User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

An Update on JAK Inhibitors in Skin Disease

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder affecting 7% of adults and 13% of children in the United States.1,2 Atopic dermatitis is characterized by pruritus, dry skin, and pain, all of which can negatively impact quality of life and put patients at higher risk for psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety and depression.3 The pathogenesis of AD is multifactorial, involving genetics, epidermal barrier dysfunction, and immune dysregulation. Overactivation of helper T cell (TH2) pathway cytokines, including IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31, is thought to propagate both inflammation and pruritus, which are central to AD. The JAK-STAT signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in the immune system dysregulation and exaggeration of TH2 cell response, making JAK-STAT inhibitors (or JAK inhibitors) strong theoretical candidates for the treatment of AD.4 In humans, the Janus kinases are composed of 4 different members—JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2—all of which can be targeted by JAK inhibitors.5

JAK inhibitors such as tofacitinib have already been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat various inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and psoriatic arthritis; other JAK inhibitors such as baricitinib are only approved for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.6,7 The success of these small molecule inhibitors in these immune-mediated conditions make them attractive candidates for the treatment of AD. Several JAK inhibitors are in phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials as oral therapies (moderate to severe AD) or as topical treatments (mild to moderate AD). Currently, ruxolitinib (RUX) is the only topical JAK inhibitor that is FDA approved for the treatment of AD in the United States.8 In this editorial, we focus on recent trials of JAK inhibitors tested in patients with AD, including topical RUX, as well as oral abrocitinib, upadacitinib, and baricitinib.

Topical RUX in AD

Ruxolitinib is a topical JAK1/2 small molecule inhibitor approved by the FDA for the treatment of AD in 2021. In a randomized trial by Kim et al9 in 2020, all tested regimens of RUX demonstrated significant improvement in eczema area and severity index (EASI) scores vs vehicle; notably, RUX cream 1.5% applied twice daily achieved the greatest mean percentage change in baseline EASI score vs vehicle at 4 weeks (76.1% vs 15.5%; P<.0001). Ruxolitinib cream was well tolerated through week 8 of the trial, and all adverse events (AEs) were mild to moderate in severity and comparable to those in the vehicle group.9

Topical JAK inhibitors appear to be effective for mild to moderate AD and have had an acceptable safety profile in clinical trials thus far. Although topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors can have great clinical benefit in AD, they are recommended for short-term use given side effects such as thinning of the skin, burning, or telangiectasia formation.10,11 The hope is that topical JAK inhibitors may be an alternative to standard topical treatments for AD, as they can be used for longer periods due to a safer side-effect profile.

Oral JAK Inhibitors in AD

Several oral JAK inhibitors are undergoing investigation for the systemic treatment of moderate to severe AD. Abrocitinib is an oral JAK1 inhibitor that has demonstrated efficacy in several phase 3 trials in patients with moderate to severe AD. In a 2021 trial, patients were randomized in a 2:2:2:1 ratio to receive abrocitinib 200 mg daily, abrocitinib 100 mg daily, subcutaneous dupilumab 300 mg every other week, or placebo, respectively.12 Patients in both abrocitinib groups showed significant improvement in AD vs placebo, and EASI-75 response was achieved in 70.3%, 58.7%, 58.1%, and 27.1% of patients, respectively (P<.001 for both abrocitinib doses vs placebo). Adverse events occurred more frequently in the abrocitinib 200-mg group vs placebo. Nausea, acne, nasopharyngitis, and headache were the most frequently reported AEs with abrocitinib.12 Another phase 3 trial by Silverberg et al13 (N=391) had similar treatment results, with 38.1% of participants receiving abrocitinib 200 mg and 28.4% of participants receiving abrocitinib 100 mg achieving investigator global assessment scores of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) vs 9.1% of participants receiving placebo (P<.001). Abrocitinib was well tolerated in this trial with few serious AEs (ie, herpangina [0.6%], pneumonia [0.6%]).13 In both trials, there were rare instances of laboratory values indicating thrombocytopenia with the 200-mg dose (0.9%12 and 3.2%13) without any clinical manifestations. Although a decrease in platelets was observed, no thrombocytopenia occurred in the abrocitinib 100-mg group in the latter trial.13

Baricitinib is another oral inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK2 with potential for the treatment of AD. One randomized trial (N=329) demonstrated its efficacy in combination with a topical corticosteroid (TCS). At 16 weeks, a higher number of participants treated with baricitinib and TCS achieved investigator global assessment scores of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) compared to those who received placebo and TCS (31% with baricitinib 4 mg + TCS, 24% with baricitinib 2 mg + TCS, and 15% with placebo + TCS).14 Similarly, in BREEZE-AD5,another phase 3 trial (N=440), baricitinib monotherapy demonstrated a higher rate of treatment success vs placebo.15 Specifically, 13% of patients treated with baricitinib 1 mg and 30% of those treated with baricitinib 2 mg achieved 75% or greater reduction in EASI scores compared to 8% in the placebo group. The most common AEs associated with baricitinib were nasopharyngitis and headache. Adverse events occurred with similar frequency across both experimental and control groups.15 Reich et al14 demonstrated a higher overall rate of AEs—most commonly nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infections, and folliculitis—in baricitinib-treated patients; however, serious AEs occurred with similar frequency across all groups, including the control group.

The selective JAK1 inhibitor upadacitinib also is undergoing testing in treating moderate to severe AD. In one trial, 167 patients were randomized to once daily oral upadacitinib 7.5 mg, 15 mg, or 30 mg or placebo.16 All doses of upadacitinib demonstrated considerably higher percentage improvements from baseline in EASI scores compared to placebo at 16 weeks with a clear dose-response relationship (39%, 62%, and 74% vs 23%, respectively). In this trial, there were no dose-limiting safety events. Serious AEs were infrequent, occurring in 4.8%, 2.4%, and 0% of upadacitinib groups vs 2.5% for placebo. The serious AEs observed with upadacitinib were 1 case of appendicitis, lower jaw pericoronitis in a patient with a history of repeated tooth infections, and an exacerbation of AD.16

Tofacitinib, another JAK inhibitor, has been shown to increase the risk for blood clots and death in a large trial in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Following this study, the FDA is requiring black box warnings for tofacitinib and also for the 2 JAK inhibitors baricitinib and upadacitinib regarding the risks for heart-related events, cancer, blood clots, and death. Given that these medications share a similar mechanism of action to tofacitinib, they may have similar risks, though they have not yet been fully evaluated in large safety trials.17

With more recent investigation into novel therapeutics for AD, oral JAK inhibitors may play an important role in the future to treat patients with moderate to severe AD with inadequate response or contraindications to other systemic therapies. In trials thus far, oral JAK inhibitors have exhibited acceptable safety profiles and have demonstrated treatment success in AD. More randomized, controlled, phase 3 studies with larger patient populations are required to confirm their potential as effective treatments and elucidate their long-term safety.

Deucravacitinib in Psoriasis

Deucravacitinib is a first-in-class, oral, selective TYK2 inhibitor currently undergoing testing for the treatment of psoriasis. A randomized phase 2 trial (N=267) found that deucravacitinib was more effective than placebo in treating chronic plaque psoriasis at doses of 3 to 12 mg daily.18 The percentage of participants with a 75% or greater reduction from baseline in the psoriasis area and severity index score was 7% with placebo, 9% with deucravacitinib 3 mg every other day (P=.49 vs placebo), 39% with 3 mg once daily (P<.001 vs placebo), 69% with 3 mg twice daily (P<.001 vs placebo), 67% with 6 mg twice daily (P<.001 vs placebo), and 75% with 12 mg once daily (P<.001 vs placebo). The most commonly reported AEs were nasopharyngitis, headache, diarrhea, nausea, and upper respiratory tract infection. Adverse events occurred in 51% of participants in the control group and in 55% to 80% of those in the experimental groups. Additionally, there was 1 reported case of melanoma (stage 0) 96 days after the start of treatment in a patient in the 3-mg once-daily group. Serious AEs occurred in only 0% to 2% of participants who received deucravacitinib.18

Two phase 3 trials—POETYK PSO-1 and POETYK PSO-2 (N=1686)—found deucravacitinib to be notably more effective than both placebo and apremilast in treating psoriasis.19 Among participants receiving deucravacitinib 6 mg daily, 58.7% and 53.6% in the 2 respective trials achieved psoriasis area and severity index 75 response vs 12.7% and 9.4% receiving placebo and 35.1% and 40.2% receiving apremilast. Overall, the treatment was well tolerated, with a low rate of discontinuation of deucravacitinib due to AEs (2.4% of patients on deucravacitinib compared to 3.8% on placebo and 5.2% on apremilast). The most frequently observed AEs with deucravacitinib were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection. The full results of these trials are expected to be published soon.19,20

Final Thoughts

Overall, JAK inhibitors are a novel class of therapeutics that may have further success in the treatment of other dermatologic conditions that negatively affect patients’ quality of life and productivity. We should look forward to additional successful trials with these promising medications.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583-590.

- Silverberg JI , Simpson EL. Associations of childhood eczema severity: a US population-based study. Dermatitis. 2014;25:107-114.

- Schonmann Y, Mansfield KE, Hayes JF, et al. Atopic eczema in adulthood and risk of depression and anxiety: a population-based cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:248-257.e16.

- Bao L, Zhang H, Chan LS. The involvement of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway in chronic inflammatory skin disease atopic dermatitis. JAKSTAT. 2013;2:e24137.

- Villarino AV, Kanno Y, O’Shea JJ. Mechanisms and consequences of Jak-STAT signaling in the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:374-384.

- Xeljanz FDA approval history. Drugs.com website. Updated December 14, 2021. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.drugs.com/history/xeljanz.html

- Mullard A. FDA approves Eli Lilly’s baricitinib. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:460.

- FDA approves Opzelura. Drugs.com website. Published September 2021. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.drugs.com/newdrugs/fda-approves-opzelura-ruxolitinib-cream-atopic-dermatitis-ad-5666.html

- Kim BS, Sun K, Papp K, et al. Effects of ruxolitinib cream on pruritus and quality of life in atopic dermatitis: results from a phase 2, randomized, dose-ranging, vehicle- and active-controlled study.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1305-1313.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2, management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:657-682.

- Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, et al. Abrocitinib versus placebo or dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1101-1112.

- Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Thyssen JP, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:863-873.

- Reich K, Kabashima K, Peris K, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib combined with topical corticosteroids for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1333-1343.

- Simpson EL, Forman S, Silverberg JI, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized monotherapy phase 3 trial in the United States and Canada (BREEZE-AD5). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:62-70.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Thaçi D, Pangan AL, et al. Upadacitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: 16-week results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:877-884.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA requires warnings about increased risk of serious heart-related events, cancer, blood clots, and death for JAK inhibitors that treat certain chronic inflammatory conditions. Published September 1, 2022. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requires-warnings-about-increased-risk-serious-heart-related-events-cancer-blood-clots-and-death

- Papp K, Gordon K, Thaçi D, et al. Phase 2 trial of selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibition in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1313-1321.

- Bristol Myers Squibb presents positive data from two pivotal phase 3 psoriasis studies demonstrating superiority of deucravacitinib compared to placebo and Otezla® (apremilast). Press release. Bristol Meyers Squibb. April 23, 2021. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://news.bms.com/news/details/2021/Bristol-Myers-Squibb-Presents-Positive-Data-from-Two-Pivotal-Phase-3-Psoriasis-Studies-Demonstrating-Superiority-of-Deucravacitinib-Compared-to-Placebo-and-Otezla-apremilast/default.aspx

- Armstrong A, Gooderham M, Warren R, et al. Efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib, an oral, selective tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor, compared with placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results from the POETYK PSO-1 study [abstract]. Abstract presented at: 2021 American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting; April 23-25, 2021; San Francisco, California.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder affecting 7% of adults and 13% of children in the United States.1,2 Atopic dermatitis is characterized by pruritus, dry skin, and pain, all of which can negatively impact quality of life and put patients at higher risk for psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety and depression.3 The pathogenesis of AD is multifactorial, involving genetics, epidermal barrier dysfunction, and immune dysregulation. Overactivation of helper T cell (TH2) pathway cytokines, including IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31, is thought to propagate both inflammation and pruritus, which are central to AD. The JAK-STAT signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in the immune system dysregulation and exaggeration of TH2 cell response, making JAK-STAT inhibitors (or JAK inhibitors) strong theoretical candidates for the treatment of AD.4 In humans, the Janus kinases are composed of 4 different members—JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2—all of which can be targeted by JAK inhibitors.5

JAK inhibitors such as tofacitinib have already been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat various inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and psoriatic arthritis; other JAK inhibitors such as baricitinib are only approved for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.6,7 The success of these small molecule inhibitors in these immune-mediated conditions make them attractive candidates for the treatment of AD. Several JAK inhibitors are in phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials as oral therapies (moderate to severe AD) or as topical treatments (mild to moderate AD). Currently, ruxolitinib (RUX) is the only topical JAK inhibitor that is FDA approved for the treatment of AD in the United States.8 In this editorial, we focus on recent trials of JAK inhibitors tested in patients with AD, including topical RUX, as well as oral abrocitinib, upadacitinib, and baricitinib.

Topical RUX in AD

Ruxolitinib is a topical JAK1/2 small molecule inhibitor approved by the FDA for the treatment of AD in 2021. In a randomized trial by Kim et al9 in 2020, all tested regimens of RUX demonstrated significant improvement in eczema area and severity index (EASI) scores vs vehicle; notably, RUX cream 1.5% applied twice daily achieved the greatest mean percentage change in baseline EASI score vs vehicle at 4 weeks (76.1% vs 15.5%; P<.0001). Ruxolitinib cream was well tolerated through week 8 of the trial, and all adverse events (AEs) were mild to moderate in severity and comparable to those in the vehicle group.9

Topical JAK inhibitors appear to be effective for mild to moderate AD and have had an acceptable safety profile in clinical trials thus far. Although topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors can have great clinical benefit in AD, they are recommended for short-term use given side effects such as thinning of the skin, burning, or telangiectasia formation.10,11 The hope is that topical JAK inhibitors may be an alternative to standard topical treatments for AD, as they can be used for longer periods due to a safer side-effect profile.

Oral JAK Inhibitors in AD

Several oral JAK inhibitors are undergoing investigation for the systemic treatment of moderate to severe AD. Abrocitinib is an oral JAK1 inhibitor that has demonstrated efficacy in several phase 3 trials in patients with moderate to severe AD. In a 2021 trial, patients were randomized in a 2:2:2:1 ratio to receive abrocitinib 200 mg daily, abrocitinib 100 mg daily, subcutaneous dupilumab 300 mg every other week, or placebo, respectively.12 Patients in both abrocitinib groups showed significant improvement in AD vs placebo, and EASI-75 response was achieved in 70.3%, 58.7%, 58.1%, and 27.1% of patients, respectively (P<.001 for both abrocitinib doses vs placebo). Adverse events occurred more frequently in the abrocitinib 200-mg group vs placebo. Nausea, acne, nasopharyngitis, and headache were the most frequently reported AEs with abrocitinib.12 Another phase 3 trial by Silverberg et al13 (N=391) had similar treatment results, with 38.1% of participants receiving abrocitinib 200 mg and 28.4% of participants receiving abrocitinib 100 mg achieving investigator global assessment scores of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) vs 9.1% of participants receiving placebo (P<.001). Abrocitinib was well tolerated in this trial with few serious AEs (ie, herpangina [0.6%], pneumonia [0.6%]).13 In both trials, there were rare instances of laboratory values indicating thrombocytopenia with the 200-mg dose (0.9%12 and 3.2%13) without any clinical manifestations. Although a decrease in platelets was observed, no thrombocytopenia occurred in the abrocitinib 100-mg group in the latter trial.13

Baricitinib is another oral inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK2 with potential for the treatment of AD. One randomized trial (N=329) demonstrated its efficacy in combination with a topical corticosteroid (TCS). At 16 weeks, a higher number of participants treated with baricitinib and TCS achieved investigator global assessment scores of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) compared to those who received placebo and TCS (31% with baricitinib 4 mg + TCS, 24% with baricitinib 2 mg + TCS, and 15% with placebo + TCS).14 Similarly, in BREEZE-AD5,another phase 3 trial (N=440), baricitinib monotherapy demonstrated a higher rate of treatment success vs placebo.15 Specifically, 13% of patients treated with baricitinib 1 mg and 30% of those treated with baricitinib 2 mg achieved 75% or greater reduction in EASI scores compared to 8% in the placebo group. The most common AEs associated with baricitinib were nasopharyngitis and headache. Adverse events occurred with similar frequency across both experimental and control groups.15 Reich et al14 demonstrated a higher overall rate of AEs—most commonly nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infections, and folliculitis—in baricitinib-treated patients; however, serious AEs occurred with similar frequency across all groups, including the control group.

The selective JAK1 inhibitor upadacitinib also is undergoing testing in treating moderate to severe AD. In one trial, 167 patients were randomized to once daily oral upadacitinib 7.5 mg, 15 mg, or 30 mg or placebo.16 All doses of upadacitinib demonstrated considerably higher percentage improvements from baseline in EASI scores compared to placebo at 16 weeks with a clear dose-response relationship (39%, 62%, and 74% vs 23%, respectively). In this trial, there were no dose-limiting safety events. Serious AEs were infrequent, occurring in 4.8%, 2.4%, and 0% of upadacitinib groups vs 2.5% for placebo. The serious AEs observed with upadacitinib were 1 case of appendicitis, lower jaw pericoronitis in a patient with a history of repeated tooth infections, and an exacerbation of AD.16

Tofacitinib, another JAK inhibitor, has been shown to increase the risk for blood clots and death in a large trial in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Following this study, the FDA is requiring black box warnings for tofacitinib and also for the 2 JAK inhibitors baricitinib and upadacitinib regarding the risks for heart-related events, cancer, blood clots, and death. Given that these medications share a similar mechanism of action to tofacitinib, they may have similar risks, though they have not yet been fully evaluated in large safety trials.17

With more recent investigation into novel therapeutics for AD, oral JAK inhibitors may play an important role in the future to treat patients with moderate to severe AD with inadequate response or contraindications to other systemic therapies. In trials thus far, oral JAK inhibitors have exhibited acceptable safety profiles and have demonstrated treatment success in AD. More randomized, controlled, phase 3 studies with larger patient populations are required to confirm their potential as effective treatments and elucidate their long-term safety.

Deucravacitinib in Psoriasis

Deucravacitinib is a first-in-class, oral, selective TYK2 inhibitor currently undergoing testing for the treatment of psoriasis. A randomized phase 2 trial (N=267) found that deucravacitinib was more effective than placebo in treating chronic plaque psoriasis at doses of 3 to 12 mg daily.18 The percentage of participants with a 75% or greater reduction from baseline in the psoriasis area and severity index score was 7% with placebo, 9% with deucravacitinib 3 mg every other day (P=.49 vs placebo), 39% with 3 mg once daily (P<.001 vs placebo), 69% with 3 mg twice daily (P<.001 vs placebo), 67% with 6 mg twice daily (P<.001 vs placebo), and 75% with 12 mg once daily (P<.001 vs placebo). The most commonly reported AEs were nasopharyngitis, headache, diarrhea, nausea, and upper respiratory tract infection. Adverse events occurred in 51% of participants in the control group and in 55% to 80% of those in the experimental groups. Additionally, there was 1 reported case of melanoma (stage 0) 96 days after the start of treatment in a patient in the 3-mg once-daily group. Serious AEs occurred in only 0% to 2% of participants who received deucravacitinib.18

Two phase 3 trials—POETYK PSO-1 and POETYK PSO-2 (N=1686)—found deucravacitinib to be notably more effective than both placebo and apremilast in treating psoriasis.19 Among participants receiving deucravacitinib 6 mg daily, 58.7% and 53.6% in the 2 respective trials achieved psoriasis area and severity index 75 response vs 12.7% and 9.4% receiving placebo and 35.1% and 40.2% receiving apremilast. Overall, the treatment was well tolerated, with a low rate of discontinuation of deucravacitinib due to AEs (2.4% of patients on deucravacitinib compared to 3.8% on placebo and 5.2% on apremilast). The most frequently observed AEs with deucravacitinib were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection. The full results of these trials are expected to be published soon.19,20

Final Thoughts

Overall, JAK inhibitors are a novel class of therapeutics that may have further success in the treatment of other dermatologic conditions that negatively affect patients’ quality of life and productivity. We should look forward to additional successful trials with these promising medications.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder affecting 7% of adults and 13% of children in the United States.1,2 Atopic dermatitis is characterized by pruritus, dry skin, and pain, all of which can negatively impact quality of life and put patients at higher risk for psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety and depression.3 The pathogenesis of AD is multifactorial, involving genetics, epidermal barrier dysfunction, and immune dysregulation. Overactivation of helper T cell (TH2) pathway cytokines, including IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31, is thought to propagate both inflammation and pruritus, which are central to AD. The JAK-STAT signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in the immune system dysregulation and exaggeration of TH2 cell response, making JAK-STAT inhibitors (or JAK inhibitors) strong theoretical candidates for the treatment of AD.4 In humans, the Janus kinases are composed of 4 different members—JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2—all of which can be targeted by JAK inhibitors.5

JAK inhibitors such as tofacitinib have already been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat various inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and psoriatic arthritis; other JAK inhibitors such as baricitinib are only approved for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.6,7 The success of these small molecule inhibitors in these immune-mediated conditions make them attractive candidates for the treatment of AD. Several JAK inhibitors are in phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials as oral therapies (moderate to severe AD) or as topical treatments (mild to moderate AD). Currently, ruxolitinib (RUX) is the only topical JAK inhibitor that is FDA approved for the treatment of AD in the United States.8 In this editorial, we focus on recent trials of JAK inhibitors tested in patients with AD, including topical RUX, as well as oral abrocitinib, upadacitinib, and baricitinib.

Topical RUX in AD

Ruxolitinib is a topical JAK1/2 small molecule inhibitor approved by the FDA for the treatment of AD in 2021. In a randomized trial by Kim et al9 in 2020, all tested regimens of RUX demonstrated significant improvement in eczema area and severity index (EASI) scores vs vehicle; notably, RUX cream 1.5% applied twice daily achieved the greatest mean percentage change in baseline EASI score vs vehicle at 4 weeks (76.1% vs 15.5%; P<.0001). Ruxolitinib cream was well tolerated through week 8 of the trial, and all adverse events (AEs) were mild to moderate in severity and comparable to those in the vehicle group.9

Topical JAK inhibitors appear to be effective for mild to moderate AD and have had an acceptable safety profile in clinical trials thus far. Although topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors can have great clinical benefit in AD, they are recommended for short-term use given side effects such as thinning of the skin, burning, or telangiectasia formation.10,11 The hope is that topical JAK inhibitors may be an alternative to standard topical treatments for AD, as they can be used for longer periods due to a safer side-effect profile.

Oral JAK Inhibitors in AD

Several oral JAK inhibitors are undergoing investigation for the systemic treatment of moderate to severe AD. Abrocitinib is an oral JAK1 inhibitor that has demonstrated efficacy in several phase 3 trials in patients with moderate to severe AD. In a 2021 trial, patients were randomized in a 2:2:2:1 ratio to receive abrocitinib 200 mg daily, abrocitinib 100 mg daily, subcutaneous dupilumab 300 mg every other week, or placebo, respectively.12 Patients in both abrocitinib groups showed significant improvement in AD vs placebo, and EASI-75 response was achieved in 70.3%, 58.7%, 58.1%, and 27.1% of patients, respectively (P<.001 for both abrocitinib doses vs placebo). Adverse events occurred more frequently in the abrocitinib 200-mg group vs placebo. Nausea, acne, nasopharyngitis, and headache were the most frequently reported AEs with abrocitinib.12 Another phase 3 trial by Silverberg et al13 (N=391) had similar treatment results, with 38.1% of participants receiving abrocitinib 200 mg and 28.4% of participants receiving abrocitinib 100 mg achieving investigator global assessment scores of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) vs 9.1% of participants receiving placebo (P<.001). Abrocitinib was well tolerated in this trial with few serious AEs (ie, herpangina [0.6%], pneumonia [0.6%]).13 In both trials, there were rare instances of laboratory values indicating thrombocytopenia with the 200-mg dose (0.9%12 and 3.2%13) without any clinical manifestations. Although a decrease in platelets was observed, no thrombocytopenia occurred in the abrocitinib 100-mg group in the latter trial.13

Baricitinib is another oral inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK2 with potential for the treatment of AD. One randomized trial (N=329) demonstrated its efficacy in combination with a topical corticosteroid (TCS). At 16 weeks, a higher number of participants treated with baricitinib and TCS achieved investigator global assessment scores of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) compared to those who received placebo and TCS (31% with baricitinib 4 mg + TCS, 24% with baricitinib 2 mg + TCS, and 15% with placebo + TCS).14 Similarly, in BREEZE-AD5,another phase 3 trial (N=440), baricitinib monotherapy demonstrated a higher rate of treatment success vs placebo.15 Specifically, 13% of patients treated with baricitinib 1 mg and 30% of those treated with baricitinib 2 mg achieved 75% or greater reduction in EASI scores compared to 8% in the placebo group. The most common AEs associated with baricitinib were nasopharyngitis and headache. Adverse events occurred with similar frequency across both experimental and control groups.15 Reich et al14 demonstrated a higher overall rate of AEs—most commonly nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infections, and folliculitis—in baricitinib-treated patients; however, serious AEs occurred with similar frequency across all groups, including the control group.

The selective JAK1 inhibitor upadacitinib also is undergoing testing in treating moderate to severe AD. In one trial, 167 patients were randomized to once daily oral upadacitinib 7.5 mg, 15 mg, or 30 mg or placebo.16 All doses of upadacitinib demonstrated considerably higher percentage improvements from baseline in EASI scores compared to placebo at 16 weeks with a clear dose-response relationship (39%, 62%, and 74% vs 23%, respectively). In this trial, there were no dose-limiting safety events. Serious AEs were infrequent, occurring in 4.8%, 2.4%, and 0% of upadacitinib groups vs 2.5% for placebo. The serious AEs observed with upadacitinib were 1 case of appendicitis, lower jaw pericoronitis in a patient with a history of repeated tooth infections, and an exacerbation of AD.16

Tofacitinib, another JAK inhibitor, has been shown to increase the risk for blood clots and death in a large trial in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Following this study, the FDA is requiring black box warnings for tofacitinib and also for the 2 JAK inhibitors baricitinib and upadacitinib regarding the risks for heart-related events, cancer, blood clots, and death. Given that these medications share a similar mechanism of action to tofacitinib, they may have similar risks, though they have not yet been fully evaluated in large safety trials.17

With more recent investigation into novel therapeutics for AD, oral JAK inhibitors may play an important role in the future to treat patients with moderate to severe AD with inadequate response or contraindications to other systemic therapies. In trials thus far, oral JAK inhibitors have exhibited acceptable safety profiles and have demonstrated treatment success in AD. More randomized, controlled, phase 3 studies with larger patient populations are required to confirm their potential as effective treatments and elucidate their long-term safety.

Deucravacitinib in Psoriasis

Deucravacitinib is a first-in-class, oral, selective TYK2 inhibitor currently undergoing testing for the treatment of psoriasis. A randomized phase 2 trial (N=267) found that deucravacitinib was more effective than placebo in treating chronic plaque psoriasis at doses of 3 to 12 mg daily.18 The percentage of participants with a 75% or greater reduction from baseline in the psoriasis area and severity index score was 7% with placebo, 9% with deucravacitinib 3 mg every other day (P=.49 vs placebo), 39% with 3 mg once daily (P<.001 vs placebo), 69% with 3 mg twice daily (P<.001 vs placebo), 67% with 6 mg twice daily (P<.001 vs placebo), and 75% with 12 mg once daily (P<.001 vs placebo). The most commonly reported AEs were nasopharyngitis, headache, diarrhea, nausea, and upper respiratory tract infection. Adverse events occurred in 51% of participants in the control group and in 55% to 80% of those in the experimental groups. Additionally, there was 1 reported case of melanoma (stage 0) 96 days after the start of treatment in a patient in the 3-mg once-daily group. Serious AEs occurred in only 0% to 2% of participants who received deucravacitinib.18

Two phase 3 trials—POETYK PSO-1 and POETYK PSO-2 (N=1686)—found deucravacitinib to be notably more effective than both placebo and apremilast in treating psoriasis.19 Among participants receiving deucravacitinib 6 mg daily, 58.7% and 53.6% in the 2 respective trials achieved psoriasis area and severity index 75 response vs 12.7% and 9.4% receiving placebo and 35.1% and 40.2% receiving apremilast. Overall, the treatment was well tolerated, with a low rate of discontinuation of deucravacitinib due to AEs (2.4% of patients on deucravacitinib compared to 3.8% on placebo and 5.2% on apremilast). The most frequently observed AEs with deucravacitinib were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection. The full results of these trials are expected to be published soon.19,20

Final Thoughts

Overall, JAK inhibitors are a novel class of therapeutics that may have further success in the treatment of other dermatologic conditions that negatively affect patients’ quality of life and productivity. We should look forward to additional successful trials with these promising medications.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583-590.

- Silverberg JI , Simpson EL. Associations of childhood eczema severity: a US population-based study. Dermatitis. 2014;25:107-114.

- Schonmann Y, Mansfield KE, Hayes JF, et al. Atopic eczema in adulthood and risk of depression and anxiety: a population-based cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:248-257.e16.

- Bao L, Zhang H, Chan LS. The involvement of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway in chronic inflammatory skin disease atopic dermatitis. JAKSTAT. 2013;2:e24137.

- Villarino AV, Kanno Y, O’Shea JJ. Mechanisms and consequences of Jak-STAT signaling in the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:374-384.

- Xeljanz FDA approval history. Drugs.com website. Updated December 14, 2021. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.drugs.com/history/xeljanz.html

- Mullard A. FDA approves Eli Lilly’s baricitinib. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:460.

- FDA approves Opzelura. Drugs.com website. Published September 2021. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.drugs.com/newdrugs/fda-approves-opzelura-ruxolitinib-cream-atopic-dermatitis-ad-5666.html

- Kim BS, Sun K, Papp K, et al. Effects of ruxolitinib cream on pruritus and quality of life in atopic dermatitis: results from a phase 2, randomized, dose-ranging, vehicle- and active-controlled study.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1305-1313.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2, management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:657-682.

- Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, et al. Abrocitinib versus placebo or dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1101-1112.

- Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Thyssen JP, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:863-873.

- Reich K, Kabashima K, Peris K, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib combined with topical corticosteroids for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1333-1343.

- Simpson EL, Forman S, Silverberg JI, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized monotherapy phase 3 trial in the United States and Canada (BREEZE-AD5). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:62-70.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Thaçi D, Pangan AL, et al. Upadacitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: 16-week results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:877-884.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA requires warnings about increased risk of serious heart-related events, cancer, blood clots, and death for JAK inhibitors that treat certain chronic inflammatory conditions. Published September 1, 2022. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requires-warnings-about-increased-risk-serious-heart-related-events-cancer-blood-clots-and-death

- Papp K, Gordon K, Thaçi D, et al. Phase 2 trial of selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibition in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1313-1321.

- Bristol Myers Squibb presents positive data from two pivotal phase 3 psoriasis studies demonstrating superiority of deucravacitinib compared to placebo and Otezla® (apremilast). Press release. Bristol Meyers Squibb. April 23, 2021. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://news.bms.com/news/details/2021/Bristol-Myers-Squibb-Presents-Positive-Data-from-Two-Pivotal-Phase-3-Psoriasis-Studies-Demonstrating-Superiority-of-Deucravacitinib-Compared-to-Placebo-and-Otezla-apremilast/default.aspx

- Armstrong A, Gooderham M, Warren R, et al. Efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib, an oral, selective tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor, compared with placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results from the POETYK PSO-1 study [abstract]. Abstract presented at: 2021 American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting; April 23-25, 2021; San Francisco, California.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583-590.

- Silverberg JI , Simpson EL. Associations of childhood eczema severity: a US population-based study. Dermatitis. 2014;25:107-114.

- Schonmann Y, Mansfield KE, Hayes JF, et al. Atopic eczema in adulthood and risk of depression and anxiety: a population-based cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:248-257.e16.

- Bao L, Zhang H, Chan LS. The involvement of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway in chronic inflammatory skin disease atopic dermatitis. JAKSTAT. 2013;2:e24137.

- Villarino AV, Kanno Y, O’Shea JJ. Mechanisms and consequences of Jak-STAT signaling in the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:374-384.

- Xeljanz FDA approval history. Drugs.com website. Updated December 14, 2021. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.drugs.com/history/xeljanz.html

- Mullard A. FDA approves Eli Lilly’s baricitinib. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:460.

- FDA approves Opzelura. Drugs.com website. Published September 2021. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.drugs.com/newdrugs/fda-approves-opzelura-ruxolitinib-cream-atopic-dermatitis-ad-5666.html

- Kim BS, Sun K, Papp K, et al. Effects of ruxolitinib cream on pruritus and quality of life in atopic dermatitis: results from a phase 2, randomized, dose-ranging, vehicle- and active-controlled study.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1305-1313.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2, management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:657-682.

- Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, et al. Abrocitinib versus placebo or dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1101-1112.

- Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Thyssen JP, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:863-873.

- Reich K, Kabashima K, Peris K, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib combined with topical corticosteroids for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1333-1343.

- Simpson EL, Forman S, Silverberg JI, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized monotherapy phase 3 trial in the United States and Canada (BREEZE-AD5). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:62-70.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Thaçi D, Pangan AL, et al. Upadacitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: 16-week results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:877-884.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA requires warnings about increased risk of serious heart-related events, cancer, blood clots, and death for JAK inhibitors that treat certain chronic inflammatory conditions. Published September 1, 2022. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requires-warnings-about-increased-risk-serious-heart-related-events-cancer-blood-clots-and-death

- Papp K, Gordon K, Thaçi D, et al. Phase 2 trial of selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibition in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1313-1321.

- Bristol Myers Squibb presents positive data from two pivotal phase 3 psoriasis studies demonstrating superiority of deucravacitinib compared to placebo and Otezla® (apremilast). Press release. Bristol Meyers Squibb. April 23, 2021. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://news.bms.com/news/details/2021/Bristol-Myers-Squibb-Presents-Positive-Data-from-Two-Pivotal-Phase-3-Psoriasis-Studies-Demonstrating-Superiority-of-Deucravacitinib-Compared-to-Placebo-and-Otezla-apremilast/default.aspx

- Armstrong A, Gooderham M, Warren R, et al. Efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib, an oral, selective tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor, compared with placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results from the POETYK PSO-1 study [abstract]. Abstract presented at: 2021 American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting; April 23-25, 2021; San Francisco, California.

Discoid Lupus

THE COMPARISON

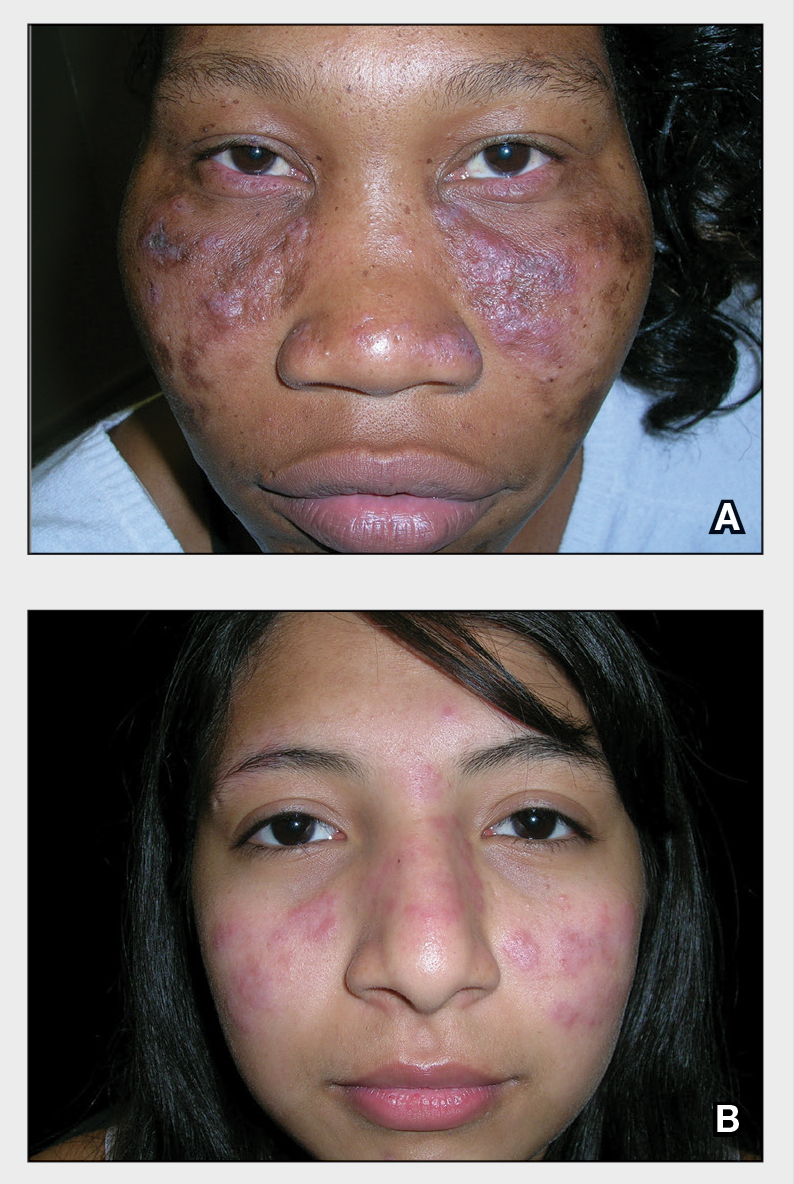

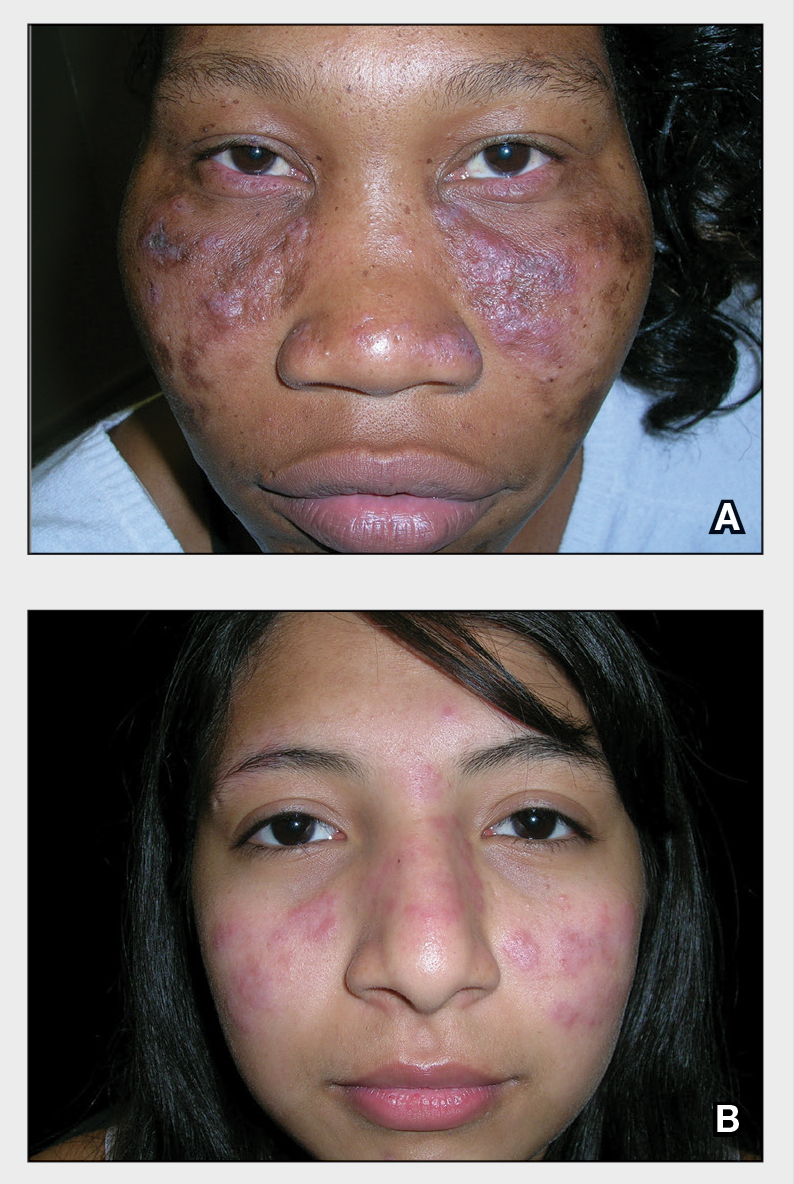

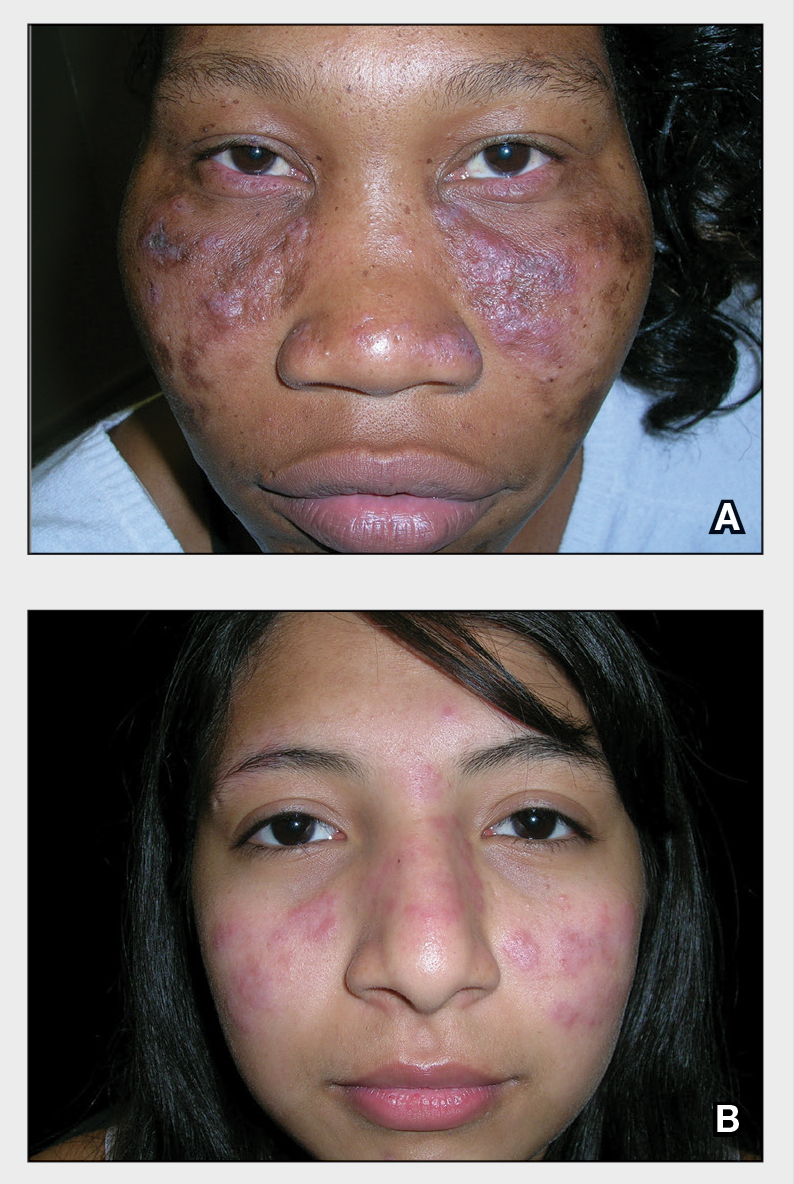

A Multicolored (pink, brown, and white) indurated plaques in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 30-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Pink, elevated, indurated plaques with hypopigmentation in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 19-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus may occur with or without systemic lupus erythematosus. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a form of chronic cutaneous lupus, is most commonly found on the scalp, face, and ears.1

Epidemiology

Discoid lupus erythematosus is most common in adult women (age range, 20–40 years).2 It occurs more frequently in women of African descent.3,4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones:

Clinical features of DLE lesions include erythema, induration, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, and scarring alopecia.1 In patients of African descent, lesions may be annular and hypopigmented to depigmented centrally with a border of hyperpigmentation. Active lesions may be painful and/or pruritic.2

Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions occur in photodistributed areas, although not exclusively. Photoprotective clothing and sunscreen are an important part of the treatment plan.1 Although sunscreen is recommended for patients with DLE, those with darker skin tones may find some sunscreens cosmetically unappealing due to a mismatch with their normal skin color.5 Tinted sunscreens may be beneficial additions.

Worth noting

Approximately 5% to 25% of patients with cutaneous lupus go on to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.6

Health disparity highlight

Discoid lesions may cause cutaneous scars that are quite disfiguring and may negatively impact quality of life. Some patients may have a few scattered lesions, whereas others have extensive disease covering most of the scalp. Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions of the scalp have classic clinical features including hair loss, erythema, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation. The clinician’s comfort with performing a scalp examination with cultural humility is an important acquired skill and is especially important when the examination is performed on patients with more tightly coiled hair.7 For example, physicians may adopt the “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method when counseling patients.8

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Otberg N, Wu W-Y, McElwee KJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x

- Callen JP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. clinical, laboratory, therapeutic, and prognostic examination of 62 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:412-416. doi:10.1001/archderm.118.6.412

- McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260-1270. doi:10.1002/art.1780380914

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. In press.

- Zhou W, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. New insights into the progression from cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:829-837. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2020.1805316

- Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patientphysician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

- Grayson C, Heath CR. Counseling about traction alopecia: a “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method. Cutis. 2021;108:20-22.

THE COMPARISON

A Multicolored (pink, brown, and white) indurated plaques in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 30-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Pink, elevated, indurated plaques with hypopigmentation in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 19-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus may occur with or without systemic lupus erythematosus. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a form of chronic cutaneous lupus, is most commonly found on the scalp, face, and ears.1

Epidemiology

Discoid lupus erythematosus is most common in adult women (age range, 20–40 years).2 It occurs more frequently in women of African descent.3,4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones:

Clinical features of DLE lesions include erythema, induration, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, and scarring alopecia.1 In patients of African descent, lesions may be annular and hypopigmented to depigmented centrally with a border of hyperpigmentation. Active lesions may be painful and/or pruritic.2

Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions occur in photodistributed areas, although not exclusively. Photoprotective clothing and sunscreen are an important part of the treatment plan.1 Although sunscreen is recommended for patients with DLE, those with darker skin tones may find some sunscreens cosmetically unappealing due to a mismatch with their normal skin color.5 Tinted sunscreens may be beneficial additions.

Worth noting

Approximately 5% to 25% of patients with cutaneous lupus go on to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.6

Health disparity highlight

Discoid lesions may cause cutaneous scars that are quite disfiguring and may negatively impact quality of life. Some patients may have a few scattered lesions, whereas others have extensive disease covering most of the scalp. Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions of the scalp have classic clinical features including hair loss, erythema, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation. The clinician’s comfort with performing a scalp examination with cultural humility is an important acquired skill and is especially important when the examination is performed on patients with more tightly coiled hair.7 For example, physicians may adopt the “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method when counseling patients.8

THE COMPARISON

A Multicolored (pink, brown, and white) indurated plaques in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 30-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Pink, elevated, indurated plaques with hypopigmentation in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 19-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus may occur with or without systemic lupus erythematosus. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a form of chronic cutaneous lupus, is most commonly found on the scalp, face, and ears.1

Epidemiology

Discoid lupus erythematosus is most common in adult women (age range, 20–40 years).2 It occurs more frequently in women of African descent.3,4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones:

Clinical features of DLE lesions include erythema, induration, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, and scarring alopecia.1 In patients of African descent, lesions may be annular and hypopigmented to depigmented centrally with a border of hyperpigmentation. Active lesions may be painful and/or pruritic.2

Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions occur in photodistributed areas, although not exclusively. Photoprotective clothing and sunscreen are an important part of the treatment plan.1 Although sunscreen is recommended for patients with DLE, those with darker skin tones may find some sunscreens cosmetically unappealing due to a mismatch with their normal skin color.5 Tinted sunscreens may be beneficial additions.

Worth noting

Approximately 5% to 25% of patients with cutaneous lupus go on to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.6

Health disparity highlight

Discoid lesions may cause cutaneous scars that are quite disfiguring and may negatively impact quality of life. Some patients may have a few scattered lesions, whereas others have extensive disease covering most of the scalp. Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions of the scalp have classic clinical features including hair loss, erythema, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation. The clinician’s comfort with performing a scalp examination with cultural humility is an important acquired skill and is especially important when the examination is performed on patients with more tightly coiled hair.7 For example, physicians may adopt the “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method when counseling patients.8

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Otberg N, Wu W-Y, McElwee KJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x

- Callen JP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. clinical, laboratory, therapeutic, and prognostic examination of 62 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:412-416. doi:10.1001/archderm.118.6.412

- McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260-1270. doi:10.1002/art.1780380914

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. In press.

- Zhou W, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. New insights into the progression from cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:829-837. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2020.1805316

- Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patientphysician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

- Grayson C, Heath CR. Counseling about traction alopecia: a “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method. Cutis. 2021;108:20-22.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Otberg N, Wu W-Y, McElwee KJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x

- Callen JP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. clinical, laboratory, therapeutic, and prognostic examination of 62 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:412-416. doi:10.1001/archderm.118.6.412

- McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260-1270. doi:10.1002/art.1780380914

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. In press.

- Zhou W, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. New insights into the progression from cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:829-837. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2020.1805316

- Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patientphysician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

- Grayson C, Heath CR. Counseling about traction alopecia: a “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method. Cutis. 2021;108:20-22.

Leukemia Cutis Manifesting as Nonpalpable Purpura

To the Editor:

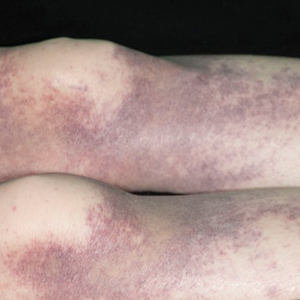

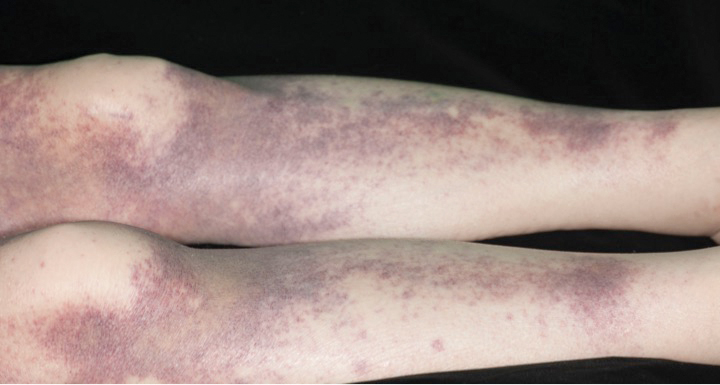

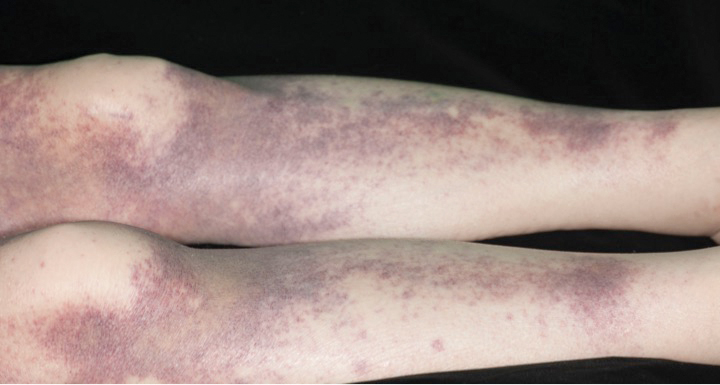

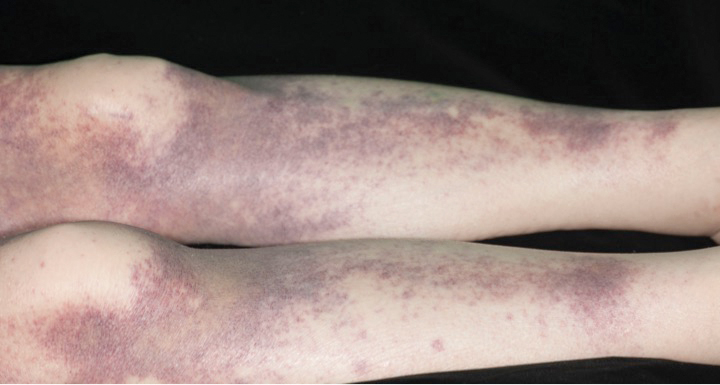

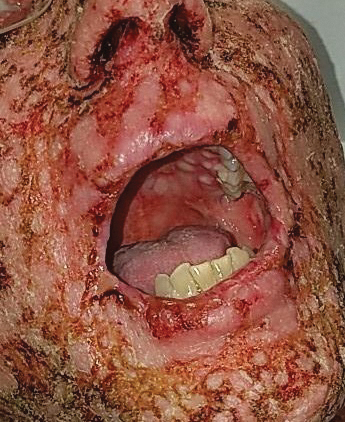

A 72-year-old man presented with symptomatic anemia and nonpalpable purpura of the legs, abdomen, and arms of 2 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). There were no associated perifollicular papules. Physical examination of the hair and gingiva were normal.

The patient’s medical history was notable for a poorly differentiated pancreatic adenocarcinoma (pT3N1M0) resected 7 months prior using a Whipple operation (pancreaticoduodenectomy). Adjuvant therapy consisted of 5 cycles of intravenous gemcitabine and paclitaxel. Treatment was discontinued 1 month prior due to progressive weight loss and the presence of new liver metastases on computed tomography. There was no recent history of corticosteroid, antiplatelet, or anticoagulant use. The patient had no known history of trauma at the affected sites.

The patient’s laboratory workup revealed the following results: hemoglobin, 5.5 g/dL (reference range, 13–18 g/dL); platelets, 128×109/L (reference range, 150–400×109/L); total white blood cell count (24.0×109/L [reference range, 4.0–11.0×109/L]), consisting of neutrophils (2.4×109/L [reference range, 2.0–7.5×109/L]), lymphocytes (3.1×109/L [reference range, 1.5–4.0×109/L]), and monocytes (18.5×109/L [reference range, 0.2–0.8×109/L]). Fibrinogen, activated partial thromboplastin time, and prothrombin time were within reference range. Results of a bone marrow biopsy showed 64% blasts. The lactate dehydrogenase level was 286 U/L (reference range, 135–220 U/L) and CA-19-9 antigen was 238 U/mL (reference range, 0–39 U/mL).

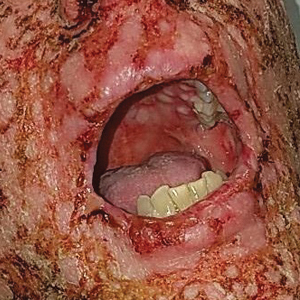

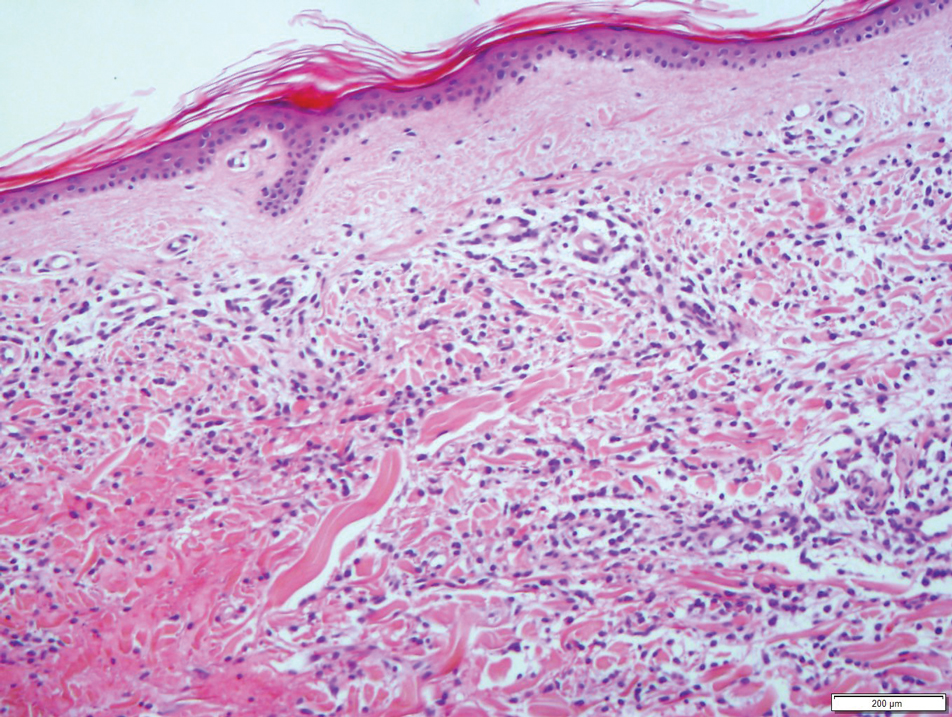

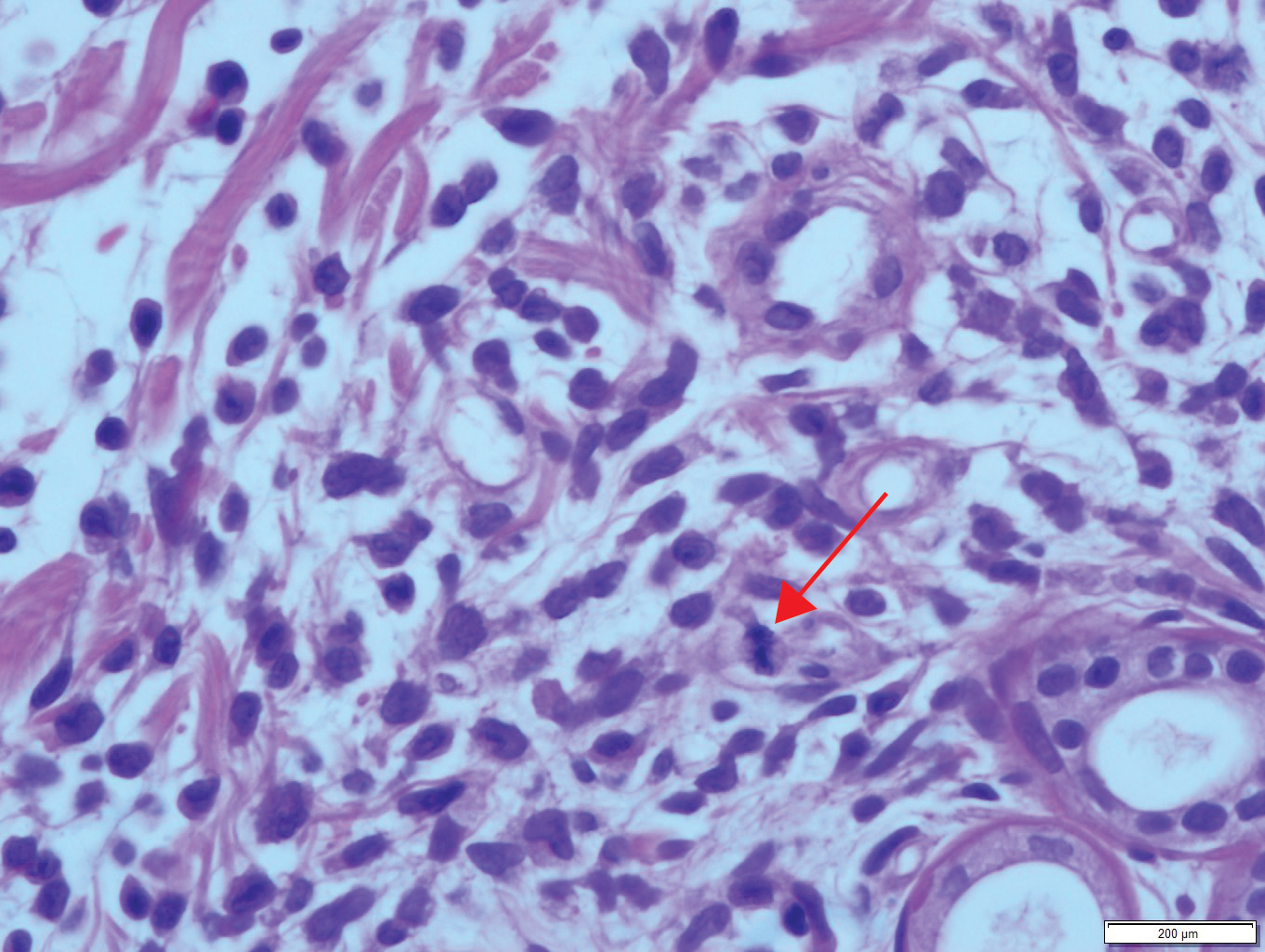

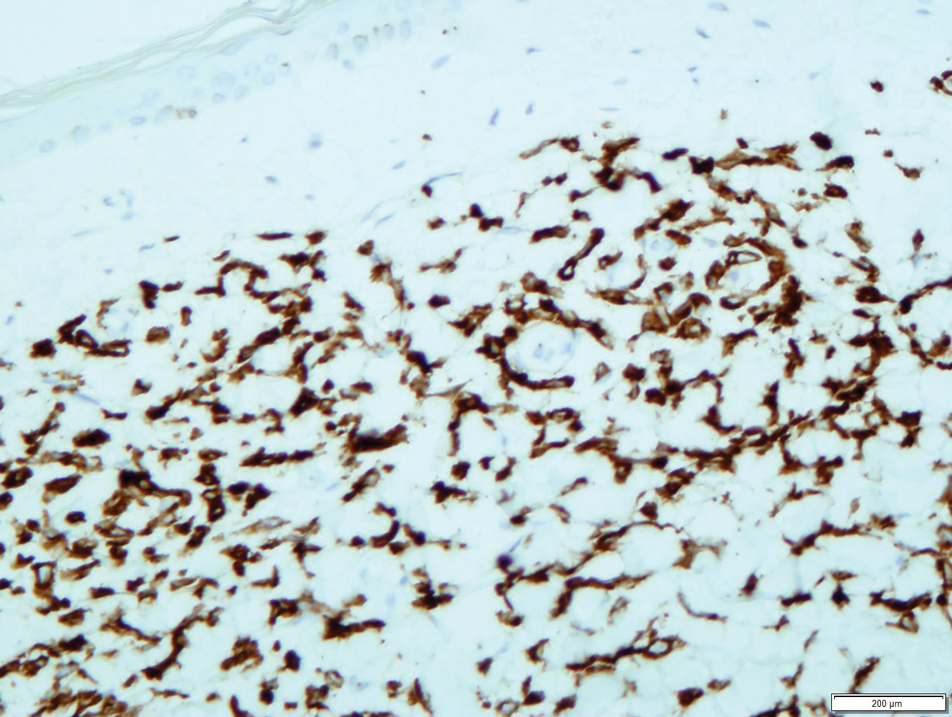

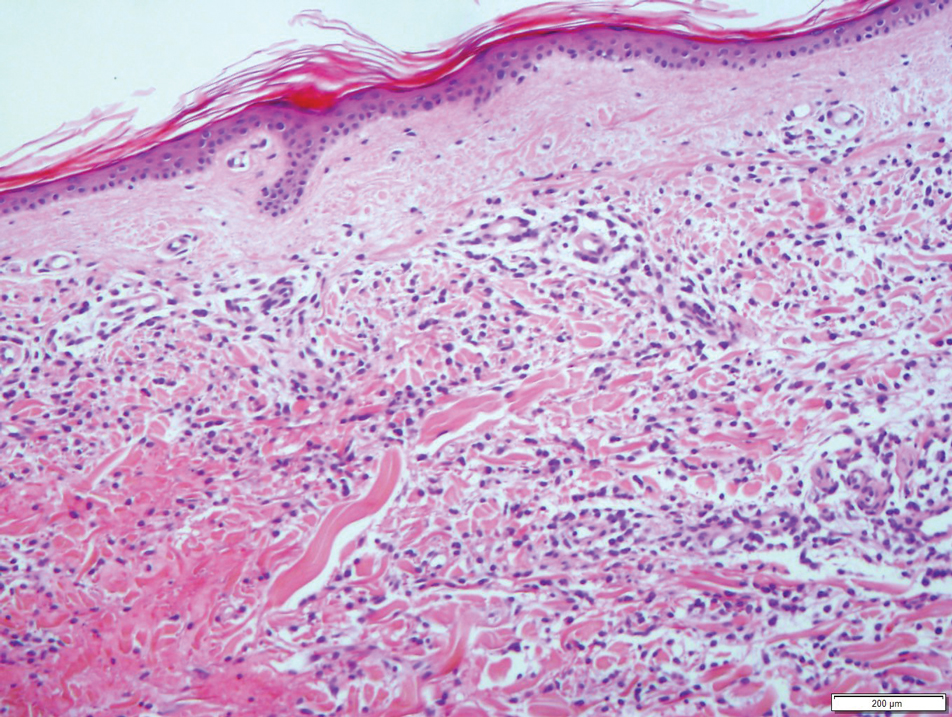

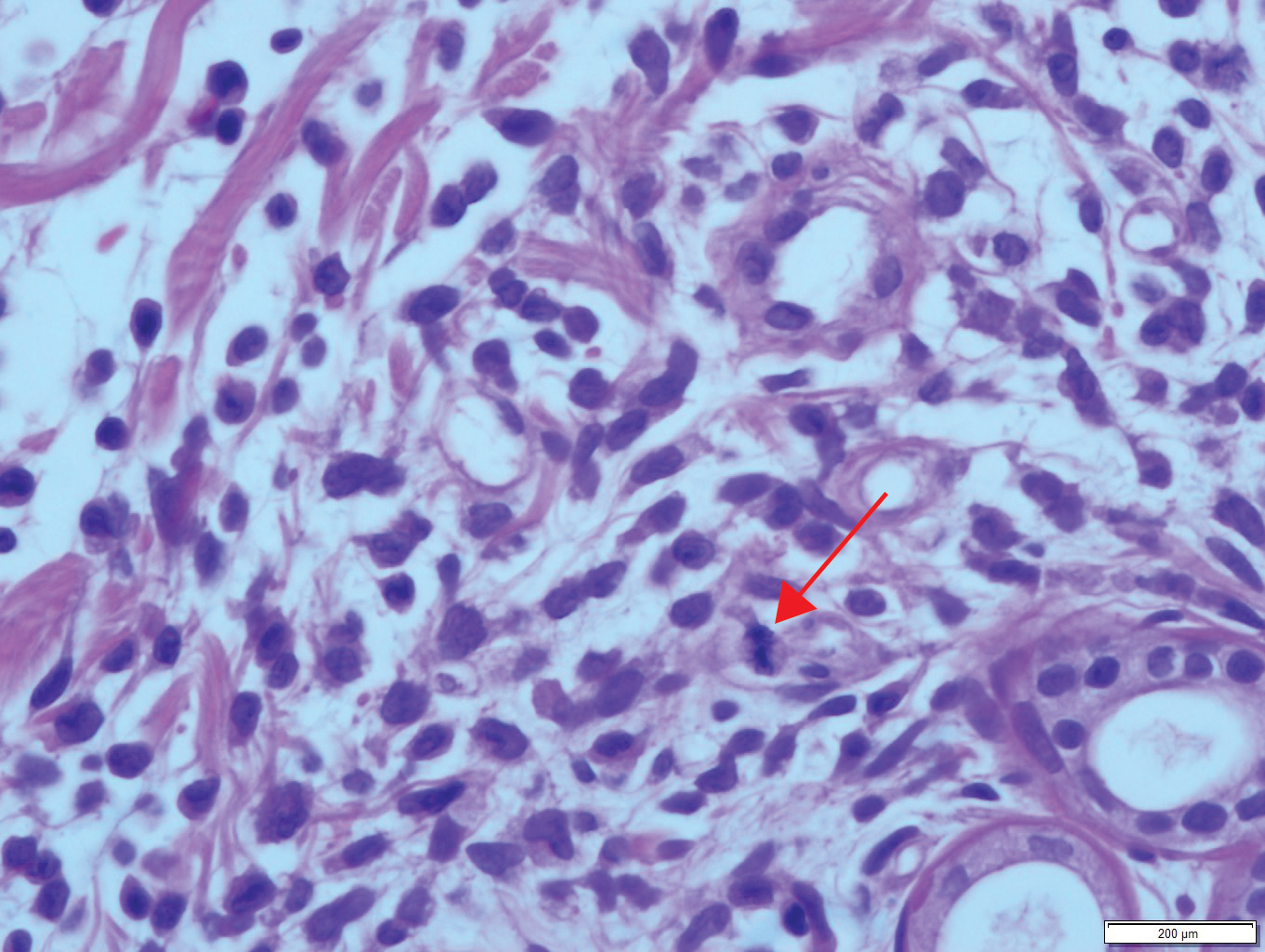

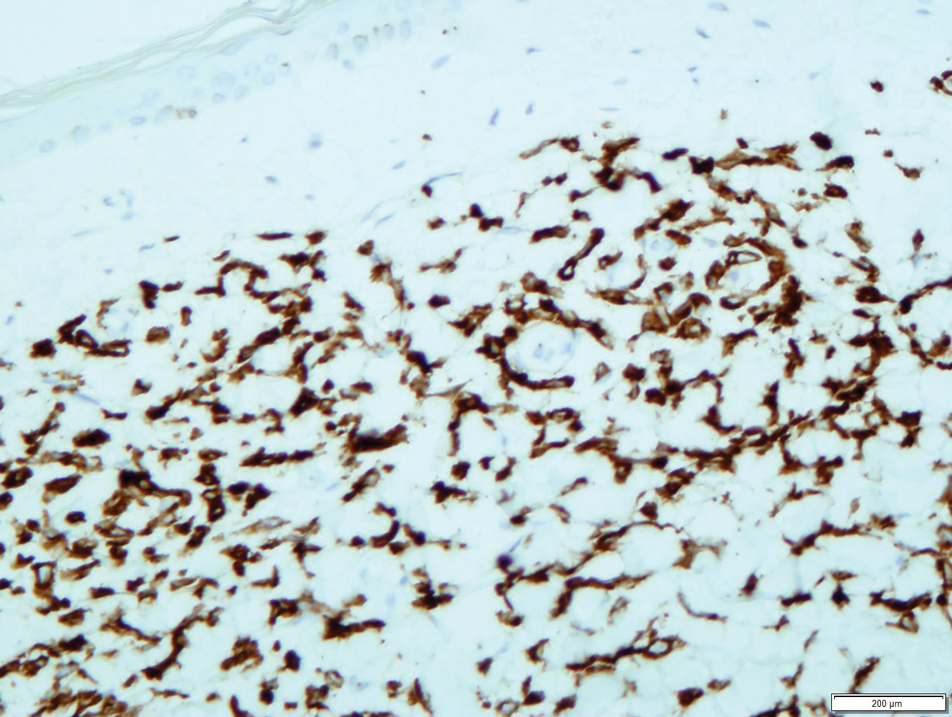

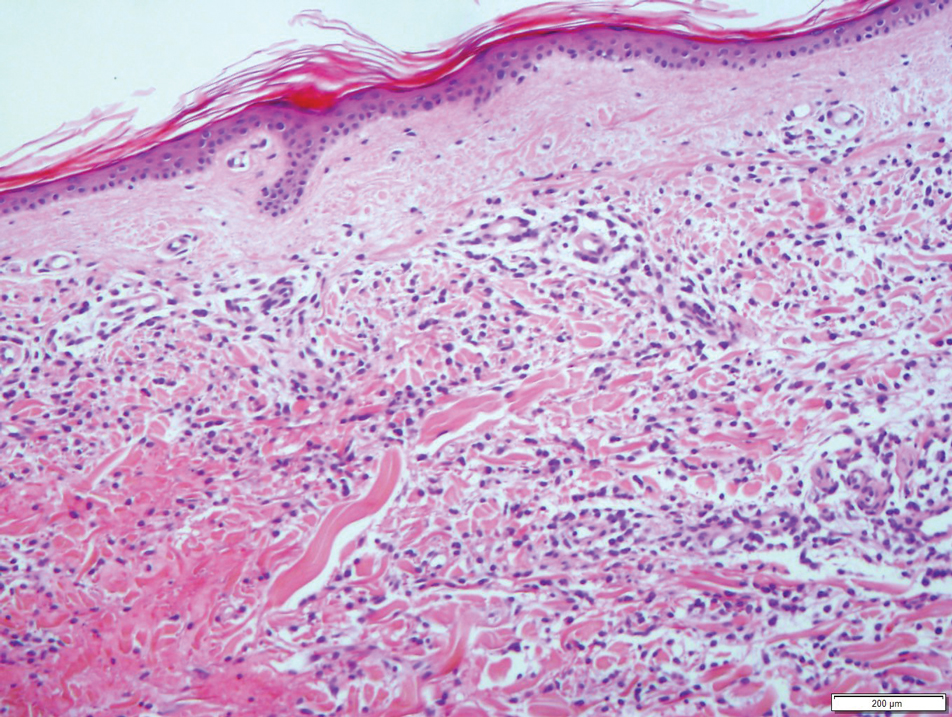

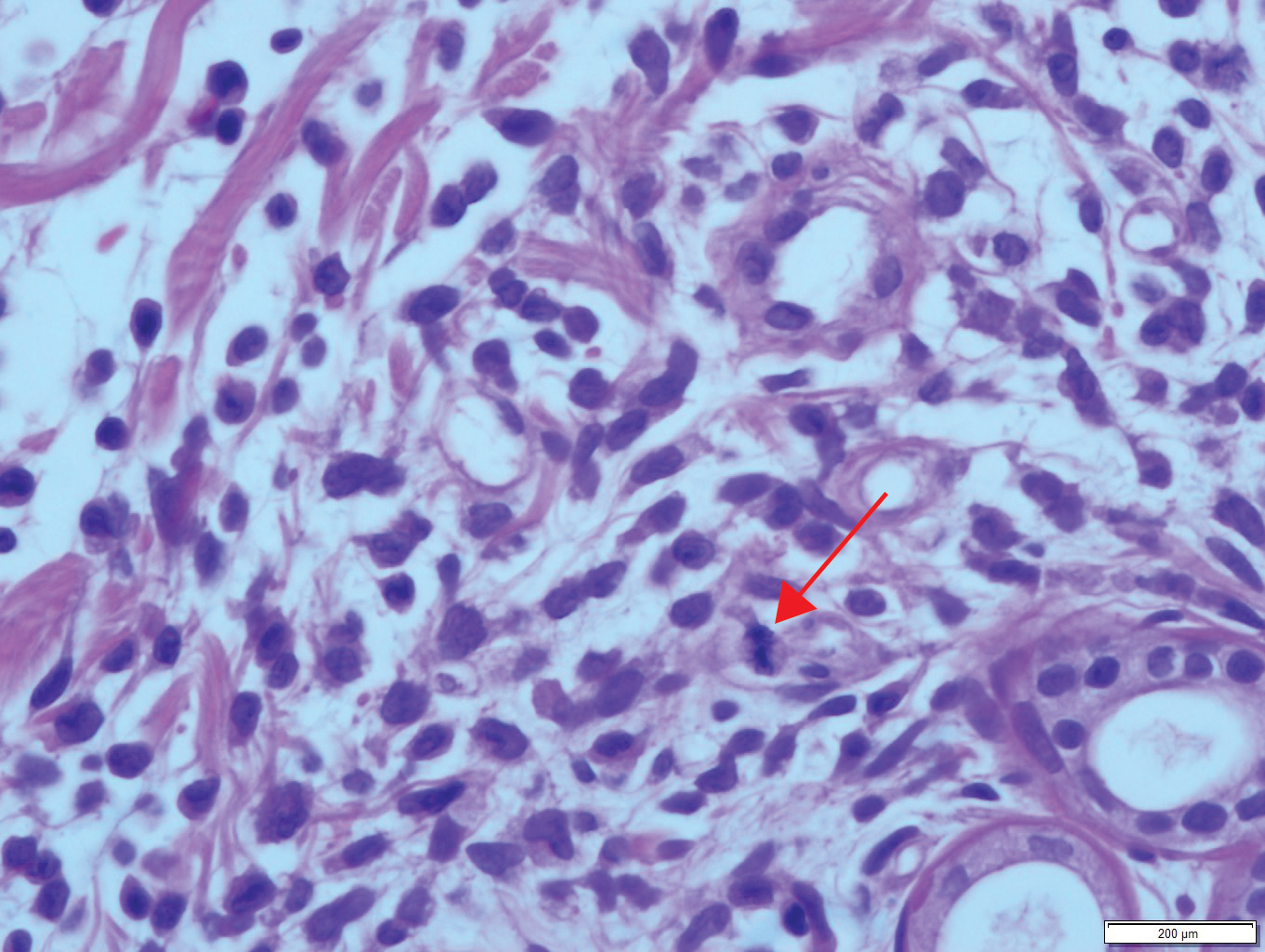

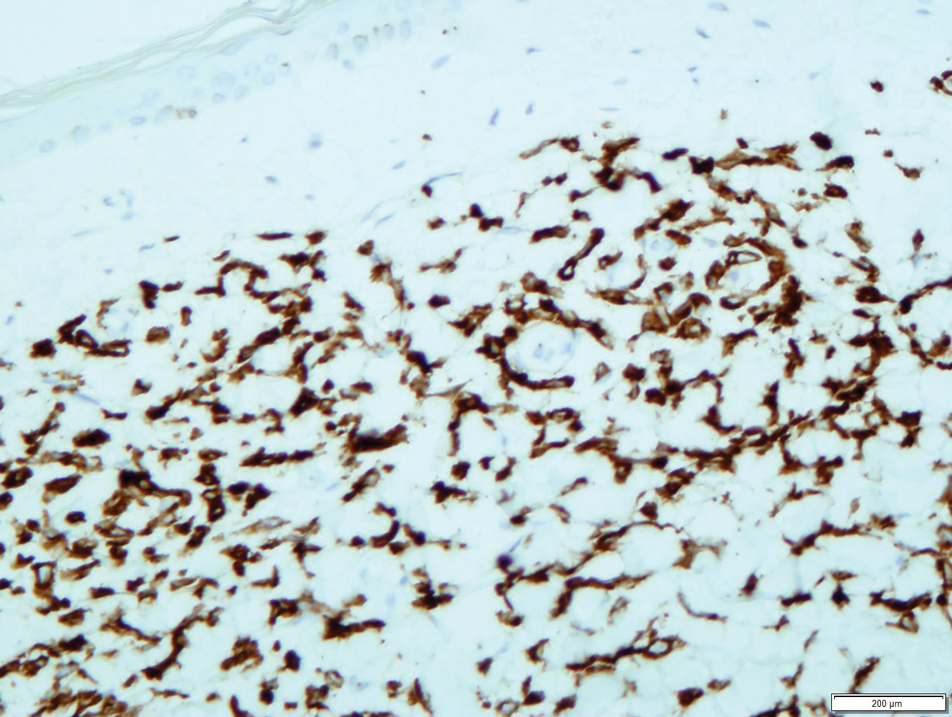

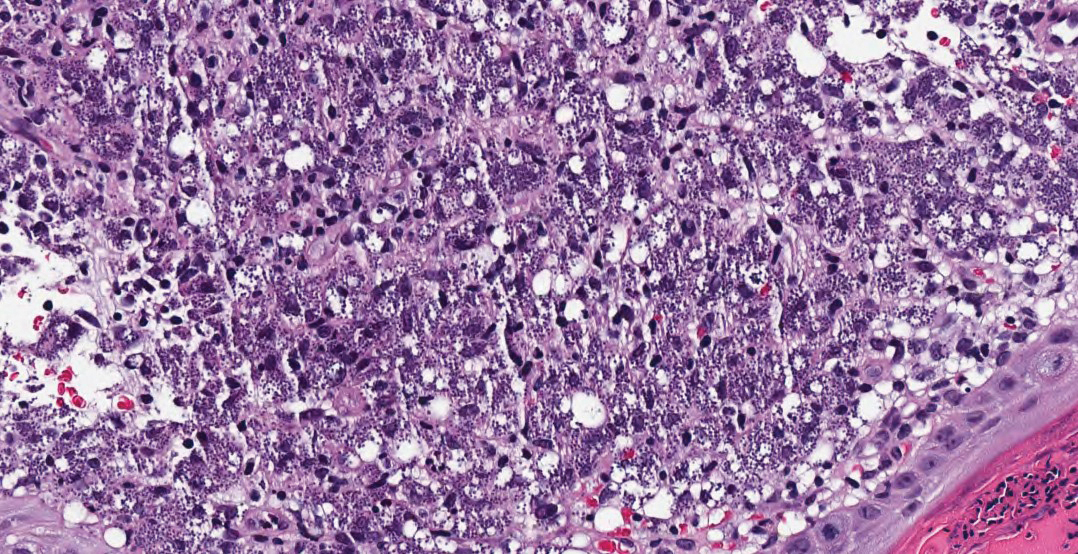

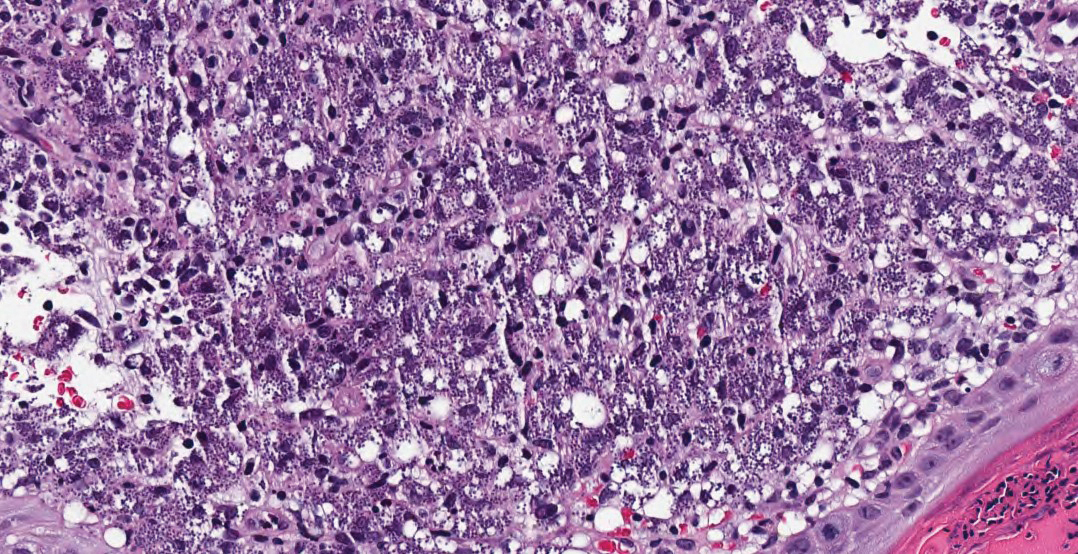

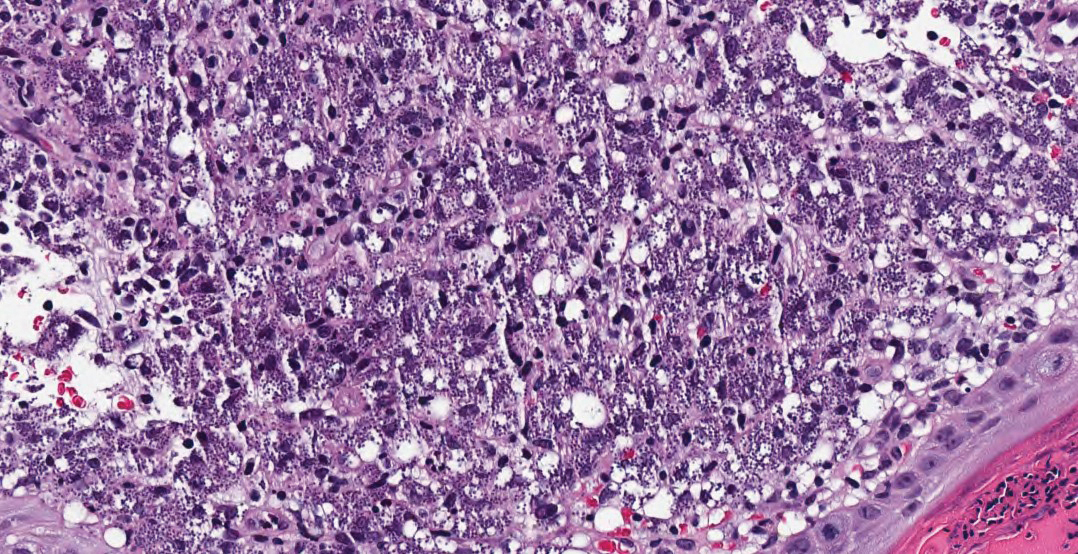

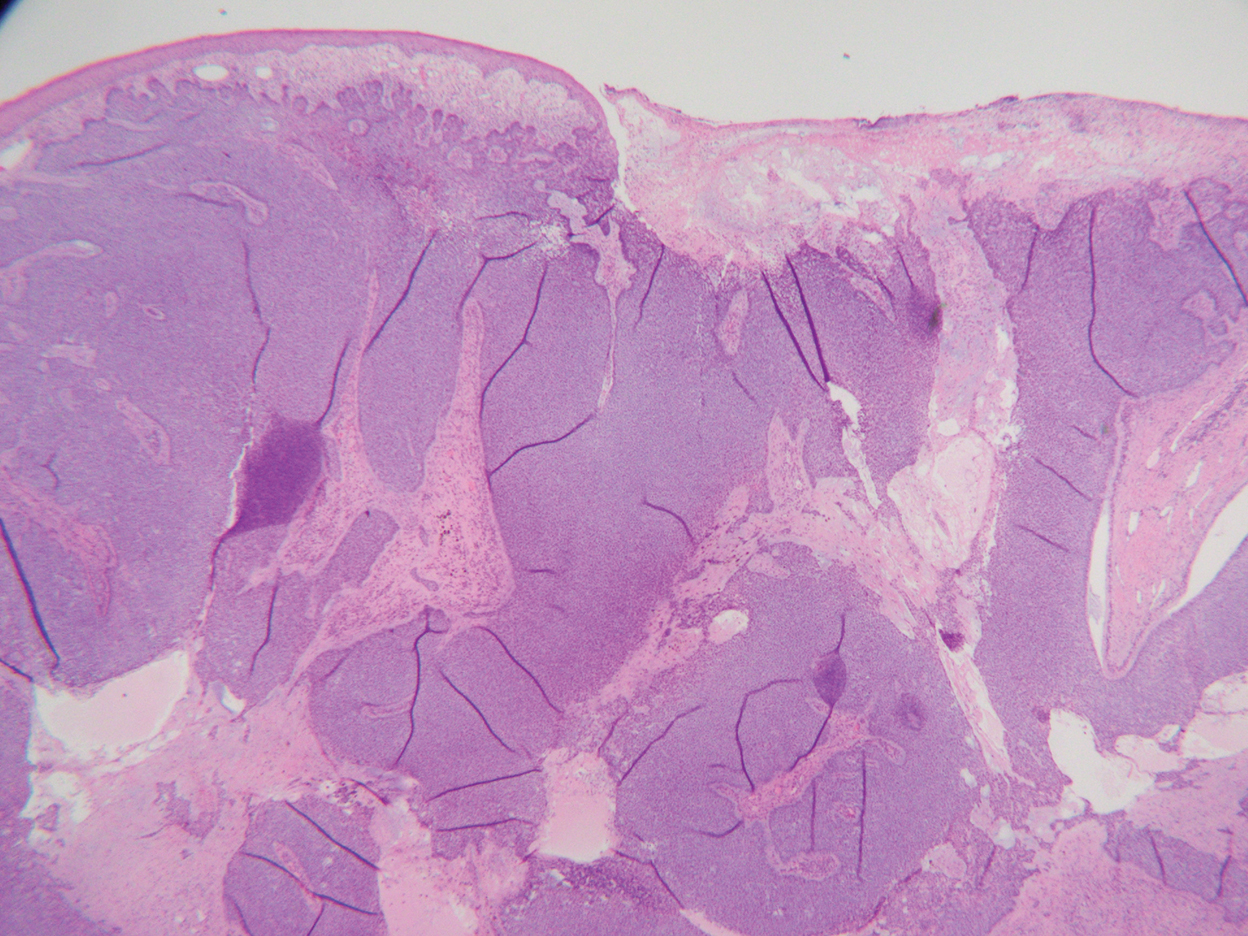

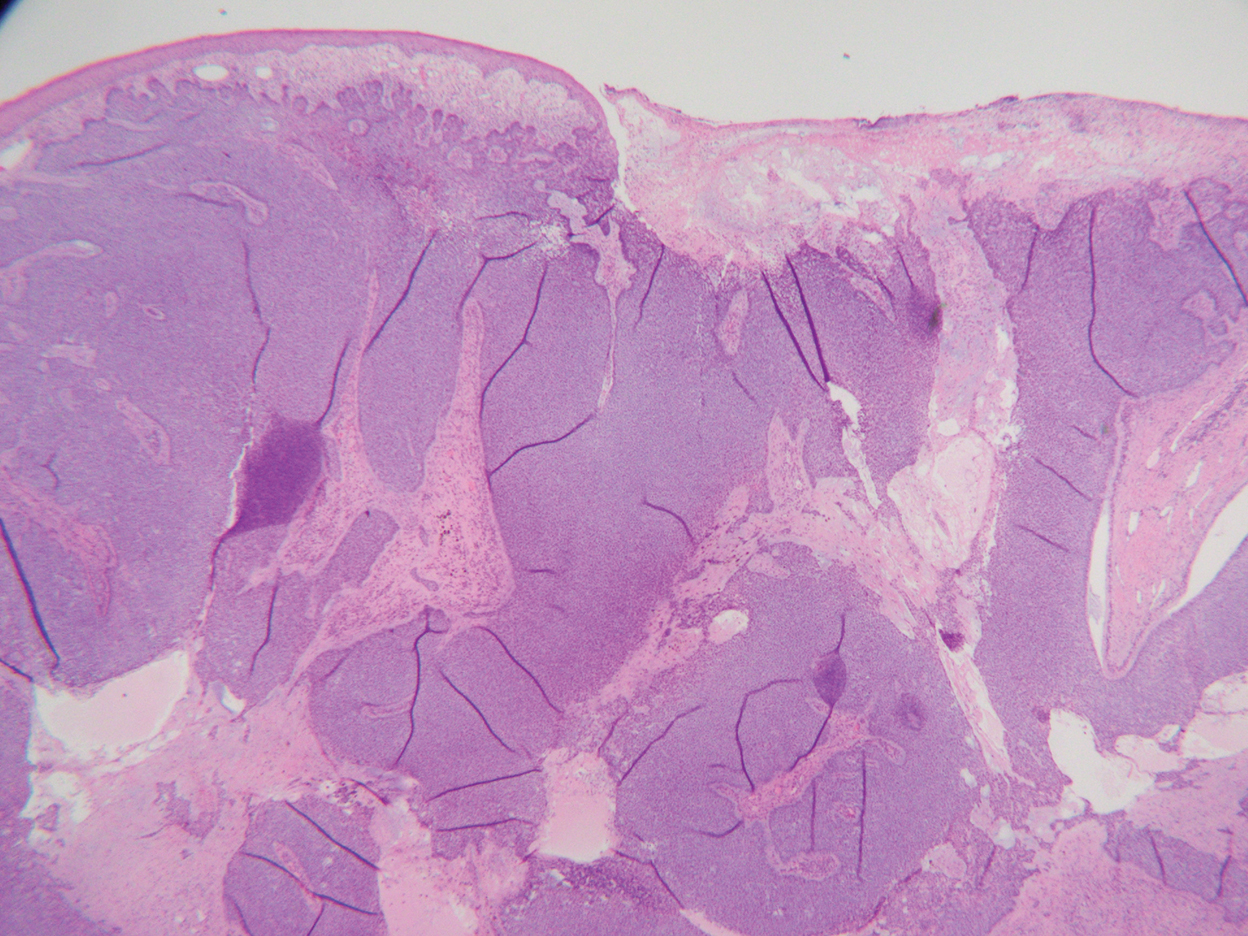

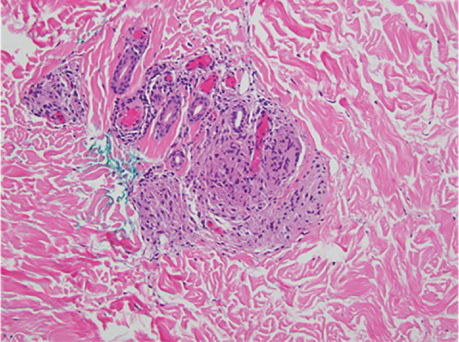

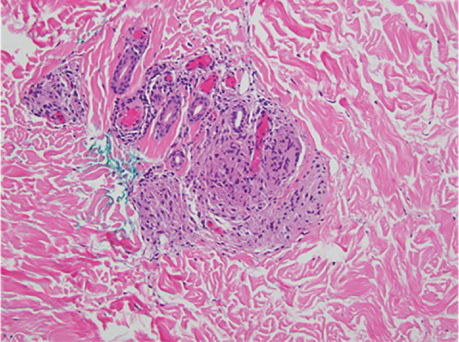

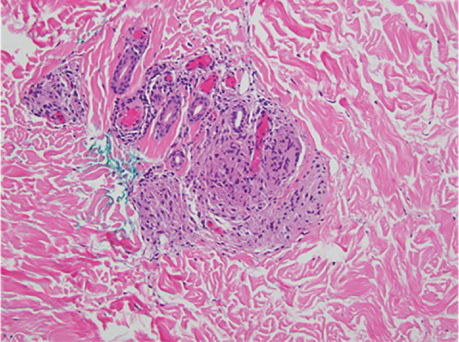

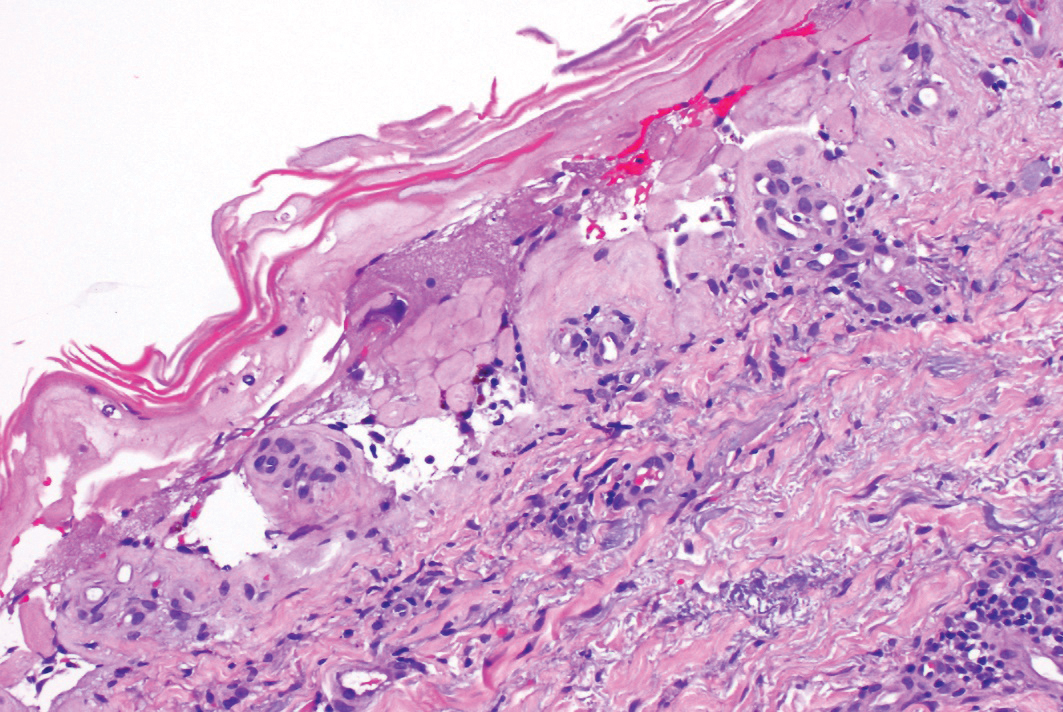

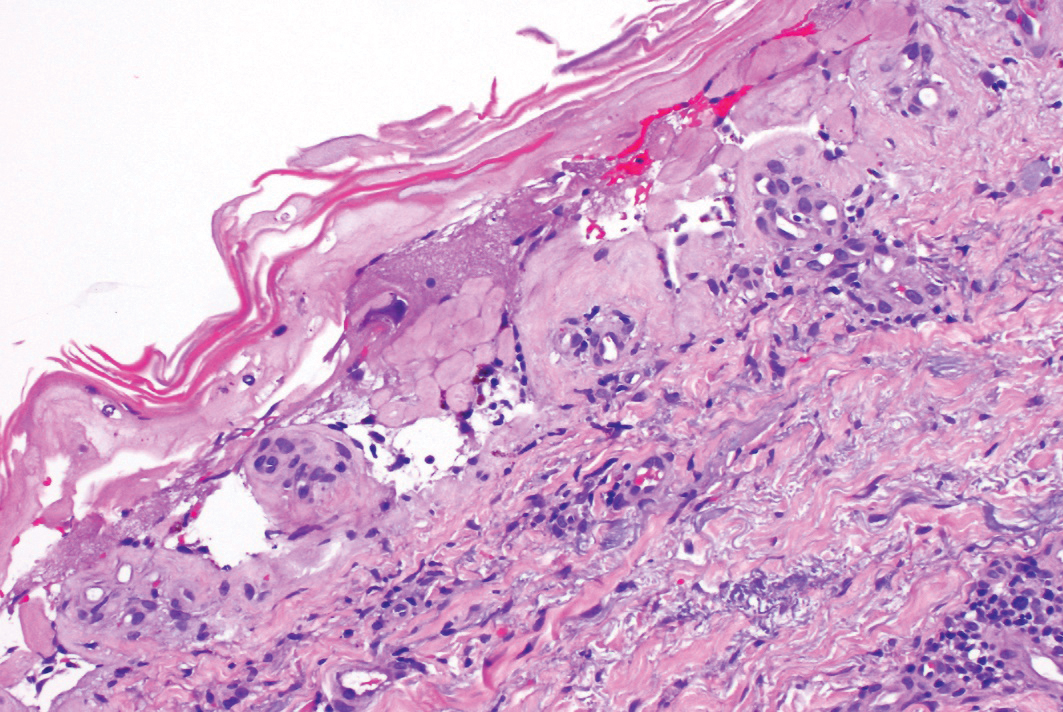

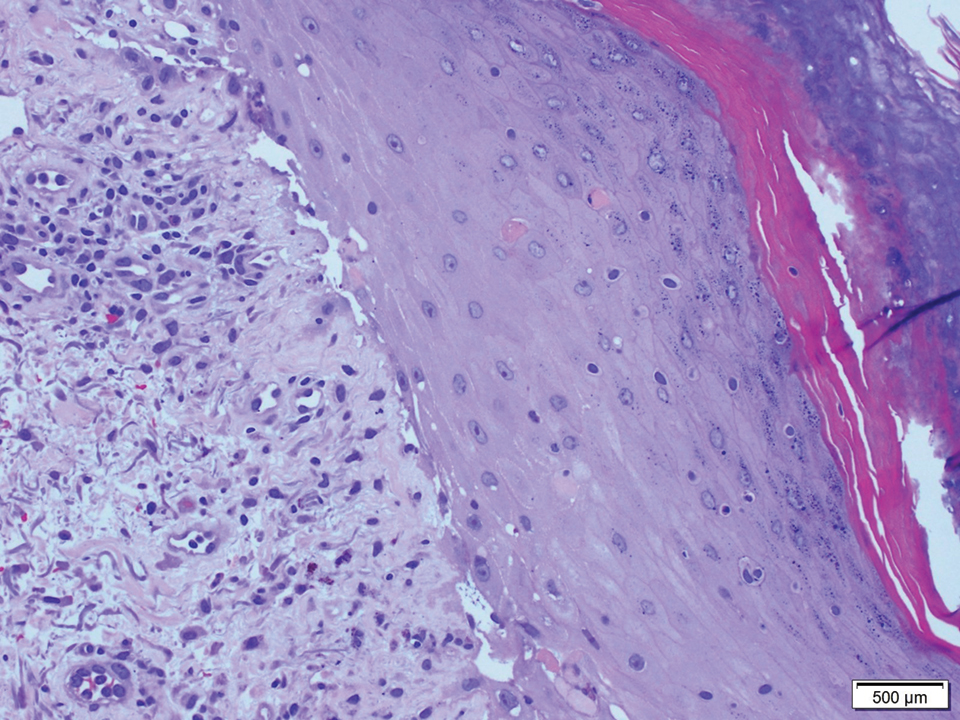

Results from a skin punch biopsy from the right leg showed a normal epidermis and papillary dermis. The reticular dermis was expanded by a diffuse cellular infiltrate with dermal edema and separation of collagen bundles (Figure 2), which consisted of small cells with irregular, cleaved, and notched nuclei, containing a variable amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Mitotic figures were present (Figure 3). There was no evidence of vasculitis, and Congo red stain for amyloid was negative. These atypical cells were positive for the leukocyte common antigen, favoring a hematopoietic infiltrate (Figure 4). Other positive markers included CD4 (associated with helper T cells, and mature and immature monocytes), CD68 (a monocyte/macrophage marker), and CD56 (associated with natural killer cells, myeloma, acute myeloid leukemia [AML], and neuroendocrine tumors). The cells were negative for CD3 (T-cell lineage–specific antigen), CD5 (marker of T cells and a subset of IgM-secreting B cells), CD34 (early hematopoietic marker), and CD20 (B-cell marker). Other negative myeloid markers included myeloperoxidase, CD117, and CD138. These findings suggested leukemic cell recruitment at the site of a reactive infiltrate. The patient completed 2 cycles of intravenous azacitidine with little response and subsequently opted for palliative measures.

Nonpalpable purpura has a broad differential diagnosis including primary and secondary thrombocytopenia; coagulopathies, including vitamin K deficiency, specific clotting factor deficiencies, and amyloid-related purpura; genetic or acquired collagen disorders, including vitamin C deficiency; and eruptions induced by drugs and herbal remedies.

Leukemia cutis is a relatively rare cause of purpura and is defined as cutaneous infiltration by neoplastic leucocytes.1 It most commonly is associated with AML and complicates approximately 5% to 15%of all adult cases.2 Cutaneous involvement occurs predominantly in monocytic variants; acute myelomonocytic leukemia and acute monocytic leukemia may arise in up to 50% of these cases.3 The clinical presentation may vary from papules, nodules, and plaques to rarer manifestations including purpura. A leukemic infiltrate often is associated with sites of inflammation, such as infection or ulceration,4 though there was no reported history of any known triggering events in our patient. Lesions usually involve the legs, followed by the arms, back, chest, scalp, and face.4 One-third of cases coincide with systemic symptoms, and approximately 10% precede bone marrow or peripheral blood involvement, referred to as aleukemic leukemia. The remainder of cases arise following an established diagnosis of systemic leukemia.5 Leukemia cutis is considered a marker of poor prognosis in AML,4,6 requiring treatment for the underlying systemic disease. Our case also was complicated by a concurrent pancreatic malignancy and relatively advanced age, which limited the feasibility of further treatment.

- Strutton G. Cutaneous infiltrates: lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Weedon D, ed. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2002:1118-1120.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:966-978.

- Paydas S, Zorludemir S. Leukaemia cutis and leukaemic vasculitis. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:773-779.

- Shaikh BS, Frantz E, Lookingbill DP. Histologically proven leukemia cutis carries a poor prognosis in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Cutis. 1987;39:57-60.

- Su WP. Clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical correlations in leukemia cutis. Semin Dermatol. 1994;13:223-230.

To the Editor:

A 72-year-old man presented with symptomatic anemia and nonpalpable purpura of the legs, abdomen, and arms of 2 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). There were no associated perifollicular papules. Physical examination of the hair and gingiva were normal.

The patient’s medical history was notable for a poorly differentiated pancreatic adenocarcinoma (pT3N1M0) resected 7 months prior using a Whipple operation (pancreaticoduodenectomy). Adjuvant therapy consisted of 5 cycles of intravenous gemcitabine and paclitaxel. Treatment was discontinued 1 month prior due to progressive weight loss and the presence of new liver metastases on computed tomography. There was no recent history of corticosteroid, antiplatelet, or anticoagulant use. The patient had no known history of trauma at the affected sites.

The patient’s laboratory workup revealed the following results: hemoglobin, 5.5 g/dL (reference range, 13–18 g/dL); platelets, 128×109/L (reference range, 150–400×109/L); total white blood cell count (24.0×109/L [reference range, 4.0–11.0×109/L]), consisting of neutrophils (2.4×109/L [reference range, 2.0–7.5×109/L]), lymphocytes (3.1×109/L [reference range, 1.5–4.0×109/L]), and monocytes (18.5×109/L [reference range, 0.2–0.8×109/L]). Fibrinogen, activated partial thromboplastin time, and prothrombin time were within reference range. Results of a bone marrow biopsy showed 64% blasts. The lactate dehydrogenase level was 286 U/L (reference range, 135–220 U/L) and CA-19-9 antigen was 238 U/mL (reference range, 0–39 U/mL).

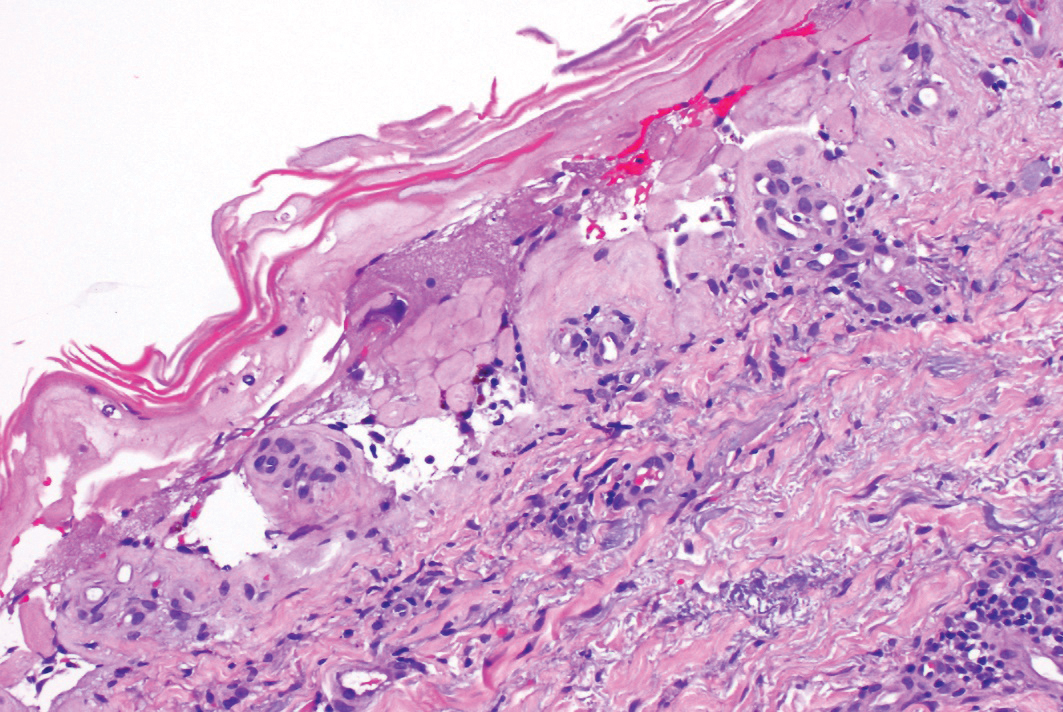

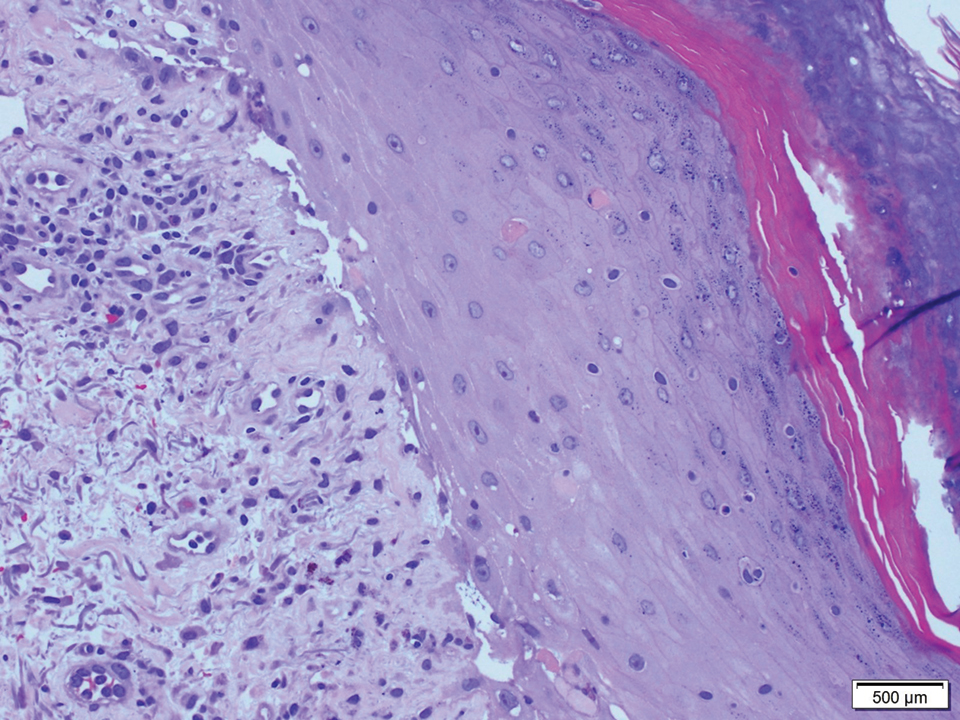

Results from a skin punch biopsy from the right leg showed a normal epidermis and papillary dermis. The reticular dermis was expanded by a diffuse cellular infiltrate with dermal edema and separation of collagen bundles (Figure 2), which consisted of small cells with irregular, cleaved, and notched nuclei, containing a variable amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Mitotic figures were present (Figure 3). There was no evidence of vasculitis, and Congo red stain for amyloid was negative. These atypical cells were positive for the leukocyte common antigen, favoring a hematopoietic infiltrate (Figure 4). Other positive markers included CD4 (associated with helper T cells, and mature and immature monocytes), CD68 (a monocyte/macrophage marker), and CD56 (associated with natural killer cells, myeloma, acute myeloid leukemia [AML], and neuroendocrine tumors). The cells were negative for CD3 (T-cell lineage–specific antigen), CD5 (marker of T cells and a subset of IgM-secreting B cells), CD34 (early hematopoietic marker), and CD20 (B-cell marker). Other negative myeloid markers included myeloperoxidase, CD117, and CD138. These findings suggested leukemic cell recruitment at the site of a reactive infiltrate. The patient completed 2 cycles of intravenous azacitidine with little response and subsequently opted for palliative measures.

Nonpalpable purpura has a broad differential diagnosis including primary and secondary thrombocytopenia; coagulopathies, including vitamin K deficiency, specific clotting factor deficiencies, and amyloid-related purpura; genetic or acquired collagen disorders, including vitamin C deficiency; and eruptions induced by drugs and herbal remedies.

Leukemia cutis is a relatively rare cause of purpura and is defined as cutaneous infiltration by neoplastic leucocytes.1 It most commonly is associated with AML and complicates approximately 5% to 15%of all adult cases.2 Cutaneous involvement occurs predominantly in monocytic variants; acute myelomonocytic leukemia and acute monocytic leukemia may arise in up to 50% of these cases.3 The clinical presentation may vary from papules, nodules, and plaques to rarer manifestations including purpura. A leukemic infiltrate often is associated with sites of inflammation, such as infection or ulceration,4 though there was no reported history of any known triggering events in our patient. Lesions usually involve the legs, followed by the arms, back, chest, scalp, and face.4 One-third of cases coincide with systemic symptoms, and approximately 10% precede bone marrow or peripheral blood involvement, referred to as aleukemic leukemia. The remainder of cases arise following an established diagnosis of systemic leukemia.5 Leukemia cutis is considered a marker of poor prognosis in AML,4,6 requiring treatment for the underlying systemic disease. Our case also was complicated by a concurrent pancreatic malignancy and relatively advanced age, which limited the feasibility of further treatment.

To the Editor:

A 72-year-old man presented with symptomatic anemia and nonpalpable purpura of the legs, abdomen, and arms of 2 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). There were no associated perifollicular papules. Physical examination of the hair and gingiva were normal.

The patient’s medical history was notable for a poorly differentiated pancreatic adenocarcinoma (pT3N1M0) resected 7 months prior using a Whipple operation (pancreaticoduodenectomy). Adjuvant therapy consisted of 5 cycles of intravenous gemcitabine and paclitaxel. Treatment was discontinued 1 month prior due to progressive weight loss and the presence of new liver metastases on computed tomography. There was no recent history of corticosteroid, antiplatelet, or anticoagulant use. The patient had no known history of trauma at the affected sites.

The patient’s laboratory workup revealed the following results: hemoglobin, 5.5 g/dL (reference range, 13–18 g/dL); platelets, 128×109/L (reference range, 150–400×109/L); total white blood cell count (24.0×109/L [reference range, 4.0–11.0×109/L]), consisting of neutrophils (2.4×109/L [reference range, 2.0–7.5×109/L]), lymphocytes (3.1×109/L [reference range, 1.5–4.0×109/L]), and monocytes (18.5×109/L [reference range, 0.2–0.8×109/L]). Fibrinogen, activated partial thromboplastin time, and prothrombin time were within reference range. Results of a bone marrow biopsy showed 64% blasts. The lactate dehydrogenase level was 286 U/L (reference range, 135–220 U/L) and CA-19-9 antigen was 238 U/mL (reference range, 0–39 U/mL).

Results from a skin punch biopsy from the right leg showed a normal epidermis and papillary dermis. The reticular dermis was expanded by a diffuse cellular infiltrate with dermal edema and separation of collagen bundles (Figure 2), which consisted of small cells with irregular, cleaved, and notched nuclei, containing a variable amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Mitotic figures were present (Figure 3). There was no evidence of vasculitis, and Congo red stain for amyloid was negative. These atypical cells were positive for the leukocyte common antigen, favoring a hematopoietic infiltrate (Figure 4). Other positive markers included CD4 (associated with helper T cells, and mature and immature monocytes), CD68 (a monocyte/macrophage marker), and CD56 (associated with natural killer cells, myeloma, acute myeloid leukemia [AML], and neuroendocrine tumors). The cells were negative for CD3 (T-cell lineage–specific antigen), CD5 (marker of T cells and a subset of IgM-secreting B cells), CD34 (early hematopoietic marker), and CD20 (B-cell marker). Other negative myeloid markers included myeloperoxidase, CD117, and CD138. These findings suggested leukemic cell recruitment at the site of a reactive infiltrate. The patient completed 2 cycles of intravenous azacitidine with little response and subsequently opted for palliative measures.

Nonpalpable purpura has a broad differential diagnosis including primary and secondary thrombocytopenia; coagulopathies, including vitamin K deficiency, specific clotting factor deficiencies, and amyloid-related purpura; genetic or acquired collagen disorders, including vitamin C deficiency; and eruptions induced by drugs and herbal remedies.

Leukemia cutis is a relatively rare cause of purpura and is defined as cutaneous infiltration by neoplastic leucocytes.1 It most commonly is associated with AML and complicates approximately 5% to 15%of all adult cases.2 Cutaneous involvement occurs predominantly in monocytic variants; acute myelomonocytic leukemia and acute monocytic leukemia may arise in up to 50% of these cases.3 The clinical presentation may vary from papules, nodules, and plaques to rarer manifestations including purpura. A leukemic infiltrate often is associated with sites of inflammation, such as infection or ulceration,4 though there was no reported history of any known triggering events in our patient. Lesions usually involve the legs, followed by the arms, back, chest, scalp, and face.4 One-third of cases coincide with systemic symptoms, and approximately 10% precede bone marrow or peripheral blood involvement, referred to as aleukemic leukemia. The remainder of cases arise following an established diagnosis of systemic leukemia.5 Leukemia cutis is considered a marker of poor prognosis in AML,4,6 requiring treatment for the underlying systemic disease. Our case also was complicated by a concurrent pancreatic malignancy and relatively advanced age, which limited the feasibility of further treatment.

- Strutton G. Cutaneous infiltrates: lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Weedon D, ed. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2002:1118-1120.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:966-978.

- Paydas S, Zorludemir S. Leukaemia cutis and leukaemic vasculitis. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:773-779.

- Shaikh BS, Frantz E, Lookingbill DP. Histologically proven leukemia cutis carries a poor prognosis in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Cutis. 1987;39:57-60.

- Su WP. Clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical correlations in leukemia cutis. Semin Dermatol. 1994;13:223-230.

- Strutton G. Cutaneous infiltrates: lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Weedon D, ed. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2002:1118-1120.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:966-978.

- Paydas S, Zorludemir S. Leukaemia cutis and leukaemic vasculitis. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:773-779.

- Shaikh BS, Frantz E, Lookingbill DP. Histologically proven leukemia cutis carries a poor prognosis in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Cutis. 1987;39:57-60.

- Su WP. Clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical correlations in leukemia cutis. Semin Dermatol. 1994;13:223-230.

Practice Points

- Leukemia cutis complicates 5% to 15% of all cases of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in adults.

- The appearance of leukemia cutis may be highly variable. Therefore, it should be included in the differential diagnosis for any cutaneous presentation in patients with an existing diagnosis or high likelihood of AML.

- Leukemic infiltrates are associated with sites of inflammation.

Treatment of Elephantiasic Pretibial Myxedema With Rituximab Therapy

To the Editor:

Pretibial myxedema (PTM) is bilateral, nonpitting, scaly thickening and induration of the skin that most commonly occurs on the anterior aspects of the legs and feet. Pretibial myxedema occurs in approximately 0.5% to 4.3% of patients with hyperthyroidism.1 Thyroid dermopathy often is thought of as the classic nonpitting PTM with skin induration and color change. However, rarer forms of PTM, including plaque, nodular, and elephantiasic, also are important to note.2

Elephantiasic PTM is extremely rare, occurring in less than 1% of patients with PTM.2 Elephantiasic PTM is characterized by the persistent swelling of 1 or both legs; thickening of the skin overlying the dorsum of the feet, ankles, and toes; and verrucous irregular plaques that often are fleshy and flattened. The clinical differential diagnosis of elephantiasic PTM includes elephantiasis nostra verrucosa, a late-stage complication of chronic lymphedema that can be related to a variety of infectious or noninfectious obstructive processes. Few effective therapeutic modalities exist in the treatment of elephantiasic PTM. We present a case of elephantiasic PTM.

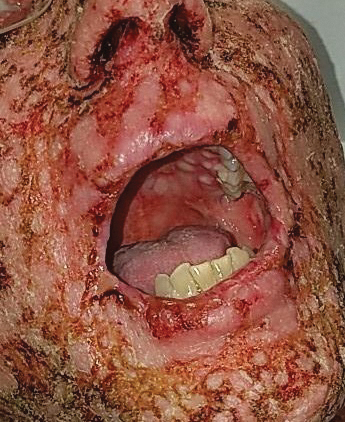

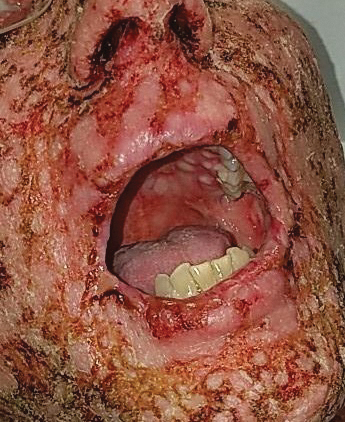

A 59-year-old man presented to dermatology with leonine facies with pronounced glabellar creases and indentations of the earlobes. He had diffuse woody induration, hyperpigmentation, and nonpitting edema of the lower extremities as well as several flesh-colored exophytic nodules scattered throughout the anterior shins and dorsal feet (Figure 1). On the left posterior calf, there was a large, 3-cm, exophytic, firm, flesh-colored nodule. Examination of the hands revealed mild hyperpigmentation of the distal digits, clubbing of the distal phalanges, and cheiroarthropathy.

The patient was diagnosed with Graves disease after experiencing the classic symptoms of hyperthyroidism, including heat intolerance, tremor, palpitations, and anxiety. He received thyroid ablation and subsequently was supplemented with levothyroxine 75 mg daily. Twelve years later, he was diagnosed with Graves ophthalmopathy with ocular proptosis requiring multiple courses of retro-orbital irradiation and surgical procedures for decompression. Approximately 1 year later, he noted increased swelling, firmness, and darkening of the pretibial surfaces. Initially, he was referred to vascular surgery and underwent bilateral saphenous vein ablation. He also was referred to a lymphedema specialist, and workup revealed an unremarkable lymphatic system. Minimal improvement was noted following the saphenous vein ablation, and he subsequently was referred to dermatology for further workup.

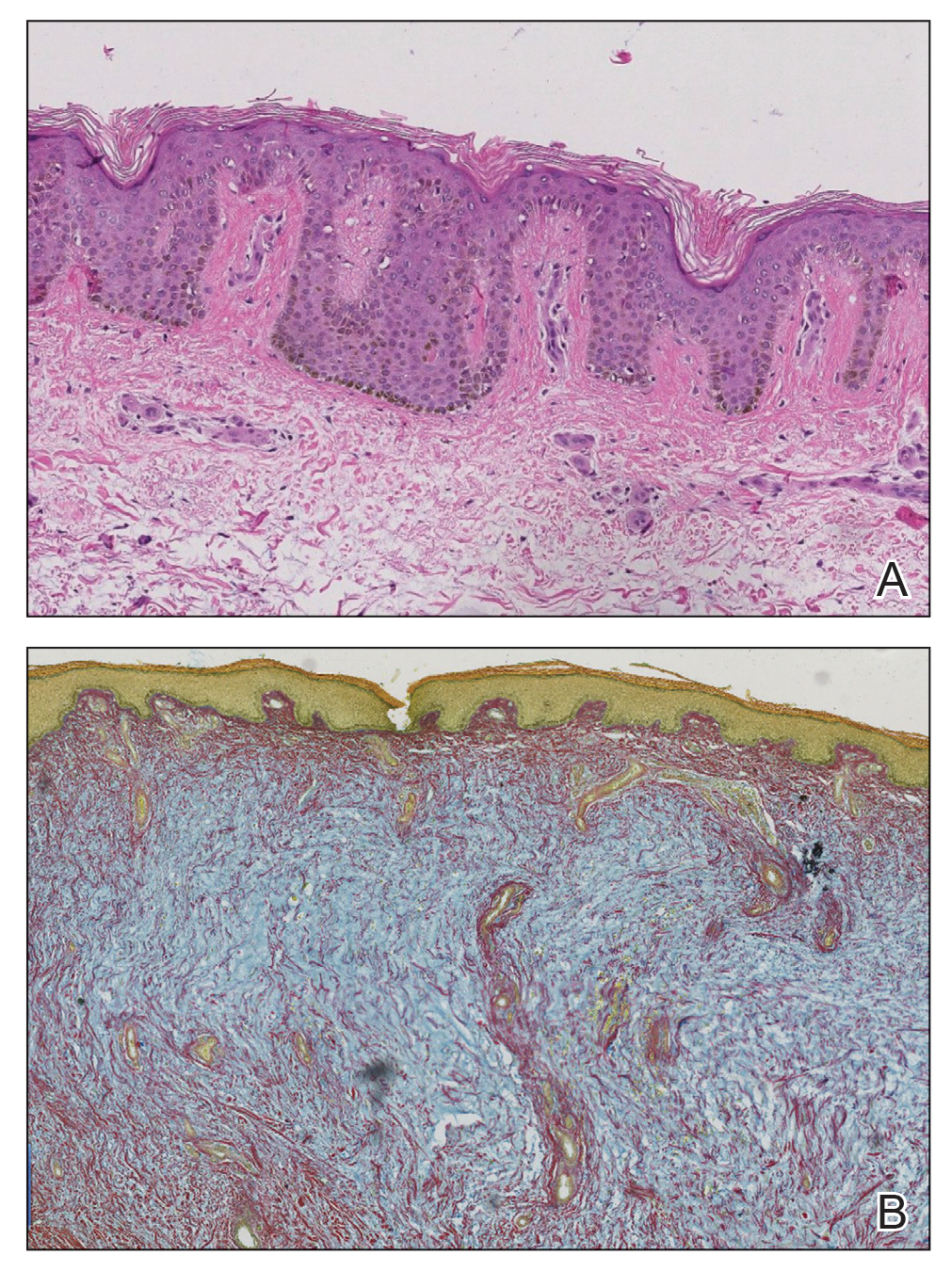

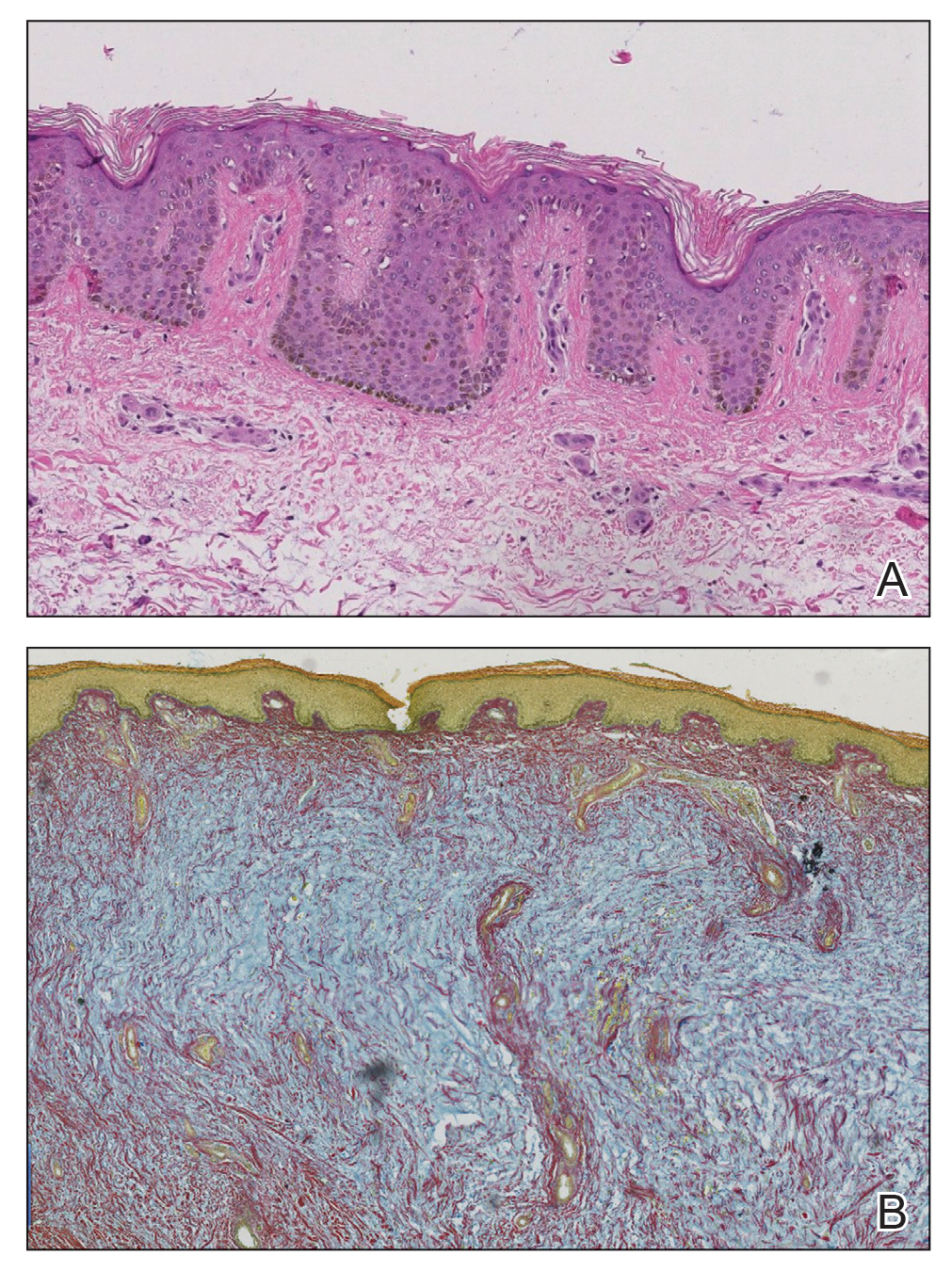

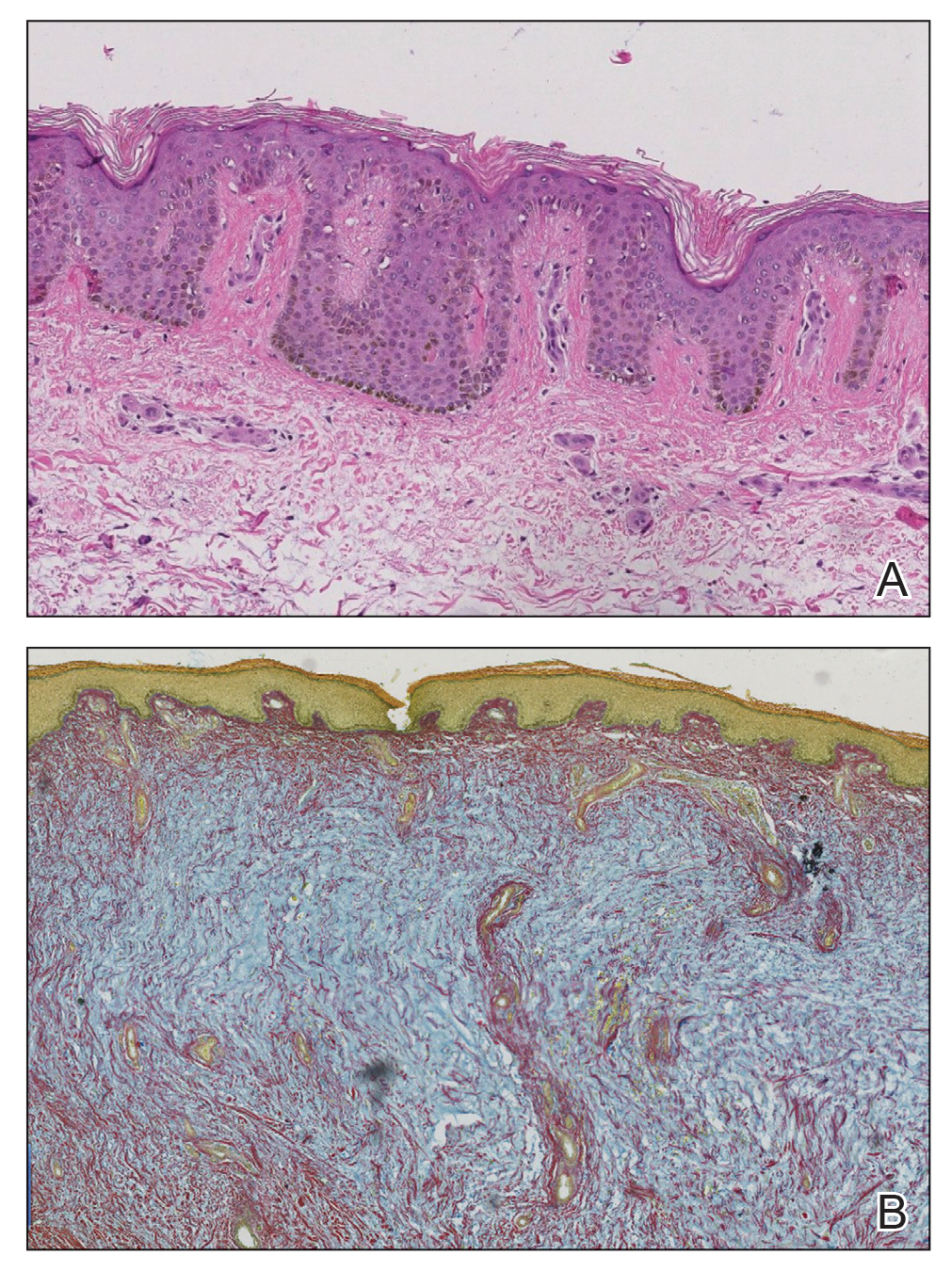

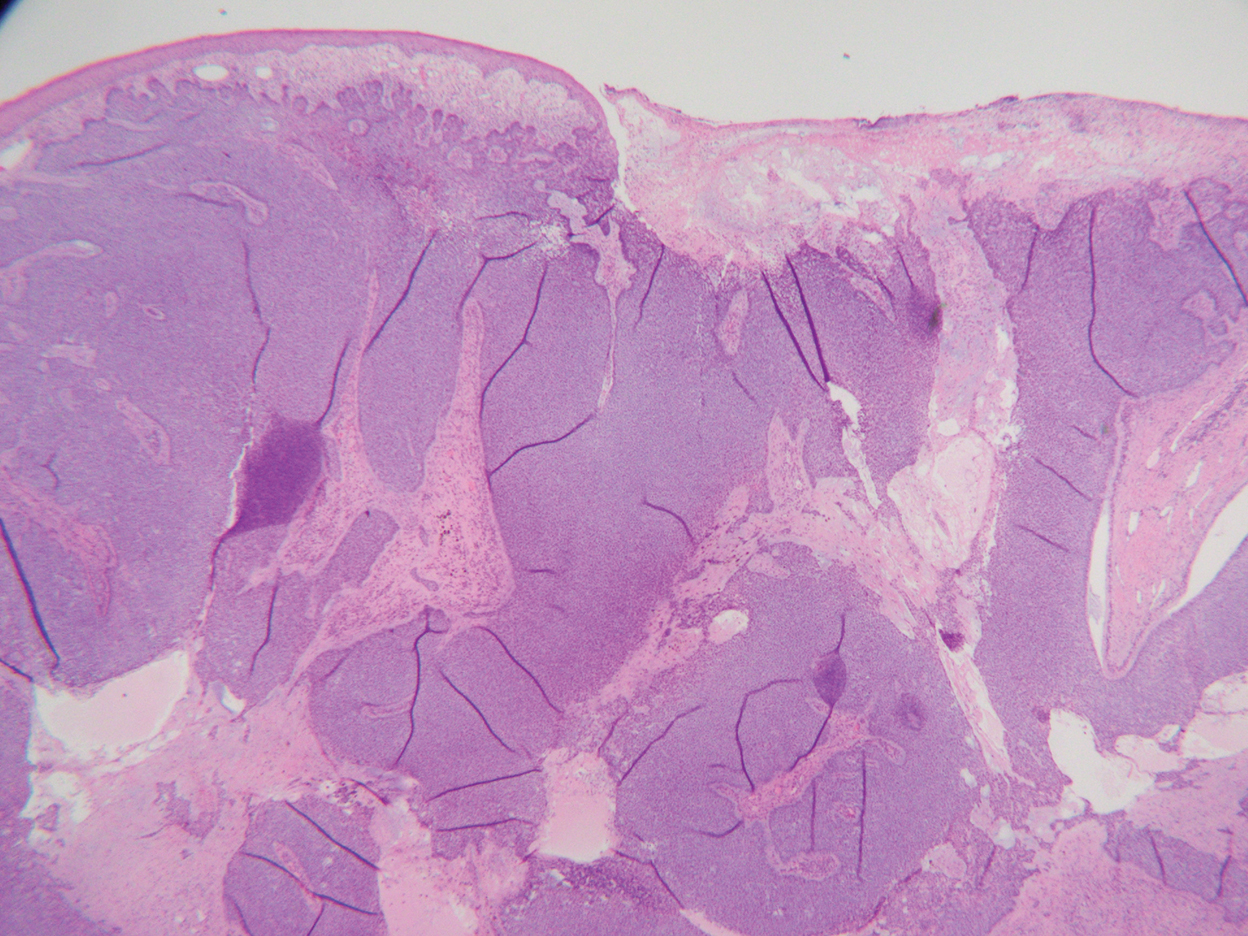

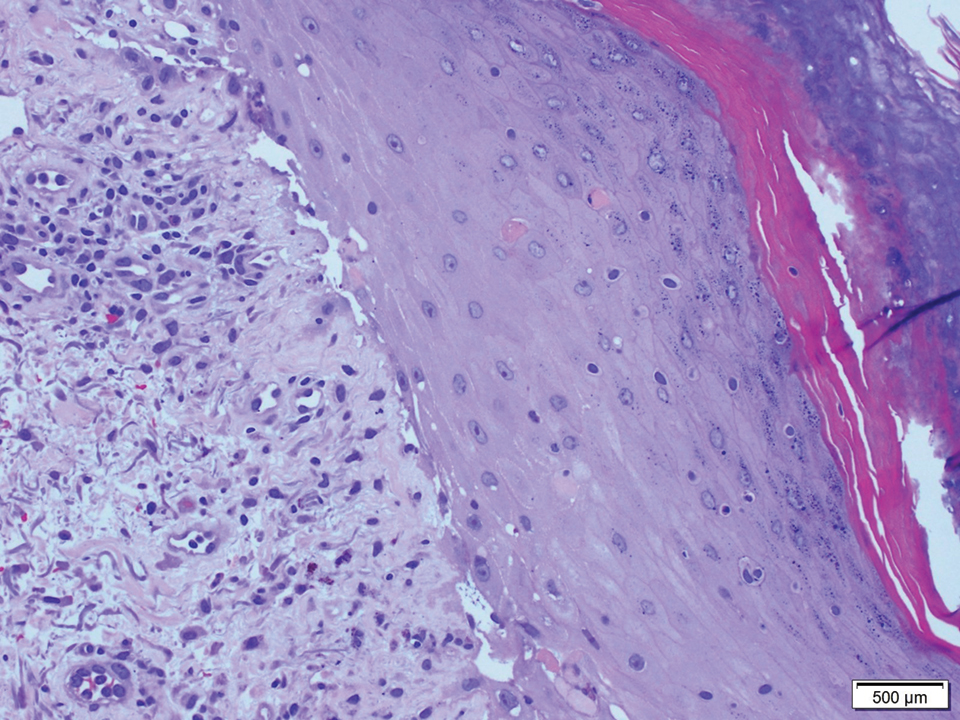

At the current presentation, laboratory analysis revealed a low thyrotropin level (0.03 mIU/L [reference range, 0.4–4.2 mIU/L]), and free thyroxine was within reference range. Radiography of the chest was unremarkable; however, radiography of the hand demonstrated arthrosis of the left fifth proximal interphalangeal joint. Nuclear medicine lymphoscintigraphy and lower extremity ultrasonography were unremarkable. Punch biopsies were performed of the left lateral leg and posterior calf. Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated marked mucin deposition extending to the deep dermis along with deep fibroplasia and was read as consistent with PTM. Colloidal iron highlighted prominent mucin within the dermis (Figure 2).

The patient’s medical history, physical examination, laboratory analysis, imaging, and biopsies were considered, and a diagnosis of elephantiasic PTM was made. Minimal improvement was noted with initial therapeutic interventions including compression therapy and application of super high–potency topical corticosteroids. After further evaluation in our multidisciplinary rheumatology-dermatology clinic, the decision was made to initiate rituximab infusions.

Two months after 1 course of rituximab consisting of two 1000-mg infusions separated by 2 weeks, the patient showed substantial clinical improvement. There was striking improvement of the pretibial surfaces with resolution of the exophytic nodules and improvement of the induration (Figure 3). In addition, there was decreased induration of the glabella and earlobes and decreased fullness of the digital pulp on the hands. The patient also reported subjective improvements in mobility.

Our patient demonstrated all 3 aspects of the Diamond triad: PTM, exophthalmos, and acropachy. Patients present with all 3 features in less than 1% of reported cases of Graves disease.3 Although all 3 features are seen together infrequently, thyroid dermopathy and acropachy often are markers of severe Graves ophthalmopathy. In a study of 114 patients with Graves ophthalmopathy, patients who also had dermopathy and acropachy were more likely to have optic neuropathy or require orbital decompression.4

After overcoming the diagnostic dilemma that the elephantiasic presentation of PTM can present, therapeutic management remains a challenge. Heyes et al5 documented the successful treatment of highly recalcitrant elephantiasic PTM with rituximab and plasmapheresis therapy. In this case, a 44-year-old woman with an 11-year history of Graves disease and elephantiasic PTM received 29 rituximab infusions and 241 plasmapheresis treatments over the course of 3.5 years. Her elephantiasic PTM clinically resolved, and she was able to resume daily activities and wear normal shoes after being nonambulatory for years.5