User login

How to respond to flu vaccine doubters

The benefits of influenza vaccination are clear to those in the medical community. Yet misinformation and unfounded fears continue to discourage some people from getting a flu shot. During the 2018–2019 influenza season, only 45% of US adults and 63% of children were vaccinated.1

‘IT DOESN’T WORK FOR MANY PEOPLE’

Multiple studies have shown that the flu vaccine prevents millions of flu cases and flu-related doctor’s visits each year. During the 2016–2017 flu season, flu vaccine prevented an estimated 5.3 million influenza cases, 2.6 million influenza-associated medical visits, and 85,000 influenza-associated hospitalizations.2

Several viral and host factors affect vaccine effectiveness. In seasons when the vaccine viruses have matched circulating strains, flu vaccine has been shown to reduce the following:

- The risk of having to go to the doctor with flu by 40% to 60%

- Children’s risk of flu-related death and intensive care unit (ICU) admission by 74%

- The risk in adults of flu-associated hospitalizations by 40% and ICU admission by 82%

- The rate of cardiac events in people with heart disease

- Hospitalizations in people with diabetes or underlying chronic lung disease.3

In people hospitalized with influenza despite receiving the flu vaccine for the season, studies have shown that receiving the flu vaccine shortens the average duration of hospitalization, reduces the chance of ICU admission by 59%, shortens the duration of ICU stay by 4 days, and reduces deaths.3

‘IT TARGETS THE WRONG VIRUS’

Selecting an effective influenza vaccine is a challenge. Every year, the World Health Organization and the CDC decide on the influenza strains expected to circulate in the upcoming flu season in the Northern Hemisphere, based on data for circulating strains in the Southern Hemisphere. This decision takes place about 7 months before the expected onset of the flu season. Flu viruses may mutate between the time the decision is made and the time the vaccine is administered (as well as after the flu season starts). Also, vaccine production in eggs needs time, which is why this decision must be made several months ahead of the flu season.

Vaccine effectiveness varies by virus serotype. Vaccines are typically less effective against influenza A H3N2 viruses than against influenza A H1N1 and influenza B viruses. Effectiveness also varies from season to season depending on how close the vaccine serotypes match the circulating serotypes, but some effectiveness is retained even in seasons when some of the serotypes don’t match circulating viruses. For example, in the 2017–2018 season, when the influenza A H3N2 vaccine serotype did not match the circulating serotype, the overall effectiveness in preventing medically attended, laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infection was 36%.5

A universal flu vaccine that does not need to be updated annually is the ultimate solution, but according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, such a vaccine is likely several years away.6

‘IT MAKES PEOPLE SICK’

Pain at the injection site of a flu shot occurs in 10% to 65% of people, lasts less than 2 days, and does not usually interfere with daily activities.7

Systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, and myalgia may occur in people who have had no previous exposure to the influenza virus antigens in the vaccine, particularly in children. In adults, the frequency of systemic symptoms after the flu shot is similar to that with placebo.

The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, which has been capturing data since 1990, shows that the influenza vaccine accounted for 5.7% of people who developed malaise after receiving any vaccine.8

The injectable inactivated influenza vaccine cannot biologically cause an influenza virus-related illness, since the inactivated vaccine viruses can elicit a protective immune response but cannot replicate. The nasal live-attenuated flu vaccine can in theory cause acute illness in the person receiving it, but because it is cold-adapted, it multiplies only in the colder environment of the nasal epithelium, not in the lower airways where the temperature is higher. Consequently, the vaccine virus triggers immunity by multiplying in the nose, but doesn’t infect the lungs.

From 10% to 50% of people who receive the nasal live-attenuated vaccine develop runny nose, wheezing, headache, vomiting, muscle aches, fever, sore throat, or cough shortly after receiving the vaccine, but these symptoms are usually mild and short-lived.

The most common reactions people have to flu vaccines are considerably less severe than the symptoms caused by actual flu illness.

While influenza illness results in natural immunity to the specific viral serotype causing it, this illness results in hospitalization in 2% and is fatal in 0.16% of people. Influenza vaccine results in immunity to the serotypes included in the vaccine, and multiple studies have not found a causal relationship between vaccination and death.9

‘IT CAUSES GUILLAIN-BARRÉ SYNDROME’

In the United States, 3,000 to 6,000 people per year develop Guillain-Barré syndrome, or 1 to 2 of every 100,000, which translates to 80 to 160 cases per week.10 While the exact cause of Guillain-Barré syndrome is unknown, about two-thirds of people have an acute diarrheal or respiratory illness within 3 months before the onset of symptoms. In 1976, the estimated attributable risk of influenza vaccine-related Guillain-Barré syndrome in the US adult population was 1 case per 100,000 in the 6 weeks after vaccination.11 Studies in subsequent influenza seasons have not shown similar findings.12 In fact, one study showed that the risk of developing Guillain-Barré syndrome was 15 times higher after influenza illness than after influenza vaccination.13

Since 5% to 15% of the US population develop symptomatic influenza annually,14 the decision to vaccinate with respect to the risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome should be obvious: vaccinate. The correct question to ask before influenza vaccination should be, “Have you previously developed Guillain-Barré syndrome within 6 weeks after receiving the flu vaccine?” If the answer is yes, the CDC considers this a caution, not a contraindication against receiving the influenza vaccine, since the benefit may still outweigh the risk.

‘I GOT THE FLU SHOT AND STILL GOT SICK’

The flu vaccine does not prevent illnesses caused by other viruses or bacteria that can make people sick during flu season. Influenza, the common cold, and streptococcal pharyngitis can have similar symptoms that make it difficult for patients—and, frequently, even healthcare providers—to distinguish between these illnesses with certainty.

One study suggested that influenza vaccine recipients had an increased risk of virologically confirmed noninfluenza respiratory viral infections,15 citing the phenomenon of virus interference that was described in the 1940s16 as a potential explanation. In essence, people protected against influenza by the vaccine may lack temporary nonspecific immunity against other respiratory viruses. However, these findings have not been replicated in subsequent studies.17

Viral gastroenteritis, mistakenly called “stomach flu,” is also not prevented by influenza vaccination.

‘I’M ALLERGIC TO EGGS’

The prevalence of egg allergy in US children is 0.5% to 2.5%.18 Most outgrow it by school age, but in one-third, the allergy persists into adulthood.

In general, people who can eat lightly cooked eggs (eg, scrambled eggs) without a reaction are unlikely to be allergic. On the other hand, the fact that egg-allergic people may tolerate egg included in baked products does not exclude the possibility of egg allergy. Egg allergy can be confirmed by a consistent medical history of adverse reaction to eggs and egg-containing foods, in addition to skin or blood testing for immunoglobulin E directed against egg proteins.19

Most currently available influenza vaccines are prepared by propagation of virus in embryonated eggs and so may contain trace amounts of egg proteins such as ovalbumin, with the exception of the inactivated quadrivalent recombinant influenza vaccine (Flublok) and the inactivated quadrivalent cell culture-based vaccine (Flucelvax).

The ACIP recommends that persons with a history of urticaria (hives) after exposure to eggs should receive any licensed, recommended influenza vaccine that is otherwise appropriate for their age and health status. Persons who report having angioedema, respiratory distress, lightheadedness, or recurrent vomiting, or who required epinephrine or another emergency medical intervention after exposure to eggs, should receive the influenza vaccine in an inpatient or outpatient medical setting under the supervision of a healthcare provider who is able to recognize and manage severe allergic reactions.

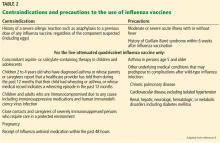

A history of severe allergic reaction such as anaphylaxis to a previous dose of any influenza vaccine, regardless of the vaccine component (including eggs) suspected of being responsible for the reaction, is a contraindication to influenza vaccination. The ACIP recommends that vaccine providers consider observing patients for 15 minutes after administration of any vaccine (regardless of history of egg allergy) to decrease the risk of injury should syncope occur.20

‘I DON’T WANT TO PUT POISONOUS MERCURY IN MY BODY’

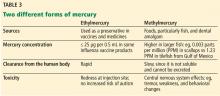

A process of biomagnification of methylmercury occurs when humans eat large fish that have eaten smaller fish. Thus, larger fish such as shark can be hazardous for women who are or may become pregnant, for nursing mothers, and for young children, while smaller fish such as herring are relatively safe.

As a precautionary measure, thimerosal was taken out of childhood vaccines in the United States in 2001. Thimerosal-free influenza vaccine formulations include the nasal live-attenuated flu vaccine, the inactivated quadrivalent recombinant influenza vaccine, and the inactivated quadrivalent cell culture-based vaccine.

‘I DON’T LIKE NEEDLES’

At least 10% of US adults have aichmophobia, the fear of sharp objects including needles.22 Vasovagal syncope is the most common manifestation. Behavioral therapy, topical anesthetics, and systemic anxiolytics have variable efficacy in treating needle phobia. For those who are absolutely averse to needles, the nasal flu vaccine is an appropriate alternative.

‘I DON’T WANT TO TAKE ANYTHING THAT CAN MESS WITH MY OTHER MEDICATIONS’

Some immunosuppressive medications may decrease influenza vaccine immunogenicity. Concomitant administration of the inactivated influenza vaccine with other vaccines is safe and does not alter immunogenicity of other vaccines.1 The live-attenuated influenza vaccine is contraindicated in children and adolescents taking aspirin or other salicylates due to the risk of Reye syndrome.

‘I’M AFRAID IT WILL TRIGGER AN IMMUNE RESPONSE THAT WILL MAKE MY ASTHMA WORSE’

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the inactivated influenza vaccine is not associated with asthma exacerbation.23 However, the nasal live-attenuated influenza vaccine is contraindicated in children 2 to 4 years old who have asthma and should be used with caution in persons with asthma 5 years old and older. In the systematic review, influenza vaccine prevented 59% to 78% of asthma attacks leading to emergency visits or hospitalization.23 In other immune-mediated diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, influenza vaccine does not precipitate exacerbations.24

‘I HAD AN ORGAN TRANSPLANT, AND I’M AFRAID THE FLU SHOT WILL CAUSE ORGAN REJECTION’

A study of 51,730 kidney transplant recipients found that receipt of the inactivated influenza vaccine in the first year after transplant was associated with a lower risk of subsequent allograft loss (adjusted hazard ratio 0.77; 95% confidence interval 0.69–0.85; P < .001) and death (adjusted hazard ratio 0.82; 95% confidence interval 0.76–0.89; P < .001).25 In the same study, although acute rejection in the first year was not associated with influenza vaccination, influenza infection in the first year was associated with rejection (odds ratio 1.58; 95% confidence interval 1.10–2.26; P < 0.001), but not with graft loss or death. Solid organ transplant recipients should receive the inactivated influenza vaccine starting 3 months after transplant.26

Influenza vaccination has not been shown to precipitate graft-vs-host disease in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. These patients should also receive the inactivated influenza vaccine starting 3 to 6 months after transplant.27

The nasal live-attenuated influenza vaccine is contraindicated in these immunocompromised patients.

‘I’M PREGNANT, AND I DON’T WANT TO EXPOSE MY UNBORN BABY TO ANYTHING POTENTIALLY HARMFUL’

The morbidity and mortality risk from influenza is high in children under 2 years old because of low immunogenicity to flu vaccine. This is particularly true in children younger than 6 months, but the vaccine is not recommended in this population. The best way to protect infants is for all household members to be vaccinated against the flu.

Equally important, morbidity and mortality risk from influenza is much higher in pregnant women than in the general population. Many studies have shown the value of influenza vaccination during pregnancy for both mothers and their infants. A recently published study showed that 18% of infants who developed influenza required hospitalization.28 In that study, prenatal and postpartum maternal influenza vaccination decreased the odds of influenza in infants by 61% and 53%, respectively. Another study showed that vaccine effectiveness did not vary by gestational age at vaccination.29 A post hoc analysis of an influenza vaccination study in pregnant women suggested that the vaccine was also associated with decreased rates of pertussis in these women.30

Healthcare providers should try to understand the public’s misconceptions31 about seasonal influenza and influenza vaccines in order to best address them.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2018–19 influenza season. www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1819estimates.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Immunogenicity, efficacy, and effectiveness of influenza vaccines. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/immunogenicity.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). What are the benefits of flu vaccination? www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/vaccine-benefits.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Broder KR, Walter EB, Fry AM, Jernigan DB. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2019–20 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep 2019; 68(3):1–21. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6803a1

- Flannery B, Chung JR, Belongia EA, et al. Interim estimates of 2017–18 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67(6):180–185. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6706a2

- Erbelding EJ, Post DJ, Stemmy EJ, et al. A universal influenza vaccine: the strategic plan for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. J Infect Dis 2018; 218(3):347–354. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiy103

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Seasonal influenza vaccine safety: a summary for clinicians. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/vaccine_safety.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). About the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). https://wonder.cdc.gov/vaers.html. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Miller ER, Moro PL, Cano M, Shimabukuro TT. Deaths following vaccination: what does the evidence show? Vaccine 2015; 33(29):3288–3292. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.023

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guillain-Barré syndrome and flu vaccine. www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/guillainbarre.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Schonberger LB, Bregman DJ, Sullivan-Bolyai JZ, et al. Guillain-Barre syndrome following vaccination in the national influenza immunization program, United States, 1976–1977. Am J Epidemiol 1979; 110(2):105–123. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112795

- Baxter R, Bakshi N, Fireman B, et al. Lack of association of Guillain-Barré syndrome with vaccinations. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57(2):197–204. doi:10.1093/cid/cit222

- Kwong JC, Vasa PP, Campitelli MA, et al. Risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome after seasonal influenza vaccination and influenza health-care encounters: a self-controlled study. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13(9):769–776. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70104-X

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Disease burden of influenza. www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Cowling BJ, Fang VJ, Nishiura H, et al. Increased risk of noninfluenza respiratory virus infections associated with receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54(12):1778–1783. doi:10.1093/cid/cis307

- Henle W, Henle G. Interference of inactive virus with the propagation of virus of influenza. Science 1943; 98(2534):87–89. doi:10.1126/science.98.2534.87

- Sundaram ME, McClure DL, VanWormer JJ, Friedrich TC, Meece JK, Belongia EA. Influenza vaccination is not associated with detection of noninfluenza respiratory viruses in seasonal studies of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57(6):789–793. doi:10.1093/cid/cit379

- Caubet JC, Wang J. Current understanding of egg allergy. Pediatr Clin North Am 2011; 58(2):427–443. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2011.02.014

- Erlewyn-Lajeunesse M, Brathwaite N, Lucas JS, Warner JO. Recommendations for the administration of influenza vaccine in children allergic to egg. BMJ 2009; 339:b3680. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3680

- Ezeanolue E, Harriman K, Hunter P, Kroger A, Pellegrini C. General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization. Best Practices Guidance of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/downloads/general-recs.pdf. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Thimerosal in vaccines. www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/thimerosal/index.html. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Hamilton JG. Needle phobia: a neglected diagnosis. J Fam Pract 1995; 41(2):169–175. pmid:7636457

- Vasileiou E, Sheikh A, Butler C, et al. Effectiveness of influenza vaccines in asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65(8):1388–1395. doi:10.1093/cid/cix524

- Fomin I, Caspi D, Levy V, et al. Vaccination against influenza in rheumatoid arthritis: the effect of disease modifying drugs, including TNF alpha blockers. Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65(2):191–194. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.036434

- Hurst FP, Lee JJ, Jindal RM, Agodoa LY, Abbott KC. Outcomes associated with influenza vaccination in the first year after kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6(5):1192–1197. doi:10.2215/CJN.05430610

- Chong PP, Handler L, Weber DJ. A systematic review of safety and immunogenicity of influenza vaccination strategies in solid organ transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(11):1802–1811. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1081

- Ljungman P, Avetisyan G. Influenza vaccination in hematopoietic SCT recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008; 42(10):637–641. doi:10.1038/bmt.2008.264

- Ohfuji S, Deguchi M, Tachibana D, et al; Osaka Pregnant Women Influenza Study Group. Protective effect of maternal influenza vaccination on influenza in their infants: a prospective cohort study. J Infect Dis 2018; 217(6):878–886. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix629

- Katz J, Englund JA, Steinhoff MC, et al. Impact of timing of influenza vaccination in pregnancy on transplacental antibody transfer, influenza incidence, and birth outcomes: a randomized trial in rural Nepal. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67(3):334–340. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy090

- Nunes MC, Cutland CL, Madhi SA. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy and protection against pertussis. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(13):1257–1258. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1705208

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Misconceptions about seasonal flu and flu vaccines. www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/misconceptions.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

The benefits of influenza vaccination are clear to those in the medical community. Yet misinformation and unfounded fears continue to discourage some people from getting a flu shot. During the 2018–2019 influenza season, only 45% of US adults and 63% of children were vaccinated.1

‘IT DOESN’T WORK FOR MANY PEOPLE’

Multiple studies have shown that the flu vaccine prevents millions of flu cases and flu-related doctor’s visits each year. During the 2016–2017 flu season, flu vaccine prevented an estimated 5.3 million influenza cases, 2.6 million influenza-associated medical visits, and 85,000 influenza-associated hospitalizations.2

Several viral and host factors affect vaccine effectiveness. In seasons when the vaccine viruses have matched circulating strains, flu vaccine has been shown to reduce the following:

- The risk of having to go to the doctor with flu by 40% to 60%

- Children’s risk of flu-related death and intensive care unit (ICU) admission by 74%

- The risk in adults of flu-associated hospitalizations by 40% and ICU admission by 82%

- The rate of cardiac events in people with heart disease

- Hospitalizations in people with diabetes or underlying chronic lung disease.3

In people hospitalized with influenza despite receiving the flu vaccine for the season, studies have shown that receiving the flu vaccine shortens the average duration of hospitalization, reduces the chance of ICU admission by 59%, shortens the duration of ICU stay by 4 days, and reduces deaths.3

‘IT TARGETS THE WRONG VIRUS’

Selecting an effective influenza vaccine is a challenge. Every year, the World Health Organization and the CDC decide on the influenza strains expected to circulate in the upcoming flu season in the Northern Hemisphere, based on data for circulating strains in the Southern Hemisphere. This decision takes place about 7 months before the expected onset of the flu season. Flu viruses may mutate between the time the decision is made and the time the vaccine is administered (as well as after the flu season starts). Also, vaccine production in eggs needs time, which is why this decision must be made several months ahead of the flu season.

Vaccine effectiveness varies by virus serotype. Vaccines are typically less effective against influenza A H3N2 viruses than against influenza A H1N1 and influenza B viruses. Effectiveness also varies from season to season depending on how close the vaccine serotypes match the circulating serotypes, but some effectiveness is retained even in seasons when some of the serotypes don’t match circulating viruses. For example, in the 2017–2018 season, when the influenza A H3N2 vaccine serotype did not match the circulating serotype, the overall effectiveness in preventing medically attended, laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infection was 36%.5

A universal flu vaccine that does not need to be updated annually is the ultimate solution, but according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, such a vaccine is likely several years away.6

‘IT MAKES PEOPLE SICK’

Pain at the injection site of a flu shot occurs in 10% to 65% of people, lasts less than 2 days, and does not usually interfere with daily activities.7

Systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, and myalgia may occur in people who have had no previous exposure to the influenza virus antigens in the vaccine, particularly in children. In adults, the frequency of systemic symptoms after the flu shot is similar to that with placebo.

The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, which has been capturing data since 1990, shows that the influenza vaccine accounted for 5.7% of people who developed malaise after receiving any vaccine.8

The injectable inactivated influenza vaccine cannot biologically cause an influenza virus-related illness, since the inactivated vaccine viruses can elicit a protective immune response but cannot replicate. The nasal live-attenuated flu vaccine can in theory cause acute illness in the person receiving it, but because it is cold-adapted, it multiplies only in the colder environment of the nasal epithelium, not in the lower airways where the temperature is higher. Consequently, the vaccine virus triggers immunity by multiplying in the nose, but doesn’t infect the lungs.

From 10% to 50% of people who receive the nasal live-attenuated vaccine develop runny nose, wheezing, headache, vomiting, muscle aches, fever, sore throat, or cough shortly after receiving the vaccine, but these symptoms are usually mild and short-lived.

The most common reactions people have to flu vaccines are considerably less severe than the symptoms caused by actual flu illness.

While influenza illness results in natural immunity to the specific viral serotype causing it, this illness results in hospitalization in 2% and is fatal in 0.16% of people. Influenza vaccine results in immunity to the serotypes included in the vaccine, and multiple studies have not found a causal relationship between vaccination and death.9

‘IT CAUSES GUILLAIN-BARRÉ SYNDROME’

In the United States, 3,000 to 6,000 people per year develop Guillain-Barré syndrome, or 1 to 2 of every 100,000, which translates to 80 to 160 cases per week.10 While the exact cause of Guillain-Barré syndrome is unknown, about two-thirds of people have an acute diarrheal or respiratory illness within 3 months before the onset of symptoms. In 1976, the estimated attributable risk of influenza vaccine-related Guillain-Barré syndrome in the US adult population was 1 case per 100,000 in the 6 weeks after vaccination.11 Studies in subsequent influenza seasons have not shown similar findings.12 In fact, one study showed that the risk of developing Guillain-Barré syndrome was 15 times higher after influenza illness than after influenza vaccination.13

Since 5% to 15% of the US population develop symptomatic influenza annually,14 the decision to vaccinate with respect to the risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome should be obvious: vaccinate. The correct question to ask before influenza vaccination should be, “Have you previously developed Guillain-Barré syndrome within 6 weeks after receiving the flu vaccine?” If the answer is yes, the CDC considers this a caution, not a contraindication against receiving the influenza vaccine, since the benefit may still outweigh the risk.

‘I GOT THE FLU SHOT AND STILL GOT SICK’

The flu vaccine does not prevent illnesses caused by other viruses or bacteria that can make people sick during flu season. Influenza, the common cold, and streptococcal pharyngitis can have similar symptoms that make it difficult for patients—and, frequently, even healthcare providers—to distinguish between these illnesses with certainty.

One study suggested that influenza vaccine recipients had an increased risk of virologically confirmed noninfluenza respiratory viral infections,15 citing the phenomenon of virus interference that was described in the 1940s16 as a potential explanation. In essence, people protected against influenza by the vaccine may lack temporary nonspecific immunity against other respiratory viruses. However, these findings have not been replicated in subsequent studies.17

Viral gastroenteritis, mistakenly called “stomach flu,” is also not prevented by influenza vaccination.

‘I’M ALLERGIC TO EGGS’

The prevalence of egg allergy in US children is 0.5% to 2.5%.18 Most outgrow it by school age, but in one-third, the allergy persists into adulthood.

In general, people who can eat lightly cooked eggs (eg, scrambled eggs) without a reaction are unlikely to be allergic. On the other hand, the fact that egg-allergic people may tolerate egg included in baked products does not exclude the possibility of egg allergy. Egg allergy can be confirmed by a consistent medical history of adverse reaction to eggs and egg-containing foods, in addition to skin or blood testing for immunoglobulin E directed against egg proteins.19

Most currently available influenza vaccines are prepared by propagation of virus in embryonated eggs and so may contain trace amounts of egg proteins such as ovalbumin, with the exception of the inactivated quadrivalent recombinant influenza vaccine (Flublok) and the inactivated quadrivalent cell culture-based vaccine (Flucelvax).

The ACIP recommends that persons with a history of urticaria (hives) after exposure to eggs should receive any licensed, recommended influenza vaccine that is otherwise appropriate for their age and health status. Persons who report having angioedema, respiratory distress, lightheadedness, or recurrent vomiting, or who required epinephrine or another emergency medical intervention after exposure to eggs, should receive the influenza vaccine in an inpatient or outpatient medical setting under the supervision of a healthcare provider who is able to recognize and manage severe allergic reactions.

A history of severe allergic reaction such as anaphylaxis to a previous dose of any influenza vaccine, regardless of the vaccine component (including eggs) suspected of being responsible for the reaction, is a contraindication to influenza vaccination. The ACIP recommends that vaccine providers consider observing patients for 15 minutes after administration of any vaccine (regardless of history of egg allergy) to decrease the risk of injury should syncope occur.20

‘I DON’T WANT TO PUT POISONOUS MERCURY IN MY BODY’

A process of biomagnification of methylmercury occurs when humans eat large fish that have eaten smaller fish. Thus, larger fish such as shark can be hazardous for women who are or may become pregnant, for nursing mothers, and for young children, while smaller fish such as herring are relatively safe.

As a precautionary measure, thimerosal was taken out of childhood vaccines in the United States in 2001. Thimerosal-free influenza vaccine formulations include the nasal live-attenuated flu vaccine, the inactivated quadrivalent recombinant influenza vaccine, and the inactivated quadrivalent cell culture-based vaccine.

‘I DON’T LIKE NEEDLES’

At least 10% of US adults have aichmophobia, the fear of sharp objects including needles.22 Vasovagal syncope is the most common manifestation. Behavioral therapy, topical anesthetics, and systemic anxiolytics have variable efficacy in treating needle phobia. For those who are absolutely averse to needles, the nasal flu vaccine is an appropriate alternative.

‘I DON’T WANT TO TAKE ANYTHING THAT CAN MESS WITH MY OTHER MEDICATIONS’

Some immunosuppressive medications may decrease influenza vaccine immunogenicity. Concomitant administration of the inactivated influenza vaccine with other vaccines is safe and does not alter immunogenicity of other vaccines.1 The live-attenuated influenza vaccine is contraindicated in children and adolescents taking aspirin or other salicylates due to the risk of Reye syndrome.

‘I’M AFRAID IT WILL TRIGGER AN IMMUNE RESPONSE THAT WILL MAKE MY ASTHMA WORSE’

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the inactivated influenza vaccine is not associated with asthma exacerbation.23 However, the nasal live-attenuated influenza vaccine is contraindicated in children 2 to 4 years old who have asthma and should be used with caution in persons with asthma 5 years old and older. In the systematic review, influenza vaccine prevented 59% to 78% of asthma attacks leading to emergency visits or hospitalization.23 In other immune-mediated diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, influenza vaccine does not precipitate exacerbations.24

‘I HAD AN ORGAN TRANSPLANT, AND I’M AFRAID THE FLU SHOT WILL CAUSE ORGAN REJECTION’

A study of 51,730 kidney transplant recipients found that receipt of the inactivated influenza vaccine in the first year after transplant was associated with a lower risk of subsequent allograft loss (adjusted hazard ratio 0.77; 95% confidence interval 0.69–0.85; P < .001) and death (adjusted hazard ratio 0.82; 95% confidence interval 0.76–0.89; P < .001).25 In the same study, although acute rejection in the first year was not associated with influenza vaccination, influenza infection in the first year was associated with rejection (odds ratio 1.58; 95% confidence interval 1.10–2.26; P < 0.001), but not with graft loss or death. Solid organ transplant recipients should receive the inactivated influenza vaccine starting 3 months after transplant.26

Influenza vaccination has not been shown to precipitate graft-vs-host disease in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. These patients should also receive the inactivated influenza vaccine starting 3 to 6 months after transplant.27

The nasal live-attenuated influenza vaccine is contraindicated in these immunocompromised patients.

‘I’M PREGNANT, AND I DON’T WANT TO EXPOSE MY UNBORN BABY TO ANYTHING POTENTIALLY HARMFUL’

The morbidity and mortality risk from influenza is high in children under 2 years old because of low immunogenicity to flu vaccine. This is particularly true in children younger than 6 months, but the vaccine is not recommended in this population. The best way to protect infants is for all household members to be vaccinated against the flu.

Equally important, morbidity and mortality risk from influenza is much higher in pregnant women than in the general population. Many studies have shown the value of influenza vaccination during pregnancy for both mothers and their infants. A recently published study showed that 18% of infants who developed influenza required hospitalization.28 In that study, prenatal and postpartum maternal influenza vaccination decreased the odds of influenza in infants by 61% and 53%, respectively. Another study showed that vaccine effectiveness did not vary by gestational age at vaccination.29 A post hoc analysis of an influenza vaccination study in pregnant women suggested that the vaccine was also associated with decreased rates of pertussis in these women.30

Healthcare providers should try to understand the public’s misconceptions31 about seasonal influenza and influenza vaccines in order to best address them.

The benefits of influenza vaccination are clear to those in the medical community. Yet misinformation and unfounded fears continue to discourage some people from getting a flu shot. During the 2018–2019 influenza season, only 45% of US adults and 63% of children were vaccinated.1

‘IT DOESN’T WORK FOR MANY PEOPLE’

Multiple studies have shown that the flu vaccine prevents millions of flu cases and flu-related doctor’s visits each year. During the 2016–2017 flu season, flu vaccine prevented an estimated 5.3 million influenza cases, 2.6 million influenza-associated medical visits, and 85,000 influenza-associated hospitalizations.2

Several viral and host factors affect vaccine effectiveness. In seasons when the vaccine viruses have matched circulating strains, flu vaccine has been shown to reduce the following:

- The risk of having to go to the doctor with flu by 40% to 60%

- Children’s risk of flu-related death and intensive care unit (ICU) admission by 74%

- The risk in adults of flu-associated hospitalizations by 40% and ICU admission by 82%

- The rate of cardiac events in people with heart disease

- Hospitalizations in people with diabetes or underlying chronic lung disease.3

In people hospitalized with influenza despite receiving the flu vaccine for the season, studies have shown that receiving the flu vaccine shortens the average duration of hospitalization, reduces the chance of ICU admission by 59%, shortens the duration of ICU stay by 4 days, and reduces deaths.3

‘IT TARGETS THE WRONG VIRUS’

Selecting an effective influenza vaccine is a challenge. Every year, the World Health Organization and the CDC decide on the influenza strains expected to circulate in the upcoming flu season in the Northern Hemisphere, based on data for circulating strains in the Southern Hemisphere. This decision takes place about 7 months before the expected onset of the flu season. Flu viruses may mutate between the time the decision is made and the time the vaccine is administered (as well as after the flu season starts). Also, vaccine production in eggs needs time, which is why this decision must be made several months ahead of the flu season.

Vaccine effectiveness varies by virus serotype. Vaccines are typically less effective against influenza A H3N2 viruses than against influenza A H1N1 and influenza B viruses. Effectiveness also varies from season to season depending on how close the vaccine serotypes match the circulating serotypes, but some effectiveness is retained even in seasons when some of the serotypes don’t match circulating viruses. For example, in the 2017–2018 season, when the influenza A H3N2 vaccine serotype did not match the circulating serotype, the overall effectiveness in preventing medically attended, laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infection was 36%.5

A universal flu vaccine that does not need to be updated annually is the ultimate solution, but according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, such a vaccine is likely several years away.6

‘IT MAKES PEOPLE SICK’

Pain at the injection site of a flu shot occurs in 10% to 65% of people, lasts less than 2 days, and does not usually interfere with daily activities.7

Systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, and myalgia may occur in people who have had no previous exposure to the influenza virus antigens in the vaccine, particularly in children. In adults, the frequency of systemic symptoms after the flu shot is similar to that with placebo.

The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, which has been capturing data since 1990, shows that the influenza vaccine accounted for 5.7% of people who developed malaise after receiving any vaccine.8

The injectable inactivated influenza vaccine cannot biologically cause an influenza virus-related illness, since the inactivated vaccine viruses can elicit a protective immune response but cannot replicate. The nasal live-attenuated flu vaccine can in theory cause acute illness in the person receiving it, but because it is cold-adapted, it multiplies only in the colder environment of the nasal epithelium, not in the lower airways where the temperature is higher. Consequently, the vaccine virus triggers immunity by multiplying in the nose, but doesn’t infect the lungs.

From 10% to 50% of people who receive the nasal live-attenuated vaccine develop runny nose, wheezing, headache, vomiting, muscle aches, fever, sore throat, or cough shortly after receiving the vaccine, but these symptoms are usually mild and short-lived.

The most common reactions people have to flu vaccines are considerably less severe than the symptoms caused by actual flu illness.

While influenza illness results in natural immunity to the specific viral serotype causing it, this illness results in hospitalization in 2% and is fatal in 0.16% of people. Influenza vaccine results in immunity to the serotypes included in the vaccine, and multiple studies have not found a causal relationship between vaccination and death.9

‘IT CAUSES GUILLAIN-BARRÉ SYNDROME’

In the United States, 3,000 to 6,000 people per year develop Guillain-Barré syndrome, or 1 to 2 of every 100,000, which translates to 80 to 160 cases per week.10 While the exact cause of Guillain-Barré syndrome is unknown, about two-thirds of people have an acute diarrheal or respiratory illness within 3 months before the onset of symptoms. In 1976, the estimated attributable risk of influenza vaccine-related Guillain-Barré syndrome in the US adult population was 1 case per 100,000 in the 6 weeks after vaccination.11 Studies in subsequent influenza seasons have not shown similar findings.12 In fact, one study showed that the risk of developing Guillain-Barré syndrome was 15 times higher after influenza illness than after influenza vaccination.13

Since 5% to 15% of the US population develop symptomatic influenza annually,14 the decision to vaccinate with respect to the risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome should be obvious: vaccinate. The correct question to ask before influenza vaccination should be, “Have you previously developed Guillain-Barré syndrome within 6 weeks after receiving the flu vaccine?” If the answer is yes, the CDC considers this a caution, not a contraindication against receiving the influenza vaccine, since the benefit may still outweigh the risk.

‘I GOT THE FLU SHOT AND STILL GOT SICK’

The flu vaccine does not prevent illnesses caused by other viruses or bacteria that can make people sick during flu season. Influenza, the common cold, and streptococcal pharyngitis can have similar symptoms that make it difficult for patients—and, frequently, even healthcare providers—to distinguish between these illnesses with certainty.

One study suggested that influenza vaccine recipients had an increased risk of virologically confirmed noninfluenza respiratory viral infections,15 citing the phenomenon of virus interference that was described in the 1940s16 as a potential explanation. In essence, people protected against influenza by the vaccine may lack temporary nonspecific immunity against other respiratory viruses. However, these findings have not been replicated in subsequent studies.17

Viral gastroenteritis, mistakenly called “stomach flu,” is also not prevented by influenza vaccination.

‘I’M ALLERGIC TO EGGS’

The prevalence of egg allergy in US children is 0.5% to 2.5%.18 Most outgrow it by school age, but in one-third, the allergy persists into adulthood.

In general, people who can eat lightly cooked eggs (eg, scrambled eggs) without a reaction are unlikely to be allergic. On the other hand, the fact that egg-allergic people may tolerate egg included in baked products does not exclude the possibility of egg allergy. Egg allergy can be confirmed by a consistent medical history of adverse reaction to eggs and egg-containing foods, in addition to skin or blood testing for immunoglobulin E directed against egg proteins.19

Most currently available influenza vaccines are prepared by propagation of virus in embryonated eggs and so may contain trace amounts of egg proteins such as ovalbumin, with the exception of the inactivated quadrivalent recombinant influenza vaccine (Flublok) and the inactivated quadrivalent cell culture-based vaccine (Flucelvax).

The ACIP recommends that persons with a history of urticaria (hives) after exposure to eggs should receive any licensed, recommended influenza vaccine that is otherwise appropriate for their age and health status. Persons who report having angioedema, respiratory distress, lightheadedness, or recurrent vomiting, or who required epinephrine or another emergency medical intervention after exposure to eggs, should receive the influenza vaccine in an inpatient or outpatient medical setting under the supervision of a healthcare provider who is able to recognize and manage severe allergic reactions.

A history of severe allergic reaction such as anaphylaxis to a previous dose of any influenza vaccine, regardless of the vaccine component (including eggs) suspected of being responsible for the reaction, is a contraindication to influenza vaccination. The ACIP recommends that vaccine providers consider observing patients for 15 minutes after administration of any vaccine (regardless of history of egg allergy) to decrease the risk of injury should syncope occur.20

‘I DON’T WANT TO PUT POISONOUS MERCURY IN MY BODY’

A process of biomagnification of methylmercury occurs when humans eat large fish that have eaten smaller fish. Thus, larger fish such as shark can be hazardous for women who are or may become pregnant, for nursing mothers, and for young children, while smaller fish such as herring are relatively safe.

As a precautionary measure, thimerosal was taken out of childhood vaccines in the United States in 2001. Thimerosal-free influenza vaccine formulations include the nasal live-attenuated flu vaccine, the inactivated quadrivalent recombinant influenza vaccine, and the inactivated quadrivalent cell culture-based vaccine.

‘I DON’T LIKE NEEDLES’

At least 10% of US adults have aichmophobia, the fear of sharp objects including needles.22 Vasovagal syncope is the most common manifestation. Behavioral therapy, topical anesthetics, and systemic anxiolytics have variable efficacy in treating needle phobia. For those who are absolutely averse to needles, the nasal flu vaccine is an appropriate alternative.

‘I DON’T WANT TO TAKE ANYTHING THAT CAN MESS WITH MY OTHER MEDICATIONS’

Some immunosuppressive medications may decrease influenza vaccine immunogenicity. Concomitant administration of the inactivated influenza vaccine with other vaccines is safe and does not alter immunogenicity of other vaccines.1 The live-attenuated influenza vaccine is contraindicated in children and adolescents taking aspirin or other salicylates due to the risk of Reye syndrome.

‘I’M AFRAID IT WILL TRIGGER AN IMMUNE RESPONSE THAT WILL MAKE MY ASTHMA WORSE’

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the inactivated influenza vaccine is not associated with asthma exacerbation.23 However, the nasal live-attenuated influenza vaccine is contraindicated in children 2 to 4 years old who have asthma and should be used with caution in persons with asthma 5 years old and older. In the systematic review, influenza vaccine prevented 59% to 78% of asthma attacks leading to emergency visits or hospitalization.23 In other immune-mediated diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, influenza vaccine does not precipitate exacerbations.24

‘I HAD AN ORGAN TRANSPLANT, AND I’M AFRAID THE FLU SHOT WILL CAUSE ORGAN REJECTION’

A study of 51,730 kidney transplant recipients found that receipt of the inactivated influenza vaccine in the first year after transplant was associated with a lower risk of subsequent allograft loss (adjusted hazard ratio 0.77; 95% confidence interval 0.69–0.85; P < .001) and death (adjusted hazard ratio 0.82; 95% confidence interval 0.76–0.89; P < .001).25 In the same study, although acute rejection in the first year was not associated with influenza vaccination, influenza infection in the first year was associated with rejection (odds ratio 1.58; 95% confidence interval 1.10–2.26; P < 0.001), but not with graft loss or death. Solid organ transplant recipients should receive the inactivated influenza vaccine starting 3 months after transplant.26

Influenza vaccination has not been shown to precipitate graft-vs-host disease in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. These patients should also receive the inactivated influenza vaccine starting 3 to 6 months after transplant.27

The nasal live-attenuated influenza vaccine is contraindicated in these immunocompromised patients.

‘I’M PREGNANT, AND I DON’T WANT TO EXPOSE MY UNBORN BABY TO ANYTHING POTENTIALLY HARMFUL’

The morbidity and mortality risk from influenza is high in children under 2 years old because of low immunogenicity to flu vaccine. This is particularly true in children younger than 6 months, but the vaccine is not recommended in this population. The best way to protect infants is for all household members to be vaccinated against the flu.

Equally important, morbidity and mortality risk from influenza is much higher in pregnant women than in the general population. Many studies have shown the value of influenza vaccination during pregnancy for both mothers and their infants. A recently published study showed that 18% of infants who developed influenza required hospitalization.28 In that study, prenatal and postpartum maternal influenza vaccination decreased the odds of influenza in infants by 61% and 53%, respectively. Another study showed that vaccine effectiveness did not vary by gestational age at vaccination.29 A post hoc analysis of an influenza vaccination study in pregnant women suggested that the vaccine was also associated with decreased rates of pertussis in these women.30

Healthcare providers should try to understand the public’s misconceptions31 about seasonal influenza and influenza vaccines in order to best address them.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2018–19 influenza season. www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1819estimates.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Immunogenicity, efficacy, and effectiveness of influenza vaccines. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/immunogenicity.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). What are the benefits of flu vaccination? www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/vaccine-benefits.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Broder KR, Walter EB, Fry AM, Jernigan DB. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2019–20 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep 2019; 68(3):1–21. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6803a1

- Flannery B, Chung JR, Belongia EA, et al. Interim estimates of 2017–18 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67(6):180–185. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6706a2

- Erbelding EJ, Post DJ, Stemmy EJ, et al. A universal influenza vaccine: the strategic plan for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. J Infect Dis 2018; 218(3):347–354. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiy103

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Seasonal influenza vaccine safety: a summary for clinicians. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/vaccine_safety.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). About the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). https://wonder.cdc.gov/vaers.html. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Miller ER, Moro PL, Cano M, Shimabukuro TT. Deaths following vaccination: what does the evidence show? Vaccine 2015; 33(29):3288–3292. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.023

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guillain-Barré syndrome and flu vaccine. www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/guillainbarre.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Schonberger LB, Bregman DJ, Sullivan-Bolyai JZ, et al. Guillain-Barre syndrome following vaccination in the national influenza immunization program, United States, 1976–1977. Am J Epidemiol 1979; 110(2):105–123. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112795

- Baxter R, Bakshi N, Fireman B, et al. Lack of association of Guillain-Barré syndrome with vaccinations. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57(2):197–204. doi:10.1093/cid/cit222

- Kwong JC, Vasa PP, Campitelli MA, et al. Risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome after seasonal influenza vaccination and influenza health-care encounters: a self-controlled study. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13(9):769–776. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70104-X

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Disease burden of influenza. www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Cowling BJ, Fang VJ, Nishiura H, et al. Increased risk of noninfluenza respiratory virus infections associated with receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54(12):1778–1783. doi:10.1093/cid/cis307

- Henle W, Henle G. Interference of inactive virus with the propagation of virus of influenza. Science 1943; 98(2534):87–89. doi:10.1126/science.98.2534.87

- Sundaram ME, McClure DL, VanWormer JJ, Friedrich TC, Meece JK, Belongia EA. Influenza vaccination is not associated with detection of noninfluenza respiratory viruses in seasonal studies of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57(6):789–793. doi:10.1093/cid/cit379

- Caubet JC, Wang J. Current understanding of egg allergy. Pediatr Clin North Am 2011; 58(2):427–443. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2011.02.014

- Erlewyn-Lajeunesse M, Brathwaite N, Lucas JS, Warner JO. Recommendations for the administration of influenza vaccine in children allergic to egg. BMJ 2009; 339:b3680. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3680

- Ezeanolue E, Harriman K, Hunter P, Kroger A, Pellegrini C. General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization. Best Practices Guidance of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/downloads/general-recs.pdf. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Thimerosal in vaccines. www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/thimerosal/index.html. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Hamilton JG. Needle phobia: a neglected diagnosis. J Fam Pract 1995; 41(2):169–175. pmid:7636457

- Vasileiou E, Sheikh A, Butler C, et al. Effectiveness of influenza vaccines in asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65(8):1388–1395. doi:10.1093/cid/cix524

- Fomin I, Caspi D, Levy V, et al. Vaccination against influenza in rheumatoid arthritis: the effect of disease modifying drugs, including TNF alpha blockers. Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65(2):191–194. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.036434

- Hurst FP, Lee JJ, Jindal RM, Agodoa LY, Abbott KC. Outcomes associated with influenza vaccination in the first year after kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6(5):1192–1197. doi:10.2215/CJN.05430610

- Chong PP, Handler L, Weber DJ. A systematic review of safety and immunogenicity of influenza vaccination strategies in solid organ transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(11):1802–1811. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1081

- Ljungman P, Avetisyan G. Influenza vaccination in hematopoietic SCT recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008; 42(10):637–641. doi:10.1038/bmt.2008.264

- Ohfuji S, Deguchi M, Tachibana D, et al; Osaka Pregnant Women Influenza Study Group. Protective effect of maternal influenza vaccination on influenza in their infants: a prospective cohort study. J Infect Dis 2018; 217(6):878–886. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix629

- Katz J, Englund JA, Steinhoff MC, et al. Impact of timing of influenza vaccination in pregnancy on transplacental antibody transfer, influenza incidence, and birth outcomes: a randomized trial in rural Nepal. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67(3):334–340. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy090

- Nunes MC, Cutland CL, Madhi SA. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy and protection against pertussis. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(13):1257–1258. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1705208

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Misconceptions about seasonal flu and flu vaccines. www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/misconceptions.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2018–19 influenza season. www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1819estimates.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Immunogenicity, efficacy, and effectiveness of influenza vaccines. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/immunogenicity.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). What are the benefits of flu vaccination? www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/vaccine-benefits.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Broder KR, Walter EB, Fry AM, Jernigan DB. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2019–20 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep 2019; 68(3):1–21. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6803a1

- Flannery B, Chung JR, Belongia EA, et al. Interim estimates of 2017–18 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67(6):180–185. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6706a2

- Erbelding EJ, Post DJ, Stemmy EJ, et al. A universal influenza vaccine: the strategic plan for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. J Infect Dis 2018; 218(3):347–354. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiy103

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Seasonal influenza vaccine safety: a summary for clinicians. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/vaccine_safety.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). About the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). https://wonder.cdc.gov/vaers.html. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Miller ER, Moro PL, Cano M, Shimabukuro TT. Deaths following vaccination: what does the evidence show? Vaccine 2015; 33(29):3288–3292. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.023

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guillain-Barré syndrome and flu vaccine. www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/guillainbarre.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Schonberger LB, Bregman DJ, Sullivan-Bolyai JZ, et al. Guillain-Barre syndrome following vaccination in the national influenza immunization program, United States, 1976–1977. Am J Epidemiol 1979; 110(2):105–123. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112795

- Baxter R, Bakshi N, Fireman B, et al. Lack of association of Guillain-Barré syndrome with vaccinations. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57(2):197–204. doi:10.1093/cid/cit222

- Kwong JC, Vasa PP, Campitelli MA, et al. Risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome after seasonal influenza vaccination and influenza health-care encounters: a self-controlled study. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13(9):769–776. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70104-X

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Disease burden of influenza. www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Cowling BJ, Fang VJ, Nishiura H, et al. Increased risk of noninfluenza respiratory virus infections associated with receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54(12):1778–1783. doi:10.1093/cid/cis307

- Henle W, Henle G. Interference of inactive virus with the propagation of virus of influenza. Science 1943; 98(2534):87–89. doi:10.1126/science.98.2534.87

- Sundaram ME, McClure DL, VanWormer JJ, Friedrich TC, Meece JK, Belongia EA. Influenza vaccination is not associated with detection of noninfluenza respiratory viruses in seasonal studies of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57(6):789–793. doi:10.1093/cid/cit379

- Caubet JC, Wang J. Current understanding of egg allergy. Pediatr Clin North Am 2011; 58(2):427–443. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2011.02.014

- Erlewyn-Lajeunesse M, Brathwaite N, Lucas JS, Warner JO. Recommendations for the administration of influenza vaccine in children allergic to egg. BMJ 2009; 339:b3680. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3680

- Ezeanolue E, Harriman K, Hunter P, Kroger A, Pellegrini C. General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization. Best Practices Guidance of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/downloads/general-recs.pdf. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Thimerosal in vaccines. www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/thimerosal/index.html. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- Hamilton JG. Needle phobia: a neglected diagnosis. J Fam Pract 1995; 41(2):169–175. pmid:7636457

- Vasileiou E, Sheikh A, Butler C, et al. Effectiveness of influenza vaccines in asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65(8):1388–1395. doi:10.1093/cid/cix524

- Fomin I, Caspi D, Levy V, et al. Vaccination against influenza in rheumatoid arthritis: the effect of disease modifying drugs, including TNF alpha blockers. Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65(2):191–194. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.036434

- Hurst FP, Lee JJ, Jindal RM, Agodoa LY, Abbott KC. Outcomes associated with influenza vaccination in the first year after kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6(5):1192–1197. doi:10.2215/CJN.05430610

- Chong PP, Handler L, Weber DJ. A systematic review of safety and immunogenicity of influenza vaccination strategies in solid organ transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(11):1802–1811. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1081

- Ljungman P, Avetisyan G. Influenza vaccination in hematopoietic SCT recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008; 42(10):637–641. doi:10.1038/bmt.2008.264

- Ohfuji S, Deguchi M, Tachibana D, et al; Osaka Pregnant Women Influenza Study Group. Protective effect of maternal influenza vaccination on influenza in their infants: a prospective cohort study. J Infect Dis 2018; 217(6):878–886. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix629

- Katz J, Englund JA, Steinhoff MC, et al. Impact of timing of influenza vaccination in pregnancy on transplacental antibody transfer, influenza incidence, and birth outcomes: a randomized trial in rural Nepal. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67(3):334–340. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy090

- Nunes MC, Cutland CL, Madhi SA. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy and protection against pertussis. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(13):1257–1258. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1705208

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Misconceptions about seasonal flu and flu vaccines. www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/misconceptions.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

Click for Credit: PPI use & dementia; Weight loss after gastroplasty; more

Here are 5 articles from the December issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Sustainable weight loss seen 5 years after endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/37lteRX

Expires May 16, 2020

2. PT beats steroid injections for knee OA

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2KIWKY6

Expires May 17, 2020

3. Better screening needed to reduce pregnancy-related overdose, death

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2XEZyuG

Expires May 17, 2020

4. Meta-analysis finds no link between PPI use and risk of dementia

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Xzs7JM

Expires June 3, 2020

5. Study: Cardiac biomarkers predicted CV events in CAP

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/33bAH2u

Expires August 13, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the December issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Sustainable weight loss seen 5 years after endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/37lteRX

Expires May 16, 2020

2. PT beats steroid injections for knee OA

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2KIWKY6

Expires May 17, 2020

3. Better screening needed to reduce pregnancy-related overdose, death

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2XEZyuG

Expires May 17, 2020

4. Meta-analysis finds no link between PPI use and risk of dementia

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Xzs7JM

Expires June 3, 2020

5. Study: Cardiac biomarkers predicted CV events in CAP

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/33bAH2u

Expires August 13, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the December issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Sustainable weight loss seen 5 years after endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/37lteRX

Expires May 16, 2020

2. PT beats steroid injections for knee OA

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2KIWKY6

Expires May 17, 2020

3. Better screening needed to reduce pregnancy-related overdose, death

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2XEZyuG

Expires May 17, 2020

4. Meta-analysis finds no link between PPI use and risk of dementia

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Xzs7JM

Expires June 3, 2020

5. Study: Cardiac biomarkers predicted CV events in CAP

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/33bAH2u

Expires August 13, 2020

ART treatment at birth found to benefit neonates with HIV

Initiating antiretroviral therapy within an hour after birth, rather than waiting a few weeks, lowers the reservoir of HIV virus and improves immune response, early results from an ongoing study in Botswana, Africa, showed.

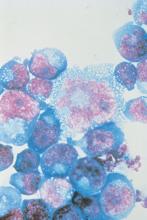

Despite advances in treatment programs during pregnancy that prevent mother to child HIV transmission, 300-500 pediatric HIV infections occur each day in sub-Saharan Africa, Roger Shapiro, MD, MPH, said during a media teleconference organized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “Most pediatric HIV diagnosis programs currently test children at 4-6 weeks of age to identify infections that occur either in pregnancy or during delivery,” said Dr. Shapiro, associate professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. “However, these programs miss the opportunity to begin immediate antiretroviral treatment for children who can be identified earlier. There are benefits to starting treatment and arresting HIV replication in the first week of life. These include limiting the viral reservoir or the population of infected cells, limiting potentially harmful immune responses to the virus, and preventing the rapid decline in health that can occur in the early weeks of HIV infection in infants. Without treatment, 50% of HIV-infected children regress to death by 2 years. Starting treatment in the first weeks or months of life has been shown to improve survival.”

With these benefits in mind, he and his associates initiated the Early Infant Treatment (EIT) study in 2015 to diagnose and treat HIV infected infants in Botswana in the first week of life or as early as possible after infection. They screened more than 10,000 children and identified 40 that were HIV infected. “This low transmission rate is a testament to the fact that most HIV-positive women in Botswana receive three-drug treatment in pregnancy, which is highly successful in blocking transmission,” Dr. Shapiro said. “When we identified an HIV-infected infant, we consented mothers to allow us to start treatment right away. We used a series of regimens because there are limited options. The available options include older drugs, some of which are no longer used for adults but which were the only options for children.”

The researchers initiated three initial drugs approved for newborns: nevirapine, zidovudine, and lamivudine, and then changed the regimen slightly after a few weeks, when they used ritonavir-boosted lopinavir, plus the lamivudine and zidovudine. “We followed the children weekly at first, then at monthly refill visits, and kept close track of how they were taking the medicines and the level of virus in each child’s blood,” Dr. Shapiro said.

In a manuscript published online in Science Translational Medicine on Nov. 27, 2019, he and his associates reported results of the first 10 children enrolled in the EIT study who reached about 96 weeks on treatment. For comparison, they also enrolled a group of children as controls, who started treatment later in the first year of life, after being identified at a more standard time of 4-6 weeks. Tests performed included droplet digital polymerase chain reaction, HIV near-full-genome sequencing, whole-genome amplification, and flow cytometry.

“What we wanted to focus on are the HIV reservoir cells that are persisting in the setting of antiretroviral treatment,” study coauthor Mathias Lichterfeld, MD, PhD, explained during the teleconference. “Those are the cells that would cause viral rebound if treatment were to be interrupted. We used complex technology to look at these cells, using next-generation sequencing, which allows us to identify those cells that harbor HIV that has the ability to initiate new viral replication.”

He and his colleagues observed that the number of reservoir cells was significantly smaller than in adults who were on ART for a median of 16 years. It also was smaller than in infected infants who started ART treatment weeks after birth.

In addition, immune activation was reduced in the cohort of infants who were treated immediately after birth.

“We are seeing a distinct advantage of early treatment initiation,” said Dr. Lichterfeld of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. “By doing these assays we see both virological benefits in terms of a very-low reservoir size, and we see immune system characteristics that are also associated with better abilities for antimicrobial immune defense and a lower level of immune activation.”

Another study coauthor, Daniel R. Kuritzkes, MD, chief of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, said the findings show “how critically important” it is to extend studies of HIV cure or long-term remission to infants and children. “Very-early intervention in neonates limits the size of the reservoir and offers us the best opportunity for future interventions aimed at cure and long-term drug-free remission of HIV infection,” he said. “We don’t think the current intervention is itself curative, but it sets the stage for the capacity to offer additional innovative interventions in the future. Beyond the importance of this work for cure research per se, this very early intervention in neonates also has the potential of conferring important clinical benefits to the children who participated in this study. Finally, our study demonstrates the feasibility and importance of doing this type of research in neonates in resource-limited settings, given the appropriate infrastructure.”

EIT is supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lichterfeld disclosed having received speaking and consulting honoraria from Merck and Gilead. Dr. Kuritzkes disclosed having received consulting honoraria and/or research support from Gilead, Merck, and ViiV.

SOURCE: Garcia-Broncano P et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Nov 27. eaax7350.

Initiating antiretroviral therapy within an hour after birth, rather than waiting a few weeks, lowers the reservoir of HIV virus and improves immune response, early results from an ongoing study in Botswana, Africa, showed.

Despite advances in treatment programs during pregnancy that prevent mother to child HIV transmission, 300-500 pediatric HIV infections occur each day in sub-Saharan Africa, Roger Shapiro, MD, MPH, said during a media teleconference organized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “Most pediatric HIV diagnosis programs currently test children at 4-6 weeks of age to identify infections that occur either in pregnancy or during delivery,” said Dr. Shapiro, associate professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. “However, these programs miss the opportunity to begin immediate antiretroviral treatment for children who can be identified earlier. There are benefits to starting treatment and arresting HIV replication in the first week of life. These include limiting the viral reservoir or the population of infected cells, limiting potentially harmful immune responses to the virus, and preventing the rapid decline in health that can occur in the early weeks of HIV infection in infants. Without treatment, 50% of HIV-infected children regress to death by 2 years. Starting treatment in the first weeks or months of life has been shown to improve survival.”

With these benefits in mind, he and his associates initiated the Early Infant Treatment (EIT) study in 2015 to diagnose and treat HIV infected infants in Botswana in the first week of life or as early as possible after infection. They screened more than 10,000 children and identified 40 that were HIV infected. “This low transmission rate is a testament to the fact that most HIV-positive women in Botswana receive three-drug treatment in pregnancy, which is highly successful in blocking transmission,” Dr. Shapiro said. “When we identified an HIV-infected infant, we consented mothers to allow us to start treatment right away. We used a series of regimens because there are limited options. The available options include older drugs, some of which are no longer used for adults but which were the only options for children.”

The researchers initiated three initial drugs approved for newborns: nevirapine, zidovudine, and lamivudine, and then changed the regimen slightly after a few weeks, when they used ritonavir-boosted lopinavir, plus the lamivudine and zidovudine. “We followed the children weekly at first, then at monthly refill visits, and kept close track of how they were taking the medicines and the level of virus in each child’s blood,” Dr. Shapiro said.

In a manuscript published online in Science Translational Medicine on Nov. 27, 2019, he and his associates reported results of the first 10 children enrolled in the EIT study who reached about 96 weeks on treatment. For comparison, they also enrolled a group of children as controls, who started treatment later in the first year of life, after being identified at a more standard time of 4-6 weeks. Tests performed included droplet digital polymerase chain reaction, HIV near-full-genome sequencing, whole-genome amplification, and flow cytometry.

“What we wanted to focus on are the HIV reservoir cells that are persisting in the setting of antiretroviral treatment,” study coauthor Mathias Lichterfeld, MD, PhD, explained during the teleconference. “Those are the cells that would cause viral rebound if treatment were to be interrupted. We used complex technology to look at these cells, using next-generation sequencing, which allows us to identify those cells that harbor HIV that has the ability to initiate new viral replication.”

He and his colleagues observed that the number of reservoir cells was significantly smaller than in adults who were on ART for a median of 16 years. It also was smaller than in infected infants who started ART treatment weeks after birth.

In addition, immune activation was reduced in the cohort of infants who were treated immediately after birth.

“We are seeing a distinct advantage of early treatment initiation,” said Dr. Lichterfeld of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. “By doing these assays we see both virological benefits in terms of a very-low reservoir size, and we see immune system characteristics that are also associated with better abilities for antimicrobial immune defense and a lower level of immune activation.”

Another study coauthor, Daniel R. Kuritzkes, MD, chief of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, said the findings show “how critically important” it is to extend studies of HIV cure or long-term remission to infants and children. “Very-early intervention in neonates limits the size of the reservoir and offers us the best opportunity for future interventions aimed at cure and long-term drug-free remission of HIV infection,” he said. “We don’t think the current intervention is itself curative, but it sets the stage for the capacity to offer additional innovative interventions in the future. Beyond the importance of this work for cure research per se, this very early intervention in neonates also has the potential of conferring important clinical benefits to the children who participated in this study. Finally, our study demonstrates the feasibility and importance of doing this type of research in neonates in resource-limited settings, given the appropriate infrastructure.”

EIT is supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lichterfeld disclosed having received speaking and consulting honoraria from Merck and Gilead. Dr. Kuritzkes disclosed having received consulting honoraria and/or research support from Gilead, Merck, and ViiV.

SOURCE: Garcia-Broncano P et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Nov 27. eaax7350.

Initiating antiretroviral therapy within an hour after birth, rather than waiting a few weeks, lowers the reservoir of HIV virus and improves immune response, early results from an ongoing study in Botswana, Africa, showed.

Despite advances in treatment programs during pregnancy that prevent mother to child HIV transmission, 300-500 pediatric HIV infections occur each day in sub-Saharan Africa, Roger Shapiro, MD, MPH, said during a media teleconference organized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “Most pediatric HIV diagnosis programs currently test children at 4-6 weeks of age to identify infections that occur either in pregnancy or during delivery,” said Dr. Shapiro, associate professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. “However, these programs miss the opportunity to begin immediate antiretroviral treatment for children who can be identified earlier. There are benefits to starting treatment and arresting HIV replication in the first week of life. These include limiting the viral reservoir or the population of infected cells, limiting potentially harmful immune responses to the virus, and preventing the rapid decline in health that can occur in the early weeks of HIV infection in infants. Without treatment, 50% of HIV-infected children regress to death by 2 years. Starting treatment in the first weeks or months of life has been shown to improve survival.”

With these benefits in mind, he and his associates initiated the Early Infant Treatment (EIT) study in 2015 to diagnose and treat HIV infected infants in Botswana in the first week of life or as early as possible after infection. They screened more than 10,000 children and identified 40 that were HIV infected. “This low transmission rate is a testament to the fact that most HIV-positive women in Botswana receive three-drug treatment in pregnancy, which is highly successful in blocking transmission,” Dr. Shapiro said. “When we identified an HIV-infected infant, we consented mothers to allow us to start treatment right away. We used a series of regimens because there are limited options. The available options include older drugs, some of which are no longer used for adults but which were the only options for children.”

The researchers initiated three initial drugs approved for newborns: nevirapine, zidovudine, and lamivudine, and then changed the regimen slightly after a few weeks, when they used ritonavir-boosted lopinavir, plus the lamivudine and zidovudine. “We followed the children weekly at first, then at monthly refill visits, and kept close track of how they were taking the medicines and the level of virus in each child’s blood,” Dr. Shapiro said.