User login

Get patients vaccinated: Avoid unwelcome international travel souvenirs

Summer officially began June 21, 2019, but many of your patients already may have departed or will soon be headed to international destinations. Reasons for travel are as variable as their destinations and include but are not limited to family vacations, mission trips, study abroad, parental job relocation, and visiting friends and relatives. The majority of the trips are planned at least 3 months in advance; however, for many travelers and their parents, they suddenly get an aha moment and realize there is/are specific vaccines required to obtain a visa or entry to their final destination. Unfortunately, too much emphasis is focused on required vaccines. The well-informed traveler knows that they may be exposed to multiple diseases and many are vaccine preventable.

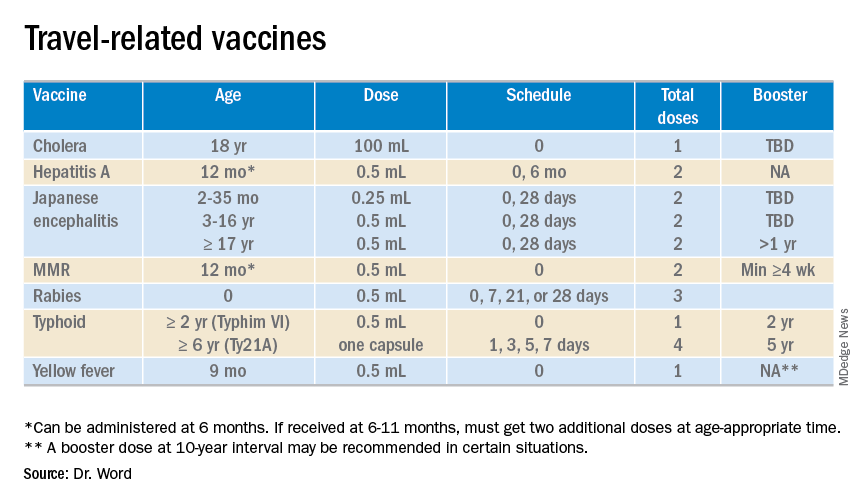

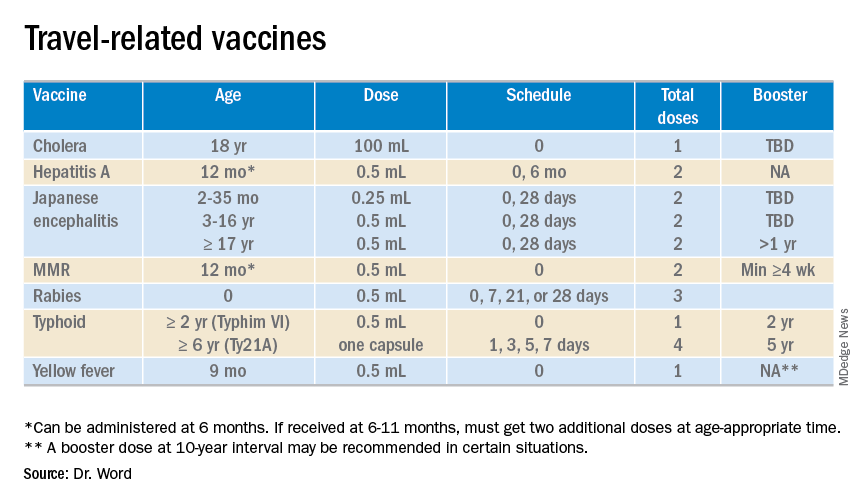

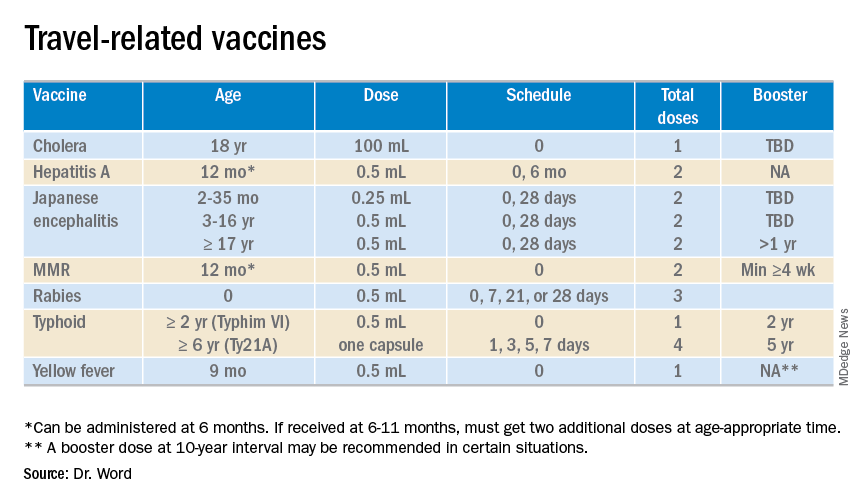

The accompanying table lists vaccines traditionally considered to be travel vaccines. Several require multiple doses administered over 21-28 days to provide protection. Others such as cholera and yellow fever must be completed at least 10 days prior to departure to be effective. Typhoid has two formulations: The oral and injectable typhoid vaccines should be completed 1 and 2 weeks, respectively, prior to travel. Several vaccines have age limitations. Routine immunization of all infants against hepatitis A was recommended in 2006. Depending on your region, there may be adolescents who have not been immunized. Fortunately, hepatitis A vaccine works immediately.

One of the challenges you face is identifying someone in your area that provides travel medicine advice and immunizations to children and adolescents. Most children and teens travel with their parents, but today many adolescents travel independently with organized groups. Most of the vaccines listed are not routinely administered at your office, yet you most likely will be the first call a parent makes seeking travel advice.

Let me tell you about a few vaccines in particular.

Japanese encephalitis

This is most common cause of encephalitis in Asia and parts of the western Pacific. Risk generally is limited to rural agricultural areas where the causative virus is transmitted by a mosquito. Fatality rates are 20%-30%. Among survivors, 30%-50% have significant neurologic, cognitive, and psychiatric sequelae. Candidates for this vaccine are long-term travelers and short-term travelers with extensive outdoor rural activities.

Meningococcal conjugate vaccines (MCV4)

All travelers to the Hajj Pilgrimage (Aug. 9-14, 2019) and/or Umrah must show proof of immunization. Vaccine must be received at least 10 days prior to and no greater than 5 years prior to arrival to Saudi Arabia. Conjugate vaccine must clearly be documented for validity of 5 years. For all health entry requirements, go to www.moh.gov.sa/en/hajj/pages/healthregulations.aspx.

Measles

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends all infants 6-11 months old receive one dose of MMR prior to international travel regardless of the destination. This should be followed by two additional countable doses. All persons at least 12 months of age and born after 1956 should receive two doses of MMR at least 28 days apart prior to international travel.

Rabies

Rabies is a viral disease endemic in more than 150 countries with approximately 60,000 fatal cases worldwide each year. Asia and Africa are the areas with the highest risk of exposure, and dogs are the principal hosts. Human rabies is almost always fatal once symptoms develop. Preexposure vaccine is recommended for persons with prolonged and/or remote travel to countries where rabies immunoglobulin is unavailable and the occurrence of animal rabies is high. Post exposure vaccination on days 0 and 3 still would be required.*

Typhoid

A bacterial infection caused by Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi and Paratyphi manifests with fever, headache, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or constipation. When bacteremia occurs, it usually is referred to as enteric fever. It is acquired by consumption of food/water contaminated with human feces. Highest risk areas include Africa, Southern Asia, and Southeast Asia

Yellow fever

Risk is limited to sub-Saharan Africa and the tropical areas of South America. It is transmitted by the bite of an infected mosquito. The vaccine is required for entry into at least 16 countries. In a country where yellow fever is present, persons transiting through for more than 12 hours to reach their final destination may actually cause a change in the entry requirements for the destination country. For example, travel from the United States to Tanzania requires no yellow fever vaccine while travel from the United States to Nairobi (more than 12 hours) to Tanzania requires yellow fever vaccine for entry into Tanzania. Travel sequence and duration is extremely important. Check the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention yellow fever site and/or the consulate for the most up-to-date yellow fever vaccine requirements.

YF-Vax (yellow fever vaccine) produced by Sanofi Pasteur in the United States currently is unavailable. The company is building a new facility, and vaccine will not be available for the remainder of 2019. To assure vaccine for U.S. travelers, Stamaril, a yellow fever vaccine produced by Sanofi Pasteur in France has been made available at more than 250 sites nationwide. Because Stamaril is offered at a limited number of locations, persons in need of vaccine should not delay seeking it. Because of increased demand related to summer travel, travelers in some areas have reported delays of several weeks in scheduling an appointment. To locate a Stamaril site in your area, go to wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/search-for-stamaril-clinics.

There are several other diseases transmitted by mosquitoes and ticks including malaria, dengue, Zika and rickettsial diseases. Vigilant use of mosquito repellents is a must. Prophylactic medication is available for only malaria and should be initiated prior to exposure. Frequency and duration depends on the medication selected.

So how do you assist your patients?

Once you’ve identified a travel medicine facility in your area, encourage them to seek pretravel advice 4-6 weeks prior to international travel and make sure their routine immunizations are up to date. Generally, this is not an issue. One challenge is the early administration of MMR. While most practitioners know that early administration for international travel has been recommended for years, many office staff are accustomed to administration at only the 12 month and 4 year visit. When parents call requesting immunization, they often are informed that is it unnecessary and the appointment denied. This is a challenge, especially when coordination of administration of another live vaccine, such as yellow fever, is planned. Familiarizing all members of the health care team with current vaccine recommendations is critical.

For country-specific information, up-to-date travel alerts, and to locate a travel medicine clinic, visit www.cdc.gov/travel.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

*This article was updated 6/18/2019.

Summer officially began June 21, 2019, but many of your patients already may have departed or will soon be headed to international destinations. Reasons for travel are as variable as their destinations and include but are not limited to family vacations, mission trips, study abroad, parental job relocation, and visiting friends and relatives. The majority of the trips are planned at least 3 months in advance; however, for many travelers and their parents, they suddenly get an aha moment and realize there is/are specific vaccines required to obtain a visa or entry to their final destination. Unfortunately, too much emphasis is focused on required vaccines. The well-informed traveler knows that they may be exposed to multiple diseases and many are vaccine preventable.

The accompanying table lists vaccines traditionally considered to be travel vaccines. Several require multiple doses administered over 21-28 days to provide protection. Others such as cholera and yellow fever must be completed at least 10 days prior to departure to be effective. Typhoid has two formulations: The oral and injectable typhoid vaccines should be completed 1 and 2 weeks, respectively, prior to travel. Several vaccines have age limitations. Routine immunization of all infants against hepatitis A was recommended in 2006. Depending on your region, there may be adolescents who have not been immunized. Fortunately, hepatitis A vaccine works immediately.

One of the challenges you face is identifying someone in your area that provides travel medicine advice and immunizations to children and adolescents. Most children and teens travel with their parents, but today many adolescents travel independently with organized groups. Most of the vaccines listed are not routinely administered at your office, yet you most likely will be the first call a parent makes seeking travel advice.

Let me tell you about a few vaccines in particular.

Japanese encephalitis

This is most common cause of encephalitis in Asia and parts of the western Pacific. Risk generally is limited to rural agricultural areas where the causative virus is transmitted by a mosquito. Fatality rates are 20%-30%. Among survivors, 30%-50% have significant neurologic, cognitive, and psychiatric sequelae. Candidates for this vaccine are long-term travelers and short-term travelers with extensive outdoor rural activities.

Meningococcal conjugate vaccines (MCV4)

All travelers to the Hajj Pilgrimage (Aug. 9-14, 2019) and/or Umrah must show proof of immunization. Vaccine must be received at least 10 days prior to and no greater than 5 years prior to arrival to Saudi Arabia. Conjugate vaccine must clearly be documented for validity of 5 years. For all health entry requirements, go to www.moh.gov.sa/en/hajj/pages/healthregulations.aspx.

Measles

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends all infants 6-11 months old receive one dose of MMR prior to international travel regardless of the destination. This should be followed by two additional countable doses. All persons at least 12 months of age and born after 1956 should receive two doses of MMR at least 28 days apart prior to international travel.

Rabies

Rabies is a viral disease endemic in more than 150 countries with approximately 60,000 fatal cases worldwide each year. Asia and Africa are the areas with the highest risk of exposure, and dogs are the principal hosts. Human rabies is almost always fatal once symptoms develop. Preexposure vaccine is recommended for persons with prolonged and/or remote travel to countries where rabies immunoglobulin is unavailable and the occurrence of animal rabies is high. Post exposure vaccination on days 0 and 3 still would be required.*

Typhoid

A bacterial infection caused by Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi and Paratyphi manifests with fever, headache, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or constipation. When bacteremia occurs, it usually is referred to as enteric fever. It is acquired by consumption of food/water contaminated with human feces. Highest risk areas include Africa, Southern Asia, and Southeast Asia

Yellow fever

Risk is limited to sub-Saharan Africa and the tropical areas of South America. It is transmitted by the bite of an infected mosquito. The vaccine is required for entry into at least 16 countries. In a country where yellow fever is present, persons transiting through for more than 12 hours to reach their final destination may actually cause a change in the entry requirements for the destination country. For example, travel from the United States to Tanzania requires no yellow fever vaccine while travel from the United States to Nairobi (more than 12 hours) to Tanzania requires yellow fever vaccine for entry into Tanzania. Travel sequence and duration is extremely important. Check the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention yellow fever site and/or the consulate for the most up-to-date yellow fever vaccine requirements.

YF-Vax (yellow fever vaccine) produced by Sanofi Pasteur in the United States currently is unavailable. The company is building a new facility, and vaccine will not be available for the remainder of 2019. To assure vaccine for U.S. travelers, Stamaril, a yellow fever vaccine produced by Sanofi Pasteur in France has been made available at more than 250 sites nationwide. Because Stamaril is offered at a limited number of locations, persons in need of vaccine should not delay seeking it. Because of increased demand related to summer travel, travelers in some areas have reported delays of several weeks in scheduling an appointment. To locate a Stamaril site in your area, go to wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/search-for-stamaril-clinics.

There are several other diseases transmitted by mosquitoes and ticks including malaria, dengue, Zika and rickettsial diseases. Vigilant use of mosquito repellents is a must. Prophylactic medication is available for only malaria and should be initiated prior to exposure. Frequency and duration depends on the medication selected.

So how do you assist your patients?

Once you’ve identified a travel medicine facility in your area, encourage them to seek pretravel advice 4-6 weeks prior to international travel and make sure their routine immunizations are up to date. Generally, this is not an issue. One challenge is the early administration of MMR. While most practitioners know that early administration for international travel has been recommended for years, many office staff are accustomed to administration at only the 12 month and 4 year visit. When parents call requesting immunization, they often are informed that is it unnecessary and the appointment denied. This is a challenge, especially when coordination of administration of another live vaccine, such as yellow fever, is planned. Familiarizing all members of the health care team with current vaccine recommendations is critical.

For country-specific information, up-to-date travel alerts, and to locate a travel medicine clinic, visit www.cdc.gov/travel.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

*This article was updated 6/18/2019.

Summer officially began June 21, 2019, but many of your patients already may have departed or will soon be headed to international destinations. Reasons for travel are as variable as their destinations and include but are not limited to family vacations, mission trips, study abroad, parental job relocation, and visiting friends and relatives. The majority of the trips are planned at least 3 months in advance; however, for many travelers and their parents, they suddenly get an aha moment and realize there is/are specific vaccines required to obtain a visa or entry to their final destination. Unfortunately, too much emphasis is focused on required vaccines. The well-informed traveler knows that they may be exposed to multiple diseases and many are vaccine preventable.

The accompanying table lists vaccines traditionally considered to be travel vaccines. Several require multiple doses administered over 21-28 days to provide protection. Others such as cholera and yellow fever must be completed at least 10 days prior to departure to be effective. Typhoid has two formulations: The oral and injectable typhoid vaccines should be completed 1 and 2 weeks, respectively, prior to travel. Several vaccines have age limitations. Routine immunization of all infants against hepatitis A was recommended in 2006. Depending on your region, there may be adolescents who have not been immunized. Fortunately, hepatitis A vaccine works immediately.

One of the challenges you face is identifying someone in your area that provides travel medicine advice and immunizations to children and adolescents. Most children and teens travel with their parents, but today many adolescents travel independently with organized groups. Most of the vaccines listed are not routinely administered at your office, yet you most likely will be the first call a parent makes seeking travel advice.

Let me tell you about a few vaccines in particular.

Japanese encephalitis

This is most common cause of encephalitis in Asia and parts of the western Pacific. Risk generally is limited to rural agricultural areas where the causative virus is transmitted by a mosquito. Fatality rates are 20%-30%. Among survivors, 30%-50% have significant neurologic, cognitive, and psychiatric sequelae. Candidates for this vaccine are long-term travelers and short-term travelers with extensive outdoor rural activities.

Meningococcal conjugate vaccines (MCV4)

All travelers to the Hajj Pilgrimage (Aug. 9-14, 2019) and/or Umrah must show proof of immunization. Vaccine must be received at least 10 days prior to and no greater than 5 years prior to arrival to Saudi Arabia. Conjugate vaccine must clearly be documented for validity of 5 years. For all health entry requirements, go to www.moh.gov.sa/en/hajj/pages/healthregulations.aspx.

Measles

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends all infants 6-11 months old receive one dose of MMR prior to international travel regardless of the destination. This should be followed by two additional countable doses. All persons at least 12 months of age and born after 1956 should receive two doses of MMR at least 28 days apart prior to international travel.

Rabies

Rabies is a viral disease endemic in more than 150 countries with approximately 60,000 fatal cases worldwide each year. Asia and Africa are the areas with the highest risk of exposure, and dogs are the principal hosts. Human rabies is almost always fatal once symptoms develop. Preexposure vaccine is recommended for persons with prolonged and/or remote travel to countries where rabies immunoglobulin is unavailable and the occurrence of animal rabies is high. Post exposure vaccination on days 0 and 3 still would be required.*

Typhoid

A bacterial infection caused by Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi and Paratyphi manifests with fever, headache, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or constipation. When bacteremia occurs, it usually is referred to as enteric fever. It is acquired by consumption of food/water contaminated with human feces. Highest risk areas include Africa, Southern Asia, and Southeast Asia

Yellow fever

Risk is limited to sub-Saharan Africa and the tropical areas of South America. It is transmitted by the bite of an infected mosquito. The vaccine is required for entry into at least 16 countries. In a country where yellow fever is present, persons transiting through for more than 12 hours to reach their final destination may actually cause a change in the entry requirements for the destination country. For example, travel from the United States to Tanzania requires no yellow fever vaccine while travel from the United States to Nairobi (more than 12 hours) to Tanzania requires yellow fever vaccine for entry into Tanzania. Travel sequence and duration is extremely important. Check the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention yellow fever site and/or the consulate for the most up-to-date yellow fever vaccine requirements.

YF-Vax (yellow fever vaccine) produced by Sanofi Pasteur in the United States currently is unavailable. The company is building a new facility, and vaccine will not be available for the remainder of 2019. To assure vaccine for U.S. travelers, Stamaril, a yellow fever vaccine produced by Sanofi Pasteur in France has been made available at more than 250 sites nationwide. Because Stamaril is offered at a limited number of locations, persons in need of vaccine should not delay seeking it. Because of increased demand related to summer travel, travelers in some areas have reported delays of several weeks in scheduling an appointment. To locate a Stamaril site in your area, go to wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/search-for-stamaril-clinics.

There are several other diseases transmitted by mosquitoes and ticks including malaria, dengue, Zika and rickettsial diseases. Vigilant use of mosquito repellents is a must. Prophylactic medication is available for only malaria and should be initiated prior to exposure. Frequency and duration depends on the medication selected.

So how do you assist your patients?

Once you’ve identified a travel medicine facility in your area, encourage them to seek pretravel advice 4-6 weeks prior to international travel and make sure their routine immunizations are up to date. Generally, this is not an issue. One challenge is the early administration of MMR. While most practitioners know that early administration for international travel has been recommended for years, many office staff are accustomed to administration at only the 12 month and 4 year visit. When parents call requesting immunization, they often are informed that is it unnecessary and the appointment denied. This is a challenge, especially when coordination of administration of another live vaccine, such as yellow fever, is planned. Familiarizing all members of the health care team with current vaccine recommendations is critical.

For country-specific information, up-to-date travel alerts, and to locate a travel medicine clinic, visit www.cdc.gov/travel.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

*This article was updated 6/18/2019.

Crossword: HIV PrEP

How to have ‘the talk’ with vaccine skeptics

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – An effective strategy in helping vaccine skeptics to come around to accepting immunizations for their children is to pivot the conversation away from vaccine safety and focus instead on the disease itself and its potential consequences, Saad B. Omer, MBBS, PhD, asserted at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“Why do we cede ground by focusing too much on the vaccine itself? I call it the disease salience approach,” said Dr. Omer, professor of global health, epidemiology, and pediatrics at Emory University in Atlanta.

It’s a strategy guided by developments in social psychology, persuasion theory, and communication theory. But if applied incorrectly, the disease salience approach can backfire, causing behavioral paralysis and an inability to act, he cautioned.

Dr. Omer explained that it’s a matter of framing.

“Always include a solution to promote self-efficacy and response-efficacy. After you inform parents of disease risks, provide them with actions they can take. Now readdress the vaccine, pointing out that this is the single best way to protect yourself and your baby,” he said. “The lesson is that since vaccines are a social norm, reframe nonvaccination as an active act, rather than vaccination as an active act.”

Don’t attempt to wow parents with statistics on how vaccine complication rates are dwarfed by the disease risk if left unvaccinated, he advised. Studies have shown that‘s generally not effective. What actually works is to provide narratives of disease severity.

“We are excellent linguists, but really, really poor statisticians,” Dr. Omer observed.

Is it ethical to talk to parents about disease risks to influence their behavior? Absolutely, in his view.

“We’re not selling toothpaste. We are in the business of life-saving vaccines. And I would submit that if it’s done correctly it’s entirely ethical to talk about the disease, and sometimes even the severe risks of the disease, instead of the vaccine,” said Dr. Omer.

If parents cite a myth about vaccines, it’s necessary to address it head on without lingering on it. But debunking a myth is tricky because people tend to remember negative information they received earlier.

“If you’re going to debunk a myth, clearly label it as a myth in the headline as you introduce it. State why it’s not true. Replace the myth with the best alternative explanation. Think of it like a blank space where the myth used to reside. That space needs to be filled with an alternative explanation or the myth will come back,” Dr. Omer said.

He is a coauthor of a book titled, ‘The Clinician’s Vaccine Safety Resource Guide: Optimizing Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Across the Lifespan.’

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – An effective strategy in helping vaccine skeptics to come around to accepting immunizations for their children is to pivot the conversation away from vaccine safety and focus instead on the disease itself and its potential consequences, Saad B. Omer, MBBS, PhD, asserted at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“Why do we cede ground by focusing too much on the vaccine itself? I call it the disease salience approach,” said Dr. Omer, professor of global health, epidemiology, and pediatrics at Emory University in Atlanta.

It’s a strategy guided by developments in social psychology, persuasion theory, and communication theory. But if applied incorrectly, the disease salience approach can backfire, causing behavioral paralysis and an inability to act, he cautioned.

Dr. Omer explained that it’s a matter of framing.

“Always include a solution to promote self-efficacy and response-efficacy. After you inform parents of disease risks, provide them with actions they can take. Now readdress the vaccine, pointing out that this is the single best way to protect yourself and your baby,” he said. “The lesson is that since vaccines are a social norm, reframe nonvaccination as an active act, rather than vaccination as an active act.”

Don’t attempt to wow parents with statistics on how vaccine complication rates are dwarfed by the disease risk if left unvaccinated, he advised. Studies have shown that‘s generally not effective. What actually works is to provide narratives of disease severity.

“We are excellent linguists, but really, really poor statisticians,” Dr. Omer observed.

Is it ethical to talk to parents about disease risks to influence their behavior? Absolutely, in his view.

“We’re not selling toothpaste. We are in the business of life-saving vaccines. And I would submit that if it’s done correctly it’s entirely ethical to talk about the disease, and sometimes even the severe risks of the disease, instead of the vaccine,” said Dr. Omer.

If parents cite a myth about vaccines, it’s necessary to address it head on without lingering on it. But debunking a myth is tricky because people tend to remember negative information they received earlier.

“If you’re going to debunk a myth, clearly label it as a myth in the headline as you introduce it. State why it’s not true. Replace the myth with the best alternative explanation. Think of it like a blank space where the myth used to reside. That space needs to be filled with an alternative explanation or the myth will come back,” Dr. Omer said.

He is a coauthor of a book titled, ‘The Clinician’s Vaccine Safety Resource Guide: Optimizing Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Across the Lifespan.’

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – An effective strategy in helping vaccine skeptics to come around to accepting immunizations for their children is to pivot the conversation away from vaccine safety and focus instead on the disease itself and its potential consequences, Saad B. Omer, MBBS, PhD, asserted at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“Why do we cede ground by focusing too much on the vaccine itself? I call it the disease salience approach,” said Dr. Omer, professor of global health, epidemiology, and pediatrics at Emory University in Atlanta.

It’s a strategy guided by developments in social psychology, persuasion theory, and communication theory. But if applied incorrectly, the disease salience approach can backfire, causing behavioral paralysis and an inability to act, he cautioned.

Dr. Omer explained that it’s a matter of framing.

“Always include a solution to promote self-efficacy and response-efficacy. After you inform parents of disease risks, provide them with actions they can take. Now readdress the vaccine, pointing out that this is the single best way to protect yourself and your baby,” he said. “The lesson is that since vaccines are a social norm, reframe nonvaccination as an active act, rather than vaccination as an active act.”

Don’t attempt to wow parents with statistics on how vaccine complication rates are dwarfed by the disease risk if left unvaccinated, he advised. Studies have shown that‘s generally not effective. What actually works is to provide narratives of disease severity.

“We are excellent linguists, but really, really poor statisticians,” Dr. Omer observed.

Is it ethical to talk to parents about disease risks to influence their behavior? Absolutely, in his view.

“We’re not selling toothpaste. We are in the business of life-saving vaccines. And I would submit that if it’s done correctly it’s entirely ethical to talk about the disease, and sometimes even the severe risks of the disease, instead of the vaccine,” said Dr. Omer.

If parents cite a myth about vaccines, it’s necessary to address it head on without lingering on it. But debunking a myth is tricky because people tend to remember negative information they received earlier.

“If you’re going to debunk a myth, clearly label it as a myth in the headline as you introduce it. State why it’s not true. Replace the myth with the best alternative explanation. Think of it like a blank space where the myth used to reside. That space needs to be filled with an alternative explanation or the myth will come back,” Dr. Omer said.

He is a coauthor of a book titled, ‘The Clinician’s Vaccine Safety Resource Guide: Optimizing Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Across the Lifespan.’

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ESPID 2019

Scabies rates plummeted with community mass drug administration

MILAN – In a region where scabies is endemic, a , findings that may have implications for future treatment of scabies or other infestations in other regions, dermatologist Margot Whitfield, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

“Mass drug administration is highly effective and safe in the treatment of endemic scabies,” she said.

Using a strategy of directly observed treatment (DOT) with oral ivermectin or topical permethrin for all residents of two separate island groups in Fiji, Dr. Whitfield, together with epidemiologist Lucia Romani, PhD, both of the University of New South Wales, Sydney, and coinvestigators, demonstrated large and sustained decreases in the rates of scabies and impetigo (N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec 10;373[24]:2305-13).

Across study arms, which included a usual care arm, the baseline rate for scabies ranged from 30% to 40%. With usual care, the rate dropped from 36.6% to 18.8% at the end of 12 months, a relative reduction of 49%. However, the 15.8% prevalence rate 12 months after permethrin DOT (from 41.7%), and the 1.9% rate 12 months after ivermectin DOT (from 32.1%) – reductions of 62% and 94%, respectively – represented much larger decreases, “especially since these reductions were seen without any further interventions,” Dr. Whitfield said. “This was extremely exciting, and a game-changer as far as the management of endemic scabies is concerned.”

At baseline, impetigo rates hovered around 20%-25%, and usual care resulted in a 32% reduction at 12 months. With permethrin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 54%; with ivermectin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 67%. “The community level of impetigo went down, purely as a result of treating the scabies,” Dr. Whitfield said.

The outcomes of this study, she noted, “have contributed to the global discussion of the treatment of scabies.”

Two years after the mass drug administration (MDA) campaign, scabies prevalence remained much lower than at baseline, with clinical scabies diagnosed in 15.2% of the usual care group, 13.5% of the permethrin group, and just 3.6% of the ivermectin group. “The exciting thing for us was that these levels ... were able to be sustained at 2 years,” Dr. Whitfield noted.

The islands that had received ivermectin saw a continued decline in impetigo prevalence as well: By 24 months, impetigo was seen in 2.6% of participants in that arm.

Scabies is a neglected – but highly treatable – tropical disease, she noted. It is associated with intense pruritus, which results in reduced quality of life, and excoriations predispose those affected to bacterial superinfections, commonly impetigo in the young.

In Fiji, the scabies mite infests nearly 40% of those aged 5-9 years, and over one-third of those younger than 5 years. Rates drop steeply with increasing age and then climb again for the elderly; still, prevalence tops 10% for all Fijian age groups, Dr. Whitfield pointed out. Overall, scabies prevalence is 23% in Fiji, with resultant impetigo affecting 19% of the population.

Providing more details about the study, she said that she and her collaborators – working in conjunction with the Fijian Ministry of Health – took advantage of the geography of the island country, whose 850,000 residents live on 300 islands, to compare mass drug treatment with either ivermectin or permethrin with usual care. “We actually didn’t look for ‘infected scabies,’ ” she explained. “We looked for scabies as one outcome, and infection as another.”

The study was designed to take advantage of lessons from previous public health work addressing filariasis and soil-transmitted helminths, and addressed the following question: In Fiji, could a single round of MDA for scabies control lead to sustained reductions in scabies and impetigo prevalence 12 months later, compared with standard care?

The study applied standard-of-care scabies treatment to residents of one island; here, all residents of the island were assessed for scabies, and those who received a clinical diagnosis of scabies, along with family members and close contacts, were treated. Another group of three small islands received permethrin MDA. A third pair of neighboring islands received ivermectin MDA.

For one MDA arm, island residents received oral ivermectin via DOT. A second DOT dose was administered for those with clinically diagnosed scabies. For pregnant and breastfeeding women, children weighing less than 15 kg, and those with ivermectin hypersensitivity, permethrin was used, Dr. Whitfield said.

The individuals in the permethrin MDA arm received one topical dose via DOT, with a second round of topical permethrin for those with topical scabies.

In all, 803 Fijians were assigned to receive standard of care, 532 permethrin MDA, and 716 ivermectin MDA. Of these, 623 received ivermectin DOT, and 93 received permethrin. In all, DOT was achieved for 96% of those receiving the first dose. At baseline, 230 patients had scabies, with 200 receiving ivermectin and 30 permethrin; the DOT rate was 100% for the second dose.

For the permethrin arm, just 307 of 532 participants (58%) had DOT, though all were given permethrin. Scabies was present at baseline for 222 participants, and of these, 181 had DOT. “It’s much easier to do the direct observed therapy with an oral medication than with a cream,” Dr. Whitfield said. Data were not collected for the Fijians who received usual care at community health centers.

Outcomes were clinically determined via the child skin assessment algorithm of the World Health Organization’s International Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) guidelines.

Dr. Whitfield acknowledged that the study was not a true cluster-randomized trial, and differences existed between the communities studies. Also, “dermatoscopy was not a practical option” for this real-world trial in a resource-limited setting, but validated clinical criteria were used, she said.

Going forward, she and her colleagues are continuing to track durability of reduced scabies rates, as well as downstream sequelae such as impetigo and septicemia. Also, “we need to see whether this community- and island-based project could be scaled up to a national or regional level,” she said.

The burden of disease from scabies globally is probably underestimated, and changing migration patterns may bring endemic scabies to the doorsteps of more developed nations, prompting consideration of MDA as a strategy in expanded circumstances.

Dr. Whitfield reported that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

MILAN – In a region where scabies is endemic, a , findings that may have implications for future treatment of scabies or other infestations in other regions, dermatologist Margot Whitfield, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

“Mass drug administration is highly effective and safe in the treatment of endemic scabies,” she said.

Using a strategy of directly observed treatment (DOT) with oral ivermectin or topical permethrin for all residents of two separate island groups in Fiji, Dr. Whitfield, together with epidemiologist Lucia Romani, PhD, both of the University of New South Wales, Sydney, and coinvestigators, demonstrated large and sustained decreases in the rates of scabies and impetigo (N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec 10;373[24]:2305-13).

Across study arms, which included a usual care arm, the baseline rate for scabies ranged from 30% to 40%. With usual care, the rate dropped from 36.6% to 18.8% at the end of 12 months, a relative reduction of 49%. However, the 15.8% prevalence rate 12 months after permethrin DOT (from 41.7%), and the 1.9% rate 12 months after ivermectin DOT (from 32.1%) – reductions of 62% and 94%, respectively – represented much larger decreases, “especially since these reductions were seen without any further interventions,” Dr. Whitfield said. “This was extremely exciting, and a game-changer as far as the management of endemic scabies is concerned.”

At baseline, impetigo rates hovered around 20%-25%, and usual care resulted in a 32% reduction at 12 months. With permethrin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 54%; with ivermectin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 67%. “The community level of impetigo went down, purely as a result of treating the scabies,” Dr. Whitfield said.

The outcomes of this study, she noted, “have contributed to the global discussion of the treatment of scabies.”

Two years after the mass drug administration (MDA) campaign, scabies prevalence remained much lower than at baseline, with clinical scabies diagnosed in 15.2% of the usual care group, 13.5% of the permethrin group, and just 3.6% of the ivermectin group. “The exciting thing for us was that these levels ... were able to be sustained at 2 years,” Dr. Whitfield noted.

The islands that had received ivermectin saw a continued decline in impetigo prevalence as well: By 24 months, impetigo was seen in 2.6% of participants in that arm.

Scabies is a neglected – but highly treatable – tropical disease, she noted. It is associated with intense pruritus, which results in reduced quality of life, and excoriations predispose those affected to bacterial superinfections, commonly impetigo in the young.

In Fiji, the scabies mite infests nearly 40% of those aged 5-9 years, and over one-third of those younger than 5 years. Rates drop steeply with increasing age and then climb again for the elderly; still, prevalence tops 10% for all Fijian age groups, Dr. Whitfield pointed out. Overall, scabies prevalence is 23% in Fiji, with resultant impetigo affecting 19% of the population.

Providing more details about the study, she said that she and her collaborators – working in conjunction with the Fijian Ministry of Health – took advantage of the geography of the island country, whose 850,000 residents live on 300 islands, to compare mass drug treatment with either ivermectin or permethrin with usual care. “We actually didn’t look for ‘infected scabies,’ ” she explained. “We looked for scabies as one outcome, and infection as another.”

The study was designed to take advantage of lessons from previous public health work addressing filariasis and soil-transmitted helminths, and addressed the following question: In Fiji, could a single round of MDA for scabies control lead to sustained reductions in scabies and impetigo prevalence 12 months later, compared with standard care?

The study applied standard-of-care scabies treatment to residents of one island; here, all residents of the island were assessed for scabies, and those who received a clinical diagnosis of scabies, along with family members and close contacts, were treated. Another group of three small islands received permethrin MDA. A third pair of neighboring islands received ivermectin MDA.

For one MDA arm, island residents received oral ivermectin via DOT. A second DOT dose was administered for those with clinically diagnosed scabies. For pregnant and breastfeeding women, children weighing less than 15 kg, and those with ivermectin hypersensitivity, permethrin was used, Dr. Whitfield said.

The individuals in the permethrin MDA arm received one topical dose via DOT, with a second round of topical permethrin for those with topical scabies.

In all, 803 Fijians were assigned to receive standard of care, 532 permethrin MDA, and 716 ivermectin MDA. Of these, 623 received ivermectin DOT, and 93 received permethrin. In all, DOT was achieved for 96% of those receiving the first dose. At baseline, 230 patients had scabies, with 200 receiving ivermectin and 30 permethrin; the DOT rate was 100% for the second dose.

For the permethrin arm, just 307 of 532 participants (58%) had DOT, though all were given permethrin. Scabies was present at baseline for 222 participants, and of these, 181 had DOT. “It’s much easier to do the direct observed therapy with an oral medication than with a cream,” Dr. Whitfield said. Data were not collected for the Fijians who received usual care at community health centers.

Outcomes were clinically determined via the child skin assessment algorithm of the World Health Organization’s International Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) guidelines.

Dr. Whitfield acknowledged that the study was not a true cluster-randomized trial, and differences existed between the communities studies. Also, “dermatoscopy was not a practical option” for this real-world trial in a resource-limited setting, but validated clinical criteria were used, she said.

Going forward, she and her colleagues are continuing to track durability of reduced scabies rates, as well as downstream sequelae such as impetigo and septicemia. Also, “we need to see whether this community- and island-based project could be scaled up to a national or regional level,” she said.

The burden of disease from scabies globally is probably underestimated, and changing migration patterns may bring endemic scabies to the doorsteps of more developed nations, prompting consideration of MDA as a strategy in expanded circumstances.

Dr. Whitfield reported that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

MILAN – In a region where scabies is endemic, a , findings that may have implications for future treatment of scabies or other infestations in other regions, dermatologist Margot Whitfield, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

“Mass drug administration is highly effective and safe in the treatment of endemic scabies,” she said.

Using a strategy of directly observed treatment (DOT) with oral ivermectin or topical permethrin for all residents of two separate island groups in Fiji, Dr. Whitfield, together with epidemiologist Lucia Romani, PhD, both of the University of New South Wales, Sydney, and coinvestigators, demonstrated large and sustained decreases in the rates of scabies and impetigo (N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec 10;373[24]:2305-13).

Across study arms, which included a usual care arm, the baseline rate for scabies ranged from 30% to 40%. With usual care, the rate dropped from 36.6% to 18.8% at the end of 12 months, a relative reduction of 49%. However, the 15.8% prevalence rate 12 months after permethrin DOT (from 41.7%), and the 1.9% rate 12 months after ivermectin DOT (from 32.1%) – reductions of 62% and 94%, respectively – represented much larger decreases, “especially since these reductions were seen without any further interventions,” Dr. Whitfield said. “This was extremely exciting, and a game-changer as far as the management of endemic scabies is concerned.”

At baseline, impetigo rates hovered around 20%-25%, and usual care resulted in a 32% reduction at 12 months. With permethrin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 54%; with ivermectin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 67%. “The community level of impetigo went down, purely as a result of treating the scabies,” Dr. Whitfield said.

The outcomes of this study, she noted, “have contributed to the global discussion of the treatment of scabies.”

Two years after the mass drug administration (MDA) campaign, scabies prevalence remained much lower than at baseline, with clinical scabies diagnosed in 15.2% of the usual care group, 13.5% of the permethrin group, and just 3.6% of the ivermectin group. “The exciting thing for us was that these levels ... were able to be sustained at 2 years,” Dr. Whitfield noted.

The islands that had received ivermectin saw a continued decline in impetigo prevalence as well: By 24 months, impetigo was seen in 2.6% of participants in that arm.

Scabies is a neglected – but highly treatable – tropical disease, she noted. It is associated with intense pruritus, which results in reduced quality of life, and excoriations predispose those affected to bacterial superinfections, commonly impetigo in the young.

In Fiji, the scabies mite infests nearly 40% of those aged 5-9 years, and over one-third of those younger than 5 years. Rates drop steeply with increasing age and then climb again for the elderly; still, prevalence tops 10% for all Fijian age groups, Dr. Whitfield pointed out. Overall, scabies prevalence is 23% in Fiji, with resultant impetigo affecting 19% of the population.

Providing more details about the study, she said that she and her collaborators – working in conjunction with the Fijian Ministry of Health – took advantage of the geography of the island country, whose 850,000 residents live on 300 islands, to compare mass drug treatment with either ivermectin or permethrin with usual care. “We actually didn’t look for ‘infected scabies,’ ” she explained. “We looked for scabies as one outcome, and infection as another.”

The study was designed to take advantage of lessons from previous public health work addressing filariasis and soil-transmitted helminths, and addressed the following question: In Fiji, could a single round of MDA for scabies control lead to sustained reductions in scabies and impetigo prevalence 12 months later, compared with standard care?

The study applied standard-of-care scabies treatment to residents of one island; here, all residents of the island were assessed for scabies, and those who received a clinical diagnosis of scabies, along with family members and close contacts, were treated. Another group of three small islands received permethrin MDA. A third pair of neighboring islands received ivermectin MDA.

For one MDA arm, island residents received oral ivermectin via DOT. A second DOT dose was administered for those with clinically diagnosed scabies. For pregnant and breastfeeding women, children weighing less than 15 kg, and those with ivermectin hypersensitivity, permethrin was used, Dr. Whitfield said.

The individuals in the permethrin MDA arm received one topical dose via DOT, with a second round of topical permethrin for those with topical scabies.

In all, 803 Fijians were assigned to receive standard of care, 532 permethrin MDA, and 716 ivermectin MDA. Of these, 623 received ivermectin DOT, and 93 received permethrin. In all, DOT was achieved for 96% of those receiving the first dose. At baseline, 230 patients had scabies, with 200 receiving ivermectin and 30 permethrin; the DOT rate was 100% for the second dose.

For the permethrin arm, just 307 of 532 participants (58%) had DOT, though all were given permethrin. Scabies was present at baseline for 222 participants, and of these, 181 had DOT. “It’s much easier to do the direct observed therapy with an oral medication than with a cream,” Dr. Whitfield said. Data were not collected for the Fijians who received usual care at community health centers.

Outcomes were clinically determined via the child skin assessment algorithm of the World Health Organization’s International Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) guidelines.

Dr. Whitfield acknowledged that the study was not a true cluster-randomized trial, and differences existed between the communities studies. Also, “dermatoscopy was not a practical option” for this real-world trial in a resource-limited setting, but validated clinical criteria were used, she said.

Going forward, she and her colleagues are continuing to track durability of reduced scabies rates, as well as downstream sequelae such as impetigo and septicemia. Also, “we need to see whether this community- and island-based project could be scaled up to a national or regional level,” she said.

The burden of disease from scabies globally is probably underestimated, and changing migration patterns may bring endemic scabies to the doorsteps of more developed nations, prompting consideration of MDA as a strategy in expanded circumstances.

Dr. Whitfield reported that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCD2019

CDC activates Emergency Operations Center for Congo Ebola outbreak

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). With over 2,000 confirmed cases, the outbreak is the second largest ever recorded.

It recently spread to neighboring Uganda, by a family who crossed the border from the DRC.

As of June 11, 187 CDC staff have completed 278 deployments to the DRC, Uganda, and other neighboring countries, as well as to the World Health Organization in Geneva.

“We are activating the Emergency Operations Center at CDC headquarters to provide enhanced operational support to our” Ebola response team in the Congo. The level 3 activation – the lowest level – “allows the agency to provide increased operational support” and “logistics planning for a longer term, sustained effort,” CDC said in a press release.

Activation “does not mean that the threat of Ebola to the United States has increased.” The risk of global spread remains low, CDC said.

The outbreak is occurring in an area of armed conflict and other problems that complicate public health efforts and increase the risk of disease spread.

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). With over 2,000 confirmed cases, the outbreak is the second largest ever recorded.

It recently spread to neighboring Uganda, by a family who crossed the border from the DRC.

As of June 11, 187 CDC staff have completed 278 deployments to the DRC, Uganda, and other neighboring countries, as well as to the World Health Organization in Geneva.

“We are activating the Emergency Operations Center at CDC headquarters to provide enhanced operational support to our” Ebola response team in the Congo. The level 3 activation – the lowest level – “allows the agency to provide increased operational support” and “logistics planning for a longer term, sustained effort,” CDC said in a press release.

Activation “does not mean that the threat of Ebola to the United States has increased.” The risk of global spread remains low, CDC said.

The outbreak is occurring in an area of armed conflict and other problems that complicate public health efforts and increase the risk of disease spread.

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). With over 2,000 confirmed cases, the outbreak is the second largest ever recorded.

It recently spread to neighboring Uganda, by a family who crossed the border from the DRC.

As of June 11, 187 CDC staff have completed 278 deployments to the DRC, Uganda, and other neighboring countries, as well as to the World Health Organization in Geneva.

“We are activating the Emergency Operations Center at CDC headquarters to provide enhanced operational support to our” Ebola response team in the Congo. The level 3 activation – the lowest level – “allows the agency to provide increased operational support” and “logistics planning for a longer term, sustained effort,” CDC said in a press release.

Activation “does not mean that the threat of Ebola to the United States has increased.” The risk of global spread remains low, CDC said.

The outbreak is occurring in an area of armed conflict and other problems that complicate public health efforts and increase the risk of disease spread.

FDA invites sample submission for FDA-ARGOS database

which seeks to support research and regulatory decisions regarding DNA testing for pathogens with quality-controlled and curated genomic sequence data. Such testing and devices could be used as medical countermeasures against biothreats such as Ebola and Zika.

Infectious disease next-generation sequencing could use DNA analysis to help identify pathogens – from viruses to parasites – faster and more efficiently by, in theory, accomplishing with one test what was only possible before with many, according to the FDA. In order to not only further development of such tests and devices but also aid regulatory and scientific review of them, the FDA has collaborated with the Department of Defense, the National Center for Biotechnology Information, and Institute for Genome Sciences at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, to create FDA-ARGOS.

However, the FDA and its collaborators need samples of pathogens to continue developing the database, so they’ve invited health care professionals to submit samples for that purpose. More information, including preferred organism list and submission guidelines, can be found on the FDA-ARGOS website.

which seeks to support research and regulatory decisions regarding DNA testing for pathogens with quality-controlled and curated genomic sequence data. Such testing and devices could be used as medical countermeasures against biothreats such as Ebola and Zika.

Infectious disease next-generation sequencing could use DNA analysis to help identify pathogens – from viruses to parasites – faster and more efficiently by, in theory, accomplishing with one test what was only possible before with many, according to the FDA. In order to not only further development of such tests and devices but also aid regulatory and scientific review of them, the FDA has collaborated with the Department of Defense, the National Center for Biotechnology Information, and Institute for Genome Sciences at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, to create FDA-ARGOS.

However, the FDA and its collaborators need samples of pathogens to continue developing the database, so they’ve invited health care professionals to submit samples for that purpose. More information, including preferred organism list and submission guidelines, can be found on the FDA-ARGOS website.

which seeks to support research and regulatory decisions regarding DNA testing for pathogens with quality-controlled and curated genomic sequence data. Such testing and devices could be used as medical countermeasures against biothreats such as Ebola and Zika.

Infectious disease next-generation sequencing could use DNA analysis to help identify pathogens – from viruses to parasites – faster and more efficiently by, in theory, accomplishing with one test what was only possible before with many, according to the FDA. In order to not only further development of such tests and devices but also aid regulatory and scientific review of them, the FDA has collaborated with the Department of Defense, the National Center for Biotechnology Information, and Institute for Genome Sciences at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, to create FDA-ARGOS.

However, the FDA and its collaborators need samples of pathogens to continue developing the database, so they’ve invited health care professionals to submit samples for that purpose. More information, including preferred organism list and submission guidelines, can be found on the FDA-ARGOS website.

Acute Graft-vs-host Disease Following Liver Transplantation

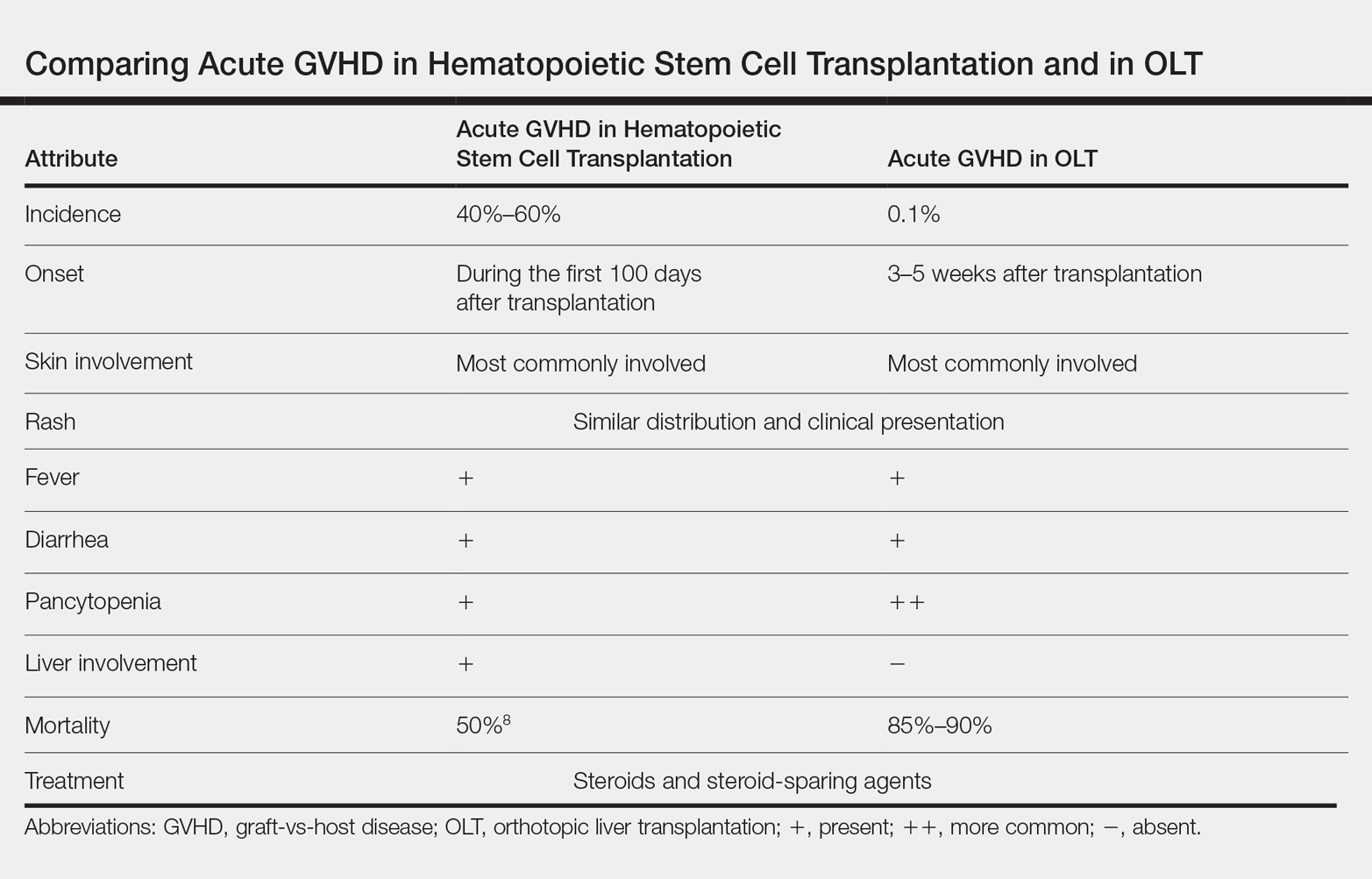

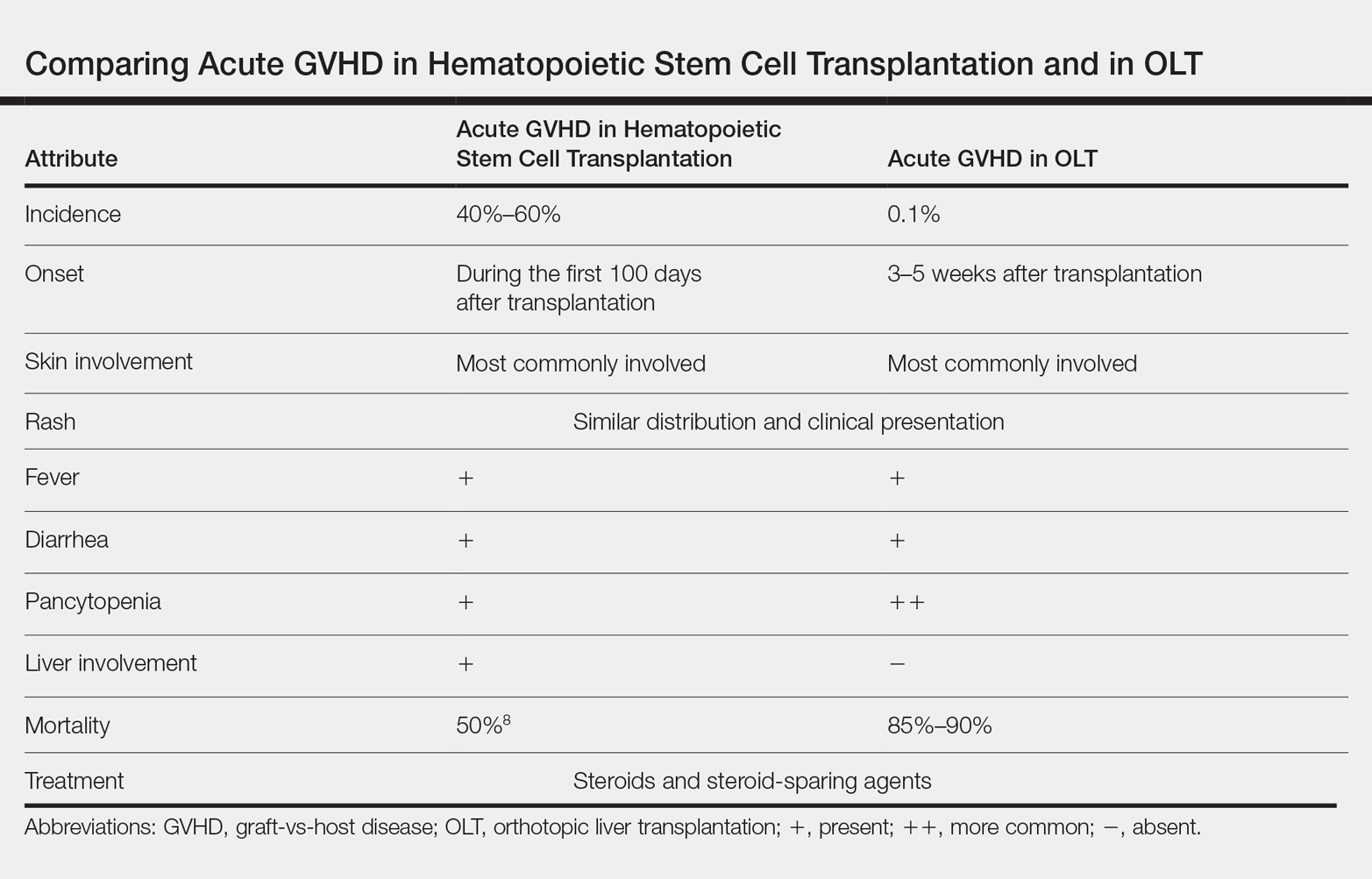

Acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) is a T-cell mediated immunogenic response in which T lymphocytes from a donor regard host tissue as foreign and attack it in the setting of immunosuppression.1 The most common cause of acute GVHD is allogeneic stem cell transplantation, with solid-organ transplantation being a much less common cause.2 The incidence of acute GVHD following orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is 0.1%, as reported by the United Network for Organ Sharing, compared to an incidence of 40% to 60% in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.3,4

Early recognition and treatment of acute GVHD following liver transplantation is imperative, as the mortality rate is 85% to 90%.2 We present a case of acute GVHD in a liver transplantation patient, with a focus on diagnostic criteria and comparison to acute GVHD following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C virus infection, hepatocellular carcinoma, and OLT 1 month prior presented to the hospital with fever and abdominal cellulitis in close proximity to the surgical site of 1 week’s duration. The patient was started on vancomycin and cefepime; pan cultures were performed.

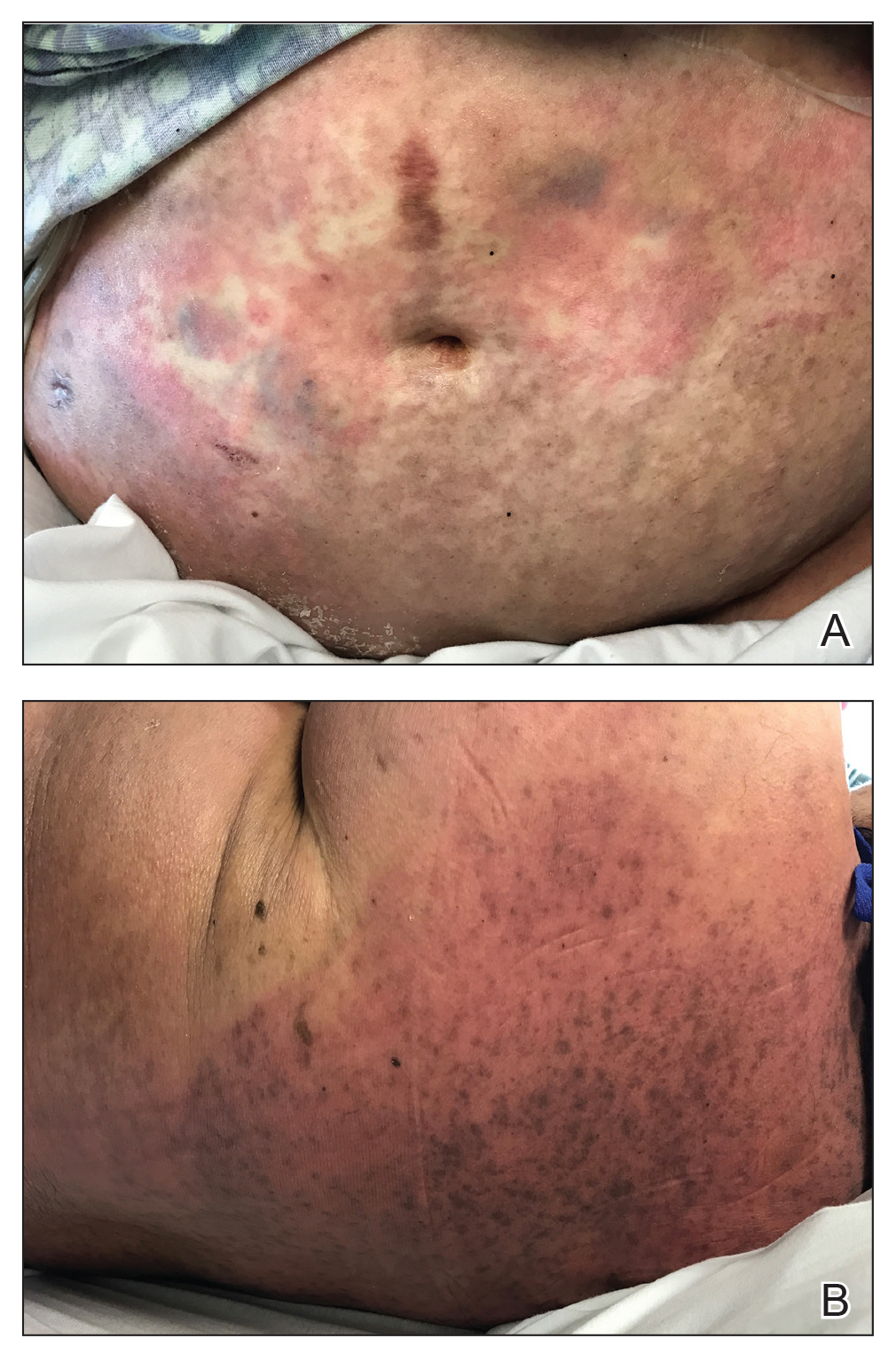

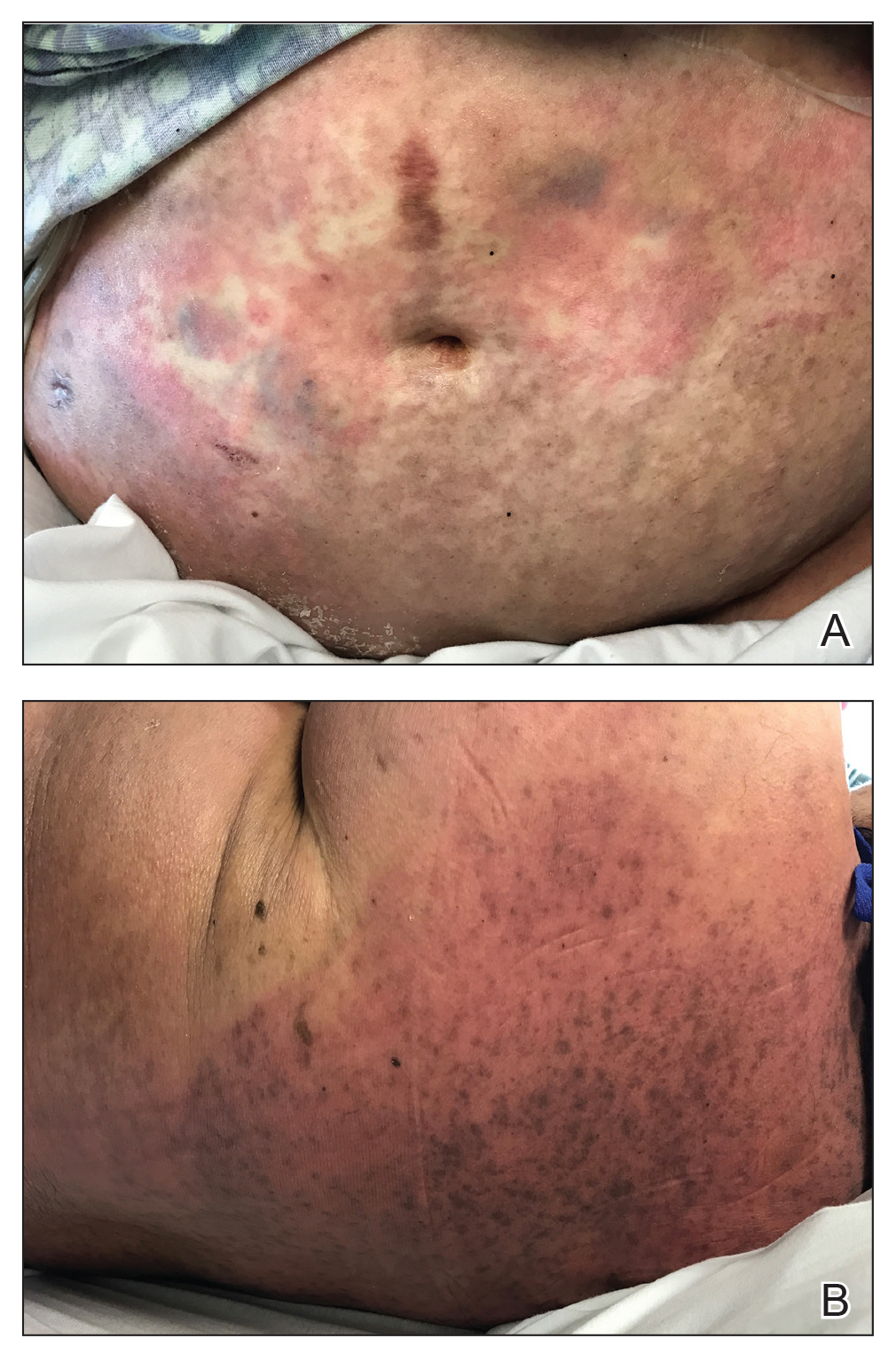

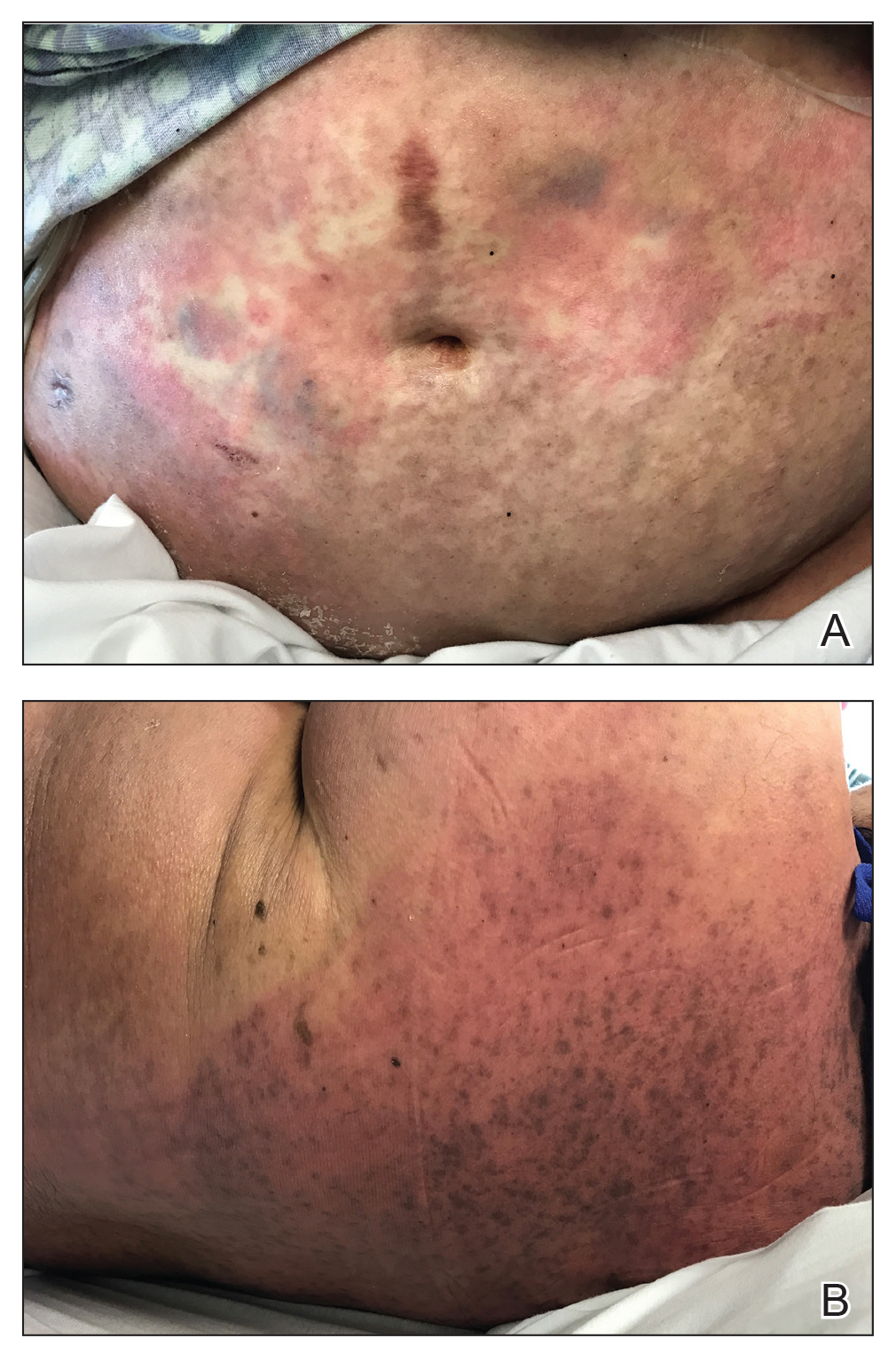

At 10 days of hospitalization, the patient developed a pruritic, nontender, erythematous rash on the abdomen, with extension onto the chest and legs. The rash was associated with low-grade fever but not with diarrhea. Physical examination was notable for a few erythematous macules and scattered papules over the neck and chest and a large erythematous plaque with multiple ecchymoses over the lower abdomen (Figure 1A). Erythematous macules and papules coalescing into plaques were present on the lower back (Figure 1B) and proximal thighs. Oral, ocular, and genital lesions were absent.

The differential diagnosis included drug reaction, viral infection, and acute GVHD. A skin biopsy was performed from the left side of the chest. Cefepime and vancomycin were discontinued; triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and antihistamines as needed for itching were started.

Over a 2-day period, the rash progressed to diffuse erythematous papules over the chest (Figure 2A) and bilateral arms (Figure 2B) including the palms. The patient also developed erythematous papules over the jawline and forehead as well as confluent erythematous plaques over the back with extension of the rash to involve the legs. She also had erythema and swelling bilaterally over the ears. She reported diarrhea. The low-grade fever resolved.

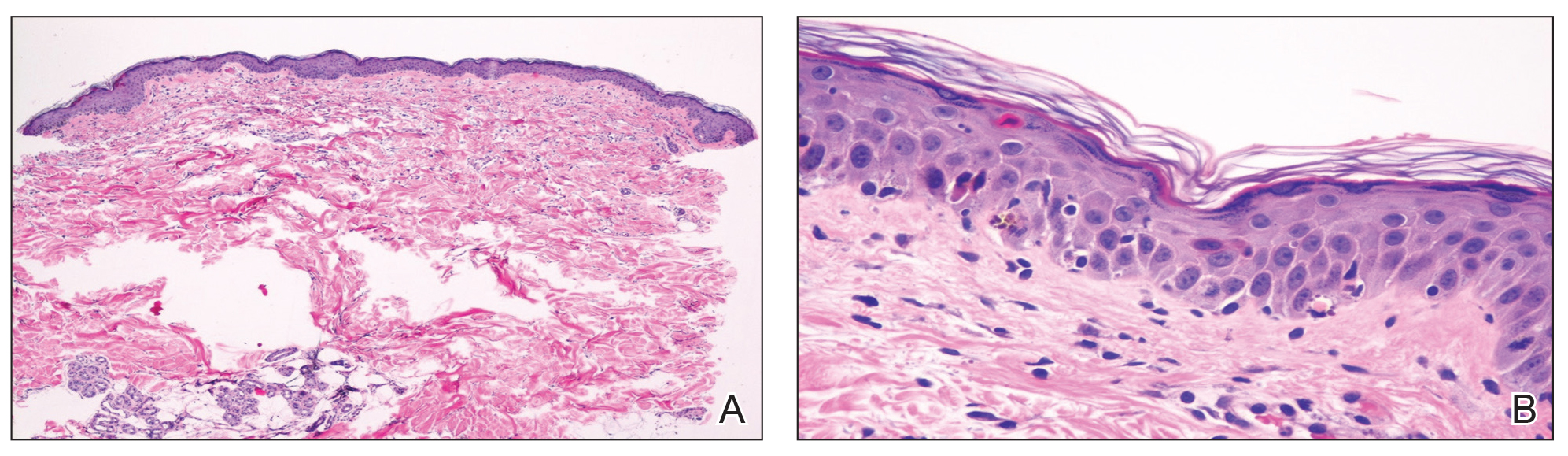

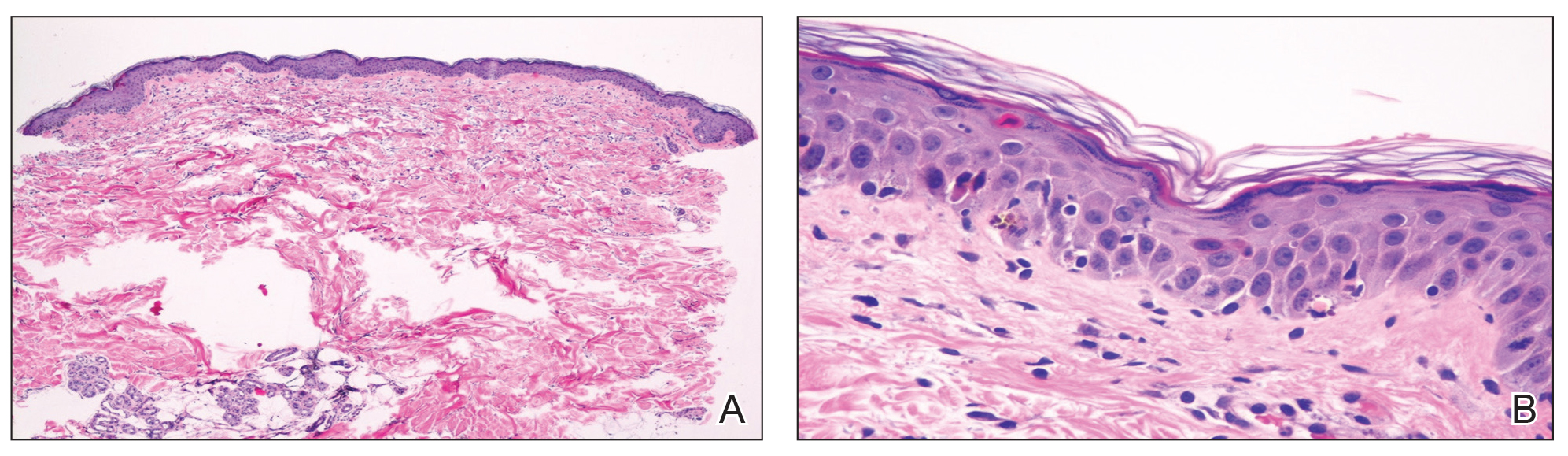

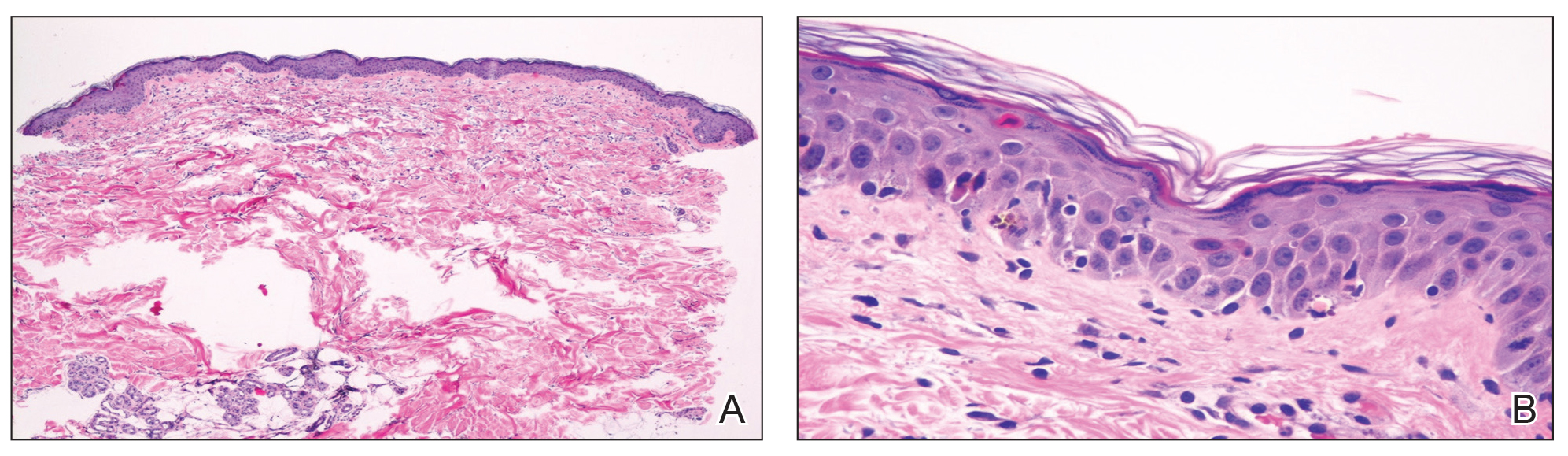

Laboratory review showed new-onset pancytopenia, normal liver function, and an elevated creatinine level of 2.3 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL), consistent with the patient’s baseline of stage 3 chronic kidney disease. Polymerase chain reaction analysis for cytomegalovirus was negative. Histology revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis with apoptotic keratinocytes, consistent with grade I GVHD (Figure 3). Duodenal biopsy revealed rare patchy glands with increased apoptosis, compatible with grade I GVHD.

The patient was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg for 3 days, then transitioned to an oral steroid taper, with improvement of the rash and other systemic symptoms.

Comment

GVHD Subtypes

The 2 types of GVHD are humoral and cellular.5 The humoral type results from ABO blood type incompatibility between donor and recipient and causes mild hemolytic anemia and fever. The cellular type is directed against major histocompatibility complexes and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.

Presentation of GVHD

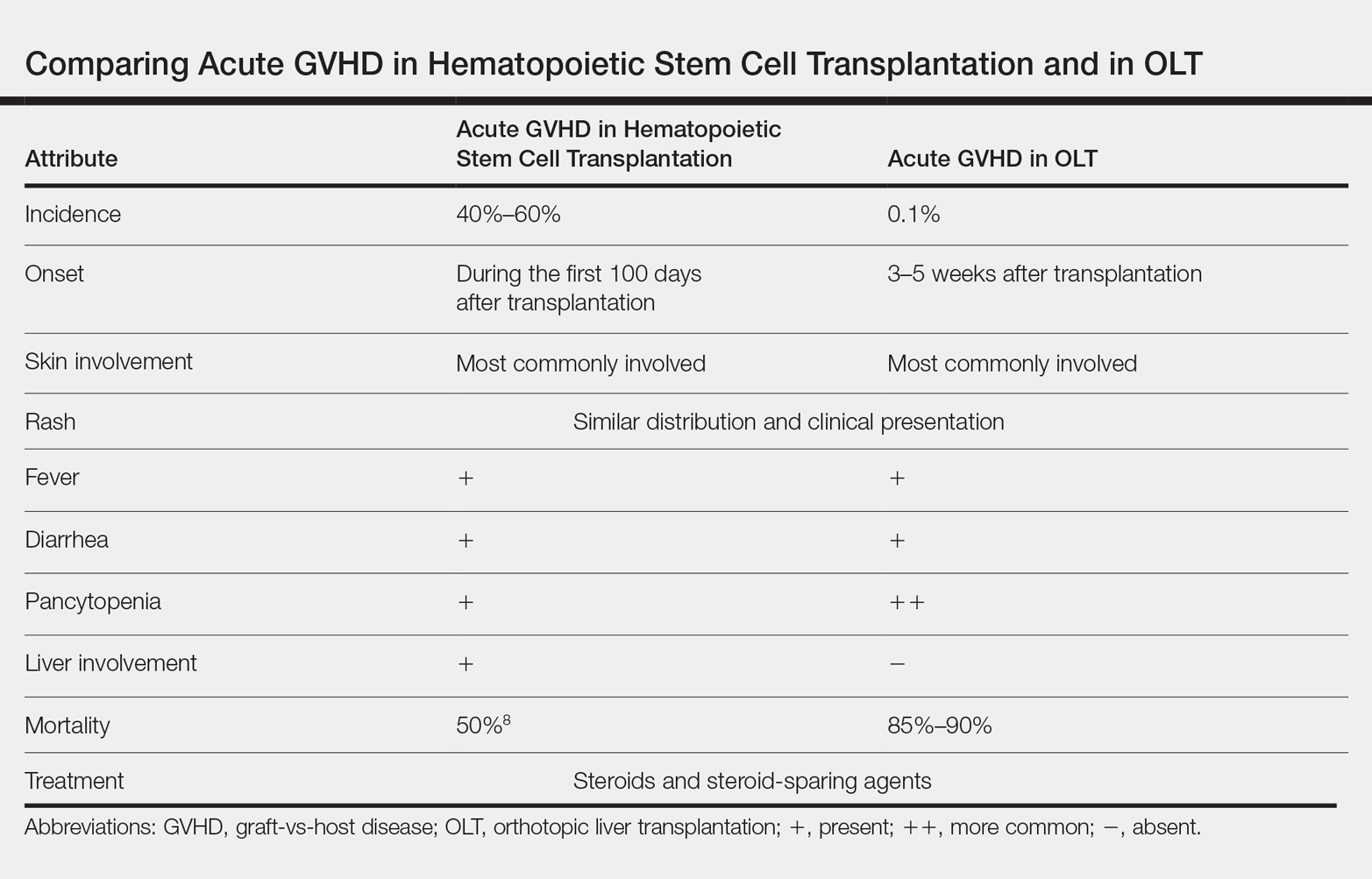

Acute GVHD following OLT usually occurs 3 to 5 weeks after transplantation,6 as in our patient. Symptoms include rash, fever, pancytopenia, and diarrhea.2 Skin is the most commonly involved organ in acute GVHD; rash is the earliest manifestation.1 The rash can be asymptomatic or associated with pain and pruritus. Initial cutaneous manifestations include palmar erythema and erythematous to violaceous discoloration of the face and ears. A diffuse maculopapular rash can develop, involving the face, abdomen, and trunk. The rash may progress to formation of bullae or skin sloughing, resembling Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis.1 The skin manifestation of acute GVHD following OLT is similar to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Table).7,8

Pancytopenia is a common manifestation of GVHD following liver transplantation and is rarely seen following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.7 Donor lymphocytes engraft and proliferate in the bone marrow, attacking recipient hematopoietic stem cells. It is important to note that more common causes of cytopenia following liver transplantation, including infection and drug-induced bone marrow suppression, should be ruled out before diagnosing acute GVHD.6

Acute GVHD can affect the gastrointestinal tract, causing diarrhea; however, other infectious and medication-induced causes of diarrhea also should be considered.6 In contrast to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, in which the liver is usually involved,1 the liver is spared in acute GVHD following liver transplantation.5

Diagnosis of GVHD

The diagnosis of acute GVHD following liver transplantation can be challenging because the clinical manifestations can be caused by a drug reaction or viral infection, such as cytomegalovirus infection.2 Patients who are older than 50 years and glucose intolerant are at a higher risk of acute GVHD following OLT. The combination of younger donor age and the presence of an HLA class I match also increases the risk of acute GVHD.6 The diagnosis of acute GVHD is confirmed with biopsy of the skin or gastrointestinal tract.

Morbidity and Mortality of GVHD

Because of the high morbidity and mortality associated with acute GVHD following liver transplantation, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial.5 Death in patients with acute GVHD following OLT is mainly attributable to sepsis, multiorgan failure, and gastrointestinal tract bleeding.6 It remains unclear whether this high mortality is associated with delayed diagnosis due to nonspecific signs of acute GVHD following OLT or to the lack of appropriate treatment guidelines.6

Treatment Options

Because of the low incidence of acute GVHD following OLT, most treatment modalities are extrapolated from the literature on acute GVHD following stem cell transplantation.5 The most commonly used therapies include high-dose systemic steroids and anti–thymocyte globulin that attacks activated donor T cells.6 Other treatment modalities, including anti–tumor necrosis factor agents and antibodies to CD20, have been reported to be effective in steroid-refractory GVHD.2 The major drawback of systemic steroids is an increase in the risk for sepsis and infection; therefore, these patients should be diligently screened for infection and covered with antibiotics and antifungals. Extracorporeal photopheresis is another treatment modality that does not cause generalized immunosuppression but is not well studied in the setting of acute GVHD following OLT.6

Prevention

Acute GVHD following OLT can be prevented by eliminating donor T lymphocytes from the liver before transplantation. However, because the incidence of acute GVHD following OLT is very low, this approach is not routinely taken.2

Conclusion

Acute GVHD following liver transplantation is a rare complication; however, it has high mortality, necessitating further research regarding treatment and prevention. Early recognition and treatment of this condition can improve outcomes. Dermatologists should be familiar with the skin manifestations of acute GVHD following liver transplantation due to the rising number of cases of solid-organ transplantation.

- Hu SW, Cotliar J. Acute graft-versus-host disease following hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:411-423.

- Akbulut S, Yilmaz M, Yilmaz S. Graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation: a comprehensive literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5240-5248.

- Taylor AL, Gibbs P, Bradley JA. Acute graft versus host disease following liver transplantation: the enemy within. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:466-474.

- Jagasia M, Arora M, Flowers ME, et al. Risk factor for acute GVHD and survival after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;119:296-307.

- Kang WH, Hwang S, Song GW, et al. Acute graft-vs-host disease after liver transplantation: experience at a high-volume liver transplantation center in Korea. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:3368-3372.

- Murali AR, Chandra S, Stewart Z, et al. Graft versus host disease after liver transplantation in adults: a case series, review of literature, and an approach to management. Transplantation. 2016;100:2661-2670.

- Chaib E, Silva FD, Figueira ER, et al. Graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66:1115-1118.

- Barton-Burke M, Dwinell DM, Kafkas L, et al. Graft-versus-host disease: a complex long-term side effect of hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Oncology (Williston Park). 2008;22(11 Suppl Nurse Ed):31-45.

Acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) is a T-cell mediated immunogenic response in which T lymphocytes from a donor regard host tissue as foreign and attack it in the setting of immunosuppression.1 The most common cause of acute GVHD is allogeneic stem cell transplantation, with solid-organ transplantation being a much less common cause.2 The incidence of acute GVHD following orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is 0.1%, as reported by the United Network for Organ Sharing, compared to an incidence of 40% to 60% in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.3,4

Early recognition and treatment of acute GVHD following liver transplantation is imperative, as the mortality rate is 85% to 90%.2 We present a case of acute GVHD in a liver transplantation patient, with a focus on diagnostic criteria and comparison to acute GVHD following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C virus infection, hepatocellular carcinoma, and OLT 1 month prior presented to the hospital with fever and abdominal cellulitis in close proximity to the surgical site of 1 week’s duration. The patient was started on vancomycin and cefepime; pan cultures were performed.

At 10 days of hospitalization, the patient developed a pruritic, nontender, erythematous rash on the abdomen, with extension onto the chest and legs. The rash was associated with low-grade fever but not with diarrhea. Physical examination was notable for a few erythematous macules and scattered papules over the neck and chest and a large erythematous plaque with multiple ecchymoses over the lower abdomen (Figure 1A). Erythematous macules and papules coalescing into plaques were present on the lower back (Figure 1B) and proximal thighs. Oral, ocular, and genital lesions were absent.

The differential diagnosis included drug reaction, viral infection, and acute GVHD. A skin biopsy was performed from the left side of the chest. Cefepime and vancomycin were discontinued; triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and antihistamines as needed for itching were started.

Over a 2-day period, the rash progressed to diffuse erythematous papules over the chest (Figure 2A) and bilateral arms (Figure 2B) including the palms. The patient also developed erythematous papules over the jawline and forehead as well as confluent erythematous plaques over the back with extension of the rash to involve the legs. She also had erythema and swelling bilaterally over the ears. She reported diarrhea. The low-grade fever resolved.

Laboratory review showed new-onset pancytopenia, normal liver function, and an elevated creatinine level of 2.3 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL), consistent with the patient’s baseline of stage 3 chronic kidney disease. Polymerase chain reaction analysis for cytomegalovirus was negative. Histology revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis with apoptotic keratinocytes, consistent with grade I GVHD (Figure 3). Duodenal biopsy revealed rare patchy glands with increased apoptosis, compatible with grade I GVHD.

The patient was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg for 3 days, then transitioned to an oral steroid taper, with improvement of the rash and other systemic symptoms.

Comment

GVHD Subtypes

The 2 types of GVHD are humoral and cellular.5 The humoral type results from ABO blood type incompatibility between donor and recipient and causes mild hemolytic anemia and fever. The cellular type is directed against major histocompatibility complexes and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.

Presentation of GVHD

Acute GVHD following OLT usually occurs 3 to 5 weeks after transplantation,6 as in our patient. Symptoms include rash, fever, pancytopenia, and diarrhea.2 Skin is the most commonly involved organ in acute GVHD; rash is the earliest manifestation.1 The rash can be asymptomatic or associated with pain and pruritus. Initial cutaneous manifestations include palmar erythema and erythematous to violaceous discoloration of the face and ears. A diffuse maculopapular rash can develop, involving the face, abdomen, and trunk. The rash may progress to formation of bullae or skin sloughing, resembling Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis.1 The skin manifestation of acute GVHD following OLT is similar to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Table).7,8

Pancytopenia is a common manifestation of GVHD following liver transplantation and is rarely seen following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.7 Donor lymphocytes engraft and proliferate in the bone marrow, attacking recipient hematopoietic stem cells. It is important to note that more common causes of cytopenia following liver transplantation, including infection and drug-induced bone marrow suppression, should be ruled out before diagnosing acute GVHD.6

Acute GVHD can affect the gastrointestinal tract, causing diarrhea; however, other infectious and medication-induced causes of diarrhea also should be considered.6 In contrast to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, in which the liver is usually involved,1 the liver is spared in acute GVHD following liver transplantation.5

Diagnosis of GVHD

The diagnosis of acute GVHD following liver transplantation can be challenging because the clinical manifestations can be caused by a drug reaction or viral infection, such as cytomegalovirus infection.2 Patients who are older than 50 years and glucose intolerant are at a higher risk of acute GVHD following OLT. The combination of younger donor age and the presence of an HLA class I match also increases the risk of acute GVHD.6 The diagnosis of acute GVHD is confirmed with biopsy of the skin or gastrointestinal tract.

Morbidity and Mortality of GVHD

Because of the high morbidity and mortality associated with acute GVHD following liver transplantation, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial.5 Death in patients with acute GVHD following OLT is mainly attributable to sepsis, multiorgan failure, and gastrointestinal tract bleeding.6 It remains unclear whether this high mortality is associated with delayed diagnosis due to nonspecific signs of acute GVHD following OLT or to the lack of appropriate treatment guidelines.6

Treatment Options

Because of the low incidence of acute GVHD following OLT, most treatment modalities are extrapolated from the literature on acute GVHD following stem cell transplantation.5 The most commonly used therapies include high-dose systemic steroids and anti–thymocyte globulin that attacks activated donor T cells.6 Other treatment modalities, including anti–tumor necrosis factor agents and antibodies to CD20, have been reported to be effective in steroid-refractory GVHD.2 The major drawback of systemic steroids is an increase in the risk for sepsis and infection; therefore, these patients should be diligently screened for infection and covered with antibiotics and antifungals. Extracorporeal photopheresis is another treatment modality that does not cause generalized immunosuppression but is not well studied in the setting of acute GVHD following OLT.6

Prevention

Acute GVHD following OLT can be prevented by eliminating donor T lymphocytes from the liver before transplantation. However, because the incidence of acute GVHD following OLT is very low, this approach is not routinely taken.2

Conclusion

Acute GVHD following liver transplantation is a rare complication; however, it has high mortality, necessitating further research regarding treatment and prevention. Early recognition and treatment of this condition can improve outcomes. Dermatologists should be familiar with the skin manifestations of acute GVHD following liver transplantation due to the rising number of cases of solid-organ transplantation.

Acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) is a T-cell mediated immunogenic response in which T lymphocytes from a donor regard host tissue as foreign and attack it in the setting of immunosuppression.1 The most common cause of acute GVHD is allogeneic stem cell transplantation, with solid-organ transplantation being a much less common cause.2 The incidence of acute GVHD following orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is 0.1%, as reported by the United Network for Organ Sharing, compared to an incidence of 40% to 60% in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.3,4

Early recognition and treatment of acute GVHD following liver transplantation is imperative, as the mortality rate is 85% to 90%.2 We present a case of acute GVHD in a liver transplantation patient, with a focus on diagnostic criteria and comparison to acute GVHD following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C virus infection, hepatocellular carcinoma, and OLT 1 month prior presented to the hospital with fever and abdominal cellulitis in close proximity to the surgical site of 1 week’s duration. The patient was started on vancomycin and cefepime; pan cultures were performed.

At 10 days of hospitalization, the patient developed a pruritic, nontender, erythematous rash on the abdomen, with extension onto the chest and legs. The rash was associated with low-grade fever but not with diarrhea. Physical examination was notable for a few erythematous macules and scattered papules over the neck and chest and a large erythematous plaque with multiple ecchymoses over the lower abdomen (Figure 1A). Erythematous macules and papules coalescing into plaques were present on the lower back (Figure 1B) and proximal thighs. Oral, ocular, and genital lesions were absent.

The differential diagnosis included drug reaction, viral infection, and acute GVHD. A skin biopsy was performed from the left side of the chest. Cefepime and vancomycin were discontinued; triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and antihistamines as needed for itching were started.

Over a 2-day period, the rash progressed to diffuse erythematous papules over the chest (Figure 2A) and bilateral arms (Figure 2B) including the palms. The patient also developed erythematous papules over the jawline and forehead as well as confluent erythematous plaques over the back with extension of the rash to involve the legs. She also had erythema and swelling bilaterally over the ears. She reported diarrhea. The low-grade fever resolved.

Laboratory review showed new-onset pancytopenia, normal liver function, and an elevated creatinine level of 2.3 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL), consistent with the patient’s baseline of stage 3 chronic kidney disease. Polymerase chain reaction analysis for cytomegalovirus was negative. Histology revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis with apoptotic keratinocytes, consistent with grade I GVHD (Figure 3). Duodenal biopsy revealed rare patchy glands with increased apoptosis, compatible with grade I GVHD.

The patient was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg for 3 days, then transitioned to an oral steroid taper, with improvement of the rash and other systemic symptoms.

Comment

GVHD Subtypes

The 2 types of GVHD are humoral and cellular.5 The humoral type results from ABO blood type incompatibility between donor and recipient and causes mild hemolytic anemia and fever. The cellular type is directed against major histocompatibility complexes and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.

Presentation of GVHD

Acute GVHD following OLT usually occurs 3 to 5 weeks after transplantation,6 as in our patient. Symptoms include rash, fever, pancytopenia, and diarrhea.2 Skin is the most commonly involved organ in acute GVHD; rash is the earliest manifestation.1 The rash can be asymptomatic or associated with pain and pruritus. Initial cutaneous manifestations include palmar erythema and erythematous to violaceous discoloration of the face and ears. A diffuse maculopapular rash can develop, involving the face, abdomen, and trunk. The rash may progress to formation of bullae or skin sloughing, resembling Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis.1 The skin manifestation of acute GVHD following OLT is similar to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Table).7,8

Pancytopenia is a common manifestation of GVHD following liver transplantation and is rarely seen following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.7 Donor lymphocytes engraft and proliferate in the bone marrow, attacking recipient hematopoietic stem cells. It is important to note that more common causes of cytopenia following liver transplantation, including infection and drug-induced bone marrow suppression, should be ruled out before diagnosing acute GVHD.6

Acute GVHD can affect the gastrointestinal tract, causing diarrhea; however, other infectious and medication-induced causes of diarrhea also should be considered.6 In contrast to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, in which the liver is usually involved,1 the liver is spared in acute GVHD following liver transplantation.5

Diagnosis of GVHD