User login

Host stress response may be a factor in early-stage HCV clearance

The cellular stress response in hepatocytes may play a major role in controlling hepatitis C virus (HCV). This response may be an important host factor for virus clearance during the early stages of HCV infection, according to a review of acute and chronic HCV infection by W. Alfredo Ríos-Ocampo, MD, and his colleagues (Virus Res. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.12.013).

The reviewers examined the mechanisms of induction and modulation of oxidative stress and endoplasmic-reticular stress with regard to viral persistence and cell survival. The accumulated research indicates that the activation of the eIF2-alpha/ATF4 pathway and selective autophagy induction are involved in the elimination of harmful viral proteins after oxidative stress induction. This all suggests a negative role of autophagy upon HCV infection or a negative regulation of viral replication.

“We conclude from published studies and our own research that viral protein synthesis activates adaptive responses, including autophagy pathways, that act to limit viral protein load and thereby reduce oxidative stress and cell death. Exploitation of these pathways to reduce viral replication will be the next goal and might be a valuable addition to antiviral therapy,” the reviewers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ríos-Ocampo, WA, et al. Virus Res. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.12.013).

The cellular stress response in hepatocytes may play a major role in controlling hepatitis C virus (HCV). This response may be an important host factor for virus clearance during the early stages of HCV infection, according to a review of acute and chronic HCV infection by W. Alfredo Ríos-Ocampo, MD, and his colleagues (Virus Res. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.12.013).

The reviewers examined the mechanisms of induction and modulation of oxidative stress and endoplasmic-reticular stress with regard to viral persistence and cell survival. The accumulated research indicates that the activation of the eIF2-alpha/ATF4 pathway and selective autophagy induction are involved in the elimination of harmful viral proteins after oxidative stress induction. This all suggests a negative role of autophagy upon HCV infection or a negative regulation of viral replication.

“We conclude from published studies and our own research that viral protein synthesis activates adaptive responses, including autophagy pathways, that act to limit viral protein load and thereby reduce oxidative stress and cell death. Exploitation of these pathways to reduce viral replication will be the next goal and might be a valuable addition to antiviral therapy,” the reviewers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ríos-Ocampo, WA, et al. Virus Res. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.12.013).

The cellular stress response in hepatocytes may play a major role in controlling hepatitis C virus (HCV). This response may be an important host factor for virus clearance during the early stages of HCV infection, according to a review of acute and chronic HCV infection by W. Alfredo Ríos-Ocampo, MD, and his colleagues (Virus Res. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.12.013).

The reviewers examined the mechanisms of induction and modulation of oxidative stress and endoplasmic-reticular stress with regard to viral persistence and cell survival. The accumulated research indicates that the activation of the eIF2-alpha/ATF4 pathway and selective autophagy induction are involved in the elimination of harmful viral proteins after oxidative stress induction. This all suggests a negative role of autophagy upon HCV infection or a negative regulation of viral replication.

“We conclude from published studies and our own research that viral protein synthesis activates adaptive responses, including autophagy pathways, that act to limit viral protein load and thereby reduce oxidative stress and cell death. Exploitation of these pathways to reduce viral replication will be the next goal and might be a valuable addition to antiviral therapy,” the reviewers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ríos-Ocampo, WA, et al. Virus Res. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.12.013).

FROM VIRUS RESEARCH

FDA approves Adacel for repeat Tdap vaccinations

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the expanded use of Adacel (Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid and Acellular Pertussis (Tdap) Vaccine Adsorbed) to include repeat vaccinations 8 years or more after the first vaccination in people aged 10-64 years.

The expanded indication was based on results of a randomized, controlled trial, published in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, in which more than 1,300 adults aged 18-64 years received either Adacel or a Td (tetanus-diphtheria) vaccine 8-12 years after receiving a previous dose of Adacel.

Over the course of the study, no significant difference in adverse event incidence was observed between groups. Injection-site reaction was the most common adverse event during the study, occurring in 87.7% of those who received Adacel and 88.0% of those who received the Td vaccine. Other common adverse events associated with Adacel include headache, body ache or muscle weakness, tiredness, muscle aches, and general discomfort.

“While strong vaccination programs are in place for young adolescents, a single Tdap immunization does not offer lifetime protection against pertussis due to waning immunity. The licensure of Adacel as the first Tdap vaccine in the U.S. for repeat vaccination is an important step for eligible patients and offers flexibility for health care providers to help manage their immunization schedules,” said David P. Greenberg, MD, regional medical head North America at Sanofi Pasteur, in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Sanofi website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the expanded use of Adacel (Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid and Acellular Pertussis (Tdap) Vaccine Adsorbed) to include repeat vaccinations 8 years or more after the first vaccination in people aged 10-64 years.

The expanded indication was based on results of a randomized, controlled trial, published in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, in which more than 1,300 adults aged 18-64 years received either Adacel or a Td (tetanus-diphtheria) vaccine 8-12 years after receiving a previous dose of Adacel.

Over the course of the study, no significant difference in adverse event incidence was observed between groups. Injection-site reaction was the most common adverse event during the study, occurring in 87.7% of those who received Adacel and 88.0% of those who received the Td vaccine. Other common adverse events associated with Adacel include headache, body ache or muscle weakness, tiredness, muscle aches, and general discomfort.

“While strong vaccination programs are in place for young adolescents, a single Tdap immunization does not offer lifetime protection against pertussis due to waning immunity. The licensure of Adacel as the first Tdap vaccine in the U.S. for repeat vaccination is an important step for eligible patients and offers flexibility for health care providers to help manage their immunization schedules,” said David P. Greenberg, MD, regional medical head North America at Sanofi Pasteur, in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Sanofi website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the expanded use of Adacel (Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid and Acellular Pertussis (Tdap) Vaccine Adsorbed) to include repeat vaccinations 8 years or more after the first vaccination in people aged 10-64 years.

The expanded indication was based on results of a randomized, controlled trial, published in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, in which more than 1,300 adults aged 18-64 years received either Adacel or a Td (tetanus-diphtheria) vaccine 8-12 years after receiving a previous dose of Adacel.

Over the course of the study, no significant difference in adverse event incidence was observed between groups. Injection-site reaction was the most common adverse event during the study, occurring in 87.7% of those who received Adacel and 88.0% of those who received the Td vaccine. Other common adverse events associated with Adacel include headache, body ache or muscle weakness, tiredness, muscle aches, and general discomfort.

“While strong vaccination programs are in place for young adolescents, a single Tdap immunization does not offer lifetime protection against pertussis due to waning immunity. The licensure of Adacel as the first Tdap vaccine in the U.S. for repeat vaccination is an important step for eligible patients and offers flexibility for health care providers to help manage their immunization schedules,” said David P. Greenberg, MD, regional medical head North America at Sanofi Pasteur, in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Sanofi website.

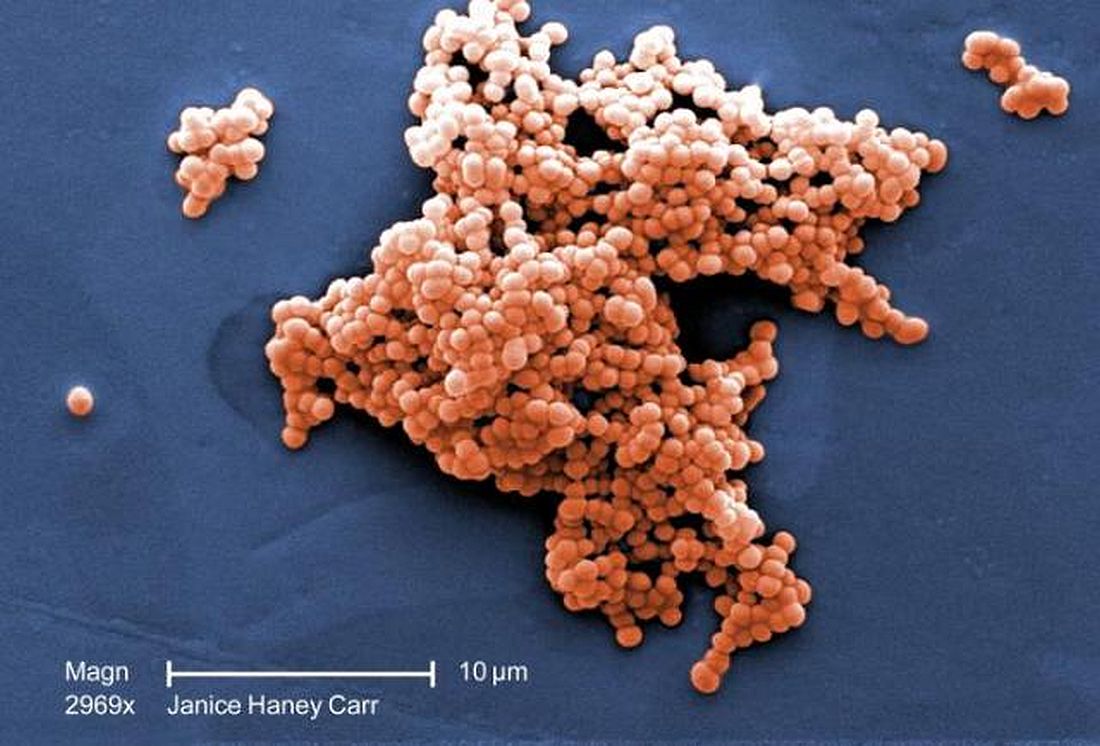

Incidence of late-onset GBS cases are higher than early-onset disease

according to a multistate study of invasive group B streptococcal disease published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using data from the Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program, Srinivas Acharya Nanduri, MD, MPH, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues performed an analysis of early-onset disease (EOD) and late-onset disease (LOD) cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) in infants from 10 different states between 2006 and 2015, and whether mothers of infants with EOD received intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP). EOD was defined as between 0 and 6 days old, while LOD occurred between 7 days and 89 days old.

They found 1,277 cases of EOD and 1,387 cases of LOD in total, with a decrease in incidence of EOD from 0.37 per 1,000 live births in 2006 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births in 2015 (P less than .001); LOD incidence remained stable at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births during the same time period.

In 2015, the national burden for EOD and LOD was estimated at 840 and 1,265 cases, respectively. Mothers of infants with EOD did not have indications for and did not receive IAP in 617 cases (48%) and did not receive IAP despite indications in 278 (22%) cases.

“While the current culture-based screening strategy has been highly successful in reducing EOD burden, our data show that almost half of remaining infants with EOD were born to mothers with no indication for receiving IAP,” Dr. Nanduri and colleagues wrote.

Because there currently is no effective prevention strategy against LOS GBS, the investigators wrote that a maternal vaccine against the most common serotypes “holds promise to prevent a substantial portion of this remaining burden,” and noted several GBS candidate vaccines were in advanced stages of development.

The researchers also looked at GBS serotype data in 1,743 patients from seven different centers. The most commonly found serotype isolates of 887 EOD cases were Ia (242 cases, 27%) and III (242 cases, 27%) overall. Serotype III was most common for LOD cases (481 cases, 56%) and increased in incidence from 0.12 per 1,000 live births to 0.20 per 1,000 live births during the study period (P less than .001), while serotype IV was responsible for 53 cases (6%) of both EOD and LOD.

Dr. Nanduri and associates wrote that over 99% of the serotyped EOD (881 cases) and serotyped LOD (853 cases) cases were caused by serotypes Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, and V. With regard to antimicrobial resistance, there were no cases of beta-lactam resistance, but there was constitutive clindamycin resistance in 359 isolate test results (21%).

The researchers noted that they were limited in the study by 1 year of whole-genome sequencing data, the ABCs capturing only 10% of live birth data in the United States, and conclusions on EOD prevention restricted to data from labor and delivery records.

This study was funded in part by the CDC. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

Perinatal group B Streptococcus (GBS) disease prevention guidelines are credited for the low rate of early-onset disease (EOD) cases of GBS in the United States, but the practice of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) remains controversial in places like the United Kingdom where the National Health Service does not recommend screening-based IAP for GBS, Sagori Mukhopadhyay, MD, MMSc, and Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

One reason for concern about GBS IAP policies is that, despite the decreased number of EOD cases after implementation of IAP, the rate of late-onset disease (LOD) cases remain the same, the authors wrote. And implementation of IAP is not perfect: In some cases IAP was used for less than the recommended duration, used less effective drugs, or given too late so fetal infections were already established.

In addition, some may be uncomfortable with increased perinatal exposure to antibiotics – “a long-held concern about the extent to which widespread perinatal antibiotic use may contribute to the emergence and expansion of antibiotic-resistant GBS,” they added. However, despite the concern, the fatality ratio for EOD was 7% in the study by Nanduri et al., and one complication of GBS in survivors is neurodevelopmental impairment, according to a meta-analysis of 18 studies.

One solution that could address both EOD and LOD cases of GBS is the development of a GBS vaccine. Although there is reluctance to vaccinate pregnant women, recent studies have shown success in vaccinating women for influenza, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis; these recent efforts have “reinvigorated” academia’s interest in vaccine research for this population.

“Vaccination certainly could be a first step to eliminating neonatal GBS disease in the United States and may be the only available approach to addressing the substantial international burden of GBS-associated stillbirth, preterm birth, and neonatal disease morbidity and mortality,” the authors wrote. “But for now, while GBS IAP may be imperfect, it is the success we have.”

Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo are from the division of neonatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo commented on the study by Nanduri et al. in an accompanying editorial (Mukhopadhyay et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4824). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Perinatal group B Streptococcus (GBS) disease prevention guidelines are credited for the low rate of early-onset disease (EOD) cases of GBS in the United States, but the practice of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) remains controversial in places like the United Kingdom where the National Health Service does not recommend screening-based IAP for GBS, Sagori Mukhopadhyay, MD, MMSc, and Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

One reason for concern about GBS IAP policies is that, despite the decreased number of EOD cases after implementation of IAP, the rate of late-onset disease (LOD) cases remain the same, the authors wrote. And implementation of IAP is not perfect: In some cases IAP was used for less than the recommended duration, used less effective drugs, or given too late so fetal infections were already established.

In addition, some may be uncomfortable with increased perinatal exposure to antibiotics – “a long-held concern about the extent to which widespread perinatal antibiotic use may contribute to the emergence and expansion of antibiotic-resistant GBS,” they added. However, despite the concern, the fatality ratio for EOD was 7% in the study by Nanduri et al., and one complication of GBS in survivors is neurodevelopmental impairment, according to a meta-analysis of 18 studies.

One solution that could address both EOD and LOD cases of GBS is the development of a GBS vaccine. Although there is reluctance to vaccinate pregnant women, recent studies have shown success in vaccinating women for influenza, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis; these recent efforts have “reinvigorated” academia’s interest in vaccine research for this population.

“Vaccination certainly could be a first step to eliminating neonatal GBS disease in the United States and may be the only available approach to addressing the substantial international burden of GBS-associated stillbirth, preterm birth, and neonatal disease morbidity and mortality,” the authors wrote. “But for now, while GBS IAP may be imperfect, it is the success we have.”

Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo are from the division of neonatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo commented on the study by Nanduri et al. in an accompanying editorial (Mukhopadhyay et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4824). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Perinatal group B Streptococcus (GBS) disease prevention guidelines are credited for the low rate of early-onset disease (EOD) cases of GBS in the United States, but the practice of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) remains controversial in places like the United Kingdom where the National Health Service does not recommend screening-based IAP for GBS, Sagori Mukhopadhyay, MD, MMSc, and Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

One reason for concern about GBS IAP policies is that, despite the decreased number of EOD cases after implementation of IAP, the rate of late-onset disease (LOD) cases remain the same, the authors wrote. And implementation of IAP is not perfect: In some cases IAP was used for less than the recommended duration, used less effective drugs, or given too late so fetal infections were already established.

In addition, some may be uncomfortable with increased perinatal exposure to antibiotics – “a long-held concern about the extent to which widespread perinatal antibiotic use may contribute to the emergence and expansion of antibiotic-resistant GBS,” they added. However, despite the concern, the fatality ratio for EOD was 7% in the study by Nanduri et al., and one complication of GBS in survivors is neurodevelopmental impairment, according to a meta-analysis of 18 studies.

One solution that could address both EOD and LOD cases of GBS is the development of a GBS vaccine. Although there is reluctance to vaccinate pregnant women, recent studies have shown success in vaccinating women for influenza, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis; these recent efforts have “reinvigorated” academia’s interest in vaccine research for this population.

“Vaccination certainly could be a first step to eliminating neonatal GBS disease in the United States and may be the only available approach to addressing the substantial international burden of GBS-associated stillbirth, preterm birth, and neonatal disease morbidity and mortality,” the authors wrote. “But for now, while GBS IAP may be imperfect, it is the success we have.”

Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo are from the division of neonatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo commented on the study by Nanduri et al. in an accompanying editorial (Mukhopadhyay et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4824). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

according to a multistate study of invasive group B streptococcal disease published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using data from the Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program, Srinivas Acharya Nanduri, MD, MPH, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues performed an analysis of early-onset disease (EOD) and late-onset disease (LOD) cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) in infants from 10 different states between 2006 and 2015, and whether mothers of infants with EOD received intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP). EOD was defined as between 0 and 6 days old, while LOD occurred between 7 days and 89 days old.

They found 1,277 cases of EOD and 1,387 cases of LOD in total, with a decrease in incidence of EOD from 0.37 per 1,000 live births in 2006 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births in 2015 (P less than .001); LOD incidence remained stable at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births during the same time period.

In 2015, the national burden for EOD and LOD was estimated at 840 and 1,265 cases, respectively. Mothers of infants with EOD did not have indications for and did not receive IAP in 617 cases (48%) and did not receive IAP despite indications in 278 (22%) cases.

“While the current culture-based screening strategy has been highly successful in reducing EOD burden, our data show that almost half of remaining infants with EOD were born to mothers with no indication for receiving IAP,” Dr. Nanduri and colleagues wrote.

Because there currently is no effective prevention strategy against LOS GBS, the investigators wrote that a maternal vaccine against the most common serotypes “holds promise to prevent a substantial portion of this remaining burden,” and noted several GBS candidate vaccines were in advanced stages of development.

The researchers also looked at GBS serotype data in 1,743 patients from seven different centers. The most commonly found serotype isolates of 887 EOD cases were Ia (242 cases, 27%) and III (242 cases, 27%) overall. Serotype III was most common for LOD cases (481 cases, 56%) and increased in incidence from 0.12 per 1,000 live births to 0.20 per 1,000 live births during the study period (P less than .001), while serotype IV was responsible for 53 cases (6%) of both EOD and LOD.

Dr. Nanduri and associates wrote that over 99% of the serotyped EOD (881 cases) and serotyped LOD (853 cases) cases were caused by serotypes Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, and V. With regard to antimicrobial resistance, there were no cases of beta-lactam resistance, but there was constitutive clindamycin resistance in 359 isolate test results (21%).

The researchers noted that they were limited in the study by 1 year of whole-genome sequencing data, the ABCs capturing only 10% of live birth data in the United States, and conclusions on EOD prevention restricted to data from labor and delivery records.

This study was funded in part by the CDC. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

according to a multistate study of invasive group B streptococcal disease published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using data from the Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program, Srinivas Acharya Nanduri, MD, MPH, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues performed an analysis of early-onset disease (EOD) and late-onset disease (LOD) cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) in infants from 10 different states between 2006 and 2015, and whether mothers of infants with EOD received intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP). EOD was defined as between 0 and 6 days old, while LOD occurred between 7 days and 89 days old.

They found 1,277 cases of EOD and 1,387 cases of LOD in total, with a decrease in incidence of EOD from 0.37 per 1,000 live births in 2006 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births in 2015 (P less than .001); LOD incidence remained stable at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births during the same time period.

In 2015, the national burden for EOD and LOD was estimated at 840 and 1,265 cases, respectively. Mothers of infants with EOD did not have indications for and did not receive IAP in 617 cases (48%) and did not receive IAP despite indications in 278 (22%) cases.

“While the current culture-based screening strategy has been highly successful in reducing EOD burden, our data show that almost half of remaining infants with EOD were born to mothers with no indication for receiving IAP,” Dr. Nanduri and colleagues wrote.

Because there currently is no effective prevention strategy against LOS GBS, the investigators wrote that a maternal vaccine against the most common serotypes “holds promise to prevent a substantial portion of this remaining burden,” and noted several GBS candidate vaccines were in advanced stages of development.

The researchers also looked at GBS serotype data in 1,743 patients from seven different centers. The most commonly found serotype isolates of 887 EOD cases were Ia (242 cases, 27%) and III (242 cases, 27%) overall. Serotype III was most common for LOD cases (481 cases, 56%) and increased in incidence from 0.12 per 1,000 live births to 0.20 per 1,000 live births during the study period (P less than .001), while serotype IV was responsible for 53 cases (6%) of both EOD and LOD.

Dr. Nanduri and associates wrote that over 99% of the serotyped EOD (881 cases) and serotyped LOD (853 cases) cases were caused by serotypes Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, and V. With regard to antimicrobial resistance, there were no cases of beta-lactam resistance, but there was constitutive clindamycin resistance in 359 isolate test results (21%).

The researchers noted that they were limited in the study by 1 year of whole-genome sequencing data, the ABCs capturing only 10% of live birth data in the United States, and conclusions on EOD prevention restricted to data from labor and delivery records.

This study was funded in part by the CDC. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Between 2006 and 2015, early-onset disease cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) declined, while the incidence of late-onset cases did not change.

Major finding: The rate of early-onset GBS declined from 0.37 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births and the rate of late-onset GBS cases remained at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births.

Study details: A population-based study of infants with early-onset disease and late-onset disease GBS from 10 different states in the Active Bacterial Core surveillance program between 2006 and 2015.

Disclosures: This study was funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Source: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

Flu season showing signs of decline

The 2018-2019 flu season may have peaked as measures of influenza-like illness (ILI) activity dropped in the first week of the new year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatients visits for ILI dropped to 3.5% for the week ending Jan. 5, 2019, after reaching 4.0% the previous week. Outpatient ILI visits first topped the national baseline of 2.2% during the week ending Dec. 8, 2018, and have remained above that value for 5 consecutive weeks, the CDC’s influenza division said on Jan. 11.

Flu activity reported by the states reflects the national drop: 10 states came in at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of activity for the week ending Jan. 5 – down from 12 the week before – and a total of 15 were in the high range from 8 to 10, compared with 19 the previous week, the CDC said. Two states, Mississippi and Texas, dropped from level 10 to level 7, which the CDC categorizes as moderate activity.

A total of 73 ILI-related deaths were reported during the week ending Dec. 29 (the latest with data available; reporting less than 68% complete), which already exceeds the 71 deaths reported for the week ending Dec. 22 (reporting 85% complete). Flu deaths totaled 437 through the first 13 weeks of the 2018-2019 season, compared with the 1,659 that occurred during weeks 1-13 of the very severe 2017-2018 season, CDC data show.

For the week ending Jan. 5, the CDC received reports of three flu-related pediatric deaths, all of which occurred the previous week. For the season so far, there have been 16 pediatric deaths, compared with 20 at this point in the 2017-2018 season.

Estimates released during the flu season for the first time show that between 6 and 7 million Americans have been infected since Oct. 1, 2018, and that 69,000-84,000 people have been hospitalized with the flu through Jan. 5, 2019. These cumulative totals have previously been available only at the end of the season, the CDC noted.

The 2018-2019 flu season may have peaked as measures of influenza-like illness (ILI) activity dropped in the first week of the new year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatients visits for ILI dropped to 3.5% for the week ending Jan. 5, 2019, after reaching 4.0% the previous week. Outpatient ILI visits first topped the national baseline of 2.2% during the week ending Dec. 8, 2018, and have remained above that value for 5 consecutive weeks, the CDC’s influenza division said on Jan. 11.

Flu activity reported by the states reflects the national drop: 10 states came in at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of activity for the week ending Jan. 5 – down from 12 the week before – and a total of 15 were in the high range from 8 to 10, compared with 19 the previous week, the CDC said. Two states, Mississippi and Texas, dropped from level 10 to level 7, which the CDC categorizes as moderate activity.

A total of 73 ILI-related deaths were reported during the week ending Dec. 29 (the latest with data available; reporting less than 68% complete), which already exceeds the 71 deaths reported for the week ending Dec. 22 (reporting 85% complete). Flu deaths totaled 437 through the first 13 weeks of the 2018-2019 season, compared with the 1,659 that occurred during weeks 1-13 of the very severe 2017-2018 season, CDC data show.

For the week ending Jan. 5, the CDC received reports of three flu-related pediatric deaths, all of which occurred the previous week. For the season so far, there have been 16 pediatric deaths, compared with 20 at this point in the 2017-2018 season.

Estimates released during the flu season for the first time show that between 6 and 7 million Americans have been infected since Oct. 1, 2018, and that 69,000-84,000 people have been hospitalized with the flu through Jan. 5, 2019. These cumulative totals have previously been available only at the end of the season, the CDC noted.

The 2018-2019 flu season may have peaked as measures of influenza-like illness (ILI) activity dropped in the first week of the new year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatients visits for ILI dropped to 3.5% for the week ending Jan. 5, 2019, after reaching 4.0% the previous week. Outpatient ILI visits first topped the national baseline of 2.2% during the week ending Dec. 8, 2018, and have remained above that value for 5 consecutive weeks, the CDC’s influenza division said on Jan. 11.

Flu activity reported by the states reflects the national drop: 10 states came in at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of activity for the week ending Jan. 5 – down from 12 the week before – and a total of 15 were in the high range from 8 to 10, compared with 19 the previous week, the CDC said. Two states, Mississippi and Texas, dropped from level 10 to level 7, which the CDC categorizes as moderate activity.

A total of 73 ILI-related deaths were reported during the week ending Dec. 29 (the latest with data available; reporting less than 68% complete), which already exceeds the 71 deaths reported for the week ending Dec. 22 (reporting 85% complete). Flu deaths totaled 437 through the first 13 weeks of the 2018-2019 season, compared with the 1,659 that occurred during weeks 1-13 of the very severe 2017-2018 season, CDC data show.

For the week ending Jan. 5, the CDC received reports of three flu-related pediatric deaths, all of which occurred the previous week. For the season so far, there have been 16 pediatric deaths, compared with 20 at this point in the 2017-2018 season.

Estimates released during the flu season for the first time show that between 6 and 7 million Americans have been infected since Oct. 1, 2018, and that 69,000-84,000 people have been hospitalized with the flu through Jan. 5, 2019. These cumulative totals have previously been available only at the end of the season, the CDC noted.

Children who are coughing: Is it flu or bacterial pneumonia?

We are in the middle of flu season, and many of our patients are coughing. Is it the flu or might the child have a secondary bacterial pneumonia? Let’s start with the history for a tip off. The course of flu and respiratory viral infections in general involves a typical pattern of timing for fever and cough.

A late-developing fever or fever that subsides then recurs should raise concern. A prolonged cough or cough that subsides then recurs also should raise concern. The respiratory rate and chest retractions are key physical findings that can aid in distinguishing children with bacterial pneumonia. Rales and decreased breath sounds in lung segments are best heard with deep breaths.

What diagnostic laboratory and imaging tests should be used

Fortunately, rapid tests to detect influenza are available, and many providers have added those to their laboratory evaluation. A complete blood count and differential may be helpful. If a pulse oximeter is available, checking oxygen saturation might be helpful. The American Academy of Pediatrics community pneumonia guideline states that routine chest radiographs are not necessary for the confirmation of suspected community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in patients well enough to be treated in the outpatient setting (Clin Inf Dis. 2011 Oct;53[7]:e25–e76). Blood cultures should not be performed routinely in nontoxic, fully immunized children with CAP managed in the outpatient setting.

What antibiotic should be used

Antimicrobial therapy is not routinely required for preschool-aged children with cough, even cough caused by CAP, because viral pathogens are responsible for the great majority of clinical disease. If the diagnosis of CAP is made, the AAP endorses amoxicillin as first-line therapy for previously healthy, appropriately immunized infants and preschool children with mild to moderate CAP suspected to be of bacterial origin. For previously healthy, appropriately immunized school-aged children and adolescents with mild to moderate CAP, amoxicillin is recommended for treatment of Streptococcus pneumoniae, the most prominent invasive bacterial pathogen.

However, the treatment paradigm is complicated because Mycoplasma pneumoniae also should be considered in management decisions. Children with signs and symptoms suspicious for M. pneumoniae should be tested to help guide antibiotic selection. This may be a simple bedside cold agglutinin test. The highest incidence of Mycoplasma pneumonia is in 5- to 20-year-olds (51% in 5- to 9-year-olds, 74% in 9- to 15-year-olds, and 3%-18% in adults with pneumonia), but 9% of CAP occurs in patients younger than 5 years old. The clinical features of Mycoplasma pneumonia resemble influenza: The patient has gradual onset of headache, malaise, fever, sore throat, and cough. Mycoplasma pneumonia has a similar incidence of productive cough, rales, and diarrhea as pneumococcal CAP, but with more frequent upper respiratory symptoms and a normal leukocyte count. Mycoplasma bronchopneumonia occurs 30 times more frequently than Mycoplasma lobar pneumonia. The radiologic features of Mycoplasma is typical of a bronchopneumonia, usually involving a single lobe, subsegmental atelectasis, peribronchial thickening, and streaky interstitial densities. While Mycoplasma pneumonia is usually self-limited, the duration of illness is shortened by oral treatment with doxycycline, erythromycin, clarithromycin, or azithromycin.

What is the appropriate duration of antimicrobial therapy

Recommendations by the AAP for CAP note that treatment courses of 10 days have been best studied, although shorter courses may be just as effective, particularly for mild disease managed on an outpatient basis.

When should children be hospitalized

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He had no conflicts to declare. Email him at [email protected].

We are in the middle of flu season, and many of our patients are coughing. Is it the flu or might the child have a secondary bacterial pneumonia? Let’s start with the history for a tip off. The course of flu and respiratory viral infections in general involves a typical pattern of timing for fever and cough.

A late-developing fever or fever that subsides then recurs should raise concern. A prolonged cough or cough that subsides then recurs also should raise concern. The respiratory rate and chest retractions are key physical findings that can aid in distinguishing children with bacterial pneumonia. Rales and decreased breath sounds in lung segments are best heard with deep breaths.

What diagnostic laboratory and imaging tests should be used

Fortunately, rapid tests to detect influenza are available, and many providers have added those to their laboratory evaluation. A complete blood count and differential may be helpful. If a pulse oximeter is available, checking oxygen saturation might be helpful. The American Academy of Pediatrics community pneumonia guideline states that routine chest radiographs are not necessary for the confirmation of suspected community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in patients well enough to be treated in the outpatient setting (Clin Inf Dis. 2011 Oct;53[7]:e25–e76). Blood cultures should not be performed routinely in nontoxic, fully immunized children with CAP managed in the outpatient setting.

What antibiotic should be used

Antimicrobial therapy is not routinely required for preschool-aged children with cough, even cough caused by CAP, because viral pathogens are responsible for the great majority of clinical disease. If the diagnosis of CAP is made, the AAP endorses amoxicillin as first-line therapy for previously healthy, appropriately immunized infants and preschool children with mild to moderate CAP suspected to be of bacterial origin. For previously healthy, appropriately immunized school-aged children and adolescents with mild to moderate CAP, amoxicillin is recommended for treatment of Streptococcus pneumoniae, the most prominent invasive bacterial pathogen.

However, the treatment paradigm is complicated because Mycoplasma pneumoniae also should be considered in management decisions. Children with signs and symptoms suspicious for M. pneumoniae should be tested to help guide antibiotic selection. This may be a simple bedside cold agglutinin test. The highest incidence of Mycoplasma pneumonia is in 5- to 20-year-olds (51% in 5- to 9-year-olds, 74% in 9- to 15-year-olds, and 3%-18% in adults with pneumonia), but 9% of CAP occurs in patients younger than 5 years old. The clinical features of Mycoplasma pneumonia resemble influenza: The patient has gradual onset of headache, malaise, fever, sore throat, and cough. Mycoplasma pneumonia has a similar incidence of productive cough, rales, and diarrhea as pneumococcal CAP, but with more frequent upper respiratory symptoms and a normal leukocyte count. Mycoplasma bronchopneumonia occurs 30 times more frequently than Mycoplasma lobar pneumonia. The radiologic features of Mycoplasma is typical of a bronchopneumonia, usually involving a single lobe, subsegmental atelectasis, peribronchial thickening, and streaky interstitial densities. While Mycoplasma pneumonia is usually self-limited, the duration of illness is shortened by oral treatment with doxycycline, erythromycin, clarithromycin, or azithromycin.

What is the appropriate duration of antimicrobial therapy

Recommendations by the AAP for CAP note that treatment courses of 10 days have been best studied, although shorter courses may be just as effective, particularly for mild disease managed on an outpatient basis.

When should children be hospitalized

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He had no conflicts to declare. Email him at [email protected].

We are in the middle of flu season, and many of our patients are coughing. Is it the flu or might the child have a secondary bacterial pneumonia? Let’s start with the history for a tip off. The course of flu and respiratory viral infections in general involves a typical pattern of timing for fever and cough.

A late-developing fever or fever that subsides then recurs should raise concern. A prolonged cough or cough that subsides then recurs also should raise concern. The respiratory rate and chest retractions are key physical findings that can aid in distinguishing children with bacterial pneumonia. Rales and decreased breath sounds in lung segments are best heard with deep breaths.

What diagnostic laboratory and imaging tests should be used

Fortunately, rapid tests to detect influenza are available, and many providers have added those to their laboratory evaluation. A complete blood count and differential may be helpful. If a pulse oximeter is available, checking oxygen saturation might be helpful. The American Academy of Pediatrics community pneumonia guideline states that routine chest radiographs are not necessary for the confirmation of suspected community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in patients well enough to be treated in the outpatient setting (Clin Inf Dis. 2011 Oct;53[7]:e25–e76). Blood cultures should not be performed routinely in nontoxic, fully immunized children with CAP managed in the outpatient setting.

What antibiotic should be used

Antimicrobial therapy is not routinely required for preschool-aged children with cough, even cough caused by CAP, because viral pathogens are responsible for the great majority of clinical disease. If the diagnosis of CAP is made, the AAP endorses amoxicillin as first-line therapy for previously healthy, appropriately immunized infants and preschool children with mild to moderate CAP suspected to be of bacterial origin. For previously healthy, appropriately immunized school-aged children and adolescents with mild to moderate CAP, amoxicillin is recommended for treatment of Streptococcus pneumoniae, the most prominent invasive bacterial pathogen.

However, the treatment paradigm is complicated because Mycoplasma pneumoniae also should be considered in management decisions. Children with signs and symptoms suspicious for M. pneumoniae should be tested to help guide antibiotic selection. This may be a simple bedside cold agglutinin test. The highest incidence of Mycoplasma pneumonia is in 5- to 20-year-olds (51% in 5- to 9-year-olds, 74% in 9- to 15-year-olds, and 3%-18% in adults with pneumonia), but 9% of CAP occurs in patients younger than 5 years old. The clinical features of Mycoplasma pneumonia resemble influenza: The patient has gradual onset of headache, malaise, fever, sore throat, and cough. Mycoplasma pneumonia has a similar incidence of productive cough, rales, and diarrhea as pneumococcal CAP, but with more frequent upper respiratory symptoms and a normal leukocyte count. Mycoplasma bronchopneumonia occurs 30 times more frequently than Mycoplasma lobar pneumonia. The radiologic features of Mycoplasma is typical of a bronchopneumonia, usually involving a single lobe, subsegmental atelectasis, peribronchial thickening, and streaky interstitial densities. While Mycoplasma pneumonia is usually self-limited, the duration of illness is shortened by oral treatment with doxycycline, erythromycin, clarithromycin, or azithromycin.

What is the appropriate duration of antimicrobial therapy

Recommendations by the AAP for CAP note that treatment courses of 10 days have been best studied, although shorter courses may be just as effective, particularly for mild disease managed on an outpatient basis.

When should children be hospitalized

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He had no conflicts to declare. Email him at [email protected].

Chronic infections such as HCV, HIV, and TB cause unique problems for psoriasis patients

In a review of therapeutic issues for psoriasis patients who have such chronic infections as hepatitis, HIV, or latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) or those who fall into the category of special populations (pregnant women or children), significant concerns were directly tied to the mode of action of the drugs involved.

In particular, “Most systemic agents for psoriasis are immunosuppressive, which poses a unique treatment challenge in patients with psoriasis with chronic infections because they are already immunosuppressed,” according to Shivani B. Kaushik, MD, a resident in the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and her colleague Mark G. Lebwohl, MD, professor and system chair of the department.

For example, the reviewers detailed a report of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) reactivation in patients with psoriasis who were taking biologics. Virus reactivation was noted in 2/175 patients who were positive for anti-HBc antibody, 3/97 patients with HCV infection, and 8/40 patients who were positive for HBsAg (the surface antigen of HBV). From this, they concluded that “biologics pose minimal risk for viral reactivation in patients with anti-HCV or anti-HBc antibodies, but they are of considerable risk in HBsAg-positive patients.” (J Amer Acad Derm. 2019 Jan;80:43-53).

Giving a specific example, Dr. Kaushik and her colleague pointed out that the safety of ustekinumab in patients with psoriasis with concurrent HCV and HBV infection was not clear. Viral reactivation and hepatocellular cancer were reported in one of four patients with HCV and in two of seven HBsAg-positive patients; and yet, another study showed that the successful use of ustekinumab for psoriasis had no impact on liver function or viral load in a patient with coexisting HCV.

Overall, “Patients should not be treated with immunosuppressive therapies during the acute stage. However, biologic treatment can be initiated in patients with chronic or resolved hepatitis under close monitoring and collaboration with a gastroenterologist,” the researchers stated.

In addition, they pointed out that methotrexate, another commonly prescribed drug for psoriasis, is absolutely contraindicated, although the use of cyclosporine remains controversial for those patients who are HCV-antibody positive.

“Most systemic agents used in psoriasis are immunosuppressive and require appropriate screening, monitoring, and prophylaxis when used in [psoriasis] patients with chronic infections, such as hepatitis, HIV, and LTBI,” the authors concluded.

The authors reported receiving funding from a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Kaushik BS et al. J Amer Acad Derm. 2019;80:43-53.

In a review of therapeutic issues for psoriasis patients who have such chronic infections as hepatitis, HIV, or latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) or those who fall into the category of special populations (pregnant women or children), significant concerns were directly tied to the mode of action of the drugs involved.

In particular, “Most systemic agents for psoriasis are immunosuppressive, which poses a unique treatment challenge in patients with psoriasis with chronic infections because they are already immunosuppressed,” according to Shivani B. Kaushik, MD, a resident in the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and her colleague Mark G. Lebwohl, MD, professor and system chair of the department.

For example, the reviewers detailed a report of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) reactivation in patients with psoriasis who were taking biologics. Virus reactivation was noted in 2/175 patients who were positive for anti-HBc antibody, 3/97 patients with HCV infection, and 8/40 patients who were positive for HBsAg (the surface antigen of HBV). From this, they concluded that “biologics pose minimal risk for viral reactivation in patients with anti-HCV or anti-HBc antibodies, but they are of considerable risk in HBsAg-positive patients.” (J Amer Acad Derm. 2019 Jan;80:43-53).

Giving a specific example, Dr. Kaushik and her colleague pointed out that the safety of ustekinumab in patients with psoriasis with concurrent HCV and HBV infection was not clear. Viral reactivation and hepatocellular cancer were reported in one of four patients with HCV and in two of seven HBsAg-positive patients; and yet, another study showed that the successful use of ustekinumab for psoriasis had no impact on liver function or viral load in a patient with coexisting HCV.

Overall, “Patients should not be treated with immunosuppressive therapies during the acute stage. However, biologic treatment can be initiated in patients with chronic or resolved hepatitis under close monitoring and collaboration with a gastroenterologist,” the researchers stated.

In addition, they pointed out that methotrexate, another commonly prescribed drug for psoriasis, is absolutely contraindicated, although the use of cyclosporine remains controversial for those patients who are HCV-antibody positive.

“Most systemic agents used in psoriasis are immunosuppressive and require appropriate screening, monitoring, and prophylaxis when used in [psoriasis] patients with chronic infections, such as hepatitis, HIV, and LTBI,” the authors concluded.

The authors reported receiving funding from a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Kaushik BS et al. J Amer Acad Derm. 2019;80:43-53.

In a review of therapeutic issues for psoriasis patients who have such chronic infections as hepatitis, HIV, or latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) or those who fall into the category of special populations (pregnant women or children), significant concerns were directly tied to the mode of action of the drugs involved.

In particular, “Most systemic agents for psoriasis are immunosuppressive, which poses a unique treatment challenge in patients with psoriasis with chronic infections because they are already immunosuppressed,” according to Shivani B. Kaushik, MD, a resident in the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and her colleague Mark G. Lebwohl, MD, professor and system chair of the department.

For example, the reviewers detailed a report of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) reactivation in patients with psoriasis who were taking biologics. Virus reactivation was noted in 2/175 patients who were positive for anti-HBc antibody, 3/97 patients with HCV infection, and 8/40 patients who were positive for HBsAg (the surface antigen of HBV). From this, they concluded that “biologics pose minimal risk for viral reactivation in patients with anti-HCV or anti-HBc antibodies, but they are of considerable risk in HBsAg-positive patients.” (J Amer Acad Derm. 2019 Jan;80:43-53).

Giving a specific example, Dr. Kaushik and her colleague pointed out that the safety of ustekinumab in patients with psoriasis with concurrent HCV and HBV infection was not clear. Viral reactivation and hepatocellular cancer were reported in one of four patients with HCV and in two of seven HBsAg-positive patients; and yet, another study showed that the successful use of ustekinumab for psoriasis had no impact on liver function or viral load in a patient with coexisting HCV.

Overall, “Patients should not be treated with immunosuppressive therapies during the acute stage. However, biologic treatment can be initiated in patients with chronic or resolved hepatitis under close monitoring and collaboration with a gastroenterologist,” the researchers stated.

In addition, they pointed out that methotrexate, another commonly prescribed drug for psoriasis, is absolutely contraindicated, although the use of cyclosporine remains controversial for those patients who are HCV-antibody positive.

“Most systemic agents used in psoriasis are immunosuppressive and require appropriate screening, monitoring, and prophylaxis when used in [psoriasis] patients with chronic infections, such as hepatitis, HIV, and LTBI,” the authors concluded.

The authors reported receiving funding from a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Kaushik BS et al. J Amer Acad Derm. 2019;80:43-53.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Opioid clinic physicians report lack of competency in managing patients with HCV

A survey of clinicians who provide opioid agonist therapy (OAT) to people who inject drugs (PWID), showed several areas where self-reported competency in the management and treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) could be improved.

The C-SCOPE study consisted of a self-administered survey among physicians practicing at clinics providing OAT in Australia, Canada, Europe, and the United States during April-May of 2017. Among 203 physicians – 40% in the United States, 45% in Europe, and 14% in Australia/Canada – 21% were addiction medicine specialists, and 29% were psychiatrists.

The majority reported that HCV testing (86%) and treatment (82%) among PWID were important.

The minority reported less than average competence with respect to regular screening (12%) and interpretation of HCV test results (14%), while greater proportions reported less than average competence in advising patients about new HCV therapies (28%), knowledge of new treatments (37%), and treatment/management of HCV (40%). Although a minority of participants self-reported average or less competency related to the ability to ensure regular screening for HCV (34%) and in the ability to interpret HCV test results (39%), more than half of the participants self-reported average or less competency in other areas. These areas included the ability to assess liver disease (52%), the ability to treat HCV and manage side effects (65%), and knowledge of new HCV treatments (64%). This trend was consistent with findings from previous studies among competency related to HCV infection among primary care providers, according to the authors (Int J Drug Policy. 2019;63:29-38).

“These low levels of reported competency in HCV management and treatment highlight a critical need for improved HCV education and training in how to manage and treat HCV among PWID,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported grant funding and consultancy with a number of pharmaceutical companies. Funding was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme and the Australian government.

SOURCE: Grebely J et al. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;63:29-38.

A survey of clinicians who provide opioid agonist therapy (OAT) to people who inject drugs (PWID), showed several areas where self-reported competency in the management and treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) could be improved.

The C-SCOPE study consisted of a self-administered survey among physicians practicing at clinics providing OAT in Australia, Canada, Europe, and the United States during April-May of 2017. Among 203 physicians – 40% in the United States, 45% in Europe, and 14% in Australia/Canada – 21% were addiction medicine specialists, and 29% were psychiatrists.

The majority reported that HCV testing (86%) and treatment (82%) among PWID were important.

The minority reported less than average competence with respect to regular screening (12%) and interpretation of HCV test results (14%), while greater proportions reported less than average competence in advising patients about new HCV therapies (28%), knowledge of new treatments (37%), and treatment/management of HCV (40%). Although a minority of participants self-reported average or less competency related to the ability to ensure regular screening for HCV (34%) and in the ability to interpret HCV test results (39%), more than half of the participants self-reported average or less competency in other areas. These areas included the ability to assess liver disease (52%), the ability to treat HCV and manage side effects (65%), and knowledge of new HCV treatments (64%). This trend was consistent with findings from previous studies among competency related to HCV infection among primary care providers, according to the authors (Int J Drug Policy. 2019;63:29-38).

“These low levels of reported competency in HCV management and treatment highlight a critical need for improved HCV education and training in how to manage and treat HCV among PWID,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported grant funding and consultancy with a number of pharmaceutical companies. Funding was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme and the Australian government.

SOURCE: Grebely J et al. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;63:29-38.

A survey of clinicians who provide opioid agonist therapy (OAT) to people who inject drugs (PWID), showed several areas where self-reported competency in the management and treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) could be improved.

The C-SCOPE study consisted of a self-administered survey among physicians practicing at clinics providing OAT in Australia, Canada, Europe, and the United States during April-May of 2017. Among 203 physicians – 40% in the United States, 45% in Europe, and 14% in Australia/Canada – 21% were addiction medicine specialists, and 29% were psychiatrists.

The majority reported that HCV testing (86%) and treatment (82%) among PWID were important.

The minority reported less than average competence with respect to regular screening (12%) and interpretation of HCV test results (14%), while greater proportions reported less than average competence in advising patients about new HCV therapies (28%), knowledge of new treatments (37%), and treatment/management of HCV (40%). Although a minority of participants self-reported average or less competency related to the ability to ensure regular screening for HCV (34%) and in the ability to interpret HCV test results (39%), more than half of the participants self-reported average or less competency in other areas. These areas included the ability to assess liver disease (52%), the ability to treat HCV and manage side effects (65%), and knowledge of new HCV treatments (64%). This trend was consistent with findings from previous studies among competency related to HCV infection among primary care providers, according to the authors (Int J Drug Policy. 2019;63:29-38).

“These low levels of reported competency in HCV management and treatment highlight a critical need for improved HCV education and training in how to manage and treat HCV among PWID,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported grant funding and consultancy with a number of pharmaceutical companies. Funding was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme and the Australian government.

SOURCE: Grebely J et al. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;63:29-38.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF DRUG POLICY

Necrobiosis Lipoidica With Superimposed Pyoderma Vegetans

Case Report

A 26-year-old woman with a medical history of newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, and asthma was evaluated as a hospital consultation with a vegetative plaque on the left lateral ankle of 13 months’ duration. The lesion first appeared as a red scaly rash that became purulent. The lesion had been treated with multiple rounds of topical antibiotics, oral antibiotics, topical antifungals, and corticosteroids without resolution. The patient denied pain or any decrease in ankle mobility. Review of systems was otherwise negative.

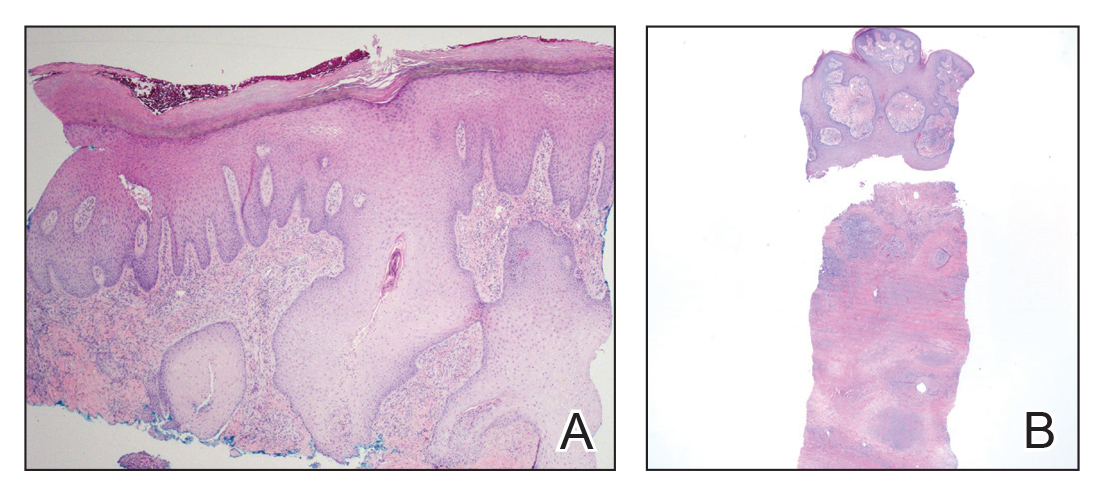

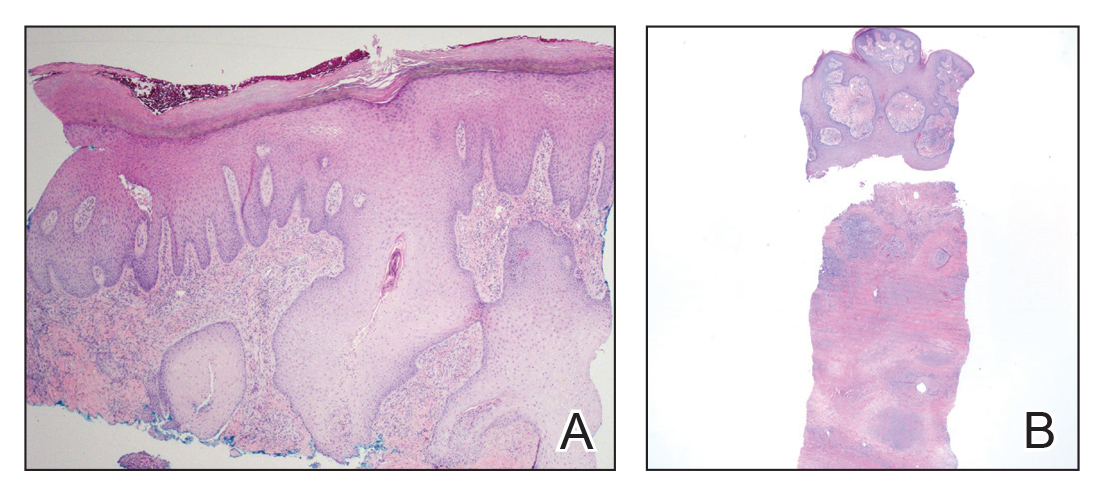

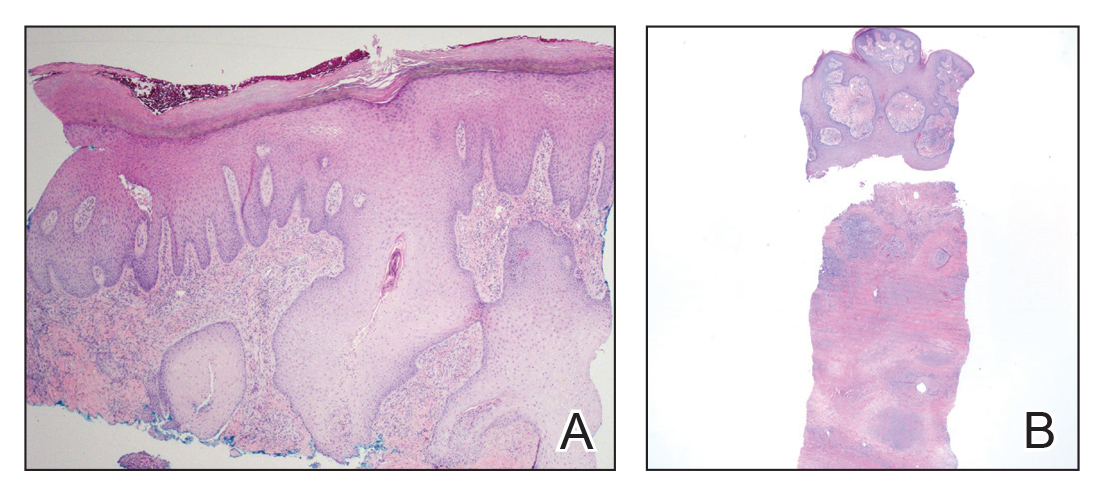

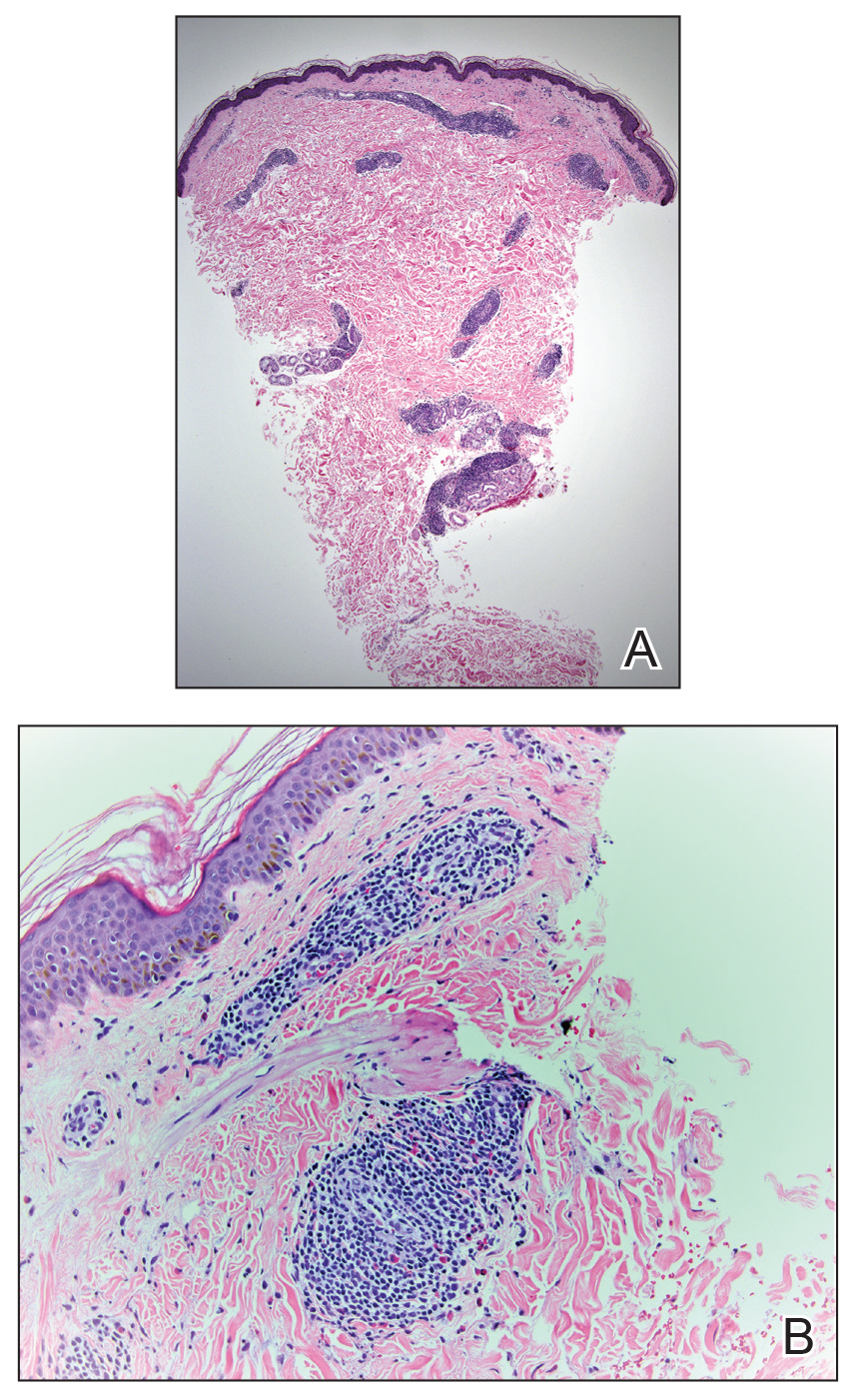

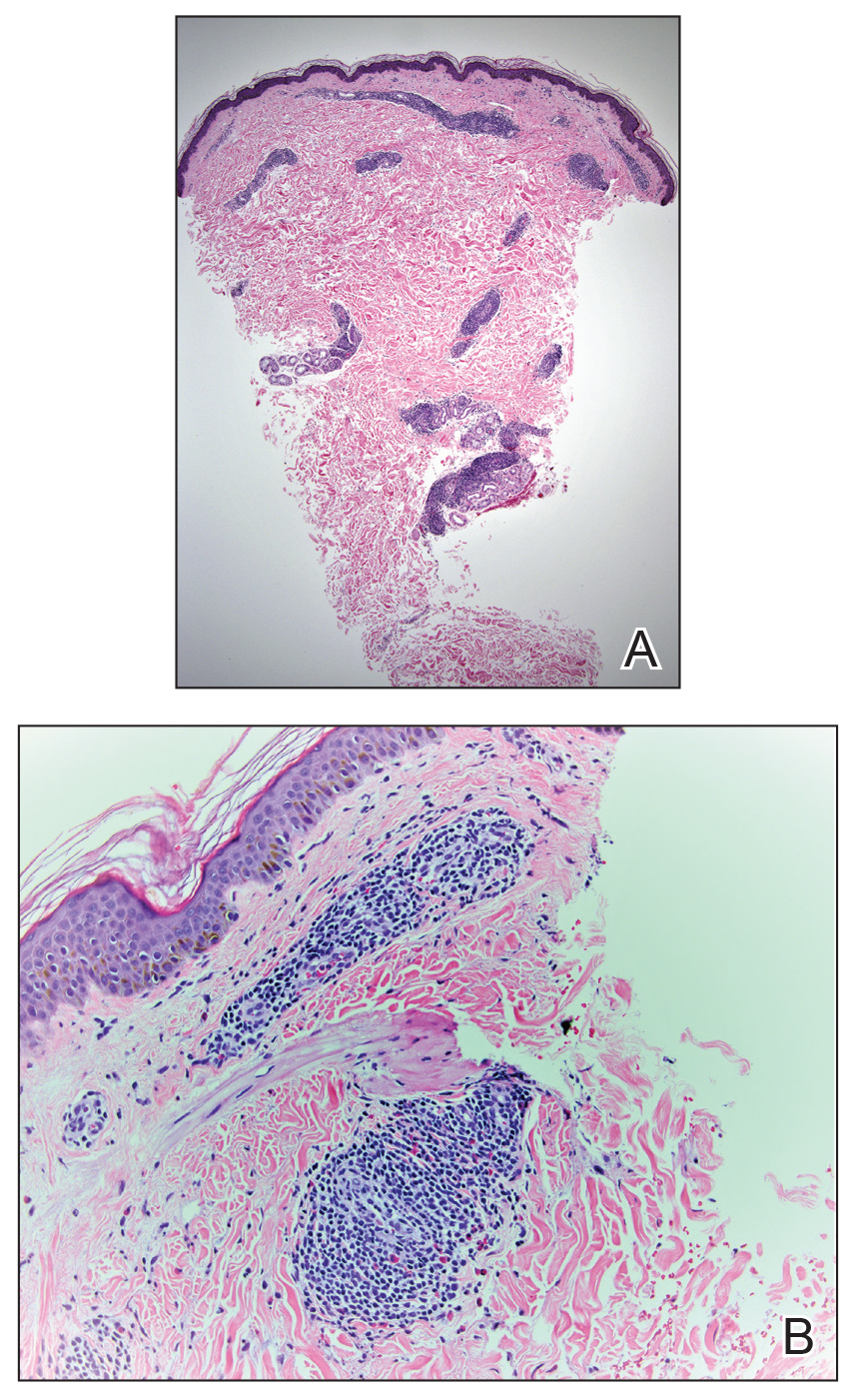

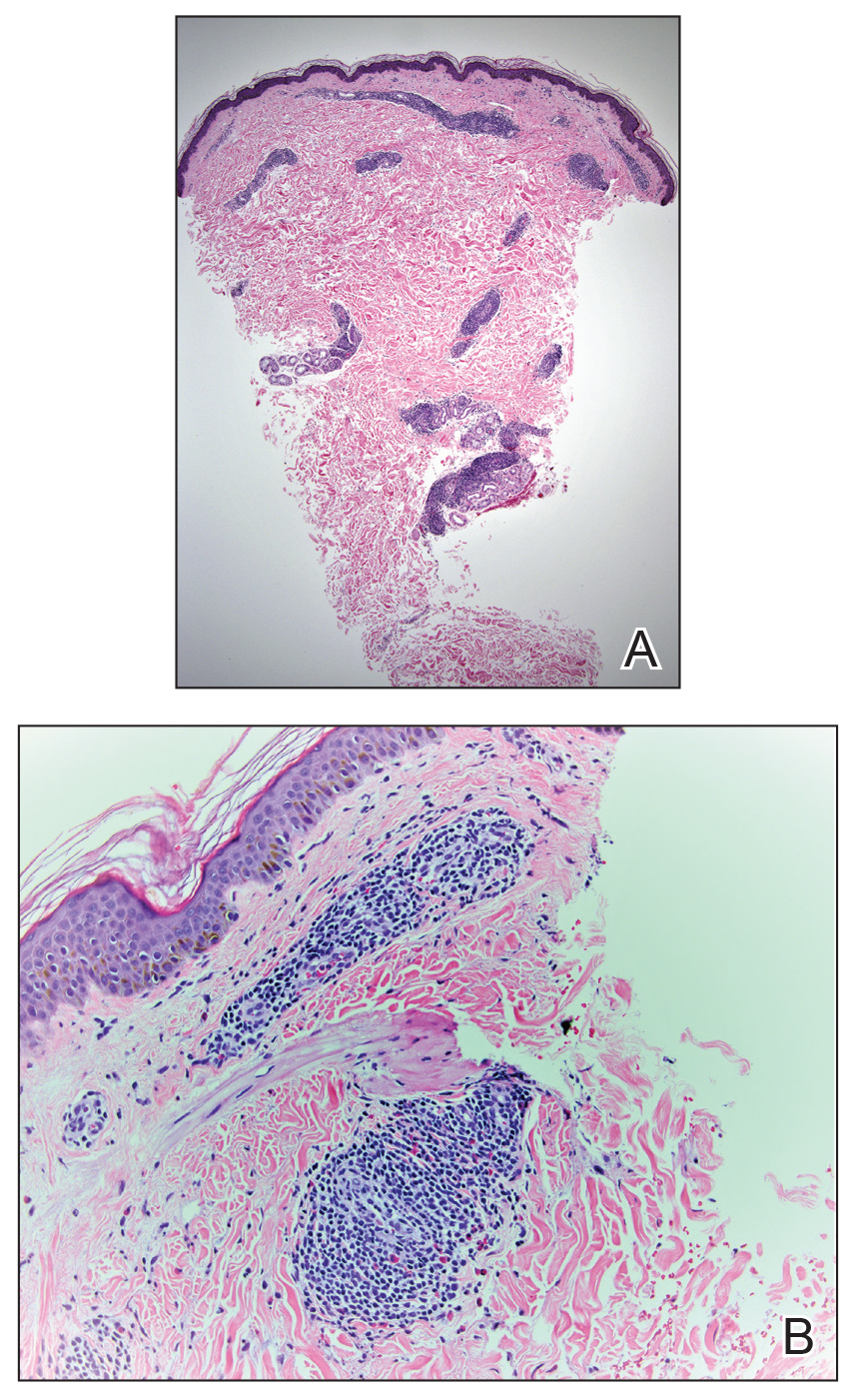

On physical examination, 3 large, pink, scaly, crusted plaques with surrounding erythema were observed (Figure 1A). On palpation, purulent drainage with a foul odor was noted in the area underlying the lesion. Initial punch biopsy demonstrated epidermal hyperplasia with neutrophil-rich sinus tracts consistent with pyoderma vegetans (PV)(Figure 2A). Tissue culture was positive for Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus anginosus. Cultures for both fungi and acid-fast bacilli were negative for growth.

The patient was treated with mupirocin ointment 2% and 3 months of cephalexin 250 mg twice daily, which cleared the purulent crust; however, serous drainage, ulceration, and erythema persisted. The patient needed an extended course of antibiotics, which had not been previously administered to clear the purulence. During this treatment regimen, the patient’s DM remained uncontrolled.

A second deeper punch biopsy revealed a layered granulomatous infiltrate with sclerosis throughout the dermis most consistent with necrobiosis lipoidica (NL)(Figure 2B). Direct immunofluorescence biopsy was negative. Once the PV was clear, betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% was initiated to address the residual lesions (Figure 1B).

Physical examination combined with histopathologic findings and staphylococcal- and streptococcal-positive tissue cultures supported a diagnosis of NL with superimposed PV.

Comment

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a chronic granulomatous disease characterized by collagen degeneration, granulomatous formation, and endothelial wall thickening.1 The condition is most commonly seen in association with insulin-dependent DM, though it also has been described in other inflammatory conditions. A case of NL in monozygotic twins has been reported, suggesting a genetic component in nondiabetic patients with NL.2 Necrobiosis lipoidica affects females more often than males.

The pathogenesis of NL is not well understood but likely involves secondary microangiopathy because of glycoprotein deposition in vessel walls, leading to vascular thickening. Histopathology reveals palisading and necrobiotic granulomas comprising large confluent areas of necrobiosis throughout the dermis, giving a layered appearance.3

Clinically, NL presents with asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, violaceous papules and nodules that coalesce into plaques on the lower extremities, face, or trunk. The plaques have a central red-brown hue that progressively becomes more yellow and atrophic. The lesions can become eroded and ulcerated if left untreated.1

Clinical diagnosis of NL can be challenging due to the similar clinical findings of other granulomatous lesions, such as granuloma annulare and cutaneous sarcoidosis. As reported by Pellicano and colleagues,4 dermoscopy has proved to be an excellent tool for differentiating these granulomatous skin lesions. Necrobiosis lipoidica demonstrates elongated serpentine telangiectases overlying a white structureless background, whereas granuloma annulare reveals orange-red structureless peripheral borders.5

Treatment of NL is difficult; patients often are refractory. Tight control of blood glucose alone has not been proven to cure NL. The mainstay of treatment is topical and intralesional corticosteroids at the active borders of the lesions. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors have shown some success, though recurrence has been reported.6 Other treatments, such as topical tretinoin and topical tacrolimus, may be of some benefit for atrophic NL lesions. Studies also have shown that skin grafting can be of surgical benefit in ulcerative NL with a low rate of recurrence.6 Control and management of DM plus lifestyle modifications may play a role in decreasing the severity of NL.7 Topical psoralen plus UVA light therapy and other experimental treatments, such as antiplatelet medications,8 also have been utilized.

The case of NL presented here was complicated by a superimposed suppurative infection consistent with PV, a rare chronic bacterial infection of the skin that presents with vegetative plaques. Pyoderma vegetans is most commonly observed in patients with underlying immunosuppression, likely secondary to DM in this case. Pyoderma vegetans is most often caused by S aureus and β-hemolytic streptococci. The clinical presentation of PV reveals verrucous vegetative plaques with pustules and abscesses. The borders of the lesions may be elevated and have a granulomatous appearance, thus complicating clinical diagnosis. There often is foul-smelling, purulent discharge within the plaques.9

Histopathology reveals pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with abscesses and sinus tracts. An acute or chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate may be observed. Basophilic fungus like granules are not seen within specimens of PV, which helps differentiate the disease from botryomycosis.10

There is no standardized treatment of PV; topical and systemic antibiotics are mainstays.10 One reported case of PV responded well to acitretin.9 Our patient responded well to 3 months of oral antibiotic therapy, followed by topical corticosteroids.

1. Reid SD, Ladizinski B, Lee K, et al. Update on necrobiosis lipoidica: a review of etiology, diagnosis, and treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:783-791.

2. Shimanovich I, Erdmann H, Grabbe J, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica in monozygotic twins. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:119-120.

3. Ghazarian D, Al Habeeb A. Necrobiotic lesions of the skin: an approach and review of the literature. Diagn Histopathol. 2009;15:186-194.

4. Pellicano R, Caldarola G, Filabozzi P, et al. Dermoscopy of necrobiosis lipoidica and granuloma annulare. Dermatology. 2013;226:319-323.

5. Bakos RM, Cartell A, Bakos L. Dermatoscopy of early-onset necrobiosis lipoidica. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:143-144.

6. Feily A, Mehraban S. Treatment modalities of necrobiosis lipoidica: a concise systematic review. Dermatol Reports. 2015;7:5749.

7. Yigit S, Estrada E. Recurrent necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum associated with venous insufficiency in an adolescent with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr. 2002;141:280-282.

8. Heng MC, Song MK, Heng MK. Healing of necrobiotic ulcers with antiplatelet therapy. Correlation with plasma thromboxane levels. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:195-197.

9. Lee Y, Jung SW, Sim HS, et al. Blastomycosis-like pyoderma with good response to acitretin. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:365-368.

10. Marschalko M, Preisz K, Harsing J, et al. Pyoderma vegetans. report on a case and review of data on pyoderma vegetans and cutaneous botryomycosis. Acta Dermatovenerol. 1995;95:55-59.

Case Report

A 26-year-old woman with a medical history of newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, and asthma was evaluated as a hospital consultation with a vegetative plaque on the left lateral ankle of 13 months’ duration. The lesion first appeared as a red scaly rash that became purulent. The lesion had been treated with multiple rounds of topical antibiotics, oral antibiotics, topical antifungals, and corticosteroids without resolution. The patient denied pain or any decrease in ankle mobility. Review of systems was otherwise negative.

On physical examination, 3 large, pink, scaly, crusted plaques with surrounding erythema were observed (Figure 1A). On palpation, purulent drainage with a foul odor was noted in the area underlying the lesion. Initial punch biopsy demonstrated epidermal hyperplasia with neutrophil-rich sinus tracts consistent with pyoderma vegetans (PV)(Figure 2A). Tissue culture was positive for Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus anginosus. Cultures for both fungi and acid-fast bacilli were negative for growth.

The patient was treated with mupirocin ointment 2% and 3 months of cephalexin 250 mg twice daily, which cleared the purulent crust; however, serous drainage, ulceration, and erythema persisted. The patient needed an extended course of antibiotics, which had not been previously administered to clear the purulence. During this treatment regimen, the patient’s DM remained uncontrolled.

A second deeper punch biopsy revealed a layered granulomatous infiltrate with sclerosis throughout the dermis most consistent with necrobiosis lipoidica (NL)(Figure 2B). Direct immunofluorescence biopsy was negative. Once the PV was clear, betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% was initiated to address the residual lesions (Figure 1B).

Physical examination combined with histopathologic findings and staphylococcal- and streptococcal-positive tissue cultures supported a diagnosis of NL with superimposed PV.

Comment

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a chronic granulomatous disease characterized by collagen degeneration, granulomatous formation, and endothelial wall thickening.1 The condition is most commonly seen in association with insulin-dependent DM, though it also has been described in other inflammatory conditions. A case of NL in monozygotic twins has been reported, suggesting a genetic component in nondiabetic patients with NL.2 Necrobiosis lipoidica affects females more often than males.

The pathogenesis of NL is not well understood but likely involves secondary microangiopathy because of glycoprotein deposition in vessel walls, leading to vascular thickening. Histopathology reveals palisading and necrobiotic granulomas comprising large confluent areas of necrobiosis throughout the dermis, giving a layered appearance.3

Clinically, NL presents with asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, violaceous papules and nodules that coalesce into plaques on the lower extremities, face, or trunk. The plaques have a central red-brown hue that progressively becomes more yellow and atrophic. The lesions can become eroded and ulcerated if left untreated.1

Clinical diagnosis of NL can be challenging due to the similar clinical findings of other granulomatous lesions, such as granuloma annulare and cutaneous sarcoidosis. As reported by Pellicano and colleagues,4 dermoscopy has proved to be an excellent tool for differentiating these granulomatous skin lesions. Necrobiosis lipoidica demonstrates elongated serpentine telangiectases overlying a white structureless background, whereas granuloma annulare reveals orange-red structureless peripheral borders.5

Treatment of NL is difficult; patients often are refractory. Tight control of blood glucose alone has not been proven to cure NL. The mainstay of treatment is topical and intralesional corticosteroids at the active borders of the lesions. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors have shown some success, though recurrence has been reported.6 Other treatments, such as topical tretinoin and topical tacrolimus, may be of some benefit for atrophic NL lesions. Studies also have shown that skin grafting can be of surgical benefit in ulcerative NL with a low rate of recurrence.6 Control and management of DM plus lifestyle modifications may play a role in decreasing the severity of NL.7 Topical psoralen plus UVA light therapy and other experimental treatments, such as antiplatelet medications,8 also have been utilized.

The case of NL presented here was complicated by a superimposed suppurative infection consistent with PV, a rare chronic bacterial infection of the skin that presents with vegetative plaques. Pyoderma vegetans is most commonly observed in patients with underlying immunosuppression, likely secondary to DM in this case. Pyoderma vegetans is most often caused by S aureus and β-hemolytic streptococci. The clinical presentation of PV reveals verrucous vegetative plaques with pustules and abscesses. The borders of the lesions may be elevated and have a granulomatous appearance, thus complicating clinical diagnosis. There often is foul-smelling, purulent discharge within the plaques.9

Histopathology reveals pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with abscesses and sinus tracts. An acute or chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate may be observed. Basophilic fungus like granules are not seen within specimens of PV, which helps differentiate the disease from botryomycosis.10

There is no standardized treatment of PV; topical and systemic antibiotics are mainstays.10 One reported case of PV responded well to acitretin.9 Our patient responded well to 3 months of oral antibiotic therapy, followed by topical corticosteroids.

Case Report

A 26-year-old woman with a medical history of newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, and asthma was evaluated as a hospital consultation with a vegetative plaque on the left lateral ankle of 13 months’ duration. The lesion first appeared as a red scaly rash that became purulent. The lesion had been treated with multiple rounds of topical antibiotics, oral antibiotics, topical antifungals, and corticosteroids without resolution. The patient denied pain or any decrease in ankle mobility. Review of systems was otherwise negative.

On physical examination, 3 large, pink, scaly, crusted plaques with surrounding erythema were observed (Figure 1A). On palpation, purulent drainage with a foul odor was noted in the area underlying the lesion. Initial punch biopsy demonstrated epidermal hyperplasia with neutrophil-rich sinus tracts consistent with pyoderma vegetans (PV)(Figure 2A). Tissue culture was positive for Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus anginosus. Cultures for both fungi and acid-fast bacilli were negative for growth.

The patient was treated with mupirocin ointment 2% and 3 months of cephalexin 250 mg twice daily, which cleared the purulent crust; however, serous drainage, ulceration, and erythema persisted. The patient needed an extended course of antibiotics, which had not been previously administered to clear the purulence. During this treatment regimen, the patient’s DM remained uncontrolled.

A second deeper punch biopsy revealed a layered granulomatous infiltrate with sclerosis throughout the dermis most consistent with necrobiosis lipoidica (NL)(Figure 2B). Direct immunofluorescence biopsy was negative. Once the PV was clear, betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% was initiated to address the residual lesions (Figure 1B).

Physical examination combined with histopathologic findings and staphylococcal- and streptococcal-positive tissue cultures supported a diagnosis of NL with superimposed PV.

Comment

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a chronic granulomatous disease characterized by collagen degeneration, granulomatous formation, and endothelial wall thickening.1 The condition is most commonly seen in association with insulin-dependent DM, though it also has been described in other inflammatory conditions. A case of NL in monozygotic twins has been reported, suggesting a genetic component in nondiabetic patients with NL.2 Necrobiosis lipoidica affects females more often than males.

The pathogenesis of NL is not well understood but likely involves secondary microangiopathy because of glycoprotein deposition in vessel walls, leading to vascular thickening. Histopathology reveals palisading and necrobiotic granulomas comprising large confluent areas of necrobiosis throughout the dermis, giving a layered appearance.3

Clinically, NL presents with asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, violaceous papules and nodules that coalesce into plaques on the lower extremities, face, or trunk. The plaques have a central red-brown hue that progressively becomes more yellow and atrophic. The lesions can become eroded and ulcerated if left untreated.1

Clinical diagnosis of NL can be challenging due to the similar clinical findings of other granulomatous lesions, such as granuloma annulare and cutaneous sarcoidosis. As reported by Pellicano and colleagues,4 dermoscopy has proved to be an excellent tool for differentiating these granulomatous skin lesions. Necrobiosis lipoidica demonstrates elongated serpentine telangiectases overlying a white structureless background, whereas granuloma annulare reveals orange-red structureless peripheral borders.5

Treatment of NL is difficult; patients often are refractory. Tight control of blood glucose alone has not been proven to cure NL. The mainstay of treatment is topical and intralesional corticosteroids at the active borders of the lesions. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors have shown some success, though recurrence has been reported.6 Other treatments, such as topical tretinoin and topical tacrolimus, may be of some benefit for atrophic NL lesions. Studies also have shown that skin grafting can be of surgical benefit in ulcerative NL with a low rate of recurrence.6 Control and management of DM plus lifestyle modifications may play a role in decreasing the severity of NL.7 Topical psoralen plus UVA light therapy and other experimental treatments, such as antiplatelet medications,8 also have been utilized.

The case of NL presented here was complicated by a superimposed suppurative infection consistent with PV, a rare chronic bacterial infection of the skin that presents with vegetative plaques. Pyoderma vegetans is most commonly observed in patients with underlying immunosuppression, likely secondary to DM in this case. Pyoderma vegetans is most often caused by S aureus and β-hemolytic streptococci. The clinical presentation of PV reveals verrucous vegetative plaques with pustules and abscesses. The borders of the lesions may be elevated and have a granulomatous appearance, thus complicating clinical diagnosis. There often is foul-smelling, purulent discharge within the plaques.9

Histopathology reveals pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with abscesses and sinus tracts. An acute or chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate may be observed. Basophilic fungus like granules are not seen within specimens of PV, which helps differentiate the disease from botryomycosis.10

There is no standardized treatment of PV; topical and systemic antibiotics are mainstays.10 One reported case of PV responded well to acitretin.9 Our patient responded well to 3 months of oral antibiotic therapy, followed by topical corticosteroids.

1. Reid SD, Ladizinski B, Lee K, et al. Update on necrobiosis lipoidica: a review of etiology, diagnosis, and treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:783-791.

2. Shimanovich I, Erdmann H, Grabbe J, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica in monozygotic twins. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:119-120.