User login

No effect of initial glucocorticoid bridging on glucocorticoid use over time in RA

Key clinical point: In patients with newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis (RA), initial glucocorticoid bridging (GB) led to more rapid clinical improvements than non-bridging, without any apparent risk for increased glucocorticoid use after the intended bridging period.

Major finding: The risk of using glucocorticoids at 12 months was higher in the GB vs non-bridging group, but this risk reduced over time and was not significantly different at 18 and 24 months. The cumulative doses did not differ significantly between groups after the planned bridging schedule. Patients in the GB group showed more rapid improvements in the mean Disease Activity Score of 28 Joints during the first 6 months (P < .001).

Study details: This individual patient data meta-analysis combined data from three randomized clinical trials and included 625 patients with newly diagnosed RA who received conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs with (n = 252) or without (n = 373) initial GB.

Disclosures: This study did not declare any specific funding source. Some authors declared receiving consultancy or speaker honoraria, fees, or grants from or providing expert advice or testimony for or serving as chair for various sources.

Source: van Ouwerkerk L et al. Initial glucocorticoid bridging in rheumatoid arthritis: Does it affect glucocorticoid use over time? Ann Rheum Dis. 2023 (Aug 22). doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-224270

Key clinical point: In patients with newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis (RA), initial glucocorticoid bridging (GB) led to more rapid clinical improvements than non-bridging, without any apparent risk for increased glucocorticoid use after the intended bridging period.

Major finding: The risk of using glucocorticoids at 12 months was higher in the GB vs non-bridging group, but this risk reduced over time and was not significantly different at 18 and 24 months. The cumulative doses did not differ significantly between groups after the planned bridging schedule. Patients in the GB group showed more rapid improvements in the mean Disease Activity Score of 28 Joints during the first 6 months (P < .001).

Study details: This individual patient data meta-analysis combined data from three randomized clinical trials and included 625 patients with newly diagnosed RA who received conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs with (n = 252) or without (n = 373) initial GB.

Disclosures: This study did not declare any specific funding source. Some authors declared receiving consultancy or speaker honoraria, fees, or grants from or providing expert advice or testimony for or serving as chair for various sources.

Source: van Ouwerkerk L et al. Initial glucocorticoid bridging in rheumatoid arthritis: Does it affect glucocorticoid use over time? Ann Rheum Dis. 2023 (Aug 22). doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-224270

Key clinical point: In patients with newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis (RA), initial glucocorticoid bridging (GB) led to more rapid clinical improvements than non-bridging, without any apparent risk for increased glucocorticoid use after the intended bridging period.

Major finding: The risk of using glucocorticoids at 12 months was higher in the GB vs non-bridging group, but this risk reduced over time and was not significantly different at 18 and 24 months. The cumulative doses did not differ significantly between groups after the planned bridging schedule. Patients in the GB group showed more rapid improvements in the mean Disease Activity Score of 28 Joints during the first 6 months (P < .001).

Study details: This individual patient data meta-analysis combined data from three randomized clinical trials and included 625 patients with newly diagnosed RA who received conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs with (n = 252) or without (n = 373) initial GB.

Disclosures: This study did not declare any specific funding source. Some authors declared receiving consultancy or speaker honoraria, fees, or grants from or providing expert advice or testimony for or serving as chair for various sources.

Source: van Ouwerkerk L et al. Initial glucocorticoid bridging in rheumatoid arthritis: Does it affect glucocorticoid use over time? Ann Rheum Dis. 2023 (Aug 22). doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-224270

No effect of initial glucocorticoid bridging on glucocorticoid use over time in RA

Key clinical point: In patients with newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis (RA), initial glucocorticoid bridging (GB) led to more rapid clinical improvements than non-bridging, without any apparent risk for increased glucocorticoid use after the intended bridging period.

Major finding: The risk of using glucocorticoids at 12 months was higher in the GB vs non-bridging group, but this risk reduced over time and was not significantly different at 18 and 24 months. The cumulative doses did not differ significantly between groups after the planned bridging schedule. Patients in the GB group showed more rapid improvements in the mean Disease Activity Score of 28 Joints during the first 6 months (P < .001).

Study details: This individual patient data meta-analysis combined data from three randomized clinical trials and included 625 patients with newly diagnosed RA who received conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs with (n = 252) or without (n = 373) initial GB.

Disclosures: This study did not declare any specific funding source. Some authors declared receiving consultancy or speaker honoraria, fees, or grants from or providing expert advice or testimony for or serving as chair for various sources.

Source: van Ouwerkerk L et al. Initial glucocorticoid bridging in rheumatoid arthritis: Does it affect glucocorticoid use over time? Ann Rheum Dis. 2023 (Aug 22). doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-224270

Key clinical point: In patients with newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis (RA), initial glucocorticoid bridging (GB) led to more rapid clinical improvements than non-bridging, without any apparent risk for increased glucocorticoid use after the intended bridging period.

Major finding: The risk of using glucocorticoids at 12 months was higher in the GB vs non-bridging group, but this risk reduced over time and was not significantly different at 18 and 24 months. The cumulative doses did not differ significantly between groups after the planned bridging schedule. Patients in the GB group showed more rapid improvements in the mean Disease Activity Score of 28 Joints during the first 6 months (P < .001).

Study details: This individual patient data meta-analysis combined data from three randomized clinical trials and included 625 patients with newly diagnosed RA who received conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs with (n = 252) or without (n = 373) initial GB.

Disclosures: This study did not declare any specific funding source. Some authors declared receiving consultancy or speaker honoraria, fees, or grants from or providing expert advice or testimony for or serving as chair for various sources.

Source: van Ouwerkerk L et al. Initial glucocorticoid bridging in rheumatoid arthritis: Does it affect glucocorticoid use over time? Ann Rheum Dis. 2023 (Aug 22). doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-224270

Key clinical point: In patients with newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis (RA), initial glucocorticoid bridging (GB) led to more rapid clinical improvements than non-bridging, without any apparent risk for increased glucocorticoid use after the intended bridging period.

Major finding: The risk of using glucocorticoids at 12 months was higher in the GB vs non-bridging group, but this risk reduced over time and was not significantly different at 18 and 24 months. The cumulative doses did not differ significantly between groups after the planned bridging schedule. Patients in the GB group showed more rapid improvements in the mean Disease Activity Score of 28 Joints during the first 6 months (P < .001).

Study details: This individual patient data meta-analysis combined data from three randomized clinical trials and included 625 patients with newly diagnosed RA who received conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs with (n = 252) or without (n = 373) initial GB.

Disclosures: This study did not declare any specific funding source. Some authors declared receiving consultancy or speaker honoraria, fees, or grants from or providing expert advice or testimony for or serving as chair for various sources.

Source: van Ouwerkerk L et al. Initial glucocorticoid bridging in rheumatoid arthritis: Does it affect glucocorticoid use over time? Ann Rheum Dis. 2023 (Aug 22). doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-224270

Tapering TNFi raises disease flare likelihood in patients with RA even in those in remission

Key clinical point: Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in long-standing remission had a significant risk of experiencing a disease flare if the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) dose is tapered to discontinuation, but most patients regained remission after the original TNFi dose was reinstated.

Major finding: The frequency of disease activity flares during the 12-month follow-up was significantly higher among patients who tapered TNFi to discontinuation vs those who continued with the stable dose (risk difference 58%; P < .0001). However, reinstatement of the initial TNFi dose led to comparable remission rates in both treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 4 ARCTIC REWIND trial including 92 patients with RA in sustained remission for ≥ 1 year on stable TNFi therapy and without swollen joints at inclusion, who were randomly assigned to either tapering of their TNFi dose to discontinuation or to a continued stable TNFi dose.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Research Council of Norway and South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority. Some authors declared receiving personal fees or grants from various sources, including the study funders.

Source: Lillegraven S et al. Effect of tapered versus stable treatment with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors on disease flares in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in remission: A randomised, open label, non-inferiority trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023 (Aug 22). doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-224476

Key clinical point: Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in long-standing remission had a significant risk of experiencing a disease flare if the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) dose is tapered to discontinuation, but most patients regained remission after the original TNFi dose was reinstated.

Major finding: The frequency of disease activity flares during the 12-month follow-up was significantly higher among patients who tapered TNFi to discontinuation vs those who continued with the stable dose (risk difference 58%; P < .0001). However, reinstatement of the initial TNFi dose led to comparable remission rates in both treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 4 ARCTIC REWIND trial including 92 patients with RA in sustained remission for ≥ 1 year on stable TNFi therapy and without swollen joints at inclusion, who were randomly assigned to either tapering of their TNFi dose to discontinuation or to a continued stable TNFi dose.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Research Council of Norway and South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority. Some authors declared receiving personal fees or grants from various sources, including the study funders.

Source: Lillegraven S et al. Effect of tapered versus stable treatment with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors on disease flares in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in remission: A randomised, open label, non-inferiority trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023 (Aug 22). doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-224476

Key clinical point: Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in long-standing remission had a significant risk of experiencing a disease flare if the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) dose is tapered to discontinuation, but most patients regained remission after the original TNFi dose was reinstated.

Major finding: The frequency of disease activity flares during the 12-month follow-up was significantly higher among patients who tapered TNFi to discontinuation vs those who continued with the stable dose (risk difference 58%; P < .0001). However, reinstatement of the initial TNFi dose led to comparable remission rates in both treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 4 ARCTIC REWIND trial including 92 patients with RA in sustained remission for ≥ 1 year on stable TNFi therapy and without swollen joints at inclusion, who were randomly assigned to either tapering of their TNFi dose to discontinuation or to a continued stable TNFi dose.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Research Council of Norway and South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority. Some authors declared receiving personal fees or grants from various sources, including the study funders.

Source: Lillegraven S et al. Effect of tapered versus stable treatment with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors on disease flares in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in remission: A randomised, open label, non-inferiority trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023 (Aug 22). doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-224476

Weight gain and increased BP concerns should not deter low-dose glucocorticoid use in RA

Key clinical point: The administration of low-dose glucocorticoids over 2 years resulted in a modest weight gain of ~1 kg but had no effect on blood pressure (BP) in patients with early and established rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: After 2 years, participants in both the low-dose glucocorticoid and control groups gained weight, but the low-dose glucocorticoid group gained an additional 1.1 kg of body weight (P < .001), with no significant between-group differences in the mean arterial pressure (P = .187).

Study details: Findings are from a pooled analysis of five randomized controlled trials including 1112 patients with early and established RA who received low-dose glucocorticoids (≤7.5 mg/day of prednisone equivalent; n = 548) or control treatment (n = 564) over at least 2 years.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any specific funding. Some authors declared receiving investigator fees, grants or contracts, consulting fees, payments or honoraria, or support for attending meetings or travel from or owning stocks or options in various sources.

Source: Palmowski A et al. The effect of low-dose glucocorticoids over two years on weight and blood pressure in rheumatoid arthritis: Individual patient data from five randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2023 (Aug 15). doi: 10.7326/M23-0192

Key clinical point: The administration of low-dose glucocorticoids over 2 years resulted in a modest weight gain of ~1 kg but had no effect on blood pressure (BP) in patients with early and established rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: After 2 years, participants in both the low-dose glucocorticoid and control groups gained weight, but the low-dose glucocorticoid group gained an additional 1.1 kg of body weight (P < .001), with no significant between-group differences in the mean arterial pressure (P = .187).

Study details: Findings are from a pooled analysis of five randomized controlled trials including 1112 patients with early and established RA who received low-dose glucocorticoids (≤7.5 mg/day of prednisone equivalent; n = 548) or control treatment (n = 564) over at least 2 years.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any specific funding. Some authors declared receiving investigator fees, grants or contracts, consulting fees, payments or honoraria, or support for attending meetings or travel from or owning stocks or options in various sources.

Source: Palmowski A et al. The effect of low-dose glucocorticoids over two years on weight and blood pressure in rheumatoid arthritis: Individual patient data from five randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2023 (Aug 15). doi: 10.7326/M23-0192

Key clinical point: The administration of low-dose glucocorticoids over 2 years resulted in a modest weight gain of ~1 kg but had no effect on blood pressure (BP) in patients with early and established rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: After 2 years, participants in both the low-dose glucocorticoid and control groups gained weight, but the low-dose glucocorticoid group gained an additional 1.1 kg of body weight (P < .001), with no significant between-group differences in the mean arterial pressure (P = .187).

Study details: Findings are from a pooled analysis of five randomized controlled trials including 1112 patients with early and established RA who received low-dose glucocorticoids (≤7.5 mg/day of prednisone equivalent; n = 548) or control treatment (n = 564) over at least 2 years.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any specific funding. Some authors declared receiving investigator fees, grants or contracts, consulting fees, payments or honoraria, or support for attending meetings or travel from or owning stocks or options in various sources.

Source: Palmowski A et al. The effect of low-dose glucocorticoids over two years on weight and blood pressure in rheumatoid arthritis: Individual patient data from five randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2023 (Aug 15). doi: 10.7326/M23-0192

Idiopathic Granulomatous Lobular Mastitis: A Mimicker of Inflammatory Breast Cancer

Idiopathic granulomatous lobular mastitis (IGLM) is a rare, chronic inflammatory breast disease first described in 1972.1 IGLM usually affects women during reproductive years and has similar clinical features to breast cancer.2 Ultrasonography and mammography yield nonspecific results and cannot adequately differentiate between malignancy and inflammation.3 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is known to be more sensitive in detecting lesions in dense breasts; however, it does not differentiate between granulomatous lesions and other disorders.4,5 Histopathology is the gold standard for diagnosis.1-12

Infectious and autoimmune causes of granulomatous mastitis must be excluded before establishing an IGLM diagnosis. The clinical quandary that remains is how to adequately manage the disease. Although there are no defined treatment guidelines, current literature has proposed a multimodal strategy.6,9 In this report, we describe a case of IGLM successfully treated with surgical excision after failed medical therapy.

Case Presentation

A 43-year-old gravida 5, para 4 White woman presented with a 2-week history of right breast tenderness, heaviness, warmth, and redness that was refractory to cephalexin and dicloxacillin. She had no personal or family history of breast cancer; never had breast surgery and breastfed all 4 children.

An examination of the right breast demonstrated erythema and an 8-cm tender mass in the right lower outer quadrant but no skin retraction or dimpling (Figure 1). The mammography, concerning for inflammatory breast cancer, was category BI-RADS 4 and demonstrated a suspicious right axillary lymph node (Figure 2).

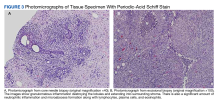

A core needle breast biopsy revealed granulomatous mastitis (Figure 3A), without evidence of malignancy. Rheumatology and endocrinology excluded secondary causes of granulomatous mastitis (ie, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and other autoimmune conditions). A pituitary MRI to assess an elevated serum prolactin level showed no evidence of microadenoma.

After a prolonged course of 8 months of unsuccessful therapy with prednisone and methotrexate, the patient was referred for surgical excision. Culture and special stains (Gram stain, periodic acid-Schiff stain, acid-fast Bacillus culture, Fite stain, and Brown and Benn stain) of the breast tissue were negative for organisms (Figure 3B). Seven months after excision the patient was doing well and had no evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

IGLM is a rare, chronic benign inflammatory breast disease of unknown etiology and more commonly reported in individuals of Mediterranean descent.13 It is believed that hyperprolactinemia causing extravasation of fat and protein during milk letdown leads to lymphocyte and macrophage migration, resulting in a localized autoimmune response in the breast ducts.10,14

There are 2 types of granulomatous mastitis: idiopathic and specific. Infectious, autoimmune, and malignant causes of granulomatous mastitis (ie, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, Corynebacterium spp, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet disease, ductal ectasia, or granulomatous reaction in a carcinoma) must be excluded prior to establishing an IGLM diagnosis, as these can be fatal if left untreated.15 The most frequent findings on ultrasound and mammography are hypoechoic masses and focal asymmetric densities, respectively.3,5 MRI has been proposed more for surveillance in patients with chronic IGLM.4,5 Histopathology—featuring lobular noncaseating granulomas with epithelioid histiocytes; and multinucleated giant cells in a background of neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils—is the gold standard for diagnosing IGLM.1-12

There are currently no universal treatment guidelines and management usually consists of observation, systemic and topical steroids, or surgery.3,13 Topical and injectable steroids have been effective in treating both initial and recurrent IGLM in patients who are unable to be treated with systemic steroids.16-18 Due to reported high recurrence rates with steroid tapers, adjunctive therapy with methotrexate, azathioprine, colchicine, and hydroxychloroquine have been proposed.1,3-6,10-12

Additionally, antibiotics are recommended only in the management of IGLM when microbial co-infection is concerning, such as with Corynebacterium spp.9,11,19-22 Histologically, this bacterium is distinct from IGLM and demonstrates granulomatous, neutrophilic inflammation within cystic spaces.19-21 Wide surgical excision with negative margins is the only definitive treatment to reduce recurrence and expedite recovery time.2,3,7-10 Notably, surgical excision has been associated with poor wound healing and occasional recurrence compared with medication alone.5,11

Although IGLM is normally a benign process, chronic disease has been related (without causality) to infiltrating breast carcinoma.4 A proposed theory for the development of malignancy suggests that chronic inflammation leading to free radical formation can result in cellular dysplasia and cancer.23

Conclusions

Fifty years after its first description, IGLM is still a poorly understood disease. There remains no consensus behind its etiology or management. In our case, we demonstrated a stepwise treatment progression, beginning with medical therapy before proceeding to surgical cure. Given concerns for poor wound healing and postsurgical infections, monitoring the response and recurrence to an initial trial of conservative medical treatment is not unreasonable. Because of possible risk for malignancy with chronic IGLM, patients should not delay surgical excision if their condition remains refractory to medical therapy alone.

1. Garcia-Rodiguez JA, Pattullo A. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: a mimicking disease in a pregnant woman: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:95. doi.10.1186/1756-0500-6-95

2. Gurleyik G, Aktekin A, Aker F, Karagulle H, Saglamc A. Medical and surgical treatment of idiopathic granulomatous lobular mastitis: a benign inflammatory disease mimicking invasive carcinoma. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15(1):119-123. doi:10.4048/jbc.2012.15.1.119

3. Hovanessian Larsen LJ, Peyvandi B, Klipfel N, Grant E, Iyengar G. Granulomatous lobular mastitis: imaging, diagnosis, and treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):574-581. doi:10.2214/AJR.08.1528

4. Mazlan L, Suhaimi SN, Jasmin SJ, Latar NH, Adzman S, Muhammad R. Breast carcinoma occurring from chronic granulomatous mastitis. Malays J Med Sci. 2012;19(2):82-85.

5. Patel RA, Strickland P, Sankara IR, Pinkston G, Many W Jr, Rodriguez M. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: case reports and review of literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):270-273. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1207-2

6. Akbulut S, Yilmaz D, Bakir S. Methotrexate in the management of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: review of 108 published cases and report of four cases. Breast J. 2011;17(6):661-668. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01162.x

7. Ergin AB, Cristofanilli M, Daw H, Tahan G, Gong Y. Recurrent granulomatous mastitis mimicking inflammatory breast cancer. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0720103156. doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2010.3156

8. Hladik M, Schoeller T, Ensat F, Wechselberger G. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: successful treatment by mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(12):1604-1607. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2011.07.01

9. Hur SM, Cho DH, Lee SK, et al. Experience of treatment of patients with granulomatous lobular mastitis. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;85(1):1-6. doi:10.4174/jkss.2013.85.1.

10. Kayahan M, Kadioglu H, Muslumanoglu M. Management of patients with granulomatous mastitis: analysis of 31 cases. Breast Care (Basel). 2012;7(3):226-230. doi:10.1159/000337758

11. Neel A, Hello M, Cottereau A, et al. Long-term outcome in idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: a western multicentre study. QJM. 2013;106(5):433-441. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hct040

12. Seo HR, Na KY, Yim HE, et al. Differential diagnosis in idiopathic granulomatous mastitis and tuberculous mastitis. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15(1):111-118. doi:10.4048/jbc.2012.15.1.111

13. Martinez-Ramos D, Simon-Monterde L, Suelves-Piqueres C, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: a systematic review of 3060 patients. Breast J. 2019;25(6):1245-1250. doi:10.1111/tbj.13446

14. Lin CH, Hsu CW, Tsao TY, Chou J. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis associated with risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:2. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-7-2

15. Goulabchand R, Hafidi A, Van de Perre P, et al. Mastitis in autoimmune diseases: review of the literature, diagnostic pathway, and pathophysiological key players. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):958. doi:10.3390/jcm9040958

16. Altintoprak F. Topical steroids to treat granulomatous mastitis: a case report. Korean J Intern Med. 2011;26(3):356-359. doi:10.3904/kjim.2011.26.3.356

17. Tang A, Dominguez DA, Edquilang JK, et al. Granulomatous mastitis: comparison of novel treatment of steroid injection and current management. J Surg Res. 2020;254:300-305. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2020.04.018

18. Toktas O, Toprak N. Treatment results of intralesional steroid injection and topical steroid administration in pregnant women with idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Eur J Breast Health. 2021;17(3):283-287. doi:10.4274/ejbh.galenos.2021.2021-2-4

19. Bercot B, Kannengiesser C, Oudin C, et al. First description of NOD2 variant associated with defective neutrophil responses in a woman with granulomatous mastitis related to corynebacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(9):3034-3037. doi:10.1128/JCM.00561-09

20. Renshaw AA, Derhagopian RP, Gould EW. Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis: an underappreciated pattern strongly associated with gram-positive bacilli. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136(3):424-427. doi:10.1309/AJCP1W9JBRYOQSNZ

21. Stary CM, Lee YS, Balfour J. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis associated with corynebacterium sp. Infection. Hawaii Med J. 2011;70(5):99-101.

22. Taylor GB, Paviour SD, Musaad S, Jones WO, Holland DJ. A clinicopathological review of 34 cases of inflammatory breast disease showing an association between corynebacteria infection and granulomatous mastitis. Pathology. 2003;35(2):109-119.

23. Rakoff-Nahoum S. Why cancer and inflammation? Yale J Biol Med. 2006;79(3-4):123-130.

Idiopathic granulomatous lobular mastitis (IGLM) is a rare, chronic inflammatory breast disease first described in 1972.1 IGLM usually affects women during reproductive years and has similar clinical features to breast cancer.2 Ultrasonography and mammography yield nonspecific results and cannot adequately differentiate between malignancy and inflammation.3 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is known to be more sensitive in detecting lesions in dense breasts; however, it does not differentiate between granulomatous lesions and other disorders.4,5 Histopathology is the gold standard for diagnosis.1-12

Infectious and autoimmune causes of granulomatous mastitis must be excluded before establishing an IGLM diagnosis. The clinical quandary that remains is how to adequately manage the disease. Although there are no defined treatment guidelines, current literature has proposed a multimodal strategy.6,9 In this report, we describe a case of IGLM successfully treated with surgical excision after failed medical therapy.

Case Presentation

A 43-year-old gravida 5, para 4 White woman presented with a 2-week history of right breast tenderness, heaviness, warmth, and redness that was refractory to cephalexin and dicloxacillin. She had no personal or family history of breast cancer; never had breast surgery and breastfed all 4 children.

An examination of the right breast demonstrated erythema and an 8-cm tender mass in the right lower outer quadrant but no skin retraction or dimpling (Figure 1). The mammography, concerning for inflammatory breast cancer, was category BI-RADS 4 and demonstrated a suspicious right axillary lymph node (Figure 2).

A core needle breast biopsy revealed granulomatous mastitis (Figure 3A), without evidence of malignancy. Rheumatology and endocrinology excluded secondary causes of granulomatous mastitis (ie, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and other autoimmune conditions). A pituitary MRI to assess an elevated serum prolactin level showed no evidence of microadenoma.

After a prolonged course of 8 months of unsuccessful therapy with prednisone and methotrexate, the patient was referred for surgical excision. Culture and special stains (Gram stain, periodic acid-Schiff stain, acid-fast Bacillus culture, Fite stain, and Brown and Benn stain) of the breast tissue were negative for organisms (Figure 3B). Seven months after excision the patient was doing well and had no evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

IGLM is a rare, chronic benign inflammatory breast disease of unknown etiology and more commonly reported in individuals of Mediterranean descent.13 It is believed that hyperprolactinemia causing extravasation of fat and protein during milk letdown leads to lymphocyte and macrophage migration, resulting in a localized autoimmune response in the breast ducts.10,14

There are 2 types of granulomatous mastitis: idiopathic and specific. Infectious, autoimmune, and malignant causes of granulomatous mastitis (ie, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, Corynebacterium spp, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet disease, ductal ectasia, or granulomatous reaction in a carcinoma) must be excluded prior to establishing an IGLM diagnosis, as these can be fatal if left untreated.15 The most frequent findings on ultrasound and mammography are hypoechoic masses and focal asymmetric densities, respectively.3,5 MRI has been proposed more for surveillance in patients with chronic IGLM.4,5 Histopathology—featuring lobular noncaseating granulomas with epithelioid histiocytes; and multinucleated giant cells in a background of neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils—is the gold standard for diagnosing IGLM.1-12

There are currently no universal treatment guidelines and management usually consists of observation, systemic and topical steroids, or surgery.3,13 Topical and injectable steroids have been effective in treating both initial and recurrent IGLM in patients who are unable to be treated with systemic steroids.16-18 Due to reported high recurrence rates with steroid tapers, adjunctive therapy with methotrexate, azathioprine, colchicine, and hydroxychloroquine have been proposed.1,3-6,10-12

Additionally, antibiotics are recommended only in the management of IGLM when microbial co-infection is concerning, such as with Corynebacterium spp.9,11,19-22 Histologically, this bacterium is distinct from IGLM and demonstrates granulomatous, neutrophilic inflammation within cystic spaces.19-21 Wide surgical excision with negative margins is the only definitive treatment to reduce recurrence and expedite recovery time.2,3,7-10 Notably, surgical excision has been associated with poor wound healing and occasional recurrence compared with medication alone.5,11

Although IGLM is normally a benign process, chronic disease has been related (without causality) to infiltrating breast carcinoma.4 A proposed theory for the development of malignancy suggests that chronic inflammation leading to free radical formation can result in cellular dysplasia and cancer.23

Conclusions

Fifty years after its first description, IGLM is still a poorly understood disease. There remains no consensus behind its etiology or management. In our case, we demonstrated a stepwise treatment progression, beginning with medical therapy before proceeding to surgical cure. Given concerns for poor wound healing and postsurgical infections, monitoring the response and recurrence to an initial trial of conservative medical treatment is not unreasonable. Because of possible risk for malignancy with chronic IGLM, patients should not delay surgical excision if their condition remains refractory to medical therapy alone.

Idiopathic granulomatous lobular mastitis (IGLM) is a rare, chronic inflammatory breast disease first described in 1972.1 IGLM usually affects women during reproductive years and has similar clinical features to breast cancer.2 Ultrasonography and mammography yield nonspecific results and cannot adequately differentiate between malignancy and inflammation.3 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is known to be more sensitive in detecting lesions in dense breasts; however, it does not differentiate between granulomatous lesions and other disorders.4,5 Histopathology is the gold standard for diagnosis.1-12

Infectious and autoimmune causes of granulomatous mastitis must be excluded before establishing an IGLM diagnosis. The clinical quandary that remains is how to adequately manage the disease. Although there are no defined treatment guidelines, current literature has proposed a multimodal strategy.6,9 In this report, we describe a case of IGLM successfully treated with surgical excision after failed medical therapy.

Case Presentation

A 43-year-old gravida 5, para 4 White woman presented with a 2-week history of right breast tenderness, heaviness, warmth, and redness that was refractory to cephalexin and dicloxacillin. She had no personal or family history of breast cancer; never had breast surgery and breastfed all 4 children.

An examination of the right breast demonstrated erythema and an 8-cm tender mass in the right lower outer quadrant but no skin retraction or dimpling (Figure 1). The mammography, concerning for inflammatory breast cancer, was category BI-RADS 4 and demonstrated a suspicious right axillary lymph node (Figure 2).

A core needle breast biopsy revealed granulomatous mastitis (Figure 3A), without evidence of malignancy. Rheumatology and endocrinology excluded secondary causes of granulomatous mastitis (ie, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and other autoimmune conditions). A pituitary MRI to assess an elevated serum prolactin level showed no evidence of microadenoma.

After a prolonged course of 8 months of unsuccessful therapy with prednisone and methotrexate, the patient was referred for surgical excision. Culture and special stains (Gram stain, periodic acid-Schiff stain, acid-fast Bacillus culture, Fite stain, and Brown and Benn stain) of the breast tissue were negative for organisms (Figure 3B). Seven months after excision the patient was doing well and had no evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

IGLM is a rare, chronic benign inflammatory breast disease of unknown etiology and more commonly reported in individuals of Mediterranean descent.13 It is believed that hyperprolactinemia causing extravasation of fat and protein during milk letdown leads to lymphocyte and macrophage migration, resulting in a localized autoimmune response in the breast ducts.10,14

There are 2 types of granulomatous mastitis: idiopathic and specific. Infectious, autoimmune, and malignant causes of granulomatous mastitis (ie, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, Corynebacterium spp, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet disease, ductal ectasia, or granulomatous reaction in a carcinoma) must be excluded prior to establishing an IGLM diagnosis, as these can be fatal if left untreated.15 The most frequent findings on ultrasound and mammography are hypoechoic masses and focal asymmetric densities, respectively.3,5 MRI has been proposed more for surveillance in patients with chronic IGLM.4,5 Histopathology—featuring lobular noncaseating granulomas with epithelioid histiocytes; and multinucleated giant cells in a background of neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils—is the gold standard for diagnosing IGLM.1-12

There are currently no universal treatment guidelines and management usually consists of observation, systemic and topical steroids, or surgery.3,13 Topical and injectable steroids have been effective in treating both initial and recurrent IGLM in patients who are unable to be treated with systemic steroids.16-18 Due to reported high recurrence rates with steroid tapers, adjunctive therapy with methotrexate, azathioprine, colchicine, and hydroxychloroquine have been proposed.1,3-6,10-12

Additionally, antibiotics are recommended only in the management of IGLM when microbial co-infection is concerning, such as with Corynebacterium spp.9,11,19-22 Histologically, this bacterium is distinct from IGLM and demonstrates granulomatous, neutrophilic inflammation within cystic spaces.19-21 Wide surgical excision with negative margins is the only definitive treatment to reduce recurrence and expedite recovery time.2,3,7-10 Notably, surgical excision has been associated with poor wound healing and occasional recurrence compared with medication alone.5,11

Although IGLM is normally a benign process, chronic disease has been related (without causality) to infiltrating breast carcinoma.4 A proposed theory for the development of malignancy suggests that chronic inflammation leading to free radical formation can result in cellular dysplasia and cancer.23

Conclusions

Fifty years after its first description, IGLM is still a poorly understood disease. There remains no consensus behind its etiology or management. In our case, we demonstrated a stepwise treatment progression, beginning with medical therapy before proceeding to surgical cure. Given concerns for poor wound healing and postsurgical infections, monitoring the response and recurrence to an initial trial of conservative medical treatment is not unreasonable. Because of possible risk for malignancy with chronic IGLM, patients should not delay surgical excision if their condition remains refractory to medical therapy alone.

1. Garcia-Rodiguez JA, Pattullo A. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: a mimicking disease in a pregnant woman: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:95. doi.10.1186/1756-0500-6-95

2. Gurleyik G, Aktekin A, Aker F, Karagulle H, Saglamc A. Medical and surgical treatment of idiopathic granulomatous lobular mastitis: a benign inflammatory disease mimicking invasive carcinoma. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15(1):119-123. doi:10.4048/jbc.2012.15.1.119

3. Hovanessian Larsen LJ, Peyvandi B, Klipfel N, Grant E, Iyengar G. Granulomatous lobular mastitis: imaging, diagnosis, and treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):574-581. doi:10.2214/AJR.08.1528

4. Mazlan L, Suhaimi SN, Jasmin SJ, Latar NH, Adzman S, Muhammad R. Breast carcinoma occurring from chronic granulomatous mastitis. Malays J Med Sci. 2012;19(2):82-85.

5. Patel RA, Strickland P, Sankara IR, Pinkston G, Many W Jr, Rodriguez M. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: case reports and review of literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):270-273. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1207-2

6. Akbulut S, Yilmaz D, Bakir S. Methotrexate in the management of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: review of 108 published cases and report of four cases. Breast J. 2011;17(6):661-668. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01162.x

7. Ergin AB, Cristofanilli M, Daw H, Tahan G, Gong Y. Recurrent granulomatous mastitis mimicking inflammatory breast cancer. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0720103156. doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2010.3156

8. Hladik M, Schoeller T, Ensat F, Wechselberger G. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: successful treatment by mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(12):1604-1607. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2011.07.01

9. Hur SM, Cho DH, Lee SK, et al. Experience of treatment of patients with granulomatous lobular mastitis. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;85(1):1-6. doi:10.4174/jkss.2013.85.1.

10. Kayahan M, Kadioglu H, Muslumanoglu M. Management of patients with granulomatous mastitis: analysis of 31 cases. Breast Care (Basel). 2012;7(3):226-230. doi:10.1159/000337758

11. Neel A, Hello M, Cottereau A, et al. Long-term outcome in idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: a western multicentre study. QJM. 2013;106(5):433-441. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hct040

12. Seo HR, Na KY, Yim HE, et al. Differential diagnosis in idiopathic granulomatous mastitis and tuberculous mastitis. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15(1):111-118. doi:10.4048/jbc.2012.15.1.111

13. Martinez-Ramos D, Simon-Monterde L, Suelves-Piqueres C, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: a systematic review of 3060 patients. Breast J. 2019;25(6):1245-1250. doi:10.1111/tbj.13446

14. Lin CH, Hsu CW, Tsao TY, Chou J. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis associated with risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:2. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-7-2

15. Goulabchand R, Hafidi A, Van de Perre P, et al. Mastitis in autoimmune diseases: review of the literature, diagnostic pathway, and pathophysiological key players. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):958. doi:10.3390/jcm9040958

16. Altintoprak F. Topical steroids to treat granulomatous mastitis: a case report. Korean J Intern Med. 2011;26(3):356-359. doi:10.3904/kjim.2011.26.3.356

17. Tang A, Dominguez DA, Edquilang JK, et al. Granulomatous mastitis: comparison of novel treatment of steroid injection and current management. J Surg Res. 2020;254:300-305. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2020.04.018

18. Toktas O, Toprak N. Treatment results of intralesional steroid injection and topical steroid administration in pregnant women with idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Eur J Breast Health. 2021;17(3):283-287. doi:10.4274/ejbh.galenos.2021.2021-2-4

19. Bercot B, Kannengiesser C, Oudin C, et al. First description of NOD2 variant associated with defective neutrophil responses in a woman with granulomatous mastitis related to corynebacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(9):3034-3037. doi:10.1128/JCM.00561-09

20. Renshaw AA, Derhagopian RP, Gould EW. Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis: an underappreciated pattern strongly associated with gram-positive bacilli. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136(3):424-427. doi:10.1309/AJCP1W9JBRYOQSNZ

21. Stary CM, Lee YS, Balfour J. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis associated with corynebacterium sp. Infection. Hawaii Med J. 2011;70(5):99-101.

22. Taylor GB, Paviour SD, Musaad S, Jones WO, Holland DJ. A clinicopathological review of 34 cases of inflammatory breast disease showing an association between corynebacteria infection and granulomatous mastitis. Pathology. 2003;35(2):109-119.

23. Rakoff-Nahoum S. Why cancer and inflammation? Yale J Biol Med. 2006;79(3-4):123-130.

1. Garcia-Rodiguez JA, Pattullo A. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: a mimicking disease in a pregnant woman: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:95. doi.10.1186/1756-0500-6-95

2. Gurleyik G, Aktekin A, Aker F, Karagulle H, Saglamc A. Medical and surgical treatment of idiopathic granulomatous lobular mastitis: a benign inflammatory disease mimicking invasive carcinoma. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15(1):119-123. doi:10.4048/jbc.2012.15.1.119

3. Hovanessian Larsen LJ, Peyvandi B, Klipfel N, Grant E, Iyengar G. Granulomatous lobular mastitis: imaging, diagnosis, and treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):574-581. doi:10.2214/AJR.08.1528

4. Mazlan L, Suhaimi SN, Jasmin SJ, Latar NH, Adzman S, Muhammad R. Breast carcinoma occurring from chronic granulomatous mastitis. Malays J Med Sci. 2012;19(2):82-85.

5. Patel RA, Strickland P, Sankara IR, Pinkston G, Many W Jr, Rodriguez M. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: case reports and review of literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):270-273. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1207-2

6. Akbulut S, Yilmaz D, Bakir S. Methotrexate in the management of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: review of 108 published cases and report of four cases. Breast J. 2011;17(6):661-668. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01162.x

7. Ergin AB, Cristofanilli M, Daw H, Tahan G, Gong Y. Recurrent granulomatous mastitis mimicking inflammatory breast cancer. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0720103156. doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2010.3156

8. Hladik M, Schoeller T, Ensat F, Wechselberger G. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: successful treatment by mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(12):1604-1607. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2011.07.01

9. Hur SM, Cho DH, Lee SK, et al. Experience of treatment of patients with granulomatous lobular mastitis. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;85(1):1-6. doi:10.4174/jkss.2013.85.1.

10. Kayahan M, Kadioglu H, Muslumanoglu M. Management of patients with granulomatous mastitis: analysis of 31 cases. Breast Care (Basel). 2012;7(3):226-230. doi:10.1159/000337758

11. Neel A, Hello M, Cottereau A, et al. Long-term outcome in idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: a western multicentre study. QJM. 2013;106(5):433-441. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hct040

12. Seo HR, Na KY, Yim HE, et al. Differential diagnosis in idiopathic granulomatous mastitis and tuberculous mastitis. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15(1):111-118. doi:10.4048/jbc.2012.15.1.111

13. Martinez-Ramos D, Simon-Monterde L, Suelves-Piqueres C, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: a systematic review of 3060 patients. Breast J. 2019;25(6):1245-1250. doi:10.1111/tbj.13446

14. Lin CH, Hsu CW, Tsao TY, Chou J. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis associated with risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:2. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-7-2

15. Goulabchand R, Hafidi A, Van de Perre P, et al. Mastitis in autoimmune diseases: review of the literature, diagnostic pathway, and pathophysiological key players. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):958. doi:10.3390/jcm9040958

16. Altintoprak F. Topical steroids to treat granulomatous mastitis: a case report. Korean J Intern Med. 2011;26(3):356-359. doi:10.3904/kjim.2011.26.3.356

17. Tang A, Dominguez DA, Edquilang JK, et al. Granulomatous mastitis: comparison of novel treatment of steroid injection and current management. J Surg Res. 2020;254:300-305. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2020.04.018

18. Toktas O, Toprak N. Treatment results of intralesional steroid injection and topical steroid administration in pregnant women with idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Eur J Breast Health. 2021;17(3):283-287. doi:10.4274/ejbh.galenos.2021.2021-2-4

19. Bercot B, Kannengiesser C, Oudin C, et al. First description of NOD2 variant associated with defective neutrophil responses in a woman with granulomatous mastitis related to corynebacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(9):3034-3037. doi:10.1128/JCM.00561-09

20. Renshaw AA, Derhagopian RP, Gould EW. Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis: an underappreciated pattern strongly associated with gram-positive bacilli. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136(3):424-427. doi:10.1309/AJCP1W9JBRYOQSNZ

21. Stary CM, Lee YS, Balfour J. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis associated with corynebacterium sp. Infection. Hawaii Med J. 2011;70(5):99-101.

22. Taylor GB, Paviour SD, Musaad S, Jones WO, Holland DJ. A clinicopathological review of 34 cases of inflammatory breast disease showing an association between corynebacteria infection and granulomatous mastitis. Pathology. 2003;35(2):109-119.

23. Rakoff-Nahoum S. Why cancer and inflammation? Yale J Biol Med. 2006;79(3-4):123-130.

Patient With Leukocytosis and Persistent Dry Cough

Discussion

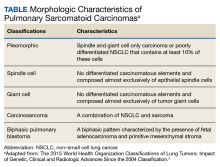

An interdisciplinary discussion regarding the diagnosis considered the clinical features of the patient along with the imaging characteristics. The histological examination demonstrating sarcomatoid features with the supporting immunohistochemistry that confirmed both mesenchymal and epithelioid presence and was used to make the diagnosis of pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma (PSC).

The incidence of PSC ranges between 0.1% and 0.4% of all lung malignancies.1,4-7 PSC usually occurs in older men whose weight is moderate to heavy and who smoke. PSC appears to have an upper lobe predilection; also, these tumors tend to be bulky with invasive tendency, early recurrence, and systemic metastases. PSC frequently involves the adjacent lung, chest wall, diaphragm, pericardium, and other tissues.1-5 The source of the sarcoma component of the PSC remains uncertain. However, prior research suggests that it is associated with a clonal evolution that induces epidermal and mesenchymal tumor histological characteristics.1,8,9 The tumor cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition may induce transformation of the carcinoma component of PSC to into a sarcoma component. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition is associated with the PSC high risk for invasiveness and induces metastasis sites, such as the esophagus, colon, rectum, kidneys, and the common sites of NSCLC.

The most common symptoms include productive cough, chest congestion, and chest pain.1,7 In view of PSC’s clinical presentation and imaging, numerous differential diagnoses should be considered, such as sarcomatoid carcinomas, primary or secondary metastatic sarcomas, malignant melanoma, and pleural mesothelioma.6,10

The tumor is initially identified by a chest CT, confirmed by histology and immunohistochemistry. Several biomarkers are useful for diagnosis and classification of an undifferentiated neoplasm/tumor of uncertain origin. Those biomarkers help to understand the tumor pathobiology, to select the therapeutic regimen, and to predict the patient’s outcome. Although immunohistochemical staining of epithelial and mesenchymal markers can be helpful, a reliable diagnosis requires a precise histopathological examination. This is often difficult on small biopsy samples, such as fine-needle aspiration, as all the histological elements of PSC required to make the correct evaluation may not be present. Adequate sampling to generate a considerable number of histological slides is essential for an accurate diagnosis, which can be reached only with surgical resection.5

Due to rarity, rapid progression, short survival, and heterogeneous pathological qualities, PSC has been difficult to formulate treatment recommendations. Compared with other histological subtypes of NSCLC, PSC is more aggressive and has a poor prognosis. Survival time on average is about 13.3 months due to early metastasis, lower than other types of NSCLC. The greatest overall survival (OS) benefit has been shown with surgery in early-stage operable PSC, which remains the standard of care. Because most patients with PSC present in the advanced stage, they lose their opportunity for curative surgery. Auxiliary methods of treatment include radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Prior studies have shown that systemic chemotherapy efficacy has varied, some showing no OS benefit; others showing a modest benefit. It has also been noted that advanced-stage PSC has minimal response to chemotherapy. Further larger prospective studies are needed to outline the efficacy and role of systemic chemotherapy and other therapeutic agents, including targeted therapies and immunotherapy.1,4,11-13 However, two-thirds of patients are not sensitive to conventional chemotherapy. In comparison with other types of NSCLC, PSC carries a poor prognosis even in early-stage disease or if tumor metastasis is present. Therefore, further research on novel treatment options is needed to improve long-term survival.1,3-8

Conclusions

PSC is diagnostically challenging because it is rare and has an aggressive progression. Identification of this tumor requires knowledge of histological criteria to identify their subtypes. Immunohistochemistry has an important role in the classification and to rule out differential diagnoses, including metastatic spread. Nevertheless, a reliable diagnosis requires precise histopathological examination, reached with surgical resection. Therefore, a detailed history, physical examination, systematic investigation, and correlation with chest imaging are needed to avoid misdiagnosis.

Our case highlights the importance of keeping this rare, aggressive tumor as part of the differential diagnosis. In view of its natural history, heterogeneity, and low incidence, published cases of PSC are limited. Thus, further investigation could optimize rapid identification and treatment options.

1. Qin Z, Huang B, Yu G, Zheng Y, Zhao K. Gingival metastasis of a mediastinal pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma: a case report. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;14(1):161. Published 2019 Sep 9. doi:10.1186/s13019-019-0991-y

2. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG, et al; WHO Panel. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Genetic, Clinical and Radiologic Advances Since the 2004 Classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(9):1243-1260. doi:10.1097/JTO.0000000000000630

3. Yendamuri S, Caty L, Pine M, et al. Outcomes of sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database analysis. Surgery. 2012;152(3):397-402. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2012.05.007

4. Karim NA, Schuster J, Eldessouki I, et al. Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma: University of Cincinnati experience. Oncotarget. 2017;9(3):4102-4108. Published 2017 Dec 18. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.23468

5. Weissferdt A. Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas: a review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2018;25(5):304-313. doi:10.1097/PAP.0000000000000202

6. Roesel C, Terjung S, Weinreich G, et al. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung: a rare histological subtype of non-small cell lung cancer with a poor prognosis even at earlier tumour stages. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2017;24(3):407-413. doi:10.1093/icvts/ivw392

7. Franks TJ, Galvin JR. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung: histologic criteria and common lesions in the differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(1):49-54. doi:10.5858/2008-0547-RAR.1

8. Thomas VT, Hinson S, Konduri K. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pulmonary carcinosarcoma: case report and literature review. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2012;4(1):31-37. doi:10.1177/1758834011421949

9. Chang YL, Wu CT, Shih JY, Lee YC. EGFR and p53 status of pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma: implications for EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors therapy of an aggressive lung malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(10):2952-2960. doi:10.1245/s10434-011-1621-7

10. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A, Nicholson AG, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. 4th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2015:88-94.

11. Huang SY, Shen SJ, Li XY. Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study and prognostic analysis of 51 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:252. Published 2013 Oct 2. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-11-252

12. Pelosi G, Sonzogni A, De Pas T, et al. Review article: pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas: a practical overview. Int J Surg Pathol. 2010;18(2):103-120. doi:10.1177/1066896908330049

13. Lin F, Liu H. Immunohistochemistry in undifferentiated neoplasm/tumor of uncertain origin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138(12):1583-1610. doi:10.5858/arpa.2014-0061-RA

Discussion

An interdisciplinary discussion regarding the diagnosis considered the clinical features of the patient along with the imaging characteristics. The histological examination demonstrating sarcomatoid features with the supporting immunohistochemistry that confirmed both mesenchymal and epithelioid presence and was used to make the diagnosis of pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma (PSC).

The incidence of PSC ranges between 0.1% and 0.4% of all lung malignancies.1,4-7 PSC usually occurs in older men whose weight is moderate to heavy and who smoke. PSC appears to have an upper lobe predilection; also, these tumors tend to be bulky with invasive tendency, early recurrence, and systemic metastases. PSC frequently involves the adjacent lung, chest wall, diaphragm, pericardium, and other tissues.1-5 The source of the sarcoma component of the PSC remains uncertain. However, prior research suggests that it is associated with a clonal evolution that induces epidermal and mesenchymal tumor histological characteristics.1,8,9 The tumor cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition may induce transformation of the carcinoma component of PSC to into a sarcoma component. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition is associated with the PSC high risk for invasiveness and induces metastasis sites, such as the esophagus, colon, rectum, kidneys, and the common sites of NSCLC.

The most common symptoms include productive cough, chest congestion, and chest pain.1,7 In view of PSC’s clinical presentation and imaging, numerous differential diagnoses should be considered, such as sarcomatoid carcinomas, primary or secondary metastatic sarcomas, malignant melanoma, and pleural mesothelioma.6,10

The tumor is initially identified by a chest CT, confirmed by histology and immunohistochemistry. Several biomarkers are useful for diagnosis and classification of an undifferentiated neoplasm/tumor of uncertain origin. Those biomarkers help to understand the tumor pathobiology, to select the therapeutic regimen, and to predict the patient’s outcome. Although immunohistochemical staining of epithelial and mesenchymal markers can be helpful, a reliable diagnosis requires a precise histopathological examination. This is often difficult on small biopsy samples, such as fine-needle aspiration, as all the histological elements of PSC required to make the correct evaluation may not be present. Adequate sampling to generate a considerable number of histological slides is essential for an accurate diagnosis, which can be reached only with surgical resection.5

Due to rarity, rapid progression, short survival, and heterogeneous pathological qualities, PSC has been difficult to formulate treatment recommendations. Compared with other histological subtypes of NSCLC, PSC is more aggressive and has a poor prognosis. Survival time on average is about 13.3 months due to early metastasis, lower than other types of NSCLC. The greatest overall survival (OS) benefit has been shown with surgery in early-stage operable PSC, which remains the standard of care. Because most patients with PSC present in the advanced stage, they lose their opportunity for curative surgery. Auxiliary methods of treatment include radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Prior studies have shown that systemic chemotherapy efficacy has varied, some showing no OS benefit; others showing a modest benefit. It has also been noted that advanced-stage PSC has minimal response to chemotherapy. Further larger prospective studies are needed to outline the efficacy and role of systemic chemotherapy and other therapeutic agents, including targeted therapies and immunotherapy.1,4,11-13 However, two-thirds of patients are not sensitive to conventional chemotherapy. In comparison with other types of NSCLC, PSC carries a poor prognosis even in early-stage disease or if tumor metastasis is present. Therefore, further research on novel treatment options is needed to improve long-term survival.1,3-8

Conclusions

PSC is diagnostically challenging because it is rare and has an aggressive progression. Identification of this tumor requires knowledge of histological criteria to identify their subtypes. Immunohistochemistry has an important role in the classification and to rule out differential diagnoses, including metastatic spread. Nevertheless, a reliable diagnosis requires precise histopathological examination, reached with surgical resection. Therefore, a detailed history, physical examination, systematic investigation, and correlation with chest imaging are needed to avoid misdiagnosis.

Our case highlights the importance of keeping this rare, aggressive tumor as part of the differential diagnosis. In view of its natural history, heterogeneity, and low incidence, published cases of PSC are limited. Thus, further investigation could optimize rapid identification and treatment options.

Discussion

An interdisciplinary discussion regarding the diagnosis considered the clinical features of the patient along with the imaging characteristics. The histological examination demonstrating sarcomatoid features with the supporting immunohistochemistry that confirmed both mesenchymal and epithelioid presence and was used to make the diagnosis of pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma (PSC).

The incidence of PSC ranges between 0.1% and 0.4% of all lung malignancies.1,4-7 PSC usually occurs in older men whose weight is moderate to heavy and who smoke. PSC appears to have an upper lobe predilection; also, these tumors tend to be bulky with invasive tendency, early recurrence, and systemic metastases. PSC frequently involves the adjacent lung, chest wall, diaphragm, pericardium, and other tissues.1-5 The source of the sarcoma component of the PSC remains uncertain. However, prior research suggests that it is associated with a clonal evolution that induces epidermal and mesenchymal tumor histological characteristics.1,8,9 The tumor cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition may induce transformation of the carcinoma component of PSC to into a sarcoma component. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition is associated with the PSC high risk for invasiveness and induces metastasis sites, such as the esophagus, colon, rectum, kidneys, and the common sites of NSCLC.

The most common symptoms include productive cough, chest congestion, and chest pain.1,7 In view of PSC’s clinical presentation and imaging, numerous differential diagnoses should be considered, such as sarcomatoid carcinomas, primary or secondary metastatic sarcomas, malignant melanoma, and pleural mesothelioma.6,10

The tumor is initially identified by a chest CT, confirmed by histology and immunohistochemistry. Several biomarkers are useful for diagnosis and classification of an undifferentiated neoplasm/tumor of uncertain origin. Those biomarkers help to understand the tumor pathobiology, to select the therapeutic regimen, and to predict the patient’s outcome. Although immunohistochemical staining of epithelial and mesenchymal markers can be helpful, a reliable diagnosis requires a precise histopathological examination. This is often difficult on small biopsy samples, such as fine-needle aspiration, as all the histological elements of PSC required to make the correct evaluation may not be present. Adequate sampling to generate a considerable number of histological slides is essential for an accurate diagnosis, which can be reached only with surgical resection.5

Due to rarity, rapid progression, short survival, and heterogeneous pathological qualities, PSC has been difficult to formulate treatment recommendations. Compared with other histological subtypes of NSCLC, PSC is more aggressive and has a poor prognosis. Survival time on average is about 13.3 months due to early metastasis, lower than other types of NSCLC. The greatest overall survival (OS) benefit has been shown with surgery in early-stage operable PSC, which remains the standard of care. Because most patients with PSC present in the advanced stage, they lose their opportunity for curative surgery. Auxiliary methods of treatment include radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Prior studies have shown that systemic chemotherapy efficacy has varied, some showing no OS benefit; others showing a modest benefit. It has also been noted that advanced-stage PSC has minimal response to chemotherapy. Further larger prospective studies are needed to outline the efficacy and role of systemic chemotherapy and other therapeutic agents, including targeted therapies and immunotherapy.1,4,11-13 However, two-thirds of patients are not sensitive to conventional chemotherapy. In comparison with other types of NSCLC, PSC carries a poor prognosis even in early-stage disease or if tumor metastasis is present. Therefore, further research on novel treatment options is needed to improve long-term survival.1,3-8

Conclusions

PSC is diagnostically challenging because it is rare and has an aggressive progression. Identification of this tumor requires knowledge of histological criteria to identify their subtypes. Immunohistochemistry has an important role in the classification and to rule out differential diagnoses, including metastatic spread. Nevertheless, a reliable diagnosis requires precise histopathological examination, reached with surgical resection. Therefore, a detailed history, physical examination, systematic investigation, and correlation with chest imaging are needed to avoid misdiagnosis.

Our case highlights the importance of keeping this rare, aggressive tumor as part of the differential diagnosis. In view of its natural history, heterogeneity, and low incidence, published cases of PSC are limited. Thus, further investigation could optimize rapid identification and treatment options.

1. Qin Z, Huang B, Yu G, Zheng Y, Zhao K. Gingival metastasis of a mediastinal pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma: a case report. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;14(1):161. Published 2019 Sep 9. doi:10.1186/s13019-019-0991-y

2. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG, et al; WHO Panel. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Genetic, Clinical and Radiologic Advances Since the 2004 Classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(9):1243-1260. doi:10.1097/JTO.0000000000000630

3. Yendamuri S, Caty L, Pine M, et al. Outcomes of sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database analysis. Surgery. 2012;152(3):397-402. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2012.05.007

4. Karim NA, Schuster J, Eldessouki I, et al. Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma: University of Cincinnati experience. Oncotarget. 2017;9(3):4102-4108. Published 2017 Dec 18. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.23468

5. Weissferdt A. Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas: a review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2018;25(5):304-313. doi:10.1097/PAP.0000000000000202

6. Roesel C, Terjung S, Weinreich G, et al. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung: a rare histological subtype of non-small cell lung cancer with a poor prognosis even at earlier tumour stages. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2017;24(3):407-413. doi:10.1093/icvts/ivw392

7. Franks TJ, Galvin JR. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung: histologic criteria and common lesions in the differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(1):49-54. doi:10.5858/2008-0547-RAR.1

8. Thomas VT, Hinson S, Konduri K. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pulmonary carcinosarcoma: case report and literature review. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2012;4(1):31-37. doi:10.1177/1758834011421949

9. Chang YL, Wu CT, Shih JY, Lee YC. EGFR and p53 status of pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma: implications for EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors therapy of an aggressive lung malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(10):2952-2960. doi:10.1245/s10434-011-1621-7

10. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A, Nicholson AG, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. 4th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2015:88-94.

11. Huang SY, Shen SJ, Li XY. Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study and prognostic analysis of 51 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:252. Published 2013 Oct 2. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-11-252

12. Pelosi G, Sonzogni A, De Pas T, et al. Review article: pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas: a practical overview. Int J Surg Pathol. 2010;18(2):103-120. doi:10.1177/1066896908330049

13. Lin F, Liu H. Immunohistochemistry in undifferentiated neoplasm/tumor of uncertain origin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138(12):1583-1610. doi:10.5858/arpa.2014-0061-RA

1. Qin Z, Huang B, Yu G, Zheng Y, Zhao K. Gingival metastasis of a mediastinal pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma: a case report. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;14(1):161. Published 2019 Sep 9. doi:10.1186/s13019-019-0991-y

2. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG, et al; WHO Panel. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Genetic, Clinical and Radiologic Advances Since the 2004 Classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(9):1243-1260. doi:10.1097/JTO.0000000000000630

3. Yendamuri S, Caty L, Pine M, et al. Outcomes of sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database analysis. Surgery. 2012;152(3):397-402. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2012.05.007

4. Karim NA, Schuster J, Eldessouki I, et al. Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma: University of Cincinnati experience. Oncotarget. 2017;9(3):4102-4108. Published 2017 Dec 18. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.23468

5. Weissferdt A. Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas: a review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2018;25(5):304-313. doi:10.1097/PAP.0000000000000202

6. Roesel C, Terjung S, Weinreich G, et al. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung: a rare histological subtype of non-small cell lung cancer with a poor prognosis even at earlier tumour stages. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2017;24(3):407-413. doi:10.1093/icvts/ivw392

7. Franks TJ, Galvin JR. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung: histologic criteria and common lesions in the differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(1):49-54. doi:10.5858/2008-0547-RAR.1

8. Thomas VT, Hinson S, Konduri K. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pulmonary carcinosarcoma: case report and literature review. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2012;4(1):31-37. doi:10.1177/1758834011421949

9. Chang YL, Wu CT, Shih JY, Lee YC. EGFR and p53 status of pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma: implications for EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors therapy of an aggressive lung malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(10):2952-2960. doi:10.1245/s10434-011-1621-7

10. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A, Nicholson AG, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. 4th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2015:88-94.

11. Huang SY, Shen SJ, Li XY. Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study and prognostic analysis of 51 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:252. Published 2013 Oct 2. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-11-252

12. Pelosi G, Sonzogni A, De Pas T, et al. Review article: pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas: a practical overview. Int J Surg Pathol. 2010;18(2):103-120. doi:10.1177/1066896908330049

13. Lin F, Liu H. Immunohistochemistry in undifferentiated neoplasm/tumor of uncertain origin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138(12):1583-1610. doi:10.5858/arpa.2014-0061-RA

Supplements Are Not a Synonym for Safe: Suspected Liver Injury From Ashwagandha

Many patients take herbals as alternative supplements to boost energy and mood. There are increasing reports of unintended adverse effects related to these supplements, particularly to the liver.1-3 A study by the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network found that liver injury caused by herbals and dietary supplements has increased from 7% in 2004 to 20% in 2013.4

The supplement ashwagandha has become increasingly popular. Ashwagandha is extracted from the root of Withania somnifera (

To date, the factors defining the population at risk for ashwagandha toxicity are unclear, and an understanding of how to diagnose drug-induced liver injury is still immature in clinical practice. The regulation and study of the herbal and dietary supplement industry remain challenging. While many so-called natural substances are well tolerated, others can have unanticipated and harmful adverse effects and drug interactions. Future research should not only identify potentially harmful substances, but also which patients may be at greatest risk.

Case Presentation

A 48-year-old man with a history of severe alcohol use disorder (AUD) complicated by fatty liver and withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens, hypertension, depression, and anxiety presented to the emergency department (ED) after 4 days of having jaundice, epigastric abdominal pain, dark urine, and pale stools. In the preceding months, he had increased his alcohol use to as many as 12 drinks daily due to depression. After experiencing a blackout, he stopped drinking 7 days before presenting to the ED. He felt withdrawal symptoms, including tremors, diaphoresis, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. On the third day of withdrawals, he reported that he had started taking an over-the-counter testosterone-boosting supplement to increase his energy, which he referred to as TestBoost—a mix of 8 ingredients, including ashwagandha, eleuthero root, Hawthorn berry, longjack, ginseng root, mushroom extract, bindii, and horny goat weed. After taking the supplement for 2 days, he noticed that his urine darkened, his stools became paler, his abdominal pain worsened, and he became jaundiced. After 2 additional days without improvement, and still taking the supplement, he presented to the ED. He reported having no fever, chills, recent illness, chest pain, shortness of breath, melena, lower extremity swelling, recent travel, or any changes in medications.

The patient had a 100.1 °F temperature, 102 beats per minute pulse; 129/94 mm Hg blood pressure, 18 beats per minute respiratory rate, and 97% oxygen saturation on room air on admission. He was in no acute distress, though his examination was notable for generalized jaundice and scleral icterus. He was mildly tender to palpation in the epigastric and right upper quadrant region. He was alert and oriented without confusion. He did not have any asterixis or spider angiomas, though he had scattered bruises on his left flank and left calf. His laboratory results were notable for mildly elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 58 U/L (reference range, 13-35); alanine transaminase (ALT), 49 U/L (reference range, 7-45); and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 98 U/L (reference range 33-94); total bilirubin, 13.6 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1.0); direct bilirubin, 8.4 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1); and international normalized ratio (INR), 1.11 (reference range, 2-3). His white blood cell and platelet counts were not remarkable at 9790/μL (reference range, 4500-11,000) and 337,000/μL (reference range, 150,000-440,000), respectively. Abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) revealed fatty liver with contracted gallbladder and no biliary dilatation. Urine ethanol levels were negative. The gastrointestinal (GI) service was consulted and agreed that his cholestatic injury was nonobstructive and likely related to the ashwagandha component of his supplement. The recommendation was cessation with close outpatient follow-up.

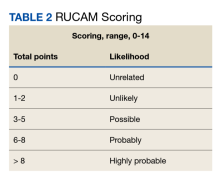

The patient was not prescribed any additional medications, such as steroids or ursodiol. He ceased supplement use following hospitalization; but relapsed into alcohol use 1 month after his discharge. Within 3 weeks, his total bilirubin had improved to 2.87 mg/dL, though AST, ALT, and ALP worsened to 127 U/L, 152 U/L, and 140 U/L, respectively. According to the notes of his psychiatrist who saw him at the time the laboratory tests were drawn, he had remained sober since discharge. His acute hepatitis panel drawn on admission was negative, and he demonstrated immunity to hepatitis A and B. Urine toxicology was negative. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) test was negative 1 year prior to discharge. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), ANA, antismooth muscle antibody, and immunoglobulins were not checked as suspicion for these etiologies was low. The Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) score was calculated as 6 (+1 for timing, +2 for drop in total bilirubin, +1 for ethanol risk factor, 0 for no other drugs, 0 for rule out of other diseases, +2 for known hepatotoxicity, 0 no repeat administration) for this patient indicating probable adverse drug reaction liver injury (Tables 1 and 2). However, we acknowledge that CMV, EBV, and herpes simplex virus status were not tested.

The 8 ingredients contained in TestBoost aside from ashwagandha did not have any major known liver adverse effects per a major database of medications. The other ingredients include eleuthero root, Hawthorn berry (crataegus laevigata), longjack (eurycoma longifolla) root, American ginseng root (American panax ginseng—panax quinquefolius), and Cordyceps mycelium (mushroom) extract, bindii (Tribulus terrestris), and epimedium grandiflorum (horny goat weed).6 No assays were performed to confirm purity of the ingredients in the patient’s supplement container.

Alcoholic hepatitis is an important consideration in this patient with AUD, though the timing of symptoms with supplement use and the cholestatic injury pattern with normal INR seems more consistent with drug-induced injury. Viral, infectious, and obstructive etiologies also were investigated. Acute viral hepatitis was ruled out based on bloodwork. The normal hepatobiliary tree on both ultrasound and CT effectively ruled out acute cholecystitis, cholangitis, and choledocholithiasis and there was no further indication for magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. There was no hepatic vein clot suggestive of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Autoimmune hepatitis was thought to be unlikely given that the etiology of injury seemed cholestatic in nature. Given the timing of the liver injury relative to supplement use it is likely that ashwagandha was a causative factor of this patient’s liver injury overlaid on an already strained liver from increased alcohol abuse.

The patient did not follow up with the GI service as an outpatient. There are no reports that the patient continued using the testosterone booster. His bilirubin improved dramatically within 1.5 months while his liver enzymes peaked 3 weeks later, with ALT ≥ AST. During his next admission 3 months later, he had relapsed, and his liver enzymes had the classic 2:1 AST to ALT ratio.

Discussion