User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Raised Linear Plaques on the Back

The Diagnosis: Flagellate Dermatitis

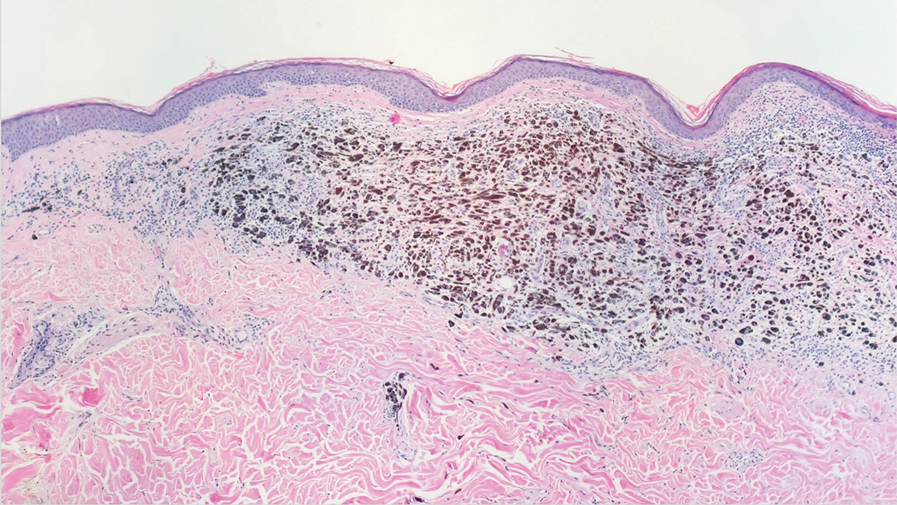

Upon further questioning by dermatology, the patient noted recent ingestion of shiitake mushrooms, which were not a part of his typical diet. Based on the appearance of the rash in the context of ingesting shiitake mushrooms, our patient was diagnosed with flagellate dermatitis. At 6-week followup, the patient’s rash had resolved spontaneously without further intervention.

Flagellate dermatitis usually appears on the torso as linear whiplike streaks.1 The eruption often is pruritic and may be preceded by severe pruritus. Flagellate dermatitis also is a well-documented complication of bleomycin sulfate therapy with an incidence rate of 8% to 66%.2

Other chemotherapeutic causes include peplomycin, bendamustine, docetaxel, cisplatin, and trastuzumab.3 Flagellate dermatitis also is seen in some patients with dermatomyositis.4 A thorough patient history, including medications and dietary habits, is necessary to differentiate flagellate dermatitis from dermatomyositis.

Flagellate dermatitis, also known as shiitake dermatitis, is observed as erythematous flagellate eruptions involving the trunk or extremities that present within 2 hours to 5 days of handling or consuming undercooked or raw shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes),5,6 as was observed in our patient. Lentinan is the polysaccharide component of the shiitake species and is destabilized by heat.6 Ingestion of polysaccharide is associated with dermatitis, particularly in Japan, China, and Korea; however, the consumption of shiitake mushrooms has increased worldwide, and cases increasingly are reported outside of these typical regions. The rash typically resolves spontaneously; therefore, treatment is supportive. However, more severe symptomatic cases may require courses of topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.6

In our case, the differential diagnosis consisted of acute urticaria, cutaneous dermatomyositis, dermatographism, and maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis. Acute urticaria displays well-circumscribed edematous papules or plaques, and individual lesions last less than 24 hours. Cutaneous dermatomyositis includes additional systemic manifestations such as fatigue, malaise, and myalgia, as well as involvement of the gastrointestinal, respiratory, or cardiac organs. Dermatographism is evoked by stroking or rubbing of the skin, which results in asymptomatic lesions that persist for 15 to 30 minutes. Cases of maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis more often are seen in children, and the histamine release most often causes gastrointestinal tract symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, as well as flushing, blushing, pruritus, respiratory difficulty, and malaise.

- Biswas A, Chaudhari PB, Sharma P, et al. Bleomycin induced flagellate erythema: revisiting a unique complication. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:500-503.

- Yagoda A, Mukherji B, Young C, et al. Bleomycin, an anti-tumor antibiotic: clinical experience in 274 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:861-870.

- Cohen PR. Trastuzumab-associated flagellate erythema: report in a woman with metastatic breast cancer and review of antineoplastic therapy-induced flagellate dermatoses. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:253-264. doi:10.1007/s13555-015-0085-2

- Grynszpan R, Niemeyer-Corbellini JP, Lopes MS, et al. Bleomycininduced flagellate dermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009764. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-009764

- Stephany MP, Chung S, Handler MZ, et al. Shiitake mushroom dermatitis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:485-489.

- Boels D, Landreau A, Bruneau C, et al. Shiitake dermatitis recorded by French Poison Control Centers—new case series with clinical observations. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52:625-628.

The Diagnosis: Flagellate Dermatitis

Upon further questioning by dermatology, the patient noted recent ingestion of shiitake mushrooms, which were not a part of his typical diet. Based on the appearance of the rash in the context of ingesting shiitake mushrooms, our patient was diagnosed with flagellate dermatitis. At 6-week followup, the patient’s rash had resolved spontaneously without further intervention.

Flagellate dermatitis usually appears on the torso as linear whiplike streaks.1 The eruption often is pruritic and may be preceded by severe pruritus. Flagellate dermatitis also is a well-documented complication of bleomycin sulfate therapy with an incidence rate of 8% to 66%.2

Other chemotherapeutic causes include peplomycin, bendamustine, docetaxel, cisplatin, and trastuzumab.3 Flagellate dermatitis also is seen in some patients with dermatomyositis.4 A thorough patient history, including medications and dietary habits, is necessary to differentiate flagellate dermatitis from dermatomyositis.

Flagellate dermatitis, also known as shiitake dermatitis, is observed as erythematous flagellate eruptions involving the trunk or extremities that present within 2 hours to 5 days of handling or consuming undercooked or raw shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes),5,6 as was observed in our patient. Lentinan is the polysaccharide component of the shiitake species and is destabilized by heat.6 Ingestion of polysaccharide is associated with dermatitis, particularly in Japan, China, and Korea; however, the consumption of shiitake mushrooms has increased worldwide, and cases increasingly are reported outside of these typical regions. The rash typically resolves spontaneously; therefore, treatment is supportive. However, more severe symptomatic cases may require courses of topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.6

In our case, the differential diagnosis consisted of acute urticaria, cutaneous dermatomyositis, dermatographism, and maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis. Acute urticaria displays well-circumscribed edematous papules or plaques, and individual lesions last less than 24 hours. Cutaneous dermatomyositis includes additional systemic manifestations such as fatigue, malaise, and myalgia, as well as involvement of the gastrointestinal, respiratory, or cardiac organs. Dermatographism is evoked by stroking or rubbing of the skin, which results in asymptomatic lesions that persist for 15 to 30 minutes. Cases of maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis more often are seen in children, and the histamine release most often causes gastrointestinal tract symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, as well as flushing, blushing, pruritus, respiratory difficulty, and malaise.

The Diagnosis: Flagellate Dermatitis

Upon further questioning by dermatology, the patient noted recent ingestion of shiitake mushrooms, which were not a part of his typical diet. Based on the appearance of the rash in the context of ingesting shiitake mushrooms, our patient was diagnosed with flagellate dermatitis. At 6-week followup, the patient’s rash had resolved spontaneously without further intervention.

Flagellate dermatitis usually appears on the torso as linear whiplike streaks.1 The eruption often is pruritic and may be preceded by severe pruritus. Flagellate dermatitis also is a well-documented complication of bleomycin sulfate therapy with an incidence rate of 8% to 66%.2

Other chemotherapeutic causes include peplomycin, bendamustine, docetaxel, cisplatin, and trastuzumab.3 Flagellate dermatitis also is seen in some patients with dermatomyositis.4 A thorough patient history, including medications and dietary habits, is necessary to differentiate flagellate dermatitis from dermatomyositis.

Flagellate dermatitis, also known as shiitake dermatitis, is observed as erythematous flagellate eruptions involving the trunk or extremities that present within 2 hours to 5 days of handling or consuming undercooked or raw shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes),5,6 as was observed in our patient. Lentinan is the polysaccharide component of the shiitake species and is destabilized by heat.6 Ingestion of polysaccharide is associated with dermatitis, particularly in Japan, China, and Korea; however, the consumption of shiitake mushrooms has increased worldwide, and cases increasingly are reported outside of these typical regions. The rash typically resolves spontaneously; therefore, treatment is supportive. However, more severe symptomatic cases may require courses of topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.6

In our case, the differential diagnosis consisted of acute urticaria, cutaneous dermatomyositis, dermatographism, and maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis. Acute urticaria displays well-circumscribed edematous papules or plaques, and individual lesions last less than 24 hours. Cutaneous dermatomyositis includes additional systemic manifestations such as fatigue, malaise, and myalgia, as well as involvement of the gastrointestinal, respiratory, or cardiac organs. Dermatographism is evoked by stroking or rubbing of the skin, which results in asymptomatic lesions that persist for 15 to 30 minutes. Cases of maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis more often are seen in children, and the histamine release most often causes gastrointestinal tract symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, as well as flushing, blushing, pruritus, respiratory difficulty, and malaise.

- Biswas A, Chaudhari PB, Sharma P, et al. Bleomycin induced flagellate erythema: revisiting a unique complication. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:500-503.

- Yagoda A, Mukherji B, Young C, et al. Bleomycin, an anti-tumor antibiotic: clinical experience in 274 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:861-870.

- Cohen PR. Trastuzumab-associated flagellate erythema: report in a woman with metastatic breast cancer and review of antineoplastic therapy-induced flagellate dermatoses. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:253-264. doi:10.1007/s13555-015-0085-2

- Grynszpan R, Niemeyer-Corbellini JP, Lopes MS, et al. Bleomycininduced flagellate dermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009764. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-009764

- Stephany MP, Chung S, Handler MZ, et al. Shiitake mushroom dermatitis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:485-489.

- Boels D, Landreau A, Bruneau C, et al. Shiitake dermatitis recorded by French Poison Control Centers—new case series with clinical observations. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52:625-628.

- Biswas A, Chaudhari PB, Sharma P, et al. Bleomycin induced flagellate erythema: revisiting a unique complication. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:500-503.

- Yagoda A, Mukherji B, Young C, et al. Bleomycin, an anti-tumor antibiotic: clinical experience in 274 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:861-870.

- Cohen PR. Trastuzumab-associated flagellate erythema: report in a woman with metastatic breast cancer and review of antineoplastic therapy-induced flagellate dermatoses. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:253-264. doi:10.1007/s13555-015-0085-2

- Grynszpan R, Niemeyer-Corbellini JP, Lopes MS, et al. Bleomycininduced flagellate dermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009764. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-009764

- Stephany MP, Chung S, Handler MZ, et al. Shiitake mushroom dermatitis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:485-489.

- Boels D, Landreau A, Bruneau C, et al. Shiitake dermatitis recorded by French Poison Control Centers—new case series with clinical observations. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52:625-628.

A 77-year-old man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and nonmelanoma skin cancer presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a new rash of 2 days’ duration. He trialed a previously prescribed triamcinolone cream 0.1% without improvement. The patient denied any recent travel, as well as fever, nausea, vomiting, or changes in bowel habits. Physical examination revealed diffuse, erythematous, raised, linear plaques on the mid to lower back.

Financial Insecurity Among US Adults With Psoriasis

To the Editor:

Approximately 3% of the US population, or 6.9 million adults, is affected by psoriasis.1 Psoriasis has a substantial impact on quality of life and is associated with increased health care expenses and medication costs. In 2013, it was reported that the estimated US annual cost—direct, indirect, intangible, and comorbidity costs—of psoriasis for adults was $112 billion.2 We investigated the prevalence and sociodemographic characteristics of adult psoriasis patients (aged ≥20 years) with financial insecurity utilizing the 2009–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data.3

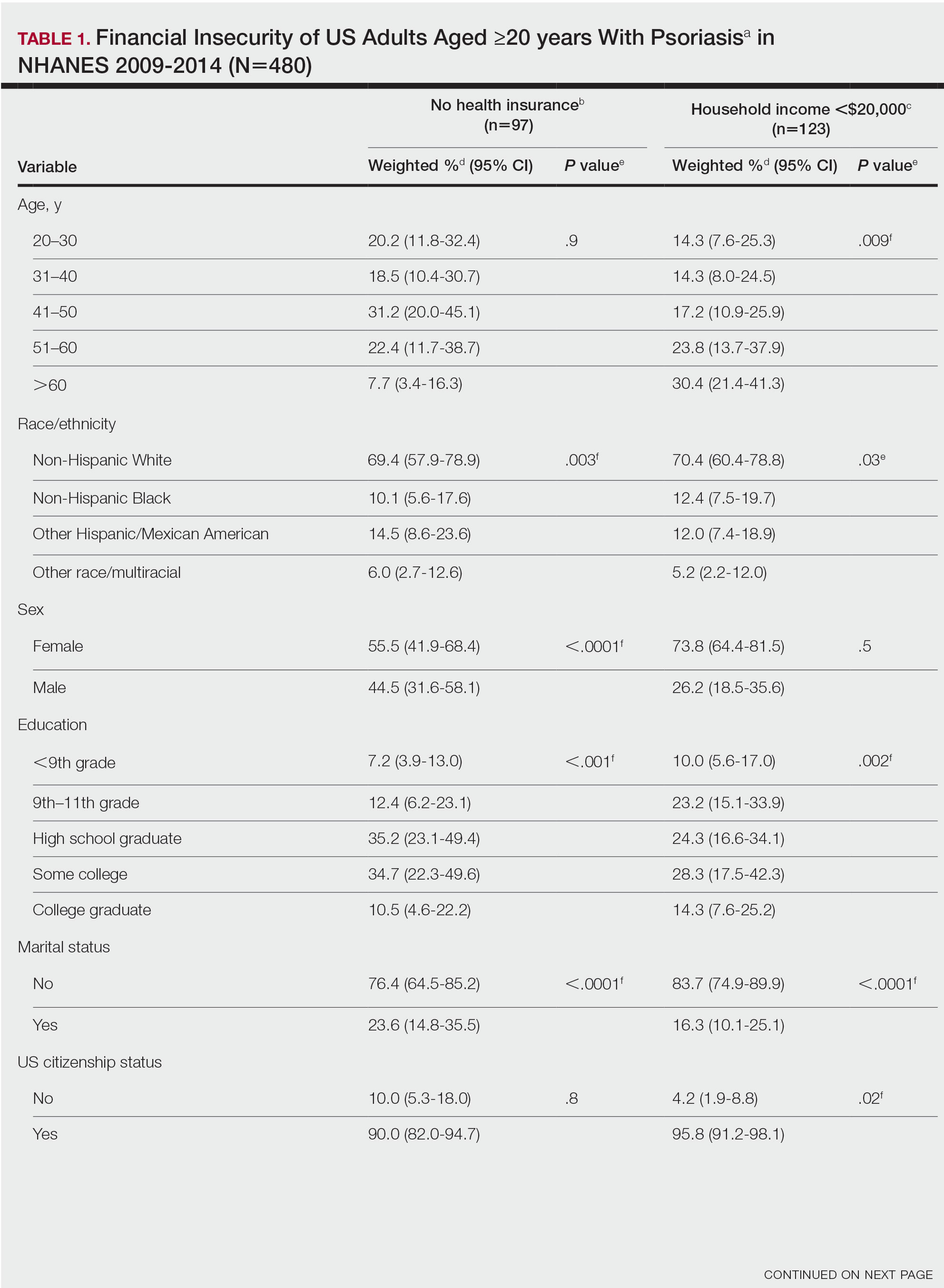

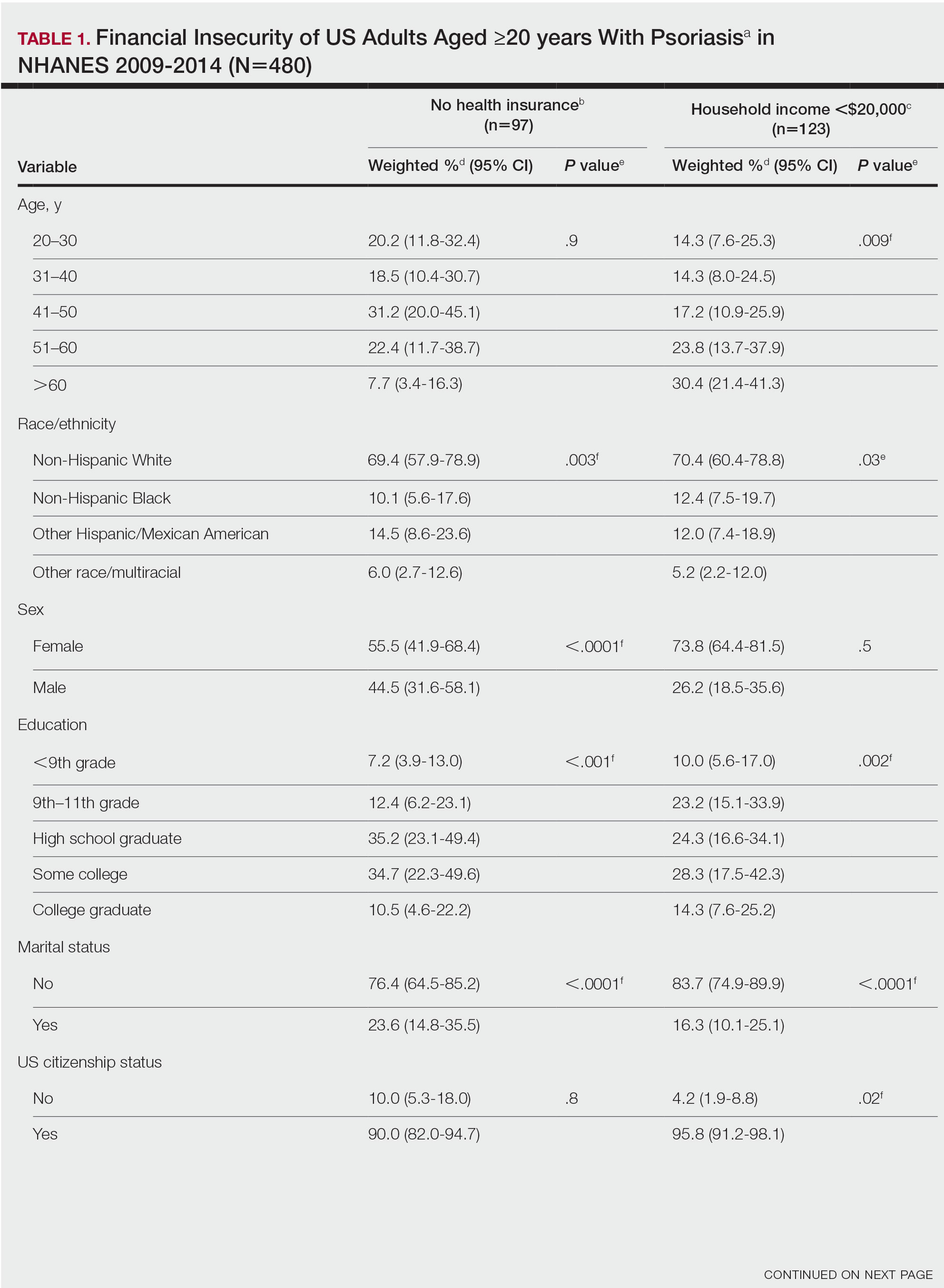

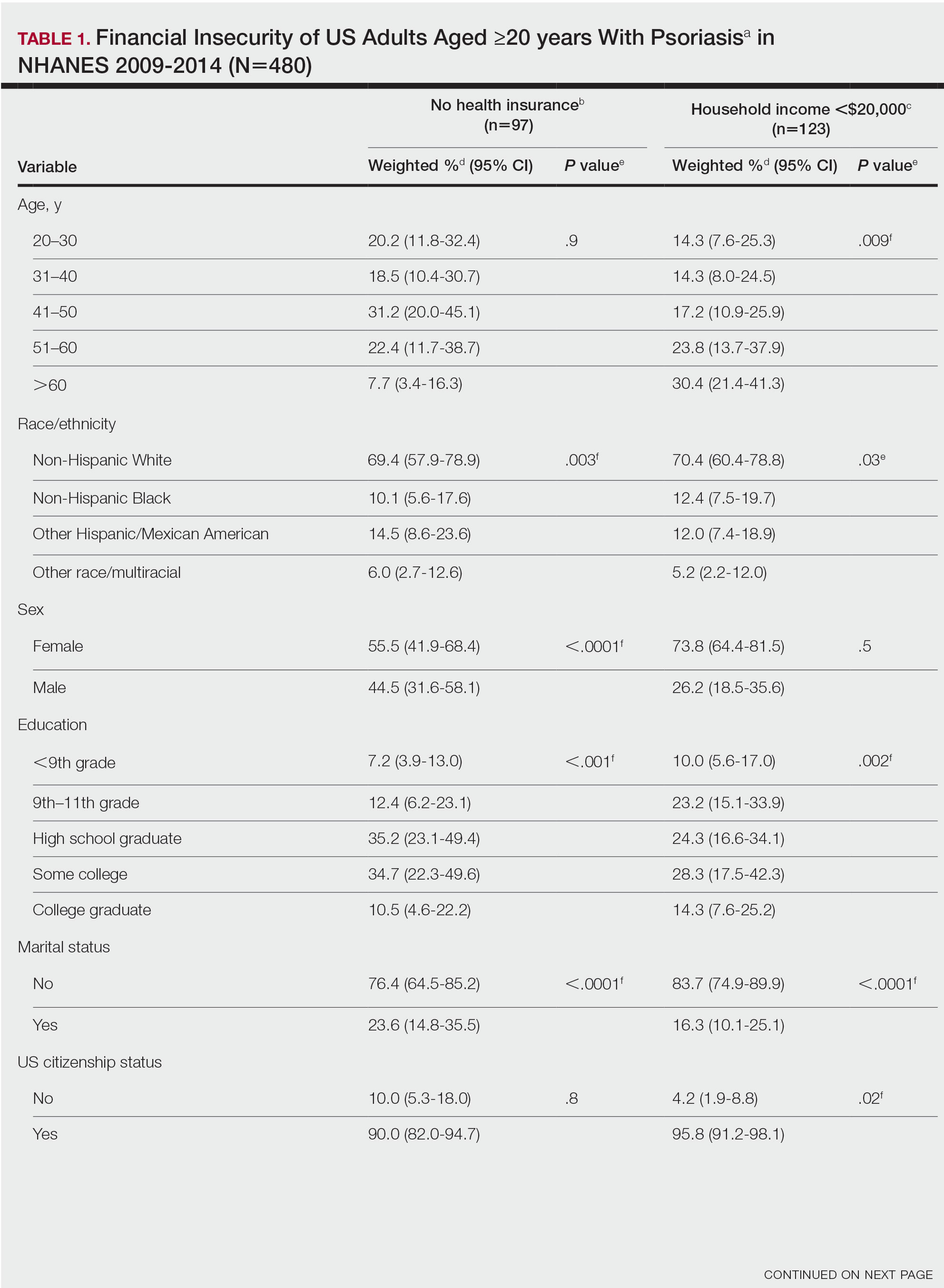

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database to evaluate financial insecurity. Financial insecurity was evaluated by 2 outcome variables. The primary outcome variable was assessed by the question “Are you covered by health insurance or some other kind of health care plan (including health insurance obtained through employment or purchased directly as well as government programs like Medicare and Medicaid that provide medical care or help pay medical bills)?”3 Our secondary outcome variable was evaluated by a reported annual household income of less than $20,000. P values in Table 1 were calculated using Pearson χ2 tests. In Table 2, multivariate logistic regressions were performed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC) to analyze associations between outcome variables and sociodemographic characteristics. Additionally, we controlled for age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, marital status, US citizenship status, and tobacco use. Subsequently, relationships with P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Our analysis comprised 480 individuals with psoriasis; 40 individuals were excluded from our analysis because they did not report annual household income and health insurance status (Table 1). Among the 480 individuals with psoriasis, approximately 16% (weighted) reported a lack of health insurance, and approximately 17% (weighted) reported an annual household income of less than $20,000. Among those who reported an annual household income of less than $20,000, approximately 38% (weighted) of them reported that they did not have health insurance.

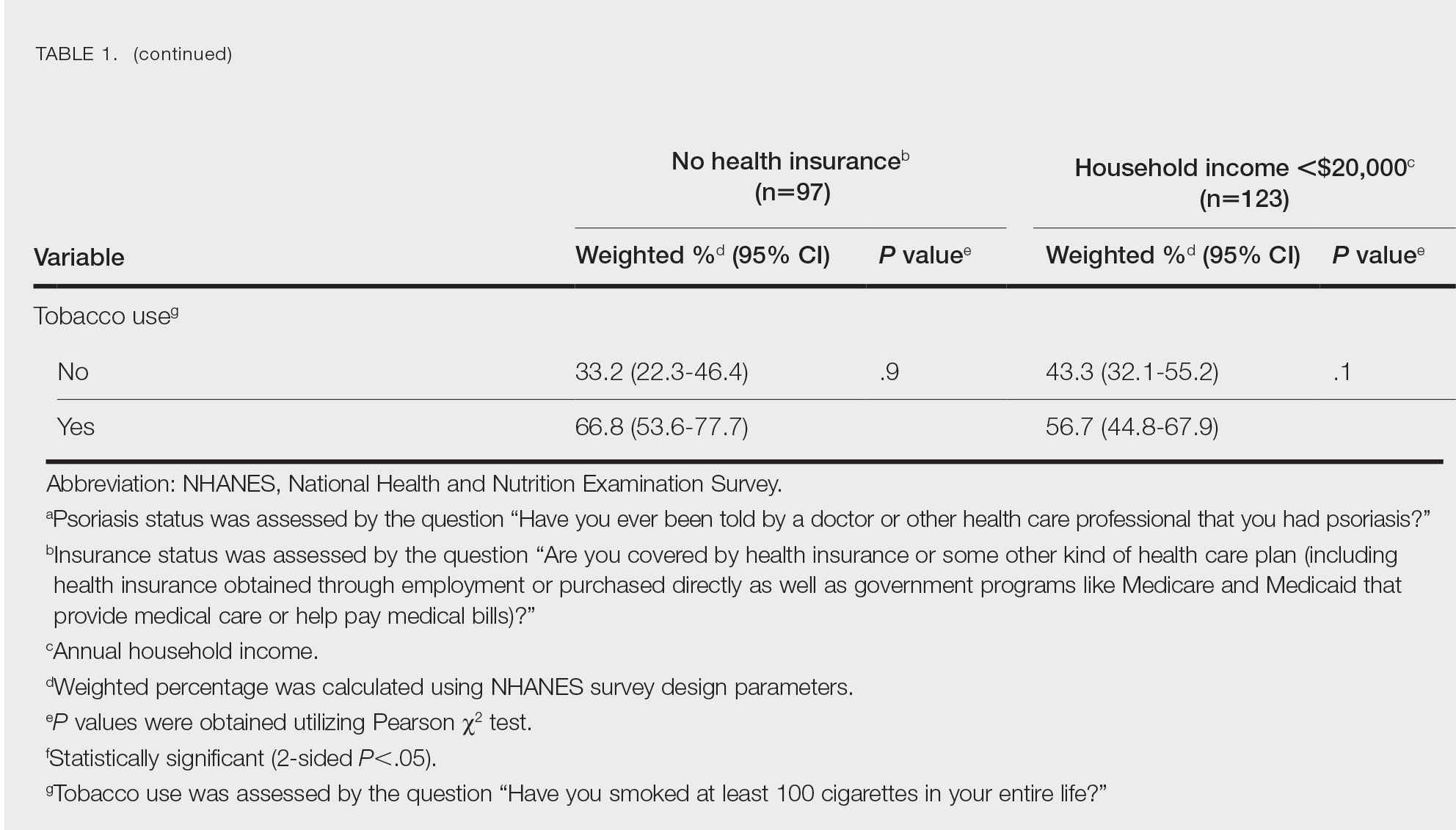

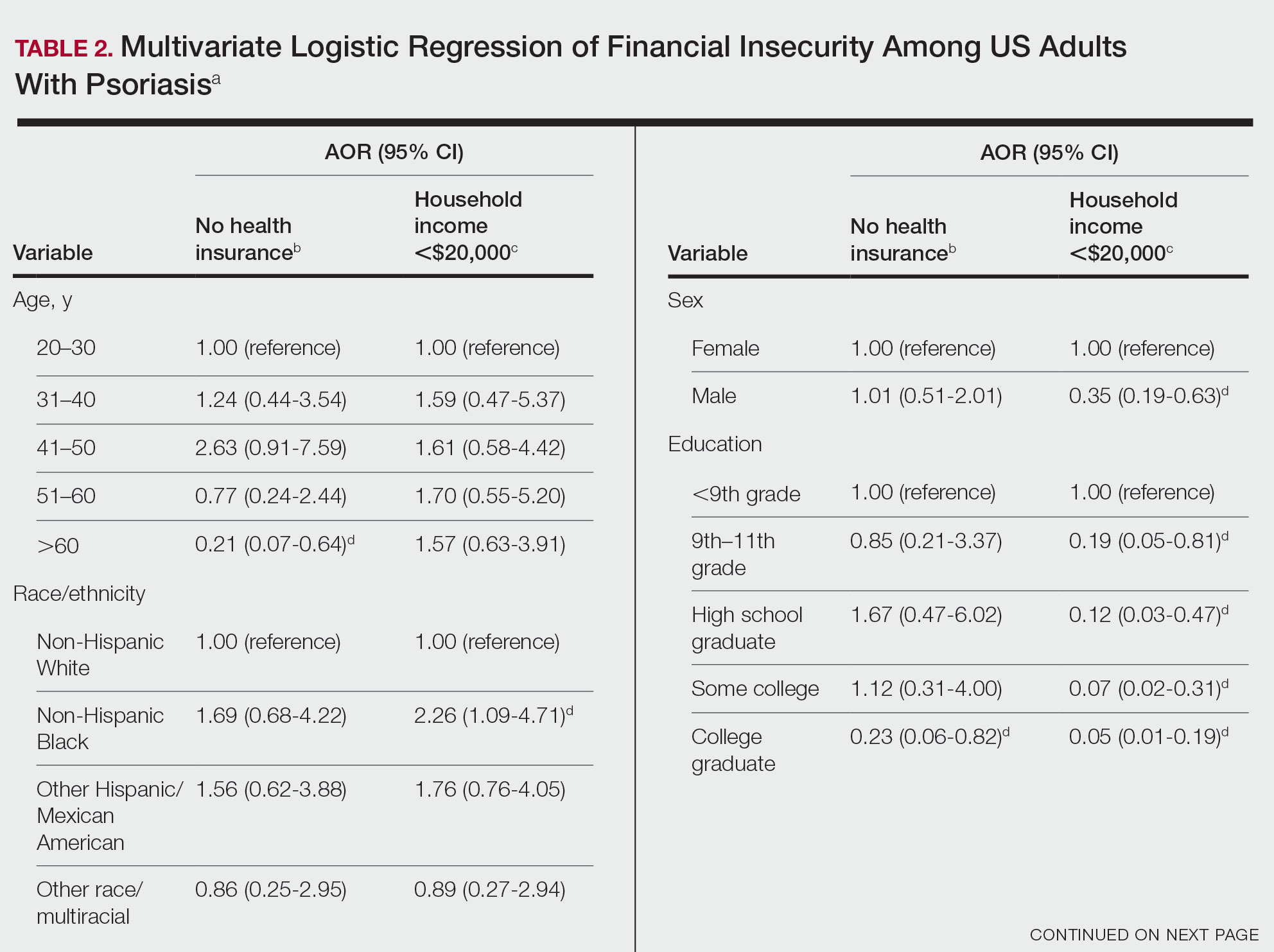

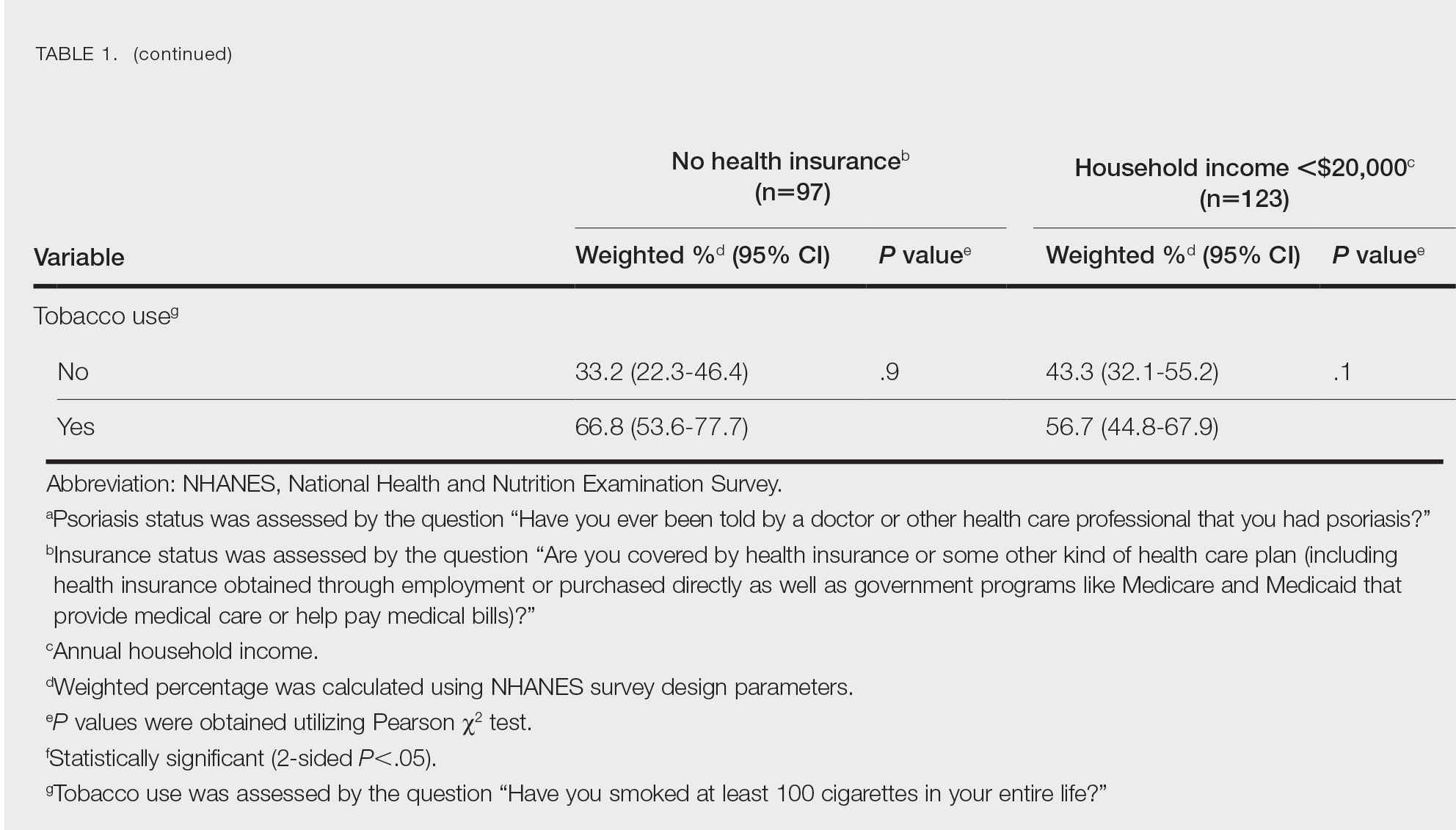

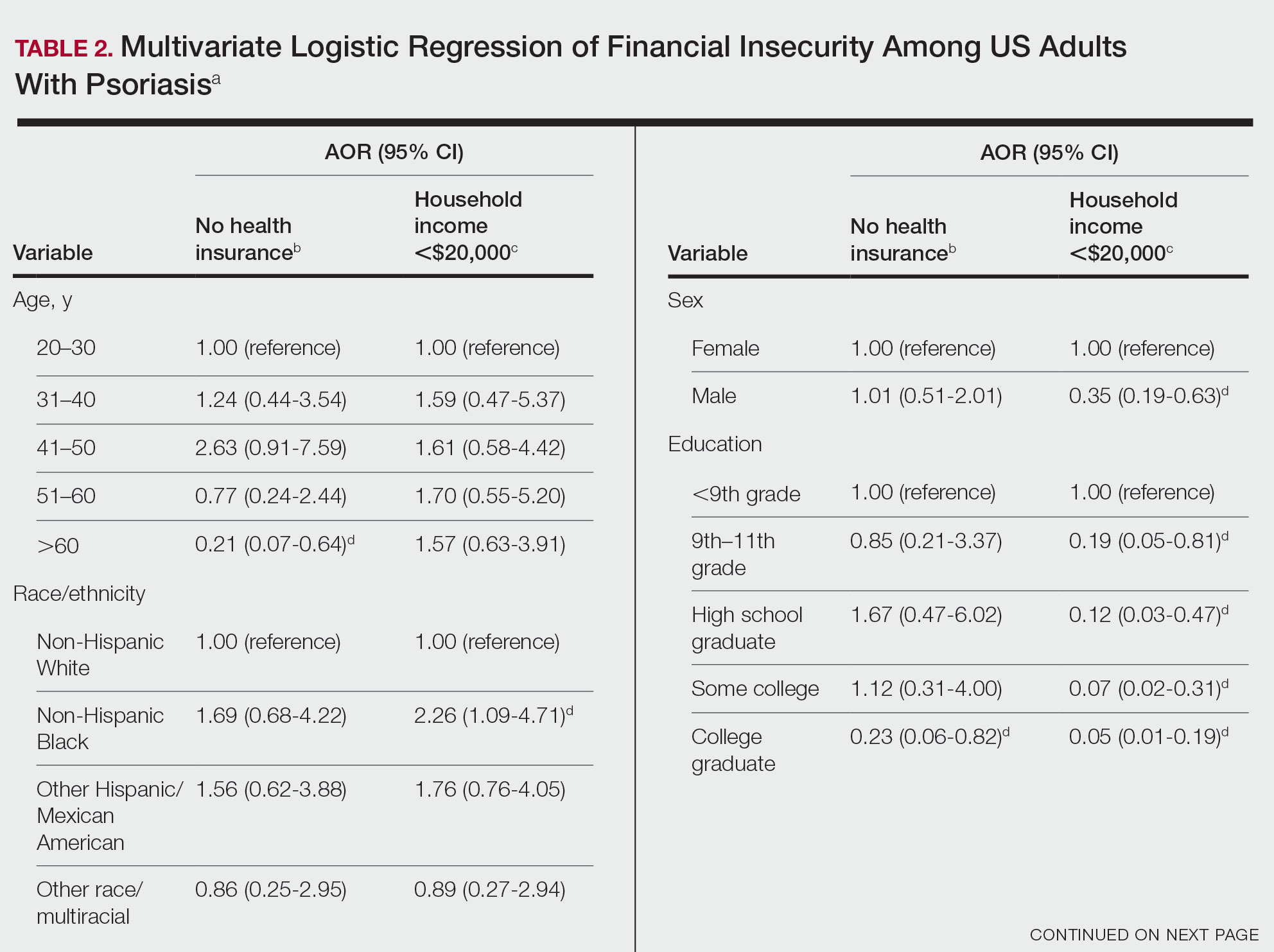

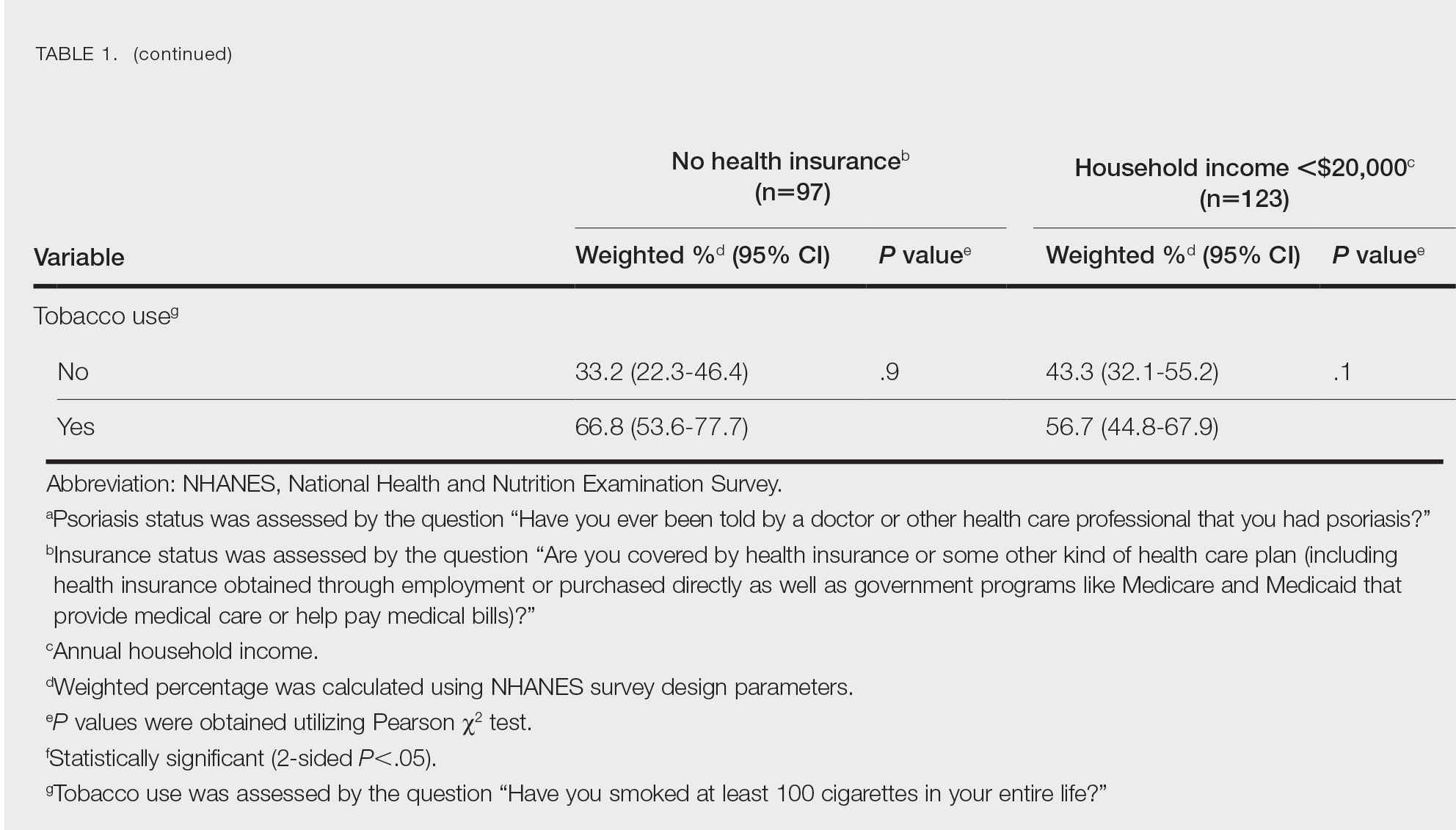

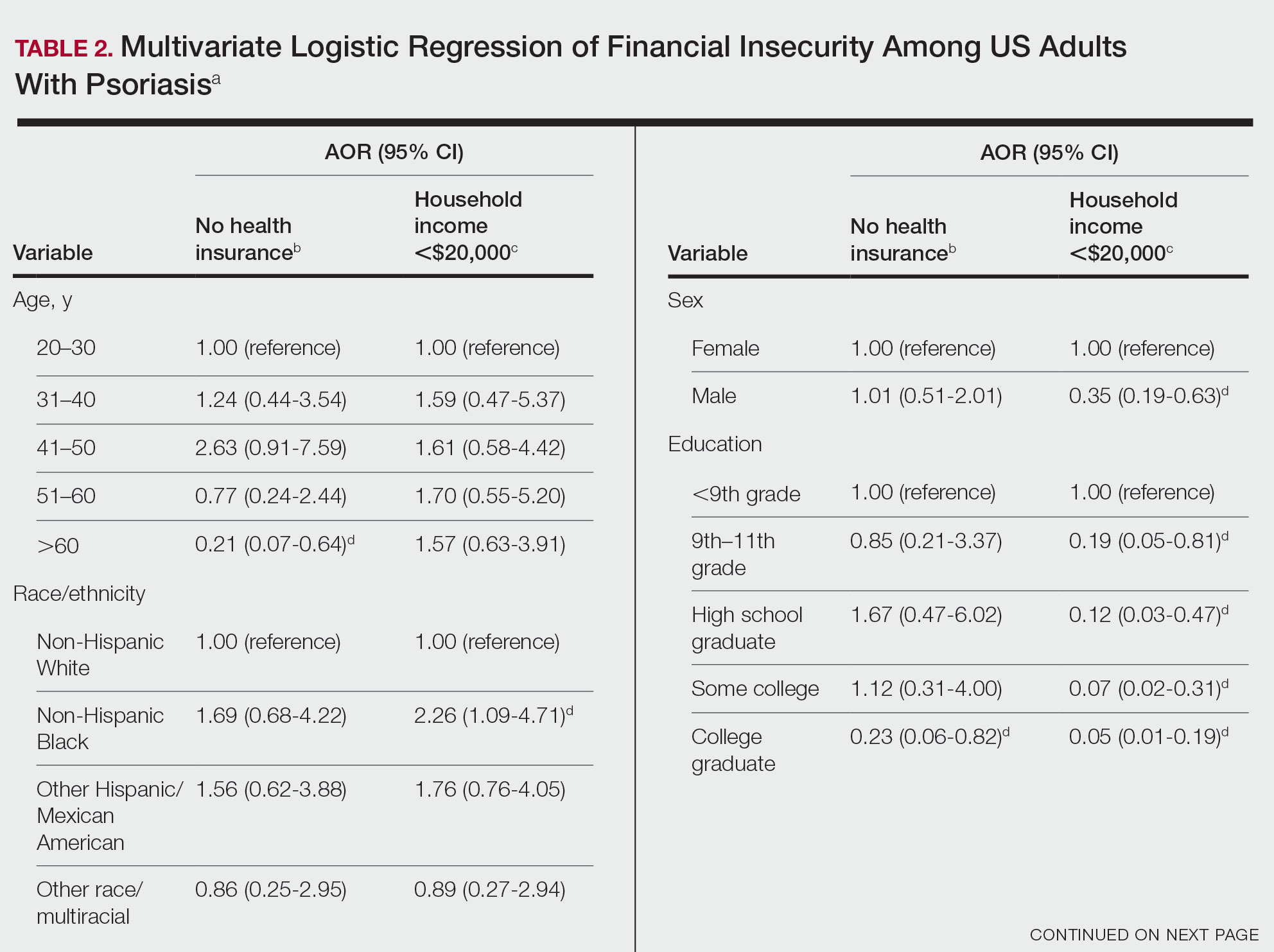

Multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that elderly individuals (aged >60 years), college graduates, married individuals, and US citizens had decreased odds of lacking health insurance (Table 2). Additionally, those with a history of tobacco use (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 2.02; 95% CI, 1.00-4.05) were associated with lacking health insurance. Non-Hispanic Black individuals (AOR 2.26; 95% CI, 1.09-4.71) and US citizens (AOR 5.01; 95% CI, 1.28-19.63) had a significant association with an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05). Lastly, males, those with education beyond ninth grade, and married individuals had a significantly decreased odds of having an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05)(Table 2).

Our findings indicate that certain sociodemographic groups of psoriasis patients have an increased risk for being financially insecure. It is important to evaluate the cost of treatment, number of necessary visits to the office, and cost of transportation, as these factors can serve as a major economic burden to patients being managed for psoriasis.4 Additionally, the cost of biologics has been increasing over time.5 Taking all of this into account when caring for psoriasis patients is crucial, as understanding the financial status of patients can assist with determining appropriate individualized treatment regimens.

- Liu J, Thatiparthi A, Martin A, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the US 2009-2010 and 2013-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:767-769. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.035

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651-658. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3593

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Maya-Rico AM, Londoño-García Á, Palacios-Barahona AU, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for patients with psoriasis in an outpatient dermatology referral service. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:295-300. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.09.004

- Cheng J, Feldman SR. The cost of biologics for psoriasis is increasing. Drugs Context. 2014;3:212266. doi:10.7573/dic.212266

To the Editor:

Approximately 3% of the US population, or 6.9 million adults, is affected by psoriasis.1 Psoriasis has a substantial impact on quality of life and is associated with increased health care expenses and medication costs. In 2013, it was reported that the estimated US annual cost—direct, indirect, intangible, and comorbidity costs—of psoriasis for adults was $112 billion.2 We investigated the prevalence and sociodemographic characteristics of adult psoriasis patients (aged ≥20 years) with financial insecurity utilizing the 2009–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data.3

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database to evaluate financial insecurity. Financial insecurity was evaluated by 2 outcome variables. The primary outcome variable was assessed by the question “Are you covered by health insurance or some other kind of health care plan (including health insurance obtained through employment or purchased directly as well as government programs like Medicare and Medicaid that provide medical care or help pay medical bills)?”3 Our secondary outcome variable was evaluated by a reported annual household income of less than $20,000. P values in Table 1 were calculated using Pearson χ2 tests. In Table 2, multivariate logistic regressions were performed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC) to analyze associations between outcome variables and sociodemographic characteristics. Additionally, we controlled for age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, marital status, US citizenship status, and tobacco use. Subsequently, relationships with P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Our analysis comprised 480 individuals with psoriasis; 40 individuals were excluded from our analysis because they did not report annual household income and health insurance status (Table 1). Among the 480 individuals with psoriasis, approximately 16% (weighted) reported a lack of health insurance, and approximately 17% (weighted) reported an annual household income of less than $20,000. Among those who reported an annual household income of less than $20,000, approximately 38% (weighted) of them reported that they did not have health insurance.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that elderly individuals (aged >60 years), college graduates, married individuals, and US citizens had decreased odds of lacking health insurance (Table 2). Additionally, those with a history of tobacco use (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 2.02; 95% CI, 1.00-4.05) were associated with lacking health insurance. Non-Hispanic Black individuals (AOR 2.26; 95% CI, 1.09-4.71) and US citizens (AOR 5.01; 95% CI, 1.28-19.63) had a significant association with an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05). Lastly, males, those with education beyond ninth grade, and married individuals had a significantly decreased odds of having an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05)(Table 2).

Our findings indicate that certain sociodemographic groups of psoriasis patients have an increased risk for being financially insecure. It is important to evaluate the cost of treatment, number of necessary visits to the office, and cost of transportation, as these factors can serve as a major economic burden to patients being managed for psoriasis.4 Additionally, the cost of biologics has been increasing over time.5 Taking all of this into account when caring for psoriasis patients is crucial, as understanding the financial status of patients can assist with determining appropriate individualized treatment regimens.

To the Editor:

Approximately 3% of the US population, or 6.9 million adults, is affected by psoriasis.1 Psoriasis has a substantial impact on quality of life and is associated with increased health care expenses and medication costs. In 2013, it was reported that the estimated US annual cost—direct, indirect, intangible, and comorbidity costs—of psoriasis for adults was $112 billion.2 We investigated the prevalence and sociodemographic characteristics of adult psoriasis patients (aged ≥20 years) with financial insecurity utilizing the 2009–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data.3

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database to evaluate financial insecurity. Financial insecurity was evaluated by 2 outcome variables. The primary outcome variable was assessed by the question “Are you covered by health insurance or some other kind of health care plan (including health insurance obtained through employment or purchased directly as well as government programs like Medicare and Medicaid that provide medical care or help pay medical bills)?”3 Our secondary outcome variable was evaluated by a reported annual household income of less than $20,000. P values in Table 1 were calculated using Pearson χ2 tests. In Table 2, multivariate logistic regressions were performed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC) to analyze associations between outcome variables and sociodemographic characteristics. Additionally, we controlled for age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, marital status, US citizenship status, and tobacco use. Subsequently, relationships with P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Our analysis comprised 480 individuals with psoriasis; 40 individuals were excluded from our analysis because they did not report annual household income and health insurance status (Table 1). Among the 480 individuals with psoriasis, approximately 16% (weighted) reported a lack of health insurance, and approximately 17% (weighted) reported an annual household income of less than $20,000. Among those who reported an annual household income of less than $20,000, approximately 38% (weighted) of them reported that they did not have health insurance.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that elderly individuals (aged >60 years), college graduates, married individuals, and US citizens had decreased odds of lacking health insurance (Table 2). Additionally, those with a history of tobacco use (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 2.02; 95% CI, 1.00-4.05) were associated with lacking health insurance. Non-Hispanic Black individuals (AOR 2.26; 95% CI, 1.09-4.71) and US citizens (AOR 5.01; 95% CI, 1.28-19.63) had a significant association with an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05). Lastly, males, those with education beyond ninth grade, and married individuals had a significantly decreased odds of having an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05)(Table 2).

Our findings indicate that certain sociodemographic groups of psoriasis patients have an increased risk for being financially insecure. It is important to evaluate the cost of treatment, number of necessary visits to the office, and cost of transportation, as these factors can serve as a major economic burden to patients being managed for psoriasis.4 Additionally, the cost of biologics has been increasing over time.5 Taking all of this into account when caring for psoriasis patients is crucial, as understanding the financial status of patients can assist with determining appropriate individualized treatment regimens.

- Liu J, Thatiparthi A, Martin A, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the US 2009-2010 and 2013-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:767-769. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.035

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651-658. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3593

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Maya-Rico AM, Londoño-García Á, Palacios-Barahona AU, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for patients with psoriasis in an outpatient dermatology referral service. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:295-300. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.09.004

- Cheng J, Feldman SR. The cost of biologics for psoriasis is increasing. Drugs Context. 2014;3:212266. doi:10.7573/dic.212266

- Liu J, Thatiparthi A, Martin A, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the US 2009-2010 and 2013-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:767-769. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.035

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651-658. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3593

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Maya-Rico AM, Londoño-García Á, Palacios-Barahona AU, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for patients with psoriasis in an outpatient dermatology referral service. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:295-300. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.09.004

- Cheng J, Feldman SR. The cost of biologics for psoriasis is increasing. Drugs Context. 2014;3:212266. doi:10.7573/dic.212266

Practice Points

- The economic burden on patients with psoriasis has been rising over time, as the disease impacts many aspects of patients’ lives.

- Various sociodemographic groups among patients with psoriasis are financially insecure. Knowing which groups are at higher risk for poor outcomes due to financial insecurity can assist with appropriate treatment regimens.

Cystic Presentation of High-Grade Ductal Carcinoma In Situ in an Inframammary Accessory Nipple

To the Editor:

The term ectopic breast tissue serves as an umbrella term that encompasses breast tissue positioned in anatomically incorrect locations, including the subtypes of supernumerary and aberrant breasts.1 However, the more frequently used term is accessory breast tissue (ABT).1 Supernumerary breasts have diverse variations of a nipple, areola, and/or ductal tissue and can span in size from a small mole to a fully functioning breast. This breast type maintains structured ductal systems connected to the overlying skin and experiences regular changes during the reproductive cycle. In contrast, an aberrant breast is isolated breast tissue that does not contain organized ductal systems.1 Accessory breast tissue is prevalent in up to 6.0% of the world population, with Japanese individuals being the most affected and White individuals being the least affected.1

Accessory breasts typically are located along the milk line—the embryologic precursor to mammary glands and nipples, which extend from the axillae to the groin and regress from the caudal end spanning to the groin.2 For this reason, incomplete regression of the mammary ridge results in ABT, most commonly in the axillary region.3 Accessory breast tissue usually is benign and is considered an anatomical variant; however, because the histomorphology is similar to mammary gland tissue, accessory breasts have the same proliferative potential as anatomically correct breasts and therefore can form fibroadenomas, cysts, abscesses, mastitis, or breast cancer.4 Accessory breast carcinomas comprise 0.3% to 0.6% of all breast malignancies.5 Certain genodermatoses (ie, Cowden syndrome) also may predispose patients to benign or malignant pathology in ABT.6 We present a rare case of accessory breast cancer in the inframammary region masquerading as a cyst. These findings were further supported by ultrasonography and mammography.

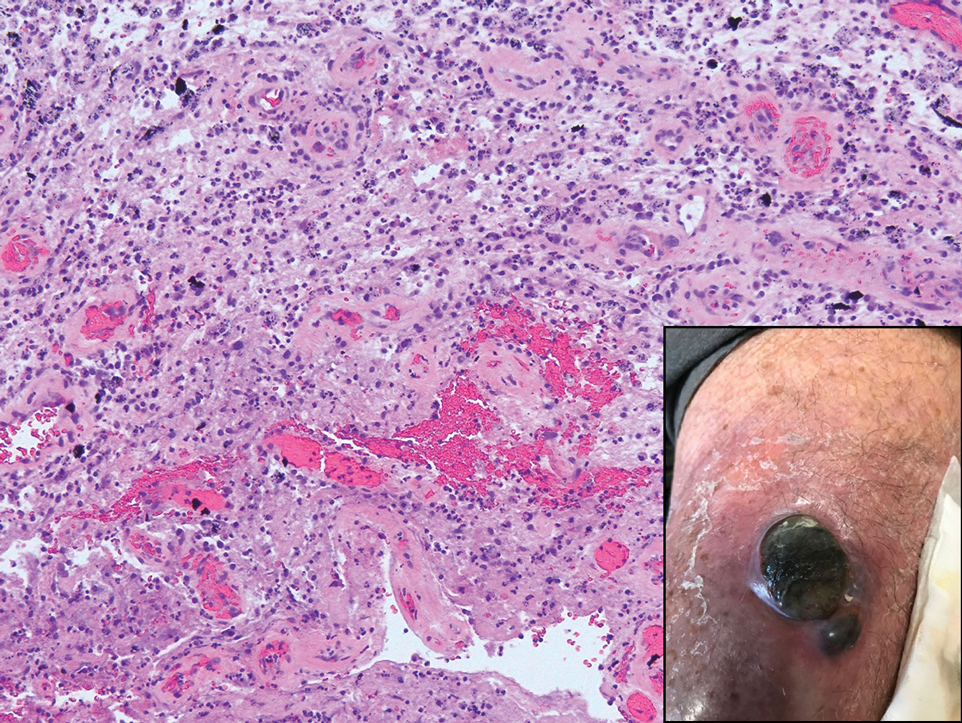

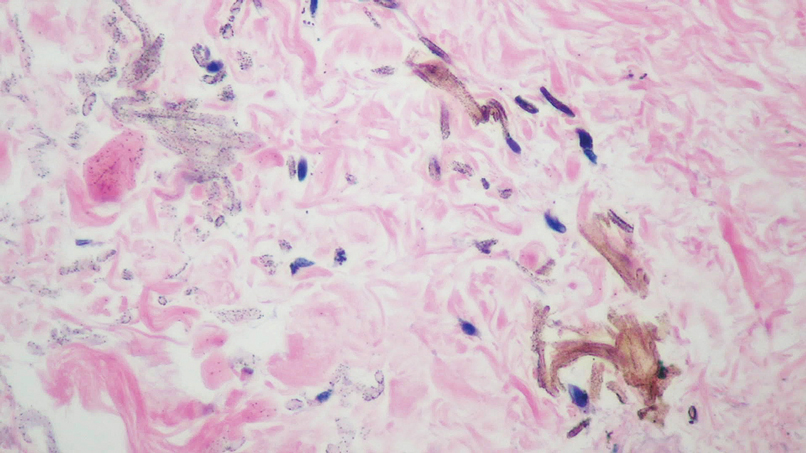

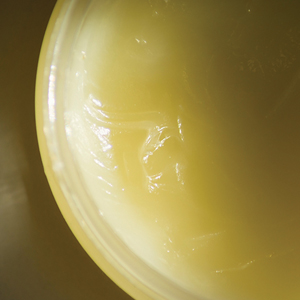

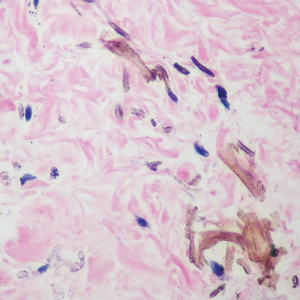

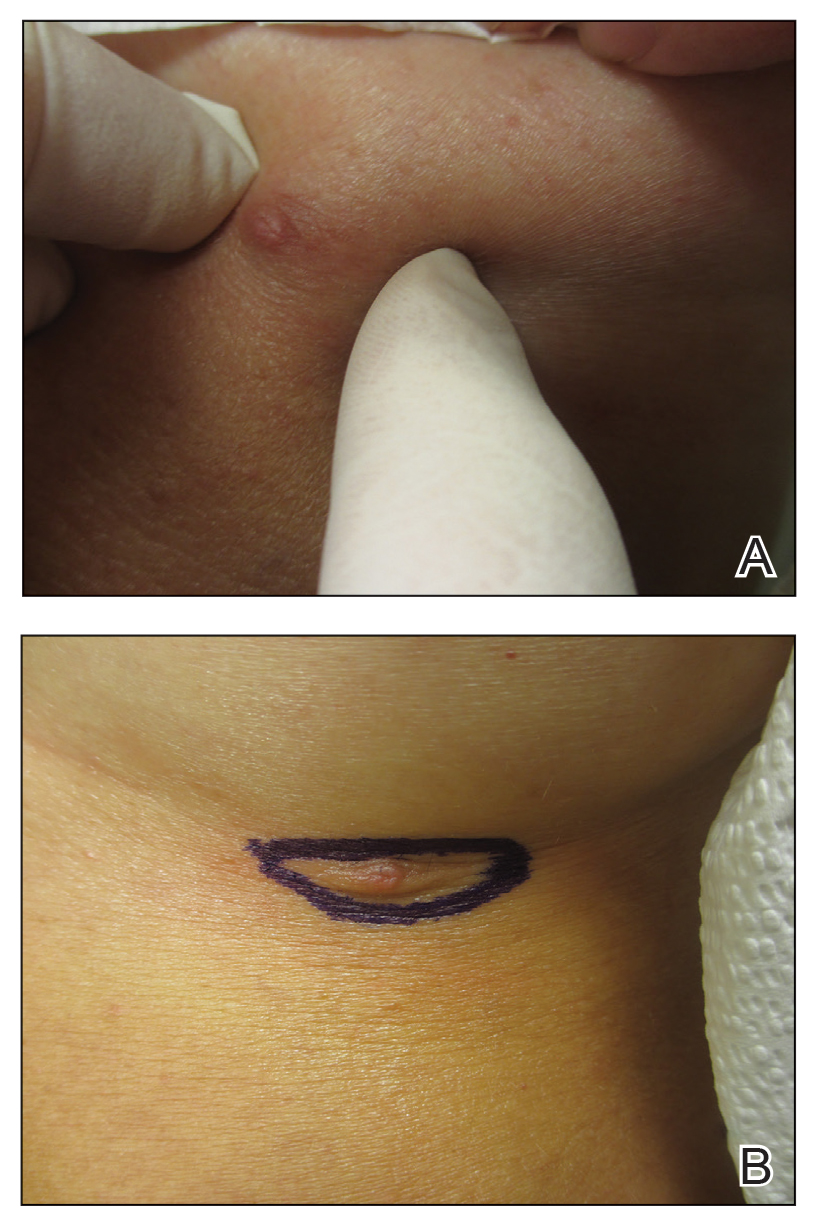

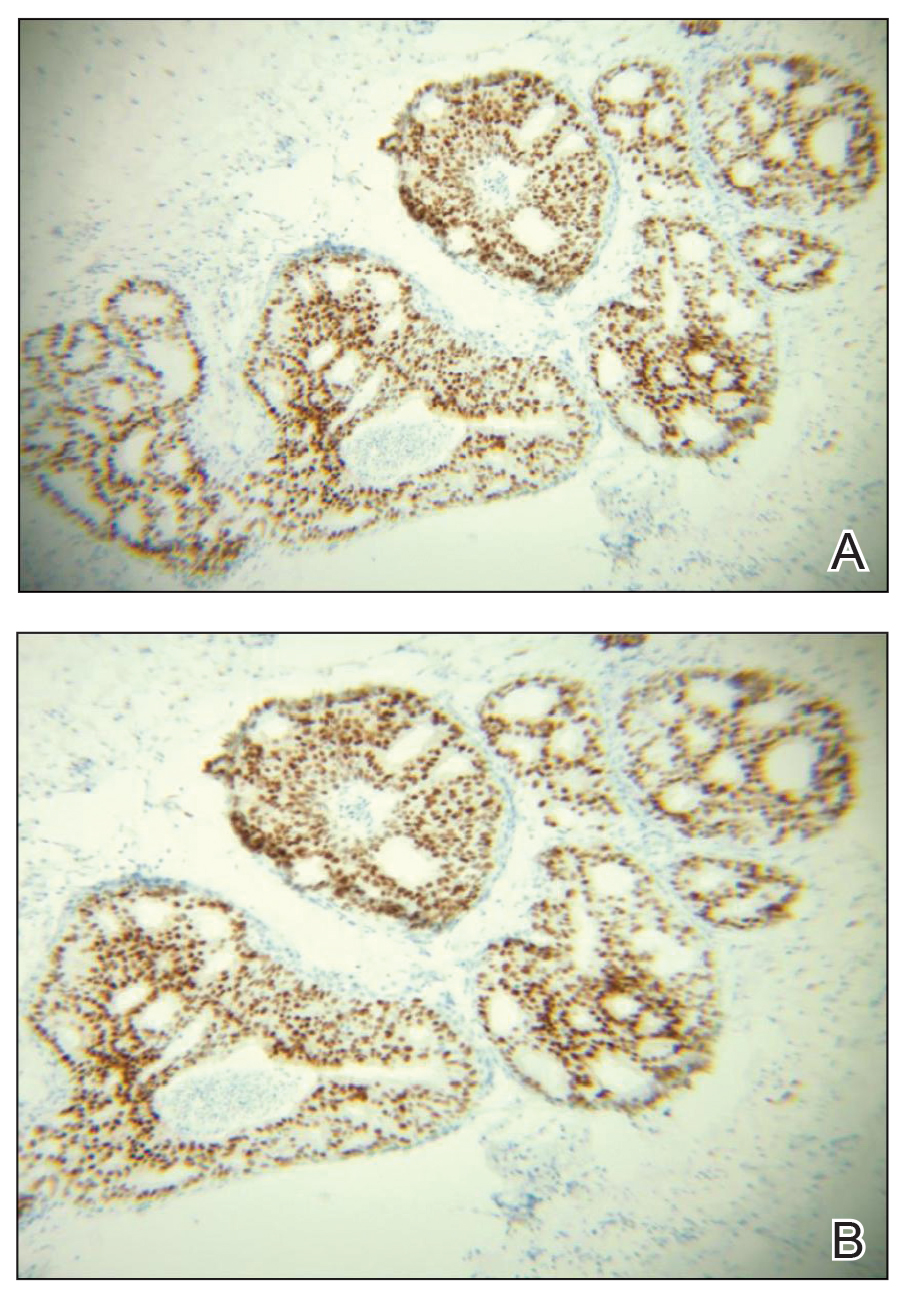

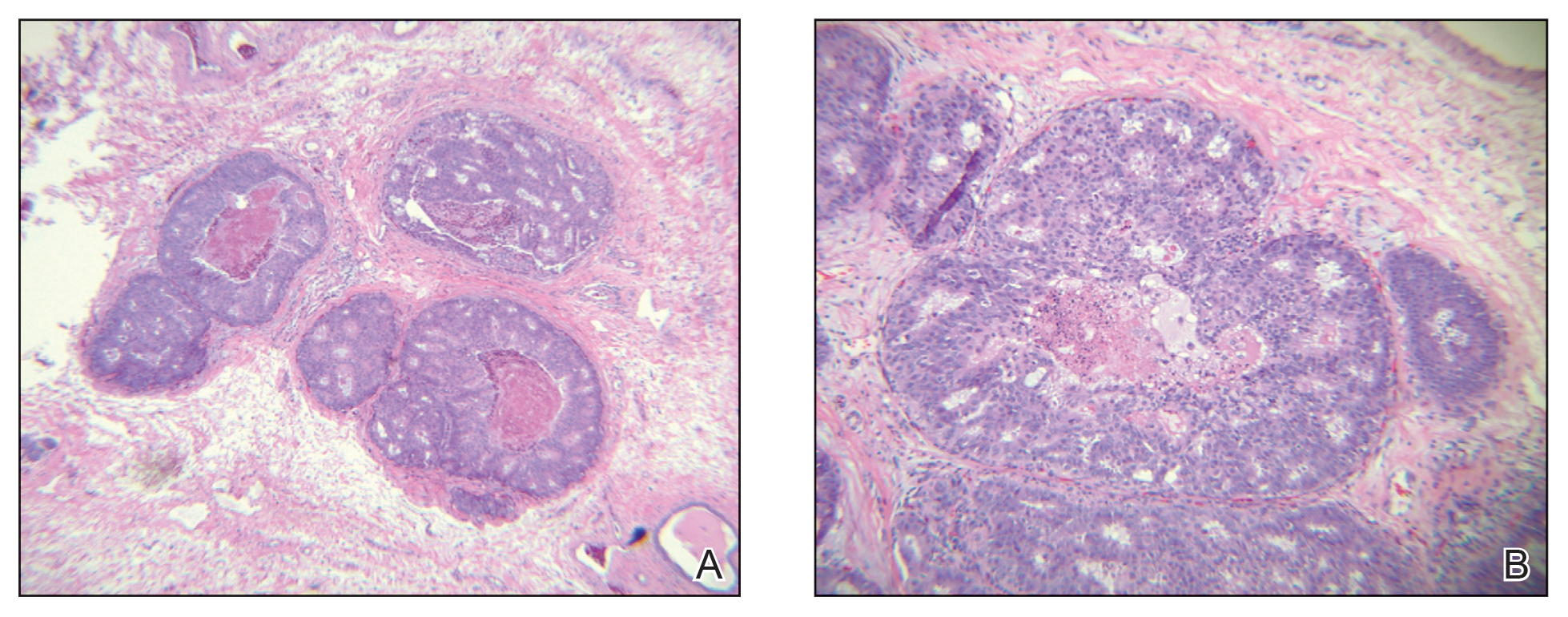

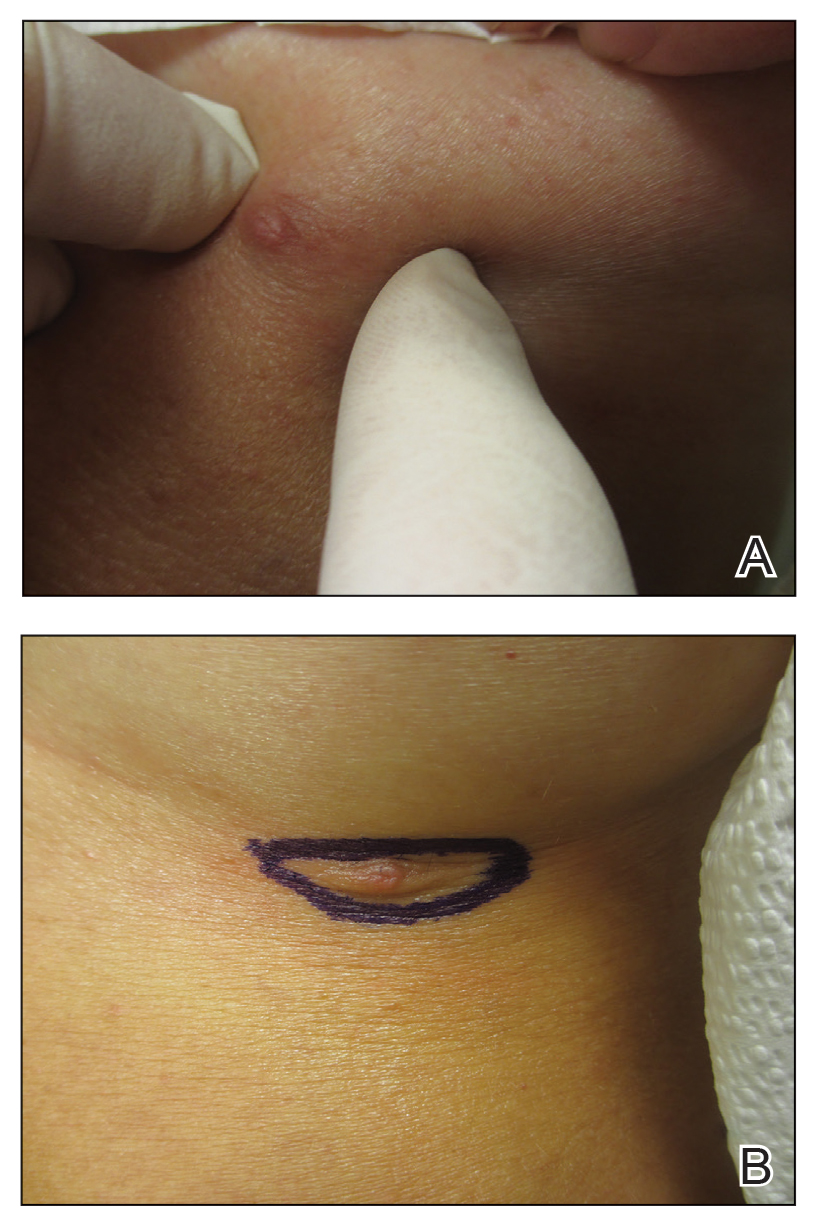

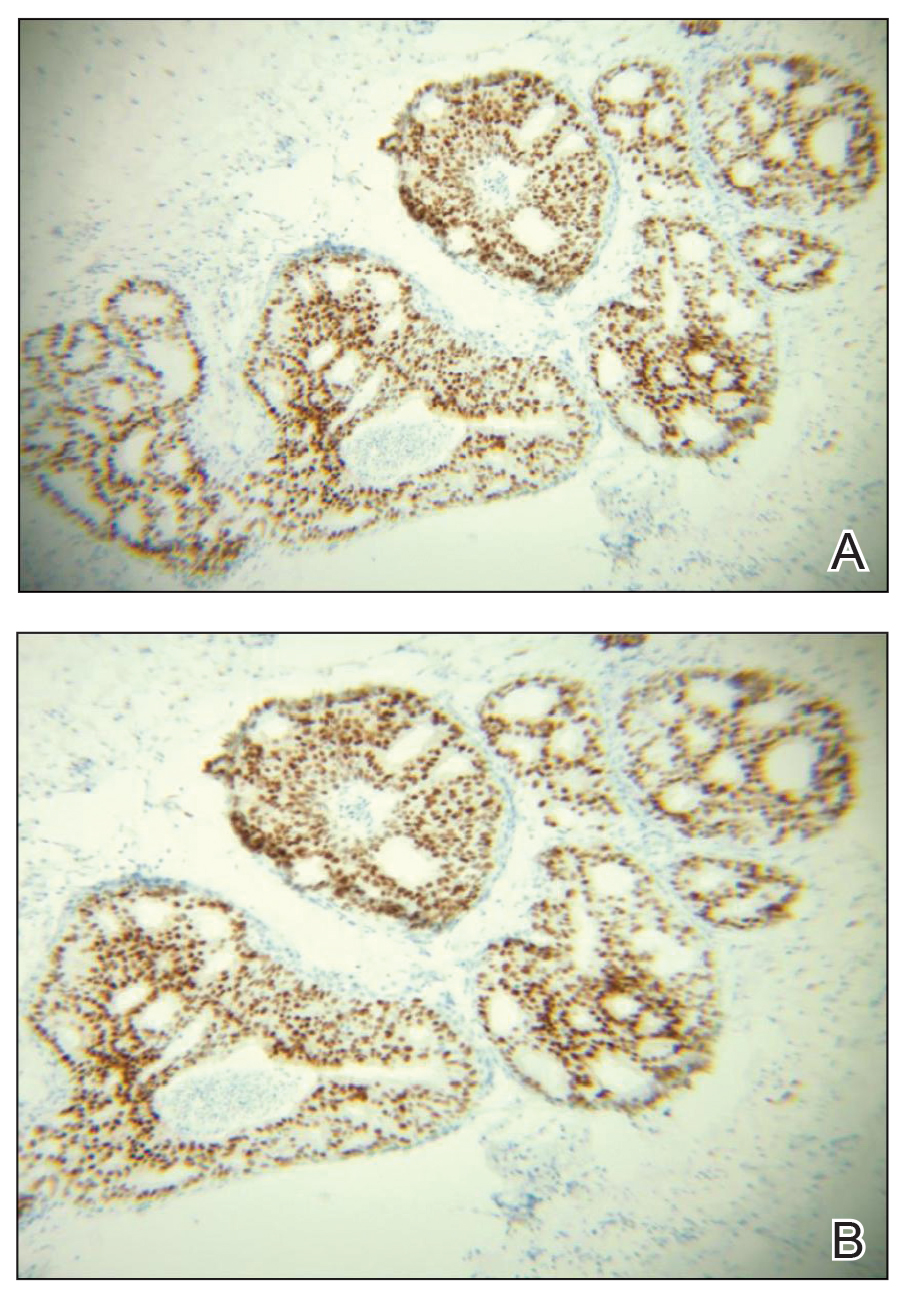

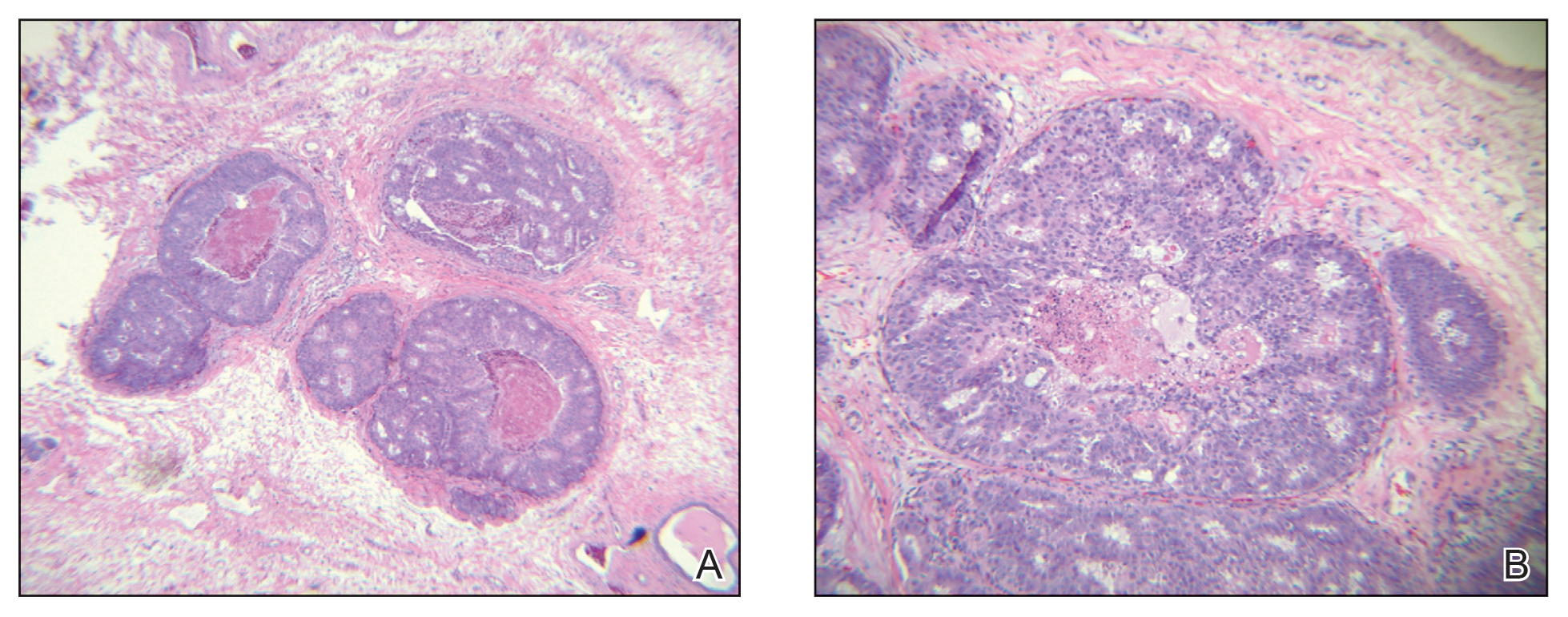

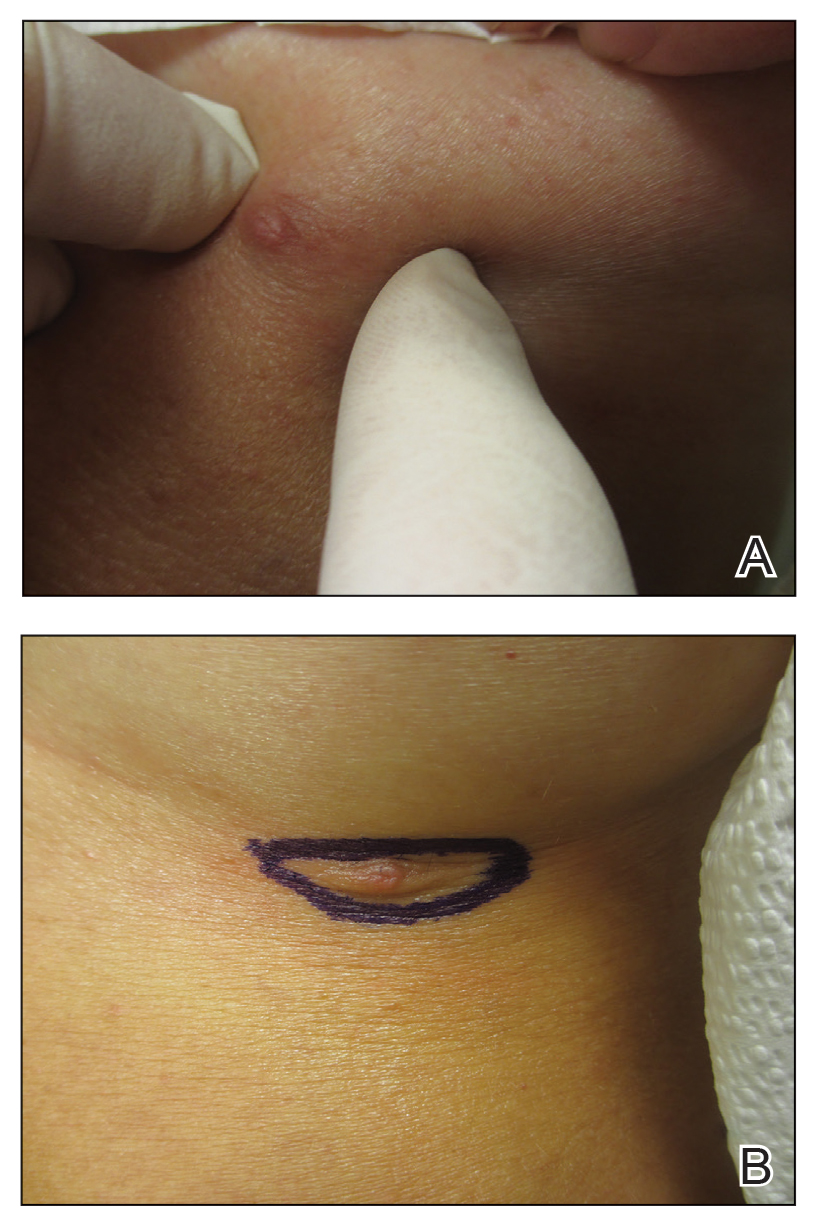

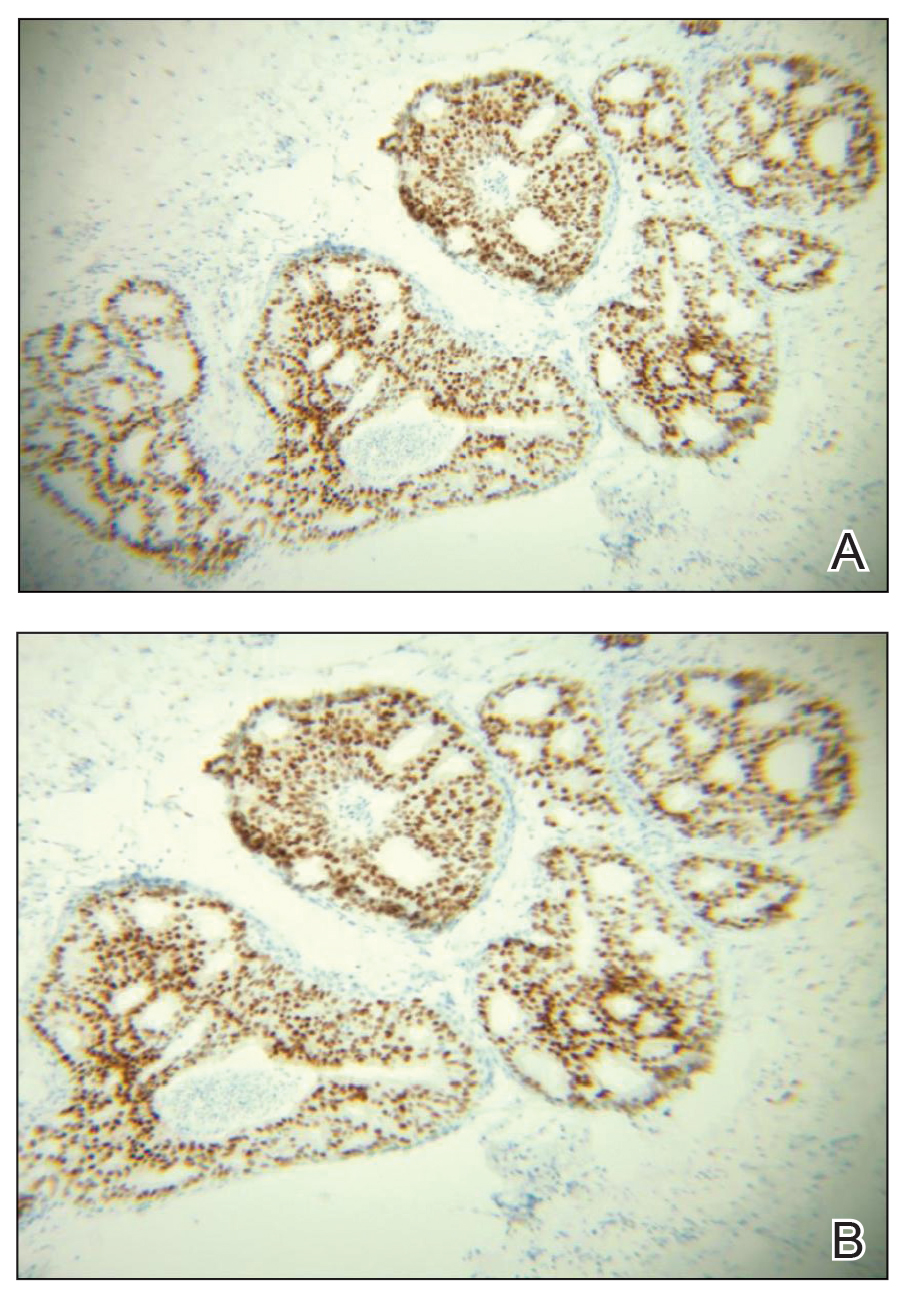

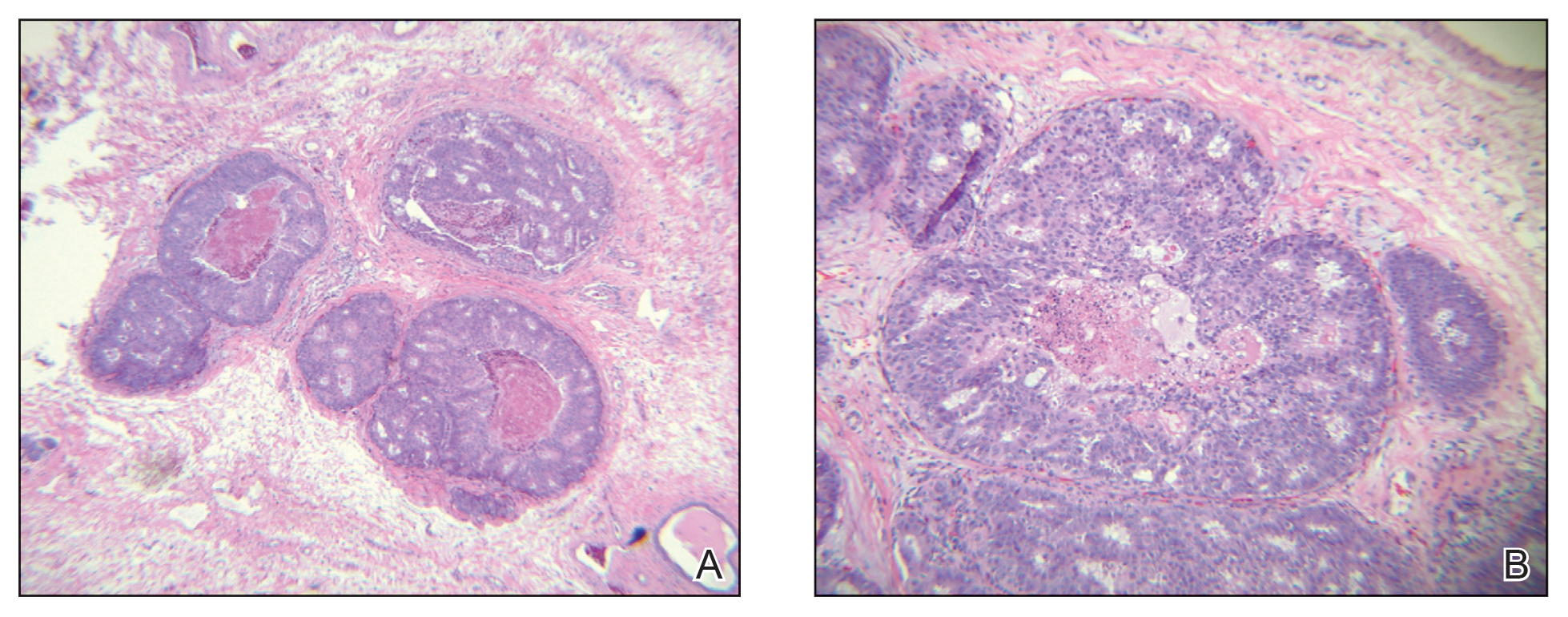

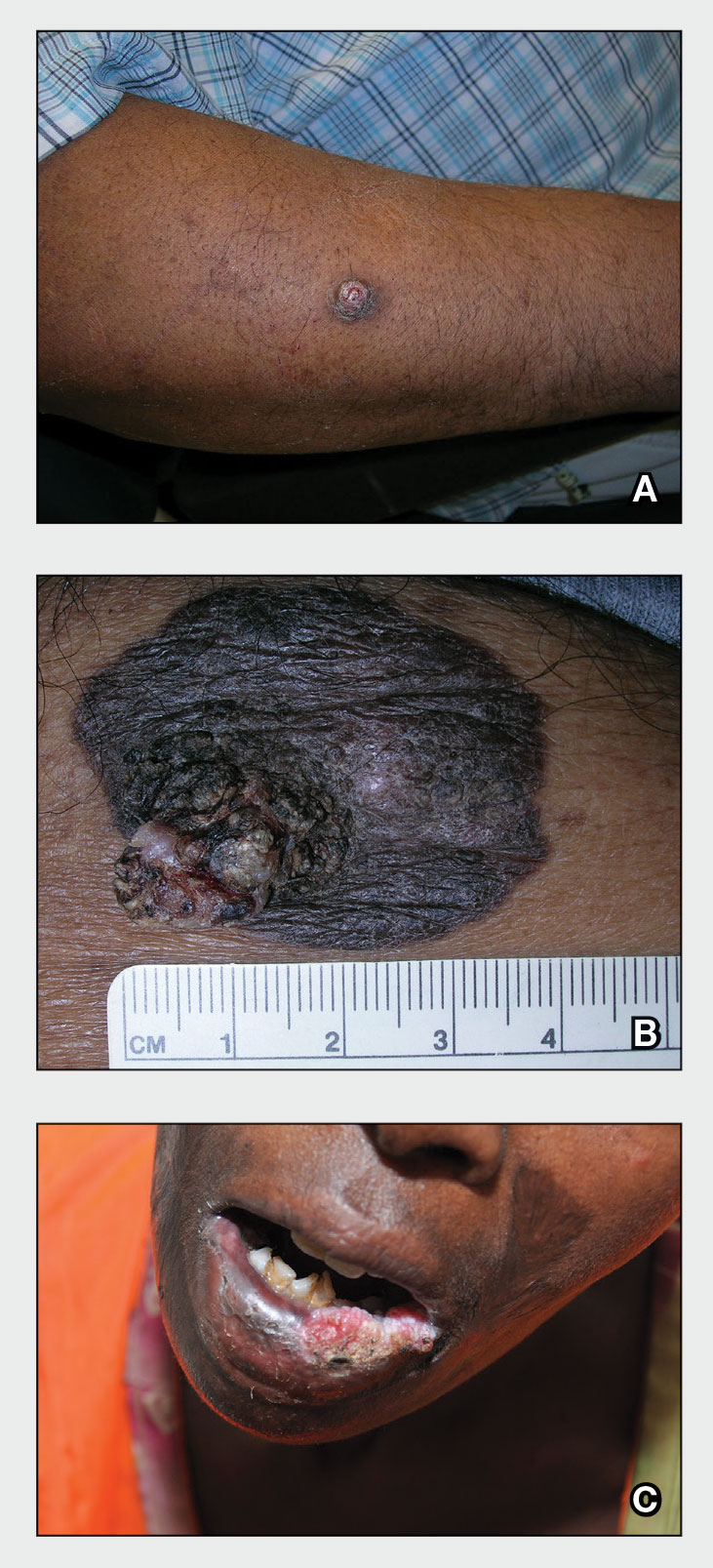

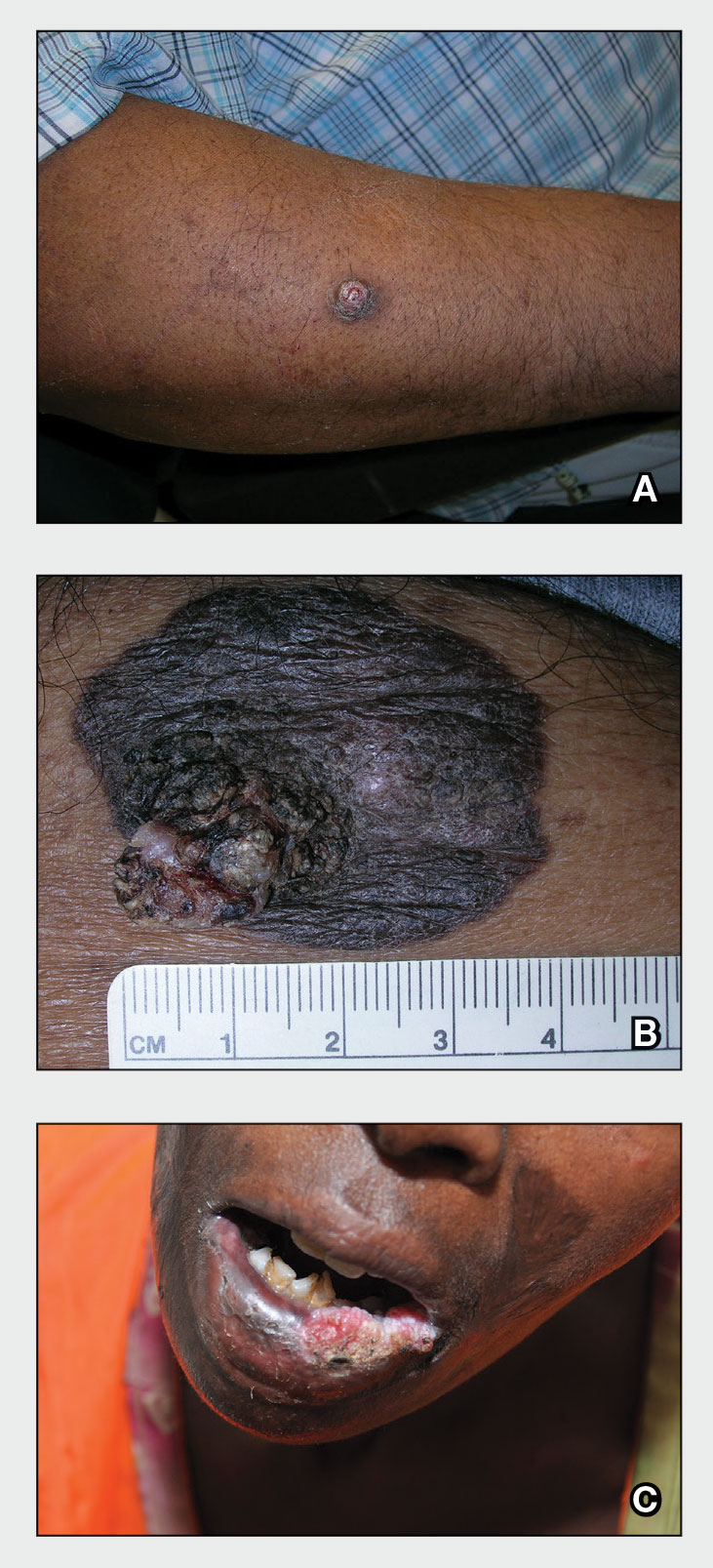

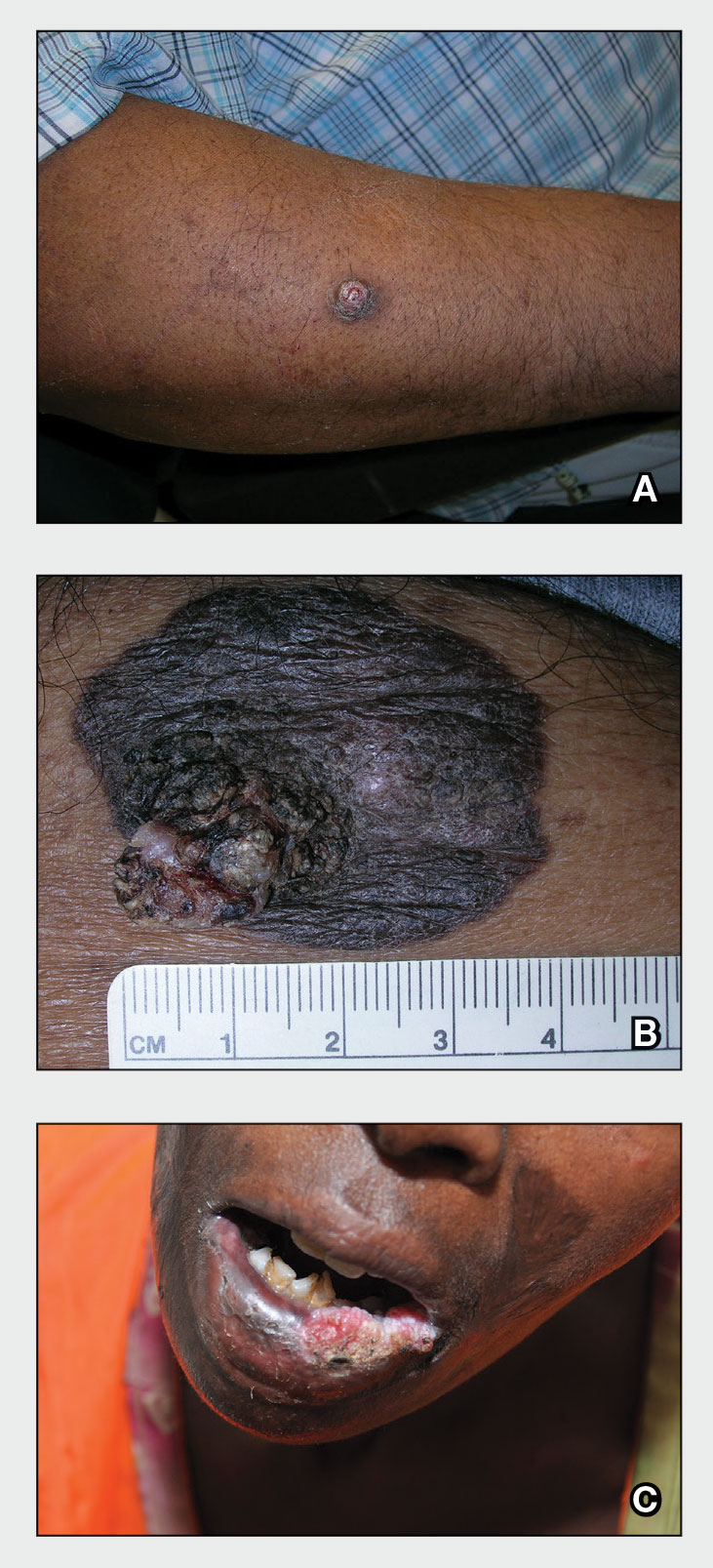

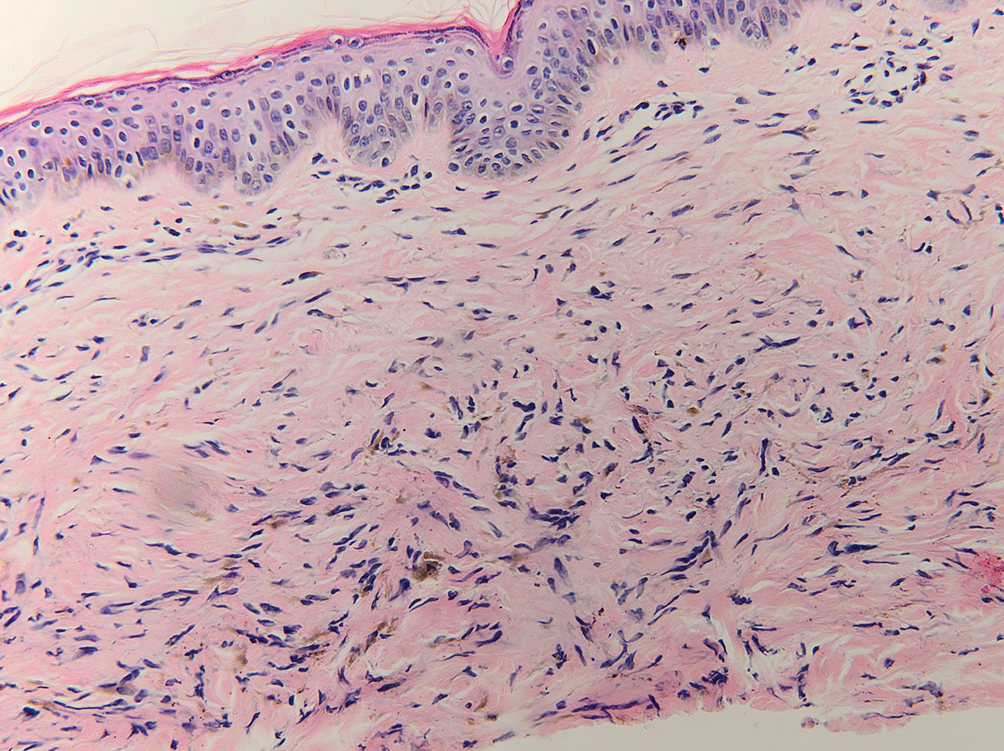

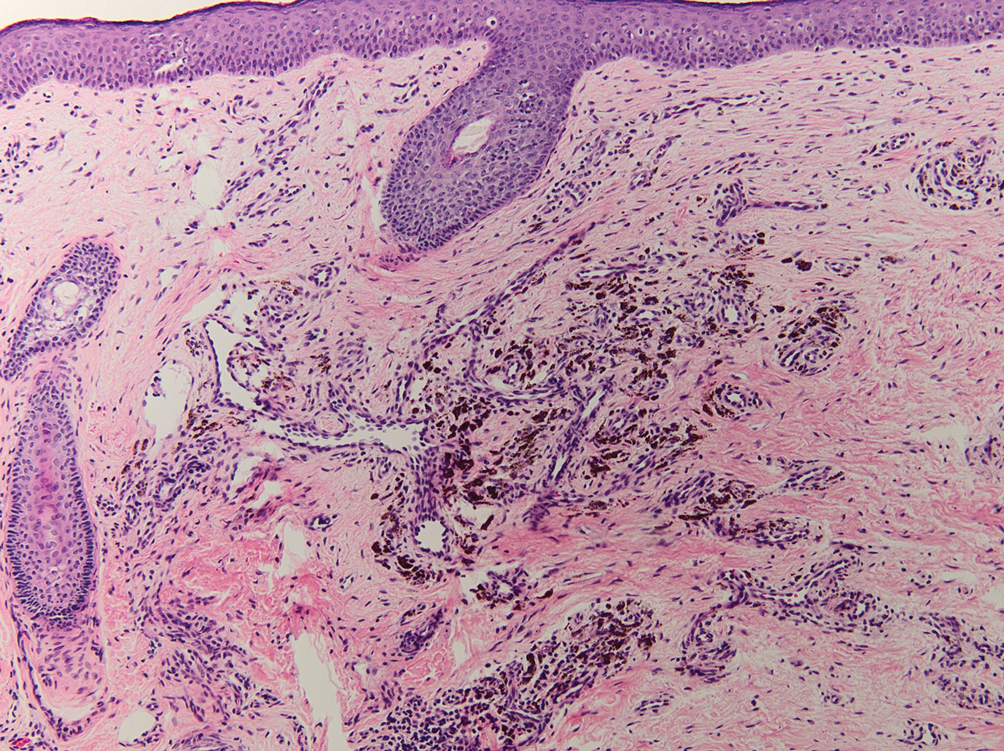

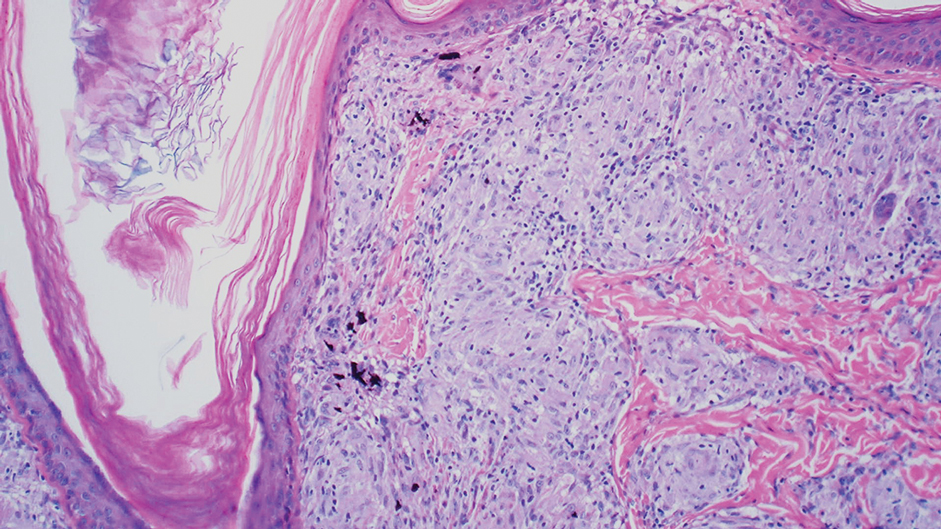

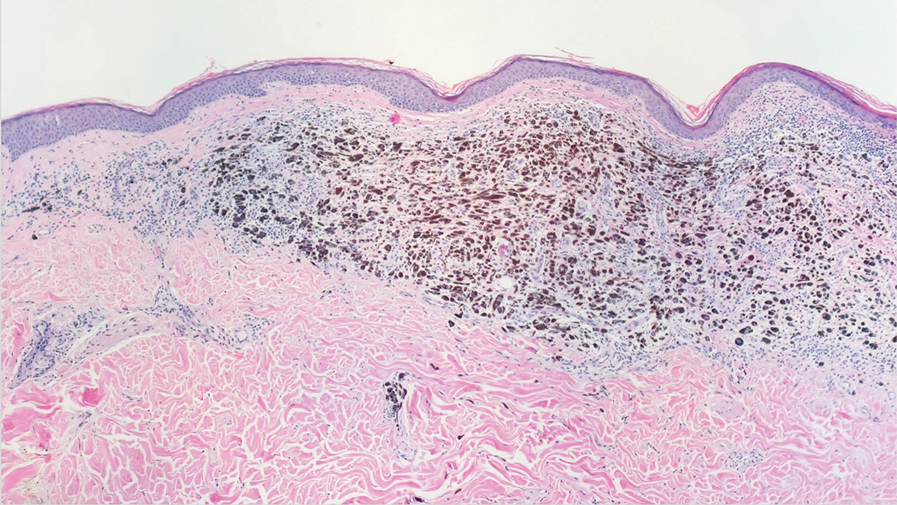

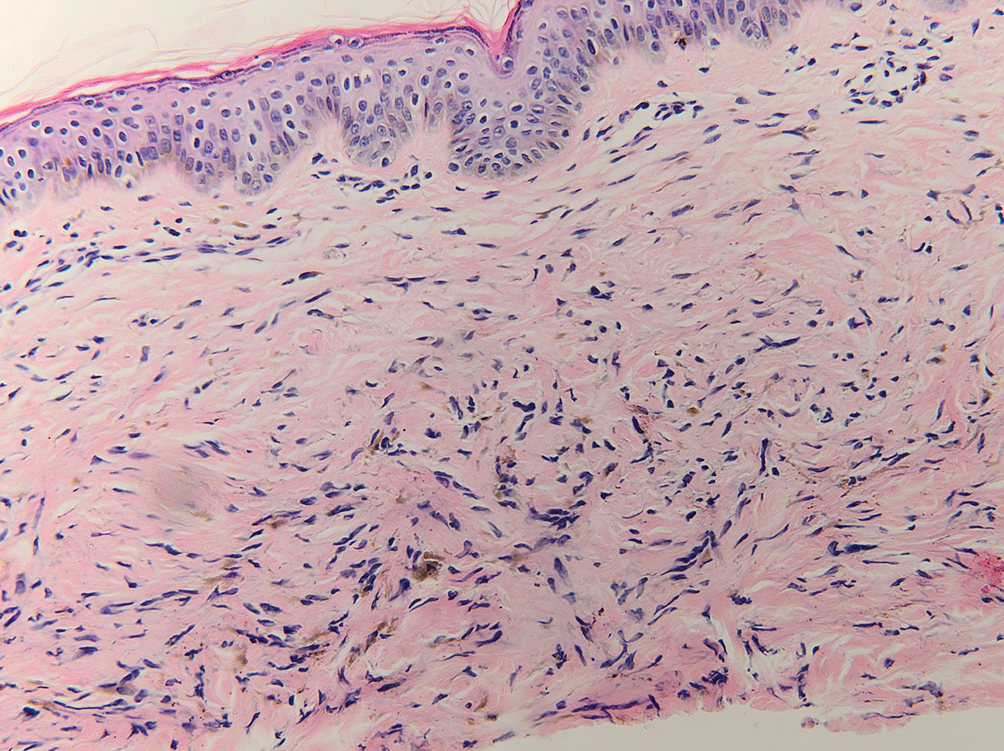

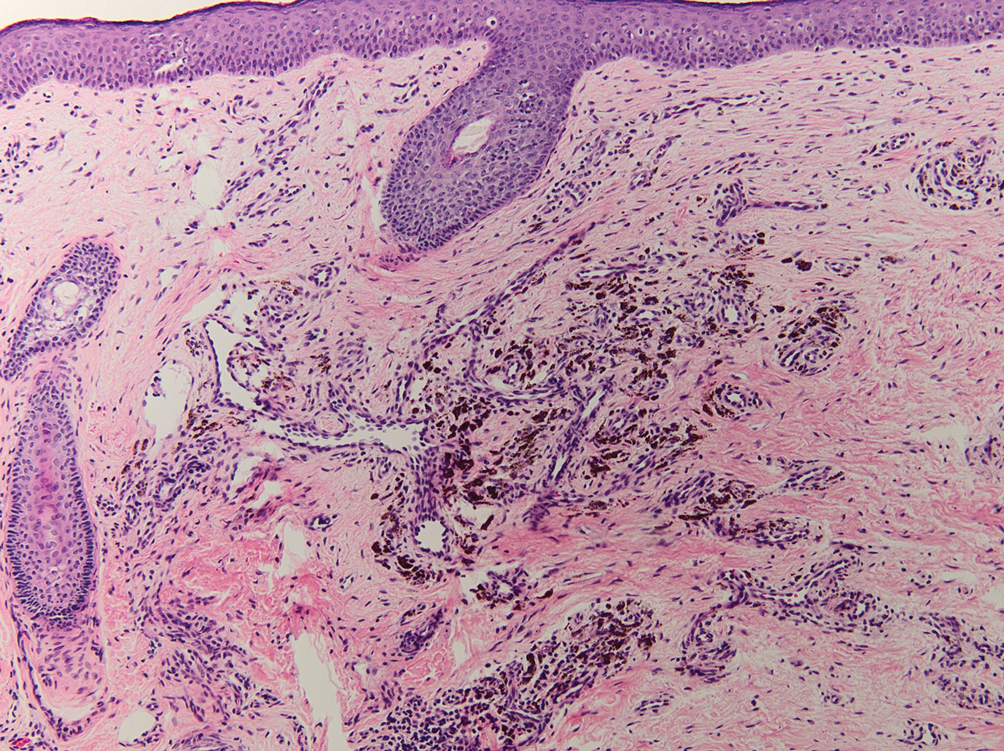

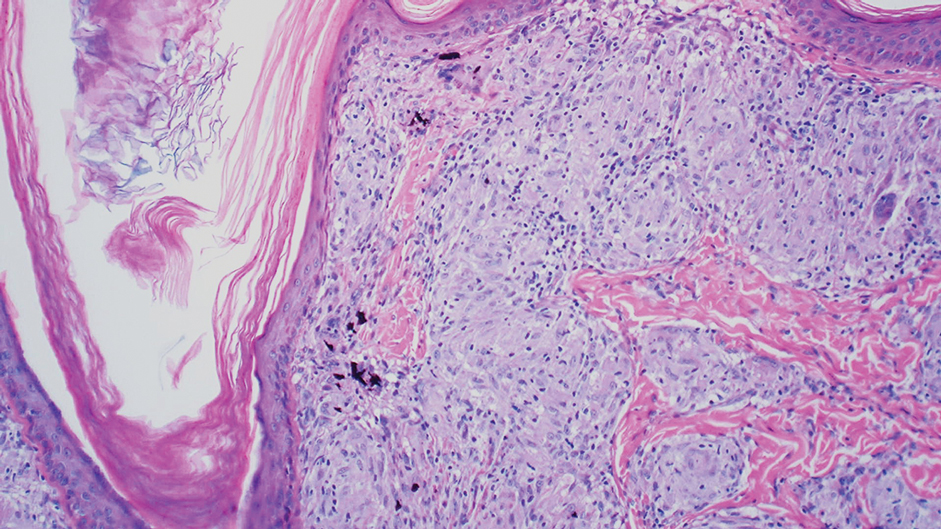

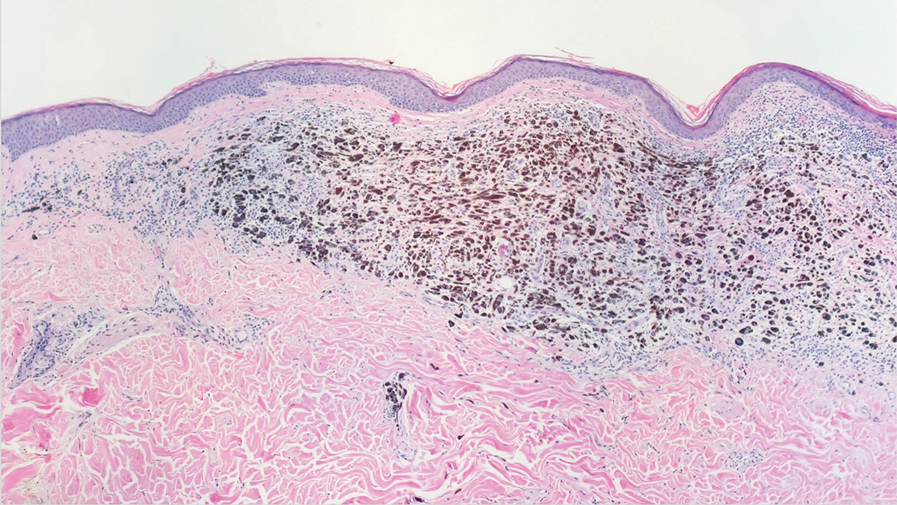

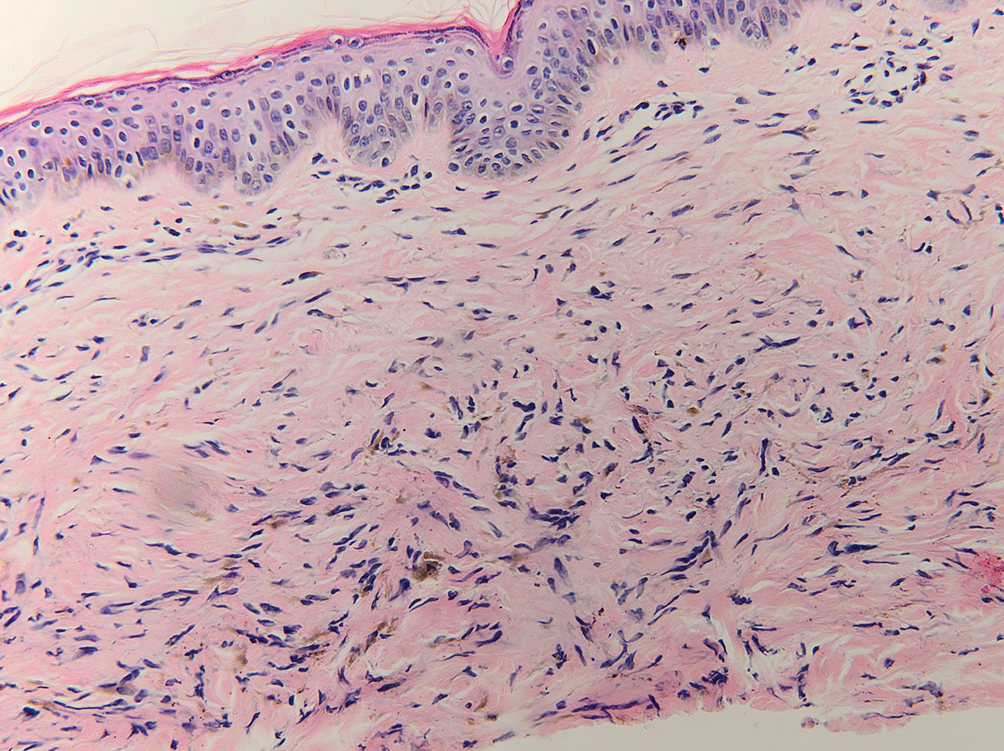

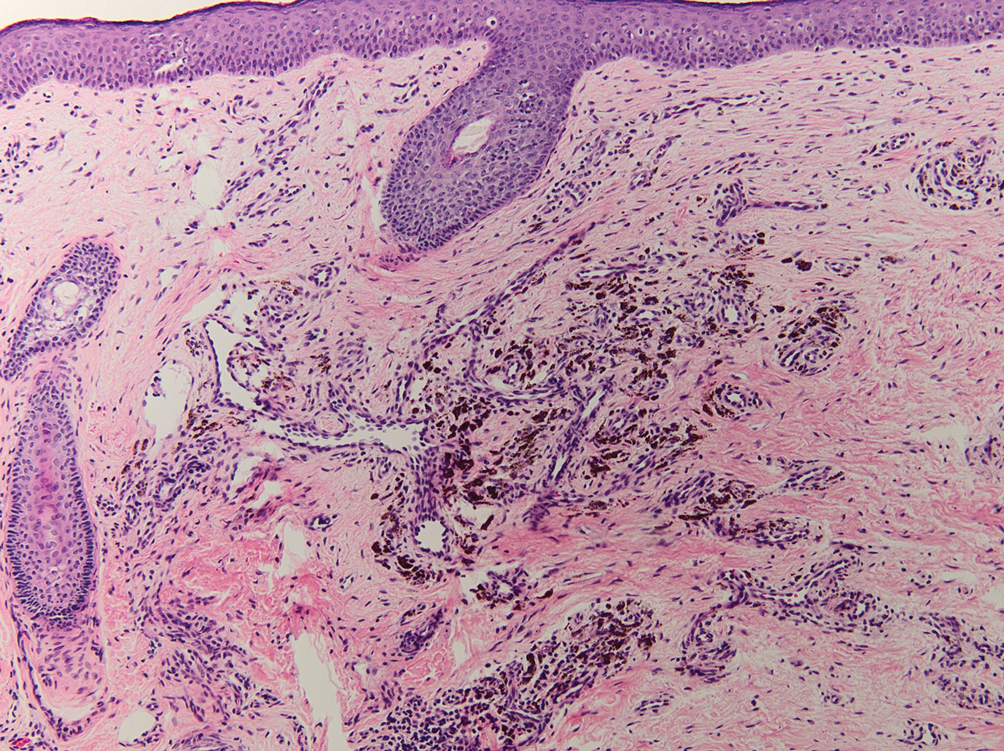

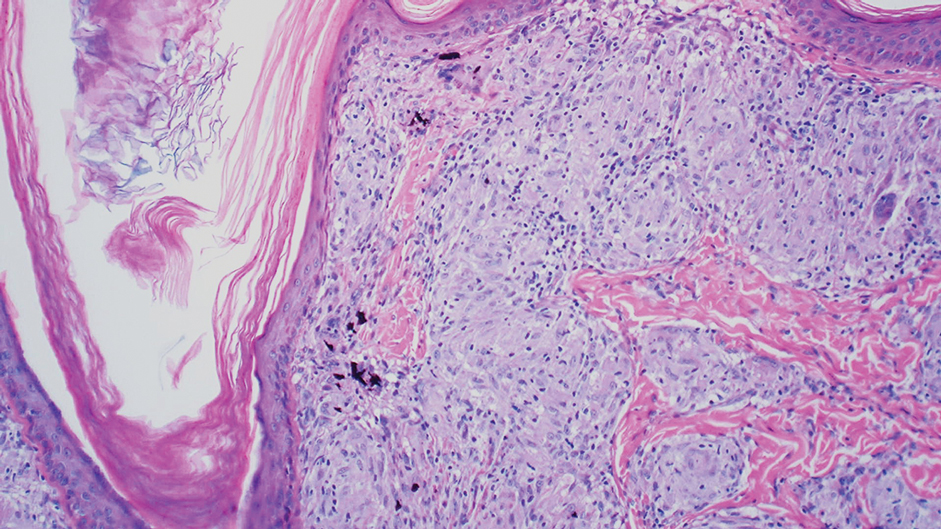

A 45-year-old White woman presented to our clinic for removal of a dermal mass underlying a supernumerary nipple at the left inframammary fold. Her medical history was noncontributory and was only remarkable for uterine fibroids. She developed pain and swelling in the left breast 1 year prior, which prompted her to seek medical attention from her primary care physician. Diagnostic mammography was negative for any concerning malignant nodules, and subsequent BRCA genetic testing also was negative. Six months after the diagnostic mammography, she continued to experience pain and swelling in the left breast and was then referred for diagnostic ultrasonography; 2 masses in the left breast suspected as infected cysts with rupture were identified (Figure 1). She was then referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation and surgical extirpation of the suspected cyst underlying the accessory breast. The area subsequently was excised under local anesthesia, and a second similar but smaller mass also was identified adjacent to the initial growth. Dermatopathologic examination revealed an estrogen receptor– (Figure 2A) and progesterone receptor–positive (Figure 2B), ERBB2 (HER2/neu)–negative, nuclear grade III ductal carcinoma in situ (Figure 3).

Various ABT classification methods have been proposed with Brightmore7 categorizing polymastia into 8 subtypes: (1) complete breast; (2) glandular tissue and nipple; (3) glandular tissue and areola; (4) glandular tissue only; (5) nipple, areola, and fat; (6) nipple only; (7) areola only; and (8) patch of hair only. De Cholnokey8 focused on axillary polymastia, dividing it into 4 classes: (1) axillary tumor in milk line without nipple or areola; (2) axillary tumor with areola with or without pigmentation; (3) nipple or areola without underlying breast tissue; and (4) complete breast with nipple, areola, and glandular tissue. Fenench’s9 method is preferred and simply describes ABT as 2 subtypes: supernumerary and aberrant.1,2,10 One study observed 6% of ABT cancers were the supernumerary type and 94% were the aberrant type.1 Ductal lumen stagnation increases the risk for accessory breast carcinoma development.10 Men have a higher prevalence of cancer in ABT compared to anatomically correct breast tissue.11

There currently is no standardized guideline for ABT cancer treatment. The initial clinical impression of cancer of ABT may be misdiagnosed as lymphadenopathy, abscesses, or lipomas.12 The risk for misdiagnosis is higher for cancer of ABT compared to normal breast tissue and is associated with a poorer prognosis.1 Despite multiple screening modalities, our patient’s initial breast cancer screenings proved unreliable. A mammogram failed to detect malignancy, likely secondary to the area of concern being out of the standard imaging field. Ultrasonography also was unreliable and led to misdiagnosis as an infected sebaceous cyst with rupture in our patient. Upon review of the ultrasound, concerns were raised by dermatology that the mass was more likely an epidermal inclusion cyst with rupture given the more superficial and sac-free nature of sebaceous cysts, which commonly are associated with steatocystoma multiplex.13 Definitive diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ was made with dermatopathologic examination.

Prophylactic surgical excision of ABT has been recommended, suggesting that excisional biopsy and histopathologic examination is the more appropriate method to rule out malignancy. Surgical treatment of ABT may omit any risk for malignant transformation and may provide psychological relief to patients for aesthetic reasons.10,12,14 The risk and benefits of prophylactic excision of ABT has been compared to prophylactic mastectomy of anatomically correct breasts,15 with some clinicians considering this definitive procedure unnecessary except in high-risk patients with a strong genetic predisposition.16,17

Accessory breast tissue should be viewed as an anatomical variant with the option of surgical removal for symptomatic concerns, such as firm nodules, discharge, and pain. Although ABT is rare and cancer in ABT is even more uncommon (<1% of all breast cancers),5,11 clinicians should be suspicious of benign diagnostic reports when the clinical situation does not fit the proposed narrative.

- Marshall MB, Moynihan JJ, Frost A, et al. Ectopic breast cancer: case report and literature review. Surg Oncol. 1994;3:295-304. doi:10.1016/0960-7404(94)90032-9

- DeFilippis EM, Arleo EK. The ABCs of accessory breast tissue: basic information every radiologist should know. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:1157-1162. doi:10.2214/AJR.13.10930

- Famá F, Cicciú M, Sindoni A, et al. Prevalence of ectopic breast tissue and tumor: a 20-year single center experience. Clin Breast Cancer. 2016;16:E107-E112. doi:10.1016/j.clbc.2016.03.004

- Brown J, Schwartz RA. Supernumerary nipples: an overview. Cutis. 2003;71:344-346.

- Nihon-Yanagi Y, Ueda T, Kameda N, et al. A case of ectopic breast cancer with a literature review. Surg Oncol. 2011;20:35-42. doi:10.1016/j.suronc.2009.09.005

- Hedayat AA, Pettus JR, Marotti JD, et al. Proliferative lesion of anogenital mammary-like glands in the setting of Cowden syndrome: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:707-710. doi:10.1111/cup.12721

- Brightmore T. Bilateral double nipples. Br J Surg. 1972;59:55-57. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800590114

- De Cholnoky T. Accessory breast tissue in the axilla. N Y State J Med. 1951;51:2245-2248.

- Fenech HB. Aberrant breast tissue; case report. Harper Hosp Bull. 1949;7:268-271.

- Francone E, Nathan MJ, Murelli F, et al. Ectopic breast cancer: case report and review of the literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:746-749. doi:10.1007/s00266-013-0125-1

- Yamamura J, Masuda N, Kodama Y, et al. Male breast cancer originating in an accessory mammary gland in the axilla: a case report. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:286210. doi:10.1155/2012/286210.

- Ghosn SH, Khatri KA, Bhawan J. Bilateral aberrant axillary breast tissue mimicking lipomas: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):9-13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00713.x

- Arceu M, Martinez G, Alfaro D, et al. Ultrasound morphologic features of steatocystoma multiplex with clinical correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39:2255-2260. doi:10.1002/jum.15320

- Lesavoy MA, Gomez-Garcia A, Nejdl R, et al. Axillary breast tissue: clinical presentation and surgical treatment. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;35:356-360. doi:10.1097/00000637-199510000-00004

- Bank J. Management of ectopic breast tissue. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:750-751. doi:10.1007/s00266-013-0143-z

- Morrow M. Prophylactic mastectomy of the contralateral breast. Breast. 2011;20(suppl 3):S108-S110. doi:10.1016/S0960-9776(11)70306-X

- Teoh V, Tasoulis M-K, Gui G. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with unilateral breast cancer who are genetic carriers, have a strong family history or are just young at presentation. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:140. doi:10.3390/cancers12010140

To the Editor:

The term ectopic breast tissue serves as an umbrella term that encompasses breast tissue positioned in anatomically incorrect locations, including the subtypes of supernumerary and aberrant breasts.1 However, the more frequently used term is accessory breast tissue (ABT).1 Supernumerary breasts have diverse variations of a nipple, areola, and/or ductal tissue and can span in size from a small mole to a fully functioning breast. This breast type maintains structured ductal systems connected to the overlying skin and experiences regular changes during the reproductive cycle. In contrast, an aberrant breast is isolated breast tissue that does not contain organized ductal systems.1 Accessory breast tissue is prevalent in up to 6.0% of the world population, with Japanese individuals being the most affected and White individuals being the least affected.1

Accessory breasts typically are located along the milk line—the embryologic precursor to mammary glands and nipples, which extend from the axillae to the groin and regress from the caudal end spanning to the groin.2 For this reason, incomplete regression of the mammary ridge results in ABT, most commonly in the axillary region.3 Accessory breast tissue usually is benign and is considered an anatomical variant; however, because the histomorphology is similar to mammary gland tissue, accessory breasts have the same proliferative potential as anatomically correct breasts and therefore can form fibroadenomas, cysts, abscesses, mastitis, or breast cancer.4 Accessory breast carcinomas comprise 0.3% to 0.6% of all breast malignancies.5 Certain genodermatoses (ie, Cowden syndrome) also may predispose patients to benign or malignant pathology in ABT.6 We present a rare case of accessory breast cancer in the inframammary region masquerading as a cyst. These findings were further supported by ultrasonography and mammography.

A 45-year-old White woman presented to our clinic for removal of a dermal mass underlying a supernumerary nipple at the left inframammary fold. Her medical history was noncontributory and was only remarkable for uterine fibroids. She developed pain and swelling in the left breast 1 year prior, which prompted her to seek medical attention from her primary care physician. Diagnostic mammography was negative for any concerning malignant nodules, and subsequent BRCA genetic testing also was negative. Six months after the diagnostic mammography, she continued to experience pain and swelling in the left breast and was then referred for diagnostic ultrasonography; 2 masses in the left breast suspected as infected cysts with rupture were identified (Figure 1). She was then referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation and surgical extirpation of the suspected cyst underlying the accessory breast. The area subsequently was excised under local anesthesia, and a second similar but smaller mass also was identified adjacent to the initial growth. Dermatopathologic examination revealed an estrogen receptor– (Figure 2A) and progesterone receptor–positive (Figure 2B), ERBB2 (HER2/neu)–negative, nuclear grade III ductal carcinoma in situ (Figure 3).

Various ABT classification methods have been proposed with Brightmore7 categorizing polymastia into 8 subtypes: (1) complete breast; (2) glandular tissue and nipple; (3) glandular tissue and areola; (4) glandular tissue only; (5) nipple, areola, and fat; (6) nipple only; (7) areola only; and (8) patch of hair only. De Cholnokey8 focused on axillary polymastia, dividing it into 4 classes: (1) axillary tumor in milk line without nipple or areola; (2) axillary tumor with areola with or without pigmentation; (3) nipple or areola without underlying breast tissue; and (4) complete breast with nipple, areola, and glandular tissue. Fenench’s9 method is preferred and simply describes ABT as 2 subtypes: supernumerary and aberrant.1,2,10 One study observed 6% of ABT cancers were the supernumerary type and 94% were the aberrant type.1 Ductal lumen stagnation increases the risk for accessory breast carcinoma development.10 Men have a higher prevalence of cancer in ABT compared to anatomically correct breast tissue.11

There currently is no standardized guideline for ABT cancer treatment. The initial clinical impression of cancer of ABT may be misdiagnosed as lymphadenopathy, abscesses, or lipomas.12 The risk for misdiagnosis is higher for cancer of ABT compared to normal breast tissue and is associated with a poorer prognosis.1 Despite multiple screening modalities, our patient’s initial breast cancer screenings proved unreliable. A mammogram failed to detect malignancy, likely secondary to the area of concern being out of the standard imaging field. Ultrasonography also was unreliable and led to misdiagnosis as an infected sebaceous cyst with rupture in our patient. Upon review of the ultrasound, concerns were raised by dermatology that the mass was more likely an epidermal inclusion cyst with rupture given the more superficial and sac-free nature of sebaceous cysts, which commonly are associated with steatocystoma multiplex.13 Definitive diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ was made with dermatopathologic examination.

Prophylactic surgical excision of ABT has been recommended, suggesting that excisional biopsy and histopathologic examination is the more appropriate method to rule out malignancy. Surgical treatment of ABT may omit any risk for malignant transformation and may provide psychological relief to patients for aesthetic reasons.10,12,14 The risk and benefits of prophylactic excision of ABT has been compared to prophylactic mastectomy of anatomically correct breasts,15 with some clinicians considering this definitive procedure unnecessary except in high-risk patients with a strong genetic predisposition.16,17

Accessory breast tissue should be viewed as an anatomical variant with the option of surgical removal for symptomatic concerns, such as firm nodules, discharge, and pain. Although ABT is rare and cancer in ABT is even more uncommon (<1% of all breast cancers),5,11 clinicians should be suspicious of benign diagnostic reports when the clinical situation does not fit the proposed narrative.

To the Editor:

The term ectopic breast tissue serves as an umbrella term that encompasses breast tissue positioned in anatomically incorrect locations, including the subtypes of supernumerary and aberrant breasts.1 However, the more frequently used term is accessory breast tissue (ABT).1 Supernumerary breasts have diverse variations of a nipple, areola, and/or ductal tissue and can span in size from a small mole to a fully functioning breast. This breast type maintains structured ductal systems connected to the overlying skin and experiences regular changes during the reproductive cycle. In contrast, an aberrant breast is isolated breast tissue that does not contain organized ductal systems.1 Accessory breast tissue is prevalent in up to 6.0% of the world population, with Japanese individuals being the most affected and White individuals being the least affected.1

Accessory breasts typically are located along the milk line—the embryologic precursor to mammary glands and nipples, which extend from the axillae to the groin and regress from the caudal end spanning to the groin.2 For this reason, incomplete regression of the mammary ridge results in ABT, most commonly in the axillary region.3 Accessory breast tissue usually is benign and is considered an anatomical variant; however, because the histomorphology is similar to mammary gland tissue, accessory breasts have the same proliferative potential as anatomically correct breasts and therefore can form fibroadenomas, cysts, abscesses, mastitis, or breast cancer.4 Accessory breast carcinomas comprise 0.3% to 0.6% of all breast malignancies.5 Certain genodermatoses (ie, Cowden syndrome) also may predispose patients to benign or malignant pathology in ABT.6 We present a rare case of accessory breast cancer in the inframammary region masquerading as a cyst. These findings were further supported by ultrasonography and mammography.

A 45-year-old White woman presented to our clinic for removal of a dermal mass underlying a supernumerary nipple at the left inframammary fold. Her medical history was noncontributory and was only remarkable for uterine fibroids. She developed pain and swelling in the left breast 1 year prior, which prompted her to seek medical attention from her primary care physician. Diagnostic mammography was negative for any concerning malignant nodules, and subsequent BRCA genetic testing also was negative. Six months after the diagnostic mammography, she continued to experience pain and swelling in the left breast and was then referred for diagnostic ultrasonography; 2 masses in the left breast suspected as infected cysts with rupture were identified (Figure 1). She was then referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation and surgical extirpation of the suspected cyst underlying the accessory breast. The area subsequently was excised under local anesthesia, and a second similar but smaller mass also was identified adjacent to the initial growth. Dermatopathologic examination revealed an estrogen receptor– (Figure 2A) and progesterone receptor–positive (Figure 2B), ERBB2 (HER2/neu)–negative, nuclear grade III ductal carcinoma in situ (Figure 3).

Various ABT classification methods have been proposed with Brightmore7 categorizing polymastia into 8 subtypes: (1) complete breast; (2) glandular tissue and nipple; (3) glandular tissue and areola; (4) glandular tissue only; (5) nipple, areola, and fat; (6) nipple only; (7) areola only; and (8) patch of hair only. De Cholnokey8 focused on axillary polymastia, dividing it into 4 classes: (1) axillary tumor in milk line without nipple or areola; (2) axillary tumor with areola with or without pigmentation; (3) nipple or areola without underlying breast tissue; and (4) complete breast with nipple, areola, and glandular tissue. Fenench’s9 method is preferred and simply describes ABT as 2 subtypes: supernumerary and aberrant.1,2,10 One study observed 6% of ABT cancers were the supernumerary type and 94% were the aberrant type.1 Ductal lumen stagnation increases the risk for accessory breast carcinoma development.10 Men have a higher prevalence of cancer in ABT compared to anatomically correct breast tissue.11

There currently is no standardized guideline for ABT cancer treatment. The initial clinical impression of cancer of ABT may be misdiagnosed as lymphadenopathy, abscesses, or lipomas.12 The risk for misdiagnosis is higher for cancer of ABT compared to normal breast tissue and is associated with a poorer prognosis.1 Despite multiple screening modalities, our patient’s initial breast cancer screenings proved unreliable. A mammogram failed to detect malignancy, likely secondary to the area of concern being out of the standard imaging field. Ultrasonography also was unreliable and led to misdiagnosis as an infected sebaceous cyst with rupture in our patient. Upon review of the ultrasound, concerns were raised by dermatology that the mass was more likely an epidermal inclusion cyst with rupture given the more superficial and sac-free nature of sebaceous cysts, which commonly are associated with steatocystoma multiplex.13 Definitive diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ was made with dermatopathologic examination.

Prophylactic surgical excision of ABT has been recommended, suggesting that excisional biopsy and histopathologic examination is the more appropriate method to rule out malignancy. Surgical treatment of ABT may omit any risk for malignant transformation and may provide psychological relief to patients for aesthetic reasons.10,12,14 The risk and benefits of prophylactic excision of ABT has been compared to prophylactic mastectomy of anatomically correct breasts,15 with some clinicians considering this definitive procedure unnecessary except in high-risk patients with a strong genetic predisposition.16,17

Accessory breast tissue should be viewed as an anatomical variant with the option of surgical removal for symptomatic concerns, such as firm nodules, discharge, and pain. Although ABT is rare and cancer in ABT is even more uncommon (<1% of all breast cancers),5,11 clinicians should be suspicious of benign diagnostic reports when the clinical situation does not fit the proposed narrative.

- Marshall MB, Moynihan JJ, Frost A, et al. Ectopic breast cancer: case report and literature review. Surg Oncol. 1994;3:295-304. doi:10.1016/0960-7404(94)90032-9

- DeFilippis EM, Arleo EK. The ABCs of accessory breast tissue: basic information every radiologist should know. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:1157-1162. doi:10.2214/AJR.13.10930

- Famá F, Cicciú M, Sindoni A, et al. Prevalence of ectopic breast tissue and tumor: a 20-year single center experience. Clin Breast Cancer. 2016;16:E107-E112. doi:10.1016/j.clbc.2016.03.004

- Brown J, Schwartz RA. Supernumerary nipples: an overview. Cutis. 2003;71:344-346.

- Nihon-Yanagi Y, Ueda T, Kameda N, et al. A case of ectopic breast cancer with a literature review. Surg Oncol. 2011;20:35-42. doi:10.1016/j.suronc.2009.09.005

- Hedayat AA, Pettus JR, Marotti JD, et al. Proliferative lesion of anogenital mammary-like glands in the setting of Cowden syndrome: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:707-710. doi:10.1111/cup.12721

- Brightmore T. Bilateral double nipples. Br J Surg. 1972;59:55-57. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800590114

- De Cholnoky T. Accessory breast tissue in the axilla. N Y State J Med. 1951;51:2245-2248.

- Fenech HB. Aberrant breast tissue; case report. Harper Hosp Bull. 1949;7:268-271.

- Francone E, Nathan MJ, Murelli F, et al. Ectopic breast cancer: case report and review of the literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:746-749. doi:10.1007/s00266-013-0125-1

- Yamamura J, Masuda N, Kodama Y, et al. Male breast cancer originating in an accessory mammary gland in the axilla: a case report. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:286210. doi:10.1155/2012/286210.

- Ghosn SH, Khatri KA, Bhawan J. Bilateral aberrant axillary breast tissue mimicking lipomas: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):9-13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00713.x

- Arceu M, Martinez G, Alfaro D, et al. Ultrasound morphologic features of steatocystoma multiplex with clinical correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39:2255-2260. doi:10.1002/jum.15320

- Lesavoy MA, Gomez-Garcia A, Nejdl R, et al. Axillary breast tissue: clinical presentation and surgical treatment. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;35:356-360. doi:10.1097/00000637-199510000-00004

- Bank J. Management of ectopic breast tissue. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:750-751. doi:10.1007/s00266-013-0143-z

- Morrow M. Prophylactic mastectomy of the contralateral breast. Breast. 2011;20(suppl 3):S108-S110. doi:10.1016/S0960-9776(11)70306-X

- Teoh V, Tasoulis M-K, Gui G. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with unilateral breast cancer who are genetic carriers, have a strong family history or are just young at presentation. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:140. doi:10.3390/cancers12010140

- Marshall MB, Moynihan JJ, Frost A, et al. Ectopic breast cancer: case report and literature review. Surg Oncol. 1994;3:295-304. doi:10.1016/0960-7404(94)90032-9

- DeFilippis EM, Arleo EK. The ABCs of accessory breast tissue: basic information every radiologist should know. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:1157-1162. doi:10.2214/AJR.13.10930

- Famá F, Cicciú M, Sindoni A, et al. Prevalence of ectopic breast tissue and tumor: a 20-year single center experience. Clin Breast Cancer. 2016;16:E107-E112. doi:10.1016/j.clbc.2016.03.004

- Brown J, Schwartz RA. Supernumerary nipples: an overview. Cutis. 2003;71:344-346.

- Nihon-Yanagi Y, Ueda T, Kameda N, et al. A case of ectopic breast cancer with a literature review. Surg Oncol. 2011;20:35-42. doi:10.1016/j.suronc.2009.09.005

- Hedayat AA, Pettus JR, Marotti JD, et al. Proliferative lesion of anogenital mammary-like glands in the setting of Cowden syndrome: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:707-710. doi:10.1111/cup.12721

- Brightmore T. Bilateral double nipples. Br J Surg. 1972;59:55-57. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800590114

- De Cholnoky T. Accessory breast tissue in the axilla. N Y State J Med. 1951;51:2245-2248.

- Fenech HB. Aberrant breast tissue; case report. Harper Hosp Bull. 1949;7:268-271.

- Francone E, Nathan MJ, Murelli F, et al. Ectopic breast cancer: case report and review of the literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:746-749. doi:10.1007/s00266-013-0125-1

- Yamamura J, Masuda N, Kodama Y, et al. Male breast cancer originating in an accessory mammary gland in the axilla: a case report. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:286210. doi:10.1155/2012/286210.

- Ghosn SH, Khatri KA, Bhawan J. Bilateral aberrant axillary breast tissue mimicking lipomas: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):9-13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00713.x

- Arceu M, Martinez G, Alfaro D, et al. Ultrasound morphologic features of steatocystoma multiplex with clinical correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39:2255-2260. doi:10.1002/jum.15320

- Lesavoy MA, Gomez-Garcia A, Nejdl R, et al. Axillary breast tissue: clinical presentation and surgical treatment. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;35:356-360. doi:10.1097/00000637-199510000-00004

- Bank J. Management of ectopic breast tissue. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:750-751. doi:10.1007/s00266-013-0143-z

- Morrow M. Prophylactic mastectomy of the contralateral breast. Breast. 2011;20(suppl 3):S108-S110. doi:10.1016/S0960-9776(11)70306-X

- Teoh V, Tasoulis M-K, Gui G. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with unilateral breast cancer who are genetic carriers, have a strong family history or are just young at presentation. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:140. doi:10.3390/cancers12010140

Practice Points

- Accessory breasts (also referred to as ectopic breast tissue) develop when breast tissue is retained along the mammary ridge outside of the usual pectoral regions.

- Because accessory breasts may contain the same structures as anatomically correct breasts, they can be subject to the same benign or malignant changes.

- Clinical and pathologic correlation is prudent when interpreting ectopic mammary tissue, as various benign or malignant neoplasms may arise in this setting, especially if there are underlying genetic aberrancies or genodermatoses.

ChatGPT in Dermatology Clinical Practice: Potential Uses and Pitfalls

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology has increasingly been incorporated in medicine. In dermatology, AI has been used to detect and diagnose skin lesions, including skin cancer.1 ChatGPT (OpenAI) is a novel, highly popular development in generative AI technology. A large language model released in 2022, ChatGPT is a chatbot designed to mimic human conversation and generate specific detailed information when prompted. Free and publicly available, it has been used by millions of people. ChatGPT’s application in the medical field currently is being evaluated across several specialties, including plastic surgery, radiology, and urology.2-4 ChatGPT has the potential to assist health care professionals, including dermatologists, though its use raises important ethical considerations. Herein, we focus on the potential benefits as well as the pitfalls of using ChatGPT in dermatology clinical practice.

Potential Uses of ChatGPT in Practice

A major benefit of ChatGPT is its ability to improve clinical efficiency. First, ChatGPT can provide quick access to general medical information, similar to a search engine but with more natural language processing and contextual understanding to synthesize information.5 This function is useful for rapid concise answers to specific and directed questions. ChatGPT also can interact with its user by asking follow-up questions to produce more precise and relevant responses; this feature may help dermatologists form more accurate differential diagnoses. Additionally, ChatGPT can increase efficiency in clinical practice by drafting generic medical documents,2 including templates for after-visit summaries, postprocedure instructions, referrals, prior authorization appeal letters, and educational handouts. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. Another useful feature of ChatGPT is its ability to output information modeling human conversation. Because of this feature, ChatGPT also could be employed in clinical practice to serve as an interpreter for patients during clinic visits. Currently, the use of virtual translators can be cumbersome and subject to technical constraints. ChatGPT can provide accurate and conversational translations for patients and dermatologists, improving the patient-provider relationship.

ChatGPT also can contribute to major advancements in the field of dermatology beyond the clinical setting. Because of its ability to draw from extensive data that have already been uploaded, there are some uses of ChatGPT in a research context: to assist in finding resources for research and reviews, formulating hypotheses, drafting study protocols, and collecting large amounts of data within seconds.6

ChatGPT also has potential in advancing medical education. It could be used by medical schools to model interactive patient encounters to help students practice taking a patient’s history and creating differential diagnoses.6 This application of ChatGPT may help medical students hone their clinical skills in a low-stress environment without the restrictions that can come with hiring and training standardized patients, especially when mimicking dermatologic clinical encounters.

Other possibilities for ChatGPT in dermatologic practice include survey administration, clinical trial recruitment, and even automatic high-risk medication monitoring. Despite the many potential applications of ChatGPT in clinical practice, the question raised in each scenario is the quality, accuracy, and safety of what it produces.

Potential Pitfalls of ChatGPT in Practice and Possible Mitigation Strategies

A main concern in using ChatGPT in clinical practice is its potential to produce inaccurate or biased information. When prompted to create a research abstract based on previously published research, ChatGPT drafted abstracts that were clear and digestible but supplemented with incorrect data.7 A group of medical researchers who reviewed these ChatGPT-generated abstracts mistook 32% of the abstracts as having been written by human researchers. The implications of this finding are worrisome. If inaccurate or false information is used by ChatGPT in documents sent to insurance companies or patients, the patient’s safety as well as the dermatologist’s license and credibility are at stake. Thus, dermatologists looking to use ChatGPT to draft generic medical documents should actively review the output to ensure that the information is accurate. Importantly, ChatGPT also is only currently programmed with information up to 2021, limiting its access to recently published research articles and updated International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes.5 The continued development of ChatGPT will lead to regular updates by OpenAI that resolve this shortcoming in the future. Further, AI models may encode and perpetuate harmful stereotypes and social biases that are present in training data.8

When considering its potential in clinical practice, ChatGPT itself states that it can aid in clinical decision-making by processing patient information, including history, current symptoms, and biopsy and test results. This is uncharted territory, and providers who use ChatGPT at this stage to aid in decision-making should regard it similarly to information retrieved from a search engine. The information produced by ChatGPT should be used to substantiate but not definitively confirm a diagnosis or dictate management. Clinical suspicion by the dermatologist should always trump ChatGPT output. If physicians recommend ChatGPT output over their own advice, it can become a liability, as the technology is not regulated to any degree. Patients also should be cautious when seeking and following medical advice from ChatGPT, as it could be misleading or incorrect and could undermine the patient-physician relationship.6

Additionally, the specific use of ChatGPT to evaluate patient health records raises concerns related to patient privacy and confidentiality. Providers should never enter patient information protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act into ChatGPT or anywhere else on the internet. Mitigation of this risk is not currently possible; ChatGPT requires more development and further understanding to even consider its integration into current electronic health records without compromising patient confidentiality.

The Bottom Line

Overall, ChatGPT has the potential to improve efficiency in clinical practice by assisting with informational searches and document drafting. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. However, dermatologists should carefully weigh the ethical issues of nonmaleficence and justice in evaluating ChatGPT for accuracy, biases, and the protection of patient confidentiality.

Finally, we asked ChatGPT on February 28, 2023, what it thinks:

User: Should dermatologists use ChatGPT in clinical practice?

ChatGPT: As an AI language model, ChatGPT can be a useful tool in dermatology clinical practice, but it should be used with caution in conjunction with other sources of information and clinical judgement.

Dermatologists should be aware of the potential benefits and risks of using ChatGPT and make informed decisions about how to integrate it into their clinical practice. It’s important to remember that ChatGPT is not a substitute for clinical expertise or human interaction with patients, and it should only be used as a supplement to enhance the quality of patient care.

Dermatologists who choose to use ChatGPT should also be aware of its limitations and potential risks, such as limited accuracy, lack of context, and liability issues if it provides incorrect information or recommendations that lead to patient harm. Dermatologists should use their professional judgement and consult with other health care professionals when making important decisions regarding patient care.

- Thomsen K, Iversen L, Titlestad TL, et al. Systematic review of machine learning for diagnosis and prognosis in dermatology. J Dermatol Treat. 2020;31:496-510. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1682500

- Shen Y, Heacock L, Elias J, et al. ChatGPT and other large language models are double-edged swords. Radiology. 2023;307:E230163. doi:10.1148/radiol.230163

- Gupta R, Pande P, Herzog I, et al. Application of ChatGPT in cosmetic plastic surgery: ally or antagonist? Aesthet Surg J. 2023;43:NP587-NP590. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjad042

- Gabrielson AT, Odisho AY, Canes D. Harnessing generative artificial intelligence to improve efficiency among urologists: welcome ChatGPT. J Urol. 2023;209:827-829. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003383

- What is ChatGPT? OpenAI. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://help.openai.com/en/articles/6783457-chatgpt-general-faq

- Haupt CE, Marks M. AI-generated medical advice—GPT and beyond. JAMA. 2023;329:1349-1350. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5321

- Gao CA, Howard FM, Markov NS, et al. Comparing Scientific Abstracts Generated by ChatGPT to Original Abstracts Using an Artificial Intelligence Output Detector, Plagiarism Detector, and Blinded Human Reviewers. Scientific Communication and Education; 2022. doi:10.1101/2022.12.23.521610

- Weidinger L, Mellor J, Rauh M, et al. Ethical and social risks of harm from language models. arXiv. Preprint posted online December 8, 2021. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2112.04359

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology has increasingly been incorporated in medicine. In dermatology, AI has been used to detect and diagnose skin lesions, including skin cancer.1 ChatGPT (OpenAI) is a novel, highly popular development in generative AI technology. A large language model released in 2022, ChatGPT is a chatbot designed to mimic human conversation and generate specific detailed information when prompted. Free and publicly available, it has been used by millions of people. ChatGPT’s application in the medical field currently is being evaluated across several specialties, including plastic surgery, radiology, and urology.2-4 ChatGPT has the potential to assist health care professionals, including dermatologists, though its use raises important ethical considerations. Herein, we focus on the potential benefits as well as the pitfalls of using ChatGPT in dermatology clinical practice.

Potential Uses of ChatGPT in Practice

A major benefit of ChatGPT is its ability to improve clinical efficiency. First, ChatGPT can provide quick access to general medical information, similar to a search engine but with more natural language processing and contextual understanding to synthesize information.5 This function is useful for rapid concise answers to specific and directed questions. ChatGPT also can interact with its user by asking follow-up questions to produce more precise and relevant responses; this feature may help dermatologists form more accurate differential diagnoses. Additionally, ChatGPT can increase efficiency in clinical practice by drafting generic medical documents,2 including templates for after-visit summaries, postprocedure instructions, referrals, prior authorization appeal letters, and educational handouts. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. Another useful feature of ChatGPT is its ability to output information modeling human conversation. Because of this feature, ChatGPT also could be employed in clinical practice to serve as an interpreter for patients during clinic visits. Currently, the use of virtual translators can be cumbersome and subject to technical constraints. ChatGPT can provide accurate and conversational translations for patients and dermatologists, improving the patient-provider relationship.

ChatGPT also can contribute to major advancements in the field of dermatology beyond the clinical setting. Because of its ability to draw from extensive data that have already been uploaded, there are some uses of ChatGPT in a research context: to assist in finding resources for research and reviews, formulating hypotheses, drafting study protocols, and collecting large amounts of data within seconds.6

ChatGPT also has potential in advancing medical education. It could be used by medical schools to model interactive patient encounters to help students practice taking a patient’s history and creating differential diagnoses.6 This application of ChatGPT may help medical students hone their clinical skills in a low-stress environment without the restrictions that can come with hiring and training standardized patients, especially when mimicking dermatologic clinical encounters.

Other possibilities for ChatGPT in dermatologic practice include survey administration, clinical trial recruitment, and even automatic high-risk medication monitoring. Despite the many potential applications of ChatGPT in clinical practice, the question raised in each scenario is the quality, accuracy, and safety of what it produces.

Potential Pitfalls of ChatGPT in Practice and Possible Mitigation Strategies

A main concern in using ChatGPT in clinical practice is its potential to produce inaccurate or biased information. When prompted to create a research abstract based on previously published research, ChatGPT drafted abstracts that were clear and digestible but supplemented with incorrect data.7 A group of medical researchers who reviewed these ChatGPT-generated abstracts mistook 32% of the abstracts as having been written by human researchers. The implications of this finding are worrisome. If inaccurate or false information is used by ChatGPT in documents sent to insurance companies or patients, the patient’s safety as well as the dermatologist’s license and credibility are at stake. Thus, dermatologists looking to use ChatGPT to draft generic medical documents should actively review the output to ensure that the information is accurate. Importantly, ChatGPT also is only currently programmed with information up to 2021, limiting its access to recently published research articles and updated International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes.5 The continued development of ChatGPT will lead to regular updates by OpenAI that resolve this shortcoming in the future. Further, AI models may encode and perpetuate harmful stereotypes and social biases that are present in training data.8

When considering its potential in clinical practice, ChatGPT itself states that it can aid in clinical decision-making by processing patient information, including history, current symptoms, and biopsy and test results. This is uncharted territory, and providers who use ChatGPT at this stage to aid in decision-making should regard it similarly to information retrieved from a search engine. The information produced by ChatGPT should be used to substantiate but not definitively confirm a diagnosis or dictate management. Clinical suspicion by the dermatologist should always trump ChatGPT output. If physicians recommend ChatGPT output over their own advice, it can become a liability, as the technology is not regulated to any degree. Patients also should be cautious when seeking and following medical advice from ChatGPT, as it could be misleading or incorrect and could undermine the patient-physician relationship.6

Additionally, the specific use of ChatGPT to evaluate patient health records raises concerns related to patient privacy and confidentiality. Providers should never enter patient information protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act into ChatGPT or anywhere else on the internet. Mitigation of this risk is not currently possible; ChatGPT requires more development and further understanding to even consider its integration into current electronic health records without compromising patient confidentiality.

The Bottom Line

Overall, ChatGPT has the potential to improve efficiency in clinical practice by assisting with informational searches and document drafting. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. However, dermatologists should carefully weigh the ethical issues of nonmaleficence and justice in evaluating ChatGPT for accuracy, biases, and the protection of patient confidentiality.

Finally, we asked ChatGPT on February 28, 2023, what it thinks:

User: Should dermatologists use ChatGPT in clinical practice?

ChatGPT: As an AI language model, ChatGPT can be a useful tool in dermatology clinical practice, but it should be used with caution in conjunction with other sources of information and clinical judgement.

Dermatologists should be aware of the potential benefits and risks of using ChatGPT and make informed decisions about how to integrate it into their clinical practice. It’s important to remember that ChatGPT is not a substitute for clinical expertise or human interaction with patients, and it should only be used as a supplement to enhance the quality of patient care.

Dermatologists who choose to use ChatGPT should also be aware of its limitations and potential risks, such as limited accuracy, lack of context, and liability issues if it provides incorrect information or recommendations that lead to patient harm. Dermatologists should use their professional judgement and consult with other health care professionals when making important decisions regarding patient care.

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology has increasingly been incorporated in medicine. In dermatology, AI has been used to detect and diagnose skin lesions, including skin cancer.1 ChatGPT (OpenAI) is a novel, highly popular development in generative AI technology. A large language model released in 2022, ChatGPT is a chatbot designed to mimic human conversation and generate specific detailed information when prompted. Free and publicly available, it has been used by millions of people. ChatGPT’s application in the medical field currently is being evaluated across several specialties, including plastic surgery, radiology, and urology.2-4 ChatGPT has the potential to assist health care professionals, including dermatologists, though its use raises important ethical considerations. Herein, we focus on the potential benefits as well as the pitfalls of using ChatGPT in dermatology clinical practice.

Potential Uses of ChatGPT in Practice

A major benefit of ChatGPT is its ability to improve clinical efficiency. First, ChatGPT can provide quick access to general medical information, similar to a search engine but with more natural language processing and contextual understanding to synthesize information.5 This function is useful for rapid concise answers to specific and directed questions. ChatGPT also can interact with its user by asking follow-up questions to produce more precise and relevant responses; this feature may help dermatologists form more accurate differential diagnoses. Additionally, ChatGPT can increase efficiency in clinical practice by drafting generic medical documents,2 including templates for after-visit summaries, postprocedure instructions, referrals, prior authorization appeal letters, and educational handouts. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. Another useful feature of ChatGPT is its ability to output information modeling human conversation. Because of this feature, ChatGPT also could be employed in clinical practice to serve as an interpreter for patients during clinic visits. Currently, the use of virtual translators can be cumbersome and subject to technical constraints. ChatGPT can provide accurate and conversational translations for patients and dermatologists, improving the patient-provider relationship.

ChatGPT also can contribute to major advancements in the field of dermatology beyond the clinical setting. Because of its ability to draw from extensive data that have already been uploaded, there are some uses of ChatGPT in a research context: to assist in finding resources for research and reviews, formulating hypotheses, drafting study protocols, and collecting large amounts of data within seconds.6

ChatGPT also has potential in advancing medical education. It could be used by medical schools to model interactive patient encounters to help students practice taking a patient’s history and creating differential diagnoses.6 This application of ChatGPT may help medical students hone their clinical skills in a low-stress environment without the restrictions that can come with hiring and training standardized patients, especially when mimicking dermatologic clinical encounters.

Other possibilities for ChatGPT in dermatologic practice include survey administration, clinical trial recruitment, and even automatic high-risk medication monitoring. Despite the many potential applications of ChatGPT in clinical practice, the question raised in each scenario is the quality, accuracy, and safety of what it produces.

Potential Pitfalls of ChatGPT in Practice and Possible Mitigation Strategies

A main concern in using ChatGPT in clinical practice is its potential to produce inaccurate or biased information. When prompted to create a research abstract based on previously published research, ChatGPT drafted abstracts that were clear and digestible but supplemented with incorrect data.7 A group of medical researchers who reviewed these ChatGPT-generated abstracts mistook 32% of the abstracts as having been written by human researchers. The implications of this finding are worrisome. If inaccurate or false information is used by ChatGPT in documents sent to insurance companies or patients, the patient’s safety as well as the dermatologist’s license and credibility are at stake. Thus, dermatologists looking to use ChatGPT to draft generic medical documents should actively review the output to ensure that the information is accurate. Importantly, ChatGPT also is only currently programmed with information up to 2021, limiting its access to recently published research articles and updated International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes.5 The continued development of ChatGPT will lead to regular updates by OpenAI that resolve this shortcoming in the future. Further, AI models may encode and perpetuate harmful stereotypes and social biases that are present in training data.8

When considering its potential in clinical practice, ChatGPT itself states that it can aid in clinical decision-making by processing patient information, including history, current symptoms, and biopsy and test results. This is uncharted territory, and providers who use ChatGPT at this stage to aid in decision-making should regard it similarly to information retrieved from a search engine. The information produced by ChatGPT should be used to substantiate but not definitively confirm a diagnosis or dictate management. Clinical suspicion by the dermatologist should always trump ChatGPT output. If physicians recommend ChatGPT output over their own advice, it can become a liability, as the technology is not regulated to any degree. Patients also should be cautious when seeking and following medical advice from ChatGPT, as it could be misleading or incorrect and could undermine the patient-physician relationship.6