User login

Study explores gender differences in pediatric melanoma

INDIANAPOLIS – .

In addition, male gender was independently associated with increased mortality, but age was not.

Those are key findings from a retrospective cohort analysis of nearly 5,000 records from the National Cancer Database.

“There are multiple studies from primarily adult populations showing females with melanoma have a different presentation and better outcomes than males,” co-first author Rebecca M. Thiede, MD, a dermatologist at the University of Arizona, Tucson, said in an interview with this news organization in advance of the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, where the abstract was presented during a poster session. “However, because melanoma is so rare in younger patients, little is known about gender differences in presentation and survival in pediatric and adolescent patients. To our knowledge, this is one of the largest studies to date in this population, and the first to explore gender differences in detail in pediatric and adolescent patients with melanoma.”

Working with co-first author Sabrina Dahak, a fourth-year medical student at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, Dr. Thiede and colleagues retrospectively analyzed the National Cancer Database to identify biopsy-confirmed invasive primary cutaneous melanoma cases diagnosed in patients 0-21 years of age between 2004 and 2018. The search yielded 4,645 cases, and the researchers used American Academy of Pediatrics definitions to categorize the patients by age, from infancy (birth to 2 years), to childhood (3-10 years), early adolescence (11-14 years), middle adolescence (15-17 years), and late adolescence (18-21 years). They used the Kaplan Meier analysis to determine overall survival and multivariate Cox regression to determine independent survival predictors.

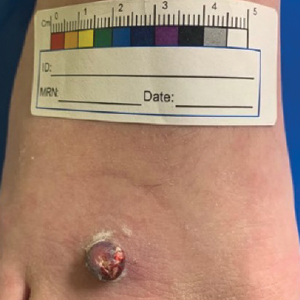

Of the 4,645 pediatric melanoma cases, 63.4% were in females and 36.6% were in males, a difference that was significant (P < .001). Dr. Thiede and colleagues also observed a significant relationship between primary site and gender (P < .001). Primary sites included the trunk (34.3% of females vs. 32.9% of males, respectively), head and neck (16.4% vs. 30.9%), upper extremities (19.5% vs. 16%), lower extremities (27.9% vs. 16.5%), and “unspecified” (1.9% vs. 3.7%).

Females had higher rates of superficial spreading melanoma while males were affected by nodular melanoma more often. For example, the median Breslow depth was higher for males (1.05 mm; interquartile range [IQR] 0.50-2.31) than for females (0.80 mm; IQR, 0.40-1.67; P < .001).

Although females accounted for a higher percentage of cases than males overall, from birth to 17 years, a higher percentage of males than females were found to have later stage of melanoma at time of diagnosis: Females were more likely to be diagnosed with stage I disease (67.8%) than were males (53.6%), and males were more likely than were females to be diagnosed with stages II (15.9% vs. 12.3%), III (27.1% vs. 18.3%), and IV disease (3.3% vs. 1.6%; P < .001 for all).

In other findings, the 5- and 10-year overall survival rates were higher for females (95.9% and 93.9%, respectively) than for males (92.0% vs. 86.7%, respectively; P < .001). However, by age group, overall survival rates were similar between females and males among infants, children, and those in early adolescence – but not for those in middle adolescence (96.7% vs. 91.9%; P < .001) or late adolescence (95.7% vs. 90.4%; P < .001).

When the researchers adjusted for confounding variables, male gender was independently associated with an increased risk of death (adjusted hazard ratio 1.37; P < .001), but age was not.

“It was particularly surprising to see that even at such a young age, there is a significant difference in overall survival between males and females, where females have better outcomes than males,” Dr. Thiede said. “When examining pediatric and adolescent patients, it is essential to maintain cutaneous melanoma on the differential,” she advised. “It is important for clinicians to perform a thorough exam at annual visits particularly for those at high risk for melanoma to catch this rare but potentially devastating diagnosis.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its reliance on one database, “as comparing multiple databases would strengthen the conclusions,” she said. “There was some missing data present in our dataset, and a large percentage of the histologic subtypes were unspecified, both of which are common issues with cancer registries. An additional limitation is related to the low death rates in adolescent and pediatric patients, which may impact the analysis related to survival and independent predictors of survival.”

Asked to comment on the study results, Carrie C. Coughlin, MD, who directs the section of pediatric dermatology Washington University/St. Louis Children’s Hospital, said that the finding that males were more likely to present with stage II or higher disease compared with females “could be related to their finding that females had more superficial spreading melanomas, whereas males had more nodular melanoma.” Those differences “could influence how providers evaluate melanocytic lesions in children,” she added.

Dr. Coughlin, who directs the pediatric dermatology fellowship at Washington University/St. Louis Children’s Hospital, said it was “interesting” that the authors found no association between older age and an increased risk of death. “It would be helpful to have more data about melanoma subtype, including information about Spitz or Spitzoid melanomas,” she said. “Also, knowing the distribution of melanoma across the age categories could provide more insight into their data.”

Ms. Dahak received an award from the National Cancer Institute to fund travel for presentation of this study at the SPD meeting. No other financial conflicts were reported by the researchers. Dr. Coughlin is on the board of the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA) and the International Immunosuppression and Transplant Skin Cancer Collaborative.

INDIANAPOLIS – .

In addition, male gender was independently associated with increased mortality, but age was not.

Those are key findings from a retrospective cohort analysis of nearly 5,000 records from the National Cancer Database.

“There are multiple studies from primarily adult populations showing females with melanoma have a different presentation and better outcomes than males,” co-first author Rebecca M. Thiede, MD, a dermatologist at the University of Arizona, Tucson, said in an interview with this news organization in advance of the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, where the abstract was presented during a poster session. “However, because melanoma is so rare in younger patients, little is known about gender differences in presentation and survival in pediatric and adolescent patients. To our knowledge, this is one of the largest studies to date in this population, and the first to explore gender differences in detail in pediatric and adolescent patients with melanoma.”

Working with co-first author Sabrina Dahak, a fourth-year medical student at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, Dr. Thiede and colleagues retrospectively analyzed the National Cancer Database to identify biopsy-confirmed invasive primary cutaneous melanoma cases diagnosed in patients 0-21 years of age between 2004 and 2018. The search yielded 4,645 cases, and the researchers used American Academy of Pediatrics definitions to categorize the patients by age, from infancy (birth to 2 years), to childhood (3-10 years), early adolescence (11-14 years), middle adolescence (15-17 years), and late adolescence (18-21 years). They used the Kaplan Meier analysis to determine overall survival and multivariate Cox regression to determine independent survival predictors.

Of the 4,645 pediatric melanoma cases, 63.4% were in females and 36.6% were in males, a difference that was significant (P < .001). Dr. Thiede and colleagues also observed a significant relationship between primary site and gender (P < .001). Primary sites included the trunk (34.3% of females vs. 32.9% of males, respectively), head and neck (16.4% vs. 30.9%), upper extremities (19.5% vs. 16%), lower extremities (27.9% vs. 16.5%), and “unspecified” (1.9% vs. 3.7%).

Females had higher rates of superficial spreading melanoma while males were affected by nodular melanoma more often. For example, the median Breslow depth was higher for males (1.05 mm; interquartile range [IQR] 0.50-2.31) than for females (0.80 mm; IQR, 0.40-1.67; P < .001).

Although females accounted for a higher percentage of cases than males overall, from birth to 17 years, a higher percentage of males than females were found to have later stage of melanoma at time of diagnosis: Females were more likely to be diagnosed with stage I disease (67.8%) than were males (53.6%), and males were more likely than were females to be diagnosed with stages II (15.9% vs. 12.3%), III (27.1% vs. 18.3%), and IV disease (3.3% vs. 1.6%; P < .001 for all).

In other findings, the 5- and 10-year overall survival rates were higher for females (95.9% and 93.9%, respectively) than for males (92.0% vs. 86.7%, respectively; P < .001). However, by age group, overall survival rates were similar between females and males among infants, children, and those in early adolescence – but not for those in middle adolescence (96.7% vs. 91.9%; P < .001) or late adolescence (95.7% vs. 90.4%; P < .001).

When the researchers adjusted for confounding variables, male gender was independently associated with an increased risk of death (adjusted hazard ratio 1.37; P < .001), but age was not.

“It was particularly surprising to see that even at such a young age, there is a significant difference in overall survival between males and females, where females have better outcomes than males,” Dr. Thiede said. “When examining pediatric and adolescent patients, it is essential to maintain cutaneous melanoma on the differential,” she advised. “It is important for clinicians to perform a thorough exam at annual visits particularly for those at high risk for melanoma to catch this rare but potentially devastating diagnosis.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its reliance on one database, “as comparing multiple databases would strengthen the conclusions,” she said. “There was some missing data present in our dataset, and a large percentage of the histologic subtypes were unspecified, both of which are common issues with cancer registries. An additional limitation is related to the low death rates in adolescent and pediatric patients, which may impact the analysis related to survival and independent predictors of survival.”

Asked to comment on the study results, Carrie C. Coughlin, MD, who directs the section of pediatric dermatology Washington University/St. Louis Children’s Hospital, said that the finding that males were more likely to present with stage II or higher disease compared with females “could be related to their finding that females had more superficial spreading melanomas, whereas males had more nodular melanoma.” Those differences “could influence how providers evaluate melanocytic lesions in children,” she added.

Dr. Coughlin, who directs the pediatric dermatology fellowship at Washington University/St. Louis Children’s Hospital, said it was “interesting” that the authors found no association between older age and an increased risk of death. “It would be helpful to have more data about melanoma subtype, including information about Spitz or Spitzoid melanomas,” she said. “Also, knowing the distribution of melanoma across the age categories could provide more insight into their data.”

Ms. Dahak received an award from the National Cancer Institute to fund travel for presentation of this study at the SPD meeting. No other financial conflicts were reported by the researchers. Dr. Coughlin is on the board of the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA) and the International Immunosuppression and Transplant Skin Cancer Collaborative.

INDIANAPOLIS – .

In addition, male gender was independently associated with increased mortality, but age was not.

Those are key findings from a retrospective cohort analysis of nearly 5,000 records from the National Cancer Database.

“There are multiple studies from primarily adult populations showing females with melanoma have a different presentation and better outcomes than males,” co-first author Rebecca M. Thiede, MD, a dermatologist at the University of Arizona, Tucson, said in an interview with this news organization in advance of the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, where the abstract was presented during a poster session. “However, because melanoma is so rare in younger patients, little is known about gender differences in presentation and survival in pediatric and adolescent patients. To our knowledge, this is one of the largest studies to date in this population, and the first to explore gender differences in detail in pediatric and adolescent patients with melanoma.”

Working with co-first author Sabrina Dahak, a fourth-year medical student at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, Dr. Thiede and colleagues retrospectively analyzed the National Cancer Database to identify biopsy-confirmed invasive primary cutaneous melanoma cases diagnosed in patients 0-21 years of age between 2004 and 2018. The search yielded 4,645 cases, and the researchers used American Academy of Pediatrics definitions to categorize the patients by age, from infancy (birth to 2 years), to childhood (3-10 years), early adolescence (11-14 years), middle adolescence (15-17 years), and late adolescence (18-21 years). They used the Kaplan Meier analysis to determine overall survival and multivariate Cox regression to determine independent survival predictors.

Of the 4,645 pediatric melanoma cases, 63.4% were in females and 36.6% were in males, a difference that was significant (P < .001). Dr. Thiede and colleagues also observed a significant relationship between primary site and gender (P < .001). Primary sites included the trunk (34.3% of females vs. 32.9% of males, respectively), head and neck (16.4% vs. 30.9%), upper extremities (19.5% vs. 16%), lower extremities (27.9% vs. 16.5%), and “unspecified” (1.9% vs. 3.7%).

Females had higher rates of superficial spreading melanoma while males were affected by nodular melanoma more often. For example, the median Breslow depth was higher for males (1.05 mm; interquartile range [IQR] 0.50-2.31) than for females (0.80 mm; IQR, 0.40-1.67; P < .001).

Although females accounted for a higher percentage of cases than males overall, from birth to 17 years, a higher percentage of males than females were found to have later stage of melanoma at time of diagnosis: Females were more likely to be diagnosed with stage I disease (67.8%) than were males (53.6%), and males were more likely than were females to be diagnosed with stages II (15.9% vs. 12.3%), III (27.1% vs. 18.3%), and IV disease (3.3% vs. 1.6%; P < .001 for all).

In other findings, the 5- and 10-year overall survival rates were higher for females (95.9% and 93.9%, respectively) than for males (92.0% vs. 86.7%, respectively; P < .001). However, by age group, overall survival rates were similar between females and males among infants, children, and those in early adolescence – but not for those in middle adolescence (96.7% vs. 91.9%; P < .001) or late adolescence (95.7% vs. 90.4%; P < .001).

When the researchers adjusted for confounding variables, male gender was independently associated with an increased risk of death (adjusted hazard ratio 1.37; P < .001), but age was not.

“It was particularly surprising to see that even at such a young age, there is a significant difference in overall survival between males and females, where females have better outcomes than males,” Dr. Thiede said. “When examining pediatric and adolescent patients, it is essential to maintain cutaneous melanoma on the differential,” she advised. “It is important for clinicians to perform a thorough exam at annual visits particularly for those at high risk for melanoma to catch this rare but potentially devastating diagnosis.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its reliance on one database, “as comparing multiple databases would strengthen the conclusions,” she said. “There was some missing data present in our dataset, and a large percentage of the histologic subtypes were unspecified, both of which are common issues with cancer registries. An additional limitation is related to the low death rates in adolescent and pediatric patients, which may impact the analysis related to survival and independent predictors of survival.”

Asked to comment on the study results, Carrie C. Coughlin, MD, who directs the section of pediatric dermatology Washington University/St. Louis Children’s Hospital, said that the finding that males were more likely to present with stage II or higher disease compared with females “could be related to their finding that females had more superficial spreading melanomas, whereas males had more nodular melanoma.” Those differences “could influence how providers evaluate melanocytic lesions in children,” she added.

Dr. Coughlin, who directs the pediatric dermatology fellowship at Washington University/St. Louis Children’s Hospital, said it was “interesting” that the authors found no association between older age and an increased risk of death. “It would be helpful to have more data about melanoma subtype, including information about Spitz or Spitzoid melanomas,” she said. “Also, knowing the distribution of melanoma across the age categories could provide more insight into their data.”

Ms. Dahak received an award from the National Cancer Institute to fund travel for presentation of this study at the SPD meeting. No other financial conflicts were reported by the researchers. Dr. Coughlin is on the board of the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA) and the International Immunosuppression and Transplant Skin Cancer Collaborative.

AT SPD 2022

Ruxolitinib found to benefit adolescents with vitiligo up to one year

INDIANAPOLIS – and a higher proportion responded at week 52, results from a pooled analysis of phase 3 data showed.

Currently, there is no treatment approved by the Food and Drug Administration to repigment patients with vitiligo, but the cream formulation of the Janus kinase inhibitor ruxolitinib was shown to be effective and have a favorable safety profile in patients aged 12 years and up in the phase 3 clinical trials, TRuE-V1 and TruE-V2. “We know that about half of patients will develop vitiligo by the age of 20, so there is a significant need to have treatments available for the pediatric population,” lead study author David Rosmarin, MD, told this news organization in advance of the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

In September 2021, topical ruxolitinib (Opzelura) was approved by the FDA for treating atopic dermatitis in nonimmunocompromised patients aged 12 years and older. The manufacturer, Incyte, has submitted an application for approval to the agency for treating vitiligo in patients ages 12 years and older based on 24-week results; the FDA is expected to make a decision by July 18.

For the current study, presented during a poster session at the meeting, Dr. Rosmarin, of the department of dermatology at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, and colleagues pooled efficacy and safety data for adolescent patients aged 12-17 years from the TRuE-V studies, which enrolled patients 12 years of age and older diagnosed with nonsegmental vitiligo with depigmentation covering up to 10% of total body surface area (BSA), including facial and total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI/T-VASI) scores of ≥ 0.5/≥ 3. Investigators randomized patients 2:1 to twice-daily 1.5% ruxolitinib cream or vehicle for 24 weeks, after which all patients could apply 1.5% ruxolitinib cream through week 52. Efficacy endpoints included the proportions of patients who achieved at least 75%, 50%, and 90% improvement from baseline in F-VASI scores (F-VASI75, F-VASI50, F-VASI90); the proportion of patients who achieved at least a 50% improvement from baseline in T-VASI (T-VASI50); the proportion of patients who achieved a Vitiligo Noticeability Scale (VNS) rating of 4 or 5; and percentage change from baseline in facial BSA (F-BSA). Safety and tolerability were also assessed.

For the pooled analysis, Dr. Rosmarin and colleagues reported results on 72 adolescents: 55 who received ruxolitinib cream and 17 who received vehicle. At week 24, 32.1% of adolescents treated with ruxolitinib cream achieved F-VASI75, compared with none of those in the vehicle group. Further, response rates at week 52 for patients who applied ruxolitinib cream from day 1 were as follows: F-VASI75, 48.0%; F-VASI50, 70.0%; F-VASI90, 24.0%; T-VASI50, 60.0%; VNS score of 4/5, 56.0%; and F-BSA mean percentage change from baseline, –41.9%.

Efficacy at week 52 among crossover patients (after 28 weeks of ruxolitinib cream) was consistent with week 24 data in patients who applied ruxolitinib cream from day 1.

“As we know that repigmentation takes time, about half of the patients achieved the F-VASI75 at the 52-week endpoint,” said Dr. Rosmarin, who is also vice-chair for research and education at Tufts Medical Center, Boston. “Particularly remarkable is that 60% of adolescents achieved a T-VASI50 [50% or more repigmentation of the whole body at the year mark] and over half the patients described their vitiligo as a lot less noticeable or no longer noticeable at the year mark.”

In terms of safety, treatment-related adverse events occurred in 12.9% of patients treated with ruxolitinib (no information was available on the specific events). Serious adverse events occurred in 1.4% of patients; none were considered related to treatment.

“Overall, these results are quite impressive,” Dr. Rosmarin said. “While it can be very challenging to repigment patients with vitiligo, ruxolitinib cream provides an effective option which can help many of my patients.” He acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including the fact that the TRuE-V studies were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, “which may have contributed to patients being lost to follow-up. Also, the majority of the patients had skin phototypes 1-3.”

Carrie C. Coughlin, MD, who was asked to comment on the study, said that patients with vitiligo need treatment options that are well-studied and covered by insurance. “This study is a great step forward in developing medications for this underserved patient population,” said Dr. Coughlin, who directs the section of pediatric dermatology at Washington University/St. Louis Children’s Hospital.

However, she continued, “the authors mention approximately 13% of patients had a treatment-related adverse reaction, but the abstract does not delineate these reactions.” In addition, the study was limited to children who had less than or equal to 10% body surface area involvement of vitiligo, she noted, adding that “more work is needed to learn about safety of application to larger surface areas.”

Going forward, “it will be important to learn the durability of response,” said Dr. Coughlin, who is also assistant professor of dermatology at Washington University in St. Louis. “Does the vitiligo return if patients stop applying the ruxolitinib cream?”

Dr. Rosmarin disclosed that he has received honoraria as a consultant for Incyte, AbbVie, Abcuro, AltruBio, Arena, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Celgene, Concert, CSL Behring, Dermavant, Dermira, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Revolo Biotherapeutics, Sanofi, Sun Pharmaceuticals, UCB, and VielaBio. He has also received research support from Incyte, AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermira, Galderma, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Regeneron; and has served as a paid speaker for Incyte, AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Incyte, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi. Dr. Coughlin is on the board of the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance and the International Immunosuppression and Transplant Skin Cancer Collaborative.

INDIANAPOLIS – and a higher proportion responded at week 52, results from a pooled analysis of phase 3 data showed.

Currently, there is no treatment approved by the Food and Drug Administration to repigment patients with vitiligo, but the cream formulation of the Janus kinase inhibitor ruxolitinib was shown to be effective and have a favorable safety profile in patients aged 12 years and up in the phase 3 clinical trials, TRuE-V1 and TruE-V2. “We know that about half of patients will develop vitiligo by the age of 20, so there is a significant need to have treatments available for the pediatric population,” lead study author David Rosmarin, MD, told this news organization in advance of the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

In September 2021, topical ruxolitinib (Opzelura) was approved by the FDA for treating atopic dermatitis in nonimmunocompromised patients aged 12 years and older. The manufacturer, Incyte, has submitted an application for approval to the agency for treating vitiligo in patients ages 12 years and older based on 24-week results; the FDA is expected to make a decision by July 18.

For the current study, presented during a poster session at the meeting, Dr. Rosmarin, of the department of dermatology at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, and colleagues pooled efficacy and safety data for adolescent patients aged 12-17 years from the TRuE-V studies, which enrolled patients 12 years of age and older diagnosed with nonsegmental vitiligo with depigmentation covering up to 10% of total body surface area (BSA), including facial and total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI/T-VASI) scores of ≥ 0.5/≥ 3. Investigators randomized patients 2:1 to twice-daily 1.5% ruxolitinib cream or vehicle for 24 weeks, after which all patients could apply 1.5% ruxolitinib cream through week 52. Efficacy endpoints included the proportions of patients who achieved at least 75%, 50%, and 90% improvement from baseline in F-VASI scores (F-VASI75, F-VASI50, F-VASI90); the proportion of patients who achieved at least a 50% improvement from baseline in T-VASI (T-VASI50); the proportion of patients who achieved a Vitiligo Noticeability Scale (VNS) rating of 4 or 5; and percentage change from baseline in facial BSA (F-BSA). Safety and tolerability were also assessed.

For the pooled analysis, Dr. Rosmarin and colleagues reported results on 72 adolescents: 55 who received ruxolitinib cream and 17 who received vehicle. At week 24, 32.1% of adolescents treated with ruxolitinib cream achieved F-VASI75, compared with none of those in the vehicle group. Further, response rates at week 52 for patients who applied ruxolitinib cream from day 1 were as follows: F-VASI75, 48.0%; F-VASI50, 70.0%; F-VASI90, 24.0%; T-VASI50, 60.0%; VNS score of 4/5, 56.0%; and F-BSA mean percentage change from baseline, –41.9%.

Efficacy at week 52 among crossover patients (after 28 weeks of ruxolitinib cream) was consistent with week 24 data in patients who applied ruxolitinib cream from day 1.

“As we know that repigmentation takes time, about half of the patients achieved the F-VASI75 at the 52-week endpoint,” said Dr. Rosmarin, who is also vice-chair for research and education at Tufts Medical Center, Boston. “Particularly remarkable is that 60% of adolescents achieved a T-VASI50 [50% or more repigmentation of the whole body at the year mark] and over half the patients described their vitiligo as a lot less noticeable or no longer noticeable at the year mark.”

In terms of safety, treatment-related adverse events occurred in 12.9% of patients treated with ruxolitinib (no information was available on the specific events). Serious adverse events occurred in 1.4% of patients; none were considered related to treatment.

“Overall, these results are quite impressive,” Dr. Rosmarin said. “While it can be very challenging to repigment patients with vitiligo, ruxolitinib cream provides an effective option which can help many of my patients.” He acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including the fact that the TRuE-V studies were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, “which may have contributed to patients being lost to follow-up. Also, the majority of the patients had skin phototypes 1-3.”

Carrie C. Coughlin, MD, who was asked to comment on the study, said that patients with vitiligo need treatment options that are well-studied and covered by insurance. “This study is a great step forward in developing medications for this underserved patient population,” said Dr. Coughlin, who directs the section of pediatric dermatology at Washington University/St. Louis Children’s Hospital.

However, she continued, “the authors mention approximately 13% of patients had a treatment-related adverse reaction, but the abstract does not delineate these reactions.” In addition, the study was limited to children who had less than or equal to 10% body surface area involvement of vitiligo, she noted, adding that “more work is needed to learn about safety of application to larger surface areas.”

Going forward, “it will be important to learn the durability of response,” said Dr. Coughlin, who is also assistant professor of dermatology at Washington University in St. Louis. “Does the vitiligo return if patients stop applying the ruxolitinib cream?”

Dr. Rosmarin disclosed that he has received honoraria as a consultant for Incyte, AbbVie, Abcuro, AltruBio, Arena, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Celgene, Concert, CSL Behring, Dermavant, Dermira, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Revolo Biotherapeutics, Sanofi, Sun Pharmaceuticals, UCB, and VielaBio. He has also received research support from Incyte, AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermira, Galderma, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Regeneron; and has served as a paid speaker for Incyte, AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Incyte, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi. Dr. Coughlin is on the board of the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance and the International Immunosuppression and Transplant Skin Cancer Collaborative.

INDIANAPOLIS – and a higher proportion responded at week 52, results from a pooled analysis of phase 3 data showed.

Currently, there is no treatment approved by the Food and Drug Administration to repigment patients with vitiligo, but the cream formulation of the Janus kinase inhibitor ruxolitinib was shown to be effective and have a favorable safety profile in patients aged 12 years and up in the phase 3 clinical trials, TRuE-V1 and TruE-V2. “We know that about half of patients will develop vitiligo by the age of 20, so there is a significant need to have treatments available for the pediatric population,” lead study author David Rosmarin, MD, told this news organization in advance of the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

In September 2021, topical ruxolitinib (Opzelura) was approved by the FDA for treating atopic dermatitis in nonimmunocompromised patients aged 12 years and older. The manufacturer, Incyte, has submitted an application for approval to the agency for treating vitiligo in patients ages 12 years and older based on 24-week results; the FDA is expected to make a decision by July 18.

For the current study, presented during a poster session at the meeting, Dr. Rosmarin, of the department of dermatology at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, and colleagues pooled efficacy and safety data for adolescent patients aged 12-17 years from the TRuE-V studies, which enrolled patients 12 years of age and older diagnosed with nonsegmental vitiligo with depigmentation covering up to 10% of total body surface area (BSA), including facial and total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI/T-VASI) scores of ≥ 0.5/≥ 3. Investigators randomized patients 2:1 to twice-daily 1.5% ruxolitinib cream or vehicle for 24 weeks, after which all patients could apply 1.5% ruxolitinib cream through week 52. Efficacy endpoints included the proportions of patients who achieved at least 75%, 50%, and 90% improvement from baseline in F-VASI scores (F-VASI75, F-VASI50, F-VASI90); the proportion of patients who achieved at least a 50% improvement from baseline in T-VASI (T-VASI50); the proportion of patients who achieved a Vitiligo Noticeability Scale (VNS) rating of 4 or 5; and percentage change from baseline in facial BSA (F-BSA). Safety and tolerability were also assessed.

For the pooled analysis, Dr. Rosmarin and colleagues reported results on 72 adolescents: 55 who received ruxolitinib cream and 17 who received vehicle. At week 24, 32.1% of adolescents treated with ruxolitinib cream achieved F-VASI75, compared with none of those in the vehicle group. Further, response rates at week 52 for patients who applied ruxolitinib cream from day 1 were as follows: F-VASI75, 48.0%; F-VASI50, 70.0%; F-VASI90, 24.0%; T-VASI50, 60.0%; VNS score of 4/5, 56.0%; and F-BSA mean percentage change from baseline, –41.9%.

Efficacy at week 52 among crossover patients (after 28 weeks of ruxolitinib cream) was consistent with week 24 data in patients who applied ruxolitinib cream from day 1.

“As we know that repigmentation takes time, about half of the patients achieved the F-VASI75 at the 52-week endpoint,” said Dr. Rosmarin, who is also vice-chair for research and education at Tufts Medical Center, Boston. “Particularly remarkable is that 60% of adolescents achieved a T-VASI50 [50% or more repigmentation of the whole body at the year mark] and over half the patients described their vitiligo as a lot less noticeable or no longer noticeable at the year mark.”

In terms of safety, treatment-related adverse events occurred in 12.9% of patients treated with ruxolitinib (no information was available on the specific events). Serious adverse events occurred in 1.4% of patients; none were considered related to treatment.

“Overall, these results are quite impressive,” Dr. Rosmarin said. “While it can be very challenging to repigment patients with vitiligo, ruxolitinib cream provides an effective option which can help many of my patients.” He acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including the fact that the TRuE-V studies were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, “which may have contributed to patients being lost to follow-up. Also, the majority of the patients had skin phototypes 1-3.”

Carrie C. Coughlin, MD, who was asked to comment on the study, said that patients with vitiligo need treatment options that are well-studied and covered by insurance. “This study is a great step forward in developing medications for this underserved patient population,” said Dr. Coughlin, who directs the section of pediatric dermatology at Washington University/St. Louis Children’s Hospital.

However, she continued, “the authors mention approximately 13% of patients had a treatment-related adverse reaction, but the abstract does not delineate these reactions.” In addition, the study was limited to children who had less than or equal to 10% body surface area involvement of vitiligo, she noted, adding that “more work is needed to learn about safety of application to larger surface areas.”

Going forward, “it will be important to learn the durability of response,” said Dr. Coughlin, who is also assistant professor of dermatology at Washington University in St. Louis. “Does the vitiligo return if patients stop applying the ruxolitinib cream?”

Dr. Rosmarin disclosed that he has received honoraria as a consultant for Incyte, AbbVie, Abcuro, AltruBio, Arena, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Celgene, Concert, CSL Behring, Dermavant, Dermira, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Revolo Biotherapeutics, Sanofi, Sun Pharmaceuticals, UCB, and VielaBio. He has also received research support from Incyte, AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermira, Galderma, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Regeneron; and has served as a paid speaker for Incyte, AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Incyte, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi. Dr. Coughlin is on the board of the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance and the International Immunosuppression and Transplant Skin Cancer Collaborative.

AT SPD 2022

To vaccinate 6-month- to 5-year-olds against SARS-CoV-2 or not to vaccinate

A family’s decision to vaccinate their child is best made jointly with a trusted medical provider who knows the child and family. The American Academy of Pediatrics created a toolkit with resources for answering questions about the recently authorized SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines (Pfizer and Moderna) for 6-month- to 5-year-olds with science-backed vaccine facts, including links to other useful AAP information websites, talking points, graphics, and videos.1

SARS-CoV-2 seasonality

SARS-CoV-2 is now endemic, not a once-a-year seasonal virus. Seasons (aka surges) will occur whenever a new variant arises (twice yearly since 2020, Omicron BA.4/BA.5 currently), or when enough vaccine holdouts, newborns, and/or those with waning of prior immunity (vaccine or infection induced) accrue.

Emergency use authorization submission data for mRNA vaccine responses in young children2,3

Moderna in 6-month- through 5-year-olds. Two 25-mcg doses given 4-8 weeks apart produced 37.8% (95% confidence interval, 20.9%-51.1%) protection against symptomatic Omicron SARS-CoV-2 infections through 3 months of follow-up. Immunobridging analysis of antibody responses compared to 18- to 25-year-olds (100-mcg doses) showed the children’s responses were noninferior. Thus, the committee inferred that vaccine effectiveness in children should be similar to that in 18- to 25-year-olds. Fever, irritability, or local reaction/pain occurred in two-thirds after the second dose. Grade 3 reactions were noted in less than 5%.

Pfizer in 6-month- through 4-year-olds. Three 3-mcg doses, two doses 3-8 weeks apart and the third dose at least 8 weeks later (median 16 weeks), produced 80.3% (95% CI, 13.9%-96.7%) protection against symptomatic COVID-19 during the 6 weeks after the third dose. Local and systemic reactions occurred in 63.8%; less than 5% had grade 3 reactions (fever in about 3%, irritability in 1.3%, fatigue in 0.8%) mostly after second dose.

Neither duration of follow-up is very long. The Moderna data tell me that a third primary dose would have been better but restarting the trial to evaluate third doses would have delayed Moderna’s EUA another 4-6 months. The three-dose Pfizer data look better but may not have been as good with another 6 weeks of follow-up.

Additional post-EUA data will be collected. Boosters will be needed when immunity from both vaccines wanes (one estimate is about 6 months after the primary series). The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices noted in their deliberations that vaccine-induced antibody responses are higher and cross-neutralize variants (even Omicron) better than infection-induced immunity.4

Are there downsides to the vaccines? Naysayers question vaccinating children less than 5 years old with reasons containing enough “truth” that they catch people’s attention, for example, “young children don’t get very sick with COVID-19,” “most have been infected already,” “RNA for the spike protein stays in the body for months,” or “myocarditis.” Naysayers can quote references in reputable journals but seem to spin selected data out of context or quote unconfirmed data from the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System.

Reasons to vaccinate

- While children have milder disease than adults, mid-June 2022 surveillance indicated 50 hospitalizations and 1 pediatric death each day from SARS-CoV-2.5

- Vaccinating young children endows a foundation of vaccine-induced SARS-CoV-2 immunity that is superior to infection-induced immunity.4

- Long-term effects of large numbers of SARS-CoV-2 particles that enter every organ of a developing child have not been determined.

- Viral loads are lowered by prior vaccine; fewer viral replications lessen chances for newer variants to arise.

- Transmission is less in breakthrough infections than infections in the unvaccinated.

- Thirty percent of 5- to 11-year-olds hospitalized for SARS-CoV-2 had no underlying conditions;6 hospitalization rates in newborn to 4-year-olds have been the highest in the Omicron surge.7

- No myocarditis or pericarditis episodes have been detected in 6-month- to 11-year-old trials.

- The AAP and ACIP recommend the mRNA vaccines.

My thoughts are that SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is just another “routine” childhood vaccine that prepares children for healthier futures, pandemic or not, and the vaccines are as safe as other routine vaccines.

And like other pediatric vaccines, it should be no surprise that boosters will be needed, even if no newer variants than Omicron BA.4/BA.5 arise. But we know newer variants will arise and, similar to influenza vaccine, new formulations, perhaps with multiple SARS-CoV-2 strain antigens, will be needed every year or so. Everyone will get SARS-CoV-2 multiple times in their lives no matter how careful they are. So isn’t it good medical practice to establish early the best available foundation for maintaining lifelong SARS-CoV-2 immunity?

To me it is like pertussis. Most pertussis-infected children are sick enough to be hospitalized; very few die. They are miserable with illnesses that take weeks to months to subside. The worst disease usually occurs in unvaccinated young children or those with underlying conditions. Reactogenicity was reduced with acellular vaccine but resulted in less immunogenicity, so we give boosters at intervals that best match waning immunity. Circulating strains can be different than the vaccine strain, so protection against infection is 80%. Finally, even the safest vaccine may very rarely have sequelae. That is why The National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program was created. Yet the benefit-to-harm ratio for children and society favors universal pertussis vaccine use. And we vaccinate even those who have had pertussis because even infection-based immunity is incomplete and protection wanes. If arguments similar to those by SARS-CoV-2 vaccine naysayers were applied to acellular pertussis vaccine, it seems they would argue against pertussis vaccine for young children.

Another major issue has been “safety concerns” about the vaccines’ small amount of mRNA for the spike protein encased in microscopic lipid bubbles injected in the arm or leg. This mRNA is picked up by human cells, and in the cytoplasm (not the nucleus where our DNA resides) produces a limited supply of spike protein that is then picked up by antigen-presenting cells for short-lived distribution (days to 2 weeks at most) to regional lymph nodes where immune-memory processes are jump-started. Contrast that to even asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection where multibillions of virus particles are produced for up to 14 days with access to every bodily organ that contains ACE-2 receptors (they all do). Each virus particle hijacks a human cell producing thousands of mRNA for spike protein (and multiple other SARS-CoV-2 proteins), eventually releasing multibillions of lipid fragments from the ruptured cell. Comparing the amount of these components in the mRNA vaccines to those from infection is like comparing a campfire to the many-thousand-acre wildfire. So, if one is worried about the effects of spike protein and lipid fragments, the limited localized amounts in mRNA vaccines should make one much less concerned than the enormous amounts circulating throughout the body as a result of a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

My take is that children 6-months to 5-years-old deserve SARS-CoV-2–induced vaccine protection and we can and should strongly recommend it as medical providers and child advocates.

*Dr. Harrison is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. AAP. 2022 Jun 21. As COVID-19 vaccines become available for children ages 6 months to 4 years, AAP urges families to reach out to pediatricians to ask questions and access vaccine. www.aap.org.

2. CDC. Grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation (GRADE): Moderna COVID-19 vaccine for children aged 6 months–5 years. www.cdc.gov.

3. CDC. ACIP evidence to recommendations for use of Moderna COVID-19 vaccine in children ages 6 months–5 years and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in children ages 6 months–4 years under an emergency use authorization. www.cdc.gov.

4. Tang J et al. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2979.

5. Children and COVID-19: State Data Report. 2022 Jun 30. www.aap.org.

6. Shi DS et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:574-81.

7. Marks KJ et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:429-36.

Other good resources for families are https://getvaccineanswers.org/ or www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/coronavirus-in-babies-and-children/art-20484405.

*This story was updated on July 19, 2022.

A family’s decision to vaccinate their child is best made jointly with a trusted medical provider who knows the child and family. The American Academy of Pediatrics created a toolkit with resources for answering questions about the recently authorized SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines (Pfizer and Moderna) for 6-month- to 5-year-olds with science-backed vaccine facts, including links to other useful AAP information websites, talking points, graphics, and videos.1

SARS-CoV-2 seasonality

SARS-CoV-2 is now endemic, not a once-a-year seasonal virus. Seasons (aka surges) will occur whenever a new variant arises (twice yearly since 2020, Omicron BA.4/BA.5 currently), or when enough vaccine holdouts, newborns, and/or those with waning of prior immunity (vaccine or infection induced) accrue.

Emergency use authorization submission data for mRNA vaccine responses in young children2,3

Moderna in 6-month- through 5-year-olds. Two 25-mcg doses given 4-8 weeks apart produced 37.8% (95% confidence interval, 20.9%-51.1%) protection against symptomatic Omicron SARS-CoV-2 infections through 3 months of follow-up. Immunobridging analysis of antibody responses compared to 18- to 25-year-olds (100-mcg doses) showed the children’s responses were noninferior. Thus, the committee inferred that vaccine effectiveness in children should be similar to that in 18- to 25-year-olds. Fever, irritability, or local reaction/pain occurred in two-thirds after the second dose. Grade 3 reactions were noted in less than 5%.

Pfizer in 6-month- through 4-year-olds. Three 3-mcg doses, two doses 3-8 weeks apart and the third dose at least 8 weeks later (median 16 weeks), produced 80.3% (95% CI, 13.9%-96.7%) protection against symptomatic COVID-19 during the 6 weeks after the third dose. Local and systemic reactions occurred in 63.8%; less than 5% had grade 3 reactions (fever in about 3%, irritability in 1.3%, fatigue in 0.8%) mostly after second dose.

Neither duration of follow-up is very long. The Moderna data tell me that a third primary dose would have been better but restarting the trial to evaluate third doses would have delayed Moderna’s EUA another 4-6 months. The three-dose Pfizer data look better but may not have been as good with another 6 weeks of follow-up.

Additional post-EUA data will be collected. Boosters will be needed when immunity from both vaccines wanes (one estimate is about 6 months after the primary series). The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices noted in their deliberations that vaccine-induced antibody responses are higher and cross-neutralize variants (even Omicron) better than infection-induced immunity.4

Are there downsides to the vaccines? Naysayers question vaccinating children less than 5 years old with reasons containing enough “truth” that they catch people’s attention, for example, “young children don’t get very sick with COVID-19,” “most have been infected already,” “RNA for the spike protein stays in the body for months,” or “myocarditis.” Naysayers can quote references in reputable journals but seem to spin selected data out of context or quote unconfirmed data from the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System.

Reasons to vaccinate

- While children have milder disease than adults, mid-June 2022 surveillance indicated 50 hospitalizations and 1 pediatric death each day from SARS-CoV-2.5

- Vaccinating young children endows a foundation of vaccine-induced SARS-CoV-2 immunity that is superior to infection-induced immunity.4

- Long-term effects of large numbers of SARS-CoV-2 particles that enter every organ of a developing child have not been determined.

- Viral loads are lowered by prior vaccine; fewer viral replications lessen chances for newer variants to arise.

- Transmission is less in breakthrough infections than infections in the unvaccinated.

- Thirty percent of 5- to 11-year-olds hospitalized for SARS-CoV-2 had no underlying conditions;6 hospitalization rates in newborn to 4-year-olds have been the highest in the Omicron surge.7

- No myocarditis or pericarditis episodes have been detected in 6-month- to 11-year-old trials.

- The AAP and ACIP recommend the mRNA vaccines.

My thoughts are that SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is just another “routine” childhood vaccine that prepares children for healthier futures, pandemic or not, and the vaccines are as safe as other routine vaccines.

And like other pediatric vaccines, it should be no surprise that boosters will be needed, even if no newer variants than Omicron BA.4/BA.5 arise. But we know newer variants will arise and, similar to influenza vaccine, new formulations, perhaps with multiple SARS-CoV-2 strain antigens, will be needed every year or so. Everyone will get SARS-CoV-2 multiple times in their lives no matter how careful they are. So isn’t it good medical practice to establish early the best available foundation for maintaining lifelong SARS-CoV-2 immunity?

To me it is like pertussis. Most pertussis-infected children are sick enough to be hospitalized; very few die. They are miserable with illnesses that take weeks to months to subside. The worst disease usually occurs in unvaccinated young children or those with underlying conditions. Reactogenicity was reduced with acellular vaccine but resulted in less immunogenicity, so we give boosters at intervals that best match waning immunity. Circulating strains can be different than the vaccine strain, so protection against infection is 80%. Finally, even the safest vaccine may very rarely have sequelae. That is why The National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program was created. Yet the benefit-to-harm ratio for children and society favors universal pertussis vaccine use. And we vaccinate even those who have had pertussis because even infection-based immunity is incomplete and protection wanes. If arguments similar to those by SARS-CoV-2 vaccine naysayers were applied to acellular pertussis vaccine, it seems they would argue against pertussis vaccine for young children.

Another major issue has been “safety concerns” about the vaccines’ small amount of mRNA for the spike protein encased in microscopic lipid bubbles injected in the arm or leg. This mRNA is picked up by human cells, and in the cytoplasm (not the nucleus where our DNA resides) produces a limited supply of spike protein that is then picked up by antigen-presenting cells for short-lived distribution (days to 2 weeks at most) to regional lymph nodes where immune-memory processes are jump-started. Contrast that to even asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection where multibillions of virus particles are produced for up to 14 days with access to every bodily organ that contains ACE-2 receptors (they all do). Each virus particle hijacks a human cell producing thousands of mRNA for spike protein (and multiple other SARS-CoV-2 proteins), eventually releasing multibillions of lipid fragments from the ruptured cell. Comparing the amount of these components in the mRNA vaccines to those from infection is like comparing a campfire to the many-thousand-acre wildfire. So, if one is worried about the effects of spike protein and lipid fragments, the limited localized amounts in mRNA vaccines should make one much less concerned than the enormous amounts circulating throughout the body as a result of a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

My take is that children 6-months to 5-years-old deserve SARS-CoV-2–induced vaccine protection and we can and should strongly recommend it as medical providers and child advocates.

*Dr. Harrison is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. AAP. 2022 Jun 21. As COVID-19 vaccines become available for children ages 6 months to 4 years, AAP urges families to reach out to pediatricians to ask questions and access vaccine. www.aap.org.

2. CDC. Grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation (GRADE): Moderna COVID-19 vaccine for children aged 6 months–5 years. www.cdc.gov.

3. CDC. ACIP evidence to recommendations for use of Moderna COVID-19 vaccine in children ages 6 months–5 years and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in children ages 6 months–4 years under an emergency use authorization. www.cdc.gov.

4. Tang J et al. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2979.

5. Children and COVID-19: State Data Report. 2022 Jun 30. www.aap.org.

6. Shi DS et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:574-81.

7. Marks KJ et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:429-36.

Other good resources for families are https://getvaccineanswers.org/ or www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/coronavirus-in-babies-and-children/art-20484405.

*This story was updated on July 19, 2022.

A family’s decision to vaccinate their child is best made jointly with a trusted medical provider who knows the child and family. The American Academy of Pediatrics created a toolkit with resources for answering questions about the recently authorized SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines (Pfizer and Moderna) for 6-month- to 5-year-olds with science-backed vaccine facts, including links to other useful AAP information websites, talking points, graphics, and videos.1

SARS-CoV-2 seasonality

SARS-CoV-2 is now endemic, not a once-a-year seasonal virus. Seasons (aka surges) will occur whenever a new variant arises (twice yearly since 2020, Omicron BA.4/BA.5 currently), or when enough vaccine holdouts, newborns, and/or those with waning of prior immunity (vaccine or infection induced) accrue.

Emergency use authorization submission data for mRNA vaccine responses in young children2,3

Moderna in 6-month- through 5-year-olds. Two 25-mcg doses given 4-8 weeks apart produced 37.8% (95% confidence interval, 20.9%-51.1%) protection against symptomatic Omicron SARS-CoV-2 infections through 3 months of follow-up. Immunobridging analysis of antibody responses compared to 18- to 25-year-olds (100-mcg doses) showed the children’s responses were noninferior. Thus, the committee inferred that vaccine effectiveness in children should be similar to that in 18- to 25-year-olds. Fever, irritability, or local reaction/pain occurred in two-thirds after the second dose. Grade 3 reactions were noted in less than 5%.

Pfizer in 6-month- through 4-year-olds. Three 3-mcg doses, two doses 3-8 weeks apart and the third dose at least 8 weeks later (median 16 weeks), produced 80.3% (95% CI, 13.9%-96.7%) protection against symptomatic COVID-19 during the 6 weeks after the third dose. Local and systemic reactions occurred in 63.8%; less than 5% had grade 3 reactions (fever in about 3%, irritability in 1.3%, fatigue in 0.8%) mostly after second dose.

Neither duration of follow-up is very long. The Moderna data tell me that a third primary dose would have been better but restarting the trial to evaluate third doses would have delayed Moderna’s EUA another 4-6 months. The three-dose Pfizer data look better but may not have been as good with another 6 weeks of follow-up.

Additional post-EUA data will be collected. Boosters will be needed when immunity from both vaccines wanes (one estimate is about 6 months after the primary series). The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices noted in their deliberations that vaccine-induced antibody responses are higher and cross-neutralize variants (even Omicron) better than infection-induced immunity.4

Are there downsides to the vaccines? Naysayers question vaccinating children less than 5 years old with reasons containing enough “truth” that they catch people’s attention, for example, “young children don’t get very sick with COVID-19,” “most have been infected already,” “RNA for the spike protein stays in the body for months,” or “myocarditis.” Naysayers can quote references in reputable journals but seem to spin selected data out of context or quote unconfirmed data from the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System.

Reasons to vaccinate

- While children have milder disease than adults, mid-June 2022 surveillance indicated 50 hospitalizations and 1 pediatric death each day from SARS-CoV-2.5

- Vaccinating young children endows a foundation of vaccine-induced SARS-CoV-2 immunity that is superior to infection-induced immunity.4

- Long-term effects of large numbers of SARS-CoV-2 particles that enter every organ of a developing child have not been determined.

- Viral loads are lowered by prior vaccine; fewer viral replications lessen chances for newer variants to arise.

- Transmission is less in breakthrough infections than infections in the unvaccinated.

- Thirty percent of 5- to 11-year-olds hospitalized for SARS-CoV-2 had no underlying conditions;6 hospitalization rates in newborn to 4-year-olds have been the highest in the Omicron surge.7

- No myocarditis or pericarditis episodes have been detected in 6-month- to 11-year-old trials.

- The AAP and ACIP recommend the mRNA vaccines.

My thoughts are that SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is just another “routine” childhood vaccine that prepares children for healthier futures, pandemic or not, and the vaccines are as safe as other routine vaccines.

And like other pediatric vaccines, it should be no surprise that boosters will be needed, even if no newer variants than Omicron BA.4/BA.5 arise. But we know newer variants will arise and, similar to influenza vaccine, new formulations, perhaps with multiple SARS-CoV-2 strain antigens, will be needed every year or so. Everyone will get SARS-CoV-2 multiple times in their lives no matter how careful they are. So isn’t it good medical practice to establish early the best available foundation for maintaining lifelong SARS-CoV-2 immunity?

To me it is like pertussis. Most pertussis-infected children are sick enough to be hospitalized; very few die. They are miserable with illnesses that take weeks to months to subside. The worst disease usually occurs in unvaccinated young children or those with underlying conditions. Reactogenicity was reduced with acellular vaccine but resulted in less immunogenicity, so we give boosters at intervals that best match waning immunity. Circulating strains can be different than the vaccine strain, so protection against infection is 80%. Finally, even the safest vaccine may very rarely have sequelae. That is why The National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program was created. Yet the benefit-to-harm ratio for children and society favors universal pertussis vaccine use. And we vaccinate even those who have had pertussis because even infection-based immunity is incomplete and protection wanes. If arguments similar to those by SARS-CoV-2 vaccine naysayers were applied to acellular pertussis vaccine, it seems they would argue against pertussis vaccine for young children.

Another major issue has been “safety concerns” about the vaccines’ small amount of mRNA for the spike protein encased in microscopic lipid bubbles injected in the arm or leg. This mRNA is picked up by human cells, and in the cytoplasm (not the nucleus where our DNA resides) produces a limited supply of spike protein that is then picked up by antigen-presenting cells for short-lived distribution (days to 2 weeks at most) to regional lymph nodes where immune-memory processes are jump-started. Contrast that to even asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection where multibillions of virus particles are produced for up to 14 days with access to every bodily organ that contains ACE-2 receptors (they all do). Each virus particle hijacks a human cell producing thousands of mRNA for spike protein (and multiple other SARS-CoV-2 proteins), eventually releasing multibillions of lipid fragments from the ruptured cell. Comparing the amount of these components in the mRNA vaccines to those from infection is like comparing a campfire to the many-thousand-acre wildfire. So, if one is worried about the effects of spike protein and lipid fragments, the limited localized amounts in mRNA vaccines should make one much less concerned than the enormous amounts circulating throughout the body as a result of a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

My take is that children 6-months to 5-years-old deserve SARS-CoV-2–induced vaccine protection and we can and should strongly recommend it as medical providers and child advocates.

*Dr. Harrison is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. AAP. 2022 Jun 21. As COVID-19 vaccines become available for children ages 6 months to 4 years, AAP urges families to reach out to pediatricians to ask questions and access vaccine. www.aap.org.

2. CDC. Grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation (GRADE): Moderna COVID-19 vaccine for children aged 6 months–5 years. www.cdc.gov.

3. CDC. ACIP evidence to recommendations for use of Moderna COVID-19 vaccine in children ages 6 months–5 years and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in children ages 6 months–4 years under an emergency use authorization. www.cdc.gov.

4. Tang J et al. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2979.

5. Children and COVID-19: State Data Report. 2022 Jun 30. www.aap.org.

6. Shi DS et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:574-81.

7. Marks KJ et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:429-36.

Other good resources for families are https://getvaccineanswers.org/ or www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/coronavirus-in-babies-and-children/art-20484405.

*This story was updated on July 19, 2022.

Precocious puberty – how early is too soon?

A 6-year-old girl presents with breast development. Her medical history is unremarkable. The parents are of average height, and the mother reports her thelarche was age 11 years. The girl is at the 97th percentile for her height and 90th percentile for her weight. She has Tanner stage 3 breast development and Tanner stage 2 pubic hair development. She has grown slightly more than 3 inches over the past year. How should she be evaluated and managed (N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2366-77)?

The premature onset of puberty, i.e., precocious puberty (PP), can be an emotionally traumatic event for the child and parents. Over the past century, improvements in public health and nutrition, and, more recently, increased obesity, have been associated with earlier puberty and the dominant factor has been attributed to genetics (Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2018;25[1]:49-54). This month’s article will focus on understanding what is considered “early” puberty, evaluating for causes, and managing precocious puberty.

More commonly seen in girls than boys, PP is defined as the onset of secondary sexual characteristics before age 7.5 years in Black and Hispanic girls, and prior to 8 years in White girls, which is 2-2.5 standard deviations below the average age of pubertal onset in healthy children (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2019;32:455-9). As a comparison, PP is diagnosed with onset before age 9 years in boys. For White compared with Black girls, the average timing of thelarche is age 10 vs. 9.5 years, peak growth velocity is age 11.5, menarche is age 12.5 vs. 12, while completion of puberty is near age 14.5 vs. 13.5, respectively (J Pediatr. 1985;107:317). Fortunately, most girls with PP have common variants rather than serious pathology.

Classification: Central (CPP) vs. peripheral (PPP)

CPP is gonadotropin dependent, meaning the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis (HPO) is prematurely activated resulting in the normal progression of puberty.

PPP is gonadotropin independent, caused by sex steroid secretion from any source – ovaries, adrenal gland, exogenous or ectopic production, e.g., germ-cell tumor. This results in a disordered progression of pubertal milestones.

Whereas CPP is typically isosexual development, i.e., consistent with the child’s gender, PPP can be isosexual or contrasexual, e.g., virilization of girls. A third classification is “benign or nonprogressive pubertal variants” manifesting as isolated premature thelarche or adrenarche.

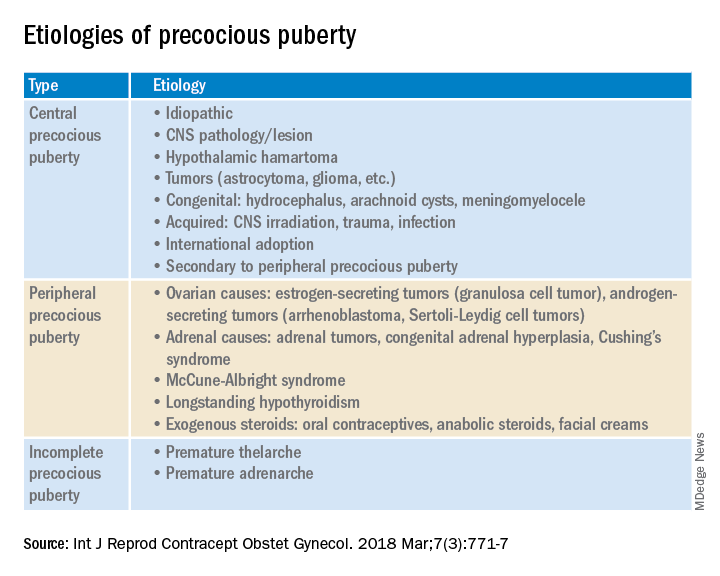

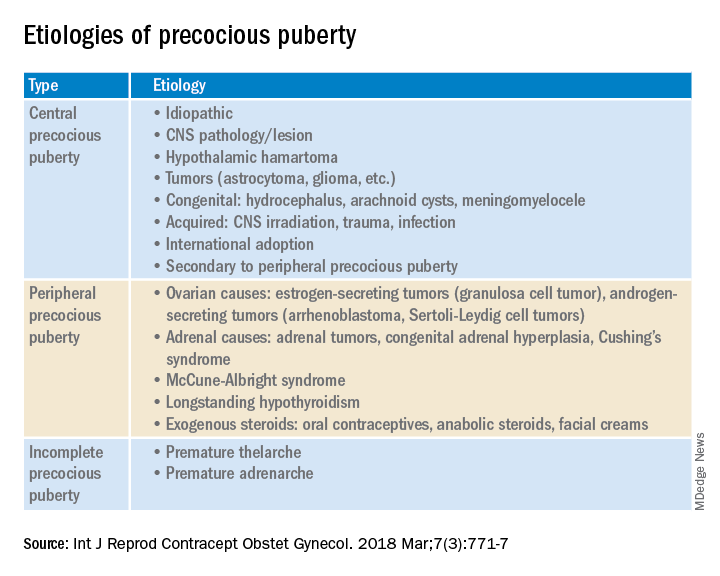

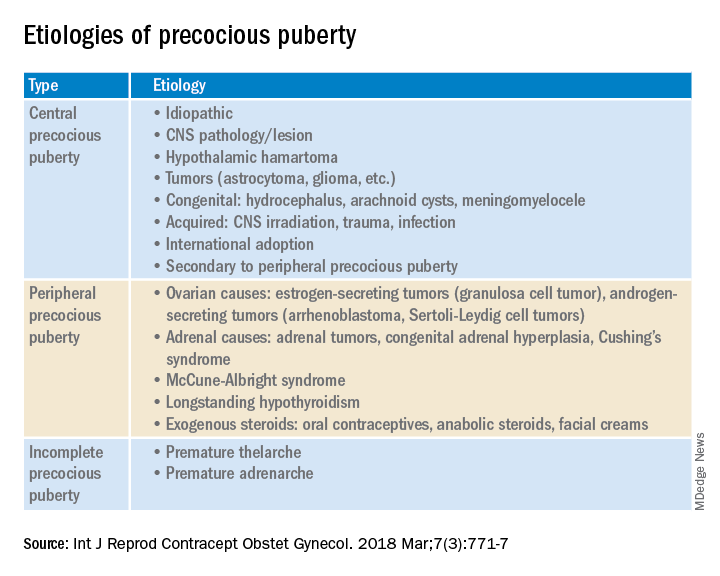

Causes (see table)

CPP. Idiopathic causes account for 80%-90% of presentations in girls and 25%-80% in boys. Remarkably, international and domestic adoption, as well as a family history of PP increases the likelihood of CPP in girls. Other etiologies include CNS lesions, e.g., hamartomas, which are the most common cause of PP in young children. MRI with contrast has been the traditional mode of diagnosis for CNS tumors, yet the yield is dubious in girls above age 6. Genetic causes are found in only a small percentage of PP cases. Rarely, CPP can result from gonadotropin-secreting tumors because of elevated luteinizing hormone levels.

PPP. As a result of sex steroid secretion, peripheral causes of PPP include ovarian cysts and ovarian tumors that increase circulating estradiol, such as granulosa cell tumors, which would cause isosexual PPP and Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors that secrete testosterone, which can result in contrasexual PPP. Mild congenital adrenal hyperplasia can result in PPP with virilization (contrasexual) and markedly advanced bone age.

McCune-Albright syndrome is rare and presents with the classic triad of PPP, skin pigmentation called café-au-lait, and fibrous dysplasia of bone. The pathophysiology of McCune-Albright syndrome is autoactivation of the G-protein leading to activation of ovarian tissue that results in formation of large ovarian cysts and extreme elevations in serum estradiol as well as the potential production of other hormones, e.g., thyrotoxicosis, excess growth hormone (acromegaly), and Cushing syndrome.

Premature thelarche. Premature thelarche typically occurs in girls between the ages of 1 and 3 years and is limited to breast enlargement. While no cause has been determined, the plausible explanations include partial activation of the HPO axis, endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), or a genetic origin. A small percentage of these girls progress to CPP.

EDCs have been considered as potential influencers of early puberty, but no consensus has been established. (Examples of EDCs in the environment include air, soil, or water supply along with food sources, personal care products, and manufactured products that can affect the endocrine system.)

Premature adenarche. Premature adrenarche presents with adult body odor and/or body hair (pubic and/or axillary) in girls who have an elevated body mass index, most commonly at the ages of 6-7 years. The presumed mechanism is normal maturation of the adrenal gland with resultant elevation of circulating androgens. Bone age may be mildly accelerated and DHEAS is prematurely elevated for age. These girls appear to be at increased risk for polycystic ovary syndrome.

Evaluation

The initial step in the evaluation of PP is to determine whether the cause is CPP or PPP; the latter includes distinguishing isosexual from contrasexual development. A thorough history (growth, headaches, behavior or visual change, seizures, abdominal pain), physical exam, including Tanner staging, and bone age is required. However, with isolated premature thelarche or adrenarche, a bone age may not be necessary, as initial close clinical observation for pubertal progression is likely sufficient.

For CPP, the diagnosis is based on serum LH, whether random levels or elevations follow GnRH stimulation. Puberty milestones progress normally although adrenarche is not consistently apparent. For girls younger than age 6, a brain MRI is recommended but not in asymptomatic older girls with CPP. LH and FSH along with estradiol or testosterone, the latter especially in boys, are the first line of serum testing. Serum TSH is recommended for suspicion of primary hypothyroidism. In girls with premature adrenarche, a bone age, testosterone, DHEAS, and 17-OHP to rule out adrenal hyperplasia should be obtained. Pelvic ultrasound may be a useful adjunct to assess uterine volume and/or ovarian cysts/tumors.

Rapidity of onset can also lead the evaluation since a normal growth chart and skeletal maturation suggests a benign pubertal variant whereas a more rapid rate can signal CPP or PPP. Of note, health care providers should ensure prescription, over-the-counter oral or topical sources of hormones, and EDCs are ruled out.

Consequences

An association between childhood sexual abuse and earlier pubertal onset has been cited. These girls may be at increased risk for psychosocial difficulties, menstrual and fertility problems, and even reproductive cancers because of prolonged exposure to sex hormones (J Adolesc Health. 2016;60[1]:65-71).

Treatment

The mainstay of CPP treatment is maximizing adult height, typically through the use of a GnRH agonist for HPO suppression from pituitary downregulation. For girls above age 8 years, attempts at improving adult height have not shown a benefit.

In girls with PPP, treatment is directed at the prevailing pathology. Interestingly, early PPP can activate the HPO axis thereby converting to “secondary” CPP. In PPP, McCune-Albright syndrome treatment targets reducing circulating estrogens through letrozole or tamoxifen as well as addressing other autoactivated hormone production. Ovarian and adrenal tumors, albeit rare, can cause PP; therefore, surgical excision is the goal of treatment.

PP should be approached with equal concerns about the physical and emotional effects while including the family to help them understand the pathophysiology and psychosocial risks.

Dr. Mark P. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

A 6-year-old girl presents with breast development. Her medical history is unremarkable. The parents are of average height, and the mother reports her thelarche was age 11 years. The girl is at the 97th percentile for her height and 90th percentile for her weight. She has Tanner stage 3 breast development and Tanner stage 2 pubic hair development. She has grown slightly more than 3 inches over the past year. How should she be evaluated and managed (N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2366-77)?

The premature onset of puberty, i.e., precocious puberty (PP), can be an emotionally traumatic event for the child and parents. Over the past century, improvements in public health and nutrition, and, more recently, increased obesity, have been associated with earlier puberty and the dominant factor has been attributed to genetics (Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2018;25[1]:49-54). This month’s article will focus on understanding what is considered “early” puberty, evaluating for causes, and managing precocious puberty.

More commonly seen in girls than boys, PP is defined as the onset of secondary sexual characteristics before age 7.5 years in Black and Hispanic girls, and prior to 8 years in White girls, which is 2-2.5 standard deviations below the average age of pubertal onset in healthy children (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2019;32:455-9). As a comparison, PP is diagnosed with onset before age 9 years in boys. For White compared with Black girls, the average timing of thelarche is age 10 vs. 9.5 years, peak growth velocity is age 11.5, menarche is age 12.5 vs. 12, while completion of puberty is near age 14.5 vs. 13.5, respectively (J Pediatr. 1985;107:317). Fortunately, most girls with PP have common variants rather than serious pathology.

Classification: Central (CPP) vs. peripheral (PPP)

CPP is gonadotropin dependent, meaning the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis (HPO) is prematurely activated resulting in the normal progression of puberty.

PPP is gonadotropin independent, caused by sex steroid secretion from any source – ovaries, adrenal gland, exogenous or ectopic production, e.g., germ-cell tumor. This results in a disordered progression of pubertal milestones.

Whereas CPP is typically isosexual development, i.e., consistent with the child’s gender, PPP can be isosexual or contrasexual, e.g., virilization of girls. A third classification is “benign or nonprogressive pubertal variants” manifesting as isolated premature thelarche or adrenarche.

Causes (see table)

CPP. Idiopathic causes account for 80%-90% of presentations in girls and 25%-80% in boys. Remarkably, international and domestic adoption, as well as a family history of PP increases the likelihood of CPP in girls. Other etiologies include CNS lesions, e.g., hamartomas, which are the most common cause of PP in young children. MRI with contrast has been the traditional mode of diagnosis for CNS tumors, yet the yield is dubious in girls above age 6. Genetic causes are found in only a small percentage of PP cases. Rarely, CPP can result from gonadotropin-secreting tumors because of elevated luteinizing hormone levels.

PPP. As a result of sex steroid secretion, peripheral causes of PPP include ovarian cysts and ovarian tumors that increase circulating estradiol, such as granulosa cell tumors, which would cause isosexual PPP and Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors that secrete testosterone, which can result in contrasexual PPP. Mild congenital adrenal hyperplasia can result in PPP with virilization (contrasexual) and markedly advanced bone age.

McCune-Albright syndrome is rare and presents with the classic triad of PPP, skin pigmentation called café-au-lait, and fibrous dysplasia of bone. The pathophysiology of McCune-Albright syndrome is autoactivation of the G-protein leading to activation of ovarian tissue that results in formation of large ovarian cysts and extreme elevations in serum estradiol as well as the potential production of other hormones, e.g., thyrotoxicosis, excess growth hormone (acromegaly), and Cushing syndrome.

Premature thelarche. Premature thelarche typically occurs in girls between the ages of 1 and 3 years and is limited to breast enlargement. While no cause has been determined, the plausible explanations include partial activation of the HPO axis, endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), or a genetic origin. A small percentage of these girls progress to CPP.

EDCs have been considered as potential influencers of early puberty, but no consensus has been established. (Examples of EDCs in the environment include air, soil, or water supply along with food sources, personal care products, and manufactured products that can affect the endocrine system.)

Premature adenarche. Premature adrenarche presents with adult body odor and/or body hair (pubic and/or axillary) in girls who have an elevated body mass index, most commonly at the ages of 6-7 years. The presumed mechanism is normal maturation of the adrenal gland with resultant elevation of circulating androgens. Bone age may be mildly accelerated and DHEAS is prematurely elevated for age. These girls appear to be at increased risk for polycystic ovary syndrome.

Evaluation

The initial step in the evaluation of PP is to determine whether the cause is CPP or PPP; the latter includes distinguishing isosexual from contrasexual development. A thorough history (growth, headaches, behavior or visual change, seizures, abdominal pain), physical exam, including Tanner staging, and bone age is required. However, with isolated premature thelarche or adrenarche, a bone age may not be necessary, as initial close clinical observation for pubertal progression is likely sufficient.

For CPP, the diagnosis is based on serum LH, whether random levels or elevations follow GnRH stimulation. Puberty milestones progress normally although adrenarche is not consistently apparent. For girls younger than age 6, a brain MRI is recommended but not in asymptomatic older girls with CPP. LH and FSH along with estradiol or testosterone, the latter especially in boys, are the first line of serum testing. Serum TSH is recommended for suspicion of primary hypothyroidism. In girls with premature adrenarche, a bone age, testosterone, DHEAS, and 17-OHP to rule out adrenal hyperplasia should be obtained. Pelvic ultrasound may be a useful adjunct to assess uterine volume and/or ovarian cysts/tumors.

Rapidity of onset can also lead the evaluation since a normal growth chart and skeletal maturation suggests a benign pubertal variant whereas a more rapid rate can signal CPP or PPP. Of note, health care providers should ensure prescription, over-the-counter oral or topical sources of hormones, and EDCs are ruled out.

Consequences

An association between childhood sexual abuse and earlier pubertal onset has been cited. These girls may be at increased risk for psychosocial difficulties, menstrual and fertility problems, and even reproductive cancers because of prolonged exposure to sex hormones (J Adolesc Health. 2016;60[1]:65-71).

Treatment

The mainstay of CPP treatment is maximizing adult height, typically through the use of a GnRH agonist for HPO suppression from pituitary downregulation. For girls above age 8 years, attempts at improving adult height have not shown a benefit.

In girls with PPP, treatment is directed at the prevailing pathology. Interestingly, early PPP can activate the HPO axis thereby converting to “secondary” CPP. In PPP, McCune-Albright syndrome treatment targets reducing circulating estrogens through letrozole or tamoxifen as well as addressing other autoactivated hormone production. Ovarian and adrenal tumors, albeit rare, can cause PP; therefore, surgical excision is the goal of treatment.