User login

COVID-19 and the psychological side effects of PPE

A few months ago, I published a short thought piece on the use of “sitters” with patients who were COVID-19 positive, or patients under investigation. In it, I recommended the use of telesitters for those who normally would warrant a human sitter, to decrease the discomfort of sitting in full personal protective equipment (PPE) (gown, mask, gloves, etc.) while monitoring a suicidal patient.

I received several queries, which I want to address here. In addition, I want to draw from my Army days in terms of the claustrophobia often experienced with PPE.

The first of the questions was about evidence-based practices. The second was about the discomfort of having sitters sit for many hours in the full gear.

I do not know of any evidence-based practices, but I hope we will develop them.

I agree that spending many hours in full PPE can be discomforting, which is why I wrote the essay.

As far as lessons learned from the Army time, I briefly learned how to wear a “gas mask” or Mission-Oriented Protective Posture (MOPP gear) while at Fort Bragg. We were run through the “gas chamber,” where sergeants released tear gas while we had the mask on. We were then asked to lift it up, and then tearing and sputtering, we could leave the small wooden building.

We wore the mask as part of our Army gear, usually on the right leg. After that, I mainly used the protective mask in its bag as a pillow when I was in the field.

Fast forward to August 1990. I arrived at Camp Casey, near the Korean demilitarized zone. Four days later, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. The gas mask moved from a pillow to something we had to wear while doing 12-mile road marches in “full ruck.” In full ruck, you have your uniform on, with TA-50, knapsack, and weapon. No, I do not remember any more what TA-50 stands for, but essentially it is the webbing that holds your bullets and bandages.

Many could not tolerate it. They developed claustrophobia – sweating, air hunger, and panic. If stationed in the Gulf for Operation Desert Storm, they were evacuated home.

I wrote a couple of short articles on treatment of gas mask phobia.1,2 I basically advised desensitization. Start by watching TV in it for 5 minutes. Graduate to ironing your uniform in the mask. Go then to shorter runs. Work up to the 12-mile road march.

In my second tour in Korea, we had exercises where we simulated being hit by nerve agents and had to operate the hospital for days at a time in partial or full PPE. It was tough but we did it, and felt more confident about surviving attacks from North Korea.

So back to the pandemic present. I have gotten more used to my constant wearing of a surgical mask. I get anxious when I see others with masks below their noses.

The pandemic is not going away anytime soon, in my opinion. Furthermore, there are other viruses that are worse, such as Ebola. It is only a matter of time.

So, let us train with our PPE. If health care workers cannot tolerate them, use desensitization- and anxiety-reducing techniques to help them.

There are no easy answers here, in the time of the COVID pandemic. However, we owe it to ourselves, our patients, and society to do the best we can.

References

1. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 1992 Feb;157(2):104-6.

2. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 2001 Dec;166. Suppl. 2(1)83-4.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington. She has no disclosures and can be reached at [email protected].

A few months ago, I published a short thought piece on the use of “sitters” with patients who were COVID-19 positive, or patients under investigation. In it, I recommended the use of telesitters for those who normally would warrant a human sitter, to decrease the discomfort of sitting in full personal protective equipment (PPE) (gown, mask, gloves, etc.) while monitoring a suicidal patient.

I received several queries, which I want to address here. In addition, I want to draw from my Army days in terms of the claustrophobia often experienced with PPE.

The first of the questions was about evidence-based practices. The second was about the discomfort of having sitters sit for many hours in the full gear.

I do not know of any evidence-based practices, but I hope we will develop them.

I agree that spending many hours in full PPE can be discomforting, which is why I wrote the essay.

As far as lessons learned from the Army time, I briefly learned how to wear a “gas mask” or Mission-Oriented Protective Posture (MOPP gear) while at Fort Bragg. We were run through the “gas chamber,” where sergeants released tear gas while we had the mask on. We were then asked to lift it up, and then tearing and sputtering, we could leave the small wooden building.

We wore the mask as part of our Army gear, usually on the right leg. After that, I mainly used the protective mask in its bag as a pillow when I was in the field.

Fast forward to August 1990. I arrived at Camp Casey, near the Korean demilitarized zone. Four days later, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. The gas mask moved from a pillow to something we had to wear while doing 12-mile road marches in “full ruck.” In full ruck, you have your uniform on, with TA-50, knapsack, and weapon. No, I do not remember any more what TA-50 stands for, but essentially it is the webbing that holds your bullets and bandages.

Many could not tolerate it. They developed claustrophobia – sweating, air hunger, and panic. If stationed in the Gulf for Operation Desert Storm, they were evacuated home.

I wrote a couple of short articles on treatment of gas mask phobia.1,2 I basically advised desensitization. Start by watching TV in it for 5 minutes. Graduate to ironing your uniform in the mask. Go then to shorter runs. Work up to the 12-mile road march.

In my second tour in Korea, we had exercises where we simulated being hit by nerve agents and had to operate the hospital for days at a time in partial or full PPE. It was tough but we did it, and felt more confident about surviving attacks from North Korea.

So back to the pandemic present. I have gotten more used to my constant wearing of a surgical mask. I get anxious when I see others with masks below their noses.

The pandemic is not going away anytime soon, in my opinion. Furthermore, there are other viruses that are worse, such as Ebola. It is only a matter of time.

So, let us train with our PPE. If health care workers cannot tolerate them, use desensitization- and anxiety-reducing techniques to help them.

There are no easy answers here, in the time of the COVID pandemic. However, we owe it to ourselves, our patients, and society to do the best we can.

References

1. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 1992 Feb;157(2):104-6.

2. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 2001 Dec;166. Suppl. 2(1)83-4.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington. She has no disclosures and can be reached at [email protected].

A few months ago, I published a short thought piece on the use of “sitters” with patients who were COVID-19 positive, or patients under investigation. In it, I recommended the use of telesitters for those who normally would warrant a human sitter, to decrease the discomfort of sitting in full personal protective equipment (PPE) (gown, mask, gloves, etc.) while monitoring a suicidal patient.

I received several queries, which I want to address here. In addition, I want to draw from my Army days in terms of the claustrophobia often experienced with PPE.

The first of the questions was about evidence-based practices. The second was about the discomfort of having sitters sit for many hours in the full gear.

I do not know of any evidence-based practices, but I hope we will develop them.

I agree that spending many hours in full PPE can be discomforting, which is why I wrote the essay.

As far as lessons learned from the Army time, I briefly learned how to wear a “gas mask” or Mission-Oriented Protective Posture (MOPP gear) while at Fort Bragg. We were run through the “gas chamber,” where sergeants released tear gas while we had the mask on. We were then asked to lift it up, and then tearing and sputtering, we could leave the small wooden building.

We wore the mask as part of our Army gear, usually on the right leg. After that, I mainly used the protective mask in its bag as a pillow when I was in the field.

Fast forward to August 1990. I arrived at Camp Casey, near the Korean demilitarized zone. Four days later, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. The gas mask moved from a pillow to something we had to wear while doing 12-mile road marches in “full ruck.” In full ruck, you have your uniform on, with TA-50, knapsack, and weapon. No, I do not remember any more what TA-50 stands for, but essentially it is the webbing that holds your bullets and bandages.

Many could not tolerate it. They developed claustrophobia – sweating, air hunger, and panic. If stationed in the Gulf for Operation Desert Storm, they were evacuated home.

I wrote a couple of short articles on treatment of gas mask phobia.1,2 I basically advised desensitization. Start by watching TV in it for 5 minutes. Graduate to ironing your uniform in the mask. Go then to shorter runs. Work up to the 12-mile road march.

In my second tour in Korea, we had exercises where we simulated being hit by nerve agents and had to operate the hospital for days at a time in partial or full PPE. It was tough but we did it, and felt more confident about surviving attacks from North Korea.

So back to the pandemic present. I have gotten more used to my constant wearing of a surgical mask. I get anxious when I see others with masks below their noses.

The pandemic is not going away anytime soon, in my opinion. Furthermore, there are other viruses that are worse, such as Ebola. It is only a matter of time.

So, let us train with our PPE. If health care workers cannot tolerate them, use desensitization- and anxiety-reducing techniques to help them.

There are no easy answers here, in the time of the COVID pandemic. However, we owe it to ourselves, our patients, and society to do the best we can.

References

1. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 1992 Feb;157(2):104-6.

2. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 2001 Dec;166. Suppl. 2(1)83-4.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington. She has no disclosures and can be reached at [email protected].

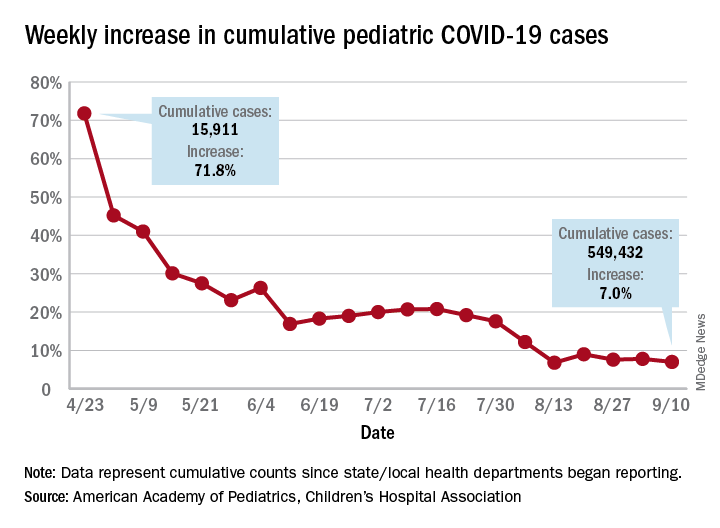

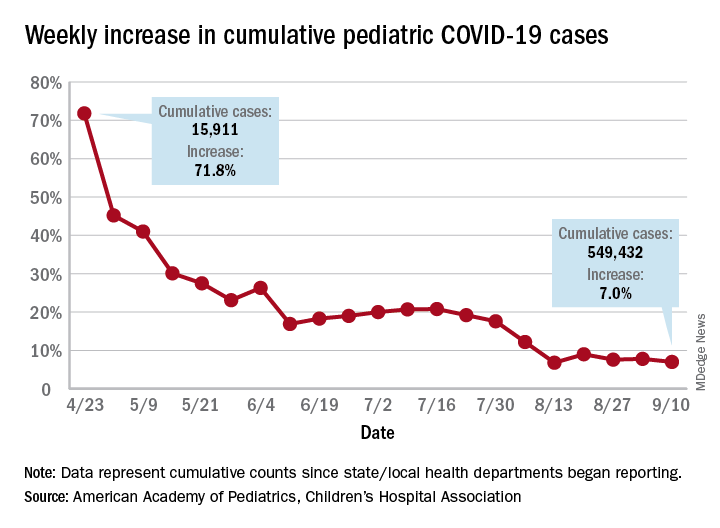

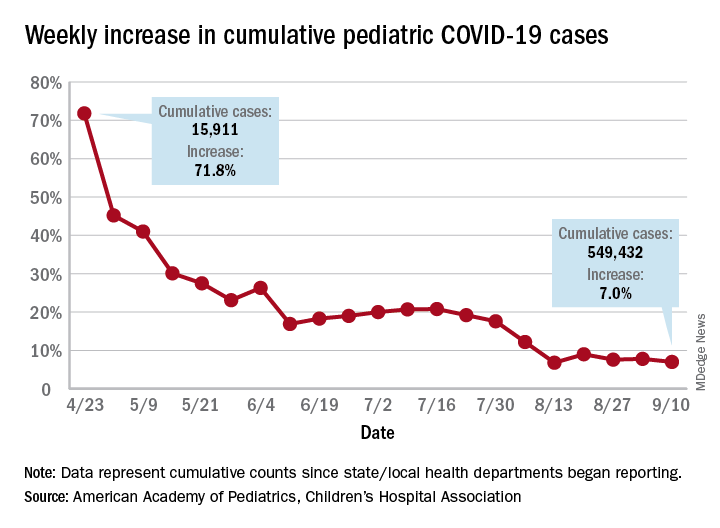

Children and COVID-19: New cases may be leveling off

Growth in new pediatric COVID-19 cases has evened out in recent weeks, but children now represent 10% of all COVID-19 cases in the United States, and that measurement has been rising throughout the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and the CHA said in the report, based on data from 49 states (New York City is included but not New York state), the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The weekly percentage of increase in the number of new cases has not reached double digits since early August and has been no higher than 7.8% over the last 3 weeks. The number of child COVID-19 cases, however, has finally reached 10% of the total for Americans of all ages, which stands at 5.49 million in the jurisdictions included in the report, the AHA and CHA reported.

Measures, however, continue to show low levels of severe illness in children, they noted, including the following:

- Child cases as a proportion of all COVID-19 hospitalizations: 1.7%.

- Hospitalization rate for children: 1.8%.

- Child deaths as a proportion of all deaths: 0.07%.

- Percent of child cases resulting in death: 0.01%.

The number of cumulative cases per 100,000 children is now up to 728.5 nationally, with a range by state that goes from 154.0 in Vermont to 1,670.3 in Tennessee, which is one of only two states reporting cases in those aged 0-20 years as children (the other is South Carolina). The age range for children is 0-17 or 0-19 for most other states, although Florida uses a range of 0-14, the report notes.

Other than Tennessee, there are 10 states with overall rates higher than 1,000 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 children, and there are nine states with cumulative totals over 15,000 cases (California is the highest with just over 75,000), according to the report.

Growth in new pediatric COVID-19 cases has evened out in recent weeks, but children now represent 10% of all COVID-19 cases in the United States, and that measurement has been rising throughout the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and the CHA said in the report, based on data from 49 states (New York City is included but not New York state), the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The weekly percentage of increase in the number of new cases has not reached double digits since early August and has been no higher than 7.8% over the last 3 weeks. The number of child COVID-19 cases, however, has finally reached 10% of the total for Americans of all ages, which stands at 5.49 million in the jurisdictions included in the report, the AHA and CHA reported.

Measures, however, continue to show low levels of severe illness in children, they noted, including the following:

- Child cases as a proportion of all COVID-19 hospitalizations: 1.7%.

- Hospitalization rate for children: 1.8%.

- Child deaths as a proportion of all deaths: 0.07%.

- Percent of child cases resulting in death: 0.01%.

The number of cumulative cases per 100,000 children is now up to 728.5 nationally, with a range by state that goes from 154.0 in Vermont to 1,670.3 in Tennessee, which is one of only two states reporting cases in those aged 0-20 years as children (the other is South Carolina). The age range for children is 0-17 or 0-19 for most other states, although Florida uses a range of 0-14, the report notes.

Other than Tennessee, there are 10 states with overall rates higher than 1,000 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 children, and there are nine states with cumulative totals over 15,000 cases (California is the highest with just over 75,000), according to the report.

Growth in new pediatric COVID-19 cases has evened out in recent weeks, but children now represent 10% of all COVID-19 cases in the United States, and that measurement has been rising throughout the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and the CHA said in the report, based on data from 49 states (New York City is included but not New York state), the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The weekly percentage of increase in the number of new cases has not reached double digits since early August and has been no higher than 7.8% over the last 3 weeks. The number of child COVID-19 cases, however, has finally reached 10% of the total for Americans of all ages, which stands at 5.49 million in the jurisdictions included in the report, the AHA and CHA reported.

Measures, however, continue to show low levels of severe illness in children, they noted, including the following:

- Child cases as a proportion of all COVID-19 hospitalizations: 1.7%.

- Hospitalization rate for children: 1.8%.

- Child deaths as a proportion of all deaths: 0.07%.

- Percent of child cases resulting in death: 0.01%.

The number of cumulative cases per 100,000 children is now up to 728.5 nationally, with a range by state that goes from 154.0 in Vermont to 1,670.3 in Tennessee, which is one of only two states reporting cases in those aged 0-20 years as children (the other is South Carolina). The age range for children is 0-17 or 0-19 for most other states, although Florida uses a range of 0-14, the report notes.

Other than Tennessee, there are 10 states with overall rates higher than 1,000 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 children, and there are nine states with cumulative totals over 15,000 cases (California is the highest with just over 75,000), according to the report.

Painful periocular rash

This patient was given a diagnosis of primary herpes simplex virus (HSV) based on the appearance of her eyelid. Swabs were performed for bacterial culture, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was done for HSV and varicella, but results were pending prior to her transfer to the Emergency Department (ED).

The patient was given a single dose of 800 mg oral acyclovir (200 mg/5mL) and 500 mg of oral cephalexin (250 mg/5mL) and referred to the ED for a more detailed eye exam and to exclude orbital erosions.

HSV classically causes clustered vesicles on an erythematous base. Superinfection with skin flora can cause pustules instead of vesicles. Severe complications of HSV can include widespread skin involvement, eczema herpeticum, local destruction, central nervous system involvement, throat infections (affecting airway and oral intake), and dissemination in immunocompromised hosts. Ocular or periorbital infections increase the risk of keratitis, corneal ulcers, and loss of sight. Viral involvement of the cornea is best seen with fluorescein staining.

In cases like this one, PCR is the preferred method of testing over viral cultures or serology, given its speed, accuracy, and temporal relevance. Ophthalmology referral is warranted, although it should not delay treatment. Topical and oral antivirals are both effective when treating corneal disease; patient preference should be considered.

Most cases of HSV may resolve without treatment; however, treatment started while vesicles are present and within 72 hours of infection may shorten the time of viral replication and prevent progression to stromal involvement.

After a 12-hour wait in the ED, this patient was seen by an ophthalmology resident who did not observe orbital erosions but did note umbilication and misdiagnosed molluscum contagiosum. Umbilication is not pathognomonic for molluscum; few experienced in diagnosing molluscum contagiosum would make this error.

The patient was instructed to stop the acyclovir. Two days later when the PCR came back positive for HSV-1 and the bacterial culture confirmed growth of superimposed Staphylococcus aureus, the patient had been lost to follow-up. A better approach would have been for the ophthalmology resident to continue the acyclovir until PCR excluded herpetic disease.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Barker NH. Ocular herpes simplex. BMJ Clin Evid. 2008;2008:0707.

This patient was given a diagnosis of primary herpes simplex virus (HSV) based on the appearance of her eyelid. Swabs were performed for bacterial culture, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was done for HSV and varicella, but results were pending prior to her transfer to the Emergency Department (ED).

The patient was given a single dose of 800 mg oral acyclovir (200 mg/5mL) and 500 mg of oral cephalexin (250 mg/5mL) and referred to the ED for a more detailed eye exam and to exclude orbital erosions.

HSV classically causes clustered vesicles on an erythematous base. Superinfection with skin flora can cause pustules instead of vesicles. Severe complications of HSV can include widespread skin involvement, eczema herpeticum, local destruction, central nervous system involvement, throat infections (affecting airway and oral intake), and dissemination in immunocompromised hosts. Ocular or periorbital infections increase the risk of keratitis, corneal ulcers, and loss of sight. Viral involvement of the cornea is best seen with fluorescein staining.

In cases like this one, PCR is the preferred method of testing over viral cultures or serology, given its speed, accuracy, and temporal relevance. Ophthalmology referral is warranted, although it should not delay treatment. Topical and oral antivirals are both effective when treating corneal disease; patient preference should be considered.

Most cases of HSV may resolve without treatment; however, treatment started while vesicles are present and within 72 hours of infection may shorten the time of viral replication and prevent progression to stromal involvement.

After a 12-hour wait in the ED, this patient was seen by an ophthalmology resident who did not observe orbital erosions but did note umbilication and misdiagnosed molluscum contagiosum. Umbilication is not pathognomonic for molluscum; few experienced in diagnosing molluscum contagiosum would make this error.

The patient was instructed to stop the acyclovir. Two days later when the PCR came back positive for HSV-1 and the bacterial culture confirmed growth of superimposed Staphylococcus aureus, the patient had been lost to follow-up. A better approach would have been for the ophthalmology resident to continue the acyclovir until PCR excluded herpetic disease.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

This patient was given a diagnosis of primary herpes simplex virus (HSV) based on the appearance of her eyelid. Swabs were performed for bacterial culture, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was done for HSV and varicella, but results were pending prior to her transfer to the Emergency Department (ED).

The patient was given a single dose of 800 mg oral acyclovir (200 mg/5mL) and 500 mg of oral cephalexin (250 mg/5mL) and referred to the ED for a more detailed eye exam and to exclude orbital erosions.

HSV classically causes clustered vesicles on an erythematous base. Superinfection with skin flora can cause pustules instead of vesicles. Severe complications of HSV can include widespread skin involvement, eczema herpeticum, local destruction, central nervous system involvement, throat infections (affecting airway and oral intake), and dissemination in immunocompromised hosts. Ocular or periorbital infections increase the risk of keratitis, corneal ulcers, and loss of sight. Viral involvement of the cornea is best seen with fluorescein staining.

In cases like this one, PCR is the preferred method of testing over viral cultures or serology, given its speed, accuracy, and temporal relevance. Ophthalmology referral is warranted, although it should not delay treatment. Topical and oral antivirals are both effective when treating corneal disease; patient preference should be considered.

Most cases of HSV may resolve without treatment; however, treatment started while vesicles are present and within 72 hours of infection may shorten the time of viral replication and prevent progression to stromal involvement.

After a 12-hour wait in the ED, this patient was seen by an ophthalmology resident who did not observe orbital erosions but did note umbilication and misdiagnosed molluscum contagiosum. Umbilication is not pathognomonic for molluscum; few experienced in diagnosing molluscum contagiosum would make this error.

The patient was instructed to stop the acyclovir. Two days later when the PCR came back positive for HSV-1 and the bacterial culture confirmed growth of superimposed Staphylococcus aureus, the patient had been lost to follow-up. A better approach would have been for the ophthalmology resident to continue the acyclovir until PCR excluded herpetic disease.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Barker NH. Ocular herpes simplex. BMJ Clin Evid. 2008;2008:0707.

Barker NH. Ocular herpes simplex. BMJ Clin Evid. 2008;2008:0707.

Tough to tell COVID from smoke inhalation symptoms — And flu season’s coming

The patients walk into Dr. Melissa Marshall’s community clinics in Northern California with the telltale symptoms. They’re having trouble breathing. It may even hurt to inhale. They’ve got a cough, and the sore throat is definitely there.

A straight case of COVID-19? Not so fast. This is wildfire country.

Up and down the West Coast, hospitals and health facilities are reporting an influx of patients with problems most likely related to smoke inhalation. As fires rage largely uncontrolled amid dry heat and high winds, smoke and ash are billowing and settling on coastal areas like San Francisco and cities and towns hundreds of miles inland as well, turning the sky orange or gray and making even ordinary breathing difficult.

But that, Marshall said, is only part of the challenge.

“Obviously, there’s overlap in the symptoms,” said Marshall, the CEO of CommuniCare, a collection of six clinics in Yolo County, near Sacramento, that treats mostly underinsured and uninsured patients. “Any time someone comes in with even some of those symptoms, we ask ourselves, ‘Is it COVID?’ At the end of the day, clinically speaking, I still want to rule out the virus.”

The protocol is to treat the symptoms, whatever their cause, while recommending that the patient quarantine until test results for the virus come back, she said.

It is a scene playing out in numerous hospitals. Administrators and physicians, finely attuned to COVID-19’s ability to spread quickly and wreak havoc, simply won’t take a chance when they recognize symptoms that could emanate from the virus.

“We’ve seen an increase in patients presenting to the emergency department with respiratory distress,” said Dr. Nanette Mickiewicz, president and CEO of Dominican Hospital in Santa Cruz. “As this can also be a symptom of COVID-19, we’re treating these patients as we would any person under investigation for coronavirus until we can rule them out through our screening process.” During the workup, symptoms that are more specific to COVID-19, like fever, would become apparent.

For the workers at Dominican, the issue moved to the top of the list quickly. Santa Cruz and San Mateo counties have borne the brunt of the CZU Lightning Complex fires, which as of Sept. 10 had burned more than 86,000 acres, destroying 1,100 structures and threatening more than 7,600 others. Nearly a month after they began, the fires were approximately 84% contained, but thousands of people remained evacuated.

Dominican, a Dignity Health hospital, is “open, safe and providing care,” Mickiewicz said. Multiple tents erected outside the building serve as an extension of its ER waiting room. They also are used to perform what has come to be understood as an essential role: separating those with symptoms of COVID-19 from those without.

At the two Solano County hospitals operated by NorthBay Healthcare, the path of some of the wildfires prompted officials to review their evacuation procedures, said spokesperson Steve Huddleston. They ultimately avoided the need to evacuate patients, and new ones arrived with COVID-like symptoms that may actually have been from smoke inhalation.

Huddleston said NorthBay’s intake process “calls for anyone with COVID characteristics to be handled as [a] patient under investigation for COVID, which means they’re separated, screened and managed by staff in special PPE.” At the two hospitals, which have handled nearly 200 COVID cases so far, the protocol is well established.

Hospitals in California, though not under siege in most cases, are dealing with multiple issues they might typically face only sporadically. In Napa County, Adventist Health St. Helena Hospital evacuated 51 patients on a single August night as a fire approached, moving them to 10 other facilities according to their needs and bed space. After a 10-day closure, the hospital was allowed to reopen as evacuation orders were lifted, the fire having been contained some distance away.

The wildfires are also taking a personal toll on health care workers. CommuniCare’s Marshall lost her family’s home in rural Winters, along with 20 acres of olive trees and other plantings that surrounded it, in the Aug. 19 fires that swept through Solano County.

“They called it a ‘firenado,’ ” Marshall said. An apparent confluence of three fires raged out of control, demolishing thousands of acres. With her family safely accounted for and temporary housing arranged by a friend, she returned to work. “Our clinics interact with a very vulnerable population,” she said, “and this is a critical time for them.”

While she pondered how her family would rebuild, the CEO was faced with another immediate crisis: the clinic’s shortage of supplies. Last month, CommuniCare got down to 19 COVID test kits on hand, and ran so low on swabs “that we were literally turning to our veterinary friends for reinforcements,” the doctor said. The clinic’s COVID test results, meanwhile, were taking nearly two weeks to be returned from an overwhelmed outside lab, rendering contact tracing almost useless.

Those situations have been addressed, at least temporarily, Marshall said. But although the West Coast is in the most dangerous time of year for wildfires, generally September to December, another complication for health providers lies on the horizon: flu season.

The Southern Hemisphere, whose influenza trends during our summer months typically predict what’s to come for the U.S., has had very little of the disease this year, presumably because of restricted travel, social distancing and face masks. But it’s too early to be sure what the U.S. flu season will entail.

“You can start to see some cases of the flu in late October,” said Marshall, “and the reality is that it’s going to carry a number of characteristics that could also be symptomatic of COVID. And nothing changes: You have to rule it out, just to eliminate the risk.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente. This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.

The patients walk into Dr. Melissa Marshall’s community clinics in Northern California with the telltale symptoms. They’re having trouble breathing. It may even hurt to inhale. They’ve got a cough, and the sore throat is definitely there.

A straight case of COVID-19? Not so fast. This is wildfire country.

Up and down the West Coast, hospitals and health facilities are reporting an influx of patients with problems most likely related to smoke inhalation. As fires rage largely uncontrolled amid dry heat and high winds, smoke and ash are billowing and settling on coastal areas like San Francisco and cities and towns hundreds of miles inland as well, turning the sky orange or gray and making even ordinary breathing difficult.

But that, Marshall said, is only part of the challenge.

“Obviously, there’s overlap in the symptoms,” said Marshall, the CEO of CommuniCare, a collection of six clinics in Yolo County, near Sacramento, that treats mostly underinsured and uninsured patients. “Any time someone comes in with even some of those symptoms, we ask ourselves, ‘Is it COVID?’ At the end of the day, clinically speaking, I still want to rule out the virus.”

The protocol is to treat the symptoms, whatever their cause, while recommending that the patient quarantine until test results for the virus come back, she said.

It is a scene playing out in numerous hospitals. Administrators and physicians, finely attuned to COVID-19’s ability to spread quickly and wreak havoc, simply won’t take a chance when they recognize symptoms that could emanate from the virus.

“We’ve seen an increase in patients presenting to the emergency department with respiratory distress,” said Dr. Nanette Mickiewicz, president and CEO of Dominican Hospital in Santa Cruz. “As this can also be a symptom of COVID-19, we’re treating these patients as we would any person under investigation for coronavirus until we can rule them out through our screening process.” During the workup, symptoms that are more specific to COVID-19, like fever, would become apparent.

For the workers at Dominican, the issue moved to the top of the list quickly. Santa Cruz and San Mateo counties have borne the brunt of the CZU Lightning Complex fires, which as of Sept. 10 had burned more than 86,000 acres, destroying 1,100 structures and threatening more than 7,600 others. Nearly a month after they began, the fires were approximately 84% contained, but thousands of people remained evacuated.

Dominican, a Dignity Health hospital, is “open, safe and providing care,” Mickiewicz said. Multiple tents erected outside the building serve as an extension of its ER waiting room. They also are used to perform what has come to be understood as an essential role: separating those with symptoms of COVID-19 from those without.

At the two Solano County hospitals operated by NorthBay Healthcare, the path of some of the wildfires prompted officials to review their evacuation procedures, said spokesperson Steve Huddleston. They ultimately avoided the need to evacuate patients, and new ones arrived with COVID-like symptoms that may actually have been from smoke inhalation.

Huddleston said NorthBay’s intake process “calls for anyone with COVID characteristics to be handled as [a] patient under investigation for COVID, which means they’re separated, screened and managed by staff in special PPE.” At the two hospitals, which have handled nearly 200 COVID cases so far, the protocol is well established.

Hospitals in California, though not under siege in most cases, are dealing with multiple issues they might typically face only sporadically. In Napa County, Adventist Health St. Helena Hospital evacuated 51 patients on a single August night as a fire approached, moving them to 10 other facilities according to their needs and bed space. After a 10-day closure, the hospital was allowed to reopen as evacuation orders were lifted, the fire having been contained some distance away.

The wildfires are also taking a personal toll on health care workers. CommuniCare’s Marshall lost her family’s home in rural Winters, along with 20 acres of olive trees and other plantings that surrounded it, in the Aug. 19 fires that swept through Solano County.

“They called it a ‘firenado,’ ” Marshall said. An apparent confluence of three fires raged out of control, demolishing thousands of acres. With her family safely accounted for and temporary housing arranged by a friend, she returned to work. “Our clinics interact with a very vulnerable population,” she said, “and this is a critical time for them.”

While she pondered how her family would rebuild, the CEO was faced with another immediate crisis: the clinic’s shortage of supplies. Last month, CommuniCare got down to 19 COVID test kits on hand, and ran so low on swabs “that we were literally turning to our veterinary friends for reinforcements,” the doctor said. The clinic’s COVID test results, meanwhile, were taking nearly two weeks to be returned from an overwhelmed outside lab, rendering contact tracing almost useless.

Those situations have been addressed, at least temporarily, Marshall said. But although the West Coast is in the most dangerous time of year for wildfires, generally September to December, another complication for health providers lies on the horizon: flu season.

The Southern Hemisphere, whose influenza trends during our summer months typically predict what’s to come for the U.S., has had very little of the disease this year, presumably because of restricted travel, social distancing and face masks. But it’s too early to be sure what the U.S. flu season will entail.

“You can start to see some cases of the flu in late October,” said Marshall, “and the reality is that it’s going to carry a number of characteristics that could also be symptomatic of COVID. And nothing changes: You have to rule it out, just to eliminate the risk.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente. This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.

The patients walk into Dr. Melissa Marshall’s community clinics in Northern California with the telltale symptoms. They’re having trouble breathing. It may even hurt to inhale. They’ve got a cough, and the sore throat is definitely there.

A straight case of COVID-19? Not so fast. This is wildfire country.

Up and down the West Coast, hospitals and health facilities are reporting an influx of patients with problems most likely related to smoke inhalation. As fires rage largely uncontrolled amid dry heat and high winds, smoke and ash are billowing and settling on coastal areas like San Francisco and cities and towns hundreds of miles inland as well, turning the sky orange or gray and making even ordinary breathing difficult.

But that, Marshall said, is only part of the challenge.

“Obviously, there’s overlap in the symptoms,” said Marshall, the CEO of CommuniCare, a collection of six clinics in Yolo County, near Sacramento, that treats mostly underinsured and uninsured patients. “Any time someone comes in with even some of those symptoms, we ask ourselves, ‘Is it COVID?’ At the end of the day, clinically speaking, I still want to rule out the virus.”

The protocol is to treat the symptoms, whatever their cause, while recommending that the patient quarantine until test results for the virus come back, she said.

It is a scene playing out in numerous hospitals. Administrators and physicians, finely attuned to COVID-19’s ability to spread quickly and wreak havoc, simply won’t take a chance when they recognize symptoms that could emanate from the virus.

“We’ve seen an increase in patients presenting to the emergency department with respiratory distress,” said Dr. Nanette Mickiewicz, president and CEO of Dominican Hospital in Santa Cruz. “As this can also be a symptom of COVID-19, we’re treating these patients as we would any person under investigation for coronavirus until we can rule them out through our screening process.” During the workup, symptoms that are more specific to COVID-19, like fever, would become apparent.

For the workers at Dominican, the issue moved to the top of the list quickly. Santa Cruz and San Mateo counties have borne the brunt of the CZU Lightning Complex fires, which as of Sept. 10 had burned more than 86,000 acres, destroying 1,100 structures and threatening more than 7,600 others. Nearly a month after they began, the fires were approximately 84% contained, but thousands of people remained evacuated.

Dominican, a Dignity Health hospital, is “open, safe and providing care,” Mickiewicz said. Multiple tents erected outside the building serve as an extension of its ER waiting room. They also are used to perform what has come to be understood as an essential role: separating those with symptoms of COVID-19 from those without.

At the two Solano County hospitals operated by NorthBay Healthcare, the path of some of the wildfires prompted officials to review their evacuation procedures, said spokesperson Steve Huddleston. They ultimately avoided the need to evacuate patients, and new ones arrived with COVID-like symptoms that may actually have been from smoke inhalation.

Huddleston said NorthBay’s intake process “calls for anyone with COVID characteristics to be handled as [a] patient under investigation for COVID, which means they’re separated, screened and managed by staff in special PPE.” At the two hospitals, which have handled nearly 200 COVID cases so far, the protocol is well established.

Hospitals in California, though not under siege in most cases, are dealing with multiple issues they might typically face only sporadically. In Napa County, Adventist Health St. Helena Hospital evacuated 51 patients on a single August night as a fire approached, moving them to 10 other facilities according to their needs and bed space. After a 10-day closure, the hospital was allowed to reopen as evacuation orders were lifted, the fire having been contained some distance away.

The wildfires are also taking a personal toll on health care workers. CommuniCare’s Marshall lost her family’s home in rural Winters, along with 20 acres of olive trees and other plantings that surrounded it, in the Aug. 19 fires that swept through Solano County.

“They called it a ‘firenado,’ ” Marshall said. An apparent confluence of three fires raged out of control, demolishing thousands of acres. With her family safely accounted for and temporary housing arranged by a friend, she returned to work. “Our clinics interact with a very vulnerable population,” she said, “and this is a critical time for them.”

While she pondered how her family would rebuild, the CEO was faced with another immediate crisis: the clinic’s shortage of supplies. Last month, CommuniCare got down to 19 COVID test kits on hand, and ran so low on swabs “that we were literally turning to our veterinary friends for reinforcements,” the doctor said. The clinic’s COVID test results, meanwhile, were taking nearly two weeks to be returned from an overwhelmed outside lab, rendering contact tracing almost useless.

Those situations have been addressed, at least temporarily, Marshall said. But although the West Coast is in the most dangerous time of year for wildfires, generally September to December, another complication for health providers lies on the horizon: flu season.

The Southern Hemisphere, whose influenza trends during our summer months typically predict what’s to come for the U.S., has had very little of the disease this year, presumably because of restricted travel, social distancing and face masks. But it’s too early to be sure what the U.S. flu season will entail.

“You can start to see some cases of the flu in late October,” said Marshall, “and the reality is that it’s going to carry a number of characteristics that could also be symptomatic of COVID. And nothing changes: You have to rule it out, just to eliminate the risk.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente. This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.

Worry over family, friends the main driver of COVID-19 stress

Individuals are more worried about family members becoming ill with COVID-19 or about unknowingly transmitting the disease to family members than they are about contracting it themselves, results of a new survey show.

Investigators surveyed over 3,000 adults, using an online questionnaire. Of the respondents, about 20% were health care workers, and most were living in locations with active stay-at-home orders at the time of the survey.

Close to half of participants were worried about family members contracting the virus, one third were worried about unknowingly infecting others, and 20% were worried about contracting the virus themselves.

“We were a little surprised to see that people were more concerned about others than about themselves, specifically worrying about whether a family member would contract COVID-19 and whether they might unintentionally infect others,” lead author Ran Barzilay, MD, PhD, child and adolescent psychiatrist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), told Medscape Medical News.

The study was published online August 20 in Translational Psychiatry.

Interactive platform

“The pandemic has provided a unique opportunity to study resilience in healthcare professionals and others,” said Barzilay, assistant professor at the Lifespan Brain Institute, a collaboration between CHOP and the University of Pennsylvania, under the directorship of Raquel Gur, MD, PhD.

“After the pandemic broke out in March, we launched a website in early April where we surveyed people for levels of resilience, mental health, and well-being during the outbreak,” he added.

Survey participants then shared it with their contacts.

“To date, over 7000 people have completed it – mostly from the US but also from Israel,” Barzilay said.

The survey was anonymous, but participants could choose to have follow-up contact. The survey included an interactive 21-item resilience questionnaire and an assessment of COVID-19-related items related to worries concerning the following: contracting, dying from, or currently having the illness; having a family member contract the illness; unknowingly infecting others; and experiencing significant financial burden.

A total of 1350 participants took a second survey on anxiety and depression that utilized the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 and the Patient Health Questionnaire–2.

“What makes the survey unique is that it’s not just a means of collecting data but also an interactive platform that gives participants immediate personalized feedback, based on their responses to the resilience and well-being surveys, with practical tips and recommendations for stress management and ways of boosting resilience,” Barzilay said.

Tend and befriend

Ten days into the survey, data were available on 3,042 participants (64% women, 54% with advanced education, 20.5% health care providers), who ranged in age from 18 to 70 years (mean [SD], 38.9 [11.9] years).

After accounting for covariates, the researchers found that participants reported more distress about family members contracting COVID-19 and about unknowingly infecting others than about getting COVID-19 themselves (48.5% and 36% vs. 19.9%, respectively; P < .0005).

Increased COVID-19-related worries were associated with 22% higher anxiety and 16.1% higher depression scores; women had higher scores than men on both.

Each 1-SD increase in the composite score of COVID-19 worries was associated with over twice the increased probability of generalized anxiety and depression (odds ratio, 2.23; 95% confidence interval, 1.88-2.65; and OR, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.41-1.98, respectively; for both, P < .001).

On the other hand, for every 1-SD increase in the resilience score, there was a 64.9% decrease in the possibility of screening positive for generalized anxiety disorder and a 69.3% decrease in the possibility of screening positive for depression (for both, P < .0001).

Compared to participants from Israel, US participants were “more stressed” about contracting, dying from, and currently having COVID-19 themselves. Overall, Israeli participants scored higher than US participants on the resilience scale.

Rates of anxiety and depression did not differ significantly between healthcare providers and others. Health care providers worried more about contracting COVID-19 themselves and worried less about finances after COVID-19.

The authors propose that survey participants were more worried about others than about themselves because of “prosocial behavior under stress” and “tend-and-befriend,” whereby, “in response to threat, humans tend to protect their close ones (tending) and seek out their social group for mutual defense (befriending).”

This type of altruistic behavior has been “described in acute situations throughout history” and has been “linked to mechanisms of resilience for overcoming adversity,” the authors indicate.

Demographic biases

Commenting on the findings for Medscape Medical News, Golnaz Tabibnia, PhD, a neuroscientist at the University of California, Irvine, who was not involved in the research, suggested that although higher resilience scores were associated with lower COVID-related worries, it is possible, “as the authors suggest, that having more resilience resources makes you less worried, but the causality could go the other direction as well, and less worry/rumination may lead to more resilience.”

Also commenting on the study for Medscape Medical News, Christiaan Vinkers, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist at the Amsterdam University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, said it was noteworthy that healthcare providers reported similar levels of mood and anxiety symptoms, compared to others.

“This is encouraging, as it suggests adequate resilience levels in professionals who work in the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic,” he said.

Resilience occurs not only at the individual level but also at the community level, which may help explain the striking differences in COVID-19-related worries and anxiety between participants from the United States and Israel, Vinkers added.

E. Alison Holman, PhD, professor, Sue and Bill Gross School of Nursing, University of California, Irvine, noted that respondents were predominantly white, female, and had relatively high incomes, “suggesting strong demographic biases in those who chose to participate.”

Holman, who was not involved with the study, told Medscape Medical News that the “findings do not address the real impact of COVID-19 on the hardest-hit communities in America – poor, Black, and Latinx communities, where a large proportion of essential workers live.”

Barzilay acknowledged that, “unfortunately, because of the way the study was circulated, it did not reach minorities, which is one of the things we want to improve.”

The study is ongoing and has been translated into Spanish, French, and Hebrew. The team plans to collect data on diverse populations.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Lifespan Brain Institute of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Penn Medicine, the University of Pennsylvania, and in part by the Zuckerman STEM Leadership Program. Barzilay serves on the scientific board and reports stock ownership in Taliaz Health. The other authors, Golnaz, Vinkers, and Holman have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Individuals are more worried about family members becoming ill with COVID-19 or about unknowingly transmitting the disease to family members than they are about contracting it themselves, results of a new survey show.

Investigators surveyed over 3,000 adults, using an online questionnaire. Of the respondents, about 20% were health care workers, and most were living in locations with active stay-at-home orders at the time of the survey.

Close to half of participants were worried about family members contracting the virus, one third were worried about unknowingly infecting others, and 20% were worried about contracting the virus themselves.

“We were a little surprised to see that people were more concerned about others than about themselves, specifically worrying about whether a family member would contract COVID-19 and whether they might unintentionally infect others,” lead author Ran Barzilay, MD, PhD, child and adolescent psychiatrist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), told Medscape Medical News.

The study was published online August 20 in Translational Psychiatry.

Interactive platform

“The pandemic has provided a unique opportunity to study resilience in healthcare professionals and others,” said Barzilay, assistant professor at the Lifespan Brain Institute, a collaboration between CHOP and the University of Pennsylvania, under the directorship of Raquel Gur, MD, PhD.

“After the pandemic broke out in March, we launched a website in early April where we surveyed people for levels of resilience, mental health, and well-being during the outbreak,” he added.

Survey participants then shared it with their contacts.

“To date, over 7000 people have completed it – mostly from the US but also from Israel,” Barzilay said.

The survey was anonymous, but participants could choose to have follow-up contact. The survey included an interactive 21-item resilience questionnaire and an assessment of COVID-19-related items related to worries concerning the following: contracting, dying from, or currently having the illness; having a family member contract the illness; unknowingly infecting others; and experiencing significant financial burden.

A total of 1350 participants took a second survey on anxiety and depression that utilized the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 and the Patient Health Questionnaire–2.

“What makes the survey unique is that it’s not just a means of collecting data but also an interactive platform that gives participants immediate personalized feedback, based on their responses to the resilience and well-being surveys, with practical tips and recommendations for stress management and ways of boosting resilience,” Barzilay said.

Tend and befriend

Ten days into the survey, data were available on 3,042 participants (64% women, 54% with advanced education, 20.5% health care providers), who ranged in age from 18 to 70 years (mean [SD], 38.9 [11.9] years).

After accounting for covariates, the researchers found that participants reported more distress about family members contracting COVID-19 and about unknowingly infecting others than about getting COVID-19 themselves (48.5% and 36% vs. 19.9%, respectively; P < .0005).

Increased COVID-19-related worries were associated with 22% higher anxiety and 16.1% higher depression scores; women had higher scores than men on both.

Each 1-SD increase in the composite score of COVID-19 worries was associated with over twice the increased probability of generalized anxiety and depression (odds ratio, 2.23; 95% confidence interval, 1.88-2.65; and OR, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.41-1.98, respectively; for both, P < .001).

On the other hand, for every 1-SD increase in the resilience score, there was a 64.9% decrease in the possibility of screening positive for generalized anxiety disorder and a 69.3% decrease in the possibility of screening positive for depression (for both, P < .0001).

Compared to participants from Israel, US participants were “more stressed” about contracting, dying from, and currently having COVID-19 themselves. Overall, Israeli participants scored higher than US participants on the resilience scale.

Rates of anxiety and depression did not differ significantly between healthcare providers and others. Health care providers worried more about contracting COVID-19 themselves and worried less about finances after COVID-19.

The authors propose that survey participants were more worried about others than about themselves because of “prosocial behavior under stress” and “tend-and-befriend,” whereby, “in response to threat, humans tend to protect their close ones (tending) and seek out their social group for mutual defense (befriending).”

This type of altruistic behavior has been “described in acute situations throughout history” and has been “linked to mechanisms of resilience for overcoming adversity,” the authors indicate.

Demographic biases

Commenting on the findings for Medscape Medical News, Golnaz Tabibnia, PhD, a neuroscientist at the University of California, Irvine, who was not involved in the research, suggested that although higher resilience scores were associated with lower COVID-related worries, it is possible, “as the authors suggest, that having more resilience resources makes you less worried, but the causality could go the other direction as well, and less worry/rumination may lead to more resilience.”

Also commenting on the study for Medscape Medical News, Christiaan Vinkers, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist at the Amsterdam University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, said it was noteworthy that healthcare providers reported similar levels of mood and anxiety symptoms, compared to others.

“This is encouraging, as it suggests adequate resilience levels in professionals who work in the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic,” he said.

Resilience occurs not only at the individual level but also at the community level, which may help explain the striking differences in COVID-19-related worries and anxiety between participants from the United States and Israel, Vinkers added.

E. Alison Holman, PhD, professor, Sue and Bill Gross School of Nursing, University of California, Irvine, noted that respondents were predominantly white, female, and had relatively high incomes, “suggesting strong demographic biases in those who chose to participate.”

Holman, who was not involved with the study, told Medscape Medical News that the “findings do not address the real impact of COVID-19 on the hardest-hit communities in America – poor, Black, and Latinx communities, where a large proportion of essential workers live.”

Barzilay acknowledged that, “unfortunately, because of the way the study was circulated, it did not reach minorities, which is one of the things we want to improve.”

The study is ongoing and has been translated into Spanish, French, and Hebrew. The team plans to collect data on diverse populations.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Lifespan Brain Institute of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Penn Medicine, the University of Pennsylvania, and in part by the Zuckerman STEM Leadership Program. Barzilay serves on the scientific board and reports stock ownership in Taliaz Health. The other authors, Golnaz, Vinkers, and Holman have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Individuals are more worried about family members becoming ill with COVID-19 or about unknowingly transmitting the disease to family members than they are about contracting it themselves, results of a new survey show.

Investigators surveyed over 3,000 adults, using an online questionnaire. Of the respondents, about 20% were health care workers, and most were living in locations with active stay-at-home orders at the time of the survey.

Close to half of participants were worried about family members contracting the virus, one third were worried about unknowingly infecting others, and 20% were worried about contracting the virus themselves.

“We were a little surprised to see that people were more concerned about others than about themselves, specifically worrying about whether a family member would contract COVID-19 and whether they might unintentionally infect others,” lead author Ran Barzilay, MD, PhD, child and adolescent psychiatrist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), told Medscape Medical News.

The study was published online August 20 in Translational Psychiatry.

Interactive platform

“The pandemic has provided a unique opportunity to study resilience in healthcare professionals and others,” said Barzilay, assistant professor at the Lifespan Brain Institute, a collaboration between CHOP and the University of Pennsylvania, under the directorship of Raquel Gur, MD, PhD.

“After the pandemic broke out in March, we launched a website in early April where we surveyed people for levels of resilience, mental health, and well-being during the outbreak,” he added.

Survey participants then shared it with their contacts.

“To date, over 7000 people have completed it – mostly from the US but also from Israel,” Barzilay said.

The survey was anonymous, but participants could choose to have follow-up contact. The survey included an interactive 21-item resilience questionnaire and an assessment of COVID-19-related items related to worries concerning the following: contracting, dying from, or currently having the illness; having a family member contract the illness; unknowingly infecting others; and experiencing significant financial burden.

A total of 1350 participants took a second survey on anxiety and depression that utilized the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 and the Patient Health Questionnaire–2.

“What makes the survey unique is that it’s not just a means of collecting data but also an interactive platform that gives participants immediate personalized feedback, based on their responses to the resilience and well-being surveys, with practical tips and recommendations for stress management and ways of boosting resilience,” Barzilay said.

Tend and befriend

Ten days into the survey, data were available on 3,042 participants (64% women, 54% with advanced education, 20.5% health care providers), who ranged in age from 18 to 70 years (mean [SD], 38.9 [11.9] years).

After accounting for covariates, the researchers found that participants reported more distress about family members contracting COVID-19 and about unknowingly infecting others than about getting COVID-19 themselves (48.5% and 36% vs. 19.9%, respectively; P < .0005).

Increased COVID-19-related worries were associated with 22% higher anxiety and 16.1% higher depression scores; women had higher scores than men on both.

Each 1-SD increase in the composite score of COVID-19 worries was associated with over twice the increased probability of generalized anxiety and depression (odds ratio, 2.23; 95% confidence interval, 1.88-2.65; and OR, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.41-1.98, respectively; for both, P < .001).

On the other hand, for every 1-SD increase in the resilience score, there was a 64.9% decrease in the possibility of screening positive for generalized anxiety disorder and a 69.3% decrease in the possibility of screening positive for depression (for both, P < .0001).

Compared to participants from Israel, US participants were “more stressed” about contracting, dying from, and currently having COVID-19 themselves. Overall, Israeli participants scored higher than US participants on the resilience scale.

Rates of anxiety and depression did not differ significantly between healthcare providers and others. Health care providers worried more about contracting COVID-19 themselves and worried less about finances after COVID-19.

The authors propose that survey participants were more worried about others than about themselves because of “prosocial behavior under stress” and “tend-and-befriend,” whereby, “in response to threat, humans tend to protect their close ones (tending) and seek out their social group for mutual defense (befriending).”

This type of altruistic behavior has been “described in acute situations throughout history” and has been “linked to mechanisms of resilience for overcoming adversity,” the authors indicate.

Demographic biases

Commenting on the findings for Medscape Medical News, Golnaz Tabibnia, PhD, a neuroscientist at the University of California, Irvine, who was not involved in the research, suggested that although higher resilience scores were associated with lower COVID-related worries, it is possible, “as the authors suggest, that having more resilience resources makes you less worried, but the causality could go the other direction as well, and less worry/rumination may lead to more resilience.”

Also commenting on the study for Medscape Medical News, Christiaan Vinkers, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist at the Amsterdam University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, said it was noteworthy that healthcare providers reported similar levels of mood and anxiety symptoms, compared to others.

“This is encouraging, as it suggests adequate resilience levels in professionals who work in the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic,” he said.

Resilience occurs not only at the individual level but also at the community level, which may help explain the striking differences in COVID-19-related worries and anxiety between participants from the United States and Israel, Vinkers added.

E. Alison Holman, PhD, professor, Sue and Bill Gross School of Nursing, University of California, Irvine, noted that respondents were predominantly white, female, and had relatively high incomes, “suggesting strong demographic biases in those who chose to participate.”

Holman, who was not involved with the study, told Medscape Medical News that the “findings do not address the real impact of COVID-19 on the hardest-hit communities in America – poor, Black, and Latinx communities, where a large proportion of essential workers live.”

Barzilay acknowledged that, “unfortunately, because of the way the study was circulated, it did not reach minorities, which is one of the things we want to improve.”

The study is ongoing and has been translated into Spanish, French, and Hebrew. The team plans to collect data on diverse populations.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Lifespan Brain Institute of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Penn Medicine, the University of Pennsylvania, and in part by the Zuckerman STEM Leadership Program. Barzilay serves on the scientific board and reports stock ownership in Taliaz Health. The other authors, Golnaz, Vinkers, and Holman have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

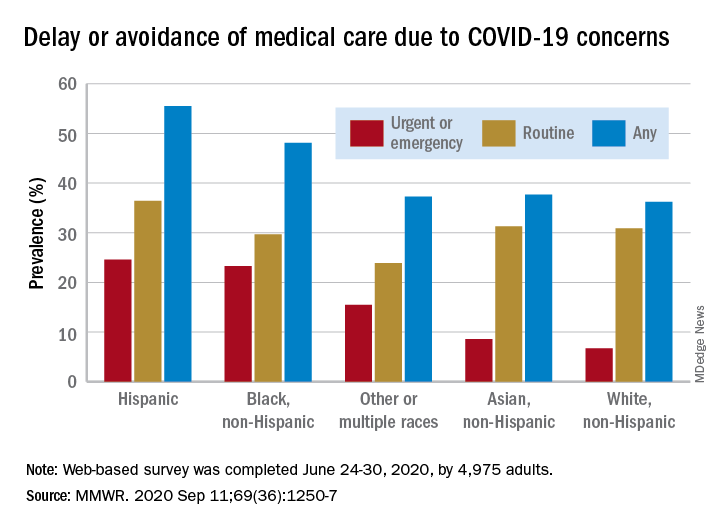

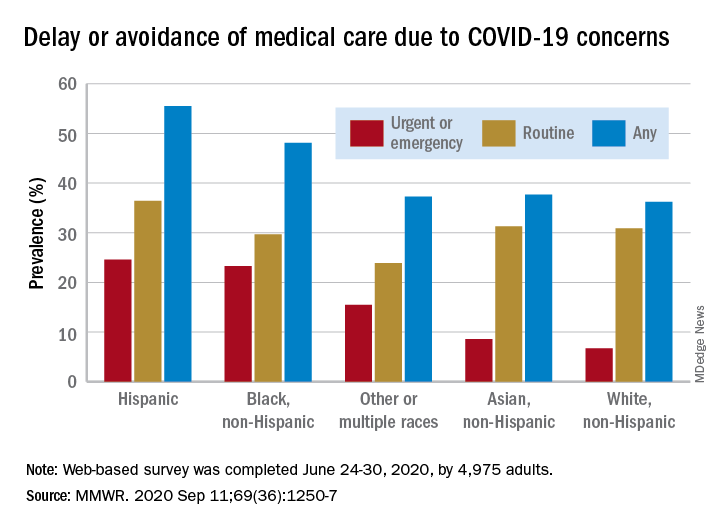

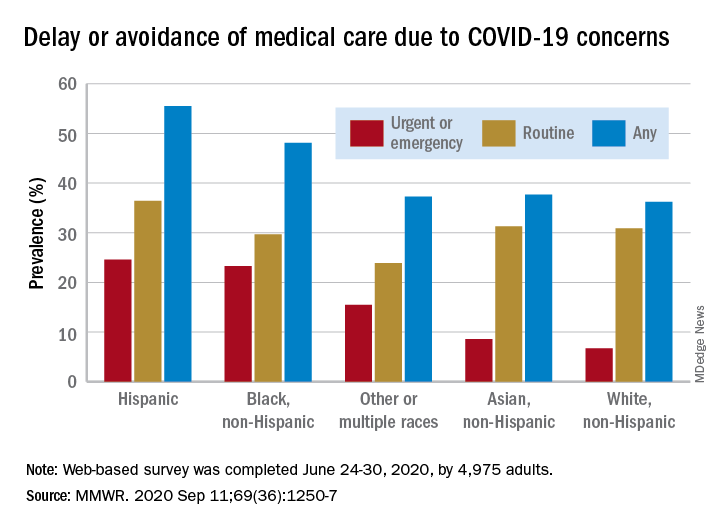

Disparities seen in COVID-19–related avoidance of care

In the early weeks and months of the COVID-19 pandemic, many people were trying to avoid the coronavirus by staying away from emergency rooms and medical offices. But how many people is “many”?

Turns out almost 41% of Americans delayed or avoided some form of medical care because of concerns about COVID-19, according to the results of a survey conducted June 24-30 by commercial survey company Qualtrics.

More specifically, the avoidance looks like this: 31.5% of the 4,975 adult respondents had avoided routine care and 12.0% had avoided urgent or emergency care, Mark E. Czeisler and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The two categories were not mutually exclusive since respondents could select both routine care and urgent/emergency care.

There were, however, a number of significant disparities hidden among those numbers for the overall population. Blacks and Hispanics, with respective prevalences of 23.3% and 24.6%, were significantly more likely to delay or avoid urgent/emergency care than were Whites (6.7%), said Mr. Czeisler, a graduate student at Monash University, Melbourne, and associates.

Those differences “are especially concerning given increased COVID-19–associated mortality among Black adults and Hispanic adults,” they noted, adding that “age-adjusted COVID-19 hospitalization rates are approximately five times higher among Black persons and four times higher among Hispanic persons than” among Whites.

Other significant disparities in urgent/emergency care avoidance included the following:

- Unpaid caregivers for adults (29.8%) vs. noncaregivers (5.4%).

- Adults with two or more underlying conditions (22.7%) vs. those without such conditions (8.2%).

- Those with a disability (22.8%) vs. those without (8.9%).

- Those with health insurance (12.4%) vs. those without (7.8%).

The highest prevalence for all types of COVID-19–related delay and avoidance came from the adult caregivers (64.3%), followed by those with a disability (60.3%) and adults aged 18-24 years (57.2%). The lowest prevalence numbers were for adults with health insurance (24.8%) and those who were not caregivers for adults (32.2%), Mr. Czeisler and associates reported.

These reports of delayed and avoided care “might reflect adherence to community mitigation efforts such as stay-at-home orders, temporary closures of health facilities, or additional factors. However, if routine care avoidance were to be sustained, adults could miss opportunities for management of chronic conditions, receipt of routine vaccinations, or early detection of new conditions, which might worsen outcomes,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Czeisler ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Sep 11;69(36):1250-7.

In the early weeks and months of the COVID-19 pandemic, many people were trying to avoid the coronavirus by staying away from emergency rooms and medical offices. But how many people is “many”?

Turns out almost 41% of Americans delayed or avoided some form of medical care because of concerns about COVID-19, according to the results of a survey conducted June 24-30 by commercial survey company Qualtrics.

More specifically, the avoidance looks like this: 31.5% of the 4,975 adult respondents had avoided routine care and 12.0% had avoided urgent or emergency care, Mark E. Czeisler and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The two categories were not mutually exclusive since respondents could select both routine care and urgent/emergency care.

There were, however, a number of significant disparities hidden among those numbers for the overall population. Blacks and Hispanics, with respective prevalences of 23.3% and 24.6%, were significantly more likely to delay or avoid urgent/emergency care than were Whites (6.7%), said Mr. Czeisler, a graduate student at Monash University, Melbourne, and associates.

Those differences “are especially concerning given increased COVID-19–associated mortality among Black adults and Hispanic adults,” they noted, adding that “age-adjusted COVID-19 hospitalization rates are approximately five times higher among Black persons and four times higher among Hispanic persons than” among Whites.

Other significant disparities in urgent/emergency care avoidance included the following:

- Unpaid caregivers for adults (29.8%) vs. noncaregivers (5.4%).

- Adults with two or more underlying conditions (22.7%) vs. those without such conditions (8.2%).

- Those with a disability (22.8%) vs. those without (8.9%).

- Those with health insurance (12.4%) vs. those without (7.8%).

The highest prevalence for all types of COVID-19–related delay and avoidance came from the adult caregivers (64.3%), followed by those with a disability (60.3%) and adults aged 18-24 years (57.2%). The lowest prevalence numbers were for adults with health insurance (24.8%) and those who were not caregivers for adults (32.2%), Mr. Czeisler and associates reported.

These reports of delayed and avoided care “might reflect adherence to community mitigation efforts such as stay-at-home orders, temporary closures of health facilities, or additional factors. However, if routine care avoidance were to be sustained, adults could miss opportunities for management of chronic conditions, receipt of routine vaccinations, or early detection of new conditions, which might worsen outcomes,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Czeisler ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Sep 11;69(36):1250-7.

In the early weeks and months of the COVID-19 pandemic, many people were trying to avoid the coronavirus by staying away from emergency rooms and medical offices. But how many people is “many”?

Turns out almost 41% of Americans delayed or avoided some form of medical care because of concerns about COVID-19, according to the results of a survey conducted June 24-30 by commercial survey company Qualtrics.

More specifically, the avoidance looks like this: 31.5% of the 4,975 adult respondents had avoided routine care and 12.0% had avoided urgent or emergency care, Mark E. Czeisler and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The two categories were not mutually exclusive since respondents could select both routine care and urgent/emergency care.

There were, however, a number of significant disparities hidden among those numbers for the overall population. Blacks and Hispanics, with respective prevalences of 23.3% and 24.6%, were significantly more likely to delay or avoid urgent/emergency care than were Whites (6.7%), said Mr. Czeisler, a graduate student at Monash University, Melbourne, and associates.

Those differences “are especially concerning given increased COVID-19–associated mortality among Black adults and Hispanic adults,” they noted, adding that “age-adjusted COVID-19 hospitalization rates are approximately five times higher among Black persons and four times higher among Hispanic persons than” among Whites.

Other significant disparities in urgent/emergency care avoidance included the following:

- Unpaid caregivers for adults (29.8%) vs. noncaregivers (5.4%).

- Adults with two or more underlying conditions (22.7%) vs. those without such conditions (8.2%).

- Those with a disability (22.8%) vs. those without (8.9%).

- Those with health insurance (12.4%) vs. those without (7.8%).

The highest prevalence for all types of COVID-19–related delay and avoidance came from the adult caregivers (64.3%), followed by those with a disability (60.3%) and adults aged 18-24 years (57.2%). The lowest prevalence numbers were for adults with health insurance (24.8%) and those who were not caregivers for adults (32.2%), Mr. Czeisler and associates reported.

These reports of delayed and avoided care “might reflect adherence to community mitigation efforts such as stay-at-home orders, temporary closures of health facilities, or additional factors. However, if routine care avoidance were to be sustained, adults could miss opportunities for management of chronic conditions, receipt of routine vaccinations, or early detection of new conditions, which might worsen outcomes,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Czeisler ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Sep 11;69(36):1250-7.

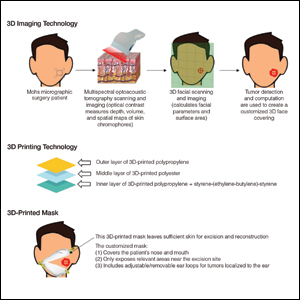

Use of 3D Technology to Support Dermatologists Returning to Practice Amid COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread across all 7 continents, including 185 countries, and infected more than 21.9 million individuals worldwide as of August 18, 2020, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. It has strained our health care system and affected all specialties, including dermatology. Dermatologists have taken important safety measures by canceling/deferring elective and nonemergency procedures and diagnosing/treating patients via telemedicine. Many residents and attending dermatologists have volunteered to care for COVID-19 inpatients and donated

N95 masks are necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic because they effectively filter at least 95% of 0.3-μm airborne particles and provide adequate face seals.1 3-Dimensional imaging integrated with 3D printers can be used to scan precise facial parameters (eg, jawline, nose) and account for facial hair density and length to produce comfortable tailored N95 masks and face seals.1,2 3-Dimensional printing utilizes robotics and

Face shields offer an additional layer of safety for the face and mucosae and also may provide longevity for N95 masks. Using synthetic polymers such as polycarbonate and polyethylene, 3D printers can be used to construct face shields via fused deposition modeling.1 These face shields may be worn over N95 masks and then can be sanitized and reused.

Mohs surgeons and staff may be at particularly high risk for COVID-19 infection due to their close proximity to the face during surgery, use of cautery, and prolonged time spent with patients while taking layers and suturing.

As dermatologists reopen and ramp up practice volume, there will be increased PPE requirements. Using 3D technology and imaging to produce N95 masks, face shields, and face coverings, we can offer effective diagnosis and treatment while optimizing safety for dermatologists, staff, and patients.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Applications of 3D printing technology to address COVID-19-related supply shortages [published online April 21, 2020]. Am J Med. 2020;133:771-773.

- Cai M, Li H, Shen S, et al. Customized design and 3D printing of face seal for an N95 filtering facepiece respirator. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2018;3:226-234.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. A review of 3-dimensional skin bioprinting techniques: applications, approaches, and trends [published online March 17, 2020]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002378.

- Banerjee SS, Burbine S, Shivaprakash NK, et al. 3D-printable PP/SEBS thermoplastic elastomeric blends: preparation and properties [published online February 17, 2019]. Polymers (Basel). doi:10.3390/polym11020347.

- Chuah SY, Attia ABE, Long V. Structural and functional 3D mapping of skin tumours with non-invasive multispectral optoacoustic tomography [published online November 2, 2016]. Skin Res Technol. 2017;23:221-226.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread across all 7 continents, including 185 countries, and infected more than 21.9 million individuals worldwide as of August 18, 2020, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. It has strained our health care system and affected all specialties, including dermatology. Dermatologists have taken important safety measures by canceling/deferring elective and nonemergency procedures and diagnosing/treating patients via telemedicine. Many residents and attending dermatologists have volunteered to care for COVID-19 inpatients and donated

N95 masks are necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic because they effectively filter at least 95% of 0.3-μm airborne particles and provide adequate face seals.1 3-Dimensional imaging integrated with 3D printers can be used to scan precise facial parameters (eg, jawline, nose) and account for facial hair density and length to produce comfortable tailored N95 masks and face seals.1,2 3-Dimensional printing utilizes robotics and

Face shields offer an additional layer of safety for the face and mucosae and also may provide longevity for N95 masks. Using synthetic polymers such as polycarbonate and polyethylene, 3D printers can be used to construct face shields via fused deposition modeling.1 These face shields may be worn over N95 masks and then can be sanitized and reused.

Mohs surgeons and staff may be at particularly high risk for COVID-19 infection due to their close proximity to the face during surgery, use of cautery, and prolonged time spent with patients while taking layers and suturing.

As dermatologists reopen and ramp up practice volume, there will be increased PPE requirements. Using 3D technology and imaging to produce N95 masks, face shields, and face coverings, we can offer effective diagnosis and treatment while optimizing safety for dermatologists, staff, and patients.