User login

Breast cancer: PTV of 9 susceptibility genes could guide gene panel testing and risk prediction

Key clinical point: Protein-truncating variants (PTV) of 9 breast cancer (BC) risk genes showed substantial differences in tumor pathology and were generally associated with triple-negative (TN) or high-grade disease.

Major finding: BRCA1 showed the highest association for TN disease (odds ratio [OR] 55.32; 95% CI 40.51-75.55) and ATM variants for the hormone receptor-positive (HR+) erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2-negative (ERBB2−) high-grade subtype (OR 4.99; 95% CI 3.68-6.76). RAD51C (OR 6.19; 95% CI 3.17-12.12), RAD51D (OR 6.19; 95% CI 2.99-12.79), and BARD1 (OR 10.05; 95% CI 5.27-19.19) were most strongly associated with TN disease. PALB2 PTVs showed higher ORs for HR+ERBB2− high-grade subtype (OR 9.43; 95% CI 6.24- 14.25) and TN disease (OR 8.05; 95% CI 5.17-12.53).

Study details: This was a case-control analysis of the BRIDGES study including 42,680 patients with BC who were matched with 46,387 healthy controls.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, Wellcome Trust, and several other sources. The authors declared receiving grants, honorariums, personal fees, or awards from several sources.

Source: Breast Cancer Association Consortium. JAMA Oncol. 2022 (Jan 27). Doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.6744.

Key clinical point: Protein-truncating variants (PTV) of 9 breast cancer (BC) risk genes showed substantial differences in tumor pathology and were generally associated with triple-negative (TN) or high-grade disease.

Major finding: BRCA1 showed the highest association for TN disease (odds ratio [OR] 55.32; 95% CI 40.51-75.55) and ATM variants for the hormone receptor-positive (HR+) erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2-negative (ERBB2−) high-grade subtype (OR 4.99; 95% CI 3.68-6.76). RAD51C (OR 6.19; 95% CI 3.17-12.12), RAD51D (OR 6.19; 95% CI 2.99-12.79), and BARD1 (OR 10.05; 95% CI 5.27-19.19) were most strongly associated with TN disease. PALB2 PTVs showed higher ORs for HR+ERBB2− high-grade subtype (OR 9.43; 95% CI 6.24- 14.25) and TN disease (OR 8.05; 95% CI 5.17-12.53).

Study details: This was a case-control analysis of the BRIDGES study including 42,680 patients with BC who were matched with 46,387 healthy controls.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, Wellcome Trust, and several other sources. The authors declared receiving grants, honorariums, personal fees, or awards from several sources.

Source: Breast Cancer Association Consortium. JAMA Oncol. 2022 (Jan 27). Doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.6744.

Key clinical point: Protein-truncating variants (PTV) of 9 breast cancer (BC) risk genes showed substantial differences in tumor pathology and were generally associated with triple-negative (TN) or high-grade disease.

Major finding: BRCA1 showed the highest association for TN disease (odds ratio [OR] 55.32; 95% CI 40.51-75.55) and ATM variants for the hormone receptor-positive (HR+) erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2-negative (ERBB2−) high-grade subtype (OR 4.99; 95% CI 3.68-6.76). RAD51C (OR 6.19; 95% CI 3.17-12.12), RAD51D (OR 6.19; 95% CI 2.99-12.79), and BARD1 (OR 10.05; 95% CI 5.27-19.19) were most strongly associated with TN disease. PALB2 PTVs showed higher ORs for HR+ERBB2− high-grade subtype (OR 9.43; 95% CI 6.24- 14.25) and TN disease (OR 8.05; 95% CI 5.17-12.53).

Study details: This was a case-control analysis of the BRIDGES study including 42,680 patients with BC who were matched with 46,387 healthy controls.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, Wellcome Trust, and several other sources. The authors declared receiving grants, honorariums, personal fees, or awards from several sources.

Source: Breast Cancer Association Consortium. JAMA Oncol. 2022 (Jan 27). Doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.6744.

Adding capecitabine to adjuvant chemotherapy improves RFS in non-BRCA1-like early TNBC

Key clinical point: A regimen consisting of docetaxel and capecitabine (TX) followed by cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and capecitabine (CEX) vs. only docetaxel followed by cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and fluorouracil (T-CEF) prolonged recurrence-free survival (RFS) in patients with non- BRCA1-like early triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC).

Major finding: Overall, patients assigned to TX-CEX vs. T-CEF arms had higher RFS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.39; P = .01), with the capecitabine-containing chemotherapy being significantly more effective than conventional chemotherapy in patients with non-BRCA1-like tumor (HR 0.23; P < .01) but not in patients with BRCA1-like tumor (HR 0.66; P = .42).

Study details: Findings are from the open-label, phase 3 FinXX study including 202 patients with early TNBC who were randomly assigned to TX-CEX or T-CEF arms. BRCA1-like status was obtained for 129 patients.

Disclosures: This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society. The authors declared serving as board members and employees or receiving fees, grants, nonfinancial, and research support from several sources.

Source: de Boo LW et al. Br J Cancer. 2022 (Feb 5). Doi: 10.1038/s41416-022-01711-y.

Key clinical point: A regimen consisting of docetaxel and capecitabine (TX) followed by cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and capecitabine (CEX) vs. only docetaxel followed by cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and fluorouracil (T-CEF) prolonged recurrence-free survival (RFS) in patients with non- BRCA1-like early triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC).

Major finding: Overall, patients assigned to TX-CEX vs. T-CEF arms had higher RFS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.39; P = .01), with the capecitabine-containing chemotherapy being significantly more effective than conventional chemotherapy in patients with non-BRCA1-like tumor (HR 0.23; P < .01) but not in patients with BRCA1-like tumor (HR 0.66; P = .42).

Study details: Findings are from the open-label, phase 3 FinXX study including 202 patients with early TNBC who were randomly assigned to TX-CEX or T-CEF arms. BRCA1-like status was obtained for 129 patients.

Disclosures: This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society. The authors declared serving as board members and employees or receiving fees, grants, nonfinancial, and research support from several sources.

Source: de Boo LW et al. Br J Cancer. 2022 (Feb 5). Doi: 10.1038/s41416-022-01711-y.

Key clinical point: A regimen consisting of docetaxel and capecitabine (TX) followed by cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and capecitabine (CEX) vs. only docetaxel followed by cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and fluorouracil (T-CEF) prolonged recurrence-free survival (RFS) in patients with non- BRCA1-like early triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC).

Major finding: Overall, patients assigned to TX-CEX vs. T-CEF arms had higher RFS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.39; P = .01), with the capecitabine-containing chemotherapy being significantly more effective than conventional chemotherapy in patients with non-BRCA1-like tumor (HR 0.23; P < .01) but not in patients with BRCA1-like tumor (HR 0.66; P = .42).

Study details: Findings are from the open-label, phase 3 FinXX study including 202 patients with early TNBC who were randomly assigned to TX-CEX or T-CEF arms. BRCA1-like status was obtained for 129 patients.

Disclosures: This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society. The authors declared serving as board members and employees or receiving fees, grants, nonfinancial, and research support from several sources.

Source: de Boo LW et al. Br J Cancer. 2022 (Feb 5). Doi: 10.1038/s41416-022-01711-y.

TNBC: Adding carboplatin to neoadjuvant chemotherapy provides long-term EFS benefit

Key clinical point: Adding carboplatin to neoadjuvant paclitaxel followed by doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide improved long-term event-free survival (EFS) along with a manageable safety profile in patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC).

Major finding: Patients receiving carboplatin+veliparib+paclitaxel vs. paclitaxel showed significant improvements in EFS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.63; P = .02), whereas EFS was not significntly different among patients assigned to carboplatin+veliparib+paclitaxel vs. carboplatin+paclitaxel (HR 1.12; P = .62). Rates of treatment-emergent and post-treatment-emergent adverse events and secondary malignancies were similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are based on the 4.5-year follow-up data from the phase 3 BrighTNess trial including 634 patients with stage II-III TNBC who were randomly assigned to receive carboplatin+veliparib, carboplatin+veliparib placebo, or carboplatin placebo+veliparib placebo, all in combination with paclitaxel.

Disclosures: This study was supported by AbbVie. Some authors declared serving on the advisory board and speaker’s bureau or receiving travel funds, writing support, honoraria, research funds, and consulting fees from several sources including AbbVie. D Maag declared being an employee or stockholder of AbbVie.

Source: Geyer CE Jr et al. Ann Oncol. 2022 (Jan 27). Doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.01.009.

Key clinical point: Adding carboplatin to neoadjuvant paclitaxel followed by doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide improved long-term event-free survival (EFS) along with a manageable safety profile in patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC).

Major finding: Patients receiving carboplatin+veliparib+paclitaxel vs. paclitaxel showed significant improvements in EFS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.63; P = .02), whereas EFS was not significntly different among patients assigned to carboplatin+veliparib+paclitaxel vs. carboplatin+paclitaxel (HR 1.12; P = .62). Rates of treatment-emergent and post-treatment-emergent adverse events and secondary malignancies were similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are based on the 4.5-year follow-up data from the phase 3 BrighTNess trial including 634 patients with stage II-III TNBC who were randomly assigned to receive carboplatin+veliparib, carboplatin+veliparib placebo, or carboplatin placebo+veliparib placebo, all in combination with paclitaxel.

Disclosures: This study was supported by AbbVie. Some authors declared serving on the advisory board and speaker’s bureau or receiving travel funds, writing support, honoraria, research funds, and consulting fees from several sources including AbbVie. D Maag declared being an employee or stockholder of AbbVie.

Source: Geyer CE Jr et al. Ann Oncol. 2022 (Jan 27). Doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.01.009.

Key clinical point: Adding carboplatin to neoadjuvant paclitaxel followed by doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide improved long-term event-free survival (EFS) along with a manageable safety profile in patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC).

Major finding: Patients receiving carboplatin+veliparib+paclitaxel vs. paclitaxel showed significant improvements in EFS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.63; P = .02), whereas EFS was not significntly different among patients assigned to carboplatin+veliparib+paclitaxel vs. carboplatin+paclitaxel (HR 1.12; P = .62). Rates of treatment-emergent and post-treatment-emergent adverse events and secondary malignancies were similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are based on the 4.5-year follow-up data from the phase 3 BrighTNess trial including 634 patients with stage II-III TNBC who were randomly assigned to receive carboplatin+veliparib, carboplatin+veliparib placebo, or carboplatin placebo+veliparib placebo, all in combination with paclitaxel.

Disclosures: This study was supported by AbbVie. Some authors declared serving on the advisory board and speaker’s bureau or receiving travel funds, writing support, honoraria, research funds, and consulting fees from several sources including AbbVie. D Maag declared being an employee or stockholder of AbbVie.

Source: Geyer CE Jr et al. Ann Oncol. 2022 (Jan 27). Doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.01.009.

Pyrotinib+capecitabine shows promise for HER2+ metastatic breast cancer and brain metastases

Key clinical point: Pyrotinib+capecitabine showed intracranial objective response and was well tolerated in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+) metastatic breast cancer (BC) and brain metastases in the PERMEATE phase 2 study.

Major finding: The intracranial objective response rate was 74.6% (95% CI 61.6%-85.0%) in radiotherapy-naive patients and 42.1% (95% CI 20.3%-66.5%) in patients with progressive disease after whole-brain radiotherapy. Common grade 3 treatment-emergent adverse events were diarrhea and decreased white blood cell count. No treatment-related deaths were reported.

Study details: Findings are from the single-arm, phase 2 PERMEATE study including 78 patients with HER2+ BC and brain metastases who were either radiotherapy-naive or had progressive disease after radiotherapy. Patients received 400 mg pyrotinib once daily and 1000 mg/m2 capecitabine twice daily for 14 days, followed by 7 days off during each 21-day cycle.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Cancer Centre Climbing Foundation Key Project of China and Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Yan M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2022 (Jan 24). Doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00716-6.

Key clinical point: Pyrotinib+capecitabine showed intracranial objective response and was well tolerated in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+) metastatic breast cancer (BC) and brain metastases in the PERMEATE phase 2 study.

Major finding: The intracranial objective response rate was 74.6% (95% CI 61.6%-85.0%) in radiotherapy-naive patients and 42.1% (95% CI 20.3%-66.5%) in patients with progressive disease after whole-brain radiotherapy. Common grade 3 treatment-emergent adverse events were diarrhea and decreased white blood cell count. No treatment-related deaths were reported.

Study details: Findings are from the single-arm, phase 2 PERMEATE study including 78 patients with HER2+ BC and brain metastases who were either radiotherapy-naive or had progressive disease after radiotherapy. Patients received 400 mg pyrotinib once daily and 1000 mg/m2 capecitabine twice daily for 14 days, followed by 7 days off during each 21-day cycle.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Cancer Centre Climbing Foundation Key Project of China and Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Yan M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2022 (Jan 24). Doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00716-6.

Key clinical point: Pyrotinib+capecitabine showed intracranial objective response and was well tolerated in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+) metastatic breast cancer (BC) and brain metastases in the PERMEATE phase 2 study.

Major finding: The intracranial objective response rate was 74.6% (95% CI 61.6%-85.0%) in radiotherapy-naive patients and 42.1% (95% CI 20.3%-66.5%) in patients with progressive disease after whole-brain radiotherapy. Common grade 3 treatment-emergent adverse events were diarrhea and decreased white blood cell count. No treatment-related deaths were reported.

Study details: Findings are from the single-arm, phase 2 PERMEATE study including 78 patients with HER2+ BC and brain metastases who were either radiotherapy-naive or had progressive disease after radiotherapy. Patients received 400 mg pyrotinib once daily and 1000 mg/m2 capecitabine twice daily for 14 days, followed by 7 days off during each 21-day cycle.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Cancer Centre Climbing Foundation Key Project of China and Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Yan M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2022 (Jan 24). Doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00716-6.

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #15 for the ObGyn

What is the most appropriate treatment for a pregnant woman who is moderately to severely ill with COVID-19 infection?

Continue to the answer...

Moderately to severely ill pregnant women with COVID-19 infection should be hospitalized and treated with supplementary oxygen, remdesivir, and dexamethasone. Other possible therapies include inhaled nitric oxide, baricitinib (a Janus kinase inhibitor), and tocilizumab (an anti-interleukin 6 receptor antibody). (RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693-704. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al; ACTT-2 Study Group. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:795-807. Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ, et al. Severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383;2451-2460.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

What is the most appropriate treatment for a pregnant woman who is moderately to severely ill with COVID-19 infection?

Continue to the answer...

Moderately to severely ill pregnant women with COVID-19 infection should be hospitalized and treated with supplementary oxygen, remdesivir, and dexamethasone. Other possible therapies include inhaled nitric oxide, baricitinib (a Janus kinase inhibitor), and tocilizumab (an anti-interleukin 6 receptor antibody). (RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693-704. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al; ACTT-2 Study Group. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:795-807. Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ, et al. Severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383;2451-2460.)

What is the most appropriate treatment for a pregnant woman who is moderately to severely ill with COVID-19 infection?

Continue to the answer...

Moderately to severely ill pregnant women with COVID-19 infection should be hospitalized and treated with supplementary oxygen, remdesivir, and dexamethasone. Other possible therapies include inhaled nitric oxide, baricitinib (a Janus kinase inhibitor), and tocilizumab (an anti-interleukin 6 receptor antibody). (RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693-704. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al; ACTT-2 Study Group. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:795-807. Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ, et al. Severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383;2451-2460.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Slow-Growing Pink Nodule in an Active-Duty Service Member

The Diagnosis: Leishmaniasis

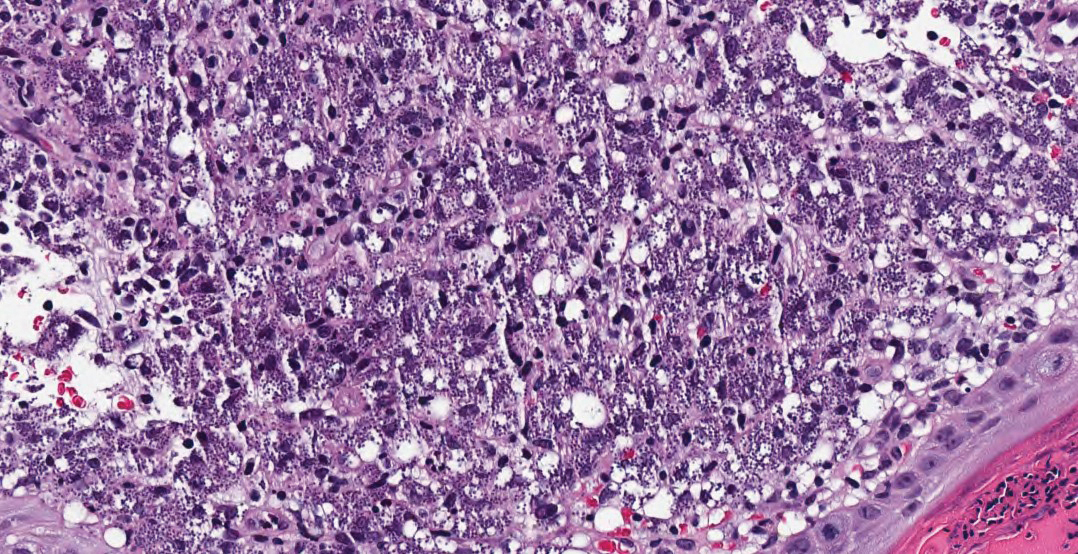

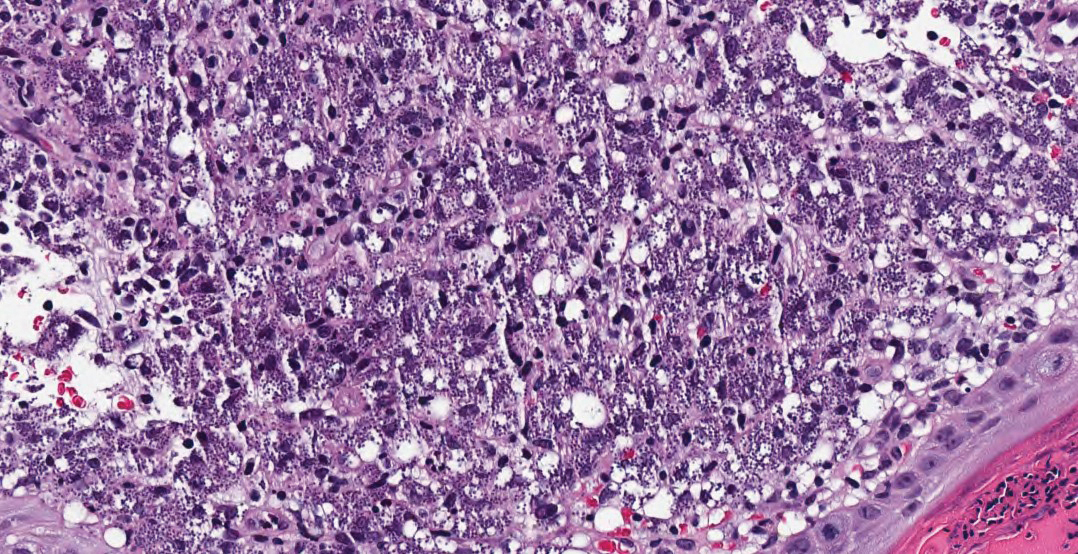

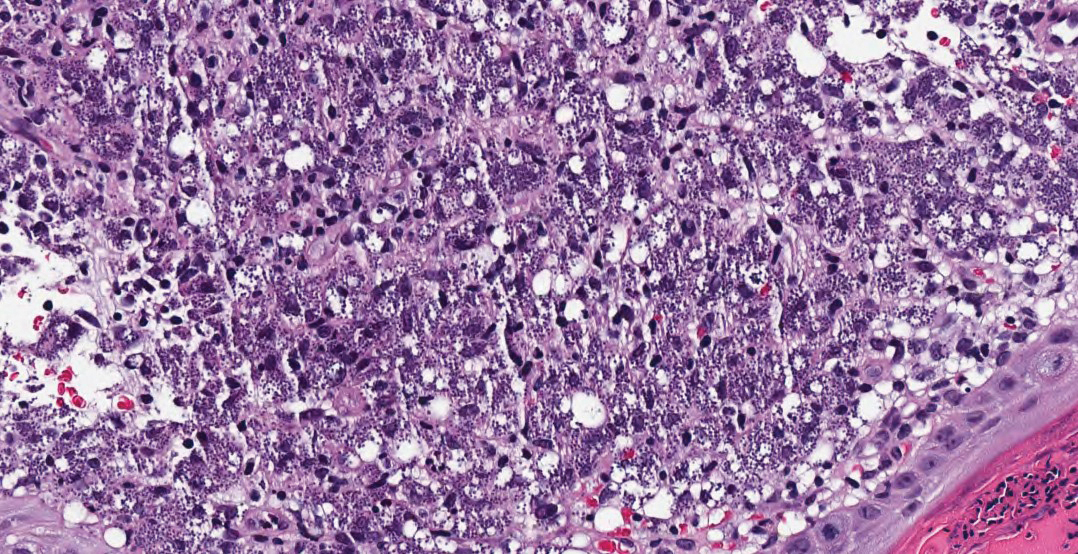

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the tissue specimen revealed a dense histiocytic infiltrate with scattered lymphocytes and neutrophils. There were round to oval basophilic structures within the macrophages consistent with amastigotes. Giemsa staining was not necessary to visualize the organisms. The infiltrate abutted the overlying epidermis, which was acanthotic with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. There were collections of neutrophils, parakeratosis, and a serum crust overlying the epidermis (Figure). Clinical and histologic findings, as well as travel history, led to a diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL).

Leishmaniases is a group of diseases caused by a parasitic infection with flagellated protozoa of the genus Leishmania. There are more than 20 different Leishmania species that are pathogenic to humans, all presenting with cutaneous findings. The presentation depends on the inoculating species and the host cellular immune response and includes cutaneous, mucosal, and visceral involvement. The disease is transmitted via the bite of an infected bloodsucking female sand fly.1 There are approximately 30 different species of sand flies that are proven to be vectors of the disease, with up to 40 more suspected of involvement in transmission, predominantly from the genera Phlebotomus (Old World) and Lutzomyia (New World).1,2 There are an estimated 1 to 2 million new cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis diagnosed annually in 70 endemic countries of the tropics, subtropics, and southern Europe.1,3,4

The differential diagnosis included cutaneous tuberculosis, which can have a similar progression and clinical appearance. Cutaneous tuberculosis starts as firm, reddish-brown, painless papules that slowly enlarge and ulcerate.5 It may be further differentiated on histopathology by the presence of tuberculoid granulomas, caseating necrosis, and acid-fast bacilli, which are easily detected in early lesions but are less prevalent after the granuloma develops.6 Sporotrichosis presents as a nodule, which may or may not ulcerate, on the extremities. However, the classic morphology is a sporotrichoid pattern, which describes the initial lesion plus subcutaneous nodular spread along the lymphatics.7 On histology, sporotrichosis has a characteristic “sporotrichoid asteroid” comprised of the yeast form surrounded by eosinophilic hyaline material in raylike processes that are found in the center of suppurative granulomas or foci.8

Atypical mycobacteria, principally Mycobacterium marinum (swimming pool granuloma) and Mycobacterium ulcerans (Buruli ulcer), are capable of causing cutaneous infections. They may be differentiated histologically by a neutrophilic infiltrate of poorly formed granulomas without caseation and extensive coagulative necrosis with little cellular infiltrate, respectively.6 Histoplasma capsulatum also infects histiocytes and may appear similar in size and shape; however, histoplasmosis is surrounded by a pseudocapsule and evenly spaced.8

Conversely, the histology of leishmaniasis lacks a pseudocapsule. The amastigotes may form the classic marquee sign by lining the periphery of the macrophage or they can be randomly spaced. Classically, the epidermis shows hyperkeratosis and acanthosis. Sometimes atrophy, ulceration, or intraepidermal abscesses also can be observed. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia can be seen in some long-standing lesions.1,4 Many of these findings were observed on hematoxylin and eosin staining from a punch biopsy obtained from the center of the lesion in our patient. For further delineation, a speciation kit was obtained from Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland). A second punch biopsy was obtained from the lesion edge, sectioned into 4 individual pieces, and placed in Schneider tissue culture medium. It was sent for tissue culture, polymerase chain reaction, and histology. Polymerase chain reaction analysis was positive for Leishmania, which was further identified as Leishmania tropica by tissue culture.

Leishmania tropica (Old World CL) commonly causes CL and is endemic to Central Asia, the Middle East, parts of North Africa, and Southeast Asia. Old and New World CL start as a small erythematous papule after a bite from an infected female sand fly. The papule develops into a nodule over weeks to months. The lesion may ulcerate and typically heals leaving an atrophic scar in months to years.1 Speciation of CL is important to guide therapy.

Leishmania mexicana, a New World species that commonly causes CL, classically is found in Central and South America, but there also have been documented cases in Texas. A 2008 case series identified 9 cases in northern Texas in residents without a travel history to endemic locations.9 Similarly, a cross-sectional study identified 41 locally endemic cases of CL over a 10-year period (2007-2017) in Texas; 22 of these cases had speciation by polymerase chain reaction, and all cases were attributed to L mexicana.10

In the United States, CL classically has been associated with travelers and military personnel returning from the Middle East; however, a growing body of literature suggests that it may be endemic to Texas, where it is now a reportable disease. Physicians should have an increased awareness of this entity and a high index of suspicion when treating patients with nonhealing cutaneous lesions.

- Bravo F. Protozoa and worms. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. WB Saunders Co; 2018:1470-1502.

- Killick-Kendrick R. The biology and control of phlebotomine sandflies. Clin Dermatol. 1999;17:279-289.

- Reithinger R, Dujardin JC, Louzir H, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:581-596.

- Patterson J. Protozoal infections. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:787-795.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Ribeiro de Castro MC. Mycobacterial infections. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. WB Saunders Co; 2018:1296-1318.

- Patterson J. Bacterial and rickettsial infections. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:673-709.

- Elewski B, Hughey L, Hunt K, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. WB Saunders Co; 2018:1329-1363.

- Patterson J. Mycoses and algal infections. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:721-755.

- Wright NA, Davis LE, Aftergut KS, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Texas: a northern spread of endemic areas [published online February 4, 2008]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:650-652. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2007.11.008.

- McIlwee BE, Weis SE, Hosler GA. Incidence of endemic human cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1032-1039. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2133

The Diagnosis: Leishmaniasis

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the tissue specimen revealed a dense histiocytic infiltrate with scattered lymphocytes and neutrophils. There were round to oval basophilic structures within the macrophages consistent with amastigotes. Giemsa staining was not necessary to visualize the organisms. The infiltrate abutted the overlying epidermis, which was acanthotic with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. There were collections of neutrophils, parakeratosis, and a serum crust overlying the epidermis (Figure). Clinical and histologic findings, as well as travel history, led to a diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL).

Leishmaniases is a group of diseases caused by a parasitic infection with flagellated protozoa of the genus Leishmania. There are more than 20 different Leishmania species that are pathogenic to humans, all presenting with cutaneous findings. The presentation depends on the inoculating species and the host cellular immune response and includes cutaneous, mucosal, and visceral involvement. The disease is transmitted via the bite of an infected bloodsucking female sand fly.1 There are approximately 30 different species of sand flies that are proven to be vectors of the disease, with up to 40 more suspected of involvement in transmission, predominantly from the genera Phlebotomus (Old World) and Lutzomyia (New World).1,2 There are an estimated 1 to 2 million new cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis diagnosed annually in 70 endemic countries of the tropics, subtropics, and southern Europe.1,3,4

The differential diagnosis included cutaneous tuberculosis, which can have a similar progression and clinical appearance. Cutaneous tuberculosis starts as firm, reddish-brown, painless papules that slowly enlarge and ulcerate.5 It may be further differentiated on histopathology by the presence of tuberculoid granulomas, caseating necrosis, and acid-fast bacilli, which are easily detected in early lesions but are less prevalent after the granuloma develops.6 Sporotrichosis presents as a nodule, which may or may not ulcerate, on the extremities. However, the classic morphology is a sporotrichoid pattern, which describes the initial lesion plus subcutaneous nodular spread along the lymphatics.7 On histology, sporotrichosis has a characteristic “sporotrichoid asteroid” comprised of the yeast form surrounded by eosinophilic hyaline material in raylike processes that are found in the center of suppurative granulomas or foci.8

Atypical mycobacteria, principally Mycobacterium marinum (swimming pool granuloma) and Mycobacterium ulcerans (Buruli ulcer), are capable of causing cutaneous infections. They may be differentiated histologically by a neutrophilic infiltrate of poorly formed granulomas without caseation and extensive coagulative necrosis with little cellular infiltrate, respectively.6 Histoplasma capsulatum also infects histiocytes and may appear similar in size and shape; however, histoplasmosis is surrounded by a pseudocapsule and evenly spaced.8

Conversely, the histology of leishmaniasis lacks a pseudocapsule. The amastigotes may form the classic marquee sign by lining the periphery of the macrophage or they can be randomly spaced. Classically, the epidermis shows hyperkeratosis and acanthosis. Sometimes atrophy, ulceration, or intraepidermal abscesses also can be observed. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia can be seen in some long-standing lesions.1,4 Many of these findings were observed on hematoxylin and eosin staining from a punch biopsy obtained from the center of the lesion in our patient. For further delineation, a speciation kit was obtained from Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland). A second punch biopsy was obtained from the lesion edge, sectioned into 4 individual pieces, and placed in Schneider tissue culture medium. It was sent for tissue culture, polymerase chain reaction, and histology. Polymerase chain reaction analysis was positive for Leishmania, which was further identified as Leishmania tropica by tissue culture.

Leishmania tropica (Old World CL) commonly causes CL and is endemic to Central Asia, the Middle East, parts of North Africa, and Southeast Asia. Old and New World CL start as a small erythematous papule after a bite from an infected female sand fly. The papule develops into a nodule over weeks to months. The lesion may ulcerate and typically heals leaving an atrophic scar in months to years.1 Speciation of CL is important to guide therapy.

Leishmania mexicana, a New World species that commonly causes CL, classically is found in Central and South America, but there also have been documented cases in Texas. A 2008 case series identified 9 cases in northern Texas in residents without a travel history to endemic locations.9 Similarly, a cross-sectional study identified 41 locally endemic cases of CL over a 10-year period (2007-2017) in Texas; 22 of these cases had speciation by polymerase chain reaction, and all cases were attributed to L mexicana.10

In the United States, CL classically has been associated with travelers and military personnel returning from the Middle East; however, a growing body of literature suggests that it may be endemic to Texas, where it is now a reportable disease. Physicians should have an increased awareness of this entity and a high index of suspicion when treating patients with nonhealing cutaneous lesions.

The Diagnosis: Leishmaniasis

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the tissue specimen revealed a dense histiocytic infiltrate with scattered lymphocytes and neutrophils. There were round to oval basophilic structures within the macrophages consistent with amastigotes. Giemsa staining was not necessary to visualize the organisms. The infiltrate abutted the overlying epidermis, which was acanthotic with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. There were collections of neutrophils, parakeratosis, and a serum crust overlying the epidermis (Figure). Clinical and histologic findings, as well as travel history, led to a diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL).

Leishmaniases is a group of diseases caused by a parasitic infection with flagellated protozoa of the genus Leishmania. There are more than 20 different Leishmania species that are pathogenic to humans, all presenting with cutaneous findings. The presentation depends on the inoculating species and the host cellular immune response and includes cutaneous, mucosal, and visceral involvement. The disease is transmitted via the bite of an infected bloodsucking female sand fly.1 There are approximately 30 different species of sand flies that are proven to be vectors of the disease, with up to 40 more suspected of involvement in transmission, predominantly from the genera Phlebotomus (Old World) and Lutzomyia (New World).1,2 There are an estimated 1 to 2 million new cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis diagnosed annually in 70 endemic countries of the tropics, subtropics, and southern Europe.1,3,4

The differential diagnosis included cutaneous tuberculosis, which can have a similar progression and clinical appearance. Cutaneous tuberculosis starts as firm, reddish-brown, painless papules that slowly enlarge and ulcerate.5 It may be further differentiated on histopathology by the presence of tuberculoid granulomas, caseating necrosis, and acid-fast bacilli, which are easily detected in early lesions but are less prevalent after the granuloma develops.6 Sporotrichosis presents as a nodule, which may or may not ulcerate, on the extremities. However, the classic morphology is a sporotrichoid pattern, which describes the initial lesion plus subcutaneous nodular spread along the lymphatics.7 On histology, sporotrichosis has a characteristic “sporotrichoid asteroid” comprised of the yeast form surrounded by eosinophilic hyaline material in raylike processes that are found in the center of suppurative granulomas or foci.8

Atypical mycobacteria, principally Mycobacterium marinum (swimming pool granuloma) and Mycobacterium ulcerans (Buruli ulcer), are capable of causing cutaneous infections. They may be differentiated histologically by a neutrophilic infiltrate of poorly formed granulomas without caseation and extensive coagulative necrosis with little cellular infiltrate, respectively.6 Histoplasma capsulatum also infects histiocytes and may appear similar in size and shape; however, histoplasmosis is surrounded by a pseudocapsule and evenly spaced.8

Conversely, the histology of leishmaniasis lacks a pseudocapsule. The amastigotes may form the classic marquee sign by lining the periphery of the macrophage or they can be randomly spaced. Classically, the epidermis shows hyperkeratosis and acanthosis. Sometimes atrophy, ulceration, or intraepidermal abscesses also can be observed. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia can be seen in some long-standing lesions.1,4 Many of these findings were observed on hematoxylin and eosin staining from a punch biopsy obtained from the center of the lesion in our patient. For further delineation, a speciation kit was obtained from Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland). A second punch biopsy was obtained from the lesion edge, sectioned into 4 individual pieces, and placed in Schneider tissue culture medium. It was sent for tissue culture, polymerase chain reaction, and histology. Polymerase chain reaction analysis was positive for Leishmania, which was further identified as Leishmania tropica by tissue culture.

Leishmania tropica (Old World CL) commonly causes CL and is endemic to Central Asia, the Middle East, parts of North Africa, and Southeast Asia. Old and New World CL start as a small erythematous papule after a bite from an infected female sand fly. The papule develops into a nodule over weeks to months. The lesion may ulcerate and typically heals leaving an atrophic scar in months to years.1 Speciation of CL is important to guide therapy.

Leishmania mexicana, a New World species that commonly causes CL, classically is found in Central and South America, but there also have been documented cases in Texas. A 2008 case series identified 9 cases in northern Texas in residents without a travel history to endemic locations.9 Similarly, a cross-sectional study identified 41 locally endemic cases of CL over a 10-year period (2007-2017) in Texas; 22 of these cases had speciation by polymerase chain reaction, and all cases were attributed to L mexicana.10

In the United States, CL classically has been associated with travelers and military personnel returning from the Middle East; however, a growing body of literature suggests that it may be endemic to Texas, where it is now a reportable disease. Physicians should have an increased awareness of this entity and a high index of suspicion when treating patients with nonhealing cutaneous lesions.

- Bravo F. Protozoa and worms. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. WB Saunders Co; 2018:1470-1502.

- Killick-Kendrick R. The biology and control of phlebotomine sandflies. Clin Dermatol. 1999;17:279-289.

- Reithinger R, Dujardin JC, Louzir H, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:581-596.

- Patterson J. Protozoal infections. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:787-795.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Ribeiro de Castro MC. Mycobacterial infections. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. WB Saunders Co; 2018:1296-1318.

- Patterson J. Bacterial and rickettsial infections. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:673-709.

- Elewski B, Hughey L, Hunt K, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. WB Saunders Co; 2018:1329-1363.

- Patterson J. Mycoses and algal infections. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:721-755.

- Wright NA, Davis LE, Aftergut KS, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Texas: a northern spread of endemic areas [published online February 4, 2008]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:650-652. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2007.11.008.

- McIlwee BE, Weis SE, Hosler GA. Incidence of endemic human cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1032-1039. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2133

- Bravo F. Protozoa and worms. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. WB Saunders Co; 2018:1470-1502.

- Killick-Kendrick R. The biology and control of phlebotomine sandflies. Clin Dermatol. 1999;17:279-289.

- Reithinger R, Dujardin JC, Louzir H, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:581-596.

- Patterson J. Protozoal infections. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:787-795.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Ribeiro de Castro MC. Mycobacterial infections. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. WB Saunders Co; 2018:1296-1318.

- Patterson J. Bacterial and rickettsial infections. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:673-709.

- Elewski B, Hughey L, Hunt K, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. WB Saunders Co; 2018:1329-1363.

- Patterson J. Mycoses and algal infections. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:721-755.

- Wright NA, Davis LE, Aftergut KS, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Texas: a northern spread of endemic areas [published online February 4, 2008]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:650-652. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2007.11.008.

- McIlwee BE, Weis SE, Hosler GA. Incidence of endemic human cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1032-1039. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2133

A 36-year-old active-duty male service member with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic nodule on the right forearm that he initially noticed approximately 1 year prior while deployed in Syria and thought that it was a mosquito bite; it continued to enlarge slowly since that time. He attempted self-extraction but was only able to express a small amount of clear fluid. No other therapies had been used. He denied any other symptoms on a review of systems and was not taking any medications. Physical examination revealed a 1.5-cm, erythematous, nonulcerated, pink nodule on the right distal volar forearm without other cutaneous findings. A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed.

Right arm rash

Common skin reactions to treatment with topical 5-FU for actinic keratosis include erythema, ulceration, and burning. In this case, however, the skin disruption opened the door to secondary impetigo.

Secondary skin infections are a known risk of treatment with topical 5-FU. The agent inhibits thymidylate synthetase, an enzyme involved in the synthesis and repair of DNA. The inhibition of this enzyme can lead to skin disruption with erosion, desquamation, and the risk of superimposed skin infections, as was seen with this patient.1

Impetigo is a common skin infection affecting the superficial layers of the epidermis and is most commonly caused by gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.2 Secondary impetigo, also known as impetiginization, is an infection of previously disrupted skin due to eczema, trauma, insect bites, and other conditions. This contrasts with primary impetigo, which results from a direct bacterial invasion of intact healthy skin. While impetigo predominantly affects children between the ages of 2 and 5 years, people of any age can be affected.2 Impetigo characteristically manifests with painful erosions, classically covered by honey-colored crusts. Thin-walled vesicles often appear and subsequently rupture.

Treatment options for impetigo include both topical and systemic antibiotics. Topical therapy is preferred for patients with limited skin involvement, while systemic therapy is indicated for patients with numerous lesions. Mupirocin and retapamulin are first-line topical treatments. Systemic antibiotic therapy should provide coverage for both S. aureus and streptococcal infections; cephalexin and dicloxacillin are preferred. Doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or clindamycin can be used if methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is suspected.3

This patient was advised to try warm soaks (to reduce the crusting) and to follow that with the application of white petrolatum bid. The patient was also prescribed doxycycline 100 mg orally bid for 10 days. At the 1-month follow-up, there was some residual erythema, but the impetigo and crusting had resolved. The actinic keratoses had resolved, as well.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Tess Pei Lemon, BA, University of New Mexico School of Medicine and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

1. Chughtai K, Gupta R, Upadhaya S, et al. Topical 5-Fluorouracil associated skin reaction. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2017;2017(8):omx043. doi:10.1093/omcr/omx043

2. Hartman-Adams H, Banvard C, Juckett G. Impetigo: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:229-235.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu296

Common skin reactions to treatment with topical 5-FU for actinic keratosis include erythema, ulceration, and burning. In this case, however, the skin disruption opened the door to secondary impetigo.

Secondary skin infections are a known risk of treatment with topical 5-FU. The agent inhibits thymidylate synthetase, an enzyme involved in the synthesis and repair of DNA. The inhibition of this enzyme can lead to skin disruption with erosion, desquamation, and the risk of superimposed skin infections, as was seen with this patient.1

Impetigo is a common skin infection affecting the superficial layers of the epidermis and is most commonly caused by gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.2 Secondary impetigo, also known as impetiginization, is an infection of previously disrupted skin due to eczema, trauma, insect bites, and other conditions. This contrasts with primary impetigo, which results from a direct bacterial invasion of intact healthy skin. While impetigo predominantly affects children between the ages of 2 and 5 years, people of any age can be affected.2 Impetigo characteristically manifests with painful erosions, classically covered by honey-colored crusts. Thin-walled vesicles often appear and subsequently rupture.

Treatment options for impetigo include both topical and systemic antibiotics. Topical therapy is preferred for patients with limited skin involvement, while systemic therapy is indicated for patients with numerous lesions. Mupirocin and retapamulin are first-line topical treatments. Systemic antibiotic therapy should provide coverage for both S. aureus and streptococcal infections; cephalexin and dicloxacillin are preferred. Doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or clindamycin can be used if methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is suspected.3

This patient was advised to try warm soaks (to reduce the crusting) and to follow that with the application of white petrolatum bid. The patient was also prescribed doxycycline 100 mg orally bid for 10 days. At the 1-month follow-up, there was some residual erythema, but the impetigo and crusting had resolved. The actinic keratoses had resolved, as well.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Tess Pei Lemon, BA, University of New Mexico School of Medicine and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

Common skin reactions to treatment with topical 5-FU for actinic keratosis include erythema, ulceration, and burning. In this case, however, the skin disruption opened the door to secondary impetigo.

Secondary skin infections are a known risk of treatment with topical 5-FU. The agent inhibits thymidylate synthetase, an enzyme involved in the synthesis and repair of DNA. The inhibition of this enzyme can lead to skin disruption with erosion, desquamation, and the risk of superimposed skin infections, as was seen with this patient.1

Impetigo is a common skin infection affecting the superficial layers of the epidermis and is most commonly caused by gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.2 Secondary impetigo, also known as impetiginization, is an infection of previously disrupted skin due to eczema, trauma, insect bites, and other conditions. This contrasts with primary impetigo, which results from a direct bacterial invasion of intact healthy skin. While impetigo predominantly affects children between the ages of 2 and 5 years, people of any age can be affected.2 Impetigo characteristically manifests with painful erosions, classically covered by honey-colored crusts. Thin-walled vesicles often appear and subsequently rupture.

Treatment options for impetigo include both topical and systemic antibiotics. Topical therapy is preferred for patients with limited skin involvement, while systemic therapy is indicated for patients with numerous lesions. Mupirocin and retapamulin are first-line topical treatments. Systemic antibiotic therapy should provide coverage for both S. aureus and streptococcal infections; cephalexin and dicloxacillin are preferred. Doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or clindamycin can be used if methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is suspected.3

This patient was advised to try warm soaks (to reduce the crusting) and to follow that with the application of white petrolatum bid. The patient was also prescribed doxycycline 100 mg orally bid for 10 days. At the 1-month follow-up, there was some residual erythema, but the impetigo and crusting had resolved. The actinic keratoses had resolved, as well.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Tess Pei Lemon, BA, University of New Mexico School of Medicine and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

1. Chughtai K, Gupta R, Upadhaya S, et al. Topical 5-Fluorouracil associated skin reaction. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2017;2017(8):omx043. doi:10.1093/omcr/omx043

2. Hartman-Adams H, Banvard C, Juckett G. Impetigo: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:229-235.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu296

1. Chughtai K, Gupta R, Upadhaya S, et al. Topical 5-Fluorouracil associated skin reaction. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2017;2017(8):omx043. doi:10.1093/omcr/omx043

2. Hartman-Adams H, Banvard C, Juckett G. Impetigo: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:229-235.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu296

Recent onset of polyuria and polydipsia

The patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of T2D.

The prevalence of T2D is increasing dramatically in children and adolescents. Like adult-onset T2D, obesity, family history, and sedentary lifestyle are major predisposing risk factors for T2D in children and adolescents. Significantly, the onset of diabetes at a younger age is associated with longer disease exposure and increased risk for chronic complications. Moreover, T2D in adolescents manifests as a severe progressive phenotype that often presents with complications, poor treatment response, and rapid progression of microvascular and macrovascular complications. Studies have shown that the risk for complications is greater in youth-onset T2D than it is in type 1 diabetes (T1D) and adult-onset T2D.

T2D has a variable presentation in children and adolescents. Approximately one third of patients are diagnosed without having typical diabetes signs or symptoms. In most cases, these patients are in their mid-adolescence are obese and were screened because of one or more positive risk factors or because glycosuria was detected on a random urine test. These patients typically have one or more of the typical characteristics of metabolic syndrome, such as hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Polyuria and polydipsia are seen in approximately 67% of youth with T2D at presentation. Recent weight loss may be present, but it is usually less severe in patients with T2D compared with T1D. Additionally, frequent fungal skin infections or severe vulvovaginitis because of Candida in adolescent girls can be the presenting complaint.

Diabetic ketoacidosis is present in less than 1 in 10 adolescents diagnosed with T2D. Most of these patients belong to ethnic minority groups, report polyuria, polydipsia, fatigue, and lethargy, and require hospital admission, rehydration, and insulin replacement therapy. Patients with symptoms such as vomiting can decline rapidly and need urgent evaluation and management.

Certain adolescent patients with obesity who present with diabetic ketoacidosis and are diagnosed with T2D at presentation can also have T1D and will require lifelong insulin treatment. Therefore, following a diagnosis of diabetes in an adolescent, it is critical to differentiate T2D from type 1 diabetes, as well as from other more rare diabetes types, to ensure proper long-term management. Given the substantial overlap between T2D and T1D symptoms, a combination of history clues, clinical characteristics, and laboratory studies must be used to reliably make the distinction. Important clues in the patient's history include:

• Age. Patients with T2D typically present after the onset of puberty, at a mean age of 13.5 years. Conversely, nearly one half of patients with T1D present before 10 years of age, regardless of race or ethnicity.

• Family history. Up to 90% of patients with T2D have an affected first- or second-degree relative; the corresponding percentage for patients with T1D is less than 10%.

• Ethnicity. T2D disproportionately affects youth of ethnic and racial minorities. Compared with White individuals, youth belonging to minority groups such as Native American, African American, Hispanic, and Pacific Islander have a much higher risk of developing T2D.

• Body weight. Most adolescents with T2D have obesity (BMI ≥ 95 percentile for age and sex), whereas those with T1D are usually of normal weight and may report a recent history of weight loss.

• Clinical findings. Adolescents with T2D usually present with features of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, such as acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and polycystic ovary syndrome, whereas these findings are rare in youth with T1D. One study showed that up to 90% of youth diagnosed with T2D had acanthosis nigricans, in contrast to only 12% of those diagnosed with T1D.

Additionally, when the diagnosis of T2D is being considered in children and adolescents, a panel of pancreatic autoantibodies should be tested to exclude the possibility of autoimmune T1D. Because T2D is not immunologically mediated, the identification of one or more pancreatic (islet) cell antibodies in a diabetic adolescent with obesity supports the diagnosis of autoimmune diabetes. Antibodies that are usually measured include islet cell antibodies (against cytoplasmic proteins in the beta cell), anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase, and tyrosine phosphatase insulinoma-associated antigen 2, as well as anti-insulin antibodies if insulin replacement therapy has not been used for more than 2 weeks. In addition, a beta cell–specific autoantibody to zinc transporter 8 is frequently detected in children with T1D and can aid in the differential diagnosis. However, up to one third of children with T2D can have at least one detectable beta-cell autoantibody; therefore, total absence of diabetes autoimmune markers is not required for the diagnosis of T2D in children and adolescents.

When a diagnosis of T2D has been established, treatment should consist of lifestyle management, diabetes self-management education, and pharmacologic therapy. According to the 2022 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care, the management of diabetes in children and adolescents cannot simply be drawn from the typical care provided to adults with diabetes. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, developmental considerations, and response to therapy in pediatric populations often vary from adult diabetes, and differences exist in recommended care for children and adolescents with T1D, T2D, and other forms of pediatric diabetes.

Because the diabetes type is often uncertain in the first few weeks of treatment, initial therapy should address the hyperglycemia and associated metabolic derangements regardless of the ultimate diabetes type; therapy should then be adjusted once metabolic compensation has been established and subsequent information, such as islet autoantibody results, becomes available.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

The patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of T2D.

The prevalence of T2D is increasing dramatically in children and adolescents. Like adult-onset T2D, obesity, family history, and sedentary lifestyle are major predisposing risk factors for T2D in children and adolescents. Significantly, the onset of diabetes at a younger age is associated with longer disease exposure and increased risk for chronic complications. Moreover, T2D in adolescents manifests as a severe progressive phenotype that often presents with complications, poor treatment response, and rapid progression of microvascular and macrovascular complications. Studies have shown that the risk for complications is greater in youth-onset T2D than it is in type 1 diabetes (T1D) and adult-onset T2D.

T2D has a variable presentation in children and adolescents. Approximately one third of patients are diagnosed without having typical diabetes signs or symptoms. In most cases, these patients are in their mid-adolescence are obese and were screened because of one or more positive risk factors or because glycosuria was detected on a random urine test. These patients typically have one or more of the typical characteristics of metabolic syndrome, such as hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Polyuria and polydipsia are seen in approximately 67% of youth with T2D at presentation. Recent weight loss may be present, but it is usually less severe in patients with T2D compared with T1D. Additionally, frequent fungal skin infections or severe vulvovaginitis because of Candida in adolescent girls can be the presenting complaint.

Diabetic ketoacidosis is present in less than 1 in 10 adolescents diagnosed with T2D. Most of these patients belong to ethnic minority groups, report polyuria, polydipsia, fatigue, and lethargy, and require hospital admission, rehydration, and insulin replacement therapy. Patients with symptoms such as vomiting can decline rapidly and need urgent evaluation and management.

Certain adolescent patients with obesity who present with diabetic ketoacidosis and are diagnosed with T2D at presentation can also have T1D and will require lifelong insulin treatment. Therefore, following a diagnosis of diabetes in an adolescent, it is critical to differentiate T2D from type 1 diabetes, as well as from other more rare diabetes types, to ensure proper long-term management. Given the substantial overlap between T2D and T1D symptoms, a combination of history clues, clinical characteristics, and laboratory studies must be used to reliably make the distinction. Important clues in the patient's history include:

• Age. Patients with T2D typically present after the onset of puberty, at a mean age of 13.5 years. Conversely, nearly one half of patients with T1D present before 10 years of age, regardless of race or ethnicity.

• Family history. Up to 90% of patients with T2D have an affected first- or second-degree relative; the corresponding percentage for patients with T1D is less than 10%.

• Ethnicity. T2D disproportionately affects youth of ethnic and racial minorities. Compared with White individuals, youth belonging to minority groups such as Native American, African American, Hispanic, and Pacific Islander have a much higher risk of developing T2D.

• Body weight. Most adolescents with T2D have obesity (BMI ≥ 95 percentile for age and sex), whereas those with T1D are usually of normal weight and may report a recent history of weight loss.

• Clinical findings. Adolescents with T2D usually present with features of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, such as acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and polycystic ovary syndrome, whereas these findings are rare in youth with T1D. One study showed that up to 90% of youth diagnosed with T2D had acanthosis nigricans, in contrast to only 12% of those diagnosed with T1D.

Additionally, when the diagnosis of T2D is being considered in children and adolescents, a panel of pancreatic autoantibodies should be tested to exclude the possibility of autoimmune T1D. Because T2D is not immunologically mediated, the identification of one or more pancreatic (islet) cell antibodies in a diabetic adolescent with obesity supports the diagnosis of autoimmune diabetes. Antibodies that are usually measured include islet cell antibodies (against cytoplasmic proteins in the beta cell), anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase, and tyrosine phosphatase insulinoma-associated antigen 2, as well as anti-insulin antibodies if insulin replacement therapy has not been used for more than 2 weeks. In addition, a beta cell–specific autoantibody to zinc transporter 8 is frequently detected in children with T1D and can aid in the differential diagnosis. However, up to one third of children with T2D can have at least one detectable beta-cell autoantibody; therefore, total absence of diabetes autoimmune markers is not required for the diagnosis of T2D in children and adolescents.

When a diagnosis of T2D has been established, treatment should consist of lifestyle management, diabetes self-management education, and pharmacologic therapy. According to the 2022 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care, the management of diabetes in children and adolescents cannot simply be drawn from the typical care provided to adults with diabetes. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, developmental considerations, and response to therapy in pediatric populations often vary from adult diabetes, and differences exist in recommended care for children and adolescents with T1D, T2D, and other forms of pediatric diabetes.

Because the diabetes type is often uncertain in the first few weeks of treatment, initial therapy should address the hyperglycemia and associated metabolic derangements regardless of the ultimate diabetes type; therapy should then be adjusted once metabolic compensation has been established and subsequent information, such as islet autoantibody results, becomes available.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

The patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of T2D.

The prevalence of T2D is increasing dramatically in children and adolescents. Like adult-onset T2D, obesity, family history, and sedentary lifestyle are major predisposing risk factors for T2D in children and adolescents. Significantly, the onset of diabetes at a younger age is associated with longer disease exposure and increased risk for chronic complications. Moreover, T2D in adolescents manifests as a severe progressive phenotype that often presents with complications, poor treatment response, and rapid progression of microvascular and macrovascular complications. Studies have shown that the risk for complications is greater in youth-onset T2D than it is in type 1 diabetes (T1D) and adult-onset T2D.

T2D has a variable presentation in children and adolescents. Approximately one third of patients are diagnosed without having typical diabetes signs or symptoms. In most cases, these patients are in their mid-adolescence are obese and were screened because of one or more positive risk factors or because glycosuria was detected on a random urine test. These patients typically have one or more of the typical characteristics of metabolic syndrome, such as hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Polyuria and polydipsia are seen in approximately 67% of youth with T2D at presentation. Recent weight loss may be present, but it is usually less severe in patients with T2D compared with T1D. Additionally, frequent fungal skin infections or severe vulvovaginitis because of Candida in adolescent girls can be the presenting complaint.

Diabetic ketoacidosis is present in less than 1 in 10 adolescents diagnosed with T2D. Most of these patients belong to ethnic minority groups, report polyuria, polydipsia, fatigue, and lethargy, and require hospital admission, rehydration, and insulin replacement therapy. Patients with symptoms such as vomiting can decline rapidly and need urgent evaluation and management.

Certain adolescent patients with obesity who present with diabetic ketoacidosis and are diagnosed with T2D at presentation can also have T1D and will require lifelong insulin treatment. Therefore, following a diagnosis of diabetes in an adolescent, it is critical to differentiate T2D from type 1 diabetes, as well as from other more rare diabetes types, to ensure proper long-term management. Given the substantial overlap between T2D and T1D symptoms, a combination of history clues, clinical characteristics, and laboratory studies must be used to reliably make the distinction. Important clues in the patient's history include:

• Age. Patients with T2D typically present after the onset of puberty, at a mean age of 13.5 years. Conversely, nearly one half of patients with T1D present before 10 years of age, regardless of race or ethnicity.

• Family history. Up to 90% of patients with T2D have an affected first- or second-degree relative; the corresponding percentage for patients with T1D is less than 10%.

• Ethnicity. T2D disproportionately affects youth of ethnic and racial minorities. Compared with White individuals, youth belonging to minority groups such as Native American, African American, Hispanic, and Pacific Islander have a much higher risk of developing T2D.

• Body weight. Most adolescents with T2D have obesity (BMI ≥ 95 percentile for age and sex), whereas those with T1D are usually of normal weight and may report a recent history of weight loss.

• Clinical findings. Adolescents with T2D usually present with features of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, such as acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and polycystic ovary syndrome, whereas these findings are rare in youth with T1D. One study showed that up to 90% of youth diagnosed with T2D had acanthosis nigricans, in contrast to only 12% of those diagnosed with T1D.

Additionally, when the diagnosis of T2D is being considered in children and adolescents, a panel of pancreatic autoantibodies should be tested to exclude the possibility of autoimmune T1D. Because T2D is not immunologically mediated, the identification of one or more pancreatic (islet) cell antibodies in a diabetic adolescent with obesity supports the diagnosis of autoimmune diabetes. Antibodies that are usually measured include islet cell antibodies (against cytoplasmic proteins in the beta cell), anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase, and tyrosine phosphatase insulinoma-associated antigen 2, as well as anti-insulin antibodies if insulin replacement therapy has not been used for more than 2 weeks. In addition, a beta cell–specific autoantibody to zinc transporter 8 is frequently detected in children with T1D and can aid in the differential diagnosis. However, up to one third of children with T2D can have at least one detectable beta-cell autoantibody; therefore, total absence of diabetes autoimmune markers is not required for the diagnosis of T2D in children and adolescents.

When a diagnosis of T2D has been established, treatment should consist of lifestyle management, diabetes self-management education, and pharmacologic therapy. According to the 2022 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care, the management of diabetes in children and adolescents cannot simply be drawn from the typical care provided to adults with diabetes. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, developmental considerations, and response to therapy in pediatric populations often vary from adult diabetes, and differences exist in recommended care for children and adolescents with T1D, T2D, and other forms of pediatric diabetes.

Because the diabetes type is often uncertain in the first few weeks of treatment, initial therapy should address the hyperglycemia and associated metabolic derangements regardless of the ultimate diabetes type; therapy should then be adjusted once metabolic compensation has been established and subsequent information, such as islet autoantibody results, becomes available.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

A 14-year-old Black girl presents with complaints of increasing fatigue and recent onset of polyuria and polydipsia. According to the patient's chart, she has lost approximately 5 lb since her last examination 8 months ago. Physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 120/80 mm Hg, pulse of 79, and temperature of 100.4°F (38°C). Her weight is 165 lb (75 kg, 96th percentile), height is 62 in (157.5 cm, 32nd percentile), and BMI is 30.2 (97th percentile). Acanthosis nigricans is present. The patient is at Tanner stage 3 of sexual development. There is a positive first-degree family history of type 2 diabetes (T2D), hypertension, and obesity, as well as premature cardiac death in an uncle. Laboratory findings include an A1c value of 7.4%, HDL-C 220 mg/dL, LDL-C 144 mg/dL, and serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL.

Mild Grisel Syndrome: Expanding the Differential for Posttonsillectomy Adenoidectomy Symptoms

Tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy (T&A) is the second most common pediatric surgical procedure in the United States.1 It is most often performed during childhood between 5 and 8 years of age with a second peak observed between 17 and 21 years of age in the adolescent and young adult populations.2 While recurrent tonsillitis has been traditionally associated with tonsillectomy, sleep disordered breathing with obstructive sleep apnea is now the primary indication for the procedure.1

Up to 97% of T&As are performed as an outpatient same-day surgery not requiring inpatient admission.2 Although largely a safe and routinely performed surgery, several complications have been described. Due to the outpatient nature of the procedure, the complications are often encountered in the emergency department (ED) and sometimes in primary care settings. Common complications (outside of the perioperative time frame) include nausea, vomiting, otalgia, odynophagia, infection of the throat (broadly), and hemorrhage; uncommon complications include subcutaneous emphysema, taste disorders, and Eagle syndrome. Some complications are rarer still and carry significant morbidity and even mortality, including mediastinitis, cervical osteomyelitis, and Grisel syndrome.3 The following case encourages the clinician to expand the differential for a patient presenting after T&A.

Case Presentation

A child aged < 3 years was brought to the ED by their mother. She reported neck pain and stiffness 10 days after T&A with concurrent tympanostomy tube placement at an outside pediatric hospital. At triage, their heart rate was 94 bpm, temperature was 98.2 °F, respiratory rate, 22 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation, 97% on room air. The mother of the patient (MOP) had been giving the prescribed oral liquid formulations of ibuprofen and acetaminophen with hydrocodone as directed. No drug allergies were reported, and immunizations were up to date for age. Other medical and surgical history included eczema and remote cutaneous hemangioma resection. The patient lived at home with 2 parents and was not exposed to smoke; their family history was noncontributory.

Since the surgery, the MOP had noticed constant and increasing neck stiffness, specifically with looking up and down but not side to side. She also had noticed swelling behind both ears. She reported no substantial decrease in intake by mouth or decrease in urine or bowel frequency. On review of systems, she reported no fever, vomiting, difficulty breathing, bleeding from the mouth or nose, eye or ear drainage, or rash.

On physical examination, the patient was alert and in no acute distress; active and playful on an electronic device but was notably not moving their head, which was held in a forward-looking position without any signs of trauma. When asked, the child would not flex or extend their neck but would rotate a few degrees from neutral to both sides. Even with moving the electronic device up and down in space, no active neck extension or flexion could be elicited. The examination of the head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat was otherwise only remarkable for palpable and mildly tender postauricular lymph nodes and diffuse erythema in the posterior pharynx. Cardiopulmonary, abdominal, skin, and extremity examinations were unremarkable.

With concern for an infectious process, the physician ordered blood chemistry and hematology tests along with neck radiography. While awaiting the results, the patient was given a weight-based bolus of normal saline, and the home pain regimen was administered. An attempt was made to passively flex and extend the neck as the child slept in their mother’s arms, but the patient immediately awoke and began to cry.

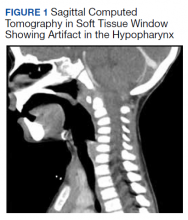

All values of the comprehensive metabolic panel were within normal limits except for a slight elevation in the blood urea nitrogen to 21 mg/dL and glucose to 159 mg/dL. The complete blood count was unrevealing. The computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast of the soft tissues of the neck was limited by motion artifact but showed a head held in axial rotation with soft tissue irregularity in the anterior aspect of the adenoids (Figure 1). There was what appeared to be normal lymphadenopathy in the hypopharynx, but the soft tissues were otherwise unremarkable.

The on-call pediatric otolaryngologist at the hospital where the procedure was performed was paged. On hearing the details of the case, the specialist was concerned for Grisel syndrome and requested to see the patient in their facility. No additional recommendations for care were provided; the mother was updated and agreed to transfer. The patient was comfortable and stable with repeat vitals as follows: heart rate, 86 beats per minute, blood pressure, 99/62, temperature, 98.3 °F, respiratory rate, 20 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation, 99% on room air.

On arrival at the receiving facility, the emergency team performed a history and physical that revealed no significant changes from the initial evaluation. They then facilitated evaluation by the pediatric otolaryngologist who conducted a more directed physical examination. Decreased active and passive range of motion (ROM) of the neck without rotatory restriction was again noted. They also observed scant fibrinous exudate within the oropharynx and tonsillar fossa, which was normal in the setting of the recent surgery. They recommended additional analgesia with intramuscular ketorolac, weight-based dosing at 1 mg/kg.

With repeat examination after this additional analgesic, ROM of the neck first passive then active had improved. The patient was then discharged to follow up in the coming days with instructions to continue the pain and anti-inflammatory regimen. They were not started on an antibiotic at that time nor were they placed in a cervical collar. At the follow-up, the MOP reported persistence of neck stiffness for a few days initially but then observed slow improvement. By postoperative day 18, the stiffness had resolved. No other follow-up or referrals related to this issue were readily apparent in review of the patient’s health record.

Discussion

Grisel syndrome is the atraumatic rotary subluxation of the atlantoaxial joint, specifically, the atlas (C1 vertebra) rotates to a fixed, nonanatomic position while the axis (C2 vertebra) remains in normal alignment in relation to the remainder of the spinal column. The subluxation occurs in the absence of ligamentous injury but is associated with an increase in ligamentous laxity.4 The atlas is a ring-shaped vertebra with 2 lateral masses connected by anterior and posterior arches; it lacks a spinous process unlike other vertebrae. It articulates with the skull by means of the 2 articular facets on the superior aspect of the lateral masses. Articulation with the axis occurs at 3 sites: 2 articular facets on the inferior portion of the lateral masses of the atlas and a facet for the dens on the posterior portion of the anterior arch. The dens projects superiorly from the body of the axis and is bound posteriorly by the transverse ligament of the atlas.5

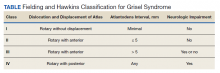

The degree of subluxation seen in Grisel syndrome correlates to the disease severity and is classified by the Fielding and Hawkins (FH) system (Table). This system accounts for the distance from the atlas to the dens (atlantodens interval) and the relative asymmetry of the atlantoaxial joint.6 In a normal adult, the upper limit of normal for the atlantodens interval is 3 mm, whereas this distance increases to 4.5 mm for the pediatric population.7 Type I (FH-I) involves rotary subluxation alone without any increase in the atlantodens interval; in FH-II, that interval has increased from normal but to no more than 5 mm. FH-I and FH-II are the most encountered and are not associated with neurologic impairment. In FH-III, neurologic deficits can be present, and the atlantodens interval is increased to > 5 mm. Different from FH-II and FH-III in which anterior dislocation of the atlas with reference to the dens is observed, FH-IV involves a rotary movement of the atlas with concurrent posterior displacement and often involves spinal cord compression.6

Subluxation and displacement without trauma are key components of Grisel syndrome. The 2-hit hypothesis is often used to explain how this can occur, ie, 2 anomalies must be present simultaneously for this condition to develop. First, the laxity of the transverse ligament, the posterior wall of the dens, and other atlantoaxial ligaments must be increased. Second, an asymmetric contraction of the deep erector muscles of the neck either abruptly or more insidiously rotate and dislocate the atlas.8 The pathophysiology is not exactly understood, but the most commonly held hypothesis describes contiguous spread of infection or inflammatory mediators from the pharynx to the ligaments and muscles described.6