User login

This month in the journal CHEST®

Editor’s picks

Revisiting mild asthma: current knowledge and future needs. By Dr. A. Mohan, et al.

Treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus pulmonary disease. By Dr. D. Griffith, et al.

The utility of the rapid shallow breathing index in predicting successful extubation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. By Dr. K. Burns, et al.

National temporal trends in hospitalization and inpatient mortality in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis in the United States between 2007 – 2018. By Dr. N. Obi Ogugua, et al.

How I Do It: Considering lung transplantation for patients with COVID-19. By Dr. S. Nathan.

Addressing race in pulmonary function testing by aligning intent and evidence with practice and perception. By Dr. N. Bhakta, et al.

Editor’s picks

Editor’s picks

Revisiting mild asthma: current knowledge and future needs. By Dr. A. Mohan, et al.

Treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus pulmonary disease. By Dr. D. Griffith, et al.

The utility of the rapid shallow breathing index in predicting successful extubation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. By Dr. K. Burns, et al.

National temporal trends in hospitalization and inpatient mortality in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis in the United States between 2007 – 2018. By Dr. N. Obi Ogugua, et al.

How I Do It: Considering lung transplantation for patients with COVID-19. By Dr. S. Nathan.

Addressing race in pulmonary function testing by aligning intent and evidence with practice and perception. By Dr. N. Bhakta, et al.

Revisiting mild asthma: current knowledge and future needs. By Dr. A. Mohan, et al.

Treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus pulmonary disease. By Dr. D. Griffith, et al.

The utility of the rapid shallow breathing index in predicting successful extubation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. By Dr. K. Burns, et al.

National temporal trends in hospitalization and inpatient mortality in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis in the United States between 2007 – 2018. By Dr. N. Obi Ogugua, et al.

How I Do It: Considering lung transplantation for patients with COVID-19. By Dr. S. Nathan.

Addressing race in pulmonary function testing by aligning intent and evidence with practice and perception. By Dr. N. Bhakta, et al.

The people’s paper

With this issue, we usher in a new era for CHEST Physician, as I hand over the reins of Editor-in-Chief to Angel Coz, MD, FCCP. I have had the pleasure of serving in this role over the last 4 years, and though I will still have the privilege of appearing within these pages with some frequency as I move into my new role as CHEST President, I would like to mark this milestone by passing along a few thoughts on how CHEST Physician has developed over the last few years, and reflecting on the goals I set for us way back in the January 2018 issue (on page 46 of that issue, for those of you holding on to our back issues).

I’ve always viewed CHEST Physician as “the People’s Paper” of CHEST. While we don’t feature first-run scientific manuscripts and authors aren’t likely to reference our articles in other publications, your editorial board and our partners at Frontline aim to give our readers a broad overview of recent publications and presentations in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine, along with expert commentary about how those developments might affect the care we provide to our patients. I can’t thank our editorial board members enough for the hours they spend selecting a small number of items to feature among all of the new medical developments each month.

One of the main goals we had established over the last few years was to create more opportunities for CHEST Physician to serve as the voice of the members and leaders of the American College of Chest Physicians. We achieved the latter part of this goal, with leadership penning quarterly columns on actions of the Board of Regents, developments within the annual meeting, as well as ongoing columns from our NetWorks. And, we have also provided a more reliable voice for our members, with authors of our Sleep Strategies, Critical Care Commentary, and Pulmonary Perspectives columns providing a broader and more representative sample of our membership than ever before.

One of the areas where I would love to see more progress is with reader engagement. It has been a delight to receive feedback from CHEST members, even when the author is taking issue with something we have published. CHEST Physician will be a better publication than it already is with your ongoing input. Please, if you see something that we write that you particularly like (or don’t!) or if there’s something you’d like to see that we haven’t written, please reach out to us! You can always reach us at [email protected].

In closing, I want to thank all of the steadfast CHEST Physician readers for making my 4 years as Editor-in-Chief enjoyable and meaningful. While I am so pleased with the current state of this publication, I cannot wait to see its ongoing evolution under the leadership of Dr. Coz and his editorial board.

With this issue, we usher in a new era for CHEST Physician, as I hand over the reins of Editor-in-Chief to Angel Coz, MD, FCCP. I have had the pleasure of serving in this role over the last 4 years, and though I will still have the privilege of appearing within these pages with some frequency as I move into my new role as CHEST President, I would like to mark this milestone by passing along a few thoughts on how CHEST Physician has developed over the last few years, and reflecting on the goals I set for us way back in the January 2018 issue (on page 46 of that issue, for those of you holding on to our back issues).

I’ve always viewed CHEST Physician as “the People’s Paper” of CHEST. While we don’t feature first-run scientific manuscripts and authors aren’t likely to reference our articles in other publications, your editorial board and our partners at Frontline aim to give our readers a broad overview of recent publications and presentations in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine, along with expert commentary about how those developments might affect the care we provide to our patients. I can’t thank our editorial board members enough for the hours they spend selecting a small number of items to feature among all of the new medical developments each month.

One of the main goals we had established over the last few years was to create more opportunities for CHEST Physician to serve as the voice of the members and leaders of the American College of Chest Physicians. We achieved the latter part of this goal, with leadership penning quarterly columns on actions of the Board of Regents, developments within the annual meeting, as well as ongoing columns from our NetWorks. And, we have also provided a more reliable voice for our members, with authors of our Sleep Strategies, Critical Care Commentary, and Pulmonary Perspectives columns providing a broader and more representative sample of our membership than ever before.

One of the areas where I would love to see more progress is with reader engagement. It has been a delight to receive feedback from CHEST members, even when the author is taking issue with something we have published. CHEST Physician will be a better publication than it already is with your ongoing input. Please, if you see something that we write that you particularly like (or don’t!) or if there’s something you’d like to see that we haven’t written, please reach out to us! You can always reach us at [email protected].

In closing, I want to thank all of the steadfast CHEST Physician readers for making my 4 years as Editor-in-Chief enjoyable and meaningful. While I am so pleased with the current state of this publication, I cannot wait to see its ongoing evolution under the leadership of Dr. Coz and his editorial board.

With this issue, we usher in a new era for CHEST Physician, as I hand over the reins of Editor-in-Chief to Angel Coz, MD, FCCP. I have had the pleasure of serving in this role over the last 4 years, and though I will still have the privilege of appearing within these pages with some frequency as I move into my new role as CHEST President, I would like to mark this milestone by passing along a few thoughts on how CHEST Physician has developed over the last few years, and reflecting on the goals I set for us way back in the January 2018 issue (on page 46 of that issue, for those of you holding on to our back issues).

I’ve always viewed CHEST Physician as “the People’s Paper” of CHEST. While we don’t feature first-run scientific manuscripts and authors aren’t likely to reference our articles in other publications, your editorial board and our partners at Frontline aim to give our readers a broad overview of recent publications and presentations in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine, along with expert commentary about how those developments might affect the care we provide to our patients. I can’t thank our editorial board members enough for the hours they spend selecting a small number of items to feature among all of the new medical developments each month.

One of the main goals we had established over the last few years was to create more opportunities for CHEST Physician to serve as the voice of the members and leaders of the American College of Chest Physicians. We achieved the latter part of this goal, with leadership penning quarterly columns on actions of the Board of Regents, developments within the annual meeting, as well as ongoing columns from our NetWorks. And, we have also provided a more reliable voice for our members, with authors of our Sleep Strategies, Critical Care Commentary, and Pulmonary Perspectives columns providing a broader and more representative sample of our membership than ever before.

One of the areas where I would love to see more progress is with reader engagement. It has been a delight to receive feedback from CHEST members, even when the author is taking issue with something we have published. CHEST Physician will be a better publication than it already is with your ongoing input. Please, if you see something that we write that you particularly like (or don’t!) or if there’s something you’d like to see that we haven’t written, please reach out to us! You can always reach us at [email protected].

In closing, I want to thank all of the steadfast CHEST Physician readers for making my 4 years as Editor-in-Chief enjoyable and meaningful. While I am so pleased with the current state of this publication, I cannot wait to see its ongoing evolution under the leadership of Dr. Coz and his editorial board.

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: Migraine January 2022

Ferrari et al1 provided information on an open label extension to the “LIBERTY” study which investigated the use of erenumab in subjects with episodic migraine that have failed multiple prior preventive medications. The initial Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibody (mAb) studies excluded more refractory patients. Most commercial insurances in the United States have a “step” policy that relates to use of these and other newer medications, meaning that the majority of patient in the US who receive these medications have previously tried other preventive medications. This raised the question whether migraine refractoriness is a negative predictive factor for erenumab.

This long-term open label study is more like the real-world use of erenumab, and as such the results are similar to what many practitioners are seeing in their clinical experience. Approximately 25% of subjects discontinued erenumab, mostly due to ineffectiveness. Adverse events were mild, and although erenumab has warnings for constipation and hypertension, this study did not show either as increasing over 2 years. Erenumab appeared to be tolerable over time. There were no newly noted safety signals in this study.

The efficacy of erenumab also appeared to be stable over time, without the development of tolerance to the medication. There is a slight decrease in the 50% responder rate at 2 years when these more refractory patients are compared to those that did not have multiple treatment failures. This study also looked at “functional parameters,” such as Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) and Headache Impact Test (HIT-6), both of which were significantly improved over time.

Although there are some significant limitations in this study-primarily the fact that it is open label—this does give a more representative and real-world sample of patients who will be prescribed erenumab in the United States. Most practitioners will be glad to find that the long-term use of erenumab appears safe, and the efficacy remains stable, even in a more difficult-to-treat population.

A randomized controlled international study investigated the preventive use of occipital nerve blocks in migraine without aura.2 The majority of the literature for the use of occipital nerve blocks is for acute treatment, and arguably the most significant study prior to this was Friedman et al3 investigating the use of this procedure in the emergency ward. Prior occipital nerve studies have been inconclusive, and although occipital nerve blocks are considered standard of care for specific conditions in most headache centers, reimbursement is usually very limited. Insurance companies have quoted prior preventive occipital nerve studies to justify non-coverage of these procedures, making access to them for many patients very limited.

Occipital nerve blocks are not performed uniformly, both regarding the medications used—some practitioners use no steroids, some use lidocaine and bupivocaine—and regarding the placement of the injections. In this a small cohort study, 55 subjects were divided into four groups for intervention—one of which was a control group of saline—and all were given one 2.5 mL injection at a point in between the occipital protuberance and the mastoid process bilaterally. Due to adverse events (alopecia and cutaneous atrophy) in two of the triamcinolone groups, recruitment was halted for those two groups. Patients were assessed based on headache duration, frequency, and severity over a 4-week course.

Compared to baseline all interventional groups had significantly decreased headache severity, which did return closer to baseline during the final week. Headache duration was decreased in the first 2 weeks post-injection. Headache frequency was seen to return to baseline at week 4, but prior to that the groups injected with lidocaine had a significant decrease in migraine frequency, with an average decrease in headache days.

Occipital nerve blocks are performed frequently for migraine, occipital neuralgia, cervicogenic headache, and many other conditions with noted tenderness over the occiput. As noted above, they are not performed uniformly—sometimes they are given for acute headache pain or status migranosus, and other times they are used in regular intervals for prevention. This data does finally show a preventive benefit with occipital nerve blocks, and this may allow for modifications in how occipital nerve blocks are currently performed. Based on this study, if given preventively, occipital nerve blocks should only contain topical anesthetics, not steroids, and should be performed on an every 2-3 week basis.

The limitations of this study are significant as well. This is a very small cohort, and the injections were performed in only one manner (one bilateral injection), whereas many practitioners will target the greater and lesser branches of the occipital nerve individually. There were no exclusion criteria for subjects that already had occipital nerve blocks performed—those patients would be unblinded as there is a different sensation when injected with a topical anesthetic versus normal saline (normal saline does not cause burning subcutaneously).

These results should pave the way for further investigations in the use of occipital and other nerve blocks in the prevention of migraine. This should allow better access for our patients and the possibility of performing these procedures more uniformly in the future.

It can be challenging for many practitioners to determine which medication is ideal for individual situations. This is especially true when treating chronic migraine, where many potential complicating factors can influence positive to negative responses to treatment. The investigators here sought to determine which factors may potentially predict a positive response to galcanezumab.4

This is an observational study, where 156 subjects with a diagnosis of chronic migraine were enrolled. There was a 1-month run-in period where the following characteristics were collected: monthly headache days, monthly abortive medication intake, clinical features of migraine, and disability scores (MIDAS and HIT-6). These were tracked over a 3-month period after starting glacanezumab.

Approximately 40% of subjects experienced a 50% reduction in headache frequency. The better responders had a lower body mass index, fewer previously failed preventive medications, unilateral headache pain, and previous good response to triptan use. Surprisingly, the presence of medication overuse was associated with persistent improvement at 3 months as well, with over 60% of subjects with medication overuse no longer overusing acute medications at 3 months.

This study is helpful in identifying specific features that may allow a practitioner to better recommend CGRP mAb medications, such as galcanezumab. Chronic migraine can offer a challenge to even the best trained clinicians. Patients will often have multiple factors that have led to a conversion from episodic to chronic migraine, and a history of medication failures or intolerances. These patients are often referred specifically due to these challenges.

When deciding on a preventive medication for patients with chronic migraine, we often first consider which oral preventive medications may allow us to treat migraine in addition to another underlying issue—such as insomnia, depression, or hypertension. Although the oral class can improve other comorbidities, intolerance is significantly higher for most of these medications as well. The CGRP mAb class is somewhat more ideal for prevention of migraine; the focus when using this class is for migraine prevention alone, and the side effect profile is more tolerable for most patients. That said, if predictive factors were known a more individualized approach to migraine prevention would be possible.

The authors’ recognition of the factors associated with improvement in patients using glacanezumab allows this better individualization. Based on these results, patients with more unilateral pain, lower BMI, and good response to triptans could be recommended glacanuzumab with a great degree of confidence. This should be irrespective of even high frequency use of acute medications, as most of subjects in this study with medication overuse reverted after 3 months.

There is never a single ideal preventive or acute treatment for migraine in any population, however, recognizing factors that allow for an individualized approach improves the quality of life for our patients, and leaves them less disabled by migraine.

References

- Ferrari MD et al. Two-year efficacy and safety of erenumab in participants with episodic migraine and 2–4 prior preventive treatment failures: results from the LIBERTY study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021(Nov 29).

- Malekian N et al. Preventive effect of greater occipital nerve block on patients with episodic migraine: A randomized double‐blind placebo‐controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia. 2021(Nov 17).

- Friedman BW et al. A Randomized, Sham-Controlled Trial of Bilateral Greater Occipital Nerve Blocks With Bupivacaine for Acute Migraine Patients Refractory to Standard Emergency Department Treatment With Metoclopramide. Headache. 2018(Oct);58(9):1427-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13395.

- Vernieri F et al. Rapid response to galcanezumab and predictive factors in chronic migraine patients: A 3-month observational, longitudinal, cohort, multicenter, Italian real-life study. Eur J Neurol. 2021(Nov 26).

Ferrari et al1 provided information on an open label extension to the “LIBERTY” study which investigated the use of erenumab in subjects with episodic migraine that have failed multiple prior preventive medications. The initial Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibody (mAb) studies excluded more refractory patients. Most commercial insurances in the United States have a “step” policy that relates to use of these and other newer medications, meaning that the majority of patient in the US who receive these medications have previously tried other preventive medications. This raised the question whether migraine refractoriness is a negative predictive factor for erenumab.

This long-term open label study is more like the real-world use of erenumab, and as such the results are similar to what many practitioners are seeing in their clinical experience. Approximately 25% of subjects discontinued erenumab, mostly due to ineffectiveness. Adverse events were mild, and although erenumab has warnings for constipation and hypertension, this study did not show either as increasing over 2 years. Erenumab appeared to be tolerable over time. There were no newly noted safety signals in this study.

The efficacy of erenumab also appeared to be stable over time, without the development of tolerance to the medication. There is a slight decrease in the 50% responder rate at 2 years when these more refractory patients are compared to those that did not have multiple treatment failures. This study also looked at “functional parameters,” such as Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) and Headache Impact Test (HIT-6), both of which were significantly improved over time.

Although there are some significant limitations in this study-primarily the fact that it is open label—this does give a more representative and real-world sample of patients who will be prescribed erenumab in the United States. Most practitioners will be glad to find that the long-term use of erenumab appears safe, and the efficacy remains stable, even in a more difficult-to-treat population.

A randomized controlled international study investigated the preventive use of occipital nerve blocks in migraine without aura.2 The majority of the literature for the use of occipital nerve blocks is for acute treatment, and arguably the most significant study prior to this was Friedman et al3 investigating the use of this procedure in the emergency ward. Prior occipital nerve studies have been inconclusive, and although occipital nerve blocks are considered standard of care for specific conditions in most headache centers, reimbursement is usually very limited. Insurance companies have quoted prior preventive occipital nerve studies to justify non-coverage of these procedures, making access to them for many patients very limited.

Occipital nerve blocks are not performed uniformly, both regarding the medications used—some practitioners use no steroids, some use lidocaine and bupivocaine—and regarding the placement of the injections. In this a small cohort study, 55 subjects were divided into four groups for intervention—one of which was a control group of saline—and all were given one 2.5 mL injection at a point in between the occipital protuberance and the mastoid process bilaterally. Due to adverse events (alopecia and cutaneous atrophy) in two of the triamcinolone groups, recruitment was halted for those two groups. Patients were assessed based on headache duration, frequency, and severity over a 4-week course.

Compared to baseline all interventional groups had significantly decreased headache severity, which did return closer to baseline during the final week. Headache duration was decreased in the first 2 weeks post-injection. Headache frequency was seen to return to baseline at week 4, but prior to that the groups injected with lidocaine had a significant decrease in migraine frequency, with an average decrease in headache days.

Occipital nerve blocks are performed frequently for migraine, occipital neuralgia, cervicogenic headache, and many other conditions with noted tenderness over the occiput. As noted above, they are not performed uniformly—sometimes they are given for acute headache pain or status migranosus, and other times they are used in regular intervals for prevention. This data does finally show a preventive benefit with occipital nerve blocks, and this may allow for modifications in how occipital nerve blocks are currently performed. Based on this study, if given preventively, occipital nerve blocks should only contain topical anesthetics, not steroids, and should be performed on an every 2-3 week basis.

The limitations of this study are significant as well. This is a very small cohort, and the injections were performed in only one manner (one bilateral injection), whereas many practitioners will target the greater and lesser branches of the occipital nerve individually. There were no exclusion criteria for subjects that already had occipital nerve blocks performed—those patients would be unblinded as there is a different sensation when injected with a topical anesthetic versus normal saline (normal saline does not cause burning subcutaneously).

These results should pave the way for further investigations in the use of occipital and other nerve blocks in the prevention of migraine. This should allow better access for our patients and the possibility of performing these procedures more uniformly in the future.

It can be challenging for many practitioners to determine which medication is ideal for individual situations. This is especially true when treating chronic migraine, where many potential complicating factors can influence positive to negative responses to treatment. The investigators here sought to determine which factors may potentially predict a positive response to galcanezumab.4

This is an observational study, where 156 subjects with a diagnosis of chronic migraine were enrolled. There was a 1-month run-in period where the following characteristics were collected: monthly headache days, monthly abortive medication intake, clinical features of migraine, and disability scores (MIDAS and HIT-6). These were tracked over a 3-month period after starting glacanezumab.

Approximately 40% of subjects experienced a 50% reduction in headache frequency. The better responders had a lower body mass index, fewer previously failed preventive medications, unilateral headache pain, and previous good response to triptan use. Surprisingly, the presence of medication overuse was associated with persistent improvement at 3 months as well, with over 60% of subjects with medication overuse no longer overusing acute medications at 3 months.

This study is helpful in identifying specific features that may allow a practitioner to better recommend CGRP mAb medications, such as galcanezumab. Chronic migraine can offer a challenge to even the best trained clinicians. Patients will often have multiple factors that have led to a conversion from episodic to chronic migraine, and a history of medication failures or intolerances. These patients are often referred specifically due to these challenges.

When deciding on a preventive medication for patients with chronic migraine, we often first consider which oral preventive medications may allow us to treat migraine in addition to another underlying issue—such as insomnia, depression, or hypertension. Although the oral class can improve other comorbidities, intolerance is significantly higher for most of these medications as well. The CGRP mAb class is somewhat more ideal for prevention of migraine; the focus when using this class is for migraine prevention alone, and the side effect profile is more tolerable for most patients. That said, if predictive factors were known a more individualized approach to migraine prevention would be possible.

The authors’ recognition of the factors associated with improvement in patients using glacanezumab allows this better individualization. Based on these results, patients with more unilateral pain, lower BMI, and good response to triptans could be recommended glacanuzumab with a great degree of confidence. This should be irrespective of even high frequency use of acute medications, as most of subjects in this study with medication overuse reverted after 3 months.

There is never a single ideal preventive or acute treatment for migraine in any population, however, recognizing factors that allow for an individualized approach improves the quality of life for our patients, and leaves them less disabled by migraine.

References

- Ferrari MD et al. Two-year efficacy and safety of erenumab in participants with episodic migraine and 2–4 prior preventive treatment failures: results from the LIBERTY study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021(Nov 29).

- Malekian N et al. Preventive effect of greater occipital nerve block on patients with episodic migraine: A randomized double‐blind placebo‐controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia. 2021(Nov 17).

- Friedman BW et al. A Randomized, Sham-Controlled Trial of Bilateral Greater Occipital Nerve Blocks With Bupivacaine for Acute Migraine Patients Refractory to Standard Emergency Department Treatment With Metoclopramide. Headache. 2018(Oct);58(9):1427-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13395.

- Vernieri F et al. Rapid response to galcanezumab and predictive factors in chronic migraine patients: A 3-month observational, longitudinal, cohort, multicenter, Italian real-life study. Eur J Neurol. 2021(Nov 26).

Ferrari et al1 provided information on an open label extension to the “LIBERTY” study which investigated the use of erenumab in subjects with episodic migraine that have failed multiple prior preventive medications. The initial Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibody (mAb) studies excluded more refractory patients. Most commercial insurances in the United States have a “step” policy that relates to use of these and other newer medications, meaning that the majority of patient in the US who receive these medications have previously tried other preventive medications. This raised the question whether migraine refractoriness is a negative predictive factor for erenumab.

This long-term open label study is more like the real-world use of erenumab, and as such the results are similar to what many practitioners are seeing in their clinical experience. Approximately 25% of subjects discontinued erenumab, mostly due to ineffectiveness. Adverse events were mild, and although erenumab has warnings for constipation and hypertension, this study did not show either as increasing over 2 years. Erenumab appeared to be tolerable over time. There were no newly noted safety signals in this study.

The efficacy of erenumab also appeared to be stable over time, without the development of tolerance to the medication. There is a slight decrease in the 50% responder rate at 2 years when these more refractory patients are compared to those that did not have multiple treatment failures. This study also looked at “functional parameters,” such as Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) and Headache Impact Test (HIT-6), both of which were significantly improved over time.

Although there are some significant limitations in this study-primarily the fact that it is open label—this does give a more representative and real-world sample of patients who will be prescribed erenumab in the United States. Most practitioners will be glad to find that the long-term use of erenumab appears safe, and the efficacy remains stable, even in a more difficult-to-treat population.

A randomized controlled international study investigated the preventive use of occipital nerve blocks in migraine without aura.2 The majority of the literature for the use of occipital nerve blocks is for acute treatment, and arguably the most significant study prior to this was Friedman et al3 investigating the use of this procedure in the emergency ward. Prior occipital nerve studies have been inconclusive, and although occipital nerve blocks are considered standard of care for specific conditions in most headache centers, reimbursement is usually very limited. Insurance companies have quoted prior preventive occipital nerve studies to justify non-coverage of these procedures, making access to them for many patients very limited.

Occipital nerve blocks are not performed uniformly, both regarding the medications used—some practitioners use no steroids, some use lidocaine and bupivocaine—and regarding the placement of the injections. In this a small cohort study, 55 subjects were divided into four groups for intervention—one of which was a control group of saline—and all were given one 2.5 mL injection at a point in between the occipital protuberance and the mastoid process bilaterally. Due to adverse events (alopecia and cutaneous atrophy) in two of the triamcinolone groups, recruitment was halted for those two groups. Patients were assessed based on headache duration, frequency, and severity over a 4-week course.

Compared to baseline all interventional groups had significantly decreased headache severity, which did return closer to baseline during the final week. Headache duration was decreased in the first 2 weeks post-injection. Headache frequency was seen to return to baseline at week 4, but prior to that the groups injected with lidocaine had a significant decrease in migraine frequency, with an average decrease in headache days.

Occipital nerve blocks are performed frequently for migraine, occipital neuralgia, cervicogenic headache, and many other conditions with noted tenderness over the occiput. As noted above, they are not performed uniformly—sometimes they are given for acute headache pain or status migranosus, and other times they are used in regular intervals for prevention. This data does finally show a preventive benefit with occipital nerve blocks, and this may allow for modifications in how occipital nerve blocks are currently performed. Based on this study, if given preventively, occipital nerve blocks should only contain topical anesthetics, not steroids, and should be performed on an every 2-3 week basis.

The limitations of this study are significant as well. This is a very small cohort, and the injections were performed in only one manner (one bilateral injection), whereas many practitioners will target the greater and lesser branches of the occipital nerve individually. There were no exclusion criteria for subjects that already had occipital nerve blocks performed—those patients would be unblinded as there is a different sensation when injected with a topical anesthetic versus normal saline (normal saline does not cause burning subcutaneously).

These results should pave the way for further investigations in the use of occipital and other nerve blocks in the prevention of migraine. This should allow better access for our patients and the possibility of performing these procedures more uniformly in the future.

It can be challenging for many practitioners to determine which medication is ideal for individual situations. This is especially true when treating chronic migraine, where many potential complicating factors can influence positive to negative responses to treatment. The investigators here sought to determine which factors may potentially predict a positive response to galcanezumab.4

This is an observational study, where 156 subjects with a diagnosis of chronic migraine were enrolled. There was a 1-month run-in period where the following characteristics were collected: monthly headache days, monthly abortive medication intake, clinical features of migraine, and disability scores (MIDAS and HIT-6). These were tracked over a 3-month period after starting glacanezumab.

Approximately 40% of subjects experienced a 50% reduction in headache frequency. The better responders had a lower body mass index, fewer previously failed preventive medications, unilateral headache pain, and previous good response to triptan use. Surprisingly, the presence of medication overuse was associated with persistent improvement at 3 months as well, with over 60% of subjects with medication overuse no longer overusing acute medications at 3 months.

This study is helpful in identifying specific features that may allow a practitioner to better recommend CGRP mAb medications, such as galcanezumab. Chronic migraine can offer a challenge to even the best trained clinicians. Patients will often have multiple factors that have led to a conversion from episodic to chronic migraine, and a history of medication failures or intolerances. These patients are often referred specifically due to these challenges.

When deciding on a preventive medication for patients with chronic migraine, we often first consider which oral preventive medications may allow us to treat migraine in addition to another underlying issue—such as insomnia, depression, or hypertension. Although the oral class can improve other comorbidities, intolerance is significantly higher for most of these medications as well. The CGRP mAb class is somewhat more ideal for prevention of migraine; the focus when using this class is for migraine prevention alone, and the side effect profile is more tolerable for most patients. That said, if predictive factors were known a more individualized approach to migraine prevention would be possible.

The authors’ recognition of the factors associated with improvement in patients using glacanezumab allows this better individualization. Based on these results, patients with more unilateral pain, lower BMI, and good response to triptans could be recommended glacanuzumab with a great degree of confidence. This should be irrespective of even high frequency use of acute medications, as most of subjects in this study with medication overuse reverted after 3 months.

There is never a single ideal preventive or acute treatment for migraine in any population, however, recognizing factors that allow for an individualized approach improves the quality of life for our patients, and leaves them less disabled by migraine.

References

- Ferrari MD et al. Two-year efficacy and safety of erenumab in participants with episodic migraine and 2–4 prior preventive treatment failures: results from the LIBERTY study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021(Nov 29).

- Malekian N et al. Preventive effect of greater occipital nerve block on patients with episodic migraine: A randomized double‐blind placebo‐controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia. 2021(Nov 17).

- Friedman BW et al. A Randomized, Sham-Controlled Trial of Bilateral Greater Occipital Nerve Blocks With Bupivacaine for Acute Migraine Patients Refractory to Standard Emergency Department Treatment With Metoclopramide. Headache. 2018(Oct);58(9):1427-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13395.

- Vernieri F et al. Rapid response to galcanezumab and predictive factors in chronic migraine patients: A 3-month observational, longitudinal, cohort, multicenter, Italian real-life study. Eur J Neurol. 2021(Nov 26).

Much lower risk of false-positive breast screen in Norway versus U.S.

Nearly 1 in 5 women who receive the recommended 10 biennial screening rounds for breast cancer in Norway will get a false positive result, and 1 in 20 women will receive a false positive result that leads to an invasive procedure, a new analysis shows.

While the risk may seem high, it is actually much lower than what researchers have reported in the U.S., the study authors note in their paper, published online Dec. 21 in Cancer.

“I am proud about the low rate of recalls we have in Norway and Europe – and hope we can keep it that low for the future,” said senior author Solveig Hofvind, PhD, head of BreastScreen Norway, a nationwide screening program that invites women aged 50 to 69 to mammographic screening every other year.

“The double reading in Europe is probably the main reason for the lower rate in Europe compared to the U.S., where single reading is used,” she said in an interview.

Until now, Dr. Hofvind and her colleagues say, no studies have been performed using exclusively empirical data to describe the cumulative risk of experiencing a false positive screening result in Europe because of the need for long-term follow-up and complete data registration.

For their study, the researchers turned to the Cancer Registry of Norway, which administers BreastScreen Norway. They focused on data from 1995 to 2019 on women aged 50 to 69 years who had attended one or more screening rounds and could potentially attend all 10 screening examinations over the 20-year period.

Women were excluded if they were diagnosed with breast cancer before attending screening, participated in interventional research, self-referred for screening, were recalled due to self-reported symptoms or technically inadequate mammograms, or declined follow-up after a positive screen.

Among more than 421,000 women who underwent nearly 1.9 million screening examinations, 11.3% experienced at least one false positive result and 3.3% experienced at least one false positive involving an invasive procedure, such as fine-needle aspiration cytology, core-needle biopsy, or open biopsy.

The cumulative risk of experiencing a first false positive screen was 18.0% and that of experiencing a false positive that involved an invasive procedure was 5.01%. Adjusting for irregular attendance, age at screening, or the number of screens attended had little effect on the estimates.

The results closely match earlier findings from Norway that have been based on assumptions rather than exclusively empirical data. However, these findings differ from results reported in U.S. studies, which have relied largely on data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium, the researchers say.

“The latter have indicated that, for women who initiate biennial screening at the age of 50 years, the cumulative risk after 10 years is 42% for experiencing at least one false-positive screening result and 6.4% for experiencing at least one false-positive screening result involving an invasive procedure,” Dr. Hofvind and her colleagues write.

Several principal investigators with the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium did not respond or were unavailable for comment when contacted by this news organization.

However, the study authors highlighted several factors that could help explain the discrepancy between the U.S. and European results.

In addition to double mammogram reading, “European guidelines recommend that breast radiologists read 3,500 to 11,000 mammograms annually, whereas 960 every 2 years are required by the U.S. Mammography Quality Standards Act,” the researchers note. They also point out that previous screening mammograms are readily available in Norway, whereas this is not always the case in the U.S.

“False-positive screening results are a part of the screening for breast cancer – and the women need to be informed about the risk,” Dr. Hofvind concluded. “The screening programs should aim to keep the rate as low as possible for the women [given] the costs.”

The study was supported by the Dam Foundation via the Norwegian Breast Cancer Society.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly 1 in 5 women who receive the recommended 10 biennial screening rounds for breast cancer in Norway will get a false positive result, and 1 in 20 women will receive a false positive result that leads to an invasive procedure, a new analysis shows.

While the risk may seem high, it is actually much lower than what researchers have reported in the U.S., the study authors note in their paper, published online Dec. 21 in Cancer.

“I am proud about the low rate of recalls we have in Norway and Europe – and hope we can keep it that low for the future,” said senior author Solveig Hofvind, PhD, head of BreastScreen Norway, a nationwide screening program that invites women aged 50 to 69 to mammographic screening every other year.

“The double reading in Europe is probably the main reason for the lower rate in Europe compared to the U.S., where single reading is used,” she said in an interview.

Until now, Dr. Hofvind and her colleagues say, no studies have been performed using exclusively empirical data to describe the cumulative risk of experiencing a false positive screening result in Europe because of the need for long-term follow-up and complete data registration.

For their study, the researchers turned to the Cancer Registry of Norway, which administers BreastScreen Norway. They focused on data from 1995 to 2019 on women aged 50 to 69 years who had attended one or more screening rounds and could potentially attend all 10 screening examinations over the 20-year period.

Women were excluded if they were diagnosed with breast cancer before attending screening, participated in interventional research, self-referred for screening, were recalled due to self-reported symptoms or technically inadequate mammograms, or declined follow-up after a positive screen.

Among more than 421,000 women who underwent nearly 1.9 million screening examinations, 11.3% experienced at least one false positive result and 3.3% experienced at least one false positive involving an invasive procedure, such as fine-needle aspiration cytology, core-needle biopsy, or open biopsy.

The cumulative risk of experiencing a first false positive screen was 18.0% and that of experiencing a false positive that involved an invasive procedure was 5.01%. Adjusting for irregular attendance, age at screening, or the number of screens attended had little effect on the estimates.

The results closely match earlier findings from Norway that have been based on assumptions rather than exclusively empirical data. However, these findings differ from results reported in U.S. studies, which have relied largely on data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium, the researchers say.

“The latter have indicated that, for women who initiate biennial screening at the age of 50 years, the cumulative risk after 10 years is 42% for experiencing at least one false-positive screening result and 6.4% for experiencing at least one false-positive screening result involving an invasive procedure,” Dr. Hofvind and her colleagues write.

Several principal investigators with the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium did not respond or were unavailable for comment when contacted by this news organization.

However, the study authors highlighted several factors that could help explain the discrepancy between the U.S. and European results.

In addition to double mammogram reading, “European guidelines recommend that breast radiologists read 3,500 to 11,000 mammograms annually, whereas 960 every 2 years are required by the U.S. Mammography Quality Standards Act,” the researchers note. They also point out that previous screening mammograms are readily available in Norway, whereas this is not always the case in the U.S.

“False-positive screening results are a part of the screening for breast cancer – and the women need to be informed about the risk,” Dr. Hofvind concluded. “The screening programs should aim to keep the rate as low as possible for the women [given] the costs.”

The study was supported by the Dam Foundation via the Norwegian Breast Cancer Society.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly 1 in 5 women who receive the recommended 10 biennial screening rounds for breast cancer in Norway will get a false positive result, and 1 in 20 women will receive a false positive result that leads to an invasive procedure, a new analysis shows.

While the risk may seem high, it is actually much lower than what researchers have reported in the U.S., the study authors note in their paper, published online Dec. 21 in Cancer.

“I am proud about the low rate of recalls we have in Norway and Europe – and hope we can keep it that low for the future,” said senior author Solveig Hofvind, PhD, head of BreastScreen Norway, a nationwide screening program that invites women aged 50 to 69 to mammographic screening every other year.

“The double reading in Europe is probably the main reason for the lower rate in Europe compared to the U.S., where single reading is used,” she said in an interview.

Until now, Dr. Hofvind and her colleagues say, no studies have been performed using exclusively empirical data to describe the cumulative risk of experiencing a false positive screening result in Europe because of the need for long-term follow-up and complete data registration.

For their study, the researchers turned to the Cancer Registry of Norway, which administers BreastScreen Norway. They focused on data from 1995 to 2019 on women aged 50 to 69 years who had attended one or more screening rounds and could potentially attend all 10 screening examinations over the 20-year period.

Women were excluded if they were diagnosed with breast cancer before attending screening, participated in interventional research, self-referred for screening, were recalled due to self-reported symptoms or technically inadequate mammograms, or declined follow-up after a positive screen.

Among more than 421,000 women who underwent nearly 1.9 million screening examinations, 11.3% experienced at least one false positive result and 3.3% experienced at least one false positive involving an invasive procedure, such as fine-needle aspiration cytology, core-needle biopsy, or open biopsy.

The cumulative risk of experiencing a first false positive screen was 18.0% and that of experiencing a false positive that involved an invasive procedure was 5.01%. Adjusting for irregular attendance, age at screening, or the number of screens attended had little effect on the estimates.

The results closely match earlier findings from Norway that have been based on assumptions rather than exclusively empirical data. However, these findings differ from results reported in U.S. studies, which have relied largely on data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium, the researchers say.

“The latter have indicated that, for women who initiate biennial screening at the age of 50 years, the cumulative risk after 10 years is 42% for experiencing at least one false-positive screening result and 6.4% for experiencing at least one false-positive screening result involving an invasive procedure,” Dr. Hofvind and her colleagues write.

Several principal investigators with the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium did not respond or were unavailable for comment when contacted by this news organization.

However, the study authors highlighted several factors that could help explain the discrepancy between the U.S. and European results.

In addition to double mammogram reading, “European guidelines recommend that breast radiologists read 3,500 to 11,000 mammograms annually, whereas 960 every 2 years are required by the U.S. Mammography Quality Standards Act,” the researchers note. They also point out that previous screening mammograms are readily available in Norway, whereas this is not always the case in the U.S.

“False-positive screening results are a part of the screening for breast cancer – and the women need to be informed about the risk,” Dr. Hofvind concluded. “The screening programs should aim to keep the rate as low as possible for the women [given] the costs.”

The study was supported by the Dam Foundation via the Norwegian Breast Cancer Society.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

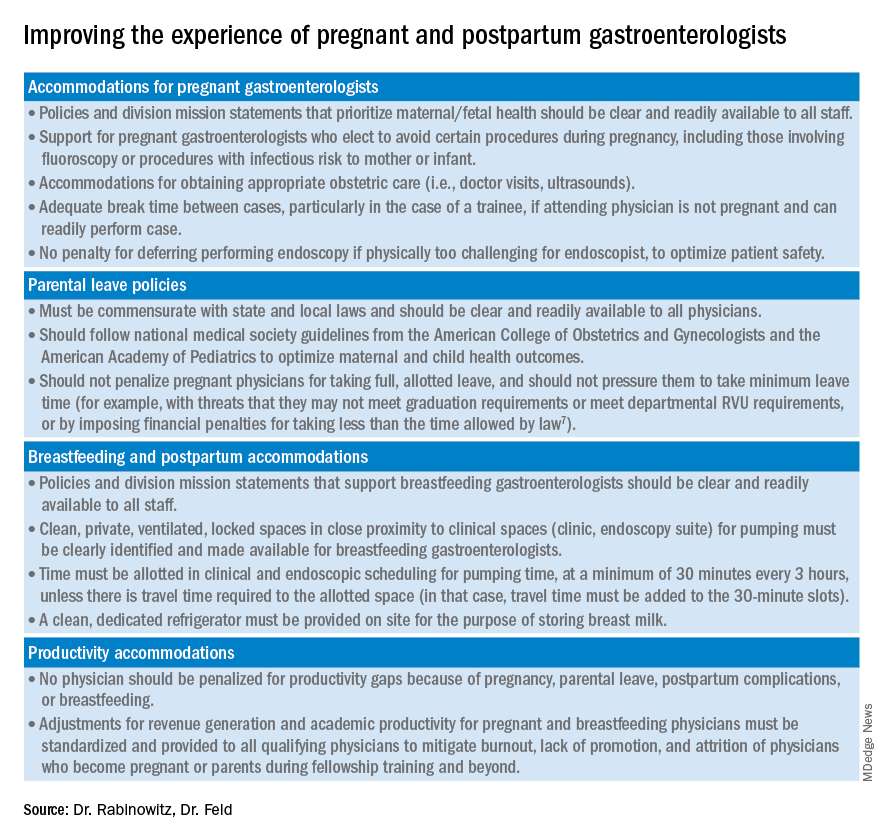

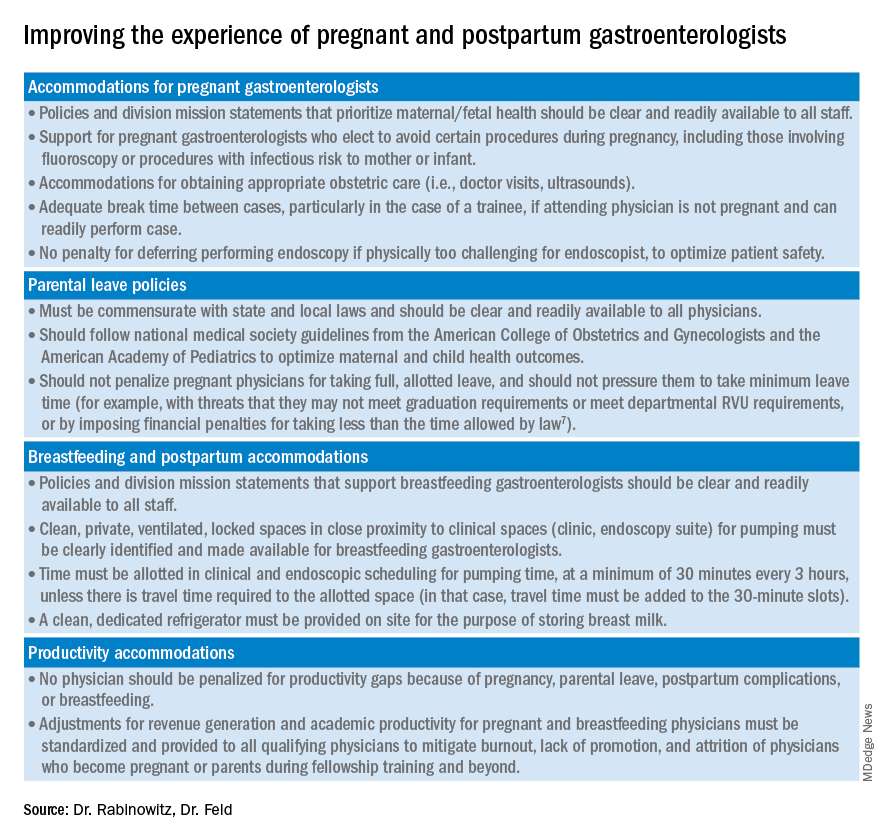

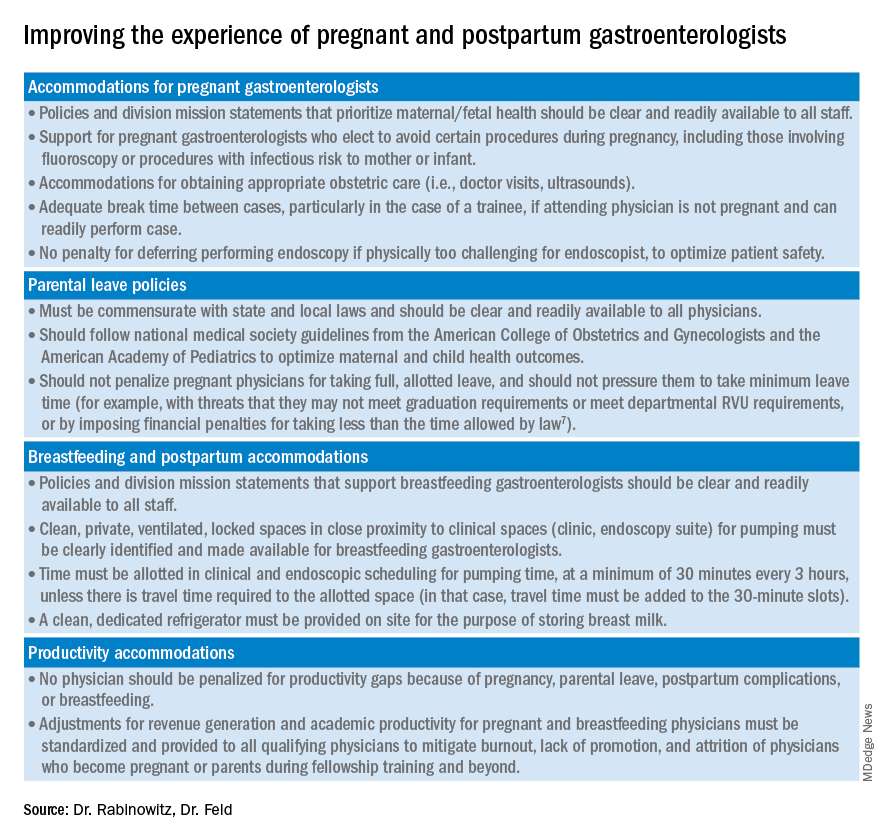

Progress still needed for pregnant and postpartum gastroenterologists

Despite increasing numbers joining the field, women remain a minority group in gastroenterology, where they constitute only 18% of these physicians.1 Additionally, women continue to be underrepresented among senior faculty and in leadership roles in both academic and private practice settings.2 While women now make up a majority of medical school matriculants3,4 women trainees are frequently dissuaded from pursuing specialty fellowships following residency, particularly in procedurally based fields like gastroenterology, because of perceived incompatibility with childbearing and child-rearing.5-8 For many who choose to enter the field despite these challenges, gastroenterology training and early practice often coincide with childbearing years.910 These structural impediments may contribute to the “leaky pipeline” and female physician attrition during the first decade of independent practice after fellowship.11-13 Urgent changes are needed in order to retain and support clinicians and physician-scientists through this period so that they, their offspring, their patients, and the field are able to thrive.

Fertility and pregnancy

The decision to have a child is a major milestone for many physicians and often occurs during gastroenterology training or early practice.10 Medical-training and early-career environments are not yet optimized to support women who become pregnant. At baseline, the formative years of a career are challenging ones, punctuated by long hours and both intellectually and emotionally demanding work. They are also often physically grueling, particularly while one is learning and becoming efficient in endoscopy. The ergonomics in the endoscopy suite (as in other areas of medicine) are not optimized for physicians of shorter stature, smaller hand sizes, and those who may have difficulty pushing a several-hundred-pound endoscopy cart bedside, all of which contribute to increased injury risk for female proceduralists.7,14-16 Methods to reduce endoscopic injuries in pregnant endoscopists have not yet been studied. Additionally, the existence of maternity and gender bias has been well-documented, in our field and beyond.17-20 Not surprisingly, women in gastroenterology commonly report delayed childbearing, with expected consequences, including increased infertility rates, compared with nonphysician peers.21 After 5 and 10 years as attendings, female gastroenterologists continue to report fewer children than male colleagues.22,23 Once pregnant, there are a number of field-specific challenges to navigate. These include decisions about the safety of performing procedures involving fluoroscopy or high infectious risk, particularly early in pregnancy when organogenesis occurs.7,24 Additionally, engaging in appropriate obstetric care can be challenging given the need for regular physician and ultrasound appointments.

Simple, cost-efficient interventions may be effective in decreasing infertility rates, pregnancy loss, and poor physician experiences during pregnancy. For one, all gastroenterology divisions could craft written policies that include a no-tolerance approach to expressions of maternity bias against pregnant or postpartum trainees and faculty.12,25 Additionally, ergonomic improvements, such as standing pads, dial extenders, and adjusted screen heights may decrease injury rates and increase comfort for female endoscopists.26,27 There should also be a no-penalty, no-questions-asked approach for any female endoscopist who defers performance of an obstetrically high-risk procedure to a nonpregnant colleague. Additionally, pregnant gastroenterologists should be supported in obtaining high-quality obstetric care. At an individual level, nonpregnant gastroenterologists, and particularly male allies, can support pregnant colleagues by agreeing to perform higher-risk procedures, stepping in if a fellow is unable to perform endoscopy because of pregnancy, and by offering to push the endoscopy cart on behalf of a pregnant colleague to bedside, if necessary.10,28

Parental leave

Following delivery, parental leave presents an additional challenge for the physician parent. Paid maternal leave has been associated with improved child and maternal outcomes and is widely available to physicians outside the United States.29,30 At present, duration of leave varies significantly by career stage (fellows versus attending), practice setting (academic center versus private practice), and geographic location. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a minimum of 12 weeks of leave.31 This length has been associated with lower rates of postpartum depression and higher rates of sustained breastfeeding, with subsequent improved health outcomes for mother and child.32-34 An increasing number of states have passed laws mandating minimum paid and unpaid parental leave time (for example, in Massachusetts, gastroenterology trainees and faculty are afforded 12 weeks of leave, in accordance with state law).35 Recent changes to board eligibility and training requirements via the American Board of Medical Specialties and the American Council for Graduate Medical Education now provide 6 weeks for parental leave. This is an improvement over prior policies which rendered many physician-parents board-ineligible if they took more than 4 weeks of leave, although it must be noted that even the revised policies allow for less time than either that of Obstetricians and Gynecologists or than the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends.

Our data, presented at the 2021 ACG conference, suggest that many trainees report receiving 4 weeks or less of parental leave, despite the ACGME and ABMS policies described above. We also found that physicians were frequently not aware of their institution or division leave policies.10 Ideally, all gastroenterology divisions in the United States would follow the recommended leave duration set forth by the medical societies of specialties that care for pregnant and postpartum mothers and their infants. Additionally, the impact of leave time on graduation and board eligibility, as well as academic and practice promotion, should be made clear at the time of leave and should minimize adverse consequences for the careers of pregnant and postpartum gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology trainees and faculty should be educated in the existence and details of their institution or practice policies, and these policies should be made readily available to all physicians and administrators.

Postpartum period

The transition back to work is a challenging one for mothers in all fields of medicine, particularly for those returning to procedurally based subspecialties such as gastroenterology. This is especially true for trainees and faculty who have returned to work sooner than the recommended 12 weeks and for those who are post cesarean section, for whom physical healing may not be complete. Long days performing endoscopy may be physically challenging or impossible for some women during the postpartum period. Additionally, expressing breast milk, a metabolically intensive activity, also necessitates time, space, and privacy to perform and is frequently made more difficult by insufficient lactation accommodations. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased logistic challenges for lactating mothers, because of the need for well-ventilated lactation spaces to minimize infectious risk.19 Our colleagues have reported pumping in their vehicles, in supply closets, and in spaces that require so much travel time (in addition to time required to express milk, store milk, and clean pump equipment) that the practice was unsustainable, and the physician stopped breastfeeding prematurely.36

The benefits of breastfeeding for mother and infant are well-established, and exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life is supported by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, whose position statement reads as follows: “Policies that protect the right of a woman and her child to breastfeed ... and that accommodate milk expression, such as ... paid maternity leave, on-site childcare, break time for expressing milk, and a clean, private location for expressing milk, are essential to sustaining breastfeeding.”37 We would add to these recommendations provision of dedicated milk storage space and establishment of clear, supportive policies that allow lactating physicians to breastfeed and express breast milk if they choose without career penalty. Several institutions offer scheduled protected clinical time and modified work relative value units (RVU) for lactating physicians, such that returning parents can have protected time for expressing breast milk and still meet RVU targets.38 Additionally, many academic institutions offer productivity adjustments for tenure-track faculty who have recently had children.

Creating a more supportive environment for women gastroenterologists who desire children allows the field to be more representative of our patient population and has been shown to positively impact outcomes from improved colorectal cancer screening rates to more guideline-directed informed consent conversations.39-41 Gastroenterology should comprise a physician workforce predicated on clinical and research excellence alone and should not require its practitioners to delay or abstain from pregnancy and child rearing. Robust, clear, and generous parental leave and postpartum accommodations will allow the field to retain and promote talented physicians, who will then contribute to the betterment of patients and the field over decades.

Dr. Rabinowitz is a faculty member in the department of medicine and division of gastroenterology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Feld is a transplant hepatology fellow, division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Rabinowitz and Dr. Feld have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

1. AAMC. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. 2018.

2. Colleges AoAM. The State of Women in Academic Medicine: The Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership, 2015-2016. 2016. www.aamc.org/download/481206/data/2015table11.pdf.

3. AAMC. Table B-3: Total U.S. Medical School Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity and Sex, 2014-2015 through 2018-2019, 2019.

4. Rabinowitz LG. Recognizing blind spots – a remedy for gender bias in medicine? (N Engl. J Med. 2018; 378[24]: 2253-5).

5. Douglas PS et al. Career preferences and perceptions of cardiology among US internal medicine trainees: Factors influencing cardiology career choice. JAMA Cardiol 2018; 3(8):682-91.

6. Stack SW et al. Childbearing decisions in residency: A multicenter survey of female residents. Acad Med 2020;95(10):1550-7.

7. David YN et al. Pregnancy and the working gastroenterologist: Perceptions, realities, and systemic challenges. Gastroenterology 2021;161(3):756-60.

8. Rembacken BJ et al. Barriers and bias standing in the way of female trainees wanting to learn advanced endoscopy. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(8):1141-5.

9. Arlow FL et al. Gastroenterology training and career choices: A prospective longitudinal study of the impact of gender and of managed care. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(2):459-69.

10. Feld L et al. Parental leave for gastroenterology fellows: A national survey of current fellows. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:S611-2.

11. Rabinowitz LG et al. Addressing gender in gastroenterology: opportunities for change. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91(1):155-61.

12. Feld LD. Baby steps in the right direction: Toward a parental leave policy for gastroenterology fellows. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):505-8.

13. Feld LD. Interviewing for two. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;116(3):445-6

14. Rabinowitz LG et al. Gender dynamics in education and practice of gastroenterology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(5):1047-56.e5.

15. Harvin G. Review of musculoskeletal injuries and prevention in the endoscopy practitioner. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(7):590-4.

16. LabX Oecs. www.labx.com/product/endoscopy-cart (accessed 2021 Nov 19.

17. Heilman ME and Okimoto TG. Motherhood: A potential source of bias in employment decisions. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(1):189-98.

18. Robinson K et al. Racism, bias, and discrimination as modifiable barriers to breastfeeding for African American women: A scoping review of the literature. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2019;64(6):734-42.

19. Rabinowitz LG and Rabinowitz DG. Women on the Frontline: A Changed Workforce and the Fight Against COVID-19. Acad Med. 2021 Jun 1;96(6):808-12.

20. Rabinowitz LG et al. Gender in the endoscopy suite. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Dec;5(12):1032-4.

21. Stentz NC et al. Fertility and childbearing among American female physicians. J Womens Health. 2016; 25(10):1059-65.

22. Burke CA et al. Gender disparity in the practice of gastroenterology: The first 5 years of a career. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(2):259-64.

23. Singh A et al. Women in gastroenterology committee of American College of G. Do gender disparities persist in gastroenterology after 10 years of practice? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(7):1589-95.

24. Krueger KJ and Hoffman BJ. Radiation exposure during gastroenterologic fluoroscopy: Risk assessment for pregnant workers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(4):429-31.

25. Krause ML et al. Impact of pregnancy and gender on internal medicine resident evaluations: A retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):648-53.

26. Pawa S et al. Are all endoscopy-related musculoskeletal injuries created equal? Results of a national gender-based survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):530-8.

27. David YN et al. Gender-specific factors influencing gastroenterologists to pursue careers in advanced endoscopy: perceptions vs reality. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):539-50.

28. Bilal M et al. The need for allyship in achieving gender equity in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Oct 19. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001508. Online ahead of print.

29. Jou J et al. Paid maternity leave in the United States: Associations with maternal and infant health. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(2):216-25.

30. Aitken Z et al. The maternal health outcomes of paid maternity leave: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;130:32-41.

31. Dodson NA and Talib HJ. Paid parental leave for mothers and fathers can improve physician wellness. AAP News. 2020 Jul 1. https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/12432.

32. Kornfeind KR and Sipsma HL. Exploring the link between maternity leave and postpartum depression. Womens Health Issues 2018;28(4):321-6.

33. Navarro-Rosenblatt D and Garmendia ML. Maternity leave and its impact on breastfeeding: A review of the literature. Breastfeed Med 2018;13(9):589-97.

34. Stack SW et al. Maternity leave in residency: A multicenter study of determinants and wellness outcomes. Acad Med. 2019;94(11):1738-45.

35. Mass.gov. Paid Family and Medical Leave Information for Massachusetts Employers. 2020.

36. Ares Segura S et al. en representacion del Comite de Lactancia Materna de la Asociacion Espanola de P. [The importance of maternal nutrition during breastfeeding: Do breastfeeding mothers need nutritional supplements?]. An Pediatr. (Barc) 2016;84(6):347 e1-7.

37. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 658: Optimizing Support for Breastfeeding as Part of Obstetric Practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(2):e86-92.

38. Porter KK et al. A lactation credit model to support breastfeeding in radiology: The new gold standard to support “liquid gold.” Clin Imaging 2021;80:16-8.

39. Davis J et al. Clinical practice patterns suggest female patients prefer female endoscopists. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(10):3149-50.

40. Menees SB et al. Women patients’ preference for women physicians is a barrier to colon cancer screening. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(2):219-23.

41. Feld LD et al. Management of code status in the periendoscopic period: A national survey of current practices and beliefs of U.S. gastroenterologists. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(1):172-7.e2.

Despite increasing numbers joining the field, women remain a minority group in gastroenterology, where they constitute only 18% of these physicians.1 Additionally, women continue to be underrepresented among senior faculty and in leadership roles in both academic and private practice settings.2 While women now make up a majority of medical school matriculants3,4 women trainees are frequently dissuaded from pursuing specialty fellowships following residency, particularly in procedurally based fields like gastroenterology, because of perceived incompatibility with childbearing and child-rearing.5-8 For many who choose to enter the field despite these challenges, gastroenterology training and early practice often coincide with childbearing years.910 These structural impediments may contribute to the “leaky pipeline” and female physician attrition during the first decade of independent practice after fellowship.11-13 Urgent changes are needed in order to retain and support clinicians and physician-scientists through this period so that they, their offspring, their patients, and the field are able to thrive.

Fertility and pregnancy

The decision to have a child is a major milestone for many physicians and often occurs during gastroenterology training or early practice.10 Medical-training and early-career environments are not yet optimized to support women who become pregnant. At baseline, the formative years of a career are challenging ones, punctuated by long hours and both intellectually and emotionally demanding work. They are also often physically grueling, particularly while one is learning and becoming efficient in endoscopy. The ergonomics in the endoscopy suite (as in other areas of medicine) are not optimized for physicians of shorter stature, smaller hand sizes, and those who may have difficulty pushing a several-hundred-pound endoscopy cart bedside, all of which contribute to increased injury risk for female proceduralists.7,14-16 Methods to reduce endoscopic injuries in pregnant endoscopists have not yet been studied. Additionally, the existence of maternity and gender bias has been well-documented, in our field and beyond.17-20 Not surprisingly, women in gastroenterology commonly report delayed childbearing, with expected consequences, including increased infertility rates, compared with nonphysician peers.21 After 5 and 10 years as attendings, female gastroenterologists continue to report fewer children than male colleagues.22,23 Once pregnant, there are a number of field-specific challenges to navigate. These include decisions about the safety of performing procedures involving fluoroscopy or high infectious risk, particularly early in pregnancy when organogenesis occurs.7,24 Additionally, engaging in appropriate obstetric care can be challenging given the need for regular physician and ultrasound appointments.

Simple, cost-efficient interventions may be effective in decreasing infertility rates, pregnancy loss, and poor physician experiences during pregnancy. For one, all gastroenterology divisions could craft written policies that include a no-tolerance approach to expressions of maternity bias against pregnant or postpartum trainees and faculty.12,25 Additionally, ergonomic improvements, such as standing pads, dial extenders, and adjusted screen heights may decrease injury rates and increase comfort for female endoscopists.26,27 There should also be a no-penalty, no-questions-asked approach for any female endoscopist who defers performance of an obstetrically high-risk procedure to a nonpregnant colleague. Additionally, pregnant gastroenterologists should be supported in obtaining high-quality obstetric care. At an individual level, nonpregnant gastroenterologists, and particularly male allies, can support pregnant colleagues by agreeing to perform higher-risk procedures, stepping in if a fellow is unable to perform endoscopy because of pregnancy, and by offering to push the endoscopy cart on behalf of a pregnant colleague to bedside, if necessary.10,28

Parental leave

Following delivery, parental leave presents an additional challenge for the physician parent. Paid maternal leave has been associated with improved child and maternal outcomes and is widely available to physicians outside the United States.29,30 At present, duration of leave varies significantly by career stage (fellows versus attending), practice setting (academic center versus private practice), and geographic location. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a minimum of 12 weeks of leave.31 This length has been associated with lower rates of postpartum depression and higher rates of sustained breastfeeding, with subsequent improved health outcomes for mother and child.32-34 An increasing number of states have passed laws mandating minimum paid and unpaid parental leave time (for example, in Massachusetts, gastroenterology trainees and faculty are afforded 12 weeks of leave, in accordance with state law).35 Recent changes to board eligibility and training requirements via the American Board of Medical Specialties and the American Council for Graduate Medical Education now provide 6 weeks for parental leave. This is an improvement over prior policies which rendered many physician-parents board-ineligible if they took more than 4 weeks of leave, although it must be noted that even the revised policies allow for less time than either that of Obstetricians and Gynecologists or than the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends.

Our data, presented at the 2021 ACG conference, suggest that many trainees report receiving 4 weeks or less of parental leave, despite the ACGME and ABMS policies described above. We also found that physicians were frequently not aware of their institution or division leave policies.10 Ideally, all gastroenterology divisions in the United States would follow the recommended leave duration set forth by the medical societies of specialties that care for pregnant and postpartum mothers and their infants. Additionally, the impact of leave time on graduation and board eligibility, as well as academic and practice promotion, should be made clear at the time of leave and should minimize adverse consequences for the careers of pregnant and postpartum gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology trainees and faculty should be educated in the existence and details of their institution or practice policies, and these policies should be made readily available to all physicians and administrators.

Postpartum period

The transition back to work is a challenging one for mothers in all fields of medicine, particularly for those returning to procedurally based subspecialties such as gastroenterology. This is especially true for trainees and faculty who have returned to work sooner than the recommended 12 weeks and for those who are post cesarean section, for whom physical healing may not be complete. Long days performing endoscopy may be physically challenging or impossible for some women during the postpartum period. Additionally, expressing breast milk, a metabolically intensive activity, also necessitates time, space, and privacy to perform and is frequently made more difficult by insufficient lactation accommodations. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased logistic challenges for lactating mothers, because of the need for well-ventilated lactation spaces to minimize infectious risk.19 Our colleagues have reported pumping in their vehicles, in supply closets, and in spaces that require so much travel time (in addition to time required to express milk, store milk, and clean pump equipment) that the practice was unsustainable, and the physician stopped breastfeeding prematurely.36

The benefits of breastfeeding for mother and infant are well-established, and exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life is supported by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, whose position statement reads as follows: “Policies that protect the right of a woman and her child to breastfeed ... and that accommodate milk expression, such as ... paid maternity leave, on-site childcare, break time for expressing milk, and a clean, private location for expressing milk, are essential to sustaining breastfeeding.”37 We would add to these recommendations provision of dedicated milk storage space and establishment of clear, supportive policies that allow lactating physicians to breastfeed and express breast milk if they choose without career penalty. Several institutions offer scheduled protected clinical time and modified work relative value units (RVU) for lactating physicians, such that returning parents can have protected time for expressing breast milk and still meet RVU targets.38 Additionally, many academic institutions offer productivity adjustments for tenure-track faculty who have recently had children.

Creating a more supportive environment for women gastroenterologists who desire children allows the field to be more representative of our patient population and has been shown to positively impact outcomes from improved colorectal cancer screening rates to more guideline-directed informed consent conversations.39-41 Gastroenterology should comprise a physician workforce predicated on clinical and research excellence alone and should not require its practitioners to delay or abstain from pregnancy and child rearing. Robust, clear, and generous parental leave and postpartum accommodations will allow the field to retain and promote talented physicians, who will then contribute to the betterment of patients and the field over decades.

Dr. Rabinowitz is a faculty member in the department of medicine and division of gastroenterology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Feld is a transplant hepatology fellow, division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Rabinowitz and Dr. Feld have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

1. AAMC. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. 2018.

2. Colleges AoAM. The State of Women in Academic Medicine: The Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership, 2015-2016. 2016. www.aamc.org/download/481206/data/2015table11.pdf.

3. AAMC. Table B-3: Total U.S. Medical School Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity and Sex, 2014-2015 through 2018-2019, 2019.

4. Rabinowitz LG. Recognizing blind spots – a remedy for gender bias in medicine? (N Engl. J Med. 2018; 378[24]: 2253-5).

5. Douglas PS et al. Career preferences and perceptions of cardiology among US internal medicine trainees: Factors influencing cardiology career choice. JAMA Cardiol 2018; 3(8):682-91.

6. Stack SW et al. Childbearing decisions in residency: A multicenter survey of female residents. Acad Med 2020;95(10):1550-7.