User login

Dear colleagues and friends,

The start age for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in average-risk individuals has been relatively uncontroversial and unchallenged, until recent guidelines that recommended decreasing the start age from 50 to 45 years. In this edition of Perspectives, two renowned experts, Dr. Patel and Dr. Rabeneck, debate the pros and cons of this paradigm change. This will be my final Perspectives contribution as associate editor for GI & Hep News. Thank you very much for your support and feedback, and I hope you have all enjoyed and learned from the Perspectives debates as much as I have. As always, your feedback and suggestions for future topics are welcome and can be sent to [email protected].

Charles J. Kahi, MD, MS, AGAF, is professor of medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

45 is the new 50

BY SWATI G. PATEL, MD, MS

The incidence and mortality rates of CRC in individuals under the age of 50 years, or early age–onset CRC, is increasing in the United States.1 We do not fully understand the cause of this trend; however, it has been observed in multiple Westernized countries, consistent with a birth cohort effect in which generation-specific risk factors are likely responsible.1 To address this rising burden of early age–onset CRC, multiple professional societies, including the United States Preventive Services Task Force,2 now recommend decreasing the starting age for CRC screening in average-risk individuals from 50 to 45 years. These recommendations are supported by the fact that CRC incidence in 45- to 49-year-olds is now the same as that of populations already eligible for screening; the yield of screening appears to be similar among those aged 45-49 years, compared to those aged 50-59 years; and modeling studies show that the benefits outweigh the risks and costs. These factors, along with the unique benefits of early detection and prevention in young patients, support that 45 is the new 50 when it comes to CRC screening.

CRC incidence rates among 45- to 49-year-olds now match populations that are already eligible for CRC screening. The rates among 45- to 49-year-olds now is similar to the incidence rates observed in 50-year-olds in 1992, before widespread CRC screening was performed. Overall incidence rates in 45- to 49-year-olds now match incidence rates observed in 45- to 49-year-old African Americans, a population in which the American College of Gastroenterology and the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force have recommended average-risk screening beginning at age 45.

Advanced colorectal neoplasia rates in 45- to 49-year-olds are similar to rates observed in 50- to 59-year-olds. One study found that advanced colorectal neoplasia rates (including advanced colorectal polyps and adenocarcinoma) in average risk–equivalent 45- to 49-year-olds are similar rates of 50- to 54-year-old average-risk individuals.3 Similarly, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 international studies including average-risk individuals undergoing colonoscopy found no significant difference between advanced colorectal neoplasia rates in 45- to 49-years-olds compared to 50- to 59-year-olds.4 These data suggest that expanding screening to average-risk individuals aged 45-49 years will have yield similar to that of those aged 50-59.

Modeling studies show that the benefits of screening outweigh the potential harms and costs. A recent cost-effectiveness analysis showed that starting average-risk screening at age 45 years with colonoscopy would cost $33,900 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) or $7,700 per QALY if annual FIT is selected as the screening modality.5 These costs are less than the widely accepted willingness to pay threshold of $50,000 per QALY and less than currently accepted average-risk screening, such as annual or biennial mammograms for breast cancer screening.

Expanding screening to 45- to 49-year-olds can improve early detection of CRC and prevention of CRC. Offering screening before age 50 years provides the opportunity to detect cancers at earlier stages, which can improve overall survival. Recent data have shown an increase in CRC incidence among 50- to 54-year-olds.1 Although the etiology of the rise in this age group is likely multifactorial (low screening rates or generational risk that individuals carry with them through the birth-cohort effect), diagnosis and removal of advanced colorectal polyps among 45- to 49-year-olds can have a positive impact on reversing this trend in 50- to 54-year-olds. Furthermore, initiating conversations about CRC screening at age 45 can improve uptake of screening among 50- to 54-year-olds who may have delayed screening when first offered at age 50.

There are unique benefits of early detection and prevention of CRC in young patients. Although the absolute incidence and mortality rates associated with CRC in those aged 45-49 are significantly lower than the rates observed in those over age 50, young individuals are more likely to be in the prime of their earning and fertility potential and are more likely to be caregivers to younger and older generations. They are more likely to face material, psychological, and behavioral financial hardships, such as difficulty paying bills. Absolute incidence rates and modeling studies that do not account for these intangible effects on survivorship also do not fully reflect the societal benefit of early detection and CRC prevention in those aged 45-49 years.

There are certainly many unanswered questions about the effects of expanding CRC screening to those age 45 and older. Ongoing studies are needed to determine the cause of rising incidence, whether screening test selection and intervals should be customized for those under age 50, and how best to ensure equitable access to screening services. Finally, expanding screening to younger individuals should not detract from the critical importance of ongoing efforts to improve screening in those over age 50. As these issues are addressed by the scientific community, we cannot stand by idly when there is sufficient evidence to support that 45 is the new 50.

Dr. Patel is associate professor of medicine in the divisions of gastroenterology & hepatology at the University of Colorado and Rocky Mountain Regional Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Aurora, Colo. She disclosed financial relationships with Olympus America, ERBE USA, and Freenome.

References

1. Siegel RL et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw322.

2. USPSTF et al. JAMA. 2021 May 18;325(19):1965-77.

3. Butterly LF et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan;116(1):171-9.

4. Kolb JM et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.006.

5. Ladabaum U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul;157(1):137-48.

50 is still 50

BY LINDA RABENECK, MD, MPH, FRCPC

CRC screening of women and men aged 50-75 years at average risk has contributed to the overall decrease in the incidence and mortality from the disease in the United States. In 2009, the American College of Gastroenterology recommended that CRC screening among African Americans begin at age 45 years, and a recent study from Kaiser Permanente reported favorable results from FIT screening in this group.1 In 2018 the American Cancer Society surprised the field by releasing an updated recommendation to begin CRC screening in all women and men at age 45 years (Qualified Recommendation). This spring the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force released its updated recommendation to begin screening at age 45 years (B recommendation).2 The rationale for these updated recommendations is based on new information on the epidemiology of the disease in the United States that was incorporated into updated modeling.

What was this new information? An evaluation of time trends in CRC incidence by age group showed that, although the incidence of colon and rectal cancer among those 50 years and older has been decreasing for more than 2 decades, the incidence has been increasing for those younger than 50 years. As important as these CRC incidence trends are to recognize and understand, this does not imply we should start screening everyone in the general population aged 45-49 years. We need to recognize that the absolute increase in CRC incidence in those younger than 50 years is small, that we lack empirical evidence to support such a major change in screening practice, and that we need to consider potential unintended impacts.

When the rise in incidence among younger Americans was first reported there was much discussion about what it meant. It appears that the rise in incidence is a birth cohort effect among people born in the 1960s and subsequent years. Birth cohort effects imply exposures occurring in early life or those experienced by younger generations. Sorting out what these exposures might be is an area of intense research activity currently. Regardless of the drivers of the relative increase in CRC incidence among younger persons, though, it is important to note that the absolute increase is small. What do we mean by this?

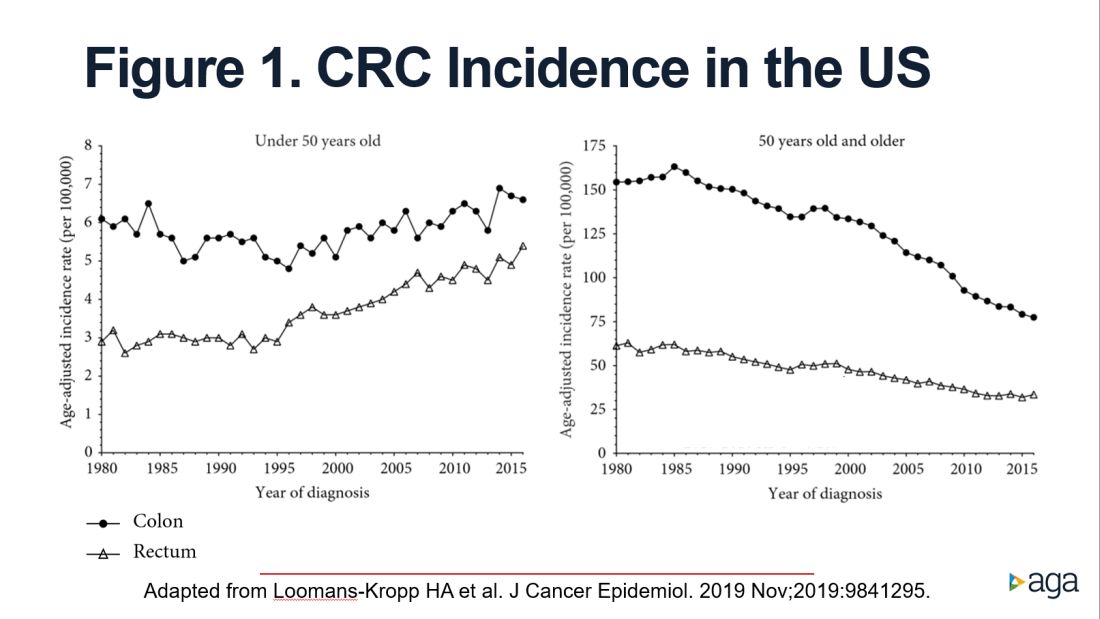

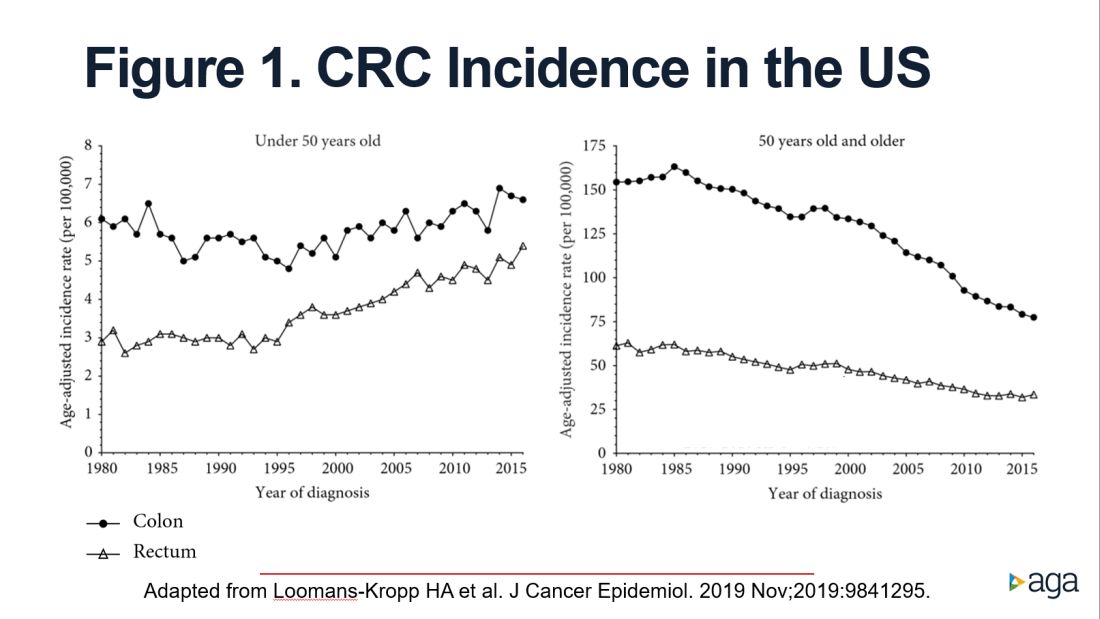

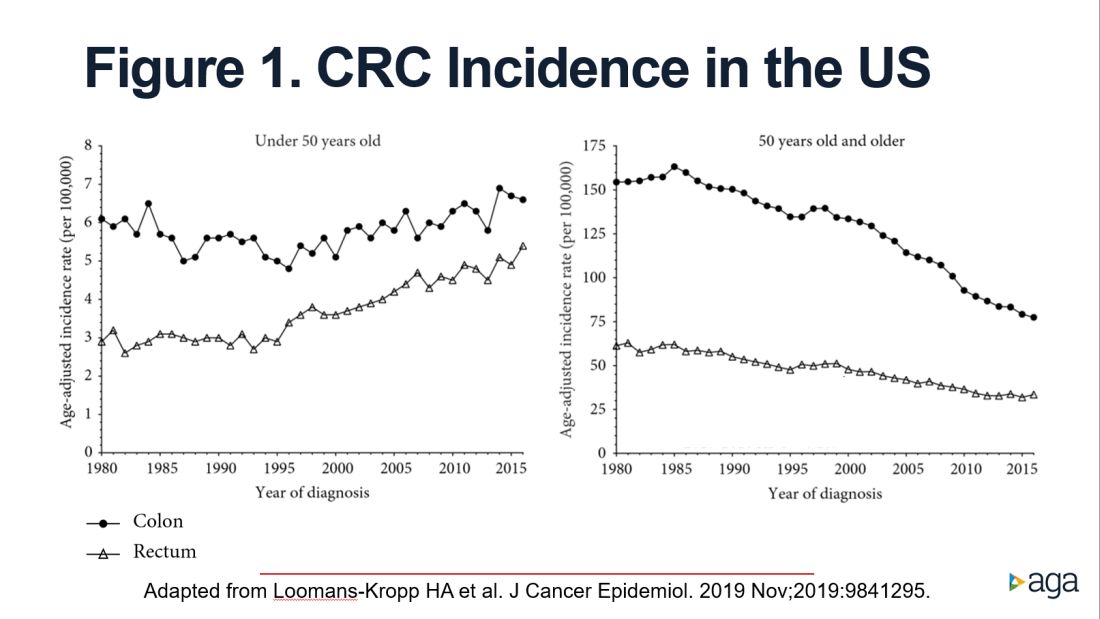

As reported by Holli Loomans-Kropp, PhD, MPH, and colleagues,3 for those under age 50 years, the age-adjusted incidence of colon cancer decreased by 0.9% annually from 1980 to 1996, and then increased by 1.3% annually from 1996 to 2016 (Figure 1).

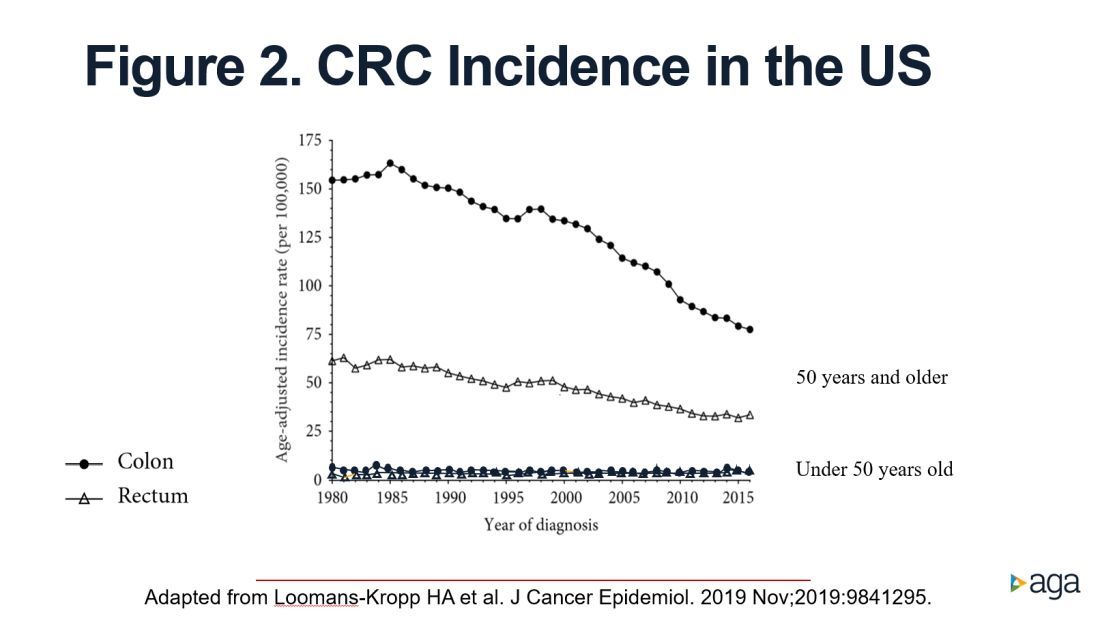

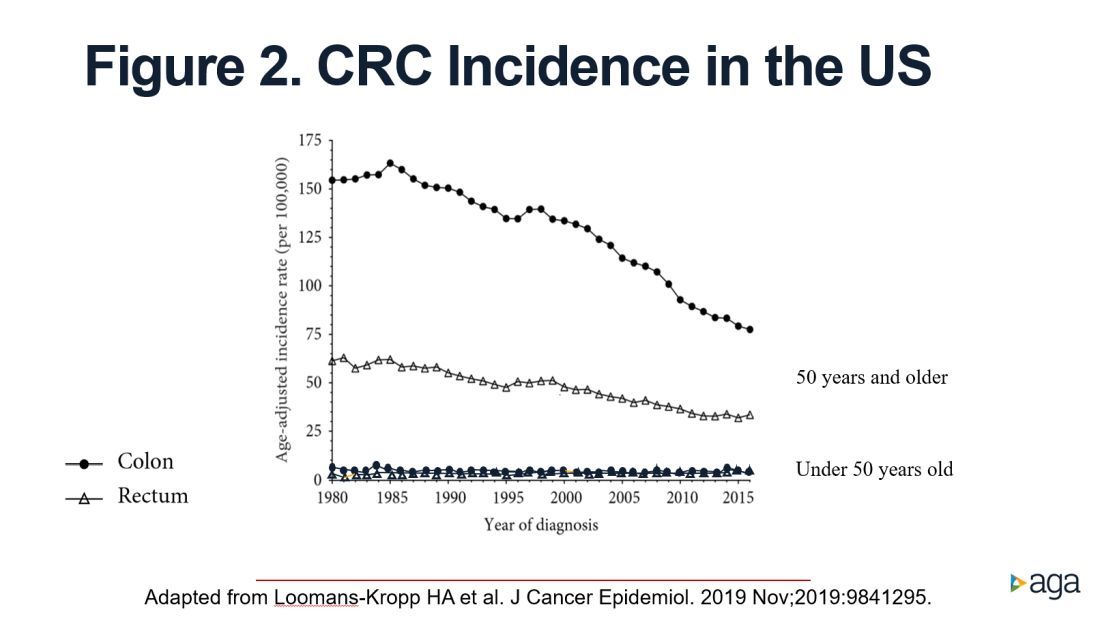

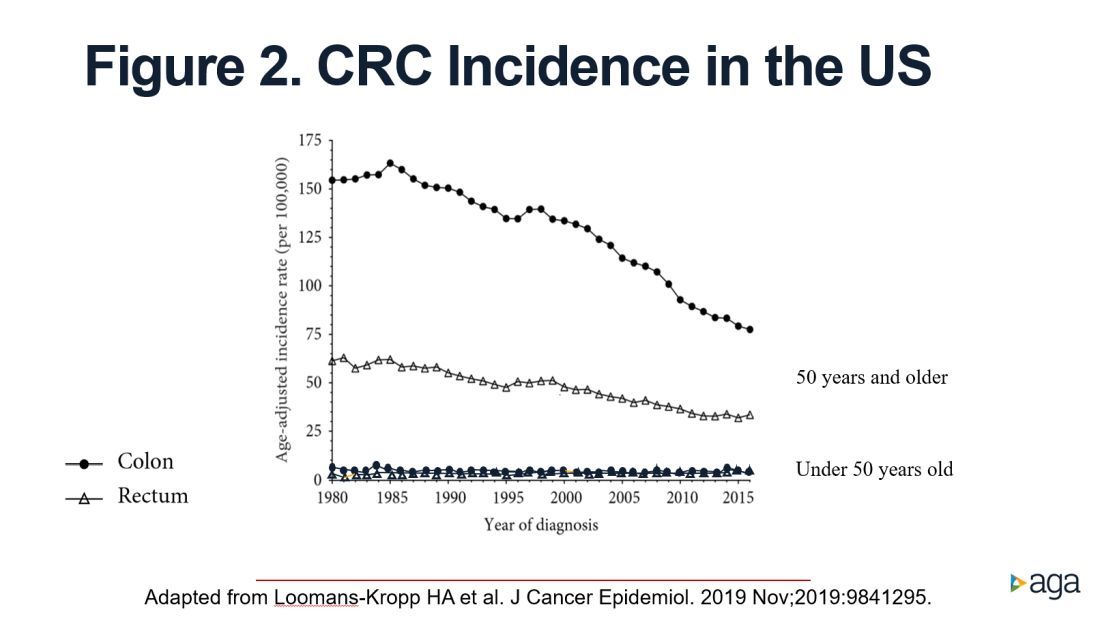

The figure shows that the age-adjusted incidence of rectal cancer among those under age 50 years increased by 2.3% annually since 1991. Figure 1 also shows declines in age-adjusted CRC incidence since 2001 for colon cancer and since 1998 for rectal cancer. However, note the differences in the scales on the Y axes between these two figures. Figure 2 shows this information plotted on the same scale (drawn by hand by author). To recap, these relative increases in incidence are real, but the absolute increases are small.

In addition, not surprisingly, we lack results from randomized controlled trials to support the change in CRC screening recommendation. We are just beginning to see results from other types of study design that seek to address this evidence gap. For example, a recent retrospective cohort study using information recorded in Florida databases evaluated the association between CRC incidence and undergoing colonoscopy at ages 45-49 versus 50-54 years. The authors reported a reduction in CRC incidence in both age groups.4

We also need to consider the resource implications. Lowering the age to start CRC screening to 45 years would expand the target population by greater than 20 million Americans, with all that this entails in terms of additional effort and resources, including colonoscopy. Modeling studies have shown that we would achieve greater clinical benefit with lower cost from directing these colonoscopy resources to those aged 50-75 years who are under/never screened and also ensuring follow-up colonoscopy among those with a positive FIT.5 For example, a study in a U.S. safety-net system reported that among 2,238 patients with a FIT+ followed over 1 year, only 55% underwent a colonoscopy.6

Finally, we need to reflect on existing disparities. If we turn our attention and resources to focus on all those aged 45-49 years in the general population, we risk worsening these disparities.

In conclusion, we need to redouble our efforts to reduce existing disparities in CRC screening participation among those aged 50-74 years and ensure colonoscopy follow-up in those with a FIT+ rather than divert our attention and resources to all those 45- to 49-year-olds who are at lower risk.

Dr. Rabeneck is professor of medicine at the University of Toronto. She has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Levin TR et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Nov;159(5):1695-704.e1.

2. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force et al. JAMA. 2021 May 18;325(19):1965-77.

3. Loomans-Kropp HA et al. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2019 Nov 11;2019:9841295.

4. Sehgal M et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):2018-28.e13.

5. Ladabaum U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul;157(1):137-48.

6. Issaka RB et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Feb;112(2):375-82.

Dear colleagues and friends,

The start age for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in average-risk individuals has been relatively uncontroversial and unchallenged, until recent guidelines that recommended decreasing the start age from 50 to 45 years. In this edition of Perspectives, two renowned experts, Dr. Patel and Dr. Rabeneck, debate the pros and cons of this paradigm change. This will be my final Perspectives contribution as associate editor for GI & Hep News. Thank you very much for your support and feedback, and I hope you have all enjoyed and learned from the Perspectives debates as much as I have. As always, your feedback and suggestions for future topics are welcome and can be sent to [email protected].

Charles J. Kahi, MD, MS, AGAF, is professor of medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

45 is the new 50

BY SWATI G. PATEL, MD, MS

The incidence and mortality rates of CRC in individuals under the age of 50 years, or early age–onset CRC, is increasing in the United States.1 We do not fully understand the cause of this trend; however, it has been observed in multiple Westernized countries, consistent with a birth cohort effect in which generation-specific risk factors are likely responsible.1 To address this rising burden of early age–onset CRC, multiple professional societies, including the United States Preventive Services Task Force,2 now recommend decreasing the starting age for CRC screening in average-risk individuals from 50 to 45 years. These recommendations are supported by the fact that CRC incidence in 45- to 49-year-olds is now the same as that of populations already eligible for screening; the yield of screening appears to be similar among those aged 45-49 years, compared to those aged 50-59 years; and modeling studies show that the benefits outweigh the risks and costs. These factors, along with the unique benefits of early detection and prevention in young patients, support that 45 is the new 50 when it comes to CRC screening.

CRC incidence rates among 45- to 49-year-olds now match populations that are already eligible for CRC screening. The rates among 45- to 49-year-olds now is similar to the incidence rates observed in 50-year-olds in 1992, before widespread CRC screening was performed. Overall incidence rates in 45- to 49-year-olds now match incidence rates observed in 45- to 49-year-old African Americans, a population in which the American College of Gastroenterology and the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force have recommended average-risk screening beginning at age 45.

Advanced colorectal neoplasia rates in 45- to 49-year-olds are similar to rates observed in 50- to 59-year-olds. One study found that advanced colorectal neoplasia rates (including advanced colorectal polyps and adenocarcinoma) in average risk–equivalent 45- to 49-year-olds are similar rates of 50- to 54-year-old average-risk individuals.3 Similarly, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 international studies including average-risk individuals undergoing colonoscopy found no significant difference between advanced colorectal neoplasia rates in 45- to 49-years-olds compared to 50- to 59-year-olds.4 These data suggest that expanding screening to average-risk individuals aged 45-49 years will have yield similar to that of those aged 50-59.

Modeling studies show that the benefits of screening outweigh the potential harms and costs. A recent cost-effectiveness analysis showed that starting average-risk screening at age 45 years with colonoscopy would cost $33,900 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) or $7,700 per QALY if annual FIT is selected as the screening modality.5 These costs are less than the widely accepted willingness to pay threshold of $50,000 per QALY and less than currently accepted average-risk screening, such as annual or biennial mammograms for breast cancer screening.

Expanding screening to 45- to 49-year-olds can improve early detection of CRC and prevention of CRC. Offering screening before age 50 years provides the opportunity to detect cancers at earlier stages, which can improve overall survival. Recent data have shown an increase in CRC incidence among 50- to 54-year-olds.1 Although the etiology of the rise in this age group is likely multifactorial (low screening rates or generational risk that individuals carry with them through the birth-cohort effect), diagnosis and removal of advanced colorectal polyps among 45- to 49-year-olds can have a positive impact on reversing this trend in 50- to 54-year-olds. Furthermore, initiating conversations about CRC screening at age 45 can improve uptake of screening among 50- to 54-year-olds who may have delayed screening when first offered at age 50.

There are unique benefits of early detection and prevention of CRC in young patients. Although the absolute incidence and mortality rates associated with CRC in those aged 45-49 are significantly lower than the rates observed in those over age 50, young individuals are more likely to be in the prime of their earning and fertility potential and are more likely to be caregivers to younger and older generations. They are more likely to face material, psychological, and behavioral financial hardships, such as difficulty paying bills. Absolute incidence rates and modeling studies that do not account for these intangible effects on survivorship also do not fully reflect the societal benefit of early detection and CRC prevention in those aged 45-49 years.

There are certainly many unanswered questions about the effects of expanding CRC screening to those age 45 and older. Ongoing studies are needed to determine the cause of rising incidence, whether screening test selection and intervals should be customized for those under age 50, and how best to ensure equitable access to screening services. Finally, expanding screening to younger individuals should not detract from the critical importance of ongoing efforts to improve screening in those over age 50. As these issues are addressed by the scientific community, we cannot stand by idly when there is sufficient evidence to support that 45 is the new 50.

Dr. Patel is associate professor of medicine in the divisions of gastroenterology & hepatology at the University of Colorado and Rocky Mountain Regional Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Aurora, Colo. She disclosed financial relationships with Olympus America, ERBE USA, and Freenome.

References

1. Siegel RL et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw322.

2. USPSTF et al. JAMA. 2021 May 18;325(19):1965-77.

3. Butterly LF et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan;116(1):171-9.

4. Kolb JM et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.006.

5. Ladabaum U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul;157(1):137-48.

50 is still 50

BY LINDA RABENECK, MD, MPH, FRCPC

CRC screening of women and men aged 50-75 years at average risk has contributed to the overall decrease in the incidence and mortality from the disease in the United States. In 2009, the American College of Gastroenterology recommended that CRC screening among African Americans begin at age 45 years, and a recent study from Kaiser Permanente reported favorable results from FIT screening in this group.1 In 2018 the American Cancer Society surprised the field by releasing an updated recommendation to begin CRC screening in all women and men at age 45 years (Qualified Recommendation). This spring the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force released its updated recommendation to begin screening at age 45 years (B recommendation).2 The rationale for these updated recommendations is based on new information on the epidemiology of the disease in the United States that was incorporated into updated modeling.

What was this new information? An evaluation of time trends in CRC incidence by age group showed that, although the incidence of colon and rectal cancer among those 50 years and older has been decreasing for more than 2 decades, the incidence has been increasing for those younger than 50 years. As important as these CRC incidence trends are to recognize and understand, this does not imply we should start screening everyone in the general population aged 45-49 years. We need to recognize that the absolute increase in CRC incidence in those younger than 50 years is small, that we lack empirical evidence to support such a major change in screening practice, and that we need to consider potential unintended impacts.

When the rise in incidence among younger Americans was first reported there was much discussion about what it meant. It appears that the rise in incidence is a birth cohort effect among people born in the 1960s and subsequent years. Birth cohort effects imply exposures occurring in early life or those experienced by younger generations. Sorting out what these exposures might be is an area of intense research activity currently. Regardless of the drivers of the relative increase in CRC incidence among younger persons, though, it is important to note that the absolute increase is small. What do we mean by this?

As reported by Holli Loomans-Kropp, PhD, MPH, and colleagues,3 for those under age 50 years, the age-adjusted incidence of colon cancer decreased by 0.9% annually from 1980 to 1996, and then increased by 1.3% annually from 1996 to 2016 (Figure 1).

The figure shows that the age-adjusted incidence of rectal cancer among those under age 50 years increased by 2.3% annually since 1991. Figure 1 also shows declines in age-adjusted CRC incidence since 2001 for colon cancer and since 1998 for rectal cancer. However, note the differences in the scales on the Y axes between these two figures. Figure 2 shows this information plotted on the same scale (drawn by hand by author). To recap, these relative increases in incidence are real, but the absolute increases are small.

In addition, not surprisingly, we lack results from randomized controlled trials to support the change in CRC screening recommendation. We are just beginning to see results from other types of study design that seek to address this evidence gap. For example, a recent retrospective cohort study using information recorded in Florida databases evaluated the association between CRC incidence and undergoing colonoscopy at ages 45-49 versus 50-54 years. The authors reported a reduction in CRC incidence in both age groups.4

We also need to consider the resource implications. Lowering the age to start CRC screening to 45 years would expand the target population by greater than 20 million Americans, with all that this entails in terms of additional effort and resources, including colonoscopy. Modeling studies have shown that we would achieve greater clinical benefit with lower cost from directing these colonoscopy resources to those aged 50-75 years who are under/never screened and also ensuring follow-up colonoscopy among those with a positive FIT.5 For example, a study in a U.S. safety-net system reported that among 2,238 patients with a FIT+ followed over 1 year, only 55% underwent a colonoscopy.6

Finally, we need to reflect on existing disparities. If we turn our attention and resources to focus on all those aged 45-49 years in the general population, we risk worsening these disparities.

In conclusion, we need to redouble our efforts to reduce existing disparities in CRC screening participation among those aged 50-74 years and ensure colonoscopy follow-up in those with a FIT+ rather than divert our attention and resources to all those 45- to 49-year-olds who are at lower risk.

Dr. Rabeneck is professor of medicine at the University of Toronto. She has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Levin TR et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Nov;159(5):1695-704.e1.

2. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force et al. JAMA. 2021 May 18;325(19):1965-77.

3. Loomans-Kropp HA et al. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2019 Nov 11;2019:9841295.

4. Sehgal M et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):2018-28.e13.

5. Ladabaum U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul;157(1):137-48.

6. Issaka RB et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Feb;112(2):375-82.

Dear colleagues and friends,

The start age for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in average-risk individuals has been relatively uncontroversial and unchallenged, until recent guidelines that recommended decreasing the start age from 50 to 45 years. In this edition of Perspectives, two renowned experts, Dr. Patel and Dr. Rabeneck, debate the pros and cons of this paradigm change. This will be my final Perspectives contribution as associate editor for GI & Hep News. Thank you very much for your support and feedback, and I hope you have all enjoyed and learned from the Perspectives debates as much as I have. As always, your feedback and suggestions for future topics are welcome and can be sent to [email protected].

Charles J. Kahi, MD, MS, AGAF, is professor of medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

45 is the new 50

BY SWATI G. PATEL, MD, MS

The incidence and mortality rates of CRC in individuals under the age of 50 years, or early age–onset CRC, is increasing in the United States.1 We do not fully understand the cause of this trend; however, it has been observed in multiple Westernized countries, consistent with a birth cohort effect in which generation-specific risk factors are likely responsible.1 To address this rising burden of early age–onset CRC, multiple professional societies, including the United States Preventive Services Task Force,2 now recommend decreasing the starting age for CRC screening in average-risk individuals from 50 to 45 years. These recommendations are supported by the fact that CRC incidence in 45- to 49-year-olds is now the same as that of populations already eligible for screening; the yield of screening appears to be similar among those aged 45-49 years, compared to those aged 50-59 years; and modeling studies show that the benefits outweigh the risks and costs. These factors, along with the unique benefits of early detection and prevention in young patients, support that 45 is the new 50 when it comes to CRC screening.

CRC incidence rates among 45- to 49-year-olds now match populations that are already eligible for CRC screening. The rates among 45- to 49-year-olds now is similar to the incidence rates observed in 50-year-olds in 1992, before widespread CRC screening was performed. Overall incidence rates in 45- to 49-year-olds now match incidence rates observed in 45- to 49-year-old African Americans, a population in which the American College of Gastroenterology and the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force have recommended average-risk screening beginning at age 45.

Advanced colorectal neoplasia rates in 45- to 49-year-olds are similar to rates observed in 50- to 59-year-olds. One study found that advanced colorectal neoplasia rates (including advanced colorectal polyps and adenocarcinoma) in average risk–equivalent 45- to 49-year-olds are similar rates of 50- to 54-year-old average-risk individuals.3 Similarly, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 international studies including average-risk individuals undergoing colonoscopy found no significant difference between advanced colorectal neoplasia rates in 45- to 49-years-olds compared to 50- to 59-year-olds.4 These data suggest that expanding screening to average-risk individuals aged 45-49 years will have yield similar to that of those aged 50-59.

Modeling studies show that the benefits of screening outweigh the potential harms and costs. A recent cost-effectiveness analysis showed that starting average-risk screening at age 45 years with colonoscopy would cost $33,900 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) or $7,700 per QALY if annual FIT is selected as the screening modality.5 These costs are less than the widely accepted willingness to pay threshold of $50,000 per QALY and less than currently accepted average-risk screening, such as annual or biennial mammograms for breast cancer screening.

Expanding screening to 45- to 49-year-olds can improve early detection of CRC and prevention of CRC. Offering screening before age 50 years provides the opportunity to detect cancers at earlier stages, which can improve overall survival. Recent data have shown an increase in CRC incidence among 50- to 54-year-olds.1 Although the etiology of the rise in this age group is likely multifactorial (low screening rates or generational risk that individuals carry with them through the birth-cohort effect), diagnosis and removal of advanced colorectal polyps among 45- to 49-year-olds can have a positive impact on reversing this trend in 50- to 54-year-olds. Furthermore, initiating conversations about CRC screening at age 45 can improve uptake of screening among 50- to 54-year-olds who may have delayed screening when first offered at age 50.

There are unique benefits of early detection and prevention of CRC in young patients. Although the absolute incidence and mortality rates associated with CRC in those aged 45-49 are significantly lower than the rates observed in those over age 50, young individuals are more likely to be in the prime of their earning and fertility potential and are more likely to be caregivers to younger and older generations. They are more likely to face material, psychological, and behavioral financial hardships, such as difficulty paying bills. Absolute incidence rates and modeling studies that do not account for these intangible effects on survivorship also do not fully reflect the societal benefit of early detection and CRC prevention in those aged 45-49 years.

There are certainly many unanswered questions about the effects of expanding CRC screening to those age 45 and older. Ongoing studies are needed to determine the cause of rising incidence, whether screening test selection and intervals should be customized for those under age 50, and how best to ensure equitable access to screening services. Finally, expanding screening to younger individuals should not detract from the critical importance of ongoing efforts to improve screening in those over age 50. As these issues are addressed by the scientific community, we cannot stand by idly when there is sufficient evidence to support that 45 is the new 50.

Dr. Patel is associate professor of medicine in the divisions of gastroenterology & hepatology at the University of Colorado and Rocky Mountain Regional Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Aurora, Colo. She disclosed financial relationships with Olympus America, ERBE USA, and Freenome.

References

1. Siegel RL et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw322.

2. USPSTF et al. JAMA. 2021 May 18;325(19):1965-77.

3. Butterly LF et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan;116(1):171-9.

4. Kolb JM et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.006.

5. Ladabaum U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul;157(1):137-48.

50 is still 50

BY LINDA RABENECK, MD, MPH, FRCPC

CRC screening of women and men aged 50-75 years at average risk has contributed to the overall decrease in the incidence and mortality from the disease in the United States. In 2009, the American College of Gastroenterology recommended that CRC screening among African Americans begin at age 45 years, and a recent study from Kaiser Permanente reported favorable results from FIT screening in this group.1 In 2018 the American Cancer Society surprised the field by releasing an updated recommendation to begin CRC screening in all women and men at age 45 years (Qualified Recommendation). This spring the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force released its updated recommendation to begin screening at age 45 years (B recommendation).2 The rationale for these updated recommendations is based on new information on the epidemiology of the disease in the United States that was incorporated into updated modeling.

What was this new information? An evaluation of time trends in CRC incidence by age group showed that, although the incidence of colon and rectal cancer among those 50 years and older has been decreasing for more than 2 decades, the incidence has been increasing for those younger than 50 years. As important as these CRC incidence trends are to recognize and understand, this does not imply we should start screening everyone in the general population aged 45-49 years. We need to recognize that the absolute increase in CRC incidence in those younger than 50 years is small, that we lack empirical evidence to support such a major change in screening practice, and that we need to consider potential unintended impacts.

When the rise in incidence among younger Americans was first reported there was much discussion about what it meant. It appears that the rise in incidence is a birth cohort effect among people born in the 1960s and subsequent years. Birth cohort effects imply exposures occurring in early life or those experienced by younger generations. Sorting out what these exposures might be is an area of intense research activity currently. Regardless of the drivers of the relative increase in CRC incidence among younger persons, though, it is important to note that the absolute increase is small. What do we mean by this?

As reported by Holli Loomans-Kropp, PhD, MPH, and colleagues,3 for those under age 50 years, the age-adjusted incidence of colon cancer decreased by 0.9% annually from 1980 to 1996, and then increased by 1.3% annually from 1996 to 2016 (Figure 1).

The figure shows that the age-adjusted incidence of rectal cancer among those under age 50 years increased by 2.3% annually since 1991. Figure 1 also shows declines in age-adjusted CRC incidence since 2001 for colon cancer and since 1998 for rectal cancer. However, note the differences in the scales on the Y axes between these two figures. Figure 2 shows this information plotted on the same scale (drawn by hand by author). To recap, these relative increases in incidence are real, but the absolute increases are small.

In addition, not surprisingly, we lack results from randomized controlled trials to support the change in CRC screening recommendation. We are just beginning to see results from other types of study design that seek to address this evidence gap. For example, a recent retrospective cohort study using information recorded in Florida databases evaluated the association between CRC incidence and undergoing colonoscopy at ages 45-49 versus 50-54 years. The authors reported a reduction in CRC incidence in both age groups.4

We also need to consider the resource implications. Lowering the age to start CRC screening to 45 years would expand the target population by greater than 20 million Americans, with all that this entails in terms of additional effort and resources, including colonoscopy. Modeling studies have shown that we would achieve greater clinical benefit with lower cost from directing these colonoscopy resources to those aged 50-75 years who are under/never screened and also ensuring follow-up colonoscopy among those with a positive FIT.5 For example, a study in a U.S. safety-net system reported that among 2,238 patients with a FIT+ followed over 1 year, only 55% underwent a colonoscopy.6

Finally, we need to reflect on existing disparities. If we turn our attention and resources to focus on all those aged 45-49 years in the general population, we risk worsening these disparities.

In conclusion, we need to redouble our efforts to reduce existing disparities in CRC screening participation among those aged 50-74 years and ensure colonoscopy follow-up in those with a FIT+ rather than divert our attention and resources to all those 45- to 49-year-olds who are at lower risk.

Dr. Rabeneck is professor of medicine at the University of Toronto. She has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Levin TR et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Nov;159(5):1695-704.e1.

2. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force et al. JAMA. 2021 May 18;325(19):1965-77.

3. Loomans-Kropp HA et al. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2019 Nov 11;2019:9841295.

4. Sehgal M et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):2018-28.e13.

5. Ladabaum U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul;157(1):137-48.

6. Issaka RB et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Feb;112(2):375-82.