User login

Puzzles

Doctors love puzzles, they say. Especially neurologists.

The detective work on a case is part of the job’s appeal. Taking clues from the history, exam, and tests to formulate a diagnosis, then a treatment plan.

But I’m not talking about that.

As I’ve written before, I’ve tried hard to divorce myself from the news. In times where the world seems to have gone mad, I just don’t want to know what’s going on. I focus on my family, my job, and the weather forecast.

But, inevitably, I need something to do. At some point I run out of notes to type, tests to review, emails to answer, and bills to pay. I used to read the news, but now I don’t do that anymore. I even avoid my favorite satire sites, like Onion and Beaverton, because they just reflect the real news (I still read the Weekly World News, which has no relationship to reality, or pretty much anything, whatsoever).

So now, when I’m done with the day’s work, I shut down the computer (which isn’t easy after 25 years of habitual surfing) and sit down with a jigsaw puzzle. I haven’t done that since I was a resident.

It usually takes me 2-3 weeks to do one (500-1,000 pieces) in the 30 minutes or so I spend on it each evening. There’s solace in the quiet, methodical process of carefully looking for matching pieces, trying a few, the brief glee at getting a fit, and then moving to the next piece.

I know I can do this on my iPad, but it’s different with real pieces. Lifting up a piece and examining it for matching shapes and colors, sorting through the tray, wondering if I made a mistake somewhere. The cardboard doesn’t light up to let me know I got it right.

Inevitably, the mind wanders as I work on them. Sometimes back to a puzzle at the office, sometimes to my doing the same puzzle (I’ve had them for a while) at my parents’ house in my teens, sometimes to my kids away at college, or a book I once read.

But that’s the point. It’s almost a form of meditation. Focusing on each piece as my mind moves in other directions. It’s actually more relaxing than I thought, and a welcome escape from the day.

And, like other seemingly unrelated tasks (such as Leo Szilard waiting for a traffic light to change, albeit on a lesser scale), sometimes it brings me an answer I’ve been searching for. A light bulb will go on for a patient case I’ve been turning over for a few days. When that happens I grab my phone and email the thought to myself at work.

It puts my mind in neutral at the end of the day. When I finally go to bed I’m less focused on things that can keep me awake at night.

Though occasionally I do dream of puzzles.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Doctors love puzzles, they say. Especially neurologists.

The detective work on a case is part of the job’s appeal. Taking clues from the history, exam, and tests to formulate a diagnosis, then a treatment plan.

But I’m not talking about that.

As I’ve written before, I’ve tried hard to divorce myself from the news. In times where the world seems to have gone mad, I just don’t want to know what’s going on. I focus on my family, my job, and the weather forecast.

But, inevitably, I need something to do. At some point I run out of notes to type, tests to review, emails to answer, and bills to pay. I used to read the news, but now I don’t do that anymore. I even avoid my favorite satire sites, like Onion and Beaverton, because they just reflect the real news (I still read the Weekly World News, which has no relationship to reality, or pretty much anything, whatsoever).

So now, when I’m done with the day’s work, I shut down the computer (which isn’t easy after 25 years of habitual surfing) and sit down with a jigsaw puzzle. I haven’t done that since I was a resident.

It usually takes me 2-3 weeks to do one (500-1,000 pieces) in the 30 minutes or so I spend on it each evening. There’s solace in the quiet, methodical process of carefully looking for matching pieces, trying a few, the brief glee at getting a fit, and then moving to the next piece.

I know I can do this on my iPad, but it’s different with real pieces. Lifting up a piece and examining it for matching shapes and colors, sorting through the tray, wondering if I made a mistake somewhere. The cardboard doesn’t light up to let me know I got it right.

Inevitably, the mind wanders as I work on them. Sometimes back to a puzzle at the office, sometimes to my doing the same puzzle (I’ve had them for a while) at my parents’ house in my teens, sometimes to my kids away at college, or a book I once read.

But that’s the point. It’s almost a form of meditation. Focusing on each piece as my mind moves in other directions. It’s actually more relaxing than I thought, and a welcome escape from the day.

And, like other seemingly unrelated tasks (such as Leo Szilard waiting for a traffic light to change, albeit on a lesser scale), sometimes it brings me an answer I’ve been searching for. A light bulb will go on for a patient case I’ve been turning over for a few days. When that happens I grab my phone and email the thought to myself at work.

It puts my mind in neutral at the end of the day. When I finally go to bed I’m less focused on things that can keep me awake at night.

Though occasionally I do dream of puzzles.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Doctors love puzzles, they say. Especially neurologists.

The detective work on a case is part of the job’s appeal. Taking clues from the history, exam, and tests to formulate a diagnosis, then a treatment plan.

But I’m not talking about that.

As I’ve written before, I’ve tried hard to divorce myself from the news. In times where the world seems to have gone mad, I just don’t want to know what’s going on. I focus on my family, my job, and the weather forecast.

But, inevitably, I need something to do. At some point I run out of notes to type, tests to review, emails to answer, and bills to pay. I used to read the news, but now I don’t do that anymore. I even avoid my favorite satire sites, like Onion and Beaverton, because they just reflect the real news (I still read the Weekly World News, which has no relationship to reality, or pretty much anything, whatsoever).

So now, when I’m done with the day’s work, I shut down the computer (which isn’t easy after 25 years of habitual surfing) and sit down with a jigsaw puzzle. I haven’t done that since I was a resident.

It usually takes me 2-3 weeks to do one (500-1,000 pieces) in the 30 minutes or so I spend on it each evening. There’s solace in the quiet, methodical process of carefully looking for matching pieces, trying a few, the brief glee at getting a fit, and then moving to the next piece.

I know I can do this on my iPad, but it’s different with real pieces. Lifting up a piece and examining it for matching shapes and colors, sorting through the tray, wondering if I made a mistake somewhere. The cardboard doesn’t light up to let me know I got it right.

Inevitably, the mind wanders as I work on them. Sometimes back to a puzzle at the office, sometimes to my doing the same puzzle (I’ve had them for a while) at my parents’ house in my teens, sometimes to my kids away at college, or a book I once read.

But that’s the point. It’s almost a form of meditation. Focusing on each piece as my mind moves in other directions. It’s actually more relaxing than I thought, and a welcome escape from the day.

And, like other seemingly unrelated tasks (such as Leo Szilard waiting for a traffic light to change, albeit on a lesser scale), sometimes it brings me an answer I’ve been searching for. A light bulb will go on for a patient case I’ve been turning over for a few days. When that happens I grab my phone and email the thought to myself at work.

It puts my mind in neutral at the end of the day. When I finally go to bed I’m less focused on things that can keep me awake at night.

Though occasionally I do dream of puzzles.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Management of gastroparesis in 2022

Introduction

Patients presenting with the symptoms of gastroparesis (Gp) are commonly seen in gastroenterology practice.

Presentation

Patients with foregut symptoms of Gp have characteristic presentations, with nausea, vomiting/retching, and abdominal pain often associated with bloating and distension, early satiety, anorexia, and heartburn. Mid- and hindgut gastrointestinal and/or urinary symptoms may be seen in patients with Gp as well.

The precise epidemiology of gastroparesis syndromes (GpS) is unknown. Classic gastroparesis, defined as delayed gastric emptying without known mechanical obstruction, has a prevalence of about 10 per 100,000 population in men and 30 per 100,000 in women with women being affected 3 to 4 times more than men.1,2 Some risk factors for GpS, such as diabetes mellitus (DM) in up to 5% of patients with Type 1 DM, are known.3 Caucasians have the highest prevalence of GpS, followed by African Americans.4,5

The classic definition of Gp has blurred with the realization that patients may have symptoms of Gp without delayed solid gastric emptying. Some patients have been described as having chronic unexplained nausea and vomiting or gastroparesis like syndrome.6 More recently the NIH Gastroparesis Consortium has proposed that disorders like functional dyspepsia may be a spectrum of the two disorders and classic Gp.7 Using this broadened definition, the number of patients with Gp symptoms is much greater, found in 10% or more of the U.S. population.8 For this discussion, GpS is used to encompass this spectrum of disorders.

The etiology of GpS is often unknown for a given patient, but clues to etiology exist in what is known about pathophysiology. Types of Gp are described as being idiopathic, diabetic, or postsurgical, each of which may have varying pathophysiology. Many patients with mild-to-moderate GpS symptoms are effectively treated with out-patient therapies; other patients may be refractory to available treatments. Refractory GpS patients have a high burden of illness affecting them, their families, providers, hospitals, and payers.

Pathophysiology

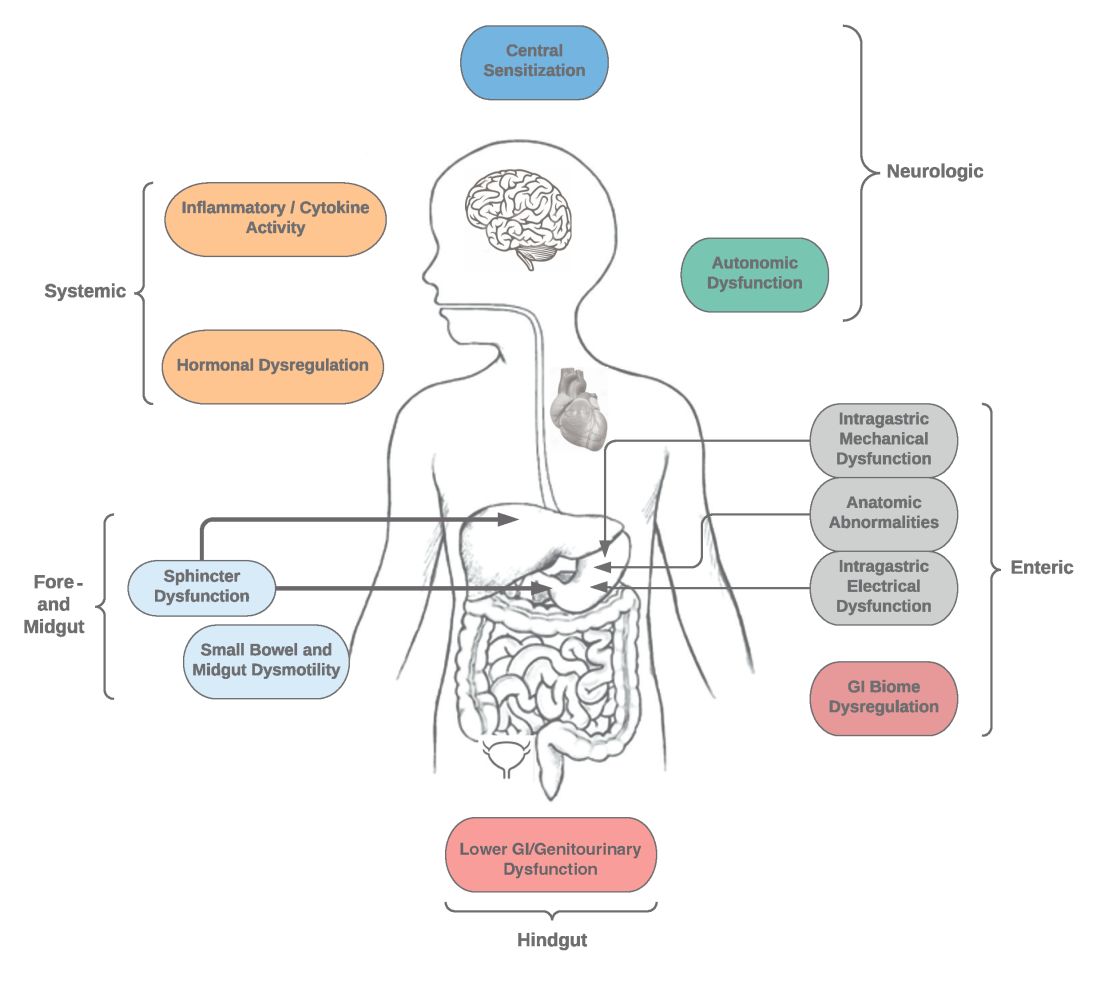

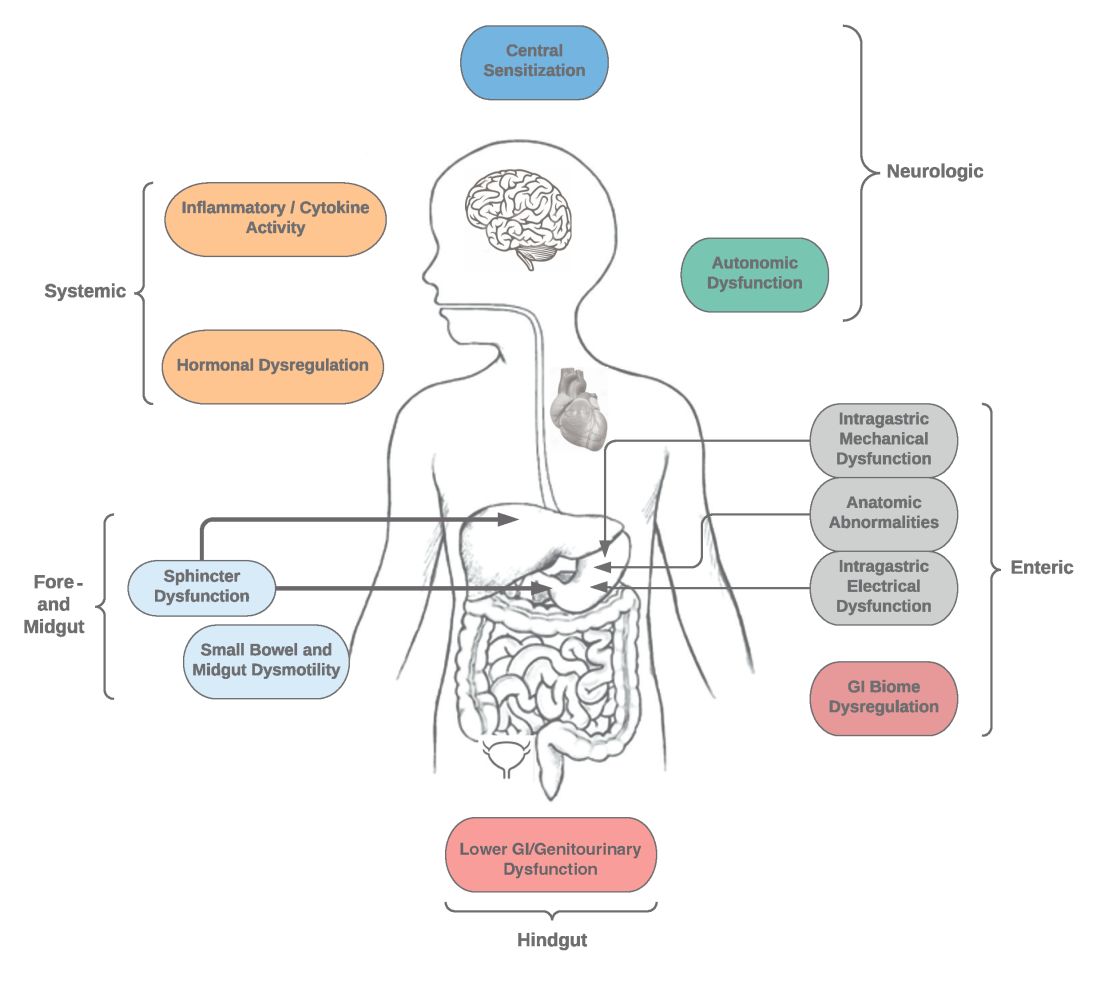

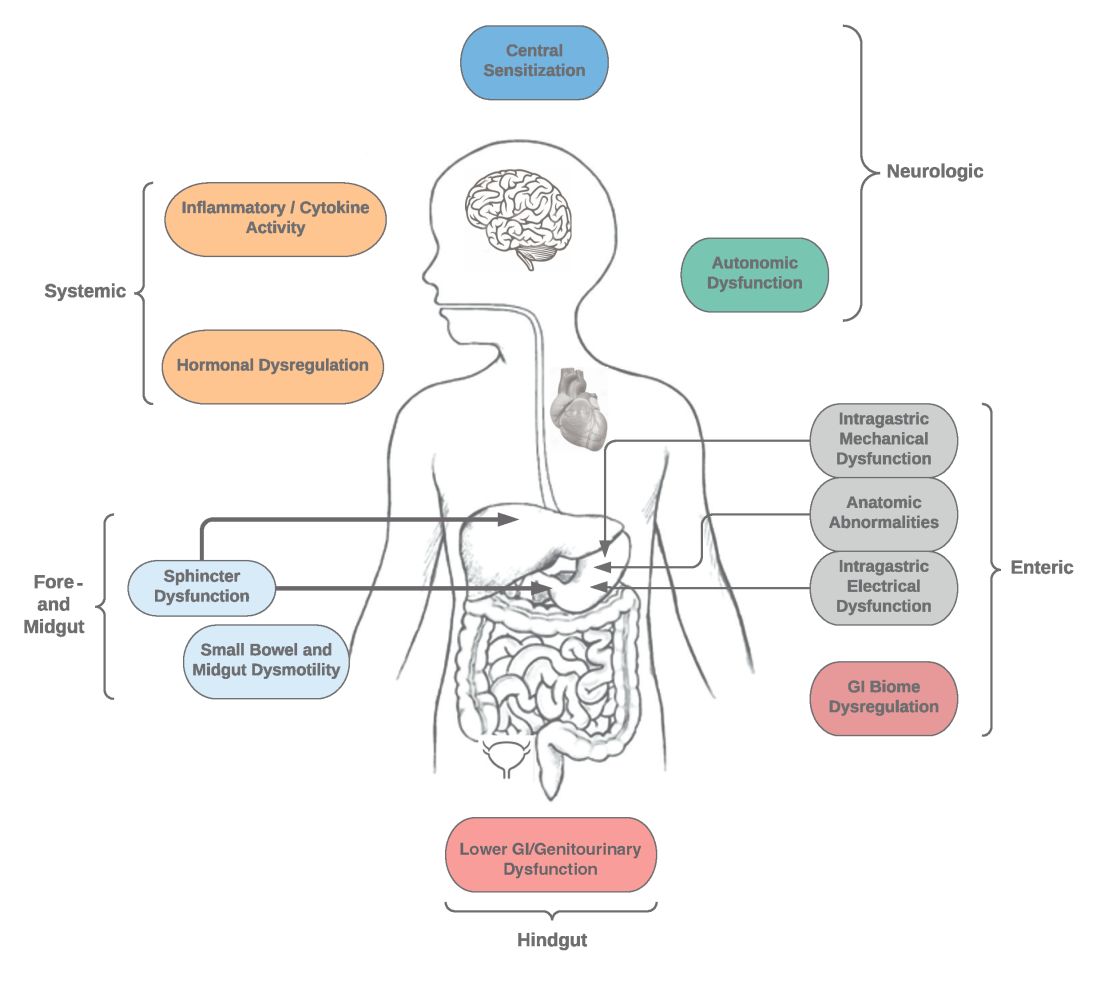

Specific types of gastroparesis syndromes have variable pathophysiology (Figure 1). In some cases, like GpS associated with DM, pathophysiology is partially related to diabetic autonomic dysfunction. GpS are multifactorial, however, and rather than focusing on subtypes, this discussion focuses on shared pathophysiology. Understanding pathophysiology is key to determining treatment options and potential future targets for therapy.

Intragastric mechanical dysfunction, both proximal (fundic relaxation and accommodation and/or lack of fundic contractility) and distal stomach (antral hypomotility) may be involved. Additionally, intragastric electrical disturbances in frequency, amplitude, and propagation of gastric electrical waves can be seen with low/high resolution gastric mapping.

Both gastroesophageal and gastropyloric sphincter dysfunction may be seen. Esophageal dysfunction is frequently seen but is not always categorized in GpS. Pyloric dysfunction is increasingly a focus of both diagnosis and therapy. GI anatomic abnormalities can be identified with gastric biopsies of full thickness muscle and mucosa. CD117/interstitial cells of Cajal, neural fibers, inflammatory and other cells can be evaluated by light microscopy, electron microscopy, and special staining techniques.

Small bowel, mid-, and hindgut dysmotility involvement has often been associated with pathologies of intragastric motility. Not only GI but genitourinary dysfunction may be associated with fore- and mid-gut dysfunction in GpS. Equally well described are abnormalities of the autonomic and sensory nervous system, which have recently been better quantified. Serologic measures, such as channelopathies and other antibody mediated abnormalities, have been recently noted.

Suspected for many years, immune dysregulation has now been documented in patients with GpS. Further investigation, including genetic dysregulation of immune measures, is ongoing. Other mechanisms include systemic and local inflammation, hormonal abnormalities, macro- and micronutrient deficiencies, dysregulation in GI microbiome, and physical frailty. The above factors may play a role in the pathophysiology of GpS, and it is likely that many of these are involved with a given patient presenting for care.9

Diagnosis of GpS

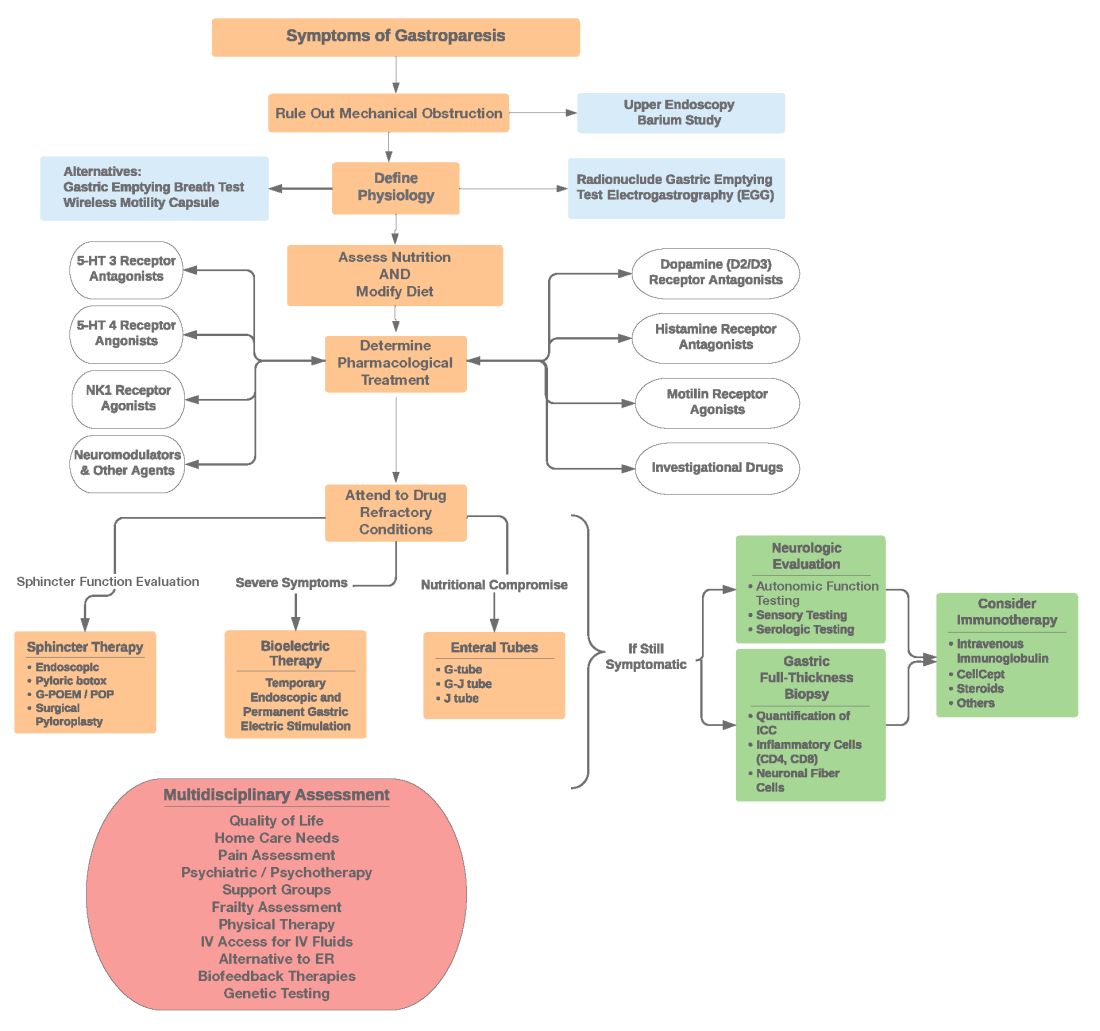

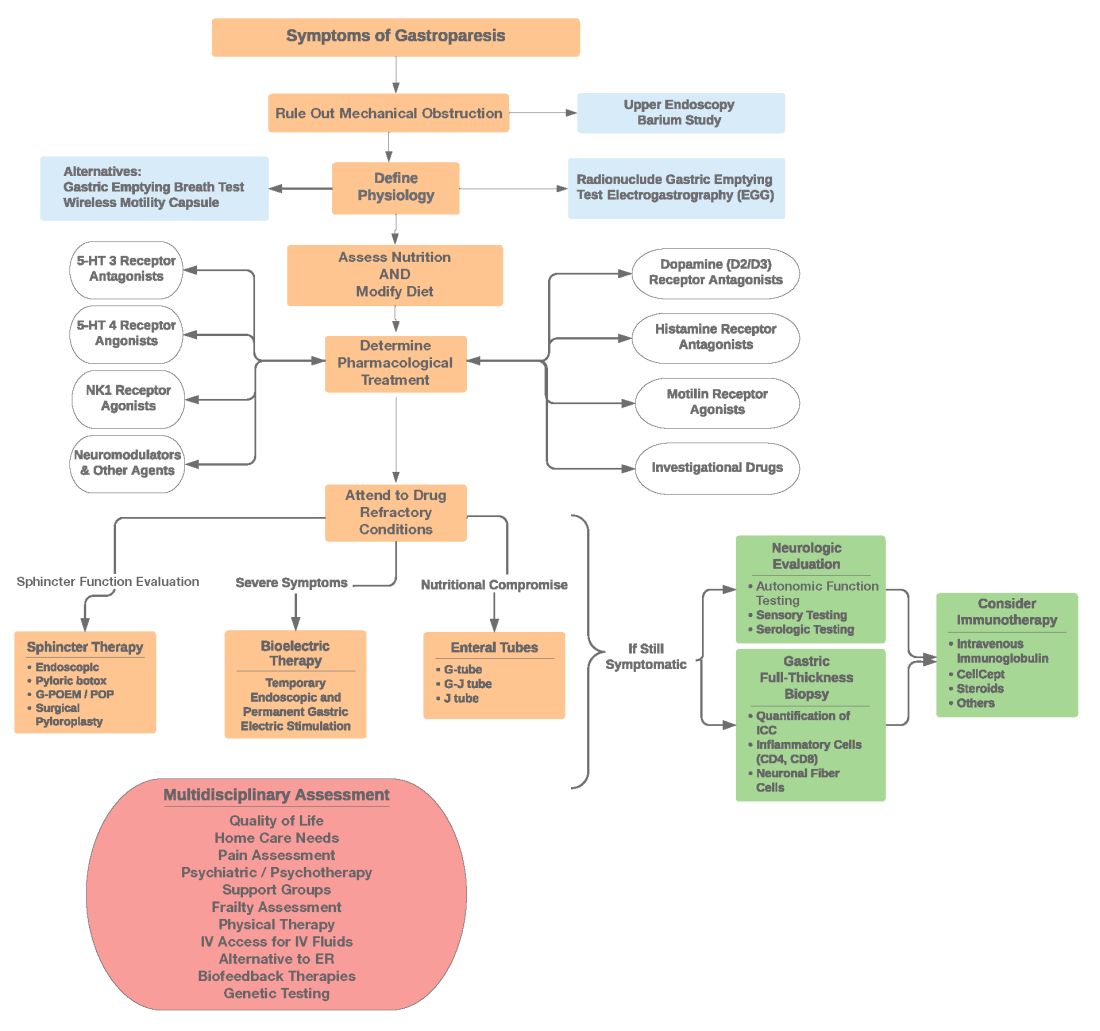

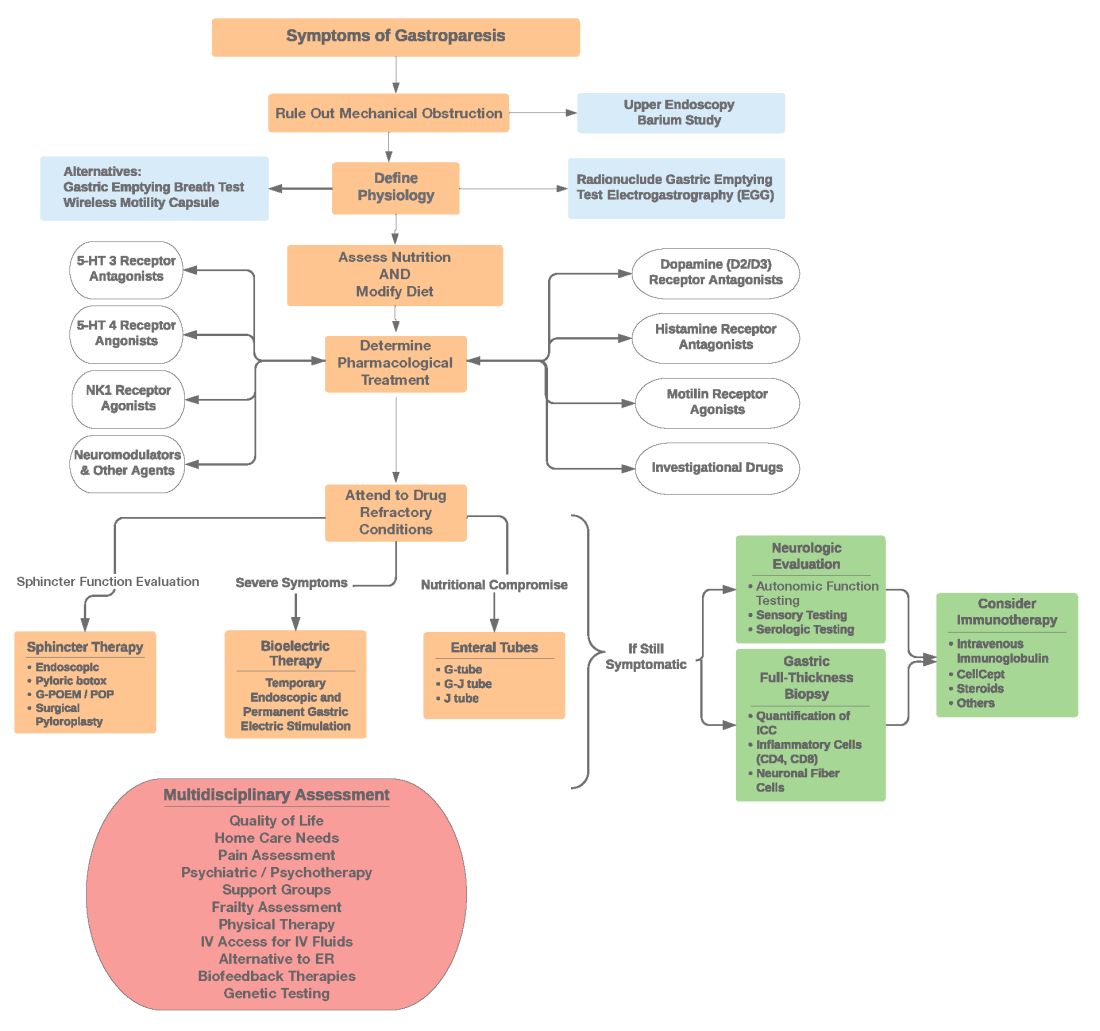

Diagnosis of GpS is often delayed and can be challenging; various tools have been developed, but not all are used. A diagnostic approach for patients with symptoms of Gp is listed below, and Figure 2 details a diagnostic approach and treatment options for symptomatic patients.

Symptom Assessment: Initially Gp symptoms can be assessed using Food and Drug Administration–approved patient-reported outcomes, including frequency and severity of nausea, vomiting, anorexia/early satiety, bloating/distention, and abdominal pain on a 0-4, 0-5 or 0-10 scale. The Gastrointestinal Cardinal Symptom Index or visual analog scales can also be used. It is also important to evaluate midgut and hindgut symptoms.9-11

Mechanical obstruction assessment: Mechanical obstruction can be ruled out using upper endoscopy or barium studies.

Physiologic testing: The most common is radionuclide gastric emptying testing (GET). Compliance with guidelines, standardization, and consistency of GETs is vital to help with an accurate diagnosis. Currently, two consensus recommendations for the standardized performance of GETs exist.12,13 Breath testing is FDA approved in the United States and can be used as an alternative. Wireless motility capsule testing can be complimentary.

Gastric dysrhythmias assessment: Assessment of gastric dysrhythmias can be performed in outpatient settings using cutaneous electrogastrogram, currently available in many referral centers. Most patients with GpS have an underlying gastric electrical abnormality.14,15

Sphincter dysfunction assessment: Both proximal and distal sphincter abnormalities have been described for many years and are of particular interest recently. Use of the functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) shows patients with GpS may have decreased sphincter distensibility when examining the comparisons of the cross-sectional area relative to pressure Using this information, sphincter therapies can be offered.16-18

Other testing: Neurologic and autonomic testing, along with psychosocial, genetic and frailty assessments, are helpful to explore.19 Nutritional evaluation can be done using standardized scales, such as subjective global assessment and serologic testing for micronutrient deficiency or electrical impedance.20

Treatment of GpS

Therapies for GpS can be viewed as the five D’s: Diet, Drug, Disruption, Devices, and Details.

Diet and nutrition: The mainstay treatment of GpS remains dietary modification. The most common recommendation is to limit meal size, often with increased meal frequency, as well as nutrient composition, in areas that may retard gastric emptying. In addition, some patients with GpS report intolerances of specific foods, such as specific carbohydrates. Nutritional consultation can assist patients with meals tailored for their current nutritional needs. Nutritional supplementation is widely used for patients with GpS.20

Pharmacological treatment: The next tier of treatment for GpS is drugs. Review of a patient’s medications is important to minimize drugs that may retard gastric emptying such as opiates and GLP-1 agonists. A full discussion of medications is beyond the scope of this article, but classes of drugs available include: prokinetics, antiemetics, neuromodulators, and investigational agents.

There is only one approved prokinetic medication for gastroparesis – the dopamine blocker metoclopramide – and most providers are aware of metoclopramide’s limitations in terms of potential side effects, such as the risk of tardive dyskinesia and labeling on duration of therapy, with a maximum of 12 weeks recommended. Alternative prokinetics, such as domperidone, are not easily available in the United States; some mediations approved for other indications, such as the 5-HT drug prucalopride, are sometimes given for GpS off-label. Antiemetics such as promethazine and ondansetron are frequently used for symptomatic control in GpS. Despite lack of positive controlled trials in Gp, neuromodulator drugs, such as tricyclic or tetracyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline or mirtazapine are often used; their efficacy is more proven in the functional dyspepsia area. Other drugs such as the NK-1 drug aprepitant have been studied in Gp and are sometimes used off-label. Drugs such as scopolamine and related compounds can also provide symptomatic relief, as can the tetrahydrocannabinol-containing drug, dronabinol. New pharmacologic agents for GpS include investigational drugs such as ghrelin agonists and several novel compounds, none of which are currently FDA approved.21,22

Fortunately, the majority of patients with GpS respond to conservative therapies, such as dietary changes and/or medications. The last part of the section on treatment of GpS includes patients that are diet and drug refractory. Patients in this group are often referred to gastroenterologists and can be complex, time consuming, and frustrating to provide care for. Many of these patients are eventually seen in referral centers, and some travel great distances and have considerable medical expenses.

Pylorus-directed therapies: The recent renewed interest in pyloric dysfunction in patients with Gp symptoms has led to a great deal of clinical activity. Gastropyloric dysfunction in Gp has been documented for decades, originally in diabetic patients with autonomic and enteric neuropathy. The use of botulinum toxin in upper- and lower-gastric sphincters has led to continuing use of this therapy for patients with GpS. Despite initial negative controlled trials of botulinum toxin in the pyloric sphincter, newer studies indicate that physiologic measures, such as the FLIP, may help with patient selection. Other disruptive pyloric therapies, including pyloromyotomy, per oral pyloromyotomy, and gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy, are supported by open-label use, despite a lack of published positive controlled trials.17

Bioelectric therapy: Another approach for patients with symptomatic drug refractory GpS is bioelectric device therapies, which can be delivered several ways, including directly to the stomach or to the spinal cord or the vagus nerve in the neck or ear, as well as by electro-acupuncture. High-frequency, low-energy gastric electrical stimulation (GES) is the best studied. First done in 1992 as an experimental therapy, GES was investigational from 1995 to 2000, when it became FDA approved as a humanitarian-use device. GES has been used in over 10,000 patients worldwide; only a small number (greater than 700 study patients) have been in controlled trials. Nine controlled trials of GES have been primarily positive, and durability for over 10 years has been shown. Temporary GES can also be performed endoscopically, although that is an off-label procedure. It has been shown to predict long-term therapy outcome.23-26

Nutritional support: Nutritional abnormalities in some cases of GpS lead to consideration of enteral tubes, starting with a trial of feeding with an N-J tube placed endoscopically. An N-J trial is most often performed in patients who have macro-malnutrition and weight loss but can be considered for other highly symptomatic patients. Other endoscopic tubes can be PEG or PEG-J or direct PEJ tubes. Some patients may require surgical placement of enteral tubes, presenting an opportunity for a small bowel or gastric full-thickness biopsy. Enteral tubes are sometimes used for decompression in highly symptomatic patients.27

For patients presenting with neurological symptoms, findings and serologic abnormalities have led to interest in immunotherapies. One is intravenous immunoglobulin, given parenterally. Several open-label studies have been published, the most recent one with 47 patients showing better response if glutamic acid decarboxylase–65 antibodies were present and with longer therapeutic dosing.28 Drawbacks to immunotherapies like intravenous immunoglobulin are cost and requiring parenteral access.

Other evaluation/treatments for drug refractory patients can be detailed as follows: First, an overall quality of life assessment can be helpful, especially one that includes impact of GpS on the patients and family. Nutritional considerations, which may not have been fully assessed, can be examined in more detail. Frailty assessments may show the need for physical therapy. Assessment for home care needs may indicate, in severe patients, needs for IV fluids at home, either enteral or parenteral, if nutrition is not adequate. Psychosocial and/or psychiatric assessments may lead to the need for medications, psychotherapy, and/or support groups. Lastly, an assessment of overall health status may lead to approaches for minimizing visits to emergency rooms and hospitalizations.29,30

Conclusion

Patients with Gp symptoms are becoming increasingly recognized and referred to gastroenterologists. Better understandings of the pathophysiology of the spectrum of gastroparesis syndromes, assisted by innovations in diagnosis, have led to expansion of existing and new therapeutic approaches. Fortunately, most patients can benefit from a standardized diagnostic approach and directed noninvasive therapies. Patients with refractory gastroparesis symptoms, often with complex issues referred to gastroenterologists, remain a challenge, and novel approaches may improve their quality of life.

Dr. Mathur is a GI motility research fellow at the University of Louisville, Ky. He reports no conflicts of interest. Dr. Abell is the Arthur M. Schoen, MD, Chair in Gastroenterology at the University of Louisville. His main funding is NIH GpCRC and NIH Definitive Evaluation of Gastric Dysrhythmia. He is an investigator for Cindome, Vanda, Allergan, and Neurogastrx; a consultant for Censa, Nuvaira, and Takeda; a speaker for Takeda and Medtronic; and a reviewer for UpToDate. He is also the founder of ADEPT-GI, which holds IP related to mucosal stimulation and autonomic and enteric profiling.

References

1. Jung HK et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1225-33.

2. Ye Y et al. Gut. 2021;70(4):644-53.

3. Oshima T et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;27(1):46-54.

4. Soykan I et al. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(11):2398-404.

5. Syed AR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54(1):50-4.

6.Pasricha PJ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(7):567-76.e1-4.

7. Pasricha PJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6):2006-17.

8. Almario CV et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1701-10.

9. Abell TL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Apr;66(4):1127-41.

10. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(3):e13534.

11. Elmasry M et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Oct 26;e14274.

12. Maurer AH et al. J Nucl Med. 2020;61(3):11N-7N.

13. Abell TL et al. J Nucl Med Technol. 2008 Mar;36(1):44-54.

14. Shine A et al. Neuromodulation. 2022 Feb 16;S1094-7159(21)06986-5.

15. O’Grady G et al. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;321(5):G527-g42.

16. Saadi M et al. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). Oct-Dec 2018;83(4):375-84.

17. Kamal F et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(2):168-77.

18. Harberson J et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(2):359-70.

19. Winston J. Gastrointestinal Disorders. 2021;3(2):78-83.

20. Parkman HP et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(2):486-98, 98.e1-7.

21. Heckroth M et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(4):279-99.

22. Camilleri M. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):19-24.

23. Payne SC et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(2):89-105.

24. Ducrotte P et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(3):506-14.e2.

25. Burlen J et al. Gastroenterology Res. 2018;11(5):349-54.

26. Hedjoudje A et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(11):e13949.

27. Petrov RV et al. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):539-56.

28. Gala K et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Dec 31. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001655.

29. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(4):263-83.

30. Camilleri M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(1):18-37.

Introduction

Patients presenting with the symptoms of gastroparesis (Gp) are commonly seen in gastroenterology practice.

Presentation

Patients with foregut symptoms of Gp have characteristic presentations, with nausea, vomiting/retching, and abdominal pain often associated with bloating and distension, early satiety, anorexia, and heartburn. Mid- and hindgut gastrointestinal and/or urinary symptoms may be seen in patients with Gp as well.

The precise epidemiology of gastroparesis syndromes (GpS) is unknown. Classic gastroparesis, defined as delayed gastric emptying without known mechanical obstruction, has a prevalence of about 10 per 100,000 population in men and 30 per 100,000 in women with women being affected 3 to 4 times more than men.1,2 Some risk factors for GpS, such as diabetes mellitus (DM) in up to 5% of patients with Type 1 DM, are known.3 Caucasians have the highest prevalence of GpS, followed by African Americans.4,5

The classic definition of Gp has blurred with the realization that patients may have symptoms of Gp without delayed solid gastric emptying. Some patients have been described as having chronic unexplained nausea and vomiting or gastroparesis like syndrome.6 More recently the NIH Gastroparesis Consortium has proposed that disorders like functional dyspepsia may be a spectrum of the two disorders and classic Gp.7 Using this broadened definition, the number of patients with Gp symptoms is much greater, found in 10% or more of the U.S. population.8 For this discussion, GpS is used to encompass this spectrum of disorders.

The etiology of GpS is often unknown for a given patient, but clues to etiology exist in what is known about pathophysiology. Types of Gp are described as being idiopathic, diabetic, or postsurgical, each of which may have varying pathophysiology. Many patients with mild-to-moderate GpS symptoms are effectively treated with out-patient therapies; other patients may be refractory to available treatments. Refractory GpS patients have a high burden of illness affecting them, their families, providers, hospitals, and payers.

Pathophysiology

Specific types of gastroparesis syndromes have variable pathophysiology (Figure 1). In some cases, like GpS associated with DM, pathophysiology is partially related to diabetic autonomic dysfunction. GpS are multifactorial, however, and rather than focusing on subtypes, this discussion focuses on shared pathophysiology. Understanding pathophysiology is key to determining treatment options and potential future targets for therapy.

Intragastric mechanical dysfunction, both proximal (fundic relaxation and accommodation and/or lack of fundic contractility) and distal stomach (antral hypomotility) may be involved. Additionally, intragastric electrical disturbances in frequency, amplitude, and propagation of gastric electrical waves can be seen with low/high resolution gastric mapping.

Both gastroesophageal and gastropyloric sphincter dysfunction may be seen. Esophageal dysfunction is frequently seen but is not always categorized in GpS. Pyloric dysfunction is increasingly a focus of both diagnosis and therapy. GI anatomic abnormalities can be identified with gastric biopsies of full thickness muscle and mucosa. CD117/interstitial cells of Cajal, neural fibers, inflammatory and other cells can be evaluated by light microscopy, electron microscopy, and special staining techniques.

Small bowel, mid-, and hindgut dysmotility involvement has often been associated with pathologies of intragastric motility. Not only GI but genitourinary dysfunction may be associated with fore- and mid-gut dysfunction in GpS. Equally well described are abnormalities of the autonomic and sensory nervous system, which have recently been better quantified. Serologic measures, such as channelopathies and other antibody mediated abnormalities, have been recently noted.

Suspected for many years, immune dysregulation has now been documented in patients with GpS. Further investigation, including genetic dysregulation of immune measures, is ongoing. Other mechanisms include systemic and local inflammation, hormonal abnormalities, macro- and micronutrient deficiencies, dysregulation in GI microbiome, and physical frailty. The above factors may play a role in the pathophysiology of GpS, and it is likely that many of these are involved with a given patient presenting for care.9

Diagnosis of GpS

Diagnosis of GpS is often delayed and can be challenging; various tools have been developed, but not all are used. A diagnostic approach for patients with symptoms of Gp is listed below, and Figure 2 details a diagnostic approach and treatment options for symptomatic patients.

Symptom Assessment: Initially Gp symptoms can be assessed using Food and Drug Administration–approved patient-reported outcomes, including frequency and severity of nausea, vomiting, anorexia/early satiety, bloating/distention, and abdominal pain on a 0-4, 0-5 or 0-10 scale. The Gastrointestinal Cardinal Symptom Index or visual analog scales can also be used. It is also important to evaluate midgut and hindgut symptoms.9-11

Mechanical obstruction assessment: Mechanical obstruction can be ruled out using upper endoscopy or barium studies.

Physiologic testing: The most common is radionuclide gastric emptying testing (GET). Compliance with guidelines, standardization, and consistency of GETs is vital to help with an accurate diagnosis. Currently, two consensus recommendations for the standardized performance of GETs exist.12,13 Breath testing is FDA approved in the United States and can be used as an alternative. Wireless motility capsule testing can be complimentary.

Gastric dysrhythmias assessment: Assessment of gastric dysrhythmias can be performed in outpatient settings using cutaneous electrogastrogram, currently available in many referral centers. Most patients with GpS have an underlying gastric electrical abnormality.14,15

Sphincter dysfunction assessment: Both proximal and distal sphincter abnormalities have been described for many years and are of particular interest recently. Use of the functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) shows patients with GpS may have decreased sphincter distensibility when examining the comparisons of the cross-sectional area relative to pressure Using this information, sphincter therapies can be offered.16-18

Other testing: Neurologic and autonomic testing, along with psychosocial, genetic and frailty assessments, are helpful to explore.19 Nutritional evaluation can be done using standardized scales, such as subjective global assessment and serologic testing for micronutrient deficiency or electrical impedance.20

Treatment of GpS

Therapies for GpS can be viewed as the five D’s: Diet, Drug, Disruption, Devices, and Details.

Diet and nutrition: The mainstay treatment of GpS remains dietary modification. The most common recommendation is to limit meal size, often with increased meal frequency, as well as nutrient composition, in areas that may retard gastric emptying. In addition, some patients with GpS report intolerances of specific foods, such as specific carbohydrates. Nutritional consultation can assist patients with meals tailored for their current nutritional needs. Nutritional supplementation is widely used for patients with GpS.20

Pharmacological treatment: The next tier of treatment for GpS is drugs. Review of a patient’s medications is important to minimize drugs that may retard gastric emptying such as opiates and GLP-1 agonists. A full discussion of medications is beyond the scope of this article, but classes of drugs available include: prokinetics, antiemetics, neuromodulators, and investigational agents.

There is only one approved prokinetic medication for gastroparesis – the dopamine blocker metoclopramide – and most providers are aware of metoclopramide’s limitations in terms of potential side effects, such as the risk of tardive dyskinesia and labeling on duration of therapy, with a maximum of 12 weeks recommended. Alternative prokinetics, such as domperidone, are not easily available in the United States; some mediations approved for other indications, such as the 5-HT drug prucalopride, are sometimes given for GpS off-label. Antiemetics such as promethazine and ondansetron are frequently used for symptomatic control in GpS. Despite lack of positive controlled trials in Gp, neuromodulator drugs, such as tricyclic or tetracyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline or mirtazapine are often used; their efficacy is more proven in the functional dyspepsia area. Other drugs such as the NK-1 drug aprepitant have been studied in Gp and are sometimes used off-label. Drugs such as scopolamine and related compounds can also provide symptomatic relief, as can the tetrahydrocannabinol-containing drug, dronabinol. New pharmacologic agents for GpS include investigational drugs such as ghrelin agonists and several novel compounds, none of which are currently FDA approved.21,22

Fortunately, the majority of patients with GpS respond to conservative therapies, such as dietary changes and/or medications. The last part of the section on treatment of GpS includes patients that are diet and drug refractory. Patients in this group are often referred to gastroenterologists and can be complex, time consuming, and frustrating to provide care for. Many of these patients are eventually seen in referral centers, and some travel great distances and have considerable medical expenses.

Pylorus-directed therapies: The recent renewed interest in pyloric dysfunction in patients with Gp symptoms has led to a great deal of clinical activity. Gastropyloric dysfunction in Gp has been documented for decades, originally in diabetic patients with autonomic and enteric neuropathy. The use of botulinum toxin in upper- and lower-gastric sphincters has led to continuing use of this therapy for patients with GpS. Despite initial negative controlled trials of botulinum toxin in the pyloric sphincter, newer studies indicate that physiologic measures, such as the FLIP, may help with patient selection. Other disruptive pyloric therapies, including pyloromyotomy, per oral pyloromyotomy, and gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy, are supported by open-label use, despite a lack of published positive controlled trials.17

Bioelectric therapy: Another approach for patients with symptomatic drug refractory GpS is bioelectric device therapies, which can be delivered several ways, including directly to the stomach or to the spinal cord or the vagus nerve in the neck or ear, as well as by electro-acupuncture. High-frequency, low-energy gastric electrical stimulation (GES) is the best studied. First done in 1992 as an experimental therapy, GES was investigational from 1995 to 2000, when it became FDA approved as a humanitarian-use device. GES has been used in over 10,000 patients worldwide; only a small number (greater than 700 study patients) have been in controlled trials. Nine controlled trials of GES have been primarily positive, and durability for over 10 years has been shown. Temporary GES can also be performed endoscopically, although that is an off-label procedure. It has been shown to predict long-term therapy outcome.23-26

Nutritional support: Nutritional abnormalities in some cases of GpS lead to consideration of enteral tubes, starting with a trial of feeding with an N-J tube placed endoscopically. An N-J trial is most often performed in patients who have macro-malnutrition and weight loss but can be considered for other highly symptomatic patients. Other endoscopic tubes can be PEG or PEG-J or direct PEJ tubes. Some patients may require surgical placement of enteral tubes, presenting an opportunity for a small bowel or gastric full-thickness biopsy. Enteral tubes are sometimes used for decompression in highly symptomatic patients.27

For patients presenting with neurological symptoms, findings and serologic abnormalities have led to interest in immunotherapies. One is intravenous immunoglobulin, given parenterally. Several open-label studies have been published, the most recent one with 47 patients showing better response if glutamic acid decarboxylase–65 antibodies were present and with longer therapeutic dosing.28 Drawbacks to immunotherapies like intravenous immunoglobulin are cost and requiring parenteral access.

Other evaluation/treatments for drug refractory patients can be detailed as follows: First, an overall quality of life assessment can be helpful, especially one that includes impact of GpS on the patients and family. Nutritional considerations, which may not have been fully assessed, can be examined in more detail. Frailty assessments may show the need for physical therapy. Assessment for home care needs may indicate, in severe patients, needs for IV fluids at home, either enteral or parenteral, if nutrition is not adequate. Psychosocial and/or psychiatric assessments may lead to the need for medications, psychotherapy, and/or support groups. Lastly, an assessment of overall health status may lead to approaches for minimizing visits to emergency rooms and hospitalizations.29,30

Conclusion

Patients with Gp symptoms are becoming increasingly recognized and referred to gastroenterologists. Better understandings of the pathophysiology of the spectrum of gastroparesis syndromes, assisted by innovations in diagnosis, have led to expansion of existing and new therapeutic approaches. Fortunately, most patients can benefit from a standardized diagnostic approach and directed noninvasive therapies. Patients with refractory gastroparesis symptoms, often with complex issues referred to gastroenterologists, remain a challenge, and novel approaches may improve their quality of life.

Dr. Mathur is a GI motility research fellow at the University of Louisville, Ky. He reports no conflicts of interest. Dr. Abell is the Arthur M. Schoen, MD, Chair in Gastroenterology at the University of Louisville. His main funding is NIH GpCRC and NIH Definitive Evaluation of Gastric Dysrhythmia. He is an investigator for Cindome, Vanda, Allergan, and Neurogastrx; a consultant for Censa, Nuvaira, and Takeda; a speaker for Takeda and Medtronic; and a reviewer for UpToDate. He is also the founder of ADEPT-GI, which holds IP related to mucosal stimulation and autonomic and enteric profiling.

References

1. Jung HK et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1225-33.

2. Ye Y et al. Gut. 2021;70(4):644-53.

3. Oshima T et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;27(1):46-54.

4. Soykan I et al. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(11):2398-404.

5. Syed AR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54(1):50-4.

6.Pasricha PJ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(7):567-76.e1-4.

7. Pasricha PJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6):2006-17.

8. Almario CV et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1701-10.

9. Abell TL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Apr;66(4):1127-41.

10. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(3):e13534.

11. Elmasry M et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Oct 26;e14274.

12. Maurer AH et al. J Nucl Med. 2020;61(3):11N-7N.

13. Abell TL et al. J Nucl Med Technol. 2008 Mar;36(1):44-54.

14. Shine A et al. Neuromodulation. 2022 Feb 16;S1094-7159(21)06986-5.

15. O’Grady G et al. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;321(5):G527-g42.

16. Saadi M et al. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). Oct-Dec 2018;83(4):375-84.

17. Kamal F et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(2):168-77.

18. Harberson J et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(2):359-70.

19. Winston J. Gastrointestinal Disorders. 2021;3(2):78-83.

20. Parkman HP et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(2):486-98, 98.e1-7.

21. Heckroth M et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(4):279-99.

22. Camilleri M. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):19-24.

23. Payne SC et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(2):89-105.

24. Ducrotte P et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(3):506-14.e2.

25. Burlen J et al. Gastroenterology Res. 2018;11(5):349-54.

26. Hedjoudje A et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(11):e13949.

27. Petrov RV et al. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):539-56.

28. Gala K et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Dec 31. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001655.

29. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(4):263-83.

30. Camilleri M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(1):18-37.

Introduction

Patients presenting with the symptoms of gastroparesis (Gp) are commonly seen in gastroenterology practice.

Presentation

Patients with foregut symptoms of Gp have characteristic presentations, with nausea, vomiting/retching, and abdominal pain often associated with bloating and distension, early satiety, anorexia, and heartburn. Mid- and hindgut gastrointestinal and/or urinary symptoms may be seen in patients with Gp as well.

The precise epidemiology of gastroparesis syndromes (GpS) is unknown. Classic gastroparesis, defined as delayed gastric emptying without known mechanical obstruction, has a prevalence of about 10 per 100,000 population in men and 30 per 100,000 in women with women being affected 3 to 4 times more than men.1,2 Some risk factors for GpS, such as diabetes mellitus (DM) in up to 5% of patients with Type 1 DM, are known.3 Caucasians have the highest prevalence of GpS, followed by African Americans.4,5

The classic definition of Gp has blurred with the realization that patients may have symptoms of Gp without delayed solid gastric emptying. Some patients have been described as having chronic unexplained nausea and vomiting or gastroparesis like syndrome.6 More recently the NIH Gastroparesis Consortium has proposed that disorders like functional dyspepsia may be a spectrum of the two disorders and classic Gp.7 Using this broadened definition, the number of patients with Gp symptoms is much greater, found in 10% or more of the U.S. population.8 For this discussion, GpS is used to encompass this spectrum of disorders.

The etiology of GpS is often unknown for a given patient, but clues to etiology exist in what is known about pathophysiology. Types of Gp are described as being idiopathic, diabetic, or postsurgical, each of which may have varying pathophysiology. Many patients with mild-to-moderate GpS symptoms are effectively treated with out-patient therapies; other patients may be refractory to available treatments. Refractory GpS patients have a high burden of illness affecting them, their families, providers, hospitals, and payers.

Pathophysiology

Specific types of gastroparesis syndromes have variable pathophysiology (Figure 1). In some cases, like GpS associated with DM, pathophysiology is partially related to diabetic autonomic dysfunction. GpS are multifactorial, however, and rather than focusing on subtypes, this discussion focuses on shared pathophysiology. Understanding pathophysiology is key to determining treatment options and potential future targets for therapy.

Intragastric mechanical dysfunction, both proximal (fundic relaxation and accommodation and/or lack of fundic contractility) and distal stomach (antral hypomotility) may be involved. Additionally, intragastric electrical disturbances in frequency, amplitude, and propagation of gastric electrical waves can be seen with low/high resolution gastric mapping.

Both gastroesophageal and gastropyloric sphincter dysfunction may be seen. Esophageal dysfunction is frequently seen but is not always categorized in GpS. Pyloric dysfunction is increasingly a focus of both diagnosis and therapy. GI anatomic abnormalities can be identified with gastric biopsies of full thickness muscle and mucosa. CD117/interstitial cells of Cajal, neural fibers, inflammatory and other cells can be evaluated by light microscopy, electron microscopy, and special staining techniques.

Small bowel, mid-, and hindgut dysmotility involvement has often been associated with pathologies of intragastric motility. Not only GI but genitourinary dysfunction may be associated with fore- and mid-gut dysfunction in GpS. Equally well described are abnormalities of the autonomic and sensory nervous system, which have recently been better quantified. Serologic measures, such as channelopathies and other antibody mediated abnormalities, have been recently noted.

Suspected for many years, immune dysregulation has now been documented in patients with GpS. Further investigation, including genetic dysregulation of immune measures, is ongoing. Other mechanisms include systemic and local inflammation, hormonal abnormalities, macro- and micronutrient deficiencies, dysregulation in GI microbiome, and physical frailty. The above factors may play a role in the pathophysiology of GpS, and it is likely that many of these are involved with a given patient presenting for care.9

Diagnosis of GpS

Diagnosis of GpS is often delayed and can be challenging; various tools have been developed, but not all are used. A diagnostic approach for patients with symptoms of Gp is listed below, and Figure 2 details a diagnostic approach and treatment options for symptomatic patients.

Symptom Assessment: Initially Gp symptoms can be assessed using Food and Drug Administration–approved patient-reported outcomes, including frequency and severity of nausea, vomiting, anorexia/early satiety, bloating/distention, and abdominal pain on a 0-4, 0-5 or 0-10 scale. The Gastrointestinal Cardinal Symptom Index or visual analog scales can also be used. It is also important to evaluate midgut and hindgut symptoms.9-11

Mechanical obstruction assessment: Mechanical obstruction can be ruled out using upper endoscopy or barium studies.

Physiologic testing: The most common is radionuclide gastric emptying testing (GET). Compliance with guidelines, standardization, and consistency of GETs is vital to help with an accurate diagnosis. Currently, two consensus recommendations for the standardized performance of GETs exist.12,13 Breath testing is FDA approved in the United States and can be used as an alternative. Wireless motility capsule testing can be complimentary.

Gastric dysrhythmias assessment: Assessment of gastric dysrhythmias can be performed in outpatient settings using cutaneous electrogastrogram, currently available in many referral centers. Most patients with GpS have an underlying gastric electrical abnormality.14,15

Sphincter dysfunction assessment: Both proximal and distal sphincter abnormalities have been described for many years and are of particular interest recently. Use of the functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) shows patients with GpS may have decreased sphincter distensibility when examining the comparisons of the cross-sectional area relative to pressure Using this information, sphincter therapies can be offered.16-18

Other testing: Neurologic and autonomic testing, along with psychosocial, genetic and frailty assessments, are helpful to explore.19 Nutritional evaluation can be done using standardized scales, such as subjective global assessment and serologic testing for micronutrient deficiency or electrical impedance.20

Treatment of GpS

Therapies for GpS can be viewed as the five D’s: Diet, Drug, Disruption, Devices, and Details.

Diet and nutrition: The mainstay treatment of GpS remains dietary modification. The most common recommendation is to limit meal size, often with increased meal frequency, as well as nutrient composition, in areas that may retard gastric emptying. In addition, some patients with GpS report intolerances of specific foods, such as specific carbohydrates. Nutritional consultation can assist patients with meals tailored for their current nutritional needs. Nutritional supplementation is widely used for patients with GpS.20

Pharmacological treatment: The next tier of treatment for GpS is drugs. Review of a patient’s medications is important to minimize drugs that may retard gastric emptying such as opiates and GLP-1 agonists. A full discussion of medications is beyond the scope of this article, but classes of drugs available include: prokinetics, antiemetics, neuromodulators, and investigational agents.

There is only one approved prokinetic medication for gastroparesis – the dopamine blocker metoclopramide – and most providers are aware of metoclopramide’s limitations in terms of potential side effects, such as the risk of tardive dyskinesia and labeling on duration of therapy, with a maximum of 12 weeks recommended. Alternative prokinetics, such as domperidone, are not easily available in the United States; some mediations approved for other indications, such as the 5-HT drug prucalopride, are sometimes given for GpS off-label. Antiemetics such as promethazine and ondansetron are frequently used for symptomatic control in GpS. Despite lack of positive controlled trials in Gp, neuromodulator drugs, such as tricyclic or tetracyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline or mirtazapine are often used; their efficacy is more proven in the functional dyspepsia area. Other drugs such as the NK-1 drug aprepitant have been studied in Gp and are sometimes used off-label. Drugs such as scopolamine and related compounds can also provide symptomatic relief, as can the tetrahydrocannabinol-containing drug, dronabinol. New pharmacologic agents for GpS include investigational drugs such as ghrelin agonists and several novel compounds, none of which are currently FDA approved.21,22

Fortunately, the majority of patients with GpS respond to conservative therapies, such as dietary changes and/or medications. The last part of the section on treatment of GpS includes patients that are diet and drug refractory. Patients in this group are often referred to gastroenterologists and can be complex, time consuming, and frustrating to provide care for. Many of these patients are eventually seen in referral centers, and some travel great distances and have considerable medical expenses.

Pylorus-directed therapies: The recent renewed interest in pyloric dysfunction in patients with Gp symptoms has led to a great deal of clinical activity. Gastropyloric dysfunction in Gp has been documented for decades, originally in diabetic patients with autonomic and enteric neuropathy. The use of botulinum toxin in upper- and lower-gastric sphincters has led to continuing use of this therapy for patients with GpS. Despite initial negative controlled trials of botulinum toxin in the pyloric sphincter, newer studies indicate that physiologic measures, such as the FLIP, may help with patient selection. Other disruptive pyloric therapies, including pyloromyotomy, per oral pyloromyotomy, and gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy, are supported by open-label use, despite a lack of published positive controlled trials.17

Bioelectric therapy: Another approach for patients with symptomatic drug refractory GpS is bioelectric device therapies, which can be delivered several ways, including directly to the stomach or to the spinal cord or the vagus nerve in the neck or ear, as well as by electro-acupuncture. High-frequency, low-energy gastric electrical stimulation (GES) is the best studied. First done in 1992 as an experimental therapy, GES was investigational from 1995 to 2000, when it became FDA approved as a humanitarian-use device. GES has been used in over 10,000 patients worldwide; only a small number (greater than 700 study patients) have been in controlled trials. Nine controlled trials of GES have been primarily positive, and durability for over 10 years has been shown. Temporary GES can also be performed endoscopically, although that is an off-label procedure. It has been shown to predict long-term therapy outcome.23-26

Nutritional support: Nutritional abnormalities in some cases of GpS lead to consideration of enteral tubes, starting with a trial of feeding with an N-J tube placed endoscopically. An N-J trial is most often performed in patients who have macro-malnutrition and weight loss but can be considered for other highly symptomatic patients. Other endoscopic tubes can be PEG or PEG-J or direct PEJ tubes. Some patients may require surgical placement of enteral tubes, presenting an opportunity for a small bowel or gastric full-thickness biopsy. Enteral tubes are sometimes used for decompression in highly symptomatic patients.27

For patients presenting with neurological symptoms, findings and serologic abnormalities have led to interest in immunotherapies. One is intravenous immunoglobulin, given parenterally. Several open-label studies have been published, the most recent one with 47 patients showing better response if glutamic acid decarboxylase–65 antibodies were present and with longer therapeutic dosing.28 Drawbacks to immunotherapies like intravenous immunoglobulin are cost and requiring parenteral access.

Other evaluation/treatments for drug refractory patients can be detailed as follows: First, an overall quality of life assessment can be helpful, especially one that includes impact of GpS on the patients and family. Nutritional considerations, which may not have been fully assessed, can be examined in more detail. Frailty assessments may show the need for physical therapy. Assessment for home care needs may indicate, in severe patients, needs for IV fluids at home, either enteral or parenteral, if nutrition is not adequate. Psychosocial and/or psychiatric assessments may lead to the need for medications, psychotherapy, and/or support groups. Lastly, an assessment of overall health status may lead to approaches for minimizing visits to emergency rooms and hospitalizations.29,30

Conclusion

Patients with Gp symptoms are becoming increasingly recognized and referred to gastroenterologists. Better understandings of the pathophysiology of the spectrum of gastroparesis syndromes, assisted by innovations in diagnosis, have led to expansion of existing and new therapeutic approaches. Fortunately, most patients can benefit from a standardized diagnostic approach and directed noninvasive therapies. Patients with refractory gastroparesis symptoms, often with complex issues referred to gastroenterologists, remain a challenge, and novel approaches may improve their quality of life.

Dr. Mathur is a GI motility research fellow at the University of Louisville, Ky. He reports no conflicts of interest. Dr. Abell is the Arthur M. Schoen, MD, Chair in Gastroenterology at the University of Louisville. His main funding is NIH GpCRC and NIH Definitive Evaluation of Gastric Dysrhythmia. He is an investigator for Cindome, Vanda, Allergan, and Neurogastrx; a consultant for Censa, Nuvaira, and Takeda; a speaker for Takeda and Medtronic; and a reviewer for UpToDate. He is also the founder of ADEPT-GI, which holds IP related to mucosal stimulation and autonomic and enteric profiling.

References

1. Jung HK et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1225-33.

2. Ye Y et al. Gut. 2021;70(4):644-53.

3. Oshima T et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;27(1):46-54.

4. Soykan I et al. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(11):2398-404.

5. Syed AR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54(1):50-4.

6.Pasricha PJ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(7):567-76.e1-4.

7. Pasricha PJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6):2006-17.

8. Almario CV et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1701-10.

9. Abell TL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Apr;66(4):1127-41.

10. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(3):e13534.

11. Elmasry M et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Oct 26;e14274.

12. Maurer AH et al. J Nucl Med. 2020;61(3):11N-7N.

13. Abell TL et al. J Nucl Med Technol. 2008 Mar;36(1):44-54.

14. Shine A et al. Neuromodulation. 2022 Feb 16;S1094-7159(21)06986-5.

15. O’Grady G et al. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;321(5):G527-g42.

16. Saadi M et al. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). Oct-Dec 2018;83(4):375-84.

17. Kamal F et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(2):168-77.

18. Harberson J et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(2):359-70.

19. Winston J. Gastrointestinal Disorders. 2021;3(2):78-83.

20. Parkman HP et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(2):486-98, 98.e1-7.

21. Heckroth M et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(4):279-99.

22. Camilleri M. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):19-24.

23. Payne SC et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(2):89-105.

24. Ducrotte P et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(3):506-14.e2.

25. Burlen J et al. Gastroenterology Res. 2018;11(5):349-54.

26. Hedjoudje A et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(11):e13949.

27. Petrov RV et al. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):539-56.

28. Gala K et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Dec 31. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001655.

29. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(4):263-83.

30. Camilleri M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(1):18-37.

How gender-affirming care is provided to adolescents in the United States

“Texas investigates parents of transgender teen.” “Court did not force dad to allow chemical castration of son.” Headlines such as these are becoming more common as transgender adolescents and young adults, as well as their families, continue to come under attack from state and local governments. In the 2021 state legislative sessions, more than 100 anti-trans bills were filed across 35 state legislatures. Texas alone saw 13 anti-trans bills, covering everything from sports participation to criminalization of best-practice medical care.1 Many of these bills are introduced under the guise of “protecting” these adolescents and young adults but are detrimental to their health. They also contain descriptions of gender-affirming care that do not reflect the evidence-based standards of care followed by clinicians across the country. Below is scientifically accurate information on gender-affirming care.

Gender identity development

Trajectories of gender identity are diverse. In a large sample of transgender adults (n = 27,715), 10% started to realize they were transgender at age 5 or younger, 16% between ages 6 and 10, 28% between 11 and 15, 29% between 16 and 20, and 18% at age 21 or older.2 In childhood, cross-gender play and preferences are a normal part of gender expression and many gender-nonconforming children will go on to identify with the sex they were assigned at birth (labeled cisgender). However, some children explicitly identify with a gender different than the sex they were assigned at birth (labeled transgender). Children who are consistent, insistent, and persistent in this identity appear likely to remain so into adolescence and adulthood. It is important to note that there is no evidence that discouraging gender nonconformity decreases the likelihood that a child will identify as transgender. In fact, this practice is no longer considered ethical, as it can have damaging effects on self-esteem and mental health. In addition, not all transgender people are noticeably gender nonconforming in childhood and that lack of childhood gender nonconformity does not invalidate someone’s transgender identity.

Gender-affirming care

For youth who identify as transgender, all steps in transition prior to puberty are social. This includes steps like changing hairstyles or clothing and using a different (affirmed) name and/or pronouns. This time period allows youth to explore their gender identity and expression. In one large study of 10,000 LGBTQ youth, among youth who reported “all or most people” used their affirmed pronoun, 12% reported a history of suicide attempt.3 In comparison, among those who reported that “no one” used their affirmed pronoun, the suicide attempt rate was 28%. Further, 14% of youth who reported that they were able to make changes in their clothing and appearance reported a past suicide attempt in comparison to 26% of those who were not able to. Many of these youth also are under the care of mental health professionals during this time.

At the onset of puberty, transgender youth are eligible for medical management, if needed, to address gender dysphoria (i.e., distress with one’s sex characteristics that is consistent and impairing). It is important to recognize that not all people who identify as transgender experience gender dysphoria or desire a medical transition. For those who do seek medical care, puberty must be confirmed either by breast/testicular exam or checking gonadotropin levels. Standards of care suggest that prior to pubertal suppression with GnRH agonists, such as leuprolide or histrelin, adolescents undergo a thorough psychosocial evaluation by a qualified, licensed clinician. After this evaluation, pubertal suppression may be initiated. These adolescents are monitored by their physicians every 3-6 months for side effects and continuing evaluation of their gender identity. GnRH agonists pause any further pubertal development while the adolescent continues to explore his/her/their gender identity. GnRH agonists are fully reversible and if they are stopped, the child’s natal puberty would recommence.

If an adolescent desires to start gender-affirming hormones, these are started as early as age 14, depending on their maturity, when they desire to start, and/or their ability to obtain parental consent. If a patient has not begun GnRH agonists and undergone a previous psychosocial evaluation, a thorough psychosocial evaluation by a qualified, licensed clinician would take place prior to initiating gender-affirming hormones. Prior to initiating hormones, a thorough informed-consent process occurs between the clinician, patient, and family. This process reviews reversible versus irreversible effects, as well of any side effects of the medication(s). Adolescents who begin hormonal treatment are then monitored every 3-6 months for medication side effects, efficacy, satisfaction with treatment, and by continued mental health assessments. Engagement in mental health therapy is not required beyond the initial evaluation (as many adolescents are well adjusted), but it is encouraged for support during the adolescent’s transition.4 It is important to note that the decision to begin hormones, or not, as well as how to adjust dosing over time, is nuanced and is individualized to each patient’s particular goals for his/her/their transition.

Care for transmasculine identified adolescents (those who were assigned female at birth) typically involves testosterone, delivered via subcutaneous injection, transdermal patch, or transdermal gel. Care for transfeminine individuals (those who were assigned male at birth) typically involves estradiol, delivered via daily pill, weekly or twice weekly transdermal patch, or intramuscular injection, as well as an androgen blocker. This is because estradiol by itself is a weak androgen inhibitor. Antiandrogen medication is delivered by daily oral spironolactone, daily oral bicalutamide (an androgen receptor blocker), or GnRH agonists similar to those used for puberty blockade.

Outcomes

At least 13 studies have documented an improvement in gender dysphoria and/or mental health for adolescents and young adults after beginning gender affirming medical care.5 A recent study by Turban et al. showed that access to gender affirming hormones during adolescence or early adulthood was associated with decreased odds of past month suicidal ideation than for those who did not have access to gender-affirming hormones.6 Tordoff et al. found that receipt of gender-affirming care, including medications, led to a 60% decrease in depressive symptoms and a 73% decrease in suicidality.7 One other question that often arises is whether youth who undergo medical treatment for their transition regret their transition or retransition back to the sex they were assigned at birth. In a large study at a gender clinic in the United Kingdom, they found a regret rate of only 0.47% (16 of 3,398 adolescents aged 13-20).8 This is similar to other studies that have also found low rates of regret. Regret is often due to lack of acceptance in society rather than lack of transgender identity.

The care of gender diverse youth takes place on a spectrum, including options that do not include medical treatment. By supporting youth where they are on their gender journey, there is a significant reduction in adverse mental health outcomes. Gender-affirming hormonal treatment is individualized and a thorough multidisciplinary evaluation and informed consent are obtained prior to initiation. There are careful, nuanced discussions with patients and their families to individualize care based on individual goals. By following established evidence-based standards of care, physicians can support their gender-diverse patients throughout their gender journey. Just like other medical treatments, procedures, or surgeries, gender-affirming care should be undertaken in the context of the sacred patient-physician relationship.

Dr. Cooper is assistant professor of pediatrics at University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, and an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas.

References

1. Equality Texas. Legislative Bill Tracker.

2. James SE et al. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. 2016. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality.

3. The Trevor Project. 2020. National Survey on LGBTQ Mental Health.

4. Lopez X et al. Curr Opin Pediatrics. 2017;29(4):475-80.

5. Turban J. The evidence for trans youth gender-affirming medical care. Psychology Today. 2022 Jan 24.

6. Turban J et al. Access to gender-affirming hormones during adolescence and mental health outcomes among transgender adults. PLOS ONE. 2022;17(1).

7. Tordoff DM et al. Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5(2).

8. Davies S et al. Detransition rates in a national UK gender identity clinic. Inside Matters. On Law, Ethics, and Religion. 2019 Apr 11.

“Texas investigates parents of transgender teen.” “Court did not force dad to allow chemical castration of son.” Headlines such as these are becoming more common as transgender adolescents and young adults, as well as their families, continue to come under attack from state and local governments. In the 2021 state legislative sessions, more than 100 anti-trans bills were filed across 35 state legislatures. Texas alone saw 13 anti-trans bills, covering everything from sports participation to criminalization of best-practice medical care.1 Many of these bills are introduced under the guise of “protecting” these adolescents and young adults but are detrimental to their health. They also contain descriptions of gender-affirming care that do not reflect the evidence-based standards of care followed by clinicians across the country. Below is scientifically accurate information on gender-affirming care.

Gender identity development

Trajectories of gender identity are diverse. In a large sample of transgender adults (n = 27,715), 10% started to realize they were transgender at age 5 or younger, 16% between ages 6 and 10, 28% between 11 and 15, 29% between 16 and 20, and 18% at age 21 or older.2 In childhood, cross-gender play and preferences are a normal part of gender expression and many gender-nonconforming children will go on to identify with the sex they were assigned at birth (labeled cisgender). However, some children explicitly identify with a gender different than the sex they were assigned at birth (labeled transgender). Children who are consistent, insistent, and persistent in this identity appear likely to remain so into adolescence and adulthood. It is important to note that there is no evidence that discouraging gender nonconformity decreases the likelihood that a child will identify as transgender. In fact, this practice is no longer considered ethical, as it can have damaging effects on self-esteem and mental health. In addition, not all transgender people are noticeably gender nonconforming in childhood and that lack of childhood gender nonconformity does not invalidate someone’s transgender identity.

Gender-affirming care

For youth who identify as transgender, all steps in transition prior to puberty are social. This includes steps like changing hairstyles or clothing and using a different (affirmed) name and/or pronouns. This time period allows youth to explore their gender identity and expression. In one large study of 10,000 LGBTQ youth, among youth who reported “all or most people” used their affirmed pronoun, 12% reported a history of suicide attempt.3 In comparison, among those who reported that “no one” used their affirmed pronoun, the suicide attempt rate was 28%. Further, 14% of youth who reported that they were able to make changes in their clothing and appearance reported a past suicide attempt in comparison to 26% of those who were not able to. Many of these youth also are under the care of mental health professionals during this time.

At the onset of puberty, transgender youth are eligible for medical management, if needed, to address gender dysphoria (i.e., distress with one’s sex characteristics that is consistent and impairing). It is important to recognize that not all people who identify as transgender experience gender dysphoria or desire a medical transition. For those who do seek medical care, puberty must be confirmed either by breast/testicular exam or checking gonadotropin levels. Standards of care suggest that prior to pubertal suppression with GnRH agonists, such as leuprolide or histrelin, adolescents undergo a thorough psychosocial evaluation by a qualified, licensed clinician. After this evaluation, pubertal suppression may be initiated. These adolescents are monitored by their physicians every 3-6 months for side effects and continuing evaluation of their gender identity. GnRH agonists pause any further pubertal development while the adolescent continues to explore his/her/their gender identity. GnRH agonists are fully reversible and if they are stopped, the child’s natal puberty would recommence.

If an adolescent desires to start gender-affirming hormones, these are started as early as age 14, depending on their maturity, when they desire to start, and/or their ability to obtain parental consent. If a patient has not begun GnRH agonists and undergone a previous psychosocial evaluation, a thorough psychosocial evaluation by a qualified, licensed clinician would take place prior to initiating gender-affirming hormones. Prior to initiating hormones, a thorough informed-consent process occurs between the clinician, patient, and family. This process reviews reversible versus irreversible effects, as well of any side effects of the medication(s). Adolescents who begin hormonal treatment are then monitored every 3-6 months for medication side effects, efficacy, satisfaction with treatment, and by continued mental health assessments. Engagement in mental health therapy is not required beyond the initial evaluation (as many adolescents are well adjusted), but it is encouraged for support during the adolescent’s transition.4 It is important to note that the decision to begin hormones, or not, as well as how to adjust dosing over time, is nuanced and is individualized to each patient’s particular goals for his/her/their transition.

Care for transmasculine identified adolescents (those who were assigned female at birth) typically involves testosterone, delivered via subcutaneous injection, transdermal patch, or transdermal gel. Care for transfeminine individuals (those who were assigned male at birth) typically involves estradiol, delivered via daily pill, weekly or twice weekly transdermal patch, or intramuscular injection, as well as an androgen blocker. This is because estradiol by itself is a weak androgen inhibitor. Antiandrogen medication is delivered by daily oral spironolactone, daily oral bicalutamide (an androgen receptor blocker), or GnRH agonists similar to those used for puberty blockade.

Outcomes

At least 13 studies have documented an improvement in gender dysphoria and/or mental health for adolescents and young adults after beginning gender affirming medical care.5 A recent study by Turban et al. showed that access to gender affirming hormones during adolescence or early adulthood was associated with decreased odds of past month suicidal ideation than for those who did not have access to gender-affirming hormones.6 Tordoff et al. found that receipt of gender-affirming care, including medications, led to a 60% decrease in depressive symptoms and a 73% decrease in suicidality.7 One other question that often arises is whether youth who undergo medical treatment for their transition regret their transition or retransition back to the sex they were assigned at birth. In a large study at a gender clinic in the United Kingdom, they found a regret rate of only 0.47% (16 of 3,398 adolescents aged 13-20).8 This is similar to other studies that have also found low rates of regret. Regret is often due to lack of acceptance in society rather than lack of transgender identity.

The care of gender diverse youth takes place on a spectrum, including options that do not include medical treatment. By supporting youth where they are on their gender journey, there is a significant reduction in adverse mental health outcomes. Gender-affirming hormonal treatment is individualized and a thorough multidisciplinary evaluation and informed consent are obtained prior to initiation. There are careful, nuanced discussions with patients and their families to individualize care based on individual goals. By following established evidence-based standards of care, physicians can support their gender-diverse patients throughout their gender journey. Just like other medical treatments, procedures, or surgeries, gender-affirming care should be undertaken in the context of the sacred patient-physician relationship.

Dr. Cooper is assistant professor of pediatrics at University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, and an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas.

References

1. Equality Texas. Legislative Bill Tracker.

2. James SE et al. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. 2016. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality.

3. The Trevor Project. 2020. National Survey on LGBTQ Mental Health.

4. Lopez X et al. Curr Opin Pediatrics. 2017;29(4):475-80.

5. Turban J. The evidence for trans youth gender-affirming medical care. Psychology Today. 2022 Jan 24.

6. Turban J et al. Access to gender-affirming hormones during adolescence and mental health outcomes among transgender adults. PLOS ONE. 2022;17(1).

7. Tordoff DM et al. Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5(2).

8. Davies S et al. Detransition rates in a national UK gender identity clinic. Inside Matters. On Law, Ethics, and Religion. 2019 Apr 11.

“Texas investigates parents of transgender teen.” “Court did not force dad to allow chemical castration of son.” Headlines such as these are becoming more common as transgender adolescents and young adults, as well as their families, continue to come under attack from state and local governments. In the 2021 state legislative sessions, more than 100 anti-trans bills were filed across 35 state legislatures. Texas alone saw 13 anti-trans bills, covering everything from sports participation to criminalization of best-practice medical care.1 Many of these bills are introduced under the guise of “protecting” these adolescents and young adults but are detrimental to their health. They also contain descriptions of gender-affirming care that do not reflect the evidence-based standards of care followed by clinicians across the country. Below is scientifically accurate information on gender-affirming care.

Gender identity development

Trajectories of gender identity are diverse. In a large sample of transgender adults (n = 27,715), 10% started to realize they were transgender at age 5 or younger, 16% between ages 6 and 10, 28% between 11 and 15, 29% between 16 and 20, and 18% at age 21 or older.2 In childhood, cross-gender play and preferences are a normal part of gender expression and many gender-nonconforming children will go on to identify with the sex they were assigned at birth (labeled cisgender). However, some children explicitly identify with a gender different than the sex they were assigned at birth (labeled transgender). Children who are consistent, insistent, and persistent in this identity appear likely to remain so into adolescence and adulthood. It is important to note that there is no evidence that discouraging gender nonconformity decreases the likelihood that a child will identify as transgender. In fact, this practice is no longer considered ethical, as it can have damaging effects on self-esteem and mental health. In addition, not all transgender people are noticeably gender nonconforming in childhood and that lack of childhood gender nonconformity does not invalidate someone’s transgender identity.

Gender-affirming care

For youth who identify as transgender, all steps in transition prior to puberty are social. This includes steps like changing hairstyles or clothing and using a different (affirmed) name and/or pronouns. This time period allows youth to explore their gender identity and expression. In one large study of 10,000 LGBTQ youth, among youth who reported “all or most people” used their affirmed pronoun, 12% reported a history of suicide attempt.3 In comparison, among those who reported that “no one” used their affirmed pronoun, the suicide attempt rate was 28%. Further, 14% of youth who reported that they were able to make changes in their clothing and appearance reported a past suicide attempt in comparison to 26% of those who were not able to. Many of these youth also are under the care of mental health professionals during this time.