User login

Could This COPD Treatment’s Cost Put It Out of Reach for Many?

Ensifentrine (Ohtuvayre), a novel medication for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, has been shown to reduce COPD exacerbations and may improve the quality of life for patients, but these potential benefits come at a high annual cost, authors of a cost-effectiveness analysis say.

Ensifentrine is a first-in-class selective dual inhibitor of both phosphodiesterase 3 (PDE-3) and PDE-4, combining both bronchodilator and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory effects in a single molecule. The drug is delivered through a standard jet nebulizer.

In the phase 3 ENHANCE 1 and 2 trials, ensifentrine significantly improved lung function based on the primary outcome of average forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) within 0-12 hours of administration compared with placebo. In addition, patients were found to tolerate the inhaled treatment well, with similar proportions of ensifentrine- and placebo-assigned patients reporting treatment-emergent adverse events. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nasopharyngitis, hypertension, and back pain, reported in < 3% of the ensifentrine group.

High Cost Barrier

But as authors of the analysis from the Boston-based Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) found, ICER is an independent, nonprofit research institute that conducts evidence-based reviews of healthcare interventions, including prescription drugs, other treatments, and diagnostic tests.

“Current evidence shows that ensifentrine decreases COPD exacerbations when used in combination with some current inhaled therapies, but there are uncertainties about how much benefit it may add to unstudied combinations of inhaled treatments,” said David Rind, MD, chief medical officer of ICER, in a statement.

In an interview, Dr. Rind noted that the high price of ensifentrine may lead payers to restrict access to an otherwise promising new therapy. “Obviously many drugs in the US are overpriced, and this one, too, looks like it is overpriced. That causes ongoing financial toxicity for individual patients and it causes problems for the entire US health system, because when we pay too much for drugs we don’t have money for other things. So I’m worried about the fact that this price is too high compared to the benefit it provides,” he said.

As previously reported, as many as 1 in 6 persons with COPD in the United States miss or delay COPD medication doses owing to high drug costs. “I think that the pricing they chose is going to cause lots of barriers to people getting access and that insurance companies will throw up barriers. Primary care physicians like me won’t even try to get approval for a drug like this given the hoops we will be made to jump through, and so fewer people will get this drug,” Dr. Rind said. He pointed out that a lower wholesale acquisition cost could encourage higher volume sales, affording the drug maker a comparable profit to the higher cost but lower volume option.

Good Drug, High Price

An independent appraisal committee for ICER determined that “current evidence is adequate to demonstrate a net health benefit for ensifentrine added to maintenance therapy when compared to maintenance therapy alone.”

But ICER also issued an access and affordability alert “to signal to stakeholders and policymakers that the amount of added health care costs associated with a new service may be difficult for the health system to absorb over the short term without displacing other needed services.” ICER recommends that payers should include coverage for smoking cessation therapies, and that drug manufacturers “set prices that will foster affordability and good access for all patients by aligning prices with the patient-centered therapeutic value of their treatments.”

“This looks like a pretty good drug,” Dr. Rind said. “It looks quite safe, and I think there will be a lot of patients, particularly those who are having frequent exacerbations, who this would be appropriate for, particularly once they’ve maxed out existing therapies, but maybe even earlier than that. And if the price comes down to the point that patients can really access this and providers can access it, people really should look at this as a potential therapy.”

Drug Not Yet Available?

However, providers have not yet had experience to gauge the new medication. “We haven’t been able to prescribe it yet,” said Corinne Young, MSN, FNP-C, FCCP, director of advance practice provider and clinical services for Colorado Springs Pulmonary Consultants and president and founder of the Association of Pulmonary Advanced Practice Providers. She learned that “they were going to release it to select specialty pharmacies in the third quarter of 2024. But all the ones we call do not have it, and no one knows who does. They haven’t sent any reps into the field in my area, so we don’t have any points of contact either,” she said.

Verona Pharma stated it anticipates ensifentrine to be available in the third quarter of 2024 “through an exclusive network of accredited specialty pharmacies.”

Funding for the ICER report came from nonprofit foundations. No funding came from health insurers, pharmacy benefit managers, or life science companies. Dr. Rind had no disclosures relevant to ensifentrine or Verona Pharma. Ms. Young is a member of the CHEST Physician Editorial Board.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ensifentrine (Ohtuvayre), a novel medication for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, has been shown to reduce COPD exacerbations and may improve the quality of life for patients, but these potential benefits come at a high annual cost, authors of a cost-effectiveness analysis say.

Ensifentrine is a first-in-class selective dual inhibitor of both phosphodiesterase 3 (PDE-3) and PDE-4, combining both bronchodilator and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory effects in a single molecule. The drug is delivered through a standard jet nebulizer.

In the phase 3 ENHANCE 1 and 2 trials, ensifentrine significantly improved lung function based on the primary outcome of average forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) within 0-12 hours of administration compared with placebo. In addition, patients were found to tolerate the inhaled treatment well, with similar proportions of ensifentrine- and placebo-assigned patients reporting treatment-emergent adverse events. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nasopharyngitis, hypertension, and back pain, reported in < 3% of the ensifentrine group.

High Cost Barrier

But as authors of the analysis from the Boston-based Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) found, ICER is an independent, nonprofit research institute that conducts evidence-based reviews of healthcare interventions, including prescription drugs, other treatments, and diagnostic tests.

“Current evidence shows that ensifentrine decreases COPD exacerbations when used in combination with some current inhaled therapies, but there are uncertainties about how much benefit it may add to unstudied combinations of inhaled treatments,” said David Rind, MD, chief medical officer of ICER, in a statement.

In an interview, Dr. Rind noted that the high price of ensifentrine may lead payers to restrict access to an otherwise promising new therapy. “Obviously many drugs in the US are overpriced, and this one, too, looks like it is overpriced. That causes ongoing financial toxicity for individual patients and it causes problems for the entire US health system, because when we pay too much for drugs we don’t have money for other things. So I’m worried about the fact that this price is too high compared to the benefit it provides,” he said.

As previously reported, as many as 1 in 6 persons with COPD in the United States miss or delay COPD medication doses owing to high drug costs. “I think that the pricing they chose is going to cause lots of barriers to people getting access and that insurance companies will throw up barriers. Primary care physicians like me won’t even try to get approval for a drug like this given the hoops we will be made to jump through, and so fewer people will get this drug,” Dr. Rind said. He pointed out that a lower wholesale acquisition cost could encourage higher volume sales, affording the drug maker a comparable profit to the higher cost but lower volume option.

Good Drug, High Price

An independent appraisal committee for ICER determined that “current evidence is adequate to demonstrate a net health benefit for ensifentrine added to maintenance therapy when compared to maintenance therapy alone.”

But ICER also issued an access and affordability alert “to signal to stakeholders and policymakers that the amount of added health care costs associated with a new service may be difficult for the health system to absorb over the short term without displacing other needed services.” ICER recommends that payers should include coverage for smoking cessation therapies, and that drug manufacturers “set prices that will foster affordability and good access for all patients by aligning prices with the patient-centered therapeutic value of their treatments.”

“This looks like a pretty good drug,” Dr. Rind said. “It looks quite safe, and I think there will be a lot of patients, particularly those who are having frequent exacerbations, who this would be appropriate for, particularly once they’ve maxed out existing therapies, but maybe even earlier than that. And if the price comes down to the point that patients can really access this and providers can access it, people really should look at this as a potential therapy.”

Drug Not Yet Available?

However, providers have not yet had experience to gauge the new medication. “We haven’t been able to prescribe it yet,” said Corinne Young, MSN, FNP-C, FCCP, director of advance practice provider and clinical services for Colorado Springs Pulmonary Consultants and president and founder of the Association of Pulmonary Advanced Practice Providers. She learned that “they were going to release it to select specialty pharmacies in the third quarter of 2024. But all the ones we call do not have it, and no one knows who does. They haven’t sent any reps into the field in my area, so we don’t have any points of contact either,” she said.

Verona Pharma stated it anticipates ensifentrine to be available in the third quarter of 2024 “through an exclusive network of accredited specialty pharmacies.”

Funding for the ICER report came from nonprofit foundations. No funding came from health insurers, pharmacy benefit managers, or life science companies. Dr. Rind had no disclosures relevant to ensifentrine or Verona Pharma. Ms. Young is a member of the CHEST Physician Editorial Board.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ensifentrine (Ohtuvayre), a novel medication for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, has been shown to reduce COPD exacerbations and may improve the quality of life for patients, but these potential benefits come at a high annual cost, authors of a cost-effectiveness analysis say.

Ensifentrine is a first-in-class selective dual inhibitor of both phosphodiesterase 3 (PDE-3) and PDE-4, combining both bronchodilator and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory effects in a single molecule. The drug is delivered through a standard jet nebulizer.

In the phase 3 ENHANCE 1 and 2 trials, ensifentrine significantly improved lung function based on the primary outcome of average forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) within 0-12 hours of administration compared with placebo. In addition, patients were found to tolerate the inhaled treatment well, with similar proportions of ensifentrine- and placebo-assigned patients reporting treatment-emergent adverse events. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nasopharyngitis, hypertension, and back pain, reported in < 3% of the ensifentrine group.

High Cost Barrier

But as authors of the analysis from the Boston-based Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) found, ICER is an independent, nonprofit research institute that conducts evidence-based reviews of healthcare interventions, including prescription drugs, other treatments, and diagnostic tests.

“Current evidence shows that ensifentrine decreases COPD exacerbations when used in combination with some current inhaled therapies, but there are uncertainties about how much benefit it may add to unstudied combinations of inhaled treatments,” said David Rind, MD, chief medical officer of ICER, in a statement.

In an interview, Dr. Rind noted that the high price of ensifentrine may lead payers to restrict access to an otherwise promising new therapy. “Obviously many drugs in the US are overpriced, and this one, too, looks like it is overpriced. That causes ongoing financial toxicity for individual patients and it causes problems for the entire US health system, because when we pay too much for drugs we don’t have money for other things. So I’m worried about the fact that this price is too high compared to the benefit it provides,” he said.

As previously reported, as many as 1 in 6 persons with COPD in the United States miss or delay COPD medication doses owing to high drug costs. “I think that the pricing they chose is going to cause lots of barriers to people getting access and that insurance companies will throw up barriers. Primary care physicians like me won’t even try to get approval for a drug like this given the hoops we will be made to jump through, and so fewer people will get this drug,” Dr. Rind said. He pointed out that a lower wholesale acquisition cost could encourage higher volume sales, affording the drug maker a comparable profit to the higher cost but lower volume option.

Good Drug, High Price

An independent appraisal committee for ICER determined that “current evidence is adequate to demonstrate a net health benefit for ensifentrine added to maintenance therapy when compared to maintenance therapy alone.”

But ICER also issued an access and affordability alert “to signal to stakeholders and policymakers that the amount of added health care costs associated with a new service may be difficult for the health system to absorb over the short term without displacing other needed services.” ICER recommends that payers should include coverage for smoking cessation therapies, and that drug manufacturers “set prices that will foster affordability and good access for all patients by aligning prices with the patient-centered therapeutic value of their treatments.”

“This looks like a pretty good drug,” Dr. Rind said. “It looks quite safe, and I think there will be a lot of patients, particularly those who are having frequent exacerbations, who this would be appropriate for, particularly once they’ve maxed out existing therapies, but maybe even earlier than that. And if the price comes down to the point that patients can really access this and providers can access it, people really should look at this as a potential therapy.”

Drug Not Yet Available?

However, providers have not yet had experience to gauge the new medication. “We haven’t been able to prescribe it yet,” said Corinne Young, MSN, FNP-C, FCCP, director of advance practice provider and clinical services for Colorado Springs Pulmonary Consultants and president and founder of the Association of Pulmonary Advanced Practice Providers. She learned that “they were going to release it to select specialty pharmacies in the third quarter of 2024. But all the ones we call do not have it, and no one knows who does. They haven’t sent any reps into the field in my area, so we don’t have any points of contact either,” she said.

Verona Pharma stated it anticipates ensifentrine to be available in the third quarter of 2024 “through an exclusive network of accredited specialty pharmacies.”

Funding for the ICER report came from nonprofit foundations. No funding came from health insurers, pharmacy benefit managers, or life science companies. Dr. Rind had no disclosures relevant to ensifentrine or Verona Pharma. Ms. Young is a member of the CHEST Physician Editorial Board.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ABIM Revokes Two Physicians’ Certifications Over Accusations of COVID Misinformation

The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has revoked certification for two physicians known for leading an organization that promotes ivermectin as a treatment for COVID-19.

Pierre Kory, MD, is no longer certified in critical care medicine, pulmonary disease, and internal medicine, according to the ABIM website. Paul Ellis Marik, MD, is no longer certified in critical care medicine or internal medicine.

Dr. Marik is the chief scientific officer and Dr. Kory is president emeritus of the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance, a group they founded in March 2020. and also offers treatments for Lyme disease.

Ivermectin was proven to not be of use in treating COVID. Studies purporting to show a benefit were later linked to errors, and some were found to have been based on potentially fraudulent research.

The ABIM declined to comment when asked by this news organization about its action. Its website indicates that “revoked” indicates “loss of certification due to disciplinary action for which ABIM has determined that the conduct underlying the sanction does not warrant a defined pathway for restoration of certification at the time of disciplinary sanction.”

In a statement emailed to this news organization, Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik said, “we believe this decision represents a dangerous shift away from the foundation principles of medical discourse and scientific debate that have historically been the bedrock of medical education associations.”

The FLCCC said in the statement that it, along with Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik, are “evaluating options to challenge these decisions.”

Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik said they were notified in May 2022 that they were facing a potential ABIM disciplinary action. An ABIM committee recommended the revocation in July 2023, saying the two men were spreading “false or inaccurate medical information,” according to FLCCC. Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik lost an appeal.

In a 2023 statement, Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik called the ABIM action an “attack on freedom of speech.”

“This isn’t a free speech question,” said Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, the Drs. William F. and Virginia Connolly Mitty Professor of Bioethics at NYU Grossman School of Medicine’s Department of Population Health, New York City. “You do have the right to free speech, but you don’t have the right to practice outside of the standard of care boundaries,” he told this news organization.

The ABIM action “is the field standing up and saying, ‘These are the limits of what you can do,’” said Dr. Caplan. It means the profession is rejecting those “who are involved in things that harm patients or delay them getting accepted treatments,” he said. Caplan noted that a disciplinary action had been a long time in coming — 3 years since the first battles over ivermectin.

Wendy Parmet, JD, Matthews Distinguished University Professor of Law at Northeastern University School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs, Boston, said that misinformation spread by physicians is especially harmful because it comes with an air of credibility.

“We certainly want people to be able to dissent,” Ms. Parmet told this news organization. To engender trust, any sanctions by a professional board should be done in a deliberative process with a strong evidentiary base, she said.

“You want to leave sufficient room for discourse and discussion within the profession, and you don’t want the board to enforce a narrow, rigid orthodoxy,” she said. But in cases where people are “peddling information that is way outside the consensus” or are “profiting off of it, for the profession to take no action, that is, I think, detrimental also to the trust in the profession,” she said.

She was not surprised that Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik would fight to retain certification. “Board certification is an important, very worthwhile thing to have,” she said. “Losing it is not trivial.”

Dr. Kory, who is licensed in California, New York, and Wisconsin, “does not require this certification for his independent practice but is evaluating next steps with attorneys,” according to the statement from FLCCC.

Dr. Marik, whose Virginia medical license expired in 2022, “is no longer treating patients and has dedicated his time and efforts to the FLCCC Alliance,” the statement said.

Dr. Caplan served as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position) and is a contributing author and advisor for this news organization. Ms. Parmet reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has revoked certification for two physicians known for leading an organization that promotes ivermectin as a treatment for COVID-19.

Pierre Kory, MD, is no longer certified in critical care medicine, pulmonary disease, and internal medicine, according to the ABIM website. Paul Ellis Marik, MD, is no longer certified in critical care medicine or internal medicine.

Dr. Marik is the chief scientific officer and Dr. Kory is president emeritus of the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance, a group they founded in March 2020. and also offers treatments for Lyme disease.

Ivermectin was proven to not be of use in treating COVID. Studies purporting to show a benefit were later linked to errors, and some were found to have been based on potentially fraudulent research.

The ABIM declined to comment when asked by this news organization about its action. Its website indicates that “revoked” indicates “loss of certification due to disciplinary action for which ABIM has determined that the conduct underlying the sanction does not warrant a defined pathway for restoration of certification at the time of disciplinary sanction.”

In a statement emailed to this news organization, Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik said, “we believe this decision represents a dangerous shift away from the foundation principles of medical discourse and scientific debate that have historically been the bedrock of medical education associations.”

The FLCCC said in the statement that it, along with Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik, are “evaluating options to challenge these decisions.”

Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik said they were notified in May 2022 that they were facing a potential ABIM disciplinary action. An ABIM committee recommended the revocation in July 2023, saying the two men were spreading “false or inaccurate medical information,” according to FLCCC. Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik lost an appeal.

In a 2023 statement, Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik called the ABIM action an “attack on freedom of speech.”

“This isn’t a free speech question,” said Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, the Drs. William F. and Virginia Connolly Mitty Professor of Bioethics at NYU Grossman School of Medicine’s Department of Population Health, New York City. “You do have the right to free speech, but you don’t have the right to practice outside of the standard of care boundaries,” he told this news organization.

The ABIM action “is the field standing up and saying, ‘These are the limits of what you can do,’” said Dr. Caplan. It means the profession is rejecting those “who are involved in things that harm patients or delay them getting accepted treatments,” he said. Caplan noted that a disciplinary action had been a long time in coming — 3 years since the first battles over ivermectin.

Wendy Parmet, JD, Matthews Distinguished University Professor of Law at Northeastern University School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs, Boston, said that misinformation spread by physicians is especially harmful because it comes with an air of credibility.

“We certainly want people to be able to dissent,” Ms. Parmet told this news organization. To engender trust, any sanctions by a professional board should be done in a deliberative process with a strong evidentiary base, she said.

“You want to leave sufficient room for discourse and discussion within the profession, and you don’t want the board to enforce a narrow, rigid orthodoxy,” she said. But in cases where people are “peddling information that is way outside the consensus” or are “profiting off of it, for the profession to take no action, that is, I think, detrimental also to the trust in the profession,” she said.

She was not surprised that Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik would fight to retain certification. “Board certification is an important, very worthwhile thing to have,” she said. “Losing it is not trivial.”

Dr. Kory, who is licensed in California, New York, and Wisconsin, “does not require this certification for his independent practice but is evaluating next steps with attorneys,” according to the statement from FLCCC.

Dr. Marik, whose Virginia medical license expired in 2022, “is no longer treating patients and has dedicated his time and efforts to the FLCCC Alliance,” the statement said.

Dr. Caplan served as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position) and is a contributing author and advisor for this news organization. Ms. Parmet reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has revoked certification for two physicians known for leading an organization that promotes ivermectin as a treatment for COVID-19.

Pierre Kory, MD, is no longer certified in critical care medicine, pulmonary disease, and internal medicine, according to the ABIM website. Paul Ellis Marik, MD, is no longer certified in critical care medicine or internal medicine.

Dr. Marik is the chief scientific officer and Dr. Kory is president emeritus of the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance, a group they founded in March 2020. and also offers treatments for Lyme disease.

Ivermectin was proven to not be of use in treating COVID. Studies purporting to show a benefit were later linked to errors, and some were found to have been based on potentially fraudulent research.

The ABIM declined to comment when asked by this news organization about its action. Its website indicates that “revoked” indicates “loss of certification due to disciplinary action for which ABIM has determined that the conduct underlying the sanction does not warrant a defined pathway for restoration of certification at the time of disciplinary sanction.”

In a statement emailed to this news organization, Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik said, “we believe this decision represents a dangerous shift away from the foundation principles of medical discourse and scientific debate that have historically been the bedrock of medical education associations.”

The FLCCC said in the statement that it, along with Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik, are “evaluating options to challenge these decisions.”

Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik said they were notified in May 2022 that they were facing a potential ABIM disciplinary action. An ABIM committee recommended the revocation in July 2023, saying the two men were spreading “false or inaccurate medical information,” according to FLCCC. Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik lost an appeal.

In a 2023 statement, Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik called the ABIM action an “attack on freedom of speech.”

“This isn’t a free speech question,” said Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, the Drs. William F. and Virginia Connolly Mitty Professor of Bioethics at NYU Grossman School of Medicine’s Department of Population Health, New York City. “You do have the right to free speech, but you don’t have the right to practice outside of the standard of care boundaries,” he told this news organization.

The ABIM action “is the field standing up and saying, ‘These are the limits of what you can do,’” said Dr. Caplan. It means the profession is rejecting those “who are involved in things that harm patients or delay them getting accepted treatments,” he said. Caplan noted that a disciplinary action had been a long time in coming — 3 years since the first battles over ivermectin.

Wendy Parmet, JD, Matthews Distinguished University Professor of Law at Northeastern University School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs, Boston, said that misinformation spread by physicians is especially harmful because it comes with an air of credibility.

“We certainly want people to be able to dissent,” Ms. Parmet told this news organization. To engender trust, any sanctions by a professional board should be done in a deliberative process with a strong evidentiary base, she said.

“You want to leave sufficient room for discourse and discussion within the profession, and you don’t want the board to enforce a narrow, rigid orthodoxy,” she said. But in cases where people are “peddling information that is way outside the consensus” or are “profiting off of it, for the profession to take no action, that is, I think, detrimental also to the trust in the profession,” she said.

She was not surprised that Dr. Kory and Dr. Marik would fight to retain certification. “Board certification is an important, very worthwhile thing to have,” she said. “Losing it is not trivial.”

Dr. Kory, who is licensed in California, New York, and Wisconsin, “does not require this certification for his independent practice but is evaluating next steps with attorneys,” according to the statement from FLCCC.

Dr. Marik, whose Virginia medical license expired in 2022, “is no longer treating patients and has dedicated his time and efforts to the FLCCC Alliance,” the statement said.

Dr. Caplan served as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position) and is a contributing author and advisor for this news organization. Ms. Parmet reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Data Trends 2024: Transgender and Gender-Affirming Care

- Herman JL, Flores AR, O’Neill KK. How many adults and youth identify as transgender in the United States? UCLA School of Law Williams Institute. June 2022. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/trans-adults-united-states/

Boyer TL, Youk AO, Haas AP, et al. Suicide, homicide, and all-cause mortality among transgender and cisgender patients in the Veterans Health Administration. LGBT Health. 2021;8(3):173-180. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2020.0235

James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. 2016. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

Jasuja GK, Reisman JI, Rao SR, et al. Social stressors and health among older transgender and gender diverse veterans. LGBT Health. 2023;10(2):148-157. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2022.0012

Shane L. VA again delays decision on transgender surgery options. Military Times. February 26, 2024. Accessed April 30, 2024. https://www.militarytimes.com/veterans/2024/02/26/va-again-delays-decision-on-transgender-surgery-options/

Henderson ER, Boyer TL, Wolfe HL, Blosnich JR. Causes of death of transgender and gender diverse veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2024;66(4):664-671. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2023.11.014

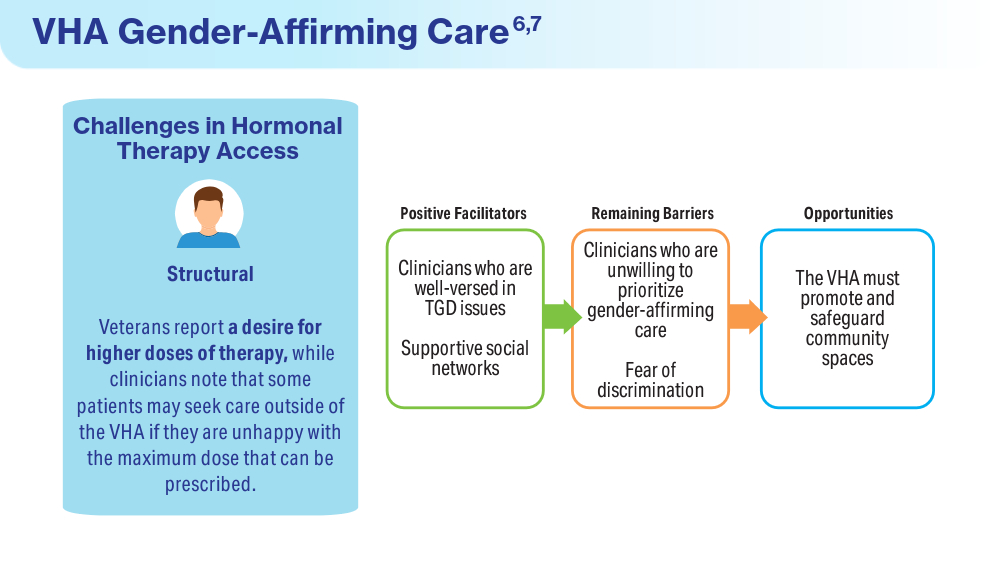

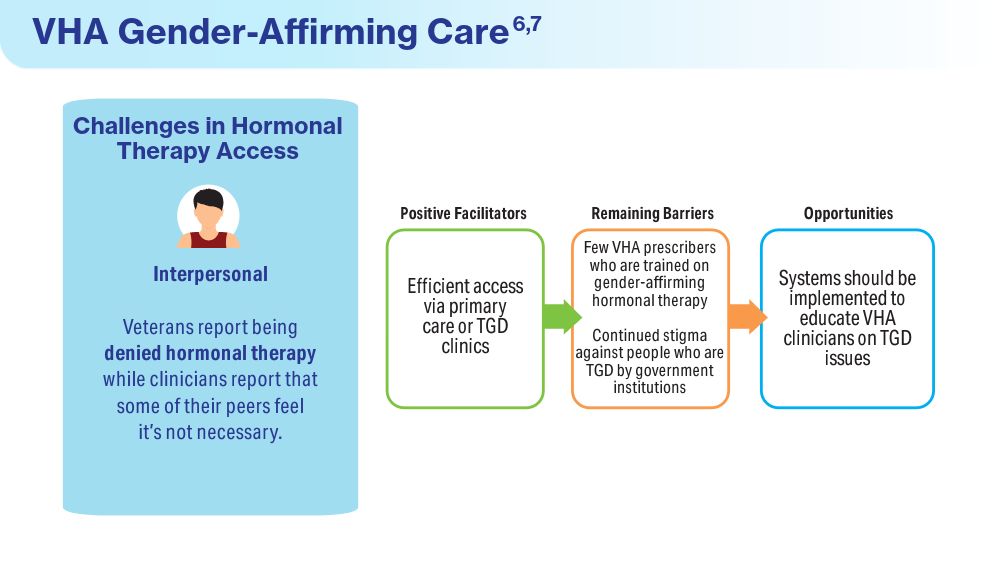

Wolfe HL, Boyer TL, Shipherd JC, Kauth MR, Jasuja GK, Blosnich JR. Barriers and facilitators to gender-affirming hormone therapy in the Veterans Health Administration. Ann Behav Med. 202316;57(12):1014-1023. doi:10.1093/abm/kaad035

- Herman JL, Flores AR, O’Neill KK. How many adults and youth identify as transgender in the United States? UCLA School of Law Williams Institute. June 2022. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/trans-adults-united-states/

Boyer TL, Youk AO, Haas AP, et al. Suicide, homicide, and all-cause mortality among transgender and cisgender patients in the Veterans Health Administration. LGBT Health. 2021;8(3):173-180. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2020.0235

James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. 2016. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

Jasuja GK, Reisman JI, Rao SR, et al. Social stressors and health among older transgender and gender diverse veterans. LGBT Health. 2023;10(2):148-157. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2022.0012

Shane L. VA again delays decision on transgender surgery options. Military Times. February 26, 2024. Accessed April 30, 2024. https://www.militarytimes.com/veterans/2024/02/26/va-again-delays-decision-on-transgender-surgery-options/

Henderson ER, Boyer TL, Wolfe HL, Blosnich JR. Causes of death of transgender and gender diverse veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2024;66(4):664-671. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2023.11.014

Wolfe HL, Boyer TL, Shipherd JC, Kauth MR, Jasuja GK, Blosnich JR. Barriers and facilitators to gender-affirming hormone therapy in the Veterans Health Administration. Ann Behav Med. 202316;57(12):1014-1023. doi:10.1093/abm/kaad035

- Herman JL, Flores AR, O’Neill KK. How many adults and youth identify as transgender in the United States? UCLA School of Law Williams Institute. June 2022. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/trans-adults-united-states/

Boyer TL, Youk AO, Haas AP, et al. Suicide, homicide, and all-cause mortality among transgender and cisgender patients in the Veterans Health Administration. LGBT Health. 2021;8(3):173-180. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2020.0235

James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. 2016. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

Jasuja GK, Reisman JI, Rao SR, et al. Social stressors and health among older transgender and gender diverse veterans. LGBT Health. 2023;10(2):148-157. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2022.0012

Shane L. VA again delays decision on transgender surgery options. Military Times. February 26, 2024. Accessed April 30, 2024. https://www.militarytimes.com/veterans/2024/02/26/va-again-delays-decision-on-transgender-surgery-options/

Henderson ER, Boyer TL, Wolfe HL, Blosnich JR. Causes of death of transgender and gender diverse veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2024;66(4):664-671. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2023.11.014

Wolfe HL, Boyer TL, Shipherd JC, Kauth MR, Jasuja GK, Blosnich JR. Barriers and facilitators to gender-affirming hormone therapy in the Veterans Health Administration. Ann Behav Med. 202316;57(12):1014-1023. doi:10.1093/abm/kaad035

FDA Grants Livdelzi Accelerated Approval for Primary Biliary Cholangitis

, or as monotherapy in those who can’t tolerate UDCA.

Livdelzi, a selective agonist of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor delta, is not recommended in adults who have or develop decompensated cirrhosis.

PBC is a rare, chronic, autoimmune disease of the bile ducts that affects roughly 130,000 Americans, primarily women, and can cause liver damage and possible liver failure if untreated. The disease currently has no cure.

The FDA approved Livdelzi based largely on results of the phase 3 RESPONSE study, in which the drug significantly improved liver biomarkers of disease activity and bothersome symptoms of pruritus in adults with PBC.

The primary endpoint of the trial was a biochemical response, defined as an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level < 1.67 times the upper limit of the normal range, with a decrease of 15% or more from baseline, and a normal total bilirubin level, at 12 months.

After 12 months, 62% of patients taking Livdelzi met the primary endpoint vs 20% of patients taking placebo.

In addition, significantly more patients taking Livdelzi than placebo had normalization of the ALP level (25% vs 0%). The average decrease in ALP from baseline was 42.4% in the Livdelzi group vs 4.3% in the placebo group.

At 12 months, alanine aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyl transferase levels were reduced by 23.5% and 39.1%, respectively, in the Livdelzi group compared with 6.5% and 11.4%, respectively, in the placebo group.

A key secondary endpoint was change in patient-reported pruritus.

At baseline, 38.3% of patients in the Livdelzi group and 35.4% of those in the placebo group had moderate to severe pruritus, with a daily numerical rating scale (NRS) score ≥ 4 out of 10.

Among these patients, the reduction from baseline in the pruritus NRS score at month 6 was significantly greater with Livdelzi than with placebo (change from baseline, -3.2 vs -1.7 points). These improvements were sustained through 12 months.

Improvements on the 5-D Itch Scale in both the moderate- to severe-pruritis population and the overall population also favored Livdelzi over placebo for itch relief, which had a positive impact on sleep.

“The availability of a new treatment option that can help reduce [the] intense itching while also improving biomarkers of active liver disease is a milestone for our community,” Carol Roberts, president, The PBCers Organization, said in a news release announcing the approval.

The most common adverse reactions with Livdelzi were headache, abdominal pain, nausea, abdominal distension, and dizziness.

The company noted that the FDA granted accelerated approval for Livdelzi based on a reduction of ALP. Improvement in survival or prevention of liver decompensation events have not been demonstrated. Continued approval of Livdelzi for PBC may be contingent on verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trial(s).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, or as monotherapy in those who can’t tolerate UDCA.

Livdelzi, a selective agonist of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor delta, is not recommended in adults who have or develop decompensated cirrhosis.

PBC is a rare, chronic, autoimmune disease of the bile ducts that affects roughly 130,000 Americans, primarily women, and can cause liver damage and possible liver failure if untreated. The disease currently has no cure.

The FDA approved Livdelzi based largely on results of the phase 3 RESPONSE study, in which the drug significantly improved liver biomarkers of disease activity and bothersome symptoms of pruritus in adults with PBC.

The primary endpoint of the trial was a biochemical response, defined as an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level < 1.67 times the upper limit of the normal range, with a decrease of 15% or more from baseline, and a normal total bilirubin level, at 12 months.

After 12 months, 62% of patients taking Livdelzi met the primary endpoint vs 20% of patients taking placebo.

In addition, significantly more patients taking Livdelzi than placebo had normalization of the ALP level (25% vs 0%). The average decrease in ALP from baseline was 42.4% in the Livdelzi group vs 4.3% in the placebo group.

At 12 months, alanine aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyl transferase levels were reduced by 23.5% and 39.1%, respectively, in the Livdelzi group compared with 6.5% and 11.4%, respectively, in the placebo group.

A key secondary endpoint was change in patient-reported pruritus.

At baseline, 38.3% of patients in the Livdelzi group and 35.4% of those in the placebo group had moderate to severe pruritus, with a daily numerical rating scale (NRS) score ≥ 4 out of 10.

Among these patients, the reduction from baseline in the pruritus NRS score at month 6 was significantly greater with Livdelzi than with placebo (change from baseline, -3.2 vs -1.7 points). These improvements were sustained through 12 months.

Improvements on the 5-D Itch Scale in both the moderate- to severe-pruritis population and the overall population also favored Livdelzi over placebo for itch relief, which had a positive impact on sleep.

“The availability of a new treatment option that can help reduce [the] intense itching while also improving biomarkers of active liver disease is a milestone for our community,” Carol Roberts, president, The PBCers Organization, said in a news release announcing the approval.

The most common adverse reactions with Livdelzi were headache, abdominal pain, nausea, abdominal distension, and dizziness.

The company noted that the FDA granted accelerated approval for Livdelzi based on a reduction of ALP. Improvement in survival or prevention of liver decompensation events have not been demonstrated. Continued approval of Livdelzi for PBC may be contingent on verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trial(s).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, or as monotherapy in those who can’t tolerate UDCA.

Livdelzi, a selective agonist of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor delta, is not recommended in adults who have or develop decompensated cirrhosis.

PBC is a rare, chronic, autoimmune disease of the bile ducts that affects roughly 130,000 Americans, primarily women, and can cause liver damage and possible liver failure if untreated. The disease currently has no cure.

The FDA approved Livdelzi based largely on results of the phase 3 RESPONSE study, in which the drug significantly improved liver biomarkers of disease activity and bothersome symptoms of pruritus in adults with PBC.

The primary endpoint of the trial was a biochemical response, defined as an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level < 1.67 times the upper limit of the normal range, with a decrease of 15% or more from baseline, and a normal total bilirubin level, at 12 months.

After 12 months, 62% of patients taking Livdelzi met the primary endpoint vs 20% of patients taking placebo.

In addition, significantly more patients taking Livdelzi than placebo had normalization of the ALP level (25% vs 0%). The average decrease in ALP from baseline was 42.4% in the Livdelzi group vs 4.3% in the placebo group.

At 12 months, alanine aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyl transferase levels were reduced by 23.5% and 39.1%, respectively, in the Livdelzi group compared with 6.5% and 11.4%, respectively, in the placebo group.

A key secondary endpoint was change in patient-reported pruritus.

At baseline, 38.3% of patients in the Livdelzi group and 35.4% of those in the placebo group had moderate to severe pruritus, with a daily numerical rating scale (NRS) score ≥ 4 out of 10.

Among these patients, the reduction from baseline in the pruritus NRS score at month 6 was significantly greater with Livdelzi than with placebo (change from baseline, -3.2 vs -1.7 points). These improvements were sustained through 12 months.

Improvements on the 5-D Itch Scale in both the moderate- to severe-pruritis population and the overall population also favored Livdelzi over placebo for itch relief, which had a positive impact on sleep.

“The availability of a new treatment option that can help reduce [the] intense itching while also improving biomarkers of active liver disease is a milestone for our community,” Carol Roberts, president, The PBCers Organization, said in a news release announcing the approval.

The most common adverse reactions with Livdelzi were headache, abdominal pain, nausea, abdominal distension, and dizziness.

The company noted that the FDA granted accelerated approval for Livdelzi based on a reduction of ALP. Improvement in survival or prevention of liver decompensation events have not been demonstrated. Continued approval of Livdelzi for PBC may be contingent on verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trial(s).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

CBD Use in Pregnant People Double That of Nonpregnant Counterparts

Pregnant women in a large North American sample reported nearly double the rate of cannabidiol (CBD) use compared with nonpregnant women, new data published in a research letter in Obstetrics & Gynecology indicates.

Healthcare providers should be aware of the high rate of CBD use in pregnancy, especially as legal use of cannabis is increasing faster than evidence on outcomes for exposed offspring, note the researchers, led by Devika Bhatia, MD, from the Department of Psychiatry, Colorado School of Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora.

In an accompanying editorial, Torri D. Metz, MD, MS, deputy editor for obstetrics for Obstetrics & Gynecology, writes that the study “is critically important.” She points out that pregnant individuals may perceive that CBD is a safe drug to use in pregnancy, despite there being essentially no data examining whether or not this is the case.

Large Dataset From United States and Canada

Researchers used data from the International Cannabis Policy Study (2019-2021), a repeated cross-sectional survey of people aged 16-65 years in the United States and Canada. There were 66,457 women in the sample, including 1096 pregnant women.

Particularly concerning, the authors write, is the prenatal use of CBD-only products. Those products are advertised to contain only CBD, rather than tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). They point out CBD-only products are often legal in North America and often marketed as supplements.

The prevalence of CBD-only use in pregnant women in the study was 20.4% compared with 11.3% among nonpregnant women, P < .001. The top reason for use by pregnant women was anxiety (58.4%). Other top reasons included depression (40.3%), posttraumatic stress disorder (32.1%), pain (52.3%), headache (35.6%), and nausea or vomiting (31.9%).

“Nonpregnant women were significantly more likely to report using CBD for pain, sleep, general well-being, and ‘other’ physical or mental health reasons, or to not use CBD for mental health,” the authors write, adding that the reasons for CBD use highlight drivers that may be important to address in treating pregnant patients.

Provider Endorsement in Some Cases

Dr. Metz, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology with the University of Utah Health in Salt Lake City, says in some cases women may be getting endorsement of CBD use from their provider or at least implied support when CBD is prescribed. In the study, pregnant women had 2.33 times greater adjusted odds of having a CBD prescription than nonpregnant women (95% confidence interval, 1.27-2.88).

She points to another cross-sectional study of more than 10,000 participants using PRAMS (Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System) data that found that “from 2017 to 2019, 63% of pregnant women reported that they were not told to avoid cannabis use in pregnancy, and 8% noted that they were advised to use cannabis by their prenatal care practitioner.”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends against prescribing cannabis products for pregnant or lactating women.

Studies that have explored THC and its metabolites have shown “a consistent association between cannabis use and decreased fetal growth,” Dr. Metz noted. “There also remain persistent concerns about the long-term neurodevelopmental effects of maternal cannabis use on the fetus and, subsequently, the newborn.”

Limitations of the study include the self-reported responses and participants’ ability to accurately distinguish between CBD-only and THC-containing products.

Because self-reports of CBD use in pregnancy may be drastically underestimated and nonreliable, Dr. Metz writes, development of blood and urine screens to help detect CBD product use “will be helpful in moving the field forward.”

Study senior author David Hammond, PhD, has been a paid expert witness on behalf of public health authorities in response to legal challenges from the cannabis, tobacco, vaping, and food industries. Other authors did not report any potential conflicts. Dr. Metz reports personal fees from Pfizer, and grants from Pfizer for her role as a site principal investigator for SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and for her role as a site PI for RSV vaccination in pregnancy study.

Pregnant women in a large North American sample reported nearly double the rate of cannabidiol (CBD) use compared with nonpregnant women, new data published in a research letter in Obstetrics & Gynecology indicates.

Healthcare providers should be aware of the high rate of CBD use in pregnancy, especially as legal use of cannabis is increasing faster than evidence on outcomes for exposed offspring, note the researchers, led by Devika Bhatia, MD, from the Department of Psychiatry, Colorado School of Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora.

In an accompanying editorial, Torri D. Metz, MD, MS, deputy editor for obstetrics for Obstetrics & Gynecology, writes that the study “is critically important.” She points out that pregnant individuals may perceive that CBD is a safe drug to use in pregnancy, despite there being essentially no data examining whether or not this is the case.

Large Dataset From United States and Canada

Researchers used data from the International Cannabis Policy Study (2019-2021), a repeated cross-sectional survey of people aged 16-65 years in the United States and Canada. There were 66,457 women in the sample, including 1096 pregnant women.

Particularly concerning, the authors write, is the prenatal use of CBD-only products. Those products are advertised to contain only CBD, rather than tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). They point out CBD-only products are often legal in North America and often marketed as supplements.

The prevalence of CBD-only use in pregnant women in the study was 20.4% compared with 11.3% among nonpregnant women, P < .001. The top reason for use by pregnant women was anxiety (58.4%). Other top reasons included depression (40.3%), posttraumatic stress disorder (32.1%), pain (52.3%), headache (35.6%), and nausea or vomiting (31.9%).

“Nonpregnant women were significantly more likely to report using CBD for pain, sleep, general well-being, and ‘other’ physical or mental health reasons, or to not use CBD for mental health,” the authors write, adding that the reasons for CBD use highlight drivers that may be important to address in treating pregnant patients.

Provider Endorsement in Some Cases

Dr. Metz, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology with the University of Utah Health in Salt Lake City, says in some cases women may be getting endorsement of CBD use from their provider or at least implied support when CBD is prescribed. In the study, pregnant women had 2.33 times greater adjusted odds of having a CBD prescription than nonpregnant women (95% confidence interval, 1.27-2.88).

She points to another cross-sectional study of more than 10,000 participants using PRAMS (Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System) data that found that “from 2017 to 2019, 63% of pregnant women reported that they were not told to avoid cannabis use in pregnancy, and 8% noted that they were advised to use cannabis by their prenatal care practitioner.”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends against prescribing cannabis products for pregnant or lactating women.

Studies that have explored THC and its metabolites have shown “a consistent association between cannabis use and decreased fetal growth,” Dr. Metz noted. “There also remain persistent concerns about the long-term neurodevelopmental effects of maternal cannabis use on the fetus and, subsequently, the newborn.”

Limitations of the study include the self-reported responses and participants’ ability to accurately distinguish between CBD-only and THC-containing products.

Because self-reports of CBD use in pregnancy may be drastically underestimated and nonreliable, Dr. Metz writes, development of blood and urine screens to help detect CBD product use “will be helpful in moving the field forward.”

Study senior author David Hammond, PhD, has been a paid expert witness on behalf of public health authorities in response to legal challenges from the cannabis, tobacco, vaping, and food industries. Other authors did not report any potential conflicts. Dr. Metz reports personal fees from Pfizer, and grants from Pfizer for her role as a site principal investigator for SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and for her role as a site PI for RSV vaccination in pregnancy study.

Pregnant women in a large North American sample reported nearly double the rate of cannabidiol (CBD) use compared with nonpregnant women, new data published in a research letter in Obstetrics & Gynecology indicates.

Healthcare providers should be aware of the high rate of CBD use in pregnancy, especially as legal use of cannabis is increasing faster than evidence on outcomes for exposed offspring, note the researchers, led by Devika Bhatia, MD, from the Department of Psychiatry, Colorado School of Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora.

In an accompanying editorial, Torri D. Metz, MD, MS, deputy editor for obstetrics for Obstetrics & Gynecology, writes that the study “is critically important.” She points out that pregnant individuals may perceive that CBD is a safe drug to use in pregnancy, despite there being essentially no data examining whether or not this is the case.

Large Dataset From United States and Canada

Researchers used data from the International Cannabis Policy Study (2019-2021), a repeated cross-sectional survey of people aged 16-65 years in the United States and Canada. There were 66,457 women in the sample, including 1096 pregnant women.

Particularly concerning, the authors write, is the prenatal use of CBD-only products. Those products are advertised to contain only CBD, rather than tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). They point out CBD-only products are often legal in North America and often marketed as supplements.

The prevalence of CBD-only use in pregnant women in the study was 20.4% compared with 11.3% among nonpregnant women, P < .001. The top reason for use by pregnant women was anxiety (58.4%). Other top reasons included depression (40.3%), posttraumatic stress disorder (32.1%), pain (52.3%), headache (35.6%), and nausea or vomiting (31.9%).

“Nonpregnant women were significantly more likely to report using CBD for pain, sleep, general well-being, and ‘other’ physical or mental health reasons, or to not use CBD for mental health,” the authors write, adding that the reasons for CBD use highlight drivers that may be important to address in treating pregnant patients.

Provider Endorsement in Some Cases

Dr. Metz, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology with the University of Utah Health in Salt Lake City, says in some cases women may be getting endorsement of CBD use from their provider or at least implied support when CBD is prescribed. In the study, pregnant women had 2.33 times greater adjusted odds of having a CBD prescription than nonpregnant women (95% confidence interval, 1.27-2.88).

She points to another cross-sectional study of more than 10,000 participants using PRAMS (Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System) data that found that “from 2017 to 2019, 63% of pregnant women reported that they were not told to avoid cannabis use in pregnancy, and 8% noted that they were advised to use cannabis by their prenatal care practitioner.”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends against prescribing cannabis products for pregnant or lactating women.

Studies that have explored THC and its metabolites have shown “a consistent association between cannabis use and decreased fetal growth,” Dr. Metz noted. “There also remain persistent concerns about the long-term neurodevelopmental effects of maternal cannabis use on the fetus and, subsequently, the newborn.”

Limitations of the study include the self-reported responses and participants’ ability to accurately distinguish between CBD-only and THC-containing products.

Because self-reports of CBD use in pregnancy may be drastically underestimated and nonreliable, Dr. Metz writes, development of blood and urine screens to help detect CBD product use “will be helpful in moving the field forward.”

Study senior author David Hammond, PhD, has been a paid expert witness on behalf of public health authorities in response to legal challenges from the cannabis, tobacco, vaping, and food industries. Other authors did not report any potential conflicts. Dr. Metz reports personal fees from Pfizer, and grants from Pfizer for her role as a site principal investigator for SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and for her role as a site PI for RSV vaccination in pregnancy study.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

A Checklist for Compounded Semaglutide or Tirzepatide

Consider this: If you’re taking your children to the beach, how do you protect them from drowning? You don’t tell them, “Don’t go into the ocean.” You teach them how to swim; you give them floaties; and you accompany them in the water and go in only when a lifeguard is present. In other words, you give them all the tools to protect themselves because you know they will go into the ocean anyway.

Patients are diving into the ocean. Patients with obesity, who know that a treatment for their disease exists but is inaccessible, are diving into the ocean. Unfortunately, they are diving in without floaties or a lifeguard, and well-meaning bystanders are simply telling them to not go.

Compounded peptides are an ocean of alternative therapies. Even though compounding pharmacists need specialized training, facilities and equipment need to be properly certified, and final dosage forms need extensive testing, pharmacies are not equal when it comes to sterile compounding. Regulatory agencies such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have expressed caution around compounded semaglutide. Professional societies such as the Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) advise against compounded peptides because they lack clinical trials that prove their safety and efficacy. Ask any individual doctor and you are likely to receive a range of opinions.

As an endocrinologist specializing in obesity, I practice evidence-based medicine as much as possible. However, I also recognize how today’s dysfunctional medical system compels patients to dive into that ocean in search of an alternative solution.

With the help of pharmacists, compounding pharmacists, researchers, and clinicians, here is a checklist for patients who seek compounded semaglutide or tirzepatide:

- Check the state licensing board website to see if there have been any complaints or disciplinary actions made against the pharmacy facility. These government-maintained websites vary in searchability and user-friendliness, but you are specifically looking for whether the FDA ever issued a 483 form.

- Ask for the pharmacy’s state board inspection report. There should be at least one of these reports, issued at the pharmacy’s founding, and there may be more depending on individual state regulations on frequencies of inspections.

- Ask if the compounding pharmacy is accredited by the Pharmacy Compounding Accreditation Board (PCAB). Accreditation is an extra optional step that some compounding pharmacies take to be legitimized by a third party.

- Ask if the pharmacy follows Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP). CGMP is not required of 503a pharmacies, which are pharmacies that provide semaglutide or tirzepatide directly to patients, but following CGMP means an extra level of quality assurance. The bare minimum for anyone doing sterile compounding in the United States is to meet the standards found in the US Pharmacopeia, chapter <797>, Sterile Compounding.

- Ask your compounding pharmacy where they source the medication’s active pharmaceutical ingredient (API).

- Find out if this supplier is registered with the FDA by searching here or here.

- Confirm that semaglutide base, not semaglutide salt, is used in the compounding process.

- Request a certificate of analysis (COA) of the active pharmaceutical ingredient, which should be semaglutide base. This shows you whether the medication has impurities or byproducts due to its manufacturing process.

- Ask if they have third-party confirmation of potency, stability, and sterility testing of the final product.

In generating this guidance, I’m not endorsing compounded peptides, and in fact, I recognize that there is nothing keeping small-time compounding pharmacies from skirting some of these quality measures, falsifying records, and flying under the radar. However, I hope this checklist serves as a starting point for education and risk mitigation. If a compounder is unwilling or unable to answer these questions, consider it a red flag and look elsewhere.

In an ideal world, the state regulators or the FDA would proactively supervise instead of reactively monitor; trusted compounding pharmacies would be systematically activated to ease medication shortages; and patients with obesity would have access to safe and efficacious treatments for their disease. Until then, we as providers can acknowledge the disappointments of our healthcare system while still developing realistic and individualized solutions that prioritize patient care and safety.

Dr. Tchang is assistant professor, Clinical Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, Weill Cornell Medicine, and a physician, Department of Medicine, Iris Cantor Women’s Health Center, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, New York. She is an adviser for Novo Nordisk, which manufactures Wegovy, and an adviser for Ro, a telehealth company that offers compounded semaglutide, and serves or has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Gelesis and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Consider this: If you’re taking your children to the beach, how do you protect them from drowning? You don’t tell them, “Don’t go into the ocean.” You teach them how to swim; you give them floaties; and you accompany them in the water and go in only when a lifeguard is present. In other words, you give them all the tools to protect themselves because you know they will go into the ocean anyway.

Patients are diving into the ocean. Patients with obesity, who know that a treatment for their disease exists but is inaccessible, are diving into the ocean. Unfortunately, they are diving in without floaties or a lifeguard, and well-meaning bystanders are simply telling them to not go.

Compounded peptides are an ocean of alternative therapies. Even though compounding pharmacists need specialized training, facilities and equipment need to be properly certified, and final dosage forms need extensive testing, pharmacies are not equal when it comes to sterile compounding. Regulatory agencies such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have expressed caution around compounded semaglutide. Professional societies such as the Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) advise against compounded peptides because they lack clinical trials that prove their safety and efficacy. Ask any individual doctor and you are likely to receive a range of opinions.

As an endocrinologist specializing in obesity, I practice evidence-based medicine as much as possible. However, I also recognize how today’s dysfunctional medical system compels patients to dive into that ocean in search of an alternative solution.

With the help of pharmacists, compounding pharmacists, researchers, and clinicians, here is a checklist for patients who seek compounded semaglutide or tirzepatide:

- Check the state licensing board website to see if there have been any complaints or disciplinary actions made against the pharmacy facility. These government-maintained websites vary in searchability and user-friendliness, but you are specifically looking for whether the FDA ever issued a 483 form.

- Ask for the pharmacy’s state board inspection report. There should be at least one of these reports, issued at the pharmacy’s founding, and there may be more depending on individual state regulations on frequencies of inspections.

- Ask if the compounding pharmacy is accredited by the Pharmacy Compounding Accreditation Board (PCAB). Accreditation is an extra optional step that some compounding pharmacies take to be legitimized by a third party.

- Ask if the pharmacy follows Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP). CGMP is not required of 503a pharmacies, which are pharmacies that provide semaglutide or tirzepatide directly to patients, but following CGMP means an extra level of quality assurance. The bare minimum for anyone doing sterile compounding in the United States is to meet the standards found in the US Pharmacopeia, chapter <797>, Sterile Compounding.

- Ask your compounding pharmacy where they source the medication’s active pharmaceutical ingredient (API).

- Find out if this supplier is registered with the FDA by searching here or here.

- Confirm that semaglutide base, not semaglutide salt, is used in the compounding process.

- Request a certificate of analysis (COA) of the active pharmaceutical ingredient, which should be semaglutide base. This shows you whether the medication has impurities or byproducts due to its manufacturing process.

- Ask if they have third-party confirmation of potency, stability, and sterility testing of the final product.

In generating this guidance, I’m not endorsing compounded peptides, and in fact, I recognize that there is nothing keeping small-time compounding pharmacies from skirting some of these quality measures, falsifying records, and flying under the radar. However, I hope this checklist serves as a starting point for education and risk mitigation. If a compounder is unwilling or unable to answer these questions, consider it a red flag and look elsewhere.

In an ideal world, the state regulators or the FDA would proactively supervise instead of reactively monitor; trusted compounding pharmacies would be systematically activated to ease medication shortages; and patients with obesity would have access to safe and efficacious treatments for their disease. Until then, we as providers can acknowledge the disappointments of our healthcare system while still developing realistic and individualized solutions that prioritize patient care and safety.

Dr. Tchang is assistant professor, Clinical Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, Weill Cornell Medicine, and a physician, Department of Medicine, Iris Cantor Women’s Health Center, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, New York. She is an adviser for Novo Nordisk, which manufactures Wegovy, and an adviser for Ro, a telehealth company that offers compounded semaglutide, and serves or has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Gelesis and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Consider this: If you’re taking your children to the beach, how do you protect them from drowning? You don’t tell them, “Don’t go into the ocean.” You teach them how to swim; you give them floaties; and you accompany them in the water and go in only when a lifeguard is present. In other words, you give them all the tools to protect themselves because you know they will go into the ocean anyway.

Patients are diving into the ocean. Patients with obesity, who know that a treatment for their disease exists but is inaccessible, are diving into the ocean. Unfortunately, they are diving in without floaties or a lifeguard, and well-meaning bystanders are simply telling them to not go.

Compounded peptides are an ocean of alternative therapies. Even though compounding pharmacists need specialized training, facilities and equipment need to be properly certified, and final dosage forms need extensive testing, pharmacies are not equal when it comes to sterile compounding. Regulatory agencies such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have expressed caution around compounded semaglutide. Professional societies such as the Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) advise against compounded peptides because they lack clinical trials that prove their safety and efficacy. Ask any individual doctor and you are likely to receive a range of opinions.

As an endocrinologist specializing in obesity, I practice evidence-based medicine as much as possible. However, I also recognize how today’s dysfunctional medical system compels patients to dive into that ocean in search of an alternative solution.

With the help of pharmacists, compounding pharmacists, researchers, and clinicians, here is a checklist for patients who seek compounded semaglutide or tirzepatide:

- Check the state licensing board website to see if there have been any complaints or disciplinary actions made against the pharmacy facility. These government-maintained websites vary in searchability and user-friendliness, but you are specifically looking for whether the FDA ever issued a 483 form.

- Ask for the pharmacy’s state board inspection report. There should be at least one of these reports, issued at the pharmacy’s founding, and there may be more depending on individual state regulations on frequencies of inspections.

- Ask if the compounding pharmacy is accredited by the Pharmacy Compounding Accreditation Board (PCAB). Accreditation is an extra optional step that some compounding pharmacies take to be legitimized by a third party.

- Ask if the pharmacy follows Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP). CGMP is not required of 503a pharmacies, which are pharmacies that provide semaglutide or tirzepatide directly to patients, but following CGMP means an extra level of quality assurance. The bare minimum for anyone doing sterile compounding in the United States is to meet the standards found in the US Pharmacopeia, chapter <797>, Sterile Compounding.

- Ask your compounding pharmacy where they source the medication’s active pharmaceutical ingredient (API).

- Find out if this supplier is registered with the FDA by searching here or here.

- Confirm that semaglutide base, not semaglutide salt, is used in the compounding process.

- Request a certificate of analysis (COA) of the active pharmaceutical ingredient, which should be semaglutide base. This shows you whether the medication has impurities or byproducts due to its manufacturing process.

- Ask if they have third-party confirmation of potency, stability, and sterility testing of the final product.

In generating this guidance, I’m not endorsing compounded peptides, and in fact, I recognize that there is nothing keeping small-time compounding pharmacies from skirting some of these quality measures, falsifying records, and flying under the radar. However, I hope this checklist serves as a starting point for education and risk mitigation. If a compounder is unwilling or unable to answer these questions, consider it a red flag and look elsewhere.

In an ideal world, the state regulators or the FDA would proactively supervise instead of reactively monitor; trusted compounding pharmacies would be systematically activated to ease medication shortages; and patients with obesity would have access to safe and efficacious treatments for their disease. Until then, we as providers can acknowledge the disappointments of our healthcare system while still developing realistic and individualized solutions that prioritize patient care and safety.

Dr. Tchang is assistant professor, Clinical Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, Weill Cornell Medicine, and a physician, Department of Medicine, Iris Cantor Women’s Health Center, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, New York. She is an adviser for Novo Nordisk, which manufactures Wegovy, and an adviser for Ro, a telehealth company that offers compounded semaglutide, and serves or has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Gelesis and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

PTSD Needs a New Name, Experts Say — Here’s Why

In a bid to reduce stigma and improve treatment rates, for inclusion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). The APA’s policy is that a rolling name change is available if the current term is determined to be harmful.

Currently led by anesthesiologist Eugene Lipov, MD, clinical assistant professor, University of Illinois Chicago, and chief medical officer of Stella Center, also in Chicago, the formal request for the proposed name change to the APA’s DSM-5-TR Steering Committee in August 2023.

The APA Steering Committee rejected the proposed name change in November 2023, citing a “lack of convincing evidence.” However, Dr. Lipov and colleagues remain undeterred and continue to advocate for the change.

“The word ‘disorder’ is both imprecise and stigmatizing,” Dr. Lipov said. “Because of stigma, many people with PTSD — especially those in the military — don’t get help, which my research has demonstrated.”

Patients are more likely to seek help if their symptoms are framed as manifestations of an injury that is diagnosable and treatable, like a broken leg, Dr. Lipov said. “Stigma can kill in very real ways, since delayed care or lack of care can directly lead to suicides, thus satisfying the reduce harm requirement for the name change.”

Neurobiology of Trauma

Dr. Lipov grew up with a veteran father affected by PTSD and a mother with debilitating depression who eventually took her life. “I understand the impact of trauma very well,” he said.

Although not a psychiatrist, Dr. Lipov pioneered a highly successful treatment for PTSD by adapting an anesthetic technique — the stellate ganglion block (SGB) — to reverse many trauma symptoms through the process of “rebooting.”

This involves reversing the activity of the sympathetic nervous system — the fight-or-flight response — to the pretrauma state by anesthetizing the sympathetic ganglion in the neck. Investigating how SGB can help ameliorate the symptoms of PTSD led him to investigate and describe the neurobiology of PTSD and the mechanism of action of SGB.

The impact of SGD on PTSD was supported by a small neuroimaging study demonstrating that the right amygdala — the area of the brain associated with the fear response — was overactivated in patients with PTSD but that this region was deactivated after the administration of SGB, Dr. Lipov said.

“I believe that psychiatric conditions are actually physiologic brain changes that can be measured by advanced neuroimaging technologies and then physiologically treated,” he stated.

He noted that a growing body of literature suggests that use of the SGB for PTSD can be effective “because PTSD has a neurobiological basis and is essentially caused by an actual injury to the brain.”

A Natural Response, Not a Disorder

Dr. Lipov’s clinical work treating PTSD as a brain injury led him to connect with Frank Ochberg, MD, a founding board member of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, former associate director of the National Institute of Mental Health, and former director of the Michigan Department of Mental Health.

In 2012, Dr. Ochberg teamed up with retired Army General Peter Chiarelli and Jonathan Shay, MD, PhD, author of Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character, to petition the DSM-5 Steering Committee to change the name of PTSD to PTSI in the upcoming DSM-5.

Dr. Ochberg explained that Gen. Chiarelli believed the term “disorder” suggests a preexisting issue prior to enlistment, potentially making an individual appear “weak.” He noted that this stigma is particularly troubling for military personnel, who often avoid seeking so they are not perceived as vulnerable, which can lead to potentially dire consequences, including suicide.

“We received endorsements from many quarters, not only advocates for service members or veterans,” Dr. Ochberg said.

This included feminists like Gloria Steinem, who championed the rights of women who had survived rape, incest, and domestic violence. As one advocate put it: “The natural human reaction to a life-threatening event should not be labeled a disorder.”

The DSM-5 Steering Committee declined to change the name. “Their feeling was that if we change the word ‘disorder’ to something else, we’d have to change every condition in the DSM that’s called a ‘disorder’. And they felt there really was nothing wrong with the word,” said Dr. Ochberg.

However, Dr. Lipov noted that other diagnoses have undergone name changes in the DSM for the sake of accuracy or stigma reduction. For example, the term mental retardation (DSM-IV) was changed to intellectual disability in DSM-5, and gender identity disorder was changed to gender dysphoria.

A decade later, Dr. Lipov decided to try again. To bolster his contention, he conducted a telephone survey of 1025 individuals. Of these, about 50% had a PTSD diagnosis.

Approximately two thirds of respondents agreed that a name change to PTSI would reduce the stigma associated with the term “PTSD.” Over half said it would increase the likelihood they would seek medical help. Those diagnosed with PTSD were most likely to endorse the name change.

Dr. Lipov conducts an ongoing survey of psychiatrists to ascertain their views on the potential name change and hopes to include findings in future research and communication with the DSM-5 Steering Committee. In addition, he has developed a new survey that expands upon his original survey, which specifically looked at individuals with PTSD.

“The new survey includes a wide range of people, many of whom have never been diagnosed. One of the questions we ask is whether they’ve ever heard of PTSD, and then we ask them about their reaction to the term,” he said.

A Barrier to Care

Psychiatrist Marcel Green, MD, director of Hudson Mind in New York City, refers to himself as an “interventional psychiatrist,” as he employs a comprehensive approach that includes not only medication and psychotherapy but also specialized techniques like SBG for severe anxiety-related physical symptoms and certain pain conditions.