User login

Waning pertussis immunity may be linked to acellular vaccine

A large Kaiser Permanente study paints a nuanced picture of the acellular pertussis vaccine, with more cases occurring in fully vaccinated children, but the highest risk of disease occurring among the under- and unvaccinated.

Among nearly half a million children, the unvaccinated were 13 times more likely to develop pertussis than fully vaccinated children, Ousseny Zerbo, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California in Oakland and colleagues wrote in Pediatrics. But 82% of cases occurred in fully vaccinated children and just 5% in undervaccinated children – and rates increased in both groups the farther they were in time from the last vaccination.

“Within our study population, greater than 80% of pertussis cases occurred among age-appropriately vaccinated children,” the team wrote. “Children who were further away from their last DTaP dose were at increased risk of pertussis, even after controlling for undervaccination. Our results suggest that, in this population, possibly in conjunction with other factors not addressed in this study, suboptimal vaccine efficacy and waning [immunity] played a major role in recent pertussis epidemics.”

The results are consistent with several prior studies, including one finding that the odds of the disease increased by 33% for every additional year after the third or fifth DTaP dose (Pediatrics. 2015;135[2]:331-43).

The current study comprised 469,982 children aged between 3 months and 11 years, who were followed for a mean of 4.6 years. Over the entire study period, there were 738 lab-confirmed pertussis cases. Most of these (515; 70%) occurred in fully vaccinated children. Another 99 (13%) occurred in unvaccinated children, 36 (5%) in undervaccinated children, and 88 (12%) in fully vaccinated plus one dose.

In a multivariate analysis, the risk of pertussis was 13 times higher among the unvaccinated (adjusted hazard ratio, 13) and almost 2 times higher among the undervaccinated (aHR, 1.9), compared with fully vaccinated children. Those who had been fully vaccinated and received a booster had the lowest risk, about half that of fully vaccinated children (aHR, 0.48).

Risk varied according to age, but also was significantly higher among unvaccinated children at each time point. Risk ranged from 4 times higher among those aged 3-5 months to 23 times higher among those aged 19-84 months. Undervaccinated children aged 5-7 months and 19-84 months also were at significantly increased risk for pertussis, compared with fully vaccinated children. Children who were fully vaccinated plus one dose had a significantly reduced risk at 7-19 months and at 19-84 months, compared with the fully vaccinated reference group.

“Across all follow-up and all age groups, VE [vaccine effectiveness] was 86% ... for undervaccinated children, compared with unvaccinated children,” Dr. Zerbo and associates wrote. “VE was even higher for fully vaccinated children [93%] and for those who were fully vaccinated plus one dose [96%].”

But VE waned as time progressed farther from the last DTaP dose. The multivariate model found more than a 100% increased risk for those whose last DTaP was at least 3 years past, compared with less than 1 year past (aHR, 2.58).

The model also found time-bound risk increases among fully vaccinated children, with a more than 300% increased risk among those at least 6 years out from the last DTaP dose, compared with 3 years out (aHR, 4.66).

The results indicate that other factors besides adherence to the recommended vaccine schedule may be at work in recent pertussis outbreaks.

“Although waning immunity is clearly an important factor driving pertussis epidemics in recent years, other factors that we did not evaluate in this study might also contribute to pertussis epidemics individually or in synergy,” Dr. Zerbo and associates wrote. “Results from studies in baboons suggest that the acellular pertussis vaccines are unable to prevent colonization, carriage, and transmission. If this is also true for humans, this could contribute to pertussis epidemics. The causes of recent pertussis epidemics are complex, and we were only able to address some aspects in our study.”

The study was funded by Kaiser Permanente Northern California, the National Institutes of Health, and in part by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant. One coauthor reported receiving research grant support from Sanofi Pasteur, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, MedImmune, Pfizer, and Dynavax for unrelated studies; the other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zerbo O et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jun 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3466.

Fixing one problem with the pertussis vaccine seemed to have created another, Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The current acellular vaccine was approved in 1997. It was considered a less reactive substitute for the previous whole-cell vaccine, which was associated with injection site pain, swelling, fever, and febrile seizures, Dr. Edwards wrote. “For about a decade, all seemed to be going well with pertussis control. Serological methods were employed to diagnose pertussis infections in adolescents and adults, and polymerase chain reaction methods were devised to more accurately detect pertussis organisms. Thus, the burden of pertussis disease was increasingly appreciated as the diagnostic methods improved.”

But things soon changed. There were pertussis outbreaks, some of them quite large. The increasing disease rates showed that protection conferred by the acellular vaccine waned much more quickly than that conferred by the whole-cell vaccine. “In the current study, Zerbo et al. add to the body of evidence documenting the increase in pertussis risk with time after DTaP vaccination,” she noted.

This has several practical implications, Dr. Edwards wrote.

“First, given the markedly increased risk of pertussis in unvaccinated and undervaccinated children, universal DTaP vaccination should be strongly recommended. Second, the addition of maternal Tdap vaccination administered during pregnancy has been shown to significantly reduce infant disease before primary immunization and should remain the standard,” Dr. Edwards wrote.

More problematic is how to address the waning DTaP immunity now seen. “One option presented [at an international meeting] was a live-attenuated pertussis vaccine administered intranasally that would stimulate local immune responses and prevent colonization with pertussis organisms. This vaccine is currently being studied in adults and might provide a solution for waning immunity seen with DTaP vaccine,” she noted.

Another possibility is adding the live vaccine to the current DTaP, which should, in theory, stimulate more long-lasting immunity. But numerous safety studies in young children would be necessary before adopting such an approach, Dr. Edwards wrote.

Adding more antigens to the acellular vaccine also might work, and investigational vaccines like this are in development.

Studies in animals and humans show that acellular vaccines “generate functionally different T-cell responses than those seen after whole-cell vaccines, with the whole cell vaccines generating more protective T-cell responses. Studies are ongoing to determine if adjuvants can be added to acellular vaccines to modify their T-cell responses to a more protective immune response or whether the T-cell response remains fixed once primed with DTaP vaccine,” she wrote.

Dr. Edwards is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. She wrote an editorial to accompany Zerbo et al (Pediatrics. 2019. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1276). She reported no financial disclosures, and received no funding to write the editorial.

Fixing one problem with the pertussis vaccine seemed to have created another, Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The current acellular vaccine was approved in 1997. It was considered a less reactive substitute for the previous whole-cell vaccine, which was associated with injection site pain, swelling, fever, and febrile seizures, Dr. Edwards wrote. “For about a decade, all seemed to be going well with pertussis control. Serological methods were employed to diagnose pertussis infections in adolescents and adults, and polymerase chain reaction methods were devised to more accurately detect pertussis organisms. Thus, the burden of pertussis disease was increasingly appreciated as the diagnostic methods improved.”

But things soon changed. There were pertussis outbreaks, some of them quite large. The increasing disease rates showed that protection conferred by the acellular vaccine waned much more quickly than that conferred by the whole-cell vaccine. “In the current study, Zerbo et al. add to the body of evidence documenting the increase in pertussis risk with time after DTaP vaccination,” she noted.

This has several practical implications, Dr. Edwards wrote.

“First, given the markedly increased risk of pertussis in unvaccinated and undervaccinated children, universal DTaP vaccination should be strongly recommended. Second, the addition of maternal Tdap vaccination administered during pregnancy has been shown to significantly reduce infant disease before primary immunization and should remain the standard,” Dr. Edwards wrote.

More problematic is how to address the waning DTaP immunity now seen. “One option presented [at an international meeting] was a live-attenuated pertussis vaccine administered intranasally that would stimulate local immune responses and prevent colonization with pertussis organisms. This vaccine is currently being studied in adults and might provide a solution for waning immunity seen with DTaP vaccine,” she noted.

Another possibility is adding the live vaccine to the current DTaP, which should, in theory, stimulate more long-lasting immunity. But numerous safety studies in young children would be necessary before adopting such an approach, Dr. Edwards wrote.

Adding more antigens to the acellular vaccine also might work, and investigational vaccines like this are in development.

Studies in animals and humans show that acellular vaccines “generate functionally different T-cell responses than those seen after whole-cell vaccines, with the whole cell vaccines generating more protective T-cell responses. Studies are ongoing to determine if adjuvants can be added to acellular vaccines to modify their T-cell responses to a more protective immune response or whether the T-cell response remains fixed once primed with DTaP vaccine,” she wrote.

Dr. Edwards is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. She wrote an editorial to accompany Zerbo et al (Pediatrics. 2019. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1276). She reported no financial disclosures, and received no funding to write the editorial.

Fixing one problem with the pertussis vaccine seemed to have created another, Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The current acellular vaccine was approved in 1997. It was considered a less reactive substitute for the previous whole-cell vaccine, which was associated with injection site pain, swelling, fever, and febrile seizures, Dr. Edwards wrote. “For about a decade, all seemed to be going well with pertussis control. Serological methods were employed to diagnose pertussis infections in adolescents and adults, and polymerase chain reaction methods were devised to more accurately detect pertussis organisms. Thus, the burden of pertussis disease was increasingly appreciated as the diagnostic methods improved.”

But things soon changed. There were pertussis outbreaks, some of them quite large. The increasing disease rates showed that protection conferred by the acellular vaccine waned much more quickly than that conferred by the whole-cell vaccine. “In the current study, Zerbo et al. add to the body of evidence documenting the increase in pertussis risk with time after DTaP vaccination,” she noted.

This has several practical implications, Dr. Edwards wrote.

“First, given the markedly increased risk of pertussis in unvaccinated and undervaccinated children, universal DTaP vaccination should be strongly recommended. Second, the addition of maternal Tdap vaccination administered during pregnancy has been shown to significantly reduce infant disease before primary immunization and should remain the standard,” Dr. Edwards wrote.

More problematic is how to address the waning DTaP immunity now seen. “One option presented [at an international meeting] was a live-attenuated pertussis vaccine administered intranasally that would stimulate local immune responses and prevent colonization with pertussis organisms. This vaccine is currently being studied in adults and might provide a solution for waning immunity seen with DTaP vaccine,” she noted.

Another possibility is adding the live vaccine to the current DTaP, which should, in theory, stimulate more long-lasting immunity. But numerous safety studies in young children would be necessary before adopting such an approach, Dr. Edwards wrote.

Adding more antigens to the acellular vaccine also might work, and investigational vaccines like this are in development.

Studies in animals and humans show that acellular vaccines “generate functionally different T-cell responses than those seen after whole-cell vaccines, with the whole cell vaccines generating more protective T-cell responses. Studies are ongoing to determine if adjuvants can be added to acellular vaccines to modify their T-cell responses to a more protective immune response or whether the T-cell response remains fixed once primed with DTaP vaccine,” she wrote.

Dr. Edwards is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. She wrote an editorial to accompany Zerbo et al (Pediatrics. 2019. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1276). She reported no financial disclosures, and received no funding to write the editorial.

A large Kaiser Permanente study paints a nuanced picture of the acellular pertussis vaccine, with more cases occurring in fully vaccinated children, but the highest risk of disease occurring among the under- and unvaccinated.

Among nearly half a million children, the unvaccinated were 13 times more likely to develop pertussis than fully vaccinated children, Ousseny Zerbo, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California in Oakland and colleagues wrote in Pediatrics. But 82% of cases occurred in fully vaccinated children and just 5% in undervaccinated children – and rates increased in both groups the farther they were in time from the last vaccination.

“Within our study population, greater than 80% of pertussis cases occurred among age-appropriately vaccinated children,” the team wrote. “Children who were further away from their last DTaP dose were at increased risk of pertussis, even after controlling for undervaccination. Our results suggest that, in this population, possibly in conjunction with other factors not addressed in this study, suboptimal vaccine efficacy and waning [immunity] played a major role in recent pertussis epidemics.”

The results are consistent with several prior studies, including one finding that the odds of the disease increased by 33% for every additional year after the third or fifth DTaP dose (Pediatrics. 2015;135[2]:331-43).

The current study comprised 469,982 children aged between 3 months and 11 years, who were followed for a mean of 4.6 years. Over the entire study period, there were 738 lab-confirmed pertussis cases. Most of these (515; 70%) occurred in fully vaccinated children. Another 99 (13%) occurred in unvaccinated children, 36 (5%) in undervaccinated children, and 88 (12%) in fully vaccinated plus one dose.

In a multivariate analysis, the risk of pertussis was 13 times higher among the unvaccinated (adjusted hazard ratio, 13) and almost 2 times higher among the undervaccinated (aHR, 1.9), compared with fully vaccinated children. Those who had been fully vaccinated and received a booster had the lowest risk, about half that of fully vaccinated children (aHR, 0.48).

Risk varied according to age, but also was significantly higher among unvaccinated children at each time point. Risk ranged from 4 times higher among those aged 3-5 months to 23 times higher among those aged 19-84 months. Undervaccinated children aged 5-7 months and 19-84 months also were at significantly increased risk for pertussis, compared with fully vaccinated children. Children who were fully vaccinated plus one dose had a significantly reduced risk at 7-19 months and at 19-84 months, compared with the fully vaccinated reference group.

“Across all follow-up and all age groups, VE [vaccine effectiveness] was 86% ... for undervaccinated children, compared with unvaccinated children,” Dr. Zerbo and associates wrote. “VE was even higher for fully vaccinated children [93%] and for those who were fully vaccinated plus one dose [96%].”

But VE waned as time progressed farther from the last DTaP dose. The multivariate model found more than a 100% increased risk for those whose last DTaP was at least 3 years past, compared with less than 1 year past (aHR, 2.58).

The model also found time-bound risk increases among fully vaccinated children, with a more than 300% increased risk among those at least 6 years out from the last DTaP dose, compared with 3 years out (aHR, 4.66).

The results indicate that other factors besides adherence to the recommended vaccine schedule may be at work in recent pertussis outbreaks.

“Although waning immunity is clearly an important factor driving pertussis epidemics in recent years, other factors that we did not evaluate in this study might also contribute to pertussis epidemics individually or in synergy,” Dr. Zerbo and associates wrote. “Results from studies in baboons suggest that the acellular pertussis vaccines are unable to prevent colonization, carriage, and transmission. If this is also true for humans, this could contribute to pertussis epidemics. The causes of recent pertussis epidemics are complex, and we were only able to address some aspects in our study.”

The study was funded by Kaiser Permanente Northern California, the National Institutes of Health, and in part by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant. One coauthor reported receiving research grant support from Sanofi Pasteur, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, MedImmune, Pfizer, and Dynavax for unrelated studies; the other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zerbo O et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jun 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3466.

A large Kaiser Permanente study paints a nuanced picture of the acellular pertussis vaccine, with more cases occurring in fully vaccinated children, but the highest risk of disease occurring among the under- and unvaccinated.

Among nearly half a million children, the unvaccinated were 13 times more likely to develop pertussis than fully vaccinated children, Ousseny Zerbo, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California in Oakland and colleagues wrote in Pediatrics. But 82% of cases occurred in fully vaccinated children and just 5% in undervaccinated children – and rates increased in both groups the farther they were in time from the last vaccination.

“Within our study population, greater than 80% of pertussis cases occurred among age-appropriately vaccinated children,” the team wrote. “Children who were further away from their last DTaP dose were at increased risk of pertussis, even after controlling for undervaccination. Our results suggest that, in this population, possibly in conjunction with other factors not addressed in this study, suboptimal vaccine efficacy and waning [immunity] played a major role in recent pertussis epidemics.”

The results are consistent with several prior studies, including one finding that the odds of the disease increased by 33% for every additional year after the third or fifth DTaP dose (Pediatrics. 2015;135[2]:331-43).

The current study comprised 469,982 children aged between 3 months and 11 years, who were followed for a mean of 4.6 years. Over the entire study period, there were 738 lab-confirmed pertussis cases. Most of these (515; 70%) occurred in fully vaccinated children. Another 99 (13%) occurred in unvaccinated children, 36 (5%) in undervaccinated children, and 88 (12%) in fully vaccinated plus one dose.

In a multivariate analysis, the risk of pertussis was 13 times higher among the unvaccinated (adjusted hazard ratio, 13) and almost 2 times higher among the undervaccinated (aHR, 1.9), compared with fully vaccinated children. Those who had been fully vaccinated and received a booster had the lowest risk, about half that of fully vaccinated children (aHR, 0.48).

Risk varied according to age, but also was significantly higher among unvaccinated children at each time point. Risk ranged from 4 times higher among those aged 3-5 months to 23 times higher among those aged 19-84 months. Undervaccinated children aged 5-7 months and 19-84 months also were at significantly increased risk for pertussis, compared with fully vaccinated children. Children who were fully vaccinated plus one dose had a significantly reduced risk at 7-19 months and at 19-84 months, compared with the fully vaccinated reference group.

“Across all follow-up and all age groups, VE [vaccine effectiveness] was 86% ... for undervaccinated children, compared with unvaccinated children,” Dr. Zerbo and associates wrote. “VE was even higher for fully vaccinated children [93%] and for those who were fully vaccinated plus one dose [96%].”

But VE waned as time progressed farther from the last DTaP dose. The multivariate model found more than a 100% increased risk for those whose last DTaP was at least 3 years past, compared with less than 1 year past (aHR, 2.58).

The model also found time-bound risk increases among fully vaccinated children, with a more than 300% increased risk among those at least 6 years out from the last DTaP dose, compared with 3 years out (aHR, 4.66).

The results indicate that other factors besides adherence to the recommended vaccine schedule may be at work in recent pertussis outbreaks.

“Although waning immunity is clearly an important factor driving pertussis epidemics in recent years, other factors that we did not evaluate in this study might also contribute to pertussis epidemics individually or in synergy,” Dr. Zerbo and associates wrote. “Results from studies in baboons suggest that the acellular pertussis vaccines are unable to prevent colonization, carriage, and transmission. If this is also true for humans, this could contribute to pertussis epidemics. The causes of recent pertussis epidemics are complex, and we were only able to address some aspects in our study.”

The study was funded by Kaiser Permanente Northern California, the National Institutes of Health, and in part by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant. One coauthor reported receiving research grant support from Sanofi Pasteur, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, MedImmune, Pfizer, and Dynavax for unrelated studies; the other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zerbo O et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jun 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3466.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Fewer antibiotics prescribed with PCR than conventional stool testing

SAN DIEGO – However, antibiotics were still prescribed for more than one in three patients tested by any method.

“A positive test by any modality did result in decreased utilization of endoscopy, radiology, and antibiotic prescribing, but this effect appeared to be much greater for the GI PCR assay,” said Jordan Axelrad, MD, speaking at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

“Overall, patients who received GI PCR were 12% less likely to undergo endoscopy, 7% less likely to undergo abdominal radiography, and 11% less likely to be prescribed any antibiotic,” compared with patients who were tested by conventional stool culture, said Dr. Axelrad, a gastroenterologist at New York University.

In a cross-sectional study, Dr. Axelrad and his coauthors looked at patients who underwent stool testing for the 26 months before (n = 5,986) and after (n = 9,402) March 2015, when Dr. Axelrad’s home institution switched from conventional stool culture to the GI PCR panel. For the earlier time period, the investigators included patients who received stool culture both with and without an ova and parasites exam, as well as those who underwent enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay viral testing for rotavirus and adenovirus.

Patient demographic data were included as study variables; additionally, the study tracked utilization of endoscopy, abdominal, or other radiology studies, and ED visits for 30 days after testing. They also included any antibiotic prescribing within the 14 days post testing.

Roughly one-third of patients were tested as outpatients, 1 in 10 in the ED, and the remainder as inpatients. Patient age was a mean 46.7 years for the culture group, and 45.5 years for the GI PCR group.

The multiplex PCR test used in the study tested for 12 gastrointestinal pathogenic bacteria, 4 parasites, and 5 viruses.

As expected, PCR testing yielded a higher positive test rate than conventional stool testing, even when EIA tests were included (29.2% vs. 4.1%). In the 2,746 patients with a positive GI PCR test, a total of 3,804 pathogens were identified. Adenovirus accounted for 39% of these positive results. Positive bacterial results were seen in about 65.0% of the positive subgroup, with Escherichia coli subtypes seen in 51.7% of the positive tests.

Overall, positive results for viruses, bacteria, and multiple pathogens were more likely with GI PCR testing, compared with conventional testing (P = .001 for all). Parasites accounted for only 8.2% of the positive PCR test results, but this was significantly more than the 3.7% seen with conventional testing (P = .011).

At the 14-day mark post testing, “Patients who underwent a GI panel were less likely to be prescribed any antibiotic. But overall, antibiotics were fairly common in both groups,” said Dr. Axelrad, noting that 41% of patients who underwent stool culture received an antibiotic by 14 days, compared with 36% for patients who underwent a GI PCR panel (P = .001).

By the end of 30 days, most patients in each group had not received an endoscopic procedure, with significantly more procedure-free patients in the PCR group (91.6% vs. 90.4%; P = .008).

Against a backdrop of slightly higher overall radiology utilization in the PCR group – potentially attributable to practice trends over time – abdominal radiology was less likely for these patients than for the culture group (11.4% vs. 12.8%; P = .011).

The 30-day ED visit rate was low and similar between groups (11.4% for PCR vs. 12.8% for culture; P = .116).

The much quicker turnaround for the GI PCR panel didn’t translate into a shorter length of stay, though: Inpatient length of stay was a median 5 days in both groups.

“We feel that the outcomes that we noted were likely due to the increased sensitivity and specificity” of the PCR-based testing, said Dr. Axelrad. “Obviously, if you have more pathogen-positive findings, you may be less likely to order extensive testing. And if you’ve identified something like norovirus, you may feel reassured, and not order further testing.”

Dr. Axelrad pointed out that his institution’s overall PCR positivity rates were lower than the 70% rates some other studies have reported. “We feel that, given our large sample size, our results may more accurately reflect clinical practice, and perhaps that lower positivity rate may reflect increased use of this test in an inpatient setting,” he said. “We’re looking at that.”

Study limitations included the retrospective nature of the study. “Also, as we all know, PCR testing fails to discriminate between active infection and asymptomatic colonization,” raising questions about whether a positive PCR test really indicates true infection, noted Dr. Axelrad.

“Coupled with a high-sensitivity rapid turnaround, there’s the potential to reduce costs, but the cost-effectiveness of these assays has not been fully determined. There are several studies looking at this,” with results still to come, he said.

The notable reduction in antibiotic prescribing for those patients who received PCR-based testing means that GI PCR panels could be a useful tool to promote antibiotic stewardship, though Dr. Axelrad also noted that “antibiotics were still used in about a third of all patients.”

Dr. Axelrad reported no outside sources of funding. He has performed consulting services for and received research funding from BioFire, which manufactured the GI PCR assay used in the study, but BioFire did not fund this research.

SOURCE: Axelrad J et al. DDW 2019, Presentation 978.

SAN DIEGO – However, antibiotics were still prescribed for more than one in three patients tested by any method.

“A positive test by any modality did result in decreased utilization of endoscopy, radiology, and antibiotic prescribing, but this effect appeared to be much greater for the GI PCR assay,” said Jordan Axelrad, MD, speaking at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

“Overall, patients who received GI PCR were 12% less likely to undergo endoscopy, 7% less likely to undergo abdominal radiography, and 11% less likely to be prescribed any antibiotic,” compared with patients who were tested by conventional stool culture, said Dr. Axelrad, a gastroenterologist at New York University.

In a cross-sectional study, Dr. Axelrad and his coauthors looked at patients who underwent stool testing for the 26 months before (n = 5,986) and after (n = 9,402) March 2015, when Dr. Axelrad’s home institution switched from conventional stool culture to the GI PCR panel. For the earlier time period, the investigators included patients who received stool culture both with and without an ova and parasites exam, as well as those who underwent enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay viral testing for rotavirus and adenovirus.

Patient demographic data were included as study variables; additionally, the study tracked utilization of endoscopy, abdominal, or other radiology studies, and ED visits for 30 days after testing. They also included any antibiotic prescribing within the 14 days post testing.

Roughly one-third of patients were tested as outpatients, 1 in 10 in the ED, and the remainder as inpatients. Patient age was a mean 46.7 years for the culture group, and 45.5 years for the GI PCR group.

The multiplex PCR test used in the study tested for 12 gastrointestinal pathogenic bacteria, 4 parasites, and 5 viruses.

As expected, PCR testing yielded a higher positive test rate than conventional stool testing, even when EIA tests were included (29.2% vs. 4.1%). In the 2,746 patients with a positive GI PCR test, a total of 3,804 pathogens were identified. Adenovirus accounted for 39% of these positive results. Positive bacterial results were seen in about 65.0% of the positive subgroup, with Escherichia coli subtypes seen in 51.7% of the positive tests.

Overall, positive results for viruses, bacteria, and multiple pathogens were more likely with GI PCR testing, compared with conventional testing (P = .001 for all). Parasites accounted for only 8.2% of the positive PCR test results, but this was significantly more than the 3.7% seen with conventional testing (P = .011).

At the 14-day mark post testing, “Patients who underwent a GI panel were less likely to be prescribed any antibiotic. But overall, antibiotics were fairly common in both groups,” said Dr. Axelrad, noting that 41% of patients who underwent stool culture received an antibiotic by 14 days, compared with 36% for patients who underwent a GI PCR panel (P = .001).

By the end of 30 days, most patients in each group had not received an endoscopic procedure, with significantly more procedure-free patients in the PCR group (91.6% vs. 90.4%; P = .008).

Against a backdrop of slightly higher overall radiology utilization in the PCR group – potentially attributable to practice trends over time – abdominal radiology was less likely for these patients than for the culture group (11.4% vs. 12.8%; P = .011).

The 30-day ED visit rate was low and similar between groups (11.4% for PCR vs. 12.8% for culture; P = .116).

The much quicker turnaround for the GI PCR panel didn’t translate into a shorter length of stay, though: Inpatient length of stay was a median 5 days in both groups.

“We feel that the outcomes that we noted were likely due to the increased sensitivity and specificity” of the PCR-based testing, said Dr. Axelrad. “Obviously, if you have more pathogen-positive findings, you may be less likely to order extensive testing. And if you’ve identified something like norovirus, you may feel reassured, and not order further testing.”

Dr. Axelrad pointed out that his institution’s overall PCR positivity rates were lower than the 70% rates some other studies have reported. “We feel that, given our large sample size, our results may more accurately reflect clinical practice, and perhaps that lower positivity rate may reflect increased use of this test in an inpatient setting,” he said. “We’re looking at that.”

Study limitations included the retrospective nature of the study. “Also, as we all know, PCR testing fails to discriminate between active infection and asymptomatic colonization,” raising questions about whether a positive PCR test really indicates true infection, noted Dr. Axelrad.

“Coupled with a high-sensitivity rapid turnaround, there’s the potential to reduce costs, but the cost-effectiveness of these assays has not been fully determined. There are several studies looking at this,” with results still to come, he said.

The notable reduction in antibiotic prescribing for those patients who received PCR-based testing means that GI PCR panels could be a useful tool to promote antibiotic stewardship, though Dr. Axelrad also noted that “antibiotics were still used in about a third of all patients.”

Dr. Axelrad reported no outside sources of funding. He has performed consulting services for and received research funding from BioFire, which manufactured the GI PCR assay used in the study, but BioFire did not fund this research.

SOURCE: Axelrad J et al. DDW 2019, Presentation 978.

SAN DIEGO – However, antibiotics were still prescribed for more than one in three patients tested by any method.

“A positive test by any modality did result in decreased utilization of endoscopy, radiology, and antibiotic prescribing, but this effect appeared to be much greater for the GI PCR assay,” said Jordan Axelrad, MD, speaking at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

“Overall, patients who received GI PCR were 12% less likely to undergo endoscopy, 7% less likely to undergo abdominal radiography, and 11% less likely to be prescribed any antibiotic,” compared with patients who were tested by conventional stool culture, said Dr. Axelrad, a gastroenterologist at New York University.

In a cross-sectional study, Dr. Axelrad and his coauthors looked at patients who underwent stool testing for the 26 months before (n = 5,986) and after (n = 9,402) March 2015, when Dr. Axelrad’s home institution switched from conventional stool culture to the GI PCR panel. For the earlier time period, the investigators included patients who received stool culture both with and without an ova and parasites exam, as well as those who underwent enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay viral testing for rotavirus and adenovirus.

Patient demographic data were included as study variables; additionally, the study tracked utilization of endoscopy, abdominal, or other radiology studies, and ED visits for 30 days after testing. They also included any antibiotic prescribing within the 14 days post testing.

Roughly one-third of patients were tested as outpatients, 1 in 10 in the ED, and the remainder as inpatients. Patient age was a mean 46.7 years for the culture group, and 45.5 years for the GI PCR group.

The multiplex PCR test used in the study tested for 12 gastrointestinal pathogenic bacteria, 4 parasites, and 5 viruses.

As expected, PCR testing yielded a higher positive test rate than conventional stool testing, even when EIA tests were included (29.2% vs. 4.1%). In the 2,746 patients with a positive GI PCR test, a total of 3,804 pathogens were identified. Adenovirus accounted for 39% of these positive results. Positive bacterial results were seen in about 65.0% of the positive subgroup, with Escherichia coli subtypes seen in 51.7% of the positive tests.

Overall, positive results for viruses, bacteria, and multiple pathogens were more likely with GI PCR testing, compared with conventional testing (P = .001 for all). Parasites accounted for only 8.2% of the positive PCR test results, but this was significantly more than the 3.7% seen with conventional testing (P = .011).

At the 14-day mark post testing, “Patients who underwent a GI panel were less likely to be prescribed any antibiotic. But overall, antibiotics were fairly common in both groups,” said Dr. Axelrad, noting that 41% of patients who underwent stool culture received an antibiotic by 14 days, compared with 36% for patients who underwent a GI PCR panel (P = .001).

By the end of 30 days, most patients in each group had not received an endoscopic procedure, with significantly more procedure-free patients in the PCR group (91.6% vs. 90.4%; P = .008).

Against a backdrop of slightly higher overall radiology utilization in the PCR group – potentially attributable to practice trends over time – abdominal radiology was less likely for these patients than for the culture group (11.4% vs. 12.8%; P = .011).

The 30-day ED visit rate was low and similar between groups (11.4% for PCR vs. 12.8% for culture; P = .116).

The much quicker turnaround for the GI PCR panel didn’t translate into a shorter length of stay, though: Inpatient length of stay was a median 5 days in both groups.

“We feel that the outcomes that we noted were likely due to the increased sensitivity and specificity” of the PCR-based testing, said Dr. Axelrad. “Obviously, if you have more pathogen-positive findings, you may be less likely to order extensive testing. And if you’ve identified something like norovirus, you may feel reassured, and not order further testing.”

Dr. Axelrad pointed out that his institution’s overall PCR positivity rates were lower than the 70% rates some other studies have reported. “We feel that, given our large sample size, our results may more accurately reflect clinical practice, and perhaps that lower positivity rate may reflect increased use of this test in an inpatient setting,” he said. “We’re looking at that.”

Study limitations included the retrospective nature of the study. “Also, as we all know, PCR testing fails to discriminate between active infection and asymptomatic colonization,” raising questions about whether a positive PCR test really indicates true infection, noted Dr. Axelrad.

“Coupled with a high-sensitivity rapid turnaround, there’s the potential to reduce costs, but the cost-effectiveness of these assays has not been fully determined. There are several studies looking at this,” with results still to come, he said.

The notable reduction in antibiotic prescribing for those patients who received PCR-based testing means that GI PCR panels could be a useful tool to promote antibiotic stewardship, though Dr. Axelrad also noted that “antibiotics were still used in about a third of all patients.”

Dr. Axelrad reported no outside sources of funding. He has performed consulting services for and received research funding from BioFire, which manufactured the GI PCR assay used in the study, but BioFire did not fund this research.

SOURCE: Axelrad J et al. DDW 2019, Presentation 978.

REPORTING FROM DDW 2019

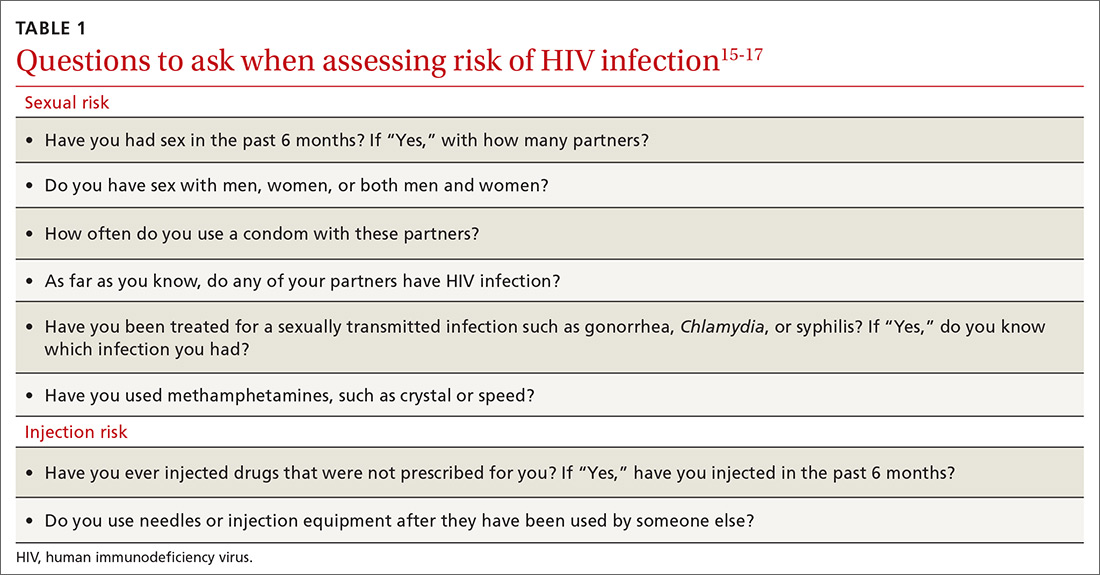

USPSTF recommends PrEP combo for adults at high risk of HIV infection

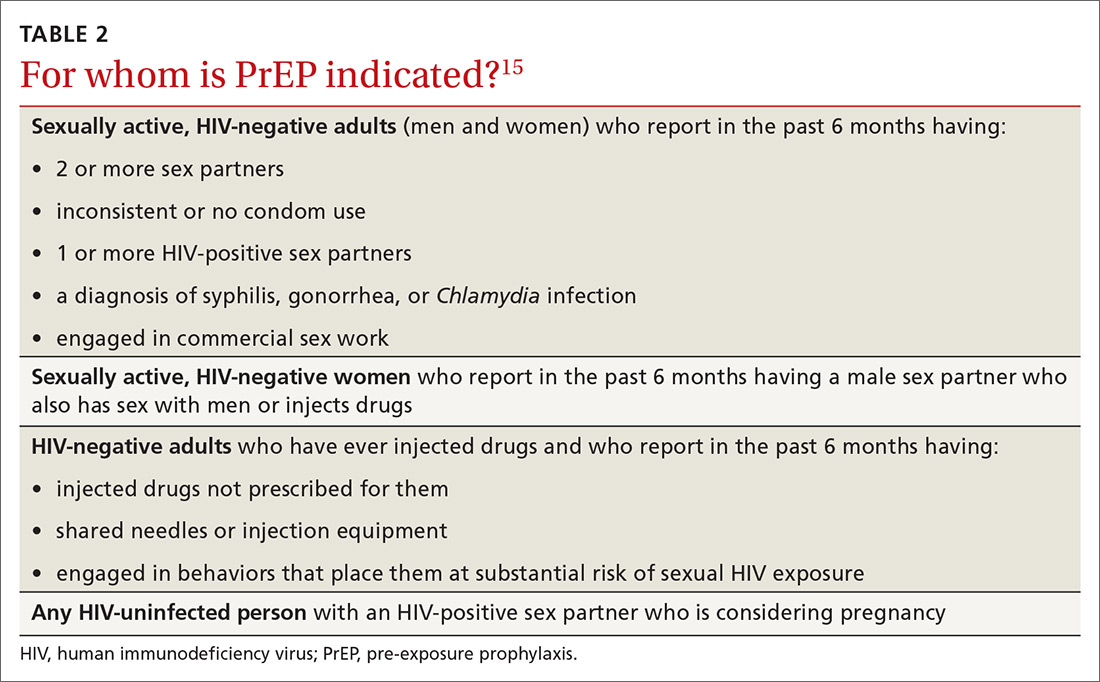

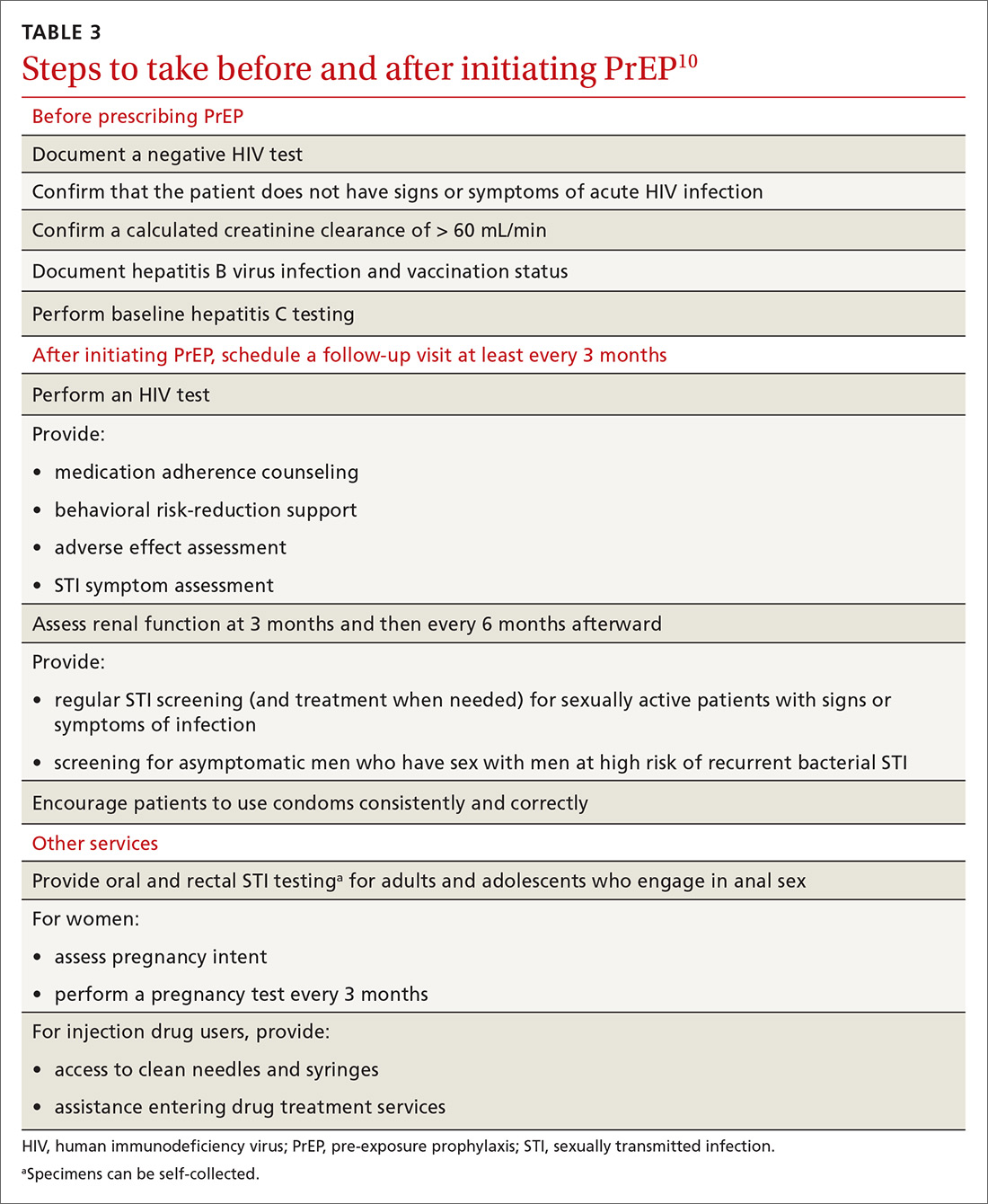

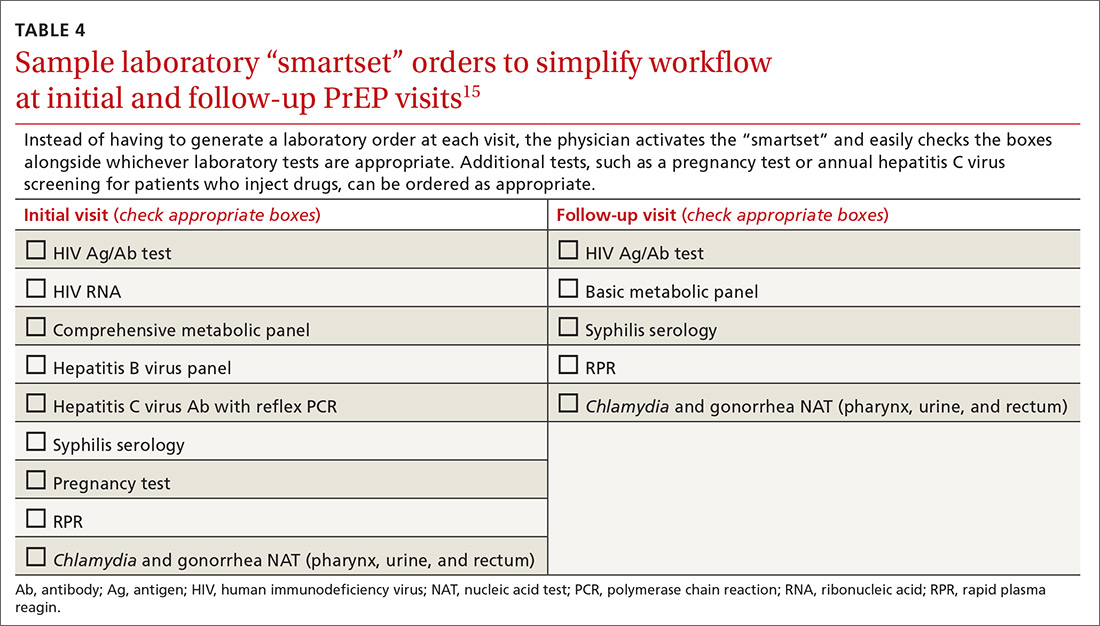

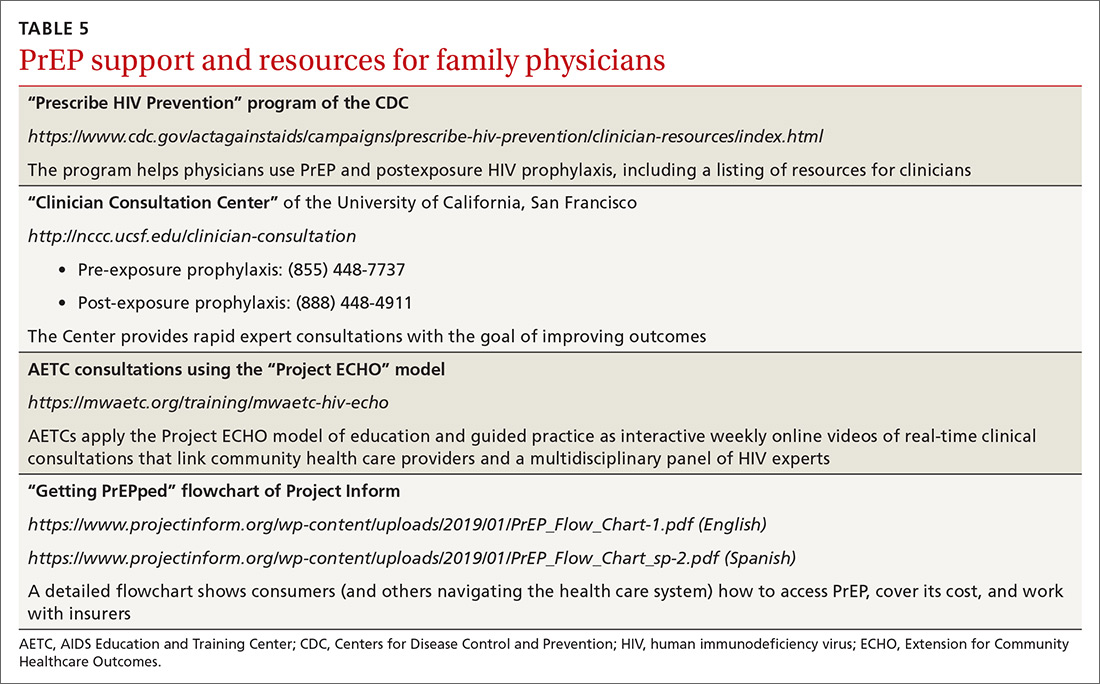

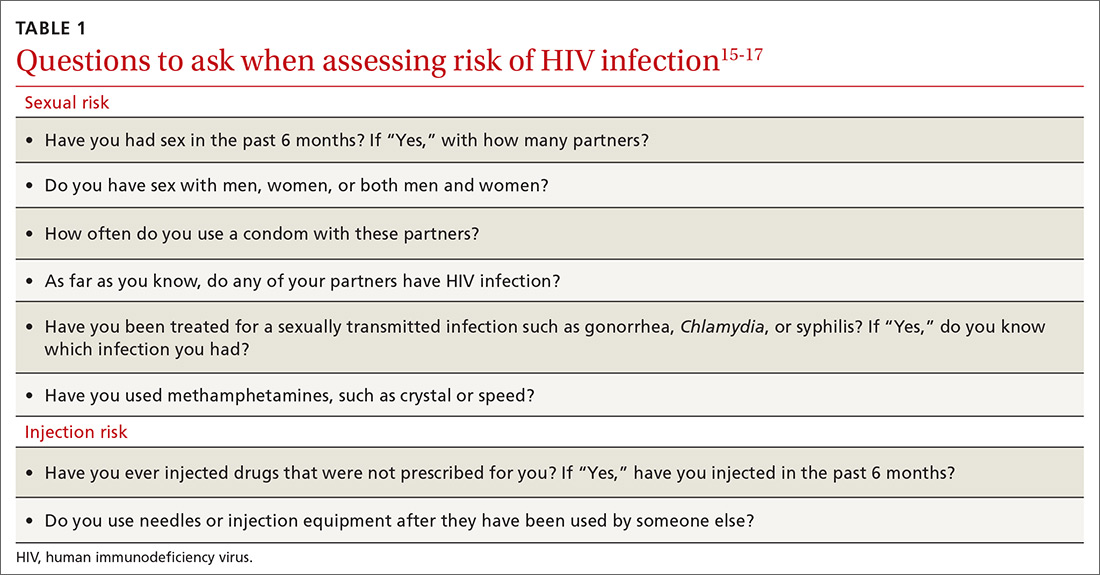

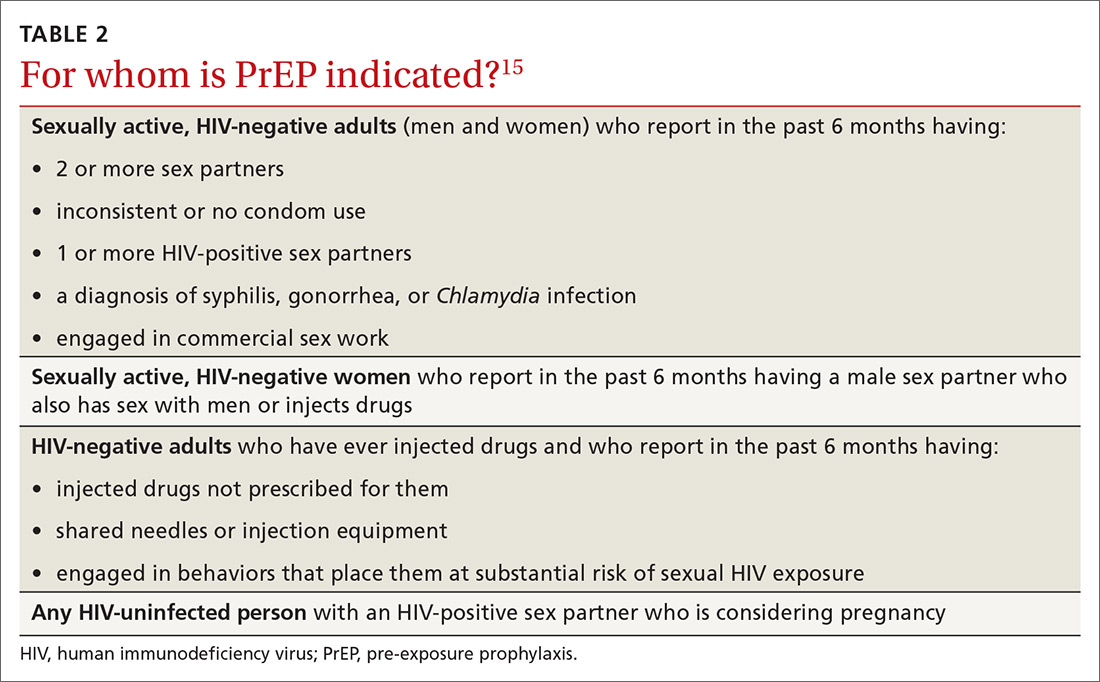

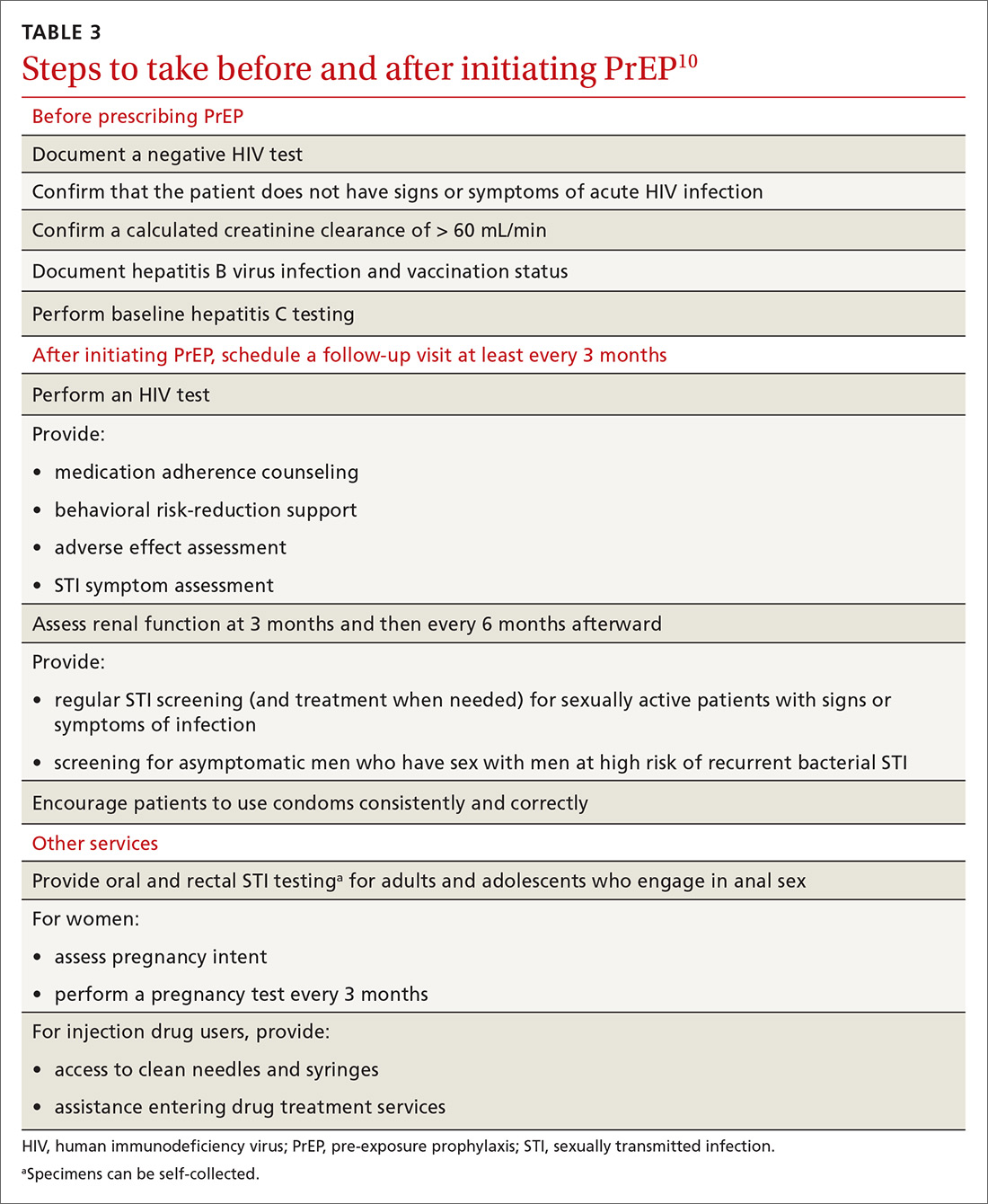

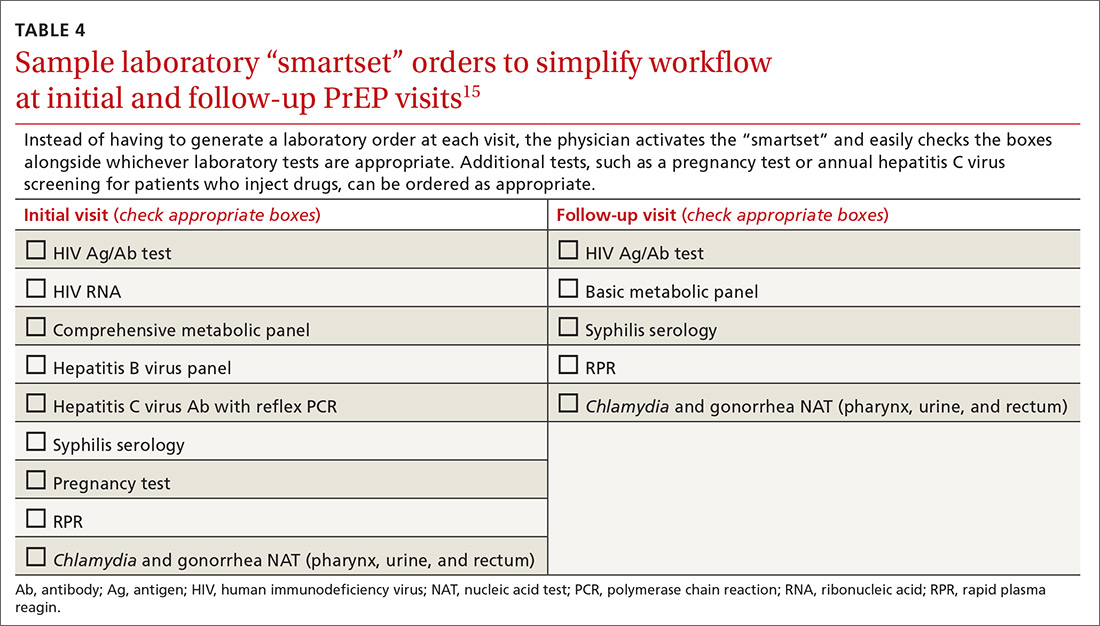

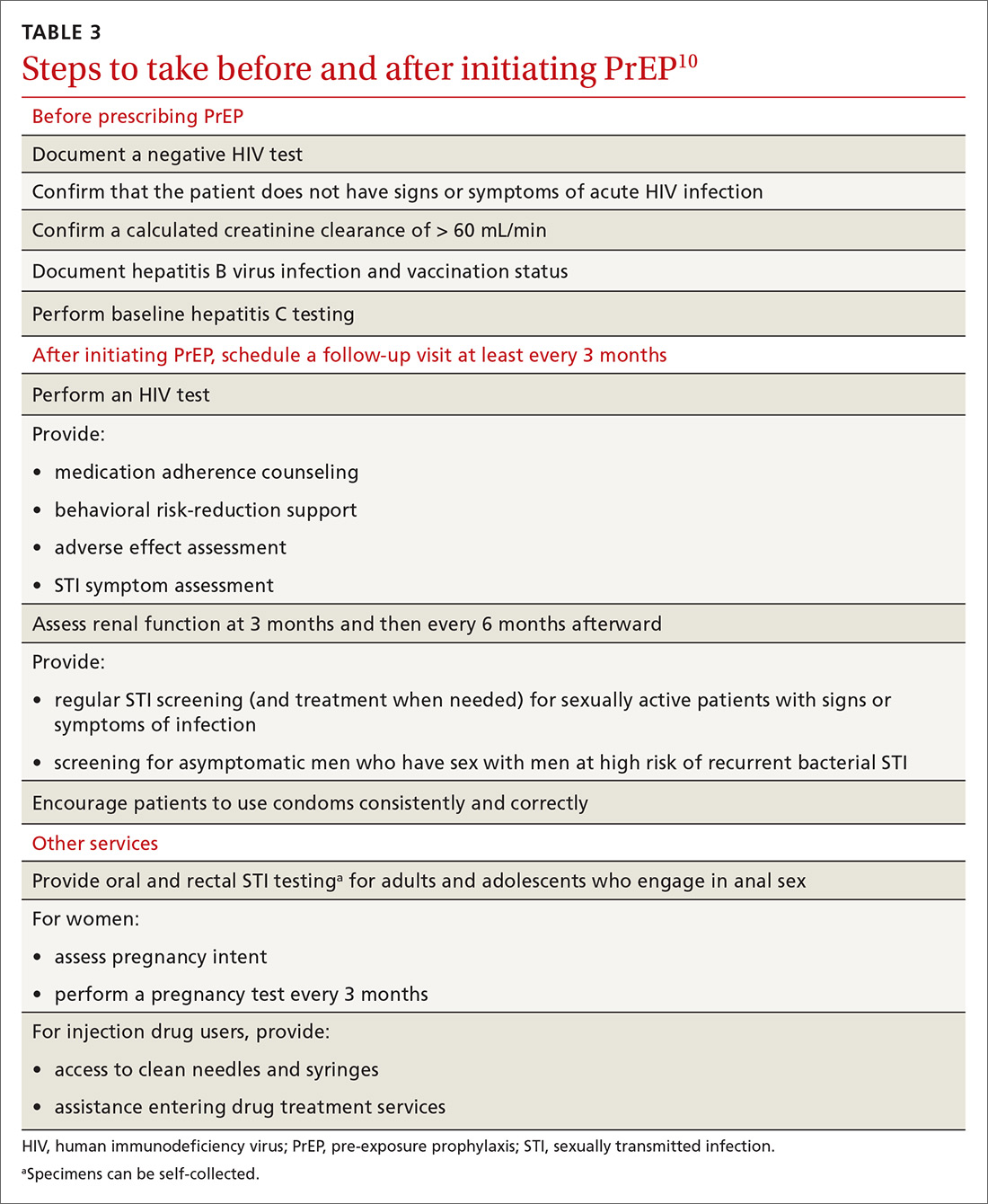

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) plus effective antiretroviral therapy should be offered to people at high risk of HIV acquisition, according to a new recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

“The USPSTF concludes with high certainty that the net benefit of the use of PrEP to reduce the risk of acquisition of HIV infection in persons at high risk of HIV infection is substantial,” wrote first author Douglas K. Owens, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and fellow members of the USPSTF. The recommendation was published in JAMA.

In various at-risk groups – including men who have sex with men, people at risk through heterosexual contact, and people who inject drugs – the USPSTF recommends a Food and Drug Adminstration–approved, once-daily oral treatment with combined tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine.

This recommendation was developed after a systematic review of PrEP’s effects on HIV, adherence to the treatment, and accuracy in identifying potential treatment candidates. “The findings of this review are generally consistent with those from other recent meta-analyses that found PrEP to be effective at reducing risk of HIV infection and found greater effectiveness in trials reporting higher adherence,” wrote Roger Chou, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University in Portland and coauthors. Their study was also published in JAMA.

To comprehensively assess PrEP and thus inform the USPSTF’s HIV prevention recommendations, the researchers reviewed criteria-meeting studies on oral PrEP with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate monotherapy; on the diagnostic accuracy of instruments to predict HIV infection; and on PrEP adherence. The final analysis included 14 randomized clinical trials, 8 observational studies, and 7 studies of diagnostic accuracy.

In 11 of the trials, PrEP was associated with reduced risk of HIV infection versus placebo or no PrEP (relative risk, 0.46; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.66). In 6 trials with adherence 70% or greater, the relative risk was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.19-0.39). In 7 studies on risk assessment tools for HIV infection, the instruments had moderate discrimination, though several of the studies had methodological shortcomings. As for serious adverse events, an analysis of 12 trials found no significant difference between PrEP and placebo (RR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.77-1.12).

Dr. Chou and coauthors noted their study’s limitations, including analyzing English-language articles only and the random-effects model used to pool studies potentially returning narrow CIs. They did note, however, that the “analyses were repeated using the profile likelihood method,” which produced similar findings.

All members of the USPSTF receive travel reimbursement and an honorarium for participating in meetings. The study was funded by the Department of Health and Human Services. One of the authors reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse and serving as principal investigator of NIH-funded clinical trials that received donated drugs from two pharmaceutical companies. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.6390; Chou R et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.2591.

To end HIV, guidelines like this one that reflect and promote advances in treatment are needed, according to Hyman Scott, MD, MPH, of the San Francisco Department of Public Health and Paul A. Volberding, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco.

With less than 10% of individuals with an indication for PrEP currently receiving the medication, it is now time to support policies aimed at broadening the access of PrEP to people at risk, the coauthors wrote. They noted that recent USPSTF guidelines show that evidence and policy in HIV medicine has matured not only in the United States but across the globe.

That said, sometimes the simplest solutions are also the best. Though the systematic review from Roger Chou, MD, and associates notes the necessity and importance of adherence, if a clinician thinks that a candidate for PrEP might be nonadherent, that clinicians should not withhold the medication, they wrote. Averting new HIV infections is the goal, and fully endorsing treatments like PrEP is an important step in that direction.*

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Jun 11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.2590). Dr. Volberding reported serving on a data and safety monitoring board for Merck.

*This article was updated on 6/11/2019.

To end HIV, guidelines like this one that reflect and promote advances in treatment are needed, according to Hyman Scott, MD, MPH, of the San Francisco Department of Public Health and Paul A. Volberding, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco.

With less than 10% of individuals with an indication for PrEP currently receiving the medication, it is now time to support policies aimed at broadening the access of PrEP to people at risk, the coauthors wrote. They noted that recent USPSTF guidelines show that evidence and policy in HIV medicine has matured not only in the United States but across the globe.

That said, sometimes the simplest solutions are also the best. Though the systematic review from Roger Chou, MD, and associates notes the necessity and importance of adherence, if a clinician thinks that a candidate for PrEP might be nonadherent, that clinicians should not withhold the medication, they wrote. Averting new HIV infections is the goal, and fully endorsing treatments like PrEP is an important step in that direction.*

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Jun 11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.2590). Dr. Volberding reported serving on a data and safety monitoring board for Merck.

*This article was updated on 6/11/2019.

To end HIV, guidelines like this one that reflect and promote advances in treatment are needed, according to Hyman Scott, MD, MPH, of the San Francisco Department of Public Health and Paul A. Volberding, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco.

With less than 10% of individuals with an indication for PrEP currently receiving the medication, it is now time to support policies aimed at broadening the access of PrEP to people at risk, the coauthors wrote. They noted that recent USPSTF guidelines show that evidence and policy in HIV medicine has matured not only in the United States but across the globe.

That said, sometimes the simplest solutions are also the best. Though the systematic review from Roger Chou, MD, and associates notes the necessity and importance of adherence, if a clinician thinks that a candidate for PrEP might be nonadherent, that clinicians should not withhold the medication, they wrote. Averting new HIV infections is the goal, and fully endorsing treatments like PrEP is an important step in that direction.*

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Jun 11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.2590). Dr. Volberding reported serving on a data and safety monitoring board for Merck.

*This article was updated on 6/11/2019.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) plus effective antiretroviral therapy should be offered to people at high risk of HIV acquisition, according to a new recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

“The USPSTF concludes with high certainty that the net benefit of the use of PrEP to reduce the risk of acquisition of HIV infection in persons at high risk of HIV infection is substantial,” wrote first author Douglas K. Owens, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and fellow members of the USPSTF. The recommendation was published in JAMA.

In various at-risk groups – including men who have sex with men, people at risk through heterosexual contact, and people who inject drugs – the USPSTF recommends a Food and Drug Adminstration–approved, once-daily oral treatment with combined tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine.

This recommendation was developed after a systematic review of PrEP’s effects on HIV, adherence to the treatment, and accuracy in identifying potential treatment candidates. “The findings of this review are generally consistent with those from other recent meta-analyses that found PrEP to be effective at reducing risk of HIV infection and found greater effectiveness in trials reporting higher adherence,” wrote Roger Chou, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University in Portland and coauthors. Their study was also published in JAMA.

To comprehensively assess PrEP and thus inform the USPSTF’s HIV prevention recommendations, the researchers reviewed criteria-meeting studies on oral PrEP with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate monotherapy; on the diagnostic accuracy of instruments to predict HIV infection; and on PrEP adherence. The final analysis included 14 randomized clinical trials, 8 observational studies, and 7 studies of diagnostic accuracy.

In 11 of the trials, PrEP was associated with reduced risk of HIV infection versus placebo or no PrEP (relative risk, 0.46; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.66). In 6 trials with adherence 70% or greater, the relative risk was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.19-0.39). In 7 studies on risk assessment tools for HIV infection, the instruments had moderate discrimination, though several of the studies had methodological shortcomings. As for serious adverse events, an analysis of 12 trials found no significant difference between PrEP and placebo (RR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.77-1.12).

Dr. Chou and coauthors noted their study’s limitations, including analyzing English-language articles only and the random-effects model used to pool studies potentially returning narrow CIs. They did note, however, that the “analyses were repeated using the profile likelihood method,” which produced similar findings.

All members of the USPSTF receive travel reimbursement and an honorarium for participating in meetings. The study was funded by the Department of Health and Human Services. One of the authors reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse and serving as principal investigator of NIH-funded clinical trials that received donated drugs from two pharmaceutical companies. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.6390; Chou R et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.2591.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) plus effective antiretroviral therapy should be offered to people at high risk of HIV acquisition, according to a new recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

“The USPSTF concludes with high certainty that the net benefit of the use of PrEP to reduce the risk of acquisition of HIV infection in persons at high risk of HIV infection is substantial,” wrote first author Douglas K. Owens, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and fellow members of the USPSTF. The recommendation was published in JAMA.

In various at-risk groups – including men who have sex with men, people at risk through heterosexual contact, and people who inject drugs – the USPSTF recommends a Food and Drug Adminstration–approved, once-daily oral treatment with combined tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine.

This recommendation was developed after a systematic review of PrEP’s effects on HIV, adherence to the treatment, and accuracy in identifying potential treatment candidates. “The findings of this review are generally consistent with those from other recent meta-analyses that found PrEP to be effective at reducing risk of HIV infection and found greater effectiveness in trials reporting higher adherence,” wrote Roger Chou, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University in Portland and coauthors. Their study was also published in JAMA.

To comprehensively assess PrEP and thus inform the USPSTF’s HIV prevention recommendations, the researchers reviewed criteria-meeting studies on oral PrEP with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate monotherapy; on the diagnostic accuracy of instruments to predict HIV infection; and on PrEP adherence. The final analysis included 14 randomized clinical trials, 8 observational studies, and 7 studies of diagnostic accuracy.

In 11 of the trials, PrEP was associated with reduced risk of HIV infection versus placebo or no PrEP (relative risk, 0.46; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.66). In 6 trials with adherence 70% or greater, the relative risk was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.19-0.39). In 7 studies on risk assessment tools for HIV infection, the instruments had moderate discrimination, though several of the studies had methodological shortcomings. As for serious adverse events, an analysis of 12 trials found no significant difference between PrEP and placebo (RR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.77-1.12).

Dr. Chou and coauthors noted their study’s limitations, including analyzing English-language articles only and the random-effects model used to pool studies potentially returning narrow CIs. They did note, however, that the “analyses were repeated using the profile likelihood method,” which produced similar findings.

All members of the USPSTF receive travel reimbursement and an honorarium for participating in meetings. The study was funded by the Department of Health and Human Services. One of the authors reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse and serving as principal investigator of NIH-funded clinical trials that received donated drugs from two pharmaceutical companies. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.6390; Chou R et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.2591.

FROM JAMA

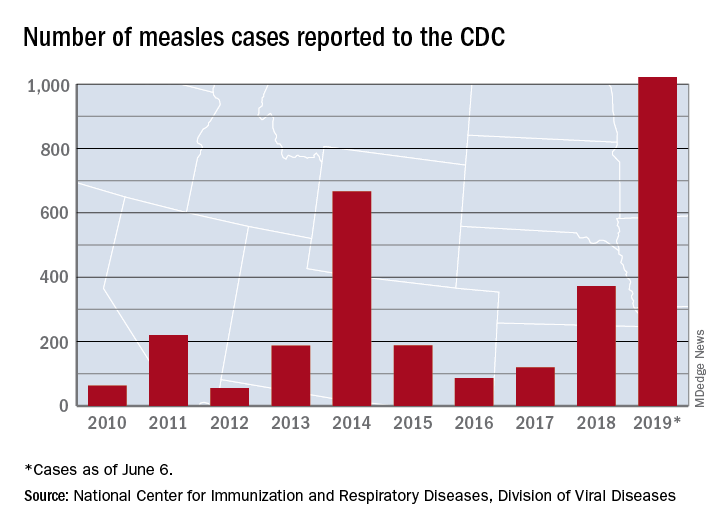

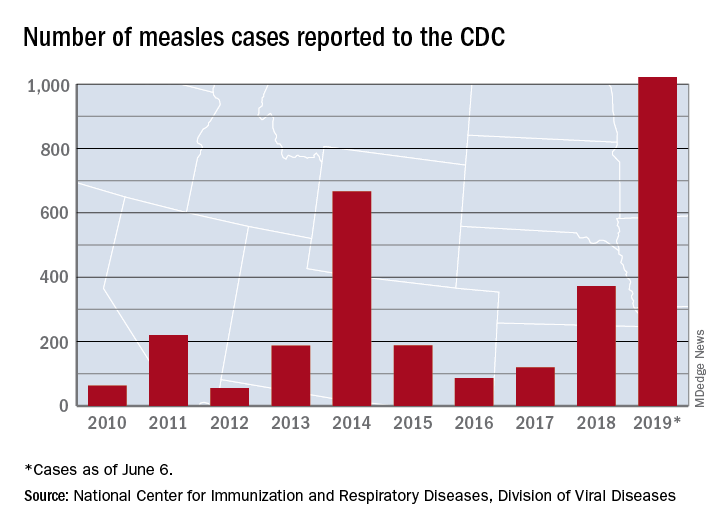

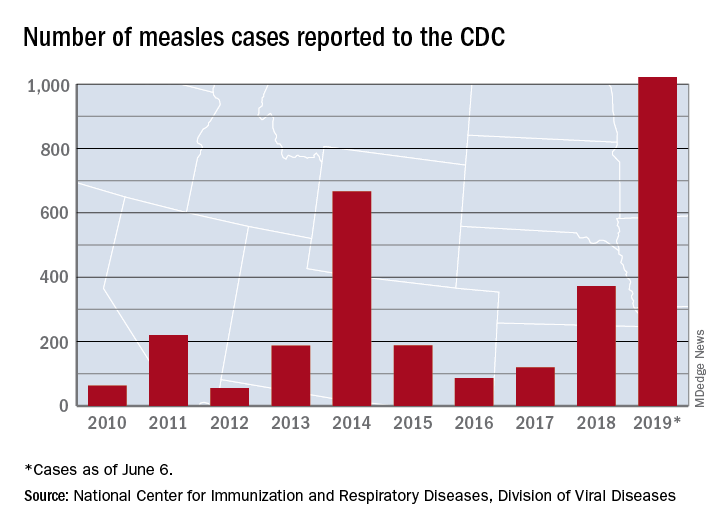

United States now over 1,000 measles cases this year

The 41 new cases reported for the week ending June 6 bring the total for the year to 1,022, the CDC reported June 10, and that is more than any year since 1992, when there were 2,237 cases.

Idaho and Virginia reported their first cases of 2019, which makes a total of 28 states with measles cases this year. The Idaho case was reported in Latah County and is the state’s first since 2001. In Virginia, health officials are investigating possible contacts with an infected individual at Dulles International Airport and two other locations on June 2 and 4.

Outbreaks in Georgia, Maryland, and Michigan have ended, while seven others continue in California (Butte, Los Angeles, and Sacramento Counties), New York (Rockland County and New York City), Pennsylvania, and Washington, the CDC said. New York City has the largest outbreak this year with 509 cases through June 3, most of them occurring in Brooklyn.

The 41 new cases reported for the week ending June 6 bring the total for the year to 1,022, the CDC reported June 10, and that is more than any year since 1992, when there were 2,237 cases.

Idaho and Virginia reported their first cases of 2019, which makes a total of 28 states with measles cases this year. The Idaho case was reported in Latah County and is the state’s first since 2001. In Virginia, health officials are investigating possible contacts with an infected individual at Dulles International Airport and two other locations on June 2 and 4.

Outbreaks in Georgia, Maryland, and Michigan have ended, while seven others continue in California (Butte, Los Angeles, and Sacramento Counties), New York (Rockland County and New York City), Pennsylvania, and Washington, the CDC said. New York City has the largest outbreak this year with 509 cases through June 3, most of them occurring in Brooklyn.

The 41 new cases reported for the week ending June 6 bring the total for the year to 1,022, the CDC reported June 10, and that is more than any year since 1992, when there were 2,237 cases.

Idaho and Virginia reported their first cases of 2019, which makes a total of 28 states with measles cases this year. The Idaho case was reported in Latah County and is the state’s first since 2001. In Virginia, health officials are investigating possible contacts with an infected individual at Dulles International Airport and two other locations on June 2 and 4.

Outbreaks in Georgia, Maryland, and Michigan have ended, while seven others continue in California (Butte, Los Angeles, and Sacramento Counties), New York (Rockland County and New York City), Pennsylvania, and Washington, the CDC said. New York City has the largest outbreak this year with 509 cases through June 3, most of them occurring in Brooklyn.

Rituximab serious infection risk predicted by immunoglobulin levels

Monitoring immunoglobulin (Ig) levels at baseline and before each cycle of rituximab could reduce the risk of serious infection events (SIEs) in patients needing repeated treatment, according to research published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

In a large, single-center, longitudinal study conducted at a tertiary referral center, having low IgG (less than 6 g/L) in particular was associated with a higher rate of SIEs, compared with having normal IgG levels (6-16 g/L). Considering 103 of 700 patients who had low levels of IgG before starting treatment with rituximab for various rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs), there were 16.4 SIEs per 100 patient-years. In those who developed low IgG during subsequent cycles of rituximab therapy, the SIE rate was even higher, at 21.3 per 100 patient-years. By comparison, the SIE rate for those with normal IgG levels was 9.7 per 100 patient-years.

“We really have to monitor immunoglobulins at baseline and also before we re-treat the patients, because higher IgG level is protective of serious infections,” study first author Md Yuzaiful Md Yusof, MBChB, PhD, said in an interview.

Low IgG has been linked to a higher risk of SIEs in the first 12 months of rituximab therapy but, until now, there have been limited data on infection predictors during repeated cycles of treatment. While IgG is a consistent marker of SIEs associated with repeated rituximab treatment, IgM and IgA should also be monitored to give a full picture of any hyperglobulinemia that may be present.

“There is no formal guidance on how to safely monitor patients on rituximab,” observed Dr. Md Yusof, who will present these data at the 2019 European Congress of Rheumatology in Madrid. The study’s findings could help to change that, however, as they offer a practical way to help predict and thus prevent SIEs. The study’s findings not only validate previous work, he noted, but also add new insights into why some patients treated with repeat rituximab cycles but not others may experience a higher rate of such infections.

Altogether, the investigators examined data on 700 patients with RMDs treated with rituximab who were consecutively seen during 2012-2017 at Dr. Md Yusof’s institution – the Leeds (England) Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, which is part of the University of Leeds. Their immunoglobulin levels had been measured before starting rituximab therapy and every 4-6 months after each cycle of rituximab treatment.

Patients with any RMD being treated with at least one cycle of rituximab were eligible for inclusion in the retrospective study, with the majority (72%) taking it for rheumatoid arthritis and some for systemic lupus erythematosus (13%) or antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–associated vasculitis (7%).

One of the main aims of the study was to look for predictors of SIEs during the first 12 months and during repeated cycles of rituximab. Dr. Md Yusof and his associates also looked at how secondary hypogammaglobulinemia might affect SIE rates and the humoral response to vaccination challenge and its persistence following treatment discontinuation. Their ultimate aim was to see if these findings could then be used to develop a treatment algorithm for rituximab administration in RMDs.

Over a follow-up period encompassing 2,880 patient-years of treatment, 281 SIEs were recorded in 176 patients, giving a rate of 9.8 infections per 100 patient-years. Most (61%) of these were due to lower respiratory tract infections.

The proportion of patients experiencing their first SIE increased with time: 16% within 6 weeks of starting rituximab therapy, 35% at 12 weeks, 72% at 26 weeks, 83% at 38 weeks, and 100% by 1 year of repeated treatment.

Multivariable analysis showed that the presence of several comorbidities at baseline – notably chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, heart failure, and prior cancer – raised the risk for SIEs with repeated rituximab therapy. The biggest factor, however, was a history of SIEs – with a sixfold increased risk of further serious infection.

Higher corticosteroid dose and factors specific to rituximab – low IgG, neutropenia, high IgM, and a longer time to retreatment – were also predictive of SIEs.

“Low IgG also results in poor humoral response to vaccination,” Dr. Md Yusof said, noting that the IgG level remains below the lower limit of normal for several years after rituximab is discontinued in most patients.

In the study, 5 of 8 (64%) patients had impaired humoral response to pneumococcal and haemophilus following vaccination challenge and 4 of 11 patients had IgG normalized after switching to another biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD).

Cyclophosphamide is commonly used as a first-line agent to induce remission in patients with severe and refractory systemic lupus erythematosus and ANCA-associated vasculitis, with patients switched to rituximab at relapse. The effect of this prior treatment was examined in 20 patients in the study, with a marked decline in almost all immunoglobulin classes seen up to 18 months. Prior treatment with immunosuppressants such as intravenous cyclophosphamide could be behind progressive reductions in Ig levels seen with repeated rituximab treatment rather than entirely because of rituximab, Dr. Md Yusof said.

Dr. Md Yusof, who is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Academic Clinical Lecturer at the University of Leeds, said the value of the study, compared with others, is that hospital data for all patients treated with rituximab with at least 3 months follow-up were included, making it an almost complete data set.

“By carefully reviewing records of every patient to capture all infection episodes in the largest single-center cohort study to date, our findings provide insights on predictors of SIEs as well as a foundation for safety monitoring of rituximab,” he and his coauthors wrote.

They acknowledge reporting a higher rate of SIEs than seen in registry and clinical studies with rituximab, which may reflect a “channeling bias” as the patients comprised those with multiple comorbidities including those that represent a relative contraindication for bDMARD use. That said, the findings clearly show that Ig levels should be monitored before and after each rituximab cycle, especially in those with comorbid diseases and those with low IgG levels to start with.

They conclude that an “individualized benefit-risk assessment” is needed to determine whether rituximab should be repeated in those with low IgG as this is a “consistent predictor” of SIE and may “increase infection profiles when [rituximab] is switched to different bDMARDs.”

The research was supported by Octapharma, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), and NIHR Leeds Biomedical Research Centre based at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust in England. Dr. Md Yusof had no conflicts of interest. Several coauthors disclosed financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies, including Roche.

SOURCE: Md Yusof MY et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 May 27. doi: 10.1002/art.40937.

Monitoring immunoglobulin (Ig) levels at baseline and before each cycle of rituximab could reduce the risk of serious infection events (SIEs) in patients needing repeated treatment, according to research published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

In a large, single-center, longitudinal study conducted at a tertiary referral center, having low IgG (less than 6 g/L) in particular was associated with a higher rate of SIEs, compared with having normal IgG levels (6-16 g/L). Considering 103 of 700 patients who had low levels of IgG before starting treatment with rituximab for various rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs), there were 16.4 SIEs per 100 patient-years. In those who developed low IgG during subsequent cycles of rituximab therapy, the SIE rate was even higher, at 21.3 per 100 patient-years. By comparison, the SIE rate for those with normal IgG levels was 9.7 per 100 patient-years.

“We really have to monitor immunoglobulins at baseline and also before we re-treat the patients, because higher IgG level is protective of serious infections,” study first author Md Yuzaiful Md Yusof, MBChB, PhD, said in an interview.

Low IgG has been linked to a higher risk of SIEs in the first 12 months of rituximab therapy but, until now, there have been limited data on infection predictors during repeated cycles of treatment. While IgG is a consistent marker of SIEs associated with repeated rituximab treatment, IgM and IgA should also be monitored to give a full picture of any hyperglobulinemia that may be present.

“There is no formal guidance on how to safely monitor patients on rituximab,” observed Dr. Md Yusof, who will present these data at the 2019 European Congress of Rheumatology in Madrid. The study’s findings could help to change that, however, as they offer a practical way to help predict and thus prevent SIEs. The study’s findings not only validate previous work, he noted, but also add new insights into why some patients treated with repeat rituximab cycles but not others may experience a higher rate of such infections.

Altogether, the investigators examined data on 700 patients with RMDs treated with rituximab who were consecutively seen during 2012-2017 at Dr. Md Yusof’s institution – the Leeds (England) Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, which is part of the University of Leeds. Their immunoglobulin levels had been measured before starting rituximab therapy and every 4-6 months after each cycle of rituximab treatment.

Patients with any RMD being treated with at least one cycle of rituximab were eligible for inclusion in the retrospective study, with the majority (72%) taking it for rheumatoid arthritis and some for systemic lupus erythematosus (13%) or antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–associated vasculitis (7%).

One of the main aims of the study was to look for predictors of SIEs during the first 12 months and during repeated cycles of rituximab. Dr. Md Yusof and his associates also looked at how secondary hypogammaglobulinemia might affect SIE rates and the humoral response to vaccination challenge and its persistence following treatment discontinuation. Their ultimate aim was to see if these findings could then be used to develop a treatment algorithm for rituximab administration in RMDs.

Over a follow-up period encompassing 2,880 patient-years of treatment, 281 SIEs were recorded in 176 patients, giving a rate of 9.8 infections per 100 patient-years. Most (61%) of these were due to lower respiratory tract infections.

The proportion of patients experiencing their first SIE increased with time: 16% within 6 weeks of starting rituximab therapy, 35% at 12 weeks, 72% at 26 weeks, 83% at 38 weeks, and 100% by 1 year of repeated treatment.

Multivariable analysis showed that the presence of several comorbidities at baseline – notably chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, heart failure, and prior cancer – raised the risk for SIEs with repeated rituximab therapy. The biggest factor, however, was a history of SIEs – with a sixfold increased risk of further serious infection.

Higher corticosteroid dose and factors specific to rituximab – low IgG, neutropenia, high IgM, and a longer time to retreatment – were also predictive of SIEs.

“Low IgG also results in poor humoral response to vaccination,” Dr. Md Yusof said, noting that the IgG level remains below the lower limit of normal for several years after rituximab is discontinued in most patients.

In the study, 5 of 8 (64%) patients had impaired humoral response to pneumococcal and haemophilus following vaccination challenge and 4 of 11 patients had IgG normalized after switching to another biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD).

Cyclophosphamide is commonly used as a first-line agent to induce remission in patients with severe and refractory systemic lupus erythematosus and ANCA-associated vasculitis, with patients switched to rituximab at relapse. The effect of this prior treatment was examined in 20 patients in the study, with a marked decline in almost all immunoglobulin classes seen up to 18 months. Prior treatment with immunosuppressants such as intravenous cyclophosphamide could be behind progressive reductions in Ig levels seen with repeated rituximab treatment rather than entirely because of rituximab, Dr. Md Yusof said.

Dr. Md Yusof, who is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Academic Clinical Lecturer at the University of Leeds, said the value of the study, compared with others, is that hospital data for all patients treated with rituximab with at least 3 months follow-up were included, making it an almost complete data set.

“By carefully reviewing records of every patient to capture all infection episodes in the largest single-center cohort study to date, our findings provide insights on predictors of SIEs as well as a foundation for safety monitoring of rituximab,” he and his coauthors wrote.

They acknowledge reporting a higher rate of SIEs than seen in registry and clinical studies with rituximab, which may reflect a “channeling bias” as the patients comprised those with multiple comorbidities including those that represent a relative contraindication for bDMARD use. That said, the findings clearly show that Ig levels should be monitored before and after each rituximab cycle, especially in those with comorbid diseases and those with low IgG levels to start with.

They conclude that an “individualized benefit-risk assessment” is needed to determine whether rituximab should be repeated in those with low IgG as this is a “consistent predictor” of SIE and may “increase infection profiles when [rituximab] is switched to different bDMARDs.”

The research was supported by Octapharma, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), and NIHR Leeds Biomedical Research Centre based at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust in England. Dr. Md Yusof had no conflicts of interest. Several coauthors disclosed financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies, including Roche.

SOURCE: Md Yusof MY et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 May 27. doi: 10.1002/art.40937.

Monitoring immunoglobulin (Ig) levels at baseline and before each cycle of rituximab could reduce the risk of serious infection events (SIEs) in patients needing repeated treatment, according to research published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

In a large, single-center, longitudinal study conducted at a tertiary referral center, having low IgG (less than 6 g/L) in particular was associated with a higher rate of SIEs, compared with having normal IgG levels (6-16 g/L). Considering 103 of 700 patients who had low levels of IgG before starting treatment with rituximab for various rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs), there were 16.4 SIEs per 100 patient-years. In those who developed low IgG during subsequent cycles of rituximab therapy, the SIE rate was even higher, at 21.3 per 100 patient-years. By comparison, the SIE rate for those with normal IgG levels was 9.7 per 100 patient-years.

“We really have to monitor immunoglobulins at baseline and also before we re-treat the patients, because higher IgG level is protective of serious infections,” study first author Md Yuzaiful Md Yusof, MBChB, PhD, said in an interview.

Low IgG has been linked to a higher risk of SIEs in the first 12 months of rituximab therapy but, until now, there have been limited data on infection predictors during repeated cycles of treatment. While IgG is a consistent marker of SIEs associated with repeated rituximab treatment, IgM and IgA should also be monitored to give a full picture of any hyperglobulinemia that may be present.

“There is no formal guidance on how to safely monitor patients on rituximab,” observed Dr. Md Yusof, who will present these data at the 2019 European Congress of Rheumatology in Madrid. The study’s findings could help to change that, however, as they offer a practical way to help predict and thus prevent SIEs. The study’s findings not only validate previous work, he noted, but also add new insights into why some patients treated with repeat rituximab cycles but not others may experience a higher rate of such infections.

Altogether, the investigators examined data on 700 patients with RMDs treated with rituximab who were consecutively seen during 2012-2017 at Dr. Md Yusof’s institution – the Leeds (England) Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, which is part of the University of Leeds. Their immunoglobulin levels had been measured before starting rituximab therapy and every 4-6 months after each cycle of rituximab treatment.

Patients with any RMD being treated with at least one cycle of rituximab were eligible for inclusion in the retrospective study, with the majority (72%) taking it for rheumatoid arthritis and some for systemic lupus erythematosus (13%) or antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–associated vasculitis (7%).

One of the main aims of the study was to look for predictors of SIEs during the first 12 months and during repeated cycles of rituximab. Dr. Md Yusof and his associates also looked at how secondary hypogammaglobulinemia might affect SIE rates and the humoral response to vaccination challenge and its persistence following treatment discontinuation. Their ultimate aim was to see if these findings could then be used to develop a treatment algorithm for rituximab administration in RMDs.

Over a follow-up period encompassing 2,880 patient-years of treatment, 281 SIEs were recorded in 176 patients, giving a rate of 9.8 infections per 100 patient-years. Most (61%) of these were due to lower respiratory tract infections.

The proportion of patients experiencing their first SIE increased with time: 16% within 6 weeks of starting rituximab therapy, 35% at 12 weeks, 72% at 26 weeks, 83% at 38 weeks, and 100% by 1 year of repeated treatment.

Multivariable analysis showed that the presence of several comorbidities at baseline – notably chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, heart failure, and prior cancer – raised the risk for SIEs with repeated rituximab therapy. The biggest factor, however, was a history of SIEs – with a sixfold increased risk of further serious infection.

Higher corticosteroid dose and factors specific to rituximab – low IgG, neutropenia, high IgM, and a longer time to retreatment – were also predictive of SIEs.

“Low IgG also results in poor humoral response to vaccination,” Dr. Md Yusof said, noting that the IgG level remains below the lower limit of normal for several years after rituximab is discontinued in most patients.

In the study, 5 of 8 (64%) patients had impaired humoral response to pneumococcal and haemophilus following vaccination challenge and 4 of 11 patients had IgG normalized after switching to another biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD).

Cyclophosphamide is commonly used as a first-line agent to induce remission in patients with severe and refractory systemic lupus erythematosus and ANCA-associated vasculitis, with patients switched to rituximab at relapse. The effect of this prior treatment was examined in 20 patients in the study, with a marked decline in almost all immunoglobulin classes seen up to 18 months. Prior treatment with immunosuppressants such as intravenous cyclophosphamide could be behind progressive reductions in Ig levels seen with repeated rituximab treatment rather than entirely because of rituximab, Dr. Md Yusof said.

Dr. Md Yusof, who is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Academic Clinical Lecturer at the University of Leeds, said the value of the study, compared with others, is that hospital data for all patients treated with rituximab with at least 3 months follow-up were included, making it an almost complete data set.

“By carefully reviewing records of every patient to capture all infection episodes in the largest single-center cohort study to date, our findings provide insights on predictors of SIEs as well as a foundation for safety monitoring of rituximab,” he and his coauthors wrote.

They acknowledge reporting a higher rate of SIEs than seen in registry and clinical studies with rituximab, which may reflect a “channeling bias” as the patients comprised those with multiple comorbidities including those that represent a relative contraindication for bDMARD use. That said, the findings clearly show that Ig levels should be monitored before and after each rituximab cycle, especially in those with comorbid diseases and those with low IgG levels to start with.

They conclude that an “individualized benefit-risk assessment” is needed to determine whether rituximab should be repeated in those with low IgG as this is a “consistent predictor” of SIE and may “increase infection profiles when [rituximab] is switched to different bDMARDs.”

The research was supported by Octapharma, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), and NIHR Leeds Biomedical Research Centre based at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust in England. Dr. Md Yusof had no conflicts of interest. Several coauthors disclosed financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies, including Roche.

SOURCE: Md Yusof MY et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 May 27. doi: 10.1002/art.40937.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Immunoglobulin should be monitored at baseline and before each rituximab cycle to identify patients at risk of serious infection events (SIEs).

Major finding: SIE rates per 100 patient-years were 16.4 and 21.3 in patients with low (less than 6 g/L) IgG at baseline and during rituximab cycles versus 9.7 for patients with normal (6–16 g/L) IgG levels.