User login

Cutaneous Eruption in an Immunocompromised Patient

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

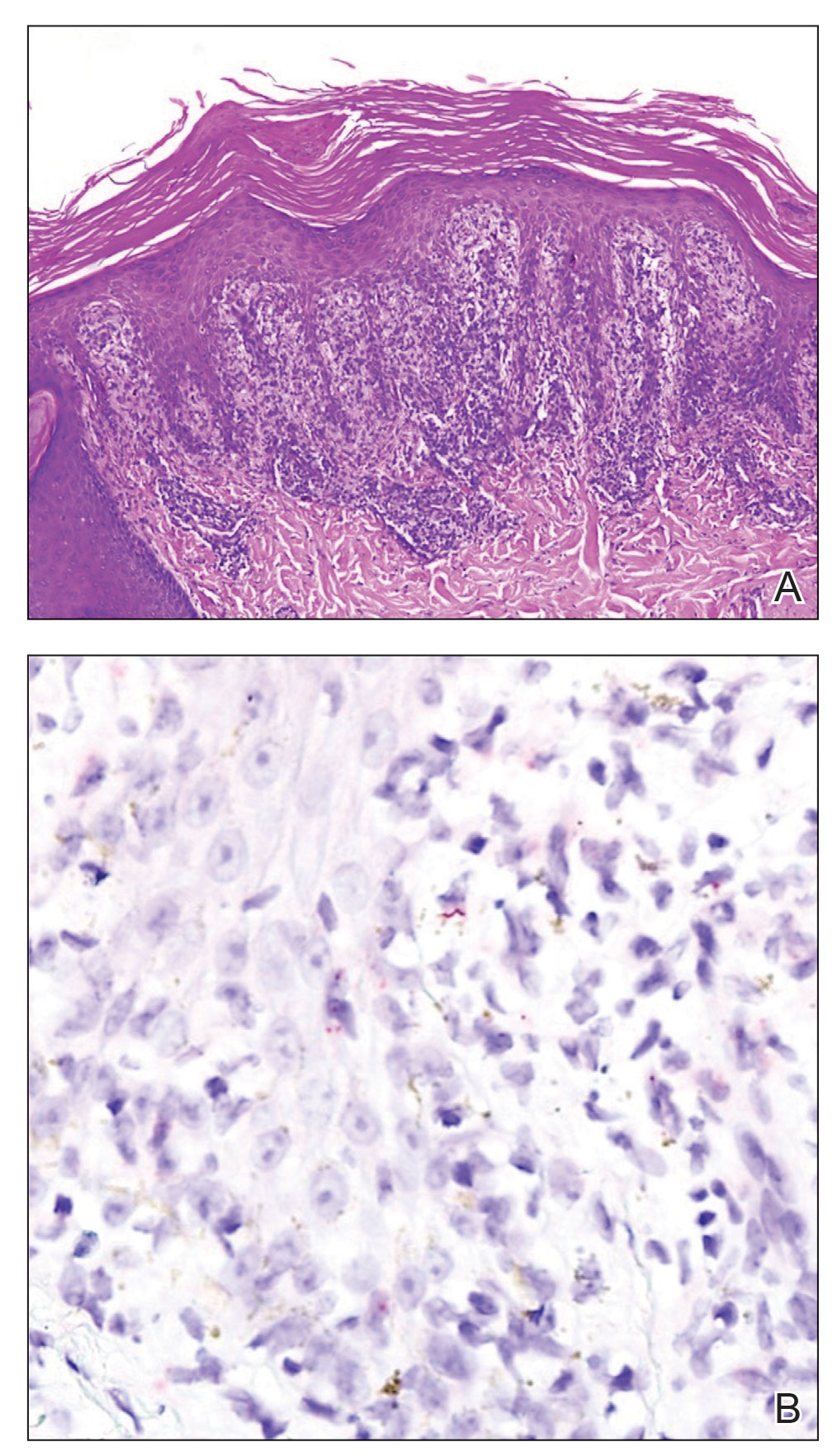

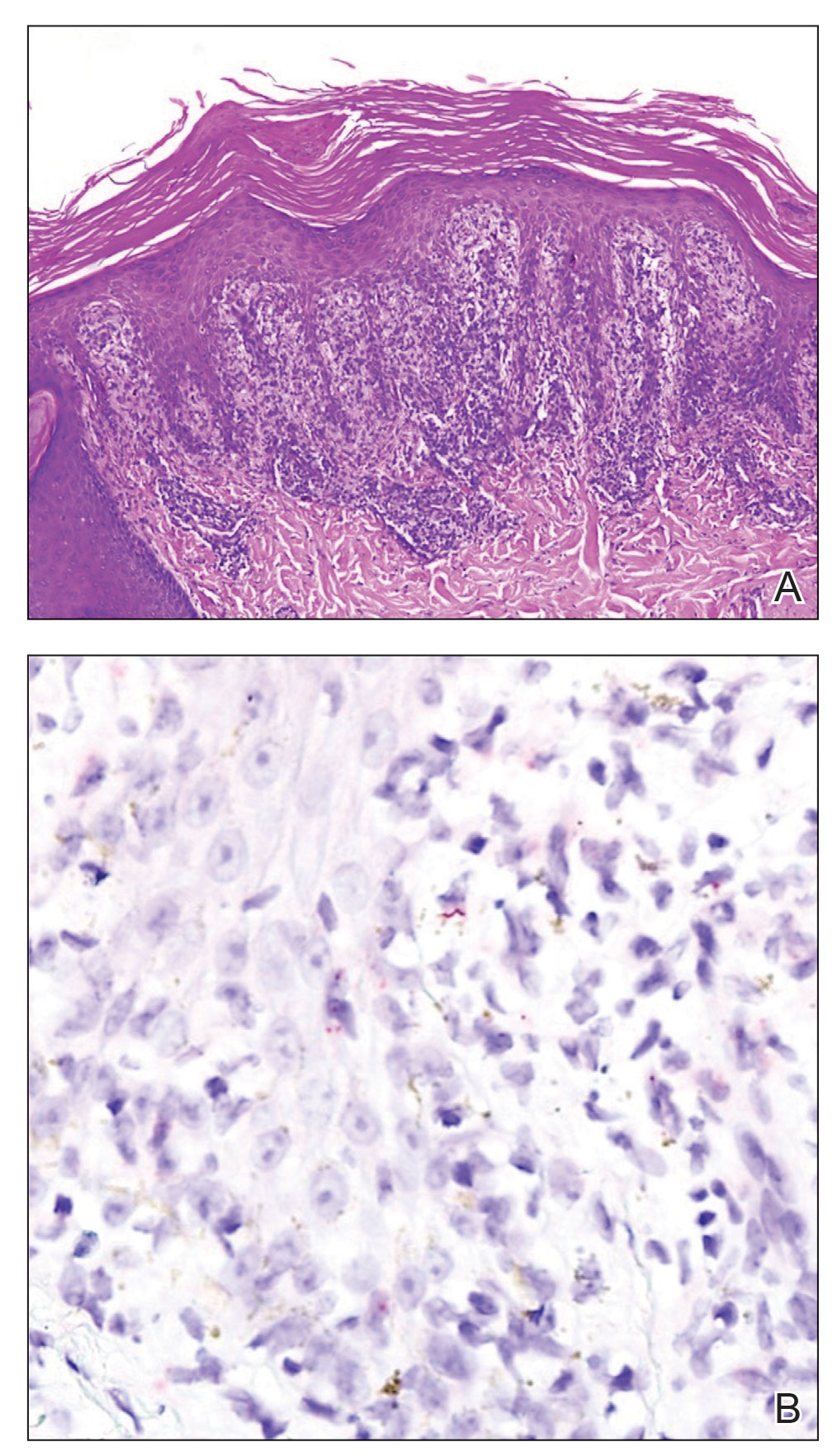

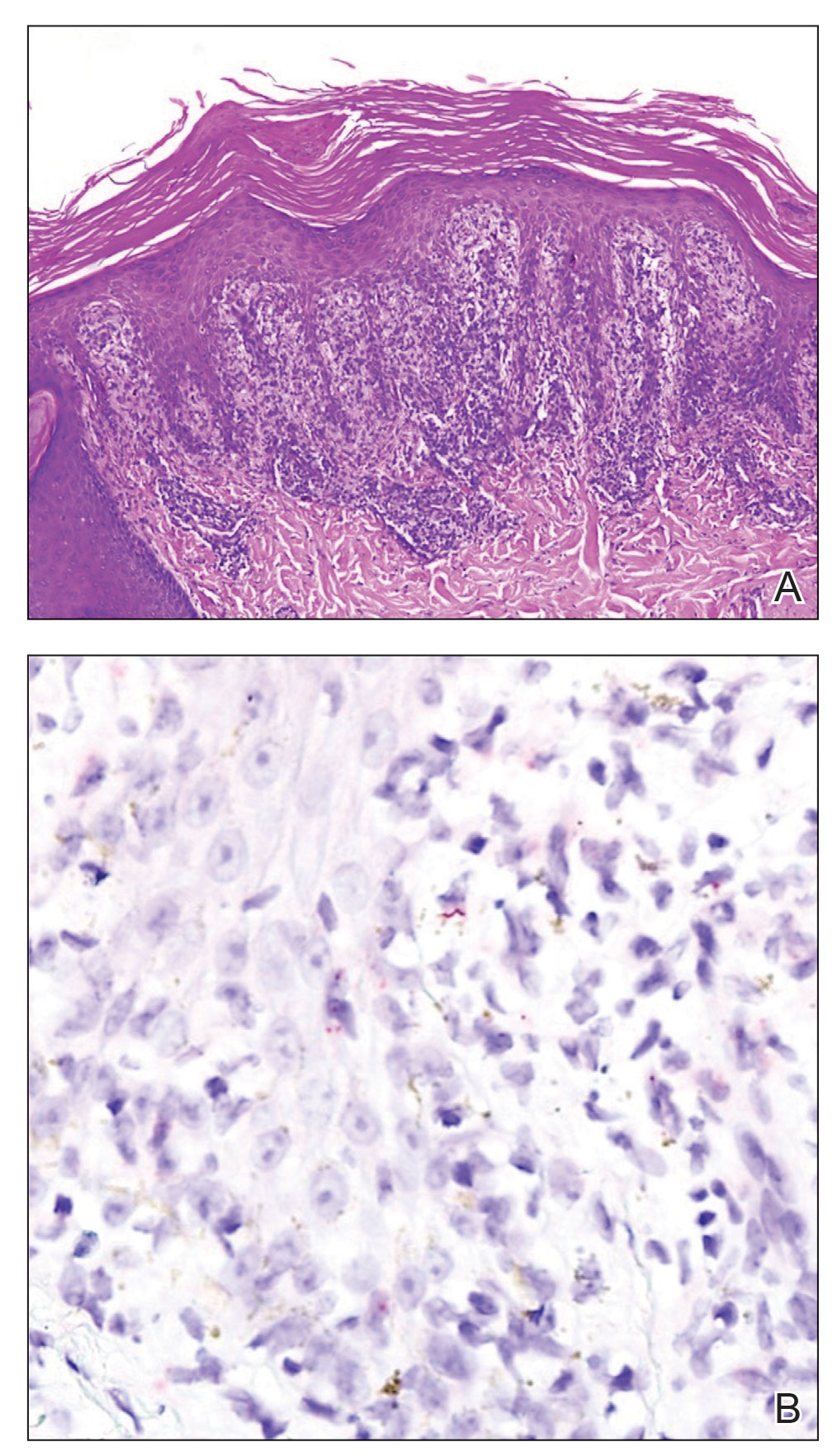

Histopathology revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia (Figure 1A). A single spirochete was identified using immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1B). Laboratory workup revealed positive IgG and IgM treponemal antibodies and reactive rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:2048. A VDRL test performed on a cerebrospinal fluid specimen also was reactive at 1:8. A diagnosis of secondary syphilis with neurologic involvement was made, and the patient was treated with intravenous penicillin G for 14 days. Following treatment, his rapid plasma reagin decreased 4-fold with an improvement in his ocular and cutaneous symptoms.

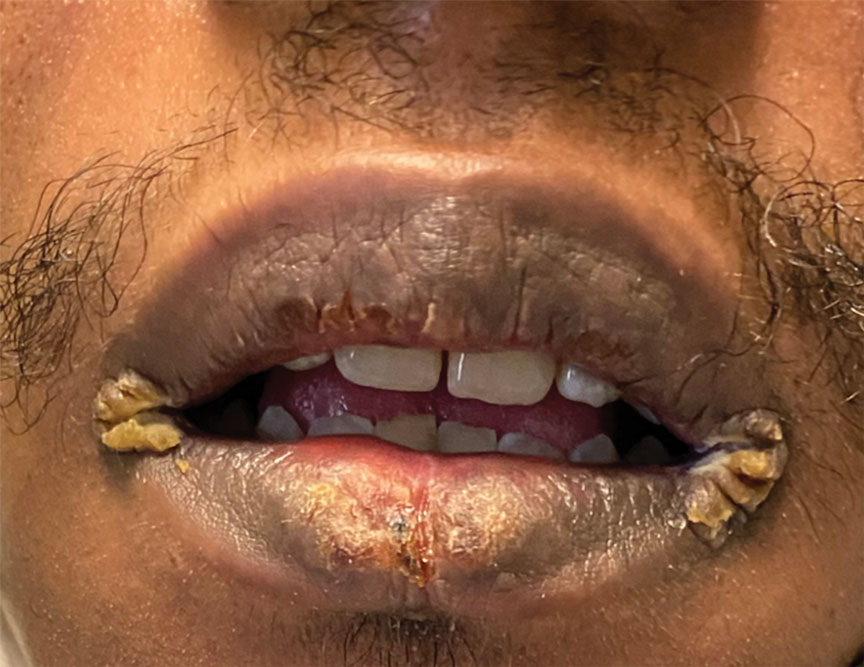

Mucocutaneus manifestations of secondary syphilis are multitudinous. As in our patient, the classic presentation is a generalized morbilliform and papulosquamous eruption involving the palms (Figure 2) and soles. Split papules at the oral commissures, mucosal patches, and condyloma lata are the characteristic mucosal lesions of secondary syphilis.1 Patchy nonscarring alopecia is not uncommon and can be the only manifestation of secondary syphilis.2 The histopathologic features of secondary syphilis vary depending on the location and type of the skin eruption. Psoriasiform or lichenoid changes commonly occur in the epidermis and dermoepidermal junction.3 The dermal inflammatory patterns that have been described include granulomatous, nodular, and superficial and deep perivascular inflammation. The infiltrate often is composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histocytes. Reactive endothelial cells and perineural plasma cell infiltrates also are common histologic features.3,4 Spirochetes can be identified in most cases using immunohistochemical staining; however, the absence of spirochetes does not exclude syphilis.3 The sensitivity of immunohistochemical staining in secondary syphilis is reported to be 71% to 100% with a very high specificity.5 The treatment for all stages of syphilis is benzathine penicillin G, and the route of administration and duration of treatment depend on the stage of disease.6

A broad differential diagnosis must be considered when encountering skin eruptions in patients with HIV. Psoriasis usually presents as circumscribed erythematous plaques with dry and silvery scaling and a predilection for the extensor surfaces of the limbs, sacrum, scalp, and nails. Nail manifestations include distal onycholysis, irregular pitting, oil spots, salmon patches, and subungual hyperkeratosis. Alopecia occasionally may be seen within scalp lesions7; however, the constellation of alopecia with a moth-eaten appearance, subungual hyperkeratosis, papulosquamous eruption, and split papules was more suggestive of secondary syphilis in our patient. In immunocompromised patients, crusted scabies can be considered for the diagnosis of papulosquamous eruptions involving the palms and soles. It often presents with symmetric, mildly pruritic, psoriasiform dermatitis that favors acral sites, but widespread involvement can be observed.8 Areas of the scalp and face can be affected in infants, elderly patients, and immunocompromised individuals. Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in scabies.

Sarcoidosis is common in Black individuals, and similar to syphilis, it is considered a great imitator of other dermatologic diseases. Frequently, it presents as redviolaceous papules, nodules, or plaques; however, rare variants including psoriasiform, ichthyosiform, verrucous, and lichenoid skin eruptions can occur. Nail dystrophy, split papules, and alopecia also have been observed.9 Ocular involvement is common and frequently presents as uveitis.10 The pathologic hallmark of sarcoidosis is noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, which also may occur in syphilitic lesions9; however, a papulosquamous eruption involving the palms and soles, positive serology, and the finding of interface lichenoid dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia confirmed the diagnosis of secondary syphilis in our patient. Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a rare papulosquamous disorder that can be associated with HIV (type VI/HIVassociated follicular syndrome). It presents with generalized red-orange keratotic papules and often is associated with acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa, and lichen spinulosus.11 Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in pityriasis rubra pilaris.

This case highlights many classical findings of secondary syphilis and demonstrates that, while helpful, routine skin biopsy may not be required. Treatment should be guided by clinical presentation and serologic testing while reserving skin biopsy for equivocal cases.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: historical aspects, microbiology, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1-14.

- Balagula Y, Mattei PL, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revisited: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:595-599.

- Flamm A, Parikh K, Xie Q, et al. Histologic features of secondary syphilis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1025-1030.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: laboratory diagnosis, management, and prevention [published online February 8, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:17-28.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386:983-994.

- Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:699.e1-718.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part II. extracutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:719.e1-730.

- Miralles E, Núñez M, De Las Heras M, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:990-993.

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

Histopathology revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia (Figure 1A). A single spirochete was identified using immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1B). Laboratory workup revealed positive IgG and IgM treponemal antibodies and reactive rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:2048. A VDRL test performed on a cerebrospinal fluid specimen also was reactive at 1:8. A diagnosis of secondary syphilis with neurologic involvement was made, and the patient was treated with intravenous penicillin G for 14 days. Following treatment, his rapid plasma reagin decreased 4-fold with an improvement in his ocular and cutaneous symptoms.

Mucocutaneus manifestations of secondary syphilis are multitudinous. As in our patient, the classic presentation is a generalized morbilliform and papulosquamous eruption involving the palms (Figure 2) and soles. Split papules at the oral commissures, mucosal patches, and condyloma lata are the characteristic mucosal lesions of secondary syphilis.1 Patchy nonscarring alopecia is not uncommon and can be the only manifestation of secondary syphilis.2 The histopathologic features of secondary syphilis vary depending on the location and type of the skin eruption. Psoriasiform or lichenoid changes commonly occur in the epidermis and dermoepidermal junction.3 The dermal inflammatory patterns that have been described include granulomatous, nodular, and superficial and deep perivascular inflammation. The infiltrate often is composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histocytes. Reactive endothelial cells and perineural plasma cell infiltrates also are common histologic features.3,4 Spirochetes can be identified in most cases using immunohistochemical staining; however, the absence of spirochetes does not exclude syphilis.3 The sensitivity of immunohistochemical staining in secondary syphilis is reported to be 71% to 100% with a very high specificity.5 The treatment for all stages of syphilis is benzathine penicillin G, and the route of administration and duration of treatment depend on the stage of disease.6

A broad differential diagnosis must be considered when encountering skin eruptions in patients with HIV. Psoriasis usually presents as circumscribed erythematous plaques with dry and silvery scaling and a predilection for the extensor surfaces of the limbs, sacrum, scalp, and nails. Nail manifestations include distal onycholysis, irregular pitting, oil spots, salmon patches, and subungual hyperkeratosis. Alopecia occasionally may be seen within scalp lesions7; however, the constellation of alopecia with a moth-eaten appearance, subungual hyperkeratosis, papulosquamous eruption, and split papules was more suggestive of secondary syphilis in our patient. In immunocompromised patients, crusted scabies can be considered for the diagnosis of papulosquamous eruptions involving the palms and soles. It often presents with symmetric, mildly pruritic, psoriasiform dermatitis that favors acral sites, but widespread involvement can be observed.8 Areas of the scalp and face can be affected in infants, elderly patients, and immunocompromised individuals. Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in scabies.

Sarcoidosis is common in Black individuals, and similar to syphilis, it is considered a great imitator of other dermatologic diseases. Frequently, it presents as redviolaceous papules, nodules, or plaques; however, rare variants including psoriasiform, ichthyosiform, verrucous, and lichenoid skin eruptions can occur. Nail dystrophy, split papules, and alopecia also have been observed.9 Ocular involvement is common and frequently presents as uveitis.10 The pathologic hallmark of sarcoidosis is noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, which also may occur in syphilitic lesions9; however, a papulosquamous eruption involving the palms and soles, positive serology, and the finding of interface lichenoid dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia confirmed the diagnosis of secondary syphilis in our patient. Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a rare papulosquamous disorder that can be associated with HIV (type VI/HIVassociated follicular syndrome). It presents with generalized red-orange keratotic papules and often is associated with acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa, and lichen spinulosus.11 Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in pityriasis rubra pilaris.

This case highlights many classical findings of secondary syphilis and demonstrates that, while helpful, routine skin biopsy may not be required. Treatment should be guided by clinical presentation and serologic testing while reserving skin biopsy for equivocal cases.

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

Histopathology revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia (Figure 1A). A single spirochete was identified using immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1B). Laboratory workup revealed positive IgG and IgM treponemal antibodies and reactive rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:2048. A VDRL test performed on a cerebrospinal fluid specimen also was reactive at 1:8. A diagnosis of secondary syphilis with neurologic involvement was made, and the patient was treated with intravenous penicillin G for 14 days. Following treatment, his rapid plasma reagin decreased 4-fold with an improvement in his ocular and cutaneous symptoms.

Mucocutaneus manifestations of secondary syphilis are multitudinous. As in our patient, the classic presentation is a generalized morbilliform and papulosquamous eruption involving the palms (Figure 2) and soles. Split papules at the oral commissures, mucosal patches, and condyloma lata are the characteristic mucosal lesions of secondary syphilis.1 Patchy nonscarring alopecia is not uncommon and can be the only manifestation of secondary syphilis.2 The histopathologic features of secondary syphilis vary depending on the location and type of the skin eruption. Psoriasiform or lichenoid changes commonly occur in the epidermis and dermoepidermal junction.3 The dermal inflammatory patterns that have been described include granulomatous, nodular, and superficial and deep perivascular inflammation. The infiltrate often is composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histocytes. Reactive endothelial cells and perineural plasma cell infiltrates also are common histologic features.3,4 Spirochetes can be identified in most cases using immunohistochemical staining; however, the absence of spirochetes does not exclude syphilis.3 The sensitivity of immunohistochemical staining in secondary syphilis is reported to be 71% to 100% with a very high specificity.5 The treatment for all stages of syphilis is benzathine penicillin G, and the route of administration and duration of treatment depend on the stage of disease.6

A broad differential diagnosis must be considered when encountering skin eruptions in patients with HIV. Psoriasis usually presents as circumscribed erythematous plaques with dry and silvery scaling and a predilection for the extensor surfaces of the limbs, sacrum, scalp, and nails. Nail manifestations include distal onycholysis, irregular pitting, oil spots, salmon patches, and subungual hyperkeratosis. Alopecia occasionally may be seen within scalp lesions7; however, the constellation of alopecia with a moth-eaten appearance, subungual hyperkeratosis, papulosquamous eruption, and split papules was more suggestive of secondary syphilis in our patient. In immunocompromised patients, crusted scabies can be considered for the diagnosis of papulosquamous eruptions involving the palms and soles. It often presents with symmetric, mildly pruritic, psoriasiform dermatitis that favors acral sites, but widespread involvement can be observed.8 Areas of the scalp and face can be affected in infants, elderly patients, and immunocompromised individuals. Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in scabies.

Sarcoidosis is common in Black individuals, and similar to syphilis, it is considered a great imitator of other dermatologic diseases. Frequently, it presents as redviolaceous papules, nodules, or plaques; however, rare variants including psoriasiform, ichthyosiform, verrucous, and lichenoid skin eruptions can occur. Nail dystrophy, split papules, and alopecia also have been observed.9 Ocular involvement is common and frequently presents as uveitis.10 The pathologic hallmark of sarcoidosis is noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, which also may occur in syphilitic lesions9; however, a papulosquamous eruption involving the palms and soles, positive serology, and the finding of interface lichenoid dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia confirmed the diagnosis of secondary syphilis in our patient. Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a rare papulosquamous disorder that can be associated with HIV (type VI/HIVassociated follicular syndrome). It presents with generalized red-orange keratotic papules and often is associated with acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa, and lichen spinulosus.11 Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in pityriasis rubra pilaris.

This case highlights many classical findings of secondary syphilis and demonstrates that, while helpful, routine skin biopsy may not be required. Treatment should be guided by clinical presentation and serologic testing while reserving skin biopsy for equivocal cases.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: historical aspects, microbiology, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1-14.

- Balagula Y, Mattei PL, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revisited: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:595-599.

- Flamm A, Parikh K, Xie Q, et al. Histologic features of secondary syphilis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1025-1030.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: laboratory diagnosis, management, and prevention [published online February 8, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:17-28.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386:983-994.

- Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:699.e1-718.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part II. extracutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:719.e1-730.

- Miralles E, Núñez M, De Las Heras M, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:990-993.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: historical aspects, microbiology, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1-14.

- Balagula Y, Mattei PL, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revisited: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:595-599.

- Flamm A, Parikh K, Xie Q, et al. Histologic features of secondary syphilis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1025-1030.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: laboratory diagnosis, management, and prevention [published online February 8, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:17-28.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386:983-994.

- Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:699.e1-718.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part II. extracutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:719.e1-730.

- Miralles E, Núñez M, De Las Heras M, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:990-993.

A 29-year-old Black man with long-standing untreated HIV presented with mildly pruritic, scaly plaques on the palms and soles of 2 weeks’ duration. His medical history was notable for primary syphilis treated approximately 1 year prior. A review of symptoms was positive for blurry vision and floaters but negative for constitutional symptoms. Physical examination revealed well-defined scaly plaques over the palms, soles, and elbows with subungual hyperkeratosis. Patches of nonscarring alopecia over the scalp and split papules at the oral commissures also were noted. There were no palpable lymph nodes or genital involvement. Eye examination showed conjunctival injection and 20 cells per field in the vitreous humor. Laboratory evaluation revealed an HIV viral load of 31,623 copies/mL and a CD4 count of 47 cells/μL (reference range, 362–1531 cells/μL). A shave biopsy of the left elbow was performed for histopathologic evaluation.

BREEZE-AD-PEDS: First data for baricitinib in childhood eczema reported

The oral Janus kinase

After 16 weeks of treatment, the primary endpoint – an Investigators Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1 with at least a 2-point improvement from baseline – was met by 41.7% of patients given 2 mg (those younger than age 10) or 4 mg of baricitinib (those aged 10-17 years), the highest dose studied in each of those two age groups.

By comparison, the primary endpoint was met in 16.4% of children in the placebo group (P < .001).

Baricitinib is approved for the treatment of AD in adults in many countries, Antonio Torrelo, MD, of the Hospital Infantil Niño Jesús, Madrid, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating adults with severe alopecia areata in June and is under FDA review for the treatment of AD.

The phase 3 BREEZE-AD-PEDS trial

BREEZE-AD-PEDS was a randomized, double-blind trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of baricitinib in 483 children and adolescents with moderate to severe AD. Participants were aged 2-17 years. Those aged 2-5 years had been diagnosed with AD for at least 6 months; if they were older, they had been diagnosed for at least 12 months.

Three dosing levels of baricitinib were tested: 121 patients were given a low dose, which was 0.5 mg/day in children aged 2 to less than 10 years and 1 mg/day in those aged 10 to less than 18 years. A medium dose – 1 mg/day in the younger children and 2 mg/day in the older children – was given to 120 children, while a high dose – 2 mg/day and 4 mg/day, respectively – was given to another 120 children.

Topical treatments were permitted, although for entry into the trial, participants had to have had an inadequate response to steroids and an inadequate or no response to topical calcineurin inhibitors. In all groups, age, gender, race, geographic region, age at diagnosis of AD, and duration of AD “were more or less similar,” Dr. Torello said.

Good results, but only with highest dose

The primary IGA endpoint was reached by 25.8% of children in the medium-dose group and by 18.2% in the low-dose group. Neither result was statistically significant in comparison with placebo (16.4%).

When breaking down the results between different ages, “the results in the IGA scores are consistent in both age subgroups – below 10 years and over 10 years,” Dr. Torello noted. The results are also consistent across body weights (< 20 kg, 20-60 kg, and > 60 kg), he added.

Among those treated with the high dose of baricitinib, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) 75% and 95% improvement scores were reached in 52.5% and 30% of patients, respectively. Corresponding figures for the medium dose were 40% and 21.7%; for the low baricitinib dose, 32.2% and 11.6%; and for placebo, 32% and 12.3%. Again, only the results for the highest baricitinib dose were significant in comparison with placebo.

A similar pattern was seen for improvement in itch, and there was a 75% improvement in Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD75) results.

Safety of baricitinib in children

The labeling for JAK inhibitors that have been approved to date, including baricitinib, include a boxed warning regarding risks for thrombosis, major adverse cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality. The warning is based on use by patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Dr. Torello summarized baricitinib’s safety profile in the trial as being “consistent with the well-known safety profile for baricitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.”

In the study, no severe adverse effects were noted, and no new safety signals were observed, he said. The rate of any treatment-emergent effect among patients was around 50% and was similar across all baricitinib and placebo groups. Study discontinuations because of a side effect were more frequent in the placebo arm (1.6% of patients) than in the baricitinib low-, medium-, and high-dose arms (0.8%, 0%, and 0.8%, respectively).

There were no cases of deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or other adverse effects of special interest, including major adverse cardiovascular events, gastrointestinal perforations, and opportunistic infections, Dr. Torrelo said.

No patient experienced elevations in liver enzyme levels, although there were some cases of elevated creatinine phosphokinase levels (16% in the placebo group and 19% in the baricitinib arms altogether) that were not from muscle injury. There was a possible increase in low-density cholesterol level (3.3% of those taking placebo vs. 10.1% of baricitinib-treated patients).

Is there a role for baricitinib?

“Baricitinib is a potential therapeutic option with a favorable benefit-to-risk profile for children between 2 and 18 years who have moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, and candidates for systemic therapy,” Dr. Torrelo said. “No single drug is capable to treat every patient with atopic dermatitis,” he added in discussing the possible place of baricitinib in pediatric practice.

“There are patients who do not respond to dupilumab, who apparently respond later to JAK inhibitors,” he noted.

“We are trying to work phenotypically, trying to learn what kind of patients – especially children who have a more heterogeneous disease than adults – can be better treated with JAK inhibitors or dupilumab.” There may be other important considerations in choosing a treatment in children, Dr. Torrelo said, including that JAK inhibitors can be given orally, while dupilumab is administered by injection.

Asked to comment on the results, Jashin J. Wu, MD, founder and CEO of the Dermatology Research and Education Foundation in Irvine, Calif., pointed out that “only the higher dose is significantly more effective than placebo.”

In his view, “the potentially severe adverse events are not worth the risk compared to more effective agents, such as dupilumab, in this pediatric population,” added Dr. Wu, who recently authored a review of the role of JAK inhibitors in skin disease. He was not involved with the baricitinib study.

The study was funded by Eli Lilly in collaboration with Incyte. Dr. Torello has participated in advisory boards and/or has served as a principal investigator in clinical trials for AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi. Dr. Wu has been an investigator, consultant, or speaker for multiple pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The oral Janus kinase

After 16 weeks of treatment, the primary endpoint – an Investigators Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1 with at least a 2-point improvement from baseline – was met by 41.7% of patients given 2 mg (those younger than age 10) or 4 mg of baricitinib (those aged 10-17 years), the highest dose studied in each of those two age groups.

By comparison, the primary endpoint was met in 16.4% of children in the placebo group (P < .001).

Baricitinib is approved for the treatment of AD in adults in many countries, Antonio Torrelo, MD, of the Hospital Infantil Niño Jesús, Madrid, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating adults with severe alopecia areata in June and is under FDA review for the treatment of AD.

The phase 3 BREEZE-AD-PEDS trial

BREEZE-AD-PEDS was a randomized, double-blind trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of baricitinib in 483 children and adolescents with moderate to severe AD. Participants were aged 2-17 years. Those aged 2-5 years had been diagnosed with AD for at least 6 months; if they were older, they had been diagnosed for at least 12 months.

Three dosing levels of baricitinib were tested: 121 patients were given a low dose, which was 0.5 mg/day in children aged 2 to less than 10 years and 1 mg/day in those aged 10 to less than 18 years. A medium dose – 1 mg/day in the younger children and 2 mg/day in the older children – was given to 120 children, while a high dose – 2 mg/day and 4 mg/day, respectively – was given to another 120 children.

Topical treatments were permitted, although for entry into the trial, participants had to have had an inadequate response to steroids and an inadequate or no response to topical calcineurin inhibitors. In all groups, age, gender, race, geographic region, age at diagnosis of AD, and duration of AD “were more or less similar,” Dr. Torello said.

Good results, but only with highest dose

The primary IGA endpoint was reached by 25.8% of children in the medium-dose group and by 18.2% in the low-dose group. Neither result was statistically significant in comparison with placebo (16.4%).

When breaking down the results between different ages, “the results in the IGA scores are consistent in both age subgroups – below 10 years and over 10 years,” Dr. Torello noted. The results are also consistent across body weights (< 20 kg, 20-60 kg, and > 60 kg), he added.

Among those treated with the high dose of baricitinib, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) 75% and 95% improvement scores were reached in 52.5% and 30% of patients, respectively. Corresponding figures for the medium dose were 40% and 21.7%; for the low baricitinib dose, 32.2% and 11.6%; and for placebo, 32% and 12.3%. Again, only the results for the highest baricitinib dose were significant in comparison with placebo.

A similar pattern was seen for improvement in itch, and there was a 75% improvement in Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD75) results.

Safety of baricitinib in children

The labeling for JAK inhibitors that have been approved to date, including baricitinib, include a boxed warning regarding risks for thrombosis, major adverse cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality. The warning is based on use by patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Dr. Torello summarized baricitinib’s safety profile in the trial as being “consistent with the well-known safety profile for baricitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.”

In the study, no severe adverse effects were noted, and no new safety signals were observed, he said. The rate of any treatment-emergent effect among patients was around 50% and was similar across all baricitinib and placebo groups. Study discontinuations because of a side effect were more frequent in the placebo arm (1.6% of patients) than in the baricitinib low-, medium-, and high-dose arms (0.8%, 0%, and 0.8%, respectively).

There were no cases of deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or other adverse effects of special interest, including major adverse cardiovascular events, gastrointestinal perforations, and opportunistic infections, Dr. Torrelo said.

No patient experienced elevations in liver enzyme levels, although there were some cases of elevated creatinine phosphokinase levels (16% in the placebo group and 19% in the baricitinib arms altogether) that were not from muscle injury. There was a possible increase in low-density cholesterol level (3.3% of those taking placebo vs. 10.1% of baricitinib-treated patients).

Is there a role for baricitinib?

“Baricitinib is a potential therapeutic option with a favorable benefit-to-risk profile for children between 2 and 18 years who have moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, and candidates for systemic therapy,” Dr. Torrelo said. “No single drug is capable to treat every patient with atopic dermatitis,” he added in discussing the possible place of baricitinib in pediatric practice.

“There are patients who do not respond to dupilumab, who apparently respond later to JAK inhibitors,” he noted.

“We are trying to work phenotypically, trying to learn what kind of patients – especially children who have a more heterogeneous disease than adults – can be better treated with JAK inhibitors or dupilumab.” There may be other important considerations in choosing a treatment in children, Dr. Torrelo said, including that JAK inhibitors can be given orally, while dupilumab is administered by injection.

Asked to comment on the results, Jashin J. Wu, MD, founder and CEO of the Dermatology Research and Education Foundation in Irvine, Calif., pointed out that “only the higher dose is significantly more effective than placebo.”

In his view, “the potentially severe adverse events are not worth the risk compared to more effective agents, such as dupilumab, in this pediatric population,” added Dr. Wu, who recently authored a review of the role of JAK inhibitors in skin disease. He was not involved with the baricitinib study.

The study was funded by Eli Lilly in collaboration with Incyte. Dr. Torello has participated in advisory boards and/or has served as a principal investigator in clinical trials for AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi. Dr. Wu has been an investigator, consultant, or speaker for multiple pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The oral Janus kinase

After 16 weeks of treatment, the primary endpoint – an Investigators Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1 with at least a 2-point improvement from baseline – was met by 41.7% of patients given 2 mg (those younger than age 10) or 4 mg of baricitinib (those aged 10-17 years), the highest dose studied in each of those two age groups.

By comparison, the primary endpoint was met in 16.4% of children in the placebo group (P < .001).

Baricitinib is approved for the treatment of AD in adults in many countries, Antonio Torrelo, MD, of the Hospital Infantil Niño Jesús, Madrid, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating adults with severe alopecia areata in June and is under FDA review for the treatment of AD.

The phase 3 BREEZE-AD-PEDS trial

BREEZE-AD-PEDS was a randomized, double-blind trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of baricitinib in 483 children and adolescents with moderate to severe AD. Participants were aged 2-17 years. Those aged 2-5 years had been diagnosed with AD for at least 6 months; if they were older, they had been diagnosed for at least 12 months.

Three dosing levels of baricitinib were tested: 121 patients were given a low dose, which was 0.5 mg/day in children aged 2 to less than 10 years and 1 mg/day in those aged 10 to less than 18 years. A medium dose – 1 mg/day in the younger children and 2 mg/day in the older children – was given to 120 children, while a high dose – 2 mg/day and 4 mg/day, respectively – was given to another 120 children.

Topical treatments were permitted, although for entry into the trial, participants had to have had an inadequate response to steroids and an inadequate or no response to topical calcineurin inhibitors. In all groups, age, gender, race, geographic region, age at diagnosis of AD, and duration of AD “were more or less similar,” Dr. Torello said.

Good results, but only with highest dose

The primary IGA endpoint was reached by 25.8% of children in the medium-dose group and by 18.2% in the low-dose group. Neither result was statistically significant in comparison with placebo (16.4%).

When breaking down the results between different ages, “the results in the IGA scores are consistent in both age subgroups – below 10 years and over 10 years,” Dr. Torello noted. The results are also consistent across body weights (< 20 kg, 20-60 kg, and > 60 kg), he added.

Among those treated with the high dose of baricitinib, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) 75% and 95% improvement scores were reached in 52.5% and 30% of patients, respectively. Corresponding figures for the medium dose were 40% and 21.7%; for the low baricitinib dose, 32.2% and 11.6%; and for placebo, 32% and 12.3%. Again, only the results for the highest baricitinib dose were significant in comparison with placebo.

A similar pattern was seen for improvement in itch, and there was a 75% improvement in Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD75) results.

Safety of baricitinib in children

The labeling for JAK inhibitors that have been approved to date, including baricitinib, include a boxed warning regarding risks for thrombosis, major adverse cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality. The warning is based on use by patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Dr. Torello summarized baricitinib’s safety profile in the trial as being “consistent with the well-known safety profile for baricitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.”

In the study, no severe adverse effects were noted, and no new safety signals were observed, he said. The rate of any treatment-emergent effect among patients was around 50% and was similar across all baricitinib and placebo groups. Study discontinuations because of a side effect were more frequent in the placebo arm (1.6% of patients) than in the baricitinib low-, medium-, and high-dose arms (0.8%, 0%, and 0.8%, respectively).

There were no cases of deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or other adverse effects of special interest, including major adverse cardiovascular events, gastrointestinal perforations, and opportunistic infections, Dr. Torrelo said.

No patient experienced elevations in liver enzyme levels, although there were some cases of elevated creatinine phosphokinase levels (16% in the placebo group and 19% in the baricitinib arms altogether) that were not from muscle injury. There was a possible increase in low-density cholesterol level (3.3% of those taking placebo vs. 10.1% of baricitinib-treated patients).

Is there a role for baricitinib?

“Baricitinib is a potential therapeutic option with a favorable benefit-to-risk profile for children between 2 and 18 years who have moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, and candidates for systemic therapy,” Dr. Torrelo said. “No single drug is capable to treat every patient with atopic dermatitis,” he added in discussing the possible place of baricitinib in pediatric practice.

“There are patients who do not respond to dupilumab, who apparently respond later to JAK inhibitors,” he noted.

“We are trying to work phenotypically, trying to learn what kind of patients – especially children who have a more heterogeneous disease than adults – can be better treated with JAK inhibitors or dupilumab.” There may be other important considerations in choosing a treatment in children, Dr. Torrelo said, including that JAK inhibitors can be given orally, while dupilumab is administered by injection.

Asked to comment on the results, Jashin J. Wu, MD, founder and CEO of the Dermatology Research and Education Foundation in Irvine, Calif., pointed out that “only the higher dose is significantly more effective than placebo.”

In his view, “the potentially severe adverse events are not worth the risk compared to more effective agents, such as dupilumab, in this pediatric population,” added Dr. Wu, who recently authored a review of the role of JAK inhibitors in skin disease. He was not involved with the baricitinib study.

The study was funded by Eli Lilly in collaboration with Incyte. Dr. Torello has participated in advisory boards and/or has served as a principal investigator in clinical trials for AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi. Dr. Wu has been an investigator, consultant, or speaker for multiple pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

High-dose folic acid during pregnancy tied to cancer risk in children

new data from a Scandinavian registry of more than 3 million pregnancies suggests.

The increased risk for cancer did not change after considering other factors that could explain the risk, such as use of antiseizure medication (ASM).

There was no increased risk for cancer in children of mothers without epilepsy who used high-dose folic acid.

The results of this study “should be considered when the risks and benefits of folic acid supplements for women with epilepsy are discussed and before decisions about optimal dose recommendations are made,” the authors write.

“Although we believe that the association between prescription fills for high-dose folic acid and cancer in children born to mothers with epilepsy is robust, it is important to underline that these are the findings of one study only,” first author Håkon Magne Vegrim, MD, with University of Bergen (Norway) told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology.

Risks and benefits

Women with epilepsy are advised to take high doses of folic acid before and during pregnancy owing to the risk for congenital malformations associated with ASM. Whether high-dose folic acid is associated with increases in the risk for childhood cancer is unknown.

To investigate, the researchers analyzed registry data from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden for 3.3 million children followed to a median age of 7.3 years.

Among the 27,784 children born to mothers with epilepsy, 5,934 (21.4%) were exposed to high-dose folic acid (mean dose, 4.3 mg), with a cancer incidence rate of 42.5 per 100,000 person-years in 18 exposed cancer cases compared with 18.4 per 100,000 person-years in 29 unexposed cancer cases – yielding an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.7 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-6.3).

The absolute risk with exposure was 1.5% (95% CI, 0.5%-3.5%) in children of mothers with epilepsy compared with 0.6% (95% CI, 0.3%-1.1%) in children of mothers with epilepsy who were not exposed high-dose folic acid.

Prenatal exposure to high-dose folic acid was not associated with an increased risk for cancer in children of mothers without epilepsy.

In children of mothers without epilepsy, 46,646 (1.4%) were exposed to high-dose folic acid (mean dose, 2.9 mg). There were 69 exposed and 4,927 unexposed cancer cases and an aHR for cancer of 1.1 (95% CI, 0.9-1.4) and absolute risk for cancer of 0.4% (95% CI, 0.3%-0.5%).

There was no association between any specific ASM and childhood cancer.

“Removing mothers with any prescription fills for carbamazepine and valproate was not associated with the point estimate. Hence, these two ASMs were not important effect modifiers for the cancer association,” the investigators note in their study.

They also note that the most common childhood cancer types in children among mothers with epilepsy who took high-dose folic acid did not differ from the distribution in the general population.

“We need to get more knowledge about the potential mechanisms behind high-dose folic acid and childhood cancer, and it is important to identify the optimal dose to balance risks and benefits – and whether folic acid supplementation should be more individualized, based on factors like the serum level of folate and what type of antiseizure medication that is being used,” said Dr. Vegrim.

Practice changing?

Weighing in on the study, Elizabeth E. Gerard, MD, director of the Women with Epilepsy Program and associate professor of neurology at Northwestern University in Chicago, said, “There are known benefits of folic acid supplementation during pregnancy including a decreased risk of neural tube defects in the general population and improved neurodevelopmental outcomes in children born to mothers with and without epilepsy.”

“However, despite some expert guidelines recommending high-dose folic acid supplementation, there is a lack of certainty surrounding the ‘just right’ dose for patients with epilepsy who may become pregnant,” said Dr. Gerard, who wasn’t involved in the study.

Dr. Gerard, a member of the American Epilepsy Society, noted that other epidemiologic studies of folic acid supplementation and cancer have had “contradictory results, thus further research on this association will be needed. Additionally, differences in maternal/fetal folate metabolism and blood levels may be an important factor to study in the future.

“That said, this study definitely should cause us to pause and reevaluate the common practice of high-dose folic acid supplementation for patients with epilepsy who are considering pregnancy,” said Dr. Gerard.

The study was supported by the NordForsk Nordic Program on Health and Welfare. Dr. Vegrim and Dr. Gerard report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new data from a Scandinavian registry of more than 3 million pregnancies suggests.

The increased risk for cancer did not change after considering other factors that could explain the risk, such as use of antiseizure medication (ASM).

There was no increased risk for cancer in children of mothers without epilepsy who used high-dose folic acid.

The results of this study “should be considered when the risks and benefits of folic acid supplements for women with epilepsy are discussed and before decisions about optimal dose recommendations are made,” the authors write.

“Although we believe that the association between prescription fills for high-dose folic acid and cancer in children born to mothers with epilepsy is robust, it is important to underline that these are the findings of one study only,” first author Håkon Magne Vegrim, MD, with University of Bergen (Norway) told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology.

Risks and benefits

Women with epilepsy are advised to take high doses of folic acid before and during pregnancy owing to the risk for congenital malformations associated with ASM. Whether high-dose folic acid is associated with increases in the risk for childhood cancer is unknown.

To investigate, the researchers analyzed registry data from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden for 3.3 million children followed to a median age of 7.3 years.

Among the 27,784 children born to mothers with epilepsy, 5,934 (21.4%) were exposed to high-dose folic acid (mean dose, 4.3 mg), with a cancer incidence rate of 42.5 per 100,000 person-years in 18 exposed cancer cases compared with 18.4 per 100,000 person-years in 29 unexposed cancer cases – yielding an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.7 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-6.3).

The absolute risk with exposure was 1.5% (95% CI, 0.5%-3.5%) in children of mothers with epilepsy compared with 0.6% (95% CI, 0.3%-1.1%) in children of mothers with epilepsy who were not exposed high-dose folic acid.

Prenatal exposure to high-dose folic acid was not associated with an increased risk for cancer in children of mothers without epilepsy.

In children of mothers without epilepsy, 46,646 (1.4%) were exposed to high-dose folic acid (mean dose, 2.9 mg). There were 69 exposed and 4,927 unexposed cancer cases and an aHR for cancer of 1.1 (95% CI, 0.9-1.4) and absolute risk for cancer of 0.4% (95% CI, 0.3%-0.5%).

There was no association between any specific ASM and childhood cancer.

“Removing mothers with any prescription fills for carbamazepine and valproate was not associated with the point estimate. Hence, these two ASMs were not important effect modifiers for the cancer association,” the investigators note in their study.

They also note that the most common childhood cancer types in children among mothers with epilepsy who took high-dose folic acid did not differ from the distribution in the general population.

“We need to get more knowledge about the potential mechanisms behind high-dose folic acid and childhood cancer, and it is important to identify the optimal dose to balance risks and benefits – and whether folic acid supplementation should be more individualized, based on factors like the serum level of folate and what type of antiseizure medication that is being used,” said Dr. Vegrim.

Practice changing?

Weighing in on the study, Elizabeth E. Gerard, MD, director of the Women with Epilepsy Program and associate professor of neurology at Northwestern University in Chicago, said, “There are known benefits of folic acid supplementation during pregnancy including a decreased risk of neural tube defects in the general population and improved neurodevelopmental outcomes in children born to mothers with and without epilepsy.”

“However, despite some expert guidelines recommending high-dose folic acid supplementation, there is a lack of certainty surrounding the ‘just right’ dose for patients with epilepsy who may become pregnant,” said Dr. Gerard, who wasn’t involved in the study.

Dr. Gerard, a member of the American Epilepsy Society, noted that other epidemiologic studies of folic acid supplementation and cancer have had “contradictory results, thus further research on this association will be needed. Additionally, differences in maternal/fetal folate metabolism and blood levels may be an important factor to study in the future.

“That said, this study definitely should cause us to pause and reevaluate the common practice of high-dose folic acid supplementation for patients with epilepsy who are considering pregnancy,” said Dr. Gerard.

The study was supported by the NordForsk Nordic Program on Health and Welfare. Dr. Vegrim and Dr. Gerard report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new data from a Scandinavian registry of more than 3 million pregnancies suggests.

The increased risk for cancer did not change after considering other factors that could explain the risk, such as use of antiseizure medication (ASM).

There was no increased risk for cancer in children of mothers without epilepsy who used high-dose folic acid.

The results of this study “should be considered when the risks and benefits of folic acid supplements for women with epilepsy are discussed and before decisions about optimal dose recommendations are made,” the authors write.

“Although we believe that the association between prescription fills for high-dose folic acid and cancer in children born to mothers with epilepsy is robust, it is important to underline that these are the findings of one study only,” first author Håkon Magne Vegrim, MD, with University of Bergen (Norway) told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology.

Risks and benefits

Women with epilepsy are advised to take high doses of folic acid before and during pregnancy owing to the risk for congenital malformations associated with ASM. Whether high-dose folic acid is associated with increases in the risk for childhood cancer is unknown.

To investigate, the researchers analyzed registry data from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden for 3.3 million children followed to a median age of 7.3 years.

Among the 27,784 children born to mothers with epilepsy, 5,934 (21.4%) were exposed to high-dose folic acid (mean dose, 4.3 mg), with a cancer incidence rate of 42.5 per 100,000 person-years in 18 exposed cancer cases compared with 18.4 per 100,000 person-years in 29 unexposed cancer cases – yielding an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.7 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-6.3).

The absolute risk with exposure was 1.5% (95% CI, 0.5%-3.5%) in children of mothers with epilepsy compared with 0.6% (95% CI, 0.3%-1.1%) in children of mothers with epilepsy who were not exposed high-dose folic acid.

Prenatal exposure to high-dose folic acid was not associated with an increased risk for cancer in children of mothers without epilepsy.

In children of mothers without epilepsy, 46,646 (1.4%) were exposed to high-dose folic acid (mean dose, 2.9 mg). There were 69 exposed and 4,927 unexposed cancer cases and an aHR for cancer of 1.1 (95% CI, 0.9-1.4) and absolute risk for cancer of 0.4% (95% CI, 0.3%-0.5%).

There was no association between any specific ASM and childhood cancer.

“Removing mothers with any prescription fills for carbamazepine and valproate was not associated with the point estimate. Hence, these two ASMs were not important effect modifiers for the cancer association,” the investigators note in their study.

They also note that the most common childhood cancer types in children among mothers with epilepsy who took high-dose folic acid did not differ from the distribution in the general population.

“We need to get more knowledge about the potential mechanisms behind high-dose folic acid and childhood cancer, and it is important to identify the optimal dose to balance risks and benefits – and whether folic acid supplementation should be more individualized, based on factors like the serum level of folate and what type of antiseizure medication that is being used,” said Dr. Vegrim.

Practice changing?

Weighing in on the study, Elizabeth E. Gerard, MD, director of the Women with Epilepsy Program and associate professor of neurology at Northwestern University in Chicago, said, “There are known benefits of folic acid supplementation during pregnancy including a decreased risk of neural tube defects in the general population and improved neurodevelopmental outcomes in children born to mothers with and without epilepsy.”

“However, despite some expert guidelines recommending high-dose folic acid supplementation, there is a lack of certainty surrounding the ‘just right’ dose for patients with epilepsy who may become pregnant,” said Dr. Gerard, who wasn’t involved in the study.

Dr. Gerard, a member of the American Epilepsy Society, noted that other epidemiologic studies of folic acid supplementation and cancer have had “contradictory results, thus further research on this association will be needed. Additionally, differences in maternal/fetal folate metabolism and blood levels may be an important factor to study in the future.

“That said, this study definitely should cause us to pause and reevaluate the common practice of high-dose folic acid supplementation for patients with epilepsy who are considering pregnancy,” said Dr. Gerard.

The study was supported by the NordForsk Nordic Program on Health and Welfare. Dr. Vegrim and Dr. Gerard report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Antifibrotic shows mixed results in RA-ILD

The antifibrotic pirfenidone (Esbriet) did not change the decline in forced vital capacity percentage (FVC%) from baseline of 10% or more or the risk of death compared with placebo in patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD). However, the drug appeared to slow the rate of decline in lung function, a phase 2 study indicated.

“This is the first randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial focused only on patients with RA-ILD,” observed Joshua Solomon, MD, National Jewish Health, Denver, and fellow TRAIL1 Network investigators.

in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and evidence of fibrotic interstitial lung disease and the totality of the evidence suggests that pirfenidone is effective in the treatment of RA-ILD,” they suggest.

The study was published online in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

TRAIL1

The treatment for Rheumatoid Arthritis and Interstitial Lung Disease 1 (TRAIL1) was carried out in 34 academic centers specializing in ILD. Patients had RA and the presence of ILD on high-resolution CT scan and, where possible, lung biopsy. A total of 231 patients were randomly assigned to the pirfenidone group and the remainder to placebo. The mean age of patients was 66 (interquartile range (IQR, 61.0-74.0) in the pirfenidone group and 69.56 (IQR, 63.-74.5) among placebo controls.

Patients received pirfenidone at a dose of 2,403 mg per day, given in divided doses of three 267-mg tablets, three times a day, titrated to full dose over the course of 2 weeks. High-resolution CT scans were done at the beginning and the end of the study interval. Several disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDS) were used for the treatment of RA but no differences were observed between treatment groups accounting for the DMARD classes.

“The primary endpoint was the incidence of the composite endpoint of a decline from baseline in [FVC%] of 10% or more or death during the 52-week treatment period,” Dr. Solomon and colleagues observed. The primary outcome was measured in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population.

Some 11% of patients in the active treatment group vs. 15% of patients in the placebo group met the composite primary endpoint, as investigators reported. For the secondary endpoint of the change in FVC over 52 weeks, patients treated with pirfenidone had a slow rate of decline in lung function compared with placebo patients as measured by estimated annual change in absolute FVC (–66 ml vs. –146 mL; P = .0082).

Moreover, in a post hoc analysis by CT pattern, the effect of the antifibrotic therapy on decline in FVC was more pronounced in those with usual interstitial pneumonia pattern on imaging compared with those with any pattern of ILD, the investigators observed. Indeed, approximately half of patients with the usual interstitial pneumonia in the pirfenidone group had a significantly smaller reduction in annual change in FVC at 52 weeks compared with over three-quarters of patients with usual interstitial pneumonia treated with placebo.

In contrast, the two groups were similar with regard to the decline in FVC% by 10% more or the frequency of progression. All-cause mortality rates were similar between the two groups. Adverse events thought to be related to treatment were more frequently reported in the pirfenidone group at 44% vs. 30% of placebo patients, the most frequent of which were nausea, fatigue, and diarrhea.

“These adverse events were generally grade 1 and were not clinically significant,” as the authors emphasized, although 24% of patients receiving pirfenidone discontinued treatment because of AEs vs. only 10% of placebo patients.

Limitations of the trial included early termination because of slow recruitment and the COVID-19 pandemic. This led to underpowering of the study.

Wrong endpoint?

In an accompanying editorial, Marco Sebastiani and Andreina Manfredi, MD, said that the choice of the primary outcome of an FVC decline from a baseline of 10% or more could have negatively influenced results because an FVC decline of 10% or more was probably too challenging to show a difference between the two groups. Indeed, the updated 2022 guidelines proposed a decline of 5% or more in FVC as a “significant threshold” for disease progression in patients with progressive pulmonary fibrosis, as the editorialists pointed out.

Nevertheless, the editorialists felt that the effect of pirfenidone on the decline in FVC seems to be significant, particularly when patients with usual interstitial pneumonia are considered. ”The magnitude of the effect of pirfenidone in patients with usual interstitial pneumonia-rheumatoid arthritis-interstitial lung disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [enrolled in a different study] was very similar,” they noted, “suggesting that a careful identification of usual interstitial pneumonia pattern at HRCT [high resolution CT] could be relevant in patients with RA-ILD. Moreover, given that pirfenidone did not modify its safety in these patients, the fact that pirfenidone can be safely used with DMARD therapy is important in clinical practice.

Dr. Solomon had no conflicts of interest to declare. Dr. Sebastiani disclosed ties with Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Lilly, Amgen, Janssen, and Celltrion. Dr. Manfredi disclosed ties with Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, and Boehringer-Ingelheim. The study was funded by Genentech.

The antifibrotic pirfenidone (Esbriet) did not change the decline in forced vital capacity percentage (FVC%) from baseline of 10% or more or the risk of death compared with placebo in patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD). However, the drug appeared to slow the rate of decline in lung function, a phase 2 study indicated.

“This is the first randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial focused only on patients with RA-ILD,” observed Joshua Solomon, MD, National Jewish Health, Denver, and fellow TRAIL1 Network investigators.

in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and evidence of fibrotic interstitial lung disease and the totality of the evidence suggests that pirfenidone is effective in the treatment of RA-ILD,” they suggest.

The study was published online in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

TRAIL1

The treatment for Rheumatoid Arthritis and Interstitial Lung Disease 1 (TRAIL1) was carried out in 34 academic centers specializing in ILD. Patients had RA and the presence of ILD on high-resolution CT scan and, where possible, lung biopsy. A total of 231 patients were randomly assigned to the pirfenidone group and the remainder to placebo. The mean age of patients was 66 (interquartile range (IQR, 61.0-74.0) in the pirfenidone group and 69.56 (IQR, 63.-74.5) among placebo controls.

Patients received pirfenidone at a dose of 2,403 mg per day, given in divided doses of three 267-mg tablets, three times a day, titrated to full dose over the course of 2 weeks. High-resolution CT scans were done at the beginning and the end of the study interval. Several disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDS) were used for the treatment of RA but no differences were observed between treatment groups accounting for the DMARD classes.

“The primary endpoint was the incidence of the composite endpoint of a decline from baseline in [FVC%] of 10% or more or death during the 52-week treatment period,” Dr. Solomon and colleagues observed. The primary outcome was measured in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population.

Some 11% of patients in the active treatment group vs. 15% of patients in the placebo group met the composite primary endpoint, as investigators reported. For the secondary endpoint of the change in FVC over 52 weeks, patients treated with pirfenidone had a slow rate of decline in lung function compared with placebo patients as measured by estimated annual change in absolute FVC (–66 ml vs. –146 mL; P = .0082).

Moreover, in a post hoc analysis by CT pattern, the effect of the antifibrotic therapy on decline in FVC was more pronounced in those with usual interstitial pneumonia pattern on imaging compared with those with any pattern of ILD, the investigators observed. Indeed, approximately half of patients with the usual interstitial pneumonia in the pirfenidone group had a significantly smaller reduction in annual change in FVC at 52 weeks compared with over three-quarters of patients with usual interstitial pneumonia treated with placebo.

In contrast, the two groups were similar with regard to the decline in FVC% by 10% more or the frequency of progression. All-cause mortality rates were similar between the two groups. Adverse events thought to be related to treatment were more frequently reported in the pirfenidone group at 44% vs. 30% of placebo patients, the most frequent of which were nausea, fatigue, and diarrhea.

“These adverse events were generally grade 1 and were not clinically significant,” as the authors emphasized, although 24% of patients receiving pirfenidone discontinued treatment because of AEs vs. only 10% of placebo patients.

Limitations of the trial included early termination because of slow recruitment and the COVID-19 pandemic. This led to underpowering of the study.

Wrong endpoint?

In an accompanying editorial, Marco Sebastiani and Andreina Manfredi, MD, said that the choice of the primary outcome of an FVC decline from a baseline of 10% or more could have negatively influenced results because an FVC decline of 10% or more was probably too challenging to show a difference between the two groups. Indeed, the updated 2022 guidelines proposed a decline of 5% or more in FVC as a “significant threshold” for disease progression in patients with progressive pulmonary fibrosis, as the editorialists pointed out.

Nevertheless, the editorialists felt that the effect of pirfenidone on the decline in FVC seems to be significant, particularly when patients with usual interstitial pneumonia are considered. ”The magnitude of the effect of pirfenidone in patients with usual interstitial pneumonia-rheumatoid arthritis-interstitial lung disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [enrolled in a different study] was very similar,” they noted, “suggesting that a careful identification of usual interstitial pneumonia pattern at HRCT [high resolution CT] could be relevant in patients with RA-ILD. Moreover, given that pirfenidone did not modify its safety in these patients, the fact that pirfenidone can be safely used with DMARD therapy is important in clinical practice.

Dr. Solomon had no conflicts of interest to declare. Dr. Sebastiani disclosed ties with Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Lilly, Amgen, Janssen, and Celltrion. Dr. Manfredi disclosed ties with Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, and Boehringer-Ingelheim. The study was funded by Genentech.

The antifibrotic pirfenidone (Esbriet) did not change the decline in forced vital capacity percentage (FVC%) from baseline of 10% or more or the risk of death compared with placebo in patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD). However, the drug appeared to slow the rate of decline in lung function, a phase 2 study indicated.

“This is the first randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial focused only on patients with RA-ILD,” observed Joshua Solomon, MD, National Jewish Health, Denver, and fellow TRAIL1 Network investigators.

in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and evidence of fibrotic interstitial lung disease and the totality of the evidence suggests that pirfenidone is effective in the treatment of RA-ILD,” they suggest.

The study was published online in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

TRAIL1

The treatment for Rheumatoid Arthritis and Interstitial Lung Disease 1 (TRAIL1) was carried out in 34 academic centers specializing in ILD. Patients had RA and the presence of ILD on high-resolution CT scan and, where possible, lung biopsy. A total of 231 patients were randomly assigned to the pirfenidone group and the remainder to placebo. The mean age of patients was 66 (interquartile range (IQR, 61.0-74.0) in the pirfenidone group and 69.56 (IQR, 63.-74.5) among placebo controls.

Patients received pirfenidone at a dose of 2,403 mg per day, given in divided doses of three 267-mg tablets, three times a day, titrated to full dose over the course of 2 weeks. High-resolution CT scans were done at the beginning and the end of the study interval. Several disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDS) were used for the treatment of RA but no differences were observed between treatment groups accounting for the DMARD classes.

“The primary endpoint was the incidence of the composite endpoint of a decline from baseline in [FVC%] of 10% or more or death during the 52-week treatment period,” Dr. Solomon and colleagues observed. The primary outcome was measured in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population.

Some 11% of patients in the active treatment group vs. 15% of patients in the placebo group met the composite primary endpoint, as investigators reported. For the secondary endpoint of the change in FVC over 52 weeks, patients treated with pirfenidone had a slow rate of decline in lung function compared with placebo patients as measured by estimated annual change in absolute FVC (–66 ml vs. –146 mL; P = .0082).

Moreover, in a post hoc analysis by CT pattern, the effect of the antifibrotic therapy on decline in FVC was more pronounced in those with usual interstitial pneumonia pattern on imaging compared with those with any pattern of ILD, the investigators observed. Indeed, approximately half of patients with the usual interstitial pneumonia in the pirfenidone group had a significantly smaller reduction in annual change in FVC at 52 weeks compared with over three-quarters of patients with usual interstitial pneumonia treated with placebo.

In contrast, the two groups were similar with regard to the decline in FVC% by 10% more or the frequency of progression. All-cause mortality rates were similar between the two groups. Adverse events thought to be related to treatment were more frequently reported in the pirfenidone group at 44% vs. 30% of placebo patients, the most frequent of which were nausea, fatigue, and diarrhea.

“These adverse events were generally grade 1 and were not clinically significant,” as the authors emphasized, although 24% of patients receiving pirfenidone discontinued treatment because of AEs vs. only 10% of placebo patients.

Limitations of the trial included early termination because of slow recruitment and the COVID-19 pandemic. This led to underpowering of the study.

Wrong endpoint?

In an accompanying editorial, Marco Sebastiani and Andreina Manfredi, MD, said that the choice of the primary outcome of an FVC decline from a baseline of 10% or more could have negatively influenced results because an FVC decline of 10% or more was probably too challenging to show a difference between the two groups. Indeed, the updated 2022 guidelines proposed a decline of 5% or more in FVC as a “significant threshold” for disease progression in patients with progressive pulmonary fibrosis, as the editorialists pointed out.

Nevertheless, the editorialists felt that the effect of pirfenidone on the decline in FVC seems to be significant, particularly when patients with usual interstitial pneumonia are considered. ”The magnitude of the effect of pirfenidone in patients with usual interstitial pneumonia-rheumatoid arthritis-interstitial lung disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [enrolled in a different study] was very similar,” they noted, “suggesting that a careful identification of usual interstitial pneumonia pattern at HRCT [high resolution CT] could be relevant in patients with RA-ILD. Moreover, given that pirfenidone did not modify its safety in these patients, the fact that pirfenidone can be safely used with DMARD therapy is important in clinical practice.

Dr. Solomon had no conflicts of interest to declare. Dr. Sebastiani disclosed ties with Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Lilly, Amgen, Janssen, and Celltrion. Dr. Manfredi disclosed ties with Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, and Boehringer-Ingelheim. The study was funded by Genentech.

FROM THE LANCET RESPIRATORY MEDICINE

CDC: Masking no longer required in health care settings

It’s a “major departure” from the CDC’s previous recommendation of universal masking to fight the COVID-19 pandemic, The Hill says.

“Updates were made to reflect the high levels of vaccine-and infection-induced immunity and the availability of effective treatments and prevention tools,” the CDC’s new guidance says.

The agency now says that facilities in areas without high transmission can decide for themselves whether to require everyone – doctors, patients, and visitors – to wear masks.

Community transmission “is the metric currently recommended to guide select practices in healthcare settings to allow for earlier intervention, before there is strain on the health care system and to better protect the individuals seeking care in these settings,” the CDC said.

About 73% of the country is having “high” rates of transmission, The Hill said.

“Community transmission” is different from the “community level” metric that’s used for non–health care settings.

Community transmission refers to measures of the presence and spread of SARS-CoV-2, the CDC said. “Community levels place an emphasis on measures of the impact of COVID-19 in terms of hospitalizations and health care system strain, while accounting for transmission in the community.”

Just 7% of counties are considered high risk, while nearly 62 percent are low.

The new guidance applies wherever health care is delivered, including nursing homes and home health, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It’s a “major departure” from the CDC’s previous recommendation of universal masking to fight the COVID-19 pandemic, The Hill says.

“Updates were made to reflect the high levels of vaccine-and infection-induced immunity and the availability of effective treatments and prevention tools,” the CDC’s new guidance says.

The agency now says that facilities in areas without high transmission can decide for themselves whether to require everyone – doctors, patients, and visitors – to wear masks.

Community transmission “is the metric currently recommended to guide select practices in healthcare settings to allow for earlier intervention, before there is strain on the health care system and to better protect the individuals seeking care in these settings,” the CDC said.

About 73% of the country is having “high” rates of transmission, The Hill said.

“Community transmission” is different from the “community level” metric that’s used for non–health care settings.

Community transmission refers to measures of the presence and spread of SARS-CoV-2, the CDC said. “Community levels place an emphasis on measures of the impact of COVID-19 in terms of hospitalizations and health care system strain, while accounting for transmission in the community.”

Just 7% of counties are considered high risk, while nearly 62 percent are low.

The new guidance applies wherever health care is delivered, including nursing homes and home health, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It’s a “major departure” from the CDC’s previous recommendation of universal masking to fight the COVID-19 pandemic, The Hill says.

“Updates were made to reflect the high levels of vaccine-and infection-induced immunity and the availability of effective treatments and prevention tools,” the CDC’s new guidance says.

The agency now says that facilities in areas without high transmission can decide for themselves whether to require everyone – doctors, patients, and visitors – to wear masks.

Community transmission “is the metric currently recommended to guide select practices in healthcare settings to allow for earlier intervention, before there is strain on the health care system and to better protect the individuals seeking care in these settings,” the CDC said.

About 73% of the country is having “high” rates of transmission, The Hill said.

“Community transmission” is different from the “community level” metric that’s used for non–health care settings.

Community transmission refers to measures of the presence and spread of SARS-CoV-2, the CDC said. “Community levels place an emphasis on measures of the impact of COVID-19 in terms of hospitalizations and health care system strain, while accounting for transmission in the community.”

Just 7% of counties are considered high risk, while nearly 62 percent are low.

The new guidance applies wherever health care is delivered, including nursing homes and home health, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FDA approves futibatinib (Lytgobi) for certain biliary tract cancers

Futibatinib was granted priority review and breakthrough designation, the agency said in its announcement.

Futibatinib is indicated for use in adult patients with previously treated, unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma harboring fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) gene fusions or other rearrangements.

The FDA noted that efficacy was evaluated in a multicenter, open-label, single-arm trial (known as TAS-120-101 [NCT02052778]), which involved 103 patients with such tumors. The presence of FGFR2 fusions or other rearrangements was determined using next-generation sequencing.

All the patients in this trial received futibatinib (20 mg orally once daily) until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The overall response rate was 42% (95% confidence interval, 32%-52%), and all of the 43 patients who responded achieved partial responses.

The median duration of response was 9.7 months (95% CI, 7.6-17.1).

The most common adverse reactions that occurred in 20% or more of patients were nail toxicity, musculoskeletal pain, constipation, diarrhea, fatigue, dry mouth, alopecia, stomatitis, abdominal pain, dry skin, arthralgia, dysgeusia, dry eye, nausea, decreased appetite, urinary tract infection, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome, and vomiting.

The manufacturer noted in its announcement that futibatinib covalently binds to FGFR2 and inhibits the signaling pathway. The other approved FGFR inhibitors are reversible ATP-competitive inhibitors.

The company also provided some background information on the cancer.

As a whole, cholangiocarcinoma is an aggressive cancer of the bile ducts. It is diagnosed in approximately 8000 individuals each year in the United States, the company noted.

These cases include both intrahepatic (inside the liver) and extrahepatic (outside the liver) forms of the disease. Approximately 20% of patients diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma have the intrahepatic form of the disease. Among these 20%, approximately 10%-16% of patients have FGFR2 gene rearrangements, including fusions, which promote tumor proliferation.

Futibatinib is “a key example of the potential of precision medicine in iCCA [intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma] and represents another advance in the treatment of this rare and challenging disease,” said medical oncologist Lipika Goyal, MD, MPhil, of the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, Boston, and lead investigator of the pivotal study that supported the approval.

“I am encouraged that treatment options continue to expand and evolve for this disease through the dedicated efforts of many over several years,” she commented in the company’s press release.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Futibatinib was granted priority review and breakthrough designation, the agency said in its announcement.

Futibatinib is indicated for use in adult patients with previously treated, unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma harboring fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) gene fusions or other rearrangements.

The FDA noted that efficacy was evaluated in a multicenter, open-label, single-arm trial (known as TAS-120-101 [NCT02052778]), which involved 103 patients with such tumors. The presence of FGFR2 fusions or other rearrangements was determined using next-generation sequencing.