User login

Violaceous Nodules on the Hard Palate

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

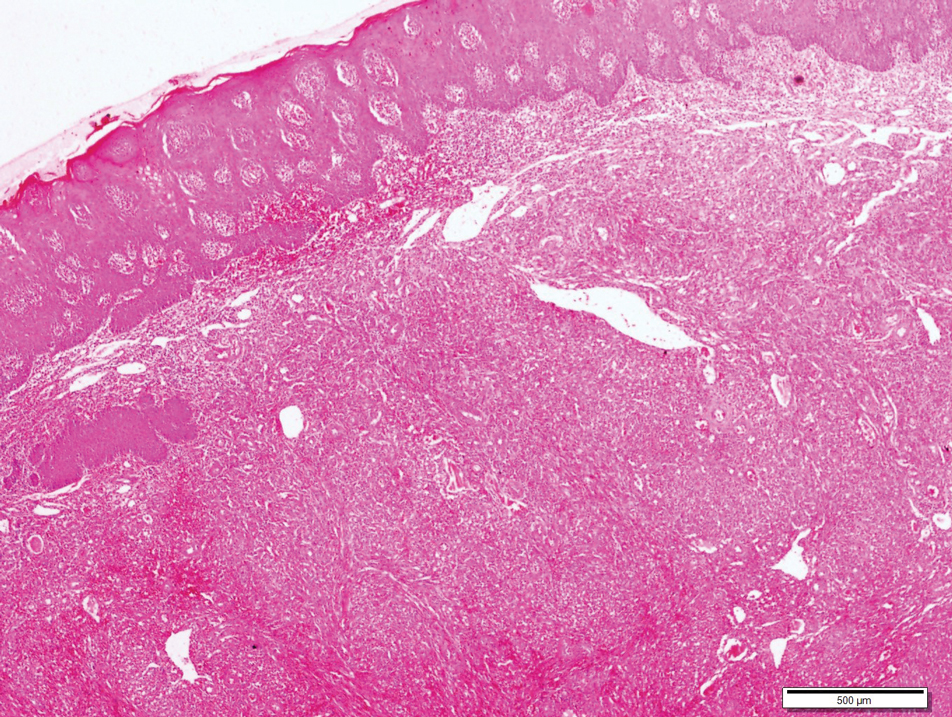

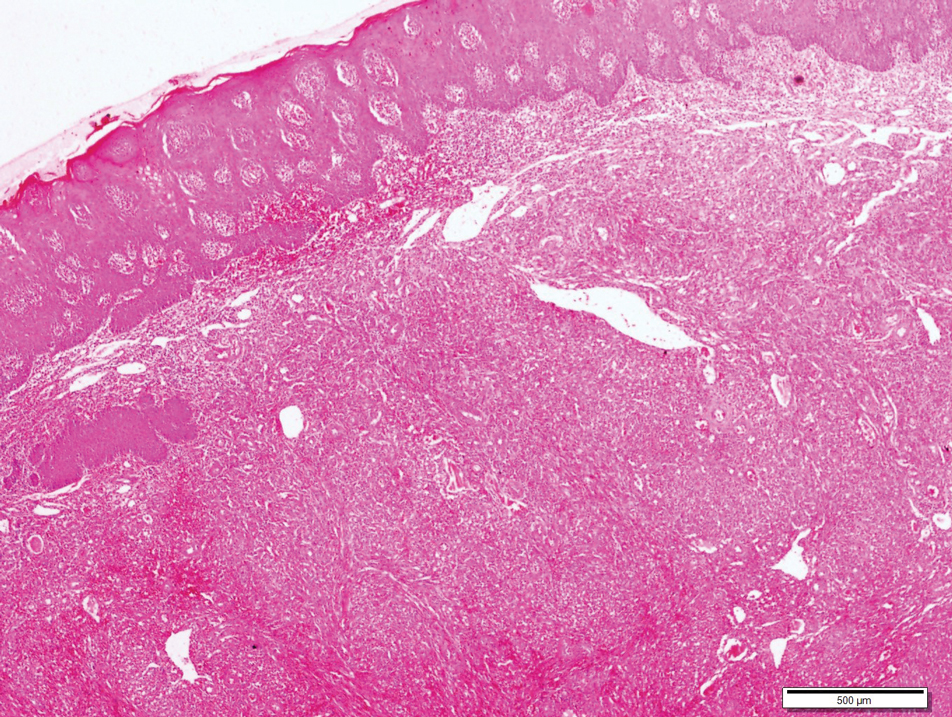

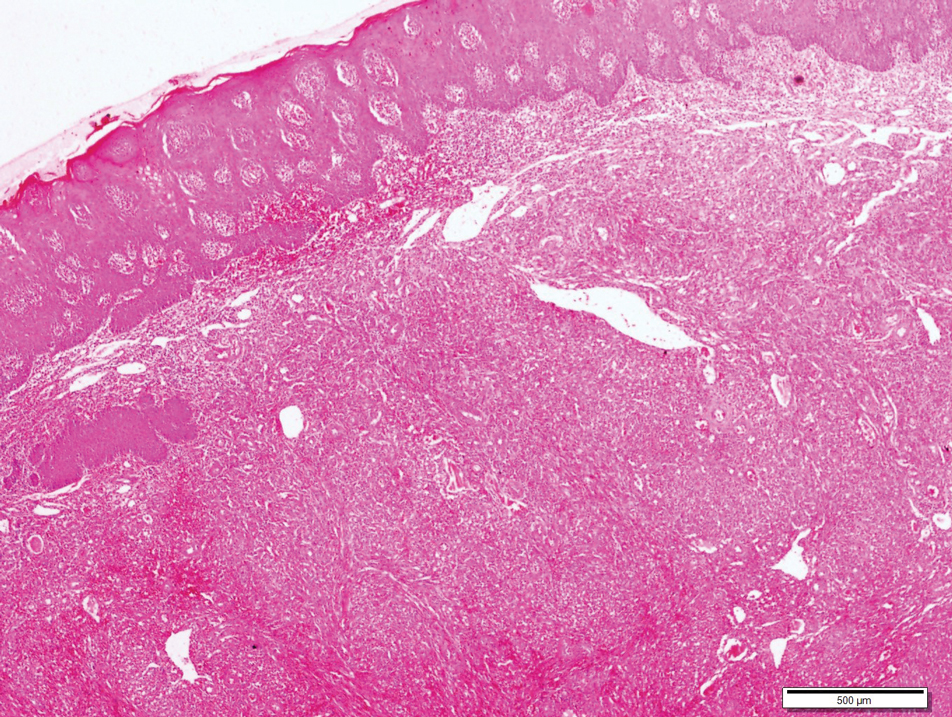

A 4-mm punch biopsy from the border of an ulcerated nodular lesion on the hard palate demonstrated diffusely distributed spindle cells, cleftlike microvascularity with extravasated erythrocytes, and widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity on histopathology (Figure 1). Serologic tests were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; HIV RNA was 14,584 IU/mL and the CD4 count was 254/mm3. The patient was diagnosed with Kaposi sarcoma (KS) and referred to the infectious disease department for initiation of antiviral therapy. Marked regression was detected after 6 months of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) without any additional treatment (Figure 2).

widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity (H&E, original magnification ×4).

Kaposi sarcoma is a human herpesvirus 8-associated angioproliferative disorder with low-grade malignant potential. There are 4 well-known clinical types: classic, endemic, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated.1 Involvement of the oral cavity may be seen in all types but mostly is associated with the AIDS-associated type, which also could be a signal for undiagnosed asymptomatic HIV infection.2 Oral KS most often affects the hard and soft palate, gingiva, and dorsal tongue, with plaques or tumors ranging from nonpigmented to brownish red or violaceous. AIDS-associated KS is known to be related to cytokine expression, which is induced by HIV infection causing immune dysregulation by altering the expression of cytokines, including IL-1, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-6.1 An in vitro study showed that cytokines secrete a number of angiogenic growth factors that, along with HIV proteins, induce and proliferate cells to become sarcoma cells. Integrins and the apoptosis process also are important in proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3

Bacillary angiomatosis (BA) is a rare manifestation of infection caused by Bartonella species, which leads to vasoproliferative lesions of the skin and other organs. Bacillary angiomatosis affects individuals with advanced HIV or other immunocompromised individuals and may clinically mimic KS, which is similarly characterized by red-purple papules, nodules, or plaques. Differentiating BA from KS largely depends on histopathologic examination, with BA demonstrating protuberant endothelial cells surrounded by clumps of bacilli that are visible on Warthin-Starry silver stain.

Lymphangioma is a benign hamartomatous hyperplasia of the lymphatic vessels. The majority of lymphangiomas are superficial, but a few may extend deeply into the connective tissue. Intraoral lymphangiomas occur more frequently on the dorsum of the tongue, followed by the palate, buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. They may be differentiated with their soft quality, pebblelike surface, and translucent vesicles.

Malignant tumors of the oral cavity are rare, representing only 5% of tumors occurring in the body.4 Among malignant tumors of the oral cavity, squamous cell carcinomas are the most frequent type (90%-98%), and lymphomas and melanoma are the most outstanding among the remaining 2% to 10%. Both for lymphoma and mucosal melanoma, the most common sites of involvement are the soft tissues of the oral cavity, palatal mucosa, gingiva, tongue, cheeks, floor of the mouth, and lips.4 Although mucosal melanoma lesions usually are characterized by pigmented and ulcerated lesions, amelanotic variants also should be kept in mind. Histopathologic examination is mandatory for diagnosis.

Intralesional chemotherapy with vinblastine or bleomycin, radiotherapy, electrochemotherapy, systemic antiretroviral therapy (ie, HAART), and chemotherapy with daunorubicin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin are the main treatment options.5,6 The immune system activator role of HAART leads to an increased CD4 count and reduces HIV proteins, which helps induction of the proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3 This effect may help resolution of KS with localized involvement and allows physicians to utilize HAART without any other additional local and systemic chemotherapy treatment.

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Oral Kaposi's sarcoma: a review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:666-672.

- Martorano LM, Cannella JD, Lloyd JR. Mucocutaneous presentation of Kaposi sarcoma in an asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-positive man. Cutis. 2015;95:E19-E22.

- Stebbing J, Portsmouth S, Gazzard B. How does HAART lead to the resolution of Kaposi's sarcoma? J Antimicrobial Chemother. 2003;51:1095-1098.

- Guevara-Canales JO, Morales-Vadillo R, Sacsaquispe-Contreras SJ, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the oral cavity and the maxillofacial region: overall survivalprognostic factors. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18:E619-E626.

- Donato V, Guarnaccia R, Dognini J, et al. Radiation therapy in the treatment of HIV-related Kaposi's sarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:2153-2157.

- Gbabe OF, Okwundu CI, Dedicoat M, et al. Treatment of severe or progressive Kaposi's sarcoma in HIV-infected adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003256.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

A 4-mm punch biopsy from the border of an ulcerated nodular lesion on the hard palate demonstrated diffusely distributed spindle cells, cleftlike microvascularity with extravasated erythrocytes, and widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity on histopathology (Figure 1). Serologic tests were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; HIV RNA was 14,584 IU/mL and the CD4 count was 254/mm3. The patient was diagnosed with Kaposi sarcoma (KS) and referred to the infectious disease department for initiation of antiviral therapy. Marked regression was detected after 6 months of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) without any additional treatment (Figure 2).

widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity (H&E, original magnification ×4).

Kaposi sarcoma is a human herpesvirus 8-associated angioproliferative disorder with low-grade malignant potential. There are 4 well-known clinical types: classic, endemic, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated.1 Involvement of the oral cavity may be seen in all types but mostly is associated with the AIDS-associated type, which also could be a signal for undiagnosed asymptomatic HIV infection.2 Oral KS most often affects the hard and soft palate, gingiva, and dorsal tongue, with plaques or tumors ranging from nonpigmented to brownish red or violaceous. AIDS-associated KS is known to be related to cytokine expression, which is induced by HIV infection causing immune dysregulation by altering the expression of cytokines, including IL-1, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-6.1 An in vitro study showed that cytokines secrete a number of angiogenic growth factors that, along with HIV proteins, induce and proliferate cells to become sarcoma cells. Integrins and the apoptosis process also are important in proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3

Bacillary angiomatosis (BA) is a rare manifestation of infection caused by Bartonella species, which leads to vasoproliferative lesions of the skin and other organs. Bacillary angiomatosis affects individuals with advanced HIV or other immunocompromised individuals and may clinically mimic KS, which is similarly characterized by red-purple papules, nodules, or plaques. Differentiating BA from KS largely depends on histopathologic examination, with BA demonstrating protuberant endothelial cells surrounded by clumps of bacilli that are visible on Warthin-Starry silver stain.

Lymphangioma is a benign hamartomatous hyperplasia of the lymphatic vessels. The majority of lymphangiomas are superficial, but a few may extend deeply into the connective tissue. Intraoral lymphangiomas occur more frequently on the dorsum of the tongue, followed by the palate, buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. They may be differentiated with their soft quality, pebblelike surface, and translucent vesicles.

Malignant tumors of the oral cavity are rare, representing only 5% of tumors occurring in the body.4 Among malignant tumors of the oral cavity, squamous cell carcinomas are the most frequent type (90%-98%), and lymphomas and melanoma are the most outstanding among the remaining 2% to 10%. Both for lymphoma and mucosal melanoma, the most common sites of involvement are the soft tissues of the oral cavity, palatal mucosa, gingiva, tongue, cheeks, floor of the mouth, and lips.4 Although mucosal melanoma lesions usually are characterized by pigmented and ulcerated lesions, amelanotic variants also should be kept in mind. Histopathologic examination is mandatory for diagnosis.

Intralesional chemotherapy with vinblastine or bleomycin, radiotherapy, electrochemotherapy, systemic antiretroviral therapy (ie, HAART), and chemotherapy with daunorubicin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin are the main treatment options.5,6 The immune system activator role of HAART leads to an increased CD4 count and reduces HIV proteins, which helps induction of the proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3 This effect may help resolution of KS with localized involvement and allows physicians to utilize HAART without any other additional local and systemic chemotherapy treatment.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

A 4-mm punch biopsy from the border of an ulcerated nodular lesion on the hard palate demonstrated diffusely distributed spindle cells, cleftlike microvascularity with extravasated erythrocytes, and widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity on histopathology (Figure 1). Serologic tests were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; HIV RNA was 14,584 IU/mL and the CD4 count was 254/mm3. The patient was diagnosed with Kaposi sarcoma (KS) and referred to the infectious disease department for initiation of antiviral therapy. Marked regression was detected after 6 months of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) without any additional treatment (Figure 2).

widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity (H&E, original magnification ×4).

Kaposi sarcoma is a human herpesvirus 8-associated angioproliferative disorder with low-grade malignant potential. There are 4 well-known clinical types: classic, endemic, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated.1 Involvement of the oral cavity may be seen in all types but mostly is associated with the AIDS-associated type, which also could be a signal for undiagnosed asymptomatic HIV infection.2 Oral KS most often affects the hard and soft palate, gingiva, and dorsal tongue, with plaques or tumors ranging from nonpigmented to brownish red or violaceous. AIDS-associated KS is known to be related to cytokine expression, which is induced by HIV infection causing immune dysregulation by altering the expression of cytokines, including IL-1, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-6.1 An in vitro study showed that cytokines secrete a number of angiogenic growth factors that, along with HIV proteins, induce and proliferate cells to become sarcoma cells. Integrins and the apoptosis process also are important in proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3

Bacillary angiomatosis (BA) is a rare manifestation of infection caused by Bartonella species, which leads to vasoproliferative lesions of the skin and other organs. Bacillary angiomatosis affects individuals with advanced HIV or other immunocompromised individuals and may clinically mimic KS, which is similarly characterized by red-purple papules, nodules, or plaques. Differentiating BA from KS largely depends on histopathologic examination, with BA demonstrating protuberant endothelial cells surrounded by clumps of bacilli that are visible on Warthin-Starry silver stain.

Lymphangioma is a benign hamartomatous hyperplasia of the lymphatic vessels. The majority of lymphangiomas are superficial, but a few may extend deeply into the connective tissue. Intraoral lymphangiomas occur more frequently on the dorsum of the tongue, followed by the palate, buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. They may be differentiated with their soft quality, pebblelike surface, and translucent vesicles.

Malignant tumors of the oral cavity are rare, representing only 5% of tumors occurring in the body.4 Among malignant tumors of the oral cavity, squamous cell carcinomas are the most frequent type (90%-98%), and lymphomas and melanoma are the most outstanding among the remaining 2% to 10%. Both for lymphoma and mucosal melanoma, the most common sites of involvement are the soft tissues of the oral cavity, palatal mucosa, gingiva, tongue, cheeks, floor of the mouth, and lips.4 Although mucosal melanoma lesions usually are characterized by pigmented and ulcerated lesions, amelanotic variants also should be kept in mind. Histopathologic examination is mandatory for diagnosis.

Intralesional chemotherapy with vinblastine or bleomycin, radiotherapy, electrochemotherapy, systemic antiretroviral therapy (ie, HAART), and chemotherapy with daunorubicin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin are the main treatment options.5,6 The immune system activator role of HAART leads to an increased CD4 count and reduces HIV proteins, which helps induction of the proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3 This effect may help resolution of KS with localized involvement and allows physicians to utilize HAART without any other additional local and systemic chemotherapy treatment.

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Oral Kaposi's sarcoma: a review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:666-672.

- Martorano LM, Cannella JD, Lloyd JR. Mucocutaneous presentation of Kaposi sarcoma in an asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-positive man. Cutis. 2015;95:E19-E22.

- Stebbing J, Portsmouth S, Gazzard B. How does HAART lead to the resolution of Kaposi's sarcoma? J Antimicrobial Chemother. 2003;51:1095-1098.

- Guevara-Canales JO, Morales-Vadillo R, Sacsaquispe-Contreras SJ, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the oral cavity and the maxillofacial region: overall survivalprognostic factors. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18:E619-E626.

- Donato V, Guarnaccia R, Dognini J, et al. Radiation therapy in the treatment of HIV-related Kaposi's sarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:2153-2157.

- Gbabe OF, Okwundu CI, Dedicoat M, et al. Treatment of severe or progressive Kaposi's sarcoma in HIV-infected adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003256.

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Oral Kaposi's sarcoma: a review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:666-672.

- Martorano LM, Cannella JD, Lloyd JR. Mucocutaneous presentation of Kaposi sarcoma in an asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-positive man. Cutis. 2015;95:E19-E22.

- Stebbing J, Portsmouth S, Gazzard B. How does HAART lead to the resolution of Kaposi's sarcoma? J Antimicrobial Chemother. 2003;51:1095-1098.

- Guevara-Canales JO, Morales-Vadillo R, Sacsaquispe-Contreras SJ, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the oral cavity and the maxillofacial region: overall survivalprognostic factors. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18:E619-E626.

- Donato V, Guarnaccia R, Dognini J, et al. Radiation therapy in the treatment of HIV-related Kaposi's sarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:2153-2157.

- Gbabe OF, Okwundu CI, Dedicoat M, et al. Treatment of severe or progressive Kaposi's sarcoma in HIV-infected adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003256.

A 30-year-old man presented to our outpatient clinic with rapidly growing, ulcerated, violaceous lesions on the hard palate of 4 months' duration. Physical examination revealed approximately 2.0×1.5-cm, centrally ulcerated, violaceous, nodular lesions on the hard palate, as well as a 4-mm pinkish papular lesion on the soft palate.

Weekly ciprofloxacin as effective as daily norfloxacin in prevention of SBP

Clinical question: Does ciprofloxacin administered once weekly prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) as effectively as daily norfloxacin?

Background: Studies have shown that daily administration of norfloxacin is effective for primary prophylaxis as well as secondary prevention of SBP in patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Prior studies have demonstrated efficacy of weekly ciprofloxacin, but no previous studies have compared the two antibiotics.

Study design: Investigator initiated open-label randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Seven tertiary hospitals in South Korea.

Synopsis: The investigators enrolled 124 patients aged 20-75 with cirrhosis and ascites, ascitic cell count less than 250/mm3, and either ascitic protein less than 1.5g/dL or a history of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. The patients were randomized to receive norfloxacin 400 mg daily or ciprofloxacin 750 mg weekly, with routine visits during the 12-month study period.

The primary end point of SBP prevention rates at 1 year were 92.7% (51/55) in the norfloxacin group and 96.5% (55/57) in the ciprofloxacin group (P = .712), which met criteria for noninferiority. Other outcomes included no difference in rates of liver transplantation, infectious complications, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, and hepatocellular carcinoma. A subgroup analysis of patients at higher risk of developing SBP showed 87% prevention rates for the norfloxacin group and 94% for the ciprofloxacin group, although this result was not statistically significant.

The major limitation of this study is that it was not double blinded, so patients were aware of which medication they were taking. Additionally, almost 10% of the cohort was lost to follow-up, but this was accounted for in the sample-size calculation.

Bottom line: Once weekly administration of ciprofloxacin is not inferior to daily norfloxacin for the prevention of SBP in patients with cirrhosis and low ascitic protein levels and may provide a more cost-effective therapy with greater patient compliance.

Citation: Yim HJ et al. Daily norfloxacin vs weekly ciprofloxacin to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Aug;113:1167-76.

Dr. Angeli is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of New Mexico.

Clinical question: Does ciprofloxacin administered once weekly prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) as effectively as daily norfloxacin?

Background: Studies have shown that daily administration of norfloxacin is effective for primary prophylaxis as well as secondary prevention of SBP in patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Prior studies have demonstrated efficacy of weekly ciprofloxacin, but no previous studies have compared the two antibiotics.

Study design: Investigator initiated open-label randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Seven tertiary hospitals in South Korea.

Synopsis: The investigators enrolled 124 patients aged 20-75 with cirrhosis and ascites, ascitic cell count less than 250/mm3, and either ascitic protein less than 1.5g/dL or a history of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. The patients were randomized to receive norfloxacin 400 mg daily or ciprofloxacin 750 mg weekly, with routine visits during the 12-month study period.

The primary end point of SBP prevention rates at 1 year were 92.7% (51/55) in the norfloxacin group and 96.5% (55/57) in the ciprofloxacin group (P = .712), which met criteria for noninferiority. Other outcomes included no difference in rates of liver transplantation, infectious complications, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, and hepatocellular carcinoma. A subgroup analysis of patients at higher risk of developing SBP showed 87% prevention rates for the norfloxacin group and 94% for the ciprofloxacin group, although this result was not statistically significant.

The major limitation of this study is that it was not double blinded, so patients were aware of which medication they were taking. Additionally, almost 10% of the cohort was lost to follow-up, but this was accounted for in the sample-size calculation.

Bottom line: Once weekly administration of ciprofloxacin is not inferior to daily norfloxacin for the prevention of SBP in patients with cirrhosis and low ascitic protein levels and may provide a more cost-effective therapy with greater patient compliance.

Citation: Yim HJ et al. Daily norfloxacin vs weekly ciprofloxacin to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Aug;113:1167-76.

Dr. Angeli is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of New Mexico.

Clinical question: Does ciprofloxacin administered once weekly prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) as effectively as daily norfloxacin?

Background: Studies have shown that daily administration of norfloxacin is effective for primary prophylaxis as well as secondary prevention of SBP in patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Prior studies have demonstrated efficacy of weekly ciprofloxacin, but no previous studies have compared the two antibiotics.

Study design: Investigator initiated open-label randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Seven tertiary hospitals in South Korea.

Synopsis: The investigators enrolled 124 patients aged 20-75 with cirrhosis and ascites, ascitic cell count less than 250/mm3, and either ascitic protein less than 1.5g/dL or a history of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. The patients were randomized to receive norfloxacin 400 mg daily or ciprofloxacin 750 mg weekly, with routine visits during the 12-month study period.

The primary end point of SBP prevention rates at 1 year were 92.7% (51/55) in the norfloxacin group and 96.5% (55/57) in the ciprofloxacin group (P = .712), which met criteria for noninferiority. Other outcomes included no difference in rates of liver transplantation, infectious complications, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, and hepatocellular carcinoma. A subgroup analysis of patients at higher risk of developing SBP showed 87% prevention rates for the norfloxacin group and 94% for the ciprofloxacin group, although this result was not statistically significant.

The major limitation of this study is that it was not double blinded, so patients were aware of which medication they were taking. Additionally, almost 10% of the cohort was lost to follow-up, but this was accounted for in the sample-size calculation.

Bottom line: Once weekly administration of ciprofloxacin is not inferior to daily norfloxacin for the prevention of SBP in patients with cirrhosis and low ascitic protein levels and may provide a more cost-effective therapy with greater patient compliance.

Citation: Yim HJ et al. Daily norfloxacin vs weekly ciprofloxacin to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Aug;113:1167-76.

Dr. Angeli is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of New Mexico.

New recommendations on TB screening for health care workers

U.S. health care personnel no longer need to undergo routine tuberculosis testing in the absence of known exposure, according to new screening guidelines from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC.

The revised guidelines on tuberculosis screening, testing, and treatment of U.S. health care personnel, published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, are the first update since 2005. The new recommendations reflect a reduction in concern about U.S. health care personnel’s risk of occupational exposure to latent and active tuberculosis infection.

Lynn E. Sosa, MD, from the Connecticut Department of Public Health and National Tuberculosis Controllers Association, and coauthors wrote that rates of tuberculosis infection in the United States have declined by 73% since 1991, from 10.4/100,000 population in 1991 to 2.8/100,000 in 2017. This has been matched by similar declines among health care workers, which the authors said raised questions about the cost-effectiveness of the previously recommended routine serial occupational testing.

“In addition, a recent retrospective cohort study of approximately 40,000 health care personnel at a tertiary U.S. medical center in a low TB-incidence state found an extremely low rate of TST conversion (0.3%) during 1998-2014, with a limited proportion attributable to occupational exposure,” they wrote.

The new guidelines recommend health care personnel undergo baseline or preplacement tuberculosis testing with an interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) or a tuberculin skin test (TST), as well as individual risk assessment and symptom evaluation.

The individual risk assessment considers whether the person has lived in a country with a high tuberculosis rate, whether they are immunosuppressed, or whether they have had close contact with someone with infectious tuberculosis.

This risk assessment can help decide how to interpret an initial positive test result, the authors said.

“For example, health care personnel with a positive test who are asymptomatic, unlikely to be infected with M. [Mycobacterium] tuberculosis, and at low risk for progression on the basis of their risk assessment should have a second test (either an IGRA or a TST) as recommended in the 2017 TB diagnostic guidelines of the American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America, and CDC,” they wrote. “In this example, the health care personnel should be considered infected with M. tuberculosis only if both the first and second tests are positive.”

After that baseline testing, personnel do not need to undergo routine serial testing except in the case of known exposure or ongoing transmission. The guideline authors suggested serial screening might be considered for health care workers whose work puts them at greater risk – for example, pulmonologists or respiratory therapists – or for those working in settings in which transmission has happened in the past.

For personnel with latent tuberculosis infection, the guidelines recommend “encouragement of treatment” unless it is contraindicated, and annual symptom screening in those not undergoing treatment.

The guideline committee also advocated for annual tuberculosis education for all health care workers.

The new recommendations were based on a systematic review of 36 studies of tuberculosis screening and testing among health care personnel, 16 of which were performed in the United States, and all but two of which were conducted in a hospital setting.

The authors stressed that recommendations from the 2005 CDC guidelines – which do not pertain to health care personnel screening, testing, treatment and education – remain unchanged.

One author declared personal fees from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association during the conduct of the study. Two others reported unrelated grants and personal fees from private industry. No other conflicts of interest were disclosed.

SOURCE: Sosa L et al. MMWR. 2019;68:439-43.

U.S. health care personnel no longer need to undergo routine tuberculosis testing in the absence of known exposure, according to new screening guidelines from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC.

The revised guidelines on tuberculosis screening, testing, and treatment of U.S. health care personnel, published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, are the first update since 2005. The new recommendations reflect a reduction in concern about U.S. health care personnel’s risk of occupational exposure to latent and active tuberculosis infection.

Lynn E. Sosa, MD, from the Connecticut Department of Public Health and National Tuberculosis Controllers Association, and coauthors wrote that rates of tuberculosis infection in the United States have declined by 73% since 1991, from 10.4/100,000 population in 1991 to 2.8/100,000 in 2017. This has been matched by similar declines among health care workers, which the authors said raised questions about the cost-effectiveness of the previously recommended routine serial occupational testing.

“In addition, a recent retrospective cohort study of approximately 40,000 health care personnel at a tertiary U.S. medical center in a low TB-incidence state found an extremely low rate of TST conversion (0.3%) during 1998-2014, with a limited proportion attributable to occupational exposure,” they wrote.

The new guidelines recommend health care personnel undergo baseline or preplacement tuberculosis testing with an interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) or a tuberculin skin test (TST), as well as individual risk assessment and symptom evaluation.

The individual risk assessment considers whether the person has lived in a country with a high tuberculosis rate, whether they are immunosuppressed, or whether they have had close contact with someone with infectious tuberculosis.

This risk assessment can help decide how to interpret an initial positive test result, the authors said.

“For example, health care personnel with a positive test who are asymptomatic, unlikely to be infected with M. [Mycobacterium] tuberculosis, and at low risk for progression on the basis of their risk assessment should have a second test (either an IGRA or a TST) as recommended in the 2017 TB diagnostic guidelines of the American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America, and CDC,” they wrote. “In this example, the health care personnel should be considered infected with M. tuberculosis only if both the first and second tests are positive.”

After that baseline testing, personnel do not need to undergo routine serial testing except in the case of known exposure or ongoing transmission. The guideline authors suggested serial screening might be considered for health care workers whose work puts them at greater risk – for example, pulmonologists or respiratory therapists – or for those working in settings in which transmission has happened in the past.

For personnel with latent tuberculosis infection, the guidelines recommend “encouragement of treatment” unless it is contraindicated, and annual symptom screening in those not undergoing treatment.

The guideline committee also advocated for annual tuberculosis education for all health care workers.

The new recommendations were based on a systematic review of 36 studies of tuberculosis screening and testing among health care personnel, 16 of which were performed in the United States, and all but two of which were conducted in a hospital setting.

The authors stressed that recommendations from the 2005 CDC guidelines – which do not pertain to health care personnel screening, testing, treatment and education – remain unchanged.

One author declared personal fees from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association during the conduct of the study. Two others reported unrelated grants and personal fees from private industry. No other conflicts of interest were disclosed.

SOURCE: Sosa L et al. MMWR. 2019;68:439-43.

U.S. health care personnel no longer need to undergo routine tuberculosis testing in the absence of known exposure, according to new screening guidelines from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC.

The revised guidelines on tuberculosis screening, testing, and treatment of U.S. health care personnel, published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, are the first update since 2005. The new recommendations reflect a reduction in concern about U.S. health care personnel’s risk of occupational exposure to latent and active tuberculosis infection.

Lynn E. Sosa, MD, from the Connecticut Department of Public Health and National Tuberculosis Controllers Association, and coauthors wrote that rates of tuberculosis infection in the United States have declined by 73% since 1991, from 10.4/100,000 population in 1991 to 2.8/100,000 in 2017. This has been matched by similar declines among health care workers, which the authors said raised questions about the cost-effectiveness of the previously recommended routine serial occupational testing.

“In addition, a recent retrospective cohort study of approximately 40,000 health care personnel at a tertiary U.S. medical center in a low TB-incidence state found an extremely low rate of TST conversion (0.3%) during 1998-2014, with a limited proportion attributable to occupational exposure,” they wrote.

The new guidelines recommend health care personnel undergo baseline or preplacement tuberculosis testing with an interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) or a tuberculin skin test (TST), as well as individual risk assessment and symptom evaluation.

The individual risk assessment considers whether the person has lived in a country with a high tuberculosis rate, whether they are immunosuppressed, or whether they have had close contact with someone with infectious tuberculosis.

This risk assessment can help decide how to interpret an initial positive test result, the authors said.

“For example, health care personnel with a positive test who are asymptomatic, unlikely to be infected with M. [Mycobacterium] tuberculosis, and at low risk for progression on the basis of their risk assessment should have a second test (either an IGRA or a TST) as recommended in the 2017 TB diagnostic guidelines of the American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America, and CDC,” they wrote. “In this example, the health care personnel should be considered infected with M. tuberculosis only if both the first and second tests are positive.”

After that baseline testing, personnel do not need to undergo routine serial testing except in the case of known exposure or ongoing transmission. The guideline authors suggested serial screening might be considered for health care workers whose work puts them at greater risk – for example, pulmonologists or respiratory therapists – or for those working in settings in which transmission has happened in the past.

For personnel with latent tuberculosis infection, the guidelines recommend “encouragement of treatment” unless it is contraindicated, and annual symptom screening in those not undergoing treatment.

The guideline committee also advocated for annual tuberculosis education for all health care workers.

The new recommendations were based on a systematic review of 36 studies of tuberculosis screening and testing among health care personnel, 16 of which were performed in the United States, and all but two of which were conducted in a hospital setting.

The authors stressed that recommendations from the 2005 CDC guidelines – which do not pertain to health care personnel screening, testing, treatment and education – remain unchanged.

One author declared personal fees from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association during the conduct of the study. Two others reported unrelated grants and personal fees from private industry. No other conflicts of interest were disclosed.

SOURCE: Sosa L et al. MMWR. 2019;68:439-43.

FROM MMWR

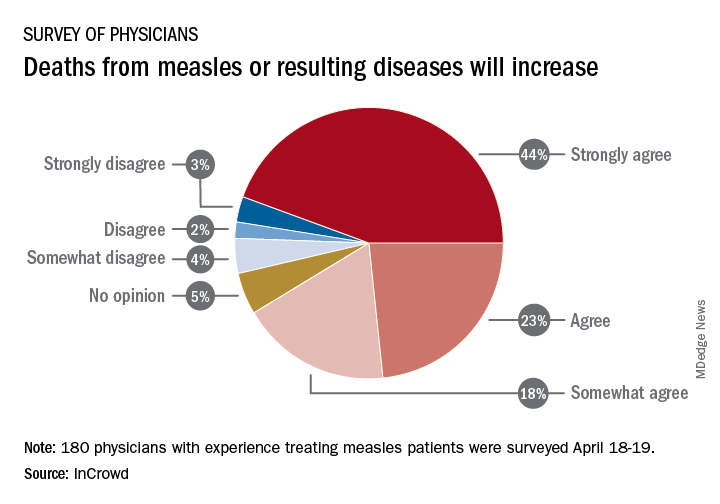

Survey: Physicians predict increase in measles deaths

by real-time market insights technology firm InCrowd.

Among the 180 physicians with experience treating measles, 23% agreed and 44% said that they strongly agreed with the statement that measles deaths would increase, and another 18% said that they somewhat agreed. Only 9% expressed some level of disagreement, InCrowd said.

Most of those respondents also believe that summer travel will increase measles outbreaks (29% agreed and 30% strongly agreed) and that more communities will adopt requirements for measles vaccinations (26% and 36%). A majority also said that education about vaccinations will improve (26% agreed and 29% strongly agreed), but almost half of the physicians surveyed also expect vaccination misinformation to get worse (29% and 19%), InCrowd reported.

“With 44% of respondents predicting a high likelihood that deaths caused by measles will increase, the data show the imperative for physicians and patients to keep up the dialogue. … We have a long way to go before declaring victory,” said Diane Hayes, PhD, president and cofounder of InCrowd.

The InCrowd 5-minute microsurvey was conducted on April 18-19, 2019, and included 455 primary care physicians, of whom 40% said that they have treated or knew of colleagues in their facility or community who have treated patients with measles. Of those 180 respondents, 89 were pediatricians and 91 were in other primary care specialties.

by real-time market insights technology firm InCrowd.

Among the 180 physicians with experience treating measles, 23% agreed and 44% said that they strongly agreed with the statement that measles deaths would increase, and another 18% said that they somewhat agreed. Only 9% expressed some level of disagreement, InCrowd said.

Most of those respondents also believe that summer travel will increase measles outbreaks (29% agreed and 30% strongly agreed) and that more communities will adopt requirements for measles vaccinations (26% and 36%). A majority also said that education about vaccinations will improve (26% agreed and 29% strongly agreed), but almost half of the physicians surveyed also expect vaccination misinformation to get worse (29% and 19%), InCrowd reported.

“With 44% of respondents predicting a high likelihood that deaths caused by measles will increase, the data show the imperative for physicians and patients to keep up the dialogue. … We have a long way to go before declaring victory,” said Diane Hayes, PhD, president and cofounder of InCrowd.

The InCrowd 5-minute microsurvey was conducted on April 18-19, 2019, and included 455 primary care physicians, of whom 40% said that they have treated or knew of colleagues in their facility or community who have treated patients with measles. Of those 180 respondents, 89 were pediatricians and 91 were in other primary care specialties.

by real-time market insights technology firm InCrowd.

Among the 180 physicians with experience treating measles, 23% agreed and 44% said that they strongly agreed with the statement that measles deaths would increase, and another 18% said that they somewhat agreed. Only 9% expressed some level of disagreement, InCrowd said.

Most of those respondents also believe that summer travel will increase measles outbreaks (29% agreed and 30% strongly agreed) and that more communities will adopt requirements for measles vaccinations (26% and 36%). A majority also said that education about vaccinations will improve (26% agreed and 29% strongly agreed), but almost half of the physicians surveyed also expect vaccination misinformation to get worse (29% and 19%), InCrowd reported.

“With 44% of respondents predicting a high likelihood that deaths caused by measles will increase, the data show the imperative for physicians and patients to keep up the dialogue. … We have a long way to go before declaring victory,” said Diane Hayes, PhD, president and cofounder of InCrowd.

The InCrowd 5-minute microsurvey was conducted on April 18-19, 2019, and included 455 primary care physicians, of whom 40% said that they have treated or knew of colleagues in their facility or community who have treated patients with measles. Of those 180 respondents, 89 were pediatricians and 91 were in other primary care specialties.

Young children with neuromuscular disease are vulnerable to respiratory viruses

This highlights the need for new vaccines

Influenza gets a lot of attention each winter, but respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and other respiratory viruses have as much or more impact on pediatric populations, particularly certain high-risk groups. But currently there are no vaccines for noninfluenza respiratory viruses. That said, several are under development, for RSV and parainfluenza.

Which groups are likely to get the most benefit from these newer vaccines?

We all are aware of the extra vulnerability to respiratory viruses (RSV being the most frequent) in premature infants, those with chronic lung disease, or those with congenital heart syndromes; such vulnerable patients are not infrequently seen in routine practice. A recent report shined a brighter light on such a group.

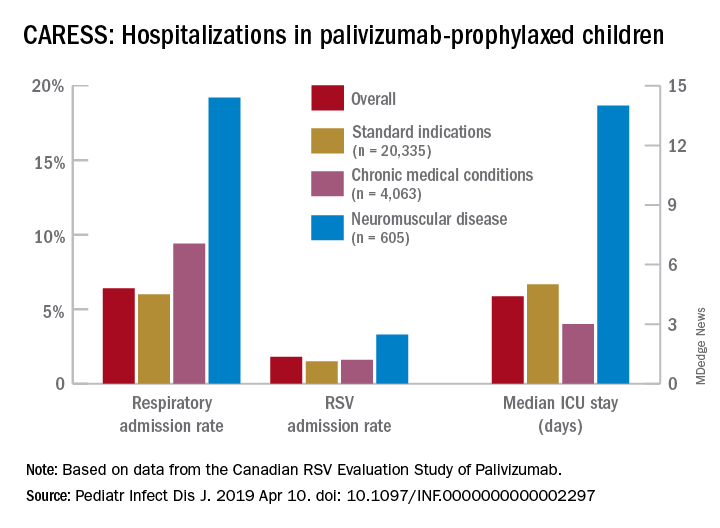

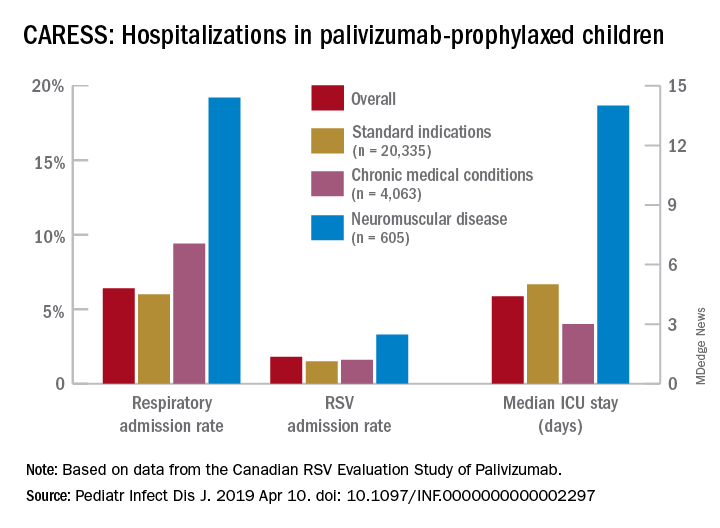

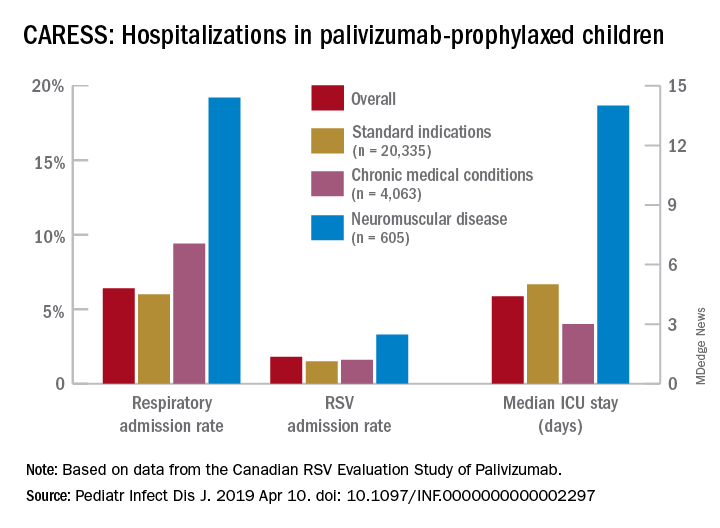

Real-world data from a nationwide Canadian surveillance system (CARESS) was used to analyze relative risks of categories of young children who are thought to be vulnerable to respiratory viruses, with a particular focus on those with neuromuscular disease. The CARESS investigators analyzed 12 years’ data on respiratory hospitalizations from among palivizumab-prophylaxed patients (including specific data on RSV when patients were tested for RSV per standard of care).1 Unfortunately, RSV testing was not universal despite hospitalization, so the true incidence of RSV-specific hospitalizations was likely underestimated.

Nevertheless, more than 25,000 children from 2005 through 2017 were grouped into three categories of palivizumab-prophylaxed high-risk children: standard indications (SI), n = 20,335; chronic medical conditions (CMD), n = 4,063; and neuromuscular disease (NMD), n = 605. This study is notable for having a relatively large number of neuromuscular disease subjects. Two-thirds of each group were fully palivizumab adherent.

The SI group included the standard American Academy of Pediatrics–recommended groups, such as premature infants, congenital heart disease, etc.

The CMD group included conditions that lead clinicians to use palivizumab off label, such as cystic fibrosis, congenital airway anomalies, immunodeficiency, and pulmonary disorders.

The NMD participants were subdivided into two groups. Group 1 comprised general hypotonic neuromuscular diseases such as hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, Prader-Willi syndrome, chromosomal disorders, and migration/demyelinating diseases. Group 2 included more severe infantile neuromuscular disorders, such as spinal muscular atrophy, myotonic dystrophy, centronuclear and nemaline myopathy, mitochondrial and glycogen storage myopathies, or arthrogryposis.

Overall, 6.9% of CARESS RSV-prophylaxed subjects were hospitalized. About one in five hospitalized patients from each group was hospitalized more than once. Specific respiratory hospitalization rates for each group were 6% (n = 1,228) for SI subjects and 9.4% (n = 380) for CMD, compared with 19.2% (n = 116) for NMD subjects.

It is unclear what proportion underwent RSV testing, but a total of 334 were confirmed RSV positive: 261 were SI, 54 were CMD and 19 were NMD. The RSV-test-positive rate was 1.5% for SI, 1.6% for CMD and 3.3% for NMD; so while a higher number of SI children were RSV positive, the rate of RSV positivity was actually highest with NMD.

RSV-positive subjects needing ICU care among NMD patients also had longer ICU stays (median 14 days), compared with RSV-positive CMD or SI subjects (median 3 and 5 days, respectively). Further, hospitalized RSV-positive NMD subjects presented more frequently with pneumonia (42% vs. 30% for CMD and 20% for SI) while hospitalized RSV-positive SI subjects more often had apnea (17% vs. 10% for NMD and 5% for CMD, P less than .05).

These differences in the courses of NMD patients raise the question as to whether the NMD group was somehow different from the SI and CMD groups, other than muscular weakness that likely leads to less ability to clear secretions and a less efficient cough. It turns out that NMD children were older and had worse neonatal medical courses (longer hospital stays, more often ventilated, and used oxygen longer). It could be argued that these differences may have been in part due to the muscular weakness inherent in their underlying disease, but they appear to be predictors of worse respiratory infectious disease than other vulnerable populations as the NMD children get older.

Indeed, the overall risk of any respiratory admission among NMD subjects was nearly twice as high, compared with SI (hazard ratio, 1.90, P less than .0005); but the somewhat higher risk for NMD vs. CMD was not significant (HR, 1.33, P = .090). However, when looking specifically at RSV confirmed admissions, NMD had more than twice the hospitalization risk than either other group (HR, 2.26, P = .001 vs. SI; and HR, 2.74, P = .001 vs. CMD).

Further, an NMD subgroup analysis showed 1.69 times the overall respiratory hospitalization risk among the more severe vs. less severe NMD group, but a similar risk of RSV admission. The authors point out that one reason for this discrepancy may be a higher probability of aspiration causing hospitalization because of more dramatic acute events during respiratory infections in patients with more severe NMD. It also may be that palivizumab evened the playing field for RSV but not for other viruses such as parainfluenza, adenovirus, or even rhinovirus.

Nevertheless, these data tell us that risk of respiratory disease severe enough to need hospitalization continues to an older age in NMD than SI or CMD patients, well past 2 years of age. And the risk is not only from RSV. That said, RSV remains a player in some patients (particularly NMD patients) despite palivizumab prophylaxis, highlighting the need for RSV as well as parainfluenza vaccines. While these vaccines should help all young children, they seem likely to be even more beneficial for high-risk children including those with NMD, and particularly those with more severe NMD.

Eleven among 60 total candidate RSV vaccines (live attenuated, particle based, or vector based) are currently in clinical trials.2 Fewer parainfluenza vaccines are in the pipeline, but clinical trials also are underway.3-5 Approval of such vaccines is not expected until the mid-2020s, so at present we are left with providing palivizumab to our vulnerable patients while emphasizing nonmedical strategies that may help prevent respiratory viruses. These only partially successful preventive interventions include breastfeeding, avoiding secondhand smoke, and avoiding known high-risk exposures, such as large day care centers.

My hope is for quicker than projected progress on the vaccine front so that winter admissions for respiratory viruses might decrease in numbers similar to the decrease we have noted with another vaccine successful against a seasonally active pathogen – rotavirus.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital–Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines. The hospital also receives CDC funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus. Email Dr. Harrison at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019 Apr 10. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002297.

2. “Advances in RSV Vaccine Research and Development – A Global Agenda.”

3. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2015 Dec;4(4): e143-6.

4. J Virol. 2015 Oct;89(20):10319-32.

5. Vaccine. 2017 Dec 18;35(51):7139-46.

This highlights the need for new vaccines

This highlights the need for new vaccines

Influenza gets a lot of attention each winter, but respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and other respiratory viruses have as much or more impact on pediatric populations, particularly certain high-risk groups. But currently there are no vaccines for noninfluenza respiratory viruses. That said, several are under development, for RSV and parainfluenza.

Which groups are likely to get the most benefit from these newer vaccines?

We all are aware of the extra vulnerability to respiratory viruses (RSV being the most frequent) in premature infants, those with chronic lung disease, or those with congenital heart syndromes; such vulnerable patients are not infrequently seen in routine practice. A recent report shined a brighter light on such a group.

Real-world data from a nationwide Canadian surveillance system (CARESS) was used to analyze relative risks of categories of young children who are thought to be vulnerable to respiratory viruses, with a particular focus on those with neuromuscular disease. The CARESS investigators analyzed 12 years’ data on respiratory hospitalizations from among palivizumab-prophylaxed patients (including specific data on RSV when patients were tested for RSV per standard of care).1 Unfortunately, RSV testing was not universal despite hospitalization, so the true incidence of RSV-specific hospitalizations was likely underestimated.

Nevertheless, more than 25,000 children from 2005 through 2017 were grouped into three categories of palivizumab-prophylaxed high-risk children: standard indications (SI), n = 20,335; chronic medical conditions (CMD), n = 4,063; and neuromuscular disease (NMD), n = 605. This study is notable for having a relatively large number of neuromuscular disease subjects. Two-thirds of each group were fully palivizumab adherent.

The SI group included the standard American Academy of Pediatrics–recommended groups, such as premature infants, congenital heart disease, etc.

The CMD group included conditions that lead clinicians to use palivizumab off label, such as cystic fibrosis, congenital airway anomalies, immunodeficiency, and pulmonary disorders.

The NMD participants were subdivided into two groups. Group 1 comprised general hypotonic neuromuscular diseases such as hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, Prader-Willi syndrome, chromosomal disorders, and migration/demyelinating diseases. Group 2 included more severe infantile neuromuscular disorders, such as spinal muscular atrophy, myotonic dystrophy, centronuclear and nemaline myopathy, mitochondrial and glycogen storage myopathies, or arthrogryposis.

Overall, 6.9% of CARESS RSV-prophylaxed subjects were hospitalized. About one in five hospitalized patients from each group was hospitalized more than once. Specific respiratory hospitalization rates for each group were 6% (n = 1,228) for SI subjects and 9.4% (n = 380) for CMD, compared with 19.2% (n = 116) for NMD subjects.

It is unclear what proportion underwent RSV testing, but a total of 334 were confirmed RSV positive: 261 were SI, 54 were CMD and 19 were NMD. The RSV-test-positive rate was 1.5% for SI, 1.6% for CMD and 3.3% for NMD; so while a higher number of SI children were RSV positive, the rate of RSV positivity was actually highest with NMD.

RSV-positive subjects needing ICU care among NMD patients also had longer ICU stays (median 14 days), compared with RSV-positive CMD or SI subjects (median 3 and 5 days, respectively). Further, hospitalized RSV-positive NMD subjects presented more frequently with pneumonia (42% vs. 30% for CMD and 20% for SI) while hospitalized RSV-positive SI subjects more often had apnea (17% vs. 10% for NMD and 5% for CMD, P less than .05).

These differences in the courses of NMD patients raise the question as to whether the NMD group was somehow different from the SI and CMD groups, other than muscular weakness that likely leads to less ability to clear secretions and a less efficient cough. It turns out that NMD children were older and had worse neonatal medical courses (longer hospital stays, more often ventilated, and used oxygen longer). It could be argued that these differences may have been in part due to the muscular weakness inherent in their underlying disease, but they appear to be predictors of worse respiratory infectious disease than other vulnerable populations as the NMD children get older.

Indeed, the overall risk of any respiratory admission among NMD subjects was nearly twice as high, compared with SI (hazard ratio, 1.90, P less than .0005); but the somewhat higher risk for NMD vs. CMD was not significant (HR, 1.33, P = .090). However, when looking specifically at RSV confirmed admissions, NMD had more than twice the hospitalization risk than either other group (HR, 2.26, P = .001 vs. SI; and HR, 2.74, P = .001 vs. CMD).

Further, an NMD subgroup analysis showed 1.69 times the overall respiratory hospitalization risk among the more severe vs. less severe NMD group, but a similar risk of RSV admission. The authors point out that one reason for this discrepancy may be a higher probability of aspiration causing hospitalization because of more dramatic acute events during respiratory infections in patients with more severe NMD. It also may be that palivizumab evened the playing field for RSV but not for other viruses such as parainfluenza, adenovirus, or even rhinovirus.

Nevertheless, these data tell us that risk of respiratory disease severe enough to need hospitalization continues to an older age in NMD than SI or CMD patients, well past 2 years of age. And the risk is not only from RSV. That said, RSV remains a player in some patients (particularly NMD patients) despite palivizumab prophylaxis, highlighting the need for RSV as well as parainfluenza vaccines. While these vaccines should help all young children, they seem likely to be even more beneficial for high-risk children including those with NMD, and particularly those with more severe NMD.

Eleven among 60 total candidate RSV vaccines (live attenuated, particle based, or vector based) are currently in clinical trials.2 Fewer parainfluenza vaccines are in the pipeline, but clinical trials also are underway.3-5 Approval of such vaccines is not expected until the mid-2020s, so at present we are left with providing palivizumab to our vulnerable patients while emphasizing nonmedical strategies that may help prevent respiratory viruses. These only partially successful preventive interventions include breastfeeding, avoiding secondhand smoke, and avoiding known high-risk exposures, such as large day care centers.

My hope is for quicker than projected progress on the vaccine front so that winter admissions for respiratory viruses might decrease in numbers similar to the decrease we have noted with another vaccine successful against a seasonally active pathogen – rotavirus.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital–Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines. The hospital also receives CDC funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus. Email Dr. Harrison at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019 Apr 10. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002297.

2. “Advances in RSV Vaccine Research and Development – A Global Agenda.”

3. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2015 Dec;4(4): e143-6.

4. J Virol. 2015 Oct;89(20):10319-32.

5. Vaccine. 2017 Dec 18;35(51):7139-46.

Influenza gets a lot of attention each winter, but respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and other respiratory viruses have as much or more impact on pediatric populations, particularly certain high-risk groups. But currently there are no vaccines for noninfluenza respiratory viruses. That said, several are under development, for RSV and parainfluenza.

Which groups are likely to get the most benefit from these newer vaccines?

We all are aware of the extra vulnerability to respiratory viruses (RSV being the most frequent) in premature infants, those with chronic lung disease, or those with congenital heart syndromes; such vulnerable patients are not infrequently seen in routine practice. A recent report shined a brighter light on such a group.

Real-world data from a nationwide Canadian surveillance system (CARESS) was used to analyze relative risks of categories of young children who are thought to be vulnerable to respiratory viruses, with a particular focus on those with neuromuscular disease. The CARESS investigators analyzed 12 years’ data on respiratory hospitalizations from among palivizumab-prophylaxed patients (including specific data on RSV when patients were tested for RSV per standard of care).1 Unfortunately, RSV testing was not universal despite hospitalization, so the true incidence of RSV-specific hospitalizations was likely underestimated.

Nevertheless, more than 25,000 children from 2005 through 2017 were grouped into three categories of palivizumab-prophylaxed high-risk children: standard indications (SI), n = 20,335; chronic medical conditions (CMD), n = 4,063; and neuromuscular disease (NMD), n = 605. This study is notable for having a relatively large number of neuromuscular disease subjects. Two-thirds of each group were fully palivizumab adherent.

The SI group included the standard American Academy of Pediatrics–recommended groups, such as premature infants, congenital heart disease, etc.

The CMD group included conditions that lead clinicians to use palivizumab off label, such as cystic fibrosis, congenital airway anomalies, immunodeficiency, and pulmonary disorders.

The NMD participants were subdivided into two groups. Group 1 comprised general hypotonic neuromuscular diseases such as hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, Prader-Willi syndrome, chromosomal disorders, and migration/demyelinating diseases. Group 2 included more severe infantile neuromuscular disorders, such as spinal muscular atrophy, myotonic dystrophy, centronuclear and nemaline myopathy, mitochondrial and glycogen storage myopathies, or arthrogryposis.

Overall, 6.9% of CARESS RSV-prophylaxed subjects were hospitalized. About one in five hospitalized patients from each group was hospitalized more than once. Specific respiratory hospitalization rates for each group were 6% (n = 1,228) for SI subjects and 9.4% (n = 380) for CMD, compared with 19.2% (n = 116) for NMD subjects.

It is unclear what proportion underwent RSV testing, but a total of 334 were confirmed RSV positive: 261 were SI, 54 were CMD and 19 were NMD. The RSV-test-positive rate was 1.5% for SI, 1.6% for CMD and 3.3% for NMD; so while a higher number of SI children were RSV positive, the rate of RSV positivity was actually highest with NMD.

RSV-positive subjects needing ICU care among NMD patients also had longer ICU stays (median 14 days), compared with RSV-positive CMD or SI subjects (median 3 and 5 days, respectively). Further, hospitalized RSV-positive NMD subjects presented more frequently with pneumonia (42% vs. 30% for CMD and 20% for SI) while hospitalized RSV-positive SI subjects more often had apnea (17% vs. 10% for NMD and 5% for CMD, P less than .05).

These differences in the courses of NMD patients raise the question as to whether the NMD group was somehow different from the SI and CMD groups, other than muscular weakness that likely leads to less ability to clear secretions and a less efficient cough. It turns out that NMD children were older and had worse neonatal medical courses (longer hospital stays, more often ventilated, and used oxygen longer). It could be argued that these differences may have been in part due to the muscular weakness inherent in their underlying disease, but they appear to be predictors of worse respiratory infectious disease than other vulnerable populations as the NMD children get older.

Indeed, the overall risk of any respiratory admission among NMD subjects was nearly twice as high, compared with SI (hazard ratio, 1.90, P less than .0005); but the somewhat higher risk for NMD vs. CMD was not significant (HR, 1.33, P = .090). However, when looking specifically at RSV confirmed admissions, NMD had more than twice the hospitalization risk than either other group (HR, 2.26, P = .001 vs. SI; and HR, 2.74, P = .001 vs. CMD).

Further, an NMD subgroup analysis showed 1.69 times the overall respiratory hospitalization risk among the more severe vs. less severe NMD group, but a similar risk of RSV admission. The authors point out that one reason for this discrepancy may be a higher probability of aspiration causing hospitalization because of more dramatic acute events during respiratory infections in patients with more severe NMD. It also may be that palivizumab evened the playing field for RSV but not for other viruses such as parainfluenza, adenovirus, or even rhinovirus.

Nevertheless, these data tell us that risk of respiratory disease severe enough to need hospitalization continues to an older age in NMD than SI or CMD patients, well past 2 years of age. And the risk is not only from RSV. That said, RSV remains a player in some patients (particularly NMD patients) despite palivizumab prophylaxis, highlighting the need for RSV as well as parainfluenza vaccines. While these vaccines should help all young children, they seem likely to be even more beneficial for high-risk children including those with NMD, and particularly those with more severe NMD.

Eleven among 60 total candidate RSV vaccines (live attenuated, particle based, or vector based) are currently in clinical trials.2 Fewer parainfluenza vaccines are in the pipeline, but clinical trials also are underway.3-5 Approval of such vaccines is not expected until the mid-2020s, so at present we are left with providing palivizumab to our vulnerable patients while emphasizing nonmedical strategies that may help prevent respiratory viruses. These only partially successful preventive interventions include breastfeeding, avoiding secondhand smoke, and avoiding known high-risk exposures, such as large day care centers.

My hope is for quicker than projected progress on the vaccine front so that winter admissions for respiratory viruses might decrease in numbers similar to the decrease we have noted with another vaccine successful against a seasonally active pathogen – rotavirus.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital–Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines. The hospital also receives CDC funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus. Email Dr. Harrison at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019 Apr 10. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002297.

2. “Advances in RSV Vaccine Research and Development – A Global Agenda.”

3. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2015 Dec;4(4): e143-6.

4. J Virol. 2015 Oct;89(20):10319-32.

5. Vaccine. 2017 Dec 18;35(51):7139-46.

Measles complications in the U.S. unchanged in posteradication era

CHICAGO – An evaluation of the measles threat in the modern era gives no indication that the risk of complications or death is any different than it was before a vaccine became available, according to an analysis of inpatient complications between 2002 and 2013.

In 2000, measles was declared eliminated in the United States, but for those who have been infected since that time, the risk of serious complications and death has not diminished, noted Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, in a session at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

By eliminated, the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention – which reported 86 confirmed cases of measles in 2000 – was referring to a technical definition of no new endemic or continuous transmissions in the previous 12 months. It was expected that a modest number of cases of this reportable disease would continue to accrue for an infection that remains common elsewhere in the world.

“Worldwide there are about 20 million cases of measles annually with an estimated 100,000 deaths attributed to this cause,” said Dr. Chovatiya, who is a dermatology resident at Northwestern University, Chicago.

In the United States, posteradication infection rates remained at low levels for several years but were already rising from 2002 to 2013, when Dr. Chovatiya and his coinvestigators sought to describe the incidence, associations, comorbidities, and outcomes of hospitalizations for measles. Toward the end of the period the researchers were examining the incidence rates climbed more steeply.

“So far this year, 764 CDC cases of measles [were] reported. That is the most we have seen in the U.S. since 1994,” Dr. Chovatiya said.

Based on his analysis of hospitalizations from 2002 to 2013, the threat of these outbreaks is no different then that before the disease was declared eliminated or before a vaccine became available.

The cross-sectional study was conducted with data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, an all-payer database that is considered to be a representative of national trends.

Characteristic of measles, the majority of the 582 hospitalizations evaluated over this period occurred in children aged between 1 and 9 years. The proportion of patients with preexisting chronic comorbid conditions was low. Rather, “most were pretty healthy” prior to admission, according to Dr. Chovatiya, who said that the majority of admissions were from an emergency department.

Measles, which targets epithelial cells and depresses the immune system, is a potentially serious disease because of its ability to produce complications in essentially every organ of the body, including the lungs, kidneys, blood, and central nervous system. Consistent with past studies, the most common complication in this series was pneumonia, observed in 20% of patients. The list of other serious complications identified in this study period, including encephalitis and acute renal failure, was long.

“We observed death in 4.3% of our 582 cases, or about 25 cases,” reported Dr. Chovatiya. He indicated that this is a high percentage among a population composed largely of children who were well before hospitalization.

The mortality rate from measles was numerically but not statistically higher than that of overall hospital admissions during this period, but an admission for measles was associated with significantly longer average length of stay (3.7 vs. 3.5 days) and slightly but significantly higher direct costs ($18,907 vs. $18,474).

“I want to point out that these are just direct inpatient costs,” Dr. Chovatiya said. Extrapolating from published data about indirect expenses, he said that the total health cost burden “is absolutely staggering.”

Previous studies have suggested that about 25% of patients with measles require hospitalization and 1 in every 1,000 patients will die. The data collected by Dr. Chovatiya support these often-cited figures, indicating that they remain unchanged in the modern era.

particularly insufficient penetration of vaccination in many communities.

The vaccine “is inexpensive, extremely effective, and lifesaving,” said Dr. Chovatiya, making the point that all of the morbidity, mortality, and costs he described are largely avoidable.

Attempting to provide perspective of the measles threat and the impact of the vaccine, Dr. Chovatiya cited a hypothetical calculation that 732,000 deaths from measles would have been expected in the United States among the pool of children born between 1994 and 2013 had no vaccine been offered. Again, most of these deaths would have occurred in otherwise healthy children.

Dr. Chovatiya reported no potential conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – An evaluation of the measles threat in the modern era gives no indication that the risk of complications or death is any different than it was before a vaccine became available, according to an analysis of inpatient complications between 2002 and 2013.

In 2000, measles was declared eliminated in the United States, but for those who have been infected since that time, the risk of serious complications and death has not diminished, noted Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, in a session at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

By eliminated, the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention – which reported 86 confirmed cases of measles in 2000 – was referring to a technical definition of no new endemic or continuous transmissions in the previous 12 months. It was expected that a modest number of cases of this reportable disease would continue to accrue for an infection that remains common elsewhere in the world.

“Worldwide there are about 20 million cases of measles annually with an estimated 100,000 deaths attributed to this cause,” said Dr. Chovatiya, who is a dermatology resident at Northwestern University, Chicago.

In the United States, posteradication infection rates remained at low levels for several years but were already rising from 2002 to 2013, when Dr. Chovatiya and his coinvestigators sought to describe the incidence, associations, comorbidities, and outcomes of hospitalizations for measles. Toward the end of the period the researchers were examining the incidence rates climbed more steeply.

“So far this year, 764 CDC cases of measles [were] reported. That is the most we have seen in the U.S. since 1994,” Dr. Chovatiya said.

Based on his analysis of hospitalizations from 2002 to 2013, the threat of these outbreaks is no different then that before the disease was declared eliminated or before a vaccine became available.

The cross-sectional study was conducted with data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, an all-payer database that is considered to be a representative of national trends.

Characteristic of measles, the majority of the 582 hospitalizations evaluated over this period occurred in children aged between 1 and 9 years. The proportion of patients with preexisting chronic comorbid conditions was low. Rather, “most were pretty healthy” prior to admission, according to Dr. Chovatiya, who said that the majority of admissions were from an emergency department.

Measles, which targets epithelial cells and depresses the immune system, is a potentially serious disease because of its ability to produce complications in essentially every organ of the body, including the lungs, kidneys, blood, and central nervous system. Consistent with past studies, the most common complication in this series was pneumonia, observed in 20% of patients. The list of other serious complications identified in this study period, including encephalitis and acute renal failure, was long.

“We observed death in 4.3% of our 582 cases, or about 25 cases,” reported Dr. Chovatiya. He indicated that this is a high percentage among a population composed largely of children who were well before hospitalization.

The mortality rate from measles was numerically but not statistically higher than that of overall hospital admissions during this period, but an admission for measles was associated with significantly longer average length of stay (3.7 vs. 3.5 days) and slightly but significantly higher direct costs ($18,907 vs. $18,474).

“I want to point out that these are just direct inpatient costs,” Dr. Chovatiya said. Extrapolating from published data about indirect expenses, he said that the total health cost burden “is absolutely staggering.”

Previous studies have suggested that about 25% of patients with measles require hospitalization and 1 in every 1,000 patients will die. The data collected by Dr. Chovatiya support these often-cited figures, indicating that they remain unchanged in the modern era.

particularly insufficient penetration of vaccination in many communities.

The vaccine “is inexpensive, extremely effective, and lifesaving,” said Dr. Chovatiya, making the point that all of the morbidity, mortality, and costs he described are largely avoidable.

Attempting to provide perspective of the measles threat and the impact of the vaccine, Dr. Chovatiya cited a hypothetical calculation that 732,000 deaths from measles would have been expected in the United States among the pool of children born between 1994 and 2013 had no vaccine been offered. Again, most of these deaths would have occurred in otherwise healthy children.

Dr. Chovatiya reported no potential conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – An evaluation of the measles threat in the modern era gives no indication that the risk of complications or death is any different than it was before a vaccine became available, according to an analysis of inpatient complications between 2002 and 2013.

In 2000, measles was declared eliminated in the United States, but for those who have been infected since that time, the risk of serious complications and death has not diminished, noted Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, in a session at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

By eliminated, the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention – which reported 86 confirmed cases of measles in 2000 – was referring to a technical definition of no new endemic or continuous transmissions in the previous 12 months. It was expected that a modest number of cases of this reportable disease would continue to accrue for an infection that remains common elsewhere in the world.

“Worldwide there are about 20 million cases of measles annually with an estimated 100,000 deaths attributed to this cause,” said Dr. Chovatiya, who is a dermatology resident at Northwestern University, Chicago.

In the United States, posteradication infection rates remained at low levels for several years but were already rising from 2002 to 2013, when Dr. Chovatiya and his coinvestigators sought to describe the incidence, associations, comorbidities, and outcomes of hospitalizations for measles. Toward the end of the period the researchers were examining the incidence rates climbed more steeply.

“So far this year, 764 CDC cases of measles [were] reported. That is the most we have seen in the U.S. since 1994,” Dr. Chovatiya said.

Based on his analysis of hospitalizations from 2002 to 2013, the threat of these outbreaks is no different then that before the disease was declared eliminated or before a vaccine became available.

The cross-sectional study was conducted with data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, an all-payer database that is considered to be a representative of national trends.

Characteristic of measles, the majority of the 582 hospitalizations evaluated over this period occurred in children aged between 1 and 9 years. The proportion of patients with preexisting chronic comorbid conditions was low. Rather, “most were pretty healthy” prior to admission, according to Dr. Chovatiya, who said that the majority of admissions were from an emergency department.

Measles, which targets epithelial cells and depresses the immune system, is a potentially serious disease because of its ability to produce complications in essentially every organ of the body, including the lungs, kidneys, blood, and central nervous system. Consistent with past studies, the most common complication in this series was pneumonia, observed in 20% of patients. The list of other serious complications identified in this study period, including encephalitis and acute renal failure, was long.

“We observed death in 4.3% of our 582 cases, or about 25 cases,” reported Dr. Chovatiya. He indicated that this is a high percentage among a population composed largely of children who were well before hospitalization.

The mortality rate from measles was numerically but not statistically higher than that of overall hospital admissions during this period, but an admission for measles was associated with significantly longer average length of stay (3.7 vs. 3.5 days) and slightly but significantly higher direct costs ($18,907 vs. $18,474).

“I want to point out that these are just direct inpatient costs,” Dr. Chovatiya said. Extrapolating from published data about indirect expenses, he said that the total health cost burden “is absolutely staggering.”

Previous studies have suggested that about 25% of patients with measles require hospitalization and 1 in every 1,000 patients will die. The data collected by Dr. Chovatiya support these often-cited figures, indicating that they remain unchanged in the modern era.

particularly insufficient penetration of vaccination in many communities.

The vaccine “is inexpensive, extremely effective, and lifesaving,” said Dr. Chovatiya, making the point that all of the morbidity, mortality, and costs he described are largely avoidable.

Attempting to provide perspective of the measles threat and the impact of the vaccine, Dr. Chovatiya cited a hypothetical calculation that 732,000 deaths from measles would have been expected in the United States among the pool of children born between 1994 and 2013 had no vaccine been offered. Again, most of these deaths would have occurred in otherwise healthy children.

Dr. Chovatiya reported no potential conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM SID 2019

Maternal immunization protects against serious RSV infection in infancy

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Passive protection of infants from severe respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infection during the first 6 months of life has convincingly been achieved through maternal immunization using a novel nanoparticle vaccine in the landmark PREPARE trial.

“I think it’s important for everyone, especially people like myself who’ve been working on maternal immunization for about 20 years, to realize that this is a historic study,” Flor M. Munoz, MD, declared in reporting the study results at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“We have here for the first time a phase-3, global, randomized, placebo-controlled, observer-blinded clinical trial looking at an experimental vaccine in pregnant women for the protection of infants from a disease for which we really don’t have other potential solutions quite yet, and in a period of high vulnerability,” said Dr. Munoz, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Indeed, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the No. 2 cause of mortality worldwide during the first year of life. Moreover, most cases of severe RSV lower respiratory tract infection occur in otherwise healthy infants aged less than 5 months, when active immunization presents daunting challenges.

“While certainly mortality is uncommon in high-income countries, we do see significant hospitalization there due to severe RSV lower respiratory tract infection in the first year of life, sometimes more than other common diseases, like influenza,” she noted.

PREPARE included 4,636 women with low-risk pregnancies who were randomized 2:1 to a single intramuscular injection of the investigational RSV vaccine or placebo during gestational weeks 28-36, with efficacy assessed through the first 180 days of life. The study took place at 87 sites in 11 countries during 4 years worth of RSV seasons. Roughly half of participants were South African, one-quarter were in the United States, and the rest were drawn from nine other low-, middle-, or high-income countries in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. The median gestational age at vaccination was 32 weeks.