User login

Preparing for back to school amid monkeypox outbreak and ever-changing COVID landscape

Unlike last school year, there are now vaccines available for all over the age of 6 months, and home rapid antigen tests are more readily available. Additionally, many have now been exposed either by infection or vaccination to the virus.

The CDC has removed the recommendations for maintaining cohorts in the K-12 population. This changing landscape along with differing levels of personal risk make it challenging to counsel families about what to expect in terms of COVID this year.

The best defense that we currently have against COVID is the vaccine. Although it seems that many are susceptible to the virus despite the vaccine, those who have been vaccinated are less susceptible to serious disease, including young children.

As older children may be heading to college, it is important

to encourage them to isolate when they have symptoms, even when they test negative for COVID as we would all like to avoid being sick in general.

Additionally, they should pay attention to the COVID risk level in their area and wear masks, particularly when indoors, as the levels increase. College students should have a plan for where they can isolate when not feeling well. If anyone does test positive for COVID, they should follow the most recent quarantine guidelines, including wearing a well fitted mask when they do begin returning to activities.

Monkeypox

We now have a new health concern for this school year.

Monkeypox has come onto the scene with information changing as rapidly as information previously did for COVID. With this virus, we must particularly counsel those heading away to college to be careful to limit their exposure to this disease.

Dormitories and other congregate settings are high-risk locations for the spread of monkeypox. Particularly, students headed to stay in dormitories should be counseled about avoiding:

- sexual activity with those with lesions consistent with monkeypox;

- sharing eating and drinking utensils; and

- sleeping in the same bed as or sharing bedding or towels with anyone with a diagnosis of or lesions consistent with monkeypox.

Additionally, as with prevention of all infections, it is important to frequently wash hands or use alcohol-based sanitizer before eating, and avoid touching the face after using the restroom.

Guidance for those eligible for vaccines against monkeypox seems to be quickly changing as well.

At the time of this article, CDC guidance recommends the vaccine against monkeypox for:

- those considered to be at high risk for it, including those identified by public health officials as a contact of someone with monkeypox;

- those who are aware that a sexual partner had a diagnosis of monkeypox within the past 2 weeks;

- those with multiple sex partners in the past 2 weeks in an area with known monkeypox; and

- those whose jobs may expose them to monkeypox.

Currently, the CDC recommends the vaccine JYNNEOS, a two-dose vaccine that reaches maximum protection after fourteen days. Ultimately, guidance is likely to continue to quickly change for both COVID-19 and Monkeypox throughout the fall. It is possible that new vaccinations will become available, and families and physicians alike will have many questions.

Primary care offices should ensure that someone is keeping up to date with the latest guidance to share with the office so that physicians may share accurate information with their patients.

Families should be counseled that we anticipate information about monkeypox, particularly related to vaccinations, to continue to change, as it has during all stages of the COVID pandemic.

As always, patients should be reminded to continue regular routine vaccinations, including the annual influenza vaccine.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center and program director of Northwestern University’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, both in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at [email protected].

Unlike last school year, there are now vaccines available for all over the age of 6 months, and home rapid antigen tests are more readily available. Additionally, many have now been exposed either by infection or vaccination to the virus.

The CDC has removed the recommendations for maintaining cohorts in the K-12 population. This changing landscape along with differing levels of personal risk make it challenging to counsel families about what to expect in terms of COVID this year.

The best defense that we currently have against COVID is the vaccine. Although it seems that many are susceptible to the virus despite the vaccine, those who have been vaccinated are less susceptible to serious disease, including young children.

As older children may be heading to college, it is important

to encourage them to isolate when they have symptoms, even when they test negative for COVID as we would all like to avoid being sick in general.

Additionally, they should pay attention to the COVID risk level in their area and wear masks, particularly when indoors, as the levels increase. College students should have a plan for where they can isolate when not feeling well. If anyone does test positive for COVID, they should follow the most recent quarantine guidelines, including wearing a well fitted mask when they do begin returning to activities.

Monkeypox

We now have a new health concern for this school year.

Monkeypox has come onto the scene with information changing as rapidly as information previously did for COVID. With this virus, we must particularly counsel those heading away to college to be careful to limit their exposure to this disease.

Dormitories and other congregate settings are high-risk locations for the spread of monkeypox. Particularly, students headed to stay in dormitories should be counseled about avoiding:

- sexual activity with those with lesions consistent with monkeypox;

- sharing eating and drinking utensils; and

- sleeping in the same bed as or sharing bedding or towels with anyone with a diagnosis of or lesions consistent with monkeypox.

Additionally, as with prevention of all infections, it is important to frequently wash hands or use alcohol-based sanitizer before eating, and avoid touching the face after using the restroom.

Guidance for those eligible for vaccines against monkeypox seems to be quickly changing as well.

At the time of this article, CDC guidance recommends the vaccine against monkeypox for:

- those considered to be at high risk for it, including those identified by public health officials as a contact of someone with monkeypox;

- those who are aware that a sexual partner had a diagnosis of monkeypox within the past 2 weeks;

- those with multiple sex partners in the past 2 weeks in an area with known monkeypox; and

- those whose jobs may expose them to monkeypox.

Currently, the CDC recommends the vaccine JYNNEOS, a two-dose vaccine that reaches maximum protection after fourteen days. Ultimately, guidance is likely to continue to quickly change for both COVID-19 and Monkeypox throughout the fall. It is possible that new vaccinations will become available, and families and physicians alike will have many questions.

Primary care offices should ensure that someone is keeping up to date with the latest guidance to share with the office so that physicians may share accurate information with their patients.

Families should be counseled that we anticipate information about monkeypox, particularly related to vaccinations, to continue to change, as it has during all stages of the COVID pandemic.

As always, patients should be reminded to continue regular routine vaccinations, including the annual influenza vaccine.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center and program director of Northwestern University’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, both in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at [email protected].

Unlike last school year, there are now vaccines available for all over the age of 6 months, and home rapid antigen tests are more readily available. Additionally, many have now been exposed either by infection or vaccination to the virus.

The CDC has removed the recommendations for maintaining cohorts in the K-12 population. This changing landscape along with differing levels of personal risk make it challenging to counsel families about what to expect in terms of COVID this year.

The best defense that we currently have against COVID is the vaccine. Although it seems that many are susceptible to the virus despite the vaccine, those who have been vaccinated are less susceptible to serious disease, including young children.

As older children may be heading to college, it is important

to encourage them to isolate when they have symptoms, even when they test negative for COVID as we would all like to avoid being sick in general.

Additionally, they should pay attention to the COVID risk level in their area and wear masks, particularly when indoors, as the levels increase. College students should have a plan for where they can isolate when not feeling well. If anyone does test positive for COVID, they should follow the most recent quarantine guidelines, including wearing a well fitted mask when they do begin returning to activities.

Monkeypox

We now have a new health concern for this school year.

Monkeypox has come onto the scene with information changing as rapidly as information previously did for COVID. With this virus, we must particularly counsel those heading away to college to be careful to limit their exposure to this disease.

Dormitories and other congregate settings are high-risk locations for the spread of monkeypox. Particularly, students headed to stay in dormitories should be counseled about avoiding:

- sexual activity with those with lesions consistent with monkeypox;

- sharing eating and drinking utensils; and

- sleeping in the same bed as or sharing bedding or towels with anyone with a diagnosis of or lesions consistent with monkeypox.

Additionally, as with prevention of all infections, it is important to frequently wash hands or use alcohol-based sanitizer before eating, and avoid touching the face after using the restroom.

Guidance for those eligible for vaccines against monkeypox seems to be quickly changing as well.

At the time of this article, CDC guidance recommends the vaccine against monkeypox for:

- those considered to be at high risk for it, including those identified by public health officials as a contact of someone with monkeypox;

- those who are aware that a sexual partner had a diagnosis of monkeypox within the past 2 weeks;

- those with multiple sex partners in the past 2 weeks in an area with known monkeypox; and

- those whose jobs may expose them to monkeypox.

Currently, the CDC recommends the vaccine JYNNEOS, a two-dose vaccine that reaches maximum protection after fourteen days. Ultimately, guidance is likely to continue to quickly change for both COVID-19 and Monkeypox throughout the fall. It is possible that new vaccinations will become available, and families and physicians alike will have many questions.

Primary care offices should ensure that someone is keeping up to date with the latest guidance to share with the office so that physicians may share accurate information with their patients.

Families should be counseled that we anticipate information about monkeypox, particularly related to vaccinations, to continue to change, as it has during all stages of the COVID pandemic.

As always, patients should be reminded to continue regular routine vaccinations, including the annual influenza vaccine.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center and program director of Northwestern University’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, both in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at [email protected].

FDA clears tubeless, automated insulin system for children age 2 and older

The Food and Drug Administration has approved use of the Omnipod 5 automated insulin delivery system (Insulet Corp) for children aged 2 years and older with type 1 diabetes, the company announced on Aug. 22.

Omnipod 5 was originally cleared for use in individuals age 6 and older in Jan. 2022, as previously reported by this news organization. It is the third semi-automated closed-loop system approved in the United States but the first that is tubing-free. It integrates with the Dexcom G6 continuous glucose monitor system and a compatible smartphone to automatically adjust insulin and protect against high and low glucose levels.

“We received tremendous first-hand reports of how Omnipod 5 made diabetes management easier for our pivotal trial participants, and the clinical data demonstrated impressive glycemic improvements as well,” Trang Ly, MBBS, PhD, senior vice president and medical director at Insulet, said in a news release. “This expanded indication for younger children gives us great pride, knowing we can further ease the burden of glucose management for these children and their caregivers with our simple to use, elegant, automated insulin delivery system.”

In a recent clinical trial in very young children (age 2-5.9 years) with type 1 diabetes, Jennifer L. Sherr, MD, PhD, and colleagues found that the Omnipod 5 lowered A1c by 0.55 percentage points and reduced time in hypoglycemia (< 70 mg/dL) by 0.27%. According to their findings, published in Diabetes Care, time spent in target glucose range (70-180 mg/dL) increased by 11%, or by 2.6 hours more per day, in children in the study.

According to the release, the Omnipod 5 can now be prescribed to patients with insurance coverage. Patients can access their prescription through the pharmacy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved use of the Omnipod 5 automated insulin delivery system (Insulet Corp) for children aged 2 years and older with type 1 diabetes, the company announced on Aug. 22.

Omnipod 5 was originally cleared for use in individuals age 6 and older in Jan. 2022, as previously reported by this news organization. It is the third semi-automated closed-loop system approved in the United States but the first that is tubing-free. It integrates with the Dexcom G6 continuous glucose monitor system and a compatible smartphone to automatically adjust insulin and protect against high and low glucose levels.

“We received tremendous first-hand reports of how Omnipod 5 made diabetes management easier for our pivotal trial participants, and the clinical data demonstrated impressive glycemic improvements as well,” Trang Ly, MBBS, PhD, senior vice president and medical director at Insulet, said in a news release. “This expanded indication for younger children gives us great pride, knowing we can further ease the burden of glucose management for these children and their caregivers with our simple to use, elegant, automated insulin delivery system.”

In a recent clinical trial in very young children (age 2-5.9 years) with type 1 diabetes, Jennifer L. Sherr, MD, PhD, and colleagues found that the Omnipod 5 lowered A1c by 0.55 percentage points and reduced time in hypoglycemia (< 70 mg/dL) by 0.27%. According to their findings, published in Diabetes Care, time spent in target glucose range (70-180 mg/dL) increased by 11%, or by 2.6 hours more per day, in children in the study.

According to the release, the Omnipod 5 can now be prescribed to patients with insurance coverage. Patients can access their prescription through the pharmacy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved use of the Omnipod 5 automated insulin delivery system (Insulet Corp) for children aged 2 years and older with type 1 diabetes, the company announced on Aug. 22.

Omnipod 5 was originally cleared for use in individuals age 6 and older in Jan. 2022, as previously reported by this news organization. It is the third semi-automated closed-loop system approved in the United States but the first that is tubing-free. It integrates with the Dexcom G6 continuous glucose monitor system and a compatible smartphone to automatically adjust insulin and protect against high and low glucose levels.

“We received tremendous first-hand reports of how Omnipod 5 made diabetes management easier for our pivotal trial participants, and the clinical data demonstrated impressive glycemic improvements as well,” Trang Ly, MBBS, PhD, senior vice president and medical director at Insulet, said in a news release. “This expanded indication for younger children gives us great pride, knowing we can further ease the burden of glucose management for these children and their caregivers with our simple to use, elegant, automated insulin delivery system.”

In a recent clinical trial in very young children (age 2-5.9 years) with type 1 diabetes, Jennifer L. Sherr, MD, PhD, and colleagues found that the Omnipod 5 lowered A1c by 0.55 percentage points and reduced time in hypoglycemia (< 70 mg/dL) by 0.27%. According to their findings, published in Diabetes Care, time spent in target glucose range (70-180 mg/dL) increased by 11%, or by 2.6 hours more per day, in children in the study.

According to the release, the Omnipod 5 can now be prescribed to patients with insurance coverage. Patients can access their prescription through the pharmacy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Large genetic study links 72 genes to autism spectrum disorders

according to a study published in Nature Genetics. The findings, based on analysis of more than 150,000 people’s genetics, arose from a collaboration of five research groups whose work included comparisons of ASD cohorts with separate cohorts of individuals with developmental delay or schizophrenia.

“We know that many genes, when mutated, contribute to autism,” and this study brought together “multiple types of mutations in a wide array of samples to get a much richer sense of the genes and genetic architecture involved in autism and other neurodevelopmental conditions,” co–senior author Joseph D. Buxbaum, PhD, director of the Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment at Mount Sinai and a professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, both in New York, said in a prepared statement. “This is significant in that we now have more insights as to the biology of the brain changes that underlie autism and more potential targets for treatment.”

Glen Elliott, PhD, MD, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Stanford (Calif.) University who was not involved in the study, said the paper is important paper for informing clinicians of where the basic research is headed. “We’re still in for a long road” before it bears fruit in terms of therapeutics. The value of studies like these, that investigate which genes are most associated with ASD, is that they may lead toward understanding the pathways in the brain that give rise to certain symptoms of ASD, which can then become therapeutic targets, Dr. Elliott said.

Investigating large cohorts

The researchers analyzed genetic exome sequencing data from 33 ASD cohorts with a total of 63,237 people and then compared these data with another cohort of people with developmental delay and a cohort of people with schizophrenia. The combined ASD cohorts included 15,036 individuals with ASD, 28,522 parents, and 5,492 unaffected siblings. The remaining participants were 5,591 people with ASD and 8,597 matched controls from case control studies.

In the ASD cohorts, the researchers identified 72 genes that were associated with ASD. De novo variants were eight times more likely in cases (4%) than in controls (0.5%). Ten genes occurred at least twice in ASD cases but never occurred in unaffected siblings.

Then the researchers integrated these ASD genetic data with a cohort of 91,605 people that included 31,058 people with developmental delay and their parents. Substantial overlap with gene mutations existed between these two cohorts: 70.1% of the genes related to developmental delay appeared linked to risk for ASD, and 86.6% of genes associated with ASD risk also had associations with developmental delay. Overall, the researchers identified 373 genes strongly associated with ASD and/or developmental delay and 664 genes with a likely association.

“Isolating genes that exert a greater effect on ASD than they do on other developmental delays has remained challenging due to the frequent comorbidity of these phenotypes,” wrote lead author Jack M. Fu, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, and colleagues. “Still, an estimated 13.4% of the transmission and de novo association–ASD genes show little evidence for association in the developmental delay cohort.”

ASD, developmental delay, and schizophrenia

When the researchers compared the cells where the genetic mutations occurred in fetal brains, they found that genes associated with developmental delay more often occurred in less differentiated cell types – less mature cells in the developmental process. Gene mutations associated with ASD, on the other hand, occurred in more mature cell types, particularly in maturing excitatory neurons and related cells.

”Our results are consistent with developmental delay-predominant genes being expressed earlier in development and in less differentiated cells than ASD-predominant genes,” they wrote.

The researchers also compared the specific gene mutations found in these two cohorts with a previously published set of 244 genes associated with schizophrenia. Of these, 234 genes are among those with a transmission and de novo association to ASD and/or developmental delay. Of the 72 genes linked to ASD, eight appear in the set of genes linked to schizophrenia, and 61 were associated with developmental delay, though these two subsets do not overlap each other much.

“The ASD-schizophrenia overlap was significantly enriched, while the developmental delay-schizophrenia overlap was not,” they reported. ”Together, these data suggest that one subset of ASD risk genes may overlap developmental delay while a different subset overlaps schizophrenia.”

Chasing therapy targets by backtracking through genes

The findings are a substantial step forward in understanding the potential genetic contribution to ASD, but they also highlight the challenges of eventually trying to use this information in a clinically meaningful way.

“Given the substantial overlap between the genes implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders writ large and those implicated directly in ASD, disentangling the relative impact of individual genes on neurodevelopment and phenotypic spectra is a daunting yet important challenge,” the researchers wrote. “To identify the key neurobiological features of ASD will likely require convergence of evidence from many ASD genes and studies.”

Dr. Elliott said the biggest takeaway from this study is a better understanding of how the paradigm has shifted away from finding “one gene” for autism or a cure based on genetics and more toward understanding the pathophysiology of symptoms that can point to therapies for better management of the condition.

“Basic researchers have completely changed the strategy for trying to understand the biology of major disorders,” including, in this case, autism, Dr. Elliott said. “The intent is to try to find the underlying systems [in the brain] by backtracking through genes. Meanwhile, given that scientists have made substantial progress in identifying genes that have specific effects on brain development, “the hope is that will mesh with this kind of research, to begin to identify systems that might ultimately be targets for treating.”

The end goal is to be able to offer targeted approaches, based on the pathways causing a symptom, which can be linked backward to a gene.

”So this is not going to offer an immediate cure – it’s probably not going to offer a cure at all – but it may actually lead to much more targeted medications than we currently have for specific types of symptoms within the autism spectrum,” Dr. Elliott said. “What they’re trying to do, ultimately, is to say, when this system is really badly affected because of a genetic abnormality, even though that genetic abnormality is very rare, it leads to these specific kinds of symptoms. If we can find out the neuroregulators underlying that change, then that would be the target, even if that gene were not present.”

The research was funded by the Simons Foundation for Autism Research Initiative, the SPARK project, the National Human Genome Research Institute Home, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Child Health and Development, AMED, and the Beatrice and Samuel Seaver Foundation. Five authors reported financial disclosures linked to Desitin, Roche, BioMarin, BrigeBio Pharma, Illumina, Levo Therapeutics, and Microsoft.

according to a study published in Nature Genetics. The findings, based on analysis of more than 150,000 people’s genetics, arose from a collaboration of five research groups whose work included comparisons of ASD cohorts with separate cohorts of individuals with developmental delay or schizophrenia.

“We know that many genes, when mutated, contribute to autism,” and this study brought together “multiple types of mutations in a wide array of samples to get a much richer sense of the genes and genetic architecture involved in autism and other neurodevelopmental conditions,” co–senior author Joseph D. Buxbaum, PhD, director of the Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment at Mount Sinai and a professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, both in New York, said in a prepared statement. “This is significant in that we now have more insights as to the biology of the brain changes that underlie autism and more potential targets for treatment.”

Glen Elliott, PhD, MD, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Stanford (Calif.) University who was not involved in the study, said the paper is important paper for informing clinicians of where the basic research is headed. “We’re still in for a long road” before it bears fruit in terms of therapeutics. The value of studies like these, that investigate which genes are most associated with ASD, is that they may lead toward understanding the pathways in the brain that give rise to certain symptoms of ASD, which can then become therapeutic targets, Dr. Elliott said.

Investigating large cohorts

The researchers analyzed genetic exome sequencing data from 33 ASD cohorts with a total of 63,237 people and then compared these data with another cohort of people with developmental delay and a cohort of people with schizophrenia. The combined ASD cohorts included 15,036 individuals with ASD, 28,522 parents, and 5,492 unaffected siblings. The remaining participants were 5,591 people with ASD and 8,597 matched controls from case control studies.

In the ASD cohorts, the researchers identified 72 genes that were associated with ASD. De novo variants were eight times more likely in cases (4%) than in controls (0.5%). Ten genes occurred at least twice in ASD cases but never occurred in unaffected siblings.

Then the researchers integrated these ASD genetic data with a cohort of 91,605 people that included 31,058 people with developmental delay and their parents. Substantial overlap with gene mutations existed between these two cohorts: 70.1% of the genes related to developmental delay appeared linked to risk for ASD, and 86.6% of genes associated with ASD risk also had associations with developmental delay. Overall, the researchers identified 373 genes strongly associated with ASD and/or developmental delay and 664 genes with a likely association.

“Isolating genes that exert a greater effect on ASD than they do on other developmental delays has remained challenging due to the frequent comorbidity of these phenotypes,” wrote lead author Jack M. Fu, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, and colleagues. “Still, an estimated 13.4% of the transmission and de novo association–ASD genes show little evidence for association in the developmental delay cohort.”

ASD, developmental delay, and schizophrenia

When the researchers compared the cells where the genetic mutations occurred in fetal brains, they found that genes associated with developmental delay more often occurred in less differentiated cell types – less mature cells in the developmental process. Gene mutations associated with ASD, on the other hand, occurred in more mature cell types, particularly in maturing excitatory neurons and related cells.

”Our results are consistent with developmental delay-predominant genes being expressed earlier in development and in less differentiated cells than ASD-predominant genes,” they wrote.

The researchers also compared the specific gene mutations found in these two cohorts with a previously published set of 244 genes associated with schizophrenia. Of these, 234 genes are among those with a transmission and de novo association to ASD and/or developmental delay. Of the 72 genes linked to ASD, eight appear in the set of genes linked to schizophrenia, and 61 were associated with developmental delay, though these two subsets do not overlap each other much.

“The ASD-schizophrenia overlap was significantly enriched, while the developmental delay-schizophrenia overlap was not,” they reported. ”Together, these data suggest that one subset of ASD risk genes may overlap developmental delay while a different subset overlaps schizophrenia.”

Chasing therapy targets by backtracking through genes

The findings are a substantial step forward in understanding the potential genetic contribution to ASD, but they also highlight the challenges of eventually trying to use this information in a clinically meaningful way.

“Given the substantial overlap between the genes implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders writ large and those implicated directly in ASD, disentangling the relative impact of individual genes on neurodevelopment and phenotypic spectra is a daunting yet important challenge,” the researchers wrote. “To identify the key neurobiological features of ASD will likely require convergence of evidence from many ASD genes and studies.”

Dr. Elliott said the biggest takeaway from this study is a better understanding of how the paradigm has shifted away from finding “one gene” for autism or a cure based on genetics and more toward understanding the pathophysiology of symptoms that can point to therapies for better management of the condition.

“Basic researchers have completely changed the strategy for trying to understand the biology of major disorders,” including, in this case, autism, Dr. Elliott said. “The intent is to try to find the underlying systems [in the brain] by backtracking through genes. Meanwhile, given that scientists have made substantial progress in identifying genes that have specific effects on brain development, “the hope is that will mesh with this kind of research, to begin to identify systems that might ultimately be targets for treating.”

The end goal is to be able to offer targeted approaches, based on the pathways causing a symptom, which can be linked backward to a gene.

”So this is not going to offer an immediate cure – it’s probably not going to offer a cure at all – but it may actually lead to much more targeted medications than we currently have for specific types of symptoms within the autism spectrum,” Dr. Elliott said. “What they’re trying to do, ultimately, is to say, when this system is really badly affected because of a genetic abnormality, even though that genetic abnormality is very rare, it leads to these specific kinds of symptoms. If we can find out the neuroregulators underlying that change, then that would be the target, even if that gene were not present.”

The research was funded by the Simons Foundation for Autism Research Initiative, the SPARK project, the National Human Genome Research Institute Home, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Child Health and Development, AMED, and the Beatrice and Samuel Seaver Foundation. Five authors reported financial disclosures linked to Desitin, Roche, BioMarin, BrigeBio Pharma, Illumina, Levo Therapeutics, and Microsoft.

according to a study published in Nature Genetics. The findings, based on analysis of more than 150,000 people’s genetics, arose from a collaboration of five research groups whose work included comparisons of ASD cohorts with separate cohorts of individuals with developmental delay or schizophrenia.

“We know that many genes, when mutated, contribute to autism,” and this study brought together “multiple types of mutations in a wide array of samples to get a much richer sense of the genes and genetic architecture involved in autism and other neurodevelopmental conditions,” co–senior author Joseph D. Buxbaum, PhD, director of the Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment at Mount Sinai and a professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, both in New York, said in a prepared statement. “This is significant in that we now have more insights as to the biology of the brain changes that underlie autism and more potential targets for treatment.”

Glen Elliott, PhD, MD, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Stanford (Calif.) University who was not involved in the study, said the paper is important paper for informing clinicians of where the basic research is headed. “We’re still in for a long road” before it bears fruit in terms of therapeutics. The value of studies like these, that investigate which genes are most associated with ASD, is that they may lead toward understanding the pathways in the brain that give rise to certain symptoms of ASD, which can then become therapeutic targets, Dr. Elliott said.

Investigating large cohorts

The researchers analyzed genetic exome sequencing data from 33 ASD cohorts with a total of 63,237 people and then compared these data with another cohort of people with developmental delay and a cohort of people with schizophrenia. The combined ASD cohorts included 15,036 individuals with ASD, 28,522 parents, and 5,492 unaffected siblings. The remaining participants were 5,591 people with ASD and 8,597 matched controls from case control studies.

In the ASD cohorts, the researchers identified 72 genes that were associated with ASD. De novo variants were eight times more likely in cases (4%) than in controls (0.5%). Ten genes occurred at least twice in ASD cases but never occurred in unaffected siblings.

Then the researchers integrated these ASD genetic data with a cohort of 91,605 people that included 31,058 people with developmental delay and their parents. Substantial overlap with gene mutations existed between these two cohorts: 70.1% of the genes related to developmental delay appeared linked to risk for ASD, and 86.6% of genes associated with ASD risk also had associations with developmental delay. Overall, the researchers identified 373 genes strongly associated with ASD and/or developmental delay and 664 genes with a likely association.

“Isolating genes that exert a greater effect on ASD than they do on other developmental delays has remained challenging due to the frequent comorbidity of these phenotypes,” wrote lead author Jack M. Fu, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, and colleagues. “Still, an estimated 13.4% of the transmission and de novo association–ASD genes show little evidence for association in the developmental delay cohort.”

ASD, developmental delay, and schizophrenia

When the researchers compared the cells where the genetic mutations occurred in fetal brains, they found that genes associated with developmental delay more often occurred in less differentiated cell types – less mature cells in the developmental process. Gene mutations associated with ASD, on the other hand, occurred in more mature cell types, particularly in maturing excitatory neurons and related cells.

”Our results are consistent with developmental delay-predominant genes being expressed earlier in development and in less differentiated cells than ASD-predominant genes,” they wrote.

The researchers also compared the specific gene mutations found in these two cohorts with a previously published set of 244 genes associated with schizophrenia. Of these, 234 genes are among those with a transmission and de novo association to ASD and/or developmental delay. Of the 72 genes linked to ASD, eight appear in the set of genes linked to schizophrenia, and 61 were associated with developmental delay, though these two subsets do not overlap each other much.

“The ASD-schizophrenia overlap was significantly enriched, while the developmental delay-schizophrenia overlap was not,” they reported. ”Together, these data suggest that one subset of ASD risk genes may overlap developmental delay while a different subset overlaps schizophrenia.”

Chasing therapy targets by backtracking through genes

The findings are a substantial step forward in understanding the potential genetic contribution to ASD, but they also highlight the challenges of eventually trying to use this information in a clinically meaningful way.

“Given the substantial overlap between the genes implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders writ large and those implicated directly in ASD, disentangling the relative impact of individual genes on neurodevelopment and phenotypic spectra is a daunting yet important challenge,” the researchers wrote. “To identify the key neurobiological features of ASD will likely require convergence of evidence from many ASD genes and studies.”

Dr. Elliott said the biggest takeaway from this study is a better understanding of how the paradigm has shifted away from finding “one gene” for autism or a cure based on genetics and more toward understanding the pathophysiology of symptoms that can point to therapies for better management of the condition.

“Basic researchers have completely changed the strategy for trying to understand the biology of major disorders,” including, in this case, autism, Dr. Elliott said. “The intent is to try to find the underlying systems [in the brain] by backtracking through genes. Meanwhile, given that scientists have made substantial progress in identifying genes that have specific effects on brain development, “the hope is that will mesh with this kind of research, to begin to identify systems that might ultimately be targets for treating.”

The end goal is to be able to offer targeted approaches, based on the pathways causing a symptom, which can be linked backward to a gene.

”So this is not going to offer an immediate cure – it’s probably not going to offer a cure at all – but it may actually lead to much more targeted medications than we currently have for specific types of symptoms within the autism spectrum,” Dr. Elliott said. “What they’re trying to do, ultimately, is to say, when this system is really badly affected because of a genetic abnormality, even though that genetic abnormality is very rare, it leads to these specific kinds of symptoms. If we can find out the neuroregulators underlying that change, then that would be the target, even if that gene were not present.”

The research was funded by the Simons Foundation for Autism Research Initiative, the SPARK project, the National Human Genome Research Institute Home, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Child Health and Development, AMED, and the Beatrice and Samuel Seaver Foundation. Five authors reported financial disclosures linked to Desitin, Roche, BioMarin, BrigeBio Pharma, Illumina, Levo Therapeutics, and Microsoft.

FROM NATURE GENETICS

Pfizer seeks approval for updated COVID booster

Pfizer has sent an application to the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use authorization of its updated COVID-19 booster vaccine for the fall of 2022, the company announced on Aug. 22.

The vaccine, which is adapted for the BA.4 and BA.5 Omicron variants, would be meant for ages 12 and older. If authorized by the FDA, the doses could ship as soon as September.

“Having rapidly scaled up production, we are positioned to immediately begin distribution of the bivalent Omicron BA.4/BA.5 boosters, if authorized, to help protect individuals and families as we prepare for potential fall and winter surges,” Albert Bourla, PhD, Pfizer’s chairman and CEO, said in the statement.

Earlier this year, the FDA ordered vaccine makers such as Pfizer and Moderna to update their shots to target BA.4 and BA.5, which are better at escaping immunity from earlier vaccines and previous infections.

The United States has a contract to buy 105 million of the Pfizer doses and 66 million of the Moderna doses, according to The Associated Press. Moderna is expected to file its FDA application soon as well.

The new shots target both the original spike protein on the coronavirus and the spike mutations carried by BA.4 and BA.5. For now, BA.5 is causing 89% of new infections in the United States, followed by BA.4.6 with 6.3% and BA.4 with 4.3%, according to the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

There’s no way to tell if BA.5 will still be the dominant strain this winter or if new variant will replace it, the AP reported. But public health officials have supported the updated boosters as a way to target the most recent strains and increase immunity again.

On Aug. 15, Great Britain became the first country to authorize another one of Moderna’s updated vaccines, which adds protection against BA.1, or the original Omicron strain that became dominant in the winter of 2021-2022. European regulators are considering this shot, the AP reported, but the United States opted not to use this version since new Omicron variants have become dominant.

To approve the latest Pfizer shot, the FDA will rely on scientific testing of prior updates to the vaccine, rather than the newest boosters, to decide whether to fast-track the updated shots for fall, the AP reported. This method is like how flu vaccines are updated each year without large studies that take months.

Previously, Pfizer announced results from a study that found the earlier Omicron update significantly boosted antibodies capable of fighting the BA.1 variant and provided some protection against BA.4 and BA.5. The company’s latest FDA application contains that data and animal testing on the newest booster, the AP reported.

Pfizer will start a trial using the BA.4/BA.5 booster in coming weeks to get more data on how well the latest shot works. Moderna has begun a similar study.

The full results from these studies won’t be available before a fall booster campaign, which is why the FDA and public health officials have called for an updated shot to be ready for distribution in September.

“It’s clear that none of these vaccines are going to completely prevent infection,” Rachel Presti, MD, a researcher with the Moderna trial and an infectious diseases specialist at Washington University in St. Louis, told the AP.

But previous studies of variant booster candidates have shown that “you still get a broader immune response giving a variant booster than giving the same booster,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Pfizer has sent an application to the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use authorization of its updated COVID-19 booster vaccine for the fall of 2022, the company announced on Aug. 22.

The vaccine, which is adapted for the BA.4 and BA.5 Omicron variants, would be meant for ages 12 and older. If authorized by the FDA, the doses could ship as soon as September.

“Having rapidly scaled up production, we are positioned to immediately begin distribution of the bivalent Omicron BA.4/BA.5 boosters, if authorized, to help protect individuals and families as we prepare for potential fall and winter surges,” Albert Bourla, PhD, Pfizer’s chairman and CEO, said in the statement.

Earlier this year, the FDA ordered vaccine makers such as Pfizer and Moderna to update their shots to target BA.4 and BA.5, which are better at escaping immunity from earlier vaccines and previous infections.

The United States has a contract to buy 105 million of the Pfizer doses and 66 million of the Moderna doses, according to The Associated Press. Moderna is expected to file its FDA application soon as well.

The new shots target both the original spike protein on the coronavirus and the spike mutations carried by BA.4 and BA.5. For now, BA.5 is causing 89% of new infections in the United States, followed by BA.4.6 with 6.3% and BA.4 with 4.3%, according to the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

There’s no way to tell if BA.5 will still be the dominant strain this winter or if new variant will replace it, the AP reported. But public health officials have supported the updated boosters as a way to target the most recent strains and increase immunity again.

On Aug. 15, Great Britain became the first country to authorize another one of Moderna’s updated vaccines, which adds protection against BA.1, or the original Omicron strain that became dominant in the winter of 2021-2022. European regulators are considering this shot, the AP reported, but the United States opted not to use this version since new Omicron variants have become dominant.

To approve the latest Pfizer shot, the FDA will rely on scientific testing of prior updates to the vaccine, rather than the newest boosters, to decide whether to fast-track the updated shots for fall, the AP reported. This method is like how flu vaccines are updated each year without large studies that take months.

Previously, Pfizer announced results from a study that found the earlier Omicron update significantly boosted antibodies capable of fighting the BA.1 variant and provided some protection against BA.4 and BA.5. The company’s latest FDA application contains that data and animal testing on the newest booster, the AP reported.

Pfizer will start a trial using the BA.4/BA.5 booster in coming weeks to get more data on how well the latest shot works. Moderna has begun a similar study.

The full results from these studies won’t be available before a fall booster campaign, which is why the FDA and public health officials have called for an updated shot to be ready for distribution in September.

“It’s clear that none of these vaccines are going to completely prevent infection,” Rachel Presti, MD, a researcher with the Moderna trial and an infectious diseases specialist at Washington University in St. Louis, told the AP.

But previous studies of variant booster candidates have shown that “you still get a broader immune response giving a variant booster than giving the same booster,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Pfizer has sent an application to the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use authorization of its updated COVID-19 booster vaccine for the fall of 2022, the company announced on Aug. 22.

The vaccine, which is adapted for the BA.4 and BA.5 Omicron variants, would be meant for ages 12 and older. If authorized by the FDA, the doses could ship as soon as September.

“Having rapidly scaled up production, we are positioned to immediately begin distribution of the bivalent Omicron BA.4/BA.5 boosters, if authorized, to help protect individuals and families as we prepare for potential fall and winter surges,” Albert Bourla, PhD, Pfizer’s chairman and CEO, said in the statement.

Earlier this year, the FDA ordered vaccine makers such as Pfizer and Moderna to update their shots to target BA.4 and BA.5, which are better at escaping immunity from earlier vaccines and previous infections.

The United States has a contract to buy 105 million of the Pfizer doses and 66 million of the Moderna doses, according to The Associated Press. Moderna is expected to file its FDA application soon as well.

The new shots target both the original spike protein on the coronavirus and the spike mutations carried by BA.4 and BA.5. For now, BA.5 is causing 89% of new infections in the United States, followed by BA.4.6 with 6.3% and BA.4 with 4.3%, according to the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

There’s no way to tell if BA.5 will still be the dominant strain this winter or if new variant will replace it, the AP reported. But public health officials have supported the updated boosters as a way to target the most recent strains and increase immunity again.

On Aug. 15, Great Britain became the first country to authorize another one of Moderna’s updated vaccines, which adds protection against BA.1, or the original Omicron strain that became dominant in the winter of 2021-2022. European regulators are considering this shot, the AP reported, but the United States opted not to use this version since new Omicron variants have become dominant.

To approve the latest Pfizer shot, the FDA will rely on scientific testing of prior updates to the vaccine, rather than the newest boosters, to decide whether to fast-track the updated shots for fall, the AP reported. This method is like how flu vaccines are updated each year without large studies that take months.

Previously, Pfizer announced results from a study that found the earlier Omicron update significantly boosted antibodies capable of fighting the BA.1 variant and provided some protection against BA.4 and BA.5. The company’s latest FDA application contains that data and animal testing on the newest booster, the AP reported.

Pfizer will start a trial using the BA.4/BA.5 booster in coming weeks to get more data on how well the latest shot works. Moderna has begun a similar study.

The full results from these studies won’t be available before a fall booster campaign, which is why the FDA and public health officials have called for an updated shot to be ready for distribution in September.

“It’s clear that none of these vaccines are going to completely prevent infection,” Rachel Presti, MD, a researcher with the Moderna trial and an infectious diseases specialist at Washington University in St. Louis, told the AP.

But previous studies of variant booster candidates have shown that “you still get a broader immune response giving a variant booster than giving the same booster,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Young children with leukemia are outliving teens

“Outcomes are improving. However, additional efforts, support, and resources are needed to further improve short- and long-term survival for acute leukemia survivors. Targeted efforts focused on populations that face greater disparities in their survival are needed to move the needle faster,” Michael Roth, MD, codirector of the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Program at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, said in an interview.

In one study, released in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, an international team of researchers tracked survival outcomes from various types of leukemia in 61 nations. The study focused on the years 2000-2014 and followed patients aged 0-24.

“Age-standardized 5-year net survival in children, adolescents, and young adults for all leukemias combined during 2010-14 varied widely, ranging from 46% in Mexico to more than 85% in Canada, Cyprus, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, and Australia,” the researchers wrote. “Throughout 2000-14, survival from all leukemias combined remained consistently higher for children than adolescents and young adults, and minimal improvement was seen for adolescents and young adults in most countries.”

The U.S. data came from 41 states that cover 86% of the nation’s population, lead author Naomi Ssenyonga, a research fellow at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said in an interview.

The 5-year survival rate for acute lymphoid leukemia (ALL) rose from 80% during 2000-2004 to 86% during 2010-2014. Survival in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) was lower than for other subtypes: 66% in 2010-2014 vs. 57% in 2000-2004.

In regard to all leukemias, “we noted a steady increase in the U.S. of 6 percentage points in 5-year survival, up from 77% for patients diagnosed during 2000-2004 to 83% for those diagnosed during 2010-2014,” Ms. Ssenyonga said. “The gains were largely driven by the improvements seen among children.”

Why haven’t adolescents and young adults gained as much ground in survival?

“They often have unique clinical needs,” Ms. Ssenyonga said. “Over the past few years, adolescents and young adults with leukemia in some parts of the world, including the U.S., have increasingly been treated under pediatric protocols. This has led to higher survival. However, this approach has not been adopted consistently, and survival for adolescents and young adults with leukemia is still generally lower than survival for children.”

Gwen Nichols, MD, chief medical officer of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, agreed that pediatric treatment protocols hold promise as treatments for young adults. However, “because we arbitrarily set an age cutoff for being an adult, many of these patients are treated by an adult [nonpediatric] hematologist/oncologist, and some patients in the 20-39 age group do not receive the more intensive treatment regimens given to children,” she said in an interview.

In another study, published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, & Prevention, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center’s Dr. Roth and colleagues tracked 1,938 patients with ALL and 2,350 with AML who were diagnosed at ages 15-39 from 1980 to 2009. All lived at least 5 years after diagnosis. In both groups, about 58% were White, and most of the rest were Hispanic. The median age of diagnosis for ALL was 23 (range: 15-39) and 28 years for AML (range: 15-39).

“For ALL, 10-year survival for those diagnosed in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s was 83%, 88%, and 88%, respectively,” the researchers reported. “Ten-year survival for AML was 82%, 90%, and 90% for those diagnosed in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, respectively.”

“Early mortality within 10 years of diagnosis was mostly secondary to leukemia progressing or recurring. We believe that later mortality is secondary to the development of late side effects from their cancer treatment,” Dr. Roth said.

He noted that many adolescents and young adults with ALL or AML receive stem-cell transplants. “This treatment approach is effective. However, it is associated with short- and long-term toxicity that impacts patients’ health for many years after treatment.”

Indeed, up to 80% of acute leukemia survivors have significant health complications after therapy, said the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society’s Dr. Nichols, who wasn’t surprised by the findings. According to the society, “even when treatments are effective, more than 70% of childhood cancer survivors have a chronic health condition and 42% have a severe, disabling or life-threatening condition 30 years after diagnosis.”

“It would be interesting to understand the male predominance better,” she added, noting that the study found that male patients had worse long-term survival than females (survival time ratio: 0.61, 95% confidence interval, 0.45-0.82). “While it is tempting to suggest it is due to difference in cardiac disease, I am not aware of data to support why there is this survival difference.”

What’s next? “In ALL, we now have a number of new modalities to treat high-risk and relapsed disease such as antibodies and CAR-T,” Dr. Nichols said. “We anticipate that 5-year survival can improve utilizing these modalities due to getting more patients into remission, hopefully while reducing chemotherapeutic toxicity.”

Dr. Nichol’s also highlighted the society’s new genomic-led Pediatric Acute Leukemia (PedAL) Master Clinical Trial, which began enrolling children with acute leukemia in the United States and Canada this year, in an effort to transform medicine’s traditional high-level chemotherapy strategy to their care. The project was launched in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute, Children’s Oncology Group, and the European Pediatric Acute Leukemia Foundation.

As part of the screening process, the biology of each child’s cancer will be identified, and families will be encouraged to enroll them in appropriate targeted therapy trials.

“Until we are able to decrease the toxicity of leukemia regimens, we won’t see a dramatic shift in late effects and thus in morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Nichols said. “The trial is an effort to test newer, less toxic regimens to begin to change that cycle.”

The 5-year survival study was funded by Children with Cancer UK, Institut National du Cancer, La Ligue Contre le Cancer, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Swiss Re, Swiss Cancer Research foundation, Swiss Cancer League, Rossy Family Foundation, National Cancer Institute, and the American Cancer Society. One author reports a grant from Macmillan Cancer Support, consultancy fees from Pfizer, and unsolicited small gifts from Moondance Cancer Initiative for philanthropic work. The other authors report no disclosures.

The long-term survival study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the Archer Foundation and LyondellBasell Industries. Dr. Roth reports no disclosures; other authors report various disclosures. Dr. Nichols reports no disclosures.

“Outcomes are improving. However, additional efforts, support, and resources are needed to further improve short- and long-term survival for acute leukemia survivors. Targeted efforts focused on populations that face greater disparities in their survival are needed to move the needle faster,” Michael Roth, MD, codirector of the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Program at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, said in an interview.

In one study, released in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, an international team of researchers tracked survival outcomes from various types of leukemia in 61 nations. The study focused on the years 2000-2014 and followed patients aged 0-24.

“Age-standardized 5-year net survival in children, adolescents, and young adults for all leukemias combined during 2010-14 varied widely, ranging from 46% in Mexico to more than 85% in Canada, Cyprus, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, and Australia,” the researchers wrote. “Throughout 2000-14, survival from all leukemias combined remained consistently higher for children than adolescents and young adults, and minimal improvement was seen for adolescents and young adults in most countries.”

The U.S. data came from 41 states that cover 86% of the nation’s population, lead author Naomi Ssenyonga, a research fellow at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said in an interview.

The 5-year survival rate for acute lymphoid leukemia (ALL) rose from 80% during 2000-2004 to 86% during 2010-2014. Survival in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) was lower than for other subtypes: 66% in 2010-2014 vs. 57% in 2000-2004.

In regard to all leukemias, “we noted a steady increase in the U.S. of 6 percentage points in 5-year survival, up from 77% for patients diagnosed during 2000-2004 to 83% for those diagnosed during 2010-2014,” Ms. Ssenyonga said. “The gains were largely driven by the improvements seen among children.”

Why haven’t adolescents and young adults gained as much ground in survival?

“They often have unique clinical needs,” Ms. Ssenyonga said. “Over the past few years, adolescents and young adults with leukemia in some parts of the world, including the U.S., have increasingly been treated under pediatric protocols. This has led to higher survival. However, this approach has not been adopted consistently, and survival for adolescents and young adults with leukemia is still generally lower than survival for children.”

Gwen Nichols, MD, chief medical officer of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, agreed that pediatric treatment protocols hold promise as treatments for young adults. However, “because we arbitrarily set an age cutoff for being an adult, many of these patients are treated by an adult [nonpediatric] hematologist/oncologist, and some patients in the 20-39 age group do not receive the more intensive treatment regimens given to children,” she said in an interview.

In another study, published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, & Prevention, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center’s Dr. Roth and colleagues tracked 1,938 patients with ALL and 2,350 with AML who were diagnosed at ages 15-39 from 1980 to 2009. All lived at least 5 years after diagnosis. In both groups, about 58% were White, and most of the rest were Hispanic. The median age of diagnosis for ALL was 23 (range: 15-39) and 28 years for AML (range: 15-39).

“For ALL, 10-year survival for those diagnosed in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s was 83%, 88%, and 88%, respectively,” the researchers reported. “Ten-year survival for AML was 82%, 90%, and 90% for those diagnosed in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, respectively.”

“Early mortality within 10 years of diagnosis was mostly secondary to leukemia progressing or recurring. We believe that later mortality is secondary to the development of late side effects from their cancer treatment,” Dr. Roth said.

He noted that many adolescents and young adults with ALL or AML receive stem-cell transplants. “This treatment approach is effective. However, it is associated with short- and long-term toxicity that impacts patients’ health for many years after treatment.”

Indeed, up to 80% of acute leukemia survivors have significant health complications after therapy, said the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society’s Dr. Nichols, who wasn’t surprised by the findings. According to the society, “even when treatments are effective, more than 70% of childhood cancer survivors have a chronic health condition and 42% have a severe, disabling or life-threatening condition 30 years after diagnosis.”

“It would be interesting to understand the male predominance better,” she added, noting that the study found that male patients had worse long-term survival than females (survival time ratio: 0.61, 95% confidence interval, 0.45-0.82). “While it is tempting to suggest it is due to difference in cardiac disease, I am not aware of data to support why there is this survival difference.”

What’s next? “In ALL, we now have a number of new modalities to treat high-risk and relapsed disease such as antibodies and CAR-T,” Dr. Nichols said. “We anticipate that 5-year survival can improve utilizing these modalities due to getting more patients into remission, hopefully while reducing chemotherapeutic toxicity.”

Dr. Nichol’s also highlighted the society’s new genomic-led Pediatric Acute Leukemia (PedAL) Master Clinical Trial, which began enrolling children with acute leukemia in the United States and Canada this year, in an effort to transform medicine’s traditional high-level chemotherapy strategy to their care. The project was launched in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute, Children’s Oncology Group, and the European Pediatric Acute Leukemia Foundation.

As part of the screening process, the biology of each child’s cancer will be identified, and families will be encouraged to enroll them in appropriate targeted therapy trials.

“Until we are able to decrease the toxicity of leukemia regimens, we won’t see a dramatic shift in late effects and thus in morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Nichols said. “The trial is an effort to test newer, less toxic regimens to begin to change that cycle.”

The 5-year survival study was funded by Children with Cancer UK, Institut National du Cancer, La Ligue Contre le Cancer, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Swiss Re, Swiss Cancer Research foundation, Swiss Cancer League, Rossy Family Foundation, National Cancer Institute, and the American Cancer Society. One author reports a grant from Macmillan Cancer Support, consultancy fees from Pfizer, and unsolicited small gifts from Moondance Cancer Initiative for philanthropic work. The other authors report no disclosures.

The long-term survival study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the Archer Foundation and LyondellBasell Industries. Dr. Roth reports no disclosures; other authors report various disclosures. Dr. Nichols reports no disclosures.

“Outcomes are improving. However, additional efforts, support, and resources are needed to further improve short- and long-term survival for acute leukemia survivors. Targeted efforts focused on populations that face greater disparities in their survival are needed to move the needle faster,” Michael Roth, MD, codirector of the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Program at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, said in an interview.

In one study, released in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, an international team of researchers tracked survival outcomes from various types of leukemia in 61 nations. The study focused on the years 2000-2014 and followed patients aged 0-24.

“Age-standardized 5-year net survival in children, adolescents, and young adults for all leukemias combined during 2010-14 varied widely, ranging from 46% in Mexico to more than 85% in Canada, Cyprus, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, and Australia,” the researchers wrote. “Throughout 2000-14, survival from all leukemias combined remained consistently higher for children than adolescents and young adults, and minimal improvement was seen for adolescents and young adults in most countries.”

The U.S. data came from 41 states that cover 86% of the nation’s population, lead author Naomi Ssenyonga, a research fellow at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said in an interview.

The 5-year survival rate for acute lymphoid leukemia (ALL) rose from 80% during 2000-2004 to 86% during 2010-2014. Survival in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) was lower than for other subtypes: 66% in 2010-2014 vs. 57% in 2000-2004.

In regard to all leukemias, “we noted a steady increase in the U.S. of 6 percentage points in 5-year survival, up from 77% for patients diagnosed during 2000-2004 to 83% for those diagnosed during 2010-2014,” Ms. Ssenyonga said. “The gains were largely driven by the improvements seen among children.”

Why haven’t adolescents and young adults gained as much ground in survival?

“They often have unique clinical needs,” Ms. Ssenyonga said. “Over the past few years, adolescents and young adults with leukemia in some parts of the world, including the U.S., have increasingly been treated under pediatric protocols. This has led to higher survival. However, this approach has not been adopted consistently, and survival for adolescents and young adults with leukemia is still generally lower than survival for children.”

Gwen Nichols, MD, chief medical officer of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, agreed that pediatric treatment protocols hold promise as treatments for young adults. However, “because we arbitrarily set an age cutoff for being an adult, many of these patients are treated by an adult [nonpediatric] hematologist/oncologist, and some patients in the 20-39 age group do not receive the more intensive treatment regimens given to children,” she said in an interview.

In another study, published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, & Prevention, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center’s Dr. Roth and colleagues tracked 1,938 patients with ALL and 2,350 with AML who were diagnosed at ages 15-39 from 1980 to 2009. All lived at least 5 years after diagnosis. In both groups, about 58% were White, and most of the rest were Hispanic. The median age of diagnosis for ALL was 23 (range: 15-39) and 28 years for AML (range: 15-39).

“For ALL, 10-year survival for those diagnosed in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s was 83%, 88%, and 88%, respectively,” the researchers reported. “Ten-year survival for AML was 82%, 90%, and 90% for those diagnosed in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, respectively.”

“Early mortality within 10 years of diagnosis was mostly secondary to leukemia progressing or recurring. We believe that later mortality is secondary to the development of late side effects from their cancer treatment,” Dr. Roth said.

He noted that many adolescents and young adults with ALL or AML receive stem-cell transplants. “This treatment approach is effective. However, it is associated with short- and long-term toxicity that impacts patients’ health for many years after treatment.”

Indeed, up to 80% of acute leukemia survivors have significant health complications after therapy, said the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society’s Dr. Nichols, who wasn’t surprised by the findings. According to the society, “even when treatments are effective, more than 70% of childhood cancer survivors have a chronic health condition and 42% have a severe, disabling or life-threatening condition 30 years after diagnosis.”

“It would be interesting to understand the male predominance better,” she added, noting that the study found that male patients had worse long-term survival than females (survival time ratio: 0.61, 95% confidence interval, 0.45-0.82). “While it is tempting to suggest it is due to difference in cardiac disease, I am not aware of data to support why there is this survival difference.”

What’s next? “In ALL, we now have a number of new modalities to treat high-risk and relapsed disease such as antibodies and CAR-T,” Dr. Nichols said. “We anticipate that 5-year survival can improve utilizing these modalities due to getting more patients into remission, hopefully while reducing chemotherapeutic toxicity.”

Dr. Nichol’s also highlighted the society’s new genomic-led Pediatric Acute Leukemia (PedAL) Master Clinical Trial, which began enrolling children with acute leukemia in the United States and Canada this year, in an effort to transform medicine’s traditional high-level chemotherapy strategy to their care. The project was launched in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute, Children’s Oncology Group, and the European Pediatric Acute Leukemia Foundation.

As part of the screening process, the biology of each child’s cancer will be identified, and families will be encouraged to enroll them in appropriate targeted therapy trials.

“Until we are able to decrease the toxicity of leukemia regimens, we won’t see a dramatic shift in late effects and thus in morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Nichols said. “The trial is an effort to test newer, less toxic regimens to begin to change that cycle.”

The 5-year survival study was funded by Children with Cancer UK, Institut National du Cancer, La Ligue Contre le Cancer, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Swiss Re, Swiss Cancer Research foundation, Swiss Cancer League, Rossy Family Foundation, National Cancer Institute, and the American Cancer Society. One author reports a grant from Macmillan Cancer Support, consultancy fees from Pfizer, and unsolicited small gifts from Moondance Cancer Initiative for philanthropic work. The other authors report no disclosures.

The long-term survival study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the Archer Foundation and LyondellBasell Industries. Dr. Roth reports no disclosures; other authors report various disclosures. Dr. Nichols reports no disclosures.

Children and COVID: New cases fall again, ED rates rebound for some

The 7-day average percentage of ED visits with diagnosed COVID, which had reached a post-Omicron high of 3.5% in late July for those aged 12-15, began to fall and was down to 3.0% on Aug. 12. That trend reversed, however, and the rate was up to 3.6% on Aug. 19, the last date for which data are available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That change of COVID fortunes cannot yet be seen for all children. The 7-day average ED visit rate for those aged 0-11 years peaked at 6.8% during the last week of July and has continued to fall, dropping from 5.7% on Aug. 12 to 5.1% on Aug. 19. Children aged 16-17 years seem to be taking a middle path: Their ED-visit rate declined from late July into mid-August but held steady over the last week, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

There is a hint of the same trend regarding new admissions among children aged 0-17 years. The national rate, which had declined in recent weeks, ticked up from 0.42 to 0.43 new admissions per 100,000 population over the last week of available data, the CDC said.

Weekly cases fall below 80,000

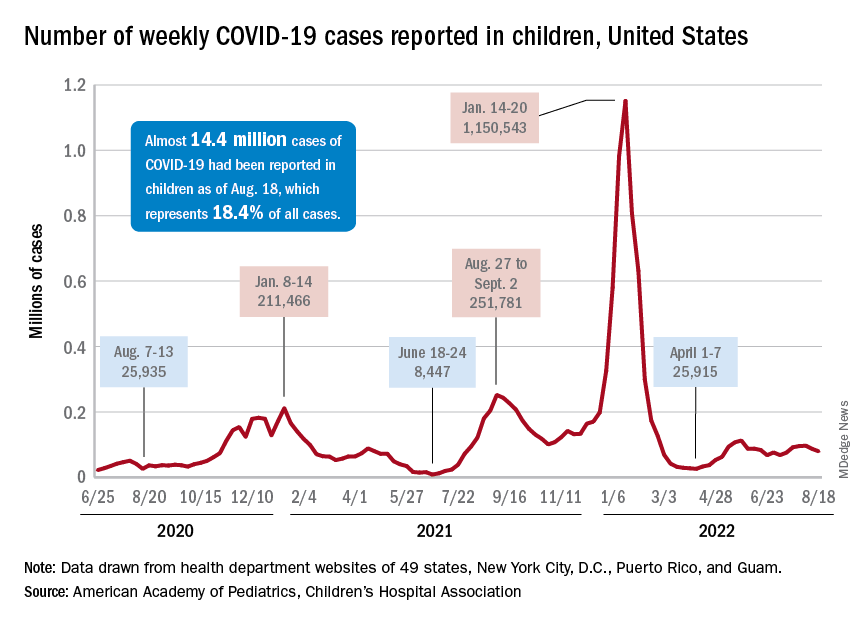

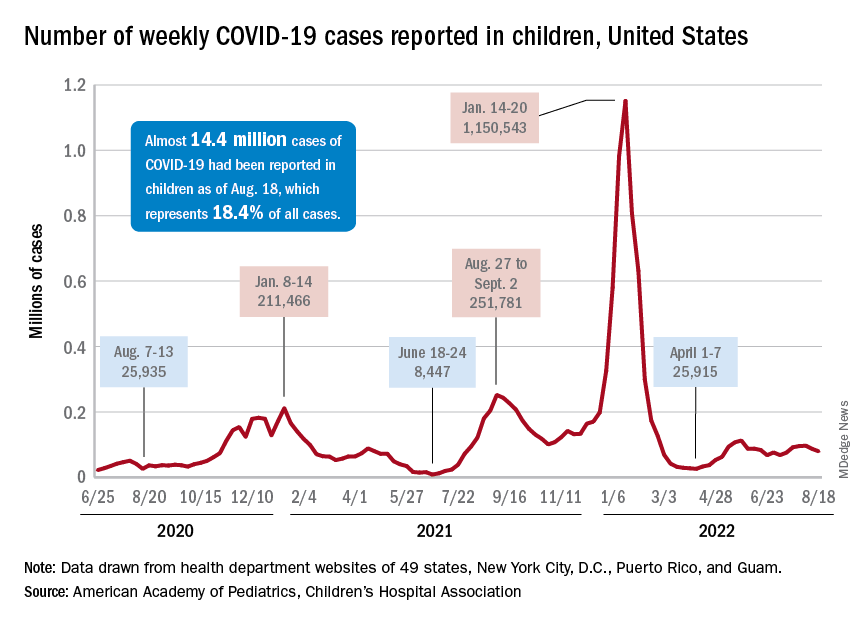

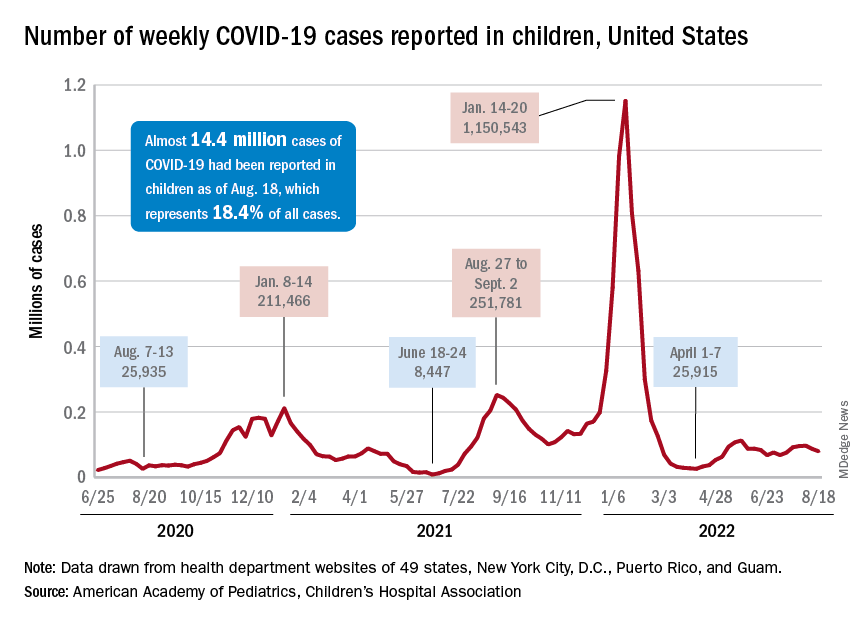

New cases in general were down by 8.5% from the previous week, dropping from 87,902 for the week of Aug. 5-11 to 79,525 for Aug. 12-18. That marked the second straight week with fewer cases after a 4-week period that saw weekly totals increase from almost 68,000 to nearly 97,000, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The AAP and CHA put the cumulative number of child COVID-19 cases at just under 14.4 million since the pandemic began, which represents 18.4% of cases among all ages. The CDC estimates that there have been almost 14.7 million cases in children aged 0-17 years, as well as 1,750 deaths, of which 14 were reported in the last week (Aug. 16-22).

The CDC age subgroups indicate that children aged 0-4 years have experienced fewer cases (2.9 million) than children aged 5-11 years (5.6 million cases) and 12-15 (3.0 million cases) but more deaths: 548 so far, versus 432 for 5- to 11-year-olds and 437 for 12- to 15-year-olds, the COVID Data Tracker shows. Those aged 0-4 make up 6% of the total U.S. population, compared with 8.7% and 5.1%, respectively, for the older children.

Most younger children still not vaccinated

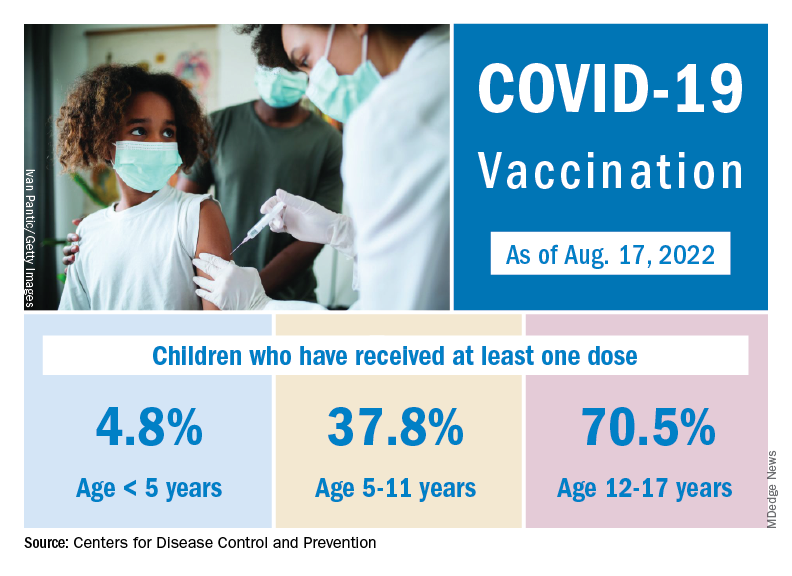

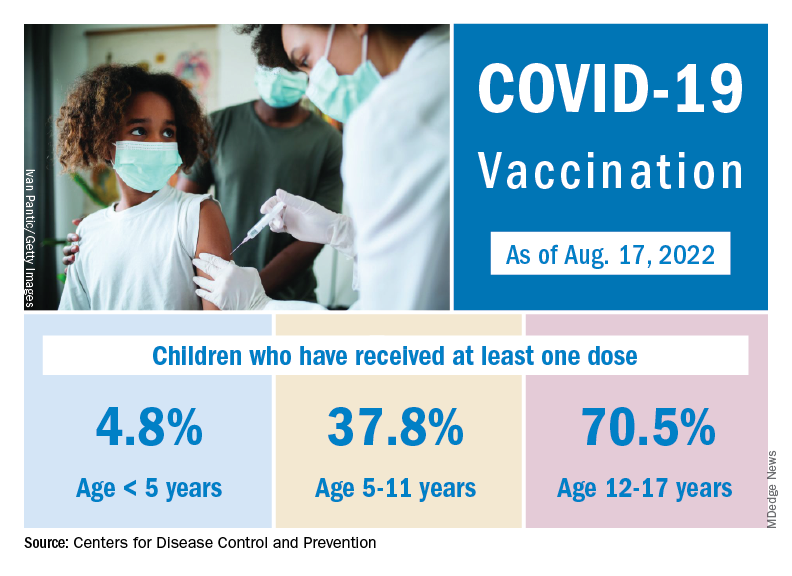

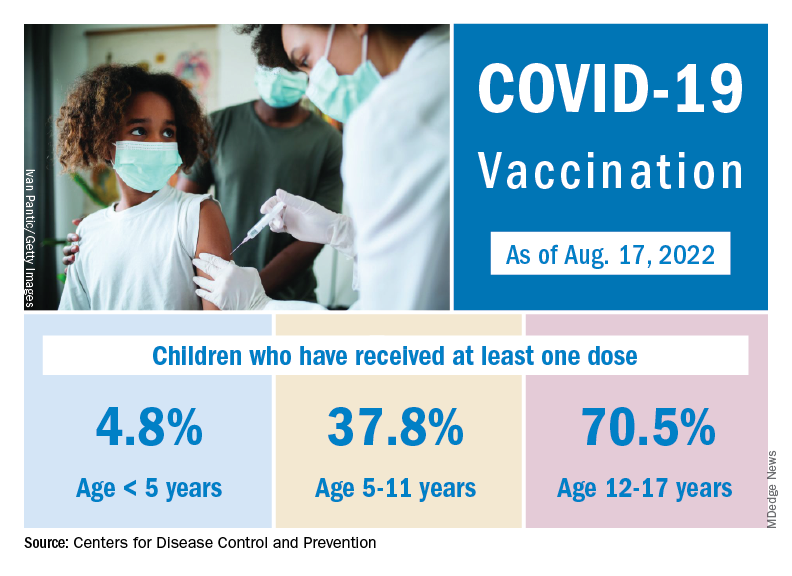

Although it may not qualify as a big push to vaccinate children before the start of the new school year, first-time vaccinations did rise somewhat in late July and August for children aged 5-17 years. Among children younger than 5 years, though, initial doses of the vaccine fell during the second full week of August, especially in 2- to 4-year-olds, based on the CDC data.

Through almost 2 months of vaccine eligibility, 4.8% of children under age 5 have received at least one dose and 0.9% are fully vaccinated as of Aug. 17. The current rates are 37.8% (one dose) and 30.4% (completed) for those aged 5-11 and 70.5% and 60.3% for 12- to 17-year-olds.

The 7-day average percentage of ED visits with diagnosed COVID, which had reached a post-Omicron high of 3.5% in late July for those aged 12-15, began to fall and was down to 3.0% on Aug. 12. That trend reversed, however, and the rate was up to 3.6% on Aug. 19, the last date for which data are available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That change of COVID fortunes cannot yet be seen for all children. The 7-day average ED visit rate for those aged 0-11 years peaked at 6.8% during the last week of July and has continued to fall, dropping from 5.7% on Aug. 12 to 5.1% on Aug. 19. Children aged 16-17 years seem to be taking a middle path: Their ED-visit rate declined from late July into mid-August but held steady over the last week, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

There is a hint of the same trend regarding new admissions among children aged 0-17 years. The national rate, which had declined in recent weeks, ticked up from 0.42 to 0.43 new admissions per 100,000 population over the last week of available data, the CDC said.

Weekly cases fall below 80,000

New cases in general were down by 8.5% from the previous week, dropping from 87,902 for the week of Aug. 5-11 to 79,525 for Aug. 12-18. That marked the second straight week with fewer cases after a 4-week period that saw weekly totals increase from almost 68,000 to nearly 97,000, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The AAP and CHA put the cumulative number of child COVID-19 cases at just under 14.4 million since the pandemic began, which represents 18.4% of cases among all ages. The CDC estimates that there have been almost 14.7 million cases in children aged 0-17 years, as well as 1,750 deaths, of which 14 were reported in the last week (Aug. 16-22).

The CDC age subgroups indicate that children aged 0-4 years have experienced fewer cases (2.9 million) than children aged 5-11 years (5.6 million cases) and 12-15 (3.0 million cases) but more deaths: 548 so far, versus 432 for 5- to 11-year-olds and 437 for 12- to 15-year-olds, the COVID Data Tracker shows. Those aged 0-4 make up 6% of the total U.S. population, compared with 8.7% and 5.1%, respectively, for the older children.

Most younger children still not vaccinated

Although it may not qualify as a big push to vaccinate children before the start of the new school year, first-time vaccinations did rise somewhat in late July and August for children aged 5-17 years. Among children younger than 5 years, though, initial doses of the vaccine fell during the second full week of August, especially in 2- to 4-year-olds, based on the CDC data.

Through almost 2 months of vaccine eligibility, 4.8% of children under age 5 have received at least one dose and 0.9% are fully vaccinated as of Aug. 17. The current rates are 37.8% (one dose) and 30.4% (completed) for those aged 5-11 and 70.5% and 60.3% for 12- to 17-year-olds.

The 7-day average percentage of ED visits with diagnosed COVID, which had reached a post-Omicron high of 3.5% in late July for those aged 12-15, began to fall and was down to 3.0% on Aug. 12. That trend reversed, however, and the rate was up to 3.6% on Aug. 19, the last date for which data are available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That change of COVID fortunes cannot yet be seen for all children. The 7-day average ED visit rate for those aged 0-11 years peaked at 6.8% during the last week of July and has continued to fall, dropping from 5.7% on Aug. 12 to 5.1% on Aug. 19. Children aged 16-17 years seem to be taking a middle path: Their ED-visit rate declined from late July into mid-August but held steady over the last week, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.