User login

Pediatric celiac disease incidence varies across U.S., Europe

, according to a new report.

The overall high incidence among pediatric patients warrants a low threshold for screening and additional research on region-specific celiac disease triggers, the authors write.

“Determining the true incidence of celiac disease (CD) is not possible without nonbiased screening for the disease. This is because many cases occur with neither a family history nor with classic symptoms,” write Edwin Liu, MD, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Children’s Hospital Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and director of the Colorado Center for Celiac Disease, and colleagues.

“Individuals may have celiac disease autoimmunity without having CD if they have transient or fluctuating antibody levels, low antibody levels without biopsy evaluation, dietary modification influencing further evaluation, or potential celiac disease,” they write.

The study was published online in The American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Celiac disease incidence

The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study prospectively follows children born between 2004 and 2010 who are at genetic risk for both type 1 diabetes and CD at six clinical sites in four countries: the United States, Finland, Germany, and Sweden. In the United States, patients are enrolled in Colorado, Georgia, and Washington.

As part of TEDDY, children are longitudinally monitored for celiac disease autoimmunity (CDA) by assessment of autoantibodies to tissue transglutaminase (tTGA). The protocol is designed to analyze the development of persistent tTGA positivity, CDA, and subsequent CD. The study population contains various DQ2.5 and DQ8.1 combinations, which represent the highest-risk human leukocyte antigen (HLA) DQ haplogentotypes for CD.

From September 2004 through February 2010, more than 424,000 newborns were screened for specific HLA haplogenotypes, and 8,676 children were enrolled in TEDDY at the six clinical sites. The eligible haplogenotypes included DQ2.5/DQ2.5, DQ2.5/DQ8.1, DQ8.1/DQ8.1, and DQ8.1/DQ4.2.

Blood samples were obtained and stored every 3 months until age 48 months and at least every 6 months after that. At age 2, participants were screened annually for tTGA. With the first tTGA-positive result, all prior collected samples from the patient were tested for tTGA to determine the earliest time point of autoimmunity.

CDA, a primary study outcome, was defined as positivity in two consecutive tTGA tests at least 3 months apart.

In seropositive children, CD was defined on the basis of a duodenal biopsy with a Marsh score of 2 or higher. The decision to perform a biopsy was determined by the clinical gastroenterologist and was outside of the study protocol. When a biopsy wasn’t performed, participants with an average tTGA of 100 units or greater from two positive tests were considered to have CD for the study purposes.

As of July 2020, among the children who had undergone one or more tTGA tests, 6,628 HLA-typed eligible children were found to carry the DQ2.5, the D8.1, or both haplogenotypes and were included in the analysis. The median follow-up period was 11.5 years.

Overall, 580 children (9%) had a first-degree relative with type 1 diabetes, and 317 children (5%) reported a first-degree relative with CD.

Among the 6,628 children, 1,299 (20%) met the CDA outcome, and 529 (8%) met the study diagnostic criteria for CD on the basis of biopsy or persistently high tTGA levels. The median age at CDA across all sites was 41 months. Most children with CDA were asymptomatic.

Overall, the 10-year cumulative incidence was highest in Sweden, at 8.4% for CDA and 3% for CD. Within the United States, Colorado had the highest cumulative incidence for both endpoints, at 6.5% for CDA and 2.4% for CD. Washington had the lowest incidence across all sites, at 4.6% for CDA and 0.9% for CD.

“CDA and CD risk varied substantially by haplogenotype and by clinical center, but the relative risk by region was preserved regardless of the haplogenotype,” the authors write. “For example, the disease burden for each region remained highest in Sweden and lowest in Washington state for all haplogenotypes.”

Site-specific risks

In the HLA, sex, and family-adjusted model, Colorado children had a 2.5-fold higher risk of CD, compared with Washington children. Likewise, Swedish children had a 1.8-fold higher risk of CD than children in Germany, a 1.7-fold higher than children in the United States, and a 1.4-fold higher risk than children in Finland.

Among DQ2.5 participants, Sweden demonstrated the highest risk, with 63.1% of patients developing CDA by age 10 and 28.3% developing CD by age 10. Finland consistently had a higher incidence of CDA than Colorado, at 60.4% versus 50.9%, for DQ2.5 participants but a lower incidence of CD than Colorado, at 20.3% versus 22.6%.

The research team performed a post hoc sensitivity analysis using a lower tTGA cutoff to reduce bias in site differences for biopsy referral and to increase sensitivity of the CD definition for incidence estimation. When the tTGA cutoff was lowered to an average two-visit tTGA of 67.4 or higher, more children met the serologic criteria for CD.

“Even with this lower cutoff, the differences in the risk of CD between clinical sites and countries were still observed with statistical significance,” the authors write. “This indicates that the regional differences in CD incidence could not be solely attributed to detection biases posed by differential biopsy rates.”

Multiple environmental factors likely account for the differences in autoimmunity among regions, the authors write. These variables include diet, chemical exposures, vaccination patterns, early-life gastrointestinal infections, and interactions among these factors. For instance, the Swedish site has the lowest rotavirus vaccination rates and the highest median gluten intake among the TEDDY sites.

Future prospective studies should capture environmental, genetic, and epigenetic exposures to assess causal pathways and plan for preventive strategies, the authors write. The TEDDY study is pursuing this research.

“From a policy standpoint, this informs future screening practices and supports efforts toward mass screening, at least in some areas,” the authors write. “In the clinical setting, this points to the importance for clinicians to have a low threshold for CD screening in the appropriate clinical setting.”

The TEDDY study is funded by several grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a new report.

The overall high incidence among pediatric patients warrants a low threshold for screening and additional research on region-specific celiac disease triggers, the authors write.

“Determining the true incidence of celiac disease (CD) is not possible without nonbiased screening for the disease. This is because many cases occur with neither a family history nor with classic symptoms,” write Edwin Liu, MD, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Children’s Hospital Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and director of the Colorado Center for Celiac Disease, and colleagues.

“Individuals may have celiac disease autoimmunity without having CD if they have transient or fluctuating antibody levels, low antibody levels without biopsy evaluation, dietary modification influencing further evaluation, or potential celiac disease,” they write.

The study was published online in The American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Celiac disease incidence

The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study prospectively follows children born between 2004 and 2010 who are at genetic risk for both type 1 diabetes and CD at six clinical sites in four countries: the United States, Finland, Germany, and Sweden. In the United States, patients are enrolled in Colorado, Georgia, and Washington.

As part of TEDDY, children are longitudinally monitored for celiac disease autoimmunity (CDA) by assessment of autoantibodies to tissue transglutaminase (tTGA). The protocol is designed to analyze the development of persistent tTGA positivity, CDA, and subsequent CD. The study population contains various DQ2.5 and DQ8.1 combinations, which represent the highest-risk human leukocyte antigen (HLA) DQ haplogentotypes for CD.

From September 2004 through February 2010, more than 424,000 newborns were screened for specific HLA haplogenotypes, and 8,676 children were enrolled in TEDDY at the six clinical sites. The eligible haplogenotypes included DQ2.5/DQ2.5, DQ2.5/DQ8.1, DQ8.1/DQ8.1, and DQ8.1/DQ4.2.

Blood samples were obtained and stored every 3 months until age 48 months and at least every 6 months after that. At age 2, participants were screened annually for tTGA. With the first tTGA-positive result, all prior collected samples from the patient were tested for tTGA to determine the earliest time point of autoimmunity.

CDA, a primary study outcome, was defined as positivity in two consecutive tTGA tests at least 3 months apart.

In seropositive children, CD was defined on the basis of a duodenal biopsy with a Marsh score of 2 or higher. The decision to perform a biopsy was determined by the clinical gastroenterologist and was outside of the study protocol. When a biopsy wasn’t performed, participants with an average tTGA of 100 units or greater from two positive tests were considered to have CD for the study purposes.

As of July 2020, among the children who had undergone one or more tTGA tests, 6,628 HLA-typed eligible children were found to carry the DQ2.5, the D8.1, or both haplogenotypes and were included in the analysis. The median follow-up period was 11.5 years.

Overall, 580 children (9%) had a first-degree relative with type 1 diabetes, and 317 children (5%) reported a first-degree relative with CD.

Among the 6,628 children, 1,299 (20%) met the CDA outcome, and 529 (8%) met the study diagnostic criteria for CD on the basis of biopsy or persistently high tTGA levels. The median age at CDA across all sites was 41 months. Most children with CDA were asymptomatic.

Overall, the 10-year cumulative incidence was highest in Sweden, at 8.4% for CDA and 3% for CD. Within the United States, Colorado had the highest cumulative incidence for both endpoints, at 6.5% for CDA and 2.4% for CD. Washington had the lowest incidence across all sites, at 4.6% for CDA and 0.9% for CD.

“CDA and CD risk varied substantially by haplogenotype and by clinical center, but the relative risk by region was preserved regardless of the haplogenotype,” the authors write. “For example, the disease burden for each region remained highest in Sweden and lowest in Washington state for all haplogenotypes.”

Site-specific risks

In the HLA, sex, and family-adjusted model, Colorado children had a 2.5-fold higher risk of CD, compared with Washington children. Likewise, Swedish children had a 1.8-fold higher risk of CD than children in Germany, a 1.7-fold higher than children in the United States, and a 1.4-fold higher risk than children in Finland.

Among DQ2.5 participants, Sweden demonstrated the highest risk, with 63.1% of patients developing CDA by age 10 and 28.3% developing CD by age 10. Finland consistently had a higher incidence of CDA than Colorado, at 60.4% versus 50.9%, for DQ2.5 participants but a lower incidence of CD than Colorado, at 20.3% versus 22.6%.

The research team performed a post hoc sensitivity analysis using a lower tTGA cutoff to reduce bias in site differences for biopsy referral and to increase sensitivity of the CD definition for incidence estimation. When the tTGA cutoff was lowered to an average two-visit tTGA of 67.4 or higher, more children met the serologic criteria for CD.

“Even with this lower cutoff, the differences in the risk of CD between clinical sites and countries were still observed with statistical significance,” the authors write. “This indicates that the regional differences in CD incidence could not be solely attributed to detection biases posed by differential biopsy rates.”

Multiple environmental factors likely account for the differences in autoimmunity among regions, the authors write. These variables include diet, chemical exposures, vaccination patterns, early-life gastrointestinal infections, and interactions among these factors. For instance, the Swedish site has the lowest rotavirus vaccination rates and the highest median gluten intake among the TEDDY sites.

Future prospective studies should capture environmental, genetic, and epigenetic exposures to assess causal pathways and plan for preventive strategies, the authors write. The TEDDY study is pursuing this research.

“From a policy standpoint, this informs future screening practices and supports efforts toward mass screening, at least in some areas,” the authors write. “In the clinical setting, this points to the importance for clinicians to have a low threshold for CD screening in the appropriate clinical setting.”

The TEDDY study is funded by several grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a new report.

The overall high incidence among pediatric patients warrants a low threshold for screening and additional research on region-specific celiac disease triggers, the authors write.

“Determining the true incidence of celiac disease (CD) is not possible without nonbiased screening for the disease. This is because many cases occur with neither a family history nor with classic symptoms,” write Edwin Liu, MD, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Children’s Hospital Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and director of the Colorado Center for Celiac Disease, and colleagues.

“Individuals may have celiac disease autoimmunity without having CD if they have transient or fluctuating antibody levels, low antibody levels without biopsy evaluation, dietary modification influencing further evaluation, or potential celiac disease,” they write.

The study was published online in The American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Celiac disease incidence

The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study prospectively follows children born between 2004 and 2010 who are at genetic risk for both type 1 diabetes and CD at six clinical sites in four countries: the United States, Finland, Germany, and Sweden. In the United States, patients are enrolled in Colorado, Georgia, and Washington.

As part of TEDDY, children are longitudinally monitored for celiac disease autoimmunity (CDA) by assessment of autoantibodies to tissue transglutaminase (tTGA). The protocol is designed to analyze the development of persistent tTGA positivity, CDA, and subsequent CD. The study population contains various DQ2.5 and DQ8.1 combinations, which represent the highest-risk human leukocyte antigen (HLA) DQ haplogentotypes for CD.

From September 2004 through February 2010, more than 424,000 newborns were screened for specific HLA haplogenotypes, and 8,676 children were enrolled in TEDDY at the six clinical sites. The eligible haplogenotypes included DQ2.5/DQ2.5, DQ2.5/DQ8.1, DQ8.1/DQ8.1, and DQ8.1/DQ4.2.

Blood samples were obtained and stored every 3 months until age 48 months and at least every 6 months after that. At age 2, participants were screened annually for tTGA. With the first tTGA-positive result, all prior collected samples from the patient were tested for tTGA to determine the earliest time point of autoimmunity.

CDA, a primary study outcome, was defined as positivity in two consecutive tTGA tests at least 3 months apart.

In seropositive children, CD was defined on the basis of a duodenal biopsy with a Marsh score of 2 or higher. The decision to perform a biopsy was determined by the clinical gastroenterologist and was outside of the study protocol. When a biopsy wasn’t performed, participants with an average tTGA of 100 units or greater from two positive tests were considered to have CD for the study purposes.

As of July 2020, among the children who had undergone one or more tTGA tests, 6,628 HLA-typed eligible children were found to carry the DQ2.5, the D8.1, or both haplogenotypes and were included in the analysis. The median follow-up period was 11.5 years.

Overall, 580 children (9%) had a first-degree relative with type 1 diabetes, and 317 children (5%) reported a first-degree relative with CD.

Among the 6,628 children, 1,299 (20%) met the CDA outcome, and 529 (8%) met the study diagnostic criteria for CD on the basis of biopsy or persistently high tTGA levels. The median age at CDA across all sites was 41 months. Most children with CDA were asymptomatic.

Overall, the 10-year cumulative incidence was highest in Sweden, at 8.4% for CDA and 3% for CD. Within the United States, Colorado had the highest cumulative incidence for both endpoints, at 6.5% for CDA and 2.4% for CD. Washington had the lowest incidence across all sites, at 4.6% for CDA and 0.9% for CD.

“CDA and CD risk varied substantially by haplogenotype and by clinical center, but the relative risk by region was preserved regardless of the haplogenotype,” the authors write. “For example, the disease burden for each region remained highest in Sweden and lowest in Washington state for all haplogenotypes.”

Site-specific risks

In the HLA, sex, and family-adjusted model, Colorado children had a 2.5-fold higher risk of CD, compared with Washington children. Likewise, Swedish children had a 1.8-fold higher risk of CD than children in Germany, a 1.7-fold higher than children in the United States, and a 1.4-fold higher risk than children in Finland.

Among DQ2.5 participants, Sweden demonstrated the highest risk, with 63.1% of patients developing CDA by age 10 and 28.3% developing CD by age 10. Finland consistently had a higher incidence of CDA than Colorado, at 60.4% versus 50.9%, for DQ2.5 participants but a lower incidence of CD than Colorado, at 20.3% versus 22.6%.

The research team performed a post hoc sensitivity analysis using a lower tTGA cutoff to reduce bias in site differences for biopsy referral and to increase sensitivity of the CD definition for incidence estimation. When the tTGA cutoff was lowered to an average two-visit tTGA of 67.4 or higher, more children met the serologic criteria for CD.

“Even with this lower cutoff, the differences in the risk of CD between clinical sites and countries were still observed with statistical significance,” the authors write. “This indicates that the regional differences in CD incidence could not be solely attributed to detection biases posed by differential biopsy rates.”

Multiple environmental factors likely account for the differences in autoimmunity among regions, the authors write. These variables include diet, chemical exposures, vaccination patterns, early-life gastrointestinal infections, and interactions among these factors. For instance, the Swedish site has the lowest rotavirus vaccination rates and the highest median gluten intake among the TEDDY sites.

Future prospective studies should capture environmental, genetic, and epigenetic exposures to assess causal pathways and plan for preventive strategies, the authors write. The TEDDY study is pursuing this research.

“From a policy standpoint, this informs future screening practices and supports efforts toward mass screening, at least in some areas,” the authors write. “In the clinical setting, this points to the importance for clinicians to have a low threshold for CD screening in the appropriate clinical setting.”

The TEDDY study is funded by several grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AMERICAN JOURNAL OF GASTROENTEROLOGY

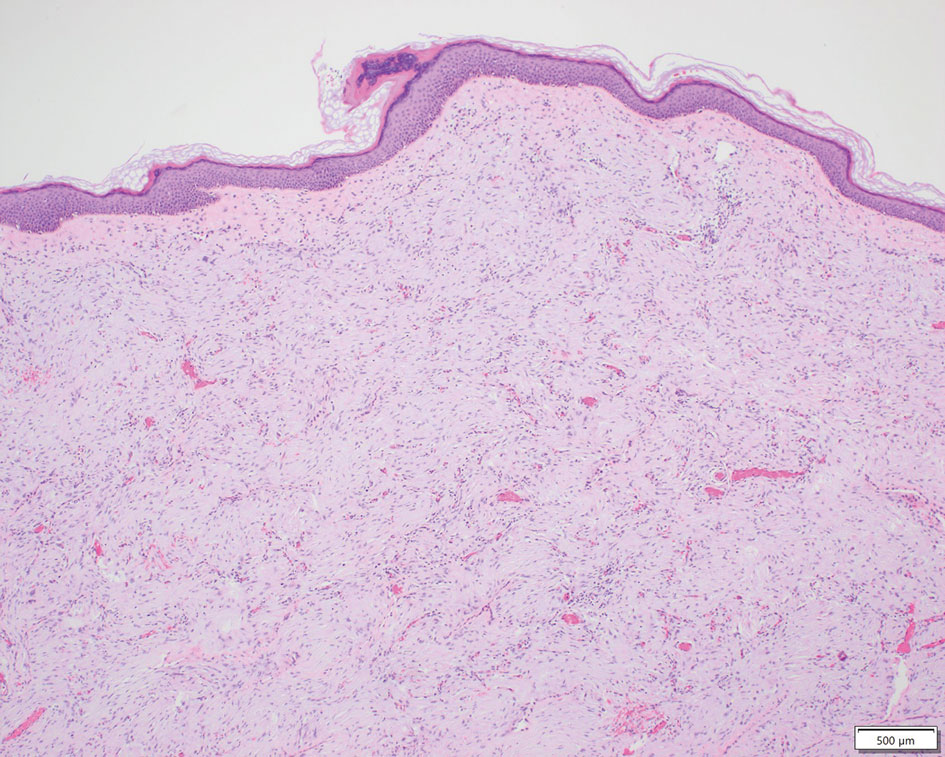

Dietary Triggers for Atopic Dermatitis in Children

It is unsurprising that food frequently is thought to be the culprit behind an eczema flare, especially in infants. Indeed, it often is said that infants do only 3 things: eat, sleep, and poop.1 For those unfortunate enough to develop the signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis (AD), food quickly emerges as a potential culprit from the tiny pool of suspects, which is against a cultural backdrop of unprecedented focus on foods and food reactions.2 The prevalence of food allergies in children, though admittedly fraught with methodological difficulties, is estimated to have more than doubled from 3.4% in 1999 to 7.6% in 2018.3 As expected, prevalence rates were higher among children with other atopic comorbidities including AD, with up to 50% of children with AD demonstrating convincing food allergy.4 It is easy to imagine a patient conflating these 2 entities and mistaking their correlation for causation. Thus, it follows that more than 90% of parents/guardians have reported that their children have had food-induced AD, and understandably—at least according to one study—75% of parents/guardians were found to have manipulated the diet in an attempt to manage the disease.5,6

Patients and parents/guardians are not the only ones who have suspected food as a driving force in AD. An article in the British Medical Journal from the 1800s beautifully encapsulated the depth and duration of this quandary: “There is probably no subject in which more deeply rooted convictions have been held, not only in the profession but by the laity, than the connection between diet and disease, both as regards the causation and treatment of the latter.”7 Herein, a wide range of food reactions is examined to highlight evidence for the role of diet in AD, which may contradict what patients—and even some clinicians—believe.

No Easy Answers

A definitive statement that food allergy is not the root cause of AD would put this issue to rest, but such simplicity does not reflect the complex reality. First, we must agree on definitions for certain terms. What do we mean by food allergy? A broader category—adverse food reactions—covers a wide range of entities, some immune mediated and some not, including lactose intolerance, irritant contact dermatitis around the mouth, and even dermatitis herpetiformis (the cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease).8 Although the term food allergy often is used synonymously with adverse food reactions, the exact definition of a food allergy is specific: “adverse immune responses to food proteins that result in typical clinical symptoms.”8 The fact that many patients and even health care practitioners seem to frequently misapply this term makes it even more confusing.

The current focus is on foods that could trigger a flare of AD, which clearly is a broader question than food allergy sensu stricto. It seems self-evident, for example, that if an infant with AD were to (messily) eat an acidic food such as an orange, a flare-up of AD around the mouth and on the cheeks and hands would be a forgone conclusion. Similar nonimmunologic scenarios unambiguously can occur with many foods, including citrus; corn; radish; mustard; garlic; onion; pineapple; and many spices, food additives, and preservatives.9 Clearly there are some scenarios whereby food could trigger an AD flare, and yet this more limited vignette generally is not what patients are referring to when suggesting that food is the root cause of their AD.

The Labyrinth of Testing for Food Allergies

Although there is no reliable method for testing for irritant dermatitis, understanding the other types of tests may help guide our thinking. Testing for IgE-mediated food allergies generally is done via an immunoenzymatic serum assay that can document sensitization to a food protein; however, this testing by itself is not sufficient to diagnose a clinical food allergy.10 Similarly, skin prick testing allows for intradermal administration of a food extract to evaluate for an urticarial reaction within 10 to 15 minutes. Although the sensitivity and specificity vary by age, population, and the specific allergen being tested, these are limited to immediate-type reactions and do not reflect the potential to drive an eczematous flare.

The gold standard, if there is one, is likely the double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC), ideally with a long enough observation period to capture later-occurring reactions such as an AD flare. However, given the nature of the test—having patients eat the foods of concern and then carefully following them for reactions—it remains time consuming, expensive, and labor intensive.11

To further complicate matters, several unvalidated tests exist such as IgG testing, atopy patch testing, kinesiology, and hair and gastric juice analysis, which remain investigational but continue to be used and may further confuse patients and clinicians.12

Classification of Food Allergies

It is useful to first separate out the classic IgE-mediated food allergy reactions that are common. In these immediate-type reactions, a person sensitized to a food protein will develop characteristic cutaneous and/or extracutaneous reactions such as urticaria, angioedema, and even anaphylaxis, usually within minutes of exposure. Although it is possible that an IgE-mediated reaction could trigger an AD flare—perhaps simply by causing pruritus, which could initiate the itch-scratch cycle—because of the near simultaneity with ingestion of the offending food and the often dramatic clinical presentations, such foods clearly do not represent “hidden” triggers for AD flares.3 The concept of food-triggered AD (FTAD) is crucial for thinking about foods that could result in true eczematous flares, which historically have been classified as early-type (<2 hours after food challenge) and late-type (≥2 hours after food challenge) reactions.13,14

A study of more than 1000 DBPCFCs performed in patients with AD was illustrative.15 Immediate reactions other than AD were fairly common and were observed in 40% of the food challenges compared to only 9% in the placebo group. These reactions included urticaria, angioedema, and gastrointestinal and respiratory tract symptoms. Immediate reactions of AD alone were exceedingly rare at only 0.7% and not significantly elevated compared to placebo. Just over 4% experienced both an immediate AD exacerbation along with other non-AD findings, which was significantly greater than placebo (P<.01). Although intermediate and late reactions manifesting as AD exacerbations did occur after food ingestion, they were rare (2.2% or less) and not significantly different from placebo. The authors concluded that an exacerbation of AD in the absence of other allergic symptoms in children was unlikely to be due to food,15 which is an important finding.

A recent retrospective review of 372 children with AD reported similar results.4 The authors defined FTAD in a different way; instead of showing a flare after a DBPCFC, they looked for “physician-noted sustained improvement in AD upon removal of a food (typically after 2–6-wk follow-up), to which the child was sensitized without any other changes in skin care.” Despite this fundamentally different approach, they similarly concluded that while food allergies were common, FTAD was relatively uncommon—found in 2% of those with mild AD, 6% of those with moderate AD, and 4% of those with severe AD.4

There are other ways that foods could contribute to disease flares, however, and one of the most compelling is that there may be broader concepts at play; perhaps some diets are not specifically driving the AD but rather are affecting inflammation in the body at large. Although somewhat speculative, there is evidence that some foods may simply be proinflammatory, working to exacerbate the disease outside of a specific mechanism, which has been seen in a variety of other conditions such as acne or rheumatoid arthritis.16,17 To speculate further, it is possible that there may be a threshold effect such that when the AD is poorly controlled, certain factors such as inflammatory foods could lead to a flare, while when under better control, these same factors may not cause an effect.

Finally, it is important to also consider the emotional and/or psychological aspects related to food and diet. The power of the placebo in dietary change has been documented in several diseases, though this certainly is not to be dismissive of the patient’s symptoms; it seems reasonable that the very act of changing such a fundamental aspect of daily life could result in a placebo effect.18,19 In the context of relapsing and remitting conditions such as AD, this effect may be magnified. A landmark study by Thompson and Hanifin20 illustrates this possibility. The authors found that in 80% of cases in which patients were convinced that food was a major contributing factor to their AD, such concerns diminished markedly once better control of the eczema was achieved.20

Navigating the Complexity of Dietary Restrictions

This brings us to what to do with an individual patient in the examination room. Because there is such widespread concern and discussion around this topic, it is important to at least briefly address it. If there are known food allergens that are being avoided, it is important to underscore the importance of continuing to avoid those foods, especially when there is actual evidence of true food allergy rather than sensitization alone. Historically, elimination diets often were recommended empirically, though more recent studies, meta-analyses, and guidance documents increasingly have recommended against them.3 In particular, there are major concerns for iatrogenic harm.

First, heavily restricted diets may result in nutritional and/or caloric deficiencies that can be dangerous and lead to poor growth.21 Practices such as drinking unpasteurized milk can expose children to dangerous infections, while feeding them exclusively rice milk can lead to severe malnutrition.22

Second, there is a dawning realization that children with AD placed on elimination diets may actually develop true IgE-mediated allergies, including fatal anaphylaxis, to the excluded foods. In fact, one retrospective review of 298 patients with a history of AD and no prior immediate reactions found that 19% of patients developed new immediate-type hypersensitivity reactions after starting an elimination diet, presumably due to the loss of tolerance to these foods. A striking one-third of these reactions were classified as anaphylaxis, with cow’s milk and egg being the most common offenders.23

It also is crucial to acknowledge that recommending sweeping lifestyle changes is not easy for patients, especially pediatric patients. Onerous dietary restrictions may add considerable stress, ironically a known trigger for AD itself.

Finally, dietary modifications can be a distraction from conventional therapy and may result in treatment delays while the patient continues to experience uncontrolled symptoms of AD.

Final Thoughts

Diet is intimately related to AD. Although the narrative continues to unfold in fascinating domains, such as the skin barrier and the microbiome, it is increasingly clear that these are intertwined and always have been. Despite the rarity of true food-triggered AD, the perception of dietary triggers is so widespread and addressing the topic is important and may help avoid unnecessary harm from unfounded extreme dietary changes. A recent multispecialty workgroup report on AD and food allergy succinctly summarized this as: “AD has many triggers and comorbidities, and food allergy is only one of the potential triggers and comorbid conditions. With regard to AD management, education and skin care are most important.”3 With proper testing, guidance, and both topical and systemic therapies, most AD can be brought under control, and for at least some patients, this may allay concerns about foods triggering their AD.

- Eat, sleep, poop—the top 3 things new parents need to know. John’s Hopkins All Children’s Hospital website. Published May 18, 2019. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.hopkinsallchildrens.org/ACH-News/General-News/Eat-Sleep-Poop-%E2%80%93-The-Top-3-Things-New-Parents-Ne

- Onyimba F, Crowe SE, Johnson S, et al. Food allergies and intolerances: a clinical approach to the diagnosis and management of adverse reactions to food. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2230-2240.e1.

- Singh AM, Anvari S, Hauk P, et al. Atopic dermatitis and food allergy: best practices and knowledge gaps—a work group report from the AAAAI Allergic Skin Diseases Committee and Leadership Institute Project. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10:697-706.

- Li JC, Arkin LM, Makhija MM, et al. Prevalence of food allergy diagnosis in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis referred to allergy and/or dermatology subspecialty clinics. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10:2469-2471.

- Thompson MM, Tofte SJ, Simpson EL, et al. Patterns of care and referral in children with atopic dermatitis and concern for food allergy. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19:91-96.

- Johnston GA, Bilbao RM, Graham-Brown RAC. The use of dietary manipulation by parents of children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:1186-1189.

- Mackenzie S. The inaugural address on the advantages to be derived from the study of dermatology: delivered to the Reading Pathological Society. Br Med J. 1896;1:193-197.

- Anvari S, Miller J, Yeh CY, et al. IgE-mediated food allergy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;57:244-260.

- Brancaccio RR, Alvarez MS. Contact allergy to food. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:302-313.

- Robison RG, Singh AM. Controversies in allergy: food testing and dietary avoidance in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:35-39.

- Sicherer SH, Morrow EH, Sampson HA. Dose-response in double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenges in children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:582-586.

- Kelso JM. Unproven diagnostic tests for adverse reactions to foods. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:362-365.

- Heratizadeh A, Wichmann K, Werfel T. Food allergy and atopic dermatitis: how are they connected? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:284-291.

- Breuer K, Heratizadeh A, Wulf A, et al. Late eczematous reactions to food in children with atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:817-824.

- Roerdink EM, Flokstra-de Blok BMJ, Blok JL, et al. Association of food allergy and atopic dermatitis exacerbations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;116:334-338.

- Fuglsang G, Madsen G, Halken S, et al. Adverse reactions to food additives in children with atopic symptoms. Allergy. 1994;49:31-37.

- Ehlers I, Worm M, Sterry W, et al. Sugar is not an aggravating factor in atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:282-284.

- Staudacher HM, Irving PM, Lomer MCE, et al. The challenges of control groups, placebos and blinding in clinical trials of dietary interventions. Proc Nutr Soc. 2017;76:203-212.

- Masi A, Lampit A, Glozier N, et al. Predictors of placebo response in pharmacological and dietary supplement treatment trials in pediatric autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:E640.

- Thompson MM, Hanifin JM. Effective therapy of childhood atopic dermatitis allays food allergy concerns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2 suppl 2):S214-S219.

- Meyer R, De Koker C, Dziubak R, et al. The impact of the elimination diet on growth and nutrient intake in children with food protein induced gastrointestinal allergies. Clin Transl Allergy. 2016;6:25.

- Webber SA, Graham-Brown RA, Hutchinson PE, et al. Dietary manipulation in childhood atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:91-98.

- Chang A, Robison R, Cai M, et al. Natural history of food-triggered atopic dermatitis and development of immediate reactions in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:229-236.e1.

It is unsurprising that food frequently is thought to be the culprit behind an eczema flare, especially in infants. Indeed, it often is said that infants do only 3 things: eat, sleep, and poop.1 For those unfortunate enough to develop the signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis (AD), food quickly emerges as a potential culprit from the tiny pool of suspects, which is against a cultural backdrop of unprecedented focus on foods and food reactions.2 The prevalence of food allergies in children, though admittedly fraught with methodological difficulties, is estimated to have more than doubled from 3.4% in 1999 to 7.6% in 2018.3 As expected, prevalence rates were higher among children with other atopic comorbidities including AD, with up to 50% of children with AD demonstrating convincing food allergy.4 It is easy to imagine a patient conflating these 2 entities and mistaking their correlation for causation. Thus, it follows that more than 90% of parents/guardians have reported that their children have had food-induced AD, and understandably—at least according to one study—75% of parents/guardians were found to have manipulated the diet in an attempt to manage the disease.5,6

Patients and parents/guardians are not the only ones who have suspected food as a driving force in AD. An article in the British Medical Journal from the 1800s beautifully encapsulated the depth and duration of this quandary: “There is probably no subject in which more deeply rooted convictions have been held, not only in the profession but by the laity, than the connection between diet and disease, both as regards the causation and treatment of the latter.”7 Herein, a wide range of food reactions is examined to highlight evidence for the role of diet in AD, which may contradict what patients—and even some clinicians—believe.

No Easy Answers

A definitive statement that food allergy is not the root cause of AD would put this issue to rest, but such simplicity does not reflect the complex reality. First, we must agree on definitions for certain terms. What do we mean by food allergy? A broader category—adverse food reactions—covers a wide range of entities, some immune mediated and some not, including lactose intolerance, irritant contact dermatitis around the mouth, and even dermatitis herpetiformis (the cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease).8 Although the term food allergy often is used synonymously with adverse food reactions, the exact definition of a food allergy is specific: “adverse immune responses to food proteins that result in typical clinical symptoms.”8 The fact that many patients and even health care practitioners seem to frequently misapply this term makes it even more confusing.

The current focus is on foods that could trigger a flare of AD, which clearly is a broader question than food allergy sensu stricto. It seems self-evident, for example, that if an infant with AD were to (messily) eat an acidic food such as an orange, a flare-up of AD around the mouth and on the cheeks and hands would be a forgone conclusion. Similar nonimmunologic scenarios unambiguously can occur with many foods, including citrus; corn; radish; mustard; garlic; onion; pineapple; and many spices, food additives, and preservatives.9 Clearly there are some scenarios whereby food could trigger an AD flare, and yet this more limited vignette generally is not what patients are referring to when suggesting that food is the root cause of their AD.

The Labyrinth of Testing for Food Allergies

Although there is no reliable method for testing for irritant dermatitis, understanding the other types of tests may help guide our thinking. Testing for IgE-mediated food allergies generally is done via an immunoenzymatic serum assay that can document sensitization to a food protein; however, this testing by itself is not sufficient to diagnose a clinical food allergy.10 Similarly, skin prick testing allows for intradermal administration of a food extract to evaluate for an urticarial reaction within 10 to 15 minutes. Although the sensitivity and specificity vary by age, population, and the specific allergen being tested, these are limited to immediate-type reactions and do not reflect the potential to drive an eczematous flare.

The gold standard, if there is one, is likely the double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC), ideally with a long enough observation period to capture later-occurring reactions such as an AD flare. However, given the nature of the test—having patients eat the foods of concern and then carefully following them for reactions—it remains time consuming, expensive, and labor intensive.11

To further complicate matters, several unvalidated tests exist such as IgG testing, atopy patch testing, kinesiology, and hair and gastric juice analysis, which remain investigational but continue to be used and may further confuse patients and clinicians.12

Classification of Food Allergies

It is useful to first separate out the classic IgE-mediated food allergy reactions that are common. In these immediate-type reactions, a person sensitized to a food protein will develop characteristic cutaneous and/or extracutaneous reactions such as urticaria, angioedema, and even anaphylaxis, usually within minutes of exposure. Although it is possible that an IgE-mediated reaction could trigger an AD flare—perhaps simply by causing pruritus, which could initiate the itch-scratch cycle—because of the near simultaneity with ingestion of the offending food and the often dramatic clinical presentations, such foods clearly do not represent “hidden” triggers for AD flares.3 The concept of food-triggered AD (FTAD) is crucial for thinking about foods that could result in true eczematous flares, which historically have been classified as early-type (<2 hours after food challenge) and late-type (≥2 hours after food challenge) reactions.13,14

A study of more than 1000 DBPCFCs performed in patients with AD was illustrative.15 Immediate reactions other than AD were fairly common and were observed in 40% of the food challenges compared to only 9% in the placebo group. These reactions included urticaria, angioedema, and gastrointestinal and respiratory tract symptoms. Immediate reactions of AD alone were exceedingly rare at only 0.7% and not significantly elevated compared to placebo. Just over 4% experienced both an immediate AD exacerbation along with other non-AD findings, which was significantly greater than placebo (P<.01). Although intermediate and late reactions manifesting as AD exacerbations did occur after food ingestion, they were rare (2.2% or less) and not significantly different from placebo. The authors concluded that an exacerbation of AD in the absence of other allergic symptoms in children was unlikely to be due to food,15 which is an important finding.

A recent retrospective review of 372 children with AD reported similar results.4 The authors defined FTAD in a different way; instead of showing a flare after a DBPCFC, they looked for “physician-noted sustained improvement in AD upon removal of a food (typically after 2–6-wk follow-up), to which the child was sensitized without any other changes in skin care.” Despite this fundamentally different approach, they similarly concluded that while food allergies were common, FTAD was relatively uncommon—found in 2% of those with mild AD, 6% of those with moderate AD, and 4% of those with severe AD.4

There are other ways that foods could contribute to disease flares, however, and one of the most compelling is that there may be broader concepts at play; perhaps some diets are not specifically driving the AD but rather are affecting inflammation in the body at large. Although somewhat speculative, there is evidence that some foods may simply be proinflammatory, working to exacerbate the disease outside of a specific mechanism, which has been seen in a variety of other conditions such as acne or rheumatoid arthritis.16,17 To speculate further, it is possible that there may be a threshold effect such that when the AD is poorly controlled, certain factors such as inflammatory foods could lead to a flare, while when under better control, these same factors may not cause an effect.

Finally, it is important to also consider the emotional and/or psychological aspects related to food and diet. The power of the placebo in dietary change has been documented in several diseases, though this certainly is not to be dismissive of the patient’s symptoms; it seems reasonable that the very act of changing such a fundamental aspect of daily life could result in a placebo effect.18,19 In the context of relapsing and remitting conditions such as AD, this effect may be magnified. A landmark study by Thompson and Hanifin20 illustrates this possibility. The authors found that in 80% of cases in which patients were convinced that food was a major contributing factor to their AD, such concerns diminished markedly once better control of the eczema was achieved.20

Navigating the Complexity of Dietary Restrictions

This brings us to what to do with an individual patient in the examination room. Because there is such widespread concern and discussion around this topic, it is important to at least briefly address it. If there are known food allergens that are being avoided, it is important to underscore the importance of continuing to avoid those foods, especially when there is actual evidence of true food allergy rather than sensitization alone. Historically, elimination diets often were recommended empirically, though more recent studies, meta-analyses, and guidance documents increasingly have recommended against them.3 In particular, there are major concerns for iatrogenic harm.

First, heavily restricted diets may result in nutritional and/or caloric deficiencies that can be dangerous and lead to poor growth.21 Practices such as drinking unpasteurized milk can expose children to dangerous infections, while feeding them exclusively rice milk can lead to severe malnutrition.22

Second, there is a dawning realization that children with AD placed on elimination diets may actually develop true IgE-mediated allergies, including fatal anaphylaxis, to the excluded foods. In fact, one retrospective review of 298 patients with a history of AD and no prior immediate reactions found that 19% of patients developed new immediate-type hypersensitivity reactions after starting an elimination diet, presumably due to the loss of tolerance to these foods. A striking one-third of these reactions were classified as anaphylaxis, with cow’s milk and egg being the most common offenders.23

It also is crucial to acknowledge that recommending sweeping lifestyle changes is not easy for patients, especially pediatric patients. Onerous dietary restrictions may add considerable stress, ironically a known trigger for AD itself.

Finally, dietary modifications can be a distraction from conventional therapy and may result in treatment delays while the patient continues to experience uncontrolled symptoms of AD.

Final Thoughts

Diet is intimately related to AD. Although the narrative continues to unfold in fascinating domains, such as the skin barrier and the microbiome, it is increasingly clear that these are intertwined and always have been. Despite the rarity of true food-triggered AD, the perception of dietary triggers is so widespread and addressing the topic is important and may help avoid unnecessary harm from unfounded extreme dietary changes. A recent multispecialty workgroup report on AD and food allergy succinctly summarized this as: “AD has many triggers and comorbidities, and food allergy is only one of the potential triggers and comorbid conditions. With regard to AD management, education and skin care are most important.”3 With proper testing, guidance, and both topical and systemic therapies, most AD can be brought under control, and for at least some patients, this may allay concerns about foods triggering their AD.

It is unsurprising that food frequently is thought to be the culprit behind an eczema flare, especially in infants. Indeed, it often is said that infants do only 3 things: eat, sleep, and poop.1 For those unfortunate enough to develop the signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis (AD), food quickly emerges as a potential culprit from the tiny pool of suspects, which is against a cultural backdrop of unprecedented focus on foods and food reactions.2 The prevalence of food allergies in children, though admittedly fraught with methodological difficulties, is estimated to have more than doubled from 3.4% in 1999 to 7.6% in 2018.3 As expected, prevalence rates were higher among children with other atopic comorbidities including AD, with up to 50% of children with AD demonstrating convincing food allergy.4 It is easy to imagine a patient conflating these 2 entities and mistaking their correlation for causation. Thus, it follows that more than 90% of parents/guardians have reported that their children have had food-induced AD, and understandably—at least according to one study—75% of parents/guardians were found to have manipulated the diet in an attempt to manage the disease.5,6

Patients and parents/guardians are not the only ones who have suspected food as a driving force in AD. An article in the British Medical Journal from the 1800s beautifully encapsulated the depth and duration of this quandary: “There is probably no subject in which more deeply rooted convictions have been held, not only in the profession but by the laity, than the connection between diet and disease, both as regards the causation and treatment of the latter.”7 Herein, a wide range of food reactions is examined to highlight evidence for the role of diet in AD, which may contradict what patients—and even some clinicians—believe.

No Easy Answers

A definitive statement that food allergy is not the root cause of AD would put this issue to rest, but such simplicity does not reflect the complex reality. First, we must agree on definitions for certain terms. What do we mean by food allergy? A broader category—adverse food reactions—covers a wide range of entities, some immune mediated and some not, including lactose intolerance, irritant contact dermatitis around the mouth, and even dermatitis herpetiformis (the cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease).8 Although the term food allergy often is used synonymously with adverse food reactions, the exact definition of a food allergy is specific: “adverse immune responses to food proteins that result in typical clinical symptoms.”8 The fact that many patients and even health care practitioners seem to frequently misapply this term makes it even more confusing.

The current focus is on foods that could trigger a flare of AD, which clearly is a broader question than food allergy sensu stricto. It seems self-evident, for example, that if an infant with AD were to (messily) eat an acidic food such as an orange, a flare-up of AD around the mouth and on the cheeks and hands would be a forgone conclusion. Similar nonimmunologic scenarios unambiguously can occur with many foods, including citrus; corn; radish; mustard; garlic; onion; pineapple; and many spices, food additives, and preservatives.9 Clearly there are some scenarios whereby food could trigger an AD flare, and yet this more limited vignette generally is not what patients are referring to when suggesting that food is the root cause of their AD.

The Labyrinth of Testing for Food Allergies

Although there is no reliable method for testing for irritant dermatitis, understanding the other types of tests may help guide our thinking. Testing for IgE-mediated food allergies generally is done via an immunoenzymatic serum assay that can document sensitization to a food protein; however, this testing by itself is not sufficient to diagnose a clinical food allergy.10 Similarly, skin prick testing allows for intradermal administration of a food extract to evaluate for an urticarial reaction within 10 to 15 minutes. Although the sensitivity and specificity vary by age, population, and the specific allergen being tested, these are limited to immediate-type reactions and do not reflect the potential to drive an eczematous flare.

The gold standard, if there is one, is likely the double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC), ideally with a long enough observation period to capture later-occurring reactions such as an AD flare. However, given the nature of the test—having patients eat the foods of concern and then carefully following them for reactions—it remains time consuming, expensive, and labor intensive.11

To further complicate matters, several unvalidated tests exist such as IgG testing, atopy patch testing, kinesiology, and hair and gastric juice analysis, which remain investigational but continue to be used and may further confuse patients and clinicians.12

Classification of Food Allergies

It is useful to first separate out the classic IgE-mediated food allergy reactions that are common. In these immediate-type reactions, a person sensitized to a food protein will develop characteristic cutaneous and/or extracutaneous reactions such as urticaria, angioedema, and even anaphylaxis, usually within minutes of exposure. Although it is possible that an IgE-mediated reaction could trigger an AD flare—perhaps simply by causing pruritus, which could initiate the itch-scratch cycle—because of the near simultaneity with ingestion of the offending food and the often dramatic clinical presentations, such foods clearly do not represent “hidden” triggers for AD flares.3 The concept of food-triggered AD (FTAD) is crucial for thinking about foods that could result in true eczematous flares, which historically have been classified as early-type (<2 hours after food challenge) and late-type (≥2 hours after food challenge) reactions.13,14

A study of more than 1000 DBPCFCs performed in patients with AD was illustrative.15 Immediate reactions other than AD were fairly common and were observed in 40% of the food challenges compared to only 9% in the placebo group. These reactions included urticaria, angioedema, and gastrointestinal and respiratory tract symptoms. Immediate reactions of AD alone were exceedingly rare at only 0.7% and not significantly elevated compared to placebo. Just over 4% experienced both an immediate AD exacerbation along with other non-AD findings, which was significantly greater than placebo (P<.01). Although intermediate and late reactions manifesting as AD exacerbations did occur after food ingestion, they were rare (2.2% or less) and not significantly different from placebo. The authors concluded that an exacerbation of AD in the absence of other allergic symptoms in children was unlikely to be due to food,15 which is an important finding.

A recent retrospective review of 372 children with AD reported similar results.4 The authors defined FTAD in a different way; instead of showing a flare after a DBPCFC, they looked for “physician-noted sustained improvement in AD upon removal of a food (typically after 2–6-wk follow-up), to which the child was sensitized without any other changes in skin care.” Despite this fundamentally different approach, they similarly concluded that while food allergies were common, FTAD was relatively uncommon—found in 2% of those with mild AD, 6% of those with moderate AD, and 4% of those with severe AD.4

There are other ways that foods could contribute to disease flares, however, and one of the most compelling is that there may be broader concepts at play; perhaps some diets are not specifically driving the AD but rather are affecting inflammation in the body at large. Although somewhat speculative, there is evidence that some foods may simply be proinflammatory, working to exacerbate the disease outside of a specific mechanism, which has been seen in a variety of other conditions such as acne or rheumatoid arthritis.16,17 To speculate further, it is possible that there may be a threshold effect such that when the AD is poorly controlled, certain factors such as inflammatory foods could lead to a flare, while when under better control, these same factors may not cause an effect.

Finally, it is important to also consider the emotional and/or psychological aspects related to food and diet. The power of the placebo in dietary change has been documented in several diseases, though this certainly is not to be dismissive of the patient’s symptoms; it seems reasonable that the very act of changing such a fundamental aspect of daily life could result in a placebo effect.18,19 In the context of relapsing and remitting conditions such as AD, this effect may be magnified. A landmark study by Thompson and Hanifin20 illustrates this possibility. The authors found that in 80% of cases in which patients were convinced that food was a major contributing factor to their AD, such concerns diminished markedly once better control of the eczema was achieved.20

Navigating the Complexity of Dietary Restrictions

This brings us to what to do with an individual patient in the examination room. Because there is such widespread concern and discussion around this topic, it is important to at least briefly address it. If there are known food allergens that are being avoided, it is important to underscore the importance of continuing to avoid those foods, especially when there is actual evidence of true food allergy rather than sensitization alone. Historically, elimination diets often were recommended empirically, though more recent studies, meta-analyses, and guidance documents increasingly have recommended against them.3 In particular, there are major concerns for iatrogenic harm.

First, heavily restricted diets may result in nutritional and/or caloric deficiencies that can be dangerous and lead to poor growth.21 Practices such as drinking unpasteurized milk can expose children to dangerous infections, while feeding them exclusively rice milk can lead to severe malnutrition.22

Second, there is a dawning realization that children with AD placed on elimination diets may actually develop true IgE-mediated allergies, including fatal anaphylaxis, to the excluded foods. In fact, one retrospective review of 298 patients with a history of AD and no prior immediate reactions found that 19% of patients developed new immediate-type hypersensitivity reactions after starting an elimination diet, presumably due to the loss of tolerance to these foods. A striking one-third of these reactions were classified as anaphylaxis, with cow’s milk and egg being the most common offenders.23

It also is crucial to acknowledge that recommending sweeping lifestyle changes is not easy for patients, especially pediatric patients. Onerous dietary restrictions may add considerable stress, ironically a known trigger for AD itself.

Finally, dietary modifications can be a distraction from conventional therapy and may result in treatment delays while the patient continues to experience uncontrolled symptoms of AD.

Final Thoughts

Diet is intimately related to AD. Although the narrative continues to unfold in fascinating domains, such as the skin barrier and the microbiome, it is increasingly clear that these are intertwined and always have been. Despite the rarity of true food-triggered AD, the perception of dietary triggers is so widespread and addressing the topic is important and may help avoid unnecessary harm from unfounded extreme dietary changes. A recent multispecialty workgroup report on AD and food allergy succinctly summarized this as: “AD has many triggers and comorbidities, and food allergy is only one of the potential triggers and comorbid conditions. With regard to AD management, education and skin care are most important.”3 With proper testing, guidance, and both topical and systemic therapies, most AD can be brought under control, and for at least some patients, this may allay concerns about foods triggering their AD.

- Eat, sleep, poop—the top 3 things new parents need to know. John’s Hopkins All Children’s Hospital website. Published May 18, 2019. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.hopkinsallchildrens.org/ACH-News/General-News/Eat-Sleep-Poop-%E2%80%93-The-Top-3-Things-New-Parents-Ne

- Onyimba F, Crowe SE, Johnson S, et al. Food allergies and intolerances: a clinical approach to the diagnosis and management of adverse reactions to food. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2230-2240.e1.

- Singh AM, Anvari S, Hauk P, et al. Atopic dermatitis and food allergy: best practices and knowledge gaps—a work group report from the AAAAI Allergic Skin Diseases Committee and Leadership Institute Project. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10:697-706.

- Li JC, Arkin LM, Makhija MM, et al. Prevalence of food allergy diagnosis in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis referred to allergy and/or dermatology subspecialty clinics. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10:2469-2471.

- Thompson MM, Tofte SJ, Simpson EL, et al. Patterns of care and referral in children with atopic dermatitis and concern for food allergy. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19:91-96.

- Johnston GA, Bilbao RM, Graham-Brown RAC. The use of dietary manipulation by parents of children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:1186-1189.

- Mackenzie S. The inaugural address on the advantages to be derived from the study of dermatology: delivered to the Reading Pathological Society. Br Med J. 1896;1:193-197.

- Anvari S, Miller J, Yeh CY, et al. IgE-mediated food allergy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;57:244-260.

- Brancaccio RR, Alvarez MS. Contact allergy to food. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:302-313.

- Robison RG, Singh AM. Controversies in allergy: food testing and dietary avoidance in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:35-39.

- Sicherer SH, Morrow EH, Sampson HA. Dose-response in double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenges in children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:582-586.

- Kelso JM. Unproven diagnostic tests for adverse reactions to foods. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:362-365.

- Heratizadeh A, Wichmann K, Werfel T. Food allergy and atopic dermatitis: how are they connected? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:284-291.

- Breuer K, Heratizadeh A, Wulf A, et al. Late eczematous reactions to food in children with atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:817-824.

- Roerdink EM, Flokstra-de Blok BMJ, Blok JL, et al. Association of food allergy and atopic dermatitis exacerbations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;116:334-338.

- Fuglsang G, Madsen G, Halken S, et al. Adverse reactions to food additives in children with atopic symptoms. Allergy. 1994;49:31-37.

- Ehlers I, Worm M, Sterry W, et al. Sugar is not an aggravating factor in atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:282-284.

- Staudacher HM, Irving PM, Lomer MCE, et al. The challenges of control groups, placebos and blinding in clinical trials of dietary interventions. Proc Nutr Soc. 2017;76:203-212.

- Masi A, Lampit A, Glozier N, et al. Predictors of placebo response in pharmacological and dietary supplement treatment trials in pediatric autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:E640.

- Thompson MM, Hanifin JM. Effective therapy of childhood atopic dermatitis allays food allergy concerns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2 suppl 2):S214-S219.

- Meyer R, De Koker C, Dziubak R, et al. The impact of the elimination diet on growth and nutrient intake in children with food protein induced gastrointestinal allergies. Clin Transl Allergy. 2016;6:25.

- Webber SA, Graham-Brown RA, Hutchinson PE, et al. Dietary manipulation in childhood atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:91-98.

- Chang A, Robison R, Cai M, et al. Natural history of food-triggered atopic dermatitis and development of immediate reactions in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:229-236.e1.

- Eat, sleep, poop—the top 3 things new parents need to know. John’s Hopkins All Children’s Hospital website. Published May 18, 2019. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.hopkinsallchildrens.org/ACH-News/General-News/Eat-Sleep-Poop-%E2%80%93-The-Top-3-Things-New-Parents-Ne

- Onyimba F, Crowe SE, Johnson S, et al. Food allergies and intolerances: a clinical approach to the diagnosis and management of adverse reactions to food. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2230-2240.e1.

- Singh AM, Anvari S, Hauk P, et al. Atopic dermatitis and food allergy: best practices and knowledge gaps—a work group report from the AAAAI Allergic Skin Diseases Committee and Leadership Institute Project. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10:697-706.

- Li JC, Arkin LM, Makhija MM, et al. Prevalence of food allergy diagnosis in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis referred to allergy and/or dermatology subspecialty clinics. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10:2469-2471.

- Thompson MM, Tofte SJ, Simpson EL, et al. Patterns of care and referral in children with atopic dermatitis and concern for food allergy. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19:91-96.

- Johnston GA, Bilbao RM, Graham-Brown RAC. The use of dietary manipulation by parents of children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:1186-1189.

- Mackenzie S. The inaugural address on the advantages to be derived from the study of dermatology: delivered to the Reading Pathological Society. Br Med J. 1896;1:193-197.

- Anvari S, Miller J, Yeh CY, et al. IgE-mediated food allergy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;57:244-260.

- Brancaccio RR, Alvarez MS. Contact allergy to food. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:302-313.

- Robison RG, Singh AM. Controversies in allergy: food testing and dietary avoidance in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:35-39.

- Sicherer SH, Morrow EH, Sampson HA. Dose-response in double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenges in children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:582-586.

- Kelso JM. Unproven diagnostic tests for adverse reactions to foods. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:362-365.

- Heratizadeh A, Wichmann K, Werfel T. Food allergy and atopic dermatitis: how are they connected? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:284-291.

- Breuer K, Heratizadeh A, Wulf A, et al. Late eczematous reactions to food in children with atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:817-824.

- Roerdink EM, Flokstra-de Blok BMJ, Blok JL, et al. Association of food allergy and atopic dermatitis exacerbations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;116:334-338.

- Fuglsang G, Madsen G, Halken S, et al. Adverse reactions to food additives in children with atopic symptoms. Allergy. 1994;49:31-37.

- Ehlers I, Worm M, Sterry W, et al. Sugar is not an aggravating factor in atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:282-284.

- Staudacher HM, Irving PM, Lomer MCE, et al. The challenges of control groups, placebos and blinding in clinical trials of dietary interventions. Proc Nutr Soc. 2017;76:203-212.

- Masi A, Lampit A, Glozier N, et al. Predictors of placebo response in pharmacological and dietary supplement treatment trials in pediatric autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:E640.

- Thompson MM, Hanifin JM. Effective therapy of childhood atopic dermatitis allays food allergy concerns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2 suppl 2):S214-S219.

- Meyer R, De Koker C, Dziubak R, et al. The impact of the elimination diet on growth and nutrient intake in children with food protein induced gastrointestinal allergies. Clin Transl Allergy. 2016;6:25.

- Webber SA, Graham-Brown RA, Hutchinson PE, et al. Dietary manipulation in childhood atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:91-98.

- Chang A, Robison R, Cai M, et al. Natural history of food-triggered atopic dermatitis and development of immediate reactions in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:229-236.e1.

Practice Points

- The perception of dietary triggers is so entrenched and widespread that it should be addressed even when thought to be irrelevant.

- It is important not to dismiss food as a factor in atopic dermatitis (AD), as it can play a number of roles in the condition.

- On the other hand, education about the wide range of food reactions and the relative rarity of true food-driven AD along with the potential risks of dietary modification may enhance both rapport and understanding between the clinician and patient.

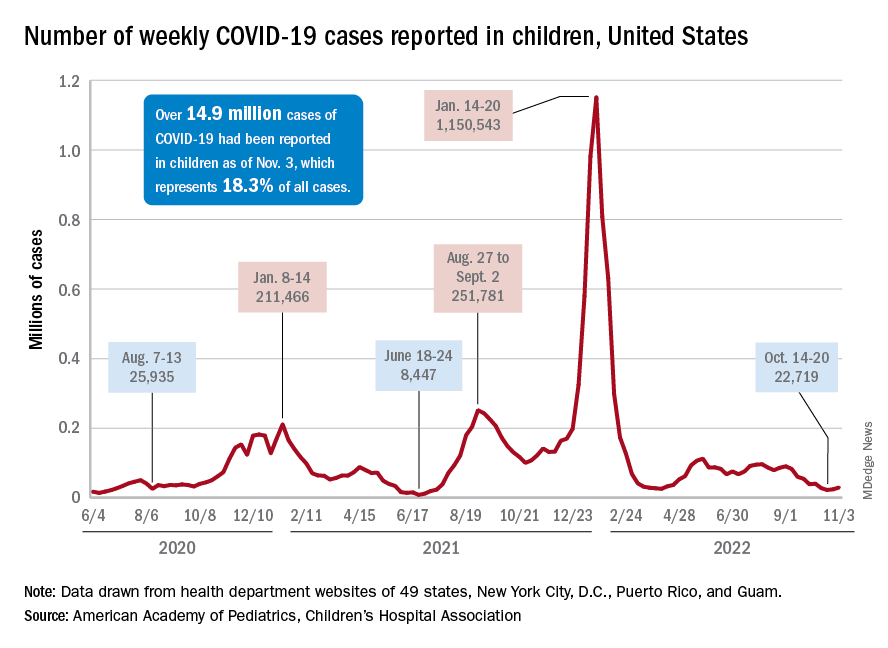

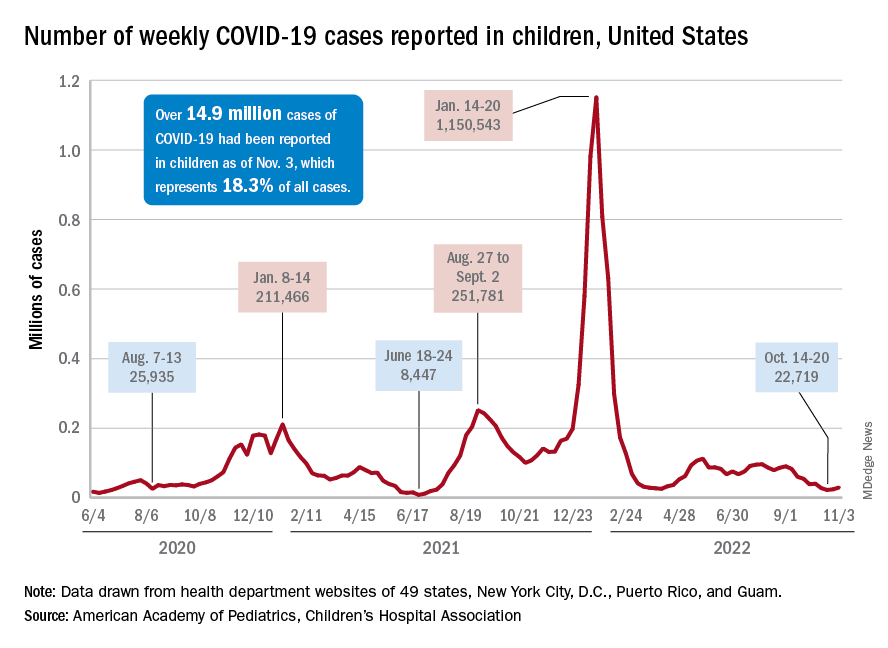

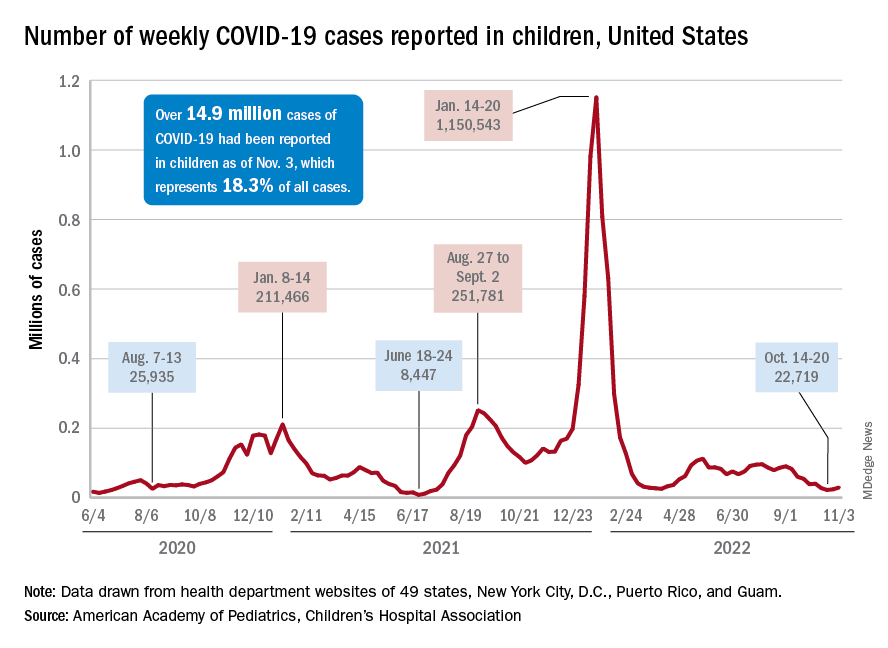

Children and COVID: New cases increase for second straight week

New COVID-19 cases rose among U.S. children for the second consecutive week, while hospitals saw signs of renewed activity on the part of SARS-CoV-2.

, when the count fell to its lowest level in more than a year, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their joint report.

The 7-day average for ED visits with diagnosed COVID was down to just 0.6% of all ED visits for 12- to 15-year-olds as late as Oct. 23 but has moved up to 0.7% since then. Among those aged 16-17 years, the 7-day average was also down to 0.6% for just one day, Oct. 19, but was up to 0.8% as of Nov. 4. So far, though, a similar increase has not yet occurred for ED visits among children aged 0-11 years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The trend is discernible, however, when looking at hospitalizations of children with confirmed COVID. The rate of new admissions of children aged 0-17 years was 0.16 per 100,000 population as late as Oct. 23 but ticked up a notch after that and has been 0.17 per 100,000 since, according to the CDC. As with the ED rate, hospitalizations had been steadily declining since late August.

Vaccine initiation continues to slow

During the week of Oct. 27 to Nov. 2, about 30,000 children under 5 years of age received their initial COVID vaccination. A month earlier (Sept. 29 to Oct. 5), that number was about 40,000. A month before that, about 53,000 children aged 0-5 years received their initial dose, the AAP said in a separate vaccination report based on CDC data.

All of that reduced interest adds up to 7.4% of the age group having received at least one dose and just 3.2% being fully vaccinated as of Nov. 2. Among children aged 5-11 years, the corresponding vaccination rates are 38.9% and 31.8%, while those aged 12-17 years are at 71.3% and 61.1%, the CDC said.

Looking at just the first 20 weeks of the vaccination experience for each age group shows that 1.6 million children under 5 years of age had received at least an initial dose, compared with 8.1 million children aged 5-11 years and 8.1 million children aged 12-15, the AAP said.

New COVID-19 cases rose among U.S. children for the second consecutive week, while hospitals saw signs of renewed activity on the part of SARS-CoV-2.

, when the count fell to its lowest level in more than a year, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their joint report.

The 7-day average for ED visits with diagnosed COVID was down to just 0.6% of all ED visits for 12- to 15-year-olds as late as Oct. 23 but has moved up to 0.7% since then. Among those aged 16-17 years, the 7-day average was also down to 0.6% for just one day, Oct. 19, but was up to 0.8% as of Nov. 4. So far, though, a similar increase has not yet occurred for ED visits among children aged 0-11 years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The trend is discernible, however, when looking at hospitalizations of children with confirmed COVID. The rate of new admissions of children aged 0-17 years was 0.16 per 100,000 population as late as Oct. 23 but ticked up a notch after that and has been 0.17 per 100,000 since, according to the CDC. As with the ED rate, hospitalizations had been steadily declining since late August.

Vaccine initiation continues to slow

During the week of Oct. 27 to Nov. 2, about 30,000 children under 5 years of age received their initial COVID vaccination. A month earlier (Sept. 29 to Oct. 5), that number was about 40,000. A month before that, about 53,000 children aged 0-5 years received their initial dose, the AAP said in a separate vaccination report based on CDC data.

All of that reduced interest adds up to 7.4% of the age group having received at least one dose and just 3.2% being fully vaccinated as of Nov. 2. Among children aged 5-11 years, the corresponding vaccination rates are 38.9% and 31.8%, while those aged 12-17 years are at 71.3% and 61.1%, the CDC said.

Looking at just the first 20 weeks of the vaccination experience for each age group shows that 1.6 million children under 5 years of age had received at least an initial dose, compared with 8.1 million children aged 5-11 years and 8.1 million children aged 12-15, the AAP said.

New COVID-19 cases rose among U.S. children for the second consecutive week, while hospitals saw signs of renewed activity on the part of SARS-CoV-2.

, when the count fell to its lowest level in more than a year, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their joint report.

The 7-day average for ED visits with diagnosed COVID was down to just 0.6% of all ED visits for 12- to 15-year-olds as late as Oct. 23 but has moved up to 0.7% since then. Among those aged 16-17 years, the 7-day average was also down to 0.6% for just one day, Oct. 19, but was up to 0.8% as of Nov. 4. So far, though, a similar increase has not yet occurred for ED visits among children aged 0-11 years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The trend is discernible, however, when looking at hospitalizations of children with confirmed COVID. The rate of new admissions of children aged 0-17 years was 0.16 per 100,000 population as late as Oct. 23 but ticked up a notch after that and has been 0.17 per 100,000 since, according to the CDC. As with the ED rate, hospitalizations had been steadily declining since late August.

Vaccine initiation continues to slow

During the week of Oct. 27 to Nov. 2, about 30,000 children under 5 years of age received their initial COVID vaccination. A month earlier (Sept. 29 to Oct. 5), that number was about 40,000. A month before that, about 53,000 children aged 0-5 years received their initial dose, the AAP said in a separate vaccination report based on CDC data.

All of that reduced interest adds up to 7.4% of the age group having received at least one dose and just 3.2% being fully vaccinated as of Nov. 2. Among children aged 5-11 years, the corresponding vaccination rates are 38.9% and 31.8%, while those aged 12-17 years are at 71.3% and 61.1%, the CDC said.

Looking at just the first 20 weeks of the vaccination experience for each age group shows that 1.6 million children under 5 years of age had received at least an initial dose, compared with 8.1 million children aged 5-11 years and 8.1 million children aged 12-15, the AAP said.

Many moms don’t remember well-child nutrition advice

Recent findings from a study examining mothers’ recall of doctors’ advice on early-child nutrition suggest that key feeding messages may not be heard, remembered, or even delivered.

During a typical child wellness visit, pediatricians provide parents with anticipatory guidance on all aspects of child development and safety, up to the age of 5 years.

The analysis of data from a subset of 1,302 mothers participating in the 2017-2019 National Survey of Family Growth showed that those older than 31 years of age and those who identified as non-Hispanic White were more likely to recall discussion of certain child nutrition topics compared with younger mothers or those who identified as Hispanic.

Of the six child-feeding topics referenced from the American Academy of Pediatrics’ “Bright Futures Guidelines,” less than half of the mothers, all of whom had a child between the ages of 6 months and 5 years, recalled guidance on limiting meals in front of the television or other electronic devices. Similarly, fewer than 50% remembered being told not to force their child to finish a bottle or food, the analysis showed.

When it came to the best time to introduce solid foods, 37% didn’t recall being told to wait at least 4 months and preferably, 6 months. In fact, these mothers reported being advised to introduce solid foods before 6 months, said Andrea McGowan, MPH, of the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and colleagues.

The study was published in the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior.

“All in all, this research draws attention to certain nutrition guidance topics or subpopulations that might be prioritized to improve receipt and recall of guidance,” said Ms. McGowan, now a first-year medical student at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, in a podcast. “This research ... implores us to consider ways to revamp the existing standard practice for pediatric well-child care to improve recall of messages.”

The analysis also included data on mothers’ recall of advice on offering foods with different tastes and textures; offering a variety of fruits and vegetables; and limiting added sugar. More than half of mothers remembered discussing four or five child nutrition topics, but 31% recalled talking about only one or two. Offering a variety of fruits and vegetables had the highest percentage of recall.

The study wasn’t powered to determine whether the nutrition guidance provided at a well-child visit was not remembered or not provided, Ms. McGowan said, adding: “So exploring this is definitely the goal of future research.”