User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Bullous Dermatoses and Quality of Life: A Summary of Tools to Assess Psychosocial Health

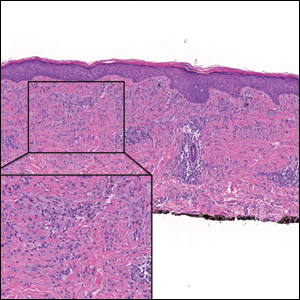

Autoimmune bullous dermatoses (ABDs) develop due to antibodies directed against antigens within the epidermis or at the dermoepidermal junction. They are categorized histologically by the location of acantholysis (separation of keratinocytes), clinical presentation, and presence of autoantibodies. The most common ABDs include pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and bullous pemphigoid (BP). These conditions present on a spectrum of symptoms and severity.1

Although multiple studies have evaluated the impact of bullous dermatoses on mental health, most were designed with a small sample size, thus limiting the generalizability of each study. Sebaratnam et al2 summarized several studies in 2012. In this review, we will analyze additional relevant literature and systematically combine the data to determine the psychological burden of disease of ABDs. We also will discuss the existing questionnaires frequently used in the dermatology setting to assess adverse psychosocial symptoms.

Methods

We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar for articles published within the last 15 years using the terms bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus, quality of life, anxiety, and depression. We reviewed the citations in each article to further our search.

Criteria for Inclusion and Exclusion—Studies that utilized validated questionnaires to evaluate the effects of pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and/or BP on mental health were included. All research participants were 18 years and older. For the questionnaires administered, each study must have included numerical scores in the results. The studies all reported statistically significant results (P<.05), but no studies were excluded on the basis of statistical significance.

Studies were excluded if they did not use a validated questionnaire to examine quality of life (QOL) or psychological status. We also excluded database, retrospective, qualitative, and observational studies. We did not include studies with a sample size less than 20. Studies that administered questionnaires that were uncommon in this realm of research such as the Attitude to Appearance Scale or The Anxiety Questionnaire also were excluded. We did not exclude articles based on their primary language.

Results

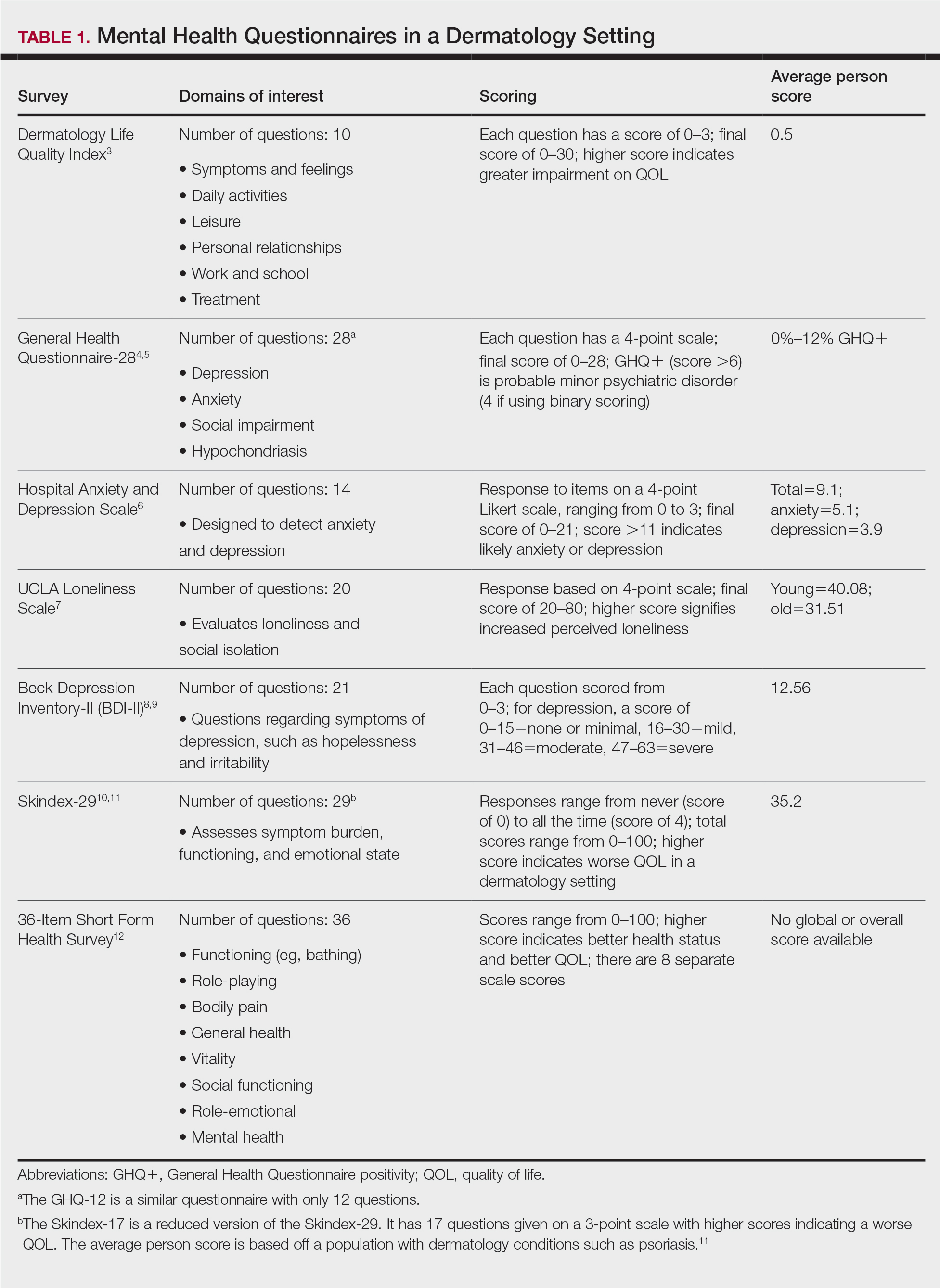

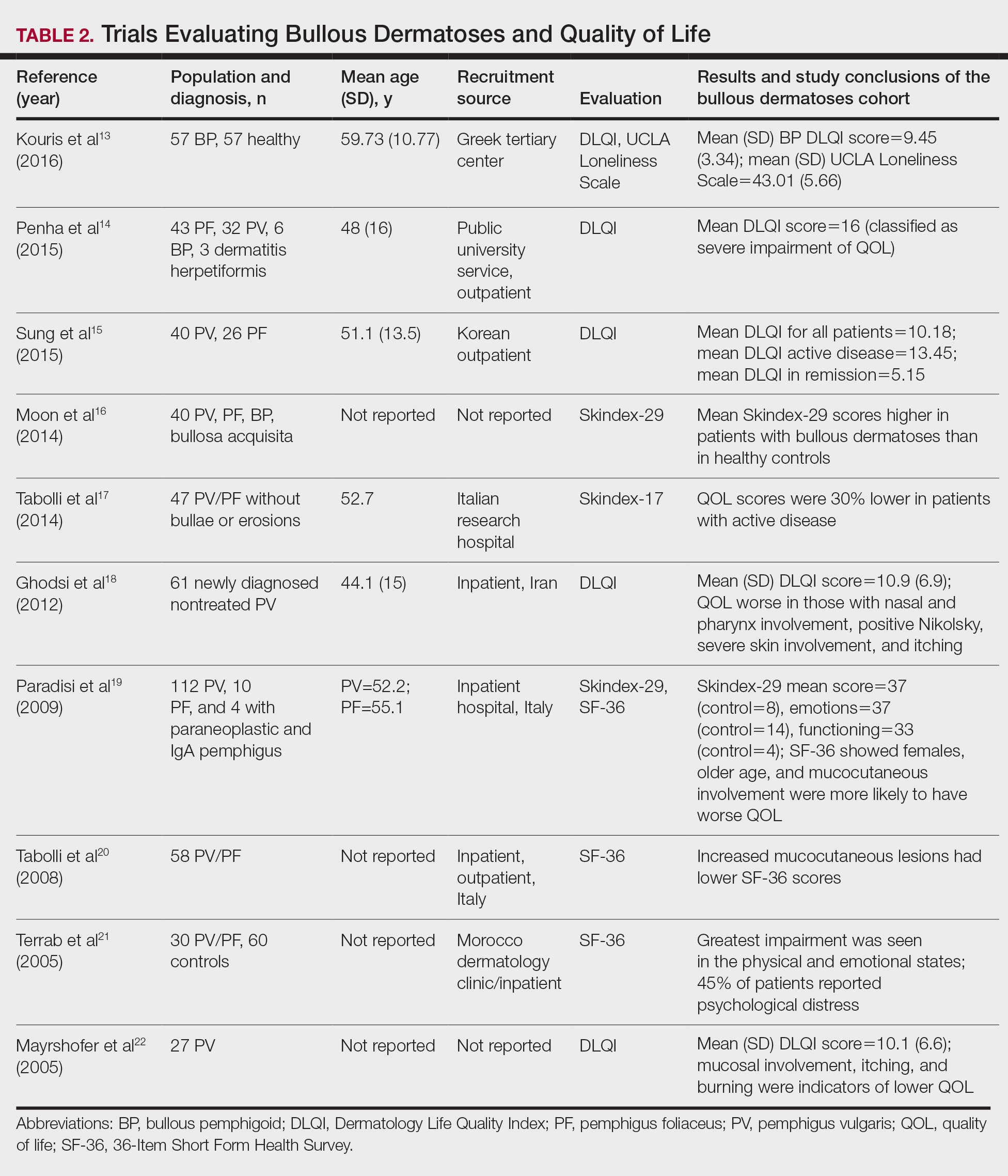

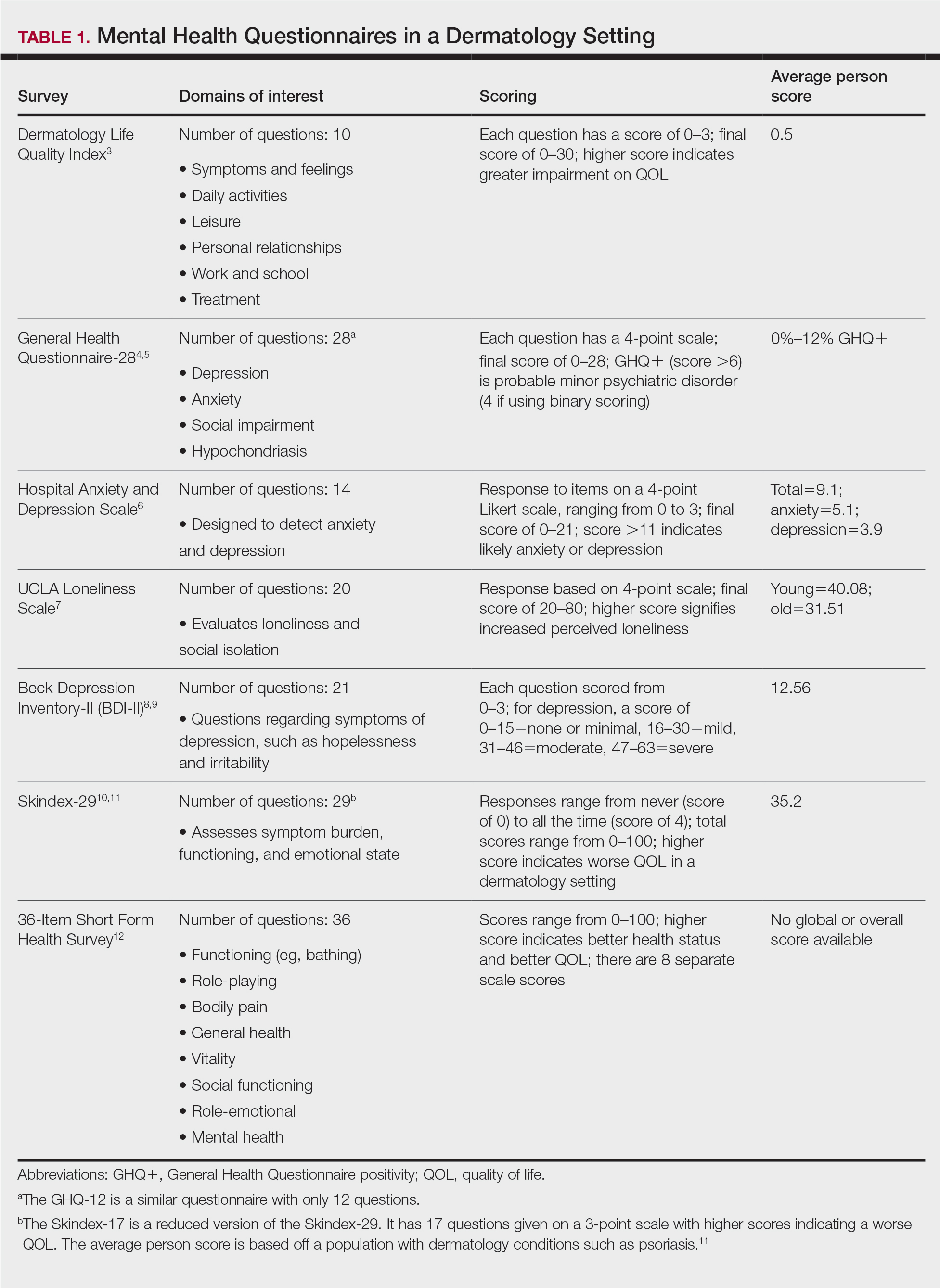

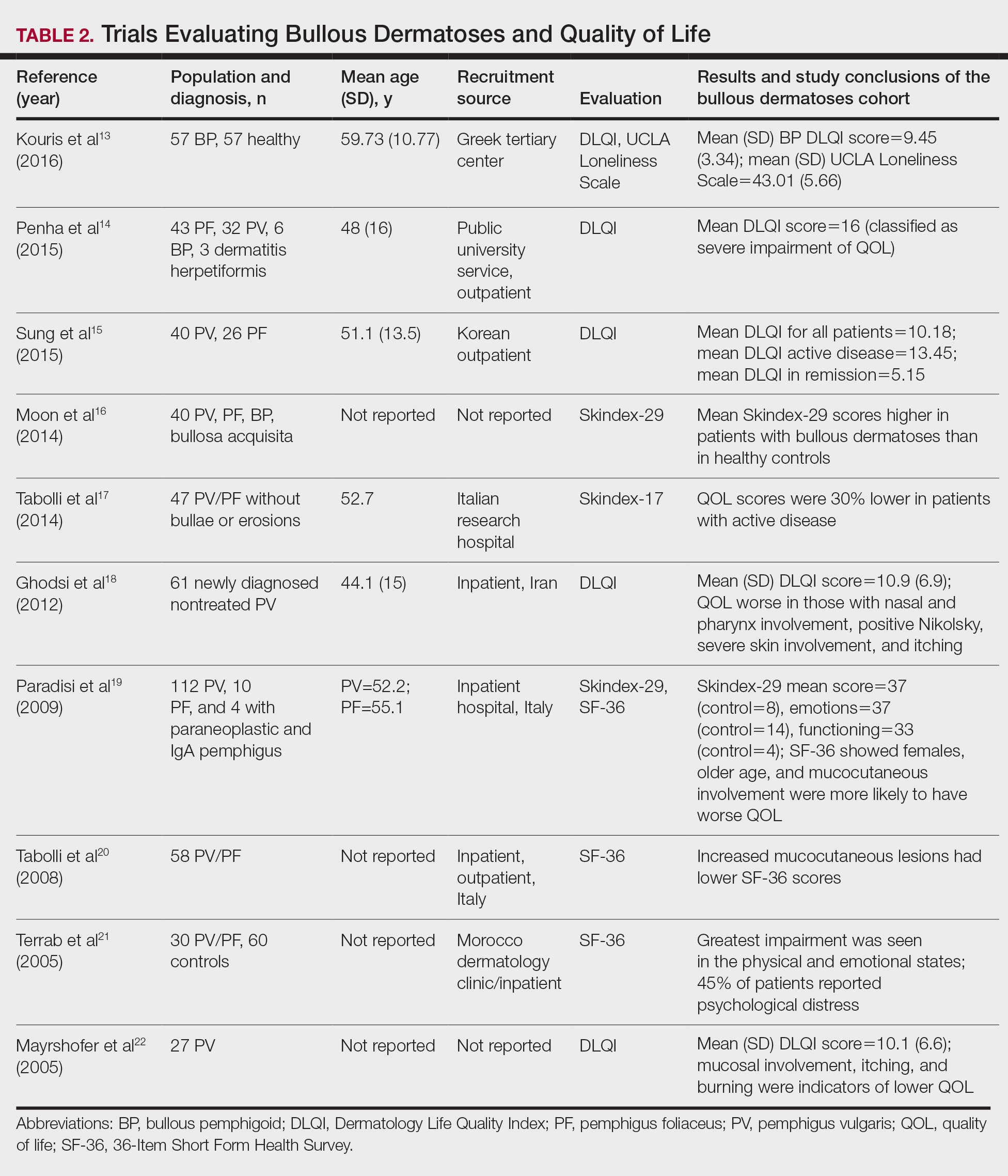

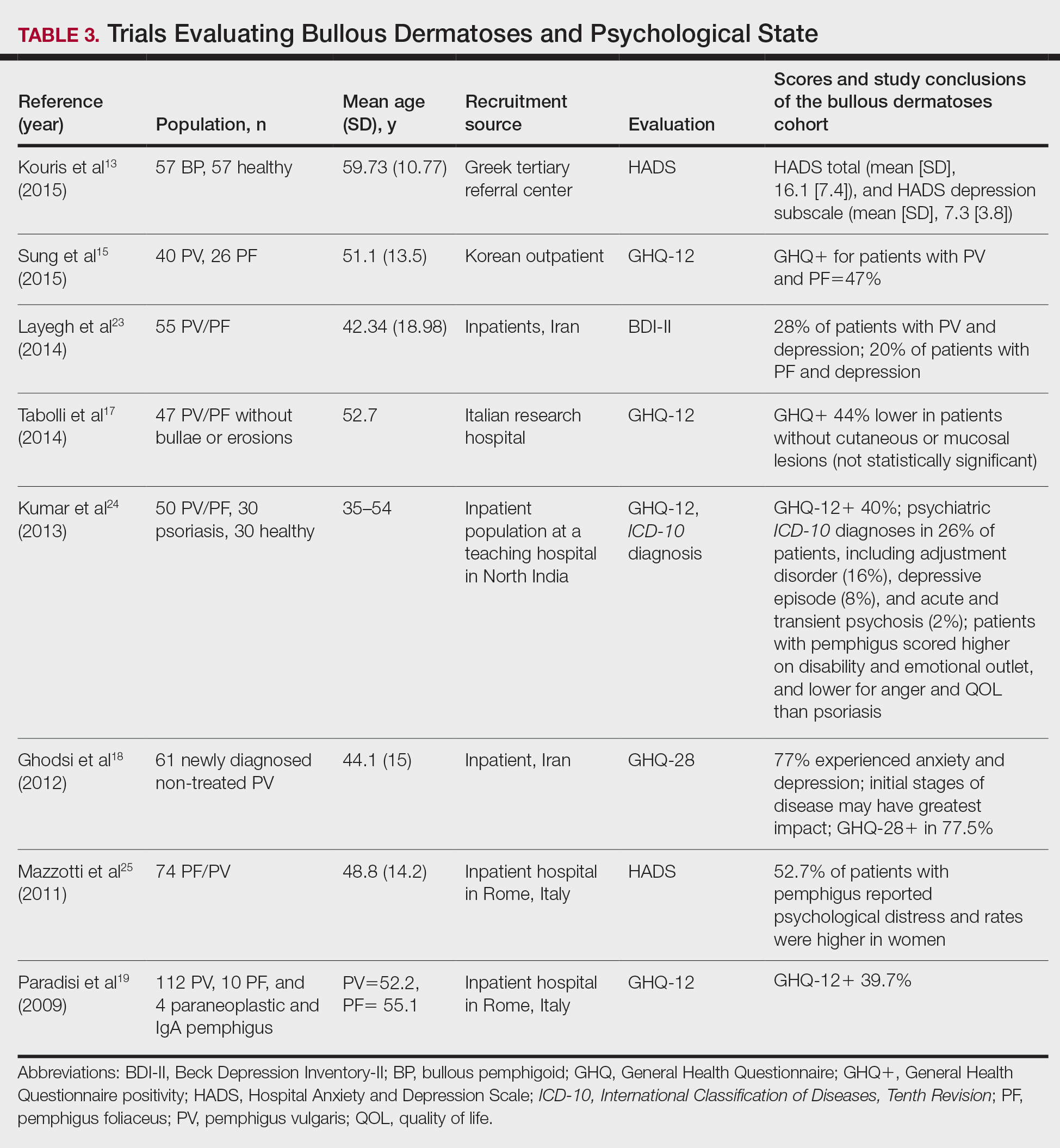

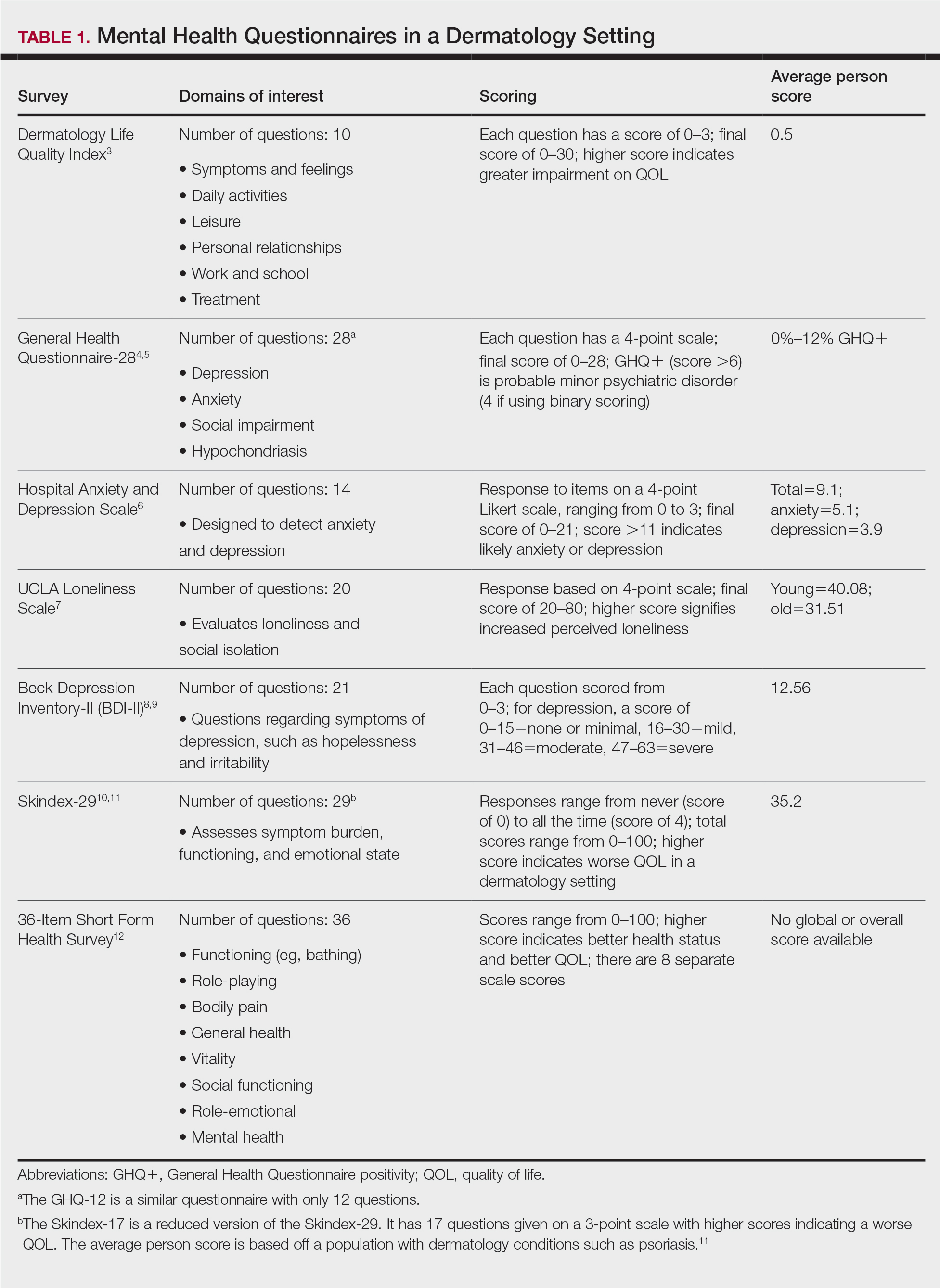

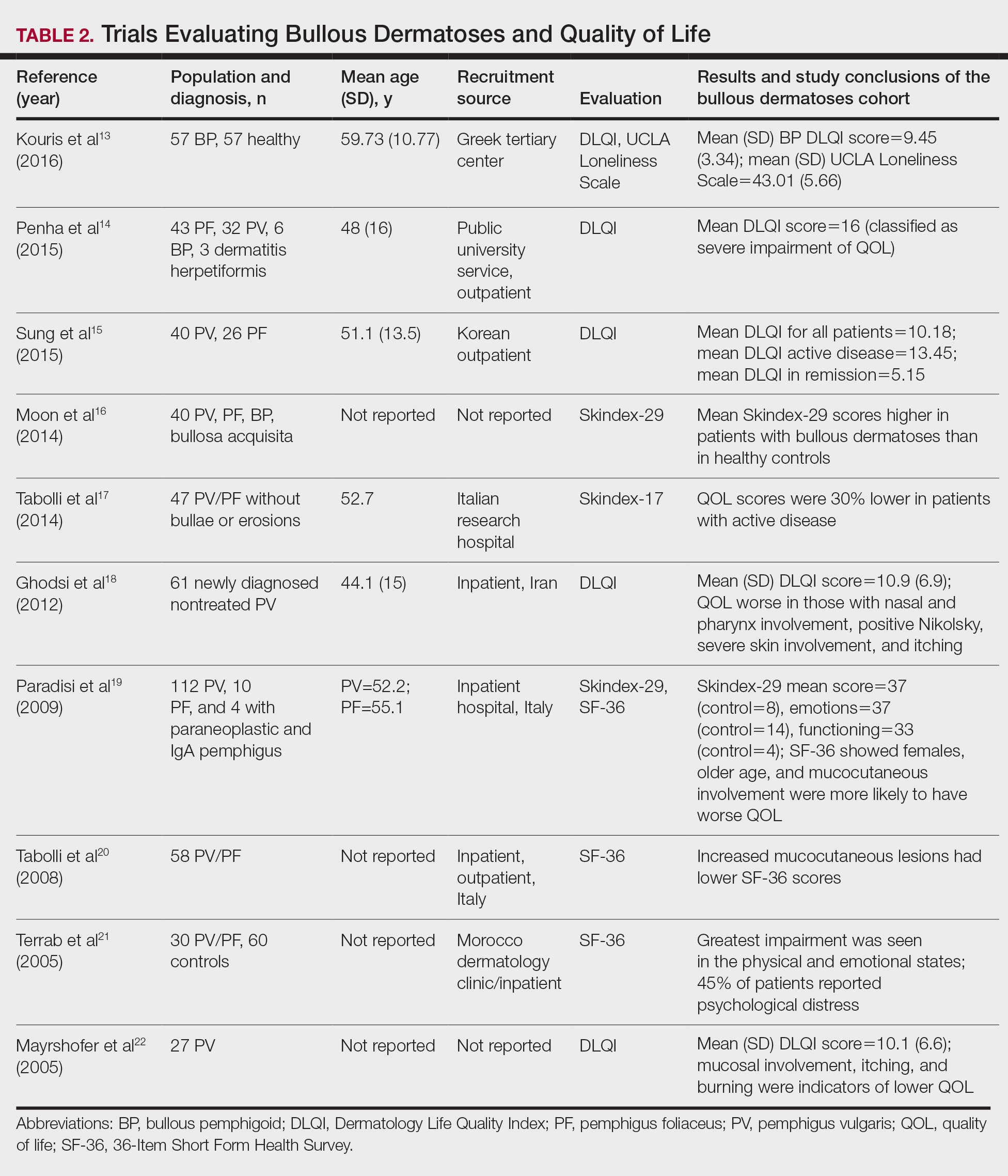

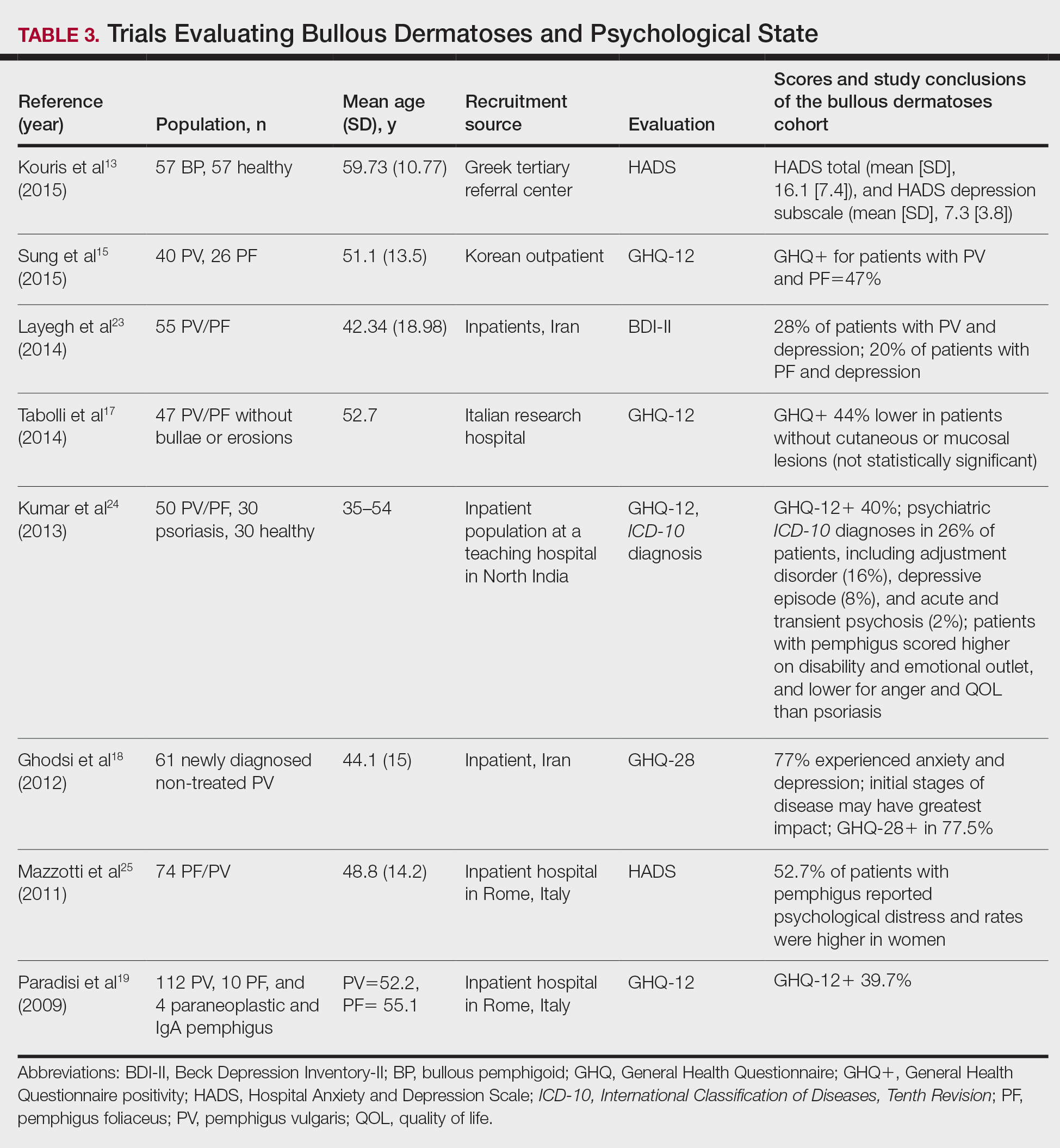

A total of 13 studies met the inclusion criteria with a total of 1716 participants enrolled in the trials. The questionnaires most commonly used are summarized in Table 1. Tables 2 and 3 demonstrate the studies that evaluate QOL and psychological state in patients with bullous dermatoses, respectively.

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) was the most utilized method for analyzing QOL followed by the Skindex-17, Skindex-29, and 36-Item Short Form Health Survey. The DLQI is a skin-specific measurement tool with higher scores translating to greater impairment in QOL. Healthy patients have an average score of 0.5.3 The mean DLQI scores for ABD patients as seen in Table 2 were 9.45, 10.18, 16, 10.9, and 10.1.13-15,18,22 The most commonly reported concerns among patients included feelings about appearance and disturbances in daily activities.18 Symptoms of mucosal involvement, itching, and burning also were indicators of lower QOL.15,18,20,22 Furthermore, women consistently had lower scores than men.15,17,19,25 Multiple studies concluded that severity of the disease correlated with a lower QOL, though the subtype of pemphigus did not have an effect on QOL scores.15,19,20,21 Lastly, recent onset of symptoms was associated with a worse QOL score.15,18-20 Age, education level, and marital status did not have an effect on QOL.

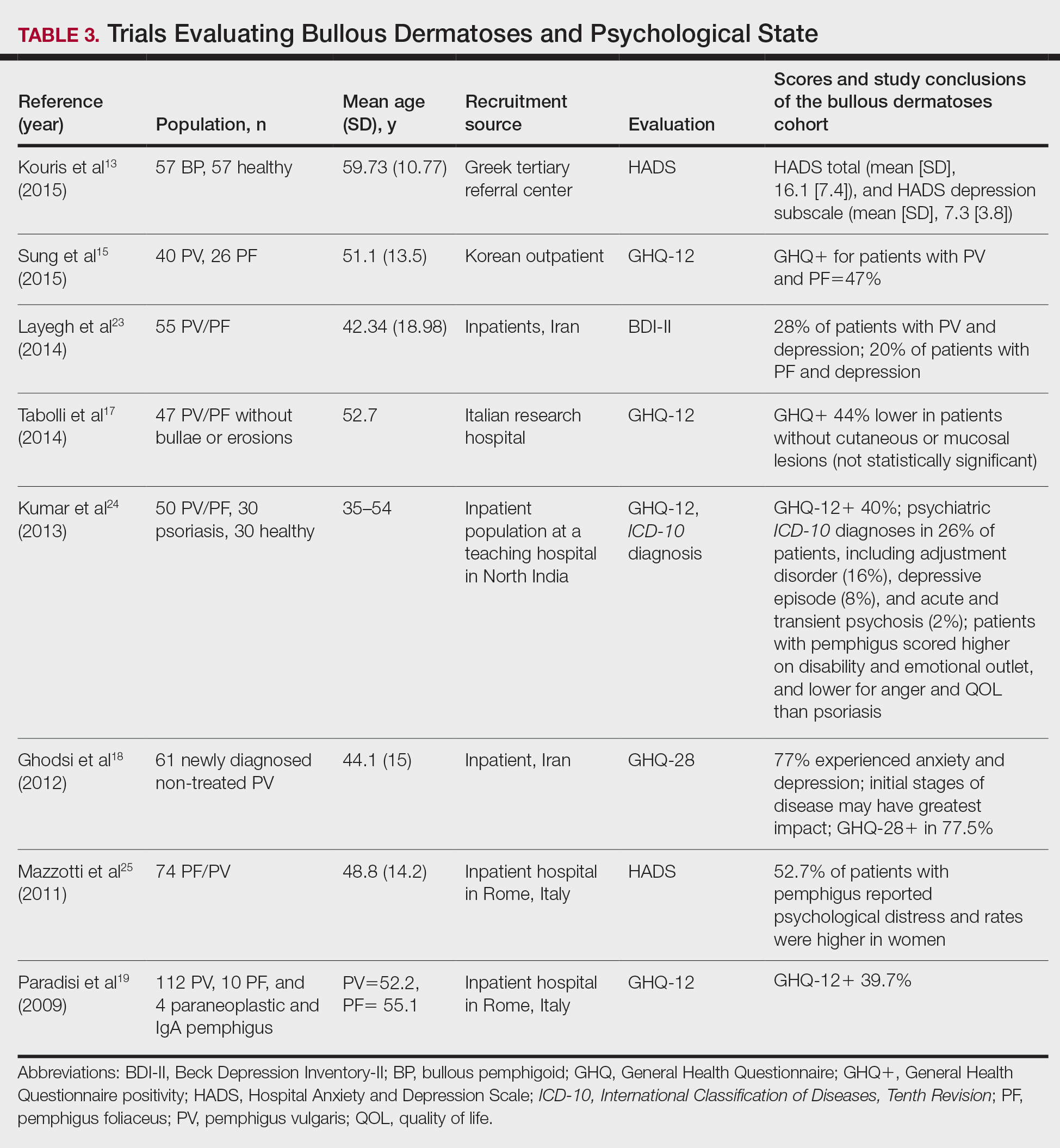

To evaluate psychological state, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-28 and -12 primarily were used, in addition to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; and the Beck Depression Inventory-II. As seen in Table 3, GHQ-12 positivity, reflecting probable minor nonpsychotic psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety, was identified in 47%, 39.7%, and 40% of patients with pemphigus15,19,24; GHQ-28 positivity was seen in 77.5% of pemphigus patients.18 In the average population, GHQ positivity was found in up to 12% of patients.26,27 Similar to the QOL scores, no significant differences were seen based on subtype of pemphigus for symptoms of depression or anxiety.20,23

Comment

Mental Health of Patients With ABDs—Immunobullous diseases are painful, potentially lifelong conditions that have no definitive cure. These conditions are characterized by bullae and erosions of the skin and mucosae that physically are disabling and often create a stigma for patients. Across multiple different validated psychosocial assessments, the 13 studies included in this review consistently reported that ABDs have a negative effect on mental well-being of patients that is more pronounced in women and worse at the onset of symptoms.13-25

QOL Scores in Patients With ABDs—Quality of life is a broad term that encompasses a general sense of psychological and overall well-being. A score of approximately 10 on the DLQI most often was reported in patients with ABDs, which translates to a moderate impact on QOL. Incomparison, a large cohort study reported the mean (SD) DLQI scores for patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis as 7.31 (5.98) and 5.93 (5.66), respectively.28 In another study, Penha et al14 found that patients with psoriasis have a mean DLQI score of 10. Reasons for the similarly low QOL scores in patients with ABDs include long hospitalization periods, disease chronicity, social anxiety, inability to control symptoms, difficulty with activities of daily living, and the belief that the disease is incurable.17,19,23 Although there is a need for increased family and social support with performing necessary daily tasks, personal relationships often are negatively affected, resulting in social isolation, loneliness, and worsening of cutaneous symptoms.

Severity of cutaneous disease and recent onset of symptoms correlated with worse QOL scores. Tabolli et al20 proposed the reason for this relates to not having had enough time to find the best treatment regimen. We believe there also may be an element of habituation involved, whereby patients become accustomed to the appearance of the lesions over time and therefore they become less distressing. Interestingly, Tabolli et al17 determined that patients in the quiescent phase of the disease—without any mucosal or cutaneous lesions—still maintained lower QOL scores than the average population, particularly on the psychosocial section of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, which may be due to a concern of disease relapse or from adverse effects of treatment. Providers should monitor patients for mental health complications not only in the disease infancy but throughout the disease course.

Future Directions—Cause and effect of the relationship between the psychosocial variables and ABD disease state has yet to be determined. Most studies included in this review were cross-sectional in design. Although many studies concluded that bullous dermatoses were the cause of impaired QOL, Ren and colleagues29 proposed that medications used to treat neuropsychiatric disorders may trigger the autoimmune antigens of BP. Possible triggers for BP have been reported including hydrochlorothiazide, ciprofloxacin, and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors.27,30-32 A longitudinal study design would better evaluate the causal relationship.

The effects of the medications were included in 2 cases, one in which the steroid dose was not found to have a significant impact on rates of depression23 and another in which patients treated with a higher dose of corticosteroids (>10 mg) had worse QOL scores.17 Sung et al15 suggested this may be because patients who took higher doses of steroids had worse symptoms and therefore also had a worse QOL. It also is possible that those patients taking higher doses had increased side effects.17 Further studies that evaluate treatment modalities and timing in relation to the disease onset would be helpful.

Study Limitations—There are potential barriers to combining these data. Multiple different questionnaires were used, and it was difficult to ascertain if all the participants were experiencing active disease. Additionally, questionnaires are not always the best proxy for what is happening in everyday life. Lastly, the sample size of each individual study was small, and the studies only included adults.

Conclusion

As demonstrated by the 13 studies in this review, patients with ABDs have lower QOL scores and higher numbers of psychological symptoms. Clinicians should be mindful of this at-risk population and create opportunities in clinic to discuss personal hardship associated with the disease process and recommend psychiatric intervention if indicated. Additionally, family members often are overburdened with the chronicity of ABDs, and they should not be forgotten. Using one of the aforementioned questionnaires is a practical way to screen patients for lower QOL scores. We agree with Paradisi and colleagues19 that although these questionnaires may be helpful, clinicians still need to determine if the use of a dermatologic QOL evaluation tool in clinical practice improves patient satisfaction.

- Baum S, Sakka N, Artsi O, et al. Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune blistering diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:482-489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.047

- Sebaratnam DF, McMillan JR, Werth VP, et al. Quality of life in patients with bullous dermatoses. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:103-107. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.03.016

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-216.

- Goldberg DP. The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire. Oxford University Press; 1972.

- Cano A, Sprafkin RP, Scaturo DJ, et al. Mental health screening in primary care: a comparison of 3 brief measures of psychological distress. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3:206-210.

- Zigmond A, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370.

- Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66:20-40. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

- Beck A, Alford B. Depression: Causes and Treatment. 2nd ed. Philadelphia University of Pennsylvania Press; 2009.

- Ghassemzadeh H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, et al. Psychometric properties of a Persian-language version of the Beck Depression Inventory—Second Edition: BDI-II-PERSIAN. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:185-192. doi:10.1002/da.20070

- Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sahay AP, et al. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:105-110.

- Nijsten TEC, Sampogna F, Chren M, et al. Testing and reducing Skindex-29 using Rasch analysis: Skindex-17. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1244-1250. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5700212

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483.

- Kouris A, Platsidaki E, Christodoulou C, et al. Quality of life, depression, anxiety and loneliness in patients with bullous pemphigoid: a case control study. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:601-603. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.2016493

- Penha MA, Farat JG, Miot HA, et al. Quality of life index in autoimmune bullous dermatosis patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:190-194. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153372

- Sung JY, Roh MR, Kim SC. Quality of life assessment in Korean patients with pemphigus. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:492-498.

- Moon SH, Kwon HI, Park HC, et al. Assessment of the quality of life in autoimmune blistering skin disease patients. Korean J Dermatol. 2014;52:402-409.

- Tabolli S, Pagliarello C, Paradisi A, et al. Burden of disease during quiescent periods in patients with pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1087-1091. doi:10.1111/bjd.12836

- Ghodsi SZ, Chams-Davatchi C, Daneshpazhooh M, et al. Quality of life and psychological status of patients with pemphigus vulgaris using Dermatology Life Quality Index and general health questionnaires. J Dermatol. 2012;39:141-144. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01382

- Paradisi A, Sampogna F, Di Pietro C, et al. Quality-of-life assessment in patients with pemphigus using a minimum set of evaluation tools. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:261-269. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.014

- Tabolli S, Mozzetta A, Antinone V, et al. The health impact of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form health survey questionnaire. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1029-1034. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08481.x

- Terrab Z, Benchikhi H, Maaroufi A, et al. Quality of life and pemphigus. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:321-328.

- Mayrshofer F, Hertl M, Sinkgraven R, et al. Significant decrease in quality of life in patients with pemphigus vulgaris: results from the German Bullous Skin Disease (BSD) Study Group [in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:431-435. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2005.05722.x

- Layegh P, Mokhber N, Javidi Z, et al. Depression in patients with pemphigus: is it a major concern? J Dermatol. 2014;40:434-437. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12067

- Kumar V, Mattoo SK, Handa S. Psychiatric morbidity in pemphigus and psoriasis: a comparative study from India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6:151-156. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2012.10.005

- Mazzotti E, Mozzetta A, Antinone V, et al. Psychological distress and investment in one’s appearance in patients with pemphigus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:285-289. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03780.x

- Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD, et al. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five epidemiologic catchment area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1988;45:977-986. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800350011002

- Cozzani E, Chinazzo C, Burlando M, et al. Ciprofloxacin as a trigger for bullous pemphigoid: the second case in the literature. Am J Ther. 2016;23:E1202-E1204. doi:10.1097/MJT.0000000000000283

- Lundberg L, Johannesson M, Silverdahl M, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis measured with SF-36, DLQI and a subjective measure of disease activity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:430-434.

- Ren Z, Hsu DY, Brieva J, et al. Hospitalization, inpatient burden and comorbidities associated with bullous pemphigoid in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:87-99. doi:10.1111/bjd.14821

- Warner C, Kwak Y, Glover MH, et al. Bullous pemphigoid induced by hydrochlorothiazide therapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:360-362.

- Mendonca FM, Martin-Gutierrez FJ, Rios-Martin JJ, et al. Three cases of bullous pemphigoid associated with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors—one due to linagliptin. Dermatology. 2016;232:249-253. doi:10.1159/000443330

- Attaway A, Mersfelder TL, Vaishnav S, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors: a case report and review of literature. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2014;8:24-28.

Autoimmune bullous dermatoses (ABDs) develop due to antibodies directed against antigens within the epidermis or at the dermoepidermal junction. They are categorized histologically by the location of acantholysis (separation of keratinocytes), clinical presentation, and presence of autoantibodies. The most common ABDs include pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and bullous pemphigoid (BP). These conditions present on a spectrum of symptoms and severity.1

Although multiple studies have evaluated the impact of bullous dermatoses on mental health, most were designed with a small sample size, thus limiting the generalizability of each study. Sebaratnam et al2 summarized several studies in 2012. In this review, we will analyze additional relevant literature and systematically combine the data to determine the psychological burden of disease of ABDs. We also will discuss the existing questionnaires frequently used in the dermatology setting to assess adverse psychosocial symptoms.

Methods

We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar for articles published within the last 15 years using the terms bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus, quality of life, anxiety, and depression. We reviewed the citations in each article to further our search.

Criteria for Inclusion and Exclusion—Studies that utilized validated questionnaires to evaluate the effects of pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and/or BP on mental health were included. All research participants were 18 years and older. For the questionnaires administered, each study must have included numerical scores in the results. The studies all reported statistically significant results (P<.05), but no studies were excluded on the basis of statistical significance.

Studies were excluded if they did not use a validated questionnaire to examine quality of life (QOL) or psychological status. We also excluded database, retrospective, qualitative, and observational studies. We did not include studies with a sample size less than 20. Studies that administered questionnaires that were uncommon in this realm of research such as the Attitude to Appearance Scale or The Anxiety Questionnaire also were excluded. We did not exclude articles based on their primary language.

Results

A total of 13 studies met the inclusion criteria with a total of 1716 participants enrolled in the trials. The questionnaires most commonly used are summarized in Table 1. Tables 2 and 3 demonstrate the studies that evaluate QOL and psychological state in patients with bullous dermatoses, respectively.

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) was the most utilized method for analyzing QOL followed by the Skindex-17, Skindex-29, and 36-Item Short Form Health Survey. The DLQI is a skin-specific measurement tool with higher scores translating to greater impairment in QOL. Healthy patients have an average score of 0.5.3 The mean DLQI scores for ABD patients as seen in Table 2 were 9.45, 10.18, 16, 10.9, and 10.1.13-15,18,22 The most commonly reported concerns among patients included feelings about appearance and disturbances in daily activities.18 Symptoms of mucosal involvement, itching, and burning also were indicators of lower QOL.15,18,20,22 Furthermore, women consistently had lower scores than men.15,17,19,25 Multiple studies concluded that severity of the disease correlated with a lower QOL, though the subtype of pemphigus did not have an effect on QOL scores.15,19,20,21 Lastly, recent onset of symptoms was associated with a worse QOL score.15,18-20 Age, education level, and marital status did not have an effect on QOL.

To evaluate psychological state, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-28 and -12 primarily were used, in addition to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; and the Beck Depression Inventory-II. As seen in Table 3, GHQ-12 positivity, reflecting probable minor nonpsychotic psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety, was identified in 47%, 39.7%, and 40% of patients with pemphigus15,19,24; GHQ-28 positivity was seen in 77.5% of pemphigus patients.18 In the average population, GHQ positivity was found in up to 12% of patients.26,27 Similar to the QOL scores, no significant differences were seen based on subtype of pemphigus for symptoms of depression or anxiety.20,23

Comment

Mental Health of Patients With ABDs—Immunobullous diseases are painful, potentially lifelong conditions that have no definitive cure. These conditions are characterized by bullae and erosions of the skin and mucosae that physically are disabling and often create a stigma for patients. Across multiple different validated psychosocial assessments, the 13 studies included in this review consistently reported that ABDs have a negative effect on mental well-being of patients that is more pronounced in women and worse at the onset of symptoms.13-25

QOL Scores in Patients With ABDs—Quality of life is a broad term that encompasses a general sense of psychological and overall well-being. A score of approximately 10 on the DLQI most often was reported in patients with ABDs, which translates to a moderate impact on QOL. Incomparison, a large cohort study reported the mean (SD) DLQI scores for patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis as 7.31 (5.98) and 5.93 (5.66), respectively.28 In another study, Penha et al14 found that patients with psoriasis have a mean DLQI score of 10. Reasons for the similarly low QOL scores in patients with ABDs include long hospitalization periods, disease chronicity, social anxiety, inability to control symptoms, difficulty with activities of daily living, and the belief that the disease is incurable.17,19,23 Although there is a need for increased family and social support with performing necessary daily tasks, personal relationships often are negatively affected, resulting in social isolation, loneliness, and worsening of cutaneous symptoms.

Severity of cutaneous disease and recent onset of symptoms correlated with worse QOL scores. Tabolli et al20 proposed the reason for this relates to not having had enough time to find the best treatment regimen. We believe there also may be an element of habituation involved, whereby patients become accustomed to the appearance of the lesions over time and therefore they become less distressing. Interestingly, Tabolli et al17 determined that patients in the quiescent phase of the disease—without any mucosal or cutaneous lesions—still maintained lower QOL scores than the average population, particularly on the psychosocial section of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, which may be due to a concern of disease relapse or from adverse effects of treatment. Providers should monitor patients for mental health complications not only in the disease infancy but throughout the disease course.

Future Directions—Cause and effect of the relationship between the psychosocial variables and ABD disease state has yet to be determined. Most studies included in this review were cross-sectional in design. Although many studies concluded that bullous dermatoses were the cause of impaired QOL, Ren and colleagues29 proposed that medications used to treat neuropsychiatric disorders may trigger the autoimmune antigens of BP. Possible triggers for BP have been reported including hydrochlorothiazide, ciprofloxacin, and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors.27,30-32 A longitudinal study design would better evaluate the causal relationship.

The effects of the medications were included in 2 cases, one in which the steroid dose was not found to have a significant impact on rates of depression23 and another in which patients treated with a higher dose of corticosteroids (>10 mg) had worse QOL scores.17 Sung et al15 suggested this may be because patients who took higher doses of steroids had worse symptoms and therefore also had a worse QOL. It also is possible that those patients taking higher doses had increased side effects.17 Further studies that evaluate treatment modalities and timing in relation to the disease onset would be helpful.

Study Limitations—There are potential barriers to combining these data. Multiple different questionnaires were used, and it was difficult to ascertain if all the participants were experiencing active disease. Additionally, questionnaires are not always the best proxy for what is happening in everyday life. Lastly, the sample size of each individual study was small, and the studies only included adults.

Conclusion

As demonstrated by the 13 studies in this review, patients with ABDs have lower QOL scores and higher numbers of psychological symptoms. Clinicians should be mindful of this at-risk population and create opportunities in clinic to discuss personal hardship associated with the disease process and recommend psychiatric intervention if indicated. Additionally, family members often are overburdened with the chronicity of ABDs, and they should not be forgotten. Using one of the aforementioned questionnaires is a practical way to screen patients for lower QOL scores. We agree with Paradisi and colleagues19 that although these questionnaires may be helpful, clinicians still need to determine if the use of a dermatologic QOL evaluation tool in clinical practice improves patient satisfaction.

Autoimmune bullous dermatoses (ABDs) develop due to antibodies directed against antigens within the epidermis or at the dermoepidermal junction. They are categorized histologically by the location of acantholysis (separation of keratinocytes), clinical presentation, and presence of autoantibodies. The most common ABDs include pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and bullous pemphigoid (BP). These conditions present on a spectrum of symptoms and severity.1

Although multiple studies have evaluated the impact of bullous dermatoses on mental health, most were designed with a small sample size, thus limiting the generalizability of each study. Sebaratnam et al2 summarized several studies in 2012. In this review, we will analyze additional relevant literature and systematically combine the data to determine the psychological burden of disease of ABDs. We also will discuss the existing questionnaires frequently used in the dermatology setting to assess adverse psychosocial symptoms.

Methods

We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar for articles published within the last 15 years using the terms bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus, quality of life, anxiety, and depression. We reviewed the citations in each article to further our search.

Criteria for Inclusion and Exclusion—Studies that utilized validated questionnaires to evaluate the effects of pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and/or BP on mental health were included. All research participants were 18 years and older. For the questionnaires administered, each study must have included numerical scores in the results. The studies all reported statistically significant results (P<.05), but no studies were excluded on the basis of statistical significance.

Studies were excluded if they did not use a validated questionnaire to examine quality of life (QOL) or psychological status. We also excluded database, retrospective, qualitative, and observational studies. We did not include studies with a sample size less than 20. Studies that administered questionnaires that were uncommon in this realm of research such as the Attitude to Appearance Scale or The Anxiety Questionnaire also were excluded. We did not exclude articles based on their primary language.

Results

A total of 13 studies met the inclusion criteria with a total of 1716 participants enrolled in the trials. The questionnaires most commonly used are summarized in Table 1. Tables 2 and 3 demonstrate the studies that evaluate QOL and psychological state in patients with bullous dermatoses, respectively.

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) was the most utilized method for analyzing QOL followed by the Skindex-17, Skindex-29, and 36-Item Short Form Health Survey. The DLQI is a skin-specific measurement tool with higher scores translating to greater impairment in QOL. Healthy patients have an average score of 0.5.3 The mean DLQI scores for ABD patients as seen in Table 2 were 9.45, 10.18, 16, 10.9, and 10.1.13-15,18,22 The most commonly reported concerns among patients included feelings about appearance and disturbances in daily activities.18 Symptoms of mucosal involvement, itching, and burning also were indicators of lower QOL.15,18,20,22 Furthermore, women consistently had lower scores than men.15,17,19,25 Multiple studies concluded that severity of the disease correlated with a lower QOL, though the subtype of pemphigus did not have an effect on QOL scores.15,19,20,21 Lastly, recent onset of symptoms was associated with a worse QOL score.15,18-20 Age, education level, and marital status did not have an effect on QOL.

To evaluate psychological state, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-28 and -12 primarily were used, in addition to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; and the Beck Depression Inventory-II. As seen in Table 3, GHQ-12 positivity, reflecting probable minor nonpsychotic psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety, was identified in 47%, 39.7%, and 40% of patients with pemphigus15,19,24; GHQ-28 positivity was seen in 77.5% of pemphigus patients.18 In the average population, GHQ positivity was found in up to 12% of patients.26,27 Similar to the QOL scores, no significant differences were seen based on subtype of pemphigus for symptoms of depression or anxiety.20,23

Comment

Mental Health of Patients With ABDs—Immunobullous diseases are painful, potentially lifelong conditions that have no definitive cure. These conditions are characterized by bullae and erosions of the skin and mucosae that physically are disabling and often create a stigma for patients. Across multiple different validated psychosocial assessments, the 13 studies included in this review consistently reported that ABDs have a negative effect on mental well-being of patients that is more pronounced in women and worse at the onset of symptoms.13-25

QOL Scores in Patients With ABDs—Quality of life is a broad term that encompasses a general sense of psychological and overall well-being. A score of approximately 10 on the DLQI most often was reported in patients with ABDs, which translates to a moderate impact on QOL. Incomparison, a large cohort study reported the mean (SD) DLQI scores for patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis as 7.31 (5.98) and 5.93 (5.66), respectively.28 In another study, Penha et al14 found that patients with psoriasis have a mean DLQI score of 10. Reasons for the similarly low QOL scores in patients with ABDs include long hospitalization periods, disease chronicity, social anxiety, inability to control symptoms, difficulty with activities of daily living, and the belief that the disease is incurable.17,19,23 Although there is a need for increased family and social support with performing necessary daily tasks, personal relationships often are negatively affected, resulting in social isolation, loneliness, and worsening of cutaneous symptoms.

Severity of cutaneous disease and recent onset of symptoms correlated with worse QOL scores. Tabolli et al20 proposed the reason for this relates to not having had enough time to find the best treatment regimen. We believe there also may be an element of habituation involved, whereby patients become accustomed to the appearance of the lesions over time and therefore they become less distressing. Interestingly, Tabolli et al17 determined that patients in the quiescent phase of the disease—without any mucosal or cutaneous lesions—still maintained lower QOL scores than the average population, particularly on the psychosocial section of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, which may be due to a concern of disease relapse or from adverse effects of treatment. Providers should monitor patients for mental health complications not only in the disease infancy but throughout the disease course.

Future Directions—Cause and effect of the relationship between the psychosocial variables and ABD disease state has yet to be determined. Most studies included in this review were cross-sectional in design. Although many studies concluded that bullous dermatoses were the cause of impaired QOL, Ren and colleagues29 proposed that medications used to treat neuropsychiatric disorders may trigger the autoimmune antigens of BP. Possible triggers for BP have been reported including hydrochlorothiazide, ciprofloxacin, and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors.27,30-32 A longitudinal study design would better evaluate the causal relationship.

The effects of the medications were included in 2 cases, one in which the steroid dose was not found to have a significant impact on rates of depression23 and another in which patients treated with a higher dose of corticosteroids (>10 mg) had worse QOL scores.17 Sung et al15 suggested this may be because patients who took higher doses of steroids had worse symptoms and therefore also had a worse QOL. It also is possible that those patients taking higher doses had increased side effects.17 Further studies that evaluate treatment modalities and timing in relation to the disease onset would be helpful.

Study Limitations—There are potential barriers to combining these data. Multiple different questionnaires were used, and it was difficult to ascertain if all the participants were experiencing active disease. Additionally, questionnaires are not always the best proxy for what is happening in everyday life. Lastly, the sample size of each individual study was small, and the studies only included adults.

Conclusion

As demonstrated by the 13 studies in this review, patients with ABDs have lower QOL scores and higher numbers of psychological symptoms. Clinicians should be mindful of this at-risk population and create opportunities in clinic to discuss personal hardship associated with the disease process and recommend psychiatric intervention if indicated. Additionally, family members often are overburdened with the chronicity of ABDs, and they should not be forgotten. Using one of the aforementioned questionnaires is a practical way to screen patients for lower QOL scores. We agree with Paradisi and colleagues19 that although these questionnaires may be helpful, clinicians still need to determine if the use of a dermatologic QOL evaluation tool in clinical practice improves patient satisfaction.

- Baum S, Sakka N, Artsi O, et al. Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune blistering diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:482-489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.047

- Sebaratnam DF, McMillan JR, Werth VP, et al. Quality of life in patients with bullous dermatoses. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:103-107. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.03.016

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-216.

- Goldberg DP. The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire. Oxford University Press; 1972.

- Cano A, Sprafkin RP, Scaturo DJ, et al. Mental health screening in primary care: a comparison of 3 brief measures of psychological distress. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3:206-210.

- Zigmond A, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370.

- Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66:20-40. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

- Beck A, Alford B. Depression: Causes and Treatment. 2nd ed. Philadelphia University of Pennsylvania Press; 2009.

- Ghassemzadeh H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, et al. Psychometric properties of a Persian-language version of the Beck Depression Inventory—Second Edition: BDI-II-PERSIAN. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:185-192. doi:10.1002/da.20070

- Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sahay AP, et al. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:105-110.

- Nijsten TEC, Sampogna F, Chren M, et al. Testing and reducing Skindex-29 using Rasch analysis: Skindex-17. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1244-1250. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5700212

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483.

- Kouris A, Platsidaki E, Christodoulou C, et al. Quality of life, depression, anxiety and loneliness in patients with bullous pemphigoid: a case control study. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:601-603. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.2016493

- Penha MA, Farat JG, Miot HA, et al. Quality of life index in autoimmune bullous dermatosis patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:190-194. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153372

- Sung JY, Roh MR, Kim SC. Quality of life assessment in Korean patients with pemphigus. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:492-498.

- Moon SH, Kwon HI, Park HC, et al. Assessment of the quality of life in autoimmune blistering skin disease patients. Korean J Dermatol. 2014;52:402-409.

- Tabolli S, Pagliarello C, Paradisi A, et al. Burden of disease during quiescent periods in patients with pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1087-1091. doi:10.1111/bjd.12836

- Ghodsi SZ, Chams-Davatchi C, Daneshpazhooh M, et al. Quality of life and psychological status of patients with pemphigus vulgaris using Dermatology Life Quality Index and general health questionnaires. J Dermatol. 2012;39:141-144. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01382

- Paradisi A, Sampogna F, Di Pietro C, et al. Quality-of-life assessment in patients with pemphigus using a minimum set of evaluation tools. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:261-269. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.014

- Tabolli S, Mozzetta A, Antinone V, et al. The health impact of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form health survey questionnaire. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1029-1034. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08481.x

- Terrab Z, Benchikhi H, Maaroufi A, et al. Quality of life and pemphigus. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:321-328.

- Mayrshofer F, Hertl M, Sinkgraven R, et al. Significant decrease in quality of life in patients with pemphigus vulgaris: results from the German Bullous Skin Disease (BSD) Study Group [in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:431-435. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2005.05722.x

- Layegh P, Mokhber N, Javidi Z, et al. Depression in patients with pemphigus: is it a major concern? J Dermatol. 2014;40:434-437. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12067

- Kumar V, Mattoo SK, Handa S. Psychiatric morbidity in pemphigus and psoriasis: a comparative study from India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6:151-156. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2012.10.005

- Mazzotti E, Mozzetta A, Antinone V, et al. Psychological distress and investment in one’s appearance in patients with pemphigus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:285-289. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03780.x

- Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD, et al. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five epidemiologic catchment area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1988;45:977-986. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800350011002

- Cozzani E, Chinazzo C, Burlando M, et al. Ciprofloxacin as a trigger for bullous pemphigoid: the second case in the literature. Am J Ther. 2016;23:E1202-E1204. doi:10.1097/MJT.0000000000000283

- Lundberg L, Johannesson M, Silverdahl M, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis measured with SF-36, DLQI and a subjective measure of disease activity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:430-434.

- Ren Z, Hsu DY, Brieva J, et al. Hospitalization, inpatient burden and comorbidities associated with bullous pemphigoid in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:87-99. doi:10.1111/bjd.14821

- Warner C, Kwak Y, Glover MH, et al. Bullous pemphigoid induced by hydrochlorothiazide therapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:360-362.

- Mendonca FM, Martin-Gutierrez FJ, Rios-Martin JJ, et al. Three cases of bullous pemphigoid associated with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors—one due to linagliptin. Dermatology. 2016;232:249-253. doi:10.1159/000443330

- Attaway A, Mersfelder TL, Vaishnav S, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors: a case report and review of literature. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2014;8:24-28.

- Baum S, Sakka N, Artsi O, et al. Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune blistering diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:482-489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.047

- Sebaratnam DF, McMillan JR, Werth VP, et al. Quality of life in patients with bullous dermatoses. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:103-107. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.03.016

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-216.

- Goldberg DP. The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire. Oxford University Press; 1972.

- Cano A, Sprafkin RP, Scaturo DJ, et al. Mental health screening in primary care: a comparison of 3 brief measures of psychological distress. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3:206-210.

- Zigmond A, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370.

- Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66:20-40. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

- Beck A, Alford B. Depression: Causes and Treatment. 2nd ed. Philadelphia University of Pennsylvania Press; 2009.

- Ghassemzadeh H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, et al. Psychometric properties of a Persian-language version of the Beck Depression Inventory—Second Edition: BDI-II-PERSIAN. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:185-192. doi:10.1002/da.20070

- Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sahay AP, et al. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:105-110.

- Nijsten TEC, Sampogna F, Chren M, et al. Testing and reducing Skindex-29 using Rasch analysis: Skindex-17. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1244-1250. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5700212

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483.

- Kouris A, Platsidaki E, Christodoulou C, et al. Quality of life, depression, anxiety and loneliness in patients with bullous pemphigoid: a case control study. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:601-603. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.2016493

- Penha MA, Farat JG, Miot HA, et al. Quality of life index in autoimmune bullous dermatosis patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:190-194. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153372

- Sung JY, Roh MR, Kim SC. Quality of life assessment in Korean patients with pemphigus. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:492-498.

- Moon SH, Kwon HI, Park HC, et al. Assessment of the quality of life in autoimmune blistering skin disease patients. Korean J Dermatol. 2014;52:402-409.

- Tabolli S, Pagliarello C, Paradisi A, et al. Burden of disease during quiescent periods in patients with pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1087-1091. doi:10.1111/bjd.12836

- Ghodsi SZ, Chams-Davatchi C, Daneshpazhooh M, et al. Quality of life and psychological status of patients with pemphigus vulgaris using Dermatology Life Quality Index and general health questionnaires. J Dermatol. 2012;39:141-144. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01382

- Paradisi A, Sampogna F, Di Pietro C, et al. Quality-of-life assessment in patients with pemphigus using a minimum set of evaluation tools. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:261-269. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.014

- Tabolli S, Mozzetta A, Antinone V, et al. The health impact of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form health survey questionnaire. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1029-1034. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08481.x

- Terrab Z, Benchikhi H, Maaroufi A, et al. Quality of life and pemphigus. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:321-328.

- Mayrshofer F, Hertl M, Sinkgraven R, et al. Significant decrease in quality of life in patients with pemphigus vulgaris: results from the German Bullous Skin Disease (BSD) Study Group [in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:431-435. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2005.05722.x

- Layegh P, Mokhber N, Javidi Z, et al. Depression in patients with pemphigus: is it a major concern? J Dermatol. 2014;40:434-437. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12067

- Kumar V, Mattoo SK, Handa S. Psychiatric morbidity in pemphigus and psoriasis: a comparative study from India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6:151-156. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2012.10.005

- Mazzotti E, Mozzetta A, Antinone V, et al. Psychological distress and investment in one’s appearance in patients with pemphigus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:285-289. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03780.x

- Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD, et al. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five epidemiologic catchment area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1988;45:977-986. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800350011002

- Cozzani E, Chinazzo C, Burlando M, et al. Ciprofloxacin as a trigger for bullous pemphigoid: the second case in the literature. Am J Ther. 2016;23:E1202-E1204. doi:10.1097/MJT.0000000000000283

- Lundberg L, Johannesson M, Silverdahl M, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis measured with SF-36, DLQI and a subjective measure of disease activity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:430-434.

- Ren Z, Hsu DY, Brieva J, et al. Hospitalization, inpatient burden and comorbidities associated with bullous pemphigoid in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:87-99. doi:10.1111/bjd.14821

- Warner C, Kwak Y, Glover MH, et al. Bullous pemphigoid induced by hydrochlorothiazide therapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:360-362.

- Mendonca FM, Martin-Gutierrez FJ, Rios-Martin JJ, et al. Three cases of bullous pemphigoid associated with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors—one due to linagliptin. Dermatology. 2016;232:249-253. doi:10.1159/000443330

- Attaway A, Mersfelder TL, Vaishnav S, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors: a case report and review of literature. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2014;8:24-28.

Practice Points

- Autoimmune bullous dermatoses cause cutaneous lesions that are painful and disfiguring. These conditions affect a patient’s ability to perform everyday tasks, and individual lesions can take years to heal.

- Providers should take necessary steps to address patient well-being, especially at disease onset in patients with bullous dermatoses.

Nuances in Training During the Age of Teledermatology

The COVID-19 pandemic largely altered the practice of medicine, including a rapid expansion of telemedicine following the March 2020 World Health Organization guidelines for social distancing, which recommended suspension of all nonurgent in-person visits.1 Expectedly, COVID-related urgent care visits initially comprised the bulk of the new telemedicine wave: NYU Langone Health (New York, New York), for example, saw a 683% increase in virtual visits between March and April 2020, most (55.3%) of which were for respiratory concerns. In-person visits, on the other hand, concurrently fell by more than 80%. Interestingly, nonurgent ambulatory care specialties also saw a considerable uptick in virtual encounters, from less than 50 visits in a typical day to an average of 7000 in a 10-day stretch.2

As a largely ambulatory specialty that relies on visual examination, dermatology was no exception to the swing toward telemedicine, or teledermatology (TD). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, 14.1% (82 of 582 respondents) of practicing US dermatologists reported having used teledermatology, compared to 96.9% (572/591) during the pandemic.3 Even at my home institution (Massachusetts General Hospital [Boston, Massachusetts] and its 12 affiliated dermatology clinics), the number of in-person visits in April 2020 (n=67) was less than 1% of that in April 2019 (n=7919), whereas there was a total of 1564 virtual visits in April 2020 compared to zero the year prior. Virtual provider-to-provider consults (e-consultations) also saw an increase of more than 20%, suggesting that dermatology’s avid adoption of TD also had improved the perceived accessibility of our specialty.4

The adoption and adaptation of TD are projected to continue to grow rapidly across the globe, as digitalization has enhanced access without increasing costs, shortened wait times, and even created opportunities for primary care providers based in rural or overseas locations to learn the diagnosis and treatment of skin disease.5 Residents and fellows should be privy to the nuances of training and practicing in this digital era, as our careers inevitably will involve some facet of TD.

The Art of Medicine

Touch, a sense that perhaps ranks second to sight in dermatology, is absent in TD. In either synchronous (live-interactive, face video visits) or asynchronous (store-and-forward, where digital photographs and clinical information sent by patients or referring physicians are assessed at a later time) TD, the skin cannot be rubbed for texture, pinched for thickness, or pushed for blanching. Instead, all we have is vision. Irwin Braverman, MD, Professor Emeritus of Dermatology at Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut), alongside Jacqueline Dolev, MD, dermatologist and Yale graduate, and Linda Friedlaender, curator at the Yale Center for British Art, founded an observational skills workshop in which trainees learn to observe and describe the paintings housed in the museum, noting all memorable details: the color of the sky, the actions of the animals, and the facial expressions of the people. A study of 90 participants over a 2-year period found that following the workshop, the ability to identify key diagnostic details from clinical photography improved by more than 10%.6 Other studies also utilizing fine art as a medical training tool to improve “visual literacy” saw similarly increased sophistication in the description of clinical imagery, which translated to better diagnostic acumen.7 Confined to video and photographs, TD necessitates trainees and practicing dermatologists to be excellent visual diagnosticians. Although surveyed dermatologists believe TD is presently appropriate for acne, benign lesions, or follow-up appointments,3 conditions for which patients have been examined via TD have included drug eruptions, premalignant or malignant neoplasms, infections, and papulosquamous or inflammatory dermatoses.8 At the very least, clinicians should be versed in identifying those conditions that require in-person evaluation, as patients cannot be held responsible to distinguish which situations can and cannot be addressed virtually.

Issues of Patient-Physician Confidentiality

Teledermatology is not without its shortcomings; critics have noted diagnostic challenges with poor quality photographs or videos, inability to perform total-body skin examinations, and socioeconomic limitations due to broadband availability and speed.5,9 Although most of these shortcomings are outside of our control, a key challenge within the purview of the provider is the protection of patient privacy.

Much of the salient concerns regarding patient-physician confidentiality involve asynchronous TD, where store-and-forward data sharing allows physicians to download patient photographs or information onto their personal email or smartphones.10 Although some hospital systems provide encryption software or hospital-sponsored devices to ensure security, physicians may opt to use their personal phones or laptops out of convenience or to save time.10,11 One study found that less than 30% of smartphone users choose to activate user authentication on their devices, even ones as simple as a passphrase.11 The digital exchange of information thus poses an immense risk for compromising protected health information (PHI), as personal devices can be easily lost, stolen, or hacked. Indeed, in 2015, more than 113 million individuals were affected by a breach of PHI, the majority over hacked network servers.12 With the growing diversity of mediums through which PHI is exchanged, such as videoconferencing and instant messaging, the potential medicolegal risks of information breach continue to climb. The US Department of Health & Human Services urges health care providers to uphold best practices for security, including encrypting data, updating all software including antivirus software, using multifactor authentication, and following local cybersecurity regulations or recommendations.13 For synchronous TD, suggested best practices include utilizing headphones during live appointments, avoiding public wireless networks, and ensuring the provider and patient both scan the room with their device’s camera before the start of the visit.14

On the Horizon of Teledermatology

What can we expect in the coming years? Increased utilization of telemedicine will translate into data that will help address questions surrounding safety, diagnostic accuracy, privacy, and accessibility. One aspect of TD in need of clarity is a guideline on payment and reimbursement, and whether TD can continue to be financially attractive to providers. Starting in 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services removed geographic restrictions for reimbursement of telemedicine visits, enabling even urban-residing patients to enjoy the convenience of TD. This followed a prior relaxation of restrictions, where even prerecorded patient information became eligible for Medicare reimbursement.9 However, as virtual visits tend to be shorter with fewer diagnostic services compared to in-person visits, the reimbursement structure of TD must be nuanced, which is the subject of ongoing study and modification in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.15

Another point to consider is the explosion of direct-to-consumer TD, which allows patients to receive virtual dermatologic care or prescription medication without a pre-established relationship with any physician. In 2017, there were 22 direct-to-consumer TD services available to US patients in 45 states, 16 (73%) of which provided dermatologic care for any concern while 6 (27%) were limited to acne or antiaging and were largely prescription oriented. Orchestrated mostly by the for-profit private sector, direct-to-consumer companies are poorly regulated and have raised concerns over questionable practices, such as the use of non–US board-certified physicians, exorbitant fees, and failure to disclose medication side effects.16 A study of 16 direct-to-consumer telemedicine sites found substantial discordance in the suggested management of the same patient, and many of the services relied heavily on patient-provided self-diagnoses, such as a case where psoriasis medication was dispensed for a psoriasis patient who submitted a photograph of his syphilitic rash.17 Despite these problems, consumers show a willingness to pay out of pocket to access these services for their shorter waiting times and convenience.18 Hence, we must learn to ask about direct-to-consumer service use when obtaining a thorough history and be open to counseling our patients on the proper use and potential risks of direct-to-consumer TD.

Final Thoughts

The telemedicine industry is expected to reach more than $130 billion by 2025, with more than 90% of surveyed health care executives planning for the adoption and incorporation of telemedicine into their business models.19 The COVID-19 pandemic was an impetus for an exponential adoption of TD, and it would behoove current residents to realize that the practice of dermatology will continue to be increasingly digitalized within the coming years. Whether through formal training or self-assessment, we must strive to grow as proficient virtual dermatologists while upholding professionalism, patient safety, and health information privacy.

- Yeboah CB, Harvey N, Krishnan R, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on teledermatology: a review. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:599-608.

- Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, et al. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: evidence from the field. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27:1132-1135.

- Kennedy J, Arey S, Hopkins Z, et al. Dermatologist perceptions of teledermatology implementation and future use after COVID-19: demographics, barriers, and insights. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:595-597.

- Su MY, Das S. Expansion of asynchronous teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E471-E472.

- Maddukuri S, Patel J, Lipoff JB. Teledermatology addressing disparities in health care access: a review [published online March 12, 2021]. Curr Dermatol Rep. doi:10.1007/s13671-021-00329-2

- Dolev JC, Friedlaender LK, Braverman IM. Use of fine art to enhance visual diagnostic skills. JAMA. 2001;286:1020-1021.

- Naghshineh S, Hafler JP, Miller AR, et al. Formal art observation training improves medical students’ visual diagnostic skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:991-997.

- Lee KJ, Finnane A, Soyer HP. Recent trends in teledermatology and teledermoscopy. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8:214-223.

- Wang RH, Barbieri JS, Nguyen HP, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of teledermatology: where are we now, and what are the barriers to adoption? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:299-307.

- Stevenson P, Finnane AR, Soyer HP. Teledermatology and clinical photography: safeguarding patient privacy and mitigating medico-legal risk. Med J Aust. 2016;204:198-200e1.

- Smith KA, Zhou L, Watzlaf VJM. User authentication in smartphones for telehealth. Int J Telerehabil. 2017;9:3-12.

- Breaches of unsecured protected health information. Health IT website. Updated July 22, 2021. Accessed January 16, 2022. https://www.healthit.gov/data/quickstats/breaches-unsecured-protected-health-information

- Jalali MS, Landman A, Gordon WJ. Telemedicine, privacy, and information security in the age of COVID-19. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28:671-672.

- Telehealth for behavioral health care: protecting patients’ privacy. United States Department of Health and Human Services website. Updated July 2, 2021. Accessed January 16, 2022. https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/telehealth-for-behavioral-health/preparing-patients-for-telebehavioral-health/protecting-patients-privacy/

- Shachar C, Engel J, Elwyn G. Implications for telehealth in a postpandemic future: regulatory and privacy issues. JAMA. 2020;323:2375-2376.

- Fogel AL, Sarin KY. A survey of direct-to-consumer teledermatology services available to US patients: explosive growth, opportunities and controversy. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23:19-25.

- Resneck JS Jr, Abrouk M, Steuer M, et al. Choice, transparency, coordination, and quality among direct-to-consumer telemedicine websites and apps treating skin disease. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:768-775.

- Snoswell CL, Whitty JA, Caffery LJ, et al. Consumer preference and willingness to pay for direct-to-consumer mobile teledermoscopy services in Australia [published online August 13, 2021]. Dermatology. doi:10.1159/000517257

- Elliott T, Yopes MC. Direct-to-consumer telemedicine. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:2546-2552.

The COVID-19 pandemic largely altered the practice of medicine, including a rapid expansion of telemedicine following the March 2020 World Health Organization guidelines for social distancing, which recommended suspension of all nonurgent in-person visits.1 Expectedly, COVID-related urgent care visits initially comprised the bulk of the new telemedicine wave: NYU Langone Health (New York, New York), for example, saw a 683% increase in virtual visits between March and April 2020, most (55.3%) of which were for respiratory concerns. In-person visits, on the other hand, concurrently fell by more than 80%. Interestingly, nonurgent ambulatory care specialties also saw a considerable uptick in virtual encounters, from less than 50 visits in a typical day to an average of 7000 in a 10-day stretch.2

As a largely ambulatory specialty that relies on visual examination, dermatology was no exception to the swing toward telemedicine, or teledermatology (TD). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, 14.1% (82 of 582 respondents) of practicing US dermatologists reported having used teledermatology, compared to 96.9% (572/591) during the pandemic.3 Even at my home institution (Massachusetts General Hospital [Boston, Massachusetts] and its 12 affiliated dermatology clinics), the number of in-person visits in April 2020 (n=67) was less than 1% of that in April 2019 (n=7919), whereas there was a total of 1564 virtual visits in April 2020 compared to zero the year prior. Virtual provider-to-provider consults (e-consultations) also saw an increase of more than 20%, suggesting that dermatology’s avid adoption of TD also had improved the perceived accessibility of our specialty.4

The adoption and adaptation of TD are projected to continue to grow rapidly across the globe, as digitalization has enhanced access without increasing costs, shortened wait times, and even created opportunities for primary care providers based in rural or overseas locations to learn the diagnosis and treatment of skin disease.5 Residents and fellows should be privy to the nuances of training and practicing in this digital era, as our careers inevitably will involve some facet of TD.

The Art of Medicine

Touch, a sense that perhaps ranks second to sight in dermatology, is absent in TD. In either synchronous (live-interactive, face video visits) or asynchronous (store-and-forward, where digital photographs and clinical information sent by patients or referring physicians are assessed at a later time) TD, the skin cannot be rubbed for texture, pinched for thickness, or pushed for blanching. Instead, all we have is vision. Irwin Braverman, MD, Professor Emeritus of Dermatology at Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut), alongside Jacqueline Dolev, MD, dermatologist and Yale graduate, and Linda Friedlaender, curator at the Yale Center for British Art, founded an observational skills workshop in which trainees learn to observe and describe the paintings housed in the museum, noting all memorable details: the color of the sky, the actions of the animals, and the facial expressions of the people. A study of 90 participants over a 2-year period found that following the workshop, the ability to identify key diagnostic details from clinical photography improved by more than 10%.6 Other studies also utilizing fine art as a medical training tool to improve “visual literacy” saw similarly increased sophistication in the description of clinical imagery, which translated to better diagnostic acumen.7 Confined to video and photographs, TD necessitates trainees and practicing dermatologists to be excellent visual diagnosticians. Although surveyed dermatologists believe TD is presently appropriate for acne, benign lesions, or follow-up appointments,3 conditions for which patients have been examined via TD have included drug eruptions, premalignant or malignant neoplasms, infections, and papulosquamous or inflammatory dermatoses.8 At the very least, clinicians should be versed in identifying those conditions that require in-person evaluation, as patients cannot be held responsible to distinguish which situations can and cannot be addressed virtually.

Issues of Patient-Physician Confidentiality

Teledermatology is not without its shortcomings; critics have noted diagnostic challenges with poor quality photographs or videos, inability to perform total-body skin examinations, and socioeconomic limitations due to broadband availability and speed.5,9 Although most of these shortcomings are outside of our control, a key challenge within the purview of the provider is the protection of patient privacy.

Much of the salient concerns regarding patient-physician confidentiality involve asynchronous TD, where store-and-forward data sharing allows physicians to download patient photographs or information onto their personal email or smartphones.10 Although some hospital systems provide encryption software or hospital-sponsored devices to ensure security, physicians may opt to use their personal phones or laptops out of convenience or to save time.10,11 One study found that less than 30% of smartphone users choose to activate user authentication on their devices, even ones as simple as a passphrase.11 The digital exchange of information thus poses an immense risk for compromising protected health information (PHI), as personal devices can be easily lost, stolen, or hacked. Indeed, in 2015, more than 113 million individuals were affected by a breach of PHI, the majority over hacked network servers.12 With the growing diversity of mediums through which PHI is exchanged, such as videoconferencing and instant messaging, the potential medicolegal risks of information breach continue to climb. The US Department of Health & Human Services urges health care providers to uphold best practices for security, including encrypting data, updating all software including antivirus software, using multifactor authentication, and following local cybersecurity regulations or recommendations.13 For synchronous TD, suggested best practices include utilizing headphones during live appointments, avoiding public wireless networks, and ensuring the provider and patient both scan the room with their device’s camera before the start of the visit.14

On the Horizon of Teledermatology

What can we expect in the coming years? Increased utilization of telemedicine will translate into data that will help address questions surrounding safety, diagnostic accuracy, privacy, and accessibility. One aspect of TD in need of clarity is a guideline on payment and reimbursement, and whether TD can continue to be financially attractive to providers. Starting in 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services removed geographic restrictions for reimbursement of telemedicine visits, enabling even urban-residing patients to enjoy the convenience of TD. This followed a prior relaxation of restrictions, where even prerecorded patient information became eligible for Medicare reimbursement.9 However, as virtual visits tend to be shorter with fewer diagnostic services compared to in-person visits, the reimbursement structure of TD must be nuanced, which is the subject of ongoing study and modification in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.15

Another point to consider is the explosion of direct-to-consumer TD, which allows patients to receive virtual dermatologic care or prescription medication without a pre-established relationship with any physician. In 2017, there were 22 direct-to-consumer TD services available to US patients in 45 states, 16 (73%) of which provided dermatologic care for any concern while 6 (27%) were limited to acne or antiaging and were largely prescription oriented. Orchestrated mostly by the for-profit private sector, direct-to-consumer companies are poorly regulated and have raised concerns over questionable practices, such as the use of non–US board-certified physicians, exorbitant fees, and failure to disclose medication side effects.16 A study of 16 direct-to-consumer telemedicine sites found substantial discordance in the suggested management of the same patient, and many of the services relied heavily on patient-provided self-diagnoses, such as a case where psoriasis medication was dispensed for a psoriasis patient who submitted a photograph of his syphilitic rash.17 Despite these problems, consumers show a willingness to pay out of pocket to access these services for their shorter waiting times and convenience.18 Hence, we must learn to ask about direct-to-consumer service use when obtaining a thorough history and be open to counseling our patients on the proper use and potential risks of direct-to-consumer TD.

Final Thoughts

The telemedicine industry is expected to reach more than $130 billion by 2025, with more than 90% of surveyed health care executives planning for the adoption and incorporation of telemedicine into their business models.19 The COVID-19 pandemic was an impetus for an exponential adoption of TD, and it would behoove current residents to realize that the practice of dermatology will continue to be increasingly digitalized within the coming years. Whether through formal training or self-assessment, we must strive to grow as proficient virtual dermatologists while upholding professionalism, patient safety, and health information privacy.

The COVID-19 pandemic largely altered the practice of medicine, including a rapid expansion of telemedicine following the March 2020 World Health Organization guidelines for social distancing, which recommended suspension of all nonurgent in-person visits.1 Expectedly, COVID-related urgent care visits initially comprised the bulk of the new telemedicine wave: NYU Langone Health (New York, New York), for example, saw a 683% increase in virtual visits between March and April 2020, most (55.3%) of which were for respiratory concerns. In-person visits, on the other hand, concurrently fell by more than 80%. Interestingly, nonurgent ambulatory care specialties also saw a considerable uptick in virtual encounters, from less than 50 visits in a typical day to an average of 7000 in a 10-day stretch.2

As a largely ambulatory specialty that relies on visual examination, dermatology was no exception to the swing toward telemedicine, or teledermatology (TD). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, 14.1% (82 of 582 respondents) of practicing US dermatologists reported having used teledermatology, compared to 96.9% (572/591) during the pandemic.3 Even at my home institution (Massachusetts General Hospital [Boston, Massachusetts] and its 12 affiliated dermatology clinics), the number of in-person visits in April 2020 (n=67) was less than 1% of that in April 2019 (n=7919), whereas there was a total of 1564 virtual visits in April 2020 compared to zero the year prior. Virtual provider-to-provider consults (e-consultations) also saw an increase of more than 20%, suggesting that dermatology’s avid adoption of TD also had improved the perceived accessibility of our specialty.4

The adoption and adaptation of TD are projected to continue to grow rapidly across the globe, as digitalization has enhanced access without increasing costs, shortened wait times, and even created opportunities for primary care providers based in rural or overseas locations to learn the diagnosis and treatment of skin disease.5 Residents and fellows should be privy to the nuances of training and practicing in this digital era, as our careers inevitably will involve some facet of TD.

The Art of Medicine

Touch, a sense that perhaps ranks second to sight in dermatology, is absent in TD. In either synchronous (live-interactive, face video visits) or asynchronous (store-and-forward, where digital photographs and clinical information sent by patients or referring physicians are assessed at a later time) TD, the skin cannot be rubbed for texture, pinched for thickness, or pushed for blanching. Instead, all we have is vision. Irwin Braverman, MD, Professor Emeritus of Dermatology at Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut), alongside Jacqueline Dolev, MD, dermatologist and Yale graduate, and Linda Friedlaender, curator at the Yale Center for British Art, founded an observational skills workshop in which trainees learn to observe and describe the paintings housed in the museum, noting all memorable details: the color of the sky, the actions of the animals, and the facial expressions of the people. A study of 90 participants over a 2-year period found that following the workshop, the ability to identify key diagnostic details from clinical photography improved by more than 10%.6 Other studies also utilizing fine art as a medical training tool to improve “visual literacy” saw similarly increased sophistication in the description of clinical imagery, which translated to better diagnostic acumen.7 Confined to video and photographs, TD necessitates trainees and practicing dermatologists to be excellent visual diagnosticians. Although surveyed dermatologists believe TD is presently appropriate for acne, benign lesions, or follow-up appointments,3 conditions for which patients have been examined via TD have included drug eruptions, premalignant or malignant neoplasms, infections, and papulosquamous or inflammatory dermatoses.8 At the very least, clinicians should be versed in identifying those conditions that require in-person evaluation, as patients cannot be held responsible to distinguish which situations can and cannot be addressed virtually.

Issues of Patient-Physician Confidentiality

Teledermatology is not without its shortcomings; critics have noted diagnostic challenges with poor quality photographs or videos, inability to perform total-body skin examinations, and socioeconomic limitations due to broadband availability and speed.5,9 Although most of these shortcomings are outside of our control, a key challenge within the purview of the provider is the protection of patient privacy.

Much of the salient concerns regarding patient-physician confidentiality involve asynchronous TD, where store-and-forward data sharing allows physicians to download patient photographs or information onto their personal email or smartphones.10 Although some hospital systems provide encryption software or hospital-sponsored devices to ensure security, physicians may opt to use their personal phones or laptops out of convenience or to save time.10,11 One study found that less than 30% of smartphone users choose to activate user authentication on their devices, even ones as simple as a passphrase.11 The digital exchange of information thus poses an immense risk for compromising protected health information (PHI), as personal devices can be easily lost, stolen, or hacked. Indeed, in 2015, more than 113 million individuals were affected by a breach of PHI, the majority over hacked network servers.12 With the growing diversity of mediums through which PHI is exchanged, such as videoconferencing and instant messaging, the potential medicolegal risks of information breach continue to climb. The US Department of Health & Human Services urges health care providers to uphold best practices for security, including encrypting data, updating all software including antivirus software, using multifactor authentication, and following local cybersecurity regulations or recommendations.13 For synchronous TD, suggested best practices include utilizing headphones during live appointments, avoiding public wireless networks, and ensuring the provider and patient both scan the room with their device’s camera before the start of the visit.14

On the Horizon of Teledermatology

What can we expect in the coming years? Increased utilization of telemedicine will translate into data that will help address questions surrounding safety, diagnostic accuracy, privacy, and accessibility. One aspect of TD in need of clarity is a guideline on payment and reimbursement, and whether TD can continue to be financially attractive to providers. Starting in 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services removed geographic restrictions for reimbursement of telemedicine visits, enabling even urban-residing patients to enjoy the convenience of TD. This followed a prior relaxation of restrictions, where even prerecorded patient information became eligible for Medicare reimbursement.9 However, as virtual visits tend to be shorter with fewer diagnostic services compared to in-person visits, the reimbursement structure of TD must be nuanced, which is the subject of ongoing study and modification in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.15

Another point to consider is the explosion of direct-to-consumer TD, which allows patients to receive virtual dermatologic care or prescription medication without a pre-established relationship with any physician. In 2017, there were 22 direct-to-consumer TD services available to US patients in 45 states, 16 (73%) of which provided dermatologic care for any concern while 6 (27%) were limited to acne or antiaging and were largely prescription oriented. Orchestrated mostly by the for-profit private sector, direct-to-consumer companies are poorly regulated and have raised concerns over questionable practices, such as the use of non–US board-certified physicians, exorbitant fees, and failure to disclose medication side effects.16 A study of 16 direct-to-consumer telemedicine sites found substantial discordance in the suggested management of the same patient, and many of the services relied heavily on patient-provided self-diagnoses, such as a case where psoriasis medication was dispensed for a psoriasis patient who submitted a photograph of his syphilitic rash.17 Despite these problems, consumers show a willingness to pay out of pocket to access these services for their shorter waiting times and convenience.18 Hence, we must learn to ask about direct-to-consumer service use when obtaining a thorough history and be open to counseling our patients on the proper use and potential risks of direct-to-consumer TD.

Final Thoughts