User login

Past, Present, and Future of Pediatric Atopic Dermatitis Management

Atopic dermatitis (AD), or eczema, is a common inflammatory skin disease notorious for its chronic, relapsing, and often frustrating disease course. Although as many as 25% of children in the United States are affected by this condition and its impact on the quality of life of affected patients and families is profound,1-3 therapeutic advances in the pediatric population have been fairly limited until recently.

Over the last 10 years, there has been robust investigation into pediatric AD therapeutics, with many topical and systemic medications either recently approved or under clinical investigation. These developments are changing the landscape of the management of pediatric AD and raise a set of fascinating questions about how early and aggressive intervention might change the course of this disease. We discuss current limitations in the field that may be addressed with additional research.

New Topical Medications

In the last several years, there has been a rapid increase in efforts to develop new topical agents to manage AD. Until the beginning of the 21st century, the dermatologist’s arsenal was limited to topical corticosteroids (TCs). In the early 2000s, attention shifted to topical calcineurin inhibitors as nonsteroidal alternatives when the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus for AD. In 2016, crisaborole (a phosphodiesterase-4 [PDE4] inhibitor) was approved by the FDA for use in mild to moderate AD in patients 2 years and older, marking a new age of development for topical AD therapies. In 2021, the FDA approved ruxolitinib (a topical Janus kinase [JAK] 1/2 inhibitor) for use in mild to moderate AD in patients 12 years and older.

Roflumilast (ARQ-151) and difamilast (OPA-15406)(members of the PDE4 inhibitor class) are undergoing investigation for pediatric AD. A phase 3 clinical trial for roflumilast for AD is underway (ClinicalTrial.gov Identifier: NCT04845620); it is already approved for psoriasis in patients 12 years and older. A phase 3 trial of difamilast (NCT03911401) was recently completed, with results supporting the drug’s safety and efficacy in AD management.4 Efforts to synthesize new better-targeted PDE4 inhibitors are ongoing.5

Tapinarof (a novel aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent) is approved for psoriasis in adults, and a phase 3 trial for management of pediatric AD is underway (NCT05032859) after phase 2 trials revealed promising results.6

Lastly, the microbiome is a target for AD topical therapies. A recently completed phase 1 trial of bacteriotherapy with Staphylococcus hominis A9 transplant lotion showed promising results (NCT03151148).7 Although this bacteriotherapy technique is early in development and has been studied only in adult patients, results are exciting because they represent a gateway to a largely unexplored realm of potential future therapies.

Standard of Care—How will these new topical therapies impact our standard of care for pediatric AD patients? Topical corticosteroids are still a pillar of topical AD therapy, but the potential for nonsteroidal topical agents as alternatives and used in combination therapeutic regimens has expanded exponentially. It is uncertain how we might individualize regimens tailored to patient-specific factors because the standard approach has been to test drugs as monotherapy, with vehicle comparisons or with reference medications in Europe.

Newer topical nonsteroidal agents may offer several opportunities. First, they may help avoid local and systemic adverse effects that often limit the use of current standard therapy.8 This capability may prove essential in bridging TC treatments and serving as long-term maintenance therapies to decrease the frequency of eczema flares. Second, they can alleviate the need for different medication strengths for different body regions, thereby allowing for simplification of regimens and potentially increased adherence and decreased disease burden—a boon to affected patients and caregivers.

Although the efficacy and long-term safety profile of these new drugs require further study, it does not seem unreasonable to look forward to achieving levels of optimization and individualization with topical regimens for AD in the near future that makes flares in patients with mild to moderate AD a phenomenon of the past.

Advances in Systemic Therapy

Systemic therapeutics in pediatric AD also recently entered an exciting era of development. Traditional systemic agents, including cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil, have existed for decades but have not been widely utilized for moderate to severe AD in the United States, especially in the pediatric population, likely because these drugs lacked FDA approval and they can cause a range of adverse effects, including notable immunosuppression.9

Introduction and approval of dupilumab in 2017 by the FDA was revolutionary in this field. As a monoclonal antibody targeted against IL-4 and IL-13, dupilumab has consistently demonstrated strong long-term efficacy for pediatric AD and has an acceptable safety profile in children and adolescents.10-14 Expansion of the label to include children as young as 6 months with moderate to severe AD seems an important milestone in pediatric AD care.

Since the approval of dupilumab for adolescents and children aged 6 to 12 years, global experience has supported expanded use of systemic agents for patients who have an inadequate response to TCs and previously approved nonsteroidal topical agents. How expansive the use of systemics will be in younger children depends on how their long-term use impacts the disease course, whether therapy is disease modifying, and whether early use can curb the development of comorbidities.

Investigations into targeted systemic therapeutics for eczematous dermatitis are not limited to dupilumab. In a study of adolescents as young as 12 years, tralokinumab (an IL-13 pathway inhibitor) demonstrated an Eczema Area Severity Index-75 of 27.8% to 28.6% and a mean decrease in the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis index of 27.5 to 29.1, with minimal adverse effects.15 Lebrikizumab, another biologic IL-13 inhibitor with strong published safety and efficacy data in adults, has completed short- and longer-term studies in adolescents (NCT04178967 and NCT04146363).16 The drug received FDA Fast Track designation for moderate to severe AD in patients 12 years and older after showing positive data.17

This push to targeted therapy stretches beyond monoclonal antibodies. In the last few years, oral JAK inhibitors have emerged as a new class of systemic therapy for eczematous dermatitis. Upadacitinib, a JAK1 selective inhibitor, was approved by the FDA in 2022 for patients 12 years and older with AD and has data that supports its efficacy in adolescents and adults.18 Other JAK inhibitors including the selective JAK1 inhibitor abrocitinib and the combined JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib are being studied for pediatric AD (NCT04564755, NCT03422822, and NCT03952559), with most evidence to date supporting their safety and efficacy, at least over the short-term.19

The study of these and other advanced systemic therapies for eczematous dermatitis is transforming the toolbox for pediatric AD care. Although long-term data are lacking for some of these medications, it is possible that newer agents may decrease reliance on older immunosuppressants, such as systemic corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. Unanswered questions include: How and which systemic medications may alter the course of the disease? What is the disease modification for AD? What is the impact on comorbidities over time?

What’s Missing?

The field of pediatric AD has experienced exciting new developments with the emergence of targeted therapeutics, but those new agents require more long-term study, though we already have longer-term data on crisaborole and dupilumab.10-14,20 Studies of the long-term use of these new treatments on comorbidities of pediatric AD—mental health outcomes, cardiovascular disease, effects on the family, and other allergic conditions—are needed.21 Furthermore, clinical guidelines that address indications, timing of use, tapering, and discontinuation of new treatments depend on long-term experience and data collection.

Therefore, it is prudent that investigators, companies, payers, patients, and families support phase 4, long-term extension, and registry studies, which will expand our knowledge of AD medications and their impact on the disease over time.

Final Thoughts

Medications to treat AD are reaching a new level of advancement—from topical agents that target novel pathways to revolutionary biologics and systemic medications. Although there are knowledge gaps on these new therapeutics, the standard of care is already rapidly changing as the expectations of clinicians, patients, and families advance with each addition to the provider’s toolbox.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: part 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-351. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.010

- Kiebert G, Sorensen SV, Revicki D, et al. Atopic dermatitis is associated with a decrement in health-related quality of life. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:151-158. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01436.x

- Al Shobaili HA. The impact of childhood atopic dermatitis on the patients’ family. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:618-623. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01215.x

- Saeki H, Baba N, Ito K, et al. Difamilast, a selective phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, ointment in paediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: a phase III randomized double-blind, vehicle-controlled trial [published online November 1, 2021]. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:40-49. doi:10.1111/bjd.20655

- Chu Z, Xu Q, Zhu Q, et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel benzoxaborole derivatives as potent PDE4 inhibitors for topical treatment of atopic dermatitis. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;213:113171. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113171

- Paller AS, Stein Gold L, Soung J, et al. Efficacy and patient-reported outcomes from a phase 2b, randomized clinical trial of tapinarof cream for the treatment of adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:632-638. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.135

- Nakatsuji T, Hata TR, Tong Y, et al. Development of a human skin commensal microbe for bacteriotherapy of atopic dermatitis and use in a phase 1 randomized clinical trial. Nat Med. 2021;27:700-709. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01256-2

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: part 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.023

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: part 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030

- Gooderham MJ, Hong HC-H, Eshtiaghi P, et al. Dupilumab: a review of its use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3 suppl 1):S28-S36. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.022

- Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:44-56. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336

- Blauvelt A, Guttman-Yassky E, Paller AS, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopicdermatitis: results through week 52 from a phase III open-label extension trial (LIBERTY AD PED-OLE). Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:365-383. doi:10.1007/s40257-022-00683-2

- Cork MJ, D, Eichenfield LF, et al. Dupilumab provides favourable long-term safety and efficacy in children aged ≥ 6 to < 12 years with uncontrolled severe atopic dermatitis: results from an open-label phase IIa study and subsequent phase III open-label extension study. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:857-870. doi:10.1111/bjd.19460

- Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Dupilumab demonstrates rapid and consistent improvement in extent and signs of atopic dermatitis across all anatomical regions in pediatric patients 6 years of age and older. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1643-1656. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00568-y

- Paller A, Blauvelt A, Soong W, et al. Efficacy and safety of tralokinumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results of the phase 3 ECZTRA 6 trial. SKIN. 2022;6:S29. doi:10.25251/skin.6.supp.s29

- Guttman-Yassky E, Blauvelt A, Eichenfield LF, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab, a high-affinity interleukin 13 inhibitor, in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2b randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:411-420. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0079

- Lebrikizumab dosed every four weeks maintained durable skin clearance in Lilly’s phase 3 monotherapy atopic dermatitis trials [news release]. Eli Lilly and Company; September 8, 2022. Accessed October 19, 2022. https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lebrikizumab-dosed-every-four-weeks-maintained-durable-skin

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397:2151-2168. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00588-2

- Chovatiya R, Paller AS. JAK inhibitors in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148:927-940. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2021.08.009

- Geng B, Hebert AA, Takiya L, et al. Efficacy and safety trends with continuous, long-term crisaborole use in patients aged ≥ 2 years with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1667-1678. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00584-y

- Appiah MM, Haft MA, Kleinman E, et al. Atopic dermatitis: review of comorbidities and therapeutics. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;129:142-149. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2022.05.015

Atopic dermatitis (AD), or eczema, is a common inflammatory skin disease notorious for its chronic, relapsing, and often frustrating disease course. Although as many as 25% of children in the United States are affected by this condition and its impact on the quality of life of affected patients and families is profound,1-3 therapeutic advances in the pediatric population have been fairly limited until recently.

Over the last 10 years, there has been robust investigation into pediatric AD therapeutics, with many topical and systemic medications either recently approved or under clinical investigation. These developments are changing the landscape of the management of pediatric AD and raise a set of fascinating questions about how early and aggressive intervention might change the course of this disease. We discuss current limitations in the field that may be addressed with additional research.

New Topical Medications

In the last several years, there has been a rapid increase in efforts to develop new topical agents to manage AD. Until the beginning of the 21st century, the dermatologist’s arsenal was limited to topical corticosteroids (TCs). In the early 2000s, attention shifted to topical calcineurin inhibitors as nonsteroidal alternatives when the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus for AD. In 2016, crisaborole (a phosphodiesterase-4 [PDE4] inhibitor) was approved by the FDA for use in mild to moderate AD in patients 2 years and older, marking a new age of development for topical AD therapies. In 2021, the FDA approved ruxolitinib (a topical Janus kinase [JAK] 1/2 inhibitor) for use in mild to moderate AD in patients 12 years and older.

Roflumilast (ARQ-151) and difamilast (OPA-15406)(members of the PDE4 inhibitor class) are undergoing investigation for pediatric AD. A phase 3 clinical trial for roflumilast for AD is underway (ClinicalTrial.gov Identifier: NCT04845620); it is already approved for psoriasis in patients 12 years and older. A phase 3 trial of difamilast (NCT03911401) was recently completed, with results supporting the drug’s safety and efficacy in AD management.4 Efforts to synthesize new better-targeted PDE4 inhibitors are ongoing.5

Tapinarof (a novel aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent) is approved for psoriasis in adults, and a phase 3 trial for management of pediatric AD is underway (NCT05032859) after phase 2 trials revealed promising results.6

Lastly, the microbiome is a target for AD topical therapies. A recently completed phase 1 trial of bacteriotherapy with Staphylococcus hominis A9 transplant lotion showed promising results (NCT03151148).7 Although this bacteriotherapy technique is early in development and has been studied only in adult patients, results are exciting because they represent a gateway to a largely unexplored realm of potential future therapies.

Standard of Care—How will these new topical therapies impact our standard of care for pediatric AD patients? Topical corticosteroids are still a pillar of topical AD therapy, but the potential for nonsteroidal topical agents as alternatives and used in combination therapeutic regimens has expanded exponentially. It is uncertain how we might individualize regimens tailored to patient-specific factors because the standard approach has been to test drugs as monotherapy, with vehicle comparisons or with reference medications in Europe.

Newer topical nonsteroidal agents may offer several opportunities. First, they may help avoid local and systemic adverse effects that often limit the use of current standard therapy.8 This capability may prove essential in bridging TC treatments and serving as long-term maintenance therapies to decrease the frequency of eczema flares. Second, they can alleviate the need for different medication strengths for different body regions, thereby allowing for simplification of regimens and potentially increased adherence and decreased disease burden—a boon to affected patients and caregivers.

Although the efficacy and long-term safety profile of these new drugs require further study, it does not seem unreasonable to look forward to achieving levels of optimization and individualization with topical regimens for AD in the near future that makes flares in patients with mild to moderate AD a phenomenon of the past.

Advances in Systemic Therapy

Systemic therapeutics in pediatric AD also recently entered an exciting era of development. Traditional systemic agents, including cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil, have existed for decades but have not been widely utilized for moderate to severe AD in the United States, especially in the pediatric population, likely because these drugs lacked FDA approval and they can cause a range of adverse effects, including notable immunosuppression.9

Introduction and approval of dupilumab in 2017 by the FDA was revolutionary in this field. As a monoclonal antibody targeted against IL-4 and IL-13, dupilumab has consistently demonstrated strong long-term efficacy for pediatric AD and has an acceptable safety profile in children and adolescents.10-14 Expansion of the label to include children as young as 6 months with moderate to severe AD seems an important milestone in pediatric AD care.

Since the approval of dupilumab for adolescents and children aged 6 to 12 years, global experience has supported expanded use of systemic agents for patients who have an inadequate response to TCs and previously approved nonsteroidal topical agents. How expansive the use of systemics will be in younger children depends on how their long-term use impacts the disease course, whether therapy is disease modifying, and whether early use can curb the development of comorbidities.

Investigations into targeted systemic therapeutics for eczematous dermatitis are not limited to dupilumab. In a study of adolescents as young as 12 years, tralokinumab (an IL-13 pathway inhibitor) demonstrated an Eczema Area Severity Index-75 of 27.8% to 28.6% and a mean decrease in the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis index of 27.5 to 29.1, with minimal adverse effects.15 Lebrikizumab, another biologic IL-13 inhibitor with strong published safety and efficacy data in adults, has completed short- and longer-term studies in adolescents (NCT04178967 and NCT04146363).16 The drug received FDA Fast Track designation for moderate to severe AD in patients 12 years and older after showing positive data.17

This push to targeted therapy stretches beyond monoclonal antibodies. In the last few years, oral JAK inhibitors have emerged as a new class of systemic therapy for eczematous dermatitis. Upadacitinib, a JAK1 selective inhibitor, was approved by the FDA in 2022 for patients 12 years and older with AD and has data that supports its efficacy in adolescents and adults.18 Other JAK inhibitors including the selective JAK1 inhibitor abrocitinib and the combined JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib are being studied for pediatric AD (NCT04564755, NCT03422822, and NCT03952559), with most evidence to date supporting their safety and efficacy, at least over the short-term.19

The study of these and other advanced systemic therapies for eczematous dermatitis is transforming the toolbox for pediatric AD care. Although long-term data are lacking for some of these medications, it is possible that newer agents may decrease reliance on older immunosuppressants, such as systemic corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. Unanswered questions include: How and which systemic medications may alter the course of the disease? What is the disease modification for AD? What is the impact on comorbidities over time?

What’s Missing?

The field of pediatric AD has experienced exciting new developments with the emergence of targeted therapeutics, but those new agents require more long-term study, though we already have longer-term data on crisaborole and dupilumab.10-14,20 Studies of the long-term use of these new treatments on comorbidities of pediatric AD—mental health outcomes, cardiovascular disease, effects on the family, and other allergic conditions—are needed.21 Furthermore, clinical guidelines that address indications, timing of use, tapering, and discontinuation of new treatments depend on long-term experience and data collection.

Therefore, it is prudent that investigators, companies, payers, patients, and families support phase 4, long-term extension, and registry studies, which will expand our knowledge of AD medications and their impact on the disease over time.

Final Thoughts

Medications to treat AD are reaching a new level of advancement—from topical agents that target novel pathways to revolutionary biologics and systemic medications. Although there are knowledge gaps on these new therapeutics, the standard of care is already rapidly changing as the expectations of clinicians, patients, and families advance with each addition to the provider’s toolbox.

Atopic dermatitis (AD), or eczema, is a common inflammatory skin disease notorious for its chronic, relapsing, and often frustrating disease course. Although as many as 25% of children in the United States are affected by this condition and its impact on the quality of life of affected patients and families is profound,1-3 therapeutic advances in the pediatric population have been fairly limited until recently.

Over the last 10 years, there has been robust investigation into pediatric AD therapeutics, with many topical and systemic medications either recently approved or under clinical investigation. These developments are changing the landscape of the management of pediatric AD and raise a set of fascinating questions about how early and aggressive intervention might change the course of this disease. We discuss current limitations in the field that may be addressed with additional research.

New Topical Medications

In the last several years, there has been a rapid increase in efforts to develop new topical agents to manage AD. Until the beginning of the 21st century, the dermatologist’s arsenal was limited to topical corticosteroids (TCs). In the early 2000s, attention shifted to topical calcineurin inhibitors as nonsteroidal alternatives when the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus for AD. In 2016, crisaborole (a phosphodiesterase-4 [PDE4] inhibitor) was approved by the FDA for use in mild to moderate AD in patients 2 years and older, marking a new age of development for topical AD therapies. In 2021, the FDA approved ruxolitinib (a topical Janus kinase [JAK] 1/2 inhibitor) for use in mild to moderate AD in patients 12 years and older.

Roflumilast (ARQ-151) and difamilast (OPA-15406)(members of the PDE4 inhibitor class) are undergoing investigation for pediatric AD. A phase 3 clinical trial for roflumilast for AD is underway (ClinicalTrial.gov Identifier: NCT04845620); it is already approved for psoriasis in patients 12 years and older. A phase 3 trial of difamilast (NCT03911401) was recently completed, with results supporting the drug’s safety and efficacy in AD management.4 Efforts to synthesize new better-targeted PDE4 inhibitors are ongoing.5

Tapinarof (a novel aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent) is approved for psoriasis in adults, and a phase 3 trial for management of pediatric AD is underway (NCT05032859) after phase 2 trials revealed promising results.6

Lastly, the microbiome is a target for AD topical therapies. A recently completed phase 1 trial of bacteriotherapy with Staphylococcus hominis A9 transplant lotion showed promising results (NCT03151148).7 Although this bacteriotherapy technique is early in development and has been studied only in adult patients, results are exciting because they represent a gateway to a largely unexplored realm of potential future therapies.

Standard of Care—How will these new topical therapies impact our standard of care for pediatric AD patients? Topical corticosteroids are still a pillar of topical AD therapy, but the potential for nonsteroidal topical agents as alternatives and used in combination therapeutic regimens has expanded exponentially. It is uncertain how we might individualize regimens tailored to patient-specific factors because the standard approach has been to test drugs as monotherapy, with vehicle comparisons or with reference medications in Europe.

Newer topical nonsteroidal agents may offer several opportunities. First, they may help avoid local and systemic adverse effects that often limit the use of current standard therapy.8 This capability may prove essential in bridging TC treatments and serving as long-term maintenance therapies to decrease the frequency of eczema flares. Second, they can alleviate the need for different medication strengths for different body regions, thereby allowing for simplification of regimens and potentially increased adherence and decreased disease burden—a boon to affected patients and caregivers.

Although the efficacy and long-term safety profile of these new drugs require further study, it does not seem unreasonable to look forward to achieving levels of optimization and individualization with topical regimens for AD in the near future that makes flares in patients with mild to moderate AD a phenomenon of the past.

Advances in Systemic Therapy

Systemic therapeutics in pediatric AD also recently entered an exciting era of development. Traditional systemic agents, including cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil, have existed for decades but have not been widely utilized for moderate to severe AD in the United States, especially in the pediatric population, likely because these drugs lacked FDA approval and they can cause a range of adverse effects, including notable immunosuppression.9

Introduction and approval of dupilumab in 2017 by the FDA was revolutionary in this field. As a monoclonal antibody targeted against IL-4 and IL-13, dupilumab has consistently demonstrated strong long-term efficacy for pediatric AD and has an acceptable safety profile in children and adolescents.10-14 Expansion of the label to include children as young as 6 months with moderate to severe AD seems an important milestone in pediatric AD care.

Since the approval of dupilumab for adolescents and children aged 6 to 12 years, global experience has supported expanded use of systemic agents for patients who have an inadequate response to TCs and previously approved nonsteroidal topical agents. How expansive the use of systemics will be in younger children depends on how their long-term use impacts the disease course, whether therapy is disease modifying, and whether early use can curb the development of comorbidities.

Investigations into targeted systemic therapeutics for eczematous dermatitis are not limited to dupilumab. In a study of adolescents as young as 12 years, tralokinumab (an IL-13 pathway inhibitor) demonstrated an Eczema Area Severity Index-75 of 27.8% to 28.6% and a mean decrease in the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis index of 27.5 to 29.1, with minimal adverse effects.15 Lebrikizumab, another biologic IL-13 inhibitor with strong published safety and efficacy data in adults, has completed short- and longer-term studies in adolescents (NCT04178967 and NCT04146363).16 The drug received FDA Fast Track designation for moderate to severe AD in patients 12 years and older after showing positive data.17

This push to targeted therapy stretches beyond monoclonal antibodies. In the last few years, oral JAK inhibitors have emerged as a new class of systemic therapy for eczematous dermatitis. Upadacitinib, a JAK1 selective inhibitor, was approved by the FDA in 2022 for patients 12 years and older with AD and has data that supports its efficacy in adolescents and adults.18 Other JAK inhibitors including the selective JAK1 inhibitor abrocitinib and the combined JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib are being studied for pediatric AD (NCT04564755, NCT03422822, and NCT03952559), with most evidence to date supporting their safety and efficacy, at least over the short-term.19

The study of these and other advanced systemic therapies for eczematous dermatitis is transforming the toolbox for pediatric AD care. Although long-term data are lacking for some of these medications, it is possible that newer agents may decrease reliance on older immunosuppressants, such as systemic corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. Unanswered questions include: How and which systemic medications may alter the course of the disease? What is the disease modification for AD? What is the impact on comorbidities over time?

What’s Missing?

The field of pediatric AD has experienced exciting new developments with the emergence of targeted therapeutics, but those new agents require more long-term study, though we already have longer-term data on crisaborole and dupilumab.10-14,20 Studies of the long-term use of these new treatments on comorbidities of pediatric AD—mental health outcomes, cardiovascular disease, effects on the family, and other allergic conditions—are needed.21 Furthermore, clinical guidelines that address indications, timing of use, tapering, and discontinuation of new treatments depend on long-term experience and data collection.

Therefore, it is prudent that investigators, companies, payers, patients, and families support phase 4, long-term extension, and registry studies, which will expand our knowledge of AD medications and their impact on the disease over time.

Final Thoughts

Medications to treat AD are reaching a new level of advancement—from topical agents that target novel pathways to revolutionary biologics and systemic medications. Although there are knowledge gaps on these new therapeutics, the standard of care is already rapidly changing as the expectations of clinicians, patients, and families advance with each addition to the provider’s toolbox.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: part 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-351. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.010

- Kiebert G, Sorensen SV, Revicki D, et al. Atopic dermatitis is associated with a decrement in health-related quality of life. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:151-158. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01436.x

- Al Shobaili HA. The impact of childhood atopic dermatitis on the patients’ family. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:618-623. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01215.x

- Saeki H, Baba N, Ito K, et al. Difamilast, a selective phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, ointment in paediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: a phase III randomized double-blind, vehicle-controlled trial [published online November 1, 2021]. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:40-49. doi:10.1111/bjd.20655

- Chu Z, Xu Q, Zhu Q, et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel benzoxaborole derivatives as potent PDE4 inhibitors for topical treatment of atopic dermatitis. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;213:113171. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113171

- Paller AS, Stein Gold L, Soung J, et al. Efficacy and patient-reported outcomes from a phase 2b, randomized clinical trial of tapinarof cream for the treatment of adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:632-638. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.135

- Nakatsuji T, Hata TR, Tong Y, et al. Development of a human skin commensal microbe for bacteriotherapy of atopic dermatitis and use in a phase 1 randomized clinical trial. Nat Med. 2021;27:700-709. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01256-2

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: part 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.023

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: part 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030

- Gooderham MJ, Hong HC-H, Eshtiaghi P, et al. Dupilumab: a review of its use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3 suppl 1):S28-S36. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.022

- Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:44-56. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336

- Blauvelt A, Guttman-Yassky E, Paller AS, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopicdermatitis: results through week 52 from a phase III open-label extension trial (LIBERTY AD PED-OLE). Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:365-383. doi:10.1007/s40257-022-00683-2

- Cork MJ, D, Eichenfield LF, et al. Dupilumab provides favourable long-term safety and efficacy in children aged ≥ 6 to < 12 years with uncontrolled severe atopic dermatitis: results from an open-label phase IIa study and subsequent phase III open-label extension study. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:857-870. doi:10.1111/bjd.19460

- Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Dupilumab demonstrates rapid and consistent improvement in extent and signs of atopic dermatitis across all anatomical regions in pediatric patients 6 years of age and older. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1643-1656. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00568-y

- Paller A, Blauvelt A, Soong W, et al. Efficacy and safety of tralokinumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results of the phase 3 ECZTRA 6 trial. SKIN. 2022;6:S29. doi:10.25251/skin.6.supp.s29

- Guttman-Yassky E, Blauvelt A, Eichenfield LF, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab, a high-affinity interleukin 13 inhibitor, in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2b randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:411-420. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0079

- Lebrikizumab dosed every four weeks maintained durable skin clearance in Lilly’s phase 3 monotherapy atopic dermatitis trials [news release]. Eli Lilly and Company; September 8, 2022. Accessed October 19, 2022. https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lebrikizumab-dosed-every-four-weeks-maintained-durable-skin

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397:2151-2168. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00588-2

- Chovatiya R, Paller AS. JAK inhibitors in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148:927-940. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2021.08.009

- Geng B, Hebert AA, Takiya L, et al. Efficacy and safety trends with continuous, long-term crisaborole use in patients aged ≥ 2 years with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1667-1678. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00584-y

- Appiah MM, Haft MA, Kleinman E, et al. Atopic dermatitis: review of comorbidities and therapeutics. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;129:142-149. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2022.05.015

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: part 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-351. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.010

- Kiebert G, Sorensen SV, Revicki D, et al. Atopic dermatitis is associated with a decrement in health-related quality of life. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:151-158. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01436.x

- Al Shobaili HA. The impact of childhood atopic dermatitis on the patients’ family. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:618-623. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01215.x

- Saeki H, Baba N, Ito K, et al. Difamilast, a selective phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, ointment in paediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: a phase III randomized double-blind, vehicle-controlled trial [published online November 1, 2021]. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:40-49. doi:10.1111/bjd.20655

- Chu Z, Xu Q, Zhu Q, et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel benzoxaborole derivatives as potent PDE4 inhibitors for topical treatment of atopic dermatitis. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;213:113171. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113171

- Paller AS, Stein Gold L, Soung J, et al. Efficacy and patient-reported outcomes from a phase 2b, randomized clinical trial of tapinarof cream for the treatment of adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:632-638. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.135

- Nakatsuji T, Hata TR, Tong Y, et al. Development of a human skin commensal microbe for bacteriotherapy of atopic dermatitis and use in a phase 1 randomized clinical trial. Nat Med. 2021;27:700-709. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01256-2

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: part 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.023

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: part 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030

- Gooderham MJ, Hong HC-H, Eshtiaghi P, et al. Dupilumab: a review of its use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3 suppl 1):S28-S36. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.022

- Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:44-56. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336

- Blauvelt A, Guttman-Yassky E, Paller AS, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopicdermatitis: results through week 52 from a phase III open-label extension trial (LIBERTY AD PED-OLE). Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:365-383. doi:10.1007/s40257-022-00683-2

- Cork MJ, D, Eichenfield LF, et al. Dupilumab provides favourable long-term safety and efficacy in children aged ≥ 6 to < 12 years with uncontrolled severe atopic dermatitis: results from an open-label phase IIa study and subsequent phase III open-label extension study. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:857-870. doi:10.1111/bjd.19460

- Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Dupilumab demonstrates rapid and consistent improvement in extent and signs of atopic dermatitis across all anatomical regions in pediatric patients 6 years of age and older. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1643-1656. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00568-y

- Paller A, Blauvelt A, Soong W, et al. Efficacy and safety of tralokinumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results of the phase 3 ECZTRA 6 trial. SKIN. 2022;6:S29. doi:10.25251/skin.6.supp.s29

- Guttman-Yassky E, Blauvelt A, Eichenfield LF, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab, a high-affinity interleukin 13 inhibitor, in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2b randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:411-420. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0079

- Lebrikizumab dosed every four weeks maintained durable skin clearance in Lilly’s phase 3 monotherapy atopic dermatitis trials [news release]. Eli Lilly and Company; September 8, 2022. Accessed October 19, 2022. https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lebrikizumab-dosed-every-four-weeks-maintained-durable-skin

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397:2151-2168. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00588-2

- Chovatiya R, Paller AS. JAK inhibitors in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148:927-940. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2021.08.009

- Geng B, Hebert AA, Takiya L, et al. Efficacy and safety trends with continuous, long-term crisaborole use in patients aged ≥ 2 years with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1667-1678. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00584-y

- Appiah MM, Haft MA, Kleinman E, et al. Atopic dermatitis: review of comorbidities and therapeutics. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;129:142-149. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2022.05.015

PRACTICE POINTS

- Pediatric atopic dermatitis (AD) therapeutics have rapidly evolved over the last decade and dermatologists should be aware of new tools in their treatment arsenal.

- New topical nonsteroidal agents serve as useful alternatives to topical corticosteroids through mitigating adverse effects from current standard therapy and potentially simplifying topical regimens.

- Monoclonal antibodies and Janus kinase inhibitors are part of an important set of new systemic therapeutics for pediatric AD.

- Long-term data on these new therapeutics is required to better understand their impact on pediatric AD comorbidities and impact on the longitudinal disease course.

Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica in an Infant

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is a rare disorder of zinc metabolism that typically presents in infancy.1 Although it is clinically characterized by acral and periorificial dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea, only 20% of cases present with this triad.2 Zinc deficiency in AE can either be acquired or inborn (congenital). Acquired forms can occur from dietary inadequacy or malabsorption, whereas genetic causes are related to an autosomal-recessive disorder affecting zinc transporters.1 We report a case of a 3-month-old female infant with acquired AE who was successfully treated with zinc supplementation over the course of 3 weeks.

Case Report

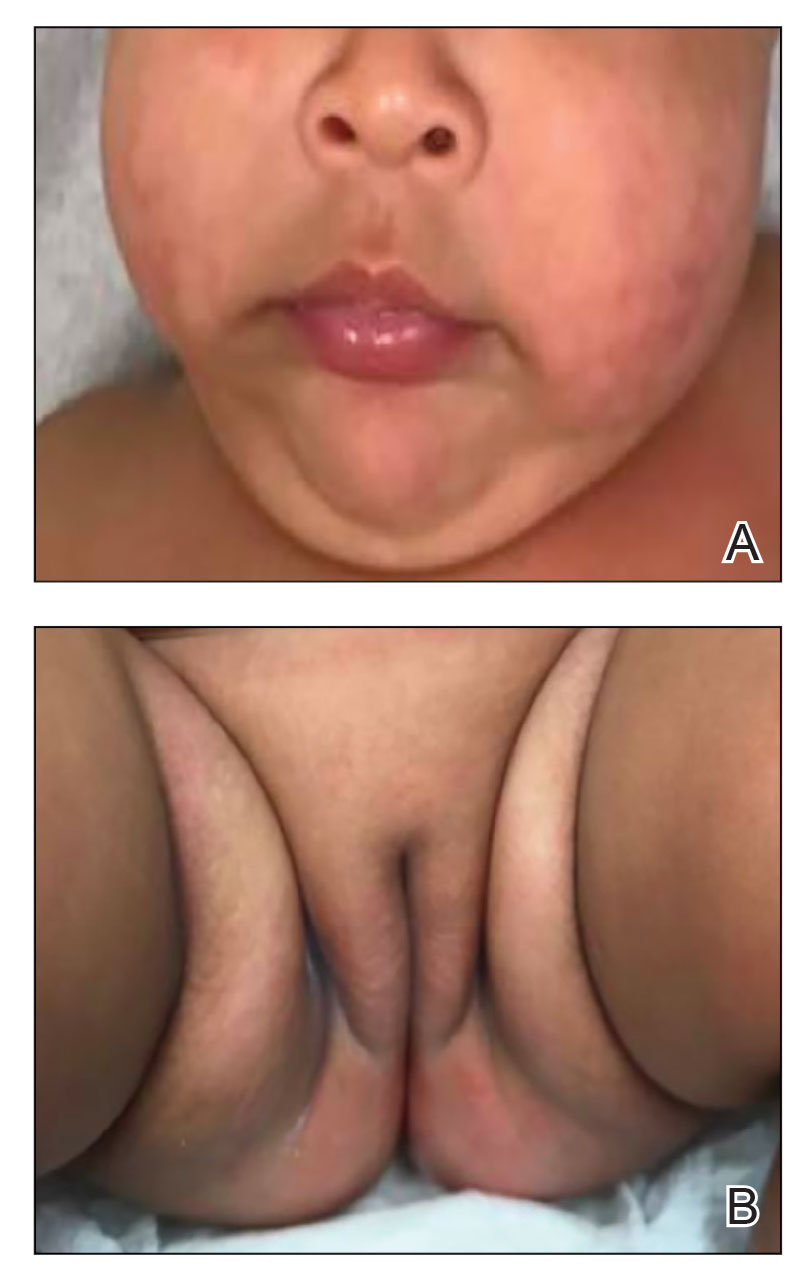

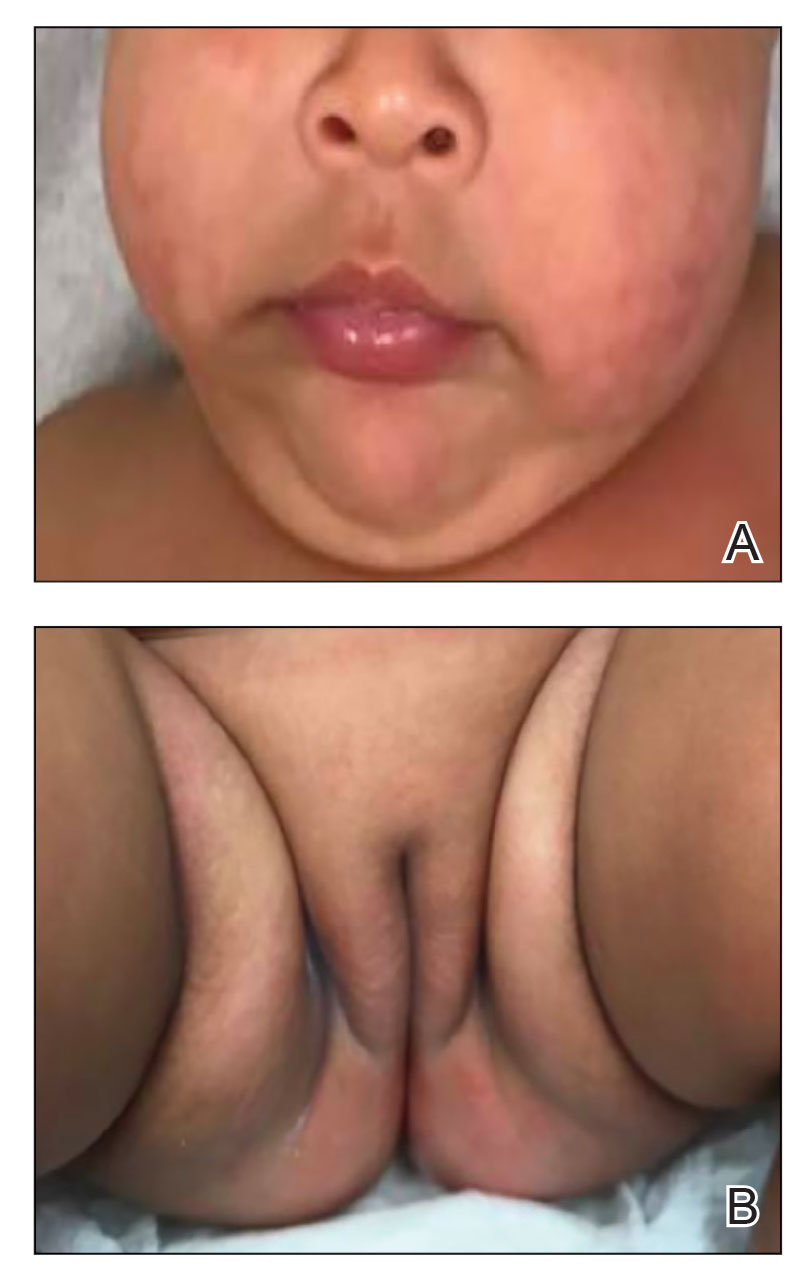

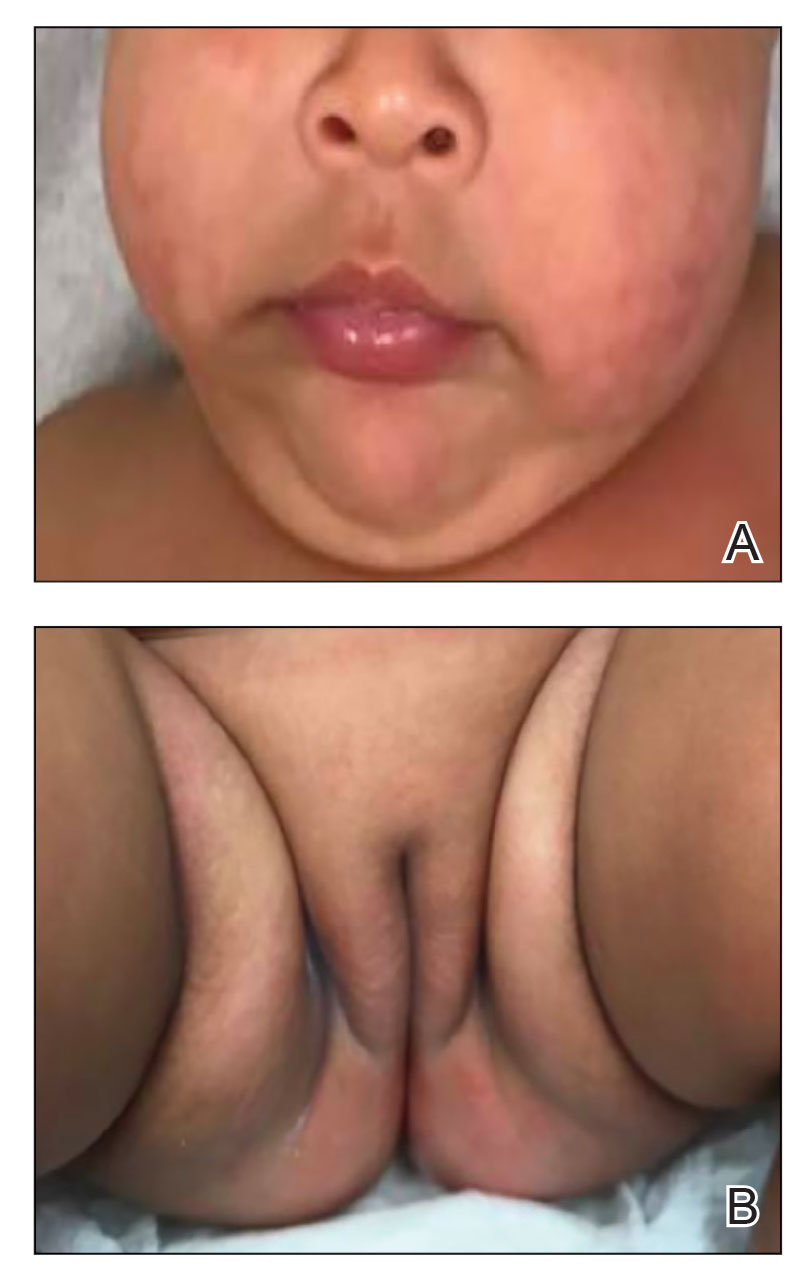

A 3-month-old female infant presented to the emergency department with a rash of 2 weeks’ duration. She was born full term with no birth complications. The patient’s mother reported that the rash started on the cheeks, then enlarged and spread to the neck, back, and perineum. The patient also had been having diarrhea during this time. She previously had received mupirocin and cephalexin with no response to treatment. Maternal history was negative for lupus, and the mother’s diet consisted of a variety of foods but not many vegetables. The patient was exclusively breastfed, and there was no pertinent history of similar rashes occurring in other family members.

Physical examination revealed the patient had annular and polycyclic, hyperkeratotic, crusted papules and plaques on the cheeks, neck, back, and axillae, as well as the perineum/groin and perianal regions (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis at the time included neonatal lupus, zinc deficiency, and syphilis. Relevant laboratory testing and a shave biopsy of the left axilla were obtained.

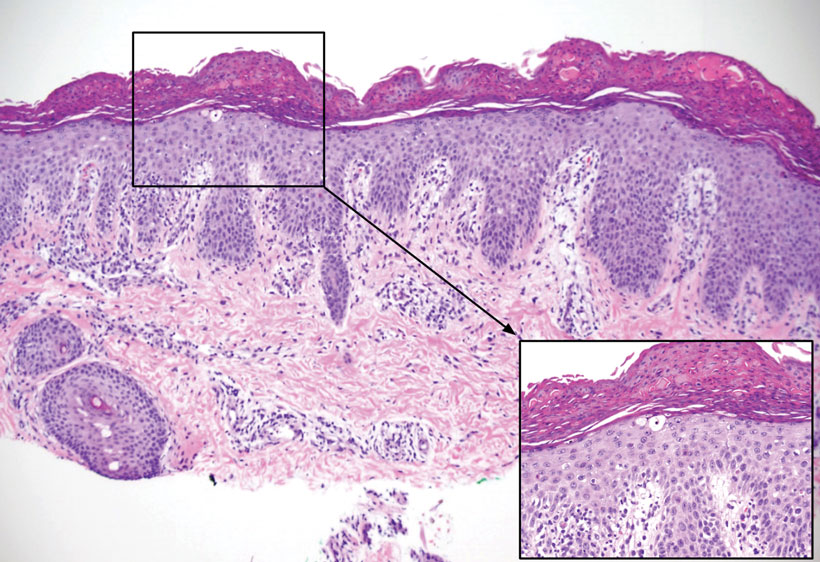

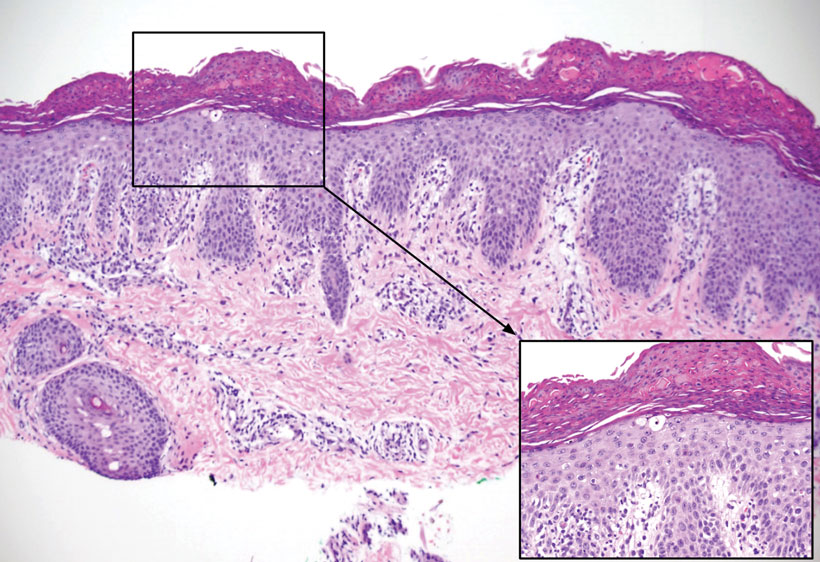

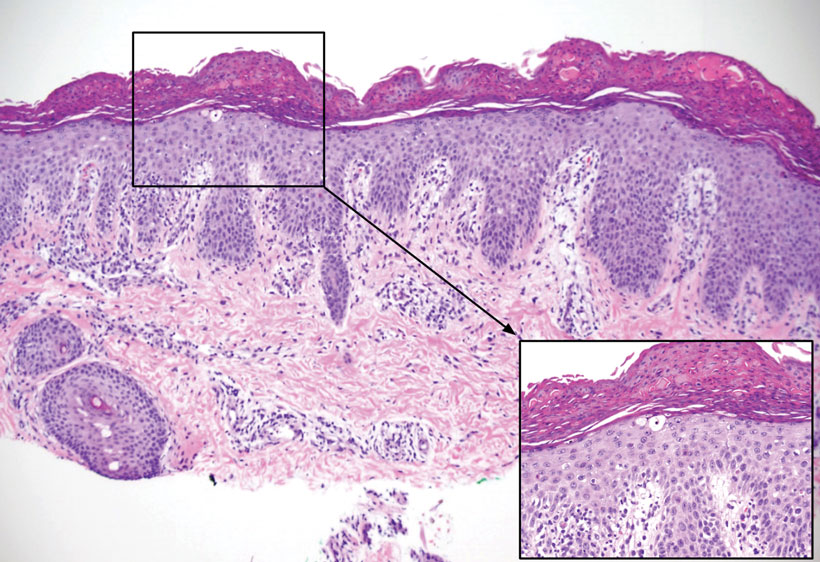

Pertinent laboratory findings included a low zinc level (23 μg/dL [reference range, 26–141 μg/dL]), low alkaline phosphatase level (74 U/L [reference range, 94–486 U/L]), and thrombocytosis (826×109/L [reference range, 150–400×109/L). Results for antinuclear antibody and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A and B antibody testing were negative. A rapid plasma reagin test was nonreactive. Histologic examination revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia with overlying confluent parakeratosis, focal spongiosis, multiple dyskeratotic keratinocytes, and mitotic figures (Figure 2). Ballooning was evident in focal cells in the subcorneal region in addition to an accompanying lymphocytic infiltrate and occasional neutrophils.

The patient was given a 10-mg/mL suspension of elemental zinc and was advised to take 1 mL (10 mg) by mouth twice daily with food. This dosage equated to 3 mg/kg/d. On follow-up 3 weeks later, the skin began to clear (Figure 3). Follow-up laboratory testing showed an increase in zinc (114 μg/dL) and alkaline phosphatase levels (313 U/L). The patient was able to discontinue the zinc supplementation, and follow-up during the next year revealed no recurrence.

Comment

Etiology of AE—Acrodermatitis enteropathica was first identified in 1942 as an acral rash associated with diarrhea3; in 1973, Barnes and Moynahan4 discovered zinc deficiency as a causal agent for these findings. The causes of AE are further subclassified as either an acquired or inborn etiology. Congenital causes commonly are seen in infants within the first few months of life, whereas acquired forms are seen at any age. Acquired forms in infants can occur from failure of the mother to secrete zinc in breast milk, low maternal serum zinc levels, or other reasons causing low nutritional intake. A single mutation in the SLC30A2 gene has been found to markedly reduce zinc concentrations in breast milk, thus causing zinc deficiency in breastfed infants.5 Other acquired forms can be caused by malabsorption, sometimes after surgery such as intestinal bypass or from intravenous nutrition without sufficient zinc.1 The congenital form of AE is an autosomal-recessive disorder occurring from mutations in the SLC39A4 gene located on band 8q24.3. Affected individuals have a decreased ability to absorb zinc in the small intestine because of defects in zinc transporters ZIP and ZnT.6 Based on our patient’s laboratory findings and history, it is believed that the zinc deficiency was acquired, as the condition normalized with repletion and has not required any supplementation in the year of follow-up. In addition, the absence of a pertinent family history supported an acquired diagnosis, which has various etiologies, whereas the congenital form primarily is a genetic disease.

Management—Treatment of AE includes supplementation with oral elemental zinc; however, there are scant evidence-based recommendations on the exact dose of zinc to be given. Generally, the recommended amount is 3 mg/kg/d.8 For individuals with the congenital form of AE, lifelong zinc supplementation is additionally recommended.9 It is important to recognize this presentation because the patient can develop worsening irritability, severe diarrhea, nail dystrophy, hair loss, immune dysfunction, and numerous ophthalmic disorders if left untreated. Acute zinc toxicity due to excess administration is rare, with symptoms of nausea and vomiting occurring with dosages of 50 to 100 mg/d. Additionally, dosages of up to 70 mg twice weekly have been provided without any toxic effect.10 In our case, 3 mg/kg/d of oral zinc supplementation proved to be effective in resolving the patient’s symptoms of acquired zinc deficiency.

Differential Diagnosis—It is important to note that deficiencies of other nutrients may present as an AE-like eruption called acrodermatitis dysmetabolica (AD). Both diseases may present with the triad of dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea; however, AD is associated with inborn errors of metabolism. There have been cases that describe AD in patients with a zinc deficiency in conjunction with a deficiency of branched-chain amino acids.11,12 It is important to consider AD in the differential diagnosis of an AE eruption, especially in the context of a metabolic disorder, as it may affect the treatment plan. One case described the dermatitis of AD as not responding to zinc supplementation alone, while another described improvement after increasing an isoleucine supplementation dose.11,12

Other considerations in the differential diagnoses include AE-like conditions such as biotinidase deficiency, multiple carboxylase deficiency, and essential fatty acid deficiency. An AE-like condition may present with the triad of dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea. However, unlike in true AE, zinc and alkaline phosphatase levels tend to be normal in these conditions. Other features seen in AE-like conditions depend on the underlying cause but often include failure to thrive, neurologic defects, ophthalmic abnormalities, and metabolic abnormalities.13

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/acrodermatitis-enteropathica/

- Perafán-Riveros C, França LFS, Alves ACF, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- Danbolt N. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. Br J Dermatol. 1979;100:37-40.

- Barnes PM, Moynahan EJ. Zinc deficiency in acrodermatitis enteropathica: multiple dietary intolerance treated with synthetic diet. Proc R Soc Med. 1973;66:327-329.

- Lee S, Zhou Y, Gill DL, et al. A genetic variant in SLC30A2 causes breast dysfunction during lactation by inducing ER stress, oxidative stress and epithelial barrier defects. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3542.

- Kaur S, Sangwan A, Sahu P, et al. Clinical variants of acrodermatitis enteropathica and its co-relation with genetics. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2016;17:35-37.

- Dela Rosa KM, James WD. Acrodermatitis enteropathica workup. Medscape. Updated June 4, 2021. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1102575-workup#showall

- Ngan V, Gangakhedkar A, Oakley A. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. DermNet. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/acrodermatitis-enteropathica/

- Ranugha P, Sethi P, Veeranna S. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: the need for sustained high dose zinc supplementation. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1w9002sr.

- Larson CP, Roy SK, Khan AI, et al. Zinc treatment to under-five children: applications to improve child survival and reduce burden of disease. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26:356-365.

- Samady JA, Schwartz RA, Shih LY, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like eruption in an infant with nonketotic hyperglycinemia. J Dermatol. 2000;27:604-608.

- Flores K, Chikowski R, Morrell DS. Acrodermatitis dysmetabolica in an infant with maple syrup urine disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:651-654.

- Jones L, Oakley A. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like conditions. DermNet. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/acrodermatitis-enteropathica-like-conditions

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is a rare disorder of zinc metabolism that typically presents in infancy.1 Although it is clinically characterized by acral and periorificial dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea, only 20% of cases present with this triad.2 Zinc deficiency in AE can either be acquired or inborn (congenital). Acquired forms can occur from dietary inadequacy or malabsorption, whereas genetic causes are related to an autosomal-recessive disorder affecting zinc transporters.1 We report a case of a 3-month-old female infant with acquired AE who was successfully treated with zinc supplementation over the course of 3 weeks.

Case Report

A 3-month-old female infant presented to the emergency department with a rash of 2 weeks’ duration. She was born full term with no birth complications. The patient’s mother reported that the rash started on the cheeks, then enlarged and spread to the neck, back, and perineum. The patient also had been having diarrhea during this time. She previously had received mupirocin and cephalexin with no response to treatment. Maternal history was negative for lupus, and the mother’s diet consisted of a variety of foods but not many vegetables. The patient was exclusively breastfed, and there was no pertinent history of similar rashes occurring in other family members.

Physical examination revealed the patient had annular and polycyclic, hyperkeratotic, crusted papules and plaques on the cheeks, neck, back, and axillae, as well as the perineum/groin and perianal regions (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis at the time included neonatal lupus, zinc deficiency, and syphilis. Relevant laboratory testing and a shave biopsy of the left axilla were obtained.

Pertinent laboratory findings included a low zinc level (23 μg/dL [reference range, 26–141 μg/dL]), low alkaline phosphatase level (74 U/L [reference range, 94–486 U/L]), and thrombocytosis (826×109/L [reference range, 150–400×109/L). Results for antinuclear antibody and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A and B antibody testing were negative. A rapid plasma reagin test was nonreactive. Histologic examination revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia with overlying confluent parakeratosis, focal spongiosis, multiple dyskeratotic keratinocytes, and mitotic figures (Figure 2). Ballooning was evident in focal cells in the subcorneal region in addition to an accompanying lymphocytic infiltrate and occasional neutrophils.

The patient was given a 10-mg/mL suspension of elemental zinc and was advised to take 1 mL (10 mg) by mouth twice daily with food. This dosage equated to 3 mg/kg/d. On follow-up 3 weeks later, the skin began to clear (Figure 3). Follow-up laboratory testing showed an increase in zinc (114 μg/dL) and alkaline phosphatase levels (313 U/L). The patient was able to discontinue the zinc supplementation, and follow-up during the next year revealed no recurrence.

Comment

Etiology of AE—Acrodermatitis enteropathica was first identified in 1942 as an acral rash associated with diarrhea3; in 1973, Barnes and Moynahan4 discovered zinc deficiency as a causal agent for these findings. The causes of AE are further subclassified as either an acquired or inborn etiology. Congenital causes commonly are seen in infants within the first few months of life, whereas acquired forms are seen at any age. Acquired forms in infants can occur from failure of the mother to secrete zinc in breast milk, low maternal serum zinc levels, or other reasons causing low nutritional intake. A single mutation in the SLC30A2 gene has been found to markedly reduce zinc concentrations in breast milk, thus causing zinc deficiency in breastfed infants.5 Other acquired forms can be caused by malabsorption, sometimes after surgery such as intestinal bypass or from intravenous nutrition without sufficient zinc.1 The congenital form of AE is an autosomal-recessive disorder occurring from mutations in the SLC39A4 gene located on band 8q24.3. Affected individuals have a decreased ability to absorb zinc in the small intestine because of defects in zinc transporters ZIP and ZnT.6 Based on our patient’s laboratory findings and history, it is believed that the zinc deficiency was acquired, as the condition normalized with repletion and has not required any supplementation in the year of follow-up. In addition, the absence of a pertinent family history supported an acquired diagnosis, which has various etiologies, whereas the congenital form primarily is a genetic disease.

Management—Treatment of AE includes supplementation with oral elemental zinc; however, there are scant evidence-based recommendations on the exact dose of zinc to be given. Generally, the recommended amount is 3 mg/kg/d.8 For individuals with the congenital form of AE, lifelong zinc supplementation is additionally recommended.9 It is important to recognize this presentation because the patient can develop worsening irritability, severe diarrhea, nail dystrophy, hair loss, immune dysfunction, and numerous ophthalmic disorders if left untreated. Acute zinc toxicity due to excess administration is rare, with symptoms of nausea and vomiting occurring with dosages of 50 to 100 mg/d. Additionally, dosages of up to 70 mg twice weekly have been provided without any toxic effect.10 In our case, 3 mg/kg/d of oral zinc supplementation proved to be effective in resolving the patient’s symptoms of acquired zinc deficiency.

Differential Diagnosis—It is important to note that deficiencies of other nutrients may present as an AE-like eruption called acrodermatitis dysmetabolica (AD). Both diseases may present with the triad of dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea; however, AD is associated with inborn errors of metabolism. There have been cases that describe AD in patients with a zinc deficiency in conjunction with a deficiency of branched-chain amino acids.11,12 It is important to consider AD in the differential diagnosis of an AE eruption, especially in the context of a metabolic disorder, as it may affect the treatment plan. One case described the dermatitis of AD as not responding to zinc supplementation alone, while another described improvement after increasing an isoleucine supplementation dose.11,12

Other considerations in the differential diagnoses include AE-like conditions such as biotinidase deficiency, multiple carboxylase deficiency, and essential fatty acid deficiency. An AE-like condition may present with the triad of dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea. However, unlike in true AE, zinc and alkaline phosphatase levels tend to be normal in these conditions. Other features seen in AE-like conditions depend on the underlying cause but often include failure to thrive, neurologic defects, ophthalmic abnormalities, and metabolic abnormalities.13

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is a rare disorder of zinc metabolism that typically presents in infancy.1 Although it is clinically characterized by acral and periorificial dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea, only 20% of cases present with this triad.2 Zinc deficiency in AE can either be acquired or inborn (congenital). Acquired forms can occur from dietary inadequacy or malabsorption, whereas genetic causes are related to an autosomal-recessive disorder affecting zinc transporters.1 We report a case of a 3-month-old female infant with acquired AE who was successfully treated with zinc supplementation over the course of 3 weeks.

Case Report

A 3-month-old female infant presented to the emergency department with a rash of 2 weeks’ duration. She was born full term with no birth complications. The patient’s mother reported that the rash started on the cheeks, then enlarged and spread to the neck, back, and perineum. The patient also had been having diarrhea during this time. She previously had received mupirocin and cephalexin with no response to treatment. Maternal history was negative for lupus, and the mother’s diet consisted of a variety of foods but not many vegetables. The patient was exclusively breastfed, and there was no pertinent history of similar rashes occurring in other family members.

Physical examination revealed the patient had annular and polycyclic, hyperkeratotic, crusted papules and plaques on the cheeks, neck, back, and axillae, as well as the perineum/groin and perianal regions (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis at the time included neonatal lupus, zinc deficiency, and syphilis. Relevant laboratory testing and a shave biopsy of the left axilla were obtained.

Pertinent laboratory findings included a low zinc level (23 μg/dL [reference range, 26–141 μg/dL]), low alkaline phosphatase level (74 U/L [reference range, 94–486 U/L]), and thrombocytosis (826×109/L [reference range, 150–400×109/L). Results for antinuclear antibody and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A and B antibody testing were negative. A rapid plasma reagin test was nonreactive. Histologic examination revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia with overlying confluent parakeratosis, focal spongiosis, multiple dyskeratotic keratinocytes, and mitotic figures (Figure 2). Ballooning was evident in focal cells in the subcorneal region in addition to an accompanying lymphocytic infiltrate and occasional neutrophils.

The patient was given a 10-mg/mL suspension of elemental zinc and was advised to take 1 mL (10 mg) by mouth twice daily with food. This dosage equated to 3 mg/kg/d. On follow-up 3 weeks later, the skin began to clear (Figure 3). Follow-up laboratory testing showed an increase in zinc (114 μg/dL) and alkaline phosphatase levels (313 U/L). The patient was able to discontinue the zinc supplementation, and follow-up during the next year revealed no recurrence.

Comment

Etiology of AE—Acrodermatitis enteropathica was first identified in 1942 as an acral rash associated with diarrhea3; in 1973, Barnes and Moynahan4 discovered zinc deficiency as a causal agent for these findings. The causes of AE are further subclassified as either an acquired or inborn etiology. Congenital causes commonly are seen in infants within the first few months of life, whereas acquired forms are seen at any age. Acquired forms in infants can occur from failure of the mother to secrete zinc in breast milk, low maternal serum zinc levels, or other reasons causing low nutritional intake. A single mutation in the SLC30A2 gene has been found to markedly reduce zinc concentrations in breast milk, thus causing zinc deficiency in breastfed infants.5 Other acquired forms can be caused by malabsorption, sometimes after surgery such as intestinal bypass or from intravenous nutrition without sufficient zinc.1 The congenital form of AE is an autosomal-recessive disorder occurring from mutations in the SLC39A4 gene located on band 8q24.3. Affected individuals have a decreased ability to absorb zinc in the small intestine because of defects in zinc transporters ZIP and ZnT.6 Based on our patient’s laboratory findings and history, it is believed that the zinc deficiency was acquired, as the condition normalized with repletion and has not required any supplementation in the year of follow-up. In addition, the absence of a pertinent family history supported an acquired diagnosis, which has various etiologies, whereas the congenital form primarily is a genetic disease.

Management—Treatment of AE includes supplementation with oral elemental zinc; however, there are scant evidence-based recommendations on the exact dose of zinc to be given. Generally, the recommended amount is 3 mg/kg/d.8 For individuals with the congenital form of AE, lifelong zinc supplementation is additionally recommended.9 It is important to recognize this presentation because the patient can develop worsening irritability, severe diarrhea, nail dystrophy, hair loss, immune dysfunction, and numerous ophthalmic disorders if left untreated. Acute zinc toxicity due to excess administration is rare, with symptoms of nausea and vomiting occurring with dosages of 50 to 100 mg/d. Additionally, dosages of up to 70 mg twice weekly have been provided without any toxic effect.10 In our case, 3 mg/kg/d of oral zinc supplementation proved to be effective in resolving the patient’s symptoms of acquired zinc deficiency.

Differential Diagnosis—It is important to note that deficiencies of other nutrients may present as an AE-like eruption called acrodermatitis dysmetabolica (AD). Both diseases may present with the triad of dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea; however, AD is associated with inborn errors of metabolism. There have been cases that describe AD in patients with a zinc deficiency in conjunction with a deficiency of branched-chain amino acids.11,12 It is important to consider AD in the differential diagnosis of an AE eruption, especially in the context of a metabolic disorder, as it may affect the treatment plan. One case described the dermatitis of AD as not responding to zinc supplementation alone, while another described improvement after increasing an isoleucine supplementation dose.11,12

Other considerations in the differential diagnoses include AE-like conditions such as biotinidase deficiency, multiple carboxylase deficiency, and essential fatty acid deficiency. An AE-like condition may present with the triad of dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea. However, unlike in true AE, zinc and alkaline phosphatase levels tend to be normal in these conditions. Other features seen in AE-like conditions depend on the underlying cause but often include failure to thrive, neurologic defects, ophthalmic abnormalities, and metabolic abnormalities.13

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/acrodermatitis-enteropathica/

- Perafán-Riveros C, França LFS, Alves ACF, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- Danbolt N. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. Br J Dermatol. 1979;100:37-40.

- Barnes PM, Moynahan EJ. Zinc deficiency in acrodermatitis enteropathica: multiple dietary intolerance treated with synthetic diet. Proc R Soc Med. 1973;66:327-329.

- Lee S, Zhou Y, Gill DL, et al. A genetic variant in SLC30A2 causes breast dysfunction during lactation by inducing ER stress, oxidative stress and epithelial barrier defects. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3542.

- Kaur S, Sangwan A, Sahu P, et al. Clinical variants of acrodermatitis enteropathica and its co-relation with genetics. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2016;17:35-37.

- Dela Rosa KM, James WD. Acrodermatitis enteropathica workup. Medscape. Updated June 4, 2021. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1102575-workup#showall

- Ngan V, Gangakhedkar A, Oakley A. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. DermNet. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/acrodermatitis-enteropathica/

- Ranugha P, Sethi P, Veeranna S. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: the need for sustained high dose zinc supplementation. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1w9002sr.

- Larson CP, Roy SK, Khan AI, et al. Zinc treatment to under-five children: applications to improve child survival and reduce burden of disease. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26:356-365.

- Samady JA, Schwartz RA, Shih LY, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like eruption in an infant with nonketotic hyperglycinemia. J Dermatol. 2000;27:604-608.

- Flores K, Chikowski R, Morrell DS. Acrodermatitis dysmetabolica in an infant with maple syrup urine disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:651-654.

- Jones L, Oakley A. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like conditions. DermNet. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/acrodermatitis-enteropathica-like-conditions

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/acrodermatitis-enteropathica/

- Perafán-Riveros C, França LFS, Alves ACF, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- Danbolt N. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. Br J Dermatol. 1979;100:37-40.

- Barnes PM, Moynahan EJ. Zinc deficiency in acrodermatitis enteropathica: multiple dietary intolerance treated with synthetic diet. Proc R Soc Med. 1973;66:327-329.

- Lee S, Zhou Y, Gill DL, et al. A genetic variant in SLC30A2 causes breast dysfunction during lactation by inducing ER stress, oxidative stress and epithelial barrier defects. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3542.

- Kaur S, Sangwan A, Sahu P, et al. Clinical variants of acrodermatitis enteropathica and its co-relation with genetics. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2016;17:35-37.

- Dela Rosa KM, James WD. Acrodermatitis enteropathica workup. Medscape. Updated June 4, 2021. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1102575-workup#showall

- Ngan V, Gangakhedkar A, Oakley A. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. DermNet. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/acrodermatitis-enteropathica/

- Ranugha P, Sethi P, Veeranna S. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: the need for sustained high dose zinc supplementation. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1w9002sr.

- Larson CP, Roy SK, Khan AI, et al. Zinc treatment to under-five children: applications to improve child survival and reduce burden of disease. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26:356-365.

- Samady JA, Schwartz RA, Shih LY, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like eruption in an infant with nonketotic hyperglycinemia. J Dermatol. 2000;27:604-608.

- Flores K, Chikowski R, Morrell DS. Acrodermatitis dysmetabolica in an infant with maple syrup urine disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:651-654.

- Jones L, Oakley A. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like conditions. DermNet. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/acrodermatitis-enteropathica-like-conditions

Practice Points

- Although clinically characterized by the triad of acral and periorificial dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea, most cases of acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) present with only partial features of this syndrome.

- Low levels of zinc-dependent enzymes such as alkaline phosphatase may support the diagnosis of AE.

Update on Tinea Capitis Diagnosis and Treatment

Tinea capitis (TC) most often is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis. The peak incidence is between 3 and 7 years of age. Noninflammatory TC typically presents as fine scaling with single or multiple scaly patches of circular alopecia (grey patches); diffuse or patchy, fine, white, adherent scaling of the scalp resembling generalized dandruff with subtle hair loss; or single or multiple patches of well-demarcated areas of alopecia with fine scale studded with broken-off hairs at the scalp surface, resulting in a black dot appearance. Inflammatory variants of TC include kerion and favus.1 Herein, updates on diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of TC are provided, as well as a discussion of changes in the fungal microbiome associated with TC. Lastly, insights to some queries that practitioners may encounter when treating children with TC are provided.

Genetic Susceptibility

Molecular techniques have identified a number of macrophage regulator, leukocyte activation and migration, and cutaneous permeability genes associated with susceptibility to TC. These findings indicate that genetically determined deficiency in adaptive immune responses may affect the predisposition to dermatophyte infections.2

Clinical Varieties of Infection

Dermatophytes causing ringworm are capable of invading the hair shafts and can simultaneously invade smooth or glabrous skin (eg, T tonsurans, Trichophyton schoenleinii, Trichophyton violaceum). Some causative dermatophytes can even penetrate the nails (eg, Trichophyton soudanense). The clinical presentation is dependent on 3 main patterns of hair invasion3:

• Ectothrix: A mid-follicular pattern of invasion with hyphae growing down to the hair bulb that commonly is caused by Microsporum species. It clinically presents with scaling and inflammation with hair shafts breaking 2 to 3 mm above the scalp level.

• Endothrix: This pattern is nonfluorescent on Wood lamp examination, and hairs often break at the scalp level (black dot type). Trichophyton tonsurans, T soudanense, Trichophyton rubrum, and T violaceum are common causes.

• Favus: In this pattern, T schoenleinii is a common cause, and hairs grow to considerable lengths above the scalp with less damage than the other patterns. The hair shafts present with characteristic air spaces, and hyphae form clusters at the level of the epidermis.

Diagnosis

Optimal treatment of TC relies on proper identification of the causative agent. Fungal culture remains the gold standard of mycologic diagnosis regardless of its delayed results, which may take up to 4 weeks for proper identification of the fungal colonies and require ample expertise to interpret the morphologic features of the grown colonies.4

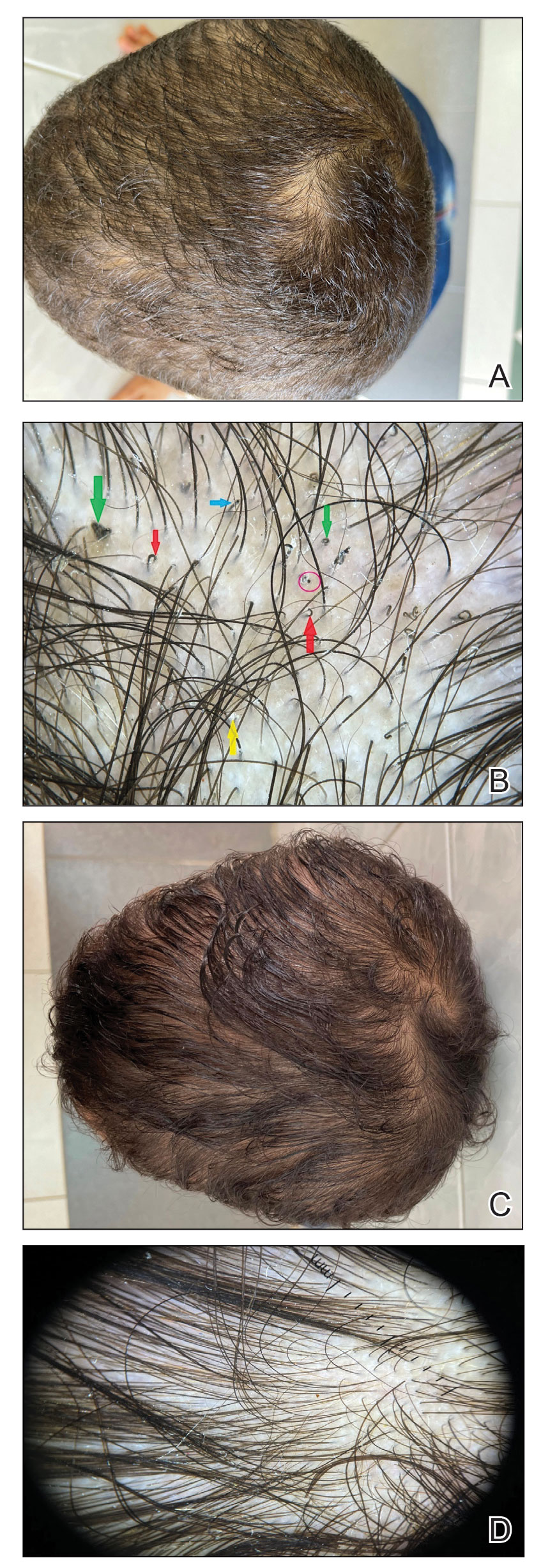

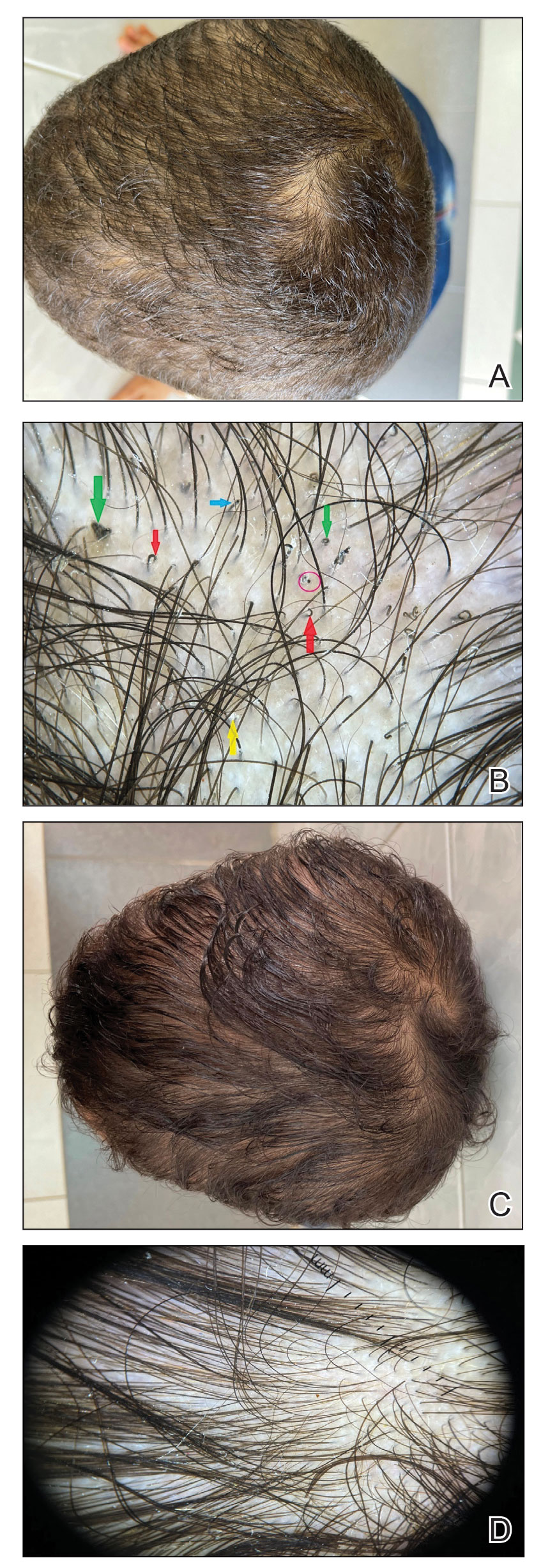

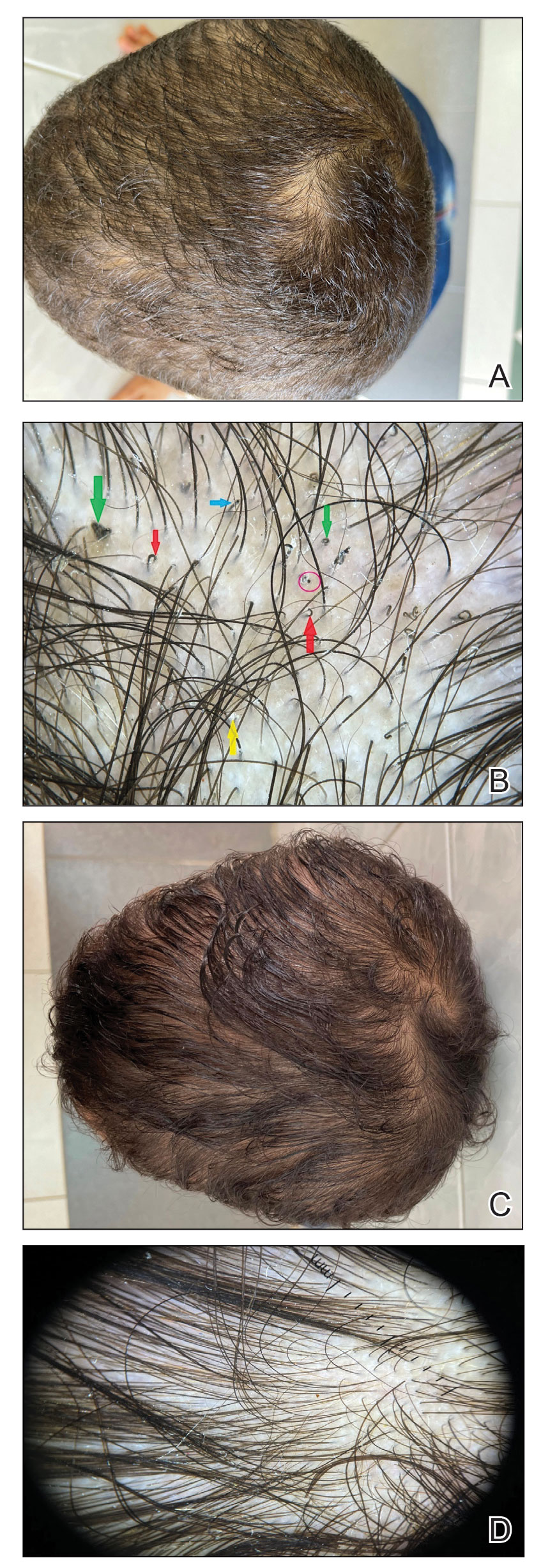

Other tests such as the potassium hydroxide preparation are nonspecific and do not identify the dermatophyte species. Although this method has been reported to have 5% to 15% false-negative results in routine practice depending on the skill of the observer and the quality of sampling, microscopic examination is essential, as it may allow the clinician to start treatment sooner pending culture results. The use of a Wood lamp is not suitable for definitive species identification, as this technique primarily is useful for observing fluorescence in ectothrix infection caused by Microsporum species, with the exception of T schoenleinii; otherwise, Trichophyton species, which cause endothrix infections, do not fluoresce.5Polymerase chain reaction is a sensitive technique that can help identify both the genus and species of common dermatophytes. Common target sequences include the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer and translation elongation factor 1α. The use of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry also has become popular for dermatophyte identification.6Trichoscopic diagnosis of TC, which is simple and noninvasive, is becoming increasingly popular. Features such as short, broken, black dot, comma, corkscrew, and/or zigzag hairs, as well as perifollicular scaling, are helpful for diagnosing TC (Figure). Moreover, trichoscopy can be useful for differentiating other common causes of hair loss, such as trichotillomania and alopecia areata. It had been reported that the trichoscopic features of TC can be seen as early as 2 weeks after starting treatment and therefore this can be a reliable period in which to follow-up with the patient to evaluate progress. The disappearance of black dots and comma hairs can be appreciated from 2 weeks onwards by trichoscopic evaluation.4

Treatment

The common recommendation for first-line treatment of TC is the use of systemic antifungals with the use of a topical agent as an adjuvant to prevent the spread of fungal spores. For almost 6 decades, griseofulvin had been the gold-standard fungistatic used for treating TC in patients older than 2 years until the 2007 US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of terbinafine fungicidal oral granules for treatment of TC in patients older than 4 years.7

Meta-analyses have demonstrated comparable efficacy for a 4-week course of terbinafine compared to 6 weeks of griseofulvin for TC based on the infectious organism. Terbinafine demonstrated superiority in treating T tonsurans and a similar efficacy in treating T violaceum, while griseofulvin was superior in treating M canis and other Microsporum species.8,9

The off-label use of fluconazole and itraconazole to treat TC is gaining popularity, with limited trials showing increased evidence of their effectiveness. There is not much clinical evidence to support the use of other oral antifungals, including the newer azoles such as voriconazole or posaconazole.9

Newer limited evidence has shown the off-label use of photodynamic therapy to be a promising alternative to systemic antifungal therapy in treating TC, pending validation by larger sample trials.10In my practice, I have found that severe cases of TC demonstrating inflammation or possible widespread id reactions are better treated with oral steroids. Ketoconazole shampoo or selenium sulfide used 2 to 3 times weekly to prevent spread in the early phases of therapy is a good adjunct to systemic treatment. Cases with kerions should be assessed for the possibility of a coexisting bacterial infection under the crusts, and if confirmed, antibiotics should be started.9The commonly used systemic antifungals generally are safe with a low side-effect profile, but there is a risk for hepatotoxicity. The FDA recommends that baseline alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase levels should be obtained prior to beginning a terbinafine-based treatment regimen.11 The American Academy of Pediatrics has specifically stated that laboratory testing of serum hepatic enzymes is not a requirement if a griseofulvin-based regimen does not exceed 8 weeks; however, transaminase levels (alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase) should be considered in patients using terbinafine at baseline or if treatment is prolonged beyond 4 to 6 weeks.12 In agreement with the FDA guidelines, the Canadian Pediatric Society has suggested that liver enzymes should be periodically monitored in patients being treated with terbinafine beyond 4 to 6 weeks.13

Changes in the Fungal Microbiome

Research has shown that changes in the fungal microbiome were associated with an altered bacterial community in patients with TC. During fungal infection, the relative abundances of Cutibacterium and Corynebacterium increased, and the relative abundance of Streptococcus decreased. In addition, some uncommon bacterial genera such as Herbaspirillum and Methylorubrum were detected on the scalp in TC.14

Carrier State