User login

A tip of the cap

“It was my wife’s walker, and I’ve never used one before. Sorry that I keep bumping into things.”

He was in his early 70s, recently widowed. He hadn’t needed a walker until yesterday, and his son had gotten it out of the garage where they’d just stowed it away. I showed him how to change the height setting on it so he didn’t have to lean so far over.

His daughter was a longstanding patient of mine, and now she and her brother were worried about their dad. He’d been so healthy for years, taking care of their mother as she declined with cancer. Now, 2 months since her death, he’d started going downhill. He’d been, understandably, depressed and had lost some weight. A few weeks ago he’d had some nonspecific upper respiratory crud, and now they were worried he wasn’t eating. He’d gotten progressively weaker in the last few days, leading to their getting out the walker.

I knew my patient for several years. She wasn’t given to panicking, and was worried about her dad. By this time, I was too. Twenty-eight years of neurology training and practice puts you on the edge for some things. The “Spidey Sense,” as I’ve always called it, was tingling.

It took a very quick neurologic exam to find what I needed. He was indeed weak, had decreased distal sensation, and was completely areflexic. It was time to take the most-dreaded outpatient neurology gamble: The direct office-to-ER admission.

I told his daughter to take him to the nearby ER and scribbled a note that said “Probable Guillain-Barré. Needs urgent workup.” They were somewhat taken aback, as they had dinner plans that night, but his daughter knew me well enough to know that I don’t pull fire alarms for fun.

As soon as they’d left I called the ER doctor and told her what was coming. My hospital days ended 2 years ago, but I wanted to do everything I could to make sure the right ball was rolling.

Then my part was over. I had other patients waiting, tests to review, phone calls to make.

This is where the anxiety began. Nobody wants to be the person who cries wolf, or admits “dumps.” I’ve been on both sides of admissions, and bashing outpatient docs for unnecessary hospital referrals is a perennial pastime of inpatient care.

I was sure of my actions, but as the hours crept by some doubt came in. What if he got to the hospital and suddenly wasn’t weak? Or it was all from a medication error he’d made at home?

No one wants to claim they saw a flare when there wasn’t one, or get the reputation of being past their game. I was worried about the patient, but also began to worry I’d screwed up and missed something else.

I finished the day and went home. After closing out my usual end-of-the-day stuff I logged into the hospital system to see what was going on.

Normal cervical spine MRI. Spinal fluid had zero cells and elevated protein.

I breathed a sigh of relief and relaxed back into my chair. I’d made the right call. The hospital neurologist had ordered IVIG. The patient would hopefully recover. No one would think I’d screwed up a potentially serious case. And, somewhere in the back of my mind, the Sherlock Holmes inside every neurologist tipped his deerstalker cap at me and gave a slight nod.

There’s the relief of having done the right thing for the patient, having made the correct diagnosis, and, at the end of the day, being reassured that (some days at least) I still know what I’m doing.

It’s those feelings that brought me here and still keep me going.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“It was my wife’s walker, and I’ve never used one before. Sorry that I keep bumping into things.”

He was in his early 70s, recently widowed. He hadn’t needed a walker until yesterday, and his son had gotten it out of the garage where they’d just stowed it away. I showed him how to change the height setting on it so he didn’t have to lean so far over.

His daughter was a longstanding patient of mine, and now she and her brother were worried about their dad. He’d been so healthy for years, taking care of their mother as she declined with cancer. Now, 2 months since her death, he’d started going downhill. He’d been, understandably, depressed and had lost some weight. A few weeks ago he’d had some nonspecific upper respiratory crud, and now they were worried he wasn’t eating. He’d gotten progressively weaker in the last few days, leading to their getting out the walker.

I knew my patient for several years. She wasn’t given to panicking, and was worried about her dad. By this time, I was too. Twenty-eight years of neurology training and practice puts you on the edge for some things. The “Spidey Sense,” as I’ve always called it, was tingling.

It took a very quick neurologic exam to find what I needed. He was indeed weak, had decreased distal sensation, and was completely areflexic. It was time to take the most-dreaded outpatient neurology gamble: The direct office-to-ER admission.

I told his daughter to take him to the nearby ER and scribbled a note that said “Probable Guillain-Barré. Needs urgent workup.” They were somewhat taken aback, as they had dinner plans that night, but his daughter knew me well enough to know that I don’t pull fire alarms for fun.

As soon as they’d left I called the ER doctor and told her what was coming. My hospital days ended 2 years ago, but I wanted to do everything I could to make sure the right ball was rolling.

Then my part was over. I had other patients waiting, tests to review, phone calls to make.

This is where the anxiety began. Nobody wants to be the person who cries wolf, or admits “dumps.” I’ve been on both sides of admissions, and bashing outpatient docs for unnecessary hospital referrals is a perennial pastime of inpatient care.

I was sure of my actions, but as the hours crept by some doubt came in. What if he got to the hospital and suddenly wasn’t weak? Or it was all from a medication error he’d made at home?

No one wants to claim they saw a flare when there wasn’t one, or get the reputation of being past their game. I was worried about the patient, but also began to worry I’d screwed up and missed something else.

I finished the day and went home. After closing out my usual end-of-the-day stuff I logged into the hospital system to see what was going on.

Normal cervical spine MRI. Spinal fluid had zero cells and elevated protein.

I breathed a sigh of relief and relaxed back into my chair. I’d made the right call. The hospital neurologist had ordered IVIG. The patient would hopefully recover. No one would think I’d screwed up a potentially serious case. And, somewhere in the back of my mind, the Sherlock Holmes inside every neurologist tipped his deerstalker cap at me and gave a slight nod.

There’s the relief of having done the right thing for the patient, having made the correct diagnosis, and, at the end of the day, being reassured that (some days at least) I still know what I’m doing.

It’s those feelings that brought me here and still keep me going.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“It was my wife’s walker, and I’ve never used one before. Sorry that I keep bumping into things.”

He was in his early 70s, recently widowed. He hadn’t needed a walker until yesterday, and his son had gotten it out of the garage where they’d just stowed it away. I showed him how to change the height setting on it so he didn’t have to lean so far over.

His daughter was a longstanding patient of mine, and now she and her brother were worried about their dad. He’d been so healthy for years, taking care of their mother as she declined with cancer. Now, 2 months since her death, he’d started going downhill. He’d been, understandably, depressed and had lost some weight. A few weeks ago he’d had some nonspecific upper respiratory crud, and now they were worried he wasn’t eating. He’d gotten progressively weaker in the last few days, leading to their getting out the walker.

I knew my patient for several years. She wasn’t given to panicking, and was worried about her dad. By this time, I was too. Twenty-eight years of neurology training and practice puts you on the edge for some things. The “Spidey Sense,” as I’ve always called it, was tingling.

It took a very quick neurologic exam to find what I needed. He was indeed weak, had decreased distal sensation, and was completely areflexic. It was time to take the most-dreaded outpatient neurology gamble: The direct office-to-ER admission.

I told his daughter to take him to the nearby ER and scribbled a note that said “Probable Guillain-Barré. Needs urgent workup.” They were somewhat taken aback, as they had dinner plans that night, but his daughter knew me well enough to know that I don’t pull fire alarms for fun.

As soon as they’d left I called the ER doctor and told her what was coming. My hospital days ended 2 years ago, but I wanted to do everything I could to make sure the right ball was rolling.

Then my part was over. I had other patients waiting, tests to review, phone calls to make.

This is where the anxiety began. Nobody wants to be the person who cries wolf, or admits “dumps.” I’ve been on both sides of admissions, and bashing outpatient docs for unnecessary hospital referrals is a perennial pastime of inpatient care.

I was sure of my actions, but as the hours crept by some doubt came in. What if he got to the hospital and suddenly wasn’t weak? Or it was all from a medication error he’d made at home?

No one wants to claim they saw a flare when there wasn’t one, or get the reputation of being past their game. I was worried about the patient, but also began to worry I’d screwed up and missed something else.

I finished the day and went home. After closing out my usual end-of-the-day stuff I logged into the hospital system to see what was going on.

Normal cervical spine MRI. Spinal fluid had zero cells and elevated protein.

I breathed a sigh of relief and relaxed back into my chair. I’d made the right call. The hospital neurologist had ordered IVIG. The patient would hopefully recover. No one would think I’d screwed up a potentially serious case. And, somewhere in the back of my mind, the Sherlock Holmes inside every neurologist tipped his deerstalker cap at me and gave a slight nod.

There’s the relief of having done the right thing for the patient, having made the correct diagnosis, and, at the end of the day, being reassured that (some days at least) I still know what I’m doing.

It’s those feelings that brought me here and still keep me going.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Commentary: Antibiotics use and vaccine antibody levels

This study of antibiotic use in the first 2 years of life in a reasonably standardized primary care office raises issues about antibiotic stewardship that can be the basis for counseling against antibiotics for viral infections or mild uncomplicated acute otitis media (AOM) above 6 months of age. Even unintended and previously undescribed downstream effects of antibiotics should play a role in our decisions and are another nudge toward prudent antibiotic use – for example, watchful waiting (WW) for AOM.

Some families ask for antibiotics for almost any infection while others may want antibiotics only if really necessary. But maybe patient family wishes are not the main driver, considering a report in Pediatrics (2022;150[1]:e2021055613). They analyzed over 2 million AOM episodes from billing/enrollment records from the MarketScan commercial claims research databases. They reported that, despite WW being the management of choice per American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for uncomplicated AOM in children over 1 year of age, WW use had not increased between 2015 and 2019. Further, they noted that WW was not related to patient factors or demographics but was associated with specialty and provider. For example, WW use was five times more likely by otolaryngologists than pediatricians and less likely by nonpediatricians than pediatricians. Further, some clinicians used WW a lot, while others almost not at all (high-volume antibiotic prescribers). Of note, having a fever significantly lowered the chance of WW.

Maturing data on antibiotic-related alterations in species distribution and quantity within children’s microbiome plus potential effects on antibody responses to vaccines are ideas families need to hear. I suggest sharing these as part of anticipatory guidance at well-child checks as early in life as is feasible.

Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. He has no financial conflicts of interest.

This study of antibiotic use in the first 2 years of life in a reasonably standardized primary care office raises issues about antibiotic stewardship that can be the basis for counseling against antibiotics for viral infections or mild uncomplicated acute otitis media (AOM) above 6 months of age. Even unintended and previously undescribed downstream effects of antibiotics should play a role in our decisions and are another nudge toward prudent antibiotic use – for example, watchful waiting (WW) for AOM.

Some families ask for antibiotics for almost any infection while others may want antibiotics only if really necessary. But maybe patient family wishes are not the main driver, considering a report in Pediatrics (2022;150[1]:e2021055613). They analyzed over 2 million AOM episodes from billing/enrollment records from the MarketScan commercial claims research databases. They reported that, despite WW being the management of choice per American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for uncomplicated AOM in children over 1 year of age, WW use had not increased between 2015 and 2019. Further, they noted that WW was not related to patient factors or demographics but was associated with specialty and provider. For example, WW use was five times more likely by otolaryngologists than pediatricians and less likely by nonpediatricians than pediatricians. Further, some clinicians used WW a lot, while others almost not at all (high-volume antibiotic prescribers). Of note, having a fever significantly lowered the chance of WW.

Maturing data on antibiotic-related alterations in species distribution and quantity within children’s microbiome plus potential effects on antibody responses to vaccines are ideas families need to hear. I suggest sharing these as part of anticipatory guidance at well-child checks as early in life as is feasible.

Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. He has no financial conflicts of interest.

This study of antibiotic use in the first 2 years of life in a reasonably standardized primary care office raises issues about antibiotic stewardship that can be the basis for counseling against antibiotics for viral infections or mild uncomplicated acute otitis media (AOM) above 6 months of age. Even unintended and previously undescribed downstream effects of antibiotics should play a role in our decisions and are another nudge toward prudent antibiotic use – for example, watchful waiting (WW) for AOM.

Some families ask for antibiotics for almost any infection while others may want antibiotics only if really necessary. But maybe patient family wishes are not the main driver, considering a report in Pediatrics (2022;150[1]:e2021055613). They analyzed over 2 million AOM episodes from billing/enrollment records from the MarketScan commercial claims research databases. They reported that, despite WW being the management of choice per American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for uncomplicated AOM in children over 1 year of age, WW use had not increased between 2015 and 2019. Further, they noted that WW was not related to patient factors or demographics but was associated with specialty and provider. For example, WW use was five times more likely by otolaryngologists than pediatricians and less likely by nonpediatricians than pediatricians. Further, some clinicians used WW a lot, while others almost not at all (high-volume antibiotic prescribers). Of note, having a fever significantly lowered the chance of WW.

Maturing data on antibiotic-related alterations in species distribution and quantity within children’s microbiome plus potential effects on antibody responses to vaccines are ideas families need to hear. I suggest sharing these as part of anticipatory guidance at well-child checks as early in life as is feasible.

Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. He has no financial conflicts of interest.

Antibiotics use and vaccine antibody levels

In this column I have previously discussed the microbiome and its importance to health, especially as it relates to infections in children. Given the appreciated connection between microbiome and immunity, my group in Rochester, N.Y., recently undertook a study of the effect of antibiotic usage on the immune response to routine early childhood vaccines. In mouse models, it was previously shown that antibiotic exposure induced a reduction in the abundance and diversity of gut microbiota that in turn negatively affected the generation and maintenance of vaccine-induced immunity.1,2 A study from Stanford University was the first experimental human trial of antibiotic effects on vaccine responses. Adult volunteers were given an antibiotic or not before seasonal influenza vaccination and the researchers identified specific bacteria in the gut that were reduced by the antibiotics given. Those normal bacteria in the gut microbiome were shown to provide positive immunity signals to the systemic immune system that potentiated vaccine responses.3

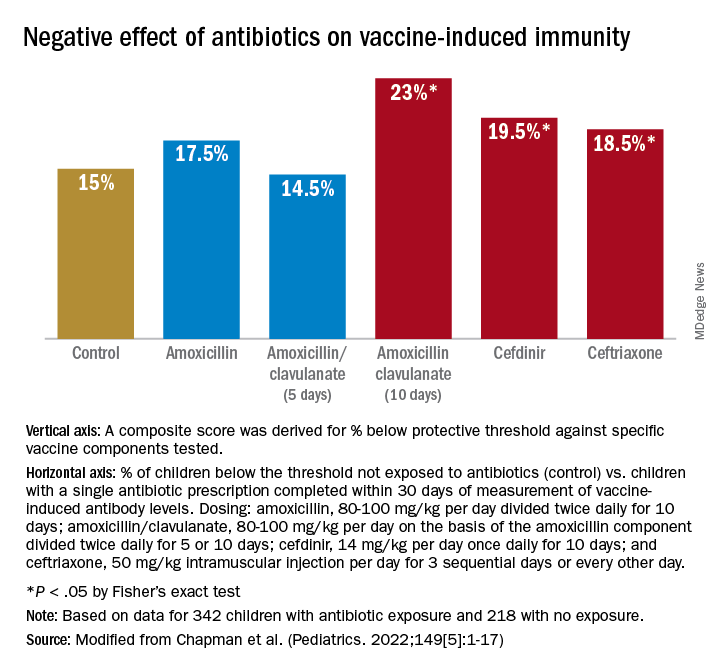

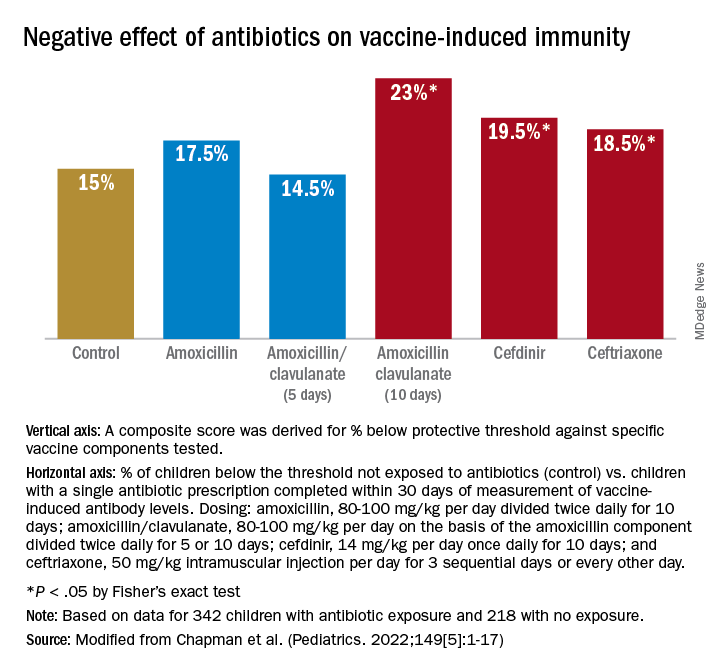

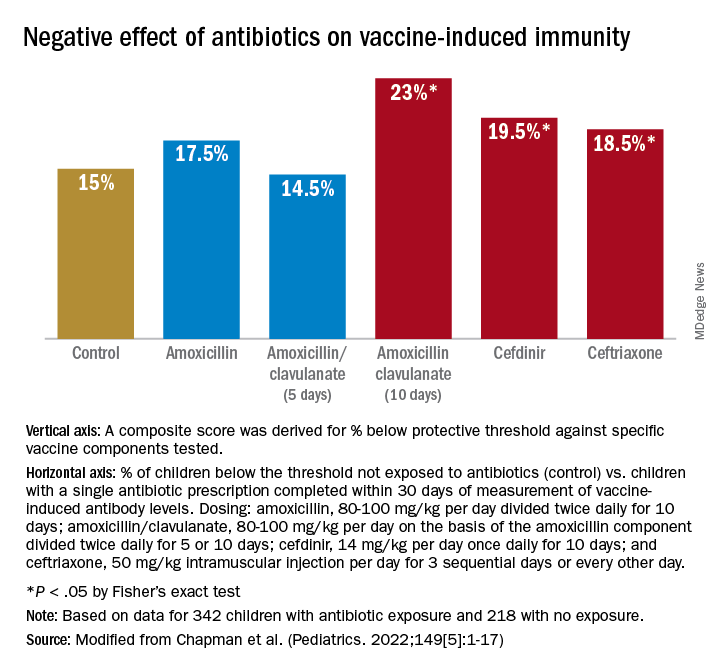

My group conducted the first-ever study in children to explore whether an association existed between antibiotic use and vaccine-induced antibody levels. In the May issue of Pediatrics we report results from 560 children studied.4 From these children, 11,888 serum antibody levels to vaccine antigens were measured. Vaccine-induced antibody levels were determined at various time points after primary vaccination at child age 2, 4, and 6 months and boosters at age 12-18 months for 10 antigens included in four vaccines: DTaP, Hib, IPV, and PCV. The antibody levels to vaccine components were measured to DTaP (diphtheria toxoid, pertussis toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin), Hib conjugate (polyribosylribitol phosphate), IPV (polio 2), and PCV (serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). A total of 342 children with 1,678 antibiotic courses prescribed were compared with 218 children with no antibiotic exposures. The predominant antibiotics prescribed were amoxicillin, cefdinir, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and ceftriaxone, since most treatments were for acute otitis media.

Of possible high clinical relevance, we found that from 9 to 24 months of age, children with antibiotic exposure had a higher frequency of vaccine-induced antibody levels below protection compared with children with no antibiotic use, placing them at risk of contracting a vaccine-preventable infection for DTaP antigens DT, TT, and PT and for PCV serotype 14.

For time points where antibody levels were determined within 30 days of completion of a course of antibiotics (recent antibiotic use), individual antibiotics were analyzed for effect on antibody levels below protective levels. Across all vaccine antigens measured, we found that all antibiotics had a negative effect on antibody levels and percentage of children achieving the protective antibody level threshold. Amoxicillin use had a lower association with lower antibody levels than the broader spectrum antibiotics, amoxicillin clavulanate (Augmentin), cefdinir, and ceftriaxone. For children receiving amoxicillin/clavulanate prescriptions, it was possible to compare the effect of shorter versus longer courses and we found that a 5-day course was associated with subprotective antibody levels similar to 10 days of amoxicillin, whereas 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate was associated with higher frequency of children having subprotective antibody levels (Figure).

We examined whether accumulation of antibiotic courses in the first year of life had an association with subsequent vaccine-induced antibody levels and found that each antibiotic prescription was associated with a reduction in the median antibody level. For DTaP, each prescription was associated with 5.8% drop in antibody level to the vaccine components. For Hib the drop was 6.8%, IPV was 11.3%, and PCV was 10.4% – all statistically significant. To determine if booster vaccination influenced this association, a second analysis was performed using antibiotic prescriptions up to 15 months of age. We found each antibiotic prescription was associated with a reduction in median vaccine-induced antibody levels for DTaP by 18%, Hib by 21%, IPV by 19%, and PCV by 12% – all statistically significant.

Our study is the first in young children during the early age window where vaccine-induced immunity is established. Antibiotic use was associated with increased frequency of subprotective antibody levels for several vaccines used in children up to 2 years of age. The lower antibody levels could leave children vulnerable to vaccine preventable diseases. Perhaps outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, such as pertussis, may be a consequence of multiple courses of antibiotics suppressing vaccine-induced immunity.

A goal of this study was to explore potential acute and long-term effects of antibiotic exposure on vaccine-induced antibody levels. Accumulated antibiotic courses up to booster immunization was associated with decreased vaccine antibody levels both before and after booster, suggesting that booster immunization was not sufficient to change the negative association with antibiotic exposure. The results were similar for all vaccines tested, suggesting that the specific vaccine formulation was not a factor.

The study has several limitations. The antibiotic prescription data and measurements of vaccine-induced antibody levels were recorded and measured prospectively; however, our analysis was done retrospectively. The group of study children was derived from my private practice in Rochester, N.Y., and may not be broadly representative of all children. The number of vaccine antibody measurements was limited by serum availability at some sampling time points in some children; and sometimes, the serum samples were collected far apart, which weakened our ability to perform longitudinal analyses. We did not collect stool samples from the children so we could not directly study the effect of antibiotic courses on the gut microbiome.

Our study adds new reasons to be cautious about overprescribing antibiotics on an individual child basis because an adverse effect extends to reduction in vaccine responses. This should be explained to parents requesting unnecessary antibiotics for colds and coughs. When antibiotics are necessary, the judicious choice of a narrow-spectrum antibiotic or a shorter duration of a broader spectrum antibiotic may reduce adverse effects on vaccine-induced immunity.

References

1. Valdez Y et al. Influence of the microbiota on vaccine effectiveness. Trends Immunol. 2014;35(11):526-37.

2. Lynn MA et al. Early-life antibiotic-driven dysbiosis leads to dysregulated vaccine immune responses in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23(5):653-60.e5.

3. Hagan T et al. Antibiotics-driven gut microbiome perturbation alters immunity to vaccines in humans. Cell. 2019;178(6):1313-28.e13.

4. Chapman T et al. Antibiotic use and vaccine antibody levels. Pediatrics. 2022;149(5);1-17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

In this column I have previously discussed the microbiome and its importance to health, especially as it relates to infections in children. Given the appreciated connection between microbiome and immunity, my group in Rochester, N.Y., recently undertook a study of the effect of antibiotic usage on the immune response to routine early childhood vaccines. In mouse models, it was previously shown that antibiotic exposure induced a reduction in the abundance and diversity of gut microbiota that in turn negatively affected the generation and maintenance of vaccine-induced immunity.1,2 A study from Stanford University was the first experimental human trial of antibiotic effects on vaccine responses. Adult volunteers were given an antibiotic or not before seasonal influenza vaccination and the researchers identified specific bacteria in the gut that were reduced by the antibiotics given. Those normal bacteria in the gut microbiome were shown to provide positive immunity signals to the systemic immune system that potentiated vaccine responses.3

My group conducted the first-ever study in children to explore whether an association existed between antibiotic use and vaccine-induced antibody levels. In the May issue of Pediatrics we report results from 560 children studied.4 From these children, 11,888 serum antibody levels to vaccine antigens were measured. Vaccine-induced antibody levels were determined at various time points after primary vaccination at child age 2, 4, and 6 months and boosters at age 12-18 months for 10 antigens included in four vaccines: DTaP, Hib, IPV, and PCV. The antibody levels to vaccine components were measured to DTaP (diphtheria toxoid, pertussis toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin), Hib conjugate (polyribosylribitol phosphate), IPV (polio 2), and PCV (serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). A total of 342 children with 1,678 antibiotic courses prescribed were compared with 218 children with no antibiotic exposures. The predominant antibiotics prescribed were amoxicillin, cefdinir, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and ceftriaxone, since most treatments were for acute otitis media.

Of possible high clinical relevance, we found that from 9 to 24 months of age, children with antibiotic exposure had a higher frequency of vaccine-induced antibody levels below protection compared with children with no antibiotic use, placing them at risk of contracting a vaccine-preventable infection for DTaP antigens DT, TT, and PT and for PCV serotype 14.

For time points where antibody levels were determined within 30 days of completion of a course of antibiotics (recent antibiotic use), individual antibiotics were analyzed for effect on antibody levels below protective levels. Across all vaccine antigens measured, we found that all antibiotics had a negative effect on antibody levels and percentage of children achieving the protective antibody level threshold. Amoxicillin use had a lower association with lower antibody levels than the broader spectrum antibiotics, amoxicillin clavulanate (Augmentin), cefdinir, and ceftriaxone. For children receiving amoxicillin/clavulanate prescriptions, it was possible to compare the effect of shorter versus longer courses and we found that a 5-day course was associated with subprotective antibody levels similar to 10 days of amoxicillin, whereas 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate was associated with higher frequency of children having subprotective antibody levels (Figure).

We examined whether accumulation of antibiotic courses in the first year of life had an association with subsequent vaccine-induced antibody levels and found that each antibiotic prescription was associated with a reduction in the median antibody level. For DTaP, each prescription was associated with 5.8% drop in antibody level to the vaccine components. For Hib the drop was 6.8%, IPV was 11.3%, and PCV was 10.4% – all statistically significant. To determine if booster vaccination influenced this association, a second analysis was performed using antibiotic prescriptions up to 15 months of age. We found each antibiotic prescription was associated with a reduction in median vaccine-induced antibody levels for DTaP by 18%, Hib by 21%, IPV by 19%, and PCV by 12% – all statistically significant.

Our study is the first in young children during the early age window where vaccine-induced immunity is established. Antibiotic use was associated with increased frequency of subprotective antibody levels for several vaccines used in children up to 2 years of age. The lower antibody levels could leave children vulnerable to vaccine preventable diseases. Perhaps outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, such as pertussis, may be a consequence of multiple courses of antibiotics suppressing vaccine-induced immunity.

A goal of this study was to explore potential acute and long-term effects of antibiotic exposure on vaccine-induced antibody levels. Accumulated antibiotic courses up to booster immunization was associated with decreased vaccine antibody levels both before and after booster, suggesting that booster immunization was not sufficient to change the negative association with antibiotic exposure. The results were similar for all vaccines tested, suggesting that the specific vaccine formulation was not a factor.

The study has several limitations. The antibiotic prescription data and measurements of vaccine-induced antibody levels were recorded and measured prospectively; however, our analysis was done retrospectively. The group of study children was derived from my private practice in Rochester, N.Y., and may not be broadly representative of all children. The number of vaccine antibody measurements was limited by serum availability at some sampling time points in some children; and sometimes, the serum samples were collected far apart, which weakened our ability to perform longitudinal analyses. We did not collect stool samples from the children so we could not directly study the effect of antibiotic courses on the gut microbiome.

Our study adds new reasons to be cautious about overprescribing antibiotics on an individual child basis because an adverse effect extends to reduction in vaccine responses. This should be explained to parents requesting unnecessary antibiotics for colds and coughs. When antibiotics are necessary, the judicious choice of a narrow-spectrum antibiotic or a shorter duration of a broader spectrum antibiotic may reduce adverse effects on vaccine-induced immunity.

References

1. Valdez Y et al. Influence of the microbiota on vaccine effectiveness. Trends Immunol. 2014;35(11):526-37.

2. Lynn MA et al. Early-life antibiotic-driven dysbiosis leads to dysregulated vaccine immune responses in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23(5):653-60.e5.

3. Hagan T et al. Antibiotics-driven gut microbiome perturbation alters immunity to vaccines in humans. Cell. 2019;178(6):1313-28.e13.

4. Chapman T et al. Antibiotic use and vaccine antibody levels. Pediatrics. 2022;149(5);1-17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

In this column I have previously discussed the microbiome and its importance to health, especially as it relates to infections in children. Given the appreciated connection between microbiome and immunity, my group in Rochester, N.Y., recently undertook a study of the effect of antibiotic usage on the immune response to routine early childhood vaccines. In mouse models, it was previously shown that antibiotic exposure induced a reduction in the abundance and diversity of gut microbiota that in turn negatively affected the generation and maintenance of vaccine-induced immunity.1,2 A study from Stanford University was the first experimental human trial of antibiotic effects on vaccine responses. Adult volunteers were given an antibiotic or not before seasonal influenza vaccination and the researchers identified specific bacteria in the gut that were reduced by the antibiotics given. Those normal bacteria in the gut microbiome were shown to provide positive immunity signals to the systemic immune system that potentiated vaccine responses.3

My group conducted the first-ever study in children to explore whether an association existed between antibiotic use and vaccine-induced antibody levels. In the May issue of Pediatrics we report results from 560 children studied.4 From these children, 11,888 serum antibody levels to vaccine antigens were measured. Vaccine-induced antibody levels were determined at various time points after primary vaccination at child age 2, 4, and 6 months and boosters at age 12-18 months for 10 antigens included in four vaccines: DTaP, Hib, IPV, and PCV. The antibody levels to vaccine components were measured to DTaP (diphtheria toxoid, pertussis toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin), Hib conjugate (polyribosylribitol phosphate), IPV (polio 2), and PCV (serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). A total of 342 children with 1,678 antibiotic courses prescribed were compared with 218 children with no antibiotic exposures. The predominant antibiotics prescribed were amoxicillin, cefdinir, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and ceftriaxone, since most treatments were for acute otitis media.

Of possible high clinical relevance, we found that from 9 to 24 months of age, children with antibiotic exposure had a higher frequency of vaccine-induced antibody levels below protection compared with children with no antibiotic use, placing them at risk of contracting a vaccine-preventable infection for DTaP antigens DT, TT, and PT and for PCV serotype 14.

For time points where antibody levels were determined within 30 days of completion of a course of antibiotics (recent antibiotic use), individual antibiotics were analyzed for effect on antibody levels below protective levels. Across all vaccine antigens measured, we found that all antibiotics had a negative effect on antibody levels and percentage of children achieving the protective antibody level threshold. Amoxicillin use had a lower association with lower antibody levels than the broader spectrum antibiotics, amoxicillin clavulanate (Augmentin), cefdinir, and ceftriaxone. For children receiving amoxicillin/clavulanate prescriptions, it was possible to compare the effect of shorter versus longer courses and we found that a 5-day course was associated with subprotective antibody levels similar to 10 days of amoxicillin, whereas 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate was associated with higher frequency of children having subprotective antibody levels (Figure).

We examined whether accumulation of antibiotic courses in the first year of life had an association with subsequent vaccine-induced antibody levels and found that each antibiotic prescription was associated with a reduction in the median antibody level. For DTaP, each prescription was associated with 5.8% drop in antibody level to the vaccine components. For Hib the drop was 6.8%, IPV was 11.3%, and PCV was 10.4% – all statistically significant. To determine if booster vaccination influenced this association, a second analysis was performed using antibiotic prescriptions up to 15 months of age. We found each antibiotic prescription was associated with a reduction in median vaccine-induced antibody levels for DTaP by 18%, Hib by 21%, IPV by 19%, and PCV by 12% – all statistically significant.

Our study is the first in young children during the early age window where vaccine-induced immunity is established. Antibiotic use was associated with increased frequency of subprotective antibody levels for several vaccines used in children up to 2 years of age. The lower antibody levels could leave children vulnerable to vaccine preventable diseases. Perhaps outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, such as pertussis, may be a consequence of multiple courses of antibiotics suppressing vaccine-induced immunity.

A goal of this study was to explore potential acute and long-term effects of antibiotic exposure on vaccine-induced antibody levels. Accumulated antibiotic courses up to booster immunization was associated with decreased vaccine antibody levels both before and after booster, suggesting that booster immunization was not sufficient to change the negative association with antibiotic exposure. The results were similar for all vaccines tested, suggesting that the specific vaccine formulation was not a factor.

The study has several limitations. The antibiotic prescription data and measurements of vaccine-induced antibody levels were recorded and measured prospectively; however, our analysis was done retrospectively. The group of study children was derived from my private practice in Rochester, N.Y., and may not be broadly representative of all children. The number of vaccine antibody measurements was limited by serum availability at some sampling time points in some children; and sometimes, the serum samples were collected far apart, which weakened our ability to perform longitudinal analyses. We did not collect stool samples from the children so we could not directly study the effect of antibiotic courses on the gut microbiome.

Our study adds new reasons to be cautious about overprescribing antibiotics on an individual child basis because an adverse effect extends to reduction in vaccine responses. This should be explained to parents requesting unnecessary antibiotics for colds and coughs. When antibiotics are necessary, the judicious choice of a narrow-spectrum antibiotic or a shorter duration of a broader spectrum antibiotic may reduce adverse effects on vaccine-induced immunity.

References

1. Valdez Y et al. Influence of the microbiota on vaccine effectiveness. Trends Immunol. 2014;35(11):526-37.

2. Lynn MA et al. Early-life antibiotic-driven dysbiosis leads to dysregulated vaccine immune responses in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23(5):653-60.e5.

3. Hagan T et al. Antibiotics-driven gut microbiome perturbation alters immunity to vaccines in humans. Cell. 2019;178(6):1313-28.e13.

4. Chapman T et al. Antibiotic use and vaccine antibody levels. Pediatrics. 2022;149(5);1-17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

It’s time to shame the fat shamers

Fat shaming doesn’t work. If it did, obesity as we know it wouldn’t exist because if the one thing society ensures isn’t lacking for people with obesity, it’s shame. We know that fat shaming doesn’t lead to weight loss and that it’s actually correlated with weight gain: More shame leads to more gain (Puhl and Suh; Sutin and Terracciano; Tomiyama et al).

Shaming and weight stigma have far more concerning associations than weight gain. People who report experiencing more weight stigma have an increased risk for depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, poor body image, substance abuse, suicidality, unhealthy eating behaviors, disordered eating, increased caloric intake, exercise avoidance, decreased exercise motivation potentially due to heightened cortisol reactivity, elevated C-reactive protein, and elevated blood pressure.

Meanwhile, people with obesity – likely in part owing to negative weight-biased experiences in health care – are reluctant to discuss weight with their health care providers and are less likely to seek care at all for any conditions. When care is sought, people with obesity are more likely to receive substandard treatment, including receiving fewer preventive health screenings, decreased health education, and decreased time spent in appointments.

Remember that obesity is not a conscious choice

A fact that is conveniently forgotten by those who are most prone to fat shaming is that obesity, like every chronic noncommunicable disease, isn’t a choice that is consciously made by patients.

And yes, though there are lifestyle means that might affect weight, there are lifestyle means that might affect all chronic diseases – yet obesity is the only one we seem to moralize about. It’s also worth noting that other chronic diseases’ lifestyle levers tend not to be governed by thousands of genes and dozens of hormones; those trying to “lifestyle” their way out of obesity are swimming against strong physiologic currents that influence our most seminally important survival drive: eating.

But forgetting about physiologic currents, there is also staggering privilege associated with intentional perpetual behavior change around food and fitness in the name of health.

Whereas medicine and the world are right and quick to embrace the fights against racism, sexism, and homophobia, the push to confront weight bias is far rarer, despite the fact that it’s been shown to be rampant among health care professionals.

Protecting the rights of people with obesity

Perhaps though, times are changing. Movements are popping up to protect the rights of people with obesity while combating hate.

Of note, Brazil seems to have embraced a campaign to fight gordofobia — the Portuguese term used to describe weight-based discrimination. For instance, laws are being passed to ensure appropriate seating is supplied in schools for children with obesity, an annual day was formalized to promote the rights of people with obesity, preferential seating is provided on subways for people with obesity, and fines have been levied against at least one comedian for making fat jokes on the grounds of the state’s duty to protect minorities.

We need to take this fight to medicine. Given the incredibly depressing prevalence of weight bias among trainees, medical schools and residency programs should ensure countering weight bias is not only part of the curriculum but that it’s explicitly examined. National medical licensing examinations should include weight bias as well.

Though we’re closer than ever before to widely effective treatment options for obesity, it’s likely to still be decades before pharmaceutical options to treat obesity are as effective, accepted, and encouraged as medications to treat hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and more are today.

If you’re curious about your own implicit weight biases, consider taking Harvard’s Implicit Association Test for Weight. You might also want to take a few moments and review the Strategies to Overcome and Prevent Obesity Alliances’ Weight Can’t Wait guide for advice on the management of obesity in primary care.

Treat patients with obesity the same as you would those with any chronic condition.

Also, consider your physical office space. Do you have chairs suitable for patients with obesity (wide base and with arms to help patients rise)? A scale that measures up to high weights that’s in a private location? Appropriately sized blood pressure cuffs?

If not,

Examples include the family doctor who hadn’t checked my patient’s blood pressure in over a decade because he couldn’t be bothered buying an appropriately sized blood pressure cuff. Or the fertility doctor who told one of my patients that perhaps her weight reflected God’s will that she does not have children.

Finally, if reading this article about treating people with obesity the same as you would patients with other chronic, noncommunicable, lifestyle responsive diseases made you angry, there’s a great chance that you’re part of the problem.

Dr. Freedhoff, is associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa and medical director of the Bariatric Medical Institute, a nonsurgical weight management center. He is one of Canada’s most outspoken obesity experts and the author of The Diet Fix: Why Diets Fail and How to Make Yours Work. He has disclosed the following: He served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Bariatric Medical Institute and Constant Health; has received research grant from Novo Nordisk, and has publicly shared opinions via Weighty Matters and social media. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fat shaming doesn’t work. If it did, obesity as we know it wouldn’t exist because if the one thing society ensures isn’t lacking for people with obesity, it’s shame. We know that fat shaming doesn’t lead to weight loss and that it’s actually correlated with weight gain: More shame leads to more gain (Puhl and Suh; Sutin and Terracciano; Tomiyama et al).

Shaming and weight stigma have far more concerning associations than weight gain. People who report experiencing more weight stigma have an increased risk for depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, poor body image, substance abuse, suicidality, unhealthy eating behaviors, disordered eating, increased caloric intake, exercise avoidance, decreased exercise motivation potentially due to heightened cortisol reactivity, elevated C-reactive protein, and elevated blood pressure.

Meanwhile, people with obesity – likely in part owing to negative weight-biased experiences in health care – are reluctant to discuss weight with their health care providers and are less likely to seek care at all for any conditions. When care is sought, people with obesity are more likely to receive substandard treatment, including receiving fewer preventive health screenings, decreased health education, and decreased time spent in appointments.

Remember that obesity is not a conscious choice

A fact that is conveniently forgotten by those who are most prone to fat shaming is that obesity, like every chronic noncommunicable disease, isn’t a choice that is consciously made by patients.

And yes, though there are lifestyle means that might affect weight, there are lifestyle means that might affect all chronic diseases – yet obesity is the only one we seem to moralize about. It’s also worth noting that other chronic diseases’ lifestyle levers tend not to be governed by thousands of genes and dozens of hormones; those trying to “lifestyle” their way out of obesity are swimming against strong physiologic currents that influence our most seminally important survival drive: eating.

But forgetting about physiologic currents, there is also staggering privilege associated with intentional perpetual behavior change around food and fitness in the name of health.

Whereas medicine and the world are right and quick to embrace the fights against racism, sexism, and homophobia, the push to confront weight bias is far rarer, despite the fact that it’s been shown to be rampant among health care professionals.

Protecting the rights of people with obesity

Perhaps though, times are changing. Movements are popping up to protect the rights of people with obesity while combating hate.

Of note, Brazil seems to have embraced a campaign to fight gordofobia — the Portuguese term used to describe weight-based discrimination. For instance, laws are being passed to ensure appropriate seating is supplied in schools for children with obesity, an annual day was formalized to promote the rights of people with obesity, preferential seating is provided on subways for people with obesity, and fines have been levied against at least one comedian for making fat jokes on the grounds of the state’s duty to protect minorities.

We need to take this fight to medicine. Given the incredibly depressing prevalence of weight bias among trainees, medical schools and residency programs should ensure countering weight bias is not only part of the curriculum but that it’s explicitly examined. National medical licensing examinations should include weight bias as well.

Though we’re closer than ever before to widely effective treatment options for obesity, it’s likely to still be decades before pharmaceutical options to treat obesity are as effective, accepted, and encouraged as medications to treat hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and more are today.

If you’re curious about your own implicit weight biases, consider taking Harvard’s Implicit Association Test for Weight. You might also want to take a few moments and review the Strategies to Overcome and Prevent Obesity Alliances’ Weight Can’t Wait guide for advice on the management of obesity in primary care.

Treat patients with obesity the same as you would those with any chronic condition.

Also, consider your physical office space. Do you have chairs suitable for patients with obesity (wide base and with arms to help patients rise)? A scale that measures up to high weights that’s in a private location? Appropriately sized blood pressure cuffs?

If not,

Examples include the family doctor who hadn’t checked my patient’s blood pressure in over a decade because he couldn’t be bothered buying an appropriately sized blood pressure cuff. Or the fertility doctor who told one of my patients that perhaps her weight reflected God’s will that she does not have children.

Finally, if reading this article about treating people with obesity the same as you would patients with other chronic, noncommunicable, lifestyle responsive diseases made you angry, there’s a great chance that you’re part of the problem.

Dr. Freedhoff, is associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa and medical director of the Bariatric Medical Institute, a nonsurgical weight management center. He is one of Canada’s most outspoken obesity experts and the author of The Diet Fix: Why Diets Fail and How to Make Yours Work. He has disclosed the following: He served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Bariatric Medical Institute and Constant Health; has received research grant from Novo Nordisk, and has publicly shared opinions via Weighty Matters and social media. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fat shaming doesn’t work. If it did, obesity as we know it wouldn’t exist because if the one thing society ensures isn’t lacking for people with obesity, it’s shame. We know that fat shaming doesn’t lead to weight loss and that it’s actually correlated with weight gain: More shame leads to more gain (Puhl and Suh; Sutin and Terracciano; Tomiyama et al).

Shaming and weight stigma have far more concerning associations than weight gain. People who report experiencing more weight stigma have an increased risk for depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, poor body image, substance abuse, suicidality, unhealthy eating behaviors, disordered eating, increased caloric intake, exercise avoidance, decreased exercise motivation potentially due to heightened cortisol reactivity, elevated C-reactive protein, and elevated blood pressure.

Meanwhile, people with obesity – likely in part owing to negative weight-biased experiences in health care – are reluctant to discuss weight with their health care providers and are less likely to seek care at all for any conditions. When care is sought, people with obesity are more likely to receive substandard treatment, including receiving fewer preventive health screenings, decreased health education, and decreased time spent in appointments.

Remember that obesity is not a conscious choice

A fact that is conveniently forgotten by those who are most prone to fat shaming is that obesity, like every chronic noncommunicable disease, isn’t a choice that is consciously made by patients.

And yes, though there are lifestyle means that might affect weight, there are lifestyle means that might affect all chronic diseases – yet obesity is the only one we seem to moralize about. It’s also worth noting that other chronic diseases’ lifestyle levers tend not to be governed by thousands of genes and dozens of hormones; those trying to “lifestyle” their way out of obesity are swimming against strong physiologic currents that influence our most seminally important survival drive: eating.

But forgetting about physiologic currents, there is also staggering privilege associated with intentional perpetual behavior change around food and fitness in the name of health.

Whereas medicine and the world are right and quick to embrace the fights against racism, sexism, and homophobia, the push to confront weight bias is far rarer, despite the fact that it’s been shown to be rampant among health care professionals.

Protecting the rights of people with obesity

Perhaps though, times are changing. Movements are popping up to protect the rights of people with obesity while combating hate.

Of note, Brazil seems to have embraced a campaign to fight gordofobia — the Portuguese term used to describe weight-based discrimination. For instance, laws are being passed to ensure appropriate seating is supplied in schools for children with obesity, an annual day was formalized to promote the rights of people with obesity, preferential seating is provided on subways for people with obesity, and fines have been levied against at least one comedian for making fat jokes on the grounds of the state’s duty to protect minorities.

We need to take this fight to medicine. Given the incredibly depressing prevalence of weight bias among trainees, medical schools and residency programs should ensure countering weight bias is not only part of the curriculum but that it’s explicitly examined. National medical licensing examinations should include weight bias as well.

Though we’re closer than ever before to widely effective treatment options for obesity, it’s likely to still be decades before pharmaceutical options to treat obesity are as effective, accepted, and encouraged as medications to treat hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and more are today.

If you’re curious about your own implicit weight biases, consider taking Harvard’s Implicit Association Test for Weight. You might also want to take a few moments and review the Strategies to Overcome and Prevent Obesity Alliances’ Weight Can’t Wait guide for advice on the management of obesity in primary care.

Treat patients with obesity the same as you would those with any chronic condition.

Also, consider your physical office space. Do you have chairs suitable for patients with obesity (wide base and with arms to help patients rise)? A scale that measures up to high weights that’s in a private location? Appropriately sized blood pressure cuffs?

If not,

Examples include the family doctor who hadn’t checked my patient’s blood pressure in over a decade because he couldn’t be bothered buying an appropriately sized blood pressure cuff. Or the fertility doctor who told one of my patients that perhaps her weight reflected God’s will that she does not have children.

Finally, if reading this article about treating people with obesity the same as you would patients with other chronic, noncommunicable, lifestyle responsive diseases made you angry, there’s a great chance that you’re part of the problem.

Dr. Freedhoff, is associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa and medical director of the Bariatric Medical Institute, a nonsurgical weight management center. He is one of Canada’s most outspoken obesity experts and the author of The Diet Fix: Why Diets Fail and How to Make Yours Work. He has disclosed the following: He served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Bariatric Medical Institute and Constant Health; has received research grant from Novo Nordisk, and has publicly shared opinions via Weighty Matters and social media. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Career pivots: A new perspective on psychiatry

Psychiatrists practice a field of medicine that relies on one’s clinical perspective to interpret observable behaviors originating from the brains of others. In this manner, psychiatry and photography are similar. And digital technology has changed them both.

In photography, there are many technical aspects for one to master when framing and capturing a shot. The length of exposure. The amount of light needed. The speed of the film, which is its sensitivity to light. The aperture that controls how much light falls on the film. The movement of the subject across the film during the exposure. Despite the fact that physical film has mostly yielded to electronic sensors over the past couple decades, these basic aspects of photography remain.

But perspective is the critical ingredient. This is what brings the greatest impact to photography. The composition, or the subject of the photograph and how its elements – foreground, background, shapes, patterns, texture, shadow, motion, leading lines, and focal points – are arranged. The most powerful way to improve the composition – more powerful than fancy camera bells and whistles – is to move. One step to the left or right, one step forward or back. Stand on your toes, or crouch to your knees. Pivot this way or that. A simple change in perspective dramatically changes the nature and the energy of the captured image.

In fact, many physicians are changing what they actually do for a living. Pivoting their clinical perspectives. And applying those perspectives to other areas. The latest catalyst fueling these career pivots, these changes in perspectives, has been the incredible global impact of the tiny little coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2. The COVID-19 pandemic that began two years ago has disrupted the entire planet. The virus has caused us all to change our perspective, to see our world differently, and our place in it.

The virus has exposed defects in our health care delivery system. And physicians have necessarily reacted, injecting changes in what they do and how they do it. Many of these changes rely on digital technology, building upon the groundwork laid over the past couple of decades to convert our paper processes into electronic processes, and our manual work flows into digital work flows. This groundwork is no small thing, as it relies on conventions and standards, such as DICOM, LOINC, AES, CDA, UMLS, FHIR, ICD, NDC, USCDI, and SNOMED-CT. Establishing, maintaining, and evolving health care standards requires organized groups of people to come together to share their diverse perspectives. This is but one of many places where physicians are using their unique clinical perspective to share what they see with others.

This column will focus on these professional pivots that physicians make when they take a step to the left or right to change their perspective and share their viewpoints in different settings with diverse groups of people. Some of these pivots are small, while others are career changing. But the theme that knits them together is about taking what one has learned while helping others achieve better health, and using that perspective to make a difference.

Dr. Daviss is chief medical officer for Optum Maryland and immediate past president of the Maryland-DC Society of Addiction Medicine, and former medical director and senior medical advisor at SAMHSA. He is coauthor of the 2011 book, Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work. Psychiatrists and other physicians may share their own experience with pivots they have made with Dr. Daviss via email ([email protected]) or Twitter (@HITshrink). The opinions expressed are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of his employer or organizations with which he is associated.

Psychiatrists practice a field of medicine that relies on one’s clinical perspective to interpret observable behaviors originating from the brains of others. In this manner, psychiatry and photography are similar. And digital technology has changed them both.

In photography, there are many technical aspects for one to master when framing and capturing a shot. The length of exposure. The amount of light needed. The speed of the film, which is its sensitivity to light. The aperture that controls how much light falls on the film. The movement of the subject across the film during the exposure. Despite the fact that physical film has mostly yielded to electronic sensors over the past couple decades, these basic aspects of photography remain.

But perspective is the critical ingredient. This is what brings the greatest impact to photography. The composition, or the subject of the photograph and how its elements – foreground, background, shapes, patterns, texture, shadow, motion, leading lines, and focal points – are arranged. The most powerful way to improve the composition – more powerful than fancy camera bells and whistles – is to move. One step to the left or right, one step forward or back. Stand on your toes, or crouch to your knees. Pivot this way or that. A simple change in perspective dramatically changes the nature and the energy of the captured image.

In fact, many physicians are changing what they actually do for a living. Pivoting their clinical perspectives. And applying those perspectives to other areas. The latest catalyst fueling these career pivots, these changes in perspectives, has been the incredible global impact of the tiny little coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2. The COVID-19 pandemic that began two years ago has disrupted the entire planet. The virus has caused us all to change our perspective, to see our world differently, and our place in it.

The virus has exposed defects in our health care delivery system. And physicians have necessarily reacted, injecting changes in what they do and how they do it. Many of these changes rely on digital technology, building upon the groundwork laid over the past couple of decades to convert our paper processes into electronic processes, and our manual work flows into digital work flows. This groundwork is no small thing, as it relies on conventions and standards, such as DICOM, LOINC, AES, CDA, UMLS, FHIR, ICD, NDC, USCDI, and SNOMED-CT. Establishing, maintaining, and evolving health care standards requires organized groups of people to come together to share their diverse perspectives. This is but one of many places where physicians are using their unique clinical perspective to share what they see with others.

This column will focus on these professional pivots that physicians make when they take a step to the left or right to change their perspective and share their viewpoints in different settings with diverse groups of people. Some of these pivots are small, while others are career changing. But the theme that knits them together is about taking what one has learned while helping others achieve better health, and using that perspective to make a difference.

Dr. Daviss is chief medical officer for Optum Maryland and immediate past president of the Maryland-DC Society of Addiction Medicine, and former medical director and senior medical advisor at SAMHSA. He is coauthor of the 2011 book, Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work. Psychiatrists and other physicians may share their own experience with pivots they have made with Dr. Daviss via email ([email protected]) or Twitter (@HITshrink). The opinions expressed are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of his employer or organizations with which he is associated.

Psychiatrists practice a field of medicine that relies on one’s clinical perspective to interpret observable behaviors originating from the brains of others. In this manner, psychiatry and photography are similar. And digital technology has changed them both.

In photography, there are many technical aspects for one to master when framing and capturing a shot. The length of exposure. The amount of light needed. The speed of the film, which is its sensitivity to light. The aperture that controls how much light falls on the film. The movement of the subject across the film during the exposure. Despite the fact that physical film has mostly yielded to electronic sensors over the past couple decades, these basic aspects of photography remain.

But perspective is the critical ingredient. This is what brings the greatest impact to photography. The composition, or the subject of the photograph and how its elements – foreground, background, shapes, patterns, texture, shadow, motion, leading lines, and focal points – are arranged. The most powerful way to improve the composition – more powerful than fancy camera bells and whistles – is to move. One step to the left or right, one step forward or back. Stand on your toes, or crouch to your knees. Pivot this way or that. A simple change in perspective dramatically changes the nature and the energy of the captured image.

In fact, many physicians are changing what they actually do for a living. Pivoting their clinical perspectives. And applying those perspectives to other areas. The latest catalyst fueling these career pivots, these changes in perspectives, has been the incredible global impact of the tiny little coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2. The COVID-19 pandemic that began two years ago has disrupted the entire planet. The virus has caused us all to change our perspective, to see our world differently, and our place in it.

The virus has exposed defects in our health care delivery system. And physicians have necessarily reacted, injecting changes in what they do and how they do it. Many of these changes rely on digital technology, building upon the groundwork laid over the past couple of decades to convert our paper processes into electronic processes, and our manual work flows into digital work flows. This groundwork is no small thing, as it relies on conventions and standards, such as DICOM, LOINC, AES, CDA, UMLS, FHIR, ICD, NDC, USCDI, and SNOMED-CT. Establishing, maintaining, and evolving health care standards requires organized groups of people to come together to share their diverse perspectives. This is but one of many places where physicians are using their unique clinical perspective to share what they see with others.

This column will focus on these professional pivots that physicians make when they take a step to the left or right to change their perspective and share their viewpoints in different settings with diverse groups of people. Some of these pivots are small, while others are career changing. But the theme that knits them together is about taking what one has learned while helping others achieve better health, and using that perspective to make a difference.

Dr. Daviss is chief medical officer for Optum Maryland and immediate past president of the Maryland-DC Society of Addiction Medicine, and former medical director and senior medical advisor at SAMHSA. He is coauthor of the 2011 book, Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work. Psychiatrists and other physicians may share their own experience with pivots they have made with Dr. Daviss via email ([email protected]) or Twitter (@HITshrink). The opinions expressed are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of his employer or organizations with which he is associated.

Screening for anxiety in young children

On April 12, 2022, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force released the draft of a recommendation statement titled Screening for Anxiety in Children and Adolescents. Based on their observation that 7.8% of children and adolescents have a current anxiety disorder and their analysis of the magnitude of the net benefit, the Task Force plans on recommending that children ages 8-18 years be screened for the condition. However, the group could not find evidence to support screening for children 7 years and younger.

Over more than 4 decades of general pediatric practice, it became obvious to me that anxiety was driving a high percentage of my office visits. Most often in young children it was parental anxiety that was prompting the phone call or office visit. In older childhood and adolescence it was patient anxiety that began to play a larger role.

Over the last 2 decades the level of anxiety in all age groups has seemed to increase. How large a role the events of Sept. 11, 2001, and other terrorist attacks were playing in this phenomenon is unclear to me. However, I suspect they were significant. More recently the pandemic and the failure of both political parties to forge a working arrangement have fueled even more anxiety in many demographic segments. It may be safe to say that everyone is anxious to one degree or another.

Broad-based anxiety in the general population and the incidence of anxiety disorders severe enough to disrupt a child’s life are certainly two different kettles of fish. However, the factors that have raised the level of anxiety across all age groups certainly hasn’t made things any easier for the child who has inherited or developed an anxiety disorder.

Glancing at the 600-page evidence synthesis that accompanies the task force’s report it is clear that they have taken their challenge seriously. However, I wonder whether looking at the 7-and-under age group with a different lens might have resulted in the inclusion of younger children in their recommendation.

I understand that to support their recommendations the U.S. Preventive Services Task Forces must rely on data from peer-reviewed studies that have looked at quantifiable outcomes. However, I suspect the task force would agree that its recommendations shouldn’t prevent the rest of us from using our own observations and intuition when deciding whether to selectively screen our younger patients for anxiety disorders.

Although it may not generate a measurable data point, providing the parents of a 5-year-old whose troubling behavior is in part the result of an anxiety disorder is invaluable. Do we need to screen all 5-year-olds? The task force says probably not given the current state of our knowledge and I agree. But, the fact that almost 8% of the pediatric population carries the diagnosis and my anecdotal observations suggest that as pediatricians we should be learning more about anxiety disorders and their wide variety of presentations. Then we should selectively screen more of our patients. In fact, I suspect we might help our patients and ourselves by questioning more parents about their own mental health histories even before we have any inkling that their child has a problem. While the degree to which anxiety disorders are inheritable and the exact mechanism is far from clear, I think this history might be a valuable piece of information to learn as early as the prenatal get-acquainted visit. A simple question to a new or expecting parent about what worries them most about becoming a parent would be a good opener. Your reassurance that you expect parents to be worried and welcome hearing about their concerns should be a step in building a strong foundation for a family-provider relationship.

Anxiety happens and unfortunately so do anxiety disorders. We need to be doing a better job of acknowledging and responding to these two realities.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

*This column was updated on 5/4/2022.

On April 12, 2022, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force released the draft of a recommendation statement titled Screening for Anxiety in Children and Adolescents. Based on their observation that 7.8% of children and adolescents have a current anxiety disorder and their analysis of the magnitude of the net benefit, the Task Force plans on recommending that children ages 8-18 years be screened for the condition. However, the group could not find evidence to support screening for children 7 years and younger.

Over more than 4 decades of general pediatric practice, it became obvious to me that anxiety was driving a high percentage of my office visits. Most often in young children it was parental anxiety that was prompting the phone call or office visit. In older childhood and adolescence it was patient anxiety that began to play a larger role.

Over the last 2 decades the level of anxiety in all age groups has seemed to increase. How large a role the events of Sept. 11, 2001, and other terrorist attacks were playing in this phenomenon is unclear to me. However, I suspect they were significant. More recently the pandemic and the failure of both political parties to forge a working arrangement have fueled even more anxiety in many demographic segments. It may be safe to say that everyone is anxious to one degree or another.

Broad-based anxiety in the general population and the incidence of anxiety disorders severe enough to disrupt a child’s life are certainly two different kettles of fish. However, the factors that have raised the level of anxiety across all age groups certainly hasn’t made things any easier for the child who has inherited or developed an anxiety disorder.

Glancing at the 600-page evidence synthesis that accompanies the task force’s report it is clear that they have taken their challenge seriously. However, I wonder whether looking at the 7-and-under age group with a different lens might have resulted in the inclusion of younger children in their recommendation.

I understand that to support their recommendations the U.S. Preventive Services Task Forces must rely on data from peer-reviewed studies that have looked at quantifiable outcomes. However, I suspect the task force would agree that its recommendations shouldn’t prevent the rest of us from using our own observations and intuition when deciding whether to selectively screen our younger patients for anxiety disorders.

Although it may not generate a measurable data point, providing the parents of a 5-year-old whose troubling behavior is in part the result of an anxiety disorder is invaluable. Do we need to screen all 5-year-olds? The task force says probably not given the current state of our knowledge and I agree. But, the fact that almost 8% of the pediatric population carries the diagnosis and my anecdotal observations suggest that as pediatricians we should be learning more about anxiety disorders and their wide variety of presentations. Then we should selectively screen more of our patients. In fact, I suspect we might help our patients and ourselves by questioning more parents about their own mental health histories even before we have any inkling that their child has a problem. While the degree to which anxiety disorders are inheritable and the exact mechanism is far from clear, I think this history might be a valuable piece of information to learn as early as the prenatal get-acquainted visit. A simple question to a new or expecting parent about what worries them most about becoming a parent would be a good opener. Your reassurance that you expect parents to be worried and welcome hearing about their concerns should be a step in building a strong foundation for a family-provider relationship.

Anxiety happens and unfortunately so do anxiety disorders. We need to be doing a better job of acknowledging and responding to these two realities.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

*This column was updated on 5/4/2022.

On April 12, 2022, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force released the draft of a recommendation statement titled Screening for Anxiety in Children and Adolescents. Based on their observation that 7.8% of children and adolescents have a current anxiety disorder and their analysis of the magnitude of the net benefit, the Task Force plans on recommending that children ages 8-18 years be screened for the condition. However, the group could not find evidence to support screening for children 7 years and younger.

Over more than 4 decades of general pediatric practice, it became obvious to me that anxiety was driving a high percentage of my office visits. Most often in young children it was parental anxiety that was prompting the phone call or office visit. In older childhood and adolescence it was patient anxiety that began to play a larger role.

Over the last 2 decades the level of anxiety in all age groups has seemed to increase. How large a role the events of Sept. 11, 2001, and other terrorist attacks were playing in this phenomenon is unclear to me. However, I suspect they were significant. More recently the pandemic and the failure of both political parties to forge a working arrangement have fueled even more anxiety in many demographic segments. It may be safe to say that everyone is anxious to one degree or another.

Broad-based anxiety in the general population and the incidence of anxiety disorders severe enough to disrupt a child’s life are certainly two different kettles of fish. However, the factors that have raised the level of anxiety across all age groups certainly hasn’t made things any easier for the child who has inherited or developed an anxiety disorder.

Glancing at the 600-page evidence synthesis that accompanies the task force’s report it is clear that they have taken their challenge seriously. However, I wonder whether looking at the 7-and-under age group with a different lens might have resulted in the inclusion of younger children in their recommendation.

I understand that to support their recommendations the U.S. Preventive Services Task Forces must rely on data from peer-reviewed studies that have looked at quantifiable outcomes. However, I suspect the task force would agree that its recommendations shouldn’t prevent the rest of us from using our own observations and intuition when deciding whether to selectively screen our younger patients for anxiety disorders.

Although it may not generate a measurable data point, providing the parents of a 5-year-old whose troubling behavior is in part the result of an anxiety disorder is invaluable. Do we need to screen all 5-year-olds? The task force says probably not given the current state of our knowledge and I agree. But, the fact that almost 8% of the pediatric population carries the diagnosis and my anecdotal observations suggest that as pediatricians we should be learning more about anxiety disorders and their wide variety of presentations. Then we should selectively screen more of our patients. In fact, I suspect we might help our patients and ourselves by questioning more parents about their own mental health histories even before we have any inkling that their child has a problem. While the degree to which anxiety disorders are inheritable and the exact mechanism is far from clear, I think this history might be a valuable piece of information to learn as early as the prenatal get-acquainted visit. A simple question to a new or expecting parent about what worries them most about becoming a parent would be a good opener. Your reassurance that you expect parents to be worried and welcome hearing about their concerns should be a step in building a strong foundation for a family-provider relationship.

Anxiety happens and unfortunately so do anxiety disorders. We need to be doing a better job of acknowledging and responding to these two realities.