User login

Three major COVID vaccine developers release detailed trial protocols

Typically, manufacturers guard the specifics of preclinical vaccine trials. This rare move follows calls for greater transparency. For example, the American Medical Association wrote a letter in late August asking the Food and Drug Administration to keep physicians informed of their COVID-19 vaccine review process.

On September 17, ModernaTx released the phase 3 trial protocol for its mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. In short order, on September 19, Pfizer/BioNTech shared their phase 1/2/3 trial vaccine protocol. AstraZeneca, which is developing a vaccine along with Oxford University, also released its protocol.

The AstraZeneca vaccine trial made headlines recently for having to be temporarily halted because of unexpected illnesses that arose in two participants, according to the New York Times and other sources.

“I applaud the release of the clinical trial protocols by the companies. The public trust in any COVID-19 vaccine is paramount, especially given the fast timeline and perceived political pressures of these candidates,” Robert Kruse, MD, PhD, told Medscape Medical News when asked to comment.

AstraZeneca takes a shot at transparency

The three primary objectives of the AstraZeneca AZD1222 trial outlined in the 110-page protocol include estimating the efficacy, safety, tolerability, and reactogenicity associated with two intramuscular doses of the vaccine in comparison with placebo in adults.

The projected enrollment is 30,000 participants, and the estimated primary completion date is Dec. 2, 2020, according to information on clinicaltrials.gov.

“Given the unprecedented global impact of the coronavirus pandemic and the need for public information, AstraZeneca has published the detailed protocol and design of our AZD1222 clinical trial,” the company said in a statement. “As with most clinical development, protocols are not typically shared publicly due to the importance of maintaining confidentiality and integrity of trials.

“AstraZeneca continues to work with industry peers to ensure a consistent approach to sharing timely clinical trial information,” the company added.

Moderna methodology

The ModernaTX 135-page protocol outlines the primary trial objectives of evaluating efficacy, safety, and reactogenicity of two injections of the vaccine administered 28 days apart. Researchers also plan to randomly assign 30,000 adults to receive either vaccine or placebo. The estimated primary completion date is Oct. 27, 2022.

A statement that was requested from ModernaTX was not received by press time.

Pfizer protocol

In the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine trial, researchers plan to evaluate different doses in different age groups in a multistep protocol. The trial features 20 primary safety objectives, which include reporting adverse events and serious adverse events, including any local or systemic events.

Efficacy endpoints are secondary objectives. The estimated enrollment is 29,481 adults; the estimated primary completion date is April 19, 2021.

“Pfizer and BioNTech recognize that the COVID-19 pandemic is a unique circumstance, and the need for transparency is clear,” Pfizer spokesperson Sharon Castillo told Medscape Medical News. By making the full protocol available, “we believe this will reinforce our long-standing commitment to scientific and regulatory rigor that benefits patients,” she said.

“Based on current infection rates, Pfizer and BioNTech continue to expect that a conclusive read-out on efficacy is likely by the end of October. Neither Pfizer nor the FDA can move faster than the data we are generating through our clinical trial,” Castillo said.

If clinical work and regulatory approval or authorization proceed as planned, Pfizer and BioNTech expect to supply up to 100 million doses worldwide by the end of 2020 and approximately 1.3 billion doses worldwide by the end of 2021.

Pfizer is not willing to sacrifice safety and efficacy in the name of expediency, Castillo said. “We will not cut corners in this pursuit. Patient safety is our highest priority, and Pfizer will not bring a vaccine to market without adequate evidence of safety and efficacy.”

A positive move

“COVID-19 vaccines will only be useful if many people are willing to receive them,” said Kruse, a postgraduate year 3 resident in the Department of Pathology at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“By giving the general public along with other scientists and physicians the opportunity to critique the protocols, everyone can understand what the metrics would be for an early look at efficacy,” Kruse said. He noted that information could help inform a potential FDA emergency use authorization.

Kruse has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Typically, manufacturers guard the specifics of preclinical vaccine trials. This rare move follows calls for greater transparency. For example, the American Medical Association wrote a letter in late August asking the Food and Drug Administration to keep physicians informed of their COVID-19 vaccine review process.

On September 17, ModernaTx released the phase 3 trial protocol for its mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. In short order, on September 19, Pfizer/BioNTech shared their phase 1/2/3 trial vaccine protocol. AstraZeneca, which is developing a vaccine along with Oxford University, also released its protocol.

The AstraZeneca vaccine trial made headlines recently for having to be temporarily halted because of unexpected illnesses that arose in two participants, according to the New York Times and other sources.

“I applaud the release of the clinical trial protocols by the companies. The public trust in any COVID-19 vaccine is paramount, especially given the fast timeline and perceived political pressures of these candidates,” Robert Kruse, MD, PhD, told Medscape Medical News when asked to comment.

AstraZeneca takes a shot at transparency

The three primary objectives of the AstraZeneca AZD1222 trial outlined in the 110-page protocol include estimating the efficacy, safety, tolerability, and reactogenicity associated with two intramuscular doses of the vaccine in comparison with placebo in adults.

The projected enrollment is 30,000 participants, and the estimated primary completion date is Dec. 2, 2020, according to information on clinicaltrials.gov.

“Given the unprecedented global impact of the coronavirus pandemic and the need for public information, AstraZeneca has published the detailed protocol and design of our AZD1222 clinical trial,” the company said in a statement. “As with most clinical development, protocols are not typically shared publicly due to the importance of maintaining confidentiality and integrity of trials.

“AstraZeneca continues to work with industry peers to ensure a consistent approach to sharing timely clinical trial information,” the company added.

Moderna methodology

The ModernaTX 135-page protocol outlines the primary trial objectives of evaluating efficacy, safety, and reactogenicity of two injections of the vaccine administered 28 days apart. Researchers also plan to randomly assign 30,000 adults to receive either vaccine or placebo. The estimated primary completion date is Oct. 27, 2022.

A statement that was requested from ModernaTX was not received by press time.

Pfizer protocol

In the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine trial, researchers plan to evaluate different doses in different age groups in a multistep protocol. The trial features 20 primary safety objectives, which include reporting adverse events and serious adverse events, including any local or systemic events.

Efficacy endpoints are secondary objectives. The estimated enrollment is 29,481 adults; the estimated primary completion date is April 19, 2021.

“Pfizer and BioNTech recognize that the COVID-19 pandemic is a unique circumstance, and the need for transparency is clear,” Pfizer spokesperson Sharon Castillo told Medscape Medical News. By making the full protocol available, “we believe this will reinforce our long-standing commitment to scientific and regulatory rigor that benefits patients,” she said.

“Based on current infection rates, Pfizer and BioNTech continue to expect that a conclusive read-out on efficacy is likely by the end of October. Neither Pfizer nor the FDA can move faster than the data we are generating through our clinical trial,” Castillo said.

If clinical work and regulatory approval or authorization proceed as planned, Pfizer and BioNTech expect to supply up to 100 million doses worldwide by the end of 2020 and approximately 1.3 billion doses worldwide by the end of 2021.

Pfizer is not willing to sacrifice safety and efficacy in the name of expediency, Castillo said. “We will not cut corners in this pursuit. Patient safety is our highest priority, and Pfizer will not bring a vaccine to market without adequate evidence of safety and efficacy.”

A positive move

“COVID-19 vaccines will only be useful if many people are willing to receive them,” said Kruse, a postgraduate year 3 resident in the Department of Pathology at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“By giving the general public along with other scientists and physicians the opportunity to critique the protocols, everyone can understand what the metrics would be for an early look at efficacy,” Kruse said. He noted that information could help inform a potential FDA emergency use authorization.

Kruse has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Typically, manufacturers guard the specifics of preclinical vaccine trials. This rare move follows calls for greater transparency. For example, the American Medical Association wrote a letter in late August asking the Food and Drug Administration to keep physicians informed of their COVID-19 vaccine review process.

On September 17, ModernaTx released the phase 3 trial protocol for its mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. In short order, on September 19, Pfizer/BioNTech shared their phase 1/2/3 trial vaccine protocol. AstraZeneca, which is developing a vaccine along with Oxford University, also released its protocol.

The AstraZeneca vaccine trial made headlines recently for having to be temporarily halted because of unexpected illnesses that arose in two participants, according to the New York Times and other sources.

“I applaud the release of the clinical trial protocols by the companies. The public trust in any COVID-19 vaccine is paramount, especially given the fast timeline and perceived political pressures of these candidates,” Robert Kruse, MD, PhD, told Medscape Medical News when asked to comment.

AstraZeneca takes a shot at transparency

The three primary objectives of the AstraZeneca AZD1222 trial outlined in the 110-page protocol include estimating the efficacy, safety, tolerability, and reactogenicity associated with two intramuscular doses of the vaccine in comparison with placebo in adults.

The projected enrollment is 30,000 participants, and the estimated primary completion date is Dec. 2, 2020, according to information on clinicaltrials.gov.

“Given the unprecedented global impact of the coronavirus pandemic and the need for public information, AstraZeneca has published the detailed protocol and design of our AZD1222 clinical trial,” the company said in a statement. “As with most clinical development, protocols are not typically shared publicly due to the importance of maintaining confidentiality and integrity of trials.

“AstraZeneca continues to work with industry peers to ensure a consistent approach to sharing timely clinical trial information,” the company added.

Moderna methodology

The ModernaTX 135-page protocol outlines the primary trial objectives of evaluating efficacy, safety, and reactogenicity of two injections of the vaccine administered 28 days apart. Researchers also plan to randomly assign 30,000 adults to receive either vaccine or placebo. The estimated primary completion date is Oct. 27, 2022.

A statement that was requested from ModernaTX was not received by press time.

Pfizer protocol

In the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine trial, researchers plan to evaluate different doses in different age groups in a multistep protocol. The trial features 20 primary safety objectives, which include reporting adverse events and serious adverse events, including any local or systemic events.

Efficacy endpoints are secondary objectives. The estimated enrollment is 29,481 adults; the estimated primary completion date is April 19, 2021.

“Pfizer and BioNTech recognize that the COVID-19 pandemic is a unique circumstance, and the need for transparency is clear,” Pfizer spokesperson Sharon Castillo told Medscape Medical News. By making the full protocol available, “we believe this will reinforce our long-standing commitment to scientific and regulatory rigor that benefits patients,” she said.

“Based on current infection rates, Pfizer and BioNTech continue to expect that a conclusive read-out on efficacy is likely by the end of October. Neither Pfizer nor the FDA can move faster than the data we are generating through our clinical trial,” Castillo said.

If clinical work and regulatory approval or authorization proceed as planned, Pfizer and BioNTech expect to supply up to 100 million doses worldwide by the end of 2020 and approximately 1.3 billion doses worldwide by the end of 2021.

Pfizer is not willing to sacrifice safety and efficacy in the name of expediency, Castillo said. “We will not cut corners in this pursuit. Patient safety is our highest priority, and Pfizer will not bring a vaccine to market without adequate evidence of safety and efficacy.”

A positive move

“COVID-19 vaccines will only be useful if many people are willing to receive them,” said Kruse, a postgraduate year 3 resident in the Department of Pathology at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“By giving the general public along with other scientists and physicians the opportunity to critique the protocols, everyone can understand what the metrics would be for an early look at efficacy,” Kruse said. He noted that information could help inform a potential FDA emergency use authorization.

Kruse has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children’s share of COVID-19 burden continues to increase

Children continue to represent an increasing proportion of reported COVID-19 cases in the United States, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The previous week, children represented 10.0% of all cases, and that proportion has continued to rise throughout the pandemic, the AAP and CHA report shows.

Looking at just new cases for the latest week, the 38,000+ pediatric cases made up almost 17% of the 228,396 cases reported for all ages, compared with 16% and 15% the two previous weeks. For the weeks ending Aug. 13 and Aug. 6, the corresponding figures were 8% and 13%, based on the data in the AAP/CHA report, which cover 49 states (New York City but not New York state), the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The state with the highest proportion of child COVID-19 cases as of Sept. 17 was Wyoming, with 20.6%, followed by North Dakota at 18.3% and Tennessee at 17.9%. New York City has a cumulative rate of just 3.4%, but New Jersey is the state with the lowest rate at 3.6%. Florida comes in at 5.9% but is using an age range of 0-14 years for children, and Texas has a rate of 6.0% but has reported ages for only 8% of confirmed cases, the AAP and CHA noted.

Severe illness, however, continues to be rare in children. The overall hospitalization rate for children was down to 1.7% among the 26 jurisdictions providing ages as Sept. 17 – down from 1.8% the week before and 2.3% on Aug. 20. The death rate is just 0.02% among 43 jurisdictions, the report said.

Children continue to represent an increasing proportion of reported COVID-19 cases in the United States, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The previous week, children represented 10.0% of all cases, and that proportion has continued to rise throughout the pandemic, the AAP and CHA report shows.

Looking at just new cases for the latest week, the 38,000+ pediatric cases made up almost 17% of the 228,396 cases reported for all ages, compared with 16% and 15% the two previous weeks. For the weeks ending Aug. 13 and Aug. 6, the corresponding figures were 8% and 13%, based on the data in the AAP/CHA report, which cover 49 states (New York City but not New York state), the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The state with the highest proportion of child COVID-19 cases as of Sept. 17 was Wyoming, with 20.6%, followed by North Dakota at 18.3% and Tennessee at 17.9%. New York City has a cumulative rate of just 3.4%, but New Jersey is the state with the lowest rate at 3.6%. Florida comes in at 5.9% but is using an age range of 0-14 years for children, and Texas has a rate of 6.0% but has reported ages for only 8% of confirmed cases, the AAP and CHA noted.

Severe illness, however, continues to be rare in children. The overall hospitalization rate for children was down to 1.7% among the 26 jurisdictions providing ages as Sept. 17 – down from 1.8% the week before and 2.3% on Aug. 20. The death rate is just 0.02% among 43 jurisdictions, the report said.

Children continue to represent an increasing proportion of reported COVID-19 cases in the United States, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The previous week, children represented 10.0% of all cases, and that proportion has continued to rise throughout the pandemic, the AAP and CHA report shows.

Looking at just new cases for the latest week, the 38,000+ pediatric cases made up almost 17% of the 228,396 cases reported for all ages, compared with 16% and 15% the two previous weeks. For the weeks ending Aug. 13 and Aug. 6, the corresponding figures were 8% and 13%, based on the data in the AAP/CHA report, which cover 49 states (New York City but not New York state), the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The state with the highest proportion of child COVID-19 cases as of Sept. 17 was Wyoming, with 20.6%, followed by North Dakota at 18.3% and Tennessee at 17.9%. New York City has a cumulative rate of just 3.4%, but New Jersey is the state with the lowest rate at 3.6%. Florida comes in at 5.9% but is using an age range of 0-14 years for children, and Texas has a rate of 6.0% but has reported ages for only 8% of confirmed cases, the AAP and CHA noted.

Severe illness, however, continues to be rare in children. The overall hospitalization rate for children was down to 1.7% among the 26 jurisdictions providing ages as Sept. 17 – down from 1.8% the week before and 2.3% on Aug. 20. The death rate is just 0.02% among 43 jurisdictions, the report said.

Signs of an ‘October vaccine surprise’ alarm career scientists

who have pledged not to release any vaccine unless it’s proved safe and effective.

In podcasts, public forums, social media and medical journals, a growing number of prominent health leaders say they fear that Mr. Trump – who has repeatedly signaled his desire for the swift approval of a vaccine and his displeasure with perceived delays at the FDA – will take matters into his own hands, running roughshod over the usual regulatory process.

It would reflect another attempt by a norm-breaking administration, poised to ram through a Supreme Court nominee opposed to existing abortion rights and the Affordable Care Act, to inject politics into sensitive public health decisions. Mr. Trump has repeatedly contradicted the advice of senior scientists on COVID-19 while pushing controversial treatments for the disease.

If the executive branch were to overrule the FDA’s scientific judgment, a vaccine of limited efficacy and, worse, unknown side effects could be rushed to market.

The worries intensified over the weekend, after Alex Azar, the administration’s secretary of Health & Human Services, asserted his agency’s rule-making authority over the FDA. HHS spokesperson Caitlin Oakley said Mr. Azar’s decision had no bearing on the vaccine approval process.

Vaccines are typically approved by the FDA. Alternatively, Mr. Azar – who reports directly to Mr. Trump – can issue an emergency use authorization, even before any vaccines have been shown to be safe and effective in late-stage clinical trials.

“Yes, this scenario is certainly possible legally and politically,” said Jerry Avorn, MD, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, who outlined such an event in the New England Journal of Medicine. He said it “seems frighteningly more plausible each day.”

Vaccine experts and public health officials are particularly vexed by the possibility because it could ruin the fragile public confidence in a COVID-19 vaccine. It might put scientific authorities in the position of urging people not to be vaccinated after years of coaxing hesitant parents to ignore baseless fears.

Physicians might refuse to administer a vaccine approved with inadequate data, said Preeti Malani, MD, chief health officer and professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, in a recent webinar. “You could have a safe, effective vaccine that no one wants to take.” A recent KFF poll found that 54% of Americans would not submit to a COVID-19 vaccine authorized before Election Day.

After this story was published, an HHS official said that Mr. Azar “will defer completely to the FDA” as the agency weighs whether to approve a vaccine produced through the government’s Operation Warp Speed effort.

“The idea the Secretary would approve or authorize a vaccine over the FDA’s objections is preposterous and betrays ignorance of the transparent process that we’re following for the development of the OWS vaccines,” HHS chief of staff Brian Harrison wrote in an email.

White House spokesperson Judd Deere dismissed the scientists’ concerns, saying Trump cared only about the public’s safety and health. “This false narrative that the media and Democrats have created that politics is influencing approvals is not only false but is a danger to the American public,” he said.

Usually, the FDA approves vaccines only after companies submit years of data proving that a vaccine is safe and effective. But a 2004 law allows the FDA to issue an emergency use authorization with much less evidence, as long as the vaccine “may be effective” and its “known and potential benefits” outweigh its “known and potential risks.”

Many scientists doubt a vaccine could meet those criteria before the election. But the terms might be legally vague enough to allow the administration to take such steps.

Moncef Slaoui, chief scientific adviser to Operation Warp Speed, the government program aiming to more quickly develop COVID-19 vaccines, said it’s “extremely unlikely” that vaccine trial results will be ready before the end of October.

Mr. Trump, however, has insisted repeatedly that a vaccine to fight the pandemic that has claimed 200,000 American lives will be distributed starting next month. He reiterated that claim Saturday at a campaign rally in Fayetteville, N.C.

The vaccine will be ready “in a matter of weeks,” he said. “We will end the pandemic from China.”

Although pharmaceutical companies have launched three clinical trials in the United States, no one can say with certainty when those trials will have enough data to determine whether the vaccines are safe and effective.

Officials at Moderna, whose vaccine is being tested in 30,000 volunteers, have said their studies could produce a result by the end of the year, although the final analysis could take place next spring.

Pfizer executives, who have expanded their clinical trial to 44,000 participants, boast that they could know their vaccine works by the end of October.

AstraZeneca’s U.S. vaccine trial, which was scheduled to enroll 30,000 volunteers, is on hold pending an investigation of a possible vaccine-related illness.

Scientists have warned for months that the Trump administration could try to win the election with an “October surprise,” authorizing a vaccine that hasn’t been fully tested. “I don’t think people are crazy to be thinking about all of this,” said William Schultz, a partner in a Washington, D.C., law firm who served as a former FDA commissioner for policy and as general counsel for HHS.

“You’ve got a president saying you’ll have an approval in October. Everybody’s wondering how that could happen.”

In an opinion piece published in the Wall Street Journal, conservative former FDA commissioners Scott Gottlieb and Mark McClellan argued that presidential intrusion was unlikely because the FDA’s “thorough and transparent process doesn’t lend itself to meddling. Any deviation would quickly be apparent.”

But the administration has demonstrated a willingness to bend the agency to its will. The FDA has been criticized for issuing emergency authorizations for two COVID-19 treatments that were boosted by the president but lacked strong evidence to support them: hydroxychloroquine and convalescent plasma.

Mr. Azar has sidelined the FDA in other ways, such as by blocking the agency from regulating lab-developed tests, including tests for the novel coronavirus.

Although FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn told the Financial Times he would be willing to approve emergency use of a vaccine before large-scale studies conclude, agency officials also have pledged to ensure the safety of any COVID-19 vaccines.

A senior FDA official who oversees vaccine approvals, Peter Marks, MD, has said he will quit if his agency rubber-stamps an unproven COVID-19 vaccine.

“I think there would be an outcry from the public health community second to none, which is my worst nightmare – my worst nightmare – because we will so confuse the public,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, in his weekly podcast.

Still, “even if a company did not want it to be done, even if the FDA did not want it to be done, he could still do that,” said Dr. Osterholm, in his podcast. “I hope that we’d never see that happen, but we have to entertain that’s a possibility.”

In the New England Journal editorial, Dr. Avorn and coauthor Aaron Kesselheim, MD, wondered whether Mr. Trump might invoke the 1950 Defense Production Act to force reluctant drug companies to manufacture their vaccines.

But Mr. Trump would have to sue a company to enforce the Defense Production Act, and the company would have a strong case in refusing, said Lawrence Gostin, director of Georgetown’s O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law.

Also, he noted that Mr. Trump could not invoke the Defense Production Act unless a vaccine were “scientifically justified and approved by the FDA.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

who have pledged not to release any vaccine unless it’s proved safe and effective.

In podcasts, public forums, social media and medical journals, a growing number of prominent health leaders say they fear that Mr. Trump – who has repeatedly signaled his desire for the swift approval of a vaccine and his displeasure with perceived delays at the FDA – will take matters into his own hands, running roughshod over the usual regulatory process.

It would reflect another attempt by a norm-breaking administration, poised to ram through a Supreme Court nominee opposed to existing abortion rights and the Affordable Care Act, to inject politics into sensitive public health decisions. Mr. Trump has repeatedly contradicted the advice of senior scientists on COVID-19 while pushing controversial treatments for the disease.

If the executive branch were to overrule the FDA’s scientific judgment, a vaccine of limited efficacy and, worse, unknown side effects could be rushed to market.

The worries intensified over the weekend, after Alex Azar, the administration’s secretary of Health & Human Services, asserted his agency’s rule-making authority over the FDA. HHS spokesperson Caitlin Oakley said Mr. Azar’s decision had no bearing on the vaccine approval process.

Vaccines are typically approved by the FDA. Alternatively, Mr. Azar – who reports directly to Mr. Trump – can issue an emergency use authorization, even before any vaccines have been shown to be safe and effective in late-stage clinical trials.

“Yes, this scenario is certainly possible legally and politically,” said Jerry Avorn, MD, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, who outlined such an event in the New England Journal of Medicine. He said it “seems frighteningly more plausible each day.”

Vaccine experts and public health officials are particularly vexed by the possibility because it could ruin the fragile public confidence in a COVID-19 vaccine. It might put scientific authorities in the position of urging people not to be vaccinated after years of coaxing hesitant parents to ignore baseless fears.

Physicians might refuse to administer a vaccine approved with inadequate data, said Preeti Malani, MD, chief health officer and professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, in a recent webinar. “You could have a safe, effective vaccine that no one wants to take.” A recent KFF poll found that 54% of Americans would not submit to a COVID-19 vaccine authorized before Election Day.

After this story was published, an HHS official said that Mr. Azar “will defer completely to the FDA” as the agency weighs whether to approve a vaccine produced through the government’s Operation Warp Speed effort.

“The idea the Secretary would approve or authorize a vaccine over the FDA’s objections is preposterous and betrays ignorance of the transparent process that we’re following for the development of the OWS vaccines,” HHS chief of staff Brian Harrison wrote in an email.

White House spokesperson Judd Deere dismissed the scientists’ concerns, saying Trump cared only about the public’s safety and health. “This false narrative that the media and Democrats have created that politics is influencing approvals is not only false but is a danger to the American public,” he said.

Usually, the FDA approves vaccines only after companies submit years of data proving that a vaccine is safe and effective. But a 2004 law allows the FDA to issue an emergency use authorization with much less evidence, as long as the vaccine “may be effective” and its “known and potential benefits” outweigh its “known and potential risks.”

Many scientists doubt a vaccine could meet those criteria before the election. But the terms might be legally vague enough to allow the administration to take such steps.

Moncef Slaoui, chief scientific adviser to Operation Warp Speed, the government program aiming to more quickly develop COVID-19 vaccines, said it’s “extremely unlikely” that vaccine trial results will be ready before the end of October.

Mr. Trump, however, has insisted repeatedly that a vaccine to fight the pandemic that has claimed 200,000 American lives will be distributed starting next month. He reiterated that claim Saturday at a campaign rally in Fayetteville, N.C.

The vaccine will be ready “in a matter of weeks,” he said. “We will end the pandemic from China.”

Although pharmaceutical companies have launched three clinical trials in the United States, no one can say with certainty when those trials will have enough data to determine whether the vaccines are safe and effective.

Officials at Moderna, whose vaccine is being tested in 30,000 volunteers, have said their studies could produce a result by the end of the year, although the final analysis could take place next spring.

Pfizer executives, who have expanded their clinical trial to 44,000 participants, boast that they could know their vaccine works by the end of October.

AstraZeneca’s U.S. vaccine trial, which was scheduled to enroll 30,000 volunteers, is on hold pending an investigation of a possible vaccine-related illness.

Scientists have warned for months that the Trump administration could try to win the election with an “October surprise,” authorizing a vaccine that hasn’t been fully tested. “I don’t think people are crazy to be thinking about all of this,” said William Schultz, a partner in a Washington, D.C., law firm who served as a former FDA commissioner for policy and as general counsel for HHS.

“You’ve got a president saying you’ll have an approval in October. Everybody’s wondering how that could happen.”

In an opinion piece published in the Wall Street Journal, conservative former FDA commissioners Scott Gottlieb and Mark McClellan argued that presidential intrusion was unlikely because the FDA’s “thorough and transparent process doesn’t lend itself to meddling. Any deviation would quickly be apparent.”

But the administration has demonstrated a willingness to bend the agency to its will. The FDA has been criticized for issuing emergency authorizations for two COVID-19 treatments that were boosted by the president but lacked strong evidence to support them: hydroxychloroquine and convalescent plasma.

Mr. Azar has sidelined the FDA in other ways, such as by blocking the agency from regulating lab-developed tests, including tests for the novel coronavirus.

Although FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn told the Financial Times he would be willing to approve emergency use of a vaccine before large-scale studies conclude, agency officials also have pledged to ensure the safety of any COVID-19 vaccines.

A senior FDA official who oversees vaccine approvals, Peter Marks, MD, has said he will quit if his agency rubber-stamps an unproven COVID-19 vaccine.

“I think there would be an outcry from the public health community second to none, which is my worst nightmare – my worst nightmare – because we will so confuse the public,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, in his weekly podcast.

Still, “even if a company did not want it to be done, even if the FDA did not want it to be done, he could still do that,” said Dr. Osterholm, in his podcast. “I hope that we’d never see that happen, but we have to entertain that’s a possibility.”

In the New England Journal editorial, Dr. Avorn and coauthor Aaron Kesselheim, MD, wondered whether Mr. Trump might invoke the 1950 Defense Production Act to force reluctant drug companies to manufacture their vaccines.

But Mr. Trump would have to sue a company to enforce the Defense Production Act, and the company would have a strong case in refusing, said Lawrence Gostin, director of Georgetown’s O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law.

Also, he noted that Mr. Trump could not invoke the Defense Production Act unless a vaccine were “scientifically justified and approved by the FDA.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

who have pledged not to release any vaccine unless it’s proved safe and effective.

In podcasts, public forums, social media and medical journals, a growing number of prominent health leaders say they fear that Mr. Trump – who has repeatedly signaled his desire for the swift approval of a vaccine and his displeasure with perceived delays at the FDA – will take matters into his own hands, running roughshod over the usual regulatory process.

It would reflect another attempt by a norm-breaking administration, poised to ram through a Supreme Court nominee opposed to existing abortion rights and the Affordable Care Act, to inject politics into sensitive public health decisions. Mr. Trump has repeatedly contradicted the advice of senior scientists on COVID-19 while pushing controversial treatments for the disease.

If the executive branch were to overrule the FDA’s scientific judgment, a vaccine of limited efficacy and, worse, unknown side effects could be rushed to market.

The worries intensified over the weekend, after Alex Azar, the administration’s secretary of Health & Human Services, asserted his agency’s rule-making authority over the FDA. HHS spokesperson Caitlin Oakley said Mr. Azar’s decision had no bearing on the vaccine approval process.

Vaccines are typically approved by the FDA. Alternatively, Mr. Azar – who reports directly to Mr. Trump – can issue an emergency use authorization, even before any vaccines have been shown to be safe and effective in late-stage clinical trials.

“Yes, this scenario is certainly possible legally and politically,” said Jerry Avorn, MD, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, who outlined such an event in the New England Journal of Medicine. He said it “seems frighteningly more plausible each day.”

Vaccine experts and public health officials are particularly vexed by the possibility because it could ruin the fragile public confidence in a COVID-19 vaccine. It might put scientific authorities in the position of urging people not to be vaccinated after years of coaxing hesitant parents to ignore baseless fears.

Physicians might refuse to administer a vaccine approved with inadequate data, said Preeti Malani, MD, chief health officer and professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, in a recent webinar. “You could have a safe, effective vaccine that no one wants to take.” A recent KFF poll found that 54% of Americans would not submit to a COVID-19 vaccine authorized before Election Day.

After this story was published, an HHS official said that Mr. Azar “will defer completely to the FDA” as the agency weighs whether to approve a vaccine produced through the government’s Operation Warp Speed effort.

“The idea the Secretary would approve or authorize a vaccine over the FDA’s objections is preposterous and betrays ignorance of the transparent process that we’re following for the development of the OWS vaccines,” HHS chief of staff Brian Harrison wrote in an email.

White House spokesperson Judd Deere dismissed the scientists’ concerns, saying Trump cared only about the public’s safety and health. “This false narrative that the media and Democrats have created that politics is influencing approvals is not only false but is a danger to the American public,” he said.

Usually, the FDA approves vaccines only after companies submit years of data proving that a vaccine is safe and effective. But a 2004 law allows the FDA to issue an emergency use authorization with much less evidence, as long as the vaccine “may be effective” and its “known and potential benefits” outweigh its “known and potential risks.”

Many scientists doubt a vaccine could meet those criteria before the election. But the terms might be legally vague enough to allow the administration to take such steps.

Moncef Slaoui, chief scientific adviser to Operation Warp Speed, the government program aiming to more quickly develop COVID-19 vaccines, said it’s “extremely unlikely” that vaccine trial results will be ready before the end of October.

Mr. Trump, however, has insisted repeatedly that a vaccine to fight the pandemic that has claimed 200,000 American lives will be distributed starting next month. He reiterated that claim Saturday at a campaign rally in Fayetteville, N.C.

The vaccine will be ready “in a matter of weeks,” he said. “We will end the pandemic from China.”

Although pharmaceutical companies have launched three clinical trials in the United States, no one can say with certainty when those trials will have enough data to determine whether the vaccines are safe and effective.

Officials at Moderna, whose vaccine is being tested in 30,000 volunteers, have said their studies could produce a result by the end of the year, although the final analysis could take place next spring.

Pfizer executives, who have expanded their clinical trial to 44,000 participants, boast that they could know their vaccine works by the end of October.

AstraZeneca’s U.S. vaccine trial, which was scheduled to enroll 30,000 volunteers, is on hold pending an investigation of a possible vaccine-related illness.

Scientists have warned for months that the Trump administration could try to win the election with an “October surprise,” authorizing a vaccine that hasn’t been fully tested. “I don’t think people are crazy to be thinking about all of this,” said William Schultz, a partner in a Washington, D.C., law firm who served as a former FDA commissioner for policy and as general counsel for HHS.

“You’ve got a president saying you’ll have an approval in October. Everybody’s wondering how that could happen.”

In an opinion piece published in the Wall Street Journal, conservative former FDA commissioners Scott Gottlieb and Mark McClellan argued that presidential intrusion was unlikely because the FDA’s “thorough and transparent process doesn’t lend itself to meddling. Any deviation would quickly be apparent.”

But the administration has demonstrated a willingness to bend the agency to its will. The FDA has been criticized for issuing emergency authorizations for two COVID-19 treatments that were boosted by the president but lacked strong evidence to support them: hydroxychloroquine and convalescent plasma.

Mr. Azar has sidelined the FDA in other ways, such as by blocking the agency from regulating lab-developed tests, including tests for the novel coronavirus.

Although FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn told the Financial Times he would be willing to approve emergency use of a vaccine before large-scale studies conclude, agency officials also have pledged to ensure the safety of any COVID-19 vaccines.

A senior FDA official who oversees vaccine approvals, Peter Marks, MD, has said he will quit if his agency rubber-stamps an unproven COVID-19 vaccine.

“I think there would be an outcry from the public health community second to none, which is my worst nightmare – my worst nightmare – because we will so confuse the public,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, in his weekly podcast.

Still, “even if a company did not want it to be done, even if the FDA did not want it to be done, he could still do that,” said Dr. Osterholm, in his podcast. “I hope that we’d never see that happen, but we have to entertain that’s a possibility.”

In the New England Journal editorial, Dr. Avorn and coauthor Aaron Kesselheim, MD, wondered whether Mr. Trump might invoke the 1950 Defense Production Act to force reluctant drug companies to manufacture their vaccines.

But Mr. Trump would have to sue a company to enforce the Defense Production Act, and the company would have a strong case in refusing, said Lawrence Gostin, director of Georgetown’s O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law.

Also, he noted that Mr. Trump could not invoke the Defense Production Act unless a vaccine were “scientifically justified and approved by the FDA.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

COVID-19 Screening and Testing Among Patients With Neurologic Dysfunction: The Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist

From the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, Division of Neuroscience Intensive Care, Jackson, MS.

Abstract

Objective: To test a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) screening tool to identify patients who qualify for testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction who are unable to answer the usual screening questions, which could help to prevent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers to COVID-19.

Methods: The Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) was implemented at our institution for 1 week as a quality improvement project to improve the pathway for COVID-19 screening and testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction.

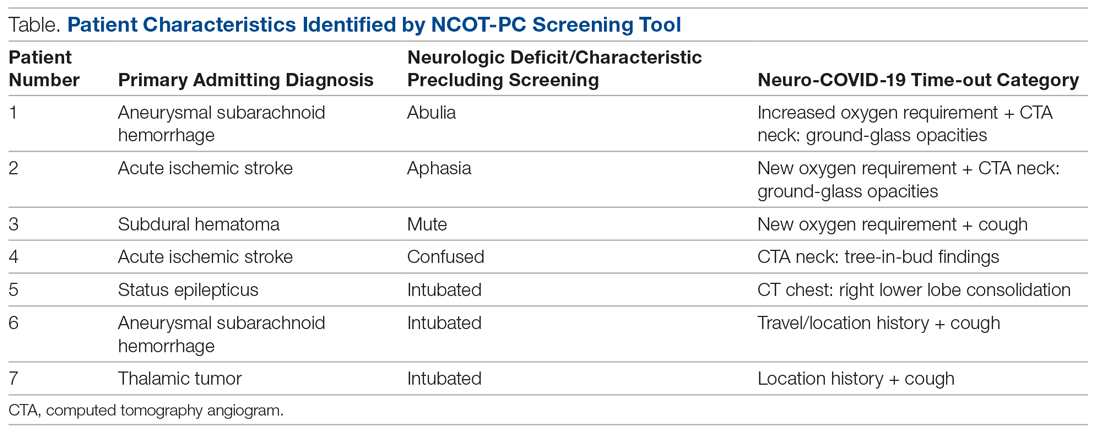

Results: A total of 14 new patients were admitted into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) service during the pilot period. The NCOT-PC was utilized on 9 (64%) patients with neurologic dysfunction; 7 of these patients were found to have a likelihood of requiring testing based on the NCOT-PC and were subsequently screened for COVID-19 testing by contacting the institution’s COVID-19 testing hotline (Med-Com). All these patients were subsequently transitioned into person-under-investigation status based on the determination from Med-Com. The NSICU staff involved were able to utilize NCOT-PC without issues. The NCOT-PC was immediately adopted into the NSICU process.

Conclusion: Use of the NCOT-PC tool was found to be feasible and improved the screening methodology of patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Keywords: coronavirus; health care planning; quality improvement; patient safety; medical decision-making; neuroscience intensive care unit.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has altered various standard emergent care pathways. Current recommendations regarding COVID-19 screening for testing involve asking patients about their symptoms, including fever, cough, chest pain, and dyspnea.1 This standard screening method poses a problem when caring for patients with neurologic dysfunction. COVID-19 patients may pre-sent with conditions that affect their ability to answer questions, such as stroke, encephalitis, neuromuscular disorders, or headache, and that may preclude the use of standard screening for testing.2 Patients with acute neurologic dysfunction who cannot undergo standard screening may leave the emergency department (ED) and transition into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) or any intensive care unit (ICU) without a reliable COVID-19 screening test.

The Protected Code Stroke pathway offers protection in the emergent setting for patients with stroke when their COVID-19 status is unknown.3 A similar process has been applied at our institution for emergent management of patients with cerebrovascular disease (stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage). However, the process from the ED after designating “difficult to screen” patients as persons under investigation (PUI) is unclear. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has delineated the priorities for testing, with not all declared PUIs requiring testing.4 This poses a great challenge, because patients designated as PUIs require the same management as a COVID-19-positive patient, with negative-pressure isolation rooms as well as use of protective personal equipment (PPE), which may not be readily available. It was also recognized that, because the ED staff can be overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients, there may not be enough time to perform detailed screening of patients with neurologic dysfunction and that “reverse masking” may not be done consistently for nonintubated patients. This may place patients and health care workers at risk of unprotected exposure.

Recognizing these challenges, we created a Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) as a quality improvement project. The aim of this project was to improve and standardize the current process of identifying patients with neurologic dysfunction who require COVID-19 testing to decrease the risk of unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

Methods

Patients and Definitions

This quality improvement project was undertaken at the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU. Because this was a quality improvement project, an Institutional Review Board exemption was granted.

The NCOT-PC was utilized in consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU during a period of 1 week. “Neurologic dysfunction” encompasses any neurologic illness affecting the mental status and/or level of alertness, subsequently precluding the ability to reliably screen the patient utilizing standard COVID-19 screening. “Med-Com” at our institution is the equivalent of the national COVID-19 testing hotline, where our institution’s infectious diseases experts screen calls for testing and determine whether testing is warranted. “Unprotected exposure” means exposure to COVID-19 without adequate and appropriate PPE.

Quality Improvement Process

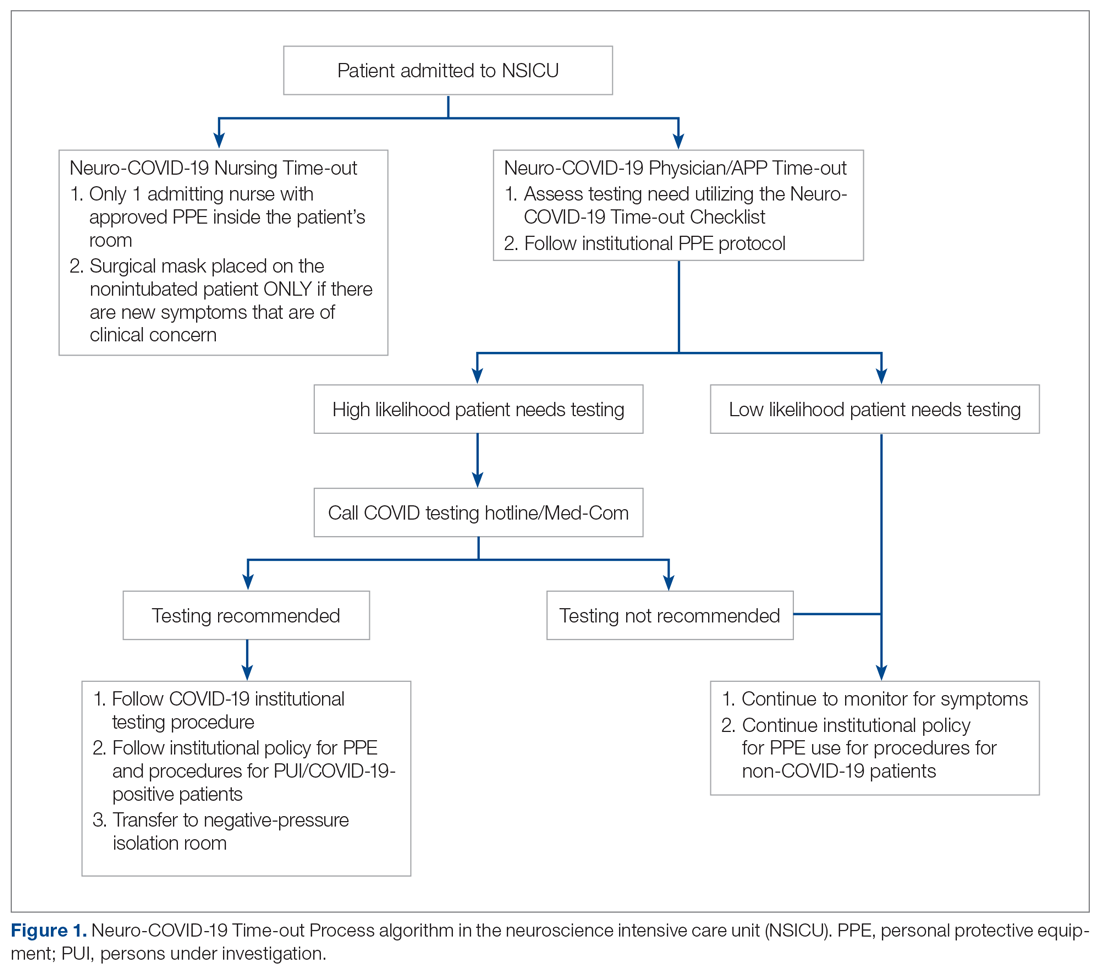

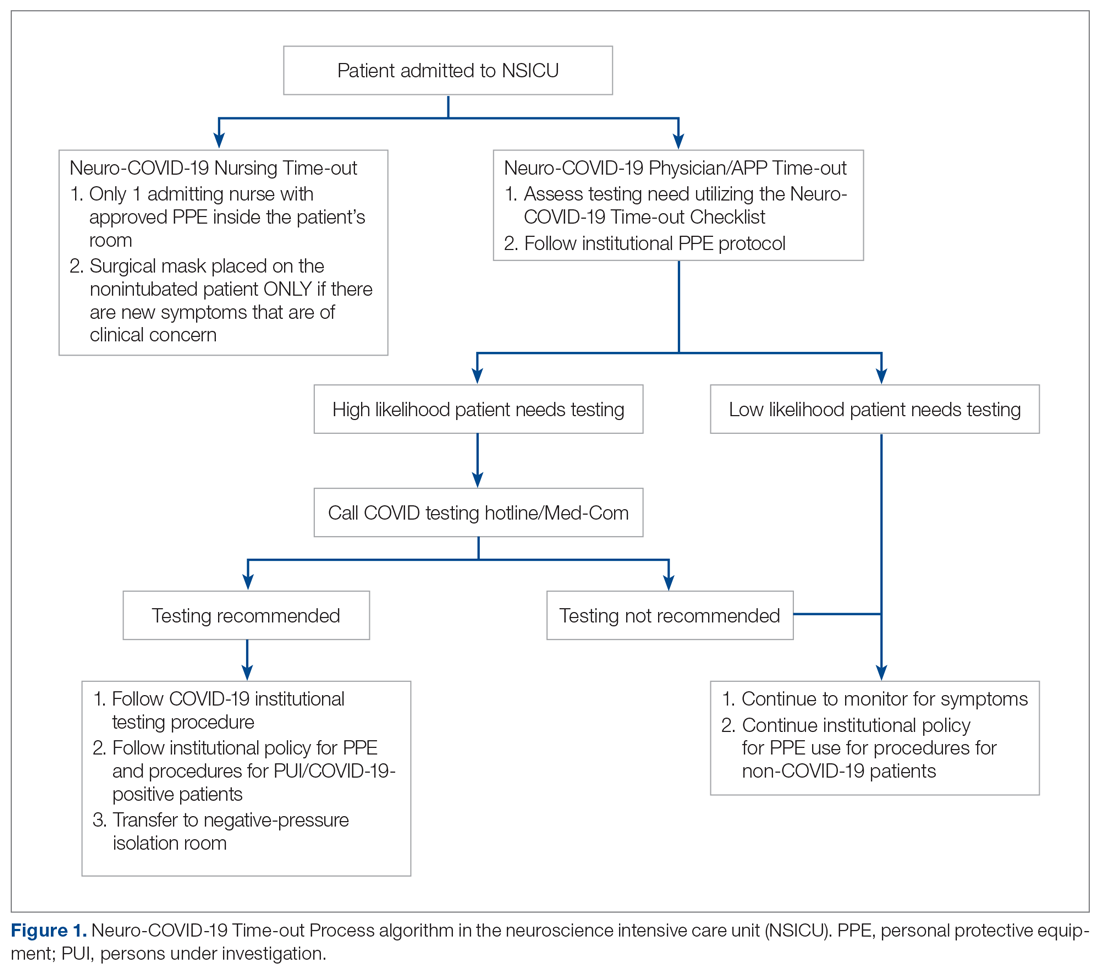

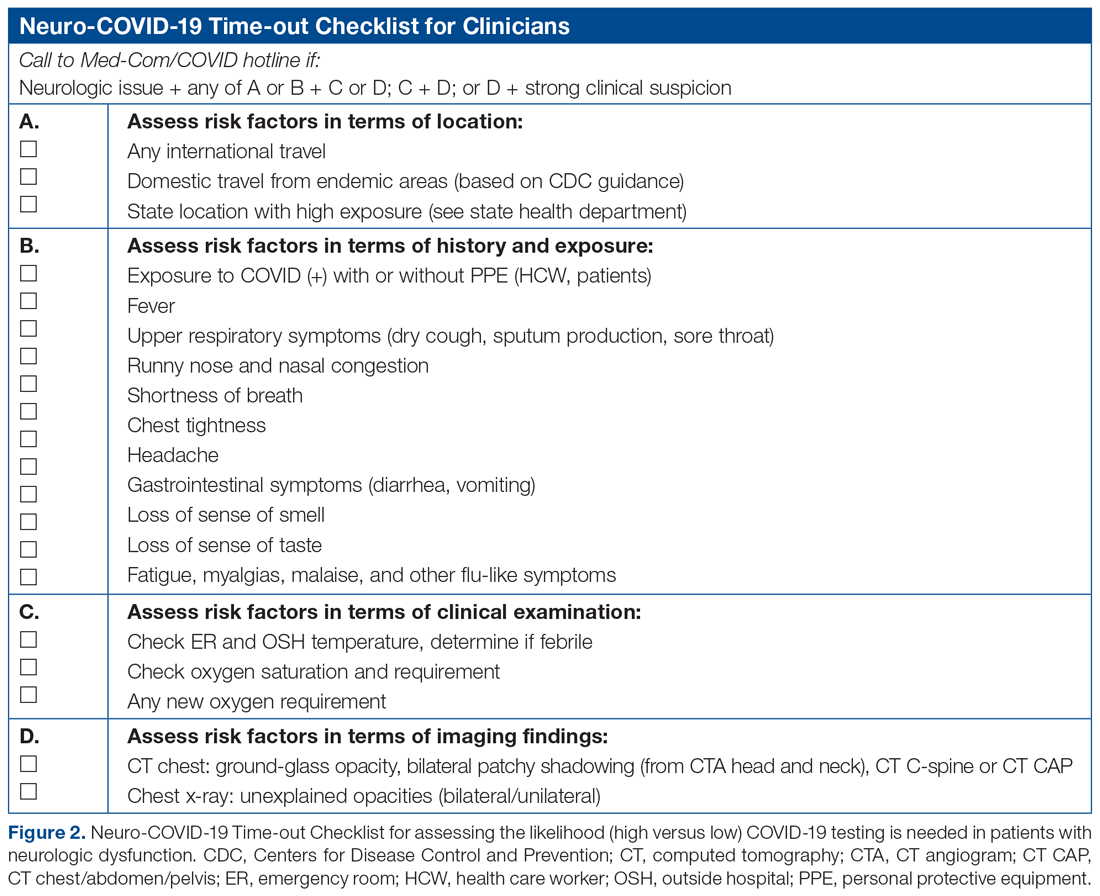

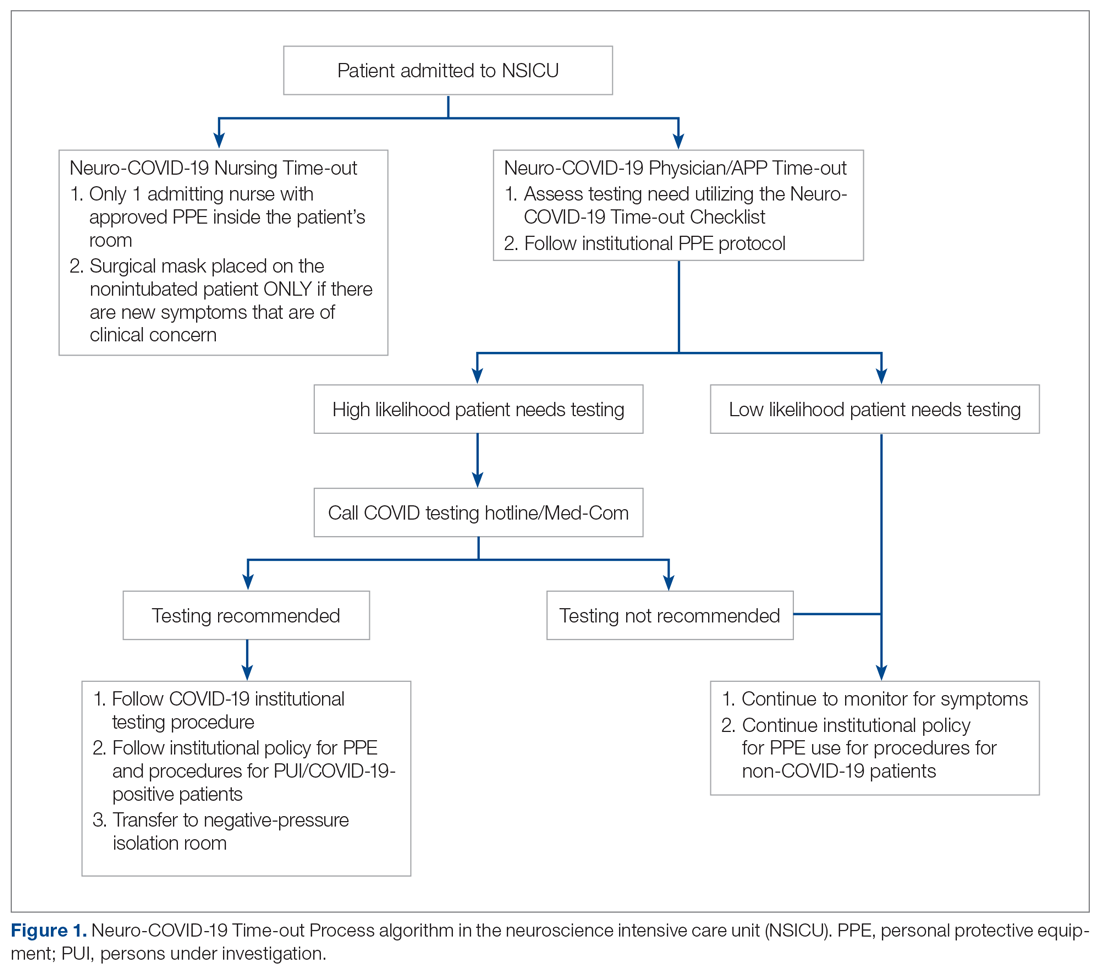

As more PUIs were being admitted to the institution, we used the Plan-Do-Study-Act method for process improvements in the NSICU.5 NSICU stakeholders, including attendings, the nurse manager, and nurse practitioners (NPs), developed an algorithm to facilitate the coordination of the NSICU staff in screening patients to identify those with a high likelihood of needing COVID-19 testing upon arrival in the NSICU (Figure 1). Once the NCOT-PC was finalized, NSICU stakeholders were educated regarding the use of this screening tool.

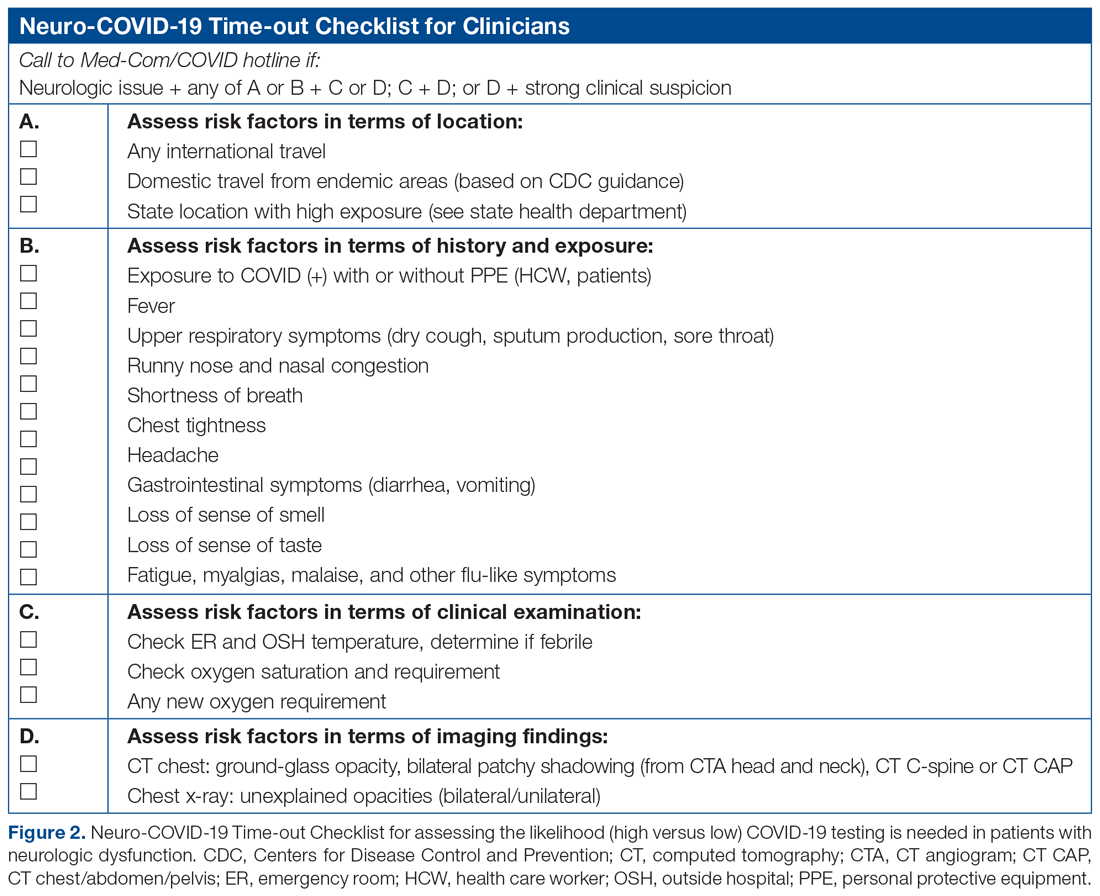

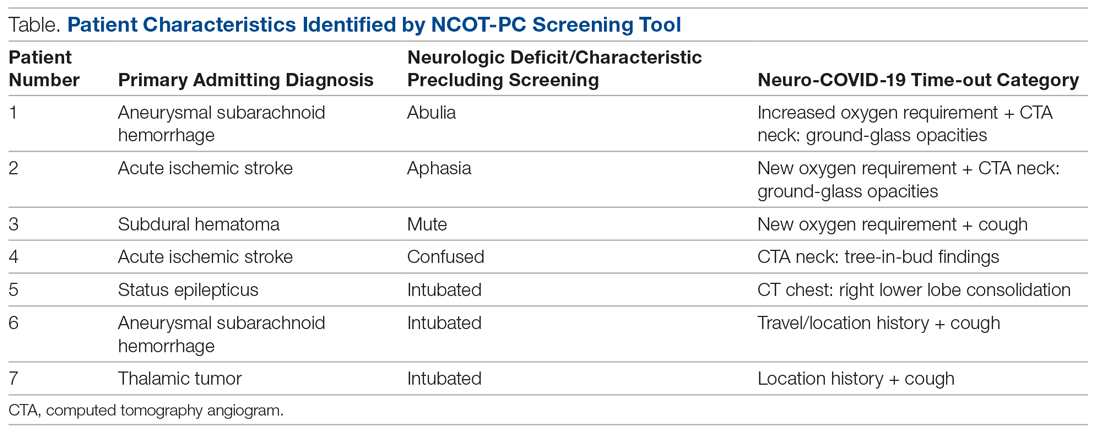

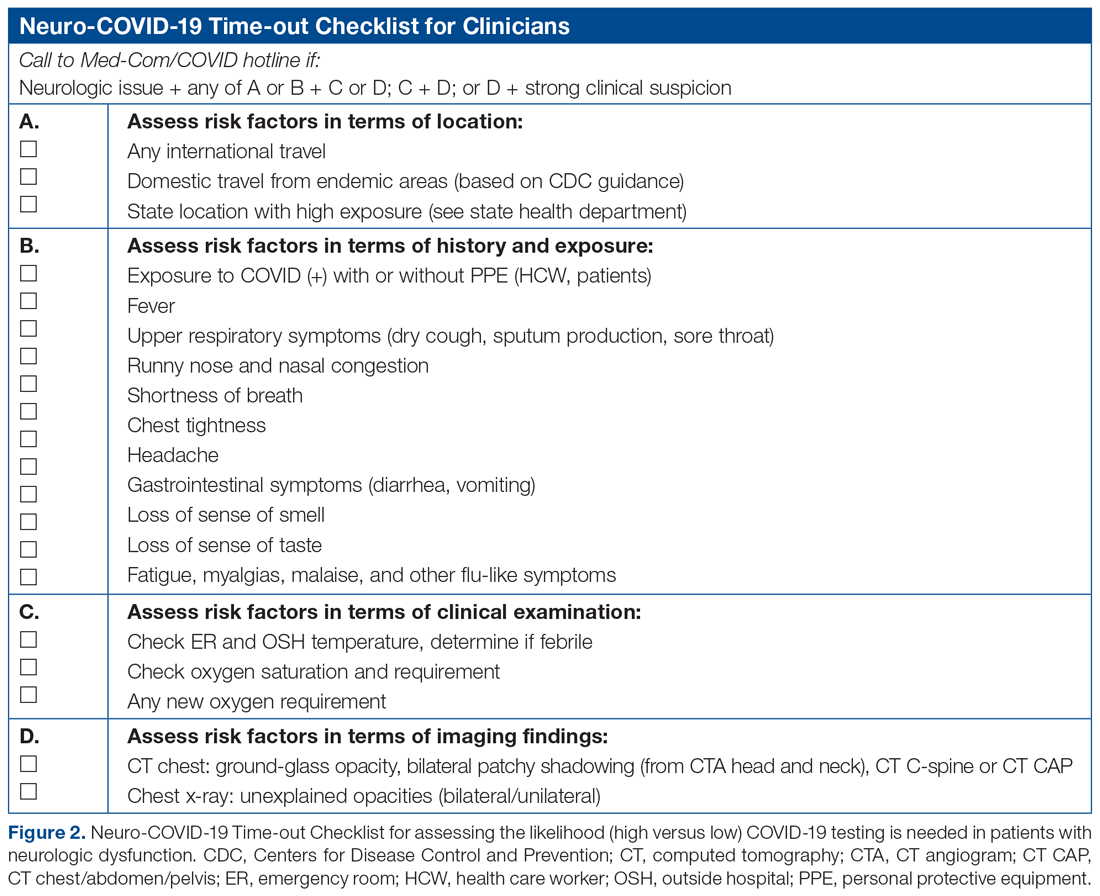

The checklist clinicians review when screening patients is shown in Figure 2. The risk factors comprising the checklist include patient history and clinical and radiographic characteristics that have been shown to be relevant for identifying patients with COVID-19.6,7 The imaging criteria utilize imaging that is part of the standard of care for NSICU patients. For example, computed tomography angiogram of the head and neck performed as part of the acute stroke protocol captures the upper part of the chest. These images are utilized for their incidental findings, such as apical ground-glass opacities and tree-in-bud formation. The risk factors applicable to the patient determine whether the clinician will call Med-Com for testing approval. Institutional COVID-19 processes were then followed accordingly.8 The decision from Med-Com was considered final, and no deviation from institutional policies was allowed.

NCOT-PC was utilized for consecutive days for 1 week before re-evaluation of its feasibility and adaptability.

Data Collection and Analysis

Consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted into the NSICU were assigned nonlinkable patient numbers. No identifiers were collected for the purpose of this project. The primary diagnosis for admission, the neurologic dysfunction that precluded standard screening, and checklist components that the patient fulfilled were collected.

To assess the tool’s feasibility, feedback regarding the ease of use of the NCOT-PC was gathered from the nurses, NPs, charge nurses, fellows, and other attendings. To assess the utility of the NCOT-PC in identifying patients who will be approved for COVID-19 testing, we calculated the proportion of patients who were deemed to have a high likelihood of testing and the proportion of patients who were approved for testing. Descriptive statistics were used, as applicable for the project, to summarize the utility of the NCOT-PC.

Results

We found that the NCOT-PC can be easily used by clinicians. The NSICU staff did not communicate any implementation issues, and since the NCOT-PC was implemented, no problems have been identified.

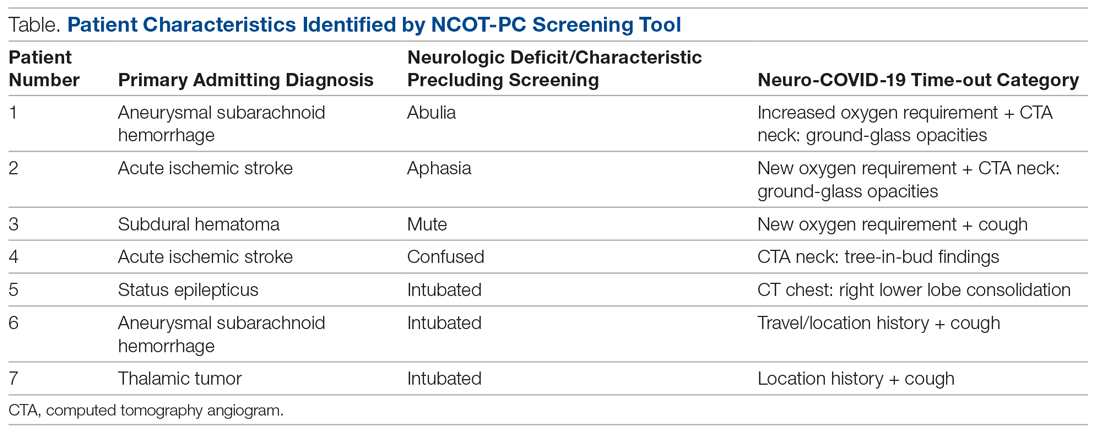

During the pilot period of the NCOT-PC, 14 new patients were admitted to the NSICU service. Nine (64%) of these had neurologic dysfunction, and the NCOT-PC was used to determine whether Med-Com should be called based on the patients’ likelihood (high vs low) of needing a COVID-19 test. Of those patients with neurologic dysfunction, 7 (78%) were deemed to have a high likelihood of needing a COVID-19 test based on the NCOT-PC. Med-Com was contacted regarding these patients, and all were deemed to require the COVID-19 test by Med-Com and were transitioned into PUI status per institutional policy (Table).

Discussion

The NCOT-PC project improved and standardized the process of identifying and screening patients with neurologic dysfunction for COVID-19 testing. The screening tool is feasible to use, and it decreased inadvertent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

The NCOT-PC was easy to administer. Educating the staff regarding the new process took only a few minutes and involved a meeting with the nurse manager, NPs, fellows, residents, and attendings. We found that this process works well in tandem with the standard institutional processes in place in terms of Protected Code Stroke pathway, PUI isolation, PPE use, and Med-Com screening for COVID-19 testing. Med-Com was called only if the patient fulfilled the checklist criteria. In addition, no extra cost was attributed to implementing the NCOT-PC, since we utilized imaging that was already done as part of the standard of care for patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The standardization of the process of screening for COVID-19 testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction improved patient selection. Before the NCOT-PC, there was no consistency in terms of who should get tested and the reason for testing patients with neurologic dysfunction. Patients can pass through the ED and arrive in the NSICU with an unclear screening status, which may cause inadvertent patient and health care worker exposure to COVID-19. With the NCOT-PC, we have avoided instances of inadvertent staff or patient exposure in the NSICU.

The NCOT-PC was adopted into the NSICU process after the first week it was piloted. Beyond the NSICU, the application of the NCOT-PC can be extended to any patient presentation that precludes standard screening, such as ED and interhospital transfers for stroke codes, trauma codes, code blue, or myocardial infarction codes. In our department, as we started the process of PCS for stroke codes, we included NCOT-PC for stroke patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The results of our initiative are largely limited by the decision-making process of Med-Com when patients are called in for testing. At the time of our project, there were no specific criteria used for patients with altered mental status, except for the standard screening methods, and it was through clinician-to-clinician discussion that testing decisions were made. Another limitation is the short period of time that the NCOT-PC was applied before adoption.

In summary, the NCOT-PC tool improved the screening process for COVID-19 testing in patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU. It was feasible and prevented unprotected staff and patient exposure to COVID-19. The NCOT-PC functionality was compatible with institutional COVID-19 policies in place, which contributed to its overall sustainability.

The Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) were utilized in preparing this manuscript.9

Acknowledgment: The authors thank the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU staff for their input with implementation of the NCOT-PC.

Corresponding author: Prashant A. Natteru, MD, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, 2500 North State St., Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Symptoms. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

2. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1-9.

3. Khosravani H, Rajendram P, Notario L, et al. Protected code stroke: hyperacute stroke management during the coronavirus disease 2019. (COVID-19) pandemic. Stroke. 2020;51:1891-1895.

4. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) evaluation and testing. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/clinical-criteria.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

5. Plan-Do-Study-Act Worksheet. Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/PlanDoStudyActWorksheet.aspx. Accessed March 31,2020.

6. Li YC, Bai WZ, Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;10.1002/jmv.25728.

7. Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;101623.

8. UMMC’s COVID-19 Clinical Processes. www.umc.edu/CoronaVirus/Mississippi-Health-Care-Professionals/Clinical-Resources/Clinical-Resources.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

9. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised Publication Guidelines from a Detailed Consensus Process. The EQUATOR Network. www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/squire/. Accessed May 12, 2020.

From the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, Division of Neuroscience Intensive Care, Jackson, MS.

Abstract

Objective: To test a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) screening tool to identify patients who qualify for testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction who are unable to answer the usual screening questions, which could help to prevent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers to COVID-19.

Methods: The Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) was implemented at our institution for 1 week as a quality improvement project to improve the pathway for COVID-19 screening and testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Results: A total of 14 new patients were admitted into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) service during the pilot period. The NCOT-PC was utilized on 9 (64%) patients with neurologic dysfunction; 7 of these patients were found to have a likelihood of requiring testing based on the NCOT-PC and were subsequently screened for COVID-19 testing by contacting the institution’s COVID-19 testing hotline (Med-Com). All these patients were subsequently transitioned into person-under-investigation status based on the determination from Med-Com. The NSICU staff involved were able to utilize NCOT-PC without issues. The NCOT-PC was immediately adopted into the NSICU process.

Conclusion: Use of the NCOT-PC tool was found to be feasible and improved the screening methodology of patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Keywords: coronavirus; health care planning; quality improvement; patient safety; medical decision-making; neuroscience intensive care unit.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has altered various standard emergent care pathways. Current recommendations regarding COVID-19 screening for testing involve asking patients about their symptoms, including fever, cough, chest pain, and dyspnea.1 This standard screening method poses a problem when caring for patients with neurologic dysfunction. COVID-19 patients may pre-sent with conditions that affect their ability to answer questions, such as stroke, encephalitis, neuromuscular disorders, or headache, and that may preclude the use of standard screening for testing.2 Patients with acute neurologic dysfunction who cannot undergo standard screening may leave the emergency department (ED) and transition into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) or any intensive care unit (ICU) without a reliable COVID-19 screening test.

The Protected Code Stroke pathway offers protection in the emergent setting for patients with stroke when their COVID-19 status is unknown.3 A similar process has been applied at our institution for emergent management of patients with cerebrovascular disease (stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage). However, the process from the ED after designating “difficult to screen” patients as persons under investigation (PUI) is unclear. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has delineated the priorities for testing, with not all declared PUIs requiring testing.4 This poses a great challenge, because patients designated as PUIs require the same management as a COVID-19-positive patient, with negative-pressure isolation rooms as well as use of protective personal equipment (PPE), which may not be readily available. It was also recognized that, because the ED staff can be overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients, there may not be enough time to perform detailed screening of patients with neurologic dysfunction and that “reverse masking” may not be done consistently for nonintubated patients. This may place patients and health care workers at risk of unprotected exposure.

Recognizing these challenges, we created a Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) as a quality improvement project. The aim of this project was to improve and standardize the current process of identifying patients with neurologic dysfunction who require COVID-19 testing to decrease the risk of unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

Methods

Patients and Definitions

This quality improvement project was undertaken at the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU. Because this was a quality improvement project, an Institutional Review Board exemption was granted.

The NCOT-PC was utilized in consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU during a period of 1 week. “Neurologic dysfunction” encompasses any neurologic illness affecting the mental status and/or level of alertness, subsequently precluding the ability to reliably screen the patient utilizing standard COVID-19 screening. “Med-Com” at our institution is the equivalent of the national COVID-19 testing hotline, where our institution’s infectious diseases experts screen calls for testing and determine whether testing is warranted. “Unprotected exposure” means exposure to COVID-19 without adequate and appropriate PPE.

Quality Improvement Process

As more PUIs were being admitted to the institution, we used the Plan-Do-Study-Act method for process improvements in the NSICU.5 NSICU stakeholders, including attendings, the nurse manager, and nurse practitioners (NPs), developed an algorithm to facilitate the coordination of the NSICU staff in screening patients to identify those with a high likelihood of needing COVID-19 testing upon arrival in the NSICU (Figure 1). Once the NCOT-PC was finalized, NSICU stakeholders were educated regarding the use of this screening tool.

The checklist clinicians review when screening patients is shown in Figure 2. The risk factors comprising the checklist include patient history and clinical and radiographic characteristics that have been shown to be relevant for identifying patients with COVID-19.6,7 The imaging criteria utilize imaging that is part of the standard of care for NSICU patients. For example, computed tomography angiogram of the head and neck performed as part of the acute stroke protocol captures the upper part of the chest. These images are utilized for their incidental findings, such as apical ground-glass opacities and tree-in-bud formation. The risk factors applicable to the patient determine whether the clinician will call Med-Com for testing approval. Institutional COVID-19 processes were then followed accordingly.8 The decision from Med-Com was considered final, and no deviation from institutional policies was allowed.

NCOT-PC was utilized for consecutive days for 1 week before re-evaluation of its feasibility and adaptability.

Data Collection and Analysis

Consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted into the NSICU were assigned nonlinkable patient numbers. No identifiers were collected for the purpose of this project. The primary diagnosis for admission, the neurologic dysfunction that precluded standard screening, and checklist components that the patient fulfilled were collected.

To assess the tool’s feasibility, feedback regarding the ease of use of the NCOT-PC was gathered from the nurses, NPs, charge nurses, fellows, and other attendings. To assess the utility of the NCOT-PC in identifying patients who will be approved for COVID-19 testing, we calculated the proportion of patients who were deemed to have a high likelihood of testing and the proportion of patients who were approved for testing. Descriptive statistics were used, as applicable for the project, to summarize the utility of the NCOT-PC.

Results

We found that the NCOT-PC can be easily used by clinicians. The NSICU staff did not communicate any implementation issues, and since the NCOT-PC was implemented, no problems have been identified.

During the pilot period of the NCOT-PC, 14 new patients were admitted to the NSICU service. Nine (64%) of these had neurologic dysfunction, and the NCOT-PC was used to determine whether Med-Com should be called based on the patients’ likelihood (high vs low) of needing a COVID-19 test. Of those patients with neurologic dysfunction, 7 (78%) were deemed to have a high likelihood of needing a COVID-19 test based on the NCOT-PC. Med-Com was contacted regarding these patients, and all were deemed to require the COVID-19 test by Med-Com and were transitioned into PUI status per institutional policy (Table).

Discussion

The NCOT-PC project improved and standardized the process of identifying and screening patients with neurologic dysfunction for COVID-19 testing. The screening tool is feasible to use, and it decreased inadvertent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

The NCOT-PC was easy to administer. Educating the staff regarding the new process took only a few minutes and involved a meeting with the nurse manager, NPs, fellows, residents, and attendings. We found that this process works well in tandem with the standard institutional processes in place in terms of Protected Code Stroke pathway, PUI isolation, PPE use, and Med-Com screening for COVID-19 testing. Med-Com was called only if the patient fulfilled the checklist criteria. In addition, no extra cost was attributed to implementing the NCOT-PC, since we utilized imaging that was already done as part of the standard of care for patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The standardization of the process of screening for COVID-19 testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction improved patient selection. Before the NCOT-PC, there was no consistency in terms of who should get tested and the reason for testing patients with neurologic dysfunction. Patients can pass through the ED and arrive in the NSICU with an unclear screening status, which may cause inadvertent patient and health care worker exposure to COVID-19. With the NCOT-PC, we have avoided instances of inadvertent staff or patient exposure in the NSICU.

The NCOT-PC was adopted into the NSICU process after the first week it was piloted. Beyond the NSICU, the application of the NCOT-PC can be extended to any patient presentation that precludes standard screening, such as ED and interhospital transfers for stroke codes, trauma codes, code blue, or myocardial infarction codes. In our department, as we started the process of PCS for stroke codes, we included NCOT-PC for stroke patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The results of our initiative are largely limited by the decision-making process of Med-Com when patients are called in for testing. At the time of our project, there were no specific criteria used for patients with altered mental status, except for the standard screening methods, and it was through clinician-to-clinician discussion that testing decisions were made. Another limitation is the short period of time that the NCOT-PC was applied before adoption.

In summary, the NCOT-PC tool improved the screening process for COVID-19 testing in patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU. It was feasible and prevented unprotected staff and patient exposure to COVID-19. The NCOT-PC functionality was compatible with institutional COVID-19 policies in place, which contributed to its overall sustainability.

The Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) were utilized in preparing this manuscript.9

Acknowledgment: The authors thank the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU staff for their input with implementation of the NCOT-PC.

Corresponding author: Prashant A. Natteru, MD, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, 2500 North State St., Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, Division of Neuroscience Intensive Care, Jackson, MS.

Abstract

Objective: To test a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) screening tool to identify patients who qualify for testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction who are unable to answer the usual screening questions, which could help to prevent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers to COVID-19.

Methods: The Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) was implemented at our institution for 1 week as a quality improvement project to improve the pathway for COVID-19 screening and testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Results: A total of 14 new patients were admitted into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) service during the pilot period. The NCOT-PC was utilized on 9 (64%) patients with neurologic dysfunction; 7 of these patients were found to have a likelihood of requiring testing based on the NCOT-PC and were subsequently screened for COVID-19 testing by contacting the institution’s COVID-19 testing hotline (Med-Com). All these patients were subsequently transitioned into person-under-investigation status based on the determination from Med-Com. The NSICU staff involved were able to utilize NCOT-PC without issues. The NCOT-PC was immediately adopted into the NSICU process.

Conclusion: Use of the NCOT-PC tool was found to be feasible and improved the screening methodology of patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Keywords: coronavirus; health care planning; quality improvement; patient safety; medical decision-making; neuroscience intensive care unit.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has altered various standard emergent care pathways. Current recommendations regarding COVID-19 screening for testing involve asking patients about their symptoms, including fever, cough, chest pain, and dyspnea.1 This standard screening method poses a problem when caring for patients with neurologic dysfunction. COVID-19 patients may pre-sent with conditions that affect their ability to answer questions, such as stroke, encephalitis, neuromuscular disorders, or headache, and that may preclude the use of standard screening for testing.2 Patients with acute neurologic dysfunction who cannot undergo standard screening may leave the emergency department (ED) and transition into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) or any intensive care unit (ICU) without a reliable COVID-19 screening test.

The Protected Code Stroke pathway offers protection in the emergent setting for patients with stroke when their COVID-19 status is unknown.3 A similar process has been applied at our institution for emergent management of patients with cerebrovascular disease (stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage). However, the process from the ED after designating “difficult to screen” patients as persons under investigation (PUI) is unclear. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has delineated the priorities for testing, with not all declared PUIs requiring testing.4 This poses a great challenge, because patients designated as PUIs require the same management as a COVID-19-positive patient, with negative-pressure isolation rooms as well as use of protective personal equipment (PPE), which may not be readily available. It was also recognized that, because the ED staff can be overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients, there may not be enough time to perform detailed screening of patients with neurologic dysfunction and that “reverse masking” may not be done consistently for nonintubated patients. This may place patients and health care workers at risk of unprotected exposure.

Recognizing these challenges, we created a Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) as a quality improvement project. The aim of this project was to improve and standardize the current process of identifying patients with neurologic dysfunction who require COVID-19 testing to decrease the risk of unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

Methods

Patients and Definitions

This quality improvement project was undertaken at the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU. Because this was a quality improvement project, an Institutional Review Board exemption was granted.

The NCOT-PC was utilized in consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU during a period of 1 week. “Neurologic dysfunction” encompasses any neurologic illness affecting the mental status and/or level of alertness, subsequently precluding the ability to reliably screen the patient utilizing standard COVID-19 screening. “Med-Com” at our institution is the equivalent of the national COVID-19 testing hotline, where our institution’s infectious diseases experts screen calls for testing and determine whether testing is warranted. “Unprotected exposure” means exposure to COVID-19 without adequate and appropriate PPE.

Quality Improvement Process

As more PUIs were being admitted to the institution, we used the Plan-Do-Study-Act method for process improvements in the NSICU.5 NSICU stakeholders, including attendings, the nurse manager, and nurse practitioners (NPs), developed an algorithm to facilitate the coordination of the NSICU staff in screening patients to identify those with a high likelihood of needing COVID-19 testing upon arrival in the NSICU (Figure 1). Once the NCOT-PC was finalized, NSICU stakeholders were educated regarding the use of this screening tool.

The checklist clinicians review when screening patients is shown in Figure 2. The risk factors comprising the checklist include patient history and clinical and radiographic characteristics that have been shown to be relevant for identifying patients with COVID-19.6,7 The imaging criteria utilize imaging that is part of the standard of care for NSICU patients. For example, computed tomography angiogram of the head and neck performed as part of the acute stroke protocol captures the upper part of the chest. These images are utilized for their incidental findings, such as apical ground-glass opacities and tree-in-bud formation. The risk factors applicable to the patient determine whether the clinician will call Med-Com for testing approval. Institutional COVID-19 processes were then followed accordingly.8 The decision from Med-Com was considered final, and no deviation from institutional policies was allowed.

NCOT-PC was utilized for consecutive days for 1 week before re-evaluation of its feasibility and adaptability.

Data Collection and Analysis

Consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted into the NSICU were assigned nonlinkable patient numbers. No identifiers were collected for the purpose of this project. The primary diagnosis for admission, the neurologic dysfunction that precluded standard screening, and checklist components that the patient fulfilled were collected.

To assess the tool’s feasibility, feedback regarding the ease of use of the NCOT-PC was gathered from the nurses, NPs, charge nurses, fellows, and other attendings. To assess the utility of the NCOT-PC in identifying patients who will be approved for COVID-19 testing, we calculated the proportion of patients who were deemed to have a high likelihood of testing and the proportion of patients who were approved for testing. Descriptive statistics were used, as applicable for the project, to summarize the utility of the NCOT-PC.

Results

We found that the NCOT-PC can be easily used by clinicians. The NSICU staff did not communicate any implementation issues, and since the NCOT-PC was implemented, no problems have been identified.

During the pilot period of the NCOT-PC, 14 new patients were admitted to the NSICU service. Nine (64%) of these had neurologic dysfunction, and the NCOT-PC was used to determine whether Med-Com should be called based on the patients’ likelihood (high vs low) of needing a COVID-19 test. Of those patients with neurologic dysfunction, 7 (78%) were deemed to have a high likelihood of needing a COVID-19 test based on the NCOT-PC. Med-Com was contacted regarding these patients, and all were deemed to require the COVID-19 test by Med-Com and were transitioned into PUI status per institutional policy (Table).

Discussion

The NCOT-PC project improved and standardized the process of identifying and screening patients with neurologic dysfunction for COVID-19 testing. The screening tool is feasible to use, and it decreased inadvertent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

The NCOT-PC was easy to administer. Educating the staff regarding the new process took only a few minutes and involved a meeting with the nurse manager, NPs, fellows, residents, and attendings. We found that this process works well in tandem with the standard institutional processes in place in terms of Protected Code Stroke pathway, PUI isolation, PPE use, and Med-Com screening for COVID-19 testing. Med-Com was called only if the patient fulfilled the checklist criteria. In addition, no extra cost was attributed to implementing the NCOT-PC, since we utilized imaging that was already done as part of the standard of care for patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The standardization of the process of screening for COVID-19 testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction improved patient selection. Before the NCOT-PC, there was no consistency in terms of who should get tested and the reason for testing patients with neurologic dysfunction. Patients can pass through the ED and arrive in the NSICU with an unclear screening status, which may cause inadvertent patient and health care worker exposure to COVID-19. With the NCOT-PC, we have avoided instances of inadvertent staff or patient exposure in the NSICU.