User login

Polio in 2022: Some concerns but vaccine still works

Who would have thought we would need to refresh our knowledge on polio virus in 2022? Fate seems cruel to add this concern on the heels of SARS-CoV-2, monkeypox, abnormal seasons for RSV, acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) linked to enteroviruses, and a summer of parechovirus causing infant meningitis. But confirmation that indeed an adult had polio with paralytic disease raises concerns among public health groups and ordinary citizens alike, particularly those who remember polio in its heyday.

History: In the summer of 1952, polio was among the most feared diseases on the planet. Families were advised to not allow children to congregate in groups or use public swimming pools; little league baseball games were being canceled and there was talk of not opening schools for the fall. Every parent’s nightmare seemed to be the nonspecific febrile summer illness that led to paralytic sequelae. TV news included videos of the iron lung wards in hospitals across the country. Medical providers felt powerless, only able to give nonspecific preventive advice. There was no specific antiviral (there still isn’t) and vaccines seemed a long way off.

Then came the news that Dr. Jonas Salk’s group had gotten an inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) approved for general use in 1955. Families were excited to have their children vaccinated. Paralytic polio cases dropped like a rock from approximately 22,000/year in 1952 to approximately 2,200 in 1956. A surge to near 6,000 cases in 1959 led to Dr. Albert Sabin’s oral polio vaccine (OPV), which supplanted IPV in 1961. OPV had the advantages of: 1) Inducing mucosal as well as serum antibodies, 2) more durable responses, and 3) immunity in unvaccinated persons exposed to vaccine virus that had been shed in stools into wastewater and rivers.

By 1964, polio had nearly disappeared. The last wild-type indigenous U.S. case was in 1979. By 1994, all the Americas were declared polio free. Because the only U.S. paralytic polio cases thereafter were foreign imports or were associated with oral vaccine strains (so-called vaccine-associated paralytic polio [VAPP]), OPV was replaced by an enhanced IPV in 2000 to prevent further VAPP.

Polio facts: Polio is asymptomatic in about 70% of infections. Among the 30% with symptoms, paralysis occurs infrequently, with the overall rate of paralytic infections being 0.5% (rate varies by virus type with type 3 having the highest rate).1 Why then was the world so afraid of polio? If every person in a U.S. birth cohort (about 3.7 million) was unvaccinated and became infected with poliovirus, more than 18,000 would get paralytic polio and almost 1,300 would die. Of note, adults have a higher chance of paralytic polio after infection than children.

Concerns in 2022: Persons vaccinated with at least three doses of either IPV or OPV have historically been protected from paralytic polio (99% protection). But are we sure that the United States remains protected against polio after 2 decades of IPV being the only vaccine? Polio could be reintroduced at any time to the United States from countries with reported cases that likely arose because of low vaccination rates related to war, famine, or political upheavals (Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan).2 The proof? The recent confirmed New York case.

International efforts resulted in global eradication of two polio wild-types viruses (type 2 in 2015 and type 3 in 2019). Nevertheless, vaccine-derived, virulent polio virus (VDPV) type 2 and VDPV-3 still circulate in some areas, particularly Africa (VDPV-2) and Israel (VDPV-3). The above-mentioned U.S. case is an unvaccinated adult traveler who went to an area where VDPV-2 circulates and developed disease after returning home.3 So, it was not an indigenous reappearance in the United States and it was not a breakthrough case in a vaccinated person. But it is sobering to realize that all who are unvaccinated remain at risk for paralytic polio in 2022, particularly because vaccination rates declined nearly everywhere during the initial COVID-19 pandemic. We are still catching up, with vaccination rates under 50% in some ZIP codes.4

Are VDPVs circulating in some parts of the United States? Interestingly, wastewater surveillance programs may be the most economical and practical way to perform polio surveillance. Such a program detected polio virus in London wastewater in June 2022.5 New York has recently detected polio in wastewater during testing begun because of the recent case.6

Good news: For paralytic polio, seropositivity at any titer indicates protection, so U.S. serosurveillance data would also be informative. How durable is polio protection in the IPV era? Available data suggest that even though we have used only IPV these past 20 years, seropositivity rates among vaccinees with at least three doses of either IPV or OPV should persist for decades and likely for life. Even before polio became a concern this year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, being proactive, wanted to ensure that the enhanced IPV was producing durable immunity and that persons of all ages remained seropositive to the three polio virus types over 10 years after discontinuing OPV use in 2012.

The CDC collaborated with investigators in Kansas City, Mo., to evaluate titers and seropositivity to all three types in a 2- to 85-year-old otherwise healthy cohort with demographics that mirrored the 2010 census for the Kansas City region, which in turn mirrored the national 2021 census data.7 There were approximately 100 persons in each age cohort, with 200 below age 11 years (the cohort that had received only IPV). Serology was performed at the CDC.

Overall seropositivity rates were high, but lower for type 3 (83.3%) and type 2 (90.7%) than type 1 (94.4%). Of note, most of those seronegative for one or more types were among 2- to 3-year-olds who had not completed their full IPV series, with most seronegative results being against polio types 1 and 3. Further, five, who were confirmed as having received no polio vaccine, were seronegative for all three types. Two with no available vaccine records (over 18 years old) were also seronegative for all three types.

So, regardless of the era in which one got polio vaccine, vaccine protection appears to persist indefinitely after three doses. Even 80-year-olds were still seropositive if they had three doses. We can confidently reassure our patients that the vaccine still works; the persons who need to fear polio in 2022 are those who are not vaccinated or have had fewer than three doses, particularly if they travel to areas of persistent polio. Wild type 1 virus persists in a few countries as does VDPV type 2 and VDPV type 3. Importantly, wild type 2 and wild type 3 (with the lowest seropositivity in 2012 study) have been eliminated globally so the only circulating type 2 and type 3 polio virus is VDPV in a few countries. Travel to these countries warrants review of polio vaccine records and CDC or WHO current recommendations for travelers to those countries.

Dr. Harrison is a professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Poliomyelitis. World Health Organization fact sheet, 2022 Jul 4..

2. Franco-Paredes C et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 Aug 16. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00548-5.

3. Link-Gelles R et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 Aug 19;71(33):1065-8.

4. “Polio vaccination rate for 2-year-olds is as low as 37% in parts of N.Y. county where paralysis case was found,” NBC News, Erika Edwards, 2022 Aug 16. 5. Vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (VDPV2) detected in environmental samples in London. Polioeradication.org. 2022 Jun 22.

6. “NYSDOH and NYCDOHMH wastewater monitoring identifies polio in New York City and urges unvaccinated New Yorkers to get vaccinated now,” nyc.gov. 2022 Aug 12.

7. Wallace GS et al. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(4):776-83.

Who would have thought we would need to refresh our knowledge on polio virus in 2022? Fate seems cruel to add this concern on the heels of SARS-CoV-2, monkeypox, abnormal seasons for RSV, acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) linked to enteroviruses, and a summer of parechovirus causing infant meningitis. But confirmation that indeed an adult had polio with paralytic disease raises concerns among public health groups and ordinary citizens alike, particularly those who remember polio in its heyday.

History: In the summer of 1952, polio was among the most feared diseases on the planet. Families were advised to not allow children to congregate in groups or use public swimming pools; little league baseball games were being canceled and there was talk of not opening schools for the fall. Every parent’s nightmare seemed to be the nonspecific febrile summer illness that led to paralytic sequelae. TV news included videos of the iron lung wards in hospitals across the country. Medical providers felt powerless, only able to give nonspecific preventive advice. There was no specific antiviral (there still isn’t) and vaccines seemed a long way off.

Then came the news that Dr. Jonas Salk’s group had gotten an inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) approved for general use in 1955. Families were excited to have their children vaccinated. Paralytic polio cases dropped like a rock from approximately 22,000/year in 1952 to approximately 2,200 in 1956. A surge to near 6,000 cases in 1959 led to Dr. Albert Sabin’s oral polio vaccine (OPV), which supplanted IPV in 1961. OPV had the advantages of: 1) Inducing mucosal as well as serum antibodies, 2) more durable responses, and 3) immunity in unvaccinated persons exposed to vaccine virus that had been shed in stools into wastewater and rivers.

By 1964, polio had nearly disappeared. The last wild-type indigenous U.S. case was in 1979. By 1994, all the Americas were declared polio free. Because the only U.S. paralytic polio cases thereafter were foreign imports or were associated with oral vaccine strains (so-called vaccine-associated paralytic polio [VAPP]), OPV was replaced by an enhanced IPV in 2000 to prevent further VAPP.

Polio facts: Polio is asymptomatic in about 70% of infections. Among the 30% with symptoms, paralysis occurs infrequently, with the overall rate of paralytic infections being 0.5% (rate varies by virus type with type 3 having the highest rate).1 Why then was the world so afraid of polio? If every person in a U.S. birth cohort (about 3.7 million) was unvaccinated and became infected with poliovirus, more than 18,000 would get paralytic polio and almost 1,300 would die. Of note, adults have a higher chance of paralytic polio after infection than children.

Concerns in 2022: Persons vaccinated with at least three doses of either IPV or OPV have historically been protected from paralytic polio (99% protection). But are we sure that the United States remains protected against polio after 2 decades of IPV being the only vaccine? Polio could be reintroduced at any time to the United States from countries with reported cases that likely arose because of low vaccination rates related to war, famine, or political upheavals (Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan).2 The proof? The recent confirmed New York case.

International efforts resulted in global eradication of two polio wild-types viruses (type 2 in 2015 and type 3 in 2019). Nevertheless, vaccine-derived, virulent polio virus (VDPV) type 2 and VDPV-3 still circulate in some areas, particularly Africa (VDPV-2) and Israel (VDPV-3). The above-mentioned U.S. case is an unvaccinated adult traveler who went to an area where VDPV-2 circulates and developed disease after returning home.3 So, it was not an indigenous reappearance in the United States and it was not a breakthrough case in a vaccinated person. But it is sobering to realize that all who are unvaccinated remain at risk for paralytic polio in 2022, particularly because vaccination rates declined nearly everywhere during the initial COVID-19 pandemic. We are still catching up, with vaccination rates under 50% in some ZIP codes.4

Are VDPVs circulating in some parts of the United States? Interestingly, wastewater surveillance programs may be the most economical and practical way to perform polio surveillance. Such a program detected polio virus in London wastewater in June 2022.5 New York has recently detected polio in wastewater during testing begun because of the recent case.6

Good news: For paralytic polio, seropositivity at any titer indicates protection, so U.S. serosurveillance data would also be informative. How durable is polio protection in the IPV era? Available data suggest that even though we have used only IPV these past 20 years, seropositivity rates among vaccinees with at least three doses of either IPV or OPV should persist for decades and likely for life. Even before polio became a concern this year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, being proactive, wanted to ensure that the enhanced IPV was producing durable immunity and that persons of all ages remained seropositive to the three polio virus types over 10 years after discontinuing OPV use in 2012.

The CDC collaborated with investigators in Kansas City, Mo., to evaluate titers and seropositivity to all three types in a 2- to 85-year-old otherwise healthy cohort with demographics that mirrored the 2010 census for the Kansas City region, which in turn mirrored the national 2021 census data.7 There were approximately 100 persons in each age cohort, with 200 below age 11 years (the cohort that had received only IPV). Serology was performed at the CDC.

Overall seropositivity rates were high, but lower for type 3 (83.3%) and type 2 (90.7%) than type 1 (94.4%). Of note, most of those seronegative for one or more types were among 2- to 3-year-olds who had not completed their full IPV series, with most seronegative results being against polio types 1 and 3. Further, five, who were confirmed as having received no polio vaccine, were seronegative for all three types. Two with no available vaccine records (over 18 years old) were also seronegative for all three types.

So, regardless of the era in which one got polio vaccine, vaccine protection appears to persist indefinitely after three doses. Even 80-year-olds were still seropositive if they had three doses. We can confidently reassure our patients that the vaccine still works; the persons who need to fear polio in 2022 are those who are not vaccinated or have had fewer than three doses, particularly if they travel to areas of persistent polio. Wild type 1 virus persists in a few countries as does VDPV type 2 and VDPV type 3. Importantly, wild type 2 and wild type 3 (with the lowest seropositivity in 2012 study) have been eliminated globally so the only circulating type 2 and type 3 polio virus is VDPV in a few countries. Travel to these countries warrants review of polio vaccine records and CDC or WHO current recommendations for travelers to those countries.

Dr. Harrison is a professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Poliomyelitis. World Health Organization fact sheet, 2022 Jul 4..

2. Franco-Paredes C et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 Aug 16. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00548-5.

3. Link-Gelles R et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 Aug 19;71(33):1065-8.

4. “Polio vaccination rate for 2-year-olds is as low as 37% in parts of N.Y. county where paralysis case was found,” NBC News, Erika Edwards, 2022 Aug 16. 5. Vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (VDPV2) detected in environmental samples in London. Polioeradication.org. 2022 Jun 22.

6. “NYSDOH and NYCDOHMH wastewater monitoring identifies polio in New York City and urges unvaccinated New Yorkers to get vaccinated now,” nyc.gov. 2022 Aug 12.

7. Wallace GS et al. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(4):776-83.

Who would have thought we would need to refresh our knowledge on polio virus in 2022? Fate seems cruel to add this concern on the heels of SARS-CoV-2, monkeypox, abnormal seasons for RSV, acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) linked to enteroviruses, and a summer of parechovirus causing infant meningitis. But confirmation that indeed an adult had polio with paralytic disease raises concerns among public health groups and ordinary citizens alike, particularly those who remember polio in its heyday.

History: In the summer of 1952, polio was among the most feared diseases on the planet. Families were advised to not allow children to congregate in groups or use public swimming pools; little league baseball games were being canceled and there was talk of not opening schools for the fall. Every parent’s nightmare seemed to be the nonspecific febrile summer illness that led to paralytic sequelae. TV news included videos of the iron lung wards in hospitals across the country. Medical providers felt powerless, only able to give nonspecific preventive advice. There was no specific antiviral (there still isn’t) and vaccines seemed a long way off.

Then came the news that Dr. Jonas Salk’s group had gotten an inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) approved for general use in 1955. Families were excited to have their children vaccinated. Paralytic polio cases dropped like a rock from approximately 22,000/year in 1952 to approximately 2,200 in 1956. A surge to near 6,000 cases in 1959 led to Dr. Albert Sabin’s oral polio vaccine (OPV), which supplanted IPV in 1961. OPV had the advantages of: 1) Inducing mucosal as well as serum antibodies, 2) more durable responses, and 3) immunity in unvaccinated persons exposed to vaccine virus that had been shed in stools into wastewater and rivers.

By 1964, polio had nearly disappeared. The last wild-type indigenous U.S. case was in 1979. By 1994, all the Americas were declared polio free. Because the only U.S. paralytic polio cases thereafter were foreign imports or were associated with oral vaccine strains (so-called vaccine-associated paralytic polio [VAPP]), OPV was replaced by an enhanced IPV in 2000 to prevent further VAPP.

Polio facts: Polio is asymptomatic in about 70% of infections. Among the 30% with symptoms, paralysis occurs infrequently, with the overall rate of paralytic infections being 0.5% (rate varies by virus type with type 3 having the highest rate).1 Why then was the world so afraid of polio? If every person in a U.S. birth cohort (about 3.7 million) was unvaccinated and became infected with poliovirus, more than 18,000 would get paralytic polio and almost 1,300 would die. Of note, adults have a higher chance of paralytic polio after infection than children.

Concerns in 2022: Persons vaccinated with at least three doses of either IPV or OPV have historically been protected from paralytic polio (99% protection). But are we sure that the United States remains protected against polio after 2 decades of IPV being the only vaccine? Polio could be reintroduced at any time to the United States from countries with reported cases that likely arose because of low vaccination rates related to war, famine, or political upheavals (Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan).2 The proof? The recent confirmed New York case.

International efforts resulted in global eradication of two polio wild-types viruses (type 2 in 2015 and type 3 in 2019). Nevertheless, vaccine-derived, virulent polio virus (VDPV) type 2 and VDPV-3 still circulate in some areas, particularly Africa (VDPV-2) and Israel (VDPV-3). The above-mentioned U.S. case is an unvaccinated adult traveler who went to an area where VDPV-2 circulates and developed disease after returning home.3 So, it was not an indigenous reappearance in the United States and it was not a breakthrough case in a vaccinated person. But it is sobering to realize that all who are unvaccinated remain at risk for paralytic polio in 2022, particularly because vaccination rates declined nearly everywhere during the initial COVID-19 pandemic. We are still catching up, with vaccination rates under 50% in some ZIP codes.4

Are VDPVs circulating in some parts of the United States? Interestingly, wastewater surveillance programs may be the most economical and practical way to perform polio surveillance. Such a program detected polio virus in London wastewater in June 2022.5 New York has recently detected polio in wastewater during testing begun because of the recent case.6

Good news: For paralytic polio, seropositivity at any titer indicates protection, so U.S. serosurveillance data would also be informative. How durable is polio protection in the IPV era? Available data suggest that even though we have used only IPV these past 20 years, seropositivity rates among vaccinees with at least three doses of either IPV or OPV should persist for decades and likely for life. Even before polio became a concern this year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, being proactive, wanted to ensure that the enhanced IPV was producing durable immunity and that persons of all ages remained seropositive to the three polio virus types over 10 years after discontinuing OPV use in 2012.

The CDC collaborated with investigators in Kansas City, Mo., to evaluate titers and seropositivity to all three types in a 2- to 85-year-old otherwise healthy cohort with demographics that mirrored the 2010 census for the Kansas City region, which in turn mirrored the national 2021 census data.7 There were approximately 100 persons in each age cohort, with 200 below age 11 years (the cohort that had received only IPV). Serology was performed at the CDC.

Overall seropositivity rates were high, but lower for type 3 (83.3%) and type 2 (90.7%) than type 1 (94.4%). Of note, most of those seronegative for one or more types were among 2- to 3-year-olds who had not completed their full IPV series, with most seronegative results being against polio types 1 and 3. Further, five, who were confirmed as having received no polio vaccine, were seronegative for all three types. Two with no available vaccine records (over 18 years old) were also seronegative for all three types.

So, regardless of the era in which one got polio vaccine, vaccine protection appears to persist indefinitely after three doses. Even 80-year-olds were still seropositive if they had three doses. We can confidently reassure our patients that the vaccine still works; the persons who need to fear polio in 2022 are those who are not vaccinated or have had fewer than three doses, particularly if they travel to areas of persistent polio. Wild type 1 virus persists in a few countries as does VDPV type 2 and VDPV type 3. Importantly, wild type 2 and wild type 3 (with the lowest seropositivity in 2012 study) have been eliminated globally so the only circulating type 2 and type 3 polio virus is VDPV in a few countries. Travel to these countries warrants review of polio vaccine records and CDC or WHO current recommendations for travelers to those countries.

Dr. Harrison is a professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Poliomyelitis. World Health Organization fact sheet, 2022 Jul 4..

2. Franco-Paredes C et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 Aug 16. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00548-5.

3. Link-Gelles R et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 Aug 19;71(33):1065-8.

4. “Polio vaccination rate for 2-year-olds is as low as 37% in parts of N.Y. county where paralysis case was found,” NBC News, Erika Edwards, 2022 Aug 16. 5. Vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (VDPV2) detected in environmental samples in London. Polioeradication.org. 2022 Jun 22.

6. “NYSDOH and NYCDOHMH wastewater monitoring identifies polio in New York City and urges unvaccinated New Yorkers to get vaccinated now,” nyc.gov. 2022 Aug 12.

7. Wallace GS et al. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(4):776-83.

Diabetes Population Health Innovations in the Age of COVID-19: Insights From the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative

From the T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Ann Mungmode, Nicole Rioles, Jesse Cases, Dr. Ebekozien); The Leona M. and Harry B. Hemsley Charitable Trust, New York, NY (Laurel Koester); and the University of Mississippi School of Population Health, Jackson, MS (Dr. Ebekozien).

Abstract

There have been remarkable innovations in diabetes management since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, but these groundbreaking innovations are drawing limited focus as the field focuses on the adverse impact of the pandemic on patients with diabetes. This article reviews select population health innovations in diabetes management that have become available over the past 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative, a learning health network that focuses on improving care and outcomes for individuals with type 1 diabetes (T1D). Such innovations include expanded telemedicine access, collection of real-world data, machine learning and artificial intelligence, and new diabetes medications and devices. In addition, multiple innovative studies have been undertaken to explore contributors to health inequities in diabetes, and advocacy efforts for specific populations have been successful. Looking to the future, work is required to explore additional health equity successes that do not further exacerbate inequities and to look for additional innovative ways to engage people with T1D in their health care through conversations on social determinants of health and societal structures.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes, learning health network, continuous glucose monitoring, health equity

One in 10 people in the United States has diabetes.1 Diabetes is the nation’s second leading cause of death, costing the US health system more than $300 billion annually.2 The COVID-19 pandemic presented additional health burdens for people living with diabetes. For example, preexisting diabetes was identified as a risk factor for COVID-19–associated morbidity and mortality.3,4 Over the past 2 years, there have been remarkable innovations in diabetes management, including stem cell therapy and new medication options. Additionally, improved technology solutions have aided in diabetes management through continuous glucose monitors (CGM), smart insulin pens, advanced hybrid closed-loop systems, and continuous subcutaneous insulin injections.5,6 Unfortunately, these groundbreaking innovations are drawing limited focus, as the field is rightfully focused on the adverse impact of the pandemic on patients with diabetes.

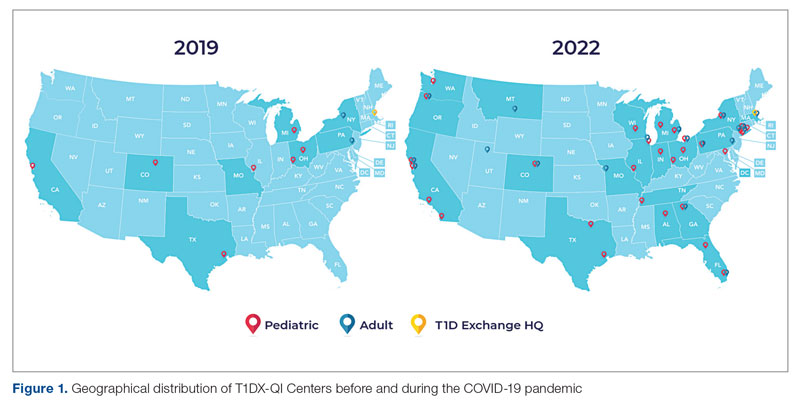

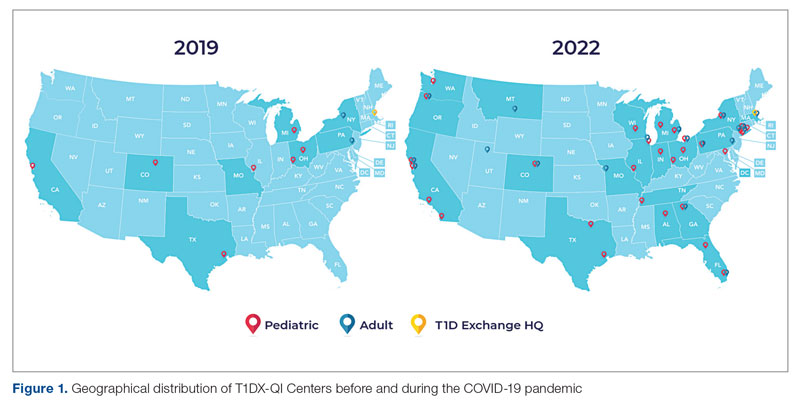

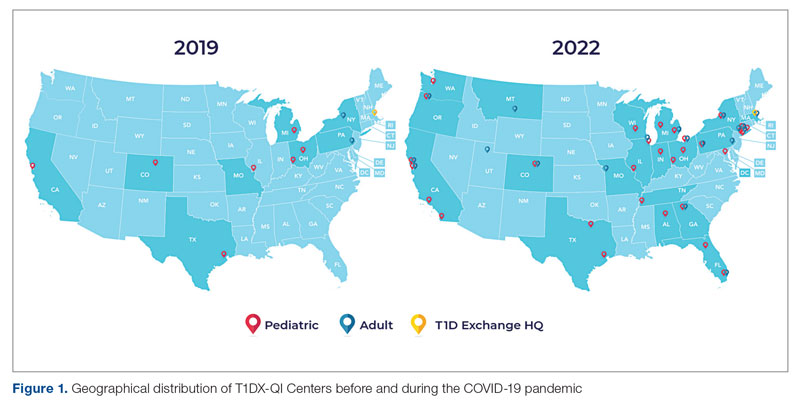

Learning health networks like the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative (T1DX-QI) have implemented some of these innovative solutions to improve care for people with diabetes.7 T1DX-QI has more than 50 data-sharing endocrinology centers that care for over 75,000 people with diabetes across the United States (Figure 1). Centers participating in the T1DX-QI use quality improvement (QI) and implementation science methods to quickly translate research into evidence-based clinical practice. T1DX-QI leads diabetes population health and health system research and supports widespread transferability across health care organizations through regular collaborative calls, conferences, and case study documentation.8

In this review, we summarize impactful population health innovations in diabetes management that have become available over the past 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of T1DX-QI (see Figure 2 for relevant definitions). This review is limited in scope and is not meant to be an exhaustive list of innovations. The review also reflects significant changes from the perspective of academic diabetes centers, which may not apply to rural or primary care diabetes practices.

Methods

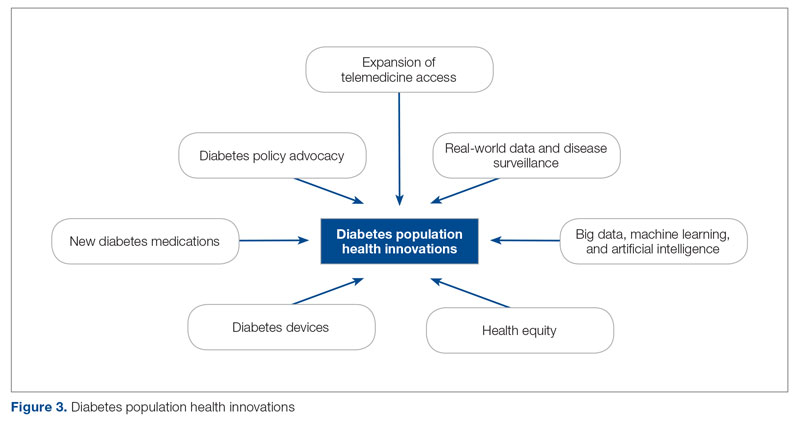

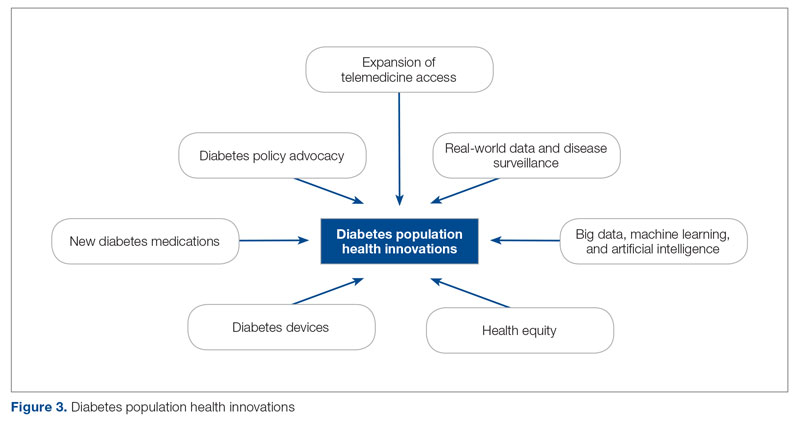

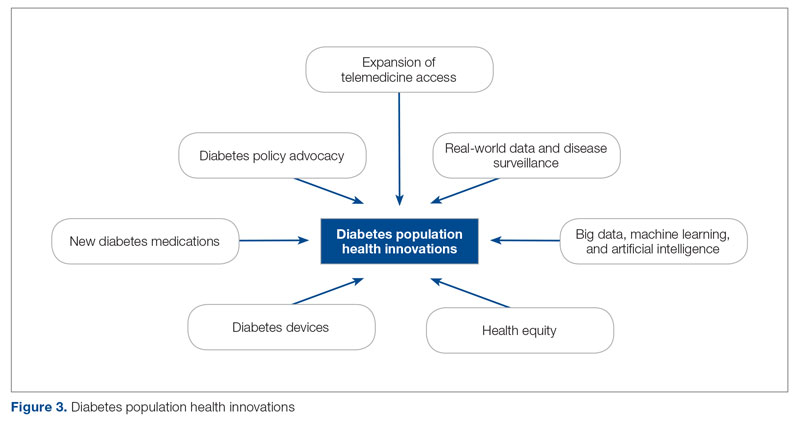

The first (A.M.), second (H.H.), and senior (O.E.) authors conducted a scoping review of published literature using terms related to diabetes, population health, and innovation on PubMed Central and Google Scholar for the period March 2020 to June 2022. To complement the review, A.M. and O.E. also reviewed abstracts from presentations at major international diabetes conferences, including the American Diabetes Association (ADA), the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD), the T1DX-QI Learning Session Conference, and the Advanced Technologies & Treatments for Diabetes (ATTD) 2020 to 2022 conferences.9-14 The authors also searched FDA.gov and ClinicalTrials.gov for relevant insights. A.M. and O.E. sorted the reviewed literature into major themes (Figure 3) from the population health improvement perspective of the T1DX-QI.

Population Health Innovations in Diabetes Management

Expansion of Telemedicine Access

Telemedicine is cost-effective for patients with diabetes,15 including those with complex cases.16 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine and virtual care were rare in diabetes management. However, the pandemic offered a new opportunity to expand the practice of telemedicine in diabetes management. A study from the T1DX-QI showed that telemedicine visits grew from comprising <1% of visits pre-pandemic (December 2019) to 95.2% during the pandemic (August 2020).17 Additional studies, like those conducted by Phillip et al,18 confirmed the noninferiority of telemedicine practice for patients with diabetes.Telemedicine was also found to be an effective strategy to educate patients on the use of diabetes technologies.19

Real-World Data and Disease Surveillance

As the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated outcomes for people with type 1 diabetes (T1D), a need arose to understand the immediate effects of the pandemic on people with T1D through real-world data and disease surveillance. In April 2020, the T1DX-QI initiated a multicenter surveillance study to collect data and analyze the impact of COVID-19 on people with T1D. The existing health collaborative served as a springboard for robust surveillance study, documenting numerous works on the effects of COVID-19.3,4,20-28 Other investigators also embraced the power of real-world surveillance and real-world data.29,30

Big Data, Machine Learning, and Artificial Intelligence

The past 2 years have seen a shift toward embracing the incredible opportunity to tap the large volume of data generated from routine care for practical insights.31 In particular, researchers have demonstrated the widespread application of machine learning and artificial intelligence to improve diabetes management.32 The T1DX-QI also harnessed the growing power of big data by expanding the functionality of innovative benchmarking software. The T1DX QI Portal uses electronic medical record data of diabetes patients for clinic-to-clinic benchmarking and data analysis, using business intelligence solutions.33

Health Equity

While inequities across various health outcomes have been well documented for years,34 the COVID-19 pandemic further exaggerated racial/ethnic health inequities in T1D.23,35 In response, several organizations have outlined specific strategies to address these health inequities. Emboldened by the pandemic, the T1DX-QI announced a multipronged approach to address health inequities among patients with T1D through the Health Equity Advancement Lab (HEAL).36 One of HEAL’s main components is using real-world data to champion population-level insights and demonstrate progress in QI efforts.

Multiple innovative studies have been undertaken to explore contributors to health inequities in diabetes, and these studies are expanding our understanding of the chasm.37 There have also been innovative solutions to addressing these inequities, with multiple studies published over the past 2 years.38 A source of inequity among patients with T1D is the lack of representation of racial/ethnic minorities with T1D in clinical trials.39 The T1DX-QI suggests that the equity-adapted framework for QI can be applied by research leaders to support trial diversity and representation, ensuring future device innovations are meaningful for all people with T1D.40

Diabetes Devices

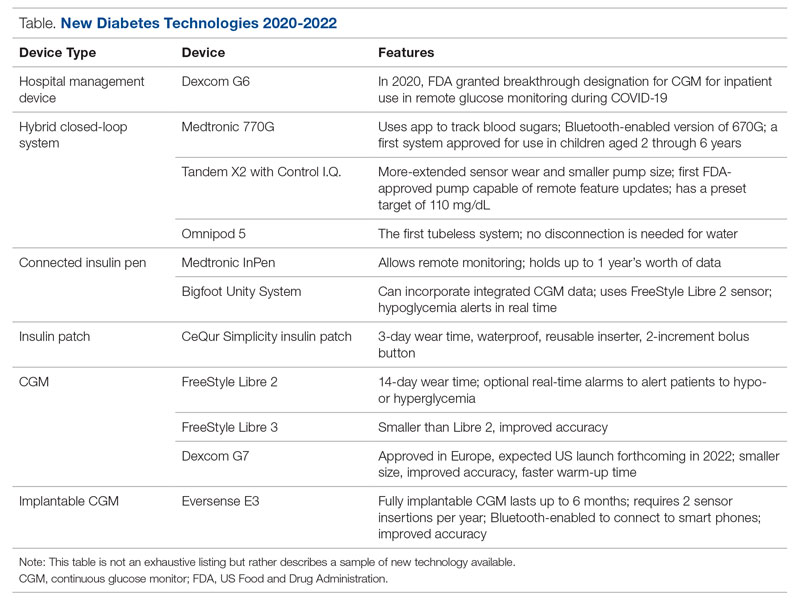

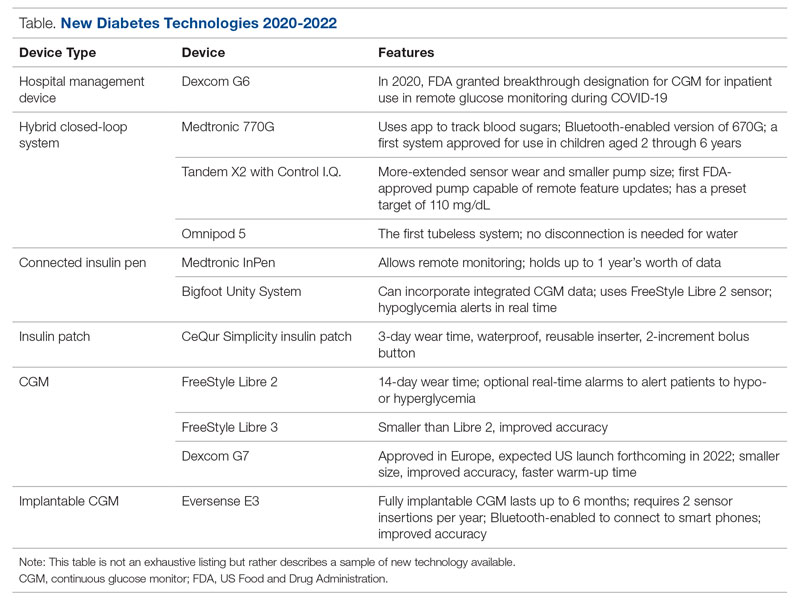

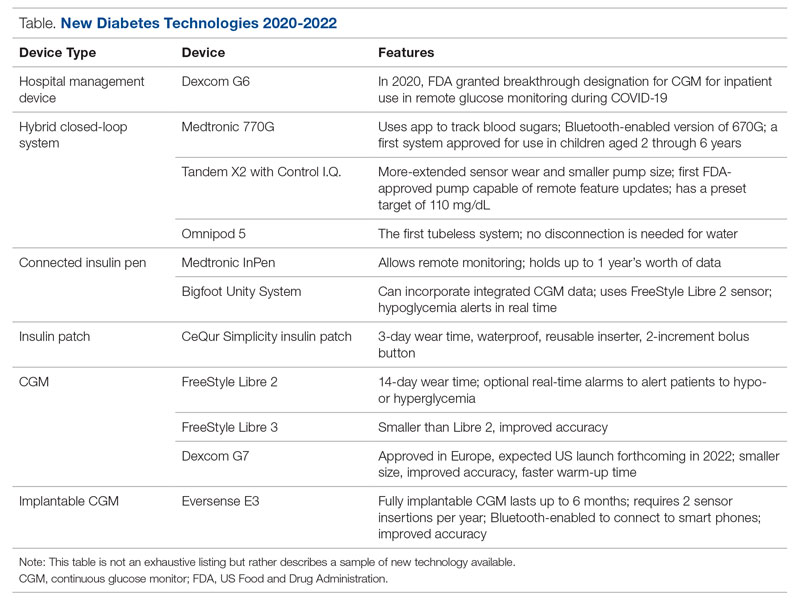

Glucose monitoring and insulin therapy are vital tools to support individuals living with T1D, and devices such as CGM and insulin pumps have become the standard of care for diabetes management (Table).41 Innovations in diabetes technology and device access are imperative for a chronic disease with no cure.

The COVID-19 pandemic created an opportunity to increase access to diabetes devices in inpatient settings. In 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration expanded the use of CGM to support remote monitoring of patients in inpatient hospital settings, simultaneously supporting the glucose monitoring needs of patients with T1D and reducing COVID-19 transmission through reduced patient-clinician contact.42 This effort has been expanded and will continue in 2022 and beyond,43 and aligns with the growing consensus that supports patients wearing both CGMs and insulin pumps in ambulatory settings to improve patient health outcomes.44

Since 2020, innovations in diabetes technology have improved and increased the variety of options available to people with T1D and made them easier to use (Table). New, advanced hybrid closed-loop systems have progressed to offer Bluetooth features, including automatic software upgrades, tubeless systems, and the ability to allow parents to use their smartphones to bolus for children.45-47 The next big step in insulin delivery innovation is the release of functioning, fully closed loop systems, of which several are currently in clinical trials.48 These systems support reduced hypoglycemia and improved time in range.49

Additional innovations in insulin delivery have improved the user experience and expanded therapeutic options, including a variety of smart insulin pens complete with dosing logs50,51 and even a patch to deliver insulin without the burden of injections.52 As barriers to diabetes technology persist,53 innovations in alternate insulin delivery provide people with T1D more options to align with their personal access and technology preferences.

Innovations in CGM address cited barriers to their use, including size or overall wear.53-55 CGMs released in the past few years are smaller in physical size, have longer durations of time between changings, are more accurate, and do not require calibrations for accuracy.

New Diabetes Medications

Many new medications and therapeutic advances have become available in the past 2 years.56 Additionally, more medications are being tested as adjunct therapies to support glycemic management in patients with T1D, including metformin, sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 and 2 inhibitors, pramlintide, glucagon-like polypeptide-1 analogs, and glucagon receptor agonists.57 Other recent advances include stem cell replacement therapy for patients with T1D.58 The ultra-long-acting biosimilar insulins are one medical innovation that has been stalled, rather than propelled, during the COVID-19 pandemic.59

Diabetes Policy Advocacy

People with T1D require insulin to survive. The cost of insulin has increased in recent years, with some studies citing a 64% to 100% increase in the past decade.60,61 In fact, 1 in 4 insulin users report that cost has impacted their insulin use, including rationing their insulin.62 Lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic stressed US families financially, increasing the urgency for insulin cost caps.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic halted national conversations on drug financing,63 advocacy efforts have succeeded for specific populations. The new Medicare Part D Senior Savings Model will cap the cost of insulin at $35 for a 30-day supply,64 and 20 states passed legislation capping insulin pricing.62 Efforts to codify national cost caps are under debate, including the passage of the Affordable Insulin Now Act, which passed the House in March 2022 and is currently under review in the Senate.65

Perspective: The Role of Private Philanthropy in Supporting Population Health Innovations

Funders and industry partners play a crucial role in leading and supporting innovations that improve the lives of people with T1D and reduce society’s costs of living with the disease. Data infrastructure is critical to supporting population health. While building the data infrastructure to support population health is both time- and resource-intensive, private foundations such as Helmsley are uniquely positioned—and have a responsibility—to take large, informed risks to help reach all communities with T1D.

The T1DX-QI is the largest source of population health data on T1D in the United States and is becoming the premiere data authority on its incidence, prevalence, and outcomes. The T1DX-QI enables a robust understanding of T1D-related health trends at the population level, as well as trends among clinics and providers. Pilot centers in the T1DX-QI have reported reductions in patients’ A1c and acute diabetes-related events, as well as improvements in device usage and depression screening. The ability to capture changes speaks to the promise and power of these data to demonstrate the clinical impact of QI interventions and to support the spread of best practices and learnings across health systems.

Additional philanthropic efforts have supported innovation in the last 2 years. For example, the JDRF, a nonprofit philanthropic equity firm, has supported efforts in developing artificial pancreas systems and cell therapies currently in clinical trials like teplizumab, a drug that has demonstrated delayed onset of T1D through JDRF’s T1D Fund.66 Industry partners also have an opportunity for significant influence in this area, as they continue to fund meaningful projects to advance care for people with T1D.67

Conclusion

We are optimistic that the innovations summarized here describe a shift in the tide of equitable T1D outcomes; however, future work is required to explore additional health equity successes that do not further exacerbate inequities. We also see further opportunities for innovative ways to engage people with T1D in their health care through conversations on social determinants of health and societal structures.

Corresponding author: Ann Mungmode, MPH, T1D Exchange, 11 Avenue de Lafayette, Boston, MA 02111; Email: [email protected]

Disclosures: Dr. Ebekozien serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for the Medtronic Advisory Board and received research grants from Medtronic Diabetes, Eli Lilly, and Dexcom.

Funding: The T1DX-QI is funded by The Leona M. and Harry B. Hemsley Charitable Trust.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report. Accessed August 30, 2022. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes fast facts. Accessed August 30, 2022. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/quick-facts.html

3. O’Malley G, Ebekozien O, Desimone M, et al. COVID-19 hospitalization in adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the T1D Exchange Multicenter Surveillance Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;106(2):e936-e942. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa825

4. Ebekozien OA, Noor N, Gallagher MP, Alonso GT. Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: preliminary findings from a multicenter surveillance study in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):e83-e85. doi:10.2337/dc20-1088

5. Zimmerman C, Albanese-O’Neill A, Haller MJ. Advances in type 1 diabetes technology over the last decade. Eur Endocrinol. 2019;15(2):70-76. doi:10.17925/ee.2019.15.2.70

6. Wake DJ, Gibb FW, Kar P, et al. Endocrinology in the time of COVID-19: remodelling diabetes services and emerging innovation. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020;183(2):G67-G77. doi:10.1530/eje-20-0377

7. Alonso GT, Corathers S, Shah A, et al. Establishment of the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative (T1DX-QI). Clin Diabetes. 2020;38(2):141-151. doi:10.2337/cd19-0032

8. Ginnard OZB, Alonso GT, Corathers SD, et al. Quality improvement in diabetes care: a review of initiatives and outcomes in the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative. Clin Diabetes. 2021;39(3):256-263. doi:10.2337/cd21-0029

9. ATTD 2021 invited speaker abstracts. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2021;23(S2):A1-A206. doi:10.1089/dia.2021.2525.abstracts

10. Rompicherla SN, Edelen N, Gallagher R, et al. Children and adolescent patients with pre-existing type 1 diabetes and additional comorbidities have an increased risk of hospitalization from COVID-19; data from the T1D Exchange COVID Registry. Pediatr Diabetes. 2021;22(S30):3-32. doi:10.1111/pedi.13268

11. Abstracts for the T1D Exchange QI Collaborative (T1DX-QI) Learning Session 2021. November 8-9, 2021. J Diabetes. 2021;13(S1):3-17. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.13227

12. The Official Journal of ATTD Advanced Technologies & Treatments for Diabetes conference 27-30 April 2022. Barcelona and online. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2022;24(S1):A1-A237. doi:10.1089/dia.2022.2525.abstracts

13. Ebekozien ON, Kamboj N, Odugbesan MK, et al. Inequities in glycemic outcomes for patients with type 1 diabetes: six-year (2016-2021) longitudinal follow-up by race and ethnicity of 36,390 patients in the T1DX-QI Collaborative. Diabetes. 2022;71(suppl 1). doi:10.2337/db22-167-OR

14. Narayan KA, Noor M, Rompicherla N, et al. No BMI increase during the COVID-pandemic in children and adults with T1D in three continents: joint analysis of ADDN, T1DX, and DPV registries. Diabetes. 2022;71(suppl 1). doi:10.2337/db22-269-OR

15. Lee JY, Lee SWH. Telemedicine cost-effectiveness for diabetes management: a systematic review. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2018;20(7):492-500. doi:10.1089/dia.2018.0098

16. McDonnell ME. Telemedicine in complex diabetes management. Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18(7):42. doi:10.1007/s11892-018-1015-3

17. Lee JM, Carlson E, Albanese-O’Neill A, et al. Adoption of telemedicine for type 1 diabetes care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2021;23(9):642-651. doi:10.1089/dia.2021.0080

18. Phillip M, Bergenstal RM, Close KL, et al. The digital/virtual diabetes clinic: the future is now–recommendations from an international panel on diabetes digital technologies introduction. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2021;23(2):146-154. doi:10.1089/dia.2020.0375

19. Garg SK, Rodriguez E. COVID‐19 pandemic and diabetes care. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2022;24(S1):S2-S20. doi:10.1089/dia.2022.2501

20. Beliard K, Ebekozien O, Demeterco-Berggren C, et al. Increased DKA at presentation among newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients with or without COVID-19: data from a multi-site surveillance registry. J Diabetes. 2021;13(3):270-272. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.13141

21. Ebekozien O, Agarwal S, Noor N, et al. Inequities in diabetic ketoacidosis among patients with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: data from 52 US clinical centers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;106(4):1755-1762. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa920

22. Alonso GT, Ebekozien O, Gallagher MP, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis drives COVID-19 related hospitalizations in children with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2021;13(8):681-687. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.13184

23. Noor N, Ebekozien O, Levin L, et al. Diabetes technology use for management of type 1 diabetes is associated with fewer adverse COVID-19 outcomes: findings from the T1D Exchange COVID-19 Surveillance Registry. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(8):e160-e162. doi:10.2337/dc21-0074

24. Demeterco-Berggren C, Ebekozien O, Rompicherla S, et al. Age and hospitalization risk in people with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: data from the T1D Exchange Surveillance Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;107(2):410-418. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab668

25. DeSalvo DJ, Noor N, Xie C, et al. Patient demographics and clinical outcomes among type 1 diabetes patients using continuous glucose monitors: data from T1D Exchange real-world observational study. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2021 Oct 9. [Epub ahead of print] doi:10.1177/19322968211049783

26. Gallagher MP, Rompicherla S, Ebekozien O, et al. Differences in COVID-19 outcomes among patients with type 1 diabetes: first vs later surges. J Clin Outcomes Manage. 2022;29(1):27-31. doi:10.12788/jcom.0084

27. Wolf RM, Noor N, Izquierdo R, et al. Increase in newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes in youth during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States: a multi-center analysis. Pediatr Diabetes. 2022;23(4):433-438. doi:10.1111/pedi.13328

28. Lavik AR, Ebekozien O, Noor N, et al. Trends in type 1 diabetic ketoacidosis during COVID-19 surges at 7 US centers: highest burden on non-Hispanic Black patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(7):1948-1955. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgac158

29. van der Linden J, Welsh JB, Hirsch IB, Garg SK. Real-time continuous glucose monitoring during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and its impact on time in range. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2021;23(S1):S1-S7. doi:10.1089/dia.2020.0649

30. Nwosu BU, Al-Halbouni L, Parajuli S, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and pediatric type 1 diabetes: no significant change in glycemic control during the pandemic lockdown of 2020. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:703905. doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.703905

31. Ellahham S. Artificial intelligence: the future for diabetes care. Am J Med. 2020;133(8):895-900. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.03.033

32. Nomura A, Noguchi M, Kometani M, et al. Artificial intelligence in current diabetes management and prediction. Curr Diab Rep. 2021;21(12):61. doi:10.1007/s11892-021-01423-2

33. Mungmode A, Noor N, Weinstock RS, et al. Making diabetes electronic medical record data actionable: promoting benchmarking and population health using the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Portal. Clin Diabetes. Forthcoming 2022.

34. Lavizzo-Mourey RJ, Besser RE, Williams DR. Understanding and mitigating health inequities—past, current, and future directions. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(18):1681-1684. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2008628

35. Majidi S, Ebekozien O, Noor N, et al. Inequities in health outcomes in children and adults with type 1 diabetes: data from the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative. Clin Diabetes. 2021;39(3):278-283. doi:10.2337/cd21-0028

36. Ebekozien O, Mungmode A, Odugbesan O, et al. Addressing type 1 diabetes health inequities in the United States: approaches from the T1D Exchange QI Collaborative. J Diabetes. 2022;14(1):79-82. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.13235

37. Odugbesan O, Addala A, Nelson G, et al. Implicit racial-ethnic and insurance-mediated bias to recommending diabetes technology: insights from T1D Exchange multicenter pediatric and adult diabetes provider cohort. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2022 Jun 13. [Epub ahead of print] doi:10.1089/dia.2022.0042

38. Schmitt J, Fogle K, Scott ML, Iyer P. Improving equitable access to continuous glucose monitors for Alabama’s children with type 1 diabetes: a quality improvement project. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2022;24(7):481-491. doi:10.1089/dia.2021.0511

39. Akturk HK, Agarwal S, Hoffecker L, Shah VN. Inequity in racial-ethnic representation in randomized controlled trials of diabetes technologies in type 1 diabetes: critical need for new standards. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(6):e121-e123. doi:10.2337/dc20-3063

40. Ebekozien O, Mungmode A, Buckingham D, et al. Achieving equity in diabetes research: borrowing from the field of quality improvement using a practical framework and improvement tools. Diabetes Spectr. 2022;35(3):304-312. doi:10.2237/dsi22-0002

41. Zhang J, Xu J, Lim J, et al. Wearable glucose monitoring and implantable drug delivery systems for diabetes management. Adv Healthc Mater. 2021;10(17):e2100194. doi:10.1002/adhm.202100194

42. FDA expands remote patient monitoring in hospitals for people with diabetes during COVID-19; manufacturers donate CGM supplies. News release. April 21, 2020. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://www.diabetes.org/newsroom/press-releases/2020/fda-remote-patient-monitoring-cgm

43. Campbell P. FDA grants Dexcom CGM breakthrough designation for in-hospital use. March 2, 2022. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://www.endocrinologynetwork.com/view/fda-grants-dexcom-cgm-breakthrough-designation-for-in-hospital-use

44. Yeh T, Yeung M, Mendelsohn Curanaj FA. Managing patients with insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors in the hospital: to wear or not to wear. Curr Diab Rep. 2021;21(2):7. doi:10.1007/s11892-021-01375-7

45. Medtronic announces FDA approval for MiniMed 770G insulin pump system. News release. September 21, 2020. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://bit.ly/3TyEna4

46. Tandem Diabetes Care announces commercial launch of the t:slim X2 insulin pump with Control-IQ technology in the United States. News release. January 15, 2020. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://investor.tandemdiabetes.com/news-releases/news-release-details/tandem-diabetes-care-announces-commercial-launch-tslim-x2-0

47. Garza M, Gutow H, Mahoney K. Omnipod 5 cleared by the FDA. Updated August 22, 2022. Accessed August 30, 2022.https://diatribe.org/omnipod-5-approved-fda

48. Boughton CK. Fully closed-loop insulin delivery—are we nearly there yet? Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3(11):e689-e690. doi:10.1016/s2589-7500(21)00218-1

49. Noor N, Kamboj MK, Triolo T, et al. Hybrid closed-loop systems and glycemic outcomes in children and adults with type 1 diabetes: real-world evidence from a U.S.-based multicenter collaborative. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(8):e118-e119. doi:10.2337/dc22-0329

50. Medtronic launches InPen with real-time Guardian Connect CGM data--the first integrated smart insulin pen for people with diabetes on MDI. News release. November 12, 2020. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://bit.ly/3CTSWPL

51. Bigfoot Biomedical receives FDA clearance for Bigfoot Unity Diabetes Management System, featuring first-of-its-kind smart pen caps for insulin pens used to treat type 1 and type 2 diabetes. News release. May 10, 2021. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://bit.ly/3BeyoAh

52. Vieira G. All about the CeQur Simplicity insulin patch. Updated May 24, 2022. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://beyondtype1.org/cequr-simplicity-insulin-patch/.

53. Messer LH, Tanenbaum ML, Cook PF, et al. Cost, hassle, and on-body experience: barriers to diabetes device use in adolescents and potential intervention targets. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2020;22(10):760-767. doi:10.1089/dia.2019.0509

54. Hilliard ME, Levy W, Anderson BJ, et al. Benefits and barriers of continuous glucose monitoring in young children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2019;21(9):493-498. doi:10.1089/dia.2019.0142

55. Dexcom G7 Release Delayed Until Late 2022. News release. August 8, 2022. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://diatribe.org/dexcom-g7-release-delayed-until-late-2022

56. Drucker DJ. Transforming type 1 diabetes: the next wave of innovation. Diabetologia. 2021;64(5):1059-1065. doi:10.1007/s00125-021-05396-5

57. Garg SK, Rodriguez E, Shah VN, Hirsch IB. New medications for the treatment of diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2022;24(S1):S190-S208. doi:10.1089/dia.2022.2513

58. Melton D. The promise of stem cell-derived islet replacement therapy. Diabetologia. 2021;64(5):1030-1036. doi:10.1007/s00125-020-05367-2

59. Danne T, Heinemann L, Bolinder J. New insulins, biosimilars, and insulin therapy. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2022;24(S1):S35-S57. doi:10.1089/dia.2022.2503

60. Kenney J. Insulin copay caps–a path to affordability. July 6, 2021. Accessed August 30, 2022.https://diatribechange.org/news/insulin-copay-caps-path-affordability

61. Glied SA, Zhu B. Not so sweet: insulin affordability over time. September 25, 2020. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/sep/not-so-sweet-insulin-affordability-over-time

62. American Diabetes Association. Insulin and drug affordability. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://www.diabetes.org/advocacy/insulin-and-drug-affordability

63. Sullivan P. Chances for drug pricing, surprise billing action fade until November. March 24, 2020. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/489334-chances-for-drug-pricing-surprise-billing-action-fade-until-november/

64. Brown TD. How Medicare’s new Senior Savings Model makes insulin more affordable. June 4, 2020. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://www.diabetes.org/blog/how-medicares-new-senior-savings-model-makes-insulin-more-affordable

65. American Diabetes Association. ADA applauds the U.S. House of Representatives passage of the Affordable Insulin Now Act. News release. April 1, 2022. https://www.diabetes.org/newsroom/official-statement/2022/ada-applauds-us-house-of-representatives-passage-of-the-affordable-insulin-now-act

66. JDRF. Driving T1D cures during challenging times. 2022.

67. Medtronic announces ongoing initiatives to address health equity for people of color living with diabetes. News release. April 7, 2021. Access August 30, 2022. https://bit.ly/3KGTOZU

From the T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Ann Mungmode, Nicole Rioles, Jesse Cases, Dr. Ebekozien); The Leona M. and Harry B. Hemsley Charitable Trust, New York, NY (Laurel Koester); and the University of Mississippi School of Population Health, Jackson, MS (Dr. Ebekozien).

Abstract

There have been remarkable innovations in diabetes management since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, but these groundbreaking innovations are drawing limited focus as the field focuses on the adverse impact of the pandemic on patients with diabetes. This article reviews select population health innovations in diabetes management that have become available over the past 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative, a learning health network that focuses on improving care and outcomes for individuals with type 1 diabetes (T1D). Such innovations include expanded telemedicine access, collection of real-world data, machine learning and artificial intelligence, and new diabetes medications and devices. In addition, multiple innovative studies have been undertaken to explore contributors to health inequities in diabetes, and advocacy efforts for specific populations have been successful. Looking to the future, work is required to explore additional health equity successes that do not further exacerbate inequities and to look for additional innovative ways to engage people with T1D in their health care through conversations on social determinants of health and societal structures.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes, learning health network, continuous glucose monitoring, health equity

One in 10 people in the United States has diabetes.1 Diabetes is the nation’s second leading cause of death, costing the US health system more than $300 billion annually.2 The COVID-19 pandemic presented additional health burdens for people living with diabetes. For example, preexisting diabetes was identified as a risk factor for COVID-19–associated morbidity and mortality.3,4 Over the past 2 years, there have been remarkable innovations in diabetes management, including stem cell therapy and new medication options. Additionally, improved technology solutions have aided in diabetes management through continuous glucose monitors (CGM), smart insulin pens, advanced hybrid closed-loop systems, and continuous subcutaneous insulin injections.5,6 Unfortunately, these groundbreaking innovations are drawing limited focus, as the field is rightfully focused on the adverse impact of the pandemic on patients with diabetes.

Learning health networks like the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative (T1DX-QI) have implemented some of these innovative solutions to improve care for people with diabetes.7 T1DX-QI has more than 50 data-sharing endocrinology centers that care for over 75,000 people with diabetes across the United States (Figure 1). Centers participating in the T1DX-QI use quality improvement (QI) and implementation science methods to quickly translate research into evidence-based clinical practice. T1DX-QI leads diabetes population health and health system research and supports widespread transferability across health care organizations through regular collaborative calls, conferences, and case study documentation.8

In this review, we summarize impactful population health innovations in diabetes management that have become available over the past 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of T1DX-QI (see Figure 2 for relevant definitions). This review is limited in scope and is not meant to be an exhaustive list of innovations. The review also reflects significant changes from the perspective of academic diabetes centers, which may not apply to rural or primary care diabetes practices.

Methods

The first (A.M.), second (H.H.), and senior (O.E.) authors conducted a scoping review of published literature using terms related to diabetes, population health, and innovation on PubMed Central and Google Scholar for the period March 2020 to June 2022. To complement the review, A.M. and O.E. also reviewed abstracts from presentations at major international diabetes conferences, including the American Diabetes Association (ADA), the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD), the T1DX-QI Learning Session Conference, and the Advanced Technologies & Treatments for Diabetes (ATTD) 2020 to 2022 conferences.9-14 The authors also searched FDA.gov and ClinicalTrials.gov for relevant insights. A.M. and O.E. sorted the reviewed literature into major themes (Figure 3) from the population health improvement perspective of the T1DX-QI.

Population Health Innovations in Diabetes Management

Expansion of Telemedicine Access

Telemedicine is cost-effective for patients with diabetes,15 including those with complex cases.16 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine and virtual care were rare in diabetes management. However, the pandemic offered a new opportunity to expand the practice of telemedicine in diabetes management. A study from the T1DX-QI showed that telemedicine visits grew from comprising <1% of visits pre-pandemic (December 2019) to 95.2% during the pandemic (August 2020).17 Additional studies, like those conducted by Phillip et al,18 confirmed the noninferiority of telemedicine practice for patients with diabetes.Telemedicine was also found to be an effective strategy to educate patients on the use of diabetes technologies.19

Real-World Data and Disease Surveillance

As the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated outcomes for people with type 1 diabetes (T1D), a need arose to understand the immediate effects of the pandemic on people with T1D through real-world data and disease surveillance. In April 2020, the T1DX-QI initiated a multicenter surveillance study to collect data and analyze the impact of COVID-19 on people with T1D. The existing health collaborative served as a springboard for robust surveillance study, documenting numerous works on the effects of COVID-19.3,4,20-28 Other investigators also embraced the power of real-world surveillance and real-world data.29,30

Big Data, Machine Learning, and Artificial Intelligence

The past 2 years have seen a shift toward embracing the incredible opportunity to tap the large volume of data generated from routine care for practical insights.31 In particular, researchers have demonstrated the widespread application of machine learning and artificial intelligence to improve diabetes management.32 The T1DX-QI also harnessed the growing power of big data by expanding the functionality of innovative benchmarking software. The T1DX QI Portal uses electronic medical record data of diabetes patients for clinic-to-clinic benchmarking and data analysis, using business intelligence solutions.33

Health Equity

While inequities across various health outcomes have been well documented for years,34 the COVID-19 pandemic further exaggerated racial/ethnic health inequities in T1D.23,35 In response, several organizations have outlined specific strategies to address these health inequities. Emboldened by the pandemic, the T1DX-QI announced a multipronged approach to address health inequities among patients with T1D through the Health Equity Advancement Lab (HEAL).36 One of HEAL’s main components is using real-world data to champion population-level insights and demonstrate progress in QI efforts.

Multiple innovative studies have been undertaken to explore contributors to health inequities in diabetes, and these studies are expanding our understanding of the chasm.37 There have also been innovative solutions to addressing these inequities, with multiple studies published over the past 2 years.38 A source of inequity among patients with T1D is the lack of representation of racial/ethnic minorities with T1D in clinical trials.39 The T1DX-QI suggests that the equity-adapted framework for QI can be applied by research leaders to support trial diversity and representation, ensuring future device innovations are meaningful for all people with T1D.40

Diabetes Devices

Glucose monitoring and insulin therapy are vital tools to support individuals living with T1D, and devices such as CGM and insulin pumps have become the standard of care for diabetes management (Table).41 Innovations in diabetes technology and device access are imperative for a chronic disease with no cure.

The COVID-19 pandemic created an opportunity to increase access to diabetes devices in inpatient settings. In 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration expanded the use of CGM to support remote monitoring of patients in inpatient hospital settings, simultaneously supporting the glucose monitoring needs of patients with T1D and reducing COVID-19 transmission through reduced patient-clinician contact.42 This effort has been expanded and will continue in 2022 and beyond,43 and aligns with the growing consensus that supports patients wearing both CGMs and insulin pumps in ambulatory settings to improve patient health outcomes.44

Since 2020, innovations in diabetes technology have improved and increased the variety of options available to people with T1D and made them easier to use (Table). New, advanced hybrid closed-loop systems have progressed to offer Bluetooth features, including automatic software upgrades, tubeless systems, and the ability to allow parents to use their smartphones to bolus for children.45-47 The next big step in insulin delivery innovation is the release of functioning, fully closed loop systems, of which several are currently in clinical trials.48 These systems support reduced hypoglycemia and improved time in range.49

Additional innovations in insulin delivery have improved the user experience and expanded therapeutic options, including a variety of smart insulin pens complete with dosing logs50,51 and even a patch to deliver insulin without the burden of injections.52 As barriers to diabetes technology persist,53 innovations in alternate insulin delivery provide people with T1D more options to align with their personal access and technology preferences.

Innovations in CGM address cited barriers to their use, including size or overall wear.53-55 CGMs released in the past few years are smaller in physical size, have longer durations of time between changings, are more accurate, and do not require calibrations for accuracy.

New Diabetes Medications

Many new medications and therapeutic advances have become available in the past 2 years.56 Additionally, more medications are being tested as adjunct therapies to support glycemic management in patients with T1D, including metformin, sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 and 2 inhibitors, pramlintide, glucagon-like polypeptide-1 analogs, and glucagon receptor agonists.57 Other recent advances include stem cell replacement therapy for patients with T1D.58 The ultra-long-acting biosimilar insulins are one medical innovation that has been stalled, rather than propelled, during the COVID-19 pandemic.59

Diabetes Policy Advocacy

People with T1D require insulin to survive. The cost of insulin has increased in recent years, with some studies citing a 64% to 100% increase in the past decade.60,61 In fact, 1 in 4 insulin users report that cost has impacted their insulin use, including rationing their insulin.62 Lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic stressed US families financially, increasing the urgency for insulin cost caps.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic halted national conversations on drug financing,63 advocacy efforts have succeeded for specific populations. The new Medicare Part D Senior Savings Model will cap the cost of insulin at $35 for a 30-day supply,64 and 20 states passed legislation capping insulin pricing.62 Efforts to codify national cost caps are under debate, including the passage of the Affordable Insulin Now Act, which passed the House in March 2022 and is currently under review in the Senate.65

Perspective: The Role of Private Philanthropy in Supporting Population Health Innovations

Funders and industry partners play a crucial role in leading and supporting innovations that improve the lives of people with T1D and reduce society’s costs of living with the disease. Data infrastructure is critical to supporting population health. While building the data infrastructure to support population health is both time- and resource-intensive, private foundations such as Helmsley are uniquely positioned—and have a responsibility—to take large, informed risks to help reach all communities with T1D.

The T1DX-QI is the largest source of population health data on T1D in the United States and is becoming the premiere data authority on its incidence, prevalence, and outcomes. The T1DX-QI enables a robust understanding of T1D-related health trends at the population level, as well as trends among clinics and providers. Pilot centers in the T1DX-QI have reported reductions in patients’ A1c and acute diabetes-related events, as well as improvements in device usage and depression screening. The ability to capture changes speaks to the promise and power of these data to demonstrate the clinical impact of QI interventions and to support the spread of best practices and learnings across health systems.

Additional philanthropic efforts have supported innovation in the last 2 years. For example, the JDRF, a nonprofit philanthropic equity firm, has supported efforts in developing artificial pancreas systems and cell therapies currently in clinical trials like teplizumab, a drug that has demonstrated delayed onset of T1D through JDRF’s T1D Fund.66 Industry partners also have an opportunity for significant influence in this area, as they continue to fund meaningful projects to advance care for people with T1D.67

Conclusion

We are optimistic that the innovations summarized here describe a shift in the tide of equitable T1D outcomes; however, future work is required to explore additional health equity successes that do not further exacerbate inequities. We also see further opportunities for innovative ways to engage people with T1D in their health care through conversations on social determinants of health and societal structures.

Corresponding author: Ann Mungmode, MPH, T1D Exchange, 11 Avenue de Lafayette, Boston, MA 02111; Email: [email protected]

Disclosures: Dr. Ebekozien serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for the Medtronic Advisory Board and received research grants from Medtronic Diabetes, Eli Lilly, and Dexcom.

Funding: The T1DX-QI is funded by The Leona M. and Harry B. Hemsley Charitable Trust.

From the T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Ann Mungmode, Nicole Rioles, Jesse Cases, Dr. Ebekozien); The Leona M. and Harry B. Hemsley Charitable Trust, New York, NY (Laurel Koester); and the University of Mississippi School of Population Health, Jackson, MS (Dr. Ebekozien).

Abstract

There have been remarkable innovations in diabetes management since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, but these groundbreaking innovations are drawing limited focus as the field focuses on the adverse impact of the pandemic on patients with diabetes. This article reviews select population health innovations in diabetes management that have become available over the past 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative, a learning health network that focuses on improving care and outcomes for individuals with type 1 diabetes (T1D). Such innovations include expanded telemedicine access, collection of real-world data, machine learning and artificial intelligence, and new diabetes medications and devices. In addition, multiple innovative studies have been undertaken to explore contributors to health inequities in diabetes, and advocacy efforts for specific populations have been successful. Looking to the future, work is required to explore additional health equity successes that do not further exacerbate inequities and to look for additional innovative ways to engage people with T1D in their health care through conversations on social determinants of health and societal structures.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes, learning health network, continuous glucose monitoring, health equity

One in 10 people in the United States has diabetes.1 Diabetes is the nation’s second leading cause of death, costing the US health system more than $300 billion annually.2 The COVID-19 pandemic presented additional health burdens for people living with diabetes. For example, preexisting diabetes was identified as a risk factor for COVID-19–associated morbidity and mortality.3,4 Over the past 2 years, there have been remarkable innovations in diabetes management, including stem cell therapy and new medication options. Additionally, improved technology solutions have aided in diabetes management through continuous glucose monitors (CGM), smart insulin pens, advanced hybrid closed-loop systems, and continuous subcutaneous insulin injections.5,6 Unfortunately, these groundbreaking innovations are drawing limited focus, as the field is rightfully focused on the adverse impact of the pandemic on patients with diabetes.

Learning health networks like the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative (T1DX-QI) have implemented some of these innovative solutions to improve care for people with diabetes.7 T1DX-QI has more than 50 data-sharing endocrinology centers that care for over 75,000 people with diabetes across the United States (Figure 1). Centers participating in the T1DX-QI use quality improvement (QI) and implementation science methods to quickly translate research into evidence-based clinical practice. T1DX-QI leads diabetes population health and health system research and supports widespread transferability across health care organizations through regular collaborative calls, conferences, and case study documentation.8

In this review, we summarize impactful population health innovations in diabetes management that have become available over the past 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of T1DX-QI (see Figure 2 for relevant definitions). This review is limited in scope and is not meant to be an exhaustive list of innovations. The review also reflects significant changes from the perspective of academic diabetes centers, which may not apply to rural or primary care diabetes practices.

Methods

The first (A.M.), second (H.H.), and senior (O.E.) authors conducted a scoping review of published literature using terms related to diabetes, population health, and innovation on PubMed Central and Google Scholar for the period March 2020 to June 2022. To complement the review, A.M. and O.E. also reviewed abstracts from presentations at major international diabetes conferences, including the American Diabetes Association (ADA), the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD), the T1DX-QI Learning Session Conference, and the Advanced Technologies & Treatments for Diabetes (ATTD) 2020 to 2022 conferences.9-14 The authors also searched FDA.gov and ClinicalTrials.gov for relevant insights. A.M. and O.E. sorted the reviewed literature into major themes (Figure 3) from the population health improvement perspective of the T1DX-QI.

Population Health Innovations in Diabetes Management

Expansion of Telemedicine Access

Telemedicine is cost-effective for patients with diabetes,15 including those with complex cases.16 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine and virtual care were rare in diabetes management. However, the pandemic offered a new opportunity to expand the practice of telemedicine in diabetes management. A study from the T1DX-QI showed that telemedicine visits grew from comprising <1% of visits pre-pandemic (December 2019) to 95.2% during the pandemic (August 2020).17 Additional studies, like those conducted by Phillip et al,18 confirmed the noninferiority of telemedicine practice for patients with diabetes.Telemedicine was also found to be an effective strategy to educate patients on the use of diabetes technologies.19

Real-World Data and Disease Surveillance

As the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated outcomes for people with type 1 diabetes (T1D), a need arose to understand the immediate effects of the pandemic on people with T1D through real-world data and disease surveillance. In April 2020, the T1DX-QI initiated a multicenter surveillance study to collect data and analyze the impact of COVID-19 on people with T1D. The existing health collaborative served as a springboard for robust surveillance study, documenting numerous works on the effects of COVID-19.3,4,20-28 Other investigators also embraced the power of real-world surveillance and real-world data.29,30

Big Data, Machine Learning, and Artificial Intelligence

The past 2 years have seen a shift toward embracing the incredible opportunity to tap the large volume of data generated from routine care for practical insights.31 In particular, researchers have demonstrated the widespread application of machine learning and artificial intelligence to improve diabetes management.32 The T1DX-QI also harnessed the growing power of big data by expanding the functionality of innovative benchmarking software. The T1DX QI Portal uses electronic medical record data of diabetes patients for clinic-to-clinic benchmarking and data analysis, using business intelligence solutions.33

Health Equity

While inequities across various health outcomes have been well documented for years,34 the COVID-19 pandemic further exaggerated racial/ethnic health inequities in T1D.23,35 In response, several organizations have outlined specific strategies to address these health inequities. Emboldened by the pandemic, the T1DX-QI announced a multipronged approach to address health inequities among patients with T1D through the Health Equity Advancement Lab (HEAL).36 One of HEAL’s main components is using real-world data to champion population-level insights and demonstrate progress in QI efforts.

Multiple innovative studies have been undertaken to explore contributors to health inequities in diabetes, and these studies are expanding our understanding of the chasm.37 There have also been innovative solutions to addressing these inequities, with multiple studies published over the past 2 years.38 A source of inequity among patients with T1D is the lack of representation of racial/ethnic minorities with T1D in clinical trials.39 The T1DX-QI suggests that the equity-adapted framework for QI can be applied by research leaders to support trial diversity and representation, ensuring future device innovations are meaningful for all people with T1D.40

Diabetes Devices

Glucose monitoring and insulin therapy are vital tools to support individuals living with T1D, and devices such as CGM and insulin pumps have become the standard of care for diabetes management (Table).41 Innovations in diabetes technology and device access are imperative for a chronic disease with no cure.

The COVID-19 pandemic created an opportunity to increase access to diabetes devices in inpatient settings. In 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration expanded the use of CGM to support remote monitoring of patients in inpatient hospital settings, simultaneously supporting the glucose monitoring needs of patients with T1D and reducing COVID-19 transmission through reduced patient-clinician contact.42 This effort has been expanded and will continue in 2022 and beyond,43 and aligns with the growing consensus that supports patients wearing both CGMs and insulin pumps in ambulatory settings to improve patient health outcomes.44

Since 2020, innovations in diabetes technology have improved and increased the variety of options available to people with T1D and made them easier to use (Table). New, advanced hybrid closed-loop systems have progressed to offer Bluetooth features, including automatic software upgrades, tubeless systems, and the ability to allow parents to use their smartphones to bolus for children.45-47 The next big step in insulin delivery innovation is the release of functioning, fully closed loop systems, of which several are currently in clinical trials.48 These systems support reduced hypoglycemia and improved time in range.49

Additional innovations in insulin delivery have improved the user experience and expanded therapeutic options, including a variety of smart insulin pens complete with dosing logs50,51 and even a patch to deliver insulin without the burden of injections.52 As barriers to diabetes technology persist,53 innovations in alternate insulin delivery provide people with T1D more options to align with their personal access and technology preferences.

Innovations in CGM address cited barriers to their use, including size or overall wear.53-55 CGMs released in the past few years are smaller in physical size, have longer durations of time between changings, are more accurate, and do not require calibrations for accuracy.

New Diabetes Medications

Many new medications and therapeutic advances have become available in the past 2 years.56 Additionally, more medications are being tested as adjunct therapies to support glycemic management in patients with T1D, including metformin, sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 and 2 inhibitors, pramlintide, glucagon-like polypeptide-1 analogs, and glucagon receptor agonists.57 Other recent advances include stem cell replacement therapy for patients with T1D.58 The ultra-long-acting biosimilar insulins are one medical innovation that has been stalled, rather than propelled, during the COVID-19 pandemic.59

Diabetes Policy Advocacy