User login

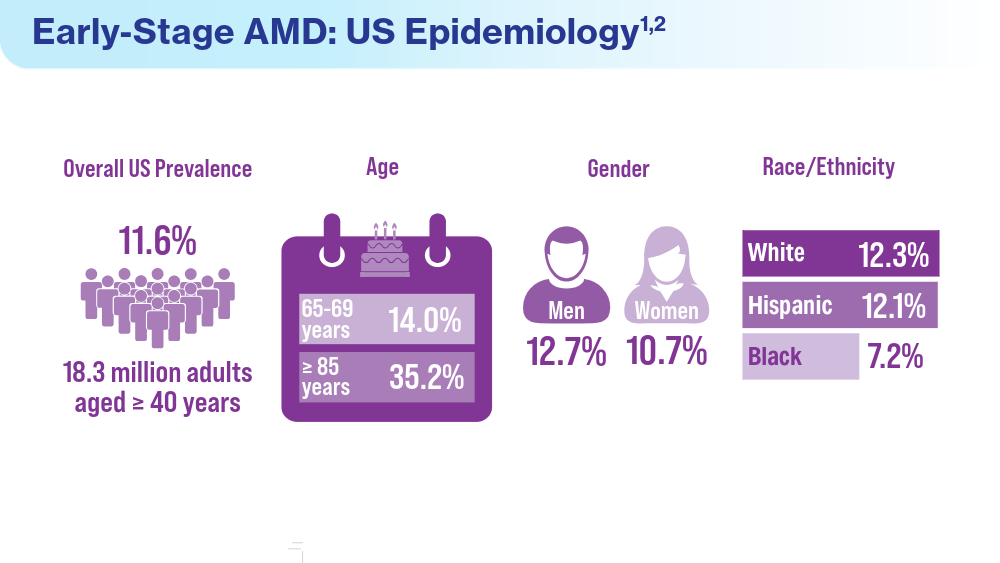

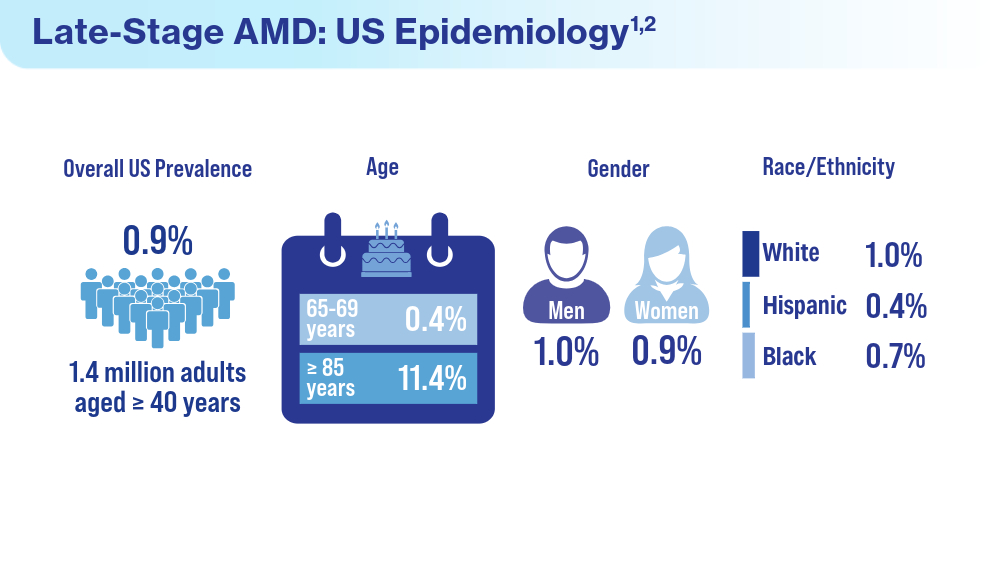

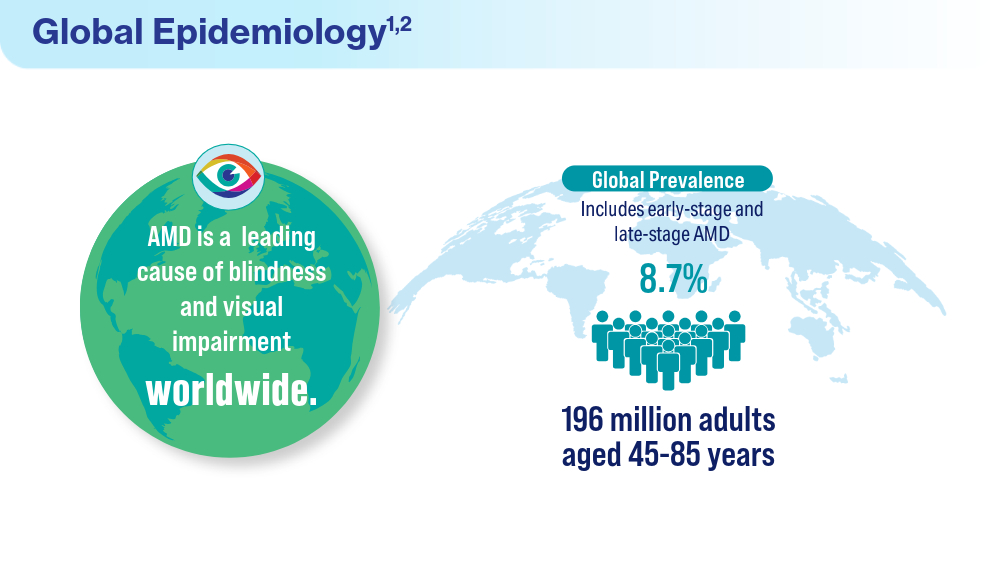

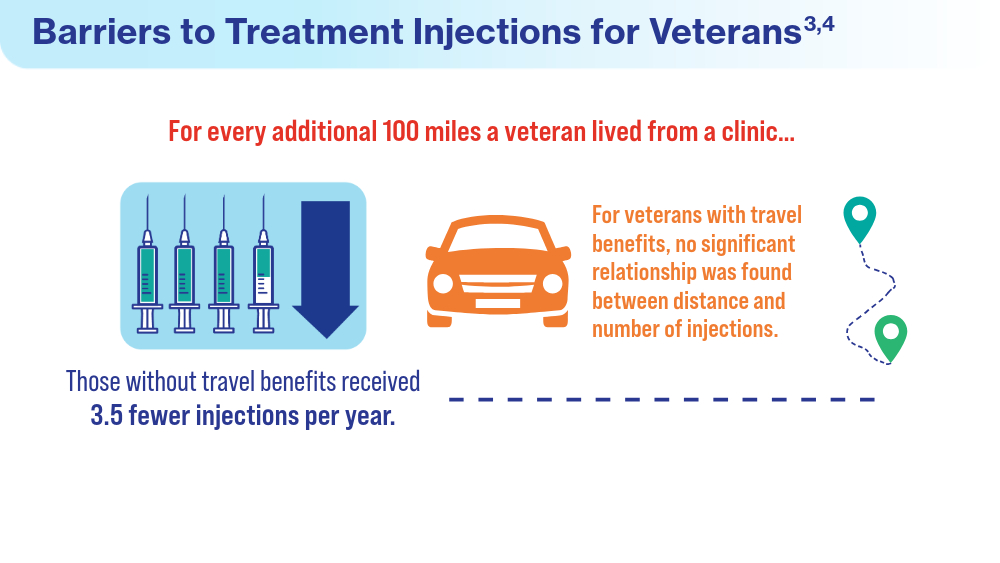

Data Trends 2024: Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)

- Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Burke-Conte Z, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the US in 2019. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140(12):1202-1208. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.4401

- Fleckenstein M, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Chakravarthy U. Age-related macular degeneration: a review. JAMA. 2024;331(2):147-157. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26074

- Meer EA, Targ S, Zhang N, Hoggatt KJ, Mehta KM, Brodie F. Age-related macular degeneration injection frequency: effects of distance traveled and travel support. Retina. 2024;44(2):230-236. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000003947

- Bhisitkul RB, Mendes TS, Rofagha S, et al. Macular atrophy progression and 7-year vision outcomes in subjects from the ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON studies: the SEVEN-UP study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(5):915-24.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2015.01.032

- Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Burke-Conte Z, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the US in 2019. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140(12):1202-1208. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.4401

- Fleckenstein M, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Chakravarthy U. Age-related macular degeneration: a review. JAMA. 2024;331(2):147-157. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26074

- Meer EA, Targ S, Zhang N, Hoggatt KJ, Mehta KM, Brodie F. Age-related macular degeneration injection frequency: effects of distance traveled and travel support. Retina. 2024;44(2):230-236. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000003947

- Bhisitkul RB, Mendes TS, Rofagha S, et al. Macular atrophy progression and 7-year vision outcomes in subjects from the ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON studies: the SEVEN-UP study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(5):915-24.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2015.01.032

- Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Burke-Conte Z, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the US in 2019. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140(12):1202-1208. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.4401

- Fleckenstein M, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Chakravarthy U. Age-related macular degeneration: a review. JAMA. 2024;331(2):147-157. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26074

- Meer EA, Targ S, Zhang N, Hoggatt KJ, Mehta KM, Brodie F. Age-related macular degeneration injection frequency: effects of distance traveled and travel support. Retina. 2024;44(2):230-236. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000003947

- Bhisitkul RB, Mendes TS, Rofagha S, et al. Macular atrophy progression and 7-year vision outcomes in subjects from the ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON studies: the SEVEN-UP study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(5):915-24.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2015.01.032

Data Trends 2024: Diabetes

- Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al; for the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. 2024 Heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149(8):e347-e913. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001209

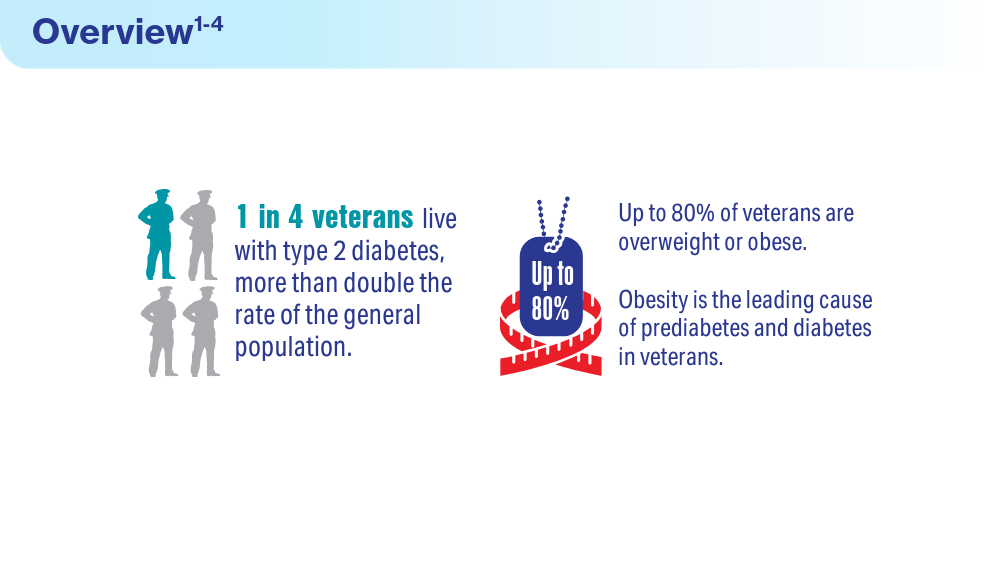

- Utech A. VA supports veterans who have type 2 diabetes. VA News. August 18, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://news.va.gov/107579/va-supportsveterans-who-have-type-2-diabetes/

- Betancourt JA, Granados PS, Pacheco GJ, Shanmugam R, Kruse CS, Fulton LV. Obesity and morbidity risk in the U.S. veteran. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(3):191. doi:10.3390/healthcare8030191

- Briskin A. Obesity and diabetes: causes, treatments, and stigma. diaTribe. October 4, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://diatribe.org/obesity-and-diabetescauses-

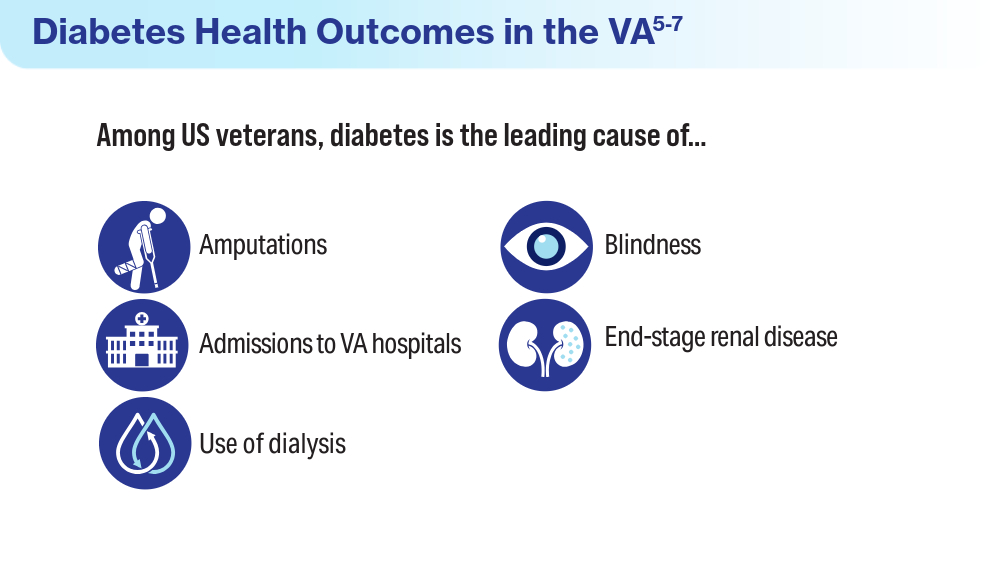

treatments-and-stigma - Leonard C, Sayre G, Williams S, et al. Understanding the experience of veterans who require lower limb amputation in the Veterans Health Administration. PLOS One. 2022;17(3):e0265620. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0265620

- Armstrong DG. Diabetic foot ulcers: a silent killer of veterans. Stat News. November 11, 2019. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.statnews.com/2019/11/11/diabetic-foot-ulcers-veterans-silent-killer/

- Koleda EW. The veteran diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) epidemic: a U.S. Department of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) services review. TreatNOW. October 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://treatnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/The-VA-Diabetic-Foot-Ulcer-Epidemic-10-14-22.pdf

- CDC identifies diabetes belt. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/46013

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Updated June 7, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp

- Avramovic S, Alemi F, Kanchi R, et al. US Veterans Administration diabetes risk (VADR) national cohort: cohort profile. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e039489. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039489

- Breland JY, Tseng CH, Toyama J, Washington DL. Influence of depression on racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes control. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2023;11(6):e003612. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2023-003612

- Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al; for the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. 2024 Heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149(8):e347-e913. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001209

- Utech A. VA supports veterans who have type 2 diabetes. VA News. August 18, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://news.va.gov/107579/va-supportsveterans-who-have-type-2-diabetes/

- Betancourt JA, Granados PS, Pacheco GJ, Shanmugam R, Kruse CS, Fulton LV. Obesity and morbidity risk in the U.S. veteran. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(3):191. doi:10.3390/healthcare8030191

- Briskin A. Obesity and diabetes: causes, treatments, and stigma. diaTribe. October 4, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://diatribe.org/obesity-and-diabetescauses-

treatments-and-stigma - Leonard C, Sayre G, Williams S, et al. Understanding the experience of veterans who require lower limb amputation in the Veterans Health Administration. PLOS One. 2022;17(3):e0265620. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0265620

- Armstrong DG. Diabetic foot ulcers: a silent killer of veterans. Stat News. November 11, 2019. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.statnews.com/2019/11/11/diabetic-foot-ulcers-veterans-silent-killer/

- Koleda EW. The veteran diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) epidemic: a U.S. Department of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) services review. TreatNOW. October 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://treatnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/The-VA-Diabetic-Foot-Ulcer-Epidemic-10-14-22.pdf

- CDC identifies diabetes belt. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/46013

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Updated June 7, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp

- Avramovic S, Alemi F, Kanchi R, et al. US Veterans Administration diabetes risk (VADR) national cohort: cohort profile. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e039489. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039489

- Breland JY, Tseng CH, Toyama J, Washington DL. Influence of depression on racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes control. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2023;11(6):e003612. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2023-003612

- Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al; for the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. 2024 Heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149(8):e347-e913. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001209

- Utech A. VA supports veterans who have type 2 diabetes. VA News. August 18, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://news.va.gov/107579/va-supportsveterans-who-have-type-2-diabetes/

- Betancourt JA, Granados PS, Pacheco GJ, Shanmugam R, Kruse CS, Fulton LV. Obesity and morbidity risk in the U.S. veteran. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(3):191. doi:10.3390/healthcare8030191

- Briskin A. Obesity and diabetes: causes, treatments, and stigma. diaTribe. October 4, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://diatribe.org/obesity-and-diabetescauses-

treatments-and-stigma - Leonard C, Sayre G, Williams S, et al. Understanding the experience of veterans who require lower limb amputation in the Veterans Health Administration. PLOS One. 2022;17(3):e0265620. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0265620

- Armstrong DG. Diabetic foot ulcers: a silent killer of veterans. Stat News. November 11, 2019. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.statnews.com/2019/11/11/diabetic-foot-ulcers-veterans-silent-killer/

- Koleda EW. The veteran diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) epidemic: a U.S. Department of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) services review. TreatNOW. October 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://treatnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/The-VA-Diabetic-Foot-Ulcer-Epidemic-10-14-22.pdf

- CDC identifies diabetes belt. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/46013

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Updated June 7, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp

- Avramovic S, Alemi F, Kanchi R, et al. US Veterans Administration diabetes risk (VADR) national cohort: cohort profile. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e039489. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039489

- Breland JY, Tseng CH, Toyama J, Washington DL. Influence of depression on racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes control. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2023;11(6):e003612. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2023-003612

As CGM Benefit Data Accrue, Primary Care Use Expands

ORLANDO, FLORIDA — As increasing data show benefit for continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices beyond just insulin-treated diabetes, efforts are being made to optimize the use of CGM in primary care settings.

Currently, Medicare and most private insurers cover CGM for people with diabetes who use insulin, regardless of the type of diabetes or the type of insulin, and for those with a history of severe hypoglycemia. Data are increasingly showing benefit for people who don’t use insulin. As of now, with the exception of some state Medicaid beneficiaries, the majority must pay out of pocket.

Such use is expected to grow with the upcoming availability of two new over-the-counter CGMs, Dexcom’s Stelo and Abbott’s Libre Rio, both made for people with diabetes who don’t use insulin. (Abbott will also launch the Lingo, a wellness CGM for people without diabetes.)

This means that CGM will become increasingly prevalent in primary care, where there is currently a great deal of variability in the capacity to manage and use the data generated by the devices to improve diabetes management, experts said during an oral abstract session at the recent American Diabetes Association (ADA) 84th Scientific Sessions and in interviews with this news organization.

“It’s picking up steam, and there’s a lot more visibility of CGM in primary care and a lot more people prescribing it,” Thomas W. Martens, MD, medical director of the International Diabetes Center at HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, told this news organization. He noted that the recent switch in many cases of CGM from billing as durable medical equipment to pharmacy has made prescribing easier, while television advertising has increased demand.

But still unclear, he noted, is how the CGM data are being used. “The question is, are prescriptions just being sent out and people using it like a finger-stick blood glucose monitor, or is primary care really using the data to move diabetes forward? I think that’s where a lot of the work on dissemination and implementation is going. How do we really make this a useful tool for optimizing diabetes care?”

Informing Food Choice, Treatment Intensification

At the ADA meeting, Dr. Martens presented topline data from a randomized multicenter controlled trial funded by Abbott, examining the effect of CGM use on guiding food choices and other behaviors in 72 adults with type 2 diabetes who were not using insulin but who were using other glucose-lowering medications.

At 3 months, with no medication changes, there was a significant overall 26% reduction in time spent above 180 mg/dL (P < .0001), which didn›t differ significantly between those randomized to CGM alone or in conjunction with a food logging app. Both groups also experienced a significant 1.1% reduction in A1c (P < .0001) and about a 4-lb weight loss (P = .014 for CGM alone, P = .0032 for CGM + app).

“The win for people not on insulin is you can see the impact of food choices really quickly with a CGM ... and then perhaps modify that to improve postprandial hyperglycemia,” Dr. Martens said.

And for the clinician, “not everybody with type 2 diabetes not on insulin can get where they need to be just by changing their diets. The CGM is a pretty good tool for knowing when you need to advance therapy.”

Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (DCESs) Assist CGM Use

Another speaker at the ADA meeting, Sean M. Oser, MD, director of the Practice Innovation Program and associated director of the Primary Care Diabetes Lab at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, noted that 90% of adults with type 2 diabetes and 50% with type 1 diabetes receive their diabetes care in primary care settings.

“CGM is increasingly becoming standard of care in diabetes ... But [primary care providers] remain relatively untrained about CGM ... What I’m concerned about is the disparity disparities in who has access and who does not. We really need to bring our primary care colleagues along,” he said.

Dr. Oser described tools he and his wife, Tamara K. Oser, MD, professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the same institution, developed in conjunction with the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), including the Transformation in Practice series (TIPS).

The PREPARE 4 CGM study examined the use of three different strategies for incorporating CGM into primary care settings: Either use of AAFP TIPS alone, TIPS plus practice facilitation services by coaches who assist the practice in implementing new workflows, or referral to a virtual CGM initiation service (virCIS) with a virtual CGM workshop that Dr. Oser and Dr. Oser also developed.

Of the 76 Colorado primary care practices participating (out of 60 planned), the 46 who chose AAFP TIPS were randomized to either the AAFP TIPS alone or to TIPS + practice facilitation. The other 30 chose virCIS with the onetime CGM basics webinar. The fact that more practices than anticipated were recruited for the study suggests that “primary care interest in CGM is very high. They want to learn,” Dr. Oser noted.

Of the 51 practice characteristics investigated, only one, the presence of a DCES, in the practice, was significantly associated with the choice of CGM implementation strategy. Of the 16 practices with access to a DCES, all of them chose self-initiation with CGM using TIPS. But of the 60 practices without a DCES, half chose the virCIS.

“We know that 36% of primary care practices have access to a DCES within the clinic, part-time or full-time, and that’s not enough, I would argue,” Dr. Oser said.

Indeed, Dr. Martens told this news organization that those professionals, formerly called “diabetes educators,” often aren’t available in primary care settings, especially in rural areas. “Unfortunately, they are not well reimbursed. A lot of care systems don’t employ as many as they ideally should because it tends not to be a moneymaker ... Something’s got to change with reimbursement for the cognitive aspects of diabetes management.”

Dr. Oser said his team’s next steps include completion of the virCIS operations, analysis of the effectiveness of the three implantation strategies in practice- and patient-level outcomes, a cost analysis of the three strategies, and further development of toolkits to assist in these efforts.

“One of our goals is to keep people at their primary care home, where they want to be ... Diabetes knows no borders. People should have access wherever they are,” Dr. Oser concluded in his ADA talk.

What Predicts Primary Care CGM Prescribing?

Further clues about effective strategies to improve CGM prescribing in primary care were provided in a study presented by Jovan Milosavljevic, MD, a second-year endocrinology fellow at the Fleischer Institute for Diabetes and Metabolism, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York.

He began by noting that there are currently 61.5 million diabetes visits annually in primary care compared with 32.0 million in specialty care and that there is a shortage of endocrinologists in the face of the rising number of people diagnosed with diabetes. “Primary care will continue to be the only point of care for most people with diabetes. So, standard-of-care treatment such as CGM must enter routine primary care practice to impact population-level health outcomes.”

Electronic health record data were examined for 39,710 patients with type 2 diabetes seen at 13 primary care sites affiliated with Montefiore Medical Center, a large safety net hospital in New York, where CGM is widely covered by public insurance. Between July 31, 2020, and July 31, 2023, a total of 3503, or just 8.8%, were prescribed CGM by a primary care provider.

Those with CGM prescribed were younger than those without (59.7 vs 62.7 years), about 40% of both groups were Hispanic or Black, and a majority were English-speaking: 84.5% of those prescribed CGM spoke English, while only 13.1% spoke Spanish. Over half (59.1%) of those prescribed CGM had commercial insurance, while only 11.2% had Medicaid and 29.7% had Medicare.

More patients with CGM prescribed had providers with more than 10 years in practice: 72.5% vs 64.5% with no CGM.

Not surprisingly, those with CGM prescribed were more likely on insulin — 21% using just basal and 35% on multiple daily injections. Those prescribed CGM had higher A1c levels before CGM prescription: 9.2% vs 7.2% for those not prescribed CGM.

No racial or ethnic bias was found in the relationships between CGM use and insulin use, provider experience, engagement with care, and A1c. However, there were differences by age, sex, and spoken language.

For example, the Hispanic group aged 65 years and older was less likely than those younger to be prescribed CGM, but this wasn’t seen in other ethnic groups. In fact, older White people were slightly more likely to have CGM prescribed. Spanish-speaking patients were about 43% less likely to have CGM prescribed than were English-speaking patients.

These findings suggest a dual approach might work best for improving CGM prescribing in primary care. “We can leverage the knowledge that some of these factors are independent of bias and promote clinical and evidence-based guidelines for CGM. Additionally, we should focus on physicians in training,” Dr. Milosavljevic said.

At the same time, “we need to tackle systemic inequity in prescription processes,” with measures such as improving prescription workflows, supporting prior authorization, and using patient hands-on support for older adults and Spanish-speaking individuals, he said.

In a message to this news organization, Tamara K. Oser, MD, wrote, “Disparities in CGM and other diabetes technology are prevalent and multifactorial. In addition to insurance barriers, implicit bias also plays a large role. Shared decision-making should always be used when deciding to prescribe diabetes technologies.”

The PREPARE 4 CGM study is evaluating willingness to pay for CGM, she noted.

“Even patients without insurance might want to purchase one sensor every few months to empower them to learn more about how food and exercise affect their glucose or to help assess the need for [adjusting] diabetes medications. It is an exciting time for people living with diabetes. Primary care, endocrinology, device manufacturers, and insurers should all do their part to assure increased access to these evidence-based technologies.”

Dr. Martens’ employer has received funds on his behalf for research and speaking support from Dexcom, Abbott Diabetes Care, Medtronic, Insulet, Tandem, Sanofi, Eli Lilly and Company, and Novo Nordisk, and for consulting from Sanofi and Eli Lilly and Company. He is employed by the nonprofit HealthPartners Institute dba International Diabetes Center and received no personal income from these activities.

The Osers have received advisory board consulting fees (through the University of Colorado) from Dexcom, Medscape Medical News, Ascensia, and Blue Circle Health and research grants (through the University of Colorado) from National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Helmsley Charitable Trust, Abbott Diabetes, Dexcom, and Insulet. They do not own stocks in any device or pharmaceutical company.

Dr. Milosavljevic’s work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Science and Einstein-Montefiore Clinical and Translational Science Awards. He had no further disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ORLANDO, FLORIDA — As increasing data show benefit for continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices beyond just insulin-treated diabetes, efforts are being made to optimize the use of CGM in primary care settings.

Currently, Medicare and most private insurers cover CGM for people with diabetes who use insulin, regardless of the type of diabetes or the type of insulin, and for those with a history of severe hypoglycemia. Data are increasingly showing benefit for people who don’t use insulin. As of now, with the exception of some state Medicaid beneficiaries, the majority must pay out of pocket.

Such use is expected to grow with the upcoming availability of two new over-the-counter CGMs, Dexcom’s Stelo and Abbott’s Libre Rio, both made for people with diabetes who don’t use insulin. (Abbott will also launch the Lingo, a wellness CGM for people without diabetes.)

This means that CGM will become increasingly prevalent in primary care, where there is currently a great deal of variability in the capacity to manage and use the data generated by the devices to improve diabetes management, experts said during an oral abstract session at the recent American Diabetes Association (ADA) 84th Scientific Sessions and in interviews with this news organization.

“It’s picking up steam, and there’s a lot more visibility of CGM in primary care and a lot more people prescribing it,” Thomas W. Martens, MD, medical director of the International Diabetes Center at HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, told this news organization. He noted that the recent switch in many cases of CGM from billing as durable medical equipment to pharmacy has made prescribing easier, while television advertising has increased demand.

But still unclear, he noted, is how the CGM data are being used. “The question is, are prescriptions just being sent out and people using it like a finger-stick blood glucose monitor, or is primary care really using the data to move diabetes forward? I think that’s where a lot of the work on dissemination and implementation is going. How do we really make this a useful tool for optimizing diabetes care?”

Informing Food Choice, Treatment Intensification

At the ADA meeting, Dr. Martens presented topline data from a randomized multicenter controlled trial funded by Abbott, examining the effect of CGM use on guiding food choices and other behaviors in 72 adults with type 2 diabetes who were not using insulin but who were using other glucose-lowering medications.

At 3 months, with no medication changes, there was a significant overall 26% reduction in time spent above 180 mg/dL (P < .0001), which didn›t differ significantly between those randomized to CGM alone or in conjunction with a food logging app. Both groups also experienced a significant 1.1% reduction in A1c (P < .0001) and about a 4-lb weight loss (P = .014 for CGM alone, P = .0032 for CGM + app).

“The win for people not on insulin is you can see the impact of food choices really quickly with a CGM ... and then perhaps modify that to improve postprandial hyperglycemia,” Dr. Martens said.

And for the clinician, “not everybody with type 2 diabetes not on insulin can get where they need to be just by changing their diets. The CGM is a pretty good tool for knowing when you need to advance therapy.”

Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (DCESs) Assist CGM Use

Another speaker at the ADA meeting, Sean M. Oser, MD, director of the Practice Innovation Program and associated director of the Primary Care Diabetes Lab at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, noted that 90% of adults with type 2 diabetes and 50% with type 1 diabetes receive their diabetes care in primary care settings.

“CGM is increasingly becoming standard of care in diabetes ... But [primary care providers] remain relatively untrained about CGM ... What I’m concerned about is the disparity disparities in who has access and who does not. We really need to bring our primary care colleagues along,” he said.

Dr. Oser described tools he and his wife, Tamara K. Oser, MD, professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the same institution, developed in conjunction with the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), including the Transformation in Practice series (TIPS).

The PREPARE 4 CGM study examined the use of three different strategies for incorporating CGM into primary care settings: Either use of AAFP TIPS alone, TIPS plus practice facilitation services by coaches who assist the practice in implementing new workflows, or referral to a virtual CGM initiation service (virCIS) with a virtual CGM workshop that Dr. Oser and Dr. Oser also developed.

Of the 76 Colorado primary care practices participating (out of 60 planned), the 46 who chose AAFP TIPS were randomized to either the AAFP TIPS alone or to TIPS + practice facilitation. The other 30 chose virCIS with the onetime CGM basics webinar. The fact that more practices than anticipated were recruited for the study suggests that “primary care interest in CGM is very high. They want to learn,” Dr. Oser noted.

Of the 51 practice characteristics investigated, only one, the presence of a DCES, in the practice, was significantly associated with the choice of CGM implementation strategy. Of the 16 practices with access to a DCES, all of them chose self-initiation with CGM using TIPS. But of the 60 practices without a DCES, half chose the virCIS.

“We know that 36% of primary care practices have access to a DCES within the clinic, part-time or full-time, and that’s not enough, I would argue,” Dr. Oser said.

Indeed, Dr. Martens told this news organization that those professionals, formerly called “diabetes educators,” often aren’t available in primary care settings, especially in rural areas. “Unfortunately, they are not well reimbursed. A lot of care systems don’t employ as many as they ideally should because it tends not to be a moneymaker ... Something’s got to change with reimbursement for the cognitive aspects of diabetes management.”

Dr. Oser said his team’s next steps include completion of the virCIS operations, analysis of the effectiveness of the three implantation strategies in practice- and patient-level outcomes, a cost analysis of the three strategies, and further development of toolkits to assist in these efforts.

“One of our goals is to keep people at their primary care home, where they want to be ... Diabetes knows no borders. People should have access wherever they are,” Dr. Oser concluded in his ADA talk.

What Predicts Primary Care CGM Prescribing?

Further clues about effective strategies to improve CGM prescribing in primary care were provided in a study presented by Jovan Milosavljevic, MD, a second-year endocrinology fellow at the Fleischer Institute for Diabetes and Metabolism, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York.

He began by noting that there are currently 61.5 million diabetes visits annually in primary care compared with 32.0 million in specialty care and that there is a shortage of endocrinologists in the face of the rising number of people diagnosed with diabetes. “Primary care will continue to be the only point of care for most people with diabetes. So, standard-of-care treatment such as CGM must enter routine primary care practice to impact population-level health outcomes.”

Electronic health record data were examined for 39,710 patients with type 2 diabetes seen at 13 primary care sites affiliated with Montefiore Medical Center, a large safety net hospital in New York, where CGM is widely covered by public insurance. Between July 31, 2020, and July 31, 2023, a total of 3503, or just 8.8%, were prescribed CGM by a primary care provider.

Those with CGM prescribed were younger than those without (59.7 vs 62.7 years), about 40% of both groups were Hispanic or Black, and a majority were English-speaking: 84.5% of those prescribed CGM spoke English, while only 13.1% spoke Spanish. Over half (59.1%) of those prescribed CGM had commercial insurance, while only 11.2% had Medicaid and 29.7% had Medicare.

More patients with CGM prescribed had providers with more than 10 years in practice: 72.5% vs 64.5% with no CGM.

Not surprisingly, those with CGM prescribed were more likely on insulin — 21% using just basal and 35% on multiple daily injections. Those prescribed CGM had higher A1c levels before CGM prescription: 9.2% vs 7.2% for those not prescribed CGM.

No racial or ethnic bias was found in the relationships between CGM use and insulin use, provider experience, engagement with care, and A1c. However, there were differences by age, sex, and spoken language.

For example, the Hispanic group aged 65 years and older was less likely than those younger to be prescribed CGM, but this wasn’t seen in other ethnic groups. In fact, older White people were slightly more likely to have CGM prescribed. Spanish-speaking patients were about 43% less likely to have CGM prescribed than were English-speaking patients.

These findings suggest a dual approach might work best for improving CGM prescribing in primary care. “We can leverage the knowledge that some of these factors are independent of bias and promote clinical and evidence-based guidelines for CGM. Additionally, we should focus on physicians in training,” Dr. Milosavljevic said.

At the same time, “we need to tackle systemic inequity in prescription processes,” with measures such as improving prescription workflows, supporting prior authorization, and using patient hands-on support for older adults and Spanish-speaking individuals, he said.

In a message to this news organization, Tamara K. Oser, MD, wrote, “Disparities in CGM and other diabetes technology are prevalent and multifactorial. In addition to insurance barriers, implicit bias also plays a large role. Shared decision-making should always be used when deciding to prescribe diabetes technologies.”

The PREPARE 4 CGM study is evaluating willingness to pay for CGM, she noted.

“Even patients without insurance might want to purchase one sensor every few months to empower them to learn more about how food and exercise affect their glucose or to help assess the need for [adjusting] diabetes medications. It is an exciting time for people living with diabetes. Primary care, endocrinology, device manufacturers, and insurers should all do their part to assure increased access to these evidence-based technologies.”

Dr. Martens’ employer has received funds on his behalf for research and speaking support from Dexcom, Abbott Diabetes Care, Medtronic, Insulet, Tandem, Sanofi, Eli Lilly and Company, and Novo Nordisk, and for consulting from Sanofi and Eli Lilly and Company. He is employed by the nonprofit HealthPartners Institute dba International Diabetes Center and received no personal income from these activities.

The Osers have received advisory board consulting fees (through the University of Colorado) from Dexcom, Medscape Medical News, Ascensia, and Blue Circle Health and research grants (through the University of Colorado) from National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Helmsley Charitable Trust, Abbott Diabetes, Dexcom, and Insulet. They do not own stocks in any device or pharmaceutical company.

Dr. Milosavljevic’s work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Science and Einstein-Montefiore Clinical and Translational Science Awards. He had no further disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ORLANDO, FLORIDA — As increasing data show benefit for continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices beyond just insulin-treated diabetes, efforts are being made to optimize the use of CGM in primary care settings.

Currently, Medicare and most private insurers cover CGM for people with diabetes who use insulin, regardless of the type of diabetes or the type of insulin, and for those with a history of severe hypoglycemia. Data are increasingly showing benefit for people who don’t use insulin. As of now, with the exception of some state Medicaid beneficiaries, the majority must pay out of pocket.

Such use is expected to grow with the upcoming availability of two new over-the-counter CGMs, Dexcom’s Stelo and Abbott’s Libre Rio, both made for people with diabetes who don’t use insulin. (Abbott will also launch the Lingo, a wellness CGM for people without diabetes.)

This means that CGM will become increasingly prevalent in primary care, where there is currently a great deal of variability in the capacity to manage and use the data generated by the devices to improve diabetes management, experts said during an oral abstract session at the recent American Diabetes Association (ADA) 84th Scientific Sessions and in interviews with this news organization.

“It’s picking up steam, and there’s a lot more visibility of CGM in primary care and a lot more people prescribing it,” Thomas W. Martens, MD, medical director of the International Diabetes Center at HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, told this news organization. He noted that the recent switch in many cases of CGM from billing as durable medical equipment to pharmacy has made prescribing easier, while television advertising has increased demand.

But still unclear, he noted, is how the CGM data are being used. “The question is, are prescriptions just being sent out and people using it like a finger-stick blood glucose monitor, or is primary care really using the data to move diabetes forward? I think that’s where a lot of the work on dissemination and implementation is going. How do we really make this a useful tool for optimizing diabetes care?”

Informing Food Choice, Treatment Intensification

At the ADA meeting, Dr. Martens presented topline data from a randomized multicenter controlled trial funded by Abbott, examining the effect of CGM use on guiding food choices and other behaviors in 72 adults with type 2 diabetes who were not using insulin but who were using other glucose-lowering medications.

At 3 months, with no medication changes, there was a significant overall 26% reduction in time spent above 180 mg/dL (P < .0001), which didn›t differ significantly between those randomized to CGM alone or in conjunction with a food logging app. Both groups also experienced a significant 1.1% reduction in A1c (P < .0001) and about a 4-lb weight loss (P = .014 for CGM alone, P = .0032 for CGM + app).

“The win for people not on insulin is you can see the impact of food choices really quickly with a CGM ... and then perhaps modify that to improve postprandial hyperglycemia,” Dr. Martens said.

And for the clinician, “not everybody with type 2 diabetes not on insulin can get where they need to be just by changing their diets. The CGM is a pretty good tool for knowing when you need to advance therapy.”

Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (DCESs) Assist CGM Use

Another speaker at the ADA meeting, Sean M. Oser, MD, director of the Practice Innovation Program and associated director of the Primary Care Diabetes Lab at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, noted that 90% of adults with type 2 diabetes and 50% with type 1 diabetes receive their diabetes care in primary care settings.

“CGM is increasingly becoming standard of care in diabetes ... But [primary care providers] remain relatively untrained about CGM ... What I’m concerned about is the disparity disparities in who has access and who does not. We really need to bring our primary care colleagues along,” he said.

Dr. Oser described tools he and his wife, Tamara K. Oser, MD, professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the same institution, developed in conjunction with the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), including the Transformation in Practice series (TIPS).

The PREPARE 4 CGM study examined the use of three different strategies for incorporating CGM into primary care settings: Either use of AAFP TIPS alone, TIPS plus practice facilitation services by coaches who assist the practice in implementing new workflows, or referral to a virtual CGM initiation service (virCIS) with a virtual CGM workshop that Dr. Oser and Dr. Oser also developed.

Of the 76 Colorado primary care practices participating (out of 60 planned), the 46 who chose AAFP TIPS were randomized to either the AAFP TIPS alone or to TIPS + practice facilitation. The other 30 chose virCIS with the onetime CGM basics webinar. The fact that more practices than anticipated were recruited for the study suggests that “primary care interest in CGM is very high. They want to learn,” Dr. Oser noted.

Of the 51 practice characteristics investigated, only one, the presence of a DCES, in the practice, was significantly associated with the choice of CGM implementation strategy. Of the 16 practices with access to a DCES, all of them chose self-initiation with CGM using TIPS. But of the 60 practices without a DCES, half chose the virCIS.

“We know that 36% of primary care practices have access to a DCES within the clinic, part-time or full-time, and that’s not enough, I would argue,” Dr. Oser said.

Indeed, Dr. Martens told this news organization that those professionals, formerly called “diabetes educators,” often aren’t available in primary care settings, especially in rural areas. “Unfortunately, they are not well reimbursed. A lot of care systems don’t employ as many as they ideally should because it tends not to be a moneymaker ... Something’s got to change with reimbursement for the cognitive aspects of diabetes management.”

Dr. Oser said his team’s next steps include completion of the virCIS operations, analysis of the effectiveness of the three implantation strategies in practice- and patient-level outcomes, a cost analysis of the three strategies, and further development of toolkits to assist in these efforts.

“One of our goals is to keep people at their primary care home, where they want to be ... Diabetes knows no borders. People should have access wherever they are,” Dr. Oser concluded in his ADA talk.

What Predicts Primary Care CGM Prescribing?

Further clues about effective strategies to improve CGM prescribing in primary care were provided in a study presented by Jovan Milosavljevic, MD, a second-year endocrinology fellow at the Fleischer Institute for Diabetes and Metabolism, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York.

He began by noting that there are currently 61.5 million diabetes visits annually in primary care compared with 32.0 million in specialty care and that there is a shortage of endocrinologists in the face of the rising number of people diagnosed with diabetes. “Primary care will continue to be the only point of care for most people with diabetes. So, standard-of-care treatment such as CGM must enter routine primary care practice to impact population-level health outcomes.”

Electronic health record data were examined for 39,710 patients with type 2 diabetes seen at 13 primary care sites affiliated with Montefiore Medical Center, a large safety net hospital in New York, where CGM is widely covered by public insurance. Between July 31, 2020, and July 31, 2023, a total of 3503, or just 8.8%, were prescribed CGM by a primary care provider.

Those with CGM prescribed were younger than those without (59.7 vs 62.7 years), about 40% of both groups were Hispanic or Black, and a majority were English-speaking: 84.5% of those prescribed CGM spoke English, while only 13.1% spoke Spanish. Over half (59.1%) of those prescribed CGM had commercial insurance, while only 11.2% had Medicaid and 29.7% had Medicare.

More patients with CGM prescribed had providers with more than 10 years in practice: 72.5% vs 64.5% with no CGM.

Not surprisingly, those with CGM prescribed were more likely on insulin — 21% using just basal and 35% on multiple daily injections. Those prescribed CGM had higher A1c levels before CGM prescription: 9.2% vs 7.2% for those not prescribed CGM.

No racial or ethnic bias was found in the relationships between CGM use and insulin use, provider experience, engagement with care, and A1c. However, there were differences by age, sex, and spoken language.

For example, the Hispanic group aged 65 years and older was less likely than those younger to be prescribed CGM, but this wasn’t seen in other ethnic groups. In fact, older White people were slightly more likely to have CGM prescribed. Spanish-speaking patients were about 43% less likely to have CGM prescribed than were English-speaking patients.

These findings suggest a dual approach might work best for improving CGM prescribing in primary care. “We can leverage the knowledge that some of these factors are independent of bias and promote clinical and evidence-based guidelines for CGM. Additionally, we should focus on physicians in training,” Dr. Milosavljevic said.

At the same time, “we need to tackle systemic inequity in prescription processes,” with measures such as improving prescription workflows, supporting prior authorization, and using patient hands-on support for older adults and Spanish-speaking individuals, he said.

In a message to this news organization, Tamara K. Oser, MD, wrote, “Disparities in CGM and other diabetes technology are prevalent and multifactorial. In addition to insurance barriers, implicit bias also plays a large role. Shared decision-making should always be used when deciding to prescribe diabetes technologies.”

The PREPARE 4 CGM study is evaluating willingness to pay for CGM, she noted.

“Even patients without insurance might want to purchase one sensor every few months to empower them to learn more about how food and exercise affect their glucose or to help assess the need for [adjusting] diabetes medications. It is an exciting time for people living with diabetes. Primary care, endocrinology, device manufacturers, and insurers should all do their part to assure increased access to these evidence-based technologies.”

Dr. Martens’ employer has received funds on his behalf for research and speaking support from Dexcom, Abbott Diabetes Care, Medtronic, Insulet, Tandem, Sanofi, Eli Lilly and Company, and Novo Nordisk, and for consulting from Sanofi and Eli Lilly and Company. He is employed by the nonprofit HealthPartners Institute dba International Diabetes Center and received no personal income from these activities.

The Osers have received advisory board consulting fees (through the University of Colorado) from Dexcom, Medscape Medical News, Ascensia, and Blue Circle Health and research grants (through the University of Colorado) from National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Helmsley Charitable Trust, Abbott Diabetes, Dexcom, and Insulet. They do not own stocks in any device or pharmaceutical company.

Dr. Milosavljevic’s work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Science and Einstein-Montefiore Clinical and Translational Science Awards. He had no further disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ADA 2024

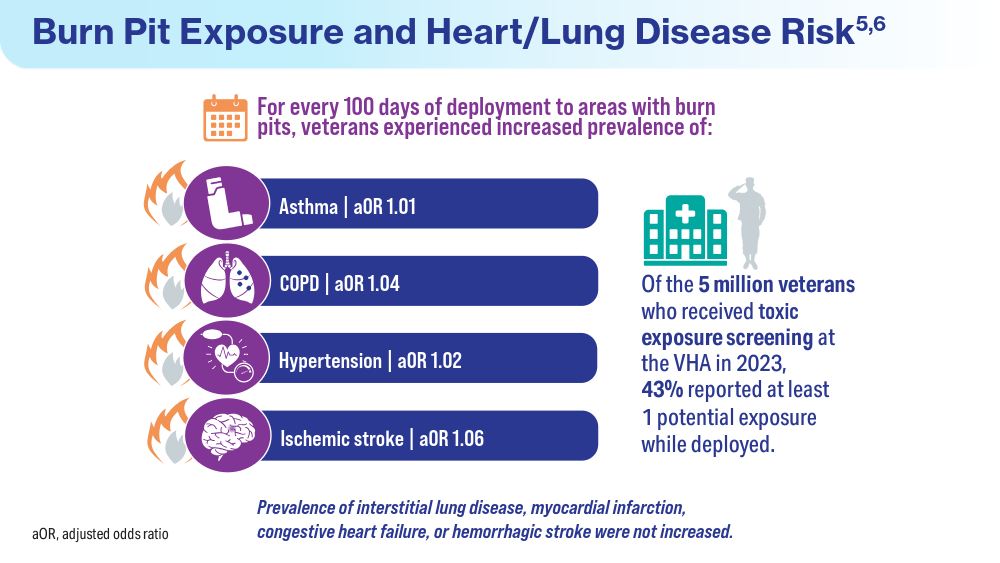

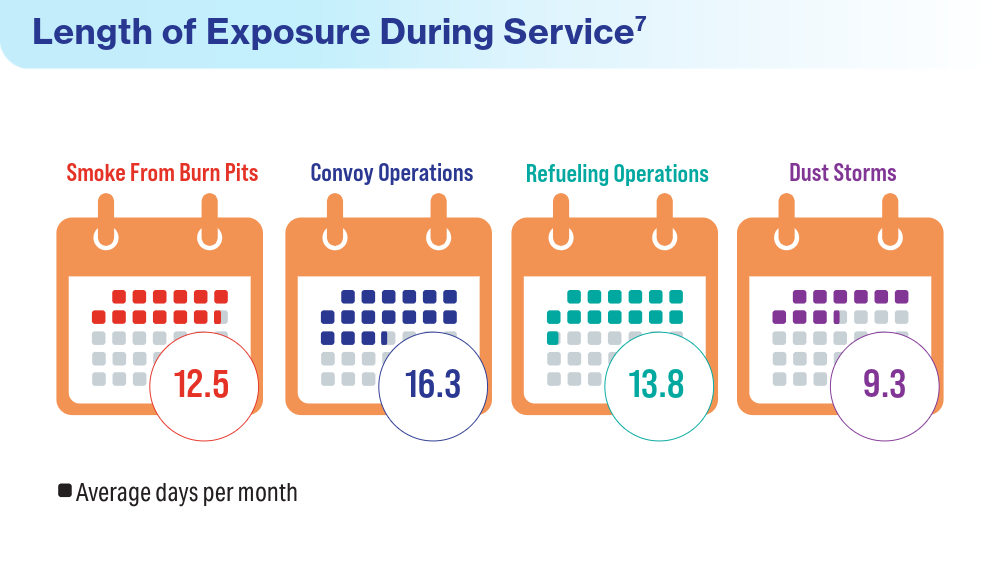

Data Trends 2024: Respiratory Health

- McVeigh C, Reid J, Carvalho P. Healthcare professionals’ views of palliative care for American war veterans with non-malignant respiratory disease living in a rural area: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0408-7

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Study finds uptick in lung disease in recent veterans. May 23, 2016. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/0516-3.cfm

- Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Frankart C, et al. Impact of illness and non-combat injury during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73(4):713-719.

- Trupin L, Schmajuk G, Ying D, Yelin E, Blanc PD. Military service and COPD risk. Chest. 2022;162(4):792-795. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2022.04.016

- Bastian LA. Pain-related anxiety intervention for smokers with chronic pain: a comparative effectiveness trial of smoking cessation counseling for veterans. Veteran’s Health Systems Research, IIR 15-092-HSR Study. Published January 2022. Accessed April 2024. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/research/abstracts.cfm?Project_ID=2141704797

- Rivera AC, Powell TM, Boyko EJ, et al; for the Millennium Cohort Study Team. New-onset asthma and combat deployment: findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(10):2136-2144. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy112

- Savitz DA, Woskie SR, Bello A, et al. Deployment to Military Bases With Open Burn Pits and Respiratory and Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e247629. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.7629

- McVeigh C, Reid J, Carvalho P. Healthcare professionals’ views of palliative care for American war veterans with non-malignant respiratory disease living in a rural area: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0408-7

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Study finds uptick in lung disease in recent veterans. May 23, 2016. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/0516-3.cfm

- Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Frankart C, et al. Impact of illness and non-combat injury during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73(4):713-719.

- Trupin L, Schmajuk G, Ying D, Yelin E, Blanc PD. Military service and COPD risk. Chest. 2022;162(4):792-795. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2022.04.016

- Bastian LA. Pain-related anxiety intervention for smokers with chronic pain: a comparative effectiveness trial of smoking cessation counseling for veterans. Veteran’s Health Systems Research, IIR 15-092-HSR Study. Published January 2022. Accessed April 2024. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/research/abstracts.cfm?Project_ID=2141704797

- Rivera AC, Powell TM, Boyko EJ, et al; for the Millennium Cohort Study Team. New-onset asthma and combat deployment: findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(10):2136-2144. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy112

- Savitz DA, Woskie SR, Bello A, et al. Deployment to Military Bases With Open Burn Pits and Respiratory and Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e247629. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.7629

- McVeigh C, Reid J, Carvalho P. Healthcare professionals’ views of palliative care for American war veterans with non-malignant respiratory disease living in a rural area: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0408-7

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Study finds uptick in lung disease in recent veterans. May 23, 2016. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/0516-3.cfm

- Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Frankart C, et al. Impact of illness and non-combat injury during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73(4):713-719.

- Trupin L, Schmajuk G, Ying D, Yelin E, Blanc PD. Military service and COPD risk. Chest. 2022;162(4):792-795. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2022.04.016

- Bastian LA. Pain-related anxiety intervention for smokers with chronic pain: a comparative effectiveness trial of smoking cessation counseling for veterans. Veteran’s Health Systems Research, IIR 15-092-HSR Study. Published January 2022. Accessed April 2024. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/research/abstracts.cfm?Project_ID=2141704797

- Rivera AC, Powell TM, Boyko EJ, et al; for the Millennium Cohort Study Team. New-onset asthma and combat deployment: findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(10):2136-2144. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy112

- Savitz DA, Woskie SR, Bello A, et al. Deployment to Military Bases With Open Burn Pits and Respiratory and Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e247629. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.7629

Are We Relying Too Much on BMI to Diagnose Obesity?

Gary* is a 60-year-old race car driver with a history of insulin resistance, elevated cholesterol, and severe reflux. His wife sent him to me when his snoring became so loud and “violent” that she could no longer sleep in the same bedroom.

She was desperate to help him lose weight in a sustained fashion. All his previous efforts were short-lived due to his self-described pizza and burger addiction. At 5 ft 9 in and 180 lb, his body mass index (BMI) was approximately 26.5 (normal is 18.5-24.9).

On exam, his arms and legs were relatively thin, but he had a hard, protuberant belly. Given his body habits, comorbidities, and family history of early heart disease, I was worried that his weight would eventually become life-threatening. Solely on the basis of BMI criteria, however, he is not considered to be at high risk.

This begs the question, are we relying too much on BMI and ignoring central adiposity (ie, belly fat) and comorbid conditions when identifying at-risk patients?

The European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) argues exactly this point in its new guidelines published in July 2024. Titled “A New Framework for the Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Obesity in Adults,” the guidelines assert that obesity should be redefined as a chronic and relapsing adiposity-based disease which may start off as asymptomatic but often becomes life-threatening.

The guidelines further argue that BMI does not appropriately predict cardiometabolic risk in patients with BMI < 35. Instead, in such patients we should incorporate the use of waist-to-height ratios to reflect the potentially deleterious presence of increased visceral fat. It expands the definition of high-risk patients to include those with BMI > 25 and a waist-to-height ratio > 0.5.

It also suggests that DEXA (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) or bioimpedance testing be used when BMI results are ambiguous. The European guidelines recommend considering screening more routinely for eating disorders (with psychometric testing) and depression. The guidelines highlight the importance of long-term goals and of physical activity, nutrition, and psychological support in addition to pharmaceutical treatments.

On the basis of these new guidelines, I attempted to start Gary on Wegovy (semaglutide) along with sending him to a health coach, dietitian, and trainer. Unfortunately, despite documenting a waist-to-height ratio of > 0.6 and elevated fat percentage of just over 30% using bioimpedance, my prior authorization and appeal were summarily rejected by his insurance provider.

In the United States, pharmacotherapy is typically approved for patients with a BMI of 27 or higher with a comorbidity (like high blood pressure or elevated cholesterol levels) or a BMI over 30. This clearly highlights the need for updated criteria for weight loss medication. Thank goodness for compounded semaglutide to fill this void until the medical world catches up with the EASO guidelines.

Now on compounded semaglutide, Gary has lost 15 lb. His once rounded belly is nearly flat, and he has a normal waist-to-height ratio. While his dietary choices still leave something to be desired, his portion sizes are much smaller. His snoring has improved considerably. His most recent bioimpedance testing showed a reduced fat percentage of just under 25%.

*Patient’s name has been changed

Caroline Messer, MD, is Clinical Assistant Professor, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and Associate Professor, Hofstra School of Medicine, both in New York. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gary* is a 60-year-old race car driver with a history of insulin resistance, elevated cholesterol, and severe reflux. His wife sent him to me when his snoring became so loud and “violent” that she could no longer sleep in the same bedroom.

She was desperate to help him lose weight in a sustained fashion. All his previous efforts were short-lived due to his self-described pizza and burger addiction. At 5 ft 9 in and 180 lb, his body mass index (BMI) was approximately 26.5 (normal is 18.5-24.9).

On exam, his arms and legs were relatively thin, but he had a hard, protuberant belly. Given his body habits, comorbidities, and family history of early heart disease, I was worried that his weight would eventually become life-threatening. Solely on the basis of BMI criteria, however, he is not considered to be at high risk.

This begs the question, are we relying too much on BMI and ignoring central adiposity (ie, belly fat) and comorbid conditions when identifying at-risk patients?

The European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) argues exactly this point in its new guidelines published in July 2024. Titled “A New Framework for the Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Obesity in Adults,” the guidelines assert that obesity should be redefined as a chronic and relapsing adiposity-based disease which may start off as asymptomatic but often becomes life-threatening.

The guidelines further argue that BMI does not appropriately predict cardiometabolic risk in patients with BMI < 35. Instead, in such patients we should incorporate the use of waist-to-height ratios to reflect the potentially deleterious presence of increased visceral fat. It expands the definition of high-risk patients to include those with BMI > 25 and a waist-to-height ratio > 0.5.

It also suggests that DEXA (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) or bioimpedance testing be used when BMI results are ambiguous. The European guidelines recommend considering screening more routinely for eating disorders (with psychometric testing) and depression. The guidelines highlight the importance of long-term goals and of physical activity, nutrition, and psychological support in addition to pharmaceutical treatments.

On the basis of these new guidelines, I attempted to start Gary on Wegovy (semaglutide) along with sending him to a health coach, dietitian, and trainer. Unfortunately, despite documenting a waist-to-height ratio of > 0.6 and elevated fat percentage of just over 30% using bioimpedance, my prior authorization and appeal were summarily rejected by his insurance provider.

In the United States, pharmacotherapy is typically approved for patients with a BMI of 27 or higher with a comorbidity (like high blood pressure or elevated cholesterol levels) or a BMI over 30. This clearly highlights the need for updated criteria for weight loss medication. Thank goodness for compounded semaglutide to fill this void until the medical world catches up with the EASO guidelines.

Now on compounded semaglutide, Gary has lost 15 lb. His once rounded belly is nearly flat, and he has a normal waist-to-height ratio. While his dietary choices still leave something to be desired, his portion sizes are much smaller. His snoring has improved considerably. His most recent bioimpedance testing showed a reduced fat percentage of just under 25%.

*Patient’s name has been changed

Caroline Messer, MD, is Clinical Assistant Professor, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and Associate Professor, Hofstra School of Medicine, both in New York. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gary* is a 60-year-old race car driver with a history of insulin resistance, elevated cholesterol, and severe reflux. His wife sent him to me when his snoring became so loud and “violent” that she could no longer sleep in the same bedroom.

She was desperate to help him lose weight in a sustained fashion. All his previous efforts were short-lived due to his self-described pizza and burger addiction. At 5 ft 9 in and 180 lb, his body mass index (BMI) was approximately 26.5 (normal is 18.5-24.9).

On exam, his arms and legs were relatively thin, but he had a hard, protuberant belly. Given his body habits, comorbidities, and family history of early heart disease, I was worried that his weight would eventually become life-threatening. Solely on the basis of BMI criteria, however, he is not considered to be at high risk.

This begs the question, are we relying too much on BMI and ignoring central adiposity (ie, belly fat) and comorbid conditions when identifying at-risk patients?

The European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) argues exactly this point in its new guidelines published in July 2024. Titled “A New Framework for the Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Obesity in Adults,” the guidelines assert that obesity should be redefined as a chronic and relapsing adiposity-based disease which may start off as asymptomatic but often becomes life-threatening.

The guidelines further argue that BMI does not appropriately predict cardiometabolic risk in patients with BMI < 35. Instead, in such patients we should incorporate the use of waist-to-height ratios to reflect the potentially deleterious presence of increased visceral fat. It expands the definition of high-risk patients to include those with BMI > 25 and a waist-to-height ratio > 0.5.

It also suggests that DEXA (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) or bioimpedance testing be used when BMI results are ambiguous. The European guidelines recommend considering screening more routinely for eating disorders (with psychometric testing) and depression. The guidelines highlight the importance of long-term goals and of physical activity, nutrition, and psychological support in addition to pharmaceutical treatments.

On the basis of these new guidelines, I attempted to start Gary on Wegovy (semaglutide) along with sending him to a health coach, dietitian, and trainer. Unfortunately, despite documenting a waist-to-height ratio of > 0.6 and elevated fat percentage of just over 30% using bioimpedance, my prior authorization and appeal were summarily rejected by his insurance provider.

In the United States, pharmacotherapy is typically approved for patients with a BMI of 27 or higher with a comorbidity (like high blood pressure or elevated cholesterol levels) or a BMI over 30. This clearly highlights the need for updated criteria for weight loss medication. Thank goodness for compounded semaglutide to fill this void until the medical world catches up with the EASO guidelines.

Now on compounded semaglutide, Gary has lost 15 lb. His once rounded belly is nearly flat, and he has a normal waist-to-height ratio. While his dietary choices still leave something to be desired, his portion sizes are much smaller. His snoring has improved considerably. His most recent bioimpedance testing showed a reduced fat percentage of just under 25%.

*Patient’s name has been changed

Caroline Messer, MD, is Clinical Assistant Professor, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and Associate Professor, Hofstra School of Medicine, both in New York. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One in Ten Chronic Pain Patients May Develop Opioid Use Disorder

TOPLINE:

Nearly 10% of patients with chronic pain treated with opioids develop opioid use disorder, whereas 30% show signs and symptoms of dependence, highlighting the need for monitoring and alternative pain management strategies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis using MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO databases from inception to January 27, 2021.

- The studies analyzed were predominantly from the United States (n = 115) as well as high-income countries such as the United Kingdom (n = 5), France (n = 3), Spain (n = 4), Germany (n = 4), and Australia (n = 2).

- A total of 148 studies from various settings with over 4.3 million participants were included, focusing on patients aged ≥ 12 years with chronic non-cancer pain of ≥ 3 months duration, treated with opioid analgesics.

- Problematic opioid use was categorized into four categories: dependence and opioid use disorder, signs and symptoms of dependence and opioid use disorder, aberrant behavior, and at risk for dependence and opioid use disorder.

TAKEAWAY:

- The pooled prevalence of dependence and opioid use disorder was 9.3% (95% CI, 5.7%-14.8%), with significant heterogeneity across studies.

- Signs and symptoms of dependence were observed in 29.6% (95% CI, 22.1%-38.3%) of patients, indicating a high prevalence of problematic opioid use.

- Aberrant behavior was reported in 22% (95% CI, 17.4%-27.3%) of patients, highlighting the need for careful monitoring and intervention.

- The prevalence of patients at risk of developing dependence was 12.4% (95% CI, 4.3%-30.7%), suggesting the importance of early identification and prevention strategies.

IN PRACTICE:

“Clinicians and policymakers need a more accurate estimate of the prevalence of problematic opioid use in pain patients so that they can gauge the true extent of the problem, change prescribing guidance if necessary, and develop and implement effective interventions to manage the problem,” Kyla H. Thomas, PhD, the lead author, noted in a press release. Knowing the size of the problem is a necessary step to managing it, she added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Dr. Thomas, Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol in England. It was published online, in Addiction.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s high heterogeneity across included studies suggests caution in interpreting the findings. The reliance on self-reported data and varying definitions of problematic opioid use may affect the accuracy of prevalence estimates. Most studies were conducted in high-income countries, limiting the generalizability to other settings.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). Dr. Thomas reported receiving financial support from the NIHR for this study.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Nearly 10% of patients with chronic pain treated with opioids develop opioid use disorder, whereas 30% show signs and symptoms of dependence, highlighting the need for monitoring and alternative pain management strategies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis using MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO databases from inception to January 27, 2021.

- The studies analyzed were predominantly from the United States (n = 115) as well as high-income countries such as the United Kingdom (n = 5), France (n = 3), Spain (n = 4), Germany (n = 4), and Australia (n = 2).

- A total of 148 studies from various settings with over 4.3 million participants were included, focusing on patients aged ≥ 12 years with chronic non-cancer pain of ≥ 3 months duration, treated with opioid analgesics.

- Problematic opioid use was categorized into four categories: dependence and opioid use disorder, signs and symptoms of dependence and opioid use disorder, aberrant behavior, and at risk for dependence and opioid use disorder.

TAKEAWAY:

- The pooled prevalence of dependence and opioid use disorder was 9.3% (95% CI, 5.7%-14.8%), with significant heterogeneity across studies.

- Signs and symptoms of dependence were observed in 29.6% (95% CI, 22.1%-38.3%) of patients, indicating a high prevalence of problematic opioid use.

- Aberrant behavior was reported in 22% (95% CI, 17.4%-27.3%) of patients, highlighting the need for careful monitoring and intervention.

- The prevalence of patients at risk of developing dependence was 12.4% (95% CI, 4.3%-30.7%), suggesting the importance of early identification and prevention strategies.

IN PRACTICE:

“Clinicians and policymakers need a more accurate estimate of the prevalence of problematic opioid use in pain patients so that they can gauge the true extent of the problem, change prescribing guidance if necessary, and develop and implement effective interventions to manage the problem,” Kyla H. Thomas, PhD, the lead author, noted in a press release. Knowing the size of the problem is a necessary step to managing it, she added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Dr. Thomas, Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol in England. It was published online, in Addiction.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s high heterogeneity across included studies suggests caution in interpreting the findings. The reliance on self-reported data and varying definitions of problematic opioid use may affect the accuracy of prevalence estimates. Most studies were conducted in high-income countries, limiting the generalizability to other settings.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). Dr. Thomas reported receiving financial support from the NIHR for this study.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Nearly 10% of patients with chronic pain treated with opioids develop opioid use disorder, whereas 30% show signs and symptoms of dependence, highlighting the need for monitoring and alternative pain management strategies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis using MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO databases from inception to January 27, 2021.

- The studies analyzed were predominantly from the United States (n = 115) as well as high-income countries such as the United Kingdom (n = 5), France (n = 3), Spain (n = 4), Germany (n = 4), and Australia (n = 2).

- A total of 148 studies from various settings with over 4.3 million participants were included, focusing on patients aged ≥ 12 years with chronic non-cancer pain of ≥ 3 months duration, treated with opioid analgesics.

- Problematic opioid use was categorized into four categories: dependence and opioid use disorder, signs and symptoms of dependence and opioid use disorder, aberrant behavior, and at risk for dependence and opioid use disorder.

TAKEAWAY:

- The pooled prevalence of dependence and opioid use disorder was 9.3% (95% CI, 5.7%-14.8%), with significant heterogeneity across studies.

- Signs and symptoms of dependence were observed in 29.6% (95% CI, 22.1%-38.3%) of patients, indicating a high prevalence of problematic opioid use.

- Aberrant behavior was reported in 22% (95% CI, 17.4%-27.3%) of patients, highlighting the need for careful monitoring and intervention.

- The prevalence of patients at risk of developing dependence was 12.4% (95% CI, 4.3%-30.7%), suggesting the importance of early identification and prevention strategies.

IN PRACTICE:

“Clinicians and policymakers need a more accurate estimate of the prevalence of problematic opioid use in pain patients so that they can gauge the true extent of the problem, change prescribing guidance if necessary, and develop and implement effective interventions to manage the problem,” Kyla H. Thomas, PhD, the lead author, noted in a press release. Knowing the size of the problem is a necessary step to managing it, she added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Dr. Thomas, Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol in England. It was published online, in Addiction.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s high heterogeneity across included studies suggests caution in interpreting the findings. The reliance on self-reported data and varying definitions of problematic opioid use may affect the accuracy of prevalence estimates. Most studies were conducted in high-income countries, limiting the generalizability to other settings.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). Dr. Thomas reported receiving financial support from the NIHR for this study.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Could Targeting ‘Zombie Cells’ Extend a Healthy Lifespan?

What if a drug could help you live a longer, healthier life?

Scientists at the University of Connecticut are working on it. In a new study in Cell Metabolism, researchers described how to target specific cells to extend the lifespan and improve the health of mice late in life.

The study builds on a growing body of research, mostly in animals, testing interventions to slow aging and prolong health span, the length of time that one is not just alive but also healthy.

“Aging is the most important risk factor for every disease that we deal with in adult human beings,” said cardiologist Douglas Vaughan, MD, director of the Potocsnak Longevity Institute at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago. (Dr. Vaughan was not involved in the new study.) “So the big hypothesis is: If we could slow down aging just a little bit, we can push back the onset of disease.”

Senescent cells — or “zombie cells” — secrete harmful substances that disrupt tissue functioning. They’ve been linked to chronic inflammation, tissue damage, and the development of age-related diseases.

Senescence can be characterized by the accumulation of cells with high levels of specific markers like p21, or p21high cells. Almost any cell can become a p21high cell, and they accumulate with age, said Ming Xu, PhD, a professor at the UConn Center on Aging, UConn Health, Farmington, Connecticut, who led the study.

By targeting and eliminating p21high senescent cells, Dr. Xu hopes to develop novel therapies that might help people live longer and enjoy more years in good health.

Such a treatment could be ready for human trials in 2-5 years, Dr. Xu said.

What the Researchers Did

Xu and colleagues used genetic engineering to eliminate p21high cells in mice, introducing into their genome something they describe as an inducible “suicide gene.” Giving the mice a certain drug (a low dose of tamoxifen) activated the suicide gene in all p21high cells, causing them to die. Administering this treatment once a month, from age 20 months (older age) until the end of life, significantly extended the rodents’ lifespan, reduced inflammation, and decreased gene activity linked to aging.

Treated mice lived, on average, for 33 months — 3 months longer than the untreated mice. The oldest treated mouse lived to 43 months — roughly 130 in human years.

But the treated mice didn’t just live longer; they were also healthier. In humans, walking speed and grip strength can be clues of overall health and vitality. The old, treated mice were able to walk faster and grip objects with greater strength than untreated mice of the same age.

Dr. Xu’s lab is now testing drugs that target p21high cells in hopes of finding one that would work in humans. Leveraging immunotherapy technology to target these cells could be another option, Dr. Xu said.

The team also plans to test whether eliminating p21high cells could prevent or alleviate diabetes or Alzheimer’s disease.

Challenges and Criticisms

The research provides “important evidence that targeting senescence and the molecular components of that pathway might provide some benefit in the long term,” Dr. Vaughan said.

But killing senescent cells could come with downsides.

“Senescence protects us from hyperproliferative responses,” potentially blocking cells from becoming malignant, Dr. Vaughan said. “There’s this effect on aging that is desirable, but at the same time, you may enhance your risk of cancer or malignancy or excessive proliferation in some cells.”

And of course, we don’t necessarily need drugs to prolong healthy life, Dr. Vaughan pointed out.

For many people, a long healthy life is already within reach. Humans live longer on average than they used to, and simple lifestyle choices — nourishing your body well, staying active, and maintaining a healthy weight — can increase one’s chances of good health.

The most consistently demonstrated intervention for extending lifespan “in almost every animal species is caloric restriction,” Dr. Vaughan said. (Dr. Xu’s team is also investigating whether fasting and exercise can lead to a decrease in p21high cells.)

As for brain health, Dr. Vaughan and colleagues at Northwestern are studying “super agers,” people who are cognitively intact into their 90s.

“The one single thing that they found that contributes to that process, and contributes to that success, is really a social network and human bonds and interaction,” Dr. Vaughan said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

What if a drug could help you live a longer, healthier life?

Scientists at the University of Connecticut are working on it. In a new study in Cell Metabolism, researchers described how to target specific cells to extend the lifespan and improve the health of mice late in life.

The study builds on a growing body of research, mostly in animals, testing interventions to slow aging and prolong health span, the length of time that one is not just alive but also healthy.

“Aging is the most important risk factor for every disease that we deal with in adult human beings,” said cardiologist Douglas Vaughan, MD, director of the Potocsnak Longevity Institute at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago. (Dr. Vaughan was not involved in the new study.) “So the big hypothesis is: If we could slow down aging just a little bit, we can push back the onset of disease.”

Senescent cells — or “zombie cells” — secrete harmful substances that disrupt tissue functioning. They’ve been linked to chronic inflammation, tissue damage, and the development of age-related diseases.

Senescence can be characterized by the accumulation of cells with high levels of specific markers like p21, or p21high cells. Almost any cell can become a p21high cell, and they accumulate with age, said Ming Xu, PhD, a professor at the UConn Center on Aging, UConn Health, Farmington, Connecticut, who led the study.

By targeting and eliminating p21high senescent cells, Dr. Xu hopes to develop novel therapies that might help people live longer and enjoy more years in good health.

Such a treatment could be ready for human trials in 2-5 years, Dr. Xu said.

What the Researchers Did

Xu and colleagues used genetic engineering to eliminate p21high cells in mice, introducing into their genome something they describe as an inducible “suicide gene.” Giving the mice a certain drug (a low dose of tamoxifen) activated the suicide gene in all p21high cells, causing them to die. Administering this treatment once a month, from age 20 months (older age) until the end of life, significantly extended the rodents’ lifespan, reduced inflammation, and decreased gene activity linked to aging.

Treated mice lived, on average, for 33 months — 3 months longer than the untreated mice. The oldest treated mouse lived to 43 months — roughly 130 in human years.

But the treated mice didn’t just live longer; they were also healthier. In humans, walking speed and grip strength can be clues of overall health and vitality. The old, treated mice were able to walk faster and grip objects with greater strength than untreated mice of the same age.

Dr. Xu’s lab is now testing drugs that target p21high cells in hopes of finding one that would work in humans. Leveraging immunotherapy technology to target these cells could be another option, Dr. Xu said.

The team also plans to test whether eliminating p21high cells could prevent or alleviate diabetes or Alzheimer’s disease.

Challenges and Criticisms

The research provides “important evidence that targeting senescence and the molecular components of that pathway might provide some benefit in the long term,” Dr. Vaughan said.

But killing senescent cells could come with downsides.

“Senescence protects us from hyperproliferative responses,” potentially blocking cells from becoming malignant, Dr. Vaughan said. “There’s this effect on aging that is desirable, but at the same time, you may enhance your risk of cancer or malignancy or excessive proliferation in some cells.”

And of course, we don’t necessarily need drugs to prolong healthy life, Dr. Vaughan pointed out.

For many people, a long healthy life is already within reach. Humans live longer on average than they used to, and simple lifestyle choices — nourishing your body well, staying active, and maintaining a healthy weight — can increase one’s chances of good health.

The most consistently demonstrated intervention for extending lifespan “in almost every animal species is caloric restriction,” Dr. Vaughan said. (Dr. Xu’s team is also investigating whether fasting and exercise can lead to a decrease in p21high cells.)

As for brain health, Dr. Vaughan and colleagues at Northwestern are studying “super agers,” people who are cognitively intact into their 90s.

“The one single thing that they found that contributes to that process, and contributes to that success, is really a social network and human bonds and interaction,” Dr. Vaughan said.