User login

A warning song to keep our children safe

Pay heed to “The House of the Rising Sun”

“There is a house in New Orleans. They call the Rising Sun. And it’s been the ruin of many a poor boy. And, God, I know I’m one.”

The 1960s rock band the Animals will tell you a tale to convince you to get vaccinated. Don’t believe me? Follow along.

The first hints of the song “House of the Rising Sun” rolled out of the hills of Appalachia.

Somewhere in the Golden Triangle, far away from New Orleans, where Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee rise in quiet desolation, a warning song about a tailor and a drunk emerged. Sometime around the Civil War, a hint of a tune began. Over the next century, it evolved, until it became cemented in rock culture 50 years ago by The Animals, existing as the version played most commonly today.

In the mid-19th century, medicine shows rambled through the South, stopping in places like Noetown or Daisy. The small towns would empty out for the day to see the entertainers, singers, and jugglers perform. Hundreds gathered in the hot summer day, the entertainment solely a pretext for the traveling doctors to sell their wares, the snake oil, and cure-alls, as well as various patent medicines.

These were isolated towns, with no deliveries, few visitors, and the railroad yet to arrive. Frequently, the only news from outside came from these caravans of entertainers and con men who swept into town. They were like Professor Marvel from The Wizard of Oz, or a current-day Dr. Oz, luring the crowd with false advertising, selling colored water, and then disappearing before you realized you were duped. Today, traveling doctors of the same ilk convince parents to not vaccinate their children, tell them to visit stem cell centers that claim false cures, and offer them a shiny object with one hand while taking their cash with the other.

Yet, there was a positive development in the wake of these patent medicine shows: the entertainment lingered. New songs traveled the same journeys as these medicine shows – new earworms that would then be warbled in the local bars, while doing chores around the barn, or simply during walks on the Appalachian trails.

In 1937, Alan Lomax arrived in Noetown, Ky., with a microphone and an acetate record and recorded the voice of 16-year-old Georgia Turner singing “House of the Rising Sun.” She didn’t know where she heard that song, but most likely picked it up at the medicine show.

One of those singers was Clarence Ashley, who would croon about the Rising Sun Blues. He sang with Doc Cloud and Doc Hauer, who offered tonics for whatever ailed you. Perhaps Georgia Turner heard the song in the early 1900s as well. Her 1937 version contains the lyrics most closely related to the Animals’ tune.

Lomax spent the 1940s gathering songs around the Appalachian South. He put these songs into a songbook and spread them throughout the country. He would also return to New York City and gather in a room with legendary folk singers. They would hear these new lyrics, new sounds, and make them their own.

In that room would be Lead Belly, Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and Josh White, the fathers of folk music. The music Lomax pulled out of the mountains in small towns would become new again in the guitars and harmonicas of the Greenwich Village singers and musicians. Pete Seeger performed with the Weavers, named because they would weave songs from the past into new versions.

“House of the Rising Sun” was woven into the folk music landscape, evolving and growing. Josh White is credited with changing the song from a major key into the minor key we know today. Bob Dylan sang a version. And then in 1964, Eric Burdon and The Animals released their version, which became the standard. An arpeggio guitar opening, the rhythm sped up, a louder sound, and that minor key provides an emotional wallop for this warning song.

Numerous covers followed, including a beautiful version of “Amazing Grace”, sung to the tune of “House of the Rising Sun” by the Blind Boys of Alabama.

The song endures for its melody as well as for its lyrics. This was a warning song, a universal song, “not to do what I have done.” The small towns in Kentucky may have heard of the sinful ways of New Orleans and would spread the message with these songs to avoid the brothels, the drink, and the broken marriages that would reverberate with visits to the Crescent City.

“House of the Rising Sun” is one of the most covered songs, traveling wide and far, no longer with the need for a medicine show. It was a pivotal moment in rock ‘n roll, turning folk music into rock music. The Animals became huge because of this song, and their version became the standard on which all subsequent covers based their version. It made Bob Dylan’s older version seem quaint.

The song has been in my head for a while now. My wife is hoping writing about it will keep it from being played in our household any more. There are various reasons it has been resonating with me, including the following:

- It traces the origins of folk music and the importance of people like Lomax and Guthrie to collect and save Americana.

- The magic of musical evolution – a reminder of how art is built on the work of those who came before, each version with its unique personality.

- The release of “House of the Rising Sun” was a seminal, transformative moment when folk became rock music.

- The lasting power of warning songs.

- The hucksters that enabled this song to be kept alive.

That last one has really stuck with me. The medicine shows are an important part of American history. For instance, Coca-Cola started as one of those patent medicines; it was one of the many concoctions of the Atlanta pharmacist John Stith Pemberton, sold to treat all that ails us. Dr. Pepper, too, was a medicine in a sugary bottle – another that often contained alcohol or cocaine. Society wants a cure-all, and the marketing and selling done during these medicine shows offered placebos.

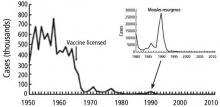

The hucksters exist in various forms today, selling detoxifications, magic diet cures, psychic powers of healing, or convincing parents that their kids don’t need vaccines. We need a warning song that goes viral to keep our children safe. We are blessed to be in a world without smallpox, almost rid of polio, and we have the knowledge and opportunity to rid the world of other preventable illnesses. Measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000; now, outbreaks emerge in every news cycle.

The CDC admits they have not been targeting misinformation well. How can we spread the science, the truth, the message faster than the lies? Better marketing? The answer may be through stories and narratives and song, with the backing of good science. “House of the Rising Sun” is a warning song. Maybe we need more. We need that deep history, that long trail to remind us of the world before vaccines, when everyone knew someone, either in their own household or next door, who succumbed to one of the childhood illnesses.

Let the “House of the Rising Sun” play on. Create a new version, and let that message reverberate, too.

Tell your children; they need to be vaccinated.

Dr. Messler is a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist group in Clearwater, Fla. He previously chaired SHM’s Quality and Patient Safety Committee and has been active in several SHM mentoring programs, most recently with Project BOOST and Glycemic Control. This article appeared originally in SHM's official blog The Hospital Leader. Read more recent posts here.

Pay heed to “The House of the Rising Sun”

Pay heed to “The House of the Rising Sun”

“There is a house in New Orleans. They call the Rising Sun. And it’s been the ruin of many a poor boy. And, God, I know I’m one.”

The 1960s rock band the Animals will tell you a tale to convince you to get vaccinated. Don’t believe me? Follow along.

The first hints of the song “House of the Rising Sun” rolled out of the hills of Appalachia.

Somewhere in the Golden Triangle, far away from New Orleans, where Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee rise in quiet desolation, a warning song about a tailor and a drunk emerged. Sometime around the Civil War, a hint of a tune began. Over the next century, it evolved, until it became cemented in rock culture 50 years ago by The Animals, existing as the version played most commonly today.

In the mid-19th century, medicine shows rambled through the South, stopping in places like Noetown or Daisy. The small towns would empty out for the day to see the entertainers, singers, and jugglers perform. Hundreds gathered in the hot summer day, the entertainment solely a pretext for the traveling doctors to sell their wares, the snake oil, and cure-alls, as well as various patent medicines.

These were isolated towns, with no deliveries, few visitors, and the railroad yet to arrive. Frequently, the only news from outside came from these caravans of entertainers and con men who swept into town. They were like Professor Marvel from The Wizard of Oz, or a current-day Dr. Oz, luring the crowd with false advertising, selling colored water, and then disappearing before you realized you were duped. Today, traveling doctors of the same ilk convince parents to not vaccinate their children, tell them to visit stem cell centers that claim false cures, and offer them a shiny object with one hand while taking their cash with the other.

Yet, there was a positive development in the wake of these patent medicine shows: the entertainment lingered. New songs traveled the same journeys as these medicine shows – new earworms that would then be warbled in the local bars, while doing chores around the barn, or simply during walks on the Appalachian trails.

In 1937, Alan Lomax arrived in Noetown, Ky., with a microphone and an acetate record and recorded the voice of 16-year-old Georgia Turner singing “House of the Rising Sun.” She didn’t know where she heard that song, but most likely picked it up at the medicine show.

One of those singers was Clarence Ashley, who would croon about the Rising Sun Blues. He sang with Doc Cloud and Doc Hauer, who offered tonics for whatever ailed you. Perhaps Georgia Turner heard the song in the early 1900s as well. Her 1937 version contains the lyrics most closely related to the Animals’ tune.

Lomax spent the 1940s gathering songs around the Appalachian South. He put these songs into a songbook and spread them throughout the country. He would also return to New York City and gather in a room with legendary folk singers. They would hear these new lyrics, new sounds, and make them their own.

In that room would be Lead Belly, Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and Josh White, the fathers of folk music. The music Lomax pulled out of the mountains in small towns would become new again in the guitars and harmonicas of the Greenwich Village singers and musicians. Pete Seeger performed with the Weavers, named because they would weave songs from the past into new versions.

“House of the Rising Sun” was woven into the folk music landscape, evolving and growing. Josh White is credited with changing the song from a major key into the minor key we know today. Bob Dylan sang a version. And then in 1964, Eric Burdon and The Animals released their version, which became the standard. An arpeggio guitar opening, the rhythm sped up, a louder sound, and that minor key provides an emotional wallop for this warning song.

Numerous covers followed, including a beautiful version of “Amazing Grace”, sung to the tune of “House of the Rising Sun” by the Blind Boys of Alabama.

The song endures for its melody as well as for its lyrics. This was a warning song, a universal song, “not to do what I have done.” The small towns in Kentucky may have heard of the sinful ways of New Orleans and would spread the message with these songs to avoid the brothels, the drink, and the broken marriages that would reverberate with visits to the Crescent City.

“House of the Rising Sun” is one of the most covered songs, traveling wide and far, no longer with the need for a medicine show. It was a pivotal moment in rock ‘n roll, turning folk music into rock music. The Animals became huge because of this song, and their version became the standard on which all subsequent covers based their version. It made Bob Dylan’s older version seem quaint.

The song has been in my head for a while now. My wife is hoping writing about it will keep it from being played in our household any more. There are various reasons it has been resonating with me, including the following:

- It traces the origins of folk music and the importance of people like Lomax and Guthrie to collect and save Americana.

- The magic of musical evolution – a reminder of how art is built on the work of those who came before, each version with its unique personality.

- The release of “House of the Rising Sun” was a seminal, transformative moment when folk became rock music.

- The lasting power of warning songs.

- The hucksters that enabled this song to be kept alive.

That last one has really stuck with me. The medicine shows are an important part of American history. For instance, Coca-Cola started as one of those patent medicines; it was one of the many concoctions of the Atlanta pharmacist John Stith Pemberton, sold to treat all that ails us. Dr. Pepper, too, was a medicine in a sugary bottle – another that often contained alcohol or cocaine. Society wants a cure-all, and the marketing and selling done during these medicine shows offered placebos.

The hucksters exist in various forms today, selling detoxifications, magic diet cures, psychic powers of healing, or convincing parents that their kids don’t need vaccines. We need a warning song that goes viral to keep our children safe. We are blessed to be in a world without smallpox, almost rid of polio, and we have the knowledge and opportunity to rid the world of other preventable illnesses. Measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000; now, outbreaks emerge in every news cycle.

The CDC admits they have not been targeting misinformation well. How can we spread the science, the truth, the message faster than the lies? Better marketing? The answer may be through stories and narratives and song, with the backing of good science. “House of the Rising Sun” is a warning song. Maybe we need more. We need that deep history, that long trail to remind us of the world before vaccines, when everyone knew someone, either in their own household or next door, who succumbed to one of the childhood illnesses.

Let the “House of the Rising Sun” play on. Create a new version, and let that message reverberate, too.

Tell your children; they need to be vaccinated.

Dr. Messler is a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist group in Clearwater, Fla. He previously chaired SHM’s Quality and Patient Safety Committee and has been active in several SHM mentoring programs, most recently with Project BOOST and Glycemic Control. This article appeared originally in SHM's official blog The Hospital Leader. Read more recent posts here.

“There is a house in New Orleans. They call the Rising Sun. And it’s been the ruin of many a poor boy. And, God, I know I’m one.”

The 1960s rock band the Animals will tell you a tale to convince you to get vaccinated. Don’t believe me? Follow along.

The first hints of the song “House of the Rising Sun” rolled out of the hills of Appalachia.

Somewhere in the Golden Triangle, far away from New Orleans, where Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee rise in quiet desolation, a warning song about a tailor and a drunk emerged. Sometime around the Civil War, a hint of a tune began. Over the next century, it evolved, until it became cemented in rock culture 50 years ago by The Animals, existing as the version played most commonly today.

In the mid-19th century, medicine shows rambled through the South, stopping in places like Noetown or Daisy. The small towns would empty out for the day to see the entertainers, singers, and jugglers perform. Hundreds gathered in the hot summer day, the entertainment solely a pretext for the traveling doctors to sell their wares, the snake oil, and cure-alls, as well as various patent medicines.

These were isolated towns, with no deliveries, few visitors, and the railroad yet to arrive. Frequently, the only news from outside came from these caravans of entertainers and con men who swept into town. They were like Professor Marvel from The Wizard of Oz, or a current-day Dr. Oz, luring the crowd with false advertising, selling colored water, and then disappearing before you realized you were duped. Today, traveling doctors of the same ilk convince parents to not vaccinate their children, tell them to visit stem cell centers that claim false cures, and offer them a shiny object with one hand while taking their cash with the other.

Yet, there was a positive development in the wake of these patent medicine shows: the entertainment lingered. New songs traveled the same journeys as these medicine shows – new earworms that would then be warbled in the local bars, while doing chores around the barn, or simply during walks on the Appalachian trails.

In 1937, Alan Lomax arrived in Noetown, Ky., with a microphone and an acetate record and recorded the voice of 16-year-old Georgia Turner singing “House of the Rising Sun.” She didn’t know where she heard that song, but most likely picked it up at the medicine show.

One of those singers was Clarence Ashley, who would croon about the Rising Sun Blues. He sang with Doc Cloud and Doc Hauer, who offered tonics for whatever ailed you. Perhaps Georgia Turner heard the song in the early 1900s as well. Her 1937 version contains the lyrics most closely related to the Animals’ tune.

Lomax spent the 1940s gathering songs around the Appalachian South. He put these songs into a songbook and spread them throughout the country. He would also return to New York City and gather in a room with legendary folk singers. They would hear these new lyrics, new sounds, and make them their own.

In that room would be Lead Belly, Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and Josh White, the fathers of folk music. The music Lomax pulled out of the mountains in small towns would become new again in the guitars and harmonicas of the Greenwich Village singers and musicians. Pete Seeger performed with the Weavers, named because they would weave songs from the past into new versions.

“House of the Rising Sun” was woven into the folk music landscape, evolving and growing. Josh White is credited with changing the song from a major key into the minor key we know today. Bob Dylan sang a version. And then in 1964, Eric Burdon and The Animals released their version, which became the standard. An arpeggio guitar opening, the rhythm sped up, a louder sound, and that minor key provides an emotional wallop for this warning song.

Numerous covers followed, including a beautiful version of “Amazing Grace”, sung to the tune of “House of the Rising Sun” by the Blind Boys of Alabama.

The song endures for its melody as well as for its lyrics. This was a warning song, a universal song, “not to do what I have done.” The small towns in Kentucky may have heard of the sinful ways of New Orleans and would spread the message with these songs to avoid the brothels, the drink, and the broken marriages that would reverberate with visits to the Crescent City.

“House of the Rising Sun” is one of the most covered songs, traveling wide and far, no longer with the need for a medicine show. It was a pivotal moment in rock ‘n roll, turning folk music into rock music. The Animals became huge because of this song, and their version became the standard on which all subsequent covers based their version. It made Bob Dylan’s older version seem quaint.

The song has been in my head for a while now. My wife is hoping writing about it will keep it from being played in our household any more. There are various reasons it has been resonating with me, including the following:

- It traces the origins of folk music and the importance of people like Lomax and Guthrie to collect and save Americana.

- The magic of musical evolution – a reminder of how art is built on the work of those who came before, each version with its unique personality.

- The release of “House of the Rising Sun” was a seminal, transformative moment when folk became rock music.

- The lasting power of warning songs.

- The hucksters that enabled this song to be kept alive.

That last one has really stuck with me. The medicine shows are an important part of American history. For instance, Coca-Cola started as one of those patent medicines; it was one of the many concoctions of the Atlanta pharmacist John Stith Pemberton, sold to treat all that ails us. Dr. Pepper, too, was a medicine in a sugary bottle – another that often contained alcohol or cocaine. Society wants a cure-all, and the marketing and selling done during these medicine shows offered placebos.

The hucksters exist in various forms today, selling detoxifications, magic diet cures, psychic powers of healing, or convincing parents that their kids don’t need vaccines. We need a warning song that goes viral to keep our children safe. We are blessed to be in a world without smallpox, almost rid of polio, and we have the knowledge and opportunity to rid the world of other preventable illnesses. Measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000; now, outbreaks emerge in every news cycle.

The CDC admits they have not been targeting misinformation well. How can we spread the science, the truth, the message faster than the lies? Better marketing? The answer may be through stories and narratives and song, with the backing of good science. “House of the Rising Sun” is a warning song. Maybe we need more. We need that deep history, that long trail to remind us of the world before vaccines, when everyone knew someone, either in their own household or next door, who succumbed to one of the childhood illnesses.

Let the “House of the Rising Sun” play on. Create a new version, and let that message reverberate, too.

Tell your children; they need to be vaccinated.

Dr. Messler is a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist group in Clearwater, Fla. He previously chaired SHM’s Quality and Patient Safety Committee and has been active in several SHM mentoring programs, most recently with Project BOOST and Glycemic Control. This article appeared originally in SHM's official blog The Hospital Leader. Read more recent posts here.

Consider measles vaccine booster in HIV-positive patients

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A “surprisingly low” prevalence of protective antibodies against measles is present in adolescents and adults living with HIV infection despite their prior vaccination against the resurgent disease, Raquel M. Simakawa, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“With the present concern about the global reemergence of measles, we should consider measuring measles antibodies in people living with HIV, especially those who acquired the infection vertically, and then revaccinating those with low titers,” said Dr. Simakawa of the Federal University of São Paolo.

She presented interim findings of an ongoing study of the measles immunologic status of persons living with HIV, which for this analysis included 57 patients who acquired HIV from their mother via vertical transmission and 24 with horizontally acquired HIV. The vertical-transmission group was significantly younger, with a median age of 20 years, compared with 31 years in the horizontal group, who were diagnosed with HIV infection at an average age of 24 years. The vast majority of subjects were on combination antiretroviral therapy. No detectable HIV viral load had been present for a median of 70 months in the vertical group and 25 months in the horizontal group.

Only a mere 7% of the vertical transmission group had protective levels of measles IgG antibodies as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, as did 29% of the horizontal group. The likely explanation for the higher rate of protection in the horizontal group, she said, is that they received their routine measles vaccination before they acquired HIV infection, and some of them didn’t lose their protective antibodies during their immune system’s fight against HIV infection.

Session chair Nico G. Hartwig, MD, of Franciscus Hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, posed a question: Given the sky-high rate of measles seronegativity status among the vertically transmitted HIV-positive group – the patient population pediatricians focus on – why bother to measure their measles antibody level? Why not just give them all a measles booster?

Dr. Simakawa replied that that’s worth considering in routine clinical practice now that her study has shown that this group is more vulnerable to measles because of their poor response to immunization. But the study is ongoing, with larger numbers of patients to be enrolled. Also, in the second phase of the study, which will include a control group, measles IgG antibodies will be remeasured 1 month after administration of a new dose of measles vaccine.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A “surprisingly low” prevalence of protective antibodies against measles is present in adolescents and adults living with HIV infection despite their prior vaccination against the resurgent disease, Raquel M. Simakawa, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“With the present concern about the global reemergence of measles, we should consider measuring measles antibodies in people living with HIV, especially those who acquired the infection vertically, and then revaccinating those with low titers,” said Dr. Simakawa of the Federal University of São Paolo.

She presented interim findings of an ongoing study of the measles immunologic status of persons living with HIV, which for this analysis included 57 patients who acquired HIV from their mother via vertical transmission and 24 with horizontally acquired HIV. The vertical-transmission group was significantly younger, with a median age of 20 years, compared with 31 years in the horizontal group, who were diagnosed with HIV infection at an average age of 24 years. The vast majority of subjects were on combination antiretroviral therapy. No detectable HIV viral load had been present for a median of 70 months in the vertical group and 25 months in the horizontal group.

Only a mere 7% of the vertical transmission group had protective levels of measles IgG antibodies as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, as did 29% of the horizontal group. The likely explanation for the higher rate of protection in the horizontal group, she said, is that they received their routine measles vaccination before they acquired HIV infection, and some of them didn’t lose their protective antibodies during their immune system’s fight against HIV infection.

Session chair Nico G. Hartwig, MD, of Franciscus Hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, posed a question: Given the sky-high rate of measles seronegativity status among the vertically transmitted HIV-positive group – the patient population pediatricians focus on – why bother to measure their measles antibody level? Why not just give them all a measles booster?

Dr. Simakawa replied that that’s worth considering in routine clinical practice now that her study has shown that this group is more vulnerable to measles because of their poor response to immunization. But the study is ongoing, with larger numbers of patients to be enrolled. Also, in the second phase of the study, which will include a control group, measles IgG antibodies will be remeasured 1 month after administration of a new dose of measles vaccine.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A “surprisingly low” prevalence of protective antibodies against measles is present in adolescents and adults living with HIV infection despite their prior vaccination against the resurgent disease, Raquel M. Simakawa, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“With the present concern about the global reemergence of measles, we should consider measuring measles antibodies in people living with HIV, especially those who acquired the infection vertically, and then revaccinating those with low titers,” said Dr. Simakawa of the Federal University of São Paolo.

She presented interim findings of an ongoing study of the measles immunologic status of persons living with HIV, which for this analysis included 57 patients who acquired HIV from their mother via vertical transmission and 24 with horizontally acquired HIV. The vertical-transmission group was significantly younger, with a median age of 20 years, compared with 31 years in the horizontal group, who were diagnosed with HIV infection at an average age of 24 years. The vast majority of subjects were on combination antiretroviral therapy. No detectable HIV viral load had been present for a median of 70 months in the vertical group and 25 months in the horizontal group.

Only a mere 7% of the vertical transmission group had protective levels of measles IgG antibodies as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, as did 29% of the horizontal group. The likely explanation for the higher rate of protection in the horizontal group, she said, is that they received their routine measles vaccination before they acquired HIV infection, and some of them didn’t lose their protective antibodies during their immune system’s fight against HIV infection.

Session chair Nico G. Hartwig, MD, of Franciscus Hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, posed a question: Given the sky-high rate of measles seronegativity status among the vertically transmitted HIV-positive group – the patient population pediatricians focus on – why bother to measure their measles antibody level? Why not just give them all a measles booster?

Dr. Simakawa replied that that’s worth considering in routine clinical practice now that her study has shown that this group is more vulnerable to measles because of their poor response to immunization. But the study is ongoing, with larger numbers of patients to be enrolled. Also, in the second phase of the study, which will include a control group, measles IgG antibodies will be remeasured 1 month after administration of a new dose of measles vaccine.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

Once-Daily 2-Drug versus 3-Drug Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Treatment-naive Adults: Less Is Best?

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate the efficacy and safety of a once-daily 2-drug antiretroviral (ARV) regimen, dolutegravir plus lamivudine, for the treatment of HIV-1 infection in adults naive to antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Design. GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 were 2 identically designed multicenter, double-blind, randomized, noninferiority, phase 3 clinical trials conducted between July 18, 2016 and March 31, 2017. Participants were stratified to receive 1 of 2 once-daily HIV regimens: the study regimen, consisting of once-daily dolutegravir 50 mg plus lamivudine 300 mg, or the standard-of-care regimen, consisting of once-daily dolutegravir 50 mg plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) 300 mg plus emtricitabine 200 mg. While this article presents results at week 48, both trials are scheduled to evaluate participants up to week 148 in an attempt to evaluate long-term efficacy and safety.

Setting and participants. Eligible participants had to be aged 18 years or older with treatment-naive HIV-1 infection. Women were eligible if they were not (1) pregnant, (2) lactating, or (3) of reproductive potential, defined by various means, including tubal ligation, hysterectomy, postmenopausal, and the use of highly effective contraception. Initially, eligibility screening restricted participation to those with viral loads between 1000 and 100,000 copies/mL. However, the upper limit was later increased to 500,000 copies/mL based on an independent review of results from other clinical trials1,2 evaluating dual therapy with dolutegravir and lamivudine, which indicated efficacy in patients with viral loads up to 500,000.3-5

Notable exclusion criteria included: (1) major mutations to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and protease inhibitors; (2) evidence of hepatitis B infection; (3) hepatitis C infection with anticipation of initiating treatment within 48 weeks of study enrollment; and (4) stage 3 HIV disease, per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria, with the exception of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma and CD4 cell counts < 200 cells/mL.

Main outcome measures. The primary endpoint was demonstration of noninferiority of the 2-drug ARV regimen through assessment of the proportion of participants who achieved virologic suppression at week 48 in the intent-to-treat-exposed population. For the purposes of this study, virologic suppression was defined as having fewer than 50 copies of HIV-1 RNA per mL at week 48. For evaluation of safety and toxicity concerns, renal and bone biomarkers were assessed at study entry and at weeks 24 and 48. In addition, participants who met virological withdrawal criteria were evaluated for integrase strand transfer inhibitor mutations. Virological withdrawal was defined as the presence of 1 of the following: (1) HIV RNA > 200 copies/mL at week 24, (2) HIV RNA > 200 copies/mL after previous HIV RNA < 200 copies/mL (confirmed rebound), and (3) a < 1 log10 copies/mL decrease from baseline (unless already < 200 copies/mL).

Main results. GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 randomized a combined total of 1441 participants to receive either the once-daily 2-drug ARV regimen (dolutegravir and lamivudine, n = 719) or the once-daily 3-drug ARV regimen (dolutegravir, TDF, and emtricitabine, n = 722). Of the 533 participants who did not meet inclusion criteria, the predominant reasons for exclusion were either having preexisting major viral resistance mutations (n = 246) or viral loads outside the range of 1000 to 500,000 copies/mL (n = 133).

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between both groups. The median age was 33 years (10% were over 50 years of age), and participants were mostly male (85%) and white (68%). Baseline HIV RNA counts of > 100,000 copies/mL were found in 293 participants (20%), and 188 (8%) participants had CD4 counts of ≤ 200 cells/mL.

Noninferiority of the once-daily 2-drug versus the once-daily 3-drug ARV regimen was demonstrated in both the GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 trials for the intent-to-treat-exposed population. In GEMINI-1, 90% (n = 320) in the 2-drug ARV group achieved virologic suppression at week 48 compared to 93% (n = 332) in the 3-drug ARV group (no statistically significant difference). In GEMINI-2, 93% (n =335 ) in the 2-drug ARV group achieved virologic suppression at week 48 compared to 94% (n = 337) in the 3-drug ARV group (no statistically significant difference).

A subgroup analysis found no significant impact of baseline HIV RNA (> 100,000 compared to ≤ 100,000 copies/mL) on achieving virologic suppression at week 48. However, a subgroup analysis did find that participants with CD4 counts < 200 copies/mL had a reduced response in the once-daily 2-drug versus 3-drug ARV regimen for achieving virologic response at week 48 (79% versus 93%, respectively).

Overall, 10 participants met virological withdrawal criteria during the study period, and 4 of these were on the 2-drug ARV regimen. For these 10 participants, genotypic testing did not find emergence of resistance to either nucleoside reverse transcriptase or integrase strand transfer inhibitors.

Regarding renal biomarkers, increases of both serum creatinine and urinary excretion of protein creatinine were significantly greater in the 3-drug ARV group. Also, biomarkers indicating increased bone turnover were elevated in both groups, but the degree of elevation was significantly lower in the 2-drug ARV regimen cohort. It is unclear whether these findings reflect an increased or decreased risk of developing osteopenia or osteoporosis in the 2 study groups.

Conclusion. The once-daily 2-drug ARV regimen dolutegravir and lamivudine is noninferior to the guideline-recommended once-daily 3-drug ARV regimen dolutegravir, TDF, and emtricitabine at achieving viral suppression in ART-naive HIV-1 infected individuals with HIV RNA counts < 500,000 copies/mL. However, the efficacy of this ARV regimen may be compromised in individuals with CD4 counts < 200 cells/mL.

Commentary

Currently, the mainstay of HIV pharmacotherapy is a 3-drug regimen consisting of 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in combination with 1 drug from another class, with an integrase strand transfer inhibitor being the preferred third drug.6 Despite the improved tolerability of contemporary ARVs, there remains concern among HIV practitioners regarding potential toxicities associated with cumulative drug exposure, specifically related to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. As a result, there has been much interest in evaluating 2-drug ARV regimens for HIV treatment in order to reduce overall drug exposure.7-10

The 48-week results of the GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 trials, published in early 2019, further expand our understanding regarding the efficacy and safety of 2-drug regimens in HIV treatment. These identically designed studies evaluated once-daily dolutegravir and lamivudine for HIV in a treatment-naive population. This goes a step further than the SWORD-1 and SWORD-2 trials, which evaluated once-daily dolutegravir and rilpivirine as a step-down therapy for virologically suppressed individuals and led to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the single-tablet combination regimen dolutegravir/rilpivirine (Juluca).10 Therefore, whereas the SWORD trials evaluated a 2-drug regimen for maintenance of virologic suppression, the GEMINI trials assessed whether a 2-drug regimen can both achieve and maintain virologic suppression.

The results of the GEMINI trials are promising for a future direction in HIV care. The rates of virologic suppression achieved in these trials are comparable to those seen in the SWORD trials.10 Furthermore, the virologic response seen in the GEMINI trials is comparable to that seen in similar trials that evaluated a 3-drug ARV regimen consisting of an integrase strand transfer inhibitor–based backbone in ART-naive individuals.11,12

A major confounder to the design of this trial was that it included TDF as one of the components in the comparator arm, an agent that has already been demonstrated to have detrimental effects on both renal and bone health.13,14 Additionally, the bone biomarker results were inconclusive, and the agents’ effects on bone would have been better demonstrated through bone mineral density testing, as had been done in prior trials.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Given the recent FDA approval of the single-tablet combination regimen dolutegravir and lamivudine (Dovato), this once-daily 2-drug ARV regimen will begin making its way into clinical practice for certain patients. Prior to starting this regimen, hepatitis B infection first must be ruled out due to poor efficacy of lamivudine monotherapy for management of chronic hepatitis B infection.15 Additionally, baseline genotype testing should be performed prior to starting this ART given that approximately 10% of newly diagnosed HIV patients have baseline resistance mutations.16 Obtaining rapid genotype testing may be difficult to accomplish in low-resource settings where such testing is not readily available. Finally, this approach may not be applicable to those presenting with acute HIV infection, in whom viral loads are often in the millions of copies per mL. It is likely that dolutegravir/lamivudine could assume a role similar to that of dolutegravir/rilpivirine, in which patients who present with acute HIV step down to a 2-drug regimen once their viral loads have either dropped below 500,000 copies/mL or have already been suppressed.

—Evan K. Mallory, PharmD, Banner-University Medical Center Tucson, and Norman L. Beatty, MD, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, AZ

1. Cahn P, Rolón MJ, Figueroa MI, et al. Dolutegravir-lamivudine as initial therapy in HIV-1 infected, ARV-naive patients, 48-week results of the PADDLE (Pilot Antiretroviral Design with Dolutegravir LamivudinE) study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20:21678.

2. Taiwo BO, Zheng L, Stefanescu A, et al. ACTG A5353: a pilot study of dolutegravir plus lamivudine for initial treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1)-infected participants eith HIV-1 RNA <500000 vopies/mL. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:1689-1697.

3. Min S, Sloan L, DeJesus E, et al. Antiviral activity, safety, and pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of dolutegravir as 10-day monotherapy in HIV-1-infected adults. AIDS. 2011;25:1737-1745.

4. Eron JJ, Benoit SL, Jemsek J, et al. Treatment with lamivudine, zidovudine, or both in HIV-positive patients with 200 to 500 CD4+ cells per cubic millimeter. North American HIV Working Party. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1662-1669.

5. Kuritzkes DR, Quinn JB, Benoit SL, et al. Drug resistance and virologic response in NUCA 3001, a randomized trial of lamivudine (3TC) versus zidovudine (ZDV) versus ZDV plus 3TC in previously untreated patients. AIDS. 1996;10:975-981.

6. Department of Health and Human Services. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents living with HIV. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2019.

7. Riddler SA, Haubrich R, DiRienzo AG, et al. Class-sparing regimens for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2095-2106.

8. Reynes J, Lawal A, Pulido F, et al. Examination of noninferiority, safety, and tolerability of lopinavir/ritonavir and raltegravir compared with lopinavir/ritonavir and tenofovir/ emtricitabine in antiretroviral-naïve subjects: the progress study, 48-week results. HIV Clin Trials. 2011;12:255-267.

9. Cahn P, Andrade-Villanueva J, Arribas JR, et al. Dual therapy with lopinavir and ritonavir plus lamivudine versus triple therapy with lopinavir and ritonavir plus two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in antiretroviral-therapy-naive adults with HIV-1 infection: 48 week results of the randomised, open label, non-inferiority GARDEL trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:572-580.

10. Llibre JM, Hung CC, Brinson C, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of dolutegravir-rilpivirine for the maintenance of virological suppression in adults with HIV-1: phase 3, randomised, non-inferiority SWORD-1 and SWORD-2 studies. Lancet. 2018;391:839-849.

11. Walmsley SL, Antela A, Clumeck N, et al. Dolutegravir plus abacavir-lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1807-1818.

12. Sax PE, Wohl D, Yin MT, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, coformulated with elvitegravir, cobicistat, and emtricitabine, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: two randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet. 2015;385:2606-2615.

13. Mulligan K, Glidden DV, Anderson PL, et al. Effects of emtricitabine/tenofovir on bone mineral density in HIV-negative persons in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:572-580.

14. Cooper RD, Wiebe N, Smith N, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: renal safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:496-505.

15. Kim D, Wheeler W, Ziebell R, et al. Prevalence of antiretroviral drug resistance among newly diagnosed HIV-1 infected persons, United States, 2007. 17th Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections; San Francisco, CA: 2010. Feb 16-19. Abstract 580.

16. Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67:1560-1599.

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate the efficacy and safety of a once-daily 2-drug antiretroviral (ARV) regimen, dolutegravir plus lamivudine, for the treatment of HIV-1 infection in adults naive to antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Design. GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 were 2 identically designed multicenter, double-blind, randomized, noninferiority, phase 3 clinical trials conducted between July 18, 2016 and March 31, 2017. Participants were stratified to receive 1 of 2 once-daily HIV regimens: the study regimen, consisting of once-daily dolutegravir 50 mg plus lamivudine 300 mg, or the standard-of-care regimen, consisting of once-daily dolutegravir 50 mg plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) 300 mg plus emtricitabine 200 mg. While this article presents results at week 48, both trials are scheduled to evaluate participants up to week 148 in an attempt to evaluate long-term efficacy and safety.

Setting and participants. Eligible participants had to be aged 18 years or older with treatment-naive HIV-1 infection. Women were eligible if they were not (1) pregnant, (2) lactating, or (3) of reproductive potential, defined by various means, including tubal ligation, hysterectomy, postmenopausal, and the use of highly effective contraception. Initially, eligibility screening restricted participation to those with viral loads between 1000 and 100,000 copies/mL. However, the upper limit was later increased to 500,000 copies/mL based on an independent review of results from other clinical trials1,2 evaluating dual therapy with dolutegravir and lamivudine, which indicated efficacy in patients with viral loads up to 500,000.3-5

Notable exclusion criteria included: (1) major mutations to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and protease inhibitors; (2) evidence of hepatitis B infection; (3) hepatitis C infection with anticipation of initiating treatment within 48 weeks of study enrollment; and (4) stage 3 HIV disease, per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria, with the exception of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma and CD4 cell counts < 200 cells/mL.

Main outcome measures. The primary endpoint was demonstration of noninferiority of the 2-drug ARV regimen through assessment of the proportion of participants who achieved virologic suppression at week 48 in the intent-to-treat-exposed population. For the purposes of this study, virologic suppression was defined as having fewer than 50 copies of HIV-1 RNA per mL at week 48. For evaluation of safety and toxicity concerns, renal and bone biomarkers were assessed at study entry and at weeks 24 and 48. In addition, participants who met virological withdrawal criteria were evaluated for integrase strand transfer inhibitor mutations. Virological withdrawal was defined as the presence of 1 of the following: (1) HIV RNA > 200 copies/mL at week 24, (2) HIV RNA > 200 copies/mL after previous HIV RNA < 200 copies/mL (confirmed rebound), and (3) a < 1 log10 copies/mL decrease from baseline (unless already < 200 copies/mL).

Main results. GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 randomized a combined total of 1441 participants to receive either the once-daily 2-drug ARV regimen (dolutegravir and lamivudine, n = 719) or the once-daily 3-drug ARV regimen (dolutegravir, TDF, and emtricitabine, n = 722). Of the 533 participants who did not meet inclusion criteria, the predominant reasons for exclusion were either having preexisting major viral resistance mutations (n = 246) or viral loads outside the range of 1000 to 500,000 copies/mL (n = 133).

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between both groups. The median age was 33 years (10% were over 50 years of age), and participants were mostly male (85%) and white (68%). Baseline HIV RNA counts of > 100,000 copies/mL were found in 293 participants (20%), and 188 (8%) participants had CD4 counts of ≤ 200 cells/mL.

Noninferiority of the once-daily 2-drug versus the once-daily 3-drug ARV regimen was demonstrated in both the GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 trials for the intent-to-treat-exposed population. In GEMINI-1, 90% (n = 320) in the 2-drug ARV group achieved virologic suppression at week 48 compared to 93% (n = 332) in the 3-drug ARV group (no statistically significant difference). In GEMINI-2, 93% (n =335 ) in the 2-drug ARV group achieved virologic suppression at week 48 compared to 94% (n = 337) in the 3-drug ARV group (no statistically significant difference).

A subgroup analysis found no significant impact of baseline HIV RNA (> 100,000 compared to ≤ 100,000 copies/mL) on achieving virologic suppression at week 48. However, a subgroup analysis did find that participants with CD4 counts < 200 copies/mL had a reduced response in the once-daily 2-drug versus 3-drug ARV regimen for achieving virologic response at week 48 (79% versus 93%, respectively).

Overall, 10 participants met virological withdrawal criteria during the study period, and 4 of these were on the 2-drug ARV regimen. For these 10 participants, genotypic testing did not find emergence of resistance to either nucleoside reverse transcriptase or integrase strand transfer inhibitors.

Regarding renal biomarkers, increases of both serum creatinine and urinary excretion of protein creatinine were significantly greater in the 3-drug ARV group. Also, biomarkers indicating increased bone turnover were elevated in both groups, but the degree of elevation was significantly lower in the 2-drug ARV regimen cohort. It is unclear whether these findings reflect an increased or decreased risk of developing osteopenia or osteoporosis in the 2 study groups.

Conclusion. The once-daily 2-drug ARV regimen dolutegravir and lamivudine is noninferior to the guideline-recommended once-daily 3-drug ARV regimen dolutegravir, TDF, and emtricitabine at achieving viral suppression in ART-naive HIV-1 infected individuals with HIV RNA counts < 500,000 copies/mL. However, the efficacy of this ARV regimen may be compromised in individuals with CD4 counts < 200 cells/mL.

Commentary

Currently, the mainstay of HIV pharmacotherapy is a 3-drug regimen consisting of 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in combination with 1 drug from another class, with an integrase strand transfer inhibitor being the preferred third drug.6 Despite the improved tolerability of contemporary ARVs, there remains concern among HIV practitioners regarding potential toxicities associated with cumulative drug exposure, specifically related to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. As a result, there has been much interest in evaluating 2-drug ARV regimens for HIV treatment in order to reduce overall drug exposure.7-10

The 48-week results of the GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 trials, published in early 2019, further expand our understanding regarding the efficacy and safety of 2-drug regimens in HIV treatment. These identically designed studies evaluated once-daily dolutegravir and lamivudine for HIV in a treatment-naive population. This goes a step further than the SWORD-1 and SWORD-2 trials, which evaluated once-daily dolutegravir and rilpivirine as a step-down therapy for virologically suppressed individuals and led to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the single-tablet combination regimen dolutegravir/rilpivirine (Juluca).10 Therefore, whereas the SWORD trials evaluated a 2-drug regimen for maintenance of virologic suppression, the GEMINI trials assessed whether a 2-drug regimen can both achieve and maintain virologic suppression.

The results of the GEMINI trials are promising for a future direction in HIV care. The rates of virologic suppression achieved in these trials are comparable to those seen in the SWORD trials.10 Furthermore, the virologic response seen in the GEMINI trials is comparable to that seen in similar trials that evaluated a 3-drug ARV regimen consisting of an integrase strand transfer inhibitor–based backbone in ART-naive individuals.11,12

A major confounder to the design of this trial was that it included TDF as one of the components in the comparator arm, an agent that has already been demonstrated to have detrimental effects on both renal and bone health.13,14 Additionally, the bone biomarker results were inconclusive, and the agents’ effects on bone would have been better demonstrated through bone mineral density testing, as had been done in prior trials.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Given the recent FDA approval of the single-tablet combination regimen dolutegravir and lamivudine (Dovato), this once-daily 2-drug ARV regimen will begin making its way into clinical practice for certain patients. Prior to starting this regimen, hepatitis B infection first must be ruled out due to poor efficacy of lamivudine monotherapy for management of chronic hepatitis B infection.15 Additionally, baseline genotype testing should be performed prior to starting this ART given that approximately 10% of newly diagnosed HIV patients have baseline resistance mutations.16 Obtaining rapid genotype testing may be difficult to accomplish in low-resource settings where such testing is not readily available. Finally, this approach may not be applicable to those presenting with acute HIV infection, in whom viral loads are often in the millions of copies per mL. It is likely that dolutegravir/lamivudine could assume a role similar to that of dolutegravir/rilpivirine, in which patients who present with acute HIV step down to a 2-drug regimen once their viral loads have either dropped below 500,000 copies/mL or have already been suppressed.

—Evan K. Mallory, PharmD, Banner-University Medical Center Tucson, and Norman L. Beatty, MD, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, AZ

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate the efficacy and safety of a once-daily 2-drug antiretroviral (ARV) regimen, dolutegravir plus lamivudine, for the treatment of HIV-1 infection in adults naive to antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Design. GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 were 2 identically designed multicenter, double-blind, randomized, noninferiority, phase 3 clinical trials conducted between July 18, 2016 and March 31, 2017. Participants were stratified to receive 1 of 2 once-daily HIV regimens: the study regimen, consisting of once-daily dolutegravir 50 mg plus lamivudine 300 mg, or the standard-of-care regimen, consisting of once-daily dolutegravir 50 mg plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) 300 mg plus emtricitabine 200 mg. While this article presents results at week 48, both trials are scheduled to evaluate participants up to week 148 in an attempt to evaluate long-term efficacy and safety.

Setting and participants. Eligible participants had to be aged 18 years or older with treatment-naive HIV-1 infection. Women were eligible if they were not (1) pregnant, (2) lactating, or (3) of reproductive potential, defined by various means, including tubal ligation, hysterectomy, postmenopausal, and the use of highly effective contraception. Initially, eligibility screening restricted participation to those with viral loads between 1000 and 100,000 copies/mL. However, the upper limit was later increased to 500,000 copies/mL based on an independent review of results from other clinical trials1,2 evaluating dual therapy with dolutegravir and lamivudine, which indicated efficacy in patients with viral loads up to 500,000.3-5

Notable exclusion criteria included: (1) major mutations to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and protease inhibitors; (2) evidence of hepatitis B infection; (3) hepatitis C infection with anticipation of initiating treatment within 48 weeks of study enrollment; and (4) stage 3 HIV disease, per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria, with the exception of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma and CD4 cell counts < 200 cells/mL.

Main outcome measures. The primary endpoint was demonstration of noninferiority of the 2-drug ARV regimen through assessment of the proportion of participants who achieved virologic suppression at week 48 in the intent-to-treat-exposed population. For the purposes of this study, virologic suppression was defined as having fewer than 50 copies of HIV-1 RNA per mL at week 48. For evaluation of safety and toxicity concerns, renal and bone biomarkers were assessed at study entry and at weeks 24 and 48. In addition, participants who met virological withdrawal criteria were evaluated for integrase strand transfer inhibitor mutations. Virological withdrawal was defined as the presence of 1 of the following: (1) HIV RNA > 200 copies/mL at week 24, (2) HIV RNA > 200 copies/mL after previous HIV RNA < 200 copies/mL (confirmed rebound), and (3) a < 1 log10 copies/mL decrease from baseline (unless already < 200 copies/mL).

Main results. GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 randomized a combined total of 1441 participants to receive either the once-daily 2-drug ARV regimen (dolutegravir and lamivudine, n = 719) or the once-daily 3-drug ARV regimen (dolutegravir, TDF, and emtricitabine, n = 722). Of the 533 participants who did not meet inclusion criteria, the predominant reasons for exclusion were either having preexisting major viral resistance mutations (n = 246) or viral loads outside the range of 1000 to 500,000 copies/mL (n = 133).

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between both groups. The median age was 33 years (10% were over 50 years of age), and participants were mostly male (85%) and white (68%). Baseline HIV RNA counts of > 100,000 copies/mL were found in 293 participants (20%), and 188 (8%) participants had CD4 counts of ≤ 200 cells/mL.

Noninferiority of the once-daily 2-drug versus the once-daily 3-drug ARV regimen was demonstrated in both the GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 trials for the intent-to-treat-exposed population. In GEMINI-1, 90% (n = 320) in the 2-drug ARV group achieved virologic suppression at week 48 compared to 93% (n = 332) in the 3-drug ARV group (no statistically significant difference). In GEMINI-2, 93% (n =335 ) in the 2-drug ARV group achieved virologic suppression at week 48 compared to 94% (n = 337) in the 3-drug ARV group (no statistically significant difference).

A subgroup analysis found no significant impact of baseline HIV RNA (> 100,000 compared to ≤ 100,000 copies/mL) on achieving virologic suppression at week 48. However, a subgroup analysis did find that participants with CD4 counts < 200 copies/mL had a reduced response in the once-daily 2-drug versus 3-drug ARV regimen for achieving virologic response at week 48 (79% versus 93%, respectively).

Overall, 10 participants met virological withdrawal criteria during the study period, and 4 of these were on the 2-drug ARV regimen. For these 10 participants, genotypic testing did not find emergence of resistance to either nucleoside reverse transcriptase or integrase strand transfer inhibitors.

Regarding renal biomarkers, increases of both serum creatinine and urinary excretion of protein creatinine were significantly greater in the 3-drug ARV group. Also, biomarkers indicating increased bone turnover were elevated in both groups, but the degree of elevation was significantly lower in the 2-drug ARV regimen cohort. It is unclear whether these findings reflect an increased or decreased risk of developing osteopenia or osteoporosis in the 2 study groups.

Conclusion. The once-daily 2-drug ARV regimen dolutegravir and lamivudine is noninferior to the guideline-recommended once-daily 3-drug ARV regimen dolutegravir, TDF, and emtricitabine at achieving viral suppression in ART-naive HIV-1 infected individuals with HIV RNA counts < 500,000 copies/mL. However, the efficacy of this ARV regimen may be compromised in individuals with CD4 counts < 200 cells/mL.

Commentary

Currently, the mainstay of HIV pharmacotherapy is a 3-drug regimen consisting of 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in combination with 1 drug from another class, with an integrase strand transfer inhibitor being the preferred third drug.6 Despite the improved tolerability of contemporary ARVs, there remains concern among HIV practitioners regarding potential toxicities associated with cumulative drug exposure, specifically related to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. As a result, there has been much interest in evaluating 2-drug ARV regimens for HIV treatment in order to reduce overall drug exposure.7-10

The 48-week results of the GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 trials, published in early 2019, further expand our understanding regarding the efficacy and safety of 2-drug regimens in HIV treatment. These identically designed studies evaluated once-daily dolutegravir and lamivudine for HIV in a treatment-naive population. This goes a step further than the SWORD-1 and SWORD-2 trials, which evaluated once-daily dolutegravir and rilpivirine as a step-down therapy for virologically suppressed individuals and led to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the single-tablet combination regimen dolutegravir/rilpivirine (Juluca).10 Therefore, whereas the SWORD trials evaluated a 2-drug regimen for maintenance of virologic suppression, the GEMINI trials assessed whether a 2-drug regimen can both achieve and maintain virologic suppression.

The results of the GEMINI trials are promising for a future direction in HIV care. The rates of virologic suppression achieved in these trials are comparable to those seen in the SWORD trials.10 Furthermore, the virologic response seen in the GEMINI trials is comparable to that seen in similar trials that evaluated a 3-drug ARV regimen consisting of an integrase strand transfer inhibitor–based backbone in ART-naive individuals.11,12

A major confounder to the design of this trial was that it included TDF as one of the components in the comparator arm, an agent that has already been demonstrated to have detrimental effects on both renal and bone health.13,14 Additionally, the bone biomarker results were inconclusive, and the agents’ effects on bone would have been better demonstrated through bone mineral density testing, as had been done in prior trials.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Given the recent FDA approval of the single-tablet combination regimen dolutegravir and lamivudine (Dovato), this once-daily 2-drug ARV regimen will begin making its way into clinical practice for certain patients. Prior to starting this regimen, hepatitis B infection first must be ruled out due to poor efficacy of lamivudine monotherapy for management of chronic hepatitis B infection.15 Additionally, baseline genotype testing should be performed prior to starting this ART given that approximately 10% of newly diagnosed HIV patients have baseline resistance mutations.16 Obtaining rapid genotype testing may be difficult to accomplish in low-resource settings where such testing is not readily available. Finally, this approach may not be applicable to those presenting with acute HIV infection, in whom viral loads are often in the millions of copies per mL. It is likely that dolutegravir/lamivudine could assume a role similar to that of dolutegravir/rilpivirine, in which patients who present with acute HIV step down to a 2-drug regimen once their viral loads have either dropped below 500,000 copies/mL or have already been suppressed.

—Evan K. Mallory, PharmD, Banner-University Medical Center Tucson, and Norman L. Beatty, MD, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, AZ

1. Cahn P, Rolón MJ, Figueroa MI, et al. Dolutegravir-lamivudine as initial therapy in HIV-1 infected, ARV-naive patients, 48-week results of the PADDLE (Pilot Antiretroviral Design with Dolutegravir LamivudinE) study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20:21678.

2. Taiwo BO, Zheng L, Stefanescu A, et al. ACTG A5353: a pilot study of dolutegravir plus lamivudine for initial treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1)-infected participants eith HIV-1 RNA <500000 vopies/mL. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:1689-1697.

3. Min S, Sloan L, DeJesus E, et al. Antiviral activity, safety, and pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of dolutegravir as 10-day monotherapy in HIV-1-infected adults. AIDS. 2011;25:1737-1745.

4. Eron JJ, Benoit SL, Jemsek J, et al. Treatment with lamivudine, zidovudine, or both in HIV-positive patients with 200 to 500 CD4+ cells per cubic millimeter. North American HIV Working Party. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1662-1669.

5. Kuritzkes DR, Quinn JB, Benoit SL, et al. Drug resistance and virologic response in NUCA 3001, a randomized trial of lamivudine (3TC) versus zidovudine (ZDV) versus ZDV plus 3TC in previously untreated patients. AIDS. 1996;10:975-981.

6. Department of Health and Human Services. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents living with HIV. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2019.

7. Riddler SA, Haubrich R, DiRienzo AG, et al. Class-sparing regimens for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2095-2106.

8. Reynes J, Lawal A, Pulido F, et al. Examination of noninferiority, safety, and tolerability of lopinavir/ritonavir and raltegravir compared with lopinavir/ritonavir and tenofovir/ emtricitabine in antiretroviral-naïve subjects: the progress study, 48-week results. HIV Clin Trials. 2011;12:255-267.

9. Cahn P, Andrade-Villanueva J, Arribas JR, et al. Dual therapy with lopinavir and ritonavir plus lamivudine versus triple therapy with lopinavir and ritonavir plus two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in antiretroviral-therapy-naive adults with HIV-1 infection: 48 week results of the randomised, open label, non-inferiority GARDEL trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:572-580.

10. Llibre JM, Hung CC, Brinson C, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of dolutegravir-rilpivirine for the maintenance of virological suppression in adults with HIV-1: phase 3, randomised, non-inferiority SWORD-1 and SWORD-2 studies. Lancet. 2018;391:839-849.

11. Walmsley SL, Antela A, Clumeck N, et al. Dolutegravir plus abacavir-lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1807-1818.

12. Sax PE, Wohl D, Yin MT, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, coformulated with elvitegravir, cobicistat, and emtricitabine, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: two randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet. 2015;385:2606-2615.

13. Mulligan K, Glidden DV, Anderson PL, et al. Effects of emtricitabine/tenofovir on bone mineral density in HIV-negative persons in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:572-580.

14. Cooper RD, Wiebe N, Smith N, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: renal safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:496-505.

15. Kim D, Wheeler W, Ziebell R, et al. Prevalence of antiretroviral drug resistance among newly diagnosed HIV-1 infected persons, United States, 2007. 17th Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections; San Francisco, CA: 2010. Feb 16-19. Abstract 580.

16. Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67:1560-1599.

1. Cahn P, Rolón MJ, Figueroa MI, et al. Dolutegravir-lamivudine as initial therapy in HIV-1 infected, ARV-naive patients, 48-week results of the PADDLE (Pilot Antiretroviral Design with Dolutegravir LamivudinE) study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20:21678.

2. Taiwo BO, Zheng L, Stefanescu A, et al. ACTG A5353: a pilot study of dolutegravir plus lamivudine for initial treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1)-infected participants eith HIV-1 RNA <500000 vopies/mL. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:1689-1697.

3. Min S, Sloan L, DeJesus E, et al. Antiviral activity, safety, and pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of dolutegravir as 10-day monotherapy in HIV-1-infected adults. AIDS. 2011;25:1737-1745.

4. Eron JJ, Benoit SL, Jemsek J, et al. Treatment with lamivudine, zidovudine, or both in HIV-positive patients with 200 to 500 CD4+ cells per cubic millimeter. North American HIV Working Party. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1662-1669.

5. Kuritzkes DR, Quinn JB, Benoit SL, et al. Drug resistance and virologic response in NUCA 3001, a randomized trial of lamivudine (3TC) versus zidovudine (ZDV) versus ZDV plus 3TC in previously untreated patients. AIDS. 1996;10:975-981.

6. Department of Health and Human Services. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents living with HIV. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2019.

7. Riddler SA, Haubrich R, DiRienzo AG, et al. Class-sparing regimens for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2095-2106.

8. Reynes J, Lawal A, Pulido F, et al. Examination of noninferiority, safety, and tolerability of lopinavir/ritonavir and raltegravir compared with lopinavir/ritonavir and tenofovir/ emtricitabine in antiretroviral-naïve subjects: the progress study, 48-week results. HIV Clin Trials. 2011;12:255-267.

9. Cahn P, Andrade-Villanueva J, Arribas JR, et al. Dual therapy with lopinavir and ritonavir plus lamivudine versus triple therapy with lopinavir and ritonavir plus two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in antiretroviral-therapy-naive adults with HIV-1 infection: 48 week results of the randomised, open label, non-inferiority GARDEL trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:572-580.

10. Llibre JM, Hung CC, Brinson C, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of dolutegravir-rilpivirine for the maintenance of virological suppression in adults with HIV-1: phase 3, randomised, non-inferiority SWORD-1 and SWORD-2 studies. Lancet. 2018;391:839-849.

11. Walmsley SL, Antela A, Clumeck N, et al. Dolutegravir plus abacavir-lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1807-1818.

12. Sax PE, Wohl D, Yin MT, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, coformulated with elvitegravir, cobicistat, and emtricitabine, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: two randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet. 2015;385:2606-2615.

13. Mulligan K, Glidden DV, Anderson PL, et al. Effects of emtricitabine/tenofovir on bone mineral density in HIV-negative persons in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:572-580.

14. Cooper RD, Wiebe N, Smith N, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: renal safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:496-505.

15. Kim D, Wheeler W, Ziebell R, et al. Prevalence of antiretroviral drug resistance among newly diagnosed HIV-1 infected persons, United States, 2007. 17th Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections; San Francisco, CA: 2010. Feb 16-19. Abstract 580.

16. Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67:1560-1599.

Expanded indication being considered for meningococcal group B vaccine

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – under the agency’s Breakthrough Therapy designation.

Breakthrough Therapy status is reserved for accelerated review of therapies considered to show substantial preliminary promise of effectively targeting a major unmet medical need.

The unmet need here is that there is no meningococcal group B vaccine approved for use in children under age 10 years. Yet infants and children under 5 years of age are at greatest risk of invasive meningococcal B disease, with reported case fatality rates of 8%-9%, Jason D. Maguire, MD, noted at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

Trumenba has been approved in the United States for patients aged 10-25 years and in the European Union for individuals aged 10 years or older.

Dr. Maguire, of Pfizer’s vaccine clinical research and development program, presented the results of the two phase 2 randomized safety and immunogenicity trials conducted in patients aged 1- 9 years that the company has submitted to the FDA in support of the expanded indication. One study was carried out in 352 1-year-old toddlers, the other in 400 children aged 2-9 years, whose mean age was 4 years. The studies were carried out in Australia, Finland, Poland, and the Czech Republic.

In a pooled analysis of the vaccine’s immunogenicity when administered in a three-dose schedule of 120 mcg at 0, 2, and 6 months to 193 toddlers and 274 of the children aged 2-9 years, robust bactericidal antibody responses were seen against the four major Neisseria meningitidis group B strains that cause invasive disease. In fact, at least a fourfold rise in titers from baseline to 1 month after dose three was documented in the same high proportion of 1- to 9-year-olds as previously seen in the phase 3 trials that led to vaccine licensure in adolescents and young adults.

“These results support that the use of Trumenba, when given to children ages 1 to less than 10 years at the same dose and schedule that is currently approved in adolescents and young adults, can afford a high degree of protective antibody responses that correlate with immunity in this population,” Dr. Maguire said.

The safety and tolerability analysis included all 752 children in the two phase 2 studies, including the 110 toddlers randomized to three 60-mcg doses of the vaccine, although it has subsequently become clear that 120 mcg is the dose that provides the best immunogenicity with an acceptable safety profile, according to the physician.

Across the age groups, local reactions, including redness and swelling, were more common in Trumenba recipients than in controls who received hepatitis A vaccine and saline injections. So were systemic adverse events. Fever – a systemic event of particular interest to parents and clinicians – occurred in 37% of toddlers after vaccination, compared with 25% of 2- to 9-year-olds and 10%-12% of controls. Of note, prophylactic antipyretics weren’t allowed in the study.

“There’s somewhat of an inverse relationship between age and temperature. So as we go down in age, the rate of fever rises. But after each subsequent dose, regardless of age, there’s a reduction in the incidence of fever,” Dr. Maguire observed.

Most fevers were less than 39.0° C. Only 3 of 752 (less than 1%) patients experienced fever in excess of 40.0° C.

Two children withdrew from the study after developing hip synovitis, which was transient. Another withdrew because of prolonged irritability, fatigue, and decreased appetite.

“Although Trumenba had an acceptable safety and tolerability profile in 1- to 9-year-olds, this analysis wasn’t powered enough to detect uncommon adverse events, so we’ll continue to monitor safety for things like synovitis,” he said.

In 10- to 25-year-olds, the meningococcal vaccine can be given concomitantly with other vaccines without interference. There are plans to study concurrent vaccination with MMR and pneumococcal vaccines in 1- to 9-year-olds as well, according to Dr. Maguire.

Pfizer also now is planning clinical trials of the vaccine in infants, another important group currently unprotected against meningococcal group B disease, he added.

Dr. Maguire is an employee of Pfizer, who funded the studies.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – under the agency’s Breakthrough Therapy designation.

Breakthrough Therapy status is reserved for accelerated review of therapies considered to show substantial preliminary promise of effectively targeting a major unmet medical need.

The unmet need here is that there is no meningococcal group B vaccine approved for use in children under age 10 years. Yet infants and children under 5 years of age are at greatest risk of invasive meningococcal B disease, with reported case fatality rates of 8%-9%, Jason D. Maguire, MD, noted at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

Trumenba has been approved in the United States for patients aged 10-25 years and in the European Union for individuals aged 10 years or older.

Dr. Maguire, of Pfizer’s vaccine clinical research and development program, presented the results of the two phase 2 randomized safety and immunogenicity trials conducted in patients aged 1- 9 years that the company has submitted to the FDA in support of the expanded indication. One study was carried out in 352 1-year-old toddlers, the other in 400 children aged 2-9 years, whose mean age was 4 years. The studies were carried out in Australia, Finland, Poland, and the Czech Republic.

In a pooled analysis of the vaccine’s immunogenicity when administered in a three-dose schedule of 120 mcg at 0, 2, and 6 months to 193 toddlers and 274 of the children aged 2-9 years, robust bactericidal antibody responses were seen against the four major Neisseria meningitidis group B strains that cause invasive disease. In fact, at least a fourfold rise in titers from baseline to 1 month after dose three was documented in the same high proportion of 1- to 9-year-olds as previously seen in the phase 3 trials that led to vaccine licensure in adolescents and young adults.

“These results support that the use of Trumenba, when given to children ages 1 to less than 10 years at the same dose and schedule that is currently approved in adolescents and young adults, can afford a high degree of protective antibody responses that correlate with immunity in this population,” Dr. Maguire said.

The safety and tolerability analysis included all 752 children in the two phase 2 studies, including the 110 toddlers randomized to three 60-mcg doses of the vaccine, although it has subsequently become clear that 120 mcg is the dose that provides the best immunogenicity with an acceptable safety profile, according to the physician.