User login

CDC creates interactive education module to improve RMSF recognition

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has created a first-of-its-kind interactive training module to help physicians both recognize and diagnose Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF).

A record number of cases of RMSF were reported to the CDC in 2017 (6,248, up from 4,269 in 2016), but less than 1% of those cases had sufficient laboratory evidence to be confirmed. The CDC education module includes scenarios based on real cases to aid providers in recognizing RMSF and differentiating it from similar diseases. CME is available for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, veterinarians, nurses, epidemiologists, public health professionals, educators, and health communicators.

The disease initially presents with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, headache, or rash, but if left untreated, patients may require the amputation of fingers, toes, or limbs because of low blood flow; heart and lung specialty care; and ICU management. About 20% of untreated cases are fatal; half of these deaths occur within 8 days of initial presentation.

“Rocky Mountain spotted fever can be deadly if not treated early – yet cases often go unrecognized because the signs and symptoms are similar to those of many other diseases. With tickborne diseases on the rise in the U.S., this training will better equip health care providers to identify, diagnose, and treat this potentially fatal disease,” said CDC director Robert R. Redfield, MD.

Find the full press release on the CDC website.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has created a first-of-its-kind interactive training module to help physicians both recognize and diagnose Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF).

A record number of cases of RMSF were reported to the CDC in 2017 (6,248, up from 4,269 in 2016), but less than 1% of those cases had sufficient laboratory evidence to be confirmed. The CDC education module includes scenarios based on real cases to aid providers in recognizing RMSF and differentiating it from similar diseases. CME is available for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, veterinarians, nurses, epidemiologists, public health professionals, educators, and health communicators.

The disease initially presents with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, headache, or rash, but if left untreated, patients may require the amputation of fingers, toes, or limbs because of low blood flow; heart and lung specialty care; and ICU management. About 20% of untreated cases are fatal; half of these deaths occur within 8 days of initial presentation.

“Rocky Mountain spotted fever can be deadly if not treated early – yet cases often go unrecognized because the signs and symptoms are similar to those of many other diseases. With tickborne diseases on the rise in the U.S., this training will better equip health care providers to identify, diagnose, and treat this potentially fatal disease,” said CDC director Robert R. Redfield, MD.

Find the full press release on the CDC website.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has created a first-of-its-kind interactive training module to help physicians both recognize and diagnose Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF).

A record number of cases of RMSF were reported to the CDC in 2017 (6,248, up from 4,269 in 2016), but less than 1% of those cases had sufficient laboratory evidence to be confirmed. The CDC education module includes scenarios based on real cases to aid providers in recognizing RMSF and differentiating it from similar diseases. CME is available for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, veterinarians, nurses, epidemiologists, public health professionals, educators, and health communicators.

The disease initially presents with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, headache, or rash, but if left untreated, patients may require the amputation of fingers, toes, or limbs because of low blood flow; heart and lung specialty care; and ICU management. About 20% of untreated cases are fatal; half of these deaths occur within 8 days of initial presentation.

“Rocky Mountain spotted fever can be deadly if not treated early – yet cases often go unrecognized because the signs and symptoms are similar to those of many other diseases. With tickborne diseases on the rise in the U.S., this training will better equip health care providers to identify, diagnose, and treat this potentially fatal disease,” said CDC director Robert R. Redfield, MD.

Find the full press release on the CDC website.

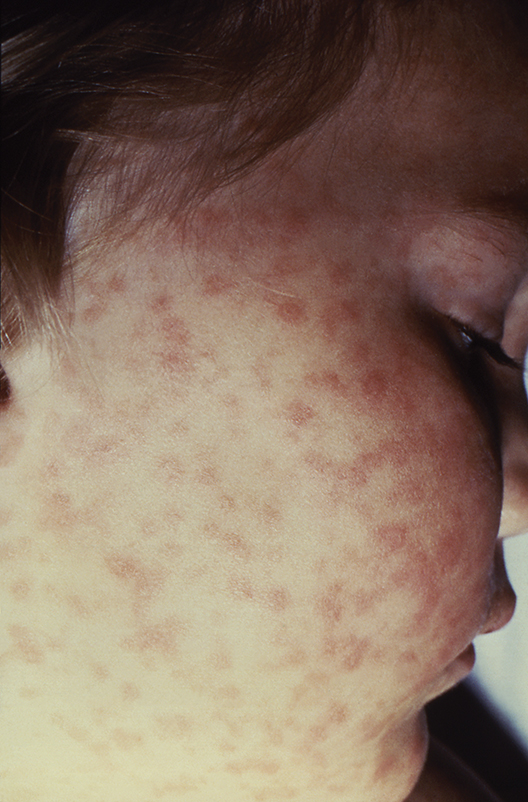

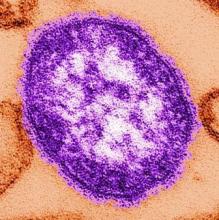

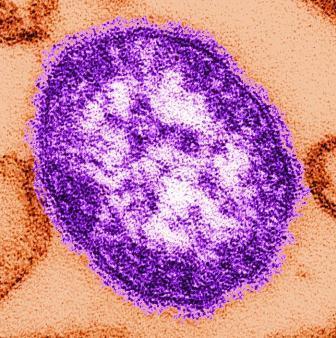

Measles cases now at highest level since 1992

With 971 cases of measles reported after just 5 months of 2019, the United States has hit another dubious milestone by surpassing the 963 cases reported in the preelimination year of 1994, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That leaves 1992, when there were 2,237 cases reported, as the next big obstacle on measles’ current path of distinction, the CDC data show. Only 312 cases were reported in 1993.

“Outbreaks in New York City and Rockland County, New York have continued for nearly 8 months. That loss would be a huge blow for the nation and erase the hard work done by all levels of public health,” the CDC said May 30.

The CDC defines measles elimination as “the absence of continuous disease transmission for 12 months or more in a specific geographic area” and notes that “measles is no longer endemic [constantly present] in the United States.”

“Measles is preventable and the way to end this outbreak is to ensure that all children and adults who can get vaccinated, do get vaccinated. Again, I want to reassure parents that vaccines are safe, they do not cause autism. The greater danger is the disease that vaccination prevents,” CDC director Robert Redfield, MD, said in a statement.

With 971 cases of measles reported after just 5 months of 2019, the United States has hit another dubious milestone by surpassing the 963 cases reported in the preelimination year of 1994, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That leaves 1992, when there were 2,237 cases reported, as the next big obstacle on measles’ current path of distinction, the CDC data show. Only 312 cases were reported in 1993.

“Outbreaks in New York City and Rockland County, New York have continued for nearly 8 months. That loss would be a huge blow for the nation and erase the hard work done by all levels of public health,” the CDC said May 30.

The CDC defines measles elimination as “the absence of continuous disease transmission for 12 months or more in a specific geographic area” and notes that “measles is no longer endemic [constantly present] in the United States.”

“Measles is preventable and the way to end this outbreak is to ensure that all children and adults who can get vaccinated, do get vaccinated. Again, I want to reassure parents that vaccines are safe, they do not cause autism. The greater danger is the disease that vaccination prevents,” CDC director Robert Redfield, MD, said in a statement.

With 971 cases of measles reported after just 5 months of 2019, the United States has hit another dubious milestone by surpassing the 963 cases reported in the preelimination year of 1994, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That leaves 1992, when there were 2,237 cases reported, as the next big obstacle on measles’ current path of distinction, the CDC data show. Only 312 cases were reported in 1993.

“Outbreaks in New York City and Rockland County, New York have continued for nearly 8 months. That loss would be a huge blow for the nation and erase the hard work done by all levels of public health,” the CDC said May 30.

The CDC defines measles elimination as “the absence of continuous disease transmission for 12 months or more in a specific geographic area” and notes that “measles is no longer endemic [constantly present] in the United States.”

“Measles is preventable and the way to end this outbreak is to ensure that all children and adults who can get vaccinated, do get vaccinated. Again, I want to reassure parents that vaccines are safe, they do not cause autism. The greater danger is the disease that vaccination prevents,” CDC director Robert Redfield, MD, said in a statement.

C-section linked to serious infection in preschoolers

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Delivery by C-section – especially when elective – carries a significantly higher hospitalization risk for severe infection in the first 5 years of life than vaginal delivery in a study of nearly 7.3 million singleton deliveries in four asset-rich countries, David Burgner, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“This is something that obstetricians might need to consider when discussing with the family the pros and cons for an elective C-section, particularly one that isn’t otherwise indicated for the baby or the mother,” said Dr. Burgner of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne.

He presented an observational study of 7.29 million singleton births in Denmark, Great Britain, Scotland, and two Australian states during 1996-2015. C-section rates ranged from a low of 17.5% in Denmark to 29.4% in Western Australia, all of which are greater than the 10%-15% rate endorsed by the World Health Organization. Elective C-section rates varied by country from 39% to 57%. Of note, pediatric hospital care in all four countries is free, so economic considerations didn’t drive admission.

The impetus for this international collaboration was to gain new insight into the differential susceptibility to childhood infection, he explained.

“We know from our clinical practice that pretty much all of the children are exposed to pretty much all potentially serious pathogens during early life. And yet it’s only a minority that develop severe infection. It’s an extremely interesting scientific question and an extremely important clinical question as to what’s driving that differential susceptibility,” according to the pediatric infectious disease specialist.

There are a number of established risk factors for infection-related hospitalization in children, including parental smoking, maternal antibiotic exposure during pregnancy, and growth measurements at birth. Dr. Burgner and coinvestigators hypothesized that another important risk factor is the nature of the microbiome transmitted from mother to baby during delivery. This postnatal microbiome varies depending upon mode of delivery: Vaginal delivery transmits the maternal enteric microbiome, which they reasoned might be through direct immunomodulation that sets up protective immune responses early in life, especially against respiratory and gastrointestinal tract infections. In contrast, delivery by C-section causes the baby to pick up the maternal skin and hospital environment microbiomes, but not the maternal enteric microbiome.

Thus, the investigators hypothesized that C-section poses a greater risk of infection-related hospitalization during the first 5 years of life than does vaginal delivery, and that elective C-section poses a higher risk than does emergency C-section because it is more likely to involve rupture of membranes.

The center-specific rates of C-section and infection-related pediatric infection, when combined into a meta-analysis, bore out the study hypothesis. Emergency C-section was associated with a 9% greater risk of infection-related hospitalization through 5 years of age than was vaginal delivery, while elective C-section was associated with a 13% increased risk, both of which were statistically significant and clinically important.

“We were quite taken with these results. We think they provide evidence that C-section is consistently associated with infection-related hospitalization. It’s an association study that can’t prove causality, but the results implicate the postnatal microbiome as the most plausible explanation in terms of what’s driving this association,” according to Dr. Burgner.

The association between C-section and infection-related hospitalization was persistent throughout the preschool years. For example, the increased risk associated with elective C-section was 16% during age 0-3 months, 20% during months 4-6, 14% in months 7-12, 13% during ages 1-2 years, and 11% among 2- to 5-year-olds, he continued.

The increased risk of severe preschool infection was highest for upper and lower respiratory tract and gastrointestinal infections, which involve the organ systems most likely to experience direct inoculation of the maternal microbiome, he noted.

Because the investigators recognized that the study results were potentially vulnerable to confounding by indication – that is, that the reason for doing a C-section might itself confer increased risk of subsequent preschool infection-related hospitalization – they repeated their analysis in a predefined low-risk subpopulation. The results closely mirrored those in the overall study population: an 8% increased risk in the emergency C-section group and a 14% increased risk with elective C-section.

Results of this large multinational study should provide further support for ongoing research aimed at supporting the infant microbiome after delivery by C-section via vaginal microbial transfer and other methods, he observed.

Dr. Burgner reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was cosponsored by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Danish Council for Independent Research, and nonprofit foundations.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Delivery by C-section – especially when elective – carries a significantly higher hospitalization risk for severe infection in the first 5 years of life than vaginal delivery in a study of nearly 7.3 million singleton deliveries in four asset-rich countries, David Burgner, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“This is something that obstetricians might need to consider when discussing with the family the pros and cons for an elective C-section, particularly one that isn’t otherwise indicated for the baby or the mother,” said Dr. Burgner of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne.

He presented an observational study of 7.29 million singleton births in Denmark, Great Britain, Scotland, and two Australian states during 1996-2015. C-section rates ranged from a low of 17.5% in Denmark to 29.4% in Western Australia, all of which are greater than the 10%-15% rate endorsed by the World Health Organization. Elective C-section rates varied by country from 39% to 57%. Of note, pediatric hospital care in all four countries is free, so economic considerations didn’t drive admission.

The impetus for this international collaboration was to gain new insight into the differential susceptibility to childhood infection, he explained.

“We know from our clinical practice that pretty much all of the children are exposed to pretty much all potentially serious pathogens during early life. And yet it’s only a minority that develop severe infection. It’s an extremely interesting scientific question and an extremely important clinical question as to what’s driving that differential susceptibility,” according to the pediatric infectious disease specialist.

There are a number of established risk factors for infection-related hospitalization in children, including parental smoking, maternal antibiotic exposure during pregnancy, and growth measurements at birth. Dr. Burgner and coinvestigators hypothesized that another important risk factor is the nature of the microbiome transmitted from mother to baby during delivery. This postnatal microbiome varies depending upon mode of delivery: Vaginal delivery transmits the maternal enteric microbiome, which they reasoned might be through direct immunomodulation that sets up protective immune responses early in life, especially against respiratory and gastrointestinal tract infections. In contrast, delivery by C-section causes the baby to pick up the maternal skin and hospital environment microbiomes, but not the maternal enteric microbiome.

Thus, the investigators hypothesized that C-section poses a greater risk of infection-related hospitalization during the first 5 years of life than does vaginal delivery, and that elective C-section poses a higher risk than does emergency C-section because it is more likely to involve rupture of membranes.

The center-specific rates of C-section and infection-related pediatric infection, when combined into a meta-analysis, bore out the study hypothesis. Emergency C-section was associated with a 9% greater risk of infection-related hospitalization through 5 years of age than was vaginal delivery, while elective C-section was associated with a 13% increased risk, both of which were statistically significant and clinically important.

“We were quite taken with these results. We think they provide evidence that C-section is consistently associated with infection-related hospitalization. It’s an association study that can’t prove causality, but the results implicate the postnatal microbiome as the most plausible explanation in terms of what’s driving this association,” according to Dr. Burgner.

The association between C-section and infection-related hospitalization was persistent throughout the preschool years. For example, the increased risk associated with elective C-section was 16% during age 0-3 months, 20% during months 4-6, 14% in months 7-12, 13% during ages 1-2 years, and 11% among 2- to 5-year-olds, he continued.

The increased risk of severe preschool infection was highest for upper and lower respiratory tract and gastrointestinal infections, which involve the organ systems most likely to experience direct inoculation of the maternal microbiome, he noted.

Because the investigators recognized that the study results were potentially vulnerable to confounding by indication – that is, that the reason for doing a C-section might itself confer increased risk of subsequent preschool infection-related hospitalization – they repeated their analysis in a predefined low-risk subpopulation. The results closely mirrored those in the overall study population: an 8% increased risk in the emergency C-section group and a 14% increased risk with elective C-section.

Results of this large multinational study should provide further support for ongoing research aimed at supporting the infant microbiome after delivery by C-section via vaginal microbial transfer and other methods, he observed.

Dr. Burgner reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was cosponsored by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Danish Council for Independent Research, and nonprofit foundations.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Delivery by C-section – especially when elective – carries a significantly higher hospitalization risk for severe infection in the first 5 years of life than vaginal delivery in a study of nearly 7.3 million singleton deliveries in four asset-rich countries, David Burgner, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“This is something that obstetricians might need to consider when discussing with the family the pros and cons for an elective C-section, particularly one that isn’t otherwise indicated for the baby or the mother,” said Dr. Burgner of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne.

He presented an observational study of 7.29 million singleton births in Denmark, Great Britain, Scotland, and two Australian states during 1996-2015. C-section rates ranged from a low of 17.5% in Denmark to 29.4% in Western Australia, all of which are greater than the 10%-15% rate endorsed by the World Health Organization. Elective C-section rates varied by country from 39% to 57%. Of note, pediatric hospital care in all four countries is free, so economic considerations didn’t drive admission.

The impetus for this international collaboration was to gain new insight into the differential susceptibility to childhood infection, he explained.

“We know from our clinical practice that pretty much all of the children are exposed to pretty much all potentially serious pathogens during early life. And yet it’s only a minority that develop severe infection. It’s an extremely interesting scientific question and an extremely important clinical question as to what’s driving that differential susceptibility,” according to the pediatric infectious disease specialist.

There are a number of established risk factors for infection-related hospitalization in children, including parental smoking, maternal antibiotic exposure during pregnancy, and growth measurements at birth. Dr. Burgner and coinvestigators hypothesized that another important risk factor is the nature of the microbiome transmitted from mother to baby during delivery. This postnatal microbiome varies depending upon mode of delivery: Vaginal delivery transmits the maternal enteric microbiome, which they reasoned might be through direct immunomodulation that sets up protective immune responses early in life, especially against respiratory and gastrointestinal tract infections. In contrast, delivery by C-section causes the baby to pick up the maternal skin and hospital environment microbiomes, but not the maternal enteric microbiome.

Thus, the investigators hypothesized that C-section poses a greater risk of infection-related hospitalization during the first 5 years of life than does vaginal delivery, and that elective C-section poses a higher risk than does emergency C-section because it is more likely to involve rupture of membranes.

The center-specific rates of C-section and infection-related pediatric infection, when combined into a meta-analysis, bore out the study hypothesis. Emergency C-section was associated with a 9% greater risk of infection-related hospitalization through 5 years of age than was vaginal delivery, while elective C-section was associated with a 13% increased risk, both of which were statistically significant and clinically important.

“We were quite taken with these results. We think they provide evidence that C-section is consistently associated with infection-related hospitalization. It’s an association study that can’t prove causality, but the results implicate the postnatal microbiome as the most plausible explanation in terms of what’s driving this association,” according to Dr. Burgner.

The association between C-section and infection-related hospitalization was persistent throughout the preschool years. For example, the increased risk associated with elective C-section was 16% during age 0-3 months, 20% during months 4-6, 14% in months 7-12, 13% during ages 1-2 years, and 11% among 2- to 5-year-olds, he continued.

The increased risk of severe preschool infection was highest for upper and lower respiratory tract and gastrointestinal infections, which involve the organ systems most likely to experience direct inoculation of the maternal microbiome, he noted.

Because the investigators recognized that the study results were potentially vulnerable to confounding by indication – that is, that the reason for doing a C-section might itself confer increased risk of subsequent preschool infection-related hospitalization – they repeated their analysis in a predefined low-risk subpopulation. The results closely mirrored those in the overall study population: an 8% increased risk in the emergency C-section group and a 14% increased risk with elective C-section.

Results of this large multinational study should provide further support for ongoing research aimed at supporting the infant microbiome after delivery by C-section via vaginal microbial transfer and other methods, he observed.

Dr. Burgner reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was cosponsored by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Danish Council for Independent Research, and nonprofit foundations.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

Antimalarials in pregnancy and lactation

According to the World Health Organization, there were about 219 million cases of malaria and an estimated 660,000 deaths in 2010. Although huge, this was a 26% decrease from the rates in 2000. Six countries in Africa account for 47% of malaria cases: Cote d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique, Nigeria, Uganda, and the United Republic of Tanzania. The second-most affected region in the world is Southeast Asia, which includes Myanmar, India, and Indonesia. In comparison, about 1,500 malaria cases and 5 deaths are reported annually in the United States, mostly from returned travelers.

if they will be traveling in any of the above regions. Malaria during pregnancy increases the risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes, including maternal anemia, prematurity, spontaneous abortion, and stillbirth.

As stated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, no antimalarial agent is 100% protective. Therefore, whatever agent is used must be combined with personal protective measures such as wearing insect repellent, long sleeves, and long pants; sleeping in a mosquito-free setting; or using an insecticide-treated bed net.

There are nine antimalarial drugs available in the United States.

Atovaquone/Proguanil Hcl (Malarone and as generic)

This agent is good for last-minute travelers because the drug is started 1-2 days before traveling to areas where malaria transmission occurs. The combination can be classified as compatible in pregnancy. No reports in breastfeeding with atovaquone or the combination have been found. Proguanil is not available in the United States as a single agent.

Chloroquine (generic)

This is the drug of choice to prevent and treat sensitive malaria species during pregnancy. The drug crosses the placenta producing fetal concentrations that are similar to those in the mother. The drug appears to be low risk for embryo-fetal harm.

It is compatible in breastfeeding.

Dapsone (generic)

This agent does not appear to represent a major risk of harm to the fetus. Although it has been used in combination with pyrimethamine (an antiparasitic) or trimethoprim (an antibiotic) to prevent malaria, the efficacy of the combination has not been confirmed.

In breastfeeding, there is one case of mild hemolytic anemia in the mother and her breastfeeding infant that may have been caused by the drug.

Hydroxychloroquine (generic)

This agent is used for the treatment of malaria, systemic erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis. For antimalarial prophylaxis, 400 mg/week appears to be low risk for embryo-fetal harm. Doses used to treat malaria have been 200-400 mg/day.

Because very low concentrations of the drug have been found in breast milk, breastfeeding is probably compatible.

Mefloquine (generic)

This agent is a quinoline-methanol agent that does not appear to cause embryo-fetal harm based on a large number of pregnancy exposures.

There are no reports of its use while breastfeeding.

Primaquine (generic)

This agent is best avoided in pregnancy. There is no human pregnancy data, but it may cause hemolytic anemia in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD). Because the fetus is relatively G6PD deficient, it is best avoided in pregnancy regardless of the mother’s status.

There are no reports describing the use of the drug during lactation. Both the mother and baby should be tested for G6PD deficiency before the drug is used during breastfeeding.

Pyrimethamine (generic)

This agent has been used for the treatment or prophylaxis of malaria. Most studies have found this agent to be relatively safe and effective.

It is excreted into breast milk and has been effective in eliminating malaria parasites from breastfeeding infants.

Quinidine (generic)

Reports linking the use of this agent with congenital defects have not been found. Although the drug has data on its use as an antiarrhythmic, its published use to treat malaria is limited.

The drug is excreted into breast milk, but there are no reports of its during breastfeeding.

Quinine (generic)

This agent has a large amount of human pregnancy data (more than 1,000 exposures) that found no increased risk of birth defects. The drug has been replaced by newer agents but still may be used for chloroquine-resistant malaria.

The drug appears to be compatible during breastfeeding.

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, as well as at Washington State University, Spokane. Mr. Briggs said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

According to the World Health Organization, there were about 219 million cases of malaria and an estimated 660,000 deaths in 2010. Although huge, this was a 26% decrease from the rates in 2000. Six countries in Africa account for 47% of malaria cases: Cote d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique, Nigeria, Uganda, and the United Republic of Tanzania. The second-most affected region in the world is Southeast Asia, which includes Myanmar, India, and Indonesia. In comparison, about 1,500 malaria cases and 5 deaths are reported annually in the United States, mostly from returned travelers.

if they will be traveling in any of the above regions. Malaria during pregnancy increases the risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes, including maternal anemia, prematurity, spontaneous abortion, and stillbirth.

As stated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, no antimalarial agent is 100% protective. Therefore, whatever agent is used must be combined with personal protective measures such as wearing insect repellent, long sleeves, and long pants; sleeping in a mosquito-free setting; or using an insecticide-treated bed net.

There are nine antimalarial drugs available in the United States.

Atovaquone/Proguanil Hcl (Malarone and as generic)

This agent is good for last-minute travelers because the drug is started 1-2 days before traveling to areas where malaria transmission occurs. The combination can be classified as compatible in pregnancy. No reports in breastfeeding with atovaquone or the combination have been found. Proguanil is not available in the United States as a single agent.

Chloroquine (generic)

This is the drug of choice to prevent and treat sensitive malaria species during pregnancy. The drug crosses the placenta producing fetal concentrations that are similar to those in the mother. The drug appears to be low risk for embryo-fetal harm.

It is compatible in breastfeeding.

Dapsone (generic)

This agent does not appear to represent a major risk of harm to the fetus. Although it has been used in combination with pyrimethamine (an antiparasitic) or trimethoprim (an antibiotic) to prevent malaria, the efficacy of the combination has not been confirmed.

In breastfeeding, there is one case of mild hemolytic anemia in the mother and her breastfeeding infant that may have been caused by the drug.

Hydroxychloroquine (generic)

This agent is used for the treatment of malaria, systemic erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis. For antimalarial prophylaxis, 400 mg/week appears to be low risk for embryo-fetal harm. Doses used to treat malaria have been 200-400 mg/day.

Because very low concentrations of the drug have been found in breast milk, breastfeeding is probably compatible.

Mefloquine (generic)

This agent is a quinoline-methanol agent that does not appear to cause embryo-fetal harm based on a large number of pregnancy exposures.

There are no reports of its use while breastfeeding.

Primaquine (generic)

This agent is best avoided in pregnancy. There is no human pregnancy data, but it may cause hemolytic anemia in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD). Because the fetus is relatively G6PD deficient, it is best avoided in pregnancy regardless of the mother’s status.

There are no reports describing the use of the drug during lactation. Both the mother and baby should be tested for G6PD deficiency before the drug is used during breastfeeding.

Pyrimethamine (generic)

This agent has been used for the treatment or prophylaxis of malaria. Most studies have found this agent to be relatively safe and effective.

It is excreted into breast milk and has been effective in eliminating malaria parasites from breastfeeding infants.

Quinidine (generic)

Reports linking the use of this agent with congenital defects have not been found. Although the drug has data on its use as an antiarrhythmic, its published use to treat malaria is limited.

The drug is excreted into breast milk, but there are no reports of its during breastfeeding.

Quinine (generic)

This agent has a large amount of human pregnancy data (more than 1,000 exposures) that found no increased risk of birth defects. The drug has been replaced by newer agents but still may be used for chloroquine-resistant malaria.

The drug appears to be compatible during breastfeeding.

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, as well as at Washington State University, Spokane. Mr. Briggs said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

According to the World Health Organization, there were about 219 million cases of malaria and an estimated 660,000 deaths in 2010. Although huge, this was a 26% decrease from the rates in 2000. Six countries in Africa account for 47% of malaria cases: Cote d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique, Nigeria, Uganda, and the United Republic of Tanzania. The second-most affected region in the world is Southeast Asia, which includes Myanmar, India, and Indonesia. In comparison, about 1,500 malaria cases and 5 deaths are reported annually in the United States, mostly from returned travelers.

if they will be traveling in any of the above regions. Malaria during pregnancy increases the risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes, including maternal anemia, prematurity, spontaneous abortion, and stillbirth.

As stated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, no antimalarial agent is 100% protective. Therefore, whatever agent is used must be combined with personal protective measures such as wearing insect repellent, long sleeves, and long pants; sleeping in a mosquito-free setting; or using an insecticide-treated bed net.

There are nine antimalarial drugs available in the United States.

Atovaquone/Proguanil Hcl (Malarone and as generic)

This agent is good for last-minute travelers because the drug is started 1-2 days before traveling to areas where malaria transmission occurs. The combination can be classified as compatible in pregnancy. No reports in breastfeeding with atovaquone or the combination have been found. Proguanil is not available in the United States as a single agent.

Chloroquine (generic)

This is the drug of choice to prevent and treat sensitive malaria species during pregnancy. The drug crosses the placenta producing fetal concentrations that are similar to those in the mother. The drug appears to be low risk for embryo-fetal harm.

It is compatible in breastfeeding.

Dapsone (generic)

This agent does not appear to represent a major risk of harm to the fetus. Although it has been used in combination with pyrimethamine (an antiparasitic) or trimethoprim (an antibiotic) to prevent malaria, the efficacy of the combination has not been confirmed.

In breastfeeding, there is one case of mild hemolytic anemia in the mother and her breastfeeding infant that may have been caused by the drug.

Hydroxychloroquine (generic)

This agent is used for the treatment of malaria, systemic erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis. For antimalarial prophylaxis, 400 mg/week appears to be low risk for embryo-fetal harm. Doses used to treat malaria have been 200-400 mg/day.

Because very low concentrations of the drug have been found in breast milk, breastfeeding is probably compatible.

Mefloquine (generic)

This agent is a quinoline-methanol agent that does not appear to cause embryo-fetal harm based on a large number of pregnancy exposures.

There are no reports of its use while breastfeeding.

Primaquine (generic)

This agent is best avoided in pregnancy. There is no human pregnancy data, but it may cause hemolytic anemia in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD). Because the fetus is relatively G6PD deficient, it is best avoided in pregnancy regardless of the mother’s status.

There are no reports describing the use of the drug during lactation. Both the mother and baby should be tested for G6PD deficiency before the drug is used during breastfeeding.

Pyrimethamine (generic)

This agent has been used for the treatment or prophylaxis of malaria. Most studies have found this agent to be relatively safe and effective.

It is excreted into breast milk and has been effective in eliminating malaria parasites from breastfeeding infants.

Quinidine (generic)

Reports linking the use of this agent with congenital defects have not been found. Although the drug has data on its use as an antiarrhythmic, its published use to treat malaria is limited.

The drug is excreted into breast milk, but there are no reports of its during breastfeeding.

Quinine (generic)

This agent has a large amount of human pregnancy data (more than 1,000 exposures) that found no increased risk of birth defects. The drug has been replaced by newer agents but still may be used for chloroquine-resistant malaria.

The drug appears to be compatible during breastfeeding.

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, as well as at Washington State University, Spokane. Mr. Briggs said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

Refrigerator-stable varicella vaccine held safe and effective

profiles when administered concomitantly with MMR vaccine, according to a study in Vaccine.

In this double-blind, controlled, multicenter study, Keith S. Reisinger of Primary Physicians Research, Pittsburgh, and his colleagues randomized 958 subjects aged 12-23 months to receive either 8,000 plaque-forming units (PFU) refrigerated vaccine (n = 320; group 1), 25,000 PFU refrigerated vaccine (n = 315; group 2), or 10,000 PFU frozen vaccine (n = 323; group 3), and subjects in all three groups also received MMR vaccine. The primary endpoint for immunogenicity was percentage of subjects with at least 5 titers of varicella antibody according to glycoprotein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay among the three groups 6 weeks post vaccination; the primary safety endpoint was incidences of vaccine-related adverse events during days 0-42 post vaccination.

The percentages of subjects meeting the primary endpoint for immunogenicity were comparable among the groups, at 93%, 94%, and 95% for groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Results for the safety endpoints also were similar among the groups; for example, rates of injection-site adverse events or vaccine-related injection-site adverse events were 44%, 40%, and 43%, with no statistically significant between-group differences.

The study authors noted that one of the problems with having only frozen formulations is how that limits availability in parts of the world where only refrigeration of 2°C–8°C is available. “Use of a refrigerator-stable formulation of varicella vaccine will allow for increased availability of the product throughout the world and may help to increase vaccination rates against varicella,” they concluded.

Strengths of the study included its head-to-head design. Limitations included how adverse events were based on parental reporting.

Some authors reported relationships, including employment, with Merck & Co, which developed the vaccine in this study and funded the study.

SOURCE: Reisinger KS et al. Vaccine. 2018 Aug 23. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.089.

profiles when administered concomitantly with MMR vaccine, according to a study in Vaccine.

In this double-blind, controlled, multicenter study, Keith S. Reisinger of Primary Physicians Research, Pittsburgh, and his colleagues randomized 958 subjects aged 12-23 months to receive either 8,000 plaque-forming units (PFU) refrigerated vaccine (n = 320; group 1), 25,000 PFU refrigerated vaccine (n = 315; group 2), or 10,000 PFU frozen vaccine (n = 323; group 3), and subjects in all three groups also received MMR vaccine. The primary endpoint for immunogenicity was percentage of subjects with at least 5 titers of varicella antibody according to glycoprotein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay among the three groups 6 weeks post vaccination; the primary safety endpoint was incidences of vaccine-related adverse events during days 0-42 post vaccination.

The percentages of subjects meeting the primary endpoint for immunogenicity were comparable among the groups, at 93%, 94%, and 95% for groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Results for the safety endpoints also were similar among the groups; for example, rates of injection-site adverse events or vaccine-related injection-site adverse events were 44%, 40%, and 43%, with no statistically significant between-group differences.

The study authors noted that one of the problems with having only frozen formulations is how that limits availability in parts of the world where only refrigeration of 2°C–8°C is available. “Use of a refrigerator-stable formulation of varicella vaccine will allow for increased availability of the product throughout the world and may help to increase vaccination rates against varicella,” they concluded.

Strengths of the study included its head-to-head design. Limitations included how adverse events were based on parental reporting.

Some authors reported relationships, including employment, with Merck & Co, which developed the vaccine in this study and funded the study.

SOURCE: Reisinger KS et al. Vaccine. 2018 Aug 23. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.089.

profiles when administered concomitantly with MMR vaccine, according to a study in Vaccine.

In this double-blind, controlled, multicenter study, Keith S. Reisinger of Primary Physicians Research, Pittsburgh, and his colleagues randomized 958 subjects aged 12-23 months to receive either 8,000 plaque-forming units (PFU) refrigerated vaccine (n = 320; group 1), 25,000 PFU refrigerated vaccine (n = 315; group 2), or 10,000 PFU frozen vaccine (n = 323; group 3), and subjects in all three groups also received MMR vaccine. The primary endpoint for immunogenicity was percentage of subjects with at least 5 titers of varicella antibody according to glycoprotein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay among the three groups 6 weeks post vaccination; the primary safety endpoint was incidences of vaccine-related adverse events during days 0-42 post vaccination.

The percentages of subjects meeting the primary endpoint for immunogenicity were comparable among the groups, at 93%, 94%, and 95% for groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Results for the safety endpoints also were similar among the groups; for example, rates of injection-site adverse events or vaccine-related injection-site adverse events were 44%, 40%, and 43%, with no statistically significant between-group differences.

The study authors noted that one of the problems with having only frozen formulations is how that limits availability in parts of the world where only refrigeration of 2°C–8°C is available. “Use of a refrigerator-stable formulation of varicella vaccine will allow for increased availability of the product throughout the world and may help to increase vaccination rates against varicella,” they concluded.

Strengths of the study included its head-to-head design. Limitations included how adverse events were based on parental reporting.

Some authors reported relationships, including employment, with Merck & Co, which developed the vaccine in this study and funded the study.

SOURCE: Reisinger KS et al. Vaccine. 2018 Aug 23. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.089.

New tickborne virus emerges in China

A new virus has been associated with febrile illness in China in patients with histories of tick bites. The data on the discovery, isolation, and characterization of the virus were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The segmented RNA virus now known as Alongshan virus (ALSV) “belongs to the unclassified jingmenvirus group in the family Flaviviridae, which includes the genera flavivirus, pestivirus, hepacivirus, and pegivirus,” wrote Ze-Dong Wang, PhD, of Foshan (China) University, and colleagues.

The index patient with ALSV was a 42-year-old female farmer from the town of Alongshan, China, who presented to a regional hospital in April 2017 with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites. The initial clinical features were similar to those seen in tickborne diseases, but a blood sample showed no RNA or antibodies for tickborne encephalitis virus. Investigators obtained a blood specimen from the index patient 4 days after the onset of illness. After culturing the sample, the investigators extracted the viral RNA genome and sequenced it.

Sequence analysis found that the new pathogen was related to segmented viruses in the jingmenvirus group of the family Flaviviridae; however, “comparison of the amino acids further confirmed that ALSV is genetically distinct from other jingmenviruses,” the investigators said.

The investigators identified 374 patients who presented to the hospital with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites during May 2017–September 2017; 86 patients had confirmed ALSV infections via nested reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction testing. Of these, 63 were men and 84 were farmers or forestry workers. Although ticks were common in the patients’ environments, no other evidence of tickborne diseases was noted. The patients ranged in age from 24 to 77 years, and the average duration of the infection was 3-7 days.

Symptoms were nonspecific and included fever, headache, fatigue, nausea, cough, and sore throat. All 86 patients were treated with intravenous ribavirin (0.5 g/day), and intramuscular benzylpenicillin sodium (2 million U/day) for 3-5 days. The median hospital stay was 11 days, and no deaths or long-term clinical complications occurred in the confirmed ALSV patients.

ALSV is similar to other jingmenviruses, but is distinct from other infections in part because of the absence of a rash or jaundice, the investigators said.

Although the investigators said they suspected the disease was carried by ticks, they would not rule out mosquitoes as a possible carrier because ALSV RNA was found in mosquitoes in a Northeastern province of China, and the RNA from those mosquitoes was found to be genetically related to the RNA assessed in this study.

Overall, “our findings suggest that ALSV may be the cause of a previously unknown febrile disease, and more studies should be conducted to determine the geographic distribution of this disease outside its current areas of identification,” they said.

The research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

SOURCE: Wang Z et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805068.

New technology and genomic surveys will continue to help identify emerging pathogens, however, “they may provide limited value in understanding the mechanisms of disease emergence,” wrote Nikos Vasilakis, PhD, and David H. Walker, MD, in an accompanying editorial. An active surveillance program allowed the investigators of the previously unknown tickborne pathogen in China to identify a group of patients with similar history. The new pathogen was classified as one of the jingmenviruses, which “reveal that RNA virus segmentation is an evolutionary process that has occurred in previously unanticipated circumstances.” This study by Wang et al. shows that these viruses are not limited to arthropod hosts but can be dangerous to humans.

The new pathogen had likely been evolving for some time before it was discovered, the editorialists said. “The key to making such discoveries is the study of ill persons, isolation of the etiologic agent, use of tools that will reveal the nature of the agent (e.g., electron microscopy), and application of the appropriate tools for definitive characterization (e.g., sequencing of the RNA genome),” they emphasized. However, to mitigate outbreaks, “proactive, real-time surveillance” may be more cost effective than extensive genomic surveys, they noted (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1901212).

Dr. Vasilakis and Dr. Walker are affiliated with the department of pathology, Center for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Center for Tropical Diseases, and the Institute for Human Infections and Immunity, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. They had no financial conflicts to disclose.

New technology and genomic surveys will continue to help identify emerging pathogens, however, “they may provide limited value in understanding the mechanisms of disease emergence,” wrote Nikos Vasilakis, PhD, and David H. Walker, MD, in an accompanying editorial. An active surveillance program allowed the investigators of the previously unknown tickborne pathogen in China to identify a group of patients with similar history. The new pathogen was classified as one of the jingmenviruses, which “reveal that RNA virus segmentation is an evolutionary process that has occurred in previously unanticipated circumstances.” This study by Wang et al. shows that these viruses are not limited to arthropod hosts but can be dangerous to humans.

The new pathogen had likely been evolving for some time before it was discovered, the editorialists said. “The key to making such discoveries is the study of ill persons, isolation of the etiologic agent, use of tools that will reveal the nature of the agent (e.g., electron microscopy), and application of the appropriate tools for definitive characterization (e.g., sequencing of the RNA genome),” they emphasized. However, to mitigate outbreaks, “proactive, real-time surveillance” may be more cost effective than extensive genomic surveys, they noted (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1901212).

Dr. Vasilakis and Dr. Walker are affiliated with the department of pathology, Center for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Center for Tropical Diseases, and the Institute for Human Infections and Immunity, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. They had no financial conflicts to disclose.

New technology and genomic surveys will continue to help identify emerging pathogens, however, “they may provide limited value in understanding the mechanisms of disease emergence,” wrote Nikos Vasilakis, PhD, and David H. Walker, MD, in an accompanying editorial. An active surveillance program allowed the investigators of the previously unknown tickborne pathogen in China to identify a group of patients with similar history. The new pathogen was classified as one of the jingmenviruses, which “reveal that RNA virus segmentation is an evolutionary process that has occurred in previously unanticipated circumstances.” This study by Wang et al. shows that these viruses are not limited to arthropod hosts but can be dangerous to humans.

The new pathogen had likely been evolving for some time before it was discovered, the editorialists said. “The key to making such discoveries is the study of ill persons, isolation of the etiologic agent, use of tools that will reveal the nature of the agent (e.g., electron microscopy), and application of the appropriate tools for definitive characterization (e.g., sequencing of the RNA genome),” they emphasized. However, to mitigate outbreaks, “proactive, real-time surveillance” may be more cost effective than extensive genomic surveys, they noted (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1901212).

Dr. Vasilakis and Dr. Walker are affiliated with the department of pathology, Center for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Center for Tropical Diseases, and the Institute for Human Infections and Immunity, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. They had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A new virus has been associated with febrile illness in China in patients with histories of tick bites. The data on the discovery, isolation, and characterization of the virus were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The segmented RNA virus now known as Alongshan virus (ALSV) “belongs to the unclassified jingmenvirus group in the family Flaviviridae, which includes the genera flavivirus, pestivirus, hepacivirus, and pegivirus,” wrote Ze-Dong Wang, PhD, of Foshan (China) University, and colleagues.

The index patient with ALSV was a 42-year-old female farmer from the town of Alongshan, China, who presented to a regional hospital in April 2017 with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites. The initial clinical features were similar to those seen in tickborne diseases, but a blood sample showed no RNA or antibodies for tickborne encephalitis virus. Investigators obtained a blood specimen from the index patient 4 days after the onset of illness. After culturing the sample, the investigators extracted the viral RNA genome and sequenced it.

Sequence analysis found that the new pathogen was related to segmented viruses in the jingmenvirus group of the family Flaviviridae; however, “comparison of the amino acids further confirmed that ALSV is genetically distinct from other jingmenviruses,” the investigators said.

The investigators identified 374 patients who presented to the hospital with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites during May 2017–September 2017; 86 patients had confirmed ALSV infections via nested reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction testing. Of these, 63 were men and 84 were farmers or forestry workers. Although ticks were common in the patients’ environments, no other evidence of tickborne diseases was noted. The patients ranged in age from 24 to 77 years, and the average duration of the infection was 3-7 days.

Symptoms were nonspecific and included fever, headache, fatigue, nausea, cough, and sore throat. All 86 patients were treated with intravenous ribavirin (0.5 g/day), and intramuscular benzylpenicillin sodium (2 million U/day) for 3-5 days. The median hospital stay was 11 days, and no deaths or long-term clinical complications occurred in the confirmed ALSV patients.

ALSV is similar to other jingmenviruses, but is distinct from other infections in part because of the absence of a rash or jaundice, the investigators said.

Although the investigators said they suspected the disease was carried by ticks, they would not rule out mosquitoes as a possible carrier because ALSV RNA was found in mosquitoes in a Northeastern province of China, and the RNA from those mosquitoes was found to be genetically related to the RNA assessed in this study.

Overall, “our findings suggest that ALSV may be the cause of a previously unknown febrile disease, and more studies should be conducted to determine the geographic distribution of this disease outside its current areas of identification,” they said.

The research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

SOURCE: Wang Z et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805068.

A new virus has been associated with febrile illness in China in patients with histories of tick bites. The data on the discovery, isolation, and characterization of the virus were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The segmented RNA virus now known as Alongshan virus (ALSV) “belongs to the unclassified jingmenvirus group in the family Flaviviridae, which includes the genera flavivirus, pestivirus, hepacivirus, and pegivirus,” wrote Ze-Dong Wang, PhD, of Foshan (China) University, and colleagues.

The index patient with ALSV was a 42-year-old female farmer from the town of Alongshan, China, who presented to a regional hospital in April 2017 with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites. The initial clinical features were similar to those seen in tickborne diseases, but a blood sample showed no RNA or antibodies for tickborne encephalitis virus. Investigators obtained a blood specimen from the index patient 4 days after the onset of illness. After culturing the sample, the investigators extracted the viral RNA genome and sequenced it.

Sequence analysis found that the new pathogen was related to segmented viruses in the jingmenvirus group of the family Flaviviridae; however, “comparison of the amino acids further confirmed that ALSV is genetically distinct from other jingmenviruses,” the investigators said.

The investigators identified 374 patients who presented to the hospital with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites during May 2017–September 2017; 86 patients had confirmed ALSV infections via nested reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction testing. Of these, 63 were men and 84 were farmers or forestry workers. Although ticks were common in the patients’ environments, no other evidence of tickborne diseases was noted. The patients ranged in age from 24 to 77 years, and the average duration of the infection was 3-7 days.

Symptoms were nonspecific and included fever, headache, fatigue, nausea, cough, and sore throat. All 86 patients were treated with intravenous ribavirin (0.5 g/day), and intramuscular benzylpenicillin sodium (2 million U/day) for 3-5 days. The median hospital stay was 11 days, and no deaths or long-term clinical complications occurred in the confirmed ALSV patients.

ALSV is similar to other jingmenviruses, but is distinct from other infections in part because of the absence of a rash or jaundice, the investigators said.

Although the investigators said they suspected the disease was carried by ticks, they would not rule out mosquitoes as a possible carrier because ALSV RNA was found in mosquitoes in a Northeastern province of China, and the RNA from those mosquitoes was found to be genetically related to the RNA assessed in this study.

Overall, “our findings suggest that ALSV may be the cause of a previously unknown febrile disease, and more studies should be conducted to determine the geographic distribution of this disease outside its current areas of identification,” they said.

The research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

SOURCE: Wang Z et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805068.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

HPV vaccine: Is one dose enough?

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – There is good news and bad news about human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination as a means of preventing cervical cancer.

The bad news is the HPV vaccines are projected to be in short supply, unable to meet global demand until at least 2024. The good news is that – in one study, for 11 years and counting – which would effectively double the existing supply, Aimee R. Kreimer, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

These data come from post hoc analyses of major phase 3 randomized controlled trials of bivalent HPV vaccine in Costa Rica and quadrivalent vaccine in India. However, these secondary analyses aren’t considered rock solid evidence because the subjects who got a single dose weren’t randomized to that strategy, they simply for one reason or another didn’t receive the recommended additional dose or doses.

“I don’t know if these studies are enough, so several studies have been launched over the past couple of years with an eye toward generating the quality of data that would be sufficient to motivate policy change, if in fact one dose is proven to be effective,” said Dr. Kreimer, a senior scientist at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md.

The first of these formal randomized, controlled trials – a delayed second-dose study in 9- to 11-year-old U.S. boys and girls – is due to be completed next year. Four other trials ongoing in Africa and Costa Rica, all in females, are expected to report findings in 2022-2025.

Dr. Kreimer is first author of a soon-to-be-published 11-year update from the phase 3 Costa Rica HPV Vaccine Trial, which was launched prior to licensure of the GlaxoSmithKline bivalent HPV vaccine. Previous analyses showed that at both 4 and 7 years of follow-up, a single dose of the vaccine was as effective as two or three in preventing infection with HPV types 16 and 18, which are covered by the vaccine.

“Now the research question has transitioned to, ‘Will one dose be sufficiently durable?’ she explained.

The answer from this study is yes. At 11 years since receipt of the bivalent HPV vaccine, there was no difference in terms of prevalent HPV 16/18 infection between the one-, two-, and three-dose groups. To address the issue of possible selection bias in this post hoc nonrandomized comparison, Dr. Kreimer and her coinvestigators looked at rates of infection with HPV 31 and 45, which aren’t covered by the vaccine. The rates were similar regardless of the number of vaccine doses received 11 years earlier, indicating women in all three dosing groups are at similar risk for acquiring HPV infection, thus bolstering the legitimacy of the conclusion that one dose provides effective long-term protection.

Intriguingly, HPV serum antibody levels in the single-dose group have remained stable for 11 years at a level that’s only about one-quarter of that associated with three doses of the vaccine, albeit an order of magnitude greater than the level induced by natural immunity.

“This really challenges the dogma of the HPV vaccine,” according to Dr. Kreimer. “It suggests that inferior [HPV] antibodies do not necessarily mean inferior protection.”

The explanation for this phenomenon appears to be that HPV subunit vaccine mimics the shell of authentic virions so well that the immune system sees it as dangerous and mounts long-term antibody production. Also, cervical infection by HPV is a relatively slow process, allowing time for vaccine-induced antibodies to interrupt it, she said.

In contrast to the encouraging findings from this post hoc analysis and another from a phase 3 trial of quadrivalent vaccine in India, numerous phase 4 vaccine effectiveness monitoring studies have shown markedly lower vaccine effectiveness for one dose of HPV vaccine. Dr. Kreimer cautioned that this is a flawed conclusion attributable to a methodologic artifact whereby the investigators have lumped together single-dose recipients who were 17 years old or more at the time with those who were younger.

“The problem is that many people who are aged 17-18 years already have HPV infection, so when they are vaccinated it shows up as a vaccine failure. That’s not correct. These are prophylactic HPV vaccines. They’re not meant to help clear an infection,” she noted.

Stepping back, Dr. Kreimer observed that cervical cancer “is really a story of inequality.” Indeed, 90% of cervical cancers occur in low-income countries, where HPV vaccination uptake remains very low even more than a decade after licensure. When modelers project out in the future, they estimate that at current HPV vaccination levels in Sub-Saharan Africa, which has the highest cervical cancer rates in the world, it would take more than 100 years to achieve the World Health Organization goal of eliminating the malignancy.

Asked by an audience member how low a single-dose vaccine effectiveness level she considers acceptable to help reach the goal of eliminating cervical cancer in developing countries, Dr. Kreimer cautioned against the tendency to let ‘perfect’ become the enemy of ‘good.’

“I’ll remind everyone that, in this moment, very few of the target girls in the lower– and upper-lower–income countries are getting any vaccination. So I don’t think it’s a question of whether we should be going from two to one dose, I think it’s really a question of, for those who are at zero doses, how do we get them one dose? And with the HPV vaccine, we’ve even seen suggestions of herd immunity if we have 50% uptake,” she replied.

Dr. Kreimer reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – There is good news and bad news about human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination as a means of preventing cervical cancer.

The bad news is the HPV vaccines are projected to be in short supply, unable to meet global demand until at least 2024. The good news is that – in one study, for 11 years and counting – which would effectively double the existing supply, Aimee R. Kreimer, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

These data come from post hoc analyses of major phase 3 randomized controlled trials of bivalent HPV vaccine in Costa Rica and quadrivalent vaccine in India. However, these secondary analyses aren’t considered rock solid evidence because the subjects who got a single dose weren’t randomized to that strategy, they simply for one reason or another didn’t receive the recommended additional dose or doses.

“I don’t know if these studies are enough, so several studies have been launched over the past couple of years with an eye toward generating the quality of data that would be sufficient to motivate policy change, if in fact one dose is proven to be effective,” said Dr. Kreimer, a senior scientist at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md.

The first of these formal randomized, controlled trials – a delayed second-dose study in 9- to 11-year-old U.S. boys and girls – is due to be completed next year. Four other trials ongoing in Africa and Costa Rica, all in females, are expected to report findings in 2022-2025.

Dr. Kreimer is first author of a soon-to-be-published 11-year update from the phase 3 Costa Rica HPV Vaccine Trial, which was launched prior to licensure of the GlaxoSmithKline bivalent HPV vaccine. Previous analyses showed that at both 4 and 7 years of follow-up, a single dose of the vaccine was as effective as two or three in preventing infection with HPV types 16 and 18, which are covered by the vaccine.

“Now the research question has transitioned to, ‘Will one dose be sufficiently durable?’ she explained.

The answer from this study is yes. At 11 years since receipt of the bivalent HPV vaccine, there was no difference in terms of prevalent HPV 16/18 infection between the one-, two-, and three-dose groups. To address the issue of possible selection bias in this post hoc nonrandomized comparison, Dr. Kreimer and her coinvestigators looked at rates of infection with HPV 31 and 45, which aren’t covered by the vaccine. The rates were similar regardless of the number of vaccine doses received 11 years earlier, indicating women in all three dosing groups are at similar risk for acquiring HPV infection, thus bolstering the legitimacy of the conclusion that one dose provides effective long-term protection.

Intriguingly, HPV serum antibody levels in the single-dose group have remained stable for 11 years at a level that’s only about one-quarter of that associated with three doses of the vaccine, albeit an order of magnitude greater than the level induced by natural immunity.

“This really challenges the dogma of the HPV vaccine,” according to Dr. Kreimer. “It suggests that inferior [HPV] antibodies do not necessarily mean inferior protection.”

The explanation for this phenomenon appears to be that HPV subunit vaccine mimics the shell of authentic virions so well that the immune system sees it as dangerous and mounts long-term antibody production. Also, cervical infection by HPV is a relatively slow process, allowing time for vaccine-induced antibodies to interrupt it, she said.

In contrast to the encouraging findings from this post hoc analysis and another from a phase 3 trial of quadrivalent vaccine in India, numerous phase 4 vaccine effectiveness monitoring studies have shown markedly lower vaccine effectiveness for one dose of HPV vaccine. Dr. Kreimer cautioned that this is a flawed conclusion attributable to a methodologic artifact whereby the investigators have lumped together single-dose recipients who were 17 years old or more at the time with those who were younger.

“The problem is that many people who are aged 17-18 years already have HPV infection, so when they are vaccinated it shows up as a vaccine failure. That’s not correct. These are prophylactic HPV vaccines. They’re not meant to help clear an infection,” she noted.

Stepping back, Dr. Kreimer observed that cervical cancer “is really a story of inequality.” Indeed, 90% of cervical cancers occur in low-income countries, where HPV vaccination uptake remains very low even more than a decade after licensure. When modelers project out in the future, they estimate that at current HPV vaccination levels in Sub-Saharan Africa, which has the highest cervical cancer rates in the world, it would take more than 100 years to achieve the World Health Organization goal of eliminating the malignancy.

Asked by an audience member how low a single-dose vaccine effectiveness level she considers acceptable to help reach the goal of eliminating cervical cancer in developing countries, Dr. Kreimer cautioned against the tendency to let ‘perfect’ become the enemy of ‘good.’

“I’ll remind everyone that, in this moment, very few of the target girls in the lower– and upper-lower–income countries are getting any vaccination. So I don’t think it’s a question of whether we should be going from two to one dose, I think it’s really a question of, for those who are at zero doses, how do we get them one dose? And with the HPV vaccine, we’ve even seen suggestions of herd immunity if we have 50% uptake,” she replied.

Dr. Kreimer reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – There is good news and bad news about human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination as a means of preventing cervical cancer.

The bad news is the HPV vaccines are projected to be in short supply, unable to meet global demand until at least 2024. The good news is that – in one study, for 11 years and counting – which would effectively double the existing supply, Aimee R. Kreimer, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

These data come from post hoc analyses of major phase 3 randomized controlled trials of bivalent HPV vaccine in Costa Rica and quadrivalent vaccine in India. However, these secondary analyses aren’t considered rock solid evidence because the subjects who got a single dose weren’t randomized to that strategy, they simply for one reason or another didn’t receive the recommended additional dose or doses.

“I don’t know if these studies are enough, so several studies have been launched over the past couple of years with an eye toward generating the quality of data that would be sufficient to motivate policy change, if in fact one dose is proven to be effective,” said Dr. Kreimer, a senior scientist at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md.

The first of these formal randomized, controlled trials – a delayed second-dose study in 9- to 11-year-old U.S. boys and girls – is due to be completed next year. Four other trials ongoing in Africa and Costa Rica, all in females, are expected to report findings in 2022-2025.

Dr. Kreimer is first author of a soon-to-be-published 11-year update from the phase 3 Costa Rica HPV Vaccine Trial, which was launched prior to licensure of the GlaxoSmithKline bivalent HPV vaccine. Previous analyses showed that at both 4 and 7 years of follow-up, a single dose of the vaccine was as effective as two or three in preventing infection with HPV types 16 and 18, which are covered by the vaccine.

“Now the research question has transitioned to, ‘Will one dose be sufficiently durable?’ she explained.

The answer from this study is yes. At 11 years since receipt of the bivalent HPV vaccine, there was no difference in terms of prevalent HPV 16/18 infection between the one-, two-, and three-dose groups. To address the issue of possible selection bias in this post hoc nonrandomized comparison, Dr. Kreimer and her coinvestigators looked at rates of infection with HPV 31 and 45, which aren’t covered by the vaccine. The rates were similar regardless of the number of vaccine doses received 11 years earlier, indicating women in all three dosing groups are at similar risk for acquiring HPV infection, thus bolstering the legitimacy of the conclusion that one dose provides effective long-term protection.

Intriguingly, HPV serum antibody levels in the single-dose group have remained stable for 11 years at a level that’s only about one-quarter of that associated with three doses of the vaccine, albeit an order of magnitude greater than the level induced by natural immunity.

“This really challenges the dogma of the HPV vaccine,” according to Dr. Kreimer. “It suggests that inferior [HPV] antibodies do not necessarily mean inferior protection.”

The explanation for this phenomenon appears to be that HPV subunit vaccine mimics the shell of authentic virions so well that the immune system sees it as dangerous and mounts long-term antibody production. Also, cervical infection by HPV is a relatively slow process, allowing time for vaccine-induced antibodies to interrupt it, she said.

In contrast to the encouraging findings from this post hoc analysis and another from a phase 3 trial of quadrivalent vaccine in India, numerous phase 4 vaccine effectiveness monitoring studies have shown markedly lower vaccine effectiveness for one dose of HPV vaccine. Dr. Kreimer cautioned that this is a flawed conclusion attributable to a methodologic artifact whereby the investigators have lumped together single-dose recipients who were 17 years old or more at the time with those who were younger.

“The problem is that many people who are aged 17-18 years already have HPV infection, so when they are vaccinated it shows up as a vaccine failure. That’s not correct. These are prophylactic HPV vaccines. They’re not meant to help clear an infection,” she noted.

Stepping back, Dr. Kreimer observed that cervical cancer “is really a story of inequality.” Indeed, 90% of cervical cancers occur in low-income countries, where HPV vaccination uptake remains very low even more than a decade after licensure. When modelers project out in the future, they estimate that at current HPV vaccination levels in Sub-Saharan Africa, which has the highest cervical cancer rates in the world, it would take more than 100 years to achieve the World Health Organization goal of eliminating the malignancy.

Asked by an audience member how low a single-dose vaccine effectiveness level she considers acceptable to help reach the goal of eliminating cervical cancer in developing countries, Dr. Kreimer cautioned against the tendency to let ‘perfect’ become the enemy of ‘good.’

“I’ll remind everyone that, in this moment, very few of the target girls in the lower– and upper-lower–income countries are getting any vaccination. So I don’t think it’s a question of whether we should be going from two to one dose, I think it’s really a question of, for those who are at zero doses, how do we get them one dose? And with the HPV vaccine, we’ve even seen suggestions of herd immunity if we have 50% uptake,” she replied.

Dr. Kreimer reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ESPID 2019

10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine confers similar protection to boys and girls

according to Heta Nieminen, MD, of the National Institute for Health and Welfare in Tampere, Finland, and associates.

For the study, published in Vaccine, the investigators conducted a post hoc analysis of the phase III/IV, cluster-randomized, double-blind FinIP trial, in which more than 30,000 infants received the PHiD-CV10 vaccine or a placebo. Patients were aged less than 7 months when they received their first vaccination, and received two or three primary doses, plus a booster shot after the age of 11 months (Vaccine. 2019 May 20. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.05.033).

In term infants, vaccine effectiveness was similar in boys and girls; while the vaccine worked marginally better in girls, the difference was not significant. Infants who received the 2 + 1 schedule had vaccine effectiveness similar to that of those who received the 3 + 1 schedule. In a smaller subanalysis of 1,519 preterm infants, outcomes of pneumonia were more common, but the vaccine seemed to confer protection, although the sample size was not large enough for statistical significance to be reached.

“The point estimates of vaccine effectiveness suggest protection in both sexes, and also among the preterm and low-birth-weight infants. ... There were no significant differences between the 2 + 1 and 3 + 1 schedules in any of the subgroups analyzed. Based on this study, the 2 + 1 or “Nordic” schedule is sufficient also for the risk groups such as the preterm or low-birth-weight infants,” the investigators concluded.

Five study authors are employees of the National Institute for Health and Welfare, which received funding for the study from GlaxoSmithKline. Four coauthors are employees of GlaxoSmithKline; three of them own shares in the company.

according to Heta Nieminen, MD, of the National Institute for Health and Welfare in Tampere, Finland, and associates.

For the study, published in Vaccine, the investigators conducted a post hoc analysis of the phase III/IV, cluster-randomized, double-blind FinIP trial, in which more than 30,000 infants received the PHiD-CV10 vaccine or a placebo. Patients were aged less than 7 months when they received their first vaccination, and received two or three primary doses, plus a booster shot after the age of 11 months (Vaccine. 2019 May 20. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.05.033).