User login

Painless Nodule on the Lower Eyelid

Painless Nodule on the Lower Eyelid

THE DIAGNOSIS: Idiopathic Facial Aseptic Granuloma

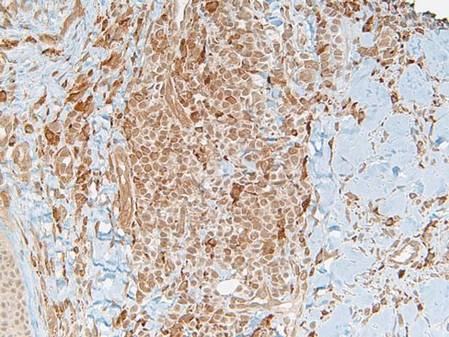

Histopathology showed a ruptured follicle, perifollicular granulomatous inflammation, and admixed multinucleated giant cells in the superficial dermis. The deeper tissue exhibited edema, histiocytic/granulomatous inflammation forming ill-defined loose granulomas, and a single neutrophilic microabscess (Figure). Stains for periodic acid-Schiff with diastase and acid-fast bacillus were negative for microorganisms. The clinical examination and pathology findings supported a diagnosis of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG).

First reported in 1999, IFAG was described using the French term pyodermite froide du visage, which translates to “cold pyoderma of the face”; however, it was renamed to represent its granulomatous characteristics and noninfectious etiology.1 The pathogenesis of IFAG is unknown, but the leading hypothesis is that it may be a type of childhood granulomatous rosacea, given its association with relapsing chalazions, papulopustular eruptions on the face, and facial flushing.2 Other hypotheses are that IFAG is idiopathic or a granulomatous response to an insect bite, minor trauma, or embryologic remnant.3

A rare condition arising in early childhood, IFAG manifests as a single or multiple, painless, erythematous or violaceous nodule(s) on the face, most often on the cheeks or eyelids.4 A thorough history and clinical examination often suffice for diagnosis. Dermoscopy may reveal white perifollicular halos and follicular plugs on an erythematous base with linear vessels.4 If diagnostic tests are performed, there are notable characteristic findings: ultrasonography often shows a well-circumscribed, hypoechoic, ovoid dermal lesion without calcifications. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures commonly are negative.4 On biopsy, histopathology may reveal granulomatous inflammation in the superficial and deep dermis, multinucleated giant cells, and surrounding lymphocytic, neutrophilic, and eosinophilic infiltration with no calcium deposits.3,5,6 Histopathology findings for IFAG and rosacea lesions are similar; both may demonstrate folliculitis, perifollicular granulomas, and admixed lymphohistiocytic inflammation.7

Differentiating IFAG from other dermatologic lesions can be challenging, as the differential includes benign neoplasms (eg, dermoid cyst, chalazion, pilomatricoma, xanthoma, xanthogranuloma2) and infectious etiologies such as bacterial pyoderma and mycobacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections (eg, cutaneous leishmaniasis). Pilomatricomas, although often seen on the face or extremities in young girls, more often are well circumscribed and located in the dermis. Ultrasonography of a pilomatricoma classically shows variable foci of calcification. Xanthoma and xanthogranuloma also were considered in our case since the lesion was subtly yellowish on examination. Similar to IFAG, these conditions may manifest as single or multiple lesions. Abnormalities in the patient’s blood lipid panel or family history may be needed to diagnose xanthoma. Biopsy of a juvenile xanthogranuloma would exhibit a dense dermal nodular proliferation of histiocytic cells with a smaller number of admixed lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils, in contrast to the multiple smaller loose epithelioid granulomas seen in IFAG. Additional diagnoses in the differential for IFAG include pyogenic granuloma, Spitz nevus, nodulocystic infantile acne, granulomatous rosacea, and hemangioma.1,3,9 In particular, granulomatous rosacea is challenging to differentiate from IFAG given the overlapping clinical findings. Multiple lesions, the presence of papules and pustules, and associated rosacea symptoms such as flushing suggest a diagnosis of granulomatous rosacea over IFAG.2

The prognosis for IFAG is excellent; most lesions self-resolve without treatment or procedural intervention within 1 year without scarring or relapse.3 Topical and oral antibiotic treatments such as metronidazole 0.75% gel or cream, oral erythromycin, oral clarithromycin, and doxycycline (in patients older than 8 years) have been used to treat IFAG with variable clinic responses.2,3,6,8 Persistent IFAG has been treated with surgical excision.3 Our patient was treated with a combination of gentamicin ointment 0.3% and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% and experienced approximately 50% improvement in the first month of treatment.

- Roul S, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Idiopathic aseptic facial granuloma (pyodermite froide du visage): a pediatric entity? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1253-1255.

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. IFAG and childhood rosacea: a possible link? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:429-432. doi:10.1111/pde.12137

- Boralevi F, Léauté-Labrèze C, Lepreux S, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma: a multicentre prospective study of 30 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:705-708. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07741.x

- Lobato-Berezo A, Montoro-Romero S, Pujol RM, et al. Dermoscopic features of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E308-E309. doi:10.1111/pde.13582

- González Rodríguez AJ, Jordá Cuevas E. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:298-300. doi:10.1111/ced.12535

- Orion C, Sfecci A, Tisseau L, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a 13-year-old boy dramatically improved with oral doxycycline and topical metronidazole: evidence for a link with childhood rosacea. Case Rep Dermatol. 2016;8:197-201. doi:10.1159/000447624

- Neri I, Raone B, Dondi A, et al. Should idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma be considered granulomatous rosacea? report of three pediatric cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:109-111. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2011.01689.x

- Miconi F, Principi N, Cassiani L, et al. A cheek nodule in a child: be aware of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma and its differential diagnosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2471. doi:10.3390/ijerph16142471

- Baroni A, Russo T, Faccenda F, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a child: a possible expression of childhood rosacea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:394-395. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01805.x

THE DIAGNOSIS: Idiopathic Facial Aseptic Granuloma

Histopathology showed a ruptured follicle, perifollicular granulomatous inflammation, and admixed multinucleated giant cells in the superficial dermis. The deeper tissue exhibited edema, histiocytic/granulomatous inflammation forming ill-defined loose granulomas, and a single neutrophilic microabscess (Figure). Stains for periodic acid-Schiff with diastase and acid-fast bacillus were negative for microorganisms. The clinical examination and pathology findings supported a diagnosis of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG).

First reported in 1999, IFAG was described using the French term pyodermite froide du visage, which translates to “cold pyoderma of the face”; however, it was renamed to represent its granulomatous characteristics and noninfectious etiology.1 The pathogenesis of IFAG is unknown, but the leading hypothesis is that it may be a type of childhood granulomatous rosacea, given its association with relapsing chalazions, papulopustular eruptions on the face, and facial flushing.2 Other hypotheses are that IFAG is idiopathic or a granulomatous response to an insect bite, minor trauma, or embryologic remnant.3

A rare condition arising in early childhood, IFAG manifests as a single or multiple, painless, erythematous or violaceous nodule(s) on the face, most often on the cheeks or eyelids.4 A thorough history and clinical examination often suffice for diagnosis. Dermoscopy may reveal white perifollicular halos and follicular plugs on an erythematous base with linear vessels.4 If diagnostic tests are performed, there are notable characteristic findings: ultrasonography often shows a well-circumscribed, hypoechoic, ovoid dermal lesion without calcifications. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures commonly are negative.4 On biopsy, histopathology may reveal granulomatous inflammation in the superficial and deep dermis, multinucleated giant cells, and surrounding lymphocytic, neutrophilic, and eosinophilic infiltration with no calcium deposits.3,5,6 Histopathology findings for IFAG and rosacea lesions are similar; both may demonstrate folliculitis, perifollicular granulomas, and admixed lymphohistiocytic inflammation.7

Differentiating IFAG from other dermatologic lesions can be challenging, as the differential includes benign neoplasms (eg, dermoid cyst, chalazion, pilomatricoma, xanthoma, xanthogranuloma2) and infectious etiologies such as bacterial pyoderma and mycobacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections (eg, cutaneous leishmaniasis). Pilomatricomas, although often seen on the face or extremities in young girls, more often are well circumscribed and located in the dermis. Ultrasonography of a pilomatricoma classically shows variable foci of calcification. Xanthoma and xanthogranuloma also were considered in our case since the lesion was subtly yellowish on examination. Similar to IFAG, these conditions may manifest as single or multiple lesions. Abnormalities in the patient’s blood lipid panel or family history may be needed to diagnose xanthoma. Biopsy of a juvenile xanthogranuloma would exhibit a dense dermal nodular proliferation of histiocytic cells with a smaller number of admixed lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils, in contrast to the multiple smaller loose epithelioid granulomas seen in IFAG. Additional diagnoses in the differential for IFAG include pyogenic granuloma, Spitz nevus, nodulocystic infantile acne, granulomatous rosacea, and hemangioma.1,3,9 In particular, granulomatous rosacea is challenging to differentiate from IFAG given the overlapping clinical findings. Multiple lesions, the presence of papules and pustules, and associated rosacea symptoms such as flushing suggest a diagnosis of granulomatous rosacea over IFAG.2

The prognosis for IFAG is excellent; most lesions self-resolve without treatment or procedural intervention within 1 year without scarring or relapse.3 Topical and oral antibiotic treatments such as metronidazole 0.75% gel or cream, oral erythromycin, oral clarithromycin, and doxycycline (in patients older than 8 years) have been used to treat IFAG with variable clinic responses.2,3,6,8 Persistent IFAG has been treated with surgical excision.3 Our patient was treated with a combination of gentamicin ointment 0.3% and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% and experienced approximately 50% improvement in the first month of treatment.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Idiopathic Facial Aseptic Granuloma

Histopathology showed a ruptured follicle, perifollicular granulomatous inflammation, and admixed multinucleated giant cells in the superficial dermis. The deeper tissue exhibited edema, histiocytic/granulomatous inflammation forming ill-defined loose granulomas, and a single neutrophilic microabscess (Figure). Stains for periodic acid-Schiff with diastase and acid-fast bacillus were negative for microorganisms. The clinical examination and pathology findings supported a diagnosis of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG).

First reported in 1999, IFAG was described using the French term pyodermite froide du visage, which translates to “cold pyoderma of the face”; however, it was renamed to represent its granulomatous characteristics and noninfectious etiology.1 The pathogenesis of IFAG is unknown, but the leading hypothesis is that it may be a type of childhood granulomatous rosacea, given its association with relapsing chalazions, papulopustular eruptions on the face, and facial flushing.2 Other hypotheses are that IFAG is idiopathic or a granulomatous response to an insect bite, minor trauma, or embryologic remnant.3

A rare condition arising in early childhood, IFAG manifests as a single or multiple, painless, erythematous or violaceous nodule(s) on the face, most often on the cheeks or eyelids.4 A thorough history and clinical examination often suffice for diagnosis. Dermoscopy may reveal white perifollicular halos and follicular plugs on an erythematous base with linear vessels.4 If diagnostic tests are performed, there are notable characteristic findings: ultrasonography often shows a well-circumscribed, hypoechoic, ovoid dermal lesion without calcifications. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures commonly are negative.4 On biopsy, histopathology may reveal granulomatous inflammation in the superficial and deep dermis, multinucleated giant cells, and surrounding lymphocytic, neutrophilic, and eosinophilic infiltration with no calcium deposits.3,5,6 Histopathology findings for IFAG and rosacea lesions are similar; both may demonstrate folliculitis, perifollicular granulomas, and admixed lymphohistiocytic inflammation.7

Differentiating IFAG from other dermatologic lesions can be challenging, as the differential includes benign neoplasms (eg, dermoid cyst, chalazion, pilomatricoma, xanthoma, xanthogranuloma2) and infectious etiologies such as bacterial pyoderma and mycobacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections (eg, cutaneous leishmaniasis). Pilomatricomas, although often seen on the face or extremities in young girls, more often are well circumscribed and located in the dermis. Ultrasonography of a pilomatricoma classically shows variable foci of calcification. Xanthoma and xanthogranuloma also were considered in our case since the lesion was subtly yellowish on examination. Similar to IFAG, these conditions may manifest as single or multiple lesions. Abnormalities in the patient’s blood lipid panel or family history may be needed to diagnose xanthoma. Biopsy of a juvenile xanthogranuloma would exhibit a dense dermal nodular proliferation of histiocytic cells with a smaller number of admixed lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils, in contrast to the multiple smaller loose epithelioid granulomas seen in IFAG. Additional diagnoses in the differential for IFAG include pyogenic granuloma, Spitz nevus, nodulocystic infantile acne, granulomatous rosacea, and hemangioma.1,3,9 In particular, granulomatous rosacea is challenging to differentiate from IFAG given the overlapping clinical findings. Multiple lesions, the presence of papules and pustules, and associated rosacea symptoms such as flushing suggest a diagnosis of granulomatous rosacea over IFAG.2

The prognosis for IFAG is excellent; most lesions self-resolve without treatment or procedural intervention within 1 year without scarring or relapse.3 Topical and oral antibiotic treatments such as metronidazole 0.75% gel or cream, oral erythromycin, oral clarithromycin, and doxycycline (in patients older than 8 years) have been used to treat IFAG with variable clinic responses.2,3,6,8 Persistent IFAG has been treated with surgical excision.3 Our patient was treated with a combination of gentamicin ointment 0.3% and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% and experienced approximately 50% improvement in the first month of treatment.

- Roul S, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Idiopathic aseptic facial granuloma (pyodermite froide du visage): a pediatric entity? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1253-1255.

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. IFAG and childhood rosacea: a possible link? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:429-432. doi:10.1111/pde.12137

- Boralevi F, Léauté-Labrèze C, Lepreux S, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma: a multicentre prospective study of 30 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:705-708. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07741.x

- Lobato-Berezo A, Montoro-Romero S, Pujol RM, et al. Dermoscopic features of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E308-E309. doi:10.1111/pde.13582

- González Rodríguez AJ, Jordá Cuevas E. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:298-300. doi:10.1111/ced.12535

- Orion C, Sfecci A, Tisseau L, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a 13-year-old boy dramatically improved with oral doxycycline and topical metronidazole: evidence for a link with childhood rosacea. Case Rep Dermatol. 2016;8:197-201. doi:10.1159/000447624

- Neri I, Raone B, Dondi A, et al. Should idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma be considered granulomatous rosacea? report of three pediatric cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:109-111. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2011.01689.x

- Miconi F, Principi N, Cassiani L, et al. A cheek nodule in a child: be aware of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma and its differential diagnosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2471. doi:10.3390/ijerph16142471

- Baroni A, Russo T, Faccenda F, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a child: a possible expression of childhood rosacea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:394-395. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01805.x

- Roul S, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Idiopathic aseptic facial granuloma (pyodermite froide du visage): a pediatric entity? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1253-1255.

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. IFAG and childhood rosacea: a possible link? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:429-432. doi:10.1111/pde.12137

- Boralevi F, Léauté-Labrèze C, Lepreux S, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma: a multicentre prospective study of 30 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:705-708. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07741.x

- Lobato-Berezo A, Montoro-Romero S, Pujol RM, et al. Dermoscopic features of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E308-E309. doi:10.1111/pde.13582

- González Rodríguez AJ, Jordá Cuevas E. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:298-300. doi:10.1111/ced.12535

- Orion C, Sfecci A, Tisseau L, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a 13-year-old boy dramatically improved with oral doxycycline and topical metronidazole: evidence for a link with childhood rosacea. Case Rep Dermatol. 2016;8:197-201. doi:10.1159/000447624

- Neri I, Raone B, Dondi A, et al. Should idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma be considered granulomatous rosacea? report of three pediatric cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:109-111. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2011.01689.x

- Miconi F, Principi N, Cassiani L, et al. A cheek nodule in a child: be aware of idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma and its differential diagnosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2471. doi:10.3390/ijerph16142471

- Baroni A, Russo T, Faccenda F, et al. Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a child: a possible expression of childhood rosacea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:394-395. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01805.x

Painless Nodule on the Lower Eyelid

Painless Nodule on the Lower Eyelid

A 4-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a painless, red to golden-yellowish nodule on the right lower eyelid of 4 months’ duration. The patient had no history of skin disease and was otherwise healthy. Physical examination revealed a single 1-cm, soft, erythematous and yellowish plaque on the right lower eyelid that was subtly fluctuant on palpation. She had no associated systemic symptoms or lymphadenopathy. A punch biopsy of the lesion was performed.

Leukemia Cutis Presenting as Scrotal Ulcerations in a Patient With Acute Myelogenous Leukemia

To the Editor:

Cutaneous manifestations of leukemia can be defined as specific or nonspecific skin lesions. Specific skin lesions include papules, nodules, tumors, or ulcerating plaques caused by the infiltration of leukemic cells (eg, leukemia cutis), while nonspecific skin lesions include petechiae, purpura, ecchymosis, or infection. Leukemia cutis is a rare entity that denotes a poor prognosis. We present a case of leukemia cutis with scrotal ulcerations, which heralded the onset of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Other causes of painful cutaneous ulcers to consider in a patient with a hematologic malignancy include a variety of infectious and inflammatory etiologies.

A 63-year-old man with long-standing essential thrombocytosis was admitted to the hospital with increasing fatigue and fever. A complete blood cell count revealed anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and leukocytosis with 49% blasts. He was immediately placed on broad-spectrum antifungal, antiviral, and antibiotic agents after blood and urine cultures were obtained and while subsequent diagnostic tests were being performed. The patient developed antibiotic-associated Clostridium difficile diarrhea after several days in the hospital. The nursing staff noted “genital irritation from feces” while cleaning the patient and reported the findings to the primary team. Dermatology was consulted for treatment recommendations and wound care.

A full-body skin examination revealed discrete and coalescing painful scrotal and perineal ulcers with fecal contamination (Figure 1), along with numerous petechial macules on the anteromedial thighs. The patient was unsure of the onset of the ulcers, but he claimed to have scrotal and perineal pain prior to admission, which suggested their long-standing presence. No crepitus or rapid contiguous spread was noted on serial physical examination over the next 12 to 24 hours. Punch biopsies for tissue culture and histopathologic examination were obtained from the scrotum.

Subsequent diagnostic studies, including a bone marrow biopsy touch preparation that showed 44.7% blasts, along with cytogenetics analysis yielded the diagnosis of AML with an unfavorable karyotype: 5q deletion, 17p deletion, and monosomy 16. Induction chemotherapy with multiple cycles of a combination of cytarabine and daunorubicin was initiated, albeit with an unfavorable response. Blood, urine, bone marrow, and stool cultures remained negative. Serologic testing for herpes simplex virus (HSV), cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus was negative.

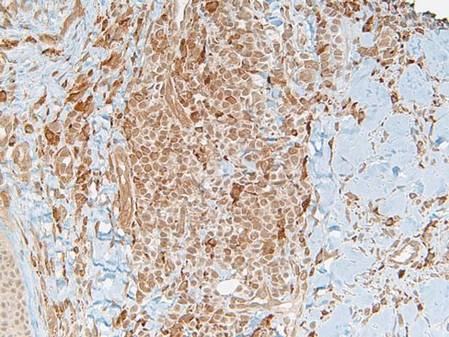

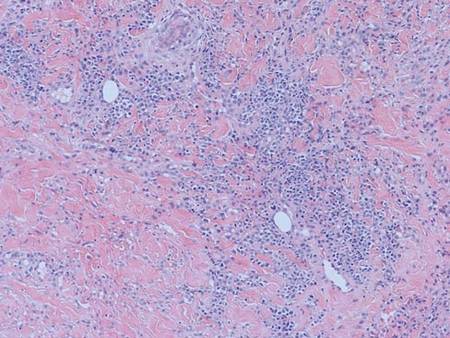

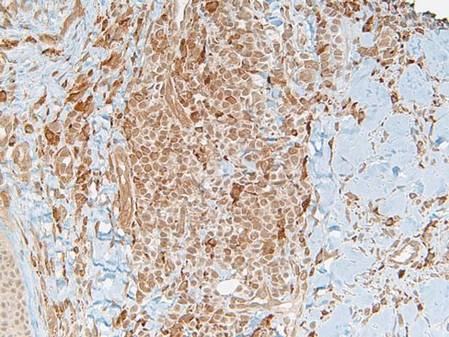

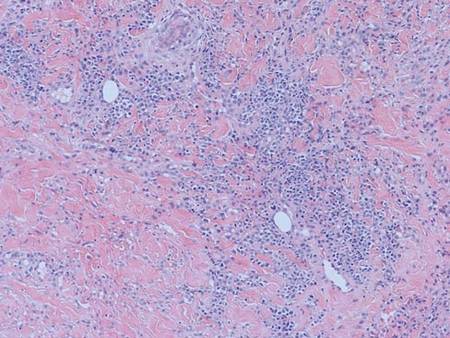

Histopathology showed an ulcerated epidermis along with a dense dermal perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of myeloid blasts (Figure 2). Lesional cells were diffusely CD68+ (Figure 3), myeloperoxidase positive (Figure 4), and CD34-, correlating with findings on the bone marrow biopsy. Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, and Gram stains highlighted several bacterial cocci, yeast forms, and pseudohyphae on the ulcer surface with no organisms seen in the dermis. Tissue culture did not yield any organisms. There was no overt evidence of HSV infection. The histopathologic features were consistent with a diagnosis of leukemia cutis in the setting of AML. After failed chemotherapy and a complicated hospital course with a poor long-term prognosis, the patient and his family opted for home hospice care.

|

|

Cases of leukemia cutis manifesting as scrotal ulcerations are rare.1 Typically, most dermatologic lesions seen in leukemia patients are of a nonleukemic origin.2 Leukemia cutis is a rare entity that is associated with a poor prognosis.3 It was accordingly an ominous finding in our patient, as his AML had an unfavorable karyotype and was unresponsive to chemotherapy.

In hematologic malignancies, the morphology and distribution of specific cutaneous lesions tends to vary by the type of leukemia. For example, chronic lymphocytic leukemia presents with papules, nodules, and ulcerating plaques more often than acute lymphocytic leukemia.4 Acute myelocytic papules, nodules, or tumors tend to appear on the face, while chronic lesions commonly are seen on the face and extremities.5 Generally, for all forms of leukemia, lesions on the genitalia are uncommon.

This case of ulcerative scrotal AML lesions is unique, as myelogenous leukemia cutis typically appears as a tumor that infrequently ulcerates and rarely is located on the genitalia.6 Tissue culture, blood culture, viral serology, and biopsy failed to reveal an infectious etiology of the genital ulcerations in our patient. Therefore, the leukemic infiltrate likely preceded the ulceration and an antecedent infection did not elicit an inflammatory response, resulting in the attraction of a leukemic infiltrate to the area. This latter phenomenon also has been demonstrated in the setting of recent surgical scars, trauma, burns, herpes zoster, HSV, and intramuscular injection sites.1,7

The differential diagnosis of painful cutaneous ulcers in the setting of hematologic malignancy includes a variety of infectious and inflammatory etiologies such as ulcerative HSV, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, amoebic skin ulcerations, opportunistic fungal infections, bacterial infections, pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), histoplasmosis,1 Fournier gangrene, and vasculitis, all of which were ruled out in our case.

We report a case of a patient with a history of essential thrombocytosis who developed leukemia cutis presenting as scrotal ulcerations, which preceded the diagnosis of AML. Ulcerative leukemic lesions on the genitalia are atypical and extremely rare. However, the lesions are notable because they may be suggestive of a poor prognostic outcome, as in our patient whose induction therapy with cytarabine and daunorubicin failed. We propose that leukemia cutis be included in the differential diagnosis of chronic skin ulcerations of the genitalia.

1. Zax RH, Kulp-Shorten CL, Callen JP. Leukemia cutis presenting as a scrotal ulcer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(2, pt 2):410-413.

2. Wadhwa N, Batra M, Singh B. Nonhealing ulcer—a rare initial presentation of chronic myeloid leukemia diagnosed on aspiration cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:135-137.

3. Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:121-128.

4. Boggs DR, Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE. The acute leukemias. analysis of 322 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1962;41:163-225.

5. Stawiski MA. Skin manifestations of leukemias and lymphomas. Cutis. 1978;21:814-818.

6. Costello MJ, Canizares O, Montague M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of myelogenous leukemia. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;71:605-614.

7. Koizumi H, Kumakiri M, Ishizuka M, et al. Leukemia cutis in acute myelomonocytic leukemia: infiltration to minor traumas and scars. J Dermatol. 1991;18:281-285.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous manifestations of leukemia can be defined as specific or nonspecific skin lesions. Specific skin lesions include papules, nodules, tumors, or ulcerating plaques caused by the infiltration of leukemic cells (eg, leukemia cutis), while nonspecific skin lesions include petechiae, purpura, ecchymosis, or infection. Leukemia cutis is a rare entity that denotes a poor prognosis. We present a case of leukemia cutis with scrotal ulcerations, which heralded the onset of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Other causes of painful cutaneous ulcers to consider in a patient with a hematologic malignancy include a variety of infectious and inflammatory etiologies.

A 63-year-old man with long-standing essential thrombocytosis was admitted to the hospital with increasing fatigue and fever. A complete blood cell count revealed anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and leukocytosis with 49% blasts. He was immediately placed on broad-spectrum antifungal, antiviral, and antibiotic agents after blood and urine cultures were obtained and while subsequent diagnostic tests were being performed. The patient developed antibiotic-associated Clostridium difficile diarrhea after several days in the hospital. The nursing staff noted “genital irritation from feces” while cleaning the patient and reported the findings to the primary team. Dermatology was consulted for treatment recommendations and wound care.

A full-body skin examination revealed discrete and coalescing painful scrotal and perineal ulcers with fecal contamination (Figure 1), along with numerous petechial macules on the anteromedial thighs. The patient was unsure of the onset of the ulcers, but he claimed to have scrotal and perineal pain prior to admission, which suggested their long-standing presence. No crepitus or rapid contiguous spread was noted on serial physical examination over the next 12 to 24 hours. Punch biopsies for tissue culture and histopathologic examination were obtained from the scrotum.

Subsequent diagnostic studies, including a bone marrow biopsy touch preparation that showed 44.7% blasts, along with cytogenetics analysis yielded the diagnosis of AML with an unfavorable karyotype: 5q deletion, 17p deletion, and monosomy 16. Induction chemotherapy with multiple cycles of a combination of cytarabine and daunorubicin was initiated, albeit with an unfavorable response. Blood, urine, bone marrow, and stool cultures remained negative. Serologic testing for herpes simplex virus (HSV), cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus was negative.

Histopathology showed an ulcerated epidermis along with a dense dermal perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of myeloid blasts (Figure 2). Lesional cells were diffusely CD68+ (Figure 3), myeloperoxidase positive (Figure 4), and CD34-, correlating with findings on the bone marrow biopsy. Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, and Gram stains highlighted several bacterial cocci, yeast forms, and pseudohyphae on the ulcer surface with no organisms seen in the dermis. Tissue culture did not yield any organisms. There was no overt evidence of HSV infection. The histopathologic features were consistent with a diagnosis of leukemia cutis in the setting of AML. After failed chemotherapy and a complicated hospital course with a poor long-term prognosis, the patient and his family opted for home hospice care.

|

|

Cases of leukemia cutis manifesting as scrotal ulcerations are rare.1 Typically, most dermatologic lesions seen in leukemia patients are of a nonleukemic origin.2 Leukemia cutis is a rare entity that is associated with a poor prognosis.3 It was accordingly an ominous finding in our patient, as his AML had an unfavorable karyotype and was unresponsive to chemotherapy.

In hematologic malignancies, the morphology and distribution of specific cutaneous lesions tends to vary by the type of leukemia. For example, chronic lymphocytic leukemia presents with papules, nodules, and ulcerating plaques more often than acute lymphocytic leukemia.4 Acute myelocytic papules, nodules, or tumors tend to appear on the face, while chronic lesions commonly are seen on the face and extremities.5 Generally, for all forms of leukemia, lesions on the genitalia are uncommon.

This case of ulcerative scrotal AML lesions is unique, as myelogenous leukemia cutis typically appears as a tumor that infrequently ulcerates and rarely is located on the genitalia.6 Tissue culture, blood culture, viral serology, and biopsy failed to reveal an infectious etiology of the genital ulcerations in our patient. Therefore, the leukemic infiltrate likely preceded the ulceration and an antecedent infection did not elicit an inflammatory response, resulting in the attraction of a leukemic infiltrate to the area. This latter phenomenon also has been demonstrated in the setting of recent surgical scars, trauma, burns, herpes zoster, HSV, and intramuscular injection sites.1,7

The differential diagnosis of painful cutaneous ulcers in the setting of hematologic malignancy includes a variety of infectious and inflammatory etiologies such as ulcerative HSV, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, amoebic skin ulcerations, opportunistic fungal infections, bacterial infections, pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), histoplasmosis,1 Fournier gangrene, and vasculitis, all of which were ruled out in our case.

We report a case of a patient with a history of essential thrombocytosis who developed leukemia cutis presenting as scrotal ulcerations, which preceded the diagnosis of AML. Ulcerative leukemic lesions on the genitalia are atypical and extremely rare. However, the lesions are notable because they may be suggestive of a poor prognostic outcome, as in our patient whose induction therapy with cytarabine and daunorubicin failed. We propose that leukemia cutis be included in the differential diagnosis of chronic skin ulcerations of the genitalia.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous manifestations of leukemia can be defined as specific or nonspecific skin lesions. Specific skin lesions include papules, nodules, tumors, or ulcerating plaques caused by the infiltration of leukemic cells (eg, leukemia cutis), while nonspecific skin lesions include petechiae, purpura, ecchymosis, or infection. Leukemia cutis is a rare entity that denotes a poor prognosis. We present a case of leukemia cutis with scrotal ulcerations, which heralded the onset of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Other causes of painful cutaneous ulcers to consider in a patient with a hematologic malignancy include a variety of infectious and inflammatory etiologies.

A 63-year-old man with long-standing essential thrombocytosis was admitted to the hospital with increasing fatigue and fever. A complete blood cell count revealed anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and leukocytosis with 49% blasts. He was immediately placed on broad-spectrum antifungal, antiviral, and antibiotic agents after blood and urine cultures were obtained and while subsequent diagnostic tests were being performed. The patient developed antibiotic-associated Clostridium difficile diarrhea after several days in the hospital. The nursing staff noted “genital irritation from feces” while cleaning the patient and reported the findings to the primary team. Dermatology was consulted for treatment recommendations and wound care.

A full-body skin examination revealed discrete and coalescing painful scrotal and perineal ulcers with fecal contamination (Figure 1), along with numerous petechial macules on the anteromedial thighs. The patient was unsure of the onset of the ulcers, but he claimed to have scrotal and perineal pain prior to admission, which suggested their long-standing presence. No crepitus or rapid contiguous spread was noted on serial physical examination over the next 12 to 24 hours. Punch biopsies for tissue culture and histopathologic examination were obtained from the scrotum.

Subsequent diagnostic studies, including a bone marrow biopsy touch preparation that showed 44.7% blasts, along with cytogenetics analysis yielded the diagnosis of AML with an unfavorable karyotype: 5q deletion, 17p deletion, and monosomy 16. Induction chemotherapy with multiple cycles of a combination of cytarabine and daunorubicin was initiated, albeit with an unfavorable response. Blood, urine, bone marrow, and stool cultures remained negative. Serologic testing for herpes simplex virus (HSV), cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus was negative.

Histopathology showed an ulcerated epidermis along with a dense dermal perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of myeloid blasts (Figure 2). Lesional cells were diffusely CD68+ (Figure 3), myeloperoxidase positive (Figure 4), and CD34-, correlating with findings on the bone marrow biopsy. Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, and Gram stains highlighted several bacterial cocci, yeast forms, and pseudohyphae on the ulcer surface with no organisms seen in the dermis. Tissue culture did not yield any organisms. There was no overt evidence of HSV infection. The histopathologic features were consistent with a diagnosis of leukemia cutis in the setting of AML. After failed chemotherapy and a complicated hospital course with a poor long-term prognosis, the patient and his family opted for home hospice care.

|

|

Cases of leukemia cutis manifesting as scrotal ulcerations are rare.1 Typically, most dermatologic lesions seen in leukemia patients are of a nonleukemic origin.2 Leukemia cutis is a rare entity that is associated with a poor prognosis.3 It was accordingly an ominous finding in our patient, as his AML had an unfavorable karyotype and was unresponsive to chemotherapy.

In hematologic malignancies, the morphology and distribution of specific cutaneous lesions tends to vary by the type of leukemia. For example, chronic lymphocytic leukemia presents with papules, nodules, and ulcerating plaques more often than acute lymphocytic leukemia.4 Acute myelocytic papules, nodules, or tumors tend to appear on the face, while chronic lesions commonly are seen on the face and extremities.5 Generally, for all forms of leukemia, lesions on the genitalia are uncommon.

This case of ulcerative scrotal AML lesions is unique, as myelogenous leukemia cutis typically appears as a tumor that infrequently ulcerates and rarely is located on the genitalia.6 Tissue culture, blood culture, viral serology, and biopsy failed to reveal an infectious etiology of the genital ulcerations in our patient. Therefore, the leukemic infiltrate likely preceded the ulceration and an antecedent infection did not elicit an inflammatory response, resulting in the attraction of a leukemic infiltrate to the area. This latter phenomenon also has been demonstrated in the setting of recent surgical scars, trauma, burns, herpes zoster, HSV, and intramuscular injection sites.1,7

The differential diagnosis of painful cutaneous ulcers in the setting of hematologic malignancy includes a variety of infectious and inflammatory etiologies such as ulcerative HSV, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, amoebic skin ulcerations, opportunistic fungal infections, bacterial infections, pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), histoplasmosis,1 Fournier gangrene, and vasculitis, all of which were ruled out in our case.

We report a case of a patient with a history of essential thrombocytosis who developed leukemia cutis presenting as scrotal ulcerations, which preceded the diagnosis of AML. Ulcerative leukemic lesions on the genitalia are atypical and extremely rare. However, the lesions are notable because they may be suggestive of a poor prognostic outcome, as in our patient whose induction therapy with cytarabine and daunorubicin failed. We propose that leukemia cutis be included in the differential diagnosis of chronic skin ulcerations of the genitalia.

1. Zax RH, Kulp-Shorten CL, Callen JP. Leukemia cutis presenting as a scrotal ulcer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(2, pt 2):410-413.

2. Wadhwa N, Batra M, Singh B. Nonhealing ulcer—a rare initial presentation of chronic myeloid leukemia diagnosed on aspiration cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:135-137.

3. Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:121-128.

4. Boggs DR, Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE. The acute leukemias. analysis of 322 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1962;41:163-225.

5. Stawiski MA. Skin manifestations of leukemias and lymphomas. Cutis. 1978;21:814-818.

6. Costello MJ, Canizares O, Montague M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of myelogenous leukemia. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;71:605-614.

7. Koizumi H, Kumakiri M, Ishizuka M, et al. Leukemia cutis in acute myelomonocytic leukemia: infiltration to minor traumas and scars. J Dermatol. 1991;18:281-285.

1. Zax RH, Kulp-Shorten CL, Callen JP. Leukemia cutis presenting as a scrotal ulcer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(2, pt 2):410-413.

2. Wadhwa N, Batra M, Singh B. Nonhealing ulcer—a rare initial presentation of chronic myeloid leukemia diagnosed on aspiration cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:135-137.

3. Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:121-128.

4. Boggs DR, Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE. The acute leukemias. analysis of 322 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1962;41:163-225.

5. Stawiski MA. Skin manifestations of leukemias and lymphomas. Cutis. 1978;21:814-818.

6. Costello MJ, Canizares O, Montague M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of myelogenous leukemia. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;71:605-614.

7. Koizumi H, Kumakiri M, Ishizuka M, et al. Leukemia cutis in acute myelomonocytic leukemia: infiltration to minor traumas and scars. J Dermatol. 1991;18:281-285.