User login

Could exercise improve bone health in youth with type 1 diabetes?

In a small cross-sectional study of 10- to 16-year-old girls with and without type 1 diabetes, both groups were equally physically active, based on their replies to the bone-specific physical activity questionnaire (BPAQ).

However, among the more sedentary girls (with BPAQ scores below the median), those with type 1 diabetes had worse markers of bone health in imaging tests compared with the girls without diabetes.

the researchers summarize in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research.

However, this is early research and further study is needed, the group cautions.

“Ongoing studies with objective measures of physical activity as well as interventional studies will clarify whether increasing physical activity may improve bone health and reduce fracture risk in this vulnerable group,” they conclude.

“If you look at the sedentary kids, there’s a big discrepancy between the kids who have diabetes and the control kids, and that’s if we’re looking at radius or tibia or trabecular bone density or estimated failure load,” senior author Deborah M. Mitchell, MD, said in an interview at the poster session.

However, “when we look at the kids who are more physically active, we’re really not seeing as much difference [in bone health] between the kids with and without diabetes,” said Dr. Mitchell, a pediatric endocrinologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

But she also acknowledged, “There’s all sorts of caveats, including that this is retrospective questionnaire data.”

However, if further, rigorous studies confirm these findings, “physical activity is potentially a really effective means of improving bone quality in kids with type 1 diabetes.”

“This study suggests that bone-loading physical activity can substantially improve skeletal health in children with [type 1 diabetes] and should provide hope for patients and their families that they can take some action to prevent or mitigate the effects of diabetes on bone,” coauthor and incoming ASBMR President Mary L. Bouxsein, PhD, told this news organization in an email.

“We interpret these data as an important reason to advocate for increased time in moderate to vigorous bone-loading activity,” said Dr. Bouxsein, professor, department of orthopedic surgery, Harvard Medical School, Boston, “though the ‘dose’ in terms of hours per day or episodes per week to promote optimal bone health is still to be determined.”

“Ongoing debate,” “need stronger proof”

Asked for comment, Laura K. Bachrach, MD, who was not involved with the research, noted: “Activity benefits the development of bone strength through effects on bone geometry more than ‘density,’ and conversely, lack of physical activity can compromise gains in cortical bone diameter and thickness.”

However, “there is ongoing debate about the impact of type 1 diabetes on bone health and the factor(s) determining risk,” Dr. Bachrach, a pediatric endocrinologist at Stanford Children’s Health, Palo Alto, Calif., told this news organization in an email.

The current findings suggest “that physical activity in adolescent girls provided protection against potential adverse effects of type 1 diabetes,” said Dr. Bachrach, who spoke about bone fragility in childhood in a video commentary in 2021.

Study strengths, she noted, “include the rigor and expertise of the investigators, use of multiple surrogate measures that capture bone geometry/microarchitecture, as well as the inclusion of healthy local controls.”

“The study is limited by the cross-sectional design and subjects who opted, or not, to be active,” she added. “Stronger proof of the protective effects of activity on bone health in type 1 diabetes would require a randomized longitudinal intervention study, as alluded to by the authors of the study.”

Hypothesis: Those with type 1 diabetes acquire less bone mass in early 20s

The excess fracture risk in children with type 1 diabetes has been previously reported and is 14%-35% higher than the fracture risk in children without diabetes, Dr. Bouxsein explained. And “between 30% to 50% of kids [with type 1 diabetes] will have a fracture before the age of 18, so the excess fracture risk in diabetes is not clinically obvious,” she added.

However, “several lines of evidence strongly suggest that bone mass and microarchitecture at the time of peak bone mass (early 20s) is a major determinant of fracture risk throughout the lifespan,” she noted.

“Our hypothesis,” Dr. Bouxsein said, “is that the metabolic disruptions of diabetes, when they are present during the acquisition of peak bone mass, interfere with optimal bone development, and therefore may contribute to increased fracture risk later in life.”

Dr. Bachrach agreed that “peak bone strength is achieved by early adulthood, making childhood and adolescence important times to optimize bone health,” and that “peak bone strength is a predictor of lifetime risk of osteoporosis.”

“The diagnosis of pediatric osteoporosis is made when a child or teen sustains a vertebral fracture or femur fracture with minimal or no trauma,” she explained. “The diagnosis can also be made in a pediatric patient with low BMD [bone mineral density] for age in combination with a history of several long-bone fractures.”

Dr. Mitchell noted that type 1 diabetes is associated with a higher risk of fractures, which is sixfold in adults. In another study, she said, the group showed that in 10- to 16-year-old girls who’ve only had diabetes for a few years, “trabecular bone density is lower, they have lower estimated failure load, and longitudinally when we follow them, at least at the radius, we’re seeing bone loss at a relatively young age when we wouldn’t be expecting to see bone loss.”

80 girls enrolled, half had type 1 diabetes

Researchers enrolled 36 girls with type 1 diabetes and 44 girls without type 1 diabetes (controls) who were a mean age of 14.7 years and most (92%) were White. The girls with and without diabetes had similar rates of previous fractures (44% and 51%).

Those with diabetes had been diagnosed at a mean age of 9 years and had had diabetes for a mean of 4.6 years.

Researchers calculated participants’ total BPAQ scores based on type, duration, and frequency of bone-loading activities.

Participants had dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans to determine areal bone mineral density (BMD) at the total hip, femoral neck, lumbar spine, and whole body less head.

They also had high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography at the distal tibia and radius to determine volumetric BMD, bone microarchitecture, and estimated bone strength (calculated using microfinite element analysis).

The two groups had similar total BPAQ scores (57.3 and 64.6), with a median score of 49.

BPAQ scores were positively associated with areal BMD at all sites (whole body, lumbar spine, total hip, femoral neck, and 1/3 radius) and with trabecular BMD and estimated failure load at the distal radius and tibia (P < .05 for all, adjusted for bone age).

Among participants with low physical activity (BPAQ below the median), compared with controls, those with type 1 diabetes had 6.6% lower aerial BMD at the lumbar spine (0.868 vs. 0.929 g/cm3; P = .04), 8% lower trabecular volumetric BMD at the distal radius (128.5 vs. 156.8 mg/cm3; P = .01), and 12% lower estimated failure load. Results at the distal tibia were similar.

Next steps

“More observational studies in males and females across a broader age spectrum would be helpful,” Dr. Bachrach noted. “The ‘gold standard’ model would be a long-term randomized controlled activity intervention study.”

“Further studies are underway [in girls and boys] using objective measures of activity including accelerometry and longitudinal observation to help confirm the findings from the current study,” Dr. Bouxsein said. “Ultimately, trials of activity interventions in children with [type 1 diabetes] will be the gold standard to determine to what extent physical activity can mitigate bone disease in [type 1 diabetes],” she agreed.

The study authors and Dr. Bachrach have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a small cross-sectional study of 10- to 16-year-old girls with and without type 1 diabetes, both groups were equally physically active, based on their replies to the bone-specific physical activity questionnaire (BPAQ).

However, among the more sedentary girls (with BPAQ scores below the median), those with type 1 diabetes had worse markers of bone health in imaging tests compared with the girls without diabetes.

the researchers summarize in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research.

However, this is early research and further study is needed, the group cautions.

“Ongoing studies with objective measures of physical activity as well as interventional studies will clarify whether increasing physical activity may improve bone health and reduce fracture risk in this vulnerable group,” they conclude.

“If you look at the sedentary kids, there’s a big discrepancy between the kids who have diabetes and the control kids, and that’s if we’re looking at radius or tibia or trabecular bone density or estimated failure load,” senior author Deborah M. Mitchell, MD, said in an interview at the poster session.

However, “when we look at the kids who are more physically active, we’re really not seeing as much difference [in bone health] between the kids with and without diabetes,” said Dr. Mitchell, a pediatric endocrinologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

But she also acknowledged, “There’s all sorts of caveats, including that this is retrospective questionnaire data.”

However, if further, rigorous studies confirm these findings, “physical activity is potentially a really effective means of improving bone quality in kids with type 1 diabetes.”

“This study suggests that bone-loading physical activity can substantially improve skeletal health in children with [type 1 diabetes] and should provide hope for patients and their families that they can take some action to prevent or mitigate the effects of diabetes on bone,” coauthor and incoming ASBMR President Mary L. Bouxsein, PhD, told this news organization in an email.

“We interpret these data as an important reason to advocate for increased time in moderate to vigorous bone-loading activity,” said Dr. Bouxsein, professor, department of orthopedic surgery, Harvard Medical School, Boston, “though the ‘dose’ in terms of hours per day or episodes per week to promote optimal bone health is still to be determined.”

“Ongoing debate,” “need stronger proof”

Asked for comment, Laura K. Bachrach, MD, who was not involved with the research, noted: “Activity benefits the development of bone strength through effects on bone geometry more than ‘density,’ and conversely, lack of physical activity can compromise gains in cortical bone diameter and thickness.”

However, “there is ongoing debate about the impact of type 1 diabetes on bone health and the factor(s) determining risk,” Dr. Bachrach, a pediatric endocrinologist at Stanford Children’s Health, Palo Alto, Calif., told this news organization in an email.

The current findings suggest “that physical activity in adolescent girls provided protection against potential adverse effects of type 1 diabetes,” said Dr. Bachrach, who spoke about bone fragility in childhood in a video commentary in 2021.

Study strengths, she noted, “include the rigor and expertise of the investigators, use of multiple surrogate measures that capture bone geometry/microarchitecture, as well as the inclusion of healthy local controls.”

“The study is limited by the cross-sectional design and subjects who opted, or not, to be active,” she added. “Stronger proof of the protective effects of activity on bone health in type 1 diabetes would require a randomized longitudinal intervention study, as alluded to by the authors of the study.”

Hypothesis: Those with type 1 diabetes acquire less bone mass in early 20s

The excess fracture risk in children with type 1 diabetes has been previously reported and is 14%-35% higher than the fracture risk in children without diabetes, Dr. Bouxsein explained. And “between 30% to 50% of kids [with type 1 diabetes] will have a fracture before the age of 18, so the excess fracture risk in diabetes is not clinically obvious,” she added.

However, “several lines of evidence strongly suggest that bone mass and microarchitecture at the time of peak bone mass (early 20s) is a major determinant of fracture risk throughout the lifespan,” she noted.

“Our hypothesis,” Dr. Bouxsein said, “is that the metabolic disruptions of diabetes, when they are present during the acquisition of peak bone mass, interfere with optimal bone development, and therefore may contribute to increased fracture risk later in life.”

Dr. Bachrach agreed that “peak bone strength is achieved by early adulthood, making childhood and adolescence important times to optimize bone health,” and that “peak bone strength is a predictor of lifetime risk of osteoporosis.”

“The diagnosis of pediatric osteoporosis is made when a child or teen sustains a vertebral fracture or femur fracture with minimal or no trauma,” she explained. “The diagnosis can also be made in a pediatric patient with low BMD [bone mineral density] for age in combination with a history of several long-bone fractures.”

Dr. Mitchell noted that type 1 diabetes is associated with a higher risk of fractures, which is sixfold in adults. In another study, she said, the group showed that in 10- to 16-year-old girls who’ve only had diabetes for a few years, “trabecular bone density is lower, they have lower estimated failure load, and longitudinally when we follow them, at least at the radius, we’re seeing bone loss at a relatively young age when we wouldn’t be expecting to see bone loss.”

80 girls enrolled, half had type 1 diabetes

Researchers enrolled 36 girls with type 1 diabetes and 44 girls without type 1 diabetes (controls) who were a mean age of 14.7 years and most (92%) were White. The girls with and without diabetes had similar rates of previous fractures (44% and 51%).

Those with diabetes had been diagnosed at a mean age of 9 years and had had diabetes for a mean of 4.6 years.

Researchers calculated participants’ total BPAQ scores based on type, duration, and frequency of bone-loading activities.

Participants had dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans to determine areal bone mineral density (BMD) at the total hip, femoral neck, lumbar spine, and whole body less head.

They also had high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography at the distal tibia and radius to determine volumetric BMD, bone microarchitecture, and estimated bone strength (calculated using microfinite element analysis).

The two groups had similar total BPAQ scores (57.3 and 64.6), with a median score of 49.

BPAQ scores were positively associated with areal BMD at all sites (whole body, lumbar spine, total hip, femoral neck, and 1/3 radius) and with trabecular BMD and estimated failure load at the distal radius and tibia (P < .05 for all, adjusted for bone age).

Among participants with low physical activity (BPAQ below the median), compared with controls, those with type 1 diabetes had 6.6% lower aerial BMD at the lumbar spine (0.868 vs. 0.929 g/cm3; P = .04), 8% lower trabecular volumetric BMD at the distal radius (128.5 vs. 156.8 mg/cm3; P = .01), and 12% lower estimated failure load. Results at the distal tibia were similar.

Next steps

“More observational studies in males and females across a broader age spectrum would be helpful,” Dr. Bachrach noted. “The ‘gold standard’ model would be a long-term randomized controlled activity intervention study.”

“Further studies are underway [in girls and boys] using objective measures of activity including accelerometry and longitudinal observation to help confirm the findings from the current study,” Dr. Bouxsein said. “Ultimately, trials of activity interventions in children with [type 1 diabetes] will be the gold standard to determine to what extent physical activity can mitigate bone disease in [type 1 diabetes],” she agreed.

The study authors and Dr. Bachrach have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a small cross-sectional study of 10- to 16-year-old girls with and without type 1 diabetes, both groups were equally physically active, based on their replies to the bone-specific physical activity questionnaire (BPAQ).

However, among the more sedentary girls (with BPAQ scores below the median), those with type 1 diabetes had worse markers of bone health in imaging tests compared with the girls without diabetes.

the researchers summarize in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research.

However, this is early research and further study is needed, the group cautions.

“Ongoing studies with objective measures of physical activity as well as interventional studies will clarify whether increasing physical activity may improve bone health and reduce fracture risk in this vulnerable group,” they conclude.

“If you look at the sedentary kids, there’s a big discrepancy between the kids who have diabetes and the control kids, and that’s if we’re looking at radius or tibia or trabecular bone density or estimated failure load,” senior author Deborah M. Mitchell, MD, said in an interview at the poster session.

However, “when we look at the kids who are more physically active, we’re really not seeing as much difference [in bone health] between the kids with and without diabetes,” said Dr. Mitchell, a pediatric endocrinologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

But she also acknowledged, “There’s all sorts of caveats, including that this is retrospective questionnaire data.”

However, if further, rigorous studies confirm these findings, “physical activity is potentially a really effective means of improving bone quality in kids with type 1 diabetes.”

“This study suggests that bone-loading physical activity can substantially improve skeletal health in children with [type 1 diabetes] and should provide hope for patients and their families that they can take some action to prevent or mitigate the effects of diabetes on bone,” coauthor and incoming ASBMR President Mary L. Bouxsein, PhD, told this news organization in an email.

“We interpret these data as an important reason to advocate for increased time in moderate to vigorous bone-loading activity,” said Dr. Bouxsein, professor, department of orthopedic surgery, Harvard Medical School, Boston, “though the ‘dose’ in terms of hours per day or episodes per week to promote optimal bone health is still to be determined.”

“Ongoing debate,” “need stronger proof”

Asked for comment, Laura K. Bachrach, MD, who was not involved with the research, noted: “Activity benefits the development of bone strength through effects on bone geometry more than ‘density,’ and conversely, lack of physical activity can compromise gains in cortical bone diameter and thickness.”

However, “there is ongoing debate about the impact of type 1 diabetes on bone health and the factor(s) determining risk,” Dr. Bachrach, a pediatric endocrinologist at Stanford Children’s Health, Palo Alto, Calif., told this news organization in an email.

The current findings suggest “that physical activity in adolescent girls provided protection against potential adverse effects of type 1 diabetes,” said Dr. Bachrach, who spoke about bone fragility in childhood in a video commentary in 2021.

Study strengths, she noted, “include the rigor and expertise of the investigators, use of multiple surrogate measures that capture bone geometry/microarchitecture, as well as the inclusion of healthy local controls.”

“The study is limited by the cross-sectional design and subjects who opted, or not, to be active,” she added. “Stronger proof of the protective effects of activity on bone health in type 1 diabetes would require a randomized longitudinal intervention study, as alluded to by the authors of the study.”

Hypothesis: Those with type 1 diabetes acquire less bone mass in early 20s

The excess fracture risk in children with type 1 diabetes has been previously reported and is 14%-35% higher than the fracture risk in children without diabetes, Dr. Bouxsein explained. And “between 30% to 50% of kids [with type 1 diabetes] will have a fracture before the age of 18, so the excess fracture risk in diabetes is not clinically obvious,” she added.

However, “several lines of evidence strongly suggest that bone mass and microarchitecture at the time of peak bone mass (early 20s) is a major determinant of fracture risk throughout the lifespan,” she noted.

“Our hypothesis,” Dr. Bouxsein said, “is that the metabolic disruptions of diabetes, when they are present during the acquisition of peak bone mass, interfere with optimal bone development, and therefore may contribute to increased fracture risk later in life.”

Dr. Bachrach agreed that “peak bone strength is achieved by early adulthood, making childhood and adolescence important times to optimize bone health,” and that “peak bone strength is a predictor of lifetime risk of osteoporosis.”

“The diagnosis of pediatric osteoporosis is made when a child or teen sustains a vertebral fracture or femur fracture with minimal or no trauma,” she explained. “The diagnosis can also be made in a pediatric patient with low BMD [bone mineral density] for age in combination with a history of several long-bone fractures.”

Dr. Mitchell noted that type 1 diabetes is associated with a higher risk of fractures, which is sixfold in adults. In another study, she said, the group showed that in 10- to 16-year-old girls who’ve only had diabetes for a few years, “trabecular bone density is lower, they have lower estimated failure load, and longitudinally when we follow them, at least at the radius, we’re seeing bone loss at a relatively young age when we wouldn’t be expecting to see bone loss.”

80 girls enrolled, half had type 1 diabetes

Researchers enrolled 36 girls with type 1 diabetes and 44 girls without type 1 diabetes (controls) who were a mean age of 14.7 years and most (92%) were White. The girls with and without diabetes had similar rates of previous fractures (44% and 51%).

Those with diabetes had been diagnosed at a mean age of 9 years and had had diabetes for a mean of 4.6 years.

Researchers calculated participants’ total BPAQ scores based on type, duration, and frequency of bone-loading activities.

Participants had dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans to determine areal bone mineral density (BMD) at the total hip, femoral neck, lumbar spine, and whole body less head.

They also had high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography at the distal tibia and radius to determine volumetric BMD, bone microarchitecture, and estimated bone strength (calculated using microfinite element analysis).

The two groups had similar total BPAQ scores (57.3 and 64.6), with a median score of 49.

BPAQ scores were positively associated with areal BMD at all sites (whole body, lumbar spine, total hip, femoral neck, and 1/3 radius) and with trabecular BMD and estimated failure load at the distal radius and tibia (P < .05 for all, adjusted for bone age).

Among participants with low physical activity (BPAQ below the median), compared with controls, those with type 1 diabetes had 6.6% lower aerial BMD at the lumbar spine (0.868 vs. 0.929 g/cm3; P = .04), 8% lower trabecular volumetric BMD at the distal radius (128.5 vs. 156.8 mg/cm3; P = .01), and 12% lower estimated failure load. Results at the distal tibia were similar.

Next steps

“More observational studies in males and females across a broader age spectrum would be helpful,” Dr. Bachrach noted. “The ‘gold standard’ model would be a long-term randomized controlled activity intervention study.”

“Further studies are underway [in girls and boys] using objective measures of activity including accelerometry and longitudinal observation to help confirm the findings from the current study,” Dr. Bouxsein said. “Ultimately, trials of activity interventions in children with [type 1 diabetes] will be the gold standard to determine to what extent physical activity can mitigate bone disease in [type 1 diabetes],” she agreed.

The study authors and Dr. Bachrach have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ASBMR 2022

Children born from frozen embryos may have increased cancer risk

, a large registry study suggests.

The results, however, “should be interpreted cautiously,” the authors noted, given the low number of cancer cases reported among children born using FET.

Still, the findings do “raise concerns considering the increasing use of FET, in particular freeze-all strategies without clear medical indications,” the authors concluded.

The study was published online in PLOS Medicine.

The number of children born after FET has increased globally and even exceeds the number of those born after fresh embryo transfer in many countries. In the United States, for instance, the FET rate has doubled since 2015; FETs constituted almost 80% of all embryo transfers using assisted reproductive technology (ART) without a donor in 2019.

Despite the benefits associated with FET, which include improved embryo survival and higher live birth rates, some previous research has hinted at a higher risk of childhood cancer in this population.

In the current study, researchers from the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, wanted to better understand the risk of childhood cancer following FET. The investigators analyzed data from 171,774 children born via ART, including 22,630 born after FET, as well as roughly 7.7 million children born after spontaneous conception in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden.

After a mean follow-up of about 10 years, the incidence rate of cancer diagnosed before age 18 years was 16.7 per 100,000 person-years for children born after spontaneous conception (16,184 cases) and 19.3 per 100,000 person-years for children born after ART (329 cases).

The researchers found no increased risk of cancer before age 18 years in the group of children conceived via ART compared with those conceived spontaneously.

However, children born after FET had a significantly higher risk of cancer compared with children born after fresh embryo transfer (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.59) and spontaneous conception (aHR, 1.65). Specifically with regard to ART, the incidence rate for those born after FET was 30.1 per 100,000 person-years – 48 total cases – compared with 18.8 per 1000,000 person-years after fresh embryo transfer.

Adjustment for macrosomia, birth weight, or major birth defects influenced the association only marginally.

For specific cancer types, children born after FET had more than a twofold higher risk for leukemia in comparison with those born after fresh embryo transfer (aHR, 2.25) and spontaneous conception (aHR, 2.22).

Still, the authors said these results should be interpreted “cautiously,” given the small number of children diagnosed with cancer after FET. The researchers also acknowledged that they do not know why children born after FET would face a higher risk of cancer.

These findings, however, do align with those from a 2019 Dutch population-based study. In the Dutch study, which included more than 24,000 ART-conceived children and more than 23,000 naturally conceived children, the risk of cancer after ART was not higher overall, but it was greater when only those conceived after FET were considered (aHR 1.80); this increased risk, however, was not statistically significant.

“Since the use of FET is substantially increasing, it is important to tease out whether the increased cancer risk is a true risk increase due to the ART procedures using FET, or due to chance or confounding by other factors,” authors of the 2019 Dutch study, Mandy Spaan, PhD, and Flora E. van Leeuwen, PhD, said in an interview.

“But, as childhood cancer is (fortunately) a rare disease, it is very difficult to study this research question among ART children due to limited numbers,” said Dr. Spaan and Dr. van Leeuwen, who are with the Netherlands Cancer Institute.

Given this, the two experts call for additional large population-based cohort studies to investigate the risk of cancer after ART, especially FET, and for a subsequent analysis that pools these data. They hope this strategy “will lead to reliable estimates” and provide information on the risks of FET in comparison with approaches that involve fresh embryos.

The current study had no commercial funding. The study authors as well as Dr. Spaan and Dr. van Leeuwen have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a large registry study suggests.

The results, however, “should be interpreted cautiously,” the authors noted, given the low number of cancer cases reported among children born using FET.

Still, the findings do “raise concerns considering the increasing use of FET, in particular freeze-all strategies without clear medical indications,” the authors concluded.

The study was published online in PLOS Medicine.

The number of children born after FET has increased globally and even exceeds the number of those born after fresh embryo transfer in many countries. In the United States, for instance, the FET rate has doubled since 2015; FETs constituted almost 80% of all embryo transfers using assisted reproductive technology (ART) without a donor in 2019.

Despite the benefits associated with FET, which include improved embryo survival and higher live birth rates, some previous research has hinted at a higher risk of childhood cancer in this population.

In the current study, researchers from the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, wanted to better understand the risk of childhood cancer following FET. The investigators analyzed data from 171,774 children born via ART, including 22,630 born after FET, as well as roughly 7.7 million children born after spontaneous conception in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden.

After a mean follow-up of about 10 years, the incidence rate of cancer diagnosed before age 18 years was 16.7 per 100,000 person-years for children born after spontaneous conception (16,184 cases) and 19.3 per 100,000 person-years for children born after ART (329 cases).

The researchers found no increased risk of cancer before age 18 years in the group of children conceived via ART compared with those conceived spontaneously.

However, children born after FET had a significantly higher risk of cancer compared with children born after fresh embryo transfer (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.59) and spontaneous conception (aHR, 1.65). Specifically with regard to ART, the incidence rate for those born after FET was 30.1 per 100,000 person-years – 48 total cases – compared with 18.8 per 1000,000 person-years after fresh embryo transfer.

Adjustment for macrosomia, birth weight, or major birth defects influenced the association only marginally.

For specific cancer types, children born after FET had more than a twofold higher risk for leukemia in comparison with those born after fresh embryo transfer (aHR, 2.25) and spontaneous conception (aHR, 2.22).

Still, the authors said these results should be interpreted “cautiously,” given the small number of children diagnosed with cancer after FET. The researchers also acknowledged that they do not know why children born after FET would face a higher risk of cancer.

These findings, however, do align with those from a 2019 Dutch population-based study. In the Dutch study, which included more than 24,000 ART-conceived children and more than 23,000 naturally conceived children, the risk of cancer after ART was not higher overall, but it was greater when only those conceived after FET were considered (aHR 1.80); this increased risk, however, was not statistically significant.

“Since the use of FET is substantially increasing, it is important to tease out whether the increased cancer risk is a true risk increase due to the ART procedures using FET, or due to chance or confounding by other factors,” authors of the 2019 Dutch study, Mandy Spaan, PhD, and Flora E. van Leeuwen, PhD, said in an interview.

“But, as childhood cancer is (fortunately) a rare disease, it is very difficult to study this research question among ART children due to limited numbers,” said Dr. Spaan and Dr. van Leeuwen, who are with the Netherlands Cancer Institute.

Given this, the two experts call for additional large population-based cohort studies to investigate the risk of cancer after ART, especially FET, and for a subsequent analysis that pools these data. They hope this strategy “will lead to reliable estimates” and provide information on the risks of FET in comparison with approaches that involve fresh embryos.

The current study had no commercial funding. The study authors as well as Dr. Spaan and Dr. van Leeuwen have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a large registry study suggests.

The results, however, “should be interpreted cautiously,” the authors noted, given the low number of cancer cases reported among children born using FET.

Still, the findings do “raise concerns considering the increasing use of FET, in particular freeze-all strategies without clear medical indications,” the authors concluded.

The study was published online in PLOS Medicine.

The number of children born after FET has increased globally and even exceeds the number of those born after fresh embryo transfer in many countries. In the United States, for instance, the FET rate has doubled since 2015; FETs constituted almost 80% of all embryo transfers using assisted reproductive technology (ART) without a donor in 2019.

Despite the benefits associated with FET, which include improved embryo survival and higher live birth rates, some previous research has hinted at a higher risk of childhood cancer in this population.

In the current study, researchers from the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, wanted to better understand the risk of childhood cancer following FET. The investigators analyzed data from 171,774 children born via ART, including 22,630 born after FET, as well as roughly 7.7 million children born after spontaneous conception in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden.

After a mean follow-up of about 10 years, the incidence rate of cancer diagnosed before age 18 years was 16.7 per 100,000 person-years for children born after spontaneous conception (16,184 cases) and 19.3 per 100,000 person-years for children born after ART (329 cases).

The researchers found no increased risk of cancer before age 18 years in the group of children conceived via ART compared with those conceived spontaneously.

However, children born after FET had a significantly higher risk of cancer compared with children born after fresh embryo transfer (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.59) and spontaneous conception (aHR, 1.65). Specifically with regard to ART, the incidence rate for those born after FET was 30.1 per 100,000 person-years – 48 total cases – compared with 18.8 per 1000,000 person-years after fresh embryo transfer.

Adjustment for macrosomia, birth weight, or major birth defects influenced the association only marginally.

For specific cancer types, children born after FET had more than a twofold higher risk for leukemia in comparison with those born after fresh embryo transfer (aHR, 2.25) and spontaneous conception (aHR, 2.22).

Still, the authors said these results should be interpreted “cautiously,” given the small number of children diagnosed with cancer after FET. The researchers also acknowledged that they do not know why children born after FET would face a higher risk of cancer.

These findings, however, do align with those from a 2019 Dutch population-based study. In the Dutch study, which included more than 24,000 ART-conceived children and more than 23,000 naturally conceived children, the risk of cancer after ART was not higher overall, but it was greater when only those conceived after FET were considered (aHR 1.80); this increased risk, however, was not statistically significant.

“Since the use of FET is substantially increasing, it is important to tease out whether the increased cancer risk is a true risk increase due to the ART procedures using FET, or due to chance or confounding by other factors,” authors of the 2019 Dutch study, Mandy Spaan, PhD, and Flora E. van Leeuwen, PhD, said in an interview.

“But, as childhood cancer is (fortunately) a rare disease, it is very difficult to study this research question among ART children due to limited numbers,” said Dr. Spaan and Dr. van Leeuwen, who are with the Netherlands Cancer Institute.

Given this, the two experts call for additional large population-based cohort studies to investigate the risk of cancer after ART, especially FET, and for a subsequent analysis that pools these data. They hope this strategy “will lead to reliable estimates” and provide information on the risks of FET in comparison with approaches that involve fresh embryos.

The current study had no commercial funding. The study authors as well as Dr. Spaan and Dr. van Leeuwen have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

Children with sickle cell anemia not getting treatments, screening

Fewer than half of children aged 2-16 years with sickle cell anemia are receiving recommended annual screening for stroke, a common complication of the disease, according to a new Vital Signs report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Many of these children also are not receiving the recommended medication, hydroxyurea, which can reduce pain and acute chest syndrome and improve anemia and quality of life, according to the report released Sept. 20.

Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is the most severe form of sickle cell disease (SCD), which is a red blood cell disorder that primarily affects Black and African American people in the United States. It is associated with severe complications such as stroke, vison damage, frequent infections, and delayed growth, and a reduction in lifespan of more than 20 years.

SCD affects approximately 100,000 Americans and SCA accounts for about 75% of those cases.

Physician remembers her patients’ pain

In a briefing to reporters in advance of the report’s release, Debra Houry, MD, MPH, the CDC’s acting principal deputy director, recalled “long, tough nights with these young sickle cell warriors” in her career as an emergency department physician.

“[S]eeing children and teens suffering from the severe pain that often accompanies sickle cell anemia was heartbreaking,” she said.

She asked health care providers to confront racism as they build better systems for ensuring optimal treatment for children and adolescents with SCA.

“Health care providers can educate themselves, their colleagues, and their institutions about the specialized needs of people with sickle cell anemia, including how racism inhibits optimal care,” Dr. Houry said.

She said people with SCA report difficulty accessing care and when they do, they often report feeling stigmatized.

Lead author of the report, Laura Schieve, PhD, an epidemiologist with CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, and colleagues looked at data from more than 3,300 children with SCA who were continuously enrolled in Medicaid during 2019. The data came from the IBM MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database.

Key recommendations issued in 2014

In 2014, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) issued two key recommendations to prevent or reduce complications in children and adolescents with SCA.

One was annual screening of children and adolescents aged 2-16 years with transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound to identify those at risk for stroke. The second was offering hydroxyurea therapy, which keeps red blood cells from sickling and blocking small blood vessels, to children and adolescents who were at least 9 months old to reduce pain and the risk for several life-threatening complications.

The researchers, however, found that in 2019, only 47% and 38% of children and adolescents aged 2-9 and 10-16 years, respectively, had TCD screening and 38% and 53% of children and adolescents aged 2-9 years and 10-16 years, respectively, used hydroxyurea.

“These complications are preventable – not inevitable. We must do more to help lessen the pain and complications associated with this disease by increasing the number of children who are screened for stroke and using the medication that can help reduce painful episodes,” said Karen Remley, MD, MPH, director of CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, said in a press release.

Bridging the gap

Providers, parents, health systems, and governmental agencies all have roles in bringing evidence-based recommended care to young SCA patients, Dr. Houry noted.

Community organizations can also help connect families with resources and tools to increase understanding.

Dr. Schieve pointed to access barriers in that families may have trouble traveling to specialized centers where the TCD screening is given. In addition, appointments for the screening may be limited.

Children taking hydroxyurea must be monitored for the proper dosage of medication, she explained, and that can be logistically challenging as well.

Providers report they often don’t get timely information back from TCD screening programs to keep up with which children need their annual screening.

Overall, the nation lacks providers with expertise in SCD and that can lead to symptoms being dismissed, Dr. Schieve said.

Hematologists and others have a role in advocating for patients with governmental entities to raise awareness of this issue, she added.

It’s also important that electronic health records give prompts and provide information so that all providers who care for a child can track screening and medication for the condition, Dr. Schieve and Dr. Houry said.

New funding for sickle cell data collection

Recent funding to the CDC Sickle Cell Data Collection Program may help more people get appropriate care, Dr. Houry said.

The program is currently active in 11 states and collects data from people all over the United States with SCD to study trends and treatment access for those with the disease.

The data help drive decisions such as where new sickle cell clinics are needed.

“We will expand to more states serving more people affected by this disease,” Dr. Houry said.

The authors declared no relevant financial relationships.

Fewer than half of children aged 2-16 years with sickle cell anemia are receiving recommended annual screening for stroke, a common complication of the disease, according to a new Vital Signs report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Many of these children also are not receiving the recommended medication, hydroxyurea, which can reduce pain and acute chest syndrome and improve anemia and quality of life, according to the report released Sept. 20.

Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is the most severe form of sickle cell disease (SCD), which is a red blood cell disorder that primarily affects Black and African American people in the United States. It is associated with severe complications such as stroke, vison damage, frequent infections, and delayed growth, and a reduction in lifespan of more than 20 years.

SCD affects approximately 100,000 Americans and SCA accounts for about 75% of those cases.

Physician remembers her patients’ pain

In a briefing to reporters in advance of the report’s release, Debra Houry, MD, MPH, the CDC’s acting principal deputy director, recalled “long, tough nights with these young sickle cell warriors” in her career as an emergency department physician.

“[S]eeing children and teens suffering from the severe pain that often accompanies sickle cell anemia was heartbreaking,” she said.

She asked health care providers to confront racism as they build better systems for ensuring optimal treatment for children and adolescents with SCA.

“Health care providers can educate themselves, their colleagues, and their institutions about the specialized needs of people with sickle cell anemia, including how racism inhibits optimal care,” Dr. Houry said.

She said people with SCA report difficulty accessing care and when they do, they often report feeling stigmatized.

Lead author of the report, Laura Schieve, PhD, an epidemiologist with CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, and colleagues looked at data from more than 3,300 children with SCA who were continuously enrolled in Medicaid during 2019. The data came from the IBM MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database.

Key recommendations issued in 2014

In 2014, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) issued two key recommendations to prevent or reduce complications in children and adolescents with SCA.

One was annual screening of children and adolescents aged 2-16 years with transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound to identify those at risk for stroke. The second was offering hydroxyurea therapy, which keeps red blood cells from sickling and blocking small blood vessels, to children and adolescents who were at least 9 months old to reduce pain and the risk for several life-threatening complications.

The researchers, however, found that in 2019, only 47% and 38% of children and adolescents aged 2-9 and 10-16 years, respectively, had TCD screening and 38% and 53% of children and adolescents aged 2-9 years and 10-16 years, respectively, used hydroxyurea.

“These complications are preventable – not inevitable. We must do more to help lessen the pain and complications associated with this disease by increasing the number of children who are screened for stroke and using the medication that can help reduce painful episodes,” said Karen Remley, MD, MPH, director of CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, said in a press release.

Bridging the gap

Providers, parents, health systems, and governmental agencies all have roles in bringing evidence-based recommended care to young SCA patients, Dr. Houry noted.

Community organizations can also help connect families with resources and tools to increase understanding.

Dr. Schieve pointed to access barriers in that families may have trouble traveling to specialized centers where the TCD screening is given. In addition, appointments for the screening may be limited.

Children taking hydroxyurea must be monitored for the proper dosage of medication, she explained, and that can be logistically challenging as well.

Providers report they often don’t get timely information back from TCD screening programs to keep up with which children need their annual screening.

Overall, the nation lacks providers with expertise in SCD and that can lead to symptoms being dismissed, Dr. Schieve said.

Hematologists and others have a role in advocating for patients with governmental entities to raise awareness of this issue, she added.

It’s also important that electronic health records give prompts and provide information so that all providers who care for a child can track screening and medication for the condition, Dr. Schieve and Dr. Houry said.

New funding for sickle cell data collection

Recent funding to the CDC Sickle Cell Data Collection Program may help more people get appropriate care, Dr. Houry said.

The program is currently active in 11 states and collects data from people all over the United States with SCD to study trends and treatment access for those with the disease.

The data help drive decisions such as where new sickle cell clinics are needed.

“We will expand to more states serving more people affected by this disease,” Dr. Houry said.

The authors declared no relevant financial relationships.

Fewer than half of children aged 2-16 years with sickle cell anemia are receiving recommended annual screening for stroke, a common complication of the disease, according to a new Vital Signs report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Many of these children also are not receiving the recommended medication, hydroxyurea, which can reduce pain and acute chest syndrome and improve anemia and quality of life, according to the report released Sept. 20.

Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is the most severe form of sickle cell disease (SCD), which is a red blood cell disorder that primarily affects Black and African American people in the United States. It is associated with severe complications such as stroke, vison damage, frequent infections, and delayed growth, and a reduction in lifespan of more than 20 years.

SCD affects approximately 100,000 Americans and SCA accounts for about 75% of those cases.

Physician remembers her patients’ pain

In a briefing to reporters in advance of the report’s release, Debra Houry, MD, MPH, the CDC’s acting principal deputy director, recalled “long, tough nights with these young sickle cell warriors” in her career as an emergency department physician.

“[S]eeing children and teens suffering from the severe pain that often accompanies sickle cell anemia was heartbreaking,” she said.

She asked health care providers to confront racism as they build better systems for ensuring optimal treatment for children and adolescents with SCA.

“Health care providers can educate themselves, their colleagues, and their institutions about the specialized needs of people with sickle cell anemia, including how racism inhibits optimal care,” Dr. Houry said.

She said people with SCA report difficulty accessing care and when they do, they often report feeling stigmatized.

Lead author of the report, Laura Schieve, PhD, an epidemiologist with CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, and colleagues looked at data from more than 3,300 children with SCA who were continuously enrolled in Medicaid during 2019. The data came from the IBM MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database.

Key recommendations issued in 2014

In 2014, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) issued two key recommendations to prevent or reduce complications in children and adolescents with SCA.

One was annual screening of children and adolescents aged 2-16 years with transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound to identify those at risk for stroke. The second was offering hydroxyurea therapy, which keeps red blood cells from sickling and blocking small blood vessels, to children and adolescents who were at least 9 months old to reduce pain and the risk for several life-threatening complications.

The researchers, however, found that in 2019, only 47% and 38% of children and adolescents aged 2-9 and 10-16 years, respectively, had TCD screening and 38% and 53% of children and adolescents aged 2-9 years and 10-16 years, respectively, used hydroxyurea.

“These complications are preventable – not inevitable. We must do more to help lessen the pain and complications associated with this disease by increasing the number of children who are screened for stroke and using the medication that can help reduce painful episodes,” said Karen Remley, MD, MPH, director of CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, said in a press release.

Bridging the gap

Providers, parents, health systems, and governmental agencies all have roles in bringing evidence-based recommended care to young SCA patients, Dr. Houry noted.

Community organizations can also help connect families with resources and tools to increase understanding.

Dr. Schieve pointed to access barriers in that families may have trouble traveling to specialized centers where the TCD screening is given. In addition, appointments for the screening may be limited.

Children taking hydroxyurea must be monitored for the proper dosage of medication, she explained, and that can be logistically challenging as well.

Providers report they often don’t get timely information back from TCD screening programs to keep up with which children need their annual screening.

Overall, the nation lacks providers with expertise in SCD and that can lead to symptoms being dismissed, Dr. Schieve said.

Hematologists and others have a role in advocating for patients with governmental entities to raise awareness of this issue, she added.

It’s also important that electronic health records give prompts and provide information so that all providers who care for a child can track screening and medication for the condition, Dr. Schieve and Dr. Houry said.

New funding for sickle cell data collection

Recent funding to the CDC Sickle Cell Data Collection Program may help more people get appropriate care, Dr. Houry said.

The program is currently active in 11 states and collects data from people all over the United States with SCD to study trends and treatment access for those with the disease.

The data help drive decisions such as where new sickle cell clinics are needed.

“We will expand to more states serving more people affected by this disease,” Dr. Houry said.

The authors declared no relevant financial relationships.

FROM THE MMWR

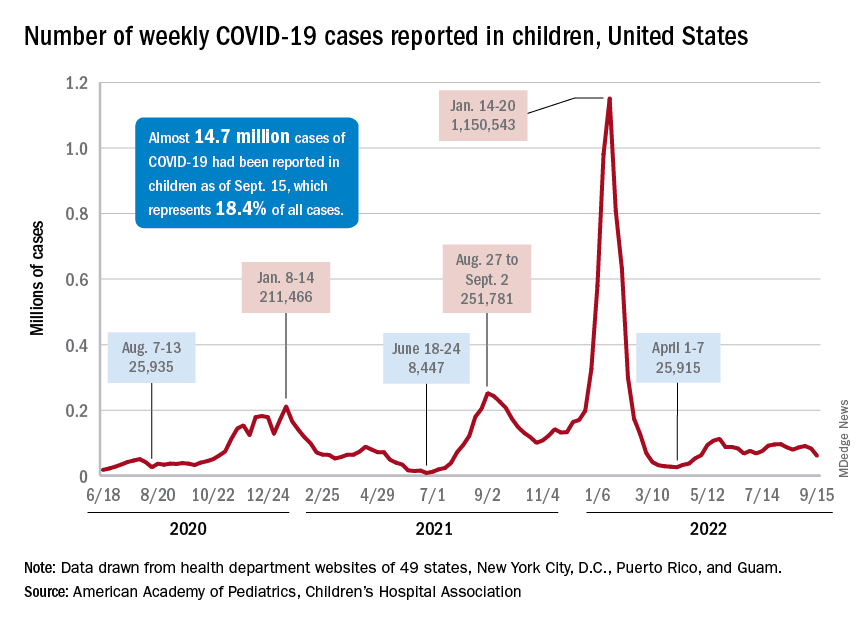

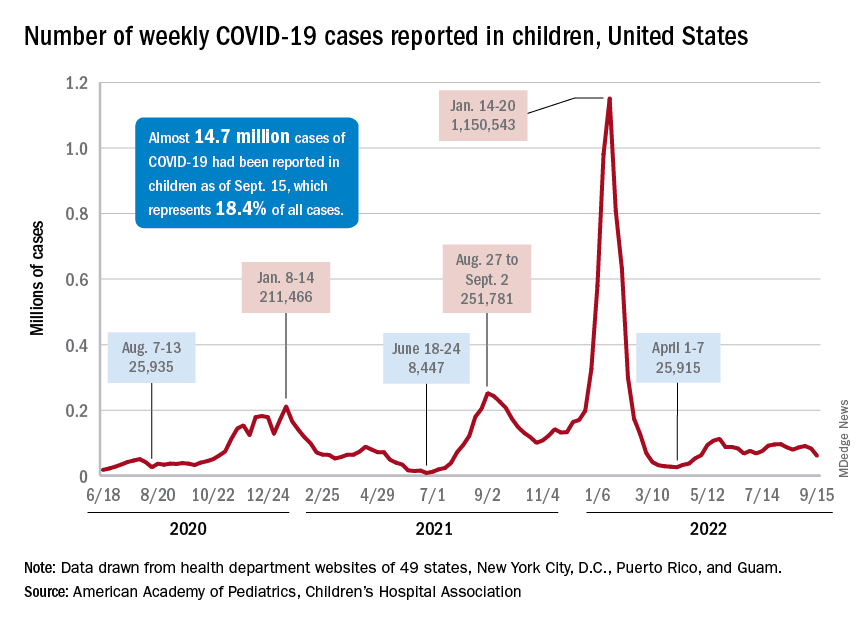

Children and COVID: Weekly cases drop to lowest level since April

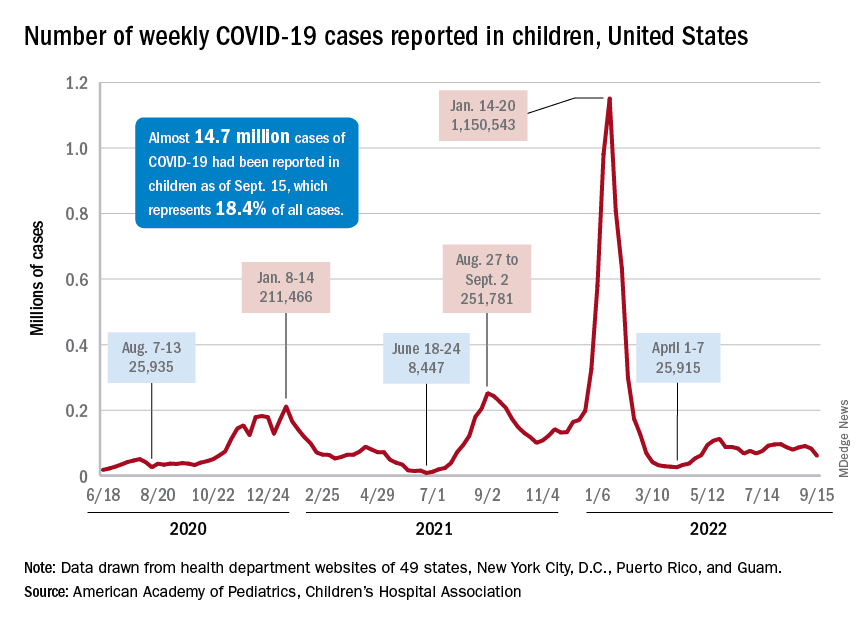

A hefty decline in new COVID-19 cases among children resulted in the lowest weekly total since late April, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, making for 2 consecutive weeks of declines after almost 91,000 cases were recorded for the week ending Sept. 1, the AAP and CHA said in their latest COVID report of state-level data.

The last time the weekly count was under 60,000 came during the week of April 22-28, when 53,000 were reported by state and territorial health departments in the midst of a 7-week stretch of rising cases. Since that streak ended in mid-May, however, “reported weekly cases have plateaued, fluctuating between a low, now of 60,300 cases and a high of about 112,000,” the AAP noted.

Emergency department visits and hospital admissions, which showed less fluctuation over the summer and more steady rise and fall, have both dropped in recent weeks and are now approaching late May/early June rates, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

On Sept. 15, for example, ED visits for children under 12 years with diagnosed COVID were just 2.2% of all visits, lower than at any time since May 19 and down from a summer high of 6.8% in late July. Hospital admissions for children aged 0-17 years also rose steadily through June and July, reaching 0.46 per 100,000 population on July 30, but have since slipped to 0.29 per 100,000 as of Sept. 17, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

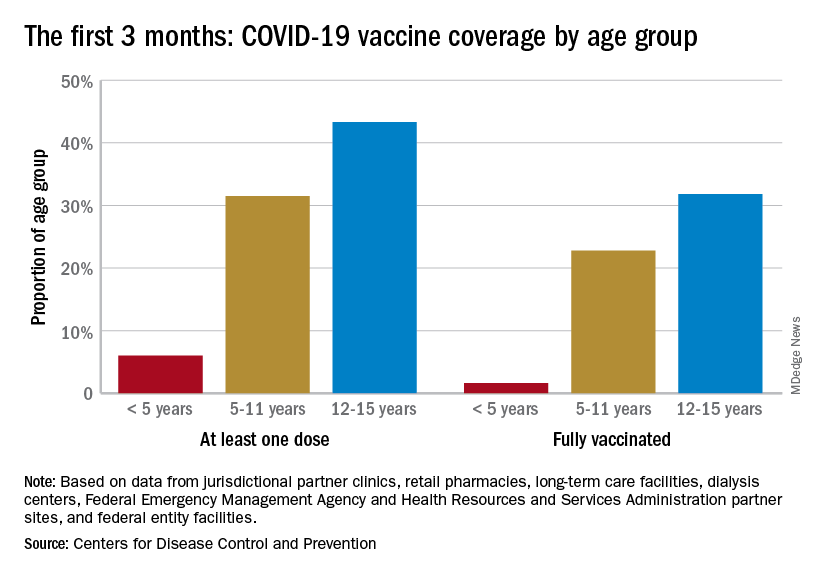

Vaccination continues to be a tough sell

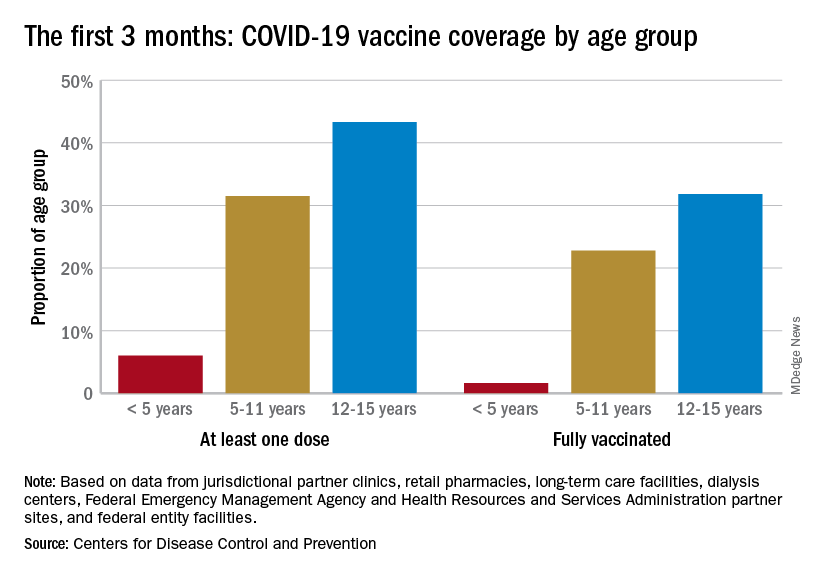

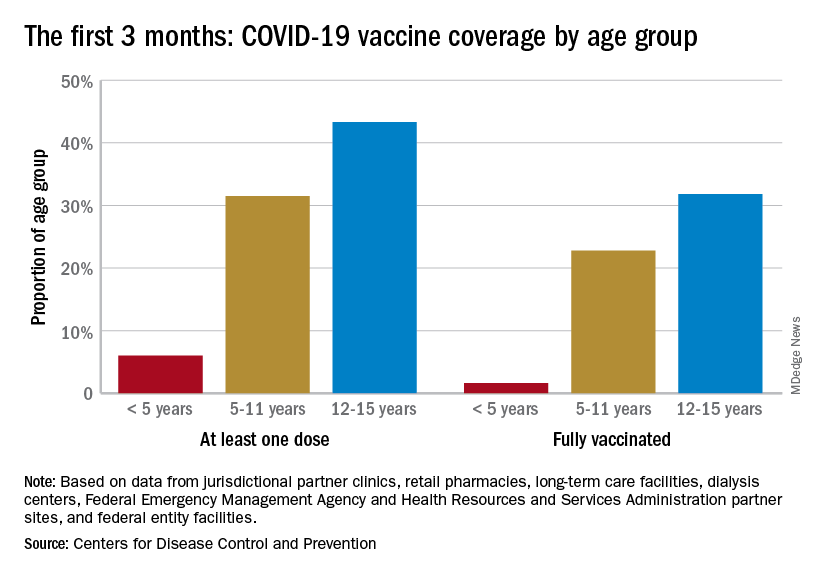

Vaccination activity among the most recently eligible age group, in the meantime, remains tepid. Just 6.0% of children under age 5 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of Sept. 13, about 3 months since its final approval in June, and 1.6% were fully vaccinated. For the two older groups of children with separate vaccine approvals, 31.5% of those aged 5-11 years and 43.3% of those aged 12-15 had received at least one dose 3 months after their vaccinations began, the CDC data show.

In the 2 weeks ending Sept. 14, almost 59,000 children under age 5 received their initial COVID-19 vaccine dose, as did 28,000 5- to 11-year-olds and 14,000 children aged 12-17. Children under age 5 years represented almost 20% of all Americans getting a first dose during Sept. 1-14, compared with 9.7% for those aged 5-11 and 4.8% for the 12- to 17-year-olds, the CDC said.

At the state level, children under age 5 years in the District of Columbia, where 28% have received at least one dose, and Vermont, at 24%, are the most likely to be vaccinated. The states with the lowest rates in this age group are Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi, all of which are at 2%. Vermont and D.C. have the highest rates for ages 5-11 at 70% each, and Alabama (17%) is the lowest, while D.C. (100%), Rhode Island (99%), and Massachusetts (99%) are highest for children aged 12-17 years and Wyoming (41%) is the lowest, the AAP said in a separate report.

A hefty decline in new COVID-19 cases among children resulted in the lowest weekly total since late April, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, making for 2 consecutive weeks of declines after almost 91,000 cases were recorded for the week ending Sept. 1, the AAP and CHA said in their latest COVID report of state-level data.

The last time the weekly count was under 60,000 came during the week of April 22-28, when 53,000 were reported by state and territorial health departments in the midst of a 7-week stretch of rising cases. Since that streak ended in mid-May, however, “reported weekly cases have plateaued, fluctuating between a low, now of 60,300 cases and a high of about 112,000,” the AAP noted.

Emergency department visits and hospital admissions, which showed less fluctuation over the summer and more steady rise and fall, have both dropped in recent weeks and are now approaching late May/early June rates, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

On Sept. 15, for example, ED visits for children under 12 years with diagnosed COVID were just 2.2% of all visits, lower than at any time since May 19 and down from a summer high of 6.8% in late July. Hospital admissions for children aged 0-17 years also rose steadily through June and July, reaching 0.46 per 100,000 population on July 30, but have since slipped to 0.29 per 100,000 as of Sept. 17, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Vaccination continues to be a tough sell

Vaccination activity among the most recently eligible age group, in the meantime, remains tepid. Just 6.0% of children under age 5 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of Sept. 13, about 3 months since its final approval in June, and 1.6% were fully vaccinated. For the two older groups of children with separate vaccine approvals, 31.5% of those aged 5-11 years and 43.3% of those aged 12-15 had received at least one dose 3 months after their vaccinations began, the CDC data show.

In the 2 weeks ending Sept. 14, almost 59,000 children under age 5 received their initial COVID-19 vaccine dose, as did 28,000 5- to 11-year-olds and 14,000 children aged 12-17. Children under age 5 years represented almost 20% of all Americans getting a first dose during Sept. 1-14, compared with 9.7% for those aged 5-11 and 4.8% for the 12- to 17-year-olds, the CDC said.

At the state level, children under age 5 years in the District of Columbia, where 28% have received at least one dose, and Vermont, at 24%, are the most likely to be vaccinated. The states with the lowest rates in this age group are Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi, all of which are at 2%. Vermont and D.C. have the highest rates for ages 5-11 at 70% each, and Alabama (17%) is the lowest, while D.C. (100%), Rhode Island (99%), and Massachusetts (99%) are highest for children aged 12-17 years and Wyoming (41%) is the lowest, the AAP said in a separate report.

A hefty decline in new COVID-19 cases among children resulted in the lowest weekly total since late April, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, making for 2 consecutive weeks of declines after almost 91,000 cases were recorded for the week ending Sept. 1, the AAP and CHA said in their latest COVID report of state-level data.

The last time the weekly count was under 60,000 came during the week of April 22-28, when 53,000 were reported by state and territorial health departments in the midst of a 7-week stretch of rising cases. Since that streak ended in mid-May, however, “reported weekly cases have plateaued, fluctuating between a low, now of 60,300 cases and a high of about 112,000,” the AAP noted.

Emergency department visits and hospital admissions, which showed less fluctuation over the summer and more steady rise and fall, have both dropped in recent weeks and are now approaching late May/early June rates, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

On Sept. 15, for example, ED visits for children under 12 years with diagnosed COVID were just 2.2% of all visits, lower than at any time since May 19 and down from a summer high of 6.8% in late July. Hospital admissions for children aged 0-17 years also rose steadily through June and July, reaching 0.46 per 100,000 population on July 30, but have since slipped to 0.29 per 100,000 as of Sept. 17, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Vaccination continues to be a tough sell

Vaccination activity among the most recently eligible age group, in the meantime, remains tepid. Just 6.0% of children under age 5 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of Sept. 13, about 3 months since its final approval in June, and 1.6% were fully vaccinated. For the two older groups of children with separate vaccine approvals, 31.5% of those aged 5-11 years and 43.3% of those aged 12-15 had received at least one dose 3 months after their vaccinations began, the CDC data show.

In the 2 weeks ending Sept. 14, almost 59,000 children under age 5 received their initial COVID-19 vaccine dose, as did 28,000 5- to 11-year-olds and 14,000 children aged 12-17. Children under age 5 years represented almost 20% of all Americans getting a first dose during Sept. 1-14, compared with 9.7% for those aged 5-11 and 4.8% for the 12- to 17-year-olds, the CDC said.

At the state level, children under age 5 years in the District of Columbia, where 28% have received at least one dose, and Vermont, at 24%, are the most likely to be vaccinated. The states with the lowest rates in this age group are Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi, all of which are at 2%. Vermont and D.C. have the highest rates for ages 5-11 at 70% each, and Alabama (17%) is the lowest, while D.C. (100%), Rhode Island (99%), and Massachusetts (99%) are highest for children aged 12-17 years and Wyoming (41%) is the lowest, the AAP said in a separate report.

Experts debate infant chiropractic care on TikTok

Several chiropractors in the United States are posting TikTok videos of themselves working with newborns, babies, and toddlers, often promoting treatments that aren’t backed by science, according to The Washington Post.

The videos include various devices and treatments, such as vibrating handheld massagers, spinal adjustments, and body movements, which are meant to address colic, constipation, reflux, musculoskeletal problems, and even trauma that babies experience during childbirth.

Chiropractors say the treatments are safe and gentle for babies and are unlike the more strenuous movements associated with adult chiropractic care. However, some doctors have said the videos are concerning because babies have softer bones and looser joints.

“Ultimately, there is no way you’re going to get an improvement in a newborn from a manipulation,” Sean Tabaie, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, told the newspaper.

Dr. Tabaie said his colleagues are shocked when he sends them Instagram or TikTok videos of chiropractic clinics treating infants.

“The only thing that you might possibly cause is harm,” he said.

Generally, chiropractors are licensed health professionals who use stretching, pressure, and joint manipulation on the spine to treat patients. Although chiropractic care is typically seen as an “alternative therapy,” some data in adults suggest that chiropractic treatments can help some conditions, such as low back pain.

“To my knowledge, there is little to no evidence that chiropractic care changes the natural history of any disease or condition,” Anthony Stans, MD, a pediatric orthopedic surgeon at Mayo Clinic Children’s Center, Rochester, Minn., told the newspaper. Stans said he would caution parents and recommend against chiropractic treatment for babies.

For some parents, the treatments and TikTok videos seem appealing because they promise relief for problems that traditional medicine can’t always address, especially colic, the newspaper reported. Colic, which features intense and prolonged crying in an otherwise healthy baby, tends to resolve over time without treatment.

Recent studies have attempted to study chiropractic care in infants. In a 2021 study, researchers in Denmark conducted a randomized controlled trial with 186 babies to test light pressure treatments. Although excessive crying was reduced by half an hour in the group that received treatment, the findings weren’t statistically significant in the end.

In a new study, researchers in Spain conducted a randomized trial with 58 babies to test “light touch manual therapy.” The babies who received treatment appeared to cry significantly less, but the parents weren’t “blinded” and were aware of the study’s treatment conditions, which can bias the results.

However, it can be challenging to “get that level of evidence” to support manual therapies such as chiropractic care, Joy Weydert, MD, director of pediatric integrative medicine at the University of Arizona, Tucson, told the newspaper. Certain treatments could help reduce the discomfort of colic or reflux, which can be difficult to measures in infants, she said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics told The Post that it doesn’t have an “official policy” on chiropractic care for infants or toddlers. At the same time, a 2017 report released by the organization concluded that “high-quality evidence” is lacking for spinal manipulation in children.

The American Chiropractic Association said chiropractic treatments are safe and effective for children, yet more research is needed to prove they work.

“We still haven’t been able to demonstrate in the research the effectiveness that we’ve seen clinically,” Jennifer Brocker, president of the group’s Council on Chiropractic Pediatrics, told the newspaper.

“We can’t really say for sure what’s happening,” she said. “It’s sort of like a black box. But what we do know is that, clinically, what we’re doing is effective because we see a change in the symptoms of the child.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Several chiropractors in the United States are posting TikTok videos of themselves working with newborns, babies, and toddlers, often promoting treatments that aren’t backed by science, according to The Washington Post.

The videos include various devices and treatments, such as vibrating handheld massagers, spinal adjustments, and body movements, which are meant to address colic, constipation, reflux, musculoskeletal problems, and even trauma that babies experience during childbirth.

Chiropractors say the treatments are safe and gentle for babies and are unlike the more strenuous movements associated with adult chiropractic care. However, some doctors have said the videos are concerning because babies have softer bones and looser joints.

“Ultimately, there is no way you’re going to get an improvement in a newborn from a manipulation,” Sean Tabaie, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, told the newspaper.

Dr. Tabaie said his colleagues are shocked when he sends them Instagram or TikTok videos of chiropractic clinics treating infants.

“The only thing that you might possibly cause is harm,” he said.

Generally, chiropractors are licensed health professionals who use stretching, pressure, and joint manipulation on the spine to treat patients. Although chiropractic care is typically seen as an “alternative therapy,” some data in adults suggest that chiropractic treatments can help some conditions, such as low back pain.

“To my knowledge, there is little to no evidence that chiropractic care changes the natural history of any disease or condition,” Anthony Stans, MD, a pediatric orthopedic surgeon at Mayo Clinic Children’s Center, Rochester, Minn., told the newspaper. Stans said he would caution parents and recommend against chiropractic treatment for babies.

For some parents, the treatments and TikTok videos seem appealing because they promise relief for problems that traditional medicine can’t always address, especially colic, the newspaper reported. Colic, which features intense and prolonged crying in an otherwise healthy baby, tends to resolve over time without treatment.

Recent studies have attempted to study chiropractic care in infants. In a 2021 study, researchers in Denmark conducted a randomized controlled trial with 186 babies to test light pressure treatments. Although excessive crying was reduced by half an hour in the group that received treatment, the findings weren’t statistically significant in the end.

In a new study, researchers in Spain conducted a randomized trial with 58 babies to test “light touch manual therapy.” The babies who received treatment appeared to cry significantly less, but the parents weren’t “blinded” and were aware of the study’s treatment conditions, which can bias the results.

However, it can be challenging to “get that level of evidence” to support manual therapies such as chiropractic care, Joy Weydert, MD, director of pediatric integrative medicine at the University of Arizona, Tucson, told the newspaper. Certain treatments could help reduce the discomfort of colic or reflux, which can be difficult to measures in infants, she said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics told The Post that it doesn’t have an “official policy” on chiropractic care for infants or toddlers. At the same time, a 2017 report released by the organization concluded that “high-quality evidence” is lacking for spinal manipulation in children.

The American Chiropractic Association said chiropractic treatments are safe and effective for children, yet more research is needed to prove they work.

“We still haven’t been able to demonstrate in the research the effectiveness that we’ve seen clinically,” Jennifer Brocker, president of the group’s Council on Chiropractic Pediatrics, told the newspaper.

“We can’t really say for sure what’s happening,” she said. “It’s sort of like a black box. But what we do know is that, clinically, what we’re doing is effective because we see a change in the symptoms of the child.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Several chiropractors in the United States are posting TikTok videos of themselves working with newborns, babies, and toddlers, often promoting treatments that aren’t backed by science, according to The Washington Post.

The videos include various devices and treatments, such as vibrating handheld massagers, spinal adjustments, and body movements, which are meant to address colic, constipation, reflux, musculoskeletal problems, and even trauma that babies experience during childbirth.

Chiropractors say the treatments are safe and gentle for babies and are unlike the more strenuous movements associated with adult chiropractic care. However, some doctors have said the videos are concerning because babies have softer bones and looser joints.

“Ultimately, there is no way you’re going to get an improvement in a newborn from a manipulation,” Sean Tabaie, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, told the newspaper.

Dr. Tabaie said his colleagues are shocked when he sends them Instagram or TikTok videos of chiropractic clinics treating infants.

“The only thing that you might possibly cause is harm,” he said.

Generally, chiropractors are licensed health professionals who use stretching, pressure, and joint manipulation on the spine to treat patients. Although chiropractic care is typically seen as an “alternative therapy,” some data in adults suggest that chiropractic treatments can help some conditions, such as low back pain.

“To my knowledge, there is little to no evidence that chiropractic care changes the natural history of any disease or condition,” Anthony Stans, MD, a pediatric orthopedic surgeon at Mayo Clinic Children’s Center, Rochester, Minn., told the newspaper. Stans said he would caution parents and recommend against chiropractic treatment for babies.

For some parents, the treatments and TikTok videos seem appealing because they promise relief for problems that traditional medicine can’t always address, especially colic, the newspaper reported. Colic, which features intense and prolonged crying in an otherwise healthy baby, tends to resolve over time without treatment.

Recent studies have attempted to study chiropractic care in infants. In a 2021 study, researchers in Denmark conducted a randomized controlled trial with 186 babies to test light pressure treatments. Although excessive crying was reduced by half an hour in the group that received treatment, the findings weren’t statistically significant in the end.

In a new study, researchers in Spain conducted a randomized trial with 58 babies to test “light touch manual therapy.” The babies who received treatment appeared to cry significantly less, but the parents weren’t “blinded” and were aware of the study’s treatment conditions, which can bias the results.

However, it can be challenging to “get that level of evidence” to support manual therapies such as chiropractic care, Joy Weydert, MD, director of pediatric integrative medicine at the University of Arizona, Tucson, told the newspaper. Certain treatments could help reduce the discomfort of colic or reflux, which can be difficult to measures in infants, she said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics told The Post that it doesn’t have an “official policy” on chiropractic care for infants or toddlers. At the same time, a 2017 report released by the organization concluded that “high-quality evidence” is lacking for spinal manipulation in children.

The American Chiropractic Association said chiropractic treatments are safe and effective for children, yet more research is needed to prove they work.

“We still haven’t been able to demonstrate in the research the effectiveness that we’ve seen clinically,” Jennifer Brocker, president of the group’s Council on Chiropractic Pediatrics, told the newspaper.

“We can’t really say for sure what’s happening,” she said. “It’s sort of like a black box. But what we do know is that, clinically, what we’re doing is effective because we see a change in the symptoms of the child.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Apremilast alleviates severe psoriasis in some children, data show

not controlled by topical therapy, according to the results of a phase 3 trial.

“Unfortunately, there are limited treatment options for pediatric patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis” who do not respond to or cannot use topical therapy, said study investigator Anna Belloni Fortina, MD, speaking at the annual meeting of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“In this randomized, placebo-controlled trial, oral apremilast demonstrated effectiveness and was well tolerated,” added Dr. Belloni Fortina, of Azienda Ospedale Università Padova (Italy). “I underline oral because for children, oral administration is better than the injection treatment.”

Key findings

Dubbed the SPROUT study, the trial set a primary endpoint of the percentage of children with a Physician’s Global Assessment (sPGA) response after 16 weeks of treatment or placebo. The sPGA is a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (clear) to 4 (severe). The study enrolled children with an sPGA greater than or equal to 3. Response was defined as a sPGA score of 0 or 1, indicating clear or almost clear skin, with at least a 2-point reduction from baseline values.

At week 16, the primary endpoint was met by 33% of 163 children treated with apremilast versus 11% of 82 children who had been given a placebo, a treatment difference of 21.7% (95% confidence interval, 11.2%-32.1%).

A greater proportion of children treated with apremilast also achieved a major secondary endpoint, a 75% or greater reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI-75) (45.4% vs. 16.1%), a treatment difference of 29.4% (95% CI, 17.8%-40.9%).

Results unaffected by weight and age

Regarding apremilast, “it’s important to underline that patients were dosed according to their weight,” Dr. Belloni Fortina said.

A dose of 20 mg twice daily was given to children who weighed between 20 kg and less than 50 kg, and a 30-mg twice-daily dose was given to those who weighed greater than or equal to 50 kg.

When the data were analyzed according to weight, proportionately more children on apremilast saw a sPGA response: 47.4% versus 21.8% in the lower weight and dose range and 19.2% versus 1.6% in the higher weight and dose range.

As for PASI-75, a greater proportion of children on apremilast also responded in both the lower and upper weight ranges, a respective 52.4% and 38.7% of patients, compared with 21.4% and 11% of those treated with placebo.

Data were also evaluated according to age, with a younger (aged 6-11 years) and older (age 12-17 years) group. The mean age of children was 12 years overall. Results showed a similar pattern for weight: The psoriasis of more children treated with apremilast was reduced by both measures, sPGA response, and PASI-75.

Safety of apremilast in children