User login

Study finds most adverse events from microneedling are minimal

according to the results of a systematic review of nearly 3,000 patients.

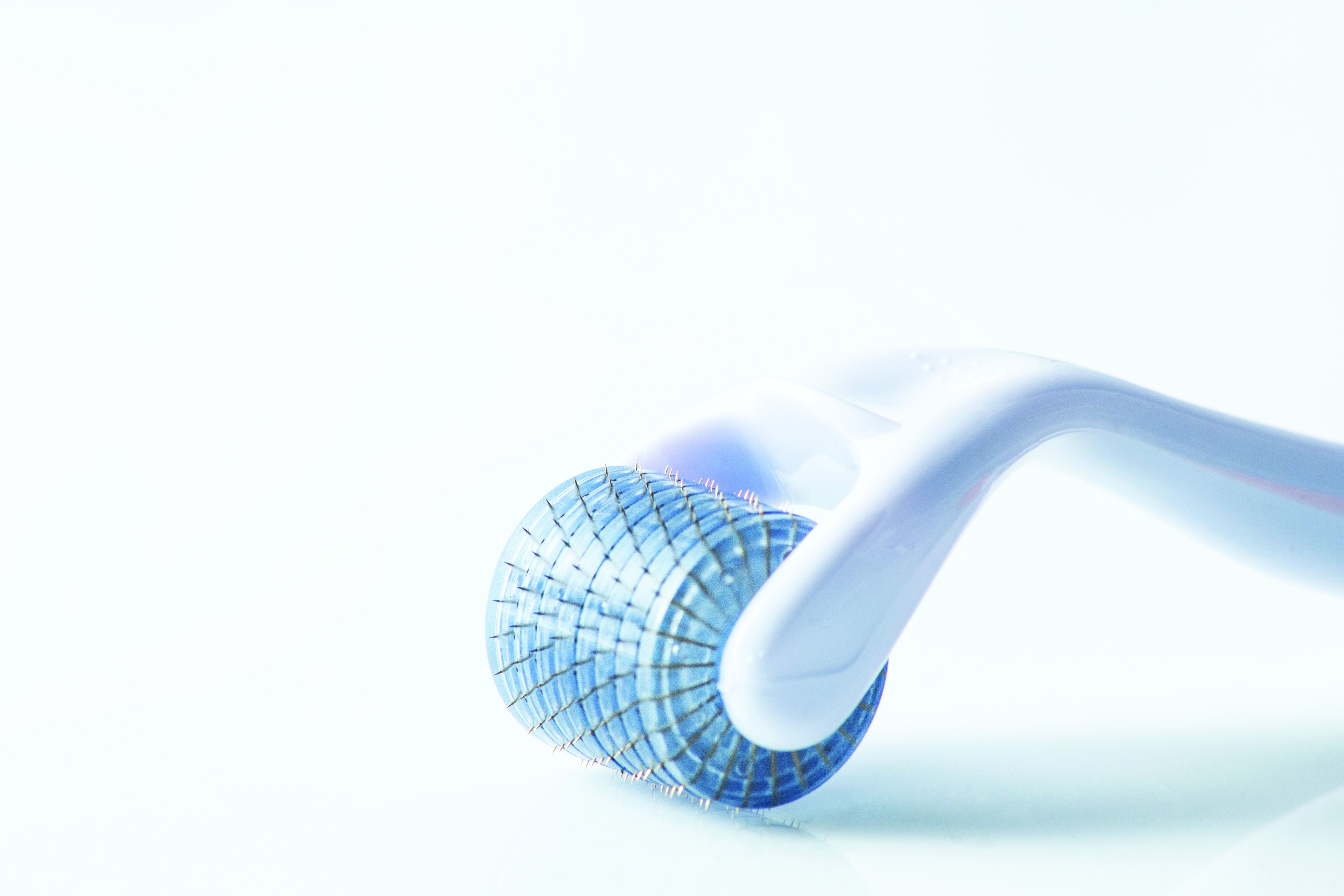

Microneedling involves the use of instruments including dermarollers and microneedling pens to cause controlled microtraumas at various skin depths and induce a wounding cascade that ultimately improves the visual appearance of the skin, Sherman Chu, DO, of the department of dermatology at the University of California, Irvine, and colleagues wrote.

Microneedling has increased in popularity because of its relatively low cost, effectiveness, and ease of use, and is often promoted as “a safe alternative treatment, particularly in skin of color, but the safety of microneedling and its complications are not often discussed,” the researchers noted.

In the study, published in Dermatologic Surgery, Dr. Chu and coauthors identified 85 articles for the systematic review of safety data on microneedling. The studies included 30 randomized, controlled trials; 24 prospective studies; 16 case series; 12 case reports; and 3 retrospective cohort studies, with a total of 2,805 patients treated with microneedling.

The devices used in the studies were primarily dermarollers (1,758 procedures), but 425 procedures involved dermapens, and 176 involved unidentified microneedling devices.

The most common adverse effect after microneedling with any device was any of anticipated transient procedural side effects including transient erythema or edema, pain, burning, bruising, pruritus, stinging, bleeding, crusting, and desquamation. Overall, these effects resolved within a week with little or no treatment, the researchers said.

The most commonly reported postprocedure side effects of microneedling were postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (46 incidents), followed by dry skin and exfoliation (41 incidents). Fewer than 15 incidents were reported of each the following: acne flare, pruritus, persistent erythema, herpetic infection, flushing, seborrheic dermatitis, burning, headache, stinging, milia, tram-track scarring, facial allergic granulomatous reaction and systematic hypersensitivity, and tender cervical lymphadenopathy. In addition, one incident each was reported of periorbital dermatitis, phototoxic reaction, pressure urticaria, irritant contact dermatitis, widespread facial inoculation of varicella, pustular folliculitis, and tinea corporis.

The studies suggest that microneedling is generally well tolerated, the researchers wrote. Factors that increased the risk of adverse events included the presence of active infections, darker skin types, metal allergies, and the use of combination therapies. For example, they noted, one randomized, controlled trial showed greater skin irritation in patients treated with both microneedling and tranexamic acid compared with those treated with tranexamic acid alone.

Other studies described increased risk of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients treated with both microneedling and platelet-rich plasma, and with microneedling and topical 5-FU or tacrolimus. Also, in one of the studies in the review, “the development of a delayed granulomatous hypersensitivity reaction in 2 patients was attributed to a reaction to vitamin C serum, whereas another study attributes vitamin A and vitamin C oil to be the cause of a patient’s prolonged erythema and pruritus,” the researchers said.

The study findings were limited to adverse events reported by clinicians in published literature, and did not account for adverse events that occur when microneedling is performed at home or in medical spas. Although the results suggest that microneedling is relatively safe for patients of most skin types, “great caution should be taken when performing microneedling with products not approved to be used intradermally,” they emphasized.

“Further studies are needed to determine which patients are at a higher chance of developing scarring because depth of the needle and skin type do not directly correlate as initially believed,” they concluded.

Microneedling offers safe alternative to lasers

“Microneedling is a popular procedure that can be used as an alternative to laser treatments to provide low down time, and lower-cost treatments for similar indications in which lasers are used, such as rhytides and scars,” Catherine M. DiGiorgio, MD, a laser and cosmetic dermatologist at the Boston Center for Facial Rejuvenation, said in an interview.

“Many clinicians and/or providers utilize microneedling in their practice also because they may not have the ability to perform laser and energy-based device treatments,” noted Dr. DiGiorgio, who was asked to comment on the study findings. “Microneedling is safer than energy-based devices in darker skin types due to the lack of energy or heat being delivered to the epidermis. However, as shown in this study, darker skin types remain at risk for [postinflammatory hyperpigmentation], particularly in the hands of an unskilled, inexperienced operator.”

Dr. DiGiorgio said she was not surprised by the study findings. “Microneedling creates microwounds in the skin, which contributes to the risk of all of the side effects listed in the study. Further, the proper use of microneedling devices by the providers performing the procedure is variable and depths of penetration can vary based on which device or roller pen is used and the experience of the person performing the procedures. Depth, after a certain point, can be inaccurate and can superficially abrade the epidermis rather than the intended individual microneedle punctures.”

Laser and energy-based device treatments can be performed safely in patients with darker skin types in the hands of skilled and experienced laser surgeons, said Dr. DiGiorgio. However, “more studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of microneedling alone compared to other treatment modalities. Patients tend to select microneedling due to affordability and less down time; however, sometimes it may not be the best treatment option for their skin condition.

“Patient education is an important factor because one treatment that worked for one of their friends, for example, may not be the best treatment option for their skin complaints.”

Dr. DiGiorgio added that there are few randomized, controlled trials comparing microneedling to laser treatment. “More studies of this nature would benefit the scientific literature and the addition of histological analysis would help us better understand how these treatments compare on a microscopic level.”

The study received no outside funding and the author has no disclosures. Dr. DiGiorgio has served as a consultant for Allergan Aesthetics.

according to the results of a systematic review of nearly 3,000 patients.

Microneedling involves the use of instruments including dermarollers and microneedling pens to cause controlled microtraumas at various skin depths and induce a wounding cascade that ultimately improves the visual appearance of the skin, Sherman Chu, DO, of the department of dermatology at the University of California, Irvine, and colleagues wrote.

Microneedling has increased in popularity because of its relatively low cost, effectiveness, and ease of use, and is often promoted as “a safe alternative treatment, particularly in skin of color, but the safety of microneedling and its complications are not often discussed,” the researchers noted.

In the study, published in Dermatologic Surgery, Dr. Chu and coauthors identified 85 articles for the systematic review of safety data on microneedling. The studies included 30 randomized, controlled trials; 24 prospective studies; 16 case series; 12 case reports; and 3 retrospective cohort studies, with a total of 2,805 patients treated with microneedling.

The devices used in the studies were primarily dermarollers (1,758 procedures), but 425 procedures involved dermapens, and 176 involved unidentified microneedling devices.

The most common adverse effect after microneedling with any device was any of anticipated transient procedural side effects including transient erythema or edema, pain, burning, bruising, pruritus, stinging, bleeding, crusting, and desquamation. Overall, these effects resolved within a week with little or no treatment, the researchers said.

The most commonly reported postprocedure side effects of microneedling were postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (46 incidents), followed by dry skin and exfoliation (41 incidents). Fewer than 15 incidents were reported of each the following: acne flare, pruritus, persistent erythema, herpetic infection, flushing, seborrheic dermatitis, burning, headache, stinging, milia, tram-track scarring, facial allergic granulomatous reaction and systematic hypersensitivity, and tender cervical lymphadenopathy. In addition, one incident each was reported of periorbital dermatitis, phototoxic reaction, pressure urticaria, irritant contact dermatitis, widespread facial inoculation of varicella, pustular folliculitis, and tinea corporis.

The studies suggest that microneedling is generally well tolerated, the researchers wrote. Factors that increased the risk of adverse events included the presence of active infections, darker skin types, metal allergies, and the use of combination therapies. For example, they noted, one randomized, controlled trial showed greater skin irritation in patients treated with both microneedling and tranexamic acid compared with those treated with tranexamic acid alone.

Other studies described increased risk of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients treated with both microneedling and platelet-rich plasma, and with microneedling and topical 5-FU or tacrolimus. Also, in one of the studies in the review, “the development of a delayed granulomatous hypersensitivity reaction in 2 patients was attributed to a reaction to vitamin C serum, whereas another study attributes vitamin A and vitamin C oil to be the cause of a patient’s prolonged erythema and pruritus,” the researchers said.

The study findings were limited to adverse events reported by clinicians in published literature, and did not account for adverse events that occur when microneedling is performed at home or in medical spas. Although the results suggest that microneedling is relatively safe for patients of most skin types, “great caution should be taken when performing microneedling with products not approved to be used intradermally,” they emphasized.

“Further studies are needed to determine which patients are at a higher chance of developing scarring because depth of the needle and skin type do not directly correlate as initially believed,” they concluded.

Microneedling offers safe alternative to lasers

“Microneedling is a popular procedure that can be used as an alternative to laser treatments to provide low down time, and lower-cost treatments for similar indications in which lasers are used, such as rhytides and scars,” Catherine M. DiGiorgio, MD, a laser and cosmetic dermatologist at the Boston Center for Facial Rejuvenation, said in an interview.

“Many clinicians and/or providers utilize microneedling in their practice also because they may not have the ability to perform laser and energy-based device treatments,” noted Dr. DiGiorgio, who was asked to comment on the study findings. “Microneedling is safer than energy-based devices in darker skin types due to the lack of energy or heat being delivered to the epidermis. However, as shown in this study, darker skin types remain at risk for [postinflammatory hyperpigmentation], particularly in the hands of an unskilled, inexperienced operator.”

Dr. DiGiorgio said she was not surprised by the study findings. “Microneedling creates microwounds in the skin, which contributes to the risk of all of the side effects listed in the study. Further, the proper use of microneedling devices by the providers performing the procedure is variable and depths of penetration can vary based on which device or roller pen is used and the experience of the person performing the procedures. Depth, after a certain point, can be inaccurate and can superficially abrade the epidermis rather than the intended individual microneedle punctures.”

Laser and energy-based device treatments can be performed safely in patients with darker skin types in the hands of skilled and experienced laser surgeons, said Dr. DiGiorgio. However, “more studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of microneedling alone compared to other treatment modalities. Patients tend to select microneedling due to affordability and less down time; however, sometimes it may not be the best treatment option for their skin condition.

“Patient education is an important factor because one treatment that worked for one of their friends, for example, may not be the best treatment option for their skin complaints.”

Dr. DiGiorgio added that there are few randomized, controlled trials comparing microneedling to laser treatment. “More studies of this nature would benefit the scientific literature and the addition of histological analysis would help us better understand how these treatments compare on a microscopic level.”

The study received no outside funding and the author has no disclosures. Dr. DiGiorgio has served as a consultant for Allergan Aesthetics.

according to the results of a systematic review of nearly 3,000 patients.

Microneedling involves the use of instruments including dermarollers and microneedling pens to cause controlled microtraumas at various skin depths and induce a wounding cascade that ultimately improves the visual appearance of the skin, Sherman Chu, DO, of the department of dermatology at the University of California, Irvine, and colleagues wrote.

Microneedling has increased in popularity because of its relatively low cost, effectiveness, and ease of use, and is often promoted as “a safe alternative treatment, particularly in skin of color, but the safety of microneedling and its complications are not often discussed,” the researchers noted.

In the study, published in Dermatologic Surgery, Dr. Chu and coauthors identified 85 articles for the systematic review of safety data on microneedling. The studies included 30 randomized, controlled trials; 24 prospective studies; 16 case series; 12 case reports; and 3 retrospective cohort studies, with a total of 2,805 patients treated with microneedling.

The devices used in the studies were primarily dermarollers (1,758 procedures), but 425 procedures involved dermapens, and 176 involved unidentified microneedling devices.

The most common adverse effect after microneedling with any device was any of anticipated transient procedural side effects including transient erythema or edema, pain, burning, bruising, pruritus, stinging, bleeding, crusting, and desquamation. Overall, these effects resolved within a week with little or no treatment, the researchers said.

The most commonly reported postprocedure side effects of microneedling were postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (46 incidents), followed by dry skin and exfoliation (41 incidents). Fewer than 15 incidents were reported of each the following: acne flare, pruritus, persistent erythema, herpetic infection, flushing, seborrheic dermatitis, burning, headache, stinging, milia, tram-track scarring, facial allergic granulomatous reaction and systematic hypersensitivity, and tender cervical lymphadenopathy. In addition, one incident each was reported of periorbital dermatitis, phototoxic reaction, pressure urticaria, irritant contact dermatitis, widespread facial inoculation of varicella, pustular folliculitis, and tinea corporis.

The studies suggest that microneedling is generally well tolerated, the researchers wrote. Factors that increased the risk of adverse events included the presence of active infections, darker skin types, metal allergies, and the use of combination therapies. For example, they noted, one randomized, controlled trial showed greater skin irritation in patients treated with both microneedling and tranexamic acid compared with those treated with tranexamic acid alone.

Other studies described increased risk of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients treated with both microneedling and platelet-rich plasma, and with microneedling and topical 5-FU or tacrolimus. Also, in one of the studies in the review, “the development of a delayed granulomatous hypersensitivity reaction in 2 patients was attributed to a reaction to vitamin C serum, whereas another study attributes vitamin A and vitamin C oil to be the cause of a patient’s prolonged erythema and pruritus,” the researchers said.

The study findings were limited to adverse events reported by clinicians in published literature, and did not account for adverse events that occur when microneedling is performed at home or in medical spas. Although the results suggest that microneedling is relatively safe for patients of most skin types, “great caution should be taken when performing microneedling with products not approved to be used intradermally,” they emphasized.

“Further studies are needed to determine which patients are at a higher chance of developing scarring because depth of the needle and skin type do not directly correlate as initially believed,” they concluded.

Microneedling offers safe alternative to lasers

“Microneedling is a popular procedure that can be used as an alternative to laser treatments to provide low down time, and lower-cost treatments for similar indications in which lasers are used, such as rhytides and scars,” Catherine M. DiGiorgio, MD, a laser and cosmetic dermatologist at the Boston Center for Facial Rejuvenation, said in an interview.

“Many clinicians and/or providers utilize microneedling in their practice also because they may not have the ability to perform laser and energy-based device treatments,” noted Dr. DiGiorgio, who was asked to comment on the study findings. “Microneedling is safer than energy-based devices in darker skin types due to the lack of energy or heat being delivered to the epidermis. However, as shown in this study, darker skin types remain at risk for [postinflammatory hyperpigmentation], particularly in the hands of an unskilled, inexperienced operator.”

Dr. DiGiorgio said she was not surprised by the study findings. “Microneedling creates microwounds in the skin, which contributes to the risk of all of the side effects listed in the study. Further, the proper use of microneedling devices by the providers performing the procedure is variable and depths of penetration can vary based on which device or roller pen is used and the experience of the person performing the procedures. Depth, after a certain point, can be inaccurate and can superficially abrade the epidermis rather than the intended individual microneedle punctures.”

Laser and energy-based device treatments can be performed safely in patients with darker skin types in the hands of skilled and experienced laser surgeons, said Dr. DiGiorgio. However, “more studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of microneedling alone compared to other treatment modalities. Patients tend to select microneedling due to affordability and less down time; however, sometimes it may not be the best treatment option for their skin condition.

“Patient education is an important factor because one treatment that worked for one of their friends, for example, may not be the best treatment option for their skin complaints.”

Dr. DiGiorgio added that there are few randomized, controlled trials comparing microneedling to laser treatment. “More studies of this nature would benefit the scientific literature and the addition of histological analysis would help us better understand how these treatments compare on a microscopic level.”

The study received no outside funding and the author has no disclosures. Dr. DiGiorgio has served as a consultant for Allergan Aesthetics.

FROM DERMATOLOGIC SURGERY

Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: Early Treatment Leading to an Excellent Outcome

HLH is a rare and deadly disease increasingly more present in adults, but following treatment protocol may yield favorable results.

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare and deadly disease in which unregulated proliferation of histiocytes and T-cell infiltration takes place. It is known as a pediatric disease in which gene defects result in impaired cytotoxic NK- and T-cell function. It has been associated with autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Without therapy, survival for these patients with active familial HLH is approximately 2 months.

Recognition of the disease has increased over the years, and as a result the diagnosis of HLH in adults also has increased. An acquired form can be triggered by viruses like Epstein-Barr virus, influenza, HIV, lymphoid malignancies, rheumatologic disorders, or immunodeficiency disorders. Survival rates for untreated HLH have been reported at < 5%.1 Despite early recognition and adequate treatment, HLH carries an overall mortality of 50% in the initial presentation, 90% die in the first 8 weeks of treatment due to uncontrolled disease.2

Case Presentation

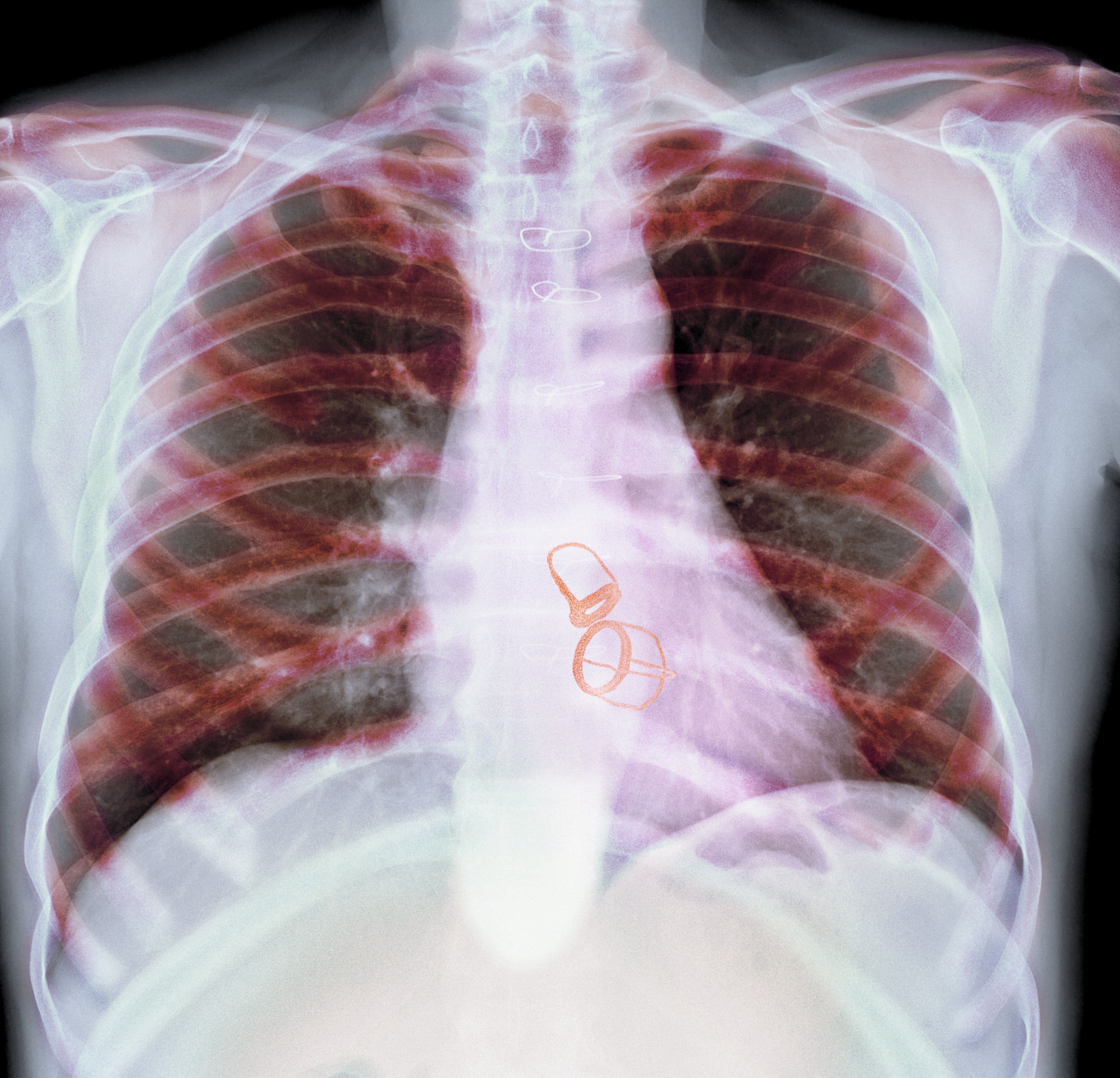

A 56-year-old man with no active medical issues except for a remote history of non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and splenectomy in 1990 presented to the Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan, Puerto Rico. He was admitted to the medicine ward due to community acquired pneumonia. Three days into admission his clinical status deteriorated, and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) due to acute respiratory failure and sepsis secondary to worsening pneumonia. Chest imaging demonstrated rapidly progressing diffuse bilateral infiltrates. Due to the severity of the chest imaging, a diagnostic bronchoscopy was performed.

The patient’s antibiotics regimen was empirically escalated to vancomycin 1500 mg IV every 12 hours and meropenem 2 g IV every 8 hours. Despite optimization of therapy, the patient did not show clinical signs of improvement. Febrile episodes persisted, pulmonary infiltrates and hypoxemia worsened, and the patient required a neuromuscular blockade. Since the bronchoscopy was nondiagnostic and deterioration persistent, the differential diagnosis was broadened. This led to the ordering of inflammatory markers. Laboratory testing showed ferritin levels > 16,000 ng/mL, pointing to HLH as a possible diagnosis. Further workup was remarkable for triglycerides of 1234 mg/dL and a fibrinogen of 0.77 g/L. In the setting of bicytopenia and persistent fever, HLH-94 regimen was started with dexamethasone 40 mg daily and etoposide 100 mg/m2. CD25 levels of 154,701 pg/mL were demonstrated as well as a decreased immunoglobulin (Ig) G levels with absent IgM and IgA. Bone marrow biopsy was consistent with hemophagocytosis. The patient eventually was extubated and sent to the oncology ward to continue chemotherapy.

Discussion

A high clinical suspicion is warranted for rapid diagnosis and treatment as HLH evolves in most cases to multiorgan failure and death. The diagnostic criteria for HLH was developed by the Histiocyte Society in 1991 and then restructured in 2004.3,4 In the first diagnostic tool developed in 1991, diagnosis was based on 5 criteria (fever, splenomegaly, bicytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia and/or hypofibrinogenemia, and hemophagocytosis). Three additional laboratory findings were also described as part of HLH diagnosis since 2004: low or absent NK-cell-activity, hyperferritinemia of > 500 ng/dL, and high-soluble interleukin-2-receptor levels (CD25) > 2400 U/mL. Overall, 5 of 8 criteria are needed for the HLH diagnosis.

Despite the common use of these diagnostic criteria, they were developed for the pediatric population but have not been validated for adult patients.5 For adult patients, the HScore was developed in 2014. It has 9 variables: 3 are based on clinical findings (known underlying immunosuppression, high temperature, and organomegaly; 5 are based on laboratory values (ferritin, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, cytopenia, triglycerides, and fibrinogen levels); the last variable uses cytologic findings in the bone marrow. In the initial study, probability of having HLH ranged from < 1% with an HScore of ≤ 90% to > 99% with an HScore of ≥ 250 in noncritically ill adults.5 A recently published retrospective study demonstrated the diagnostic reliability of both the HLH-2004 criteria and HScore in critically ill adult patients. This study concluded that the best prediction accuracy of HLH diagnosis for a cutoff of 4 fulfilled HLH-2004 criteria had a 95.0% sensitivity and 93.6% specificity and HScore cutoff of 168 reached a 100% sensitivity and 94.1% specificity.6

The early negative bronchoscopy lowered the possibility of an infection as the etiology of the clinical presentation and narrowed the hyperferritinemia differential diagnosis. Hyperferritinemia has a sensitivity and specificity of > 90% for diagnosis when above 10,000 ng/dL in the pediatric population.7 This is not the case in adults. Hyperferritinemia is a marker of different inflammatory responses, such as histoplasmosis infection, malignancy, or iron overload rather than an isolated diagnostic tool for HLH.8 It has been reported that CD25 levels less than the diagnostic threshold of 2400 U/mL have a 100% sensitivity for the diagnosis and therefore can rule out the diagnosis. When this is taken into consideration, it can be concluded that CD25 level is a better diagnostic tool when compared with ferritin, but its main limitation is its lack of widespread availability.9 Still, there is a limited number of pathologies that are associated with marked hyperferritinemia, specifically using thresholds of more than 6000 ng/dL.10 Taking into consideration the high mortality of untreated HLH, isolated hyperferritinemia still warrants HLH workup to aggressively pursue the diagnosis and improve outcomes.

The goal of therapy in HLH is prompt inactivation of the dysregulated inflammation with aggressive immunosuppression. In our deteriorating patient, the treatment was started with only 4 of the 8 HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria being met. As per the 2018 Histiocyte Society consensus statement, the decision to start the HLH-94 treatment relies on not only the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria, but also the patient’s clinical evolution.11 In 1994 the Histiocyte Society also published a treatment protocol termed HLH-94. A Korean retrospective study demonstrated that this protocol led to a 5-year survival rate of 60 to 80% depending on the HLH trigger and response to initial treatment.12 The protocol consists of etoposide at 150 mg/m2, 2 weekly doses in the first 2 weeks and then 1 dose weekly for the next 6 weeks. Dexamethasone is the steroid of choice as it readily crosses the blood-brain barrier. Its dosage consists of 10 mg/m2 for the first 2 weeks and then it is halved every 2 weeks until the eighth week of treatment. A slow taper follows to avoid adrenal insufficiency. Once 8 weeks of treatment have been completed, cyclosporine is added to a goal trough of 200 mcg/dL. If there is central nervous system (CNS) involvement, early aggressive treatment with intrathecal methotrexate is indicated if no improvement is noted during initial therapy.11

In 2004 the Histiocyte Society restructured the HLH-94 treatment protocol with the aim of presenting a more aggressive treatment strategy. The protocol added cyclosporine to the initial induction therapy, rather than later in the ninth week as HLH-94. Neither the use of cyclosporine nor the HLH-2004 have been demonstrated to be superior to the use of etoposide and dexamethasone alone or in the HLH-94 protocol, respectively.13 Cyclosporine is associated with adverse effects (AEs) and may have many contraindications in the acute phase of the disease. Therefore, the HLH-94 protocol is still the recommended regimen.11

To assess adequate clinical response, several clinical and laboratory parameters are followed. Clinically, resolution of fever, improvement in hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and mental status can be useful. Laboratories can be used to assess improvement from organ specific damage such as hepatic involvement or cytopenia. The limitation of these diagnostic studies is that they could falsely suggest an inadequate response to treatment due to concomitant infection or medication AEs. Other markers such as ferritin levels, CD25, and NK cell activity levels are more specific to HLH. Out of them, a decreasing ferritin level has the needed specificity and widespread availability for repeated assessment. On the other hand, both CD25 and NK cell activity are readily available only in specialized centers. An initial high ferritin level is a marker for a poor prognosis, and the rate of decline correlates with mortality. Studies have demonstrated that persistently elevated ferritin levels after treatment initiation are associated with worse outcomes.14,15

Several salvage treatments have been identified in recalcitrant or relapsing disease. In general, chemotherapy needs to be intensified, either by returning to the initial high dosage if recurrence occurs in the weaning phase of treatment or adding other agents if no response was initially achieved. Emapalumab, an interferon γ antibody, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of intractable HLH after it demonstrated that when added to dexamethasone, it lead to treatment response in 17 out of 27 pediatric patients, with a relatively safe AE profile.16 The goal of intensifying chemotherapy is to have the patient tolerate allogenic stem cell transplant, which is clinically indicated in familial HLH, malignancy induced HLH, and recalcitrant cases. In patients who undergo hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) there is a tendency to increase survival to 66% at 5 years.12

Conclusions

HLH is a rare and deadly disease increasingly more present in adults. Our patient who initially presented with a sepsis diagnosis was suspected of having a hematologic etiology for his clinical findings due to markedly elevated ferritin levels. In our patient, the HLH-94 treatment protocol was used, yielding favorable results. Given the lack of specific scientific data backing updated protocols such as HLH-2004 and a comparatively favorable safety profile, current guidelines still recommend using the HLH-94 treatment protocol. Decreasing ferritin levels may be used in conjunction with clinical improvement to demonstrate therapeutic response. Persistence of disease despite standard treatment may warrant novel therapies, such as emapalumab or HCT. Physicians need to be wary of an HLH diagnosis as early identification and treatment may improve its otherwise grim prognosis.

1. Chen TY, Hsu MH, Kuo HC, Sheen JM, Cheng MC, Lin YJ. Outcome analysis of pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2021;120(1, pt 1):172-179. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2020.03.025

2. Henter JI, Samuelsson-Horne A, Aricò M, et al. Treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with HLH-94 immunochemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2002;100(7):2367-2373. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-01-0172

3. Henter JI, Elinder G, Ost A. Diagnostic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The FHL Study Group of the Histiocyte Society. Semin Oncol. 1991;18(1):29-33.

4. Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124-131. doi:10.1002/pbc.21039

5. Knaak C, Nyvlt P, Schuster FS, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in critically ill patients: diagnostic reliability of HLH-2004 criteria and HScore. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):244. Published 2020 May 24. doi:10.1186/s13054-020-02941-3

6. Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(9):2613-2620. doi:10.1002/art.38690

7. La Rosée P, Horne A, Hines M, et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2019;133(23):2465-2477. doi:10.1182/blood.2018894618

8. Schaffner M, Rosenstein L, Ballas Z, Suneja M. Significance of Hyperferritinemia in Hospitalized Adults. Am J Med Sci. 2017;354(2):152-158. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2017.04.016

9. Hayden A, Lin M, Park S, et al. Soluble interleukin-2 receptor is a sensitive diagnostic test in adult HLH. Blood Adv. 2017;1(26):2529-2534. Published 2017 Dec 6. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2017012310

10. Belfeki N, Strazzulla A, Picque M, Diamantis S. Extreme hyperferritinemia: etiological spectrum and impact on prognosis. Reumatismo. 2020;71(4):199-202. Published 2020 Jan 28. doi:10.4081/reumatismo.2019.1221

11. Ehl S, Astigarraga I, von Bahr Greenwood T, et al. Recommendations for the use of etoposide-based therapy and bone marrow transplantation for the treatment of HLH: consensus statements by the HLH Steering Committee of the Histiocyte Society. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(5):1508-1517. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.05.031

12. Yoon JH, Park SS, Jeon YW, et al. Treatment outcomes and prognostic factors in adult patients with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis not associated with malignancy. Haematologica. 2019;104(2):269-276. doi:10.3324/haematol.2018.198655

13. Bergsten E, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. Confirmed efficacy of etoposide and dexamethasone in HLH treatment: long-term results of the cooperative HLH-2004 study. Blood. 2017;130(25):2728-2738. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-06-788349

14. Lin TF, Ferlic-Stark LL, Allen CE, Kozinetz CA, McClain KL. Rate of decline of ferritin in patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis as a prognostic variable for mortality. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(1):154-155. doi:10.1002/pbc.22774

15. Zhou J, Zhou J, Shen DT, Goyal H, Wu ZQ, Xu HG. Development and validation of the prognostic value of ferritin in adult patients with Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):71. Published 2020 Mar 12. doi:10.1186/s13023-020-1336-616. Locatelli F, Jordan MB, Allen CE, et al. Safety and efficacy of emapalumab in pediatric patients with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Presented at: American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting, November 29, 2018. Blood. 2018;132(suppl 1):LBA-6. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-120810

HLH is a rare and deadly disease increasingly more present in adults, but following treatment protocol may yield favorable results.

HLH is a rare and deadly disease increasingly more present in adults, but following treatment protocol may yield favorable results.

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare and deadly disease in which unregulated proliferation of histiocytes and T-cell infiltration takes place. It is known as a pediatric disease in which gene defects result in impaired cytotoxic NK- and T-cell function. It has been associated with autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Without therapy, survival for these patients with active familial HLH is approximately 2 months.

Recognition of the disease has increased over the years, and as a result the diagnosis of HLH in adults also has increased. An acquired form can be triggered by viruses like Epstein-Barr virus, influenza, HIV, lymphoid malignancies, rheumatologic disorders, or immunodeficiency disorders. Survival rates for untreated HLH have been reported at < 5%.1 Despite early recognition and adequate treatment, HLH carries an overall mortality of 50% in the initial presentation, 90% die in the first 8 weeks of treatment due to uncontrolled disease.2

Case Presentation

A 56-year-old man with no active medical issues except for a remote history of non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and splenectomy in 1990 presented to the Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan, Puerto Rico. He was admitted to the medicine ward due to community acquired pneumonia. Three days into admission his clinical status deteriorated, and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) due to acute respiratory failure and sepsis secondary to worsening pneumonia. Chest imaging demonstrated rapidly progressing diffuse bilateral infiltrates. Due to the severity of the chest imaging, a diagnostic bronchoscopy was performed.

The patient’s antibiotics regimen was empirically escalated to vancomycin 1500 mg IV every 12 hours and meropenem 2 g IV every 8 hours. Despite optimization of therapy, the patient did not show clinical signs of improvement. Febrile episodes persisted, pulmonary infiltrates and hypoxemia worsened, and the patient required a neuromuscular blockade. Since the bronchoscopy was nondiagnostic and deterioration persistent, the differential diagnosis was broadened. This led to the ordering of inflammatory markers. Laboratory testing showed ferritin levels > 16,000 ng/mL, pointing to HLH as a possible diagnosis. Further workup was remarkable for triglycerides of 1234 mg/dL and a fibrinogen of 0.77 g/L. In the setting of bicytopenia and persistent fever, HLH-94 regimen was started with dexamethasone 40 mg daily and etoposide 100 mg/m2. CD25 levels of 154,701 pg/mL were demonstrated as well as a decreased immunoglobulin (Ig) G levels with absent IgM and IgA. Bone marrow biopsy was consistent with hemophagocytosis. The patient eventually was extubated and sent to the oncology ward to continue chemotherapy.

Discussion

A high clinical suspicion is warranted for rapid diagnosis and treatment as HLH evolves in most cases to multiorgan failure and death. The diagnostic criteria for HLH was developed by the Histiocyte Society in 1991 and then restructured in 2004.3,4 In the first diagnostic tool developed in 1991, diagnosis was based on 5 criteria (fever, splenomegaly, bicytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia and/or hypofibrinogenemia, and hemophagocytosis). Three additional laboratory findings were also described as part of HLH diagnosis since 2004: low or absent NK-cell-activity, hyperferritinemia of > 500 ng/dL, and high-soluble interleukin-2-receptor levels (CD25) > 2400 U/mL. Overall, 5 of 8 criteria are needed for the HLH diagnosis.

Despite the common use of these diagnostic criteria, they were developed for the pediatric population but have not been validated for adult patients.5 For adult patients, the HScore was developed in 2014. It has 9 variables: 3 are based on clinical findings (known underlying immunosuppression, high temperature, and organomegaly; 5 are based on laboratory values (ferritin, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, cytopenia, triglycerides, and fibrinogen levels); the last variable uses cytologic findings in the bone marrow. In the initial study, probability of having HLH ranged from < 1% with an HScore of ≤ 90% to > 99% with an HScore of ≥ 250 in noncritically ill adults.5 A recently published retrospective study demonstrated the diagnostic reliability of both the HLH-2004 criteria and HScore in critically ill adult patients. This study concluded that the best prediction accuracy of HLH diagnosis for a cutoff of 4 fulfilled HLH-2004 criteria had a 95.0% sensitivity and 93.6% specificity and HScore cutoff of 168 reached a 100% sensitivity and 94.1% specificity.6

The early negative bronchoscopy lowered the possibility of an infection as the etiology of the clinical presentation and narrowed the hyperferritinemia differential diagnosis. Hyperferritinemia has a sensitivity and specificity of > 90% for diagnosis when above 10,000 ng/dL in the pediatric population.7 This is not the case in adults. Hyperferritinemia is a marker of different inflammatory responses, such as histoplasmosis infection, malignancy, or iron overload rather than an isolated diagnostic tool for HLH.8 It has been reported that CD25 levels less than the diagnostic threshold of 2400 U/mL have a 100% sensitivity for the diagnosis and therefore can rule out the diagnosis. When this is taken into consideration, it can be concluded that CD25 level is a better diagnostic tool when compared with ferritin, but its main limitation is its lack of widespread availability.9 Still, there is a limited number of pathologies that are associated with marked hyperferritinemia, specifically using thresholds of more than 6000 ng/dL.10 Taking into consideration the high mortality of untreated HLH, isolated hyperferritinemia still warrants HLH workup to aggressively pursue the diagnosis and improve outcomes.

The goal of therapy in HLH is prompt inactivation of the dysregulated inflammation with aggressive immunosuppression. In our deteriorating patient, the treatment was started with only 4 of the 8 HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria being met. As per the 2018 Histiocyte Society consensus statement, the decision to start the HLH-94 treatment relies on not only the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria, but also the patient’s clinical evolution.11 In 1994 the Histiocyte Society also published a treatment protocol termed HLH-94. A Korean retrospective study demonstrated that this protocol led to a 5-year survival rate of 60 to 80% depending on the HLH trigger and response to initial treatment.12 The protocol consists of etoposide at 150 mg/m2, 2 weekly doses in the first 2 weeks and then 1 dose weekly for the next 6 weeks. Dexamethasone is the steroid of choice as it readily crosses the blood-brain barrier. Its dosage consists of 10 mg/m2 for the first 2 weeks and then it is halved every 2 weeks until the eighth week of treatment. A slow taper follows to avoid adrenal insufficiency. Once 8 weeks of treatment have been completed, cyclosporine is added to a goal trough of 200 mcg/dL. If there is central nervous system (CNS) involvement, early aggressive treatment with intrathecal methotrexate is indicated if no improvement is noted during initial therapy.11

In 2004 the Histiocyte Society restructured the HLH-94 treatment protocol with the aim of presenting a more aggressive treatment strategy. The protocol added cyclosporine to the initial induction therapy, rather than later in the ninth week as HLH-94. Neither the use of cyclosporine nor the HLH-2004 have been demonstrated to be superior to the use of etoposide and dexamethasone alone or in the HLH-94 protocol, respectively.13 Cyclosporine is associated with adverse effects (AEs) and may have many contraindications in the acute phase of the disease. Therefore, the HLH-94 protocol is still the recommended regimen.11

To assess adequate clinical response, several clinical and laboratory parameters are followed. Clinically, resolution of fever, improvement in hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and mental status can be useful. Laboratories can be used to assess improvement from organ specific damage such as hepatic involvement or cytopenia. The limitation of these diagnostic studies is that they could falsely suggest an inadequate response to treatment due to concomitant infection or medication AEs. Other markers such as ferritin levels, CD25, and NK cell activity levels are more specific to HLH. Out of them, a decreasing ferritin level has the needed specificity and widespread availability for repeated assessment. On the other hand, both CD25 and NK cell activity are readily available only in specialized centers. An initial high ferritin level is a marker for a poor prognosis, and the rate of decline correlates with mortality. Studies have demonstrated that persistently elevated ferritin levels after treatment initiation are associated with worse outcomes.14,15

Several salvage treatments have been identified in recalcitrant or relapsing disease. In general, chemotherapy needs to be intensified, either by returning to the initial high dosage if recurrence occurs in the weaning phase of treatment or adding other agents if no response was initially achieved. Emapalumab, an interferon γ antibody, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of intractable HLH after it demonstrated that when added to dexamethasone, it lead to treatment response in 17 out of 27 pediatric patients, with a relatively safe AE profile.16 The goal of intensifying chemotherapy is to have the patient tolerate allogenic stem cell transplant, which is clinically indicated in familial HLH, malignancy induced HLH, and recalcitrant cases. In patients who undergo hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) there is a tendency to increase survival to 66% at 5 years.12

Conclusions

HLH is a rare and deadly disease increasingly more present in adults. Our patient who initially presented with a sepsis diagnosis was suspected of having a hematologic etiology for his clinical findings due to markedly elevated ferritin levels. In our patient, the HLH-94 treatment protocol was used, yielding favorable results. Given the lack of specific scientific data backing updated protocols such as HLH-2004 and a comparatively favorable safety profile, current guidelines still recommend using the HLH-94 treatment protocol. Decreasing ferritin levels may be used in conjunction with clinical improvement to demonstrate therapeutic response. Persistence of disease despite standard treatment may warrant novel therapies, such as emapalumab or HCT. Physicians need to be wary of an HLH diagnosis as early identification and treatment may improve its otherwise grim prognosis.

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare and deadly disease in which unregulated proliferation of histiocytes and T-cell infiltration takes place. It is known as a pediatric disease in which gene defects result in impaired cytotoxic NK- and T-cell function. It has been associated with autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Without therapy, survival for these patients with active familial HLH is approximately 2 months.

Recognition of the disease has increased over the years, and as a result the diagnosis of HLH in adults also has increased. An acquired form can be triggered by viruses like Epstein-Barr virus, influenza, HIV, lymphoid malignancies, rheumatologic disorders, or immunodeficiency disorders. Survival rates for untreated HLH have been reported at < 5%.1 Despite early recognition and adequate treatment, HLH carries an overall mortality of 50% in the initial presentation, 90% die in the first 8 weeks of treatment due to uncontrolled disease.2

Case Presentation

A 56-year-old man with no active medical issues except for a remote history of non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and splenectomy in 1990 presented to the Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan, Puerto Rico. He was admitted to the medicine ward due to community acquired pneumonia. Three days into admission his clinical status deteriorated, and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) due to acute respiratory failure and sepsis secondary to worsening pneumonia. Chest imaging demonstrated rapidly progressing diffuse bilateral infiltrates. Due to the severity of the chest imaging, a diagnostic bronchoscopy was performed.

The patient’s antibiotics regimen was empirically escalated to vancomycin 1500 mg IV every 12 hours and meropenem 2 g IV every 8 hours. Despite optimization of therapy, the patient did not show clinical signs of improvement. Febrile episodes persisted, pulmonary infiltrates and hypoxemia worsened, and the patient required a neuromuscular blockade. Since the bronchoscopy was nondiagnostic and deterioration persistent, the differential diagnosis was broadened. This led to the ordering of inflammatory markers. Laboratory testing showed ferritin levels > 16,000 ng/mL, pointing to HLH as a possible diagnosis. Further workup was remarkable for triglycerides of 1234 mg/dL and a fibrinogen of 0.77 g/L. In the setting of bicytopenia and persistent fever, HLH-94 regimen was started with dexamethasone 40 mg daily and etoposide 100 mg/m2. CD25 levels of 154,701 pg/mL were demonstrated as well as a decreased immunoglobulin (Ig) G levels with absent IgM and IgA. Bone marrow biopsy was consistent with hemophagocytosis. The patient eventually was extubated and sent to the oncology ward to continue chemotherapy.

Discussion

A high clinical suspicion is warranted for rapid diagnosis and treatment as HLH evolves in most cases to multiorgan failure and death. The diagnostic criteria for HLH was developed by the Histiocyte Society in 1991 and then restructured in 2004.3,4 In the first diagnostic tool developed in 1991, diagnosis was based on 5 criteria (fever, splenomegaly, bicytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia and/or hypofibrinogenemia, and hemophagocytosis). Three additional laboratory findings were also described as part of HLH diagnosis since 2004: low or absent NK-cell-activity, hyperferritinemia of > 500 ng/dL, and high-soluble interleukin-2-receptor levels (CD25) > 2400 U/mL. Overall, 5 of 8 criteria are needed for the HLH diagnosis.

Despite the common use of these diagnostic criteria, they were developed for the pediatric population but have not been validated for adult patients.5 For adult patients, the HScore was developed in 2014. It has 9 variables: 3 are based on clinical findings (known underlying immunosuppression, high temperature, and organomegaly; 5 are based on laboratory values (ferritin, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, cytopenia, triglycerides, and fibrinogen levels); the last variable uses cytologic findings in the bone marrow. In the initial study, probability of having HLH ranged from < 1% with an HScore of ≤ 90% to > 99% with an HScore of ≥ 250 in noncritically ill adults.5 A recently published retrospective study demonstrated the diagnostic reliability of both the HLH-2004 criteria and HScore in critically ill adult patients. This study concluded that the best prediction accuracy of HLH diagnosis for a cutoff of 4 fulfilled HLH-2004 criteria had a 95.0% sensitivity and 93.6% specificity and HScore cutoff of 168 reached a 100% sensitivity and 94.1% specificity.6

The early negative bronchoscopy lowered the possibility of an infection as the etiology of the clinical presentation and narrowed the hyperferritinemia differential diagnosis. Hyperferritinemia has a sensitivity and specificity of > 90% for diagnosis when above 10,000 ng/dL in the pediatric population.7 This is not the case in adults. Hyperferritinemia is a marker of different inflammatory responses, such as histoplasmosis infection, malignancy, or iron overload rather than an isolated diagnostic tool for HLH.8 It has been reported that CD25 levels less than the diagnostic threshold of 2400 U/mL have a 100% sensitivity for the diagnosis and therefore can rule out the diagnosis. When this is taken into consideration, it can be concluded that CD25 level is a better diagnostic tool when compared with ferritin, but its main limitation is its lack of widespread availability.9 Still, there is a limited number of pathologies that are associated with marked hyperferritinemia, specifically using thresholds of more than 6000 ng/dL.10 Taking into consideration the high mortality of untreated HLH, isolated hyperferritinemia still warrants HLH workup to aggressively pursue the diagnosis and improve outcomes.

The goal of therapy in HLH is prompt inactivation of the dysregulated inflammation with aggressive immunosuppression. In our deteriorating patient, the treatment was started with only 4 of the 8 HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria being met. As per the 2018 Histiocyte Society consensus statement, the decision to start the HLH-94 treatment relies on not only the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria, but also the patient’s clinical evolution.11 In 1994 the Histiocyte Society also published a treatment protocol termed HLH-94. A Korean retrospective study demonstrated that this protocol led to a 5-year survival rate of 60 to 80% depending on the HLH trigger and response to initial treatment.12 The protocol consists of etoposide at 150 mg/m2, 2 weekly doses in the first 2 weeks and then 1 dose weekly for the next 6 weeks. Dexamethasone is the steroid of choice as it readily crosses the blood-brain barrier. Its dosage consists of 10 mg/m2 for the first 2 weeks and then it is halved every 2 weeks until the eighth week of treatment. A slow taper follows to avoid adrenal insufficiency. Once 8 weeks of treatment have been completed, cyclosporine is added to a goal trough of 200 mcg/dL. If there is central nervous system (CNS) involvement, early aggressive treatment with intrathecal methotrexate is indicated if no improvement is noted during initial therapy.11

In 2004 the Histiocyte Society restructured the HLH-94 treatment protocol with the aim of presenting a more aggressive treatment strategy. The protocol added cyclosporine to the initial induction therapy, rather than later in the ninth week as HLH-94. Neither the use of cyclosporine nor the HLH-2004 have been demonstrated to be superior to the use of etoposide and dexamethasone alone or in the HLH-94 protocol, respectively.13 Cyclosporine is associated with adverse effects (AEs) and may have many contraindications in the acute phase of the disease. Therefore, the HLH-94 protocol is still the recommended regimen.11

To assess adequate clinical response, several clinical and laboratory parameters are followed. Clinically, resolution of fever, improvement in hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and mental status can be useful. Laboratories can be used to assess improvement from organ specific damage such as hepatic involvement or cytopenia. The limitation of these diagnostic studies is that they could falsely suggest an inadequate response to treatment due to concomitant infection or medication AEs. Other markers such as ferritin levels, CD25, and NK cell activity levels are more specific to HLH. Out of them, a decreasing ferritin level has the needed specificity and widespread availability for repeated assessment. On the other hand, both CD25 and NK cell activity are readily available only in specialized centers. An initial high ferritin level is a marker for a poor prognosis, and the rate of decline correlates with mortality. Studies have demonstrated that persistently elevated ferritin levels after treatment initiation are associated with worse outcomes.14,15

Several salvage treatments have been identified in recalcitrant or relapsing disease. In general, chemotherapy needs to be intensified, either by returning to the initial high dosage if recurrence occurs in the weaning phase of treatment or adding other agents if no response was initially achieved. Emapalumab, an interferon γ antibody, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of intractable HLH after it demonstrated that when added to dexamethasone, it lead to treatment response in 17 out of 27 pediatric patients, with a relatively safe AE profile.16 The goal of intensifying chemotherapy is to have the patient tolerate allogenic stem cell transplant, which is clinically indicated in familial HLH, malignancy induced HLH, and recalcitrant cases. In patients who undergo hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) there is a tendency to increase survival to 66% at 5 years.12

Conclusions

HLH is a rare and deadly disease increasingly more present in adults. Our patient who initially presented with a sepsis diagnosis was suspected of having a hematologic etiology for his clinical findings due to markedly elevated ferritin levels. In our patient, the HLH-94 treatment protocol was used, yielding favorable results. Given the lack of specific scientific data backing updated protocols such as HLH-2004 and a comparatively favorable safety profile, current guidelines still recommend using the HLH-94 treatment protocol. Decreasing ferritin levels may be used in conjunction with clinical improvement to demonstrate therapeutic response. Persistence of disease despite standard treatment may warrant novel therapies, such as emapalumab or HCT. Physicians need to be wary of an HLH diagnosis as early identification and treatment may improve its otherwise grim prognosis.

1. Chen TY, Hsu MH, Kuo HC, Sheen JM, Cheng MC, Lin YJ. Outcome analysis of pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2021;120(1, pt 1):172-179. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2020.03.025

2. Henter JI, Samuelsson-Horne A, Aricò M, et al. Treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with HLH-94 immunochemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2002;100(7):2367-2373. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-01-0172

3. Henter JI, Elinder G, Ost A. Diagnostic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The FHL Study Group of the Histiocyte Society. Semin Oncol. 1991;18(1):29-33.

4. Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124-131. doi:10.1002/pbc.21039

5. Knaak C, Nyvlt P, Schuster FS, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in critically ill patients: diagnostic reliability of HLH-2004 criteria and HScore. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):244. Published 2020 May 24. doi:10.1186/s13054-020-02941-3

6. Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(9):2613-2620. doi:10.1002/art.38690

7. La Rosée P, Horne A, Hines M, et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2019;133(23):2465-2477. doi:10.1182/blood.2018894618

8. Schaffner M, Rosenstein L, Ballas Z, Suneja M. Significance of Hyperferritinemia in Hospitalized Adults. Am J Med Sci. 2017;354(2):152-158. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2017.04.016

9. Hayden A, Lin M, Park S, et al. Soluble interleukin-2 receptor is a sensitive diagnostic test in adult HLH. Blood Adv. 2017;1(26):2529-2534. Published 2017 Dec 6. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2017012310

10. Belfeki N, Strazzulla A, Picque M, Diamantis S. Extreme hyperferritinemia: etiological spectrum and impact on prognosis. Reumatismo. 2020;71(4):199-202. Published 2020 Jan 28. doi:10.4081/reumatismo.2019.1221

11. Ehl S, Astigarraga I, von Bahr Greenwood T, et al. Recommendations for the use of etoposide-based therapy and bone marrow transplantation for the treatment of HLH: consensus statements by the HLH Steering Committee of the Histiocyte Society. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(5):1508-1517. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.05.031

12. Yoon JH, Park SS, Jeon YW, et al. Treatment outcomes and prognostic factors in adult patients with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis not associated with malignancy. Haematologica. 2019;104(2):269-276. doi:10.3324/haematol.2018.198655

13. Bergsten E, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. Confirmed efficacy of etoposide and dexamethasone in HLH treatment: long-term results of the cooperative HLH-2004 study. Blood. 2017;130(25):2728-2738. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-06-788349

14. Lin TF, Ferlic-Stark LL, Allen CE, Kozinetz CA, McClain KL. Rate of decline of ferritin in patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis as a prognostic variable for mortality. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(1):154-155. doi:10.1002/pbc.22774

15. Zhou J, Zhou J, Shen DT, Goyal H, Wu ZQ, Xu HG. Development and validation of the prognostic value of ferritin in adult patients with Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):71. Published 2020 Mar 12. doi:10.1186/s13023-020-1336-616. Locatelli F, Jordan MB, Allen CE, et al. Safety and efficacy of emapalumab in pediatric patients with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Presented at: American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting, November 29, 2018. Blood. 2018;132(suppl 1):LBA-6. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-120810

1. Chen TY, Hsu MH, Kuo HC, Sheen JM, Cheng MC, Lin YJ. Outcome analysis of pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2021;120(1, pt 1):172-179. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2020.03.025

2. Henter JI, Samuelsson-Horne A, Aricò M, et al. Treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with HLH-94 immunochemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2002;100(7):2367-2373. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-01-0172

3. Henter JI, Elinder G, Ost A. Diagnostic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The FHL Study Group of the Histiocyte Society. Semin Oncol. 1991;18(1):29-33.

4. Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124-131. doi:10.1002/pbc.21039

5. Knaak C, Nyvlt P, Schuster FS, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in critically ill patients: diagnostic reliability of HLH-2004 criteria and HScore. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):244. Published 2020 May 24. doi:10.1186/s13054-020-02941-3

6. Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(9):2613-2620. doi:10.1002/art.38690

7. La Rosée P, Horne A, Hines M, et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2019;133(23):2465-2477. doi:10.1182/blood.2018894618

8. Schaffner M, Rosenstein L, Ballas Z, Suneja M. Significance of Hyperferritinemia in Hospitalized Adults. Am J Med Sci. 2017;354(2):152-158. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2017.04.016

9. Hayden A, Lin M, Park S, et al. Soluble interleukin-2 receptor is a sensitive diagnostic test in adult HLH. Blood Adv. 2017;1(26):2529-2534. Published 2017 Dec 6. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2017012310

10. Belfeki N, Strazzulla A, Picque M, Diamantis S. Extreme hyperferritinemia: etiological spectrum and impact on prognosis. Reumatismo. 2020;71(4):199-202. Published 2020 Jan 28. doi:10.4081/reumatismo.2019.1221

11. Ehl S, Astigarraga I, von Bahr Greenwood T, et al. Recommendations for the use of etoposide-based therapy and bone marrow transplantation for the treatment of HLH: consensus statements by the HLH Steering Committee of the Histiocyte Society. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(5):1508-1517. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.05.031

12. Yoon JH, Park SS, Jeon YW, et al. Treatment outcomes and prognostic factors in adult patients with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis not associated with malignancy. Haematologica. 2019;104(2):269-276. doi:10.3324/haematol.2018.198655

13. Bergsten E, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. Confirmed efficacy of etoposide and dexamethasone in HLH treatment: long-term results of the cooperative HLH-2004 study. Blood. 2017;130(25):2728-2738. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-06-788349

14. Lin TF, Ferlic-Stark LL, Allen CE, Kozinetz CA, McClain KL. Rate of decline of ferritin in patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis as a prognostic variable for mortality. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(1):154-155. doi:10.1002/pbc.22774

15. Zhou J, Zhou J, Shen DT, Goyal H, Wu ZQ, Xu HG. Development and validation of the prognostic value of ferritin in adult patients with Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):71. Published 2020 Mar 12. doi:10.1186/s13023-020-1336-616. Locatelli F, Jordan MB, Allen CE, et al. Safety and efficacy of emapalumab in pediatric patients with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Presented at: American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting, November 29, 2018. Blood. 2018;132(suppl 1):LBA-6. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-120810

Genetic shift increases susceptibility to childhood ALL

A genetically induced shift toward higher lymphocyte counts was found to increase susceptibility to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia, according to the results of a large genome-wide association study of 2,666 childhood patients with ALL as compared with 60,272 control individuals.

The development of ALL is thought to follow a two-hit model of leukemogenesis; in utero formation of a preleukemic clone and subsequent postnatal acquisition of secondary somatic mutations that leads to overt leukemia, according to Linda Kachuri, PhD, of the department of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

The development of ALL is thought to follow a two-hit model of leukemogenesis; in utero formation of a preleukemic clone and subsequent postnatal acquisition of secondary somatic mutations that leads to overt leukemia, according to Linda Kachuri, PhD, of the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California San Francisco, and colleagues.

Previous research has shown that several childhood-ALL–risk regions have also been associated with variation in blood-cell traits and a recent phenome-wide association study of childhood ALL identified platelet count as the most enriched trait among known ALL-risk loci. To further explore this issue, the researchers conducted their comprehensive study of the role of blood-cell-trait variation in the etiology of childhood ALL.

The researchers identified 3,000 blood-cell-trait–associated variants, which accounted for 4.0% to 23.9% of trait variation and included 115 loci associated with blood-cell ratios: lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR); neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR); and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), according to a report published online in The American Journal of Human Genetics.

Lymphocyte risk

The researchers found that ALL susceptibility was genetically correlated with lymphocyte counts (rg = 0.088, P = .0004) and PLR (rg = 0.072, P = .0017).

Using Mendelian randomization analyses, a genetically predicted increase in lymphocyte counts was found to be associated with increased ALL risk (odds ratio [OR] = 1.16, P = .031). This correlation was strengthened after the researchers accounted for other cell types (OR = 1.43, P = .0009).

The researchers observed positive associations with increasing LMR (OR = 1.22, P = .0017) as well as inverse effects for NLR (OR = 0.67, P = .0003) and PLR (OR = 0.80, P = .002).

“We identified the cell-type ratios LMR, NLR, and PLR as independent risk factors for ALL and found evidence that these ratios have distinct genetic mechanisms that are not captured by their component traits. In multivariable MR analyses that concurrently modeled the effects of lymphocyte, monocyte, neutrophil, and platelet counts on ALL, lymphocytes remained as the only independent risk factor and this association with ALL strengthened compared to univariate analyses,” the researchers stated.

They reported that they had no competing interests.

A genetically induced shift toward higher lymphocyte counts was found to increase susceptibility to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia, according to the results of a large genome-wide association study of 2,666 childhood patients with ALL as compared with 60,272 control individuals.

The development of ALL is thought to follow a two-hit model of leukemogenesis; in utero formation of a preleukemic clone and subsequent postnatal acquisition of secondary somatic mutations that leads to overt leukemia, according to Linda Kachuri, PhD, of the department of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

The development of ALL is thought to follow a two-hit model of leukemogenesis; in utero formation of a preleukemic clone and subsequent postnatal acquisition of secondary somatic mutations that leads to overt leukemia, according to Linda Kachuri, PhD, of the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California San Francisco, and colleagues.

Previous research has shown that several childhood-ALL–risk regions have also been associated with variation in blood-cell traits and a recent phenome-wide association study of childhood ALL identified platelet count as the most enriched trait among known ALL-risk loci. To further explore this issue, the researchers conducted their comprehensive study of the role of blood-cell-trait variation in the etiology of childhood ALL.

The researchers identified 3,000 blood-cell-trait–associated variants, which accounted for 4.0% to 23.9% of trait variation and included 115 loci associated with blood-cell ratios: lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR); neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR); and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), according to a report published online in The American Journal of Human Genetics.

Lymphocyte risk

The researchers found that ALL susceptibility was genetically correlated with lymphocyte counts (rg = 0.088, P = .0004) and PLR (rg = 0.072, P = .0017).

Using Mendelian randomization analyses, a genetically predicted increase in lymphocyte counts was found to be associated with increased ALL risk (odds ratio [OR] = 1.16, P = .031). This correlation was strengthened after the researchers accounted for other cell types (OR = 1.43, P = .0009).

The researchers observed positive associations with increasing LMR (OR = 1.22, P = .0017) as well as inverse effects for NLR (OR = 0.67, P = .0003) and PLR (OR = 0.80, P = .002).

“We identified the cell-type ratios LMR, NLR, and PLR as independent risk factors for ALL and found evidence that these ratios have distinct genetic mechanisms that are not captured by their component traits. In multivariable MR analyses that concurrently modeled the effects of lymphocyte, monocyte, neutrophil, and platelet counts on ALL, lymphocytes remained as the only independent risk factor and this association with ALL strengthened compared to univariate analyses,” the researchers stated.

They reported that they had no competing interests.

A genetically induced shift toward higher lymphocyte counts was found to increase susceptibility to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia, according to the results of a large genome-wide association study of 2,666 childhood patients with ALL as compared with 60,272 control individuals.

The development of ALL is thought to follow a two-hit model of leukemogenesis; in utero formation of a preleukemic clone and subsequent postnatal acquisition of secondary somatic mutations that leads to overt leukemia, according to Linda Kachuri, PhD, of the department of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

The development of ALL is thought to follow a two-hit model of leukemogenesis; in utero formation of a preleukemic clone and subsequent postnatal acquisition of secondary somatic mutations that leads to overt leukemia, according to Linda Kachuri, PhD, of the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California San Francisco, and colleagues.

Previous research has shown that several childhood-ALL–risk regions have also been associated with variation in blood-cell traits and a recent phenome-wide association study of childhood ALL identified platelet count as the most enriched trait among known ALL-risk loci. To further explore this issue, the researchers conducted their comprehensive study of the role of blood-cell-trait variation in the etiology of childhood ALL.

The researchers identified 3,000 blood-cell-trait–associated variants, which accounted for 4.0% to 23.9% of trait variation and included 115 loci associated with blood-cell ratios: lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR); neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR); and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), according to a report published online in The American Journal of Human Genetics.

Lymphocyte risk

The researchers found that ALL susceptibility was genetically correlated with lymphocyte counts (rg = 0.088, P = .0004) and PLR (rg = 0.072, P = .0017).

Using Mendelian randomization analyses, a genetically predicted increase in lymphocyte counts was found to be associated with increased ALL risk (odds ratio [OR] = 1.16, P = .031). This correlation was strengthened after the researchers accounted for other cell types (OR = 1.43, P = .0009).

The researchers observed positive associations with increasing LMR (OR = 1.22, P = .0017) as well as inverse effects for NLR (OR = 0.67, P = .0003) and PLR (OR = 0.80, P = .002).

“We identified the cell-type ratios LMR, NLR, and PLR as independent risk factors for ALL and found evidence that these ratios have distinct genetic mechanisms that are not captured by their component traits. In multivariable MR analyses that concurrently modeled the effects of lymphocyte, monocyte, neutrophil, and platelet counts on ALL, lymphocytes remained as the only independent risk factor and this association with ALL strengthened compared to univariate analyses,” the researchers stated.

They reported that they had no competing interests.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF HUMAN GENETICS

Facial eruptions

This was a vigorous response to the 5-FU treatment and was actually within the range of expected outcomes for a patient with a heavy burden of AKs. The erythema and superficial skin flaking spared areas unaffected by pre-cancers.

AKs manifest as rough, pink to brown macules or papules on sun-damaged skin and represent a precancerous change in keratinocytes that can lead to invasive squamous cell carcinoma. For this reason, AKs are often treated when they are observed. When targeting an entire “field” of AKs, a gold standard therapy is topical 5-FU. Prescribing 5-FU is safe and effective, but requires patient education, therapy customization, and anticipatory guidance.

Compared with other field treatments (eg, photodynamic therapy, topical diclofenac, imiquimod), 5-FU is the most successful and cost effective; it is first-line therapy and has the longest track record.1,2 5-FU represses DNA synthesis. It’s helpful to describe 5-FU to patients as “fake DNA” that targets precancerous cells that are dividing rapidly. But a word of caution: Patients should be advised, in advance, to avoid significant sun exposure while using 5-FU, as the drug will lose its targeted effect and cause more generalized skin damage.

Physicians can modulate the severity of the response to 5-FU by decreasing the frequency or length of therapy by using a weaker (and more expensive) once daily 0.5% long-acting formulation. Additionally, to improve comfort, low-potency topical steroids such as hydrocortisone ointment 0.5% to 2.5% can be applied after completion of therapy to speed up the healing process. These adjustments improve tolerance of therapy, but the precise effect on efficacy is unknown.

Because of the degree of redness and erythema that developed in this patient, treatment was stopped a week early. There was also concern about possible bacterial involvement in the heavy skin sloughing, so the patient was given topical mupirocin ointment to apply TID for 7 days. Her skin cleared after 3 weeks and all previous AKs were clinically eliminated.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Gupta AK, Paquet M. Network meta-analysis of the outcome 'participant complete clearance' in nonimmunosuppressed participants of eight interventions for actinic keratosis: a follow-up on a Cochrane review. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:250-259. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12343

2. Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Merks I, et al. A trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis of topical 5-fluorouracil vs. imiquimod vs. ingenol mebutate vs. methyl aminolaevulinate conventional photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis in the head and neck area performed in the Netherlands. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:738-744. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18884

This was a vigorous response to the 5-FU treatment and was actually within the range of expected outcomes for a patient with a heavy burden of AKs. The erythema and superficial skin flaking spared areas unaffected by pre-cancers.

AKs manifest as rough, pink to brown macules or papules on sun-damaged skin and represent a precancerous change in keratinocytes that can lead to invasive squamous cell carcinoma. For this reason, AKs are often treated when they are observed. When targeting an entire “field” of AKs, a gold standard therapy is topical 5-FU. Prescribing 5-FU is safe and effective, but requires patient education, therapy customization, and anticipatory guidance.

Compared with other field treatments (eg, photodynamic therapy, topical diclofenac, imiquimod), 5-FU is the most successful and cost effective; it is first-line therapy and has the longest track record.1,2 5-FU represses DNA synthesis. It’s helpful to describe 5-FU to patients as “fake DNA” that targets precancerous cells that are dividing rapidly. But a word of caution: Patients should be advised, in advance, to avoid significant sun exposure while using 5-FU, as the drug will lose its targeted effect and cause more generalized skin damage.

Physicians can modulate the severity of the response to 5-FU by decreasing the frequency or length of therapy by using a weaker (and more expensive) once daily 0.5% long-acting formulation. Additionally, to improve comfort, low-potency topical steroids such as hydrocortisone ointment 0.5% to 2.5% can be applied after completion of therapy to speed up the healing process. These adjustments improve tolerance of therapy, but the precise effect on efficacy is unknown.

Because of the degree of redness and erythema that developed in this patient, treatment was stopped a week early. There was also concern about possible bacterial involvement in the heavy skin sloughing, so the patient was given topical mupirocin ointment to apply TID for 7 days. Her skin cleared after 3 weeks and all previous AKs were clinically eliminated.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

This was a vigorous response to the 5-FU treatment and was actually within the range of expected outcomes for a patient with a heavy burden of AKs. The erythema and superficial skin flaking spared areas unaffected by pre-cancers.

AKs manifest as rough, pink to brown macules or papules on sun-damaged skin and represent a precancerous change in keratinocytes that can lead to invasive squamous cell carcinoma. For this reason, AKs are often treated when they are observed. When targeting an entire “field” of AKs, a gold standard therapy is topical 5-FU. Prescribing 5-FU is safe and effective, but requires patient education, therapy customization, and anticipatory guidance.

Compared with other field treatments (eg, photodynamic therapy, topical diclofenac, imiquimod), 5-FU is the most successful and cost effective; it is first-line therapy and has the longest track record.1,2 5-FU represses DNA synthesis. It’s helpful to describe 5-FU to patients as “fake DNA” that targets precancerous cells that are dividing rapidly. But a word of caution: Patients should be advised, in advance, to avoid significant sun exposure while using 5-FU, as the drug will lose its targeted effect and cause more generalized skin damage.