User login

EULAR recommendations define strategies to improve adherence in RMDs

Clinicians who care for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) can now refer to a new set of strategies and points to consider from a European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) task force in building a patient-centered approach to improve adherence to treatments.

Nonadherence to treatments is concerning given that 30%-80% of patients who have RMDs are thought to not follow a recommended treatment plan according to their physicians’ instructions, according to first author Valentin Ritschl of the Medical University of Vienna and colleagues.

“The problem of poor adherence is addressed in some EULAR recommendations/points to consider on the management of specific health conditions or on the role of professionals,” Mr. Ritschl said in an interview. “However, all these recommendations focus on limited aspects of nonadherence and do not cover the multifaceted nature of this phenomenon.”

Mr. Ritschl and colleagues conducted an extensive systematic literature review, the results of which they presented to a task force consisting of a panel of international experts hailing from 12 different countries. The task force included rheumatologists and other health professionals in rheumatology, as well as patient representatives.

The collaboration resulted in investigators crafting a definition of adherence in addition to drafting four overarching principles and nine points to consider, which were published Dec. 18 in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

They defined adherence as “the extent to which a person’s behavior corresponds with the agreed prescription, of pharmacological or nonpharmacological treatments, by a health care provider.”

The four overarching principles emphasize the following concepts: that adherence affects outcomes in people who have RMDs; the importance of shared decision-making, with the understanding that the adherence describes the patient’s behavior “following an agreed prescription”; that numerous factors can affect adherence; and the notion of adherence being a dynamic process that, consequently, requires continuous evaluation.

Among the nine points to consider, Mr. Ritschl and coauthors encouraged all health care providers involved in caring for RMD patients to assume responsibility for promoting adherence. Practitioners should also strive to create an ongoing, open dialogue to discuss adherence, especially in cases in which the patient’s RMD is not well controlled. The patient-centered recommendations include taking into account the patient’s goals and preferences because these greatly contribute to the patient’s ability to adhere to any medication regimen. Another arm of that exploration also requires the medical professional to evaluate any circumstances that could bear a negative effect on the patient’s adherence – whether it be medication access issues related to cost or availability, or functional challenges such as memory, motivation, or complexity of the medication regimen.

Mr. Ritschl believed the task force’s recommendations will add value and help improve overall outcomes in RMD population management.

“Until today, there are no recommendations or points to consider developed in order to support our patients to be adherent to the agreed treatment plan,” he said. “In our project/initiative, we therefore developed for the first time points to consider to detect, assess, and manage nonadherence in people with RMDs.”

Additionally, the recommendations offer some strategic insights to help improve clinical trials because the deleterious effects of nonadherence also affect study results.

Looking ahead, Mr. Ritschl said randomized, controlled trials are necessary to test strategies that might improve adherence. He strongly emphasized the importance of designing future research studies that are heavily patient centered and effective for shared decision-making.

The project was funded by EULAR. Mr. Ritschl reported having no disclosures, but many of his coauthors reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Ritschl V et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Dec 18. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218986.

Clinicians who care for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) can now refer to a new set of strategies and points to consider from a European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) task force in building a patient-centered approach to improve adherence to treatments.

Nonadherence to treatments is concerning given that 30%-80% of patients who have RMDs are thought to not follow a recommended treatment plan according to their physicians’ instructions, according to first author Valentin Ritschl of the Medical University of Vienna and colleagues.

“The problem of poor adherence is addressed in some EULAR recommendations/points to consider on the management of specific health conditions or on the role of professionals,” Mr. Ritschl said in an interview. “However, all these recommendations focus on limited aspects of nonadherence and do not cover the multifaceted nature of this phenomenon.”

Mr. Ritschl and colleagues conducted an extensive systematic literature review, the results of which they presented to a task force consisting of a panel of international experts hailing from 12 different countries. The task force included rheumatologists and other health professionals in rheumatology, as well as patient representatives.

The collaboration resulted in investigators crafting a definition of adherence in addition to drafting four overarching principles and nine points to consider, which were published Dec. 18 in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

They defined adherence as “the extent to which a person’s behavior corresponds with the agreed prescription, of pharmacological or nonpharmacological treatments, by a health care provider.”

The four overarching principles emphasize the following concepts: that adherence affects outcomes in people who have RMDs; the importance of shared decision-making, with the understanding that the adherence describes the patient’s behavior “following an agreed prescription”; that numerous factors can affect adherence; and the notion of adherence being a dynamic process that, consequently, requires continuous evaluation.

Among the nine points to consider, Mr. Ritschl and coauthors encouraged all health care providers involved in caring for RMD patients to assume responsibility for promoting adherence. Practitioners should also strive to create an ongoing, open dialogue to discuss adherence, especially in cases in which the patient’s RMD is not well controlled. The patient-centered recommendations include taking into account the patient’s goals and preferences because these greatly contribute to the patient’s ability to adhere to any medication regimen. Another arm of that exploration also requires the medical professional to evaluate any circumstances that could bear a negative effect on the patient’s adherence – whether it be medication access issues related to cost or availability, or functional challenges such as memory, motivation, or complexity of the medication regimen.

Mr. Ritschl believed the task force’s recommendations will add value and help improve overall outcomes in RMD population management.

“Until today, there are no recommendations or points to consider developed in order to support our patients to be adherent to the agreed treatment plan,” he said. “In our project/initiative, we therefore developed for the first time points to consider to detect, assess, and manage nonadherence in people with RMDs.”

Additionally, the recommendations offer some strategic insights to help improve clinical trials because the deleterious effects of nonadherence also affect study results.

Looking ahead, Mr. Ritschl said randomized, controlled trials are necessary to test strategies that might improve adherence. He strongly emphasized the importance of designing future research studies that are heavily patient centered and effective for shared decision-making.

The project was funded by EULAR. Mr. Ritschl reported having no disclosures, but many of his coauthors reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Ritschl V et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Dec 18. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218986.

Clinicians who care for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) can now refer to a new set of strategies and points to consider from a European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) task force in building a patient-centered approach to improve adherence to treatments.

Nonadherence to treatments is concerning given that 30%-80% of patients who have RMDs are thought to not follow a recommended treatment plan according to their physicians’ instructions, according to first author Valentin Ritschl of the Medical University of Vienna and colleagues.

“The problem of poor adherence is addressed in some EULAR recommendations/points to consider on the management of specific health conditions or on the role of professionals,” Mr. Ritschl said in an interview. “However, all these recommendations focus on limited aspects of nonadherence and do not cover the multifaceted nature of this phenomenon.”

Mr. Ritschl and colleagues conducted an extensive systematic literature review, the results of which they presented to a task force consisting of a panel of international experts hailing from 12 different countries. The task force included rheumatologists and other health professionals in rheumatology, as well as patient representatives.

The collaboration resulted in investigators crafting a definition of adherence in addition to drafting four overarching principles and nine points to consider, which were published Dec. 18 in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

They defined adherence as “the extent to which a person’s behavior corresponds with the agreed prescription, of pharmacological or nonpharmacological treatments, by a health care provider.”

The four overarching principles emphasize the following concepts: that adherence affects outcomes in people who have RMDs; the importance of shared decision-making, with the understanding that the adherence describes the patient’s behavior “following an agreed prescription”; that numerous factors can affect adherence; and the notion of adherence being a dynamic process that, consequently, requires continuous evaluation.

Among the nine points to consider, Mr. Ritschl and coauthors encouraged all health care providers involved in caring for RMD patients to assume responsibility for promoting adherence. Practitioners should also strive to create an ongoing, open dialogue to discuss adherence, especially in cases in which the patient’s RMD is not well controlled. The patient-centered recommendations include taking into account the patient’s goals and preferences because these greatly contribute to the patient’s ability to adhere to any medication regimen. Another arm of that exploration also requires the medical professional to evaluate any circumstances that could bear a negative effect on the patient’s adherence – whether it be medication access issues related to cost or availability, or functional challenges such as memory, motivation, or complexity of the medication regimen.

Mr. Ritschl believed the task force’s recommendations will add value and help improve overall outcomes in RMD population management.

“Until today, there are no recommendations or points to consider developed in order to support our patients to be adherent to the agreed treatment plan,” he said. “In our project/initiative, we therefore developed for the first time points to consider to detect, assess, and manage nonadherence in people with RMDs.”

Additionally, the recommendations offer some strategic insights to help improve clinical trials because the deleterious effects of nonadherence also affect study results.

Looking ahead, Mr. Ritschl said randomized, controlled trials are necessary to test strategies that might improve adherence. He strongly emphasized the importance of designing future research studies that are heavily patient centered and effective for shared decision-making.

The project was funded by EULAR. Mr. Ritschl reported having no disclosures, but many of his coauthors reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Ritschl V et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Dec 18. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218986.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

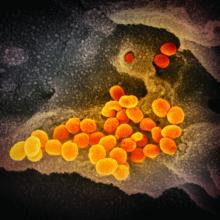

U.S. hits 20 million cases as COVID variant spreads

The United States started 2021 they way it ended 2020: Setting new records amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

The country passed the 20 million mark for coronavirus cases on Friday, setting the mark sometime around noon, according to Johns Hopkins University’s COVID-19 tracker. The total is nearly twice as many as the next worst country – India, which has 10.28 million cases.

Along with the case count, more than 346,000 Americans have now died of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. That is 77% more fatalities than Brazil, which ranks second globally with 194,949 deaths.

More than 125,370 coronavirus patients were hospitalized on Thursday, the fourth record-setting day in a row, according to the COVID Tracking Project.

Going by official tallies, it took 292 days for the United States to reach its first 10 million cases, and just 54 more days to double it, CNN reported.

Meanwhile, 12.41 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been distributed in the United States as of Wednesday, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Yet only 2.8 million people have received the first of a two-shot regimen.

The slower-than-hoped-for rollout of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines comes as a new variant of the coronavirus has emerged in a third state. Florida officials announced a confirmed case of the new variant – believed to have originated in the United Kingdom – in Martin County in southeast Florida.

The state health department said on Twitter that the patient is a man in his 20s with no history of travel. The department said it is working with the CDC to investigate.

The variant has also been confirmed in cases in Colorado and California. It is believed to be more contagious. The BBC reported that the new variant increases the reproduction, or “R number,” by 0.4 and 0.7. The UK’s most recent R number has been estimated at 1.1-1.3, meaning anyone who has the coronavirus could be assumed to spread it to up to 1.3 people.

The R number needs to be below 1.0 for the spread of the virus to fall.

“There is a huge difference in how easily the variant virus spreads,” Professor Axel Gandy of London’s Imperial College told BBC News. “This is the most serious change in the virus since the epidemic began.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The United States started 2021 they way it ended 2020: Setting new records amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

The country passed the 20 million mark for coronavirus cases on Friday, setting the mark sometime around noon, according to Johns Hopkins University’s COVID-19 tracker. The total is nearly twice as many as the next worst country – India, which has 10.28 million cases.

Along with the case count, more than 346,000 Americans have now died of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. That is 77% more fatalities than Brazil, which ranks second globally with 194,949 deaths.

More than 125,370 coronavirus patients were hospitalized on Thursday, the fourth record-setting day in a row, according to the COVID Tracking Project.

Going by official tallies, it took 292 days for the United States to reach its first 10 million cases, and just 54 more days to double it, CNN reported.

Meanwhile, 12.41 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been distributed in the United States as of Wednesday, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Yet only 2.8 million people have received the first of a two-shot regimen.

The slower-than-hoped-for rollout of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines comes as a new variant of the coronavirus has emerged in a third state. Florida officials announced a confirmed case of the new variant – believed to have originated in the United Kingdom – in Martin County in southeast Florida.

The state health department said on Twitter that the patient is a man in his 20s with no history of travel. The department said it is working with the CDC to investigate.

The variant has also been confirmed in cases in Colorado and California. It is believed to be more contagious. The BBC reported that the new variant increases the reproduction, or “R number,” by 0.4 and 0.7. The UK’s most recent R number has been estimated at 1.1-1.3, meaning anyone who has the coronavirus could be assumed to spread it to up to 1.3 people.

The R number needs to be below 1.0 for the spread of the virus to fall.

“There is a huge difference in how easily the variant virus spreads,” Professor Axel Gandy of London’s Imperial College told BBC News. “This is the most serious change in the virus since the epidemic began.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The United States started 2021 they way it ended 2020: Setting new records amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

The country passed the 20 million mark for coronavirus cases on Friday, setting the mark sometime around noon, according to Johns Hopkins University’s COVID-19 tracker. The total is nearly twice as many as the next worst country – India, which has 10.28 million cases.

Along with the case count, more than 346,000 Americans have now died of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. That is 77% more fatalities than Brazil, which ranks second globally with 194,949 deaths.

More than 125,370 coronavirus patients were hospitalized on Thursday, the fourth record-setting day in a row, according to the COVID Tracking Project.

Going by official tallies, it took 292 days for the United States to reach its first 10 million cases, and just 54 more days to double it, CNN reported.

Meanwhile, 12.41 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been distributed in the United States as of Wednesday, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Yet only 2.8 million people have received the first of a two-shot regimen.

The slower-than-hoped-for rollout of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines comes as a new variant of the coronavirus has emerged in a third state. Florida officials announced a confirmed case of the new variant – believed to have originated in the United Kingdom – in Martin County in southeast Florida.

The state health department said on Twitter that the patient is a man in his 20s with no history of travel. The department said it is working with the CDC to investigate.

The variant has also been confirmed in cases in Colorado and California. It is believed to be more contagious. The BBC reported that the new variant increases the reproduction, or “R number,” by 0.4 and 0.7. The UK’s most recent R number has been estimated at 1.1-1.3, meaning anyone who has the coronavirus could be assumed to spread it to up to 1.3 people.

The R number needs to be below 1.0 for the spread of the virus to fall.

“There is a huge difference in how easily the variant virus spreads,” Professor Axel Gandy of London’s Imperial College told BBC News. “This is the most serious change in the virus since the epidemic began.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Racism in medicine: Implicit and explicit

With the shootings of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and other Black citizens setting off protests and unrest, race was at the forefront of national conversation in the United States – along with COVID-19 – over the past year.

“We’ve heard things like, ‘We’re in a post-racial society,’ but I think 2020 in particular has emphasized that we’re not,” said Gregory Johnson, MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of hospital medicine at Sound Physicians, a national physician practice. “Racism is very present in our lives, it’s very present in our world, and it is absolutely present in medicine.”

Yes, race is still an issue in the U.S. as we head into 2021, though this may have come as something of a surprise to people who do not live with racism daily.

“If you have a brain, you have bias, and that bias will likely apply to race as well,” Dr. Johnson said. “When we’re talking about institutional racism, the educational system and the media have led us to create presumptions and prejudices that we don’t necessarily recognize off the top because they’ve just been a part of the fabric of who we are as we’ve grown up.”

The term “racism” has extremely negative connotations because there’s character judgment attached to it, but to say someone is racist or racially insensitive does not equate them with being a Klansman, said Dr. Johnson. “I think we as people have to acknowledge that, yes, it’s possible for me to be racist and I might not be 100% aware of it. It’s being open to the possibility – or rather probability – that you are and then taking steps to figure out how you can address that, so you can limit it. And that requires constant self-evaluation and work,” he said.

Racism in the medical environment

Institutional racism is evident before students are even accepted into medical school, said Areeba Kara, MD, SFHM, associate professor of clinical medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis, and a hospitalist at IU Health Physicians.

Mean MCAT scores are lower for applicants traditionally underrepresented in medicine (UIM) compared to the scores of well-represented groups.1 “Lower scores are associated with lower acceptance rates into medical school,” Dr. Kara said. “These differences reflect unequal educational opportunities rooted in centuries of legal discrimination.”

Racism is apparent in both the hidden medical education curriculum and in lessons implicitly taught to students, said Ndidi Unaka, MD, MEd, associate program director of the pediatric residency training program at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

“These lessons inform the way in which we as physicians see our patients, each other, and how we practice,” she said. “We reinforce race-based medicine and shape clinical decision making through flawed guidelines and practices, which exacerbates health inequities. We teach that race – rather than racism – is a risk factor for poor health outcomes. Our students and trainees watch as we assume the worst of our patients from marginalized communities of color.”

Terms describing patients of color, such as “difficult,” “non-compliant,” or “frequent flyer” are thrown around and sometimes, instead of finding out why, “we view these states of being as static, root causes for poor outcomes rather than symptoms of social conditions and obstacles that impact overall health and wellbeing,” Dr. Unaka said.

Leadership opportunities

Though hospital medicine is a growing field, Dr. Kara noted that the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine Report found that only 5.5% of hospital medical group leaders were Black, and just 2.2% were Hispanic/Latino.2 “I think these numbers speak for themselves,” she said.

Dr. Unaka said that the lack of UIM hospitalists and physician leaders creates fewer opportunities for “race-concordant mentorship relationships.” It also forces UIM physicians to shoulder more responsibilities – often obligations that do little to help them move forward in their careers – all in the name of diversity. And when UIM physicians are given leadership opportunities, Dr. Unaka said they are often unsure as to whether their appointments are genuine or just a hollow gesture made for the sake of diversity.

Dr. Johnson pointed out that Black and Latinx populations primarily get their care from hospital-based specialties, yet this is not reflected in the number of UIM practitioners in leadership roles. He said race and ethnicity, as well as gender, need to be factors when individuals are evaluated for leadership opportunities – for the individual’s sake, as well as for the community he or she is serving.

“When we can evaluate for unconscious bias and factor in that diverse groups tend to have better outcomes, whether it’s business or clinical outcomes, it’s one of the opportunities that we collectively have in the specialty to improve what we’re delivering for hospitals and, more importantly, for patients,” he said.

Relationships with colleagues and patients

Racism creeps into interactions and relationships with others as well, whether it’s between clinicians, clinician to patient, or patient to clinician. Sometimes it’s blatant; often it’s subtle.

A common, recurring example Dr. Unaka has experienced in the clinician to clinician relationship is being confused for other Black physicians, making her feel invisible. “The everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults from colleagues are frequent and contribute to feelings of exclusion, isolation, and exhaustion,” she said. Despite this, she is still expected to “address microaggressions and other forms of interpersonal racism and find ways to move through professional spaces in spite of the trauma, fear, and stress associated with my reality and lived experiences.” She said that clinicians who remain silent on the topic of racism participate in the violence and contribute to the disillusionment of UIM physicians.

Dr. Kara said that the discrimination from the health care team is the hardest to deal with. In the clinician to clinician relationship, there is a sense among UIM physicians that they’re being watched more closely and “have to prove themselves at every single turn.” Unfortunately, this comes from the environment, which tends to be adversarial rather than supportive and nurturing, she said.

“There are lots of opportunities for racism or racial insensitivity to crop up from clinician to clinician,” said Dr. Johnson. When he started his career as a physician after his training, Dr. Johnson was informed that his colleagues were watching him because they were not sure about his clinical skills. The fact that he was a former chief resident and board certified in two specialties did not seem to make any difference.

Patients refusing care from UIM physicians or expressing disapproval – both verbal and nonverbal – of such care, happens all too often. “It’s easier for me to excuse patients and their families as we often meet them on their worst days,” said Dr. Kara. Still, “understanding my oath to care for people and do no harm, but at the same time, recognizing that this is an individual that is rejecting my care without having any idea of who I am as a physician is frustrating,” Dr. Johnson acknowledged.

Then there’s the complex clinician to patient relationship, which research clearly shows contributes to health disparities.3 For one thing, the physician workforce does not reflect the patient population, Dr. Unaka said. “We cannot ignore the lack of race concordance between patients and clinicians, nor can the continued misplacement of blame for medical mistrust be at the feet of our patients,” she said.

Dr. Unaka feels that clinicians need to accept both that health inequities exist and that frontline physicians themselves contribute to the inequities. “Our diagnostic and therapeutic decisions are not immune to bias and are influenced by our deeply held beliefs about specific populations,” she said. “And the health care system that our patients navigate is no different than other systems, settings, and environments that are marred by racism in all its forms.”

Systemic racism greatly impacts patient care, said Dr. Kara. She pointed to several examples: Research showing that race concordance between patients and providers in an emergency department setting led to better pain control with fewer analgesics.4 The high maternal and infant mortality rates amongst Black women and children.5 Evidence of poorer outcomes in sepsis patients with limited English proficiency.6 “There are plenty more,” she said. “We need to be asking ourselves what we are going to do about it.”

Moving forward

That racial biases are steeped so thoroughly into our culture and consciousness means that moving beyond them is a continual, purposeful work in progress. But it is work that is critical for everyone, and certainly necessary for those who care for their fellow human beings when they are in a vulnerable state.

Health care systems need to move toward equity – giving everyone what they need to thrive – rather than focusing on equality – giving everyone the same thing, said Jenny Baenziger, MD, assistant professor of clinical medicine and pediatrics at Indiana University, Indianapolis, and associate director of education at IU Center for Global Health. “We know that minoritized patients are going to need more attention, more advocacy, more sensitivity, and more creative solutions in order to help them achieve health in a world that is often stacked against them,” she said.

“The unique needs of each patient, family unit, and/or population must be taken into consideration,” said Dr. Unaka. She said hospitalists need to embrace creative approaches that can better serve the specific needs of patients. Equitable practices should be the default, which means data transparency, thoroughly dissecting hospital processes to find existing inequities, giving stakeholders – especially patients and families of color – a voice, and tearing down oppressive systems that contribute to poor health outcomes and oppression, she said.

“It’s time for us to talk about racism openly,” said Dr. Kara. “Believe your colleagues when they share their fears and treat each other with respect. We should be actively learning about and celebrating our diversity.” She encourages finding out what your institution is doing on this front and getting involved.

Dr. Johnson believes that first and foremost, hospitalists need to be exposed to the data on health care disparities. “The next step is asking what we as hospitalists, or any other specialty, can do to intervene and improve in those areas,” he said. Focusing on unconscious bias training is important, he said, so clinicians can see what biases they might be bringing into the hospital and to the bedside. Maintaining a diverse workforce and bringing UIM physicians into leadership roles to encourage diversity of ideas and approaches are also critical to promoting equity, he said.

“You cannot fix what you cannot face,” said Dr. Unaka. Education on how racism impacts patients and colleagues is essential, she believes, as is advocacy for changing inequitable health system policies. She recommends expanding social and professional circles. “Diverse social groups allow us to consider the perspectives of others; diverse professional groups allow us to ask better research questions and practice better medicine.”

Start by developing the ability to question personal assumptions and pinpoint implicit biases, suggested Dr. Baenziger. “Asking for feedback can be scary and difficult, but we should take a deep breath and do it anyway,” she said. “Simply ask your team, ‘I’ve been thinking a lot about racial equity and disparities. How can I do better at my interactions with people of color? What are my blind spots?’” Dr. Baenziger said that “to help us remember how beautifully complicated and diverse people are,” all health care professionals need to watch Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED talk “The Danger of a Single Story.”

Dr. Baenziger also stressed the importance of conversations about “places where race is built into our clinical assessments, like eGFR,” as well as being aware that many of the research studies that are used to support everyday clinical decisions didn’t include people of color. She also encouraged clinicians to consider how and when they include race in their notes.7 “Is it really helpful to make sure people know right away that you are treating a ‘46-year-old Hispanic male’ or can the fact that he is Hispanic be saved for the social history section with other important details of his life such as being a father, veteran, and mechanic?” she asked.

“Racism is real and very much a part of our history. We can no longer be in denial regarding the racism that exists in medicine and the impact it has on our patients,” Dr. Unaka said. “As a profession, we cannot hide behind our espoused core values. We must live up to them.”

References

1. Lucey CR, Saguil, A. The Consequences of Structural Racism on MCAT Scores and Medical School Admissions: The Past Is Prologue. Acad Med. 2020 Mar;95(3):351-356. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002939.

2. Flores L. Increasing racial diversity in hospital medicine’s leadership ranks. The Hospitalist. 2020 Oct 21.

3. Smedley BD, et al, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington: National Academies Press; 2003.

4. Heins A, et al. Physician Race/Ethnicity Predicts Successful Emergency Department Analgesia. J Pain. 2010 July;11(7):692-697. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.017.

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Serves, Office of Minority Health. Infant Mortality and African Americans. 2019 Nov 8. minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=23.

6. Jacobs ZG, et al. The Association between Limited English Proficiency and Sepsis Mortality. J Hosp Med. 2020;3;140-146. Published Online First 2019 Nov 20. doi:10.12788/jhm.3334.

7. Finucane TE. Mention of a Patient’s “Race” in Clinical Presentations. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16(6):423-427. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.6.ecas1-1406.

With the shootings of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and other Black citizens setting off protests and unrest, race was at the forefront of national conversation in the United States – along with COVID-19 – over the past year.

“We’ve heard things like, ‘We’re in a post-racial society,’ but I think 2020 in particular has emphasized that we’re not,” said Gregory Johnson, MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of hospital medicine at Sound Physicians, a national physician practice. “Racism is very present in our lives, it’s very present in our world, and it is absolutely present in medicine.”

Yes, race is still an issue in the U.S. as we head into 2021, though this may have come as something of a surprise to people who do not live with racism daily.

“If you have a brain, you have bias, and that bias will likely apply to race as well,” Dr. Johnson said. “When we’re talking about institutional racism, the educational system and the media have led us to create presumptions and prejudices that we don’t necessarily recognize off the top because they’ve just been a part of the fabric of who we are as we’ve grown up.”

The term “racism” has extremely negative connotations because there’s character judgment attached to it, but to say someone is racist or racially insensitive does not equate them with being a Klansman, said Dr. Johnson. “I think we as people have to acknowledge that, yes, it’s possible for me to be racist and I might not be 100% aware of it. It’s being open to the possibility – or rather probability – that you are and then taking steps to figure out how you can address that, so you can limit it. And that requires constant self-evaluation and work,” he said.

Racism in the medical environment

Institutional racism is evident before students are even accepted into medical school, said Areeba Kara, MD, SFHM, associate professor of clinical medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis, and a hospitalist at IU Health Physicians.

Mean MCAT scores are lower for applicants traditionally underrepresented in medicine (UIM) compared to the scores of well-represented groups.1 “Lower scores are associated with lower acceptance rates into medical school,” Dr. Kara said. “These differences reflect unequal educational opportunities rooted in centuries of legal discrimination.”

Racism is apparent in both the hidden medical education curriculum and in lessons implicitly taught to students, said Ndidi Unaka, MD, MEd, associate program director of the pediatric residency training program at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

“These lessons inform the way in which we as physicians see our patients, each other, and how we practice,” she said. “We reinforce race-based medicine and shape clinical decision making through flawed guidelines and practices, which exacerbates health inequities. We teach that race – rather than racism – is a risk factor for poor health outcomes. Our students and trainees watch as we assume the worst of our patients from marginalized communities of color.”

Terms describing patients of color, such as “difficult,” “non-compliant,” or “frequent flyer” are thrown around and sometimes, instead of finding out why, “we view these states of being as static, root causes for poor outcomes rather than symptoms of social conditions and obstacles that impact overall health and wellbeing,” Dr. Unaka said.

Leadership opportunities

Though hospital medicine is a growing field, Dr. Kara noted that the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine Report found that only 5.5% of hospital medical group leaders were Black, and just 2.2% were Hispanic/Latino.2 “I think these numbers speak for themselves,” she said.

Dr. Unaka said that the lack of UIM hospitalists and physician leaders creates fewer opportunities for “race-concordant mentorship relationships.” It also forces UIM physicians to shoulder more responsibilities – often obligations that do little to help them move forward in their careers – all in the name of diversity. And when UIM physicians are given leadership opportunities, Dr. Unaka said they are often unsure as to whether their appointments are genuine or just a hollow gesture made for the sake of diversity.

Dr. Johnson pointed out that Black and Latinx populations primarily get their care from hospital-based specialties, yet this is not reflected in the number of UIM practitioners in leadership roles. He said race and ethnicity, as well as gender, need to be factors when individuals are evaluated for leadership opportunities – for the individual’s sake, as well as for the community he or she is serving.

“When we can evaluate for unconscious bias and factor in that diverse groups tend to have better outcomes, whether it’s business or clinical outcomes, it’s one of the opportunities that we collectively have in the specialty to improve what we’re delivering for hospitals and, more importantly, for patients,” he said.

Relationships with colleagues and patients

Racism creeps into interactions and relationships with others as well, whether it’s between clinicians, clinician to patient, or patient to clinician. Sometimes it’s blatant; often it’s subtle.

A common, recurring example Dr. Unaka has experienced in the clinician to clinician relationship is being confused for other Black physicians, making her feel invisible. “The everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults from colleagues are frequent and contribute to feelings of exclusion, isolation, and exhaustion,” she said. Despite this, she is still expected to “address microaggressions and other forms of interpersonal racism and find ways to move through professional spaces in spite of the trauma, fear, and stress associated with my reality and lived experiences.” She said that clinicians who remain silent on the topic of racism participate in the violence and contribute to the disillusionment of UIM physicians.

Dr. Kara said that the discrimination from the health care team is the hardest to deal with. In the clinician to clinician relationship, there is a sense among UIM physicians that they’re being watched more closely and “have to prove themselves at every single turn.” Unfortunately, this comes from the environment, which tends to be adversarial rather than supportive and nurturing, she said.

“There are lots of opportunities for racism or racial insensitivity to crop up from clinician to clinician,” said Dr. Johnson. When he started his career as a physician after his training, Dr. Johnson was informed that his colleagues were watching him because they were not sure about his clinical skills. The fact that he was a former chief resident and board certified in two specialties did not seem to make any difference.

Patients refusing care from UIM physicians or expressing disapproval – both verbal and nonverbal – of such care, happens all too often. “It’s easier for me to excuse patients and their families as we often meet them on their worst days,” said Dr. Kara. Still, “understanding my oath to care for people and do no harm, but at the same time, recognizing that this is an individual that is rejecting my care without having any idea of who I am as a physician is frustrating,” Dr. Johnson acknowledged.

Then there’s the complex clinician to patient relationship, which research clearly shows contributes to health disparities.3 For one thing, the physician workforce does not reflect the patient population, Dr. Unaka said. “We cannot ignore the lack of race concordance between patients and clinicians, nor can the continued misplacement of blame for medical mistrust be at the feet of our patients,” she said.

Dr. Unaka feels that clinicians need to accept both that health inequities exist and that frontline physicians themselves contribute to the inequities. “Our diagnostic and therapeutic decisions are not immune to bias and are influenced by our deeply held beliefs about specific populations,” she said. “And the health care system that our patients navigate is no different than other systems, settings, and environments that are marred by racism in all its forms.”

Systemic racism greatly impacts patient care, said Dr. Kara. She pointed to several examples: Research showing that race concordance between patients and providers in an emergency department setting led to better pain control with fewer analgesics.4 The high maternal and infant mortality rates amongst Black women and children.5 Evidence of poorer outcomes in sepsis patients with limited English proficiency.6 “There are plenty more,” she said. “We need to be asking ourselves what we are going to do about it.”

Moving forward

That racial biases are steeped so thoroughly into our culture and consciousness means that moving beyond them is a continual, purposeful work in progress. But it is work that is critical for everyone, and certainly necessary for those who care for their fellow human beings when they are in a vulnerable state.

Health care systems need to move toward equity – giving everyone what they need to thrive – rather than focusing on equality – giving everyone the same thing, said Jenny Baenziger, MD, assistant professor of clinical medicine and pediatrics at Indiana University, Indianapolis, and associate director of education at IU Center for Global Health. “We know that minoritized patients are going to need more attention, more advocacy, more sensitivity, and more creative solutions in order to help them achieve health in a world that is often stacked against them,” she said.

“The unique needs of each patient, family unit, and/or population must be taken into consideration,” said Dr. Unaka. She said hospitalists need to embrace creative approaches that can better serve the specific needs of patients. Equitable practices should be the default, which means data transparency, thoroughly dissecting hospital processes to find existing inequities, giving stakeholders – especially patients and families of color – a voice, and tearing down oppressive systems that contribute to poor health outcomes and oppression, she said.

“It’s time for us to talk about racism openly,” said Dr. Kara. “Believe your colleagues when they share their fears and treat each other with respect. We should be actively learning about and celebrating our diversity.” She encourages finding out what your institution is doing on this front and getting involved.

Dr. Johnson believes that first and foremost, hospitalists need to be exposed to the data on health care disparities. “The next step is asking what we as hospitalists, or any other specialty, can do to intervene and improve in those areas,” he said. Focusing on unconscious bias training is important, he said, so clinicians can see what biases they might be bringing into the hospital and to the bedside. Maintaining a diverse workforce and bringing UIM physicians into leadership roles to encourage diversity of ideas and approaches are also critical to promoting equity, he said.

“You cannot fix what you cannot face,” said Dr. Unaka. Education on how racism impacts patients and colleagues is essential, she believes, as is advocacy for changing inequitable health system policies. She recommends expanding social and professional circles. “Diverse social groups allow us to consider the perspectives of others; diverse professional groups allow us to ask better research questions and practice better medicine.”

Start by developing the ability to question personal assumptions and pinpoint implicit biases, suggested Dr. Baenziger. “Asking for feedback can be scary and difficult, but we should take a deep breath and do it anyway,” she said. “Simply ask your team, ‘I’ve been thinking a lot about racial equity and disparities. How can I do better at my interactions with people of color? What are my blind spots?’” Dr. Baenziger said that “to help us remember how beautifully complicated and diverse people are,” all health care professionals need to watch Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED talk “The Danger of a Single Story.”

Dr. Baenziger also stressed the importance of conversations about “places where race is built into our clinical assessments, like eGFR,” as well as being aware that many of the research studies that are used to support everyday clinical decisions didn’t include people of color. She also encouraged clinicians to consider how and when they include race in their notes.7 “Is it really helpful to make sure people know right away that you are treating a ‘46-year-old Hispanic male’ or can the fact that he is Hispanic be saved for the social history section with other important details of his life such as being a father, veteran, and mechanic?” she asked.

“Racism is real and very much a part of our history. We can no longer be in denial regarding the racism that exists in medicine and the impact it has on our patients,” Dr. Unaka said. “As a profession, we cannot hide behind our espoused core values. We must live up to them.”

References

1. Lucey CR, Saguil, A. The Consequences of Structural Racism on MCAT Scores and Medical School Admissions: The Past Is Prologue. Acad Med. 2020 Mar;95(3):351-356. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002939.

2. Flores L. Increasing racial diversity in hospital medicine’s leadership ranks. The Hospitalist. 2020 Oct 21.

3. Smedley BD, et al, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington: National Academies Press; 2003.

4. Heins A, et al. Physician Race/Ethnicity Predicts Successful Emergency Department Analgesia. J Pain. 2010 July;11(7):692-697. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.017.

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Serves, Office of Minority Health. Infant Mortality and African Americans. 2019 Nov 8. minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=23.

6. Jacobs ZG, et al. The Association between Limited English Proficiency and Sepsis Mortality. J Hosp Med. 2020;3;140-146. Published Online First 2019 Nov 20. doi:10.12788/jhm.3334.

7. Finucane TE. Mention of a Patient’s “Race” in Clinical Presentations. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16(6):423-427. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.6.ecas1-1406.

With the shootings of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and other Black citizens setting off protests and unrest, race was at the forefront of national conversation in the United States – along with COVID-19 – over the past year.

“We’ve heard things like, ‘We’re in a post-racial society,’ but I think 2020 in particular has emphasized that we’re not,” said Gregory Johnson, MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of hospital medicine at Sound Physicians, a national physician practice. “Racism is very present in our lives, it’s very present in our world, and it is absolutely present in medicine.”

Yes, race is still an issue in the U.S. as we head into 2021, though this may have come as something of a surprise to people who do not live with racism daily.

“If you have a brain, you have bias, and that bias will likely apply to race as well,” Dr. Johnson said. “When we’re talking about institutional racism, the educational system and the media have led us to create presumptions and prejudices that we don’t necessarily recognize off the top because they’ve just been a part of the fabric of who we are as we’ve grown up.”

The term “racism” has extremely negative connotations because there’s character judgment attached to it, but to say someone is racist or racially insensitive does not equate them with being a Klansman, said Dr. Johnson. “I think we as people have to acknowledge that, yes, it’s possible for me to be racist and I might not be 100% aware of it. It’s being open to the possibility – or rather probability – that you are and then taking steps to figure out how you can address that, so you can limit it. And that requires constant self-evaluation and work,” he said.

Racism in the medical environment

Institutional racism is evident before students are even accepted into medical school, said Areeba Kara, MD, SFHM, associate professor of clinical medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis, and a hospitalist at IU Health Physicians.

Mean MCAT scores are lower for applicants traditionally underrepresented in medicine (UIM) compared to the scores of well-represented groups.1 “Lower scores are associated with lower acceptance rates into medical school,” Dr. Kara said. “These differences reflect unequal educational opportunities rooted in centuries of legal discrimination.”

Racism is apparent in both the hidden medical education curriculum and in lessons implicitly taught to students, said Ndidi Unaka, MD, MEd, associate program director of the pediatric residency training program at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

“These lessons inform the way in which we as physicians see our patients, each other, and how we practice,” she said. “We reinforce race-based medicine and shape clinical decision making through flawed guidelines and practices, which exacerbates health inequities. We teach that race – rather than racism – is a risk factor for poor health outcomes. Our students and trainees watch as we assume the worst of our patients from marginalized communities of color.”

Terms describing patients of color, such as “difficult,” “non-compliant,” or “frequent flyer” are thrown around and sometimes, instead of finding out why, “we view these states of being as static, root causes for poor outcomes rather than symptoms of social conditions and obstacles that impact overall health and wellbeing,” Dr. Unaka said.

Leadership opportunities

Though hospital medicine is a growing field, Dr. Kara noted that the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine Report found that only 5.5% of hospital medical group leaders were Black, and just 2.2% were Hispanic/Latino.2 “I think these numbers speak for themselves,” she said.

Dr. Unaka said that the lack of UIM hospitalists and physician leaders creates fewer opportunities for “race-concordant mentorship relationships.” It also forces UIM physicians to shoulder more responsibilities – often obligations that do little to help them move forward in their careers – all in the name of diversity. And when UIM physicians are given leadership opportunities, Dr. Unaka said they are often unsure as to whether their appointments are genuine or just a hollow gesture made for the sake of diversity.

Dr. Johnson pointed out that Black and Latinx populations primarily get their care from hospital-based specialties, yet this is not reflected in the number of UIM practitioners in leadership roles. He said race and ethnicity, as well as gender, need to be factors when individuals are evaluated for leadership opportunities – for the individual’s sake, as well as for the community he or she is serving.

“When we can evaluate for unconscious bias and factor in that diverse groups tend to have better outcomes, whether it’s business or clinical outcomes, it’s one of the opportunities that we collectively have in the specialty to improve what we’re delivering for hospitals and, more importantly, for patients,” he said.

Relationships with colleagues and patients

Racism creeps into interactions and relationships with others as well, whether it’s between clinicians, clinician to patient, or patient to clinician. Sometimes it’s blatant; often it’s subtle.

A common, recurring example Dr. Unaka has experienced in the clinician to clinician relationship is being confused for other Black physicians, making her feel invisible. “The everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults from colleagues are frequent and contribute to feelings of exclusion, isolation, and exhaustion,” she said. Despite this, she is still expected to “address microaggressions and other forms of interpersonal racism and find ways to move through professional spaces in spite of the trauma, fear, and stress associated with my reality and lived experiences.” She said that clinicians who remain silent on the topic of racism participate in the violence and contribute to the disillusionment of UIM physicians.

Dr. Kara said that the discrimination from the health care team is the hardest to deal with. In the clinician to clinician relationship, there is a sense among UIM physicians that they’re being watched more closely and “have to prove themselves at every single turn.” Unfortunately, this comes from the environment, which tends to be adversarial rather than supportive and nurturing, she said.

“There are lots of opportunities for racism or racial insensitivity to crop up from clinician to clinician,” said Dr. Johnson. When he started his career as a physician after his training, Dr. Johnson was informed that his colleagues were watching him because they were not sure about his clinical skills. The fact that he was a former chief resident and board certified in two specialties did not seem to make any difference.

Patients refusing care from UIM physicians or expressing disapproval – both verbal and nonverbal – of such care, happens all too often. “It’s easier for me to excuse patients and their families as we often meet them on their worst days,” said Dr. Kara. Still, “understanding my oath to care for people and do no harm, but at the same time, recognizing that this is an individual that is rejecting my care without having any idea of who I am as a physician is frustrating,” Dr. Johnson acknowledged.

Then there’s the complex clinician to patient relationship, which research clearly shows contributes to health disparities.3 For one thing, the physician workforce does not reflect the patient population, Dr. Unaka said. “We cannot ignore the lack of race concordance between patients and clinicians, nor can the continued misplacement of blame for medical mistrust be at the feet of our patients,” she said.

Dr. Unaka feels that clinicians need to accept both that health inequities exist and that frontline physicians themselves contribute to the inequities. “Our diagnostic and therapeutic decisions are not immune to bias and are influenced by our deeply held beliefs about specific populations,” she said. “And the health care system that our patients navigate is no different than other systems, settings, and environments that are marred by racism in all its forms.”

Systemic racism greatly impacts patient care, said Dr. Kara. She pointed to several examples: Research showing that race concordance between patients and providers in an emergency department setting led to better pain control with fewer analgesics.4 The high maternal and infant mortality rates amongst Black women and children.5 Evidence of poorer outcomes in sepsis patients with limited English proficiency.6 “There are plenty more,” she said. “We need to be asking ourselves what we are going to do about it.”

Moving forward

That racial biases are steeped so thoroughly into our culture and consciousness means that moving beyond them is a continual, purposeful work in progress. But it is work that is critical for everyone, and certainly necessary for those who care for their fellow human beings when they are in a vulnerable state.

Health care systems need to move toward equity – giving everyone what they need to thrive – rather than focusing on equality – giving everyone the same thing, said Jenny Baenziger, MD, assistant professor of clinical medicine and pediatrics at Indiana University, Indianapolis, and associate director of education at IU Center for Global Health. “We know that minoritized patients are going to need more attention, more advocacy, more sensitivity, and more creative solutions in order to help them achieve health in a world that is often stacked against them,” she said.

“The unique needs of each patient, family unit, and/or population must be taken into consideration,” said Dr. Unaka. She said hospitalists need to embrace creative approaches that can better serve the specific needs of patients. Equitable practices should be the default, which means data transparency, thoroughly dissecting hospital processes to find existing inequities, giving stakeholders – especially patients and families of color – a voice, and tearing down oppressive systems that contribute to poor health outcomes and oppression, she said.

“It’s time for us to talk about racism openly,” said Dr. Kara. “Believe your colleagues when they share their fears and treat each other with respect. We should be actively learning about and celebrating our diversity.” She encourages finding out what your institution is doing on this front and getting involved.

Dr. Johnson believes that first and foremost, hospitalists need to be exposed to the data on health care disparities. “The next step is asking what we as hospitalists, or any other specialty, can do to intervene and improve in those areas,” he said. Focusing on unconscious bias training is important, he said, so clinicians can see what biases they might be bringing into the hospital and to the bedside. Maintaining a diverse workforce and bringing UIM physicians into leadership roles to encourage diversity of ideas and approaches are also critical to promoting equity, he said.

“You cannot fix what you cannot face,” said Dr. Unaka. Education on how racism impacts patients and colleagues is essential, she believes, as is advocacy for changing inequitable health system policies. She recommends expanding social and professional circles. “Diverse social groups allow us to consider the perspectives of others; diverse professional groups allow us to ask better research questions and practice better medicine.”

Start by developing the ability to question personal assumptions and pinpoint implicit biases, suggested Dr. Baenziger. “Asking for feedback can be scary and difficult, but we should take a deep breath and do it anyway,” she said. “Simply ask your team, ‘I’ve been thinking a lot about racial equity and disparities. How can I do better at my interactions with people of color? What are my blind spots?’” Dr. Baenziger said that “to help us remember how beautifully complicated and diverse people are,” all health care professionals need to watch Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED talk “The Danger of a Single Story.”

Dr. Baenziger also stressed the importance of conversations about “places where race is built into our clinical assessments, like eGFR,” as well as being aware that many of the research studies that are used to support everyday clinical decisions didn’t include people of color. She also encouraged clinicians to consider how and when they include race in their notes.7 “Is it really helpful to make sure people know right away that you are treating a ‘46-year-old Hispanic male’ or can the fact that he is Hispanic be saved for the social history section with other important details of his life such as being a father, veteran, and mechanic?” she asked.

“Racism is real and very much a part of our history. We can no longer be in denial regarding the racism that exists in medicine and the impact it has on our patients,” Dr. Unaka said. “As a profession, we cannot hide behind our espoused core values. We must live up to them.”

References

1. Lucey CR, Saguil, A. The Consequences of Structural Racism on MCAT Scores and Medical School Admissions: The Past Is Prologue. Acad Med. 2020 Mar;95(3):351-356. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002939.

2. Flores L. Increasing racial diversity in hospital medicine’s leadership ranks. The Hospitalist. 2020 Oct 21.

3. Smedley BD, et al, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington: National Academies Press; 2003.

4. Heins A, et al. Physician Race/Ethnicity Predicts Successful Emergency Department Analgesia. J Pain. 2010 July;11(7):692-697. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.017.

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Serves, Office of Minority Health. Infant Mortality and African Americans. 2019 Nov 8. minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=23.

6. Jacobs ZG, et al. The Association between Limited English Proficiency and Sepsis Mortality. J Hosp Med. 2020;3;140-146. Published Online First 2019 Nov 20. doi:10.12788/jhm.3334.

7. Finucane TE. Mention of a Patient’s “Race” in Clinical Presentations. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16(6):423-427. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.6.ecas1-1406.

Retroperitoneal anatomy and parametrial dissection in robotic uterine artery-sparing radical trachelectomy

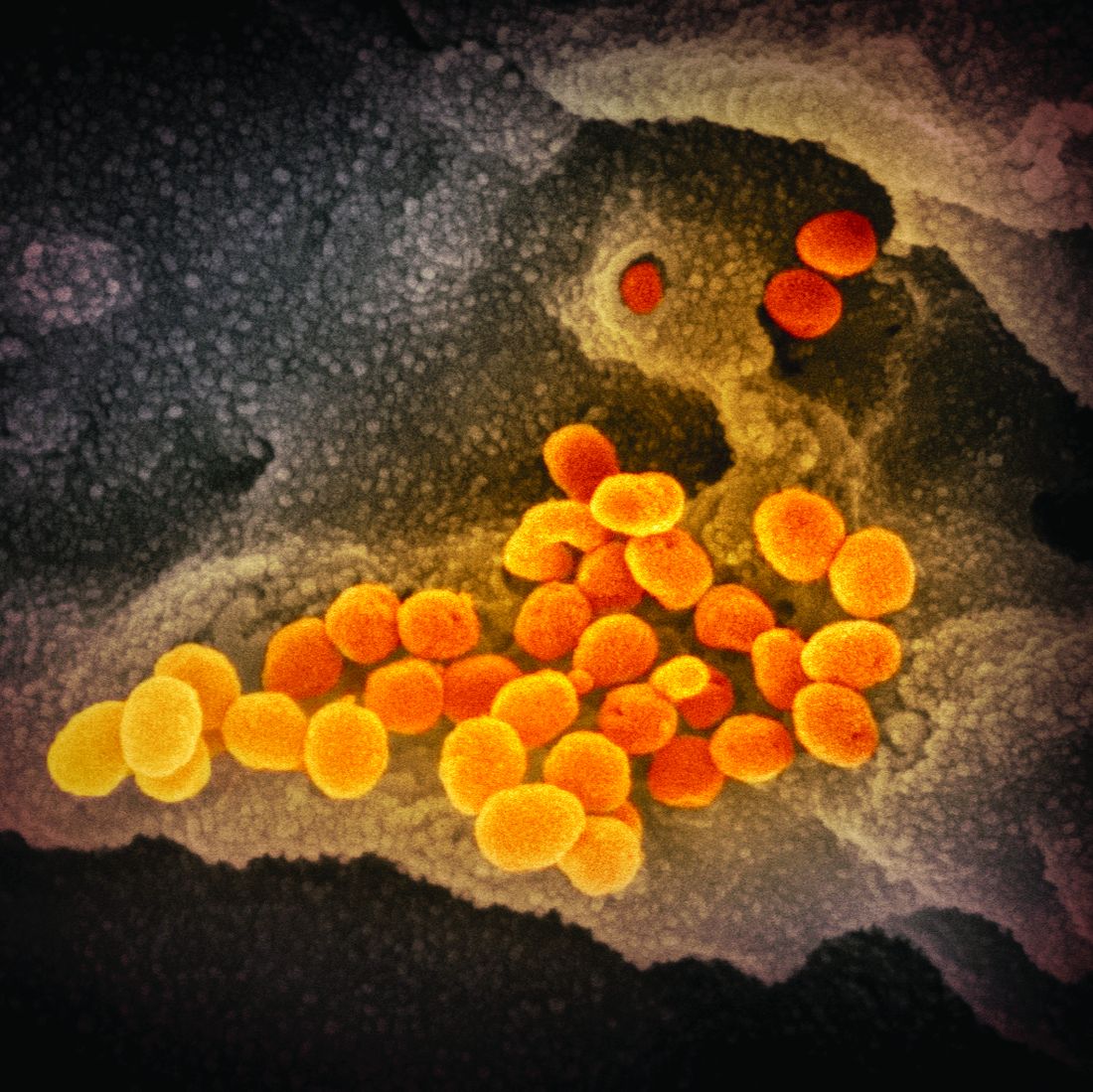

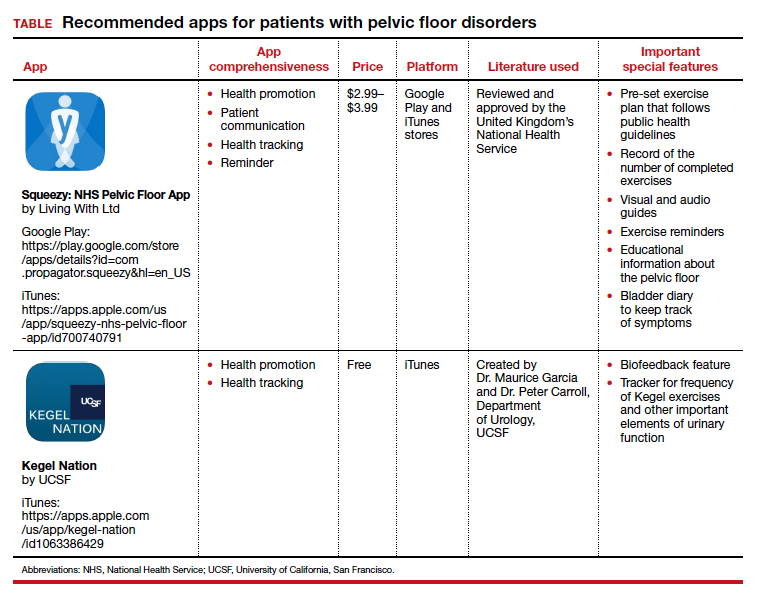

Two at-home apps for patients with pelvic floor disorders

In the “You asked, Dr. Jen Gunter answered” series in The New York Times, Dr. Gunter writes that “pelvic floor exercises (also known as Kegel exercises) can be very helpful for urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence.” She continues to say that “pelvic floor exercises can be hard to master correctly, so it is important to make sure [one has] the correct technique. Many women can learn to do them after reading instructions like the ones found at the National Association for Continence, but some women may need their technique checked by their doctor, or help from a specialized pelvic floor physical therapist.”1

Similarly, Sudol and colleagues write that “guidelines from multiple medical societies emphasize the importance of patient education, behavioral therapy, and/or exercise regimens in the initial treatment and management of women with pelvic floor disorders. However, even with well-established recommendations, engaging patients and maintaining adherence to treatment plans and unmonitored programs at home are often difficult.”2 To help patients, those authors identified and evaluated patient-centered apps on topics in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.2

Two apps that assist patients in Kegel exercises are presented here. The Squeezy app includes guided pelvic floor muscle exercises with reminders, and the Kegel Nation app has a biofeedback feature.

The TABLE details the features of the 2 apps based on a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and important special features).3

I hope clinicians find these apps helpful to their patients with pelvic floor disorders.

- Gunter J. You asked, Dr. Jen Gunter answered. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/ask/answers/kegels-pelvic-floor-exercises-yoni-eggs. Accessed December 22, 2020.

- Sudol NT, Adams-Piper E, Perry R, et al. In search of mobile applications for patients with pelvic floor disorders. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25:252-256.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

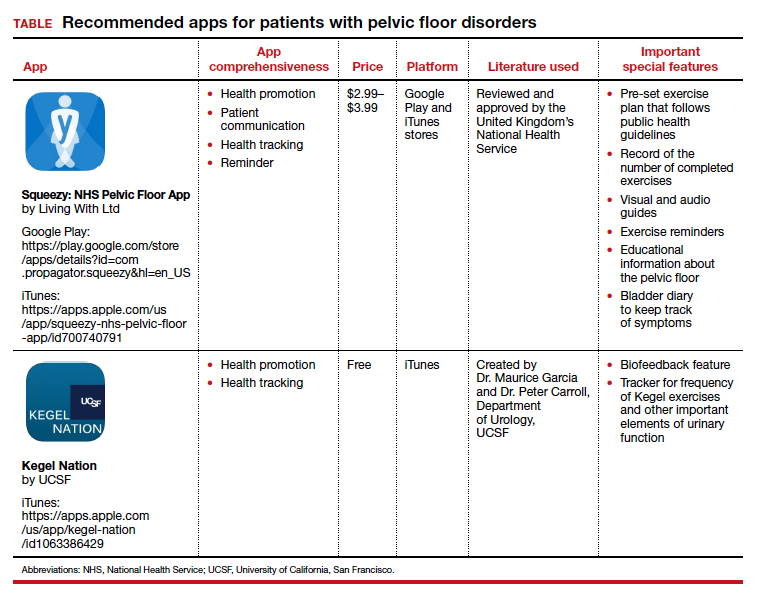

In the “You asked, Dr. Jen Gunter answered” series in The New York Times, Dr. Gunter writes that “pelvic floor exercises (also known as Kegel exercises) can be very helpful for urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence.” She continues to say that “pelvic floor exercises can be hard to master correctly, so it is important to make sure [one has] the correct technique. Many women can learn to do them after reading instructions like the ones found at the National Association for Continence, but some women may need their technique checked by their doctor, or help from a specialized pelvic floor physical therapist.”1

Similarly, Sudol and colleagues write that “guidelines from multiple medical societies emphasize the importance of patient education, behavioral therapy, and/or exercise regimens in the initial treatment and management of women with pelvic floor disorders. However, even with well-established recommendations, engaging patients and maintaining adherence to treatment plans and unmonitored programs at home are often difficult.”2 To help patients, those authors identified and evaluated patient-centered apps on topics in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.2

Two apps that assist patients in Kegel exercises are presented here. The Squeezy app includes guided pelvic floor muscle exercises with reminders, and the Kegel Nation app has a biofeedback feature.

The TABLE details the features of the 2 apps based on a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and important special features).3

I hope clinicians find these apps helpful to their patients with pelvic floor disorders.

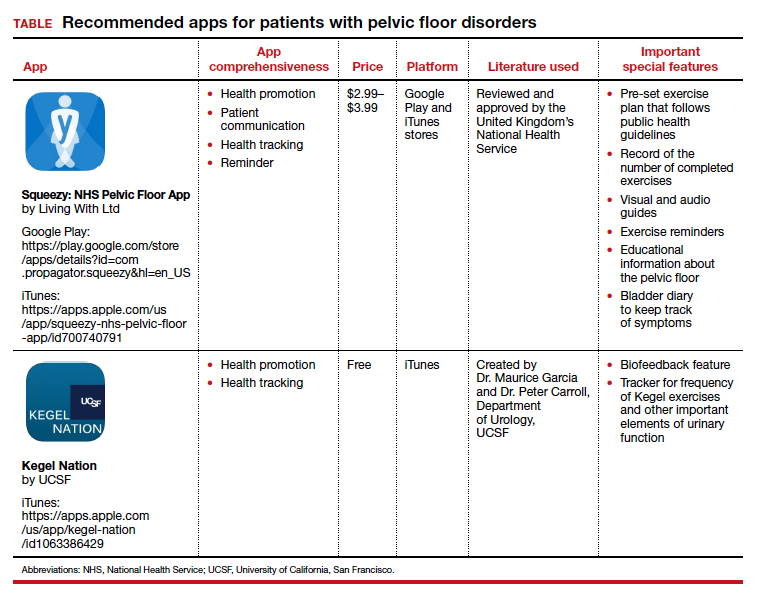

In the “You asked, Dr. Jen Gunter answered” series in The New York Times, Dr. Gunter writes that “pelvic floor exercises (also known as Kegel exercises) can be very helpful for urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence.” She continues to say that “pelvic floor exercises can be hard to master correctly, so it is important to make sure [one has] the correct technique. Many women can learn to do them after reading instructions like the ones found at the National Association for Continence, but some women may need their technique checked by their doctor, or help from a specialized pelvic floor physical therapist.”1

Similarly, Sudol and colleagues write that “guidelines from multiple medical societies emphasize the importance of patient education, behavioral therapy, and/or exercise regimens in the initial treatment and management of women with pelvic floor disorders. However, even with well-established recommendations, engaging patients and maintaining adherence to treatment plans and unmonitored programs at home are often difficult.”2 To help patients, those authors identified and evaluated patient-centered apps on topics in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.2

Two apps that assist patients in Kegel exercises are presented here. The Squeezy app includes guided pelvic floor muscle exercises with reminders, and the Kegel Nation app has a biofeedback feature.

The TABLE details the features of the 2 apps based on a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and important special features).3

I hope clinicians find these apps helpful to their patients with pelvic floor disorders.

- Gunter J. You asked, Dr. Jen Gunter answered. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/ask/answers/kegels-pelvic-floor-exercises-yoni-eggs. Accessed December 22, 2020.

- Sudol NT, Adams-Piper E, Perry R, et al. In search of mobile applications for patients with pelvic floor disorders. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25:252-256.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

- Gunter J. You asked, Dr. Jen Gunter answered. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/ask/answers/kegels-pelvic-floor-exercises-yoni-eggs. Accessed December 22, 2020.

- Sudol NT, Adams-Piper E, Perry R, et al. In search of mobile applications for patients with pelvic floor disorders. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25:252-256.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

Still happening: Pelvic exams on anesthetized patients. Why?

“When I was doing ob.gyn. as a med student, the attending would have me do a pelvic right after the patient was under and before we started surgery,” said one participant in an online forum. “We didn’t exactly get permission but it was for teaching purposes.”

Yet others don’t see what the commotion is about. “There are a hundred things that are done during a surgery that don’t require your specific consent (some of them much more ‘humiliating’ than a pelvic exam). ... There’s not really much left to be shy about during a gyn/rectal/prostate surgery, let me put it that way,” one doctor wrote.

However, many physicians are adamantly opposed to the practice, and laws intended to stop or limit it are being enacted throughout the nation.

Renewed concerns have prompted new state laws

A few states have required consent for pelvic exams for many years, beginning with California in 2003. But up until 2019, providing pelvic exams without informed consent was illegal in only six states.

Continuing reports of unauthorized pelvic exams indicate that the practice has not disappeared. University of Michigan professor Maya M. Hammoud, MD, past president of the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics, and many others attribute renewed interest in the issue to a 2018 article in the journal Bioethics by Phoebe Friesen, a medical ethicist at McGill University, Montreal, that laid out the ethical arguments against the practice.

Starting in 2019, an outpouring of new state bills have been introduced, and nine more states have passed laws. In addition, 14 other states considered similar bills but did not pass them, in some cases because teaching institutions argued that they were already dealing with the issue. This happened in Connecticut and Massachusetts, after representatives of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., met with legislators.

Laws against the practice have been passed by 15 states, including California, Florida, Illinois, and New York. Some teaching institutions have recently been clamping down on the practice, while many teaching physicians insist that at this point, it has all but ended.

A practice that may still continue

For many years, ethicists, women’s rights groups, state legislators, and organized medicine have been trying to eliminate the practice of unauthorized pelvic exams by medical students. Several key medical groups have come out against it, including the American Medical Association, the Association of American Medical Colleges, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“Fifteen years ago, studies found a substantial number of cases, but my sense is that most of that has stopped,” said Dr. Hammoud.

Yet despite these changes, there are some disturbing signs that the practice persists.

“I don’t have data, but anecdotally I see it still going on,” said Peter Ubel, MD, a professor at Duke University, Durham, N.C., who was involved in one of those early studies. “Every so often when I’m making a speech, a medical student tells me about performing a pelvic exam without getting permission.

“Perhaps in some cases the attending [physician] did get permission and didn’t tell the medical student, but that would also be a problem,” Dr. Ubel said. “The medical student should be informed that permission was given. This helps them be sensitive to the need to get consent.”

In a 2019 survey of medical students, 92% said they performed a pelvic exam on an anesthetized female patient, and of those, 61% did so without explicit patient consent.

The survey – involving 101 medical students at seven U.S. medical schools – also found that 11% of the medical students said they were extremely uncomfortable with the practice. But nearly one-third of the medical students said that opting out might jeopardize their grades and future careers.

“I tried to opt out once from doing a pelvic exam when I hadn’t met the patient beforehand,” one of them wrote. “The resident told me no.”

Some physicians defend the practice

Why do many medical students and doctors think that getting consent for pelvic exams is not necessary?

Some argue that patients implicitly give consent when they walk through the doors of a teaching hospital. “Sorry, but you inherently agree to that when you’re seen in an academic teaching hospital,” wrote one participant in a Student Doctor Network forum. “You agree to have residents and medical students participate in your care, not just an attending. If you just want an attending, then you are free to go to a nonteaching hospital. That’s the deal.”

Others argued that since the anesthetized patient couldn’t feel what was going on, it shouldn’t matter. “Things like pelvic exams, rectal exams, or even heroic trauma surgery occur for training purposes when there is no memory, no sensation and no harm to be done [and] society gains a better practitioner of the art of medicine,” a physician in Columbus, Ohio, wrote on Quora, an online forum.

Some doctors argue that they don’t ask for specific consent when they touch a variety of other body parts, and pelvic exams should be no different. Pelvic exams are needed before surgery of the pelvic area, but they have also been given to women undergoing surgery in a different part of the body.

In 2019 a woman told Deseret News in Utah that she had been recovering from stomach surgery when a resident physician mentioned something she had noticed “when we looked at your cervix.” When she asked why the physician had examined her cervix to prepare for stomach surgery, “no one could give her a good answer.”

A ‘positive goal’ doesn’t make it okay

What is missing in many defenses of the practice is any recognition that genitals are the most intimate part of the body, and that a patient’s desire for privacy ought to come first. In a survey of women undergoing gynecologic surgery, 72% expected to be asked for consent before medical students undertook pelvic examinations under anesthesia.

Overruling patients’ concerns about their own privacy is unethical, said Eli Y. Adashi, MD, professor of medical science and former dean of medicine and biological sciences at Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Dr. Adashi said the principle of patient autonomy in medical ethics directs that patients must be involved in decision-making about their care – even when caretakers are pursuing a positive goal, such as helping to educate future doctors.

“Conducting pelvic exams on unconscious women without their specific consent is simply untenable and never has been tenable, and it ought to be discontinued if it hasn’t been already,” says Dr. Adashi, who wrote an opinion piece on the issue for JAMA.

Furthermore, it has been shown that ignoring the need to get consent for pelvic exams makes physicians less concerned about getting patient consent in general. A study led by Dr. Ubel found that medical students who had completed an ob.gyn. clerkship thought getting patients’ consent was significantly less important than those who had not completed that clerkship.

Why give pelvic exams to anesthetized women?

Despite the controversy, a number of medical educators continue to direct medical students to perform pelvic exams on anesthetized women. Why is that?

“Pelvic exams are not easy to do,” Dr. Hammoud said. “Learners need to keep working on them; they have to do a lot of them in order to do them well.”

To teach pelvic exams, most medical schools provide standardized patients – paid volunteers who submit to exams and critique the medical student’s work afterwards – but these encounters are limited because of their cost, says Guy Benrubi, MD, professor and emeritus chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Florida, Jacksonville.

He said teaching programs therefore need to supplement exams on standardized patients with exams on unpaid volunteers who provide consent. Programs prefer anesthetized patients, Dr. Benrubi said, because they are easier for novices to work on. “With patients under anesthesia, the muscles are relaxed and it’s easier for learners to detect organs. All the same, you need to get consent.”

Teaching institutions stiffen consent requirements

Faced with growing opposition to pelvic exams without consent, teaching institutions as well as gynecologic educators have recently been tightening their policies.

Dr. Hammoud said she has always informed patients orally about the possibility of medical students performing pelvic exams on them, but now some institutions, including her own, want a more involved process. The university recently began consent in writing for pelvic exams.

In addition, the university also now requires that medical students meet patients before performing pelvic exams and that teaching physicians explain the students’ involvement.

Dr. Hammoud said some institutions now require a separate consent form for pelvic exams, but the University of Michigan simply directs that the possibility of the patient getting a pelvic exam be part of the consent form.

This requirement, called “explicit consent,” was endorsed by APGO. It differs from having a separate consent form for pelvic exams, which would highlight the possibility of a pelvic exam, as many women’s rights activists are calling for.

Why not have a separate form? Dr. Hammoud is concerned that it would unnecessarily alarm patients. “When you point out a certain issue, you’re in effect saying to the patient that this is not normal,” she said, noting that, when asked for consent to do the exams, most women agree to it.