User login

Children with low-risk thyroid cancer can skip radioactive iodine

MONTREAL – Pediatric patients with low-risk differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) who are spared radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy show no increases in the risk of remission, compared with those who do receive it, supporting guidelines that recommend against use of RAI in such patients.

“In 2015, when the American Thyroid Association [ATA] created their pediatric guidelines [on RAI therapy in DTC], they were taking a leap of faith that these [pediatric DTC] patients would be able to achieve remission without RAI,” said first author Mya Bojarsky, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), when presenting the findings at the American Thyroid Association annual meeting.

“This is the first study to validate those guidelines and support the sentiment that for ATA low-risk pediatric thyroid cancer patients, withholding RAI therapy is clinically beneficial as it reduces exposure to radiation while having no negative impact on remission,” she said.

Prior to 2015, thyroidectomy in combination with RAI was the standard treatment for DTC in pediatric patients. However, data showing that radiation exposure in children increases the risk of secondary hematologic malignancies by 51% and solid malignancies by 23% over a lifetime raised concerns and led to a push to change the treatment approach.

In response, the 2015 ATA pediatric guidelines recommended that patients not receive RAI for the treatment of DTC that was mostly confined to the thyroid (N0 or minimal N1a disease).

Senior author Andrew J. Bauer, MD, noted that, in addition to being the first study to confirm that withholding RAI in low-risk patients is associated with the same rate of achieving remission as patients treated with RAI, the study also endorses that assessments at 1 year can be reliable predictors of remission.

“For these patients, the 1-year mark post-initial treatment (thyroidectomy) is an early and accurate time point for initial assessment of remission, with increasing rates of remission with continued surveillance (at last clinical follow-up) of approximately 90% 2 years post initial treatment,” said Dr. Bauer, medical director, CHOP, and professor of pediatrics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“This approach has recently been validated through a prospective study in adult patients,” he added. A large recent study of 730 patients, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, supported the omission of RAI in low-risk DTC in adults, showing that, compared with those who received RAI, the no-RAI group was noninferior in the occurrence of functional, structural, and biologic events at 3 years.

Safe to eliminate RAI therapy in low-risk DTC in children

With limited data on how or if the change in treatment had an impact on rates of remission in pediatric patients, Ms. Bojarsky and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients under the age of 19 years with ATA low-risk DTC who had undergone a total thyroidectomy at CHOP between 2010 and 2020.

Overall, they identified 95 patients, including 50 who had been treated with RAI in addition to thyroidectomy and 45 who did not receive RAI. Among those who did receive RAI, 31 were treated prior to 2015, and 19 were treated after 2019.

For the study, remission was defined as having undetectable thyroglobulin levels as well as no evidence of disease by ultrasound, Ms. Bojarsky said.

“This is important to show, because we want to ensure that as we are reducing our RAI use in the pediatric population, we were not negatively impacting their ability to achieve remission,” she explained.

The percentage of low-risk pediatric patients with DTC treated with RAI had already dropped from 100% in 2010 down to 38% by 2015 when the guidelines were issued, and after a slight rise to 50% by 2018, the practice plummeted to 0% by 2020, the study shows.

In terms of remission, at 1 year post-treatment, 80% of patients who received RAI were in remission, and the rate was even slightly higher, at 84%, among those who did not receive RAI, for a difference that was not significant.

Further looking at disease status as of the last clinical evaluation, 90% in the group treated with RAI had no evidence of disease at a median of 4.9 years of follow-up, and the rate was 87% in the group not receiving RAI, which had a median of 2.7 years of follow-up.

“In ATA low-risk patients, there is no detriment in achieving remission if RAI therapy is withheld,” say investigators.

The median tumor size in the RAI group was larger (19.5 mm vs. 12.0 mm; P < .001), and the primary tumor was T1 in 44% of the RAI group but 82% in the no-RAI group (P < .001).

The lymph node status was N0 in 72% of those receiving RAI and 76% in the no RAI group, which was not significantly different.

The leading risk factors associated with treatment with RAI included larger primary tumor size (OR, 1.07; P = .003), lymph node metastasis (OR, 3.72; P = .036), and surgery pre-2015 (OR, 9.83; P < .001).

RAI administration, N1a disease, and surgery prior to 2015 were not independent risk factors for evidence of persistent disease or indeterminate status.

Ms. Bojarsky has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MONTREAL – Pediatric patients with low-risk differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) who are spared radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy show no increases in the risk of remission, compared with those who do receive it, supporting guidelines that recommend against use of RAI in such patients.

“In 2015, when the American Thyroid Association [ATA] created their pediatric guidelines [on RAI therapy in DTC], they were taking a leap of faith that these [pediatric DTC] patients would be able to achieve remission without RAI,” said first author Mya Bojarsky, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), when presenting the findings at the American Thyroid Association annual meeting.

“This is the first study to validate those guidelines and support the sentiment that for ATA low-risk pediatric thyroid cancer patients, withholding RAI therapy is clinically beneficial as it reduces exposure to radiation while having no negative impact on remission,” she said.

Prior to 2015, thyroidectomy in combination with RAI was the standard treatment for DTC in pediatric patients. However, data showing that radiation exposure in children increases the risk of secondary hematologic malignancies by 51% and solid malignancies by 23% over a lifetime raised concerns and led to a push to change the treatment approach.

In response, the 2015 ATA pediatric guidelines recommended that patients not receive RAI for the treatment of DTC that was mostly confined to the thyroid (N0 or minimal N1a disease).

Senior author Andrew J. Bauer, MD, noted that, in addition to being the first study to confirm that withholding RAI in low-risk patients is associated with the same rate of achieving remission as patients treated with RAI, the study also endorses that assessments at 1 year can be reliable predictors of remission.

“For these patients, the 1-year mark post-initial treatment (thyroidectomy) is an early and accurate time point for initial assessment of remission, with increasing rates of remission with continued surveillance (at last clinical follow-up) of approximately 90% 2 years post initial treatment,” said Dr. Bauer, medical director, CHOP, and professor of pediatrics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“This approach has recently been validated through a prospective study in adult patients,” he added. A large recent study of 730 patients, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, supported the omission of RAI in low-risk DTC in adults, showing that, compared with those who received RAI, the no-RAI group was noninferior in the occurrence of functional, structural, and biologic events at 3 years.

Safe to eliminate RAI therapy in low-risk DTC in children

With limited data on how or if the change in treatment had an impact on rates of remission in pediatric patients, Ms. Bojarsky and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients under the age of 19 years with ATA low-risk DTC who had undergone a total thyroidectomy at CHOP between 2010 and 2020.

Overall, they identified 95 patients, including 50 who had been treated with RAI in addition to thyroidectomy and 45 who did not receive RAI. Among those who did receive RAI, 31 were treated prior to 2015, and 19 were treated after 2019.

For the study, remission was defined as having undetectable thyroglobulin levels as well as no evidence of disease by ultrasound, Ms. Bojarsky said.

“This is important to show, because we want to ensure that as we are reducing our RAI use in the pediatric population, we were not negatively impacting their ability to achieve remission,” she explained.

The percentage of low-risk pediatric patients with DTC treated with RAI had already dropped from 100% in 2010 down to 38% by 2015 when the guidelines were issued, and after a slight rise to 50% by 2018, the practice plummeted to 0% by 2020, the study shows.

In terms of remission, at 1 year post-treatment, 80% of patients who received RAI were in remission, and the rate was even slightly higher, at 84%, among those who did not receive RAI, for a difference that was not significant.

Further looking at disease status as of the last clinical evaluation, 90% in the group treated with RAI had no evidence of disease at a median of 4.9 years of follow-up, and the rate was 87% in the group not receiving RAI, which had a median of 2.7 years of follow-up.

“In ATA low-risk patients, there is no detriment in achieving remission if RAI therapy is withheld,” say investigators.

The median tumor size in the RAI group was larger (19.5 mm vs. 12.0 mm; P < .001), and the primary tumor was T1 in 44% of the RAI group but 82% in the no-RAI group (P < .001).

The lymph node status was N0 in 72% of those receiving RAI and 76% in the no RAI group, which was not significantly different.

The leading risk factors associated with treatment with RAI included larger primary tumor size (OR, 1.07; P = .003), lymph node metastasis (OR, 3.72; P = .036), and surgery pre-2015 (OR, 9.83; P < .001).

RAI administration, N1a disease, and surgery prior to 2015 were not independent risk factors for evidence of persistent disease or indeterminate status.

Ms. Bojarsky has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MONTREAL – Pediatric patients with low-risk differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) who are spared radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy show no increases in the risk of remission, compared with those who do receive it, supporting guidelines that recommend against use of RAI in such patients.

“In 2015, when the American Thyroid Association [ATA] created their pediatric guidelines [on RAI therapy in DTC], they were taking a leap of faith that these [pediatric DTC] patients would be able to achieve remission without RAI,” said first author Mya Bojarsky, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), when presenting the findings at the American Thyroid Association annual meeting.

“This is the first study to validate those guidelines and support the sentiment that for ATA low-risk pediatric thyroid cancer patients, withholding RAI therapy is clinically beneficial as it reduces exposure to radiation while having no negative impact on remission,” she said.

Prior to 2015, thyroidectomy in combination with RAI was the standard treatment for DTC in pediatric patients. However, data showing that radiation exposure in children increases the risk of secondary hematologic malignancies by 51% and solid malignancies by 23% over a lifetime raised concerns and led to a push to change the treatment approach.

In response, the 2015 ATA pediatric guidelines recommended that patients not receive RAI for the treatment of DTC that was mostly confined to the thyroid (N0 or minimal N1a disease).

Senior author Andrew J. Bauer, MD, noted that, in addition to being the first study to confirm that withholding RAI in low-risk patients is associated with the same rate of achieving remission as patients treated with RAI, the study also endorses that assessments at 1 year can be reliable predictors of remission.

“For these patients, the 1-year mark post-initial treatment (thyroidectomy) is an early and accurate time point for initial assessment of remission, with increasing rates of remission with continued surveillance (at last clinical follow-up) of approximately 90% 2 years post initial treatment,” said Dr. Bauer, medical director, CHOP, and professor of pediatrics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“This approach has recently been validated through a prospective study in adult patients,” he added. A large recent study of 730 patients, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, supported the omission of RAI in low-risk DTC in adults, showing that, compared with those who received RAI, the no-RAI group was noninferior in the occurrence of functional, structural, and biologic events at 3 years.

Safe to eliminate RAI therapy in low-risk DTC in children

With limited data on how or if the change in treatment had an impact on rates of remission in pediatric patients, Ms. Bojarsky and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients under the age of 19 years with ATA low-risk DTC who had undergone a total thyroidectomy at CHOP between 2010 and 2020.

Overall, they identified 95 patients, including 50 who had been treated with RAI in addition to thyroidectomy and 45 who did not receive RAI. Among those who did receive RAI, 31 were treated prior to 2015, and 19 were treated after 2019.

For the study, remission was defined as having undetectable thyroglobulin levels as well as no evidence of disease by ultrasound, Ms. Bojarsky said.

“This is important to show, because we want to ensure that as we are reducing our RAI use in the pediatric population, we were not negatively impacting their ability to achieve remission,” she explained.

The percentage of low-risk pediatric patients with DTC treated with RAI had already dropped from 100% in 2010 down to 38% by 2015 when the guidelines were issued, and after a slight rise to 50% by 2018, the practice plummeted to 0% by 2020, the study shows.

In terms of remission, at 1 year post-treatment, 80% of patients who received RAI were in remission, and the rate was even slightly higher, at 84%, among those who did not receive RAI, for a difference that was not significant.

Further looking at disease status as of the last clinical evaluation, 90% in the group treated with RAI had no evidence of disease at a median of 4.9 years of follow-up, and the rate was 87% in the group not receiving RAI, which had a median of 2.7 years of follow-up.

“In ATA low-risk patients, there is no detriment in achieving remission if RAI therapy is withheld,” say investigators.

The median tumor size in the RAI group was larger (19.5 mm vs. 12.0 mm; P < .001), and the primary tumor was T1 in 44% of the RAI group but 82% in the no-RAI group (P < .001).

The lymph node status was N0 in 72% of those receiving RAI and 76% in the no RAI group, which was not significantly different.

The leading risk factors associated with treatment with RAI included larger primary tumor size (OR, 1.07; P = .003), lymph node metastasis (OR, 3.72; P = .036), and surgery pre-2015 (OR, 9.83; P < .001).

RAI administration, N1a disease, and surgery prior to 2015 were not independent risk factors for evidence of persistent disease or indeterminate status.

Ms. Bojarsky has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ATA 2022

In childhood sickle cell disease stroke prevention is key

CINCINNATI – Sickle cell disease is well known for its associated anemia, but patients experience a range of other complications as well. These include vision and kidney problems, delayed growth, susceptibility to infection, and pain.

Another issue, not always as well recognized, is a considerably heightened risk for childhood stroke. “, and there’s also an elevated risk of five times the general population in adults with sickle cell disease,” said Lori Jordan, MD, PhD, in an interview.

At the 2022 annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society, Dr. Jordan spoke about stroke as a complication of sickle cell disease, and the role that neurologists can play in preventing primary or secondary strokes. “At least in children, studies have shown that if we screen and identify patients who are at highest risk of stroke, there are primary prevention therapies – usually implemented by hematologists, but that neurologists often are involved with – both monitoring for cognitive effects of silent cerebral infarct and also with treating patients who unfortunately still have an acute stroke,” said Dr. Jordan, who is an associate professor of pediatrics, neurology, and radiology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. She also is director of the pediatric stroke program at Vanderbilt.

Time is of the essence

“In general, stroke in children is rare, but it’s more common in sickle cell disease, so it’s really important for providers to know that stroke risk is higher in those patients, particularly in those children, and then identify it and treat it earlier. Time is of the essence, and if we can give them the same therapeutics that we give the general stroke population, then time really becomes a factor, so it’s important that people know that it’s an issue for this population,” said Eboni Lance, MD, PhD, who coordinated the session where Dr. Jordan spoke.

Sickle cell disease is caused by a double mutation in the gene encoding the hemoglobin gene, producing the altered sickle hemoglobin (hemoglobin S). The change causes the hemoglobin proteins to tend to stick to one another, which can lead red blood cells to adopt a sickle-like shape. The sickle-shaped blood cells in turn have a tendency to aggregate and can block blood flow or lead to endothelial injury. Symptoms of stroke in children can include hemiparesis, aphasia, and seizure, but they can also be silent.

If no preventive is employed, one in nine with sickle cell disease will experience a stroke by the age of 19. Cerebrovascular symptoms are the most frequent debilitating complication of the condition. Nearly 40% of patients with sickle cell disease will have a silent cerebral infarct by age 18, as will 50% by age 30. Silent strokes have been associated with worse educational attainment and a greater need for educational special services.

Factors contributing to stroke in children with sickle cell disease include anemia and a low blood oxygen count, reduced oxygen affinity of hemoglobin variant, and cerebral vasculopathy. An estimated 10%-15% of young adults with sickle cell disease have severe intracranial stenosis.

Primary and secondary stroke prevention strategies

The dire consequences of stroke in this patient population underline the importance of primary stroke prevention, which requires the use of transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound. It has been validated as a tool to screen for initial stroke risk in children with no history of stroke. High velocity measured on TCD indicates a narrowed blood vessel or elevated blood that is compensating for anemia. It adds up to a “struggling brain,” said Dr. Jordan, during her talk. If the TCD ultrasound velocity is greater than 200 cm/sec (or 170 cm/sec, depending on nonimaging versus imaging TCD), the TWiTCH trial showed that seven monthly transfusions is the number needed to treat to prevent one stroke. After 1 year, patients can be switched from transfusions to hydroxyurea if the patient has no significant intracranial stenosis. Hydroxyurea boosts both fetal and total hemoglobin, and also counters inflammation.

Following an acute stroke or transient ischemic attack, patients should receive a transfusion within 2 hours of presenting in the health care setting. American Society of Hematology guidelines recommend exchange transfusion rather than a simple transfusion. A simple transfusion can be initiated if an exchange transfusion is not available within 2 hours and hemoglobin values are less than 8.5 g/dL, to be followed by performance of exchange transfusion when available.

For chronic secondary stroke prevention, transfusions should be performed approximately monthly with the goal of maintaining hemoglobin above 9 g/dL at all times, as well as suppressing hemoglobin S levels to 30% or less of total hemoglobin.

Sudden, severe headache is a potential harbinger of complications like aneurysm, which occurs 10-fold more often among patients with sickle cell disease than the general population. It could also indicate increased intracranial pressure or cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

Treatment of acute headache in sickle cell disease should avoid use of triptans, since vasoconstriction can counter the increased cerebral blood flow that compensates for anemia. Gabapentin and amitriptyline are good treatment choices.

New-onset seizures are a potential sign of stroke or posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy (PRES) in patients with sickle cell disease. Urgent MRI should be considered for all new-onset seizures. If blood pressure is high, PRES may be present. Seizures may also be an indicator of a previous brain injury.

Dr. Jordan has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Lance has served on an advisory board for Novartis.

CINCINNATI – Sickle cell disease is well known for its associated anemia, but patients experience a range of other complications as well. These include vision and kidney problems, delayed growth, susceptibility to infection, and pain.

Another issue, not always as well recognized, is a considerably heightened risk for childhood stroke. “, and there’s also an elevated risk of five times the general population in adults with sickle cell disease,” said Lori Jordan, MD, PhD, in an interview.

At the 2022 annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society, Dr. Jordan spoke about stroke as a complication of sickle cell disease, and the role that neurologists can play in preventing primary or secondary strokes. “At least in children, studies have shown that if we screen and identify patients who are at highest risk of stroke, there are primary prevention therapies – usually implemented by hematologists, but that neurologists often are involved with – both monitoring for cognitive effects of silent cerebral infarct and also with treating patients who unfortunately still have an acute stroke,” said Dr. Jordan, who is an associate professor of pediatrics, neurology, and radiology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. She also is director of the pediatric stroke program at Vanderbilt.

Time is of the essence

“In general, stroke in children is rare, but it’s more common in sickle cell disease, so it’s really important for providers to know that stroke risk is higher in those patients, particularly in those children, and then identify it and treat it earlier. Time is of the essence, and if we can give them the same therapeutics that we give the general stroke population, then time really becomes a factor, so it’s important that people know that it’s an issue for this population,” said Eboni Lance, MD, PhD, who coordinated the session where Dr. Jordan spoke.

Sickle cell disease is caused by a double mutation in the gene encoding the hemoglobin gene, producing the altered sickle hemoglobin (hemoglobin S). The change causes the hemoglobin proteins to tend to stick to one another, which can lead red blood cells to adopt a sickle-like shape. The sickle-shaped blood cells in turn have a tendency to aggregate and can block blood flow or lead to endothelial injury. Symptoms of stroke in children can include hemiparesis, aphasia, and seizure, but they can also be silent.

If no preventive is employed, one in nine with sickle cell disease will experience a stroke by the age of 19. Cerebrovascular symptoms are the most frequent debilitating complication of the condition. Nearly 40% of patients with sickle cell disease will have a silent cerebral infarct by age 18, as will 50% by age 30. Silent strokes have been associated with worse educational attainment and a greater need for educational special services.

Factors contributing to stroke in children with sickle cell disease include anemia and a low blood oxygen count, reduced oxygen affinity of hemoglobin variant, and cerebral vasculopathy. An estimated 10%-15% of young adults with sickle cell disease have severe intracranial stenosis.

Primary and secondary stroke prevention strategies

The dire consequences of stroke in this patient population underline the importance of primary stroke prevention, which requires the use of transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound. It has been validated as a tool to screen for initial stroke risk in children with no history of stroke. High velocity measured on TCD indicates a narrowed blood vessel or elevated blood that is compensating for anemia. It adds up to a “struggling brain,” said Dr. Jordan, during her talk. If the TCD ultrasound velocity is greater than 200 cm/sec (or 170 cm/sec, depending on nonimaging versus imaging TCD), the TWiTCH trial showed that seven monthly transfusions is the number needed to treat to prevent one stroke. After 1 year, patients can be switched from transfusions to hydroxyurea if the patient has no significant intracranial stenosis. Hydroxyurea boosts both fetal and total hemoglobin, and also counters inflammation.

Following an acute stroke or transient ischemic attack, patients should receive a transfusion within 2 hours of presenting in the health care setting. American Society of Hematology guidelines recommend exchange transfusion rather than a simple transfusion. A simple transfusion can be initiated if an exchange transfusion is not available within 2 hours and hemoglobin values are less than 8.5 g/dL, to be followed by performance of exchange transfusion when available.

For chronic secondary stroke prevention, transfusions should be performed approximately monthly with the goal of maintaining hemoglobin above 9 g/dL at all times, as well as suppressing hemoglobin S levels to 30% or less of total hemoglobin.

Sudden, severe headache is a potential harbinger of complications like aneurysm, which occurs 10-fold more often among patients with sickle cell disease than the general population. It could also indicate increased intracranial pressure or cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

Treatment of acute headache in sickle cell disease should avoid use of triptans, since vasoconstriction can counter the increased cerebral blood flow that compensates for anemia. Gabapentin and amitriptyline are good treatment choices.

New-onset seizures are a potential sign of stroke or posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy (PRES) in patients with sickle cell disease. Urgent MRI should be considered for all new-onset seizures. If blood pressure is high, PRES may be present. Seizures may also be an indicator of a previous brain injury.

Dr. Jordan has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Lance has served on an advisory board for Novartis.

CINCINNATI – Sickle cell disease is well known for its associated anemia, but patients experience a range of other complications as well. These include vision and kidney problems, delayed growth, susceptibility to infection, and pain.

Another issue, not always as well recognized, is a considerably heightened risk for childhood stroke. “, and there’s also an elevated risk of five times the general population in adults with sickle cell disease,” said Lori Jordan, MD, PhD, in an interview.

At the 2022 annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society, Dr. Jordan spoke about stroke as a complication of sickle cell disease, and the role that neurologists can play in preventing primary or secondary strokes. “At least in children, studies have shown that if we screen and identify patients who are at highest risk of stroke, there are primary prevention therapies – usually implemented by hematologists, but that neurologists often are involved with – both monitoring for cognitive effects of silent cerebral infarct and also with treating patients who unfortunately still have an acute stroke,” said Dr. Jordan, who is an associate professor of pediatrics, neurology, and radiology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. She also is director of the pediatric stroke program at Vanderbilt.

Time is of the essence

“In general, stroke in children is rare, but it’s more common in sickle cell disease, so it’s really important for providers to know that stroke risk is higher in those patients, particularly in those children, and then identify it and treat it earlier. Time is of the essence, and if we can give them the same therapeutics that we give the general stroke population, then time really becomes a factor, so it’s important that people know that it’s an issue for this population,” said Eboni Lance, MD, PhD, who coordinated the session where Dr. Jordan spoke.

Sickle cell disease is caused by a double mutation in the gene encoding the hemoglobin gene, producing the altered sickle hemoglobin (hemoglobin S). The change causes the hemoglobin proteins to tend to stick to one another, which can lead red blood cells to adopt a sickle-like shape. The sickle-shaped blood cells in turn have a tendency to aggregate and can block blood flow or lead to endothelial injury. Symptoms of stroke in children can include hemiparesis, aphasia, and seizure, but they can also be silent.

If no preventive is employed, one in nine with sickle cell disease will experience a stroke by the age of 19. Cerebrovascular symptoms are the most frequent debilitating complication of the condition. Nearly 40% of patients with sickle cell disease will have a silent cerebral infarct by age 18, as will 50% by age 30. Silent strokes have been associated with worse educational attainment and a greater need for educational special services.

Factors contributing to stroke in children with sickle cell disease include anemia and a low blood oxygen count, reduced oxygen affinity of hemoglobin variant, and cerebral vasculopathy. An estimated 10%-15% of young adults with sickle cell disease have severe intracranial stenosis.

Primary and secondary stroke prevention strategies

The dire consequences of stroke in this patient population underline the importance of primary stroke prevention, which requires the use of transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound. It has been validated as a tool to screen for initial stroke risk in children with no history of stroke. High velocity measured on TCD indicates a narrowed blood vessel or elevated blood that is compensating for anemia. It adds up to a “struggling brain,” said Dr. Jordan, during her talk. If the TCD ultrasound velocity is greater than 200 cm/sec (or 170 cm/sec, depending on nonimaging versus imaging TCD), the TWiTCH trial showed that seven monthly transfusions is the number needed to treat to prevent one stroke. After 1 year, patients can be switched from transfusions to hydroxyurea if the patient has no significant intracranial stenosis. Hydroxyurea boosts both fetal and total hemoglobin, and also counters inflammation.

Following an acute stroke or transient ischemic attack, patients should receive a transfusion within 2 hours of presenting in the health care setting. American Society of Hematology guidelines recommend exchange transfusion rather than a simple transfusion. A simple transfusion can be initiated if an exchange transfusion is not available within 2 hours and hemoglobin values are less than 8.5 g/dL, to be followed by performance of exchange transfusion when available.

For chronic secondary stroke prevention, transfusions should be performed approximately monthly with the goal of maintaining hemoglobin above 9 g/dL at all times, as well as suppressing hemoglobin S levels to 30% or less of total hemoglobin.

Sudden, severe headache is a potential harbinger of complications like aneurysm, which occurs 10-fold more often among patients with sickle cell disease than the general population. It could also indicate increased intracranial pressure or cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

Treatment of acute headache in sickle cell disease should avoid use of triptans, since vasoconstriction can counter the increased cerebral blood flow that compensates for anemia. Gabapentin and amitriptyline are good treatment choices.

New-onset seizures are a potential sign of stroke or posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy (PRES) in patients with sickle cell disease. Urgent MRI should be considered for all new-onset seizures. If blood pressure is high, PRES may be present. Seizures may also be an indicator of a previous brain injury.

Dr. Jordan has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Lance has served on an advisory board for Novartis.

FROM CNS 2022

Remote assessment of atopic dermatitis is feasible with patient-provided images: Study

MONTREAL – , as well as the possibility of conducting remote clinical trials that would be less expensive and less burdensome for participants, according to investigators, who presented the study at the annual meeting of the International Society of Atopic Dermatitis.

Still, practical barriers need to be addressed, particularly the problem of image quality, noted study investigator Aviël Ragamin, MD, from the department of dermatology, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

“Good-quality images are crucial, [and] in our study, patients didn’t have any incentive to provide images because they had already received their medical consultation,” he explained. He suggested that this problem could be overcome by providing technical support for patients and compensation for trial participants.

The study included 87 children (median age, 7 years), who were assessed for AD severity at an academic outpatient clinic. The in-person visit included assessment with the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score, as well as the collection of whole-body clinical images. Parents were then asked to return home and to provide their own clinical images and self-administered EASI assessments of their child for comparison. Four raters were asked to rate all images twice and to compare in-clinic and self-administered EASI scores based on the images.

At the in-clinic visit, the median EASI score of the group was 8.8. The majority of patients had moderate (46.6%) or severe (14.8%) AD. Roughly 40% of the patients had darker skin (Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI).

Using Spearman rank correlation of 1,534 in-clinic and 425 patient-provided images, the study found good inter- and intra-rater reliability for clinical image assessment and strong agreement between images and the in-clinic EASI scores. The top outliers in the assessment were individuals with either darker skin or significant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which are “the most difficult cases to rate, based on images,” Dr. Ragamin noted.

There was only moderate correlation between the in-clinic and self-administered EASI scores, with a significant number of patients either underestimating or overestimating their AD severity, he added.

Overall, the main problem with remote assessment seems to be the feasibility of patients providing images, said Dr. Ragamin. Only 36.8% of parents provided any images at all, and of these, 1 of 5 were deemed too blurry, leaving just 13 for final assessment, he explained.

“Pragmatically, it’s tricky,” said Aaron Drucker, MD, a dermatologist at Women’s College Hospital and associate professor at the University of Toronto, who was asked to comment on the study. “It takes long enough to do an EASI score in person, let alone looking through blurry pictures that take too long to load into your electronic medical record. We know it works, but when our hospital went virtual [during the COVID pandemic] ... most of my patients with chronic eczema weren’t even sending me pictures.”

Regarding the utility of remote, full-body photography in clinical practice, he said, “There’s too many feasibility hoops to jump through at this point. The most promise I see is for clinical trials, where it’s hard to get people to come in.”

Dr. Ragamin and Dr. Drucker have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MONTREAL – , as well as the possibility of conducting remote clinical trials that would be less expensive and less burdensome for participants, according to investigators, who presented the study at the annual meeting of the International Society of Atopic Dermatitis.

Still, practical barriers need to be addressed, particularly the problem of image quality, noted study investigator Aviël Ragamin, MD, from the department of dermatology, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

“Good-quality images are crucial, [and] in our study, patients didn’t have any incentive to provide images because they had already received their medical consultation,” he explained. He suggested that this problem could be overcome by providing technical support for patients and compensation for trial participants.

The study included 87 children (median age, 7 years), who were assessed for AD severity at an academic outpatient clinic. The in-person visit included assessment with the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score, as well as the collection of whole-body clinical images. Parents were then asked to return home and to provide their own clinical images and self-administered EASI assessments of their child for comparison. Four raters were asked to rate all images twice and to compare in-clinic and self-administered EASI scores based on the images.

At the in-clinic visit, the median EASI score of the group was 8.8. The majority of patients had moderate (46.6%) or severe (14.8%) AD. Roughly 40% of the patients had darker skin (Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI).

Using Spearman rank correlation of 1,534 in-clinic and 425 patient-provided images, the study found good inter- and intra-rater reliability for clinical image assessment and strong agreement between images and the in-clinic EASI scores. The top outliers in the assessment were individuals with either darker skin or significant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which are “the most difficult cases to rate, based on images,” Dr. Ragamin noted.

There was only moderate correlation between the in-clinic and self-administered EASI scores, with a significant number of patients either underestimating or overestimating their AD severity, he added.

Overall, the main problem with remote assessment seems to be the feasibility of patients providing images, said Dr. Ragamin. Only 36.8% of parents provided any images at all, and of these, 1 of 5 were deemed too blurry, leaving just 13 for final assessment, he explained.

“Pragmatically, it’s tricky,” said Aaron Drucker, MD, a dermatologist at Women’s College Hospital and associate professor at the University of Toronto, who was asked to comment on the study. “It takes long enough to do an EASI score in person, let alone looking through blurry pictures that take too long to load into your electronic medical record. We know it works, but when our hospital went virtual [during the COVID pandemic] ... most of my patients with chronic eczema weren’t even sending me pictures.”

Regarding the utility of remote, full-body photography in clinical practice, he said, “There’s too many feasibility hoops to jump through at this point. The most promise I see is for clinical trials, where it’s hard to get people to come in.”

Dr. Ragamin and Dr. Drucker have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MONTREAL – , as well as the possibility of conducting remote clinical trials that would be less expensive and less burdensome for participants, according to investigators, who presented the study at the annual meeting of the International Society of Atopic Dermatitis.

Still, practical barriers need to be addressed, particularly the problem of image quality, noted study investigator Aviël Ragamin, MD, from the department of dermatology, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

“Good-quality images are crucial, [and] in our study, patients didn’t have any incentive to provide images because they had already received their medical consultation,” he explained. He suggested that this problem could be overcome by providing technical support for patients and compensation for trial participants.

The study included 87 children (median age, 7 years), who were assessed for AD severity at an academic outpatient clinic. The in-person visit included assessment with the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score, as well as the collection of whole-body clinical images. Parents were then asked to return home and to provide their own clinical images and self-administered EASI assessments of their child for comparison. Four raters were asked to rate all images twice and to compare in-clinic and self-administered EASI scores based on the images.

At the in-clinic visit, the median EASI score of the group was 8.8. The majority of patients had moderate (46.6%) or severe (14.8%) AD. Roughly 40% of the patients had darker skin (Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI).

Using Spearman rank correlation of 1,534 in-clinic and 425 patient-provided images, the study found good inter- and intra-rater reliability for clinical image assessment and strong agreement between images and the in-clinic EASI scores. The top outliers in the assessment were individuals with either darker skin or significant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which are “the most difficult cases to rate, based on images,” Dr. Ragamin noted.

There was only moderate correlation between the in-clinic and self-administered EASI scores, with a significant number of patients either underestimating or overestimating their AD severity, he added.

Overall, the main problem with remote assessment seems to be the feasibility of patients providing images, said Dr. Ragamin. Only 36.8% of parents provided any images at all, and of these, 1 of 5 were deemed too blurry, leaving just 13 for final assessment, he explained.

“Pragmatically, it’s tricky,” said Aaron Drucker, MD, a dermatologist at Women’s College Hospital and associate professor at the University of Toronto, who was asked to comment on the study. “It takes long enough to do an EASI score in person, let alone looking through blurry pictures that take too long to load into your electronic medical record. We know it works, but when our hospital went virtual [during the COVID pandemic] ... most of my patients with chronic eczema weren’t even sending me pictures.”

Regarding the utility of remote, full-body photography in clinical practice, he said, “There’s too many feasibility hoops to jump through at this point. The most promise I see is for clinical trials, where it’s hard to get people to come in.”

Dr. Ragamin and Dr. Drucker have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

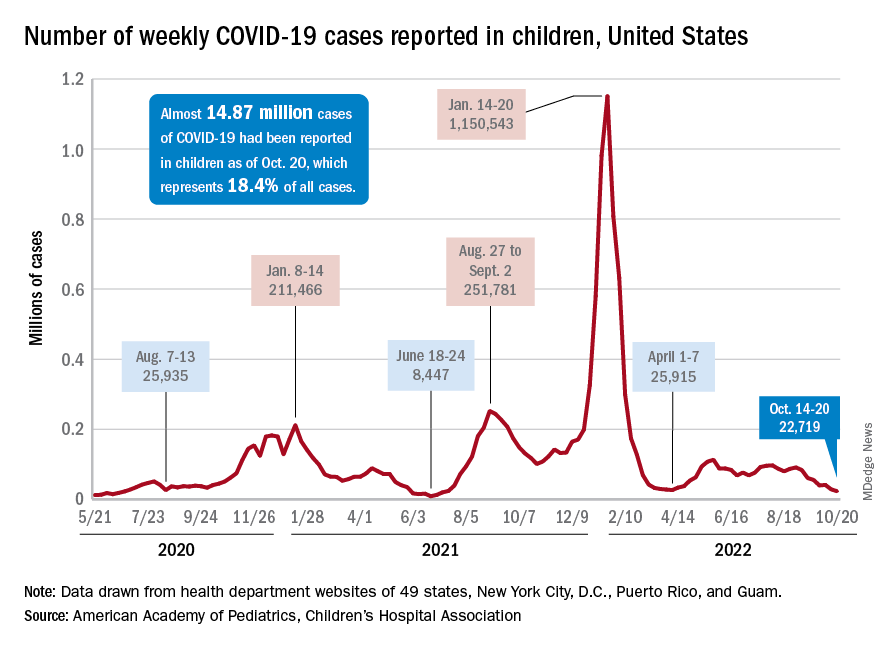

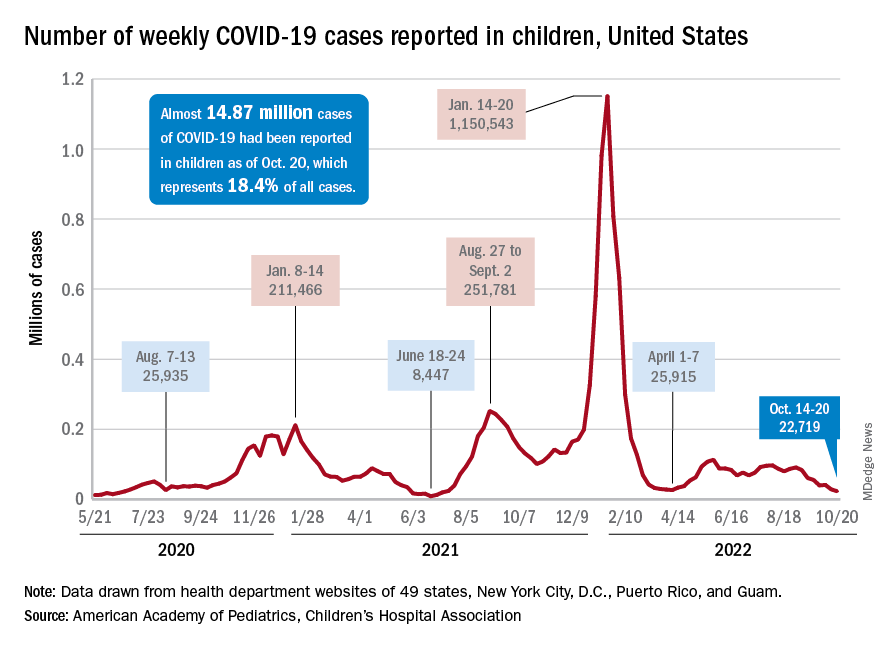

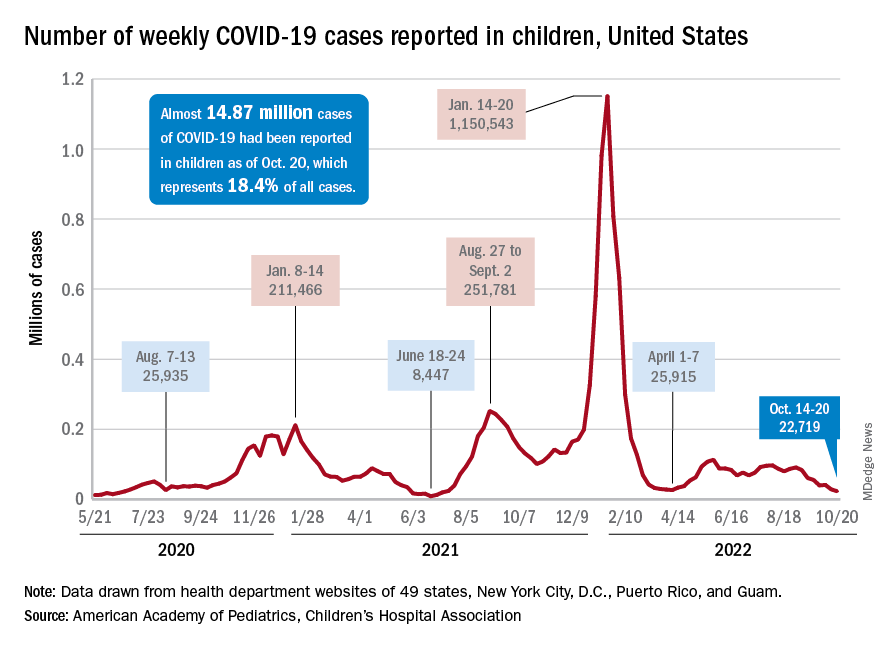

Children and COVID: Weekly cases fall to lowest level in over a year

With the third autumn of the COVID era now upon us, the discussion has turned again to a possible influenza/COVID twindemic, as well as the new-for-2022 influenza/COVID/respiratory syncytial virus tripledemic. It appears, however, that COVID may have missed the memo.

For the sixth time in the last 7 weeks, the number of new COVID cases in children fell, with just under 23,000 reported during the week of Oct. 14-20, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association. That is the lowest weekly count so far this year, and the lowest since early July of 2021, just as the Delta surge was starting. New pediatric cases had dipped to 8,500, the lowest for any week during the pandemic, a couple of weeks before that, the AAP/CHA data show.

Weekly cases have fallen by almost 75% since over 90,000 were reported for the week of Aug. 26 to Sept. 1, even as children have returned to school and vaccine uptake remains slow in the youngest age groups. Rates of emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID also have continued to drop, as have new admissions, and both are nearing their 2021 lows, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

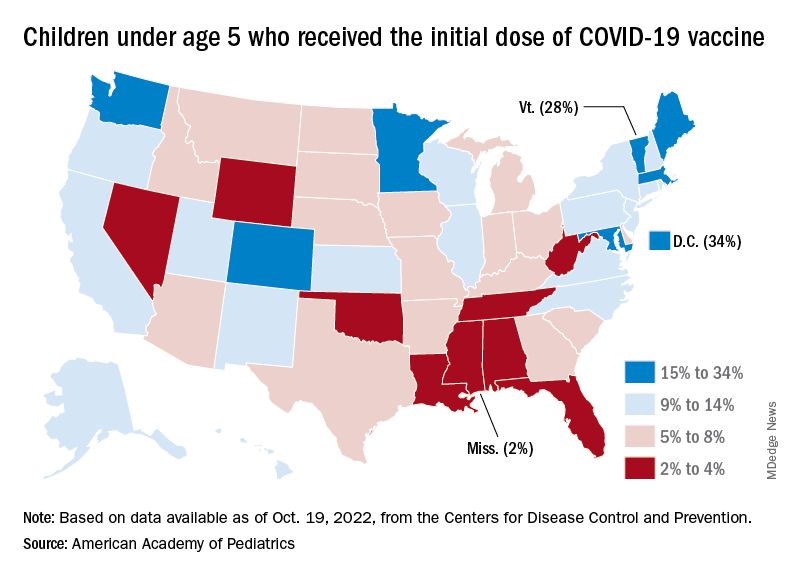

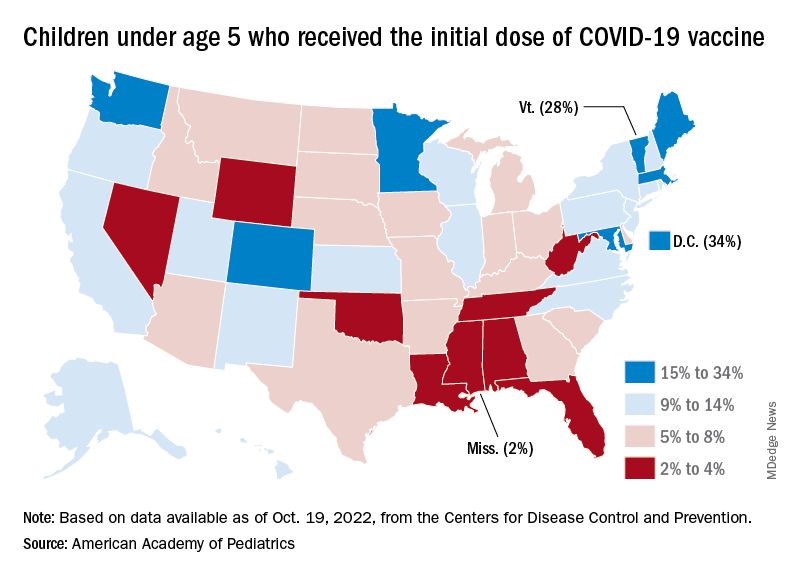

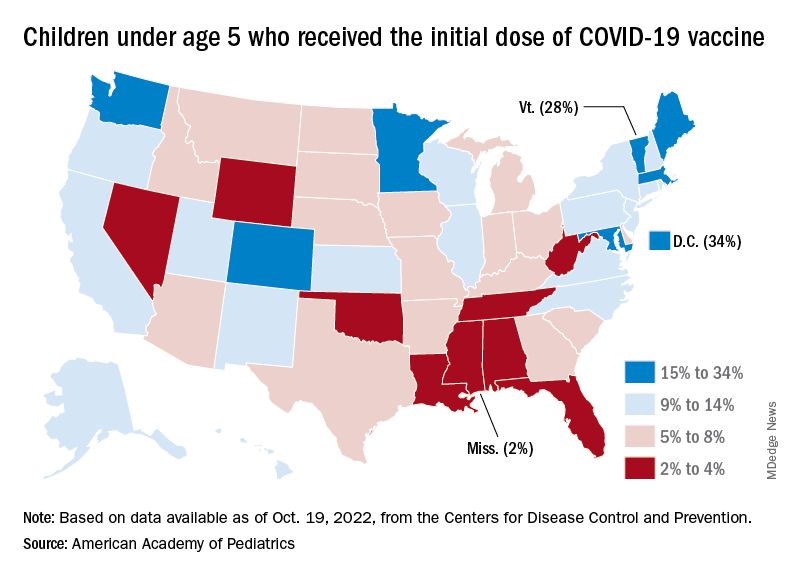

New vaccinations in children under age 5 years were up slightly for the most recent week (Oct. 13-19), but total uptake for that age group is only 7.1% for an initial dose and 2.9% for full vaccination. Among children aged 5-11 years, 38.7% have received at least one dose and 31.6% have completed the primary series, with corresponding figures of 71.2% and 60.9% for those aged 12-17, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Despite the low overall numbers, though, the youngest children are, in one respect, punching above their weight when it comes to vaccinations. In the 2 weeks from Oct. 6 to Oct. 19, children under 5 years of age, who represent 5.9% of the U.S. population, received 9.2% of the initial vaccine doses administered. Children aged 5-11 years, who represent 8.7% of the total population, got just 4.2% of all first doses over those same 2 weeks, while 12- to 17-year-olds, who make up 7.6% of the population, got 3.4% of the vaccine doses, the CDC reported.

On the vaccine-approval front, the Food and Drug Administration recently announced that the new bivalent COVID-19 vaccines are now included in the emergency use authorizations for children who have completed primary or booster vaccination. The Moderna vaccine is authorized as a single-dose booster for children as young as 6 years and the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine can be given as a single booster dose in children as young as 5 years, the FDA said.

“These bivalent COVID-19 vaccines include an mRNA component of the original strain to provide an immune response that is broadly protective against COVID-19 and an mRNA component in common between the omicron variant BA.4 and BA.5 lineages,” the FDA said.

With the third autumn of the COVID era now upon us, the discussion has turned again to a possible influenza/COVID twindemic, as well as the new-for-2022 influenza/COVID/respiratory syncytial virus tripledemic. It appears, however, that COVID may have missed the memo.

For the sixth time in the last 7 weeks, the number of new COVID cases in children fell, with just under 23,000 reported during the week of Oct. 14-20, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association. That is the lowest weekly count so far this year, and the lowest since early July of 2021, just as the Delta surge was starting. New pediatric cases had dipped to 8,500, the lowest for any week during the pandemic, a couple of weeks before that, the AAP/CHA data show.

Weekly cases have fallen by almost 75% since over 90,000 were reported for the week of Aug. 26 to Sept. 1, even as children have returned to school and vaccine uptake remains slow in the youngest age groups. Rates of emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID also have continued to drop, as have new admissions, and both are nearing their 2021 lows, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New vaccinations in children under age 5 years were up slightly for the most recent week (Oct. 13-19), but total uptake for that age group is only 7.1% for an initial dose and 2.9% for full vaccination. Among children aged 5-11 years, 38.7% have received at least one dose and 31.6% have completed the primary series, with corresponding figures of 71.2% and 60.9% for those aged 12-17, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Despite the low overall numbers, though, the youngest children are, in one respect, punching above their weight when it comes to vaccinations. In the 2 weeks from Oct. 6 to Oct. 19, children under 5 years of age, who represent 5.9% of the U.S. population, received 9.2% of the initial vaccine doses administered. Children aged 5-11 years, who represent 8.7% of the total population, got just 4.2% of all first doses over those same 2 weeks, while 12- to 17-year-olds, who make up 7.6% of the population, got 3.4% of the vaccine doses, the CDC reported.

On the vaccine-approval front, the Food and Drug Administration recently announced that the new bivalent COVID-19 vaccines are now included in the emergency use authorizations for children who have completed primary or booster vaccination. The Moderna vaccine is authorized as a single-dose booster for children as young as 6 years and the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine can be given as a single booster dose in children as young as 5 years, the FDA said.

“These bivalent COVID-19 vaccines include an mRNA component of the original strain to provide an immune response that is broadly protective against COVID-19 and an mRNA component in common between the omicron variant BA.4 and BA.5 lineages,” the FDA said.

With the third autumn of the COVID era now upon us, the discussion has turned again to a possible influenza/COVID twindemic, as well as the new-for-2022 influenza/COVID/respiratory syncytial virus tripledemic. It appears, however, that COVID may have missed the memo.

For the sixth time in the last 7 weeks, the number of new COVID cases in children fell, with just under 23,000 reported during the week of Oct. 14-20, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association. That is the lowest weekly count so far this year, and the lowest since early July of 2021, just as the Delta surge was starting. New pediatric cases had dipped to 8,500, the lowest for any week during the pandemic, a couple of weeks before that, the AAP/CHA data show.

Weekly cases have fallen by almost 75% since over 90,000 were reported for the week of Aug. 26 to Sept. 1, even as children have returned to school and vaccine uptake remains slow in the youngest age groups. Rates of emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID also have continued to drop, as have new admissions, and both are nearing their 2021 lows, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New vaccinations in children under age 5 years were up slightly for the most recent week (Oct. 13-19), but total uptake for that age group is only 7.1% for an initial dose and 2.9% for full vaccination. Among children aged 5-11 years, 38.7% have received at least one dose and 31.6% have completed the primary series, with corresponding figures of 71.2% and 60.9% for those aged 12-17, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Despite the low overall numbers, though, the youngest children are, in one respect, punching above their weight when it comes to vaccinations. In the 2 weeks from Oct. 6 to Oct. 19, children under 5 years of age, who represent 5.9% of the U.S. population, received 9.2% of the initial vaccine doses administered. Children aged 5-11 years, who represent 8.7% of the total population, got just 4.2% of all first doses over those same 2 weeks, while 12- to 17-year-olds, who make up 7.6% of the population, got 3.4% of the vaccine doses, the CDC reported.

On the vaccine-approval front, the Food and Drug Administration recently announced that the new bivalent COVID-19 vaccines are now included in the emergency use authorizations for children who have completed primary or booster vaccination. The Moderna vaccine is authorized as a single-dose booster for children as young as 6 years and the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine can be given as a single booster dose in children as young as 5 years, the FDA said.

“These bivalent COVID-19 vaccines include an mRNA component of the original strain to provide an immune response that is broadly protective against COVID-19 and an mRNA component in common between the omicron variant BA.4 and BA.5 lineages,” the FDA said.

Sexual health care for disabled youth: Tough and getting tougher

The developmentally disabled girl was just 10 years old when Margaret Thew, DNP, medical director of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin, Milwaukee, helped care for her. Providing that care was not emotionally easy. “Her brother’s friend sexually assaulted her and impregnated her,” Dr. Thew said.

The girl was able to obtain an abortion, a decision her parents supported. The alternative could have been deadly. “She was a tiny little person and would not have been able to carry a fetus,” Dr. Thew, a nurse practitioner, said.

Dr. Thew said she’s thankful that tragic case occurred before 2022. After the United States Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June, Wisconsin reverted to an 1849 law banning abortion. Although the law is currently being challenged, Dr. Thew wonders how the situation would have played out now. (Weeks after the Supreme Court’s decision, a similar case occurred in Ohio. In that case, a 10-year-old girl had to travel out of the state to obtain an abortion after having been raped.)

Talking to adolescents and young adults about reproductive health, whether regarding an unexpected pregnancy, the need for contraception, or to provide information about sexual activity, can be a challenge even for experienced health care providers.

The talks, decisions, and care are particularly complex when patients have developmental and intellectual disabilities. Among the many factors, Dr. Thew said, are dealing with menstruation, finding the right contraceptives, and counseling parents who might not want to acknowledge their children’s emerging sexuality.

Statistics: How many?

Because the definitions of disabilities vary and they represent a spectrum, estimates for how many youth have intellectual or developmental disabilities range widely.

In 2019, the National Survey of Children’s Health found that 1 in 4 children and adolescents aged 12-17 years have special health care needs because of disability. The American Community Survey estimates more than 1.3 million people aged 16-20 have a disability.

Intellectual disabilities can occur when a person’s IQ is below 70, significantly impeding the ability to perform activities of daily living, such as eating, dressing, and communicating. Developmental disabilities are impairments in physical, learning, language, and behavior, according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Among the conditions are attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorders, fragile X syndrome, learning and language problems, spina bifida, and other conditions.

Addressing common issues, concerns

April Kayser is a health educator for the Multnomah County Health Department, Portland, Ore. In 2016, Ms. Kayser and other experts conducted interviews with 11 youth with developmental and intellectual disabilities and 34 support people, either parents or professionals who provide services. The survey was part of the SHEIDD Project – short for Sexual Health Equity for Individuals with Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities – at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU).

From their findings, the researchers compiled guidelines. They provided scenarios that health care providers need to be aware of and that they need to be ready to address:

- A boy, 14, who is unclear about what to do when he feels sexually excited and wants to masturbate but isn’t at home. He has been told that masturbation is appropriate in private.

- A 20-year-old woman who lives in a group home is pregnant. She confesses to her parents during a visit that another resident is her boyfriend and that he is the father of the child she is expecting.

- A 17-year-old boy wants to ask out another student, who is 15.

Some developmentally and intellectually disabled youth can’t turn to their parents for help. One person in the survey said his father told him, “You don’t need to worry about any of that stuff. You’re too young.” Another said the job of a health care provider was to offer reproductive and sex education “to make sure you don’t screw up in some bad way.”

One finding stood out: Health care providers were at the top of the list of those whom young people trusted for information about reproductive and sexual health, Ms. Kayser said. Yet in her experience, she said, health care professionals are hesitant to bring up the issues with all youth, “especially those with intellectual and developmental disabilities.”

Health care providers often talk both to the patient and to the parents. Those conversations can be critical when a child is developmentally or intellectually disabled.

Women with disabilities have been shown to have a higher risk for adverse outcomes of pregnancy, said Willi Horner-Johnson, PhD, associate professor at OHSU–Portland State University School of Public Health.

In a recent study, she and her colleagues analyzed data from the CDC’s National Survey of Family Growth that included self-reported disability status. They found that the number of women with disabilities who give birth is far higher than was previously thought.

The researchers found that 19.5% of respondents who gave birth reported at least one sensory, cognitive, or mobility-related disability, a rate that is much greater than the less than 1%-6.6% estimates that are based on hospital discharge data.

Her group reported other troubling findings: Women with disabilities are twice as likely to have smoked during their pregnancy (19% vs. 8.9%) and are more likely to have preterm and low-birthweight babies.

Clinicians play an important role

Dr. Horner-Johnson agreed with the finding from the Multnomah County survey that health care providers play an important role in providing those with intellectual and developmental disabilities reproductive health care that meets their needs. “Clinicians need to be asking people with disabilities about their reproductive plans,” she said.

In the Multnomah County report, the researchers advised health care providers to recognize that people with disabilities are social and sexual beings; to learn about their goals, including those regarding sex and reproductive health; and to help youth build skills for healthy relationships and sexual activity.

Dr. Horner-Johnson pointed out that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists “recommends that clinicians discuss reproductive plans at every visit, for example, by asking one key question – ‘Would you like to become pregnant in the next year?’ – of every woman of reproductive age.”

Some women will not be able to answer that question, and health care providers at times must rely on a caregiver for input. But many women, even those with disabilities, could answer if given a chance. She estimated that only about 5% of disabled people are unable to communicate. “Clinicians defer to the caregiver more than they need to,” she said.

Clinicians are becoming better at providing care to those with disabilities, Dr. Horner-Johnson said, yet they have a way to go. Clinician biases may prevent some from asking all women, including those with disabilities, about their reproductive plans. “Women with disabilities have described clinicians treating them as nonsexual, assuming or implying that they would not or should not get pregnant,” she writes in her report.

Such biases, she said, could be reduced by increased education of providers. A 2018 study in Health Equity found that only 19.3% of ob.gyns. said they felt equipped to manage the pregnancy of a woman with disabilities.

Managing sexuality and sexual health for youth with disabilities can be highly complex, according to Margaret Thew, DNP, medical director of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Challenges include the following:

- Parents often can’t deal with the reality that their teen or young adult is sexually active or may become so. Parents she helps often prefer to use the term “hormones,” not contraceptives, when talking about pregnancy prevention.

- Menstruation is a frequent concern, especially for youth with severe disabilities. Some react strongly to seeing a sanitary pad with blood, for example, by throwing it. Parents worry that caregivers will balk at changing pads regularly. As a result, some parents want complete menstrual suppression, Dr. Thew said. The American Academy of Pediatrics outlines how to approach menstrual suppression through methods such as the use of estrogen-progestin, progesterone, a ring, or a patch. In late August, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists released its clinical consensus on medical management of menstrual suppression.

- Some parents want to know how to obtain a complete hysterectomy for the patient – an option Dr. Thew and the AAP discourage. “We will tell them that’s not the best and safest approach, as you want to have the estrogen for bone health,” she said.

- After a discussion of all the options, an intrauterine device proves best for many. “That gives 7-8 years of protection,” she said, which is the approved effective duration for such devices. “They are less apt to have heavy monthly menstrual bleeding.”

- Parents of boys with disabilities, especially those with Down syndrome, often ask for sex education and guidance when sexual desires develop.

- Many parents want effective birth control for their children because of fear that their teen or young adult will be assaulted, a fear that isn’t groundless. Such cases are common, and caregivers frequently are the perpetrators.

Ms. Kayser, Dr. Horner-Johnson, and Dr. Thew have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The developmentally disabled girl was just 10 years old when Margaret Thew, DNP, medical director of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin, Milwaukee, helped care for her. Providing that care was not emotionally easy. “Her brother’s friend sexually assaulted her and impregnated her,” Dr. Thew said.

The girl was able to obtain an abortion, a decision her parents supported. The alternative could have been deadly. “She was a tiny little person and would not have been able to carry a fetus,” Dr. Thew, a nurse practitioner, said.

Dr. Thew said she’s thankful that tragic case occurred before 2022. After the United States Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June, Wisconsin reverted to an 1849 law banning abortion. Although the law is currently being challenged, Dr. Thew wonders how the situation would have played out now. (Weeks after the Supreme Court’s decision, a similar case occurred in Ohio. In that case, a 10-year-old girl had to travel out of the state to obtain an abortion after having been raped.)

Talking to adolescents and young adults about reproductive health, whether regarding an unexpected pregnancy, the need for contraception, or to provide information about sexual activity, can be a challenge even for experienced health care providers.

The talks, decisions, and care are particularly complex when patients have developmental and intellectual disabilities. Among the many factors, Dr. Thew said, are dealing with menstruation, finding the right contraceptives, and counseling parents who might not want to acknowledge their children’s emerging sexuality.

Statistics: How many?

Because the definitions of disabilities vary and they represent a spectrum, estimates for how many youth have intellectual or developmental disabilities range widely.

In 2019, the National Survey of Children’s Health found that 1 in 4 children and adolescents aged 12-17 years have special health care needs because of disability. The American Community Survey estimates more than 1.3 million people aged 16-20 have a disability.

Intellectual disabilities can occur when a person’s IQ is below 70, significantly impeding the ability to perform activities of daily living, such as eating, dressing, and communicating. Developmental disabilities are impairments in physical, learning, language, and behavior, according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Among the conditions are attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorders, fragile X syndrome, learning and language problems, spina bifida, and other conditions.

Addressing common issues, concerns

April Kayser is a health educator for the Multnomah County Health Department, Portland, Ore. In 2016, Ms. Kayser and other experts conducted interviews with 11 youth with developmental and intellectual disabilities and 34 support people, either parents or professionals who provide services. The survey was part of the SHEIDD Project – short for Sexual Health Equity for Individuals with Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities – at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU).

From their findings, the researchers compiled guidelines. They provided scenarios that health care providers need to be aware of and that they need to be ready to address:

- A boy, 14, who is unclear about what to do when he feels sexually excited and wants to masturbate but isn’t at home. He has been told that masturbation is appropriate in private.

- A 20-year-old woman who lives in a group home is pregnant. She confesses to her parents during a visit that another resident is her boyfriend and that he is the father of the child she is expecting.

- A 17-year-old boy wants to ask out another student, who is 15.

Some developmentally and intellectually disabled youth can’t turn to their parents for help. One person in the survey said his father told him, “You don’t need to worry about any of that stuff. You’re too young.” Another said the job of a health care provider was to offer reproductive and sex education “to make sure you don’t screw up in some bad way.”

One finding stood out: Health care providers were at the top of the list of those whom young people trusted for information about reproductive and sexual health, Ms. Kayser said. Yet in her experience, she said, health care professionals are hesitant to bring up the issues with all youth, “especially those with intellectual and developmental disabilities.”

Health care providers often talk both to the patient and to the parents. Those conversations can be critical when a child is developmentally or intellectually disabled.

Women with disabilities have been shown to have a higher risk for adverse outcomes of pregnancy, said Willi Horner-Johnson, PhD, associate professor at OHSU–Portland State University School of Public Health.

In a recent study, she and her colleagues analyzed data from the CDC’s National Survey of Family Growth that included self-reported disability status. They found that the number of women with disabilities who give birth is far higher than was previously thought.

The researchers found that 19.5% of respondents who gave birth reported at least one sensory, cognitive, or mobility-related disability, a rate that is much greater than the less than 1%-6.6% estimates that are based on hospital discharge data.

Her group reported other troubling findings: Women with disabilities are twice as likely to have smoked during their pregnancy (19% vs. 8.9%) and are more likely to have preterm and low-birthweight babies.

Clinicians play an important role

Dr. Horner-Johnson agreed with the finding from the Multnomah County survey that health care providers play an important role in providing those with intellectual and developmental disabilities reproductive health care that meets their needs. “Clinicians need to be asking people with disabilities about their reproductive plans,” she said.

In the Multnomah County report, the researchers advised health care providers to recognize that people with disabilities are social and sexual beings; to learn about their goals, including those regarding sex and reproductive health; and to help youth build skills for healthy relationships and sexual activity.

Dr. Horner-Johnson pointed out that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists “recommends that clinicians discuss reproductive plans at every visit, for example, by asking one key question – ‘Would you like to become pregnant in the next year?’ – of every woman of reproductive age.”

Some women will not be able to answer that question, and health care providers at times must rely on a caregiver for input. But many women, even those with disabilities, could answer if given a chance. She estimated that only about 5% of disabled people are unable to communicate. “Clinicians defer to the caregiver more than they need to,” she said.

Clinicians are becoming better at providing care to those with disabilities, Dr. Horner-Johnson said, yet they have a way to go. Clinician biases may prevent some from asking all women, including those with disabilities, about their reproductive plans. “Women with disabilities have described clinicians treating them as nonsexual, assuming or implying that they would not or should not get pregnant,” she writes in her report.

Such biases, she said, could be reduced by increased education of providers. A 2018 study in Health Equity found that only 19.3% of ob.gyns. said they felt equipped to manage the pregnancy of a woman with disabilities.

Managing sexuality and sexual health for youth with disabilities can be highly complex, according to Margaret Thew, DNP, medical director of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Challenges include the following:

- Parents often can’t deal with the reality that their teen or young adult is sexually active or may become so. Parents she helps often prefer to use the term “hormones,” not contraceptives, when talking about pregnancy prevention.

- Menstruation is a frequent concern, especially for youth with severe disabilities. Some react strongly to seeing a sanitary pad with blood, for example, by throwing it. Parents worry that caregivers will balk at changing pads regularly. As a result, some parents want complete menstrual suppression, Dr. Thew said. The American Academy of Pediatrics outlines how to approach menstrual suppression through methods such as the use of estrogen-progestin, progesterone, a ring, or a patch. In late August, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists released its clinical consensus on medical management of menstrual suppression.

- Some parents want to know how to obtain a complete hysterectomy for the patient – an option Dr. Thew and the AAP discourage. “We will tell them that’s not the best and safest approach, as you want to have the estrogen for bone health,” she said.

- After a discussion of all the options, an intrauterine device proves best for many. “That gives 7-8 years of protection,” she said, which is the approved effective duration for such devices. “They are less apt to have heavy monthly menstrual bleeding.”

- Parents of boys with disabilities, especially those with Down syndrome, often ask for sex education and guidance when sexual desires develop.

- Many parents want effective birth control for their children because of fear that their teen or young adult will be assaulted, a fear that isn’t groundless. Such cases are common, and caregivers frequently are the perpetrators.

Ms. Kayser, Dr. Horner-Johnson, and Dr. Thew have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The developmentally disabled girl was just 10 years old when Margaret Thew, DNP, medical director of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin, Milwaukee, helped care for her. Providing that care was not emotionally easy. “Her brother’s friend sexually assaulted her and impregnated her,” Dr. Thew said.

The girl was able to obtain an abortion, a decision her parents supported. The alternative could have been deadly. “She was a tiny little person and would not have been able to carry a fetus,” Dr. Thew, a nurse practitioner, said.

Dr. Thew said she’s thankful that tragic case occurred before 2022. After the United States Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June, Wisconsin reverted to an 1849 law banning abortion. Although the law is currently being challenged, Dr. Thew wonders how the situation would have played out now. (Weeks after the Supreme Court’s decision, a similar case occurred in Ohio. In that case, a 10-year-old girl had to travel out of the state to obtain an abortion after having been raped.)

Talking to adolescents and young adults about reproductive health, whether regarding an unexpected pregnancy, the need for contraception, or to provide information about sexual activity, can be a challenge even for experienced health care providers.

The talks, decisions, and care are particularly complex when patients have developmental and intellectual disabilities. Among the many factors, Dr. Thew said, are dealing with menstruation, finding the right contraceptives, and counseling parents who might not want to acknowledge their children’s emerging sexuality.

Statistics: How many?

Because the definitions of disabilities vary and they represent a spectrum, estimates for how many youth have intellectual or developmental disabilities range widely.

In 2019, the National Survey of Children’s Health found that 1 in 4 children and adolescents aged 12-17 years have special health care needs because of disability. The American Community Survey estimates more than 1.3 million people aged 16-20 have a disability.

Intellectual disabilities can occur when a person’s IQ is below 70, significantly impeding the ability to perform activities of daily living, such as eating, dressing, and communicating. Developmental disabilities are impairments in physical, learning, language, and behavior, according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Among the conditions are attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorders, fragile X syndrome, learning and language problems, spina bifida, and other conditions.

Addressing common issues, concerns

April Kayser is a health educator for the Multnomah County Health Department, Portland, Ore. In 2016, Ms. Kayser and other experts conducted interviews with 11 youth with developmental and intellectual disabilities and 34 support people, either parents or professionals who provide services. The survey was part of the SHEIDD Project – short for Sexual Health Equity for Individuals with Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities – at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU).

From their findings, the researchers compiled guidelines. They provided scenarios that health care providers need to be aware of and that they need to be ready to address:

- A boy, 14, who is unclear about what to do when he feels sexually excited and wants to masturbate but isn’t at home. He has been told that masturbation is appropriate in private.

- A 20-year-old woman who lives in a group home is pregnant. She confesses to her parents during a visit that another resident is her boyfriend and that he is the father of the child she is expecting.

- A 17-year-old boy wants to ask out another student, who is 15.

Some developmentally and intellectually disabled youth can’t turn to their parents for help. One person in the survey said his father told him, “You don’t need to worry about any of that stuff. You’re too young.” Another said the job of a health care provider was to offer reproductive and sex education “to make sure you don’t screw up in some bad way.”

One finding stood out: Health care providers were at the top of the list of those whom young people trusted for information about reproductive and sexual health, Ms. Kayser said. Yet in her experience, she said, health care professionals are hesitant to bring up the issues with all youth, “especially those with intellectual and developmental disabilities.”

Health care providers often talk both to the patient and to the parents. Those conversations can be critical when a child is developmentally or intellectually disabled.

Women with disabilities have been shown to have a higher risk for adverse outcomes of pregnancy, said Willi Horner-Johnson, PhD, associate professor at OHSU–Portland State University School of Public Health.

In a recent study, she and her colleagues analyzed data from the CDC’s National Survey of Family Growth that included self-reported disability status. They found that the number of women with disabilities who give birth is far higher than was previously thought.

The researchers found that 19.5% of respondents who gave birth reported at least one sensory, cognitive, or mobility-related disability, a rate that is much greater than the less than 1%-6.6% estimates that are based on hospital discharge data.

Her group reported other troubling findings: Women with disabilities are twice as likely to have smoked during their pregnancy (19% vs. 8.9%) and are more likely to have preterm and low-birthweight babies.

Clinicians play an important role

Dr. Horner-Johnson agreed with the finding from the Multnomah County survey that health care providers play an important role in providing those with intellectual and developmental disabilities reproductive health care that meets their needs. “Clinicians need to be asking people with disabilities about their reproductive plans,” she said.

In the Multnomah County report, the researchers advised health care providers to recognize that people with disabilities are social and sexual beings; to learn about their goals, including those regarding sex and reproductive health; and to help youth build skills for healthy relationships and sexual activity.

Dr. Horner-Johnson pointed out that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists “recommends that clinicians discuss reproductive plans at every visit, for example, by asking one key question – ‘Would you like to become pregnant in the next year?’ – of every woman of reproductive age.”

Some women will not be able to answer that question, and health care providers at times must rely on a caregiver for input. But many women, even those with disabilities, could answer if given a chance. She estimated that only about 5% of disabled people are unable to communicate. “Clinicians defer to the caregiver more than they need to,” she said.