User login

For MD-IQ use only

Acquired Factor VIII Deficiency Presenting as Compartment Syndrome

Compartment syndrome occurs when the interstitial tissue pressures within a confined space are elevated to a level at which the arterial perfusion is diminished. Multiple etiologies exist and can be extrinsic (a cast that is too tight or prolonged compression on a limb), iatrogenic (aggressive resuscitation, drug infiltration, arterial puncture, or a spontaneous bleed from anticoagulation), and traumatic (fracture, snake envenomation, circumferential burn, or electrocution). If the compartments are not released, irreversible changes happen to the cells, including nerve and muscle death.1 Definitive management of this emergency requires prompt fasciotomy to decompress the compartment(s).1-3

Case Presentation

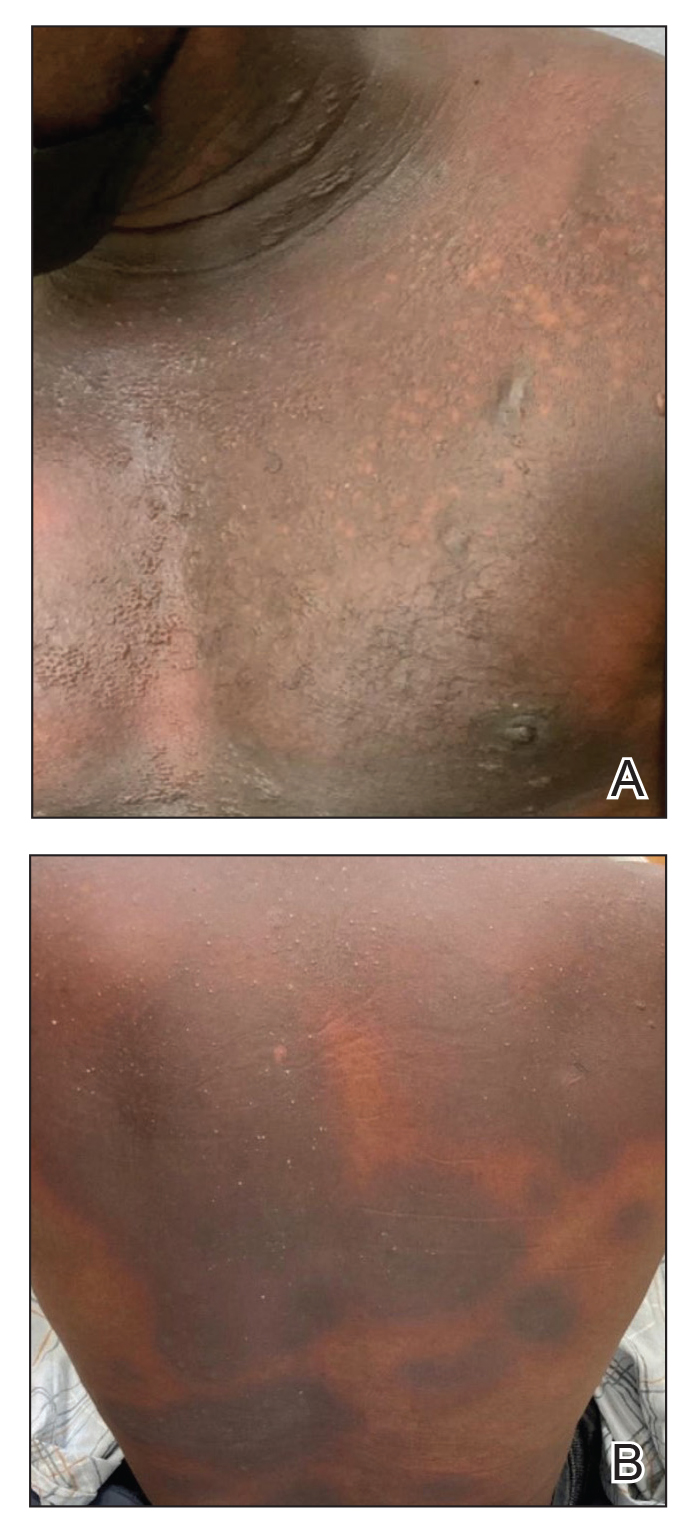

A 76-year-old right-handed woman with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia presented to the emergency department with 2 days of extensive right upper extremity ecchymosis and severe pain that was localized to her forearm (Figure 1). She was taking low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) for left subclavian stenosis and over-the-counter ginkgo biloba. Leading up to the presentation, the patient was able to perform routine household chores, including yard work, cleaning, and taking care of her cats. Wrist and elbow X-rays were negative for a fracture. An upper extremity ultrasound found no venous occlusion. A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of her arm and chest found diffuse edema around the right elbow and forearm without pulmonary or right upper extremity emboli, fractures, hematoma, abscess, or air in the tissues.

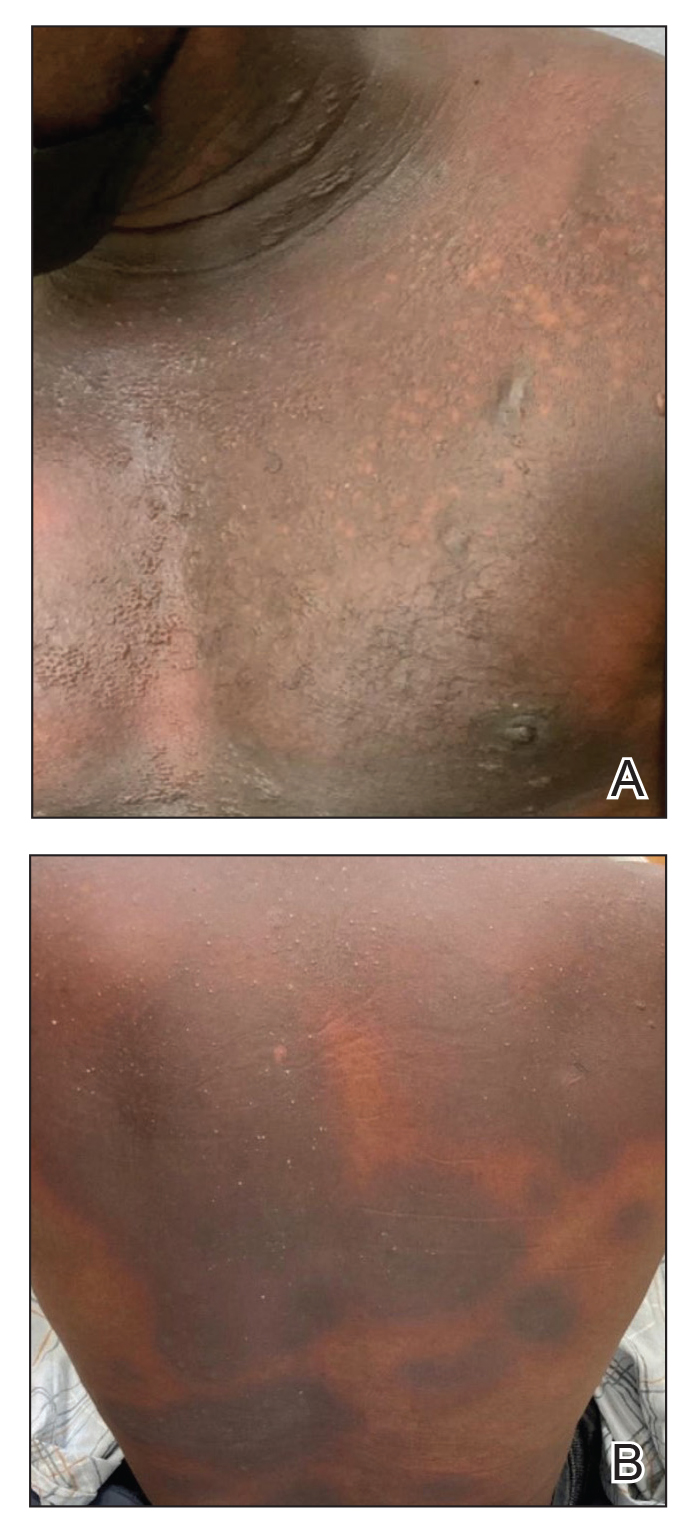

The plastic surgery service was consulted. The patient was found to have a very tense forearm and pain to passive digital extension. The 2-point discrimination and pulses were intact. The patient was diagnosed with compartment syndrome based on the examination alone and gave consent for an emergent forearm and hand fasciotomy. A carpal tunnel release and a standard S-shaped volar forearm fasciotomy release were performed, which provided immediate decompression (Figure 2). The rest of the hand and extremity were soft. Edematous, healthy flexor muscle belly was identified without a hematoma. Most of the forearm wound was left open because the skin could not be reapproximated. Oxidized regenerated cellulose (Surgicel) was placed around the wound edges and the muscle was covered with a nonadherent dressing. Hemoglobin on admission was 12.9 g/dL(reference range, 12 to 16 g/dL). Kidney function was within normal limits. The rest of the complete blood count was unremarkable. Postoperative hemoglobin was 8.6 g/dL. Over the next several days, the patient's skin edges and muscle bellies continued to slowly bleed, and her hemoglobin fell to 5.6 g/dL by postoperative Day 2. The bleeding was managed with topical oxidized regenerated cellulose, thrombin spray, a hemostatic dressing made with kaolin (QuikClot), and a transfusion of 2 units of packed red blood cells.

A hematology consultation was requested. The patient was noted to have an elevated partial thromboplastin time (PTT) since admission measuring between 39.9 to 61.7 seconds (reference range, 26.2 to 37.2 seconds) and a normal prothrombin time test with an international normalized ratio. A PTT measured 17 months prior to admission was within the normal range. She reported no personal or family history of bleeding disorders. Until recently, she had never had easy bruisability. She reported no history of heavy menses or epistaxis. The patient had no children and had never been pregnant. She had tolerated an exploratory laparotomy 40 years prior to admission without bleeding complications and had never required blood transfusions before. A PTT 1:1 mixing study revealed incomplete correction. Subsequent workup included factor VIII (FVIII) activity, factor IX activity, factor XI activity, von Willebrand factor antigen, ristocetin cofactor assay, and von Willebrand factor multimers. FVIII activity was severely reduced at 7.8% (reference, > 54%) with a positive Bethesda assay of 300 to 400 Bodansky units (BU), indicating a strong FVIII inhibitor was present and establishing a diagnosis of acquired hemophilia A. Further workup for secondary causes of acquired hemophilia A including abdominal and pelvic CT, serum protein electrophoresis, and serum free light chains, were negative. She was started on prednisone 1 mg/kg daily and rituximab 375 mg/m2. Her hemoglobin stabilized, and she required no further blood transfusions.

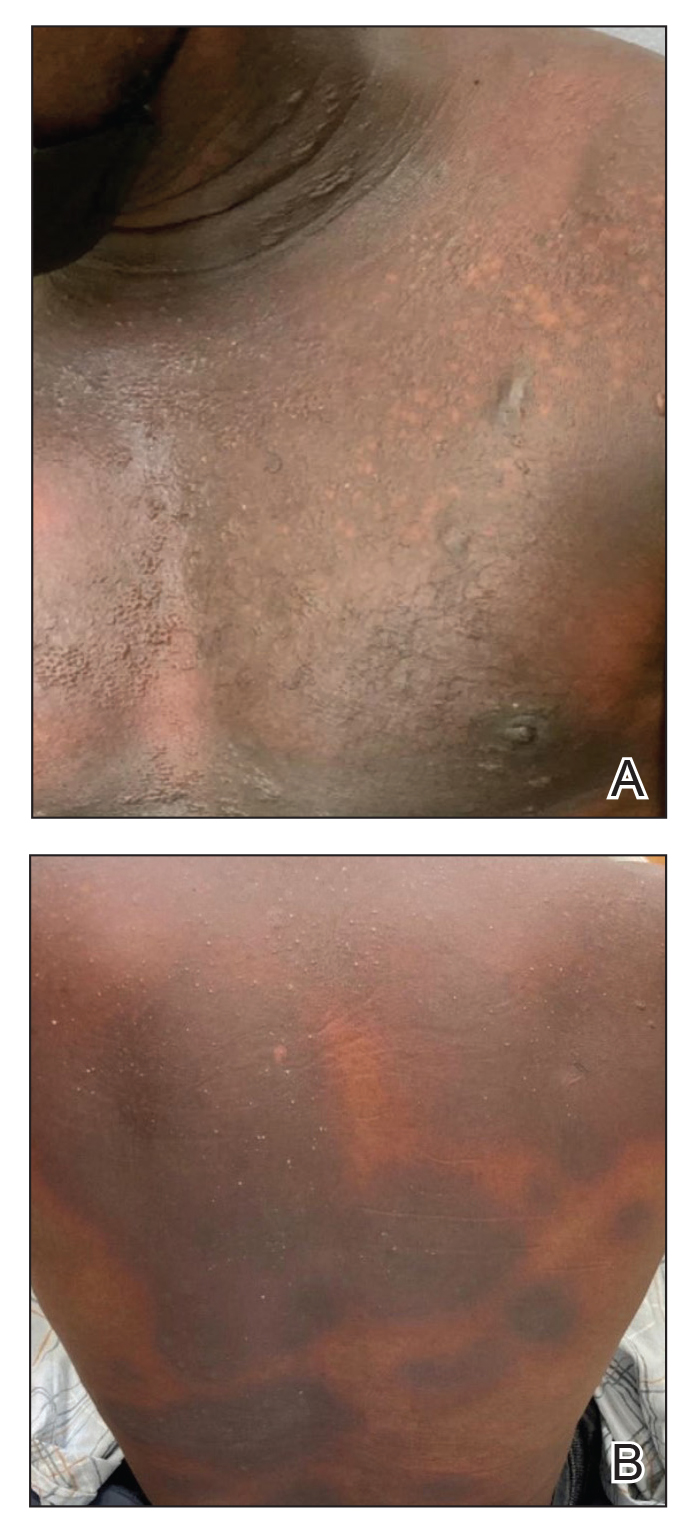

The patient underwent wound closure on postoperative Day 11. At the time of the second surgery, there was still no improvement in her FVIII levels or PTT; therefore, 70 mcg/kg of recombinant coagulation-activated FVII was given just before surgery with no bleeding complications. The skin was closed primarily except for the most distal 3 cm (Figure 3). Due to concerns regarding further bleeding with skin graft, the remaining wound was allowed to close by secondary intention. As a precaution, the wound was covered with oxidized regenerated cellulose and thrombin spray. The patient continued to progress postoperatively without bleeding complications or a need for additional transfusions. She was seen by the hand therapist before and after the second surgery to help with edema management and joint mobility. She completed 4 weekly doses of 375 mg/m² rituximab and prednisone was tapered by 10 mg weekly.

Three weeks after starting treatment, her PTT normalized, and her FVIII increased to 33.7%. The Bethesda assay remained high at 198 BU, although it was lower than at admission. She was discharged home with dressing changes and monthly follow-up appointments. The wounds were fully closed at her 3-month appointment when she proudly demonstrated full digital extension and flexion into her palm.

Discussion

Forearm compartment syndrome is most often caused by fractures—distal radius in adults and supracondylar in children.2 This case initially presented as a diagnostic puzzle to the emergency department due to the patient’s lucid review of several days of nontraumatic injury.

The clinical hallmarks of compartment syndrome are the 5 Ps: pain, pallor, paresthesia, paralysis, and pulselessness. Patients will describe the pain as out of proportion to the nature of the injury; the compartments will be tense and swollen, they will have pain to passive muscle stretch, and sensation will progressively diminish. Distal pulses are the last to go, and permanent tissue damage can still occur when pulses are present.1

Compartment Syndrome

Compartment syndrome is generally a clinical diagnosis; however, in patients who are sedated or uncooperative, or if the clinical findings are equivocal, the examination can be supplemented with intercompartmental pressures using an arterial line transducer system.2 In general, a tissue pressure of 30 mm Hg or a 20- to 30-mm Hg difference between the diastolic and compartment pressures are indications for fasciotomy.1 The hand is treated with an open carpal tunnel release, interosseous muscle release through 2 dorsal hand incisions, and thenar and hypothenar muscle release. The forearm is treated through a curved volar incision that usually decompresses the dorsal compartment, as it did in our patient. If pressures are still high in the forearm, a longitudinal dorsal incision over the mobile wad is necessary. Wounds can be closed primarily days later, left open to close by secondary intention, or reconstructed with skin grafts.2 In our patient, compartment syndrome was isolated to her forearm and the carpal tunnel release was performed prophylactically since it did not add significant time or morbidity to the surgery.

Nontraumatic upper extremity compartment syndrome is rare. A 2021 review of acute nontraumatic upper extremity compartment syndrome found a bleeding disorder as the etiology in 3 cases published in the literature between 1993 and 2016.4 One of these cases was secondary to a known diagnosis of hemophilia A in a teenager.5 Ogrodnik and colleagues described a spontaneous hand hematoma secondary to previously undiagnosed acquired hemophilia A and Waldenström macroglobulinemia.4 Ilyas and colleagues described a spontaneous hematoma in the forearm dorsal compartment in a 67-year-old woman, which presented as compartment syndrome and elevated PTT and led to a diagnosis of acquired FVIII inhibitor. The authors recommended prompt hematology consultation to coordinate treatment once this diagnosis issuspected.6 Compartment syndrome also has been found to develop slowly over weeks in patients with acquired FVIII deficiency, suggesting a high index of suspicion and frequent examinations are needed when patients with known acquired hemophilia A present with a painful extremity.7

Nontraumatic compartment syndrome in the lower extremity in patients with previously undiagnosed acquired hemophilia A has also been described in the literature.8-11 Case reports describe the delay in diagnosis as the patients were originally seen by clinicians for lower extremity pain and swelling within days of presenting to the emergency room with compartment syndrome. Persistent bleeding and abnormal laboratory results prompted further tests and examinations.8,9,11 This underscores the need to be suspicious of this unusual pathology without a history of trauma.

Acquired Hemophilia A

Acquired hemophilia A is an autoimmune disease most often found in older individuals, with a mean age of approximately 70 years.12 It is caused by the spontaneous production of neutralizing immunoglobin autoantibodies that target endogenous FVIII. Many cases are idiopathic; however, up to 50% of cases are associated with underlying autoimmunity, malignancy (especially lymphoproliferative disorders), or pregnancy. It often presents as bleeding that is subcutaneous or in the gastrointestinal system, muscle, retroperitoneal space, or genitourinary system. Unlike congenital hemophilia A, joint bleeding is rare.13

The diagnosis is suspected with an isolated elevated PTT in the absence of other coagulation abnormalities. A 1:1 mixing study will typically show incomplete correction, which suggests the presence of an inhibitor. FVIII activity is reduced, and the FVIII inhibitor is confirmed with the Bethesda assay. Clinically active bleeding is treated with bypassing agents such as recombinant coagulation-activated FVII, activated prothrombin complex concentrates such as anti-inhibitor coagulant complex (FEIBA), or recombinant porcine FVIII.12,14 Not all patients require hemostatic treatment, but close monitoring, education, recognition, and immediate treatment, if needed, are indicated.13 Immunosuppressive therapy (corticosteroids, rituximab, and/or cyclophosphamide) is prescribed to eradicate the antibodies and induce remission.12

Conclusions

An older woman without a preceding trauma was diagnosed with an unusual case of acute compartment syndrome in the forearm. No hematoma was found, but muscle and skin bleeding plus an elevated PTT prompted a hematology workup, and, ultimately, the diagnosis of FVIII inhibitor secondary to acquired hemophilia A.

While a nontraumatic cause of compartment syndrome is rare, it should be considered in differential diagnosis for clinicians who see hand and upper extremity emergencies. An isolated elevated PTT in a patient with a bleed should raise suspicions and trigger immediate further evaluation. Once suspected, multidisciplinary treatment is indicated for immediate and long-term successful outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is the result of work supported withresources and the use of facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Gainesville, Florida.

1. Leversedge FJ, Moore TJ, Peterson BC, Seiler JG 3rd. Compartment syndrome of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:544-559. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.12.008

2. Kalyani BS, Fisher BE, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Compartment syndrome of the forearm: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:535-543. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.12.007

3. Steadman W, Wu R, Hamilton AT, Richardson MD, Wall CJ. Review article: a comprehensive review of unusual causes of acute limb compartment syndrome. Emerg Med Australas. 2022;34:871-876. doi:10.1111/1742-6723.14098

4. Ogrodnik J, Oliver JD, Cani D, Boczar D, Huayllani MT, Restrepo DJ, et al. Clinical case of acute non-traumatic hand compartment syndrome and systematic review for the upper extremity. Hand (N Y). 2021;16:285-291. doi:10.1177/1558944719856106

5. Kim J, Zelken J, Sacks JM. Case report. Spontaneous forearm compartment syndrome in a boy with hemophilia a: a therapeutic dilemma. Eplasty. 2013:13:e16.

6. Ilyas AM, Wisbeck JM, Shaffer GW, Thoder JJ. Upper extremity compartment syndrome secondary to acquired factor VIII inhibitor. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1606-1608. doi:10.2106/JBJS.C.01720

7. Adeclat GJ, Hayes M, Amick M, Kahan J, Halim A. Acute forearm compartment syndrome in the setting of acquired hemophilia A. Case Reports Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2022;9:140-144. doi:10.1080/23320885.2022.2071274

8. Abudaqqa RY, Arun KP, Mas AJA, Abushaaban FA. Acute atraumatic compartment syndrome of the thigh due to acquired coagulopathy disorder: a case report in known healthy patient. J Orthop Case Rep. 2021;11:59-62. doi:10.13107/jocr.2021.v11.i08.2366

9. Alidoost M, Conte GA, Chaudry R, Nahum K, Marchesani D. A unique presentation of spontaneous compartment syndrome due to acquired hemophilia A and associated malignancy: case report and literature review. World J Oncol. 2020;11:72-75. doi:10.14740/wjon1260

10. Jentzsch T, Brand-Staufer B, Schäfer FP, Wanner GA, Simmen H-P. Illustrated operative management of spontaneous bleeding and compartment syndrome of the lower extremity in a patient with acquired hemophilia A: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:132. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-8-132

11. Pham TV, Sorenson CA, Nable JV. Acquired factor VIII deficiency presenting with compartment syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:195.e1-2. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.09.022

12. Tiede A, Zieger B, Lisman T. Acquired bleeding disorders. Haemophilia. 2022;28(suppl 4):68-76. doi:10.1111/hae.14548

13. Kruse-Jarres R, Kempton CL, Baudo F, Collins PW, Knoebl P, Leissinger CA, et al. Acquired hemophilia A: updated review of evidence and treatment guidance. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:695-705. doi:10.1002/ajh.24777

14. Ilkhchoui Y, Koshkin E, Windsor JJ, Petersen TR, Charles M, Pack JD. Perioperative management of acquired hemophilia A: a case report and review of literature. Anesth Pain Med. 2013;4:e11906. doi:10.5812/aapm.11906

Compartment syndrome occurs when the interstitial tissue pressures within a confined space are elevated to a level at which the arterial perfusion is diminished. Multiple etiologies exist and can be extrinsic (a cast that is too tight or prolonged compression on a limb), iatrogenic (aggressive resuscitation, drug infiltration, arterial puncture, or a spontaneous bleed from anticoagulation), and traumatic (fracture, snake envenomation, circumferential burn, or electrocution). If the compartments are not released, irreversible changes happen to the cells, including nerve and muscle death.1 Definitive management of this emergency requires prompt fasciotomy to decompress the compartment(s).1-3

Case Presentation

A 76-year-old right-handed woman with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia presented to the emergency department with 2 days of extensive right upper extremity ecchymosis and severe pain that was localized to her forearm (Figure 1). She was taking low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) for left subclavian stenosis and over-the-counter ginkgo biloba. Leading up to the presentation, the patient was able to perform routine household chores, including yard work, cleaning, and taking care of her cats. Wrist and elbow X-rays were negative for a fracture. An upper extremity ultrasound found no venous occlusion. A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of her arm and chest found diffuse edema around the right elbow and forearm without pulmonary or right upper extremity emboli, fractures, hematoma, abscess, or air in the tissues.

The plastic surgery service was consulted. The patient was found to have a very tense forearm and pain to passive digital extension. The 2-point discrimination and pulses were intact. The patient was diagnosed with compartment syndrome based on the examination alone and gave consent for an emergent forearm and hand fasciotomy. A carpal tunnel release and a standard S-shaped volar forearm fasciotomy release were performed, which provided immediate decompression (Figure 2). The rest of the hand and extremity were soft. Edematous, healthy flexor muscle belly was identified without a hematoma. Most of the forearm wound was left open because the skin could not be reapproximated. Oxidized regenerated cellulose (Surgicel) was placed around the wound edges and the muscle was covered with a nonadherent dressing. Hemoglobin on admission was 12.9 g/dL(reference range, 12 to 16 g/dL). Kidney function was within normal limits. The rest of the complete blood count was unremarkable. Postoperative hemoglobin was 8.6 g/dL. Over the next several days, the patient's skin edges and muscle bellies continued to slowly bleed, and her hemoglobin fell to 5.6 g/dL by postoperative Day 2. The bleeding was managed with topical oxidized regenerated cellulose, thrombin spray, a hemostatic dressing made with kaolin (QuikClot), and a transfusion of 2 units of packed red blood cells.

A hematology consultation was requested. The patient was noted to have an elevated partial thromboplastin time (PTT) since admission measuring between 39.9 to 61.7 seconds (reference range, 26.2 to 37.2 seconds) and a normal prothrombin time test with an international normalized ratio. A PTT measured 17 months prior to admission was within the normal range. She reported no personal or family history of bleeding disorders. Until recently, she had never had easy bruisability. She reported no history of heavy menses or epistaxis. The patient had no children and had never been pregnant. She had tolerated an exploratory laparotomy 40 years prior to admission without bleeding complications and had never required blood transfusions before. A PTT 1:1 mixing study revealed incomplete correction. Subsequent workup included factor VIII (FVIII) activity, factor IX activity, factor XI activity, von Willebrand factor antigen, ristocetin cofactor assay, and von Willebrand factor multimers. FVIII activity was severely reduced at 7.8% (reference, > 54%) with a positive Bethesda assay of 300 to 400 Bodansky units (BU), indicating a strong FVIII inhibitor was present and establishing a diagnosis of acquired hemophilia A. Further workup for secondary causes of acquired hemophilia A including abdominal and pelvic CT, serum protein electrophoresis, and serum free light chains, were negative. She was started on prednisone 1 mg/kg daily and rituximab 375 mg/m2. Her hemoglobin stabilized, and she required no further blood transfusions.

The patient underwent wound closure on postoperative Day 11. At the time of the second surgery, there was still no improvement in her FVIII levels or PTT; therefore, 70 mcg/kg of recombinant coagulation-activated FVII was given just before surgery with no bleeding complications. The skin was closed primarily except for the most distal 3 cm (Figure 3). Due to concerns regarding further bleeding with skin graft, the remaining wound was allowed to close by secondary intention. As a precaution, the wound was covered with oxidized regenerated cellulose and thrombin spray. The patient continued to progress postoperatively without bleeding complications or a need for additional transfusions. She was seen by the hand therapist before and after the second surgery to help with edema management and joint mobility. She completed 4 weekly doses of 375 mg/m² rituximab and prednisone was tapered by 10 mg weekly.

Three weeks after starting treatment, her PTT normalized, and her FVIII increased to 33.7%. The Bethesda assay remained high at 198 BU, although it was lower than at admission. She was discharged home with dressing changes and monthly follow-up appointments. The wounds were fully closed at her 3-month appointment when she proudly demonstrated full digital extension and flexion into her palm.

Discussion

Forearm compartment syndrome is most often caused by fractures—distal radius in adults and supracondylar in children.2 This case initially presented as a diagnostic puzzle to the emergency department due to the patient’s lucid review of several days of nontraumatic injury.

The clinical hallmarks of compartment syndrome are the 5 Ps: pain, pallor, paresthesia, paralysis, and pulselessness. Patients will describe the pain as out of proportion to the nature of the injury; the compartments will be tense and swollen, they will have pain to passive muscle stretch, and sensation will progressively diminish. Distal pulses are the last to go, and permanent tissue damage can still occur when pulses are present.1

Compartment Syndrome

Compartment syndrome is generally a clinical diagnosis; however, in patients who are sedated or uncooperative, or if the clinical findings are equivocal, the examination can be supplemented with intercompartmental pressures using an arterial line transducer system.2 In general, a tissue pressure of 30 mm Hg or a 20- to 30-mm Hg difference between the diastolic and compartment pressures are indications for fasciotomy.1 The hand is treated with an open carpal tunnel release, interosseous muscle release through 2 dorsal hand incisions, and thenar and hypothenar muscle release. The forearm is treated through a curved volar incision that usually decompresses the dorsal compartment, as it did in our patient. If pressures are still high in the forearm, a longitudinal dorsal incision over the mobile wad is necessary. Wounds can be closed primarily days later, left open to close by secondary intention, or reconstructed with skin grafts.2 In our patient, compartment syndrome was isolated to her forearm and the carpal tunnel release was performed prophylactically since it did not add significant time or morbidity to the surgery.

Nontraumatic upper extremity compartment syndrome is rare. A 2021 review of acute nontraumatic upper extremity compartment syndrome found a bleeding disorder as the etiology in 3 cases published in the literature between 1993 and 2016.4 One of these cases was secondary to a known diagnosis of hemophilia A in a teenager.5 Ogrodnik and colleagues described a spontaneous hand hematoma secondary to previously undiagnosed acquired hemophilia A and Waldenström macroglobulinemia.4 Ilyas and colleagues described a spontaneous hematoma in the forearm dorsal compartment in a 67-year-old woman, which presented as compartment syndrome and elevated PTT and led to a diagnosis of acquired FVIII inhibitor. The authors recommended prompt hematology consultation to coordinate treatment once this diagnosis issuspected.6 Compartment syndrome also has been found to develop slowly over weeks in patients with acquired FVIII deficiency, suggesting a high index of suspicion and frequent examinations are needed when patients with known acquired hemophilia A present with a painful extremity.7

Nontraumatic compartment syndrome in the lower extremity in patients with previously undiagnosed acquired hemophilia A has also been described in the literature.8-11 Case reports describe the delay in diagnosis as the patients were originally seen by clinicians for lower extremity pain and swelling within days of presenting to the emergency room with compartment syndrome. Persistent bleeding and abnormal laboratory results prompted further tests and examinations.8,9,11 This underscores the need to be suspicious of this unusual pathology without a history of trauma.

Acquired Hemophilia A

Acquired hemophilia A is an autoimmune disease most often found in older individuals, with a mean age of approximately 70 years.12 It is caused by the spontaneous production of neutralizing immunoglobin autoantibodies that target endogenous FVIII. Many cases are idiopathic; however, up to 50% of cases are associated with underlying autoimmunity, malignancy (especially lymphoproliferative disorders), or pregnancy. It often presents as bleeding that is subcutaneous or in the gastrointestinal system, muscle, retroperitoneal space, or genitourinary system. Unlike congenital hemophilia A, joint bleeding is rare.13

The diagnosis is suspected with an isolated elevated PTT in the absence of other coagulation abnormalities. A 1:1 mixing study will typically show incomplete correction, which suggests the presence of an inhibitor. FVIII activity is reduced, and the FVIII inhibitor is confirmed with the Bethesda assay. Clinically active bleeding is treated with bypassing agents such as recombinant coagulation-activated FVII, activated prothrombin complex concentrates such as anti-inhibitor coagulant complex (FEIBA), or recombinant porcine FVIII.12,14 Not all patients require hemostatic treatment, but close monitoring, education, recognition, and immediate treatment, if needed, are indicated.13 Immunosuppressive therapy (corticosteroids, rituximab, and/or cyclophosphamide) is prescribed to eradicate the antibodies and induce remission.12

Conclusions

An older woman without a preceding trauma was diagnosed with an unusual case of acute compartment syndrome in the forearm. No hematoma was found, but muscle and skin bleeding plus an elevated PTT prompted a hematology workup, and, ultimately, the diagnosis of FVIII inhibitor secondary to acquired hemophilia A.

While a nontraumatic cause of compartment syndrome is rare, it should be considered in differential diagnosis for clinicians who see hand and upper extremity emergencies. An isolated elevated PTT in a patient with a bleed should raise suspicions and trigger immediate further evaluation. Once suspected, multidisciplinary treatment is indicated for immediate and long-term successful outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is the result of work supported withresources and the use of facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Gainesville, Florida.

Compartment syndrome occurs when the interstitial tissue pressures within a confined space are elevated to a level at which the arterial perfusion is diminished. Multiple etiologies exist and can be extrinsic (a cast that is too tight or prolonged compression on a limb), iatrogenic (aggressive resuscitation, drug infiltration, arterial puncture, or a spontaneous bleed from anticoagulation), and traumatic (fracture, snake envenomation, circumferential burn, or electrocution). If the compartments are not released, irreversible changes happen to the cells, including nerve and muscle death.1 Definitive management of this emergency requires prompt fasciotomy to decompress the compartment(s).1-3

Case Presentation

A 76-year-old right-handed woman with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia presented to the emergency department with 2 days of extensive right upper extremity ecchymosis and severe pain that was localized to her forearm (Figure 1). She was taking low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) for left subclavian stenosis and over-the-counter ginkgo biloba. Leading up to the presentation, the patient was able to perform routine household chores, including yard work, cleaning, and taking care of her cats. Wrist and elbow X-rays were negative for a fracture. An upper extremity ultrasound found no venous occlusion. A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of her arm and chest found diffuse edema around the right elbow and forearm without pulmonary or right upper extremity emboli, fractures, hematoma, abscess, or air in the tissues.

The plastic surgery service was consulted. The patient was found to have a very tense forearm and pain to passive digital extension. The 2-point discrimination and pulses were intact. The patient was diagnosed with compartment syndrome based on the examination alone and gave consent for an emergent forearm and hand fasciotomy. A carpal tunnel release and a standard S-shaped volar forearm fasciotomy release were performed, which provided immediate decompression (Figure 2). The rest of the hand and extremity were soft. Edematous, healthy flexor muscle belly was identified without a hematoma. Most of the forearm wound was left open because the skin could not be reapproximated. Oxidized regenerated cellulose (Surgicel) was placed around the wound edges and the muscle was covered with a nonadherent dressing. Hemoglobin on admission was 12.9 g/dL(reference range, 12 to 16 g/dL). Kidney function was within normal limits. The rest of the complete blood count was unremarkable. Postoperative hemoglobin was 8.6 g/dL. Over the next several days, the patient's skin edges and muscle bellies continued to slowly bleed, and her hemoglobin fell to 5.6 g/dL by postoperative Day 2. The bleeding was managed with topical oxidized regenerated cellulose, thrombin spray, a hemostatic dressing made with kaolin (QuikClot), and a transfusion of 2 units of packed red blood cells.

A hematology consultation was requested. The patient was noted to have an elevated partial thromboplastin time (PTT) since admission measuring between 39.9 to 61.7 seconds (reference range, 26.2 to 37.2 seconds) and a normal prothrombin time test with an international normalized ratio. A PTT measured 17 months prior to admission was within the normal range. She reported no personal or family history of bleeding disorders. Until recently, she had never had easy bruisability. She reported no history of heavy menses or epistaxis. The patient had no children and had never been pregnant. She had tolerated an exploratory laparotomy 40 years prior to admission without bleeding complications and had never required blood transfusions before. A PTT 1:1 mixing study revealed incomplete correction. Subsequent workup included factor VIII (FVIII) activity, factor IX activity, factor XI activity, von Willebrand factor antigen, ristocetin cofactor assay, and von Willebrand factor multimers. FVIII activity was severely reduced at 7.8% (reference, > 54%) with a positive Bethesda assay of 300 to 400 Bodansky units (BU), indicating a strong FVIII inhibitor was present and establishing a diagnosis of acquired hemophilia A. Further workup for secondary causes of acquired hemophilia A including abdominal and pelvic CT, serum protein electrophoresis, and serum free light chains, were negative. She was started on prednisone 1 mg/kg daily and rituximab 375 mg/m2. Her hemoglobin stabilized, and she required no further blood transfusions.

The patient underwent wound closure on postoperative Day 11. At the time of the second surgery, there was still no improvement in her FVIII levels or PTT; therefore, 70 mcg/kg of recombinant coagulation-activated FVII was given just before surgery with no bleeding complications. The skin was closed primarily except for the most distal 3 cm (Figure 3). Due to concerns regarding further bleeding with skin graft, the remaining wound was allowed to close by secondary intention. As a precaution, the wound was covered with oxidized regenerated cellulose and thrombin spray. The patient continued to progress postoperatively without bleeding complications or a need for additional transfusions. She was seen by the hand therapist before and after the second surgery to help with edema management and joint mobility. She completed 4 weekly doses of 375 mg/m² rituximab and prednisone was tapered by 10 mg weekly.

Three weeks after starting treatment, her PTT normalized, and her FVIII increased to 33.7%. The Bethesda assay remained high at 198 BU, although it was lower than at admission. She was discharged home with dressing changes and monthly follow-up appointments. The wounds were fully closed at her 3-month appointment when she proudly demonstrated full digital extension and flexion into her palm.

Discussion

Forearm compartment syndrome is most often caused by fractures—distal radius in adults and supracondylar in children.2 This case initially presented as a diagnostic puzzle to the emergency department due to the patient’s lucid review of several days of nontraumatic injury.

The clinical hallmarks of compartment syndrome are the 5 Ps: pain, pallor, paresthesia, paralysis, and pulselessness. Patients will describe the pain as out of proportion to the nature of the injury; the compartments will be tense and swollen, they will have pain to passive muscle stretch, and sensation will progressively diminish. Distal pulses are the last to go, and permanent tissue damage can still occur when pulses are present.1

Compartment Syndrome

Compartment syndrome is generally a clinical diagnosis; however, in patients who are sedated or uncooperative, or if the clinical findings are equivocal, the examination can be supplemented with intercompartmental pressures using an arterial line transducer system.2 In general, a tissue pressure of 30 mm Hg or a 20- to 30-mm Hg difference between the diastolic and compartment pressures are indications for fasciotomy.1 The hand is treated with an open carpal tunnel release, interosseous muscle release through 2 dorsal hand incisions, and thenar and hypothenar muscle release. The forearm is treated through a curved volar incision that usually decompresses the dorsal compartment, as it did in our patient. If pressures are still high in the forearm, a longitudinal dorsal incision over the mobile wad is necessary. Wounds can be closed primarily days later, left open to close by secondary intention, or reconstructed with skin grafts.2 In our patient, compartment syndrome was isolated to her forearm and the carpal tunnel release was performed prophylactically since it did not add significant time or morbidity to the surgery.

Nontraumatic upper extremity compartment syndrome is rare. A 2021 review of acute nontraumatic upper extremity compartment syndrome found a bleeding disorder as the etiology in 3 cases published in the literature between 1993 and 2016.4 One of these cases was secondary to a known diagnosis of hemophilia A in a teenager.5 Ogrodnik and colleagues described a spontaneous hand hematoma secondary to previously undiagnosed acquired hemophilia A and Waldenström macroglobulinemia.4 Ilyas and colleagues described a spontaneous hematoma in the forearm dorsal compartment in a 67-year-old woman, which presented as compartment syndrome and elevated PTT and led to a diagnosis of acquired FVIII inhibitor. The authors recommended prompt hematology consultation to coordinate treatment once this diagnosis issuspected.6 Compartment syndrome also has been found to develop slowly over weeks in patients with acquired FVIII deficiency, suggesting a high index of suspicion and frequent examinations are needed when patients with known acquired hemophilia A present with a painful extremity.7

Nontraumatic compartment syndrome in the lower extremity in patients with previously undiagnosed acquired hemophilia A has also been described in the literature.8-11 Case reports describe the delay in diagnosis as the patients were originally seen by clinicians for lower extremity pain and swelling within days of presenting to the emergency room with compartment syndrome. Persistent bleeding and abnormal laboratory results prompted further tests and examinations.8,9,11 This underscores the need to be suspicious of this unusual pathology without a history of trauma.

Acquired Hemophilia A

Acquired hemophilia A is an autoimmune disease most often found in older individuals, with a mean age of approximately 70 years.12 It is caused by the spontaneous production of neutralizing immunoglobin autoantibodies that target endogenous FVIII. Many cases are idiopathic; however, up to 50% of cases are associated with underlying autoimmunity, malignancy (especially lymphoproliferative disorders), or pregnancy. It often presents as bleeding that is subcutaneous or in the gastrointestinal system, muscle, retroperitoneal space, or genitourinary system. Unlike congenital hemophilia A, joint bleeding is rare.13

The diagnosis is suspected with an isolated elevated PTT in the absence of other coagulation abnormalities. A 1:1 mixing study will typically show incomplete correction, which suggests the presence of an inhibitor. FVIII activity is reduced, and the FVIII inhibitor is confirmed with the Bethesda assay. Clinically active bleeding is treated with bypassing agents such as recombinant coagulation-activated FVII, activated prothrombin complex concentrates such as anti-inhibitor coagulant complex (FEIBA), or recombinant porcine FVIII.12,14 Not all patients require hemostatic treatment, but close monitoring, education, recognition, and immediate treatment, if needed, are indicated.13 Immunosuppressive therapy (corticosteroids, rituximab, and/or cyclophosphamide) is prescribed to eradicate the antibodies and induce remission.12

Conclusions

An older woman without a preceding trauma was diagnosed with an unusual case of acute compartment syndrome in the forearm. No hematoma was found, but muscle and skin bleeding plus an elevated PTT prompted a hematology workup, and, ultimately, the diagnosis of FVIII inhibitor secondary to acquired hemophilia A.

While a nontraumatic cause of compartment syndrome is rare, it should be considered in differential diagnosis for clinicians who see hand and upper extremity emergencies. An isolated elevated PTT in a patient with a bleed should raise suspicions and trigger immediate further evaluation. Once suspected, multidisciplinary treatment is indicated for immediate and long-term successful outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is the result of work supported withresources and the use of facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Gainesville, Florida.

1. Leversedge FJ, Moore TJ, Peterson BC, Seiler JG 3rd. Compartment syndrome of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:544-559. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.12.008

2. Kalyani BS, Fisher BE, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Compartment syndrome of the forearm: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:535-543. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.12.007

3. Steadman W, Wu R, Hamilton AT, Richardson MD, Wall CJ. Review article: a comprehensive review of unusual causes of acute limb compartment syndrome. Emerg Med Australas. 2022;34:871-876. doi:10.1111/1742-6723.14098

4. Ogrodnik J, Oliver JD, Cani D, Boczar D, Huayllani MT, Restrepo DJ, et al. Clinical case of acute non-traumatic hand compartment syndrome and systematic review for the upper extremity. Hand (N Y). 2021;16:285-291. doi:10.1177/1558944719856106

5. Kim J, Zelken J, Sacks JM. Case report. Spontaneous forearm compartment syndrome in a boy with hemophilia a: a therapeutic dilemma. Eplasty. 2013:13:e16.

6. Ilyas AM, Wisbeck JM, Shaffer GW, Thoder JJ. Upper extremity compartment syndrome secondary to acquired factor VIII inhibitor. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1606-1608. doi:10.2106/JBJS.C.01720

7. Adeclat GJ, Hayes M, Amick M, Kahan J, Halim A. Acute forearm compartment syndrome in the setting of acquired hemophilia A. Case Reports Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2022;9:140-144. doi:10.1080/23320885.2022.2071274

8. Abudaqqa RY, Arun KP, Mas AJA, Abushaaban FA. Acute atraumatic compartment syndrome of the thigh due to acquired coagulopathy disorder: a case report in known healthy patient. J Orthop Case Rep. 2021;11:59-62. doi:10.13107/jocr.2021.v11.i08.2366

9. Alidoost M, Conte GA, Chaudry R, Nahum K, Marchesani D. A unique presentation of spontaneous compartment syndrome due to acquired hemophilia A and associated malignancy: case report and literature review. World J Oncol. 2020;11:72-75. doi:10.14740/wjon1260

10. Jentzsch T, Brand-Staufer B, Schäfer FP, Wanner GA, Simmen H-P. Illustrated operative management of spontaneous bleeding and compartment syndrome of the lower extremity in a patient with acquired hemophilia A: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:132. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-8-132

11. Pham TV, Sorenson CA, Nable JV. Acquired factor VIII deficiency presenting with compartment syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:195.e1-2. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.09.022

12. Tiede A, Zieger B, Lisman T. Acquired bleeding disorders. Haemophilia. 2022;28(suppl 4):68-76. doi:10.1111/hae.14548

13. Kruse-Jarres R, Kempton CL, Baudo F, Collins PW, Knoebl P, Leissinger CA, et al. Acquired hemophilia A: updated review of evidence and treatment guidance. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:695-705. doi:10.1002/ajh.24777

14. Ilkhchoui Y, Koshkin E, Windsor JJ, Petersen TR, Charles M, Pack JD. Perioperative management of acquired hemophilia A: a case report and review of literature. Anesth Pain Med. 2013;4:e11906. doi:10.5812/aapm.11906

1. Leversedge FJ, Moore TJ, Peterson BC, Seiler JG 3rd. Compartment syndrome of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:544-559. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.12.008

2. Kalyani BS, Fisher BE, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Compartment syndrome of the forearm: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:535-543. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.12.007

3. Steadman W, Wu R, Hamilton AT, Richardson MD, Wall CJ. Review article: a comprehensive review of unusual causes of acute limb compartment syndrome. Emerg Med Australas. 2022;34:871-876. doi:10.1111/1742-6723.14098

4. Ogrodnik J, Oliver JD, Cani D, Boczar D, Huayllani MT, Restrepo DJ, et al. Clinical case of acute non-traumatic hand compartment syndrome and systematic review for the upper extremity. Hand (N Y). 2021;16:285-291. doi:10.1177/1558944719856106

5. Kim J, Zelken J, Sacks JM. Case report. Spontaneous forearm compartment syndrome in a boy with hemophilia a: a therapeutic dilemma. Eplasty. 2013:13:e16.

6. Ilyas AM, Wisbeck JM, Shaffer GW, Thoder JJ. Upper extremity compartment syndrome secondary to acquired factor VIII inhibitor. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1606-1608. doi:10.2106/JBJS.C.01720

7. Adeclat GJ, Hayes M, Amick M, Kahan J, Halim A. Acute forearm compartment syndrome in the setting of acquired hemophilia A. Case Reports Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2022;9:140-144. doi:10.1080/23320885.2022.2071274

8. Abudaqqa RY, Arun KP, Mas AJA, Abushaaban FA. Acute atraumatic compartment syndrome of the thigh due to acquired coagulopathy disorder: a case report in known healthy patient. J Orthop Case Rep. 2021;11:59-62. doi:10.13107/jocr.2021.v11.i08.2366

9. Alidoost M, Conte GA, Chaudry R, Nahum K, Marchesani D. A unique presentation of spontaneous compartment syndrome due to acquired hemophilia A and associated malignancy: case report and literature review. World J Oncol. 2020;11:72-75. doi:10.14740/wjon1260

10. Jentzsch T, Brand-Staufer B, Schäfer FP, Wanner GA, Simmen H-P. Illustrated operative management of spontaneous bleeding and compartment syndrome of the lower extremity in a patient with acquired hemophilia A: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:132. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-8-132

11. Pham TV, Sorenson CA, Nable JV. Acquired factor VIII deficiency presenting with compartment syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:195.e1-2. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.09.022

12. Tiede A, Zieger B, Lisman T. Acquired bleeding disorders. Haemophilia. 2022;28(suppl 4):68-76. doi:10.1111/hae.14548

13. Kruse-Jarres R, Kempton CL, Baudo F, Collins PW, Knoebl P, Leissinger CA, et al. Acquired hemophilia A: updated review of evidence and treatment guidance. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:695-705. doi:10.1002/ajh.24777

14. Ilkhchoui Y, Koshkin E, Windsor JJ, Petersen TR, Charles M, Pack JD. Perioperative management of acquired hemophilia A: a case report and review of literature. Anesth Pain Med. 2013;4:e11906. doi:10.5812/aapm.11906

Prognostication in Hospice Care: Challenges, Opportunities, and the Importance of Functional Status

Predicting life expectancy and providing an end-of-life diagnosis in hospice and palliative care is a challenge for most clinicians. Lack of training, limited communication skills, and relationships with patients are all contributing factors. These skills can improve with the use of functional scoring tools in conjunction with the patient’s comorbidities and physical/psychological symptoms. The Palliative Performance Scale (PPS), Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS), and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Scale (ECOG) are commonly used functional scoring tools.

The PPS measures 5 functional dimensions including ambulation, activity level, ability to administer self-care, oral intake, and level of consciousness.1 It has been shown to be valid for a broad range of palliative care patients, including those with advanced cancer or life-threatening noncancer diagnoses in hospitals or hospice care.2 The scale, measured in 10% increments, runs from 100% (completely functional) to 0% (dead). A PPS ≤ 70% helps meet hospice eligibility criteria.

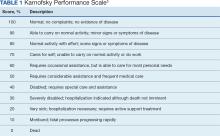

The KPS evaluates functional impairment and helps with prognostication. Developed in 1948, it evaluates a patient’s functional ability to tolerate chemotherapy, specifically in lung cancer, and has since been validated to predict mortality across older adults and in chronic disease populations.3,4 The KPS is also measured in 10% increments ranging from 100% (completely functional without assistance) to 0% (dead). A KPS ≤ 70% assists with hospice eligibility criteria (Table 1).5

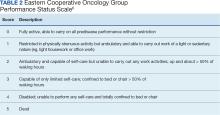

Developed in 1974, the ECOG has been identified as one of the most important functional status tools in adult cancer care.6 It describes a cancer patient’s functional ability, evaluating their ability to care for oneself and participate in daily activities.7 The ECOG is a 6-point scale; patients can receive scores ranging from 0 (fully active) to 5 (dead). An ECOG score of 4 (sometimes 3) is generally supportive of meeting hospice eligibility (Table 2).6

CASE Presentation

An 80-year-old patient was admitted to the hospice service at the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) community living center (CLC) in Tacoma, Washington, from a community-based acute care hospital. His medical history included prostate cancer with metastasis to his pelvis and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which was stable with treatment with oral medication. Six weeks earlier the patient reported a severe frontal headache that was not responding to over-the-counter analgesics. After 2 days with these symptoms, including a ground-level fall without injuries, he presented to the VAPSHCS emergency department (ED) where a complete neurological examination, including magnetic resonance imaging, revealed a left frontoparietal brain lesion that was 4.2 cm × 3.4 cm × 4.2 cm.

The patient experienced a seizure during his ED evaluation and was admitted for treatment. He underwent a craniotomy where most, but not all the lesions were successfully removed. Postoperatively, the patient exhibited right-sided neglect, gait instability, emotional lability, and cognitive communication disorder. The patient completed 15 of 20 planned radiation treatments but declined further radiation or chemotherapy. The patient decided to halt radiation treatments after being informed by the oncology service that the treatments would likely only add 1 to 2 months to his overall survival, which was < 6 months. The patient elected to focus his goals of care on comfort, dignity, and respect at the end of life and accepted recommendations to be placed into end-of-life hospice care. He was then transferred to the VAPSHCS CLC in Tacoma, Washington, for hospice care.

Upon admission, the patient weighed 94 kg, his vital signs were within reference range, and he reported no pain or headaches. His initial laboratory results revealed a 13.2 g/dL hemoglobin, 3.6 g/dL serum albumin, and a 5.5% hemoglobin A1c, all of which fall into a normal reference range. He had a reported ECOG score of 3 and a KPS score of 50% by the transferring medical team. The patient’s medications included scheduled dexamethasone, metformin, senna, levetiracetam, and as-needed midazolam nasal spray for breakthrough seizures. He also had as-needed acetaminophen for pain. He was alert, oriented ×3, and fully ambulatory but continuously used a 4-wheeled walker for safety and gait instability.

After the patient’s first night, the hospice team met with him to discuss his understanding of his health issues. The patient appeared to have low health literacy but told the team, “I know I am dying.” He had completed written advance directives and a Portable Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment indicating that life-sustaining treatments, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation, supplemental mechanical feeding, or intubation, were not to be used to keep him alive.

At his first 90-day recertification, the patient had gained 8 kg and laboratory results revealed a 14.6 g/dL hemoglobin, 3.8 g/dL serum albumin, and a 6.1% hemoglobin A1c. His ECOG score remained at 3, but his KPS score had increased to 60%. The patient exhibited no new neurologic symptoms or seizures and reported no headaches but had 2 ground-level falls without injury. On both occasions the patient chose not to use his walker to go to the bathroom because it was “too far from my bed.” Per VA policy, after discussions with the hospice team, he was recertified for 90 more days of hospice care. At the end of 6 months in CLC, the patient’s weight remained stable, as did his complete blood count and comprehensive medical panel. He had 1 additional noninjurious ground-level fall and again reported no pain and no use of as-needed acetaminophen. His only medical complication was testing positive for COVID-19, but he remained asymptomatic. The patient was graduated from hospice care and referred to a nearby non-VA adult family home in the community after 180 days. At that time his ECOG score was 2 and his KPS score had increased to 70%.

DISCUSSION

Primary brain tumors account for about 2% of all malignant neoplasms in adults. About half of them represent gliomas. Glioblastoma multiforme derived from neuroepithelial cells is the most frequent and deadly primary malignant central nervous system tumor in adults.8 About 50% of patients with glioblastomas are aged ≥ 65 years at diagnosis.9 A retrospective study of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services claims data paired with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database indicated a median survival of 4 months for patients with glioblastoma multiforme aged > 65 years, including all treatment modalities.10 Surgical resection combined with radiation and chemotherapy offers the best prognosis for the preservation of neurologic function.11 However, comorbidities, adverse drug effects, and the potential for postoperative complications pose significant risks, especially for older patients. Ultimately, goals of care conversations and advance directives play a very important role in evaluating benefits vs risks with this malignancy.

Our patient was aged 80 years and had previously been diagnosed with metastatic prostate malignancy. His goals of care focused on spending time with his friends, leaving his room to eat in the facility dining area, and continuing his daily walks. He remained clear that he did not want his care team to institute life-sustaining treatments to be kept alive and felt the information regarding the risks vs benefits of accepting chemotherapy was not aligned with his goals of care. Over the 6 months that he received hospice care, he gained weight, improved his hemoglobin and serum albumin levels, and ambulated with the use of a 4-wheeled walker. As the patient exhibited no functional decline or new comorbidities and his functional status improved, the clinical staff felt he no longer needed hospice services. The patient had an ECOG score of 2 and a KPS score of 70% at his hospice graduation.

Medical prognostication is one of the biggest challenges clinicians face. Clinicians are generally “over prognosticators,” and their thoughts tend to be based on the patient relationship, overall experiences in health care, and desire to treat and cure patients.12 In hospice we are asked to define the usual, normal, or expected course of a disease, but what does that mean? Although metastatic malignancies usually have a predictable course in comparison to diagnoses such as dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or congestive heart failure, the challenges to improve prognostic ability andpredict disease course continue.13-15 Focusing on functional status, goals of care, and comorbidities are keys to helping with prognosis. Given the challenge, we find the PPS, KPS, and ECOG scales important tools.

When prognosticating, we attempt to define quantity and quality of life (which our patients must define independently or from the voice of their surrogate) and their ability to perform daily activities. Quality of life in patients with glioblastoma is progressively and significantly impacted due to the emergence of debilitating neurologic symptoms arising from infiltrative tumor growth into functionally intact brain tissue that restricts and disrupts normal day-to-day activities. However, functional status plays a significant role in helping the hospice team improve its overall prognosis.

Conclusions

This case study illustrates the difficulty that comes with prognostication(s) despite a patient's severely morbid disease, history of metastatic prostate cancer, and advanced age. Although a diagnosis may be concerning, documenting a patient’s status using functional scales prior to hospice admission and during the recertification process is helpful in prognostication. Doing so will allow health care professionals to have an accepted medical standard to use regardless how distinct the patient's diagnosis. The expression, “as the disease does not read the textbook,” may serve as a helpful reminder in talking with patients and their families. This is important as most patient’s clinical disease courses are different and having the opportunity to use performance status scales may help improve prognostic skills.

1. Cleary TA. The Palliative Performance Scale (PPSv2) Version 2. In: Downing GM, ed. Medical Care of the Dying. 4th ed. Victoria Hospice Society, Learning Centre for Palliative Care; 2006:120.

2. Palliative Performance Scale. ePrognosis, University of California San Francisco. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://eprognosis.ucsf.edu/pps.php

3. Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The Clinical Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents in Cancer. In: MacLeod CM, ed. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Columbia University Press; 1949:191-205.

4. Khalid MA, Achakzai IK, Ahmed Khan S, et al. The use of Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) as a predictor of 3 month post discharge mortality in cirrhotic patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2018;11(4):301-305.

5. Karnofsky Performance Scale. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.hiv.va.gov/provider/tools/karnofsky-performance-scale.asp

6. Mischel A-M, Rosielle DA. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. December 10, 2021. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/eastern-cooperative-oncology-group-performance-status/

7. Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649-655.

8. Nizamutdinov D, Stock EM, Dandashi JA, et al. Prognostication of survival outcomes in patients diagnosed with glioblastoma. World Neurosurg. 2018;109:e67-e74. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.104

9. Kita D Ciernik IFVaccarella S Age as a predictive factor in glioblastomas: population-based study. Neuroepidemiology. 2009;33(1):17-22. doi:10.1159/000210017

10. Jordan JT, Gerstner ER, Batchelor TT, Cahill DP, Plotkin SR. Glioblastoma care in the elderly. Cancer. 2016;122(2):189-197. doi:10.1002/cnr.29742

11. Brown, NF, Ottaviani D, Tazare J, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(13):3161. doi:10.3390/cancers14133161

12. Christalakis NA. Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care. University of Chicago Press; 2000.

13. Weissman DE. Determining Prognosis in Advanced Cancer. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. January 28, 2019. Accessed June 14, 2014. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/determining-prognosis-in-advanced-cancer/

14. Childers JW, Arnold R, Curtis JR. Prognosis in End-Stage COPD. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. February 11, 2019. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/prognosis-in-end-stage-copd/

15. Reisfield GM, Wilson GR. Prognostication in Heart Failure. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. February 11, 2019. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/prognostication-in-heart-failure/

Predicting life expectancy and providing an end-of-life diagnosis in hospice and palliative care is a challenge for most clinicians. Lack of training, limited communication skills, and relationships with patients are all contributing factors. These skills can improve with the use of functional scoring tools in conjunction with the patient’s comorbidities and physical/psychological symptoms. The Palliative Performance Scale (PPS), Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS), and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Scale (ECOG) are commonly used functional scoring tools.

The PPS measures 5 functional dimensions including ambulation, activity level, ability to administer self-care, oral intake, and level of consciousness.1 It has been shown to be valid for a broad range of palliative care patients, including those with advanced cancer or life-threatening noncancer diagnoses in hospitals or hospice care.2 The scale, measured in 10% increments, runs from 100% (completely functional) to 0% (dead). A PPS ≤ 70% helps meet hospice eligibility criteria.

The KPS evaluates functional impairment and helps with prognostication. Developed in 1948, it evaluates a patient’s functional ability to tolerate chemotherapy, specifically in lung cancer, and has since been validated to predict mortality across older adults and in chronic disease populations.3,4 The KPS is also measured in 10% increments ranging from 100% (completely functional without assistance) to 0% (dead). A KPS ≤ 70% assists with hospice eligibility criteria (Table 1).5

Developed in 1974, the ECOG has been identified as one of the most important functional status tools in adult cancer care.6 It describes a cancer patient’s functional ability, evaluating their ability to care for oneself and participate in daily activities.7 The ECOG is a 6-point scale; patients can receive scores ranging from 0 (fully active) to 5 (dead). An ECOG score of 4 (sometimes 3) is generally supportive of meeting hospice eligibility (Table 2).6

CASE Presentation

An 80-year-old patient was admitted to the hospice service at the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) community living center (CLC) in Tacoma, Washington, from a community-based acute care hospital. His medical history included prostate cancer with metastasis to his pelvis and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which was stable with treatment with oral medication. Six weeks earlier the patient reported a severe frontal headache that was not responding to over-the-counter analgesics. After 2 days with these symptoms, including a ground-level fall without injuries, he presented to the VAPSHCS emergency department (ED) where a complete neurological examination, including magnetic resonance imaging, revealed a left frontoparietal brain lesion that was 4.2 cm × 3.4 cm × 4.2 cm.

The patient experienced a seizure during his ED evaluation and was admitted for treatment. He underwent a craniotomy where most, but not all the lesions were successfully removed. Postoperatively, the patient exhibited right-sided neglect, gait instability, emotional lability, and cognitive communication disorder. The patient completed 15 of 20 planned radiation treatments but declined further radiation or chemotherapy. The patient decided to halt radiation treatments after being informed by the oncology service that the treatments would likely only add 1 to 2 months to his overall survival, which was < 6 months. The patient elected to focus his goals of care on comfort, dignity, and respect at the end of life and accepted recommendations to be placed into end-of-life hospice care. He was then transferred to the VAPSHCS CLC in Tacoma, Washington, for hospice care.

Upon admission, the patient weighed 94 kg, his vital signs were within reference range, and he reported no pain or headaches. His initial laboratory results revealed a 13.2 g/dL hemoglobin, 3.6 g/dL serum albumin, and a 5.5% hemoglobin A1c, all of which fall into a normal reference range. He had a reported ECOG score of 3 and a KPS score of 50% by the transferring medical team. The patient’s medications included scheduled dexamethasone, metformin, senna, levetiracetam, and as-needed midazolam nasal spray for breakthrough seizures. He also had as-needed acetaminophen for pain. He was alert, oriented ×3, and fully ambulatory but continuously used a 4-wheeled walker for safety and gait instability.

After the patient’s first night, the hospice team met with him to discuss his understanding of his health issues. The patient appeared to have low health literacy but told the team, “I know I am dying.” He had completed written advance directives and a Portable Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment indicating that life-sustaining treatments, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation, supplemental mechanical feeding, or intubation, were not to be used to keep him alive.

At his first 90-day recertification, the patient had gained 8 kg and laboratory results revealed a 14.6 g/dL hemoglobin, 3.8 g/dL serum albumin, and a 6.1% hemoglobin A1c. His ECOG score remained at 3, but his KPS score had increased to 60%. The patient exhibited no new neurologic symptoms or seizures and reported no headaches but had 2 ground-level falls without injury. On both occasions the patient chose not to use his walker to go to the bathroom because it was “too far from my bed.” Per VA policy, after discussions with the hospice team, he was recertified for 90 more days of hospice care. At the end of 6 months in CLC, the patient’s weight remained stable, as did his complete blood count and comprehensive medical panel. He had 1 additional noninjurious ground-level fall and again reported no pain and no use of as-needed acetaminophen. His only medical complication was testing positive for COVID-19, but he remained asymptomatic. The patient was graduated from hospice care and referred to a nearby non-VA adult family home in the community after 180 days. At that time his ECOG score was 2 and his KPS score had increased to 70%.

DISCUSSION

Primary brain tumors account for about 2% of all malignant neoplasms in adults. About half of them represent gliomas. Glioblastoma multiforme derived from neuroepithelial cells is the most frequent and deadly primary malignant central nervous system tumor in adults.8 About 50% of patients with glioblastomas are aged ≥ 65 years at diagnosis.9 A retrospective study of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services claims data paired with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database indicated a median survival of 4 months for patients with glioblastoma multiforme aged > 65 years, including all treatment modalities.10 Surgical resection combined with radiation and chemotherapy offers the best prognosis for the preservation of neurologic function.11 However, comorbidities, adverse drug effects, and the potential for postoperative complications pose significant risks, especially for older patients. Ultimately, goals of care conversations and advance directives play a very important role in evaluating benefits vs risks with this malignancy.

Our patient was aged 80 years and had previously been diagnosed with metastatic prostate malignancy. His goals of care focused on spending time with his friends, leaving his room to eat in the facility dining area, and continuing his daily walks. He remained clear that he did not want his care team to institute life-sustaining treatments to be kept alive and felt the information regarding the risks vs benefits of accepting chemotherapy was not aligned with his goals of care. Over the 6 months that he received hospice care, he gained weight, improved his hemoglobin and serum albumin levels, and ambulated with the use of a 4-wheeled walker. As the patient exhibited no functional decline or new comorbidities and his functional status improved, the clinical staff felt he no longer needed hospice services. The patient had an ECOG score of 2 and a KPS score of 70% at his hospice graduation.

Medical prognostication is one of the biggest challenges clinicians face. Clinicians are generally “over prognosticators,” and their thoughts tend to be based on the patient relationship, overall experiences in health care, and desire to treat and cure patients.12 In hospice we are asked to define the usual, normal, or expected course of a disease, but what does that mean? Although metastatic malignancies usually have a predictable course in comparison to diagnoses such as dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or congestive heart failure, the challenges to improve prognostic ability andpredict disease course continue.13-15 Focusing on functional status, goals of care, and comorbidities are keys to helping with prognosis. Given the challenge, we find the PPS, KPS, and ECOG scales important tools.

When prognosticating, we attempt to define quantity and quality of life (which our patients must define independently or from the voice of their surrogate) and their ability to perform daily activities. Quality of life in patients with glioblastoma is progressively and significantly impacted due to the emergence of debilitating neurologic symptoms arising from infiltrative tumor growth into functionally intact brain tissue that restricts and disrupts normal day-to-day activities. However, functional status plays a significant role in helping the hospice team improve its overall prognosis.

Conclusions

This case study illustrates the difficulty that comes with prognostication(s) despite a patient's severely morbid disease, history of metastatic prostate cancer, and advanced age. Although a diagnosis may be concerning, documenting a patient’s status using functional scales prior to hospice admission and during the recertification process is helpful in prognostication. Doing so will allow health care professionals to have an accepted medical standard to use regardless how distinct the patient's diagnosis. The expression, “as the disease does not read the textbook,” may serve as a helpful reminder in talking with patients and their families. This is important as most patient’s clinical disease courses are different and having the opportunity to use performance status scales may help improve prognostic skills.

Predicting life expectancy and providing an end-of-life diagnosis in hospice and palliative care is a challenge for most clinicians. Lack of training, limited communication skills, and relationships with patients are all contributing factors. These skills can improve with the use of functional scoring tools in conjunction with the patient’s comorbidities and physical/psychological symptoms. The Palliative Performance Scale (PPS), Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS), and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Scale (ECOG) are commonly used functional scoring tools.

The PPS measures 5 functional dimensions including ambulation, activity level, ability to administer self-care, oral intake, and level of consciousness.1 It has been shown to be valid for a broad range of palliative care patients, including those with advanced cancer or life-threatening noncancer diagnoses in hospitals or hospice care.2 The scale, measured in 10% increments, runs from 100% (completely functional) to 0% (dead). A PPS ≤ 70% helps meet hospice eligibility criteria.

The KPS evaluates functional impairment and helps with prognostication. Developed in 1948, it evaluates a patient’s functional ability to tolerate chemotherapy, specifically in lung cancer, and has since been validated to predict mortality across older adults and in chronic disease populations.3,4 The KPS is also measured in 10% increments ranging from 100% (completely functional without assistance) to 0% (dead). A KPS ≤ 70% assists with hospice eligibility criteria (Table 1).5

Developed in 1974, the ECOG has been identified as one of the most important functional status tools in adult cancer care.6 It describes a cancer patient’s functional ability, evaluating their ability to care for oneself and participate in daily activities.7 The ECOG is a 6-point scale; patients can receive scores ranging from 0 (fully active) to 5 (dead). An ECOG score of 4 (sometimes 3) is generally supportive of meeting hospice eligibility (Table 2).6

CASE Presentation

An 80-year-old patient was admitted to the hospice service at the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) community living center (CLC) in Tacoma, Washington, from a community-based acute care hospital. His medical history included prostate cancer with metastasis to his pelvis and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which was stable with treatment with oral medication. Six weeks earlier the patient reported a severe frontal headache that was not responding to over-the-counter analgesics. After 2 days with these symptoms, including a ground-level fall without injuries, he presented to the VAPSHCS emergency department (ED) where a complete neurological examination, including magnetic resonance imaging, revealed a left frontoparietal brain lesion that was 4.2 cm × 3.4 cm × 4.2 cm.

The patient experienced a seizure during his ED evaluation and was admitted for treatment. He underwent a craniotomy where most, but not all the lesions were successfully removed. Postoperatively, the patient exhibited right-sided neglect, gait instability, emotional lability, and cognitive communication disorder. The patient completed 15 of 20 planned radiation treatments but declined further radiation or chemotherapy. The patient decided to halt radiation treatments after being informed by the oncology service that the treatments would likely only add 1 to 2 months to his overall survival, which was < 6 months. The patient elected to focus his goals of care on comfort, dignity, and respect at the end of life and accepted recommendations to be placed into end-of-life hospice care. He was then transferred to the VAPSHCS CLC in Tacoma, Washington, for hospice care.

Upon admission, the patient weighed 94 kg, his vital signs were within reference range, and he reported no pain or headaches. His initial laboratory results revealed a 13.2 g/dL hemoglobin, 3.6 g/dL serum albumin, and a 5.5% hemoglobin A1c, all of which fall into a normal reference range. He had a reported ECOG score of 3 and a KPS score of 50% by the transferring medical team. The patient’s medications included scheduled dexamethasone, metformin, senna, levetiracetam, and as-needed midazolam nasal spray for breakthrough seizures. He also had as-needed acetaminophen for pain. He was alert, oriented ×3, and fully ambulatory but continuously used a 4-wheeled walker for safety and gait instability.

After the patient’s first night, the hospice team met with him to discuss his understanding of his health issues. The patient appeared to have low health literacy but told the team, “I know I am dying.” He had completed written advance directives and a Portable Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment indicating that life-sustaining treatments, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation, supplemental mechanical feeding, or intubation, were not to be used to keep him alive.

At his first 90-day recertification, the patient had gained 8 kg and laboratory results revealed a 14.6 g/dL hemoglobin, 3.8 g/dL serum albumin, and a 6.1% hemoglobin A1c. His ECOG score remained at 3, but his KPS score had increased to 60%. The patient exhibited no new neurologic symptoms or seizures and reported no headaches but had 2 ground-level falls without injury. On both occasions the patient chose not to use his walker to go to the bathroom because it was “too far from my bed.” Per VA policy, after discussions with the hospice team, he was recertified for 90 more days of hospice care. At the end of 6 months in CLC, the patient’s weight remained stable, as did his complete blood count and comprehensive medical panel. He had 1 additional noninjurious ground-level fall and again reported no pain and no use of as-needed acetaminophen. His only medical complication was testing positive for COVID-19, but he remained asymptomatic. The patient was graduated from hospice care and referred to a nearby non-VA adult family home in the community after 180 days. At that time his ECOG score was 2 and his KPS score had increased to 70%.

DISCUSSION

Primary brain tumors account for about 2% of all malignant neoplasms in adults. About half of them represent gliomas. Glioblastoma multiforme derived from neuroepithelial cells is the most frequent and deadly primary malignant central nervous system tumor in adults.8 About 50% of patients with glioblastomas are aged ≥ 65 years at diagnosis.9 A retrospective study of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services claims data paired with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database indicated a median survival of 4 months for patients with glioblastoma multiforme aged > 65 years, including all treatment modalities.10 Surgical resection combined with radiation and chemotherapy offers the best prognosis for the preservation of neurologic function.11 However, comorbidities, adverse drug effects, and the potential for postoperative complications pose significant risks, especially for older patients. Ultimately, goals of care conversations and advance directives play a very important role in evaluating benefits vs risks with this malignancy.

Our patient was aged 80 years and had previously been diagnosed with metastatic prostate malignancy. His goals of care focused on spending time with his friends, leaving his room to eat in the facility dining area, and continuing his daily walks. He remained clear that he did not want his care team to institute life-sustaining treatments to be kept alive and felt the information regarding the risks vs benefits of accepting chemotherapy was not aligned with his goals of care. Over the 6 months that he received hospice care, he gained weight, improved his hemoglobin and serum albumin levels, and ambulated with the use of a 4-wheeled walker. As the patient exhibited no functional decline or new comorbidities and his functional status improved, the clinical staff felt he no longer needed hospice services. The patient had an ECOG score of 2 and a KPS score of 70% at his hospice graduation.

Medical prognostication is one of the biggest challenges clinicians face. Clinicians are generally “over prognosticators,” and their thoughts tend to be based on the patient relationship, overall experiences in health care, and desire to treat and cure patients.12 In hospice we are asked to define the usual, normal, or expected course of a disease, but what does that mean? Although metastatic malignancies usually have a predictable course in comparison to diagnoses such as dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or congestive heart failure, the challenges to improve prognostic ability andpredict disease course continue.13-15 Focusing on functional status, goals of care, and comorbidities are keys to helping with prognosis. Given the challenge, we find the PPS, KPS, and ECOG scales important tools.

When prognosticating, we attempt to define quantity and quality of life (which our patients must define independently or from the voice of their surrogate) and their ability to perform daily activities. Quality of life in patients with glioblastoma is progressively and significantly impacted due to the emergence of debilitating neurologic symptoms arising from infiltrative tumor growth into functionally intact brain tissue that restricts and disrupts normal day-to-day activities. However, functional status plays a significant role in helping the hospice team improve its overall prognosis.

Conclusions

This case study illustrates the difficulty that comes with prognostication(s) despite a patient's severely morbid disease, history of metastatic prostate cancer, and advanced age. Although a diagnosis may be concerning, documenting a patient’s status using functional scales prior to hospice admission and during the recertification process is helpful in prognostication. Doing so will allow health care professionals to have an accepted medical standard to use regardless how distinct the patient's diagnosis. The expression, “as the disease does not read the textbook,” may serve as a helpful reminder in talking with patients and their families. This is important as most patient’s clinical disease courses are different and having the opportunity to use performance status scales may help improve prognostic skills.

1. Cleary TA. The Palliative Performance Scale (PPSv2) Version 2. In: Downing GM, ed. Medical Care of the Dying. 4th ed. Victoria Hospice Society, Learning Centre for Palliative Care; 2006:120.

2. Palliative Performance Scale. ePrognosis, University of California San Francisco. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://eprognosis.ucsf.edu/pps.php

3. Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The Clinical Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents in Cancer. In: MacLeod CM, ed. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Columbia University Press; 1949:191-205.

4. Khalid MA, Achakzai IK, Ahmed Khan S, et al. The use of Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) as a predictor of 3 month post discharge mortality in cirrhotic patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2018;11(4):301-305.

5. Karnofsky Performance Scale. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.hiv.va.gov/provider/tools/karnofsky-performance-scale.asp

6. Mischel A-M, Rosielle DA. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. December 10, 2021. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/eastern-cooperative-oncology-group-performance-status/

7. Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649-655.

8. Nizamutdinov D, Stock EM, Dandashi JA, et al. Prognostication of survival outcomes in patients diagnosed with glioblastoma. World Neurosurg. 2018;109:e67-e74. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.104