User login

Building better flu vaccines is daunting

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Don’t hold your breath waiting for a substantially better, more reliably effective influenza vaccine.

That was a key cautionary message provided by vaccine expert Edward A. Belongia, MD, at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccine varies from 10% to 60% year by year, leaving enormous room for improvement. But many obstacles exist to developing a more consistent and reliably effective version of the seasonal influenza vaccine. And the lofty goal of creating a universal vaccine is even more ambitious, although the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has declared it to be a top priority and mapped out a strategic plan for getting there (J Infect Dis. 2018 Jul 2;218[3]:347-54).

“Ultimately the Holy Grail is a universal flu vaccine that would provide pan-A and pan-B protection that would last for more than 1 year, with protection against avian and pandemic viruses, and would work for both children and adults. We are nowhere near that. Every 5 years someone says we’re 5 years away, and then 5 years go by and we’re still 5 years away. So I’m not making any predictions on that,” said Dr. Belongia, director of the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Population Health at the Marshfield (Wisc.) Clinic Research Institute, which is part of the U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

One of the big problems in creating a more effective flu vaccine, particularly for children, is the H3N2 virus subtype. Dr. Belongia was first author of a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of more than a dozen recent flu seasons showing that although vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 varied widely from year to year, it was consistently lower than against influenza type B and H1N1 (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Aug;16[8]:942-51).

And that’s especially true in children and adolescents. Notably, in the 2014-2015 U.S. flu season, vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 in children aged 6 months to 8 years was low at 23%, but shockingly lower at a mere 7% in the 9- to 17-year-olds. Whereas in the 2017-2018 season, vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 in the 9- to 17-year-olds jumped to 46% while remaining low but consistent at 22% in the younger children.

“We see a very different age pattern here for the older children compared to the younger children, and quite frankly we don’t really understand what’s doing this,” said Dr. Belongia.

What is well understood, however, is that the problematic performance of influenza vaccines when it comes to protecting against H3N2 is a complicated matter stemming from three sources: the virus itself; the current egg-based vaccine manufacturing methodology, which is now 7 decades old; and host factors.

That troublesome H3N2 virus

Antigenic evolution of the H3N2 virus occurs at a 5- to 6-fold higher rate than for influenza B virus and roughly 17-fold faster than for H1N1. That high mutation rate makes for a moving target that’s a real problem when trying to keep a vaccine current. Also, the globular head of the virus is prone to glycosylation, which enables the virus to evade immune detection.

Vaccine-related factors

It’s likely that the availability of the flu vaccine for the upcoming 2019-2020 season is going to be delayed because of late selection of the strains for inclusion. The World Health Organization ordinarily selects strains for vaccines for the Northern Hemisphere in February, giving vaccine manufacturers 6-8 months to produce their vaccines and ship them in time for administration from September through November. This year, however, the WHO delayed selection of the H3N2 component until March because of the high level of antigenic and genetic diversity of circulating strains.

“This hasn’t happened since 2003 – it’s a very rare occurrence – but it does increase the potential that there’s going to be a delay in the availability of the vaccine in the fall,” he explained.

Eventually, the WHO selected a new clade 3C.3a virus called A/Kansas/14/2017 for the 2019-2020 vaccine. It should cover the circulating strains of H3N2 “reasonably well,” according to the physician.

Another issue: H3N2 has become adapted to the mammalian environment, so growing the virus in eggs introduces strong selection pressure for mutations leading to reduced vaccine effectiveness. Yet only two flu vaccines licensed in the United States are manufactured without eggs: Flucelvax, marketed by Seqirus for patients aged 4 years and up, and Sanofi’s Flublok, which is licensed for individuals who are 18 years of age or older. Studies are underway looking at the relative effectiveness of egg-based versus cell culture-manufactured flu vaccines in real-world settings.

Host factors

Hemagglutinin imprinting, sometimes referred to as “original antigenic sin,” is a decades-old concept whereby early childhood exposure to influenza viruses shapes future vaccine response.

“It suggests there could be some birth cohort effects in vaccine responsiveness, depending on what was circulating in the first 2-3 years after birth. It would complicate vaccine strategy quite a bit if you had to have different strategies for different birth cohorts,” Dr. Belongia observed.

Another host factor issue is the controversial topic of negative interference stemming from repeated vaccinations. It’s unclear how important this is in the real world, because studies have been inconsistent. Reassuringly, Dr. Belongia and coworkers found no association between prior-season influenza vaccination and diminished vaccine effectiveness in 3,369 U.S. children aged 2-17 years studied during the 2013-14 through 2015-16 flu seasons (JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Oct 5;1[6]:e183742. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3742).

“We found no suggestion at all of a problem with being vaccinated two seasons in a row,” according to Dr. Belongia.

How to build a better influenza vaccine for children

“I would say that even before we get to a universal vaccine, the next generation of flu vaccines that are more effective are not going to be manufactured using eggs, although we’re not real close to that. But I think that’s eventually where we’re going,” he said.

“I think it’s going to take a systems biology approach in order to really understand the adaptive immune response to infection and vaccination in early life. That means a much more detailed understanding of what is underlying the imprinting mechanisms and what is the adaptive response to repeated vaccination and infection. I think this is going to take prospective infant cohort studies; the National Institutes of Health is funding some that will begin within the next year,” Dr. Belongia added.

Many investigational approaches to improving influenza virus subtype-level protection are being explored. These include novel adjuvants, nanoparticle vaccines, computationally optimized broadly reactive antigens, and standardization of neuraminidase content.

And as for the much-desired universal flu vaccine?

“I will say that if a universal vaccine is going to work it’s probably going to work first in children. They have a much shorter immune history and their antibody landscape is a lot smaller, so you have a much better opportunity, I think, to generate a broad response to a universal vaccine compared to adults, who have much more complex immune landscapes,” he said.

Dr. Belongia reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Don’t hold your breath waiting for a substantially better, more reliably effective influenza vaccine.

That was a key cautionary message provided by vaccine expert Edward A. Belongia, MD, at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccine varies from 10% to 60% year by year, leaving enormous room for improvement. But many obstacles exist to developing a more consistent and reliably effective version of the seasonal influenza vaccine. And the lofty goal of creating a universal vaccine is even more ambitious, although the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has declared it to be a top priority and mapped out a strategic plan for getting there (J Infect Dis. 2018 Jul 2;218[3]:347-54).

“Ultimately the Holy Grail is a universal flu vaccine that would provide pan-A and pan-B protection that would last for more than 1 year, with protection against avian and pandemic viruses, and would work for both children and adults. We are nowhere near that. Every 5 years someone says we’re 5 years away, and then 5 years go by and we’re still 5 years away. So I’m not making any predictions on that,” said Dr. Belongia, director of the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Population Health at the Marshfield (Wisc.) Clinic Research Institute, which is part of the U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

One of the big problems in creating a more effective flu vaccine, particularly for children, is the H3N2 virus subtype. Dr. Belongia was first author of a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of more than a dozen recent flu seasons showing that although vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 varied widely from year to year, it was consistently lower than against influenza type B and H1N1 (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Aug;16[8]:942-51).

And that’s especially true in children and adolescents. Notably, in the 2014-2015 U.S. flu season, vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 in children aged 6 months to 8 years was low at 23%, but shockingly lower at a mere 7% in the 9- to 17-year-olds. Whereas in the 2017-2018 season, vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 in the 9- to 17-year-olds jumped to 46% while remaining low but consistent at 22% in the younger children.

“We see a very different age pattern here for the older children compared to the younger children, and quite frankly we don’t really understand what’s doing this,” said Dr. Belongia.

What is well understood, however, is that the problematic performance of influenza vaccines when it comes to protecting against H3N2 is a complicated matter stemming from three sources: the virus itself; the current egg-based vaccine manufacturing methodology, which is now 7 decades old; and host factors.

That troublesome H3N2 virus

Antigenic evolution of the H3N2 virus occurs at a 5- to 6-fold higher rate than for influenza B virus and roughly 17-fold faster than for H1N1. That high mutation rate makes for a moving target that’s a real problem when trying to keep a vaccine current. Also, the globular head of the virus is prone to glycosylation, which enables the virus to evade immune detection.

Vaccine-related factors

It’s likely that the availability of the flu vaccine for the upcoming 2019-2020 season is going to be delayed because of late selection of the strains for inclusion. The World Health Organization ordinarily selects strains for vaccines for the Northern Hemisphere in February, giving vaccine manufacturers 6-8 months to produce their vaccines and ship them in time for administration from September through November. This year, however, the WHO delayed selection of the H3N2 component until March because of the high level of antigenic and genetic diversity of circulating strains.

“This hasn’t happened since 2003 – it’s a very rare occurrence – but it does increase the potential that there’s going to be a delay in the availability of the vaccine in the fall,” he explained.

Eventually, the WHO selected a new clade 3C.3a virus called A/Kansas/14/2017 for the 2019-2020 vaccine. It should cover the circulating strains of H3N2 “reasonably well,” according to the physician.

Another issue: H3N2 has become adapted to the mammalian environment, so growing the virus in eggs introduces strong selection pressure for mutations leading to reduced vaccine effectiveness. Yet only two flu vaccines licensed in the United States are manufactured without eggs: Flucelvax, marketed by Seqirus for patients aged 4 years and up, and Sanofi’s Flublok, which is licensed for individuals who are 18 years of age or older. Studies are underway looking at the relative effectiveness of egg-based versus cell culture-manufactured flu vaccines in real-world settings.

Host factors

Hemagglutinin imprinting, sometimes referred to as “original antigenic sin,” is a decades-old concept whereby early childhood exposure to influenza viruses shapes future vaccine response.

“It suggests there could be some birth cohort effects in vaccine responsiveness, depending on what was circulating in the first 2-3 years after birth. It would complicate vaccine strategy quite a bit if you had to have different strategies for different birth cohorts,” Dr. Belongia observed.

Another host factor issue is the controversial topic of negative interference stemming from repeated vaccinations. It’s unclear how important this is in the real world, because studies have been inconsistent. Reassuringly, Dr. Belongia and coworkers found no association between prior-season influenza vaccination and diminished vaccine effectiveness in 3,369 U.S. children aged 2-17 years studied during the 2013-14 through 2015-16 flu seasons (JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Oct 5;1[6]:e183742. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3742).

“We found no suggestion at all of a problem with being vaccinated two seasons in a row,” according to Dr. Belongia.

How to build a better influenza vaccine for children

“I would say that even before we get to a universal vaccine, the next generation of flu vaccines that are more effective are not going to be manufactured using eggs, although we’re not real close to that. But I think that’s eventually where we’re going,” he said.

“I think it’s going to take a systems biology approach in order to really understand the adaptive immune response to infection and vaccination in early life. That means a much more detailed understanding of what is underlying the imprinting mechanisms and what is the adaptive response to repeated vaccination and infection. I think this is going to take prospective infant cohort studies; the National Institutes of Health is funding some that will begin within the next year,” Dr. Belongia added.

Many investigational approaches to improving influenza virus subtype-level protection are being explored. These include novel adjuvants, nanoparticle vaccines, computationally optimized broadly reactive antigens, and standardization of neuraminidase content.

And as for the much-desired universal flu vaccine?

“I will say that if a universal vaccine is going to work it’s probably going to work first in children. They have a much shorter immune history and their antibody landscape is a lot smaller, so you have a much better opportunity, I think, to generate a broad response to a universal vaccine compared to adults, who have much more complex immune landscapes,” he said.

Dr. Belongia reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Don’t hold your breath waiting for a substantially better, more reliably effective influenza vaccine.

That was a key cautionary message provided by vaccine expert Edward A. Belongia, MD, at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccine varies from 10% to 60% year by year, leaving enormous room for improvement. But many obstacles exist to developing a more consistent and reliably effective version of the seasonal influenza vaccine. And the lofty goal of creating a universal vaccine is even more ambitious, although the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has declared it to be a top priority and mapped out a strategic plan for getting there (J Infect Dis. 2018 Jul 2;218[3]:347-54).

“Ultimately the Holy Grail is a universal flu vaccine that would provide pan-A and pan-B protection that would last for more than 1 year, with protection against avian and pandemic viruses, and would work for both children and adults. We are nowhere near that. Every 5 years someone says we’re 5 years away, and then 5 years go by and we’re still 5 years away. So I’m not making any predictions on that,” said Dr. Belongia, director of the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Population Health at the Marshfield (Wisc.) Clinic Research Institute, which is part of the U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

One of the big problems in creating a more effective flu vaccine, particularly for children, is the H3N2 virus subtype. Dr. Belongia was first author of a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of more than a dozen recent flu seasons showing that although vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 varied widely from year to year, it was consistently lower than against influenza type B and H1N1 (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Aug;16[8]:942-51).

And that’s especially true in children and adolescents. Notably, in the 2014-2015 U.S. flu season, vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 in children aged 6 months to 8 years was low at 23%, but shockingly lower at a mere 7% in the 9- to 17-year-olds. Whereas in the 2017-2018 season, vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 in the 9- to 17-year-olds jumped to 46% while remaining low but consistent at 22% in the younger children.

“We see a very different age pattern here for the older children compared to the younger children, and quite frankly we don’t really understand what’s doing this,” said Dr. Belongia.

What is well understood, however, is that the problematic performance of influenza vaccines when it comes to protecting against H3N2 is a complicated matter stemming from three sources: the virus itself; the current egg-based vaccine manufacturing methodology, which is now 7 decades old; and host factors.

That troublesome H3N2 virus

Antigenic evolution of the H3N2 virus occurs at a 5- to 6-fold higher rate than for influenza B virus and roughly 17-fold faster than for H1N1. That high mutation rate makes for a moving target that’s a real problem when trying to keep a vaccine current. Also, the globular head of the virus is prone to glycosylation, which enables the virus to evade immune detection.

Vaccine-related factors

It’s likely that the availability of the flu vaccine for the upcoming 2019-2020 season is going to be delayed because of late selection of the strains for inclusion. The World Health Organization ordinarily selects strains for vaccines for the Northern Hemisphere in February, giving vaccine manufacturers 6-8 months to produce their vaccines and ship them in time for administration from September through November. This year, however, the WHO delayed selection of the H3N2 component until March because of the high level of antigenic and genetic diversity of circulating strains.

“This hasn’t happened since 2003 – it’s a very rare occurrence – but it does increase the potential that there’s going to be a delay in the availability of the vaccine in the fall,” he explained.

Eventually, the WHO selected a new clade 3C.3a virus called A/Kansas/14/2017 for the 2019-2020 vaccine. It should cover the circulating strains of H3N2 “reasonably well,” according to the physician.

Another issue: H3N2 has become adapted to the mammalian environment, so growing the virus in eggs introduces strong selection pressure for mutations leading to reduced vaccine effectiveness. Yet only two flu vaccines licensed in the United States are manufactured without eggs: Flucelvax, marketed by Seqirus for patients aged 4 years and up, and Sanofi’s Flublok, which is licensed for individuals who are 18 years of age or older. Studies are underway looking at the relative effectiveness of egg-based versus cell culture-manufactured flu vaccines in real-world settings.

Host factors

Hemagglutinin imprinting, sometimes referred to as “original antigenic sin,” is a decades-old concept whereby early childhood exposure to influenza viruses shapes future vaccine response.

“It suggests there could be some birth cohort effects in vaccine responsiveness, depending on what was circulating in the first 2-3 years after birth. It would complicate vaccine strategy quite a bit if you had to have different strategies for different birth cohorts,” Dr. Belongia observed.

Another host factor issue is the controversial topic of negative interference stemming from repeated vaccinations. It’s unclear how important this is in the real world, because studies have been inconsistent. Reassuringly, Dr. Belongia and coworkers found no association between prior-season influenza vaccination and diminished vaccine effectiveness in 3,369 U.S. children aged 2-17 years studied during the 2013-14 through 2015-16 flu seasons (JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Oct 5;1[6]:e183742. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3742).

“We found no suggestion at all of a problem with being vaccinated two seasons in a row,” according to Dr. Belongia.

How to build a better influenza vaccine for children

“I would say that even before we get to a universal vaccine, the next generation of flu vaccines that are more effective are not going to be manufactured using eggs, although we’re not real close to that. But I think that’s eventually where we’re going,” he said.

“I think it’s going to take a systems biology approach in order to really understand the adaptive immune response to infection and vaccination in early life. That means a much more detailed understanding of what is underlying the imprinting mechanisms and what is the adaptive response to repeated vaccination and infection. I think this is going to take prospective infant cohort studies; the National Institutes of Health is funding some that will begin within the next year,” Dr. Belongia added.

Many investigational approaches to improving influenza virus subtype-level protection are being explored. These include novel adjuvants, nanoparticle vaccines, computationally optimized broadly reactive antigens, and standardization of neuraminidase content.

And as for the much-desired universal flu vaccine?

“I will say that if a universal vaccine is going to work it’s probably going to work first in children. They have a much shorter immune history and their antibody landscape is a lot smaller, so you have a much better opportunity, I think, to generate a broad response to a universal vaccine compared to adults, who have much more complex immune landscapes,” he said.

Dr. Belongia reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

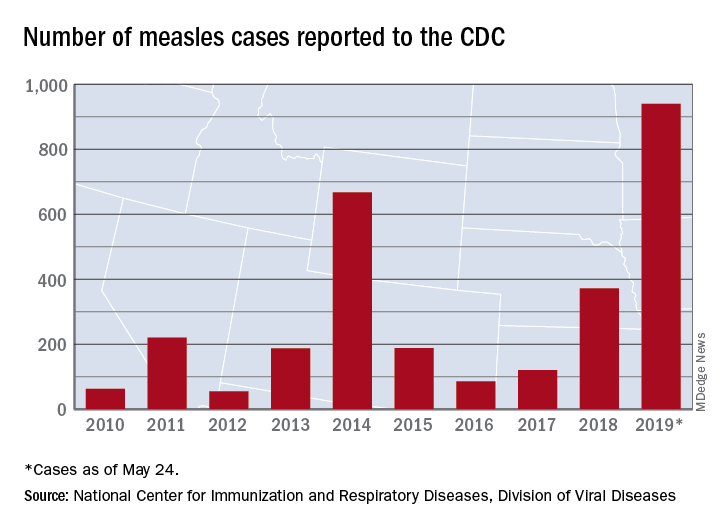

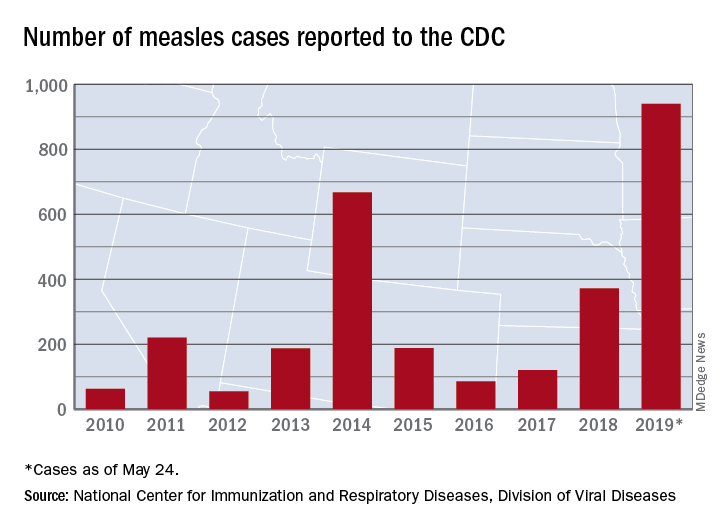

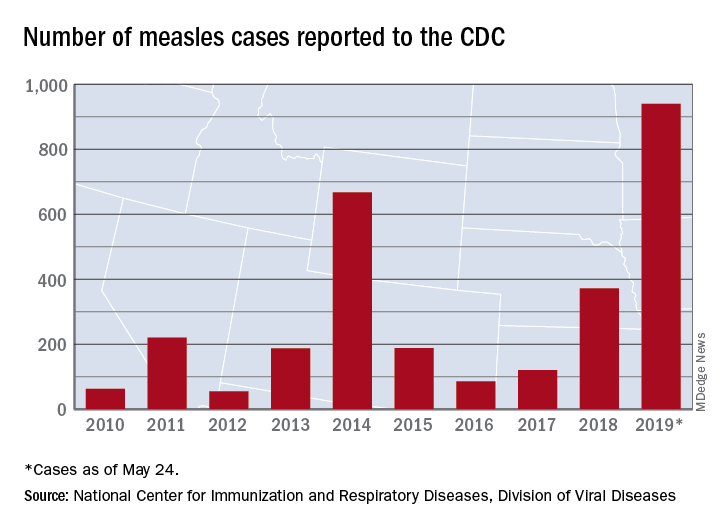

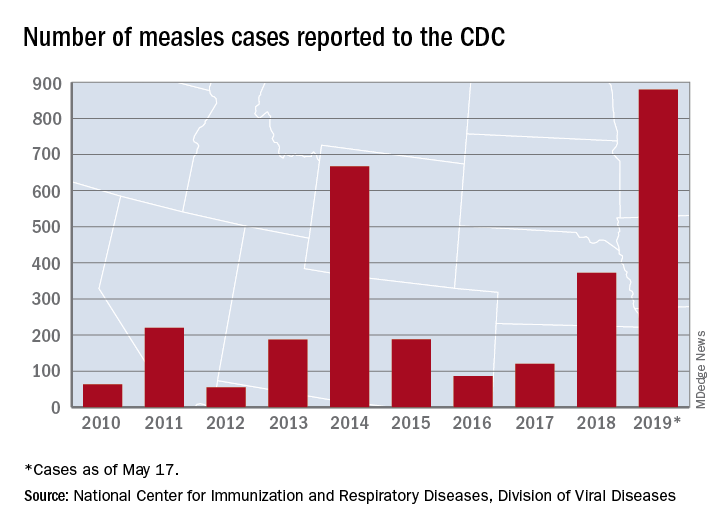

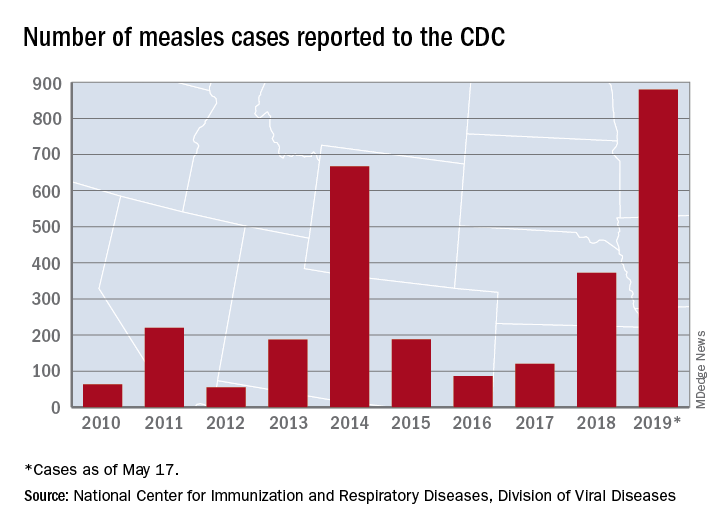

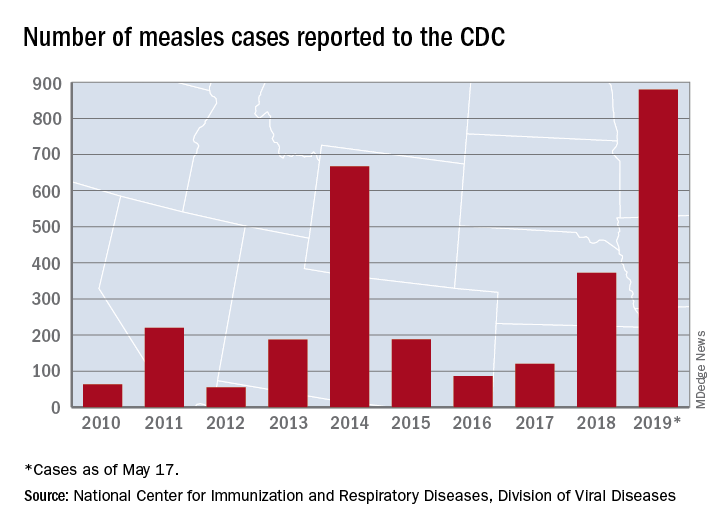

Measles count for 2019 now over 900 cases

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC received reports of 60 new measles cases last week – up from 41 the previous week – bringing the U.S. total to 940 for the year as of May 24. The CDC is currently tracking 10 outbreaks in seven states: California (3), Georgia, Maryland, Michigan, New York (2), Pennsylvania, and Washington.

The Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the state’s first case on May 20. The school-aged child from Somerset County had been vaccinated and is fully recovered from the disease. It’s not yet known where the child was exposed to measles, but sporadic cases are not unexpected, the Maine CDC said.

New Mexico’s first measles case of the year, a 1-year-old in Sierra County, has at least one state lawmaker considering changes to the state’s immunization exemption laws, the Farmington Daily Times reported.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC received reports of 60 new measles cases last week – up from 41 the previous week – bringing the U.S. total to 940 for the year as of May 24. The CDC is currently tracking 10 outbreaks in seven states: California (3), Georgia, Maryland, Michigan, New York (2), Pennsylvania, and Washington.

The Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the state’s first case on May 20. The school-aged child from Somerset County had been vaccinated and is fully recovered from the disease. It’s not yet known where the child was exposed to measles, but sporadic cases are not unexpected, the Maine CDC said.

New Mexico’s first measles case of the year, a 1-year-old in Sierra County, has at least one state lawmaker considering changes to the state’s immunization exemption laws, the Farmington Daily Times reported.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC received reports of 60 new measles cases last week – up from 41 the previous week – bringing the U.S. total to 940 for the year as of May 24. The CDC is currently tracking 10 outbreaks in seven states: California (3), Georgia, Maryland, Michigan, New York (2), Pennsylvania, and Washington.

The Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the state’s first case on May 20. The school-aged child from Somerset County had been vaccinated and is fully recovered from the disease. It’s not yet known where the child was exposed to measles, but sporadic cases are not unexpected, the Maine CDC said.

New Mexico’s first measles case of the year, a 1-year-old in Sierra County, has at least one state lawmaker considering changes to the state’s immunization exemption laws, the Farmington Daily Times reported.

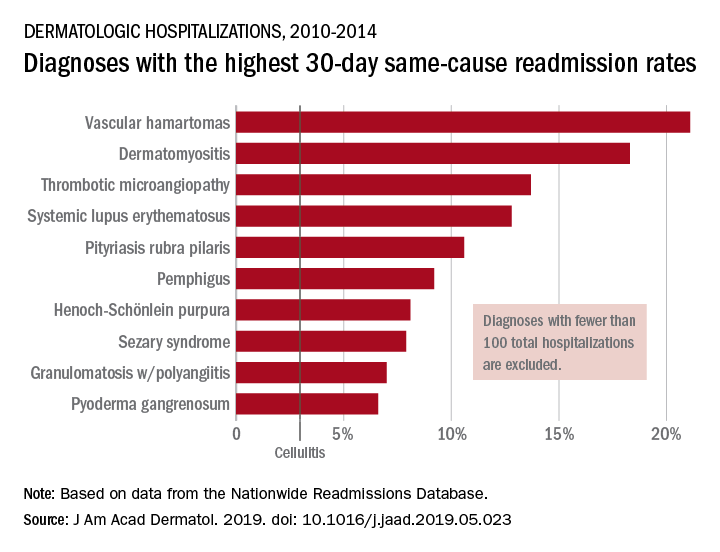

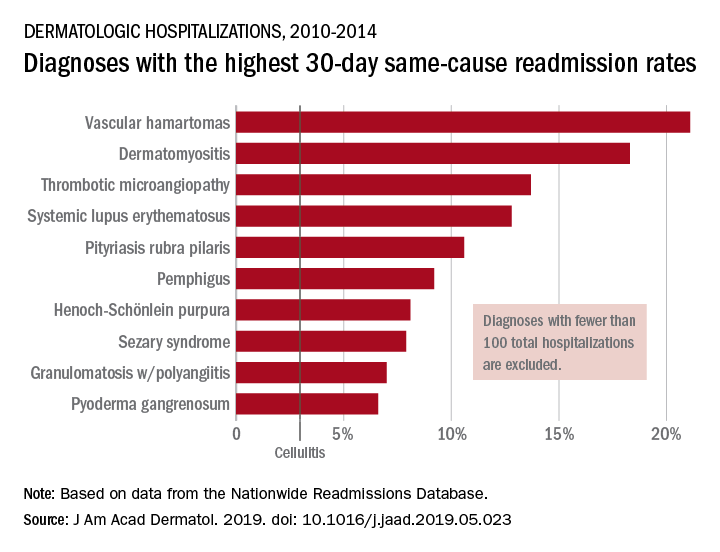

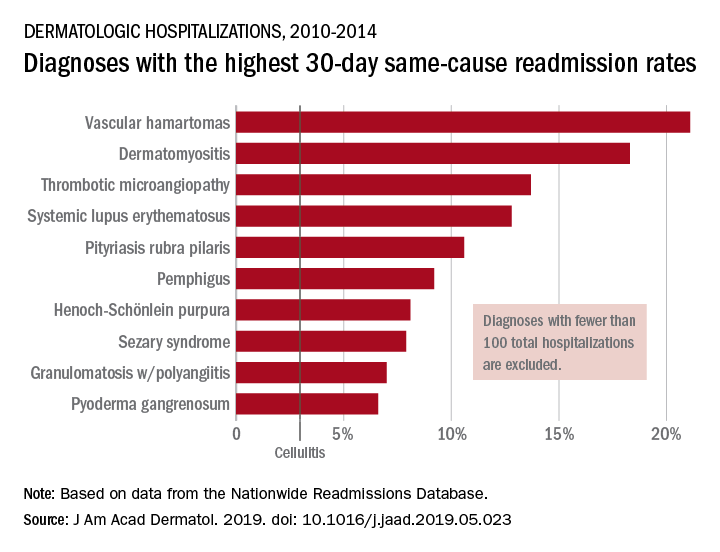

By the numbers: Readmissions for skin conditions

Almost 10% of patients

Data from the Nationwide Readmissions Database also showed that the same-cause readmission rate was 3.3% after 30 days and 7.8% within the calendar year (CY) over the 5-year study period of 2010-2014, Myron Zhang, MD, of the department of dermatology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and his associates reported in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The total cost of the CY readmissions was $2.54 billion, which works out to $508 million per year or $8,995 per visit. The most common dermatologic diagnosis – cellulitis made up 83.6% of all hospitalizations – was also the most expensive in terms of readmissions, resulting in $1.9 billion in CY costs, Dr. Zhang and associates wrote.

Overall readmission rates for cellulitis were not provided, but annual rates ranged from 9.1% to 9.3% (30-day all cause), from 7.7% to 8.1% (CY same cause), and from 3.1% to 3.3% (30-day same cause), they wrote.

The dermatologic diagnosis with the highest 30-day same-cause readmission rate was vascular hamartomas at 21.1%, followed by dermatomyositis (18.3%) and thrombotic microangiopathy (13.7%). Dermatomyositis had the highest CY same-cause readmission rate (30.8%) and mycosis fungoides had the highest 30-day all-cause rate (32.3%), according to the investigators.

“Diseases, characteristics, and comorbidities associated with high readmission rates should trigger hospitals to consider dermatology consultation, coordinate outpatient follow-up, and support underinsured outpatient access. These measures have been shown to reduce readmissions or hospital visits in general dermatologic settings, but outcomes in individual diseases are not well studied,” Dr. Zhang and associates wrote. They noted that there have been “very few prior studies of readmissions for skin diseases.”

[email protected]

SOURCE: Zhang M et al. J Am Acad. Dermatol. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.023. .

Almost 10% of patients

Data from the Nationwide Readmissions Database also showed that the same-cause readmission rate was 3.3% after 30 days and 7.8% within the calendar year (CY) over the 5-year study period of 2010-2014, Myron Zhang, MD, of the department of dermatology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and his associates reported in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The total cost of the CY readmissions was $2.54 billion, which works out to $508 million per year or $8,995 per visit. The most common dermatologic diagnosis – cellulitis made up 83.6% of all hospitalizations – was also the most expensive in terms of readmissions, resulting in $1.9 billion in CY costs, Dr. Zhang and associates wrote.

Overall readmission rates for cellulitis were not provided, but annual rates ranged from 9.1% to 9.3% (30-day all cause), from 7.7% to 8.1% (CY same cause), and from 3.1% to 3.3% (30-day same cause), they wrote.

The dermatologic diagnosis with the highest 30-day same-cause readmission rate was vascular hamartomas at 21.1%, followed by dermatomyositis (18.3%) and thrombotic microangiopathy (13.7%). Dermatomyositis had the highest CY same-cause readmission rate (30.8%) and mycosis fungoides had the highest 30-day all-cause rate (32.3%), according to the investigators.

“Diseases, characteristics, and comorbidities associated with high readmission rates should trigger hospitals to consider dermatology consultation, coordinate outpatient follow-up, and support underinsured outpatient access. These measures have been shown to reduce readmissions or hospital visits in general dermatologic settings, but outcomes in individual diseases are not well studied,” Dr. Zhang and associates wrote. They noted that there have been “very few prior studies of readmissions for skin diseases.”

[email protected]

SOURCE: Zhang M et al. J Am Acad. Dermatol. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.023. .

Almost 10% of patients

Data from the Nationwide Readmissions Database also showed that the same-cause readmission rate was 3.3% after 30 days and 7.8% within the calendar year (CY) over the 5-year study period of 2010-2014, Myron Zhang, MD, of the department of dermatology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and his associates reported in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The total cost of the CY readmissions was $2.54 billion, which works out to $508 million per year or $8,995 per visit. The most common dermatologic diagnosis – cellulitis made up 83.6% of all hospitalizations – was also the most expensive in terms of readmissions, resulting in $1.9 billion in CY costs, Dr. Zhang and associates wrote.

Overall readmission rates for cellulitis were not provided, but annual rates ranged from 9.1% to 9.3% (30-day all cause), from 7.7% to 8.1% (CY same cause), and from 3.1% to 3.3% (30-day same cause), they wrote.

The dermatologic diagnosis with the highest 30-day same-cause readmission rate was vascular hamartomas at 21.1%, followed by dermatomyositis (18.3%) and thrombotic microangiopathy (13.7%). Dermatomyositis had the highest CY same-cause readmission rate (30.8%) and mycosis fungoides had the highest 30-day all-cause rate (32.3%), according to the investigators.

“Diseases, characteristics, and comorbidities associated with high readmission rates should trigger hospitals to consider dermatology consultation, coordinate outpatient follow-up, and support underinsured outpatient access. These measures have been shown to reduce readmissions or hospital visits in general dermatologic settings, but outcomes in individual diseases are not well studied,” Dr. Zhang and associates wrote. They noted that there have been “very few prior studies of readmissions for skin diseases.”

[email protected]

SOURCE: Zhang M et al. J Am Acad. Dermatol. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.023. .

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

mTORC1 inhibitor protects elderly asthmatics from viral respiratory tract infections

DALLAS – A molecule that boosts innate viral immunity may protect elderly people with asthma from the root cause of most exacerbations – viral respiratory tract infections.

Dubbed RTB101, the oral medication is a selective, potent inhibitor of target of rapamycin complex 1 (TORC1). In phase 2b data presented at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference, RTB101 decreased by 52% the number of elderly subjects with severe, lab-confirmed respiratory tract infections (RTI) symptoms.

But the molecule was even more effective in patients with asthma aged 65 years and older, Joan Mannick, MD, said in an interview during the meeting. In this group, it reduced by 69% the percentage of subjects who developed RTIs and reduced the rate of infection by about 79%, compared with placebo.

“The core cause of asthma exacerbations in these patients is viral respiratory tract infection,” said Dr. Mannick, chief medical officer of resTORbio, the Boston company developing RTB101. “About 80% of the viruses detected in these infections are rhinoviruses, and there are 170 rhinovirus serotypes. We have never been able to develop a vaccine against rhinovirus, and we have no treatment other than to treat the inflammation caused by the infection.”

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention mortality records confirm the impact of viral respiratory infections on older people who experience asthma exacerbations: 6 of 10,000 will die, compared with less than 2 per 10,000 for all other age groups. Decreasing the number of these infections in older people with asthma would prevent morbidity and mortality and save considerable health care dollars.

“One of the reasons that asthmatics have such difficulty when they get respiratory infections is that they seem to have deficient antiviral immunity in the airways,” Dr. Mannick said. She pointed to a 2008 study of bronchial epithelial cells from both patients with asthma and healthy controls. When inoculated with rhinovirus, the cells from asthmatic airways were unable to mount a healthy immune response and were particularly deficient in producing interferon-beta.

By inhibiting mammalian TORC1 (mTORC1), RBT101 also inhibits sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 2, a pathway that influences cholesterol synthesis. Cells perceive cholesterol synthesis attenuation as a threat, Dr. Mannick said, and react by up-regulating a number of immune response genes – including some specifically antiviral genes that up-regulate interferon-alpha and -beta production and immune cytokine signaling pathways.

RTB101 is not a particularly new molecule; Novartis originally investigated it as an anticancer agent. “It failed, because it was too selective for mTORC1,” Dr. Mannick said. After Novartis dropped the molecule, resTORbio, a Novartis spin-off, began to investigate it as an immunotherapy for RTIs, particularly in patients with asthma.

reSTORbio’s phase 2 studies on RTB101 comprised 264 healthy subjects aged 65 years and older, who received placebo or 10 mg RTB101 daily for 6 weeks, during cold and flu season. They were followed for a year, confirming the antiviral gene up-regulation. Treatment was also associated with a 42% reduction in the rate of respiratory tract infections.

Conversations with the Food and Drug Administration and payers collected, Dr. Mannick said. “They said that where this drug could really make a difference was if it could decrease these infections in high-risk elderly, who are expensive to treat. So, we targeted people 65 years and older with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and smokers, and people who are 85 years or older.”

The phase 2b trial comprised 652 of these elderly high-risk subjects randomized to the following treatment arms: RTB101 5 mg once daily (n = 61), RTB101 10 mg once daily (n = 176), RTB101 10 mg b.i.d. (n = 120), RTB101 10 mg plus everolimus 0.1 mg daily (n = 115), or matching placebo (n = 180) over 16 weeks, during the entire cold and flu season. The primary endpoint was laboratory-confirmed RTIs in all groups.

The RTB101 10-mg, once-daily group had the best results with a 30.6% reduction in the percentage of patients with lab-confirmed RTIs, compared with placebo, and a 52% reduction in the percentage with severe symptoms.

A subgroup analysis found even more benefit to those with asthma. Among these patients, RTB101 effected a 58.2% decrease in patients with RTIs, and a 66.4% decrease in the rate of infections, compared with placebo.

RTB101 was most effective against rhinoviruses, but it also prevented RTIs associated with influenza A and coronavirus OC43. It also decreased the incidence of RTIs caused by respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza 4, influenza B, metapneumovirus, or other coronavirus serotypes.

There were no safety signals, Dr. Mannick noted. Adverse events were similar in both placebo and active groups, and none were deemed related to the study drug. About 5% of each group discontinued the drug because an adverse event.

Plans for a phase 3 trial are underway. A phase 3, placebo-controlled study in the Southern Hemisphere is now ongoing, during the winter cold and flu season. The Northern Hemisphere phase 3 will commence fall and winter of 2019.

Whether RBT101 can help younger people with asthma is an open question. Elderly patients not only have the asthma-related immune deficiency, but also the general age-related immune issues. Younger patients, however, still express the same asthma-related impairment of bronchial immunity.

“We would like to investigate this in younger people and in children, but that will have to wait until our other phase 3 studies are complete,” Dr. Mannick said.

The trial was sponsored by resTORbio.

SOURCE: Mannick J et al. ATS 2019, Abstract A2623.

CORRECTION 5/24/2019 The article was corrected to state a decreased the incidence of RTIs caused by respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza 4, influenza B, metapneumovirus, or other coronavirus serotypes.

DALLAS – A molecule that boosts innate viral immunity may protect elderly people with asthma from the root cause of most exacerbations – viral respiratory tract infections.

Dubbed RTB101, the oral medication is a selective, potent inhibitor of target of rapamycin complex 1 (TORC1). In phase 2b data presented at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference, RTB101 decreased by 52% the number of elderly subjects with severe, lab-confirmed respiratory tract infections (RTI) symptoms.

But the molecule was even more effective in patients with asthma aged 65 years and older, Joan Mannick, MD, said in an interview during the meeting. In this group, it reduced by 69% the percentage of subjects who developed RTIs and reduced the rate of infection by about 79%, compared with placebo.

“The core cause of asthma exacerbations in these patients is viral respiratory tract infection,” said Dr. Mannick, chief medical officer of resTORbio, the Boston company developing RTB101. “About 80% of the viruses detected in these infections are rhinoviruses, and there are 170 rhinovirus serotypes. We have never been able to develop a vaccine against rhinovirus, and we have no treatment other than to treat the inflammation caused by the infection.”

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention mortality records confirm the impact of viral respiratory infections on older people who experience asthma exacerbations: 6 of 10,000 will die, compared with less than 2 per 10,000 for all other age groups. Decreasing the number of these infections in older people with asthma would prevent morbidity and mortality and save considerable health care dollars.

“One of the reasons that asthmatics have such difficulty when they get respiratory infections is that they seem to have deficient antiviral immunity in the airways,” Dr. Mannick said. She pointed to a 2008 study of bronchial epithelial cells from both patients with asthma and healthy controls. When inoculated with rhinovirus, the cells from asthmatic airways were unable to mount a healthy immune response and were particularly deficient in producing interferon-beta.

By inhibiting mammalian TORC1 (mTORC1), RBT101 also inhibits sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 2, a pathway that influences cholesterol synthesis. Cells perceive cholesterol synthesis attenuation as a threat, Dr. Mannick said, and react by up-regulating a number of immune response genes – including some specifically antiviral genes that up-regulate interferon-alpha and -beta production and immune cytokine signaling pathways.

RTB101 is not a particularly new molecule; Novartis originally investigated it as an anticancer agent. “It failed, because it was too selective for mTORC1,” Dr. Mannick said. After Novartis dropped the molecule, resTORbio, a Novartis spin-off, began to investigate it as an immunotherapy for RTIs, particularly in patients with asthma.

reSTORbio’s phase 2 studies on RTB101 comprised 264 healthy subjects aged 65 years and older, who received placebo or 10 mg RTB101 daily for 6 weeks, during cold and flu season. They were followed for a year, confirming the antiviral gene up-regulation. Treatment was also associated with a 42% reduction in the rate of respiratory tract infections.

Conversations with the Food and Drug Administration and payers collected, Dr. Mannick said. “They said that where this drug could really make a difference was if it could decrease these infections in high-risk elderly, who are expensive to treat. So, we targeted people 65 years and older with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and smokers, and people who are 85 years or older.”

The phase 2b trial comprised 652 of these elderly high-risk subjects randomized to the following treatment arms: RTB101 5 mg once daily (n = 61), RTB101 10 mg once daily (n = 176), RTB101 10 mg b.i.d. (n = 120), RTB101 10 mg plus everolimus 0.1 mg daily (n = 115), or matching placebo (n = 180) over 16 weeks, during the entire cold and flu season. The primary endpoint was laboratory-confirmed RTIs in all groups.

The RTB101 10-mg, once-daily group had the best results with a 30.6% reduction in the percentage of patients with lab-confirmed RTIs, compared with placebo, and a 52% reduction in the percentage with severe symptoms.

A subgroup analysis found even more benefit to those with asthma. Among these patients, RTB101 effected a 58.2% decrease in patients with RTIs, and a 66.4% decrease in the rate of infections, compared with placebo.

RTB101 was most effective against rhinoviruses, but it also prevented RTIs associated with influenza A and coronavirus OC43. It also decreased the incidence of RTIs caused by respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza 4, influenza B, metapneumovirus, or other coronavirus serotypes.

There were no safety signals, Dr. Mannick noted. Adverse events were similar in both placebo and active groups, and none were deemed related to the study drug. About 5% of each group discontinued the drug because an adverse event.

Plans for a phase 3 trial are underway. A phase 3, placebo-controlled study in the Southern Hemisphere is now ongoing, during the winter cold and flu season. The Northern Hemisphere phase 3 will commence fall and winter of 2019.

Whether RBT101 can help younger people with asthma is an open question. Elderly patients not only have the asthma-related immune deficiency, but also the general age-related immune issues. Younger patients, however, still express the same asthma-related impairment of bronchial immunity.

“We would like to investigate this in younger people and in children, but that will have to wait until our other phase 3 studies are complete,” Dr. Mannick said.

The trial was sponsored by resTORbio.

SOURCE: Mannick J et al. ATS 2019, Abstract A2623.

CORRECTION 5/24/2019 The article was corrected to state a decreased the incidence of RTIs caused by respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza 4, influenza B, metapneumovirus, or other coronavirus serotypes.

DALLAS – A molecule that boosts innate viral immunity may protect elderly people with asthma from the root cause of most exacerbations – viral respiratory tract infections.

Dubbed RTB101, the oral medication is a selective, potent inhibitor of target of rapamycin complex 1 (TORC1). In phase 2b data presented at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference, RTB101 decreased by 52% the number of elderly subjects with severe, lab-confirmed respiratory tract infections (RTI) symptoms.

But the molecule was even more effective in patients with asthma aged 65 years and older, Joan Mannick, MD, said in an interview during the meeting. In this group, it reduced by 69% the percentage of subjects who developed RTIs and reduced the rate of infection by about 79%, compared with placebo.

“The core cause of asthma exacerbations in these patients is viral respiratory tract infection,” said Dr. Mannick, chief medical officer of resTORbio, the Boston company developing RTB101. “About 80% of the viruses detected in these infections are rhinoviruses, and there are 170 rhinovirus serotypes. We have never been able to develop a vaccine against rhinovirus, and we have no treatment other than to treat the inflammation caused by the infection.”

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention mortality records confirm the impact of viral respiratory infections on older people who experience asthma exacerbations: 6 of 10,000 will die, compared with less than 2 per 10,000 for all other age groups. Decreasing the number of these infections in older people with asthma would prevent morbidity and mortality and save considerable health care dollars.

“One of the reasons that asthmatics have such difficulty when they get respiratory infections is that they seem to have deficient antiviral immunity in the airways,” Dr. Mannick said. She pointed to a 2008 study of bronchial epithelial cells from both patients with asthma and healthy controls. When inoculated with rhinovirus, the cells from asthmatic airways were unable to mount a healthy immune response and were particularly deficient in producing interferon-beta.

By inhibiting mammalian TORC1 (mTORC1), RBT101 also inhibits sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 2, a pathway that influences cholesterol synthesis. Cells perceive cholesterol synthesis attenuation as a threat, Dr. Mannick said, and react by up-regulating a number of immune response genes – including some specifically antiviral genes that up-regulate interferon-alpha and -beta production and immune cytokine signaling pathways.

RTB101 is not a particularly new molecule; Novartis originally investigated it as an anticancer agent. “It failed, because it was too selective for mTORC1,” Dr. Mannick said. After Novartis dropped the molecule, resTORbio, a Novartis spin-off, began to investigate it as an immunotherapy for RTIs, particularly in patients with asthma.

reSTORbio’s phase 2 studies on RTB101 comprised 264 healthy subjects aged 65 years and older, who received placebo or 10 mg RTB101 daily for 6 weeks, during cold and flu season. They were followed for a year, confirming the antiviral gene up-regulation. Treatment was also associated with a 42% reduction in the rate of respiratory tract infections.

Conversations with the Food and Drug Administration and payers collected, Dr. Mannick said. “They said that where this drug could really make a difference was if it could decrease these infections in high-risk elderly, who are expensive to treat. So, we targeted people 65 years and older with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and smokers, and people who are 85 years or older.”

The phase 2b trial comprised 652 of these elderly high-risk subjects randomized to the following treatment arms: RTB101 5 mg once daily (n = 61), RTB101 10 mg once daily (n = 176), RTB101 10 mg b.i.d. (n = 120), RTB101 10 mg plus everolimus 0.1 mg daily (n = 115), or matching placebo (n = 180) over 16 weeks, during the entire cold and flu season. The primary endpoint was laboratory-confirmed RTIs in all groups.

The RTB101 10-mg, once-daily group had the best results with a 30.6% reduction in the percentage of patients with lab-confirmed RTIs, compared with placebo, and a 52% reduction in the percentage with severe symptoms.

A subgroup analysis found even more benefit to those with asthma. Among these patients, RTB101 effected a 58.2% decrease in patients with RTIs, and a 66.4% decrease in the rate of infections, compared with placebo.

RTB101 was most effective against rhinoviruses, but it also prevented RTIs associated with influenza A and coronavirus OC43. It also decreased the incidence of RTIs caused by respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza 4, influenza B, metapneumovirus, or other coronavirus serotypes.

There were no safety signals, Dr. Mannick noted. Adverse events were similar in both placebo and active groups, and none were deemed related to the study drug. About 5% of each group discontinued the drug because an adverse event.

Plans for a phase 3 trial are underway. A phase 3, placebo-controlled study in the Southern Hemisphere is now ongoing, during the winter cold and flu season. The Northern Hemisphere phase 3 will commence fall and winter of 2019.

Whether RBT101 can help younger people with asthma is an open question. Elderly patients not only have the asthma-related immune deficiency, but also the general age-related immune issues. Younger patients, however, still express the same asthma-related impairment of bronchial immunity.

“We would like to investigate this in younger people and in children, but that will have to wait until our other phase 3 studies are complete,” Dr. Mannick said.

The trial was sponsored by resTORbio.

SOURCE: Mannick J et al. ATS 2019, Abstract A2623.

CORRECTION 5/24/2019 The article was corrected to state a decreased the incidence of RTIs caused by respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza 4, influenza B, metapneumovirus, or other coronavirus serotypes.

REPORTING FROM ATS 2019

FDA grants marketing clearance for chlamydia and gonorrhea extragenital tests

The new tests, the Aptima Combo 2 Assay and Xpert CT/NG, use samples from the throat and rectum to test for chlamydia and gonorrhea, according to a statement from the FDA.

“It is best for patients if both [chlamydia and gonorrhea] are caught and treated right away, as significant complications can occur if left untreated,” noted Tim Stenzel, MD, in the statement.

“Today’s clearances provide a mechanism for more easily diagnosing these infections,” said Dr. Stenzel, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

The two tests were reviewed through the premarket notification – or 510(k) – pathway, which seeks to demonstrate to the FDA that the device to be marketed is equivalent or better in safety and effectiveness to the legally marketed device.

In the FDA’s evaluation of the tests, it reviewed clinical data from a multisite study of more than 2,500 patients. This study evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of multiple commercially available nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis from throat and rectal sites. The results of this study and other information reviewed by the FDA demonstrated that the two tests “are safe and effective for extragenital testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea,” according to the statement.

The data were collected through a cross-sectional study coordinated by the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group, which is funded and supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The FDA granted marketing clearance to Hologic and Cepheid for the Aptima Combo 2 Assay and the Xpert CT/NG, respectively.

The new tests, the Aptima Combo 2 Assay and Xpert CT/NG, use samples from the throat and rectum to test for chlamydia and gonorrhea, according to a statement from the FDA.

“It is best for patients if both [chlamydia and gonorrhea] are caught and treated right away, as significant complications can occur if left untreated,” noted Tim Stenzel, MD, in the statement.

“Today’s clearances provide a mechanism for more easily diagnosing these infections,” said Dr. Stenzel, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

The two tests were reviewed through the premarket notification – or 510(k) – pathway, which seeks to demonstrate to the FDA that the device to be marketed is equivalent or better in safety and effectiveness to the legally marketed device.

In the FDA’s evaluation of the tests, it reviewed clinical data from a multisite study of more than 2,500 patients. This study evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of multiple commercially available nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis from throat and rectal sites. The results of this study and other information reviewed by the FDA demonstrated that the two tests “are safe and effective for extragenital testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea,” according to the statement.

The data were collected through a cross-sectional study coordinated by the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group, which is funded and supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The FDA granted marketing clearance to Hologic and Cepheid for the Aptima Combo 2 Assay and the Xpert CT/NG, respectively.

The new tests, the Aptima Combo 2 Assay and Xpert CT/NG, use samples from the throat and rectum to test for chlamydia and gonorrhea, according to a statement from the FDA.

“It is best for patients if both [chlamydia and gonorrhea] are caught and treated right away, as significant complications can occur if left untreated,” noted Tim Stenzel, MD, in the statement.

“Today’s clearances provide a mechanism for more easily diagnosing these infections,” said Dr. Stenzel, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

The two tests were reviewed through the premarket notification – or 510(k) – pathway, which seeks to demonstrate to the FDA that the device to be marketed is equivalent or better in safety and effectiveness to the legally marketed device.

In the FDA’s evaluation of the tests, it reviewed clinical data from a multisite study of more than 2,500 patients. This study evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of multiple commercially available nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis from throat and rectal sites. The results of this study and other information reviewed by the FDA demonstrated that the two tests “are safe and effective for extragenital testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea,” according to the statement.

The data were collected through a cross-sectional study coordinated by the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group, which is funded and supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The FDA granted marketing clearance to Hologic and Cepheid for the Aptima Combo 2 Assay and the Xpert CT/NG, respectively.

Zoster vaccination is underused but looks effective in IBD

For men with inflammatory bowel disease, herpes zoster vaccination was associated with about a 46% decrease in risk of associated infection, according to the results of a retrospective study from the national Veterans Affairs Healthcare System.

Crude rates of herpes zoster infection were 4.09 cases per 1,000 person-years among vaccinated patients versus 6.97 cases per 1,000 person-years among unvaccinated patients, for an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.54 (95% confidence interval, 0.44-0.68), reported Nabeel Khan, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and associates. “This vaccine is therefore effective in patients with IBD, but underused,” they wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Studies have linked IBD with a 1.2- to 1.8-fold increased risk of herpes zoster infection, the researchers noted. Relevant risk factors include older age, disease flare, recent use or high cumulative use of prednisone, and use of thiopurines, either alone or in combination with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor. Although the American College of Gastroenterology recommends that all patients with IBD receive the herpes zoster vaccine by age 50 years, the efficacy of the vaccine in these patients remains unclear.

For their study, Dr. Khan and associates analyzed International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes and other medical record data from 39,983 veterans with IBD who had not received the herpes zoster vaccine by age 60 years. In all, 97% of patients were male, and 94% were white. Most patients had high rates of health care utilization: Approximately half visited VA clinics or hospitals at least 13 times per year, and another third made 6-12 annual visits.

Despite their many contacts with VA health care systems, only 7,170 (17.9%) patients received the herpes zoster vaccine during 2000-2016, the researchers found. Vaccination rates varied substantially by region – they were highest in the Midwest (35%) and North Atlantic states (29%) but reached only 9% in Montana, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana, collectively.

The crude rate of herpes zoster infection among unvaccinated patients with IBD resembled the incidence reported in prior studies, the researchers said. After researchers accounted for differences in geography, demographics, and health care utilization between vaccinated and unvaccinated veterans with IBD, they found that vaccination was associated with an approximately 46% decrease in the risk of herpes zoster infection.

Very few patients were vaccinated for herpes zoster while on a TNF inhibitor, precluding the ability to study this subgroup. However, the vaccine showed a protective effect (adjusted HR, 0.63) among patients who received thiopurines without a TNF inhibitor. This effect did not reach statistical significance, perhaps because of lack of power, the researchers noted. “Among the 315 patients who were [vaccinated while] on thiopurines, none developed a documented painful or painless vesicular rash within 42 days of herpes zoster vaccination,” they added. One patient developed a painful blister 20 days post vaccination without vesicles or long-term sequelae.

Pfizer provided funding. Dr. Khan disclosed research funding from Pfizer, Luitpold, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to Pfizer, Gilead, Merck, AbbVie, Lilly, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, UCB, and Nestle Health Science. The remaining researchers disclosed no conflicts.

SOURCE: Khan N et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Oct 13. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.10.016.

Preventive care is an underemphasized component of IBD management because the primary focus tends to be control of active symptoms. However, as patients are treated with immunosuppression, particularly combinations of therapies and newer mechanisms of action such as the Janus kinase inhibitors, the risk of infections increases, including those that are vaccine preventable including shingles and its related complications.

This study by Khan et al. highlights several important messages for patients and providers. First, in this large older IBD cohort, the vaccination rates were very low at 18% even though more than 80% of patients had more than six annual visits to the VA Health Systems during the study period. These represent multiple missed opportunities to discuss and administer vaccinations. Second, the authors highlighted the vaccine’s efficacy: Persons receiving herpes zoster vaccination had a clearly decreased risk of subsequent infection. While the number of vaccinated patients on immunosuppression was too small to draw conclusions about efficacy, the live attenuated vaccination is contraindicated for immunosuppressed patients. However, the newer recombinant shingles vaccine offers the opportunity to extend the reach of shingles vaccination to include those on immunosuppression. As utilization of the newer vaccine series increases, we will be able to evaluate the efficacy for immunosuppressed IBD patients, although studies from other disease states suggest efficacy. However, vaccinations will never work if they aren’t administered. Counseling patients and providers regarding the importance of vaccinations is a low-risk, efficacious means to decrease infection and associated morbidity.

Christina Ha, MD, AGAF, associate professor of medicine, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, division of digestive diseases, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. She is a speaker, consultant, or on the advisory board for AbbVie, Janssen, Genentech, Samsung Bioepis, and Takeda. She received grant funding from Pfizer.

Preventive care is an underemphasized component of IBD management because the primary focus tends to be control of active symptoms. However, as patients are treated with immunosuppression, particularly combinations of therapies and newer mechanisms of action such as the Janus kinase inhibitors, the risk of infections increases, including those that are vaccine preventable including shingles and its related complications.

This study by Khan et al. highlights several important messages for patients and providers. First, in this large older IBD cohort, the vaccination rates were very low at 18% even though more than 80% of patients had more than six annual visits to the VA Health Systems during the study period. These represent multiple missed opportunities to discuss and administer vaccinations. Second, the authors highlighted the vaccine’s efficacy: Persons receiving herpes zoster vaccination had a clearly decreased risk of subsequent infection. While the number of vaccinated patients on immunosuppression was too small to draw conclusions about efficacy, the live attenuated vaccination is contraindicated for immunosuppressed patients. However, the newer recombinant shingles vaccine offers the opportunity to extend the reach of shingles vaccination to include those on immunosuppression. As utilization of the newer vaccine series increases, we will be able to evaluate the efficacy for immunosuppressed IBD patients, although studies from other disease states suggest efficacy. However, vaccinations will never work if they aren’t administered. Counseling patients and providers regarding the importance of vaccinations is a low-risk, efficacious means to decrease infection and associated morbidity.

Christina Ha, MD, AGAF, associate professor of medicine, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, division of digestive diseases, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. She is a speaker, consultant, or on the advisory board for AbbVie, Janssen, Genentech, Samsung Bioepis, and Takeda. She received grant funding from Pfizer.

Preventive care is an underemphasized component of IBD management because the primary focus tends to be control of active symptoms. However, as patients are treated with immunosuppression, particularly combinations of therapies and newer mechanisms of action such as the Janus kinase inhibitors, the risk of infections increases, including those that are vaccine preventable including shingles and its related complications.

This study by Khan et al. highlights several important messages for patients and providers. First, in this large older IBD cohort, the vaccination rates were very low at 18% even though more than 80% of patients had more than six annual visits to the VA Health Systems during the study period. These represent multiple missed opportunities to discuss and administer vaccinations. Second, the authors highlighted the vaccine’s efficacy: Persons receiving herpes zoster vaccination had a clearly decreased risk of subsequent infection. While the number of vaccinated patients on immunosuppression was too small to draw conclusions about efficacy, the live attenuated vaccination is contraindicated for immunosuppressed patients. However, the newer recombinant shingles vaccine offers the opportunity to extend the reach of shingles vaccination to include those on immunosuppression. As utilization of the newer vaccine series increases, we will be able to evaluate the efficacy for immunosuppressed IBD patients, although studies from other disease states suggest efficacy. However, vaccinations will never work if they aren’t administered. Counseling patients and providers regarding the importance of vaccinations is a low-risk, efficacious means to decrease infection and associated morbidity.

Christina Ha, MD, AGAF, associate professor of medicine, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, division of digestive diseases, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. She is a speaker, consultant, or on the advisory board for AbbVie, Janssen, Genentech, Samsung Bioepis, and Takeda. She received grant funding from Pfizer.

For men with inflammatory bowel disease, herpes zoster vaccination was associated with about a 46% decrease in risk of associated infection, according to the results of a retrospective study from the national Veterans Affairs Healthcare System.

Crude rates of herpes zoster infection were 4.09 cases per 1,000 person-years among vaccinated patients versus 6.97 cases per 1,000 person-years among unvaccinated patients, for an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.54 (95% confidence interval, 0.44-0.68), reported Nabeel Khan, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and associates. “This vaccine is therefore effective in patients with IBD, but underused,” they wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Studies have linked IBD with a 1.2- to 1.8-fold increased risk of herpes zoster infection, the researchers noted. Relevant risk factors include older age, disease flare, recent use or high cumulative use of prednisone, and use of thiopurines, either alone or in combination with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor. Although the American College of Gastroenterology recommends that all patients with IBD receive the herpes zoster vaccine by age 50 years, the efficacy of the vaccine in these patients remains unclear.

For their study, Dr. Khan and associates analyzed International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes and other medical record data from 39,983 veterans with IBD who had not received the herpes zoster vaccine by age 60 years. In all, 97% of patients were male, and 94% were white. Most patients had high rates of health care utilization: Approximately half visited VA clinics or hospitals at least 13 times per year, and another third made 6-12 annual visits.

Despite their many contacts with VA health care systems, only 7,170 (17.9%) patients received the herpes zoster vaccine during 2000-2016, the researchers found. Vaccination rates varied substantially by region – they were highest in the Midwest (35%) and North Atlantic states (29%) but reached only 9% in Montana, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana, collectively.

The crude rate of herpes zoster infection among unvaccinated patients with IBD resembled the incidence reported in prior studies, the researchers said. After researchers accounted for differences in geography, demographics, and health care utilization between vaccinated and unvaccinated veterans with IBD, they found that vaccination was associated with an approximately 46% decrease in the risk of herpes zoster infection.

Very few patients were vaccinated for herpes zoster while on a TNF inhibitor, precluding the ability to study this subgroup. However, the vaccine showed a protective effect (adjusted HR, 0.63) among patients who received thiopurines without a TNF inhibitor. This effect did not reach statistical significance, perhaps because of lack of power, the researchers noted. “Among the 315 patients who were [vaccinated while] on thiopurines, none developed a documented painful or painless vesicular rash within 42 days of herpes zoster vaccination,” they added. One patient developed a painful blister 20 days post vaccination without vesicles or long-term sequelae.

Pfizer provided funding. Dr. Khan disclosed research funding from Pfizer, Luitpold, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to Pfizer, Gilead, Merck, AbbVie, Lilly, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, UCB, and Nestle Health Science. The remaining researchers disclosed no conflicts.

SOURCE: Khan N et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Oct 13. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.10.016.

For men with inflammatory bowel disease, herpes zoster vaccination was associated with about a 46% decrease in risk of associated infection, according to the results of a retrospective study from the national Veterans Affairs Healthcare System.

Crude rates of herpes zoster infection were 4.09 cases per 1,000 person-years among vaccinated patients versus 6.97 cases per 1,000 person-years among unvaccinated patients, for an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.54 (95% confidence interval, 0.44-0.68), reported Nabeel Khan, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and associates. “This vaccine is therefore effective in patients with IBD, but underused,” they wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Studies have linked IBD with a 1.2- to 1.8-fold increased risk of herpes zoster infection, the researchers noted. Relevant risk factors include older age, disease flare, recent use or high cumulative use of prednisone, and use of thiopurines, either alone or in combination with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor. Although the American College of Gastroenterology recommends that all patients with IBD receive the herpes zoster vaccine by age 50 years, the efficacy of the vaccine in these patients remains unclear.

For their study, Dr. Khan and associates analyzed International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes and other medical record data from 39,983 veterans with IBD who had not received the herpes zoster vaccine by age 60 years. In all, 97% of patients were male, and 94% were white. Most patients had high rates of health care utilization: Approximately half visited VA clinics or hospitals at least 13 times per year, and another third made 6-12 annual visits.

Despite their many contacts with VA health care systems, only 7,170 (17.9%) patients received the herpes zoster vaccine during 2000-2016, the researchers found. Vaccination rates varied substantially by region – they were highest in the Midwest (35%) and North Atlantic states (29%) but reached only 9% in Montana, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana, collectively.

The crude rate of herpes zoster infection among unvaccinated patients with IBD resembled the incidence reported in prior studies, the researchers said. After researchers accounted for differences in geography, demographics, and health care utilization between vaccinated and unvaccinated veterans with IBD, they found that vaccination was associated with an approximately 46% decrease in the risk of herpes zoster infection.

Very few patients were vaccinated for herpes zoster while on a TNF inhibitor, precluding the ability to study this subgroup. However, the vaccine showed a protective effect (adjusted HR, 0.63) among patients who received thiopurines without a TNF inhibitor. This effect did not reach statistical significance, perhaps because of lack of power, the researchers noted. “Among the 315 patients who were [vaccinated while] on thiopurines, none developed a documented painful or painless vesicular rash within 42 days of herpes zoster vaccination,” they added. One patient developed a painful blister 20 days post vaccination without vesicles or long-term sequelae.

Pfizer provided funding. Dr. Khan disclosed research funding from Pfizer, Luitpold, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to Pfizer, Gilead, Merck, AbbVie, Lilly, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, UCB, and Nestle Health Science. The remaining researchers disclosed no conflicts.

SOURCE: Khan N et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Oct 13. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.10.016.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Despite HCV cure, liver cancer-associated genetic changes persist

A new study showed that liver tissue from hepatitis C virus (HCV)–infected humans with and without sustained virologic response found epigenetic and gene expression alterations associated with the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), according to Nourdine Hamdane, PHD, of the Institut de Recherche sur les Maladies Virales et Hépatiques, Strasbourg, France, and colleagues.

The researchers analyzed liver tissue from 6 noninfected control patients, 18 patients with chronic HCV infection, 21 patients with cured chronic HCV, 4 patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, and 7 patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), as well as 8 paired HCC samples with HCV-induced liver disease (Gastroenterology 2019;156:2313–29).

They found that several altered pathways related to carcinogenesis persisted after cure, including TNF-alpha signaling, inflammatory response, G2M checkpoint, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and phosphoinositide 3-kinase, Akt, and mammalian target of rapamycin.

They also observed lower levels of H3K27ac mapping to genes related to oxidative phosphorylation pathways, providing evidence supporting a functional role for H3K27ac changes in establishing gene expression patterns that persist after cure and contribute to carcinogenesis, according to the authors.

“Our study exposes a previously undiscovered paradigm showing that chronic HCV infection induces H3K27ac modifications that are associated with HCC risk and that persist after HCV cure,” the authors wrote. “[This study] provides a unique opportunity to uncover novel biomarkers for HCC risk, that is, from plasma through the detection of epigenetic changes of histones bound to circulating DNA complexes. Furthermore, by uncovering virus-induced epigenetic changes as therapeutic targets, our findings offer novel perspectives for HCC prevention – a key unmet medical need,” the researchers concluded.

The authors declared that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Hamdane N, et al. 2019; Gastroenterology 156:2313–29.

A new study showed that liver tissue from hepatitis C virus (HCV)–infected humans with and without sustained virologic response found epigenetic and gene expression alterations associated with the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), according to Nourdine Hamdane, PHD, of the Institut de Recherche sur les Maladies Virales et Hépatiques, Strasbourg, France, and colleagues.

The researchers analyzed liver tissue from 6 noninfected control patients, 18 patients with chronic HCV infection, 21 patients with cured chronic HCV, 4 patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, and 7 patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), as well as 8 paired HCC samples with HCV-induced liver disease (Gastroenterology 2019;156:2313–29).

They found that several altered pathways related to carcinogenesis persisted after cure, including TNF-alpha signaling, inflammatory response, G2M checkpoint, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and phosphoinositide 3-kinase, Akt, and mammalian target of rapamycin.

They also observed lower levels of H3K27ac mapping to genes related to oxidative phosphorylation pathways, providing evidence supporting a functional role for H3K27ac changes in establishing gene expression patterns that persist after cure and contribute to carcinogenesis, according to the authors.

“Our study exposes a previously undiscovered paradigm showing that chronic HCV infection induces H3K27ac modifications that are associated with HCC risk and that persist after HCV cure,” the authors wrote. “[This study] provides a unique opportunity to uncover novel biomarkers for HCC risk, that is, from plasma through the detection of epigenetic changes of histones bound to circulating DNA complexes. Furthermore, by uncovering virus-induced epigenetic changes as therapeutic targets, our findings offer novel perspectives for HCC prevention – a key unmet medical need,” the researchers concluded.

The authors declared that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Hamdane N, et al. 2019; Gastroenterology 156:2313–29.

A new study showed that liver tissue from hepatitis C virus (HCV)–infected humans with and without sustained virologic response found epigenetic and gene expression alterations associated with the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), according to Nourdine Hamdane, PHD, of the Institut de Recherche sur les Maladies Virales et Hépatiques, Strasbourg, France, and colleagues.

The researchers analyzed liver tissue from 6 noninfected control patients, 18 patients with chronic HCV infection, 21 patients with cured chronic HCV, 4 patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, and 7 patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), as well as 8 paired HCC samples with HCV-induced liver disease (Gastroenterology 2019;156:2313–29).

They found that several altered pathways related to carcinogenesis persisted after cure, including TNF-alpha signaling, inflammatory response, G2M checkpoint, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and phosphoinositide 3-kinase, Akt, and mammalian target of rapamycin.

They also observed lower levels of H3K27ac mapping to genes related to oxidative phosphorylation pathways, providing evidence supporting a functional role for H3K27ac changes in establishing gene expression patterns that persist after cure and contribute to carcinogenesis, according to the authors.

“Our study exposes a previously undiscovered paradigm showing that chronic HCV infection induces H3K27ac modifications that are associated with HCC risk and that persist after HCV cure,” the authors wrote. “[This study] provides a unique opportunity to uncover novel biomarkers for HCC risk, that is, from plasma through the detection of epigenetic changes of histones bound to circulating DNA complexes. Furthermore, by uncovering virus-induced epigenetic changes as therapeutic targets, our findings offer novel perspectives for HCC prevention – a key unmet medical need,” the researchers concluded.

The authors declared that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Hamdane N, et al. 2019; Gastroenterology 156:2313–29.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Part 3: Talkin’ ’bout My Generation

Members of the baby boom generation (yes, my generation)—the nomenclature given to the 76 million people born between 1946 and 1964—are now in our 50s, 60s, and 70s. Many of us are enjoying our retirement while others are still working. Regardless of our circumstances, we all share one challenge: aging as comfortably as we can. It’s a fact of our lives that as we age, we battle risk factors for a variety of conditions, ranging from diabetes, heart disease, and Alzheimer disease to … sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Ever since I saw the statistics about increasing rates of STIs among older Americans, I’ve been mulling possible explanations for this trend. In conversation with my CR colleagues, the question arose as to whether the fact that the current population of senior citizens is comprised largely of Baby Boomers has had an impact. It’s certainly worth considering!