User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Dermatologic Management of Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Impact on Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease associated with hyperandrogenism and is caused by occlusion or rupture of follicular units and inflammation of the apocrine glands.1-3 The disease most commonly affects women (female to male ratio of 3:1) of childbearing age.1,2,4,5 Body areas affected include the axillae and groin, and less commonly the perineum; perianal region; and skin folds, such as gluteal, inframammary, and infraumbilical folds.1,2 Symptoms manifest as painful subcutaneous nodules with possible accompanying purulent drainage, sinus tracts, and/or dermal contractures. Although the pathophysiology is unclear, androgens affect the course of HS during pregnancy by stimulating the affected glands and altering cytokines.1,2,6

During pregnancy, maternal immune function switches from cell-mediated T helper cell (TH1) to humoral TH2 cytokine production. The activity of sebaceous and eccrine glands increases while the activity of apocrine glands decreases, thus changing the inflammatory course of HS during pregnancy.3 Approximately 20% of women with HS experience improvement of symptoms during pregnancy, while the remainder either experience no relief or deterioration of symptoms.1 Improvement in symptoms during pregnancy was found to occur more frequently in those who had worsening symptoms during menses owing to the possible hormonal effect estrogen has on inhibiting TH1 and TH17 proinflammatory cytokines, which promotes an immunosuppressive environment.4

Lactation and breastfeeding abilities may be hindered if a woman has HS affecting the apocrine glands of breast tissue and a symptom flare in the postpartum period. If HS causes notable inflammation in the nipple-areolar complex during pregnancy, the patient may experience difficulties with lactation and milk fistula formation, leading to inability to breastfeed.2 Another reason why mothers with HS may not be able to breastfeed is that the medications required to treat the disease are unsafe if passed to the infant via breast milk. In addition, the teratogenic effects of HS medications may necessitate therapy adjustments in pregnancy.1 Here, we provide a brief overview of the medical management considerations of HS in the setting of pregnancy and the impact on breastfeeding.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT AND DRUG SAFETY

Dermatologists prescribe a myriad of topical and systemic medications to ameliorate symptoms of HS. Therapy regimens often are multimodal and include antibiotics, biologics, and immunosuppressants.1,3

Antibiotics

First-line antibiotics include clindamycin, metronidazole, tetracyclines, erythromycin, rifampin, dapsone, and fluoroquinolones. Topical clindamycin 1%, metronidazole 0.75%, and erythromycin 2% are used for open or active HS lesions and are all safe to use in pregnancy since there is minimal systemic absorption and minimal excretion into breast milk.1 Topical antimicrobial washes such as benzoyl peroxide and chlorhexidine often are used in combination with systemic medications to treat HS. These washes are safe during pregnancy and lactation, as they have minimal systemic absorption.7

Of these first-line antibiotics, only tetracyclines are contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation, as they are deemed to be in category D by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Aside from tetracyclines, these antibiotics do not cause birth defects and are safe for nursing infants.1,8 Systemic clindamycin is safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Systemic metronidazole also is safe for use in pregnant patients but needs to be discontinued 12 to 24 hours prior to breastfeeding, which often prohibits appropriate dosing.1

Systemic Erythromycin—There are several forms of systemic erythromycin, including erythromycin base, erythromycin estolate, erythromycin ethylsuccinate (EES), and erythromycin stearate. Erythromycin estolate is contraindicated in pregnancy because it is associated with reversible maternal hepatoxicity and jaundice.9-11 Erythromycin ethylsuccinate is the preferred form for pregnant patients. Providers should exercise caution when prescribing EES to lactating mothers, as small amounts are still secreted through breast milk.11 Some studies have shown an increased risk for development of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis with systemic erythromycin use, especially if a neonate is exposed in the first 14 days of life. Thus, we recommend withholding EES for 2 weeks after delivery if the patient is breastfeeding. A follow-up study did not find any association between erythromycin and infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis; however, the American Academy of Pediatrics still recommends short-term use only of erythromycin if it is to be used in the systemic form.8

Rifampin—Rifampin is excreted into breast milk but without adverse effects to the infant. Rifampin also is safe in pregnancy but should be used on a case-by-case basis in pregnant or nursing women because it is a cytochrome P450 inducer.

Dapsone—Dapsone has no increased risk for congenital anomalies. However, it is associated with hemolytic anemia and neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, especially in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency.12 Newborns exposed to dapsone are at an increased risk for methemoglobinemia owing to increased sensitivity of fetal erythrocytes to oxidizing agents.13 If dapsone use is necessary, stopping dapsone treatment in the last month of gestation is recommended to minimize risk for kernicterus.9 Dapsone can be found in high concentrations in breast milk at 14.3% of the maternal dose. It is still safe to use during breastfeeding, but there is a risk of the infant developing hyperbilirubinemia/G6PD deficiency.1,8 Thus, physicians may consider performing a G6PD screen on infants to determine if breastfeeding is safe.12

Fluoroquinolones—Quinolones are not contraindicated during pregnancy, but they can damage fetal cartilage and thus should be reserved for use in complicated infections when the benefits outweigh the risks.12 Quinolones are believed to increase risk for arthropathy but are safe for use in lactation. When quinolones are digested with milk, exposure decreases below pediatric doses because of the ionized property of calcium in milk.8

Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitors—The safety of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α biologics in pregnancy is less certain when compared with antibiotics.1 Anti–TNF-α inhibitors such as etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab are all labeled as FDA category B, meaning there are no well-controlled human studies of the drugs.9 There are limited data that support safe use of TNF-α inhibitors prior to the third trimester before maternal IgG antibodies are transferred to the fetus via the placenta.1,13 Anti–TNF-α inhibitors may be safe when breastfeeding because the drugs have large molecular weights that prevent them from entering breast milk in large amounts. Absorption also is limited due to the infant’s digestive acids and enzymes breaking down the protein structure of the medication.8 Overall, TNF-α inhibitor use is still controversial and only used if the benefits outweigh the risks during pregnancy or if there is no alternative treatment.1,3,9

Ustekinumab and Anakinra—Ustekinumab (an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor) and anakinra (an IL-1α and IL-1β inhibitor) also are FDA category B drugs and have limited data supporting their use as HS treatment in pregnancy. Anakinra may have evidence of compatibility with breastfeeding, as endogenous IL-1α inhibitor is found in colostrum and mature breast milk.1

Immunosuppressants

Immunosuppressants that are used to treat HS include corticosteroids and cyclosporine.

Corticosteroids—Topical corticosteroids can be used safely in lactation if they are not applied directly to the nipple or any area that makes direct contact with the infant’s mouth. Intralesional corticosteroid injections are safe for use during both pregnancy and breastfeeding to decrease inflammation of acutely flaring lesions and can be considered first-line treatment.1 Oral glucocorticoids also can be safely used for acute flares during pregnancy; however, prolonged use is associated with pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, premature delivery, and gestational diabetes.12 There also is a small risk of oral cleft deformity in the infant; thus, potent corticosteroids are recommended in short durations during pregnancy, and there are no adverse effects if the maternal dose is less than 10 mg daily.8,12 Systemic steroids are safe to use with breastfeeding, but patients should be advised to wait 4 hours after ingesting medication before breastfeeding.1,8

Cyclosporine—Topical and oral calcineurin inhibitors such as cyclosporine have low risk for transmission into breast milk; however, potential effects of exposure through breast milk are unknown. For that reason, manufacturers state that cyclosporine use is contraindicated during lactation.8 If cyclosporine is to be used by a breastfeeding woman, monitoring cyclosporine concentrations in the infant is suggested to ensure that the exposure is less than 5% to 10% of the therapeutic dose.13 The use of cyclosporine has been extensively studied in pregnant transplant patients and is considered relatively safe for use in pregnancy.14 Cyclosporine is lipid soluble and thus is quickly metabolized and spread throughout the body; it can easily cross the placenta.9,13 Blood concentration in the fetus is 30% to 64% that of the maternal circulation. However, cyclosporine is only toxic to the fetus at maternally toxic doses, which can result in low birth weight and increased prenatal and postnatal mortality.13

Isotretinoin, Oral Contraceptive Pills, and Spironolactone

Isotretinoin and hormonal treatments such as oral contraceptive pills and spironolactone (an androgen receptor blocker) commonly are used to treat HS, but all are contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation. Isotretinoin is a well-established teratogen, but adverse effects on nursing babies have not been described. However, the manufacturer of isotretinoin advises against its use in lactation. Oral contraceptive pill use in early pregnancy is associated with increased risk for Down syndrome. Oral contraceptive pill use also is contraindicated in lactation for 2 reasons: decreased milk production and risk for fetal feminization. Antiandrogenic agents such as spironolactone have been shown to be associated with hypospadias and feminization of the male fetus.7

COMMENT

Women with HS usually require ongoing medical treatment during pregnancy and immediately postpartum; thus, it is important that treatments are proven to be safe for use in this specific population. Current management guidelines are not entirely suitable for pregnant and breastfeeding women given that many HS drugs have teratogenic effects and/or can be excreted into breast milk.1 Several treatments have uncertain safety profiles in pregnancy and breastfeeding, which calls for dermatologists to change or create new regimens for their patients. Close management also is necessary to prevent excess inflammation of breast tissue and milk fistula formation, which would hinder normal breastfeeding.

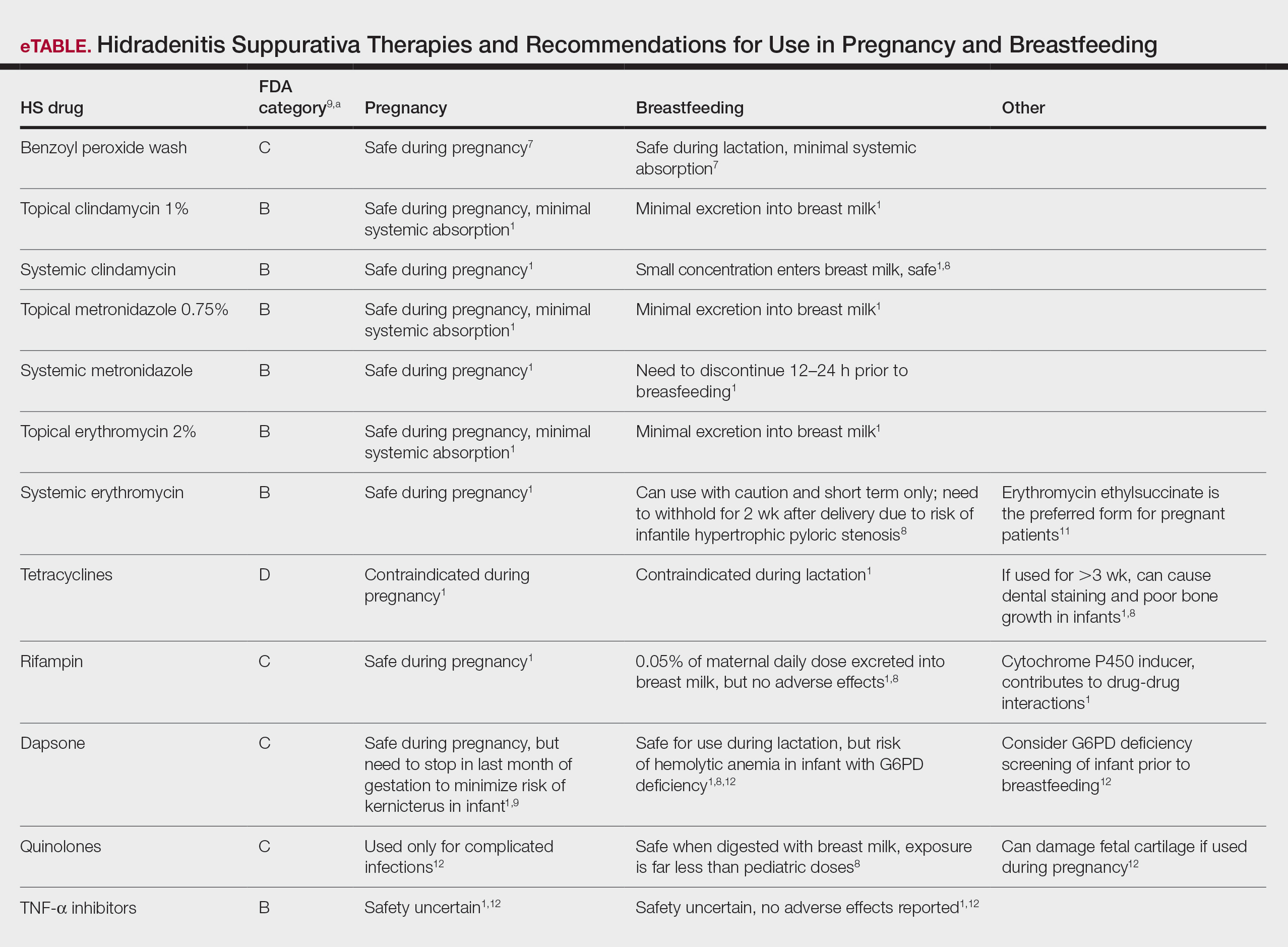

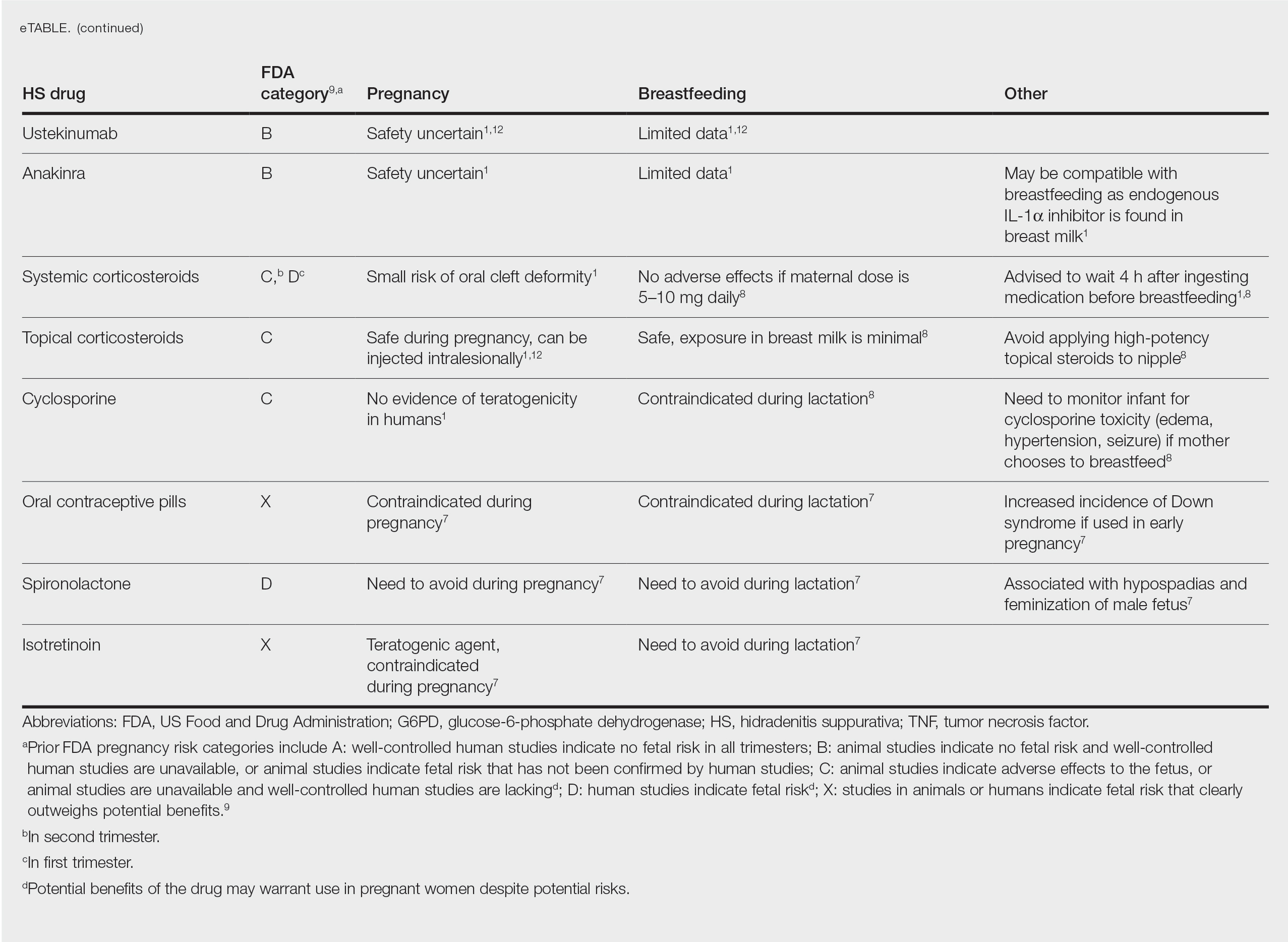

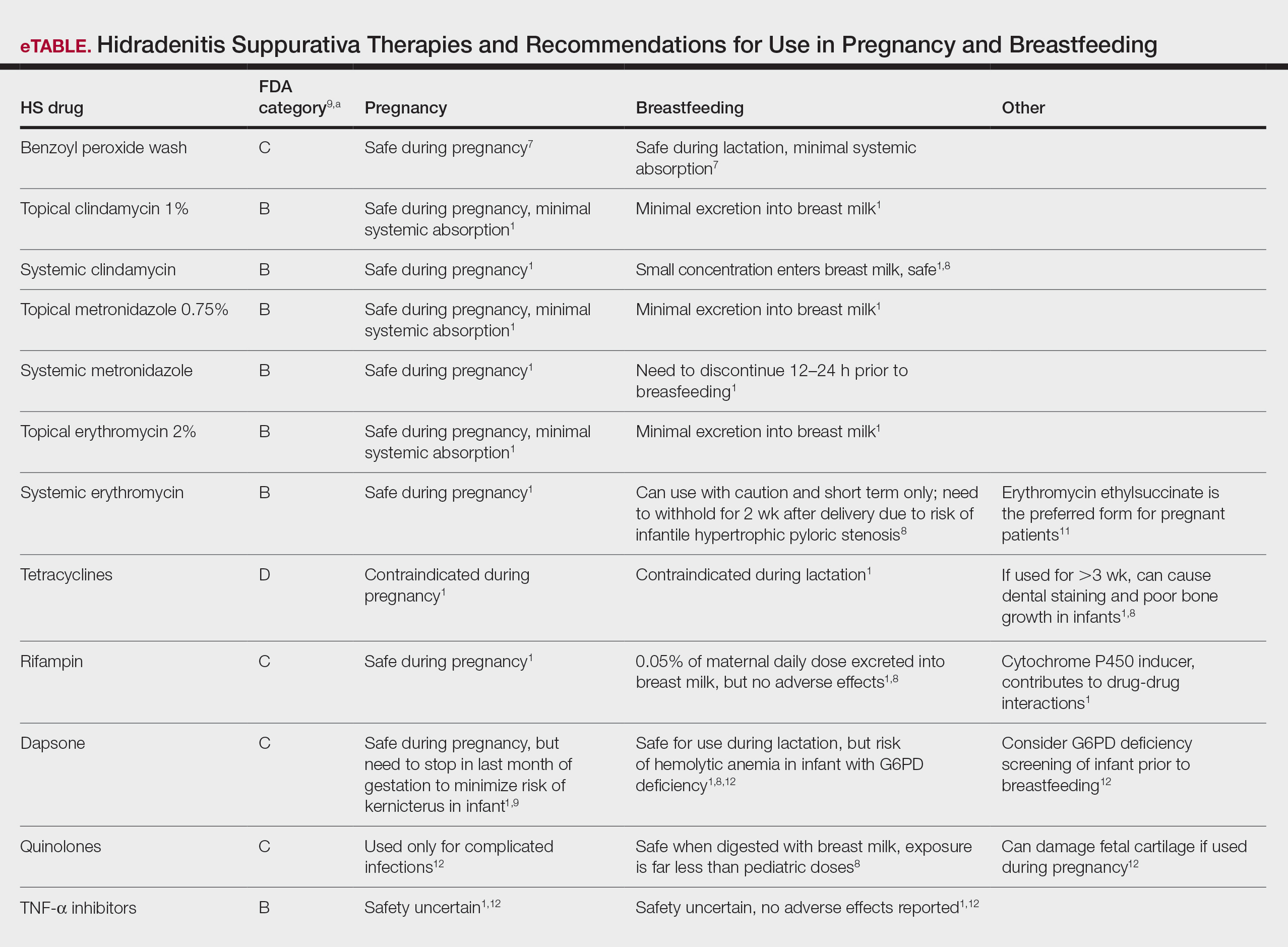

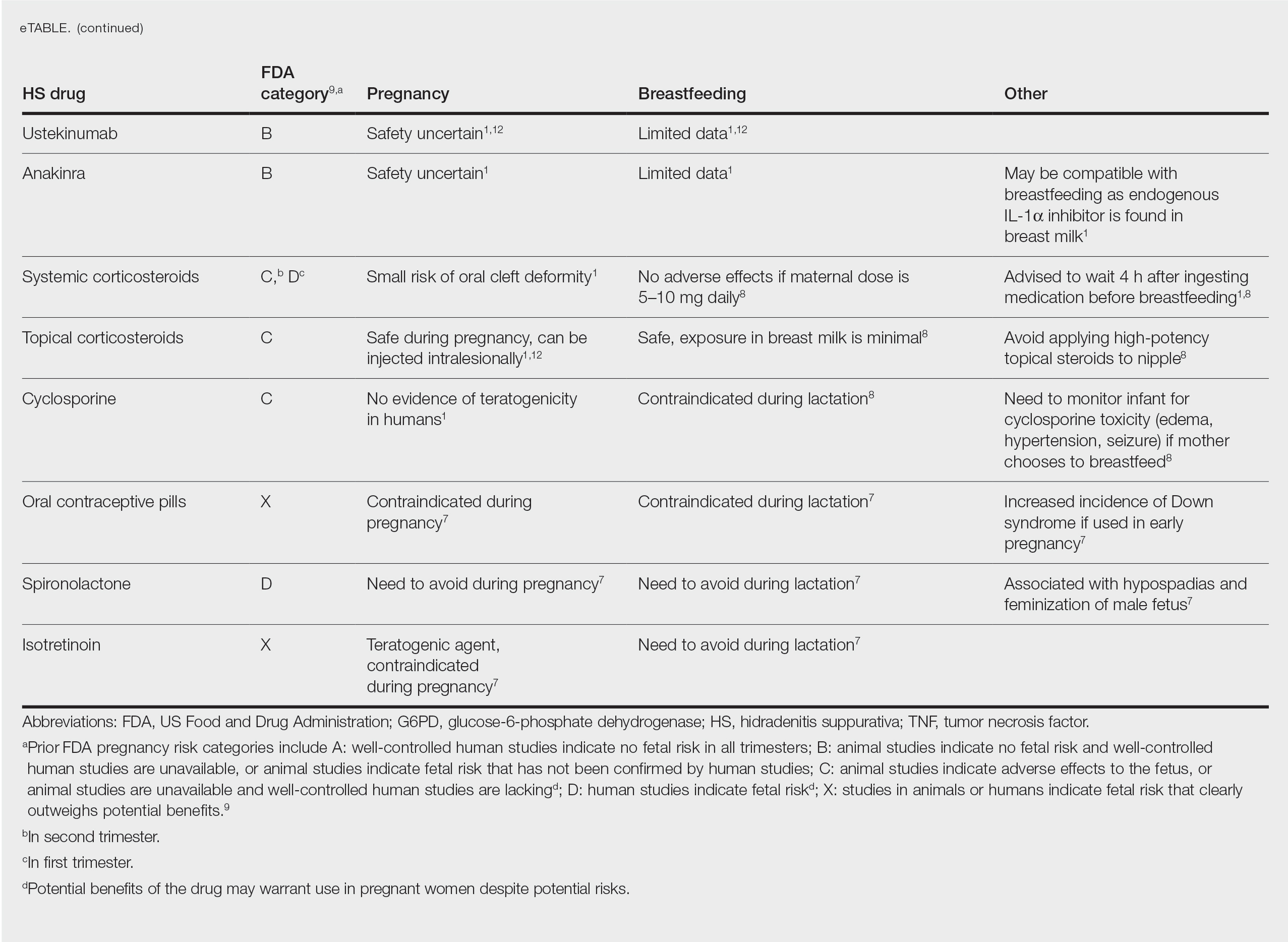

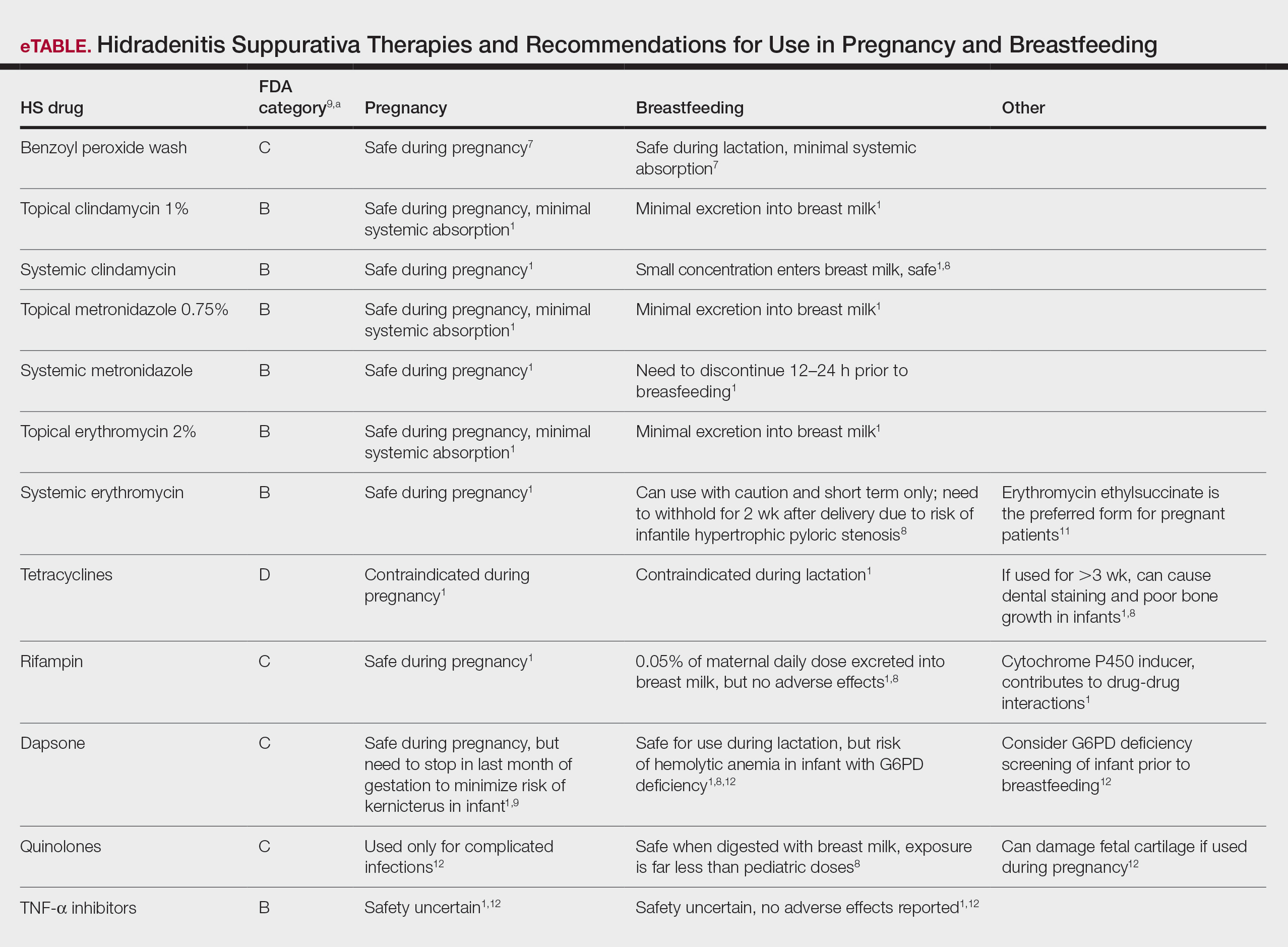

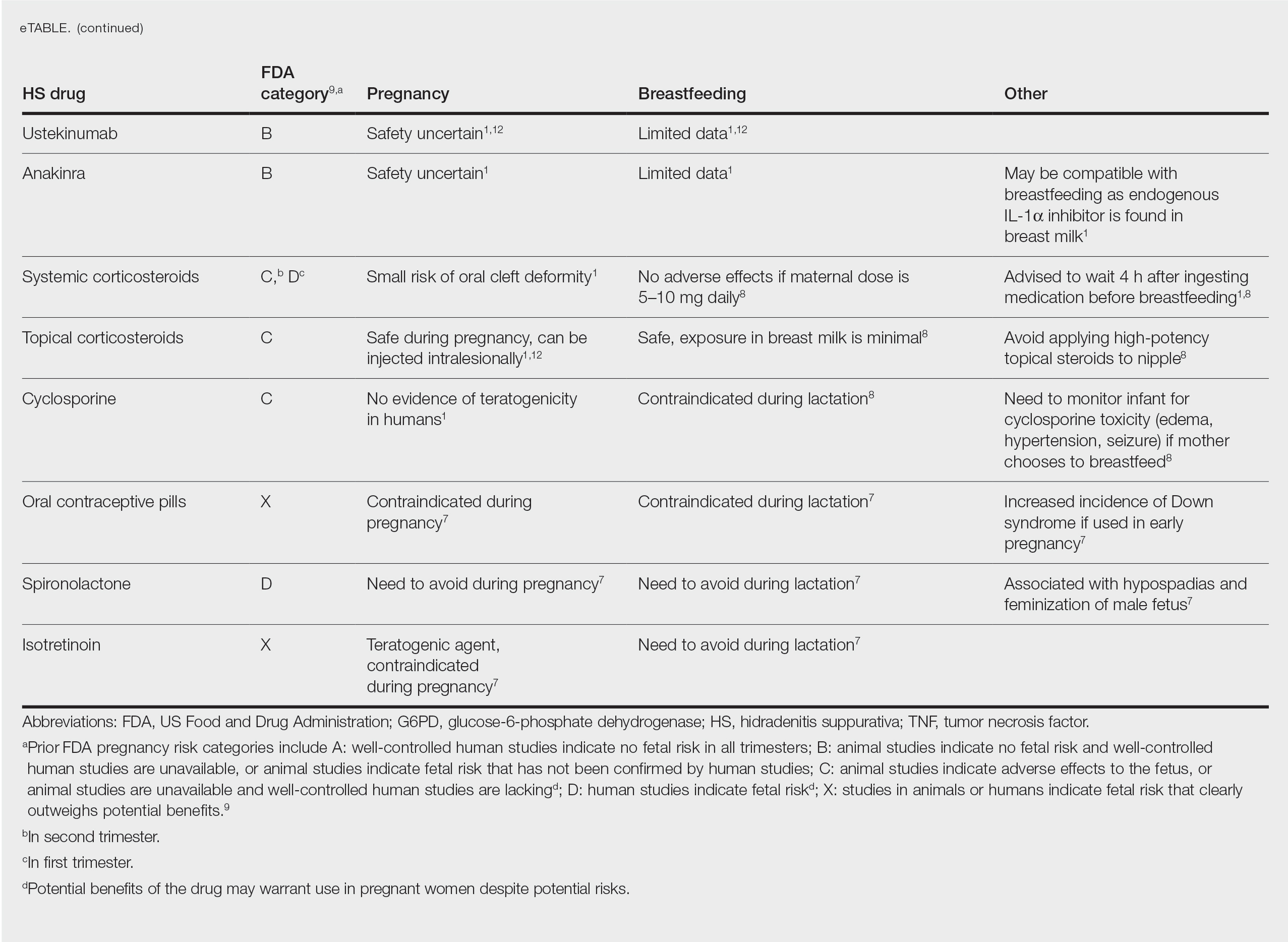

The eTable lists medications used to treat HS. The FDA category is listed next to each drug. However, it should be noted that these FDA letter categories were replaced with the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule in 2015. The letter ratings were deemed overly simplistic and replaced with narrative-based labeling that provides more detailed adverse effects and clinical considerations.9

Risk Factors of HS—Predisposing risk factors for HS flares that are controllable include obesity and smoking.2 Pregnancy weight gain may cause increased skin maceration at intertriginous sites, which can contribute to worsening HS symptoms.1,5 Adipocytes play a role in HS exacerbation by promoting secretion of TNF-α, leading to increased inflammation.5 Dermatologists can help prevent postpartum HS flares by monitoring weight gain during pregnancy, encouraging smoking cessation, and promoting weight and nutrition goals as set by an obstetrician.1 In addition to medications, management of HS should include emotional support and education on wearing loose-fitting clothing to avoid irritation of the affected areas.3 An emphasis on dermatologist counseling for all patients with HS, even for those with milder disease, can reduce exacerbations during pregnancy.5

CONCLUSION

The selection of dermatologic drugs for the treatment of HS in the setting of pregnancy involves complex decision-making. Dermatologists need more guidelines and proven safety data in human trials, especially regarding use of biologics and immunosuppressants to better treat HS in pregnancy. With more data, they can create more evidence-based treatment regimens to help prevent postpartum exacerbations of HS. Thus, patients can breastfeed their infants comfortably and without any risks of impaired child development. In the meantime, dermatologists can continue to work together with obstetricians and psychiatrists to decrease disease flares through counseling patients on nutrition and weight gain and providing emotional support.

- Perng P, Zampella JG, Okoye GA. Management of hidradenitis suppurativa in pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:979-989. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.032

- Samuel S, Tremelling A, Murray M. Presentation and surgical management of hidradenitis suppurativa of the breast during pregnancy: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;51:21-24. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.08.013

- Yang CS, Teeple M, Muglia J, et al. Inflammatory and glandular skin disease in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:335-343. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.005

- Vossen AR, van Straalen KR, Prens EP, et al. Menses and pregnancy affect symptoms in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:155-156. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.024

- Lyons AB, Peacock A, McKenzie SA, et al. Evaluation of hidradenitis suppurativa disease course during pregnancy and postpartum. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:681-685. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0777

- Riis PT, Ring HC, Themstrup L, et al. The role of androgens and estrogens in hidradenitis suppurativa—a systematic review. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2016;24:239-249.

- Kong YL, Tey HL. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation. Drugs. 2013;73:779-787. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0060-0

- Butler DC, Heller MM, Murase JE. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part II. lactation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:417:E1-E10. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.009

- Wilmer E, Chai S, Kroumpouzos G. Drug safety: pregnancy rating classifications and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:401-409. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.013

- Inman WH, Rawson NS. Erythromycin estolate and jaundice. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:1954-1955. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6382.1954

- Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

- Murase JE, Heller MM, Butler DC. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part I. pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:401.e1-14; quiz 415. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.010

- Brown SM, Aljefri K, Waas R, et al. Systemic medications used in treatment of common dermatological conditions: safety profile with respect to pregnancy, breast feeding and content in seminal fluid. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:2-18. doi:10.1080/09546634.2016.1202402

- Kamarajah SK, Arntdz K, Bundred J, et al. Outcomes of pregnancy in recipients of liver transplants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1398-1404.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.055

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease associated with hyperandrogenism and is caused by occlusion or rupture of follicular units and inflammation of the apocrine glands.1-3 The disease most commonly affects women (female to male ratio of 3:1) of childbearing age.1,2,4,5 Body areas affected include the axillae and groin, and less commonly the perineum; perianal region; and skin folds, such as gluteal, inframammary, and infraumbilical folds.1,2 Symptoms manifest as painful subcutaneous nodules with possible accompanying purulent drainage, sinus tracts, and/or dermal contractures. Although the pathophysiology is unclear, androgens affect the course of HS during pregnancy by stimulating the affected glands and altering cytokines.1,2,6

During pregnancy, maternal immune function switches from cell-mediated T helper cell (TH1) to humoral TH2 cytokine production. The activity of sebaceous and eccrine glands increases while the activity of apocrine glands decreases, thus changing the inflammatory course of HS during pregnancy.3 Approximately 20% of women with HS experience improvement of symptoms during pregnancy, while the remainder either experience no relief or deterioration of symptoms.1 Improvement in symptoms during pregnancy was found to occur more frequently in those who had worsening symptoms during menses owing to the possible hormonal effect estrogen has on inhibiting TH1 and TH17 proinflammatory cytokines, which promotes an immunosuppressive environment.4

Lactation and breastfeeding abilities may be hindered if a woman has HS affecting the apocrine glands of breast tissue and a symptom flare in the postpartum period. If HS causes notable inflammation in the nipple-areolar complex during pregnancy, the patient may experience difficulties with lactation and milk fistula formation, leading to inability to breastfeed.2 Another reason why mothers with HS may not be able to breastfeed is that the medications required to treat the disease are unsafe if passed to the infant via breast milk. In addition, the teratogenic effects of HS medications may necessitate therapy adjustments in pregnancy.1 Here, we provide a brief overview of the medical management considerations of HS in the setting of pregnancy and the impact on breastfeeding.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT AND DRUG SAFETY

Dermatologists prescribe a myriad of topical and systemic medications to ameliorate symptoms of HS. Therapy regimens often are multimodal and include antibiotics, biologics, and immunosuppressants.1,3

Antibiotics

First-line antibiotics include clindamycin, metronidazole, tetracyclines, erythromycin, rifampin, dapsone, and fluoroquinolones. Topical clindamycin 1%, metronidazole 0.75%, and erythromycin 2% are used for open or active HS lesions and are all safe to use in pregnancy since there is minimal systemic absorption and minimal excretion into breast milk.1 Topical antimicrobial washes such as benzoyl peroxide and chlorhexidine often are used in combination with systemic medications to treat HS. These washes are safe during pregnancy and lactation, as they have minimal systemic absorption.7

Of these first-line antibiotics, only tetracyclines are contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation, as they are deemed to be in category D by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Aside from tetracyclines, these antibiotics do not cause birth defects and are safe for nursing infants.1,8 Systemic clindamycin is safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Systemic metronidazole also is safe for use in pregnant patients but needs to be discontinued 12 to 24 hours prior to breastfeeding, which often prohibits appropriate dosing.1

Systemic Erythromycin—There are several forms of systemic erythromycin, including erythromycin base, erythromycin estolate, erythromycin ethylsuccinate (EES), and erythromycin stearate. Erythromycin estolate is contraindicated in pregnancy because it is associated with reversible maternal hepatoxicity and jaundice.9-11 Erythromycin ethylsuccinate is the preferred form for pregnant patients. Providers should exercise caution when prescribing EES to lactating mothers, as small amounts are still secreted through breast milk.11 Some studies have shown an increased risk for development of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis with systemic erythromycin use, especially if a neonate is exposed in the first 14 days of life. Thus, we recommend withholding EES for 2 weeks after delivery if the patient is breastfeeding. A follow-up study did not find any association between erythromycin and infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis; however, the American Academy of Pediatrics still recommends short-term use only of erythromycin if it is to be used in the systemic form.8

Rifampin—Rifampin is excreted into breast milk but without adverse effects to the infant. Rifampin also is safe in pregnancy but should be used on a case-by-case basis in pregnant or nursing women because it is a cytochrome P450 inducer.

Dapsone—Dapsone has no increased risk for congenital anomalies. However, it is associated with hemolytic anemia and neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, especially in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency.12 Newborns exposed to dapsone are at an increased risk for methemoglobinemia owing to increased sensitivity of fetal erythrocytes to oxidizing agents.13 If dapsone use is necessary, stopping dapsone treatment in the last month of gestation is recommended to minimize risk for kernicterus.9 Dapsone can be found in high concentrations in breast milk at 14.3% of the maternal dose. It is still safe to use during breastfeeding, but there is a risk of the infant developing hyperbilirubinemia/G6PD deficiency.1,8 Thus, physicians may consider performing a G6PD screen on infants to determine if breastfeeding is safe.12

Fluoroquinolones—Quinolones are not contraindicated during pregnancy, but they can damage fetal cartilage and thus should be reserved for use in complicated infections when the benefits outweigh the risks.12 Quinolones are believed to increase risk for arthropathy but are safe for use in lactation. When quinolones are digested with milk, exposure decreases below pediatric doses because of the ionized property of calcium in milk.8

Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitors—The safety of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α biologics in pregnancy is less certain when compared with antibiotics.1 Anti–TNF-α inhibitors such as etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab are all labeled as FDA category B, meaning there are no well-controlled human studies of the drugs.9 There are limited data that support safe use of TNF-α inhibitors prior to the third trimester before maternal IgG antibodies are transferred to the fetus via the placenta.1,13 Anti–TNF-α inhibitors may be safe when breastfeeding because the drugs have large molecular weights that prevent them from entering breast milk in large amounts. Absorption also is limited due to the infant’s digestive acids and enzymes breaking down the protein structure of the medication.8 Overall, TNF-α inhibitor use is still controversial and only used if the benefits outweigh the risks during pregnancy or if there is no alternative treatment.1,3,9

Ustekinumab and Anakinra—Ustekinumab (an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor) and anakinra (an IL-1α and IL-1β inhibitor) also are FDA category B drugs and have limited data supporting their use as HS treatment in pregnancy. Anakinra may have evidence of compatibility with breastfeeding, as endogenous IL-1α inhibitor is found in colostrum and mature breast milk.1

Immunosuppressants

Immunosuppressants that are used to treat HS include corticosteroids and cyclosporine.

Corticosteroids—Topical corticosteroids can be used safely in lactation if they are not applied directly to the nipple or any area that makes direct contact with the infant’s mouth. Intralesional corticosteroid injections are safe for use during both pregnancy and breastfeeding to decrease inflammation of acutely flaring lesions and can be considered first-line treatment.1 Oral glucocorticoids also can be safely used for acute flares during pregnancy; however, prolonged use is associated with pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, premature delivery, and gestational diabetes.12 There also is a small risk of oral cleft deformity in the infant; thus, potent corticosteroids are recommended in short durations during pregnancy, and there are no adverse effects if the maternal dose is less than 10 mg daily.8,12 Systemic steroids are safe to use with breastfeeding, but patients should be advised to wait 4 hours after ingesting medication before breastfeeding.1,8

Cyclosporine—Topical and oral calcineurin inhibitors such as cyclosporine have low risk for transmission into breast milk; however, potential effects of exposure through breast milk are unknown. For that reason, manufacturers state that cyclosporine use is contraindicated during lactation.8 If cyclosporine is to be used by a breastfeeding woman, monitoring cyclosporine concentrations in the infant is suggested to ensure that the exposure is less than 5% to 10% of the therapeutic dose.13 The use of cyclosporine has been extensively studied in pregnant transplant patients and is considered relatively safe for use in pregnancy.14 Cyclosporine is lipid soluble and thus is quickly metabolized and spread throughout the body; it can easily cross the placenta.9,13 Blood concentration in the fetus is 30% to 64% that of the maternal circulation. However, cyclosporine is only toxic to the fetus at maternally toxic doses, which can result in low birth weight and increased prenatal and postnatal mortality.13

Isotretinoin, Oral Contraceptive Pills, and Spironolactone

Isotretinoin and hormonal treatments such as oral contraceptive pills and spironolactone (an androgen receptor blocker) commonly are used to treat HS, but all are contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation. Isotretinoin is a well-established teratogen, but adverse effects on nursing babies have not been described. However, the manufacturer of isotretinoin advises against its use in lactation. Oral contraceptive pill use in early pregnancy is associated with increased risk for Down syndrome. Oral contraceptive pill use also is contraindicated in lactation for 2 reasons: decreased milk production and risk for fetal feminization. Antiandrogenic agents such as spironolactone have been shown to be associated with hypospadias and feminization of the male fetus.7

COMMENT

Women with HS usually require ongoing medical treatment during pregnancy and immediately postpartum; thus, it is important that treatments are proven to be safe for use in this specific population. Current management guidelines are not entirely suitable for pregnant and breastfeeding women given that many HS drugs have teratogenic effects and/or can be excreted into breast milk.1 Several treatments have uncertain safety profiles in pregnancy and breastfeeding, which calls for dermatologists to change or create new regimens for their patients. Close management also is necessary to prevent excess inflammation of breast tissue and milk fistula formation, which would hinder normal breastfeeding.

The eTable lists medications used to treat HS. The FDA category is listed next to each drug. However, it should be noted that these FDA letter categories were replaced with the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule in 2015. The letter ratings were deemed overly simplistic and replaced with narrative-based labeling that provides more detailed adverse effects and clinical considerations.9

Risk Factors of HS—Predisposing risk factors for HS flares that are controllable include obesity and smoking.2 Pregnancy weight gain may cause increased skin maceration at intertriginous sites, which can contribute to worsening HS symptoms.1,5 Adipocytes play a role in HS exacerbation by promoting secretion of TNF-α, leading to increased inflammation.5 Dermatologists can help prevent postpartum HS flares by monitoring weight gain during pregnancy, encouraging smoking cessation, and promoting weight and nutrition goals as set by an obstetrician.1 In addition to medications, management of HS should include emotional support and education on wearing loose-fitting clothing to avoid irritation of the affected areas.3 An emphasis on dermatologist counseling for all patients with HS, even for those with milder disease, can reduce exacerbations during pregnancy.5

CONCLUSION

The selection of dermatologic drugs for the treatment of HS in the setting of pregnancy involves complex decision-making. Dermatologists need more guidelines and proven safety data in human trials, especially regarding use of biologics and immunosuppressants to better treat HS in pregnancy. With more data, they can create more evidence-based treatment regimens to help prevent postpartum exacerbations of HS. Thus, patients can breastfeed their infants comfortably and without any risks of impaired child development. In the meantime, dermatologists can continue to work together with obstetricians and psychiatrists to decrease disease flares through counseling patients on nutrition and weight gain and providing emotional support.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease associated with hyperandrogenism and is caused by occlusion or rupture of follicular units and inflammation of the apocrine glands.1-3 The disease most commonly affects women (female to male ratio of 3:1) of childbearing age.1,2,4,5 Body areas affected include the axillae and groin, and less commonly the perineum; perianal region; and skin folds, such as gluteal, inframammary, and infraumbilical folds.1,2 Symptoms manifest as painful subcutaneous nodules with possible accompanying purulent drainage, sinus tracts, and/or dermal contractures. Although the pathophysiology is unclear, androgens affect the course of HS during pregnancy by stimulating the affected glands and altering cytokines.1,2,6

During pregnancy, maternal immune function switches from cell-mediated T helper cell (TH1) to humoral TH2 cytokine production. The activity of sebaceous and eccrine glands increases while the activity of apocrine glands decreases, thus changing the inflammatory course of HS during pregnancy.3 Approximately 20% of women with HS experience improvement of symptoms during pregnancy, while the remainder either experience no relief or deterioration of symptoms.1 Improvement in symptoms during pregnancy was found to occur more frequently in those who had worsening symptoms during menses owing to the possible hormonal effect estrogen has on inhibiting TH1 and TH17 proinflammatory cytokines, which promotes an immunosuppressive environment.4

Lactation and breastfeeding abilities may be hindered if a woman has HS affecting the apocrine glands of breast tissue and a symptom flare in the postpartum period. If HS causes notable inflammation in the nipple-areolar complex during pregnancy, the patient may experience difficulties with lactation and milk fistula formation, leading to inability to breastfeed.2 Another reason why mothers with HS may not be able to breastfeed is that the medications required to treat the disease are unsafe if passed to the infant via breast milk. In addition, the teratogenic effects of HS medications may necessitate therapy adjustments in pregnancy.1 Here, we provide a brief overview of the medical management considerations of HS in the setting of pregnancy and the impact on breastfeeding.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT AND DRUG SAFETY

Dermatologists prescribe a myriad of topical and systemic medications to ameliorate symptoms of HS. Therapy regimens often are multimodal and include antibiotics, biologics, and immunosuppressants.1,3

Antibiotics

First-line antibiotics include clindamycin, metronidazole, tetracyclines, erythromycin, rifampin, dapsone, and fluoroquinolones. Topical clindamycin 1%, metronidazole 0.75%, and erythromycin 2% are used for open or active HS lesions and are all safe to use in pregnancy since there is minimal systemic absorption and minimal excretion into breast milk.1 Topical antimicrobial washes such as benzoyl peroxide and chlorhexidine often are used in combination with systemic medications to treat HS. These washes are safe during pregnancy and lactation, as they have minimal systemic absorption.7

Of these first-line antibiotics, only tetracyclines are contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation, as they are deemed to be in category D by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Aside from tetracyclines, these antibiotics do not cause birth defects and are safe for nursing infants.1,8 Systemic clindamycin is safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Systemic metronidazole also is safe for use in pregnant patients but needs to be discontinued 12 to 24 hours prior to breastfeeding, which often prohibits appropriate dosing.1

Systemic Erythromycin—There are several forms of systemic erythromycin, including erythromycin base, erythromycin estolate, erythromycin ethylsuccinate (EES), and erythromycin stearate. Erythromycin estolate is contraindicated in pregnancy because it is associated with reversible maternal hepatoxicity and jaundice.9-11 Erythromycin ethylsuccinate is the preferred form for pregnant patients. Providers should exercise caution when prescribing EES to lactating mothers, as small amounts are still secreted through breast milk.11 Some studies have shown an increased risk for development of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis with systemic erythromycin use, especially if a neonate is exposed in the first 14 days of life. Thus, we recommend withholding EES for 2 weeks after delivery if the patient is breastfeeding. A follow-up study did not find any association between erythromycin and infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis; however, the American Academy of Pediatrics still recommends short-term use only of erythromycin if it is to be used in the systemic form.8

Rifampin—Rifampin is excreted into breast milk but without adverse effects to the infant. Rifampin also is safe in pregnancy but should be used on a case-by-case basis in pregnant or nursing women because it is a cytochrome P450 inducer.

Dapsone—Dapsone has no increased risk for congenital anomalies. However, it is associated with hemolytic anemia and neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, especially in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency.12 Newborns exposed to dapsone are at an increased risk for methemoglobinemia owing to increased sensitivity of fetal erythrocytes to oxidizing agents.13 If dapsone use is necessary, stopping dapsone treatment in the last month of gestation is recommended to minimize risk for kernicterus.9 Dapsone can be found in high concentrations in breast milk at 14.3% of the maternal dose. It is still safe to use during breastfeeding, but there is a risk of the infant developing hyperbilirubinemia/G6PD deficiency.1,8 Thus, physicians may consider performing a G6PD screen on infants to determine if breastfeeding is safe.12

Fluoroquinolones—Quinolones are not contraindicated during pregnancy, but they can damage fetal cartilage and thus should be reserved for use in complicated infections when the benefits outweigh the risks.12 Quinolones are believed to increase risk for arthropathy but are safe for use in lactation. When quinolones are digested with milk, exposure decreases below pediatric doses because of the ionized property of calcium in milk.8

Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitors—The safety of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α biologics in pregnancy is less certain when compared with antibiotics.1 Anti–TNF-α inhibitors such as etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab are all labeled as FDA category B, meaning there are no well-controlled human studies of the drugs.9 There are limited data that support safe use of TNF-α inhibitors prior to the third trimester before maternal IgG antibodies are transferred to the fetus via the placenta.1,13 Anti–TNF-α inhibitors may be safe when breastfeeding because the drugs have large molecular weights that prevent them from entering breast milk in large amounts. Absorption also is limited due to the infant’s digestive acids and enzymes breaking down the protein structure of the medication.8 Overall, TNF-α inhibitor use is still controversial and only used if the benefits outweigh the risks during pregnancy or if there is no alternative treatment.1,3,9

Ustekinumab and Anakinra—Ustekinumab (an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor) and anakinra (an IL-1α and IL-1β inhibitor) also are FDA category B drugs and have limited data supporting their use as HS treatment in pregnancy. Anakinra may have evidence of compatibility with breastfeeding, as endogenous IL-1α inhibitor is found in colostrum and mature breast milk.1

Immunosuppressants

Immunosuppressants that are used to treat HS include corticosteroids and cyclosporine.

Corticosteroids—Topical corticosteroids can be used safely in lactation if they are not applied directly to the nipple or any area that makes direct contact with the infant’s mouth. Intralesional corticosteroid injections are safe for use during both pregnancy and breastfeeding to decrease inflammation of acutely flaring lesions and can be considered first-line treatment.1 Oral glucocorticoids also can be safely used for acute flares during pregnancy; however, prolonged use is associated with pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, premature delivery, and gestational diabetes.12 There also is a small risk of oral cleft deformity in the infant; thus, potent corticosteroids are recommended in short durations during pregnancy, and there are no adverse effects if the maternal dose is less than 10 mg daily.8,12 Systemic steroids are safe to use with breastfeeding, but patients should be advised to wait 4 hours after ingesting medication before breastfeeding.1,8

Cyclosporine—Topical and oral calcineurin inhibitors such as cyclosporine have low risk for transmission into breast milk; however, potential effects of exposure through breast milk are unknown. For that reason, manufacturers state that cyclosporine use is contraindicated during lactation.8 If cyclosporine is to be used by a breastfeeding woman, monitoring cyclosporine concentrations in the infant is suggested to ensure that the exposure is less than 5% to 10% of the therapeutic dose.13 The use of cyclosporine has been extensively studied in pregnant transplant patients and is considered relatively safe for use in pregnancy.14 Cyclosporine is lipid soluble and thus is quickly metabolized and spread throughout the body; it can easily cross the placenta.9,13 Blood concentration in the fetus is 30% to 64% that of the maternal circulation. However, cyclosporine is only toxic to the fetus at maternally toxic doses, which can result in low birth weight and increased prenatal and postnatal mortality.13

Isotretinoin, Oral Contraceptive Pills, and Spironolactone

Isotretinoin and hormonal treatments such as oral contraceptive pills and spironolactone (an androgen receptor blocker) commonly are used to treat HS, but all are contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation. Isotretinoin is a well-established teratogen, but adverse effects on nursing babies have not been described. However, the manufacturer of isotretinoin advises against its use in lactation. Oral contraceptive pill use in early pregnancy is associated with increased risk for Down syndrome. Oral contraceptive pill use also is contraindicated in lactation for 2 reasons: decreased milk production and risk for fetal feminization. Antiandrogenic agents such as spironolactone have been shown to be associated with hypospadias and feminization of the male fetus.7

COMMENT

Women with HS usually require ongoing medical treatment during pregnancy and immediately postpartum; thus, it is important that treatments are proven to be safe for use in this specific population. Current management guidelines are not entirely suitable for pregnant and breastfeeding women given that many HS drugs have teratogenic effects and/or can be excreted into breast milk.1 Several treatments have uncertain safety profiles in pregnancy and breastfeeding, which calls for dermatologists to change or create new regimens for their patients. Close management also is necessary to prevent excess inflammation of breast tissue and milk fistula formation, which would hinder normal breastfeeding.

The eTable lists medications used to treat HS. The FDA category is listed next to each drug. However, it should be noted that these FDA letter categories were replaced with the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule in 2015. The letter ratings were deemed overly simplistic and replaced with narrative-based labeling that provides more detailed adverse effects and clinical considerations.9

Risk Factors of HS—Predisposing risk factors for HS flares that are controllable include obesity and smoking.2 Pregnancy weight gain may cause increased skin maceration at intertriginous sites, which can contribute to worsening HS symptoms.1,5 Adipocytes play a role in HS exacerbation by promoting secretion of TNF-α, leading to increased inflammation.5 Dermatologists can help prevent postpartum HS flares by monitoring weight gain during pregnancy, encouraging smoking cessation, and promoting weight and nutrition goals as set by an obstetrician.1 In addition to medications, management of HS should include emotional support and education on wearing loose-fitting clothing to avoid irritation of the affected areas.3 An emphasis on dermatologist counseling for all patients with HS, even for those with milder disease, can reduce exacerbations during pregnancy.5

CONCLUSION

The selection of dermatologic drugs for the treatment of HS in the setting of pregnancy involves complex decision-making. Dermatologists need more guidelines and proven safety data in human trials, especially regarding use of biologics and immunosuppressants to better treat HS in pregnancy. With more data, they can create more evidence-based treatment regimens to help prevent postpartum exacerbations of HS. Thus, patients can breastfeed their infants comfortably and without any risks of impaired child development. In the meantime, dermatologists can continue to work together with obstetricians and psychiatrists to decrease disease flares through counseling patients on nutrition and weight gain and providing emotional support.

- Perng P, Zampella JG, Okoye GA. Management of hidradenitis suppurativa in pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:979-989. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.032

- Samuel S, Tremelling A, Murray M. Presentation and surgical management of hidradenitis suppurativa of the breast during pregnancy: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;51:21-24. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.08.013

- Yang CS, Teeple M, Muglia J, et al. Inflammatory and glandular skin disease in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:335-343. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.005

- Vossen AR, van Straalen KR, Prens EP, et al. Menses and pregnancy affect symptoms in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:155-156. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.024

- Lyons AB, Peacock A, McKenzie SA, et al. Evaluation of hidradenitis suppurativa disease course during pregnancy and postpartum. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:681-685. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0777

- Riis PT, Ring HC, Themstrup L, et al. The role of androgens and estrogens in hidradenitis suppurativa—a systematic review. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2016;24:239-249.

- Kong YL, Tey HL. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation. Drugs. 2013;73:779-787. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0060-0

- Butler DC, Heller MM, Murase JE. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part II. lactation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:417:E1-E10. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.009

- Wilmer E, Chai S, Kroumpouzos G. Drug safety: pregnancy rating classifications and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:401-409. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.013

- Inman WH, Rawson NS. Erythromycin estolate and jaundice. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:1954-1955. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6382.1954

- Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

- Murase JE, Heller MM, Butler DC. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part I. pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:401.e1-14; quiz 415. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.010

- Brown SM, Aljefri K, Waas R, et al. Systemic medications used in treatment of common dermatological conditions: safety profile with respect to pregnancy, breast feeding and content in seminal fluid. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:2-18. doi:10.1080/09546634.2016.1202402

- Kamarajah SK, Arntdz K, Bundred J, et al. Outcomes of pregnancy in recipients of liver transplants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1398-1404.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.055

- Perng P, Zampella JG, Okoye GA. Management of hidradenitis suppurativa in pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:979-989. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.032

- Samuel S, Tremelling A, Murray M. Presentation and surgical management of hidradenitis suppurativa of the breast during pregnancy: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;51:21-24. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.08.013

- Yang CS, Teeple M, Muglia J, et al. Inflammatory and glandular skin disease in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:335-343. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.005

- Vossen AR, van Straalen KR, Prens EP, et al. Menses and pregnancy affect symptoms in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:155-156. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.024

- Lyons AB, Peacock A, McKenzie SA, et al. Evaluation of hidradenitis suppurativa disease course during pregnancy and postpartum. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:681-685. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0777

- Riis PT, Ring HC, Themstrup L, et al. The role of androgens and estrogens in hidradenitis suppurativa—a systematic review. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2016;24:239-249.

- Kong YL, Tey HL. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation. Drugs. 2013;73:779-787. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0060-0

- Butler DC, Heller MM, Murase JE. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part II. lactation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:417:E1-E10. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.009

- Wilmer E, Chai S, Kroumpouzos G. Drug safety: pregnancy rating classifications and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:401-409. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.013

- Inman WH, Rawson NS. Erythromycin estolate and jaundice. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:1954-1955. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6382.1954

- Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

- Murase JE, Heller MM, Butler DC. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part I. pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:401.e1-14; quiz 415. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.010

- Brown SM, Aljefri K, Waas R, et al. Systemic medications used in treatment of common dermatological conditions: safety profile with respect to pregnancy, breast feeding and content in seminal fluid. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:2-18. doi:10.1080/09546634.2016.1202402

- Kamarajah SK, Arntdz K, Bundred J, et al. Outcomes of pregnancy in recipients of liver transplants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1398-1404.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.055

Practice Points

- Some medications used to treat hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) may have teratogenic effects and be contraindicated during breastfeeding.

- We summarize what treatments are proven to be safe in pregnancy and breastfeeding and highlight the need for more guidelines and safety data for dermatologists to manage their pregnant patients with HS.

Reactivation of a BCG Vaccination Scar Following the First Dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in notable morbidity and mortality worldwide. In December 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization for 2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines—produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna—for the prevention of COVID-19. Phase 3 trials of the vaccine developed by Moderna showed 94.1% efficacy at preventing COVID-19 after 2 doses.1

Common cutaneous adverse effects of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine include injection-site reactions, such as pain, induration, and erythema. Less frequently reported dermatologic adverse effects include diffuse bullous rash and hypersensitivity reactions.1 We report a case of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar after the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine.

Case Report

A 48-year-old Asian man who was otherwise healthy presented with erythema, induration, and mild pruritus on the deltoid muscle of the left arm, near the scar from an earlier BCG vaccine, which he received at approximately 5 years of age when living in Taiwan. The patient received the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine approximately 5 to 7 cm distant from the BCG vaccination scar. One to 2 days after inoculation, the patient endorsed tenderness at the site of COVID-19 vaccination but denied systemic symptoms. He had never been given a diagnosis of COVID-19. His SARS-CoV-2 antibody status was unknown.

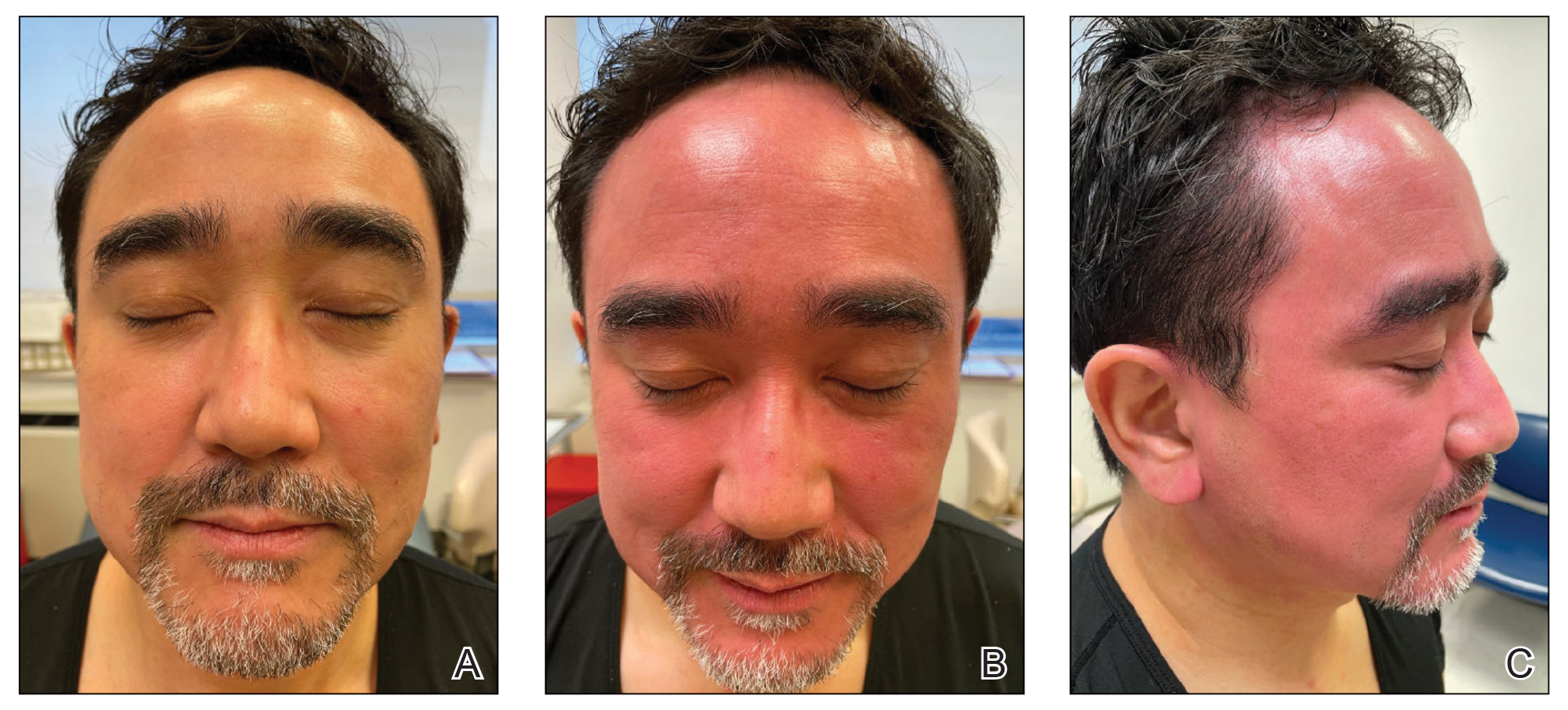

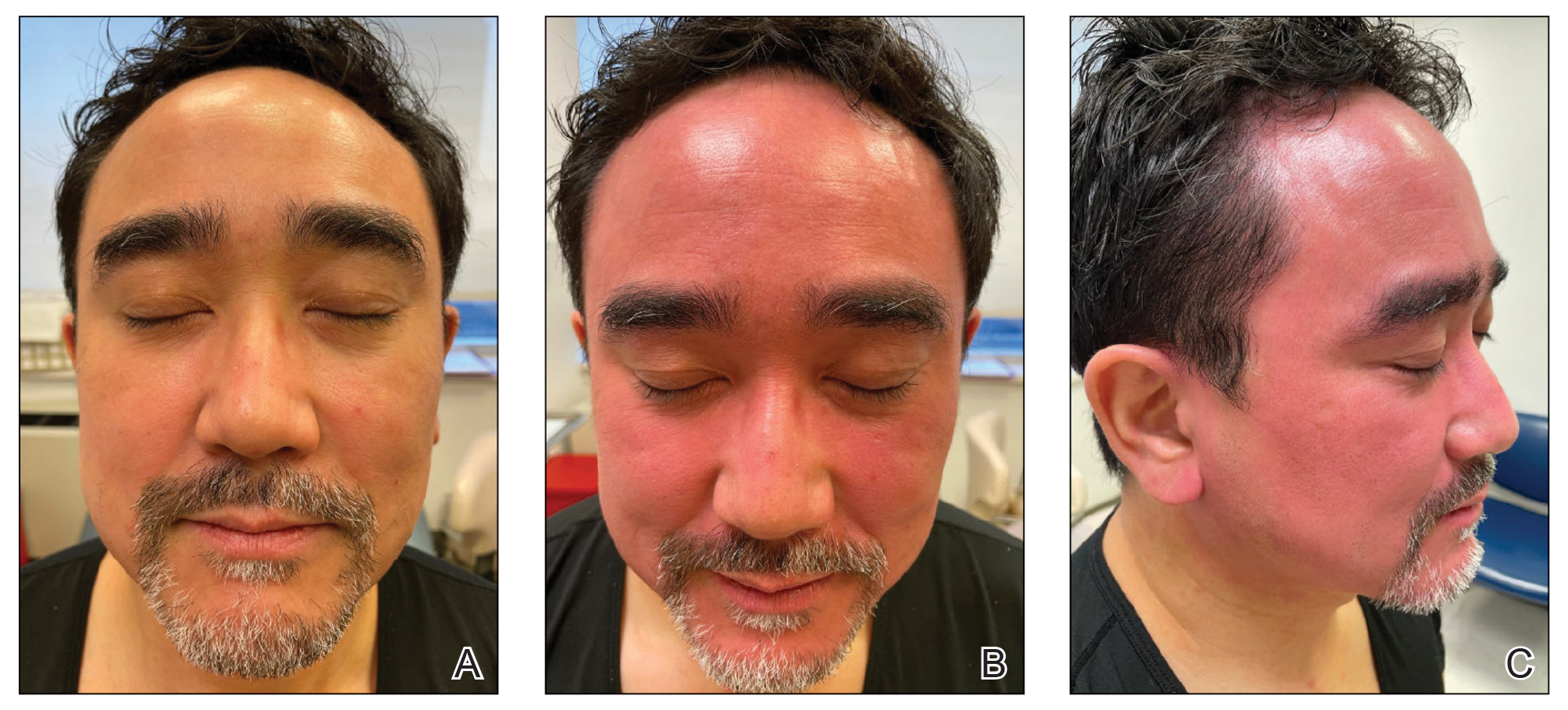

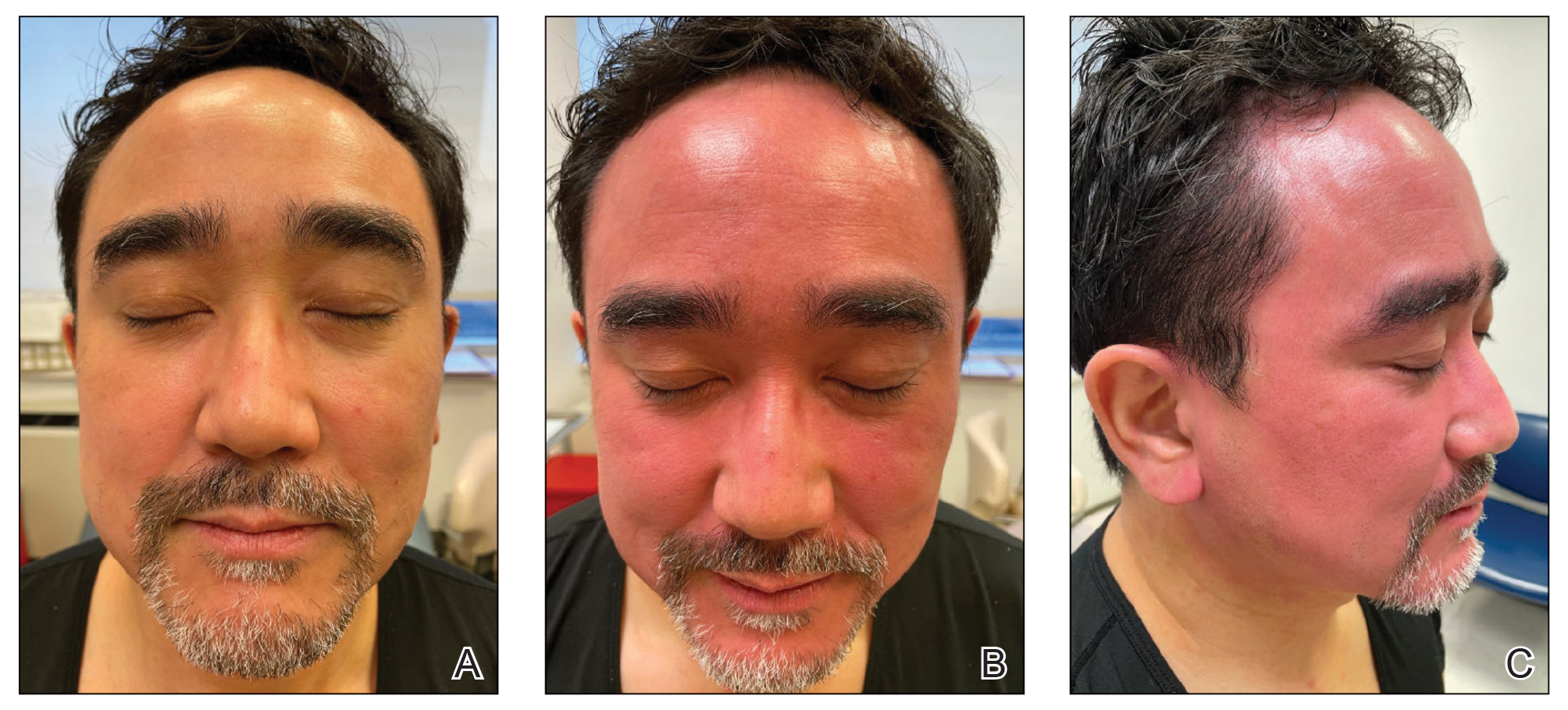

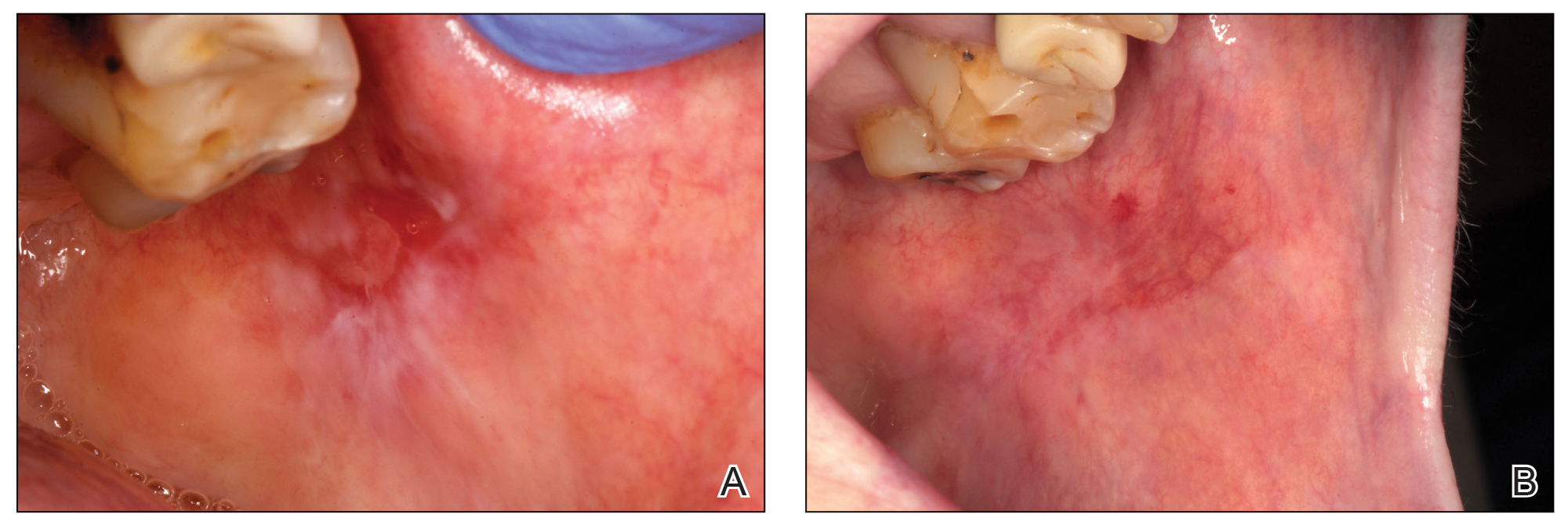

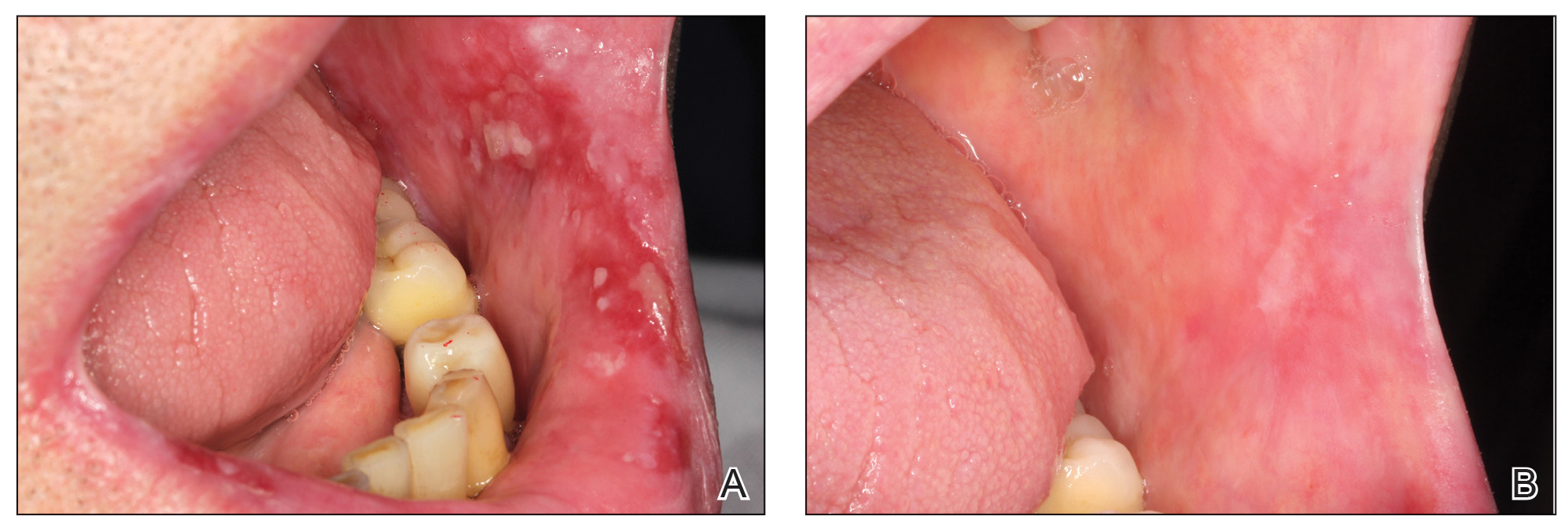

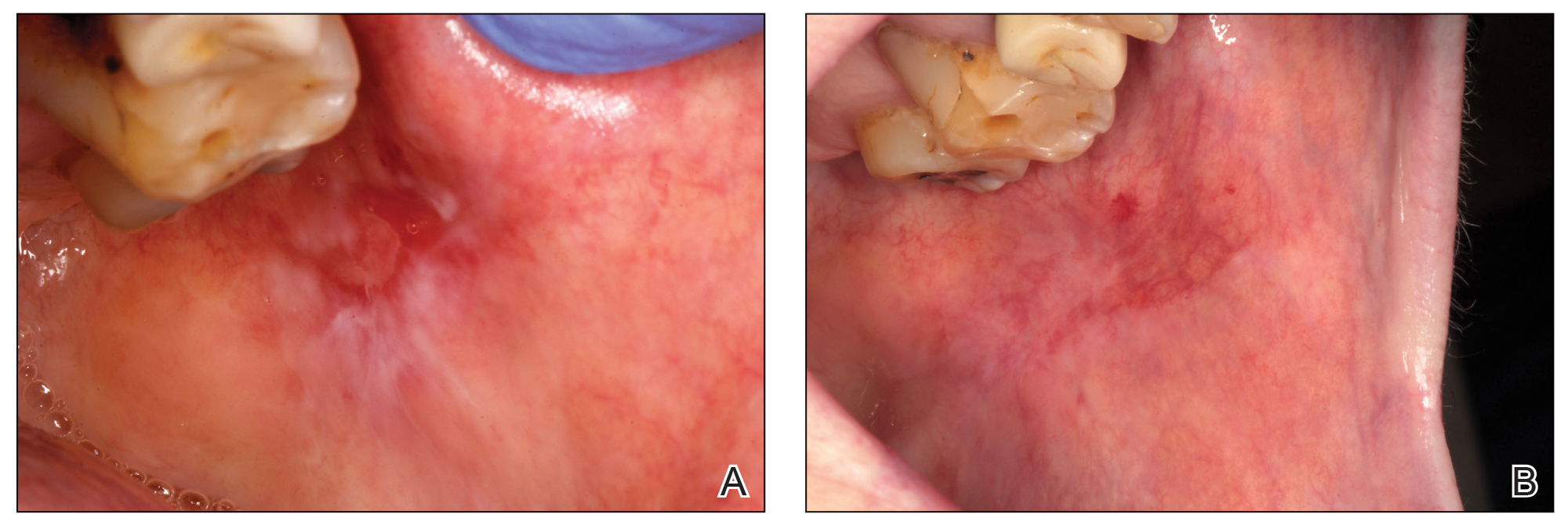

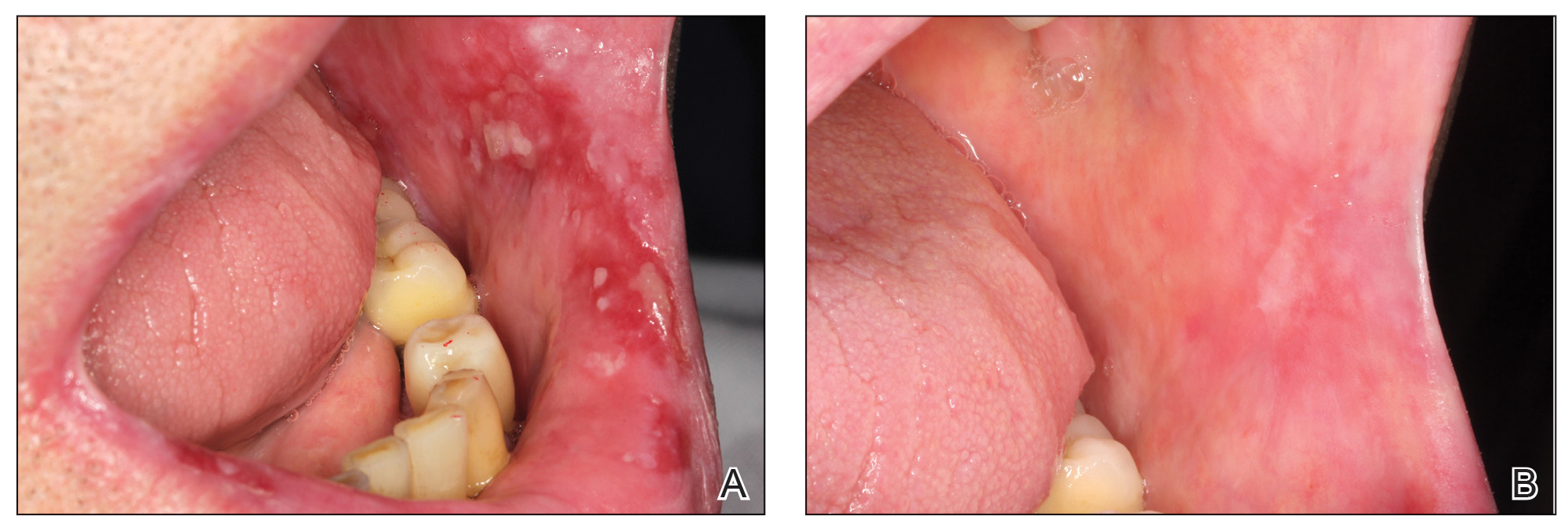

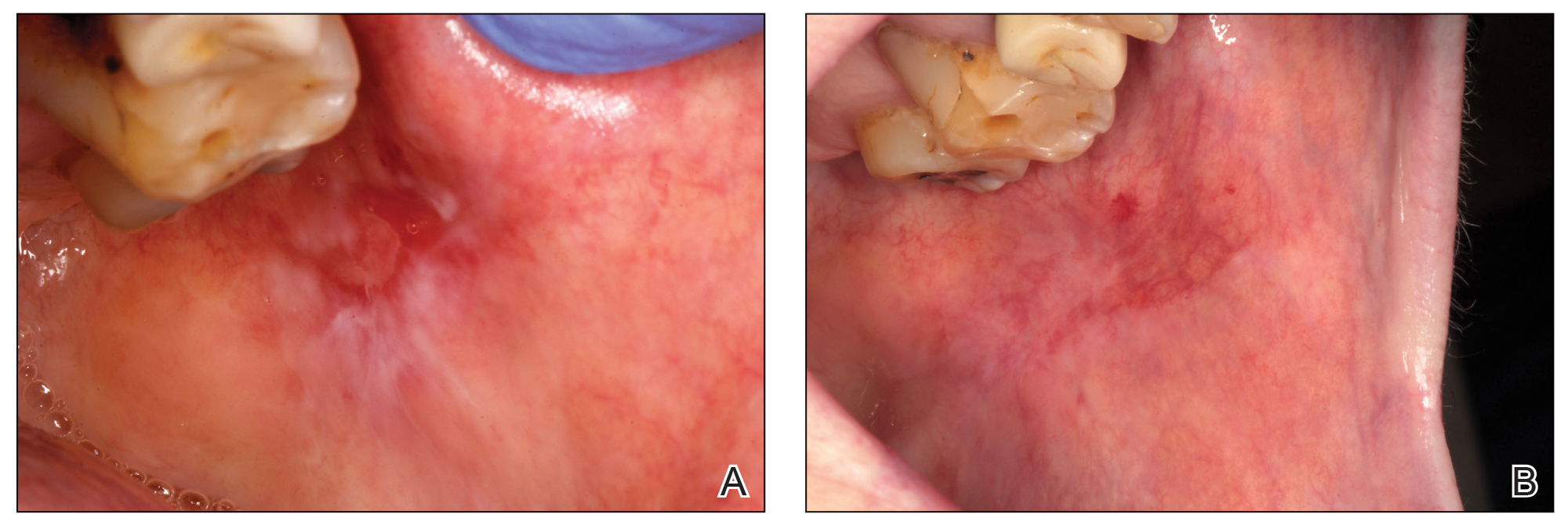

Eight days later, the patient noticed a well-defined, erythematous, indurated plaque with mild itchiness overlying and around the BCG vaccination scar that did not involve the COVID-19 vaccination site. The following day, the redness and induration became worse (Figure).

The patient was otherwise well. Vital signs were normal; there was no lymphadenopathy. The rash resolved without treatment over the next 4 days.

Comment

The BCG vaccine is an intradermal live attenuated virus vaccine used to prevent certain forms of tuberculosis and potentially other Mycobacterium infections. Although the vaccine is not routinely administered in the United States, it is part of the vaccination schedule in most countries, administered most often to newborns and infants. Administration of the BCG vaccine commonly results in mild localized erythema, swelling, and pain at the injection site. Most inoculated patients also develop an ulcer that heals with the characteristic BCG vaccination scar.2,3

There is evidence that the BCG vaccine can enhance the innate immune system response and might decrease the rate of infection by unrelated pathogens, including viruses.4 Several epidemiologic studies have suggested that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19, possibly due to a resemblance of the amino acid sequences of BCG and SARS-CoV-2, which might provoke cross-reactive T cells.5,6 Further studies are underway to determine whether the BCG vaccine is truly protective against COVID-19.

BCG vaccination scar reactivation presents as redness, swelling, or ulceration at the BCG injection site months to years after inoculation. Although erythema and induration of the BCG scar are not included in the diagnostic criteria of Kawasaki disease, likely due to variable vaccine requirements in different countries, these findings are largely recognized as specific for Kawasaki disease and present in approximately half of affected patients who received the BCG vaccine.2

Heat Shock Proteins—Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are produced by cells in response to stressors. The proposed mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation is a cross-reaction between human homologue HSP 63 and Mycobacterium HSP 65, leading to hyperactivity of the immune system against BCG.7 There also are reports of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar from measles infection and influenza vaccination.2,8,9 Most prior reports of BCG vaccination scar reactivation have been in pediatric patients; our patient is an adult who received the BCG vaccine more than 40 years ago.

Mechanism of Reactivation—The mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation in our patient, who received the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, is unclear. Possible mechanisms include (1) release of HSP mediated by the COVID-19 vaccine, leading to an immune response at the BCG vaccine scar, or (2) another immune-mediated cross-reaction between BCG and the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine mRNA nanoparticle or encoded spike protein antigen. It has been hypothesized that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19; this remains uncertain and is under further investigation.10 A recent retrospective cohort study showed that a BCG vaccination booster may decrease COVID-19 infection rates in higher-risk populations.11

Conclusion

We present a case of BCG vaccine scar reactivation occurring after a dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, a likely underreported, self-limiting, cutaneous adverse effect of this mRNA vaccine.

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:403-416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

- Muthuvelu S, Lim KS, Huang L-Y, et al. Measles infection causing bacillus Calmette-Guérin reactivation: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:251. doi:10.1186/s12887-019-1635-z

- Fatima S, Kumari A, Das G, et al. Tuberculosis vaccine: a journey from BCG to present. Life Sci. 2020;252:117594. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117594

- O’Neill LAJ, Netea MG. BCG-induced trained immunity: can it offer protection against COVID-19? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:335-337. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-0337-y

- Brooks NA, Puri A, Garg S, et al. The association of coronavirus disease-19 mortality and prior bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination: a robust ecological analysis using unsupervised machine learning. Sci Rep. 2021;11:774. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80787-z

- Tomita Y, Sato R, Ikeda T, et al. BCG vaccine may generate cross-reactive T-cells against SARS-CoV-2: in silico analyses and a hypothesis. Vaccine. 2020;38:6352-6356. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.045

- Lim KYY, Chua MC, Tan NWH, et al. Reactivation of BCG inoculation site in a child with febrile exanthema of 3 days duration: an early indicator of incomplete Kawasaki disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:E239648. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-239648

- Kondo M, Goto H, Yamamoto S. First case of redness and erosion at bacillus Calmette-Guérin inoculation site after vaccination against influenza. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1229-1231. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13365

- Chavarri-Guerra Y, Soto-Pérez-de-Celis E. Erythema at the bacillus Calmette-Guerin scar after influenza vaccination. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2019;53:E20190390. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0390-2019

- Fu W, Ho P-C, Liu C-L, et al. Reconcile the debate over protective effects of BCG vaccine against COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8356. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-87731-9

- Amirlak L, Haddad R, Hardy JD, et al. Effectiveness of booster BCG vaccination in preventing COVID-19 infection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:3913-3915. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1956228

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in notable morbidity and mortality worldwide. In December 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization for 2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines—produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna—for the prevention of COVID-19. Phase 3 trials of the vaccine developed by Moderna showed 94.1% efficacy at preventing COVID-19 after 2 doses.1

Common cutaneous adverse effects of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine include injection-site reactions, such as pain, induration, and erythema. Less frequently reported dermatologic adverse effects include diffuse bullous rash and hypersensitivity reactions.1 We report a case of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar after the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine.

Case Report

A 48-year-old Asian man who was otherwise healthy presented with erythema, induration, and mild pruritus on the deltoid muscle of the left arm, near the scar from an earlier BCG vaccine, which he received at approximately 5 years of age when living in Taiwan. The patient received the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine approximately 5 to 7 cm distant from the BCG vaccination scar. One to 2 days after inoculation, the patient endorsed tenderness at the site of COVID-19 vaccination but denied systemic symptoms. He had never been given a diagnosis of COVID-19. His SARS-CoV-2 antibody status was unknown.

Eight days later, the patient noticed a well-defined, erythematous, indurated plaque with mild itchiness overlying and around the BCG vaccination scar that did not involve the COVID-19 vaccination site. The following day, the redness and induration became worse (Figure).

The patient was otherwise well. Vital signs were normal; there was no lymphadenopathy. The rash resolved without treatment over the next 4 days.

Comment

The BCG vaccine is an intradermal live attenuated virus vaccine used to prevent certain forms of tuberculosis and potentially other Mycobacterium infections. Although the vaccine is not routinely administered in the United States, it is part of the vaccination schedule in most countries, administered most often to newborns and infants. Administration of the BCG vaccine commonly results in mild localized erythema, swelling, and pain at the injection site. Most inoculated patients also develop an ulcer that heals with the characteristic BCG vaccination scar.2,3

There is evidence that the BCG vaccine can enhance the innate immune system response and might decrease the rate of infection by unrelated pathogens, including viruses.4 Several epidemiologic studies have suggested that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19, possibly due to a resemblance of the amino acid sequences of BCG and SARS-CoV-2, which might provoke cross-reactive T cells.5,6 Further studies are underway to determine whether the BCG vaccine is truly protective against COVID-19.

BCG vaccination scar reactivation presents as redness, swelling, or ulceration at the BCG injection site months to years after inoculation. Although erythema and induration of the BCG scar are not included in the diagnostic criteria of Kawasaki disease, likely due to variable vaccine requirements in different countries, these findings are largely recognized as specific for Kawasaki disease and present in approximately half of affected patients who received the BCG vaccine.2

Heat Shock Proteins—Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are produced by cells in response to stressors. The proposed mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation is a cross-reaction between human homologue HSP 63 and Mycobacterium HSP 65, leading to hyperactivity of the immune system against BCG.7 There also are reports of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar from measles infection and influenza vaccination.2,8,9 Most prior reports of BCG vaccination scar reactivation have been in pediatric patients; our patient is an adult who received the BCG vaccine more than 40 years ago.

Mechanism of Reactivation—The mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation in our patient, who received the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, is unclear. Possible mechanisms include (1) release of HSP mediated by the COVID-19 vaccine, leading to an immune response at the BCG vaccine scar, or (2) another immune-mediated cross-reaction between BCG and the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine mRNA nanoparticle or encoded spike protein antigen. It has been hypothesized that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19; this remains uncertain and is under further investigation.10 A recent retrospective cohort study showed that a BCG vaccination booster may decrease COVID-19 infection rates in higher-risk populations.11

Conclusion

We present a case of BCG vaccine scar reactivation occurring after a dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, a likely underreported, self-limiting, cutaneous adverse effect of this mRNA vaccine.

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in notable morbidity and mortality worldwide. In December 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization for 2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines—produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna—for the prevention of COVID-19. Phase 3 trials of the vaccine developed by Moderna showed 94.1% efficacy at preventing COVID-19 after 2 doses.1

Common cutaneous adverse effects of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine include injection-site reactions, such as pain, induration, and erythema. Less frequently reported dermatologic adverse effects include diffuse bullous rash and hypersensitivity reactions.1 We report a case of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar after the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine.

Case Report

A 48-year-old Asian man who was otherwise healthy presented with erythema, induration, and mild pruritus on the deltoid muscle of the left arm, near the scar from an earlier BCG vaccine, which he received at approximately 5 years of age when living in Taiwan. The patient received the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine approximately 5 to 7 cm distant from the BCG vaccination scar. One to 2 days after inoculation, the patient endorsed tenderness at the site of COVID-19 vaccination but denied systemic symptoms. He had never been given a diagnosis of COVID-19. His SARS-CoV-2 antibody status was unknown.

Eight days later, the patient noticed a well-defined, erythematous, indurated plaque with mild itchiness overlying and around the BCG vaccination scar that did not involve the COVID-19 vaccination site. The following day, the redness and induration became worse (Figure).

The patient was otherwise well. Vital signs were normal; there was no lymphadenopathy. The rash resolved without treatment over the next 4 days.

Comment

The BCG vaccine is an intradermal live attenuated virus vaccine used to prevent certain forms of tuberculosis and potentially other Mycobacterium infections. Although the vaccine is not routinely administered in the United States, it is part of the vaccination schedule in most countries, administered most often to newborns and infants. Administration of the BCG vaccine commonly results in mild localized erythema, swelling, and pain at the injection site. Most inoculated patients also develop an ulcer that heals with the characteristic BCG vaccination scar.2,3

There is evidence that the BCG vaccine can enhance the innate immune system response and might decrease the rate of infection by unrelated pathogens, including viruses.4 Several epidemiologic studies have suggested that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19, possibly due to a resemblance of the amino acid sequences of BCG and SARS-CoV-2, which might provoke cross-reactive T cells.5,6 Further studies are underway to determine whether the BCG vaccine is truly protective against COVID-19.

BCG vaccination scar reactivation presents as redness, swelling, or ulceration at the BCG injection site months to years after inoculation. Although erythema and induration of the BCG scar are not included in the diagnostic criteria of Kawasaki disease, likely due to variable vaccine requirements in different countries, these findings are largely recognized as specific for Kawasaki disease and present in approximately half of affected patients who received the BCG vaccine.2

Heat Shock Proteins—Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are produced by cells in response to stressors. The proposed mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation is a cross-reaction between human homologue HSP 63 and Mycobacterium HSP 65, leading to hyperactivity of the immune system against BCG.7 There also are reports of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar from measles infection and influenza vaccination.2,8,9 Most prior reports of BCG vaccination scar reactivation have been in pediatric patients; our patient is an adult who received the BCG vaccine more than 40 years ago.

Mechanism of Reactivation—The mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation in our patient, who received the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, is unclear. Possible mechanisms include (1) release of HSP mediated by the COVID-19 vaccine, leading to an immune response at the BCG vaccine scar, or (2) another immune-mediated cross-reaction between BCG and the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine mRNA nanoparticle or encoded spike protein antigen. It has been hypothesized that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19; this remains uncertain and is under further investigation.10 A recent retrospective cohort study showed that a BCG vaccination booster may decrease COVID-19 infection rates in higher-risk populations.11

Conclusion

We present a case of BCG vaccine scar reactivation occurring after a dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, a likely underreported, self-limiting, cutaneous adverse effect of this mRNA vaccine.

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:403-416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

- Muthuvelu S, Lim KS, Huang L-Y, et al. Measles infection causing bacillus Calmette-Guérin reactivation: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:251. doi:10.1186/s12887-019-1635-z

- Fatima S, Kumari A, Das G, et al. Tuberculosis vaccine: a journey from BCG to present. Life Sci. 2020;252:117594. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117594

- O’Neill LAJ, Netea MG. BCG-induced trained immunity: can it offer protection against COVID-19? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:335-337. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-0337-y

- Brooks NA, Puri A, Garg S, et al. The association of coronavirus disease-19 mortality and prior bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination: a robust ecological analysis using unsupervised machine learning. Sci Rep. 2021;11:774. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80787-z

- Tomita Y, Sato R, Ikeda T, et al. BCG vaccine may generate cross-reactive T-cells against SARS-CoV-2: in silico analyses and a hypothesis. Vaccine. 2020;38:6352-6356. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.045

- Lim KYY, Chua MC, Tan NWH, et al. Reactivation of BCG inoculation site in a child with febrile exanthema of 3 days duration: an early indicator of incomplete Kawasaki disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:E239648. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-239648

- Kondo M, Goto H, Yamamoto S. First case of redness and erosion at bacillus Calmette-Guérin inoculation site after vaccination against influenza. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1229-1231. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13365

- Chavarri-Guerra Y, Soto-Pérez-de-Celis E. Erythema at the bacillus Calmette-Guerin scar after influenza vaccination. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2019;53:E20190390. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0390-2019

- Fu W, Ho P-C, Liu C-L, et al. Reconcile the debate over protective effects of BCG vaccine against COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8356. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-87731-9

- Amirlak L, Haddad R, Hardy JD, et al. Effectiveness of booster BCG vaccination in preventing COVID-19 infection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:3913-3915. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1956228

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:403-416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

- Muthuvelu S, Lim KS, Huang L-Y, et al. Measles infection causing bacillus Calmette-Guérin reactivation: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:251. doi:10.1186/s12887-019-1635-z

- Fatima S, Kumari A, Das G, et al. Tuberculosis vaccine: a journey from BCG to present. Life Sci. 2020;252:117594. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117594

- O’Neill LAJ, Netea MG. BCG-induced trained immunity: can it offer protection against COVID-19? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:335-337. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-0337-y

- Brooks NA, Puri A, Garg S, et al. The association of coronavirus disease-19 mortality and prior bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination: a robust ecological analysis using unsupervised machine learning. Sci Rep. 2021;11:774. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80787-z

- Tomita Y, Sato R, Ikeda T, et al. BCG vaccine may generate cross-reactive T-cells against SARS-CoV-2: in silico analyses and a hypothesis. Vaccine. 2020;38:6352-6356. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.045

- Lim KYY, Chua MC, Tan NWH, et al. Reactivation of BCG inoculation site in a child with febrile exanthema of 3 days duration: an early indicator of incomplete Kawasaki disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:E239648. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-239648

- Kondo M, Goto H, Yamamoto S. First case of redness and erosion at bacillus Calmette-Guérin inoculation site after vaccination against influenza. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1229-1231. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13365

- Chavarri-Guerra Y, Soto-Pérez-de-Celis E. Erythema at the bacillus Calmette-Guerin scar after influenza vaccination. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2019;53:E20190390. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0390-2019

- Fu W, Ho P-C, Liu C-L, et al. Reconcile the debate over protective effects of BCG vaccine against COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8356. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-87731-9

- Amirlak L, Haddad R, Hardy JD, et al. Effectiveness of booster BCG vaccination in preventing COVID-19 infection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:3913-3915. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1956228

Practice Points

- BCG vaccination scar reactivation is a potential benign, self-limited reaction in patients who receive the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine.

- Symptoms of BCG vaccination scar reactivation, which is seen more commonly in children with Kawasaki disease, include redness, swelling, and ulceration.

Rapidly Enlarging Bullous Plaque

The Diagnosis: Bullous Pyoderma Gangrenosum

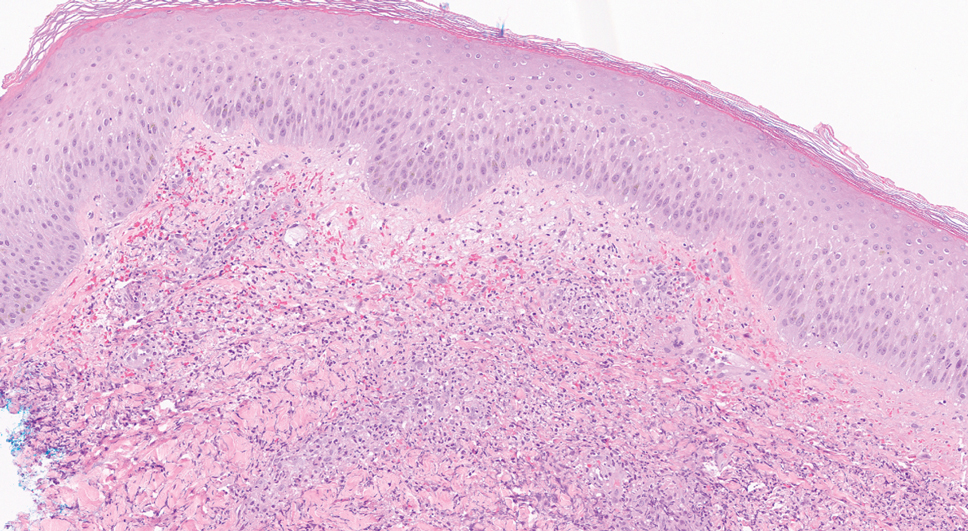

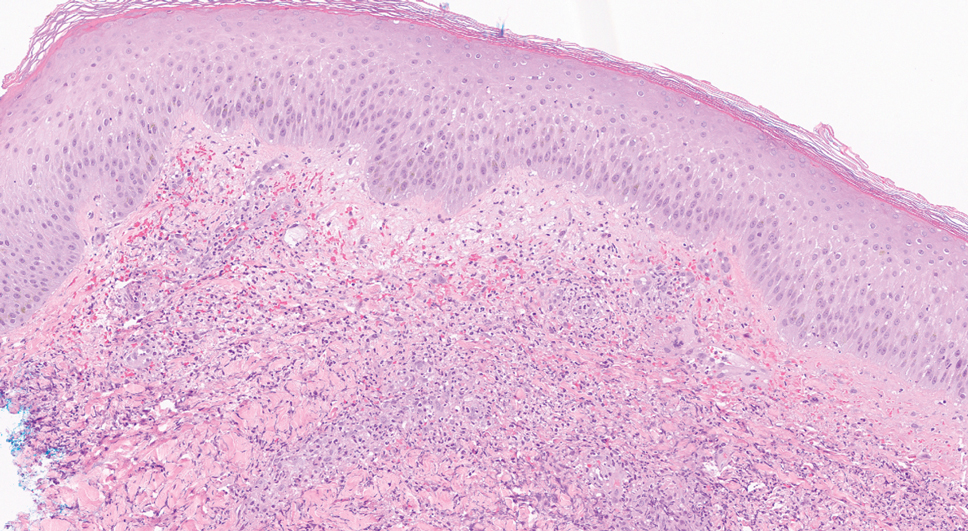

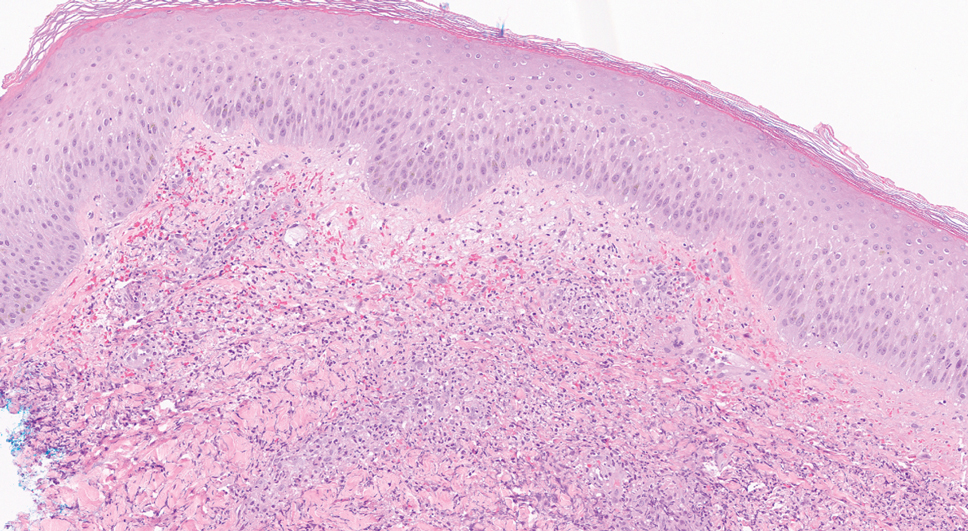

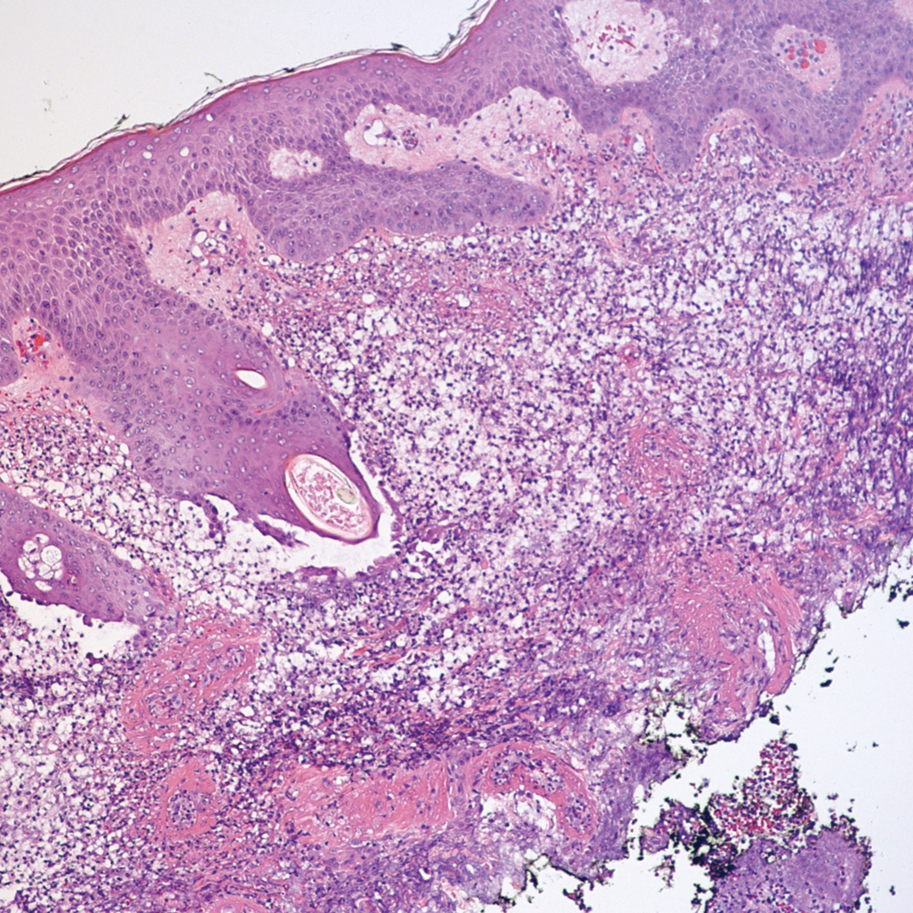

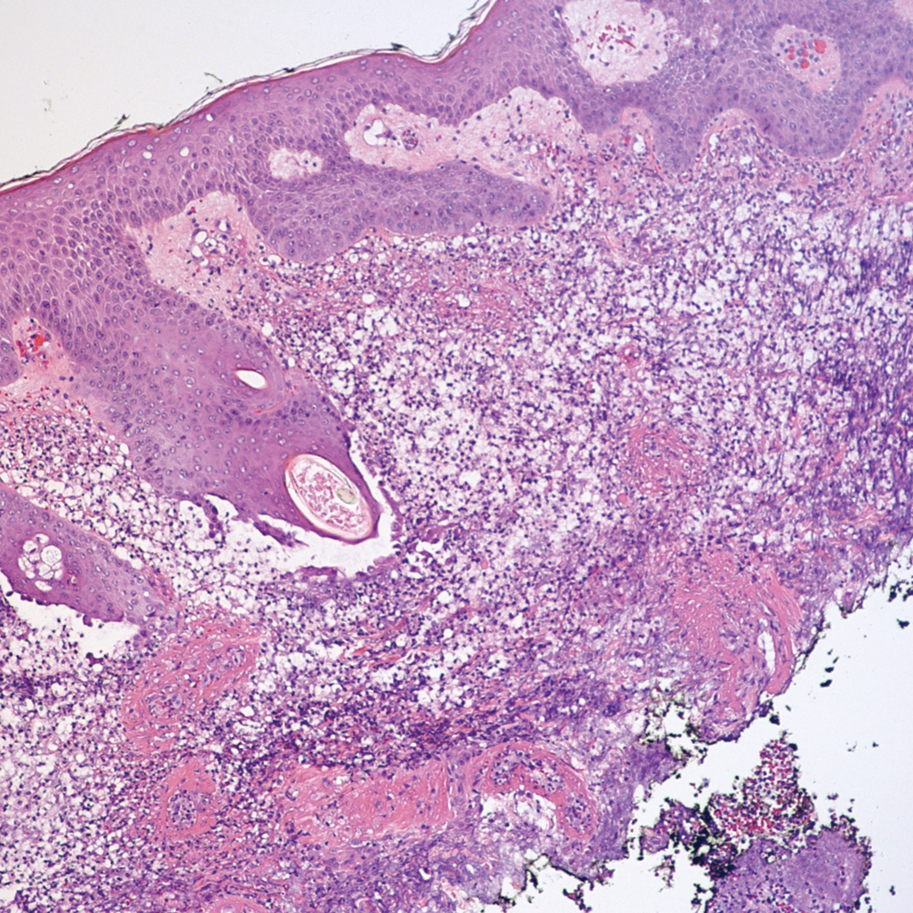

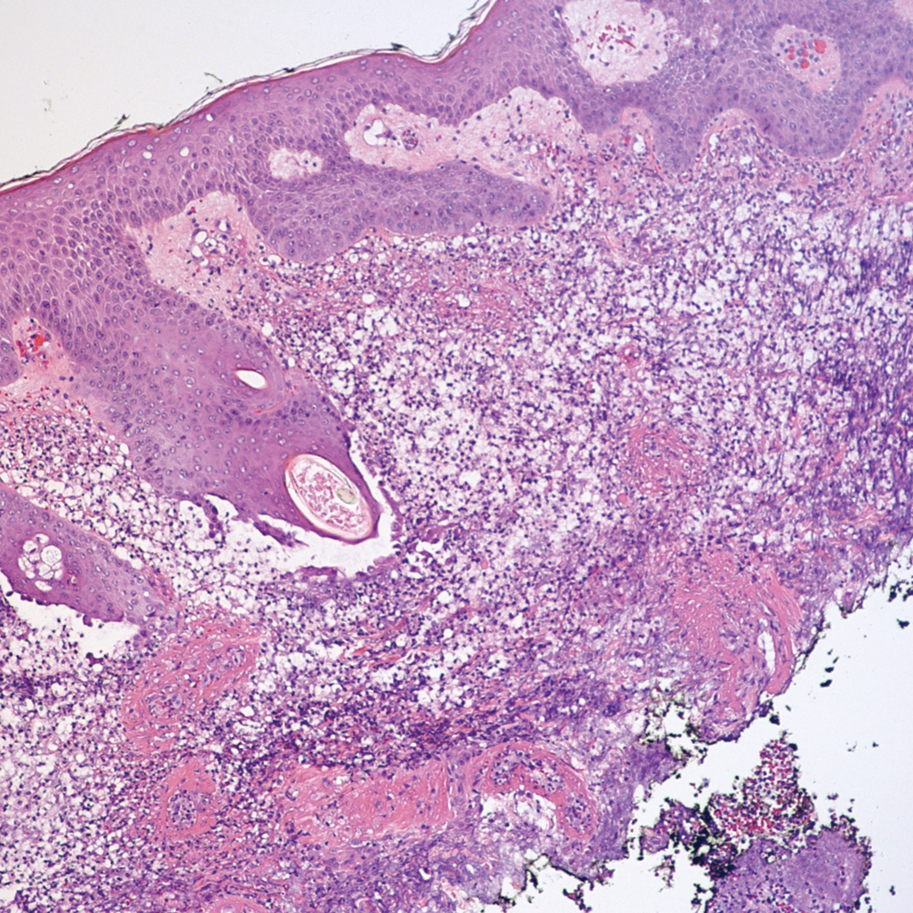

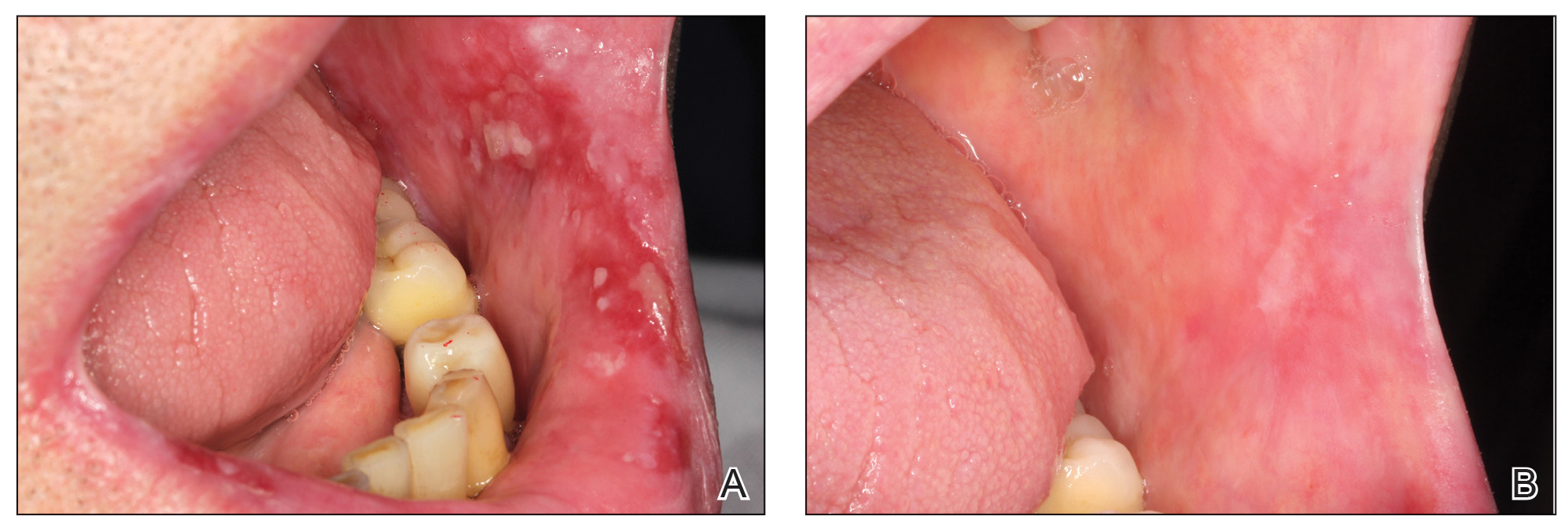

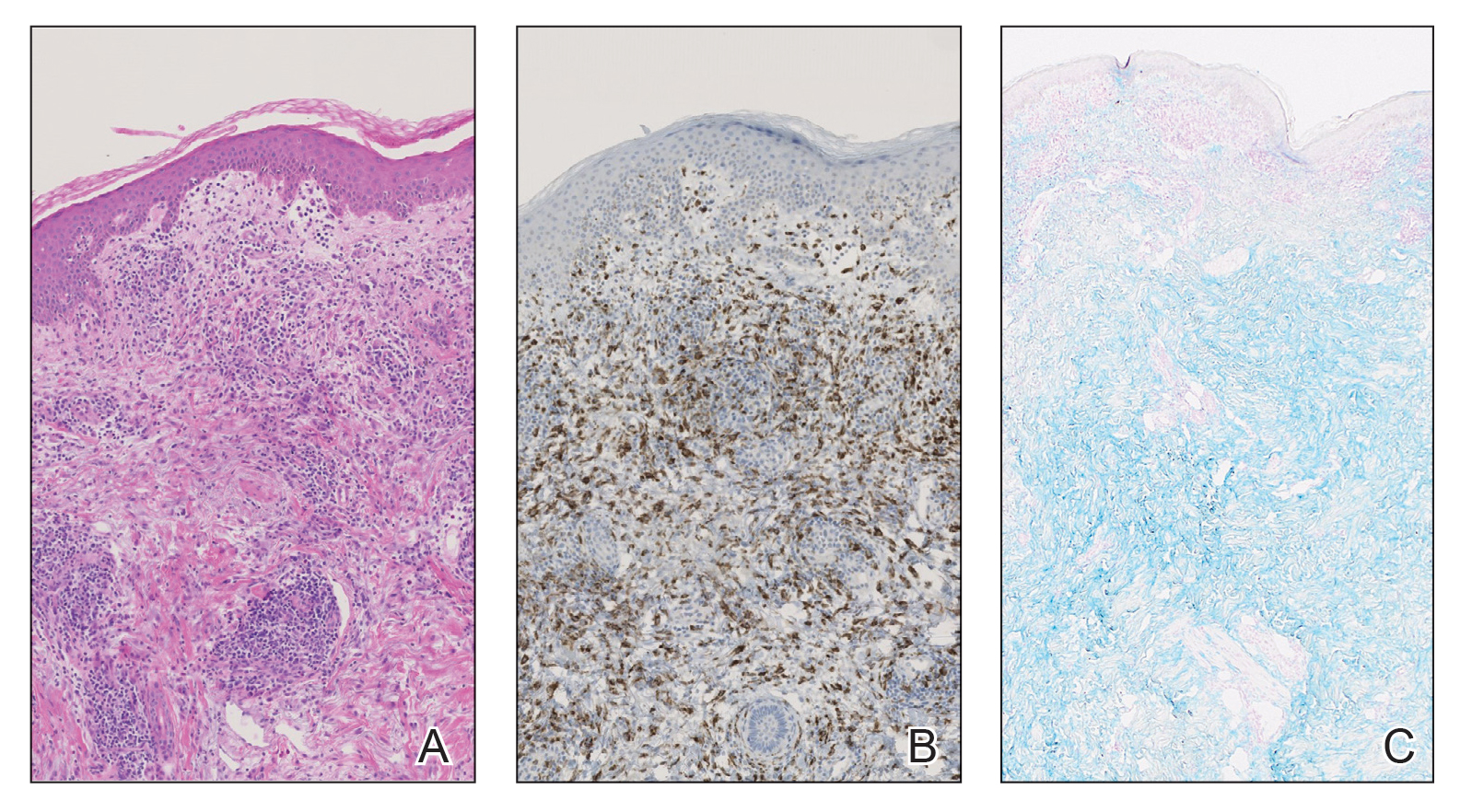

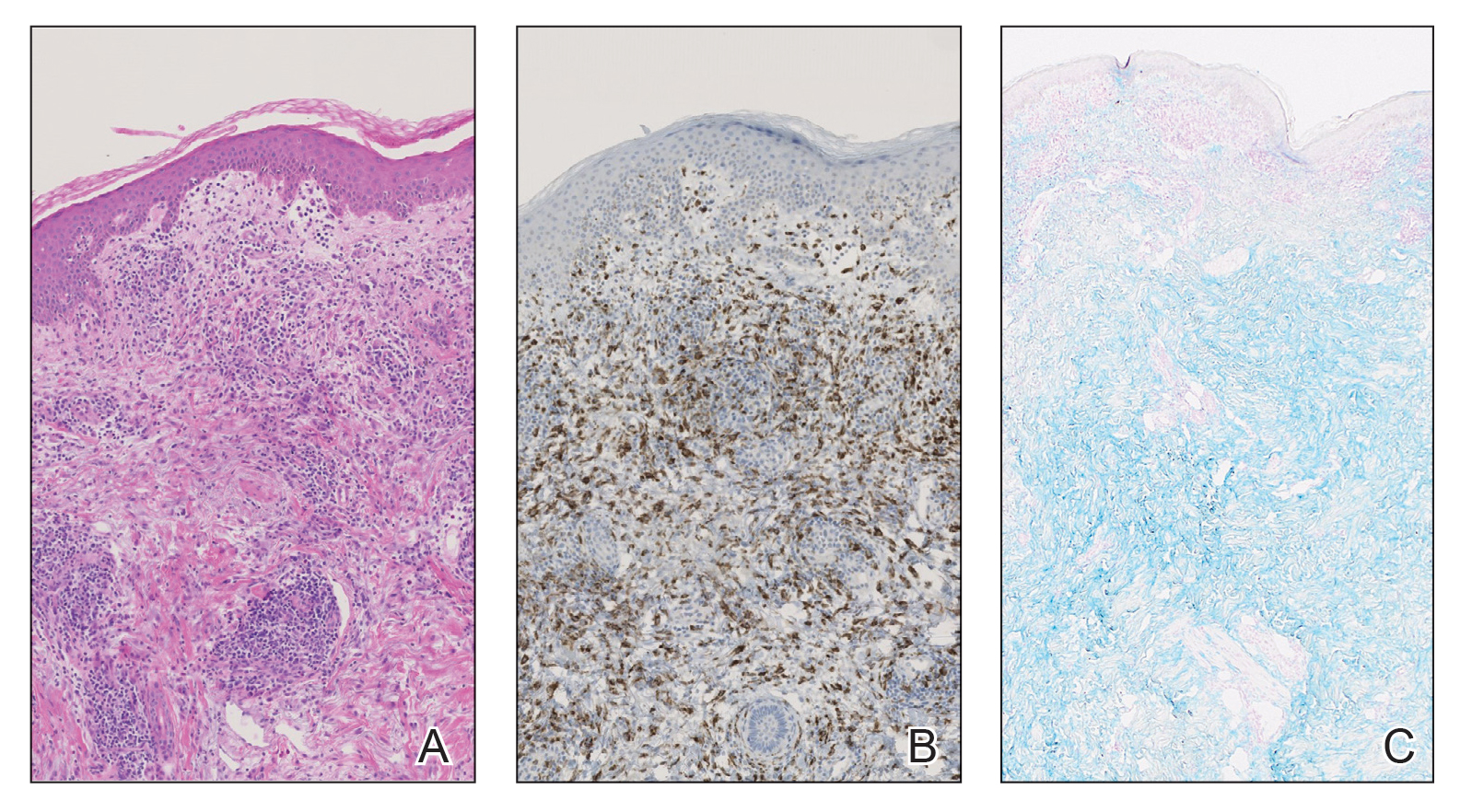

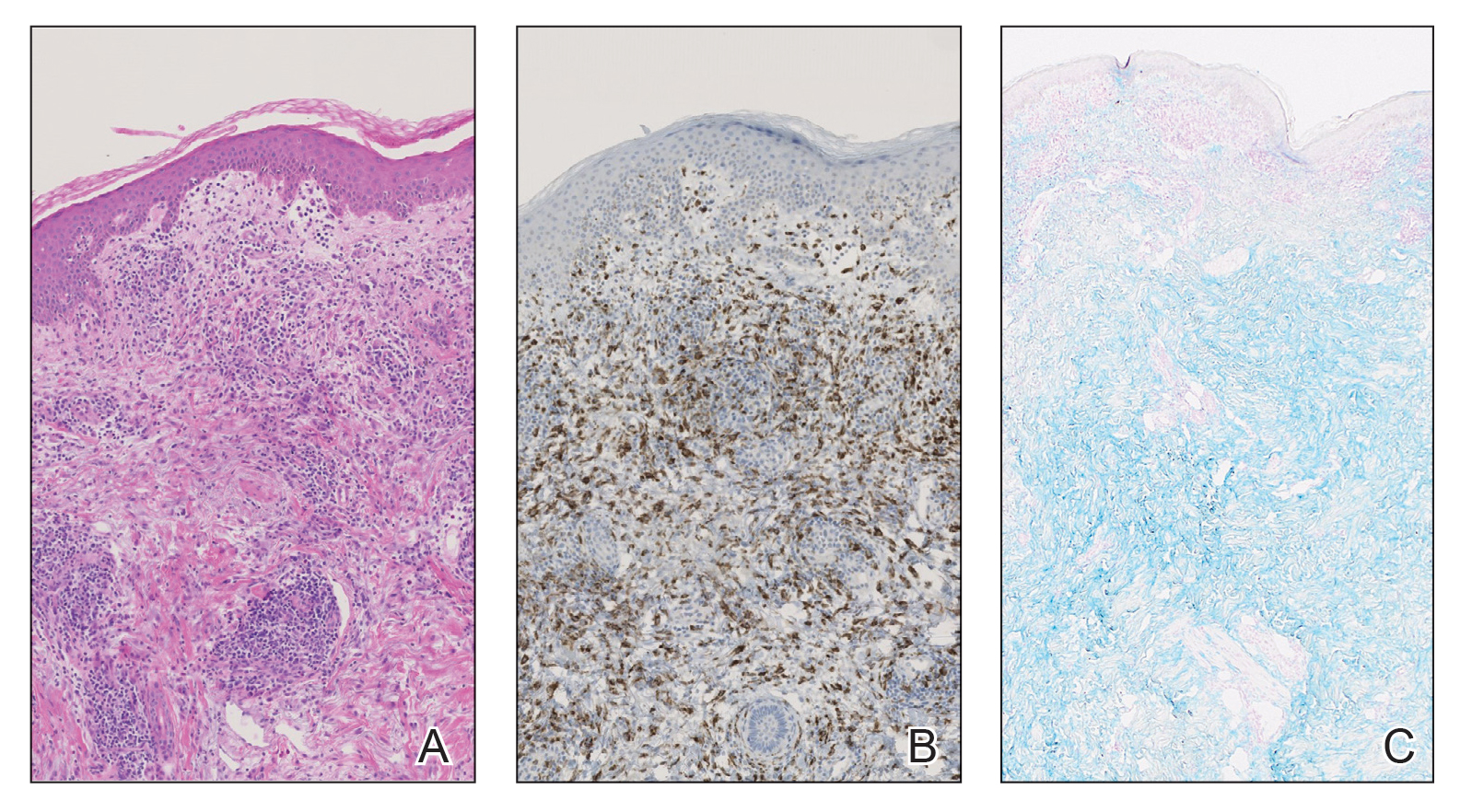

A bone marrow biopsy revealed 60% myeloblasts, leading to a diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). A biopsy obtained from the edge of the bullous plaque demonstrated a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes (Figure). Fite, Gram, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining failed to reveal infectious organisms. Tissue and blood cultures were negative. Given the pathologic findings, clinical presentation including recent diagnosis of AML, and exclusion of other underlying disease processes including infection, the diagnosis of bullous pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) was made. The lesion improved with systemic steroids and treatment of the underlying AML with fludarabine and venetoclax chemotherapy.

First recognized in 1916 by French dermatologist Louis Brocq, MD, PG is a sterile neutrophilic dermatosis that predominantly affects women older than 50 years.1,2 This disorder can develop idiopathically; secondary to trauma; or in association with systemic diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and hematologic malignancies. The pathogenesis of PG remains unclear; however, overexpression of inflammatory cytokines may mediate its development by stimulating T cells and promoting neutrophilic chemotaxis.3

Pyoderma gangrenosum classically presents as a rapidly enlarging ulcer with cribriform scarring but manifests variably. Four variants of the disorder exist: classic ulcerative, pustular, bullous, and vegetative PG. Ulcerative PG is the most common variant. Bullous PG is associated with hematologic malignancies such as primary myelofibrosis, myelodysplastic disease, and AML. In these patients, hematologic malignancy often exists prior to the development of PG and portends a poorer prognosis. This association underscores the importance of timely diagnosis and thorough hematologic evaluation by obtaining a complete blood cell count with differential, peripheral smear, serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation, and quantitative immunoglobulins (IgA, IgG, IgM). If any of the results are positive, prompt referral to a hematologist and bone marrow biopsy are paramount.3

The diagnosis of PG remains elusive, as no validated clinical or pathological criteria exist. Histopathologic evaluation may be nonspecific and variable depending on the subtype. Biopsy results for classic ulcerative PG may reveal a neutrophilic infiltrate with leukocytoclasia. Bullous PG may include subepidermal hemorrhagic bullae. Notably, bullous PG appears histologically similar to the superficial bullous variant of Sweet syndrome.

Sweet syndrome (also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) is a type of neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by fever, neutrophilia, and the sudden onset of tender erythematous lesions. Variations include idiopathic, subcutaneous, and bullous Sweet syndrome, which present as plaques, nodules, or bullae, respectively.4 Similar to PG, Sweet syndrome can manifest in patients with hematologic malignancies. Both PG and Sweet syndrome are thought to exist along a continuum and can be considered intersecting diagnoses in the setting of leukemia or other hematologic malignancies.5 There have been reports of the coexistence of distinct PG and Sweet syndrome lesions on a single patient, further supporting the belief that these entities share a common pathologic mechanism.6 Sweet syndrome also commonly can be associated with upper respiratory infections; pregnancy; and medications, with culprits including granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, azathioprine, vemurafenib, and isotretinoin.7

Other differential diagnoses include brown recluse spider bite, bullous fixed drug eruption (FDE), and necrotizing fasciitis (NF). Venom from the brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) can trigger toxin-mediated hemolysis, complement-mediated erythrocyte destruction, and basement membrane zone degradation due to the synergistic effects of the toxin’s sphingomyelinase D and protease content.8 The inciting bite is painless. After 8 hours, the site becomes painful and pruritic and presents with peripheral erythema and central pallor. After 24 hours, the lesion blisters. The blister ruptures within 3 to 4 days, resulting in eschar formation with the subsequent development of an indurated blue ulcer with a stellate center. Ulcers can take months to heal.9 Based on the clinical findings in our patient, this diagnosis was less likely.

Fixed drug eruption is a localized cutaneous reaction that manifests in fixed locations minutes to days after exposure to medications such as trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, salicylates, and oral contraceptives. Commonly affected areas include the hands, legs, genitals, and trunk. Lesions initially present as well-demarcated, erythematous to violaceous, round plaques. A rarer variant manifesting as bullae also has been described. Careful consideration of the patient’s history and physical examination findings is sufficient for establishing this diagnosis; however, a punch biopsy can provide clarity. Histopathology reveals a lichenoid tissue reaction with dyskeratosis, broad epidermal necrosis, and damage to the stratum basalis. A lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate also may appear in the dermis.10 Both the clinical findings and histopathology of our case were not characteristic of FDE.

Necrotizing fasciitis is a fulminant, life-threatening, soft-tissue infection precipitated by polymicrobial flora. Early recognition of NF is difficult, as in its early stages it can mimic cellulitis. As the infection takes its course, necrosis can extend from the skin and into the subcutaneous tissue. Patients also develop fever, leukocytosis, and signs of sepsis. Histopathology demonstrates neutrophilic infiltration with bacterial invasion as well as necrosis of the superficial fascia and subepidermal edema.11 Pyoderma gangrenosum previously has been reported to mimic NF; however, lack of responsiveness to antibiotic therapy would favor a diagnosis of PG over NF.12

Treatment of PG is driven by the extent of cutaneous involvement. In mild cases, wound care and topical therapy with corticosteroids and tacrolimus may suffice. Severe cases necessitate systemic therapy with oral corticosteroids or cyclosporine; biologic therapy also may play a role in treatment.4 In patients with hematologic malignancy, chemotherapy alone may partially or completely resolve the lesion; however, systemic corticosteroids commonly are included in management.3

- Brocq L. A new contribution to the study of geometric phagedenism. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr. 1916;9:1-39.

- Xu A, Balgobind A, Strunk A, et al. Prevalence estimates for pyoderma gangrenosum in the United States: an age- and sexadjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:425-429. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.001

- Montagnon CM, Fracica EA, Patel AA, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum in hematologic malignancies: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1346-1359. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.032

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-34

- George C, Deroide F, Rustin M. Pyoderma gangrenosum—a guide to diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19:224‐228. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.19-3-224

- Caughman W, Stern R, Haynes H. Neutrophilic dermatosis of myeloproliferative disorders. atypical forms of pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet’s syndrome associated with myeloproliferative disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:751-758. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70191-x

- Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen M. Pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome: the prototypic neutrophilic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:595-602.

- Manzoni-de-Almeida D, Squaiella-Baptistão CC, Lopes PH, et al. Loxosceles venom sphingomyelinase D activates human blood leukocytes: role of the complement system. Mol Immunol. 2018;94:45-53.