User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Acyclovir-Resistant Cutaneous Herpes Simplex Virus in DOCK8 Deficiency

Dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8 ) deficiency is the major cause of autosomal-recessive hyper-IgEsyndrome. 1 Characteristic clinical features including eosinophilia, eczema, and recurrent Staphylococcus aureus cutaneous and respiratory tract infections are common in DOCK8 deficiency, similar to the autosomal-dominant form of hyper-IgE syndrome that is due to defi c iency of signal transducer and activation of transcription 3 (STAT-3 ). 1 In addition, patients with DOCK8 deficiency are particularly susceptible to asthma; food allergies; lymphomas; and severe cutaneous viral infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), molluscum contagiosum, varicella-zoster virus, and human papillomavirus. Since the discovery of the DOCK8 gene in 2009, various studies have sought to elucidate the mechanistic contribution of DOCK8 to the dermatologic immune environment. 2 Although cutaneous viral infections such as those caused by HSV typically are short lived and self-limiting in immunocompetent hosts, they have proven to be severe and recalcitrant in the setting of DOCK8 deficiency. 1 Herein, we report the case of a 32-month-old girl with homozygous DOCK8 deficiency who developed acyclovir-resistant cutaneous HSV.

Case Report

A 32-month-old girl presented with an approximately 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus at month 9 of a hospital stay for recurrent infections. Her medical history was notable for multiple upper respiratory tract infections, diffuse eczema, and food allergies. She had presented to an outside hospital at 14 months of age with herpetic gingivostomatitis and eczema herpeticum that was successfully treated with acyclovir. She was readmitted at 20 months of age due to Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, pancytopenia, and disseminated histoplasmosis. Prophylactic oral acyclovir (20 mg/kg twice daily) was started, given her history of HSV infection. Because of recurrent infections, she underwent an immunodeficiency workup. Whole exome sequencing analysis revealed a homozygous deletion c.(528+1_529−1)_(1516+1_1517−1)del in DOCK8 gene–affecting exons 5 to 13. The patient was transferred to our hospital for continued care and as a potential candidate for bone marrow transplant following resolution of the disseminated histoplasmosis infection.

During her hospitalization at the current presentation, she was noted to have a 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus. Initial wound care with bacitracin ointment was applied to the area while specimens were obtained and empiric oral acyclovir therapy was initiated (20 mg/kg 4 times daily [QID]), given a clinical impression consistent with cutaneous HSV infection despite acyclovir prophylaxis. Direct immunofluorescence and viral cultures were positive for HSV-1, while bacterial cultures grew methicillin-susceptible S aureus. Cephalexin and mupirocin ointment were started, and acyclovir was continued. After 2 weeks of therapy, there was no visible change in the wound; cultures were repeated, again showing the wound contained HSV. Bacterial cultures this time grew Pseudomonas putida, and the antibiotic regimen was transitioned to cefepime.

After no response to the continued course of therapeutic acyclovir, HSV cultures were sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for resistance testing, and biopsy of the lesion was performed by the otolaryngology service to rule out malignancy and potential alternative diagnoses. Histopathology showed only reactive inflammation without visible microorganisms on tissue HSV-1/HSV-2 immunostain; however, tissue viral culture was positive for HSV-1. The patient was transitioned back to acyclovir (intravenous [IV] 20 mg/kg QID) with the addition of empiric foscarnet (IV 40 mg/kg 3 times daily) given the worsening appearance of the lesion. The HSV acyclovir resistance test results from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention returned soon after and were positive for resistance (median infectious dose, 3.29 µg/L [reference interval, sensitive <2.00 µg/L; resistant >1.90 µg/L]). The patient completed a 21-day course of combination foscarnet and acyclovir therapy, during which time the lesion showed notable improvement and healing. The patient was continued on prophylactic acyclovir (IV 20 mg/kg QID). Unfortunately, the patient eventually died due to complications related to pneumonia.

Comment

Infection in Patients With DOCK8 Deficiency—The gene DOCK8 has emerged as playing a central role in both innate and adaptive immunity, as it is expressed primarily in immune cells and serves as a mediator of numerous processes, including immune synapse formation, cell signaling and trafficking, antibody and cytokine production, and lymphocyte memory.3 Cells that are critical for combating cutaneous viral infections, including skin-resident memory T cells and natural killer cells, are defective, which leads to a severely immunocompromised state in DOCK8-deficient patients with a particular susceptibility to infectious and inflammatory dermatologic disease.4

Herpes simplex virus infection commonly is seen in DOCK8 deficiency, with retrospective analysis of a DOCK8-deficient cohort revealing HSV infection in approximately 38% of patients.5 Prophylactic acyclovir is essential for DOCK8-deficient individuals with a history of HSV infection given the tendency of the virus to reactivate.6 However, despite prophylaxis, our patient developed an HSV-positive posterior auricular erosion that continued to progress even after increase of the acyclovir dose. Acyclovir resistance testing of the HSV isolated from the wound was positive, confirming the clinical suspicion of the presence of acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.

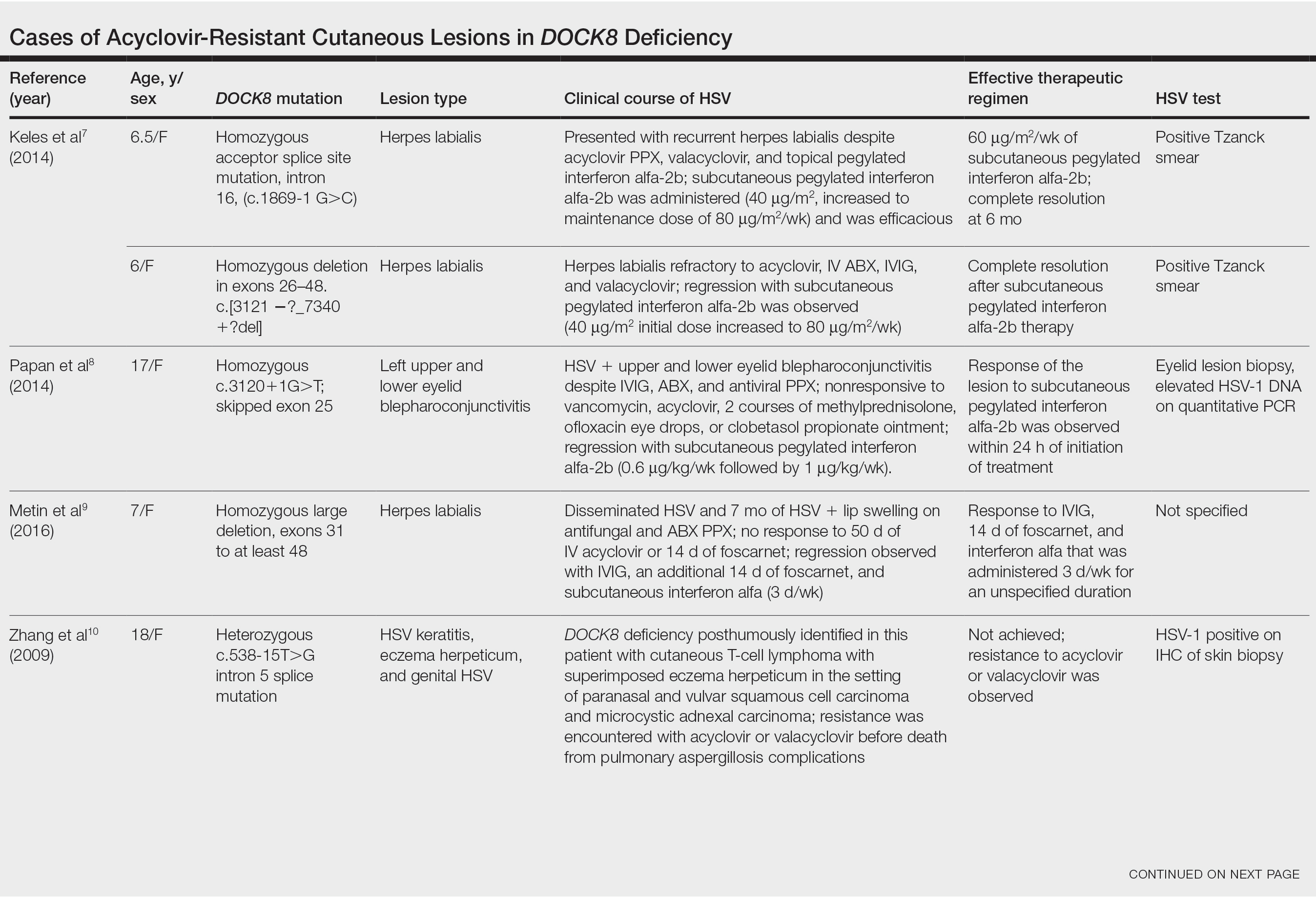

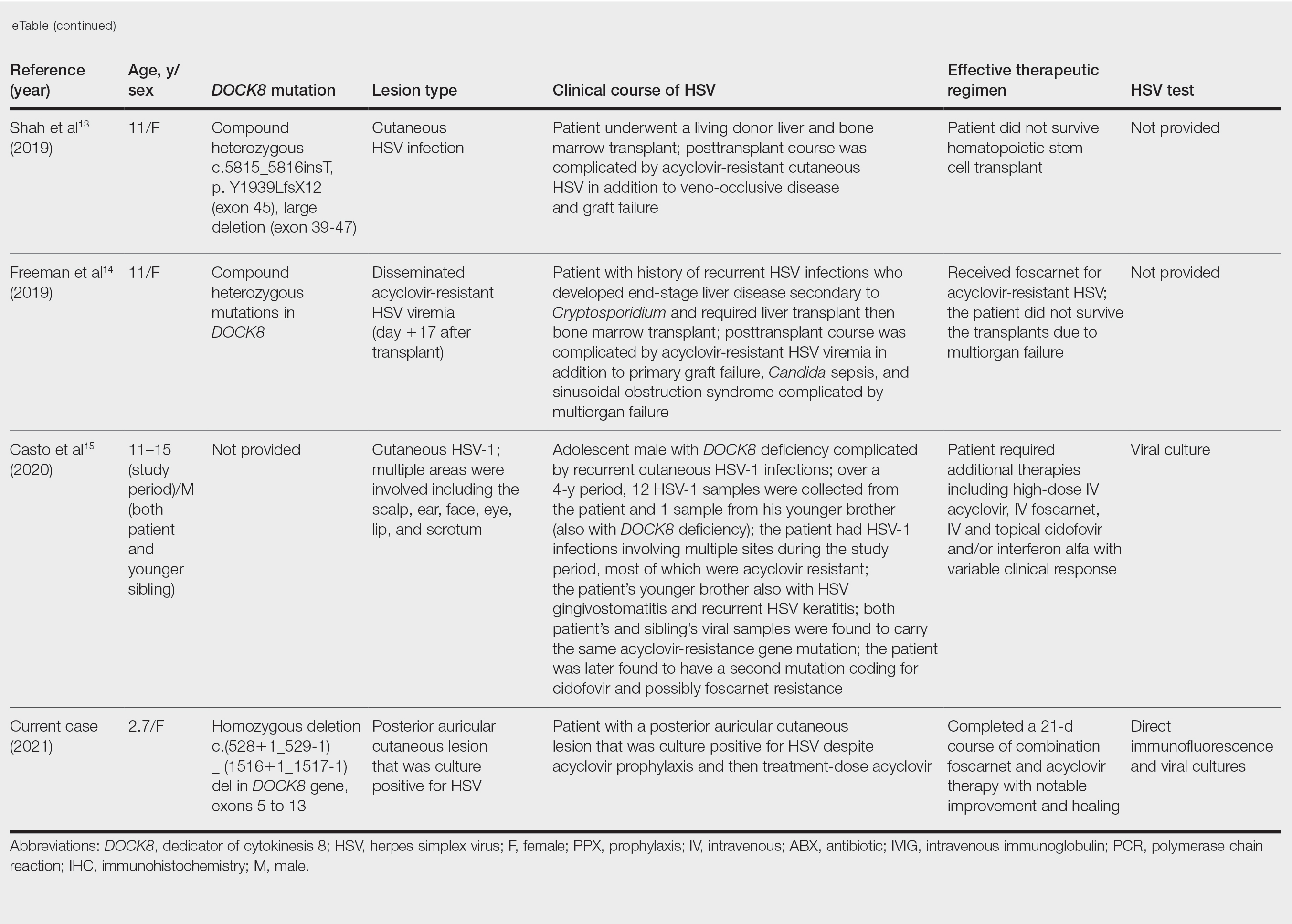

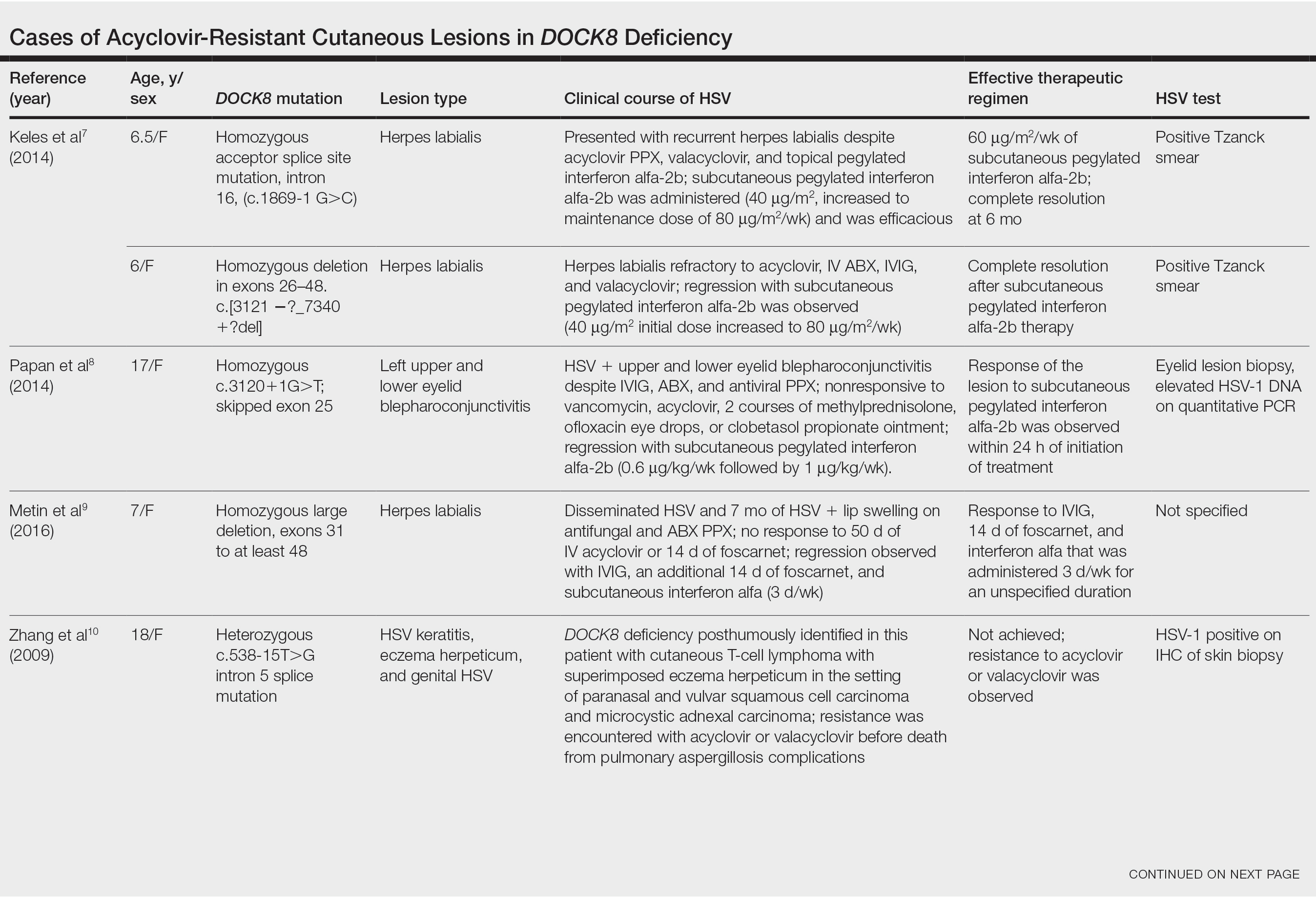

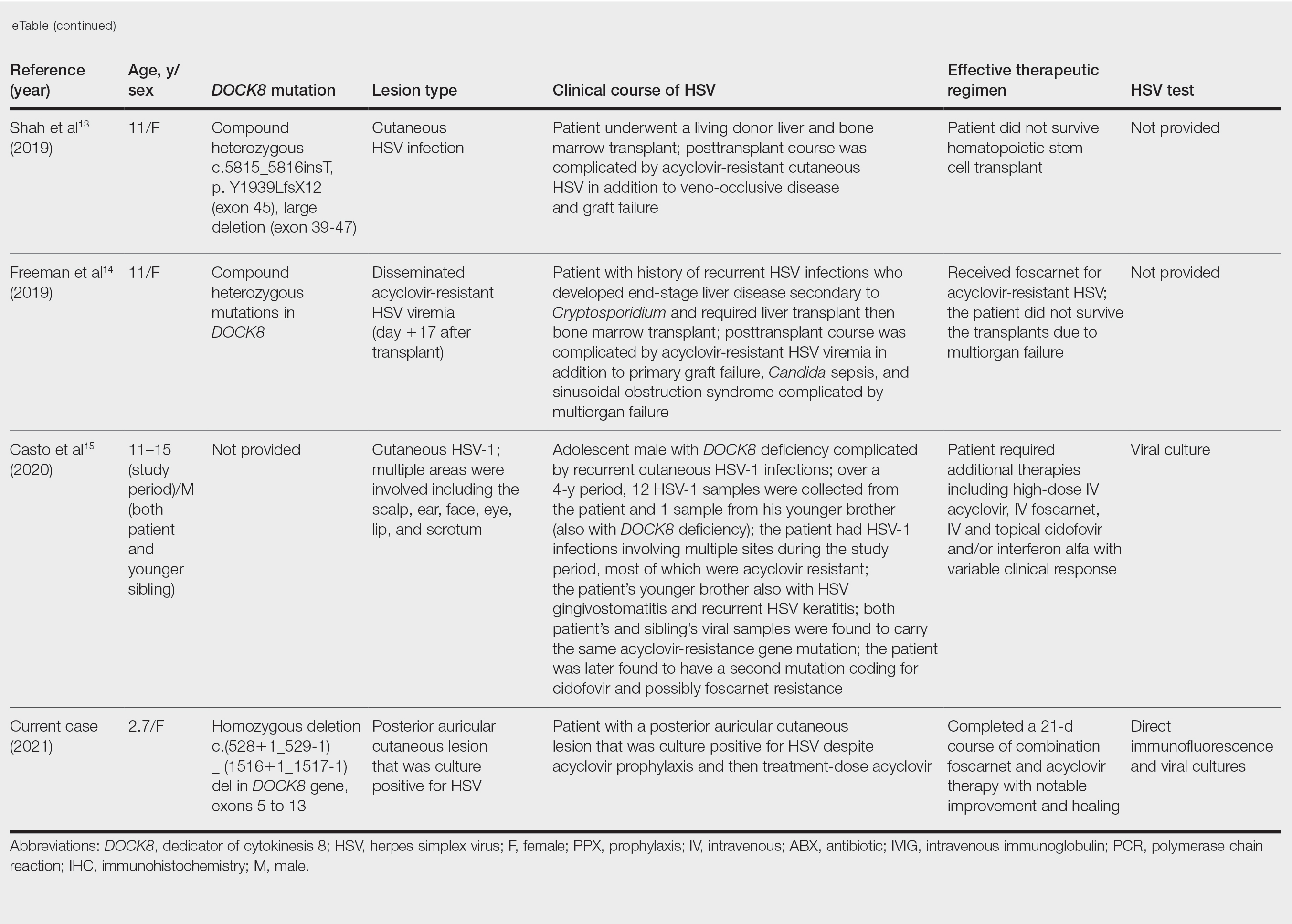

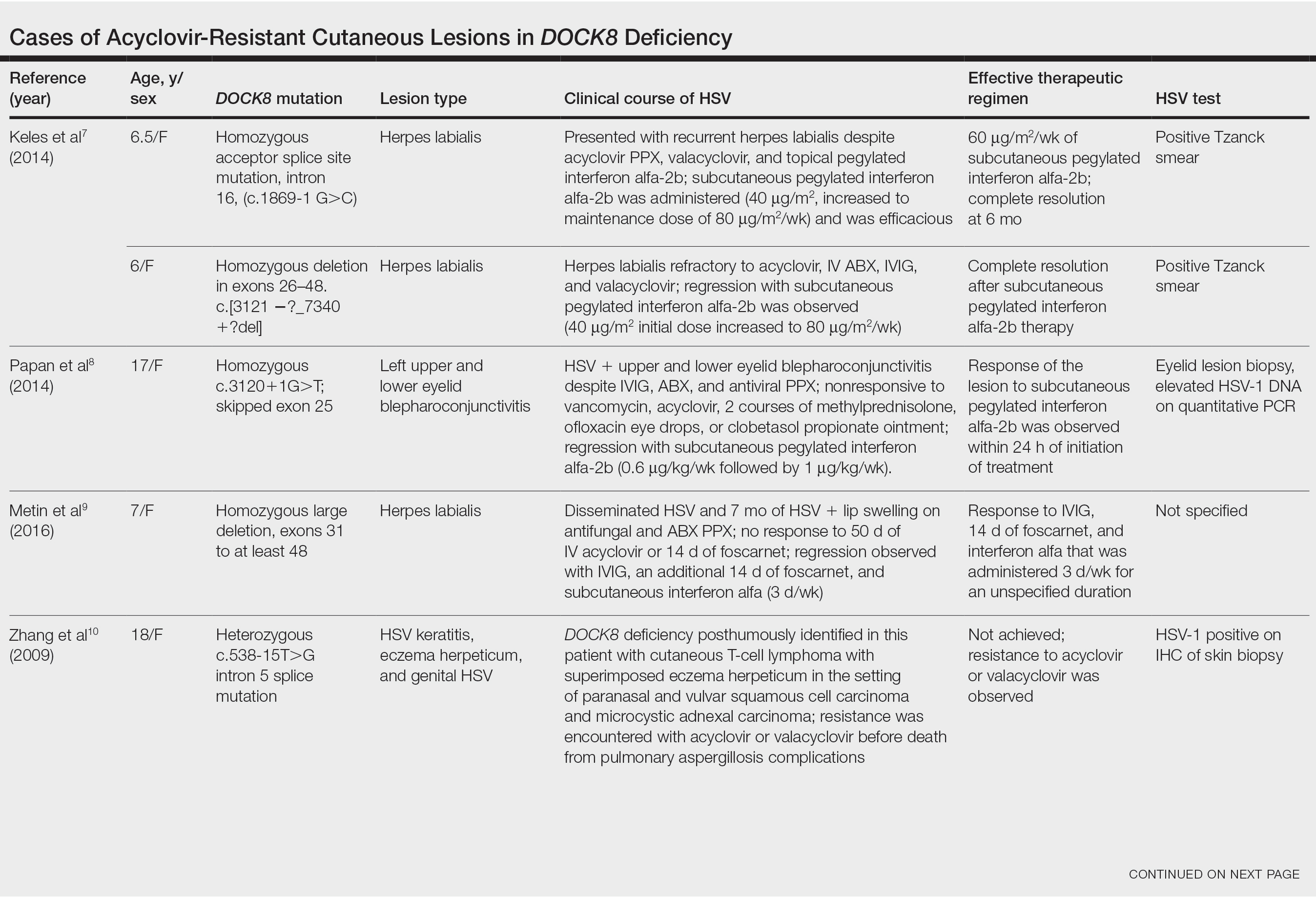

Acyclovir-Resistant HSV—Acyclovir-resistant HSV in immunosuppressed individuals was first noted in 1982, and most cases since then have occurred in the setting of AIDS and in organ transplant recipients.6 Few reports of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8 deficiency exist, and to our knowledge, our patient is the youngest DOCK8-deficient individual to be documented with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.1,7-15 We identified relevant cases from the PubMed and EMBASE databases using the search terms DOCK8 deficiency and acyclovir and DOCK8 deficiency and herpes. The eTable lists other reported cases of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8-deficient patients. The majority of cases involved school-aged females. Lesion types varied and included herpes labialis, eczema herpeticum, and blepharoconjunctivitis. Escalation of therapy and resolution of the lesion was seen in some cases with administration of subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b.

Treatment Alternatives—Acyclovir competitively inhibits viral DNA polymerase by incorporating into elongating viral DNA strands and halting chain synthesis. Acyclovir requires triphosphorylation for activation, and viral thymidine kinase is responsible for the first phosphorylation event. Ninety-five percent of cases of acyclovir resistance are secondary to mutations in viral thymidine kinase. Foscarnet also inhibits viral DNA polymerase but does so directly without the need to be phosphorylated first.6 For this reason, foscarnet often is the drug of choice in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant HSV, as evidenced in our patient. However, foscarnet-resistant HSV strains may develop from mutations in the DNA polymerase gene.

Cidofovir is a nucleotide analogue that requires phosphorylation by host, as opposed to viral, kinases for antiviral activity. Intravenous and topical formulations of cidofovir have proven effective in the treatment of acyclovir- and foscarnet-resistant HSV lesions.6 Cidofovir also can be applied intralesionally, a method that provides targeted therapy and minimizes cidofovir-associated nephrotoxicity.12 Reports of systemic interferon alfa therapy for acyclovir-resistant HSV also exist. A study found IFN-⍺ production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in DOCK8-deficient individuals to be significantly reduced relative to controls (P<.05).7 There has been complete resolution of acyclovir-resistant HSV lesions with subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b injections in several DOCK8-deficient patients.7-9

The need for escalating therapy in DOCK8-deficient individuals with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection underscores the essential role of DOCK8 in dermatologic immunity. Our case demonstrates that a high degree of suspicion for cutaneous HSV infection should be adopted in DOCK8-deficient patients of any age, regardless of acyclovir prophylaxis. Viral culture in addition to bacterial cultures should be performed early in patients with cutaneous erosions, and the threshold for HSV resistance testing should be low to minimize morbidity associated with these infections. Early resistance testing in our case could have prevented prolongation of infection and likely eliminated the need for a biopsy.

Conclusion

DOCK8 deficiency presents a unique challenge to dermatologists and other health care providers given the susceptibility of affected individuals to developing a reservoir of severe and potentially resistant viral cutaneous infections. Prophylactic acyclovir may not be sufficient for HSV suppression, even in the youngest of patients, and suspicion for resistance should be high to avoid delays in adequate treatment.

- Chu EY, Freeman AF, Jing H, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of DOCK8 deficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:79-84. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.262

- Aydin SE, Kilic SS, Aytekin C, et al. DOCK8 deficiency: clinical and immunological phenotype and treatment options—a review of 136 patients. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35:189-198. doi:10.1007/s10875-014-0126-0

- Kearney CJ, Randall KL, Oliaro J. DOCK8 regulates signal transduction events to control immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017;14:406-411. doi:10.1038/cmi.2017.9

- Zhang Q, Dove CG, Hor JL, et al. DOCK8 regulates lymphocyte shape integrity for skin antiviral immunity. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2549-2566. doi:10.1084/jem.20141307

- Engelhardt KR, Gertz EM, Keles S, et al. The extended clinical phenotype of 64 patients with DOCK8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:402-412. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1945

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320. doi:10.1016/S0733-8635(02)00093-1

- Keles S, Jabara HH, Reisli I, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell depletion in DOCK8 deficiency: rescue of severe herpetic infections with interferon alpha-2b therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1753-1755.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.032

- Papan C, Hagl B, Heinz V, et al Beneficial IFN-α treatment of tumorous herpes simplex blepharoconjunctivitis in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1456-1458. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.008

- Metin A, Kanik-Yuksek S, Ozkaya-Parlakay A, et al. Giant herpes labialis in a child with DOCK8-deficient hyper-IgE syndrome. Pediatr Neonatol. 2016;57:79-80. doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2015.04.011

- Zhang Q, Davis JC, Lamborn IT, et al. Combined immunodeficiency associated with DOCK8 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2046-2055. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0905506

- Lei JY, Wang Y, Jaffe ES, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma associated with primary immunodeficiency, recurrent diffuse herpes simplex virus infection, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:524-529. doi:10.1097/00000372-200012000-00008

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.363

- Shah NN, Freeman AF, Hickstein DD. Addendum to: haploidentical related donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:E65-E67. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.11.014

- Freeman AF, Yazigi N, Shah NN, et al. Tandem orthotopic living donor liver transplantation followed by same donor haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency. Transplantation. 2019;103:2144-2149. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000002649

- Casto AM, Stout SC, Selvarangan R, et al. Evaluation of genotypic antiviral resistance testing as an alternative to phenotypic testing in a patient with DOCK8 deficiency and severe HSV-1 disease. J Infect Dis. 2020;221:2035-2042. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa020

Dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8 ) deficiency is the major cause of autosomal-recessive hyper-IgEsyndrome. 1 Characteristic clinical features including eosinophilia, eczema, and recurrent Staphylococcus aureus cutaneous and respiratory tract infections are common in DOCK8 deficiency, similar to the autosomal-dominant form of hyper-IgE syndrome that is due to defi c iency of signal transducer and activation of transcription 3 (STAT-3 ). 1 In addition, patients with DOCK8 deficiency are particularly susceptible to asthma; food allergies; lymphomas; and severe cutaneous viral infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), molluscum contagiosum, varicella-zoster virus, and human papillomavirus. Since the discovery of the DOCK8 gene in 2009, various studies have sought to elucidate the mechanistic contribution of DOCK8 to the dermatologic immune environment. 2 Although cutaneous viral infections such as those caused by HSV typically are short lived and self-limiting in immunocompetent hosts, they have proven to be severe and recalcitrant in the setting of DOCK8 deficiency. 1 Herein, we report the case of a 32-month-old girl with homozygous DOCK8 deficiency who developed acyclovir-resistant cutaneous HSV.

Case Report

A 32-month-old girl presented with an approximately 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus at month 9 of a hospital stay for recurrent infections. Her medical history was notable for multiple upper respiratory tract infections, diffuse eczema, and food allergies. She had presented to an outside hospital at 14 months of age with herpetic gingivostomatitis and eczema herpeticum that was successfully treated with acyclovir. She was readmitted at 20 months of age due to Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, pancytopenia, and disseminated histoplasmosis. Prophylactic oral acyclovir (20 mg/kg twice daily) was started, given her history of HSV infection. Because of recurrent infections, she underwent an immunodeficiency workup. Whole exome sequencing analysis revealed a homozygous deletion c.(528+1_529−1)_(1516+1_1517−1)del in DOCK8 gene–affecting exons 5 to 13. The patient was transferred to our hospital for continued care and as a potential candidate for bone marrow transplant following resolution of the disseminated histoplasmosis infection.

During her hospitalization at the current presentation, she was noted to have a 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus. Initial wound care with bacitracin ointment was applied to the area while specimens were obtained and empiric oral acyclovir therapy was initiated (20 mg/kg 4 times daily [QID]), given a clinical impression consistent with cutaneous HSV infection despite acyclovir prophylaxis. Direct immunofluorescence and viral cultures were positive for HSV-1, while bacterial cultures grew methicillin-susceptible S aureus. Cephalexin and mupirocin ointment were started, and acyclovir was continued. After 2 weeks of therapy, there was no visible change in the wound; cultures were repeated, again showing the wound contained HSV. Bacterial cultures this time grew Pseudomonas putida, and the antibiotic regimen was transitioned to cefepime.

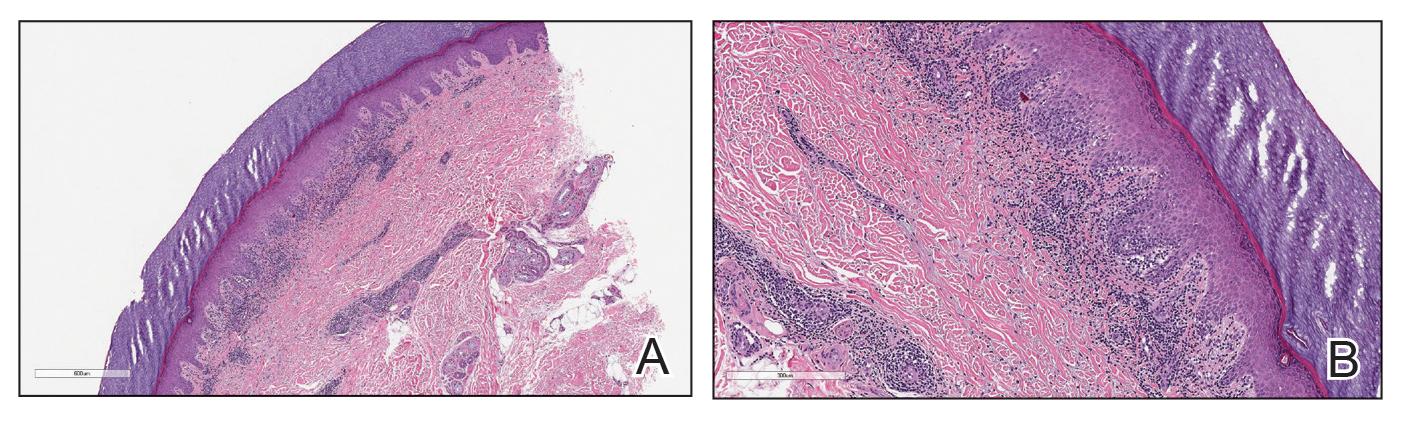

After no response to the continued course of therapeutic acyclovir, HSV cultures were sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for resistance testing, and biopsy of the lesion was performed by the otolaryngology service to rule out malignancy and potential alternative diagnoses. Histopathology showed only reactive inflammation without visible microorganisms on tissue HSV-1/HSV-2 immunostain; however, tissue viral culture was positive for HSV-1. The patient was transitioned back to acyclovir (intravenous [IV] 20 mg/kg QID) with the addition of empiric foscarnet (IV 40 mg/kg 3 times daily) given the worsening appearance of the lesion. The HSV acyclovir resistance test results from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention returned soon after and were positive for resistance (median infectious dose, 3.29 µg/L [reference interval, sensitive <2.00 µg/L; resistant >1.90 µg/L]). The patient completed a 21-day course of combination foscarnet and acyclovir therapy, during which time the lesion showed notable improvement and healing. The patient was continued on prophylactic acyclovir (IV 20 mg/kg QID). Unfortunately, the patient eventually died due to complications related to pneumonia.

Comment

Infection in Patients With DOCK8 Deficiency—The gene DOCK8 has emerged as playing a central role in both innate and adaptive immunity, as it is expressed primarily in immune cells and serves as a mediator of numerous processes, including immune synapse formation, cell signaling and trafficking, antibody and cytokine production, and lymphocyte memory.3 Cells that are critical for combating cutaneous viral infections, including skin-resident memory T cells and natural killer cells, are defective, which leads to a severely immunocompromised state in DOCK8-deficient patients with a particular susceptibility to infectious and inflammatory dermatologic disease.4

Herpes simplex virus infection commonly is seen in DOCK8 deficiency, with retrospective analysis of a DOCK8-deficient cohort revealing HSV infection in approximately 38% of patients.5 Prophylactic acyclovir is essential for DOCK8-deficient individuals with a history of HSV infection given the tendency of the virus to reactivate.6 However, despite prophylaxis, our patient developed an HSV-positive posterior auricular erosion that continued to progress even after increase of the acyclovir dose. Acyclovir resistance testing of the HSV isolated from the wound was positive, confirming the clinical suspicion of the presence of acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.

Acyclovir-Resistant HSV—Acyclovir-resistant HSV in immunosuppressed individuals was first noted in 1982, and most cases since then have occurred in the setting of AIDS and in organ transplant recipients.6 Few reports of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8 deficiency exist, and to our knowledge, our patient is the youngest DOCK8-deficient individual to be documented with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.1,7-15 We identified relevant cases from the PubMed and EMBASE databases using the search terms DOCK8 deficiency and acyclovir and DOCK8 deficiency and herpes. The eTable lists other reported cases of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8-deficient patients. The majority of cases involved school-aged females. Lesion types varied and included herpes labialis, eczema herpeticum, and blepharoconjunctivitis. Escalation of therapy and resolution of the lesion was seen in some cases with administration of subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b.

Treatment Alternatives—Acyclovir competitively inhibits viral DNA polymerase by incorporating into elongating viral DNA strands and halting chain synthesis. Acyclovir requires triphosphorylation for activation, and viral thymidine kinase is responsible for the first phosphorylation event. Ninety-five percent of cases of acyclovir resistance are secondary to mutations in viral thymidine kinase. Foscarnet also inhibits viral DNA polymerase but does so directly without the need to be phosphorylated first.6 For this reason, foscarnet often is the drug of choice in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant HSV, as evidenced in our patient. However, foscarnet-resistant HSV strains may develop from mutations in the DNA polymerase gene.

Cidofovir is a nucleotide analogue that requires phosphorylation by host, as opposed to viral, kinases for antiviral activity. Intravenous and topical formulations of cidofovir have proven effective in the treatment of acyclovir- and foscarnet-resistant HSV lesions.6 Cidofovir also can be applied intralesionally, a method that provides targeted therapy and minimizes cidofovir-associated nephrotoxicity.12 Reports of systemic interferon alfa therapy for acyclovir-resistant HSV also exist. A study found IFN-⍺ production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in DOCK8-deficient individuals to be significantly reduced relative to controls (P<.05).7 There has been complete resolution of acyclovir-resistant HSV lesions with subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b injections in several DOCK8-deficient patients.7-9

The need for escalating therapy in DOCK8-deficient individuals with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection underscores the essential role of DOCK8 in dermatologic immunity. Our case demonstrates that a high degree of suspicion for cutaneous HSV infection should be adopted in DOCK8-deficient patients of any age, regardless of acyclovir prophylaxis. Viral culture in addition to bacterial cultures should be performed early in patients with cutaneous erosions, and the threshold for HSV resistance testing should be low to minimize morbidity associated with these infections. Early resistance testing in our case could have prevented prolongation of infection and likely eliminated the need for a biopsy.

Conclusion

DOCK8 deficiency presents a unique challenge to dermatologists and other health care providers given the susceptibility of affected individuals to developing a reservoir of severe and potentially resistant viral cutaneous infections. Prophylactic acyclovir may not be sufficient for HSV suppression, even in the youngest of patients, and suspicion for resistance should be high to avoid delays in adequate treatment.

Dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8 ) deficiency is the major cause of autosomal-recessive hyper-IgEsyndrome. 1 Characteristic clinical features including eosinophilia, eczema, and recurrent Staphylococcus aureus cutaneous and respiratory tract infections are common in DOCK8 deficiency, similar to the autosomal-dominant form of hyper-IgE syndrome that is due to defi c iency of signal transducer and activation of transcription 3 (STAT-3 ). 1 In addition, patients with DOCK8 deficiency are particularly susceptible to asthma; food allergies; lymphomas; and severe cutaneous viral infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), molluscum contagiosum, varicella-zoster virus, and human papillomavirus. Since the discovery of the DOCK8 gene in 2009, various studies have sought to elucidate the mechanistic contribution of DOCK8 to the dermatologic immune environment. 2 Although cutaneous viral infections such as those caused by HSV typically are short lived and self-limiting in immunocompetent hosts, they have proven to be severe and recalcitrant in the setting of DOCK8 deficiency. 1 Herein, we report the case of a 32-month-old girl with homozygous DOCK8 deficiency who developed acyclovir-resistant cutaneous HSV.

Case Report

A 32-month-old girl presented with an approximately 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus at month 9 of a hospital stay for recurrent infections. Her medical history was notable for multiple upper respiratory tract infections, diffuse eczema, and food allergies. She had presented to an outside hospital at 14 months of age with herpetic gingivostomatitis and eczema herpeticum that was successfully treated with acyclovir. She was readmitted at 20 months of age due to Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, pancytopenia, and disseminated histoplasmosis. Prophylactic oral acyclovir (20 mg/kg twice daily) was started, given her history of HSV infection. Because of recurrent infections, she underwent an immunodeficiency workup. Whole exome sequencing analysis revealed a homozygous deletion c.(528+1_529−1)_(1516+1_1517−1)del in DOCK8 gene–affecting exons 5 to 13. The patient was transferred to our hospital for continued care and as a potential candidate for bone marrow transplant following resolution of the disseminated histoplasmosis infection.

During her hospitalization at the current presentation, she was noted to have a 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus. Initial wound care with bacitracin ointment was applied to the area while specimens were obtained and empiric oral acyclovir therapy was initiated (20 mg/kg 4 times daily [QID]), given a clinical impression consistent with cutaneous HSV infection despite acyclovir prophylaxis. Direct immunofluorescence and viral cultures were positive for HSV-1, while bacterial cultures grew methicillin-susceptible S aureus. Cephalexin and mupirocin ointment were started, and acyclovir was continued. After 2 weeks of therapy, there was no visible change in the wound; cultures were repeated, again showing the wound contained HSV. Bacterial cultures this time grew Pseudomonas putida, and the antibiotic regimen was transitioned to cefepime.

After no response to the continued course of therapeutic acyclovir, HSV cultures were sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for resistance testing, and biopsy of the lesion was performed by the otolaryngology service to rule out malignancy and potential alternative diagnoses. Histopathology showed only reactive inflammation without visible microorganisms on tissue HSV-1/HSV-2 immunostain; however, tissue viral culture was positive for HSV-1. The patient was transitioned back to acyclovir (intravenous [IV] 20 mg/kg QID) with the addition of empiric foscarnet (IV 40 mg/kg 3 times daily) given the worsening appearance of the lesion. The HSV acyclovir resistance test results from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention returned soon after and were positive for resistance (median infectious dose, 3.29 µg/L [reference interval, sensitive <2.00 µg/L; resistant >1.90 µg/L]). The patient completed a 21-day course of combination foscarnet and acyclovir therapy, during which time the lesion showed notable improvement and healing. The patient was continued on prophylactic acyclovir (IV 20 mg/kg QID). Unfortunately, the patient eventually died due to complications related to pneumonia.

Comment

Infection in Patients With DOCK8 Deficiency—The gene DOCK8 has emerged as playing a central role in both innate and adaptive immunity, as it is expressed primarily in immune cells and serves as a mediator of numerous processes, including immune synapse formation, cell signaling and trafficking, antibody and cytokine production, and lymphocyte memory.3 Cells that are critical for combating cutaneous viral infections, including skin-resident memory T cells and natural killer cells, are defective, which leads to a severely immunocompromised state in DOCK8-deficient patients with a particular susceptibility to infectious and inflammatory dermatologic disease.4

Herpes simplex virus infection commonly is seen in DOCK8 deficiency, with retrospective analysis of a DOCK8-deficient cohort revealing HSV infection in approximately 38% of patients.5 Prophylactic acyclovir is essential for DOCK8-deficient individuals with a history of HSV infection given the tendency of the virus to reactivate.6 However, despite prophylaxis, our patient developed an HSV-positive posterior auricular erosion that continued to progress even after increase of the acyclovir dose. Acyclovir resistance testing of the HSV isolated from the wound was positive, confirming the clinical suspicion of the presence of acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.

Acyclovir-Resistant HSV—Acyclovir-resistant HSV in immunosuppressed individuals was first noted in 1982, and most cases since then have occurred in the setting of AIDS and in organ transplant recipients.6 Few reports of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8 deficiency exist, and to our knowledge, our patient is the youngest DOCK8-deficient individual to be documented with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.1,7-15 We identified relevant cases from the PubMed and EMBASE databases using the search terms DOCK8 deficiency and acyclovir and DOCK8 deficiency and herpes. The eTable lists other reported cases of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8-deficient patients. The majority of cases involved school-aged females. Lesion types varied and included herpes labialis, eczema herpeticum, and blepharoconjunctivitis. Escalation of therapy and resolution of the lesion was seen in some cases with administration of subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b.

Treatment Alternatives—Acyclovir competitively inhibits viral DNA polymerase by incorporating into elongating viral DNA strands and halting chain synthesis. Acyclovir requires triphosphorylation for activation, and viral thymidine kinase is responsible for the first phosphorylation event. Ninety-five percent of cases of acyclovir resistance are secondary to mutations in viral thymidine kinase. Foscarnet also inhibits viral DNA polymerase but does so directly without the need to be phosphorylated first.6 For this reason, foscarnet often is the drug of choice in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant HSV, as evidenced in our patient. However, foscarnet-resistant HSV strains may develop from mutations in the DNA polymerase gene.

Cidofovir is a nucleotide analogue that requires phosphorylation by host, as opposed to viral, kinases for antiviral activity. Intravenous and topical formulations of cidofovir have proven effective in the treatment of acyclovir- and foscarnet-resistant HSV lesions.6 Cidofovir also can be applied intralesionally, a method that provides targeted therapy and minimizes cidofovir-associated nephrotoxicity.12 Reports of systemic interferon alfa therapy for acyclovir-resistant HSV also exist. A study found IFN-⍺ production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in DOCK8-deficient individuals to be significantly reduced relative to controls (P<.05).7 There has been complete resolution of acyclovir-resistant HSV lesions with subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b injections in several DOCK8-deficient patients.7-9

The need for escalating therapy in DOCK8-deficient individuals with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection underscores the essential role of DOCK8 in dermatologic immunity. Our case demonstrates that a high degree of suspicion for cutaneous HSV infection should be adopted in DOCK8-deficient patients of any age, regardless of acyclovir prophylaxis. Viral culture in addition to bacterial cultures should be performed early in patients with cutaneous erosions, and the threshold for HSV resistance testing should be low to minimize morbidity associated with these infections. Early resistance testing in our case could have prevented prolongation of infection and likely eliminated the need for a biopsy.

Conclusion

DOCK8 deficiency presents a unique challenge to dermatologists and other health care providers given the susceptibility of affected individuals to developing a reservoir of severe and potentially resistant viral cutaneous infections. Prophylactic acyclovir may not be sufficient for HSV suppression, even in the youngest of patients, and suspicion for resistance should be high to avoid delays in adequate treatment.

- Chu EY, Freeman AF, Jing H, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of DOCK8 deficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:79-84. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.262

- Aydin SE, Kilic SS, Aytekin C, et al. DOCK8 deficiency: clinical and immunological phenotype and treatment options—a review of 136 patients. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35:189-198. doi:10.1007/s10875-014-0126-0

- Kearney CJ, Randall KL, Oliaro J. DOCK8 regulates signal transduction events to control immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017;14:406-411. doi:10.1038/cmi.2017.9

- Zhang Q, Dove CG, Hor JL, et al. DOCK8 regulates lymphocyte shape integrity for skin antiviral immunity. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2549-2566. doi:10.1084/jem.20141307

- Engelhardt KR, Gertz EM, Keles S, et al. The extended clinical phenotype of 64 patients with DOCK8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:402-412. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1945

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320. doi:10.1016/S0733-8635(02)00093-1

- Keles S, Jabara HH, Reisli I, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell depletion in DOCK8 deficiency: rescue of severe herpetic infections with interferon alpha-2b therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1753-1755.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.032

- Papan C, Hagl B, Heinz V, et al Beneficial IFN-α treatment of tumorous herpes simplex blepharoconjunctivitis in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1456-1458. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.008

- Metin A, Kanik-Yuksek S, Ozkaya-Parlakay A, et al. Giant herpes labialis in a child with DOCK8-deficient hyper-IgE syndrome. Pediatr Neonatol. 2016;57:79-80. doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2015.04.011

- Zhang Q, Davis JC, Lamborn IT, et al. Combined immunodeficiency associated with DOCK8 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2046-2055. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0905506

- Lei JY, Wang Y, Jaffe ES, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma associated with primary immunodeficiency, recurrent diffuse herpes simplex virus infection, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:524-529. doi:10.1097/00000372-200012000-00008

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.363

- Shah NN, Freeman AF, Hickstein DD. Addendum to: haploidentical related donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:E65-E67. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.11.014

- Freeman AF, Yazigi N, Shah NN, et al. Tandem orthotopic living donor liver transplantation followed by same donor haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency. Transplantation. 2019;103:2144-2149. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000002649

- Casto AM, Stout SC, Selvarangan R, et al. Evaluation of genotypic antiviral resistance testing as an alternative to phenotypic testing in a patient with DOCK8 deficiency and severe HSV-1 disease. J Infect Dis. 2020;221:2035-2042. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa020

- Chu EY, Freeman AF, Jing H, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of DOCK8 deficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:79-84. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.262

- Aydin SE, Kilic SS, Aytekin C, et al. DOCK8 deficiency: clinical and immunological phenotype and treatment options—a review of 136 patients. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35:189-198. doi:10.1007/s10875-014-0126-0

- Kearney CJ, Randall KL, Oliaro J. DOCK8 regulates signal transduction events to control immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017;14:406-411. doi:10.1038/cmi.2017.9

- Zhang Q, Dove CG, Hor JL, et al. DOCK8 regulates lymphocyte shape integrity for skin antiviral immunity. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2549-2566. doi:10.1084/jem.20141307

- Engelhardt KR, Gertz EM, Keles S, et al. The extended clinical phenotype of 64 patients with DOCK8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:402-412. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1945

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320. doi:10.1016/S0733-8635(02)00093-1

- Keles S, Jabara HH, Reisli I, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell depletion in DOCK8 deficiency: rescue of severe herpetic infections with interferon alpha-2b therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1753-1755.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.032

- Papan C, Hagl B, Heinz V, et al Beneficial IFN-α treatment of tumorous herpes simplex blepharoconjunctivitis in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1456-1458. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.008

- Metin A, Kanik-Yuksek S, Ozkaya-Parlakay A, et al. Giant herpes labialis in a child with DOCK8-deficient hyper-IgE syndrome. Pediatr Neonatol. 2016;57:79-80. doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2015.04.011

- Zhang Q, Davis JC, Lamborn IT, et al. Combined immunodeficiency associated with DOCK8 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2046-2055. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0905506

- Lei JY, Wang Y, Jaffe ES, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma associated with primary immunodeficiency, recurrent diffuse herpes simplex virus infection, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:524-529. doi:10.1097/00000372-200012000-00008

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.363

- Shah NN, Freeman AF, Hickstein DD. Addendum to: haploidentical related donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:E65-E67. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.11.014

- Freeman AF, Yazigi N, Shah NN, et al. Tandem orthotopic living donor liver transplantation followed by same donor haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency. Transplantation. 2019;103:2144-2149. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000002649

- Casto AM, Stout SC, Selvarangan R, et al. Evaluation of genotypic antiviral resistance testing as an alternative to phenotypic testing in a patient with DOCK8 deficiency and severe HSV-1 disease. J Infect Dis. 2020;221:2035-2042. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa020

Practice Points

- Patients with dedicator of cytokinesis 8 ( DOCK 8 ) deficiency are susceptible to development of severe recalcitrant viral cutaneous infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV).

- Dermatologists should be aware that prophylactic acyclovir may not be sufficient for HSV suppression in the setting of severe immunodeficiency.

- Acyclovir-resistant cutaneous HSV lesions require escalation of therapy, which may include addition of foscarnet, cidofovir, or subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b to the therapeutic regimen.

- Viral culture should be performed on suspicious lesions in DOCK 8 -deficient patients despite acyclovir prophylaxis, and the threshold for HSV resistance testing should be low.

Atypical Presentation of Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris: Challenges in Diagnosis and Management

To the Editor:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare inflammatory dermatosis of unknown etiology characterized by erythematosquamous salmon-colored plaques with well-demarcated islands of unaffected skin and hyperkeratotic follicles.1 In the United States, an incidence of 1 in 3500to 5000 patients presenting to dermatology clinics has been reported.2 Pityriasis rubra pilaris has several subtypes and variability in presentation that can make accurate and timely diagnosis challenging.3-5 Herein, we present a case of PRP with complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

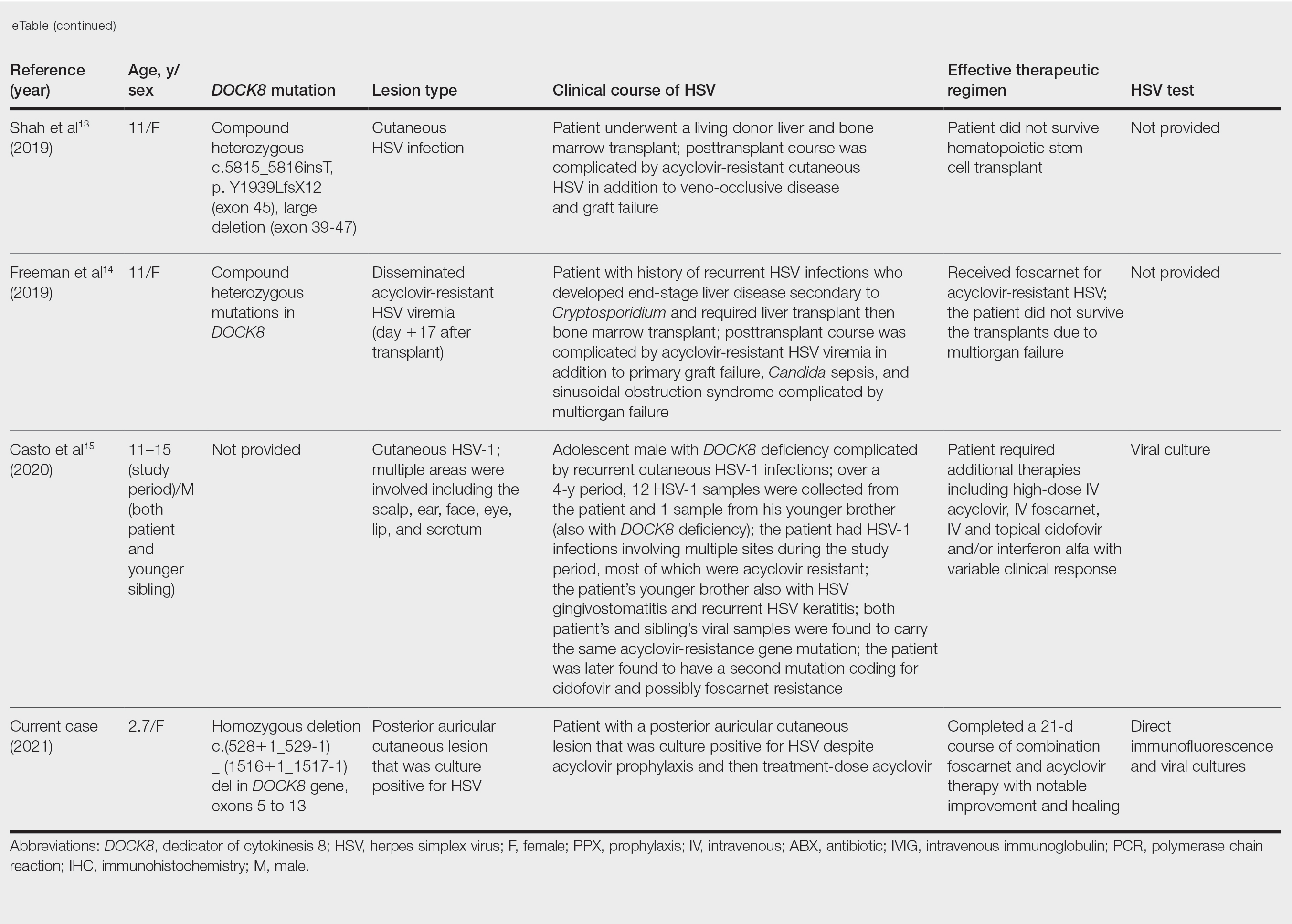

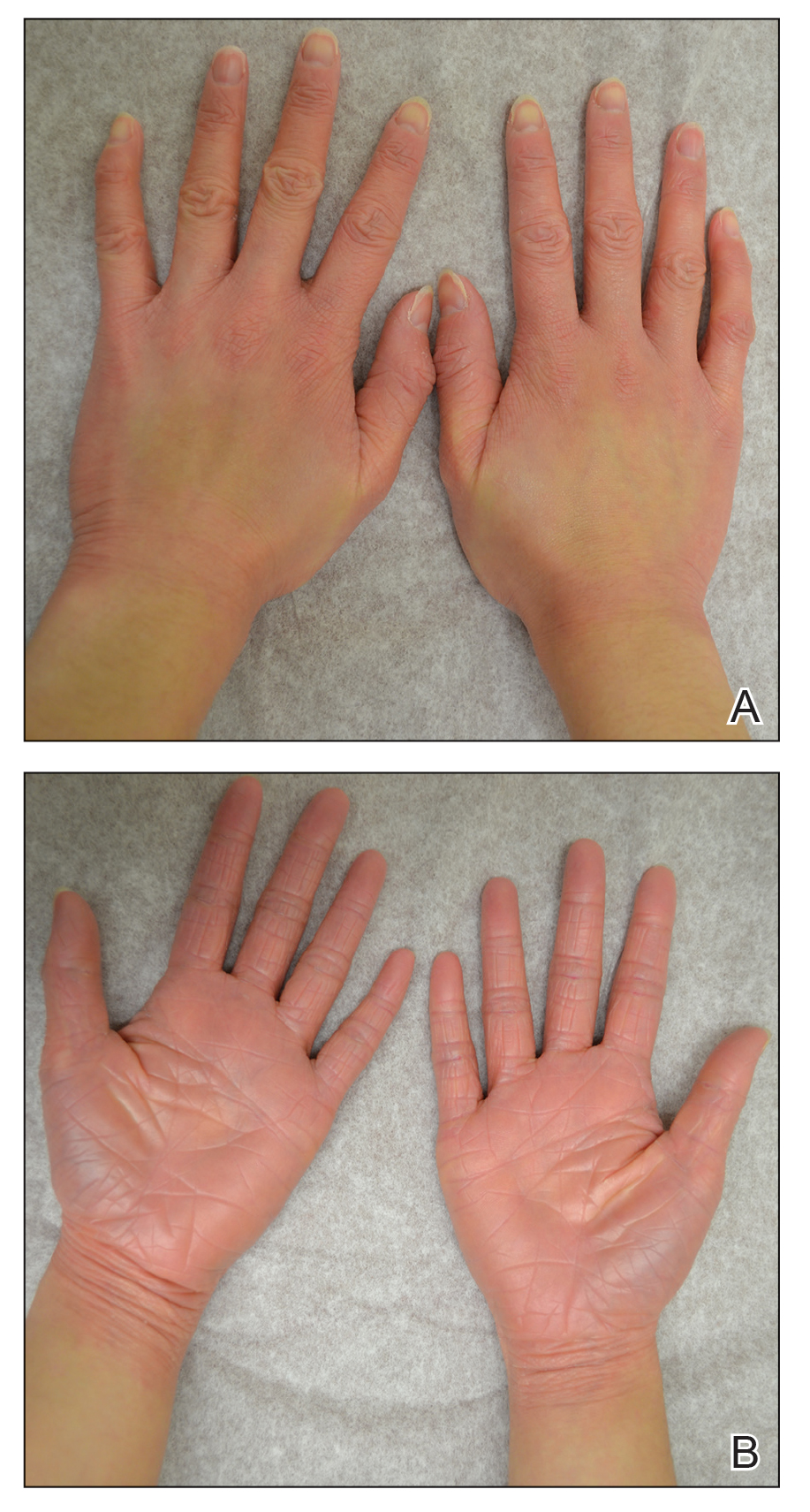

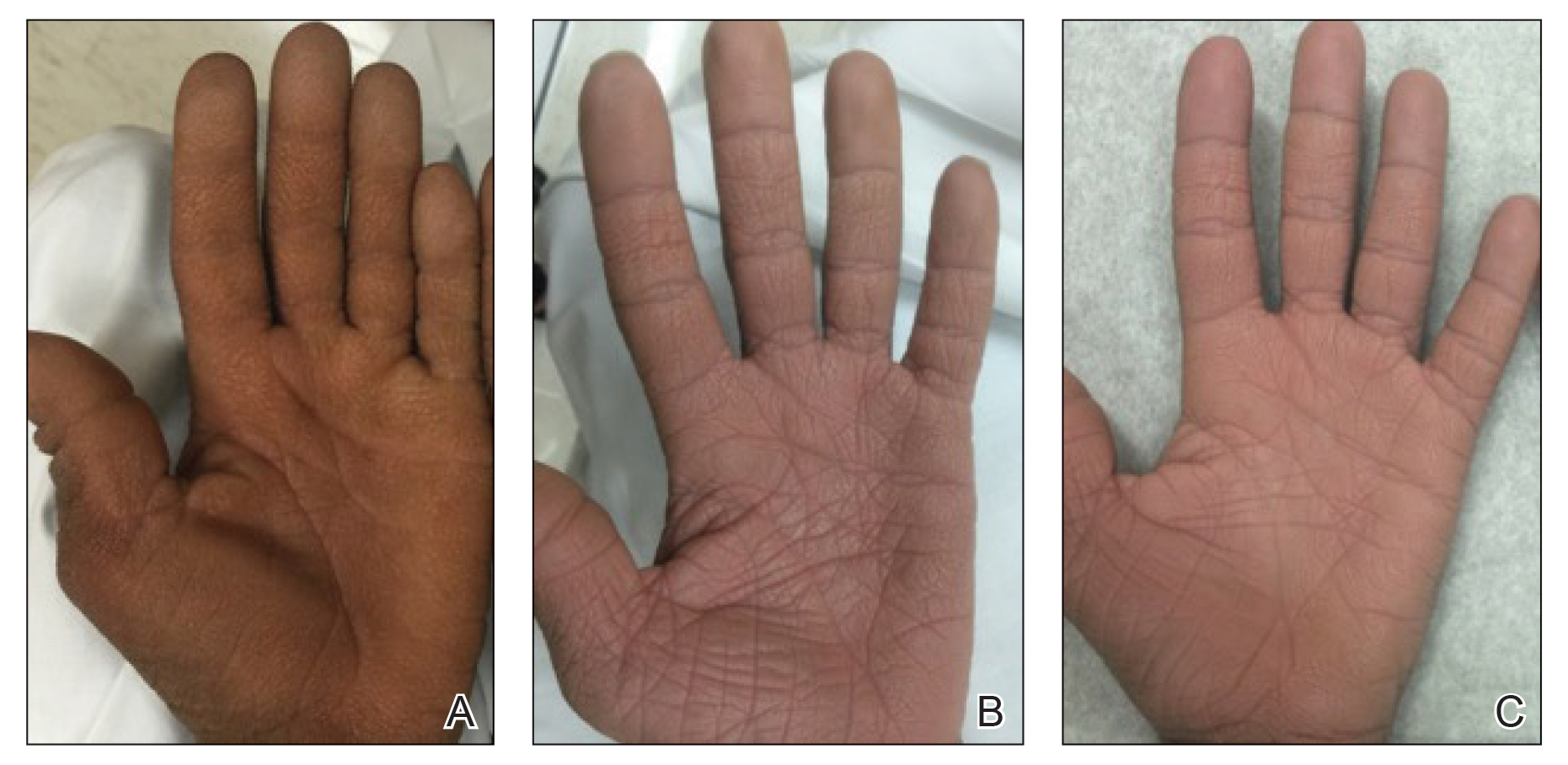

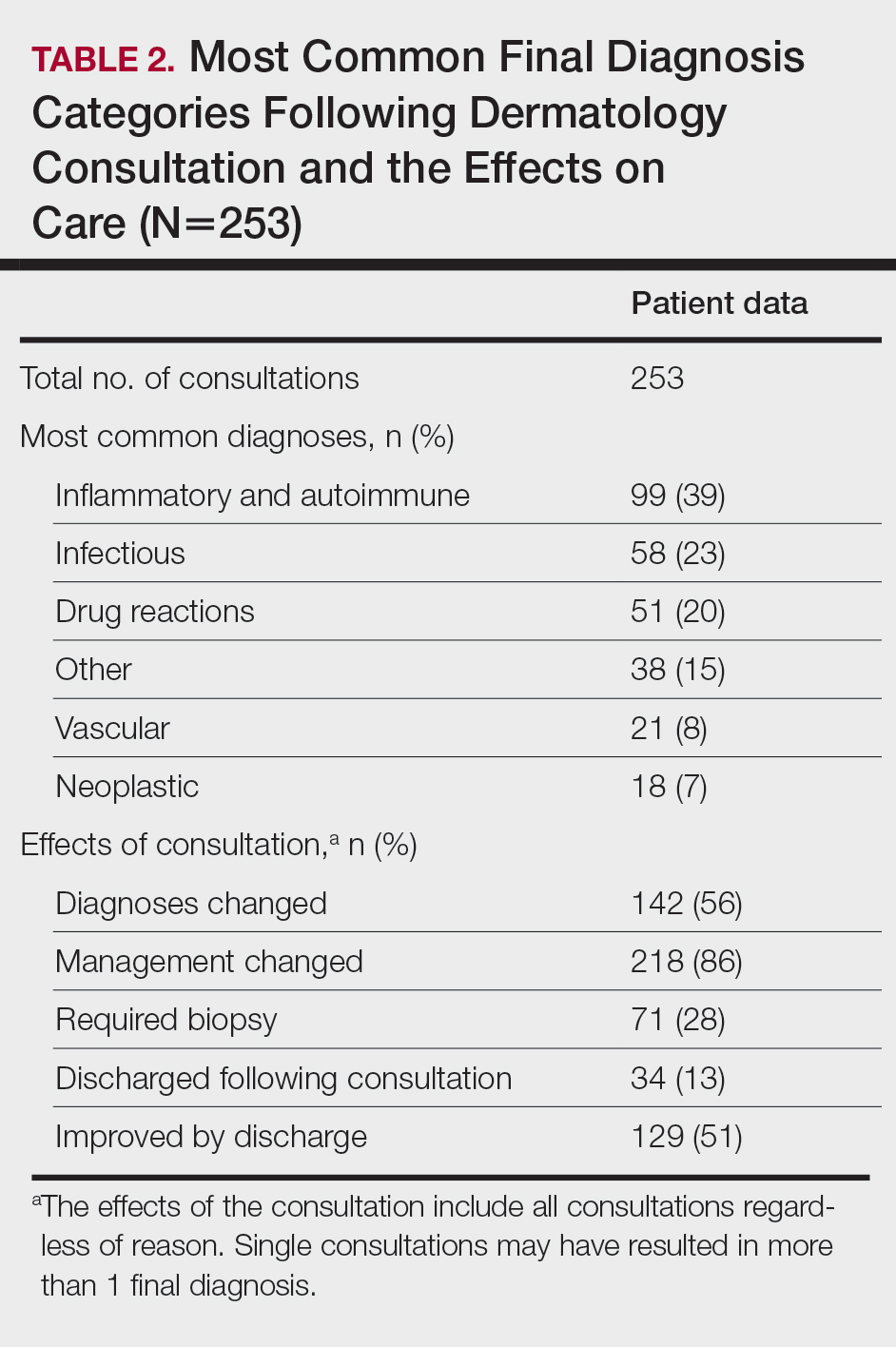

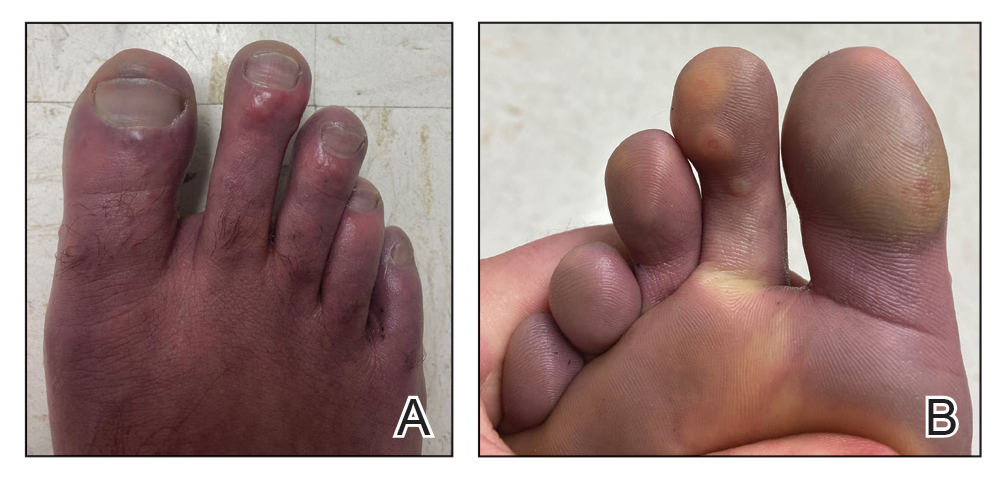

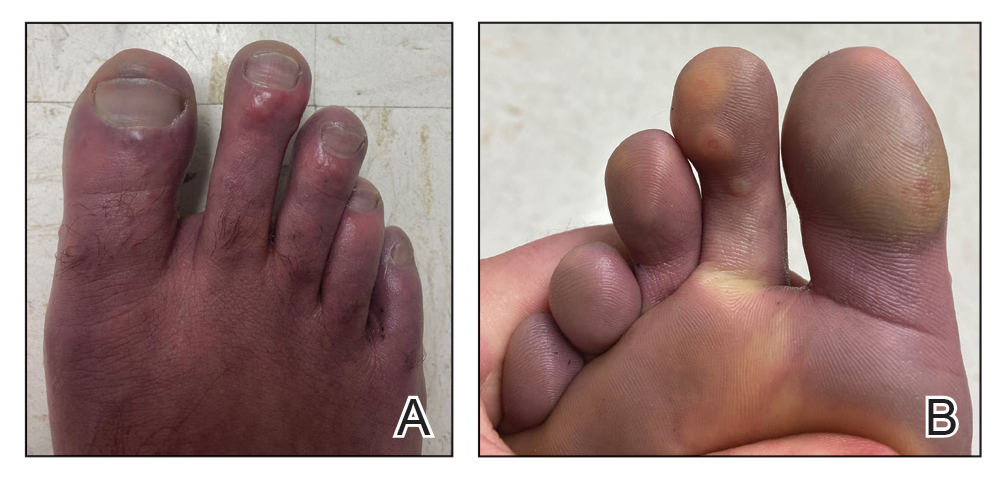

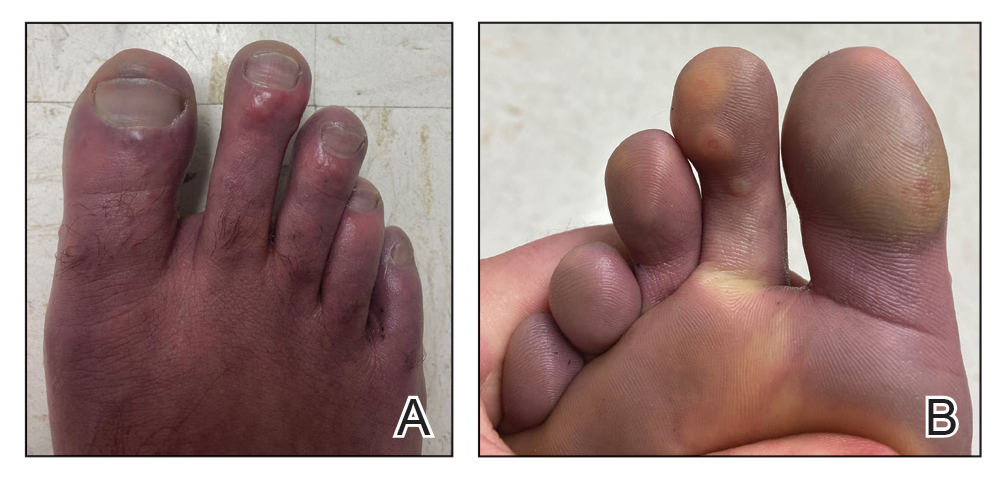

A 22-year-old woman presented with symmetrical, well-demarcated, hyperkeratotic, erythematous plaques with a carnauba wax–like appearance on the palms (Figure 1), soles, elbows, and trunk covering approximately 5% of the body surface area. Two weeks prior to presentation, she experienced an upper respiratory tract infection without any treatment and subsequently developed redness on the palms, which became very hard and scaly. The redness then spread to the elbows, soles, and trunk. She reported itching as well as pain in areas of fissuring. Hand mobility became restricted due to thick scale.

The patient’s medical history was notable for suspected psoriasis 9 years prior, but there were no records or biopsy reports that could be obtained to confirm the diagnosis. She also reported a similar skin condition in her father, which also was diagnosed as psoriasis, but this diagnosis could not be verified.

Although the morphology of the lesions was most consistent with localized PRP, atypical psoriasis, palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK), and erythroderma progressive symmetrica (EPS) also were considered given the personal and family history of suspected psoriasis. A biopsy could not be obtained due to an insurance issue. She was started on clobetasol cream 0.05% and ointment. At 2-week follow-up, her condition remained unchanged. Empiric systemic treatment was discussed, which would potentially work for diagnoses of both PRP and psoriasis. Due to the history of psoriasis and level of discomfort, cyclosporine 300 mg once daily was started to gain rapid control of the disease. Methotrexate also was considered due to its efficacy and economic considerations but was not selected due to patient concerns about the medication.

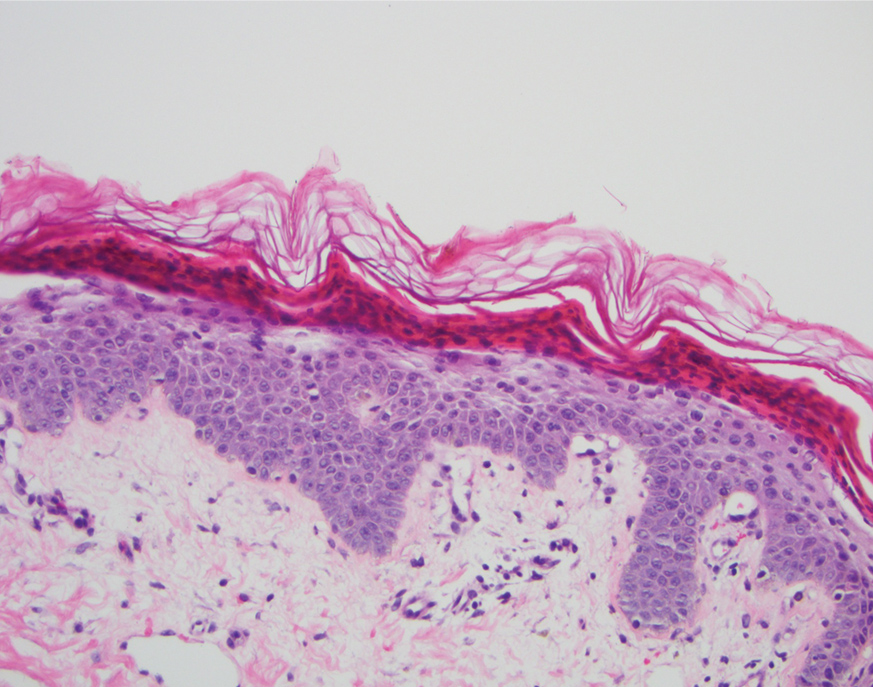

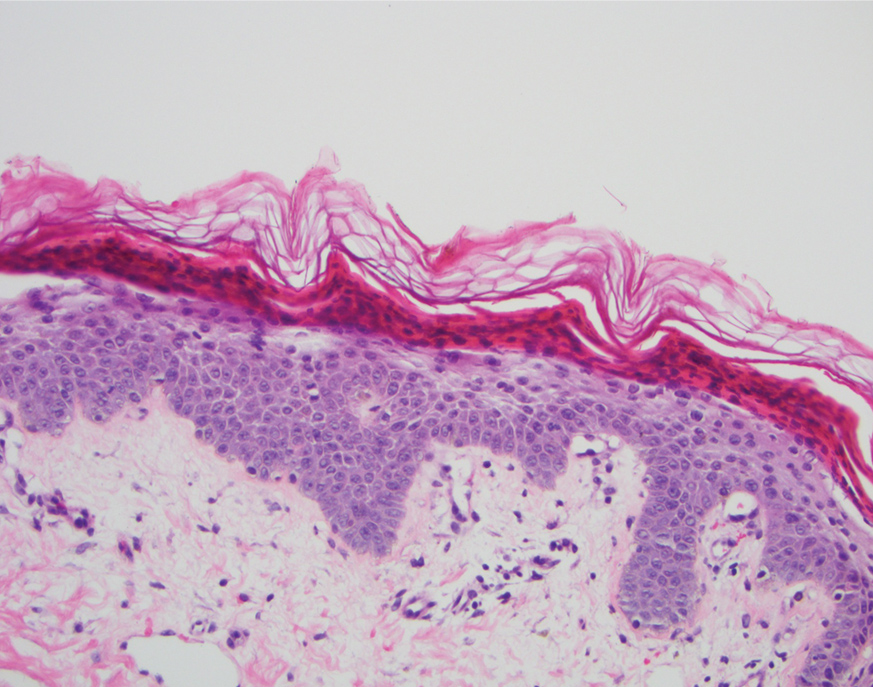

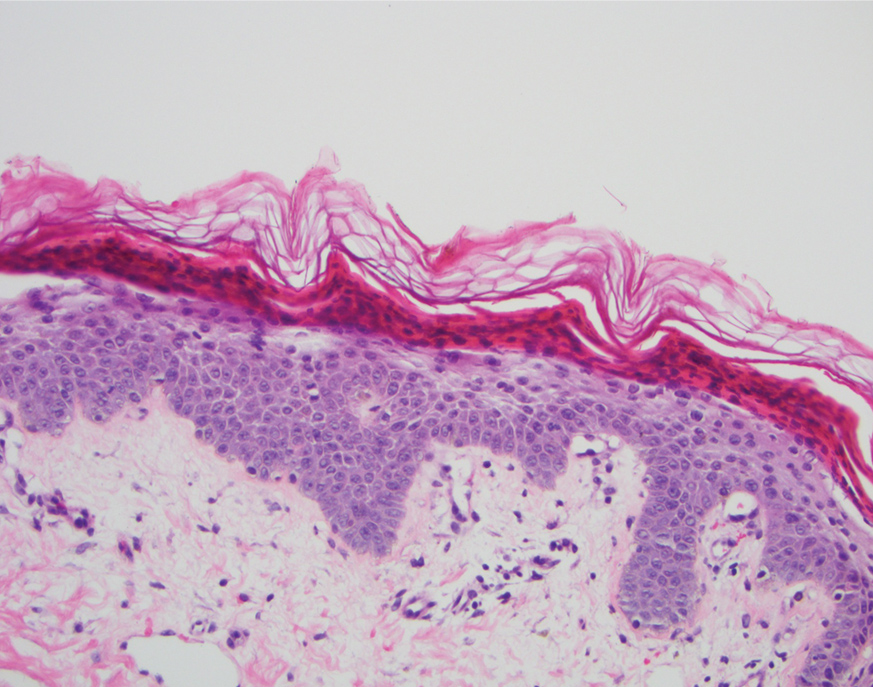

After 10 weeks of cyclosporine treatment, our patient showed some improvement of the skin with decreased scale and flattening of plaques but not complete resolution. At this point, a biopsy was able to be obtained with prior authorization. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the right flank demonstrated a psoriasiform and papillated epidermis with multifocally capped, compact parakeratosis and minimal lymphocytic infiltrate consistent with PRP. Although EPS also was on the histologic differential, clinical history was more consistent with a diagnosis of PRP. There was some minimal improvement with cyclosporine, but with the diagnosis of PRP confirmed, a systemic retinoid became the treatment of choice. Although acitretin is the preferred treatment for PRP, given that pregnancy would be contraindicated during and for 3 years following acitretin therapy, a trial of isotretinoin 40 mg once daily was started due to its shorter half-life compared to acitretin and was continued for 3 months (Figure 2).6,7

The diagnosis of PRP often can be challenging given the variety of clinical presentations. This case was an atypical presentation of PRP with several learning points, as our patient’s condition did not fit perfectly into any of the 6 types of PRP. The age of onset was atypical at 22 years old. Pityriasis rubra pilaris typically presents with a bimodal age distribution, appearing either in the first decade or the fifth to sixth decades of life.3,8 Her clinical presentation was atypical for adult-onset types I and II, which typically present with cephalocaudal progression or ichthyosiform dermatitis, respectively. Her presentation also was atypical for juvenile onset in types III, IV, and V, which tend to present in younger children and with different physical examination findings.3,8

The morphology of our patient’s lesions also was atypical for PRP, PPK, EPS, and psoriasis. The clinical presentation had features of these entities with erythema, fissuring, xerosis, carnauba wax–like appearance, symmetric scale, and well-demarcated plaques. Although these findings are not mutually exclusive, their combined presentation is atypical. Coupled with the ambiguous family history of similar skin disease in the patient’s father, the discussion of genodermatoses, particularly PPK, further confounded the diagnosis.4,9 When evaluating for PRP, especially with any family history of skin conditions, genodermatoses should be considered. Furthermore, our patient’s remote and unverifiable history of psoriasis serves as a cautionary reminder that prior diagnoses and medical history always should be reasonably scrutinized. Additionally, a drug-induced PRP eruption also should be considered. Although our patient received no medical treatment for the upper respiratory tract infection prior to the onset of PRP, there have been several reports of drug-induced PRP.10-12

The therapeutic challenge in this case is one that often is encountered in clinical practice. The health care system often may pose a barrier to diagnosis by inhibiting particular services required for adequate patient care. For our patient, diagnosis was delayed by several weeks due to difficulties obtaining a diagnostic skin biopsy. When faced with challenges from health care infrastructure, creativity with treatment options, such as finding an empiric treatment option (cyclosporine in this case), must be considered.

Systemic retinoids have been found to be efficacious treatment options for PRP, but when dealing with a woman of reproductive age, reproductive preferences must be discussed before identifying an appropriate treatment regimen.1,13-15 The half-life of acitretin compared to isotretinoin is 2 days vs 22 hours.6,16 With alcohol consumption, acitretin can be metabolized to etretinate, which has a half-life of 120 days.17 In our patient, isotretinoin was a more manageable option to allow for greater reproductive freedom upon treatment completion.

- Klein A, Landthaler M, Karrer S. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:157-170.

- Shenefelt PD. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Medscape website. Updated September 11, 2020. Accessed September 28, 2021. https://reference.medscape.com/article/1107742-overview

- Griffiths WA. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:105-112.

- Itin PH, Lautenschlager S. Palmoplantar keratoderma and associated syndromes. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:152-161.

- Guidelines of care for psoriasis. Committee on Guidelines of Care. Task Force on Psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:632-637.

- Larsen FG, Jakobsen P, Eriksen H, et al. The pharmacokinetics of acitretin and its 13-cis-metabolite in psoriatic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:477-483.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Sørensen KB, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a retrospective analysis of 43 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:405-406.

- Lucker GP, Van de Kerkhof PC, Steijlen PM. The hereditary palmoplantar keratoses: an updated review and classification. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:1-14.

- Cutaneous reactions to labetalol. Br Med J. 1978;1:987.

- Plana A, Carrascosa JM, Vilavella M. Pityriasis rubra pilaris‐like reaction induced by imatinib. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:520-522.

- Gajinov ZT, Matc´ MB, Duran VD, et al. Drug-related pityriasis rubra pilaris with acantholysis. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2013;70:871-873.

- Clayton BD, Jorizzo JL, Hitchcock MG, et al. Adult pityriasis rubra pilaris: a 10-year case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:959-964.

- Cohen PR, Prystowsky JH. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:801-807.

- Dicken CH. Isotretinoin treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(2 pt 1):297-301.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Grønhøj Larsen F, Steinkjer B, Jakobsen P, et al. Acitretin is converted to etretinate only during concomitant alcohol intake. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1164-1169.

To the Editor:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare inflammatory dermatosis of unknown etiology characterized by erythematosquamous salmon-colored plaques with well-demarcated islands of unaffected skin and hyperkeratotic follicles.1 In the United States, an incidence of 1 in 3500to 5000 patients presenting to dermatology clinics has been reported.2 Pityriasis rubra pilaris has several subtypes and variability in presentation that can make accurate and timely diagnosis challenging.3-5 Herein, we present a case of PRP with complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

A 22-year-old woman presented with symmetrical, well-demarcated, hyperkeratotic, erythematous plaques with a carnauba wax–like appearance on the palms (Figure 1), soles, elbows, and trunk covering approximately 5% of the body surface area. Two weeks prior to presentation, she experienced an upper respiratory tract infection without any treatment and subsequently developed redness on the palms, which became very hard and scaly. The redness then spread to the elbows, soles, and trunk. She reported itching as well as pain in areas of fissuring. Hand mobility became restricted due to thick scale.

The patient’s medical history was notable for suspected psoriasis 9 years prior, but there were no records or biopsy reports that could be obtained to confirm the diagnosis. She also reported a similar skin condition in her father, which also was diagnosed as psoriasis, but this diagnosis could not be verified.

Although the morphology of the lesions was most consistent with localized PRP, atypical psoriasis, palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK), and erythroderma progressive symmetrica (EPS) also were considered given the personal and family history of suspected psoriasis. A biopsy could not be obtained due to an insurance issue. She was started on clobetasol cream 0.05% and ointment. At 2-week follow-up, her condition remained unchanged. Empiric systemic treatment was discussed, which would potentially work for diagnoses of both PRP and psoriasis. Due to the history of psoriasis and level of discomfort, cyclosporine 300 mg once daily was started to gain rapid control of the disease. Methotrexate also was considered due to its efficacy and economic considerations but was not selected due to patient concerns about the medication.

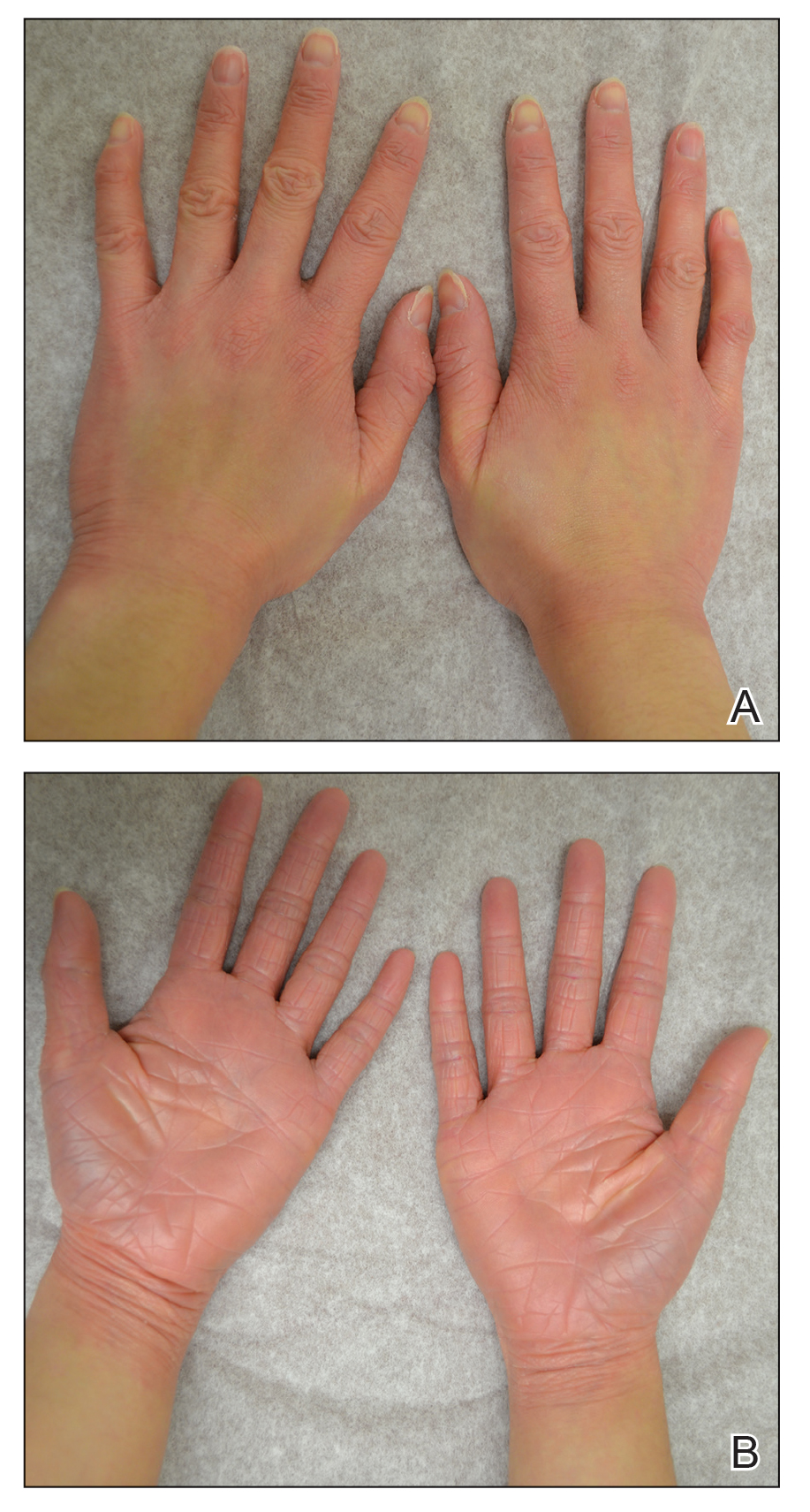

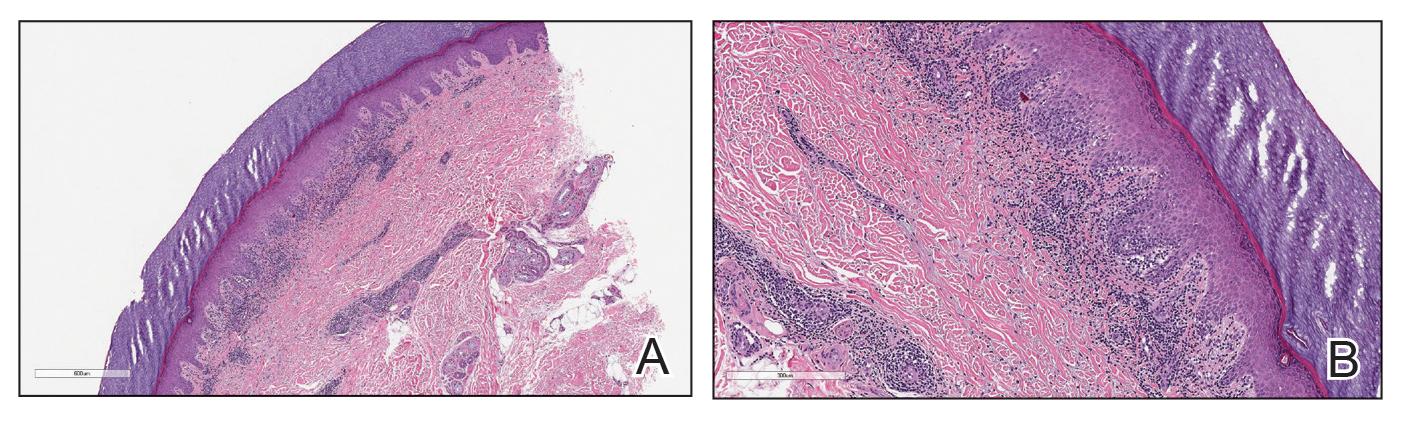

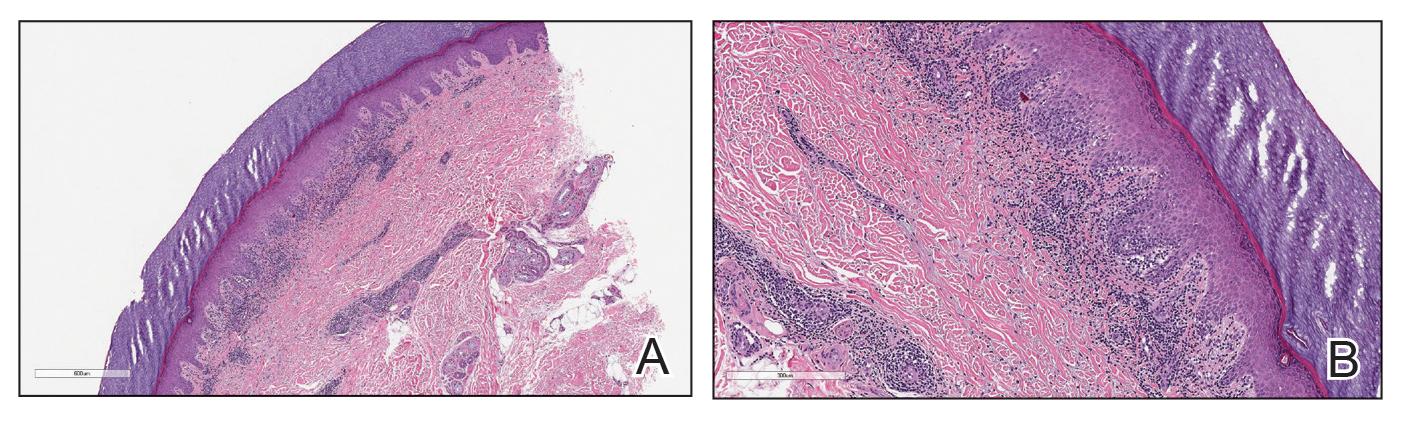

After 10 weeks of cyclosporine treatment, our patient showed some improvement of the skin with decreased scale and flattening of plaques but not complete resolution. At this point, a biopsy was able to be obtained with prior authorization. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the right flank demonstrated a psoriasiform and papillated epidermis with multifocally capped, compact parakeratosis and minimal lymphocytic infiltrate consistent with PRP. Although EPS also was on the histologic differential, clinical history was more consistent with a diagnosis of PRP. There was some minimal improvement with cyclosporine, but with the diagnosis of PRP confirmed, a systemic retinoid became the treatment of choice. Although acitretin is the preferred treatment for PRP, given that pregnancy would be contraindicated during and for 3 years following acitretin therapy, a trial of isotretinoin 40 mg once daily was started due to its shorter half-life compared to acitretin and was continued for 3 months (Figure 2).6,7

The diagnosis of PRP often can be challenging given the variety of clinical presentations. This case was an atypical presentation of PRP with several learning points, as our patient’s condition did not fit perfectly into any of the 6 types of PRP. The age of onset was atypical at 22 years old. Pityriasis rubra pilaris typically presents with a bimodal age distribution, appearing either in the first decade or the fifth to sixth decades of life.3,8 Her clinical presentation was atypical for adult-onset types I and II, which typically present with cephalocaudal progression or ichthyosiform dermatitis, respectively. Her presentation also was atypical for juvenile onset in types III, IV, and V, which tend to present in younger children and with different physical examination findings.3,8

The morphology of our patient’s lesions also was atypical for PRP, PPK, EPS, and psoriasis. The clinical presentation had features of these entities with erythema, fissuring, xerosis, carnauba wax–like appearance, symmetric scale, and well-demarcated plaques. Although these findings are not mutually exclusive, their combined presentation is atypical. Coupled with the ambiguous family history of similar skin disease in the patient’s father, the discussion of genodermatoses, particularly PPK, further confounded the diagnosis.4,9 When evaluating for PRP, especially with any family history of skin conditions, genodermatoses should be considered. Furthermore, our patient’s remote and unverifiable history of psoriasis serves as a cautionary reminder that prior diagnoses and medical history always should be reasonably scrutinized. Additionally, a drug-induced PRP eruption also should be considered. Although our patient received no medical treatment for the upper respiratory tract infection prior to the onset of PRP, there have been several reports of drug-induced PRP.10-12

The therapeutic challenge in this case is one that often is encountered in clinical practice. The health care system often may pose a barrier to diagnosis by inhibiting particular services required for adequate patient care. For our patient, diagnosis was delayed by several weeks due to difficulties obtaining a diagnostic skin biopsy. When faced with challenges from health care infrastructure, creativity with treatment options, such as finding an empiric treatment option (cyclosporine in this case), must be considered.

Systemic retinoids have been found to be efficacious treatment options for PRP, but when dealing with a woman of reproductive age, reproductive preferences must be discussed before identifying an appropriate treatment regimen.1,13-15 The half-life of acitretin compared to isotretinoin is 2 days vs 22 hours.6,16 With alcohol consumption, acitretin can be metabolized to etretinate, which has a half-life of 120 days.17 In our patient, isotretinoin was a more manageable option to allow for greater reproductive freedom upon treatment completion.

To the Editor:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare inflammatory dermatosis of unknown etiology characterized by erythematosquamous salmon-colored plaques with well-demarcated islands of unaffected skin and hyperkeratotic follicles.1 In the United States, an incidence of 1 in 3500to 5000 patients presenting to dermatology clinics has been reported.2 Pityriasis rubra pilaris has several subtypes and variability in presentation that can make accurate and timely diagnosis challenging.3-5 Herein, we present a case of PRP with complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

A 22-year-old woman presented with symmetrical, well-demarcated, hyperkeratotic, erythematous plaques with a carnauba wax–like appearance on the palms (Figure 1), soles, elbows, and trunk covering approximately 5% of the body surface area. Two weeks prior to presentation, she experienced an upper respiratory tract infection without any treatment and subsequently developed redness on the palms, which became very hard and scaly. The redness then spread to the elbows, soles, and trunk. She reported itching as well as pain in areas of fissuring. Hand mobility became restricted due to thick scale.

The patient’s medical history was notable for suspected psoriasis 9 years prior, but there were no records or biopsy reports that could be obtained to confirm the diagnosis. She also reported a similar skin condition in her father, which also was diagnosed as psoriasis, but this diagnosis could not be verified.

Although the morphology of the lesions was most consistent with localized PRP, atypical psoriasis, palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK), and erythroderma progressive symmetrica (EPS) also were considered given the personal and family history of suspected psoriasis. A biopsy could not be obtained due to an insurance issue. She was started on clobetasol cream 0.05% and ointment. At 2-week follow-up, her condition remained unchanged. Empiric systemic treatment was discussed, which would potentially work for diagnoses of both PRP and psoriasis. Due to the history of psoriasis and level of discomfort, cyclosporine 300 mg once daily was started to gain rapid control of the disease. Methotrexate also was considered due to its efficacy and economic considerations but was not selected due to patient concerns about the medication.

After 10 weeks of cyclosporine treatment, our patient showed some improvement of the skin with decreased scale and flattening of plaques but not complete resolution. At this point, a biopsy was able to be obtained with prior authorization. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the right flank demonstrated a psoriasiform and papillated epidermis with multifocally capped, compact parakeratosis and minimal lymphocytic infiltrate consistent with PRP. Although EPS also was on the histologic differential, clinical history was more consistent with a diagnosis of PRP. There was some minimal improvement with cyclosporine, but with the diagnosis of PRP confirmed, a systemic retinoid became the treatment of choice. Although acitretin is the preferred treatment for PRP, given that pregnancy would be contraindicated during and for 3 years following acitretin therapy, a trial of isotretinoin 40 mg once daily was started due to its shorter half-life compared to acitretin and was continued for 3 months (Figure 2).6,7

The diagnosis of PRP often can be challenging given the variety of clinical presentations. This case was an atypical presentation of PRP with several learning points, as our patient’s condition did not fit perfectly into any of the 6 types of PRP. The age of onset was atypical at 22 years old. Pityriasis rubra pilaris typically presents with a bimodal age distribution, appearing either in the first decade or the fifth to sixth decades of life.3,8 Her clinical presentation was atypical for adult-onset types I and II, which typically present with cephalocaudal progression or ichthyosiform dermatitis, respectively. Her presentation also was atypical for juvenile onset in types III, IV, and V, which tend to present in younger children and with different physical examination findings.3,8

The morphology of our patient’s lesions also was atypical for PRP, PPK, EPS, and psoriasis. The clinical presentation had features of these entities with erythema, fissuring, xerosis, carnauba wax–like appearance, symmetric scale, and well-demarcated plaques. Although these findings are not mutually exclusive, their combined presentation is atypical. Coupled with the ambiguous family history of similar skin disease in the patient’s father, the discussion of genodermatoses, particularly PPK, further confounded the diagnosis.4,9 When evaluating for PRP, especially with any family history of skin conditions, genodermatoses should be considered. Furthermore, our patient’s remote and unverifiable history of psoriasis serves as a cautionary reminder that prior diagnoses and medical history always should be reasonably scrutinized. Additionally, a drug-induced PRP eruption also should be considered. Although our patient received no medical treatment for the upper respiratory tract infection prior to the onset of PRP, there have been several reports of drug-induced PRP.10-12

The therapeutic challenge in this case is one that often is encountered in clinical practice. The health care system often may pose a barrier to diagnosis by inhibiting particular services required for adequate patient care. For our patient, diagnosis was delayed by several weeks due to difficulties obtaining a diagnostic skin biopsy. When faced with challenges from health care infrastructure, creativity with treatment options, such as finding an empiric treatment option (cyclosporine in this case), must be considered.

Systemic retinoids have been found to be efficacious treatment options for PRP, but when dealing with a woman of reproductive age, reproductive preferences must be discussed before identifying an appropriate treatment regimen.1,13-15 The half-life of acitretin compared to isotretinoin is 2 days vs 22 hours.6,16 With alcohol consumption, acitretin can be metabolized to etretinate, which has a half-life of 120 days.17 In our patient, isotretinoin was a more manageable option to allow for greater reproductive freedom upon treatment completion.

- Klein A, Landthaler M, Karrer S. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:157-170.

- Shenefelt PD. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Medscape website. Updated September 11, 2020. Accessed September 28, 2021. https://reference.medscape.com/article/1107742-overview

- Griffiths WA. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:105-112.

- Itin PH, Lautenschlager S. Palmoplantar keratoderma and associated syndromes. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:152-161.

- Guidelines of care for psoriasis. Committee on Guidelines of Care. Task Force on Psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:632-637.

- Larsen FG, Jakobsen P, Eriksen H, et al. The pharmacokinetics of acitretin and its 13-cis-metabolite in psoriatic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:477-483.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Sørensen KB, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a retrospective analysis of 43 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:405-406.

- Lucker GP, Van de Kerkhof PC, Steijlen PM. The hereditary palmoplantar keratoses: an updated review and classification. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:1-14.

- Cutaneous reactions to labetalol. Br Med J. 1978;1:987.

- Plana A, Carrascosa JM, Vilavella M. Pityriasis rubra pilaris‐like reaction induced by imatinib. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:520-522.

- Gajinov ZT, Matc´ MB, Duran VD, et al. Drug-related pityriasis rubra pilaris with acantholysis. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2013;70:871-873.

- Clayton BD, Jorizzo JL, Hitchcock MG, et al. Adult pityriasis rubra pilaris: a 10-year case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:959-964.

- Cohen PR, Prystowsky JH. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:801-807.

- Dicken CH. Isotretinoin treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(2 pt 1):297-301.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Grønhøj Larsen F, Steinkjer B, Jakobsen P, et al. Acitretin is converted to etretinate only during concomitant alcohol intake. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1164-1169.

- Klein A, Landthaler M, Karrer S. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:157-170.

- Shenefelt PD. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Medscape website. Updated September 11, 2020. Accessed September 28, 2021. https://reference.medscape.com/article/1107742-overview

- Griffiths WA. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:105-112.

- Itin PH, Lautenschlager S. Palmoplantar keratoderma and associated syndromes. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:152-161.

- Guidelines of care for psoriasis. Committee on Guidelines of Care. Task Force on Psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:632-637.

- Larsen FG, Jakobsen P, Eriksen H, et al. The pharmacokinetics of acitretin and its 13-cis-metabolite in psoriatic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:477-483.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Sørensen KB, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a retrospective analysis of 43 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:405-406.

- Lucker GP, Van de Kerkhof PC, Steijlen PM. The hereditary palmoplantar keratoses: an updated review and classification. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:1-14.

- Cutaneous reactions to labetalol. Br Med J. 1978;1:987.

- Plana A, Carrascosa JM, Vilavella M. Pityriasis rubra pilaris‐like reaction induced by imatinib. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:520-522.

- Gajinov ZT, Matc´ MB, Duran VD, et al. Drug-related pityriasis rubra pilaris with acantholysis. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2013;70:871-873.

- Clayton BD, Jorizzo JL, Hitchcock MG, et al. Adult pityriasis rubra pilaris: a 10-year case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:959-964.

- Cohen PR, Prystowsky JH. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:801-807.

- Dicken CH. Isotretinoin treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(2 pt 1):297-301.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Grønhøj Larsen F, Steinkjer B, Jakobsen P, et al. Acitretin is converted to etretinate only during concomitant alcohol intake. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1164-1169.

Practice Points

- Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare inflammatory dermatosis of unknown etiology characterized by erythematosquamous salmon-colored plaques with well-demarcated islands of unaffected skin and hyperkeratotic follicles.

- The diagnosis of PRP often can be challenging given the variety of clinical presentations.

Paraneoplastic Signs in Bladder Transitional Cell Carcinoma: An Unusual Presentation

To the Editor:

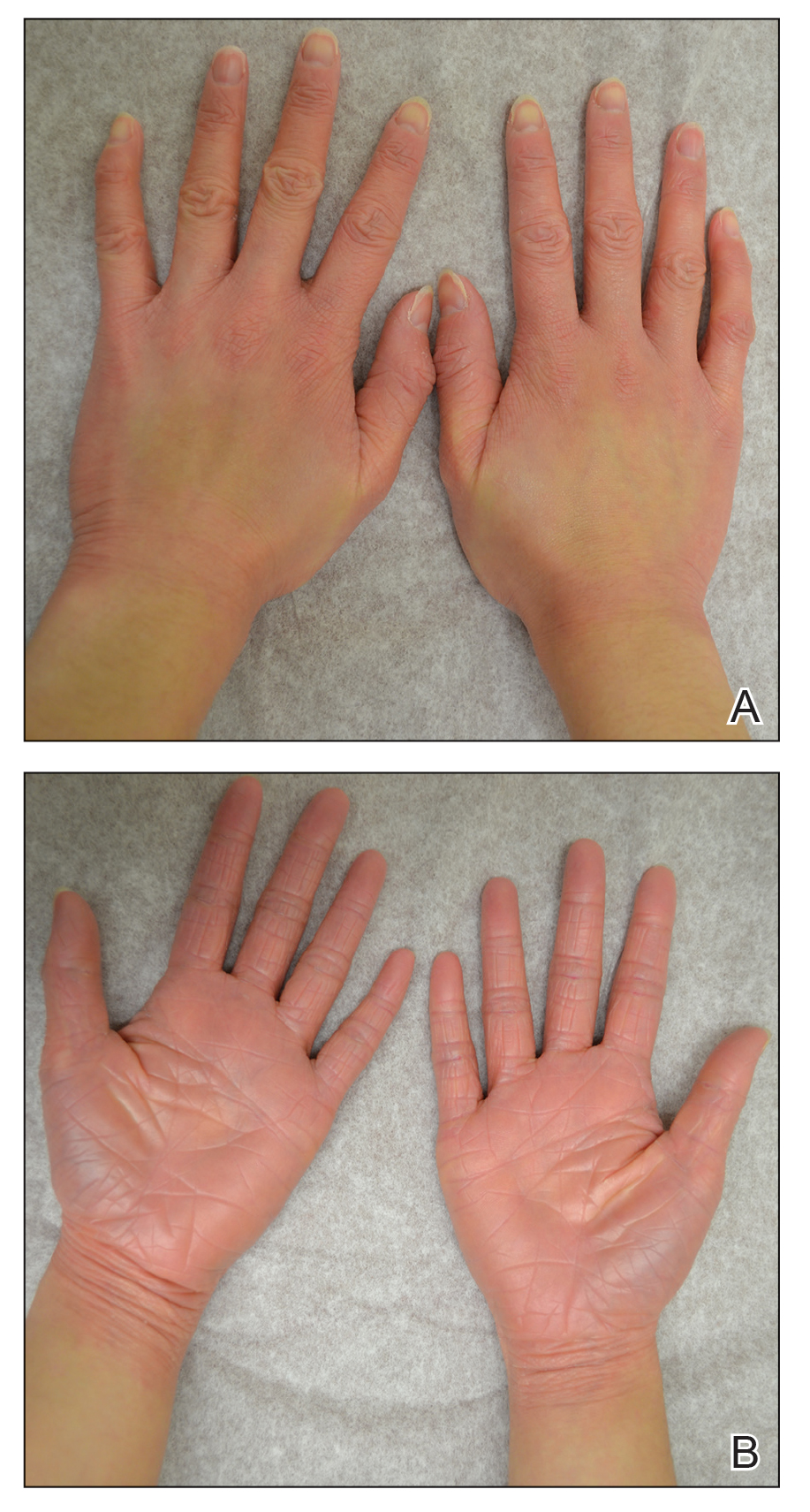

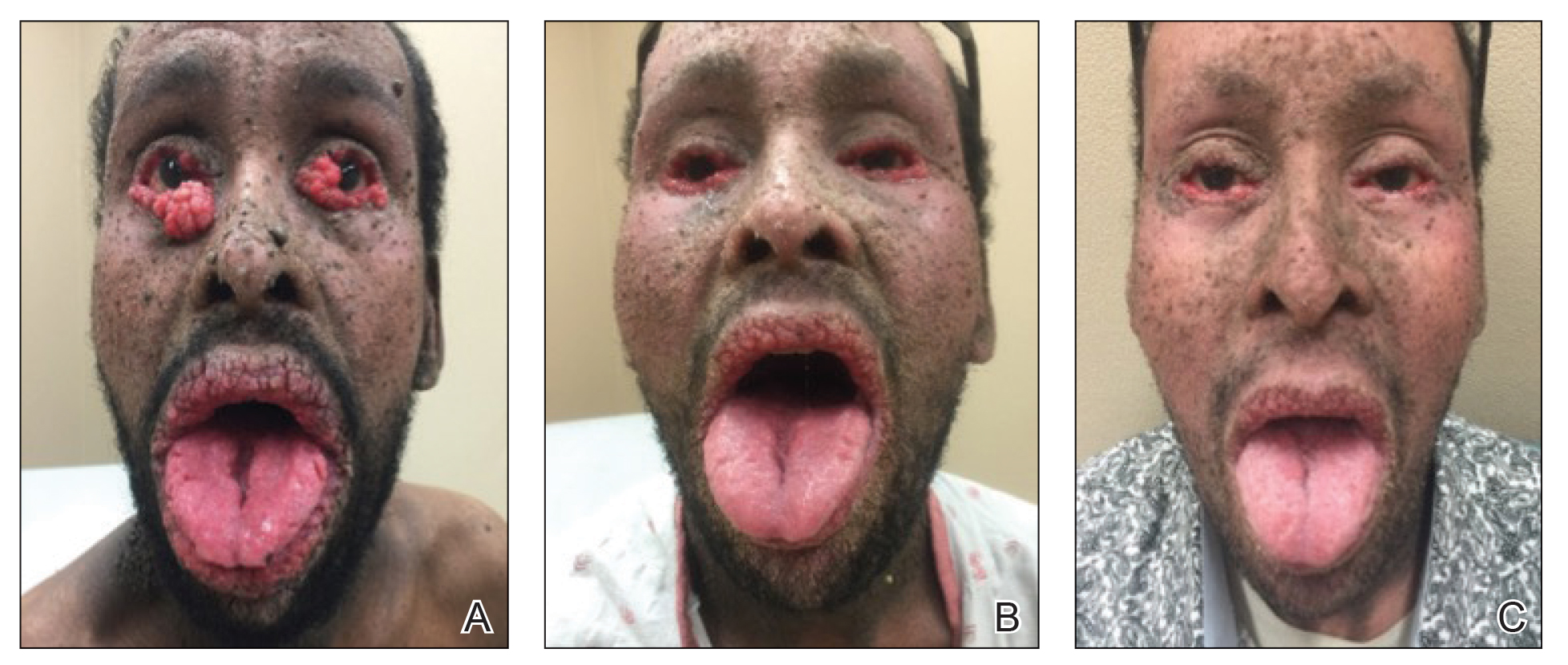

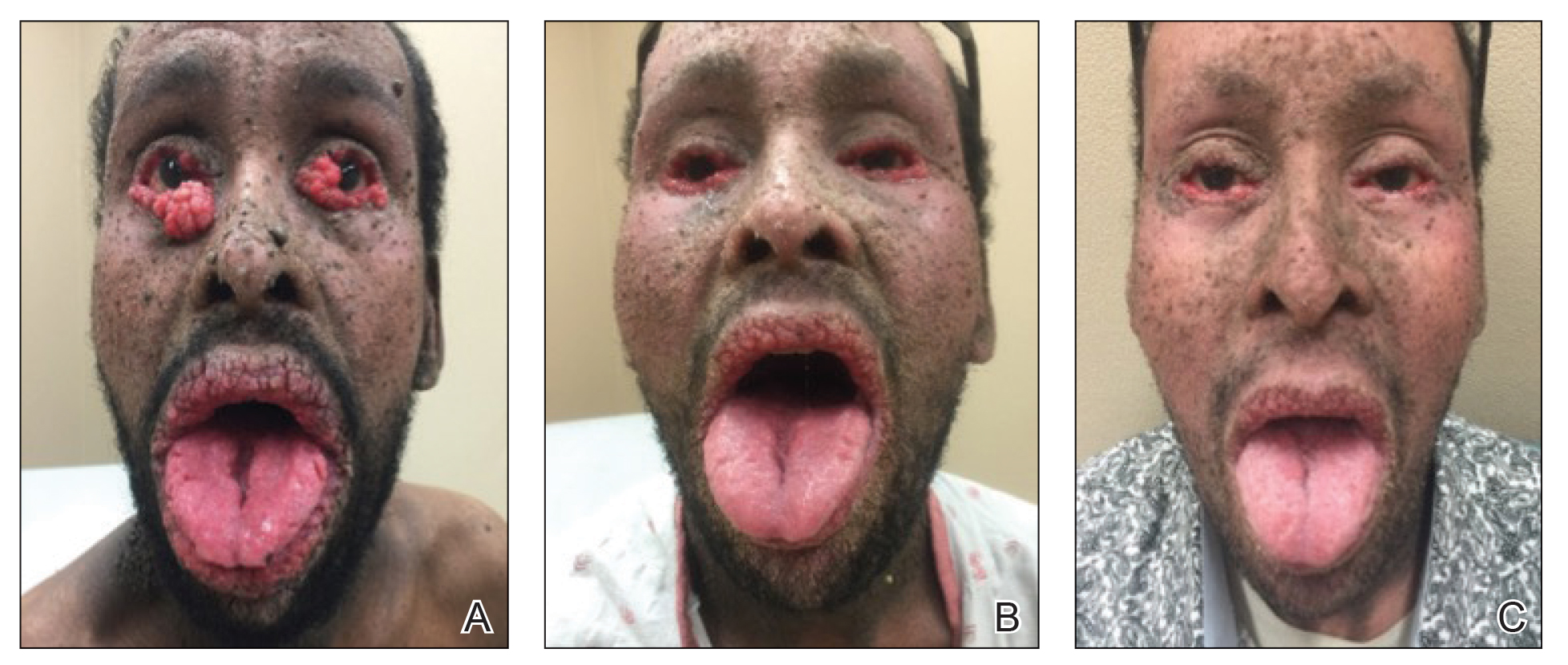

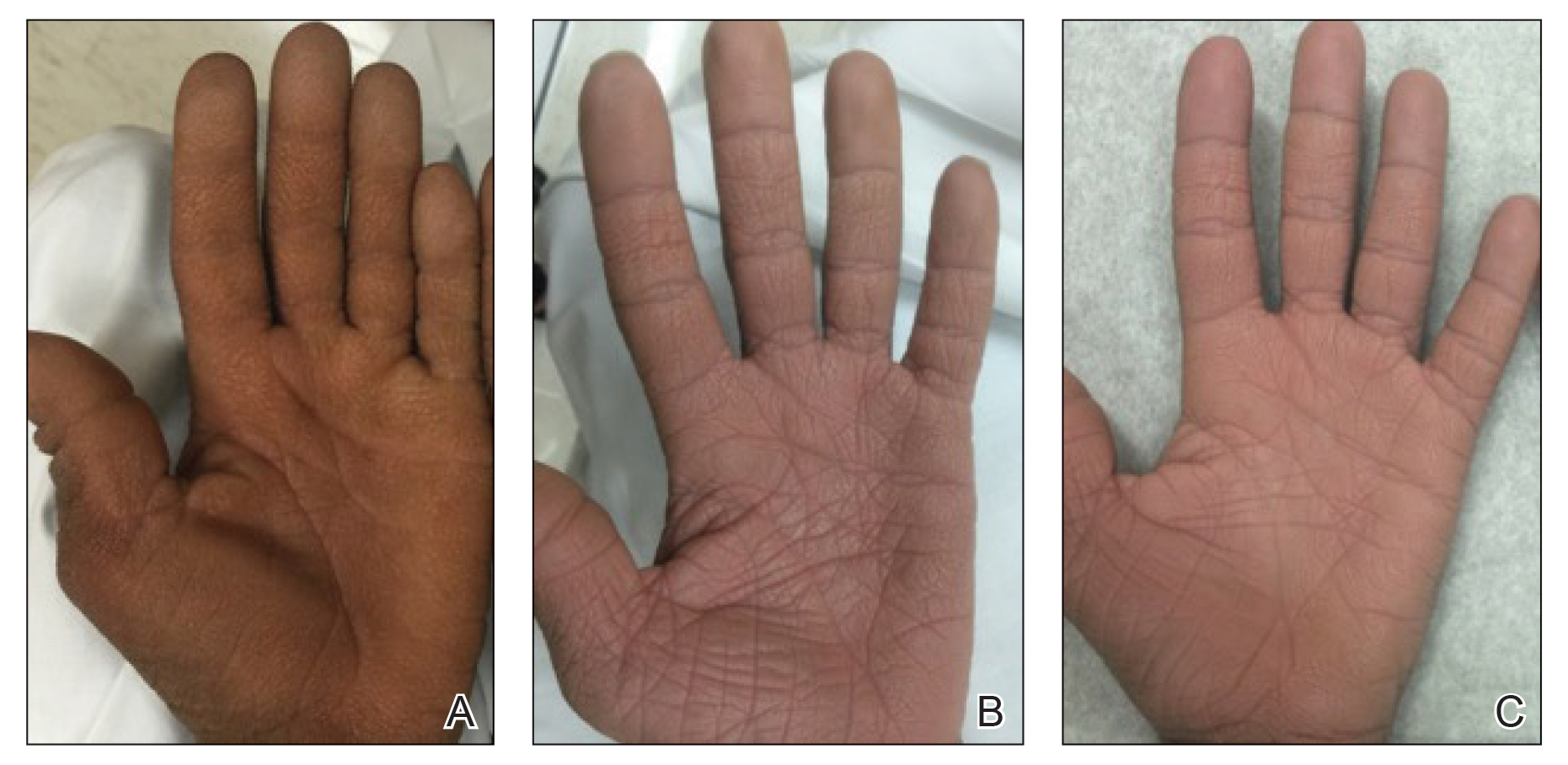

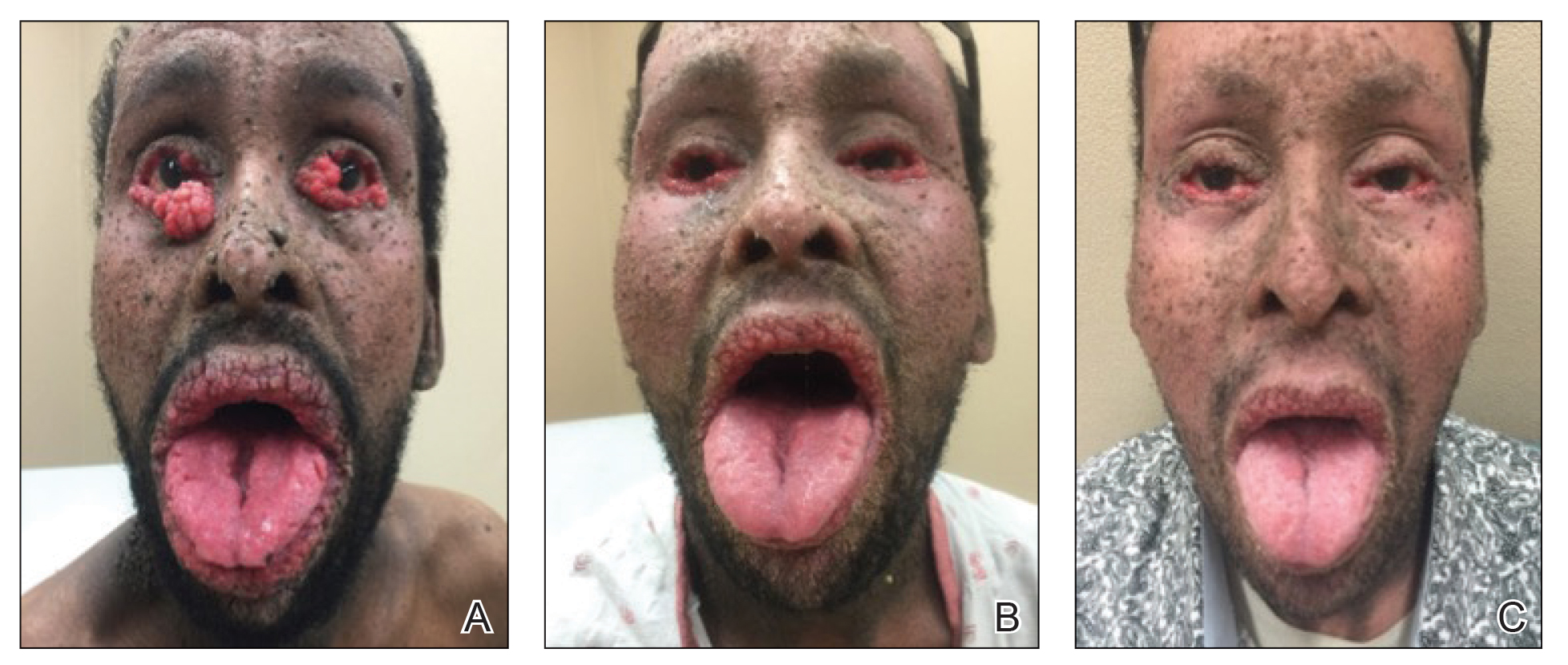

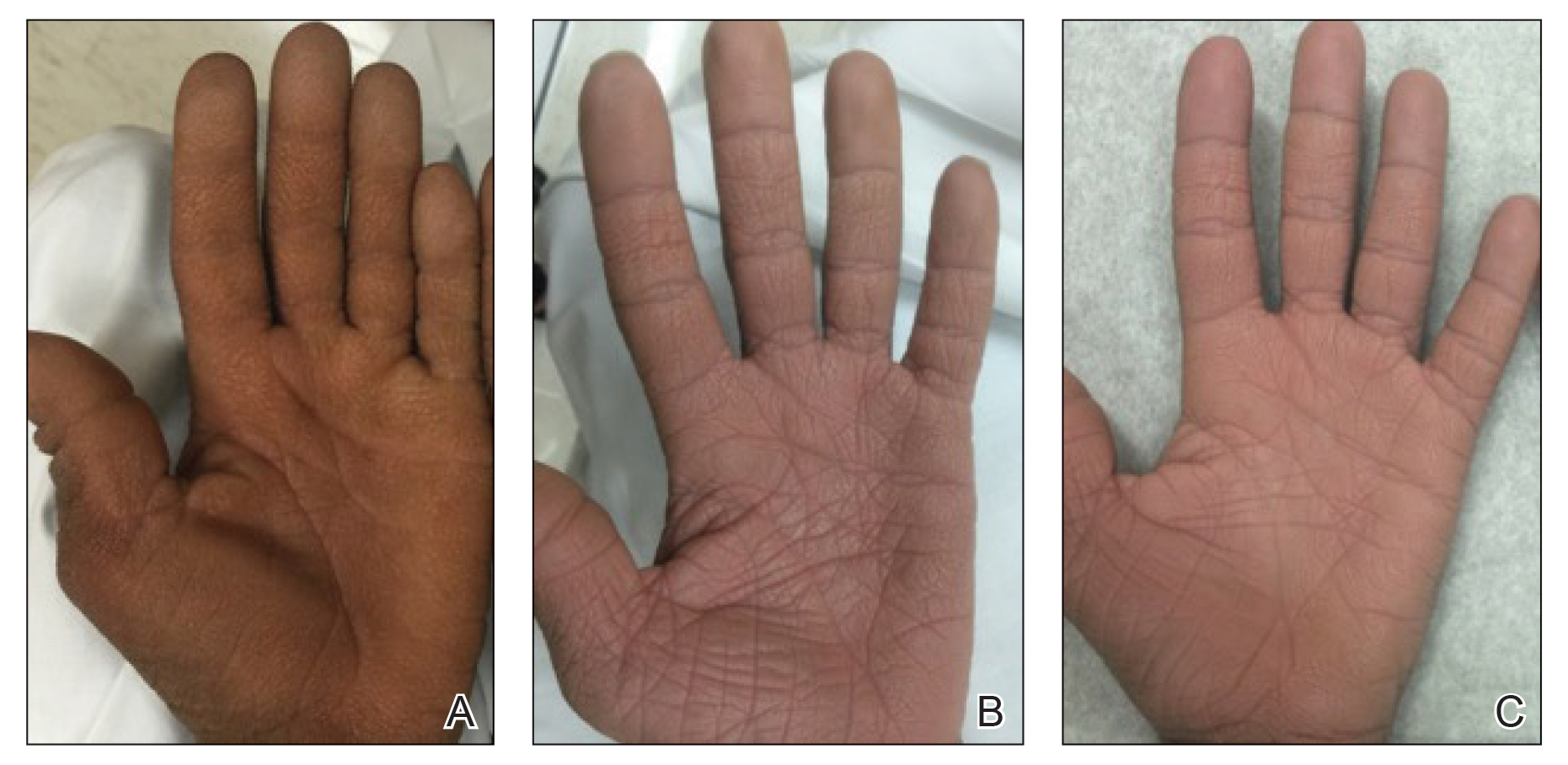

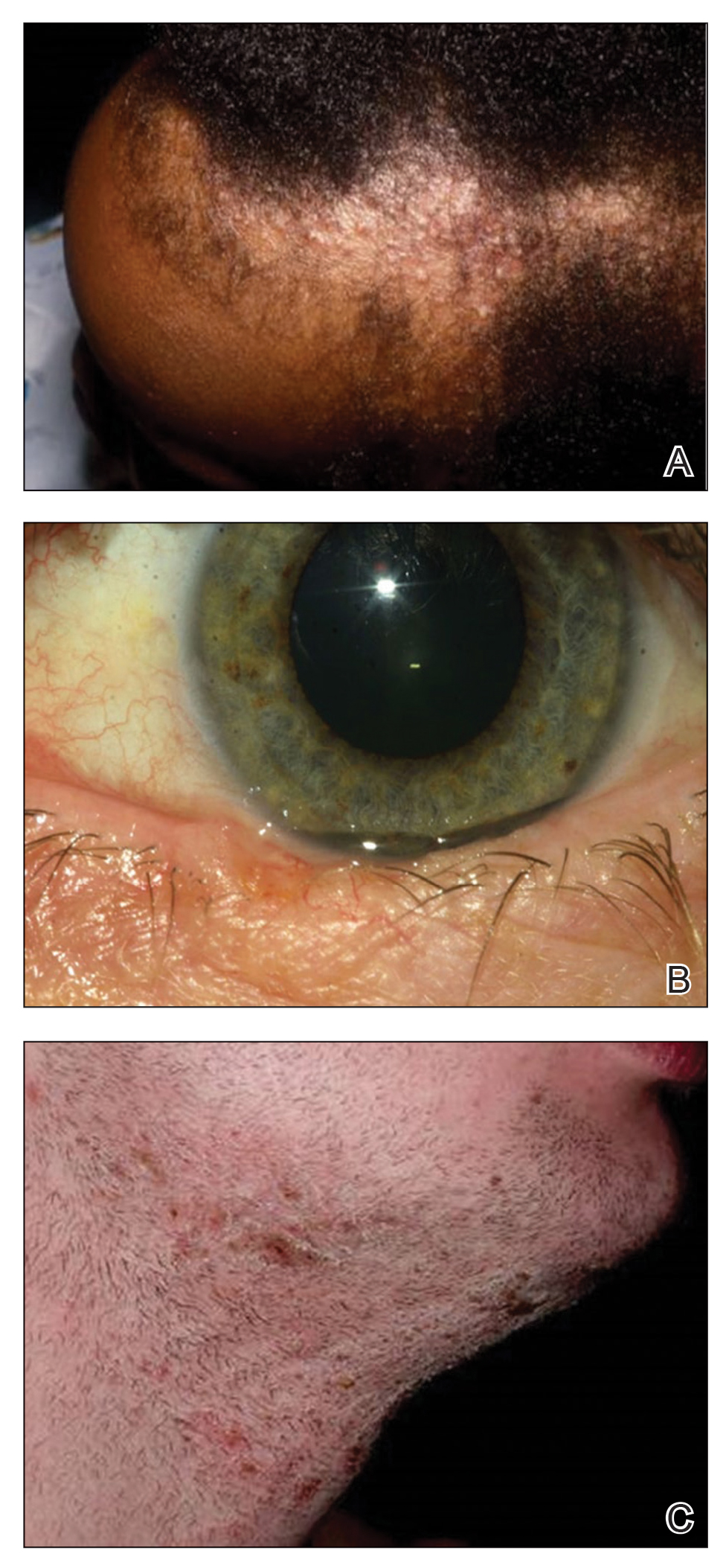

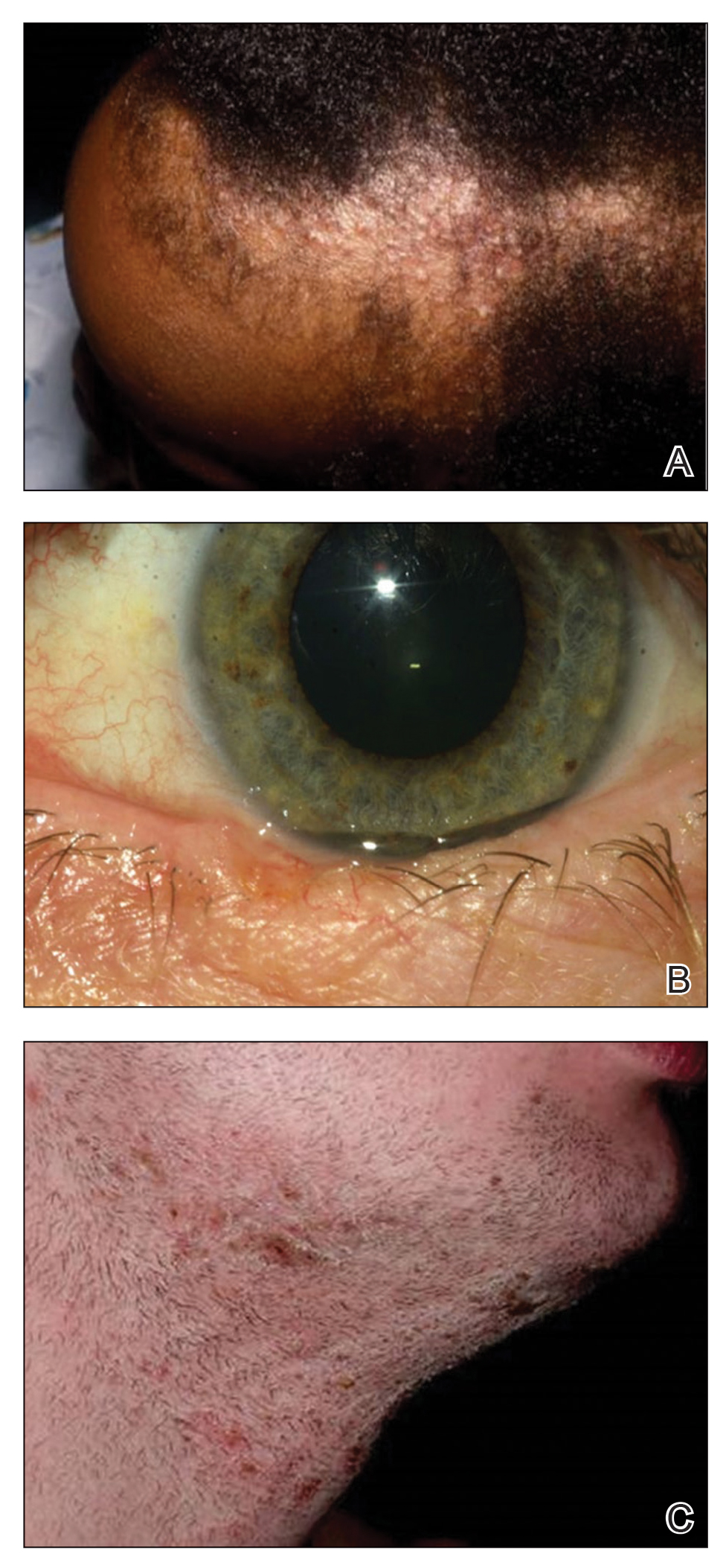

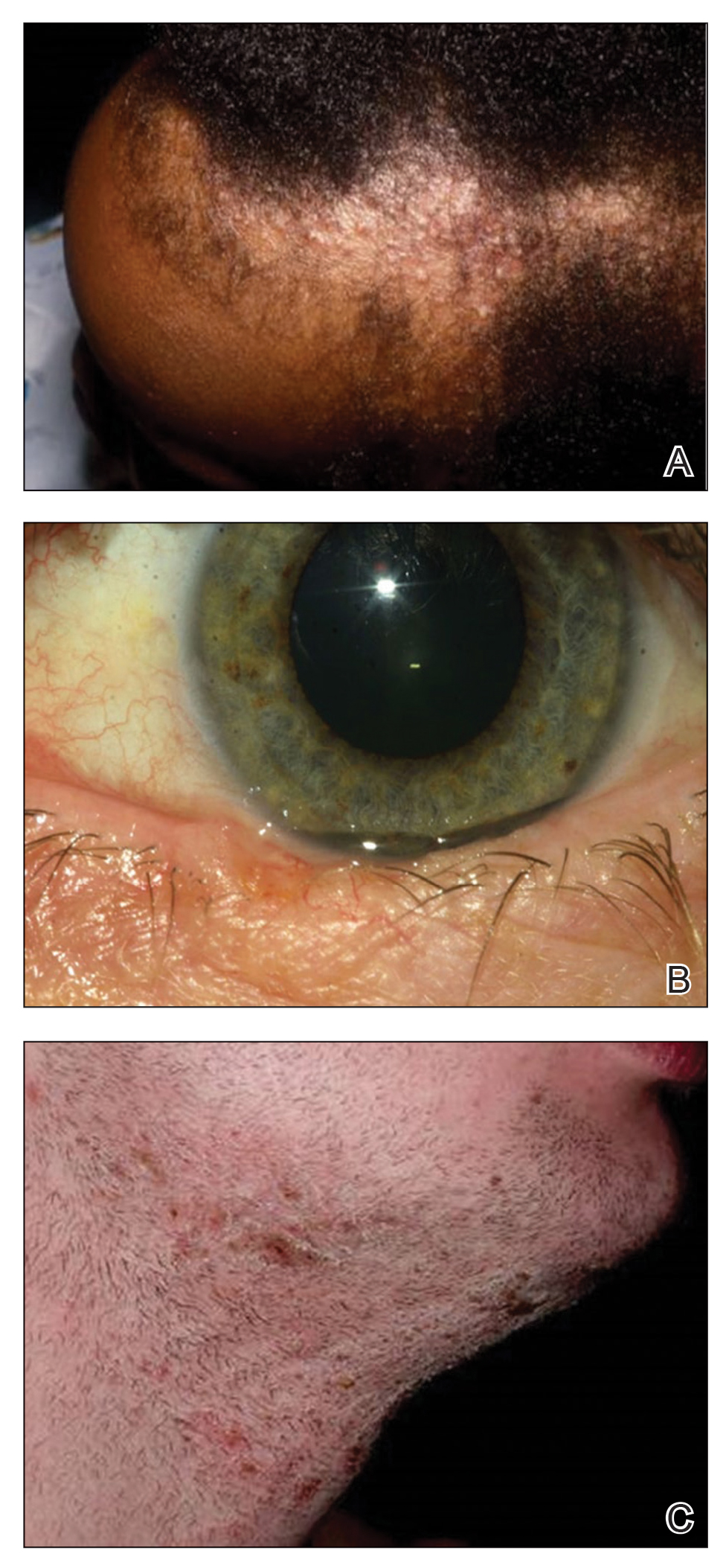

A 40-year-old Somalian man presented to the dermatology clinic with lesions on the eyelids, tongue, lips, and hands of 8 years’ duration. He was a former refugee who had faced considerable stigma from his community due to his appearance. A review of systems was remarkable for decreased appetite but no weight loss. He reported no abdominal distention, early satiety, or urinary symptoms, and he had no personal history of diabetes mellitus or obesity. Physical examination demonstrated hyperpigmented velvety plaques in all skin folds and on the genitalia. Massive papillomatosis of the eyelid margins, tongue, and lips also was noted (Figure 1A). Flesh-colored papules also were scattered across the face. Punctate, flesh-colored papules were present on the volar and palmar hands (Figure 2A). Histopathology demonstrated pronounced papillomatous epidermal hyperplasia with negative human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 and HPV-18 DNA studies. Given the appearance of malignant acanthosis nigricans with oral and conjunctival features, cutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms, concern for underlying malignancy was high. Malignancy workup, including upper and lower endoscopy as well as serial computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, was unrevealing.

Laboratory investigation revealed a positive Schistosoma IgG antibody (0.38 geometric mean egg count) and peripheral eosinophilia (1.09 ×103/μL), which normalized after praziquantel therapy. With no malignancy identified over the preceding 6-month period, treatment with acitretin 50 mg daily was initiated based on limited literature support.1-3 Treatment led to reduction in the size and number of papillomas (Figure 1B) and tripe palms (Figure 2B) with increased mobility of hands, lips, and tongue. The patient underwent oculoplastic surgery to reduce the papilloma burden along the eyelid margins. Subsequent cystoscopy 9 months after the initial presentation revealed low-grade transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Intraoperative mitomycin C led to tumor shrinkage and, with continued treatment with daily acitretin, dramatic improvement of all cutaneous and mucosal symptoms (Figure 1C and Figure 2C). To date, his cutaneous symptoms have resolved.

This case demonstrated a unique presentation of multiple paraneoplastic signs in bladder transitional cell carcinoma. The presence of malignant acanthosis nigricans (including oral and conjunctival involvement), cutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms have been individually documented in various types of gastric malignancies.4 Acanthosis nigricans often is secondary to diabetes and obesity, presenting with diffuse, thickened, velvety plaques in the flexural areas. Malignant acanthosis nigricans is a rare, rapidly progressive condition that often presents over a period of weeks to months; it almost always is associated with internal malignancies. It often has more extensive involvement, extending beyond the flexural areas, than typical acanthosis nigricans.4 Oral involvement can be either hypertrophic or papillomatous; papillomatosis of the oral mucosa was reported in over 40% of malignant acanthosis nigricans cases (N=200).5 Cases with conjunctival involvement are less common.6 Although malignant acanthosis nigricans often is codiagnosed with a malignancy, it can precede the cancer diagnosis in some cases.7,8 A majority of cases are associated with adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.4 Progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis also is a rare paraneoplastic condition that most commonly is associated with gastric adenocarcinomas. Progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis often presents rapidly as verrucous growths on cutaneous surfaces (including the hands and face) but also can affect mucosal surfaces such as the mouth and conjunctiva.9-11 Tripe palms are characterized by exaggerated dermatoglyphics with diffuse palmar ridging and hyperkeratosis. Tripe palms most often are associated with pulmonary malignancies. When tripe palms are present with malignant acanthosis nigricans, they reflect up to a one-third incidence of gastrointestinal malignancy.12,13

Despite the individual presentation of these paraneoplastic signs in a variety of malignancies, synchronous presentation is rare. A brief literature review only identified 6 cases of concurrent acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms, and progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis with an underlying gastrointestinal malignancy.1,11,14-17 Two additional reports described tripe palms with oral acanthosis nigricans and progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis in metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma and renal urothelial carcinoma.2,18 An additional case of all 3 paraneoplastic conditions was reported in the setting of metastatic cervical cancer (HPV positive).19 Per a recent case report and literature review,20 there have only been 8 cases of acanthosis nigricans reported in bladder transitional cell carcinoma,20-27 half of which have included oral malignant acanthosis nigricans.20-23 Only one report of concurrent cutaneous and oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and triple palms in the setting of bladder cancer has been reported.20 Given the extensive conjunctival involvement and cutaneous papillomatosis in our patient, ours is a rarely reported case of concurrent malignant mucocutaneous acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms, and progressive papillomatosis in transitional cell bladder carcinoma. We believe it is imperative to consider the role of this malignancy as a cause of these paraneoplastic conditions.

Although these paraneoplastic conditions rarely co-occur, our case further offers a common molecular pathway for these conditions.28 In these paraneoplastic conditions, the stimulating factor is thought to be tumor growth factor α, which is structurally related to epidermal growth factor (EGF). Epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) are found in the basal layer of the epidermis, where activation stimulates keratinocyte growth and leads to the cutaneous manifestation of symptoms.28 Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations are found in most noninvasive transitional cell tumors of the bladder.29 The fibroblast growth factor pathway is distinctly different from the tumor growth factor α and EGF pathways.30 However, this association with transitional cell carcinoma suggests that fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 also may be implicated in these paraneoplastic conditions.

Our patient responded well to treatment with acitretin 50 mg daily. The mechanism of action of retinoids involves inducing mitotic activity and desmosomal shedding.31 Retinoids downregulate EGFR expression and activation in EGF-stimulated cells.32 We hypothesize that these oral retinoids decreased the growth stimulus and thereby improved cutaneous signs in the setting of our patient’s transitional cell cancer. Although definitive therapy is malignancy management, our case highlights the utility of adjunctive measures such as oral retinoids and surgical debulking. While previous cases have reported use of retinoids at a lower dosage than used in this case, oral lesions often have only been mildly improved with little impact on other cutaneous symptoms.1,2 In one case of malignant acanthosis nigricans and oral papillomatosis, isotretinoin 25 mg once every 2 to 3 days led to a moderate decrease in hyperkeratosis and papillomas, but the patient was lost to follow-up.3 Our case highlights the use of higher daily doses of oral retinoids for over 9 months, resulting in marked improvement in both the mucosal and cutaneous symptoms of acanthosis nigricans, progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms. Therefore, oral acitretin should be considered as adjuvant therapy for these paraneoplastic conditions.

By reporting this case, we hope to demonstrate the importance of considering other forms of malignancies in the presence of paraneoplastic conditions. Although gastric malignancies more commonly are associated with these conditions, bladder carcinomas also can present with cutaneous manifestations. The presence of these paraneoplastic conditions alone or together rarely is reported in urologic cancers and generally is considered to be an indicator of poor prognosis. Paraneoplastic conditions often develop rapidly and occur in very advanced malignancies.4 The disfiguring presentation in our case also had unusual diagnostic challenges. The presence of these conditions for 8 years and nonmetastatic advanced malignancy suggest a more indolent process and that these signs are not always an indicator of poor prognosis. Future patients with these paraneoplastic conditions may benefit from both a thorough malignancy screen, including cystoscopy, and high daily doses of oral retinoids.

- Stawczyk-Macieja M, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Nowicki R, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous papillomatosis and tripe palms syndrome associated with gastric adenocarcinoma. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:56-58.

- Lee HC, Ker KJ, Chong W-S. Oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms associated with renal urothelial carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1381-1383.

- Swineford SL, Drucker CR. Palliative treatment of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans and oral florid papillomatosis with retinoids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1151-1153.

- Wick MR, Patterson JW. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes [published online January 31, 2019]. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2019;36:211-228.

- Tyler MT, Ficarra G, Silverman S, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with florid papillary oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:445-449.

- Zhang X, Liu R, Liu Y, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: a case report. BMC Ophthalmology. 2020;20:1-4.

- Curth HO. Dermatoses and malignant internal tumours. Arch Dermatol Syphil. 1955;71:95-107.

- Krawczyk M, Mykala-Cies´la J, Kolodziej-Jaskula A. Acanthosis nigricans as a paraneoplastic syndrome. case reports and review of literature. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119:180-183.

- Singhi MK, Gupta LK, Bansal M, et al. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis with adenocarcinoma of stomach in a 35 year old male. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:195-196.

- Klieb HB, Avon SL, Gilbert J, et al. Florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis: mucocutaneous markers of an underlying gastric malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:E218-E219.

- Yang YH, Zhang RZ, Kang DH, et al. Three paraneoplastic signs in the same patient with gastric adenocarcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18966.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Almeida L, et al. Tripe palms and malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:669-678.

- Chantarojanasiri T, Buranathawornsom A, Sirinawasatien A. Diffuse esophageal squamous papillomatosis: a rare disease associated with acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2020;14:702-706.

- Muhammad R, Iftikhar N, Sarfraz T, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: an indicator of internal malignancy. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2019;29:888-890.

- Brinca A, Cardoso JC, Brites MM, et al. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis and acanthosis nigricans maligna revealing gastric adenocarcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:573-577.

- Vilas-Sueiro A, Suárez-Amor O, Monteagudo B, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis, and tripe palms in a man with gastric adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:438-439.

- Paravina M, Ljubisavljevic´ D. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous papillomatosis and tripe palms syndrome associated with gastric adenocarcinoma—a case report. Serbian J Dermatology Venereol. 2015;7:5-14.

- Kleikamp S, Böhm M, Frosch P, et al. Acanthosis nigricans, papillomatosis mucosae and “tripe” palms in a patient with metastasized gastric carcinoma [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2006;131:1209-1213.

- Mikhail GR, Fachnie DM, Drukker BH, et al. Generalized malignant acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:201-202.

- Zhang R, Jiang M, Lei W, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with recurrent bladder cancer: a case report and review of literature. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;14:951.

- Olek-Hrab K, Silny W, Zaba R, et al. Co-occurrence of acanthosis nigricans and bladder adenocarcinoma-case report. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2013;17:327-330.

- Canjuga I, Mravak-Stipetic´ M, Kopic´V, et al. Oral acanthosis nigricans: case report and comparison with literature reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2008;16:91-95.

- Cairo F, Rubino I, Rotundo R, et al. Oral acanthosis nigricans as a marker of internal malignancy. a case report. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1271-1275.

- Möhrenschlager M, Vocks E, Wessner DB, et al. 2001;165:1629-1630.

- Singh GK, Sen D, Mulajker DS, et al. Acanthosis nigricans associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:722-725.

- Gohji K, Hasunuma Y, Gotoh A, et al. Acanthosis nigricans associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:433-435.

- Pinto WBVR, Badia BML, Souza PVS, et al. Paraneoplastic motor neuronopathy and malignant acanthosis nigricans. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2019;77:527.