studies including 4,682 COVID-19 patients. Case collection was from Dec. 11, 2019, to Feb. 28, 2020. Median age among studies ranged from 36 to 62 years, and 55% of patients were male.

A total of 26 studies were analyzed for the prevalence of GI symptoms, specifically nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and anorexia. Of these, anorexia and diarrhea were significantly more common in COVID-19 patients, with prevalence of 17% and 8% respectively, (P < .0001 for both).

In addition, 14 of the studies included in the analysis assessed the prevalence of abnormal liver function based on increased levels of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and total bilirubin. Of these, increased alanine aminotransferase was the most common, occurring in 25% of patients, compared with increased AST (in 24%) and total bilirubin (in 13%).

When assessed by disease severity, patients with severe disease and those in the ICU were significantly more likely than general/non-ICU patients to have anorexia (odds ratio, 2.19), diarrhea (OR, 1.65), and abdominal pain (OR, 6.38). The severely ill patients were significantly more likely to have increased AST and ALT (OR, 2.98 and 2.66, respectively).

“However, there were no significant differences between severe/ICU group and general/non-ICU group for the prevalence of nausea and vomiting and liver disease,” the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the unclear classification of digestive system disease and liver disease in many of the studies, the small sample sizes, and the lack of data on pathology of the liver or colon in COVID-19 patients, the researchers noted.

More research is needed, but the findings suggest that COVID-19 could contribute to liver damage because the most significant abnormal liver function was increased ALT, they said.

Check liver function in cases with GI symptoms

“COVID patients can present asymptomatically or with nonspecific symptoms, including GI symptoms,” said Ziad F. Gellad, MD, of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., in an interview. “While the focus of management naturally is directed to the pulmonary consequences of the disease, it is important to evaluate the patient holistically,” he said.

“I do not think these findings have profound clinical implications because they identify relatively nonspecific symptoms that are commonly seen in patients in a number of other conditions,” noted Dr. Gellad. “The management of COVID should not change, with the exception of perhaps making sure to check for abnormal liver function tests in patients that present with more typical COVID symptoms,” he said.

“Additional research is needed to understand the biologic mechanism by which COVID impacts systems outside of the lungs,” Dr. Gellad emphasized. “For example, there has been some very interesting work understanding the impact of COVID on the pancreas and risk for pancreatitis. That work is similarly needed to understand how COVID, outside of causing a general illness, specifically impacts the rest of the GI tract,” he said.

The study was supported by the Liaoning Science and Technology Foundation. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Gellad had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Dong Z-Y et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001424.

Patients with severe COVID-19 were significantly more likely than those with milder cases to have GI symptoms of anorexia and diarrhea, as well as abnormal liver function, based on data from a meta-analysis of more than 4,500 patients.

Previous studies have shown that liver damage “was more likely to be observed in severe patients during the process of disease,” and other studies have shown varying degrees of liver insufficiency in COVID-19 patients, but gastrointestinal symptoms have not been well studied, wrote Zi-yuan Dong, MD, of China Medical University, Shenyang City, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, the researchers identified 31 studies including 4,682 COVID-19 patients. Case collection was from Dec. 11, 2019, to Feb. 28, 2020. Median age among studies ranged from 36 to 62 years, and 55% of patients were male.

A total of 26 studies were analyzed for the prevalence of GI symptoms, specifically nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and anorexia. Of these, anorexia and diarrhea were significantly more common in COVID-19 patients, with prevalence of 17% and 8% respectively, (P < .0001 for both).

In addition, 14 of the studies included in the analysis assessed the prevalence of abnormal liver function based on increased levels of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and total bilirubin. Of these, increased alanine aminotransferase was the most common, occurring in 25% of patients, compared with increased AST (in 24%) and total bilirubin (in 13%).

When assessed by disease severity, patients with severe disease and those in the ICU were significantly more likely than general/non-ICU patients to have anorexia (odds ratio, 2.19), diarrhea (OR, 1.65), and abdominal pain (OR, 6.38). The severely ill patients were significantly more likely to have increased AST and ALT (OR, 2.98 and 2.66, respectively).

“However, there were no significant differences between severe/ICU group and general/non-ICU group for the prevalence of nausea and vomiting and liver disease,” the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the unclear classification of digestive system disease and liver disease in many of the studies, the small sample sizes, and the lack of data on pathology of the liver or colon in COVID-19 patients, the researchers noted.

More research is needed, but the findings suggest that COVID-19 could contribute to liver damage because the most significant abnormal liver function was increased ALT, they said.

Check liver function in cases with GI symptoms

“COVID patients can present asymptomatically or with nonspecific symptoms, including GI symptoms,” said Ziad F. Gellad, MD, of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., in an interview. “While the focus of management naturally is directed to the pulmonary consequences of the disease, it is important to evaluate the patient holistically,” he said.

“I do not think these findings have profound clinical implications because they identify relatively nonspecific symptoms that are commonly seen in patients in a number of other conditions,” noted Dr. Gellad. “The management of COVID should not change, with the exception of perhaps making sure to check for abnormal liver function tests in patients that present with more typical COVID symptoms,” he said.

“Additional research is needed to understand the biologic mechanism by which COVID impacts systems outside of the lungs,” Dr. Gellad emphasized. “For example, there has been some very interesting work understanding the impact of COVID on the pancreas and risk for pancreatitis. That work is similarly needed to understand how COVID, outside of causing a general illness, specifically impacts the rest of the GI tract,” he said.

The study was supported by the Liaoning Science and Technology Foundation. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Gellad had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Dong Z-Y et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001424.

Patients with severe COVID-19 were significantly more likely than those with milder cases to have GI symptoms of anorexia and diarrhea, as well as abnormal liver function, based on data from a meta-analysis of more than 4,500 patients.

Previous studies have shown that liver damage “was more likely to be observed in severe patients during the process of disease,” and other studies have shown varying degrees of liver insufficiency in COVID-19 patients, but gastrointestinal symptoms have not been well studied, wrote Zi-yuan Dong, MD, of China Medical University, Shenyang City, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, the researchers identified 31 studies including 4,682 COVID-19 patients. Case collection was from Dec. 11, 2019, to Feb. 28, 2020. Median age among studies ranged from 36 to 62 years, and 55% of patients were male.

A total of 26 studies were analyzed for the prevalence of GI symptoms, specifically nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and anorexia. Of these, anorexia and diarrhea were significantly more common in COVID-19 patients, with prevalence of 17% and 8% respectively, (P < .0001 for both).

In addition, 14 of the studies included in the analysis assessed the prevalence of abnormal liver function based on increased levels of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and total bilirubin. Of these, increased alanine aminotransferase was the most common, occurring in 25% of patients, compared with increased AST (in 24%) and total bilirubin (in 13%).

When assessed by disease severity, patients with severe disease and those in the ICU were significantly more likely than general/non-ICU patients to have anorexia (odds ratio, 2.19), diarrhea (OR, 1.65), and abdominal pain (OR, 6.38). The severely ill patients were significantly more likely to have increased AST and ALT (OR, 2.98 and 2.66, respectively).

“However, there were no significant differences between severe/ICU group and general/non-ICU group for the prevalence of nausea and vomiting and liver disease,” the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the unclear classification of digestive system disease and liver disease in many of the studies, the small sample sizes, and the lack of data on pathology of the liver or colon in COVID-19 patients, the researchers noted.

More research is needed, but the findings suggest that COVID-19 could contribute to liver damage because the most significant abnormal liver function was increased ALT, they said.

Check liver function in cases with GI symptoms

“COVID patients can present asymptomatically or with nonspecific symptoms, including GI symptoms,” said Ziad F. Gellad, MD, of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., in an interview. “While the focus of management naturally is directed to the pulmonary consequences of the disease, it is important to evaluate the patient holistically,” he said.

“I do not think these findings have profound clinical implications because they identify relatively nonspecific symptoms that are commonly seen in patients in a number of other conditions,” noted Dr. Gellad. “The management of COVID should not change, with the exception of perhaps making sure to check for abnormal liver function tests in patients that present with more typical COVID symptoms,” he said.

“Additional research is needed to understand the biologic mechanism by which COVID impacts systems outside of the lungs,” Dr. Gellad emphasized. “For example, there has been some very interesting work understanding the impact of COVID on the pancreas and risk for pancreatitis. That work is similarly needed to understand how COVID, outside of causing a general illness, specifically impacts the rest of the GI tract,” he said.

The study was supported by the Liaoning Science and Technology Foundation. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Gellad had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Dong Z-Y et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001424.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY

FDA okays first generic injected glucagon for hypoglycemia

The FDA determined that Amphastar’s Glucagon for Injection Emergency Kit, 1 mg, a synthetic peptide product, is bioequivalent and therapeutically equivalent to Eli Lilly’s recombinant DNA Glucagon Emergency Kit for Low Blood Sugar.

Both require a multistep mixing process that means they are complicated to use.

In 2019, FDA approved two branded, easier-to-use formulations of glucagon – one nasally administered (Baqsimi, Eli Lilly & Co) and the other a prefilled pen or syringe (Gvoke HypoPen and Gvoke PFS, respectively, Xeris Pharmaceuticals).

The new generic will have the advantage of lower cost, Amphastar spokesman Dan Dischner said in an interview.

“Our generic glucagon will be priced as a generic product so that patients will benefit from a lower price. As we are just at the beginning of the commercialization of the product, we are unable to discuss our specific product price,” he wrote.

As with the branded Lilly injectable glucagon, the new generic is also indicated as a diagnostic aid in gastrointestinal radiologic imaging, as glucagon slows gastric motility.

According to an FDA statement, glucagon is a “complex product” that has been difficult to manufacture generically despite the lifting of patent protection. This approval was the result of the FDA’s efforts to encourage the development and submission of applications for such drugs.

Amphastar specializes in “developing, manufacturing, marketing, and selling technically-challenging generic and proprietary injectable, inhalation, and intranasal products,” the company website says.

Mr. Dischner said, “Glucagon is a complex product that requires R&D and manufacturing capabilities to develop a highly purified synthetic peptide product bioequivalent and therapeutically equivalent to the recombinant DNA origin Glucagon. Given that this product has been through various review cycles, its complexity, and the technological capabilities required to manufacture, it is no surprise that there hasn’t been a generic of glucagon until now.”

Side effects of injected glucagon include nausea, vomiting, transient increase in heart rate, and redness/swelling of the injection site.

Mr. Dischner added, “We are confident that our generic to Lilly’s time-tested glucagon will provide a favorable option, at a reasonable price, to patients who rely on this product.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The FDA determined that Amphastar’s Glucagon for Injection Emergency Kit, 1 mg, a synthetic peptide product, is bioequivalent and therapeutically equivalent to Eli Lilly’s recombinant DNA Glucagon Emergency Kit for Low Blood Sugar.

Both require a multistep mixing process that means they are complicated to use.

In 2019, FDA approved two branded, easier-to-use formulations of glucagon – one nasally administered (Baqsimi, Eli Lilly & Co) and the other a prefilled pen or syringe (Gvoke HypoPen and Gvoke PFS, respectively, Xeris Pharmaceuticals).

The new generic will have the advantage of lower cost, Amphastar spokesman Dan Dischner said in an interview.

“Our generic glucagon will be priced as a generic product so that patients will benefit from a lower price. As we are just at the beginning of the commercialization of the product, we are unable to discuss our specific product price,” he wrote.

As with the branded Lilly injectable glucagon, the new generic is also indicated as a diagnostic aid in gastrointestinal radiologic imaging, as glucagon slows gastric motility.

According to an FDA statement, glucagon is a “complex product” that has been difficult to manufacture generically despite the lifting of patent protection. This approval was the result of the FDA’s efforts to encourage the development and submission of applications for such drugs.

Amphastar specializes in “developing, manufacturing, marketing, and selling technically-challenging generic and proprietary injectable, inhalation, and intranasal products,” the company website says.

Mr. Dischner said, “Glucagon is a complex product that requires R&D and manufacturing capabilities to develop a highly purified synthetic peptide product bioequivalent and therapeutically equivalent to the recombinant DNA origin Glucagon. Given that this product has been through various review cycles, its complexity, and the technological capabilities required to manufacture, it is no surprise that there hasn’t been a generic of glucagon until now.”

Side effects of injected glucagon include nausea, vomiting, transient increase in heart rate, and redness/swelling of the injection site.

Mr. Dischner added, “We are confident that our generic to Lilly’s time-tested glucagon will provide a favorable option, at a reasonable price, to patients who rely on this product.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The FDA determined that Amphastar’s Glucagon for Injection Emergency Kit, 1 mg, a synthetic peptide product, is bioequivalent and therapeutically equivalent to Eli Lilly’s recombinant DNA Glucagon Emergency Kit for Low Blood Sugar.

Both require a multistep mixing process that means they are complicated to use.

In 2019, FDA approved two branded, easier-to-use formulations of glucagon – one nasally administered (Baqsimi, Eli Lilly & Co) and the other a prefilled pen or syringe (Gvoke HypoPen and Gvoke PFS, respectively, Xeris Pharmaceuticals).

The new generic will have the advantage of lower cost, Amphastar spokesman Dan Dischner said in an interview.

“Our generic glucagon will be priced as a generic product so that patients will benefit from a lower price. As we are just at the beginning of the commercialization of the product, we are unable to discuss our specific product price,” he wrote.

As with the branded Lilly injectable glucagon, the new generic is also indicated as a diagnostic aid in gastrointestinal radiologic imaging, as glucagon slows gastric motility.

According to an FDA statement, glucagon is a “complex product” that has been difficult to manufacture generically despite the lifting of patent protection. This approval was the result of the FDA’s efforts to encourage the development and submission of applications for such drugs.

Amphastar specializes in “developing, manufacturing, marketing, and selling technically-challenging generic and proprietary injectable, inhalation, and intranasal products,” the company website says.

Mr. Dischner said, “Glucagon is a complex product that requires R&D and manufacturing capabilities to develop a highly purified synthetic peptide product bioequivalent and therapeutically equivalent to the recombinant DNA origin Glucagon. Given that this product has been through various review cycles, its complexity, and the technological capabilities required to manufacture, it is no surprise that there hasn’t been a generic of glucagon until now.”

Side effects of injected glucagon include nausea, vomiting, transient increase in heart rate, and redness/swelling of the injection site.

Mr. Dischner added, “We are confident that our generic to Lilly’s time-tested glucagon will provide a favorable option, at a reasonable price, to patients who rely on this product.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Complete blood count scoring can predict COVID-19 severity

A scoring system based on 10 parameters in a complete blood count with differential within 3 days of hospital presentation predict those with COVID-19 who are most likely to progress to critical illness, new evidence shows.

Advantages include prognosis based on a common and inexpensive clinical measure, as well as automatic generation of the score along with CBC results, noted investigators in the observational study conducted throughout 11 European hospitals.

“COVID-19 comes along with specific alterations in circulating blood cells that can be detected by a routine hematology analyzer, especially when that hematology analyzer is also capable to recognize activated immune cells and early circulating blood cells, such as erythroblast and immature granulocytes,” senior author Andre van der Ven, MD, PhD, infectious diseases specialist and professor of international health at Radboud University Medical Center’s Center for Infectious Diseases in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, said in an interview.

Furthermore, Dr. van der Ven said, “these specific changes are also seen in the early course of COVID-19 disease, and more in those that will develop serious disease compared to those with mild disease.”

The study was published online Dec. 21 in the journal eLife.

The study is “almost instinctively correct. It’s basically what clinicians do informally with complete blood count … looking at a combination of results to get the gestalt of what patients are going through,” Samuel Reichberg, MD, PhD, associate medical director of the Northwell Health Core Laboratory in Lake Success, N.Y., said in an interview.

“This is something that begs to be done for COVID-19. I’m surprised no one has done this before,” he added.

Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues created an algorithm based on 1,587 CBC assays from 923 adults. They also validated the scoring system in a second cohort of 217 CBC measurements in 202 people. The findings were concordant – the score accurately predicted the need for critical care within 14 days in 70.5% of the development cohort and 72% of the validation group.

The scoring system was superior to any of the 10 parameters alone. Over 14 days, the majority of those classified as noncritical within the first 3 days remained clinically stable, whereas the “clinical illness” group progressed. Clinical severity peaked on day 6.

Most previous COVID-19 prognosis research was geographically limited, carried a high risk for bias and/or did not validate the findings, Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues noted.

Early identification, early intervention

The aim of the score is “to assist with objective risk stratification to support patient management decision-making early on, and thus facilitate timely interventions, such as need for ICU or not, before symptoms of severe illness become clinically overt, with the intention to improve patient outcomes, and not to predict mortality,” the investigators noted.

Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues developed the score based on adults presenting from Feb. 21 to April 6, with outcomes followed until June 9. Median age of the 982 patients was 71 years and approximately two-thirds were men. They used a Sysmex Europe XN-1000 (Hamburg, Germany) hemocytometric analyzer in the study.