User login

Doctor I-Don’t-Know

Many, many years ago there was a Thanksgiving when as I was just beginning to earn a reputation in my wife’s family. There were no place cards on the table and the usual hovering and jockeying seats was well underway. From behind me I heard one of my young nieces pipe up: “I want to sit next to Doctor I-don’t-know.”

After a few words of negotiation we were all settled in our places and ready to enjoy our meal. It took only a few seconds of introspection for me to grasp how I had received that moniker, which some physicians might consider disrespectful.

I was the only physician within several generations of that family and, as such, my in-laws thought it only appropriate to ask me medical questions. They courteously seemed to avoid personal questions about their own health and were particularly careful not to roll up their sleeves or unbutton their shirts to show me a lesion or a recently acquired surgical scar. No, my wife’s family members were curious. They wanted answers to deeper questions, the hard science so to speak. “How does aspirin work?” was a typical and painful example. Maybe pharmacologists today have better answers but 40 years ago I’m not so sure; I certainly didn’t know back then and would reply, “I don’t know.” Probably for the third or fourth time that day.

Usually I genuinely didn’t know the answer. However, sometimes my answer was going to be so different from the beliefs and biases of my inquisitor that, in the interest of expediency, “I don’t know” seemed the most appropriate response.

If you were reading Letters from Maine 25 years ago, that scenario might sound familiar. I have chosen to pull it out of the archives as a jumping-off point for a consideration of the unfortunate example some of us set when the COVID pandemic threw a tsunami of unknowns at us. Too many physician-“experts” were afraid to say, “I don’t know.” Instead, and maybe because, they themselves were afraid that the patients couldn’t handle the truth that none of us in the profession knew the correct answers. When so many initial pronouncements proved incorrect, it was too late to undo the damage that had been done to the community’s trust in the rest of us.

It turns out that my in-laws were not the only folks who thought of me as Doctor I-don’t-know. One of the perks of remaining in the same community after one retires is that encounters with former patients and their parents happen frequently. On more than one occasion a parent has thanked me for admitting my ignorance. Some have even claimed that my candid approach was what they remembered most fondly. And, that quality increased their trust when I finally provided an answer.

There is an art to delivering “I don’t know.” Thirty years ago I would excuse myself and tell the family I was going to my office to pull a book off the shelf or call a previous mentor. Now one only needs to ask Dr. Google. No need to leave the room. If appropriate, the provider can swing the computer screen so that the patient can share in the search for the answer.

That strategy only works when the provider merely needs to update or expand his/her knowledge. However, there are those difficult situations when no one could know the answer given the current parameters of the patient’s situation. More lab work might be needed. It may be too early in the trajectory of the patient’s illness for the illnesses signs and symptoms to declare themselves.

In these situations “I don’t know” must be followed by a “but.” It is what comes after that “but” and how it is delivered that can convert the provider’s admission of ignorance into a demonstration of his or her character. Is he/she a caring person trying to understand the patient’s concerns? Willing to enter into a cooperative relationship as together they search for the cause and hopefully for a cure for the patient’s currently mysterious illness?

I recently read about a physician who is encouraging medical educators to incorporate more discussions of “humility” and its role in patient care into the medical school and postgraduate training curricula. He feels, as do I, that

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Many, many years ago there was a Thanksgiving when as I was just beginning to earn a reputation in my wife’s family. There were no place cards on the table and the usual hovering and jockeying seats was well underway. From behind me I heard one of my young nieces pipe up: “I want to sit next to Doctor I-don’t-know.”

After a few words of negotiation we were all settled in our places and ready to enjoy our meal. It took only a few seconds of introspection for me to grasp how I had received that moniker, which some physicians might consider disrespectful.

I was the only physician within several generations of that family and, as such, my in-laws thought it only appropriate to ask me medical questions. They courteously seemed to avoid personal questions about their own health and were particularly careful not to roll up their sleeves or unbutton their shirts to show me a lesion or a recently acquired surgical scar. No, my wife’s family members were curious. They wanted answers to deeper questions, the hard science so to speak. “How does aspirin work?” was a typical and painful example. Maybe pharmacologists today have better answers but 40 years ago I’m not so sure; I certainly didn’t know back then and would reply, “I don’t know.” Probably for the third or fourth time that day.

Usually I genuinely didn’t know the answer. However, sometimes my answer was going to be so different from the beliefs and biases of my inquisitor that, in the interest of expediency, “I don’t know” seemed the most appropriate response.

If you were reading Letters from Maine 25 years ago, that scenario might sound familiar. I have chosen to pull it out of the archives as a jumping-off point for a consideration of the unfortunate example some of us set when the COVID pandemic threw a tsunami of unknowns at us. Too many physician-“experts” were afraid to say, “I don’t know.” Instead, and maybe because, they themselves were afraid that the patients couldn’t handle the truth that none of us in the profession knew the correct answers. When so many initial pronouncements proved incorrect, it was too late to undo the damage that had been done to the community’s trust in the rest of us.

It turns out that my in-laws were not the only folks who thought of me as Doctor I-don’t-know. One of the perks of remaining in the same community after one retires is that encounters with former patients and their parents happen frequently. On more than one occasion a parent has thanked me for admitting my ignorance. Some have even claimed that my candid approach was what they remembered most fondly. And, that quality increased their trust when I finally provided an answer.

There is an art to delivering “I don’t know.” Thirty years ago I would excuse myself and tell the family I was going to my office to pull a book off the shelf or call a previous mentor. Now one only needs to ask Dr. Google. No need to leave the room. If appropriate, the provider can swing the computer screen so that the patient can share in the search for the answer.

That strategy only works when the provider merely needs to update or expand his/her knowledge. However, there are those difficult situations when no one could know the answer given the current parameters of the patient’s situation. More lab work might be needed. It may be too early in the trajectory of the patient’s illness for the illnesses signs and symptoms to declare themselves.

In these situations “I don’t know” must be followed by a “but.” It is what comes after that “but” and how it is delivered that can convert the provider’s admission of ignorance into a demonstration of his or her character. Is he/she a caring person trying to understand the patient’s concerns? Willing to enter into a cooperative relationship as together they search for the cause and hopefully for a cure for the patient’s currently mysterious illness?

I recently read about a physician who is encouraging medical educators to incorporate more discussions of “humility” and its role in patient care into the medical school and postgraduate training curricula. He feels, as do I, that

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Many, many years ago there was a Thanksgiving when as I was just beginning to earn a reputation in my wife’s family. There were no place cards on the table and the usual hovering and jockeying seats was well underway. From behind me I heard one of my young nieces pipe up: “I want to sit next to Doctor I-don’t-know.”

After a few words of negotiation we were all settled in our places and ready to enjoy our meal. It took only a few seconds of introspection for me to grasp how I had received that moniker, which some physicians might consider disrespectful.

I was the only physician within several generations of that family and, as such, my in-laws thought it only appropriate to ask me medical questions. They courteously seemed to avoid personal questions about their own health and were particularly careful not to roll up their sleeves or unbutton their shirts to show me a lesion or a recently acquired surgical scar. No, my wife’s family members were curious. They wanted answers to deeper questions, the hard science so to speak. “How does aspirin work?” was a typical and painful example. Maybe pharmacologists today have better answers but 40 years ago I’m not so sure; I certainly didn’t know back then and would reply, “I don’t know.” Probably for the third or fourth time that day.

Usually I genuinely didn’t know the answer. However, sometimes my answer was going to be so different from the beliefs and biases of my inquisitor that, in the interest of expediency, “I don’t know” seemed the most appropriate response.

If you were reading Letters from Maine 25 years ago, that scenario might sound familiar. I have chosen to pull it out of the archives as a jumping-off point for a consideration of the unfortunate example some of us set when the COVID pandemic threw a tsunami of unknowns at us. Too many physician-“experts” were afraid to say, “I don’t know.” Instead, and maybe because, they themselves were afraid that the patients couldn’t handle the truth that none of us in the profession knew the correct answers. When so many initial pronouncements proved incorrect, it was too late to undo the damage that had been done to the community’s trust in the rest of us.

It turns out that my in-laws were not the only folks who thought of me as Doctor I-don’t-know. One of the perks of remaining in the same community after one retires is that encounters with former patients and their parents happen frequently. On more than one occasion a parent has thanked me for admitting my ignorance. Some have even claimed that my candid approach was what they remembered most fondly. And, that quality increased their trust when I finally provided an answer.

There is an art to delivering “I don’t know.” Thirty years ago I would excuse myself and tell the family I was going to my office to pull a book off the shelf or call a previous mentor. Now one only needs to ask Dr. Google. No need to leave the room. If appropriate, the provider can swing the computer screen so that the patient can share in the search for the answer.

That strategy only works when the provider merely needs to update or expand his/her knowledge. However, there are those difficult situations when no one could know the answer given the current parameters of the patient’s situation. More lab work might be needed. It may be too early in the trajectory of the patient’s illness for the illnesses signs and symptoms to declare themselves.

In these situations “I don’t know” must be followed by a “but.” It is what comes after that “but” and how it is delivered that can convert the provider’s admission of ignorance into a demonstration of his or her character. Is he/she a caring person trying to understand the patient’s concerns? Willing to enter into a cooperative relationship as together they search for the cause and hopefully for a cure for the patient’s currently mysterious illness?

I recently read about a physician who is encouraging medical educators to incorporate more discussions of “humility” and its role in patient care into the medical school and postgraduate training curricula. He feels, as do I, that

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Rheumatoid Arthritis May Raise Lung Cancer Risk, Particularly in Those With ILD

TOPLINE:

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is linked with over a 50% increased risk for lung cancer, with those having RA-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) being particularly vulnerable, facing nearly a threefold higher risk.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective matched cohort study to evaluate the risk for lung cancer in participants with RA, including those with RA-ILD, within Veterans Affairs (VA) from 2000 to 2019.

- A total of 72,795 participants with RA were matched with 633,937 participants without RA on the basis of birth year, sex, and VA enrollment year.

- Among those with RA, 757 had prevalent RA-ILD and were matched with 5931 participants without RA-ILD.

- The primary outcome was incident lung cancer, assessed using the VA Oncology Raw Domain and the National Death Index.

TAKEAWAY:

- Over a mean follow-up of 6.3 years, 2974 incidences of lung cancer were reported in patients with RA, and 34 were reported in those with RA-ILD.

- The risk for lung cancer was 58% higher in patients with RA than in those without RA (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.58; 95% CI, 1.52-1.64), with this association persisting even when only never-smokers were considered (aHR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.22-2.24).

- Participants with prevalent RA-ILD had 3.25-fold higher risk for lung cancer than those without RA (aHR, 3.25; 95% CI, 2.13-4.95).

- Both patients with prevalent and those with incident RA-ILD showed a similar increase in risk for lung cancer (aHR, 2.88; 95% CI, 2.45-3.40).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our results highlight RA and RA-ILD as high-risk populations that may benefit from enhanced lung cancer screening,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Rebecca T. Brooks, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. It was published online on July 28, 2024, in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study included a predominantly male population, which may have affected the generalizability of the study. Although the study considered smoking status, data on the duration and intensity of smoking were not available. Restriction to never-smokers could not be completed for comparisons between patients with RA-ILD and those without RA because of insufficient sample sizes.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not receive funding from any source. Some authors reported receiving research funding or having ties with various pharmaceutical companies and other sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is linked with over a 50% increased risk for lung cancer, with those having RA-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) being particularly vulnerable, facing nearly a threefold higher risk.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective matched cohort study to evaluate the risk for lung cancer in participants with RA, including those with RA-ILD, within Veterans Affairs (VA) from 2000 to 2019.

- A total of 72,795 participants with RA were matched with 633,937 participants without RA on the basis of birth year, sex, and VA enrollment year.

- Among those with RA, 757 had prevalent RA-ILD and were matched with 5931 participants without RA-ILD.

- The primary outcome was incident lung cancer, assessed using the VA Oncology Raw Domain and the National Death Index.

TAKEAWAY:

- Over a mean follow-up of 6.3 years, 2974 incidences of lung cancer were reported in patients with RA, and 34 were reported in those with RA-ILD.

- The risk for lung cancer was 58% higher in patients with RA than in those without RA (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.58; 95% CI, 1.52-1.64), with this association persisting even when only never-smokers were considered (aHR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.22-2.24).

- Participants with prevalent RA-ILD had 3.25-fold higher risk for lung cancer than those without RA (aHR, 3.25; 95% CI, 2.13-4.95).

- Both patients with prevalent and those with incident RA-ILD showed a similar increase in risk for lung cancer (aHR, 2.88; 95% CI, 2.45-3.40).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our results highlight RA and RA-ILD as high-risk populations that may benefit from enhanced lung cancer screening,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Rebecca T. Brooks, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. It was published online on July 28, 2024, in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study included a predominantly male population, which may have affected the generalizability of the study. Although the study considered smoking status, data on the duration and intensity of smoking were not available. Restriction to never-smokers could not be completed for comparisons between patients with RA-ILD and those without RA because of insufficient sample sizes.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not receive funding from any source. Some authors reported receiving research funding or having ties with various pharmaceutical companies and other sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is linked with over a 50% increased risk for lung cancer, with those having RA-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) being particularly vulnerable, facing nearly a threefold higher risk.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective matched cohort study to evaluate the risk for lung cancer in participants with RA, including those with RA-ILD, within Veterans Affairs (VA) from 2000 to 2019.

- A total of 72,795 participants with RA were matched with 633,937 participants without RA on the basis of birth year, sex, and VA enrollment year.

- Among those with RA, 757 had prevalent RA-ILD and were matched with 5931 participants without RA-ILD.

- The primary outcome was incident lung cancer, assessed using the VA Oncology Raw Domain and the National Death Index.

TAKEAWAY:

- Over a mean follow-up of 6.3 years, 2974 incidences of lung cancer were reported in patients with RA, and 34 were reported in those with RA-ILD.

- The risk for lung cancer was 58% higher in patients with RA than in those without RA (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.58; 95% CI, 1.52-1.64), with this association persisting even when only never-smokers were considered (aHR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.22-2.24).

- Participants with prevalent RA-ILD had 3.25-fold higher risk for lung cancer than those without RA (aHR, 3.25; 95% CI, 2.13-4.95).

- Both patients with prevalent and those with incident RA-ILD showed a similar increase in risk for lung cancer (aHR, 2.88; 95% CI, 2.45-3.40).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our results highlight RA and RA-ILD as high-risk populations that may benefit from enhanced lung cancer screening,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Rebecca T. Brooks, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. It was published online on July 28, 2024, in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study included a predominantly male population, which may have affected the generalizability of the study. Although the study considered smoking status, data on the duration and intensity of smoking were not available. Restriction to never-smokers could not be completed for comparisons between patients with RA-ILD and those without RA because of insufficient sample sizes.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not receive funding from any source. Some authors reported receiving research funding or having ties with various pharmaceutical companies and other sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

US Experience With Infliximab Biosimilars Suggests Need for More Development Incentives

TOPLINE:

Uptake of infliximab biosimilars rose slowly across private insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare when two were available in the United States during 2016-2020 but increased significantly through 2022 after the third biosimilar became available in July 2020. However, prescriptions in Medicare still lagged behind those in private insurance and Medicaid.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analyzed electronic health records from over 1100 US rheumatologists who participated in a national registry, the Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE), for all infliximab administrations (bio-originator or biosimilar) to patients older than 18 years from April 2016 to September 2022.

- They conducted an interrupted time series to account for autocorrelation and model the effect of each infliximab biosimilar release (infliximab-dyyb in November 2016, infliximab-abda in July 2017, and infliximab-axxq in July 2020) on uptake across Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers.

TAKEAWAY:

- The researchers identified 659,988 infliximab administrations for 37,560 unique patients, with 52% on Medicare, 4.8% on Medicaid, and 43% on private insurance.

- Biosimilar uptake rose slowly with average annual increases < 5% from 2016 to June 2020 (Medicare, 3.2%; Medicaid, 5.2%; private insurance, 1.8%).

- After the third biosimilar release in July 2020, the average annual increase reached 13% for Medicaid and 16.4% for private insurance but remained low for Medicare (5.6%).

- By September 2022, biosimilar uptake was higher for Medicaid (43.8%) and private insurance (38.5%) than for Medicare (24%).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our results suggest policymakers may need to do more to allow biosimilars to get a foothold in the market by incentivizing the development and entry of multiple biosimilars, address anticompetitive pricing strategies, and may need to amend Medicare policy to [incentivize] uptake in order to ensure a competitive and sustainable biosimilar market that gradually reduces total drug expenditures and out-of-pocket costs over time,” wrote the authors of the study.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Eric T. Roberts, PhD, University of California, San Francisco. It was published online on July 30, 2024, in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

First, while the biosimilar introductions are likely catalysts for many changes in the market, some changes in slopes may also be attributable to the natural growth of the market over time. Second, this study may neither be generalizable to academic medical centers, which are underrepresented in RISE, nor be generalizable to infliximab prescriptions from other specialties. Third, uptake among privately insured patients changed shortly after November-December 2020, raising the possibility that the delay reflected negotiations between insurance companies and relevant entities regarding formulary coverage.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. One author disclosed receiving consulting fees from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Bristol-Myers Squibb and grant funding from AstraZeneca, the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation, and Aurinia.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Uptake of infliximab biosimilars rose slowly across private insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare when two were available in the United States during 2016-2020 but increased significantly through 2022 after the third biosimilar became available in July 2020. However, prescriptions in Medicare still lagged behind those in private insurance and Medicaid.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analyzed electronic health records from over 1100 US rheumatologists who participated in a national registry, the Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE), for all infliximab administrations (bio-originator or biosimilar) to patients older than 18 years from April 2016 to September 2022.

- They conducted an interrupted time series to account for autocorrelation and model the effect of each infliximab biosimilar release (infliximab-dyyb in November 2016, infliximab-abda in July 2017, and infliximab-axxq in July 2020) on uptake across Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers.

TAKEAWAY:

- The researchers identified 659,988 infliximab administrations for 37,560 unique patients, with 52% on Medicare, 4.8% on Medicaid, and 43% on private insurance.

- Biosimilar uptake rose slowly with average annual increases < 5% from 2016 to June 2020 (Medicare, 3.2%; Medicaid, 5.2%; private insurance, 1.8%).

- After the third biosimilar release in July 2020, the average annual increase reached 13% for Medicaid and 16.4% for private insurance but remained low for Medicare (5.6%).

- By September 2022, biosimilar uptake was higher for Medicaid (43.8%) and private insurance (38.5%) than for Medicare (24%).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our results suggest policymakers may need to do more to allow biosimilars to get a foothold in the market by incentivizing the development and entry of multiple biosimilars, address anticompetitive pricing strategies, and may need to amend Medicare policy to [incentivize] uptake in order to ensure a competitive and sustainable biosimilar market that gradually reduces total drug expenditures and out-of-pocket costs over time,” wrote the authors of the study.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Eric T. Roberts, PhD, University of California, San Francisco. It was published online on July 30, 2024, in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

First, while the biosimilar introductions are likely catalysts for many changes in the market, some changes in slopes may also be attributable to the natural growth of the market over time. Second, this study may neither be generalizable to academic medical centers, which are underrepresented in RISE, nor be generalizable to infliximab prescriptions from other specialties. Third, uptake among privately insured patients changed shortly after November-December 2020, raising the possibility that the delay reflected negotiations between insurance companies and relevant entities regarding formulary coverage.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. One author disclosed receiving consulting fees from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Bristol-Myers Squibb and grant funding from AstraZeneca, the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation, and Aurinia.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Uptake of infliximab biosimilars rose slowly across private insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare when two were available in the United States during 2016-2020 but increased significantly through 2022 after the third biosimilar became available in July 2020. However, prescriptions in Medicare still lagged behind those in private insurance and Medicaid.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analyzed electronic health records from over 1100 US rheumatologists who participated in a national registry, the Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE), for all infliximab administrations (bio-originator or biosimilar) to patients older than 18 years from April 2016 to September 2022.

- They conducted an interrupted time series to account for autocorrelation and model the effect of each infliximab biosimilar release (infliximab-dyyb in November 2016, infliximab-abda in July 2017, and infliximab-axxq in July 2020) on uptake across Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers.

TAKEAWAY:

- The researchers identified 659,988 infliximab administrations for 37,560 unique patients, with 52% on Medicare, 4.8% on Medicaid, and 43% on private insurance.

- Biosimilar uptake rose slowly with average annual increases < 5% from 2016 to June 2020 (Medicare, 3.2%; Medicaid, 5.2%; private insurance, 1.8%).

- After the third biosimilar release in July 2020, the average annual increase reached 13% for Medicaid and 16.4% for private insurance but remained low for Medicare (5.6%).

- By September 2022, biosimilar uptake was higher for Medicaid (43.8%) and private insurance (38.5%) than for Medicare (24%).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our results suggest policymakers may need to do more to allow biosimilars to get a foothold in the market by incentivizing the development and entry of multiple biosimilars, address anticompetitive pricing strategies, and may need to amend Medicare policy to [incentivize] uptake in order to ensure a competitive and sustainable biosimilar market that gradually reduces total drug expenditures and out-of-pocket costs over time,” wrote the authors of the study.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Eric T. Roberts, PhD, University of California, San Francisco. It was published online on July 30, 2024, in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

First, while the biosimilar introductions are likely catalysts for many changes in the market, some changes in slopes may also be attributable to the natural growth of the market over time. Second, this study may neither be generalizable to academic medical centers, which are underrepresented in RISE, nor be generalizable to infliximab prescriptions from other specialties. Third, uptake among privately insured patients changed shortly after November-December 2020, raising the possibility that the delay reflected negotiations between insurance companies and relevant entities regarding formulary coverage.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. One author disclosed receiving consulting fees from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Bristol-Myers Squibb and grant funding from AstraZeneca, the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation, and Aurinia.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Remission or Not, Biologics May Mitigate Cardiovascular Risks of RA

TOPLINE:

, suggesting that biologics may reduce cardiovascular risk in RA even if remission is not achieved.

METHODOLOGY:

- Studies reported reduced cardiovascular risk in patients with RA who respond to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors but not in nonresponders, highlighting the importance of controlling inflammation for cardiovascular protection.

- Researchers assessed whether bDMARDs modify the impact of disease activity and systemic inflammation on cardiovascular risk in 4370 patients (mean age, 55 years) with RA without cardiovascular disease from a 10-country observational cohort.

- The severity of RA disease activity was assessed using C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on CRP (DAS28-CRP).

- Endpoints were time to first MACE — a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke — and time to first ischemic cardiovascular event (iCVE) — a composite of MACE plus revascularization, angina, transient ischemic attack, and peripheral arterial disease.

TAKEAWAY:

- The interaction between use of bDMARD and DAS28-CRP (P = .017) or CRP (P = .011) was significant for MACE.

- Each unit increase in DAS28-CRP increased the risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (hazard ratio [HR], 1.21; P = .002) but not in users.

- The per log unit increase in CRP was associated with a risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (HR, 1.16; P = .009) but not in users.

- No interaction was observed between bDMARD use and DAS28-CRP or CRP for the iCVE risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“This may indicate additional bDMARD-specific benefits directly on arterial wall inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque anatomy, stability, and biology, independently of systemic inflammation,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by George Athanasios Karpouzas, MD, The Lundquist Institute, Torrance, California, was published online in RMD Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Patients with a particular interest in RA-associated cardiovascular disease were included, which may have introduced referral bias and affected the generalizability of the findings. Standard definitions were used for selected outcomes; however, differences in the reporting of outcomes may be plausible. Some patients were evaluated prospectively, while others were evaluated retrospectively, leading to differences in surveillance.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by Pfizer. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, suggesting that biologics may reduce cardiovascular risk in RA even if remission is not achieved.

METHODOLOGY:

- Studies reported reduced cardiovascular risk in patients with RA who respond to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors but not in nonresponders, highlighting the importance of controlling inflammation for cardiovascular protection.

- Researchers assessed whether bDMARDs modify the impact of disease activity and systemic inflammation on cardiovascular risk in 4370 patients (mean age, 55 years) with RA without cardiovascular disease from a 10-country observational cohort.

- The severity of RA disease activity was assessed using C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on CRP (DAS28-CRP).

- Endpoints were time to first MACE — a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke — and time to first ischemic cardiovascular event (iCVE) — a composite of MACE plus revascularization, angina, transient ischemic attack, and peripheral arterial disease.

TAKEAWAY:

- The interaction between use of bDMARD and DAS28-CRP (P = .017) or CRP (P = .011) was significant for MACE.

- Each unit increase in DAS28-CRP increased the risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (hazard ratio [HR], 1.21; P = .002) but not in users.

- The per log unit increase in CRP was associated with a risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (HR, 1.16; P = .009) but not in users.

- No interaction was observed between bDMARD use and DAS28-CRP or CRP for the iCVE risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“This may indicate additional bDMARD-specific benefits directly on arterial wall inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque anatomy, stability, and biology, independently of systemic inflammation,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by George Athanasios Karpouzas, MD, The Lundquist Institute, Torrance, California, was published online in RMD Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Patients with a particular interest in RA-associated cardiovascular disease were included, which may have introduced referral bias and affected the generalizability of the findings. Standard definitions were used for selected outcomes; however, differences in the reporting of outcomes may be plausible. Some patients were evaluated prospectively, while others were evaluated retrospectively, leading to differences in surveillance.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by Pfizer. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, suggesting that biologics may reduce cardiovascular risk in RA even if remission is not achieved.

METHODOLOGY:

- Studies reported reduced cardiovascular risk in patients with RA who respond to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors but not in nonresponders, highlighting the importance of controlling inflammation for cardiovascular protection.

- Researchers assessed whether bDMARDs modify the impact of disease activity and systemic inflammation on cardiovascular risk in 4370 patients (mean age, 55 years) with RA without cardiovascular disease from a 10-country observational cohort.

- The severity of RA disease activity was assessed using C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on CRP (DAS28-CRP).

- Endpoints were time to first MACE — a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke — and time to first ischemic cardiovascular event (iCVE) — a composite of MACE plus revascularization, angina, transient ischemic attack, and peripheral arterial disease.

TAKEAWAY:

- The interaction between use of bDMARD and DAS28-CRP (P = .017) or CRP (P = .011) was significant for MACE.

- Each unit increase in DAS28-CRP increased the risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (hazard ratio [HR], 1.21; P = .002) but not in users.

- The per log unit increase in CRP was associated with a risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (HR, 1.16; P = .009) but not in users.

- No interaction was observed between bDMARD use and DAS28-CRP or CRP for the iCVE risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“This may indicate additional bDMARD-specific benefits directly on arterial wall inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque anatomy, stability, and biology, independently of systemic inflammation,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by George Athanasios Karpouzas, MD, The Lundquist Institute, Torrance, California, was published online in RMD Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Patients with a particular interest in RA-associated cardiovascular disease were included, which may have introduced referral bias and affected the generalizability of the findings. Standard definitions were used for selected outcomes; however, differences in the reporting of outcomes may be plausible. Some patients were evaluated prospectively, while others were evaluated retrospectively, leading to differences in surveillance.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by Pfizer. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer: Encouraging Data on Laser Treatment

TOPLINE:

Published

METHODOLOGY:

- Using MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, and www.clinicaltrials.gov, researchers systematically reviewed 50 unique published articles that evaluated the role of laser therapy for NMSC.

- Of the 50 studies, 37 focused on lasers for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma (BCC), 10 on lasers for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and three on the treatment of both tumor types.

- The analysis was limited to studies published in English from the first data available through May 1, 2023.

TAKEAWAY:

- Data was strongest for the use of lasers for treating BCC, especially pulsed-dye lasers (PDL). Of 11 unique studies on PDL as monotherapy for managing BCCs, clearance rates ranged from 14.3% to 90.0%.

- For SCCs, 13 studies were identified that evaluated the use of lasers alone or in combination with PDL for treating SCC in situ. Among case reports that used PDL and thulium lasers separately, clearance rates of 100% were reported, while several case series that used the CO2 laser reported response rates that ranged from 61.5% to 100%.

- The best evidence for clearing both BCC and SCC tumors was observed when ablative lasers such as the CO2 or erbium yttrium aluminum garnet are combined with methyl aminolevulinate–photodynamic therapy (PDT) or 5-aminolevulinic acid–PDT, “likely due to increased delivery of the photosensitizing compound to neoplastic cells,” the authors wrote.

IN PRACTICE:

“Additional investigations with longer follow-up periods are needed to determine optimal laser parameters, number of treatment sessions required, and recurrence rates (using complete histologic analysis through step sectioning) before lasers can fully be adopted into clinical practice,” the authors wrote. “Surgical excision, specifically Mohs micrographic surgery,” they added, “persists as the gold standard for high-risk and cosmetically sensitive tumors, offering the highest cure rates in a single office visit.”

SOURCE:

Amanda Rosenthal, MD, of the Department of Dermatology, Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center in California, and colleagues conducted the review. The study was published in the August 2024 issue of Dermatologic Surgery.

LIMITATIONS:

Laser therapy is not FDA approved for the treatment of NMSC and remains an alternative treatment option. Also, most published studies focus on BCCs, while studies on cutaneous SCCs are more limited.

DISCLOSURES:

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Published

METHODOLOGY:

- Using MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, and www.clinicaltrials.gov, researchers systematically reviewed 50 unique published articles that evaluated the role of laser therapy for NMSC.

- Of the 50 studies, 37 focused on lasers for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma (BCC), 10 on lasers for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and three on the treatment of both tumor types.

- The analysis was limited to studies published in English from the first data available through May 1, 2023.

TAKEAWAY:

- Data was strongest for the use of lasers for treating BCC, especially pulsed-dye lasers (PDL). Of 11 unique studies on PDL as monotherapy for managing BCCs, clearance rates ranged from 14.3% to 90.0%.

- For SCCs, 13 studies were identified that evaluated the use of lasers alone or in combination with PDL for treating SCC in situ. Among case reports that used PDL and thulium lasers separately, clearance rates of 100% were reported, while several case series that used the CO2 laser reported response rates that ranged from 61.5% to 100%.

- The best evidence for clearing both BCC and SCC tumors was observed when ablative lasers such as the CO2 or erbium yttrium aluminum garnet are combined with methyl aminolevulinate–photodynamic therapy (PDT) or 5-aminolevulinic acid–PDT, “likely due to increased delivery of the photosensitizing compound to neoplastic cells,” the authors wrote.

IN PRACTICE:

“Additional investigations with longer follow-up periods are needed to determine optimal laser parameters, number of treatment sessions required, and recurrence rates (using complete histologic analysis through step sectioning) before lasers can fully be adopted into clinical practice,” the authors wrote. “Surgical excision, specifically Mohs micrographic surgery,” they added, “persists as the gold standard for high-risk and cosmetically sensitive tumors, offering the highest cure rates in a single office visit.”

SOURCE:

Amanda Rosenthal, MD, of the Department of Dermatology, Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center in California, and colleagues conducted the review. The study was published in the August 2024 issue of Dermatologic Surgery.

LIMITATIONS:

Laser therapy is not FDA approved for the treatment of NMSC and remains an alternative treatment option. Also, most published studies focus on BCCs, while studies on cutaneous SCCs are more limited.

DISCLOSURES:

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Published

METHODOLOGY:

- Using MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, and www.clinicaltrials.gov, researchers systematically reviewed 50 unique published articles that evaluated the role of laser therapy for NMSC.

- Of the 50 studies, 37 focused on lasers for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma (BCC), 10 on lasers for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and three on the treatment of both tumor types.

- The analysis was limited to studies published in English from the first data available through May 1, 2023.

TAKEAWAY:

- Data was strongest for the use of lasers for treating BCC, especially pulsed-dye lasers (PDL). Of 11 unique studies on PDL as monotherapy for managing BCCs, clearance rates ranged from 14.3% to 90.0%.

- For SCCs, 13 studies were identified that evaluated the use of lasers alone or in combination with PDL for treating SCC in situ. Among case reports that used PDL and thulium lasers separately, clearance rates of 100% were reported, while several case series that used the CO2 laser reported response rates that ranged from 61.5% to 100%.

- The best evidence for clearing both BCC and SCC tumors was observed when ablative lasers such as the CO2 or erbium yttrium aluminum garnet are combined with methyl aminolevulinate–photodynamic therapy (PDT) or 5-aminolevulinic acid–PDT, “likely due to increased delivery of the photosensitizing compound to neoplastic cells,” the authors wrote.

IN PRACTICE:

“Additional investigations with longer follow-up periods are needed to determine optimal laser parameters, number of treatment sessions required, and recurrence rates (using complete histologic analysis through step sectioning) before lasers can fully be adopted into clinical practice,” the authors wrote. “Surgical excision, specifically Mohs micrographic surgery,” they added, “persists as the gold standard for high-risk and cosmetically sensitive tumors, offering the highest cure rates in a single office visit.”

SOURCE:

Amanda Rosenthal, MD, of the Department of Dermatology, Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center in California, and colleagues conducted the review. The study was published in the August 2024 issue of Dermatologic Surgery.

LIMITATIONS:

Laser therapy is not FDA approved for the treatment of NMSC and remains an alternative treatment option. Also, most published studies focus on BCCs, while studies on cutaneous SCCs are more limited.

DISCLOSURES:

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Digital Side Effects

On July 19, what was supposed to be a harmless software upgrade brought down a huge chunk of the health care, banking, flight, and travel systems.

While my dinky little practice wasn’t affected, several of my patients were in other ways. Tests that had to be rescheduled, flights canceled ... inconveniences, but not life altering.

Things are allegedly fixed (at least until next time) but there may be fallout down the road. People who had delayed medical procedures could have a different prognosis depending on what the results showed when they were done. Hopefully this won’t happen.

But it’s a reminder of how vulnerable our whole world is to disruption of the internet, not to mention the power grid and software systems. Paper is time consuming, and takes up a lot of space, but as long as you have a decent pen and enough light to read it you’re fine.

I’m not saying we should go back to paper. It’s more expensive in the long run, takes up shelf and closet space, kills trees, has to be shredded after a time, and turns yellow around the edges. It also makes it a pain to copy and transfer records. With paper I wouldn’t be able to take all my charts with me to refer to when I leave town on a busman’s holiday. The benefits of digital far outstrip paper or we wouldn’t have switched in the first place.

But it’s still kind of scary to realize how much we depend on software to keep things running smoothly. The events of July 19 were unintentional. Someone looking to cause real trouble could do worse — and there are plenty out there who would love to — and we’re putting our faith in companies like CrowdStrike to protect us from them.

But, on the flip side, we’re asking others to do the same. We often use the phrase “trust me, I’m a doctor,” in jest, but the point is there. People come to us because we have knowledge and training they don’t, and they’re hoping we can help them. We spent a lot of time getting to the point where we can hang up a sign that says so. And we, like everyone else, are not infallible.

We’re individuals, not machines. Both are fallible, though in different ways. In CrowdStrike’s case the machines didn’t fail, they just did what the humans told them to do. Which didn’t work.

The bottom line is that even the most well-meaning will make mistakes.

But it’s still pretty scary because, even unintentionally, there will be a next time. And between now and then our world will become even more dependent on these systems. None of us want to go back to the preconnected era, it’s too much a part of our daily lives.

Like the long list of potential side effects on any drug we prescribe, it’s a trade-off that we’ve accepted. And at this point we aren’t going back.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

On July 19, what was supposed to be a harmless software upgrade brought down a huge chunk of the health care, banking, flight, and travel systems.

While my dinky little practice wasn’t affected, several of my patients were in other ways. Tests that had to be rescheduled, flights canceled ... inconveniences, but not life altering.

Things are allegedly fixed (at least until next time) but there may be fallout down the road. People who had delayed medical procedures could have a different prognosis depending on what the results showed when they were done. Hopefully this won’t happen.

But it’s a reminder of how vulnerable our whole world is to disruption of the internet, not to mention the power grid and software systems. Paper is time consuming, and takes up a lot of space, but as long as you have a decent pen and enough light to read it you’re fine.

I’m not saying we should go back to paper. It’s more expensive in the long run, takes up shelf and closet space, kills trees, has to be shredded after a time, and turns yellow around the edges. It also makes it a pain to copy and transfer records. With paper I wouldn’t be able to take all my charts with me to refer to when I leave town on a busman’s holiday. The benefits of digital far outstrip paper or we wouldn’t have switched in the first place.

But it’s still kind of scary to realize how much we depend on software to keep things running smoothly. The events of July 19 were unintentional. Someone looking to cause real trouble could do worse — and there are plenty out there who would love to — and we’re putting our faith in companies like CrowdStrike to protect us from them.

But, on the flip side, we’re asking others to do the same. We often use the phrase “trust me, I’m a doctor,” in jest, but the point is there. People come to us because we have knowledge and training they don’t, and they’re hoping we can help them. We spent a lot of time getting to the point where we can hang up a sign that says so. And we, like everyone else, are not infallible.

We’re individuals, not machines. Both are fallible, though in different ways. In CrowdStrike’s case the machines didn’t fail, they just did what the humans told them to do. Which didn’t work.

The bottom line is that even the most well-meaning will make mistakes.

But it’s still pretty scary because, even unintentionally, there will be a next time. And between now and then our world will become even more dependent on these systems. None of us want to go back to the preconnected era, it’s too much a part of our daily lives.

Like the long list of potential side effects on any drug we prescribe, it’s a trade-off that we’ve accepted. And at this point we aren’t going back.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

On July 19, what was supposed to be a harmless software upgrade brought down a huge chunk of the health care, banking, flight, and travel systems.

While my dinky little practice wasn’t affected, several of my patients were in other ways. Tests that had to be rescheduled, flights canceled ... inconveniences, but not life altering.

Things are allegedly fixed (at least until next time) but there may be fallout down the road. People who had delayed medical procedures could have a different prognosis depending on what the results showed when they were done. Hopefully this won’t happen.

But it’s a reminder of how vulnerable our whole world is to disruption of the internet, not to mention the power grid and software systems. Paper is time consuming, and takes up a lot of space, but as long as you have a decent pen and enough light to read it you’re fine.

I’m not saying we should go back to paper. It’s more expensive in the long run, takes up shelf and closet space, kills trees, has to be shredded after a time, and turns yellow around the edges. It also makes it a pain to copy and transfer records. With paper I wouldn’t be able to take all my charts with me to refer to when I leave town on a busman’s holiday. The benefits of digital far outstrip paper or we wouldn’t have switched in the first place.

But it’s still kind of scary to realize how much we depend on software to keep things running smoothly. The events of July 19 were unintentional. Someone looking to cause real trouble could do worse — and there are plenty out there who would love to — and we’re putting our faith in companies like CrowdStrike to protect us from them.

But, on the flip side, we’re asking others to do the same. We often use the phrase “trust me, I’m a doctor,” in jest, but the point is there. People come to us because we have knowledge and training they don’t, and they’re hoping we can help them. We spent a lot of time getting to the point where we can hang up a sign that says so. And we, like everyone else, are not infallible.

We’re individuals, not machines. Both are fallible, though in different ways. In CrowdStrike’s case the machines didn’t fail, they just did what the humans told them to do. Which didn’t work.

The bottom line is that even the most well-meaning will make mistakes.

But it’s still pretty scary because, even unintentionally, there will be a next time. And between now and then our world will become even more dependent on these systems. None of us want to go back to the preconnected era, it’s too much a part of our daily lives.

Like the long list of potential side effects on any drug we prescribe, it’s a trade-off that we’ve accepted. And at this point we aren’t going back.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Nemolizumab Benefits Seen in Adults, Teens With Atopic Dermatitis

TOPLINE:

(AD).

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers conducted two 48-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials, ARCADIA 1 (n = 941; 47% women) and ARCADIA 2 (n = 787; 52% women), involving patients aged 12 and older with moderate to severe AD.

- Participants were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive either 30 mg nemolizumab (with a 60-mg loading dose) or placebo, along with background topical corticosteroids with or without topical calcineurin inhibitors. The mean age range was 33.3-35.2 years.

- The coprimary endpoints were Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) success (score of 0 or 1 with at least a two-point improvement from baseline) and at least a 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-75) at week 16.

TAKEAWAY:

- At week 16, significantly more patients receiving nemolizumab vs placebo achieved IGA success in both the ARCADIA 1 (36% vs 25%; P = .0003) and ARCADIA 2 (38% vs 26%; P = .0006) trials.

- EASI-75 response rates were also significantly higher in the nemolizumab group than in the placebo group in both trials: ARCADIA 1 (44% vs 29%; P < .0001) and 2 (42% vs 30%; P = .0006).

- Significant improvements in pruritus were observed as early as week 1, with a greater proportion of participants in the nemolizumab vs placebo group achieving at least a four-point reduction in the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale score in both trials.

- Rates of adverse events were similar between the nemolizumab and placebo groups, with severe treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in 2%-4% of patients.

IN PRACTICE:

“Nemolizumab showed statistically and clinically significant improvements in inflammation and pruritus in adults and adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis and a rapid effect in reducing pruritus, as one of the primary complaints of patients. As such, nemolizumab might offer a valuable extension of the therapeutic armament if approved,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, from the Department of Dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, DC. It was published online in The Lancet.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s limitations included the absence of longer-term safety data. Additionally, the predominantly White population of the trials may limit the generalizability of the findings to other racial and ethnic groups. The use of concomitant topical therapy might have influenced the placebo response.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by Galderma. Dr. Silverberg received honoraria from pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, and his institution also received grants from Galderma, Incyte, and Pfizer. Four authors were employees of Galderma. Other authors also declared having ties with pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, outside this work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

(AD).

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers conducted two 48-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials, ARCADIA 1 (n = 941; 47% women) and ARCADIA 2 (n = 787; 52% women), involving patients aged 12 and older with moderate to severe AD.

- Participants were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive either 30 mg nemolizumab (with a 60-mg loading dose) or placebo, along with background topical corticosteroids with or without topical calcineurin inhibitors. The mean age range was 33.3-35.2 years.

- The coprimary endpoints were Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) success (score of 0 or 1 with at least a two-point improvement from baseline) and at least a 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-75) at week 16.

TAKEAWAY:

- At week 16, significantly more patients receiving nemolizumab vs placebo achieved IGA success in both the ARCADIA 1 (36% vs 25%; P = .0003) and ARCADIA 2 (38% vs 26%; P = .0006) trials.

- EASI-75 response rates were also significantly higher in the nemolizumab group than in the placebo group in both trials: ARCADIA 1 (44% vs 29%; P < .0001) and 2 (42% vs 30%; P = .0006).

- Significant improvements in pruritus were observed as early as week 1, with a greater proportion of participants in the nemolizumab vs placebo group achieving at least a four-point reduction in the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale score in both trials.

- Rates of adverse events were similar between the nemolizumab and placebo groups, with severe treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in 2%-4% of patients.

IN PRACTICE:

“Nemolizumab showed statistically and clinically significant improvements in inflammation and pruritus in adults and adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis and a rapid effect in reducing pruritus, as one of the primary complaints of patients. As such, nemolizumab might offer a valuable extension of the therapeutic armament if approved,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, from the Department of Dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, DC. It was published online in The Lancet.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s limitations included the absence of longer-term safety data. Additionally, the predominantly White population of the trials may limit the generalizability of the findings to other racial and ethnic groups. The use of concomitant topical therapy might have influenced the placebo response.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by Galderma. Dr. Silverberg received honoraria from pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, and his institution also received grants from Galderma, Incyte, and Pfizer. Four authors were employees of Galderma. Other authors also declared having ties with pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, outside this work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

(AD).

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers conducted two 48-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials, ARCADIA 1 (n = 941; 47% women) and ARCADIA 2 (n = 787; 52% women), involving patients aged 12 and older with moderate to severe AD.

- Participants were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive either 30 mg nemolizumab (with a 60-mg loading dose) or placebo, along with background topical corticosteroids with or without topical calcineurin inhibitors. The mean age range was 33.3-35.2 years.

- The coprimary endpoints were Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) success (score of 0 or 1 with at least a two-point improvement from baseline) and at least a 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-75) at week 16.

TAKEAWAY:

- At week 16, significantly more patients receiving nemolizumab vs placebo achieved IGA success in both the ARCADIA 1 (36% vs 25%; P = .0003) and ARCADIA 2 (38% vs 26%; P = .0006) trials.

- EASI-75 response rates were also significantly higher in the nemolizumab group than in the placebo group in both trials: ARCADIA 1 (44% vs 29%; P < .0001) and 2 (42% vs 30%; P = .0006).

- Significant improvements in pruritus were observed as early as week 1, with a greater proportion of participants in the nemolizumab vs placebo group achieving at least a four-point reduction in the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale score in both trials.

- Rates of adverse events were similar between the nemolizumab and placebo groups, with severe treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in 2%-4% of patients.

IN PRACTICE:

“Nemolizumab showed statistically and clinically significant improvements in inflammation and pruritus in adults and adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis and a rapid effect in reducing pruritus, as one of the primary complaints of patients. As such, nemolizumab might offer a valuable extension of the therapeutic armament if approved,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, from the Department of Dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, DC. It was published online in The Lancet.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s limitations included the absence of longer-term safety data. Additionally, the predominantly White population of the trials may limit the generalizability of the findings to other racial and ethnic groups. The use of concomitant topical therapy might have influenced the placebo response.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by Galderma. Dr. Silverberg received honoraria from pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, and his institution also received grants from Galderma, Incyte, and Pfizer. Four authors were employees of Galderma. Other authors also declared having ties with pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, outside this work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

These Four Factors Account for 18 Years of Life Expectancy

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

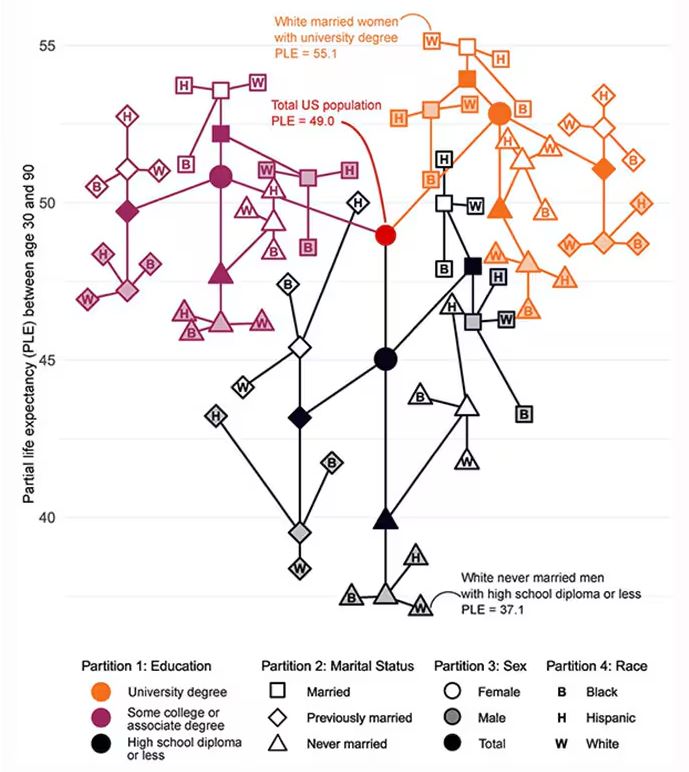

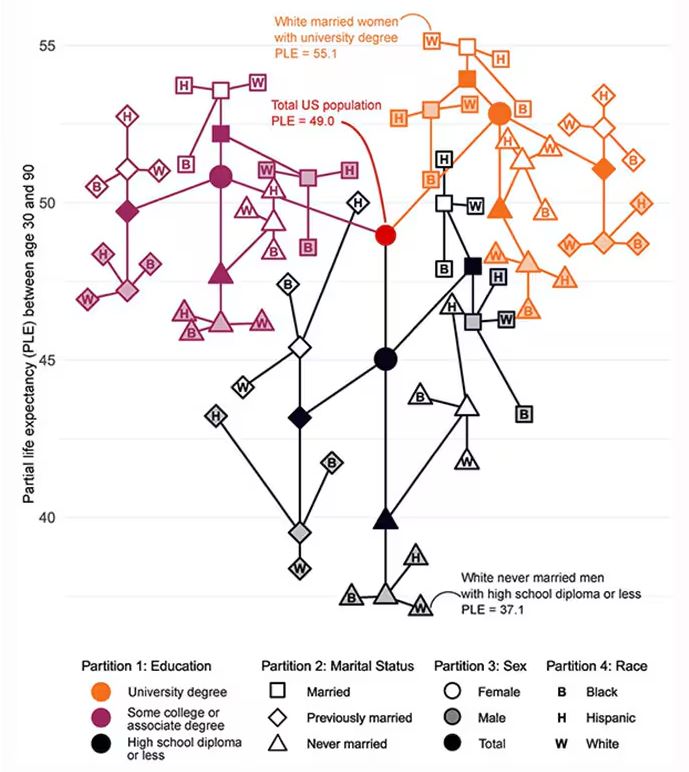

Two individuals in the United States are celebrating their 30th birthdays. It’s a good day. They are entering the prime of their lives. One is a married White woman with a university degree. The other is a never-married White man with a high school diploma.

How many more years of life can these two individuals look forward to?

There’s a fairly dramatic difference. The man can expect 37.1 more years of life on average, living to be about 67. The woman can expect to live to age 85. That’s a life-expectancy discrepancy of 18 years based solely on gender, education, and marital status.

I’m using these cases to illustrate the extremes of life expectancy across four key social determinants of health: sex, race, marital status, and education. We all have some sense of how these factors play out in terms of health, but a new study suggests that it’s actually quite a bit more complicated than we thought.

Let me start by acknowledging my own bias here. As a clinical researcher, I sometimes find it hard to appreciate the value of actuarial-type studies that look at life expectancy (or any metric, really) between groups defined by marital status, for example. I’m never quite sure what to do with the conclusion. Married people live longer, the headline says. Okay, but as a doctor, what am I supposed to do about that? Encourage my patients to settle down and commit? Studies showing that women live longer than men or that White people live longer than Black people are also hard for me to incorporate into my practice. These are not easily changeable states.

But studies examining these groups are a reasonable starting point to ask more relevant questions. Why do women live longer than men? Is it behavioral (men take more risks and are less likely to see doctors)? Or is it hormonal (estrogen has a lot of protective effects that testosterone does not)? Or is it something else?

Integrating these social determinants of health into a cohesive story is a bit harder than it might seem, as this study, appearing in BMJ Open, illustrates.

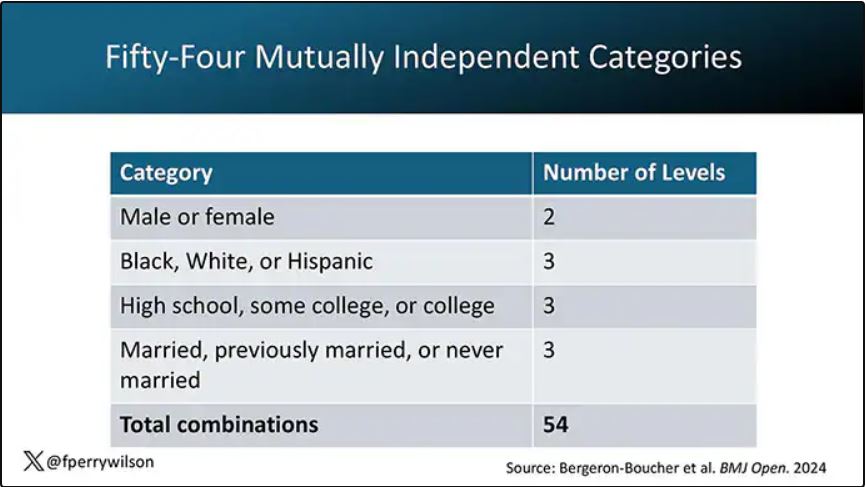

In the context of this study, every person in America can be placed into one of 54 mutually exclusive groups. You can be male or female. You can be Black, White, or Hispanic. You can have a high school diploma or less, an associate degree, or a college degree; and you can be married, previously married, or never married.

Of course, this does not capture the beautiful tapestry that is American life, but let’s give them a pass. They are working with data from the American Community Survey, which contains 8634 people — the statistics would run into trouble with more granular divisions. This survey can be population weighted, so you can scale up the results to reasonably represent the population of the United States.

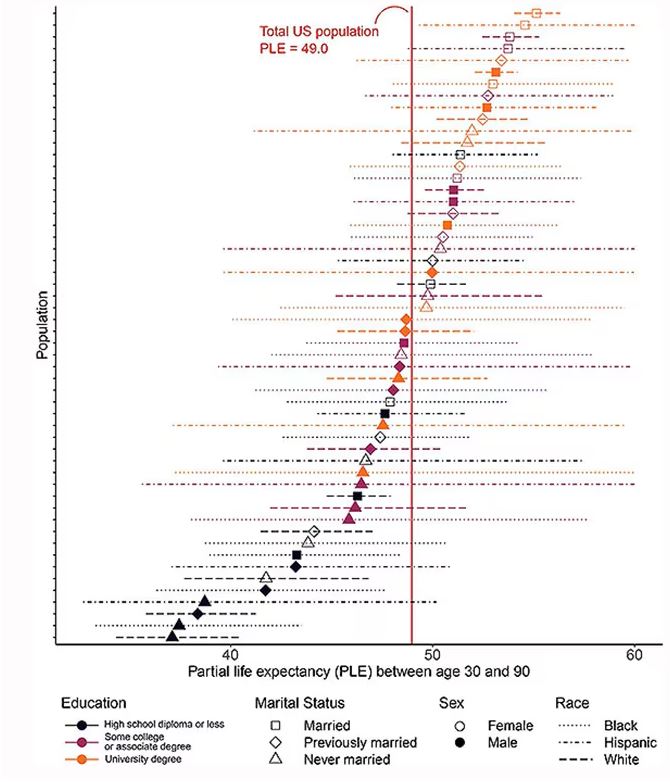

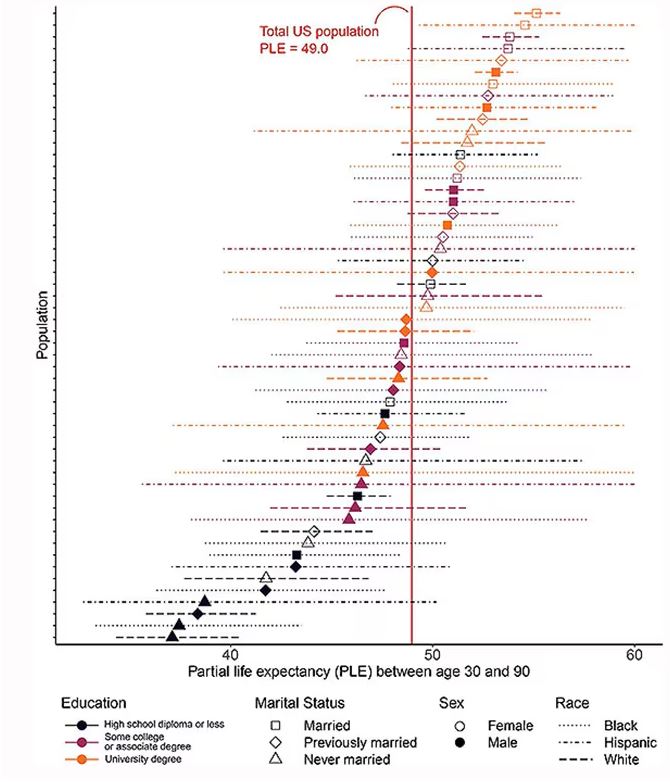

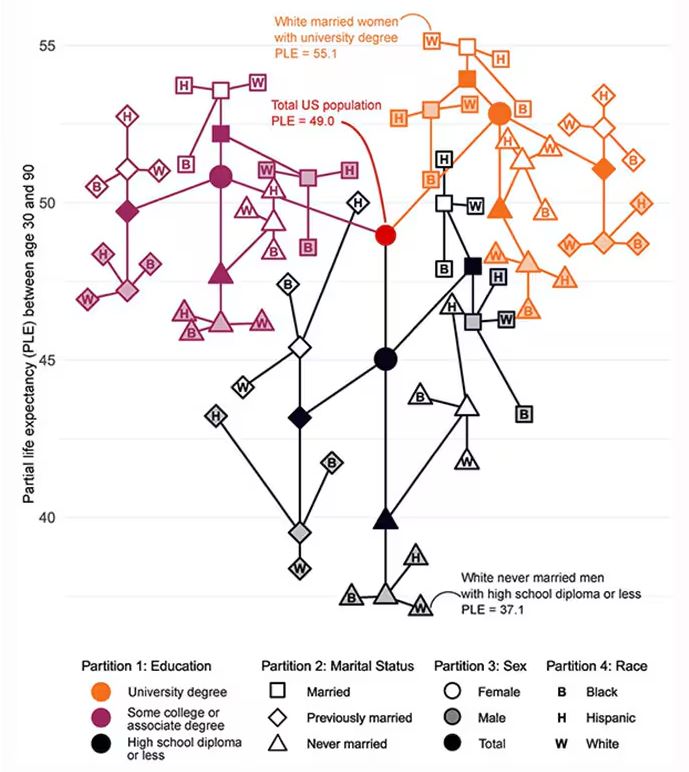

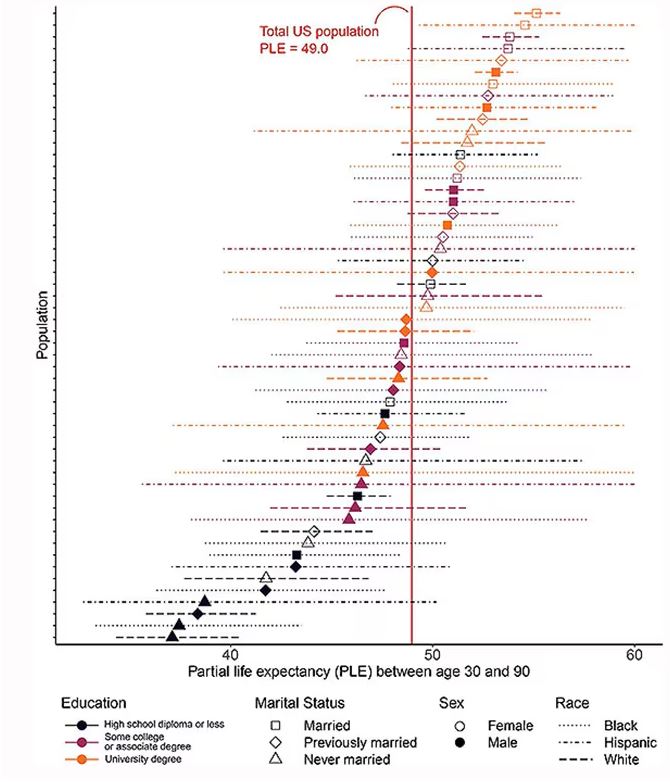

The survey collected data on the four broad categories of sex, race, education, and marital status and linked those survey results to the Multiple Cause of Death dataset from the CDC. From there, it’s a pretty simple task to rank the 54 categories in order from longest to shortest life expectancy, as you can see here.

But that’s not really the interesting part of this study. Sure, there is a lot of variation; it’s interesting that these four factors explain about 18 years’ difference in life expectancy in this country. What strikes me here, actually, is the lack of an entirely consistent message across this spectrum.

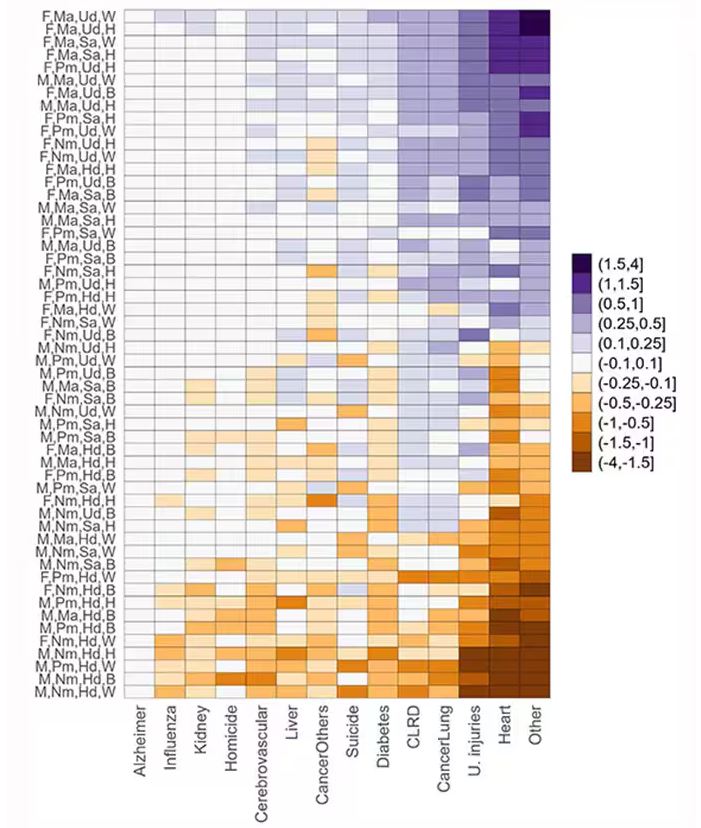

Let me walk you through the second figure in this paper, because this nicely illustrates the surprising heterogeneity that exists here.

This may seem overwhelming, but basically, shapes that are higher up on the Y-axis represent the groups with longer life expectancy.

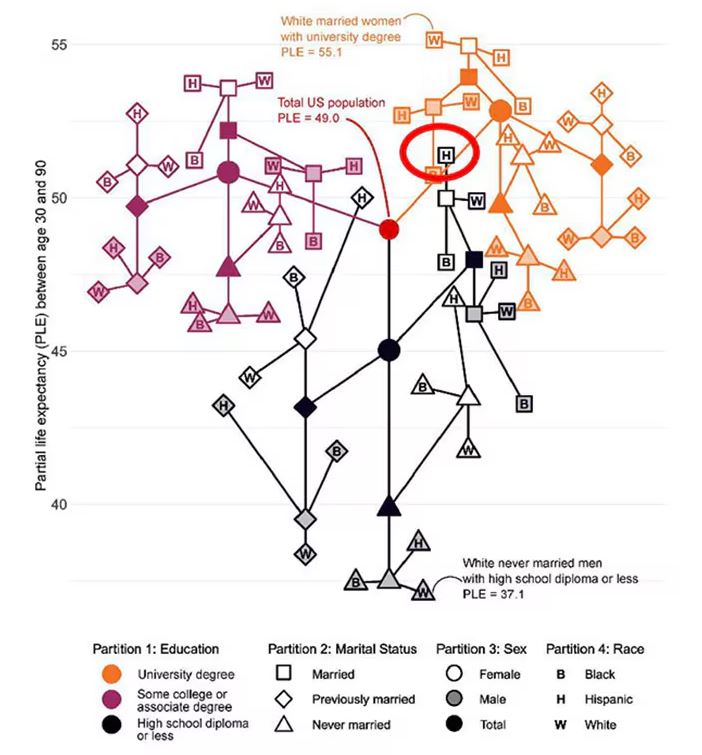

You can tell, for example, that shapes that are black in color (groups with high school educations or less) are generally lower. But not universally so. This box represents married, Hispanic females who do quite well in terms of life expectancy, even at that lower educational level.

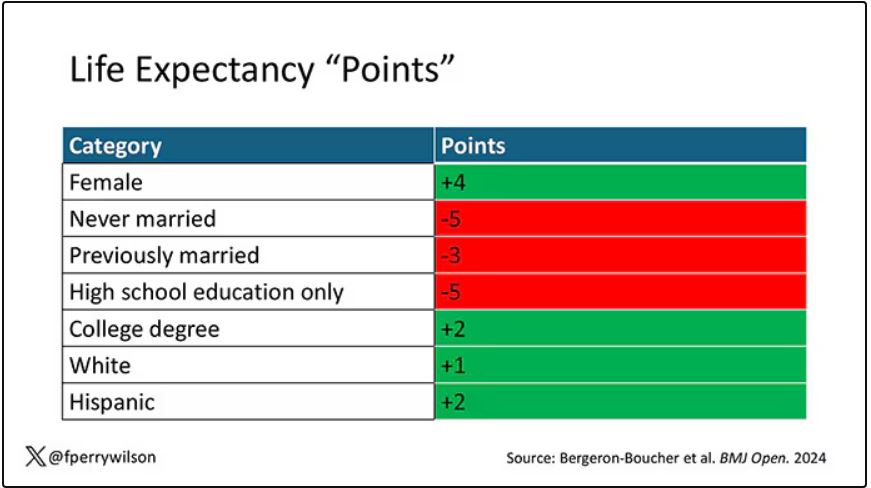

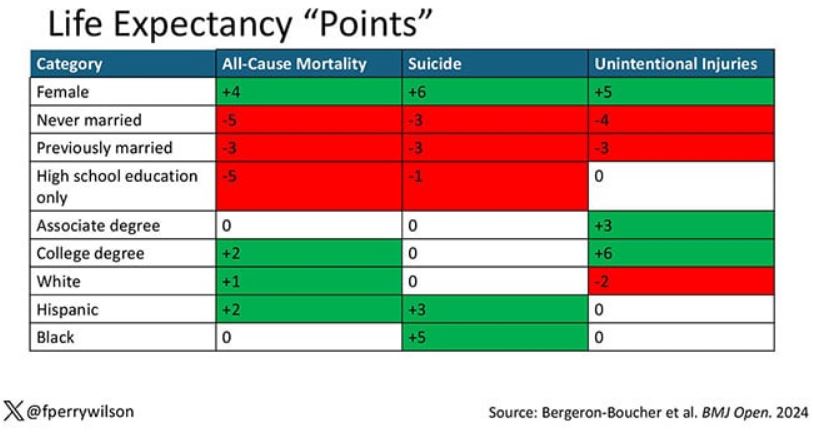

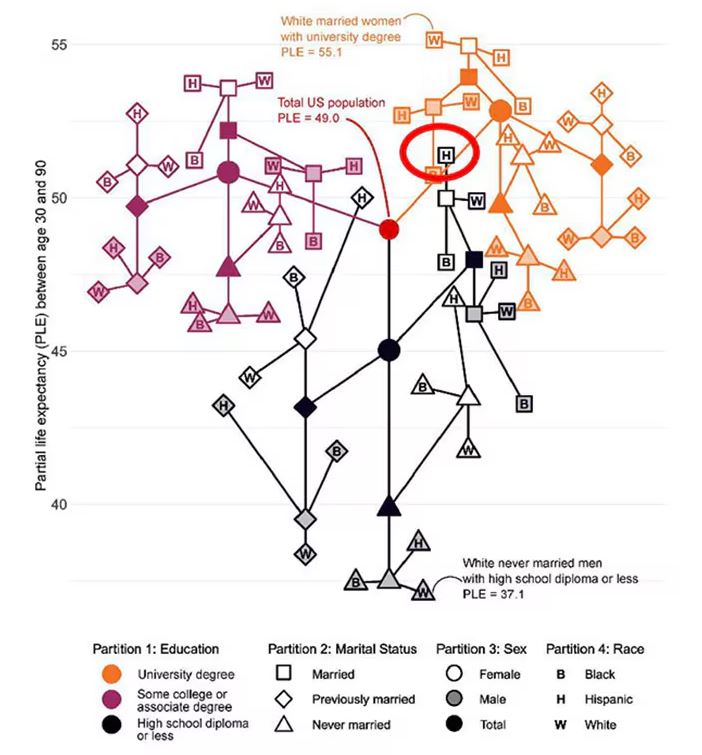

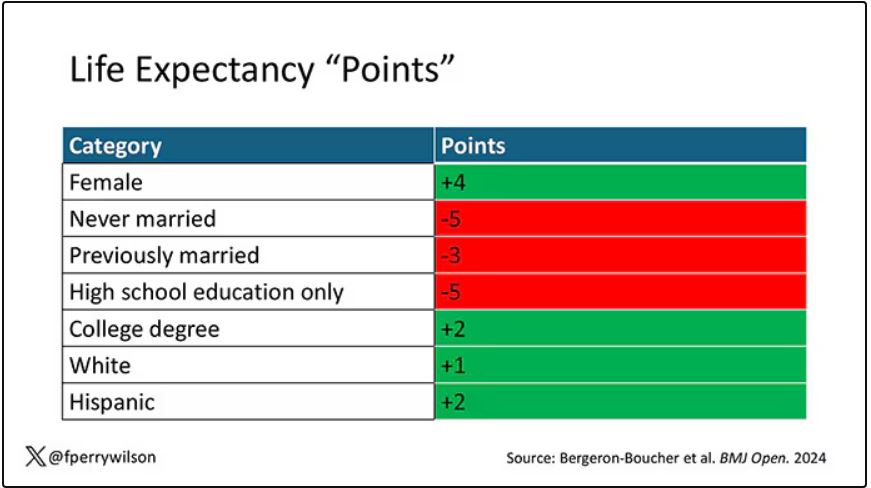

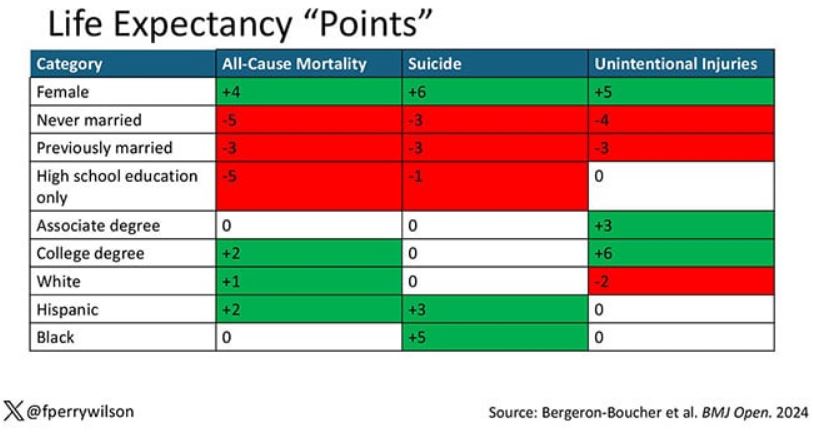

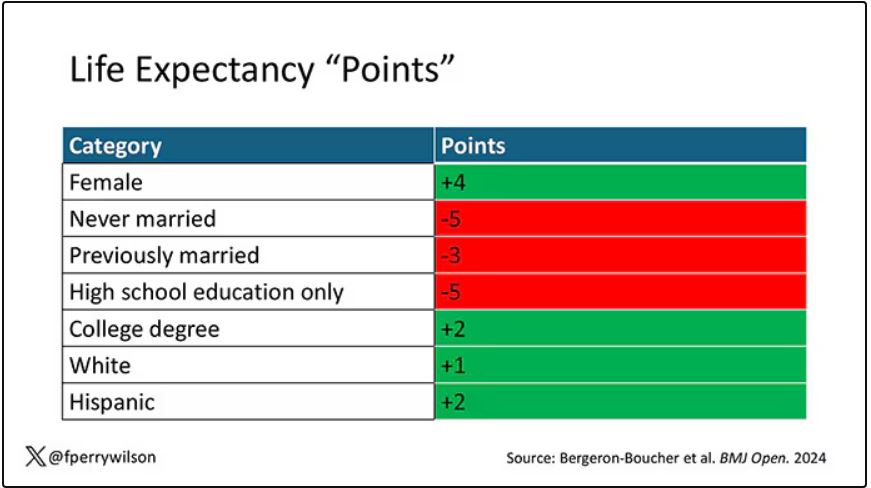

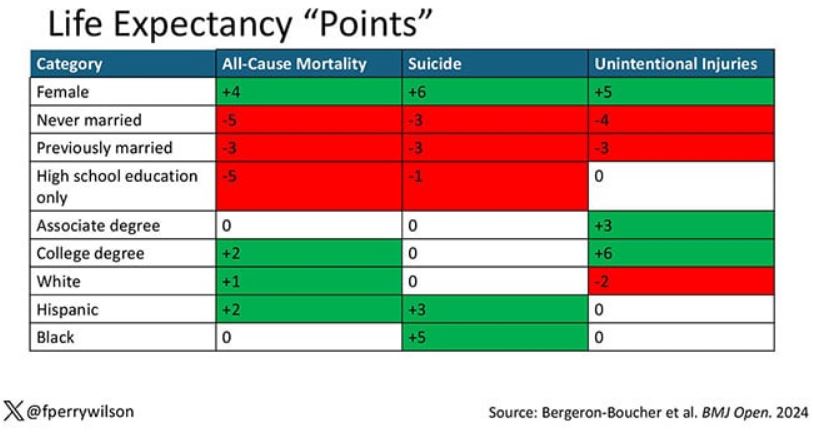

The authors quantify this phenomenon by creating a mortality risk score that integrates these findings. It looks something like this, with 0 being average morality for the United States.

As you can see, you get a bunch of points for being female, but you lose a bunch for not being married. Education plays a large role, with a big hit for those who have a high school diploma or less, and a bonus for those with a college degree. Race plays a relatively more minor role.

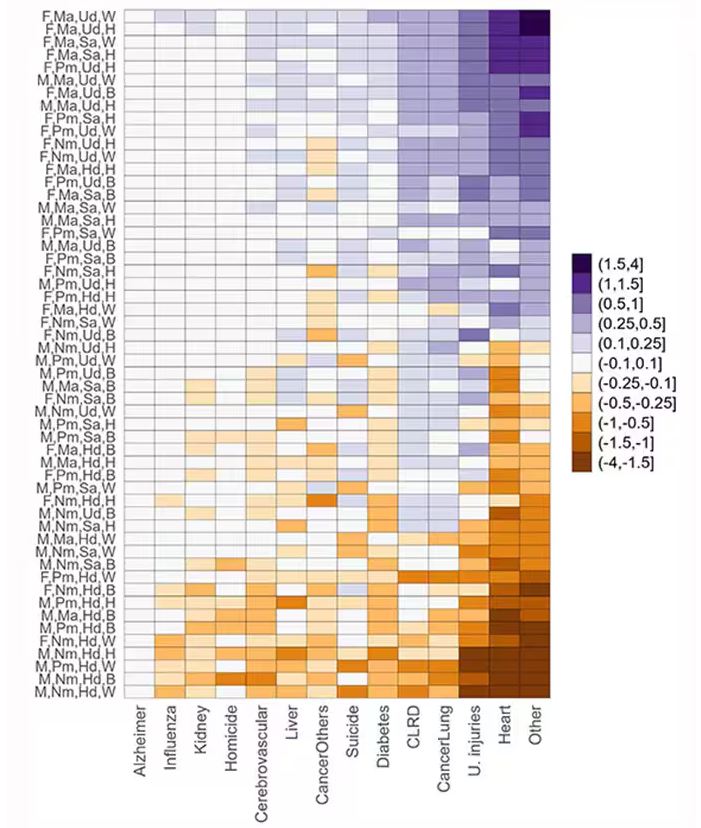

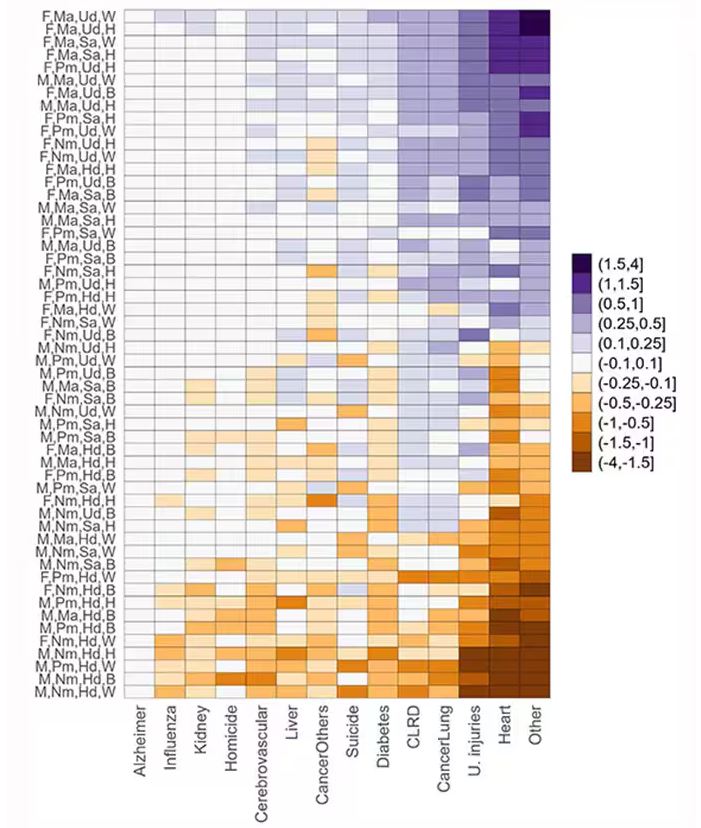

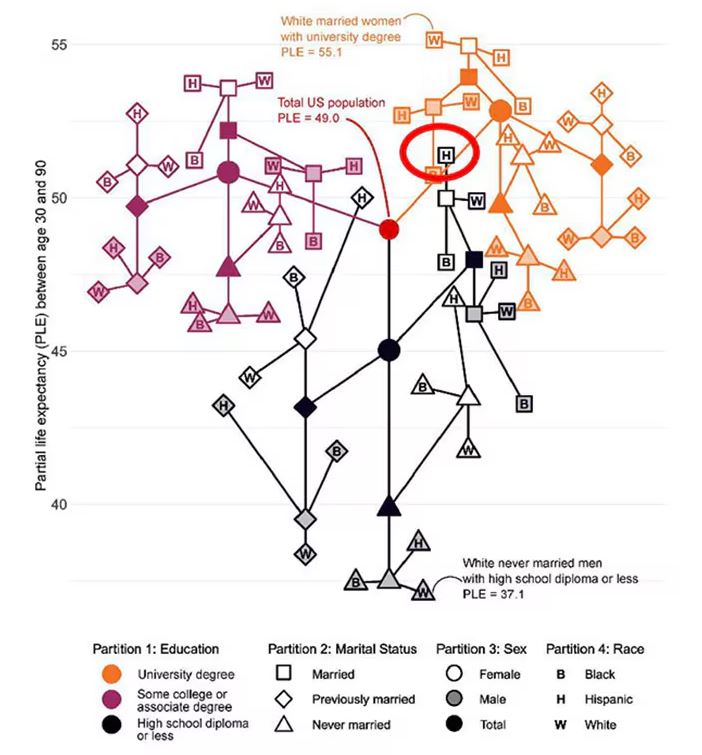

This is all very interesting, but as I said at the beginning, this isn’t terribly useful to me as a physician. More important is figuring out why these differences exist. And there are some clues in the study data, particularly when we examine causes of death. This figure ranks those 54 groups again, from the married, White, college-educated females down to the never-married, White, high school–educated males. The boxes show how much more or less likely this group is to die of a given condition than the general population.

Looking at the bottom groups, you can see a dramatically increased risk for death from unintentional injuries, heart disease, and lung cancer. You see an increased risk for suicide as well. In the upper tiers, the only place where risk seems higher than expected is for the category of “other cancers,” reminding us that many types of cancer do not respect definitions of socioeconomic status.

You can even update the risk-scoring system to reflect the risk for different causes of death. You can see here how White people, for example, are at higher risk for death from unintentional injuries relative to other populations, despite having a lower mortality overall.

So maybe, through cause of death, we get a little closer to the answer of why. But this paper is really just a start. Its primary effect should be to surprise us — that in a country as wealthy as the United States, such dramatic variation exists based on factors that, with the exception of sex, I suppose, are not really biological. Which means that to find the why, we may need to turn from physiology to sociology.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Two individuals in the United States are celebrating their 30th birthdays. It’s a good day. They are entering the prime of their lives. One is a married White woman with a university degree. The other is a never-married White man with a high school diploma.

How many more years of life can these two individuals look forward to?

There’s a fairly dramatic difference. The man can expect 37.1 more years of life on average, living to be about 67. The woman can expect to live to age 85. That’s a life-expectancy discrepancy of 18 years based solely on gender, education, and marital status.

I’m using these cases to illustrate the extremes of life expectancy across four key social determinants of health: sex, race, marital status, and education. We all have some sense of how these factors play out in terms of health, but a new study suggests that it’s actually quite a bit more complicated than we thought.

Let me start by acknowledging my own bias here. As a clinical researcher, I sometimes find it hard to appreciate the value of actuarial-type studies that look at life expectancy (or any metric, really) between groups defined by marital status, for example. I’m never quite sure what to do with the conclusion. Married people live longer, the headline says. Okay, but as a doctor, what am I supposed to do about that? Encourage my patients to settle down and commit? Studies showing that women live longer than men or that White people live longer than Black people are also hard for me to incorporate into my practice. These are not easily changeable states.

But studies examining these groups are a reasonable starting point to ask more relevant questions. Why do women live longer than men? Is it behavioral (men take more risks and are less likely to see doctors)? Or is it hormonal (estrogen has a lot of protective effects that testosterone does not)? Or is it something else?

Integrating these social determinants of health into a cohesive story is a bit harder than it might seem, as this study, appearing in BMJ Open, illustrates.

In the context of this study, every person in America can be placed into one of 54 mutually exclusive groups. You can be male or female. You can be Black, White, or Hispanic. You can have a high school diploma or less, an associate degree, or a college degree; and you can be married, previously married, or never married.

Of course, this does not capture the beautiful tapestry that is American life, but let’s give them a pass. They are working with data from the American Community Survey, which contains 8634 people — the statistics would run into trouble with more granular divisions. This survey can be population weighted, so you can scale up the results to reasonably represent the population of the United States.

The survey collected data on the four broad categories of sex, race, education, and marital status and linked those survey results to the Multiple Cause of Death dataset from the CDC. From there, it’s a pretty simple task to rank the 54 categories in order from longest to shortest life expectancy, as you can see here.

But that’s not really the interesting part of this study. Sure, there is a lot of variation; it’s interesting that these four factors explain about 18 years’ difference in life expectancy in this country. What strikes me here, actually, is the lack of an entirely consistent message across this spectrum.

Let me walk you through the second figure in this paper, because this nicely illustrates the surprising heterogeneity that exists here.

This may seem overwhelming, but basically, shapes that are higher up on the Y-axis represent the groups with longer life expectancy.

You can tell, for example, that shapes that are black in color (groups with high school educations or less) are generally lower. But not universally so. This box represents married, Hispanic females who do quite well in terms of life expectancy, even at that lower educational level.

The authors quantify this phenomenon by creating a mortality risk score that integrates these findings. It looks something like this, with 0 being average morality for the United States.

As you can see, you get a bunch of points for being female, but you lose a bunch for not being married. Education plays a large role, with a big hit for those who have a high school diploma or less, and a bonus for those with a college degree. Race plays a relatively more minor role.

This is all very interesting, but as I said at the beginning, this isn’t terribly useful to me as a physician. More important is figuring out why these differences exist. And there are some clues in the study data, particularly when we examine causes of death. This figure ranks those 54 groups again, from the married, White, college-educated females down to the never-married, White, high school–educated males. The boxes show how much more or less likely this group is to die of a given condition than the general population.

Looking at the bottom groups, you can see a dramatically increased risk for death from unintentional injuries, heart disease, and lung cancer. You see an increased risk for suicide as well. In the upper tiers, the only place where risk seems higher than expected is for the category of “other cancers,” reminding us that many types of cancer do not respect definitions of socioeconomic status.

You can even update the risk-scoring system to reflect the risk for different causes of death. You can see here how White people, for example, are at higher risk for death from unintentional injuries relative to other populations, despite having a lower mortality overall.

So maybe, through cause of death, we get a little closer to the answer of why. But this paper is really just a start. Its primary effect should be to surprise us — that in a country as wealthy as the United States, such dramatic variation exists based on factors that, with the exception of sex, I suppose, are not really biological. Which means that to find the why, we may need to turn from physiology to sociology.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.