User login

Pure Mucinous Breast Cancer Shows Better Survival Rates Than Other Subtypes

TOPLINE:

Patients with PMBC had a 5-year RFI of 96.1%, RFS of 94.9%, and OS of 98.1%.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analyzed data from 23,102 women diagnosed with hormone receptor–positive HER2-negative stage I-III breast cancer, including 20,684 with IDC, 1475 with ILC, and 943 with PMBC.

- The multicenter cohort study included patients who underwent primary breast surgery at six academic institutions in Singapore, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan between January 2000 and December 2015.

- Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines “recommend consideration of adjuvant chemotherapy only for node-positive tumors,” whereas adjuvant endocrine therapy is recommended for estrogen receptor–positive and/or progesterone receptor–positive, node-positive tumors or tumors ≥ 3 cm. Previous studies have reported no significant association between adjuvant chemotherapy and breast cancer–specific survival or OS in patients with early-stage mucinous breast carcinoma.

- The study aimed to compare the recurrence and survival outcomes of PMBC against IDC and ILC, identify clinicopathologic prognostic factors of PMBC, and explore the association of adjuvant systemic therapy with outcomes across subgroups of PMBC.

- Extracted information included patient demographics, tumor characteristics, treatment administered, and staging according to the AJCC TNM classifications.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients with PMBC had better RFI (hazard ratio [HR], 0.59; 95% CI, 0.43-0.80), RFS (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.56-0.89), and OS (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.53-0.96) than patients with IDC in multivariable Cox regression analyses.

- Fewer than half (48.7%) of the recurrences in patients with PMBC were distant, which was a lower rate than for patients with IDC (67.3%) and ILC (80.6%).

- Significant prognostic factors for RFI in PMBC included positive lymph node(s) (HR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.08-5.40), radiotherapy (HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.23-0.85), and endocrine therapy (HR, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.09-0.70).

- No differential chemotherapy associations with outcomes were detected across PMBC subgroups by nodal stage, tumor size, and age.

IN PRACTICE:

“This international multicenter cohort study on PMBC evaluated one of the largest contemporary real-world datasets for clinical prognostic factors, which also includes valuable data on relapse events, associations of adjuvant systemic therapy, and a comparison with the SEER database,” wrote the authors of the study. “In our cohort, as anticipated, PMBC showed superior RFI, RFS, and OS compared with IDC and ILC, which both had comparatively similar survival outcomes.”

SOURCE:

Corresponding author, Yoon-Sim Yap, MBBS, PhD, of the National Cancer Centre Singapore in Singapore, designed the study. The paper was published online on May 14 in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective nature over a long period and lack of a central pathology review in this study are among its limitations. The high extent of missing values for tumor grade in PMBC in the multicenter cohort could impact the identified prognostic factors. The study’s findings may not be generalizable to all populations due to the specific geographic locations of the participating institutions.

DISCLOSURES:

Study author Yeon Hee Park, MD, PhD, disclosed serving on a data safety monitoring board and on an advisory board for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Roche, Menarini, Novartis, and Daiichi Sankyo and serving as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead Sciences, Merck, Eisai, Roche, Daiichi Sankyo, Menarini, Everest Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Patients with PMBC had a 5-year RFI of 96.1%, RFS of 94.9%, and OS of 98.1%.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analyzed data from 23,102 women diagnosed with hormone receptor–positive HER2-negative stage I-III breast cancer, including 20,684 with IDC, 1475 with ILC, and 943 with PMBC.

- The multicenter cohort study included patients who underwent primary breast surgery at six academic institutions in Singapore, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan between January 2000 and December 2015.

- Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines “recommend consideration of adjuvant chemotherapy only for node-positive tumors,” whereas adjuvant endocrine therapy is recommended for estrogen receptor–positive and/or progesterone receptor–positive, node-positive tumors or tumors ≥ 3 cm. Previous studies have reported no significant association between adjuvant chemotherapy and breast cancer–specific survival or OS in patients with early-stage mucinous breast carcinoma.

- The study aimed to compare the recurrence and survival outcomes of PMBC against IDC and ILC, identify clinicopathologic prognostic factors of PMBC, and explore the association of adjuvant systemic therapy with outcomes across subgroups of PMBC.

- Extracted information included patient demographics, tumor characteristics, treatment administered, and staging according to the AJCC TNM classifications.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients with PMBC had better RFI (hazard ratio [HR], 0.59; 95% CI, 0.43-0.80), RFS (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.56-0.89), and OS (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.53-0.96) than patients with IDC in multivariable Cox regression analyses.

- Fewer than half (48.7%) of the recurrences in patients with PMBC were distant, which was a lower rate than for patients with IDC (67.3%) and ILC (80.6%).

- Significant prognostic factors for RFI in PMBC included positive lymph node(s) (HR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.08-5.40), radiotherapy (HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.23-0.85), and endocrine therapy (HR, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.09-0.70).

- No differential chemotherapy associations with outcomes were detected across PMBC subgroups by nodal stage, tumor size, and age.

IN PRACTICE:

“This international multicenter cohort study on PMBC evaluated one of the largest contemporary real-world datasets for clinical prognostic factors, which also includes valuable data on relapse events, associations of adjuvant systemic therapy, and a comparison with the SEER database,” wrote the authors of the study. “In our cohort, as anticipated, PMBC showed superior RFI, RFS, and OS compared with IDC and ILC, which both had comparatively similar survival outcomes.”

SOURCE:

Corresponding author, Yoon-Sim Yap, MBBS, PhD, of the National Cancer Centre Singapore in Singapore, designed the study. The paper was published online on May 14 in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective nature over a long period and lack of a central pathology review in this study are among its limitations. The high extent of missing values for tumor grade in PMBC in the multicenter cohort could impact the identified prognostic factors. The study’s findings may not be generalizable to all populations due to the specific geographic locations of the participating institutions.

DISCLOSURES:

Study author Yeon Hee Park, MD, PhD, disclosed serving on a data safety monitoring board and on an advisory board for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Roche, Menarini, Novartis, and Daiichi Sankyo and serving as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead Sciences, Merck, Eisai, Roche, Daiichi Sankyo, Menarini, Everest Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Patients with PMBC had a 5-year RFI of 96.1%, RFS of 94.9%, and OS of 98.1%.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analyzed data from 23,102 women diagnosed with hormone receptor–positive HER2-negative stage I-III breast cancer, including 20,684 with IDC, 1475 with ILC, and 943 with PMBC.

- The multicenter cohort study included patients who underwent primary breast surgery at six academic institutions in Singapore, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan between January 2000 and December 2015.

- Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines “recommend consideration of adjuvant chemotherapy only for node-positive tumors,” whereas adjuvant endocrine therapy is recommended for estrogen receptor–positive and/or progesterone receptor–positive, node-positive tumors or tumors ≥ 3 cm. Previous studies have reported no significant association between adjuvant chemotherapy and breast cancer–specific survival or OS in patients with early-stage mucinous breast carcinoma.

- The study aimed to compare the recurrence and survival outcomes of PMBC against IDC and ILC, identify clinicopathologic prognostic factors of PMBC, and explore the association of adjuvant systemic therapy with outcomes across subgroups of PMBC.

- Extracted information included patient demographics, tumor characteristics, treatment administered, and staging according to the AJCC TNM classifications.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients with PMBC had better RFI (hazard ratio [HR], 0.59; 95% CI, 0.43-0.80), RFS (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.56-0.89), and OS (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.53-0.96) than patients with IDC in multivariable Cox regression analyses.

- Fewer than half (48.7%) of the recurrences in patients with PMBC were distant, which was a lower rate than for patients with IDC (67.3%) and ILC (80.6%).

- Significant prognostic factors for RFI in PMBC included positive lymph node(s) (HR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.08-5.40), radiotherapy (HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.23-0.85), and endocrine therapy (HR, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.09-0.70).

- No differential chemotherapy associations with outcomes were detected across PMBC subgroups by nodal stage, tumor size, and age.

IN PRACTICE:

“This international multicenter cohort study on PMBC evaluated one of the largest contemporary real-world datasets for clinical prognostic factors, which also includes valuable data on relapse events, associations of adjuvant systemic therapy, and a comparison with the SEER database,” wrote the authors of the study. “In our cohort, as anticipated, PMBC showed superior RFI, RFS, and OS compared with IDC and ILC, which both had comparatively similar survival outcomes.”

SOURCE:

Corresponding author, Yoon-Sim Yap, MBBS, PhD, of the National Cancer Centre Singapore in Singapore, designed the study. The paper was published online on May 14 in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective nature over a long period and lack of a central pathology review in this study are among its limitations. The high extent of missing values for tumor grade in PMBC in the multicenter cohort could impact the identified prognostic factors. The study’s findings may not be generalizable to all populations due to the specific geographic locations of the participating institutions.

DISCLOSURES:

Study author Yeon Hee Park, MD, PhD, disclosed serving on a data safety monitoring board and on an advisory board for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Roche, Menarini, Novartis, and Daiichi Sankyo and serving as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead Sciences, Merck, Eisai, Roche, Daiichi Sankyo, Menarini, Everest Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Immunotherapy and Survival in Advanced NSCLC: Does Obesity Matter?

TOPLINE:

Overall, however, compared with low body mass index (BMI), overweight or obesity was associated with a lower risk for mortality among patients receiving either therapy.

METHODOLOGY:

- The association between BMI and overall survival in patients with cancer who receive immunotherapy or conventional chemotherapy in the frontline remains unclear. Patients with cancer and obesity are generally considered to have a worse prognosis, but some data suggest an obesity paradox, where patients with cancer and a higher BMI demonstrate better overall survival following immunotherapy or chemotherapy.

- To clarify whether (or how) BMI affects overall survival outcomes and the optimal frontline treatment choice, researchers evaluated 31,257 patients with advanced NSCLC from Japan who received immune checkpoint inhibitors (n = 12,816) or conventional chemotherapy (n = 18,441).

- Patient outcomes were assessed according to weight categories and frontline therapy type (immune checkpoint inhibitors or conventional chemotherapy), with overall survival as the primary outcome.

- A BMI < 18.5 was considered underweight, 18.5-24.9 was considered normal weight, 25.0-29.9 was considered overweight, and ≥ 30.0 was considered obese.

TAKEAWAY:

- In the overall population, regardless of weight, patients who received chemotherapy had a higher mortality rate than those who received immunotherapy — 35.9% vs 28.0%, respectively — over a follow-up of 3 years.

- However, overweight or obesity was associated with a lower risk for mortality compared with a lower BMI among patients with advanced NSCLC, regardless of whether they received immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy or conventional chemotherapy.

- Among patients who received immunotherapy, the risk for mortality decreased steadily as BMI increased from 15 to 24 and then increased at higher BMIs, indicating a U-shaped association.

- Immunotherapy was associated with a significant improvement in overall survival compared with conventional chemotherapy among patients with a BMI < 28; however, researchers observed no difference in overall survival between the two therapies in those with a BMI ≥ 28.

IN PRACTICE:

Overall, “these results support the presence of the obesity paradox in patients with [advanced] NSCLC who underwent either therapy,” the authors concluded.

But when focused on patients in the higher BMI group, there was no overall survival benefit with the frontline immunotherapy vs the conventional chemotherapy. “Immunotherapy therapy may not necessarily be the optimal first-line therapy for patients with overweight or obesity,” the authors wrote, adding that “the use of conventional chemotherapy should also be considered.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Yasutaka Ihara, PharmD, Osaka Metropolitan University, Osaka, Japan, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Retrospective design has inherent bias. PD-L1 status was not known, and the inclusion of Japanese population may have limited the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study received funding from the Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka Metropolitan University. Several authors reported receiving personal fees from various pharmaceutical sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Overall, however, compared with low body mass index (BMI), overweight or obesity was associated with a lower risk for mortality among patients receiving either therapy.

METHODOLOGY:

- The association between BMI and overall survival in patients with cancer who receive immunotherapy or conventional chemotherapy in the frontline remains unclear. Patients with cancer and obesity are generally considered to have a worse prognosis, but some data suggest an obesity paradox, where patients with cancer and a higher BMI demonstrate better overall survival following immunotherapy or chemotherapy.

- To clarify whether (or how) BMI affects overall survival outcomes and the optimal frontline treatment choice, researchers evaluated 31,257 patients with advanced NSCLC from Japan who received immune checkpoint inhibitors (n = 12,816) or conventional chemotherapy (n = 18,441).

- Patient outcomes were assessed according to weight categories and frontline therapy type (immune checkpoint inhibitors or conventional chemotherapy), with overall survival as the primary outcome.

- A BMI < 18.5 was considered underweight, 18.5-24.9 was considered normal weight, 25.0-29.9 was considered overweight, and ≥ 30.0 was considered obese.

TAKEAWAY:

- In the overall population, regardless of weight, patients who received chemotherapy had a higher mortality rate than those who received immunotherapy — 35.9% vs 28.0%, respectively — over a follow-up of 3 years.

- However, overweight or obesity was associated with a lower risk for mortality compared with a lower BMI among patients with advanced NSCLC, regardless of whether they received immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy or conventional chemotherapy.

- Among patients who received immunotherapy, the risk for mortality decreased steadily as BMI increased from 15 to 24 and then increased at higher BMIs, indicating a U-shaped association.

- Immunotherapy was associated with a significant improvement in overall survival compared with conventional chemotherapy among patients with a BMI < 28; however, researchers observed no difference in overall survival between the two therapies in those with a BMI ≥ 28.

IN PRACTICE:

Overall, “these results support the presence of the obesity paradox in patients with [advanced] NSCLC who underwent either therapy,” the authors concluded.

But when focused on patients in the higher BMI group, there was no overall survival benefit with the frontline immunotherapy vs the conventional chemotherapy. “Immunotherapy therapy may not necessarily be the optimal first-line therapy for patients with overweight or obesity,” the authors wrote, adding that “the use of conventional chemotherapy should also be considered.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Yasutaka Ihara, PharmD, Osaka Metropolitan University, Osaka, Japan, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Retrospective design has inherent bias. PD-L1 status was not known, and the inclusion of Japanese population may have limited the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study received funding from the Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka Metropolitan University. Several authors reported receiving personal fees from various pharmaceutical sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Overall, however, compared with low body mass index (BMI), overweight or obesity was associated with a lower risk for mortality among patients receiving either therapy.

METHODOLOGY:

- The association between BMI and overall survival in patients with cancer who receive immunotherapy or conventional chemotherapy in the frontline remains unclear. Patients with cancer and obesity are generally considered to have a worse prognosis, but some data suggest an obesity paradox, where patients with cancer and a higher BMI demonstrate better overall survival following immunotherapy or chemotherapy.

- To clarify whether (or how) BMI affects overall survival outcomes and the optimal frontline treatment choice, researchers evaluated 31,257 patients with advanced NSCLC from Japan who received immune checkpoint inhibitors (n = 12,816) or conventional chemotherapy (n = 18,441).

- Patient outcomes were assessed according to weight categories and frontline therapy type (immune checkpoint inhibitors or conventional chemotherapy), with overall survival as the primary outcome.

- A BMI < 18.5 was considered underweight, 18.5-24.9 was considered normal weight, 25.0-29.9 was considered overweight, and ≥ 30.0 was considered obese.

TAKEAWAY:

- In the overall population, regardless of weight, patients who received chemotherapy had a higher mortality rate than those who received immunotherapy — 35.9% vs 28.0%, respectively — over a follow-up of 3 years.

- However, overweight or obesity was associated with a lower risk for mortality compared with a lower BMI among patients with advanced NSCLC, regardless of whether they received immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy or conventional chemotherapy.

- Among patients who received immunotherapy, the risk for mortality decreased steadily as BMI increased from 15 to 24 and then increased at higher BMIs, indicating a U-shaped association.

- Immunotherapy was associated with a significant improvement in overall survival compared with conventional chemotherapy among patients with a BMI < 28; however, researchers observed no difference in overall survival between the two therapies in those with a BMI ≥ 28.

IN PRACTICE:

Overall, “these results support the presence of the obesity paradox in patients with [advanced] NSCLC who underwent either therapy,” the authors concluded.

But when focused on patients in the higher BMI group, there was no overall survival benefit with the frontline immunotherapy vs the conventional chemotherapy. “Immunotherapy therapy may not necessarily be the optimal first-line therapy for patients with overweight or obesity,” the authors wrote, adding that “the use of conventional chemotherapy should also be considered.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Yasutaka Ihara, PharmD, Osaka Metropolitan University, Osaka, Japan, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Retrospective design has inherent bias. PD-L1 status was not known, and the inclusion of Japanese population may have limited the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study received funding from the Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka Metropolitan University. Several authors reported receiving personal fees from various pharmaceutical sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Xanthelasma Not Linked to Heart Diseases, Study Finds

TOPLINE:

Xanthelasma palpebrarum, characterized by yellowish plaques on the eyelids, is not associated with increased rates of dyslipidemia or cardiovascular disease.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a case-control study at a single tertiary care center in Israel and analyzed data from 35,452 individuals (mean age, 52.2 years; 69% men) who underwent medical screening from 2001 to 2020.

- They compared 203 patients with xanthelasma palpebrarum with 2030 individuals without the disease (control).

- Primary outcomes were prevalence of dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease between the two groups.

TAKEAWAY:

- Lipid profiles were similar between the two groups, with no difference in total cholesterol, high- and low-density lipoprotein, and triglyceride levels (all P > .05).

- The prevalence of dyslipidemia was similar for patients with xanthelasma palpebrarum and controls (46% vs 42%, respectively; P = .29), as was the incidence of cardiovascular disease (8.9% vs 10%, respectively; P = .56).

- The incidence of diabetes (P = .13), cerebrovascular accidents (P > .99), ischemic heart disease (P = .73), and hypertension (P = .56) were not significantly different between the two groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study conducted on a large population of individuals undergoing comprehensive ophthalmic and systemic screening tests did not find a significant association between xanthelasma palpebrarum and an increased prevalence of lipid abnormalities or cardiovascular disease,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yael Lustig, MD, of the Goldschleger Eye Institute at Sheba Medical Center, in Ramat Gan, Israel. It was published online on August 5, 2024, in Ophthalmology.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective nature of the study and the single-center design may have limited the generalizability of the findings. The study population was self-selected, potentially introducing selection bias. Lack of histopathologic examination could have affected the accuracy of the diagnosis.

DISCLOSURES:

No funding sources were disclosed for this study. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Xanthelasma palpebrarum, characterized by yellowish plaques on the eyelids, is not associated with increased rates of dyslipidemia or cardiovascular disease.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a case-control study at a single tertiary care center in Israel and analyzed data from 35,452 individuals (mean age, 52.2 years; 69% men) who underwent medical screening from 2001 to 2020.

- They compared 203 patients with xanthelasma palpebrarum with 2030 individuals without the disease (control).

- Primary outcomes were prevalence of dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease between the two groups.

TAKEAWAY:

- Lipid profiles were similar between the two groups, with no difference in total cholesterol, high- and low-density lipoprotein, and triglyceride levels (all P > .05).

- The prevalence of dyslipidemia was similar for patients with xanthelasma palpebrarum and controls (46% vs 42%, respectively; P = .29), as was the incidence of cardiovascular disease (8.9% vs 10%, respectively; P = .56).

- The incidence of diabetes (P = .13), cerebrovascular accidents (P > .99), ischemic heart disease (P = .73), and hypertension (P = .56) were not significantly different between the two groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study conducted on a large population of individuals undergoing comprehensive ophthalmic and systemic screening tests did not find a significant association between xanthelasma palpebrarum and an increased prevalence of lipid abnormalities or cardiovascular disease,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yael Lustig, MD, of the Goldschleger Eye Institute at Sheba Medical Center, in Ramat Gan, Israel. It was published online on August 5, 2024, in Ophthalmology.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective nature of the study and the single-center design may have limited the generalizability of the findings. The study population was self-selected, potentially introducing selection bias. Lack of histopathologic examination could have affected the accuracy of the diagnosis.

DISCLOSURES:

No funding sources were disclosed for this study. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Xanthelasma palpebrarum, characterized by yellowish plaques on the eyelids, is not associated with increased rates of dyslipidemia or cardiovascular disease.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a case-control study at a single tertiary care center in Israel and analyzed data from 35,452 individuals (mean age, 52.2 years; 69% men) who underwent medical screening from 2001 to 2020.

- They compared 203 patients with xanthelasma palpebrarum with 2030 individuals without the disease (control).

- Primary outcomes were prevalence of dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease between the two groups.

TAKEAWAY:

- Lipid profiles were similar between the two groups, with no difference in total cholesterol, high- and low-density lipoprotein, and triglyceride levels (all P > .05).

- The prevalence of dyslipidemia was similar for patients with xanthelasma palpebrarum and controls (46% vs 42%, respectively; P = .29), as was the incidence of cardiovascular disease (8.9% vs 10%, respectively; P = .56).

- The incidence of diabetes (P = .13), cerebrovascular accidents (P > .99), ischemic heart disease (P = .73), and hypertension (P = .56) were not significantly different between the two groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study conducted on a large population of individuals undergoing comprehensive ophthalmic and systemic screening tests did not find a significant association between xanthelasma palpebrarum and an increased prevalence of lipid abnormalities or cardiovascular disease,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yael Lustig, MD, of the Goldschleger Eye Institute at Sheba Medical Center, in Ramat Gan, Israel. It was published online on August 5, 2024, in Ophthalmology.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective nature of the study and the single-center design may have limited the generalizability of the findings. The study population was self-selected, potentially introducing selection bias. Lack of histopathologic examination could have affected the accuracy of the diagnosis.

DISCLOSURES:

No funding sources were disclosed for this study. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Association Between Pruritus and Fibromyalgia: Results of a Population-Based, Cross-Sectional Study

Pruritus, which is defined as an itching sensation that elicits a desire to scratch, is the most common cutaneous condition. Pruritus is considered chronic when it lasts for more than 6 weeks.1 Etiologies implicated in chronic pruritus include but are not limited to primary skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis, systemic causes, neuropathic disorders, and psychogenic reasons.2 In approximately 8% to 35% of patients, the cause of pruritus remains elusive despite intensive investigation.3 The mechanisms of itch are multifaceted and include complex neural pathways.4 Although itch and pain share many similarities, they have distinct pathways based on their spinal connections.5 Nevertheless, both conditions show a wide overlap of receptors on peripheral nerve endings and activated brain parts.6,7 Fibromyalgia, the third most common musculoskeletal condition, affects 2% to 3% of the population worldwide and is at least 7 times more common in females.8,9 Its pathogenesis is not entirely clear but is thought to involve neurogenic inflammation, aberrations in peripheral nerves, and central pain mechanisms. Fibromyalgia is characterized by a plethora of symptoms including chronic widespread pain, autonomic disturbances, persistent fatigue and sleep disturbances, and hyperalgesia, as well as somatic and psychiatric symptoms.10

Fibromyalgia is accompanied by altered skin features including increased counts of mast cells and excessive degranulation,11 neurogenic inflammation with elevated cytokine expression,12 disrupted collagen metabolism,13 and microcirculation abnormalities.14 There has been limited research exploring the dermatologic manifestations of fibromyalgia. One retrospective study that included 845 patients with fibromyalgia reported increased occurrence of “neurodermatoses,” including pruritus, neurotic excoriations, prurigo nodules, and lichen simplex chronicus (LSC), among other cutaneous comorbidities.15 Another small study demonstrated an increased incidence of xerosis and neurotic excoriations in females with fibromyalgia.16 A paucity of large epidemiologic studies demonstrating the fibromyalgia-pruritus connection may lead to misdiagnosis, misinterpretation, and undertreatment of these patients.

Up to 49% of fibromyalgia patients experience small-fiber neuropathy.17 Electrophysiologic measurements, quantitative sensory testing, pain-related evoked potentials, and skin biopsies showed that patients with fibromyalgia have compromised small-fiber function, impaired pathways carrying fiber pain signals, and reduced skin innervation and regenerating fibers.18,19 Accordingly, pruritus that has been reported in fibromyalgia is believed to be of neuropathic origin.15 Overall, it is suspected that the same mechanism that causes hypersensitivity and pain in fibromyalgia patients also predisposes them to pruritus. Similar systemic treatments (eg, analgesics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants) prescribed for both conditions support this theory.20-25

Our large cross-sectional study sought to establish the association between fibromyalgia and pruritus as well as related pruritic conditions.

Methods

Study Design and Setting—We conducted a cross-sectional retrospective study using data-mining techniques to access information from the Clalit Health Services (CHS) database. Clalit Health Services is the largest health maintenance organization in Israel. It encompasses an extensive database with continuous real-time input from medical, administrative, and pharmaceutical computerized operating systems, which helps facilitate data collection for epidemiologic studies. A chronic disease register is gathered from these data sources and continuously updated and validated through logistic checks. The current study was approved by the institutional review board of the CHS (approval #0212-17-com2). Informed consent was not required because the data were de-identified and this was a noninterventional observational study.

Study Population and Covariates—Medical records of CHS enrollees were screened for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia, and data on prevalent cases of fibromyalgia were retrieved. The diagnosis of fibromyalgia was based on the documentation of a fibromyalgia-specific diagnostic code registered by a board-certified rheumatologist. A control group of individuals without fibromyalgia was selected through 1:2 matching based on age, sex, and primary care clinic. The control group was randomly selected from the list of CHS members frequency-matched to cases, excluding case patients with fibromyalgia. Age matching was grounded on the exact year of birth (1-year strata).

Other covariates in the analysis included pruritus-related skin disorders, including prurigo nodularis, neurotic excoriations, and LSC. There were 3 socioeconomic status categories according to patients' poverty index: low, intermediate, and high.26

Statistical Analysis—The distribution of sociodemographic and clinical features was compared between patients with fibromyalgia and controls using the χ2 test for sex and socioeconomic status and the t test for age. Conditional logistic regression then was used to calculate adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI to compare patients with fibromyalgia and controls with respect to the presence of pruritic comorbidities. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 26). P<.05 was considered statistically significant in all tests.

Results

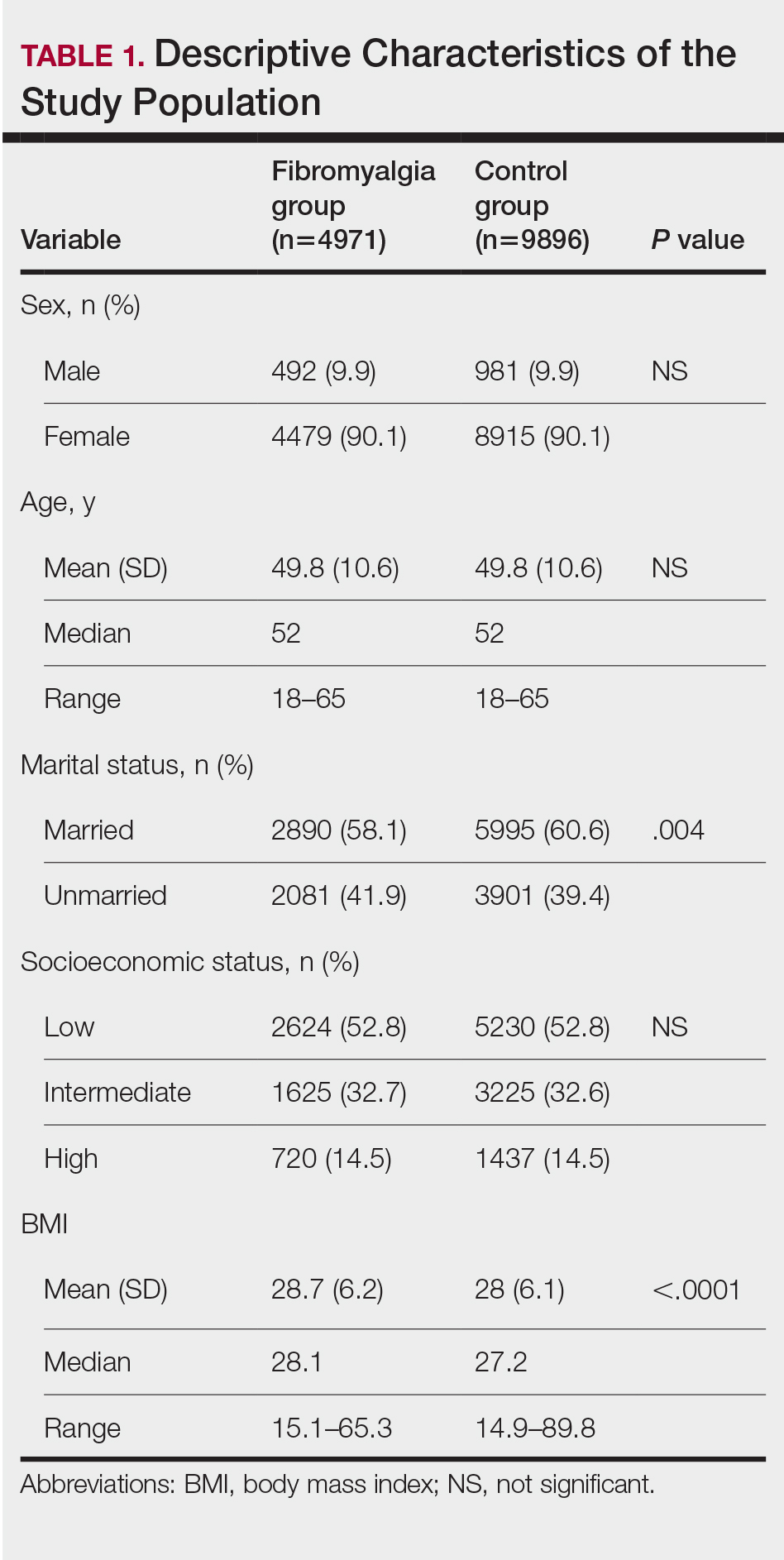

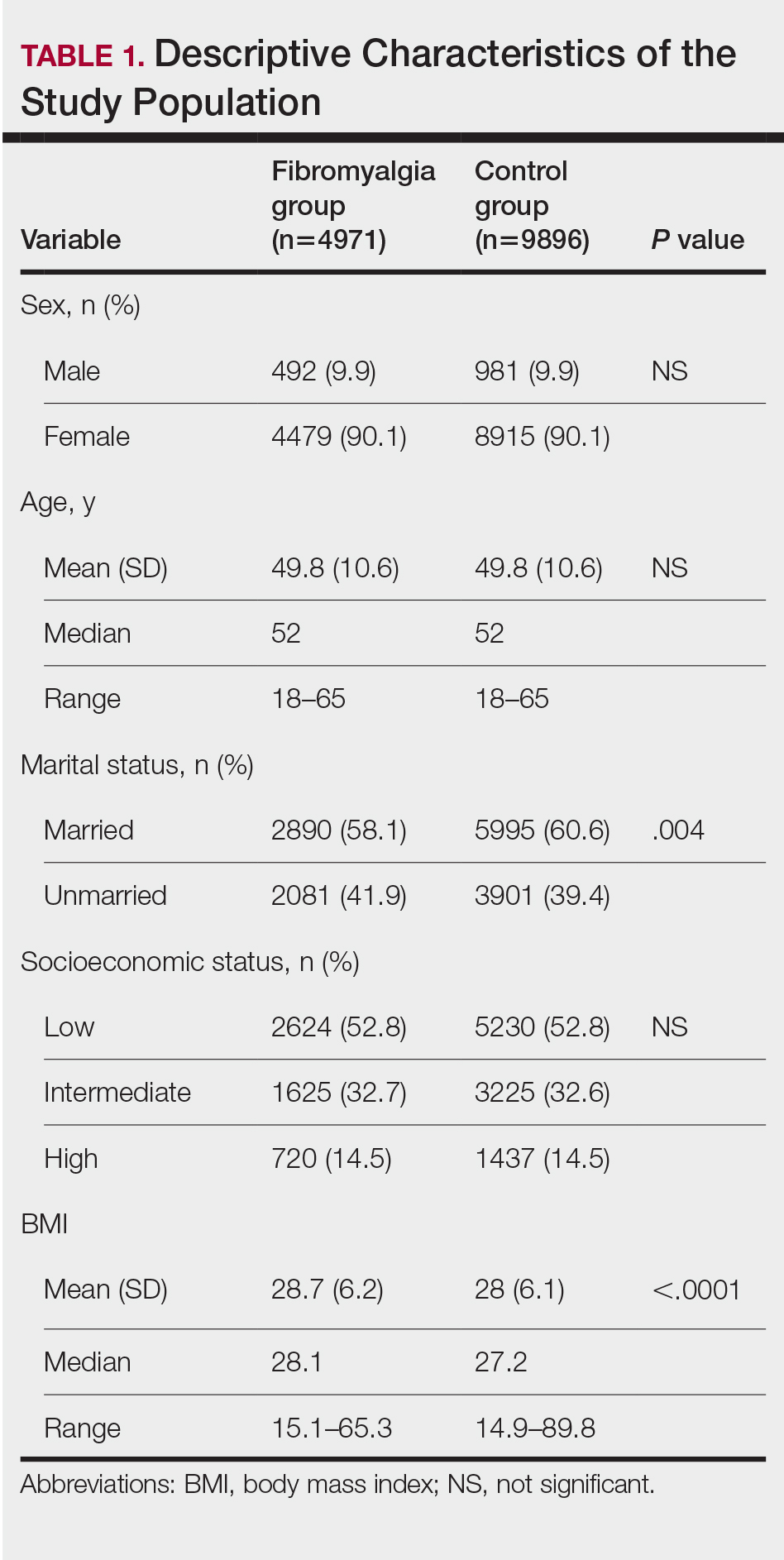

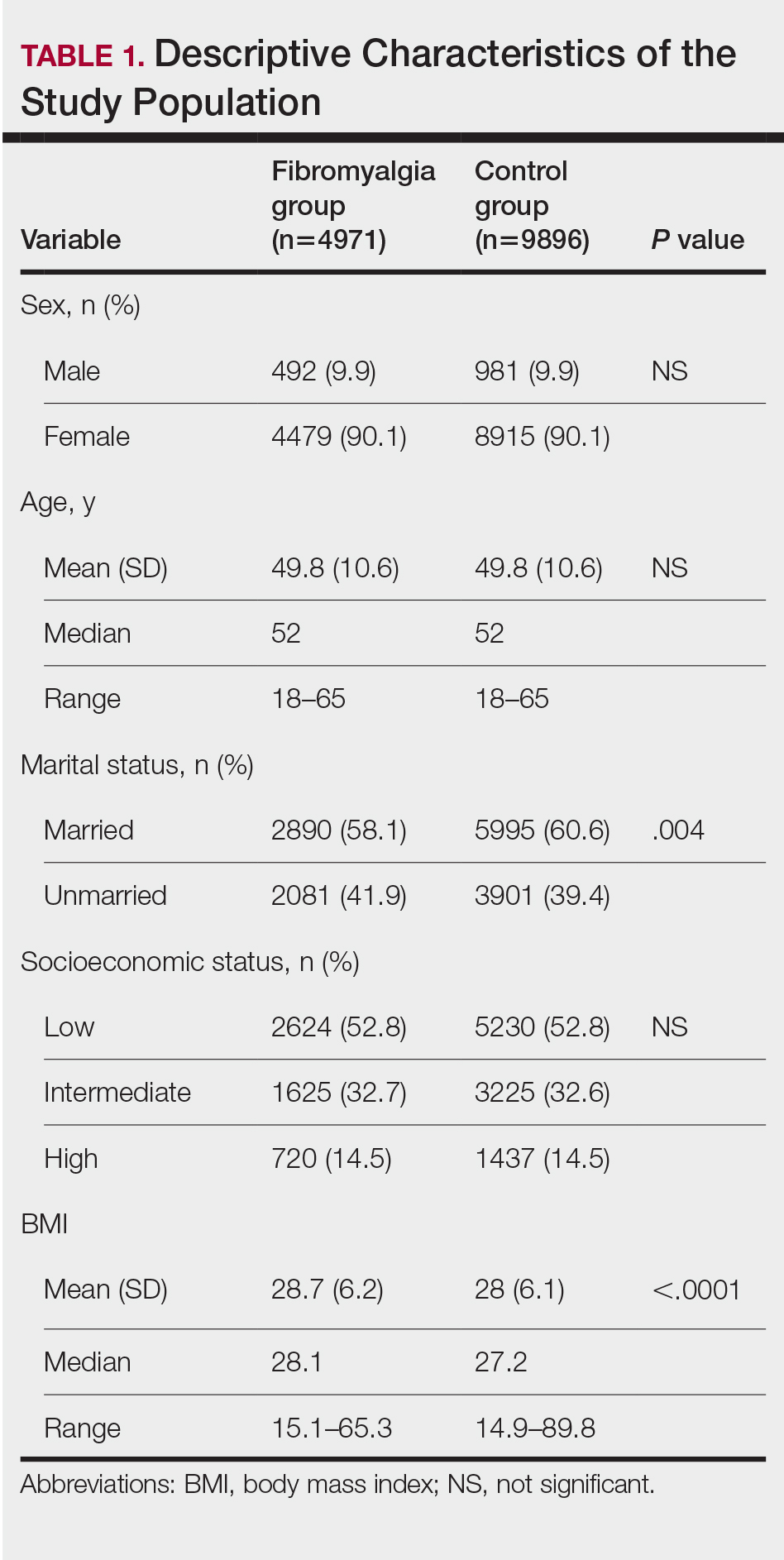

Our study population comprised 4971 patients with fibromyalgia and 9896 age- and sex-matched controls. Proportional to the reported female predominance among patients with fibromyalgia,27 4479 (90.1%) patients with fibromyalgia were females and a similar proportion was documented among controls (P=.99). There was a slightly higher proportion of unmarried patients among those with fibromyalgia compared with controls (41.9% vs 39.4%; P=.004). Socioeconomic status was matched between patients and controls (P=.99). Descriptive characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

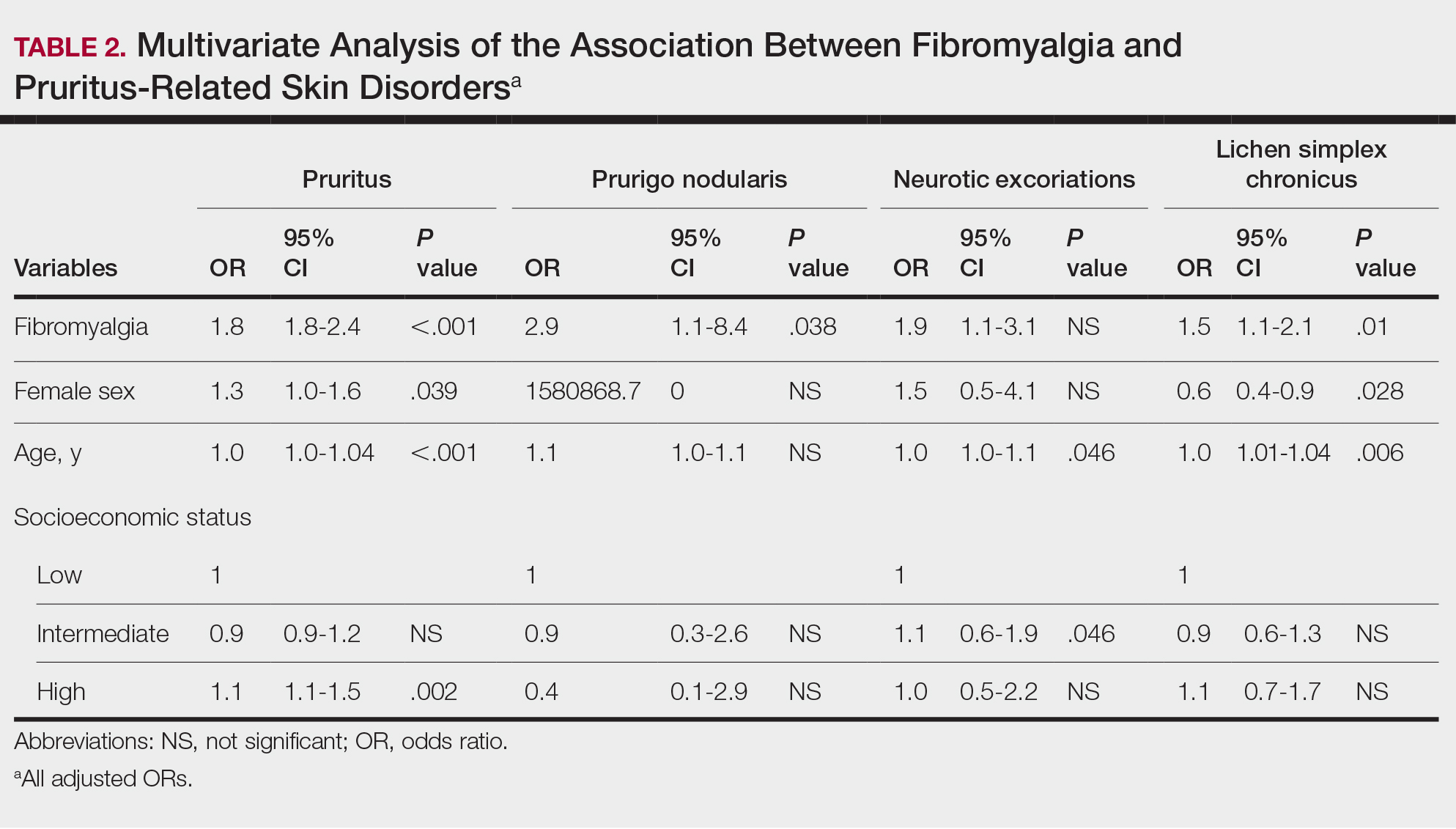

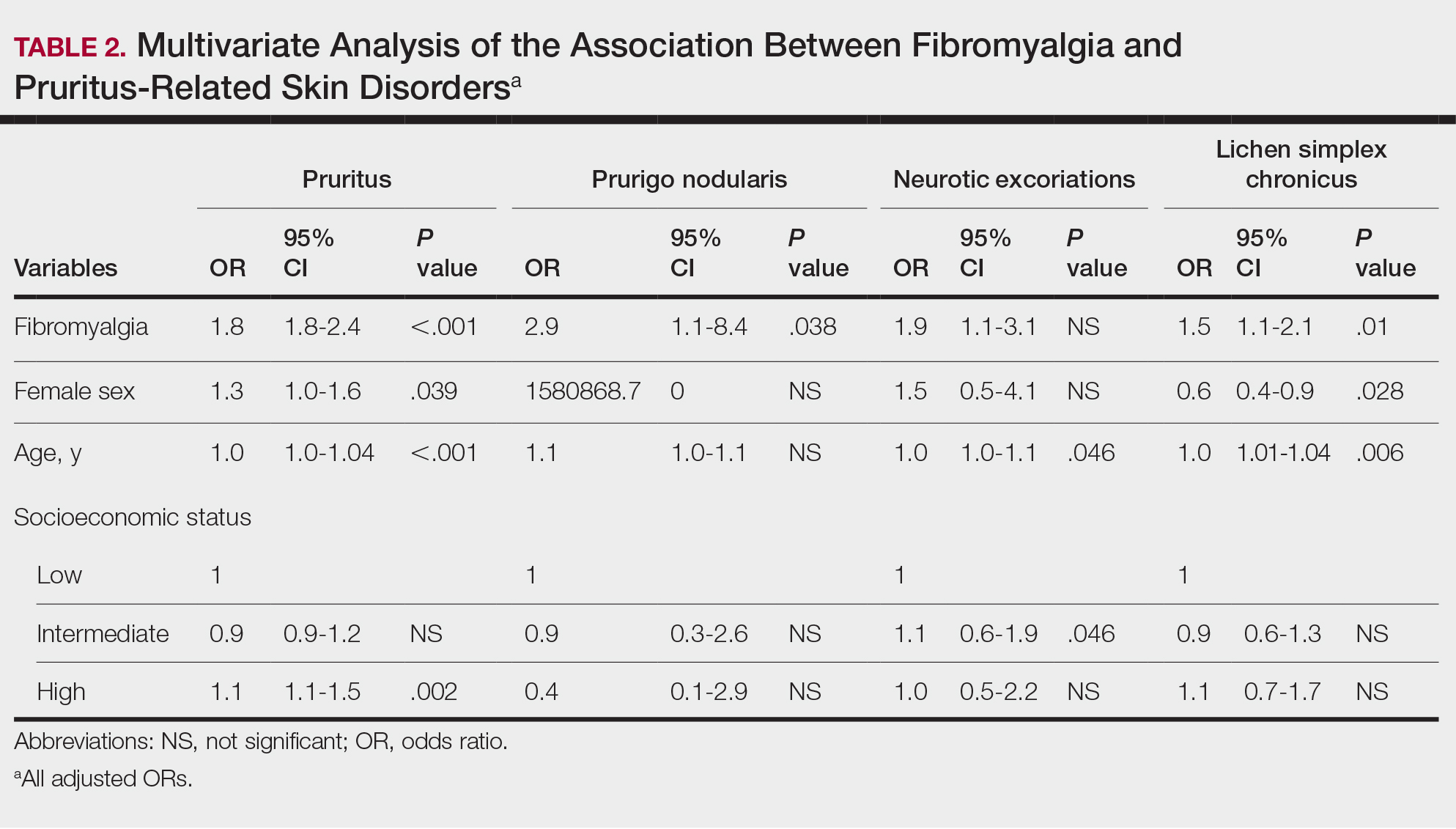

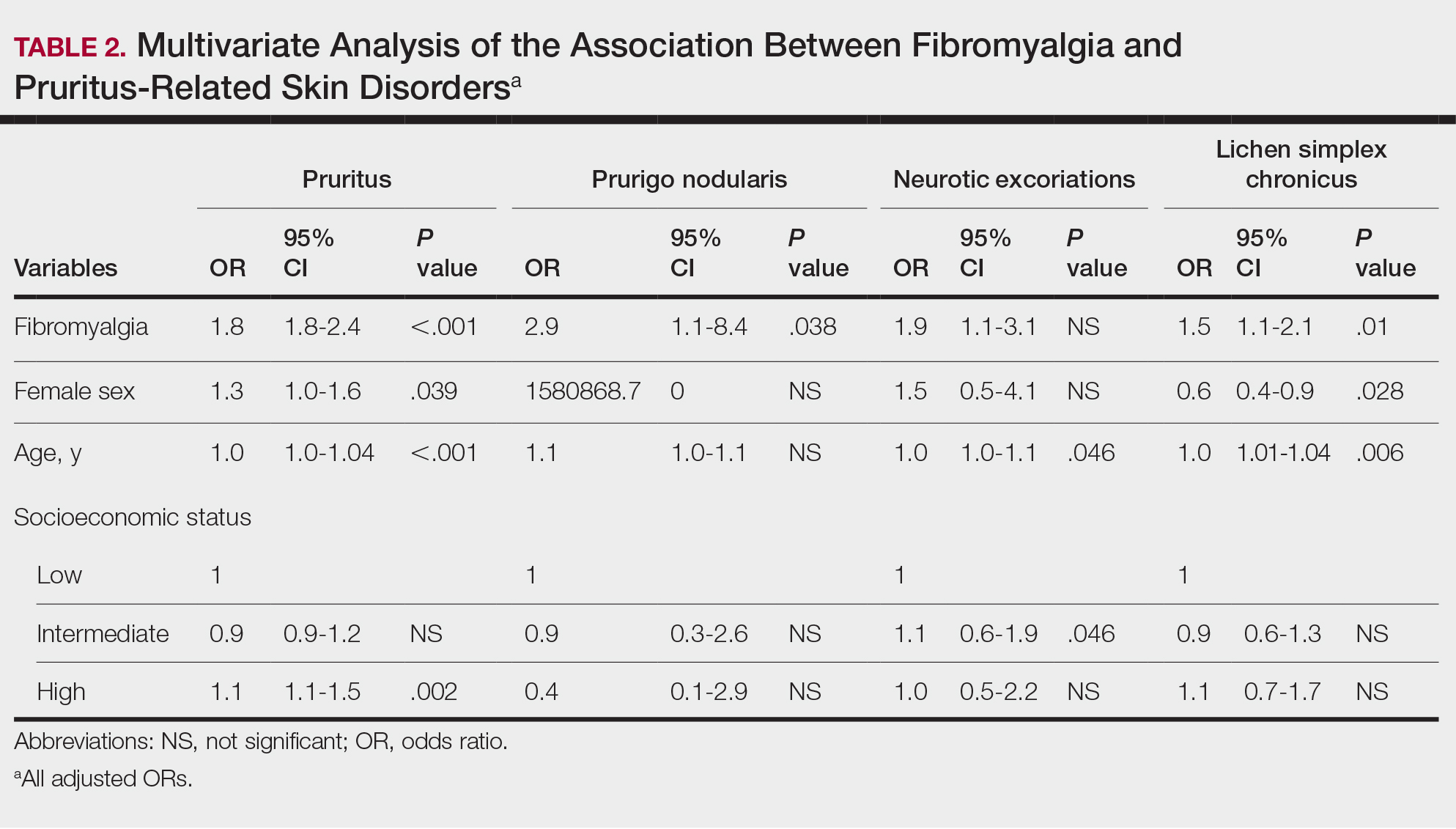

We assessed the presence of pruritus as well as 3 other pruritus-related skin disorders—prurigo nodularis, neurotic excoriations, and LSC—among patients with fibromyalgia and controls. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the independent association between fibromyalgia and pruritus. Table 2 presents the results of multivariate logistic regression models and summarizes the adjusted ORs for pruritic conditions in patients with fibromyalgia and different demographic features across the entire study sample. Fibromyalgia demonstrated strong independent associations with pruritus (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.8-2.4; P<.001), prurigo nodularis (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1-8.4; P=.038), and LSC (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P=.01); the association with neurotic excoriations was not significant. Female sex significantly increased the risk for pruritus (OR 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0-1.6; P=.039), while age slightly increased the odds for pruritus (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.0-1.04; P<.001), neurotic excoriations (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.0-1.1; P=.046), and LSC (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.01-1.04; P=.006). Finally, socioeconomic status was inversely correlated with pruritus (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.1-1.5; P=.002).

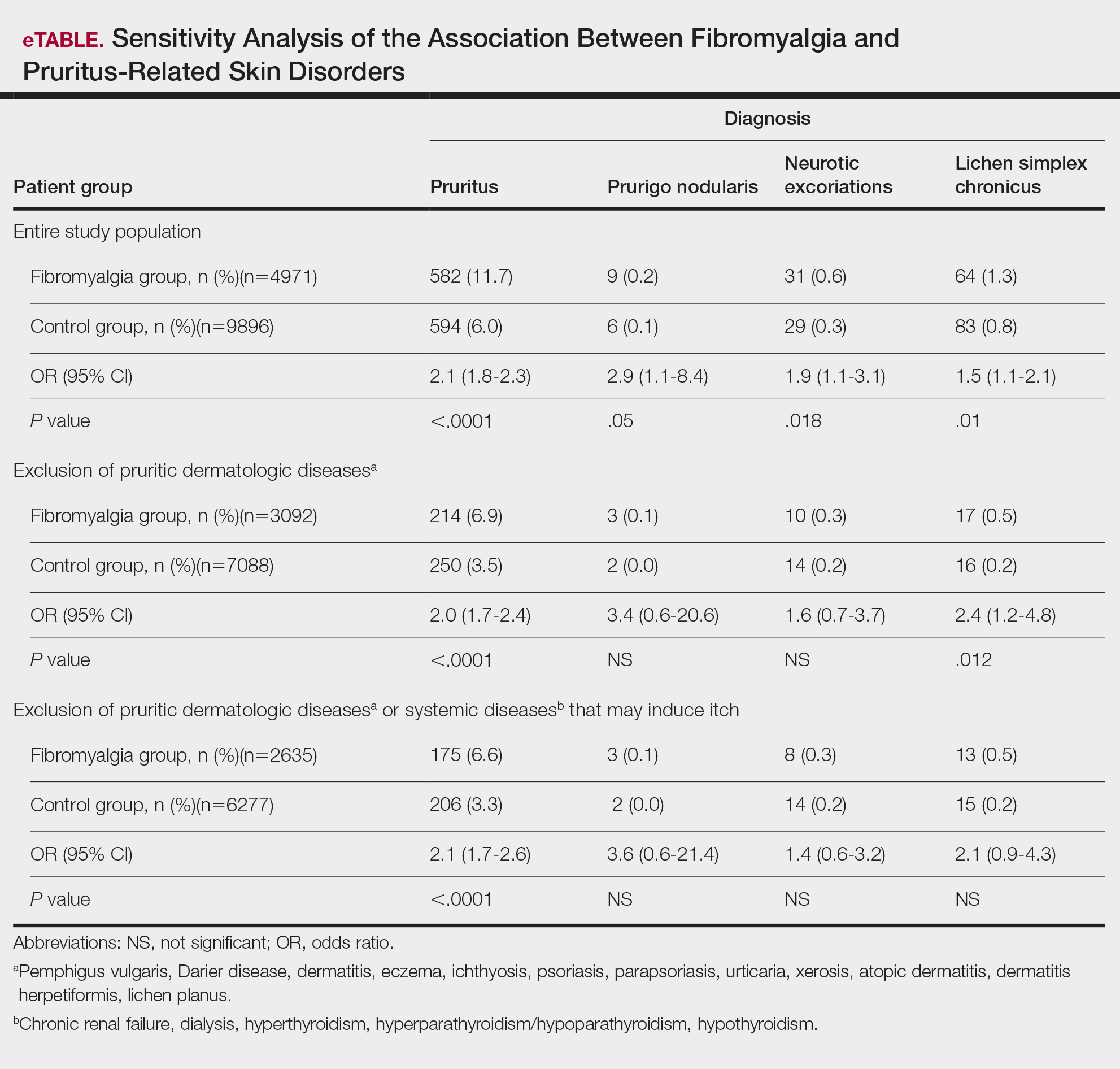

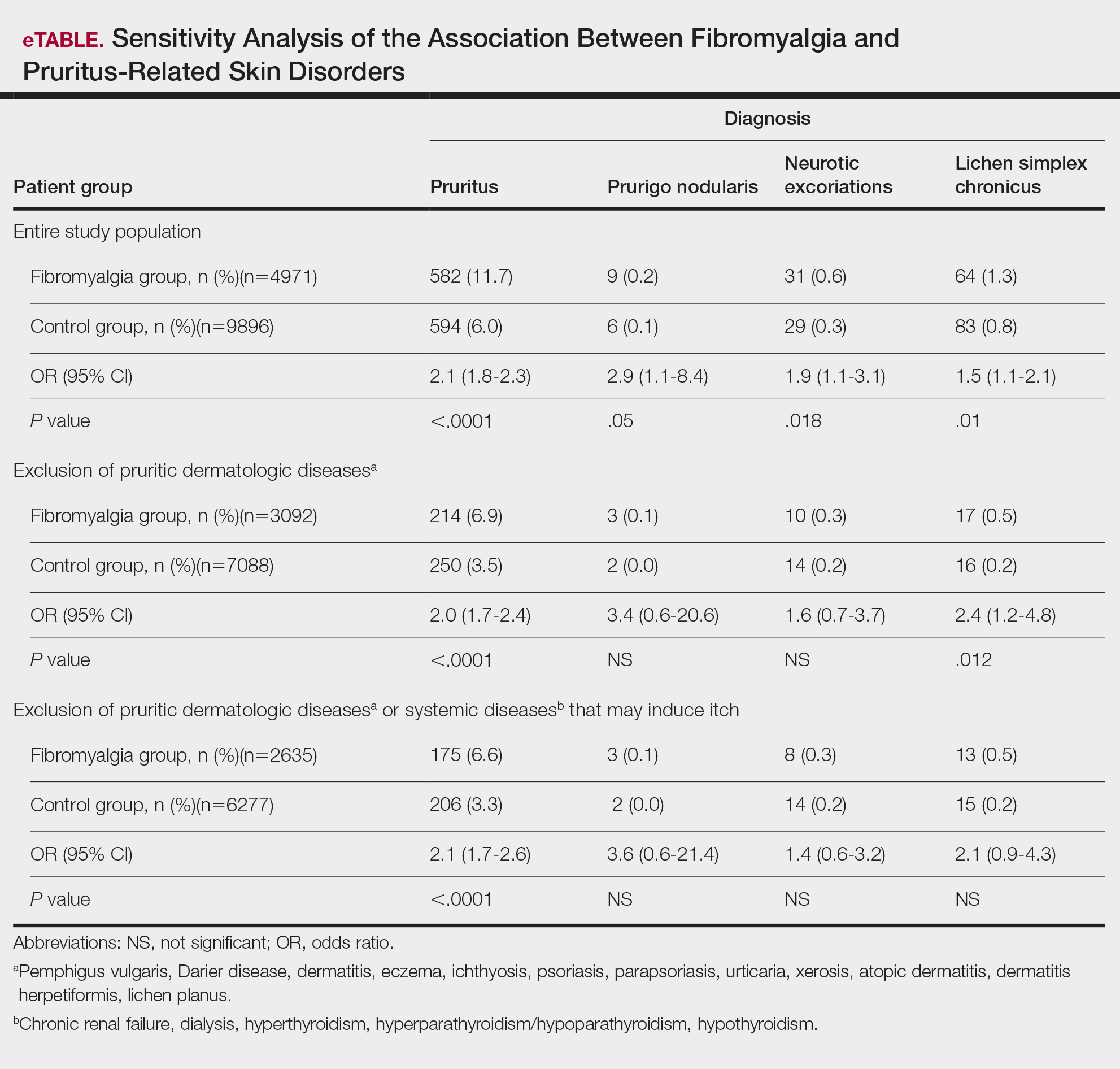

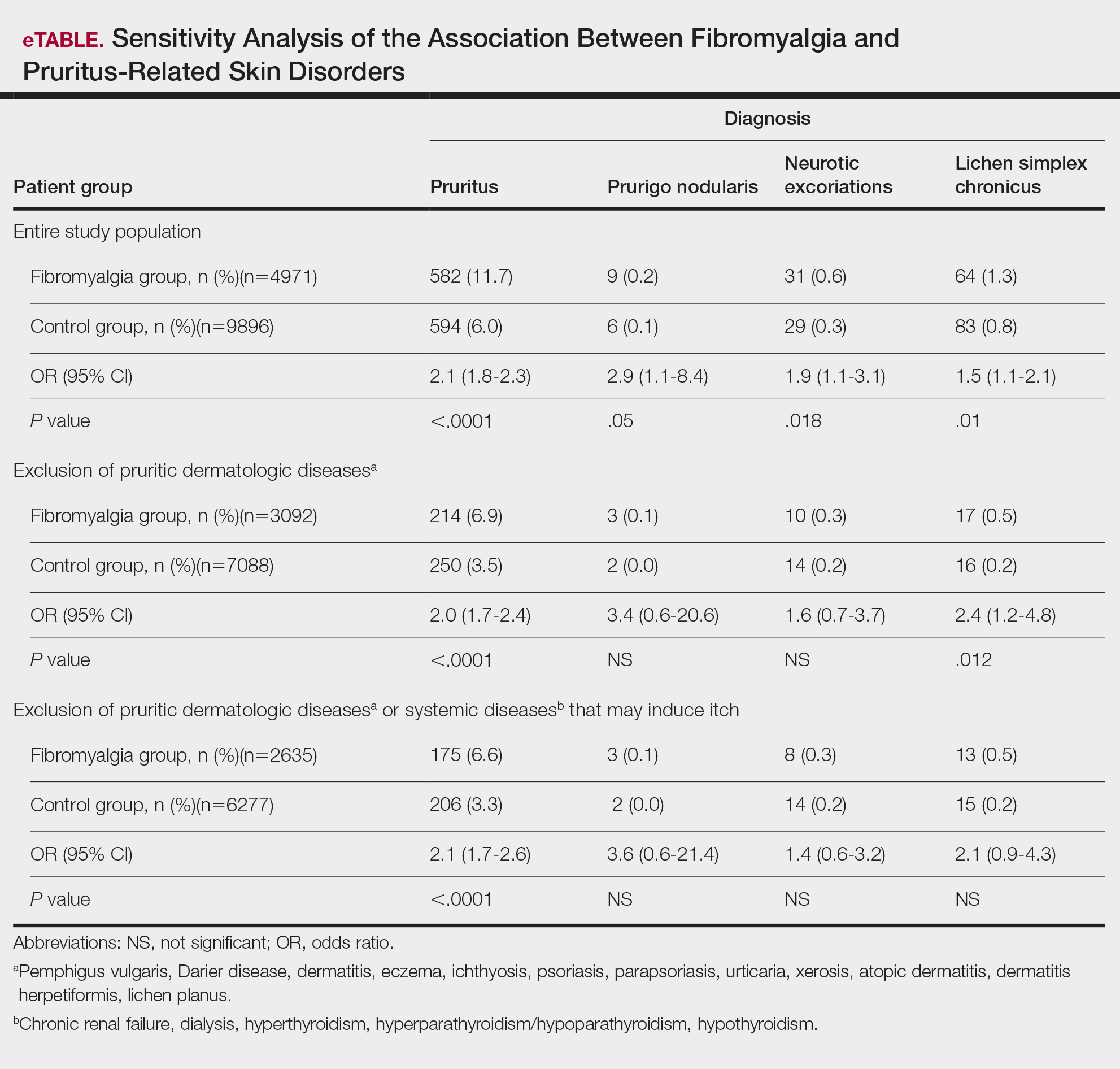

Frequencies and ORs for the association between fibromyalgia and pruritus with associated pruritic disorders stratified by exclusion of pruritic dermatologic and/or systemic diseases that may induce itch are presented in the eTable. Analyzing the entire study cohort, significant increases were observed in the odds of all 4 pruritic disorders analyzed. The frequency of pruritus was almost double in patients with fibromyalgia compared with controls (11.7% vs 6.0%; OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.8-2.3; P<.0001). Prurigo nodularis (0.2% vs 0.1%; OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1-8.4; P=.05), neurotic excoriations (0.6% vs 0.3%; OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1-3.1; P=.018), and LSC (1.3% vs 0.8%; OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P=.01) frequencies were all higher in patients with fibromyalgia than controls. When primary skin disorders that may cause itch (eg, pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, dermatitis, eczema, ichthyosis, psoriasis, parapsoriasis, urticaria, xerosis, atopic dermatitis, dermatitis herpetiformis, lichen planus) were excluded, the prevalence of pruritus in patients with fibromyalgia was still 1.97 times greater than in the controls (6.9% vs. 3.5%; OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.7-2.4; P<.0001). These results remained unchanged even when excluding pruritic dermatologic disorders as well as systemic diseases associated with pruritus (eg, chronic renal failure, dialysis, hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism/hypoparathyroidism, hypothyroidism). Patients with fibromyalgia still displayed a significantly higher prevalence of pruritus compared with the control group (6.6% vs 3.3%; OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.7-2.6; P<.0001).

Comment

A wide range of skin manifestations have been associated with fibromyalgia, but the exact mechanisms remain unclear. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that autonomic nervous system dysfunction,28-31 amplified cutaneous opioid receptor activity,32 and an elevated presence of cutaneous mast cells with excessive degranulation may partially explain the frequent occurrence of pruritus and related skin disorders such as neurotic excoriations, prurigo nodularis, and LSC in individuals with fibromyalgia.15,16 In line with these findings, our study—which was based on data from the largest health maintenance organization in Israel—demonstrated an increased prevalence of pruritus and related pruritic disorders among individuals diagnosed with fibromyalgia.

This cross-sectional study links pruritus with fibromyalgia. Few preliminary epidemiologic studies have shown an increased occurrence of cutaneous manifestations in patients with fibromyalgia. One chart review that looked at skin findings in patients with fibromyalgia revealed 32 distinct cutaneous manifestations, and pruritus was the major concern in 3.3% of 845 patients.15

A focused cross-sectional study involving only women (66 with fibromyalgia and 79 healthy controls) discovered 14 skin conditions that were more common in those with fibromyalgia. Notably, xerosis and neurotic excoriations were more prevalent compared to the control group.16

The brain and the skin—both derivatives of the embryonic ectoderm33,34—are linked by pruritus. Although itch has its dedicated neurons, there is a wide-ranging overlap of brain-activated areas between pain and itch,6 and the neural anatomy of pain and itch are closely related in both the peripheral and central nervous systems35-37; for example, diseases of the central nervous system are accompanied by pruritus in as many as 15% of cases, while postherpetic neuralgia can result in chronic pain, itching, or a combination of both.38,39 Other instances include notalgia paresthetica and brachioradial pruritus.38 Additionally, there is a noteworthy psychologic impact associated with both itch and pain,40,41 with both psychosomatic and psychologic factors implicated in chronic pruritus and in fibromyalgia.42 Lastly, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system are altered in both fibromyalgia and pruritus.43-45

Tey et al45 characterized the itch experienced in fibromyalgia as functional, which is described as pruritus associated with a somatoform disorder. In our study, we found a higher prevalence of pruritus among patients with fibromyalgia, and this association remained significant (P<.05) even when excluding other pruritic skin conditions and systemic diseases that can trigger itching. In addition, our logistic regression analyses revealed independent associations between fibromyalgia and pruritus, prurigo nodularis, and LSC.

According to Twycross et al,46 there are 4 clinical categories of itch, which may coexist7: pruritoceptive (originating in the skin), neuropathic (originating in pathology located along the afferent pathway), neurogenic (central origin but lacks a neural pathology), and psychogenic.47 Skin biopsy findings in patients with fibromyalgia include increased mast cell counts11 and degranulation,48 increased expression of δ and κ opioid receptors,32 vasoconstriction within tender points,49 and elevated IL-1β, IL-6, or tumor necrosis factor α by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction.12 A case recently was presented by Görg et al50 involving a female patient with fibromyalgia who had been experiencing chronic pruritus, which the authors attributed to small-fiber neuropathy based on evidence from a skin biopsy indicating a reduced number of intraepidermal nerves and the fact that the itching originated around tender points. Altogether, the observed alterations may work together to make patients with fibromyalgia more susceptible to various skin-related comorbidities in general, especially those related to pruritus. Eventually, it might be the case that several itch categories and related pathomechanisms are involved in the pruritus phenotype of patients with fibromyalgia.

Age-related alterations in nerve fibers, lower immune function, xerosis, polypharmacy, and increased frequency of systemic diseases with age are just a few of the factors that may predispose older individuals to pruritus.51,52 Indeed, our logistic regression model showed that age was significantly and independently associated with pruritus (P<.001), neurotic excoriations (P=.046), and LSC (P=.006). Female sex also was significantly linked with pruritus (P=.039). Intriguingly, high socioeconomic status was significantly associated with the diagnosis of pruritus (P=.002), possibly due to easier access to medical care.

There is a considerable overlap between the therapeutic approaches used in pruritus, pruritus-related skin disorders, and fibromyalgia. Antidepressants, anxiolytics, analgesics, and antiepileptics have been used to address both conditions.45 The association between these conditions advocates for a multidisciplinary approach in patients with fibromyalgia and potentially supports the rationale for unified therapeutics for both conditions.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate an association between fibromyalgia and pruritus as well as associated pruritic skin disorders. Given the convoluted and largely undiscovered mechanisms underlying fibromyalgia, managing patients with this condition may present substantial challenges.53 The data presented here support the implementation of a multidisciplinary treatment approach for patients with fibromyalgia. This approach should focus on managing fibromyalgia pain as well as addressing its concurrent skin-related conditions. It is advisable to consider treatments such as antiepileptics (eg, pregabalin, gabapentin) that specifically target neuropathic disorders in affected patients. These treatments may hold promise for alleviating fibromyalgia-related pain54 and mitigating its related cutaneous comorbidities, especially pruritus.

- Stander S, Weisshaar E, Mettang T, et al. Clinical classification of itch: a position paper of the International Forum for the Study of Itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007; 87:291-294.

- Yosipovitch G, Bernhard JD. Clinical practice. chronic pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1625-1634.

- Song J, Xian D, Yang L, et al. Pruritus: progress toward pathogenesis and treatment. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9625936.

- Potenzieri C, Undem BJ. Basic mechanisms of itch. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:8-19.

- McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M. Itching for an explanation. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:497-501.

- Drzezga A, Darsow U, Treede RD, et al. Central activation by histamine-induced itch: analogies to pain processing: a correlational analysis of O-15 H2O positron emission tomography studies. Pain. 2001; 92:295-305.

- Yosipovitch G, Greaves MW, Schmelz M. Itch. Lancet. 2003;361:690-694.

- Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008; 58:15-25.

- Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008; 58:26-35.

- Sarzi-Puttini P, Giorgi V, Marotto D, et al. Fibromyalgia: an update on clinical characteristics, aetiopathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16:645-660.

- Blanco I, Beritze N, Arguelles M, et al. Abnormal overexpression of mastocytes in skin biopsies of fibromyalgia patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:1403-1412.

- Salemi S, Rethage J, Wollina U, et al. Detection of interleukin 1beta (IL-1beta), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in skin of patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:146-150.

- Sprott H, Muller A, Heine H. Collagen cross-links in fibromyalgia syndrome. Z Rheumatol. 1998;57(suppl 2):52-55.

- Morf S, Amann-Vesti B, Forster A, et al. Microcirculation abnormalities in patients with fibromyalgia—measured by capillary microscopy and laser fluxmetry. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R209-R216.

- Laniosz V, Wetter DA, Godar DA. Dermatologic manifestations of fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:1009-1013.

- Dogramaci AC, Yalcinkaya EY. Skin problems in fibromyalgia. Nobel Med. 2009;5:50-52.

- Grayston R, Czanner G, Elhadd K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of small fiber pathology in fibromyalgia: implications for a new paradigm in fibromyalgia etiopathogenesis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48:933-940.

- Uceyler N, Zeller D, Kahn AK, et al. Small fibre pathology in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Brain. 2013;136:1857-1867.

- Devigili G, Tugnoli V, Penza P, et al. The diagnostic criteria for small fibre neuropathy: from symptoms to neuropathology. Brain. 2008; 131:1912- 1925.

- Reed C, Birnbaum HG, Ivanova JI, et al. Real-world role of tricyclic antidepressants in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Pain Pract. 2012; 12:533-540.

- Moret C, Briley M. Antidepressants in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2006;2:537-548.

- Arnold LM, Keck PE Jr, Welge JA. Antidepressant treatment of fibromyalgia. a meta-analysis and review. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:104-113.

- Moore A, Wiffen P, Kalso E. Antiepileptic drugs for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia. JAMA. 2014;312:182-183.

- Shevchenko A, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Yosipovitch G. Causes, pathophysiology, and treatment of pruritus in the mature patient. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:140-151.

- Scheinfeld N. The role of gabapentin in treating diseases with cutaneous manifestations and pain. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:491-495.

- Points Location Intelligence. Accessed July 30, 2024. https://points.co.il/en/points-location-intelligence/

- Yunus MB. The role of gender in fibromyalgia syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2001;3:128-134.

- Cakir T, Evcik D, Dundar U, et al. Evaluation of sympathetic skin response and f wave in fibromyalgia syndrome patients. Turk J Rheumatol. 2011;26:38-43.

- Ozkan O, Yildiz M, Koklukaya E. The correlation of laboratory tests and sympathetic skin response parameters by using artificial neural networks in fibromyalgia patients. J Med Syst. 2012;36:1841-1848.

- Ozkan O, Yildiz M, Arslan E, et al. A study on the effects of sympathetic skin response parameters in diagnosis of fibromyalgia using artificial neural networks. J Med Syst. 2016;40:54.

- Ulas UH, Unlu E, Hamamcioglu K, et al. Dysautonomia in fibromyalgia syndrome: sympathetic skin responses and RR interval analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:383-387.

- Salemi S, Aeschlimann A, Wollina U, et al. Up-regulation of delta-opioid receptors and kappa-opioid receptors in the skin of fibromyalgia patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2464-2466.

- Elshazzly M, Lopez MJ, Reddy V, et al. Central nervous system. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Hu MS, Borrelli MR, Hong WX, et al. Embryonic skin development and repair. Organogenesis. 2018;14:46-63.

- Davidson S, Zhang X, Yoon CH, et al. The itch-producing agents histamine and cowhage activate separate populations of primate spinothalamic tract neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10007-10014.

- Sikand P, Shimada SG, Green BG, et al. Similar itch and nociceptive sensations evoked by punctate cutaneous application of capsaicin, histamine and cowhage. Pain. 2009;144:66-75.

- Davidson S, Giesler GJ. The multiple pathways for itch and their interactions with pain. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:550-558.

- Dhand A, Aminoff MJ. The neurology of itch. Brain. 2014;137:313-322.

- Binder A, Koroschetz J, Baron R. Disease mechanisms in neuropathic itch. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4:329-337.

- Fjellner B, Arnetz BB. Psychological predictors of pruritus during mental stress. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:504-508.

- Papoiu AD, Wang H, Coghill RC, et al. Contagious itch in humans: a study of visual ‘transmission’ of itch in atopic dermatitis and healthy subjects. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1299-1303.

- Stumpf A, Schneider G, Stander S. Psychosomatic and psychiatric disorders and psychologic factors in pruritus. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:704-708.

- Herman JP, McKlveen JM, Ghosal S, et al. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical stress response. Compr Physiol. 2016;6:603-621.

- Brown ED, Micozzi MS, Craft NE, et al. Plasma carotenoids in normal men after a single ingestion of vegetables or purified beta-carotene. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;49:1258-1265.

- Tey HL, Wallengren J, Yosipovitch G. Psychosomatic factors in pruritus. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:31-40.

- Twycross R, Greaves MW, Handwerker H, et al. Itch: scratching more than the surface. QJM. 2003;96:7-26.

- Bernhard JD. Itch and pruritus: what are they, and how should itches be classified? Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:288-291.

- Enestrom S, Bengtsson A, Frodin T. Dermal IgG deposits and increase of mast cells in patients with fibromyalgia—relevant findings or epiphenomena? Scand J Rheumatol. 1997;26:308-313.

- Jeschonneck M, Grohmann G, Hein G, et al. Abnormal microcirculation and temperature in skin above tender points in patients with fibromyalgia. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39:917-921.

- Görg M, Zeidler C, Pereira MP, et al. Generalized chronic pruritus with fibromyalgia. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2021;19:909-911.

- Garibyan L, Chiou AS, Elmariah SB. Advanced aging skin and itch: addressing an unmet need. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:92-103.

- Cohen KR, Frank J, Salbu RL, et al. Pruritus in the elderly: clinical approaches to the improvement of quality of life. P T. 2012;37:227-239.

- Tzadok R, Ablin JN. Current and emerging pharmacotherapy for fibromyalgia. Pain Res Manag. 2020; 2020:6541798.

- Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Antiepileptic drugs for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia—an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD010567.

Pruritus, which is defined as an itching sensation that elicits a desire to scratch, is the most common cutaneous condition. Pruritus is considered chronic when it lasts for more than 6 weeks.1 Etiologies implicated in chronic pruritus include but are not limited to primary skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis, systemic causes, neuropathic disorders, and psychogenic reasons.2 In approximately 8% to 35% of patients, the cause of pruritus remains elusive despite intensive investigation.3 The mechanisms of itch are multifaceted and include complex neural pathways.4 Although itch and pain share many similarities, they have distinct pathways based on their spinal connections.5 Nevertheless, both conditions show a wide overlap of receptors on peripheral nerve endings and activated brain parts.6,7 Fibromyalgia, the third most common musculoskeletal condition, affects 2% to 3% of the population worldwide and is at least 7 times more common in females.8,9 Its pathogenesis is not entirely clear but is thought to involve neurogenic inflammation, aberrations in peripheral nerves, and central pain mechanisms. Fibromyalgia is characterized by a plethora of symptoms including chronic widespread pain, autonomic disturbances, persistent fatigue and sleep disturbances, and hyperalgesia, as well as somatic and psychiatric symptoms.10

Fibromyalgia is accompanied by altered skin features including increased counts of mast cells and excessive degranulation,11 neurogenic inflammation with elevated cytokine expression,12 disrupted collagen metabolism,13 and microcirculation abnormalities.14 There has been limited research exploring the dermatologic manifestations of fibromyalgia. One retrospective study that included 845 patients with fibromyalgia reported increased occurrence of “neurodermatoses,” including pruritus, neurotic excoriations, prurigo nodules, and lichen simplex chronicus (LSC), among other cutaneous comorbidities.15 Another small study demonstrated an increased incidence of xerosis and neurotic excoriations in females with fibromyalgia.16 A paucity of large epidemiologic studies demonstrating the fibromyalgia-pruritus connection may lead to misdiagnosis, misinterpretation, and undertreatment of these patients.

Up to 49% of fibromyalgia patients experience small-fiber neuropathy.17 Electrophysiologic measurements, quantitative sensory testing, pain-related evoked potentials, and skin biopsies showed that patients with fibromyalgia have compromised small-fiber function, impaired pathways carrying fiber pain signals, and reduced skin innervation and regenerating fibers.18,19 Accordingly, pruritus that has been reported in fibromyalgia is believed to be of neuropathic origin.15 Overall, it is suspected that the same mechanism that causes hypersensitivity and pain in fibromyalgia patients also predisposes them to pruritus. Similar systemic treatments (eg, analgesics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants) prescribed for both conditions support this theory.20-25

Our large cross-sectional study sought to establish the association between fibromyalgia and pruritus as well as related pruritic conditions.

Methods

Study Design and Setting—We conducted a cross-sectional retrospective study using data-mining techniques to access information from the Clalit Health Services (CHS) database. Clalit Health Services is the largest health maintenance organization in Israel. It encompasses an extensive database with continuous real-time input from medical, administrative, and pharmaceutical computerized operating systems, which helps facilitate data collection for epidemiologic studies. A chronic disease register is gathered from these data sources and continuously updated and validated through logistic checks. The current study was approved by the institutional review board of the CHS (approval #0212-17-com2). Informed consent was not required because the data were de-identified and this was a noninterventional observational study.

Study Population and Covariates—Medical records of CHS enrollees were screened for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia, and data on prevalent cases of fibromyalgia were retrieved. The diagnosis of fibromyalgia was based on the documentation of a fibromyalgia-specific diagnostic code registered by a board-certified rheumatologist. A control group of individuals without fibromyalgia was selected through 1:2 matching based on age, sex, and primary care clinic. The control group was randomly selected from the list of CHS members frequency-matched to cases, excluding case patients with fibromyalgia. Age matching was grounded on the exact year of birth (1-year strata).

Other covariates in the analysis included pruritus-related skin disorders, including prurigo nodularis, neurotic excoriations, and LSC. There were 3 socioeconomic status categories according to patients' poverty index: low, intermediate, and high.26

Statistical Analysis—The distribution of sociodemographic and clinical features was compared between patients with fibromyalgia and controls using the χ2 test for sex and socioeconomic status and the t test for age. Conditional logistic regression then was used to calculate adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI to compare patients with fibromyalgia and controls with respect to the presence of pruritic comorbidities. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 26). P<.05 was considered statistically significant in all tests.

Results

Our study population comprised 4971 patients with fibromyalgia and 9896 age- and sex-matched controls. Proportional to the reported female predominance among patients with fibromyalgia,27 4479 (90.1%) patients with fibromyalgia were females and a similar proportion was documented among controls (P=.99). There was a slightly higher proportion of unmarried patients among those with fibromyalgia compared with controls (41.9% vs 39.4%; P=.004). Socioeconomic status was matched between patients and controls (P=.99). Descriptive characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

We assessed the presence of pruritus as well as 3 other pruritus-related skin disorders—prurigo nodularis, neurotic excoriations, and LSC—among patients with fibromyalgia and controls. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the independent association between fibromyalgia and pruritus. Table 2 presents the results of multivariate logistic regression models and summarizes the adjusted ORs for pruritic conditions in patients with fibromyalgia and different demographic features across the entire study sample. Fibromyalgia demonstrated strong independent associations with pruritus (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.8-2.4; P<.001), prurigo nodularis (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1-8.4; P=.038), and LSC (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P=.01); the association with neurotic excoriations was not significant. Female sex significantly increased the risk for pruritus (OR 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0-1.6; P=.039), while age slightly increased the odds for pruritus (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.0-1.04; P<.001), neurotic excoriations (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.0-1.1; P=.046), and LSC (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.01-1.04; P=.006). Finally, socioeconomic status was inversely correlated with pruritus (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.1-1.5; P=.002).

Frequencies and ORs for the association between fibromyalgia and pruritus with associated pruritic disorders stratified by exclusion of pruritic dermatologic and/or systemic diseases that may induce itch are presented in the eTable. Analyzing the entire study cohort, significant increases were observed in the odds of all 4 pruritic disorders analyzed. The frequency of pruritus was almost double in patients with fibromyalgia compared with controls (11.7% vs 6.0%; OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.8-2.3; P<.0001). Prurigo nodularis (0.2% vs 0.1%; OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1-8.4; P=.05), neurotic excoriations (0.6% vs 0.3%; OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1-3.1; P=.018), and LSC (1.3% vs 0.8%; OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P=.01) frequencies were all higher in patients with fibromyalgia than controls. When primary skin disorders that may cause itch (eg, pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, dermatitis, eczema, ichthyosis, psoriasis, parapsoriasis, urticaria, xerosis, atopic dermatitis, dermatitis herpetiformis, lichen planus) were excluded, the prevalence of pruritus in patients with fibromyalgia was still 1.97 times greater than in the controls (6.9% vs. 3.5%; OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.7-2.4; P<.0001). These results remained unchanged even when excluding pruritic dermatologic disorders as well as systemic diseases associated with pruritus (eg, chronic renal failure, dialysis, hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism/hypoparathyroidism, hypothyroidism). Patients with fibromyalgia still displayed a significantly higher prevalence of pruritus compared with the control group (6.6% vs 3.3%; OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.7-2.6; P<.0001).

Comment

A wide range of skin manifestations have been associated with fibromyalgia, but the exact mechanisms remain unclear. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that autonomic nervous system dysfunction,28-31 amplified cutaneous opioid receptor activity,32 and an elevated presence of cutaneous mast cells with excessive degranulation may partially explain the frequent occurrence of pruritus and related skin disorders such as neurotic excoriations, prurigo nodularis, and LSC in individuals with fibromyalgia.15,16 In line with these findings, our study—which was based on data from the largest health maintenance organization in Israel—demonstrated an increased prevalence of pruritus and related pruritic disorders among individuals diagnosed with fibromyalgia.

This cross-sectional study links pruritus with fibromyalgia. Few preliminary epidemiologic studies have shown an increased occurrence of cutaneous manifestations in patients with fibromyalgia. One chart review that looked at skin findings in patients with fibromyalgia revealed 32 distinct cutaneous manifestations, and pruritus was the major concern in 3.3% of 845 patients.15

A focused cross-sectional study involving only women (66 with fibromyalgia and 79 healthy controls) discovered 14 skin conditions that were more common in those with fibromyalgia. Notably, xerosis and neurotic excoriations were more prevalent compared to the control group.16

The brain and the skin—both derivatives of the embryonic ectoderm33,34—are linked by pruritus. Although itch has its dedicated neurons, there is a wide-ranging overlap of brain-activated areas between pain and itch,6 and the neural anatomy of pain and itch are closely related in both the peripheral and central nervous systems35-37; for example, diseases of the central nervous system are accompanied by pruritus in as many as 15% of cases, while postherpetic neuralgia can result in chronic pain, itching, or a combination of both.38,39 Other instances include notalgia paresthetica and brachioradial pruritus.38 Additionally, there is a noteworthy psychologic impact associated with both itch and pain,40,41 with both psychosomatic and psychologic factors implicated in chronic pruritus and in fibromyalgia.42 Lastly, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system are altered in both fibromyalgia and pruritus.43-45

Tey et al45 characterized the itch experienced in fibromyalgia as functional, which is described as pruritus associated with a somatoform disorder. In our study, we found a higher prevalence of pruritus among patients with fibromyalgia, and this association remained significant (P<.05) even when excluding other pruritic skin conditions and systemic diseases that can trigger itching. In addition, our logistic regression analyses revealed independent associations between fibromyalgia and pruritus, prurigo nodularis, and LSC.

According to Twycross et al,46 there are 4 clinical categories of itch, which may coexist7: pruritoceptive (originating in the skin), neuropathic (originating in pathology located along the afferent pathway), neurogenic (central origin but lacks a neural pathology), and psychogenic.47 Skin biopsy findings in patients with fibromyalgia include increased mast cell counts11 and degranulation,48 increased expression of δ and κ opioid receptors,32 vasoconstriction within tender points,49 and elevated IL-1β, IL-6, or tumor necrosis factor α by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction.12 A case recently was presented by Görg et al50 involving a female patient with fibromyalgia who had been experiencing chronic pruritus, which the authors attributed to small-fiber neuropathy based on evidence from a skin biopsy indicating a reduced number of intraepidermal nerves and the fact that the itching originated around tender points. Altogether, the observed alterations may work together to make patients with fibromyalgia more susceptible to various skin-related comorbidities in general, especially those related to pruritus. Eventually, it might be the case that several itch categories and related pathomechanisms are involved in the pruritus phenotype of patients with fibromyalgia.

Age-related alterations in nerve fibers, lower immune function, xerosis, polypharmacy, and increased frequency of systemic diseases with age are just a few of the factors that may predispose older individuals to pruritus.51,52 Indeed, our logistic regression model showed that age was significantly and independently associated with pruritus (P<.001), neurotic excoriations (P=.046), and LSC (P=.006). Female sex also was significantly linked with pruritus (P=.039). Intriguingly, high socioeconomic status was significantly associated with the diagnosis of pruritus (P=.002), possibly due to easier access to medical care.

There is a considerable overlap between the therapeutic approaches used in pruritus, pruritus-related skin disorders, and fibromyalgia. Antidepressants, anxiolytics, analgesics, and antiepileptics have been used to address both conditions.45 The association between these conditions advocates for a multidisciplinary approach in patients with fibromyalgia and potentially supports the rationale for unified therapeutics for both conditions.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate an association between fibromyalgia and pruritus as well as associated pruritic skin disorders. Given the convoluted and largely undiscovered mechanisms underlying fibromyalgia, managing patients with this condition may present substantial challenges.53 The data presented here support the implementation of a multidisciplinary treatment approach for patients with fibromyalgia. This approach should focus on managing fibromyalgia pain as well as addressing its concurrent skin-related conditions. It is advisable to consider treatments such as antiepileptics (eg, pregabalin, gabapentin) that specifically target neuropathic disorders in affected patients. These treatments may hold promise for alleviating fibromyalgia-related pain54 and mitigating its related cutaneous comorbidities, especially pruritus.

Pruritus, which is defined as an itching sensation that elicits a desire to scratch, is the most common cutaneous condition. Pruritus is considered chronic when it lasts for more than 6 weeks.1 Etiologies implicated in chronic pruritus include but are not limited to primary skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis, systemic causes, neuropathic disorders, and psychogenic reasons.2 In approximately 8% to 35% of patients, the cause of pruritus remains elusive despite intensive investigation.3 The mechanisms of itch are multifaceted and include complex neural pathways.4 Although itch and pain share many similarities, they have distinct pathways based on their spinal connections.5 Nevertheless, both conditions show a wide overlap of receptors on peripheral nerve endings and activated brain parts.6,7 Fibromyalgia, the third most common musculoskeletal condition, affects 2% to 3% of the population worldwide and is at least 7 times more common in females.8,9 Its pathogenesis is not entirely clear but is thought to involve neurogenic inflammation, aberrations in peripheral nerves, and central pain mechanisms. Fibromyalgia is characterized by a plethora of symptoms including chronic widespread pain, autonomic disturbances, persistent fatigue and sleep disturbances, and hyperalgesia, as well as somatic and psychiatric symptoms.10

Fibromyalgia is accompanied by altered skin features including increased counts of mast cells and excessive degranulation,11 neurogenic inflammation with elevated cytokine expression,12 disrupted collagen metabolism,13 and microcirculation abnormalities.14 There has been limited research exploring the dermatologic manifestations of fibromyalgia. One retrospective study that included 845 patients with fibromyalgia reported increased occurrence of “neurodermatoses,” including pruritus, neurotic excoriations, prurigo nodules, and lichen simplex chronicus (LSC), among other cutaneous comorbidities.15 Another small study demonstrated an increased incidence of xerosis and neurotic excoriations in females with fibromyalgia.16 A paucity of large epidemiologic studies demonstrating the fibromyalgia-pruritus connection may lead to misdiagnosis, misinterpretation, and undertreatment of these patients.

Up to 49% of fibromyalgia patients experience small-fiber neuropathy.17 Electrophysiologic measurements, quantitative sensory testing, pain-related evoked potentials, and skin biopsies showed that patients with fibromyalgia have compromised small-fiber function, impaired pathways carrying fiber pain signals, and reduced skin innervation and regenerating fibers.18,19 Accordingly, pruritus that has been reported in fibromyalgia is believed to be of neuropathic origin.15 Overall, it is suspected that the same mechanism that causes hypersensitivity and pain in fibromyalgia patients also predisposes them to pruritus. Similar systemic treatments (eg, analgesics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants) prescribed for both conditions support this theory.20-25

Our large cross-sectional study sought to establish the association between fibromyalgia and pruritus as well as related pruritic conditions.

Methods

Study Design and Setting—We conducted a cross-sectional retrospective study using data-mining techniques to access information from the Clalit Health Services (CHS) database. Clalit Health Services is the largest health maintenance organization in Israel. It encompasses an extensive database with continuous real-time input from medical, administrative, and pharmaceutical computerized operating systems, which helps facilitate data collection for epidemiologic studies. A chronic disease register is gathered from these data sources and continuously updated and validated through logistic checks. The current study was approved by the institutional review board of the CHS (approval #0212-17-com2). Informed consent was not required because the data were de-identified and this was a noninterventional observational study.

Study Population and Covariates—Medical records of CHS enrollees were screened for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia, and data on prevalent cases of fibromyalgia were retrieved. The diagnosis of fibromyalgia was based on the documentation of a fibromyalgia-specific diagnostic code registered by a board-certified rheumatologist. A control group of individuals without fibromyalgia was selected through 1:2 matching based on age, sex, and primary care clinic. The control group was randomly selected from the list of CHS members frequency-matched to cases, excluding case patients with fibromyalgia. Age matching was grounded on the exact year of birth (1-year strata).

Other covariates in the analysis included pruritus-related skin disorders, including prurigo nodularis, neurotic excoriations, and LSC. There were 3 socioeconomic status categories according to patients' poverty index: low, intermediate, and high.26

Statistical Analysis—The distribution of sociodemographic and clinical features was compared between patients with fibromyalgia and controls using the χ2 test for sex and socioeconomic status and the t test for age. Conditional logistic regression then was used to calculate adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI to compare patients with fibromyalgia and controls with respect to the presence of pruritic comorbidities. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 26). P<.05 was considered statistically significant in all tests.

Results

Our study population comprised 4971 patients with fibromyalgia and 9896 age- and sex-matched controls. Proportional to the reported female predominance among patients with fibromyalgia,27 4479 (90.1%) patients with fibromyalgia were females and a similar proportion was documented among controls (P=.99). There was a slightly higher proportion of unmarried patients among those with fibromyalgia compared with controls (41.9% vs 39.4%; P=.004). Socioeconomic status was matched between patients and controls (P=.99). Descriptive characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

We assessed the presence of pruritus as well as 3 other pruritus-related skin disorders—prurigo nodularis, neurotic excoriations, and LSC—among patients with fibromyalgia and controls. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the independent association between fibromyalgia and pruritus. Table 2 presents the results of multivariate logistic regression models and summarizes the adjusted ORs for pruritic conditions in patients with fibromyalgia and different demographic features across the entire study sample. Fibromyalgia demonstrated strong independent associations with pruritus (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.8-2.4; P<.001), prurigo nodularis (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1-8.4; P=.038), and LSC (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P=.01); the association with neurotic excoriations was not significant. Female sex significantly increased the risk for pruritus (OR 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0-1.6; P=.039), while age slightly increased the odds for pruritus (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.0-1.04; P<.001), neurotic excoriations (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.0-1.1; P=.046), and LSC (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.01-1.04; P=.006). Finally, socioeconomic status was inversely correlated with pruritus (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.1-1.5; P=.002).

Frequencies and ORs for the association between fibromyalgia and pruritus with associated pruritic disorders stratified by exclusion of pruritic dermatologic and/or systemic diseases that may induce itch are presented in the eTable. Analyzing the entire study cohort, significant increases were observed in the odds of all 4 pruritic disorders analyzed. The frequency of pruritus was almost double in patients with fibromyalgia compared with controls (11.7% vs 6.0%; OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.8-2.3; P<.0001). Prurigo nodularis (0.2% vs 0.1%; OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1-8.4; P=.05), neurotic excoriations (0.6% vs 0.3%; OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1-3.1; P=.018), and LSC (1.3% vs 0.8%; OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P=.01) frequencies were all higher in patients with fibromyalgia than controls. When primary skin disorders that may cause itch (eg, pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, dermatitis, eczema, ichthyosis, psoriasis, parapsoriasis, urticaria, xerosis, atopic dermatitis, dermatitis herpetiformis, lichen planus) were excluded, the prevalence of pruritus in patients with fibromyalgia was still 1.97 times greater than in the controls (6.9% vs. 3.5%; OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.7-2.4; P<.0001). These results remained unchanged even when excluding pruritic dermatologic disorders as well as systemic diseases associated with pruritus (eg, chronic renal failure, dialysis, hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism/hypoparathyroidism, hypothyroidism). Patients with fibromyalgia still displayed a significantly higher prevalence of pruritus compared with the control group (6.6% vs 3.3%; OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.7-2.6; P<.0001).

Comment

A wide range of skin manifestations have been associated with fibromyalgia, but the exact mechanisms remain unclear. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that autonomic nervous system dysfunction,28-31 amplified cutaneous opioid receptor activity,32 and an elevated presence of cutaneous mast cells with excessive degranulation may partially explain the frequent occurrence of pruritus and related skin disorders such as neurotic excoriations, prurigo nodularis, and LSC in individuals with fibromyalgia.15,16 In line with these findings, our study—which was based on data from the largest health maintenance organization in Israel—demonstrated an increased prevalence of pruritus and related pruritic disorders among individuals diagnosed with fibromyalgia.

This cross-sectional study links pruritus with fibromyalgia. Few preliminary epidemiologic studies have shown an increased occurrence of cutaneous manifestations in patients with fibromyalgia. One chart review that looked at skin findings in patients with fibromyalgia revealed 32 distinct cutaneous manifestations, and pruritus was the major concern in 3.3% of 845 patients.15

A focused cross-sectional study involving only women (66 with fibromyalgia and 79 healthy controls) discovered 14 skin conditions that were more common in those with fibromyalgia. Notably, xerosis and neurotic excoriations were more prevalent compared to the control group.16

The brain and the skin—both derivatives of the embryonic ectoderm33,34—are linked by pruritus. Although itch has its dedicated neurons, there is a wide-ranging overlap of brain-activated areas between pain and itch,6 and the neural anatomy of pain and itch are closely related in both the peripheral and central nervous systems35-37; for example, diseases of the central nervous system are accompanied by pruritus in as many as 15% of cases, while postherpetic neuralgia can result in chronic pain, itching, or a combination of both.38,39 Other instances include notalgia paresthetica and brachioradial pruritus.38 Additionally, there is a noteworthy psychologic impact associated with both itch and pain,40,41 with both psychosomatic and psychologic factors implicated in chronic pruritus and in fibromyalgia.42 Lastly, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system are altered in both fibromyalgia and pruritus.43-45