User login

How racist is your algorithm?

Every time Nathan Chomilo, MD, uses a clinical decision support tool, he tells his patients they have a choice: He can input their race or keep that field blank.

Until recently, many clinicians didn’t question the use of race as a datapoint in tools used to make decisions about diagnosis and care. But that is changing.

“I’ve almost universally had patients appreciate that someone actually told them that their kidney function was being scored differently because of the color of their skin or how they were identified in the medical chart along lines of race,” Dr. Chomilo, an adjunct assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, said.

Dr. Chomilo is referring to the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), which combines results from a blood test with factors such as age, sex, and race to calculate kidney function.

The eGFR weighed an input of “African American” as automatically indicating a higher concentration of serum creatinine than a non African American patient on the basis of the unsubstantiated idea that Black people have more creatinine in their blood at baseline.

The calculator creates a picture of a Black patient who is not as sick as a White patient with the same levels of kidney failure. But race is based on the color of a patient’s skin, not on genetics or other clinical datapoints.

“I often use my own example of being a biracial Black man: My father’s family is from Cameroon, my mother’s family is from Norway. Are you going to assign my kidneys or my lungs to my mom’s side or my dad’s side? That’s not clear at all in the way we use race in medicine,” Dr. Chomilo, an executive committee member on the section on minority health equity and inclusion at the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), said.

Long before the COVID-19 pandemic so publicly exposed the depths of inequality in morbidity and mortality in the United States, health advocates had been pointing out these disparities in tools used by medical professionals. But efforts to recognize that race is a poor proxy for genetics is in its infancy.

In May, the AAP published a policy statement that kicked off its examination of clinical guidelines and policies that include race as a biological proxy. A committee for the society is combing through each guideline or calculator, evaluating the scientific basis for the use of race, and examining whether a stronger datapoint could be used instead.

The eGFR is perhaps the best example of a calculator that’s gone through the process: Health care stakeholders questioned the use of race, and investigators went back to study whether race was really a good datapoint. It wasn’t, and Dr. Chamilo’s hospital joined many others in retiring the calculator.

But the eGFR is one of countless clinical tools – from rudimentary algorithms to sophisticated machine-learning instruments – that change the course of care in part on the basis of race in the same way datapoints such as weight, age, and height are used to inform decisions about patient management. But unlike race, height, weight, and age can be objectively measured. A physician either makes a guess, or a patient enters their race on a form. And while that can be useful on a population level, race does not equal genetics or any other measurable datapoint.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, researchers reviewed 414 clinical practice guidelines from sources such as PubMed and MetaLib.gov. Almost 1 in 6 guidelines included race in an inappropriate way, such as by conflating race as a biological risk factor or establishing testing or treatment thresholds using race.

Waiting for alternatives

The University of Maryland Medical System last year embarked on a project similar to the AAP initiative but within its own system. The first use of race to be eliminated was in the eGFR. The health system also recently removed the variable from a tool for diagnosing urinary tract infections (UTIs) in children younger than 2 years.

Part of that tool includes deciding to perform a catheterized urine test. If a doctor chose “White” as the race, the tool would recommend the test. If the doctor chose “Black,” the tool would recommend to not test. Joseph Wright, MD, MPH, chief health equity officer at University of Maryland Medical System, said this step in the tool is based on the unproven assumption that young Black children had a lower likelihood of UTIs than their White peers.

“We simply want folks to not by default lob race in as a decisionmaking point when we have, with a little bit more scientific diligence, the ability to include better clinical variables,” Dr. Wright, who is also an adjunct professor of health policy and management at the University of Maryland School of Public Health, College Park, said.

The developers of the UTI tool recently released a revised version that removes race in favor of two new medical datapoints: whether the patient has had a fever for over 48 hours, and whether the patient has previously had a UTI.

The process of re-examining tools, coming up with new datapoints, and implementing changes is not simple, according to Dr. Wright.

“This is just the baby step to fix the algorithms, because we’re all going to have to examine our own house, where these calculators live, whether it’s in a textbook, whether it’s in an electronic health record, and that’s the heavy lift,” he said. “All sources of clinical guidance have to be scrutinized, and it’s going to literally take years to unroot.”

Electronic medical record vendor Cerner said it generally revises its algorithms after medical societies make changes, then communicates those fixes to providers.

Rebecca C. Winokur, MD, MPH, lead physician executive and health equity service line leader at Cerner, explained that if doctors ordered an eGFR a year ago and then another today, the results might be different because of the new code that eliminates race.

“The numbers are so different, how do you know that the patient may or may not have the same function?” Dr. Winokur said.

Dr. Winokur said the company is trying to determine at which point a message should pop up in the records workflow that would inform clinicians that they may be comparing apples to cherries. The company also is reconsidering the use of race in tools that estimate the probability of a successful vaginal birth after prior cesarean delivery, a calculator that predicts the risk of urethral stones in patients with flank pain, and another that measures lung function to help diagnose pulmonary disease.

In addition to managing the logistics of removing race, health institutions also need buy-in from clinicians. At Mass General Brigham, Boston, Thomas Sequist, MD, MPH, chief medical officer, is leading a project to examine how the system uses race in calculators.

“People struggle mainly with, well, if we shouldn’t use this calculator, what should we use, because we need a calculator. And that’s a legitimate question,” Dr. Sequist said in an interview. “If we’re going to stop using this race-based calculator, I still need to know what dose of medication I give my patient. We’re not going to pull any of these calculators until we have a safe and reliable alternative.”

For each calculator, relevant specialty chiefs come to the table with Dr. Sequist and his team; current projects include examining bone density screenings and cardiac risk scores. A large part of the work is communicating the lack of science behind the inclusion of race as a variable.

“It’s hard because these tools have been in existence for decades, and people are used to using them,” Dr. Sequist said. “So this is a big-change management project.”

Some clinicians also have difficulty discerning why their health system may stratify patient outcomes by race while providers are being told that race is being removed from the calculators they use every day. The key difference is that stratifying outcomes by race illuminates systemic problems that can be targeted by a health system.

For instance, if readmission rates are higher for Black patients overall after surgery, the reason might be that nurses are not delivering the same level of care to them as they are to non-Black patients, possibly because of hidden bias. Or, perhaps Black patients at a hospital have less access to transportation for follow-up appointments after surgery. The potential reasons can be investigated, and solutions can be created.

“If you look at a population level, what you’re looking for is not for the evidence of race as a biological construct,” Dr. Chomilo said. “You’re looking for the impact of racism on populations, and that’s the difference: It’s racism, not race.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Every time Nathan Chomilo, MD, uses a clinical decision support tool, he tells his patients they have a choice: He can input their race or keep that field blank.

Until recently, many clinicians didn’t question the use of race as a datapoint in tools used to make decisions about diagnosis and care. But that is changing.

“I’ve almost universally had patients appreciate that someone actually told them that their kidney function was being scored differently because of the color of their skin or how they were identified in the medical chart along lines of race,” Dr. Chomilo, an adjunct assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, said.

Dr. Chomilo is referring to the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), which combines results from a blood test with factors such as age, sex, and race to calculate kidney function.

The eGFR weighed an input of “African American” as automatically indicating a higher concentration of serum creatinine than a non African American patient on the basis of the unsubstantiated idea that Black people have more creatinine in their blood at baseline.

The calculator creates a picture of a Black patient who is not as sick as a White patient with the same levels of kidney failure. But race is based on the color of a patient’s skin, not on genetics or other clinical datapoints.

“I often use my own example of being a biracial Black man: My father’s family is from Cameroon, my mother’s family is from Norway. Are you going to assign my kidneys or my lungs to my mom’s side or my dad’s side? That’s not clear at all in the way we use race in medicine,” Dr. Chomilo, an executive committee member on the section on minority health equity and inclusion at the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), said.

Long before the COVID-19 pandemic so publicly exposed the depths of inequality in morbidity and mortality in the United States, health advocates had been pointing out these disparities in tools used by medical professionals. But efforts to recognize that race is a poor proxy for genetics is in its infancy.

In May, the AAP published a policy statement that kicked off its examination of clinical guidelines and policies that include race as a biological proxy. A committee for the society is combing through each guideline or calculator, evaluating the scientific basis for the use of race, and examining whether a stronger datapoint could be used instead.

The eGFR is perhaps the best example of a calculator that’s gone through the process: Health care stakeholders questioned the use of race, and investigators went back to study whether race was really a good datapoint. It wasn’t, and Dr. Chamilo’s hospital joined many others in retiring the calculator.

But the eGFR is one of countless clinical tools – from rudimentary algorithms to sophisticated machine-learning instruments – that change the course of care in part on the basis of race in the same way datapoints such as weight, age, and height are used to inform decisions about patient management. But unlike race, height, weight, and age can be objectively measured. A physician either makes a guess, or a patient enters their race on a form. And while that can be useful on a population level, race does not equal genetics or any other measurable datapoint.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, researchers reviewed 414 clinical practice guidelines from sources such as PubMed and MetaLib.gov. Almost 1 in 6 guidelines included race in an inappropriate way, such as by conflating race as a biological risk factor or establishing testing or treatment thresholds using race.

Waiting for alternatives

The University of Maryland Medical System last year embarked on a project similar to the AAP initiative but within its own system. The first use of race to be eliminated was in the eGFR. The health system also recently removed the variable from a tool for diagnosing urinary tract infections (UTIs) in children younger than 2 years.

Part of that tool includes deciding to perform a catheterized urine test. If a doctor chose “White” as the race, the tool would recommend the test. If the doctor chose “Black,” the tool would recommend to not test. Joseph Wright, MD, MPH, chief health equity officer at University of Maryland Medical System, said this step in the tool is based on the unproven assumption that young Black children had a lower likelihood of UTIs than their White peers.

“We simply want folks to not by default lob race in as a decisionmaking point when we have, with a little bit more scientific diligence, the ability to include better clinical variables,” Dr. Wright, who is also an adjunct professor of health policy and management at the University of Maryland School of Public Health, College Park, said.

The developers of the UTI tool recently released a revised version that removes race in favor of two new medical datapoints: whether the patient has had a fever for over 48 hours, and whether the patient has previously had a UTI.

The process of re-examining tools, coming up with new datapoints, and implementing changes is not simple, according to Dr. Wright.

“This is just the baby step to fix the algorithms, because we’re all going to have to examine our own house, where these calculators live, whether it’s in a textbook, whether it’s in an electronic health record, and that’s the heavy lift,” he said. “All sources of clinical guidance have to be scrutinized, and it’s going to literally take years to unroot.”

Electronic medical record vendor Cerner said it generally revises its algorithms after medical societies make changes, then communicates those fixes to providers.

Rebecca C. Winokur, MD, MPH, lead physician executive and health equity service line leader at Cerner, explained that if doctors ordered an eGFR a year ago and then another today, the results might be different because of the new code that eliminates race.

“The numbers are so different, how do you know that the patient may or may not have the same function?” Dr. Winokur said.

Dr. Winokur said the company is trying to determine at which point a message should pop up in the records workflow that would inform clinicians that they may be comparing apples to cherries. The company also is reconsidering the use of race in tools that estimate the probability of a successful vaginal birth after prior cesarean delivery, a calculator that predicts the risk of urethral stones in patients with flank pain, and another that measures lung function to help diagnose pulmonary disease.

In addition to managing the logistics of removing race, health institutions also need buy-in from clinicians. At Mass General Brigham, Boston, Thomas Sequist, MD, MPH, chief medical officer, is leading a project to examine how the system uses race in calculators.

“People struggle mainly with, well, if we shouldn’t use this calculator, what should we use, because we need a calculator. And that’s a legitimate question,” Dr. Sequist said in an interview. “If we’re going to stop using this race-based calculator, I still need to know what dose of medication I give my patient. We’re not going to pull any of these calculators until we have a safe and reliable alternative.”

For each calculator, relevant specialty chiefs come to the table with Dr. Sequist and his team; current projects include examining bone density screenings and cardiac risk scores. A large part of the work is communicating the lack of science behind the inclusion of race as a variable.

“It’s hard because these tools have been in existence for decades, and people are used to using them,” Dr. Sequist said. “So this is a big-change management project.”

Some clinicians also have difficulty discerning why their health system may stratify patient outcomes by race while providers are being told that race is being removed from the calculators they use every day. The key difference is that stratifying outcomes by race illuminates systemic problems that can be targeted by a health system.

For instance, if readmission rates are higher for Black patients overall after surgery, the reason might be that nurses are not delivering the same level of care to them as they are to non-Black patients, possibly because of hidden bias. Or, perhaps Black patients at a hospital have less access to transportation for follow-up appointments after surgery. The potential reasons can be investigated, and solutions can be created.

“If you look at a population level, what you’re looking for is not for the evidence of race as a biological construct,” Dr. Chomilo said. “You’re looking for the impact of racism on populations, and that’s the difference: It’s racism, not race.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Every time Nathan Chomilo, MD, uses a clinical decision support tool, he tells his patients they have a choice: He can input their race or keep that field blank.

Until recently, many clinicians didn’t question the use of race as a datapoint in tools used to make decisions about diagnosis and care. But that is changing.

“I’ve almost universally had patients appreciate that someone actually told them that their kidney function was being scored differently because of the color of their skin or how they were identified in the medical chart along lines of race,” Dr. Chomilo, an adjunct assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, said.

Dr. Chomilo is referring to the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), which combines results from a blood test with factors such as age, sex, and race to calculate kidney function.

The eGFR weighed an input of “African American” as automatically indicating a higher concentration of serum creatinine than a non African American patient on the basis of the unsubstantiated idea that Black people have more creatinine in their blood at baseline.

The calculator creates a picture of a Black patient who is not as sick as a White patient with the same levels of kidney failure. But race is based on the color of a patient’s skin, not on genetics or other clinical datapoints.

“I often use my own example of being a biracial Black man: My father’s family is from Cameroon, my mother’s family is from Norway. Are you going to assign my kidneys or my lungs to my mom’s side or my dad’s side? That’s not clear at all in the way we use race in medicine,” Dr. Chomilo, an executive committee member on the section on minority health equity and inclusion at the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), said.

Long before the COVID-19 pandemic so publicly exposed the depths of inequality in morbidity and mortality in the United States, health advocates had been pointing out these disparities in tools used by medical professionals. But efforts to recognize that race is a poor proxy for genetics is in its infancy.

In May, the AAP published a policy statement that kicked off its examination of clinical guidelines and policies that include race as a biological proxy. A committee for the society is combing through each guideline or calculator, evaluating the scientific basis for the use of race, and examining whether a stronger datapoint could be used instead.

The eGFR is perhaps the best example of a calculator that’s gone through the process: Health care stakeholders questioned the use of race, and investigators went back to study whether race was really a good datapoint. It wasn’t, and Dr. Chamilo’s hospital joined many others in retiring the calculator.

But the eGFR is one of countless clinical tools – from rudimentary algorithms to sophisticated machine-learning instruments – that change the course of care in part on the basis of race in the same way datapoints such as weight, age, and height are used to inform decisions about patient management. But unlike race, height, weight, and age can be objectively measured. A physician either makes a guess, or a patient enters their race on a form. And while that can be useful on a population level, race does not equal genetics or any other measurable datapoint.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, researchers reviewed 414 clinical practice guidelines from sources such as PubMed and MetaLib.gov. Almost 1 in 6 guidelines included race in an inappropriate way, such as by conflating race as a biological risk factor or establishing testing or treatment thresholds using race.

Waiting for alternatives

The University of Maryland Medical System last year embarked on a project similar to the AAP initiative but within its own system. The first use of race to be eliminated was in the eGFR. The health system also recently removed the variable from a tool for diagnosing urinary tract infections (UTIs) in children younger than 2 years.

Part of that tool includes deciding to perform a catheterized urine test. If a doctor chose “White” as the race, the tool would recommend the test. If the doctor chose “Black,” the tool would recommend to not test. Joseph Wright, MD, MPH, chief health equity officer at University of Maryland Medical System, said this step in the tool is based on the unproven assumption that young Black children had a lower likelihood of UTIs than their White peers.

“We simply want folks to not by default lob race in as a decisionmaking point when we have, with a little bit more scientific diligence, the ability to include better clinical variables,” Dr. Wright, who is also an adjunct professor of health policy and management at the University of Maryland School of Public Health, College Park, said.

The developers of the UTI tool recently released a revised version that removes race in favor of two new medical datapoints: whether the patient has had a fever for over 48 hours, and whether the patient has previously had a UTI.

The process of re-examining tools, coming up with new datapoints, and implementing changes is not simple, according to Dr. Wright.

“This is just the baby step to fix the algorithms, because we’re all going to have to examine our own house, where these calculators live, whether it’s in a textbook, whether it’s in an electronic health record, and that’s the heavy lift,” he said. “All sources of clinical guidance have to be scrutinized, and it’s going to literally take years to unroot.”

Electronic medical record vendor Cerner said it generally revises its algorithms after medical societies make changes, then communicates those fixes to providers.

Rebecca C. Winokur, MD, MPH, lead physician executive and health equity service line leader at Cerner, explained that if doctors ordered an eGFR a year ago and then another today, the results might be different because of the new code that eliminates race.

“The numbers are so different, how do you know that the patient may or may not have the same function?” Dr. Winokur said.

Dr. Winokur said the company is trying to determine at which point a message should pop up in the records workflow that would inform clinicians that they may be comparing apples to cherries. The company also is reconsidering the use of race in tools that estimate the probability of a successful vaginal birth after prior cesarean delivery, a calculator that predicts the risk of urethral stones in patients with flank pain, and another that measures lung function to help diagnose pulmonary disease.

In addition to managing the logistics of removing race, health institutions also need buy-in from clinicians. At Mass General Brigham, Boston, Thomas Sequist, MD, MPH, chief medical officer, is leading a project to examine how the system uses race in calculators.

“People struggle mainly with, well, if we shouldn’t use this calculator, what should we use, because we need a calculator. And that’s a legitimate question,” Dr. Sequist said in an interview. “If we’re going to stop using this race-based calculator, I still need to know what dose of medication I give my patient. We’re not going to pull any of these calculators until we have a safe and reliable alternative.”

For each calculator, relevant specialty chiefs come to the table with Dr. Sequist and his team; current projects include examining bone density screenings and cardiac risk scores. A large part of the work is communicating the lack of science behind the inclusion of race as a variable.

“It’s hard because these tools have been in existence for decades, and people are used to using them,” Dr. Sequist said. “So this is a big-change management project.”

Some clinicians also have difficulty discerning why their health system may stratify patient outcomes by race while providers are being told that race is being removed from the calculators they use every day. The key difference is that stratifying outcomes by race illuminates systemic problems that can be targeted by a health system.

For instance, if readmission rates are higher for Black patients overall after surgery, the reason might be that nurses are not delivering the same level of care to them as they are to non-Black patients, possibly because of hidden bias. Or, perhaps Black patients at a hospital have less access to transportation for follow-up appointments after surgery. The potential reasons can be investigated, and solutions can be created.

“If you look at a population level, what you’re looking for is not for the evidence of race as a biological construct,” Dr. Chomilo said. “You’re looking for the impact of racism on populations, and that’s the difference: It’s racism, not race.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

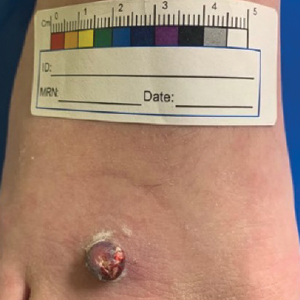

Erythematous Pedunculated Plaque on the Dorsal Aspect of the Foot

The Diagnosis: Molluscum Contagiosum

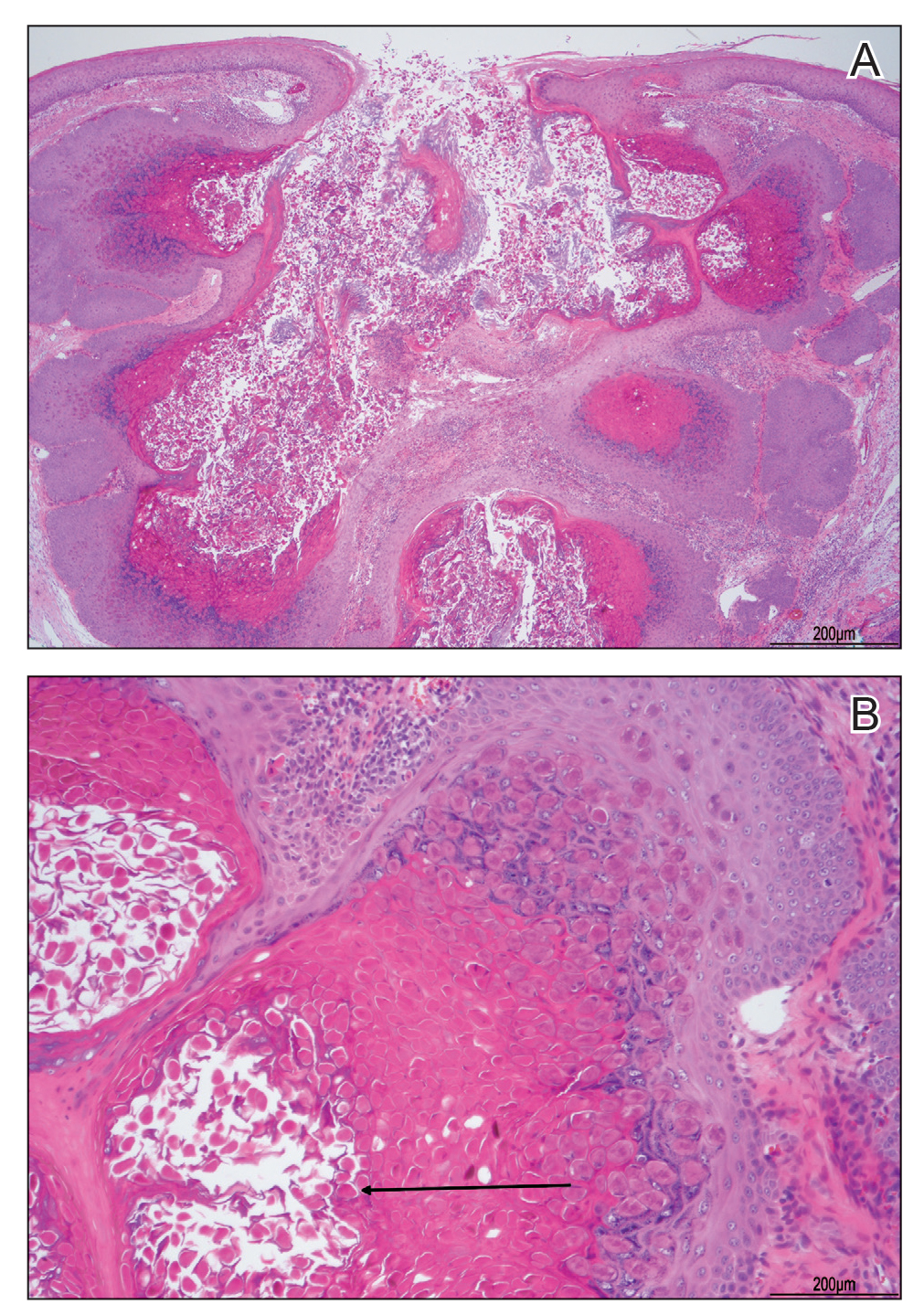

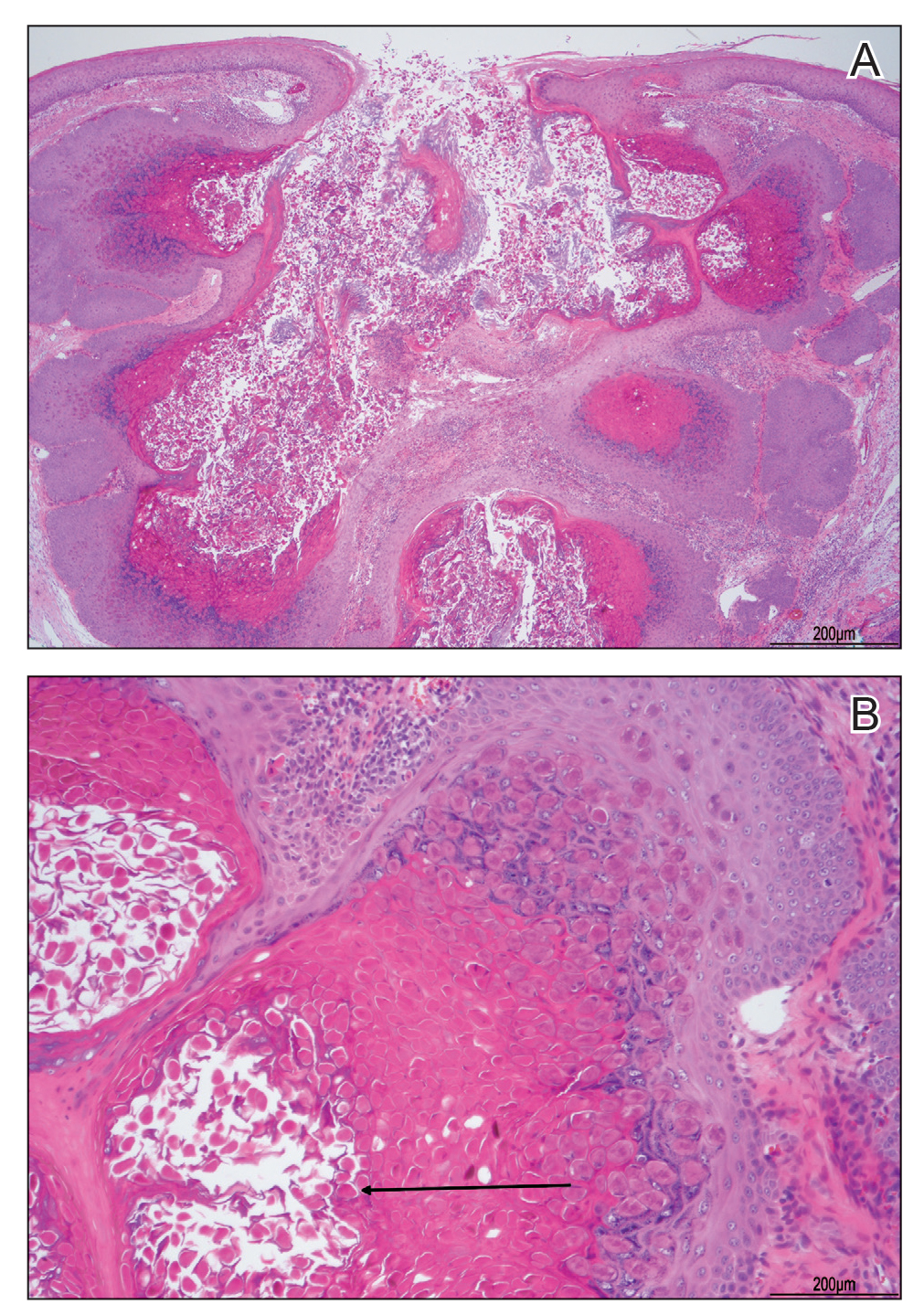

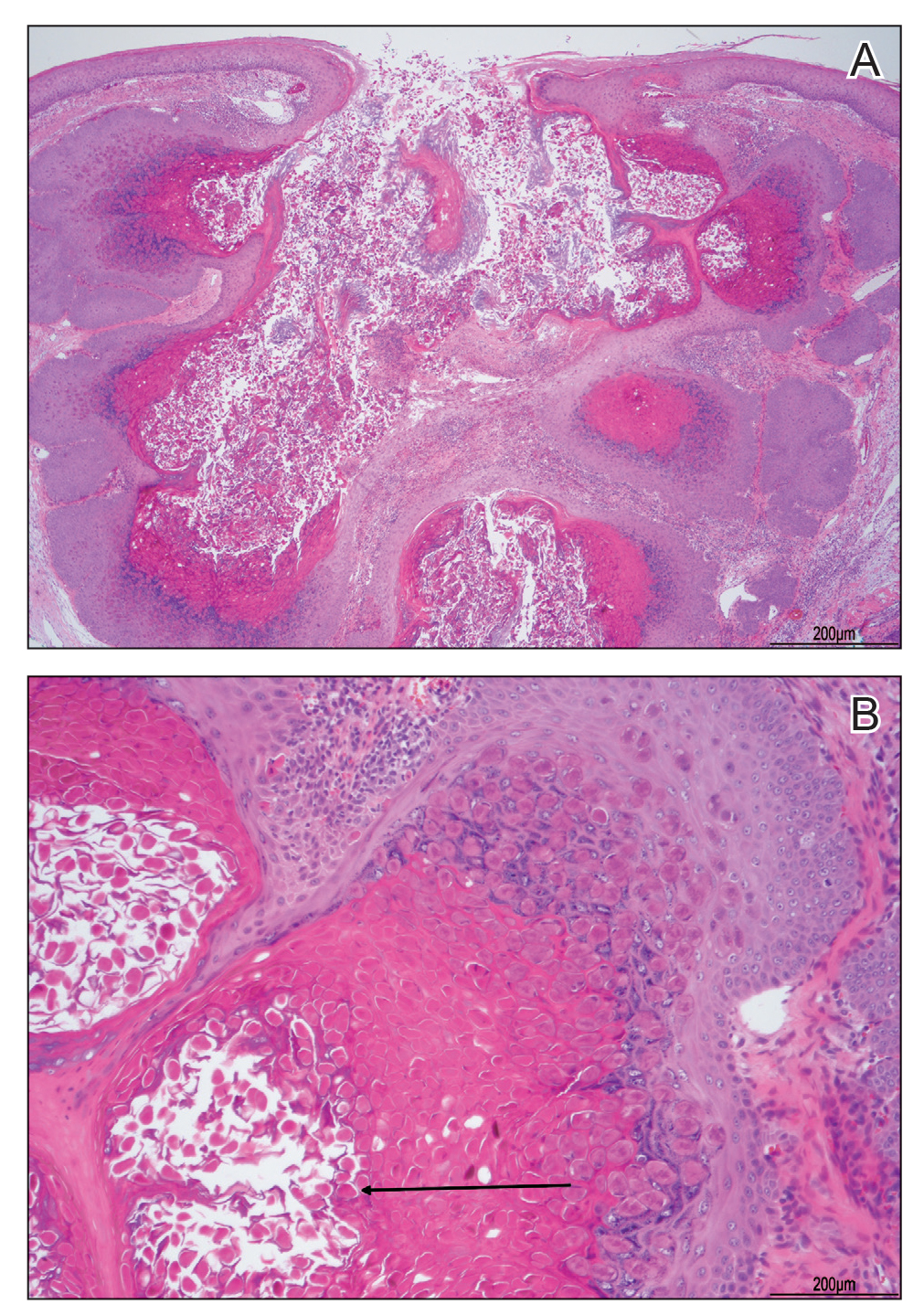

A tangential shave removal with electrocautery was performed. Histopathology demonstrated numerous eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Figure), confirming a diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum (MC).

Molluscum contagiosum is a common poxvirus infection that is transmitted through fomites, contact, or self-inoculation.1 This infection most frequently occurs in school-aged children younger than 8 years1-3; peak incidence is 6 years of age.2,3 The worldwide estimated prevalence in children is 5.1% to 11.5%.1,3 In children cohabitating with others infected by MC, approximately 40% of households experienced a spread of infection; the risk of transmission is not associated with greater number of lesions.4 In adults, infection most commonly occurs in the setting of immunodeficiency or as a sexually transmitted infection in immunocompetent patients.3 Molluscum contagiosum infection classically presents as 1- to 3-mm, flesh- or white-colored, dome-shaped, smooth papules with central umbilication.1 Lesions often occur in clusters or lines, indicating local spread. The trunk, extremities, and face are areas that frequently are involved.2,3

Atypical presentations of MC infection can occur, as demonstrated by our case. Involvement of hair follicles by the infection can result in follicular induction.1,5 Secondary infection can mimic abscess formation.1 Inflamed MC lesions demonstrating the “beginning of the end” sign often are mistaken for primary infection, which is thought to be an inflammatory immune response to the virus.6 Lesions located on the eye or eyelid can present as unilateral conjunctivitis, conjunctival or corneal nodules, eyelid abscesses, or chalazions.1 Giant MC is a nodular variant of this infection measuring larger than 1 cm in size that can present similar to epidermoid cysts, condyloma acuminatum, or verruca vulgaris.1,7 Other reported mimicked conditions include basal cell carcinoma, trichoepithelioma, appendageal tumors, keratoacanthoma, foreign body granulomas, nevus sebaceous, or ecthyma.1,3 Molluscum contagiosum also has been reported to present as large ulcerative growths.8 In immunocompromised patients, deep fungal infection is another mimicker.1 Lesions on the plantar surfaces of the feet often are misdiagnosed as plantar verruca and present with pain during ambulation.9

The diagnosis of MC is clinical, with additional diagnostic tools reserved for more challenging situations.1 In cases with atypical presentations, dermoscopy may aid diagnosis through visualization of orifices and vascular patterns including crown, radial, and punctiform vessels.10 Biopsy or fine-needle aspiration also can be utilized as a diagnostic tool. Histopathology often reveals pathognomonic intracytoplasmic inclusions or Henderson-Paterson bodies.8,10 The appearance of MC can mimic other conditions that should be included in the differential diagnosis. Pyogenic granuloma often presents as a benign red papule that may grow rapidly and become pedunculated, sometimes with bleeding and crusting, though histology reveals groups of proliferating capillaries.11 More than half of amelanotic melanomas present in the papulonodular form as vascular or ulcerated nodules, and others may appear as erythematous macules. Diagnosis of amelanotic melanoma is made through histologic examination, which reveals atypical melanocytes in nests or cords, in conjunction with immunohistochemical stains such as S-100.12 Spitz nevi often appear as round, dome-shaped papules that most commonly are red, pink, or fleshcolored. They appear histologically similar to melanoma with nests of atypical melanocytes and nuclear atypia.13

A variety of treatment modalities can be used for MC including cantharidin, curettage, and cryotherapy.14 Imiquimod no longer is recommended due to a lack of demonstrated superiority over placebo in recent studies as well as its adverse effects.3 Topical retinoids have been recommended; however, their use frequently is limited by local irritation.3,14 Cantharidin is the most frequently utilized treatment by pediatric dermatologists. Most health care providers report subjective satisfaction with its results and efficacy, though some side effects may occur including discomfort and temporary changes in pigmentation. Treatment for MC is not required, as the condition is self-limiting.14 Therapy often is reserved for those with extensive disease, complications from lesions, cosmetic or psychological concerns, or genital involvement given the potential for sexual transmission.3 Time to resolution without treatment varies and is more prolonged in immunocompromised patients. Mean time to resolution in immunocompetent hosts has been reported as 13.3 months, but most infections are noted to clear within 2 to 4 years.1,4 Although resolution without treatment occurs, transmission to others and negative impact on quality of life (QOL) can occur and support the need for treatment. Greater impact on QOL was observed in females, those with more lesions, and patients with a longer duration of symptoms. Moderate impact on QOL was reported in 28% of patients (n=301), and severe effects were reported in 11%.4

In conclusion, MC is a common, benign, treatable cutaneous viral infection that often presents as small, flesh-colored papules in children. Its appearance can mimic a variety of other conditions. In cases with abnormal presentations, definitive diagnosis with pathology can be important to differentiate MC from more dangerous etiologies that may require further treatment.

- Brown J, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA, et al. Childhood molluscum contagiosum. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:93-99. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2006.02737.x

- Dohil MA, Lin P, Lee J, et al. The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:47-54. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.035

- Robinson G, Townsend S, Jahnke MN. Molluscum contagiosum: review and update on clinical presentation, diagnosis, risk, prevention, and treatment. Curr Derm Rep. 2020;9:83-92.

- Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Finlay AY, et al. Time to resolution and effect on quality of life of molluscum contagiosum in children in the UK: a prospective community cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:190-195. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71053-9

- Davey J, Biswas A. Follicular induction in a case of molluscum contagiosum: possible link with secondary anetoderma-like changes? Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:E19-E21. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31828bc7c7

- Butala N, Siegfried E, Weissler A. Molluscum BOTE sign: a predictor of imminent resolution. Pediatrics. 2013;131:E1650-E1653. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2933

- Uzuncakmak TK, Kuru BC, Zemheri EI, et al. Isolated giant molluscum contagiosum mimicking epidermoid cyst. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:71-73. doi:10.5826/dpc.0603a15

- Singh S, Swain M, Shukla S, et al. An unusual presentation of giant molluscum contagiosum diagnosed on cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:794-796. doi:10.1002/dc.23964

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Plantar molluscum contagiosum: a case report of molluscum contagiosum occurring on the sole of the foot and a review of the world literature. Cutis. 2012;90:35-41.

- Megalla M, Bronsnick T, Noor O, et al. Dermoscopic, confocal microscopic, and histologic characteristics of an atypical presentation of molluscum contagiosum. Ann Clin Pathol. 2014;2:1038.

- Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-276. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1991.tb00931.x

- Gong H-Z, Zheng H-Y, Li J. Amelanotic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2019;29:221-230. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000571

- Casso EM, Grin-Jorgensen CM, Grant-Kels JM. Spitz nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(6 pt 1):901-913. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70286-o

- Coloe J, Morrell DS. Cantharidin use among pediatric dermatologists in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:405-408.

The Diagnosis: Molluscum Contagiosum

A tangential shave removal with electrocautery was performed. Histopathology demonstrated numerous eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Figure), confirming a diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum (MC).

Molluscum contagiosum is a common poxvirus infection that is transmitted through fomites, contact, or self-inoculation.1 This infection most frequently occurs in school-aged children younger than 8 years1-3; peak incidence is 6 years of age.2,3 The worldwide estimated prevalence in children is 5.1% to 11.5%.1,3 In children cohabitating with others infected by MC, approximately 40% of households experienced a spread of infection; the risk of transmission is not associated with greater number of lesions.4 In adults, infection most commonly occurs in the setting of immunodeficiency or as a sexually transmitted infection in immunocompetent patients.3 Molluscum contagiosum infection classically presents as 1- to 3-mm, flesh- or white-colored, dome-shaped, smooth papules with central umbilication.1 Lesions often occur in clusters or lines, indicating local spread. The trunk, extremities, and face are areas that frequently are involved.2,3

Atypical presentations of MC infection can occur, as demonstrated by our case. Involvement of hair follicles by the infection can result in follicular induction.1,5 Secondary infection can mimic abscess formation.1 Inflamed MC lesions demonstrating the “beginning of the end” sign often are mistaken for primary infection, which is thought to be an inflammatory immune response to the virus.6 Lesions located on the eye or eyelid can present as unilateral conjunctivitis, conjunctival or corneal nodules, eyelid abscesses, or chalazions.1 Giant MC is a nodular variant of this infection measuring larger than 1 cm in size that can present similar to epidermoid cysts, condyloma acuminatum, or verruca vulgaris.1,7 Other reported mimicked conditions include basal cell carcinoma, trichoepithelioma, appendageal tumors, keratoacanthoma, foreign body granulomas, nevus sebaceous, or ecthyma.1,3 Molluscum contagiosum also has been reported to present as large ulcerative growths.8 In immunocompromised patients, deep fungal infection is another mimicker.1 Lesions on the plantar surfaces of the feet often are misdiagnosed as plantar verruca and present with pain during ambulation.9

The diagnosis of MC is clinical, with additional diagnostic tools reserved for more challenging situations.1 In cases with atypical presentations, dermoscopy may aid diagnosis through visualization of orifices and vascular patterns including crown, radial, and punctiform vessels.10 Biopsy or fine-needle aspiration also can be utilized as a diagnostic tool. Histopathology often reveals pathognomonic intracytoplasmic inclusions or Henderson-Paterson bodies.8,10 The appearance of MC can mimic other conditions that should be included in the differential diagnosis. Pyogenic granuloma often presents as a benign red papule that may grow rapidly and become pedunculated, sometimes with bleeding and crusting, though histology reveals groups of proliferating capillaries.11 More than half of amelanotic melanomas present in the papulonodular form as vascular or ulcerated nodules, and others may appear as erythematous macules. Diagnosis of amelanotic melanoma is made through histologic examination, which reveals atypical melanocytes in nests or cords, in conjunction with immunohistochemical stains such as S-100.12 Spitz nevi often appear as round, dome-shaped papules that most commonly are red, pink, or fleshcolored. They appear histologically similar to melanoma with nests of atypical melanocytes and nuclear atypia.13

A variety of treatment modalities can be used for MC including cantharidin, curettage, and cryotherapy.14 Imiquimod no longer is recommended due to a lack of demonstrated superiority over placebo in recent studies as well as its adverse effects.3 Topical retinoids have been recommended; however, their use frequently is limited by local irritation.3,14 Cantharidin is the most frequently utilized treatment by pediatric dermatologists. Most health care providers report subjective satisfaction with its results and efficacy, though some side effects may occur including discomfort and temporary changes in pigmentation. Treatment for MC is not required, as the condition is self-limiting.14 Therapy often is reserved for those with extensive disease, complications from lesions, cosmetic or psychological concerns, or genital involvement given the potential for sexual transmission.3 Time to resolution without treatment varies and is more prolonged in immunocompromised patients. Mean time to resolution in immunocompetent hosts has been reported as 13.3 months, but most infections are noted to clear within 2 to 4 years.1,4 Although resolution without treatment occurs, transmission to others and negative impact on quality of life (QOL) can occur and support the need for treatment. Greater impact on QOL was observed in females, those with more lesions, and patients with a longer duration of symptoms. Moderate impact on QOL was reported in 28% of patients (n=301), and severe effects were reported in 11%.4

In conclusion, MC is a common, benign, treatable cutaneous viral infection that often presents as small, flesh-colored papules in children. Its appearance can mimic a variety of other conditions. In cases with abnormal presentations, definitive diagnosis with pathology can be important to differentiate MC from more dangerous etiologies that may require further treatment.

The Diagnosis: Molluscum Contagiosum

A tangential shave removal with electrocautery was performed. Histopathology demonstrated numerous eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Figure), confirming a diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum (MC).

Molluscum contagiosum is a common poxvirus infection that is transmitted through fomites, contact, or self-inoculation.1 This infection most frequently occurs in school-aged children younger than 8 years1-3; peak incidence is 6 years of age.2,3 The worldwide estimated prevalence in children is 5.1% to 11.5%.1,3 In children cohabitating with others infected by MC, approximately 40% of households experienced a spread of infection; the risk of transmission is not associated with greater number of lesions.4 In adults, infection most commonly occurs in the setting of immunodeficiency or as a sexually transmitted infection in immunocompetent patients.3 Molluscum contagiosum infection classically presents as 1- to 3-mm, flesh- or white-colored, dome-shaped, smooth papules with central umbilication.1 Lesions often occur in clusters or lines, indicating local spread. The trunk, extremities, and face are areas that frequently are involved.2,3

Atypical presentations of MC infection can occur, as demonstrated by our case. Involvement of hair follicles by the infection can result in follicular induction.1,5 Secondary infection can mimic abscess formation.1 Inflamed MC lesions demonstrating the “beginning of the end” sign often are mistaken for primary infection, which is thought to be an inflammatory immune response to the virus.6 Lesions located on the eye or eyelid can present as unilateral conjunctivitis, conjunctival or corneal nodules, eyelid abscesses, or chalazions.1 Giant MC is a nodular variant of this infection measuring larger than 1 cm in size that can present similar to epidermoid cysts, condyloma acuminatum, or verruca vulgaris.1,7 Other reported mimicked conditions include basal cell carcinoma, trichoepithelioma, appendageal tumors, keratoacanthoma, foreign body granulomas, nevus sebaceous, or ecthyma.1,3 Molluscum contagiosum also has been reported to present as large ulcerative growths.8 In immunocompromised patients, deep fungal infection is another mimicker.1 Lesions on the plantar surfaces of the feet often are misdiagnosed as plantar verruca and present with pain during ambulation.9

The diagnosis of MC is clinical, with additional diagnostic tools reserved for more challenging situations.1 In cases with atypical presentations, dermoscopy may aid diagnosis through visualization of orifices and vascular patterns including crown, radial, and punctiform vessels.10 Biopsy or fine-needle aspiration also can be utilized as a diagnostic tool. Histopathology often reveals pathognomonic intracytoplasmic inclusions or Henderson-Paterson bodies.8,10 The appearance of MC can mimic other conditions that should be included in the differential diagnosis. Pyogenic granuloma often presents as a benign red papule that may grow rapidly and become pedunculated, sometimes with bleeding and crusting, though histology reveals groups of proliferating capillaries.11 More than half of amelanotic melanomas present in the papulonodular form as vascular or ulcerated nodules, and others may appear as erythematous macules. Diagnosis of amelanotic melanoma is made through histologic examination, which reveals atypical melanocytes in nests or cords, in conjunction with immunohistochemical stains such as S-100.12 Spitz nevi often appear as round, dome-shaped papules that most commonly are red, pink, or fleshcolored. They appear histologically similar to melanoma with nests of atypical melanocytes and nuclear atypia.13

A variety of treatment modalities can be used for MC including cantharidin, curettage, and cryotherapy.14 Imiquimod no longer is recommended due to a lack of demonstrated superiority over placebo in recent studies as well as its adverse effects.3 Topical retinoids have been recommended; however, their use frequently is limited by local irritation.3,14 Cantharidin is the most frequently utilized treatment by pediatric dermatologists. Most health care providers report subjective satisfaction with its results and efficacy, though some side effects may occur including discomfort and temporary changes in pigmentation. Treatment for MC is not required, as the condition is self-limiting.14 Therapy often is reserved for those with extensive disease, complications from lesions, cosmetic or psychological concerns, or genital involvement given the potential for sexual transmission.3 Time to resolution without treatment varies and is more prolonged in immunocompromised patients. Mean time to resolution in immunocompetent hosts has been reported as 13.3 months, but most infections are noted to clear within 2 to 4 years.1,4 Although resolution without treatment occurs, transmission to others and negative impact on quality of life (QOL) can occur and support the need for treatment. Greater impact on QOL was observed in females, those with more lesions, and patients with a longer duration of symptoms. Moderate impact on QOL was reported in 28% of patients (n=301), and severe effects were reported in 11%.4

In conclusion, MC is a common, benign, treatable cutaneous viral infection that often presents as small, flesh-colored papules in children. Its appearance can mimic a variety of other conditions. In cases with abnormal presentations, definitive diagnosis with pathology can be important to differentiate MC from more dangerous etiologies that may require further treatment.

- Brown J, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA, et al. Childhood molluscum contagiosum. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:93-99. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2006.02737.x

- Dohil MA, Lin P, Lee J, et al. The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:47-54. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.035

- Robinson G, Townsend S, Jahnke MN. Molluscum contagiosum: review and update on clinical presentation, diagnosis, risk, prevention, and treatment. Curr Derm Rep. 2020;9:83-92.

- Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Finlay AY, et al. Time to resolution and effect on quality of life of molluscum contagiosum in children in the UK: a prospective community cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:190-195. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71053-9

- Davey J, Biswas A. Follicular induction in a case of molluscum contagiosum: possible link with secondary anetoderma-like changes? Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:E19-E21. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31828bc7c7

- Butala N, Siegfried E, Weissler A. Molluscum BOTE sign: a predictor of imminent resolution. Pediatrics. 2013;131:E1650-E1653. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2933

- Uzuncakmak TK, Kuru BC, Zemheri EI, et al. Isolated giant molluscum contagiosum mimicking epidermoid cyst. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:71-73. doi:10.5826/dpc.0603a15

- Singh S, Swain M, Shukla S, et al. An unusual presentation of giant molluscum contagiosum diagnosed on cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:794-796. doi:10.1002/dc.23964

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Plantar molluscum contagiosum: a case report of molluscum contagiosum occurring on the sole of the foot and a review of the world literature. Cutis. 2012;90:35-41.

- Megalla M, Bronsnick T, Noor O, et al. Dermoscopic, confocal microscopic, and histologic characteristics of an atypical presentation of molluscum contagiosum. Ann Clin Pathol. 2014;2:1038.

- Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-276. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1991.tb00931.x

- Gong H-Z, Zheng H-Y, Li J. Amelanotic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2019;29:221-230. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000571

- Casso EM, Grin-Jorgensen CM, Grant-Kels JM. Spitz nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(6 pt 1):901-913. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70286-o

- Coloe J, Morrell DS. Cantharidin use among pediatric dermatologists in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:405-408.

- Brown J, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA, et al. Childhood molluscum contagiosum. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:93-99. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2006.02737.x

- Dohil MA, Lin P, Lee J, et al. The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:47-54. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.035

- Robinson G, Townsend S, Jahnke MN. Molluscum contagiosum: review and update on clinical presentation, diagnosis, risk, prevention, and treatment. Curr Derm Rep. 2020;9:83-92.

- Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Finlay AY, et al. Time to resolution and effect on quality of life of molluscum contagiosum in children in the UK: a prospective community cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:190-195. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71053-9

- Davey J, Biswas A. Follicular induction in a case of molluscum contagiosum: possible link with secondary anetoderma-like changes? Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:E19-E21. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31828bc7c7

- Butala N, Siegfried E, Weissler A. Molluscum BOTE sign: a predictor of imminent resolution. Pediatrics. 2013;131:E1650-E1653. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2933

- Uzuncakmak TK, Kuru BC, Zemheri EI, et al. Isolated giant molluscum contagiosum mimicking epidermoid cyst. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:71-73. doi:10.5826/dpc.0603a15

- Singh S, Swain M, Shukla S, et al. An unusual presentation of giant molluscum contagiosum diagnosed on cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:794-796. doi:10.1002/dc.23964

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Plantar molluscum contagiosum: a case report of molluscum contagiosum occurring on the sole of the foot and a review of the world literature. Cutis. 2012;90:35-41.

- Megalla M, Bronsnick T, Noor O, et al. Dermoscopic, confocal microscopic, and histologic characteristics of an atypical presentation of molluscum contagiosum. Ann Clin Pathol. 2014;2:1038.

- Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-276. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1991.tb00931.x

- Gong H-Z, Zheng H-Y, Li J. Amelanotic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2019;29:221-230. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000571

- Casso EM, Grin-Jorgensen CM, Grant-Kels JM. Spitz nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(6 pt 1):901-913. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70286-o

- Coloe J, Morrell DS. Cantharidin use among pediatric dermatologists in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:405-408.

A 13-year-old adolescent girl presented for evaluation of a lesion on the dorsal aspect of the right foot of 1 week’s duration. She had a history of acne vulgaris and seasonal allergic rhinitis. She previously had noticed a persistent, small, flesh-colored bump of unknown chronicity in the same location, which had been diagnosed as a skin tag at an outside clinic. She denied any prior treatment in this area. Approximately a week prior to presentation, the lesion became painful, larger, and darkened in color before draining yellowish fluid. Due to concern for superinfection, the patient was prescribed cephalexin by her pediatrician. Dermatologic examination revealed a 1-cm, violaceous, pedunculated plaque with hemorrhagic crust on the dorsal aspect of the right foot with surrounding erythema and tenderness.

Heart attack care not equal for women and people of color

Radiating chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, lightheadedness. Everyone knows the telltale signs of a myocardial infarction. Yet a new study shows that despite this widespread recognition, heart attacks aren’t attended to quickly across the board. Historically, the study says, women and people of color wait longer to access emergency care for a heart attack.

Researchers from the University of California, San Francisco published these findings in the Annals of Emergency Medicine. The study used the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development dataset to gather information on 453,136 cases of heart attack in California between 2005 and 2015. They found that over time, differences in timely treatment between the demographics narrowed, but the gap still existed.

The study defined timely treatment as receiving care for a heart attack within 3 days of admission to a hospital. Women and people of color were found to wait 3 days or more to receive care than their White male counterparts. A disparity of this sort can cause ripples of health effects across society, ripples that doctors should be aware of, says lead author Juan Carlos Montoy, MD. Dr. Montoy was “sadly surprised by our findings that disparities for women and for Black patients only decreased slightly or not at all over time.”

In the study, the team separated the dataset between the two primary types of heart attack: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), caused by blood vessel blockage, and non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), caused by a narrowing or temporary blockage of the artery.

Regardless of the type of heart attack, the standard first step in treatment is a coronary angiogram. After finding out where blood flow is disrupted using the angiogram, a physician can proceed with treatment.

But when looking back, the team found that it took a while for many patients to receive this first step in treatment. In 2005, 50% of men and 35.7% of women with STEMI and 45% of men and 33.1% of women with NSTEMI had a timely angiography. In the same year, 46% of White patients and 31.2% of Black patients with STEMI underwent timely angiography.

By 2015, timely treatment increased across the board, but there were still discrepancies, with 76.7% of men and 66.8% of women with STEMI undergoing timely angiography and 56.3% of men and 45.9% of women with NSTEMI undergoing timely angiography. Also in 2015, 75.2% of White patients and 69.2% of Black patients underwent timely angiography for STEMI.

Although differences in care decreased between the demographics, the gap still exists. Whereas this dataset only extends to 2015, this trend may still persist today, says Robert Glatter, MD, an emergency medicine physician at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, who was not involved in the study. Therefore, physicians need to consider this bias when treating patients. “The bottom line is that we continue to have much work to do to achieve equality in managing not only medical conditions but treating people who have them equally,” Dr. Glatter said.

“Raising awareness of ongoing inequality in care related to gender and ethnic disparities is critical to drive change in our institutions,” he emphasized. “We simply cannot accept the status quo.”

The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Glatter and the authors declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Radiating chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, lightheadedness. Everyone knows the telltale signs of a myocardial infarction. Yet a new study shows that despite this widespread recognition, heart attacks aren’t attended to quickly across the board. Historically, the study says, women and people of color wait longer to access emergency care for a heart attack.

Researchers from the University of California, San Francisco published these findings in the Annals of Emergency Medicine. The study used the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development dataset to gather information on 453,136 cases of heart attack in California between 2005 and 2015. They found that over time, differences in timely treatment between the demographics narrowed, but the gap still existed.

The study defined timely treatment as receiving care for a heart attack within 3 days of admission to a hospital. Women and people of color were found to wait 3 days or more to receive care than their White male counterparts. A disparity of this sort can cause ripples of health effects across society, ripples that doctors should be aware of, says lead author Juan Carlos Montoy, MD. Dr. Montoy was “sadly surprised by our findings that disparities for women and for Black patients only decreased slightly or not at all over time.”

In the study, the team separated the dataset between the two primary types of heart attack: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), caused by blood vessel blockage, and non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), caused by a narrowing or temporary blockage of the artery.

Regardless of the type of heart attack, the standard first step in treatment is a coronary angiogram. After finding out where blood flow is disrupted using the angiogram, a physician can proceed with treatment.

But when looking back, the team found that it took a while for many patients to receive this first step in treatment. In 2005, 50% of men and 35.7% of women with STEMI and 45% of men and 33.1% of women with NSTEMI had a timely angiography. In the same year, 46% of White patients and 31.2% of Black patients with STEMI underwent timely angiography.

By 2015, timely treatment increased across the board, but there were still discrepancies, with 76.7% of men and 66.8% of women with STEMI undergoing timely angiography and 56.3% of men and 45.9% of women with NSTEMI undergoing timely angiography. Also in 2015, 75.2% of White patients and 69.2% of Black patients underwent timely angiography for STEMI.

Although differences in care decreased between the demographics, the gap still exists. Whereas this dataset only extends to 2015, this trend may still persist today, says Robert Glatter, MD, an emergency medicine physician at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, who was not involved in the study. Therefore, physicians need to consider this bias when treating patients. “The bottom line is that we continue to have much work to do to achieve equality in managing not only medical conditions but treating people who have them equally,” Dr. Glatter said.

“Raising awareness of ongoing inequality in care related to gender and ethnic disparities is critical to drive change in our institutions,” he emphasized. “We simply cannot accept the status quo.”

The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Glatter and the authors declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Radiating chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, lightheadedness. Everyone knows the telltale signs of a myocardial infarction. Yet a new study shows that despite this widespread recognition, heart attacks aren’t attended to quickly across the board. Historically, the study says, women and people of color wait longer to access emergency care for a heart attack.

Researchers from the University of California, San Francisco published these findings in the Annals of Emergency Medicine. The study used the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development dataset to gather information on 453,136 cases of heart attack in California between 2005 and 2015. They found that over time, differences in timely treatment between the demographics narrowed, but the gap still existed.

The study defined timely treatment as receiving care for a heart attack within 3 days of admission to a hospital. Women and people of color were found to wait 3 days or more to receive care than their White male counterparts. A disparity of this sort can cause ripples of health effects across society, ripples that doctors should be aware of, says lead author Juan Carlos Montoy, MD. Dr. Montoy was “sadly surprised by our findings that disparities for women and for Black patients only decreased slightly or not at all over time.”

In the study, the team separated the dataset between the two primary types of heart attack: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), caused by blood vessel blockage, and non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), caused by a narrowing or temporary blockage of the artery.

Regardless of the type of heart attack, the standard first step in treatment is a coronary angiogram. After finding out where blood flow is disrupted using the angiogram, a physician can proceed with treatment.

But when looking back, the team found that it took a while for many patients to receive this first step in treatment. In 2005, 50% of men and 35.7% of women with STEMI and 45% of men and 33.1% of women with NSTEMI had a timely angiography. In the same year, 46% of White patients and 31.2% of Black patients with STEMI underwent timely angiography.

By 2015, timely treatment increased across the board, but there were still discrepancies, with 76.7% of men and 66.8% of women with STEMI undergoing timely angiography and 56.3% of men and 45.9% of women with NSTEMI undergoing timely angiography. Also in 2015, 75.2% of White patients and 69.2% of Black patients underwent timely angiography for STEMI.

Although differences in care decreased between the demographics, the gap still exists. Whereas this dataset only extends to 2015, this trend may still persist today, says Robert Glatter, MD, an emergency medicine physician at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, who was not involved in the study. Therefore, physicians need to consider this bias when treating patients. “The bottom line is that we continue to have much work to do to achieve equality in managing not only medical conditions but treating people who have them equally,” Dr. Glatter said.

“Raising awareness of ongoing inequality in care related to gender and ethnic disparities is critical to drive change in our institutions,” he emphasized. “We simply cannot accept the status quo.”

The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Glatter and the authors declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE

Two genetic intestinal diseases linked

Two genes that have been linked separately to rare intestinal diseases appear to share a functional relationship. The genes have independently been linked to osteo-oto-hepato-enteric (O2HE) syndrome and microvillus inclusion disease (MVID), which are characterized by congenital diarrhea and, in some patients, intrahepatic cholestasis.

It appears that one gene, UNC45A, is directly responsible for the proper function of the protein encoded by the other gene, called MYO5B, according to investigators, who published their findings in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. UNC45A is a chaperone protein that helps proteins fold properly. It has been linked to O2HE patients experiencing congenital diarrhea and intrahepatic cholestasis. The mutation has been identified in four patients from three different families with O2HE, which can also present with sensorineural hearing loss and bone fragility. Cellular analyses have shown that the mutation leads to reduction in protein expression by 70%-90%.

Intestinal symptoms similar to those in O2HE have also been described in diseases caused by mutations in genes that encode the myosin motor proteins that are involved in cellular protein trafficking. This group of disorders includes MVID. The researchers hypothesized that the UNC45A mutation in O2HE might lead to similar symptoms as MVID and others through the altered protein’s failure to assist in the folding of myosin proteins, although to date only the myosin IIa protein has been shown to be a target of UNC45A.

To investigate the possibility, they examined in more detail the relationship between UNC45A and intestinal symptoms. There are various known mutations in myosin proteins. Some have been linked to deafness, but these do not appear to contribute to intestinal symptoms since patients with myelin-related inherited deafness don’t typically have diarrhea. Bone fragility, also sometimes caused by myosin mutations, also appears to be unrelated to intestinal symptoms.

Previous experiments in yeast suggest that the related gene UNC45 may serve as a chaperone for type V myosin: Loss of a yeast version of UNC45 caused a type V myosin called MYO4P to be mislocalized in yeast. In zebrafish, reduction in intestinal levels of the UNC45A gene or the fish’s version of MYO5B interfered with development of intestinal folds.

The researchers used CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing and site-directed mutagenesis in intestinal epithelial and liver cell lines to investigate the relationships between UNC45A and MYO5B mutants. UNC45A depletion or introduction of the UNC45A mutation found in patients led to lower MYO5B expression. Within epithelial cells, loss of UNC45A led to changes in MYO5B–linked processes that are known to play a role in MVID pathogenesis. These included alteration of microvilli development and interference with the location of rat sarcoma–associated binding protein (RAB) 11A–positive recycling endosomes. When normal UNC45A was reintroduced to these cells, MYO5B expression returned. Reintroduction of either UNC45A or MYO5B repaired the alterations to recycling endosome position and microvilli development.

Loss of UNC45A did not appear to affect transcription of the MYO5B gen, which suggests a suggesting a functional interaction between the two at a protein level.

UNC45A has been shown to destabilize microtubules. Exposure of a kidney epithelial cell line to the microtubule-stabilizing drug taxol also led to displacement of RAB11A-positve recycling endosomes, though the specific changes were different than what is seen in MYO5B mutants. The researchers were unable to validate the findings in tissue derived from O2HE patients because of insufficient material, but they maintain that the cell lines used have proven to be highly predictive for the cellular characteristics of MVID.

Overall, the study suggests that reductions in MYO5B and subsequent changes to the cellular processes that depend on it may underlie the intestinal symptoms in O2HE.

The researchers noted that O2HE patients have different phenotypes. Of the four patients they studied, three had severe chronic diarrhea and required parenteral nutrition. One patient later had the diarrhea resolve and her sister did not have diarrhea at all. This heterogeneity in severity and duration of clinical symptoms may be driven by differences in the molecular effects of patient-specific mutations. The two siblings had mutations in a different region of the UNC45A gene than the other two participants.

“Taken together, this study revealed a functional relationship between UNC45A and MYO5B protein expression, thereby connecting two rare congenital diseases with overlapping intestinal symptoms at the molecular level,” the authors wrote.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

This article was updated 7/13/22.

Congenital diarrheas and enteropathies (CoDEs) are rare monogenic disorders caused by genes important for intestinal epithelial function. The increasing availability of exome sequencing in clinical practice has accelerated the discovery of new genes associated with these disorders over the past few years. Several CoDE disorders revolve around defects in trafficking of vesicles in epithelial cells. One of these is microvillus inclusion disease which is caused by loss-of-function variants in the gene MYO5B, which encodes an important epithelial motor protein. This study by Li and colleagues reveals that a recently discovered novel CoDE gene and protein, UNC45A, is functionally linked to MYO5B and that loss of UNC45A in cells causes a very similar cellular phenotype to MYO5B-deficient cells.

Jay Thiagarajah, MD, PhD, attending in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition and codirector of the congenital enteropathy program at Boston Children’s Hospital, as well as assistant professor in pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. Dr. Thiagarajah stated he had no relevant conflicts to disclose.

Congenital diarrheas and enteropathies (CoDEs) are rare monogenic disorders caused by genes important for intestinal epithelial function. The increasing availability of exome sequencing in clinical practice has accelerated the discovery of new genes associated with these disorders over the past few years. Several CoDE disorders revolve around defects in trafficking of vesicles in epithelial cells. One of these is microvillus inclusion disease which is caused by loss-of-function variants in the gene MYO5B, which encodes an important epithelial motor protein. This study by Li and colleagues reveals that a recently discovered novel CoDE gene and protein, UNC45A, is functionally linked to MYO5B and that loss of UNC45A in cells causes a very similar cellular phenotype to MYO5B-deficient cells.

Jay Thiagarajah, MD, PhD, attending in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition and codirector of the congenital enteropathy program at Boston Children’s Hospital, as well as assistant professor in pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. Dr. Thiagarajah stated he had no relevant conflicts to disclose.

Congenital diarrheas and enteropathies (CoDEs) are rare monogenic disorders caused by genes important for intestinal epithelial function. The increasing availability of exome sequencing in clinical practice has accelerated the discovery of new genes associated with these disorders over the past few years. Several CoDE disorders revolve around defects in trafficking of vesicles in epithelial cells. One of these is microvillus inclusion disease which is caused by loss-of-function variants in the gene MYO5B, which encodes an important epithelial motor protein. This study by Li and colleagues reveals that a recently discovered novel CoDE gene and protein, UNC45A, is functionally linked to MYO5B and that loss of UNC45A in cells causes a very similar cellular phenotype to MYO5B-deficient cells.

Jay Thiagarajah, MD, PhD, attending in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition and codirector of the congenital enteropathy program at Boston Children’s Hospital, as well as assistant professor in pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. Dr. Thiagarajah stated he had no relevant conflicts to disclose.

Two genes that have been linked separately to rare intestinal diseases appear to share a functional relationship. The genes have independently been linked to osteo-oto-hepato-enteric (O2HE) syndrome and microvillus inclusion disease (MVID), which are characterized by congenital diarrhea and, in some patients, intrahepatic cholestasis.

It appears that one gene, UNC45A, is directly responsible for the proper function of the protein encoded by the other gene, called MYO5B, according to investigators, who published their findings in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. UNC45A is a chaperone protein that helps proteins fold properly. It has been linked to O2HE patients experiencing congenital diarrhea and intrahepatic cholestasis. The mutation has been identified in four patients from three different families with O2HE, which can also present with sensorineural hearing loss and bone fragility. Cellular analyses have shown that the mutation leads to reduction in protein expression by 70%-90%.

Intestinal symptoms similar to those in O2HE have also been described in diseases caused by mutations in genes that encode the myosin motor proteins that are involved in cellular protein trafficking. This group of disorders includes MVID. The researchers hypothesized that the UNC45A mutation in O2HE might lead to similar symptoms as MVID and others through the altered protein’s failure to assist in the folding of myosin proteins, although to date only the myosin IIa protein has been shown to be a target of UNC45A.

To investigate the possibility, they examined in more detail the relationship between UNC45A and intestinal symptoms. There are various known mutations in myosin proteins. Some have been linked to deafness, but these do not appear to contribute to intestinal symptoms since patients with myelin-related inherited deafness don’t typically have diarrhea. Bone fragility, also sometimes caused by myosin mutations, also appears to be unrelated to intestinal symptoms.

Previous experiments in yeast suggest that the related gene UNC45 may serve as a chaperone for type V myosin: Loss of a yeast version of UNC45 caused a type V myosin called MYO4P to be mislocalized in yeast. In zebrafish, reduction in intestinal levels of the UNC45A gene or the fish’s version of MYO5B interfered with development of intestinal folds.

The researchers used CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing and site-directed mutagenesis in intestinal epithelial and liver cell lines to investigate the relationships between UNC45A and MYO5B mutants. UNC45A depletion or introduction of the UNC45A mutation found in patients led to lower MYO5B expression. Within epithelial cells, loss of UNC45A led to changes in MYO5B–linked processes that are known to play a role in MVID pathogenesis. These included alteration of microvilli development and interference with the location of rat sarcoma–associated binding protein (RAB) 11A–positive recycling endosomes. When normal UNC45A was reintroduced to these cells, MYO5B expression returned. Reintroduction of either UNC45A or MYO5B repaired the alterations to recycling endosome position and microvilli development.

Loss of UNC45A did not appear to affect transcription of the MYO5B gen, which suggests a suggesting a functional interaction between the two at a protein level.

UNC45A has been shown to destabilize microtubules. Exposure of a kidney epithelial cell line to the microtubule-stabilizing drug taxol also led to displacement of RAB11A-positve recycling endosomes, though the specific changes were different than what is seen in MYO5B mutants. The researchers were unable to validate the findings in tissue derived from O2HE patients because of insufficient material, but they maintain that the cell lines used have proven to be highly predictive for the cellular characteristics of MVID.

Overall, the study suggests that reductions in MYO5B and subsequent changes to the cellular processes that depend on it may underlie the intestinal symptoms in O2HE.

The researchers noted that O2HE patients have different phenotypes. Of the four patients they studied, three had severe chronic diarrhea and required parenteral nutrition. One patient later had the diarrhea resolve and her sister did not have diarrhea at all. This heterogeneity in severity and duration of clinical symptoms may be driven by differences in the molecular effects of patient-specific mutations. The two siblings had mutations in a different region of the UNC45A gene than the other two participants.

“Taken together, this study revealed a functional relationship between UNC45A and MYO5B protein expression, thereby connecting two rare congenital diseases with overlapping intestinal symptoms at the molecular level,” the authors wrote.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

This article was updated 7/13/22.

Two genes that have been linked separately to rare intestinal diseases appear to share a functional relationship. The genes have independently been linked to osteo-oto-hepato-enteric (O2HE) syndrome and microvillus inclusion disease (MVID), which are characterized by congenital diarrhea and, in some patients, intrahepatic cholestasis.

It appears that one gene, UNC45A, is directly responsible for the proper function of the protein encoded by the other gene, called MYO5B, according to investigators, who published their findings in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. UNC45A is a chaperone protein that helps proteins fold properly. It has been linked to O2HE patients experiencing congenital diarrhea and intrahepatic cholestasis. The mutation has been identified in four patients from three different families with O2HE, which can also present with sensorineural hearing loss and bone fragility. Cellular analyses have shown that the mutation leads to reduction in protein expression by 70%-90%.

Intestinal symptoms similar to those in O2HE have also been described in diseases caused by mutations in genes that encode the myosin motor proteins that are involved in cellular protein trafficking. This group of disorders includes MVID. The researchers hypothesized that the UNC45A mutation in O2HE might lead to similar symptoms as MVID and others through the altered protein’s failure to assist in the folding of myosin proteins, although to date only the myosin IIa protein has been shown to be a target of UNC45A.

To investigate the possibility, they examined in more detail the relationship between UNC45A and intestinal symptoms. There are various known mutations in myosin proteins. Some have been linked to deafness, but these do not appear to contribute to intestinal symptoms since patients with myelin-related inherited deafness don’t typically have diarrhea. Bone fragility, also sometimes caused by myosin mutations, also appears to be unrelated to intestinal symptoms.

Previous experiments in yeast suggest that the related gene UNC45 may serve as a chaperone for type V myosin: Loss of a yeast version of UNC45 caused a type V myosin called MYO4P to be mislocalized in yeast. In zebrafish, reduction in intestinal levels of the UNC45A gene or the fish’s version of MYO5B interfered with development of intestinal folds.

The researchers used CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing and site-directed mutagenesis in intestinal epithelial and liver cell lines to investigate the relationships between UNC45A and MYO5B mutants. UNC45A depletion or introduction of the UNC45A mutation found in patients led to lower MYO5B expression. Within epithelial cells, loss of UNC45A led to changes in MYO5B–linked processes that are known to play a role in MVID pathogenesis. These included alteration of microvilli development and interference with the location of rat sarcoma–associated binding protein (RAB) 11A–positive recycling endosomes. When normal UNC45A was reintroduced to these cells, MYO5B expression returned. Reintroduction of either UNC45A or MYO5B repaired the alterations to recycling endosome position and microvilli development.

Loss of UNC45A did not appear to affect transcription of the MYO5B gen, which suggests a suggesting a functional interaction between the two at a protein level.