User login

For MD-IQ use only

Remembering Why We Are In Medicine

Dear Friends,

There have been recent policy changes that may be affecting trainees and practicing physicians, whether directly impacting our current practices or influencing the decisions that shape our careers. During these challenging times, I am trying to remind myself more often of why I am in medicine – my patients. I will continue to advocate for my patients on Hill Days to affect change in policy. I will continue to provide the best care I can and fight for resources to do so. I will continue to adapt to the changing climate and do what is best for my practice so that I can deliver the care I think my patients need. By remembering why I am in medicine, I can fight for a future of medicine and science that is still bright.

In this issue’s “In Focus” article, Dr. Yasmin G. Hernandez-Barco and Dr. Motaz Ashkar review the diagnostic and treatment approaches to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, including common symptoms, differential diagnoses, and the different pancreatic enzyme replacement therapies.

Medications for weight loss are becoming more widely available; however, the literature on what to do with these medications in gastrointestinal endoscopy is still lacking. Dr. Sitharthan Sekar and Dr. Nikiya Asamoah summarize the current data and available guidelines in our “Short Clinical Review.”

With another new academic year upon us, this issue’s “Early Career” section features Dr. Allon Kahn’s top tips for becoming an effective gastroenterology consultant. He describes the 5 principles that would improve patient care and relationships with referring providers.

In the “Finance/Legal” section, Dr. Koushik Das dissects what happens when a physician gets sued, including the basis of malpractice suits, consequences, and anticipated timeline.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]) or Danielle Kiefer ([email protected]), Communications/Managing Editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact, because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: the pancreas was first discovered by a Greek surgeon, Herophilus, in 336 BC, but its exocrine and endocrine functions were not described until the 1850s-1860s by D. Moyse in Paris and Paul Langerhans in Berlin, respectively.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

There have been recent policy changes that may be affecting trainees and practicing physicians, whether directly impacting our current practices or influencing the decisions that shape our careers. During these challenging times, I am trying to remind myself more often of why I am in medicine – my patients. I will continue to advocate for my patients on Hill Days to affect change in policy. I will continue to provide the best care I can and fight for resources to do so. I will continue to adapt to the changing climate and do what is best for my practice so that I can deliver the care I think my patients need. By remembering why I am in medicine, I can fight for a future of medicine and science that is still bright.

In this issue’s “In Focus” article, Dr. Yasmin G. Hernandez-Barco and Dr. Motaz Ashkar review the diagnostic and treatment approaches to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, including common symptoms, differential diagnoses, and the different pancreatic enzyme replacement therapies.

Medications for weight loss are becoming more widely available; however, the literature on what to do with these medications in gastrointestinal endoscopy is still lacking. Dr. Sitharthan Sekar and Dr. Nikiya Asamoah summarize the current data and available guidelines in our “Short Clinical Review.”

With another new academic year upon us, this issue’s “Early Career” section features Dr. Allon Kahn’s top tips for becoming an effective gastroenterology consultant. He describes the 5 principles that would improve patient care and relationships with referring providers.

In the “Finance/Legal” section, Dr. Koushik Das dissects what happens when a physician gets sued, including the basis of malpractice suits, consequences, and anticipated timeline.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]) or Danielle Kiefer ([email protected]), Communications/Managing Editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact, because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: the pancreas was first discovered by a Greek surgeon, Herophilus, in 336 BC, but its exocrine and endocrine functions were not described until the 1850s-1860s by D. Moyse in Paris and Paul Langerhans in Berlin, respectively.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

There have been recent policy changes that may be affecting trainees and practicing physicians, whether directly impacting our current practices or influencing the decisions that shape our careers. During these challenging times, I am trying to remind myself more often of why I am in medicine – my patients. I will continue to advocate for my patients on Hill Days to affect change in policy. I will continue to provide the best care I can and fight for resources to do so. I will continue to adapt to the changing climate and do what is best for my practice so that I can deliver the care I think my patients need. By remembering why I am in medicine, I can fight for a future of medicine and science that is still bright.

In this issue’s “In Focus” article, Dr. Yasmin G. Hernandez-Barco and Dr. Motaz Ashkar review the diagnostic and treatment approaches to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, including common symptoms, differential diagnoses, and the different pancreatic enzyme replacement therapies.

Medications for weight loss are becoming more widely available; however, the literature on what to do with these medications in gastrointestinal endoscopy is still lacking. Dr. Sitharthan Sekar and Dr. Nikiya Asamoah summarize the current data and available guidelines in our “Short Clinical Review.”

With another new academic year upon us, this issue’s “Early Career” section features Dr. Allon Kahn’s top tips for becoming an effective gastroenterology consultant. He describes the 5 principles that would improve patient care and relationships with referring providers.

In the “Finance/Legal” section, Dr. Koushik Das dissects what happens when a physician gets sued, including the basis of malpractice suits, consequences, and anticipated timeline.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]) or Danielle Kiefer ([email protected]), Communications/Managing Editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact, because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: the pancreas was first discovered by a Greek surgeon, Herophilus, in 336 BC, but its exocrine and endocrine functions were not described until the 1850s-1860s by D. Moyse in Paris and Paul Langerhans in Berlin, respectively.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

Weight Loss Before Military Training May Cut Injury Risk

TOPLINE:

Army recruits who lost excess weight to enter military training experienced fewer musculoskeletal injuries (MSKIs), particularly in the lower extremities, during basic combat training than those who did not lose weight to join the service.

METHODOLOGY:

- The nation’s obesity epidemic means that fewer individuals meet the US Army’s weight and body-fat standards for entering basic combat training. Only 29% of 17- to 24-year-olds in the country would have qualified to join the military in 2018, with overweight and obesity among the leading disqualifying factors.

- Researchers analyzed data from 3168 Army trainees (mean age, 20.96 years; 62.34% men; mean maximum-ever BMI, 26.71) to examine the association between weight loss before enlistment and rates of MSKI during basic combat training.

- Trainees completed a baseline questionnaire that asked whether the person lost weight to enter the Army and included follow-up questions about the amount of weight lost, duration of weight loss, methods used, and prior physical activity.

- MSKIs were classified as any injury to the musculoskeletal system and further categorized by body region (lower extremities, upper extremities, spine/back, and other areas, including the torso and head/neck).

- Researchers identified MSKIs from medical records collected throughout basic combat training and for up to 6 weeks afterward to capture injuries that occurred during training but were documented only after its completion.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 829 trainees (26.16%) reported losing weight to enter the Army, and they tended to have higher mean maximum-ever BMI, body-fat percentage, and lean mass compared with those who did not lose weight to join the service. The mean weight loss was 9.06 kg at a rate of 1.27 kg/wk among the 723 trainees with complete data.

- The most commonly reported weight-loss methods were exercising more (83.7%), changing diet (61.0%), skipping meals (39.3%), and sweating using a sauna or rubber suit (25.6%).

- Trainees who lost weight to join the service had a lower risk of any MSKI (hazard ratio [HR], 0.86) and lower extremity MSKIs (HR, 0.84) during training than those who did not lose weight to enter the Army. No difference was found between the two groups in the risk of upper extremity, spine/back, or other MSKIs.

- Among trainees who lost weight to join the Army, the amount of time it took to lose weight was not associated with the risk for any MSKI or region-specific MSKIs.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings highlight that losing excess weight before entering military training may reduce MSKI risk for incoming recruits, enforcing the benefits of healthy weight loss programs,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Vy T. Nguyen, MS, DSc, Military Performance Division, US Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, Natick, Massachusetts, was published online in Obesity .

LIMITATIONS:

The study did not assess whether the association between weight loss and the rate of MSKIs persisted over long-term military service. How the two most frequently reported weight loss methods — increased exercise and dietary changes — may have influenced the observed association remains unclear. Medical records may not have captured all MSKIs if trainees did not seek medical care due to concerns about graduating on time or being placed on limited duty.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the US Army Medical Research and Development Command’s Military Operational Medicine Program. Two authors received support from the funder.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Army recruits who lost excess weight to enter military training experienced fewer musculoskeletal injuries (MSKIs), particularly in the lower extremities, during basic combat training than those who did not lose weight to join the service.

METHODOLOGY:

- The nation’s obesity epidemic means that fewer individuals meet the US Army’s weight and body-fat standards for entering basic combat training. Only 29% of 17- to 24-year-olds in the country would have qualified to join the military in 2018, with overweight and obesity among the leading disqualifying factors.

- Researchers analyzed data from 3168 Army trainees (mean age, 20.96 years; 62.34% men; mean maximum-ever BMI, 26.71) to examine the association between weight loss before enlistment and rates of MSKI during basic combat training.

- Trainees completed a baseline questionnaire that asked whether the person lost weight to enter the Army and included follow-up questions about the amount of weight lost, duration of weight loss, methods used, and prior physical activity.

- MSKIs were classified as any injury to the musculoskeletal system and further categorized by body region (lower extremities, upper extremities, spine/back, and other areas, including the torso and head/neck).

- Researchers identified MSKIs from medical records collected throughout basic combat training and for up to 6 weeks afterward to capture injuries that occurred during training but were documented only after its completion.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 829 trainees (26.16%) reported losing weight to enter the Army, and they tended to have higher mean maximum-ever BMI, body-fat percentage, and lean mass compared with those who did not lose weight to join the service. The mean weight loss was 9.06 kg at a rate of 1.27 kg/wk among the 723 trainees with complete data.

- The most commonly reported weight-loss methods were exercising more (83.7%), changing diet (61.0%), skipping meals (39.3%), and sweating using a sauna or rubber suit (25.6%).

- Trainees who lost weight to join the service had a lower risk of any MSKI (hazard ratio [HR], 0.86) and lower extremity MSKIs (HR, 0.84) during training than those who did not lose weight to enter the Army. No difference was found between the two groups in the risk of upper extremity, spine/back, or other MSKIs.

- Among trainees who lost weight to join the Army, the amount of time it took to lose weight was not associated with the risk for any MSKI or region-specific MSKIs.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings highlight that losing excess weight before entering military training may reduce MSKI risk for incoming recruits, enforcing the benefits of healthy weight loss programs,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Vy T. Nguyen, MS, DSc, Military Performance Division, US Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, Natick, Massachusetts, was published online in Obesity .

LIMITATIONS:

The study did not assess whether the association between weight loss and the rate of MSKIs persisted over long-term military service. How the two most frequently reported weight loss methods — increased exercise and dietary changes — may have influenced the observed association remains unclear. Medical records may not have captured all MSKIs if trainees did not seek medical care due to concerns about graduating on time or being placed on limited duty.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the US Army Medical Research and Development Command’s Military Operational Medicine Program. Two authors received support from the funder.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Army recruits who lost excess weight to enter military training experienced fewer musculoskeletal injuries (MSKIs), particularly in the lower extremities, during basic combat training than those who did not lose weight to join the service.

METHODOLOGY:

- The nation’s obesity epidemic means that fewer individuals meet the US Army’s weight and body-fat standards for entering basic combat training. Only 29% of 17- to 24-year-olds in the country would have qualified to join the military in 2018, with overweight and obesity among the leading disqualifying factors.

- Researchers analyzed data from 3168 Army trainees (mean age, 20.96 years; 62.34% men; mean maximum-ever BMI, 26.71) to examine the association between weight loss before enlistment and rates of MSKI during basic combat training.

- Trainees completed a baseline questionnaire that asked whether the person lost weight to enter the Army and included follow-up questions about the amount of weight lost, duration of weight loss, methods used, and prior physical activity.

- MSKIs were classified as any injury to the musculoskeletal system and further categorized by body region (lower extremities, upper extremities, spine/back, and other areas, including the torso and head/neck).

- Researchers identified MSKIs from medical records collected throughout basic combat training and for up to 6 weeks afterward to capture injuries that occurred during training but were documented only after its completion.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 829 trainees (26.16%) reported losing weight to enter the Army, and they tended to have higher mean maximum-ever BMI, body-fat percentage, and lean mass compared with those who did not lose weight to join the service. The mean weight loss was 9.06 kg at a rate of 1.27 kg/wk among the 723 trainees with complete data.

- The most commonly reported weight-loss methods were exercising more (83.7%), changing diet (61.0%), skipping meals (39.3%), and sweating using a sauna or rubber suit (25.6%).

- Trainees who lost weight to join the service had a lower risk of any MSKI (hazard ratio [HR], 0.86) and lower extremity MSKIs (HR, 0.84) during training than those who did not lose weight to enter the Army. No difference was found between the two groups in the risk of upper extremity, spine/back, or other MSKIs.

- Among trainees who lost weight to join the Army, the amount of time it took to lose weight was not associated with the risk for any MSKI or region-specific MSKIs.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings highlight that losing excess weight before entering military training may reduce MSKI risk for incoming recruits, enforcing the benefits of healthy weight loss programs,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Vy T. Nguyen, MS, DSc, Military Performance Division, US Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, Natick, Massachusetts, was published online in Obesity .

LIMITATIONS:

The study did not assess whether the association between weight loss and the rate of MSKIs persisted over long-term military service. How the two most frequently reported weight loss methods — increased exercise and dietary changes — may have influenced the observed association remains unclear. Medical records may not have captured all MSKIs if trainees did not seek medical care due to concerns about graduating on time or being placed on limited duty.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the US Army Medical Research and Development Command’s Military Operational Medicine Program. Two authors received support from the funder.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Painless Nodule on the Lower Eyelid

Painless Nodule on the Lower Eyelid

THE DIAGNOSIS: Idiopathic Facial Aseptic Granuloma

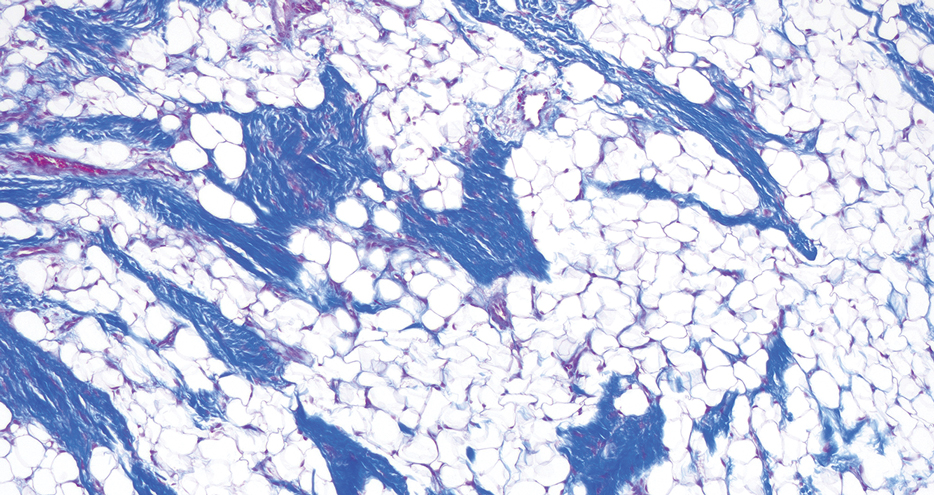

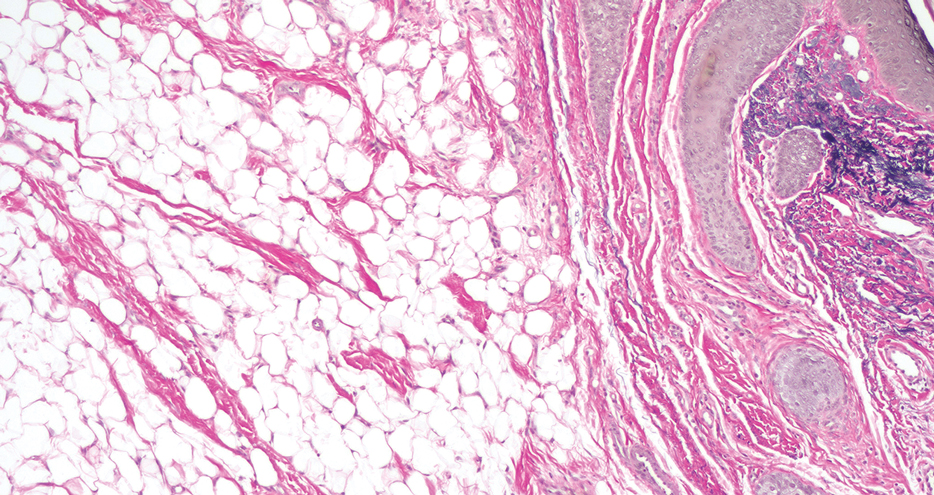

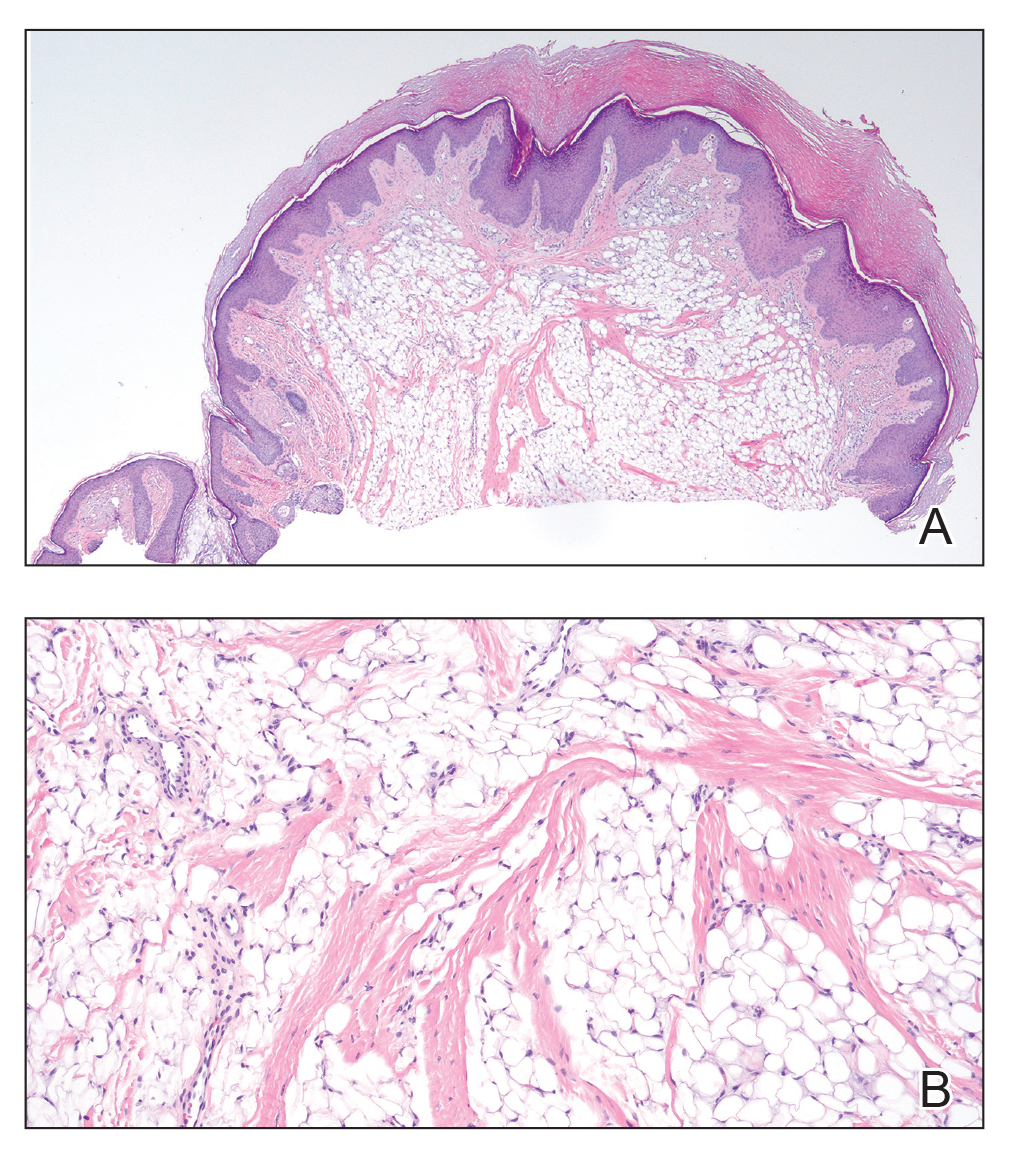

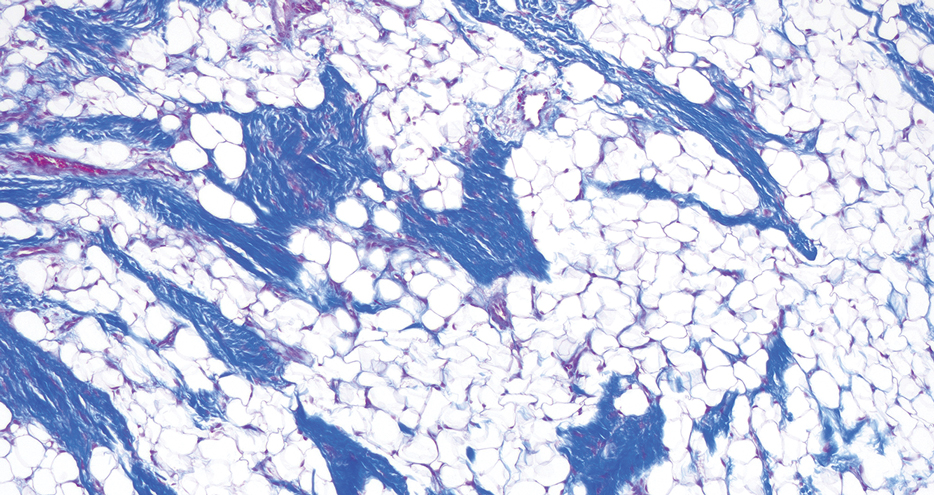

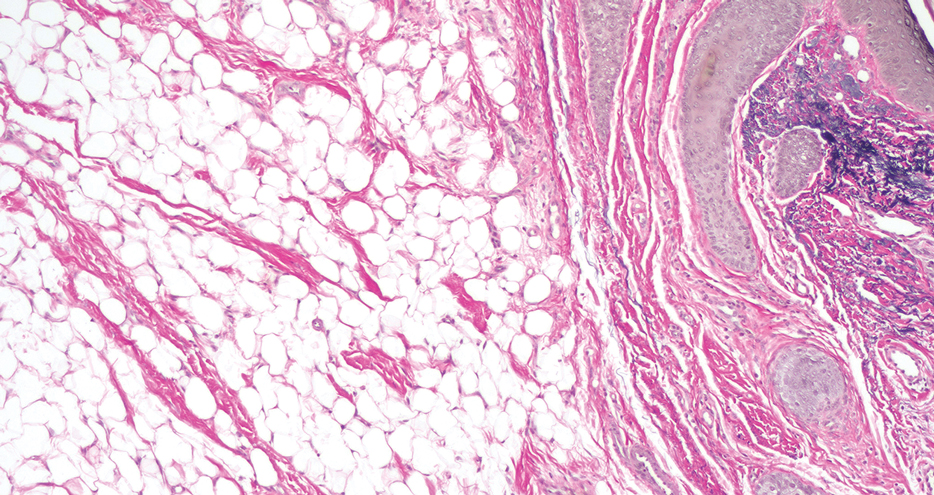

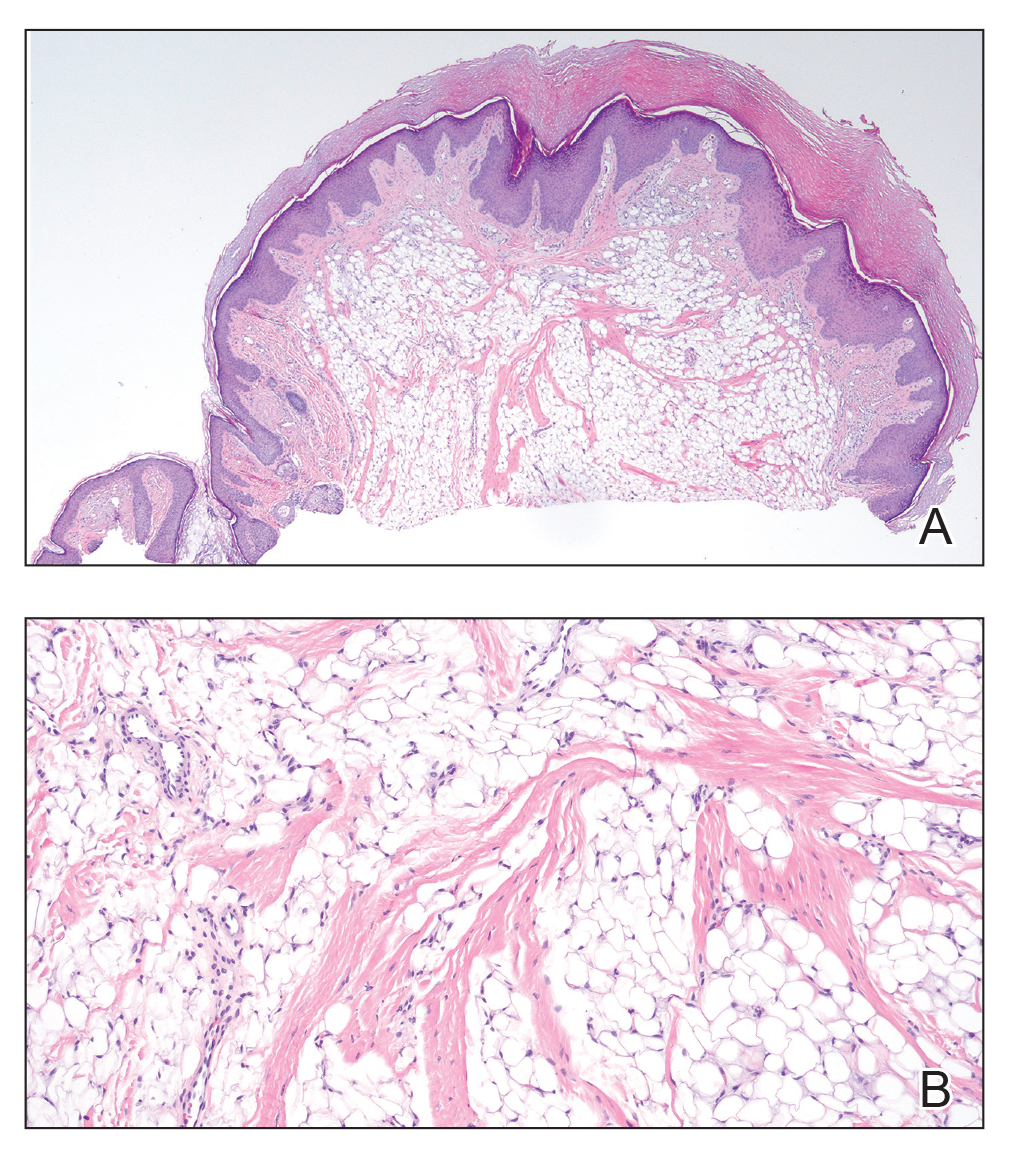

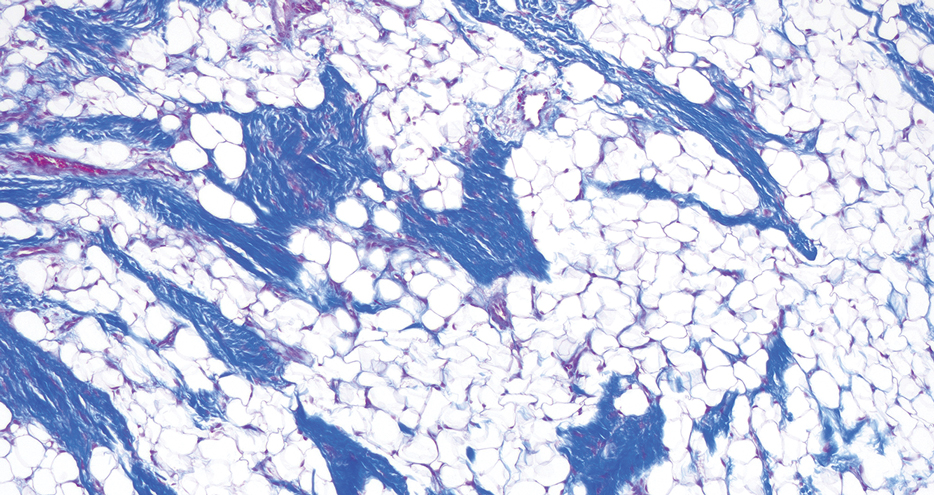

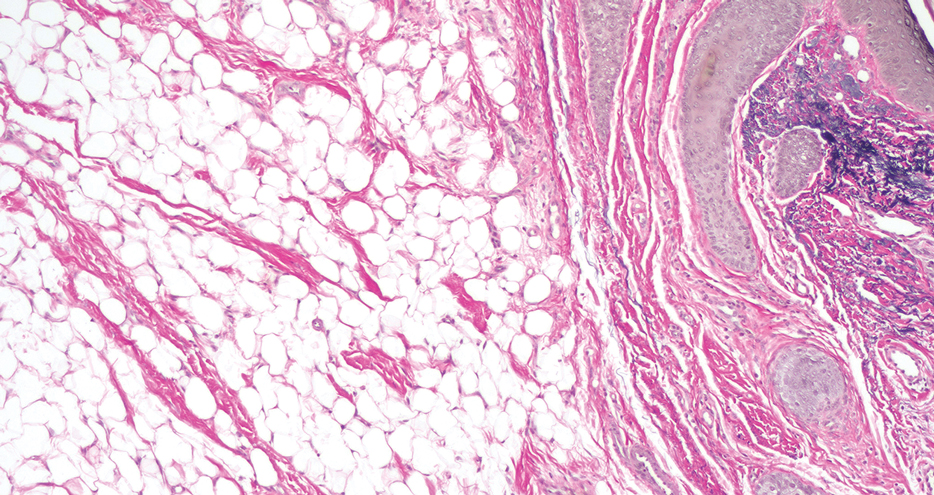

Histopathology showed a ruptured follicle, perifollicular granulomatous inflammation, and admixed multinucleated giant cells in the superficial dermis. The deeper tissue exhibited edema, histiocytic/granulomatous inflammation forming ill-defined loose granulomas, and a single neutrophilic microabscess (Figure). Stains for periodic acid-Schiff with diastase and acid-fast bacillus were negative for microorganisms. The clinical examination and pathology findings supported a diagnosis of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG).

First reported in 1999, IFAG was described using the French term pyodermite froide du visage, which translates to “cold pyoderma of the face”; however, it was renamed to represent its granulomatous characteristics and noninfectious etiology.1 The pathogenesis of IFAG is unknown, but the leading hypothesis is that it may be a type of childhood granulomatous rosacea, given its association with relapsing chalazions, papulopustular eruptions on the face, and facial flushing.2 Other hypotheses are that IFAG is idiopathic or a granulomatous response to an insect bite, minor trauma, or embryologic remnant.3

A rare condition arising in early childhood, IFAG manifests as a single or multiple, painless, erythematous or violaceous nodule(s) on the face, most often on the cheeks or eyelids.4 A thorough history and clinical examination often suffice for diagnosis. Dermoscopy may reveal white perifollicular halos and follicular plugs on an erythematous base with linear vessels.4 If diagnostic tests are performed, there are notable characteristic findings: ultrasonography often shows a well-circumscribed, hypoechoic, ovoid dermal lesion without calcifications. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures commonly are negative.4 On biopsy, histopathology may reveal granulomatous inflammation in the superficial and deep dermis, multinucleated giant cells, and surrounding lymphocytic, neutrophilic, and eosinophilic infiltration with no calcium deposits.3,5,6 Histopathology findings for IFAG and rosacea lesions are similar; both may demonstrate folliculitis, perifollicular granulomas, and admixed lymphohistiocytic inflammation.7

Differentiating IFAG from other dermatologic lesions can be challenging, as the differential includes benign neoplasms (eg, dermoid cyst, chalazion, pilomatricoma, xanthoma, xanthogranuloma2) and infectious etiologies such as bacterial pyoderma and mycobacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections (eg, cutaneous leishmaniasis). Pilomatricomas, although often seen on the face or extremities in young girls, more often are well circumscribed and located in the dermis. Ultrasonography of a pilomatricoma classically shows variable foci of calcification. Xanthoma and xanthogranuloma also were considered in our case since the lesion was subtly yellowish on examination. Similar to IFAG, these conditions may manifest as single or multiple lesions. Abnormalities in the patient’s blood lipid panel or family history may be needed to diagnose xanthoma. Biopsy of a juvenile xanthogranuloma would exhibit a dense dermal nodular proliferation of histiocytic cells with a smaller number of admixed lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils, in contrast to the multiple smaller loose epithelioid granulomas seen in IFAG. Additional diagnoses in the differential for IFAG include pyogenic granuloma, Spitz nevus, nodulocystic infantile acne, granulomatous rosacea, and hemangioma.1,3,9 In particular, granulomatous rosacea is challenging to differentiate from IFAG given the overlapping clinical findings. Multiple lesions, the presence of papules and pustules, and associated rosacea symptoms such as flushing suggest a diagnosis of granulomatous rosacea over IFAG.2

The prognosis for IFAG is excellent; most lesions self-resolve without treatment or procedural intervention within 1 year without scarring or relapse.3 Topical and oral antibiotic treatments such as metronidazole 0.75% gel or cream, oral erythromycin, oral clarithromycin, and doxycycline (in patients older than 8 years) have been used to treat IFAG with variable clinic responses.2,3,6,8 Persistent IFAG has been treated with surgical excision.3 Our patient was treated with a combination of gentamicin ointment 0.3% and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% and experienced approximately 50% improvement in the first month of treatment.

- Roul S, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Idiopathic aseptic facial granuloma (pyodermite froide du visage): a pediatric entity? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1253-1255.

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. IFAG and childhood rosacea: a possible link? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:429-432. doi:10.1111/pde.12137

- Boralevi F, Léauté-Labrèze C, Lepreux S, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma: a multicentre prospective study of 30 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:705-708. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07741.x

- Lobato-Berezo A, Montoro-Romero S, Pujol RM, et al. Dermoscopic features of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E308-E309. doi:10.1111/pde.13582

- González Rodríguez AJ, Jordá Cuevas E. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:298-300. doi:10.1111/ced.12535

- Orion C, Sfecci A, Tisseau L, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a 13-year-old boy dramatically improved with oral doxycycline and topical metronidazole: evidence for a link with childhood rosacea. Case Rep Dermatol. 2016;8:197-201. doi:10.1159/000447624

- Neri I, Raone B, Dondi A, et al. Should idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma be considered granulomatous rosacea? report of three pediatric cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:109-111. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2011.01689.x

- Miconi F, Principi N, Cassiani L, et al. A cheek nodule in a child: be aware of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma and its differential diagnosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2471. doi:10.3390/ijerph16142471

- Baroni A, Russo T, Faccenda F, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a child: a possible expression of childhood rosacea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:394-395. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01805.x

THE DIAGNOSIS: Idiopathic Facial Aseptic Granuloma

Histopathology showed a ruptured follicle, perifollicular granulomatous inflammation, and admixed multinucleated giant cells in the superficial dermis. The deeper tissue exhibited edema, histiocytic/granulomatous inflammation forming ill-defined loose granulomas, and a single neutrophilic microabscess (Figure). Stains for periodic acid-Schiff with diastase and acid-fast bacillus were negative for microorganisms. The clinical examination and pathology findings supported a diagnosis of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG).

First reported in 1999, IFAG was described using the French term pyodermite froide du visage, which translates to “cold pyoderma of the face”; however, it was renamed to represent its granulomatous characteristics and noninfectious etiology.1 The pathogenesis of IFAG is unknown, but the leading hypothesis is that it may be a type of childhood granulomatous rosacea, given its association with relapsing chalazions, papulopustular eruptions on the face, and facial flushing.2 Other hypotheses are that IFAG is idiopathic or a granulomatous response to an insect bite, minor trauma, or embryologic remnant.3

A rare condition arising in early childhood, IFAG manifests as a single or multiple, painless, erythematous or violaceous nodule(s) on the face, most often on the cheeks or eyelids.4 A thorough history and clinical examination often suffice for diagnosis. Dermoscopy may reveal white perifollicular halos and follicular plugs on an erythematous base with linear vessels.4 If diagnostic tests are performed, there are notable characteristic findings: ultrasonography often shows a well-circumscribed, hypoechoic, ovoid dermal lesion without calcifications. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures commonly are negative.4 On biopsy, histopathology may reveal granulomatous inflammation in the superficial and deep dermis, multinucleated giant cells, and surrounding lymphocytic, neutrophilic, and eosinophilic infiltration with no calcium deposits.3,5,6 Histopathology findings for IFAG and rosacea lesions are similar; both may demonstrate folliculitis, perifollicular granulomas, and admixed lymphohistiocytic inflammation.7

Differentiating IFAG from other dermatologic lesions can be challenging, as the differential includes benign neoplasms (eg, dermoid cyst, chalazion, pilomatricoma, xanthoma, xanthogranuloma2) and infectious etiologies such as bacterial pyoderma and mycobacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections (eg, cutaneous leishmaniasis). Pilomatricomas, although often seen on the face or extremities in young girls, more often are well circumscribed and located in the dermis. Ultrasonography of a pilomatricoma classically shows variable foci of calcification. Xanthoma and xanthogranuloma also were considered in our case since the lesion was subtly yellowish on examination. Similar to IFAG, these conditions may manifest as single or multiple lesions. Abnormalities in the patient’s blood lipid panel or family history may be needed to diagnose xanthoma. Biopsy of a juvenile xanthogranuloma would exhibit a dense dermal nodular proliferation of histiocytic cells with a smaller number of admixed lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils, in contrast to the multiple smaller loose epithelioid granulomas seen in IFAG. Additional diagnoses in the differential for IFAG include pyogenic granuloma, Spitz nevus, nodulocystic infantile acne, granulomatous rosacea, and hemangioma.1,3,9 In particular, granulomatous rosacea is challenging to differentiate from IFAG given the overlapping clinical findings. Multiple lesions, the presence of papules and pustules, and associated rosacea symptoms such as flushing suggest a diagnosis of granulomatous rosacea over IFAG.2

The prognosis for IFAG is excellent; most lesions self-resolve without treatment or procedural intervention within 1 year without scarring or relapse.3 Topical and oral antibiotic treatments such as metronidazole 0.75% gel or cream, oral erythromycin, oral clarithromycin, and doxycycline (in patients older than 8 years) have been used to treat IFAG with variable clinic responses.2,3,6,8 Persistent IFAG has been treated with surgical excision.3 Our patient was treated with a combination of gentamicin ointment 0.3% and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% and experienced approximately 50% improvement in the first month of treatment.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Idiopathic Facial Aseptic Granuloma

Histopathology showed a ruptured follicle, perifollicular granulomatous inflammation, and admixed multinucleated giant cells in the superficial dermis. The deeper tissue exhibited edema, histiocytic/granulomatous inflammation forming ill-defined loose granulomas, and a single neutrophilic microabscess (Figure). Stains for periodic acid-Schiff with diastase and acid-fast bacillus were negative for microorganisms. The clinical examination and pathology findings supported a diagnosis of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG).

First reported in 1999, IFAG was described using the French term pyodermite froide du visage, which translates to “cold pyoderma of the face”; however, it was renamed to represent its granulomatous characteristics and noninfectious etiology.1 The pathogenesis of IFAG is unknown, but the leading hypothesis is that it may be a type of childhood granulomatous rosacea, given its association with relapsing chalazions, papulopustular eruptions on the face, and facial flushing.2 Other hypotheses are that IFAG is idiopathic or a granulomatous response to an insect bite, minor trauma, or embryologic remnant.3

A rare condition arising in early childhood, IFAG manifests as a single or multiple, painless, erythematous or violaceous nodule(s) on the face, most often on the cheeks or eyelids.4 A thorough history and clinical examination often suffice for diagnosis. Dermoscopy may reveal white perifollicular halos and follicular plugs on an erythematous base with linear vessels.4 If diagnostic tests are performed, there are notable characteristic findings: ultrasonography often shows a well-circumscribed, hypoechoic, ovoid dermal lesion without calcifications. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures commonly are negative.4 On biopsy, histopathology may reveal granulomatous inflammation in the superficial and deep dermis, multinucleated giant cells, and surrounding lymphocytic, neutrophilic, and eosinophilic infiltration with no calcium deposits.3,5,6 Histopathology findings for IFAG and rosacea lesions are similar; both may demonstrate folliculitis, perifollicular granulomas, and admixed lymphohistiocytic inflammation.7

Differentiating IFAG from other dermatologic lesions can be challenging, as the differential includes benign neoplasms (eg, dermoid cyst, chalazion, pilomatricoma, xanthoma, xanthogranuloma2) and infectious etiologies such as bacterial pyoderma and mycobacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections (eg, cutaneous leishmaniasis). Pilomatricomas, although often seen on the face or extremities in young girls, more often are well circumscribed and located in the dermis. Ultrasonography of a pilomatricoma classically shows variable foci of calcification. Xanthoma and xanthogranuloma also were considered in our case since the lesion was subtly yellowish on examination. Similar to IFAG, these conditions may manifest as single or multiple lesions. Abnormalities in the patient’s blood lipid panel or family history may be needed to diagnose xanthoma. Biopsy of a juvenile xanthogranuloma would exhibit a dense dermal nodular proliferation of histiocytic cells with a smaller number of admixed lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils, in contrast to the multiple smaller loose epithelioid granulomas seen in IFAG. Additional diagnoses in the differential for IFAG include pyogenic granuloma, Spitz nevus, nodulocystic infantile acne, granulomatous rosacea, and hemangioma.1,3,9 In particular, granulomatous rosacea is challenging to differentiate from IFAG given the overlapping clinical findings. Multiple lesions, the presence of papules and pustules, and associated rosacea symptoms such as flushing suggest a diagnosis of granulomatous rosacea over IFAG.2

The prognosis for IFAG is excellent; most lesions self-resolve without treatment or procedural intervention within 1 year without scarring or relapse.3 Topical and oral antibiotic treatments such as metronidazole 0.75% gel or cream, oral erythromycin, oral clarithromycin, and doxycycline (in patients older than 8 years) have been used to treat IFAG with variable clinic responses.2,3,6,8 Persistent IFAG has been treated with surgical excision.3 Our patient was treated with a combination of gentamicin ointment 0.3% and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% and experienced approximately 50% improvement in the first month of treatment.

- Roul S, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Idiopathic aseptic facial granuloma (pyodermite froide du visage): a pediatric entity? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1253-1255.

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. IFAG and childhood rosacea: a possible link? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:429-432. doi:10.1111/pde.12137

- Boralevi F, Léauté-Labrèze C, Lepreux S, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma: a multicentre prospective study of 30 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:705-708. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07741.x

- Lobato-Berezo A, Montoro-Romero S, Pujol RM, et al. Dermoscopic features of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E308-E309. doi:10.1111/pde.13582

- González Rodríguez AJ, Jordá Cuevas E. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:298-300. doi:10.1111/ced.12535

- Orion C, Sfecci A, Tisseau L, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a 13-year-old boy dramatically improved with oral doxycycline and topical metronidazole: evidence for a link with childhood rosacea. Case Rep Dermatol. 2016;8:197-201. doi:10.1159/000447624

- Neri I, Raone B, Dondi A, et al. Should idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma be considered granulomatous rosacea? report of three pediatric cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:109-111. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2011.01689.x

- Miconi F, Principi N, Cassiani L, et al. A cheek nodule in a child: be aware of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma and its differential diagnosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2471. doi:10.3390/ijerph16142471

- Baroni A, Russo T, Faccenda F, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a child: a possible expression of childhood rosacea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:394-395. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01805.x

- Roul S, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Idiopathic aseptic facial granuloma (pyodermite froide du visage): a pediatric entity? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1253-1255.

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. IFAG and childhood rosacea: a possible link? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:429-432. doi:10.1111/pde.12137

- Boralevi F, Léauté-Labrèze C, Lepreux S, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma: a multicentre prospective study of 30 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:705-708. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07741.x

- Lobato-Berezo A, Montoro-Romero S, Pujol RM, et al. Dermoscopic features of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E308-E309. doi:10.1111/pde.13582

- González Rodríguez AJ, Jordá Cuevas E. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:298-300. doi:10.1111/ced.12535

- Orion C, Sfecci A, Tisseau L, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a 13-year-old boy dramatically improved with oral doxycycline and topical metronidazole: evidence for a link with childhood rosacea. Case Rep Dermatol. 2016;8:197-201. doi:10.1159/000447624

- Neri I, Raone B, Dondi A, et al. Should idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma be considered granulomatous rosacea? report of three pediatric cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:109-111. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2011.01689.x

- Miconi F, Principi N, Cassiani L, et al. A cheek nodule in a child: be aware of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma and its differential diagnosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2471. doi:10.3390/ijerph16142471

- Baroni A, Russo T, Faccenda F, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a child: a possible expression of childhood rosacea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:394-395. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01805.x

Painless Nodule on the Lower Eyelid

Painless Nodule on the Lower Eyelid

A 4-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a painless, red to golden-yellowish nodule on the right lower eyelid of 4 months’ duration. The patient had no history of skin disease and was otherwise healthy. Physical examination revealed a single 1-cm, soft, erythematous and yellowish plaque on the right lower eyelid that was subtly fluctuant on palpation. She had no associated systemic symptoms or lymphadenopathy. A punch biopsy of the lesion was performed.

Top 5 Tips for Becoming an Effective Gastroenterology Consultant

Gastroenterology (GI) subspecialty training is carefully designed to develop expertise in digestive diseases and gastrointestinal endoscopy, while facilitating the transition from generalist to subspecialty consultant. The concept of effective consultation extends far beyond clinical expertise and has been explored repeatedly, beginning with Goldman’s “Ten Commandments” in 1983.1,2 How should these best practices be specifically applied to GI? More importantly, what kind of experience would you want if you were the referring provider or the patient themselves?

Below are

1. Be Kind

Survey studies of medical/surgical residents and attending hospitalists have demonstrated that willingness to accept consultation requests was the single factor consistently rated as most important in determining the quality of the consultation interaction.3,4 Unfortunately, nearly 65% of respondents reported encountering pushback when requesting subspecialty consultation. It is critical to recognize that when you receive a GI consult request, the requester has already decided that it is needed. Whether that request comports with our individual notion of “necessary” or “important,” this is a colleague’s request for help. There are myriad reasons why a request may be made, but they are unified in this principle.

Effective teamwork in healthcare settings enhances clinical performance and patient safety. Positive relationships with colleagues and healthcare team members also mitigate the emotional basis for physician burnout.5 Be kind and courteous to those who seek your assistance. Move beyond the notion of the “bad” or “soft” consult and seek instead to understand how you can help.

A requesting physician may phrase the consult question vaguely or may know that the patient is having a GI-related issue, but simply lack the specific knowledge to know what is needed. In these instances, it is our role to listen and help guide them to the correct thought process to ensure the best care of the patient. These important interactions establish our reputation, create our referral bases, and directly affect our sense of personal satisfaction.

2. Be Timely

GI presents an appealing breadth of pathology, but this also corresponds to a wide variety of indications for consultation and, therefore, urgency of need. In a busy clinical practice, not all requests can be urgently prioritized. However, it is the consultant’s responsibility to identify patients that require urgent evaluation and intervention to avert a potential adverse outcome.

We are well-trained in the medical triage of consultations. There are explicit guidelines for assessing urgency for GI bleeding, foreign body ingestion, choledocholithiasis, and many other indications. However, there are often special contextual circumstances that will elevate the urgency of a seemingly non-urgent consult request. Does the patient have an upcoming surgery or treatment that will depend on your input? Are they facing an imminent loss of insurance coverage? Is their non-severe GI disease leading to more severe impact on non-GI organ systems? The referring provider knows the patient better than you – seek to understand the context of the consult request.

Timeliness also applies to our communication. Communicate recommendations directly to the consulting service as soon as the patient is seen. When a colleague reaches out with a concern about a patient, make sure to take that request seriously. If you are unable to address the concern immediately, at least provide acknowledgment and an estimated timeline for response. As the maxim states, the effectiveness of a consultant is just as dependent on availability as it is on ability.

3. Be Specific

The same survey studies indicate that the second most critical aspect of successful subspecialty consultation is delivering clear recommendations. Accordingly, I always urge my trainees to challenge me when we leave a consult interaction if they feel that our plan is vague or imprecise.

Specificity in consult recommendations is an essential way to demonstrate your expertise and provide value. Clear and definitive recommendations enhance others’ perception of your skill, reduce the need for additional clarifying communication, and lead to more efficient, higher quality care. Avoid vague language, such as asking the requester to “consider” a test or intervention. When recommending medication, specify the dose, frequency, duration, and expected timeline of effect. Rather than recommending “cross-sectional imaging,” specify what modality and protocol. Instead of recommending “adequate resuscitation,” specify your target endpoints. If you engage in multidisciplinary discussion, ensure you strive for a specific group consensus plan and communicate this to all members of the team.

Specificity also applies to the quality of your documentation. Ensure that your clinical notes outline your rationale for your recommended plan, specific contingencies based on results of recommended testing, and a plan for follow-up care. When referring for open-access endoscopy, specifically outline what to look for and which specimens or endoscopic interventions are needed. Be precise in your procedure documentation – avoid vague terms such as small/medium/large and instead quantify in terms of millimeter/centimeter measurement. If you do not adopt specific classification schemes (e.g. Prague classification, Paris classification, Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score, etc.), ensure you provide enough descriptive language to convey an adequate understanding of the findings.

4. Be Helpful

A consultant’s primary directive is to be of service to the consulting provider and the patient. As an educational leader, I am often asked what attributes separate a high-performing trainee from an average one. My feeling is that the most critical attribute is a sense of ownership over patient care.

As a consultant, when others feel we are exhibiting engagement and ownership in a patient’s care, they perceive that we are working together as an effective healthcare team. Interestingly, survey studies of inpatient care show that primary services do not necessarily value assistance with orders or care coordination – they consider these as core aspects of their daily work. What they did value was ongoing daily progress notes/communication, regardless of patient acuity or consulting specialty. This is a potent signal that our continued engagement (both inpatient and outpatient) is perceived as helpful.

Helpfulness is further aided by ensuring mutual understanding. While survey data indicate that sharing specific literature citations may not always be perceived positively, explaining the consultant’s rationale for their recommendations is highly valued. Take the time to tactfully explain your assessment of the patient and why you arrived at your specific recommendations. If your recommendations differ from what the requester expected (e.g. a procedure was expected but is not offered), ensure you explain why and answer questions they may have. This fosters mutual respect and proactively averts conflict or discontent from misunderstanding.

Multidisciplinary collaboration is another important avenue for aiding our patients and colleagues. Studies across a wide range of disease processes (including GI bleeding, IBD, etc.) and medical settings have demonstrated that multidisciplinary collaboration unequivocally improves patient outcomes.6 The success of these collaborations relies on our willingness to fully engage in these conversations, despite the fact that they may often be logistically challenging.

We all know how difficult it can be to locate and organize multiple medical specialists with complex varying clinical schedules and busy personal lives. Choosing to do so demonstrates a dedication to providing the highest level of care and elevates both patient and physician satisfaction. Having chosen to cultivate several ongoing multidisciplinary conferences/collaborations, I can attest to the notion that the outcome is well worth the effort.

5. Be Honest

While we always strive to provide the answers for our patients and colleagues, we must also acknowledge our limitations. Be honest with yourself when you encounter a scenario that pushes beyond the boundaries of your knowledge and comfort. Be willing to admit when you yourself need to consult others or seek an outside referral to provide the care a patient needs. Aspiring physicians often espouse that a devotion to lifelong learning is a key driver of their desire to pursue a career in medicine. These scenarios provide a key opportunity to expand our knowledge while doing what is right for our patients.

Be equally honest about your comfort with “curbside” consultations. Studies show that subspecialists receive on average of 3-4 such requests per week.7 The perception of these interactions is starkly discrepant between the requester and recipient. While over 80% of surveyed primary nonsurgical services felt that curbside consultations were helpful in patient care, a similar proportion of subspecialists expressed concern that insufficient clinical information was provided, even leading to a fear of litigation. While straightforward, informal conversations on narrow, well-defined questions can be helpful and efficient, the consultant should always feel comfortable seeking an opportunity for formal consultation when the details are unclear or the case/question is complex.

Closing Thoughts

Being an effective GI consultant isn’t just about what you know—it’s about how you apply it, how you communicate it, and how you make others feel in the process.

The attributes outlined above are not ancillary traits—they are essential components of high-quality consultation. When consistently applied, they enhance collaboration, improve patient outcomes, and reinforce trust within the healthcare system. By committing to them, you establish your reputation of excellence and play a role in elevating the field of gastroenterology more broadly.

Dr. Kahn is based in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona. He reports no conflicts of interest in regard to this article.

References

1. Goldman L, et al. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983 Sep.

2. Salerno SM, et al. Principles of effective consultation: an update for the 21st-century consultant. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Feb. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.271.

3. Adams TN, et al. Hospitalist Perspective of Interactions with Medicine Subspecialty Consult Services. J Hosp Med. 2018 May. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2882.

4. Matsuo T, et al. Essential consultants’ skills and attitudes (Willing CONSULT): a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ. 2021 Jul. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02810-9.

5. Welp A, Manser T. Integrating teamwork, clinician occupational well-being and patient safety - development of a conceptual framework based on a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1535-y.

6. Webster CS, et al. Interprofessional Learning in Multidisciplinary Healthcare Teams Is Associated With Reduced Patient Mortality: A Quantitative Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Patient Saf. 2024 Jan. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000001170.

7. Lin M, et al. Curbside Consultations: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.09.026.

Gastroenterology (GI) subspecialty training is carefully designed to develop expertise in digestive diseases and gastrointestinal endoscopy, while facilitating the transition from generalist to subspecialty consultant. The concept of effective consultation extends far beyond clinical expertise and has been explored repeatedly, beginning with Goldman’s “Ten Commandments” in 1983.1,2 How should these best practices be specifically applied to GI? More importantly, what kind of experience would you want if you were the referring provider or the patient themselves?

Below are

1. Be Kind

Survey studies of medical/surgical residents and attending hospitalists have demonstrated that willingness to accept consultation requests was the single factor consistently rated as most important in determining the quality of the consultation interaction.3,4 Unfortunately, nearly 65% of respondents reported encountering pushback when requesting subspecialty consultation. It is critical to recognize that when you receive a GI consult request, the requester has already decided that it is needed. Whether that request comports with our individual notion of “necessary” or “important,” this is a colleague’s request for help. There are myriad reasons why a request may be made, but they are unified in this principle.

Effective teamwork in healthcare settings enhances clinical performance and patient safety. Positive relationships with colleagues and healthcare team members also mitigate the emotional basis for physician burnout.5 Be kind and courteous to those who seek your assistance. Move beyond the notion of the “bad” or “soft” consult and seek instead to understand how you can help.

A requesting physician may phrase the consult question vaguely or may know that the patient is having a GI-related issue, but simply lack the specific knowledge to know what is needed. In these instances, it is our role to listen and help guide them to the correct thought process to ensure the best care of the patient. These important interactions establish our reputation, create our referral bases, and directly affect our sense of personal satisfaction.

2. Be Timely

GI presents an appealing breadth of pathology, but this also corresponds to a wide variety of indications for consultation and, therefore, urgency of need. In a busy clinical practice, not all requests can be urgently prioritized. However, it is the consultant’s responsibility to identify patients that require urgent evaluation and intervention to avert a potential adverse outcome.

We are well-trained in the medical triage of consultations. There are explicit guidelines for assessing urgency for GI bleeding, foreign body ingestion, choledocholithiasis, and many other indications. However, there are often special contextual circumstances that will elevate the urgency of a seemingly non-urgent consult request. Does the patient have an upcoming surgery or treatment that will depend on your input? Are they facing an imminent loss of insurance coverage? Is their non-severe GI disease leading to more severe impact on non-GI organ systems? The referring provider knows the patient better than you – seek to understand the context of the consult request.

Timeliness also applies to our communication. Communicate recommendations directly to the consulting service as soon as the patient is seen. When a colleague reaches out with a concern about a patient, make sure to take that request seriously. If you are unable to address the concern immediately, at least provide acknowledgment and an estimated timeline for response. As the maxim states, the effectiveness of a consultant is just as dependent on availability as it is on ability.

3. Be Specific

The same survey studies indicate that the second most critical aspect of successful subspecialty consultation is delivering clear recommendations. Accordingly, I always urge my trainees to challenge me when we leave a consult interaction if they feel that our plan is vague or imprecise.

Specificity in consult recommendations is an essential way to demonstrate your expertise and provide value. Clear and definitive recommendations enhance others’ perception of your skill, reduce the need for additional clarifying communication, and lead to more efficient, higher quality care. Avoid vague language, such as asking the requester to “consider” a test or intervention. When recommending medication, specify the dose, frequency, duration, and expected timeline of effect. Rather than recommending “cross-sectional imaging,” specify what modality and protocol. Instead of recommending “adequate resuscitation,” specify your target endpoints. If you engage in multidisciplinary discussion, ensure you strive for a specific group consensus plan and communicate this to all members of the team.

Specificity also applies to the quality of your documentation. Ensure that your clinical notes outline your rationale for your recommended plan, specific contingencies based on results of recommended testing, and a plan for follow-up care. When referring for open-access endoscopy, specifically outline what to look for and which specimens or endoscopic interventions are needed. Be precise in your procedure documentation – avoid vague terms such as small/medium/large and instead quantify in terms of millimeter/centimeter measurement. If you do not adopt specific classification schemes (e.g. Prague classification, Paris classification, Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score, etc.), ensure you provide enough descriptive language to convey an adequate understanding of the findings.

4. Be Helpful

A consultant’s primary directive is to be of service to the consulting provider and the patient. As an educational leader, I am often asked what attributes separate a high-performing trainee from an average one. My feeling is that the most critical attribute is a sense of ownership over patient care.

As a consultant, when others feel we are exhibiting engagement and ownership in a patient’s care, they perceive that we are working together as an effective healthcare team. Interestingly, survey studies of inpatient care show that primary services do not necessarily value assistance with orders or care coordination – they consider these as core aspects of their daily work. What they did value was ongoing daily progress notes/communication, regardless of patient acuity or consulting specialty. This is a potent signal that our continued engagement (both inpatient and outpatient) is perceived as helpful.

Helpfulness is further aided by ensuring mutual understanding. While survey data indicate that sharing specific literature citations may not always be perceived positively, explaining the consultant’s rationale for their recommendations is highly valued. Take the time to tactfully explain your assessment of the patient and why you arrived at your specific recommendations. If your recommendations differ from what the requester expected (e.g. a procedure was expected but is not offered), ensure you explain why and answer questions they may have. This fosters mutual respect and proactively averts conflict or discontent from misunderstanding.

Multidisciplinary collaboration is another important avenue for aiding our patients and colleagues. Studies across a wide range of disease processes (including GI bleeding, IBD, etc.) and medical settings have demonstrated that multidisciplinary collaboration unequivocally improves patient outcomes.6 The success of these collaborations relies on our willingness to fully engage in these conversations, despite the fact that they may often be logistically challenging.

We all know how difficult it can be to locate and organize multiple medical specialists with complex varying clinical schedules and busy personal lives. Choosing to do so demonstrates a dedication to providing the highest level of care and elevates both patient and physician satisfaction. Having chosen to cultivate several ongoing multidisciplinary conferences/collaborations, I can attest to the notion that the outcome is well worth the effort.

5. Be Honest

While we always strive to provide the answers for our patients and colleagues, we must also acknowledge our limitations. Be honest with yourself when you encounter a scenario that pushes beyond the boundaries of your knowledge and comfort. Be willing to admit when you yourself need to consult others or seek an outside referral to provide the care a patient needs. Aspiring physicians often espouse that a devotion to lifelong learning is a key driver of their desire to pursue a career in medicine. These scenarios provide a key opportunity to expand our knowledge while doing what is right for our patients.

Be equally honest about your comfort with “curbside” consultations. Studies show that subspecialists receive on average of 3-4 such requests per week.7 The perception of these interactions is starkly discrepant between the requester and recipient. While over 80% of surveyed primary nonsurgical services felt that curbside consultations were helpful in patient care, a similar proportion of subspecialists expressed concern that insufficient clinical information was provided, even leading to a fear of litigation. While straightforward, informal conversations on narrow, well-defined questions can be helpful and efficient, the consultant should always feel comfortable seeking an opportunity for formal consultation when the details are unclear or the case/question is complex.

Closing Thoughts

Being an effective GI consultant isn’t just about what you know—it’s about how you apply it, how you communicate it, and how you make others feel in the process.

The attributes outlined above are not ancillary traits—they are essential components of high-quality consultation. When consistently applied, they enhance collaboration, improve patient outcomes, and reinforce trust within the healthcare system. By committing to them, you establish your reputation of excellence and play a role in elevating the field of gastroenterology more broadly.

Dr. Kahn is based in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona. He reports no conflicts of interest in regard to this article.

References

1. Goldman L, et al. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983 Sep.

2. Salerno SM, et al. Principles of effective consultation: an update for the 21st-century consultant. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Feb. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.271.

3. Adams TN, et al. Hospitalist Perspective of Interactions with Medicine Subspecialty Consult Services. J Hosp Med. 2018 May. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2882.

4. Matsuo T, et al. Essential consultants’ skills and attitudes (Willing CONSULT): a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ. 2021 Jul. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02810-9.

5. Welp A, Manser T. Integrating teamwork, clinician occupational well-being and patient safety - development of a conceptual framework based on a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1535-y.

6. Webster CS, et al. Interprofessional Learning in Multidisciplinary Healthcare Teams Is Associated With Reduced Patient Mortality: A Quantitative Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Patient Saf. 2024 Jan. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000001170.

7. Lin M, et al. Curbside Consultations: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.09.026.

Gastroenterology (GI) subspecialty training is carefully designed to develop expertise in digestive diseases and gastrointestinal endoscopy, while facilitating the transition from generalist to subspecialty consultant. The concept of effective consultation extends far beyond clinical expertise and has been explored repeatedly, beginning with Goldman’s “Ten Commandments” in 1983.1,2 How should these best practices be specifically applied to GI? More importantly, what kind of experience would you want if you were the referring provider or the patient themselves?

Below are

1. Be Kind

Survey studies of medical/surgical residents and attending hospitalists have demonstrated that willingness to accept consultation requests was the single factor consistently rated as most important in determining the quality of the consultation interaction.3,4 Unfortunately, nearly 65% of respondents reported encountering pushback when requesting subspecialty consultation. It is critical to recognize that when you receive a GI consult request, the requester has already decided that it is needed. Whether that request comports with our individual notion of “necessary” or “important,” this is a colleague’s request for help. There are myriad reasons why a request may be made, but they are unified in this principle.

Effective teamwork in healthcare settings enhances clinical performance and patient safety. Positive relationships with colleagues and healthcare team members also mitigate the emotional basis for physician burnout.5 Be kind and courteous to those who seek your assistance. Move beyond the notion of the “bad” or “soft” consult and seek instead to understand how you can help.

A requesting physician may phrase the consult question vaguely or may know that the patient is having a GI-related issue, but simply lack the specific knowledge to know what is needed. In these instances, it is our role to listen and help guide them to the correct thought process to ensure the best care of the patient. These important interactions establish our reputation, create our referral bases, and directly affect our sense of personal satisfaction.

2. Be Timely

GI presents an appealing breadth of pathology, but this also corresponds to a wide variety of indications for consultation and, therefore, urgency of need. In a busy clinical practice, not all requests can be urgently prioritized. However, it is the consultant’s responsibility to identify patients that require urgent evaluation and intervention to avert a potential adverse outcome.

We are well-trained in the medical triage of consultations. There are explicit guidelines for assessing urgency for GI bleeding, foreign body ingestion, choledocholithiasis, and many other indications. However, there are often special contextual circumstances that will elevate the urgency of a seemingly non-urgent consult request. Does the patient have an upcoming surgery or treatment that will depend on your input? Are they facing an imminent loss of insurance coverage? Is their non-severe GI disease leading to more severe impact on non-GI organ systems? The referring provider knows the patient better than you – seek to understand the context of the consult request.

Timeliness also applies to our communication. Communicate recommendations directly to the consulting service as soon as the patient is seen. When a colleague reaches out with a concern about a patient, make sure to take that request seriously. If you are unable to address the concern immediately, at least provide acknowledgment and an estimated timeline for response. As the maxim states, the effectiveness of a consultant is just as dependent on availability as it is on ability.

3. Be Specific

The same survey studies indicate that the second most critical aspect of successful subspecialty consultation is delivering clear recommendations. Accordingly, I always urge my trainees to challenge me when we leave a consult interaction if they feel that our plan is vague or imprecise.

Specificity in consult recommendations is an essential way to demonstrate your expertise and provide value. Clear and definitive recommendations enhance others’ perception of your skill, reduce the need for additional clarifying communication, and lead to more efficient, higher quality care. Avoid vague language, such as asking the requester to “consider” a test or intervention. When recommending medication, specify the dose, frequency, duration, and expected timeline of effect. Rather than recommending “cross-sectional imaging,” specify what modality and protocol. Instead of recommending “adequate resuscitation,” specify your target endpoints. If you engage in multidisciplinary discussion, ensure you strive for a specific group consensus plan and communicate this to all members of the team.

Specificity also applies to the quality of your documentation. Ensure that your clinical notes outline your rationale for your recommended plan, specific contingencies based on results of recommended testing, and a plan for follow-up care. When referring for open-access endoscopy, specifically outline what to look for and which specimens or endoscopic interventions are needed. Be precise in your procedure documentation – avoid vague terms such as small/medium/large and instead quantify in terms of millimeter/centimeter measurement. If you do not adopt specific classification schemes (e.g. Prague classification, Paris classification, Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score, etc.), ensure you provide enough descriptive language to convey an adequate understanding of the findings.

4. Be Helpful

A consultant’s primary directive is to be of service to the consulting provider and the patient. As an educational leader, I am often asked what attributes separate a high-performing trainee from an average one. My feeling is that the most critical attribute is a sense of ownership over patient care.

As a consultant, when others feel we are exhibiting engagement and ownership in a patient’s care, they perceive that we are working together as an effective healthcare team. Interestingly, survey studies of inpatient care show that primary services do not necessarily value assistance with orders or care coordination – they consider these as core aspects of their daily work. What they did value was ongoing daily progress notes/communication, regardless of patient acuity or consulting specialty. This is a potent signal that our continued engagement (both inpatient and outpatient) is perceived as helpful.

Helpfulness is further aided by ensuring mutual understanding. While survey data indicate that sharing specific literature citations may not always be perceived positively, explaining the consultant’s rationale for their recommendations is highly valued. Take the time to tactfully explain your assessment of the patient and why you arrived at your specific recommendations. If your recommendations differ from what the requester expected (e.g. a procedure was expected but is not offered), ensure you explain why and answer questions they may have. This fosters mutual respect and proactively averts conflict or discontent from misunderstanding.

Multidisciplinary collaboration is another important avenue for aiding our patients and colleagues. Studies across a wide range of disease processes (including GI bleeding, IBD, etc.) and medical settings have demonstrated that multidisciplinary collaboration unequivocally improves patient outcomes.6 The success of these collaborations relies on our willingness to fully engage in these conversations, despite the fact that they may often be logistically challenging.

We all know how difficult it can be to locate and organize multiple medical specialists with complex varying clinical schedules and busy personal lives. Choosing to do so demonstrates a dedication to providing the highest level of care and elevates both patient and physician satisfaction. Having chosen to cultivate several ongoing multidisciplinary conferences/collaborations, I can attest to the notion that the outcome is well worth the effort.

5. Be Honest

While we always strive to provide the answers for our patients and colleagues, we must also acknowledge our limitations. Be honest with yourself when you encounter a scenario that pushes beyond the boundaries of your knowledge and comfort. Be willing to admit when you yourself need to consult others or seek an outside referral to provide the care a patient needs. Aspiring physicians often espouse that a devotion to lifelong learning is a key driver of their desire to pursue a career in medicine. These scenarios provide a key opportunity to expand our knowledge while doing what is right for our patients.

Be equally honest about your comfort with “curbside” consultations. Studies show that subspecialists receive on average of 3-4 such requests per week.7 The perception of these interactions is starkly discrepant between the requester and recipient. While over 80% of surveyed primary nonsurgical services felt that curbside consultations were helpful in patient care, a similar proportion of subspecialists expressed concern that insufficient clinical information was provided, even leading to a fear of litigation. While straightforward, informal conversations on narrow, well-defined questions can be helpful and efficient, the consultant should always feel comfortable seeking an opportunity for formal consultation when the details are unclear or the case/question is complex.

Closing Thoughts

Being an effective GI consultant isn’t just about what you know—it’s about how you apply it, how you communicate it, and how you make others feel in the process.

The attributes outlined above are not ancillary traits—they are essential components of high-quality consultation. When consistently applied, they enhance collaboration, improve patient outcomes, and reinforce trust within the healthcare system. By committing to them, you establish your reputation of excellence and play a role in elevating the field of gastroenterology more broadly.

Dr. Kahn is based in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona. He reports no conflicts of interest in regard to this article.

References

1. Goldman L, et al. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983 Sep.

2. Salerno SM, et al. Principles of effective consultation: an update for the 21st-century consultant. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Feb. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.271.

3. Adams TN, et al. Hospitalist Perspective of Interactions with Medicine Subspecialty Consult Services. J Hosp Med. 2018 May. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2882.

4. Matsuo T, et al. Essential consultants’ skills and attitudes (Willing CONSULT): a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ. 2021 Jul. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02810-9.

5. Welp A, Manser T. Integrating teamwork, clinician occupational well-being and patient safety - development of a conceptual framework based on a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1535-y.

6. Webster CS, et al. Interprofessional Learning in Multidisciplinary Healthcare Teams Is Associated With Reduced Patient Mortality: A Quantitative Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Patient Saf. 2024 Jan. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000001170.

7. Lin M, et al. Curbside Consultations: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.09.026.

Military Imposters: What Drives Them and How They Damage Us All

Military Imposters: What Drives Them and How They Damage Us All

The better part of valor is discretion.

Henry IV, Part 1 by William Shakespeare1

This is the second part of an exploration of the phenomenon of stolen valor, where individuals claim military exploits or acts of heroism that are either fabricated or exaggerated, and/or awards and medals they did not earn.2 In June, I focused on the unsettling story of Sarah Cavanaugh, a young US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) social worker who posed as a decorated, heroic, and seriously wounded Marine veteran for years. Cavanaugh’s manipulative masquerade allowed her to receive coveted spots in veteran recovery programs, thousands of dollars in fraudulent donations, the leadership of a local Veterans of Foreign Wars post, and eventually a federal conviction and prison sentence.3 The first column focused on the legal history of stolen valor; this editorial analyzes the clinical import and ethical impact of the behavior of military imposters. Military imposters are the culprits who steal valor.

It would be easy and perhaps reassuring to assume that stolen valor has emerged as another deplorable example of a national culture in which the betrayal of trust in human beings and loss of faith in institutions and aspirations has reached a nadir. Ironically, stolen valor is inextricably linked to the founding of the United States. When General George Washington inaugurated the American military tradition of awarding decorations to honor the bravery and sacrifices of the patriot Army, he anticipated military imposters. He tried to deter stolen valor through the threat of chastisement: “Should any who are not entitled to these honors have the insolence to assume the badges of them, they shall be severely punished,” Washington warned.4

It is plausible to think such despicable conduct occurs only as the ugly side of the beauty of our unparalleled national freedom, but this is a mistake. Cases of stolen valor have been reported in many countries around the world, with some of the most infamous found in the United Kingdom.5

While many brazen military imposters like Cavanaugh never serve, there is a small subset who honorably wore a uniform yet embellish their service record with secret missions and meritorious gallantry that purportedly earned them high rank and even higher awards. A most puzzling and disturbing example of this group is an allegation that surfaced when celebrated Navy SEAL Chris Kyle declared in American Sniper that he had won 3 additional combat awards for combat valor in addition to the Silver Star and 3 Bronze Stars actually listed in his service record.6

The fact that for centuries stolen valor has plagued multiple nations suggests, at least to this psychiatrically trained mind, that something deeper and darker in human nature than profit alone drives military imposters. Philosopher Verna Gehring has distilled these less tangible motivations into the concept of virtue imposters. According to Gehring, military phonies are a notorious exemplar: “The military phony adopts a past not her own, acts of courage she did not perform—she impersonates the heroic character and virtues she does not possess.”7 There could be no more apposite depiction of Cavanaugh, other military imposters, or a legion of other offenders of honor. 8

As with Cavanaugh, financial gain is a byproduct of the machinations of military imposters and is usually secondary to the pursuit of nonmaterial rewards such as power, influence, admiration, emulation, empathy, and charity. Gehring contends, and I agree, that virtue imposters are more pernicious and culpable than the plethora of more prosaic scammers and swindlers who use deceit primarily as a means of economic exploitation: “The virtue impostor by contrast plays on people’s better natures—their generosity, humility, and their need for heroes.”7

Military imposters cause real and lasting harm. Every veteran who exaggerates claims or scams the VA unjustly steals human and monetary resources from other deserving veterans whose integrity would not permit them to break the rules.9 Yet, even more harmful is the potential damage to therapeutic relationships: federal practitioners may become skeptical of a veteran’s history even when there is little to no grounds for suspicion. Veterans, in turn, may experience a breach of trust and betrayal not only from health care professionals and VA leaders but from their brothers and sisters in arms. On an ever-wider scale, every military impostor who is exposed may diminish the respect and honor all veterans have earned.

It is clear, then, why a small group of former service members has adopted the cause of uncovering military imposters and adroitly using the media to identify signs of stolen valor.10 Yet deception mars even these mostly well-intentioned campaigns, as some more zealous stolen valor hunters may make allegations that turn out to be false.11 Nevertheless, 500 years ago and in a very different context Shakespeare was, right on the mark: the better part of valor is discretion in describing one’s achievements, in relying on the veracity of our veteran’s narratives, and when there are sound reasons to do so verifying the truth of what our patients, friends, and even family tell us about their time in the military.1

- Shakespeare W. Introduction in: Henry IV, Part 1. Folger Sharespeare Library. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/henry-iv-part-1/

- Geppert CM. What about stolen valor actually is illegal? Fed Pract. 2025;42(6):218-219. doi:10.12788/fp.0599

- Lehrfeld J. Woman who faked being cancer-stricken Marine gets 6 years in prison. Military Times. March 15, 2023. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2023/03/15/woman-who-faked-being-sick-marine-purple-heart-gets-6-years-in-prison/