User login

Preserving kidney function in patients with lupus nephritis

Lupus nephritis is a serious complication of lupus for which there is a great unmet therapeutic need. The first step to preserve kidney function is to identify kidney involvement with blood and urine tests, and to assess whether a kidney biopsy is needed. Dr. Richard Furie, Chief of Rheumatology at Northwell Health, shares recommendations for evaluating whether a patient is a candidate for kidney biopsy based on their protein/creatinine ratio and serologic activity.

Dr. Furie also reviews treatment options based on biopsy results, including steroids, immunosuppressive agents, and calcineurin inhibitors, as well as significant findings from the recent BLISS-LN, NOBILITY, and AURORA trials.

--

Chief of Rheumatology, Northwell Health

Professor, Center for Autoimmune, Musculoskeletal and Hematopoietic Diseases, Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research

Professor of Medicine, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell

Richard A. Furie, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for AstraZeneca; GlaxoSmithKline; Genentech; Biogen; Aurinia; Bristol-Myers Squibb; EMD Serono.

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from AstraZeneca; GlaxoSmithKline; Genentech; Biogen; Aurinia; Bristol-Myers Squibb; EMD Serono.

Lupus nephritis is a serious complication of lupus for which there is a great unmet therapeutic need. The first step to preserve kidney function is to identify kidney involvement with blood and urine tests, and to assess whether a kidney biopsy is needed. Dr. Richard Furie, Chief of Rheumatology at Northwell Health, shares recommendations for evaluating whether a patient is a candidate for kidney biopsy based on their protein/creatinine ratio and serologic activity.

Dr. Furie also reviews treatment options based on biopsy results, including steroids, immunosuppressive agents, and calcineurin inhibitors, as well as significant findings from the recent BLISS-LN, NOBILITY, and AURORA trials.

--

Chief of Rheumatology, Northwell Health

Professor, Center for Autoimmune, Musculoskeletal and Hematopoietic Diseases, Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research

Professor of Medicine, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell

Richard A. Furie, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for AstraZeneca; GlaxoSmithKline; Genentech; Biogen; Aurinia; Bristol-Myers Squibb; EMD Serono.

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from AstraZeneca; GlaxoSmithKline; Genentech; Biogen; Aurinia; Bristol-Myers Squibb; EMD Serono.

Lupus nephritis is a serious complication of lupus for which there is a great unmet therapeutic need. The first step to preserve kidney function is to identify kidney involvement with blood and urine tests, and to assess whether a kidney biopsy is needed. Dr. Richard Furie, Chief of Rheumatology at Northwell Health, shares recommendations for evaluating whether a patient is a candidate for kidney biopsy based on their protein/creatinine ratio and serologic activity.

Dr. Furie also reviews treatment options based on biopsy results, including steroids, immunosuppressive agents, and calcineurin inhibitors, as well as significant findings from the recent BLISS-LN, NOBILITY, and AURORA trials.

--

Chief of Rheumatology, Northwell Health

Professor, Center for Autoimmune, Musculoskeletal and Hematopoietic Diseases, Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research

Professor of Medicine, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell

Richard A. Furie, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for AstraZeneca; GlaxoSmithKline; Genentech; Biogen; Aurinia; Bristol-Myers Squibb; EMD Serono.

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from AstraZeneca; GlaxoSmithKline; Genentech; Biogen; Aurinia; Bristol-Myers Squibb; EMD Serono.

Collective trauma could lead to posttraumatic growth

Reflections for 2021

When we went to medical school, how many of us thought we would practice through a pandemic? For most of us, 2020 was the most challenging professional year of our lives. As a psychiatrist, I found it particularly odd to be struggling with the same issues as all of my patients and to have all my patients in crisis at the same time. I was repeatedly asked by friends, “How are your patients doing?” My reply, “About the same as the rest of us.” After a period of adapting, I felt truly blessed to be able to practice online. I know many of my colleagues did not have that luxury, and the stress you endured is hard to fathom.

Yet, as Friedrich Nietzsche said in so many words, “What doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger,” and here we are in a new year. As we enter 2021, we know so much more about COVID-19 than we did mere months ago, and many of us have been fortunate enough to be vaccinated already.

We should be very proud of our medical and scientific community, which has worked so hard to prevent and treat COVID-19. It is indeed a miracle of modern medicine that two vaccines made their way through development to distribution in under a year. It is a great relief that health care workers are first in line: Of the 4 million vaccine doses given worldwide, 2 million were to U.S. medical personnel. We can now track the number of people vaccinated around the globe.

Yet, “the darkest hour is just before the dawn.” We are currently in the riskiest part of the pandemic, and we must continue to work hard.

As 2021 progresses, we can expect to begin the long recovery process. We know we are innately wired to adapt to adversity and are therefore resilient. The key is to tap into this wiring by developing behaviors, habits, and strategies that support us.

Posttraumatic growth (PTG) is a theory in mental health that explains a kind of transformation following trauma. It was developed by psychologists Richard Tedeschi, PhD, and Lawrence Calhoun, PhD, in the mid-1990s. They studied how people experienced positive growth following adversity. Dr. Tedeschi has said: “People develop new understandings of themselves, the world they live in, how to relate to other people, the kind of future they might have and a better understanding of how to live life.” One-half to two-thirds of individuals experiencing trauma will experience PTG. Given that our entire profession has gone through this collective trauma, far better times may indeed be ahead.

Resilience expert Eva Selhub, MD, suggests cultivating these six pillars:

- Physical vitality: The toll of 2020 has been enormous. If we are to rebound, we must care for ourselves. In our training, we were taught to put our health aside and work grueling hours. But to recover from trauma, we must attend to our own needs. Even after we are vaccinated, we must keep our nutritional status and immunity functioning at optimal levels. Let’s not get COVID-19 complacency. Clearly, health matters most. Ours included!

- Mental toughness: We made it through an incredibly grueling year, and we had to “build it as we sailed.” We figured out how to save as many lives as we could and simultaneously keep ourselves and our families safe. We have seen things previously unimaginable. We have adjusted to telemedicine. We have lived with far fewer pleasures. We have cultivated multiple ways to tame our anxieties. The year 2020 is one we can be proud of for ourselves and our colleagues. We have come a long way in a short time.

- Emotional balance: Anxiety and depression were easy to fall into in 2020. But as the pandemic subsides, the pendulum will swing the other way. The 1918 pandemic gave rise to the Roaring Twenties. What will the next chapter in our civilization bring?

- Loving and strong connections. Our relationships are what give depth and meaning to our lives, and these relationships are crucial now so we can heal. How can we nourish our connections? What toll has the pandemic taken on those closest to you? Did some friends or family step up and help? Can we move out of our caretaker role and allow others to care for us?

- Spiritual connection: Facing so much grief and suffering, we have had an opportunity to look at our own lives from a different perspective. It has been an important year for reflection. How can we cultivate a deeper appreciation recognizing that every day is truly a gift? Did you find more purpose in your work last year? What sustained you in your time of need?

- Inspiring leadership: As health care professionals, we must set an example. We must show our patients and our families how resilient we can be. Let’s grow from trauma and avoid succumbing to depression, self-destructive tendencies, and divisiveness. We must continue to care for ourselves, our patients, and our community and work together to ensure a brighter and safer future for all.

Wishing you a safe, happy and healthy 2021.

“I am not what happened to me, I am what I choose to become.”

– Carl Jung, PhD

Dr. Ritvo, a psychiatrist with more than 25 years’ experience, practices in Miami Beach. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Mimosa Publishing, 2018). She has no conflicts of interest.

Reflections for 2021

Reflections for 2021

When we went to medical school, how many of us thought we would practice through a pandemic? For most of us, 2020 was the most challenging professional year of our lives. As a psychiatrist, I found it particularly odd to be struggling with the same issues as all of my patients and to have all my patients in crisis at the same time. I was repeatedly asked by friends, “How are your patients doing?” My reply, “About the same as the rest of us.” After a period of adapting, I felt truly blessed to be able to practice online. I know many of my colleagues did not have that luxury, and the stress you endured is hard to fathom.

Yet, as Friedrich Nietzsche said in so many words, “What doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger,” and here we are in a new year. As we enter 2021, we know so much more about COVID-19 than we did mere months ago, and many of us have been fortunate enough to be vaccinated already.

We should be very proud of our medical and scientific community, which has worked so hard to prevent and treat COVID-19. It is indeed a miracle of modern medicine that two vaccines made their way through development to distribution in under a year. It is a great relief that health care workers are first in line: Of the 4 million vaccine doses given worldwide, 2 million were to U.S. medical personnel. We can now track the number of people vaccinated around the globe.

Yet, “the darkest hour is just before the dawn.” We are currently in the riskiest part of the pandemic, and we must continue to work hard.

As 2021 progresses, we can expect to begin the long recovery process. We know we are innately wired to adapt to adversity and are therefore resilient. The key is to tap into this wiring by developing behaviors, habits, and strategies that support us.

Posttraumatic growth (PTG) is a theory in mental health that explains a kind of transformation following trauma. It was developed by psychologists Richard Tedeschi, PhD, and Lawrence Calhoun, PhD, in the mid-1990s. They studied how people experienced positive growth following adversity. Dr. Tedeschi has said: “People develop new understandings of themselves, the world they live in, how to relate to other people, the kind of future they might have and a better understanding of how to live life.” One-half to two-thirds of individuals experiencing trauma will experience PTG. Given that our entire profession has gone through this collective trauma, far better times may indeed be ahead.

Resilience expert Eva Selhub, MD, suggests cultivating these six pillars:

- Physical vitality: The toll of 2020 has been enormous. If we are to rebound, we must care for ourselves. In our training, we were taught to put our health aside and work grueling hours. But to recover from trauma, we must attend to our own needs. Even after we are vaccinated, we must keep our nutritional status and immunity functioning at optimal levels. Let’s not get COVID-19 complacency. Clearly, health matters most. Ours included!

- Mental toughness: We made it through an incredibly grueling year, and we had to “build it as we sailed.” We figured out how to save as many lives as we could and simultaneously keep ourselves and our families safe. We have seen things previously unimaginable. We have adjusted to telemedicine. We have lived with far fewer pleasures. We have cultivated multiple ways to tame our anxieties. The year 2020 is one we can be proud of for ourselves and our colleagues. We have come a long way in a short time.

- Emotional balance: Anxiety and depression were easy to fall into in 2020. But as the pandemic subsides, the pendulum will swing the other way. The 1918 pandemic gave rise to the Roaring Twenties. What will the next chapter in our civilization bring?

- Loving and strong connections. Our relationships are what give depth and meaning to our lives, and these relationships are crucial now so we can heal. How can we nourish our connections? What toll has the pandemic taken on those closest to you? Did some friends or family step up and help? Can we move out of our caretaker role and allow others to care for us?

- Spiritual connection: Facing so much grief and suffering, we have had an opportunity to look at our own lives from a different perspective. It has been an important year for reflection. How can we cultivate a deeper appreciation recognizing that every day is truly a gift? Did you find more purpose in your work last year? What sustained you in your time of need?

- Inspiring leadership: As health care professionals, we must set an example. We must show our patients and our families how resilient we can be. Let’s grow from trauma and avoid succumbing to depression, self-destructive tendencies, and divisiveness. We must continue to care for ourselves, our patients, and our community and work together to ensure a brighter and safer future for all.

Wishing you a safe, happy and healthy 2021.

“I am not what happened to me, I am what I choose to become.”

– Carl Jung, PhD

Dr. Ritvo, a psychiatrist with more than 25 years’ experience, practices in Miami Beach. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Mimosa Publishing, 2018). She has no conflicts of interest.

When we went to medical school, how many of us thought we would practice through a pandemic? For most of us, 2020 was the most challenging professional year of our lives. As a psychiatrist, I found it particularly odd to be struggling with the same issues as all of my patients and to have all my patients in crisis at the same time. I was repeatedly asked by friends, “How are your patients doing?” My reply, “About the same as the rest of us.” After a period of adapting, I felt truly blessed to be able to practice online. I know many of my colleagues did not have that luxury, and the stress you endured is hard to fathom.

Yet, as Friedrich Nietzsche said in so many words, “What doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger,” and here we are in a new year. As we enter 2021, we know so much more about COVID-19 than we did mere months ago, and many of us have been fortunate enough to be vaccinated already.

We should be very proud of our medical and scientific community, which has worked so hard to prevent and treat COVID-19. It is indeed a miracle of modern medicine that two vaccines made their way through development to distribution in under a year. It is a great relief that health care workers are first in line: Of the 4 million vaccine doses given worldwide, 2 million were to U.S. medical personnel. We can now track the number of people vaccinated around the globe.

Yet, “the darkest hour is just before the dawn.” We are currently in the riskiest part of the pandemic, and we must continue to work hard.

As 2021 progresses, we can expect to begin the long recovery process. We know we are innately wired to adapt to adversity and are therefore resilient. The key is to tap into this wiring by developing behaviors, habits, and strategies that support us.

Posttraumatic growth (PTG) is a theory in mental health that explains a kind of transformation following trauma. It was developed by psychologists Richard Tedeschi, PhD, and Lawrence Calhoun, PhD, in the mid-1990s. They studied how people experienced positive growth following adversity. Dr. Tedeschi has said: “People develop new understandings of themselves, the world they live in, how to relate to other people, the kind of future they might have and a better understanding of how to live life.” One-half to two-thirds of individuals experiencing trauma will experience PTG. Given that our entire profession has gone through this collective trauma, far better times may indeed be ahead.

Resilience expert Eva Selhub, MD, suggests cultivating these six pillars:

- Physical vitality: The toll of 2020 has been enormous. If we are to rebound, we must care for ourselves. In our training, we were taught to put our health aside and work grueling hours. But to recover from trauma, we must attend to our own needs. Even after we are vaccinated, we must keep our nutritional status and immunity functioning at optimal levels. Let’s not get COVID-19 complacency. Clearly, health matters most. Ours included!

- Mental toughness: We made it through an incredibly grueling year, and we had to “build it as we sailed.” We figured out how to save as many lives as we could and simultaneously keep ourselves and our families safe. We have seen things previously unimaginable. We have adjusted to telemedicine. We have lived with far fewer pleasures. We have cultivated multiple ways to tame our anxieties. The year 2020 is one we can be proud of for ourselves and our colleagues. We have come a long way in a short time.

- Emotional balance: Anxiety and depression were easy to fall into in 2020. But as the pandemic subsides, the pendulum will swing the other way. The 1918 pandemic gave rise to the Roaring Twenties. What will the next chapter in our civilization bring?

- Loving and strong connections. Our relationships are what give depth and meaning to our lives, and these relationships are crucial now so we can heal. How can we nourish our connections? What toll has the pandemic taken on those closest to you? Did some friends or family step up and help? Can we move out of our caretaker role and allow others to care for us?

- Spiritual connection: Facing so much grief and suffering, we have had an opportunity to look at our own lives from a different perspective. It has been an important year for reflection. How can we cultivate a deeper appreciation recognizing that every day is truly a gift? Did you find more purpose in your work last year? What sustained you in your time of need?

- Inspiring leadership: As health care professionals, we must set an example. We must show our patients and our families how resilient we can be. Let’s grow from trauma and avoid succumbing to depression, self-destructive tendencies, and divisiveness. We must continue to care for ourselves, our patients, and our community and work together to ensure a brighter and safer future for all.

Wishing you a safe, happy and healthy 2021.

“I am not what happened to me, I am what I choose to become.”

– Carl Jung, PhD

Dr. Ritvo, a psychiatrist with more than 25 years’ experience, practices in Miami Beach. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Mimosa Publishing, 2018). She has no conflicts of interest.

Happy New Year! May 2021 be better

As politics and politicians enhance divisiveness in our country, science and scientists will save us. The power of collective science, careful data analysis, and cautious interpretation has never been more evident than during this pandemic. Unfortunately, we still are learning the most effective means of communicating scientific knowledge where development is iterative and rarely definitive in the early stages of hypothesis testing. Once again, we see the destructive power and effectiveness of the techniques detailed in The Merchants of Doubt.

I choose to focus on successes of scientists and our care delivery workforce. In a mere 11 months, researchers created a new vaccine methodology, tested its safety and efficacy against COVID-19, and provided it to experts building the logistic infrastructure to vaccinate billions of people. Simultaneously, thousands of health care workers risked their lives in a daily battle against Coronavirus and saved countless lives. This is why we became scientists and providers.

I had difficulty choosing page one articles this month because of the wealth of material. On page one, we read about the most dramatic changes to Medicare E/M documentation in the last 30 years (resulting in an estimated 4% decrease in overall GI reimbursements). Another article reports on real reductions in liver-related deaths in states that expanded Medicaid coverage, once again demonstrating that we save lives if people have access to health care. The third article on page one discusses seronegative enteropathy – a difficult diagnosis but one with emerging answers.

Elsewhere in GI and Hepatology News, read about best practices to care for elderly IBD patients, EUS interventional advances, and interesting information that may lead to more targeted obesity therapies.

Articles highlighted above and others in this month’s issue show us that scientific inquiry, research and solution-finding is alive and well.

“The good thing about science is that it’s true whether or not you believe in it.” -- Neil deGrasse Tyson

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

As politics and politicians enhance divisiveness in our country, science and scientists will save us. The power of collective science, careful data analysis, and cautious interpretation has never been more evident than during this pandemic. Unfortunately, we still are learning the most effective means of communicating scientific knowledge where development is iterative and rarely definitive in the early stages of hypothesis testing. Once again, we see the destructive power and effectiveness of the techniques detailed in The Merchants of Doubt.

I choose to focus on successes of scientists and our care delivery workforce. In a mere 11 months, researchers created a new vaccine methodology, tested its safety and efficacy against COVID-19, and provided it to experts building the logistic infrastructure to vaccinate billions of people. Simultaneously, thousands of health care workers risked their lives in a daily battle against Coronavirus and saved countless lives. This is why we became scientists and providers.

I had difficulty choosing page one articles this month because of the wealth of material. On page one, we read about the most dramatic changes to Medicare E/M documentation in the last 30 years (resulting in an estimated 4% decrease in overall GI reimbursements). Another article reports on real reductions in liver-related deaths in states that expanded Medicaid coverage, once again demonstrating that we save lives if people have access to health care. The third article on page one discusses seronegative enteropathy – a difficult diagnosis but one with emerging answers.

Elsewhere in GI and Hepatology News, read about best practices to care for elderly IBD patients, EUS interventional advances, and interesting information that may lead to more targeted obesity therapies.

Articles highlighted above and others in this month’s issue show us that scientific inquiry, research and solution-finding is alive and well.

“The good thing about science is that it’s true whether or not you believe in it.” -- Neil deGrasse Tyson

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

As politics and politicians enhance divisiveness in our country, science and scientists will save us. The power of collective science, careful data analysis, and cautious interpretation has never been more evident than during this pandemic. Unfortunately, we still are learning the most effective means of communicating scientific knowledge where development is iterative and rarely definitive in the early stages of hypothesis testing. Once again, we see the destructive power and effectiveness of the techniques detailed in The Merchants of Doubt.

I choose to focus on successes of scientists and our care delivery workforce. In a mere 11 months, researchers created a new vaccine methodology, tested its safety and efficacy against COVID-19, and provided it to experts building the logistic infrastructure to vaccinate billions of people. Simultaneously, thousands of health care workers risked their lives in a daily battle against Coronavirus and saved countless lives. This is why we became scientists and providers.

I had difficulty choosing page one articles this month because of the wealth of material. On page one, we read about the most dramatic changes to Medicare E/M documentation in the last 30 years (resulting in an estimated 4% decrease in overall GI reimbursements). Another article reports on real reductions in liver-related deaths in states that expanded Medicaid coverage, once again demonstrating that we save lives if people have access to health care. The third article on page one discusses seronegative enteropathy – a difficult diagnosis but one with emerging answers.

Elsewhere in GI and Hepatology News, read about best practices to care for elderly IBD patients, EUS interventional advances, and interesting information that may lead to more targeted obesity therapies.

Articles highlighted above and others in this month’s issue show us that scientific inquiry, research and solution-finding is alive and well.

“The good thing about science is that it’s true whether or not you believe in it.” -- Neil deGrasse Tyson

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

COVID-19 mortality in hospitalized HF patients: Nearly 1 in 4

Patients with heart failure who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 are at high risk for complications, with nearly 1 in 4 dying during hospitalization, according to a large database analysis that included more than 8,000 patients who had heart failure and COVID-19.

In-hospital mortality was 24.2% for patients who had a history of heart failure and were hospitalized with COVID-19, as compared with 14.2% for individuals without heart failure who were hospitalized with COVID-19.

For perspective, the researchers compared the patients with heart failure and COVID-19 with patients who had a history of heart failure and were hospitalized for an acute worsening episode: the risk for death was about 10-fold higher with COVID-19.

“These patients really face remarkably high risk, and when we compare that to the risk of in-hospital death with something we are a lot more familiar with – acute heart failure – we see that the risk was about 10-fold greater,” said first author Ankeet S. Bhatt, MD, MBA, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

In an article published online in JACC Heart Failure on Dec. 28, a group led by Dr. Bhatt and senior author Scott D. Solomon, MD, reported an analysis of administrative data on a total of 2,041,855 incident hospitalizations logged in the Premier Healthcare Database between April 1, 2020, and Sept. 30, 2020.

The Premier Healthcare Database comprises data from more than 1 billion patient encounters, which equates to approximately 1 in every 5 of all inpatient discharges in the United States.

Of 132,312 hospitalizations of patients with a history of heart failure, 23,843 (18.0%) were hospitalized with acute heart failure, 8,383 patients (6.4%) were hospitalized with COVID-19, and 100,068 (75.6%) were hospitalized for other reasons.

Outcomes and resource utilization were compared with 141,895 COVID-19 hospitalizations of patients who did not have heart failure.

Patients were deemed to have a history of heart failure if they were hospitalized at least once for heart failure from Jan. 1, 2019, to March 21, 2020, or had at least two heart failure outpatient visits during that period.

In a comment, Dr. Solomon noted some of the pros and cons of the data used in this study.

“Premier is a huge database, encompassing about one-quarter of all the health care facilities in the United States and one-fifth of all inpatient visits, so for that reason we’re able to look at things that are very difficult to look at in smaller hospital systems, but the data are also limited in that you don’t have as much granular detail as you might in smaller datasets,” said Dr. Solomon.

“One thing to recognize is that our data start at the point of hospital admission, so were looking only at individuals who have crossed the threshold in terms of their illness and been admitted,” he added.

Use of in-hospital resources was significantly greater for patients with heart failure hospitalized for COVID-19, compared with patients hospitalized for acute heart failure or for other reasons. This included “multifold” higher rates of ICU care (29% vs. 15%), mechanical ventilation (17% vs. 6%), and central venous catheter insertion (19% vs. 7%; P < .001 for all).

The proportion of patients who required mechanical ventilation and care in the ICU in the group with COVID-19 but who did not have no heart failure was similar to those who had both conditions.

The greater odds of in-hospital mortality among patients with both heart failure and COVID-19, compared with individuals with heart failure hospitalized for other reasons, was strongest in April, with an adjusted odds ratio of 14.48, compared with subsequent months (adjusted OR for May-September, 10.11; P for interaction < .001).

“We’re obviously not able to say with certainty what was happening in April, but I think that maybe the patients who were most vulnerable to COVID-19 may be more represented in that population, so the patients with comorbidities or who are immunosuppressed or otherwise,” said Dr. Bhatt in an interview.

“The other thing we think is that there may be a learning curve in terms of how to care for patients with acute severe respiratory illness. That includes increased institutional knowledge – like the use of prone ventilation – but also therapies that were subsequently shown to have benefit in randomized clinical trials, such as dexamethasone,” he added.

“These results should remind us to be innovative and thoughtful in our management of patients with heart failure while trying to maintain equity and good health for all,” wrote Nasrien E. Ibrahim, MD, from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Ersilia DeFillipis, MD, Columbia University, New York; and Mitchel Psotka, MD, PhD, Innova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, Va., in an editorial accompanying the study.

The data emphasize the importance of ensuring equal access to services such as telemedicine, virtual visits, home nursing visits, and remote monitoring, they noted.

“As the COVID-19 pandemic rages on and disproportionately ravages socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, we should focus our efforts on strategies that minimize these inequities,” the editorialists wrote.

Dr. Solomon noted that, although Black and Hispanic patients were overrepresented in the population of heart failure patients hospitalized with COVID-19, once in the hospital, race was not a predictor of in-hospital mortality or the need for mechanical ventilation.

Dr. Bhatt has received speaker fees from Sanofi Pasteur and is supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute postdoctoral training grant. Dr. Solomon has received grant support and/or speaking fees from a number of companies and from the NIH/NHLBI. The editorialists disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with heart failure who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 are at high risk for complications, with nearly 1 in 4 dying during hospitalization, according to a large database analysis that included more than 8,000 patients who had heart failure and COVID-19.

In-hospital mortality was 24.2% for patients who had a history of heart failure and were hospitalized with COVID-19, as compared with 14.2% for individuals without heart failure who were hospitalized with COVID-19.

For perspective, the researchers compared the patients with heart failure and COVID-19 with patients who had a history of heart failure and were hospitalized for an acute worsening episode: the risk for death was about 10-fold higher with COVID-19.

“These patients really face remarkably high risk, and when we compare that to the risk of in-hospital death with something we are a lot more familiar with – acute heart failure – we see that the risk was about 10-fold greater,” said first author Ankeet S. Bhatt, MD, MBA, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

In an article published online in JACC Heart Failure on Dec. 28, a group led by Dr. Bhatt and senior author Scott D. Solomon, MD, reported an analysis of administrative data on a total of 2,041,855 incident hospitalizations logged in the Premier Healthcare Database between April 1, 2020, and Sept. 30, 2020.

The Premier Healthcare Database comprises data from more than 1 billion patient encounters, which equates to approximately 1 in every 5 of all inpatient discharges in the United States.

Of 132,312 hospitalizations of patients with a history of heart failure, 23,843 (18.0%) were hospitalized with acute heart failure, 8,383 patients (6.4%) were hospitalized with COVID-19, and 100,068 (75.6%) were hospitalized for other reasons.

Outcomes and resource utilization were compared with 141,895 COVID-19 hospitalizations of patients who did not have heart failure.

Patients were deemed to have a history of heart failure if they were hospitalized at least once for heart failure from Jan. 1, 2019, to March 21, 2020, or had at least two heart failure outpatient visits during that period.

In a comment, Dr. Solomon noted some of the pros and cons of the data used in this study.

“Premier is a huge database, encompassing about one-quarter of all the health care facilities in the United States and one-fifth of all inpatient visits, so for that reason we’re able to look at things that are very difficult to look at in smaller hospital systems, but the data are also limited in that you don’t have as much granular detail as you might in smaller datasets,” said Dr. Solomon.

“One thing to recognize is that our data start at the point of hospital admission, so were looking only at individuals who have crossed the threshold in terms of their illness and been admitted,” he added.

Use of in-hospital resources was significantly greater for patients with heart failure hospitalized for COVID-19, compared with patients hospitalized for acute heart failure or for other reasons. This included “multifold” higher rates of ICU care (29% vs. 15%), mechanical ventilation (17% vs. 6%), and central venous catheter insertion (19% vs. 7%; P < .001 for all).

The proportion of patients who required mechanical ventilation and care in the ICU in the group with COVID-19 but who did not have no heart failure was similar to those who had both conditions.

The greater odds of in-hospital mortality among patients with both heart failure and COVID-19, compared with individuals with heart failure hospitalized for other reasons, was strongest in April, with an adjusted odds ratio of 14.48, compared with subsequent months (adjusted OR for May-September, 10.11; P for interaction < .001).

“We’re obviously not able to say with certainty what was happening in April, but I think that maybe the patients who were most vulnerable to COVID-19 may be more represented in that population, so the patients with comorbidities or who are immunosuppressed or otherwise,” said Dr. Bhatt in an interview.

“The other thing we think is that there may be a learning curve in terms of how to care for patients with acute severe respiratory illness. That includes increased institutional knowledge – like the use of prone ventilation – but also therapies that were subsequently shown to have benefit in randomized clinical trials, such as dexamethasone,” he added.

“These results should remind us to be innovative and thoughtful in our management of patients with heart failure while trying to maintain equity and good health for all,” wrote Nasrien E. Ibrahim, MD, from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Ersilia DeFillipis, MD, Columbia University, New York; and Mitchel Psotka, MD, PhD, Innova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, Va., in an editorial accompanying the study.

The data emphasize the importance of ensuring equal access to services such as telemedicine, virtual visits, home nursing visits, and remote monitoring, they noted.

“As the COVID-19 pandemic rages on and disproportionately ravages socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, we should focus our efforts on strategies that minimize these inequities,” the editorialists wrote.

Dr. Solomon noted that, although Black and Hispanic patients were overrepresented in the population of heart failure patients hospitalized with COVID-19, once in the hospital, race was not a predictor of in-hospital mortality or the need for mechanical ventilation.

Dr. Bhatt has received speaker fees from Sanofi Pasteur and is supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute postdoctoral training grant. Dr. Solomon has received grant support and/or speaking fees from a number of companies and from the NIH/NHLBI. The editorialists disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with heart failure who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 are at high risk for complications, with nearly 1 in 4 dying during hospitalization, according to a large database analysis that included more than 8,000 patients who had heart failure and COVID-19.

In-hospital mortality was 24.2% for patients who had a history of heart failure and were hospitalized with COVID-19, as compared with 14.2% for individuals without heart failure who were hospitalized with COVID-19.

For perspective, the researchers compared the patients with heart failure and COVID-19 with patients who had a history of heart failure and were hospitalized for an acute worsening episode: the risk for death was about 10-fold higher with COVID-19.

“These patients really face remarkably high risk, and when we compare that to the risk of in-hospital death with something we are a lot more familiar with – acute heart failure – we see that the risk was about 10-fold greater,” said first author Ankeet S. Bhatt, MD, MBA, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

In an article published online in JACC Heart Failure on Dec. 28, a group led by Dr. Bhatt and senior author Scott D. Solomon, MD, reported an analysis of administrative data on a total of 2,041,855 incident hospitalizations logged in the Premier Healthcare Database between April 1, 2020, and Sept. 30, 2020.

The Premier Healthcare Database comprises data from more than 1 billion patient encounters, which equates to approximately 1 in every 5 of all inpatient discharges in the United States.

Of 132,312 hospitalizations of patients with a history of heart failure, 23,843 (18.0%) were hospitalized with acute heart failure, 8,383 patients (6.4%) were hospitalized with COVID-19, and 100,068 (75.6%) were hospitalized for other reasons.

Outcomes and resource utilization were compared with 141,895 COVID-19 hospitalizations of patients who did not have heart failure.

Patients were deemed to have a history of heart failure if they were hospitalized at least once for heart failure from Jan. 1, 2019, to March 21, 2020, or had at least two heart failure outpatient visits during that period.

In a comment, Dr. Solomon noted some of the pros and cons of the data used in this study.

“Premier is a huge database, encompassing about one-quarter of all the health care facilities in the United States and one-fifth of all inpatient visits, so for that reason we’re able to look at things that are very difficult to look at in smaller hospital systems, but the data are also limited in that you don’t have as much granular detail as you might in smaller datasets,” said Dr. Solomon.

“One thing to recognize is that our data start at the point of hospital admission, so were looking only at individuals who have crossed the threshold in terms of their illness and been admitted,” he added.

Use of in-hospital resources was significantly greater for patients with heart failure hospitalized for COVID-19, compared with patients hospitalized for acute heart failure or for other reasons. This included “multifold” higher rates of ICU care (29% vs. 15%), mechanical ventilation (17% vs. 6%), and central venous catheter insertion (19% vs. 7%; P < .001 for all).

The proportion of patients who required mechanical ventilation and care in the ICU in the group with COVID-19 but who did not have no heart failure was similar to those who had both conditions.

The greater odds of in-hospital mortality among patients with both heart failure and COVID-19, compared with individuals with heart failure hospitalized for other reasons, was strongest in April, with an adjusted odds ratio of 14.48, compared with subsequent months (adjusted OR for May-September, 10.11; P for interaction < .001).

“We’re obviously not able to say with certainty what was happening in April, but I think that maybe the patients who were most vulnerable to COVID-19 may be more represented in that population, so the patients with comorbidities or who are immunosuppressed or otherwise,” said Dr. Bhatt in an interview.

“The other thing we think is that there may be a learning curve in terms of how to care for patients with acute severe respiratory illness. That includes increased institutional knowledge – like the use of prone ventilation – but also therapies that were subsequently shown to have benefit in randomized clinical trials, such as dexamethasone,” he added.

“These results should remind us to be innovative and thoughtful in our management of patients with heart failure while trying to maintain equity and good health for all,” wrote Nasrien E. Ibrahim, MD, from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Ersilia DeFillipis, MD, Columbia University, New York; and Mitchel Psotka, MD, PhD, Innova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, Va., in an editorial accompanying the study.

The data emphasize the importance of ensuring equal access to services such as telemedicine, virtual visits, home nursing visits, and remote monitoring, they noted.

“As the COVID-19 pandemic rages on and disproportionately ravages socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, we should focus our efforts on strategies that minimize these inequities,” the editorialists wrote.

Dr. Solomon noted that, although Black and Hispanic patients were overrepresented in the population of heart failure patients hospitalized with COVID-19, once in the hospital, race was not a predictor of in-hospital mortality or the need for mechanical ventilation.

Dr. Bhatt has received speaker fees from Sanofi Pasteur and is supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute postdoctoral training grant. Dr. Solomon has received grant support and/or speaking fees from a number of companies and from the NIH/NHLBI. The editorialists disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

DOACs look safe in elective endoscopic procedures

Among patients taking direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), elective endoscopy procedures carry a risk of bleeding and thromboembolic events similar to that seen in those receiving vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), according to a multicenter, prospective observational study conducted at 12 Spanish academic and community centers.

DOACs have several advantages over VKAs, including more predictable pharmacokinetic profiles and fewer food and drug interactions, but they have not been well studied in the elective endoscopy setting. Some previous studies suggested a lower risk with DOACs than with VKAs, but they were retrospective or based on administrative databases.

It also remains unclear when anticoagulant therapy should be resumed following high-risk procedures. The new study, which was led by Enrique Rodríguez de Santiago of Universidad de Alcalá (Spain) and published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, suggested that early resumption may be safe. “It certainly showed there was an acceptable rate of clinically significant rate of bleeding for patients on anticoagulants, and the thing I appreciated the most was that there was no statistically significant difference in terms of bleeding depending on when you resumed the anticoagulant,” said Robert Jay Sealock, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Dr. Sealock was not involved in the study.

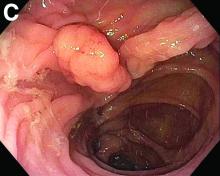

The researchers examined data from 1,623 patients who underwent 1,874 endoscopic procedures. Among these patients, 62.7% were taking VKAs, and 37.3% were taking DOACs; 58.9% were men, and the mean age was 74.2 years. Overall, 75.5% were on anticoagulant therapy for atrial fibrillation.

The most common procedures were colonoscopy (68.3%) and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (27.3%).

Within 30 days, The risk of bleeding was similar between patients taking VKAs (6.2%; 95% confidence interval, 4.8-7.8%) and DOACs (6.7%; 95% CI, 4.9-9%). This was true regardless of intervention and site. Overall, 1.4% of subjects experienced a thromboembolic event (95% CI, 0.9-2.1%), and there was no significant difference between the VKA group (1.3%; 95% CI, 0.8-2.2%) and the DOAC group (1.5%; 95% CI, 0.8-2.8%).

Clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding occurred in 6.4% of subjects (95% CI, 5.3-7.7%); 2.7% of clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding events were intraprocedural and 4.1% were delayed. The lowest risk of bleeding occurred with diagnostic endoscopy (1.1%) and biopsy (2.2%). The risk of bleeding for high-risk procedures was 11.5% (95% CI, 9.4-14%).

The overall mortality was 1.4%, with two deaths related to thromboembolic events, both in the DOAC group. The other deaths were considered to be unrelated to the procedure or periprocedural interruption of anticoagulants.

The researchers also examined the timing of anticoagulant resumption. Overall, 59.2% of subjects received bridging therapy, including 85% of the VKA group and 16% of the DOAC group (P < .001). This was not associated with increased endoscopy-related bleeding in either the VKA (3.3% with bridging therapy vs. 6.4% without; P = .14) or the DOAC group (8.3% vs. 6.4%; P = .48).

A total of 747 patients underwent a high-risk procedure, 46.3% of patients resumed anticoagulant therapy within 24 hours of the procedure, and 46.2% between 24 and 48 hours. After inverse probability of treatment weighting adjustment, a delay in anticoagulant resumption was not associated with a reduction in the frequency of postprocedural clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding.

Still, the research left some questions unanswered. Most of the high-risk procedures were hot (41.8%) or cold snare polypectomies (39.8%). There weren’t enough data in the study to evaluate risk in patients undergoing other high-risk procedures such as balloon dilation for strictures, endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration, and sphincterotomy. “That’s one group that we still don’t really have enough data about, particularly those patients who are on DOACs,” said Dr. Sealock.

The study also found a high number of patients on bridging therapy. “It highlighted the fact that we probably use bridging therapy too much in patients undergoing endoscopy,” said Dr. Sealock. He recommended using tools that generate recommendations for bridging therapy and timing for withholding and resuming anticoagulants based on procedure and patient characteristics.

SOURCE: de Santiago ER et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Dec 03. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.11.037.

Among patients taking direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), elective endoscopy procedures carry a risk of bleeding and thromboembolic events similar to that seen in those receiving vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), according to a multicenter, prospective observational study conducted at 12 Spanish academic and community centers.

DOACs have several advantages over VKAs, including more predictable pharmacokinetic profiles and fewer food and drug interactions, but they have not been well studied in the elective endoscopy setting. Some previous studies suggested a lower risk with DOACs than with VKAs, but they were retrospective or based on administrative databases.

It also remains unclear when anticoagulant therapy should be resumed following high-risk procedures. The new study, which was led by Enrique Rodríguez de Santiago of Universidad de Alcalá (Spain) and published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, suggested that early resumption may be safe. “It certainly showed there was an acceptable rate of clinically significant rate of bleeding for patients on anticoagulants, and the thing I appreciated the most was that there was no statistically significant difference in terms of bleeding depending on when you resumed the anticoagulant,” said Robert Jay Sealock, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Dr. Sealock was not involved in the study.

The researchers examined data from 1,623 patients who underwent 1,874 endoscopic procedures. Among these patients, 62.7% were taking VKAs, and 37.3% were taking DOACs; 58.9% were men, and the mean age was 74.2 years. Overall, 75.5% were on anticoagulant therapy for atrial fibrillation.

The most common procedures were colonoscopy (68.3%) and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (27.3%).

Within 30 days, The risk of bleeding was similar between patients taking VKAs (6.2%; 95% confidence interval, 4.8-7.8%) and DOACs (6.7%; 95% CI, 4.9-9%). This was true regardless of intervention and site. Overall, 1.4% of subjects experienced a thromboembolic event (95% CI, 0.9-2.1%), and there was no significant difference between the VKA group (1.3%; 95% CI, 0.8-2.2%) and the DOAC group (1.5%; 95% CI, 0.8-2.8%).

Clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding occurred in 6.4% of subjects (95% CI, 5.3-7.7%); 2.7% of clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding events were intraprocedural and 4.1% were delayed. The lowest risk of bleeding occurred with diagnostic endoscopy (1.1%) and biopsy (2.2%). The risk of bleeding for high-risk procedures was 11.5% (95% CI, 9.4-14%).

The overall mortality was 1.4%, with two deaths related to thromboembolic events, both in the DOAC group. The other deaths were considered to be unrelated to the procedure or periprocedural interruption of anticoagulants.

The researchers also examined the timing of anticoagulant resumption. Overall, 59.2% of subjects received bridging therapy, including 85% of the VKA group and 16% of the DOAC group (P < .001). This was not associated with increased endoscopy-related bleeding in either the VKA (3.3% with bridging therapy vs. 6.4% without; P = .14) or the DOAC group (8.3% vs. 6.4%; P = .48).

A total of 747 patients underwent a high-risk procedure, 46.3% of patients resumed anticoagulant therapy within 24 hours of the procedure, and 46.2% between 24 and 48 hours. After inverse probability of treatment weighting adjustment, a delay in anticoagulant resumption was not associated with a reduction in the frequency of postprocedural clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding.

Still, the research left some questions unanswered. Most of the high-risk procedures were hot (41.8%) or cold snare polypectomies (39.8%). There weren’t enough data in the study to evaluate risk in patients undergoing other high-risk procedures such as balloon dilation for strictures, endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration, and sphincterotomy. “That’s one group that we still don’t really have enough data about, particularly those patients who are on DOACs,” said Dr. Sealock.

The study also found a high number of patients on bridging therapy. “It highlighted the fact that we probably use bridging therapy too much in patients undergoing endoscopy,” said Dr. Sealock. He recommended using tools that generate recommendations for bridging therapy and timing for withholding and resuming anticoagulants based on procedure and patient characteristics.

SOURCE: de Santiago ER et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Dec 03. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.11.037.

Among patients taking direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), elective endoscopy procedures carry a risk of bleeding and thromboembolic events similar to that seen in those receiving vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), according to a multicenter, prospective observational study conducted at 12 Spanish academic and community centers.

DOACs have several advantages over VKAs, including more predictable pharmacokinetic profiles and fewer food and drug interactions, but they have not been well studied in the elective endoscopy setting. Some previous studies suggested a lower risk with DOACs than with VKAs, but they were retrospective or based on administrative databases.

It also remains unclear when anticoagulant therapy should be resumed following high-risk procedures. The new study, which was led by Enrique Rodríguez de Santiago of Universidad de Alcalá (Spain) and published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, suggested that early resumption may be safe. “It certainly showed there was an acceptable rate of clinically significant rate of bleeding for patients on anticoagulants, and the thing I appreciated the most was that there was no statistically significant difference in terms of bleeding depending on when you resumed the anticoagulant,” said Robert Jay Sealock, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Dr. Sealock was not involved in the study.

The researchers examined data from 1,623 patients who underwent 1,874 endoscopic procedures. Among these patients, 62.7% were taking VKAs, and 37.3% were taking DOACs; 58.9% were men, and the mean age was 74.2 years. Overall, 75.5% were on anticoagulant therapy for atrial fibrillation.

The most common procedures were colonoscopy (68.3%) and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (27.3%).

Within 30 days, The risk of bleeding was similar between patients taking VKAs (6.2%; 95% confidence interval, 4.8-7.8%) and DOACs (6.7%; 95% CI, 4.9-9%). This was true regardless of intervention and site. Overall, 1.4% of subjects experienced a thromboembolic event (95% CI, 0.9-2.1%), and there was no significant difference between the VKA group (1.3%; 95% CI, 0.8-2.2%) and the DOAC group (1.5%; 95% CI, 0.8-2.8%).

Clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding occurred in 6.4% of subjects (95% CI, 5.3-7.7%); 2.7% of clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding events were intraprocedural and 4.1% were delayed. The lowest risk of bleeding occurred with diagnostic endoscopy (1.1%) and biopsy (2.2%). The risk of bleeding for high-risk procedures was 11.5% (95% CI, 9.4-14%).

The overall mortality was 1.4%, with two deaths related to thromboembolic events, both in the DOAC group. The other deaths were considered to be unrelated to the procedure or periprocedural interruption of anticoagulants.

The researchers also examined the timing of anticoagulant resumption. Overall, 59.2% of subjects received bridging therapy, including 85% of the VKA group and 16% of the DOAC group (P < .001). This was not associated with increased endoscopy-related bleeding in either the VKA (3.3% with bridging therapy vs. 6.4% without; P = .14) or the DOAC group (8.3% vs. 6.4%; P = .48).

A total of 747 patients underwent a high-risk procedure, 46.3% of patients resumed anticoagulant therapy within 24 hours of the procedure, and 46.2% between 24 and 48 hours. After inverse probability of treatment weighting adjustment, a delay in anticoagulant resumption was not associated with a reduction in the frequency of postprocedural clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding.

Still, the research left some questions unanswered. Most of the high-risk procedures were hot (41.8%) or cold snare polypectomies (39.8%). There weren’t enough data in the study to evaluate risk in patients undergoing other high-risk procedures such as balloon dilation for strictures, endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration, and sphincterotomy. “That’s one group that we still don’t really have enough data about, particularly those patients who are on DOACs,” said Dr. Sealock.

The study also found a high number of patients on bridging therapy. “It highlighted the fact that we probably use bridging therapy too much in patients undergoing endoscopy,” said Dr. Sealock. He recommended using tools that generate recommendations for bridging therapy and timing for withholding and resuming anticoagulants based on procedure and patient characteristics.

SOURCE: de Santiago ER et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Dec 03. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.11.037.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

NETs a possible therapeutic target for COVID-19 thrombosis?

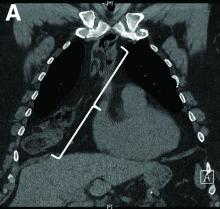

Researchers in Madrid may have found a clue to the pathogenesis of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in patients with COVID-19; it might also offer a therapeutic target to counter the hypercoagulability seen with COVID-19.

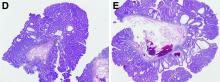

In a case series of five patients with COVID-19 who had an STEMI, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) were detected in coronary thrombi of all five patients. The median density was 66%, which is significantly higher than that seen in a historical series of patients with STEMI. In that series, NETs were found in only two-thirds of patients; in that series, the median density was 19%.

In the patients with COVID-19 and STEMI and in the patients reported in the prepandemic historical series from 2015, intracoronary aspirates were obtained during percutaneous coronary intervention using a thrombus aspiration device.

Histologically, findings in the patients from 2015 differed from those of patients with COVID-19. In the patients with COVID, thrombi were composed mostly of fibrin and polymorphonuclear cells. None showed fragments of atherosclerotic plaque or iron deposits indicative of previous episodes of plaque rupture. In contrast, 65% of thrombi from the 2015 series contained plaque fragments.

Ana Blasco, MD, PhD, Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid, and colleagues report their findings in an article published online Dec. 29 in JAMA Cardiology.

Commenting on the findings in an interview, Irene Lang, MD, from the Medical University of Vienna said, “This is really a very small series, purely observational, and suffering from the problem that acute STEMI is uncommon in COVID-19, but it does serve to demonstrate once more the abundance of NETs in acute myocardial infarction.”

“NETs are very much at the cutting edge of thrombosis research, and NET formation provides yet another link between inflammation and clot formation,” added Peter Libby, MD, from Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“Multiple observations have shown thrombosis of arteries large and small, microvessels, and veins in COVID-19. The observations of Blasco et al. add to the growing literature about NETs as contributors to the havoc wrought in multiple organs in advanced COVID-19,” he added in an email exchange with this news organization.

Neither Dr. Lang nor Dr. Libby were involved in this research; both have been actively studying NETs and their contribution to cardiothrombotic disease in recent years.

NETs are newly recognized contributors to venous and arterial thrombosis. These weblike DNA strands are extruded by activated or dying neutrophils and have protein mediators that ensnare pathogens while minimizing damage to the host cell.

First described in 2004, exaggerated NET formation has also been linked to the initiation and accretion of inflammation and thrombosis.

“NETs thus furnish a previously unsuspected link between inflammation, innate immunity, thrombosis, oxidative stress, and cardiovascular diseases,” Dr. Libby and his coauthors wrote in an article on the topic published in Circulation Research earlier this year.

Limiting NET formation or “dissolving” existing NETs could provide a therapeutic avenue not just for patients with COVID-19 but for all patients with thrombotic disease.

“The concept of NETs as a therapeutic target is appealing, in and out of COVID times,” said Dr. Lang.

“I personally believe that the work helps to raise awareness for the potential use of deoxyribonuclease (DNase), an enzyme that acts to clear NETs by dissolving the DNA strands, in the acute treatment of STEMI. Rapid injection of engineered recombinant DNases could potentially wipe away coronary obstructions, ideally before they may cause damage to the myocardium,” she added.

Dr. Blasco and colleagues and Dr. Lang have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Libby is an unpaid consultant or member of the advisory board for a number of companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers in Madrid may have found a clue to the pathogenesis of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in patients with COVID-19; it might also offer a therapeutic target to counter the hypercoagulability seen with COVID-19.

In a case series of five patients with COVID-19 who had an STEMI, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) were detected in coronary thrombi of all five patients. The median density was 66%, which is significantly higher than that seen in a historical series of patients with STEMI. In that series, NETs were found in only two-thirds of patients; in that series, the median density was 19%.

In the patients with COVID-19 and STEMI and in the patients reported in the prepandemic historical series from 2015, intracoronary aspirates were obtained during percutaneous coronary intervention using a thrombus aspiration device.

Histologically, findings in the patients from 2015 differed from those of patients with COVID-19. In the patients with COVID, thrombi were composed mostly of fibrin and polymorphonuclear cells. None showed fragments of atherosclerotic plaque or iron deposits indicative of previous episodes of plaque rupture. In contrast, 65% of thrombi from the 2015 series contained plaque fragments.

Ana Blasco, MD, PhD, Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid, and colleagues report their findings in an article published online Dec. 29 in JAMA Cardiology.

Commenting on the findings in an interview, Irene Lang, MD, from the Medical University of Vienna said, “This is really a very small series, purely observational, and suffering from the problem that acute STEMI is uncommon in COVID-19, but it does serve to demonstrate once more the abundance of NETs in acute myocardial infarction.”

“NETs are very much at the cutting edge of thrombosis research, and NET formation provides yet another link between inflammation and clot formation,” added Peter Libby, MD, from Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“Multiple observations have shown thrombosis of arteries large and small, microvessels, and veins in COVID-19. The observations of Blasco et al. add to the growing literature about NETs as contributors to the havoc wrought in multiple organs in advanced COVID-19,” he added in an email exchange with this news organization.

Neither Dr. Lang nor Dr. Libby were involved in this research; both have been actively studying NETs and their contribution to cardiothrombotic disease in recent years.

NETs are newly recognized contributors to venous and arterial thrombosis. These weblike DNA strands are extruded by activated or dying neutrophils and have protein mediators that ensnare pathogens while minimizing damage to the host cell.

First described in 2004, exaggerated NET formation has also been linked to the initiation and accretion of inflammation and thrombosis.

“NETs thus furnish a previously unsuspected link between inflammation, innate immunity, thrombosis, oxidative stress, and cardiovascular diseases,” Dr. Libby and his coauthors wrote in an article on the topic published in Circulation Research earlier this year.

Limiting NET formation or “dissolving” existing NETs could provide a therapeutic avenue not just for patients with COVID-19 but for all patients with thrombotic disease.

“The concept of NETs as a therapeutic target is appealing, in and out of COVID times,” said Dr. Lang.

“I personally believe that the work helps to raise awareness for the potential use of deoxyribonuclease (DNase), an enzyme that acts to clear NETs by dissolving the DNA strands, in the acute treatment of STEMI. Rapid injection of engineered recombinant DNases could potentially wipe away coronary obstructions, ideally before they may cause damage to the myocardium,” she added.

Dr. Blasco and colleagues and Dr. Lang have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Libby is an unpaid consultant or member of the advisory board for a number of companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers in Madrid may have found a clue to the pathogenesis of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in patients with COVID-19; it might also offer a therapeutic target to counter the hypercoagulability seen with COVID-19.

In a case series of five patients with COVID-19 who had an STEMI, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) were detected in coronary thrombi of all five patients. The median density was 66%, which is significantly higher than that seen in a historical series of patients with STEMI. In that series, NETs were found in only two-thirds of patients; in that series, the median density was 19%.

In the patients with COVID-19 and STEMI and in the patients reported in the prepandemic historical series from 2015, intracoronary aspirates were obtained during percutaneous coronary intervention using a thrombus aspiration device.

Histologically, findings in the patients from 2015 differed from those of patients with COVID-19. In the patients with COVID, thrombi were composed mostly of fibrin and polymorphonuclear cells. None showed fragments of atherosclerotic plaque or iron deposits indicative of previous episodes of plaque rupture. In contrast, 65% of thrombi from the 2015 series contained plaque fragments.

Ana Blasco, MD, PhD, Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid, and colleagues report their findings in an article published online Dec. 29 in JAMA Cardiology.

Commenting on the findings in an interview, Irene Lang, MD, from the Medical University of Vienna said, “This is really a very small series, purely observational, and suffering from the problem that acute STEMI is uncommon in COVID-19, but it does serve to demonstrate once more the abundance of NETs in acute myocardial infarction.”

“NETs are very much at the cutting edge of thrombosis research, and NET formation provides yet another link between inflammation and clot formation,” added Peter Libby, MD, from Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“Multiple observations have shown thrombosis of arteries large and small, microvessels, and veins in COVID-19. The observations of Blasco et al. add to the growing literature about NETs as contributors to the havoc wrought in multiple organs in advanced COVID-19,” he added in an email exchange with this news organization.

Neither Dr. Lang nor Dr. Libby were involved in this research; both have been actively studying NETs and their contribution to cardiothrombotic disease in recent years.

NETs are newly recognized contributors to venous and arterial thrombosis. These weblike DNA strands are extruded by activated or dying neutrophils and have protein mediators that ensnare pathogens while minimizing damage to the host cell.

First described in 2004, exaggerated NET formation has also been linked to the initiation and accretion of inflammation and thrombosis.

“NETs thus furnish a previously unsuspected link between inflammation, innate immunity, thrombosis, oxidative stress, and cardiovascular diseases,” Dr. Libby and his coauthors wrote in an article on the topic published in Circulation Research earlier this year.

Limiting NET formation or “dissolving” existing NETs could provide a therapeutic avenue not just for patients with COVID-19 but for all patients with thrombotic disease.

“The concept of NETs as a therapeutic target is appealing, in and out of COVID times,” said Dr. Lang.

“I personally believe that the work helps to raise awareness for the potential use of deoxyribonuclease (DNase), an enzyme that acts to clear NETs by dissolving the DNA strands, in the acute treatment of STEMI. Rapid injection of engineered recombinant DNases could potentially wipe away coronary obstructions, ideally before they may cause damage to the myocardium,” she added.

Dr. Blasco and colleagues and Dr. Lang have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Libby is an unpaid consultant or member of the advisory board for a number of companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In utero SARS-CoV-2 transmission unlikely, but neonates may be unprotected

No maternal viremia, placental infection, or vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 occurred during a biorepository study that included 64 women with SARS-CoV-2 infection, researchers reported in JAMA Network Open.

But SARS-CoV-2 antibodies transferred relatively inefficiently across the placenta in the third trimester, which suggests that neonates whose mothers had COVID-19 during pregnancy still may be vulnerable to the virus, the investigators said. Antibodies may transfer more efficiently with second-trimester infections, data from another study indicate.

“These findings suggest that, although low rates of maternal viremia and patterns of placental SARS-CoV-2 receptor distribution may underlie the rarity of vertical transmission, reduced transplacental transfer of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies may leave neonates at risk for infection,” wrote study author Andrea G. Edlow, MD, MSc, and colleagues. Dr. Edlow is an assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School and a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston.

In another study published in Cell, the research team found that, unlike with third trimester infections, SARS-CoV-2 antibodies transferred efficiently after infection in the second trimester. “Understanding how de novo antibody transfer varies by trimester may point to critical windows in pregnancy that may be most desirable for induction of antibodies through vaccination to optimize protection for both the mother and her infant,” they wrote.

It is unclear whether antibodies that are elicited by recently authorized vaccines will transfer differently than those elicited by natural infection.

Reassurance, questions, and concerns

“Although it is not known whether the inefficient transplacental transfer of antibodies ... will also extend to antibodies elicited by future SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, it underscores the susceptibility of infants,” said Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, of Emory University, Atlanta, and Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, MS, of the University of Florida, Gainesville, in an editorial accompanying the JAMA Network Open study.

And while the lack of vertical disease transmission in this study is reassuring, more research is needed, according to the director of a federal institute that helped fund the research.

“This study provides some reassurance that SARS-CoV-2 infections during the third trimester are unlikely to pass through the placenta to the fetus, but more research needs to be done to confirm this finding,” said Diana W. Bianchi, MD, director of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, in a news release.

The study authors theorize that the low incidence of maternal viremia and nonoverlapping expression of SARS-CoV-2 receptors ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in the placenta may protect against placental infection and vertical transmission.

Testing at 3 centers

To quantify SARS-CoV-2 viral load in maternal and neonatal biofluids and the transplacental passage of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, Dr. Edlow and collaborators enrolled 127 pregnant women at three tertiary care centers in Boston between April 2 and June 13, 2020. Follow-up occurred through July 10. Researchers tested neonates born to women with SARS-CoV-2 infection by nasopharyngeal swab at age 24 hours.

Of 64 women with SARS-CoV-2 infection, 36% were asymptomatic, 34% had mild disease, 11% had moderate disease, 16% had severe disease, and 3% had critical disease. Viral load analyses did not detect viremia in maternal or cord blood, and there was no evidence of vertical transmission.

Transfer of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies was significantly lower than transfer of anti-influenza antibodies The average cord-to-maternal antibody ratio was 0.72 for anti–receptor binding domain IgG and 0.74 for antinucleocapsid, whereas the ratio for anti-influenza antibodies was 1.44. The expected cord-to-maternal antibody ratio is approximately 1.5 for pathogens such as pertussis, influenza, and measles, the authors noted.

Among participants who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, 35-week intrauterine fetal demise occurred in an asymptomatic woman, and 22-week neonatal demise secondary to extreme prematurity in the setting of abruption and preterm labor occurred in a symptomatic patient.

Maternal disease severity was significantly associated with detectable respiratory viral load. In addition, disease severity was positively correlated with serum concentration of C-reactive protein and ALT, and negatively correlated with white blood cell count.

In the Cell study that further examined antibody transfer, the investigators focused on maternal and cord blood plasma samples from 22 mother-cord dyads with SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy and 34 uninfected mother-neonate dyads, as well as a second trimester cohort of 29 mother-neonate dyads and a third trimester validation cohort of 28 mother-neonate dyads.

Protecting infants

The results support “previous studies that have found that, while intrauterine transmission is possible, it is not common,” Dr. Jamieson and Dr. Rasmussen noted. “Most viral infections can be transmitted transplacentally; however, why some viruses are transmitted relatively easily across the placenta (e.g., HIV, Zika, herpes simplex virus), while others, such as influenza, are transmitted rarely is not well understood.”

Data indicate that infants are at higher risk of severe COVID-19, compared with older children. Nonetheless, research suggests that strict hygiene measures can protect infants born to mothers with SARS-CoV-2 infection, they added.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health; the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; a gift from Mark, Lisa, and Enid Schwartz; and by the Massachusetts General Hospital department of pathology Vickery-Colvin Award and other nonprofit groups. Dr. Edlow, Dr. Jamieson, and Dr. Rasmussen had no conflict of interest disclosures.

The coauthors of both studies disclosed ties to pharmaceutical companies, grants from foundations and government agencies, a patent for a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, and author royalties from publishers.

No maternal viremia, placental infection, or vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 occurred during a biorepository study that included 64 women with SARS-CoV-2 infection, researchers reported in JAMA Network Open.

But SARS-CoV-2 antibodies transferred relatively inefficiently across the placenta in the third trimester, which suggests that neonates whose mothers had COVID-19 during pregnancy still may be vulnerable to the virus, the investigators said. Antibodies may transfer more efficiently with second-trimester infections, data from another study indicate.

“These findings suggest that, although low rates of maternal viremia and patterns of placental SARS-CoV-2 receptor distribution may underlie the rarity of vertical transmission, reduced transplacental transfer of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies may leave neonates at risk for infection,” wrote study author Andrea G. Edlow, MD, MSc, and colleagues. Dr. Edlow is an assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School and a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston.

In another study published in Cell, the research team found that, unlike with third trimester infections, SARS-CoV-2 antibodies transferred efficiently after infection in the second trimester. “Understanding how de novo antibody transfer varies by trimester may point to critical windows in pregnancy that may be most desirable for induction of antibodies through vaccination to optimize protection for both the mother and her infant,” they wrote.

It is unclear whether antibodies that are elicited by recently authorized vaccines will transfer differently than those elicited by natural infection.

Reassurance, questions, and concerns

“Although it is not known whether the inefficient transplacental transfer of antibodies ... will also extend to antibodies elicited by future SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, it underscores the susceptibility of infants,” said Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, of Emory University, Atlanta, and Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, MS, of the University of Florida, Gainesville, in an editorial accompanying the JAMA Network Open study.

And while the lack of vertical disease transmission in this study is reassuring, more research is needed, according to the director of a federal institute that helped fund the research.