User login

Repeat Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy for Duplicated Gallbladder After 16-Year Interval

Gallbladder duplication is a congenital abnormality of the hepatobiliary system and often is not considered in the evaluation of a patient with right upper quadrant pain. Accuracy of the most commonly used imaging study to assess for biliary disease, abdominal ultrasound, is highly dependent on the skills of the ultrasonographer, and given its relative rarity, this condition is often not considered prior to planned cholecystectomy.1 Small case reviews found that < 50% of gallbladder duplications are diagnosed preoperatively despite use of ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan.2-4 Failure to recognize duplicate gallbladder anatomy in symptomatic patients may result in incomplete surgical management, an increase in perioperative complications, and years of morbidity due to unresolved symptoms. Once a patient has had a cholecystectomy, symptoms are presumed to be due to a nonbiliary etiology and an extensive, often repetitive, workup is pursued before “repeat cholecystectomy” is considered.5

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old man was referred to gastroenterology for recurrent episodic right upper quadrant pain. He reported intermittent both right and left upper abdominal pain that was variable in quality. At times it was associated with an empty stomach prior to meals; at other times, onset was 30 to 60 minutes after meals. The patient also reported significant flatulence and bloating and intermittent loose stools. Sixteen years before, he underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. He reported that the pain he experienced before the cholecystectomy never resolved after surgery but occurred less frequently. For the next 16 years, the patient did not seek evaluation of his ongoing but infrequent symptoms until his pain became a daily occurrence. The patient’s surgical history included a remote open vagotomy and antrectomy for peptic ulcer disease, laparoscopic appendectomy, and a laparoscopic cholecystectomy for reported biliary colic.

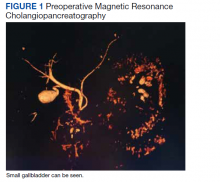

The gastroenterology evaluation included a colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD); both were benign and without findings specific to identify the etiology for the patient’s pain. The patient was given a course of rifaximin 1200 mg daily for 7 days for possible bacterial overgrowth and placed on a proton pump inhibitor twice daily. Neither of these interventions helped resolve the patient’s symptoms. Further workup was pursued by gastroenterology to include a right upper quadrant ultrasound that showed a structure most consistent with a small gallbladder containing a small polyp vs stone. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) also was performed and showed the presence of a small gallbladder with a small 2-mm filling defect and an otherwise benign biliary tree. MRCP images and EGD documented a Billroth 1 reconstruction at the time of his remote antrectomy and vagotomy (Figure 1).

The patient was referred to general surgery for consideration of a repeat cholecystectomy. He confirmed the history of intermittent upper abdominal pain for the past 16 years, which was similar to the symptoms he had experienced before his original laparoscopic cholecystectomy. On examination, the patient had a body mass index of 38, had a large upper midline incision from his prior antrectomy and vagotomy procedure, and several scars presumed to be port incision scars to the right lateral abdominal wall. Hospital records were obtained from the patient’s prior workup for biliary colic and cholecystectomy 16 years before. The preoperative abdominal ultrasound examination showed a mildly distended gallbladder but was notably described as “quite limited due to patient’s body habitus and liver is not well seen.” No additional imaging was documented in his presurgical evaluation notes and imaging records.

The operative report described a gallbladder that was densely adherent to adjacent fat and omental tissue with significant adhesions secondary to the prior vagotomy and antrectomy procedure. The cystic duct and artery were dissected free at the level of their junction with the gallbladder infundibulum. The cystic artery was divided with a harmonic scalpel. Following this the gallbladder body was dissected free from the liver bed in top-down fashion. A 0 Vicryl Endoloop suture was placed over the gallbladder and secured just past the origin of the cystic duct on the gallbladder infundibulum and the cystic duct divided above this suture. No surgical clips were used, which corresponded with the lack of surgical clips seen in imaging in his recent gastroenterology workup. No documentation of an intraoperative cholangiogram existed or was considered in the operative report.

The pathology report from this first cholecystectomy procedure noted the removed specimen to be an unopened 6-cm gallbladder containing 2 small yellow stones that otherwise were benign. At the time of this patient’s re-presentation to general surgery, there was suspicion that the patient’s prior surgical procedure had not been a cholecystectomy but rather a subtotal cholecystectomy. However, after appropriate workup and review of prior records, the patient had, indeed, previously undergone cholecystectomy and represented a rare case of gallbladder duplication resulting in abdominal pain for 16 years after his index operation.

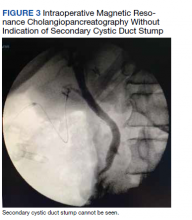

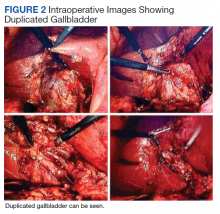

The patient was consented for repeat cholecystectomy and underwent a laparoscopic lysis of adhesions, cholecystectomy, and intraoperative cholangiogram. Significant scarring was found at the liver undersurface that would have been exposed during the original laparoscopic resection of the gallbladder from its liver bed. Deeper to this, a small saccular structure was identified as the duplicate gallbladder (Figure 2). Though the visualized gallbladder was small with a deep intrahepatic lie, the critical view of safety was achieved and was without additional variation. An intraoperative cholangiogram was performed to determine whether residual ductal stumps or other additional evidence of the previously removed gallbladder could be identified. The cholangiogram showed clear visualization of the cystic duct, common bile duct, right and left hepatic ducts, and contrast into the duodenum without abnormal variants. There was no visualized accessory or secondary cystic duct stump seen on the cholangiogram (Figure 3). Pathology of the repeat cholecystectomy specimen confirmed a 3-cm gallbladder with a distinct duct leading out of the gallbladder and the presence of several gallstones. The patient had an uneventful recovery after the repeat laparoscopic cholecystectomy with complete resolution of his upper abdominal pain.

Discussion

The first reported human case of gallbladder duplication was noted in a sacrificial victim of Emperor Augustus in 31 BCE. Sherren reported the first documented case of double accessory gallbladder in a living human in 1911.1,6 Though the exact incidence of gallbladder duplication is not fully known due to primary documentation from case reports, incidence is approximately 1 in 4000 to 5000 people. It was first formally classified by Boyden in 1926.7 Further anatomic classification based on morphology and embryogenesis was delineated by Harlaftis and colleagues in 1977, establishing type 1 and 2 structures of a duplicated gallbladder.8 Type 1 duplicated gallbladder anatomy shares a single cystic duct, whereas in type 2 each gallbladder has its own cystic duct. Later reports and studies identified triple gallbladders as well as trabecular variants with the most common classification used currently being the modified Harlaftis classification.9,10

The case presented here most likely represents either a Y-shaped type 1 primordial gallbladder or a type 2 accessory gallbladder based on historical data and intraoperative cholangiogram findings at the time of repeat cholecystectomy. Gallbladder duplication is clinically indistinguishable from regular gallbladder pathology preoperatively and can only be identified on imaging or intraoperatively.11 Prior case reports and studies have found that it is frequently missed on preoperative abdominal ultrasonography and CT in up to 50% of cases.12-14

The differential diagnosis of gallbladder duplication seen on preoperative imaging includes a gallbladder diverticulum, choledochal cyst, focal adenonomyomatosis, Phrygian cap, or folded gallbladder.1,2 Historically, the most definitive test for gallbladder duplication has been either intraoperative cholangiography, which can also clarify biliary anatomy, or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with cholangiography.1,3 The debate over routine use of intraoperative cholangiography has been ongoing for the past several decades.15 Though intraoperative cholangiogram remains one of the most definitive tests for gallbladder duplication, given the overall low incidence of this variant, recommendation for routine intraoperative cholangiography solely to rule out gallbladder duplication cannot be definitively recommended based on our review of the literature. Currently, preoperative MRCP is the study of choice when there is concern from historical facts or from other imaging of gallbladder duplication as it is noninvasive and has a high degree of detail, particularly with 3D reconstructions.14,16 At the time of surgery, the most critical step to avoid inadvertent ductal injury is clear visualization of ductal anatomy and obtaining the critical view of safety.17 Though this will also assist in identifying some cases of gallbladder duplication, given the great variation of duplication, it will not prevent missing some variants. In our case, extensive local scarring from the patient’s prior antrectomy and vagotomy along with lack of the use of intraoperative cholangiography likely contributed to missing his duplication at the time of his index cholecystectomy.

Undiagnosed gallbladder duplication can lead to additional morbidity related to common entities associated with gallbladder pathology, such as biliary colic, cholecystitis, cholangitis, and pancreatitis. Additionally, case reports in the literature have documented more rare associations, such as empyema, carcinoma, cholecystoenteric fistula, and torsion, all associated with a duplicated gallbladder.18-21 Once identified pre- or intraoperatively, it is generally recommended that all gallbladders be removed in symptomatic patients and that intraoperative cholangiography be done to assure complete resection of the duplicated gallbladders and to avoid injury to the biliary trees.22-25

Conclusions

Gallbladder duplication and other congenital biliary anatomic variations should be considered before a biliary operation and included in the differential diagnosis when evaluating patients who have clinical symptoms consistent with biliary pathology. In addition, intraoperative cholangiogram should be performed during cholecystectomy if the inferior liver edge cannot be visualized well, as in the case of this patient where a prior foregut operation resulted in extensive adhesive disease. Intraoperative cholangiogram also should be considered in patients whose preoperative imaging does not visualize the right upper quadrant well due to patient habitus. Doing so may identify gallbladder duplication and allow for complete cholecystectomy as well as proper identification and management of cystic duct variants. Awareness and consideration of duplicated biliary variants can help prevent intraoperative complications related to biliary anomalies and avoid the morbidity related to recurrent biliary disease and the need for repeat operative procedures.

Acknowledgments

We extend our thanks to Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Healthcare System and the Departments of Surgery and Radiology for their support of this case report, and Lorrie Langdale, MD, and Roger Tatum, MD, for their mentorship of this project

1. Vezakis A, Pantiora E, Giannoulopoulos D, et al. A duplicated gallbladder in a patient presenting with acute cholangitis. A case study and a literature review. Ann Hepatol. 2019;18(1):240-245. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0012.7932

2. Barut Í, Tarhan ÖR, Dog^ru U, Bülbül M. Gallbladder duplication: diagnosed and treated by laparoscopy. Eur J Gen Med. 2006;3(3):142-145. doi:10.29333/ejgm/82396 3. Cozacov Y, Subhas G, Jacobs M, Parikh J. Total laparoscopic removal of accessory gallbladder: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;7(12):398-402. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v7.i12.398

4. Musleh MG, Burnett H, Rajashanker B, Ammori BJ. Laparoscopic double cholecystectomy for duplicated gallbladder: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;41:502-504. Published 2017 Nov 27. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.11.046

5. Walbolt TD, Lalezarzadeh F. Laparoscopic management of a duplicated gallbladder: a case study and anatomic history. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21(3):e156-e158. doi:10.1097/SLE.0b013e31821d47ce

6. Sherren J. A double gall-bladder removed by operation. Ann Surg. 1911;54(2):204-205. doi:10.1097/00000658-191108000-00009

7. Boyden EA. The accessory gall-bladder—an embryological and comparative study of aberrant biliary vesicles occurring in man and the domestic mammals. Am J Anat. 1926; 38(2):177-231. doi:10.1002/aja.1000380202

8. Harlaftis N, Gray SW, Skandalakis JE. Multiple gallbladders. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1977;145(6):928-934.

9. Kim RD, Zendejas I, Velopulos C, et al. Duplicate gallbladder arising from the left hepatic duct: report of a case. Surg Today. 2009;39(6):536-539. doi:10.1007/s00595-008-3878-4

10. Causey MW, Miller S, Fernelius CA, Burgess JR, Brown TA, Newton C. Gallbladder duplication: evaluation, treatment, and classification. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(2):443-446. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.12.015

11. Apolo Romero EX, Gálvez Salazar PF, Estrada Chandi JA, et al. Gallbladder duplication and cholecystitis. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018(7):rjy158. Published 2018 Jul 3. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjy158

12. Gorecki PJ, Andrei VE, Musacchio T, Schein M. Double gallbladder originating from left hepatic duct: a case report and review of literature. JSLS. 1998;2(4):337-339.

13. Cueto García J, Weber A, Serrano Berry F, Tanur Tatz B. Double gallbladder treated successfully by laparoscopy. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1993;3(2):153-155. doi:10.1089/lps.1993.3.153

14. Fazio V, Damiano G, Palumbo VD, et al. An unexpected surprise at the end of a “quiet” cholecystectomy. A case report and review of the literature. Ann Ital Chir. 2012;83(3):265-267.

15. Flum DR, Dellinger EP, Cheadle A, Chan L, Koepsell T. Intraoperative cholangiography and risk of common bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. JAMA. 2003;289(13):1639-1644. doi:10.1001/jama.289.13.1639

16. Botsford A, McKay K, Hartery A, Hapgood C. MRCP imaging of duplicate gallbladder: a case report and review of the literature. Surg Radiol Anat. 2015;37(5):425-429. doi:10.1007/s00276-015-1456-1

17. Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180(1):101-125.

18. Raymond SW, Thrift CB. Carcinoma of a duplicated gall bladder. Ill Med J. 1956;110(5):239-240.

19. Cunningham JJ. Empyema of a duplicated gallbladder: echographic findings. J Clin Ultrasound. 1980;8(6):511-512. doi:10.1002/jcu.1870080612

20. Recht W. Torsion of a double gallbladder; a report of a case and a review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1952;39(156):342-344. doi:10.1002/bjs.18003915616

21. Ritchie AW, Crucioli V. Double gallbladder with cholecystocolic fistula: a case report. Br J Surg. 1980;67(2):145-146. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800670226

22. Shapiro T, Rennie W. Duplicate gallbladder cholecystitis after open cholecystectomy. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(5):584-587. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70348-3

23. Hobbs MS, Mai Q, Knuiman MW, Fletcher DR, Ridout SC. Surgeon experience and trends in intraoperative complications in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2006;93(7):844-853. doi:10.1002/bjs.5333

24. Davidoff AM, Pappas TN, Murray EA, et al. Mechanisms of major biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 1992;215(3):196-202. doi:10.1097/00000658-199203000-00002

25. Flowers JL, Zucker KA, Graham SM, Scovill WA, Imbembo AL, Bailey RW. Laparoscopic cholangiography. Results and indications. Ann Surg. 1992;215(3):209-216. doi:10.1097/00000658-199203000-00004

Gallbladder duplication is a congenital abnormality of the hepatobiliary system and often is not considered in the evaluation of a patient with right upper quadrant pain. Accuracy of the most commonly used imaging study to assess for biliary disease, abdominal ultrasound, is highly dependent on the skills of the ultrasonographer, and given its relative rarity, this condition is often not considered prior to planned cholecystectomy.1 Small case reviews found that < 50% of gallbladder duplications are diagnosed preoperatively despite use of ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan.2-4 Failure to recognize duplicate gallbladder anatomy in symptomatic patients may result in incomplete surgical management, an increase in perioperative complications, and years of morbidity due to unresolved symptoms. Once a patient has had a cholecystectomy, symptoms are presumed to be due to a nonbiliary etiology and an extensive, often repetitive, workup is pursued before “repeat cholecystectomy” is considered.5

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old man was referred to gastroenterology for recurrent episodic right upper quadrant pain. He reported intermittent both right and left upper abdominal pain that was variable in quality. At times it was associated with an empty stomach prior to meals; at other times, onset was 30 to 60 minutes after meals. The patient also reported significant flatulence and bloating and intermittent loose stools. Sixteen years before, he underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. He reported that the pain he experienced before the cholecystectomy never resolved after surgery but occurred less frequently. For the next 16 years, the patient did not seek evaluation of his ongoing but infrequent symptoms until his pain became a daily occurrence. The patient’s surgical history included a remote open vagotomy and antrectomy for peptic ulcer disease, laparoscopic appendectomy, and a laparoscopic cholecystectomy for reported biliary colic.

The gastroenterology evaluation included a colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD); both were benign and without findings specific to identify the etiology for the patient’s pain. The patient was given a course of rifaximin 1200 mg daily for 7 days for possible bacterial overgrowth and placed on a proton pump inhibitor twice daily. Neither of these interventions helped resolve the patient’s symptoms. Further workup was pursued by gastroenterology to include a right upper quadrant ultrasound that showed a structure most consistent with a small gallbladder containing a small polyp vs stone. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) also was performed and showed the presence of a small gallbladder with a small 2-mm filling defect and an otherwise benign biliary tree. MRCP images and EGD documented a Billroth 1 reconstruction at the time of his remote antrectomy and vagotomy (Figure 1).

The patient was referred to general surgery for consideration of a repeat cholecystectomy. He confirmed the history of intermittent upper abdominal pain for the past 16 years, which was similar to the symptoms he had experienced before his original laparoscopic cholecystectomy. On examination, the patient had a body mass index of 38, had a large upper midline incision from his prior antrectomy and vagotomy procedure, and several scars presumed to be port incision scars to the right lateral abdominal wall. Hospital records were obtained from the patient’s prior workup for biliary colic and cholecystectomy 16 years before. The preoperative abdominal ultrasound examination showed a mildly distended gallbladder but was notably described as “quite limited due to patient’s body habitus and liver is not well seen.” No additional imaging was documented in his presurgical evaluation notes and imaging records.

The operative report described a gallbladder that was densely adherent to adjacent fat and omental tissue with significant adhesions secondary to the prior vagotomy and antrectomy procedure. The cystic duct and artery were dissected free at the level of their junction with the gallbladder infundibulum. The cystic artery was divided with a harmonic scalpel. Following this the gallbladder body was dissected free from the liver bed in top-down fashion. A 0 Vicryl Endoloop suture was placed over the gallbladder and secured just past the origin of the cystic duct on the gallbladder infundibulum and the cystic duct divided above this suture. No surgical clips were used, which corresponded with the lack of surgical clips seen in imaging in his recent gastroenterology workup. No documentation of an intraoperative cholangiogram existed or was considered in the operative report.

The pathology report from this first cholecystectomy procedure noted the removed specimen to be an unopened 6-cm gallbladder containing 2 small yellow stones that otherwise were benign. At the time of this patient’s re-presentation to general surgery, there was suspicion that the patient’s prior surgical procedure had not been a cholecystectomy but rather a subtotal cholecystectomy. However, after appropriate workup and review of prior records, the patient had, indeed, previously undergone cholecystectomy and represented a rare case of gallbladder duplication resulting in abdominal pain for 16 years after his index operation.

The patient was consented for repeat cholecystectomy and underwent a laparoscopic lysis of adhesions, cholecystectomy, and intraoperative cholangiogram. Significant scarring was found at the liver undersurface that would have been exposed during the original laparoscopic resection of the gallbladder from its liver bed. Deeper to this, a small saccular structure was identified as the duplicate gallbladder (Figure 2). Though the visualized gallbladder was small with a deep intrahepatic lie, the critical view of safety was achieved and was without additional variation. An intraoperative cholangiogram was performed to determine whether residual ductal stumps or other additional evidence of the previously removed gallbladder could be identified. The cholangiogram showed clear visualization of the cystic duct, common bile duct, right and left hepatic ducts, and contrast into the duodenum without abnormal variants. There was no visualized accessory or secondary cystic duct stump seen on the cholangiogram (Figure 3). Pathology of the repeat cholecystectomy specimen confirmed a 3-cm gallbladder with a distinct duct leading out of the gallbladder and the presence of several gallstones. The patient had an uneventful recovery after the repeat laparoscopic cholecystectomy with complete resolution of his upper abdominal pain.

Discussion

The first reported human case of gallbladder duplication was noted in a sacrificial victim of Emperor Augustus in 31 BCE. Sherren reported the first documented case of double accessory gallbladder in a living human in 1911.1,6 Though the exact incidence of gallbladder duplication is not fully known due to primary documentation from case reports, incidence is approximately 1 in 4000 to 5000 people. It was first formally classified by Boyden in 1926.7 Further anatomic classification based on morphology and embryogenesis was delineated by Harlaftis and colleagues in 1977, establishing type 1 and 2 structures of a duplicated gallbladder.8 Type 1 duplicated gallbladder anatomy shares a single cystic duct, whereas in type 2 each gallbladder has its own cystic duct. Later reports and studies identified triple gallbladders as well as trabecular variants with the most common classification used currently being the modified Harlaftis classification.9,10

The case presented here most likely represents either a Y-shaped type 1 primordial gallbladder or a type 2 accessory gallbladder based on historical data and intraoperative cholangiogram findings at the time of repeat cholecystectomy. Gallbladder duplication is clinically indistinguishable from regular gallbladder pathology preoperatively and can only be identified on imaging or intraoperatively.11 Prior case reports and studies have found that it is frequently missed on preoperative abdominal ultrasonography and CT in up to 50% of cases.12-14

The differential diagnosis of gallbladder duplication seen on preoperative imaging includes a gallbladder diverticulum, choledochal cyst, focal adenonomyomatosis, Phrygian cap, or folded gallbladder.1,2 Historically, the most definitive test for gallbladder duplication has been either intraoperative cholangiography, which can also clarify biliary anatomy, or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with cholangiography.1,3 The debate over routine use of intraoperative cholangiography has been ongoing for the past several decades.15 Though intraoperative cholangiogram remains one of the most definitive tests for gallbladder duplication, given the overall low incidence of this variant, recommendation for routine intraoperative cholangiography solely to rule out gallbladder duplication cannot be definitively recommended based on our review of the literature. Currently, preoperative MRCP is the study of choice when there is concern from historical facts or from other imaging of gallbladder duplication as it is noninvasive and has a high degree of detail, particularly with 3D reconstructions.14,16 At the time of surgery, the most critical step to avoid inadvertent ductal injury is clear visualization of ductal anatomy and obtaining the critical view of safety.17 Though this will also assist in identifying some cases of gallbladder duplication, given the great variation of duplication, it will not prevent missing some variants. In our case, extensive local scarring from the patient’s prior antrectomy and vagotomy along with lack of the use of intraoperative cholangiography likely contributed to missing his duplication at the time of his index cholecystectomy.

Undiagnosed gallbladder duplication can lead to additional morbidity related to common entities associated with gallbladder pathology, such as biliary colic, cholecystitis, cholangitis, and pancreatitis. Additionally, case reports in the literature have documented more rare associations, such as empyema, carcinoma, cholecystoenteric fistula, and torsion, all associated with a duplicated gallbladder.18-21 Once identified pre- or intraoperatively, it is generally recommended that all gallbladders be removed in symptomatic patients and that intraoperative cholangiography be done to assure complete resection of the duplicated gallbladders and to avoid injury to the biliary trees.22-25

Conclusions

Gallbladder duplication and other congenital biliary anatomic variations should be considered before a biliary operation and included in the differential diagnosis when evaluating patients who have clinical symptoms consistent with biliary pathology. In addition, intraoperative cholangiogram should be performed during cholecystectomy if the inferior liver edge cannot be visualized well, as in the case of this patient where a prior foregut operation resulted in extensive adhesive disease. Intraoperative cholangiogram also should be considered in patients whose preoperative imaging does not visualize the right upper quadrant well due to patient habitus. Doing so may identify gallbladder duplication and allow for complete cholecystectomy as well as proper identification and management of cystic duct variants. Awareness and consideration of duplicated biliary variants can help prevent intraoperative complications related to biliary anomalies and avoid the morbidity related to recurrent biliary disease and the need for repeat operative procedures.

Acknowledgments

We extend our thanks to Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Healthcare System and the Departments of Surgery and Radiology for their support of this case report, and Lorrie Langdale, MD, and Roger Tatum, MD, for their mentorship of this project

Gallbladder duplication is a congenital abnormality of the hepatobiliary system and often is not considered in the evaluation of a patient with right upper quadrant pain. Accuracy of the most commonly used imaging study to assess for biliary disease, abdominal ultrasound, is highly dependent on the skills of the ultrasonographer, and given its relative rarity, this condition is often not considered prior to planned cholecystectomy.1 Small case reviews found that < 50% of gallbladder duplications are diagnosed preoperatively despite use of ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan.2-4 Failure to recognize duplicate gallbladder anatomy in symptomatic patients may result in incomplete surgical management, an increase in perioperative complications, and years of morbidity due to unresolved symptoms. Once a patient has had a cholecystectomy, symptoms are presumed to be due to a nonbiliary etiology and an extensive, often repetitive, workup is pursued before “repeat cholecystectomy” is considered.5

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old man was referred to gastroenterology for recurrent episodic right upper quadrant pain. He reported intermittent both right and left upper abdominal pain that was variable in quality. At times it was associated with an empty stomach prior to meals; at other times, onset was 30 to 60 minutes after meals. The patient also reported significant flatulence and bloating and intermittent loose stools. Sixteen years before, he underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. He reported that the pain he experienced before the cholecystectomy never resolved after surgery but occurred less frequently. For the next 16 years, the patient did not seek evaluation of his ongoing but infrequent symptoms until his pain became a daily occurrence. The patient’s surgical history included a remote open vagotomy and antrectomy for peptic ulcer disease, laparoscopic appendectomy, and a laparoscopic cholecystectomy for reported biliary colic.

The gastroenterology evaluation included a colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD); both were benign and without findings specific to identify the etiology for the patient’s pain. The patient was given a course of rifaximin 1200 mg daily for 7 days for possible bacterial overgrowth and placed on a proton pump inhibitor twice daily. Neither of these interventions helped resolve the patient’s symptoms. Further workup was pursued by gastroenterology to include a right upper quadrant ultrasound that showed a structure most consistent with a small gallbladder containing a small polyp vs stone. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) also was performed and showed the presence of a small gallbladder with a small 2-mm filling defect and an otherwise benign biliary tree. MRCP images and EGD documented a Billroth 1 reconstruction at the time of his remote antrectomy and vagotomy (Figure 1).

The patient was referred to general surgery for consideration of a repeat cholecystectomy. He confirmed the history of intermittent upper abdominal pain for the past 16 years, which was similar to the symptoms he had experienced before his original laparoscopic cholecystectomy. On examination, the patient had a body mass index of 38, had a large upper midline incision from his prior antrectomy and vagotomy procedure, and several scars presumed to be port incision scars to the right lateral abdominal wall. Hospital records were obtained from the patient’s prior workup for biliary colic and cholecystectomy 16 years before. The preoperative abdominal ultrasound examination showed a mildly distended gallbladder but was notably described as “quite limited due to patient’s body habitus and liver is not well seen.” No additional imaging was documented in his presurgical evaluation notes and imaging records.

The operative report described a gallbladder that was densely adherent to adjacent fat and omental tissue with significant adhesions secondary to the prior vagotomy and antrectomy procedure. The cystic duct and artery were dissected free at the level of their junction with the gallbladder infundibulum. The cystic artery was divided with a harmonic scalpel. Following this the gallbladder body was dissected free from the liver bed in top-down fashion. A 0 Vicryl Endoloop suture was placed over the gallbladder and secured just past the origin of the cystic duct on the gallbladder infundibulum and the cystic duct divided above this suture. No surgical clips were used, which corresponded with the lack of surgical clips seen in imaging in his recent gastroenterology workup. No documentation of an intraoperative cholangiogram existed or was considered in the operative report.

The pathology report from this first cholecystectomy procedure noted the removed specimen to be an unopened 6-cm gallbladder containing 2 small yellow stones that otherwise were benign. At the time of this patient’s re-presentation to general surgery, there was suspicion that the patient’s prior surgical procedure had not been a cholecystectomy but rather a subtotal cholecystectomy. However, after appropriate workup and review of prior records, the patient had, indeed, previously undergone cholecystectomy and represented a rare case of gallbladder duplication resulting in abdominal pain for 16 years after his index operation.

The patient was consented for repeat cholecystectomy and underwent a laparoscopic lysis of adhesions, cholecystectomy, and intraoperative cholangiogram. Significant scarring was found at the liver undersurface that would have been exposed during the original laparoscopic resection of the gallbladder from its liver bed. Deeper to this, a small saccular structure was identified as the duplicate gallbladder (Figure 2). Though the visualized gallbladder was small with a deep intrahepatic lie, the critical view of safety was achieved and was without additional variation. An intraoperative cholangiogram was performed to determine whether residual ductal stumps or other additional evidence of the previously removed gallbladder could be identified. The cholangiogram showed clear visualization of the cystic duct, common bile duct, right and left hepatic ducts, and contrast into the duodenum without abnormal variants. There was no visualized accessory or secondary cystic duct stump seen on the cholangiogram (Figure 3). Pathology of the repeat cholecystectomy specimen confirmed a 3-cm gallbladder with a distinct duct leading out of the gallbladder and the presence of several gallstones. The patient had an uneventful recovery after the repeat laparoscopic cholecystectomy with complete resolution of his upper abdominal pain.

Discussion

The first reported human case of gallbladder duplication was noted in a sacrificial victim of Emperor Augustus in 31 BCE. Sherren reported the first documented case of double accessory gallbladder in a living human in 1911.1,6 Though the exact incidence of gallbladder duplication is not fully known due to primary documentation from case reports, incidence is approximately 1 in 4000 to 5000 people. It was first formally classified by Boyden in 1926.7 Further anatomic classification based on morphology and embryogenesis was delineated by Harlaftis and colleagues in 1977, establishing type 1 and 2 structures of a duplicated gallbladder.8 Type 1 duplicated gallbladder anatomy shares a single cystic duct, whereas in type 2 each gallbladder has its own cystic duct. Later reports and studies identified triple gallbladders as well as trabecular variants with the most common classification used currently being the modified Harlaftis classification.9,10

The case presented here most likely represents either a Y-shaped type 1 primordial gallbladder or a type 2 accessory gallbladder based on historical data and intraoperative cholangiogram findings at the time of repeat cholecystectomy. Gallbladder duplication is clinically indistinguishable from regular gallbladder pathology preoperatively and can only be identified on imaging or intraoperatively.11 Prior case reports and studies have found that it is frequently missed on preoperative abdominal ultrasonography and CT in up to 50% of cases.12-14

The differential diagnosis of gallbladder duplication seen on preoperative imaging includes a gallbladder diverticulum, choledochal cyst, focal adenonomyomatosis, Phrygian cap, or folded gallbladder.1,2 Historically, the most definitive test for gallbladder duplication has been either intraoperative cholangiography, which can also clarify biliary anatomy, or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with cholangiography.1,3 The debate over routine use of intraoperative cholangiography has been ongoing for the past several decades.15 Though intraoperative cholangiogram remains one of the most definitive tests for gallbladder duplication, given the overall low incidence of this variant, recommendation for routine intraoperative cholangiography solely to rule out gallbladder duplication cannot be definitively recommended based on our review of the literature. Currently, preoperative MRCP is the study of choice when there is concern from historical facts or from other imaging of gallbladder duplication as it is noninvasive and has a high degree of detail, particularly with 3D reconstructions.14,16 At the time of surgery, the most critical step to avoid inadvertent ductal injury is clear visualization of ductal anatomy and obtaining the critical view of safety.17 Though this will also assist in identifying some cases of gallbladder duplication, given the great variation of duplication, it will not prevent missing some variants. In our case, extensive local scarring from the patient’s prior antrectomy and vagotomy along with lack of the use of intraoperative cholangiography likely contributed to missing his duplication at the time of his index cholecystectomy.

Undiagnosed gallbladder duplication can lead to additional morbidity related to common entities associated with gallbladder pathology, such as biliary colic, cholecystitis, cholangitis, and pancreatitis. Additionally, case reports in the literature have documented more rare associations, such as empyema, carcinoma, cholecystoenteric fistula, and torsion, all associated with a duplicated gallbladder.18-21 Once identified pre- or intraoperatively, it is generally recommended that all gallbladders be removed in symptomatic patients and that intraoperative cholangiography be done to assure complete resection of the duplicated gallbladders and to avoid injury to the biliary trees.22-25

Conclusions

Gallbladder duplication and other congenital biliary anatomic variations should be considered before a biliary operation and included in the differential diagnosis when evaluating patients who have clinical symptoms consistent with biliary pathology. In addition, intraoperative cholangiogram should be performed during cholecystectomy if the inferior liver edge cannot be visualized well, as in the case of this patient where a prior foregut operation resulted in extensive adhesive disease. Intraoperative cholangiogram also should be considered in patients whose preoperative imaging does not visualize the right upper quadrant well due to patient habitus. Doing so may identify gallbladder duplication and allow for complete cholecystectomy as well as proper identification and management of cystic duct variants. Awareness and consideration of duplicated biliary variants can help prevent intraoperative complications related to biliary anomalies and avoid the morbidity related to recurrent biliary disease and the need for repeat operative procedures.

Acknowledgments

We extend our thanks to Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Healthcare System and the Departments of Surgery and Radiology for their support of this case report, and Lorrie Langdale, MD, and Roger Tatum, MD, for their mentorship of this project

1. Vezakis A, Pantiora E, Giannoulopoulos D, et al. A duplicated gallbladder in a patient presenting with acute cholangitis. A case study and a literature review. Ann Hepatol. 2019;18(1):240-245. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0012.7932

2. Barut Í, Tarhan ÖR, Dog^ru U, Bülbül M. Gallbladder duplication: diagnosed and treated by laparoscopy. Eur J Gen Med. 2006;3(3):142-145. doi:10.29333/ejgm/82396 3. Cozacov Y, Subhas G, Jacobs M, Parikh J. Total laparoscopic removal of accessory gallbladder: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;7(12):398-402. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v7.i12.398

4. Musleh MG, Burnett H, Rajashanker B, Ammori BJ. Laparoscopic double cholecystectomy for duplicated gallbladder: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;41:502-504. Published 2017 Nov 27. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.11.046

5. Walbolt TD, Lalezarzadeh F. Laparoscopic management of a duplicated gallbladder: a case study and anatomic history. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21(3):e156-e158. doi:10.1097/SLE.0b013e31821d47ce

6. Sherren J. A double gall-bladder removed by operation. Ann Surg. 1911;54(2):204-205. doi:10.1097/00000658-191108000-00009

7. Boyden EA. The accessory gall-bladder—an embryological and comparative study of aberrant biliary vesicles occurring in man and the domestic mammals. Am J Anat. 1926; 38(2):177-231. doi:10.1002/aja.1000380202

8. Harlaftis N, Gray SW, Skandalakis JE. Multiple gallbladders. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1977;145(6):928-934.

9. Kim RD, Zendejas I, Velopulos C, et al. Duplicate gallbladder arising from the left hepatic duct: report of a case. Surg Today. 2009;39(6):536-539. doi:10.1007/s00595-008-3878-4

10. Causey MW, Miller S, Fernelius CA, Burgess JR, Brown TA, Newton C. Gallbladder duplication: evaluation, treatment, and classification. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(2):443-446. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.12.015

11. Apolo Romero EX, Gálvez Salazar PF, Estrada Chandi JA, et al. Gallbladder duplication and cholecystitis. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018(7):rjy158. Published 2018 Jul 3. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjy158

12. Gorecki PJ, Andrei VE, Musacchio T, Schein M. Double gallbladder originating from left hepatic duct: a case report and review of literature. JSLS. 1998;2(4):337-339.

13. Cueto García J, Weber A, Serrano Berry F, Tanur Tatz B. Double gallbladder treated successfully by laparoscopy. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1993;3(2):153-155. doi:10.1089/lps.1993.3.153

14. Fazio V, Damiano G, Palumbo VD, et al. An unexpected surprise at the end of a “quiet” cholecystectomy. A case report and review of the literature. Ann Ital Chir. 2012;83(3):265-267.

15. Flum DR, Dellinger EP, Cheadle A, Chan L, Koepsell T. Intraoperative cholangiography and risk of common bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. JAMA. 2003;289(13):1639-1644. doi:10.1001/jama.289.13.1639

16. Botsford A, McKay K, Hartery A, Hapgood C. MRCP imaging of duplicate gallbladder: a case report and review of the literature. Surg Radiol Anat. 2015;37(5):425-429. doi:10.1007/s00276-015-1456-1

17. Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180(1):101-125.

18. Raymond SW, Thrift CB. Carcinoma of a duplicated gall bladder. Ill Med J. 1956;110(5):239-240.

19. Cunningham JJ. Empyema of a duplicated gallbladder: echographic findings. J Clin Ultrasound. 1980;8(6):511-512. doi:10.1002/jcu.1870080612

20. Recht W. Torsion of a double gallbladder; a report of a case and a review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1952;39(156):342-344. doi:10.1002/bjs.18003915616

21. Ritchie AW, Crucioli V. Double gallbladder with cholecystocolic fistula: a case report. Br J Surg. 1980;67(2):145-146. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800670226

22. Shapiro T, Rennie W. Duplicate gallbladder cholecystitis after open cholecystectomy. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(5):584-587. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70348-3

23. Hobbs MS, Mai Q, Knuiman MW, Fletcher DR, Ridout SC. Surgeon experience and trends in intraoperative complications in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2006;93(7):844-853. doi:10.1002/bjs.5333

24. Davidoff AM, Pappas TN, Murray EA, et al. Mechanisms of major biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 1992;215(3):196-202. doi:10.1097/00000658-199203000-00002

25. Flowers JL, Zucker KA, Graham SM, Scovill WA, Imbembo AL, Bailey RW. Laparoscopic cholangiography. Results and indications. Ann Surg. 1992;215(3):209-216. doi:10.1097/00000658-199203000-00004

1. Vezakis A, Pantiora E, Giannoulopoulos D, et al. A duplicated gallbladder in a patient presenting with acute cholangitis. A case study and a literature review. Ann Hepatol. 2019;18(1):240-245. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0012.7932

2. Barut Í, Tarhan ÖR, Dog^ru U, Bülbül M. Gallbladder duplication: diagnosed and treated by laparoscopy. Eur J Gen Med. 2006;3(3):142-145. doi:10.29333/ejgm/82396 3. Cozacov Y, Subhas G, Jacobs M, Parikh J. Total laparoscopic removal of accessory gallbladder: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;7(12):398-402. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v7.i12.398

4. Musleh MG, Burnett H, Rajashanker B, Ammori BJ. Laparoscopic double cholecystectomy for duplicated gallbladder: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;41:502-504. Published 2017 Nov 27. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.11.046

5. Walbolt TD, Lalezarzadeh F. Laparoscopic management of a duplicated gallbladder: a case study and anatomic history. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21(3):e156-e158. doi:10.1097/SLE.0b013e31821d47ce

6. Sherren J. A double gall-bladder removed by operation. Ann Surg. 1911;54(2):204-205. doi:10.1097/00000658-191108000-00009

7. Boyden EA. The accessory gall-bladder—an embryological and comparative study of aberrant biliary vesicles occurring in man and the domestic mammals. Am J Anat. 1926; 38(2):177-231. doi:10.1002/aja.1000380202

8. Harlaftis N, Gray SW, Skandalakis JE. Multiple gallbladders. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1977;145(6):928-934.

9. Kim RD, Zendejas I, Velopulos C, et al. Duplicate gallbladder arising from the left hepatic duct: report of a case. Surg Today. 2009;39(6):536-539. doi:10.1007/s00595-008-3878-4

10. Causey MW, Miller S, Fernelius CA, Burgess JR, Brown TA, Newton C. Gallbladder duplication: evaluation, treatment, and classification. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(2):443-446. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.12.015

11. Apolo Romero EX, Gálvez Salazar PF, Estrada Chandi JA, et al. Gallbladder duplication and cholecystitis. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018(7):rjy158. Published 2018 Jul 3. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjy158

12. Gorecki PJ, Andrei VE, Musacchio T, Schein M. Double gallbladder originating from left hepatic duct: a case report and review of literature. JSLS. 1998;2(4):337-339.

13. Cueto García J, Weber A, Serrano Berry F, Tanur Tatz B. Double gallbladder treated successfully by laparoscopy. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1993;3(2):153-155. doi:10.1089/lps.1993.3.153

14. Fazio V, Damiano G, Palumbo VD, et al. An unexpected surprise at the end of a “quiet” cholecystectomy. A case report and review of the literature. Ann Ital Chir. 2012;83(3):265-267.

15. Flum DR, Dellinger EP, Cheadle A, Chan L, Koepsell T. Intraoperative cholangiography and risk of common bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. JAMA. 2003;289(13):1639-1644. doi:10.1001/jama.289.13.1639

16. Botsford A, McKay K, Hartery A, Hapgood C. MRCP imaging of duplicate gallbladder: a case report and review of the literature. Surg Radiol Anat. 2015;37(5):425-429. doi:10.1007/s00276-015-1456-1

17. Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180(1):101-125.

18. Raymond SW, Thrift CB. Carcinoma of a duplicated gall bladder. Ill Med J. 1956;110(5):239-240.

19. Cunningham JJ. Empyema of a duplicated gallbladder: echographic findings. J Clin Ultrasound. 1980;8(6):511-512. doi:10.1002/jcu.1870080612

20. Recht W. Torsion of a double gallbladder; a report of a case and a review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1952;39(156):342-344. doi:10.1002/bjs.18003915616

21. Ritchie AW, Crucioli V. Double gallbladder with cholecystocolic fistula: a case report. Br J Surg. 1980;67(2):145-146. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800670226

22. Shapiro T, Rennie W. Duplicate gallbladder cholecystitis after open cholecystectomy. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(5):584-587. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70348-3

23. Hobbs MS, Mai Q, Knuiman MW, Fletcher DR, Ridout SC. Surgeon experience and trends in intraoperative complications in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2006;93(7):844-853. doi:10.1002/bjs.5333

24. Davidoff AM, Pappas TN, Murray EA, et al. Mechanisms of major biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 1992;215(3):196-202. doi:10.1097/00000658-199203000-00002

25. Flowers JL, Zucker KA, Graham SM, Scovill WA, Imbembo AL, Bailey RW. Laparoscopic cholangiography. Results and indications. Ann Surg. 1992;215(3):209-216. doi:10.1097/00000658-199203000-00004

Symptoms of fatigue and abdominal pain

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of Crohn disease.

Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that is becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide. It is estimated to affect three to 20 persons per 100,000. When not effectively managed, Crohn disease is associated with substantial morbidity and significant impairments in lifestyle and daily activities during flares and remissions. It is characterized by a transmural granulomatous inflammation that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract — usually, the ileum, colon, or both.

Abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue are often prominent symptoms in patients with Crohn disease. Crampy or steady right lower quadrant or periumbilical pain may develop; the pain both precedes and may be partially relieved by defecation. Diarrhea is frequently intermittent and is not usually grossly bloody. Diffuse abdominal pain accompanied by mucus, blood, and pus in the stool may be reported by patients if the colon is involved. Involvement of the small intestine usually presents with evidence of malabsorption, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and anorexia, which may be subtle early in the disease course. Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are more common in patients with gastroduodenal involvement, whereas debilitating perirectal pain, malodorous discharge from a fistula, and disfiguring scars from active disease or previous surgery may be present in patients with perianal disease. Patients may also present with symptoms suggestive of intestinal obstruction, or with anemia, recurrent fistulas, or fever.

As stated in guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), multiple streams of information, including history and physical examination, laboratory tests, endoscopy results, pathology findings, and radiographic tests, must be incorporated to arrive at a clinical diagnosis of Crohn disease. In most cases, the presence of chronic intestinal inflammation solidifies a diagnosis of Crohn disease. However, it can be challenging to differentiate Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis, particularly when the inflammation is confined to the colon. Bleeding is much more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn disease, whereas intestinal obstruction is common in Crohn disease and uncommon in ulcerative colitis. Fistulae and perianal disease are common in Crohn disease but are absent or rare in ulcerative colitis. Moreover, weight loss is typical in patients with Crohn disease but is uncommon in ulcerative colitis.

Additional diagnostic clues for Crohn disease include discontinuous involvement with skip areas; sparing of the rectum; deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Only a small percentage of patients have granulomas on biopsy. The presence of ileitis in a patient with extensive colitis (ie, backwash ileitis) can also make determining the inflammatory bowel disease subtype challenging.

Arthropathy (both axial and peripheral) is a classic extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease, as are dermatologic manifestations (including pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum); ocular manifestations (including uveitis, scleritis, and episcleritis); and hepatobiliary disease (ie, primary sclerosing cholangitis). Less common extraintestinal complications of Crohn disease include:

• Thromboembolism (both venous and arterial)

• Metabolic bone diseases

• Osteonecrosis

• Cholelithiasis

• Nephrolithiasis.

Only 20%-30% of patients with Crohn disease will have a nonprogressive or indolent course. Clinical features that are associated with a high risk for progressive disease burden include young age at diagnosis, initial extensive bowel involvement, ileal or ileocolonic involvement, perianal or severe rectal disease, and a penetrating or stenosis disease phenotype.

According to the AGA's Clinical Care Pathway for Crohn Disease, clinical laboratory testing in a patient with symptoms of Crohn disease should include:

• Complete blood cell count (anemia and leukocytosis are the most common abnormalities seen)

• C-reactive protein (not a specific marker, but may correlate with disease activity in a subset of patients)

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Fecal calprotectin (may correlate with intestinal inflammation; can help distinguish inflammatory bowel disorders from irritable bowel syndrome)

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (may be elevated in some patients; not a specific marker)

Ileocolonoscopy with biopsies should be performed in the evaluation of patients with suspected Crohn disease, and disease distribution and severity should be documented at the time of diagnosis. Biopsies of uninvolved mucosa are recommended to identify the extent of histologic disease.

Consult the AGA guidelines for more extensive details on the workup for Crohn disease, including indications for additional imaging and phenotypic classification.

In recent years, outcomes in Crohn disease have improved, which is probably the result of earlier diagnosis, increasing use of biologics, escalation or alteration of therapy based on disease severity, and endoscopic management of colorectal cancer. As noted above, Crohn disease includes multiple phenotypes, characterized by the Montreal Classification as stricturing, penetrating, inflammatory (nonstricturing and nonpenetrating), and perianal disease. Each of these phenotypes can present with a range in severity from mild to severe disease.

In general, therapeutic recommendations for patients are based on disease location, disease severity, disease-associated complications, and future disease prognosis and are individualized according to the symptomatic response and tolerance. Current therapeutic approaches should be considered a sequential continuum to treat acute disease or induce clinical remission, then maintain response or remission. Pharmacologic options include antidiarrheal agents, anti-inflammatory therapies (eg, sulfasalazine, mesalamine), corticosteroids (a short course for severe disease), biologic therapies (eg, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, natalizumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab), and occasionally immunosuppressive agents (tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil). In addition to their 2014 guidelines on the management of Crohn disease in adults, the AGA recently released guidelines specific to the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and fistulizing Crohn disease.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of Crohn disease.

Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that is becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide. It is estimated to affect three to 20 persons per 100,000. When not effectively managed, Crohn disease is associated with substantial morbidity and significant impairments in lifestyle and daily activities during flares and remissions. It is characterized by a transmural granulomatous inflammation that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract — usually, the ileum, colon, or both.

Abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue are often prominent symptoms in patients with Crohn disease. Crampy or steady right lower quadrant or periumbilical pain may develop; the pain both precedes and may be partially relieved by defecation. Diarrhea is frequently intermittent and is not usually grossly bloody. Diffuse abdominal pain accompanied by mucus, blood, and pus in the stool may be reported by patients if the colon is involved. Involvement of the small intestine usually presents with evidence of malabsorption, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and anorexia, which may be subtle early in the disease course. Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are more common in patients with gastroduodenal involvement, whereas debilitating perirectal pain, malodorous discharge from a fistula, and disfiguring scars from active disease or previous surgery may be present in patients with perianal disease. Patients may also present with symptoms suggestive of intestinal obstruction, or with anemia, recurrent fistulas, or fever.

As stated in guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), multiple streams of information, including history and physical examination, laboratory tests, endoscopy results, pathology findings, and radiographic tests, must be incorporated to arrive at a clinical diagnosis of Crohn disease. In most cases, the presence of chronic intestinal inflammation solidifies a diagnosis of Crohn disease. However, it can be challenging to differentiate Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis, particularly when the inflammation is confined to the colon. Bleeding is much more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn disease, whereas intestinal obstruction is common in Crohn disease and uncommon in ulcerative colitis. Fistulae and perianal disease are common in Crohn disease but are absent or rare in ulcerative colitis. Moreover, weight loss is typical in patients with Crohn disease but is uncommon in ulcerative colitis.

Additional diagnostic clues for Crohn disease include discontinuous involvement with skip areas; sparing of the rectum; deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Only a small percentage of patients have granulomas on biopsy. The presence of ileitis in a patient with extensive colitis (ie, backwash ileitis) can also make determining the inflammatory bowel disease subtype challenging.

Arthropathy (both axial and peripheral) is a classic extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease, as are dermatologic manifestations (including pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum); ocular manifestations (including uveitis, scleritis, and episcleritis); and hepatobiliary disease (ie, primary sclerosing cholangitis). Less common extraintestinal complications of Crohn disease include:

• Thromboembolism (both venous and arterial)

• Metabolic bone diseases

• Osteonecrosis

• Cholelithiasis

• Nephrolithiasis.

Only 20%-30% of patients with Crohn disease will have a nonprogressive or indolent course. Clinical features that are associated with a high risk for progressive disease burden include young age at diagnosis, initial extensive bowel involvement, ileal or ileocolonic involvement, perianal or severe rectal disease, and a penetrating or stenosis disease phenotype.

According to the AGA's Clinical Care Pathway for Crohn Disease, clinical laboratory testing in a patient with symptoms of Crohn disease should include:

• Complete blood cell count (anemia and leukocytosis are the most common abnormalities seen)

• C-reactive protein (not a specific marker, but may correlate with disease activity in a subset of patients)

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Fecal calprotectin (may correlate with intestinal inflammation; can help distinguish inflammatory bowel disorders from irritable bowel syndrome)

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (may be elevated in some patients; not a specific marker)

Ileocolonoscopy with biopsies should be performed in the evaluation of patients with suspected Crohn disease, and disease distribution and severity should be documented at the time of diagnosis. Biopsies of uninvolved mucosa are recommended to identify the extent of histologic disease.

Consult the AGA guidelines for more extensive details on the workup for Crohn disease, including indications for additional imaging and phenotypic classification.

In recent years, outcomes in Crohn disease have improved, which is probably the result of earlier diagnosis, increasing use of biologics, escalation or alteration of therapy based on disease severity, and endoscopic management of colorectal cancer. As noted above, Crohn disease includes multiple phenotypes, characterized by the Montreal Classification as stricturing, penetrating, inflammatory (nonstricturing and nonpenetrating), and perianal disease. Each of these phenotypes can present with a range in severity from mild to severe disease.

In general, therapeutic recommendations for patients are based on disease location, disease severity, disease-associated complications, and future disease prognosis and are individualized according to the symptomatic response and tolerance. Current therapeutic approaches should be considered a sequential continuum to treat acute disease or induce clinical remission, then maintain response or remission. Pharmacologic options include antidiarrheal agents, anti-inflammatory therapies (eg, sulfasalazine, mesalamine), corticosteroids (a short course for severe disease), biologic therapies (eg, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, natalizumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab), and occasionally immunosuppressive agents (tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil). In addition to their 2014 guidelines on the management of Crohn disease in adults, the AGA recently released guidelines specific to the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and fistulizing Crohn disease.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of Crohn disease.

Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that is becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide. It is estimated to affect three to 20 persons per 100,000. When not effectively managed, Crohn disease is associated with substantial morbidity and significant impairments in lifestyle and daily activities during flares and remissions. It is characterized by a transmural granulomatous inflammation that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract — usually, the ileum, colon, or both.

Abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue are often prominent symptoms in patients with Crohn disease. Crampy or steady right lower quadrant or periumbilical pain may develop; the pain both precedes and may be partially relieved by defecation. Diarrhea is frequently intermittent and is not usually grossly bloody. Diffuse abdominal pain accompanied by mucus, blood, and pus in the stool may be reported by patients if the colon is involved. Involvement of the small intestine usually presents with evidence of malabsorption, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and anorexia, which may be subtle early in the disease course. Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are more common in patients with gastroduodenal involvement, whereas debilitating perirectal pain, malodorous discharge from a fistula, and disfiguring scars from active disease or previous surgery may be present in patients with perianal disease. Patients may also present with symptoms suggestive of intestinal obstruction, or with anemia, recurrent fistulas, or fever.

As stated in guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), multiple streams of information, including history and physical examination, laboratory tests, endoscopy results, pathology findings, and radiographic tests, must be incorporated to arrive at a clinical diagnosis of Crohn disease. In most cases, the presence of chronic intestinal inflammation solidifies a diagnosis of Crohn disease. However, it can be challenging to differentiate Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis, particularly when the inflammation is confined to the colon. Bleeding is much more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn disease, whereas intestinal obstruction is common in Crohn disease and uncommon in ulcerative colitis. Fistulae and perianal disease are common in Crohn disease but are absent or rare in ulcerative colitis. Moreover, weight loss is typical in patients with Crohn disease but is uncommon in ulcerative colitis.

Additional diagnostic clues for Crohn disease include discontinuous involvement with skip areas; sparing of the rectum; deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Only a small percentage of patients have granulomas on biopsy. The presence of ileitis in a patient with extensive colitis (ie, backwash ileitis) can also make determining the inflammatory bowel disease subtype challenging.

Arthropathy (both axial and peripheral) is a classic extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease, as are dermatologic manifestations (including pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum); ocular manifestations (including uveitis, scleritis, and episcleritis); and hepatobiliary disease (ie, primary sclerosing cholangitis). Less common extraintestinal complications of Crohn disease include:

• Thromboembolism (both venous and arterial)

• Metabolic bone diseases

• Osteonecrosis

• Cholelithiasis

• Nephrolithiasis.

Only 20%-30% of patients with Crohn disease will have a nonprogressive or indolent course. Clinical features that are associated with a high risk for progressive disease burden include young age at diagnosis, initial extensive bowel involvement, ileal or ileocolonic involvement, perianal or severe rectal disease, and a penetrating or stenosis disease phenotype.

According to the AGA's Clinical Care Pathway for Crohn Disease, clinical laboratory testing in a patient with symptoms of Crohn disease should include:

• Complete blood cell count (anemia and leukocytosis are the most common abnormalities seen)

• C-reactive protein (not a specific marker, but may correlate with disease activity in a subset of patients)

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Fecal calprotectin (may correlate with intestinal inflammation; can help distinguish inflammatory bowel disorders from irritable bowel syndrome)

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (may be elevated in some patients; not a specific marker)

Ileocolonoscopy with biopsies should be performed in the evaluation of patients with suspected Crohn disease, and disease distribution and severity should be documented at the time of diagnosis. Biopsies of uninvolved mucosa are recommended to identify the extent of histologic disease.

Consult the AGA guidelines for more extensive details on the workup for Crohn disease, including indications for additional imaging and phenotypic classification.

In recent years, outcomes in Crohn disease have improved, which is probably the result of earlier diagnosis, increasing use of biologics, escalation or alteration of therapy based on disease severity, and endoscopic management of colorectal cancer. As noted above, Crohn disease includes multiple phenotypes, characterized by the Montreal Classification as stricturing, penetrating, inflammatory (nonstricturing and nonpenetrating), and perianal disease. Each of these phenotypes can present with a range in severity from mild to severe disease.

In general, therapeutic recommendations for patients are based on disease location, disease severity, disease-associated complications, and future disease prognosis and are individualized according to the symptomatic response and tolerance. Current therapeutic approaches should be considered a sequential continuum to treat acute disease or induce clinical remission, then maintain response or remission. Pharmacologic options include antidiarrheal agents, anti-inflammatory therapies (eg, sulfasalazine, mesalamine), corticosteroids (a short course for severe disease), biologic therapies (eg, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, natalizumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab), and occasionally immunosuppressive agents (tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil). In addition to their 2014 guidelines on the management of Crohn disease in adults, the AGA recently released guidelines specific to the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and fistulizing Crohn disease.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

An 18-year-old man presents with increasing fatigue, prolonged diarrhea, and intermittent abdominal pain. The patient is nearly 6 months into his freshman year at the local university, where he resides. He states that his symptoms began approximately 12 weeks earlier. He describes passing an average of eight to 10 watery stools per day, including nocturnal diarrhea, with no noticeable blood or mucus and no rectal urgency. The patient has lost 13 lb since his symptoms began, which he attributes to the diarrhea and to adjusting to dormitory life and institutional meals. He also notes a slight decrease in appetite. His symptoms typically begin within an hour of awakening, after he has had his morning meal. The patient admits to smoking and occasional use of cannabis. He is not taking any medications or over-the-counter products.

Physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 120/70 mm Hg, pulse of 74 beats/min, and temperature of 98.4 °F (37 °C). His weight is 139 lb and his height is 5 ft 10 in. Diffuse abdominal tenderness is present; inspection of the perianal region and rectal examination are normal. There is a positive first-degree family history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and inflammatory bowel disease. His paternal grandmother died of colon cancer at 77 years of age and his maternal grandfather died of ischemic stroke at 82 years of age.

Laboratory findings are all within the normal range and stool testing excludes infectious etiologies. Subsequent endoscopic findings include multiple colonic ulcers longitudinally arranged with a cobblestone appearance.

Crohn Disease: Presentation and Diagnosis

Unfavorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer: EBRT plus BT improve survival

Key clinical point: External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) plus brachytherapy (BT) boost improves survival in patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer vs. brachytherapy alone.

Major finding: The median follow-up was 68 months. In weight-adjusted analysis, EBRT plus BT (hazard ratio [HR] 0.82; P = .000005) vs. BT alone significantly improves overall survival (OS). At 10 years, the OS rate was 62.4% and 69.3% in the BT alone and EBRT plus BT groups, respectively (P < .0001).

Study details: This was a retrospective study of 11,721 patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer diagnosed between 2004 and 2015. The patients received either definitive BT without androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), BT with ADT, EBRT with ADT, or EBRT with BT and ADT.

Disclosures: This work was supported by Washington University in St. Louis Medical School and Barnes Jewish Hospital. The authors received advisory/consulting/scientific fees and honoraria outside this work.

Source: Andruska N et al. Brachytherapy. 2022 (Feb 2). Doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2021.12.008.

Key clinical point: External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) plus brachytherapy (BT) boost improves survival in patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer vs. brachytherapy alone.

Major finding: The median follow-up was 68 months. In weight-adjusted analysis, EBRT plus BT (hazard ratio [HR] 0.82; P = .000005) vs. BT alone significantly improves overall survival (OS). At 10 years, the OS rate was 62.4% and 69.3% in the BT alone and EBRT plus BT groups, respectively (P < .0001).

Study details: This was a retrospective study of 11,721 patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer diagnosed between 2004 and 2015. The patients received either definitive BT without androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), BT with ADT, EBRT with ADT, or EBRT with BT and ADT.

Disclosures: This work was supported by Washington University in St. Louis Medical School and Barnes Jewish Hospital. The authors received advisory/consulting/scientific fees and honoraria outside this work.

Source: Andruska N et al. Brachytherapy. 2022 (Feb 2). Doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2021.12.008.

Key clinical point: External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) plus brachytherapy (BT) boost improves survival in patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer vs. brachytherapy alone.

Major finding: The median follow-up was 68 months. In weight-adjusted analysis, EBRT plus BT (hazard ratio [HR] 0.82; P = .000005) vs. BT alone significantly improves overall survival (OS). At 10 years, the OS rate was 62.4% and 69.3% in the BT alone and EBRT plus BT groups, respectively (P < .0001).

Study details: This was a retrospective study of 11,721 patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer diagnosed between 2004 and 2015. The patients received either definitive BT without androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), BT with ADT, EBRT with ADT, or EBRT with BT and ADT.

Disclosures: This work was supported by Washington University in St. Louis Medical School and Barnes Jewish Hospital. The authors received advisory/consulting/scientific fees and honoraria outside this work.

Source: Andruska N et al. Brachytherapy. 2022 (Feb 2). Doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2021.12.008.

Intermediate-/high-risk prostate cancer: Focal HIFU provides good control

Key clinical point: Focal high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) shows good cancer control in patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer.

Major finding: At 7 years, failure-free survival was 69% (95% CI 64%-74%). In patients with intermediate- and high-risk cancers, failure-free survival at 7 years was 68% (95% CI 62%-75%) and 65% (95% CI 56%-74%), respectively.

Study details: This was a study of 1,379 patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer including intermediate- (65%) and high-risk (28%) categories from a prospective registry who received focal therapy using HIFU during 2005-2020.

Disclosures: This work was supported by Sonacare Inc. The authors received research funding, consulting/advisory fees, and travel grants. Some of the authors were paid proctors to give training on the procedures.

Source: Reddy D et al. Eur Urol. 2022 (Feb 3). Doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.01.005.

Key clinical point: Focal high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) shows good cancer control in patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer.

Major finding: At 7 years, failure-free survival was 69% (95% CI 64%-74%). In patients with intermediate- and high-risk cancers, failure-free survival at 7 years was 68% (95% CI 62%-75%) and 65% (95% CI 56%-74%), respectively.

Study details: This was a study of 1,379 patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer including intermediate- (65%) and high-risk (28%) categories from a prospective registry who received focal therapy using HIFU during 2005-2020.

Disclosures: This work was supported by Sonacare Inc. The authors received research funding, consulting/advisory fees, and travel grants. Some of the authors were paid proctors to give training on the procedures.

Source: Reddy D et al. Eur Urol. 2022 (Feb 3). Doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.01.005.

Key clinical point: Focal high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) shows good cancer control in patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer.

Major finding: At 7 years, failure-free survival was 69% (95% CI 64%-74%). In patients with intermediate- and high-risk cancers, failure-free survival at 7 years was 68% (95% CI 62%-75%) and 65% (95% CI 56%-74%), respectively.

Study details: This was a study of 1,379 patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer including intermediate- (65%) and high-risk (28%) categories from a prospective registry who received focal therapy using HIFU during 2005-2020.

Disclosures: This work was supported by Sonacare Inc. The authors received research funding, consulting/advisory fees, and travel grants. Some of the authors were paid proctors to give training on the procedures.

Source: Reddy D et al. Eur Urol. 2022 (Feb 3). Doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.01.005.

Beta-blocker use at surgery lowers prostate cancer recurrence risk

Key clinical point: Use of nonselective beta-blockers at the time of radical prostatectomy is associated with a lower odds of treatment initiation for recurrence in patients with prostate cancer.

Major finding: The use of nonselective beta-blockers at the time of surgery was associated with a significantly lower odds of treatment for cancer recurrence (adjusted hazard ratio 0.64; P = .03). The most common nonselective beta-blockers used were carvedilol (56.9%) and propranolol (25.4%).

Study details: This was a retrospective cohort study of 11,117 patients with prostate cancer who underwent radical prostatectomy between 2008 and 2015.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Norwegian Cancer Society. The authors received grants from the Norwegian Cancer Society during this work.

Source: Sivanesan S et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2022 (Jan 26). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.45230.

Key clinical point: Use of nonselective beta-blockers at the time of radical prostatectomy is associated with a lower odds of treatment initiation for recurrence in patients with prostate cancer.

Major finding: The use of nonselective beta-blockers at the time of surgery was associated with a significantly lower odds of treatment for cancer recurrence (adjusted hazard ratio 0.64; P = .03). The most common nonselective beta-blockers used were carvedilol (56.9%) and propranolol (25.4%).

Study details: This was a retrospective cohort study of 11,117 patients with prostate cancer who underwent radical prostatectomy between 2008 and 2015.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Norwegian Cancer Society. The authors received grants from the Norwegian Cancer Society during this work.