User login

Gut microbiota and symptoms of psychosis: Is there a link?

The human microbiota refers to the collection of bacteria, archaea, eukarya, and viruses that reside within the human body. The term gut microbiome indicates the composition of these microbes and genetic codes in the intestine.1 Harkening back to the ancient Greek physician Galen, who treated gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms to relieve mental disturbances such as psychosis, the gut has been a therapeutic target in schizophrenia long before antipsychotics and the DSM.2 In recent years, research into the gut microbiome has drastically increased, with genetic sequencing affording a more precise look into the specific bacteria that call the human intestines their home. This has led to the recognition that the gut microbiome may be severely disrupted in schizophrenia, a condition known as dysbiosis. Preliminary research suggests that gut bacteria are more helpful than many human genes in distinguishing individuals with schizophrenia from their healthy counterparts.3,4 In this article, we discuss the potential role of the gut microbiome in schizophrenia, including new research correlating clinical symptoms of psychosis with dysbiosis. We also provide recommendations for promoting a healthy gut microbiome.

The enteric brain across life

The composition of our bodies is far more microbiota than human. Strikingly, microbiota cells in the gut outnumber human cells, and the distal gut alone hosts bacteria with 100 times the genetic content of the entire genome.5 The intricate meshwork of nerves in the gut is often called the enteric brain because the gut consists of 100 million neurons and synthesizes many neuroactive chemicals implicated in mood disorders and psychosis, including serotonin, dopamine, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and acetylcholine.6 The variety of neuroimmunologic, hormonal, and metabolic paths by which the gut microbiome and the brain interact are collectively known as the gut-microbiota-brain axis.7

How do we acquire our gut microbiome, and how does it come to influence our brain and behavior? On the first day of life, as babies pass through the birth canal, they are bathed in their mother’s vaginal microbiota. In the following weeks, the microbiome expands and colonizes the gut as bacteria are introduced from environmental sources such as skin-to-skin contact and breastmilk.8 The microbiome continues to evolve throughout early life. As children expand their diets and navigate new aspects of the physical world, additional bacteria join the unseen ecosystem growing inside.9 The development of the microbiome coincides with the development of the brain. From preclinical studies, we know the gut microbiome mediates important aspects of neurodevelopment such as the formation of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), synaptic pruning, glial activation, and myelination.10 Interestingly, many of the risk factors for schizophrenia are associated with gut dysbiosis, including obstetric complications, infections treated with antibiotics, and urbanization.11-15

Throughout human life, the gut and brain remain in close communication. The gut microbiota continue to produce monoamines, along with other metabolites that are able to cross the BBB.6 The HPA axis, stimulation of the immune system, and the vagus nerve all provide highways of communication between the gut and the brain.7 The relationship between the enteric brain and cephalic brain continues through life, even up to a person’s final hour. One autopsy study that is often cited (but soberingly, cannot be found online) allegedly revealed that 92% of schizophrenia patients had developed colitis by the time of death.16,17

First-episode psychosis and antipsychotic treatment

For patients with schizophrenia, first-episode psychosis (FEP) represents a cocktail of mounting genetic and environmental factors. Typically, by the time a patient receives psychiatric care, they present with characteristic psychotic symptoms—hallucinations, delusions, bizarre behavior, and unusual thought process—along with a unique gut microbiome profile.

This disrupted microbiome coincides with a marked state of inflammation in the intestines. Inflammation triggers increased endothelial barrier permeability, similar to the way immune signals increase capillary permeability to allow immune cells into the periphery of the blood. Specific gut bacteria play specific roles in maintaining the gut barrier.18,19 Disruptions in the bacteria that maintain the gut barrier, combined with inflammation, contribute to a leaky gut. A leaky gut barrier allows bacterial and immune products to more easily enter the bloodstream and then the brain, which is a potential source of neuroinflammation in schizophrenia.20 This increase in gut permeability (leaky gut syndrome) is likely one of several reasons low-grade inflammation is common in schizophrenia—numerous studies show higher serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines along with antibacterial immunoglobulins in patients with FEP.21,22

Fortunately, antipsychotics, especially the second-generation agents, help restore a healthy gut microbiome and have substantial anti-inflammatory properties.23,24 These medications interact heavily with the gut microbiome: they have been found to have antibiotic properties, even in doses lower than would normally reach the gut microbiome.25 In humans, a randomized controlled trial of probiotic supplementation for schizophrenia patients taking antipsychotics showed a reduction in GI symptoms but no significant improvement in psychotic symptoms.26

Dysbiosis in schizophrenia: cause or effect?

There is no consensus on what constitutes a healthy gut microbiome because the gut microbiome is highly variable, even among healthy individuals, and can change quickly. Those who adopt new diets, for example, see drastic shifts in the gut microbiome within a few days.27 Despite this variation, the main separation between a healthy and dysbiotic gut comes from the diversity of bacteria present in the gut—a healthy gut microbiome is associated with increased diversity. Numerous disease states have been associated with decreased bacterial diversity, including Clostridium difficile infection, Parkinson disease, depression, Crohn disease, and schizophrenia spectrum disorders.28,29

Although there are ethical limitations to studying causality in humans directly, animal models have provided a great deal of insight into the gut microbiome’s role in the development of schizophrenia. A recent study used fecal transplant to provide the gut microbiome from patients with schizophrenia to a group of germ-free mice and compared these animals to a group of mice that received a fecal transplant from individuals with a healthy gut microbiome. The mice receiving the schizophrenia microbiome showed an increased startle response and hyperactivity.3 This was consistent with mouse models of schizophrenia, although with obvious limitations.30 In addition, the brains of these animals showed changes in glutamate, glutamine, and GABA in the hippocampus; these chemicals play a role in the neurophysiology of schizophrenia.3,31 This study has not yet been replicated, and considerable variation remains within the schizophrenia biosignature.

Continue to: Clinical symptoms of psychosis and the gut microbiome

Clinical symptoms of psychosis and the gut microbiome

Previous literature has grouped patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders as 1 unified study group. But as is the case with many psychiatric conditions, there is a great deal of heterogeneity in neurobiology, genetics, and microbiome composition among individuals with schizophrenia.32

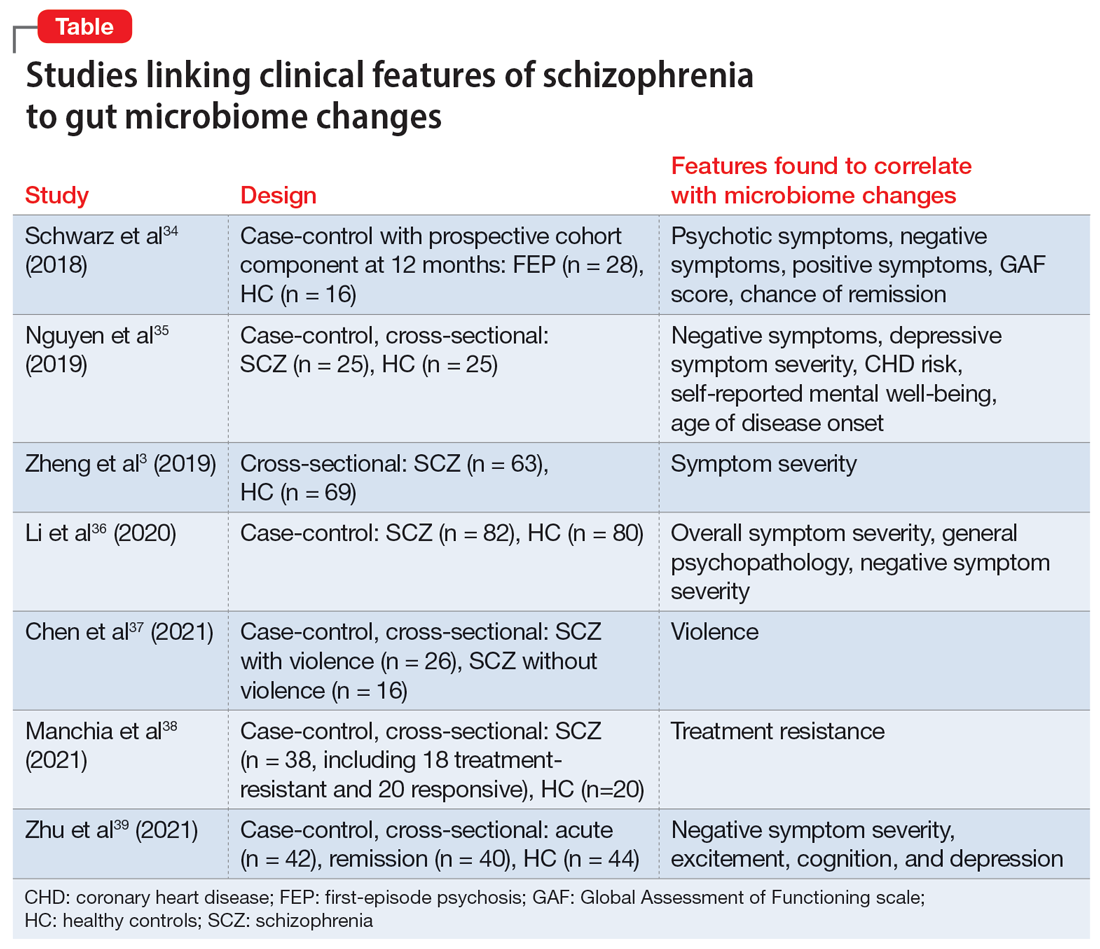

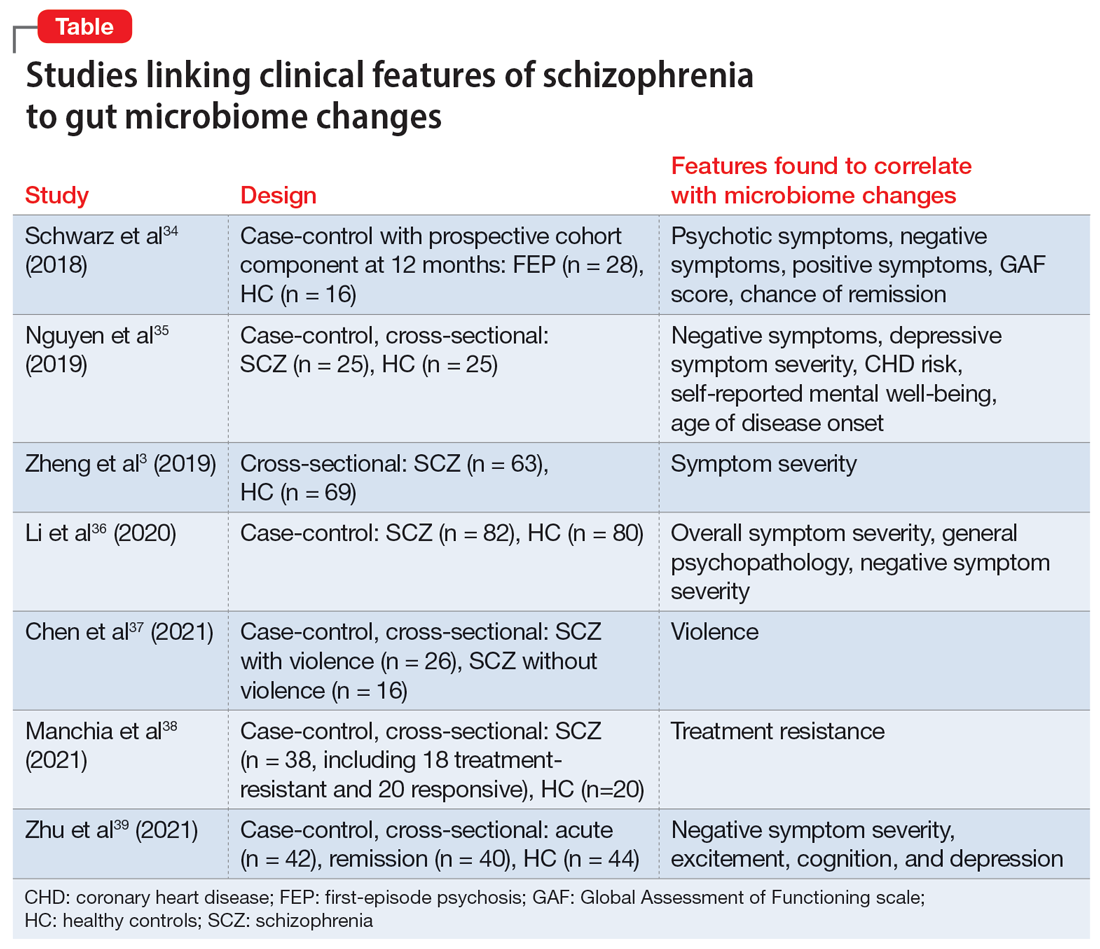

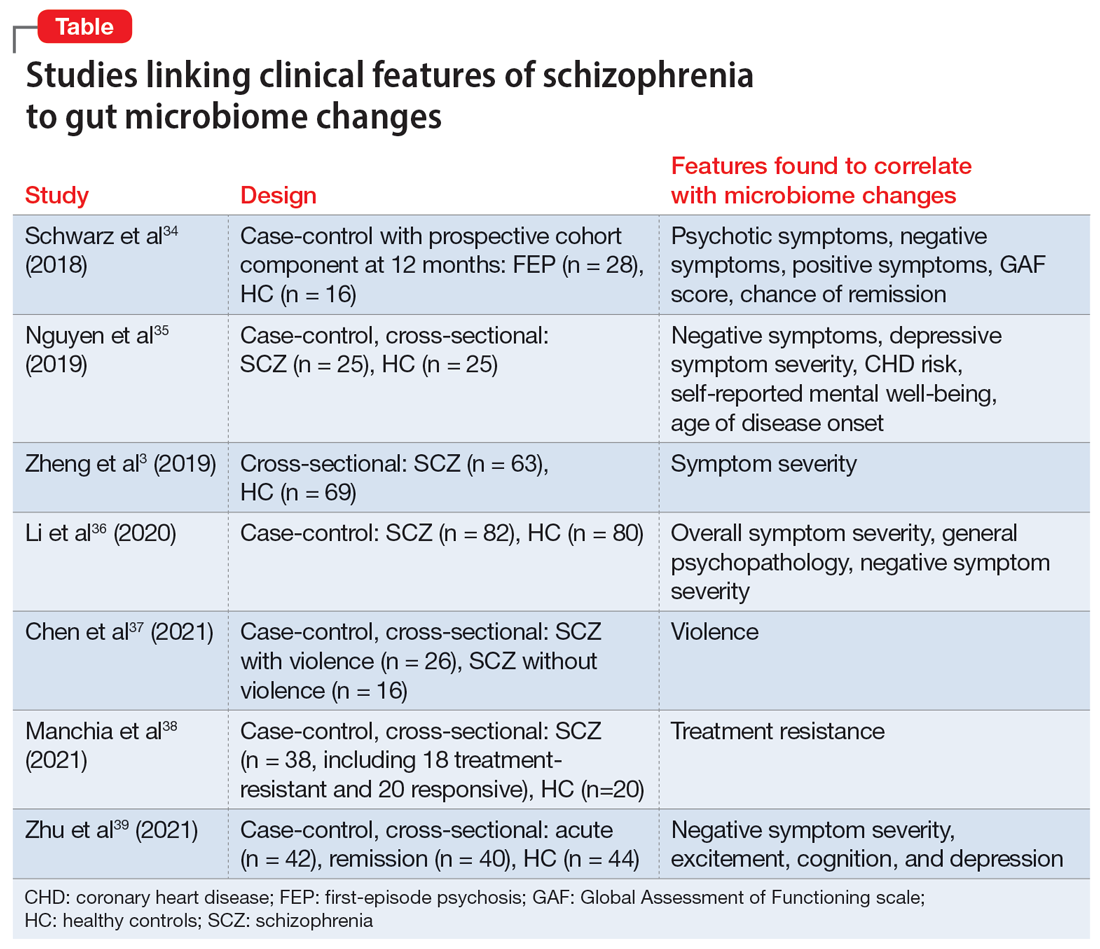

Researchers have begun to investigate ways in which the gut microbiome varies regarding the clinical symptoms of psychosis.33 The Table3,34-39 provides an overview of 7 human studies of gut microbiome changes relating to clinical features of schizophrenia. In these studies, researchers have found correlations between the gut microbiome and a tendency toward violence,37 cognitive deficits,34-36,39 depressive symptoms,35,39 and numerous other clinical features of psychosis. Most of these correlations have not yet been replicated by further studies. But among studies with similar clinical questions, 3 reported changes in gut microbiome correlated with overall symptom severity, and 4 studies correlated changes with negative symptom severity. In 2 studies,3,34 Lachnospiraceae was correlated with worsened symptom severity. However, this may have been the result of poor control for antipsychotic use, as 1 study in bipolar patients found that Lachnospiraceae was increased in those taking antipsychotics compared to those who were not treated with antipsychotics.40 The specific shifts in bacteria seen for overall symptom and negative symptom severity were not consistent across studies. This is not surprising because the gut microbiome varies with diet and geographic region,41 and patients in these studies were from a variety of regions. Multiple studies demonstrated gut microbiome alterations for patients with more severe negative symptoms. This is particularly interesting because negative symptoms are often difficult to treat and do not respond to antipsychotics.42 This research suggests the gut microbiome may be helpful in developing future treatments for patients with negative symptoms that do not respond to existing treatments.

Research of probiotic supplementation for ameliorating symptoms of schizophrenia has yielded mixed results.43 It is possible that studies of probiotic supplementation have failed to consider the variations in the gut microbiome among individuals with schizophrenia. A better understanding of the variations in gut microbiome may allow for the development of more personalized interventions.

Recommendations for a healthy gut microbiome

In addition to antipsychotics, many other evidence-based interventions can be used to help restore a healthy gut microbiome in patients with schizophrenia. To improve the gut microbiome, we suggest discussing the following changes with patients:

- Quitting smoking. Smoking is common among patients with schizophrenia but decreases gut microbiome diversity.44

- Avoiding excessive alcohol use. Excessive alcohol use contributes to dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability.45 Moderate alcohol consumption does not appear to have the same harmful effects on the microbiome.46

- Avoiding the use of recreational drugs, including marijuana, which impact the gut microbiome.47

- Consuming a diet rich in fiber.48 Presently, there is not enough evidence to recommend probiotic supplementation to reduce symptoms of schizophrenia.41 Similar to probiotics, fermented foods contain Lactobacillus, a bacterial species that produces lactic acid.49 Lactobacillus is enriched in the gut microbiome in some neurodegenerative diseases, and lactic acid can be neurotoxic at high levels.50-52 Therefore, clinicians should not explicitly recommend fermented foods under the assumption of improved brain health. A diet rich in soluble fiber has been consistently shown to promote anti-inflammatory bacteria and is much more likely to be beneficial.53,54 Soluble fiber is found in foods such as fruits, vegetables, beans, and oats.

- Exercising can increase microbiome diversity and provide anti-inflammatory effects in the gut.55,56 A recent review found that steady-state aerobic and high-intensity exercise interventions have positive effects on mood, cognition, and other negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.55

- Minimizing stress. Psychological stress and physiological stress from untreated medical conditions are toxic to healthy gut bacteria and weaken the gut barrier.57

- Mitigating exposure to pollution. Environmental pollution, including exposures to air pollution, heavy metals, and pesticides, disrupts the gut microbiome.58

The American Heart Association publishes lifestyle recommendations for individuals with heart disease and the National Institutes of Health publishes lifestyle recommendations for patients with chronic kidney disease. This leads us to question why the American Psychiatric Association has not published lifestyle recommendations for those with severe mental illness. The effects of lifestyle on both the gut microbiome and symptom mitigation is critical. With increasingly shortened appointments, standardized guidelines would benefit psychiatrists and patients alike.

Bottom Line

The gut microbiome is connected to the clinical symptoms of psychosis via a variety of hormonal, neuroimmune, and metabolic mechanisms active across the lifespan. Despite advances in research, there is still much to be understood regarding this relationship. Clinicians should discuss with patients ways to promote a healthy gut microbiome, including consuming a diet rich in fiber, avoiding use of recreational drugs, and exercising regularly.

Related Resources

- Nocera A, Nasrallah HA. The association of the gut microbiota with clinical features in schizophrenia. Behav Sci. 2022;12(4):89.

- Nasrallah HA. It takes guts to be mentally ill: microbiota and psychopathology. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(9):4-6.

1. Bäckhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, et al. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307(5717):1915-1920. doi:10.1126/science.1104816

2. Jackson SW. Galen—on mental disorders. J Hist Behav Sci. 1969;5(4):365-384. doi:10.1002/1520-6696(196910)5:4<365::AID-JHBS2300050408>3.0.CO;2-9

3. Zheng P, Zeng B, Liu M, et al. The gut microbiome from patients with schizophrenia modulates the glutamate-glutamine-GABA cycle and schizophrenia-relevant behaviors in mice. Sci Adv. 2019;5(2):eaau8317. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aau8317

4. Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511(7510):421-427. doi:10.1038/nature13595

5. Gill SR, Pop M, DeBoy RT, et al. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science. 2006;312(5778):1355-1359. doi:10.1126/science.1124234

6. Alam R, Abdolmaleky HM, Zhou JR. Microbiome, inflammation, epigenetic alterations, and mental diseases. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2017;174(6):651-660. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.32567

7. Cryan JF, O’Riordan KJ, Cowan CSM, et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(4):1877-2013. doi:10.1152/physrev.00018.2018

8. Mueller NT, Bakacs E, Combellick J, et al. The infant microbiome development: mom matters. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21(2):109-117. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2014.12.002

9. Fouhy F, Watkins C, Hill CJ, et al. Perinatal factors affect the gut microbiota up to four years after birth. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1517. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09252-4

10. Sharon G, Sampson TR, Geschwind DH, et al. The central nervous system and the gut microbiome. Cell. 2016;167(4):915-932. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.027

11. Hill CJ, Lynch DB, Murphy K, et al. Evolution of gut microbiota composition from birth to 24 weeks in the INFANTMET Cohort. Microbiome. 2017;5:4. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0213-y

12. Gareau MG, Wine E, Rodrigues DM, et al. Bacterial infection causes stress-induced memory dysfunction in mice. Gut. 2011;60(3):307-317. doi:10.1136/gut.2009.202515

13. Bokulich NA, Chung J, Battaglia T, et al. Antibiotics, birth mode, and diet shape microbiome maturation during early life. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(343):343ra82. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7121

14. Mancabelli L, Milani C, Lugli GA, et al. Meta-analysis of the human gut microbiome from urbanized and pre-agricultural populations. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19(4):1379-1390. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.13692

15. Stilo SA, Murray RM. Non-genetic factors in schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(10):100. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-1091-3

16. Buscaino VM. Patologia extraneurale della schizofrenia: fegato, tubo digerente, sistema reticolo-endoteliale. Acta Neurologica. 1953;VIII:1-60.

17. Hemmings G. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2004;364(9442):1312-1313. doi:10.1016/S0140- 6736(04)17181-X

18. Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Commensal host-bacterial relationships in the gut. Science. 2001;292(5519):1115-1118. doi:10.1126/science.1058709

19. Ewaschuk JB, Diaz H, Meddings L, et al. Secreted bioactive factors from Bifidobacterium infantis enhance epithelial cell barrier function. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295(5):G1025-G1034. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.90227.2008

20. Alhasson F, Das S, Seth R, et al. Altered gut microbiome in a mouse model of Gulf War Illness causes neuroinflammation and intestinal injury via leaky gut and TLR4 activation. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0172914. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172914

21. Fillman SG, Cloonan N, Catts VS, et al. Increased inflammatory markers identified in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(2):206-214. doi:10.1038/mp.2012.110

22. Miller BJ, Buckley P, Seabolt W, et al. Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(7):663-671. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.04.013

23. Al-Amin M, Uddin MMN, Reza HM. Effects of antipsychotics on the inflammatory response system of patients with schizophrenia in peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2013;11(3):144-151. doi:10.9758/cpn.2013.11.3.144

24. Yuan X, Zhang P, Wang Y, et al. Changes in metabolism and microbiota after 24-week risperidone treatment in drug naïve, normal weight patients with first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;201:299-306. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2018.05.017

25. Maier L, Pruteanu M, Kuhn M, et al. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature. 2018;555(7698):623-628. doi:10.1038/nature25979

26. Dickerson FB, Stallings C, Origoni A, et al. Effect of probiotic supplementation on schizophrenia symptoms and association with gastrointestinal functioning: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;15(1):PCC.13m01579. doi:10.4088/PCC.13m01579

27. David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505(7484):559-563. doi:10.1038/nature12820

28. Bien J, Palagani V, Bozko P. The intestinal microbiota dysbiosis and Clostridium difficile infection: is there a relationship with inflammatory bowel disease? Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6(1):53-68. doi:10.1177/1756283X12454590

29. Cryan JF, O’Riordan KJ, Sandhu K, et al. The gut microbiome in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(2):179-194. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30356-4

30. Jones CA, Watson DJG, Fone KCF. Animal models of schizophrenia. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(4):1162-1194. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01386.x

31. Schmidt MJ, Mirnics K. Neurodevelopment, GABA system dysfunction, and schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(1):190-206. doi:10.1038/npp.2014.95

32. Nasrallah, HA. The daunting challenge of schizophrenia: hundreds of biotypes and dozens of theories. Curr. Psychiatry 2018;17(12):4-6,50.

33. Nocera A, Nasrallah HA. The association of the gut microbiota with clinical features in schizophrenia. Behav Sci (Basel). 2022;12(4):89. doi:10.3390/bs12040089

34. Schwarz E, Maukonen J, Hyytiäinen T, et al. Analysis of microbiota in first episode psychosis identifies preliminary associations with symptom severity and treatment response. Schizophr Res. 2018;192:398-403. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2017.04.017

35. Nguyen TT, Kosciolek T, Maldonado Y, et al. Differences in gut microbiome composition between persons with chronic schizophrenia and healthy comparison subjects. Schizophr Res. 2019;204:23-29. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2018.09.014

36. Li S, Zhuo M, Huang X, et al. Altered gut microbiota associated with symptom severity in schizophrenia. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9574. doi:10.7717/peerj.9574

37. Chen X, Xu J, Wang H, et al. Profiling the differences of gut microbial structure between schizophrenia patients with and without violent behaviors based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Int J Legal Med. 2021;135(1):131-141. doi:10.1007/s00414-020-02439-1

38. Manchia M, Fontana A, Panebianco C, et al. Involvement of gut microbiota in schizophrenia and treatment resistance to antipsychotics. Biomedicines. 2021;9(8):875. doi:10.3390/biomedicines9080875

39. Zhu C, Zheng M, Ali U, et al. Association between abundance of haemophilus in the gut microbiota and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:685910. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.685910

40. Flowers SA, Evans SJ, Ward KM, et al. Interaction between atypical antipsychotics and the gut microbiome in a bipolar disease cohort. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37(3):261-267. doi:10.1002/phar.1890

41. Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486(7402):222-227. doi:10.1038/nature11053

42. Buchanan RW. Persistent negative symptoms in schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(4):1013-1022. doi:10.1093/schbul/sb1057

43. Liu JCW, Gorbovskaya I, Hahn MK, et al. The gut microbiome in schizophrenia and the potential benefits of prebiotic and probiotic treatment. Nutrients. 2021;13(4):1152. doi:10.3390/nu13041152

44. Biedermann L, Zeitz J, Mwinyi J, et al. Smoking cessation induces profound changes in the composition of the intestinal microbiota in humans. PloS One. 2013;8(3):e59260. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059260

45. Leclercq S, Matamoros S, Cani PD, et al. Intestinal permeability, gut-bacterial dysbiosis, and behavioral markers of alcohol-dependence severity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(42):e4485-e4493. doi:10.1073/pnas.1415174111

46. Hernández-Quiroz F, Nirmalkar K, Villalobos-Flores LE, et al. Influence of moderate beer consumption on human gut microbiota and its impact on fasting glucose and ß-cell function. Alcohol. 2020;85:77-94. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2019.05.006

47. Panee J, Gerschenson M, Chang L. Associations between microbiota, mitochondrial function, and cognition in chronic marijuana users. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2018;13(1):113-122. doi:10.1007/s11481-017-9767-0

48. Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334(6052):105-108. doi:10.1126/science.1208344

49. Rezac S, Kok CR, Heermann M, et al. Fermented foods as a dietary source of live organisms. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1785. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01785

50. Chen X, Zhang Y, Wang H, et al. The regulatory effects of lactic acid on neuropsychiatric disorders. Discover Ment Health. 2022;2(1). doi:10.1007/s44192-022-00011-4

51. Karbownik MS, Mokros Ł, Dobielska M, et al. Association between consumption of fermented food and food-derived prebiotics with cognitive performance, depressive, and anxiety symptoms in psychiatrically healthy medical students under psychological stress: a prospective cohort study. Front Nutr. 2022;9:850249. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.850249

52. Romano S, Savva GM, Bedarf JR, et al. Meta-analysis of the Parkinson’s disease gut microbiome suggests alterations linked to intestinal inflammation. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2021;7(1):27. doi:10.1038/s41531-021-00156-z

53. Bourassa MW, Alim I, Bultman SJ, et al. Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: can a high fiber diet improve brain health? Neurosci Lett. 2016;625:56-63. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2016.02.009

54. Matt SM, Allen JM, Lawson MA, et al. Butyrate and dietary soluble fiber improve neuroinflammation associated with aging in mice. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1832. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01832

55. Mittal VA, Vargas T, Osborne KJ, et al. Exercise treatments for psychosis: a review. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2017;4(2):152-166. doi:10.1007/s40501-017-0112-2

56. Estaki M, Pither J, Baumeister P, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a predictor of intestinal microbial diversity and distinct metagenomic functions. Microbiome. 2016;4(1):42. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0189-7

57. Karl JP, Margolis LM, Madslien EH, et al. Changes in intestinal microbiota composition and metabolism coincide with increased intestinal permeability in young adults under prolonged physiological stress. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2017;312(6):G559-G571. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00066.2017

58. Claus SP, Guillou H, Ellero-Simatos S. The gut microbiota: a major player in the toxicity of environmental pollutants? NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2016;2:16003. doi:10.1038/npjbiofilms.2016.3

The human microbiota refers to the collection of bacteria, archaea, eukarya, and viruses that reside within the human body. The term gut microbiome indicates the composition of these microbes and genetic codes in the intestine.1 Harkening back to the ancient Greek physician Galen, who treated gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms to relieve mental disturbances such as psychosis, the gut has been a therapeutic target in schizophrenia long before antipsychotics and the DSM.2 In recent years, research into the gut microbiome has drastically increased, with genetic sequencing affording a more precise look into the specific bacteria that call the human intestines their home. This has led to the recognition that the gut microbiome may be severely disrupted in schizophrenia, a condition known as dysbiosis. Preliminary research suggests that gut bacteria are more helpful than many human genes in distinguishing individuals with schizophrenia from their healthy counterparts.3,4 In this article, we discuss the potential role of the gut microbiome in schizophrenia, including new research correlating clinical symptoms of psychosis with dysbiosis. We also provide recommendations for promoting a healthy gut microbiome.

The enteric brain across life

The composition of our bodies is far more microbiota than human. Strikingly, microbiota cells in the gut outnumber human cells, and the distal gut alone hosts bacteria with 100 times the genetic content of the entire genome.5 The intricate meshwork of nerves in the gut is often called the enteric brain because the gut consists of 100 million neurons and synthesizes many neuroactive chemicals implicated in mood disorders and psychosis, including serotonin, dopamine, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and acetylcholine.6 The variety of neuroimmunologic, hormonal, and metabolic paths by which the gut microbiome and the brain interact are collectively known as the gut-microbiota-brain axis.7

How do we acquire our gut microbiome, and how does it come to influence our brain and behavior? On the first day of life, as babies pass through the birth canal, they are bathed in their mother’s vaginal microbiota. In the following weeks, the microbiome expands and colonizes the gut as bacteria are introduced from environmental sources such as skin-to-skin contact and breastmilk.8 The microbiome continues to evolve throughout early life. As children expand their diets and navigate new aspects of the physical world, additional bacteria join the unseen ecosystem growing inside.9 The development of the microbiome coincides with the development of the brain. From preclinical studies, we know the gut microbiome mediates important aspects of neurodevelopment such as the formation of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), synaptic pruning, glial activation, and myelination.10 Interestingly, many of the risk factors for schizophrenia are associated with gut dysbiosis, including obstetric complications, infections treated with antibiotics, and urbanization.11-15

Throughout human life, the gut and brain remain in close communication. The gut microbiota continue to produce monoamines, along with other metabolites that are able to cross the BBB.6 The HPA axis, stimulation of the immune system, and the vagus nerve all provide highways of communication between the gut and the brain.7 The relationship between the enteric brain and cephalic brain continues through life, even up to a person’s final hour. One autopsy study that is often cited (but soberingly, cannot be found online) allegedly revealed that 92% of schizophrenia patients had developed colitis by the time of death.16,17

First-episode psychosis and antipsychotic treatment

For patients with schizophrenia, first-episode psychosis (FEP) represents a cocktail of mounting genetic and environmental factors. Typically, by the time a patient receives psychiatric care, they present with characteristic psychotic symptoms—hallucinations, delusions, bizarre behavior, and unusual thought process—along with a unique gut microbiome profile.

This disrupted microbiome coincides with a marked state of inflammation in the intestines. Inflammation triggers increased endothelial barrier permeability, similar to the way immune signals increase capillary permeability to allow immune cells into the periphery of the blood. Specific gut bacteria play specific roles in maintaining the gut barrier.18,19 Disruptions in the bacteria that maintain the gut barrier, combined with inflammation, contribute to a leaky gut. A leaky gut barrier allows bacterial and immune products to more easily enter the bloodstream and then the brain, which is a potential source of neuroinflammation in schizophrenia.20 This increase in gut permeability (leaky gut syndrome) is likely one of several reasons low-grade inflammation is common in schizophrenia—numerous studies show higher serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines along with antibacterial immunoglobulins in patients with FEP.21,22

Fortunately, antipsychotics, especially the second-generation agents, help restore a healthy gut microbiome and have substantial anti-inflammatory properties.23,24 These medications interact heavily with the gut microbiome: they have been found to have antibiotic properties, even in doses lower than would normally reach the gut microbiome.25 In humans, a randomized controlled trial of probiotic supplementation for schizophrenia patients taking antipsychotics showed a reduction in GI symptoms but no significant improvement in psychotic symptoms.26

Dysbiosis in schizophrenia: cause or effect?

There is no consensus on what constitutes a healthy gut microbiome because the gut microbiome is highly variable, even among healthy individuals, and can change quickly. Those who adopt new diets, for example, see drastic shifts in the gut microbiome within a few days.27 Despite this variation, the main separation between a healthy and dysbiotic gut comes from the diversity of bacteria present in the gut—a healthy gut microbiome is associated with increased diversity. Numerous disease states have been associated with decreased bacterial diversity, including Clostridium difficile infection, Parkinson disease, depression, Crohn disease, and schizophrenia spectrum disorders.28,29

Although there are ethical limitations to studying causality in humans directly, animal models have provided a great deal of insight into the gut microbiome’s role in the development of schizophrenia. A recent study used fecal transplant to provide the gut microbiome from patients with schizophrenia to a group of germ-free mice and compared these animals to a group of mice that received a fecal transplant from individuals with a healthy gut microbiome. The mice receiving the schizophrenia microbiome showed an increased startle response and hyperactivity.3 This was consistent with mouse models of schizophrenia, although with obvious limitations.30 In addition, the brains of these animals showed changes in glutamate, glutamine, and GABA in the hippocampus; these chemicals play a role in the neurophysiology of schizophrenia.3,31 This study has not yet been replicated, and considerable variation remains within the schizophrenia biosignature.

Continue to: Clinical symptoms of psychosis and the gut microbiome

Clinical symptoms of psychosis and the gut microbiome

Previous literature has grouped patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders as 1 unified study group. But as is the case with many psychiatric conditions, there is a great deal of heterogeneity in neurobiology, genetics, and microbiome composition among individuals with schizophrenia.32

Researchers have begun to investigate ways in which the gut microbiome varies regarding the clinical symptoms of psychosis.33 The Table3,34-39 provides an overview of 7 human studies of gut microbiome changes relating to clinical features of schizophrenia. In these studies, researchers have found correlations between the gut microbiome and a tendency toward violence,37 cognitive deficits,34-36,39 depressive symptoms,35,39 and numerous other clinical features of psychosis. Most of these correlations have not yet been replicated by further studies. But among studies with similar clinical questions, 3 reported changes in gut microbiome correlated with overall symptom severity, and 4 studies correlated changes with negative symptom severity. In 2 studies,3,34 Lachnospiraceae was correlated with worsened symptom severity. However, this may have been the result of poor control for antipsychotic use, as 1 study in bipolar patients found that Lachnospiraceae was increased in those taking antipsychotics compared to those who were not treated with antipsychotics.40 The specific shifts in bacteria seen for overall symptom and negative symptom severity were not consistent across studies. This is not surprising because the gut microbiome varies with diet and geographic region,41 and patients in these studies were from a variety of regions. Multiple studies demonstrated gut microbiome alterations for patients with more severe negative symptoms. This is particularly interesting because negative symptoms are often difficult to treat and do not respond to antipsychotics.42 This research suggests the gut microbiome may be helpful in developing future treatments for patients with negative symptoms that do not respond to existing treatments.

Research of probiotic supplementation for ameliorating symptoms of schizophrenia has yielded mixed results.43 It is possible that studies of probiotic supplementation have failed to consider the variations in the gut microbiome among individuals with schizophrenia. A better understanding of the variations in gut microbiome may allow for the development of more personalized interventions.

Recommendations for a healthy gut microbiome

In addition to antipsychotics, many other evidence-based interventions can be used to help restore a healthy gut microbiome in patients with schizophrenia. To improve the gut microbiome, we suggest discussing the following changes with patients:

- Quitting smoking. Smoking is common among patients with schizophrenia but decreases gut microbiome diversity.44

- Avoiding excessive alcohol use. Excessive alcohol use contributes to dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability.45 Moderate alcohol consumption does not appear to have the same harmful effects on the microbiome.46

- Avoiding the use of recreational drugs, including marijuana, which impact the gut microbiome.47

- Consuming a diet rich in fiber.48 Presently, there is not enough evidence to recommend probiotic supplementation to reduce symptoms of schizophrenia.41 Similar to probiotics, fermented foods contain Lactobacillus, a bacterial species that produces lactic acid.49 Lactobacillus is enriched in the gut microbiome in some neurodegenerative diseases, and lactic acid can be neurotoxic at high levels.50-52 Therefore, clinicians should not explicitly recommend fermented foods under the assumption of improved brain health. A diet rich in soluble fiber has been consistently shown to promote anti-inflammatory bacteria and is much more likely to be beneficial.53,54 Soluble fiber is found in foods such as fruits, vegetables, beans, and oats.

- Exercising can increase microbiome diversity and provide anti-inflammatory effects in the gut.55,56 A recent review found that steady-state aerobic and high-intensity exercise interventions have positive effects on mood, cognition, and other negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.55

- Minimizing stress. Psychological stress and physiological stress from untreated medical conditions are toxic to healthy gut bacteria and weaken the gut barrier.57

- Mitigating exposure to pollution. Environmental pollution, including exposures to air pollution, heavy metals, and pesticides, disrupts the gut microbiome.58

The American Heart Association publishes lifestyle recommendations for individuals with heart disease and the National Institutes of Health publishes lifestyle recommendations for patients with chronic kidney disease. This leads us to question why the American Psychiatric Association has not published lifestyle recommendations for those with severe mental illness. The effects of lifestyle on both the gut microbiome and symptom mitigation is critical. With increasingly shortened appointments, standardized guidelines would benefit psychiatrists and patients alike.

Bottom Line

The gut microbiome is connected to the clinical symptoms of psychosis via a variety of hormonal, neuroimmune, and metabolic mechanisms active across the lifespan. Despite advances in research, there is still much to be understood regarding this relationship. Clinicians should discuss with patients ways to promote a healthy gut microbiome, including consuming a diet rich in fiber, avoiding use of recreational drugs, and exercising regularly.

Related Resources

- Nocera A, Nasrallah HA. The association of the gut microbiota with clinical features in schizophrenia. Behav Sci. 2022;12(4):89.

- Nasrallah HA. It takes guts to be mentally ill: microbiota and psychopathology. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(9):4-6.

The human microbiota refers to the collection of bacteria, archaea, eukarya, and viruses that reside within the human body. The term gut microbiome indicates the composition of these microbes and genetic codes in the intestine.1 Harkening back to the ancient Greek physician Galen, who treated gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms to relieve mental disturbances such as psychosis, the gut has been a therapeutic target in schizophrenia long before antipsychotics and the DSM.2 In recent years, research into the gut microbiome has drastically increased, with genetic sequencing affording a more precise look into the specific bacteria that call the human intestines their home. This has led to the recognition that the gut microbiome may be severely disrupted in schizophrenia, a condition known as dysbiosis. Preliminary research suggests that gut bacteria are more helpful than many human genes in distinguishing individuals with schizophrenia from their healthy counterparts.3,4 In this article, we discuss the potential role of the gut microbiome in schizophrenia, including new research correlating clinical symptoms of psychosis with dysbiosis. We also provide recommendations for promoting a healthy gut microbiome.

The enteric brain across life

The composition of our bodies is far more microbiota than human. Strikingly, microbiota cells in the gut outnumber human cells, and the distal gut alone hosts bacteria with 100 times the genetic content of the entire genome.5 The intricate meshwork of nerves in the gut is often called the enteric brain because the gut consists of 100 million neurons and synthesizes many neuroactive chemicals implicated in mood disorders and psychosis, including serotonin, dopamine, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and acetylcholine.6 The variety of neuroimmunologic, hormonal, and metabolic paths by which the gut microbiome and the brain interact are collectively known as the gut-microbiota-brain axis.7

How do we acquire our gut microbiome, and how does it come to influence our brain and behavior? On the first day of life, as babies pass through the birth canal, they are bathed in their mother’s vaginal microbiota. In the following weeks, the microbiome expands and colonizes the gut as bacteria are introduced from environmental sources such as skin-to-skin contact and breastmilk.8 The microbiome continues to evolve throughout early life. As children expand their diets and navigate new aspects of the physical world, additional bacteria join the unseen ecosystem growing inside.9 The development of the microbiome coincides with the development of the brain. From preclinical studies, we know the gut microbiome mediates important aspects of neurodevelopment such as the formation of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), synaptic pruning, glial activation, and myelination.10 Interestingly, many of the risk factors for schizophrenia are associated with gut dysbiosis, including obstetric complications, infections treated with antibiotics, and urbanization.11-15

Throughout human life, the gut and brain remain in close communication. The gut microbiota continue to produce monoamines, along with other metabolites that are able to cross the BBB.6 The HPA axis, stimulation of the immune system, and the vagus nerve all provide highways of communication between the gut and the brain.7 The relationship between the enteric brain and cephalic brain continues through life, even up to a person’s final hour. One autopsy study that is often cited (but soberingly, cannot be found online) allegedly revealed that 92% of schizophrenia patients had developed colitis by the time of death.16,17

First-episode psychosis and antipsychotic treatment

For patients with schizophrenia, first-episode psychosis (FEP) represents a cocktail of mounting genetic and environmental factors. Typically, by the time a patient receives psychiatric care, they present with characteristic psychotic symptoms—hallucinations, delusions, bizarre behavior, and unusual thought process—along with a unique gut microbiome profile.

This disrupted microbiome coincides with a marked state of inflammation in the intestines. Inflammation triggers increased endothelial barrier permeability, similar to the way immune signals increase capillary permeability to allow immune cells into the periphery of the blood. Specific gut bacteria play specific roles in maintaining the gut barrier.18,19 Disruptions in the bacteria that maintain the gut barrier, combined with inflammation, contribute to a leaky gut. A leaky gut barrier allows bacterial and immune products to more easily enter the bloodstream and then the brain, which is a potential source of neuroinflammation in schizophrenia.20 This increase in gut permeability (leaky gut syndrome) is likely one of several reasons low-grade inflammation is common in schizophrenia—numerous studies show higher serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines along with antibacterial immunoglobulins in patients with FEP.21,22

Fortunately, antipsychotics, especially the second-generation agents, help restore a healthy gut microbiome and have substantial anti-inflammatory properties.23,24 These medications interact heavily with the gut microbiome: they have been found to have antibiotic properties, even in doses lower than would normally reach the gut microbiome.25 In humans, a randomized controlled trial of probiotic supplementation for schizophrenia patients taking antipsychotics showed a reduction in GI symptoms but no significant improvement in psychotic symptoms.26

Dysbiosis in schizophrenia: cause or effect?

There is no consensus on what constitutes a healthy gut microbiome because the gut microbiome is highly variable, even among healthy individuals, and can change quickly. Those who adopt new diets, for example, see drastic shifts in the gut microbiome within a few days.27 Despite this variation, the main separation between a healthy and dysbiotic gut comes from the diversity of bacteria present in the gut—a healthy gut microbiome is associated with increased diversity. Numerous disease states have been associated with decreased bacterial diversity, including Clostridium difficile infection, Parkinson disease, depression, Crohn disease, and schizophrenia spectrum disorders.28,29

Although there are ethical limitations to studying causality in humans directly, animal models have provided a great deal of insight into the gut microbiome’s role in the development of schizophrenia. A recent study used fecal transplant to provide the gut microbiome from patients with schizophrenia to a group of germ-free mice and compared these animals to a group of mice that received a fecal transplant from individuals with a healthy gut microbiome. The mice receiving the schizophrenia microbiome showed an increased startle response and hyperactivity.3 This was consistent with mouse models of schizophrenia, although with obvious limitations.30 In addition, the brains of these animals showed changes in glutamate, glutamine, and GABA in the hippocampus; these chemicals play a role in the neurophysiology of schizophrenia.3,31 This study has not yet been replicated, and considerable variation remains within the schizophrenia biosignature.

Continue to: Clinical symptoms of psychosis and the gut microbiome

Clinical symptoms of psychosis and the gut microbiome

Previous literature has grouped patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders as 1 unified study group. But as is the case with many psychiatric conditions, there is a great deal of heterogeneity in neurobiology, genetics, and microbiome composition among individuals with schizophrenia.32

Researchers have begun to investigate ways in which the gut microbiome varies regarding the clinical symptoms of psychosis.33 The Table3,34-39 provides an overview of 7 human studies of gut microbiome changes relating to clinical features of schizophrenia. In these studies, researchers have found correlations between the gut microbiome and a tendency toward violence,37 cognitive deficits,34-36,39 depressive symptoms,35,39 and numerous other clinical features of psychosis. Most of these correlations have not yet been replicated by further studies. But among studies with similar clinical questions, 3 reported changes in gut microbiome correlated with overall symptom severity, and 4 studies correlated changes with negative symptom severity. In 2 studies,3,34 Lachnospiraceae was correlated with worsened symptom severity. However, this may have been the result of poor control for antipsychotic use, as 1 study in bipolar patients found that Lachnospiraceae was increased in those taking antipsychotics compared to those who were not treated with antipsychotics.40 The specific shifts in bacteria seen for overall symptom and negative symptom severity were not consistent across studies. This is not surprising because the gut microbiome varies with diet and geographic region,41 and patients in these studies were from a variety of regions. Multiple studies demonstrated gut microbiome alterations for patients with more severe negative symptoms. This is particularly interesting because negative symptoms are often difficult to treat and do not respond to antipsychotics.42 This research suggests the gut microbiome may be helpful in developing future treatments for patients with negative symptoms that do not respond to existing treatments.

Research of probiotic supplementation for ameliorating symptoms of schizophrenia has yielded mixed results.43 It is possible that studies of probiotic supplementation have failed to consider the variations in the gut microbiome among individuals with schizophrenia. A better understanding of the variations in gut microbiome may allow for the development of more personalized interventions.

Recommendations for a healthy gut microbiome

In addition to antipsychotics, many other evidence-based interventions can be used to help restore a healthy gut microbiome in patients with schizophrenia. To improve the gut microbiome, we suggest discussing the following changes with patients:

- Quitting smoking. Smoking is common among patients with schizophrenia but decreases gut microbiome diversity.44

- Avoiding excessive alcohol use. Excessive alcohol use contributes to dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability.45 Moderate alcohol consumption does not appear to have the same harmful effects on the microbiome.46

- Avoiding the use of recreational drugs, including marijuana, which impact the gut microbiome.47

- Consuming a diet rich in fiber.48 Presently, there is not enough evidence to recommend probiotic supplementation to reduce symptoms of schizophrenia.41 Similar to probiotics, fermented foods contain Lactobacillus, a bacterial species that produces lactic acid.49 Lactobacillus is enriched in the gut microbiome in some neurodegenerative diseases, and lactic acid can be neurotoxic at high levels.50-52 Therefore, clinicians should not explicitly recommend fermented foods under the assumption of improved brain health. A diet rich in soluble fiber has been consistently shown to promote anti-inflammatory bacteria and is much more likely to be beneficial.53,54 Soluble fiber is found in foods such as fruits, vegetables, beans, and oats.

- Exercising can increase microbiome diversity and provide anti-inflammatory effects in the gut.55,56 A recent review found that steady-state aerobic and high-intensity exercise interventions have positive effects on mood, cognition, and other negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.55

- Minimizing stress. Psychological stress and physiological stress from untreated medical conditions are toxic to healthy gut bacteria and weaken the gut barrier.57

- Mitigating exposure to pollution. Environmental pollution, including exposures to air pollution, heavy metals, and pesticides, disrupts the gut microbiome.58

The American Heart Association publishes lifestyle recommendations for individuals with heart disease and the National Institutes of Health publishes lifestyle recommendations for patients with chronic kidney disease. This leads us to question why the American Psychiatric Association has not published lifestyle recommendations for those with severe mental illness. The effects of lifestyle on both the gut microbiome and symptom mitigation is critical. With increasingly shortened appointments, standardized guidelines would benefit psychiatrists and patients alike.

Bottom Line

The gut microbiome is connected to the clinical symptoms of psychosis via a variety of hormonal, neuroimmune, and metabolic mechanisms active across the lifespan. Despite advances in research, there is still much to be understood regarding this relationship. Clinicians should discuss with patients ways to promote a healthy gut microbiome, including consuming a diet rich in fiber, avoiding use of recreational drugs, and exercising regularly.

Related Resources

- Nocera A, Nasrallah HA. The association of the gut microbiota with clinical features in schizophrenia. Behav Sci. 2022;12(4):89.

- Nasrallah HA. It takes guts to be mentally ill: microbiota and psychopathology. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(9):4-6.

1. Bäckhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, et al. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307(5717):1915-1920. doi:10.1126/science.1104816

2. Jackson SW. Galen—on mental disorders. J Hist Behav Sci. 1969;5(4):365-384. doi:10.1002/1520-6696(196910)5:4<365::AID-JHBS2300050408>3.0.CO;2-9

3. Zheng P, Zeng B, Liu M, et al. The gut microbiome from patients with schizophrenia modulates the glutamate-glutamine-GABA cycle and schizophrenia-relevant behaviors in mice. Sci Adv. 2019;5(2):eaau8317. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aau8317

4. Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511(7510):421-427. doi:10.1038/nature13595

5. Gill SR, Pop M, DeBoy RT, et al. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science. 2006;312(5778):1355-1359. doi:10.1126/science.1124234

6. Alam R, Abdolmaleky HM, Zhou JR. Microbiome, inflammation, epigenetic alterations, and mental diseases. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2017;174(6):651-660. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.32567

7. Cryan JF, O’Riordan KJ, Cowan CSM, et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(4):1877-2013. doi:10.1152/physrev.00018.2018

8. Mueller NT, Bakacs E, Combellick J, et al. The infant microbiome development: mom matters. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21(2):109-117. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2014.12.002

9. Fouhy F, Watkins C, Hill CJ, et al. Perinatal factors affect the gut microbiota up to four years after birth. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1517. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09252-4

10. Sharon G, Sampson TR, Geschwind DH, et al. The central nervous system and the gut microbiome. Cell. 2016;167(4):915-932. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.027

11. Hill CJ, Lynch DB, Murphy K, et al. Evolution of gut microbiota composition from birth to 24 weeks in the INFANTMET Cohort. Microbiome. 2017;5:4. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0213-y

12. Gareau MG, Wine E, Rodrigues DM, et al. Bacterial infection causes stress-induced memory dysfunction in mice. Gut. 2011;60(3):307-317. doi:10.1136/gut.2009.202515

13. Bokulich NA, Chung J, Battaglia T, et al. Antibiotics, birth mode, and diet shape microbiome maturation during early life. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(343):343ra82. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7121

14. Mancabelli L, Milani C, Lugli GA, et al. Meta-analysis of the human gut microbiome from urbanized and pre-agricultural populations. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19(4):1379-1390. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.13692

15. Stilo SA, Murray RM. Non-genetic factors in schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(10):100. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-1091-3

16. Buscaino VM. Patologia extraneurale della schizofrenia: fegato, tubo digerente, sistema reticolo-endoteliale. Acta Neurologica. 1953;VIII:1-60.

17. Hemmings G. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2004;364(9442):1312-1313. doi:10.1016/S0140- 6736(04)17181-X

18. Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Commensal host-bacterial relationships in the gut. Science. 2001;292(5519):1115-1118. doi:10.1126/science.1058709

19. Ewaschuk JB, Diaz H, Meddings L, et al. Secreted bioactive factors from Bifidobacterium infantis enhance epithelial cell barrier function. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295(5):G1025-G1034. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.90227.2008

20. Alhasson F, Das S, Seth R, et al. Altered gut microbiome in a mouse model of Gulf War Illness causes neuroinflammation and intestinal injury via leaky gut and TLR4 activation. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0172914. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172914

21. Fillman SG, Cloonan N, Catts VS, et al. Increased inflammatory markers identified in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(2):206-214. doi:10.1038/mp.2012.110

22. Miller BJ, Buckley P, Seabolt W, et al. Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(7):663-671. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.04.013

23. Al-Amin M, Uddin MMN, Reza HM. Effects of antipsychotics on the inflammatory response system of patients with schizophrenia in peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2013;11(3):144-151. doi:10.9758/cpn.2013.11.3.144

24. Yuan X, Zhang P, Wang Y, et al. Changes in metabolism and microbiota after 24-week risperidone treatment in drug naïve, normal weight patients with first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;201:299-306. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2018.05.017

25. Maier L, Pruteanu M, Kuhn M, et al. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature. 2018;555(7698):623-628. doi:10.1038/nature25979

26. Dickerson FB, Stallings C, Origoni A, et al. Effect of probiotic supplementation on schizophrenia symptoms and association with gastrointestinal functioning: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;15(1):PCC.13m01579. doi:10.4088/PCC.13m01579

27. David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505(7484):559-563. doi:10.1038/nature12820

28. Bien J, Palagani V, Bozko P. The intestinal microbiota dysbiosis and Clostridium difficile infection: is there a relationship with inflammatory bowel disease? Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6(1):53-68. doi:10.1177/1756283X12454590

29. Cryan JF, O’Riordan KJ, Sandhu K, et al. The gut microbiome in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(2):179-194. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30356-4

30. Jones CA, Watson DJG, Fone KCF. Animal models of schizophrenia. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(4):1162-1194. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01386.x

31. Schmidt MJ, Mirnics K. Neurodevelopment, GABA system dysfunction, and schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(1):190-206. doi:10.1038/npp.2014.95

32. Nasrallah, HA. The daunting challenge of schizophrenia: hundreds of biotypes and dozens of theories. Curr. Psychiatry 2018;17(12):4-6,50.

33. Nocera A, Nasrallah HA. The association of the gut microbiota with clinical features in schizophrenia. Behav Sci (Basel). 2022;12(4):89. doi:10.3390/bs12040089

34. Schwarz E, Maukonen J, Hyytiäinen T, et al. Analysis of microbiota in first episode psychosis identifies preliminary associations with symptom severity and treatment response. Schizophr Res. 2018;192:398-403. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2017.04.017

35. Nguyen TT, Kosciolek T, Maldonado Y, et al. Differences in gut microbiome composition between persons with chronic schizophrenia and healthy comparison subjects. Schizophr Res. 2019;204:23-29. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2018.09.014

36. Li S, Zhuo M, Huang X, et al. Altered gut microbiota associated with symptom severity in schizophrenia. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9574. doi:10.7717/peerj.9574

37. Chen X, Xu J, Wang H, et al. Profiling the differences of gut microbial structure between schizophrenia patients with and without violent behaviors based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Int J Legal Med. 2021;135(1):131-141. doi:10.1007/s00414-020-02439-1

38. Manchia M, Fontana A, Panebianco C, et al. Involvement of gut microbiota in schizophrenia and treatment resistance to antipsychotics. Biomedicines. 2021;9(8):875. doi:10.3390/biomedicines9080875

39. Zhu C, Zheng M, Ali U, et al. Association between abundance of haemophilus in the gut microbiota and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:685910. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.685910

40. Flowers SA, Evans SJ, Ward KM, et al. Interaction between atypical antipsychotics and the gut microbiome in a bipolar disease cohort. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37(3):261-267. doi:10.1002/phar.1890

41. Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486(7402):222-227. doi:10.1038/nature11053

42. Buchanan RW. Persistent negative symptoms in schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(4):1013-1022. doi:10.1093/schbul/sb1057

43. Liu JCW, Gorbovskaya I, Hahn MK, et al. The gut microbiome in schizophrenia and the potential benefits of prebiotic and probiotic treatment. Nutrients. 2021;13(4):1152. doi:10.3390/nu13041152

44. Biedermann L, Zeitz J, Mwinyi J, et al. Smoking cessation induces profound changes in the composition of the intestinal microbiota in humans. PloS One. 2013;8(3):e59260. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059260

45. Leclercq S, Matamoros S, Cani PD, et al. Intestinal permeability, gut-bacterial dysbiosis, and behavioral markers of alcohol-dependence severity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(42):e4485-e4493. doi:10.1073/pnas.1415174111

46. Hernández-Quiroz F, Nirmalkar K, Villalobos-Flores LE, et al. Influence of moderate beer consumption on human gut microbiota and its impact on fasting glucose and ß-cell function. Alcohol. 2020;85:77-94. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2019.05.006

47. Panee J, Gerschenson M, Chang L. Associations between microbiota, mitochondrial function, and cognition in chronic marijuana users. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2018;13(1):113-122. doi:10.1007/s11481-017-9767-0

48. Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334(6052):105-108. doi:10.1126/science.1208344

49. Rezac S, Kok CR, Heermann M, et al. Fermented foods as a dietary source of live organisms. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1785. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01785

50. Chen X, Zhang Y, Wang H, et al. The regulatory effects of lactic acid on neuropsychiatric disorders. Discover Ment Health. 2022;2(1). doi:10.1007/s44192-022-00011-4

51. Karbownik MS, Mokros Ł, Dobielska M, et al. Association between consumption of fermented food and food-derived prebiotics with cognitive performance, depressive, and anxiety symptoms in psychiatrically healthy medical students under psychological stress: a prospective cohort study. Front Nutr. 2022;9:850249. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.850249

52. Romano S, Savva GM, Bedarf JR, et al. Meta-analysis of the Parkinson’s disease gut microbiome suggests alterations linked to intestinal inflammation. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2021;7(1):27. doi:10.1038/s41531-021-00156-z

53. Bourassa MW, Alim I, Bultman SJ, et al. Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: can a high fiber diet improve brain health? Neurosci Lett. 2016;625:56-63. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2016.02.009

54. Matt SM, Allen JM, Lawson MA, et al. Butyrate and dietary soluble fiber improve neuroinflammation associated with aging in mice. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1832. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01832

55. Mittal VA, Vargas T, Osborne KJ, et al. Exercise treatments for psychosis: a review. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2017;4(2):152-166. doi:10.1007/s40501-017-0112-2

56. Estaki M, Pither J, Baumeister P, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a predictor of intestinal microbial diversity and distinct metagenomic functions. Microbiome. 2016;4(1):42. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0189-7

57. Karl JP, Margolis LM, Madslien EH, et al. Changes in intestinal microbiota composition and metabolism coincide with increased intestinal permeability in young adults under prolonged physiological stress. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2017;312(6):G559-G571. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00066.2017

58. Claus SP, Guillou H, Ellero-Simatos S. The gut microbiota: a major player in the toxicity of environmental pollutants? NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2016;2:16003. doi:10.1038/npjbiofilms.2016.3

1. Bäckhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, et al. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307(5717):1915-1920. doi:10.1126/science.1104816

2. Jackson SW. Galen—on mental disorders. J Hist Behav Sci. 1969;5(4):365-384. doi:10.1002/1520-6696(196910)5:4<365::AID-JHBS2300050408>3.0.CO;2-9

3. Zheng P, Zeng B, Liu M, et al. The gut microbiome from patients with schizophrenia modulates the glutamate-glutamine-GABA cycle and schizophrenia-relevant behaviors in mice. Sci Adv. 2019;5(2):eaau8317. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aau8317

4. Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511(7510):421-427. doi:10.1038/nature13595

5. Gill SR, Pop M, DeBoy RT, et al. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science. 2006;312(5778):1355-1359. doi:10.1126/science.1124234

6. Alam R, Abdolmaleky HM, Zhou JR. Microbiome, inflammation, epigenetic alterations, and mental diseases. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2017;174(6):651-660. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.32567

7. Cryan JF, O’Riordan KJ, Cowan CSM, et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(4):1877-2013. doi:10.1152/physrev.00018.2018

8. Mueller NT, Bakacs E, Combellick J, et al. The infant microbiome development: mom matters. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21(2):109-117. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2014.12.002

9. Fouhy F, Watkins C, Hill CJ, et al. Perinatal factors affect the gut microbiota up to four years after birth. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1517. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09252-4

10. Sharon G, Sampson TR, Geschwind DH, et al. The central nervous system and the gut microbiome. Cell. 2016;167(4):915-932. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.027

11. Hill CJ, Lynch DB, Murphy K, et al. Evolution of gut microbiota composition from birth to 24 weeks in the INFANTMET Cohort. Microbiome. 2017;5:4. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0213-y

12. Gareau MG, Wine E, Rodrigues DM, et al. Bacterial infection causes stress-induced memory dysfunction in mice. Gut. 2011;60(3):307-317. doi:10.1136/gut.2009.202515

13. Bokulich NA, Chung J, Battaglia T, et al. Antibiotics, birth mode, and diet shape microbiome maturation during early life. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(343):343ra82. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7121

14. Mancabelli L, Milani C, Lugli GA, et al. Meta-analysis of the human gut microbiome from urbanized and pre-agricultural populations. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19(4):1379-1390. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.13692

15. Stilo SA, Murray RM. Non-genetic factors in schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(10):100. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-1091-3

16. Buscaino VM. Patologia extraneurale della schizofrenia: fegato, tubo digerente, sistema reticolo-endoteliale. Acta Neurologica. 1953;VIII:1-60.

17. Hemmings G. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2004;364(9442):1312-1313. doi:10.1016/S0140- 6736(04)17181-X

18. Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Commensal host-bacterial relationships in the gut. Science. 2001;292(5519):1115-1118. doi:10.1126/science.1058709

19. Ewaschuk JB, Diaz H, Meddings L, et al. Secreted bioactive factors from Bifidobacterium infantis enhance epithelial cell barrier function. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295(5):G1025-G1034. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.90227.2008

20. Alhasson F, Das S, Seth R, et al. Altered gut microbiome in a mouse model of Gulf War Illness causes neuroinflammation and intestinal injury via leaky gut and TLR4 activation. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0172914. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172914

21. Fillman SG, Cloonan N, Catts VS, et al. Increased inflammatory markers identified in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(2):206-214. doi:10.1038/mp.2012.110

22. Miller BJ, Buckley P, Seabolt W, et al. Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(7):663-671. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.04.013

23. Al-Amin M, Uddin MMN, Reza HM. Effects of antipsychotics on the inflammatory response system of patients with schizophrenia in peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2013;11(3):144-151. doi:10.9758/cpn.2013.11.3.144

24. Yuan X, Zhang P, Wang Y, et al. Changes in metabolism and microbiota after 24-week risperidone treatment in drug naïve, normal weight patients with first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;201:299-306. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2018.05.017

25. Maier L, Pruteanu M, Kuhn M, et al. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature. 2018;555(7698):623-628. doi:10.1038/nature25979

26. Dickerson FB, Stallings C, Origoni A, et al. Effect of probiotic supplementation on schizophrenia symptoms and association with gastrointestinal functioning: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;15(1):PCC.13m01579. doi:10.4088/PCC.13m01579

27. David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505(7484):559-563. doi:10.1038/nature12820

28. Bien J, Palagani V, Bozko P. The intestinal microbiota dysbiosis and Clostridium difficile infection: is there a relationship with inflammatory bowel disease? Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6(1):53-68. doi:10.1177/1756283X12454590

29. Cryan JF, O’Riordan KJ, Sandhu K, et al. The gut microbiome in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(2):179-194. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30356-4

30. Jones CA, Watson DJG, Fone KCF. Animal models of schizophrenia. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(4):1162-1194. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01386.x

31. Schmidt MJ, Mirnics K. Neurodevelopment, GABA system dysfunction, and schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(1):190-206. doi:10.1038/npp.2014.95

32. Nasrallah, HA. The daunting challenge of schizophrenia: hundreds of biotypes and dozens of theories. Curr. Psychiatry 2018;17(12):4-6,50.

33. Nocera A, Nasrallah HA. The association of the gut microbiota with clinical features in schizophrenia. Behav Sci (Basel). 2022;12(4):89. doi:10.3390/bs12040089

34. Schwarz E, Maukonen J, Hyytiäinen T, et al. Analysis of microbiota in first episode psychosis identifies preliminary associations with symptom severity and treatment response. Schizophr Res. 2018;192:398-403. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2017.04.017

35. Nguyen TT, Kosciolek T, Maldonado Y, et al. Differences in gut microbiome composition between persons with chronic schizophrenia and healthy comparison subjects. Schizophr Res. 2019;204:23-29. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2018.09.014

36. Li S, Zhuo M, Huang X, et al. Altered gut microbiota associated with symptom severity in schizophrenia. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9574. doi:10.7717/peerj.9574

37. Chen X, Xu J, Wang H, et al. Profiling the differences of gut microbial structure between schizophrenia patients with and without violent behaviors based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Int J Legal Med. 2021;135(1):131-141. doi:10.1007/s00414-020-02439-1

38. Manchia M, Fontana A, Panebianco C, et al. Involvement of gut microbiota in schizophrenia and treatment resistance to antipsychotics. Biomedicines. 2021;9(8):875. doi:10.3390/biomedicines9080875

39. Zhu C, Zheng M, Ali U, et al. Association between abundance of haemophilus in the gut microbiota and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:685910. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.685910

40. Flowers SA, Evans SJ, Ward KM, et al. Interaction between atypical antipsychotics and the gut microbiome in a bipolar disease cohort. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37(3):261-267. doi:10.1002/phar.1890

41. Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486(7402):222-227. doi:10.1038/nature11053

42. Buchanan RW. Persistent negative symptoms in schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(4):1013-1022. doi:10.1093/schbul/sb1057

43. Liu JCW, Gorbovskaya I, Hahn MK, et al. The gut microbiome in schizophrenia and the potential benefits of prebiotic and probiotic treatment. Nutrients. 2021;13(4):1152. doi:10.3390/nu13041152

44. Biedermann L, Zeitz J, Mwinyi J, et al. Smoking cessation induces profound changes in the composition of the intestinal microbiota in humans. PloS One. 2013;8(3):e59260. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059260

45. Leclercq S, Matamoros S, Cani PD, et al. Intestinal permeability, gut-bacterial dysbiosis, and behavioral markers of alcohol-dependence severity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(42):e4485-e4493. doi:10.1073/pnas.1415174111

46. Hernández-Quiroz F, Nirmalkar K, Villalobos-Flores LE, et al. Influence of moderate beer consumption on human gut microbiota and its impact on fasting glucose and ß-cell function. Alcohol. 2020;85:77-94. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2019.05.006

47. Panee J, Gerschenson M, Chang L. Associations between microbiota, mitochondrial function, and cognition in chronic marijuana users. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2018;13(1):113-122. doi:10.1007/s11481-017-9767-0

48. Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334(6052):105-108. doi:10.1126/science.1208344

49. Rezac S, Kok CR, Heermann M, et al. Fermented foods as a dietary source of live organisms. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1785. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01785

50. Chen X, Zhang Y, Wang H, et al. The regulatory effects of lactic acid on neuropsychiatric disorders. Discover Ment Health. 2022;2(1). doi:10.1007/s44192-022-00011-4

51. Karbownik MS, Mokros Ł, Dobielska M, et al. Association between consumption of fermented food and food-derived prebiotics with cognitive performance, depressive, and anxiety symptoms in psychiatrically healthy medical students under psychological stress: a prospective cohort study. Front Nutr. 2022;9:850249. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.850249

52. Romano S, Savva GM, Bedarf JR, et al. Meta-analysis of the Parkinson’s disease gut microbiome suggests alterations linked to intestinal inflammation. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2021;7(1):27. doi:10.1038/s41531-021-00156-z

53. Bourassa MW, Alim I, Bultman SJ, et al. Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: can a high fiber diet improve brain health? Neurosci Lett. 2016;625:56-63. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2016.02.009

54. Matt SM, Allen JM, Lawson MA, et al. Butyrate and dietary soluble fiber improve neuroinflammation associated with aging in mice. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1832. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01832

55. Mittal VA, Vargas T, Osborne KJ, et al. Exercise treatments for psychosis: a review. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2017;4(2):152-166. doi:10.1007/s40501-017-0112-2

56. Estaki M, Pither J, Baumeister P, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a predictor of intestinal microbial diversity and distinct metagenomic functions. Microbiome. 2016;4(1):42. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0189-7

57. Karl JP, Margolis LM, Madslien EH, et al. Changes in intestinal microbiota composition and metabolism coincide with increased intestinal permeability in young adults under prolonged physiological stress. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2017;312(6):G559-G571. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00066.2017

58. Claus SP, Guillou H, Ellero-Simatos S. The gut microbiota: a major player in the toxicity of environmental pollutants? NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2016;2:16003. doi:10.1038/npjbiofilms.2016.3

Depression guidelines fall short in characterizing withdrawal

Previous research suggests that approximately half of patients who discontinue or decrease dosage of antidepressants experience withdrawal symptoms, wrote Anders Sørensen, MD, of Copenhagen University Hospital, and colleagues. These symptoms are diverse and may include flulike symptoms, fatigue, anxiety, and sensations of electric shock, they noted. Most withdrawal effects last for a few weeks, but some persist for months or years, sometimes described as persistent postwithdrawal disorder, they added.

“Symptoms of withdrawal and depression overlap considerably but constitute two fundamentally different clinical conditions, which makes it important to distinguish between the two,” the researchers emphasized.

In a study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders, the researchers identified 21 clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for depression published between 1998 and 2022. The guidelines were published in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, Singapore, Ireland, and New Zealand. They compared descriptions of withdrawal from antidepressants and calculated the proportion of CPGs with different information.

Overall, 15 of the 21 studies in the review (71%) noted that antidepressants are associated with withdrawal symptoms, but less than half (43%) used the term “withdrawal symptoms,” or similar. Of the nine guidelines that mentioned withdrawal symptoms, five used the term interchangeably with “discontinuation symptoms” and six used the term “discontinuation symptoms” only when discussing antidepressant withdrawal. In addition, six CPGs specifically stated that patients who stop antidepressants can experience withdrawal symptoms, and five stated that these symptoms also can occur in patients who are reducing or tapering their doses.

The type of withdrawal symptoms was mentioned in 10 CPGs, and the other 11 had no information on potential withdrawal symptoms, the researchers noted. Of the CPGs that mentioned symptoms specifically associated with withdrawal, the number of potential symptoms ranged from 4 to 39.

“None of the CPGs provided an exhaustive list of the potential withdrawal symptoms identified in the research literature,” the researchers wrote in their discussion.

Only four of the guidelines (19%) mentioned the overlap in symptoms between withdrawal from antidepressants and depression relapse, and only one provided guidance on distinguishing between the two conditions. Most of the symptoms of withdrawal, when described, were characterized as mild, brief, or self-limiting, the researchers noted.

“Being in withdrawal is a fundamentally different clinical situation than experiencing relapse, requiring two distinctly different treatment approaches,” the researchers emphasized. “Withdrawal reactions that are more severe and longer lasting than currently defined in the CPGs could risk getting misinterpreted as relapse, potentially leading to resumed unnecessary long-term antidepressant treatment in some patients,” they added.

The findings were limited by several factors including the inclusion only of guidelines from English-speaking countries, which may limit generalizability, the researchers noted. Other potential limitations include the subjective judgments involved in creating different guidelines, they said.

However, the results support the need for improved CPGs that help clinicians distinguish potential withdrawal reactions from depression relapse, and the need for more research on optimal dose reduction strategies for antidepressants, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Previous research suggests that approximately half of patients who discontinue or decrease dosage of antidepressants experience withdrawal symptoms, wrote Anders Sørensen, MD, of Copenhagen University Hospital, and colleagues. These symptoms are diverse and may include flulike symptoms, fatigue, anxiety, and sensations of electric shock, they noted. Most withdrawal effects last for a few weeks, but some persist for months or years, sometimes described as persistent postwithdrawal disorder, they added.

“Symptoms of withdrawal and depression overlap considerably but constitute two fundamentally different clinical conditions, which makes it important to distinguish between the two,” the researchers emphasized.

In a study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders, the researchers identified 21 clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for depression published between 1998 and 2022. The guidelines were published in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, Singapore, Ireland, and New Zealand. They compared descriptions of withdrawal from antidepressants and calculated the proportion of CPGs with different information.