User login

Painless Nodule on the Lower Eyelid

Painless Nodule on the Lower Eyelid

THE DIAGNOSIS: Idiopathic Facial Aseptic Granuloma

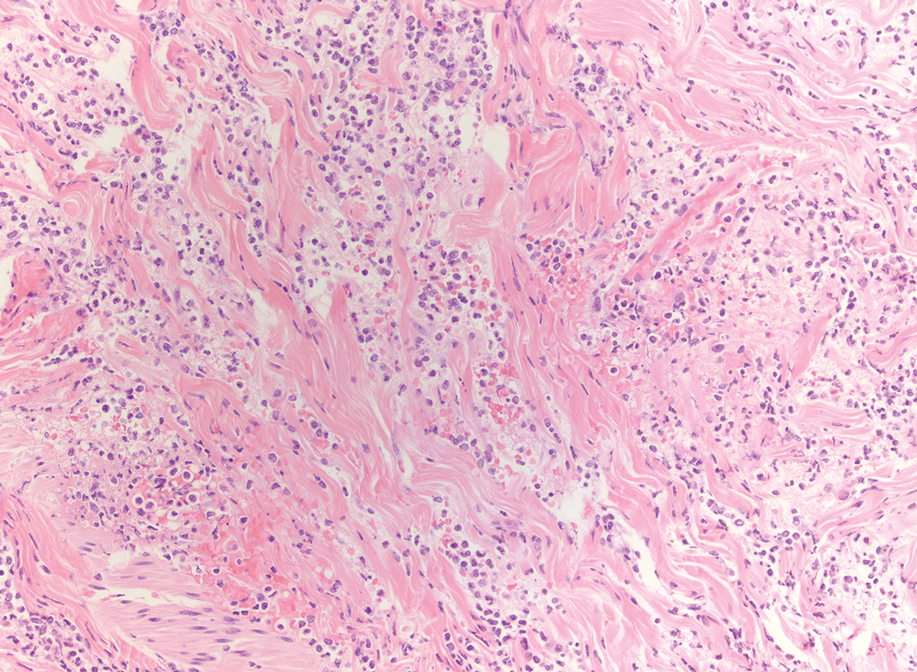

Histopathology showed a ruptured follicle, perifollicular granulomatous inflammation, and admixed multinucleated giant cells in the superficial dermis. The deeper tissue exhibited edema, histiocytic/granulomatous inflammation forming ill-defined loose granulomas, and a single neutrophilic microabscess (Figure). Stains for periodic acid-Schiff with diastase and acid-fast bacillus were negative for microorganisms. The clinical examination and pathology findings supported a diagnosis of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG).

First reported in 1999, IFAG was described using the French term pyodermite froide du visage, which translates to “cold pyoderma of the face”; however, it was renamed to represent its granulomatous characteristics and noninfectious etiology.1 The pathogenesis of IFAG is unknown, but the leading hypothesis is that it may be a type of childhood granulomatous rosacea, given its association with relapsing chalazions, papulopustular eruptions on the face, and facial flushing.2 Other hypotheses are that IFAG is idiopathic or a granulomatous response to an insect bite, minor trauma, or embryologic remnant.3

A rare condition arising in early childhood, IFAG manifests as a single or multiple, painless, erythematous or violaceous nodule(s) on the face, most often on the cheeks or eyelids.4 A thorough history and clinical examination often suffice for diagnosis. Dermoscopy may reveal white perifollicular halos and follicular plugs on an erythematous base with linear vessels.4 If diagnostic tests are performed, there are notable characteristic findings: ultrasonography often shows a well-circumscribed, hypoechoic, ovoid dermal lesion without calcifications. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures commonly are negative.4 On biopsy, histopathology may reveal granulomatous inflammation in the superficial and deep dermis, multinucleated giant cells, and surrounding lymphocytic, neutrophilic, and eosinophilic infiltration with no calcium deposits.3,5,6 Histopathology findings for IFAG and rosacea lesions are similar; both may demonstrate folliculitis, perifollicular granulomas, and admixed lymphohistiocytic inflammation.7

Differentiating IFAG from other dermatologic lesions can be challenging, as the differential includes benign neoplasms (eg, dermoid cyst, chalazion, pilomatricoma, xanthoma, xanthogranuloma2) and infectious etiologies such as bacterial pyoderma and mycobacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections (eg, cutaneous leishmaniasis). Pilomatricomas, although often seen on the face or extremities in young girls, more often are well circumscribed and located in the dermis. Ultrasonography of a pilomatricoma classically shows variable foci of calcification. Xanthoma and xanthogranuloma also were considered in our case since the lesion was subtly yellowish on examination. Similar to IFAG, these conditions may manifest as single or multiple lesions. Abnormalities in the patient’s blood lipid panel or family history may be needed to diagnose xanthoma. Biopsy of a juvenile xanthogranuloma would exhibit a dense dermal nodular proliferation of histiocytic cells with a smaller number of admixed lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils, in contrast to the multiple smaller loose epithelioid granulomas seen in IFAG. Additional diagnoses in the differential for IFAG include pyogenic granuloma, Spitz nevus, nodulocystic infantile acne, granulomatous rosacea, and hemangioma.1,3,9 In particular, granulomatous rosacea is challenging to differentiate from IFAG given the overlapping clinical findings. Multiple lesions, the presence of papules and pustules, and associated rosacea symptoms such as flushing suggest a diagnosis of granulomatous rosacea over IFAG.2

The prognosis for IFAG is excellent; most lesions self-resolve without treatment or procedural intervention within 1 year without scarring or relapse.3 Topical and oral antibiotic treatments such as metronidazole 0.75% gel or cream, oral erythromycin, oral clarithromycin, and doxycycline (in patients older than 8 years) have been used to treat IFAG with variable clinic responses.2,3,6,8 Persistent IFAG has been treated with surgical excision.3 Our patient was treated with a combination of gentamicin ointment 0.3% and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% and experienced approximately 50% improvement in the first month of treatment.

- Roul S, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Idiopathic aseptic facial granuloma (pyodermite froide du visage): a pediatric entity? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1253-1255.

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. IFAG and childhood rosacea: a possible link? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:429-432. doi:10.1111/pde.12137

- Boralevi F, Léauté-Labrèze C, Lepreux S, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma: a multicentre prospective study of 30 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:705-708. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07741.x

- Lobato-Berezo A, Montoro-Romero S, Pujol RM, et al. Dermoscopic features of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E308-E309. doi:10.1111/pde.13582

- González Rodríguez AJ, Jordá Cuevas E. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:298-300. doi:10.1111/ced.12535

- Orion C, Sfecci A, Tisseau L, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a 13-year-old boy dramatically improved with oral doxycycline and topical metronidazole: evidence for a link with childhood rosacea. Case Rep Dermatol. 2016;8:197-201. doi:10.1159/000447624

- Neri I, Raone B, Dondi A, et al. Should idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma be considered granulomatous rosacea? report of three pediatric cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:109-111. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2011.01689.x

- Miconi F, Principi N, Cassiani L, et al. A cheek nodule in a child: be aware of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma and its differential diagnosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2471. doi:10.3390/ijerph16142471

- Baroni A, Russo T, Faccenda F, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a child: a possible expression of childhood rosacea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:394-395. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01805.x

THE DIAGNOSIS: Idiopathic Facial Aseptic Granuloma

Histopathology showed a ruptured follicle, perifollicular granulomatous inflammation, and admixed multinucleated giant cells in the superficial dermis. The deeper tissue exhibited edema, histiocytic/granulomatous inflammation forming ill-defined loose granulomas, and a single neutrophilic microabscess (Figure). Stains for periodic acid-Schiff with diastase and acid-fast bacillus were negative for microorganisms. The clinical examination and pathology findings supported a diagnosis of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG).

First reported in 1999, IFAG was described using the French term pyodermite froide du visage, which translates to “cold pyoderma of the face”; however, it was renamed to represent its granulomatous characteristics and noninfectious etiology.1 The pathogenesis of IFAG is unknown, but the leading hypothesis is that it may be a type of childhood granulomatous rosacea, given its association with relapsing chalazions, papulopustular eruptions on the face, and facial flushing.2 Other hypotheses are that IFAG is idiopathic or a granulomatous response to an insect bite, minor trauma, or embryologic remnant.3

A rare condition arising in early childhood, IFAG manifests as a single or multiple, painless, erythematous or violaceous nodule(s) on the face, most often on the cheeks or eyelids.4 A thorough history and clinical examination often suffice for diagnosis. Dermoscopy may reveal white perifollicular halos and follicular plugs on an erythematous base with linear vessels.4 If diagnostic tests are performed, there are notable characteristic findings: ultrasonography often shows a well-circumscribed, hypoechoic, ovoid dermal lesion without calcifications. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures commonly are negative.4 On biopsy, histopathology may reveal granulomatous inflammation in the superficial and deep dermis, multinucleated giant cells, and surrounding lymphocytic, neutrophilic, and eosinophilic infiltration with no calcium deposits.3,5,6 Histopathology findings for IFAG and rosacea lesions are similar; both may demonstrate folliculitis, perifollicular granulomas, and admixed lymphohistiocytic inflammation.7

Differentiating IFAG from other dermatologic lesions can be challenging, as the differential includes benign neoplasms (eg, dermoid cyst, chalazion, pilomatricoma, xanthoma, xanthogranuloma2) and infectious etiologies such as bacterial pyoderma and mycobacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections (eg, cutaneous leishmaniasis). Pilomatricomas, although often seen on the face or extremities in young girls, more often are well circumscribed and located in the dermis. Ultrasonography of a pilomatricoma classically shows variable foci of calcification. Xanthoma and xanthogranuloma also were considered in our case since the lesion was subtly yellowish on examination. Similar to IFAG, these conditions may manifest as single or multiple lesions. Abnormalities in the patient’s blood lipid panel or family history may be needed to diagnose xanthoma. Biopsy of a juvenile xanthogranuloma would exhibit a dense dermal nodular proliferation of histiocytic cells with a smaller number of admixed lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils, in contrast to the multiple smaller loose epithelioid granulomas seen in IFAG. Additional diagnoses in the differential for IFAG include pyogenic granuloma, Spitz nevus, nodulocystic infantile acne, granulomatous rosacea, and hemangioma.1,3,9 In particular, granulomatous rosacea is challenging to differentiate from IFAG given the overlapping clinical findings. Multiple lesions, the presence of papules and pustules, and associated rosacea symptoms such as flushing suggest a diagnosis of granulomatous rosacea over IFAG.2

The prognosis for IFAG is excellent; most lesions self-resolve without treatment or procedural intervention within 1 year without scarring or relapse.3 Topical and oral antibiotic treatments such as metronidazole 0.75% gel or cream, oral erythromycin, oral clarithromycin, and doxycycline (in patients older than 8 years) have been used to treat IFAG with variable clinic responses.2,3,6,8 Persistent IFAG has been treated with surgical excision.3 Our patient was treated with a combination of gentamicin ointment 0.3% and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% and experienced approximately 50% improvement in the first month of treatment.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Idiopathic Facial Aseptic Granuloma

Histopathology showed a ruptured follicle, perifollicular granulomatous inflammation, and admixed multinucleated giant cells in the superficial dermis. The deeper tissue exhibited edema, histiocytic/granulomatous inflammation forming ill-defined loose granulomas, and a single neutrophilic microabscess (Figure). Stains for periodic acid-Schiff with diastase and acid-fast bacillus were negative for microorganisms. The clinical examination and pathology findings supported a diagnosis of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG).

First reported in 1999, IFAG was described using the French term pyodermite froide du visage, which translates to “cold pyoderma of the face”; however, it was renamed to represent its granulomatous characteristics and noninfectious etiology.1 The pathogenesis of IFAG is unknown, but the leading hypothesis is that it may be a type of childhood granulomatous rosacea, given its association with relapsing chalazions, papulopustular eruptions on the face, and facial flushing.2 Other hypotheses are that IFAG is idiopathic or a granulomatous response to an insect bite, minor trauma, or embryologic remnant.3

A rare condition arising in early childhood, IFAG manifests as a single or multiple, painless, erythematous or violaceous nodule(s) on the face, most often on the cheeks or eyelids.4 A thorough history and clinical examination often suffice for diagnosis. Dermoscopy may reveal white perifollicular halos and follicular plugs on an erythematous base with linear vessels.4 If diagnostic tests are performed, there are notable characteristic findings: ultrasonography often shows a well-circumscribed, hypoechoic, ovoid dermal lesion without calcifications. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures commonly are negative.4 On biopsy, histopathology may reveal granulomatous inflammation in the superficial and deep dermis, multinucleated giant cells, and surrounding lymphocytic, neutrophilic, and eosinophilic infiltration with no calcium deposits.3,5,6 Histopathology findings for IFAG and rosacea lesions are similar; both may demonstrate folliculitis, perifollicular granulomas, and admixed lymphohistiocytic inflammation.7

Differentiating IFAG from other dermatologic lesions can be challenging, as the differential includes benign neoplasms (eg, dermoid cyst, chalazion, pilomatricoma, xanthoma, xanthogranuloma2) and infectious etiologies such as bacterial pyoderma and mycobacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections (eg, cutaneous leishmaniasis). Pilomatricomas, although often seen on the face or extremities in young girls, more often are well circumscribed and located in the dermis. Ultrasonography of a pilomatricoma classically shows variable foci of calcification. Xanthoma and xanthogranuloma also were considered in our case since the lesion was subtly yellowish on examination. Similar to IFAG, these conditions may manifest as single or multiple lesions. Abnormalities in the patient’s blood lipid panel or family history may be needed to diagnose xanthoma. Biopsy of a juvenile xanthogranuloma would exhibit a dense dermal nodular proliferation of histiocytic cells with a smaller number of admixed lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils, in contrast to the multiple smaller loose epithelioid granulomas seen in IFAG. Additional diagnoses in the differential for IFAG include pyogenic granuloma, Spitz nevus, nodulocystic infantile acne, granulomatous rosacea, and hemangioma.1,3,9 In particular, granulomatous rosacea is challenging to differentiate from IFAG given the overlapping clinical findings. Multiple lesions, the presence of papules and pustules, and associated rosacea symptoms such as flushing suggest a diagnosis of granulomatous rosacea over IFAG.2

The prognosis for IFAG is excellent; most lesions self-resolve without treatment or procedural intervention within 1 year without scarring or relapse.3 Topical and oral antibiotic treatments such as metronidazole 0.75% gel or cream, oral erythromycin, oral clarithromycin, and doxycycline (in patients older than 8 years) have been used to treat IFAG with variable clinic responses.2,3,6,8 Persistent IFAG has been treated with surgical excision.3 Our patient was treated with a combination of gentamicin ointment 0.3% and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% and experienced approximately 50% improvement in the first month of treatment.

- Roul S, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Idiopathic aseptic facial granuloma (pyodermite froide du visage): a pediatric entity? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1253-1255.

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. IFAG and childhood rosacea: a possible link? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:429-432. doi:10.1111/pde.12137

- Boralevi F, Léauté-Labrèze C, Lepreux S, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma: a multicentre prospective study of 30 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:705-708. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07741.x

- Lobato-Berezo A, Montoro-Romero S, Pujol RM, et al. Dermoscopic features of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E308-E309. doi:10.1111/pde.13582

- González Rodríguez AJ, Jordá Cuevas E. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:298-300. doi:10.1111/ced.12535

- Orion C, Sfecci A, Tisseau L, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a 13-year-old boy dramatically improved with oral doxycycline and topical metronidazole: evidence for a link with childhood rosacea. Case Rep Dermatol. 2016;8:197-201. doi:10.1159/000447624

- Neri I, Raone B, Dondi A, et al. Should idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma be considered granulomatous rosacea? report of three pediatric cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:109-111. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2011.01689.x

- Miconi F, Principi N, Cassiani L, et al. A cheek nodule in a child: be aware of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma and its differential diagnosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2471. doi:10.3390/ijerph16142471

- Baroni A, Russo T, Faccenda F, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a child: a possible expression of childhood rosacea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:394-395. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01805.x

- Roul S, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Idiopathic aseptic facial granuloma (pyodermite froide du visage): a pediatric entity? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1253-1255.

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. IFAG and childhood rosacea: a possible link? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:429-432. doi:10.1111/pde.12137

- Boralevi F, Léauté-Labrèze C, Lepreux S, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma: a multicentre prospective study of 30 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:705-708. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07741.x

- Lobato-Berezo A, Montoro-Romero S, Pujol RM, et al. Dermoscopic features of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E308-E309. doi:10.1111/pde.13582

- González Rodríguez AJ, Jordá Cuevas E. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:298-300. doi:10.1111/ced.12535

- Orion C, Sfecci A, Tisseau L, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a 13-year-old boy dramatically improved with oral doxycycline and topical metronidazole: evidence for a link with childhood rosacea. Case Rep Dermatol. 2016;8:197-201. doi:10.1159/000447624

- Neri I, Raone B, Dondi A, et al. Should idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma be considered granulomatous rosacea? report of three pediatric cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:109-111. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2011.01689.x

- Miconi F, Principi N, Cassiani L, et al. A cheek nodule in a child: be aware of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma and its differential diagnosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2471. doi:10.3390/ijerph16142471

- Baroni A, Russo T, Faccenda F, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a child: a possible expression of childhood rosacea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:394-395. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01805.x

Painless Nodule on the Lower Eyelid

Painless Nodule on the Lower Eyelid

A 4-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a painless, red to golden-yellowish nodule on the right lower eyelid of 4 months’ duration. The patient had no history of skin disease and was otherwise healthy. Physical examination revealed a single 1-cm, soft, erythematous and yellowish plaque on the right lower eyelid that was subtly fluctuant on palpation. She had no associated systemic symptoms or lymphadenopathy. A punch biopsy of the lesion was performed.

Histiocytoid Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A Challenging Case With Features of Sweet Syndrome

To the Editor:

Neutrophilic dermatoses—a group of inflammatory cutaneous conditions—include acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), pyoderma gangrenosum, and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands. Histopathology shows a dense dermal infiltrate of mature neutrophils. In 2005, the histiocytoid subtype of Sweet syndrome was introduced with histopathologic findings of a dermal infiltrate composed of immature myeloid cells that resemble histiocytes in appearance but stain strongly with neutrophil markers on immunohistochemistry.1 We present a case of histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum with histopathology that showed a dense dermal histiocytoid infiltrate with strong positivity for neutrophil markers on immunohistochemistry.

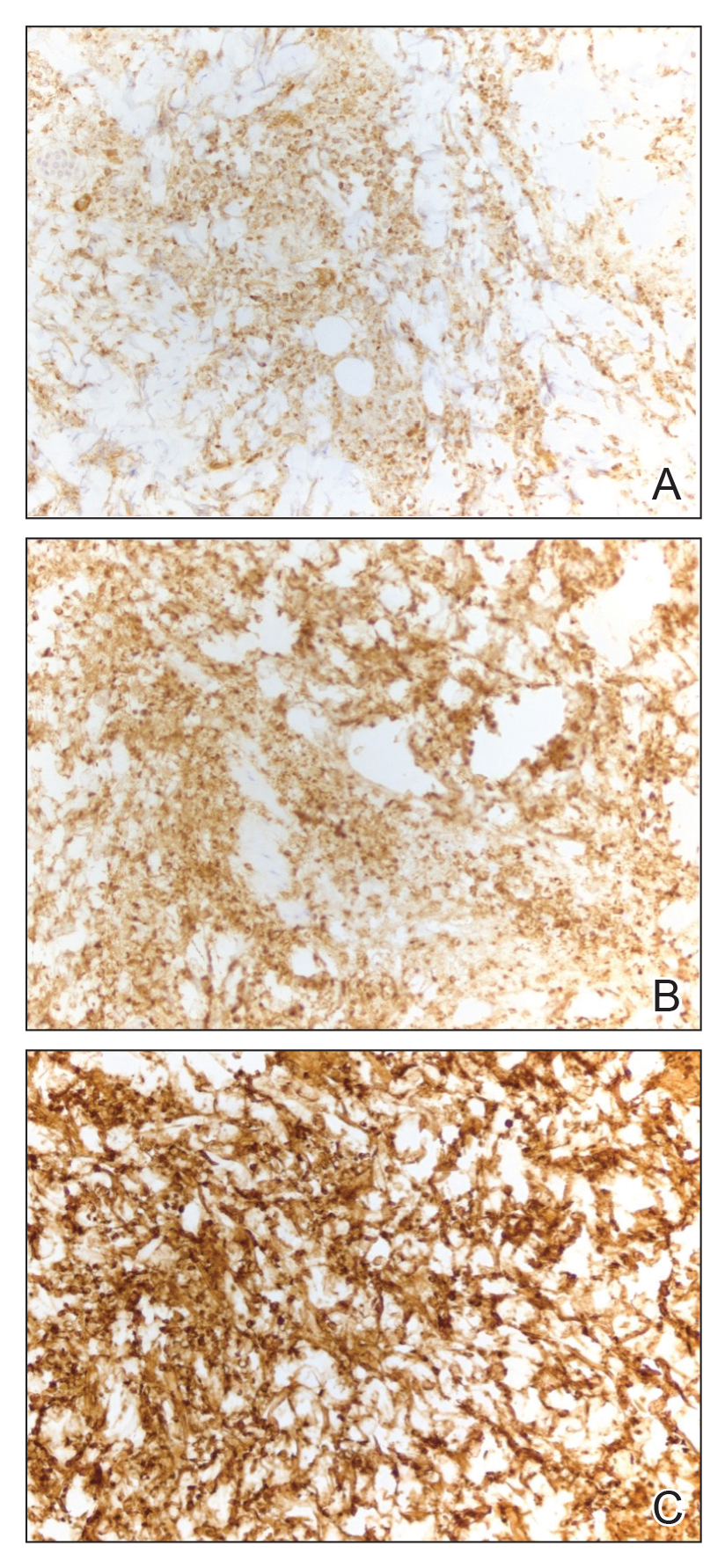

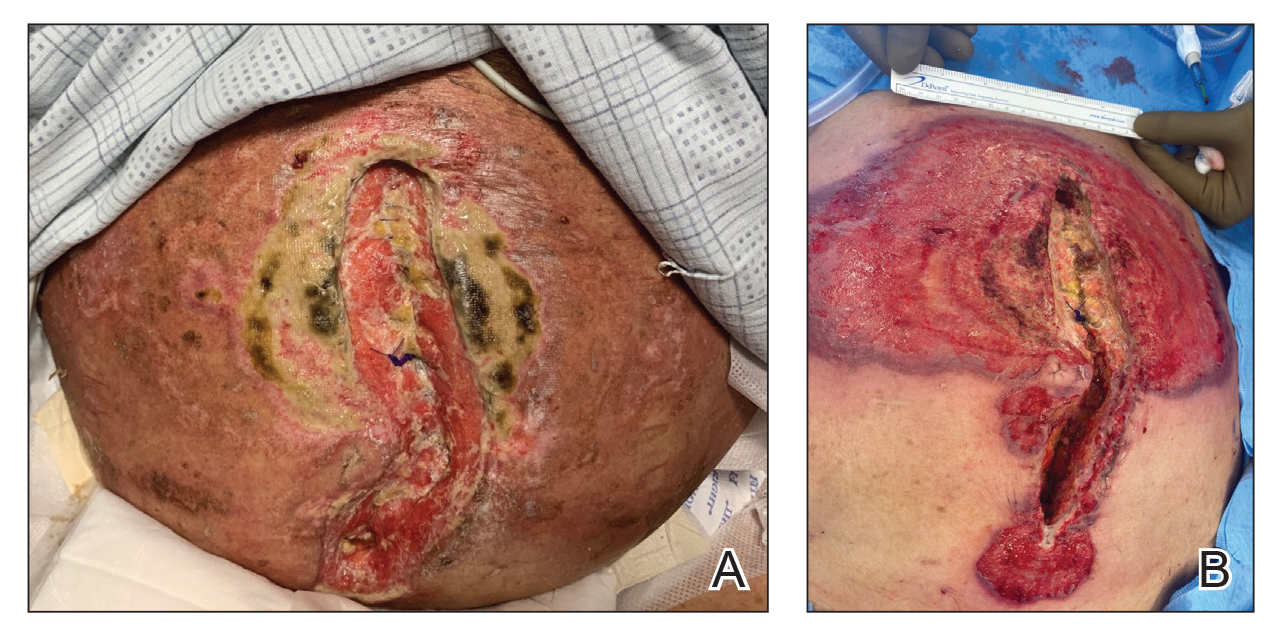

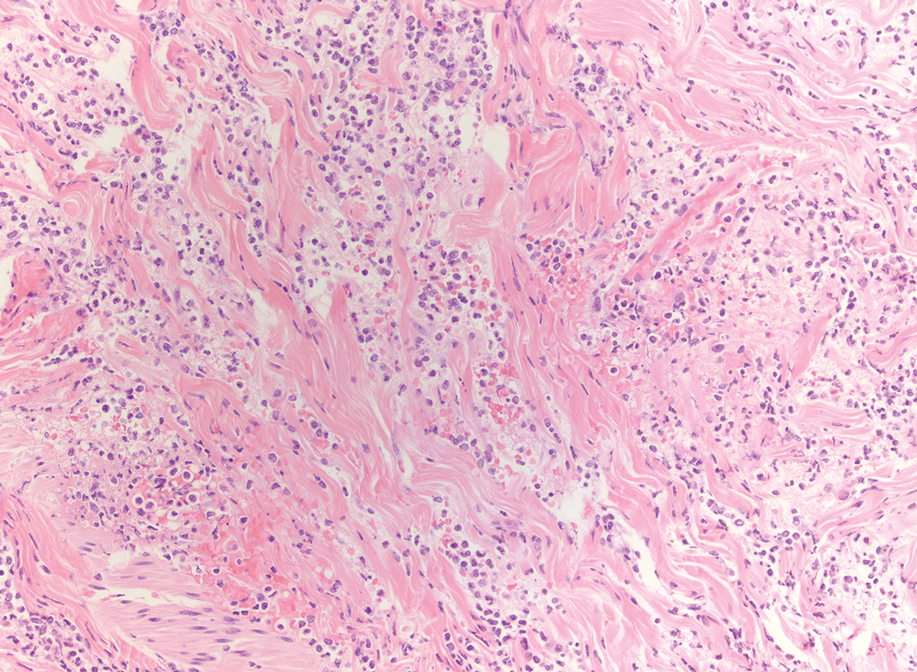

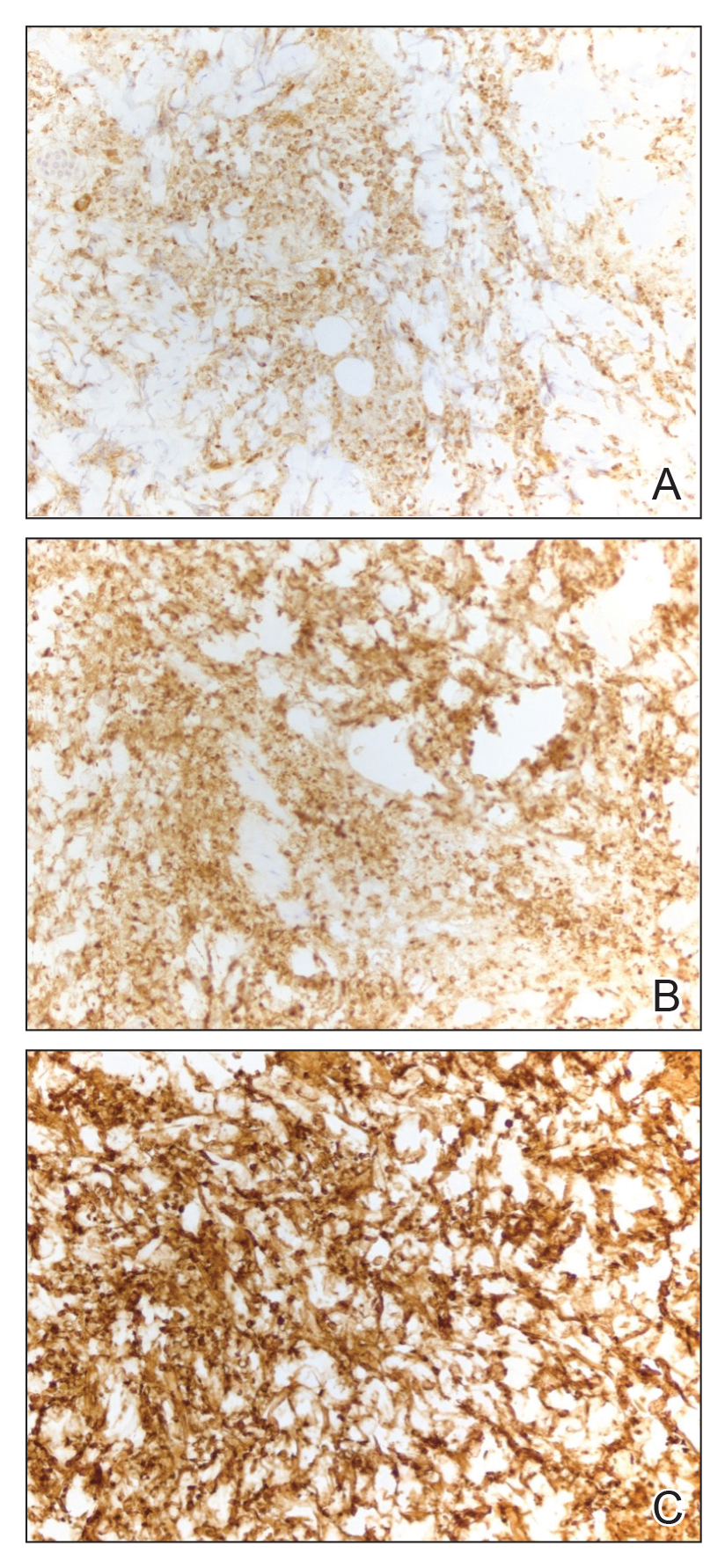

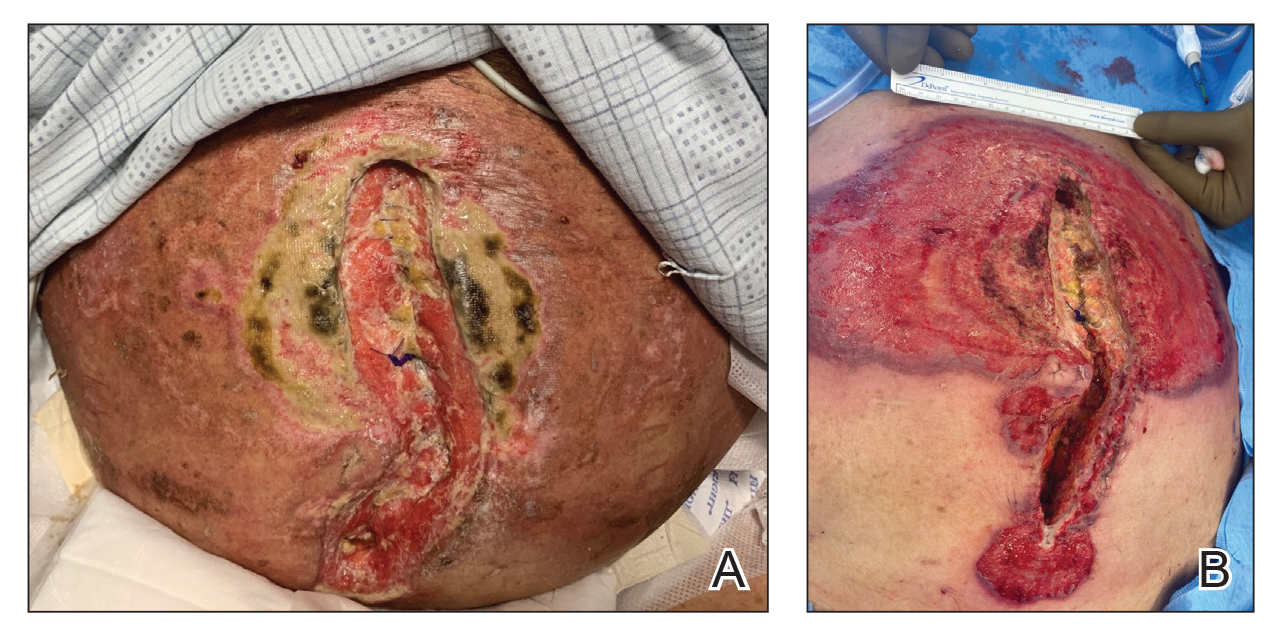

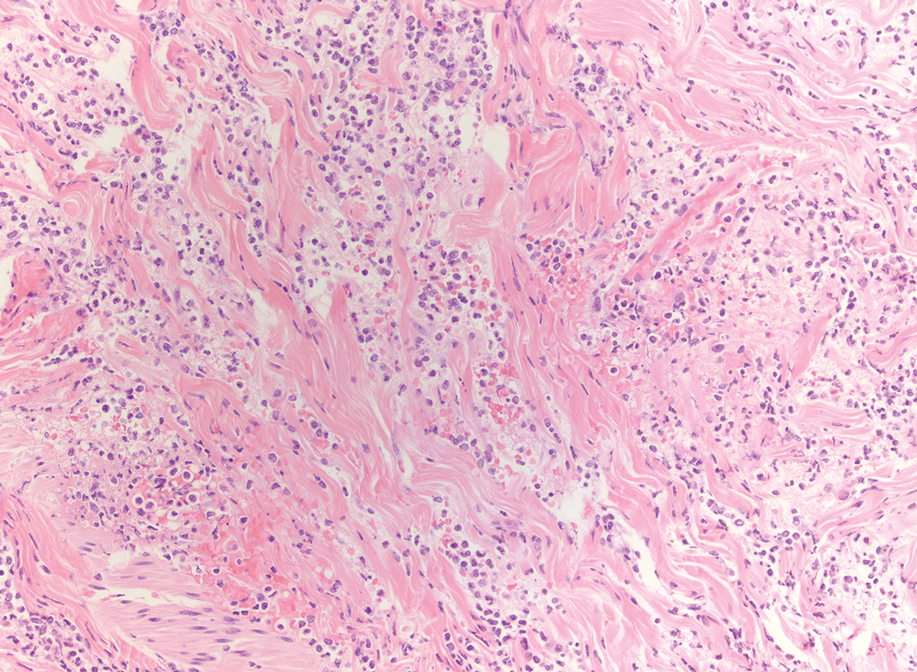

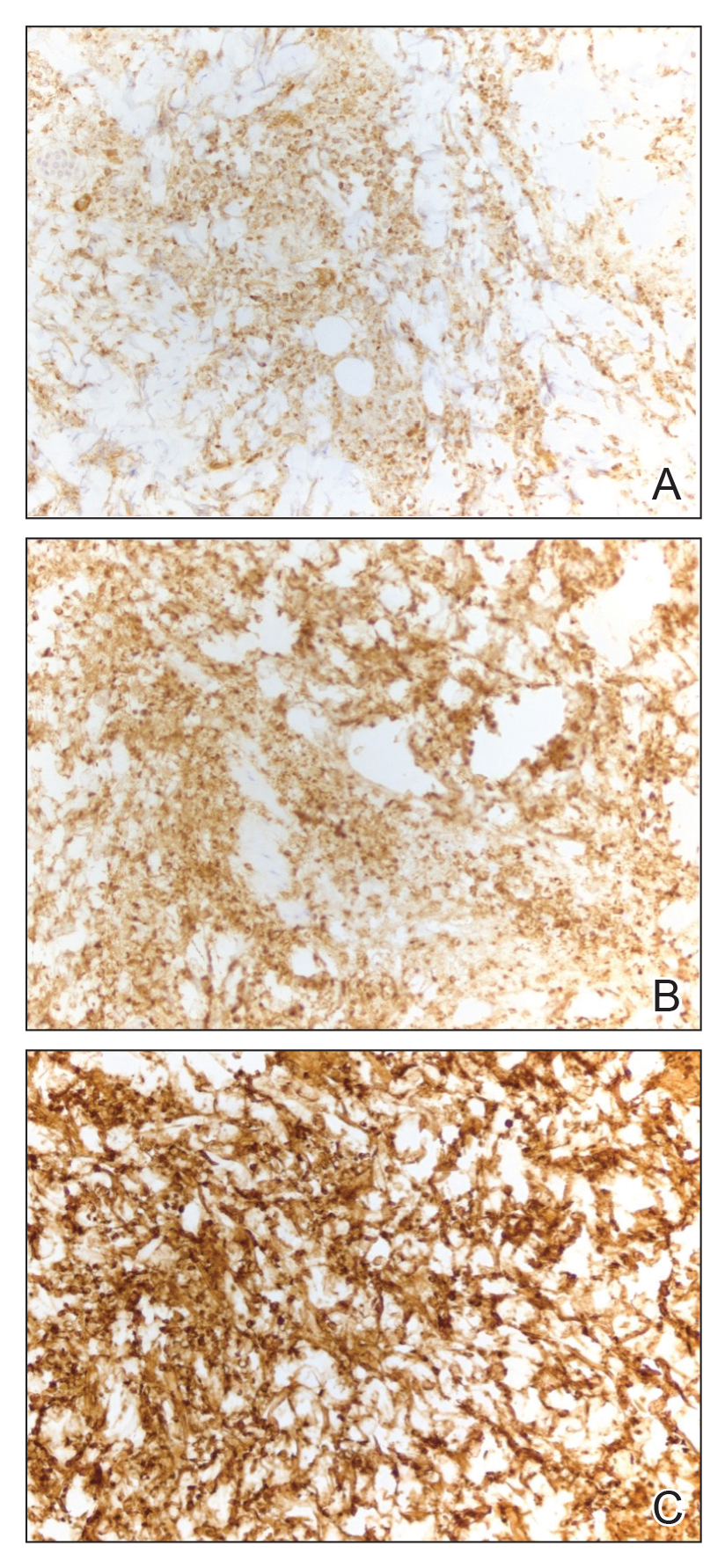

An 85-year-old man was seen by dermatology in the inpatient setting for a new-onset painful abdominal wound. He had a medical history of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), high-grade invasive papillary urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, and a recent diagnosis of low-grade invasive ascending colon adenocarcinoma. Ten days prior he underwent a right colectomy without intraoperative complications that was followed by septic shock. Workup with urinalysis and urine culture showed minimal pyuria with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Additional studies, including blood cultures, abdominal wound cultures, computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, renal ultrasound, and chest radiographs, were unremarkable and showed no signs of surgical site infection, intra-abdominal or pelvic abscess formation, or pulmonary embolism. Broad-spectrum antibiotics—vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam—were started. Persistent fever (Tmax of 102.3 °F [39.1 °C]) and leukocytosis (45.3×109/L [4.2–10×109/L]) despite antibiotic therapy, increasing pressor requirements, and progressive painful erythema and purulence at the abdominal surgical site led to debridement of the wound by the general surgery team on day 9 following the initial surgery due to suspected necrotizing infection. Within 24 hours, dermatology was consulted for continued rapid expansion of the wound. Physical examination of the abdomen revealed a large, well-demarcated, pink-red, indurated, ulcerated plaque with clear to purulent exudate and superficial erosions with violaceous undermined borders extending centrifugally from the abdominal surgical incision line (Figure 1A). Two punch biopsies sent for histopathologic evaluation and tissue culture showed dermal edema with a dense histiocytic infiltrate with nodular foci and admixed mature neutrophils to a lesser degree (Figure 2). Special staining was negative for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria. Immunohistochemistry revealed positive staining of the dermal inflammatory infiltrate with CD68, myeloperoxidase, and lysozyme, as well as negative staining with CD34 (Figure 3). These findings were suggestive of a histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatosis such as Sweet syndrome or pyoderma gangrenosum. Due to the morphology of the solitary lesion and the abrupt exacerbation shortly after surgical intervention, the patient was diagnosed with histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. At the same time, the patient’s septic shock was treated with intravenous hydrocortisone (100 mg 3 times daily) for 2 days and also achieved a prompt response in the cutaneous symptoms (Figure 1B).

Sweet syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum are considered distinct neutrophilic dermatoses that rarely coexist but share several clinical and histopathologic features, which can become a diagnostic challenge.2 Both conditions can manifest clinically as abrupt-onset, tender, erythematous papules; vesiculopustular lesions; or bullae with ulcerative changes. They also exhibit pathergy; present with systemic symptoms such as pyrexia, malaise, and joint pain; are associated with underlying systemic conditions such as infections and/or malignancy; demonstrate a dense neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis on histopathology; and respond promptly to systemic corticosteroids.2-6 Bullous Sweet syndrome, which can present as vesicles, pustules, or bullae that progress to superficial ulcerations, may represent a variant of neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by features seen in both Sweet syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum, suggesting that these 2 conditions may be on a spectrum.5Clinical features such as erythema with a blue, gray, or purple hue; undermined and ragged borders; and healing of skin lesions with atrophic or cribriform scarring may favor pyoderma gangrenosum, whereas a dull red or plum color and resolution of lesions without scarring may support the diagnosis of Sweet syndrome.7 Although both conditions can exhibit pathergy secondary to minor skin trauma such as venipuncture and biopsies,2,3,5,8 Sweet syndrome rarely has been described to develop after surgery in a patient without a known history of the condition.9 In contrast, postsurgical pyoderma gangrenosum has been well described as secondary to the pathergy phenomenon.5

Our patient was favored to have pyoderma gangrenosum given the solitary lesion, its abrupt development after surgery, and the morphology of the lesion that exhibited a large violaceous to red ulcerative and exudative plaque with undermined borders with atrophic scarring. In patients with skin disease that cannot be distinguished with certainty as either Sweet syndrome or pyoderma gangrenosum, it is essential to recognize that, as neutrophilic dermatoses, both conditions can be managed with either the first-line treatment option of high-dose systemic steroids or one of the shared alternative first-line or second-line steroid-sparing treatments, such as dapsone and cyclosporine.2

Although the exact pathogenesis of pyoderma gangrenosum remains to be fully understood, paraneoplastic pyoderma gangrenosum is a frequently described phenomenon.10,11 Our patient’s history of multiple malignancies, both solid and hematologic, supports the likelihood of malignancy-induced pyoderma gangrenosum; however, given his history of MDS, several other conditions were ruled out prior to making the diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum.

Classically, neutrophilic dermatoses such as pyoderma gangrenosum have a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate. Concurrent myeloproliferative disorders can alter the maturation of leukocytes, subsequently leading to an atypical appearance of the inflammatory cells on histopathology. Further, in the setting of myeloproliferative disorders, conditions such as leukemia cutis, in which there can be a cutaneous infiltrate of immature or mature myeloid or lymphocytic cells, must be considered. To ensure our patient’s abdominal skin changes were not a cutaneous manifestation of hematologic malignancy, immunohistochemical staining with CD20 and CD3 was performed and showed only the rare presence of B and T lymphocytes, respectively. Staining with CD34 for lymphocytic and myeloid progenitor cells was negative in the dermal infiltrate and further reduced the likelihood of leukemia cutis. Alternatively, patients can have aleukemic cutaneous myeloid sarcoma or leukemia cutis without an underlying hematologic condition or with latent peripheral blood or bone marrow myeloproliferative disorder, but our patient’s history of MDS eliminated this possibility.12 After exclusion of cutaneous infiltration by malignant leukocytes, our patient was diagnosed with histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatosis.

Multiple reports have described histiocytoid Sweet syndrome, in which there is a dense dermal histiocytoid infiltrate on histopathology that demonstrates myeloid lineage with immunologic staining.1,13 The typical pattern of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome includes a predominantly unaffected epidermis with papillary dermal edema, an absence of vasculitis, and a dense dermal infiltrate primarily composed of immature histiocytelike mononuclear cells with a basophilic elongated, twisted, or kidney-shaped nucleus and pale eosinophilic cytoplasm.1,13 In an analogous manner, Morin et al12 described a patient with congenital hypogammaglobulinemia who presented with lesions that clinically resembled pyoderma gangrenosum but revealed a dense dermal infiltrate mostly made of large immature histiocytoid mononuclear cells on histopathology, consistent with the histopathologic features observed in histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. The patient ultimately was diagnosed with histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. Similarly, we believe that our patient also developed histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. As with histiocytoid Sweet syndrome, this diagnosis is based on histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings of a dense dermal infiltrate composed of histiocyte-resembling immature neutrophils.

Typically, pyoderma gangrenosum responds promptly to treatment with systemic corticosteroids.4 Steroid-sparing agents such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, dapsone, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors also may be used.4,10 In the setting of MDS, clearance of pyoderma gangrenosum has been reported upon treatment of the underlying malignancy,14 high-dose systemic corticosteroids,11,15 cyclosporine with systemic steroids,16 thalidomide,17 combination therapy with thalidomide and interferon alfa-2a,18 and ustekinumab with vacuum-assisted closure therapy.19 Our patient’s histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of solid and hematologic malignancy cleared rapidly with high-dose systemic hydrocortisone.

In the setting of malignancy, as in our patient, neutrophilic dermatoses may develop from an aberrant immune system or tumor-induced cytokine dysregulation that leads to increased neutrophil production or dysfunction.4,10,11 Although our patient’s MDS may have contributed to the atypical appearance of the dermal inflammatory infiltrate, it is unclear whether the hematologic disorder increased his risk for the histiocytoid variant of neutrophilic dermatoses. Alegría-Landa et al13 reported that histiocytoid Sweet syndrome is associated with hematologic malignancy at a similar frequency as classic Sweet syndrome. It is unknown if histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum would have a strong association with hematologic malignancy. Future reports may elucidate a better understanding of the histiocytoid subtype of pyoderma gangrenosum and its clinical implications.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842.

- Cohen PR. Neutrophilic dermatoses: a review of current treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:301-312.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Braswell SF, Kostopoulos TC, Ortega-Loayza AG. Pathophysiology of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): an updated review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:691-698.

- Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD. Pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome: the prototypic neutrophilic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:595-602.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- Lear JT, Atherton MT, Byrne JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet’s syndrome. Postgrad Med. 1997;73:65-68.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006.

- Minocha R, Sebaratnam DF, Choi JY. Sweet’s syndrome following surgery: cutaneous trauma as a possible aetiological co-factor in neutrophilic dermatoses. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:E74-E76.

- Shah M, Sachdeva M, Gefri A, et al. Paraneoplastic pyoderma gangrenosum in solid organ malignancy: a literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:154-158.

- Montagnon CM, Fracica EA, Patel AA, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum in hematologic malignancies: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1346-1359.

- Morin CB, Côté B, Belisle A. An interesting case of pyoderma gangrenosum with immature histiocytoid neutrophils. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:63-66.

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659.

- Saleh MFM, Saunthararajah Y. Severe pyoderma gangrenosum caused by myelodysplastic syndrome successfully treated with decitabine administered by a noncytotoxic regimen. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5:2025-2027.

- Yamauchi R, Ishida K, Iwashima Y, et al. Successful treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum that developed in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Infect Chemother. 2003;9:268-271.

- Ha JW, Hahm JE, Kim KS, et al. A case of pyoderma gangrenosum with myelodysplastic syndrome. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30:392-393.

- Malkan UY, Gunes G, Eliacik E, et al. Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum with thalidomide in a myelodysplastic syndrome case. Int J Med Case Rep. 2016;9:61-64.

- Koca E, Duman AE, Cetiner D, et al. Successful treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Neth J Med. 2006;64:422-424.

- Nieto D, Sendagorta E, Rueda JM, et al. Successful treatment with ustekinumab and vacuum-assisted closure therapy in recalcitrant myelodysplastic syndrome-associated pyoderma gangrenosum: case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:116-119.

To the Editor:

Neutrophilic dermatoses—a group of inflammatory cutaneous conditions—include acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), pyoderma gangrenosum, and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands. Histopathology shows a dense dermal infiltrate of mature neutrophils. In 2005, the histiocytoid subtype of Sweet syndrome was introduced with histopathologic findings of a dermal infiltrate composed of immature myeloid cells that resemble histiocytes in appearance but stain strongly with neutrophil markers on immunohistochemistry.1 We present a case of histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum with histopathology that showed a dense dermal histiocytoid infiltrate with strong positivity for neutrophil markers on immunohistochemistry.

An 85-year-old man was seen by dermatology in the inpatient setting for a new-onset painful abdominal wound. He had a medical history of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), high-grade invasive papillary urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, and a recent diagnosis of low-grade invasive ascending colon adenocarcinoma. Ten days prior he underwent a right colectomy without intraoperative complications that was followed by septic shock. Workup with urinalysis and urine culture showed minimal pyuria with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Additional studies, including blood cultures, abdominal wound cultures, computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, renal ultrasound, and chest radiographs, were unremarkable and showed no signs of surgical site infection, intra-abdominal or pelvic abscess formation, or pulmonary embolism. Broad-spectrum antibiotics—vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam—were started. Persistent fever (Tmax of 102.3 °F [39.1 °C]) and leukocytosis (45.3×109/L [4.2–10×109/L]) despite antibiotic therapy, increasing pressor requirements, and progressive painful erythema and purulence at the abdominal surgical site led to debridement of the wound by the general surgery team on day 9 following the initial surgery due to suspected necrotizing infection. Within 24 hours, dermatology was consulted for continued rapid expansion of the wound. Physical examination of the abdomen revealed a large, well-demarcated, pink-red, indurated, ulcerated plaque with clear to purulent exudate and superficial erosions with violaceous undermined borders extending centrifugally from the abdominal surgical incision line (Figure 1A). Two punch biopsies sent for histopathologic evaluation and tissue culture showed dermal edema with a dense histiocytic infiltrate with nodular foci and admixed mature neutrophils to a lesser degree (Figure 2). Special staining was negative for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria. Immunohistochemistry revealed positive staining of the dermal inflammatory infiltrate with CD68, myeloperoxidase, and lysozyme, as well as negative staining with CD34 (Figure 3). These findings were suggestive of a histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatosis such as Sweet syndrome or pyoderma gangrenosum. Due to the morphology of the solitary lesion and the abrupt exacerbation shortly after surgical intervention, the patient was diagnosed with histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. At the same time, the patient’s septic shock was treated with intravenous hydrocortisone (100 mg 3 times daily) for 2 days and also achieved a prompt response in the cutaneous symptoms (Figure 1B).

Sweet syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum are considered distinct neutrophilic dermatoses that rarely coexist but share several clinical and histopathologic features, which can become a diagnostic challenge.2 Both conditions can manifest clinically as abrupt-onset, tender, erythematous papules; vesiculopustular lesions; or bullae with ulcerative changes. They also exhibit pathergy; present with systemic symptoms such as pyrexia, malaise, and joint pain; are associated with underlying systemic conditions such as infections and/or malignancy; demonstrate a dense neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis on histopathology; and respond promptly to systemic corticosteroids.2-6 Bullous Sweet syndrome, which can present as vesicles, pustules, or bullae that progress to superficial ulcerations, may represent a variant of neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by features seen in both Sweet syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum, suggesting that these 2 conditions may be on a spectrum.5Clinical features such as erythema with a blue, gray, or purple hue; undermined and ragged borders; and healing of skin lesions with atrophic or cribriform scarring may favor pyoderma gangrenosum, whereas a dull red or plum color and resolution of lesions without scarring may support the diagnosis of Sweet syndrome.7 Although both conditions can exhibit pathergy secondary to minor skin trauma such as venipuncture and biopsies,2,3,5,8 Sweet syndrome rarely has been described to develop after surgery in a patient without a known history of the condition.9 In contrast, postsurgical pyoderma gangrenosum has been well described as secondary to the pathergy phenomenon.5

Our patient was favored to have pyoderma gangrenosum given the solitary lesion, its abrupt development after surgery, and the morphology of the lesion that exhibited a large violaceous to red ulcerative and exudative plaque with undermined borders with atrophic scarring. In patients with skin disease that cannot be distinguished with certainty as either Sweet syndrome or pyoderma gangrenosum, it is essential to recognize that, as neutrophilic dermatoses, both conditions can be managed with either the first-line treatment option of high-dose systemic steroids or one of the shared alternative first-line or second-line steroid-sparing treatments, such as dapsone and cyclosporine.2

Although the exact pathogenesis of pyoderma gangrenosum remains to be fully understood, paraneoplastic pyoderma gangrenosum is a frequently described phenomenon.10,11 Our patient’s history of multiple malignancies, both solid and hematologic, supports the likelihood of malignancy-induced pyoderma gangrenosum; however, given his history of MDS, several other conditions were ruled out prior to making the diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum.

Classically, neutrophilic dermatoses such as pyoderma gangrenosum have a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate. Concurrent myeloproliferative disorders can alter the maturation of leukocytes, subsequently leading to an atypical appearance of the inflammatory cells on histopathology. Further, in the setting of myeloproliferative disorders, conditions such as leukemia cutis, in which there can be a cutaneous infiltrate of immature or mature myeloid or lymphocytic cells, must be considered. To ensure our patient’s abdominal skin changes were not a cutaneous manifestation of hematologic malignancy, immunohistochemical staining with CD20 and CD3 was performed and showed only the rare presence of B and T lymphocytes, respectively. Staining with CD34 for lymphocytic and myeloid progenitor cells was negative in the dermal infiltrate and further reduced the likelihood of leukemia cutis. Alternatively, patients can have aleukemic cutaneous myeloid sarcoma or leukemia cutis without an underlying hematologic condition or with latent peripheral blood or bone marrow myeloproliferative disorder, but our patient’s history of MDS eliminated this possibility.12 After exclusion of cutaneous infiltration by malignant leukocytes, our patient was diagnosed with histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatosis.

Multiple reports have described histiocytoid Sweet syndrome, in which there is a dense dermal histiocytoid infiltrate on histopathology that demonstrates myeloid lineage with immunologic staining.1,13 The typical pattern of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome includes a predominantly unaffected epidermis with papillary dermal edema, an absence of vasculitis, and a dense dermal infiltrate primarily composed of immature histiocytelike mononuclear cells with a basophilic elongated, twisted, or kidney-shaped nucleus and pale eosinophilic cytoplasm.1,13 In an analogous manner, Morin et al12 described a patient with congenital hypogammaglobulinemia who presented with lesions that clinically resembled pyoderma gangrenosum but revealed a dense dermal infiltrate mostly made of large immature histiocytoid mononuclear cells on histopathology, consistent with the histopathologic features observed in histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. The patient ultimately was diagnosed with histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. Similarly, we believe that our patient also developed histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. As with histiocytoid Sweet syndrome, this diagnosis is based on histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings of a dense dermal infiltrate composed of histiocyte-resembling immature neutrophils.

Typically, pyoderma gangrenosum responds promptly to treatment with systemic corticosteroids.4 Steroid-sparing agents such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, dapsone, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors also may be used.4,10 In the setting of MDS, clearance of pyoderma gangrenosum has been reported upon treatment of the underlying malignancy,14 high-dose systemic corticosteroids,11,15 cyclosporine with systemic steroids,16 thalidomide,17 combination therapy with thalidomide and interferon alfa-2a,18 and ustekinumab with vacuum-assisted closure therapy.19 Our patient’s histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of solid and hematologic malignancy cleared rapidly with high-dose systemic hydrocortisone.

In the setting of malignancy, as in our patient, neutrophilic dermatoses may develop from an aberrant immune system or tumor-induced cytokine dysregulation that leads to increased neutrophil production or dysfunction.4,10,11 Although our patient’s MDS may have contributed to the atypical appearance of the dermal inflammatory infiltrate, it is unclear whether the hematologic disorder increased his risk for the histiocytoid variant of neutrophilic dermatoses. Alegría-Landa et al13 reported that histiocytoid Sweet syndrome is associated with hematologic malignancy at a similar frequency as classic Sweet syndrome. It is unknown if histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum would have a strong association with hematologic malignancy. Future reports may elucidate a better understanding of the histiocytoid subtype of pyoderma gangrenosum and its clinical implications.

To the Editor:

Neutrophilic dermatoses—a group of inflammatory cutaneous conditions—include acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), pyoderma gangrenosum, and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands. Histopathology shows a dense dermal infiltrate of mature neutrophils. In 2005, the histiocytoid subtype of Sweet syndrome was introduced with histopathologic findings of a dermal infiltrate composed of immature myeloid cells that resemble histiocytes in appearance but stain strongly with neutrophil markers on immunohistochemistry.1 We present a case of histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum with histopathology that showed a dense dermal histiocytoid infiltrate with strong positivity for neutrophil markers on immunohistochemistry.

An 85-year-old man was seen by dermatology in the inpatient setting for a new-onset painful abdominal wound. He had a medical history of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), high-grade invasive papillary urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, and a recent diagnosis of low-grade invasive ascending colon adenocarcinoma. Ten days prior he underwent a right colectomy without intraoperative complications that was followed by septic shock. Workup with urinalysis and urine culture showed minimal pyuria with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Additional studies, including blood cultures, abdominal wound cultures, computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, renal ultrasound, and chest radiographs, were unremarkable and showed no signs of surgical site infection, intra-abdominal or pelvic abscess formation, or pulmonary embolism. Broad-spectrum antibiotics—vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam—were started. Persistent fever (Tmax of 102.3 °F [39.1 °C]) and leukocytosis (45.3×109/L [4.2–10×109/L]) despite antibiotic therapy, increasing pressor requirements, and progressive painful erythema and purulence at the abdominal surgical site led to debridement of the wound by the general surgery team on day 9 following the initial surgery due to suspected necrotizing infection. Within 24 hours, dermatology was consulted for continued rapid expansion of the wound. Physical examination of the abdomen revealed a large, well-demarcated, pink-red, indurated, ulcerated plaque with clear to purulent exudate and superficial erosions with violaceous undermined borders extending centrifugally from the abdominal surgical incision line (Figure 1A). Two punch biopsies sent for histopathologic evaluation and tissue culture showed dermal edema with a dense histiocytic infiltrate with nodular foci and admixed mature neutrophils to a lesser degree (Figure 2). Special staining was negative for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria. Immunohistochemistry revealed positive staining of the dermal inflammatory infiltrate with CD68, myeloperoxidase, and lysozyme, as well as negative staining with CD34 (Figure 3). These findings were suggestive of a histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatosis such as Sweet syndrome or pyoderma gangrenosum. Due to the morphology of the solitary lesion and the abrupt exacerbation shortly after surgical intervention, the patient was diagnosed with histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. At the same time, the patient’s septic shock was treated with intravenous hydrocortisone (100 mg 3 times daily) for 2 days and also achieved a prompt response in the cutaneous symptoms (Figure 1B).

Sweet syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum are considered distinct neutrophilic dermatoses that rarely coexist but share several clinical and histopathologic features, which can become a diagnostic challenge.2 Both conditions can manifest clinically as abrupt-onset, tender, erythematous papules; vesiculopustular lesions; or bullae with ulcerative changes. They also exhibit pathergy; present with systemic symptoms such as pyrexia, malaise, and joint pain; are associated with underlying systemic conditions such as infections and/or malignancy; demonstrate a dense neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis on histopathology; and respond promptly to systemic corticosteroids.2-6 Bullous Sweet syndrome, which can present as vesicles, pustules, or bullae that progress to superficial ulcerations, may represent a variant of neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by features seen in both Sweet syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum, suggesting that these 2 conditions may be on a spectrum.5Clinical features such as erythema with a blue, gray, or purple hue; undermined and ragged borders; and healing of skin lesions with atrophic or cribriform scarring may favor pyoderma gangrenosum, whereas a dull red or plum color and resolution of lesions without scarring may support the diagnosis of Sweet syndrome.7 Although both conditions can exhibit pathergy secondary to minor skin trauma such as venipuncture and biopsies,2,3,5,8 Sweet syndrome rarely has been described to develop after surgery in a patient without a known history of the condition.9 In contrast, postsurgical pyoderma gangrenosum has been well described as secondary to the pathergy phenomenon.5

Our patient was favored to have pyoderma gangrenosum given the solitary lesion, its abrupt development after surgery, and the morphology of the lesion that exhibited a large violaceous to red ulcerative and exudative plaque with undermined borders with atrophic scarring. In patients with skin disease that cannot be distinguished with certainty as either Sweet syndrome or pyoderma gangrenosum, it is essential to recognize that, as neutrophilic dermatoses, both conditions can be managed with either the first-line treatment option of high-dose systemic steroids or one of the shared alternative first-line or second-line steroid-sparing treatments, such as dapsone and cyclosporine.2

Although the exact pathogenesis of pyoderma gangrenosum remains to be fully understood, paraneoplastic pyoderma gangrenosum is a frequently described phenomenon.10,11 Our patient’s history of multiple malignancies, both solid and hematologic, supports the likelihood of malignancy-induced pyoderma gangrenosum; however, given his history of MDS, several other conditions were ruled out prior to making the diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum.

Classically, neutrophilic dermatoses such as pyoderma gangrenosum have a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate. Concurrent myeloproliferative disorders can alter the maturation of leukocytes, subsequently leading to an atypical appearance of the inflammatory cells on histopathology. Further, in the setting of myeloproliferative disorders, conditions such as leukemia cutis, in which there can be a cutaneous infiltrate of immature or mature myeloid or lymphocytic cells, must be considered. To ensure our patient’s abdominal skin changes were not a cutaneous manifestation of hematologic malignancy, immunohistochemical staining with CD20 and CD3 was performed and showed only the rare presence of B and T lymphocytes, respectively. Staining with CD34 for lymphocytic and myeloid progenitor cells was negative in the dermal infiltrate and further reduced the likelihood of leukemia cutis. Alternatively, patients can have aleukemic cutaneous myeloid sarcoma or leukemia cutis without an underlying hematologic condition or with latent peripheral blood or bone marrow myeloproliferative disorder, but our patient’s history of MDS eliminated this possibility.12 After exclusion of cutaneous infiltration by malignant leukocytes, our patient was diagnosed with histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatosis.

Multiple reports have described histiocytoid Sweet syndrome, in which there is a dense dermal histiocytoid infiltrate on histopathology that demonstrates myeloid lineage with immunologic staining.1,13 The typical pattern of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome includes a predominantly unaffected epidermis with papillary dermal edema, an absence of vasculitis, and a dense dermal infiltrate primarily composed of immature histiocytelike mononuclear cells with a basophilic elongated, twisted, or kidney-shaped nucleus and pale eosinophilic cytoplasm.1,13 In an analogous manner, Morin et al12 described a patient with congenital hypogammaglobulinemia who presented with lesions that clinically resembled pyoderma gangrenosum but revealed a dense dermal infiltrate mostly made of large immature histiocytoid mononuclear cells on histopathology, consistent with the histopathologic features observed in histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. The patient ultimately was diagnosed with histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. Similarly, we believe that our patient also developed histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum. As with histiocytoid Sweet syndrome, this diagnosis is based on histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings of a dense dermal infiltrate composed of histiocyte-resembling immature neutrophils.

Typically, pyoderma gangrenosum responds promptly to treatment with systemic corticosteroids.4 Steroid-sparing agents such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, dapsone, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors also may be used.4,10 In the setting of MDS, clearance of pyoderma gangrenosum has been reported upon treatment of the underlying malignancy,14 high-dose systemic corticosteroids,11,15 cyclosporine with systemic steroids,16 thalidomide,17 combination therapy with thalidomide and interferon alfa-2a,18 and ustekinumab with vacuum-assisted closure therapy.19 Our patient’s histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of solid and hematologic malignancy cleared rapidly with high-dose systemic hydrocortisone.

In the setting of malignancy, as in our patient, neutrophilic dermatoses may develop from an aberrant immune system or tumor-induced cytokine dysregulation that leads to increased neutrophil production or dysfunction.4,10,11 Although our patient’s MDS may have contributed to the atypical appearance of the dermal inflammatory infiltrate, it is unclear whether the hematologic disorder increased his risk for the histiocytoid variant of neutrophilic dermatoses. Alegría-Landa et al13 reported that histiocytoid Sweet syndrome is associated with hematologic malignancy at a similar frequency as classic Sweet syndrome. It is unknown if histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum would have a strong association with hematologic malignancy. Future reports may elucidate a better understanding of the histiocytoid subtype of pyoderma gangrenosum and its clinical implications.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842.

- Cohen PR. Neutrophilic dermatoses: a review of current treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:301-312.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Braswell SF, Kostopoulos TC, Ortega-Loayza AG. Pathophysiology of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): an updated review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:691-698.

- Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD. Pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome: the prototypic neutrophilic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:595-602.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- Lear JT, Atherton MT, Byrne JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet’s syndrome. Postgrad Med. 1997;73:65-68.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006.

- Minocha R, Sebaratnam DF, Choi JY. Sweet’s syndrome following surgery: cutaneous trauma as a possible aetiological co-factor in neutrophilic dermatoses. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:E74-E76.

- Shah M, Sachdeva M, Gefri A, et al. Paraneoplastic pyoderma gangrenosum in solid organ malignancy: a literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:154-158.

- Montagnon CM, Fracica EA, Patel AA, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum in hematologic malignancies: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1346-1359.

- Morin CB, Côté B, Belisle A. An interesting case of pyoderma gangrenosum with immature histiocytoid neutrophils. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:63-66.

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659.

- Saleh MFM, Saunthararajah Y. Severe pyoderma gangrenosum caused by myelodysplastic syndrome successfully treated with decitabine administered by a noncytotoxic regimen. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5:2025-2027.

- Yamauchi R, Ishida K, Iwashima Y, et al. Successful treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum that developed in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Infect Chemother. 2003;9:268-271.

- Ha JW, Hahm JE, Kim KS, et al. A case of pyoderma gangrenosum with myelodysplastic syndrome. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30:392-393.

- Malkan UY, Gunes G, Eliacik E, et al. Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum with thalidomide in a myelodysplastic syndrome case. Int J Med Case Rep. 2016;9:61-64.

- Koca E, Duman AE, Cetiner D, et al. Successful treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Neth J Med. 2006;64:422-424.

- Nieto D, Sendagorta E, Rueda JM, et al. Successful treatment with ustekinumab and vacuum-assisted closure therapy in recalcitrant myelodysplastic syndrome-associated pyoderma gangrenosum: case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:116-119.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842.

- Cohen PR. Neutrophilic dermatoses: a review of current treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:301-312.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Braswell SF, Kostopoulos TC, Ortega-Loayza AG. Pathophysiology of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): an updated review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:691-698.

- Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD. Pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome: the prototypic neutrophilic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:595-602.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- Lear JT, Atherton MT, Byrne JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet’s syndrome. Postgrad Med. 1997;73:65-68.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006.

- Minocha R, Sebaratnam DF, Choi JY. Sweet’s syndrome following surgery: cutaneous trauma as a possible aetiological co-factor in neutrophilic dermatoses. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:E74-E76.

- Shah M, Sachdeva M, Gefri A, et al. Paraneoplastic pyoderma gangrenosum in solid organ malignancy: a literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:154-158.

- Montagnon CM, Fracica EA, Patel AA, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum in hematologic malignancies: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1346-1359.

- Morin CB, Côté B, Belisle A. An interesting case of pyoderma gangrenosum with immature histiocytoid neutrophils. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:63-66.

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659.

- Saleh MFM, Saunthararajah Y. Severe pyoderma gangrenosum caused by myelodysplastic syndrome successfully treated with decitabine administered by a noncytotoxic regimen. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5:2025-2027.

- Yamauchi R, Ishida K, Iwashima Y, et al. Successful treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum that developed in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Infect Chemother. 2003;9:268-271.

- Ha JW, Hahm JE, Kim KS, et al. A case of pyoderma gangrenosum with myelodysplastic syndrome. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30:392-393.

- Malkan UY, Gunes G, Eliacik E, et al. Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum with thalidomide in a myelodysplastic syndrome case. Int J Med Case Rep. 2016;9:61-64.

- Koca E, Duman AE, Cetiner D, et al. Successful treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Neth J Med. 2006;64:422-424.

- Nieto D, Sendagorta E, Rueda JM, et al. Successful treatment with ustekinumab and vacuum-assisted closure therapy in recalcitrant myelodysplastic syndrome-associated pyoderma gangrenosum: case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:116-119.

Practice Points:

- Dermatologists and dermatopathologists should be aware of the histiocytoid variant of pyoderma gangrenosum, which can clinical and histologic features that overlap with histiocytoid Sweet syndrome.

- When considering a diagnosis of histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatoses, leukemia cutis or aleukemic cutaneous myeloid sarcoma should be ruled out.

- Similar to histiocytoid Sweet syndrome and neutrophilic dermatoses in the setting of hematologic or solid organ malignancy, histiocytoid pyoderma gangrenosum may respond well to high-dose systemic corticosteroids.