User login

Married docs remove girl’s lethal facial tumor in ‘excruciatingly difficult’ procedure

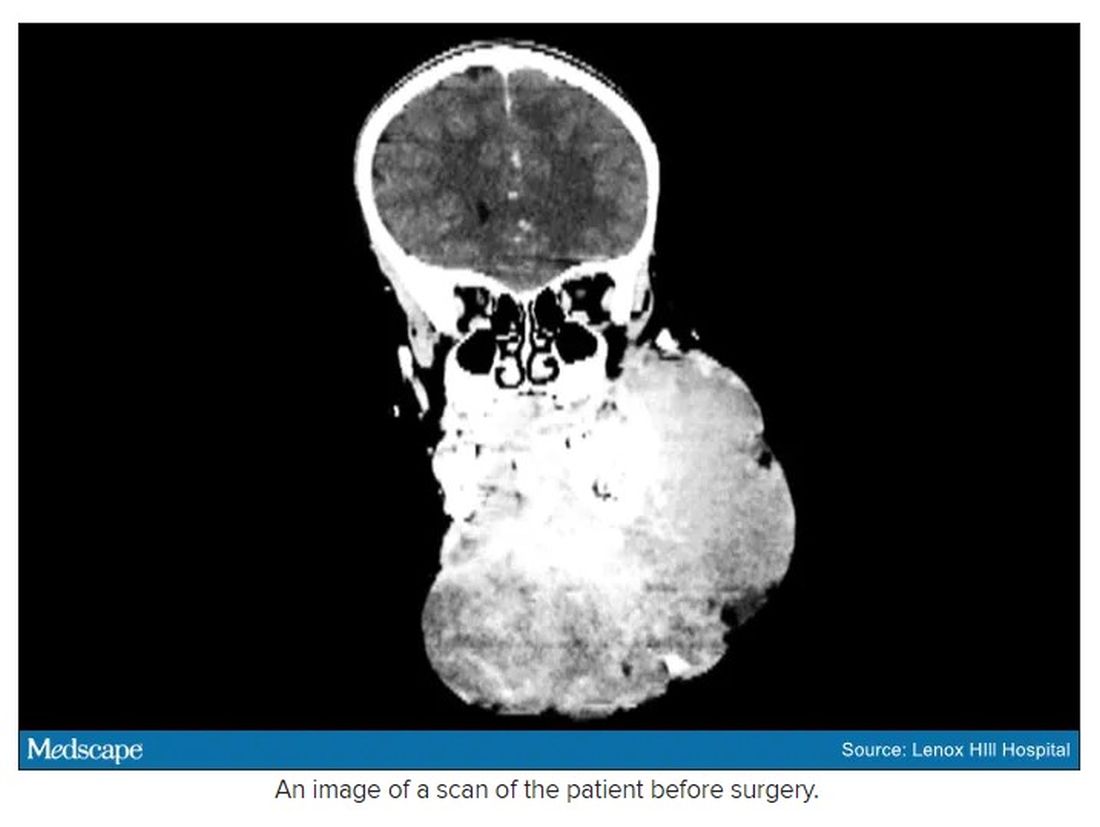

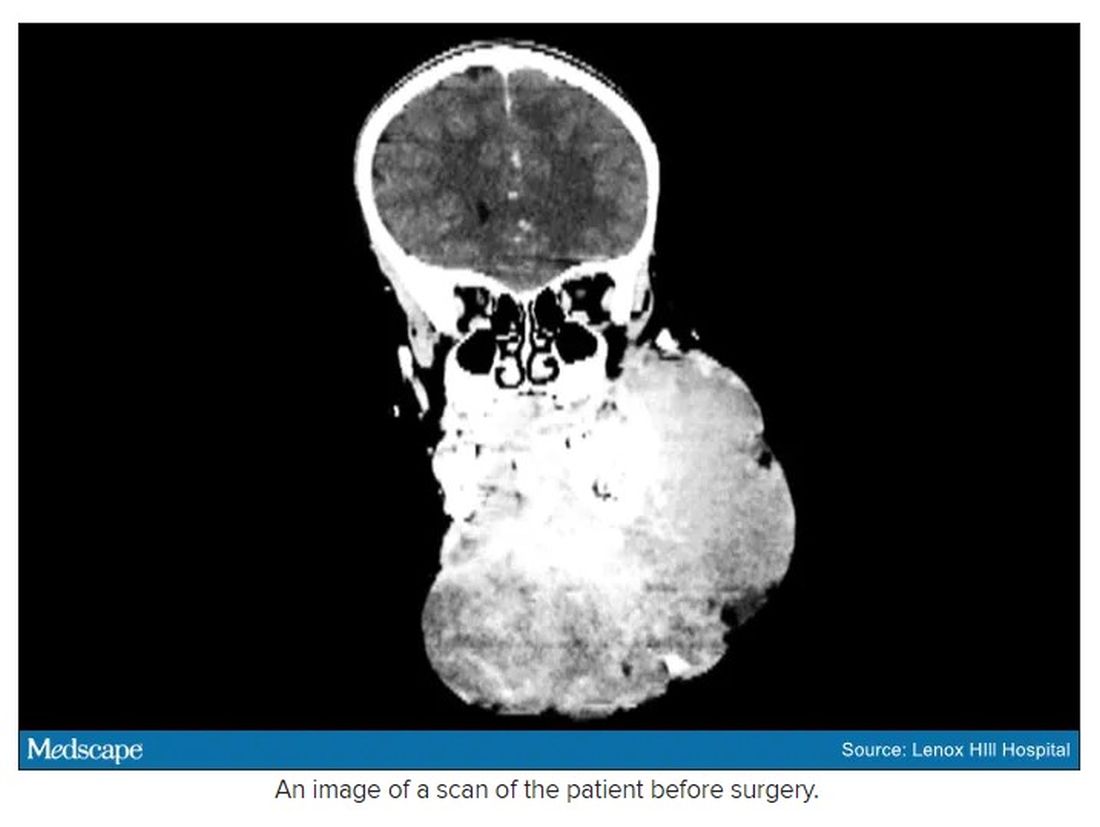

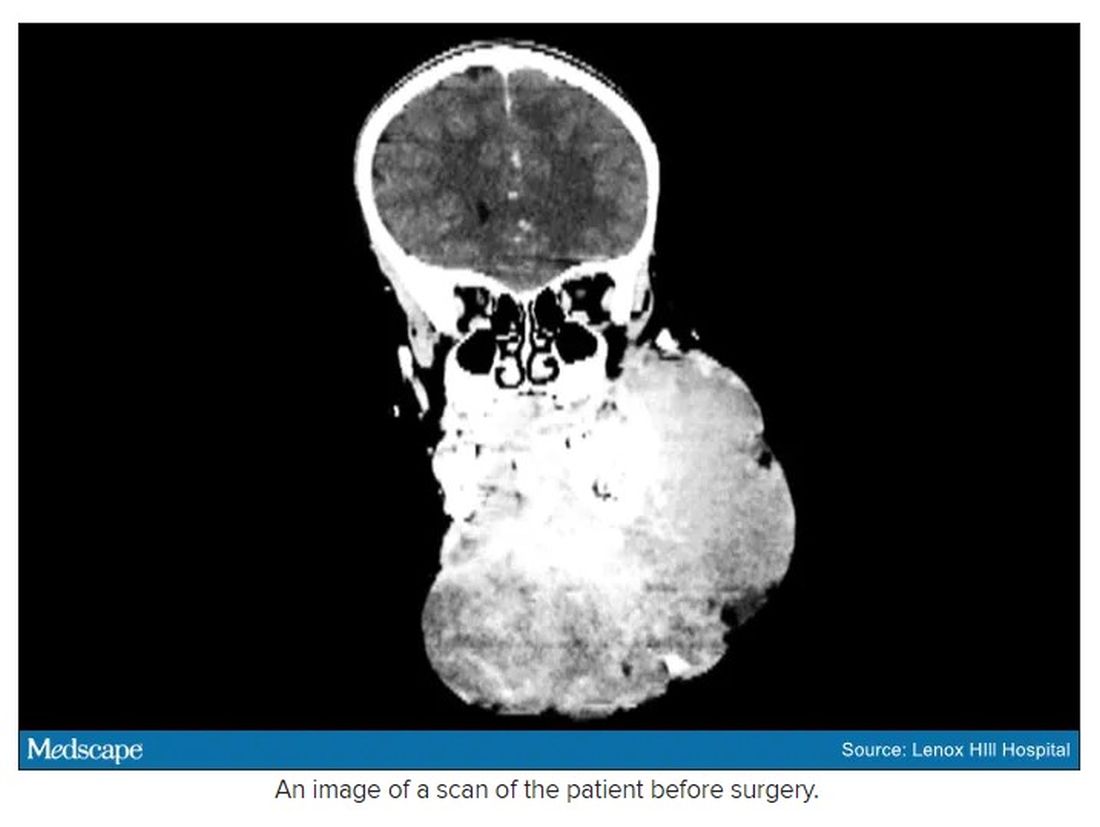

In 2019, doctors in London saw a 5-year old girl from rural Ethiopia with an enormous tumor extending from her cheek to her lower jaw. Her name was Negalem and the tumor was a vascular malformation, a life-threatening web of tangled blood vessels.

Surgery to remove it was impossible, the doctors told the foundation advocating for the girl. The child would never make it off the operating table. After a closer examination, the London group still declined to do the procedure, but told the child’s parents and advocates that if anyone was going to attempt this, they’d need to get the little girl to New York.

In New York City, on 64th St. in Manhattan, is the Vascular Birthmark Institute, founded by Milton Waner, MD, who has exclusively treated hemangiomas and vascular malformations for the last 30 years. “I’m the only person in the [United] States whose practice is exclusively [treating] vascular anomalies,” Dr. Waner said in an interview.

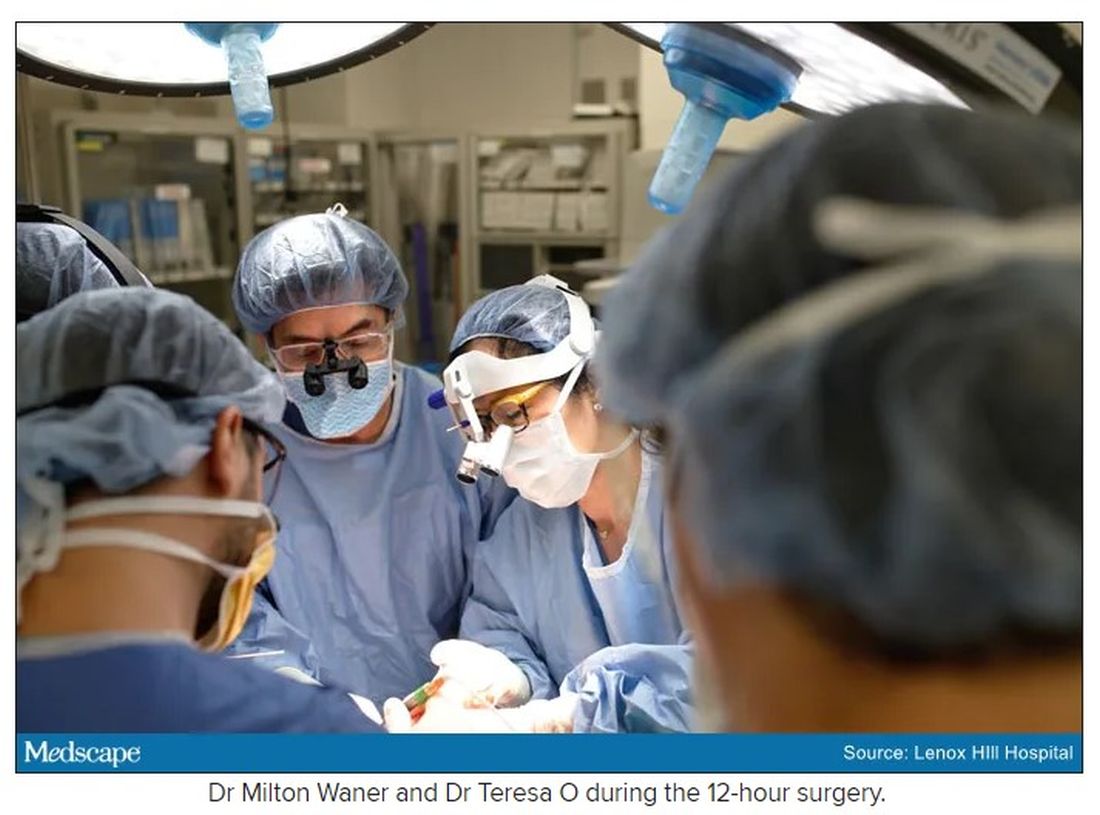

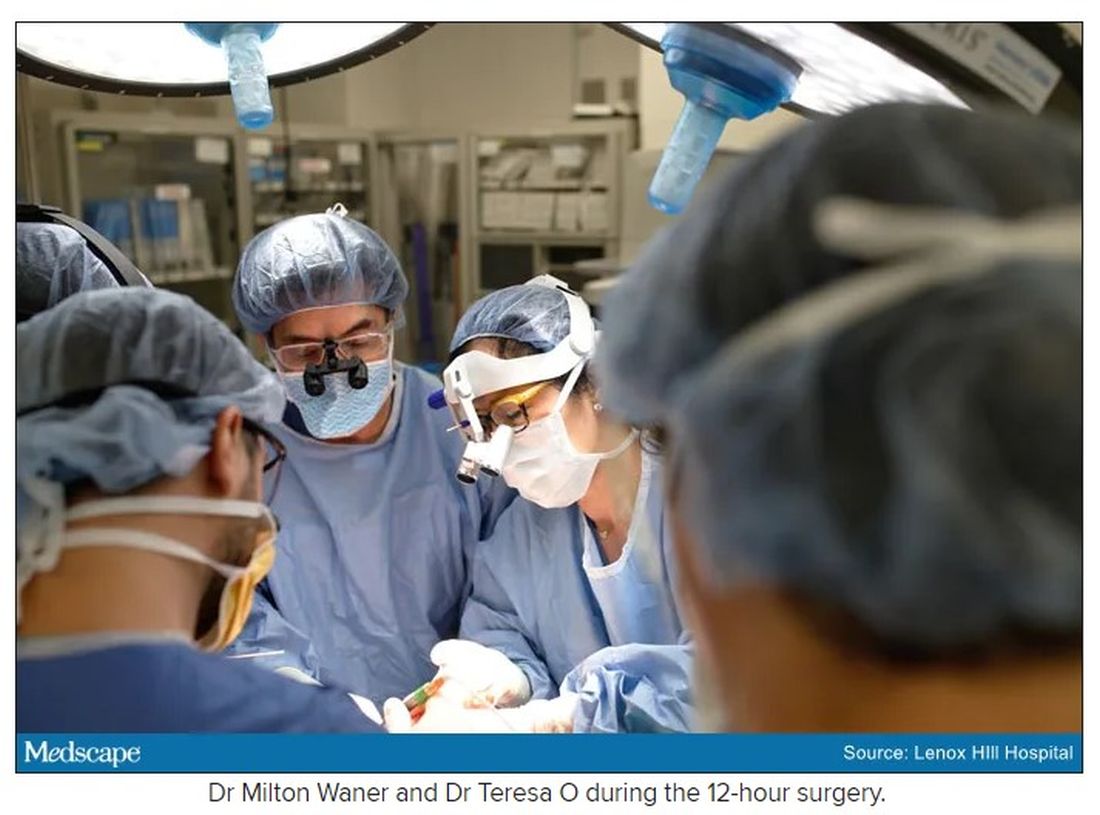

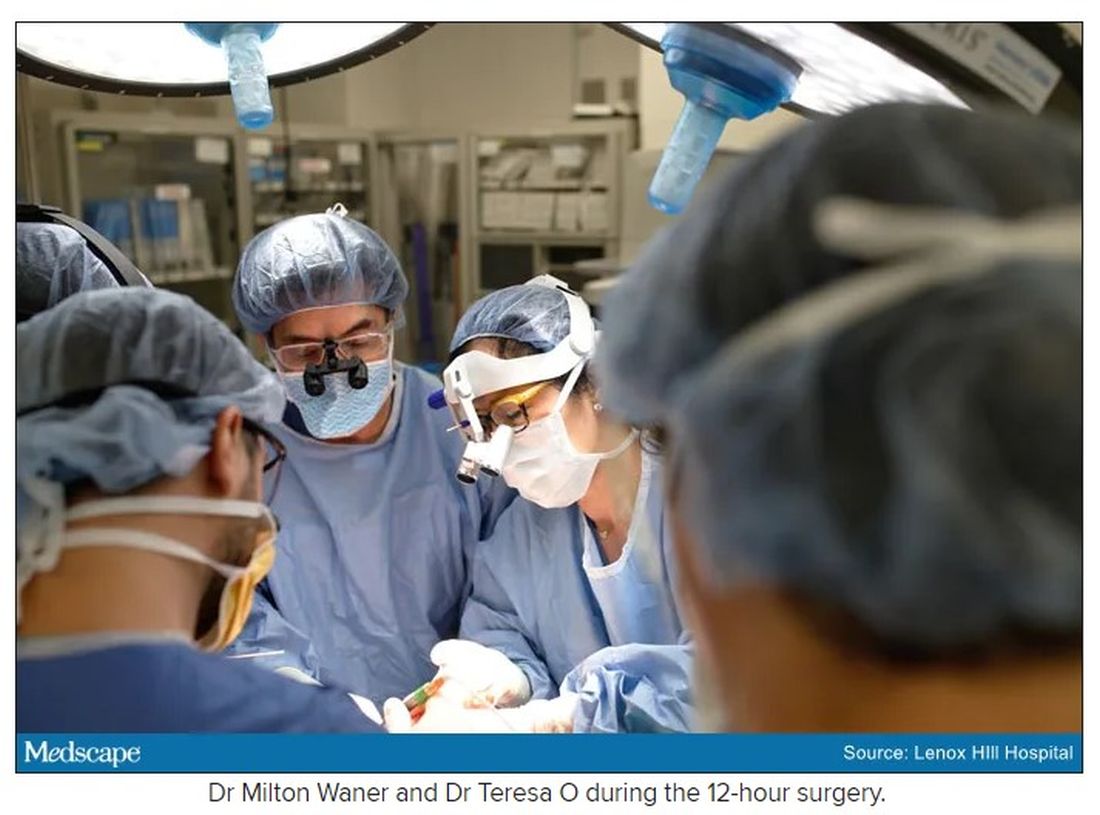

Dr. Waner has assembled a multidisciplinary team of experts at the institute’s offices in Lenox Hill – including his wife Teresa O, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon and neurospecialist. “People often ask how the hell do you spend so much time with your spouse?” Dr. Waner says. “We work extremely well together. We complement each other.”

Dr. O and Dr. Waner each manage half of the cases at VBI. And in January they received an email about Negalem. After corresponding with the child’s advocate and reviewing images,

The challenge with vascular malformations in children, Dr. Waner said, is that they have a fraction of the blood an adult has. Where adults have an average of 5 L of blood, a child this age has only 1 L. To lose 200 or 300 mL of blood, “that’s 20% or 30% of their blood volume,” Dr. Waner said. So the removal of such a mass, which requires a meticulous dissection around many blood vessels, carries a high risk of the child bleeding out.

There were some logistical hurdles, but the patient arrived in Manhattan in mid-June, at no cost to her family. The medical visa was organized by a volunteer who also work for USAID. Healing the Children Northeast paid for her travel and the Waner Kids Foundation paid for her hotel stay. Lenox Hill Hospital and Northwell Health covered all hospital costs and postsurgery care. And Dr. O and Dr. Waner did the planning, consult visits, and procedure pro bono.

The surgery was possible because of the generosity of several organizations, but the two surgeons still had a limited time to remove the mass. Under different circumstances, and with the luxury of more time, the patient would have undergone several rounds of sclerotherapy. This procedure, done by interventional radiologists, involves injecting a toxin into the blood vessels, which causes them to clot. Done prior to surgery it can help limit bleeding risk.

On June 23, the morning of the surgery, the patient underwent one round of sclerotherapy. However, it didn’t have the intended effect, Dr. Waner said, “because the lesion was just so massive.”

The team had planned several of their moves ahead of time. But this isn’t the sort of surgery you’d find in a textbook. Because it’s such a unique field, Dr. Waner and Dr. O have developed many of their own techniques along the way. This patient was much like the cases they treat every day, only “several orders of magnitudes greater,” Dr. Waner said. “On a scale of 1 to 10 she was a 12.”

The morning of the surgery, “I was very apprehensive,” Dr. Waner recalled. He vividly remembers the girl’s father repeatedly kissing her to say goodbye as she lay on the operating table, fully aware that this procedure was a life-threatening one. And from the beginning there were challenges, like getting her under anesthesia when the anatomy of her mouth, deformed by the tumor, didn’t allow the anesthesiologists to use their typical tubing. Then, once the skin was removed, it became clear how dilated and tangled the involved blood vessels were. There were many vital structures tangled in the anomaly. “The jugular vein was right there. The carotid artery was right there,” Dr. Waner said. It was extremely difficult to delineate and preserve them, he said.

“That’s why we really took our time. We just went very slowly and deliberately,” Dr. O said. The blood vessels were so dilated that their only option was to move painstakingly slow – otherwise a small nick could be devastating.

But even with the slow pace the surgery was “excruciatingly difficult,” Dr. Waner said. And early on in the dissection he wasn’t quite sure they’d make it out. The sclerotherapy hadn’t done much to prevent bleeding. “At one point every millimeter or 2 that we advanced we got into some bleeding,” Dr. Waner said. “Brisk bleeding.”

Once they got into the surgery they also realized that the growth had adhered to the jaw bone. “There were vessels traversing into the bone, which were hard to control,” Dr. O said.

But finally, both doctors realized they’d be able to remove it. With the lesion removed they began the work of reconstruction and reanimation.

The child’s jaw and cheek bone had grown beyond their normal size to support the growth. They had to shave them down to achieve facial symmetry. The tumor had also inhibited much of the child’s facial nerve control. With it gone, Dr. O began the work of finding all the facial nerve branches and assembling them to reanimate the child’s face.

Before medicine, Dr. O trained as an architect, which, according to Dr. Waner, has equipped her with very good spatial awareness – a valuable skill in the surgical reconstruction phase. After seeing a lecture by Dr. Waner, she immediately saw a fit for her unique interest and skill set. She did fellowship training with Dr. Waner in vascular anomalies, and then went on to specialize in facial nerve reanimation. The proof of Dr. O’s expertise is Negalem’s new, beautiful smile, Dr. Waner said.

The surgery drew out over 8 hours, as long as a day of surgeries for the two doctors. When Dr. O finally walked into the waiting room to inform the family of the success, the first words out of the father’s mouth were: “Is my daughter alive?”

A growth like Negalem had is not compatible with a normal life. Dr. Waner’s mantra is that every child has the right to look normal. But this case went beyond aesthetics. If the growth hadn’t been removed, the child was expected to live only 4-6 more years, Dr. Waner said. Without the surgery, she could have suffocated, starved without the ability to swallow, or suffered a fatal bleed.

Dr. O and Dr. Waner are uniquely equipped to do this kind of work, but both are adamant that treating vascular anomalies is a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach. Specialties in anesthesiology, radiology, lasers, facial nerves – they are all critical to these procedures. And often patients with these kinds of lesions require medical and radiologic interventions in addition to surgery. In this particular case, from logistics to post op, “it was a lot of teamwork,” Dr. O said, “a lot of international teams coming together.”

Though extremely difficult, “in the end the result was exactly what we wanted,” Dr. Waner said. Negalem can live a normal life. And as for the surgical duo, both feel very fortunate to do this work. Dr. O said, “I’m honored to have found this specialty and to be able to train with and work with Milton. I’m so happy to do what I do every day.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2019, doctors in London saw a 5-year old girl from rural Ethiopia with an enormous tumor extending from her cheek to her lower jaw. Her name was Negalem and the tumor was a vascular malformation, a life-threatening web of tangled blood vessels.

Surgery to remove it was impossible, the doctors told the foundation advocating for the girl. The child would never make it off the operating table. After a closer examination, the London group still declined to do the procedure, but told the child’s parents and advocates that if anyone was going to attempt this, they’d need to get the little girl to New York.

In New York City, on 64th St. in Manhattan, is the Vascular Birthmark Institute, founded by Milton Waner, MD, who has exclusively treated hemangiomas and vascular malformations for the last 30 years. “I’m the only person in the [United] States whose practice is exclusively [treating] vascular anomalies,” Dr. Waner said in an interview.

Dr. Waner has assembled a multidisciplinary team of experts at the institute’s offices in Lenox Hill – including his wife Teresa O, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon and neurospecialist. “People often ask how the hell do you spend so much time with your spouse?” Dr. Waner says. “We work extremely well together. We complement each other.”

Dr. O and Dr. Waner each manage half of the cases at VBI. And in January they received an email about Negalem. After corresponding with the child’s advocate and reviewing images,

The challenge with vascular malformations in children, Dr. Waner said, is that they have a fraction of the blood an adult has. Where adults have an average of 5 L of blood, a child this age has only 1 L. To lose 200 or 300 mL of blood, “that’s 20% or 30% of their blood volume,” Dr. Waner said. So the removal of such a mass, which requires a meticulous dissection around many blood vessels, carries a high risk of the child bleeding out.

There were some logistical hurdles, but the patient arrived in Manhattan in mid-June, at no cost to her family. The medical visa was organized by a volunteer who also work for USAID. Healing the Children Northeast paid for her travel and the Waner Kids Foundation paid for her hotel stay. Lenox Hill Hospital and Northwell Health covered all hospital costs and postsurgery care. And Dr. O and Dr. Waner did the planning, consult visits, and procedure pro bono.

The surgery was possible because of the generosity of several organizations, but the two surgeons still had a limited time to remove the mass. Under different circumstances, and with the luxury of more time, the patient would have undergone several rounds of sclerotherapy. This procedure, done by interventional radiologists, involves injecting a toxin into the blood vessels, which causes them to clot. Done prior to surgery it can help limit bleeding risk.

On June 23, the morning of the surgery, the patient underwent one round of sclerotherapy. However, it didn’t have the intended effect, Dr. Waner said, “because the lesion was just so massive.”

The team had planned several of their moves ahead of time. But this isn’t the sort of surgery you’d find in a textbook. Because it’s such a unique field, Dr. Waner and Dr. O have developed many of their own techniques along the way. This patient was much like the cases they treat every day, only “several orders of magnitudes greater,” Dr. Waner said. “On a scale of 1 to 10 she was a 12.”

The morning of the surgery, “I was very apprehensive,” Dr. Waner recalled. He vividly remembers the girl’s father repeatedly kissing her to say goodbye as she lay on the operating table, fully aware that this procedure was a life-threatening one. And from the beginning there were challenges, like getting her under anesthesia when the anatomy of her mouth, deformed by the tumor, didn’t allow the anesthesiologists to use their typical tubing. Then, once the skin was removed, it became clear how dilated and tangled the involved blood vessels were. There were many vital structures tangled in the anomaly. “The jugular vein was right there. The carotid artery was right there,” Dr. Waner said. It was extremely difficult to delineate and preserve them, he said.

“That’s why we really took our time. We just went very slowly and deliberately,” Dr. O said. The blood vessels were so dilated that their only option was to move painstakingly slow – otherwise a small nick could be devastating.

But even with the slow pace the surgery was “excruciatingly difficult,” Dr. Waner said. And early on in the dissection he wasn’t quite sure they’d make it out. The sclerotherapy hadn’t done much to prevent bleeding. “At one point every millimeter or 2 that we advanced we got into some bleeding,” Dr. Waner said. “Brisk bleeding.”

Once they got into the surgery they also realized that the growth had adhered to the jaw bone. “There were vessels traversing into the bone, which were hard to control,” Dr. O said.

But finally, both doctors realized they’d be able to remove it. With the lesion removed they began the work of reconstruction and reanimation.

The child’s jaw and cheek bone had grown beyond their normal size to support the growth. They had to shave them down to achieve facial symmetry. The tumor had also inhibited much of the child’s facial nerve control. With it gone, Dr. O began the work of finding all the facial nerve branches and assembling them to reanimate the child’s face.

Before medicine, Dr. O trained as an architect, which, according to Dr. Waner, has equipped her with very good spatial awareness – a valuable skill in the surgical reconstruction phase. After seeing a lecture by Dr. Waner, she immediately saw a fit for her unique interest and skill set. She did fellowship training with Dr. Waner in vascular anomalies, and then went on to specialize in facial nerve reanimation. The proof of Dr. O’s expertise is Negalem’s new, beautiful smile, Dr. Waner said.

The surgery drew out over 8 hours, as long as a day of surgeries for the two doctors. When Dr. O finally walked into the waiting room to inform the family of the success, the first words out of the father’s mouth were: “Is my daughter alive?”

A growth like Negalem had is not compatible with a normal life. Dr. Waner’s mantra is that every child has the right to look normal. But this case went beyond aesthetics. If the growth hadn’t been removed, the child was expected to live only 4-6 more years, Dr. Waner said. Without the surgery, she could have suffocated, starved without the ability to swallow, or suffered a fatal bleed.

Dr. O and Dr. Waner are uniquely equipped to do this kind of work, but both are adamant that treating vascular anomalies is a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach. Specialties in anesthesiology, radiology, lasers, facial nerves – they are all critical to these procedures. And often patients with these kinds of lesions require medical and radiologic interventions in addition to surgery. In this particular case, from logistics to post op, “it was a lot of teamwork,” Dr. O said, “a lot of international teams coming together.”

Though extremely difficult, “in the end the result was exactly what we wanted,” Dr. Waner said. Negalem can live a normal life. And as for the surgical duo, both feel very fortunate to do this work. Dr. O said, “I’m honored to have found this specialty and to be able to train with and work with Milton. I’m so happy to do what I do every day.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2019, doctors in London saw a 5-year old girl from rural Ethiopia with an enormous tumor extending from her cheek to her lower jaw. Her name was Negalem and the tumor was a vascular malformation, a life-threatening web of tangled blood vessels.

Surgery to remove it was impossible, the doctors told the foundation advocating for the girl. The child would never make it off the operating table. After a closer examination, the London group still declined to do the procedure, but told the child’s parents and advocates that if anyone was going to attempt this, they’d need to get the little girl to New York.

In New York City, on 64th St. in Manhattan, is the Vascular Birthmark Institute, founded by Milton Waner, MD, who has exclusively treated hemangiomas and vascular malformations for the last 30 years. “I’m the only person in the [United] States whose practice is exclusively [treating] vascular anomalies,” Dr. Waner said in an interview.

Dr. Waner has assembled a multidisciplinary team of experts at the institute’s offices in Lenox Hill – including his wife Teresa O, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon and neurospecialist. “People often ask how the hell do you spend so much time with your spouse?” Dr. Waner says. “We work extremely well together. We complement each other.”

Dr. O and Dr. Waner each manage half of the cases at VBI. And in January they received an email about Negalem. After corresponding with the child’s advocate and reviewing images,

The challenge with vascular malformations in children, Dr. Waner said, is that they have a fraction of the blood an adult has. Where adults have an average of 5 L of blood, a child this age has only 1 L. To lose 200 or 300 mL of blood, “that’s 20% or 30% of their blood volume,” Dr. Waner said. So the removal of such a mass, which requires a meticulous dissection around many blood vessels, carries a high risk of the child bleeding out.

There were some logistical hurdles, but the patient arrived in Manhattan in mid-June, at no cost to her family. The medical visa was organized by a volunteer who also work for USAID. Healing the Children Northeast paid for her travel and the Waner Kids Foundation paid for her hotel stay. Lenox Hill Hospital and Northwell Health covered all hospital costs and postsurgery care. And Dr. O and Dr. Waner did the planning, consult visits, and procedure pro bono.

The surgery was possible because of the generosity of several organizations, but the two surgeons still had a limited time to remove the mass. Under different circumstances, and with the luxury of more time, the patient would have undergone several rounds of sclerotherapy. This procedure, done by interventional radiologists, involves injecting a toxin into the blood vessels, which causes them to clot. Done prior to surgery it can help limit bleeding risk.

On June 23, the morning of the surgery, the patient underwent one round of sclerotherapy. However, it didn’t have the intended effect, Dr. Waner said, “because the lesion was just so massive.”

The team had planned several of their moves ahead of time. But this isn’t the sort of surgery you’d find in a textbook. Because it’s such a unique field, Dr. Waner and Dr. O have developed many of their own techniques along the way. This patient was much like the cases they treat every day, only “several orders of magnitudes greater,” Dr. Waner said. “On a scale of 1 to 10 she was a 12.”

The morning of the surgery, “I was very apprehensive,” Dr. Waner recalled. He vividly remembers the girl’s father repeatedly kissing her to say goodbye as she lay on the operating table, fully aware that this procedure was a life-threatening one. And from the beginning there were challenges, like getting her under anesthesia when the anatomy of her mouth, deformed by the tumor, didn’t allow the anesthesiologists to use their typical tubing. Then, once the skin was removed, it became clear how dilated and tangled the involved blood vessels were. There were many vital structures tangled in the anomaly. “The jugular vein was right there. The carotid artery was right there,” Dr. Waner said. It was extremely difficult to delineate and preserve them, he said.

“That’s why we really took our time. We just went very slowly and deliberately,” Dr. O said. The blood vessels were so dilated that their only option was to move painstakingly slow – otherwise a small nick could be devastating.

But even with the slow pace the surgery was “excruciatingly difficult,” Dr. Waner said. And early on in the dissection he wasn’t quite sure they’d make it out. The sclerotherapy hadn’t done much to prevent bleeding. “At one point every millimeter or 2 that we advanced we got into some bleeding,” Dr. Waner said. “Brisk bleeding.”

Once they got into the surgery they also realized that the growth had adhered to the jaw bone. “There were vessels traversing into the bone, which were hard to control,” Dr. O said.

But finally, both doctors realized they’d be able to remove it. With the lesion removed they began the work of reconstruction and reanimation.

The child’s jaw and cheek bone had grown beyond their normal size to support the growth. They had to shave them down to achieve facial symmetry. The tumor had also inhibited much of the child’s facial nerve control. With it gone, Dr. O began the work of finding all the facial nerve branches and assembling them to reanimate the child’s face.

Before medicine, Dr. O trained as an architect, which, according to Dr. Waner, has equipped her with very good spatial awareness – a valuable skill in the surgical reconstruction phase. After seeing a lecture by Dr. Waner, she immediately saw a fit for her unique interest and skill set. She did fellowship training with Dr. Waner in vascular anomalies, and then went on to specialize in facial nerve reanimation. The proof of Dr. O’s expertise is Negalem’s new, beautiful smile, Dr. Waner said.

The surgery drew out over 8 hours, as long as a day of surgeries for the two doctors. When Dr. O finally walked into the waiting room to inform the family of the success, the first words out of the father’s mouth were: “Is my daughter alive?”

A growth like Negalem had is not compatible with a normal life. Dr. Waner’s mantra is that every child has the right to look normal. But this case went beyond aesthetics. If the growth hadn’t been removed, the child was expected to live only 4-6 more years, Dr. Waner said. Without the surgery, she could have suffocated, starved without the ability to swallow, or suffered a fatal bleed.

Dr. O and Dr. Waner are uniquely equipped to do this kind of work, but both are adamant that treating vascular anomalies is a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach. Specialties in anesthesiology, radiology, lasers, facial nerves – they are all critical to these procedures. And often patients with these kinds of lesions require medical and radiologic interventions in addition to surgery. In this particular case, from logistics to post op, “it was a lot of teamwork,” Dr. O said, “a lot of international teams coming together.”

Though extremely difficult, “in the end the result was exactly what we wanted,” Dr. Waner said. Negalem can live a normal life. And as for the surgical duo, both feel very fortunate to do this work. Dr. O said, “I’m honored to have found this specialty and to be able to train with and work with Milton. I’m so happy to do what I do every day.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Finding room for hope

Dear colleagues,

I’m thrilled to introduce the August edition of The New Gastroenterologist, which features an excellent line-up of articles! Summer has been in full swing, and gradually, we eased into aspects of our prepandemic routine. The fear, caution, and isolation that characterized the last year and a half was less pervasive, and the ability to reconnect in person felt both refreshing and liberating. While new threats of variants and rising infection rates have emerged, there is hope that, with the availability of vaccines, the worst of the pandemic may still be behind us.

One of the most difficult aspects of treating patients with inflammatory bowel disease is acute pain management. Dr. Jami Kinnucan and Dr. Mehwish Ahmed (University of Michigan) outline an expert approach on differentiating between visceral and somatic pain and how to manage each accordingly.

The diagnosis of microscopic colitis can be elusive because colonic mucosa typically appears endoscopically normal and the pathognomonic findings are histologic. Management can also be challenging given the frequently relapsing and remitting nature of its clinical course. The “In Focus” feature for August, written by Dr. June Tome, Dr. Amrit Kamboj, and Dr. Darrell Pardi (Mayo Clinic), is an absolute must-read as it provides a detailed review on the diagnosis, management, and therapeutic options for microscopic colitis.

As gastroenterologists, we are often asked to place percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes. This can be a difficult situation to navigate especially when the indication or timing of placement seems questionable. In our ethics case for this quarter, Dr. David Seres and Dr. Jane Cowan (Columbia University) unpack the ethical considerations of PEG tube placement in order to facilitate discharge to subacute nursing facilities.

Months in quarantine have incited many to crave larger living spaces, lending to a chaotic housing market. Jon Solitro (FinancialMD) offers sound financial advice for physicians interested purchasing a home – including factors to consider when choosing a home, how much to spend, and whether or not to consider a doctor’s loan.

Success in research can be particularly difficult for fellows and early career gastroenterologists as they juggle the many responsibilities inherent to busy training programs or adjust to independent practice. Dr. Dionne Rebello and Dr. Michelle Long (Boston University) compile a list of incredibly helpful tips on how to optimize productivity. For those interested in ways to harness experiences in clinical medicine into health technology, Dr. Simon Matthews (Johns Hopkins) discusses his role as chief medical officer in a health tech start-up in our postfellowship pathways section.

Lastly, our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives article, written by Dr. George Dickstein (Greater Boston Gastroenterology), nicely summarizes lessons learned from the pandemic and how a practice can be adequately prepared for a post-pandemic surge of procedures.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]) or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Stay well,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor in Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition

Dear colleagues,

I’m thrilled to introduce the August edition of The New Gastroenterologist, which features an excellent line-up of articles! Summer has been in full swing, and gradually, we eased into aspects of our prepandemic routine. The fear, caution, and isolation that characterized the last year and a half was less pervasive, and the ability to reconnect in person felt both refreshing and liberating. While new threats of variants and rising infection rates have emerged, there is hope that, with the availability of vaccines, the worst of the pandemic may still be behind us.

One of the most difficult aspects of treating patients with inflammatory bowel disease is acute pain management. Dr. Jami Kinnucan and Dr. Mehwish Ahmed (University of Michigan) outline an expert approach on differentiating between visceral and somatic pain and how to manage each accordingly.

The diagnosis of microscopic colitis can be elusive because colonic mucosa typically appears endoscopically normal and the pathognomonic findings are histologic. Management can also be challenging given the frequently relapsing and remitting nature of its clinical course. The “In Focus” feature for August, written by Dr. June Tome, Dr. Amrit Kamboj, and Dr. Darrell Pardi (Mayo Clinic), is an absolute must-read as it provides a detailed review on the diagnosis, management, and therapeutic options for microscopic colitis.

As gastroenterologists, we are often asked to place percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes. This can be a difficult situation to navigate especially when the indication or timing of placement seems questionable. In our ethics case for this quarter, Dr. David Seres and Dr. Jane Cowan (Columbia University) unpack the ethical considerations of PEG tube placement in order to facilitate discharge to subacute nursing facilities.

Months in quarantine have incited many to crave larger living spaces, lending to a chaotic housing market. Jon Solitro (FinancialMD) offers sound financial advice for physicians interested purchasing a home – including factors to consider when choosing a home, how much to spend, and whether or not to consider a doctor’s loan.

Success in research can be particularly difficult for fellows and early career gastroenterologists as they juggle the many responsibilities inherent to busy training programs or adjust to independent practice. Dr. Dionne Rebello and Dr. Michelle Long (Boston University) compile a list of incredibly helpful tips on how to optimize productivity. For those interested in ways to harness experiences in clinical medicine into health technology, Dr. Simon Matthews (Johns Hopkins) discusses his role as chief medical officer in a health tech start-up in our postfellowship pathways section.

Lastly, our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives article, written by Dr. George Dickstein (Greater Boston Gastroenterology), nicely summarizes lessons learned from the pandemic and how a practice can be adequately prepared for a post-pandemic surge of procedures.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]) or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Stay well,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor in Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition

Dear colleagues,

I’m thrilled to introduce the August edition of The New Gastroenterologist, which features an excellent line-up of articles! Summer has been in full swing, and gradually, we eased into aspects of our prepandemic routine. The fear, caution, and isolation that characterized the last year and a half was less pervasive, and the ability to reconnect in person felt both refreshing and liberating. While new threats of variants and rising infection rates have emerged, there is hope that, with the availability of vaccines, the worst of the pandemic may still be behind us.

One of the most difficult aspects of treating patients with inflammatory bowel disease is acute pain management. Dr. Jami Kinnucan and Dr. Mehwish Ahmed (University of Michigan) outline an expert approach on differentiating between visceral and somatic pain and how to manage each accordingly.

The diagnosis of microscopic colitis can be elusive because colonic mucosa typically appears endoscopically normal and the pathognomonic findings are histologic. Management can also be challenging given the frequently relapsing and remitting nature of its clinical course. The “In Focus” feature for August, written by Dr. June Tome, Dr. Amrit Kamboj, and Dr. Darrell Pardi (Mayo Clinic), is an absolute must-read as it provides a detailed review on the diagnosis, management, and therapeutic options for microscopic colitis.

As gastroenterologists, we are often asked to place percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes. This can be a difficult situation to navigate especially when the indication or timing of placement seems questionable. In our ethics case for this quarter, Dr. David Seres and Dr. Jane Cowan (Columbia University) unpack the ethical considerations of PEG tube placement in order to facilitate discharge to subacute nursing facilities.

Months in quarantine have incited many to crave larger living spaces, lending to a chaotic housing market. Jon Solitro (FinancialMD) offers sound financial advice for physicians interested purchasing a home – including factors to consider when choosing a home, how much to spend, and whether or not to consider a doctor’s loan.

Success in research can be particularly difficult for fellows and early career gastroenterologists as they juggle the many responsibilities inherent to busy training programs or adjust to independent practice. Dr. Dionne Rebello and Dr. Michelle Long (Boston University) compile a list of incredibly helpful tips on how to optimize productivity. For those interested in ways to harness experiences in clinical medicine into health technology, Dr. Simon Matthews (Johns Hopkins) discusses his role as chief medical officer in a health tech start-up in our postfellowship pathways section.

Lastly, our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives article, written by Dr. George Dickstein (Greater Boston Gastroenterology), nicely summarizes lessons learned from the pandemic and how a practice can be adequately prepared for a post-pandemic surge of procedures.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]) or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Stay well,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor in Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition

Microscopic colitis: A common, yet often overlooked, cause of chronic diarrhea

Microscopic colitis is an inflammatory disease of the colon and a frequent cause of chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. MC consists of two subtypes, collagenous colitis (CC) and lymphocytic colitis (LC). While the primary symptom is diarrhea, other signs and symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities may also be present depending on disease severity.1 In MC, the colonic mucosa usually appears normal on colonoscopy, and the diagnosis is made by histologic findings of intraepithelial lymphocytosis with (CC) or without (LC) a prominent subepithelial collagen band. The management approaches to CC and LC are similar and should be directed based on the severity of symptoms.2 We review the epidemiology, risk factors, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management for this condition, as well as novel therapeutic approaches.

Epidemiology

Although the incidence of MC increased in the late twentieth century, more recently, it has stabilized with an estimated incidence varying from 1 to 25 per 100,000 person-years.3-5 A recent meta-analysis revealed a pooled incidence of 4.85 per 100,000 persons for LC and 4.14 per 100,000 persons for CC.6 Proposed explanations for the rising incidence in the late twentieth century include improved clinical awareness of the disease, possible increased use of drugs associated with MC, and increased performance of diagnostic colonoscopies for chronic diarrhea. Since MC is now well-recognized, the recent plateau in incidence rates may reflect decreased detection bias.

The prevalence of MC ranges from 10%-20% in patients undergoing colonoscopy for chronic watery diarrhea.6,7 The prevalence of LC is approximately 63.1 cases per 100,000 person-years and, for CC, is 49.2 cases per 100,000 person-years.6-8 Recent studies have demonstrated increasing prevalence of MC likely resulting from an aging population.9,10

Risk stratification

Female gender, increasing age, concomitant autoimmune disease, and the use of certain drugs, including NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), statins, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have been associated with an increased risk of MC.11,12 Autoimmune disorders, including celiac disease (CD), rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism, are more common in patients with MC. The association with CD, in particular, is clinically important, as CD is associated with a 50-70 times greater risk of MC, and 2%-9% of patients with MC have CD.13,14

Several medications have been associated with MC. In a British multicenter prospective study, MC was associated with the use of NSAIDs, PPIs, and SSRIs;15 however, recent studies have questioned the association of MC with some of these medications, which might worsen diarrhea but not actually cause MC.16

An additional risk factor for MC is smoking. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that current and former smokers had an increased risk of MC (odds ratio, 2.99; 95% confidence interval, 2.15-4.15 and OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.37-1.94, respectively), compared with nonsmokers.17 Smokers develop MC at a younger age, and smoking is associated with increased disease severity and decreased likelihood of attaining remission.18,19

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of MC remains largely unknown, although there are several hypotheses. The leading proposed mechanisms include reaction to luminal antigens, dysregulated collagen metabolism, genetic predisposition, autoimmunity, and bile acid malabsorption.

MC may be caused by abnormal epithelial barrier function, leading to increased permeability and reaction to luminal antigens, including dietary antigens, certain drugs, and bacterial products, 20,21 which themselves lead to the immune dysregulation and intestinal inflammation seen in MC. This mechanism may explain the association of several drugs with MC. Histological changes resembling LC are reported in patients with CD who consume gluten; however, large population-based studies have not found specific dietary associations with the development of MC.22

Another potential mechanism of MC is dysregulated collagen deposition. Collagen accumulation in the subepithelial layer in CC may result from increased levels of fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor–beta and vascular endothelial growth factor.23 Nonetheless, studies have not found an association between the severity of diarrhea in patients with CC and the thickness of the subepithelial collagen band.

Thirdly, autoimmunity and genetic predisposition have been postulated in the pathogenesis of MC. As previously discussed, MC is associated with several autoimmune diseases and predominantly occurs in women, a distinctive feature of autoimmune disorders. Several studies have demonstrated an association between MC and HLA-DQ2 and -DQ3 haplotypes,24 as well as potential polymorphisms in the serotonin transporter gene promoter.25 It is important to note, however, that only a few familial cases of MC have been reported to date.26

Lastly, bile acid malabsorption may play a role in the etiology of MC. Histologic findings of inflammation, along with villous atrophy and collagen deposition, have been reported in the ileum of patients with MC;27,28 however, because patients with MC without bile acid malabsorption may also respond to bile acid binders such as cholestyramine, these findings unlikely to be the sole mechanism explaining the development of the disease.

Despite the different proposed mechanisms for the pathogenesis of MC, no definite conclusions can be drawn because of the limited size of these studies and their often conflicting results.

Clinical features

Clinicians should suspect MC in patients with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. Other risk factors include female gender, use of certain culprit medications, smoking, and presence of other autoimmune diseases. The clinical manifestations of MC subtypes LC and CC are similar with no significant clinical differences.1,2 In addition to diarrhea, patients with MC may have abdominal pain, fatigue, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities depending on disease severity. Patients may also present with fecal urgency, incontinence, and nocturnal stools. Quality of life is often reduced in these patients, predominantly in those with severe or refractory symptoms.29,30 The natural course of MC is highly variable, with some patients achieving spontaneous resolution after one episode and others developing chronic symptoms.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of chronic watery diarrhea is broad and includes malabsorption/maldigestion, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome, and medication side effects. In addition, although gastrointestinal infections typically cause acute or subacute diarrhea, some can present with chronic diarrhea. Malabsorption/maldigestion may occur because of CD, lactose intolerance, and pancreatic insufficiency, among other conditions. A thorough history, regarding recent antibiotic and medication use, travel, and immunosuppression, should be obtained in patients with chronic diarrhea. Additionally, laboratory and endoscopic evaluation with random biopsies of the colon can further help differentiate these diseases from MC. A few studies suggest fecal calprotectin may be used to differentiate MC from other noninflammatory conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, as well as to monitor disease activity. This test is not expected to distinguish MC from other inflammatory causes of diarrhea, such as IBD, and therefore, its role in clinical practice is uncertain.31

The diagnosis of MC is made by biopsy of the colonic mucosa demonstrating characteristic pathologic features.32 Unlike in diseases such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, the colon usually appears normal in MC, although mild nonspecific changes, such as erythema or edema, may be visualized. There is no consensus on the ideal location to obtain biopsies for MC or whether biopsies from both the left and the right colon are required.2,33 The procedure of choice for the diagnosis of MC is colonoscopy with random biopsies taken throughout the colon. More limited evaluation by flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsies may miss cases of MC as inflammation and collagen thickening are not necessarily uniform throughout the colon; however, in a patient that has undergone a recent colonoscopy for colon cancer screening without colon biopsies, a flexible sigmoidoscopy may be a reasonable next test for evaluation of MC, provided biopsies are obtained above the rectosigmoid colon.34

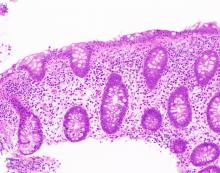

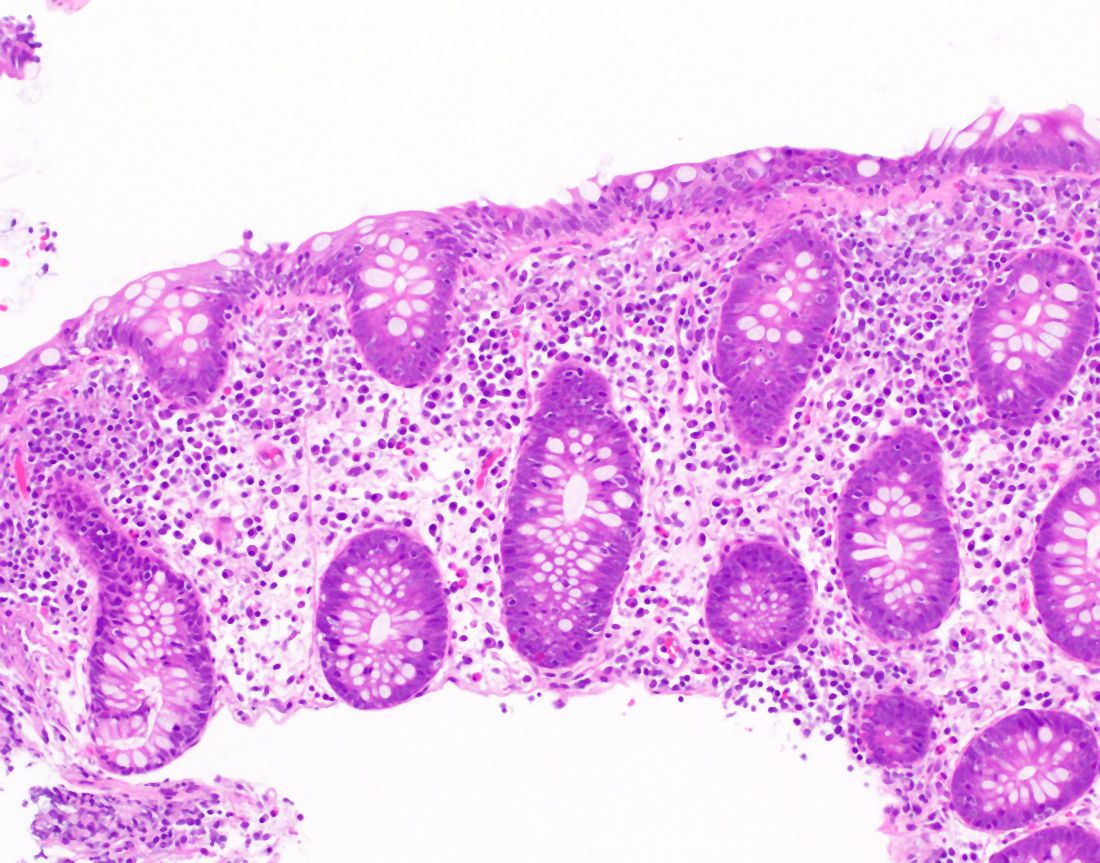

The MC subtypes are differentiated based on histology. The hallmark of LC is less than 20 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 surface epithelial cells (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1A). CC is characterized by a thickened subepithelial collagen band greater than 7-10 micrometers (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1B). For a subgroup of patients with milder abnormalities that do not meet these histological criteria, the terms “microscopic colitis, not otherwise specified” or “microscopic colitis, incomplete” may be used.35 These patients often respond to standard treatments for MC. There is an additional subset of patients with biopsy demonstrating features of both CC and LC simultaneously, as well as patients transitioning from one MC subtype to another over time.32,35

Management approach

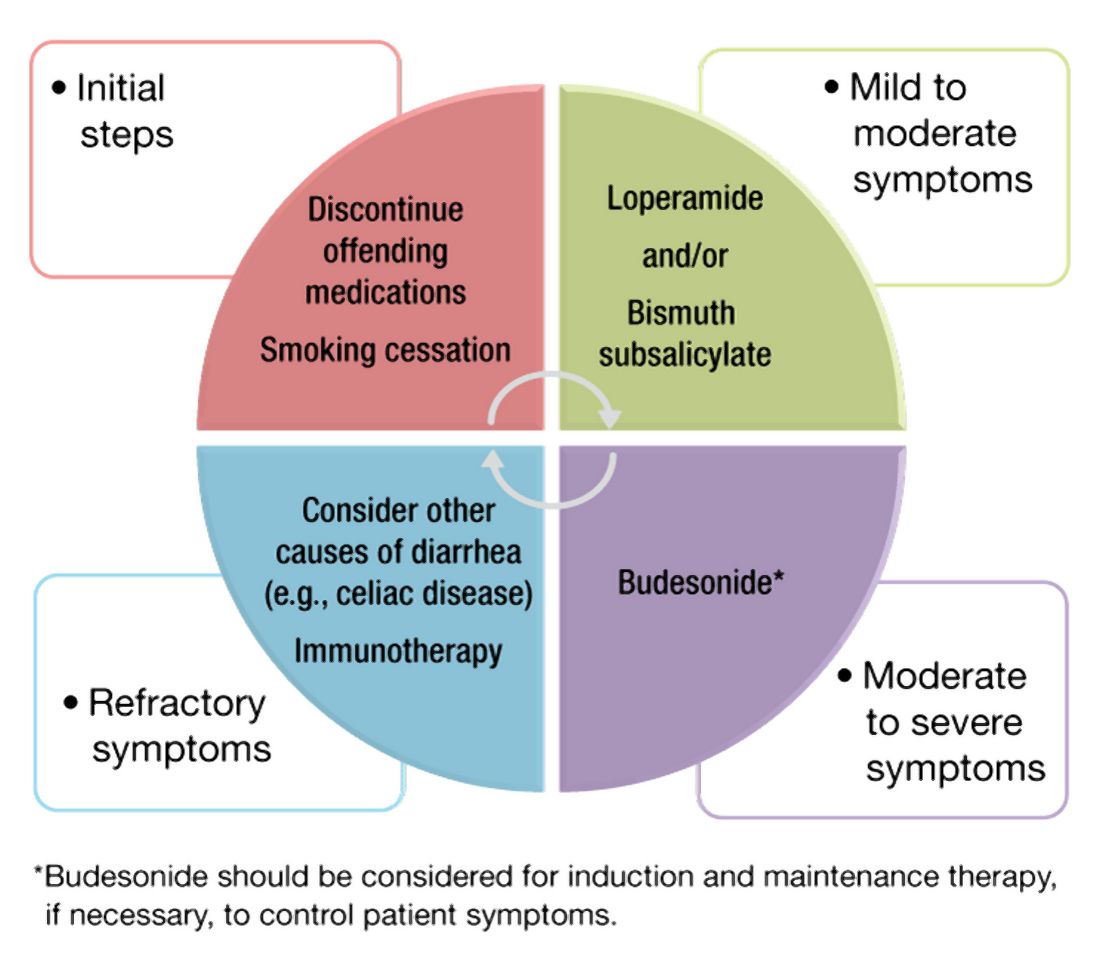

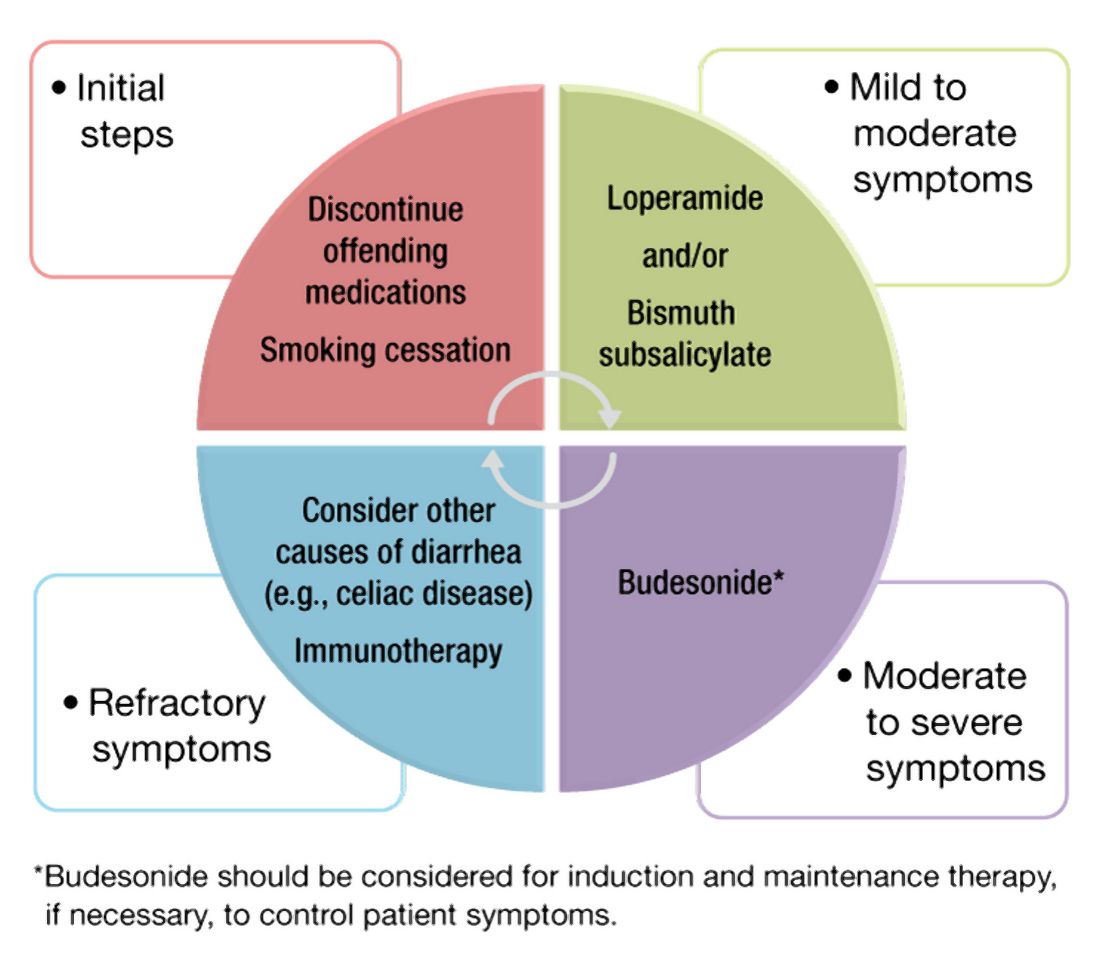

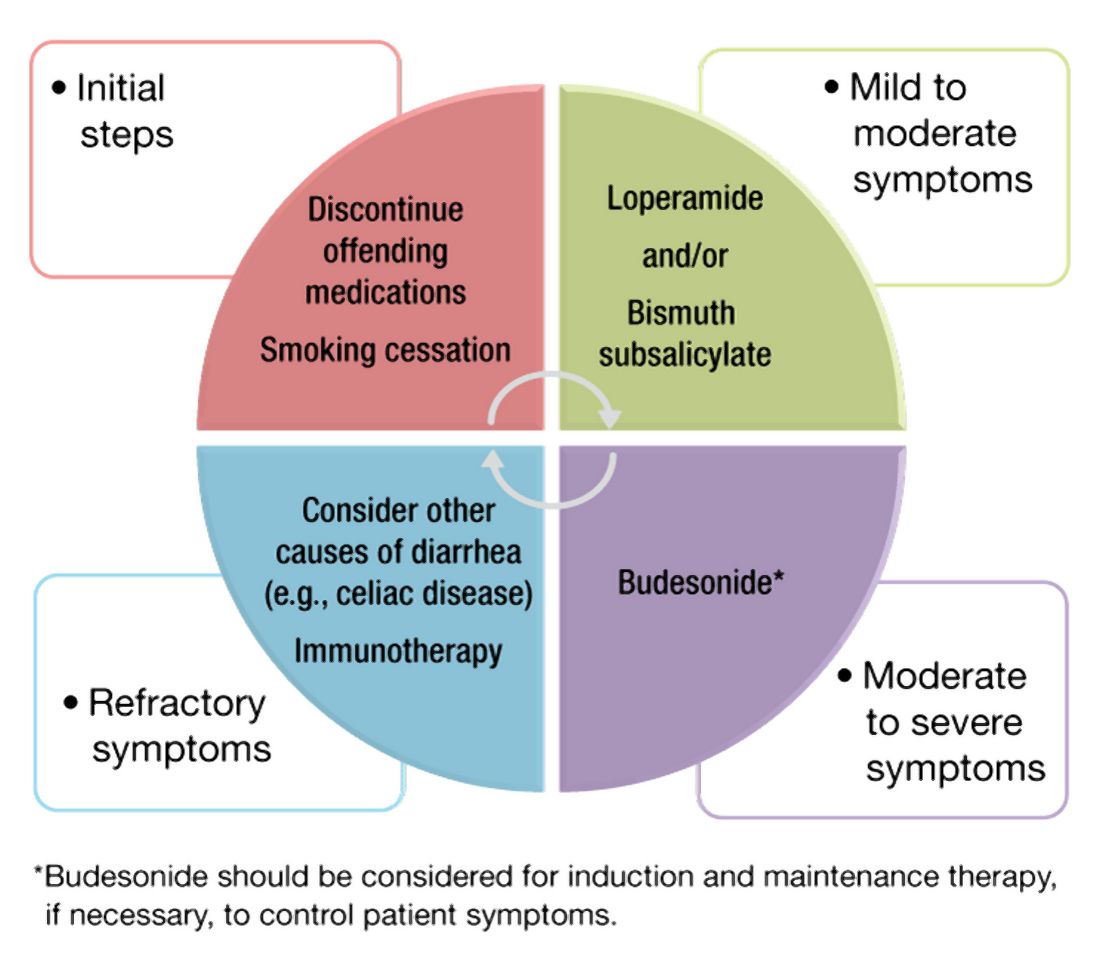

The first step in management of patients with MC includes stopping culprit medications if there is a temporal relationship between the initiation of the medication and the onset of diarrhea, as well as encouraging smoking cessation. These steps alone, however, are unlikely to achieve clinical remission in most patients. A stepwise pharmacological approach is used in the management of MC based on disease severity (Figure 2). For patients with mild symptoms, antidiarrheal medications, such as loperamide, may be helpful.36 Long-term use of loperamide at therapeutic doses no greater than 16 mg daily appears to be safe if required to maintain symptom response. For those with persistent symptoms despite antidiarrheal medications, bismuth subsalicylate at three 262 mg tablets three times daily for 6-8 weeks can be considered. Long-term use of bismuth subsalicylate is not advised, especially at this dose, because of possible neurotoxicity.37

For patients refractory to the above treatments or those with moderate-to-severe symptoms, an 8-week course of budesonide at 9 mg daily is the first-line treatment.38 The dose was tapered before discontinuation in some studies but not in others. Both strategies appear effective. A recent meta-analysis of nine randomized trials demonstrated pooled ORs of 7.34 (95% CI, 4.08-13.19) and 8.35 (95% CI, 4.14-16.85) for response to budesonide induction and maintenance, respectively.39

Cholestyramine is another medication considered in the management of MC and warrants further investigation. To date, no randomized clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate bile acid sequestrants in MC, but they should be considered before placing patients on immunosuppressive medications. Some providers use mesalamine in this setting, although mesalamine is inferior to budesonide in the induction of clinical remission in MC.40

Despite high rates of response to budesonide, relapse after discontinuation is frequent (60%-80%), and time to relapse is variable41,42 The American Gastroenterological Association recommends budesonide for maintenance of remission in patients with recurrence following discontinuation of induction therapy. The lowest effective dose that maintains resolution of symptoms should be prescribed, ideally at 6 mg daily or lower.38 Although budesonide has a greater first-pass metabolism, compared with other glucocorticoids, patients should be monitored for possible side effects including hypertension, diabetes, and osteoporosis, as well as ophthalmologic disease, including cataracts and glaucoma.

For those who are intolerant to budesonide or have refractory symptoms, concomitant disorders such as CD that may be contributing to symptoms must be excluded. Immunosuppressive medications – such as thiopurines and biologic agents, including tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors or vedolizumab – may be considered in refractory cases.43,44 Of note, there are limited studies evaluating the use of these medications for MC. Lastly, surgeries including ileostomy with or without colectomy have been performed in the most severe cases for resistant disease that has failed numerous pharmacological therapies.45

Patients should be counseled that, while symptoms from MC can be quite bothersome and disabling, there appears to be a normal life expectancy and no association between MC and colon cancer, unlike with other inflammatory conditions of the colon such as IBD.46,47

Conclusion and future outlook

As a common cause of chronic watery diarrhea, MC will be commonly encountered in primary care and gastroenterology practices. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients presenting with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, especially with female gender, autoimmune disease, and increasing age. The management of MC requires an algorithmic approach directed by symptom severity, with a subgroup of patients requiring maintenance therapy for relapsing symptoms. The care of patients with MC will continue to evolve in the future. Further work is needed to explore long-term safety outcomes with budesonide and the role of immunomodulators and newer biologic agents for patients with complex, refractory disease.

Dr. Tome is with the department of internal medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Kamboj, and Dr. Pardi are with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Mayo Clinic. Dr. Pardi has grant funding from Pfizer, Vedanta, Seres, Finch, Applied Molecular Transport, and Takeda and has consulted for Vedanta and Otsuka. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. Nyhlin N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:963-72.

2. Miehlke S et al. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;20-8.

3. Pardi DS et al. Gut. 2007;56:504-8.

4. Fernández-Bañares F et al. J Crohn’s Colitis.2016;10(7):805-11.

5. Gentile NM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):838-42.

6. Tong J et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:265-76.

7. Olesen M et al. Gut. 2004;53(3):346-50.

8. Bergman D et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(11):1395-400.

9. Guagnozzi D et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(5):384-8.

10. Münch A et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(9):932-45.

11. Macaigne G et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014; 09(9):1461-70.

12. Verhaegh BP et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(9):1004-13.

13. Stewart M et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(12):1340-9.

14. Green PHR et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(11):1210-6.

15. Masclee GM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:749-59.

16. Zylberberg H et al. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Jun;53(11)1209-15.

17. Jaruvongvanich V et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(4):672-8.

18. Fernández-Bañares F et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19(7):1470-6.

19. Yen EF et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(10):1835-41.

20. Barmeyer C et al. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(10):1090-100.

21. Morgan DM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(4):984-6.

22. Larsson JK et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:1309-17.

23. Madisch A et al.. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(11):2295-8.

24. Stahl E et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(2):549-61.

25. Sikander A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2015; 60:887-94.

26. Abdo AA et al. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15(5):341-3.

27. Fernandez-Bañares F et al. Dig Dis Sci.2001;46(10):2231-8.

28. Lyutakov I et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;1;33(3):380-7.

29. Hjortswang H et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2011 Feb;43(2):102-9.

30. Cotter TG= et al. Gut. 2018;67(3):441-6.

31. Von Arnim U et al. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:97-103.

32. Langner C et al. Histopathology. 2015;66:613-26.

33. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee and Sharaf RN et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:216-24.

34. Macaigne G et al. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2017;41(3):333-40.

35. Bjørnbak C et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(10):1225-34.

36. Pardi DS et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(1):247-74.

37. Masannat Y and Nazer E. West Virginia Med J. 2013;109(3):32-4.

38. Nguyen GC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150(1):242-6.

39. Sebastian S et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Aug;31(8):919-27.

40. Miehlke S et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):1222-30.

41. Gentile NM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:256-9.

42. Münch A et al. Gut. 2016; 65(1):47-56.

43. Cotter TG et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 46(2):169-74.

44. Esteve M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(6):612-8.

45. Cottreau J et al. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2016;9:140-4.

46. Kamboj AK et al. Program No. P1876. ACG 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American College of Gastroenterology.

47. Yen EF et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:161-9.

Microscopic colitis is an inflammatory disease of the colon and a frequent cause of chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. MC consists of two subtypes, collagenous colitis (CC) and lymphocytic colitis (LC). While the primary symptom is diarrhea, other signs and symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities may also be present depending on disease severity.1 In MC, the colonic mucosa usually appears normal on colonoscopy, and the diagnosis is made by histologic findings of intraepithelial lymphocytosis with (CC) or without (LC) a prominent subepithelial collagen band. The management approaches to CC and LC are similar and should be directed based on the severity of symptoms.2 We review the epidemiology, risk factors, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management for this condition, as well as novel therapeutic approaches.

Epidemiology

Although the incidence of MC increased in the late twentieth century, more recently, it has stabilized with an estimated incidence varying from 1 to 25 per 100,000 person-years.3-5 A recent meta-analysis revealed a pooled incidence of 4.85 per 100,000 persons for LC and 4.14 per 100,000 persons for CC.6 Proposed explanations for the rising incidence in the late twentieth century include improved clinical awareness of the disease, possible increased use of drugs associated with MC, and increased performance of diagnostic colonoscopies for chronic diarrhea. Since MC is now well-recognized, the recent plateau in incidence rates may reflect decreased detection bias.

The prevalence of MC ranges from 10%-20% in patients undergoing colonoscopy for chronic watery diarrhea.6,7 The prevalence of LC is approximately 63.1 cases per 100,000 person-years and, for CC, is 49.2 cases per 100,000 person-years.6-8 Recent studies have demonstrated increasing prevalence of MC likely resulting from an aging population.9,10

Risk stratification

Female gender, increasing age, concomitant autoimmune disease, and the use of certain drugs, including NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), statins, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have been associated with an increased risk of MC.11,12 Autoimmune disorders, including celiac disease (CD), rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism, are more common in patients with MC. The association with CD, in particular, is clinically important, as CD is associated with a 50-70 times greater risk of MC, and 2%-9% of patients with MC have CD.13,14

Several medications have been associated with MC. In a British multicenter prospective study, MC was associated with the use of NSAIDs, PPIs, and SSRIs;15 however, recent studies have questioned the association of MC with some of these medications, which might worsen diarrhea but not actually cause MC.16

An additional risk factor for MC is smoking. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that current and former smokers had an increased risk of MC (odds ratio, 2.99; 95% confidence interval, 2.15-4.15 and OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.37-1.94, respectively), compared with nonsmokers.17 Smokers develop MC at a younger age, and smoking is associated with increased disease severity and decreased likelihood of attaining remission.18,19

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of MC remains largely unknown, although there are several hypotheses. The leading proposed mechanisms include reaction to luminal antigens, dysregulated collagen metabolism, genetic predisposition, autoimmunity, and bile acid malabsorption.

MC may be caused by abnormal epithelial barrier function, leading to increased permeability and reaction to luminal antigens, including dietary antigens, certain drugs, and bacterial products, 20,21 which themselves lead to the immune dysregulation and intestinal inflammation seen in MC. This mechanism may explain the association of several drugs with MC. Histological changes resembling LC are reported in patients with CD who consume gluten; however, large population-based studies have not found specific dietary associations with the development of MC.22

Another potential mechanism of MC is dysregulated collagen deposition. Collagen accumulation in the subepithelial layer in CC may result from increased levels of fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor–beta and vascular endothelial growth factor.23 Nonetheless, studies have not found an association between the severity of diarrhea in patients with CC and the thickness of the subepithelial collagen band.

Thirdly, autoimmunity and genetic predisposition have been postulated in the pathogenesis of MC. As previously discussed, MC is associated with several autoimmune diseases and predominantly occurs in women, a distinctive feature of autoimmune disorders. Several studies have demonstrated an association between MC and HLA-DQ2 and -DQ3 haplotypes,24 as well as potential polymorphisms in the serotonin transporter gene promoter.25 It is important to note, however, that only a few familial cases of MC have been reported to date.26

Lastly, bile acid malabsorption may play a role in the etiology of MC. Histologic findings of inflammation, along with villous atrophy and collagen deposition, have been reported in the ileum of patients with MC;27,28 however, because patients with MC without bile acid malabsorption may also respond to bile acid binders such as cholestyramine, these findings unlikely to be the sole mechanism explaining the development of the disease.

Despite the different proposed mechanisms for the pathogenesis of MC, no definite conclusions can be drawn because of the limited size of these studies and their often conflicting results.

Clinical features

Clinicians should suspect MC in patients with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. Other risk factors include female gender, use of certain culprit medications, smoking, and presence of other autoimmune diseases. The clinical manifestations of MC subtypes LC and CC are similar with no significant clinical differences.1,2 In addition to diarrhea, patients with MC may have abdominal pain, fatigue, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities depending on disease severity. Patients may also present with fecal urgency, incontinence, and nocturnal stools. Quality of life is often reduced in these patients, predominantly in those with severe or refractory symptoms.29,30 The natural course of MC is highly variable, with some patients achieving spontaneous resolution after one episode and others developing chronic symptoms.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of chronic watery diarrhea is broad and includes malabsorption/maldigestion, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome, and medication side effects. In addition, although gastrointestinal infections typically cause acute or subacute diarrhea, some can present with chronic diarrhea. Malabsorption/maldigestion may occur because of CD, lactose intolerance, and pancreatic insufficiency, among other conditions. A thorough history, regarding recent antibiotic and medication use, travel, and immunosuppression, should be obtained in patients with chronic diarrhea. Additionally, laboratory and endoscopic evaluation with random biopsies of the colon can further help differentiate these diseases from MC. A few studies suggest fecal calprotectin may be used to differentiate MC from other noninflammatory conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, as well as to monitor disease activity. This test is not expected to distinguish MC from other inflammatory causes of diarrhea, such as IBD, and therefore, its role in clinical practice is uncertain.31

The diagnosis of MC is made by biopsy of the colonic mucosa demonstrating characteristic pathologic features.32 Unlike in diseases such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, the colon usually appears normal in MC, although mild nonspecific changes, such as erythema or edema, may be visualized. There is no consensus on the ideal location to obtain biopsies for MC or whether biopsies from both the left and the right colon are required.2,33 The procedure of choice for the diagnosis of MC is colonoscopy with random biopsies taken throughout the colon. More limited evaluation by flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsies may miss cases of MC as inflammation and collagen thickening are not necessarily uniform throughout the colon; however, in a patient that has undergone a recent colonoscopy for colon cancer screening without colon biopsies, a flexible sigmoidoscopy may be a reasonable next test for evaluation of MC, provided biopsies are obtained above the rectosigmoid colon.34

The MC subtypes are differentiated based on histology. The hallmark of LC is less than 20 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 surface epithelial cells (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1A). CC is characterized by a thickened subepithelial collagen band greater than 7-10 micrometers (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1B). For a subgroup of patients with milder abnormalities that do not meet these histological criteria, the terms “microscopic colitis, not otherwise specified” or “microscopic colitis, incomplete” may be used.35 These patients often respond to standard treatments for MC. There is an additional subset of patients with biopsy demonstrating features of both CC and LC simultaneously, as well as patients transitioning from one MC subtype to another over time.32,35

Management approach

The first step in management of patients with MC includes stopping culprit medications if there is a temporal relationship between the initiation of the medication and the onset of diarrhea, as well as encouraging smoking cessation. These steps alone, however, are unlikely to achieve clinical remission in most patients. A stepwise pharmacological approach is used in the management of MC based on disease severity (Figure 2). For patients with mild symptoms, antidiarrheal medications, such as loperamide, may be helpful.36 Long-term use of loperamide at therapeutic doses no greater than 16 mg daily appears to be safe if required to maintain symptom response. For those with persistent symptoms despite antidiarrheal medications, bismuth subsalicylate at three 262 mg tablets three times daily for 6-8 weeks can be considered. Long-term use of bismuth subsalicylate is not advised, especially at this dose, because of possible neurotoxicity.37

For patients refractory to the above treatments or those with moderate-to-severe symptoms, an 8-week course of budesonide at 9 mg daily is the first-line treatment.38 The dose was tapered before discontinuation in some studies but not in others. Both strategies appear effective. A recent meta-analysis of nine randomized trials demonstrated pooled ORs of 7.34 (95% CI, 4.08-13.19) and 8.35 (95% CI, 4.14-16.85) for response to budesonide induction and maintenance, respectively.39

Cholestyramine is another medication considered in the management of MC and warrants further investigation. To date, no randomized clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate bile acid sequestrants in MC, but they should be considered before placing patients on immunosuppressive medications. Some providers use mesalamine in this setting, although mesalamine is inferior to budesonide in the induction of clinical remission in MC.40

Despite high rates of response to budesonide, relapse after discontinuation is frequent (60%-80%), and time to relapse is variable41,42 The American Gastroenterological Association recommends budesonide for maintenance of remission in patients with recurrence following discontinuation of induction therapy. The lowest effective dose that maintains resolution of symptoms should be prescribed, ideally at 6 mg daily or lower.38 Although budesonide has a greater first-pass metabolism, compared with other glucocorticoids, patients should be monitored for possible side effects including hypertension, diabetes, and osteoporosis, as well as ophthalmologic disease, including cataracts and glaucoma.

For those who are intolerant to budesonide or have refractory symptoms, concomitant disorders such as CD that may be contributing to symptoms must be excluded. Immunosuppressive medications – such as thiopurines and biologic agents, including tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors or vedolizumab – may be considered in refractory cases.43,44 Of note, there are limited studies evaluating the use of these medications for MC. Lastly, surgeries including ileostomy with or without colectomy have been performed in the most severe cases for resistant disease that has failed numerous pharmacological therapies.45

Patients should be counseled that, while symptoms from MC can be quite bothersome and disabling, there appears to be a normal life expectancy and no association between MC and colon cancer, unlike with other inflammatory conditions of the colon such as IBD.46,47

Conclusion and future outlook

As a common cause of chronic watery diarrhea, MC will be commonly encountered in primary care and gastroenterology practices. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients presenting with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, especially with female gender, autoimmune disease, and increasing age. The management of MC requires an algorithmic approach directed by symptom severity, with a subgroup of patients requiring maintenance therapy for relapsing symptoms. The care of patients with MC will continue to evolve in the future. Further work is needed to explore long-term safety outcomes with budesonide and the role of immunomodulators and newer biologic agents for patients with complex, refractory disease.

Dr. Tome is with the department of internal medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Kamboj, and Dr. Pardi are with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Mayo Clinic. Dr. Pardi has grant funding from Pfizer, Vedanta, Seres, Finch, Applied Molecular Transport, and Takeda and has consulted for Vedanta and Otsuka. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. Nyhlin N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:963-72.

2. Miehlke S et al. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;20-8.

3. Pardi DS et al. Gut. 2007;56:504-8.

4. Fernández-Bañares F et al. J Crohn’s Colitis.2016;10(7):805-11.

5. Gentile NM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):838-42.

6. Tong J et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:265-76.

7. Olesen M et al. Gut. 2004;53(3):346-50.

8. Bergman D et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(11):1395-400.

9. Guagnozzi D et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(5):384-8.

10. Münch A et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(9):932-45.

11. Macaigne G et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014; 09(9):1461-70.

12. Verhaegh BP et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(9):1004-13.

13. Stewart M et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(12):1340-9.

14. Green PHR et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(11):1210-6.

15. Masclee GM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:749-59.

16. Zylberberg H et al. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Jun;53(11)1209-15.

17. Jaruvongvanich V et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(4):672-8.

18. Fernández-Bañares F et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19(7):1470-6.

19. Yen EF et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(10):1835-41.

20. Barmeyer C et al. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(10):1090-100.

21. Morgan DM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(4):984-6.

22. Larsson JK et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:1309-17.

23. Madisch A et al.. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(11):2295-8.

24. Stahl E et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(2):549-61.

25. Sikander A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2015; 60:887-94.

26. Abdo AA et al. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15(5):341-3.

27. Fernandez-Bañares F et al. Dig Dis Sci.2001;46(10):2231-8.

28. Lyutakov I et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;1;33(3):380-7.

29. Hjortswang H et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2011 Feb;43(2):102-9.

30. Cotter TG= et al. Gut. 2018;67(3):441-6.

31. Von Arnim U et al. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:97-103.

32. Langner C et al. Histopathology. 2015;66:613-26.

33. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee and Sharaf RN et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:216-24.

34. Macaigne G et al. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2017;41(3):333-40.

35. Bjørnbak C et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(10):1225-34.

36. Pardi DS et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(1):247-74.

37. Masannat Y and Nazer E. West Virginia Med J. 2013;109(3):32-4.

38. Nguyen GC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150(1):242-6.

39. Sebastian S et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Aug;31(8):919-27.

40. Miehlke S et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):1222-30.

41. Gentile NM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:256-9.

42. Münch A et al. Gut. 2016; 65(1):47-56.

43. Cotter TG et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 46(2):169-74.

44. Esteve M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(6):612-8.

45. Cottreau J et al. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2016;9:140-4.

46. Kamboj AK et al. Program No. P1876. ACG 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American College of Gastroenterology.

47. Yen EF et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:161-9.

Microscopic colitis is an inflammatory disease of the colon and a frequent cause of chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. MC consists of two subtypes, collagenous colitis (CC) and lymphocytic colitis (LC). While the primary symptom is diarrhea, other signs and symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities may also be present depending on disease severity.1 In MC, the colonic mucosa usually appears normal on colonoscopy, and the diagnosis is made by histologic findings of intraepithelial lymphocytosis with (CC) or without (LC) a prominent subepithelial collagen band. The management approaches to CC and LC are similar and should be directed based on the severity of symptoms.2 We review the epidemiology, risk factors, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management for this condition, as well as novel therapeutic approaches.

Epidemiology

Although the incidence of MC increased in the late twentieth century, more recently, it has stabilized with an estimated incidence varying from 1 to 25 per 100,000 person-years.3-5 A recent meta-analysis revealed a pooled incidence of 4.85 per 100,000 persons for LC and 4.14 per 100,000 persons for CC.6 Proposed explanations for the rising incidence in the late twentieth century include improved clinical awareness of the disease, possible increased use of drugs associated with MC, and increased performance of diagnostic colonoscopies for chronic diarrhea. Since MC is now well-recognized, the recent plateau in incidence rates may reflect decreased detection bias.

The prevalence of MC ranges from 10%-20% in patients undergoing colonoscopy for chronic watery diarrhea.6,7 The prevalence of LC is approximately 63.1 cases per 100,000 person-years and, for CC, is 49.2 cases per 100,000 person-years.6-8 Recent studies have demonstrated increasing prevalence of MC likely resulting from an aging population.9,10

Risk stratification

Female gender, increasing age, concomitant autoimmune disease, and the use of certain drugs, including NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), statins, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have been associated with an increased risk of MC.11,12 Autoimmune disorders, including celiac disease (CD), rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism, are more common in patients with MC. The association with CD, in particular, is clinically important, as CD is associated with a 50-70 times greater risk of MC, and 2%-9% of patients with MC have CD.13,14

Several medications have been associated with MC. In a British multicenter prospective study, MC was associated with the use of NSAIDs, PPIs, and SSRIs;15 however, recent studies have questioned the association of MC with some of these medications, which might worsen diarrhea but not actually cause MC.16

An additional risk factor for MC is smoking. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that current and former smokers had an increased risk of MC (odds ratio, 2.99; 95% confidence interval, 2.15-4.15 and OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.37-1.94, respectively), compared with nonsmokers.17 Smokers develop MC at a younger age, and smoking is associated with increased disease severity and decreased likelihood of attaining remission.18,19

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of MC remains largely unknown, although there are several hypotheses. The leading proposed mechanisms include reaction to luminal antigens, dysregulated collagen metabolism, genetic predisposition, autoimmunity, and bile acid malabsorption.

MC may be caused by abnormal epithelial barrier function, leading to increased permeability and reaction to luminal antigens, including dietary antigens, certain drugs, and bacterial products, 20,21 which themselves lead to the immune dysregulation and intestinal inflammation seen in MC. This mechanism may explain the association of several drugs with MC. Histological changes resembling LC are reported in patients with CD who consume gluten; however, large population-based studies have not found specific dietary associations with the development of MC.22

Another potential mechanism of MC is dysregulated collagen deposition. Collagen accumulation in the subepithelial layer in CC may result from increased levels of fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor–beta and vascular endothelial growth factor.23 Nonetheless, studies have not found an association between the severity of diarrhea in patients with CC and the thickness of the subepithelial collagen band.

Thirdly, autoimmunity and genetic predisposition have been postulated in the pathogenesis of MC. As previously discussed, MC is associated with several autoimmune diseases and predominantly occurs in women, a distinctive feature of autoimmune disorders. Several studies have demonstrated an association between MC and HLA-DQ2 and -DQ3 haplotypes,24 as well as potential polymorphisms in the serotonin transporter gene promoter.25 It is important to note, however, that only a few familial cases of MC have been reported to date.26

Lastly, bile acid malabsorption may play a role in the etiology of MC. Histologic findings of inflammation, along with villous atrophy and collagen deposition, have been reported in the ileum of patients with MC;27,28 however, because patients with MC without bile acid malabsorption may also respond to bile acid binders such as cholestyramine, these findings unlikely to be the sole mechanism explaining the development of the disease.

Despite the different proposed mechanisms for the pathogenesis of MC, no definite conclusions can be drawn because of the limited size of these studies and their often conflicting results.

Clinical features

Clinicians should suspect MC in patients with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. Other risk factors include female gender, use of certain culprit medications, smoking, and presence of other autoimmune diseases. The clinical manifestations of MC subtypes LC and CC are similar with no significant clinical differences.1,2 In addition to diarrhea, patients with MC may have abdominal pain, fatigue, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities depending on disease severity. Patients may also present with fecal urgency, incontinence, and nocturnal stools. Quality of life is often reduced in these patients, predominantly in those with severe or refractory symptoms.29,30 The natural course of MC is highly variable, with some patients achieving spontaneous resolution after one episode and others developing chronic symptoms.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of chronic watery diarrhea is broad and includes malabsorption/maldigestion, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome, and medication side effects. In addition, although gastrointestinal infections typically cause acute or subacute diarrhea, some can present with chronic diarrhea. Malabsorption/maldigestion may occur because of CD, lactose intolerance, and pancreatic insufficiency, among other conditions. A thorough history, regarding recent antibiotic and medication use, travel, and immunosuppression, should be obtained in patients with chronic diarrhea. Additionally, laboratory and endoscopic evaluation with random biopsies of the colon can further help differentiate these diseases from MC. A few studies suggest fecal calprotectin may be used to differentiate MC from other noninflammatory conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, as well as to monitor disease activity. This test is not expected to distinguish MC from other inflammatory causes of diarrhea, such as IBD, and therefore, its role in clinical practice is uncertain.31

The diagnosis of MC is made by biopsy of the colonic mucosa demonstrating characteristic pathologic features.32 Unlike in diseases such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, the colon usually appears normal in MC, although mild nonspecific changes, such as erythema or edema, may be visualized. There is no consensus on the ideal location to obtain biopsies for MC or whether biopsies from both the left and the right colon are required.2,33 The procedure of choice for the diagnosis of MC is colonoscopy with random biopsies taken throughout the colon. More limited evaluation by flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsies may miss cases of MC as inflammation and collagen thickening are not necessarily uniform throughout the colon; however, in a patient that has undergone a recent colonoscopy for colon cancer screening without colon biopsies, a flexible sigmoidoscopy may be a reasonable next test for evaluation of MC, provided biopsies are obtained above the rectosigmoid colon.34

The MC subtypes are differentiated based on histology. The hallmark of LC is less than 20 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 surface epithelial cells (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1A). CC is characterized by a thickened subepithelial collagen band greater than 7-10 micrometers (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1B). For a subgroup of patients with milder abnormalities that do not meet these histological criteria, the terms “microscopic colitis, not otherwise specified” or “microscopic colitis, incomplete” may be used.35 These patients often respond to standard treatments for MC. There is an additional subset of patients with biopsy demonstrating features of both CC and LC simultaneously, as well as patients transitioning from one MC subtype to another over time.32,35

Management approach

The first step in management of patients with MC includes stopping culprit medications if there is a temporal relationship between the initiation of the medication and the onset of diarrhea, as well as encouraging smoking cessation. These steps alone, however, are unlikely to achieve clinical remission in most patients. A stepwise pharmacological approach is used in the management of MC based on disease severity (Figure 2). For patients with mild symptoms, antidiarrheal medications, such as loperamide, may be helpful.36 Long-term use of loperamide at therapeutic doses no greater than 16 mg daily appears to be safe if required to maintain symptom response. For those with persistent symptoms despite antidiarrheal medications, bismuth subsalicylate at three 262 mg tablets three times daily for 6-8 weeks can be considered. Long-term use of bismuth subsalicylate is not advised, especially at this dose, because of possible neurotoxicity.37

For patients refractory to the above treatments or those with moderate-to-severe symptoms, an 8-week course of budesonide at 9 mg daily is the first-line treatment.38 The dose was tapered before discontinuation in some studies but not in others. Both strategies appear effective. A recent meta-analysis of nine randomized trials demonstrated pooled ORs of 7.34 (95% CI, 4.08-13.19) and 8.35 (95% CI, 4.14-16.85) for response to budesonide induction and maintenance, respectively.39

Cholestyramine is another medication considered in the management of MC and warrants further investigation. To date, no randomized clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate bile acid sequestrants in MC, but they should be considered before placing patients on immunosuppressive medications. Some providers use mesalamine in this setting, although mesalamine is inferior to budesonide in the induction of clinical remission in MC.40